The Netherlands: The Populist Temptation

The Netherlands in face of the crisis: the dike is leaking, but the flow has been stemmed

The crisis in Netherlands

A shallow recession for a resilient economy

Sound fundamentals

The Netherlands in the face of structural challenges: rebuilding the dikes

Welfare state and intergenerational choices

The integration challenge

Polarisation around Islam and the debate about identity

The Dutch paradoxes in Europe: the end of the Euro-malaise?

Who is watching over the dikes? Managing the crisis and the crisis management

Balkenende or “retropolitics”

The persistent call of populism and the crisis in the ruling coalition

Historical perspective

The end of dutch exception?

Appendices

Christophe de Voogd,

Lecturer in history at Sciences Po, author of Histoire des Pays-Bas des origines à nos jours (Fayard, 2003).

In the Netherlands’ bicameral system, the Second Chamber of the States General, elected by a direct vote under a proportional system, is pre-eminent. It has 150 members.

Few European countries have seen their international image change as radically as the Netherlands in such a short space of time. As recently as 2000, the Dutch economy, boasting one of the highest rates of growth in the OECD, focused international attention on the virtues of the polder-model, a blend of cooperation and moderation between business leaders and trade unions in a constant search for compromise. On social issues, the Dutch “laboratory”, with its liberal penal climate, its acceptance of gay marriage, the re-opening of brothels, its permissive policies on drugs and the legalisation of euthanasia, inspired interest around the world.

The perspective has changed enormously since the tragic events of 2002 and 2004, with the assassination of populist leader Pim Fortuyn and polemic filmmaker Theo Van Gogh, which brought the Netherlands face-to-face with the spectre of political violence, something that had previously been absolutely proscribed from national politics. Dutch society has also been beset by doubts about the continuation of its vanguard experiments – particularly in respect to drugs – and the increase in crime has prompted calls for limits to be placed on the sacrosanct principle of gedogen, or tolerance, in all areas.

This has coincided with a lasting downturn in the economic environment, sending the Netherlands to the bottom of Europe’s economic performance tables in the years 2001-2005. With growth averaging just 0.7% per annum over that period, a budget deficit and increasing unemployment, it looked a lot as though the poldermodel had broken down.

Social frustration and the economic downturn translated into a degree of electoral volatility and political instability that the Netherlands had not witnessed for more than 20 years: between 2002 and 2007, four governments fell and the Second Chamber1 was dissolved twice; new parties with shifting political fortunes emerged, while some of the most prominent parties, such as Labour (Partij van de Arbeid, PvdA) and the liberally minded People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, VVD), experienced big swings in support. It could, however, be contended that the robust electoral results over the recent period of the Christian Democratic Appeal (Christen Democratisch Appèl, CDA), which lies at the centre of the Dutch political spectrum, and the fact that a single Prime Minister, Jan Peter Balkenende, remained at the head of the national government for nearly eight years point to a return to a certain measure of stability.

It is also true that the years 2006 and 2007 saw a marked improvement in the Netherlands’ economic performance, with a return to growth of 3% or more, leading to a spectacular recovery in the public finances. Politically speaking, it could be said that the Netherlands’ decision to adopt its own version of the “grand coalition”, spanning the country’s two biggest traditional parties, the CDA and the PvdA, after the November 2006 parliamentary elections, signalled both a return to business as usual and a renewed sense of national unity.

But the grand coalition is now history: recent events in the Netherlands, namely the resignation of the fourth Balkenende government after three years (22 February 2007-20 February 2010) show that the era of political instability is not over.

After the “false start of the 21st century” (Jos de Beus), the question remains whether the shockwaves of 2002, with the assassination of Pim Fortuyn and his posthumous electoral success, have been fully absorbed. This question, which has been central to public debate for several years, became even more pressing when the global financial crisis hit in 2008. The fall of the government once again brought it into sharp focus.

The Netherlands in face of the crisis: the dike is leaking, but the flow has been stemmed

The crisis in Netherlands

The challenge represented by the global financial crisis was compounded for the Netherlands by the structural characteristics of the country’s economy, particularly its sensitivity to a contraction in international trade and a shock emanating from the banking sector. The world’s sixteenth-biggest producer, but its sixth-biggest exporter (and the third- biggest in agriculture), the Netherlands occupies a prominent place in international investment flows, both as a source (ranked sixth) and a recipient (ranked seventh). In appearance a small country, its economy is actually one of the most open ones in the world, dominated by the services: financial services alone account for 7% of gross national product (GNP). The repercussions of the shock that came from the United States, where the Dutch rank among the leading investors, were bound to be swift and severe. The impact of the financial crisis was exacerbated by the fact that the Dutch banking sector was in the process of restructuring, after the acquisition of national giant ABN-AMRO by a consortium of banks, including Fortis, one of the first European victims of the (virtual) global crash. As such, the Dutch banking industry experienced particular trouble in the latter part of 2008, notching up aggregate losses of €28 billion on the back of substantial write-downs of financial transactions and the need to set aside large provisions to cover the big increase in doubtful international loans.

As elsewhere, this shock spread to the rest of the economy: in 2008, the Netherlands’ trade surplus narrowed by 11%. Full-year projections for 2009 pointed to a decline of nearly 15% in exports; the budget deficit, under the combined impact of lower tax receipts (€6 billion in the space of six months) and government stimulus measures, swelled to 4.6% of GNP, and public debt surged at one of the fastest rates in the euro area, crossing the threshold of 60% of GNP by the end of the summer of 2009. The Netherlands crashed through the upper limits set under the stability and growth pact. Unemployment increased to about 5% of the active population. But the biggest concern was the anticipated dive of roughly 25% in investments over two years. The only positive factor, in the Netherlands and elsewhere, was the big drop in the inflation rate, after a period of overheating in the summer of 2008.

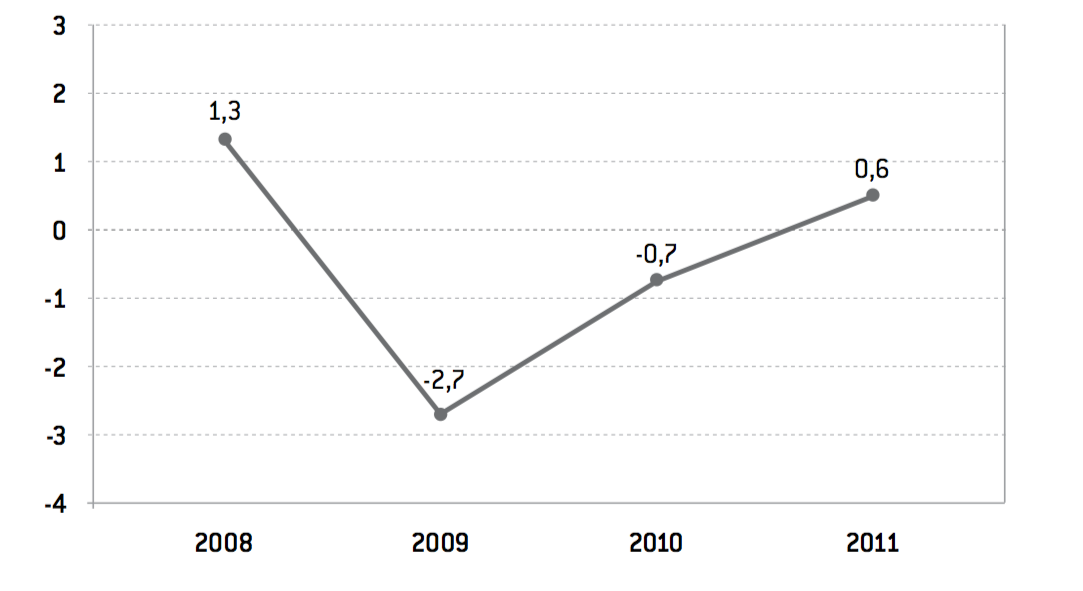

A shallow recession for a resilient economy

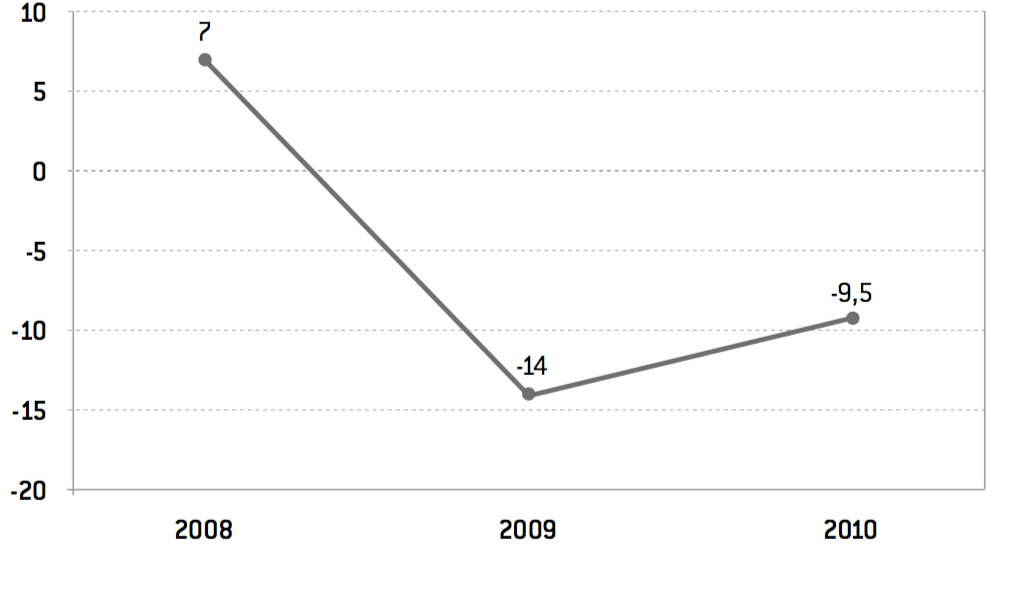

Source: French Economic and Financial Mission in the Netherlands, based on Centraal Planbureau (CPB) projections.

In retrospect, it is clear that the situation remained under control, and that while the current recession is the deepest the country has experienced since the Second World War, it has not at this stage prompted a true depression.

The recovery in exports in the summer of 2009 was confirmed by slight growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in the third quarter. The full-year outcome is now expected to be a contraction of roughly 3.5%, as opposed to the initial anticipation of a 4.5% decline; most economists are less pessimistic for 2010, and are now expecting GDP to edge up slightly. Similarly, unemployment is now expected to peak at 6.5%, as opposed to the 8% that was feared for a time.2

This is attributable to the stabilisation of the global economic environment, which is obviously having a positive impact on the Netherlands’ open economy. The Dutch government’s policies have also helped. Not least of which, the energetic response of the Labour finance minister, Wouter Bos, to the woes of the banking sector: acquisition in the autumn of 2008 of Fortis’s interest in ABN AMRO leading to that bank’s de facto nationalisation and creation of a guarantee fund (totalling €200 billion) to underwrite interbank loans. A stimulus plan was also finalised in March 2009, with new government spending totalling €6 billion over two years, including support for the labour market, a “sustainable” investment programme, particularly in renewable energies (with a doubling of offshore wind-power capacity) and support for business liquidity.

However, commentators generally emphasised the modest nature of the Dutch stimulus package, compared with the French or even German plans. Most government support has come through automatic stabilisers (for about €40 billion), which are decisive in a country where collective expenditure (public and social welfare) accounts for nearly 40% of GDP. As such, the government’s real contribution has been to defer until 2011 any effort to bring down the budget deficit. This is consistent with OECD recommendations and was made possible by the Dutch economy’s sound fundamentals. Indeed, numerous experts and opposition members maintain that the health of the Dutch economy would have been possible to adopt much more aggressive policies.

Sound fundamentals

When the crisis hit, the Netherlands’ main economic indicators were very well oriented, thanks to efforts in earlier years to put the economy on a sound footing: unemployment was below 4%, the trade account was in surplus, as was the government’s budget, and public debt accounted for 45% of GDP. This proved to be a real advantage in comparison with most of the country’s neighbours, which did not have the same room for manoeuvre in such unprecedented economic conditions. The solidity of the financial sector allowed banks and insurance companies to preserve their solvability ratios. And while powerful pension funds initially suffered from the bear market in equities,3 which left them with huge amounts of underfunded commitments, the combined impact of the end to the indexation of pensions, the increase in pension contributions and the rally in equity markets have put them back on the road to a recovery.

But the most important factor was no doubt to be found elsewhere: in the astonishing resilience of the Dutch economy, and especially the country’s public finances. To appreciate this fully, we need to cast our eyes back at least 25 years. We need to bear in mind the very parlous situation in which the country found itself in the early 1980s, when unemployment was 13% and the budget deficit accounted for 10% of GNP (1982) in an environment characterised by stagflation, a combination of symptoms that foreign commentators were quick to dub the “Dutch disease”. Since then, considerable productivity gains, obtained by keeping wage increases moderate and tightly managing the public finances, have helped put the country’s finances back on track, while at the same time prompting a spectacular increase in national wealth, propelling the Netherlands into third place in the OECD on a per-capita basis in 2006. In other words, the country’s underlying situation has been rosy for at least ten years. As such, the crisis had only a limited impact on the population, which was not the case in numerous countries that slipped into recession without having addressed their structural imbalances. The results of the standard Eurobarometer survey 724 clearly show that the Dutch see the prevailing environment in a much more positive light than their neighbours in other countries.

The Dutch have one of the highest feel-good factors in Europe (95%, compared with the EU average of 78% in response to the question “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied or not at all satisfied with the life you lead?”), which is backed up by the country’s ninth ranking in the United Nation’s human development index (HDI) and the lowest rate of poverty in the European Union.5

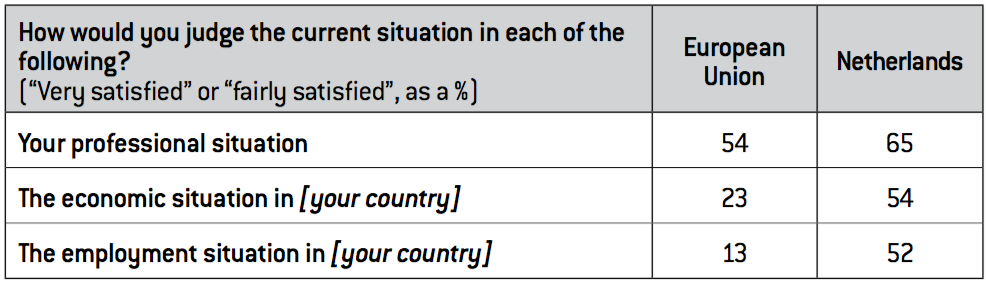

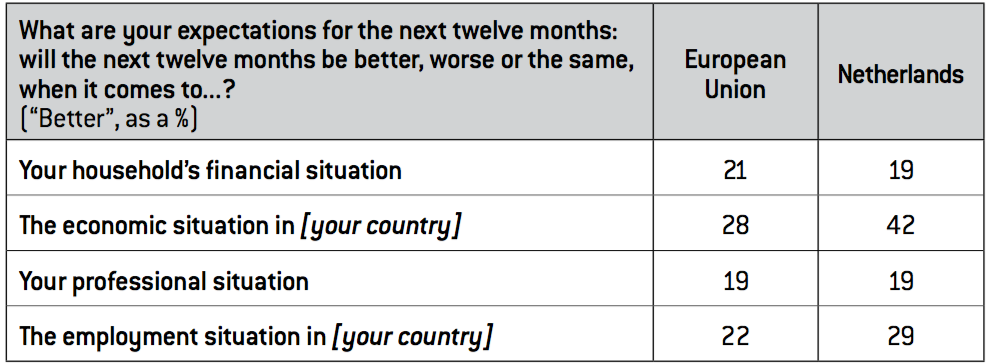

Table 1 (source: Standard Eurobarometer 72, January 2010).

In addition, the Dutch have demonstrated their capacity to keep the lid on both unemployment and inflation, not to mention their national debt. This would tend to inspire confidence in the capacity of the Dutch economy to recover, especially with the experience of past recoveries, prompting a relatively bright view of the country’s medium-term out- look. However, the Dutch do not necessarily share the expert assessment of their country’s capacity for resilience, and express conflicting views on a number of matters.

Table 2

Source :

Standard Eurobarometer 72, January 2010.

Eurobarometer 71, September 2009.

The two tables above highlight the same gap between personal considerations and collective perceptions that can be found across the entire European Union: while Dutch people’s responses were similar to their neighbours’ in areas with a direct impact on their personal situation, their view of the short-term economic outlook – not only for the Dutch economy, but also the entire European and, indeed, global economies – was more upbeat. It is worth noting that the situation was the exact opposite in the preceding spring, when they were among the most down-beat people in Europe.6

In reality, it could be said that the shifting and ambiguous responses of the Dutch reflect a blend of perplexity and serenity. This mixture is perceptible in all opinion surveys; to understand this phenomenon, it will be necessary to have a look at the Dutch notion of samenleven, or “living together”.

The Netherlands in the face of structural challenges: rebuilding the dikes

The crisis emerged at a time when the Dutch, like most of their neighbours, were facing a three-pronged challenge: the survival of the welfare state in the context of globalisation and an ageing population; the need to integrate significant ethnic minorities, often with different cultures and religious beliefs; and, lastly, the redefinition of the Netherlands’ place in an enlarged European Union with 27 members.

Welfare state and intergenerational choices

All the demographic indicators below are drawn from CBS (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek) data.

Maintaining the country’s social security is one of Dutch people’s top political priorities, according to the survey on the state of the social welfare system (De sociale staat van Nederland), hereinafter referred to as the SSN, conducted by the Sociaal en Culturel Planbureau and published in November 2009.

Contrary to received wisdom, Protestantism has never been the predominant religion in the Netherlands, but the length of its social and political dominance makes it, in the well-known Marxian vision, the dominant ideology of a nation where the Catholics have in many respects been “Calvinised”.

In the most recent Eurobarometer, it is cited as the third-biggest preoccupation of Dutch people for their country after the overall economic situation and unemployment, but their leading personal preoccupation.

Source: There is a very big difference between men and women in respect to part-time work: while 25% of jobs held by men are part-time, this is the case for 75% of jobs held by women.

Source: Eurostat.

Source: SSN.

Source: Eurostat.

Source: Eurobarometer 72, January 2010.

The first of these issues, the future of the welfare state, is closely linked to the question of intergenerational choices, namely between the funding of pensions and healthcare, and that of education, and also has a bearing on the management of public debt and environmental policy, and even research and development policy (R&D).

With the combined effect of a moderate birth rate (11‰)7 and increasing life expectancy, the age structure of the Dutch population shows that the Netherlands, like all its neighbours, is in the process of ageing. It is, in this respect, within the European average. Less than one-quarter of the population is currently aged under 20, while people aged over 65 (the retirement age in the Netherlands) account for 15% of the total. Projections for 2050 underscore the extent of the problem: by then, there will be one person in the Netherlands aged 65 and over for every two people of working age (15-64 years). This shows the importance of the employment rate in the latter category in terms of the future funding of state pensions.

The challenge ahead is especially painful in that the welfare state built in the 1960s and 70s has gradually become one of the pillars of the national identity.8 The Dutch version, known as verzorgingstaat, is closely entwined with fundamental values forming the collective mentality, covering the notions of “concern” and “care”: accordingly, the Dutch welfare state is not like the all-encompassing French system; nor does it have the strictly material connotations of the British model. It is simply a state that has real concern for its citizens. This is compounded by the profound egalitarian aspirations stemming from Protestantism,9 recycled and reinforced by a powerful Socialist movement. Lastly, the state’s determination, expressing itself as the desire to intervene legitimately in all parts of Dutch society, has been driven by the idea of a “socially engineered society” (maakbare samenleving), to quote a popular slogan in the 1970s. This harks back to the Netherlands’ long fight for physical survival: its modelling of its natural environment is in itself an engineering feat. In short, maakbare samenleving is a genuine social project, which mobilised significant symbolic resources in the depths of the nation, while at the same time benefiting from other natural resources, namely the abundant Groningue gas field.

But this ambitious programme has come up against harsh realities: successive oil shocks, a fresh wave of globalisation and the ageing of the population combined to show the financial limits of a model that, if unchecked, threatened to undermine both the public finances and the country’s overall competitiveness. In other words, to use an appropriate metaphor, the flow of collective expenditure threatened, in the early 1980s, to submerge Dutch society.

So much so indeed that the history of Dutch social policy over the last 25 years has been one of successive reforms, in three directions: increasingly restrictive conditions on the entry into the various protection schemes, reduction in benefits and a switch from public funding to private schemes – whatever party has been in power. On top of that, fiscal policy has remained very strict, reducing the weight of the civil service and privatising numerous sectors (transport, energy, telecommunications). Together, this has sparked a spectacular reduction in public debt, which narrowed by 30 points between 1997 and 2007, thereby limiting the transfer of current charges to future generations.

The results have nevertheless been mixed in the various areas. The pension system is a blend of a state-run pay-as-you-go scheme (AOW), which provides all Dutch people with an enviable basic income, and personal schemes, in the shape of pension funds, which have so far enabled the country to cope with demographic trends. Early retirement plans (VUT) have been placed under strict control, after a long period during which they were very free. Lastly, the outgoing government recently moved, honouring a pledge contained in the coalition agreement, to increase the retirement age by phases from 65 to 67 starting in 2020.

The results are even more mixed in terms of healthcare: budgetary restrictions and strict rules about prescriptions led to a situation in the early 2000s where healthcare was being rationed, with lengthening waiting lists in hospitals, even for urgent operations. The decision to privatise health insurance for most people whose earnings were above a certain threshold helped make the system more flexible, but engendered patent inequality in treatments. As it happens, healthcare remains, in opinion surveys, one of Dutch people’s main preoccupations.10

But the reform of the Invalidity Insurance Act (WAO) without question provides the best illustration of the excesses of the welfare state, the long march of reforms and their ambivalent results. The sustainable “fortune” of this scheme, created in 1967 and since become a veritable national speciality, stems from the explosive conjunction of the various interests in play: used by restructuring businesses to cut jobs painlessly, accepted by the unions due to the high level of benefits, it is also popular with politicians because it has helped cut unemployment statistics. Indeed, by the early 2000s, the WAO accounted for no less than 6% of GNP and had nearly 1 million beneficiaries, i.e. 13% of the population of working age. This was despite a series of reforms dating back to the late 1980s aimed at trimming the scheme’s sails by reducing benefits, reinforcing checks and transferring the financial burden, during the first two years of a person’s invalidity, to their former employer.

Will the most recent of these reforms (2005), which symbolically changed the scheme’s name to WIA (Working Capacity Act) and ushered in a radical difference of treatment on the basis of the degree of invalidity (indemnities for the most seriously affected, return to the job market for the others), help break the cycle? Even though invalidity numbers are down, the scheme remains one of the most costly in Europe (4.1% of GNP), and the current crisis could well prompt a return to old habits…

Still, measures taken in this area or others taken on early retirement or part-time work (the Dutch are the champions of Europe in this area, with nearly half the jobs in the country being part-time11) and, more broadly, the “activation” of the job market, together provided a clear result: a big increase in the employed population to 76% of potentially active people, putting the country in second place in Europe (just behind Denmark)12 – an employment rate that, by extending the social contribution and tax base, has also helped bolster the social welfare and government Results in education have been less favourable: despite a decline in the school dropout rate and improved results for children from underprivileged backgrounds, 13% of the 18-24 age group leave the school system early.13 With spending cuts on the one hand and misplaced teaching reforms on the other hand, the system is clearly not coping today, making it a leading source of concern for public opinion. It is worth noting that the 5% of GNP devoted to education is one of the lowest levels among developed countries. While higher education is not faring too badly in budgetary terms, public R&D efforts are timid in comparison with those of comparable European countries. The percentage of degrees in scientific and technological disciplines is one of the lowest in Europe. No doubt the importance of applied research in the Netherlands’ major multinationals (Philips, AkzoNobel) partially makes up for this phenomenon, but the country still tanks only ninth in Europe in terms of total R&D spending (1.7% of GNP, compared with 3.8% for Sweden14). This poses a threat to the country’s long-term competitiveness.

These occasionally profound upheavals in the social welfare system and state intervention are depicted by some as the end of the welfare state and by others as simply the trimming of the sails. Others point to them as the proof of the resilience of a system that could in fact prove to be more in tune with the demands of globalisation than is generally thought, by fostering social calm, training and mass consumerism.

Granted, the collective party of the 1970s, lit by the gas of the Groningue field, is over. One key figure demonstrates both the gradual nature of the method and the extent of the results: government expenditure as a percentage of GNP has fallen by 20% in the space of 20 years. It would nevertheless be wrong to infer from this that the Netherlands is giving in to unrestrained liberalism. The Prime Minister has noted that “the Netherlands is not the United States” and the outgoing coalition included three parties with a profound commitment to solidarity, a value that consistently obtains high scores in opinion surveys. It could be that the return to order will involve not so much a clear break with the dominant discourse, but rather its reformulation: while the overall objectives remain the same (personal “emancipation” and “fulfilment”, successful “integration” into society), they are now to be achieved not by wide-scale assistance, but by individual responsibility and work, with a safety net available for anyone in need.

All things considered, the Dutch appear to have started responding to the crisis in the welfare state by protecting it against its own excesses and by a blend of pragmatism and solidarity. The social welfare system is now mixed, with private insurance and a pay-as-you-go system, private and public funding all apparently cohabiting peacefully. To stick with the metaphor, it could be said that the Netherlands have gradually rebuilt the dikes destined to protect the financial foundations of their samenleven. But the sacrifices – demanded and made – have, as we will see, come at a high political cost for the parties of government. The issue of pensions is exemplary in all respects: while the Dutch hold the European record for the private funding of pensions (nearly half their total amount), they worry a great deal about the future of a system undermined by the stock-market crisis and government reforms. This issue has jumped up the list of preoccupations, and now ranks fifth.15

The integration challenge

In official Dutch terminology, an “allochtoon” is a resident with at least one parent born outside the Netherlands.

In the space of 10 years, the percentage of allochtoon pupils with poor results has fallen It is true, however, that assessment methods and criteria have been the object of fierce debate (source: SSN).

This followed the independence of Surinam and the autonomy of the Antilles.

International comparisons are complicated by the existence or otherwise, from one country to another, of ethnic statistics, which are standard in the Netherlands.

Source: SSN.

Allochtoons account for more than 80% of enrolments in half the schools in Amsterdam.

Source: SSN.

Paul Scheffer, “Het Multiculturele Drama”, NRC, 29 January 2000.

The same desire to rebuild the dikes can also be seen in respect to immigration and integration. These twin issues crystallise – at the price of considerable simplification – a good number of Dutch people’s frustrations and worries. Not that the Dutch need to be particularly embarrassed by their record in these areas. The parliamentary commission formed in 2004 to look into these issues came to very positive conclusions, finding that “the integration of allochtoons16 has been a partial or total success, constituting a considerable achievement, both for immigrants and for the recipient society”.

Without doubt, there has been success in the areas of housing policy, living standards and even education,17 where migrants enjoy a more enviable situation than their counterparts in many neighbouring countries. And despite periodic tensions, the Netherlands has not so far experienced urban riots like those seen in the United Kingdom or France. Allochtoons have notched up considerable successes in Dutch society – and not just in the national football team. “New Dutch” faces are familiar in literature, politics and the media.

Here again, it is important to put things into an historical perspective in order to draw unbiased conclusions. The challenge of mass immigration is a new one for Dutch society, bearing in mind that the Netherlands, unlike France, was a country of emigration until the 1950s, with people leaving for North America, Australia and New Zealand – not to mention South Africa. In this regard, the received wisdom bearing on the country’s tradition of accepting newcomers (Iberian and Ashkenazi Jews, French Huguenots) refers to a period that was well and truly over when the latest wave of contemporary immigration, involving large numbers of Turks and Moroccans, started in the 1960s.

This wave was suddenly amplified in the mid-1970s by the conjunction of two phenomena: the regrouping of the families of immigrant workers from the earlier period and the mass arrival of immigrants from Surinam or the Dutch Antilles.18 This was compounded by the attraction exercised by generous political asylum laws, making the Netherlands one of the top destinations for asylum seekers at the start of the 21st century. In 2001, the Netherlands posted record immigration figures, with 133,000 new arrivals.

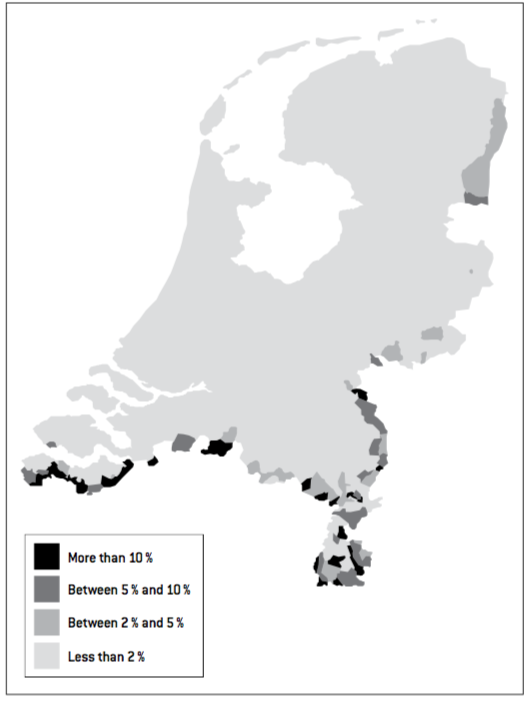

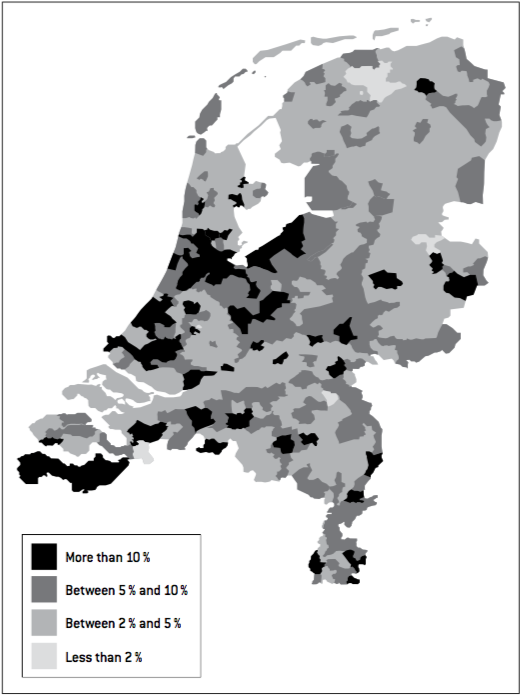

Allochtoons no doubt represent a smaller percentage of the total population (20%, just under half of whom are not “Westerners”) than they do in other countries (France, Switzerland, Belgium).19 But it is important to bear in mind that the Netherlands is a small country – one of the most densely populated in Europe – and that the feeling that “the Netherlands is full” (Pim Fortuyn) is largely echoed by public opinion and exploited by populist movements. Moreover, the fact that immigrant populations will become the majority in the country’s three biggest cities in the 2020s underscores the acuteness of integration problems. Several factors imply that the integration process is not working as well as it might. Mixed marriages are rare, especially in the Moroccan and Turkish communities, the unemployment rate is between two and four times higher than among the “native” Dutch, depending on the community (2.8 times on average20), high delinquency rates have made the Netherlands the European country with the highest level of people from ethnic minorities serving prison terms and, in schooling, there is de facto segregation between “black” schools (zwarte scholen) and “white” ones (witte scholen). This is because the principle of freedom of education makes it easy for parents to send their children to schools in other zones, but has resulted in the overrepresentation, sometimes to a considerable extent, of allochtoons – or, inversely, native Dutch people – in relation to population mix in the surrounding area.21 The mass of second-generation immigrant children looks to be condemned to nothing more than a short period of preparatory middle-level applied education (VMBO). And despite the progress achieved over the last ten years, allochtoons account for only 14% of pupils in general secondary education.22

With numbers like these in mind, it was surprising to say the least that the parliamentary inquiry into the spontaneous integration process should have come to such positive conclusions. In fact, the very same commission echoed the majority opinion by criticising public integration policy over the last 30 years across the board, citing insufficient budgets, inconsistencies and even a touch of naivety.

The biggest error was to maintain the goal of “integration with the preservation of one’s original culture” until the end of the 1990s. This unofficial policy goal was clearly the inspiration behind public policy in this area – and offered much scope for potential contradictions. The benefit of the generous social advantages given by the Dutch welfare state to immigrant workers (often thrown out of work after the oil shocks in the 1970s) was never particularly compatible with the simultaneous affirmation of their vocation to return home. In reality, these advantages have remained. But above all, the policy went against the genuine integration of large minorities stemming from family regroupings – minorities that were clearly destined to remain in the Netherlands, which official documents in the 1980s and 90s described as a “country of immigration”.

How can the Dutch future of the second generation be safeguarded if it has not mastered the culture of its new home?

The Netherlands no doubt acted, in this respect, in accordance with its national tradition of integration, which worked well for foreign minorities in earlier periods, namely Jews and underprivileged “natives”, such as Catholics and workers: a policy aimed at ensuring collective emancipation within a “segregated” society, built on pillars (zuilen) comprising various religious or ideological groups. The various pillars were responsible for their own organisation in all areas, and their respective leaders cooperated at the national level to run the country – which is the origin of the “pillarisation”, or verzuiling, which emerged gradually at the end of the 19th century. In other words, the Dutch went back – like other countries confronted with the same phenomenon of mass immigration – to the system adopted at the time of their construction as a nation.

But this was a mistake, both historically and culturally, in the late – 20th century context. It was applied to new migrants at a time when the Netherlands was in the throes of an accelerated process of individualisation and secularisation. Already slammed by Pim Fortuyn and blasted in a watershed article by Socialist Paul Scheffer,23 the ideal of a “multicultural society” came asunder with the rise of ghettos and the ambiguities contained in its defining terms: a genuine respect for foreign cultures or a profound indifference towards them?

Accordingly, since the late 1990s, and even more so since 2003, Dutch immigration policy has undergone profound change. Conditions have been toughened considerably for new immigrants: applicants are obliged to learn Dutch, age and income conditions are applied for family regroupings, and the possibility of appealing unfavourable decisions on applications for political asylum has been restricted drastically. These measures quickly restricted the flow of new arrivals, in conjunction with an increase in emigration flows: between 2006 and 2008, 125,000 people left the country, an unprecedented number since the 1950s.

Together, these factors have left the Netherlands with slightly negative migratory flows since 2003 (except in 2008), a phenomenon not seen anywhere else in Europe. In other words – and a point that is rarely raised in public debate in the Netherlands – the country is no longer, strictly speaking, a “country of immigration”. Pim Fortuyn’s programme has indeed been implemented in this area.

The PvdA no doubt won, as a condition of its entry into the government in 2007, an amnesty for all people whose application for political asylum had been rejected but who were still in the Netherlands, but the measure, largely symbolic at that date, did not reverse a policy clearly directed towards stemming the tide of new migrants. The same goes for the pending reform of the Dutch Civil Code, which aims to outlaw marriages between cousins, so as to end the so-called “import brides” phenomenon. Policy with respect to allochtoons has also changed considerably. The plan announced in 2006 by then Integration Minister Rita Verdonk, which would have imposed civic-integration (inburgering) examinations (at their own cost), failed because it was deemed to be in contradiction with the principle of non-discrimination, which features in the first article of the Dutch Constitution. In any event, public policy has, for the last ten years, been focused on individual insertion – in particular via training and employment – and no longer on collective emancipation. Training starts with the Dutch language, the teaching of which is now emphasised in schools to the detriment of ethnic languages.

While there is no talk of “assimilation” in the French sense, it is becoming more common to hear people, especially in the government, talking about the pre-eminence of “fundamental Dutch standards and values”, which allochtoons are expected to adopt or, at the very least, respect.

Polarisation around Islam and the debate about identity

The attempted terrorist attack on 25 December 2009 on board an aircraft headed for the United States by a terrorist who had boarded the place at Schiphol Airport was a reminder of the Netherlands’ exposure to international Islamist networks.

Singularly in Europe, the Dutch list the guarantee of freedom of expression as a leading priority, both nationally and at the European level (sources: Eurobarometer 72 and SSN).

In his book Het Land van Aankomst (The Land of arrival), published in 2005.

Available at http://entoen.nu, the website set up to brief teachers on the contents of these “windows”.

Source: Continu Onderzoek Burgerperspectiven 2009/3 (Ongoing survey of citizen perspectives), third quarter of 2009, hereinafter referred to as This quarterly Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau publication shows trends in public opinion on a wide range of topics, ranging from political life to important social issues.

Source: COB.

The fact that roughly 60% of non-Western allochtoons are Muslim (the second-highest proportion in Europe after France) complicates the situation in the post-911 context. Since 2001, the issue of Islam, often raised in the early 1990s by Liberal leader Frits Bolkestein before being taken up by Pim Fortuyn, has tended to crystallise the debate over allochtoon integration – having initially sparked a hostile reaction in the political class and most of the media. The naivety and internal contradictions of the multicultural ideal could well be replaced by a tendency to over simplify.

It is true that several fundamentalist groups have been uncovered in the Netherlands, which previously believed itself to have been preserved from this phenomenon. The violent murder of filmmaker Theo Van Gogh in an Amsterdam street in November 2004, at the hands of Mohammed Bouyeri, a radical Islamist of Moroccan descent, but born, raised and educated in the Netherlands, showed that Islamic violence was not just an imported phenomenon.24

Tension has regularly been revived since 2004 by a succession of incidents. They include the bashing of homosexuals by young Moroccans in Amsterdam and death threats against public figures. The most spectacular case was that of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Liberal parliamentarian, originally from Somalia – who was awarded political asylum in the Netherlands – and a virulent critic of a number of Islamic traditions, particularly those touching on women. She had worked on Submission, the last film made by Theo Van Gogh (the filming of this work was the direct motive for Van Gogh’s murder). The letter left by Theo Van Gogh’s murderer on his victim’s body named Ayaan Hirsi Ali as his next target. Under constant police surveillance, but refusing to tone down her language, Hirsi Ali became an embarrassment for her political allies, who condemned her “provocations”. In 2006, the Hirsi Ali case provoked a major political upheaval: having acknowledged on television that her request for political asylum in the Netherlands was based on a false declaration, she was stripped of her Dutch citizenship. This decision was made in record time by Hirsi Ali’s fellow Liberal – and another media favourite – Rita Verdonk, who was at the time fighting against political asylum abuses. The depth of feeling engendered by the affair, both inside and outside the Netherlands, led, after much toing and froing, to Ayaan Hirsi Ali being given back her Dutch passport. Too late: sick of the controversy, Hirsi Ali had left the Netherlands for the United States.

Since these events, the split has widened between the radical adversaries of Islam, believers in Islamic fundamentalism – a very small but equally active minority – and the partisans of a Dutch Islam, such as the city of Rotterdam, run by a major of Moroccan origin, Ahmed Aboutaleb. The city has launched an ambitious programme on the theme of “Islam and Integration”. But the supporters of dialogue and appeasement have experienced a few problems since their choice of a controversial figure, Tariq Ramadan, a Swiss expert in Islamic studies, to occupy the chair created as part of the Rotterdam programme at the prestigious Erasmus University and to serve as the Town Hall’s special adviser on integration. Here again, after a series of controversies, the affair finished badly, when Ramadan’s involvement with an Iranian television network sparked a huge outcry and led to his removal in the summer of 2009. Each of these events has shown that the debate is focused on the compatibility of Islam with the fundamental principles of Dutch samenleven: freedom of expression,25 religious pluralism, separation of church and state, and sexual equality. Public opinion is even more perplexed by the question of the compatibility of these principles with others, no less vital, such as non-discrimination, which provides the basis for the freedom of education and equal subsidies for state and religious schools.

The issue of integration accordingly reflects on Dutch society itself, redefining its basic identity: “integration”, yes, but integration in what? To cite Paul Scheffer,26 we could define the problem as an equation with two unknowns: migrants’ capacity to fit into Dutch society, which involves soft-pedalling Islam, and the capacity of “natives” to accept foreigners, which requires genuine self-awareness and a clearly stated set of rules.

The Netherlands’ crisis of identity can be measured in the extraordinary flowering, over the last ten years or so, of books, articles and impassioned debates on the question of what is it to be Dutch today. This is a new phenomenon in a country that previously left this sort of “navel-gazing” and “nationalism” to others. And comments on all sides, from Job Cohen, the Labour mayor of Amsterdam, to Christian Democrat Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende, on the need for a “new citizenship” (nieuwe burgerschap) are multiplying.

One of the main public initiatives in this respect was the writing, in 2005, of a “canon” for the teaching of history, namely the setting and transmission of outlines allowing pupils to place themselves in Dutch history. While the virtual ignorance of the past in a large part of the population was unanimously condemned, there was a big controversy on the underlying memorial issues. After much debate, historians came together to say yes to the transmission of knowledge, but no to a new “national story” aimed at cementing a view of the national identity, which is what a number of politicians were accused of seeking. The commission tasked with setting the new curriculum went no further than to open “50 windows” into the past, namely a selection of key events, illuminating not only great figures of the national tradition, but also less well-known figures from Dutch history, from causes of legitimate pride to darker events, including some that took place in the Netherlands’ “Golden Age”.27

Observers in any event have been struck by the tone of these debates, characterised by an aggressiveness that sits fairly uneasily with the Dutch perception of the “mildness” of its political morays, from which political correctness, which was so omnipresent until the mid-1990s, appears to have disappeared. Is this climate responsible for the discomfort felt by many young people of foreign extraction, 18% of whom express the desire to leave the Netherlands?28

It would be excessive to speak purely and simply of a rise in racism; for this issue as for others, there is growing confusion and polarisation. Forty-one percent of Dutch people feel that the “presence of different cultures enriches society”, but just about as many again (39%) believe that “the Netherlands would be a better country if there were fewer migrants”.29 Contemporary Dutch cinema provides a good reflection of this disorientation, with, for instance, the grating film by (critical) Socialist Eddy Terstall, Vox populi (2008), which depicts a leftwing politician, with clear references to Hans Van Mierlo, the historic leader of Democrats 66 (Democraten 66, D66), a leading light of the emancipation movement of the 1960s and 70s, sympathising with working class “natives” whose language is overtly racist. But their language does not impede them from having excellent relations with some allochtoons, who freely stigmatise in turn other ethnic minorities…

The Dutch paradoxes in Europe: the end of the Euro-malaise?

The SP (Socialist Party) caused a sensation during the referendum campaign with a poster showing a map of Europe from which the Netherlands had quite simply disappeared.

Europe has been the other victim of the malaise in public opinion, with the resounding failure of the referendum on the European constitutional treaty in 2005 (rejected by 61.6% of voters) on the heels of massive abstention in the 2004 European election (60.7%). The late start to campaigning in favour of the constitutional treaty, the arrogance of the treaty’s supporters, the role of scapegoat attributed to Europe, even by some of its official partisans, notably the Liberals, who imprudently played with the “bureaucracy” theme, and the amount, deemed excessive, of the Dutch contribution were all factors in the victory of the No vote. Voters, who slammed their lack of information on the treaty, expressed their fear of seeing a dilution of the Dutch identity.

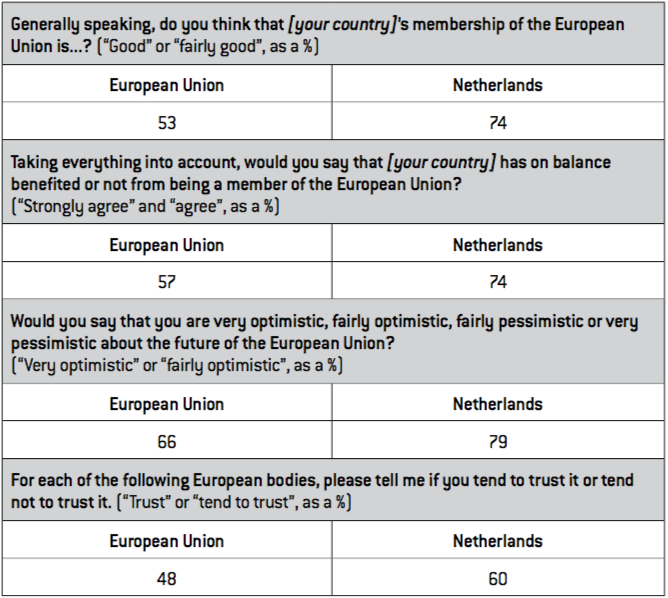

A few days after France, the Netherlands thus became the second country to reject the proposed treaty. While the reasons for the No vote and its political hue differed in the two countries, there were clearly many similarities between the two situations, and it is the same loss of their bearings that caused two of the European Union’s founding members to turn their back on the Constitution. The French feared the disappearance of the “French social model”, while the Dutch took up arms against the disappearance of the “tiny Netherlands” in a suddenly enlarged European Union.30 In both causes, identity issues were the root cause. However, more than four years after the event, one could argue, in the light of Standard Eurobarometer 72, that the “Euro-malaise” is a thing of the past, now that Dutch people’s feelings towards the European Union rank among the most favourable of any of the 27 members.

Table 3

Source :

Standard Eurobarometer 72, January 2010.

It was the vexed question of Icesave, the online Icelandic bank that collapsed in the autumn of 2008, that raised the question of the guarantee given to Dutch and British deposits.

Having been among the leading players – and beneficiaries – of the “first globalisation”, that of Modern Times, the Dutch see globalisation in terms of the opportunities it offers their Accordingly, even at the peak of the global financial crisis, in the spring of 2009, 61% of them still believed that “globalisation is an opportunity for their enterprises”, while 30% expressed the opposing view (20% and 73% respectively in France) (source: Eurobarometer 71). Their long history as traders and colonisers has made the Dutch much more confident in the globalisation process than a good number of their neighbours.

On all questions, the Dutch are among the most upbeat respondents –sometimes along with the Scandinavian countries, sometimes with the new members – and appear overall to be the happiest members of the club. It would be tempting therefore to see the failure of the 2005 referendum as an accident, and/or to attribute it to exogenous factors. This temptation would be backed up by a comparison with the French situation, where the 2005 “Euro-malaise” continues.

In short, the “burial” of the constitutional treaty, after the Netherlands’ No vote in 2005, could well have had a paradoxical effect: the No vote provided an outlet for a growing malaise and calmed the Dutch people’s relationship with Europe. This is compounded by the effects of the financial crisis, namely renewed confidence in the euro, replacing earlier scepticism, due to the shield provided by the single currency. Having witnessed with anxiety the financial wreckage of Iceland, where lots of Dutch people had invested their savings, the Dutch are now particularly attached to the euro.31

On this question as well as others, the hypothesis of a “return to normal” after the early troubled years of the new century wins out. After all, have the Dutch not always been determined Europeans and even the champions, against all comers – even France – of supranationality?

There are, however, serious objections to this interpretation. The first is the new record in abstention (63%) at the June 2009 European election, reflecting relatively muted Euro-enthusiasm to say the least. And the results, with on the one hand the increase in support for Geert Wilders’s resolutely Eurosceptical Party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) and on the other hand the success of the no less Europhile Democraten 66, plead for a more nuanced reading of Dutch public opinion on Europe. The results are in any event more contrasted than the conclusions drawn from standard Eurobarometer 71, conducted in conjunction with the European election, in the spring of 2009.

In truth, the results of the various Eurobarometers are worth a closer look. The responses to some questions do not reflect the Euro-enthusiasm noted in others. For instance, when asked to describe their “overall view” of the European Union, the Dutch are relatively reserved: only 49% (compared with an EU27 average of 48%) had a positive view, while 39% did not express an opinion and 11% were unfavourable.

Doubts about the exact nature and depth of the Dutch people’s commitment to Europe were strengthened by their response to a question about the best way of dealing with the global financial crisis. Only 14% – compared with an EU27 average of 22% – felt that the European Union was well placed to act, whereas 41% cited the G20 (the highest number in the EU27), to which the Netherlands belongs. Similarly, the United Nations inspire more confidence than Europe, signalling an idiosyncratic openness to the world as a whole rather than just its European corner.32

When one also takes into account Dutch people’s perception of their national sphere, which they see as having a much greater impact on their personal life than the European Union, it would appear that Europe, in limbo between the global level on the one hand and the strictly national level on the other hand, is having trouble finding its place and has a bad image.

These ambivalent results will not come as a surprise to observers who are familiar with the Dutch national identity and the ambiguities of the European policies of successive governments. The same holds for supranationality, which the Netherlands has long championed. Most historians agree that this position is a negotiating stance rather than a genuine political option: first because it was incompatible with another simultaneous Dutch demand, namely accession for the United Kingdom; second, because it went hand-in-hand, in the field of defence, with a clear preference for the Atlantic alliance and protection from America; third, and above all, because it aimed at neutralising or limiting the influence of the “large countries” on European construction.

The risk of being dominated by powerful neighbours, illustrated by all too many episodes in history, from Louis XIV to Hitler, is a constant preoccupation of Dutch diplomacy and public opinion. It is consistent with legitimate and easily grasped national interest.

The desire to have a voice in an enlarged Europe Union with 27 members is another clear inspiration behind Dutch policy, which has officially been “reoriented” since the early 2000s. In European terms, this has led to a point-by-point defence of the national interest, from the contribution to the EU budget to the calculation of voting rights in the European Council or representation in the European Parliament, subjects on which The Hague has won in negotiations from Nice to Lisbon.

This pragmatic approach has been backed up by strengthened cooperation in numerous sectors, including policing, justice and defence. It now clearly precludes any political ambitions in the direction of federalism. The fight waged by Dutch diplomacy – where it notched up another victory – to take supranational symbols such as the European flag and the anthem out of the Lisbon Treaty provide the most telling illustration of this new direction.

But it also underscores the limits to the Netherlands’ European commitment, which was motivated first and foremost by practical considerations and has lost its affective implications as the generation of the Second World War has gradually died. The Dutch live in a small and densely populated country, and sometimes feel hemmed in, so Europe is seen above all as the opportunity to move around in a larger space. It is no longer, for most Dutch people today – who are, it should be added, a good deal less familiar with the culture of their neighbours than their elders were – an “imaginary community”. Are they alone in that respect?

Who is watching over the dikes? Managing the crisis and the crisis management

Balkenende or “retropolitics”

The next parliamentary elections, initially scheduled for the spring of 2011, will take place on 9 June 2010.

The Dutch have one of the highest rates of confidence in their domestic institutions in the entire European Union.

Standards and values were seen by public opinion as the biggest issue facing the country in 2008 (source: SNN).

The list should also include Piet Hein Donner, a central figure of the CDA and Minister for Justice and Social Affairs since 2002, who also hailed from an orthodox Protestant background, and who also studied at the VUA.

Large orthodox Protestant communities are to be found from Friesland, in the country’s North-West, to Zeeland, in the South-West.

Submitted in 1992 and very significantly entitled, Overheidsregelgeving en maatschappelijke organisaties (Administrative regulation and social organisations).

Kuyper, an early theorist of verzuiling in the face of the ambitions of the Leviathan state, represented by the French Revolution, defended the principle of sphere sovereignty (soevereiniteit in eigen kring), or the notion that each sphere of life (or each social group, especially religious groups) has its own distinct authority.

Thus named due to the colours of the two main government parties of the time: the Liberal Party (blue) and the Socialist Party (pale red).

Interview with the author.

In traditional Dutch society, a key figure, the dike count (dijkgraaf), was responsible for managing the battle against water, and more specifically to watch over the dikes. He ran the local communities, grouped together in water boards (waterschappen), where the Netherlands’ very particular model of governance was formed. To use this metaphor, who are the present-day dike counts?

The importance of that question is underscored by the fact that the severe crisis within the ruling coalition since February 2007 has led to early elections being called.33 Furthermore, the questioning of Dutch governance was a central focus for Pim Fortuyn, and in truth touched on a number of issues. Criticised for being stuck in ivory towers, the national elites, both political and economic, in public administration or intellectual life, were the constant targets of his attacks: the late populist leader’s language was dominated by the denunciation of the “incestuous” relations between the members of the elite, their irresponsibility, their ineffectiveness and their abdication of the true national interest.

In fact, such denunciations are a key trait of populism in Eastern and Western Europe, and are by no means specific to the Dutch. But, here too, the stakes must be seen in the light of the national context. In contrast to the confrontational models that characterise a good number of their neighbours, the Dutch project – and claim – the image of a democracy characterised by a high level of confidence in its elites.34

Against this backdrop, how can we judge the leadership of Jan Peter Balkenende, who has managed to stay on top of his party since 2002, albeit in a succession of different coalitions? There is no doubt that the Prime Minister’s cherished discourse on “standards and values” (normen en warden), which must be respected across the board if the Dutch samenleven is to function correctly, struck a chord with disoriented voters.35 Over recent years, the fact that the national government has featured three men (Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende, Labour leader Wouter Bos and Christian Democratic leader André Rouvoet) who all received strict Protestant upbringings (gereformeerd) and were all graduates of the Free University of Amsterdam (VUA),36 as well as the presence of two Christian parties (the CDA and the smaller Christian Union) in the outgoing government, could imply that the country has fallen back on its cultural and historical “fundamentals”. After all, the Prime Minister famously proclaimed that the Netherlands remains a “Christian nation”.

Such is no doubt the dream of a man whose background is especially telling. Born in Zeeland, a Calvinist stronghold forming the southern part of the Dutch Bible Belt,37 Mr Balkenende spent his entire career in the CDA apparatus as a member of the scientific bureau. While he is not perceived as such by the country’s intelligentsia, which looks down on him to an extent, the man is an ideologist. Since writing his doctoral thesis,38 he has consistently pleaded for a redefinition of the split in roles between the state and civil society, which he believes should be responsible for overseeing individuals within intermediate groups (families, churches, associations, unions, etc.): in short twin goals of rolling back the state and making society more moral, harking back to the central proposal of Abraham Kuyper, one of the founders of contemporary Dutch society in the final quarter of the 19th century, whose intellectual heritage Mr Balkenende has claimed. Kuyper was the founder of the Anti-Revolutionary Party (Anti-Revolutionaire Partij, ARP), the Netherlands’ first national political party and one of the components of today’s CDA, as well as the Free University of Amsterdam.39 After the excesses of the society of tolerance, attributed by large swathes of public opinion to the “violet coalition”40 of the period between 1994 and 2002, and the agitated period that followed, it is possible that part of the Dutch population – particularly older people – is nostalgic for the 1950s, which marked the peak of verzuiling. In the collective imagination, people, infused with profound public spiritedness (although one could also say conformism) led a peaceful life in those days, under the paternal guidance of the “grand coalitions” between the Christian Democrats and Labour, with moderate, austere and conscientious leaders. Known as Harry Potter because of his resemblance to a well-behaved boy and model pupil, Mr Balkenende, through his very faults, such as absolute lack of public-speaking skills, undisputedly reminds people of the discreet and ever so reassuring politicians of the past. A good father and a loving husband, he looks more like your average Joe than someone like Pim Fortuyn, a flamboyant homosexual, Bentley fan and lover of Italy, but has nevertheless borrowed a number of Fortuyn’s favourite themes: a return to the national “values”, identity and pride. His very ordinariness, despite the sarcasm it often provokes, has been the most reliable key to his popularity and his successive electoral vic- tories. It remains to be seen whether this form of “retropolitics of little men in black”, to cite journalist Yoeri Albrecht,41 will be up to dealing with the big issues facing the country, beyond the current political crisis, and whether it truly corresponds to the desire of a majority of voters, especially the youngest ones.

In this regard, the “standards and values” debate dear to the Prime Minister has shown that a restoration of public morals is not really on the popular agenda, for one simple reason: there is no agreement on the concrete content of these principles. While the population may be tired of impoliteness in all walks of life, it remains fundamentally individualistic and does not acknowledge the right of any body in society, and even less so a political body, to lay down the samenleven rules. The Scientific Council for Government Policy (Wettenschappeke Raad voor het Regeringbeleid, WRR), consulted by the government in 2003 on the question of standards and values, pointed the Prime Minister back in the direction of his own convictions, by finding that it was up to society, and not the state, to meet this challenge.

The persistent call of populism and the crisis in the ruling coalition

Ms Verdonk went on to found her own party, with the evocative name Proud of the Netherlands (Trots op Nederland), credited with two seats in Parliament in opinion surveys early in 2010.

Even this decision ha polarised public opinion, 50% of Dutch people condemn it, while 43% are favourable.

It would be necessary to conduct a more in-depth analysis and extend it to other countries to draw reliable conclusions, but it is possible to infer that Dutch responses to the Eurobarometer could be affected by an “image effect”, in other words the display, for the outside world, of greater collective satisfaction and openness of mind than are expressed in strictly national Feelings towards migrants and the European Union are much more reserved in the latter, although one must also take into account differences in formulation and the choices offered to respondents.

The maximum sentence allowed under the Penal Code was increased in 2003 to 30 years, and the number of prisoners increased by a third between 1999 and 2004.

The assassination attempt against the royal family on Queen’s Day in April 2009 was a shock to Dutch public opinion.

The Netherlands did not take part in any European war between 1815 and 1940.

The main conclusions of the Davids Commission were that the legal justification for the war in Iraq was insufficient, that the Chamber not been properly informed, that the Prime Minister had shown a lack of This came as somewhat of a surprise, as the Commission had been appointed by the government itself…

To quote Paul Schnabel, director of the Sociaal en Culturel Planbureau.

There is no disputing the lasting presence of a powerful populist current, even after Pim Fortuyn’s death. Granted, Mr Fortuyn’s direct successors quickly tore themselves asunder in what had become his party, the Pim Fortuyn List (Lijst Pim Fortuyn, LPF), and what journalist Hendrik Jan Schoo aptly termed a “political suicide club”. But the cause has been taken up by others, even in the established parties, such as Liberal Rita Verdonk, whose hard-line position on integration ultimately forced a split with the VVD.42

But impassioned debate is now focused on Geert Wilders, another former VVD member. Mr Wilders is tight-lipped about his Indo-Dutch origins, and emphasises his roots in the very Catholic province of Limburg, which is one of his electoral strongholds. His party, the Party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV), was one of the winners of the 2009 European election (coming second, with 17% of the vote) and is consistently notching up impressive gains in opinion polls. If these polls translate into votes in a general election, the PVV would beat Labour and move closer to the Christian Democrats. Some surveys go so far as to suggest that it could top the polling.

In short, the current situation is not unlike that prevailing in 2002: Mr Wilders’s discourse owes a lot to that of Pim Fortuyn, with a clear emphasis on the issues of governance and Islam; his speaking style is built on abuse, even though he does not have the charisma and humour of his predecessor; his ideas and personality are extremely polarising; and there have been attempts, just as there were in 2002, to make the outspoken Mr Wilders the scapegoat for the prevailing malaise. Recently described as a man of the “far right” by a group of experts tasked with looking at the country’s ongoing “radicalisation” and regularly abused in Parliament, Geert Wilders is bearing the cross of all those who rattle the collective cage, from Fortuyn to Ramadan, and not forgetting Van Gogh, Hirsi Ali and Rita Verdonk: he is being excluded from public debate. As it happens, the Amsterdam Appeals Court has decided that Geert Wilders, who is the object of a complaint filed by various organisations, with the support of the Public Prosecutor, for discrimination and inciting hatred, will be tried next summer.43 All these efforts to shut Wilders up – and naturally, he is more than happy to play the victim – could well, if past experience is any judge, fail to resolve the problem of the barely perceptible yet tenacious undercurrent of discontent, that the crisis, should it last, will inevitably aggravate.

National opinion surveys paint a less rosy picture than that drawn by the Eurobarometer, notwithstanding their ambiguities. Dutch people are less unanimous about their personal happiness (82%, compared with 96%) and are more concerned about the future, especially that of their country. In the standard Eurobarometer conducted in the spring of 2009, 36% of Dutch people said that the Netherlands was going in the wrong direction; at the very same time, in the quarterly “citizen perspectives” survey (COB), the percentage was 64%.44 Over recent years, discontent has been particularly marked in respect to healthcare; the same goes for law and order, despite a significant toughening of prison terms and more repressive policies,45 and, as we noted earlier, education has become a priority.

It could be that the ingredients of a genuine political crisis, so decisive at the time of the 2002 shocks, are once again in place: the feeling that the ruling coalition has run out of steam after having carried out its entire legislative programme (which was actually quite modest); the return of “scandals”, like the recent collapse of DSB, a bank that was close to ruling circles; bad management of highly sensitive issues, like the deepening of the Western Scheldt, on which the Dutch government, led by the Prime Minister, has dragged its heels, thereby provoking the fury of the Flemish government; delays have accumulated and costs have soared on major transport infrastructure projects, from the Amsterdam-Brussels fast-rail link to the new Utrecht railway station, not to mention the North-South line of the Amsterdam metro, where work has been disfiguring the historic centre of the Dutch capital for the last ten years. Even the royal family has not been spared. The increase in the royal budget and the fiscal advantages enjoyed by some family members have annoyed people who are suffering due to the financial crisis, and spurred criticisms by partisans of a “representative monarchy”. Nevertheless, the vast majority of Dutch people (86%) still profess an attachment to the House of Orange-Nassau, at a time when there is talk of the possibility of Willem-Alexander (soon) replacing his mother, Queen Beatrix, on the throne.46

The analogy with the situation in 2002 can be taken even further. The latest coalition split was sparked by an issue of foreign policy, just as the Kok government was forced to resign eight years ago after the conclusions of the commission of inquiry into the Srebrenica massacre. This time, it was Dutch involvement in Afghanistan, in the province of Uruzgan, that triggered the breakdown. The PvdA, after much prevarication and in circumstances that had not been elucidated at the time of writing (early March 2010), refused the extension – officially requested by NATO – of the Dutch military presence in Afghanistan beyond the summer of 2010. In a country where military involvement abroad has never been popular, and where neutrality is a national trait,47 the Afghan adventure was no doubt contaminated by painful memories of Srebrenica and, more directly, the conclusions of the inquiry into the Dutch military engagement alongside the United States in 2003. These conclusions, which were very harsh on the Prime Minister,48 were made public in January 2010, and were the first nail in the coffin of government solidarity.

The PvdA’s decision to leave the coalition on the Afghan issue is no doubt attributable to the unpopularity of the Dutch military engagement; the question remains, however, whether is was in Labour’s best interests to maintain a coalition that was increasingly unpopular with its traditional voters, at a time when severe spending cuts were being examined for inclusion in the 2011 budget, which would in theory have been an election year. PvdA leader Wouter Bos, the sitting Finance Minister, would have been particularly vulnerable in the coming months.

Jan Peter Balkenende will be able to point to his consistent record. But his reforms have also had a political cost. To evaluate this cost, we need to take into account the existence of a powerful leftwing populist current, often misunderstood or minimised by commentators. It is personified in the Netherlands by the Socialist Party (Socialistische Partij, SP), which has built its support on the defence of existing benefits, particular on the extremely sensitive issue of pensions. The conjunction of the two forms of populism, left and rightwing, in a “modern conservatism”49 of sorts, is not just a threat on paper, as was shown by the 2005 European referendum, even though the SP is currently facing a leadership crisis and is not making much progress.

In the light of the successive provocations of Geert Wilders, whose proposals include banning the Koran and taxing the Islamic veil – or making it illegal to wear it in most public places – it is easy to understand why the prevailing climate in the Netherlands, where difficult choices stemming from the financial crisis are also on the agenda, is not particularly serene. At his party’s last conference, the Prime Minster himself attacked, in very strong terms, the “increasingly aggressive, increasingly tense and increasingly polarised [climate…] where caricature sets the tone […], where we go from one extreme to another, where entire groups of the population are held up to ridicule, where everything is politicised and nothing seems good any more”. In short, he said, “the year [looked] like being agitated”. He didn’t know the half of it…

Historical perspective

Source: SSN.

His book, The Netherlands, published by Routledge in 2008 is, despite a somewhat confused chronological presentation, the best summary available in English on change in Dutch society over the last 50 years.

In his book De Nederlandse Revolutie, published in 2005.

The prevailing crisis does not, however, imply that the Netherlands is on the verge of a revolution or a counter-revolution. The Dutch state of mind has undeniably changed considerably over the last 20 years. As in many European countries, the traditional values of the right (law and order, responsibility, morals) are back in vogue. The “prudently progressive” population described by the Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau at the end of the 1980s may have become “prudently conservative” with age. But the word “prudently” sums it up in both instances: Dutch society has a visceral attachment to consultation (overleg) and is suspicious of radical solutions. As for conservatism, does it not also apply to the defence of protective labour laws? The five constant political priorities of the Dutch since 1998 are extremely telling: keeping a high level of social welfare, economic stability, freedom of expression, the fight against crime, and maintaining order.50

Together, these priorities appear to be consistent with the dominant discourse among observers, which emphasises the “resilience” of the Dutch model in all areas: adjusting the welfare state within the frame-work of regulated globalisation as opposed to abandoning it; controlling migratory flows and making integration a requirement, but without giving in to xenophobia or withdrawal into the national identity; questioning Europe, but in a pragmatic and open way. In short, a form of “cosmopolitan nationalism” (Frank Lechner),51 which is actually very true to the tradition of Erasmus and Grotius. While this conclusion is not lacking solid arguments in its favour, it could smack of the sort of wishful thinking that is very prevalent in the country’s ruling circles, where it is hoped that the “regrettable” parenthesis of the 2000s will soon close. This interpretation, undermined by today’s political ups and downs, does not take into account the persistence of the populist temptation and the polarisation of public opinion, which appears to be very deeply rooted.

So much so that another way of understanding the current situation from a long-term perspective emerges, even though it is only cited by a minority of observers. It involves taking into account past experience of polarisation in Dutch history. There has been radical public debate in other periods, even during the Golden Age, when there was a split between the “states parties” and the “Orange party”, the late 18th century, with the Patriot Revolution, the late 19th century, with the grand struggle between the “liberals” and the “confessionals”, and the 1960s, which saw the demise of the verzuiling (pillarisation) system. According to historian Joost Roosendaal,52 polarisation could well constitute a largely misapprehended constant in Dutch history, possibly censored to comply with the demands of a unified reading of the past.

This is not the first time that the Dutch have questioned the legitimacy of the ruling elite in the name of the “real people”. This tradition goes back to the 1672 revolt against the De Witt brothers, the symbols of the bourgeois oligarchy of the Golden Age (known as the Regents), and stretches through to the attacks against the “new regents” in the 1960s – attacks taken up by Pim Fortuyn 30 years later – and also encompasses the diatribes of Abraham Kuyper, the defender of “little people” (kleine luyden) against the “liberalist” elites (sic), towards the end of the 19th century. If we look closely, we see that the profound nature of the Dutch social pact has been questioned at all these times.

On that basis, it could be said that Dutch society is today going through one of the major transitions that it has experienced at regular intervals over the last two centuries. In this light, today’s uncertainty and agitation is compounded by the new challenges that have sprung up over the last 40 years. Once again, past solutions no longer seem relevant and are hotly contested. In a spectacular historic turnaround – but one that first perfectly into the scheme of things – the contribution of the rebellious generation of the 1960s and 70s, and the political correctness it imposed, is now being called into question.

The perspective, in any event, argues in favour of forgetting the old cliché of a consensus society. Dutch society is in fact characterised by an ongoing compromise between the antagonistic aspirations and ways of thinking – and has been throughout the country’s history.

The end of dutch exception?

Change in the Netherlands’ permissive attitude towards drugs, with the closure of numerous coffee shops and a closer focus on dismantling the drug trade, could well symbolise this normalisation.

At the same time, a solution to this problem and, more generally, to path to successful integration do not appear to be out of There is a strong convergence of opinion on this issue between “allochtoons” and “natives”: a substantial minority – even among allochtoons – tend to believe that the “new Dutch are not doing enough to integrate themselves”. Virtually all Dutch residents feel it is vital to learn Dutch; and the immense majority – even among natives – does not believe that allochtoons should be required to renounce their own culture (source: SNN).

The other interpretation is, to put it more simply, that we are witnessing the end of the “Dutch exception”.53 All the challenges currently facing the Netherlands are shared by all its neighbours. Like other Western societies, Dutch society is beset by the major post-modern currents. The reaction to these changes in the Netherlands is very similar to reactions seen in other European countries, from the debate on the welfare state to disputes over Islam, not to mention the rise of populism, doubts about European construction and concerns over the national identity. And all this is set against the agitated and confused backdrop, in the Netherlands and elsewhere, of the trend from representative democracy to public-opinion-based democracy.

The ultimate question is whether the national identity – the desire and the capacity to reach compromises – still exists and will allow the Netherlands to find original responses to all these questions any faster than its neighbours. This question is at the heart of the conclusion of the last big survey conducted by the Sociaal en Culturel Plan – the Dutch institute for social research. As we have seen, numerous responses in opinion surveys paint the picture of a happy, supportive and confident society, while others underscore the doubts harboured by a large slice of public opinion: 47% of Dutch people are dissatisfied with politics. Most of all – and this too implies that the Dutch exception is fading – a hard core of dissatisfaction is translating into multiple forms of rejection of politics and disengagement from society, in what has traditionally been a very civic-minded country.