Introduction

What constitutes the “right” in Denmark and Sweden ?

The main currents and their history

Conservative parties

Liberal parties

Agrarian parties

Christian democratic parties

Populist parties

The right and current issues

Globalisation

Europe and the European Union

The welfare state

The political right and society

Parties and the media

Electoral performance and role in government

The centre-right in government

Prospects for the immediate future

Literature in English about politics in Scandinavia for a general audience is For denmark, Bo Lidegaard, A Short History of Denmark in the 20thCentury, 2009, offers an overview of 20th Century political history. For more specific issues, academic journals like Scandinavian Political Studies, Party Politics and Electoral Studies often public articles on subjects related to Scandinavian politics. A partial list of danish and Swedish books and articles used for this paper is included at the end.

At the beginning of 2010, Sweden and Denmark were governed by centre-right coalitions. Considering that the Scandinavian countries are often seen as a bastion of social democracy, this may appear surprising, but liberal and conservative parties have always played an important role in the politics of both countries. While centre-right governments are still very much the exception to the social democratic norm in Sweden, centre-right participation in or control of government has been more frequent in recent years compared with the situation before 1970.

Despite this, not much research has been conducted into individual centre-right parties or the centre-right as a whole in the Nordic countries. One notable exception has been a research programme investigating the history of the Swedish Moderate Party. Political journalists have covered the careers and strategies of individual politicians in biographies and other publications.1

Against this background, this paper will describe the development of the centre-right parties in Sweden and Denmark, focusing on the last 20 years. The two countries have been chosen because the centre-right has developed in very different ways there during the last two decades. In Sweden, no centre-right government has survived a general election since the 1920s, with the Social Democrats still being the natural party of government. Denmark, on the other hand, has had centre-right governments for 19 of the past 30 years and the Social Democrats have struggled to formulate a credible alternative to rightwing policies for most of the past decade.

What constitutes the “right” in Denmark and Sweden ?

A number of smaller centrist parties also belong to the group: Liberal Alliance (essentially a breakaway party from the Social Liberal Party which managed to gain parliamentary representation in the 2007 election), the Christian democrats (kristendemokraterne), without parliamentary representation since 2005) and the now defunct Centre-democrats (Centrumdemokraterne), which was represented in the danish parliament between 1973 and 2001.

Similarly, Swedish media will often refer to danish People’s Party as “the xenophobic danish People’s Party”.

The parties of the political right in Denmark and Sweden avoid using the term right (højre) or rightwing (højrefløj). In both countries, rightwing parties prefer to identify themselves as bourgeois (borgerlig), bourgeois- liberal (borgerligt-liberal) or non-socialist (ikke-socialistisk) with the term bourgeois roughly equalling the meaning of the German bürgerlich, or middle-class. Commentators occasionally use the term “centre-right” in order to emphasise the ideological spectrum covered by the parties of the right. Especially in Sweden, the parties on the left side of the political spectrum use the terms “right” or “rightwing” in order to draw attention to alleged reactionary tendencies in the centre-right parties. In Sweden, the four established centre-right parties presented themselves as The Alliance or Alliance for Sweden in the 2006 election campaign, thereby avoiding any obvious links with ideology or social class. In this paper, the term “centre-right” will be used as the best English equivalent of “bourgeois”.

Despite the complicated terminology, it is relatively easy to identify the parties belonging to the centre-right. In Denmark, the Liberal Party (Venstre) and the Conservative Party (Det konservative Folkeparti) form the historical core of the political right. The Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) is a centrist party that has often cooperated with the Social Democrats in Parliament.2

In Sweden, the Moderates (Moderata Samlingspartiet), Liberals (formally Folkpartiet Liberalerna, usually called Folkpartiet) and the Centre Party (Centerpartiet) in different constellations have formed the historical core of the centre-right, with the Christian Democrats (Kristendemokraterna) joining the group since the 1991 election.

Two parties pose special problems in the identification of the centre- right: The Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti) and the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterne). Neither party belongs to the traditional centre or right and their exact position in the party systems has been the subject of academic and public debate. The Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti) presents itself as a centrist party, but this obscures its position on the libertarian-authoritanian dimension. It is probably most correct to describe it as centrist with regard to economic policy and rightwing though not extremist on issues such as immigration and European integration. As it has supported the Liberal-Conservative government since 2001, it is now seen as an integral part of the centre- right bloc in Danish politics.

The position of the Sweden Democrats is more difficult to gauge as the party has yet to establish itself on the national political arena. Generally, the party attempts to present itself as centrist or conservative, but because of its history other Swedish parties and media in Sweden tend to describe it as a party of the extreme right or as a xenophobic party rather than a bourgeois or centre-right party.3

The main currents and their history

This only applies with some reservations for denmark, where parties to the left of the Social democrats have typically won 10-15% of the vote since the late 1960s.

During most of the 20th century, Scandinavian party systems have been characterised by a divided right facing a united left. The Social Democrats in Sweden could expect to win around 45% and the Danish Social Democrats 35-40% of the vote in general elections. While there have been communist or socialist parties to the left of the Social Democrats, they have generally been small and unable to exert political influence independently of the dominant party.4

At the same time, the right-hand side of the political spectrum has been split into three or more parties, with two or three parties claiming the position as the leader of the opposition at any time. This has made it difficult for voters, journalists and academics alike to get a clear image of the policies and strategies the political right.

In the academic literature, centre-right parties in Denmark and Sweden have been categorised into three families: conservative, liberal and agrarian. These categories reflect the complicated structure of political cleavages in all of the Nordic countries, where rural interests have played a major role in politics. The categorisation is not without its problems when we look at contemporary politics, but may still serve as a point of departure in the description of individual parties. In order to catch the full range of the centre-right, we need to add two further families: Christian-democratic and populist parties.

Conservative parties

The conservative parties in Denmark and Sweden have their roots in the political groups of the 19th and early 20th century, which opposed parliamentary government. With the introduction of parliamentary government and constitutional reforms in the early 20th century, the parties had to redefine their place in the political spectrum and reinvent themselves as modern mass parties.

The Danish Conservative People’s Party (Det konservative Folkeparti) was formed in 1915. There has always been a certain ambiguity within the party over its political direction: Some factions have favoured a broad social-conservative middle-class appeal, where the party would aim at represent urban while-collar groups, while others wanted it to focus on representing business interests. At various points in the party’s history this has led to major internal conflicts with massive electoral losses as the consequence.

The high point in the party’s history came during the 1980s, when Poul Schlüter (party leader from 1974 to 1993) led a succession of centre-right governments: the Conservatives won over 20% of the vote in the 1984 and 1987 elections. Following Schlüter’s resignation as Prime Minister and party leader due to a legal scandal, the party descended into successive internal conflicts over the leadership and direction of the party. Since the mid-1990s, it has failed in its bid to present itself as the leading centre-right party and never won more than 10% of the vote despite attaining some degree of internal stability under party leaders Bendt Bendtsen (1999-2008) and Lene Espersen (2008- ). From the late 1990s onward, the party has profiled itself on business-friendly policies, such as tax cuts for high-income earners, privatisations and a generally positive attitude to the European Union.

The Swedish Moderate Party (Moderata Samlingspartiet) was only organised as a modern mass party in the 1930s. It kept the name The Right (Högern) until 1969, when it adopted its present name as part of a comprehensive reform of its organisation and policies. Whilethe Moderates have experienced some internal conflicts over party leadership and strategy over the years, they have been less severe than those in the Danish party. The Swedish Moderates have also succeeded in keeping their position as the largest centre-right party since the 1979 general election.

Since the 1970s, the Swedish Moderates have promoted neo-liberal policies in a number of areas, calling for substantial tax cuts, deregulations and the privatisation of a number of public services. The neo- liberal orientation was obvious in the centre-right government was led by Moderate chairman Carl Bildt (1985-1998) between 1991 and 1994. Most notably, the government introduced a voucher system for pupils in primary and secondary schools, thereby opening a market for education services. The Moderates under Bildt also emphasised the foreign and security policy links between Sweden and Western Europe and the US in contrast to Social Democratic policies, which saw Sweden as a “third power” between the US and the former Soviet Union.

Bo Lundgren, Bildt’s successor as party leader (1998-2003), continued the neo-liberal line with an emphasis on promises of tax cuts. The result was an electoral disaster in 2002, with the party only winning 15.2% of the vote, its worst performance since 1973 and one which put the party’s claim of being the leader of the centre-right into serious doubt. Lundgren was deposed shortly after the election.

Under Fredrik Reinfeldt (2003- ), the party has reworked its policies and political strategy in order to present itself as more centrist. The aim has been to attract broader groups of white-collar voters who traditionally supported the Social Democrats. The emphasis on tax cuts was abandoned in favour of promises of improved welfare services. In the campaign for the 2006 election, the Moderates also made great efforts to present itself as a party of social integration and, building on the model of New Labour in the UK, rebranded itself as the New Moderates (Nya Moderaterna). Another way of distancing the party from its past was by stressing the common positions of the four centre-right parties in the Alliance for Sweden, where Moderate positions were less prominent.

Liberal parties

Venstre literally means Left, reflecting the liberals’ historical position as the leftwing in 19thcentury In denmark, both the Social Liberals and the Liberals have kept the Venstre name.

Unlike the other centre-right parties, the Social Liberal Party maintains a strict division between the parlia- mentary party and the rank-and-file The party chairman cannot be a member of Parliament, but the chairman of the parliamentary group will often be referred to as the party leader.

Besides the Social Liberal Party, a number of other parties have been placed in the political centre in the past 40 Between 1973 and 2001, the Centre-democrats, a centrist party formed by Erhard Jakobsen, a Social democratic mP, variously cooperated with Social democratic and Conservative-Liberal governments. with a thin organisational base and squeezed by the Liberal Party, the party did not survive the loss of par- liamentary representation in 2001. To a certain degree, the Liberal Alliance, which was originally formed as new Alliance (ny Alliance) in 2007 and won 2.8% of the vote in 2007, has tried to emulate Centre-democratic strategies. Unclear leadership has plagued the party and sparked defections, leaving it likely to lose its representation at the next election.

The categorisation of the liberal parties is complicated, especially in Denmark, as both the Social Liberals (Radikale Venstre, literally Radical Left) and Liberals (Venstre) use the term. Here, the Danish Social Liberal Party will be discussed along with the Swedish Liberal Party (Folkpartiet Liberalerna, literally The People’s Party, the Liberals).

The Danish Social Liberal Party was founded in 1905 following a split in the main Liberal group in the Danish parliament, with the faction wanting to continue the electoral alliance between the Liberals and the Social Democrats forming a new party. The party’s name reflected its ideological roots in both a Danish liberal tradition from the second half of the 19th century (Venstre) and a European republican tradition (Radikal, inspired by the French Parti Radical).5 The party has always had its main following among schoolteachers and people with higher education as well as some groups of smallholders. In later years it has increasingly found its support in the cities of Copenhagen and Århus.

For much of its history, the party has had a markedly antimilitaristic stance and it opposed Danish NATO membership in 1949. Similarly, the Social Liberals were divided on the issue of Danish EC membership in 1973, with a significant minority in the party favouring an extension of the Nordic cooperation as an alternative to European integration.

In the parliamentary arena, the Social Liberals have seen themselves as the party facilitating broad compromises between the political blocs on issues such as economic and education policy. At various times, it has cooperated with the Social Democrats to the left and the Liberals and Conservatives to the right. During the 1970s, the party supported Social Democratic governments under Anker Jørgensen, until Niels Helveg Petersen (party leader 1977-1990) decided in 1982 to change allegiances and support Conservative leader Poul Schlüter as Prime Minister.6

The relationship between the Social Liberals and the successive centre-right governments between 1982 and 1993 was complicated. On the one hand, the Social Liberals supported the austerity policies of the Schlüter governments during the 1980s, but on the other hand the party cooperated with the opposition Social Democrats on issues such as security and environmental policy in what became known as the “alternative majority”. In 1986, the party also opposed the Single European Act due to the introduction of formalised foreign policy cooperation. Things came to a head in 1988 and Helveg Petersen – to the surprise of most observers – decided to join the Conservatives and the Liberals in a three-party coalition.

Whatever Helveg Petersen’s motives, the government proved ineffective on the parliamentary arena and controversial internally. Following an electoral defeat in 1990, he was forced to step down as party leader in favour of Marianne Jelved (1990-2007), who had only entered parliament in 1987 but quickly proven herself a competent political leader. While Jelved continued to call for broad agreements on economic and labour market policy, she also started a slow move back towards the Social Democrats, which she saw as a more effective partner.

From 1993 to 2001, the Social Liberals participated in coalitions led by Social Democrat Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, with Marianne Jelved serving as Finance Minister. While the Social Democrats and Social Liberals generally agreed on economic and labour market policy, there were increasing conflicts between the parties over immigration policy. The Social Liberals maintained that international conventions on human rights should have priority in the formulation of immigration policies, while many Social Democrats called for tighter regulations on immigration and the integration of immigrants.

Since 2001, the Social Liberal Party has been struggling to find a new role in Danish politics. For the first time since the 1920s, the party has not been needed as a coalition partner by the government for a relatively long period of time. While it saw a rare electoral success in 2005 with 9% of the vote, the parliamentary group quickly descended into conflicts over political strategy. In May 2007, a Social Liberal MP and the Social Liberal MEP left the party to form the New Alliance party (Ny Alliance) aiming to attract voters who wanted to support a centre-right government. The defections triggered Marianne Jelved’s resignation as parliamentary leader in favour of Margrethe Vestager (2007- ).

Under Vestager, the party supports the Social Democratic leader Helle Thorning-Schmidt’s bid to become Prime Minister, but continues to hold a more liberal position than the Social Democrats in immigration and asylum policy. The Social Liberals also demand comprehensive reforms of tax and labour market policies in order to encourage people to stay in the labour market. In European policy, the party is now the most outspokenly pro-European party in Denmark and has made repeated calls for the country to enter the EMU.7

The Swedish Liberal Party (Folkpartiet Liberalerna) was founded in its present form in 1935 as a merger of two liberal parties, the Liberal Party (Sveriges Liberala Parti) and the Freeminded People’s Party (Frisinnade Folkpartiet). The existence of two parties reflected two different currents in Swedish liberalism: one building on political and economic liberalism and another representing a non-conformist religious tradition. The main political conflict dividing the two precursors to the present Liberal Party was over prohibition. The divide also reflected a cleavage between urban and rural liberals in Sweden. Like its Danish counterpart, the Swedish Liberal Party today mainly attracts well-educated people from the larger cities.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Liberal Party emerged as the main opposition party on the right, but never managed to break the Social Democrats’ hold on government. From the late 1960s, the Liberals entered a long period of electoral decline that continued while the party was in government between 1976 and 1982. Bengt Westerberg (1983- 1994) decided to profile the party on a clear social-liberal platform in order to distance it from the neo-liberal Moderates and pave the way for cooperation with the Social Democrats. While Westerberg’s strategy initially paid off in the form of an electoral success in 1985, influence proved elusive in the parliamentary arena. In 1991, support for the party had fallen back to 1970s levels.

The 1991 election put the Liberal Party in an awkward situation, with the three established centre-right parties and the Christian Democrats relying on the New Democracy party for a parliamentary majority. At the same Bengt Westerberg had distanced himself from New Democracy’s anti-immigration during the election campaign and even refused to appear on television with one of the leaders of New Democracy after the election. After giving much thought to the matter, the Liberal Party joined Carl Bildt’s government with Westerberg serving as Minister for Social Affairs and Anne Wibble as Finance Minister. Westerberg’s choice of portfolio reflected the Liberal Party’s attempt to maintain a social-liberal profile, with Wibble representing the party’s tradition for fiscal prudence.

After the 1994 election, Westerberg wanted to enter a coalition with the Social Democrats, but his advances were rejected and Westerberg resigned as party leader. The party then entered a period of confusion over its position and policies before Lars Leijonborg (1997-2007) decided to profile the party on issues such as support for European integration, a stronger focus on performance in education policy and tighter immigration policies. The latter in particular proved controversial, as the party appeared to have moved from a social-liberal position to a position where it was appealing to an anti-immigration sentiment. The party has also supported the idea of Swedish membership of NATO.

After the turn of the century, the Swedish Liberal Party’s positions on education and immigration in many ways appeared to be inspired by those of the Danish Liberal Party. On the other hand, Leijonborg could point to impressive electoral results in the 1999 European Parliament election and the 2002 general election, where the party won 13% of the vote, almost overtaking the Moderate Party as the largest centre-right party.

While the Liberals continued the more right-leaning strategy in the 2006 campaign, the results were less satisfying with 7.5% of the vote. In many ways this was as much due to the resurgence of the Moderate Party as doubts about Liberal policies or Leijonborg’s effectiveness, but the result still undermined Lars Leijonborg’s position in the party. In September 2007, his deputy Jan Björklund replaced him as party leader and Education Minister. Björklund was generally seen as one of the main forces behind the adoption of more rightwing positions on immigration and education and the change of leader has not brought about any major changes in the policies of the Liberal Party.

Agrarian parties

In the 21st century, the term “agrarian” is somewhat misleading as a description of a political party, as the percentage of the population in Denmark and Sweden occupied in agriculture is very small. The parties traditionally categorised as agrarian have had to adapt their policies in order to win support from other groups of voters. While the Swedish Centre Party enjoyed considerable electoral success in the 1970s, it has struggled to find a place in national politics since the late 1990s. On the other hand, the Danish Liberal Party has been very successful in attracting new voters in later years and has been the largest party in Denmark since the 2001 election.

The Danish Liberal Party (Venstre, Danmarks Liberale Parti, literally The Left, Danish Liberal Party) is a direct successor to the Liberal factions that fought for the introduction of parliamentary government in the second half of the 19th century. At the parliamentary level, most Liberal factions agreed to create the party in 1910, while a national membership organisation was only set up 1928. Despite this, the Liberal Party was the dominant centre-right party in Danish politics for most of the 20th century and it has always seen itself as the main challenger to the Social Democrats, even during times when the Conservative Party was the larger party.

In the international literature, the Danish Liberals used to be referred to as the Agrarian Liberals, reflecting the fact that the party’s main electoral base was among farmers and farm workers and that it found it more difficult to make inroads among the urban electorate, where the Conservatives had a firm grip on middle-class voters. The party’s policies generally reflected the interests of Danish agriculture, which was and still is heavily dependent on exports. The Liberal Party has always supported free trade-policies and Danish participation in European and global free-trade areas. Traditionally the party has been a defender of political and administrative decentralisation and was sceptical of the growth of the welfare state in the 1960s and 1970s. From the early 1960s to the late 1990s, it was the most openly pro-European of the Danish parties, again echoing agricultural interests.

In the mid-1980s, the party faced a decline in electoral support. Under Uffe Ellemann-Jensen (1985-1998), the Liberals reacted by making a determined effort to attract urban voters. The strategy was to emphasise the support for European integration and military cooperation in NATO as well as clear liberal positions in economic and tax policies. In many ways, the positions of the Danish Liberal Party during the 1980s and 1990s were close to those of the Swedish Conservatives.

While the Danish Liberals managed to raise their public profile and attract younger urban voters, the electoral results were mixed and it was only in 1990 that the party’s fortunes started to change. In 1994, the party became the largest centre-right party for the first time since 1979, but the Social Democrats were still able to deny Liberal aspirations for government power at the 1994 and 1998 elections by exposing the party’s alleged neo-liberal economic policies.

Following the 1998 election, Uffe Ellemann-Jensen resigned and was succeeded by his deputy Anders Fogh Rasmussen (1998-2009). Fogh Rasmussen and his aides began a comprehensive effort to change the image of the party in order to attract working-class voters who were disillusioned with the immigration and integration policies and labour market and welfare reforms of the Nyrup Rasmussen governments. This meant that the Liberals shed many of its economic policy standpoints of the previous two decades and presented itself as a pro-welfare and anti-immigration party. The party also toned down its support for increased European integration.

This was a courageous move, but the party’s fortunes were helped by the dramatic collapse of Social Democratic support among working-class voters following the controversial reform of the early retirement programme by the Nyrup Rasmussen government in late 1998. This made it possible for the Liberal Party to present itself as the more credible alternative to the Social Democrats in economic, welfare and immigration policy. Subsequently, in 2001, the Liberals emerged as the largest Danish party for the first time since 1920, with 31.2% of the vote. They formed a coalition government with the Conservatives, supported by Danish People’s Party. While the electoral support declined somewhat in the 2005 and 2007 elections, the Liberal Party is still the largest party in Parliament and Anders Fogh Rasmussen and his successor Lars Løkke Rasmussen have not faced challenges in their role as leaders of the centre-right.

While originally based on the same segment of the electorate as the Danish Liberal Party, the Swedish Centre Party has taken a very different political road than the Danish Liberals. The party has its roots in several different attempts to mobilise agrarian interests in the political arena, but it was only in 1921 that the existing agrarian parties were merged into the Peasants’ Union (Bondeförbundet). In the 1930s and again in the 1950s, the party entered government coalitions with the Social Democrats, making it the only centre-right party in Sweden to have cooperated formally across the left-right divide in this manner.

The decline of the rural population led the Peasants’ Union to reassess its political position and name in the late 1950s and in 1958 the party adopted the name the Centre Party (Centerpartiet), reflecting an aspiration to attract urban voters. In the same year, the party also left the coalition with the Social Democrats over the introduction of a superannuation pension scheme.

The 1970s was the most successful decade in the history of the Centre Party. Under Thorbjörn Fälldin (1970-1985), who in many ways embodied the party’s rural roots, the party profiled itself on environmental issues and attracted many urban voters by opposing the continued development of nuclear power in Sweden. At the same time, Fälldin placed the party firmly in the centre-right camp.

In 1976, the centre-right won a parliamentary majority for the first time since the 1930s and Fälldin was the obvious choice as Prime Minister, but he found it hard to reconcile the interests of the Liberals, the Moderates and the Centre Party. The question of the development of nuclear power was resolved in a messy compromise, but the price was a split in the government, forcing Fälldin to resign in 1978. In 1979, the centre-right again won a narrow parliamentary majority and Thorbjörn Fälldin returned as Prime Minister, but with the Centre Party in a weaker position. A conflict over tax policy led to a second split in 1981.

Following the return to opposition after 1982, Fälldin stayed on as party leader, only to see the party suffer a major loss in the 1985 election. After an interlude, Olof Johansson, who had served as Minister for Energy in the first Fälldin cabinet, took over as party leader in 1987. Johansson was more leftist than Fälldin, but continued the cooperation with the other centre-right parties. Another point of continuity was the emphasis on environmental policy.

Despite this, the Centre Party’s relationship with the centre-right turned out to be complicated during the 1990s. The party entered the four-party coalition under Carl Bildt in 1991, with Olof Johansson taking the environment portfolio, but Johansson left the government shortly before the 1994 election in protest against the decision to build a road and railway bridge between Malmö in southern Sweden and Copenhagen. As the other Centre Party ministers stayed in the government, this led to some confusion over the party’s position.

During the 1994-1998 Parliament, the Centre Party initially joined the opposition, but in May 1995, Olof Johansson announced that the party had entered an agreement with the Social Democratic government over economic policy. This provided the Social Democrats with a safe parliamentary majority for the austerity policies of the mid-1990s. While the Centre Party did not formally join the government, the agreement could be seen as a repeat of the coalitions of the 1930s and 1950s.

Johansson resigned as party leader shortly before the 1998 election, but his immediate successor, Lennart Daléus (1998-2001), had difficulties in halting the continued slide in electoral support for the party and left politics in 2001. Under the present party leader, Maud Olofsson (2001- ), the party has branded itself as a party for entrepreneurs with a focus on decentralisation and deregulation, while putting less emphasis on environmental policy. Unlike Olof Johansson but like Fälldin, Maud Olofsson also placed the party clearly in the centre-right bloc. At the 2006 election, the party recorded minor gains as part of the Alliance for Sweden; as leader of the second-largest party in the coalition, Olofsson was able to claim the position as Deputy Prime Minister while serving as Industry Minister in the four-party government.

Christian democratic parties

In contrast with Continental European countries, religious parties have never played a major role in Danish and Swedish politics. One reason for this was the absence of a conflict between the state and the church like the one that led to the adoption of the principle of secularism in public life and education in France. Another was that the Swedish Liberals and the Danish Liberals and Conservatives were able to make room for various conservative Christian tendencies in the existing organisations. The social upheavals of the 1960s broke this tradition, with Christian groups seeking an independent voice in politics.

In Sweden, the formation of a Christian Democratic party was triggered by the debate over the abolition of Christian religious education in Swedish schools. A group based in the Swedish Pentecostal church responded by forming a party in 1964. Besides the question of religious education, the party also profiled itself on the anti-abortion issue. For the first 20 years of its existence, the party failed to win representation in the Swedish Parliament and it was only when the Christian Democrats entered an electoral alliance with the Centre Party that the party leader Alf Svensson managed to win a seat in the 1985 election. The Christian Democrats finally managed to enter Parliament on their own in 1991. The electoral breakthrough can probably be seen as an effect of the strong neo-liberal orientation of the Moderate Party under Carl Bildt, which led socially conservative voters to look for alternatives.

While the Christian Democrats have participated in the centre-right governments under Carl Bildt and Fredrik Reinfeldt, balancing social and Christian conservatism has proved more difficult. The party leadership has toned down the anti-abortion stance in favour of general policies favouring nuclear families, a move that has not always been appreciated by party activists. Similarly, the party has loosened the historical ties with the Pentecostal Church and its interpretation of Christianity, even though all party leaders, including the present Göran Hägglund, have come from a Pentecostal background. The party still has its stronghold in the Jönköping region, which is also a stronghold of the Pentecostal Church and other free churches outside the Church of Sweden. Opinion polls conducted in 2009 suggest that the party may be struggling to retain its representation in the Swedish parliament in the 2010 election.

The Danish Christian Democratic Party was formed in 1970 following the liberalisation of pornography and the easing of abortion laws. In the 1971 election, the party was very close to gaining parliamentary representation. The Danish Christian Democrats mainly appealed to religious conservatives in some of the rural parts of Jutland, while the links to charismatic or evangelical churches have been limited.

The parliamentary breakthrough came in the 1973 landslide election and during the 1970s and 1980s the Christian Democrats established themselves as a centrist party, ready to cooperate with both left- and rightwing governments. Between 1982 and 1987, party leader Christian Christensen held the environment portfolio in Poul Schlüter’s four party- government and branded the party as a green party.

Since the late 1980s, the party has been torn between appealing broadly to social conservatives and more specifically to Christian conservatives. This conflict has led to a decline in support for the party. After participating in the first Nyrup Rasmussen cabinet between 1993 and 1994, the Christian Democrats lost their parliamentary representation in the 1994 election and while the party managed to regain its place in Parliament in 1998, it failed to make any political impact before losing its representation again in 2005. In 2007, the party only won 0.5% of the vote and it is not likely that the Christian Democrats will be able to re-enter politics at the national level.

Populist parties

While there were no direct organisational links with the Progress Party, the Justice Party, which was repre- sented in parliament from 1926 to 1960 and again during some terms the 1970s, in many ways also fits the “populist” description.

The term “populist” is problematic when it comes to describing political parties, especially as established parties often use it pejoratively to expose the allegedly “irresponsible” policies of these parties. On the other hand, Sweden and, especially, Denmark have seen a number of parties that do not fit into traditional ideological categories. Denmark has a long tradition of having “populist” parties represented in parliament with the Progress Party represented in the Folketing between 1973 and 2001 and the Danish People’s Party since 1995.8 In Sweden, populist parties have been much less prominent. New Democracy only managed to win representation in 1991, while the Sweden Democrats still have to win representation in the Riksdag.

One typical characteristic of a “populist” party in Sweden and Denmark has been that while the party has been described as a peripheral or extreme party, the party’s electorate has been fairly centrist in on the traditional left-right scale. Instead, the defining feature has been a low level of trust in established parties or representative democracy. Consequently, “populist” parties have also been described as “parties of distrust” and the problem faced by politicians and political scientists was to determine how much “populist” parties have represented a challenge to parliamentary democracy.

Mogens Glistrup, a prominent lawyer specialising in tax-evasion schemes who had not been active in politics previously, founded the Progress Party in 1972. In a TV interview in 1971, Glistrup had demonstrated that he did not pay income tax and likened tax evaders to World War II resistance fighters. The new party took off quickly and in December 1973 Mogens Glistrup and the Progress Party entered parliament with a remarkable 15.9% of the vote. No Danish party had ever succeeded in winning a similar following in such a short period of time before or since.

Compared with the other parliamentary parties, the Progress Party stood out during the 1970s in terms of both ideology and organisation. Mogens Glistrup advocated an idiosyncratic form of anarcho-liberalism, with calls for massive tax-cuts and cuts in the public sector; his approach to political leadership was equally unconventional and unpredictable. This meant that the established centre-right parties felt that they could not rely on the Progress Party as the basis for a “bourgeois” government, something which helped the Social Democrats stay in government until 1982.

Despite the unpredictability, recurring conflicts between “fundamentalists” who followed Glistrup and “realists” who wanted to cooperate with other centre-right parties and repeated defections from the parliamentary group, the party to the surprise of most observers continued to attract some 10% of the electorate until the 1980s when its support finally began to wane. The party formed part of the parliamentary basis for Poul Schlüter’s first government between 1982 and 1983, but in December 1983 Mogens Glistrup announced that he and the majority of the Progress Party group would not vote for the 1984 budget. When the government lost the vote and called a general election, the result was a major defeat for the Progress Party. Later, in 1984, Glistrup had to leave Parliament after being convicted for tax fraud and sentenced to a prison term.

The period between 1984 and 1987 was crucial for the later development of the populist right. Pia Kjærsgaard, who was not generally well known but belonged to the party’s pragmatist faction and soon proved to be an effective organiser and political campaigner, substituted Mogens Glistrup in Parliament. At the same time, immigration and asylum policy also began to emerge as a major political issue. The elections in 1987 and 1988, when the party won 9% of the vote, demonstrated that the Progress Party was still a force to be reckoned with one that centre-right parties had to accommodate if they wanted to stay in government.

After serving his prison sentence, Mogens Glistrup re-entered active politics; the period between 1988 and 1995 was characterised by renewed conflicts between a “realist” faction led by Pia Kjærsgaard and a “fundamentalist” faction which demanded that Mogens Glistrup again should be given a prominent role after being excluded from the parliamentary party in 1990. Eventually things came to a head and, after a tumultuous party conference in 1995, Pia Kjærsgaard and three other MPs left the Progress Party and formed the Danish People’s Party.

Unlike the Progress Party, the Danish People’s Party decided that it would support the welfare state, but the new party continued the anti- immigrant stance adopted by the Progress Party since the late 1980s. Another crucial difference between the Progress Party and the Danish People’s Party was that the new party would be tightly organised, with prospective members screened and both members and MPs subjected to tight discipline. In this way, the party presented itself as an attractive alternative to disillusioned social democratic voters, especially among unskilled workers, and as a credible ally for a future centre-right government. After a convincing performance, the Danish People’s Party managed to win 7.4% of the vote in the 1998 election. More surprising, the remains of the Progress Party also managed to win representation in 1998, but in 2000 the party suffered a final split when all remaining MPs left the party. In 2001 the Progress Party failed to make any impact and lost its political representation at the national level. It is now effectively defunct.

Before the 2001 election, the Danish People’s Party made two notable recruitments, when Søren Krarup and Jesper Langballe, two priests in the Church of Denmark who had been prominent in the public debate since the mid-1980s with outspoken anti-immigration views, were nominated in safe seats. As candidates and later MPs, Krarup and Langballe helped in giving the party a national-conservative rather than a traditional populist profile. The party also took a markedly Eurosceptic stance.

The 2001 election was a big success for the party, which was now able to attract large groups of traditionally Social Democratic voters, especially among older unskilled workers. Research has shown that while the party in the 2000s in many ways is seen by voters as a centrist party on economic issues, distrust in political institutions is still a major motivation for supporting the Danish People’s Party and a feature that sets the party’s voters apart.

After the 2001 election, the Danish People’s Party emerged as the only possible basis for a Liberal-Conservative government and every state budget since 2002 has been passed thanks to agreements between it and the government. The party also established itself as the government’s main partner on issues such as local government reform and especially immigration policy, where it has repeatedly called for tighter rules against immigrants from non-Western countries and asylum seekers.

As of 2010, the Danish People’s Party is an established party in the Danish party system, with steady support of around 13%. These days, the party in many ways appears as a nationalist rather than a populist party. Since 2001, it has also – unusually for a party with populist roots – been a reliable partner for the Liberal-Conservative governments, even though relations between the Danish People’s Party and the Conservative Party have at times been strained over issues like tax and environmental policy. There is also a latent conflict between the government and the Danish People’s Party over European integration, with the Danish People’s Party being markedly Eurosceptic. In the public, the party still relies heavily on leader Pia Kjærsgaard, although younger politicians like Kristian Thulesen Dahl, Søren Espersen and Morten Messerschmidt have begun to take on a higher profile without challenging the party leader or the party line.

Sweden, unlike Denmark, has limited experience with populist parties at the national level. In 1990, two businessmen, Ian Wachtmeister and Bert Karlsson, founded the New Democracy party, which managed to enter parliament in the 1991 election with 6.7% of the vote. In its campaign, the party combined an anti-tax message with a negative view on immigration.

While the party proved necessary for the three established centre-right parties and the Christian Democrats who had also entered parliament for the first time in 1991, to form a government, New Democracy was soon hit by a major conflict in its dual leadership, with Wachtmeister closer to the Moderate Party while Karlsson favoured policies more in line with Social Democratic positions. While Wachtmeister initially appeared to be the stronger of the two, he announced in early 1994 his intention to retire from politics and not stand for re-election.

At the same time, the four-party government had come to realise that New Democracy was not a reliable partner in economic policy during the massive economic crisis that hit the country in the early 1990s, and the party was left on the political sidelines during most of the 1991- 1994 Parliament. As a result of this and the complete lack of a party leadership, the initial enthusiasm among voters wore off and in 1994 the party only won 1.2% of the vote. New Democracy dissolved in 2000.

Since the turn of the century, the Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna) have taken the place left by New Democracy in the party system. The Sweden Democrats have their historical roots in the nationalist fringe of the 1980s and anti-immigration policies have always been high on its agenda. Since the late 1990s, the party leadership has worked to remove the remaining ties with the extreme right. It has also tried to copy the strategy of the Danish People’s Party by emphasising a positive stance on welfare policy to complement its anti- immigration message. Like the Danish People’s Party, it tries in this way to present itself as a nationalist pro-welfare party.

The Sweden Democrats differ from New Democracy and the Danish populist parties with regard to its organisational strategy and the way it mobilises voters. As the national media have been reluctant to report the party’s activities and programme and the established parties try to avoid debating with representatives for the Sweden Democrats, the leadership under Jimmie Åkesson has instead focused on being present in local and regional elections in the hope that local support will eventually spill over onto the national level. Bear in mind that parties in Sweden receive economic support for organisational work based on the share of the vote they receive in local elections.

The 2006 election was a partial success for the party, especially in the southernmost parts of the country and among younger working- class voters. Most notably, the party won 24% of the vote in the local election in the town of Landskrona, where it offered to support the centre-right in the local council. The Sweden Democrats still share one central characteristic with traditional populist parties, as its voters tend to have much lower levels of confidence in politicians and the political system than the average voter. The appeal to working-class voters is a continued cause for concern for the Social Democrats as success for the Sweden Democrats in the 2010 elections could deny the leftwing parties the chance of regaining power.

The right and current issues

Globalisation

The debate over globalisation in Denmark and Sweden has been influenced by the fact that both countries have traditionally been small, open economies that depend heavily upon exports and access to world markets. This means that globalisation as a general phenomenon has been less controversial in Denmark and Sweden than in many larger countries and that centre-right parties in particular have seen globalisation as a challenge to be met rather than a threat to the existing economic and social order. Most of the parties do not include special sections on globalisation in their programmes. Instead, the issue has been integrated in programmes covering education, research and industrial policies. Both on the individual and the societal level, the centre-right parties have emphasised flexibility as the appropriate response to the challenges presented by globalisation.

The point of departure has been that the continued outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to countries in Eastern Europe and Asia means that there will be a smaller demand for unskilled and some forms of skilled work in the future and that some forms of manufacturing will eventually leave Denmark and Sweden. Among centre-right parties, this has not led to calls for a protection of local markets or producers. Instead the response in both countries has been to call for increased efforts on secondary and tertiary education as well as vocational training in order to improve workers’ skills.

Another perspective on globalisation has been to argue that Denmark and Sweden should base their economies on knowledge-based industries such as pharmaceuticals or chemicals, or industries that put emphasis on production design. The question here has been how to make academic research available to the private sector in an economic system where mobility between the public and the private sector and the availability of venture capital has been limited.

In many respects, the position of the centre-right parties on globalisation is not fundamentally different from that of the Social Democrats in Denmark and Sweden, which also call for an increased effort on education and training and a development of knowledge-based industries. The most obvious difference is that centre-right parties in both countries tend to favour a hands-off approach with regard to individual firms, while Social Democrats put a bigger emphasis on the development of corporatist arrangements.

Outside this consensus on globalisation, the Danish People’s Party and the Liberal Party have raised the effects of migration as an issue in Denmark. Following the party’s general anti-immigration stance, the Danish People’s Party has consistently called for tougher rules on immigration and political asylum and a curbing of the legal rights of immigrants from non-Western countries.

Europe and the European Union

Despite the general acceptance of globalisation, European integration has been a controversial issue in all Scandinavian countries and created divisions within the centre-right during the last two decades. Support for the European Community and later the European Union in Scandinavia historically followed left-right divisions, with the left being more Eurosceptic and the right more supportive of European Community membership and European integration. One notable difference between Denmark and Sweden is that the Danish Liberal Party and agrarian interests have been more Europositive than their Swedish counterparts.

Two major issues have dominated EU policy in both countries during the last decade: The opening of labour markets following the admission of ten Central and Eastern European countries to the Union in 2004. Here, Denmark, unlike Sweden, adopted limitations for migrant workers. The second issue is the future of the de facto opt-outs, which mean that both Sweden and Denmark remain outside the European Monetary Union.9

Regarding access to national labour markets, the outcomes in Denmark and Sweden were caused by different strategies by the centre- right parties. In Denmark, the Liberal-Conservative government entered an agreement with the Social Democrats, the Socialist Party and the Social Liberals, which limited the rights of Eastern European workers on the Danish labour market. In this way the position of the trade unions, represented by the Social Democrats in the political process, influenced Danish policy. The Danish limitations expired in 2009.10

In Sweden, all centre-right parties opposed a similar proposal put forward by the Social Democratic government and they managed to secure the support of the Green Party, which otherwise was part of the government’s political base, on this issue. This alliance meant that the centre-right was able to block limitations on the movements of Eastern European workers.

The Danish opt-outs were introduced in the Edinburgh Agreement adopted in 1993 following the defeat of the original Maastricht treaty in the June 1992 referendum. The opt-outs mean that Denmark stands outside cooperation on Justice and Home Affairs (JHA), the Common Defence Policy and the EMU. A 2000 proposal by the Nyrup Rasmussen government to overturn the EMU opt-out was passed by a clear majority in Parliament but rejected at the subsequent referendum. The 2000 initiative and referendum campaign showed that the centre-right is divided on the issue, with the Liberals, the Conservatives, the Social Liberals and the Centre-Democrats supporting and the Christian Democrats and the Danish People’s Party opposing Danish membership of the EMU.

The Danish People’s Party continues to oppose any plans to overturn one or more of the opt-outs arguing that it would mean delegating to the EU powers that belong naturally to the Danish people. Aside from rejecting EMU, the party has stressed that Danish legislation on immigration should not be limited by regulations and decisions under the Justice and Home Affairs Cooperation. During the last decade, the party has become increasingly Eurosceptic in its propaganda, arguing that the EU should only be allowed to develop as a free-trade area and tendencies towards the development of supranational powers should be stopped or rolled back. Following this line, the Danish People’s Party also opposed the adoption of the European Constitution and the Lisbon Treaty.

Its position has put the Liberals and the Conservatives in a complicated political situation. While the two parties officially back the revocation of the opt-outs, they have not wanted to put any or all of them to a referendum since taking office in 2001 for fear of a repeat of the 1992 and 2000 defeats. A referendum campaign on the opt-outs would also pitch the government and its supporting party directly against one another. When discussing the possibility of revoking the JHA opt-out, government representatives have emphasised that this could only take place provided the introduction of a new opt-out securing Danish sovereignty with regard to immigration and asylum policy. On the other hand, the Liberals and the Conservatives have supported the proposed European Constitution and the Lisbon Treaty.

Unlike Denmark, Sweden does not have a formal opt-out on EMU: as part of the negotiations leading up to Swedish membership of the EU it was agreed that Swedish EMU membership would depend on a referendum at a later date. When the Social Democratic government called a referendum in 2003, the Centre Party broke ranks with the other centre-right parties and called for a rejection of the government’s proposal. Later studies have shown that while the Centre Party and the Christian Democrat voters were deeply split on the issue, a majority of the two parties’ supporters voted against adopting the EMU. The result points to the continued existence of a centre-periphery conflict over Sweden’s relations with Europe. The Centre Party continues to be sceptical about Swedish EMU membership and has called for a major inquiry into monetary policy to be carried out before a possible second referendum.

It should be noted that Danish governments since 1982 have pegged the Danish krone to first the Deutschmark and later the Euro and Denmark accepts the convergence criteria set by the Maastricht Treaty and the ECB. Since the 1992 and 1995 currency crises, the Swedish krona is technically floating, but the Swedish Central Bank applies an inflation target similar to the ECB’s. This means that the debate over EMU membership in both countries has in many ways had less to do with actual monetary policies and more to do with issues of national sovereignty and resistance to the development of a federal European Union.

On the EU level, the affiliations of the Danish and Swedish parties in the European Parliament show how the historical currents in Nordic politics do not fit easily with the European ones. The Danish Conservatives originally joined the British Conservatives in a Conservative group that merged with the Christian Democrat-dominated European People’s Party (EPP) at the end of the 1980s. After Sweden entered the EU, the Swedish Moderates and Christian Democrats also joined the EPP. As the Danish Conservatives and the Swedish Moderates are pro-European, leaving the EPP in favour of the European Conservatives and Reformists group following the 2009 election was never an issue.

The European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party (ELDR) is the second important group for the centre-right, with the Danish Liberal Party, the Swedish Liberal Party and the Swedish Centre Party all belonging. The Danish Social Liberals were also members of the ELDR group when the party was represented in the European Parliament. This means that the distinction between Liberal, Social Liberal and Agrarian traditions have been blurred to some extent on the European level.

The Danish People’s Party has invariably belonged to one of the Eurosceptic groups in the European Parliament. Following the disintegration of the Union for the Europe of Nations group in 2009, there were rumours about the party joining the group set up the British Conservatives, but the party eventually joined the Europe for Freedom and Democracy group, with the UK Independence Party as the senior partner.

The welfare state

While the development of a comprehensive and generous welfare state has traditionally been a Social Democratic project, centre-right parties in Denmark and Sweden have taken a more positive stance towards social insurance and the provision of welfare services in order to attract voters. In this way, much of the debate over transfers and services has moved from the question of social rights to that of the organisation and provision of welfare services.

Privatisations have been accepted politically since the 1990s as part of a general adoption of New Public Management programmes in the Scandinavian countries, but the centre-right parties have, at least in principle, been much more enthusiastic than the Danish and Swedish Social Democrats about contracting out of a number of welfare services such as schools, day-care for children, care for the elderly and hospital services.

Denmark and Sweden have slightly different traditions in primary education: independent schools have historically played a larger role in Denmark. On the other hand, the centre-right government that was in office in Sweden between 1991 and 1994 introduced regulations allowing any pupil to move between public and private schools, with the public sector paying tuition fees. Local councils run by the Moderate Party have promoted the privatisation of primary and secondary schools run by local councils and there have been some indications that the Swedish Liberals are uneasy about these programmes at the local level.

Regulations in Sweden allow for corporations to make an economic profit out of schools, whereas educational institutions have to be organised as non-profit corporations in Denmark. The present Danish government has not proposed to change this situation.

Another area of conflict between the centre-right parties and the Social Democrats in both countries has been the provision of hospital services. Since 2001, the Danish government, supported by the Danish People’s Party, has promoted private health insurances as a supplement to the public system by offering tax deductions for employers providing insurance schemes for their employees. Similarly, the government introduced a programme where the regions, which run the public health service, were obliged to offer patients under the public scheme treatment at private clinics if they were not able to schedule surgery within a given timeframe.

In Sweden, regional councils controlled by the Moderate Party have followed more ambitious programmes to sell off surgeries and general hospitals, which would then work as contractors for the public health service. By contrast, the Danish government has not pushed for the privatisation of existing public hospitals, but sees the private clinics as a supplement to the public institutions.

In Denmark, the new government ushered in a tax moratorium after taking office in 2001. The principle behind the moratorium was that no tax would be allowed to rise unless it was directly offset by cuts in other taxes. The moratorium proved politically popular, especially as it has curbed property taxes in a situation with a boom in house prices. The Social Liberals are only centre-right party to have openly criticised the moratorium, arguing that it has prevented a comprehensive tax reform shifting the tax burden away from incomes to property and consumption. The Conservative Party on the other hand has consistently called for cuts in income taxes, especially for high-income earners. This has led to a number of conflicts between the Conservatives and the Danish People’s Party, which maintains that tax cuts should primarily benefit lower incomes.

In Sweden, the Christian Democrats presented themselves as defenders of the family home in the run-up to the 2006 election with a proposal to abolish property taxes. The implementation of an alternative tax on houses proved complicated and had slightly perverse effects in rural parts of the country. Otherwise, the government led by the Conservatives has followed a scaled down version of earlier tax-cutting plans by concentrating on lowering taxes on work income.

The political right and society

The present danish Energy and Climate minister Lykke Friis previously worked as an advirsor for the Cdi.

SAF has since merged with Svensk Industri to form Svensk näringsliv.

Political foundations and think tanks play a minor role in the political life in Sweden and Denmark. One reason for this is the existence of an extensive network of interest organisations, which are an integral part of the political system and provide parties and the public with interpretations of social developments and policy proposals as part of their activities. Parties, on the other hand, have increasingly given priority to establishing and maintaining research units for their parliamentary groups.

In Denmark, employers’ associations, industrial organisations and businesses have historically maintained connections with most centre- right parties and directly or indirectly provided economic support for the Liberal and Conservative parties. The main industrial organisation, Dansk Industri, has maintained formal independence in relation to any of the political parties.11 There are also historical ties between agricultural associations, now merged in the Danish Agriculture and Food Council, and the Liberal Party in particular. A similar pattern can be seen in Sweden, with the Federation of Swedish Farmers being close to the Centre Party, while Svensk Näringsliv, the Confederation of Swedish Industry, is politically non-committed.

Still, a number of minor foundations and a limited number of think tanks exist in Sweden, with Timbro being the most prominent example of a centre-right think tank.12 Timbro was established in 1978 with support from the Swedish Employers’ Association, SAF, with the aim of promoting free-market ideas at a time when the Swedish Social Democrats and the labour movement appeared increasingly radicalised.13

One motive behind the creation of Timbro was that the Social Democrats and the Swedish Trade Union Council promoted plans to introduce “wage-earner funds” which would invest in Swedish industries, thereby creating a basis for trade union control of central parts of the economy. Another motive was the wish to promote in Sweden the neo-liberal economic doctrines that were beginning to take hold in the Anglo-Saxon world.

It is difficult to assess the exact impact of Timbro’s activities on public debate and politics in Sweden, but a number of former Timbro associates and researchers have gone on to have political careers, primarily in the Moderate Party, from the 1980s onwards. Today, the Swedish Free Enterprise Foundation, a foundation set up by the Confederation of Swedish Industries, is responsible for financing Timbro’s activities.

SNS, the Centre for Business and Policy Studies, is another think tank with relations to the Confederation of Swedish Industries. SNS was originally founded in 1948 and has maintained a more mainstream and less confrontational position than Timbro. A regular feature in SNS’s activities has been the establishment of councils of academic experts that publish annual reports on constitutional issues, developments and challenges in the Swedish economy and welfare policy in a broader sense.14

Among the foundations with more or less close ties to specific political parties, the Moderate Jarl Hjalmarson Foundation and the Liberal Bertil Ohlin Institute are the most prominent. The Jarl Hjalmarson Foundation was founded in 1994 to coordinate activities in the Baltic States, but these days the foundation is active in many parts of the former Soviet bloc. Its main focus lies in projects relating to the training of politicians and it is mostly financed by the Swedish Development Agency.15

By contrast, the Bertil Ohlin Institute concentrates on the domestic arena and sees its main aim as stimulating research into liberal ideas and their application in practical politics. It does so by organising seminars and the publication of original and translated works. The institute is financed by a number of foundations owning and publishing liberal newspapers around the country.16

In 2004 a group of Danish businesspeople, former and active politicians, intellectuals and artists set up a Danish parallel to Timbro to add a middle-class perspective to public debate. The result was the creation of CEPOS, the Centre for Political Studies, which in the last few years has been very active in producing reports and comments on current issues, primarily in economic and social policy, from a liberal and libertarian point of view.17 While CEPOS formally has maintained its independence from the centre-right parties, it has emerged that former Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen was active in raising funds for the centre. Saxo Bank, an investment bank, has been a highly profiled sponsor of some of CEPOS’s activities.

Parties and the media

In denmark: dR; in Sweden: SR (Radio) and SvT (Television).

These days, formal links between major national media and political parties have been severed. While there is political representation on the boards of the public service broadcasters in both countries, editors make great efforts to maintain their political independence.18 Similarly, news-papers do not identify themselves as being attached to a party but rather describe themselves as “liberal”, “conservative” or “bourgeois”.

Among the national newspapers in Sweden, Svenska Dagbladet describes itself as “independent Moderate” while Dagens Nyheter and the tabloid Expressen are “independent liberal”. In Denmark both Morgenavisen Jyllands-Posten and Berlingske Tidende identify themselves as “bourgeois”, again without reference to any particular party.

Electoral performance and role in government

Both countries have proportional representation The electoral threshold is 2% in denmark and 4% in Sweden.

It is difficult to describe the overall electoral performance of the centre- right in Denmark and Sweden in a simple way due to the large number of parties, dramatic variations in the support for individual parties over time and changes in party strategies. With these caveats, some general observations can be made about the development in support for the centre-right in Denmark and Sweden over time as well as differences between the two countries.

If we take 1970 as the point of departure, the centre-right has always been stronger in Denmark than in Sweden. In Denmark, the left, excluding the Social Liberal Party, has only won a majority among voters in the 1979 and 1990 elections; even then, it was only because the Christian Democrats failed by the smallest possible margin to win representation in Parliament in 1971 that the Social Democrats were able to form a government that year. Still, the Social Democrats were able to lead the government from 1971 to 1973 and again from 1975 to 1982 and 1993 to 2001.19

In the 1970s the reason was that the Liberals and the Conservatives were too weak to form a credible alternative to the Social Democrats. Combined, the two parties only won between 20% and 30% of the vote at general elections, too little when they would have to rely on the unpredictable Progress Party. In the 1990s, the Social Democrats were able to count on the support of the Social Liberal Party and at times the Christian Democrats and the Centre-Democrats, thus giving them an advantage over the Liberals and the Conservatives in the parliamentary arena.

In the 1980s, the Liberals and the Conservatives had gained in strength compared with the 1970s, but they still depended on a diverse coalition of parties ranging from the Social Liberals to the Progress Party to stay in power. While the Social Liberals disliked the policies and behaviour of the Progress Party deeply, the disillusionment with Social Democratic economic policies still ran sufficiently deep for them to support the various governments led by Poul Schlüter between 1982 and 1993.

The formation of the Danish People’s Party in 1995 in many ways changed the rules of the game from the late 1990s onward. While the Euroscepticism of the Danish People’s Party still bars it from entering government, the Liberals and the Conservatives not only enjoy stronger support among voters than at any time since the 1960s, but also operate in a much easier environment at the parliamentary level.

That said, figure 1 exaggerates the support for the centre-right parties in the 2000s somewhat. While the Social Liberal Party traditionally attracted voters from both sides of the political spectrum, researchers have pointed to a change in the electorate, so that the Social Liberals now shares its electoral base with the Social Democrats and the Socialists. This also poses a challenge to the party, as it will be less free to cooperate with the Liberals and the Conservatives at the parliamentary level in the future than the party leadership would like.

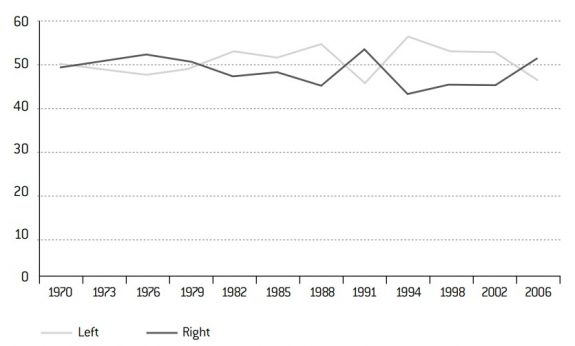

Chart 1: results of right- and leftwing parties in danish elections (1971-2007)

The absence of a major populist party makes the balance of power in the Swedish party system, as shown in figure 2, easier to describe compared with the situation in Denmark. The three old centre-right parties, the Moderates, the Liberals and the Centre Party, could very well have won a majority in the 1973 election if the Christian Democrats had not run. Instead the result was a hung parliament with both sides winning 175 seats. Similarly, the three parties could have won a clearer majority in 1979, had the Christian Democratic votes gone to the established centre-right parties.

The 1980s and 1990s saw clear leftwing majorities, with the exception of the 1991 election, when the centre-right relied on the New Democracy to form a government. If anything, the trend was for a decline in support for the centre-right from 1976 to 2002. Even voter discontent due to the austerity policies of the mid-1990s never seriously threatened the Social Democrats’ hold on power. The wins and losses recorded by individual parties during these decades were mostly due to cannibalism between the Moderates, the Liberals, the Centre Party and the Christian Democrats.

Chart 2: results of right- and leftwing parties in swedish elections (1970-2006)

It was only during the 2002-2006 electoral term that the four centre- right parties were able to change the picture. One reason for this was a general shift to the right in the mood among voters, combined with a negative view of the performance of the Social Democratic government on employment policy. Another reason was that the four parties made strong efforts to present themselves as a united alternative to the Social Democrats in the run-up to the 2006 elections, aiming to convince potential voters that a centre-right coalition would not break up mid- term.

The centre-right in government

As no single centre-right party has been close to winning a majority in the Danish or Swedish parliaments, the centre-right in both countries has always depended on forming coalitions in order to win power. The internal competition over voters and vocal policy disagreements has hin- dered the centre-right in appearing as a credible alternative to the Social Democrats.

In Sweden, centre-right governments have been notorious for their lack of stability. Centre Party leader Thorbjörn Fälldin’s first three-party government lasted only from 1976 to 1978, when the Moderates left over disagreements on energy policy. The Liberal minority government under Ola Ullsten, which was in office from 1978 until the 1979 election, was effectively a caretaker government, dependent on Social Democratic support.

In 1979, Fälldin was able to reform the three-party coalition of Centrists, Moderates and Liberals, but this coalition broke down in 1981, when the Liberals and Centrists entered an agreement with the Social Democrats on tax policy without the Moderates. This time, Fälldin was able to continue with a Centrist-Liberal minority coalition, but the three parties needed time to put their disagreements behind them.

The challenges facing Carl Bildt as Prime Minister between 1991 and 1994 were of a different kind. Even though he had consistently presented himself as a strong opponent of the Social Democrats, Bildt found it easier to cooperate with the Social Democrats than with New Democracy on economic policy when Sweden was hit by the economic downturn of the 1990s. The agreement on the Øresund Bridge, which prompted Olof Johansson to leave the government, was also made with the Social Democrats. Despite Johansson’s behaviour, the main problem was that the established parties of the centre-right had failed to win a majority in 1991.

The presentation of the Alliance for Sweden in 2004, complete with a joint website for the four parties, can be seen as a reaction to the experiences of 1976-1982 and 1991-1994: if the centre-right parties want to convince voters that they are a credible alternative to the Social Democrats, they must present themselves as a united coalition. The challenge to Fredrik Reinfeldt in 2006 was to leave enough room for Liberal, Centrist and Christian Democratic issues in what was essentially a Moderate programme. Unlike earlier coalitions, the Reinfeldt coalition has been successful so far.

The pattern of cooperation and conflict between the Danish parties has been even more complicated. In 1973, Liberal leader Poul Hartling surprised most people, including his prospective partners in the Liberal and Social Liberal parties by forming a minority government solely on Liberal votes. The experiment created much antagonism between the Liberals and the other centre-right parties and Hartling was only able to stay in office for a little over a year.

In 1978, Hartling’s successor, Henning Christophersen, in an equally surprising move, decided to enter a coalition with the Social Democrats, thereby breaking an emerging cooperation between the Liberals, the Conservatives, the Centre Democrats and the Christian Democrats. The coalition broke down after a year, but the move left an element of bad feelings toward the Liberals among the other centre-right parties. One reason for this was that the other parties felt that the Liberals had been disloyal in their attempt to demonstrate their position as the leading centre-right party.

Poul Schlüter was more careful in 1982, when he had the chance to become the first Conservative Prime Minister since the introduction of parliamentary government in 1901. As consolation for not holding the Prime Minister’s office, the Liberals were rewarded with central portfolios in the new four-party coalition. Schlüter could not form a majority coalition as the Social Liberal Party was fundamentally at odds with the government’s foreign and security policy and a number of other issues while the Progress Party under Mogens Glistrup had no interest in entering a government. Instead, he had to demonstrate a combination of negotiating skills and brinkmanship in order to stay in power.

While Schlüter stayed in the Prime Minister’s office from 1982 to 1993, his governments were less stable. The four-party coalition of Conservatives, Liberals, Centre-Democrats and Christian Democrats lasted until 1988 when Schlüter opted to include the Social Liberals in the government. This left the Centre-Democrats and Christian Democrats deeply frustrated, even though they would not bring down the government directly. Instead, Schlüter was now forced to balance between the Social Democrats and an ever more unstable Progress Party. What directly triggered his resignation in 1993 was a scandal related to the handling of Tamil asylum seekers between 1986 and 1988; another underlying cause was that the Social Liberal Party had gradually moved closer to the Social Democrats on economic and labour market policy.

The 1990s saw some competition between the Liberals and the Conservatives over who would be in the better position to cooperate with the Christian Democrats and the Centre-Democrats to the centre and the Danish People’s Party to the right. The 1998 election sealed the Liberals’ claim to the position as leader of the opposition, but it was only on election night in 2001 that it became clear that a Liberal- Conservative coalition would be able to govern with the support of the Danish People’s Party. Since then, the Liberals and the Conservatives have actively sought to win a majority for the three parties in the 2005 and 2007 elections, but due to differences over European policy, the Danish People’s Party has not yet been a candidate for government.

Prospects for the immediate future