Introduction

Solidarsnosc, melting pot of the polish right

The emergence of a free-market oriented, reformist current

The emergence of a conservative current centered on decommunization

Solidarność: same word, two different meanings

Two entirely opposed parties ?

PiS, the right party at the right time

PO: beginnings troubled by ideological trial-and-error

2005: the start of a frontal opposition between the two parties

The doctrine and historical references of PiS and PO

A comparison of the electorates of PiS and PO

The challenges of government

New developments within the right

PO takes a stab at internal party democracy

“Putting an end to the war among Poles”

In Poland, the right has a significant political advantage: its history is inextricably linked with the history of the struggle against the communist regime, and the democratic transition. The right’s historical legitimacy remains rooted therein, in contrast to the post-communist left. Despite having rapidly embraced social democracy, the left is currently experiencing an identity crisis and is having trouble reinventing itself. Today, the right dominates Poland’s political scene and mobilizes around three quarters of the electorate.

It has not always been the case. Since the early 1990s, the Polish right had been extremely divided whereas the post-communist left remained united within one stable political entity. Gradually, two main currents emerged on the right. Since 2005, the opposition between two major right-wing parties, PiS (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość – “Law and Justice”) et PO (Platforma Obywatelska – “Civic Platform”), has replaced the succession of right-wing and left-wing governments that characterized the first fifteen years of Poland’s young democracy. The left, represented essentially by SLD (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej – “Alliance of the Democratic Left”), has been continuously marginalized since losing parliamentary elections in the fall of 2005.

The unique legacy of the Polish right has not prevented it from evolving and restructuring itself around more universal dividing lines like those found in Western European democracies. Over the last five years, what used to be the dominant political pattern encountered in Central and Eastern Europe’s new democracies, centered around a struggle for power between anti-communists and post-communists, has given way in Poland to a new divide. We have decided to describe it here as a divide between “radical conservatives” or “statists” (represented by PiS) and “free-market liberals” (PO), even though this terminology remains imperfect for a number of reasons.

PiS, the Kaczyński twins’ party, was in government from 2005 to 2007. The party has approximately 22,000 members and can count on around 32%1 of the vote. PiS favors a strong state with far-reaching prerogatives, characterized by a powerful repressive and security apparatus as well as a highly developed welfare state. The party’s take on domestic policy involves the aspiration towards a certain moral order as well as state control of the country’s main industries. PiS is socially conservative and shows strong attachment to family, religious and patriotic values. This attachment, as well as the statist and authoritarian strains of PiS’ doctrine, have fuelled the project of a new constitution for Poland which the party proposed in 2005 and again in 2010, to no avail. Given its highly activist approach of institutions, and especially a tendency to create new ones, PiS cannot be considered simply a “conservative” party, which is why we chose to dub them “radical conservatives”. The term “statist” is equally fitting, since the party believes that in a quasi-omnipotent state lies the solution to nearly all problems. In the realm of foreign policy, PiS has shown itself to be very protective of the nation state, rather euroskeptic and atlanticist during its years in government, as well as extremely wary of Poland’s large neighbors, Germany and Russia. The European Parliament members affiliated with PiS were part of the Union for Europe of the Nations (UEN) political group from 2004 to 2009. Following the last European elections, they joined the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), a group which they took part in creating together with MEPs from the UK’s Conservative Party and the Czech Republic’s ODS.

In contrast, PO, which has been in power since its victory in the parliamentary elections of 2007, believes in the free market’s capacity to guarantee prosperity for Poland and strongly supports privatization as well as foreign investment. Having displayed a shifting stance on European matters at the beginning of the current decade, today, under the leadership of Prime Minister Donald Tusk, PO is a pro-European party wishing to ensure quick membership of the eurozone for Poland.

The party’s MEPs are members of the European People’s Party (EPP) since 2004. PO’s share of the vote would be situated around 41% if parliamentary elections were held in June 20102. The party has approximately 46 000 members.

With the marginalization of Poland’s main left-wing party, one might suggest that the current divide between PiS and PO mimics a traditional left-right divide. The opposition between PiS, a party wary of the market economy, eager to enforce welfare-intensive policies, and PO, enthusiastically supportive of private capital and “small government”, seems to reincarnate a left-right momentum in many ways, even though this analysis pertains mainly to the economy and not to social issues.

This anomaly adds interest to the study of the ideas and values of the contemporary Polish right. Following Poland’s special presidential election made necessary by the death of President Lech Kaczyński in the Smolensk plane crash, this analysis is meant to show how the divide between the country’s two main right-wing parties has come into being, and how these organizations continue to reinvent themselves. It seems that neither party wishes to remain rooted in an opposition between a “social Poland” and a “free-market liberal Poland”. Instead, both PiS and PO try to overcome this schematization as it limits their political opportunities33. In order to understand the “personality” of each of those parties, it is necessary to examine their past. Given the extent of their differences, it almost comes as a surprise to recall that PiS and PO have a common historical foundation: Solidarność.

Solidarsnosc, melting pot of the polish right

This question was raised by the political scientist, Pr. lena kolarska-Bobińska, in her article in the weekly Polityka, may 12, 2007, and during a conference at the Instytut Spraw Publicznych (ISP – “Institute of Public Affairs”) on november 29, 2007.

A closer look at PiS’s and PO’s common origins is a prerequisite for ana- lyzing the doctrinal differences separating them. The Polish right traces its roots back to the opposition movement against the communist regime. This movement had become consolidated in 1980 around the workers’ union Solidarność. It is extremely rare, perhaps even unprecedented in Europe, to see two right-wing political groups strongly opposed to one another, having a labor union as a common political heritage. This is a very specific legacy of Poland’s democratic transition.

This unique situation arises from the fact that Solidarność was a hete- rogeneous movement, bringing together people and groups that hailed from very different horizons. In the 1980s, the world-famous face of Solidarność was Lech Wałęsa, Nobel Peace Prize-winner and strike-leader at the Gdańsk navy yard, his lapel adorned with a badge depicting the Virgin Mary. But the political spectrum represented within his movement was exceptionally wide. To the left of the spectrum was a group of intellectuals with a strong social conscience, formerly holding communist beliefs, who had dreamed until 1968 of reforming the communist system from the inside. As agnostics, they seemed to have more in common with their Czech colleagues who had signed the 77 Charter, rather than with some of their comrades within Solidarność. On its right, Solidarność included groups that were anti-communist in their essence, strongly nationalist and catholic, with close ties to the Church. Having stayed united throughout the 1980s, held together by their struggle against the oppressive communist government, by a sense of historic opportunity and by the remarkable political skill of Lech Wałęsa, the different components of Solidarność started drifting apart following the “Round Table” negotiations with the communists in power (February- April 1989) and the first semi-free elections of June 1989.

In the early 1990s, fallings-out between Lech Wałęsa and his Solidarność colleagues were rife, resulting in break-ups within the movement. Two of these break-ups are of prime importance to our examination of the modern Polish right’s ideological origins.

The emergence of a free-market oriented, reformist current

A conflict developed over the course of the year 1990, between Lech Wałęsa and Tadeusz Mazowiecki, who had become the first non-communist head of government in September 1989. A Christian democrat, Mazowiecki was faced with an arduous task: leading a government composed of communists (who held the ministry of the interior and the ministry of defense, following the “Round Table” power-sharing agreement) and of free-market reformers, the most prominent of whom was Leszek Balcerowicz, finance minister. Mazowiecki’s government managed to implement a series of reforms at an impressive pace. The transition to a market economy was carried out according to Leszek Balcerowicz’s plan dubbed “shock therapy”. Meanwhile, Mazowiecki remained cautious in regards to the proposal of a widespread purge of Polish institutions designed to rid them of communists, which was put forward by part of Solidarność. The scale of the sacrifices, in terms of living standards, asked of the Polish population in the name of free- market “shock therapy”, as well as the government’s eagerness to draw a line upon the former regime without “cleansing” its establish- ment succeeded in alienating the Mazowiecki government and its sup- porters within Solidarność. Wałęsa and Mazowiecki ran against each other in the country’s first free presidential election in November 1990. Mazowiecki suffered a considerable political drawback after failing to make it into the second round of the election. These events led to the creation of a new political party stemming from Solidarność: Unia Demokratyczna (UD – “Democratic Union”), which became, in 1994, Unia Wolności (UW – “Freedom Union”). Amongst its successive leaders were Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Leszek Balcerowicz and Bronisław Geremek, another emblematic figure of the former free-market oriented, centrist wing of Solidarność. This party’s gradual decline in influence throughout the 1990s eventually encouraged some of its members to create a new free-market liberal party, PO, in 2001.

The emergence of a conservative current centered on decommunization

A term used to describe the verification process that investigates links of persons holding public office with the intelligence and security services of a communist The term is used mainly in Poland and in the Czech Republic.

The twins Jarosław and Lech Kaczyński, close aides of Lech Wałęsa within Solidarność, created a new party, Porozumienie Centrum (PC – “Center Agreement”) in 1990. The party supported Lech Wałęsa’s successful bid for the presidency in November 1990, strongly criticizing Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s free-market reforms and conciliatory attitude towards representatives of the communist regime. After Lech Wałęsa’s election, the Kaczyńskis became key players in power-wielding circles: Jarosław as the new president’s chief of staff, Lech as the director of the National Security Bureau (BBN). Other politicians from their party, Porozumienie Centrum, received government portfolios.

However, in the years 1992-1993 the Kaczyński brothers found them- selves increasingly at odds with the president and his entourage, whom they accused of blocking access to the communist intelligence and security services’ archives, as well as preventing lustration4. They interpreted the president’s reluctance to make public communist era documents as proof of Lech Wałęsa’s collaboration with the previous regime. Together with their supporters, the Kaczyńskis demanded to settle scores with representatives and collaborators of the communist state and violently criticized the “Round Table” negotiations of 1989 as having been too lax towards the out-going communists in exchange for a power-sharing agreement. A “lustration bill” passed in May 1992 opened the floodgates to political maneuvers aimed at destabilizing the president. The government of Jan Olszewski, a staunchly anti-communist prime minister supported by the Kaczyńskis, spearheaded this movement. This government fell after the “night of the files” (June 4-5 1992), which saw the publication of a list of alleged communist collaborators beginning with Lech Wałęsa’s name.

From that point on, the conflict between Lech Wałęsa and the Kaczyński brothers escalated into an open political battle. The brothers joined the ranks of the opposition. The leader seen around the world as one of the founders of Poland’s young democracy had become, in their eyes, a traitor. Their party, Porozumienie Centrum, fought the largescale privatization program for the industrial and banking sectors that was being implemented by a government led by Hanna Suchocka from Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s Democratic Union party. Following the setback suffered by the right in 1993, when the post-communists won Poland’s parliamentary elections, the twins’ political ambitions remained stalled until the early 2000s, when they created a new party, PiS.

Solidarność: same word, two different meanings

This brief historical account allows us to shed light on a fundamental difference in the attitude of the two main political currents within the right towards Poland’s democratic transition, in which they themselves had played key roles:

- on the one hand, the free-market liberals, represented today by PO, consider the “Round Table” negotiations and agreement as a founding gesture of Polish democracy. They fully accept the “Third Republic” (which is the name given to the regime in place since 1990) and the market reforms of Leszek Balcerowicz;

- on the other hand, the conservatives, represented by PiS, view the “Round Table” as a betrayal, an original sin of Polish democracy, which has skewed the formation of the young republic since its very beginning. The lack of radical decommunization at the foundations of the new regime means to them that the base upon which the “Third Republic” was built is not valid. In order to correct this, from 2005 to 2007, when in power, they proposed to devote their energies to the creation of a “Fourth Republic”.

One could also argue that despite their common origin, the two main currents of the Polish right do not share a common vision of their origins. There is a stark contrast between the ways in which PO and PiS view Solidarność. For PiS, Solidarność was a broad movement designed to win back national sovereignty and betrayed by some of its leaders. The Kaczyński brothers’ party has always remained connected to the base of Solidarność – unionized workers – and even today enjoys the union’s political support. In the case of PO, even though its leaders (Prime Minister Donald Tusk and President Bronisław Komorowski) had been active members of Solidarność in the 1980s, the connection to the labor union has been completely lost. PO sees Solidarność as a liberation movement having made possible the introduction of capitalism in Poland, with which the reformist Mazowiecki government is credited. In the realm of human loyalties and attachments, the two parties differ in their relationship with the leading figures of Solidarność, PiS being close to all those who broke away from Lech Wałęsa. PiS has strived to represent the Kaczyński brothers’ role in the creation and the history of the union as decisive, while minimizing the Nobel Peace Prize laureate’s role, to the point of having left him off the guest list for a 2006 ceremony commemorating the events of August 1980. In contrast, PO treats Wałęsa with reverence, and Prime Minister Tusk is regularly seen at the former president’s side.

Having presented the ideological foundations of the two main parties of the Polish right, we shall proceed to examine in more detail the circumstances of their rise, as well as their doctrine and the structure of their electoral base.

Two entirely opposed parties ?

PiS and PO were created almost simultaneously in 2001, at a time when the right, divided and exhausted by four difficult years in government, was heading for electoral defeat at the hands of the post-communist social democrats.

PiS, the right party at the right time

From 1997 to 2001, Poland was governed by a right-wing parliamentary majority composed of parties that had stemmed from Solidarność. They had come together to form a cluster called Akcja Wyborcza Solidarność (AWS – “Electoral Action Solidarność”), a political mosaic typical of the Polish right at that time. The Solidarność labor union, as well as the Kaczyński brothers’ Porozumienie Centrum party and, in total, around forty other organizations were part of this group, which was subject to permanent internal recomposition. Moreover, until the year 2000, AWS was in a government coalition with UW. During this period, Leszek Balcerowicz had returned to the helm at the ministry of finance. Four major reforms were adopted in the fields of civil service, education, healthcare and pensions. Subsequently, UW ministers left the government as their party joined the opposition. A minority government led the country until the end of its term in office, while the AWS structure was imploding.

Lech Kaczyński was minister of justice in the AWS government in 2000-2001. His eagerness in fighting crime and corruption brought him strong popularity. In 2001, this political capital helped him create PiS with his brother Jarosław. The party’s name, meaning “Law and Justice”, is a reference to Lech Kaczyński’s law enforcement campaign while in office. Created at a moment when the demise of AWS was imminent, PiS managed to attract a wide spectrum of politicians and activists, spanning from the center-right to the far right.

The two main elements of the party’s program – an uncompromising attitude towards crime and corruption, as well as the desire to ban all former communist collaborators from public office and civil service jobs – gave it a strong voice within the right-wing opposition pitched against a post-communist government. This government, in power from 2001 to 2005 and dominated by the social democrats of the SLD party, found itself severely destabilized by major corruption scandals, which helped discredit it in the eyes of the voters. During that time, PiS kick-started its ascension to power with a landslide victory in the Warsaw municipal election in November 2002. With almost 70% of the vote, Lech Kaczyński became mayor of Warsaw. He used this platform to increase his popularity as a determined crime-fighter drawing on the principle of “zero tolerance”. As mayor, he also worked towards greater recognition of the veterans of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. The memory of this tragic event, obscured for decades by the communist regime, found a committed defender in Lech Kaczyński, who initiated the construction of an Uprising Museum in the heart of the city. Through his efforts, the 60th anniversary of the Uprising was the occasion of a large-scale commemoration ceremony, with guests of honor including German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and US Secretary of State Colin Powell.

The popularity of the Kaczyński brothers and of their party was at a record level by 2005, a year of parliamentary and presidential elections. The left-wing SLD party was living out a true chronicle of a defeat fore- told: various scandals had caused the premature fall of Leszek Miller’s government and a minority government headed by the economist Marek Belka, a technocrat, was dispatching day-to-day matters. This context provided PiS with a unique political opportunity to take power and marginalize its main right-wing rival, the free-market liberal party PO.

PO: beginnings troubled by ideological trial-and-error

Two chains of political events led to the creation of PO in 2001. First, in the 2000 presidential election, while the post-communist and social democrat incumbent Aleksander Kwaśniewski was reelected in the first round of voting, an independent candidate, Andrzej Olechowski, unexpectedly came in second place with 17% of the vote. A former minister of foreign affairs, Olechowski, a free-market liberal, was looking to bring his political capital to fruition by creating a new movement. Second, the loss of influence in national politics experienced by Unia Wolności spurred discontent and rebellion within this party. Its historic figures (Leszek Balcerowicz, Bronisław Geremek…) seemed incapable of broadening its appeal after the failed coalition with AWS. Expressing their frustration, a younger generation of UW politicians headed by Donald Tusk created PO in January 2001, with the help of Andrzej Olechowski and Maciej Płażyński (formerly of AWS). From the start, Tusk, Olechowski and Płażyński did not shy away from public appearances and were quickly nicknamed “the three tenors”. However, they repeatedly postponed the public pronouncement defining the new movement’s nature and program. Often repeating, over the first months of PO’s existence, that it was “not a party, but a civic movement”, and oscillating between liberalism and conservatism, the party’s founders managed to disorient voters. Andrzej Olechowski was severely defeated by Lech Kaczyński in Warsaw’s municipal election.

These difficult beginnings did not stop PO from making its voice heard within the opposition against a left-wing government paralyzed by scandal. However, it was mainly in the field of European policy that the new party found a way of distinguishing itself. In denial of its pro- European and liberal pedigree, looking for short-term political gain, PO rejected the proposed compromise on the European constitutional treaty and applied heavy pressure on the left-wing government entrusted with negotiations during the European Council meeting of December 2003. One of PO’s main figures at the time, Jan Rokita, famously exclaimed “Nice or death!” in defense of the Nice Treaty against the draft European constitution.

Buckling under the pressure of its main rival PiS, which, through its moral stands, galvanized an electorate weary of the string of corruption scandals affecting the disgraced left, PO had trouble defining a clear ideological line. During the parliamentary election campaign in 2005, PO took turns attempting to distinguish itself from PiS through a free- market stance, and adopting, even expanding upon, some of its rival’s conservative positions.

2005: the start of a frontal opposition between the two parties

In the parliamentary elections of September 2005, PiS took first place with 26.99% of the vote, followed by PO with 24.14%. The low turnout (barely 40%) showed that the former left-wing majority which had discredited itself through a string of corruption scandals, managed in the process to discredit politics in general in the eyes of the electorate. This was further illustrated by the relative success of two small extremist, radically anti-European parties: Samoobrona (“Autodefense”), a populist party defending famers’ interests, which obtained 11.41% of the vote, and Liga Polskich Rodzin (LPR – “Polish Families’ League”), an ultra-Catholic and nationalist party, which received 7.97%. Despite having won the election, PiS did not have a majority and needed to form a coalition government. Throughout the election campaign, PO had seemed a natural coalition partner, as a party with a strong Solidarność heritage, highly critical of the outgoing post-communist government. However, the two parties soon encountered major difficulties in their negotiations. PiS was reluctant to offer PO high-profile government portfolios, intending to keep for itself the ministries of justice, of defense and of the interior. PO left the talks and a PiS minority government was approved by parliament with the votes of Samoobrona, as well as those of Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe (PSL – “Polish People’s Party”), another party representing the rural electorate, and of LPR. Forced into opposition, PO suffered a further defeat when its leader and presidential candidate Donald Tusk lost the presidential election to Lech Kaczyński (whose result was 54.04% in the second round of voting).

A more detailed study of the programs presented by PiS and PO in 2005 will shed light on the main differences separating them.

The doctrine and historical references of PiS and PO

Introduction to the draft “Constitution of the IV Republic”, PiS document, march 19, 2005.

Ibid.

The 1997 preamble stipulates that “all citizens of the Republic, those who believe in God, source of all truth, justice, good and beauty, as well as those who do not share this faith and derive those universal values from other sources”, are “equal in their rights and their duties before their common good – Poland”.

Paweł wroński, Gazeta Wyborcza, december 7, 2005.

In the 2005 parliamentary and presidential elections, PiS mobilized voters with an ambitious program, centered on the promise of building a “Fourth Republic”. The basis for this undertaking was the need, expressed by the Kaczyński brothers’ party, to put an end to what they dubbed the “system”, meaning close ties of the country’s political elites with private interests, and especially those of powerful businessmen. According to PiS, the proof of the existence of such unhealthy ties was provided by the way privatization of state-owned companies had been conducted since the early 1990s, as well as the previous governments’ eagerness to embrace private investment and the many corruption scandals that ensued. In this view, the other part of the equation was the presence of former communist officials and collaborators – considered corrupt by essence – among high-ranking public figures and in the private sector. The “Fourth Republic” was more than a slogan: it was truly a program of institutional renewal, based upon a new constitution. PiS considered that the Polish constitution adopted in 1997 displayed some disqualifying faults and had failed to create “a socially cohesive state which would be the source of social justice, or a Catholic state belonging to the Polish nation, or a strong state generating public order5”. According to PiS, this constitution was not fitting for a “democratic state characterized by the rule of law” and had allowed for “the strengthening of post-communism at the expense of the good of the Republic6”.

The new draft constitution proposed by PiS was said to have been partially inspired by the French constitution, insofar as it increased the president’s powers and gave him an enhanced role within the executive. However, this is as far as the resemblance went. The preamble opens on a classic invocatio dei, replacing the 1997 preamble which puts believers and non-believers on the same level7. The emphasis of PiS’s draft constitution was clearly placed on the “Polish nation” instead of all Polish citizens. The text did not broach the issue of ethnic minorities’ rights. The principle of the separation of powers was distorted by the scope of the president’s new powers and intervention rights. Abortion and in vitro fertilization were entirely prohibited. Moreover, international law was to be subordinated to Polish domestic law. For all these reasons, the constitutional draft proposed by PiS in 2005 (and again, with very few changes, in January 2010), is a revolutionary text, breaking away from the principles upon which the Polish state was built from 1989 onwards. PiS championed the annihilation of the communist regime’s legacy.

But it also promised to put an end to what it saw as the nation’s pauperization caused by the capitalist system. To that end, redistribution was a major element of all social and economic policies proposed by the party. The welfare state was to be strengthened and further centralized, in order to maximize “national solidarity” in the form of a generous healthcare system and widespread welfare benefits. This was to be achieved without resorting to tax hikes, cuts in other areas of public spending (such as the civil service) or new capital brought in by privatization. PiS’s economic and social policy was to be financed primarily by economic growth.

In terms of historical references preceding the Solidarność era, PiS positions itself as an heir to the ideas and actions of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, one of the main figures of the renaissance of the Polish state in 1918. Józef Piłsudski had ruled over Poland, de jure or de facto, for most of the period between 1918 and 1935. He is most notably credited for the Polish victory in the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1920. He remains a highly revered figure throughout the country, despite the communist regime’s efforts to erase his legacy. However, there was a dark side to the Marshal’s rule: his authoritarianism and anti-parliamentarism had led him to imprison his political opponents in 1930. After Piłsudski’s 1926 military coup, his policies were based upon the need for a “moral healing” (sanacja) of the Polish state, a concept with which PiS strongly identifies.

In this context, it is necessary to mention another tradition of the Polish right from the same era, known as “national democracy” (endecja), whose representatives were engaged in a power struggle with Józef Piłsudski between the two World Wars. The national democratic movement was characterized, amongst other things, by the desire to create an ethnically homogenous Polish state, and by its anti-Semitism. Today, LPR is the main Polish right-wing party positioning itself as a direct heir to the national democrats. Given that this party has been quasi-inexistent on the Polish political scene since its defeat in the 2007 parliamentary elections (having obtained no seats with 1.30% of the vote), we have chosen not to discuss it in more detail within this study.

In 2005, PO was undergoing an identity crisis so profound that an oped in the daily Gazeta Wyborcza asked, “What is the difference between PiS and PO, other than the fact that PO doesn’t know how to win elections?8”. Based on its program, PO was to be a distinctly liberal, free-market oriented party, proposing tax cuts as well as a single tax rate of 15% for income tax, businesses and VAT alike. PO also wished to cut public spending, restructure the civil service and abolish the Senate. In order to foster a “responsibility-based” attitude within the administration, PO suggested that civil servants responsible for errors and wrong decisions with financial consequences for individuals or businesses should be fined. The party was also eager to accelerate privatization of state-owned companies and encourage private investment.

However, in practice PO found it difficult to stand by its free-market oriented program. During the parliamentary election campaign in 2005, PiS accused PO of wanting to conduct a “free-market experiment” and supporting business interests against the needy. A television commercial for PiS illustrated this idea by showing an empty refrigerator as the symbol of PO’s policies. PO had trouble responding to the criticism and tried to reposition itself as a “liberal-conservative” party, with little success. After its defeat, PO adopted a center-right positioning, concentrating on criticism of the growing radicalization within PiS, the nature of the government coalition and the excesses of the new majority’s drive to “reestablish the authority of the state”.

As a liberal party favoring small government, PO does not aspire to propose a new moral or social order, nor to create new institutions.

Any major amendments to the Polish constitution proposed by the party have consistently been destined to reduce state intervention and the role of the president. PO usually speaks of the need to make the Polish state more efficient and create the conditions for dynamic development of the private sector. Although it is conservative on social issues, PO avoids any significant activism in this field. The party shows admiration for Leszek Balcerowicz’s achievements in the early 1990s and does not seem to have any historical Polish role-models going further back in time, due to the near absence of a liberal tradition in the country. At the most, elements of such a tradition could be found in the career of one 1920s politician, Władysław Grabski, treasury minister of the young Polish Republic, then later prime minister from 1923 to 1925. An agronomist and economist educated at the Parisian École libre des sciences politiques as well as the Sorbonne, Grabski carried out a comprehensive reform of the treasury, also creating the country’s main financial institutions and its currency, the złoty. An avid reformer and an eminently pragmatic politician (although originally from the national democratic movement, he favored broad and flexible political alliances), he remains a reference for today’s liberal reformers. Interestingly, his great-granddaughter Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska is a PO leader for the Warsaw region.

A comparison of the electorates of PiS and PO

These are figures from exit polls carried out by TnS OBOP for Polish television during the 2007 parliamentary elections.

The three main socio-demographic variables which define the distinction between the PiS and PO electorates are: age, education and population size of the voters’ administrative district of residence. As far as age is concerned, in the 2007 parliamentary elections, PiS had a majority only among voters aged 60 years and over (39.9%, whereas PO’s result in this category was 30.2%). On the other hand, PO had the largest lead over PiS in the 18-to-24 age group (56.4% among this group voted for PO and only 21.8% for PiS). This lead was still considerable among the 25-to-39 year olds (52.4% voted PO while 24.2% chose PiS). However, in the 40-to-59 age segment the gap between the two parties’ scores narrowed significantly, 39.7% of voters in this group having chosen PO while 33.1% voted for PiS. The influence of education is also apparent. In 2007, PiS had a very clear majority among voters with primary education, whereas PO was the dominant party among those with secondary education (44.9%, compared to 29.4% for PiS) and higher education (55.7% of them voted for PO and only 21.4% for PiS)9. Also in 2007, PO was chosen by 53.8% of voters residing in cities of over 500,000 inhabitants (PiS had a score of 27.1% in that group). On the contrary, 23.4% of voters residing in municipalities of under 5,000 inhabitants chose PO while 35.9% voted for PiS. These trends were confirmed in the 2009 European elections as well as in the presidential election of June-July 2010. However, it is important to note that PO’s strong lead among the youngest voters and those with the highest level of education was not the determining factor in its victory over PiS in 2007. Rather, it was its lesser lead over PiS within the largest population segments, such as the 40-to-59 age group and voters with secondary education, which ultimately determined the outcome of the election.

It is also interesting to point out that the abovementioned variables were less differentiating in the 2005 parliamentary elections, when PiS had enjoyed stronger support in large cities, among young voters and those with a higher education level. During the party’s time in power, its radical rhetoric seems to have alienated some of these voters.

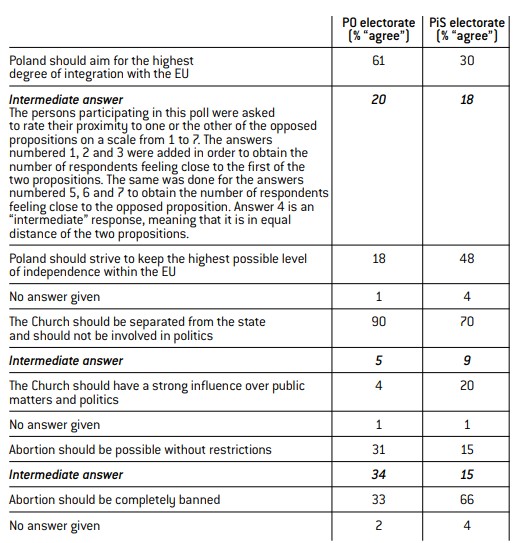

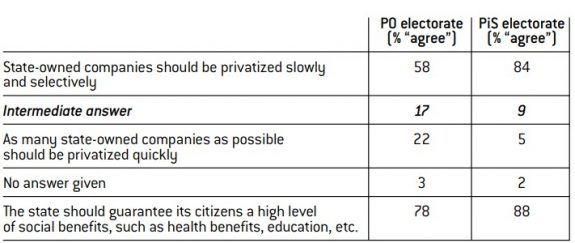

This analysis indicates that PiS has increasingly become the go-to party for those left on the sidelines of Poland’s capitalist transformation, who wish to express their fears concerning the modernization of the country and its EU membership. On the other hand, PO voters show much more enthusiasm for Poland’s recent economic evolution and EU member status. They are also less conservative than PiS voters on social and moral issues (even though PO does not seek to change the framework of relations between the Catholic Church and the state, defined by a concordat, nor does it wish to revise the current law on abortion, restraining the possibility of terminating a pregnancy to a very limited number of situations). The public opinion research center CBOS has published an interesting analysis of the issues on which the electorates of various Polish political parties differ the most. Some highlights of this report are presented in the tables below, showing several pairs of antithetical propositions as well as the percentage of PO and PiS sympathizers agreeing with each proposition.

Source :

Source: CBOS report “The electorates of the main political parties: ideological characteristics”, October 2009

Poland’s degree of integration with the EU, the role played by the Catholic Church in public affairs as well as abortion rights are three issues on which the PO and PiS electorates disagree strongly. Remarkably, a majority of backers of both parties is in favor of the separation of church and state.

Source :

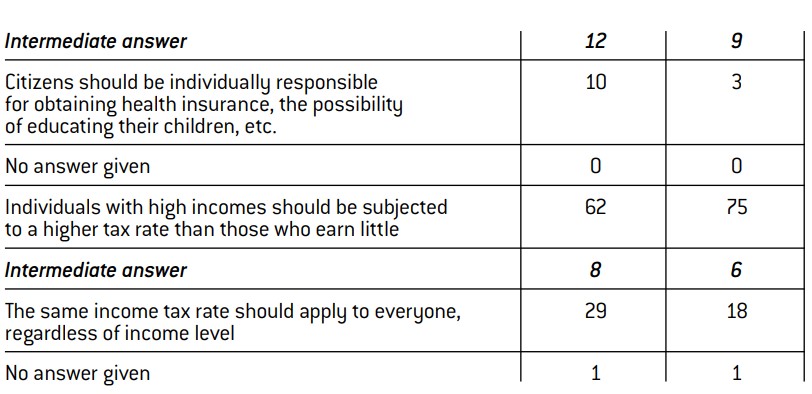

Source: CBOS report “The electorates of the main political parties: ideological characteristics”, October 2009

Looking at the answers regarding the role of the state in the country’s economy, it becomes clear that PO’s electorate is not dominated by fervent free-market liberals. Even though the party’s supporters are much more likely than those of PiS to wish for accelerated privatization or a single tax rate for all, the majority of PO’s electorate seems to advocate caution in relation to privatization, accept progressive tax rates and support the welfare state. These findings strongly challenge the idea that there is a “social Poland” and a “free-market liberal Poland”.

Individual choice between the two parties is determined by moral issues much more than by the attitude towards the state’s economic role. Strong mobilization of the PiS electorate around such issues has led commentators to the conclusion that if PO has “voters”, PiS has “followers”10.

The nature of the economic and social changes sweeping the country (an increasingly educated population, rural flight, etc.) would indicate that in the years to come, the numbers of PiS’s “followers” are bound to decrease. A linear vision of history might suggest that PiS was brought into power in 2005 by one last resurgence of fears concerning the capitalist system and Poland’s membership in the EU – fears shared within an electorate bound to shrink over time11. But this logic does not take into account any possible surprises that could still arise from future evolutions of Poland’s economic situation, or of its position within the EU. Also, given that voter turnout in national elections is generally low (between 50% and 60% of the voting-age population regularly abstains from going to the polls), mobilizing those who usually stay at home – often centrist moderates – will remain a challenge for both right-wing parties. PiS’s social conservatism and PO’s free-market ideology are both obstacles in this perspective.

The ideological differences between the two main Polish right-wing parties, already visible during the electoral campaigns of 2005, became even more obvious in the period that followed, which saw PiS, then PO in power. PiS gave the country two governments in rapid succession, headed respectively by Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz and by Jarosław Kaczyński. In 2007, early parliamentary elections brought victory for PO and a government led by Donald Tusk was sworn in.

The challenges of government

Witold Gadomski, Gazeta Wyborcza, December 19, 2015.

Mariusz Janicki, wiesław władyka, Polityka, november 5, 2005.

This opinion was expressed by Professor Tomasz nałęcz at an ISP conference on november 29, 2007.

Ibid.

According to a press release by konfederacja Pracodawców Polskich (kPP – “Polish Entrepreneurs’ Federation”), november 5, 2009.

According to data released by Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS – “Central Bureau of Statistics”), April 22, 2010.

According to monthly CBOS polls measuring government approval ratings, April 2010 and preceding months.

Ibid.

PiS actively criticized all those who had resigned themselves to “selling the state short” and who looked upon the PiS government’s new public spending programs from a “purely accounting perspective” (as Prime Minister Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz stated in his inaugural speech before parliament). However, on a social and economic level, few of PiS’s campaign promises were actually implemented. The lack of adequate funds became an obstacle as soon as late 2005, during the drafting of the 2006 state budget. This did not come as a surprise, given that the government had not increased tax revenues nor resorted to any significant cuts within the civil service. In the end, increased public spending on social and economic programs was limited to the following measures:

- longer maternity leave;

- the implementation of a childbirth allowance for all mothers, regardless of income level;

- tax breaks favoring families over unmarried and childless individuals;

- a program fighting youth malnutrition;

- increased subsidies for biofuels

Editorial writer Wiktor Gadomski observed, “all that is left from PiS’s program – a brochure boasting a couple dozen pages and promising ‘solidarity in Poland’ – are a few randomly selected goals for which financing has been found. […] For a mere 800 million złotys the government will seemingly have fulfilled its promise of pro-family, socially-oriented and farmer-friendly policies. The amount in question is not likely to solve any problems whatsoever, but it enables Marcinkiewicz to claim that he is implementing PiS’s program. Why yes, he is implementing it, but on a purely symbolic level”12.

The above-mentioned policy measures are as much a sign of the importance of family values and rural voters’ interests in PiS’s political rhetoric, as they are the result of intense lobbying by PiS’s parliamentary allies, who later became its coalition partners. LPR had demanded birthrate-enhancing policies and Samoobrona had been uncompromising in regards to measures supporting farmers. The two small parties made use of strong-arm tactics whenever it came to negotiating policies directly affecting their own fringe electorate.

For lack of means, many key points of PiS’s political platform were never enacted. The promise of a significant effort to build new housing and roads quickly proved unrealistic, as did public deficit reduction. Still, until its premature resignation in July 2006, Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz’s government had remained popular. This was due in particular to the charisma and enthusiasm of the youthful prime minister (45 years old when he took office). The government’s honeymoon period was further extended thanks to a victory at the European Council’s December 2005 meeting during the final stage of negotiations over the 2007-2013 financial perspectives. At the meeting, Poland managed to obtain 3 billion euros more than what was offered in an initial proposal put forward by a group of countries led by the United Kingdom. Moreover, the status quo on European Common Agricultural Policy funding was maintained. This episode, viewed as a major success for the government, was in line with PiS’s combative stance on European affairs, its promise to defend Polish interests at any price and help a “strong Poland” take up the space that it “deserves” on the European political scene, even if that sometimes means stalling negotiations or blocking agreements.

Beyond these achievements, it must be said that the economy in general, and specifically issues such as growth, monetary policy or public finances were neglected by PiS once the party took power. One exception is the Marcinkiewicz government’s fiscal reform adopted in 2006 (which took effect in 2009), introducing two income tax brackets (with an 18% and a 32% rate), which replaced the three previous brackets. However, the main accomplishments of this government as well as of Jarosław Kaczyński’s government which followed it in 2006, belong to the party’s traditional areas of interest. Having failed to obtain a majority in parliament, PiS was unable to move forward with its draft constitutional proposal, but pursued reforms impacting the judiciary, the security apparatus and intelligence services, as well as investigative and auditing institutions. PiS’s history in power has come to be most closely associated with the following measures:

- amendments to the civil and penal code, designed to increase overall sentence severity and to accelerate procedures, in particular with the creation of “24 hour courts” to expedite cases in which the defendants faced under five years’ imprisonment;

- a lustration bill extending the lustration procedure to new population segments (university professors, teachers in private schools, journalists…) and creating an obligation, for the individuals concerned, to submit a statement declaring one’s collaboration or non-collaboration with the communist security Those suspected of making false statements were to be prosecuted in a civil court, which would effectively have resulted in a shift of the burden of proof in such cases;

- the obligation for all civil servants to submit a statement (made public) summarizing their financial resources and property as well as indicating the provenance of these assets;

- the denial of retirement benefits to former employees of communist security services;

- the reform of military intelligence services whose personnel, according to PiS, had not been sufficiently “expurgated” of former communist collaborators;

- the creation of a new government agency designed to fight corruption, as an addition to several existing agencies with similar competencies, authorized to pursue “operational methods” such as wiretapping in the course of their surveillance This new agency, called Centralne Biuro Antykorupcyjne (CBA – “Central Anti-Corruption Bureau”), answers only to the prime minister and the parliamentary committee on intelligence services;

- the reform of the National Radio and Television Broadcasting Council, which regulates radio and television. This reform allowed PiS to replace all the members of the council with figures close to the president and the government.

Thus, PiS had attempted to implement a program designed to restructure the state. However, the judicial and institutional activism of the two PiS governments generated considerable resistance on the part of institutions, some elected officials as well as entire sectors of civil society. Poland’s Constitutional Court, whose role is to produce binding opinions on the constitutional character of bills adopted in parliament, invalidated the more controversial points of the new lustration bill. Bronisław Geremek’s opposition to the bill helped focus domestic and foreign media attention on this case. This member of the European Parliament, Solidarność veteran and internationally respected intellectual had refused to submit the personal statement called for by the new law.

Even though PiS managed to unearth further political and financial scandals involving the previous left-wing governments, it failed to fulfill its promise of prosecuting the founders of the “Third Republic” before the State Tribunal (the judicial body that deals with crimes committed by the country’s highest-ranking officials while in office). Finally, in regards to social matters, police repression of demonstrations against homophobia as well as the language used by PiS politicians commenting on the subject of homosexuality made headlines in all of Europe, but these extreme gestures were not followed by laws which would introduce even more discrimination based on sexual orientation into Polish law.

The 2005-2007 period resembled a failed overhaul of the state, as the PiS governments lacked sufficient political capital to truly transform the country. PiS’s influence has perhaps proved most permanent in the field of public media. Polish state-run television (three main channels and one news channel) as well as public radio were still under PiS control in June 2010, although this situation was then drawing to an end due to the victory of the PO candidate in the presidential election. The daily newspaper Rzeczpospolita (the country’s fourth-biggest daily with a circulation of 170,000 copies), 49% of whose shares are owned by the state, has been a proponent of PiS policies ever since it opted for a more conservative editorial policy in 2006. Among privately owned media, the weekly Wprost (with a circulation of approximately 180,000 copies) was previously known for its pro-PiS stance, but a change of ownership and a new editorial team brought around a change of direction in June 2010. PiS also enjoys the support of Catholic and nationalist media such as the daily Gazeta Polska (with a circulation of 70,000), as well as the media group controlled by the Redemptorist congregation and Father Rydzyk: the daily Nasz Dziennik (circulation unknown), Radio Maryja and the television channel Trwam. These media outlets, traditionally linked to LPR circles, were particularly courted by PiS during its coalition with the extreme-right party. Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz was the Polish first head of government to appear on Radio Maryja as a guest.

PiS’s permanent attempts at institutional revolution and the climate of witch-hunt which they had created, did not resonate well with voters. Neither did PiS’s tendency to do away with checks and balances as well as civil liberties in the name of improvements to the democratic system. The early parliamentary elections organized in the fall of 2007 following the break-up of the PiS-LPR-Samoobrona government coalition brought to the polls 4.5 million more voters than in 2005. Most of them did not vote for PiS. With 41.51% of the vote, PO emerged as the winner. PiS actually improved upon its 2005 score with 32.11% of the vote (compared to 26.99% in the previous election), managing to keep the core of its 2005 electorate (approximately 3 million voters) while attracting numerous LPR and Samoobrona voters. These two fringe parties were the main losers of this election, failing to reach the 5% threshold necessary to obtain parliamentary seats (Samoobrona with a result of 1.53% down from 11.31% in 2005, and LPR with 1.30% of the vote, down from 7.97% in 2005). The takeover of a large proportion of these parties’ electorates is perhaps PiS’s main political victory in the 2005-2007 period. Higher turnout in the 2007 election (53.88%, the highest since 1989) did not play out to PiS’s advantage. Largely absent at the polls in 2005, city-dwellers and young voters made their voice heard in 2007 by choosing PO. Turnout in cities with over 250,000 inhabitants was beyond 60%, reaching 73.44% in Warsaw. Commentators in the weekly Polityka stated, “because of the higher turnout, [PiS’s message], tailor- made for a chosen group of a couple million voters, failed. This message could not resonate with voters outside of that group; it was too simplistic and univocal”13.

PO had taken advantage of its two years in opposition to consolidate its program and emphasize its rejection of PiS’s messianic, dividing rhetoric. PO had also managed to win the office of mayor of Warsaw back from its rival, with the election of PO candidate Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz. But even though the party came in first place in the 2007 parliamentary election, it did not obtain a majority and needed a coalition partner to govern. An alliance was formed with PSL, a party boasting a mainly rural electoral base. This partner’s demands, as well as the necessity of “cohabitation” with President Lech Kaczyński (PiS) contributed to limit the scope of the government’s action between 2007 and 2010.

The need to form a coalition government with PSL has often been seen as a blessing in disguise for PO, an “excuse” exempting the party from “implementing its orthodox free-market program”14. The scope of PO’s victory in 2007 could be seen as “disproportionate compared to actual support for free-market liberalism [within the population]”15. Despite its electoral result, PO remained unable to affirm its free-market identity.

Therefore, the Tusk government did not put the proposal of a single tax rate back on the table. However, it did attempt to introduce a series of free-market oriented reforms promoting “small government” and budget cuts, most notably an overhaul of the healthcare system. This project stipulated that the debts of healthcare providers (which are run by municipalities) would be refinanced by the state, on the condition that the providers be then transformed into for-profit companies and their directors become fully responsible for their finances. The bill introducing these changes was adopted by the Sejm (lower house of parliament) but vetoed by the president, sharing the fate of seventeen other bills drafted by the government. (A presidential veto can be overruled in the Sejm by a three-fifths majority. Ever since PO took power, this has happened only in one instance, in the case of a PO-sponsored bill limiting the right to early retirement for a certain number of professions, which was adopted despite the president’s veto).

To this day, the Tusk government has suffered two major drawbacks, regarding the abovementioned healthcare reform as well as the failure to restructure a farmers’ retirement fund, heavily subsidized by the state with little contribution from farmers themselves. The European Commission has invited Poland on numerous occasions to put an end to this situation, which is a permanent obstacle to better budgetary balance. But despite widely communicated good intentions, the PO-PSL coalition did not manage to reach an agreement on an ambitious reform plan, due to the opposition of PSL’s rural electorate.

Among the government’s main achievements (beyond its victory on early retirement rights) are:

- the armed forces reform, reducing the size of the army from 150,000 to 100,000 troops and professionalizing the military (thus putting an end to military service);

- withdrawal of Polish forces from Iraq in 2008-2009 and a strengthened Polish presence in Afghanistan;

- the establishment of a road map for Poland’s inclusion in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II), and then in the eurozone. Originally, 2012 was the projected date for adopting the European currency. However, following the economic crisis of 2008, this goal was revised and the new planned date is 2015;

- a series of measures promoting free enterprise, such as lower capital requirements for new businesses, the creation of a one-stop service bureau for entrepreneurs, a remodeling of the “public-private partnership” making it a more attractive framework for investors;

- a constitutional amendment banning individuals with criminal records from running in parliamentary elections.

In total, during the first two years of the Tusk government, 57% of bills adopted by parliament concerned business- and entrepreneurship- linked issues16. The pace of lawmaking was fast in 2008 but slowed down in 2009, due to the economic crisis and the ever-present threat of a presidential veto.

In line with its free-market principles, the Tusk government did not attempt to fight the financial crisis and the downturn by injecting state funds into the economy. Crisis remedies introduced in 2008-2009 were limited to the refinancing of one bank, an extension of state guaranties protecting bank accounts, tax breaks for investors as well as increased job market flexibility. It is not easy to evaluate the effects of these measures. Still, Poland turned out to be the only EU member state to experience GDP growth in 2009 (+1.8%17). A combination of reasons was put forward to explain this result:

- a low level of “contamination” of the Polish financial market with complex, high-risk financial products carrying “toxic” components;

- low household debt, which helped maintain consumer spending on the domestic market;

- a good export situation due to the fall of the Polish złoty.

The positive economic trends seem likely to persist, as Poland’s GDP grew by 3% in the first quarter of 2010.

This economic situation partially accounts for the government’s relative popularity: in April 2010, 43% of the population expressed support for the government (29% said they did not support it). Since the Tusk government took office, its approval ratings have always stayed above its disapproval ratings, which is rare for a Polish government18. In April 2010, a majority of Poles agreed with the statement that “the government’s policies create the right conditions for an improvement of the economic situation”, for the first time since late 200819.

As far as European and foreign policy is concerned, the Tusk government has worked towards an improvement of Polish-German and Polish- Russian relations, despite PiS’s attempts to brand PO as a party pandering to foreign influence. These relations had greatly deteriorated during PiS’s time in office and through President Lech Kaczyński’s actions, most notably during the armed conflict between Russia and Georgia in 2008. Donald Tusk managed to secure Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s presence at the 70th anniversary commemoration of the start of World War II, on September 1st, 2009 in Gdańsk. Also in 2009, Jerzy Buzek, a former AWS prime minister and PO member of the European parliament since 2004, was elected president of the European parliament. This was viewed in Poland as a success for the country, its government and the ruling party.

Regarding the media, PO has found it impossible to improve relations with state-owned television and radio before the introduction of radical changes in the make-up of the National Radio and Television Broadcasting Council. However, the party enjoys the support of Gazeta Wyborcza, a historic daily newspaper founded in 1989 by prominent members of Solidarność. Gazeta is currently Poland’s second-largest daily with a circulation of approximately 460,000 copies. The weekly Polityka (200,000 copies) as well as the private television channels TVN and TVN24 are also favorable towards PO.

After two and a half years in government, PO seems to be well placed to stay in power following the 2011 election. A victory in the 2010 presidential election was needed by the party to increase its chances of future success by avoiding another painful cohabitation with a PiS president.

New developments within the right

Facing a presidential election that was to take place initially in October 2010, PO brought an innovative idea to life: the party’s leader, Prime Minister Donald Tusk, decided against running and set out to organize a primary in order to select a candidate. This procedure, which will be discussed more broadly in the next section of this article, resulted in the selection of the marshal of the Sejm (speaker of the lower house of par- liament), Bronisław Komorowski. Soon thereafter, the Smolensk tragedy brought about another surprise: following the incumbent president’s death, his brother Jarosław Kaczyński decided to represent PiS in this election. Jarosław Kaczyński’s rejection of the score-settling rhetoric to which PiS had accustomed voters, and his apparent abandon of the idea of a “Fourth Republic”, were unexpected, dividing the commentators and public opinion as to whether these were purely “stylistic” campaign choices, or the signs of a new approach towards politics on the right.

PO takes a stab at internal party democracy

Donald Tusk’s Solidarność pedigree, his government’s relative popula- rity as well as the 2009 “economic miracle” when Poland was the only EU member state to experience GDP growth could have made the prime minister a good presidential candidate. It should be said that in 2005, PiS managed to spread doubt over Tusk’s own “national identity”, emphasizing his Kashubian roots (an ethnic minority from north-west Poland) and publicizing the fact that his grandfather, a resident of western Pomerania, a traditionally Kashubian territory which was under German control, was drafted by the Wehrmacht during World War II. But since then, the matter has been considered closed and attacks of this sort now seem to anger public opinion.

Still, Donald Tusk preferred to remain prime minister, explaining that he needed to continue implementing reforms. It is also no secret that PO wishes to reduce the role of the president (as well as the president’s capacity to interpret the constitution in his favor and claim certain pre- rogatives which are not clearly attributed within the dual executive), thus moving towards a system that would be modeled after the German or Austrian one. (In February 2010, PO put forward a draft proposal of a revised constitution including such changes. However, since it does not have a parliamentary majority allowing it to modify the constitution, the party is hoping that with a PO president there will be a de facto change in the balance of power between the president and the prime minister).

The idea of selecting a candidate other than the leader of the party also made political sense within PO because of the unpopularity of the incumbent, Lech Kaczyński, considered easy to defeat as his approval ratings had never risen above 27% throughout 200920.

Last but not least, a primary election provided PO with the opportu- nity to resuscitate a certain democratic tradition dating back to its ori- gins, when the party presented itself as a “civic movement”, distancing itself from co-optation and nepotism, which were rife within AWS in the early 2000s. Months after its creation, PO had already tried organizing primaries to select candidates for the 2001 parliamentary elections, but the experience was a failure. The presidential election of 2010 seemed like a good occasion to restore the procedure to favor and modernize the party’s image. Also, a primary election provided a means of focusing media attention on PO while making PiS look like a centralized, authoritarian party where the reigns of power were held exclusively by the Kaczyński brothers.

Two candidates, Bronisław Komorowski and Radosław Sikorski, took part in the primary. The weekly Polityka described the build-up to the election as a “velvet campaign”21: the candidates took great care not to attack each other directly and to preserve a friendly tone during debates, in a display of party unity.

The 58-year-old Bronisław Komorowski, marshal of the Sejm (speaker of the lower house of parliament), comes from an aristocratic family. He joined the anti-communist opposition movement at a young age, and just like Donald Tusk and Lech Kaczyński, joined Solidarność in 1980. A member of UD, then UW, Tadeusz Mazowiecki’s party, he was deputy minister of defense in the years 1990-1993 (with the excep- tion of a short period in 1992 when the conservative government of Jan Olszewski took power). A minister of defense in 2000-2001 within Jerzy Buzek’s AWS government, he joined PO soon after it was created in 2001. In the primary election, he seemed to have the support of most PO leaders including Donald Tusk. It was said that the prime minister saw Komorowski as a consensus candidate, with broader popular appeal than his rival, the foreign affairs minister Radosław Sikorski.

A relatively young politician (at 47) with a very colorful resumé, Radosław Sikorski is a favorite of PO’s younger members. After graduating high school, he left Poland for the United Kingdom, where he studied at Oxford University and managed to obtain political asylum after martial law was introduced in Poland in December 1981. Upon graduating, he became a free-lance journalist and war correspondent, working out of Afghanistan for several British newspapers and for the conservative National Review in America. Returning to Poland at the start of the country’s democratic process, he was a correspondent for the Sunday Telegraph and an advisor to Rupert Murdoch at a time when the News Corporation was trying, unsuccessfully, to expand unto the Polish market. Radosław Sikorski joined the conservative wing of the Polish right and became deputy minister of defense within Jan Olszewski’s 1992 government. During his time in office, he was widely criticized for his dual citizenship (Polish and British, since the mid-1980s). Despite this controversy, he was appointed deputy minister of foreign affairs in Jerzy Buzek’s AWS government (1998-2001). Elected senator in 2005 for PiS, he was subsequently minister of defense in the PiS governments of Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz and Jarosław Kaczyński. A staunch atlanticist for many years, Radosław Sikorski had excellent contacts among the neoconservatives in the Bush administration. But a serious conflict with the Kaczyński brothers brought about his resignation from the foreign affairs ministry in early 2007. The same year, he switched sides and was elected member of parliament for PO, before becoming minister of foreign affairs in Donald Tusk’s government. Characterized by a combative political style and a more conflict-prone personality than his rival Bronisław Komorowski, Sikorski was also seen as less legitimate to represent PO, as a recent party member and a “flip-flopper” in 2007. This made him a perfect target for PiS. Considered a “traitor” by Jarosław Kaczyński, he was again attacked for his British citizenship (even though he had finally given it up in 2006) and his marriage to an American citizen, the Washington Post journalist Anne Applebaum. Donald Tusk must have welcomed the result of the primary with a cer- tain dose of relief: with 68.5% of the vote, Bronisław Komorowski had scored a clear victory over Radosław Sikorski (31,5 %).

PO members were given one month (February 17 till March 18 2010) to mail in their vote. Afterwards one week was devoted to online voting (March 18 to 25). Each voter had to identify themselves with their full name in order to avoid fraud. This constraint was later portrayed as a possible reason for low turnout, even though the party made it clear that members’ personal information would not be used to determine how each member voted. The turnout amounted to 47.47%: a little over 21,000 party members voted (nearly 17,000 voted online and over 4,000 mailed in their ballot). Experts agreed that the turnout was a disappointment. According to sociology professor Jacek Raciborski, given that PO is “a more of an elite, cadre party than a mass party”, its members should have been more strongly mobilized in the context of a primary. Political scientist Marek Kochan claimed that this was a way for PO members to express their dissatisfaction with Donald Tusk’s decision not to run in the election. Sociology professor Andrzej Rychard suggested that the low turnout revealed the presence of many “dead souls” within the party’s ranks, passive members who pay membership fees but show little interest in party life22.

Even though PO leaders show commitment towards party democracy and seem eager to organize other primaries in the future, it is not clear whether such initiatives can be truly successful in Poland in the coming years. Holding party primaries remains a challenge in a country with notoriously low turnout rates in national elections.

“Putting an end to the war among Poles”

From his speech in zakopane, may 29, 2010, as quoted by Gazeta Wyborcza.

From the online chat on may 13, 2010, pl.

Aleksandra Pawlicka, Wprost, June 6, 2010.

The Smolensk plane crash on April 10 shook up the Polish political stage. As Sejm marshal, Bronisław Komorowski was under the constitutional obligation to take over as interim president, while being PO’s designated presidential candidate. A special presidential election was announced for June 20 (first round) and July 4, 2010 (second round). In the context of national mourning, faced with a mass movement of people presenting their condolences and honoring the victims’ memory, the main political players could not proceed with an “ordinary” election campaign.

The PO candidate was now facing a difficult opponent: Jarosław Kaczyński, the dead president’s brother, who suddenly had the sympathy of many Poles’ due to his personal loss. An unpopular prime minister in 2006-2007, Kaczyński experienced a surge in popularity and, eventually, obtained good results in the election: 36.5% of the vote in the first round and 46.9% in the runoff (Bronisław Komorowski winning with 41.5% in the first round and 53% in the second round). Beyond his personal tragedy, the leader of PiS greatly enhanced his chances in the election by adopting a new political personality, avoiding any direct attacks on his opponent and championing national unity. With this new discourse, Jarosław Kaczyński seemed to break away from the sectarian approach that had come to characterize PiS over the years. In deep contrast to his usual, uncompromising, “Robespierre-like” attitude, he surprised commentators with the following gestures:

- his recording of a video message addressed to Poland’s“Russian friends” and broadcast on YouTube (with Russian subtitles), in which Jarosław Kaczyński, previously known to be highly “russophobic”, thanked the Russian people for the compassion that they had expressed following the presidential plane crash;

- the explicit abandon of his wish to install a new regime known as the “Fourth Republic”. In an online chat on the Salon24 web portal on May 13 – his first public pronouncement since the plane crash on April 10 – Jarosław Kaczyński stated that the controversy over the idea of regime change and the need to “cleanse” the political establishment now belonged to the past. He also expressed a “need for consensus” with the government23, as well as a wish to put an end to what he dubbed “the Polish-Polish war”24;

- his new focus on the economic challenges facing Poland, especially the challenge of economic growth and the need to make the country “attractive” to investors. Jarosław Kaczyński also declared that he sought to “reconcile modernity and tradition” in Poland in his take on economic and social issues25.

Skeptics questioned the reality of the PiS leader’s metamorphosis and coined the nickname “Dr Kaczyński and Mr Hyde”26. But regardless of how deep Jarosław Kaczyński’s aspiration towards national unity really was, he had managed to launch a rather successful offensive designed to win votes in the center of the political spectrum. While promising to continue his brother’s policies, he showed remarkable determination to open up his party and change the terms of the rather sterile rivalry with PO in which PiS had become somewhat entrapped.

Both right-wing parties tried to attract leftist voters prior to the pre- sidential election. In his role as acting president, Bronisław Komorowski submitted the candidacy of Marek Belka, an economist and former SLD prime minister, for the presidency of the Polish central bank. In parliament, the candidacy was approved with the votes of PO and SLD lawmakers. Until this event, all forms of collaboration between PO and the left had been implicitly banned. PiS also took a stab at courting the left: the good result of SLD’s young presidential candidate, Grzegorz Napieralski, in the first round of the election (13.7%) inspired the most astounding of all of Jarosław Kaczyński’s metamorphoses. On a number of occasions, the PiS candidate, previously known for his staunch anti- communism, invited left-wing voters to support him in the second round of the election, not only emphasizing the social aspects of his program, but also making positive comments about a former first secretary of the Communist Party, Edward Gierek, who was in power in the 1970s. Jarosław Kaczyński further stated that he wished to ban the term “post- communists”, preferring to speak of “left-wing politicians”. From now on, it is very likely that both PO and PiS will continue to make efforts designed to win votes from the center and the left, especially in the run-up to parliamentary elections which will take place in the fall of 2011.

Whichever terms are chosen to describe the nature of the PiS-PO divide – the clash between a “social” and a “liberal” outlook, or between “tradition” and “modernity” – it is safe to say that for both sides, this divide is neither comfortable nor satisfying. PiS seems to have become wary of its own incapacity to extend its base beyond an ageing electorate whose worldview and lifestyle are in the process of becoming extinct. PO is aware of free-market liberalism’s low appeal in Poland. In the presidential election of June-July 2010, held in a very specific climate following the Smolensk plane crash, the gap separating the two main candidates was too small to tell which party has so far been the most successful in repositioning itself in order to remain in sync with voters. Upcoming local elections in late 2010, as well as parliamentary elections in October 2011 will be more likely to provide the true test of the balance of power within the right.

Just as the history of the right has determined the history of Poland’s democratic transition, the future of the right will make its mark on the most important events in the country’s near future. The next parliamen- tary elections will take place during Poland’s European presidency, which starts on July 1, 2011. From the standpoint of European integration, will Poland’s first ever presidency be truly memorable, or will domestic elec- toral issues reduce its scope? Will the negotiations on the EU’s financial perspectives for 2014-2020 (which are to be held at the end of 2010) result in a positive outcome for Poland? Will the country manage to persuade its European partners to share its vision of “energy security”, while continuing to improve its relations with Russia? Will Poland with- draw its troops from Afghanistan without weakening its position within NATO, as Bronisław Komorowski has promised? Will the scope of its public finance reform and deficit reduction efforts be sufficient to allow Poland to join the eurozone in 2015? The political actions of the right’s leaders may well determine the answers to all these questions. More than twenty years after the start of the country’s systemic transforma- tion, the heirs of Solidarność still have a serious political and historical responsibility to carry.

No comments.