The state of the right: Spain

Introduction

History of the Spanish Right from reaction to conservatism

From the absolutist reaction to the Francoist dictatorship

The political transition towards democracy

The Spanish Right in the early 21st century

The role played by the Right in the opposition

The Spanish Right’s structures: constituency, networks, internal organisation

The PP’s electoral base

Sociological profile of the PP’s constituency

The PP’s media and intellectual networks

The PP’s internal organisation

The Spanish Right’s ideological positioning and its relationship to liberalism

The People’s Party: A political force claiming to be more liberal than the Right

An ambiguous relationship with economic liberalism

The People Party’s conservatism in societal matters

Opposing territorial autonomy

Conclusion

Summary

The Spanish Right occupies a special place in Europe. Its history, and the singular nature of its political groups distinguish it from the continent’s other right-wing movements. From the moment democracy was re-established in Spain until the present day, the right-wing party, the People’s Party, has undergone political, organizational, electoral and programme-related changes.

In what ways do they resemble, or differ from, other European right-wing parties? This article will attempt to answer that question.

Joan Marcet,

Professor, Autonomous University of Barcelona, and Director of the Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials (ICPS).

The Spanish Right occupies a special place in Europe. Its history, and the singular nature of its political groups distinguish it from the continent’s other right-wing movements. Through the 19th century and most of the 20th century, the Spanish Right has demonstrated its opposition to a democratic regime and to a Rule of Law as they emerged from the successive bourgeois revolutions that occurred in other countries of modern and contemporary Europe. From the moment democracy was re-established in Spain until the present day, right-wing parties have undergone political, organisational, electoral and program-related changes. In what ways do they resemble, or differ from, other European right-wing parties? This report will attempt to answer that question.

History of the Spanish Right from reaction to conservatism

From the absolutist reaction to the Francoist dictatorship

The best historical analysis of contempoary Spain is still the book by Raymond carr, Spain 1808-1939, Oxford University press, 1966 (Spanish version: Ediciones Ariel, 1969). A second version was published in 1982: Spain, 1808-1975, and the third version, Spain 1808-2008, was co-authored by Juan pablo Fusi (Ediciones Ariel, 2009). For more information, see volumes 6 to 12 of Historia de España, published in 12 volumes, co- directed by J. Fontana and R. Villares (Barcelona: crítica/Marcial pons [co-publishers], 2007-2008).

A. González casanova, La derecha contra el Estado. El liberalismo autoritario en España (1833-2008) (Lerida: Milenio, 2009).

VSee J. Linz, “The party System of Spain: past and Future” in S.M. Lipset and S. Rokkan (dir.), Party System and Voter Alignments (new York: Free press, 1967).

The Lliga Regionalista, and later the Lliga Cataloniana, were catalonia’s leading right-wing parties until the end of the Second See I. Molas, Lliga Cataloniana (Barcelona: Ed. 62, 1972).

See corcuera, Orígenes, ideología y organización del nacionalismo vasco (Madrid: Siglo XXI, 1980).

personal letter from pope pius XII to Franco, cited by A. González casanova, op. cit., p. 55.

An abundant bibliography is available on the Francoist We can cite Guy Hermet, L’Espagne de Franco (paris: A. colin, 1974); S.G. payne, El régimen de Franco (Madrid: Alianza, 1987); and E. Diaz, pensamiento español 1939-1975 (Madrid: Edicusa, 1978).

On political transition in Spain, see carcassonne and p. Subra, L’Espagne ou la démocratie retrouvée (paris: Enaj, 1978); J.M. Maravall, La política de la transición (Madrid: Taurus, 1981); R. Morodo, La transición polí- tica (Madrid: Tecnos, 1984); M. caciagli, Elecciones y partidos en la transición española (Madrid: cIS, 1986); cotarelo (ed.), Transición política y consolidación democrática en España 1975-1986 (Madrid: cIS, 1992).

Swept by civil wars, mutinies and military uprisings, and marked by the gradual decline of the old colonial empire, 19th-century Spain did not see the advent of a genuine State in the modern sense of the term1. The war against the French occupant, and the establishment of a conservative constitutional monarchy which would last until Primo de Rivera’s dictatorship in the early 20th century, were the two structuring periods of that century. Although the government’s right-wing political discourse remained unchanged, it was limited to supporting those institutions which enabled it to maintain its authority over the king, the army, the Church – and even the media. In a political environment marked by constitutional fragility, these seem to have been the institutions genuinely responsible for Spain’s inability to modernise itself.

As José A. González Casanova points out in a recent study,2 the two right-wing movements sharing power at that time were similarly distrustful of democracy which, in their view, would lead to social chaos. The bourgeoisie’s conservative representatives were therefore categori- cally opposed to democracy and freedom. Although representatives of the middle class embodied a more progressist liberalism, they were no more in favour of universal sufferage. In the last quarter of the 19th century, these two movements were heading towards a conservatism fiercely opposed to Democratic, Republican and Socialist theologies. Furthermore, the latter had been long discredited after the failure of the 1868-1874 revolutionary episode characterised by several attempts to reinstate a Republican regime, and which ended with the establishment of a stable constitutional monarchy. Spanish political parties remained structurally weak for many years. Political organisations were granted legal status only after the enactment of the 1887 Law on Associations. As shown in the Juan J. Linz’s pioneer study,3 Spanish parties at that time merely had an association statute, and had failed to develop any efficient organisational or membership system to such a degree that the partisan right-wing structures disintegrated when their key leaders, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo and Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, left the political scene. Despite this structural weakness, the British model-inspired bipartisan system long prevailed in the Spanish Parliament and among voters. Spain therefore experienced an alternating succession of liberal conservatives and progressist liberals.

According to Linz, multiple factors led to this power-sharing between two ideologically similar parties. It can be accounted for by caciquismo (clientelism) and corruption, voter weariness after half a century of armed civil unrest, by Spain’s socio-economic structure and lastly by the role of the Church and its relationship with the two leading parties.

The loss of the Spanish colonies at the end of the 19th century was a turning point in the countries’ political life, highlighting the decline of Spanish power. Leaders of the ruling conservative Right called into question for their lack of military and diplomatic preparedness for the wars involving Spain in South America and North Africa. In the early 20th century, new conservative party leaders Francisco Silvela and Antonio Maura acceded to power. In hopes of “reviving” Spain, they launched a political modernisation movement aimed at “revolutionising the system from the top down” and attracting greater support from the middle classes. At the same time, the right-wing regionalist parties continued to grow, buoyed by the growth of the Catalonian and Basque bourgeoisie. La Lliga Regionalista, a Catalonian regionalist party led by Enric Prat de la Riba and Francesc Cambó, gradually supplanted the dynastic parties by presenting itself as the champion of the Catalonian bourgeoisies’ conservative interests4. The Basque bourgeoisie platform was quite similar: closer to the Spanish bourgeoisie from an economic viewpoint, it gradually began to advocate a particular nationalistic sense of identity which ultimately gave rise to the founding of a Catholic- oriented political party, the Partido Nacional Vasco (EAJ-PNV) [Basque Nationalist Party].5 The regionalist parties eventually established close ties to those in power. However, due to the constant rifts among the conservatives and to electoral fraud, these attempts to modernise the Spanish constitutional monarchy failed. The last years were marked by a slow disintegration of influence, until 1923, when Primo de Rivera established a military dictatorship through a coup d’état. of the Second Republic which, in 1931, led to the first truly democratic Constitution in Spanish history. Under the Republic, inasmuch as it was no longer possible for the Spanish Right to recuperate and preserve power via traditional political channels, it embarked on an open political war against the new regime.

Ultimately, it instigated and made possible the military uprising of July 1936 led by General Franco, which caused the ensuing civil war in which the two sides of Spain whose praises were sung by the poet Antonio Machado confronted each other: that of the Right (fundamentalist and centralist Catholic) and that of the Left (anti-clerical, autonomist or regionalist). At the end of the war, Franco seized all powers associated with the new dictatorial regime and destroyed the foundations of the short-lived democratic State which the Republic had begun to set up. The Right and the Catholic Church itself celebrated in unison the rebels’ victory: “Lifting our hearts to God, we give sincere thanks with Your Excellency for the victory of Catholic Spain.”6

Under Franco’s regime, political parties were banned (not only left-wing, but also democratic parties) or dissolved (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas – CEDA) [Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right], Lliga Cataloniana, etc. From then on, the right-wing party members who had participated in the military putsch formed an organisation having little in common with a traditional political party. The Movimiento Nacional, presided over by Franco himself, attracted Falangists (militants of the Fascist-inspired party, the Falange Española founded by José A. Primo de Rivera, son of the dictator), Carlists (conservatives and traditionalists opposed to 19th-century liberals), monarchists and former partisans of the pro-Catholic Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right. Spanish Right groups were thus united under the patronage of Franco and neutralised.

Despite a few ideological differences, power struggles and minor disputes over economic issues, the political families who cohabited within the National Movement shared the same Spanish Right classic principles: traditional Catholicism, Spanish nationalism, programme for order and social peace, elitism, support of the traditional family, rejection of new democratic ideas (public freedoms, parliamentarism, political pluralism, etc.), charity and benevolence rather than “social justice.”7

After Franco died and Juan Carlos I became King of Spain, a period of political transition began which enabled the country to gradually transition from an authoritarian monarchy – the Francosit legacy – to one that was democratic and constitutional. This transitory phase started with the July 1976 appointment of Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister of Spain and ended with the Socialists’ rise to power in the autumn of 1982, under the leadership of Felipe Gonzalez.8

The political transition towards democracy

On the Extreme Right in Spain, see casals, “Spain: The Long Journey from neo-Francoism to national- populism (1975-2005),” in X. casals (éd.), Political Survival on the Extreme Right (Barcelona: IcpS, 2005).

On this party, see L. López nieto, Alianza Popular: estructura y evolución electoral de un partido conser- vador (1976-1982) (Madrid: cIS, 1988); Lagares, Génesis y desarrollo del Partido Popular de Galicia (Madrid: Tecnos, 1999); and for a more detailed history covering a longer period, see R. Baón, Historia del Partido Popular. Del franquismo a la refundación (Madrid: Ibersaf editores, 2001).

The UcD’s evolution and crisis were studied by Huneeus in La Unión de Centro Democrático y la transición a la democracia en España (Madrid: cIS, 1985), and by M. caciagli, op. cit.

On the cDc, see Marcet, Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (Madrid : cIS, 1987), and also J.B. culla et al., El pal de paller (Barcelona: pòrtic, 2001).

On the pnV, in addition to the already-cited work by corcuera, see J. L. de la Granja, El nacionalismo vasco: un siglo de historia (Madrid: Tecnos, 1995); F.J. Llera, Los vascos y la política (Bilbao: UpV, 1994); S. pérez-nieva, “The pnV: Redefining political goals at the turn of de century,” in L. de Winter and p. Lynch (dir.), Autonomist Parties in Europe (Barcelona: IcpS, 2006), Vol. 1.

Between 1976 and 1982, four general policy guidelines could be identified within the Spanish Right.

The nostalgic Right, which supported the Francoist dictatorship until the end, was against any changes in the regime and in favour of maintaining the status quo. It was composed of most of the army’s highest- ranked officers, of militants from some of the most activist Extreme Right splinter groups (successors of the former pro-Falangism, pro-Carlism or simply Francoist groups) or even of Catholic Integrists. The members of these right-wing groups repeatedly conspired against democratic reform until the aborted coup d’état of 23 February 1981 led by a group of high- ranking officers from the Spanish army and police force, the Guardia civil9. The large majority of these Extreme Right groups were eventually absorbed by the Partido Popular (PP) [People’s Party] – a merger which accounts for theis Right fringe’s lack of partisan and electoral visibility. The few remaining splinter groups represented an insignficant electoral force with a very low capacity for mobilisation. It was therefore the PP which, from the 1980s on, won this constituency’s allegiance.

The Neo-Francoists constituted a second component of the Spanish Right. Willing to accept the regime’s shift towards a “controlled democracy,” they nonetheless continued to champion a certain continuity with the past. Proponents of this movement included a large number of former ministers and senior officials of the Francoist era. They formed a group known as the Alianza Popular (AP) [People’s Alliance], a federation comprised of seven parties and political associations – all founded within a few months after Franco’s death – led by Manual Fraga Iribarne. Due to its Francoist origins, this movement from the start had the advantage of major financial contributions and the support of the still-intact Francoist State structures. It therefore seemed destined to become the largest conservative party of this new stage in Spanish democracy.10

The third component of the Right emerged under Adolfo Suárez’s leadership. As the key craftsman of the transition and the democratic reform, he created a new party, Unión del Centro Democrático (UCD) [Union of the Democratic Centre], which at first consisted of a federation of twelve parties of diverse opinions. This centre-right organisation played a ground-breaking role in Spanish politics during the transition period. Made up of Francoism’s most open movements and of small groups representing the former moderate democratic opposition, this party immediately adhered to the moderate-conservative programme. It contributed key support to the government and to the political class in power and played a consociacional role by facilitating agreement negotiations between the former regime’s supporters and the former democratic opposition. The UCD played a decisive role until the advent of democracy in the early 1980s, paving the way for the electoral and political transition led by Manuel Fraga’s People’s Alliance.11 The UCD’s officially dissolved itself early in 1983, right after the 1982 election defeat in which the party won only 6.7% of the votes and only 11 deputy seats.

The fourth component of the Spanish Right is regional. In the two nations with a political tradition – Catalonia and the Spanish Basque Country – the right-wing regionalist parties reorganised, as their ideological orientations were somewhat different from those of the national Right.

With the end of Francoism, a new centre-right group, the Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC) [Democratic Convergence of Catalonia], emerged in Catalonia, following the merger of various moderate and Catalonianist anti-Franco organisations. Presided over since its founding by Jordi Pujol, the CDC took part in the first 1977 elections at the head of a coalition, Pacte Democràtic per Catalunya (PDC) [Democratic Pact for Catalonia]. Since 1979, the CDC has formed a stable alliance with Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (UDC) [Democratic Union of Catalonia], a small Christian Democrat party founded at the end of the Second Republic.12

In the Basque Country, the moderate centre-right nationalism of the former group Partido Nacionalista Vasco (EAJ-PNV) [Basque Nationalist Party] soon recovered a key position on the political scene. This party, established in the traditional Basque forales [local] territories, professed to be a “pro-community party with a Christian Democrat programme.13

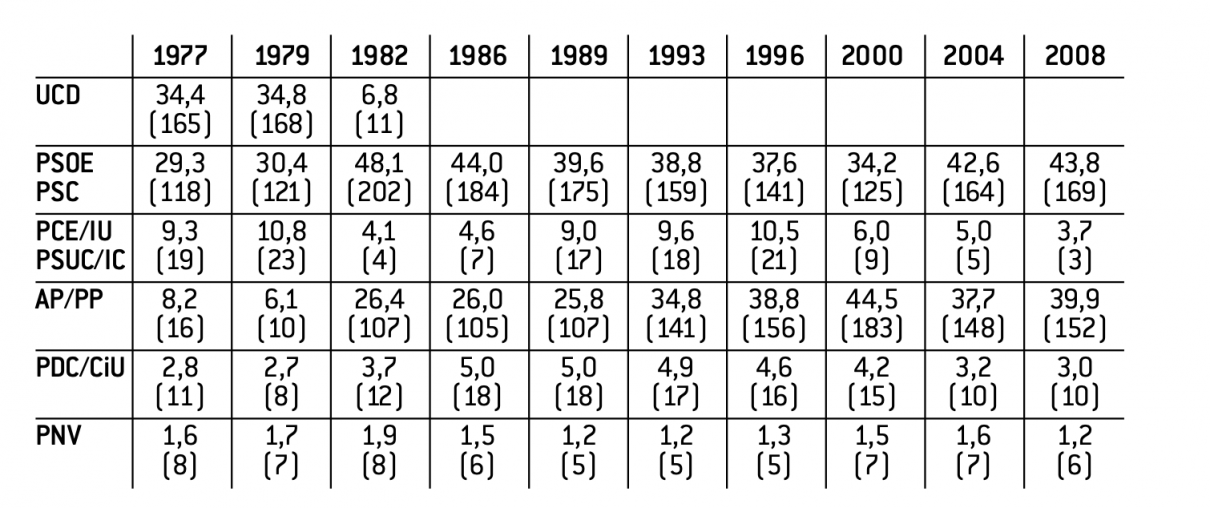

table 1 : Voting results for the chamber of Deputies’ main political parties in the various legislative elections (expressed in percentage of votes cast and number of seats won).

Source :

Table compiled by the author based on data from the Spanish Ministry of the Interior

As shown in Table 1, in the first elections of June 1977, the Right as a whole (UCD, AP, PDC, and the PNV) obtained 47% of the votes and 200 seats out of the 350 total seats in the Chamber of Deputies, as compared to 38.6% and 137 seats for the traditional left-wing parties (the Socialists and Communists). In the next elections in 1979, the outcome varied somewhat, with a gain for the Left (41.2% of the votes, 144 seats) and a slight decline for the Right (45.3% of the votes, 144 seats).

Yet the biggest change came in the 1982 elections. Thanks to increasing support for the Socialists, the Left won a broad majority (52.2 % of the votes and 206 seats) vs. a sharp drop for the Right (38.8 % of the votes and 138 seats). This time the People’s Alliance took first place, ahead of the UCD, which was rapidly losing ground. From then on, the Right was part of the opposition. In order to regain power, it adopted the “natural majority” strategy which consisted of rallying the entire Spanish Right

– then considered the country’s majority party – around the Popular Alliance. Hopes for a transfer of political power thus hinged on the political, electoral and strategic advances made by the Popular Alliance.

The Spanish Right in the early 21st century

On this point, consult the work by Baón, op. cit. and p. del castillo’s study, La financiación de partidos y candidatos en las democracias occidentales (Madrid: cIS, 1985).

The results obtained by the new pp in the 1989 elections may be qualified as “honourable” (see Table 1), considering the fact that José Aznar’s candidacy was officially announced scarcely two months prior to the date of said elections.

On the pp’s role during the 1993-1996 and 2004-2008 periods, see M. Maravall, La confrontación política (Madrid : Taurus, 2008).

See Lago and J. R. Montero, The 2004 Election in Spain: Terrorism, Accountability and Voting (Barcelona: IcpS-Wp 235, 2006).

The Popular Alliance’s strategy, as initiated in 1982 when the group was positioning itself as the sole conservative alternative to the Socialists, was not crowned with success in the 1986 elections. The movement experienced some stagnation and even a slight decline in the legislative elections and a real setback in the Basque regional elections that year. These results triggered a widespread internal crisis within the coalition. The party’s chairman, Manuel Fraga Iribarne, resigned and his entourage abandoned the party leadership.

Andalusian Antonio Hernández Mancha was chosen to head the AP at the party’s Eighth Congress in February 1987. Although an attempt was made to broaden the party’s electoral base by implementing an openly populist strategy, the AP remained subject to rifts worsened by accumulated financial debts.14 The party’s electoral defeats in the European, municipal and regional elections of 1987 – all three of which took place on the same day – underscored the new chairman’s weak leadership and accentuated the party’s crisis. The European list headed by former leader Manuel Fraga, obtained 24.7% of the votes (1.3% less than in the previous year’s legislative elections), while the AP won 20.3% of the votes in the municipal elections – a loss of more than 6 points as compared to the preceding local election of 1983. Only the regional election results mitigated the extent of these defeats: thanks to some post-electoral pacts, the AP managed to snatch away from the Socialists the governments of Aragon, the Canary Islands, and most importantly Castilla-León – whose presidency was assumed by young José M. Aznar. The Right heralded these results as a great victory.

The weakness of Hernández Mancha’s leadership continued to exacerbate the internal crisis undermining the party, which experienced a new electoral defeat in the 1988 regional Catalonian elections, in which the AP lost 2.5 points as compared to the preceding ballot, and lost 5 seats.

The Ninth Congress of January 1989 is considered to have been the one that reinvented the party. To initiate the process of politically recapturing the country, the AP’s chairmanship was once again entrusted to Manuel Fraga, whose task was to implement the movement’s strategic reorientation. Rather than attempt to unite the entire Spanish Right within a single political organisation, the goal was henceforth to seek an alliance with the remnants of other groups, ranging from the Centre to the Extreme Right, while offering a centrist and reformed image. To that end, major transformations were carried out within the internal and external workings of the party, which received a new name: Partido Popular (PP). Based on Fraga’s suggestion, José María Aznar was put at the top of the list of candidates for the presidency of the Spanish Government” (Prime Minister) in the October 1989 elections15 and served as the party’s Interim Chairman until the Tenth Congress, scheduled for April 1990. On that date, he was officially elected Chairman of the PP, and surrounded himself with a completely new and younger team, while Manuel Fraga was named Founding Chairman.

In its political messages, the new People’s Party defined itself as “a party whose broad bases unite and promote a tranquil cohabitation of liberal, conservative and Christian Democrat ideas.” The new team endowed the PP with strong structures designed to expand its stronghold throughout Spain. Thanks to this internal consolidation, the new party leaders hoped to institutionalise the party, thereby allowing it to gain better results in the polls.

The 1991 municipal and regional elections constituted the first success for the PP’s strategy. In the municipal rounds, it managed to increase its score by nearly 5 points throughout the country, thereby reducing by 3 points the distance separating it from the results obtained by the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) [Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party]. During the 1993 legislative elections, the PP rallied the support of a large coalition which, despite the Socialists’ victory, allowed the PP to reduce by 4 points the distance separating it from the PSOE (see Table 1). The new strategy for enlarging the electoral base from the Centre to the Extreme Right seemed to work in favour of the People’s Party, which enjoyed its first success in the 1994 European elections, when it outstripped the PSOE by 10 points. The 1995 municipal and regional elections consolidated this progress. In the municipal elections, the PP’s country-wide results surpassed those of the PSOE by nearly 5 points (during the preceding 1991 elections, PSOE had beaten the AP by more than 13 points), and the PP won back from the PSOE most of the pro- vincial capitals. In the regional elections, held at the same time as the municipals, the PP won the majority of seats in 11 of the 13 regional parliaments concerned by these elections, including 5 with an absolute majority.

A new stage began for the PP, which then had to consolidate and expand the newly acquired electoral base in order to win in the legislative elections. The PP’s opposition to the Socialist government was therefore implacable. All possible parliamentary, political, media, or social means were used to destabilise the PSOE, which had been in power for 13 years and whose fourth mandate was being tainted by a series of scandals.16 The Twelfth Congress of the People’s Party was held in January 1996 in anticipation of the legislative elections scheduled in March of that year.

The party set as its goal to “capture the Centre,” considering that its electoral base firmly established on the Right.

The 1996 elections brought victory by a small margin of 1.2% to the PP headed by José M. Aznar, who governed for four years with parliamentary support from the Catalan (CiU) and Basque (PNV) Right. His term was renewed in the 2000 elections, during which the PP obtained an absolute majority. Although the PP retained the support of the CiU – which needed the PP in order to maintain its government in Catalonia – it lost that of the PNV because of the Aznar government’s anti-terrorist strategy.

The period of governance by the People’s Party and José María Aznar can be broken down into two rather distinct stages. During its first legislature from 1996 to 2000, driven by the need to gain parliamentary support, the PP pursued a moderate policy despite heated confrontations with the press and José María Aznar’s increasing personalisation of power, exemplified by numerous political nominations. During the second legislature (2000-2004), thanks to its absolute majority in Parliament, the PP was able to act much more freely. Its policy was marked by an ostensibly liberal economic position and a intensifying authoritarianism. After 2002, the PP’s authority began to erode. The government started to suffer from its poor management of certain key events – notably the sinking of the sinking of the oil tanker Prestige in November 2002, and the May 2003 airplane crash in which 62 servicemen returning from Afghanistan lost their lives. Its social and territorial policies were in dispute. Labour market reform and the law concerning the Spanish National Hydrological Plan, which led to an inter-territorial confrontation, cast doubt on the PP’s competency to govern.

Two key events finalised the split between the People’s Party and its moderate constituency: Spain’s participation in the War in Iraq, which provoked turbulent demonstrations throughout the country, and its disastrous management – in terms of policy and communications – of the Islamist terrorist attack on Madrid four days before the 2004 elections.17

Aznar agreed not to serve more than eight years and had appointed Mariano Rajoy as his successor at the head of the Party and as a candi- date for the prime ministership. But the latter, after occupying positions in various ministries through the PP’s successive governments, failed to appear as a candidate in his own right, apart from his close association with J. M. Aznar’s immediate entourage.

The role played by the Right in the opposition

The Socialist Workers’ party (34.9 %) and the people’s party (35.6%) had a tie vote in the municipal elec- tions, which led both groups to declare themselves winners of the The Socialist party won a greater number of municipal councillor appointments than its rival (24,029 vs. 23,349), but the latter won a higher percentage of mayor appointments: 35.66% vs. 28.82% for the pSOE.

On the course of politics and elections in democratic Spain, see carles castro, Relato Electoral de España (1977-2007) (Barcelona: IcpS, 2008); another book containing more general data, but which is more focused on the 2004 elections, is: R. Montero, I. Lago and M. Torcal (dir.), Elecciones generales 2004 (Madrid: cIS, 2007). The same applies to J. Molins and p. Oñate (dir.), Elecciones y comportamiento electoral en la España multinivel (Madrid: cIS, 2006).

Unforeseen by any poll, the PP’s electoral defeat in March 2004 sent the Right back into the opposition. In October 2004, during the PP’s Fifteenth Congress, J. M. Aznar was proclaimed Honorary Chairman. Mariano Rajoy, who was elected Chairman, maintained a pro-Aznarist team – a choice which led to a series of internal confrontations and tensions throughout the 2004-2008 legislature.

The PP’s slim victory over the PSOE (by half a point)18 in the 2007 municipal elections was followed by a new upset in the March 2008 legislative elections which appeared to challenge Rajoy’s leadership. Nonetheless, after several months of uncertainty and internal conflict, the PP’s Sixteenth Congress in June 2008 voted to keep that Mariano Rajoy in office. The Party Chairman surrounded himself with a new team whose task it was to formulate a more centrist policy and to somewhat emancipate the Party from J. M. Aznar’s control.19

Since the advent of democracy in Spain, the right-wing regional and autonomist parties have played a key role in co-operating with the Spanish national Right on regional, as well as national, levels. The coalition – and later federation – of the parties Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya [Democratic Convergence of Catalonia] and the Unió Democràtica de Catalunya (CiU) [Democratic Union of Catalonia] thus continuously governed the Autonomous Community of Catalonia until 2003, when it was removed from government control by a coalition directed by the Partit del Socialistas de Catalunya (PSC) allied with post-Communists (ICV-EUiA) and left-wing nationalists (ERC). At the national level, CiU played a decisive role, first lending its parliamentary support to Felipe González’s Socialist government during its last years (1993-1996) and then to the PP’s government. Inspired by a very pragmatic form of Catalan nationalism, its Centre-Right, Liberal (CDC) and Christian Democrat (UDC) orientations allowed it to easily switch from Right to Left. The leader of the movement, Jordi Pujol, was President of the Government of Catalonia from 1980 to 2003 and is still President of the CDC. This political reconciliation between the CiU and the PP, and Pujol’s manifest sympathy for the Aznar government may account in part for Pujol’s defeat in Catalonia in 2003. After the Socialists came to power in 2004, the CiU refused to support the new government. Despite positions and a style very unlike those of the PP, Pujol’s party continued to support it from within the opposition.

During that same period, the Eusko Alderdi Jeltzalea-Partido Nacionalista Vasco (EAJ-PNV) [Basque Nationalist Party] which retained leadership of the Basque Autonomous Government until the April 2009 regional elections, also lent its support first to the Socialist governments and then to those of the PP. However, once its nationalist strategy had become more radical and its positions closer to those of the ETA’s entourage, the movement entered into direct competition with the People’s Party during the 2000-2004 legislature. Since 2004, the PNV policy has been to offer sporadic support to J. L. Rodriguez Zapatero’s Socialist government, despite the takeover of the Basque Autonomous Government by the PSE-PSOE in the wake of the 2009 elections. This support was facilitated by a more moderate and pragmatic leadership, which focused on the consolidation of the Basque Autonomous Government rather than on ideological confrontation.

The Spanish Right’s structures: constituency, networks, internal organisation

The PP’s electoral base

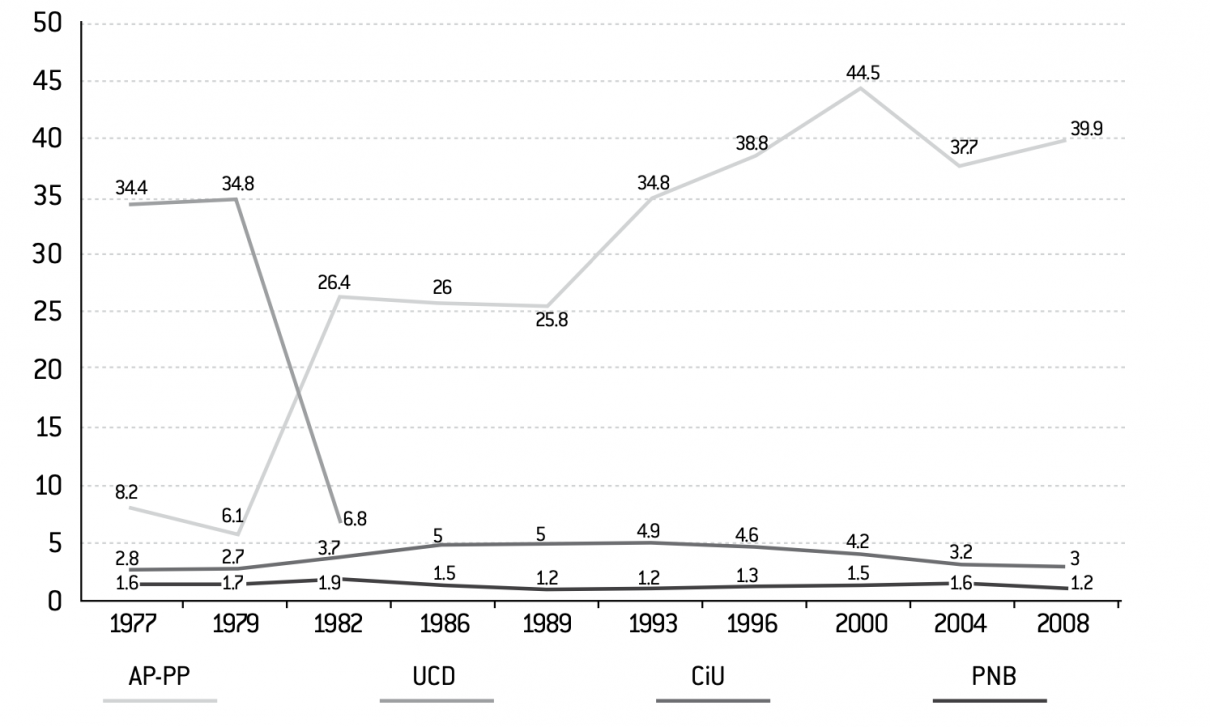

Graph 1 highlights two major trends in the Spanish Right’s voting results from the beginning of the democratic era in 1977: the progression of the popular movement (AP and later PP) and its retention as a possible alternative after its departure from the government on one hand, and the lesser – though often decisive – role of the Catalan and Basque right- wing groups on the other.

chart 1 : Voting trends of Spanish right-wing parties (expressed in percentage of votes cast): legislative elections (1977-2008)

Source :

ICPS, based on data from the Spanish Ministry of the Interior

In Galicia, the pp Government’s rule has been interrupted twice since Between September 1987 and the December 1989 regional elections, a motion to censor the people’s Government led to a Socialist government. The second interruption occurred between 2005 and 2009: after Manuel Fraga obtained four consecutive absolute majorities while at the head of the Galician pp, a coalition between the Socialist party and the Bloque nacionalista Galego [Galician nationalist Bloc] seized power, recaptured by the pp in April 2009.

After the 1977 and 1979 elections, during which a majority of the Right’s seats were occupied by the Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), the People’s Alliance (AP) won a large number of seats in 1982, establishing itself as the leading representative of the Right, despite the two subsequent elections’ disheartening results. In 1993, the Aznar-led PP made substantial gains which it consolidated in 1996 and in 2000 – the years in which it obtained its best results. In the last two electoral contests, the PP became the second strongest political power, yet maintained a solid electoral base which positioned it as the Spanish Right’s biggest party and as the Socialist government’s sole credible alternative.

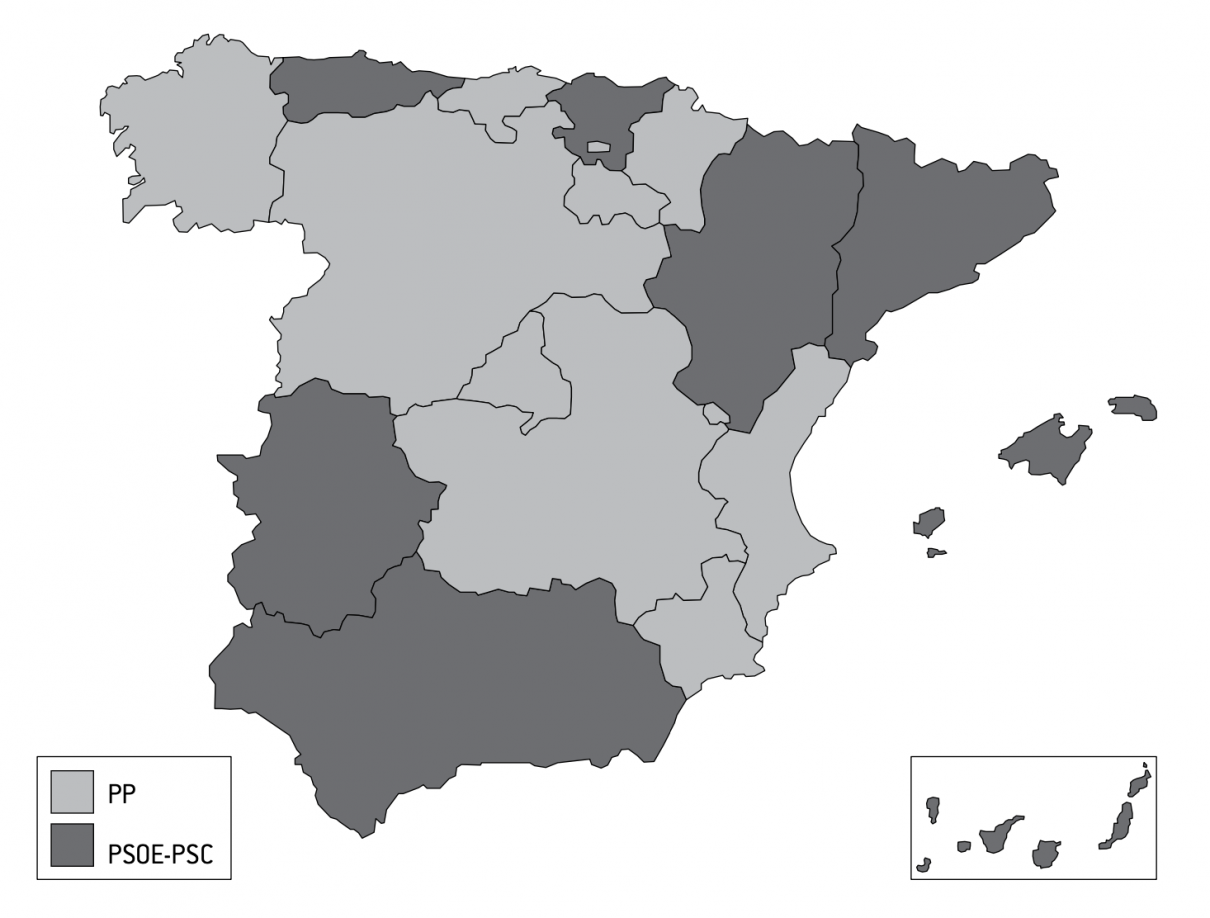

At the territorial level, the PP’s constituency is rather homogeneous, except for the Autonomous Communities of Catalonia and of the Basque Country, in which the presence of the two centre-right nationalist parties – the CiU and PNV respectively – relegate it to a third or fourth electoral position. The PP’s main electoral bastions are Madrid, the Valencian Community, Murcia, Galica and Castile-León, where it has been governing more continuously.20 The 2008 electoral map illustrates quite accurately these strongholds, which are spread out over the whole territory.

Map of voting results for the March 2008 elections to the chamber of Deputies, showing the winning party in each Autonomous community

Source :

ICPS, based on data from the Spanish Ministry of the Interior

In the June 2009 European elections, the People’s Party consolidated its positions in the aforementioned regions and recaptured first place in the Balearic and Canary Islands. In nearly all of the Autonomous Communities, the political contest was dominated by the confrontation between the PSOE and the PP, duplicating the national configuration. Catalonia and the Basque Country were natural exceptions: the political forces present were more diverse due to the regionalist issue. The Catalan and Basque Nationalist Parties in these communities were the Centre Right’s main political force. Also, the Socialists have their own organisation in Catalonia, the PSC, which is legally and formally differentiated and autonomous from the PSOE.

The PP nonetheless governs the majority of Spain’s Autonomous Communities, where it traditionally enjoys strong voter support. It is, however, struggling in the Castile-La Mancha Community, where the PSOE has won every regional election since 1983, and in the Balearic Islands where, in the most recent regional elections (2007), the PP lost the majority and the government to a large coalition led by the PSOE. In Andalusia, a Socialist electoral stronghold, an upsurge in votes for the PP was noted during the last 2008 and 2009 elections, which may mean that the PSOE may not be able to remain at the head of the regional government, as it has done since 1982.

Sociological profile of the PP’s constituency

See in this context Torcal and L. Medina, “La competencia electoral entre pSOE y pp: el peso de los anclajes de ideología, religión y clase,” in J. R. Montero, I. Lago and M. Torcal (dir.), op. cit.

Study 2757 of the cIS database.

See Molas and O. Bartomeus, Estructura de la competencia política en España: 1986-2000 (Barcelona: IcpS-Wp, 2001), no. 196.

Study 2701 of the cIS database.

The PP’s urban implantation has been growing since the 1990s. It therefore is the dominant party in municipal elections, particularly in Spain’s provincial capitals. Similarly, in legislative and European elections, it obtains the majority of votes in the large cities. The exceptions to this rule are Catalonia, where the regional Socialists have so far maintained their leadership, and the Basque Country, where the majority of urban voters are Nationalist and Socialist..

The sociological profile of the People’s Party electorate has evolved since the 1980s. In the early 1990s, shopkeepers, small entrepreneurs, farmers, and employees in distribution, administration and public service sectors began voting for the PP, joining an older electorate comprised mainly of entrepreneurs, senior public servants and members of the liberal professions. At the same time, there was a substantial increase in pro-PP voters among the religious and conservative constitutencies. 21

According to the CIS’s post-electoral study of the 2008 elections,22 the PP enjoys a majority among senior executives, liberal professionals, entrepreneurs and farmers, and obtains its best result among members of the former traditional middle classes (entrepreneurs, the self-employed, and farmers), as well as among the middle and upper bourgeoisie. Its constituency is distributed fairly homogeneously across all age groups, education levels and commune sizes. Certain population groups are more likely, however, to vote for the PP than others. It therefore obtains its best results among the 35-to-44 and over-65 age groups, among voters with an elementary or higher education, as well as those in large (400,000 to 1 million inhabitants) and medium-size (50,000 to 100,000 inhabitants) urban areas. The most loyal supporters are those with a higher education level, business owners, those whose income exceeds EUR 4,000 per month and those situated between the upper-middle class and the upper class.

As for partisan positioning, the PP is the preferred party of voters who identify with the Extreme Right (positions 9-10) or the Right (positions 7-8). A study on Spain’s political and electoral situation23 found that by enlarging its electoral base between 1996 and 2000, the PP attracted more Centrists without, in the process, losing voters who strongly support the Right. The PP has by far the majority among voters who claim to be practicing Catholics. Lastly, the CIS’s post-electoral study reveals that the PP – with a 91.1% loyalty vote, as compared to the 2004 elections – is the party with the most solid electoral base.

Although identified as a conservative party, the PP enjoys a homogeneous stronghold among the Spanish population as a whole. Another CIS study carried out in May 200724 concerning the quality of the country’s democracy confirms that the majority of People’s Party supporters identify with the Right ideologically, but that they are somewhat evenly distributed among all age groups, educational levels and urban habitat sizes. In competing against the PSOE, the People’s Party clearly has the advantage among the former middle classes. A breakdown of its electorate according to socio-professional categories shows that the PP has the majority vote among farmers and that it is almost tie with the PSOE among students, home workers and small business managers. These data confirm the PP’s electoral strength.

The PP’s media and intellectual networks

This right-wing party has benefitted, and still benefits, from the support of a broad media network and a growing number of intellectuals. It has not only been enjoying long-standing support from the daily newspaper ABC but also from the entire Vocento Group, which includes the Correo Group (of Basque origin), the TV station Telecinco (owned by Berlusconi) and the COPE radio station (owned by the Conferencia Episcopal Española). Since their first appearance in 1998, El Mundo, a general information newspaper, and the economic information magazine Expansión have decided to align themselves with the PP’s positions. In Catalonia, the most traditional newspaper, La Vanguardia, fluctuates between the CiU and the PP. Planeta, a publishing house also headquartered in Barcelona, and which controls the TV network Antena 3, the radio station Onda Cero and the newspaper La Razón (printed in Madrid since 1998), also visibly supports PP’s political views.

Since assuming government leadership, the PP has expanded its influence over the media. For example, it has not hesitated to air its views on the radio and public TV stations in the Autonomous Communities which it governs, notably in Madrid, in the Valencian Community and in Galicia. Similarly, during his first mandate, J. M. Aznar facilitated the creation of a digital TV company by merging Compañía Telefónica de España – headed at the time by one of his personal friends – with the Mexican company Televisa and a few autonomous TV stations based in the Communities governed by the PP.

In addition to this media gridwork, the People’s Party modernised its strategic think tanks to attract members of intellectual circles reticent to openly join the party. The Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales (FAES) [Foundation for Analysis and Social Studies], founded in 1989 and chaired by J. M. Aznar, thus became the party’s main think tank platform. Joined in 2003 by the former Fondation Cánovas del Castillo, and by three other PP-linked brain-storming groups, it is associated with diverse American, European and Latin American netorks, or think tanks. The FAES is a key pipeline of ideas for the People’s Party. It serves as a meeting place and forum for moderate intellectuals, some of whom are affiliated with the Left. During its twenty years of existence, the FAES has hosted discussions featuring key European and American right-wing leaders, as well as a certain number of Spanish and foreign scholars whose political views are in line with the conservative liberal political ideas which guide the Foundation. Along with the FAES, the PP can count on the Fundación Humanismo y Democracia (FHD) [Humanism and Democracy Foundation] to promote pro-Chris- tian and democratic co-operation in Latin America, as well as on the Confederación Nacional de Mujeres en Igualdad, a foundation advocating for political, economic and social equality for women.

In addition to these structures organically linked to the People’s Party, the PP has benefitted both in the government and in the opposition from the support and assistance of the Conferencia Episcopal Española, as well as from the majority of the Catholic Church hierarchy. During the 2004-2008 legislature, most of the calls to rally against the laws proposed by the Socialist government to expand civil rights (divorce simplification, homosexual marriage, educational laws, etc.) were jointly organised by the PP and the ecclesiastic hierarchy. These joint efforts have persisted through the current legislature, notably on the occasion of the reform of the abortion law. This time, however, a distinction was made between politico-parliamentary opposition and the social opposition spearheaded by the Catholic Church.

The PP’s internal organisation

On these issues, see F. chadel, Penser le changement dans les partis politiques. Le processus d’institution- nalisation au Partido Popular (Barcelona: IcpS-Wp, 2001), no. 192; see also the study by n. Lagares, Génesis y desarrollo del Partido Popular de Galicia (Madrid: Tecnos, 1999); and a comparable article by Tània Verge, “Representación política y modelos de partido en España: los casos de IU, pSOE y pp,” in J.R. Montero, R. Guhther and J.J. Linz (dir.), Partidos Políticos: viejos conceptos y nuevos retos (Madrid: Trotta, 2007).

According to its own data, the People’s Party membership has grown from 50,000 in 1979 to over 700,000 in 2008. Its bodies have been solidly centred around the person of the Chairman since the Party was founded by Manuel Fraga, although two offices – that of Founding Chairman (Manuel Fraga) and that of an Honorary Chairman (José M. Aznar), working alongside the Party’s Chairman, Mariano Rajoy – have officially existed since 2004.

The Party’s National Executive Committee is under the Chairman’s strict control. In order to maintain Party cohesion, its key officers (Secretary General, Vice-Secretary and various committee chairmen) are recruited from among every political persuasion. Moreover, the PP’s core apparatus is characterised by its specialisation, professionalisation and bureaucratisation.25

Despite this highly centralised structure, the PP’s territorial organisation have occasionally taken up the defence of specific regional interests. Although the PP’s representatives in the Autonomous Communities usually focus on the Party’s national strategy, some divergences can arise between local and national bodies in the course of certain debates. For example, a dispute occurred during a debate on water policy between the water-poor Communities – such as Valencia and Murcia – and those with surplus water – i.e., Aragon and Castile-La Mancha. Such debates are generally settled according to national objectives by the PP’s central organisation, whether the decision is to favour the central government when it is headed by the PP, or to help efforts to weaken it when it is headed by the PSOE.

The Spanish Right’s ideological positioning and its relationship to liberalism

The People’s Party: A political force claiming to be more liberal than the Right

For full details on the pp’s tactical and strategic proposals in full detail, visit the website pp.es, where various politically oriented texts have been posted from the most recent national congress in June 2008.

See A. Quintanilla navarro, “Tras el 9-M: perder o perderse,” Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político (Madrid: FAES, October 2008), no. 20. conversely, J.I. Wert “Elecciones del 9-M: entre el centro y los extremos,” Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político (Madrid: FAES, October 2008), no. 20, which makes very logical use of the scale categories in its post-electoral analysis.

See A. Quintanilla navarro, “Tras el 9-M: perder o perderse,” Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político (Madrid: FAES, October 2008), no. 20. conversely, J.I. Wert “Elecciones del 9-M: entre el centro y los extremos,” Cuadernos de Pensamiento Político (Madrid: FAES, October 2008), no. 20, which makes very logical use of the scale categories in its post-electoral analysis.

Among the most recent books published by the FAES is the work by J. de Vicente Algueró, ¡Viva la pepa! Los frutos del liberalismo español en el siglo XIX (Madrid: FAES, 2009), and J. M. Aznar et al., Antonio Maura, en el aniversario del Gobierno Largo (Madrid: FAES, 2009).

See M. porta perales, “El segundo mandato de Un ensayo de prospectiva,” cuadernos de pensamiento político (Madrid: FAES, July 2008), no. 19. In 1995, the FAES had already published an essay by Michael portillo, the prominent British conservative leader of that era, under the title Estado, libertad y respon- sabilidad.

See M. Lassalle (coordinator), Isaiah Berlin: una reflexión liberal sobre el otro (Madrid: FAES, 2001); J. Aznar et al., Isaiah Berlin: un liberal en perspectiva, (Madrid, FAES, 2008); Ibid, Milton Friedman: un econo- mista liberal (Madrid: FAES, 2008); J. L. Feito, causas y remedios de las crisis económicas. El debate económico Hayek-Keynes 70 años después (Madrid: FAES, 2008).

See Haegel, “Les droites en France et en Europe,” in p. perrineau and L. Rouban (Dir.), La politique en France et en Europe (paris: Les presses de Science po, 2007).

In 1977, the Electoral Manifesto of the People’s Alliance stressed that the organisation shared the philosophy of Europe’s popular, centrist and conservative parties, with which it had close affinities, and was far from entertaining any extreme and radical attitude towards them. The text then lists a set of proposals clearly falling within the scope of the most traditional right-wing ideology, whether Spanish or European: homeland unity, monarchism, security and order to deal with internal and external threats, a market-based economy and the free enterprise system, with a special focus on middle classes, farmers, small and medium-sized businesses, retirees and defence of the family.

Thirty years later, the People’s Party defined itself as a reformist Centre party heir to the Spanish liberalism tradition, supporting a free and socially advanced economy.26 This rallying discourse stems from the fact that in Spain – particularly after the long Francoist dictatorship – no political group wanted to define or position itself as right-wing. A recent study27 commissioned and published by the FAES following the March 2008 legislative elections, was critical of the Left-Right “false scale” used by some political scientists and sociologists in which the PP’s values, programme and proposals are presented as obeying some ideological presupposition which cannot be classified as Left or Right. In this study, the PP is called on not to equate itself with the Right, nor to attempt to be identified with it in order to obtain better election results. This study is a good example of the Spanish reluctance to adopt the label “right-wing.”

In associating itself with the tradition of Spanish liberalism, which it views as dating back to the 1812 constitutional movement and to Antonio Maura’s conservative liberalism, 28 the PP defends freedom’s creative energy and exalts the desire to surpass oneself, and merit based on labour, stimulated by education and training. The Party asserts that it wishes to assign the most important role possible to “civil society” in dealing with a State – assimilated with the government when the latter is headed by the PSOE – which must limit its intervention in the economic, social and personal lives of citizens.29 Some leaders, such as José M. Aznar, reached the point of openly criticising and ridiculing the increasing restrictions and regulatory prohibitions against tobacco, the consumption of alcohol and certain food habits.

The liberal doctrine currently espoused by the People’s Party is primarily based on Isaiah Berlin’s work, Milton Friedman’s economic theories, and on the great classic theorists of liberalism from F. A. Hayek to Karl Popper, including John Rawls and Raymond Aron, whose ideas the FAES strives to disseminate. The first book analysing Isaiah Berlin’s thought was published by the Foundation in 2001. The return of the Right to the opposition stimulated an increase in the number of works devoted to liberal philosophies and doctrines.30

Despite these statements of principle, its method of governing and the orientation of its programme place the People’s Party among the less liberal European parties, whether the issue concerned is eco- nomic, cultural or societal. As Florence Haegel shows in her analysis of European right-wing movements, the Spanish Right is the most interventionist in economic areas and the least liberal in terms of mores and social customs. 31.

An ambiguous relationship with economic liberalism

With regard to the economy, despite the eagerness to privatise shown by the various Aznar governments, neither the PP nor its electorate are inclined to renounce State intervention or to favour policies promoting market liberalisation or open competition. An analysis of the PP’s programme reveals a striking contrast between an officially liberal discourse and proposals of a marked interventionist nature. The political texts and the government programme approved at the last PP Congress in June 2008 state that: “The public sector must be a major player in a globalised world; it must promote growth and guarantee, thanks to the best possible form of protection, that the Welfare State will benefit all citizens,” or: “To be in the vanguard of the global economy and seize the opportunities afforded by globalisation, we need to have sound States, governments capable of inspiring trust and of ensuring a stable macro- economic environment, as well as a transparent control framework.” Immediately following these passages is a call for reducing taxes, controlling current expensees in the public sector and for acknowledging the values of effort, merit and talent within a free and open economy. The Party’s economic programme, intitled “Protecting Our Social Model” distances it from clearly liberal positions.

Similarly, in the environmental field, the Party vacillates between some “negationism” occasionally professed by Mariano Rajoy himself, and the adoption of a comprehensive environmental political programme ranging from the fight against climate change to green taxation.

As the government texts and programmes approved by the most recent Party Congress show, the defeat in the last two legislative elections has not altered the PP’s economic orientation. While Rodriguez Zapatero’s Socialist government has been pursuing an economic policy based on liberal orthodoxy, it has been tempered by social measures which the PP has never opposed. It was only after the start of the economic crisis, which appeared in Spain right after the 2008 elections, that the PP changed its position. Subsequent to the somewhat sluggish and disorganised reaction of the Socialist government to the collapse of the Spanish economy (an unemployment rate above 18% and a particularly strong recession), the PP proposed another economic model. Worded around neo-liberal principles, this programme turned out to be rather inefficient in practice. The PP formally opposed the government’s proposal to reform the retirement system (a two-year increase in the retirement age, new benefit computation method, etc.), without, however, offering any true alternative or viable proposals. More recently, on 9 April 2010, the PP approved a set of one-off measures adopted by the government, while also labelling them as inadequate. It therefore called for extensive reforms, particularly in labour market matters, but omitted to specify their content. Despite the seriousness of the public deficit, it ultimately asked that the VAT increase be limited, in accordance with its repeated tax-reduction proposals. In the final analysis, the public feels that the PP has failed to take advantage of Rodriguez Zapatero’s unpopularity and the opinons which the Spanish people have been expressing since the end of 2008 about the way the PSOE has been managing the government.

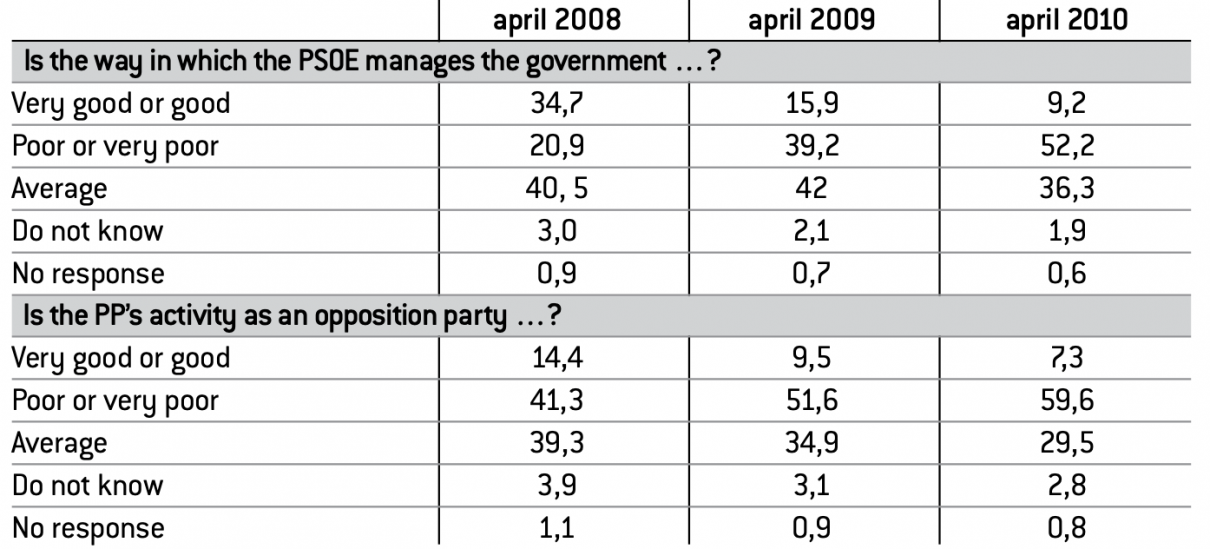

table 2 : Assessment of the government and of the opposition after the 2008 elec- tions (expressed in percentages).

Source :

Table compiled by the author based on CIS Barometer Survey nos. 2761, 2798 and 2834.

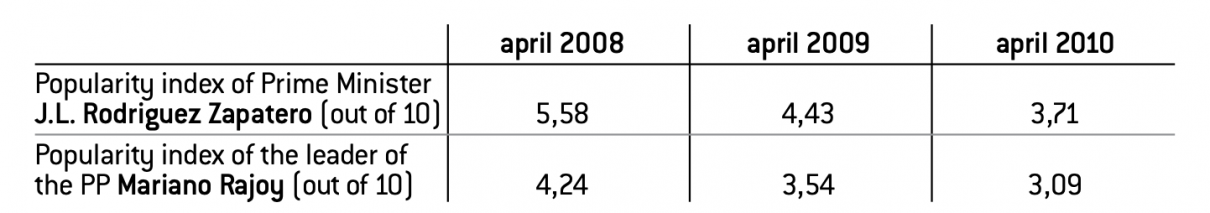

table 3 : popularity index (according to cIS calculations)

Source :

Table compiled by the author based on CIS Barometer Survey nos. 2761, 2798 and 2834.

As Tables 2 and 3 indicate, the Spanish citizens’ increasingly negative opinion of governmental policy did not at all cause them to have a better opinion of the PP. The latter’s leader, Mariano Rajoy, thus appears unable to present a credible alternative for change. The debates between the opposition and the government which punctuate the release of macroeconomic data have not enabled the PP to strengthen its credibility. Voters believe that if the Party were in charge of the government, it would not contribute better solutions to the crisis. In Parliament, the PP introduced only a small number of proposals which gained the support of the other opposition parties. Only a few of them – notably those dealing with reducing public spending (eliminating some senior official posts, ministries, etc.) – won support from other groups. This stagnation of the PP was exacerbated by accusations of corruption which it had to confront. In the last two years, some embezzlement cases have tainted the management of the various Autonomous Communities which the Party now governs (Valencian Community, Madrid, Castile-León) or recently governed (Balearic Islands), and the financial leadership of the Party itself. The reaction of Mariano Rajoy and of his entourage to these problems appeared inadequate, further damaging his credibility in the public’s eyes.

The People Party’s conservatism in societal matters

If the PP’s economic liberalism can be categorized as moderate, or even fluctuating, there is nothing liberal about its positions in the area of moraes and societal issues. The Party has revived its most conservative programme, claiming to represent Christian-inspired values and professing totally closed attitude towards introducing new individual rights. The PP has thus differentiated itself from other parties by its opposition to divorce (which already existed in the era of the UCD’s Centrist government), and to the more open regulation implemented by Zapatero’s Socialist government. It showed itself to be adamantly hostile to the decriminalisation of, and the new regulation concerning, abortion. More recently, the recognition of homosexual marriage met with radical opposition from the People’s Party. With regard to teaching, it strongly fought against the reform undertaken by Zapatero’s government aimed at supporting and improving public education, and to introduce a new subject intitled “Education for All Citizens” into the mandatory school curriculum. On all of these fronts, the ecclesiastical hierarchy has supported the PP’s positions and its mobilisation efforts. In the final analysis, the Party is taking up the defence of the traditional family, notably by advocating the creation of a “Ministry of Family and Social Welfare”, a comprehensive law in favour of the family and policies promoting family associationism.

Its position on immigration – a relatively recent phenomenon in Spain – is more moderate. Although the PP could not help but occasionally assimilate immigration with insecurity, and despite its strong criticism of regularisations carried out by Zapatero’s first government, the Party’s positions on immigration are qualified and exempt from xenophobic content. The PP’s political programme still includes a call for the integration of immigrants, accompanied by border control measures and the revision of regulation methods. During its 2008 electoral campaign, the PP had formulated a proposal for an “integration contract” which immigrants wishing to reside in Spain for more than one year would be obligated to sign. Far from being innovative, this proposal was inspired by those presented by the CiU during the 2006 Catalonia regional elections, in France by Nicolas Sarkozy in 2004, the measures adopted by the 2002 Austrian immigration law, and by the integration courses and examinations recently implemented in Belgium, Holland, Denmark and the United Kingdom. Regardless of how influenced it may have been by other European country models, the proposal was withdrawn from the programme and has never been introduced in Parliament, despite the June 2009 debate that surrounded the review of the Spanish law on immigrant rights. While they are the focus of countless theoretical and practical debates, immigration issues are viewed by the PP as a European policy matter. Similarly, with regard to most of the societal issues mentioned, Europe and its integrated policies are repeatedly being called upon. Indeed, the PP considers itself, as do all Spanish political forces, to be a European party. It belongs to the European People’s Party and is one of the “Euro-optimists” most in favour of the integration process. In this sense, it sides with the Spanish people who, in the 2005 Referendum, approved ratification of the Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe.

Opposing territorial autonomy

With regard to Spain’s territorial structure, the PP also professes highly conservative positions based on the reaffirmation of the Spanish nation as a historic subject. When the Constitution was formulated in the post-Francoist era, the issue which raised the most reticence within the People’s Alliance was the recognition of certain nationalities and regions’ right of autonomy. Later, despite its growing influence in various Autonomous Communities, the PP always retained a narrow vision of regional autonomy, regularly calling for the reform of the Spanish Constitution of 1978. From the PP’s vantage point, any proposal promoting an autonomous model, any Federalist-oriented project, and any measure to improve regional governance, constitutes a threat against the State. In addition to its very limited interpretation of the regional model, the PP stands as a defender of the letter of the Constitution, of equality and of the territorial uniformity of a country which is nonetheless both historically and culturally pluralistic. Measures increasingly favourable to the autonomy of Catalonia and the Basque Country have multiplied to such an extent in the last few years that half of the introduction to the PP’s statement of political orientation, approved during the Party’s last Congress, is devoted to the development and defence of the historic Spanish government model and opposes any autonomist plan. In the very body of the text, the Party calls for abandoning the development of the autonomous model. It clearly professes its desire to block the Communities’ statutory reforms initiated within the last two years. The Catalan statute reform approved by regional referendum in June 2006 has been the subject of a constitutional appeal filed by the PP. In this debate, defence of the Spanish (Castilian) language has become a theme taken up by the opposition. The Party has denounced the educational practices developed in Catalonia, in the Basque Country and – to a lesser degree – in Galicia, which consist of teaching first and foremost in the language specific to each of these Communities. The PP has gone so far as to propose a law guaranteeing that the Spanish language will be taught and used in schools throughout Spain.

The autonomy issue is the main point of dissension between the People’s Party and the Catalan and Basque right-wing parties, for if we exclude the territorial question, the CiU’s and PNV’s ideological positions are not that different from those of the PP, even if these parties do take a more moderate stand in economic and State modernisation matters.

This brief assessment of the main ideas and programme of the People’s Party seems to indicate that the Spanish Right is more closely linked to conservatism than to liberalism. Even if the PP professes to be centrist and reformist, it seems to be more oriented towards the Right than towards the Centre. The contradictions and ambiguities pointed out in this paper likely stem from the complex history of the Spanish Right, which had to adapt itself to Spain’s democratic and institutional modernisation without integrating the corresponding ideologies.

Such positioning was also aimed at rallying a broad electoral base going from the Right to the Centre. In terms of its strategic options, its ideologies and its programmes, the Spanish Right differs little from its European counter-parts. Moreover, the PP enjoys excellent relations – whether bilateral or falling within the scope of European institutions – with other right-wing parties.

No comments.