Introduction

The origins of British conservatism

Is there a conservative ideology ?

The conservative party today

The party’s organisation and its relations with the media

The conservative electorate

The United Kingdom Independance Party (UKIP)

The British National Party (BNP)

The right Britain today

The term Tory was originally It refers to a group of brigands from the West of Ireland and was used by Whigs to describe their conservative adversaries. Over time, its use has become, in popular speech, entirely un-polemical and it is synonymous today with “Conservative”. Academic analysts tend, however, to use the word “Tory” to denote the reformist or progressive tendency within Conservatism (see section 3 (i) below). We shall follow this practice in this essay.

Rémond, La Droite en France, Paris: Aubier-Montaigne, 1964; Les Droites aujourd’hui, Paris: Louis Audibert, 2005.

Lipset and S. Rokkan (eds), Party systems and voter alignments: cross national perspectives, New York: Free Press, 1967; P. Webb and J. Fisher, “The Changing British Party System: two-party equilibrium or the emergence of moderate pluralism?” in D. Broughton and M. Donovan (eds) Changing Party systems in Western Europe, London: Pinter, 1999, pp. 8-29.

In comparison with most continental states, the terms “left” and “right” are used infrequently in British political discourse. This does not mean that such realities do not exist in Britain: they do in all developed states. It is simply that the British label them differently. British people usually refer to the opposition between Conservatives (or Tories1) and Labour. In other words, the right-left distinction, which in France is sometimes also understood as an opposition between “order” and “movement”, is seen as being firmly incarnated within two institutions, namely the main political parties. There is no real tradition of theorising the nature of the right almost independently of those forces in which it finds expression. An approach such René Rémond’s, which postulates the existence of (at least) three distinct types of right-wing tradition in France, could have no real equivalent in Britain.2 At most, one could speak of a number of variants of conservatism, but all these would be understood as lying firmly within the ambit of one major historical party.

Using the classic typology of modern parties developed by Stein Rokkan, it is clear that the British two-class/two-party model (as the British party system has been called) postulates an opposition between the interests of the propertied (understood very broadly) and those of the propertyless.3

In modern Britain, this socioeconomic cleavage is the predominant one: right and left, Conservative and Labour, are defined primarily by refer- ence to it. The other great cleavages that beset modern societies, such as the clash between Church and State, or between centre and periphery, have in Britain been subsumed into this primary cleavage, which is the fons et origo of the modern British party system, hence of the distinction between right and left.

Having established this point, we can make a further clarification, namely the position of the British liberal tradition within the right-left spectrum. Although shorn of much of its historic power, this tradition, represented in the Liberal Democratic party, still attracts some 20% of voters. Whereas in a number of European states (Benelux, Germany), the liberals are regarded as being firmly on the right (they perform the role of the Conservatives in Britain, namely the defence of property), their British equivalents belong on the left side of the divide. Descending from the Whigs (usually considered as embodying the reformist tradition within British politics), British liberals of the nineteenth and twentieth centu- ries have usually been the “party of movement”, championing causes such as parliamentary and electoral reform, and the increase of personal freedoms. Later on, social liberals such as Lloyd George implemented numerous policies (housing, pensions) associated with modern welfare states. All of this places British liberalism on the left. Historically indeed, it was the dominant party of the left before being overtaken and mar- ginalised with remarkable speed by Labour in the 1920s. Some modern Conservatives like Margaret Thatcher may have used liberal economic theory for their own political ends, but this has very little to do with liber- alism as an organised political force, and confusion should be avoided.

The British right, then, is rooted in a long established and highly suc- cessful party, the Conservatives, which faces a left composed of Labour and Liberals. Like all successful parties, the Conservatives have faced, at different moments in their history, competition for the large space that they occupy so easily in British politics. Such challenges have some- times come from within the party (see below); latterly, they have tended to come from outside, particularly in the form of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and the British National Party (BNP), which will be treated briefly later. Invariably the Conservatives have easily withstood such challenges, and there is no reason to suppose that the current challengers will make serious inroads into their ownership of the political space of the British right.

In order to understand this Conservative hegemony, we need to go back to the beginnings of the modern era in parliamentary politics, when parties began to emerge as a serious force. Previously, governance had been a blend of monarchical interference and ad hoc alliances between ill-structured groups of notables.

The origins of British conservatism

On the early organisation of British partisan life, see O’Gorman, The Emergence of the British two-party system, 1760-1832, London: Arnold, 1982; R. Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Thatcher, London: Fontana, 1972.

Acceptance of the new status quo was by no means universal; see H. H. Green, Ideologies of conservatism: conservative political thought in the twentieth century, Oxford: OUP, 2002.

In 1965, he tried to have the Conservatives accepted as members of the Christian Democrat They were rejected on grounds of their secularist tradition and, more significantly, doubts about their real commitment to the European project. See C. Dechert, “The Christian Democrat ‘International’”, Orbis, XI, 1, 1970, pp 106-27.

For the political economy of this period, see Gamble, Britain in decline, London: Macmillan, 1981.

Wall, A Stranger in Europe: Britain and the EU from Thatcher to Blair, Oxford: OUP, 2008.

Internal party conflict in these years is often described as between the “dries” (Thatcherites) and “wets” (Tories of reformist convictions such as James Prior, Ian Gilmour or Francis Pym), who were progressively maginalised.

On the internal politics of Toryism, the authoritative work is that of Philip See “The Conservative Party: is there anyone out there?” in A. King (ed.) Britain at the polls, 2001, London: Chatham House, pp. 68-94.

Eighteenth century parliaments were perfect examples of the regimes of notables, classically described by Duverger. Local gentry, elected by highly restricted franchise in circumstances of extreme corruption, organised themselves in loose, frequently shifting groups. Often attached to a prominent personality, such men might support a ministry in return for favours.4 Although one such group had been known as Tories ever since the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which laid the basis of parlia- mentary rule in Britain, it was really only under the aegis of William Pitt after 1789 that a recognisably stable Tory faction began to be organised. It provided government leadership during the dangerous time of the French Revolution and Napoleonic period, assuring the repression of revolutionary ideas and organisations, and protecting landed capital.

By the 1830s, however, industrialisation was proceeding fast, industry now accounting for the major proportion of GDP, with over 40% of the workforce engaged in industry or mining, usually in harsh conditions. Such a proletariat represented a major threat to stability, unless it could be co-opted. One way to do this was to provide cheaper food, but this could only be done by repealing the Corn Laws (tariffs against the import of cheap food). Such a measure would, however, be against the landed interests, especially the large number of small and medium-sized enterprises that still existed (large producers were able, then as now, to compete). Tory Prime Minister Robert Peel brought in free trade in indus- trial goods and repealed the Corn Laws; in other words, he took the side of rising industrial capital against landed capital. The result was to split the Tories. The Peelites went mostly with the Whigs into a revamped Liberal Party, while the pro-landowner Tories rallied behind Disraeli (at this stage still pro-landowner). The reformist tendency in Conservatism thus ousted the resisters – at the price of weakening the party.

Two decades later, Disraeli, now convinced that reform was vital to Conservative electoral prospects, would oversee the widening of the suffrage and the passage of social laws (housing, labour rights), co-opting elements of the middle and working classes to the Conservative cause. These measures secured for the Conservatives the status of “natural party of government”, which they would retain until the late twentieth century. Their occupancy of office was punctuated only by brief Liberal and Labour interludes (before 1914 and after World War II). Not for nothing was the last century called “the Conservative century”. Under pragmatic leaders like Baldwin, Churchill and Macmillan, the Conservatives seemed to exude that governmental competence they have always prized. Since 1945, however, their hegemony has proved more difficult to secure.

The 1945 election saw a big and unexpected defeat for the Conservatives, as Britons voted massively for Labour and the building of a welfare state. For some 30 years, Conservatives would broadly accept what has come to be known as the post-war settlement. This involved a mixed economy, run by Keynesian policies of demand management; full employment was regarded as an achievable goal, and society was buttressed by an extensive welfare state offering a wide range of benefits in housing, heath and education. Economic policy was to an extent determined on neo- corporatist lines, with a strong input from trade unions. Most of this ran contrary to historic Conservatism. That it became tolerated by the party says much for the skills of rising politicians like R. A. Butler, author of the 1944 Education Act, and Iain Macleod.5 But certainly until the late 1960s, a broad consensus prevailed between the major parties, often denoted by the tag “Butskellism” (an amalgam of the names of Butler and Hugh Gaitskell, Attlee’s successor as Labour leader).

This consensual period in the party’s history was also its most pro- European moment. Churchill had spoken of a United States of Europe, but made it clear that Britain would remain outside, wedded to its Atlantic loyalties. A group of politicians around Edward Heath had a different vision. All from the generation that had fought in World War II, these men were attracted to the vision of Europe espoused by Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman, that is to say, a political entity that would eliminate conflict between neighbours with their historic rivalries.

Conservatives of pro-European views have often had the economy as their main motivation: they saw no alternative to British membership of the European Economic Community (EEC) if the economy were to grow. But the Heathites were also much more political. Heath in partic- ular was attracted to European Christian Democracy.6 Politicians from this family also believed in a post-war consensus of mixed economies, welfare states and neo-corporatist bargaining, often sharing government with social democrats; in some ways this position was not dissimilar to that of the post-1945 Conservatives. Heath became Conservative leader when they lost the 1964 election to Labour’s Harold Wilson, and immediately tried to push his party in a pro-European direction. When he unexpectedly won the 1970 election, he was able to develop a relationship with Georges Pompidou, whose willingness to discontinue General De Gaulle’s veto on UK membership finally allowed Britain into the EEC. In foreign and security policy, Heath also seemed willing to reconsider Britain’s long-standing Atlanticism in favour of a more European approach. This was the high moment of Heath’s career and of pro-Europe sentiment among Conservatives. It was domestic politics that would bring him down and change the course of the party.

For all his admiration of Christian Democracy, Heath, worried by the continuing weaknesses of the British economy, had flirted with ideas of an aggressive neo-liberal approach that would involve facing down the power of the unions. After considerable resistance, including a defeat by the miners’ strike of 1972, he abandoned such talk and returned to a more consensual style of government.7 Early in 1974, Heath faced yet another miners’ strike, which again had Britain working a three-day week owing to electricity cuts. His answer was to call an election, which he lost, extremely narrowly, to Wilson. A follow-up election in October produced another inconclusive result, and Britain would limp on unsteadily with a minority Labour government till 1979. In the meantime, however, Heath was finished: an angry party replaced him with a new leader, Margaret Thatcher, and a very different type of programme.

Thatcherism was a reaction to the growing difficulties of the UK economy: low growth yet high inflation; poor productivity; inefficient publicly owned industries (cars, steel); poor industrial relations and a high rate of strikes; very strong unions. Classical liberal economists, still numerous within Conservative ranks, found an effective ideolo- gist in Keith Joseph, who had a clear remedy. Britain needed a neo-liberal shake-up. Industry and services had to be privatised, regulation undone, and above all the unions had to be broken. A key element in the policy mix was monetarism, endorsed by the Chicago School of Milton Friedman: restriction of the money supply was seen as the key to tackling inflation. To push through such policies, which are much closer to what the traditional right in most countries believes, after years of soft consensus politics, a leader of strong convictions with powerful communication skills was needed. Thatcher had these in abundance, and she also brought a distinctly combative style to British European policy. Her accession to power in 1979 almost coincided with the end of the transitional financial arrangements for Britain’s membership of the EEC. In other words, a battle about refinancing the Community was inevitable, and Thatcher fought it hard and successfully, though it is doubtful if in fact she was as eurosceptic as some of today’s party.8 Her assertive style of leadership was given a boost by the Falklands War of 1982, when the Argentine junta foolishly invaded these islands and was duly removed by a British expeditionary force, precipitating, ironically, Argentina’s return to civilian rule. No opportunity was lost on the right to exploit this feat of arms for domestic purposes.

In domestic politics, Thatcher sped up the process of privatisation. She launched a major offensive against the trade unions, especially in the declining areas of mining and steel. Gradually tightening the regulatory framework so as to reduce unions’ power to strike, she provoked a major battle with the miners’ union in 1984-5 by beginning a series of pit closures; all means available to the state were used to crush the miners, who were forced back to work having failed to win any concessions. This victory helped speed the general decline of UK industry, a factor of little concern to Thatcher, who saw Britain’s future as a provider of finance and services. If over 70% of the workforce was employed in industry in 1970, barely 12% is today. To speed the tertiarisation of the economy, Thatcher deregulated enthusiastically and was a major ally of Jacques Delors in pushing through the Single European Act, opening the door to globalisation. When her party forced her from office in 1990, following a disastrous slump in popularity, she left a party largely purged of the more consensual, pro-European tendency associated with Heath and very much in the hands of neo-liberals.9

Her successor, John Major, won an unexpected victory in 1992 against a fast-reviving Labour, but was beset by economic recession and increasing divisions over Europe. His comprehensive defeat in 1997 left the Conservatives facing 12 years in opposition to Blair’s triumphant New Labour. For much of this time, the Tories appeared bereft of leader- ship and policy.10 In eight years, they went through four new leaders. In 2009, they were credited with poll leads of over 10%, and at the time of writing were widely expected to win the elections due in May 2010. It is uncertain, however, despite the communication skills of leader David Cameron, how far the party has really renewed itself, and how far its success is simply due to the terminal unpopularity of an exhausted Labour government.

Is there a conservative ideology ?

For a good discussion of conservative ideology generally, see Girvin, The Right in the twentieth century: conservatism and democracy, London: Pinter, 1994.

Britons vote in single-member constituencies, with one ballot This “first-past-the-post” system means that a seat can be won with as little as 35% of the poll.

D-L. Seiler, Partis et familles politiques, Paris: PUF, 1980, pp. 166-75.

The exception would be the current of Conservatism associated with Enoch Powell, from the 1960s onwards (see below).

Russel, The Conservative Party: its policies, divisions and future, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978.

Beneath policy documents and the writings and utterances of Conservatives across the ages, it is possible to distinguish a recognisable ideological core.11 The first characteristic of this is its implicit nature: in conformity to an intellectual tradition deeply embedded in British life, Conservatives are wary of theory. If pressed, they prefer to describe their thinking as common sense or pragmatism, rather than ideology. Yet, as is the case in any political community, a distinct ideology exists within Conservatism, providing Conservatives with a prism through which to make sense of the external world.

The core of this thinking is desire to preserve the established order. If changes must be made in the realm of society, economy or politics, then they should be piecemeal and gradual – a response to events rather than an attempt to impose a preconceived set of ideas (this is what the left does, in Conservative eyes). The pivot of the established order is clearly property, which supposes an elite of significant property owners whose interests need to be defended. This is not an inflexible concept, however, as the propertied elite is not fixed for all time: it can be expanded and gradually incorporated into Conservative politics. This can be seen at the level of political leadership. Initially dominated by landowning grandees, Conservatism gradually incorporated the rising industrial and commercial bourgeoisie; in later generations, as the suffrage expanded, children of the middle classes and the occasional worker made their way into the hierarchy. If the traditional type of Conservative leader is rich and privately educated, like David Cameron, the party has also been led by two grammar school children – grocer’s daughter Margaret Thatcher and gardener’s son Edward Heath. In short, meritocracy has its place in Conservative ideology.

In institutional terms, Conservatism has always favoured what constitutionalists term “the crown in parliament”. This means a government based on the majority party in the House of Commons, and an electoral system designed to ensure that such a majority always emerges from the ballot box.12 Views on the nature of the UK state have also shifted. Long regarded as the archetype of the modern centralising party,13 the Conservative and Unionist Party (to give it its full name) struggled hard against devolution of government power to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. It now accepts this move as irreversible and is happy to conduct politics asymmetrically across the UK at different levels, a decision made easier by the fact that historically it has been dominant in England. More generally, on the question of national feeling, Conservatism has tried, like the right in all countries, to claim a monopoly of patriotic sentiment, but its discourse on this question is mostly quite low-key;14 latterly this has left space for a more xenophobic right to try and claim ownership of the “national question”.

Economically, Conservatives’ instinctive preference is for a modest role for the state in an efficient market economy; but, particularly in the post-war era, the party engaged government heavily in economic management, in ways reminiscent of the Gaullist or “Colbertist” right in France. This shows the (temporary) ascendancy of the reformist or “one nation Tory” tendency within the party. Thatcherism is a brutal reassertion of older right-wing economics in the face of this.

At the level of values or culture, an old joke used to describe the Church of England as “the Conservative party at prayer”. It is true that the party long had strong connections with the established church, but increasingly it accepts atheists and members of other religions in a society it recognises as increasingly secularised. One should recall here that in contrast to most continental states, the “religious question” in the UK was solved very pragmatically in the 1820s by the Catholic Emancipation Act, which ended the ban on Catholics holding office. In terms of personal liberties and lifestyle, for a long time Conservatives held up the model of the nuclear family; but the party now respects other kinds of relationship and numbers prominent homosexuals among its elites, to the discomfort of more traditional members.

All these elements of ideology have one underlying feature, namely their extreme flexibility. At a given time on a certain issue, the party can stand for one principle, only to modify or abandon it, sometimes before even returning to office. This bespeaks above all a party concerned with power: how to win it and then how to use it. Some commentators suggest that this flexibility within Conservatism is actually enacted by means of factional struggle: there is always a right wing, which resists change, and a Tory left, which recognises the need to move on.15 According to such analyses, the right prevailed at the beginnings of the party (against Peel) and later on in the nineteenth century under Salisbury; Thatcher would be the continuator of this tradition (though the changes she made were brutal). The Tory left, on the other hand, would have been in the ascendant with Disraeli, Baldwin and post-war leaders Macmillan and Heath. Where such an analysis would place today’s leadership is not obvious. One could probably say that Cameron is trying to balance out left and right tendencies like many of his predecessors.

It is difficult to identify precisely the philosophical contributions that have defined the Conservative tradition. Whereas such an exercise is relatively easy for the socialist and even liberal families, who pride themselves on their intellectual ancestry, Conservative suspicion of theory makes the tracing of their ideological development more hazardous. That said, there is a small number of thinkers who are sometimes cited by Conservatives and who, in the view of most analysts, have contributed to reinforce the sort of ideological dispositions described above.

Pride of place should go to Edmund Burke (1729-1797). A Whig and an Irishman (at a time when Ireland was part of the Union), Burke theorised some of the basic mindset of English conservatism. His pessimistic writings, inspired by the counter-example of the French Revolution, warn against the danger of trying to determine social evolution via government; for Burke, society is an organic process, fundamentally unknowable. It is based on property and class; it is held in place by “prejudices” (which can include institutions and ideologies). To question these, even if they are apparently irrational is to miss the point. They do good simply by being there.

Burke’s negative views have helped over time to reinforce Conservative mistrust of the state and “big government”. A different tone was taken by Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), the Prime Minister who pushed through the widening of the suffrage and some social reform after 1860. In his novels and pamphlets, Disraeli saw the need for reform in order to co-opt the newly emergent middle groups and better-off workers to the party cause, rather than trusting to laissez-faire. This “one-nation Toryism” (his most famous slogan) has always been the rallying cry of the reformist tendency within Conservatism.

In recent times, two contrasting voices from the right deserve mention. In the 1960s, J. Enoch Powell (1912-1998) drew Conservative attention to the national question. An unflinching opponent of the EEC on sover- eignist grounds, Powell also attacked immigration from the (black and Asian) Commonwealth into the UK, forgetting that as Health Minister in the 1950s he had strongly encouraged West Indians to come and work in UK hospitals and services. In sometimes lurid speeches, Powell questioned whether immigration was weakening the British race, prophesying race wars in the streets. Although his own career was marginalised thereafter, he had support among many Conservatives, including working class voters. Powellism is still more widespread than liberal commentators care to admit. It made a major contribution to the ideology of the right (far beyond the party) by stressing racial issues so forcibly.

Just as strong an effect was had by the work of Keith Joseph (1918- 1994), originally a Heathite but converted to neo-liberalism by what he saw as the failure of the post-war consensus. Joseph was not an original theorist, but popularised the work of liberals like Hayek and the monetarist econo- mist, Milton Friedman. Close to Margaret Thatcher, and a key member of her early governments, he was the “organic intellectual” of Thatcherism, arguing relentlessly in favour of monetarist economics, deregulation and cuts to the welfare state (to produce less “irresponsible” behaviour by claimants). This austere figure, known unkindly as “the mad monk”, has strongly marked the modern Conservative right, albeit by amplifying themes that were already in the air (as with Reaganism in the US).

These thinkers could be seen, among many others, as exercising some influence on Conservatism. But we would stress that it remains an eclectic ideology, based on experience. To understand Conservatism, it is better to study it in action, rather than to approach it via pure theory.

The conservative party today

Interestingly, the majority of both the Cabinet and Shadow Cabinet are white middle-aged males, mostly educated at Oxford or Conservative elites come, however, mainly from private schools whereas Labour’s Oxbridge elites are practically all products of the state system. It would be simplistic to see this contrast as “privilege versus merit”, but the point is worth noting.

Hanley, “Préserver les acquis, sans préjuger l’avenir : la stratégie britannique et l’Europe”, in Défense et Stratégie no. 22, 2010 (in press).

Conservative Party, Vote for change: European electoral manifesto, London, 2009.

Hanley, Beyond the nation state: parties in the era of European integration, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2008, pp. 99-114.

T. Bale, “Between a soft and a hard place: the Conservative party, valence politics and the need for a new ‘eurorealism’”, Parliamentary Affairs 59, 2007, pp. 385-400.

Given Labour’s persistent unpopularity, it has made sense for the Conservatives to be as unspecific as possible about the policies they would seek to implement if in government. They have relied on not making mistakes, hoping that voter discontent with Brown will carry them to victory. Nevertheless, certain policy lines can be discerned (www.conservatives.com).

A major concern undoubtedly has been to distance the party (to an extent, at least) from some of the negative aspects of the Thatcher years. By the end of the Iron Lady’s reign, the party was seen in many quarters as caring only for the better off, out of touch with the mainstream of evolving British society, and possibly corrupt. It had allowed itself to be seen, in the words of Shadow Cabinet member Theresa May, as “the nasty party”. Much of Cameron’s effort has been directed at getting rid of this image and presenting his party as just as caring and compassionate as Labour. In language favoured by some policy analysts, the right has tried to take ownership of issues traditionally belonging to the left.

In consequence, Conservatives have embraced, far more firmly than in the past, the whole anti-racist and anti-discrimination agenda, including a commitment to personal libertarianism – issues that were long considered to be owned by the left. Acceptance of this change has not been universal in the party, particularly among older members. Nor has Cameron been able to recruit as many candidates of diversity (women, working class or ethnic minority members) as he would like, despite centralising candidate selection to a degree previously unknown.16 But a start has clearly been made in presenting the party as more typical of the diverse Britain of today.

On major socioeconomic issues, the Conservatives have tried to be as non-committal as possible, using as a leitmotif the need to reduce the state’s role; much of Cameron’s rhetoric ascribes the ongoing problems of British society to a surfeit of “big government”. The Conservatives were critical of Brown’s efforts to save the banks, preferring apparently to let them go to the wall (with consequences hard to imagine), and they have said that their economic priority will be to repay the public debt faster than Labour. Much of the general election debate will polarise around the extent and timing of expenditure cuts: will rapid Conservative cuts slow down the recovery, as Labour claims, or will such fiscal rectitude reassure markets and government creditors? Old right-wing instincts surface in some policy details. They seek for instance to reduce inherit- ance tax (a measure that will benefit a few thousand households), while at the same time looking for extensive (but unspecified) cuts within the public sector. In conformity with their image as a caring party, they have, however, ruled out cuts to health and overseas aid budgets.

On education, the Conservatives have been happy to follow a route opened by Blair, namely the weakening of the traditional system of public education, in which local authorities ran non-selective secondary schools. In the name of parental choice and diversity, Blair introduced such innovations as city academies, which brought in private sponsor- ship and were independent of local authorities. The Conservatives plan to develop such ideas further, including giving groups of parents the right to run their own schools. A rather less libertarian tone is taken on immigration and law-and-order issues, symbolised by the appointment of Chris Grayling as shadow Home Secretary. The Conservatives are keen to denounce what they see as excessive immigration (it is difficult to be precise about numbers, as the Home Office appears to have no proper records of entries to and exits from the UK), and call for a system of quotas, suitability tests and the creation of a Border Police Force. This approach, linked to a tougher-sounding rhetoric on crime and sentencing, is meant to assure more traditional voters, who might be put off by the new caring image of the party.

It is probably on “high policy” that the Conservatives have sought to dis- tinguish themselves most from Labour, though it is arguable how successful they have been. On defence and security, it is safe to say that there are no substantive differences between them and Labour. Both parties are firmly Atlanticist, seeing NATO as the cornerstone of security policy and regarding ESDP (European Security and Defence Policy) as very much a secondary adjunct, simply a vehicle for carrying out tasks of peacekeeping and reconstruction with which NATO does not want to be involved. The less ESDP develops by way of autonomous structures and capacity, the better from the UK point of view.17 Given their fundamental agreement about the UK’s role in the world (junior partner to the USA, with which it is said to have a “spe- cial relationship”), it is hardly surprising that Conservatives and Labour both voted overwhelmingly for the Iraq war and are both solidly behind the Afghanistan campaign. Debate between them centres not on strategy but on detail, if not trivia (typically Labour is accused of not spending enough on equipment, thus causing deaths of troops overseas); doubtless the electoral manifesto will promise increased military expenditure. Such populist tactics show clearly that there is no real disagreement on fundamentals.

European policy has therefore become the area in which Conservatives have sought to distinguish themselves. Over the years, the number and quality of pro-European figures in the leadership has declined; today, Kenneth Clarke is the last survivor of the type of European approach associated with leaders like Heath. Increasingly, new MPs and MEPs convey an angry euroscepticism. While few might actively seek UK withdrawal from the EU, the majority remain firmly opposed to further integration and are strident defenders of national sovereignty. Logically enough, given that they favour a Europe that is a single market but politically weak, they tend to favour further enlargement to states such as Turkey. The Conservatives were firmly opposed to the Lisbon Treaty and promised a referendum on it, even after the both houses of Parliament had ratified British acceptance. When Poland and the Czech Republic finally signed up, Cameron was forced to admit that his referendum could no longer be held, but promised “not to let matters rest there”.18 What this probably means is that there will be attempts by a Cameron government after 2010 to “repatriate” certain policy areas given to the EU by previous treaties (employment law, some judicial matters and pos- sibly fisheries policy), that is to bring them back under national jurisdiction. Most experts see such attempts as doomed to failure, which prompts one to ask why Cameron would ever undertake them.

The answer is that it would give him an opportunity to take up confrontational positions within EU institutions, which could then be presented to domestic opinion as proof of Conservative commitment to sovereign priorities. It is possible that the Conservatives believe that such an operation would be relatively cost-free (precisely because it is doomed to fail), although that might be to underestimate the exaspera- tion which a further bout of British obstructionism might cause to EU partners anxious to work out solutions to major problems such as climate change, energy shortages and the financial crisis, rather than spend their time dealing with bruised egos.

In truth, the Conservative high command is probably no more viscer- ally eurosceptic than the leaders of a number of European states, including some large ones. But it is very aware of the lack of positive enthusiasm for Europe among the UK public, and the relentless hostility to Europe of the Murdoch press, whose support it seeks. Much party behaviour on Europe is driven by domestic pressures of this kind, epitomised by the rise of UKIP, which attracts a more traditional type of Conservative voter with its outright rejection of the EU. In order to address such people, the Conservatives feel compelled to multiply anti-European gestures wherever possible. In reality, the way in which the EU is going (increas- ingly intergovernmental and neo-liberal in its economic orientation) suits them well, and they know that the Lisbon Treaty will do little to change this. Nor is there any prospect of the UK joining the euro, another of their sovereignist rallying cries. But they see electoral profit in campaigns against a “European super-state”, playing on the fears of large swathes of voters. The most spectacular example of this is the Conservatives’ departure from the European Peoples’ Party (EPP) group in the European Parliament (they were never in the EPP party as such). For years, the EPP has been moving towards their positions, albeit to the discomfort of some of its Christian Democrats members. It nowadays talks less about federalism and more about subsidiarity; it downplays its neo-corporatist social doctrines in favour of market liberalism, and talks about competi- tion instead of solidarity.19 Yet the Conservatives chose to leave it for an alliance with a number of East European eurosceptics, including alleged anti-Semites, climate-change deniers and champions of wartime collabo- rators with the Nazis. Clearly the credibility and influence of such a group within the European Parliament will be small; within the EPP, however, the Tories had punched above their weight, chairing numerous committees and boasting a number of highly respected legislators. That Cameron should be prepared to throw out the baby with the bathwater reveals the real nature of his European policy; namely, that it is driven entirely by short-term domestic considerations. In his defence, it could be said that Labour is hardly any different, except that it is less vocal about its total pragmatism on European issues. It remains to be seen if Cameron’s tone will change if he achieves office. We may note for now that the content of UK European policy is unlikely to change if this happens, except perhaps on the level of rhetoric; at bottom, Labour and Conservatives share the same, minimalist vision of Europe.20

The party’s organisation and its relations with the media

The main reformist factions are the Bow Group (www.bowgroup.org) and the Tory Reform Group (www.trg. uk). Prominent Thatcherite groups include No Turning Back, Conservative Way Forward (www.conwayfor. org) and, for the eurosceptics, the Bruges Group (www.brugesgroup.com). Traditionalists congregate in the Cornerstone Group (http://cornerstonegroup.wordpress.com).

Today’s party claims some 290,000 members (the figure for Labour would be about 135,000). The fee is £25 per year, a modest sum. For many years, the party had no centralised membership list or proper system of fees. The base unit is the constituency association, traditionally powerful in the selection of candidates. Cameron has clashed with a number of these as he attempts to centralise the selection process and impose more “diversity” candidates and young metropolitan high-fliers. Policy has mainly been a top-down affair: dissidents may voice disagreement at the party conference, but little notice is taken of them. Party leaders are given a free hand, but failure to deliver electoral success meets swift retribution (in contrast to Labour). The leader is now elected by a secret membership ballot, but only after MPs have drawn up a shortlist. This more democratic means of selection can misfire badly (e.g. the election of Iain Duncan Smith instead of Ken Clarke). After some lean years following 1997, when some of its rich backers deserted it, the party is now rich again, as powerful interests now deem it capable of overturning Labour. Prominent donors include betting millionaire Stuart Wheeler (£5 million), and the current Treasurer, Lord Michael Ashcroft, a Belize-based businessman.

The membership contains a broad spectrum of opinion, sometimes organised in factions or tendencies of varying degrees of visibility.21 Some commentators distinguish a reformist or left tendency (which has in our view always existed), opposed by a traditionalist wing (rejecting cultural liberalism) and a Thatcherite tendency (hardcore economic liberals). Needless to say, some of these dispositions and personnel overlap, not least on Europe; it is safe to say that the party is increasingly euro- sceptic the further down the hierarchy one goes.

A different kind of resource is provided by a number of think tanks, which have developed in the UK in emulation of US institutions such as the Cato or Heritage Institutions. Not all of these are formally connected to the party, but their ideological orientations are clear, as is their influence. Thus the Adam Smith Institute (www.adamsmith.org) or the Institute of Economic Affairs (www.iea.org.uk) have given a significant boost to neo-liberal economics since the 1970s, as has the smaller Selsdon Group (www.selsdongroup.co.uk), associated with John Redwood, a champion of the neo-liberal, nationalist right. The main force is prob- ably the Centre for Policy Studies (www.cps.org), set up by Thatcher and Joseph in 1974, which drove the campaign for monetarism and “rolling back the state”. A newer arrival is Policy Exchange (www.policyexchange.org.uk), which tries to steer Conservatives towards a more decentralised, civil-society based type of policy. Duncan-Smith’s Centre for Social Justice (www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk) works on urban problems and poverty, reflecting the Christian impulses that lie behind his particular variant of Conservatism.

The party publishes no newspaper in its own right, but benefits as a rule from the support of most of the dailies. The Daily Telegraph and Times tend to reflect more traditional Conservative views, the Daily Mail targets the middle classes with its particular variant of Thatcherism, and the Daily Express has a slightly more nationalistic tone. Of the populist “red-top” press, the Sun has returned to supporting the Conservatives, since its owner Rupert Murdoch decided that New Labour could no longer be trusted after Blair’s departure. The Spectator is the main review in which Conservatives debate current issues.

The conservative electorate

For a full list, see Blake, cit. pp. 368-70.

Historically speaking, we would agree with the thesis that beneath the UK’s apparent two-party alternation, there is, in reality one dominant party at most times.22 Thus, the Tories dominated from 1783 to 1832, before conceding half a century of Whig-Liberal supremacy. From 1886, they were dominant until 1992. The period since could be described as one of transition. Labour has never been in office long enough to assume this kind of hegemony. One way to describe continuing his- torical strength is to point out that from 1834 to 1945, Conservatives led or were dominant within 22 governments out of a total of 37; their occupancy of office covered some 60 years out of a possible 114.23

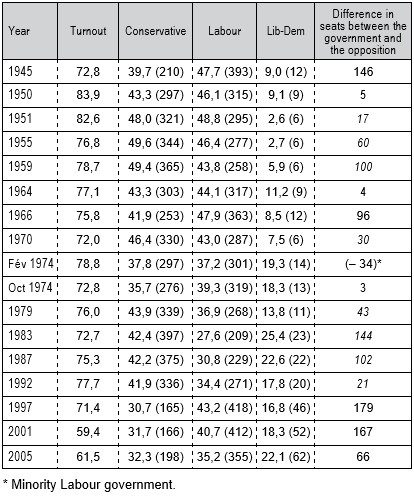

Table 1 : UK General Elections since 1945

Percentage of votes polled; numbers of seats in brackets (in italics: Conservative governments)

Logically enough for a party that began life as the representative of landed capital, Conservatism’s bastions have always been in the country- side, particularly in the South-Eastern quadrant of England. As industrial capital became prominent, the Conservatives duly conquered most of Britain’s cities and assumed a more urban profile. Birmingham and the industrial West Midlands went over to the Conservatives after 1890, the peak time of British imperial expansion; the Chamberlain family from Birmingham, who led a group of so-called “Liberal Unionists” into the party, symbolised this rallying. Imperial preference (an economic system based on growing investment overseas) would, it was hoped, bring sufficient benefits to rally a significant part of the working class to the Conservative project. Later, the textile towns of Lancashire were won over for a time by this logic.

The Conservatives have always been weak in Yorkshire and the North East, old mining and manufacturing areas. Conservatism flourished in Scotland before 1914, but has declined there ever since. Its popularity in Wales has never been great: the rural areas have kept a Liberal tradition, and the mining valleys of the South are where Labour first developed. Since the 1950s, notwithstanding a brief revival under Thatcher, Conservatism has been losing ground in the North of England, in the big cities, and in Scotland and Wales. Thatcherism was the crucial experience for these latter; both nations felt neglected by London and turned even more strongly to local Labour or the nationalist parties, subscribing enthusiastically to decentralising ideology. We encounter here the centre- periphery divide; in the UK, the centre is in the South-East, and the North and the Celtic nations are the periphery. As Ross puts it, “the famous North-South divide is rooted in an immense social reality”.24

Looking across these historical trends, we see a party dominant in rural and small-town England, which is capable of occasional surges in other areas. When this happens, the Conservatives win a general election. In 2010, in order to win a Westminster majority, they have to make some progress in Scotland, Wales and the cities, as well as taking from Labour a large number of semi-urban seats populated by commuters working in nearby big towns.

In sociological terms, Conservatism has always drawn overwhelmingly from higher social groups, the professional middle-class (AB) and white-collar workers (C1). The party’s share of these groups has been much higher than its support within the electorate as a whole. By contrast, the Conservatives have usually performed below average among the skilled manual workers (C2) and the semi-skilled and unskilled (DE). One of the keys to Thatcher’s victories was her capacity to increase the party vote among such groups (albeit only to 38% of these categories at best). This was done by incentives such as the right to buy social housing cheaply and the selling-off of cheap shares in privatised utilities. Cameron must also make new inroads into these groups. An extensive survey of voting intentions on the eve of the June 2009 European election showed the Conservatives to have an electorate similar to that of their centre-right counterparts on the continent.25 While there was little divergence between their vote and the national average in terms of age groups, they led among upper social groups ABC1 by 5%, especially among managers, but were 5% below the national average for semi-skilled and unskilled workers. In terms of income groups, they led among those above the median income. They led among private sector employees generally (5% above average), but trailed among public employees. Interestingly, a high proportion of their voters read either the “red-top” press (Sun), the middle-class tabloids (Mail) or the quality broadsheets of the right such as the Times or Telegraph. There is a clear fit between voting and ideological intake.

The United Kingdom Independance Party (UKIP)

In the 2001 election, for instance, UKIP contested 420 seats and polled only 5% of the vote.

UKIP is the most successful expression thus far of longstanding British opposition to EU membership. In terms of party cleavages, therefore, it derives from the centre/periphery cleavage, seeking to preserve sovereignty within the British nation state and prevent it from becoming the periphery of a new centre, Brussels. Founded in 1993 by historian Alan Sked, UKIP was for a time overshadowed by the Referendum Party of financier James Goldsmith. The party stood in UK general elections, as well as European, and is believed to have cost the Conservatives several seats at the 1997 election. Its breakthrough came in 1999, when it took three seats in the European Parliament, a total which it has improved in succeeding elections. It has had no MPs at Westminster (except, briefly, for a dissident Conservative), and its strength at sub-national level is weak.26 Its main effort goes into European Parliament (EP) work, where it argues, noisily, provocatively, and sometime with considerable media effect, the case for British withdrawal from the EU. It is the main force behind the sceptical EP group known as EFD (Europe of Freedoms and Democracy).

Like all small parties, UKIP has been prone to factional struggles at its summit, with several changes of leader in recent years. It briefly enjoyed the presence of TV presenter, ex-Labour MP and former political scientist Robert Kilroy Silk, though his enthusiasm did not survive long beyond his election as an MEP in 2004.

Most UKIP leaders in fact have a past in the Conservative party, including current leader Lord Pearson, and it seems clear that the Conservatives are the party nearest to UKIP. Certainly some 43% of their members believe so, and over 60% of them are said to support the party’s anti-EU stance. Millionaire Stuart Wheeler, who has backed the Conservatives to the tune of several million pounds from his betting empire, was ready to give UKIP £100,000 in March 2009, in order to shore up Cameron’s eurosceptic feelings. Thus, although the main policy of UKIP is British withdrawal from the EU, its other policies reflect, in the words of recent leader Nigel Farage, the desire to protect “traditional conservative and libertarian values”. Thus, UKIP is economically neo-liberal, favouring deregulation and a flat tax of 33%, lower corporation taxes and the abolition of inheritance tax. It is sceptical of climate change. In education, it favours vouchers to be given to parents. On a personal level, it is firmly opposed to the introduction of ID cards and denounces what it sees as the bureaucratic persecution of categories such as motorists and smokers. In short, UKIP appeals to the old-fashioned, anti-statist right wing of the Conservatives, and represents an electoral threat to the party, at least at European level. The first-past-the-post system in use for Westminster elec- tions makes it very hard for UKIP to win any seats in Parliament, however; the most they can hope for is to exert some programmatic “blackmail potential” (to use Sartori’s phrase) on the Conservatives. Judging from Cameron’s recent stances on Europe, they have had some success in this direction. British voters understand their electoral system perfectly well; 15% of them might vote for UKIP at a “secondary” election to the EP, but they are simply using this opportunity to send a (eurosceptic) message to the core parties, especially the Conservatives. At a “real” election, UKIP’s figure is more likely to be 1 or 2%.

Some people associate UKIP with the BNP, but it should be clear from the above that this is not founded. UKIP has none of the BNP’s racism, and has a number of officials and candidates from ethnic minorities. It is much more connected with an old strand of Conservatism, which it has fused with an anti-Europe dimension. The populist far right is a different matter entirely.

The British National Party (BNP)

For academic analysis of the BNP, see Copsey, Contemporary British fascism: the BNP and the search for legitimacy, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009. A left-wing perspective on everyday BNP activity comes from the Searchlight organisation (www.hopenothate.org.uk).

Britain has always had a small and peripheral extreme right. In the 1930s, the British Union of Fascists, founded by former Labour minister Oswald Mosley, attempted to imitate the politics of Mussolini. It failed to make a breakthrough, but nostalgic extremists carried on the fascist tradition after 1945, eventually merging into the National Front, which enjoyed some modest visibility during the economic hardship of the 1970s Labour governments. The BNP27 (www.bnp.org.uk) began in 1980 as a split from the National Front, led by John Tyndall; since 1995, it has been led by Nick Griffin, a Cambridge law graduate. Griffin has tried to soften the BNP’s image: it does not accept the label fascist, preferring that of nationalist. The party stands for white supremacism and recommends the repatriation of immigrants; its economic policy is rhetorically anti-capitalist and opposed to the EU, and it stresses themes of authority rather than cultural liberalism. It believes in a Christian Britain, menaced in its eyes by Islamic immigration. Some of its leaders have been caught out in examples of holocaust denial and anti-Semitic remarks.

Electoral success has been modest, with some 46 councillors out of a total of 21,000, and the election of two MEPs in 2009, on a very low turnout (the BNP vote actually declined numerically from 2004). This success has come in areas of industrial decline (East London, Lancashire textile towns), where Asian immigration is high. A typical BNP voter in 2009 was likely to be male, white, a manual worker and often a former Labour voter. The BNP poses no threat in Westminster elections (0.7% in 2005), and has clearly been the vehicle for a protest vote. It is typical of hard-right populist parties (such as the Front National or Vlaams Belang) which, no longer promoting thoroughgoing fascist ideology, make a modest political living by exploiting the problems perceived to be posed by immigrants in difficult economic times. Its future will remain limited because, whenever necessary, the Conservatives are flexible enough to shift their discourse slightly towards BNP themes, rather as Nicolas Sarkozy did vis-à-vis the FN in 2007 or indeed Margaret Thatcher in 1979.

The right Britain today

Coulson can be seen as the mirror image of Alastair Campbell, former redtop journalist and Blair’s director of He was probably one of the most powerful people within the Blair inner circle.

As the general election of 2010 approached, several questions remained unanswered. The British system of single-member constituencies effectively means that a good half of the seats in the House of Commons rarely change hands; thus even in a worst-case scenario, Labour would probably still have around 200 MPs (out of 650), elected in safe seats in its heartlands in Scotland, Wales and the North. Elections are thus decided in the hundred or so marginal seats, located mainly in the North West, the Midlands, and across the South and West of England. The Conservatives have long targeted these seats, spending heavily on polit- ical activity in them, funded by backers such as Ashcroft. Most of these seats contain a strong percentage of those salaried middle-class voters (A, B and C1) who make up “middle England”, and whose vote ultimately decides national elections. This social group displays a certain electoral volatility. From the mid-1990s, Labour captured most of their vote. Using evidence from focus groups pioneered by Philip Gould, the party talked up the aspirations of this group, implying that there was no con- flict between these and a certain measure of social justice, underpinned by strong public services. Today the Conservatives have to perform a similar exercise, as this middle group has been steadily losing confi- dence in Labour. But the exercise has not run smoothly. Reassuring this group about the need to protect public services does not sit easily with messages about the need to cut public spending drastically. Discourses on equality and non-discrimination seem odd when set alongside vague (and unquantified) pledges to give tax privileges to married couples. Warm and inclusive social rhetoric (a Cameron speciality) does not accord well with the anti-immigrant vigour and enthusiasm for more repressive penal policies of people such as Grayling. Cameron’s own support for ecological causes is known to run counter to the instincts of most of his party. Even at the level of communication, there is a gulf between the polite and polished media performances of Cameron and George Osborne (shadow Chancellor), and the crude, anti-Labour advertising promoted by Andy Coulson, Cameron’s communications director and the former editor of a ‘redtop’ tabloid paper, whose style is that of a street-fighter rather than a debater.28 Even Cameron’s most persistent theme – the need to rehabilitate civil society against the Moloch of “big government” – is very ambiguous; such ideology can be used by liberal-minded reformers but also by old-fashioned advocates of budget cuts and tax rebates. All these ambiguities bespeak a tension between the need to appeal to old values (and traditional voters) and the need to reach out wider towards middle groups.

Cameron is at the centre of this tension. Coming from a classic High Tory background (minor nobility, Eton and Oxford), he has the confident manner of his class and, as a former public relations executive, is a much better communicator than Brown. He is criticised by some in his party for his cliquish style of leadership (most of his confidants are people of similar background, a number of whom he has imposed as parliamentary candidates), but so far this problem has not proved too much of a difficulty. Labour tries to attack his “posh” background, but it is uncertain how far this is a factor in his failure to make a decisive breakthrough in the polls; voters probably sense a certain superficiality and lack of substance behind the confident image. Cameron thus risks being seen as a sort of minor version of Blair (whom he is known to admire precisely for having sold Britons the image of a new, modern- ised Labour Party). Blair excelled at communication, even if his policy output often proved disappointing. It may be that voters are wary of a second leader strong on charisma but little else.

All of this raises the question of what happens after the election. Poll predictions have varied, some giving Cameron a working majority (30+), while others have predicted a hung parliament, where no party has a majority. If this should happen, the role of the Liberal Democrats will be crucial, as it means they will have kept most of their 60 seats. Five years ago, under the leadership of Charles Kennedy, Scotsman, social democrat by instinct and, for what it is worth, Catholic, a deal with the Conservatives would have been unthinkable. In 2010, under Nick Clegg, who, Southern English and public-school educated, has moved his party towards much more neo-liberal economic positions, it would be a bold person who ruled out a Lib-Con pact, particularly if the Conservatives were the biggest party. The last Liberal government was in 1924. On the morning of 7 May, Clegg’s phone is likely to be busy.

The space on the British right belongs as much as ever to the Conservatives. UKIP and the BNP are minor nuisances, which cater for disgruntled minorities in “second-order” elections. For nearly two centuries, the Conservatives have managed to remain the only contender for office from the right. They have their tensions and internal debates, some of them carried on in think tanks beyond the party as such. But in the end, they always produce a working synthesis between different factions and different policy options. Their current stances are an eloquent proof of this, combining reassurance for those who own something with carefully chosen gestures designed to reach out beyond the Conservative core. We should not expect brilliant intellectual originality from the party, but a shrewdly calculated offer designed to win a majority of voters. This will probably be the case in 2010. Small wonder that textbooks invariably cite them as the supreme example of the “party of government”.

No comments.