Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

A global survey on the state of democracy by fondation pour l’innovation politique and the international republican institute

42 countries, 33 languages, 66,395 interviewees

A 35-question survey

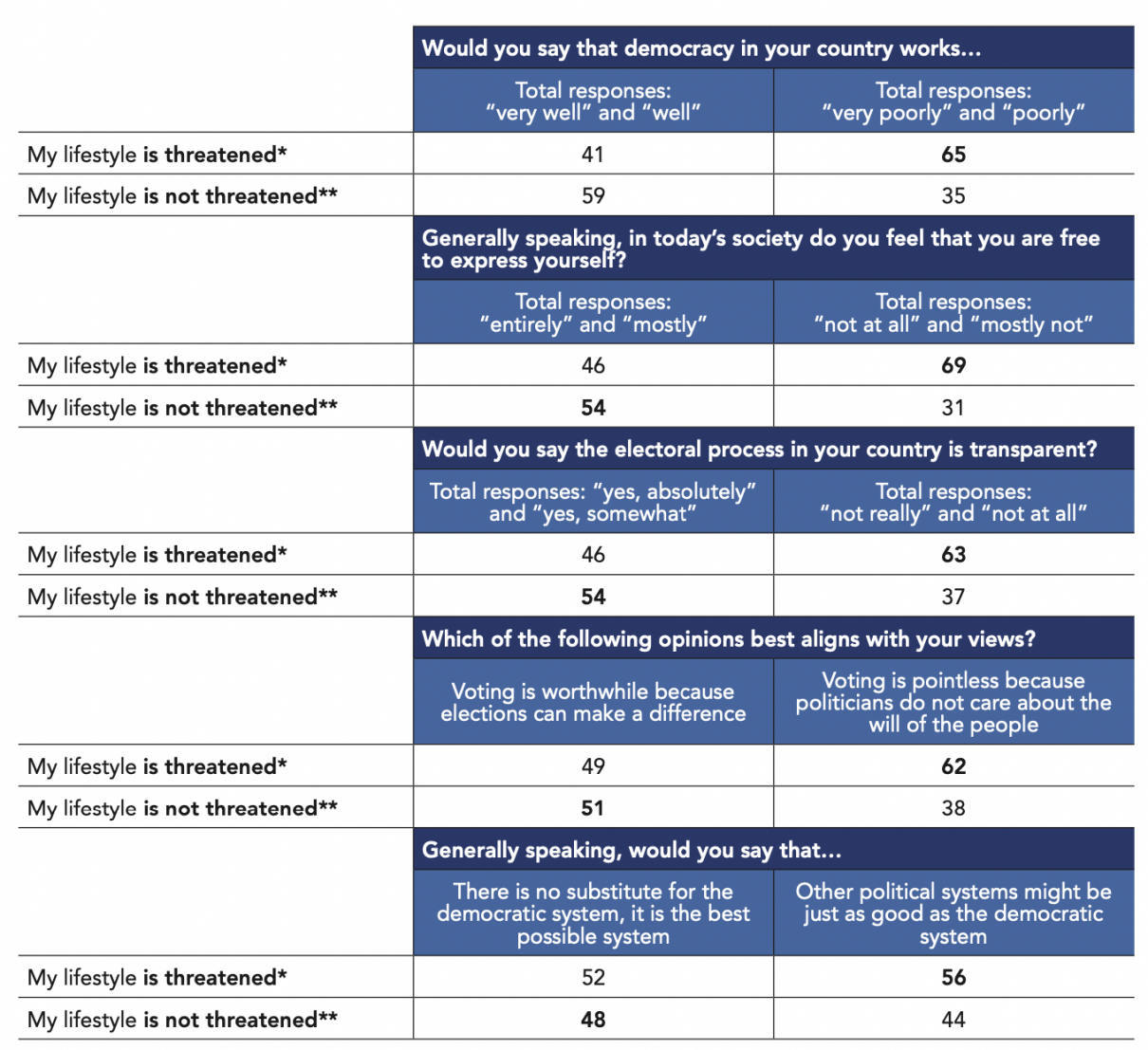

Fragile democracies

The ambiguity of commitment to democracy

The transparency of the electoral process called into question

Desinterest in politics erodes democratic ideals

Is the legitimacy of universal suffrage uncontested?

The ghosts of authoritarianism

Men and women hold different perspectives on democracy

Generational renewal: democratic deconsolidation or restructuring

Globalized democracies

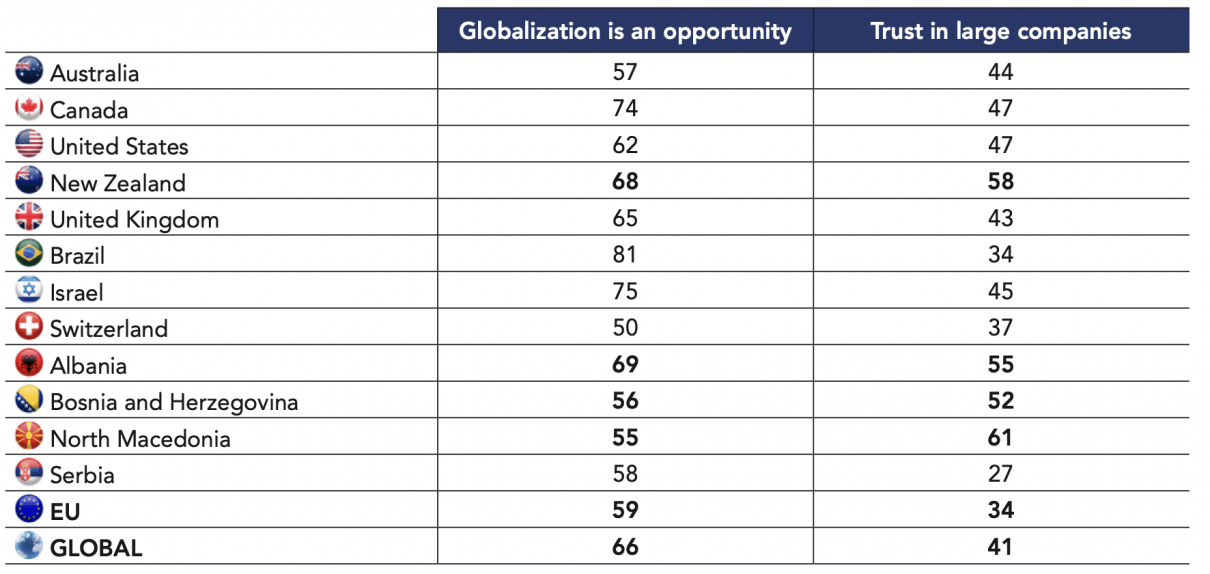

In the democratic world, globalization is an opportunity

The challenge of migration in the light of refugee issue

Territories in globalization: the metropolis and its surroundings

Islam causes concerns

Religion: tolerance and tensions

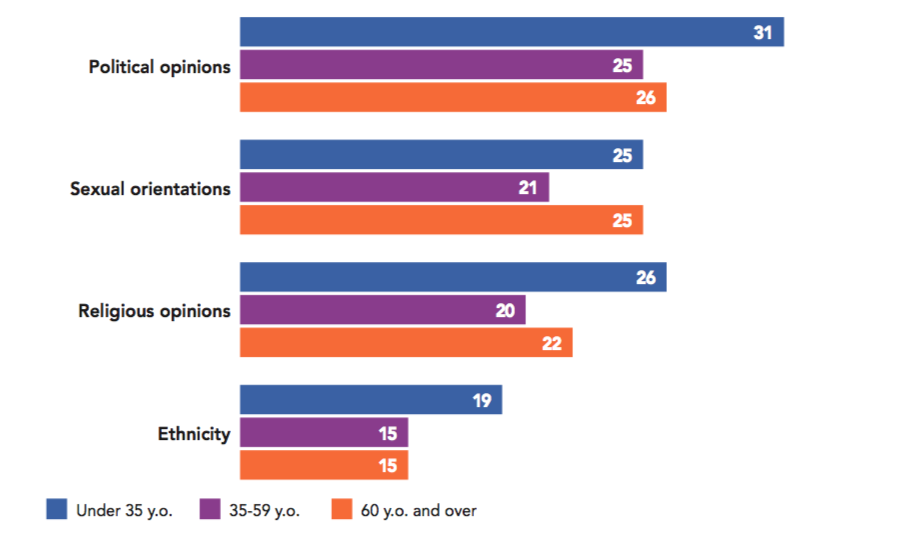

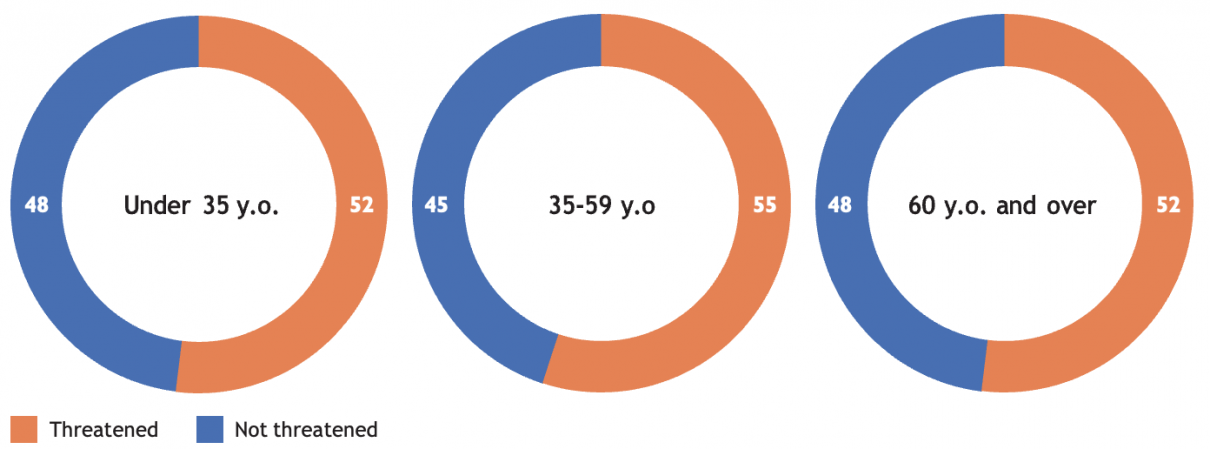

Tolerance, condition of a free society of free society: religious opinions, sexual orientations, political opinions, ethnicity

From social inequalities to social polarization : what globalization does to democracies

Who holds the power ?

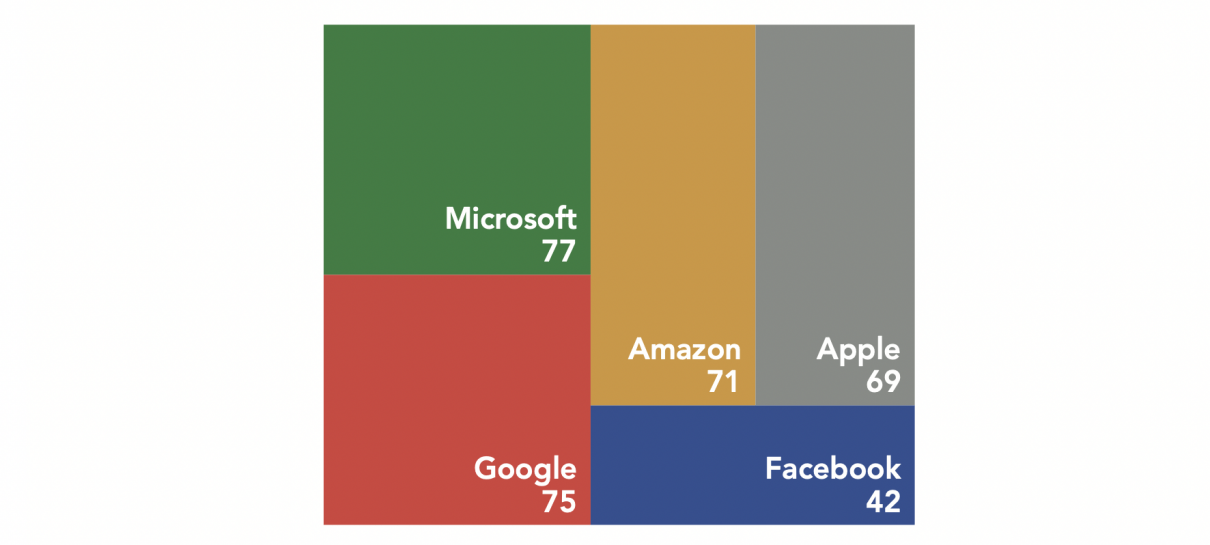

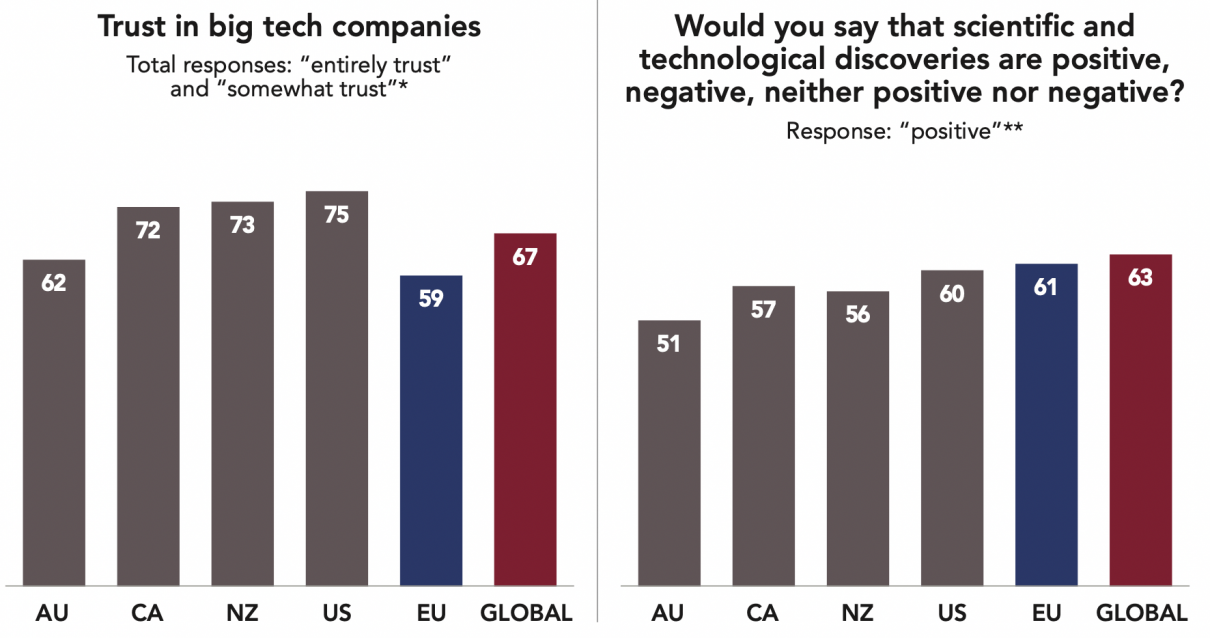

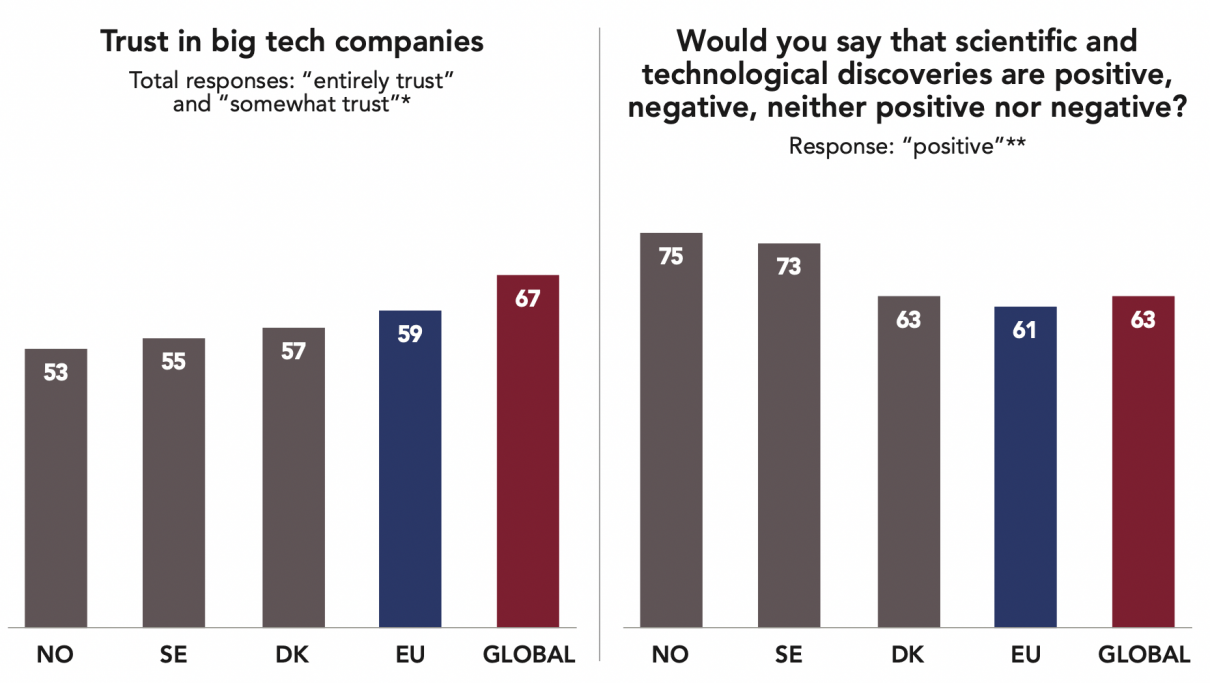

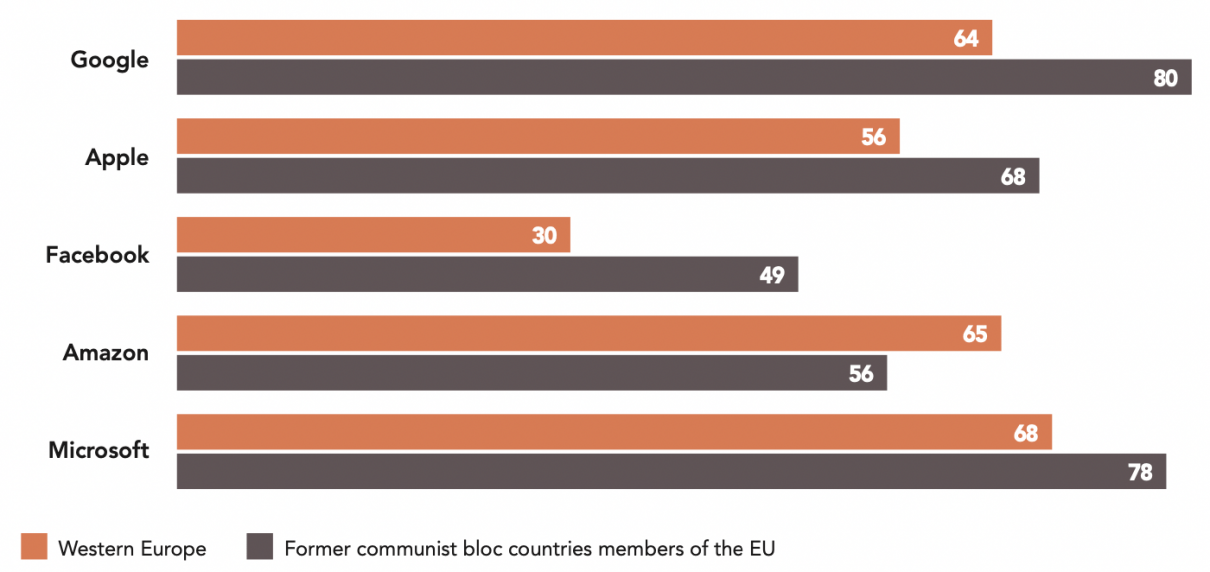

Trust in digital giants… with the exception of Facebook

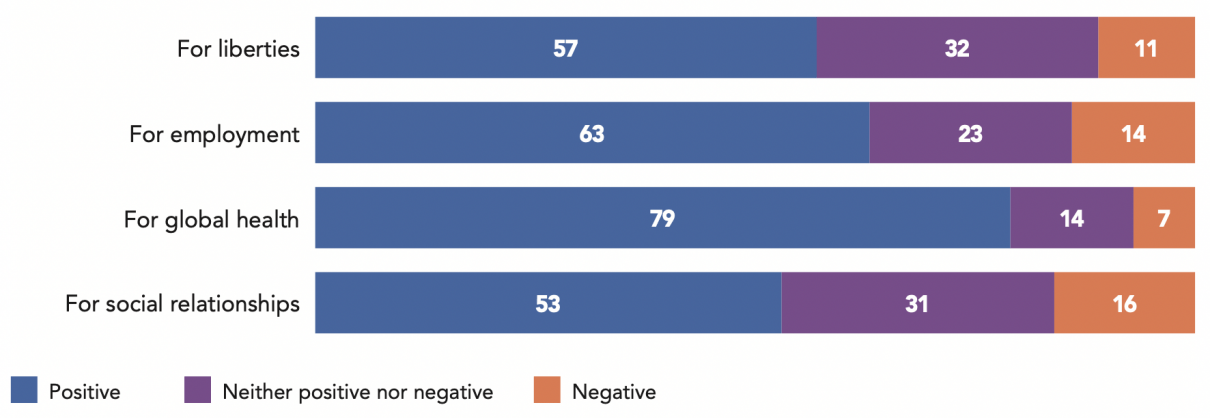

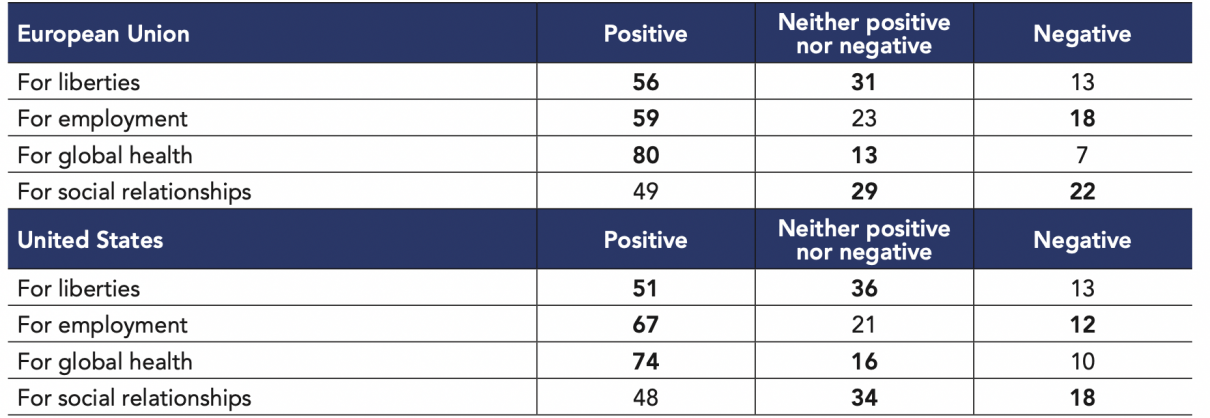

Scientific and technological innovations are seen as sources of progress

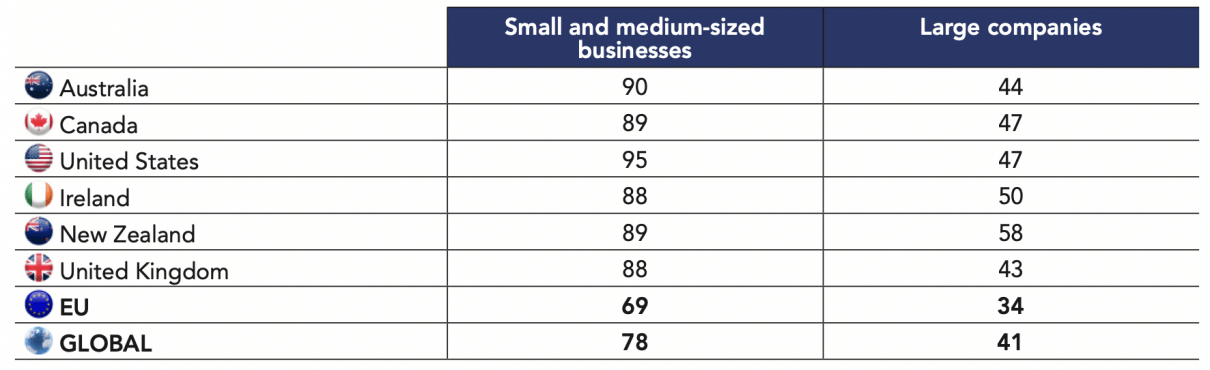

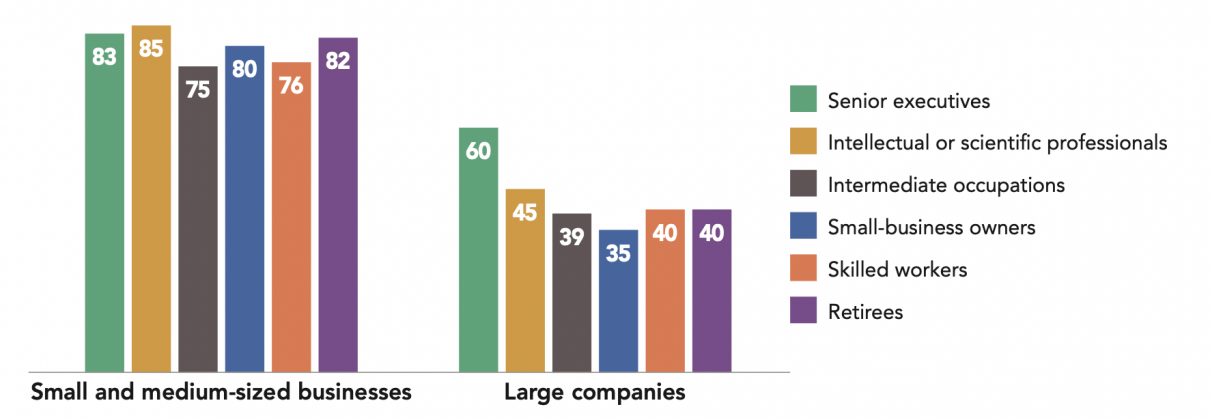

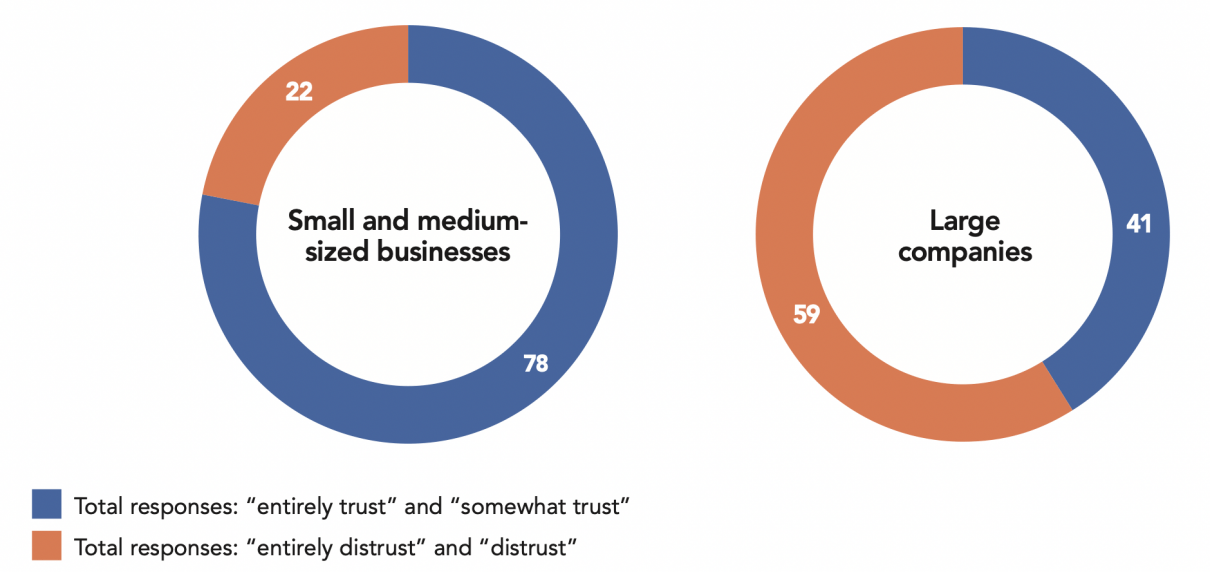

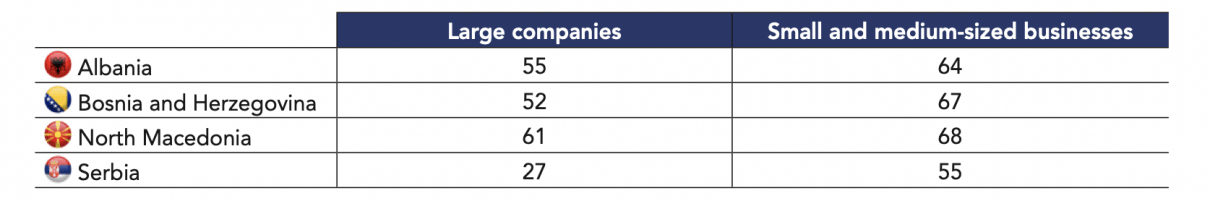

A fundamental part of the national economy or symbol of globalized capitalism: the size of companies shapes collective perceptions

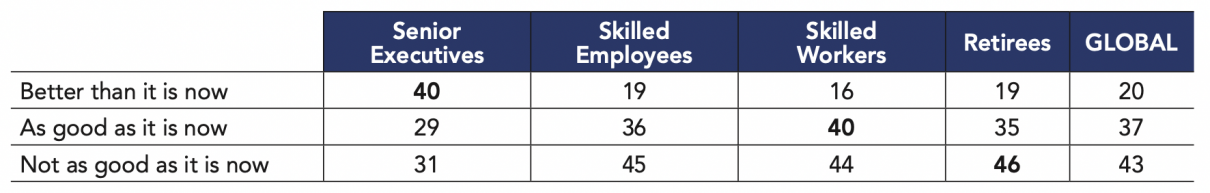

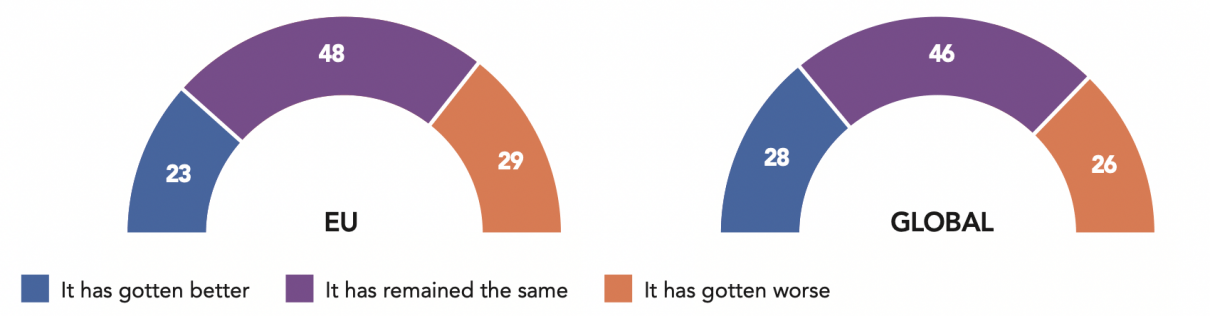

Standard of living and lifestyle : the twofold heritage crisis

Order and freedoms

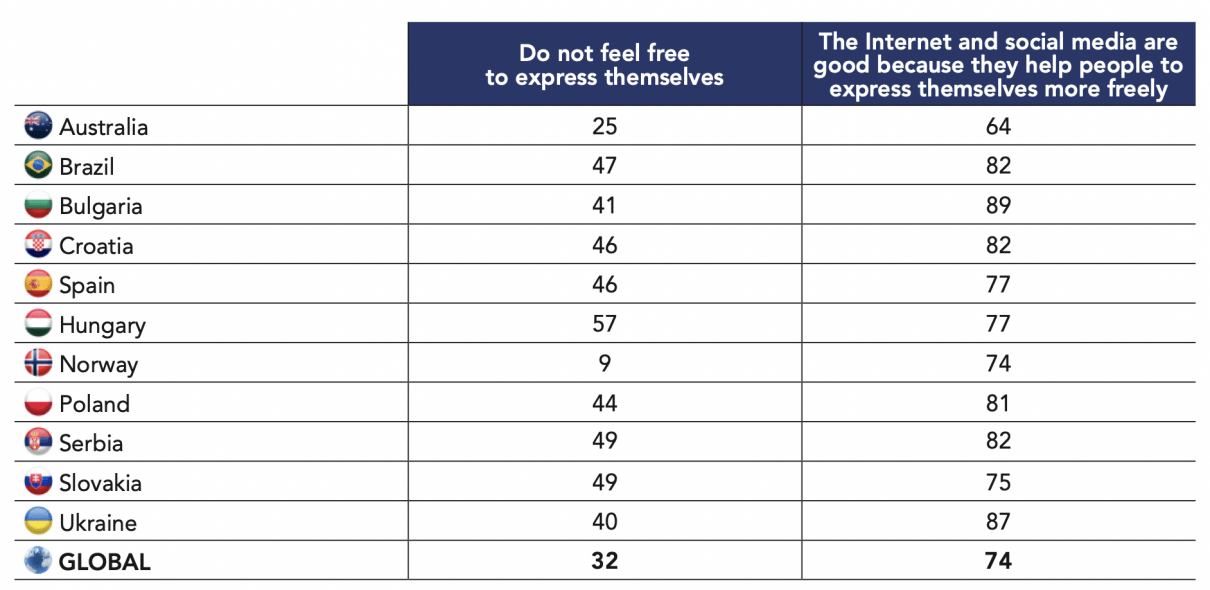

Not everyone takes freedom of expression for granted

Unanimous support for the broad principles of democratic expression

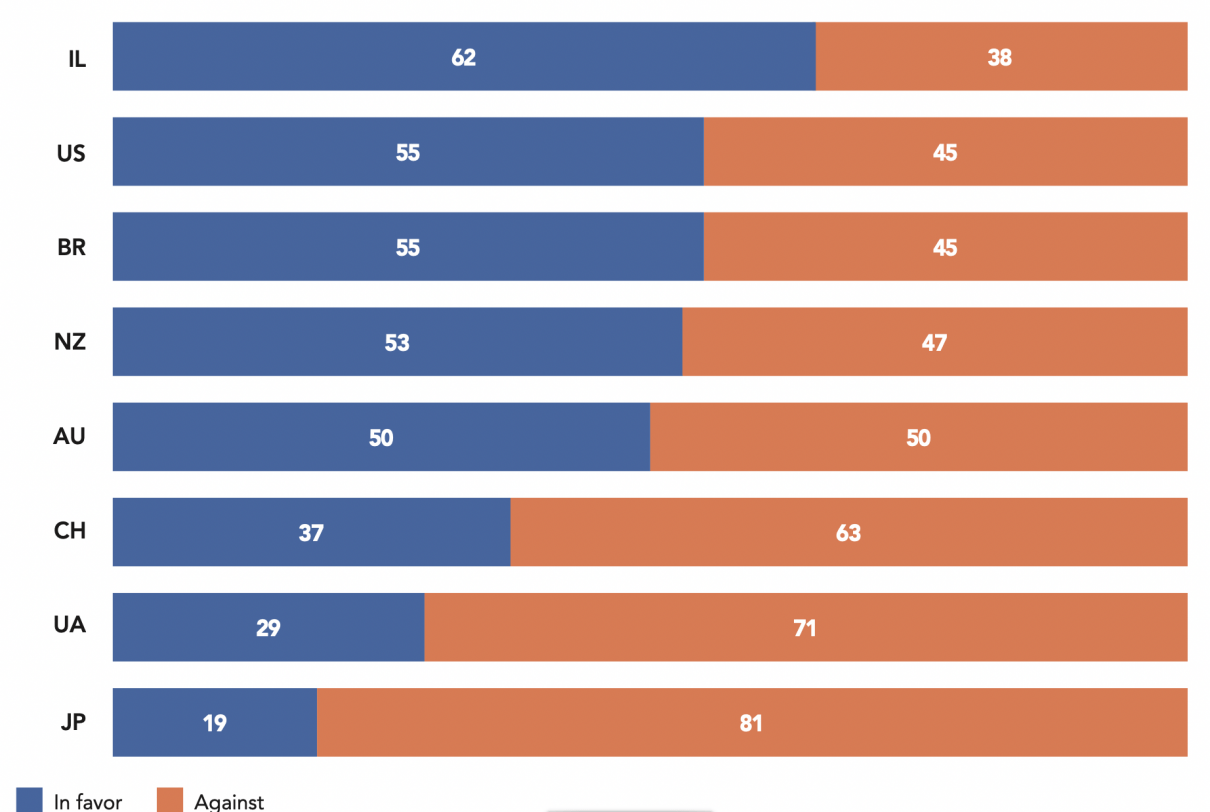

A majority of the democratic world is in favor of the death penalty

Abortion – between liberalization and moral resistance

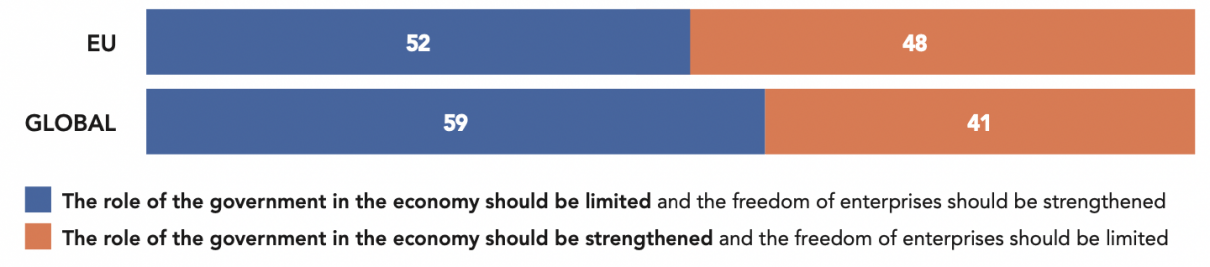

According to public opinion, the role of the state in the economy should be limited and the freedom of business increased

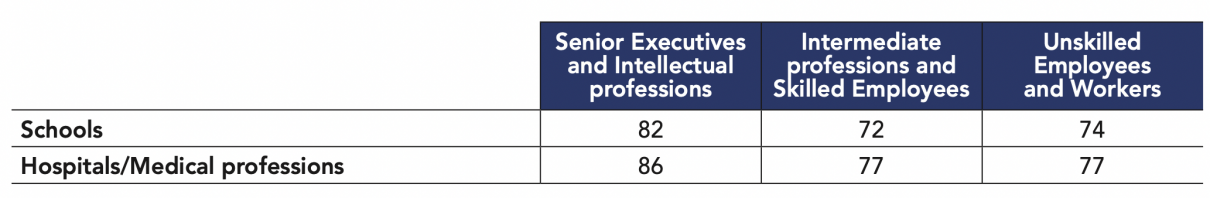

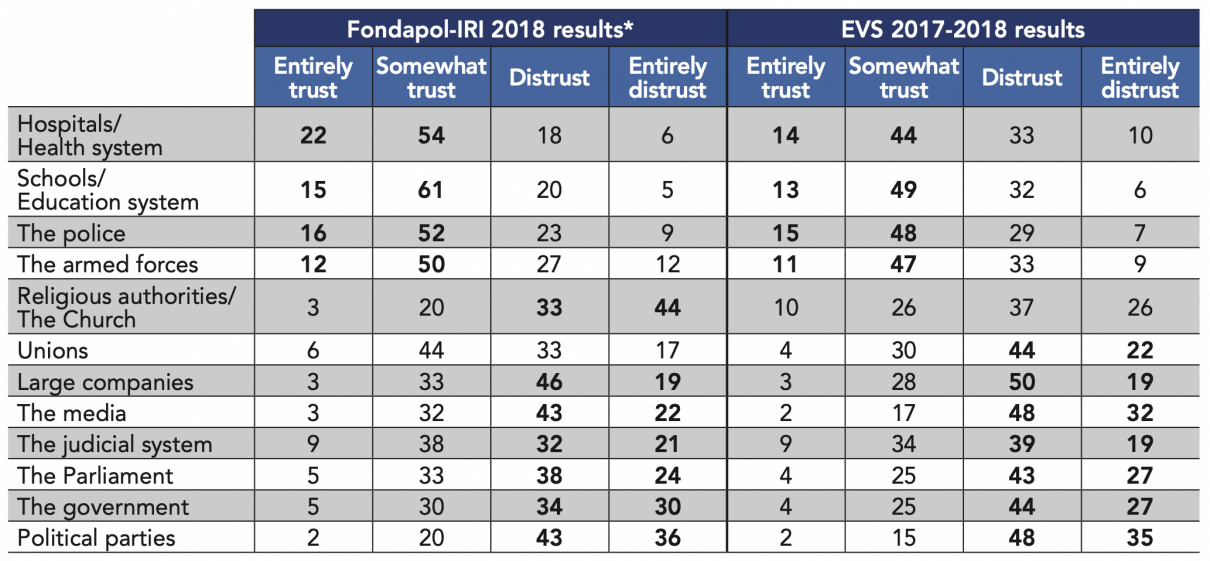

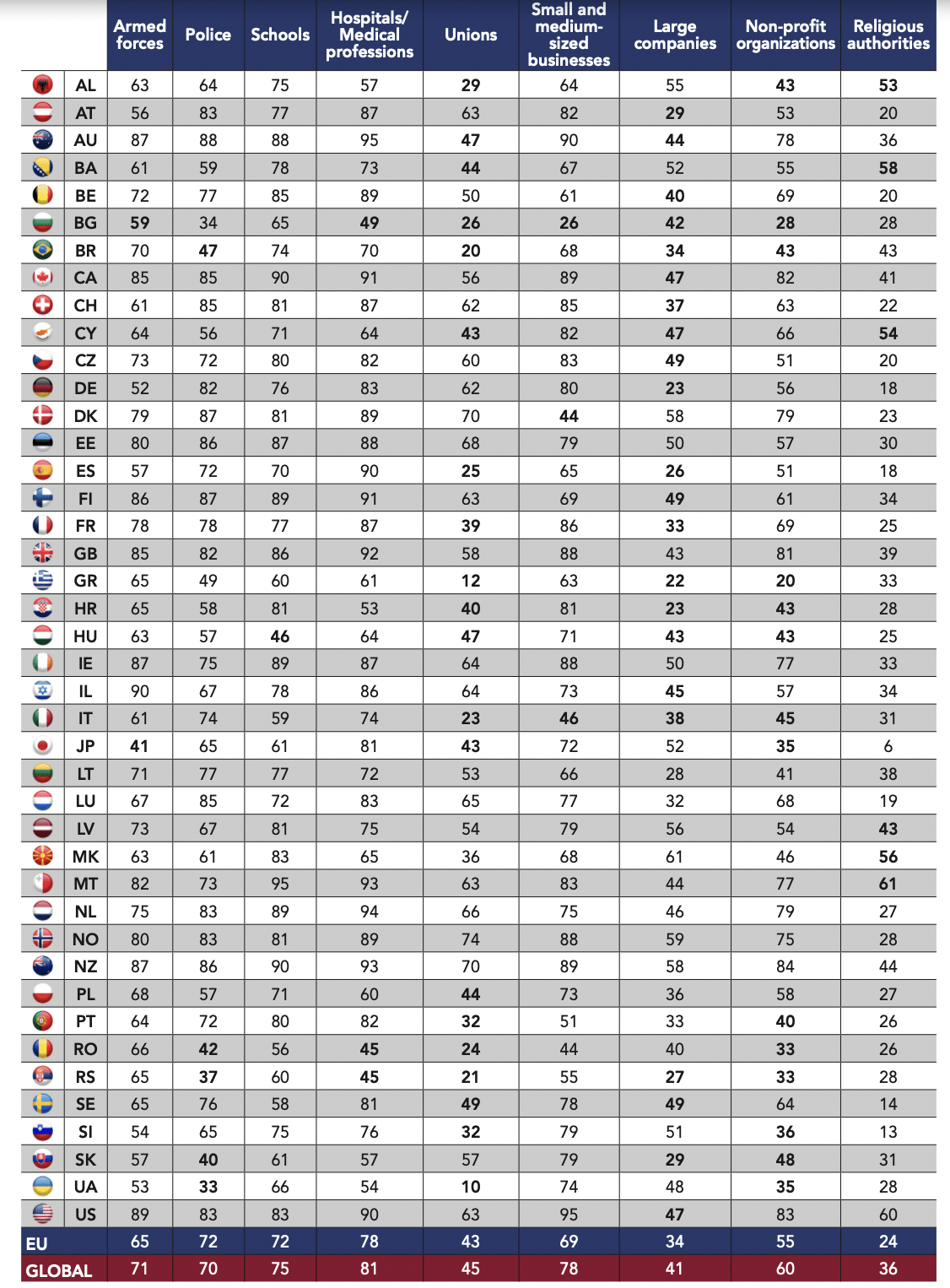

Schools and health services : particularly popular institutions

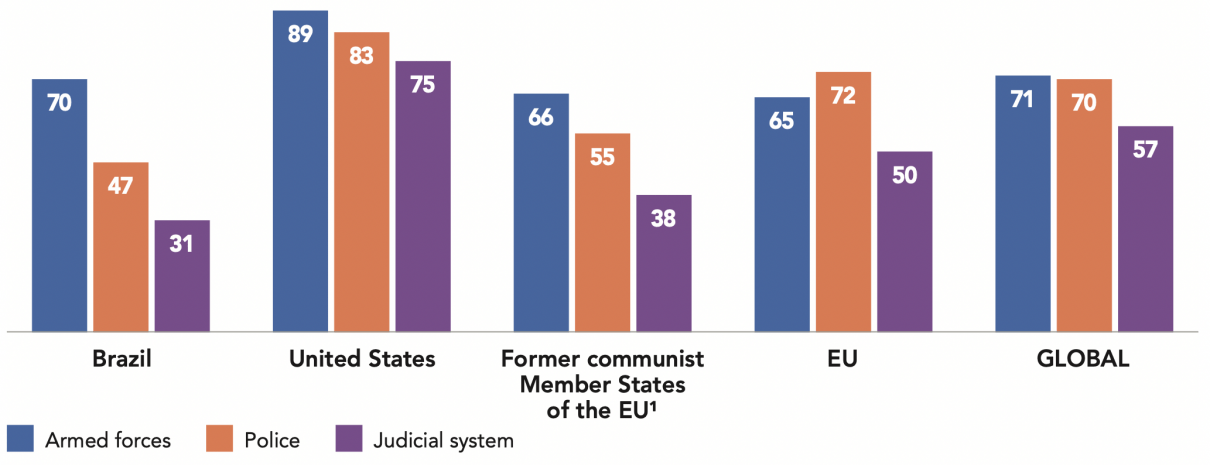

The army, police, and justice : strong support for institutions of law and order

Democracies under pressure and the European values studies : convergent data

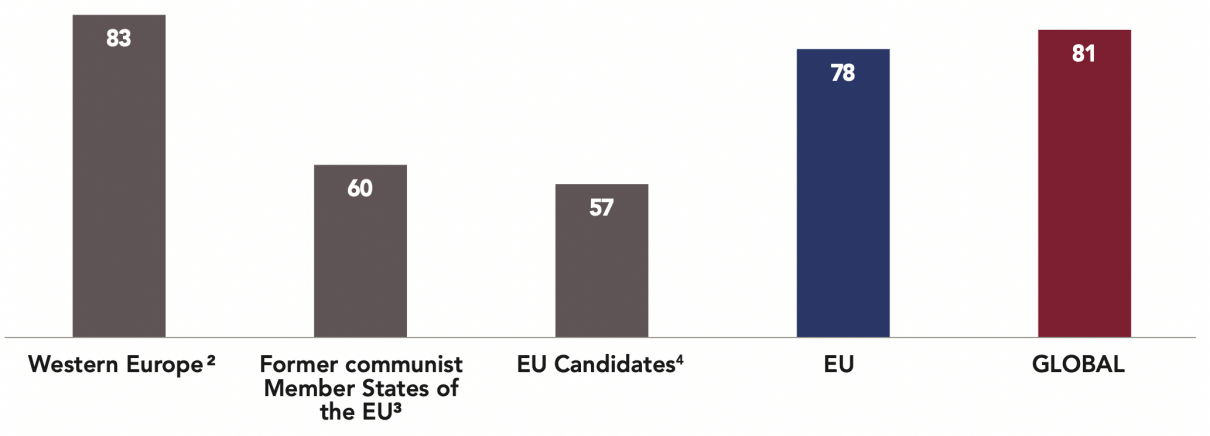

Europe and democracy : linked destinies

The western balkans* on the road to democracy

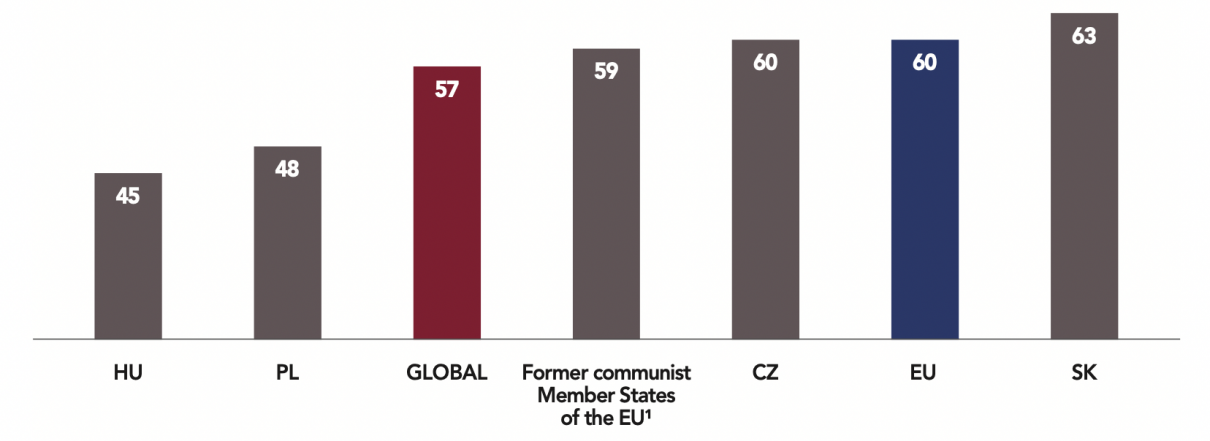

Hungarians, poles, Slovaks and Czechs feel that democracy is the best system

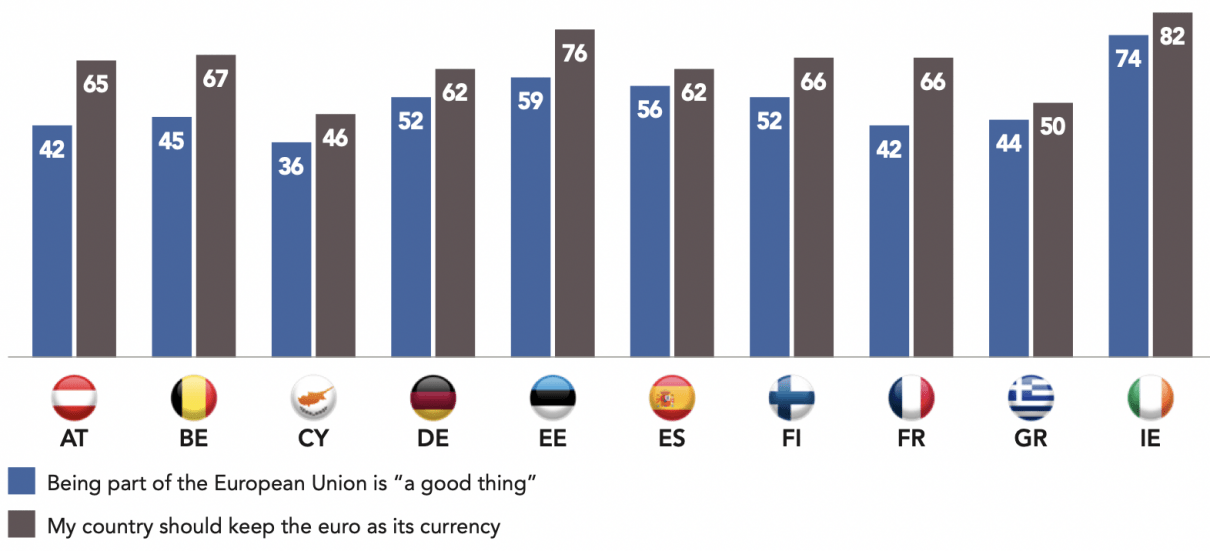

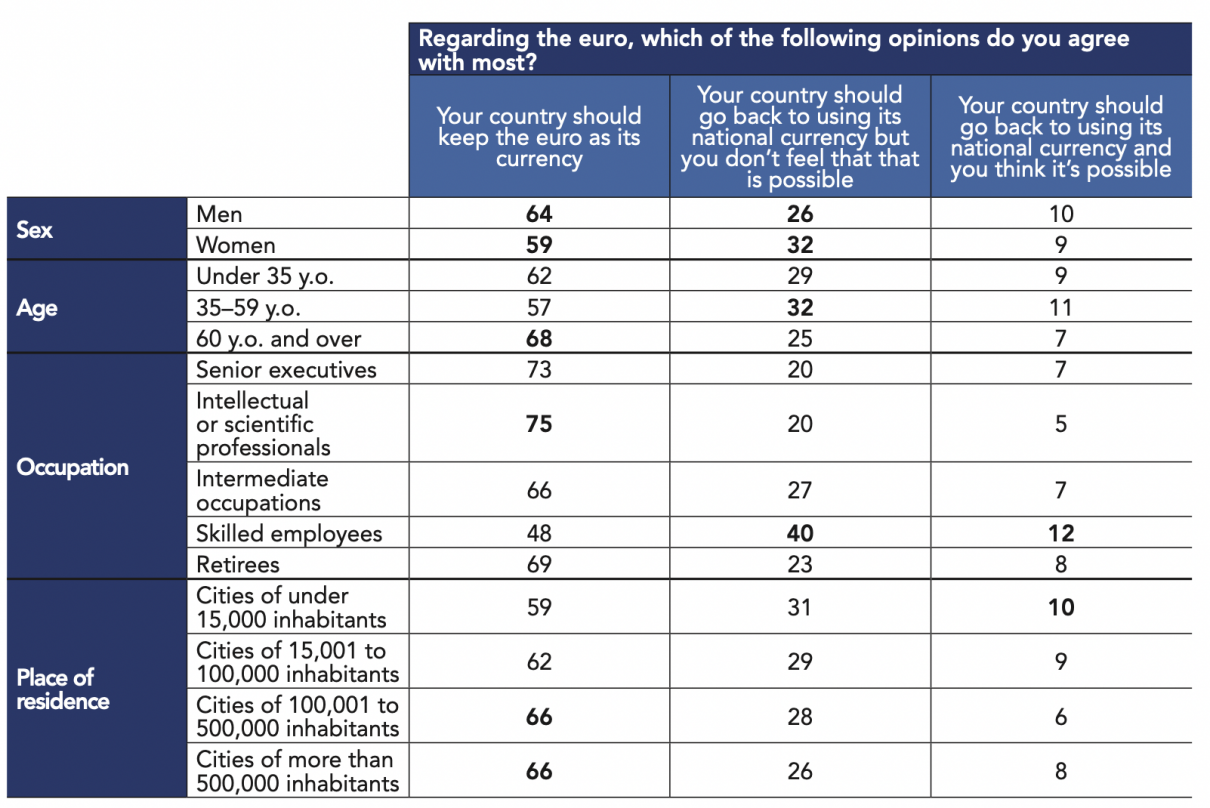

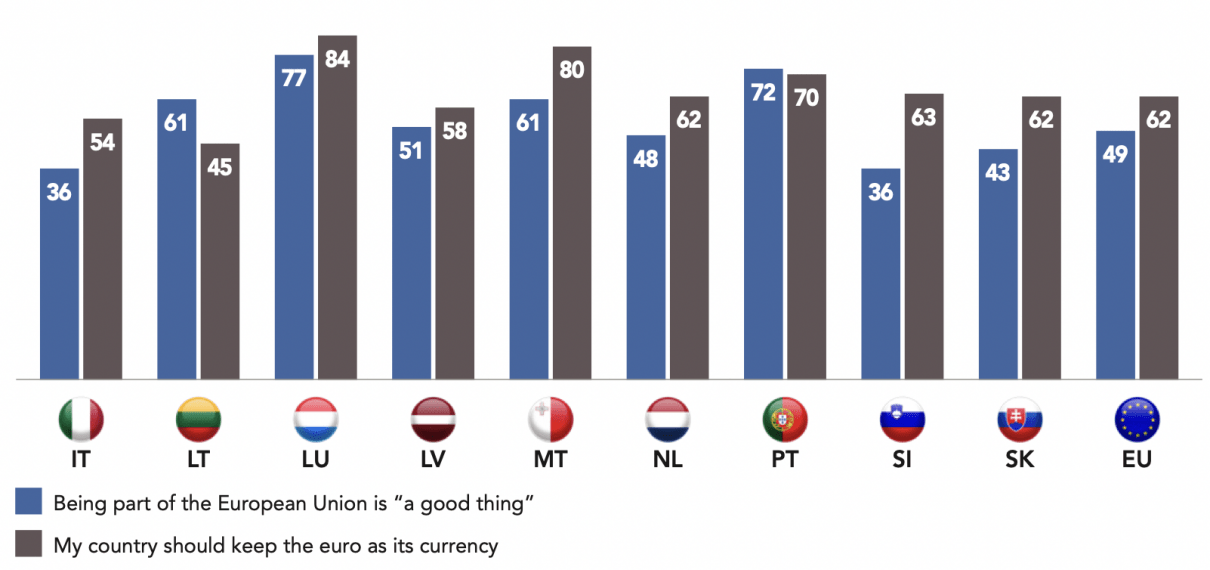

Support for the euro protects Europe

Brexit in the UK : a divided nation*

Brexit – a litmus test for generational divisions ?

The baltic states, between democratic ideals and authoritarian temptations

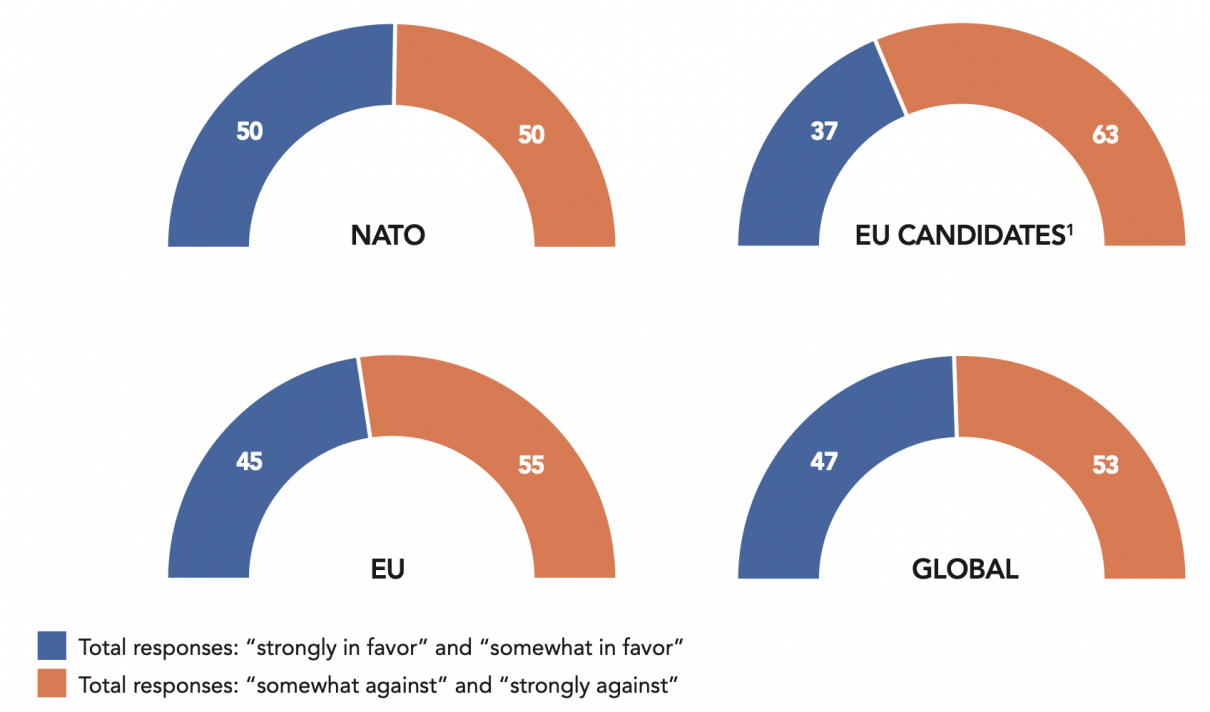

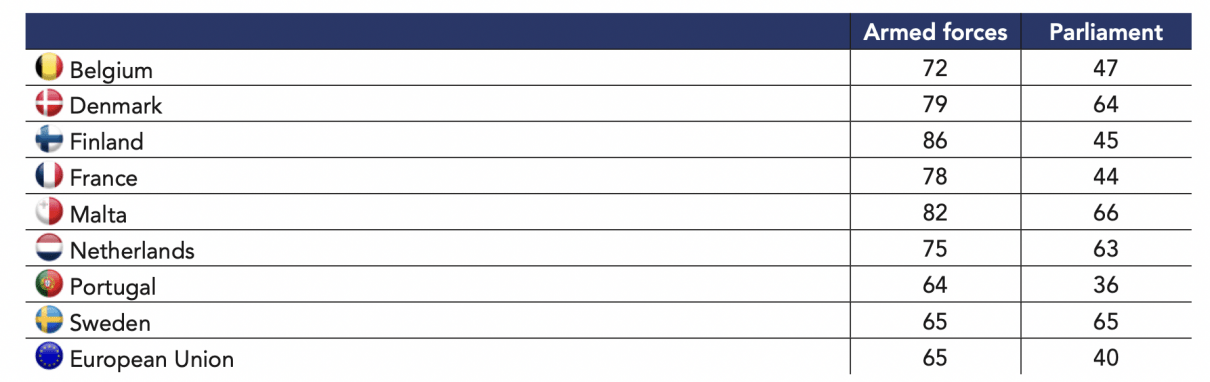

In the face of new threats, the revival of the idea of a European army

Europeans and the new public space : the media, social media & the internet

The democratic world on the defensive

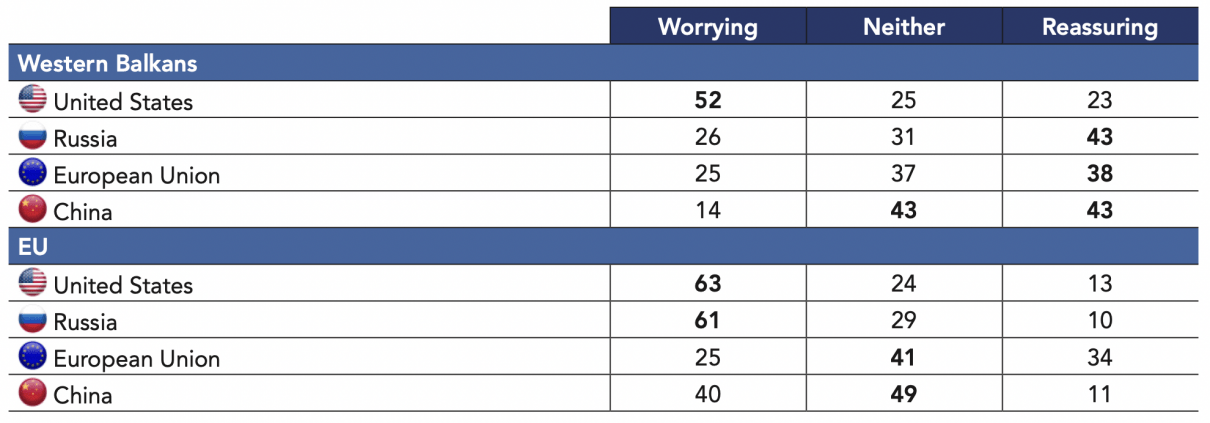

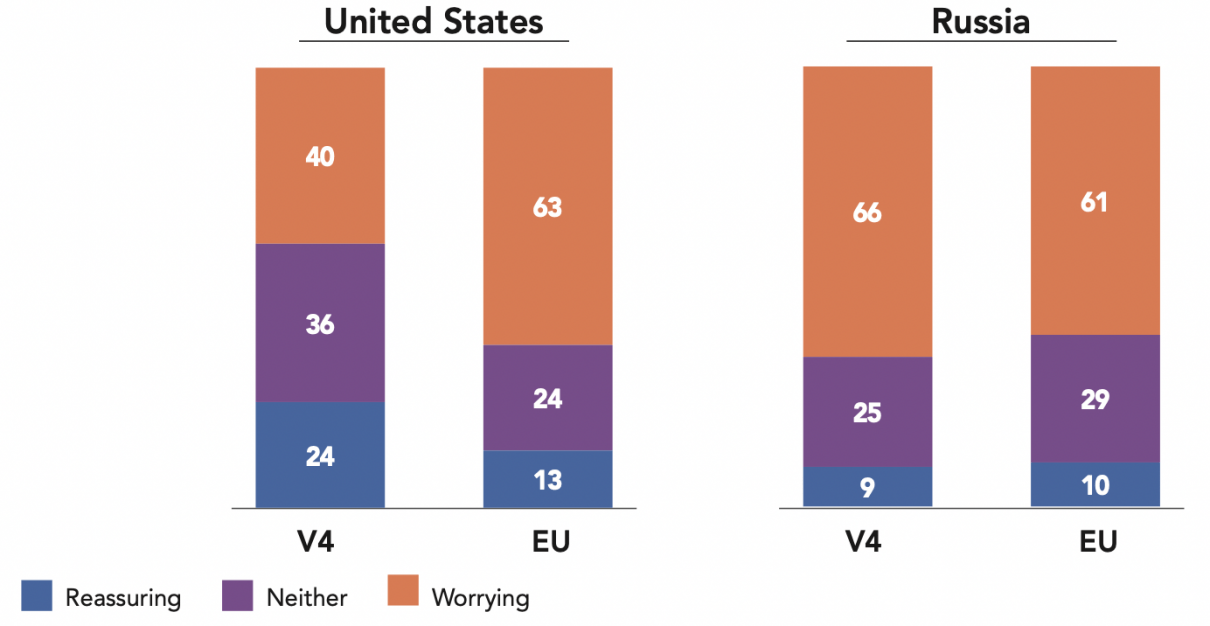

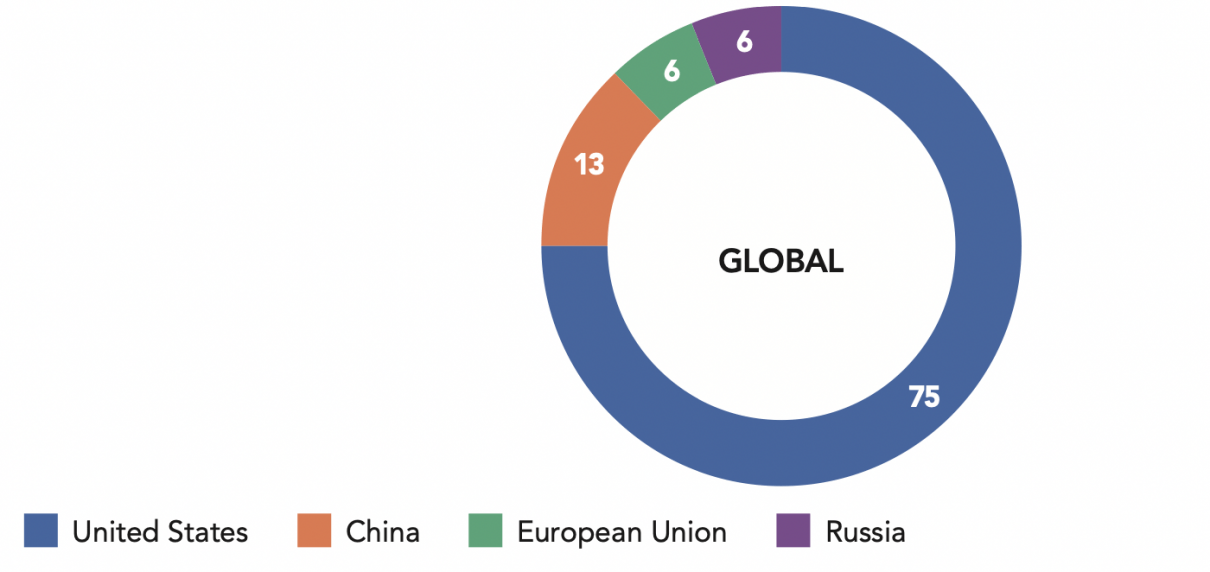

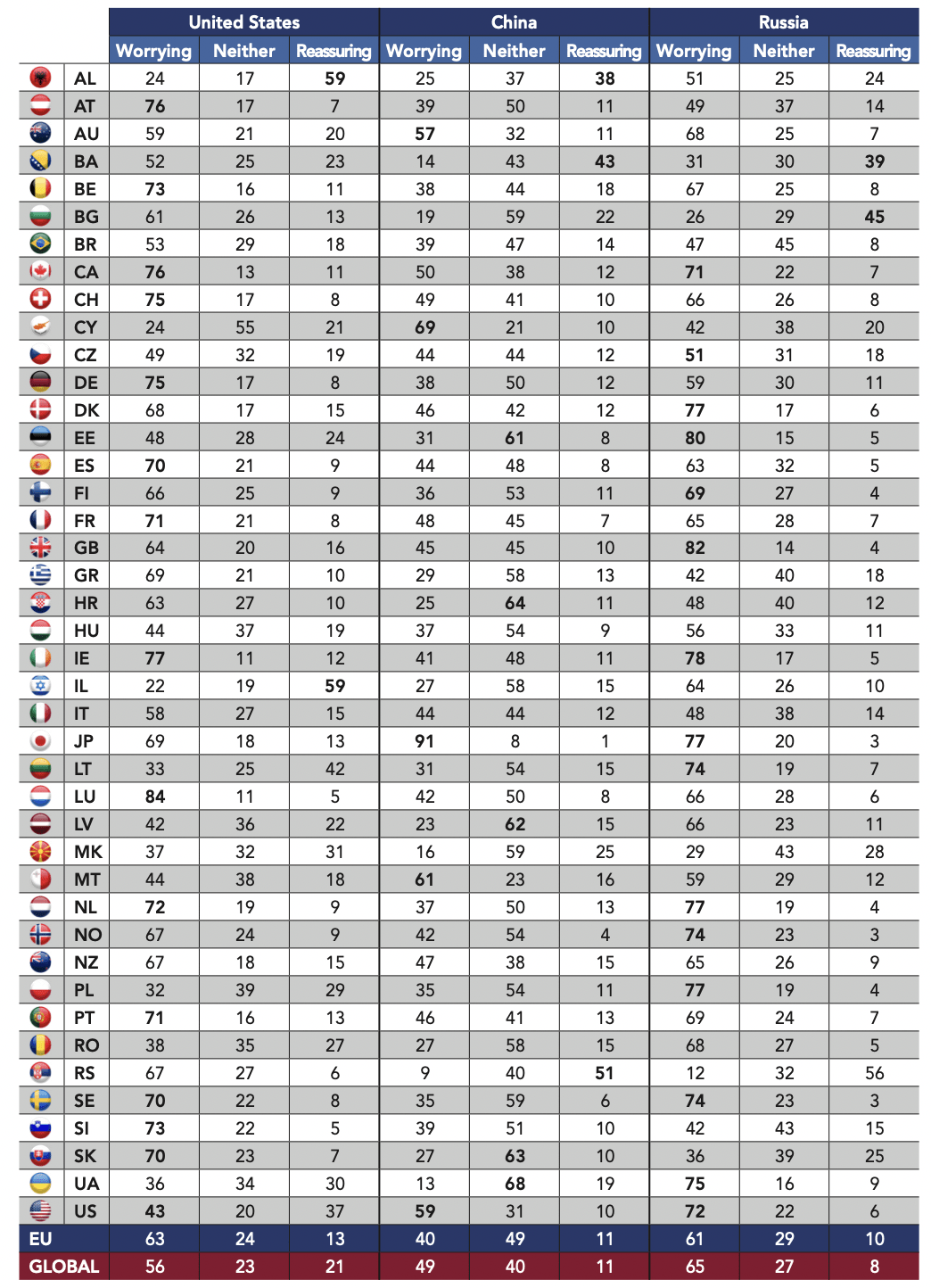

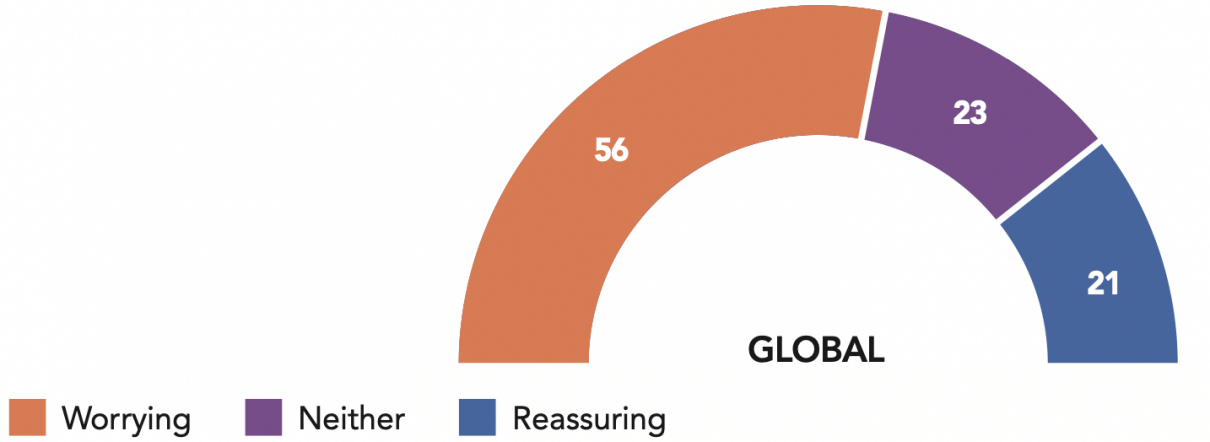

The United States, China, Russia and the European Union : friends or foes ?

Brazil : a tolerant society faced with democratic disillusionment

The anglosphere : economic and political liberalism

Trust ans mistrust in democratic societies

Military intervention in defense of democratic values is unpopular

Dominique REYNIÉ (Fondation pour l’innovation politique)

With the participation of:

Daniel TWINING (International Republican InstituteI)

With the cooperation of:

Octavio de BARROS (República do Amanhã)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique:

Loraine AMIC, Virginie DENISE, Anne FLAMBERT, Raphaël GRELON, Guillemette LANO, Julia LAUREAU, Julie NOYER, Maude PAILLARD-COYETTE, Nicolas RIGAUDIÈRE

International Republican Institute:

Sonja GLOECKLE, Emina IBRAHIMOVIC, Tucker JONES, Katie LAROQUE, Morgan MARTINEZ, Paul McCARTHY, Oleksandr MOSTBAUER, Carisa NEITSCHE, Stephen NIX, Julia SIBLEY, Borislav SPASOJEVIC, Jan SUROTCHAK, Alex TARASCIO, Benjamin THOMPSON, Diane ZELENY

República do Amanhã:

Thomás de BARROS, Vasco CALDEIRA, Anthony TAIEB, Renée ZICMAN

Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Caroline LORRIAUX, UBIQUS, WESTMILL International

Julien RÉMY

Victor DELAGE, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Thibault MUZERGUES

This survey was conducted by IPSOS

Brice TEINTURIER (Deputy Managing Director France)

Within the Politics and Opinion Department:

Federico VACAS (Deputy Manager),

Alice TÉTAZ (Research Manager),

Amandine LAMA (Account Manager)

Michael SCOTT

GALAXY Imprimeurs

2019

Governing bodies of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Nicolas BAZIRE, Chairman

Grégoire CHERTOK, Vice-Chairman

Cyrille BARDON,

Valérie BERNIS,

Aldo CARDOSO,

Geneviève FERONE CREUZET,

Pierre GIACOMETTI,

Changjian JIANG,

Olivier LABESSE,

Anne LEVADE,

Francis MER,

Tobie NATHAN,

Jean-Claude PAYE,

Sébastien PROTO,

Salima SAA

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director, University Professor at Sciences Po, Paris

Anne FLAMBERT, Administrative and Financial Director

Jean RAYNAUD, Chairman, Honorary General Prosecutor at the Cour des Comptes

Jean-Daniel LÉVY, Chartered accountant and graduate of Sciences Po, Paris

Jacques PRADON, Doctor of law and Honorary Lawyer to the Conseil d’État and the Cour de Cassation

Hélene GISSEROT, Chairwoman, Honorary General Prosecutor at the Cour des Comptes

Yves CANNAC, Honorary member of the Conseil d’État

Dominique LATOURNERIE, Member of the Conseil d’État

Christophe de VOOGD, Chairman

Bernard BACHELIER,

Bruno BENSASSON,

Élisabeth de CASTEX,

Stéphane COURTOIS,

Julien DAMON,

Laurence DAZIANO,

Marc FORNACCIARI,

Emmanuel GOLDSTEIN,

Erwan LE NOAN,

Luuk van MIDDELAAR,

Pascal PERRINEAU,

Xavier QUÉRAT-HÉMENT,

Robin RIVATON,

Alain-Gérard SLAMA

FONDATION POUR L’INNOVATION POLITIQUE

A FRENCH THINK TANK SUPPORTING EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AND THE FREE MARKET

The Fondation pour l’innovation politique provides an independent forum for expertise, reflection and exchange aimed at producing and disseminating ideas and proposals. It contributes to pluralism of thought and the renewal of public discussion from a free-market, forward-thinking and European perspective. Four main priorities guide the Foundation’s work: economic growth, the environment, values and digital technology. The website fondapol.org provides public access to all the Foundation’s work. Anyone can access and use all the data gathered for the various surveys via the ‘data fondapol’ platform and data relating to international surveys are available in several languages.

Furthermore, reflecting the Foundation’s editorial policy, our blog Anthropotechnie’ aims to explore new avenues prompted by human enhancement, reproductive cloning, human/machine hybridization, genetic engineering and germline manipulation. It contributes to thinking and debate on transhumanism. ‘Anthropotechnie’ offers articles tackling ethical, hilosophical and political issues associated with the expansion of technological innovations relating to the enhancement of human bodies and abilities.

In addition, our blog ‘Trop Libre’ casts a critical eye over the news and the world of ideas. ‘Trop Libre’ also extensively monitors the effects of the digital revolution on political, economic and social practices in its ‘Renaissance numérique’ section. The Fondation pour l’innovation politique is a state-cognized organization. It is independent and receives no financial support from any political party. Its funding comes from both public and private sources. Support both from companies and individuals contributes to the expansion of its activities.

Governing bodies of the International Republican Institute

Sen. Dan SULLIVAN - Chairman, US Senator (Alaska)

Randy SCHEUNEMANN - Vice Chairman, Kelly AYOTTE, Judy A. BLACK, Gahl Hodges BURT, J. Scott CARPENTER, Sen. Tom COTTON, Sen. Joni ERNST, Frank J. FAHRENKOPF, Alison B. FORTIER, Christopher J. FUSSNER, Sen. Lindsey GRAHAM, Rep. Kay GRANGER, Janet Mullins GRISSOM,

Cheryl F. HALPERN, William J. HYBL, Mark KIRK, James T. KOLBE, David KRAMER, Tami LONGABERGER, Peter T. MADIGAN, Général H.R. MCMASTER, Constance Berry NEWMAN, Sen. Mitt ROMNEY, Sen. Marco RUBIO, Joseph R. SCHMUCKLER, Amb. Kristen SILVERBERG, Frances TOWNSEND, Amb. Gaddi VASQUEZ, Olin L. WETHINGTON

Dr. Daniel TWINING - President

Judy Van REST - Executive Vice President

Kimber SHEARER - Counsel - Vice President for Strategy and Development

Daniel W. FISK - Chief Operations Officer

Scott MASTIC - Vice President for Programs

Diane ZELENY - Vice President for External Affairs & Global Engagement

INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE

ADVANCING DEMOCRACY WORLDWIDE

The International Republican Institute advances democracy and freedom. We link people with their governments, guide politicians to be responsive to citizens, and motivate people to engage in the political process.

IRI works with organizations and individuals across the globe to help citizens build democratic societies that are open and responsible, accountable and resilient. Collaboration is essential to fulfilling our mission in rapidly changing international landscapes. As an organization, we are agile. That allows us to quickly respond to critical, frequently dangerous situations.

For more than 30 years, we have been helping to strengthen democracy through workshops by volunteer experts from all over the world on multi-party political systems, democratic governance practices, women’s empowerment, civil society development, youth leadership, strengthening electoral processes and public opinion research. Research and qualitative and quantitative public opinion data is a cornerstone of IRI’s approach to programming. Our data ensures citizens’ needs are at the center of the political debate and guide our projects’ goals. To date, IRI has polled more than 1.3 million citizens in 70 countries. To learn more about IRI’s work around the world, get involved, or contact us, visit our website www.iri.org, listen to our podcast Global, or join the conversation on IRI’s blog Democracy Speaks about advancingdemocracy worldwide. IRI is a nonpartisan, nongovernmental Institute and receives funding through grants from the U.S. State Department, U.S. Agency for International Department, the National Endowment for Democracy, a number of European foundations and aid agencies and other Western countries. Less than one percent of IRI’s funding comes from private donations. We do not receive any money from the Republican Party or any other U.S. partisan entity.

The authors

Mantas Adomėnas

Cambridge educated Ph.D. researcher and former President of the Lithuanian Conservative think tank (Institute of Democratic Politics). He was in charge of the Homeland Union–Lithuanian Christian Democrats’ electoral strategy in the successful 2008 parliamentary election and of the Lithuanian higher education reform (2009).

Yoko Alender

Architect, city planner and politician. Member of the Estonian Parliament (the Riigikogu) since 2015 and reelected in 2019, member of the city council of Tallinn from 2013 to 2017.

Violeta Alexandru

Adviser on good governance to the Romanian president’s party (National Liberal Party – PNL) and Founding Member of the think tank Institute for Public Policy (IPP). She has contributed to, among others, several studies conducted at the Institute for Public Policy, the most recent of which are: Cost – efficiency report in public procurement (2015), Sustainable Public Procurement to make efficient investments in Romania (2013) and Transparency and Competitiveness in the Romanian Public Procurement System (2012).

Loraine Amic

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Master’s student in public administration at Science Po, Paris.

Octavio de Barros

Economist, President of República do Amanhã (“Republic of tomorrow”), a Brazilian think tank in partnership with the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the International Republican Institute in the conception of the survey Democracies under pressure. He is also the Vice-President of the Chamber of Commerce France-Brazil in São Paulo.

Oriol Bartomeus

Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Law at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB). Doctor in Political Science at UAB, author of a thesis studying the effects of generational replacement on electoral behavior in Catalonia. He contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Pierre Bréchon

Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Science Po Grenoble (PACTE research unit), and president of ARVAL, a research association focusing on value systems which administrates the survey on the European values in France. He edited, with Frédéric Gonthier and Sandrine Asror, the book La France des valeurs. Quarante ans d’évolution (Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 2019). Also author of a recent article entitled “Le mouvement des “gilets jaunes” ou le retour des valeurs matérialistes ?” (Revue politique et parlementaire, No. 1090, January-March 2019, p. 113-120).

Lolita Cigane

International consultant in good governance, campaign finance, elections and EU politics and policies. Former director of the Latvia branch of Transparency International from 2008-2010, Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Finance (2013-2014) and Chair of the European Affairs Committee (2014 -2018) in Latvia.

Julie Decroix

Assistant Director of the American Jewish Committee Europe since 2015 and Ph.D. researcher in Social Science, after working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Quai d’Orsay) as Chief of Staff for France’s special representation for Middle East peace processes.

Victor Delage

Senior Research Fellow and Communications Officer at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. He worked at the General Directorate of the Treasury at the French Ministry of Economy and Finance. Graduate of the Collège d’Europe and Science Po Grenoble. He also contributed to the book L’opinion européenne 2018 (Fondation pour l’innovation politique / Éditions Marie B, Lignes de Repères Collection, 2019).

Sophia Gaston

Researcher in Political and Social Sciences, visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has authored numerous publications, including Behind Global Britain (British Foreign Policy Group, 2019), Out of the Shadows: Thinking the Immigration Plot (HJS, 2018), At Home in One’s Past (Demos, 2018), Mediating Populism (Demos 2018) and Nothing to Fear but Fear Itself? (Demos, 2017).

Yasen Georgiev

Executive Director of the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a think tank based in Sofia (Bulgaria) dedicated in interdisciplinary socioeconomic trends in Bulgaria and in the countries of South-East Europe.

Raphaël Grelon

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and Master’s student in geopolitics and prospective analysis at the Institute of International and Strategic Relations (Iris).

Madeleine Hamel

Project Manager at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. Graduated with a Master’s degree in political science from the University of Geneva (Switzerland), specializing in international relations. She contributed to the book L’Opinion européenne 2018 (Fondation pour l’Innovation Politique / Éditions Marie B, Lignes de Repères Collection, 2019).

Katherine Hamilton

Project Manager at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique in charge of the survey Democracies under pressure. Graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in political science and international affairs from Skidmore College, New York (U.S.).

Paul-Adrien Hyppolite

Corps des Mines engineer, graduate from the École Normale Supérieure and the École Polytechnique, and visiting scholar at Harvard University. He previously worked for a merchant bank advising governments, for an investment fund, and for a space sector company. Coauthor, with Antoine Michon, of the two-part study entitled Big Tech Dominance (1. The new financial tycoons 2. A barrier to technological innovation?), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018, available at fondapol.org).

Samuel Johannes

Transatlantic Strategy Officer at the International Republican Institute (IRI) in Washington, DC, his work focuses on political parties and the media in the era of misinformation.

Aminata Kone

Master’s student in international security at Sciences Po Paris. Has completed her double Bachelor’s degree in international relations and French at the University of Sussex (United Kingdom). She contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Guillemette Lano

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Master’s Student in geopolitics and international studies at the Catholic Institute of Paris, training course for a humanities’ preparatory class.

Julia Laureau

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Master’s student in political theory at the Doctoral School of Sciences Po, Member of the Young European association.

Marc Lazar

University Professor of History and Political Sociology, Director of the Sciences Po History Center and President of the Luiss School of Government (Rome). Alongside other activities, he is coauthor with Ilvo Diamanti, of Peuplecratie. La métamorphose de nos démocraties (Gallimard, 2019) and contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Erwan Le Noan

Partner at Altermind, commentator for the newspapers L’Opinion and Les Échos, author of La France des opportunités (Les Belles Lettres, 2017). Member of the Scientific Council of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. Coauthor of Gouverner pour reformer : éléments de méthode (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2016, available at fondapol.org) and, with Dominique Reynié, of Pour une complémentaire éducation : l’école des classes moyennes (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2014, available at fondapol.org).

Johan Martinsson

Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Research Director of Opinion Media Institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Author of the study “Sweden Democrats”: an antiimmigration vote (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018 available at fondapol.org).

Antoine Michon

Corps des Mines engineer, graduated from the École Polytechnique, of which he was major of promotion. Worked for a financial data platform, for a company specialized in urban mobility solutions, as well as for a provider of data management and analysis software. Coauthor, with Paul-Adrien Hyppolite, of the two-part study entitled Big Tech Dominance (1. The new financial tycoons 2. A barrier to technological innovation?, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018, available at fondapol.org).

Patrick Moreau

Ph.D. researcher in history and Doctor of State in political science (FNSP), and CNRS researcher in the European Dynamics laboratory at the University of Strasbourg. Author of the study Alternative für Deutschland: Établissement électoral (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018, available on fondapol.org) and L’Autre Allemagne. Le réveil de l’extrême droite (Vendémiaire, 2017).

Anne Muxel

Research Director at Cevipof (CNRS-Sciences Po), specialist in the phenomena of political and democratic reconfiguration, electoral participation and the relationship of youth to politics. She is the author, among others, of Politiquement jeune (Editions de l’Aube, 2018) and contributed to the book What next democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017). Alongside Olivier Galland, she also edited the survey La Tentation radicale. Enquête auprès des lycéens (PUF, 2018).

Thibault Muzergues

Director of the Europe Program at the International Republican Institute (IRI) and author of La Quadrature des classes. Comment de nouvelles classes sociales boulversent les systèmes de partis en Occident (Le Bord de l’Eau, 2018), with an updated English version in progress. His work focuses on public opinion and European political parties.

Julie Noyer

Project Manager at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Master’s student in political science at the University of Quebec in Montreal (Canada).

Eriko Oshima

Ph.D. researcher in political science, Associate Professor (Assistant Professor) at Kinjo Gakuin University (Nagoya, Japan). Her work has focused in particular on immigrant integration policy and the French colonial past. She also participated in the research group led by Yuji Nakano which was aimed at analyzing the reports of the High Council on Integration. From 2015 to 2016, she wrote a monthly column on European policies for the website of the European Union Institute in Japan at Waseda University (EUIJ Waseda). She published a book in Japan in 2018 on the Pieds Noirs and, more recently, an article on May 1968 and Maghreb immigrants.

Maude Paillard-Coyette

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, degree in political science from London Metropolitan University (United Kingdom).

Pascal Perrineau

University Professor at Sciences Po. Coordinator of the books Le Désenchantement démocratique (Éditions de l’Aube, 2003), Le Vote disruptif, Les élections présidentielle et législatives de 2017 (Presses de Sciences Po, 2017) and, with Luc Rouban, of La Démocratie de l’entre-soi (Presses de Sciences Po, 2017) and author of Cette France de gauche qui vote FN (Seuil, 2017). He contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Ožbej Peterle

Graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Ljubljana (Slovenia) and a master’s degree in politics, security and integration at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (University College London). Assistant Professor at the School of Advanced Social Studies, Nova Gorica (Slovenia).

Paul Prososki

Program Director of the International Republican Institute in Belgrade (Serbia). Board member of the Americans for Tax Reform Foundation (Washington), a center-right think tank.

Bettina Rausch

President of the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) Academy since March 2018. Former member of the Federal Council (2008-2013) and the National Parliament of Lower Austria (2013-2018). Coeditor and coauthor of Offen für Neues (Édition noir, 2018) and of Österreichisches Jahrbuch für Politik 2018 (Böhlau Verlag, 2019).

Dominique Reynié

University Professor at Sciences Po and Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. He has authored numerous publications, including: the Triomphe de l’opinion publique. L’espace public français du xvie au xxe siècle (Odile Jacob, 1998), Vertige social nationaliste. La gauche du Non (La Table ronde, 2005) and Nouveaux Populismes (Pluriel, 2013). He also edited the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Nicolas Rigaudière

Intern at the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2nd year bachelor’s degree student majoring in politics and government at Sciences Po, Paris.

Jacques Rupnik

Research Director at Sciences Po (Ceri), Professor at the Collège d’Europe in Bruges and former Advisor to President Václav Havel. He edited the books 1989 as a Political World Event. Democracy, Europe and the New International System in the Age of Globalization (Routledge, 2014), Géopolitique de la démocratisation. L’Europe et ses voisinages (Presses de Sciences Po, 2014) and Europe at the Crossroads. Democracy, Neighborhoods, Migrations (Vaclav Havel Library, 2018). He also contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Graham Scott

Europe Program Associate at the International Republican Institute (IRI), focused on North Macedonia. Graduated with a Bachelor of Science in political science from Shepherd University and a master’s degree in political science from George Mason University.

Anne-Sophie Sebban-Bécache

Director of the American Jewish Committee in Paris since December 2018, Doctor in geopolitics at the Institut français de géopolitique (Paris VIII University), specialist on Israel and the Horn of Africa. She contributed to the book Gaz naturel, la nouvelle donne ? (Presses Universitaires de France, 2016).

Neritan Sejamini

Strategy Consultant, Policy Analyst and Publisher based in Tirana (Albania), Policy Specialist on the United States and the Western Balkans region.

Corentin Sellin

Associate Professor in CPGE Lycée Carnot (Dijon), specialist on the United States. He coauthored, with Annick Foucrier and Nicolas Vaicbourdt, the book The United States and the world, from the Monroe doctrine to the creation of the UN (1823-1945) (Atlantic, 2018) and contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Joshua Solomon

Program Officer at the International Republican Institute (IRI) for the Eurasia Program on the former Soviet countries. Worked at the National Endowment for Democracy on Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus. Master’s student in international affairs at George Washington University (U.S.).

Alex Tarascio

Program Manager at the International Republican Institute (IRI) and Bachelor of Political Science from the University of Oregon. His work focuses on regional support for political parties and measures against misinformation in Europe and Eurasia.

Christophe de Voogd

Ph.D. researcher in history, specialist on the Netherlands, Associate Professor at Sciences Po, President of the Scientific and Evaluation Council of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. He is the author of the study Réformer : quel discours pour convaincre ? (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2017, available at fondapol. org) and contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Mathieu Zagrodzki

Ph.D. researcher in Political Science at Sciences Po and Associate Researcher at the Center for Sociological Research on Criminal Law and Institutions (Cesdip), specializing in police and public security issues. He teaches at the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. He is the coauthor, with Romain Maneveau and Arthur Persais, of the study Commerce illicite de cigarettes : les cas de Barbès-La Chapelle, Saint-Denis and Aubervilliers-Quatre-Chemins (Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018, available at fondapol.org) and he contributed to the book What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (2017).

Foreword: democracies under pressure

Freedom House, Democracy in Retreat. Freedom in the World 2019, p. 4.

The idea of democracy has revolutionized the world. It is based on a political order whose main feature is making the exercise of power subject to the consent of the governed. Since its ancient and glorious Athenian roots, the idea has spread across land and sea. The English Bill of Rights in 1689, the United States Constitution in 1787, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789 marked the arrival of political freedom in the world with distinction. It spread across Europe in the 19th century, powering nations with the emancipating force of the peoples’ right to self-determination. During the 20th century it triumphed over modern tyrannies, repelling fascist regimes, the Nazis and their allies, then defeating communism after a Cold War that ended with the collapse of the USSR, defeated economically, technologically, politically and morally.

During this same period, the world also embarked on a new phase of democratization. In 1970s Europe, the Greeks, Portuguese and Spaniards overthrew their military dictatorships. In Latin America in the 1980s, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil went through the same experience. Then, on the Old Continent during the 1990s, it was Central and Eastern Europe’s turn. In 1992, a symbolic milestone was reached: more than half of the world’s States were democracies. The world was becoming democratic. The wave lasted until the beginning of the 21st century, with the number of democratic states doubling between the late 1970s and the early 2000s.

However, as we enter the 21st century, the horizon looks darker. In the 2019 edition of its annual report Freedom in the World, the NGO Freedom House expressed concern over “global declines in political rights and civil liberties for an alarming 13 consecutive years, from 2005 to 2018. The global average score has declined each year, and countries with net score declines have consistently outnumbered those with net improvements1”. Today it is no longer simply a question of strengthening the democratic process where it is still fragile, in Liberia, Uganda or Tunisia, but also of helping regain democratic momentum where countries have slid back, in South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia and encouraging progress where it can be seen, in Ethiopia, Angola, Armenia, Malaysia or Ecuador. It is now a question of protecting, or even defending, established democracies. This is the case for the countries that emerged from the post-Soviet democratic transition that seem to be tempted down a backwards path, an authoritarian transition feared throughout Europe, advocating for a paradoxical model at once democratic and “illiberal”. The wave of populist elections is weakening the European Union. Here we do not see the traditional political, economic and social factors that have always threatened the solidity of the democratic world, such as growth, employment and the educational system. These are challenges that must be faced time and time again. Rather, under the emerging concerns, the media has been disrupted by social media, where the best and the worst of humanity exist side by side. How can we keep the democratic discussion alive if the truth is to lose its mediating power, if opinions and debates are constantly oversimplified and radicalized, if the legitimacy of journalism is no longer recognized? From now on, not just election campaigns but also electoral processes themselves are likely to be seriously disrupted by new forms of public debate. The heart of democracy is under threat.

This moment of doubt is also the product of the forces unleashed by globalization. A paradoxical triumph of the West, globalization destabilizes democracies while offering unprecedented opportunities for development and expansion to new powers. Among these is China, which is no longer hiding its ambition to dominate the 21st century. It is increasingly powerful both economically and technologically. In the strategic field of artificial intelligence and biotechnology, it is fighting for the leading position. But China achieves these stunning successes without renouncing its authoritarian system, or even the hegemony of the Chinese Communist Party, by building a state model that could be described as “high-tech totalitarianism,” ready to export its concepts, methods, and tools.

For the first time since its creation, democracy is no longer certain of inspiring the world. It is in this new and troubled context that we wanted to bring together our two institutions: on the one hand, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, a French think tank committed to defending the values of freedom and progress and the ideals of the European Union; on the other, the International Republican Institute, an American organization that promotes democracy worldwide. Our two organizations were pleased to welcome the Brazilian think tank República do Amanhã into this partnership in order to carry out this international study, conducted in forty-two democracies, presented here under the title Democracies Under Pressure.

The document is comprised of two volumes: the first is devoted to themes and issues, such as trust in institutions, support for the model of representative democracy, support for abortion or the death penalty, the decline of democratic values among younger generations, etc.; the second volume is dedicated to the forty-two countries of the survey, offering a fact sheet for each that summarizes the state of national public opinion. We also present the reader with an “Index of Democratic Culture”.

It is important to specify that all survey data are made available to the public in the thirty-three languages the survey was administered in as open data on the respective websites of the three institutions. Lastly, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to the organizations’ teams, the authors and all those who enabled this project to be carried out through their competence and their dedication.

Through this project we hope to contribute to a better understanding of public opinion in different countries, particularly regarding their respective democratic systems but also in terms of democracy in general. We also hope to encourage discussions and joint projects between civil societies in the democratic world, especially on both sides of the Atlantic.

Dominique REYNIÉ,

Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique,

University Professor at Sciences Po, Paris

Daniel TWINING,

President of the International Republican Institute

Survey methodology

A global survey on the state of democracy by fondation pour l’innovation politique and the international republican institute

Albanian (Albania and North Macedonia), Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek (Greece and Cyprus), Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Latvian, Lithuanian, Luxembourgish, Macedonian, Maltese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese (Brazil and Portugal), Romanian, Russian (Estonia and Latvia), Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, and Ukrainian.

** fondapol.org, iri.org and republicadoamanha.org.

The Fondation pour l’innovation politique is a French think tank that upholds the values of freedom, progress and European ideals. The International Republican Institute is an American organization that promotes democracy around the world. The two organizations, in partnership with the Brazilian think tank República do Amanhã, joined forces to create an extensive international survey conducted across 42 countries, the results of which are published hereafter under the title: Democracies Under Pressure. All the results are available to the public in the thirty-three languages* the survey was administered in as open data on the respective websites of the three institutions**.

This project is based on a questionnaire written in French and in English by the teams of the partnered organizations. It was administered by Ipsos across national samples selected from each of the 42 surveyed countries. The scale of the survey made it possible to integrate the twenty-seven Member States of the European Union, to make comparisons between these and the European countries that are not members of the European Union (Norway, Switzerland, Ukraine), those that seek to join it (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Serbia) or even, in contrast, with the United Kingdom, which seems to have decided to leave it, although the situation in this latter country remains very unclear at the time of writing (April 25th 2019).

The goal of conducting a global survey on the state of democracy has led us to expand the group of surveyed countries by including Australia, Brazil, Canada, the United States, Israel, Japan and New Zealand in the scope of observation.

42 countries, 33 languages, 66,395 interviewees

In total, 36,395 people were surveyed. The study was conducted on the basis of representative national samples drawn from the population aged 18 years and older. Quotas for gender, age, profession, region and size of community were used to ensure the representativeness of the samples. The samples take into account the demographic weighting of each country: the size of the samples was 1,000 people in countries with more than 8 million inhabitants, 600 people for those with 5 to 8 million inhabitants and 500 people for countries with less than 5 million inhabitants. For some countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia), the sample size was increased to 800 people despite a population of less than 8 million in order to solidify the analysis of the results.

The survey, which included 35 questions published at the end of volume II, “The Countries” (pp. 107 – 114), was administered in each of the national languages, amounting to 33 languages across the 42 countries. In order to minimize the effect of situational factors, the data was collected over a five-week period (between September 6th and October 11th 2018). The interviews were conducted via a self-administered online questionnaire, with the exception of five countries where face-to-face interviews were preferred: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus, Malta and North Macedonia.

A 35-question survey

*** The opinions of the various authors who contributed to this international survey do not necessarily reflect those of the International Republican Institute.

For most of the questions, we asked respondents to answer by choosing a level on a four-point scale, of the “yes, absolutely”/”yes, somewhat” and “not really”/”not at all” type, to assess, for example, levels of satisfaction, trust or optimism. In this document, for the sake of convenience and legibility, we usually present and comment on the results by adding up, on the one hand, the “yes, absolutely”/”yes, somewhat” answers and, on the other hand, the “not really”/”not at all” answers.

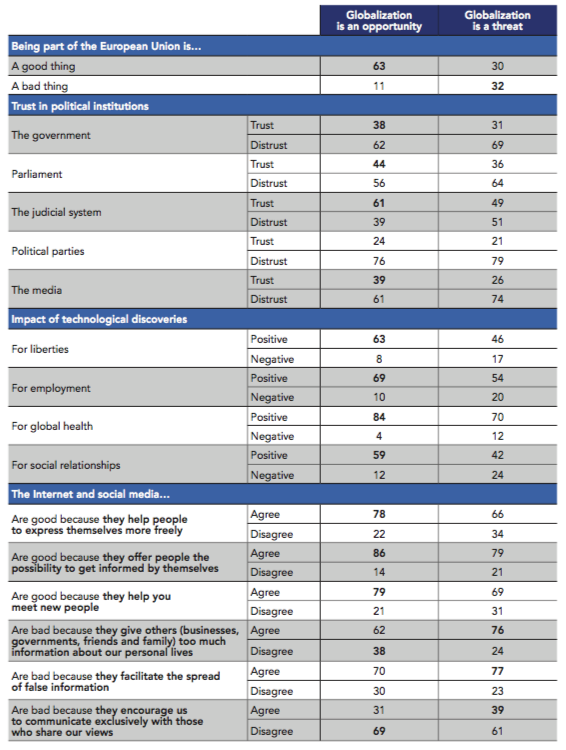

In some cases, respondents were asked to choose between two options. Thus, for example, to the question “which of the following two statements is closest to your opinion”, the options offered to the respondent were “globalization is an opportunity” or “globalization is a threat”. Some of the questions had three possible answers. For example, when asked about the benefits to their country of NATO membership, respondents could answer that the latter is “a good thing”, “a bad thing”, or “neither a good thing nor a bad thing”.

For each question, respondents received a notification if they did not respond to a certain question with the following message: “Please try to answer the question. However, if you have no opinion on this question, you may move on to the next one by clicking on the “next question” button (between 0 and 2% non-responses for both online and face-to-face answers).

Lastly, the results are presented either by country or by sub-category, such as “European Union” (EU). For a given question, the EU average corresponds to the result across the Member States of the European Union, i.e. twenty-seven countries, with values weighted according to their respective demographic weights. The decision was made not to include the United Kingdom in the “EU” calculations as the British have expressed a desire to leave the European Union.

The overall results are presented in the “GLOBAL” category. For a given question, the “GLOBAL” average therefore corresponds to the result across the 42 surveyed democracies, the value of each country having been weighted taking into account their demographic weight within the overall sample.

The reader will see that we have often grouped categories together to make the data clearer and easier to present. This never alters the value of these data, the details of which cannot be presented in full in such a volume, and which are freely accessible in full on the websites of the three institutions***.

Fragile democracies

The ambiguity of commitment to democracy

Dominique Reynié

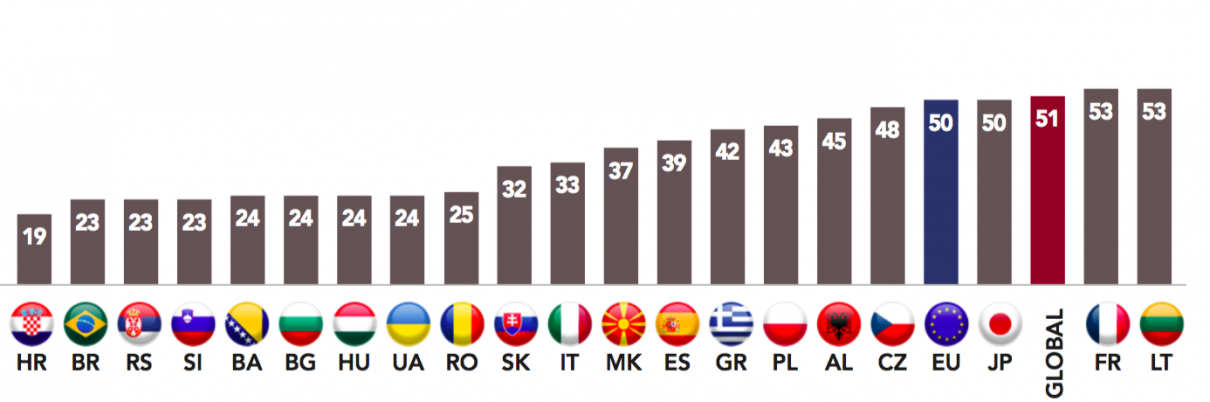

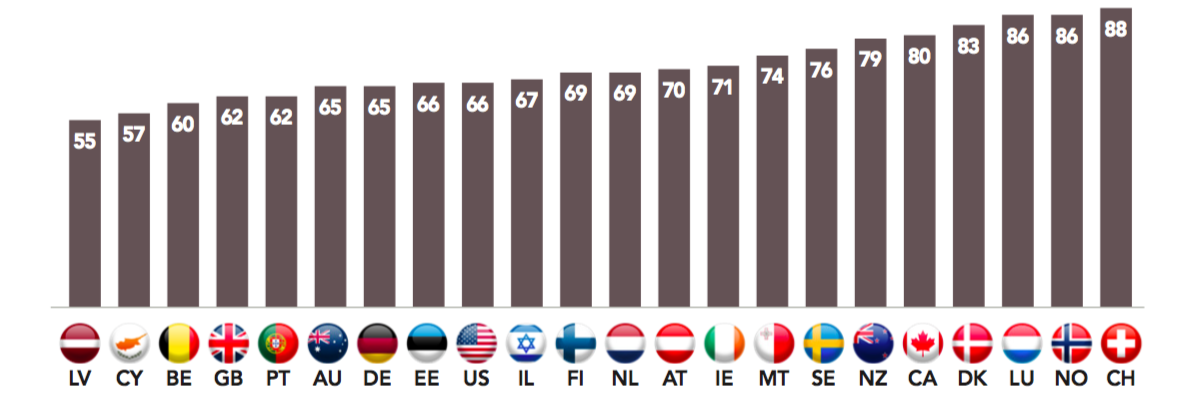

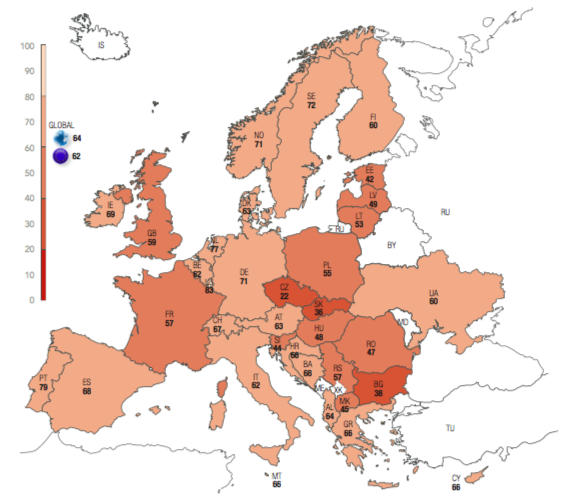

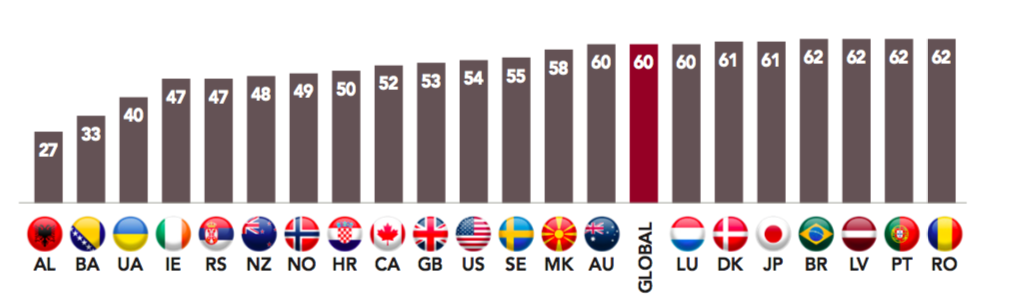

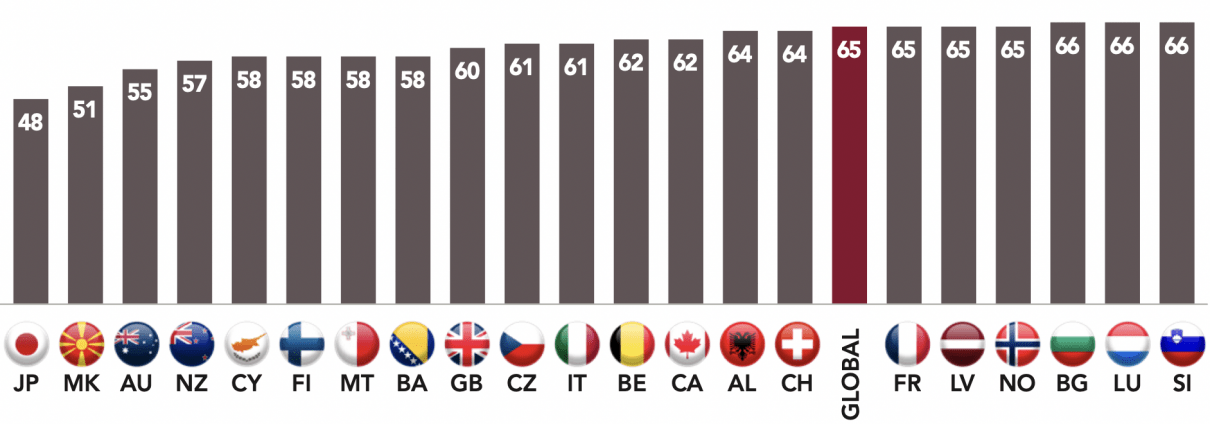

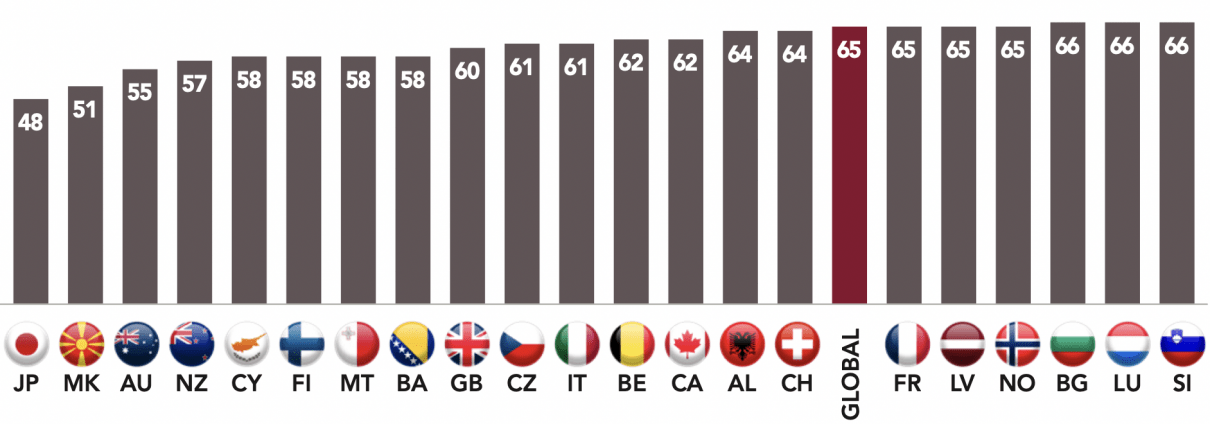

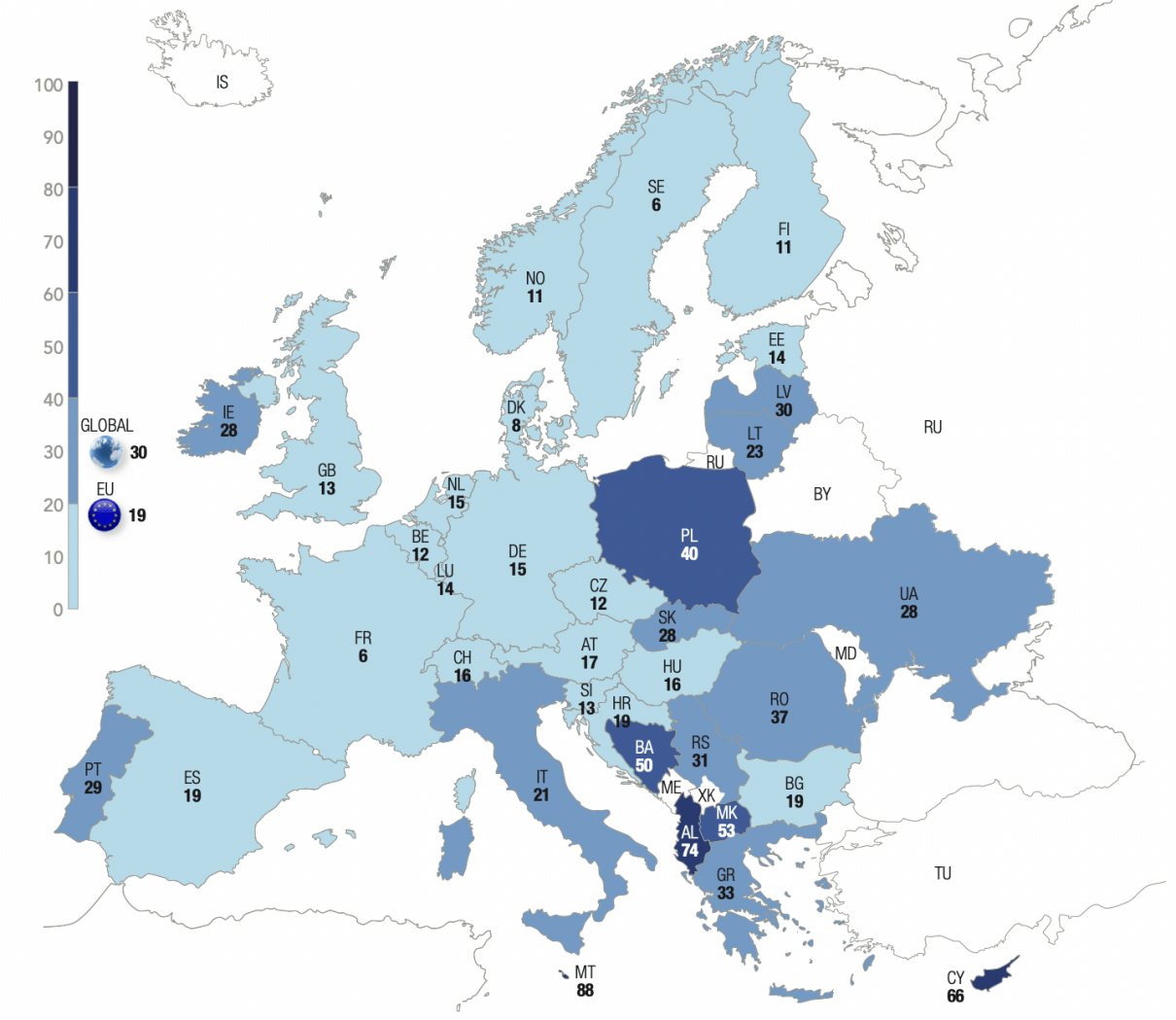

Overall, about half of respondents (49%) believe that democracy works poorly in their country. In some countries, this assessment is even more severe. More than three-quarters of Brazilians (77%) have a negative opinion of the functioning of their democracy. This must be put in the very specific context of Brazil, where the survey took place just a few weeks before a historic election. Much differently, in the United States, two years after Donald Trump’s election, two-thirds of citizens believe that democracy works well in their country (66%).

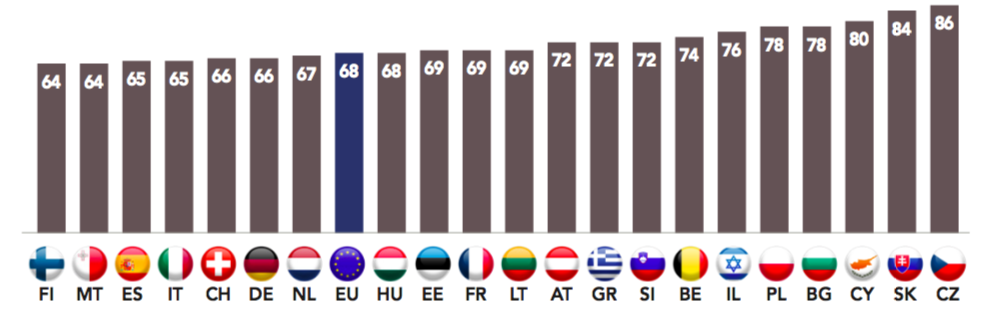

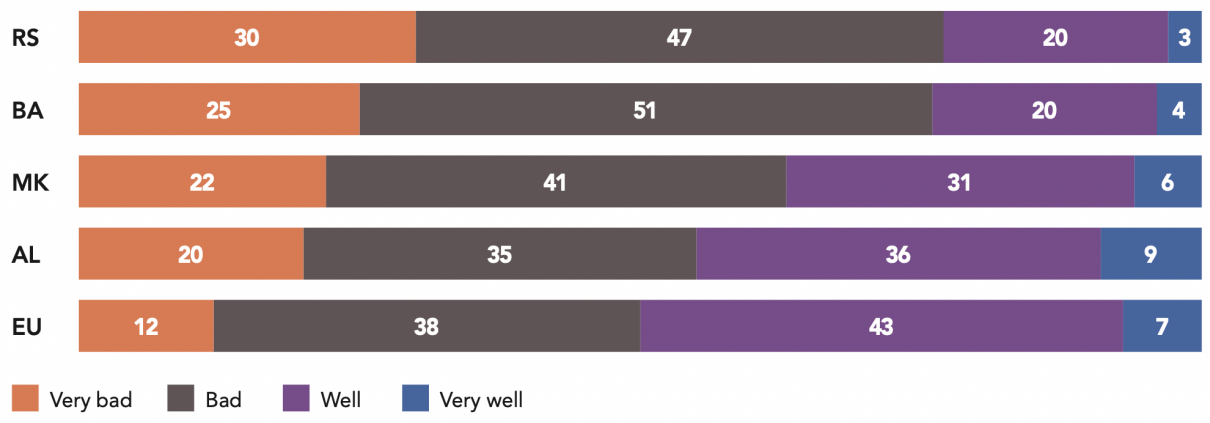

In terms of opinion, Europe presents a very mixed picture. There are several European worlds. Outside the European Union, democracy fares better if we look at Switzerland, where 88% of respondents say that democracy works well, much like in Norway (86%). Across the European Union, satisfaction is declining sharply: only 50% of respondents believe that democracy works well in their country. In a weakened democratic world, a crisis exists which is specific not to Europe, but to the European Union. One explanation lies in the state of opinion in the former communist bloc countries1. On average, in these eleven countries, two-thirds of respondents (64%) feel that their democracy is not working well. But they are not the only ones with this negative opinion. The feeling that democracy is not working well also dominates in Italy (67%), Spain (61%) and Greece (58%). It is close to the majority in France (47%). On Europe’s doorstep, this criticism is also widespread: in Albania (55%), North Macedonia (63%), and even more so, in Bosnia and Herzegovina (76%) or Serbia (77%), as well as Ukraine (76%).

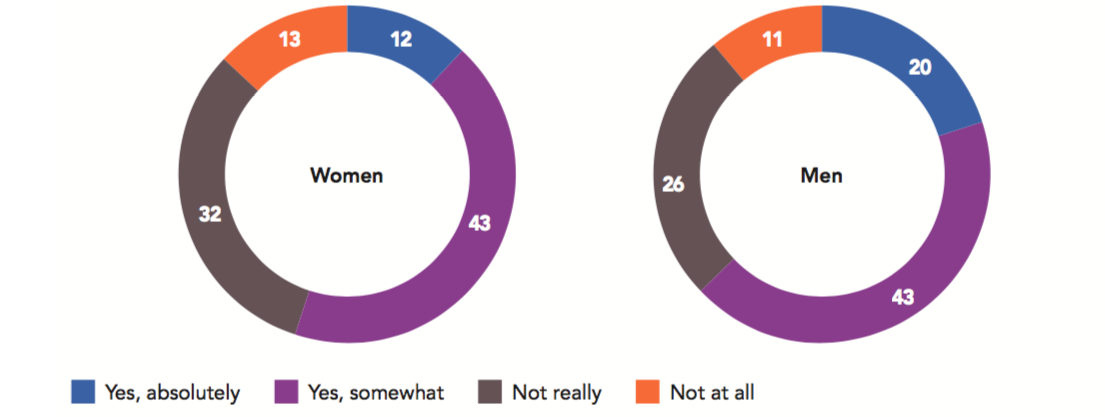

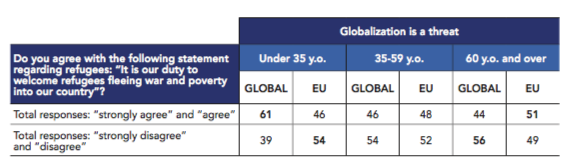

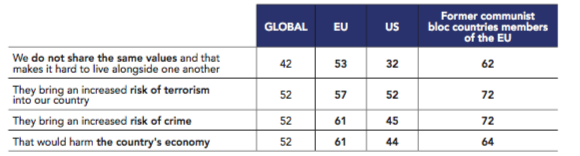

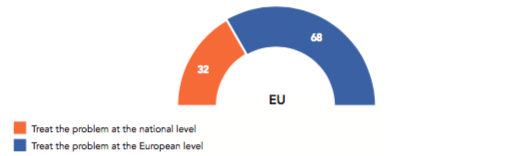

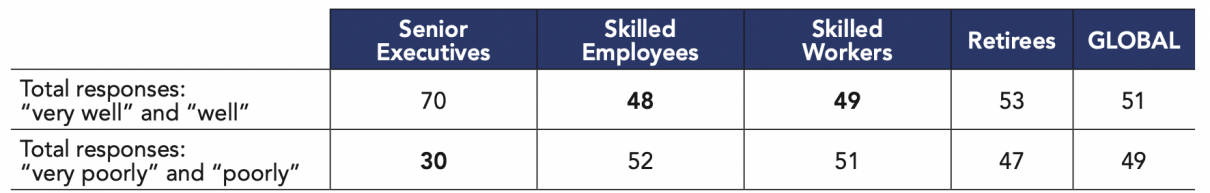

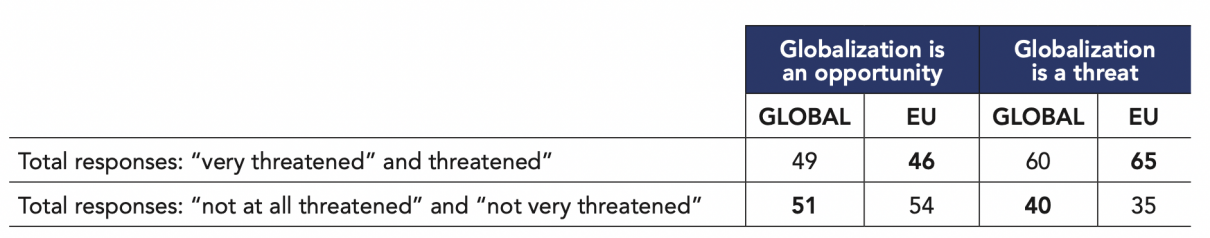

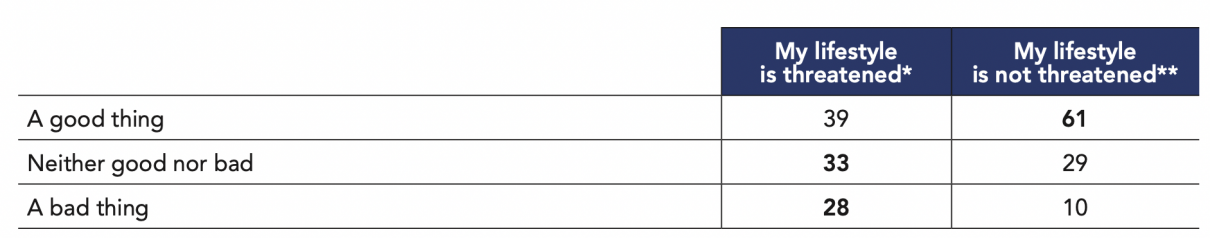

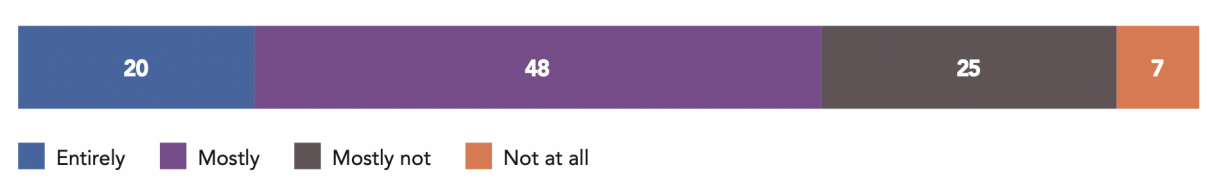

At the level of the forty-two countries studied, men (53%) more frequently believe that democracy is working well than do women (48%), but dissatisfaction is particularly prevalent in the more vulnerable categories, the small self-employed business owners (59%), the service staff and store clerks (57%), those who do not work (56%)2, the skilled employees (52%) and the skilled workers (51%). This economic and social division can be found in the link between respondents’ judgement of the functioning of democracy and their relationship to globalization: more people who view globalization as a threat (55%) believe that democracy is working poorly than do those who view globalization as an opportunity (47%). This negative assessment of the functioning of democracy is even more pronounced (60%) in those in the intermediate age group (between 35 and 59 years) for whom globalization is a threat. It should be noted that among students, the idea that democracy is working poorly is clearly the majority position (58%).

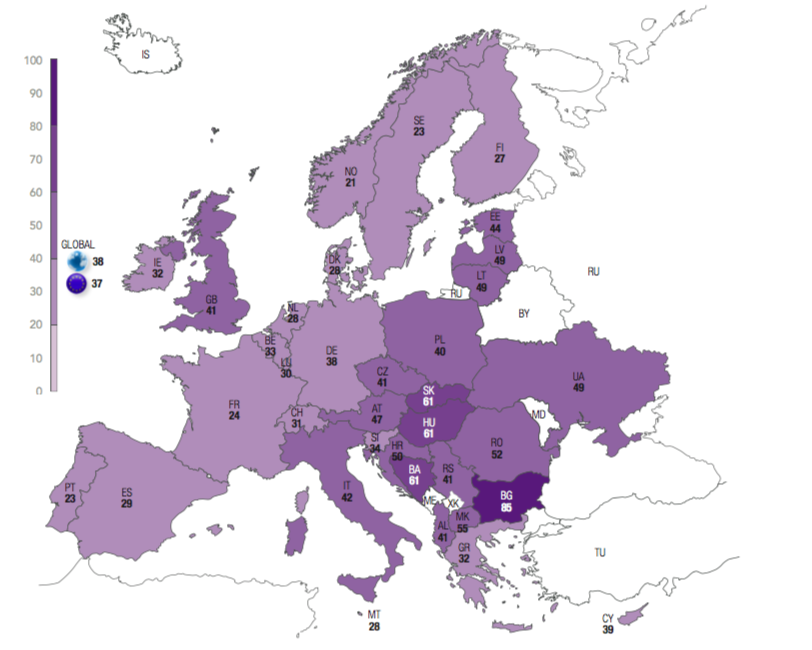

Would you say that democracy in your country works very well, well, poorly or very poorly?

Copyright :

Total responses: “very well” and “well”

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

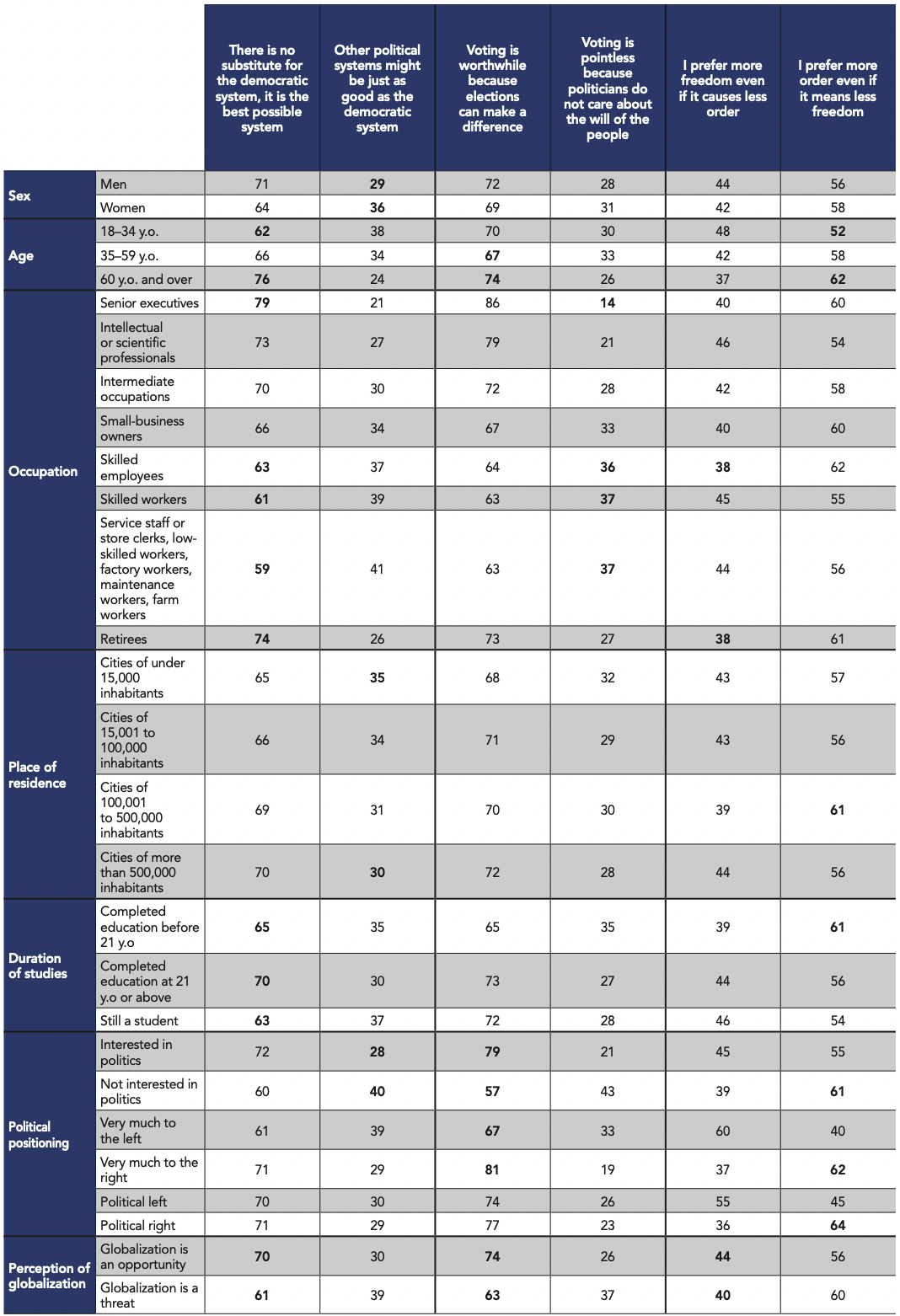

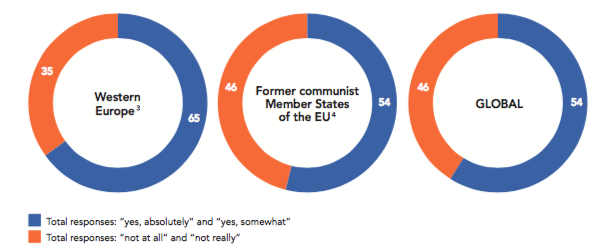

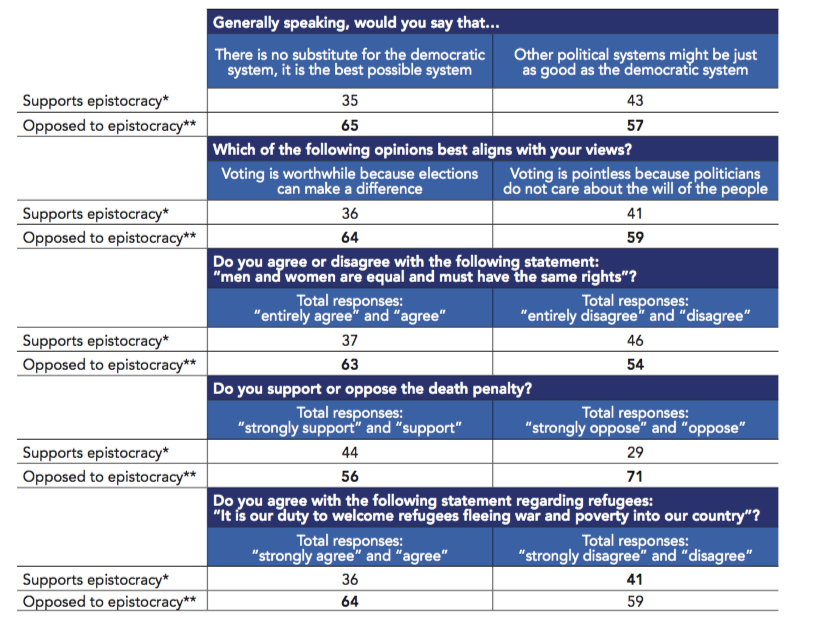

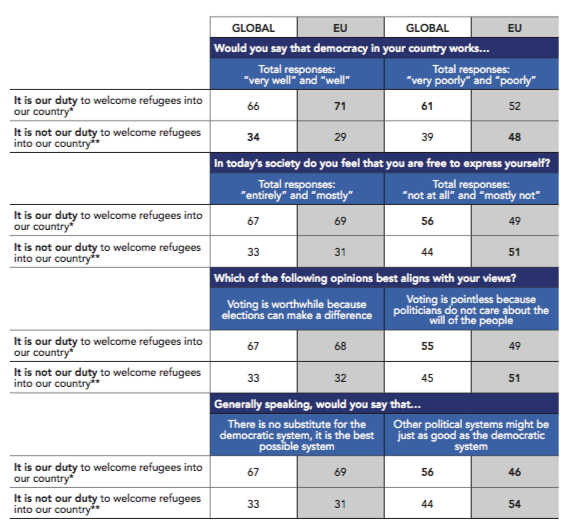

However, judging that democracy works badly in one’s country is not necessarily an expression of a rejection of democracy. On the contrary, it may even be the manifestation of a critical judgement combining support for the principle with the acknowledgement of practices that do not fulfil it, or even betray it. For example, most (83%) of those who responded that they do not feel free to express themselves also say that democracy is working poorly in their country. This is why we also invited people to choose between two statements that help better understand their attachment to democracy, offering distinct options: on the one hand, the idea that democracy is the best system and that there is no other possibility; on the other, that other systems might be just as good. The option “there is no substitute for the democratic system, it is the best possible system” was chosen by two-thirds of respondents (67%), with the remaining third choosing the option “other political systems might be just as good as the democratic system” (33%). The overall assessment of the democratic system therefore remains favorable. Furthermore, among those who say that there is no better system than democracy, a significant proportion (41%) simultaneously indicate that democracy is not working well in their country, pointing out that, in some cases, respondents are condemning the unsatisfactory manner in which democracy is functioning rather than challenging the system’s fundamental value. But, again, it is not easy to determine the meaning of the skeptical or dissident third who believe that such equally good political systems may exist.

In European Union countries, the idea that “there is no substitute for the democratic system, it is the best possible system” unites the same proportion of respondents (68%) as at the global level (67%). However, if we look at all the countries of the former Soviet bloc, the idea that “other political systems might be just as good as democracy” unites 40% of respondents. In the Balkans, public opinion in EU candidate countries engaged in democratic transition also supports the idea that other systems might be just as good as democracy, for instance among the Macedonians (45%), Bosnians (50%) and Serbs (54%). Only the Albanians match the overall level, with a large majority (63%) saying that the democratic system “is the best possible system”.

Though dominant in Central and Eastern Europe, this distance from democracy is not the exclusive preserve of the former communist countries. In the West, the Belgians are equally supportive (40%) of the option stating that “other political systems might be just as good as democracy”, as are the French (39%).

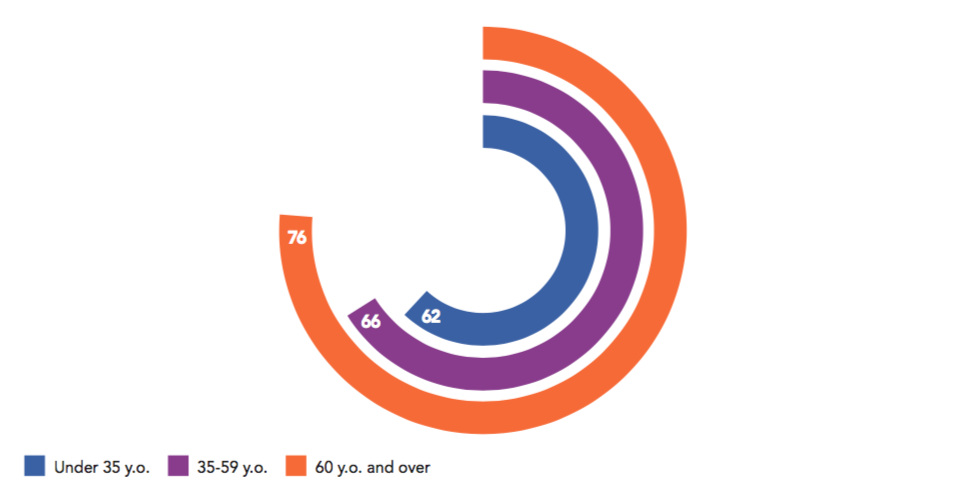

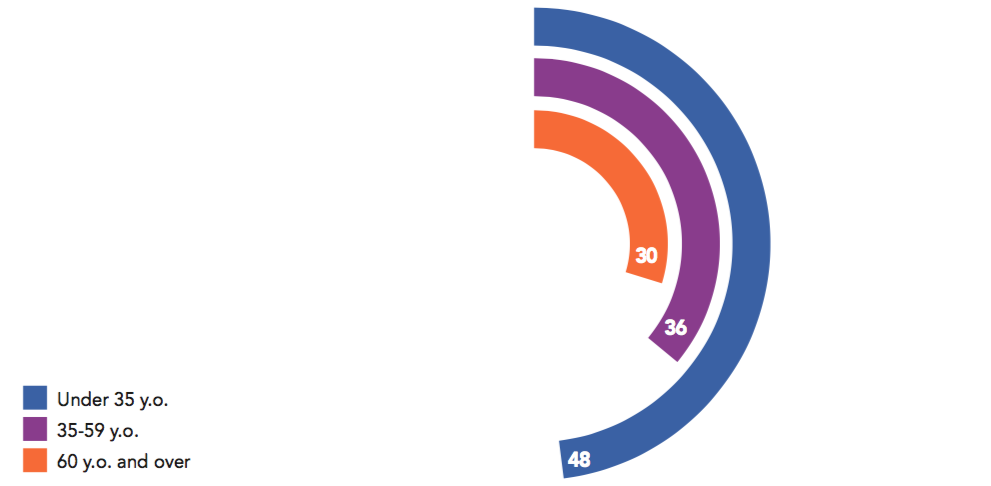

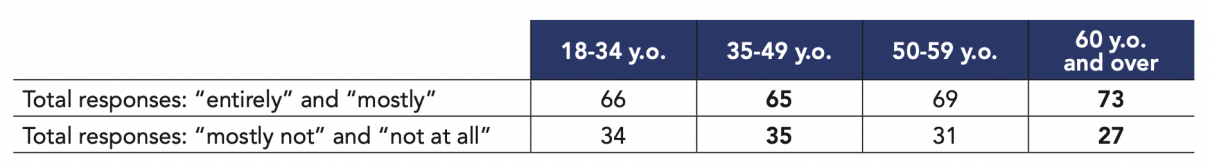

Socio-demographically, women are more likely (36%) than men (29%) to believe that an undemocratic regime might be “as good” as democracy. The effect of age is also very clear. The younger the respondents, the fewer of them think that democracy is an irreplaceable regime: 76% among those aged 60 and over, 68% among those aged 50-59, 64% among those aged 35-49 and 62% among those under 35.

Would you say that democracy in your country works very well, well, poorly or very poorly? (continued)

Copyright :

Total responses: “very well” and “well”

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

There is no substitute for the democratic system, it is the best possible system

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

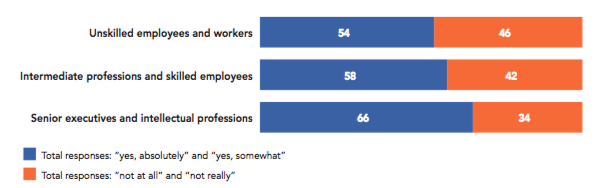

The effect of social standing is hardly surprising, but its consequence should be highlighted: the idea that there is no political system as good as the democratic system convinces senior executives (79%), intellectual and scientific professionals (73%) and the intermediate occupations (70%) much more than skilled employees (63%), skilled workers (61%) or the working-class world of service and retail workers, low-skilled blue-collar workers, maintenance workers and agricultural workers (59%). In a way, the democratic system seems to be more strongly supported by the social elite than by the working classes. This may be a kind of political and sociological truism, but it can become a particularly thorny political problem.

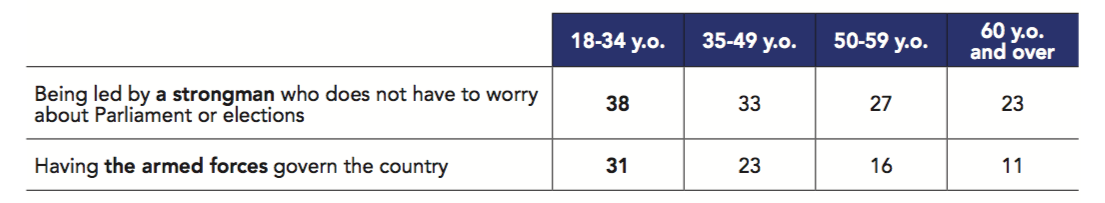

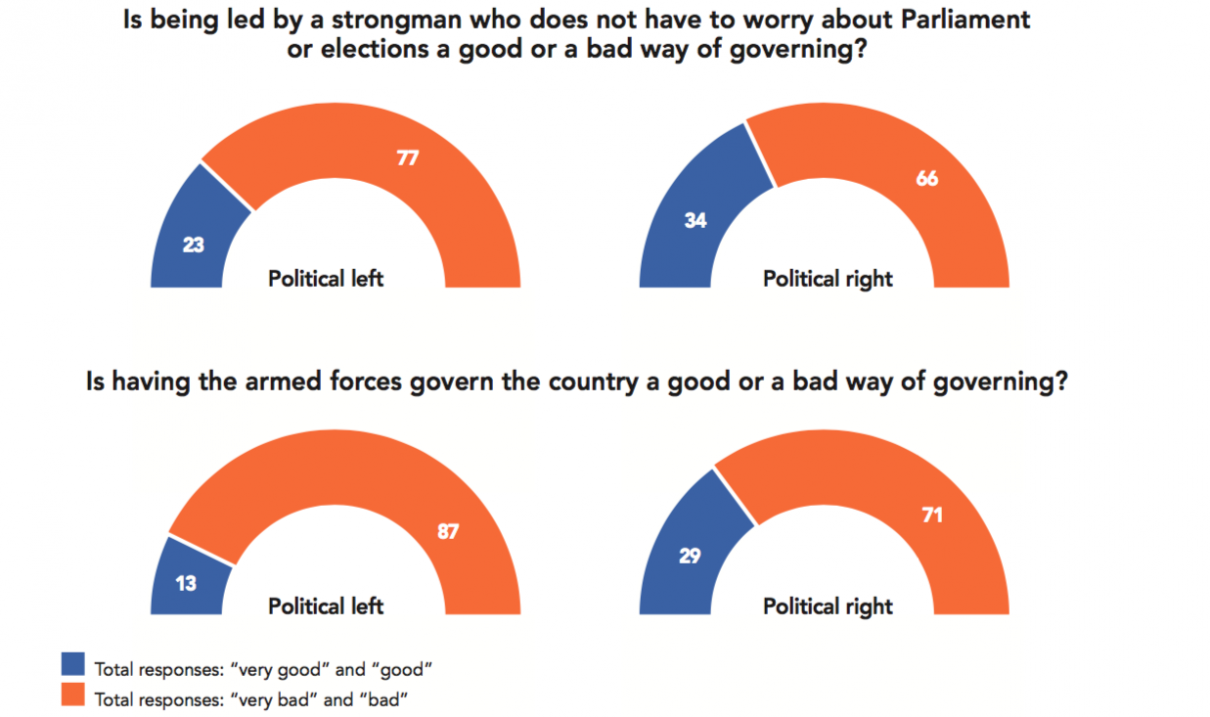

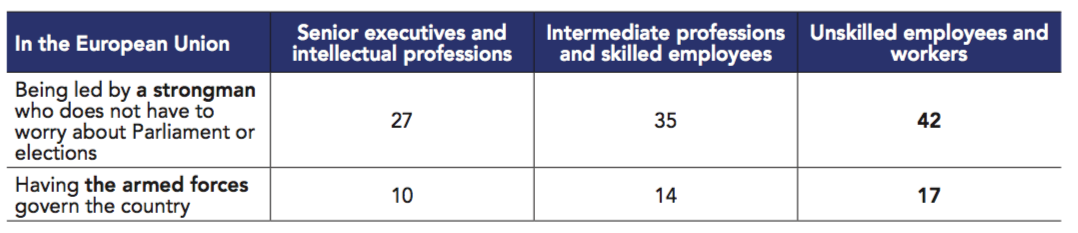

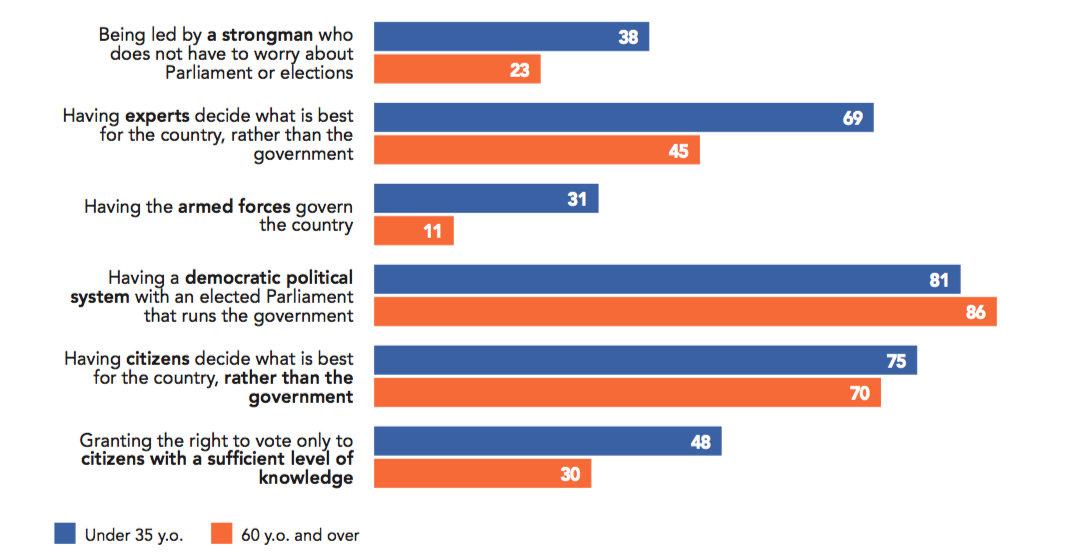

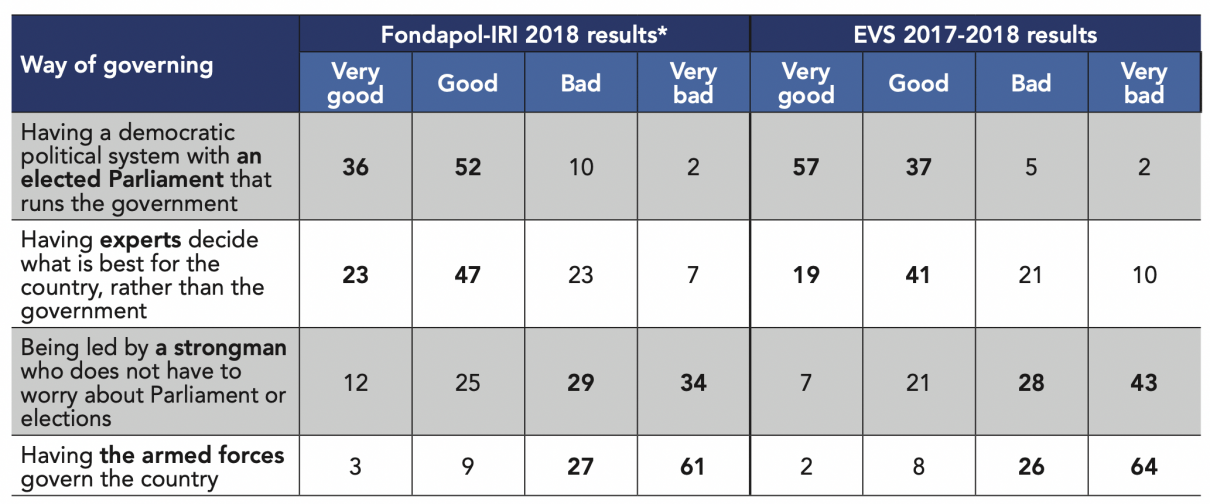

“Being led by a strongman who does not have to worry about Parliament or elections”, “Having experts decide what is best for the country, rather than the government”, “Having the armed forces govern the country”, “Having a democratic political system with an elected Parliament that controls the government”, “Having citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government”, “Granting the right to vote only to citizens with a sufficient level of knowledge”.

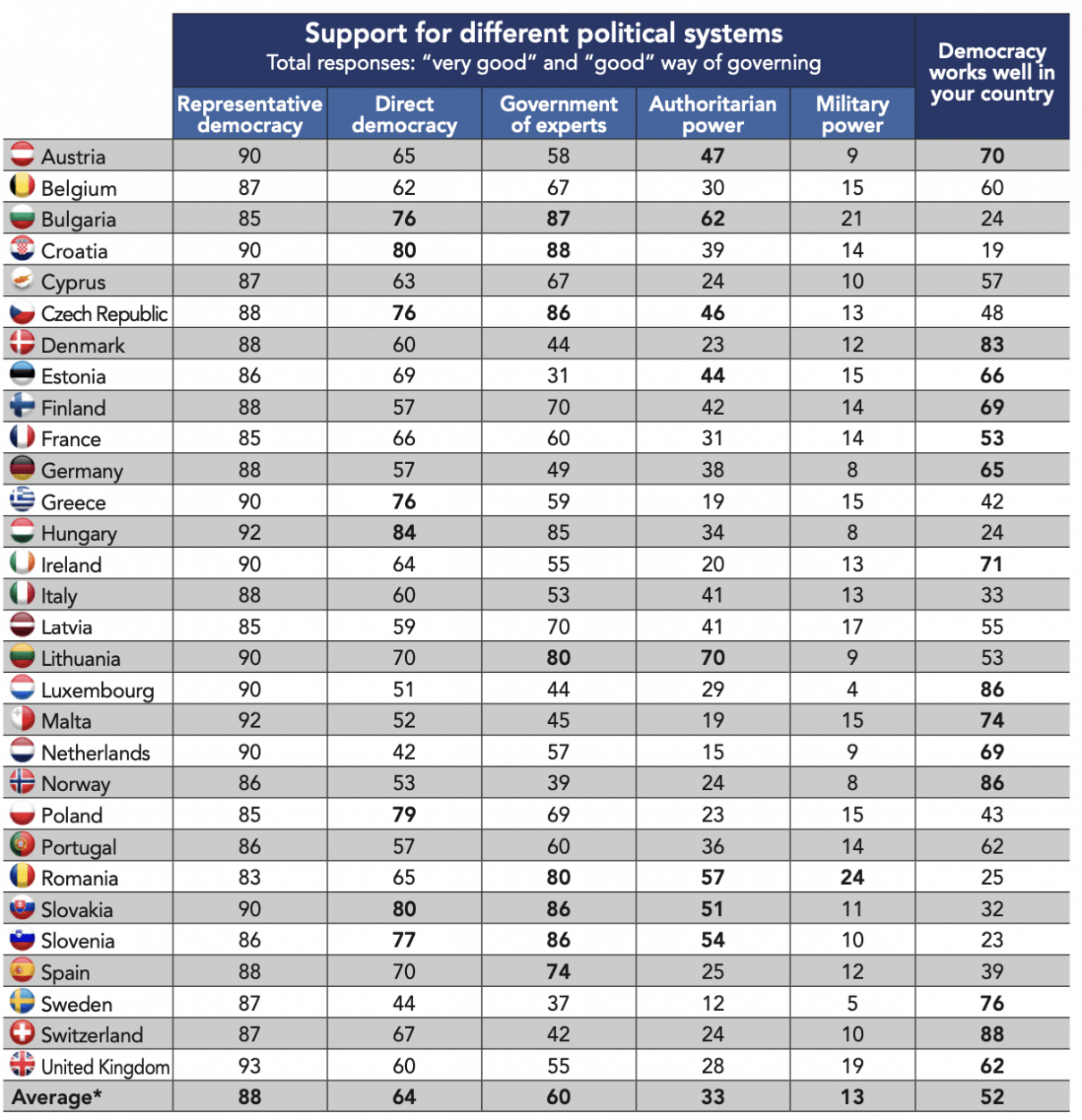

Representative democracy competes with direct democracy

As it is commonly understood, representative democracy describes a system in which citizens elect representatives who govern for them for a set period of time, a so-called mandate, at the end of which they can only continue to act on condition that they obtain the approval of the people again by means of general elections. But democracy is by nature an inexhaustible theoretical and controversial subject, since it is based on the principle of the universal right to express one’s opinion. It can also be defined by the idea of involving citizens in public decision-making more often, by combining elections and referenda, or even imagining a “direct democracy”, amounting to collectively deciding on all subjects without needing representatives to facilitate doing so.

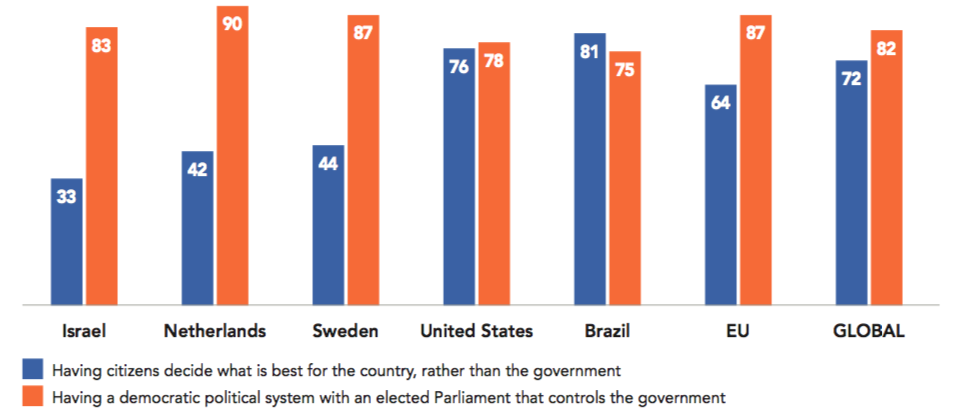

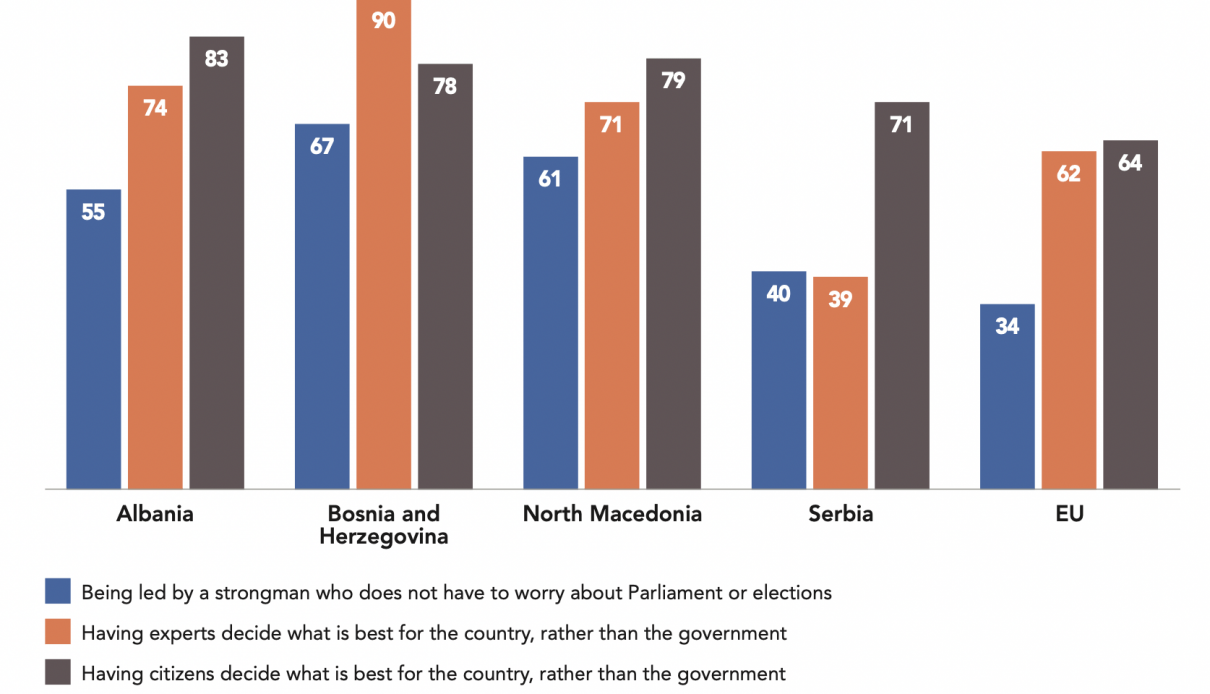

Six different systems3 were presented in our survey, inviting respondents to state, for each, whether it seemed like a good or a bad way of governing. Among these six options, the model of representative democracy (“having a democratic political system with an elected Parliament that controls the government”) has the broadest support (82%), followed by the model of direct democracy, phrased as follows: “Having citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government.” Three-quarters of respondents (72%) considered this form of democracy a good way of governing. Across all forty-two democracies, the gap between the options of direct and indirect democracy is just 10 points.

For each one, indicate whether this way of governing a country is/would be very good, good, bad, or very bad

Copyright :

Total responses: “very good” and “good”

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Europeans express a slightly higher level of support for representative democracy (87%), while direct democracy receives less support (64%), although this remains at a high level. This result, which is favorable to representative democracy, is all the more significant because it is also found in the countries of the former communist bloc. Indeed, in the East, public opinion supports the representative interpretation of democracy (86%) to the same extent. On the other hand, with regard to the level of support for direct democracy, there is a significant gap (14 points) between the sixteen countries that previously formed Western Europe (61%) and the eleven countries that previously formed the Eastern bloc (75%). Furthermore, the Swiss, who are not members of the European Union, form a sort of third Europe: even though they are renowned for their numerous referenda, they still largely (87%) approve of representative democracy. They are even less enthusiastic about direct democracy (67%) than the overall average (72%).

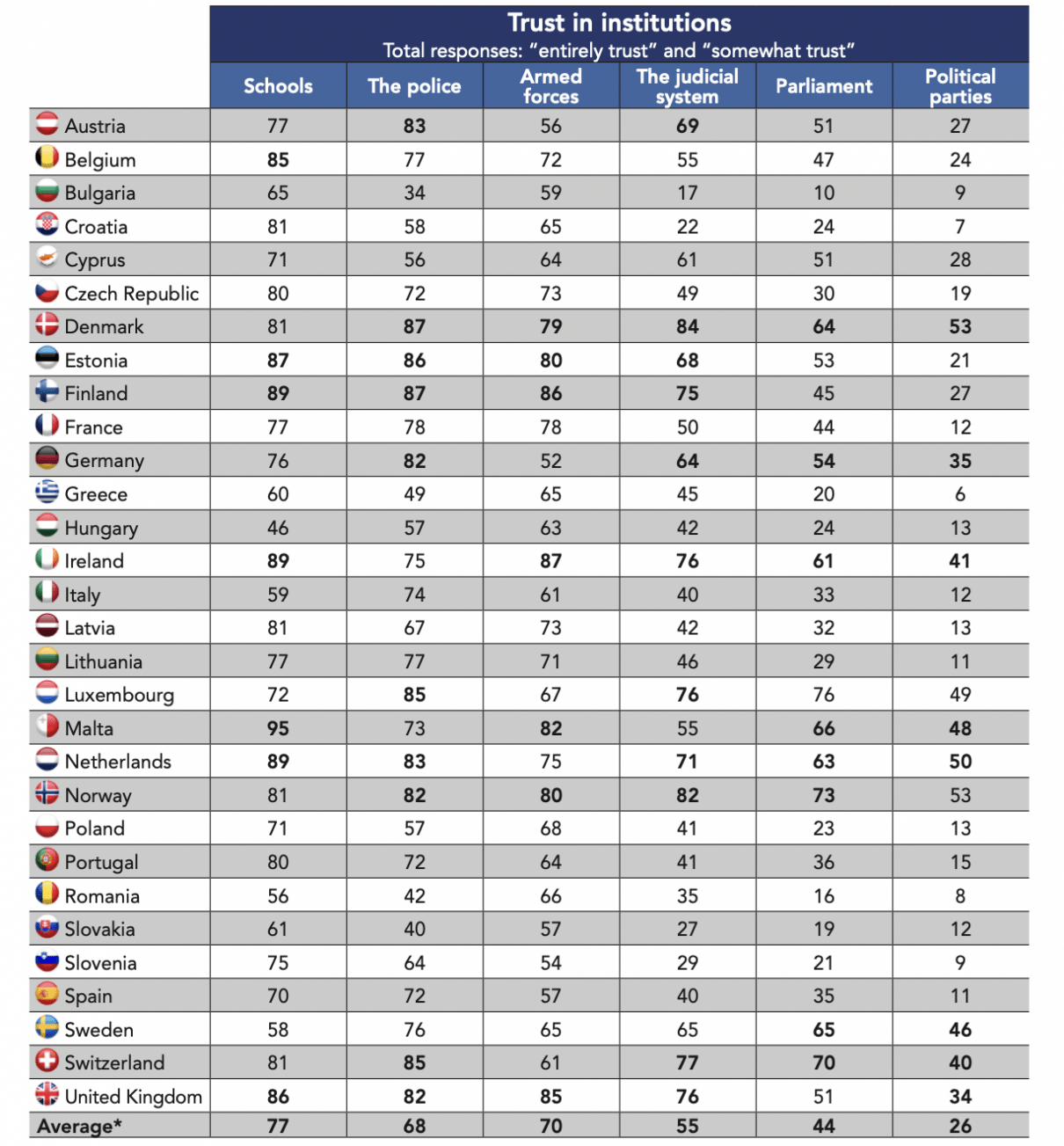

The parliamentary institution is not trusted by citizens

The widely approved model of representative democracy, organized around an elected Parliament that controls the government, is, however, in competition with support for the model of direct democracy, where it is the citizens and not a government that makes decisions. Perhaps we can begin to find an explanation for the ambivalence of opinion toward representative democracy in observing judgements not of the democratic principle, but of the representative institutions. Ambiguity can be interpreted as a sign of a weakness if one considers, despite support for the principle of representative democracy, the collapse of confidence in the institutions that organize it, whether this be Parliament or the elected representatives in general.

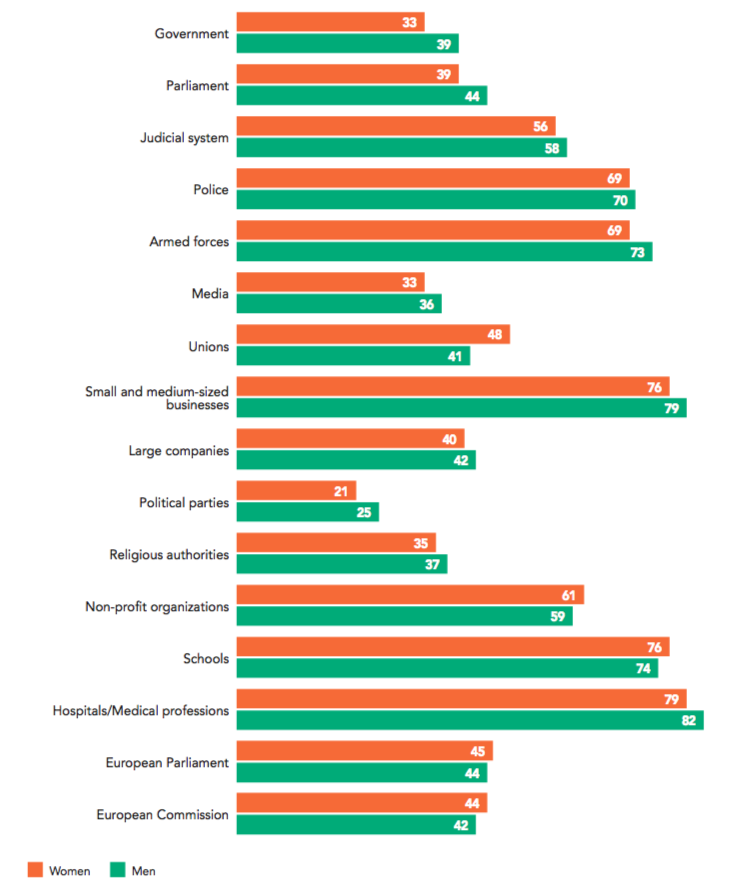

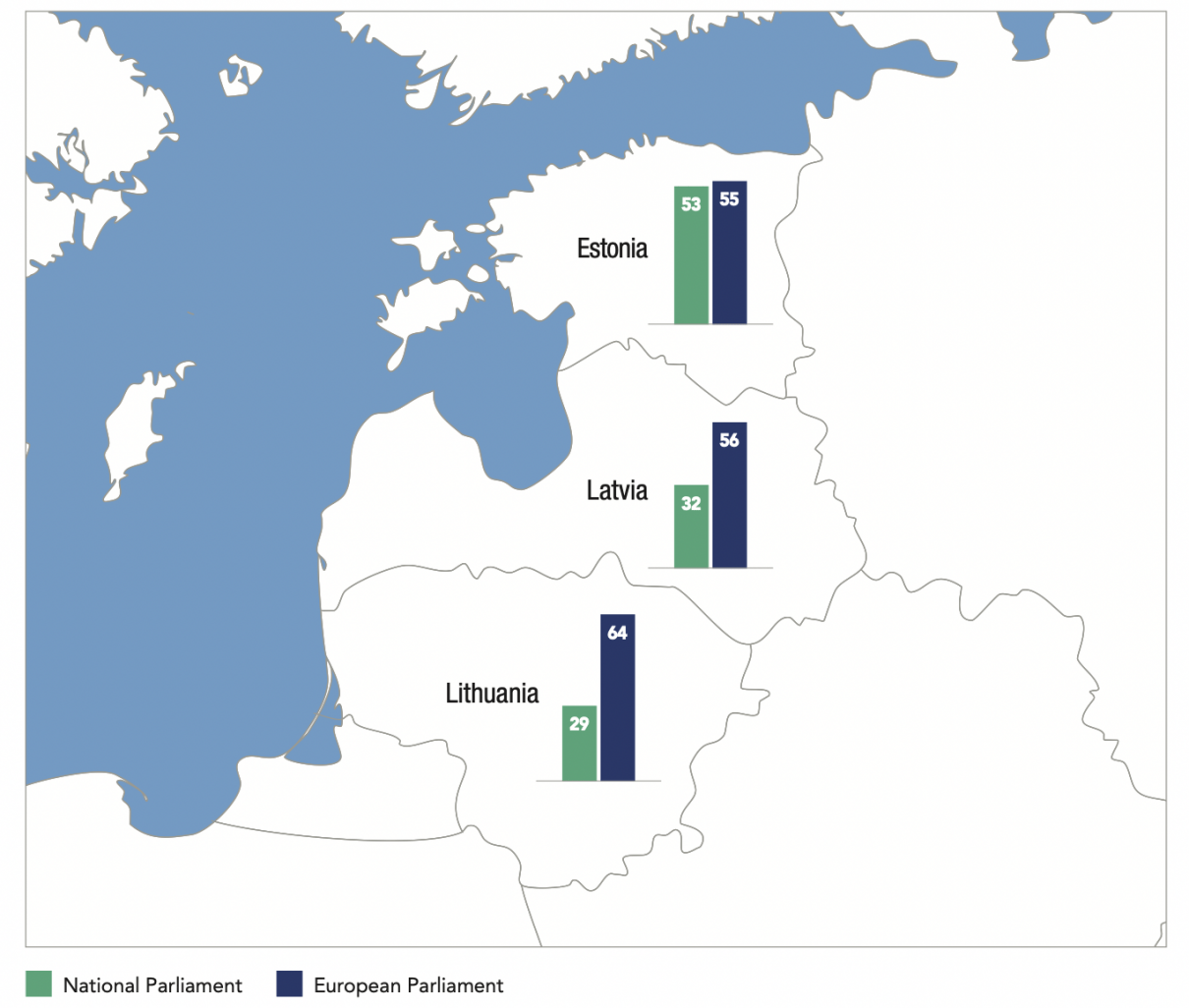

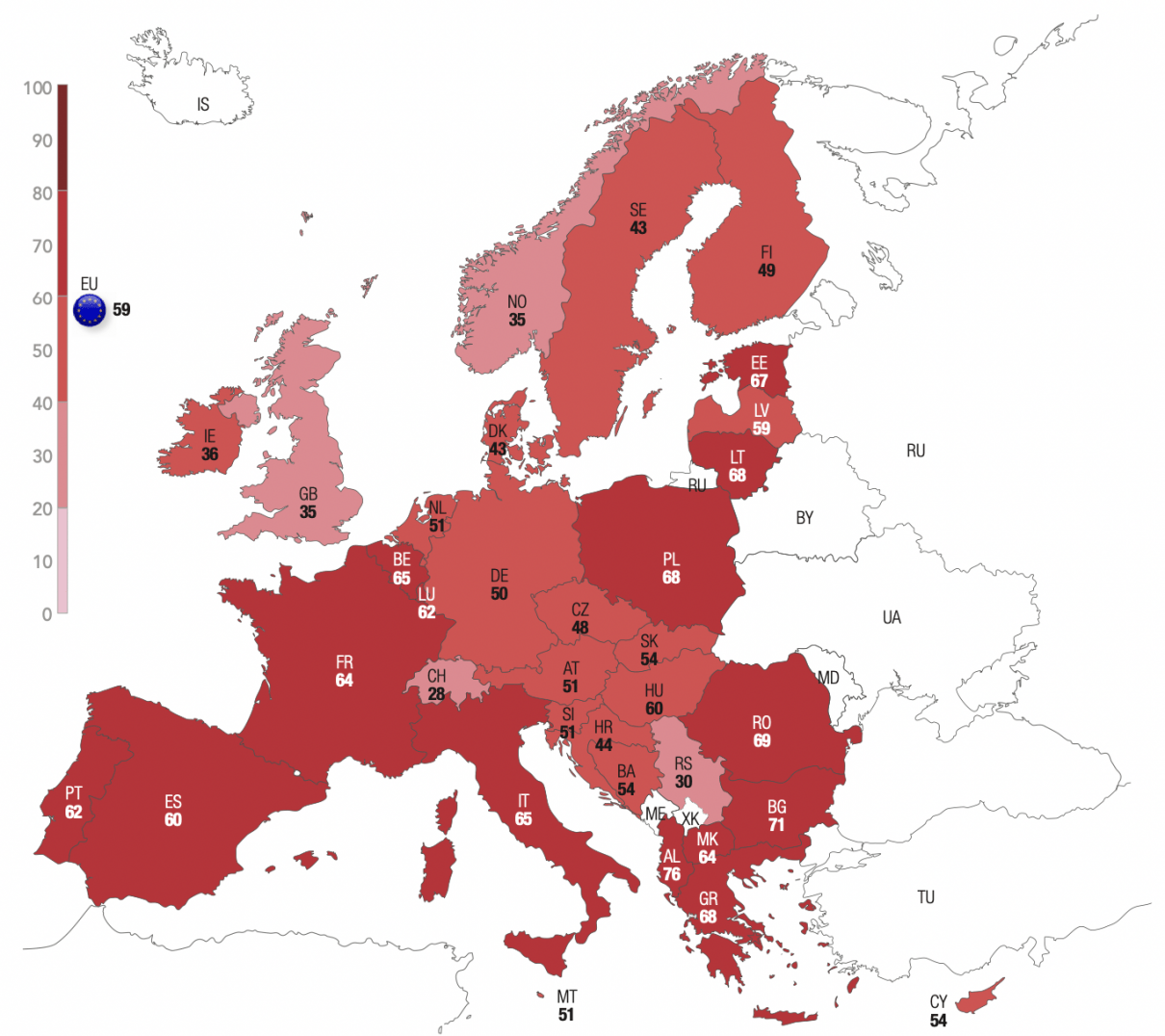

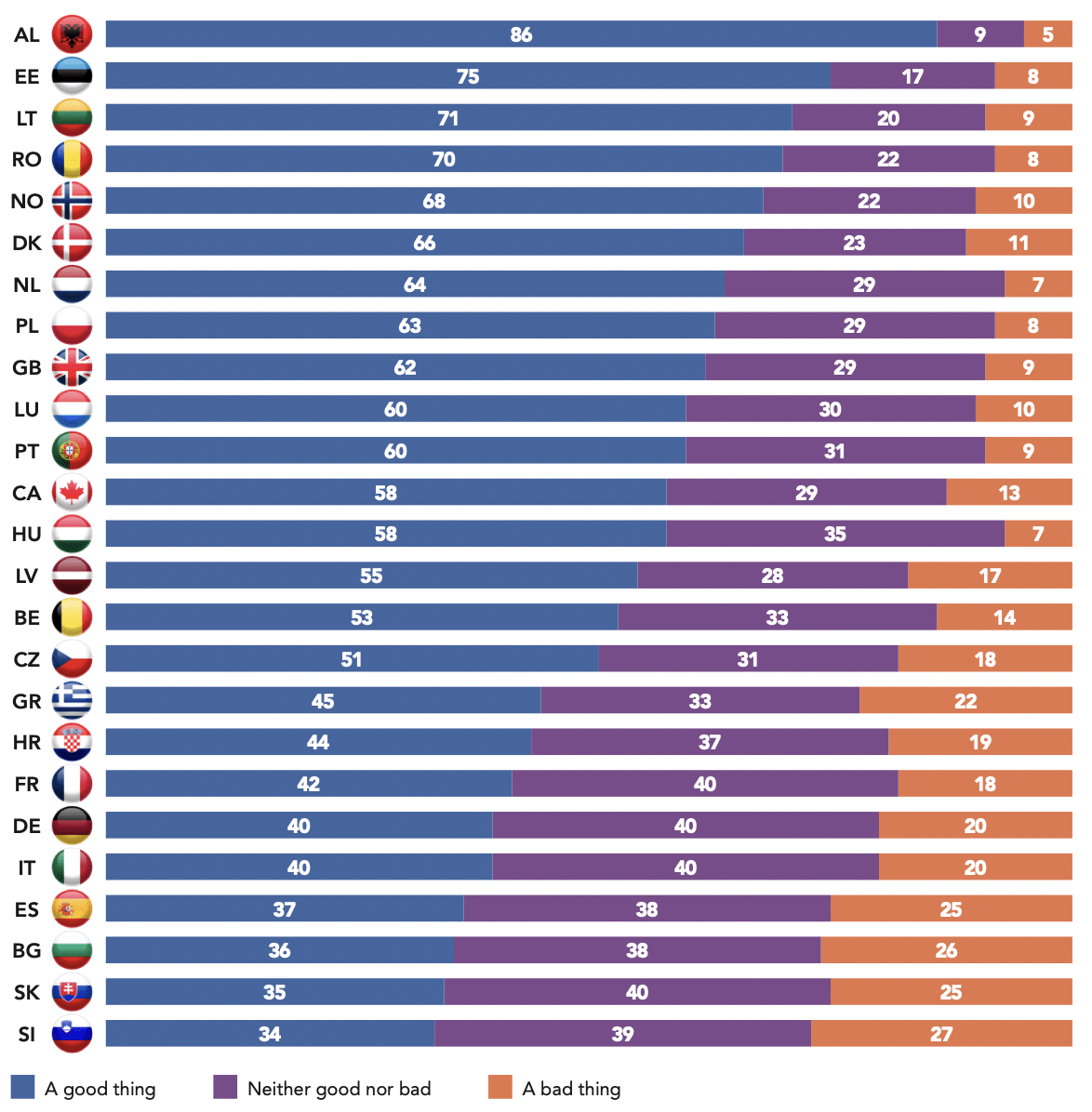

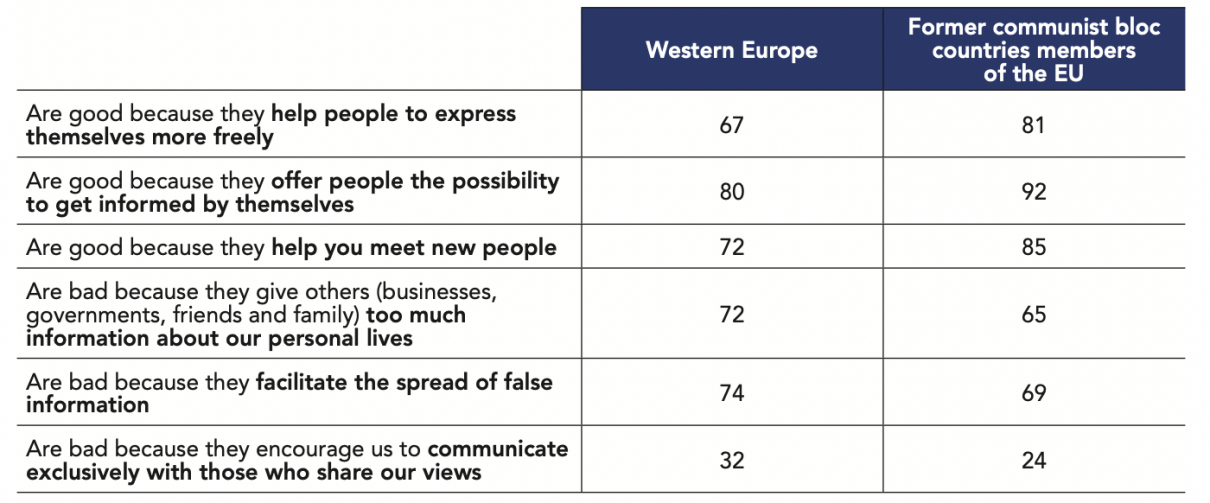

Overall, the parliamentary institution evokes the mistrust of a clear majority of respondents (59%). Trust is the majority opinion in only seventeen of the forty-two democracies. Most of these are small, rich European countries: Austria (51%), Cyprus (51%), the United Kingdom (51%), Estonia (53%), Germany (54%), Israel (58%), Ireland (61%), the Netherlands (63%), the United States (63%), Denmark (64%), Sweden (65%), Malta (66%), Canada (66%), New Zealand (70%), Switzerland (70%), Norway (73%) and Luxembourg (76%). Across the European Union, mistrust of national Parliaments reaches 60%. As for the European Parliament, although it also generates mistrust among the majority, the level is significantly lower (51%). In the countries of former communist Europe, the average lack of trust in national Parliaments is record-breaking (78%), while the European Parliament elicits more trust (50%) than suspicion (45%).

This is a further sign in favor of the hypothesis that representative democracy is less contested in principle than it is challenged due to dissatisfaction with the institutions responsible for enacting it.

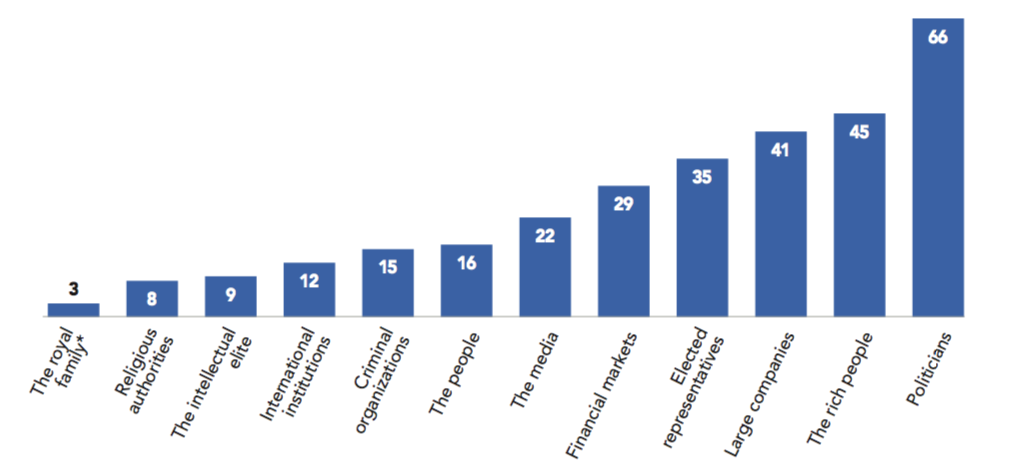

The intellectual elite, the media, financial markets, large companies, elected representatives, politicians, religious authorities, the people, criminal organizations (mafia), international institutions, the rich people and the royal family (option proposed in parliamentary monarchies only).

When asked about who holds the most power among the twelve proposed entities, respondents were instructed to answer with three options: “first”, then “second” and “third”. The total of the mentions, for a designated entity, is therefore the sum of all mentions in the positions: “first”, “second” or “third”.

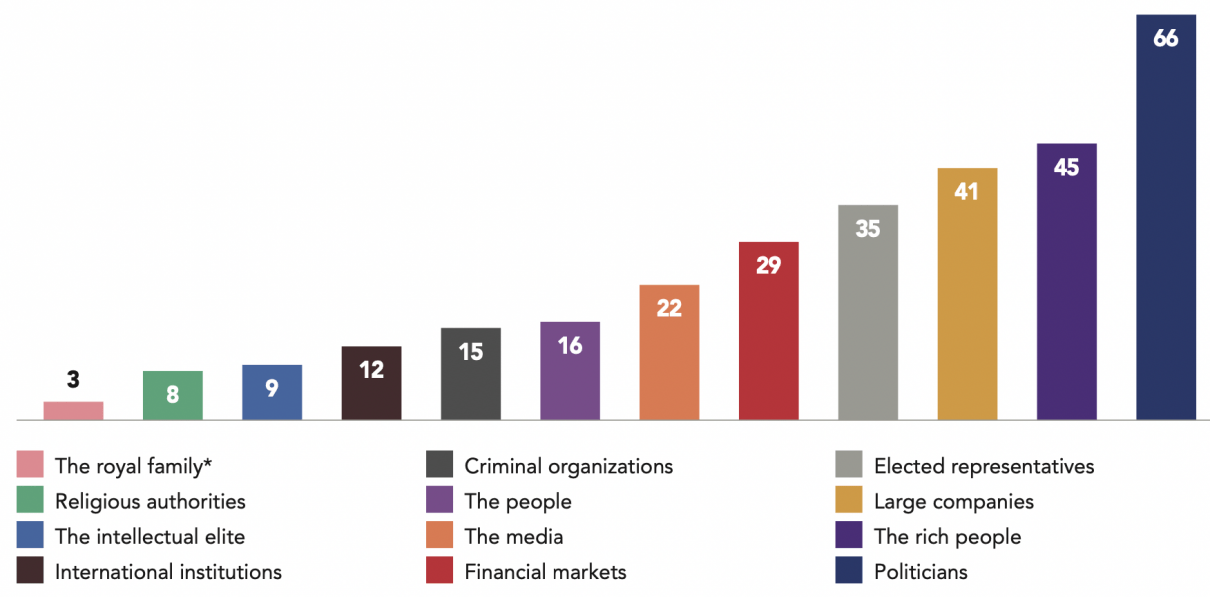

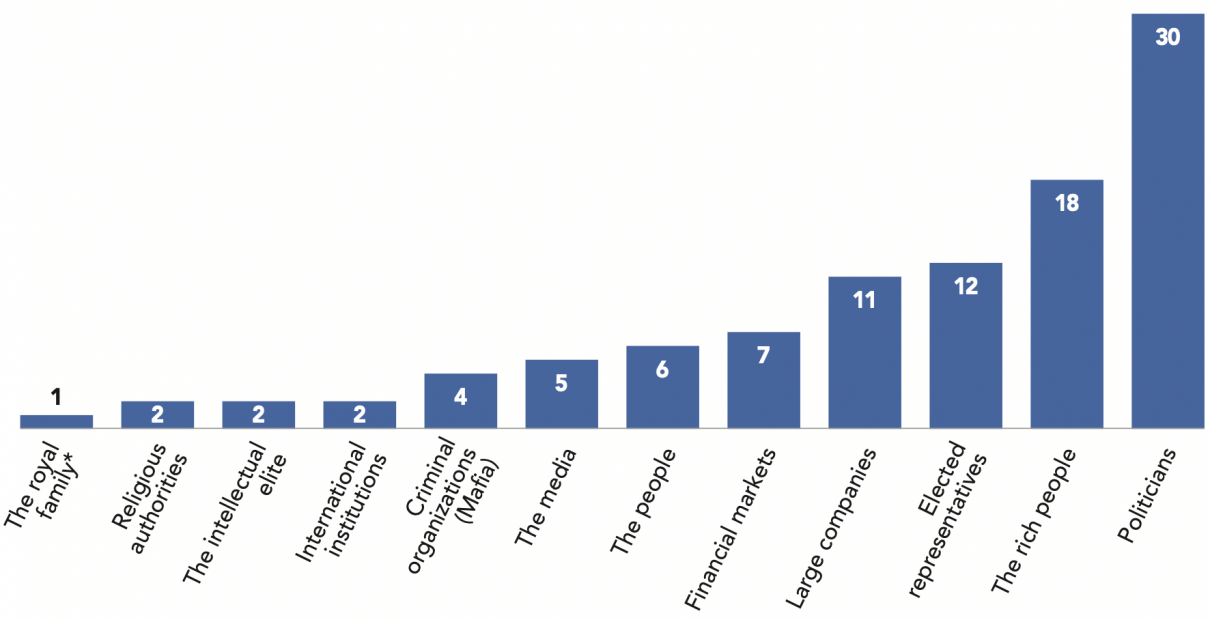

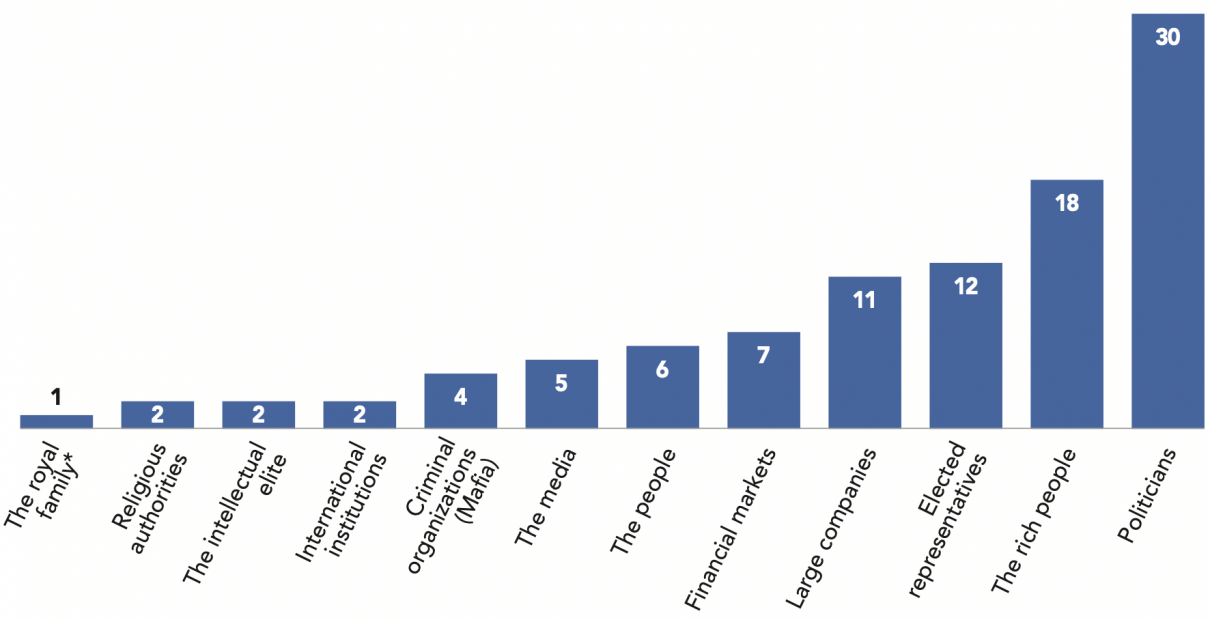

According to the public, elected representatives do not hold power

When we asked the question “who holds the most power in your country?” and offered a list comprising twelve entities4, then considered the entities cited “first” as having power, elected representatives were chosen by just 12% of respondents and come in third place, after politicians (30%), constituting, in public opinion, as we see here, a group seen as distinct from elected representatives. These are followed by the rich people (18%), the large companies (11%), financial markets (7%), ahead of the people (6%) and the media (5%). Considering the total selections at any ranking (first, second or third)5, a third (35%) of respondents cited elected representatives, placing them fourth behind politicians (66%), the rich people (45%), large companies (41%) and ahead of financial markets (29%) and the media (22%). In total, less than one-fifth of respondents cite the people (16%) among the entities deemed to have power, around the same level as criminal organizations (15%).

Which of the following categories holds the most power in your country?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

* Option proposed in parliamentary monarchies only.

On average, opinion in European Union democracies varies little when it comes to these results. On the other hand, country by country, there are major divergences within the 42 democracies in the survey.

Taking into account the total number of mentions, elected representatives, cited as holding power by an average of 35% of respondents, are most frequently selected by the Norwegians (61%), Luxembourgers (54%), Swedes (51%), Estonians and Swiss (50%); least frequently by the Albanians (14%), who nonetheless declare their attachment to representative democracy, Cypriots (16%), Italians and Macedonians (17%), and Greeks and Ukrainians (20%). Politicians, cited on average by 66% of respondents, are most commonly chosen by the Albanians (89%), Japanese (85%), Macedonians (84%), Hungarians (83%), Bosnians (82%), Estonians and Maltese (81%), Serbs (80%), Swedes (79%), Poles (78%), Croatians and Norwegians (77%), Bulgarians and Romanians (76%), Czechs (75%), Cypriots and Latvians (73%). The rich people, selected by an average of 45% of respondents, are most often cited by Ukrainians (87%), Bulgarians (71%), Albanians and Hungarians (62%), Slovaks (60%), Lithuanians (58%), Slovenians (57%), Serbs (56%), Croatians and Macedonians (54%), Romanians (53%), Czechs (52%), and Americans (51%).

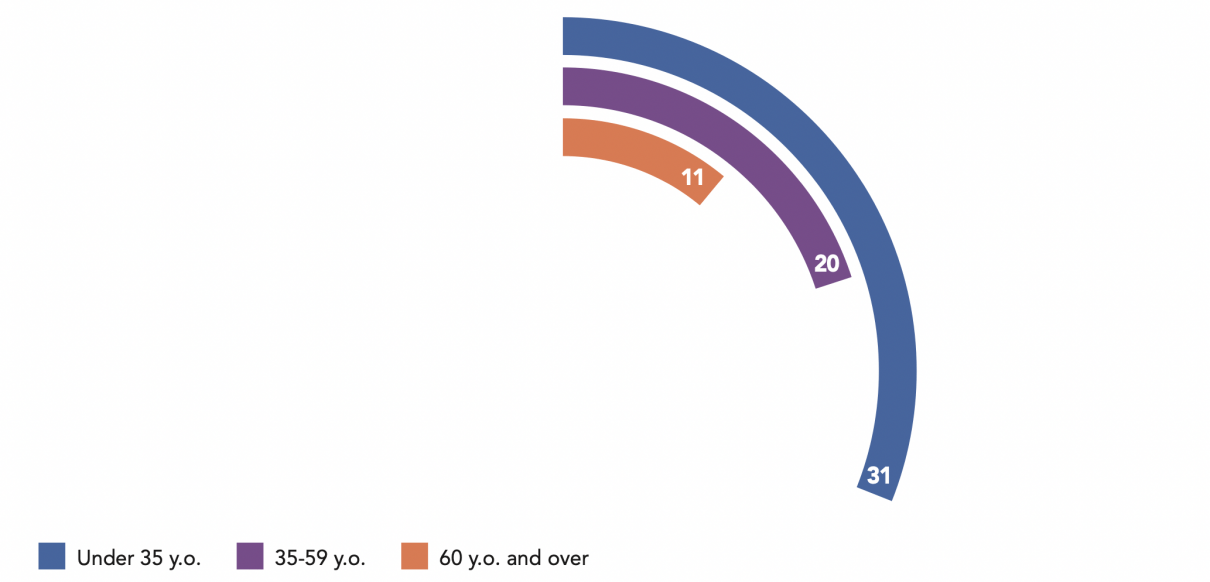

Rarely cited (35% in total, i.e. in first, second or third place), elected representatives are even less likely to be selected by younger respondents: 41% among those aged 60 and over, 37% among those aged 50-59, 32% among those aged 35-49 and 30% among those aged 18-34. The same applies to the financial markets (29% mentions in total): 35% among those aged 60 and over, 30% among those aged 50-59, 28% among those aged 35-49 and 22% among those aged 18-34. Conversely, the media (22% for the total number of mentions), are more likely to be cited as holding power by younger respondents: 19% among those aged 60 and over, 17% among those aged 50-59, 22% among those aged 35-49 and 27% among those aged 18-34.

The usefulness of voting is called into question by a third of respondents

Attachment to democracy in general, and to representative democracy in particular, is confirmed when one asks about the usefulness of voting. The survey invited people to choose between two options: “voting is worthwhile because elections can make a difference” or “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people“. More than two-thirds of respondents chose the first option (70%). If we look at opinion across the European Union itself, there is more skepticism about the usefulness of the vote, as 66% of respondents chose the first option and 34% chose the second. In the formerly communist democracies of the European Union, the level of skepticism about the usefulness of voting is similar (35%). However, it is close to the majority among Albanians and Macedonians (46%), as well as Ukrainians (48%), and reaches a majority among Serbs (54%), Bulgarians (56%), Slovenians (58%) and Croatians (64%). As we can see, this small group of countries whose citizens believe that voting serves no purpose belongs to the former Soviet world. The exit from communism and the commitment to a process of democratic transition for some, extended in certain nations by entry into the European Union, was not enough to convince people of the usefulness of voting. Apart from these cases, it should be noted that the majority of Cypriots (51%) and Belgians (56%) also responded that voting is pointless. Overall, the majority of national opinion is convinced that voting is pointless in 6 of the 42 democracies involved in our survey.

This skepticism about the usefulness of voting becomes somewhat more evident when one considers opinions on globalization. Those who believe that globalization is an opportunity are less likely (26%) to state that voting is useless than those who see globalization as a threat (37%). In other words, here again, the idea that voting serves no purpose is not necessarily, and certainly not entirely, an expression of invalidation of the electoral act. It may also be the acknowledgement of a weakening, or even challenge to the feasibility of running states democratically in a world grappling with powers beyond its control.

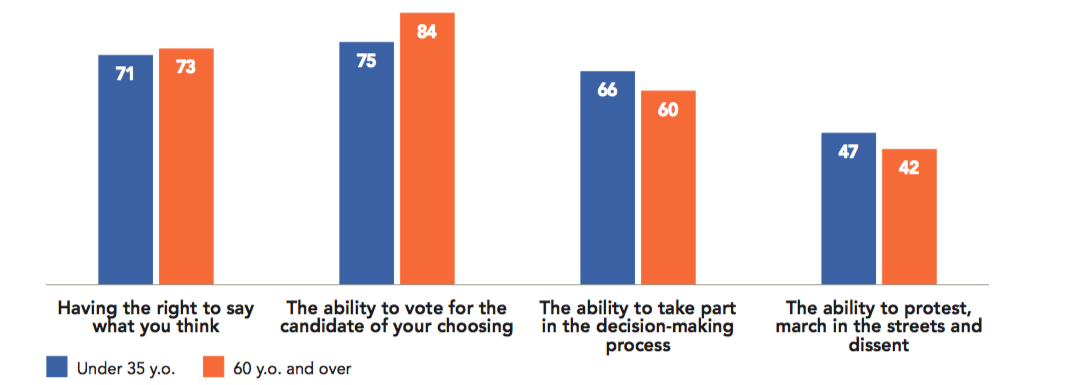

No decline in attachment to public liberties

Citizens’ skepticism about the usefulness or effectiveness of democratic political procedures and institutions does not affect their attachment to the major public freedoms. This is a critical point, since the opinion that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people” (30%) must be considered in light of the unanimous attachment to “the ability to vote for the candidate of your choosing”, deemed “very important” or “important” by 97% of interviewees, along with “the ability to take part in the decision-making process” (96%). Once again, we see that the skepticism noted is not primarily about the value of the principles or intentions contained in the institutions of representative democracy, but rather about the possibility of making them effective in the world as it is, i.e. to be capable not only of expressing but of realizing collective preferences that have been ascertained through the existing mechanisms. The same massive attachment is noted with regard to “the ability to protest, march in the streets and dissent” (82%) and “having the right to say what you think” (98%). Lastly, and this is a key element, we note the same levels of support for the great public freedoms, between 86% and 98%, in the eleven democracies that emerged from the fall of communism and are now members of the European Union.

Democratic concern about the future of democracy

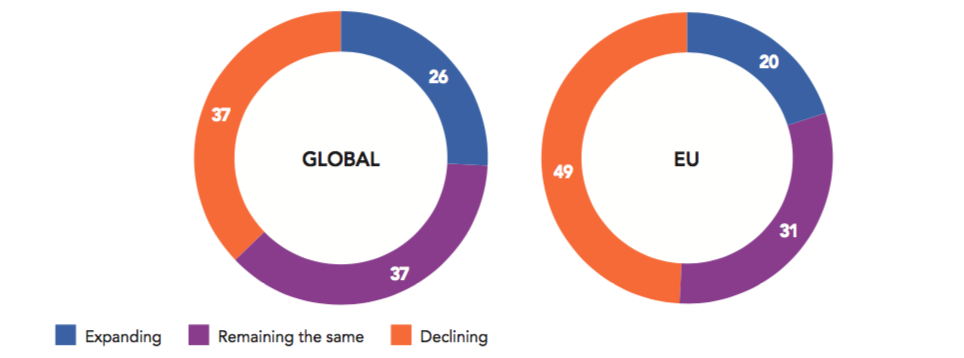

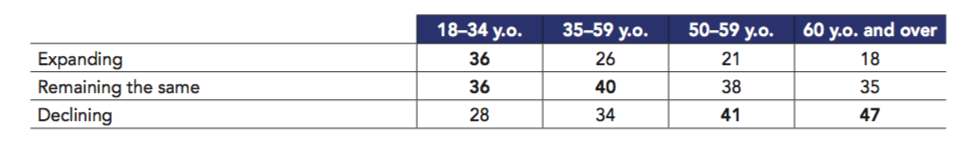

Expectations about the future of democracy were assessed using the following question: “Would you say that the number of democratic countries in the world is expanding, remaining the same, declining?”

Would you say the number of democratic countries in the world is…

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

In the democratic world, countries where the majority of citizens believe that the number of democracies in the world is in decline are all European, and most are members of the European Union: Greece (61%), Germany (60%), Austria (57%), Slovenia and Serbia (55%), Belgium and Luxembourg (54%), Hungary and the Netherlands (53%), Italy and Switzerland (52%), France (51%). It should be noted that the view of the democratic system in decline is less widely held in the eleven ex-Soviet European Union Member States (42%) than in the sixteen European Union countries that made up the Western bloc, which are now mostly pessimistic about the future of democracy (52%).

Would you say the number of democratic countries in the world is…

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

It should be noted that the younger the respondents, the more they feel that the number of democracies is expanding. The youngest (18-34 years) are even twice as likely (36%) as the oldest (18% for 60 years old and over) to believe that the democratic model is spreading. Previously reported variables, both in terms of age and professional standing, once again play a role. Overall, considering the respondents from the forty-two democracies studied, the idea that the number of democracies is in decline across the world is shared more by respondents who consider globalization a threat (44%) than an opportunity (33%). There is a link between pessimistic expectations about the future of respondents’ countries and the idea that democracy is in decline. Likewise, we note a relationship with people’s assessment of the functioning of democracy in their country.

The transparency of the electoral process called into question

Madeleine Hamel

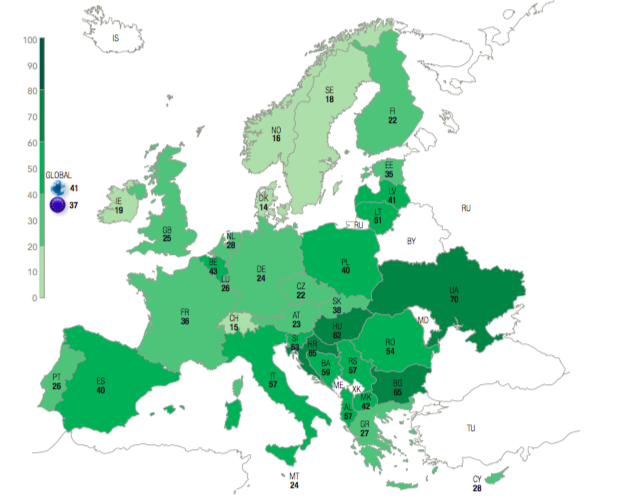

Given the centrality of the electoral process to democratic politics, it is surprising to note in our survey that less than a fifth (16%) of the citizens surveyed deem the functioning of elections in their country “absolutely” transparent. Similarly, among the 42 democracies studied, four out of ten citizens (41%) consider their country’s electoral system “not at all” or “not really” transparent.

Would you say that the electoral process is transparent in your country?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Total responses: “not at all” and “not really”

The following countries fall into this category: Australia, Canada, Cyprus, Malta, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

The following countries fall into this category: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia.

The following countries fall into this category: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

The following countries fall into this category: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

An opinion which reveals new impediments to the transparency of electoral processes

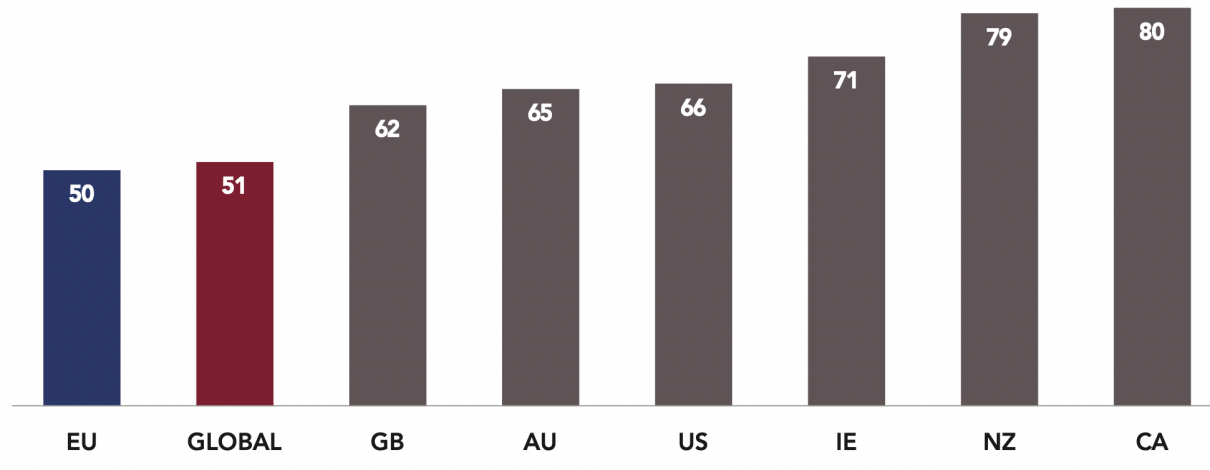

The level of public satisfaction on this crucial point varies significantly depending on the geographical areas and the countries concerned. The group reporting the highest level of satisfaction is made up of the Commonwealth countries1 covered by the study: on average, three quarters (75%) of the citizens surveyed feel that the functioning of elections in their country is “absolutely” or “somewhat” transparent. This is significantly higher than in the US (61%). The fact that nearly four out of ten Americans (39%) feel that their country’s electoral process is “not really” or “not at all” transparent reflects the scandals surrounding Russian interference in the 2016 presidential elections.

Among the responses from the inhabitants of the European Union candidate countries2, this proportion plummets by 19 points compared to the average of the European Union democracies (63%), to a minority position (44%), with one-fifth of the respondents (21%) believing that the electoral system in their country is “not at all” transparent. We can see here how joining the European Union can represent the possibility of finalizing a still-fragile democratic transition.

Denmark has the highest proportion of respondents who feel that their country’s electoral system is transparent (86%), followed by the Swiss (85%) and the Norwegians (83%). In contrast, Hungarians (38%), Croatians (35%), Bulgarians (35%) and Ukrainians (30%) are the most dissatisfied among the 42 democracies in our study. As for the British, they continue to affirm the transparency of their electoral system (75%), despite the complications brought about by the referendum on leaving the European Union. Similar figures can be found in Israel, where nearly three quarters of respondents (74%) consider their electoral process transparent. This sentiment is less widely shared by young Israelis, with more than a third of respondents aged under 35 (34%) believing that the electoral system is not transparent, compared to 22% of 35-59 year-olds and 21% of respondents aged 60 and over.

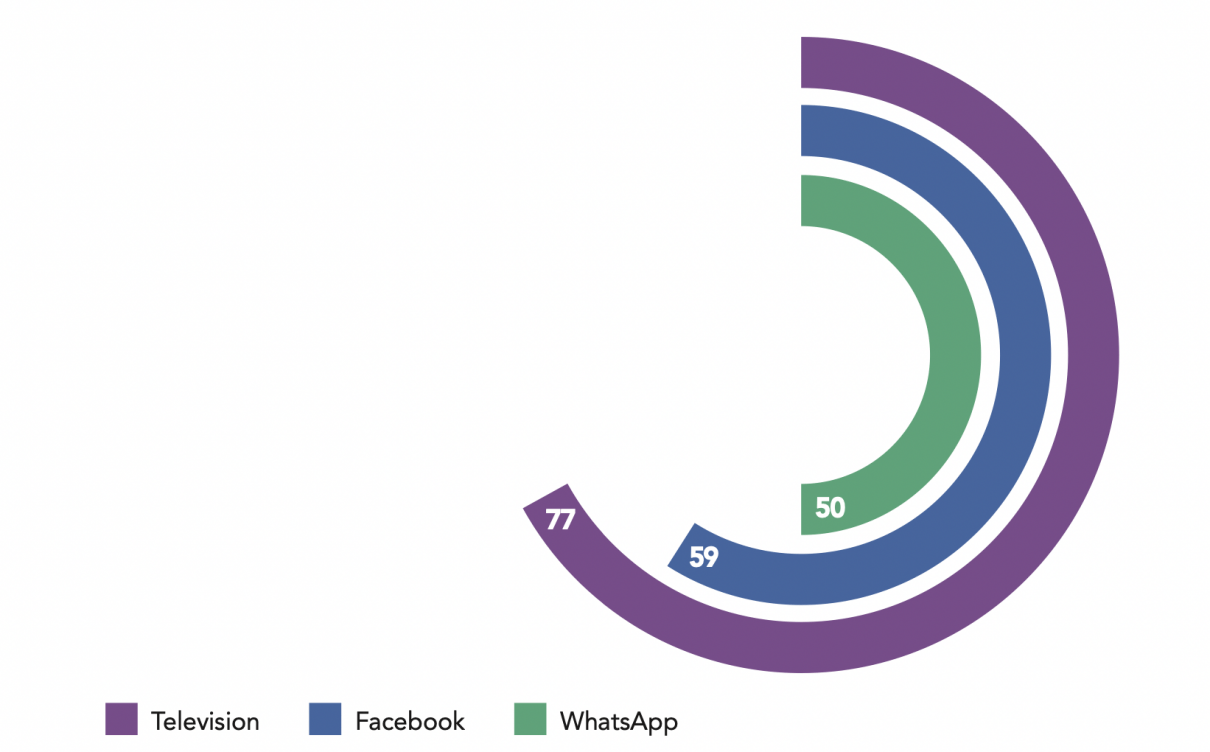

For our survey, Brazilians were interviewed on the eve of a presidential election that would bring the populist Jair Bolsonaro to power. The campaign was characterized by serious accusations from the left regarding Bolsonaro’s use of the WhatsApp messaging app to spread fake news and political propaganda messages. In our survey, the majority of respondents (54%) feel that the electoral system is not transparent. This relationship is reversed on the other side of the Pacific, with 46% of Japanese people finding their electoral system not transparent.

Would you say that the electoral process is transparent in your country?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Faith in the electoral process is strongly influenced by the profile of the people interviewed

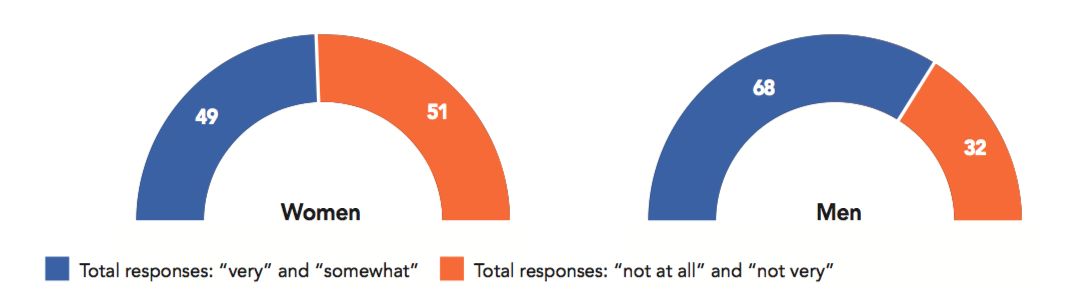

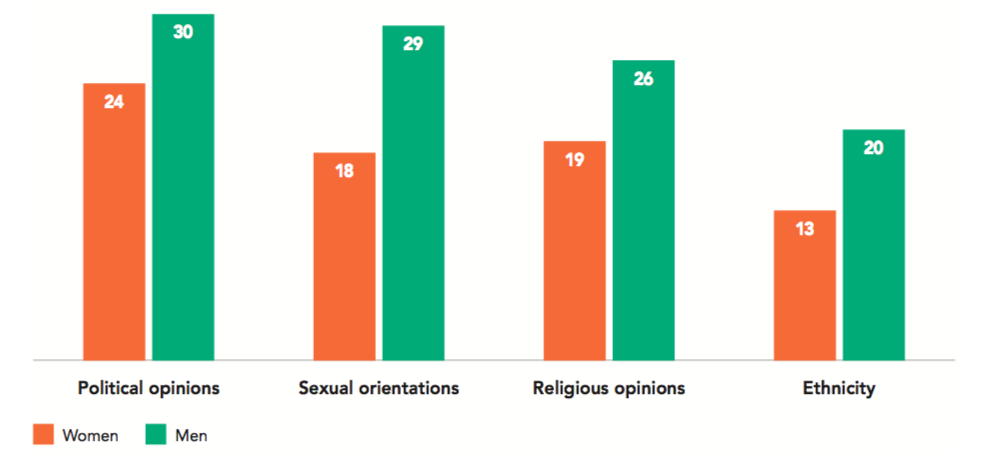

Dissatisfaction with the functioning of the electoral system varies according to the profile of the people interviewed, particularly according to gender, as 45% of women think that the electoral system is not transparent, compared to 37% of men. Another divide that may be noted is interest in politics. Indeed, the citizens surveyed who say they are interested in politics tend to see their countries’ electoral system as transparent: 64% versus 51% for those who say they have little or no interest in politics.

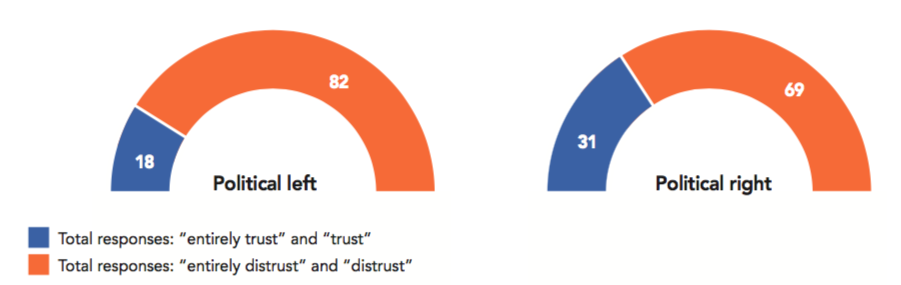

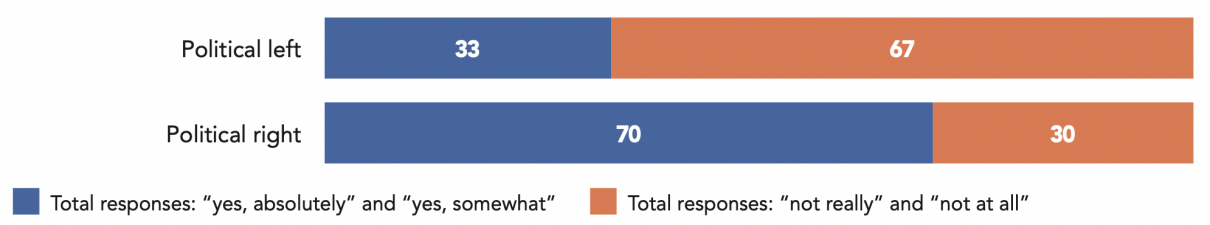

Political positioning plays an important role and gives rise to a phenomenon that is worth highlighting. On average, more people who place themselves on the right of the political spectrum judge the electoral system to be transparent (66%) than those who claim to be on the left (58%). This difference is all the more visible as we go towards both ends of the axis, with far fewer people on the far left who see the electoral system as transparent (44%) than on the far right (62%). Perhaps this is a sign of opposed movements, combining increasing disappointment among left-wing citizens and, conversely, greater satisfaction among right-wing citizens, in a democratic world marked by the decline of social democracy and the shift of majorities to the right, election after election.

Would you say that the electoral process is transparent in your country?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Opinions on the transparency of electoral procedures also interact with the perception that respondents have of their situation. A majority of those (54%) who feel that they have suffered a decline in recent years, considering their standard of living to have deteriorated, believe that the functioning of the electoral system is opaque, while this opinion is found among just one third (32%) of those who believe that their standard of living has improved. Among citizens who believe that their way of life is under threat, half (49%) also consider that electoral procedures are not transparent, while, again, this belief is shared by only a third (33%) of those who do not feel that their way of life is threatened. Furthermore, it should be noted that among those who think that things will get worse, one fifth of respondents (19%) feel that the system is “not at all” transparent.

Transparency of the system and democratic values

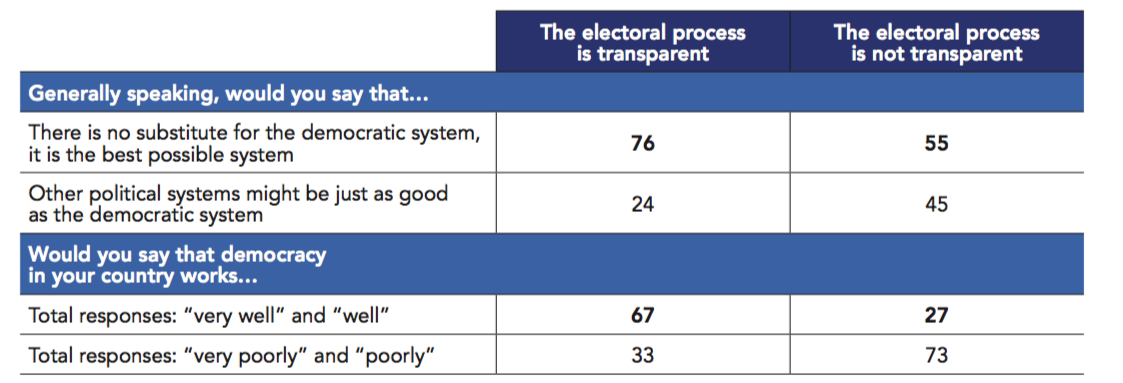

The idea that the electoral system does not function transparently is linked to a lack of confidence in democracy as a system and in the political institutions of that system.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Note for the reader: Among the respondents who believe the electoral process is transparent in their country (total of “yes, absolutely” and “yes, somewhat” responses), 76% agree with the idea that “there is no substitute for the democratic system, it is the best possible system” compared to only 55% of those who think the electoral process is not transparent (total of “not really” and “not at all” responses).

A comparable relationship can be seen in terms of faith in the representative institutions: only 9% of respondents who believe that the electoral system is not transparent say they trust the political parties, compared to a third (33%) of those who consider the procedures transparent. Similarly, only 16% of respondents expressing a lack of confidence in the functioning of the elections say they trust their government, compared to 50% of those who deem the functioning of the electoral process satisfactory.

On the other hand, there does not seem to be any fundamental difference with regard to the values that underpin democracy. For example, among people who consider that the electoral system in their country is not transparent, 52% believe that “voting is worthwhile because elections can make a difference”. For this half of respondents, this may mean that their criticism of the functioning of the electoral system has nothing to do with a rejection of the fundamental democratic procedure, but rather with a demand for sincerity and honesty without which democratic ideals and principles are trampled upon.

Desinterest in politics erodes democratic ideals

Aminata Kone

Of the 42 countries surveyed, a large majority of respondents express that they are somewhat or very interested in politics (58%) and less than half claim to be not very interested (42%), or not at all interested. But citizens’ level of attachment to politics has an effect on the significance they accord to democracy, alternative forms of government or socioeconomic issues.

How interested are you in politics?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

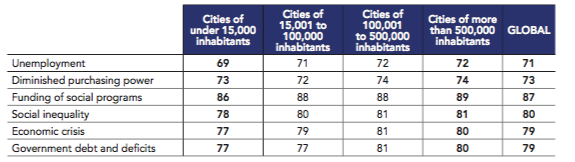

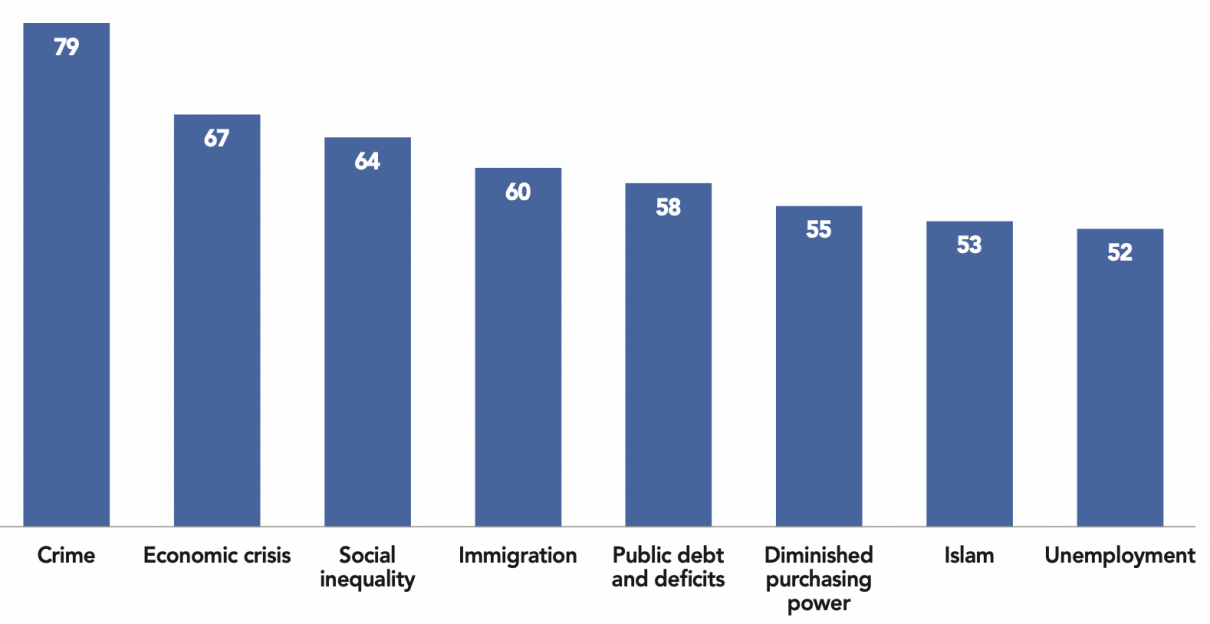

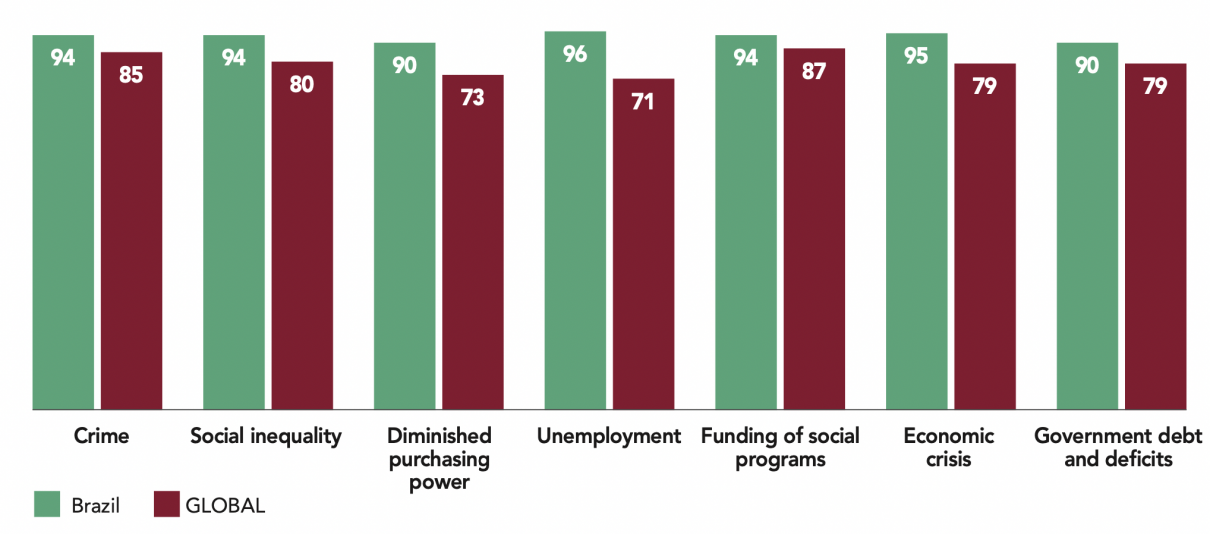

First of all, the level of interest in politics does not seem to influence respondents’ perception of socioeconomic issues. The majority are worried about issues ranging from unemployment (71%), diminished purchasing power (73%), economic crisis (79%), and social inequality (80%). Regardless of the level of interest expressed in politics, the differences between responses do not exceed 3 points, with one notable exception: the less interested respondents are in politics, the more worried they are about unemployment (74% versus 68%). The same goes for the global assessment of trust in big tech, the Internet and social media. The results vary minimally according to the level of interest in politics.

However, when it comes to the political institutions in place today in the democracies surveyed, we do note a trend of divergence. Those who are uninterested in politics tend to be less attached to democratic ideals than those who are interested. 56% of politically disinterested interviewees find democracy works poorly, while 55% of politically interested respondents find democracy works well. It is also among the respondents who say they are not interested in politics that we find the largest number of citizens (40%) who believe that “other political systems might be just as good as the democratic system”, while only 28% of politically interested respondents agree.

This strongly affects the level of attachment to democratic values: while only 14% of politically interested respondents feel that it is not important to be able to “protest, march in the streets and dissent”, this opinion is shared by one quarter (25%) of politically disinterested respondents. Even more striking, nearly half (49%) of those who are not interested in politics feel that the electoral process in their country is not transparent; on the contrary, nearly two-thirds (64%) of those interested in politics consider their electoral process to be transparent.

Support for alternative forms of government over electoral democracy is more widespread among those who are not interested in politics: 61% of them are in favor of “having experts decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” (versus 54% of those interested in politics), and one-third (33%) of politically disinterested respondents favor a government with a “strongman who does not have to worry about Parliament or elections” (compared to 28% of respondents with an interest in politics).

Disinterest in politics, whether initially due to a lack of education and information or the result of disillusionment, with civic withdrawal reflecting attitudes of protest rather than a lack of knowledge, appears to be one of the determinants of the decline of democratic values and the rise of opinions favoring an authoritarian regime.

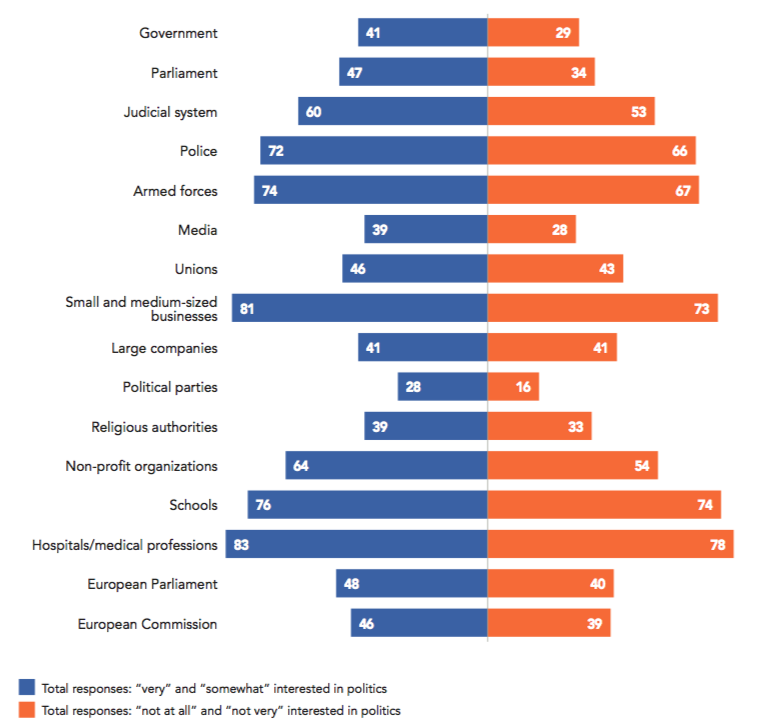

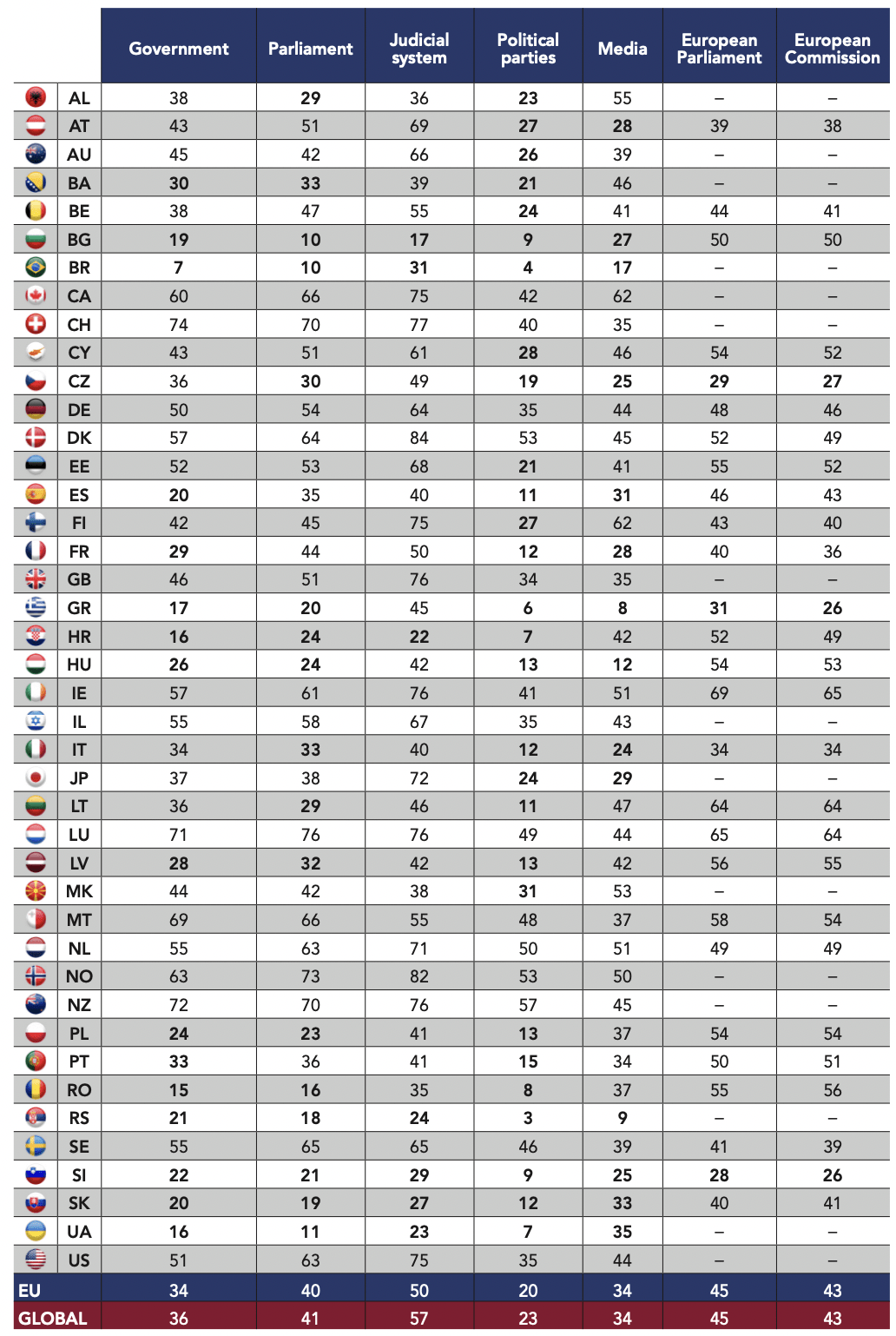

Trust in institutions

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Total responses: “entirely trust” and “somewhat trust”

Note for the reader: Among the respondents declaring to be interested in politics, 41% trust their government.

Is the legitimacy of universal suffrage uncontested?

Dominique Reynié

Universal suffrage is the theoretical and practical cornerstone of democracy. Voting has become a right that can only be made conditional upon a few fundamental criteria, most often age and nationality. The idea of making access to voting dependent on the mastery of certain skills has existed in the past. It was even an important step on the road to universal suffrage. This system has been referred to as an “epistocracy”. Today, however, making access to voting conditional on certain skills amounts to breaking with the rule of universal suffrage.

Is granting the right to vote only to citizens with a sufficient level of knowledge a good or a bad way of governing?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

Total responses: “very good” and “good”

Dominique Reynié (ed.), What next for democracy? An international survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Paris, 2017, 320 pages.

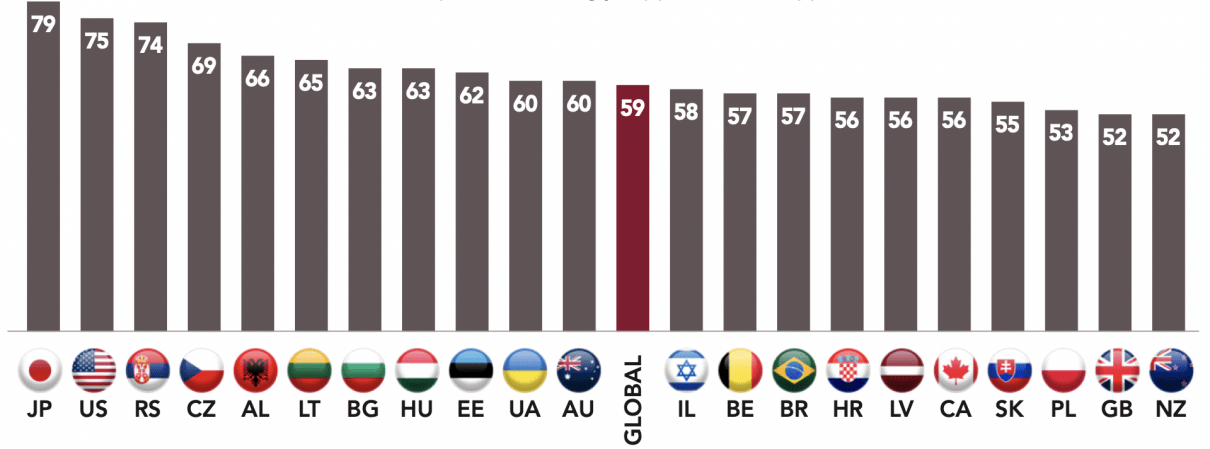

The following countries fall into this category: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The hypothesis that a democratic deconsolidation is taking place is one of the questions driving our international survey, following on from the previous one1. This deconsolidation could, for example, manifest itself in public opinion through the abandonment of the values, principles and mechanisms that structure and drive democratic politics. This is what we sought to assess by asking the following question: “Please tell me if this is/would be a good way of governing a country: ‘Granting the right to vote only to citizens with a sufficient level of knowledge’”. Over our panel as a whole, one-third (38%) of respondents approved such a restriction on access to voting. This is a striking result in itself, given the centrality of the issue.

Reading the results, one is first struck by the persistence of a divide within the European Union which clearly separates the former Eastern and Western blocks. Across the formerly communist countries which are now members of the European Union2, support for the idea of epistocracy is found among half of respondents (49%). Among the 42 democracies surveyed, Bulgarians are by far the most in favor of this type of limitation (85%). Approval for an epistocratic model is also a majority position among Hungarians and Slovaks (61%), Romanians (52%) and Croatians (50%). The approval level remains very high in Latvia and Lithuania (49%), Estonia (44%), the Czech Republic (41%) and Poland (40%). On the doorstep of the European Union, approval for the epistocratic model dominates among Bosnians (61%), Macedonians (55%) and Ukrainians (49%).

Placed on the dividing line between these two Europes, the Austrians (47%) are the most in favor of epistocracy among all the countries of the former Western block, followed by the Italians (42%). But it is in the West that epistocracy finds the lowest levels of support: among the Spanish (29%), Dutch, Danes and Maltese (28%), Finns (27%), French (24%), Portuguese (23%) and Swedes (23%). Possibly a consequence of Brexit, a significant proportion of British people (41%) agreed with the idea of making the right to vote dependent on having a “sufficient level of knowledge”, far ahead of the Swiss (31%).

Outside the European continent, support for epistocracy is above the overall average (38%) in Australia (45%) and Canada (41%); it is close to the average in the United States (39%), New Zealand (37%), Brazil (36%) and Japan (34%). But support is significantly lower than the average in Israel (23%), which, with one of the lowest levels, is comparable to Sweden, France and Portugal, with Norway having the very lowest level of support for epistocracy (21%).

Support for epistocracy, an indication of an authoritarian culture

At first glance, the epistocratic model is an idea that belongs to the democratic world’s past. However, it receives more significant support among younger respondents, perhaps suggesting that support for epistocracy is one the manifestations of a process of democratic deconsolidation.

Is granting the right to vote only to citizens with a sufficient level of knowledge a good or a bad way of governing?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique/International Republican Institute – 2019

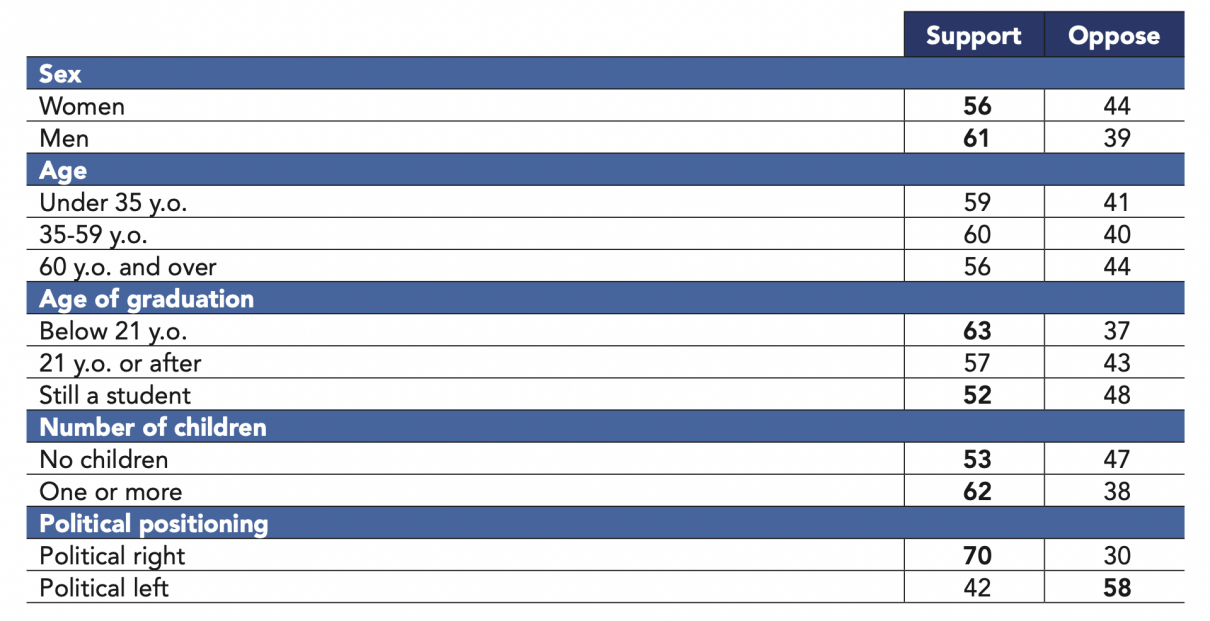

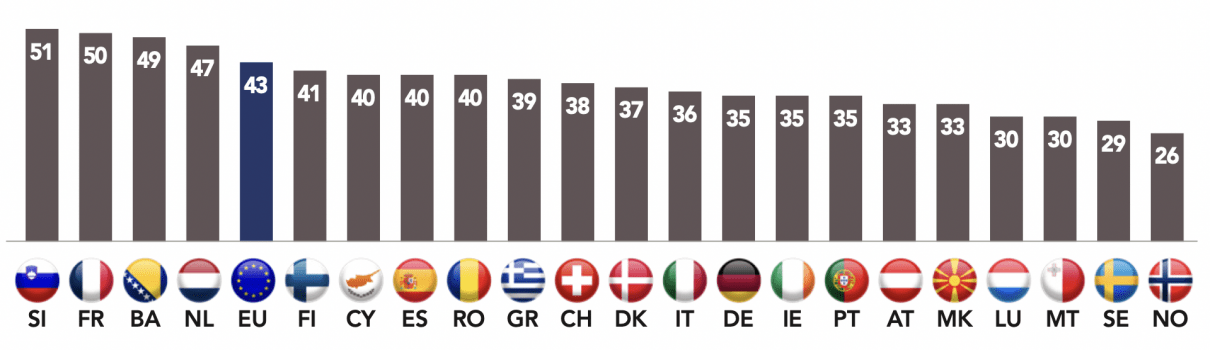

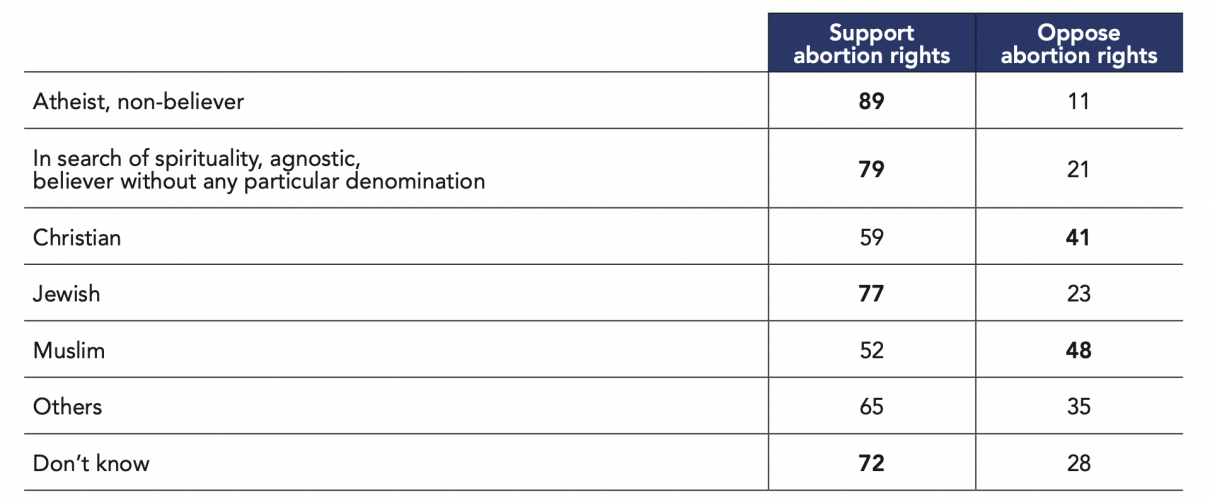

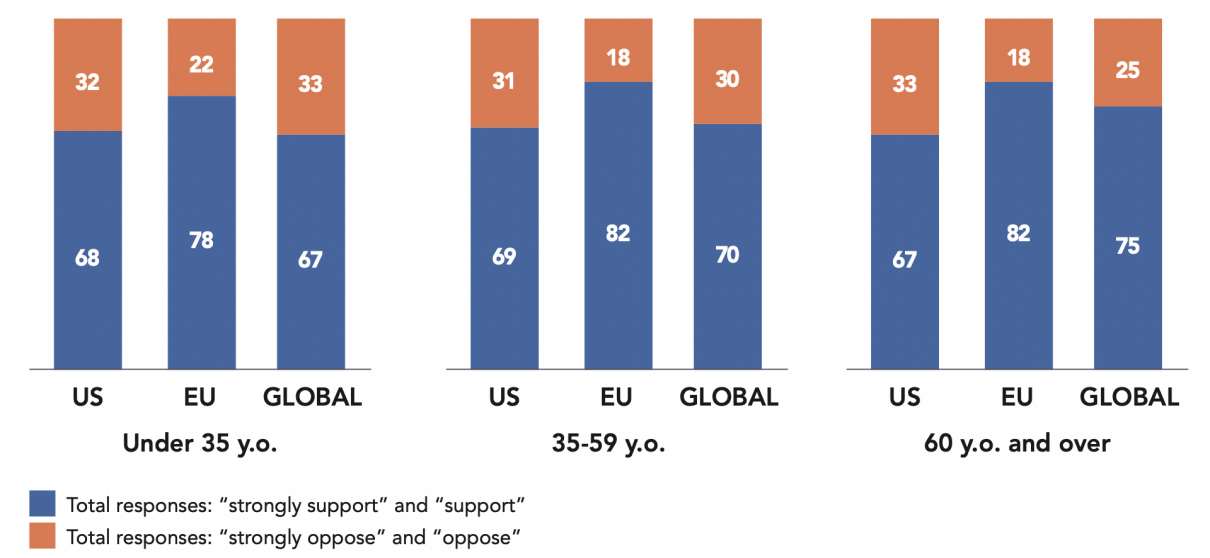

Total responses: “very good” and “good”