Four Proposals to Stem the Tide of Protectionism in Europe

The advantages of free trade

Protectionism : the right questions, but the wrong answers

Response to the good questions raised by protectionists: reinforce the action of the EU

Appendices

Nicolas Bouzou,

Founder and president of Asterès Director of studies in the Law and Management MBA School of the University of Paris-II-Assas (Paris).

Since the banking and financial crisis began in 2007, and even more so since it started spreading into the “real” economy in 2008, increasingly loud calls have been made for protectionist measures to be adopted at the European level. These calls have come from two main areas:

- national governments, which see such measures as a means of sheltering specific industrial sectors against competition from imported goods or offshoring;

- a number of experts (not generally economists, but rather demographers such as Emmanuel Todd, geographers like Hakim El Karoui or journalists such as Philippe Cohen), united under the banner of the website “Pour un protectionism européen”1 (www.protectionism.eu).

Protectionism frequently resurfaces in times of economic crisis, when self-reliance can have a certain appeal. Protectionist ideas were very much in vogue in the 1930s, and again in the 1970s, after the first oil-price shock (Jean-Marcel Jeanneney published his book Pour un nouveau protectionisme2 in 1978). The political benefits are self-evident. By erecting trade barriers to “protect” an industry (as the United States was recently tempted to do with steel, until Barack Obama took the “Buy American” provision out of his economic recovery plan), a government shows its decisiveness and its capacity to act. And it is easy to identify any jobs that are saved. Had the steel industry indeed been closed to non-American competition, it would have been easy to point to the number of jobs saved in the sector – in the short term at least. By contrast, the advantages of free trade (stronger growth, lower prices) benefit a broader section of the population and are therefore less tangible for public opinion. The goal of this essay is to show that:

- the cost for the European Union of adopting protectionist policies would far outweigh any potential benefits;

- economic policy can provide answers to the issues raised by the supporters of protectionism in four main ways: by developing Europe’s research and innovation capacity; by providing more funding for innovation; by harmonising national standards and regulations; and by coordinating macroeconomic policies.

The advantages of free trade

G. Mankiw, Principles of Economics, Fort Worth, Dryden Press, 1998.

P. R. Krugman, “Trade and Wages, Reconsidered”, project for the spring meeting of the Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, February 2008.

D. Sachs and A. Warner, “Economic Reform and the Process of Global Integration”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 199µ.

Rodriguez and D. Rodrik, “Trade Policy and Economic growth: a Skeptic’s Guide to the Cross- National Evidence”, in B. S. Bernanke and K. Rogoff (eds), Macroeconomic Annuals, NBER, Cambridge (Mass.), MIT Press, 2000.

D. Sachs, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time, New York, Penguin, 200µ.

More than two centuries of economic analysis and research have given rise to a number of clearly established theoretical and empirical results.

In theoretical terms, the superiority of free trade over protectionism is based chiefly (but not exclusively) on the analysis of comparative advantage. Let us consider two countries, France and Germany for instance. France’s productivity is greater than Germany’s in the manufacturing of consumer goods. By contrast, Germany’s productivity is greater that France’s in the production of capital goods. As such, it is obviously in France’s interest to specialise in making and exporting consumer goods, and to import any capital goods it needs. At the same time, Germany will specialise in the production of capital goods, and will import consumer goods. Now let us imagine that, following a succession of unfortunate economic policy decisions in France, Germany becomes more productive in both capital goods and in consumer goods. In theory, such a change would not alter trade flows between the two countries: if France is still better at making consumer goods than making capital goods, it would still be in its best interest to specialise in consumer goods, just as it would be in Germany’s interest to continue exporting capital goods. American economist Gregory Mankiw illustrated this point by asking whether basketball player Michael Jordan should mow his lawn himself, given that his physical prowess would allow him to do the job faster than anyone else.3 In reality, it should come as no surprise that Michael Jordan can maximise his revenues by paying his neighbour to mow his lawn, even though it would take her four hours to do so (as opposed to two hours for Michael), while he uses that time to make advertisements.

The seemingly wonderful world of comparative advantage theory loses something of its gloss when we move from theory to reality. Comparative advantage changes over time. It can be in a given country’s interest to specialise successively in textiles, then tourism and finally aerospace. This raises serious retraining issues and means that a lot of effort needs to be put into education (the basics first of all, then pro- fessional training allowing the workforce to adapt swiftly to new areas of specialisation). A country’s specialisation in sectors with high value added as it opens up to international trade can lead to an increase in wage inequality. As companies move up the value-added chain, they require more highly qualified workers, while the least-qualified labour-intensive tasks can be moved abroad. In this way, the “cost” of qualified labour increases in relation to unqualified labour. The effect of free trade on wage inequality does indeed exist in theory, and is a popular argument among the supporters of protectionism. But they never actually measure it, and it is easy to understand why: attempts to quantify the impact have never shown it to represent much. Paul Krugman, the winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in economics, has long argued that free trade is not a big factor in the rise of inequality.4 In 1995, Krugman showed that the increase in international trade was responsible for 3% of the increase in wage inequality in the United States. In 2007, he decided to update his research, to see whether his findings had been made obsolete by China’s increasing weight in international trade and the fragmentation of the value-added chain, which has prompted companies to shift low-productivity tasks from industrialised countries to emerging ones. In February 2008, Krugman said that his research at that time did not point to a significant change in the role of globalisation in increased wage inequality since his 1995 paper (“How can we quantify the actual effect of rising trade on wages? The answer, given the current state of the data, is that we can’t.”5).

The impossibility of establishing a significant empirical link between free trade and wage inequality is also found in the areas of free trade and unemployment, where a strong relationship has never been proved either. Studies on this topic have invariably shown that the growing importance of low-wage countries in international trade has only a minor impact on jobs in industrialised countries. Moreover, within the European Union, some relatively closed countries (such as France) have a much more serious unemployment problem than some more open countries (such as the Netherlands).

After comparative advantage theory, the second virtue of free trade is that it allows companies operating in a given country to benefit from economies of scale by exporting. Imagine that France and Germany are both equally productive in consumer goods and capital goods. It would still be in each country’s best interest to specialise in a single sector, even if that meant choosing it by tossing a coin, in order to extend its market beyond its national borders and to provide scope for economies of scale.

The upshot of these various analyses is that free trade allows consumers and companies to buy goods more cheaply than they would be able to if production were kept within national borders. Globalisation has been a leading factor in the fall in prices for household appliances and clothes over recent years. Even though they may be assembled in France, Airbuses contain large amounts of electrical and electronic components manufactured outside France—and increasingly far away as it happens. In other words, a dose of protectionism would immediately push up prices for households, and production costs for manufacturers.

Belief in the advantages of free trade over protectionism has sound empirical support. In a seminal paper, Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner drew up two lists of countries: “open” oness and “closed” ones.6 During the 1970-1995 period, open countries enjoyed average annual GDP growth of 4.5%, compared with 0.7% for closed countries. American economist Dani Rodrik’s work goes even further. He shows that there is less scope for nepotism and corruption in open countries than in closed ones. Openness to trade and the quality of political institutions are mutually supportive, as free trade fosters efficiency, and therefore better governance. Dani Rodrik and Francisco Rodríguez point out that no study has ever shown that protectionism can spur growth.7

China offers a particularly striking example— and one that is rich in lessons—for the industrialised economies, especially in Europe. At the start of the 16th century, China was the global economic superpower, and had been for a thousand years. According to Jeffrey Sachs, China lost its leadership in 1434, when the Ming emperor closed China to international trade, dismantling the world’s largest and most advanced fleet of ocean vessels, thereby stopping the circulation of goods.8 When Adam Smith mentioned China in The Wealth of Nations (1776), he described it as an inward-looking nation, still rich, but a lot less so than it would have been had it remained open to trade. By contrast, the reforms undertaken in the latter part of the 20th century (deregulation of farming in the late 1970s, followed by the deregulation of international trade and investment) generated a flood of foreign investment, sparking massive exports and an increase in China’s role in the global economy.

Protectionism : the right questions, but the wrong answers

Spector, “Textiles chinois, le bon marché” (Chinese textiles coming cheap), Libération, 6 June 200µ.

There are many arguments in favour of protectionism, but some do not stand up to serious analysis. First, it is important to bear in mind that the introduction of protectionist policies exposes a country to retaliatory measures. In 1930, the United States adopted the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which raised US import tariffs by 50%, despite warnings given in a petition signed by more than a thousand economists. Canada and European nations quickly took retaliatory measures. The United States’ exports, as well as its imports, fell by roughly two-thirds.

Some arguments put forward by the supporters of protectionism do however raise pertinent issues. Here are five among the most frequently cited.

- We cannot compete against low-wage countries. We have already addressed this argument. In a world of comparative advantages, it has no value. Manufacturers in industrialised countries do not need to compete against their rivals in emerging countries on price, but rather by differentiating themselves. We must also bear in mind that imports from low-wage countries generally account for less than 10% of total imports in industrialised countries.

- We must close our borders to countries that do not open This argument is one of reciprocity. It is a guiding principle in negotiations between World Trade Organisation (WTO) member countries, which can only open their borders if other countries do so. But while this argument may appear to make sense, its logic is in fact flawed: it is not because some countries want to limit imports from Europe that we should refuse ourselves the possibility of buying consumer or capital goods from them, more cheaply than it would cost to buy goods made in Europe. A few years ago, David Spector demonstrated that the flood of Chinese textiles into France, which allows consumers to buy clothes much more cheaply than in the past, represented a stimulus package worth €1.5 billion per annum, which is more than enough to pay the 7,000 people threatened with losing their jobs until retirement.9

- We need to limit imports if our independence is threatened. This argument is correct. But it only holds for a small number of sectors—ones for which such policies are often already in place. This has long been the case with agriculture, for instance, under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): export subsidies under the “first” CAP in 1962, subsidies based on the amount of land used for production under the “second” CAP in 1992.

- We have to protect nascent industries. The idea is to protect some sectors against foreign competition until they can grow and become more profitable. Once a sector has reached critical mass, it can be exposed to imports and play by the rules of international competition. In practice, governments throughout the world are keen to develop so-called “strategic” sectors, such as tourism, aerospace, new technologies, pharmaceuticals and countless others. Some countries, like Singapore have even implemented veritable long-term industrial strategies, providing companies with support for as long as it takes them to move up the value-added chain. But protectionism, which puts countries at risk of retaliation and raises input prices (imported factors of production), is not the best means of achieving this It is better to subsidise a sector or give it access to advantageous funding, such as government-guaranteed loans.

- We need to give ourselves the means of applying stimulus plans as we see fit. This argument comes in two shapes.

Keynesian macroeconomics teaches us that the impact of stimulus packages (increased government spending, reduced taxes) is greater when imports are low (the underlying notion is that, in open economies, economic stimulus benefits imports, i.e. foreign industries, a phenomenon known as “leakage”). This point is formally true. But the idea that the impact of stimulus packages can be optimised by limits on imports is pernicious. As we will see later, it is possible to resolve this issue without resorting to protectionist measures.

More generally, respect for free trade forces national governments to take measures in support of specific sectors. This point was clearly illustrated in France with the recent plan in support of the automobile industry. The main plank of this plan is a €6 billion government loan in exchange for a number of commitments on the part of France’s two carmakers. It was not so much the loan as the nature of the commitments demanded—particularly the pledge not to relocate French plants operating—that raised concerns among our European partners.

Response to the good questions raised by protectionists: reinforce the action of the EU

In the letter from French President Nicolas Sarkozy to incoming Finance Minister Christine Lagarde setting out her ministerial brief, 11 July 2007.

Some of the questions raised by the supporters of protectionism are pertinent. But protectionism is not the right answer. Instead of closing the doors to trade with non-European countries, we need to reinforce the European Union’s policies in four areas: academic research, the funding of innovation, the harmonisation of national standards and regulations, and the coordination of macroeconomic policies. It is here, and not by turning inward, that we will find the answers to the questions raised by the opponents of free trade.

Research and innovation

A year ahead of the Lisbon Strategy deadline, it is fairly obvious that Europe will not meet its goal of becoming “the most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in the world”. The United States is still the leader in research and innovation, and the emerging countries are catching up fast. A few (OECD) figures should make this abundantly clear. Labour productivity (measured by the ratio of GDP to hours worked) has increased at a rate of 1.3% per annum in the EU15 countries since 2001, or 0.9 points less than in the United States and 0.5 points less than in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as a whole. In 2006, the ratio of R&D spending to GDP was less than 1.8% in the EU27. In the same year, it stood at 2.7% in the United States and 3.4% in Japan. Japan currently spends roughly ten times more on bio- and nanotechnologies than the EU15 countries.

The lack of innovation in Europe stems largely from the dearth of new, innovative and fast-growing companies. If Europe is on the sidelines in the bio- and nanotechnology sectors, it is not because of free trade, but rather due to poor coordination between publicly- and privately-funded research and the lack of sources of funding.

A lot of the problems stopping Europe from developing new comparative advantages stem from the inability of academic research to provide a pool of ideas for entrepreneurs. America’s leading biotech companies often came to life on university campuses. This is not the case in Europe, where research virtually never translates into commercial opportunities. That is why, rather than hiding behind trade barriers, Europe must develop a system of research that is both selective (more funding to research with the best results) and more integrated (cross-border cooperation rather than competition).

Funding innovation

Innovative companies in Europe currently lack funding, and will no doubt continue to do so given the difficulties currently facing banks in the wake of the financial crisis. There are no Intels, Ciscos or Googles in Europe. That is why we must facilitate the access of new companies to private funding. Who still remembers these days that venture capital was the brainchild of the heads of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard after the Second World War? Today, America’s venture capital investments are six times greater than Europe’s. Here again, harmonisation at the European level is necessary, in the shape of an end to barriers stopping pension funds and insurance companies from investing in young companies, policies aimed at nurturing venture capital companies in Europe, etc. More European Investment Bank (EIB) funding should go towards helping innovative projects. Lastly, the creation of a single share market for innovative euro area companies could also be envisaged.

The harmonisation of national standards and regulations

Rather than closing the European market, it would be better to extend it and improve flows within it. The European market for goods and services is still highly fragmented. The administrative, legal and financial costs attached to cross-border economic transactions are still too high, which has the same (undesired) effects as protectionism. A lot of national regulations are still in place (in the services in particular), obliging companies to set up subsidiaries in different countries, whereas it would be better to allow them to grow from their domestic base. We need larger companies (which, it should be noted, could argue in favour of easing competition rules). But the size of the market that companies can address is a factor in determining their own size and the amount they can invest. This is particularly true in the services, which account for roughly 70% of the European economy, and which are a lot less integrated than the market for industrial goods.

The coordination of macroeconomic policiesGranted, economic integration is often perceived negatively by the general public, especially now that Europe has welcomed what are still emerging economies (Eastern European countries), where labour costs less than in wealthier countries like France. The hysteria around the Bolkestein directive illustrates this point. However, we need to bear in mind that the Single Market, by allowing our companies to invest and grow, constitutes a much more effective form of protection over the long term than trade barriers.

It is perfectly legitimate to want to reinforce the effectiveness of short-term stimulus plans. We know that stimulating demand (by lowering VAT for instance) would not have much of an impact in small countries, especially if they are running trade deficits. In such cases, increased sales of consumer goods would translate above all into additional imports. The solution to the problem lies not in protectionism, but in concerted stimulus. If euro area countries had been able to reach an agreement on a joint plan to stimulate demand (by lowering tax on the poorest households to the tune of about 1% of GDP), the European economy would have received a very significant boost. Leakage, in the form of imports from non-European countries, would have been limited, the euro area being large and, for that reason, relatively self-sufficient. This is why we need to reinforce the coordination of euro area macroeconomic policies.

We already have the Eurogroup. But while the institution may exist, its policies are limited, to say the least. Economic policy does not fall under the scope of joint decision-making processes, and is barely the subject of any form of joint effort. The idea is obviously not to hand responsibility for fiscal policy over to the Eurogroup. In many cases, the national level is the right one. But we could envisage the possibility of allowing the Eurogroup to adopt, by qualified majority, economic policy decisions that would then be imposed on euro area countries in certain pre-determined circumstances, such as in the event of an economic crisis.

Greater effectiveness for euro area economic policy could also involve stronger cooperation between the Eurogroup and the European Central Bank (BCE). The idea is not to call the ECB’s independence into question, as this is a macroeconomic “asset” that it would not be worth devaluing. But even in pre-euro Germany, when the independence of the Bundesbank was virtually sacred, the finance minister was one of the central bank’s key partners. Monetary policy and fiscal policy, which should be coordinated, are the two sides of the macroeconomic policy coin, and are indeed complementary.

Another advantage of this coordination is that it would allow Europe to speak with a single voice where exchange rates are concerned. In recent years, the euro’s value against the dollar has increased significantly, leading to a loss of competitiveness—at a huge cost for companies based in the euro area. The ECB can, in theory, intervene in the currency markets, within the bounds of market mechanisms, by selling euros and buying dollars. Faced with the difficulty of convincing other central banks of the pertinence of such intervention, it has not done so to date. In accordance with article 111 of the consolidated version of the treaty establishing the European Community, “the Council, acting by a qualified majority either on a recommendation from the Commission and after consulting the ECB, or on a recommendation from the ECB, may formulate general orientations for exchange rate policy in relation to these currencies”. This opens a legal window of opportunity for intervention, albeit a small one. However, the ECB still has to accept such demands. This is why Nicolas Sarkozy’s request to Christine Lagarde in 2007 that she examine “to what extent an agreement could be reached between the Eurogroup and European Central Bank clarifying the conditions of this dialogue and the terms under which exchange- rate policy is implemented”10 is economically justified.

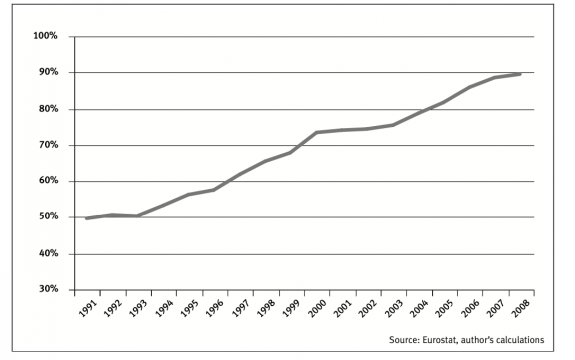

Openness ratio: exports plus imports as a proportion of GDP

America’s openness ratio has increased significantly over recent years, demonstrating that the US economy, generally said to be focused on the domestic market, is increasingly integrated into the global economy.

America’s openness ratio* (as a %), 1991-2008

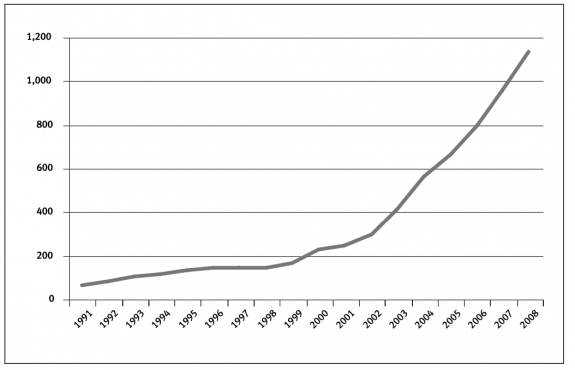

The euro area economy is very open, thanks largely to Germany’s contribution. Growth over recent years has in large part been linked to the capacity of its companies to reorganise themselves on a global basis and to start trading with countries outside the euro area.

Euro area’s openness ratio (as a %), 1991-2008

China’s imports have increased more than tenfold over the last 1µ years. So while China is seen in terms of the threat its industry poses to Western companies, it should be remembered that the country also extends our potential market considerably.

Chinese imports (in $ billion), 1991-2008

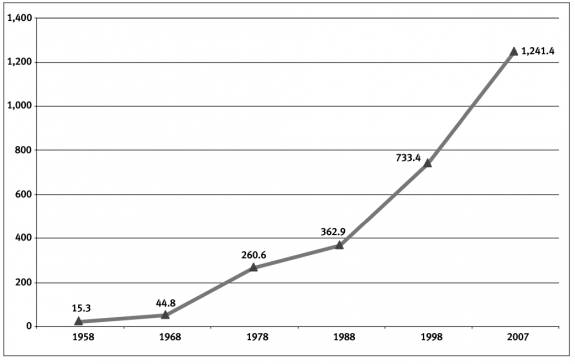

Europe’s exports to the United States, Japan and the emerging markets have been a big contributing factor to growth in the euro area since the end of the 1990s.

European Union exports (in $ billion), 1958-2007

No comments.