From 29 January to 19 March: Civil Service vs. Civil Society?

France is concerned, civil servant are dissatisfied

Globalization is transforming civil service status into an extra-temporal privilege

Civil servants benefit the most from globalization

In favour of a “social change,” opposed to “State reform”

The advent of a civil service social class

Assertion of an internal opposition to state reform

A leftist social class, yet one that is sceptical about the opposition

Conservatives and progressives among civil servants

A social justice issue and a challenge for democracy

Conclusion

Summary of Survey Findings 27 and 28 January 2009

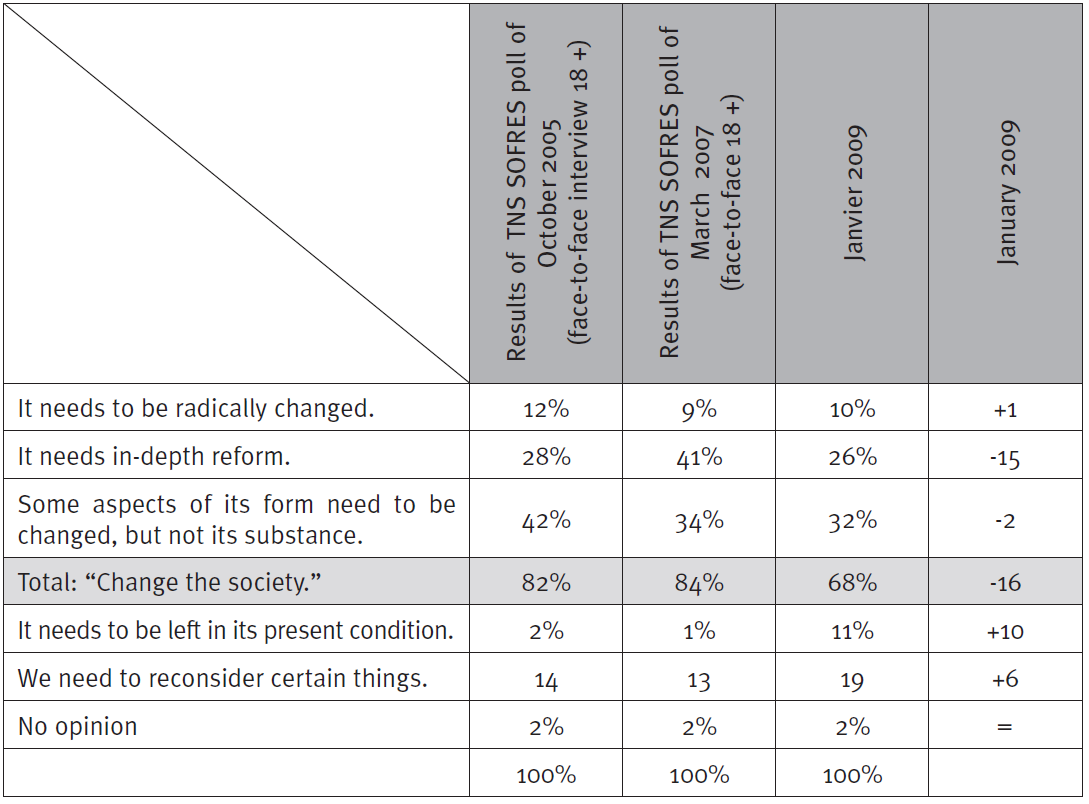

The Desire to Change Society

The Strikes of 29 January : Public opinion of the protest movement of 29 January

On 29 January, France experienced the strongest social mobilization seen since Nicolas Sarkozy was elected President of the Republic, amidst a global economic and financial crisis.

The Fondation pour l’innovation politique decided to examine the climate surrounding the events of that particular day. To that end, it designed an opinion poll which was conducted by TNS Sofres. Its initial findings were published in the economic daily La Tribune on Saturday, 31 January 2009. Beyond its analysis of this social movement and assessment of its legitimacy and its aim, the survey reveals what the French think of reform from a conceptual, as well as political, point of view.

Today, the Fondation is releasing an analysis of the survey findings produced by Dominique Reynié, the organization’s Director General and University Professor at the Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po, Paris). It highlights the cleavage behind the event: the one between civil servants and the rest of French civil society, associated with the possible emergence of a “civil service social class” which, in the absence of political arbitration, will likely raise a social justice issue and, ultimately, a challenge for democracy.

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

On 29 January 2009, strikes and protests took place throughout France. For trade unions it was a day of triumph. Media headlines cited impressive figures when estimating the number of demonstrators. Yet the strikes affected almost exclusively public services. The disruptions failed to reach previously recorded levels, perhaps due to the recently introduced minimum service guarantee ensuring a minimum provision of public services during a strike, the caution of certain trade unions regarding the costs of unpopularity, or simply the failure of the call to strike. Despite these grey areas, the overall success of 29 January is not in doubt, for this was how it was initially interpreted and reported. The financial and economic crises, as well as the weight of government reforms and political blunders, provided an ideal backdrop.

Do civil servants strike on behalf of the entire society?

On the day of the strike, and following, the events were mainly perceived to constitute a social backlash, a return to a protesting France expressing the collective anger of the salaried lower and middle classes. Many saw in the day’s events the first signs of the public’s rejection of the political leaders elected in 2007, a long-awaited reaction against a political leadership deemed to be too arrogant and an opposition focused entirely upon its own internal feuds. The eagerness to cross political swords with the Right may explain why the question was not asked: what social forces underlay the 29 January demonstrations?

Surveys indicated ongoing public sympathy for the day of protest, in accordance with a certain use of opinion polls use which has become customary since the memorable strikes of 1995. Opinion polls play a very specific role: they measure the degree of general sympathy for social conflicts. Where there is a high level of support for a strike, the concept of a “strike by proxy” has arisen—that is, suggesting that the social conflict relies on a much broader basis than it seems, and therefore of admitting that appearances can be deceiving. If appearances proved to be deceptive in 1995, and may again in 2009, it is because what is referred to as “social movement,” and which is thought to be for the benefit of all wage earners is, in reality, a protest undertaken by the small category of civil servants.

Polls analysing the degree of public sympathy with a protest movement make it possible to entertain the theory of a broad-based protest movement and therefore to undermine the opposite theory of a group-specific strike or social movement. Inasmuch as the French sympathize with—or even support—a protest movement limited to civil service—one might prematurely conclude that the civil servants taking part in the conflict acted as representatives of broader society and notably that of wage earners. Extending this theory to its logical conclusion might lead to the belief that civil servants are using their status to the benefit of society as a whole, carrying out, in the place of private sector employees—a more exposed economic sector—a protest which the latter are unable to pursue themselves without incurring significant risks. In this scenario, protected by their status, civil servants would in some way serve a representative function similar to that of union or elected representatives, sheltered by their immunity.

The “strike by proxy” theory, which can be seen in polls taken on important union action days, depicts France as a society of solidarity in which the more vulnerable wage earners entrust the protected ones with the task of publicly expressing the anger shared by all.

Reasons behind the support for the 29 January protests: a distinction to be made between «concern» and «dissatisfaction»

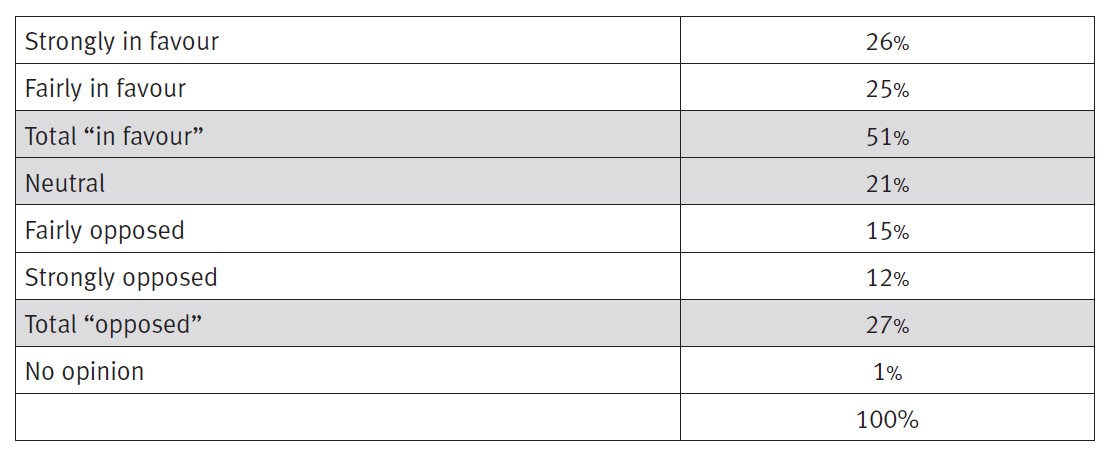

In order to document the extent to which French civil servants and the rest of the society share the same opinions, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique designed and conducted an opinion poll in cooperation with TNS Sofres. Its purpose was not only to assess the level of support for the events of 29 January 2009, but also to understand the motivations of those who declared their support for this day of protest. To avoid any misconceptions, we did not opt to ask questions testing the respondent’s “sympathy” or “understanding,” but rather their degree of support. We formulated the question as follows “Eight trade unions agreed upon a common protest platform and called for a day of strikes and demonstrations on 29 January. How do you personally perceive these protests? Are you strongly in favour of them, fairly in favour, neutral, strongly opposed or fairly opposed to them?” The questionnaire as a whole was then aimed at pinpointing and analyzing the degree of each respondent’s support in its different aspects.

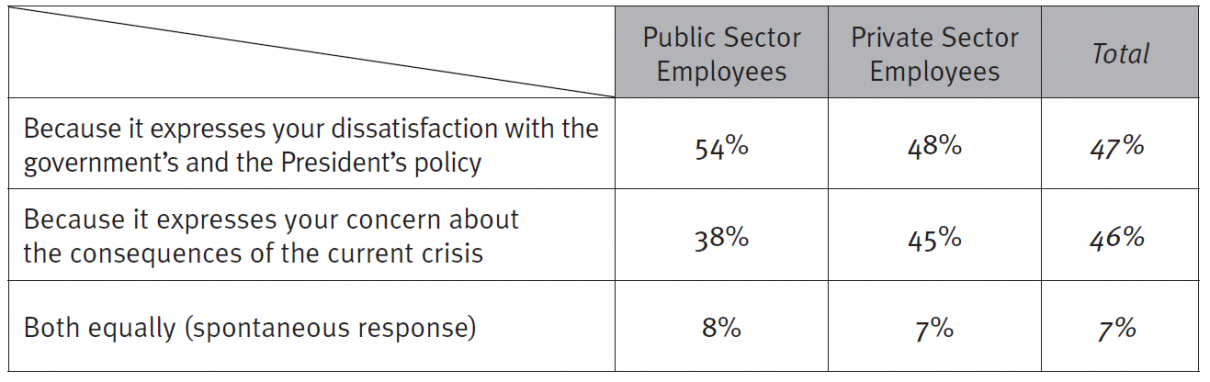

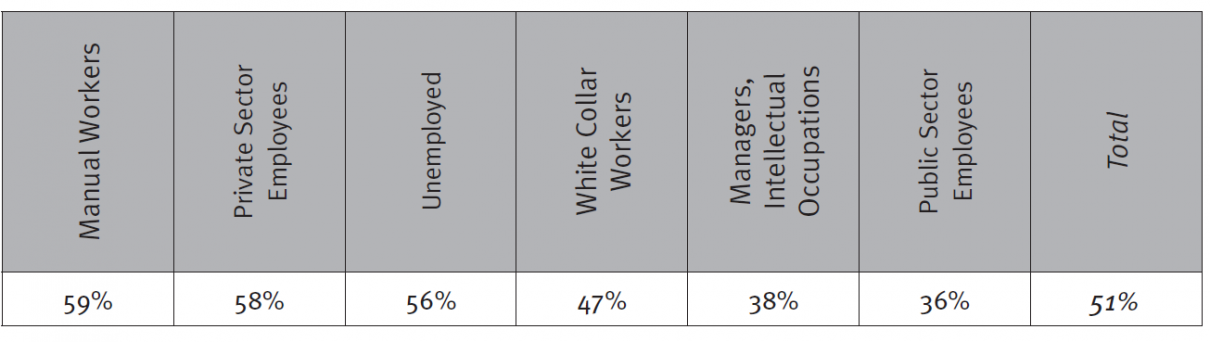

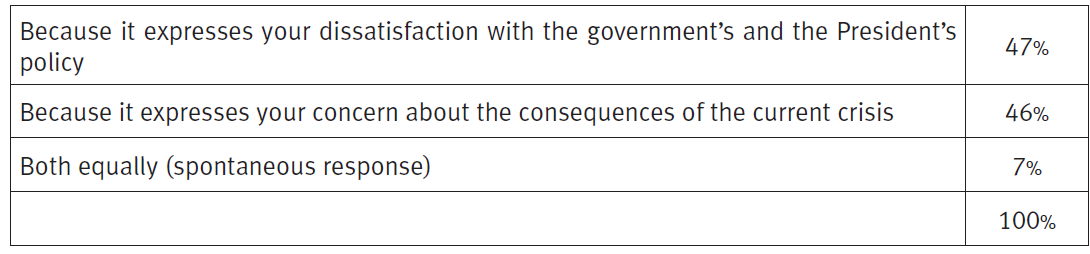

This questionnaire was administered on 27-28 January 2009 to a sample of 1,000 people representative of the French population, aged 15 years and over. The results show that 51% of the respondents were “in favour” of the protest day. Of those, half justified their support by the desire to express their dissatisfation with the government’s policy, while the other half justified it by the will to express their concerns about the consequences of the economic crisis. Those who stated that they supported the protests can therefore be divided into a “dissatisfied” group and a “concerned” group. It is all the more important to distinguish between these two opinion systems because the “dissatisfied” and “concerned” respondents belong to very different social worlds. The “dissatisfied” side consists of civil servants, while the “concerned” side consists of the exposed sector’s wage earners and working population.

France is concerned, civil servant are dissatisfied

As a social protest, the 29 January mobilization relied on the limited social bases of the civil service, which represents a highly singular world. The strikers and demonstrators were almost exclusively recruited among government employees. If civil servants demonstrated, it was not because the economic crisis affected them, but because government’s reforms concern them. The fact that public opinion, for the most part, viewed this mobilization rather favourably, and perhaps with some degree of sympathy, does not suffice to lend any credence to the theory of a broad protest movement extending beyond the usual borders of a sector-based demonstration.

What is your main reason for being in favour of this movement?

(This question is only asked of those respondents who are in favour of the day of protest, or 51% of the sampling.)

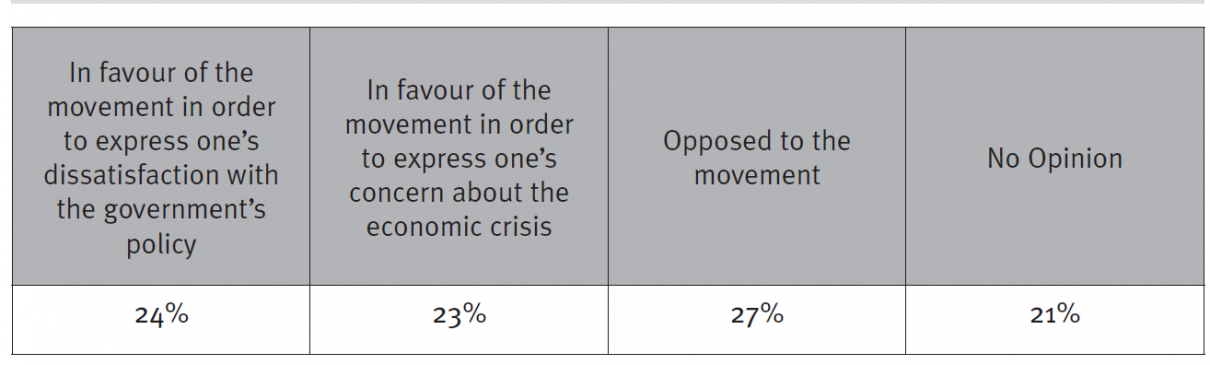

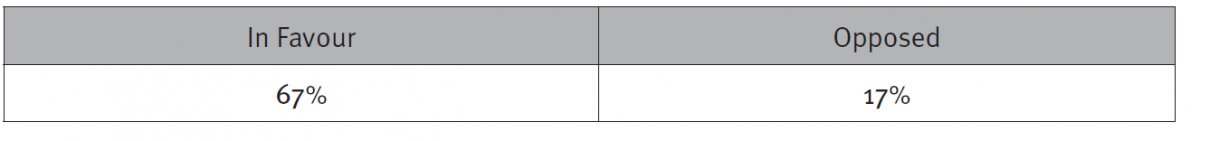

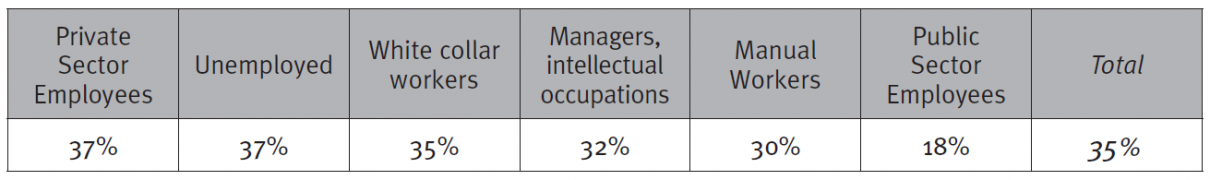

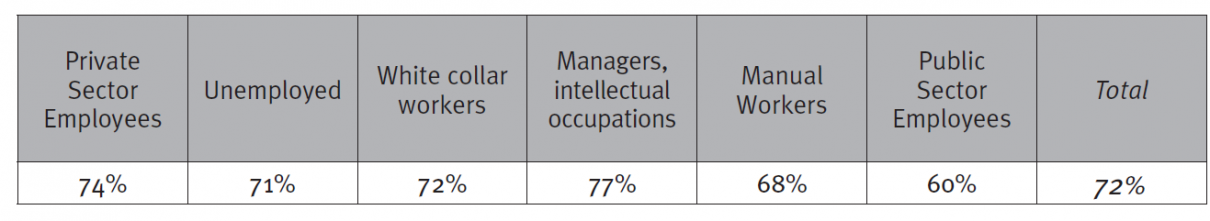

The day before 29 January, 51% of respondents stated that they were in favour of the announced protest, while 27% declared they were opposed to it and 21% had no opinion. The breakdown by status shows that the public sector employees were the category most in favour of the protest (67%), far ahead of the private sectors employees (50%). In terms of the respondents’ occupations, there was no category which surpassed the civil servants’ sympathy for the strikes, neither manual workers (58%), nor white collar workers (47%). The unemployed were at 52%.

Among the 51% of respondents who state that they were in favour of the protest of 29 January, almost half of them (47%) justified their support by expressing dissatisfaction with the government’s and the President’s policy, which represents less than one-quarter of the total surveyed population (24%). An equivalent proportion (46%) justified its support by their concern about the crisis (23%).

The four viewpoints concerning the protest movement of 29 January

Among the civil servants who stated that they supported the movement, the majority (54%) justified their opinion by indicating their dissatisfaction with the government’s policy. Among the private sector employees who stated that they supported the movement, this justification reached 48%, a difference of 6 points. Of the 50% of private sector employees who stated that they were in favour the movement, 45% justified their support by indicating their concern about the crisis. Still among those who stated that they supported the movement, the justification based upon concern amounted to 53% among manual workers and 51% among white collar workers, as compared to 38% among public sector employees. Although the 29 January demonstrators are dissatisfied, they are not concerned.

On 29 January, dissatisfied employees relied upon concerned French citizens to give their mobilization a strength it would not have had without the context of the current crisis. In other words, the civil servants benefited from the economic crisis by harnessing the concern it generates among the most vulnerable members of the working population. The dissatisfaction of some found a highly effective leverage in the concern of all the others. The former—the civil servants—can in fact say that they are dissatisfied because the government’s policy affects them directly in the form of the non-replacement of one out of every two civil servants entering retirement, or of the introduction of the guarantee of minimum services during strikes. Yet the latter—those not belonging to civil service—are hit hard by the economic crisis and not by the government’s policy.

Globalization is transforming civil service status into an extra-temporal privilege

Paying closer attention to the singularity of the French civil service will allow us to anticipate an approaching conflict. The French civil servant’s employment status encompasses at least three characteristics: their jobs are guaranteed for life, their activity cannot be relocated and their recruitment method is strictly limited to nationals. They enjoy maximum protection.

Civil servants benefit the most from globalization

We might wonder whether civil servants tend to be better paid, if we were to presume that a remuneration paid continuously throughout their working lives would ultimately provide higher pay than that which could generate, during the same period, a remuneration that at one point might be higher, but whose level could vary substantially, or even be likely to fall (for example during periods of unemployment), and would probably decline beyond a certain age. This computation could be extended to the end of the employee’s life and include the amount of retirement benefits received by both employee categories.

Such characteristics can lead to different consequences, according to the economic climate and the historic context. They obviously differ in scope and value, depending upon whether we are in 1960, 1980, or 2009. Today it would be impossible to grasp the extent of the gap between civil servants and private sector employees using the analytical grids developed in the 1950s and 1960s. At that time, France was a demographically “young” society bolstered by strong economic growth, evolving within the context of more advantageous international competition than is now the case as a result of the Cold War and “Third World” weakness. This trend lasted until the early 1990s. Since then, France has aged, and globalization has made the world more competitive for private sector employees, while public debt has reached levels of unanimous concern. This historic break has necessarily redefined the role of civil servants within the French working population by causing an exceptional relative improvement of the former’s condition. Civil servants do, indeed, benefit the most from globalization.

The well-known cleavage between a protected France and an exposed France cannot have the same impact in 2009 as it did in 1982. Between these two years, the statute establishing secure, though modest, careers—excluding here the marginal case of high-ranking civil servants—has been providing an advantage which may seem unchanged, but in reality, has expanded to the point of becoming an exorbitant privilege. The more unstable the economic world, the more civil servants benefit, the more competitive the economy, the more protected they are, and the more affected the exposed sector’s working population, the more advantageous it becomes for civil servants.1

In favour of a “social change,” opposed to “State reform”

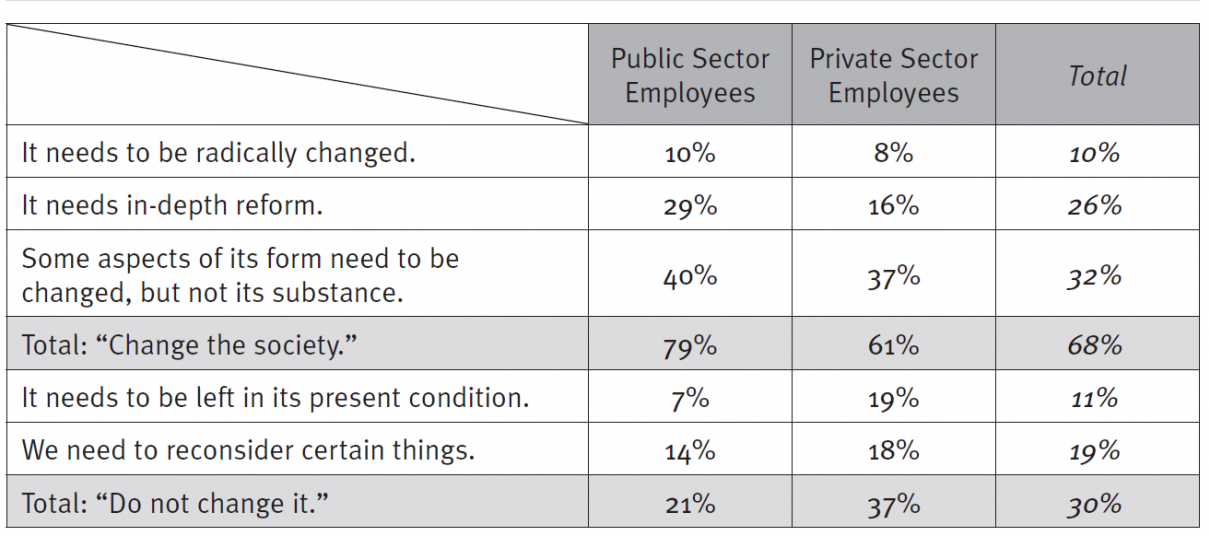

If civil servants are those most opposed to governments’ reforms which seek to reduce public spending, they are nonetheless also those most in favour of a social change.

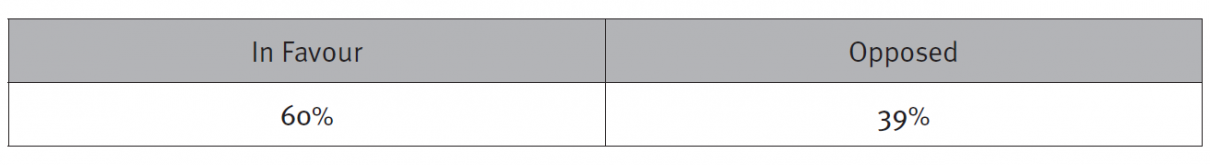

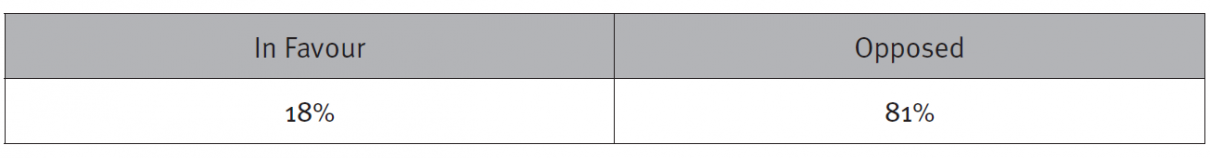

They expressed overwhelming support in favour of the idea that French society needs to be changed (79%), scoring 18 points higher than private sector employees (61%). Within the civil service, “social change” is a more popular theme than that of “State reform,” as shown by the no less massive opposition (81%) to the policy which seeks the non-replacement of one out of every two civil servants entering retirement.

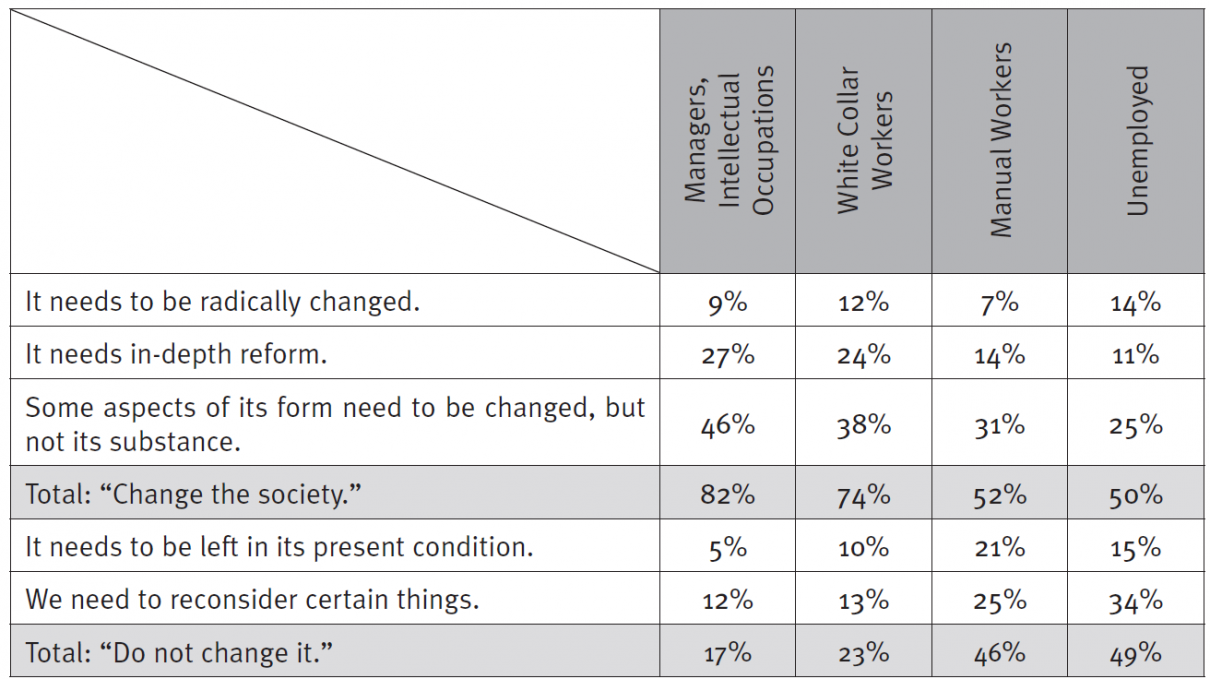

With regard to the society, what opinion is closest to yours?

The response distribution shows that the more closely a respondent is associated with a working class background, the more reluctant s/he is to changing society. Conversely, the more privileged the respondent’s social class, the more inclined s/he is to favour the change. A comparison of the collected data shows that those who declared themselves to be strongly in favour of changing the society tended to belong to the most privileged social categories. The responses provided by civil servants correspond to those of a privileged social category.

With regard to the society, what opinion is closest to yours?

Although it is obvious that the respondents did not attribute the same meaning to the idea of “change,” the lower-income and most exposed social categories are still more inclined to see in such change a threat rather than an opportunity. The conservativism of the working classes should be interpreted here not as an ideology, but merely as the expression of a demand for protection against the threats and aggressions brought about by the economic crisis and, to a larger extent, by globalization. The managers and members of intellectual occupations are less worried about the new world because they trust in their ability to seize its opportunities. Members of the civil service, on the other hand, constitute the only category of the working population not directly affected by globalization.

The advent of a civil service social class

As far as their objective situation is concerned, civil servant employees have no reason to fear economic globalization, inasmuch as they are protected. In terms of their opinions, their stated partiality for social change makes them akin to the least-concerned and most highly paid social categories. In this respect, civil servants are very different from lower-income classes in general and from the working class in particular, both of which paradoxically play a dominant role in symbolic references, social codes and rhetoric which members of the civil service refer to when carrying out their collective actions.

The cultural proximity of the civil service social class to the dominant social classes is evidenced by their ideological similarity on some themes, particularly revealing in terms of existing cleavages. This applies, for example, to the issue of illegal immigrants being escorted to the border, concerning which the opinion of civil servants is more similar to that of managers and members of intellectual occupations than it is to that of the lower-income classes.

Are you in favour of, or opposed to, the escorting to the border of at least 25,000 illegal immigrants per year? Answer: “In favour”

This table shows how the combination of the protected status and of a “nationalist” type recruiting method—insofar as it is stricter than the “national preference” principle—fosters a civil service-specific system of opinion that vastly differs from that of lower-income classes. Once again, the civil service realm is more akin to that of the higher-income classes than it is to that of the middle and, to an even greater extent, the lower-income classes. A review of these data shows that the more vulnerable the working population is to economic competition, the more sensitive it is to closing mechanisms, to protectionism—in this case, the stringent provisions against illegal immigration. In confronting a particularly thorny symbolic issue, civil servants have an opposite viewpoint to that of the working classes.

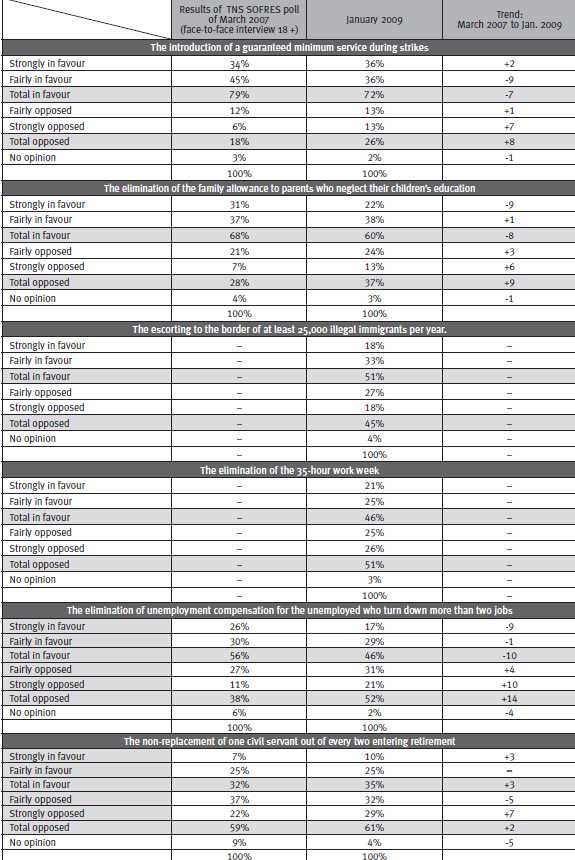

Assertion of an internal opposition to state reform

When considering all of the analytical variables, support for the protest movement of 29 January reaches or exceeds the level found within the civil service (67%) only among respondents sympathetic to the Left (76%), the Far Left (70%), or the Socialist Party (78%). Even among members of the Green Party, support is relatively weaker (56%), while it declines substantially among respondents with no political affiliation (45%). Among the State employees interviewed for this survey, 33% stated that they voted for one of the Left’s candidates during the first round of the 2007 presidential elections, 16% for François Bayrou, and 13% for Nicolas Sarkozy. Among private sector employees, responses show that 26% voted for the Left, 12% for François Bayrou, and 18% for Nicolas Sarkozy.

A leftist social class, yet one that is sceptical about the opposition

Although not universally supported by civil servants, it is nonetheless among this group that the French Socialist Party finds its greatest support: 45% of the members of the civil service stated that it expresses their ideas and expectations rather well, or well, as compared to 35% for the private sector employees, most of whom (57%) considered that this party rather poorly, or very poorly, represents their viewpoints. These specific data confirm that a large part of the support for the events of 29 January is anchored to the Left. Though not surprising, this finding does not seem to have been taken into account in the events’ commentary and interpretation, thus making it difficult to understand this movement, or to assess its scope.

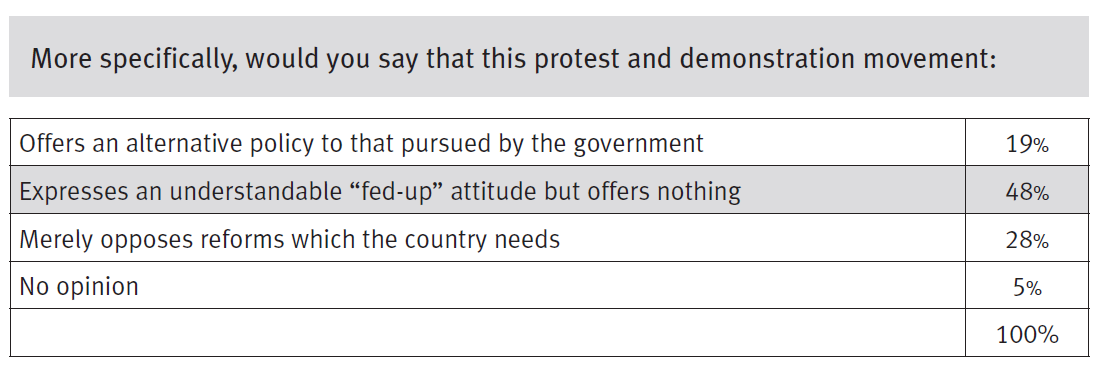

The extent of the dissatisfaction with the government’s policy is doubly limited: first because at this stage, the problems are being attributed to a crisis whose planetary dimension is momentarily clearing those in power, and second, because the opposition is not being credited with greater ability to overcome such difficulties, as attested to by the lack of political credibility given to the protest movement of 29 January, including inside the civil service.

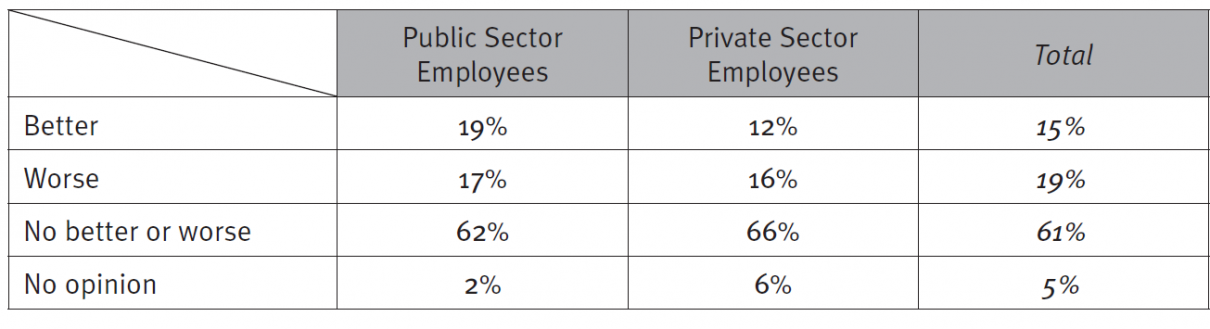

Do you think that if the Socialist Party were in power, it would do a better job, a worse job, or no better or worse a job, than the current government is doing?

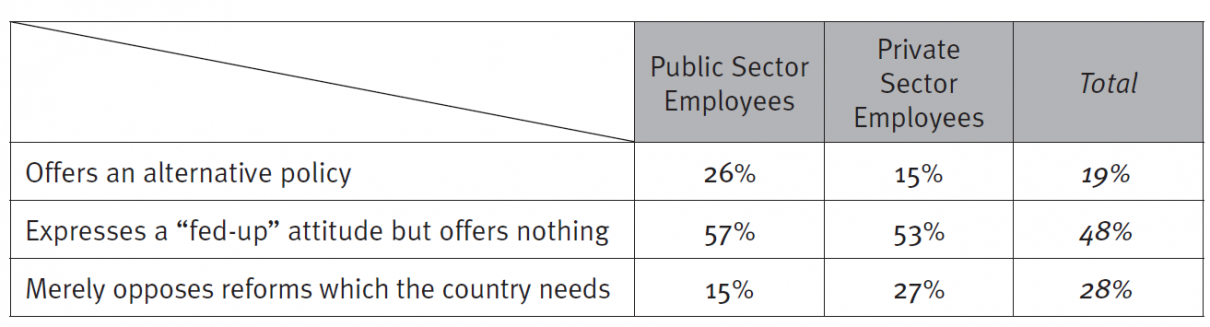

More specifically, would you say that this protest and demonstration movement:

Overall, the most notable finding was that the interviewees felt that the trade unions and the political organizations associated with the 29 January events are incapable of finding solutions to current problems. However, it should be pointed out that the difference in opinion between the two wage-earning worlds remains significant. More than one-fourth of the public sector employees saw in this movement an opportunity for an alternative policy (26%), as compared to 15% among private sector employees. Higher scores were given only by those persons stating that they had a left-wing political preference (33%). On the other hand, scores were very low among those with no political preference (11%), white collars (12%), private sector employees (15%) and manual workers (20%).

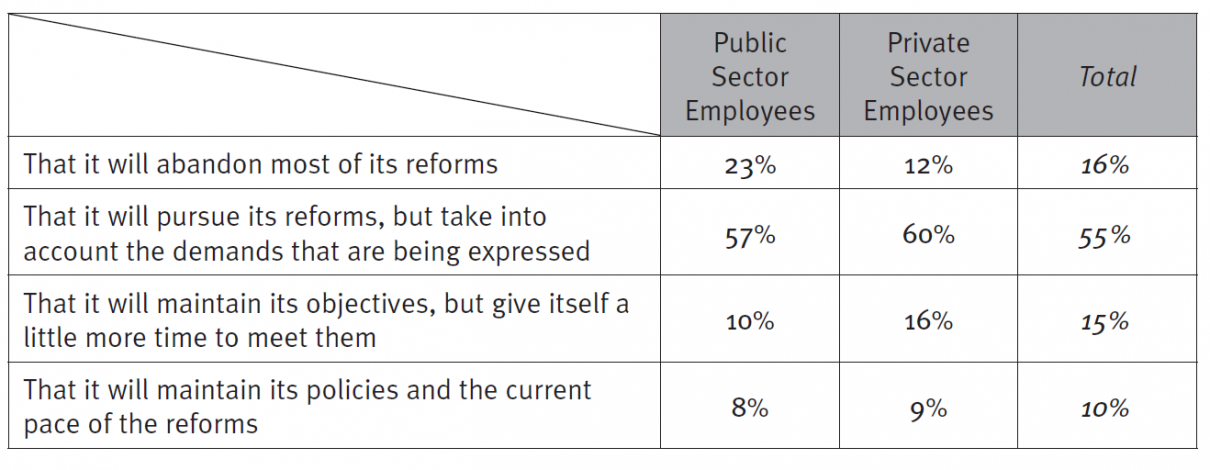

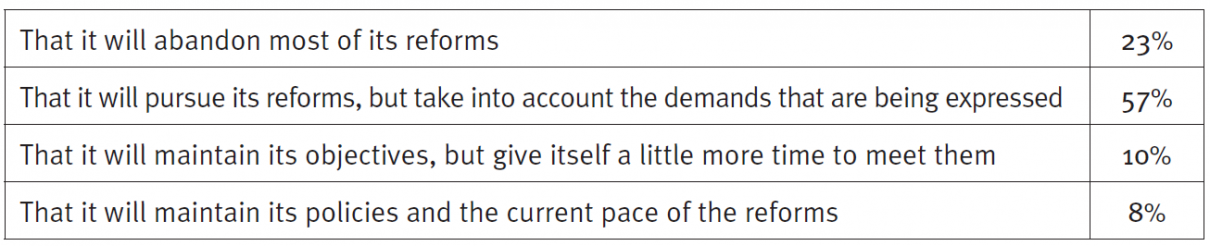

In response to this movement, what do you hope the government will do?

These findings reassert the fact that those who support change are not necessarily reform’s supporters. While public sector employees are the most in favour of the idea that society needs to be changed rather than be maintained in its present condition (79%), they are at the same time the most relatively numerous to want the government to abandon most of its reforms (23%). However, as shown by the response to the question on reforms, even if there is a dominant viewpoint within the civil service, all civil servants do not necessarily share the same point of view about the issues at stake.

Conservatives and progressives among civil servants

The survey also highlights the existence of a split within the civil service social class. As shown by the labour disputes which have occurred in the past, at least those since 1995, the civil service as a whole is not hostile to State reform, nor, for the most part, to a change in its status and role within society. The plurality of viewpoints is regularly voiced through the various positions adopted by the trade unions, as was notably seen in 2003 and in 2007.

“Eight trade unions agreed upon a common protest platform and called for a day of strikes and demonstrations on 29 January. How do you personnaly perceive these protests? Are you strongly in favour of them, fairly in favour, neutral, fairly opposed, or strongly opposed?” (Civil service only)

In response to this movement, what do you hope the government will do?

(Civil service only)

Are you in favour of, or opposed to, the introduction of the guarantee of minimum services during strikes? (Civil service only)

Are you in favour of, or opposed to, the non-replacement of one civil servant out of every two who are entering retirement? (Civil service only)

Although clearly the majority, the conservatives do not represent the civil service as a whole. The responses to the questions show that a fringe are in favour of State reform. According to the survey findings, their number is estimated to represent one-fifth to one-fourth of all civil servants.

A social justice issue and a challenge for democracy

Globalization has made civil service status more radical. A dissociation process has gotten underway which has led public sector employees to increasingly distance themselves from other wage earners. The economic crisis has accelerated this process. For historical reasons, the civil service class is steeped in progressive principles in which the concept of “vocation” and that of “free” services, and thus the notion of equality, are playing a decisive role. In the French political tradition, especially since the Conseil national de la résistance (CNR) [National Council of the Resistance] and the construction of the French Welfare State in the years following the Liberation, the government apparatus became the instrument responsible for carrying out the egalitarian project in a context characterized by the socializing ideology of the Liberation, the power of the French Communist Party—with an electoral weight of between 20% and 25% of the votes cast during the 1950s and the 1960s—and the worship of the State peculiar to the Gaullist Right.

The French State fulfilled its functions of protection, redistribution and development during “The Glorious Thirty,” but that era was incomparably more propitious than today. Since then, the government has found it increasingly difficult to carry out the numerous missions that it has chosen to undertake and has been seeking to adapt by expanding the civil service class. Thus, during the single period of 1982 to 2006, the number of civil servants rose from 3.8 million to over 5.2 million. “The Glorious Thirty,” which had enabled France to finance the continuous growth of this new social class, are long gone. Economic setbacks, the aging of the population, and increasing indebtedness have prompted governments to reduce State involvement in the economy—through privatizations—and to reconsider certain major advantages reserved for the civil service and protected employees via pension reform and elimination of special schemes. Plans have also been made to reduce the number of civil servants by taking advantage of their retirement. A clear majority of civil servants have been organizing protests against these reforms, but this conservative group is not always supported by public opinion. Associated with the country’s demographic shift globalization is and will continue for many years to raise the issue of determining whether the interests of the civil service are inconsistent with those of the rest of French society. The economic crisis is intensifying this concern to an unprecedented degree.

Paradoxically, it is this same crisis which is providing the most conservative part of the civil service class an occasion to maintain its positions, as observed during the events of 29 January 2009, when dissatisfied employees profited from the concerns of the general working population, using them as a powerful leverage in order to compel the government to abandon some aspects of State reform, while the latter is an essential condition for the redistribution of national wealth in favour of the lower-income working class—those employees most vulnerable to the effects of globalization and to the impact of the economic crisis.

The fact that the majority of the French are opposed to reducing the number of civil servants attests to how committed all wage earners are to the civil service cause. The mechanism behind this is simple: globalization and the economic crisis have heightened the concern of employees, who are hoping for State support and believe that the government will be stronger if the number of civil servants is at least maintained. It is a real cultural and political feat to have convinced a society that the quality of public services or the efficiency of existing solidarity mechanisms depends upon one’s status and not on one’s occupation.

Are you in favour, or opposed, to the non-replacement of one civil servant out of every two who enter retirement? Answer: “In favour”

Are you in favour, or opposed, to the introduction of a guaranteed minimum service during strikes? Answer: “In favour”

There is a strange mechanism now at work in French society in which the most vulnerable employees are being unwittingly mobilized so as to ensure that some of the best-protected employees in the world will be able to maintain, unimpaired, their benefits in a globalized economy. On 29 January 2009, those opposed to the government’s policy were primarily found among civil service employees because the point was to oppose the reforms which specifically concern them. Yet it was only by seizing the concern permeating a society confronted with an economic crisis that they managed to destablize the government. As far as wage earners are concerned, it is obvious that a singular redistribution is taking place, to the detriment of the most vulnerable and to the benefit of the most fortunate.

Should the project to reduce the weight of the civil service fail, it would become impossible to transfer part of the national wealth, currently allocated to the State, to civil society—today’s as well as tomorrow’s—if we take into account the need to lighten the national debt. This is another way of pointing out how readily the civil service social class can make use of civil society in order to preserve its standard of living and lifestyle, sheltered from economic setbacks and historic upheavals. In a country convinced that it is endowed with the passion of egalitarianism and which cultivates the notion of a “wealth redistributor” State, the outcome is more than paradoxical. Beyond the current economic climate, what is underway this time is a profound change of a historical nature.

In dealing with the social movement of 29 January 2009, the analytical model needs to be reversed: these are not wage earners of the exposed sector who feel they are represented in the labour disputes led by civil service employees, but the civil servants, who are finding in the general concern of the social climate additional protection from the reforms which concern them.

Protected from unemployment, job relocation and competition, today’s French civil servants are on the verge of constituting a weightless social class, and, at the same time, a party inside the State power capable of stalling—or even preventing—State reform, despite the extent of public indebtedness, despite current economic conditions, and despite the preference democratically expressed by the collectivity. Even if, in a democratic regime, the State apparatus is admittedly the instrument of popular sovereignty, it still has the option of resisting the democratic will when it is itself the target of the contemplated reforms. Between the will of the people and that of the civil service, the subordination relationship seems to be reversed.

A conflict between the civil service and the rest of the working population appears inevitable if we assume, on one hand, that vulnerable employees are calling for the State to take advantage of globalization and to get them through the emerging crisis and, on the other hand, that the mobilization of the necessary means calls for a reduction of part of the national wealth consumed by the administrative apparatus. Yet, by virtue of their status and the strategic role of their activity, civil servants can prevent this redistribution of wealth. Without arbitration on behalf of the most vulnerable, this conflict will continue to raise a pressing social justice issue and, ultimately, a serious challenge for democracy.

Summary of Survey Findings 27 and 28 January 2009

The Desire to Change Society

With regard to the society, what opinion is closest to yours?

Are you in favour or opposed to each of the following measures?

The Strikes of 29 January : Public opinion of the protest movement of 29 January

Eight trade unions agreed upon a common protest platform and called for a day of strikes and demonstrations on 29 January. How do you personally perceive these protests? Are you:

What is the main reason that you are in favour of this protest movement?

Perceived significance of the protest movement

Extent to which the public adheres to the ideas behind the protest movement

No comments.