2022 The populist risk in France

An electoral protest indicator designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politiqueAbbreviations of the different political parties used in this study

Introduction

The context of the study

The objective

Methodology

What the notion of protest electorate covershere

Estimating electoral potential

Most voters (85%) have already expressed some form of electoral dissent

Nealry one out of every two years voters (48%) has cast a populist vote in the past and 85% of respondents have already voted for a populist party, abstained from voting or cast a black vote

The election experience declared shows a populist electoral potential which is far higher than the 2017 scores

The hotbeds for the populist vote

2002 : Populist temptation in a climate of electoral protest

Abstention and voting blank are emerging as forms of electoral protest

2022 Presidential Elections: The potential populist electorate

The duel of populisms is being dominated by the RN

The case for a second Macron-Le Pen race and electoral protest votes

The unknowns around the potential for electoral protest

Electoral protest votes are multifaceted

The PS and the LR, two electorates struggling in protest landscape

Crossing partisan borders and the resources of the populist vote

The Yellow Vests, a new resource for the populist vote

Women and young people are more resistant to populist temptations, but this may mean that they form an electoral reservoir

Populist leaders suffer opposition attrition

From the Republican Front to the Monetary Front: the euro resists populism

The survey’s questionnaire

Résumé

The 2017 presidential election was marked by an anti-establishment vote of an unprecedented magnitude in our electoral history. Since then, far from ebbing, protest seems to have become a permanent feature. Moreover, it has taken on multiple forms. In addition to the usual social movements, the Yellow Vests, the ZAD, the Animalists or climate change activists, and a growing number of hyperactive organised minorities, led by political, religious, environmental or societal leaders who seem quicker than past leaders to turn to unconventional methods of political action (occupation of premises, disobedience, violence, etc.) have recently entered the political scene. The question arises as to how this unrest, unparalleled in its anomic form and in the intensity through which it has shown itself capable, will play out with regards to the 2022 presidential election.

Our indicator seeks to help understand and anticipate the outline of this future presidential election, keeping in mind that the largest political event in France is not without European consequences. This Electoral Protest Indicator was developed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The survey was administered by the polling institute OpinionWay. The full results of 2022, the populist risk in France are freely available at data.fondapol.org.

To ensure the robustness and value of the data collected, we chose to analyse a particularly

large sample. We thus interviewed 3.006 registered voters from a sample of participants, of 3.265 people representative of the French population aged 18 and over.

All results are freely available on our website fondapol.org/en.

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

What next for democracy?

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

2019 European Elections. The weight of the political electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Victor DELAGE, Virginie DENISE, Anne FLAMBERT, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Sasha MORINIÈRE

UBIQUS

Francys GRAMET, Claude SADAJ

Julien RÉMY

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

the polling institute ''opinionway

Bruno JEANBART (Deputy Managing Director)

Guillaume INIGO (Project Director)

Théo PONCHEL (Project Manager)

Abbreviations of the different political parties used in this study

DLF: Debout la France ! [Stand Up, France!]

FdG: Front de Gauche [Leftist Front]

FI: France insoumise [Unsubjugated France]

FN: Front National [National Front]

LO: Lutte Ouvrière [Workers’ Struggle]

LR: Les Républicains [The Republicans]

NPA: Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste [New Anti-Capitalist Party]

PCF: Parti Communiste Français [French Communist Party]

PS: Parti Socialiste [Socialist Party]

RN: Rassemblement National [National Rally]

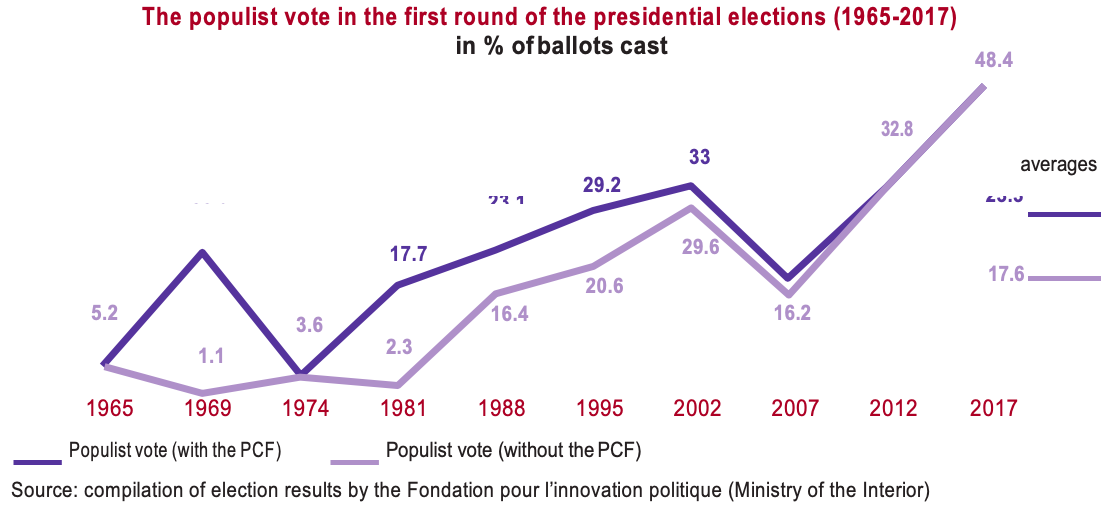

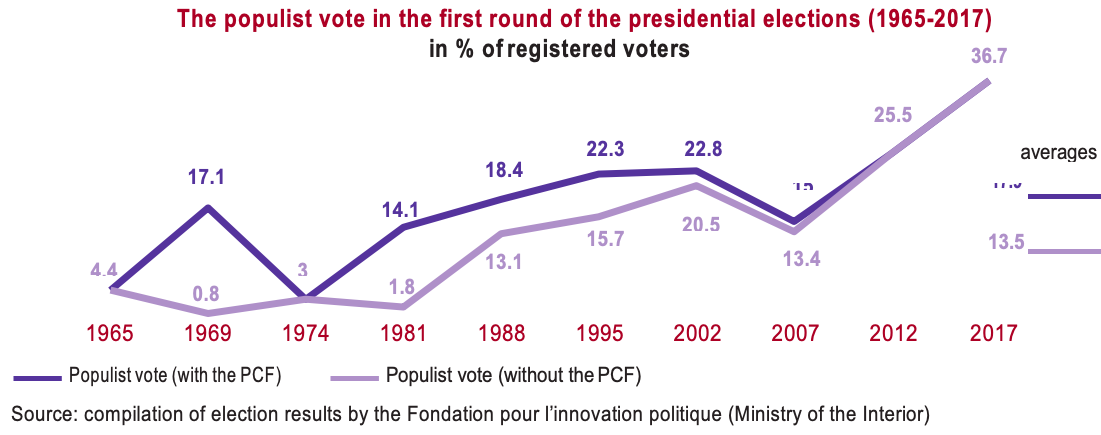

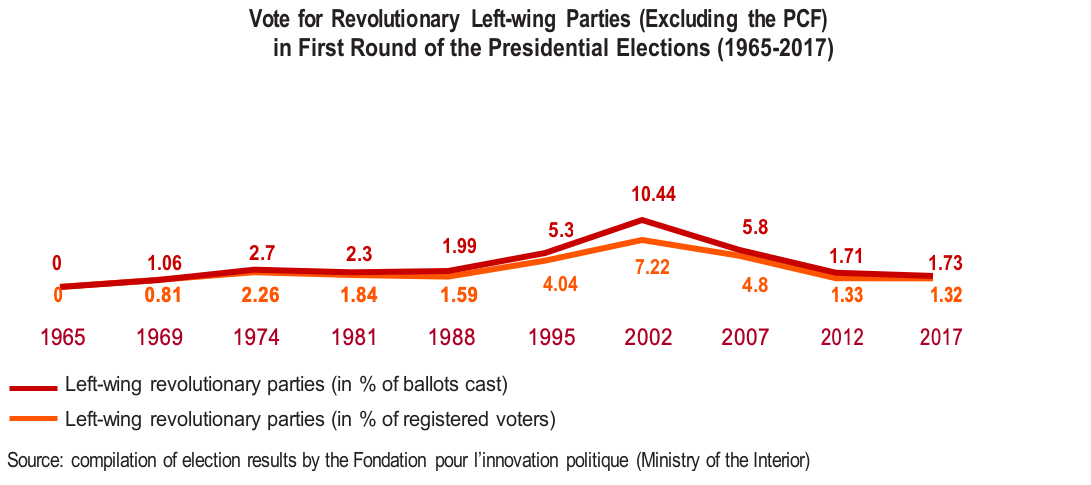

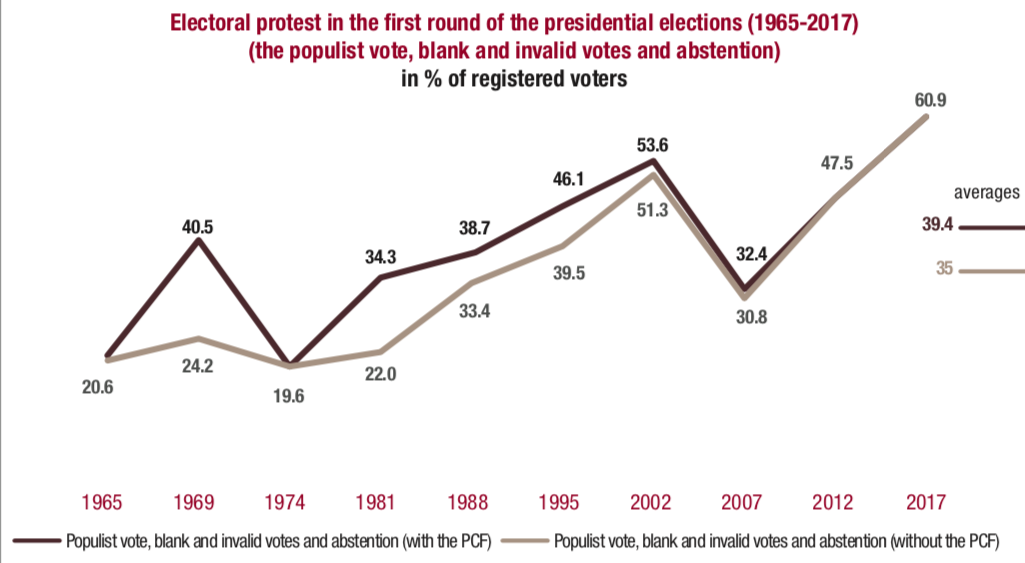

Electoral protest is on the rise. The first graph depicts populist and anti-establishment votes in the first round of the presidential election. The level varies depending on whether or not the PCF vote is included. We offer two datasets: one including the Communist vote, with the exception of Pierre Juquin’s candidacy in 1988, the other not including it. It should be noted that the results were calculated based on the ballots cast as well as the registered voters, which makes it possible to subsequently integrate abstention and blank (or invalid) votes into the same assessment, offering the possibility of an overall assessment of electoral protest from 1965 to 2017.

Selected Candidates: 1965: J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour); 1969: J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC); 1974: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR); 1981: A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF); 1988: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF); 1995: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Chemi- nade (SP); 2002: B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT); 2007: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT); 2012: Mr Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP); 2017: Mr Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F.Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N.Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP).

The context of the study

The 2017 presidential election was marked by an anti-establishment vote of an unprecedented magnitude in our electoral history. Since then, far from ebbing, protest seems to have become a permanent feature. Moreover, it has taken on multiple forms. In addi- tion to the usual social movements, the Yellow Vests, the ZAD, the Animalists and a growing number of hyperactive organised minorities, led by political, religious, environmental or societal leaders who seem quicker than past leaders to turn to unconventional methods of political action (occupation of premises, disobedience, violence, etc.) have recently entered the political scene.

The objective

The question arises as to how this unrest, unparalleled in its anomic form and in the intensity through which it has shown itself capable, will play out with regards to the 2022 presidential election. Our indicator seeks to help understand and anticipate the outline of this future presidential election, keeping in mind that the largest political event in France is not without European consequences.

Methodology

This Electoral Protest Indicator was developed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The survey was administered by the polling institute OpinionWay. The full results and the 2022, the populist risk are freely available at data.fondapol.org. To ensure the robustness and value of the data collected, we chose to analyse a particularly large sample of participants. We thus interviewed 3.006 registered voters from a sample of 3.265 people representative of the French population ages 18 and over. The representativeness of the sample was ensured using a quota method, covering the criteria of gender, age, socio-profes- sional category, conurbation category and region of residence. The interviews were conducted through a self-administered online questionnaire from 30 August to 6 September 2019. For most of the questions, the interviewees were asked to respond to each of the statements made (and not to choose a multiple-choice answer). In this case, the respondents could indicate their willingness to vote for each party/candidate listed.

The Electoral protest indicator seeks to assess the potential of different possible protest behaviours: abstention, blank voting, and voting in favour of populist or anti-establishment parties or candidates.

What the notion of protest electorate covershere

In our indicator, the idea of a protest electorate covers three types of electoral behaviour:

- Voting, or willingness to vote, for populist parties and candidates (Marine Le Pen, RN, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, FI and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and the DLF);

- Voting, or willingness to vote, for parties and candidates on the revolutionary left (LO and NPA).

- Abstentions and blank votes.

a) The populist vote

Populist voting includes votes, here meaning the willingness to vote for a populist party. We characterise populist parties using the following elements:

An appeal to the people. This is the heart of populist discourse, which is a fundamental feature of democratic politics. It is reflected in a rejection of representative democracy and an elevation of direct democracy. The populists’ appeal to the people is characterised by demands for the absolute sovereignty of electoral decisions, which are supposed to prevail over everyone and everything, including the principles and rules that form the bases of order and the rule of law. This is the fundamental difference between liberal democracy and populism, which sometimes calls itself “illiberal democracy.”

An anti-elite discourse, based on a summary social differentiation between a “people”, unified and my- thologised, and political, economic, intellectual, and media “elites”, disqualified as forming an oligarchy (“La Caste”, etc.).

A narrative and an organisation marked by an authoritarian culture, found in a form of party built around an omnipresent leader.

A nationalist programme.

A xenophobic vision.

Starting with the 4th criterion, we see a separation between two expressions of populism: the largely do- minant expression that has met with major electoral successes deploys nationalism through xenophobia, denouncing not only the ruination of the people by the elites, but also by foreign people, immigrants.

Xenophobic populism is most often right-wing, even if it exists on the left in Europe. In France, left-wing populism is represented by Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his party France insoumise. He does not want to or cannot make a lasting commitment to xenophobia, despite a few steps in that direction. He has paid the electoral price as he is outpaced by the right-wing populism of Marine Le Pen and the RN.

Finally, we note a rhetorical style characterised in particular by exaggeration, simplification, disqualification of the adversary, a tendency to conspiracy theories, etc.

As the case of Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and his DLF party is uncertain, sitting as it does between the sovereigntist right and the populist right, we have made the choice to take it into account in the calculation of the populist electoral potential. In 2017, during the two-rounds of the presidential election, the president of Debout la France had made an agreement with Marine Le Pen’s government after which he became her prime minister in case of the election of the candidate of the Front national.

Fundamentally, it is important to distinguish between populist parties and parties from the revolutionary left. In fact, some parties put forth an anti-establish- ment vision without the codes of populism, instead speaking in terms of internationalism and social classes. They claim to speak for the working class, possibly extended to include all “working people,” but not “the people” writ large. Effectively, they do not re- cognize themselves in the principles and mechanisms of electoral democracy that populists, on the contrary, claim they wish to implement. In France, these are the far-left Trotskyite parties. However, here, without dismissing these differences, we chose to integrate the far-left vote into the calculation of the populist elec- toral potential so as not to unnecessarily increase the complexity of the indicator, bearing in mind, on the one hand, that the electoral weight of this anti-esta- blishment left is marginal, with two exceptions (2002 and 2007) and, on the other hand, that the respondents who recognise themselves in the parties of this anti-establishment left and who vote for their candidates testify in our study to a great willingness to vote for populist parties.

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior)

Selected Candidates: 1965 : J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour) ; 1969 : J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC) ; 1974 : J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR) ; 1981 : A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF) ; 1988 : J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF) ; 1995 : J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Cheminade (SP) ; 2002 : B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT) ; 2007 : J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT) ; 2012 : M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP) ;

2017 : M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F. Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP).

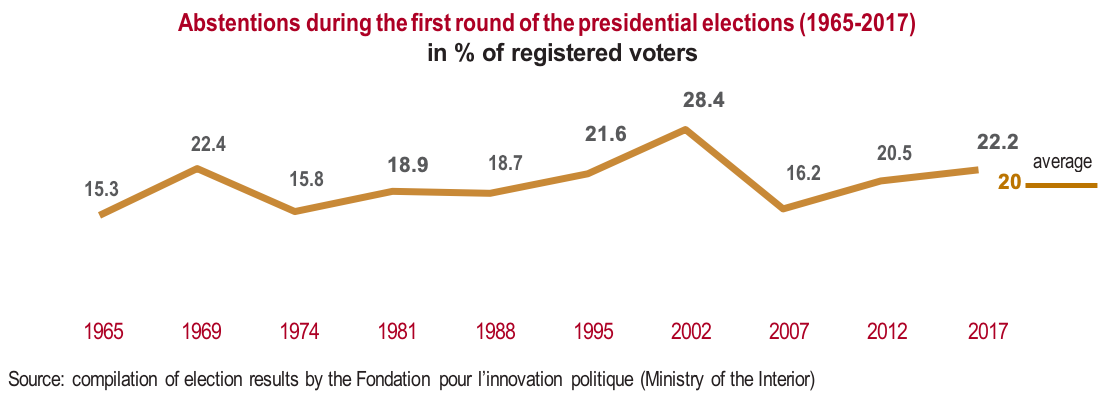

b) Abstention

There are varied forms of abstention. Notably, abstention may be systematic or intermittent. The reasons for abstention are diverse: expression of disinterest, inability to choose, expression of a rejection of the political choices or even more general discontent. Since only some abstentions are a form of electoral protest, it is difficult to assess this from electoral results. However, here we choose to include abstention in the calculation of the potential for electoral protest because we are asking people about their willingness to abstain from voting in 2022. We will also note the similarity between the abstention curve and that of the protest vote.

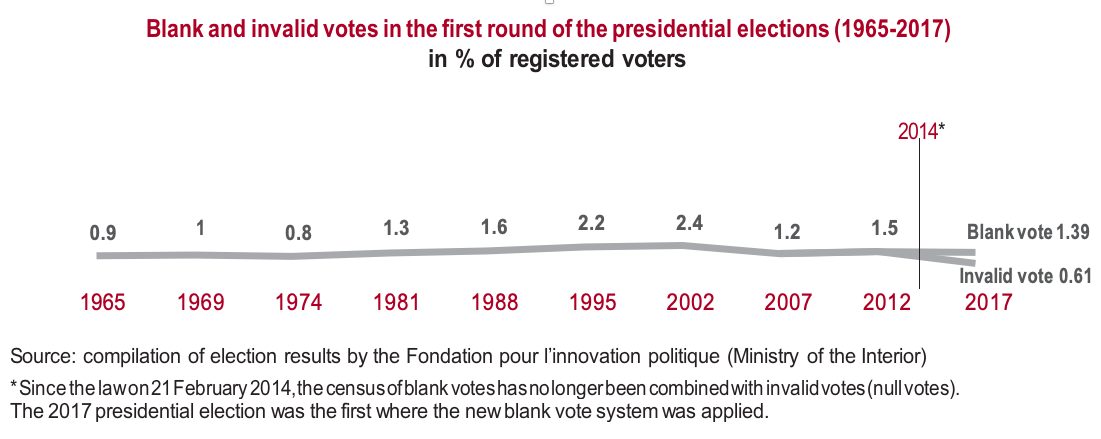

c) The blank vote

Until 2014, the census of blank votes was combined with invalid votes (null votes). The category was called “blanks and invalid”. Blank votes have been counted separately since the law of 21 February 2014. They were listed separately for the first time in the European elections in June 2014. The 2017 presidential election was the first where the new blank vote system was applied. Here, we choose to include blank voting in the calculation of the potential for electoral protest because we are asking people about their willingness to vote blank in 2022.

Estimating electoral potential

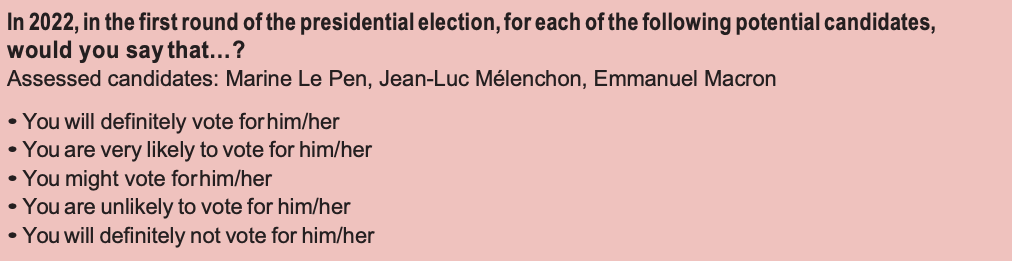

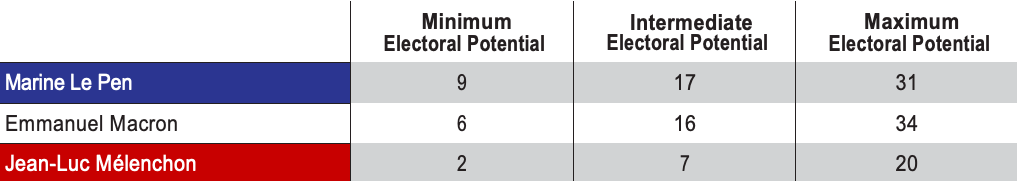

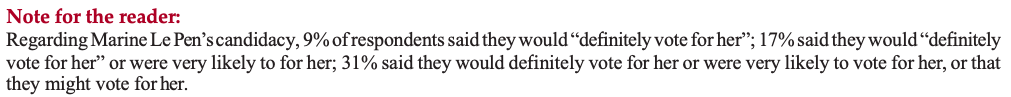

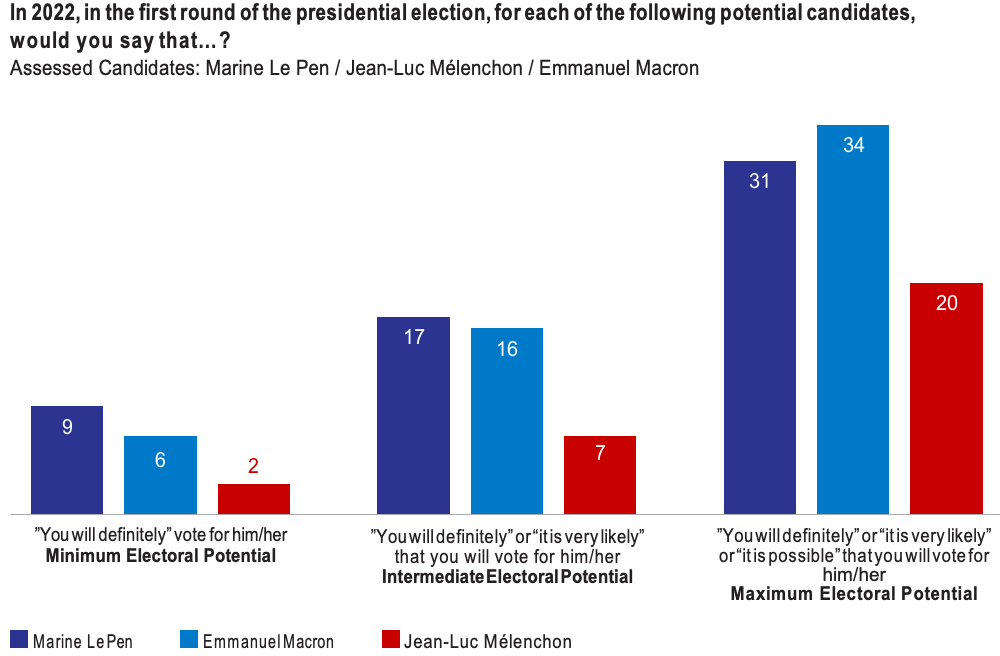

For the upcoming first round of the 2022 presidential election, the electoral potential of the parties and candidates is estimated based on the following question:

The responses provided allow us to define electoral potential on a three-point scale:

- minimum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having responded “you will definitely vote for him/her”;

- intermediate electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her” or “you are very likely to vote for him/her”;

- the maximum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her”, “you are very likely to vote for him/her” or “you might vote for him/her”.

We must distinguish here between the electoral potential of a party or a candidate, which is the willingness declared by the interviewees to vote for this party or candidate, and the potential for electoral protest, which refers to the willingness declared by the interviewees to adopt electoral protest behaviour (abstention, blank voting, or voting in favour of populist or anti-establishment parties or candidates). As such, our indicator defines the electoral potential of populist candidates and compares them with the electoral potential of Emmanuel Macron.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

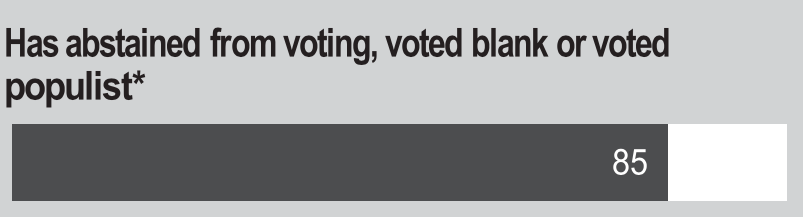

Most voters (85%) have already expressed some form of electoral dissent

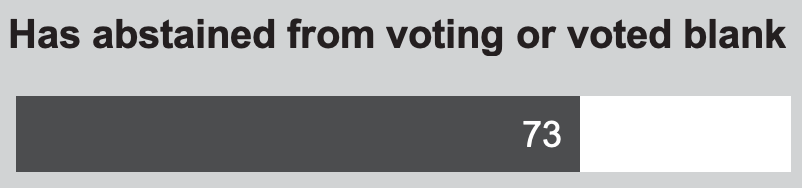

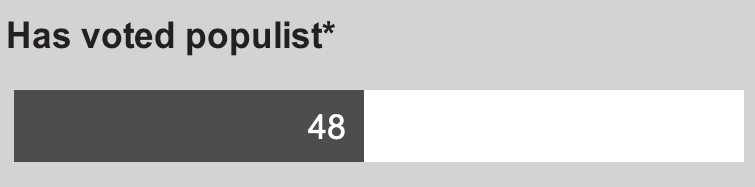

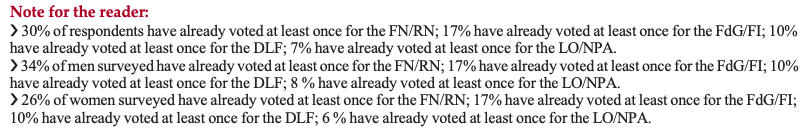

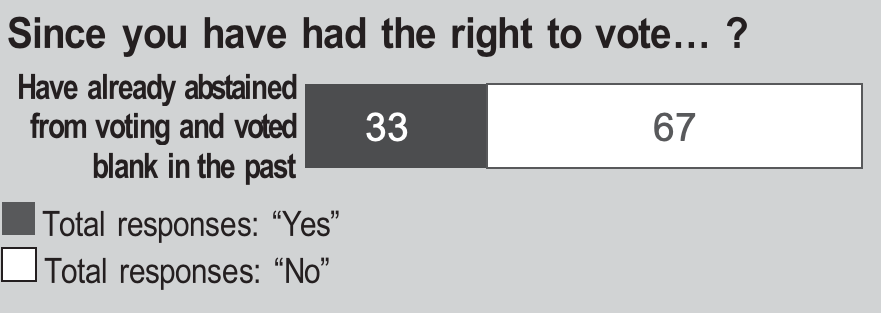

Nealry one out of every two years voters (48%) has cast a populist vote in the past and 85% of respondents have already voted for a populist party, abstained from voting or cast a black vote

Electoral protest occurs through voting for a populist party, abstention or voting blank. As a reminder, du- ring the first round of the 2017 presidential election, the total number of votes cast in favour of one of the populist candidates represented 36.69% of registered voters including the vote for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and 33.13% without this vote.

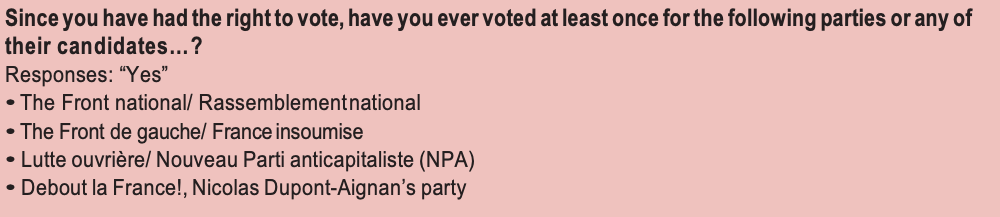

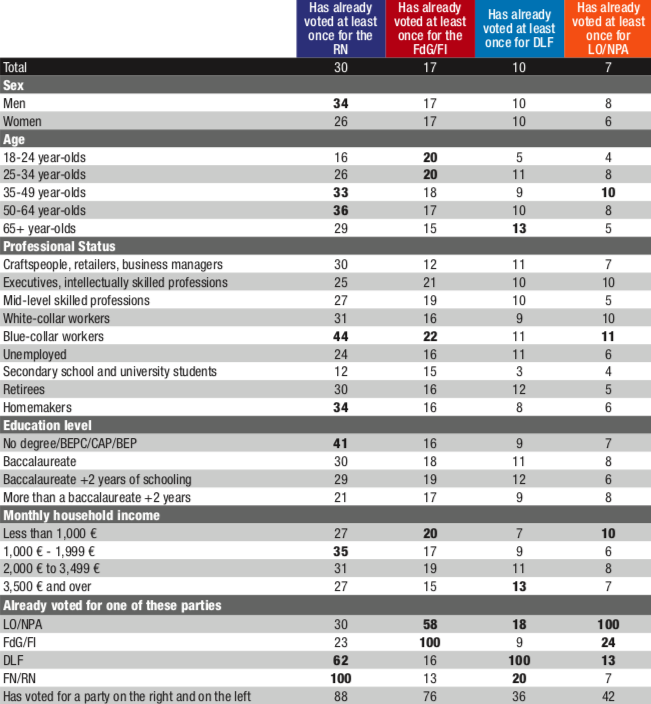

The reconstruction of past electoral behaviour tells us about the experience of voters with “electoral protest.” Interviewees had to say, for the six types of electoral behaviour that we consider to deviate from the implicit political and civic norms, if they had already engaged in that behaviour. The question was phrased as follows:

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Our survey shows that most voters have already used at least one of the aforementioned forms of electoral protest.

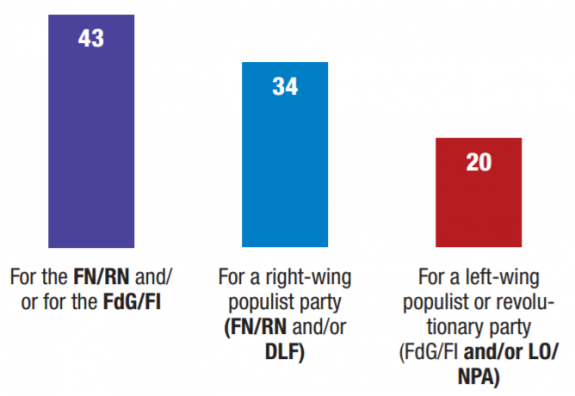

The election experience declared shows a populist electoral potential which is far higher than the 2017 scores

Our results indicate that 43% of registered voters say they have already voted at least once for one of the two main populist parties or for their candidates, either the FN/RN and Marine Le Pen or FI and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. As a reminder, in 2017, the candidacies of Mélenchon and Le Pen totaled 40.9% of the ballots cast, i.e. 31% of registered voters. The populist electoral experience recorded in the first round of our indicator thus exceeds the 2017 level by more than 10 points.

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The hotbeds for the populist vote

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

2002 : Populist temptation in a climate of electoral protest

Abstention and voting blank are emerging as forms of electoral protest

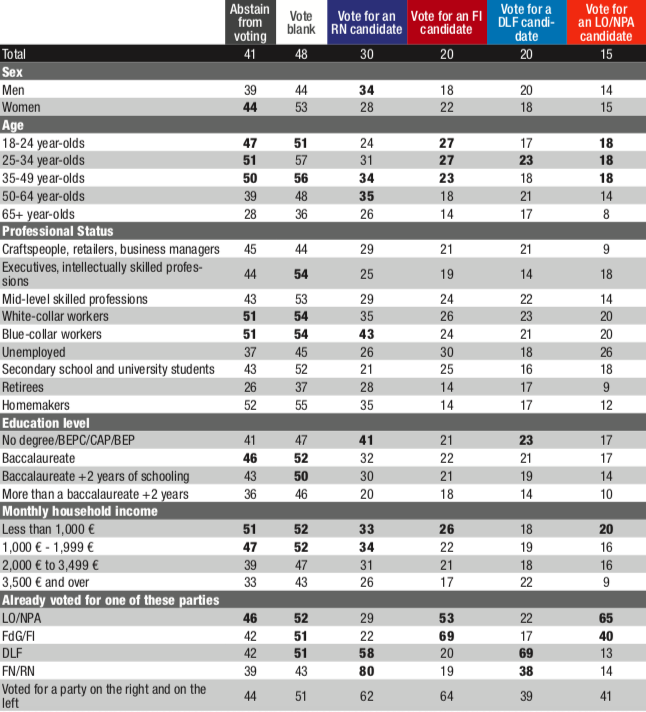

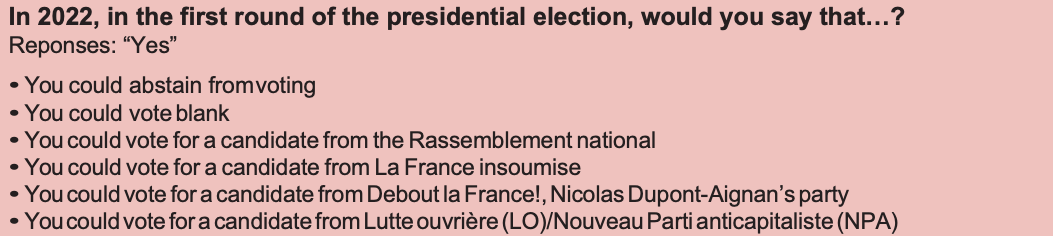

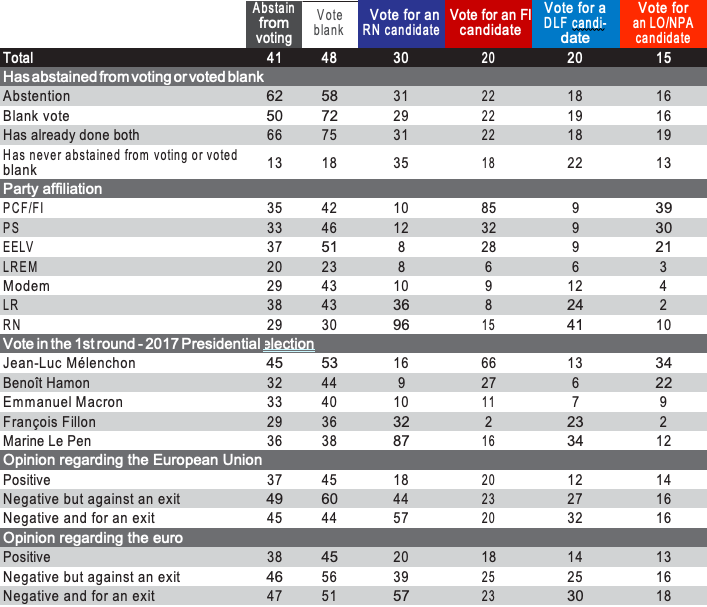

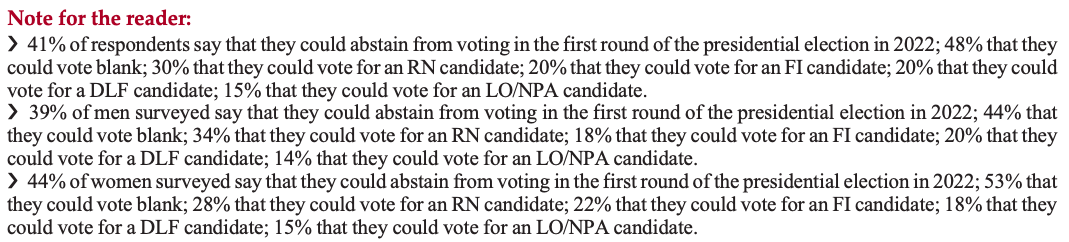

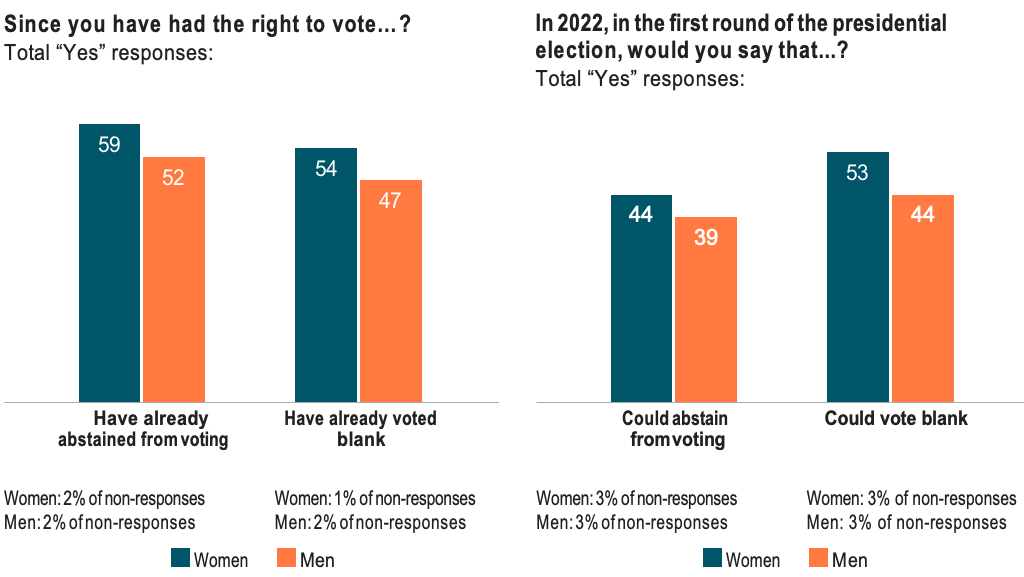

Recognition of the blank ballot, now that it is counted separately, has appeared to become a new form of electoral protest, alongside the populist vote and to some extent, abstention. Looking ahead to the 2022 presidential election, nearly one in two voters (48%) say they are capable of casting a blank ballot, and will do so either “definitely” (16%) or “probably” (32%).

The same goes for abstention: 41% of respondents said they could abstain from voting in the next pre- sidential election, “definitely” (14%) or “probably” (27%). In any exploration of the willingness to abstain from voting in 2022, one must by definition rule out practical reasons for abstention that could prevent voting, as they cannot be anticipated. The willingness to abstain from voting in 2022 expressed since September 2019 could therefore have a wide variety of very different meanings: inability or unwillingness to anticipate the 2022 election today; inability or unwillingness to anticipate one’s electoral behaviour during the next presidential election; expression of disinterest in politics which could be temporary, etc. However, the willingness declared to abstain from voting also contains the expression of a disillusioned withdrawal or even of discontent that has become mute, in a manner of speaking. Although the proportion of this protest abstention is currently difficult to assess, it will certainly be part of the overall level of electoral protest that will in fact be recorded.

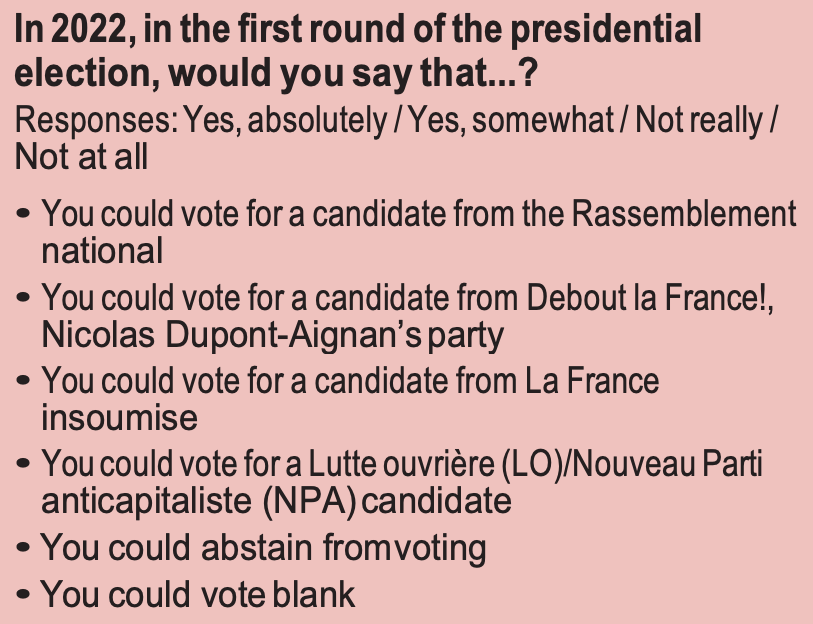

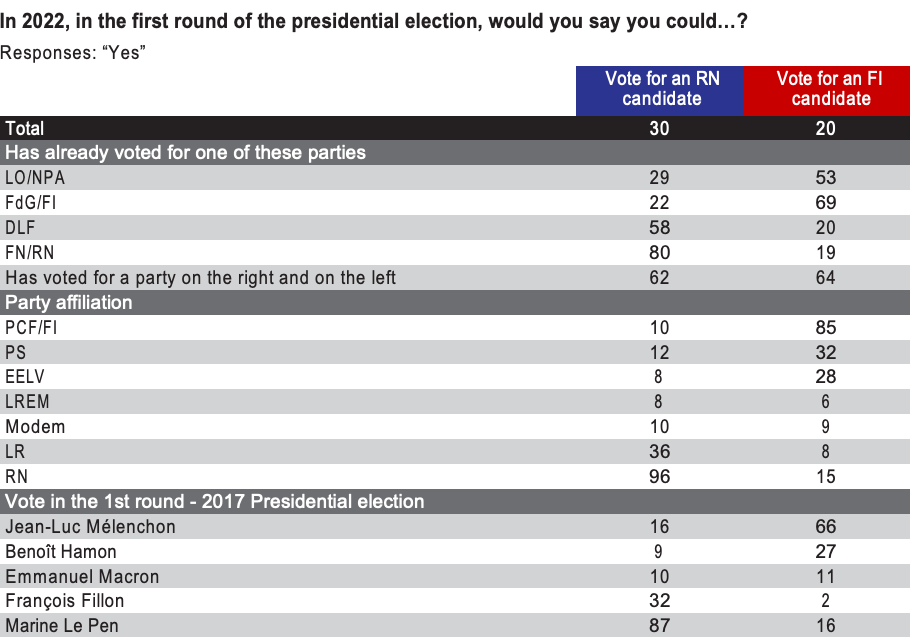

In addition to abstention and blank votes, people were asked about their willingness to vote for one of the populist or anti-establishment parties listed: RN, FI, DLF and LO/NPA. Finally, we also asked about the willingness to vote for the following candidates in the next presidential election: Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron and Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

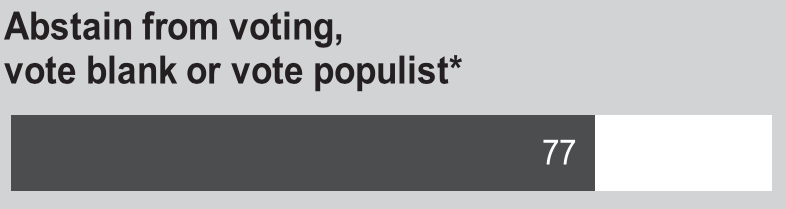

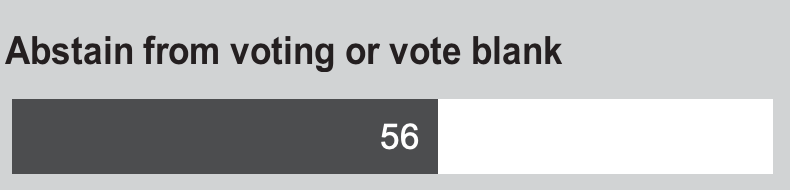

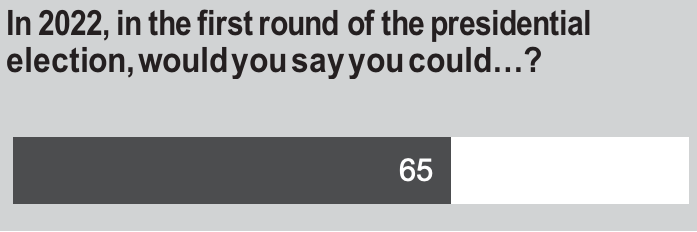

An analysis of the responses sheds light on the po- tential for electoral protest in the next presidential election. As such, more than three-quarters (77%) of voters surveyed answered “yes” to at least one of the six options: abstain from voting, vote blank, or vote for at least one of the proposed populist or anti-establishment parties. In September 2019, it appears that more than half of voters (56%) could abstain from voting or vote blank.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Source :

* The “populist vote” option includes respondents who have already voted at least once for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (FN/RN, FdG/FI, DLF, LO/NPA).

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

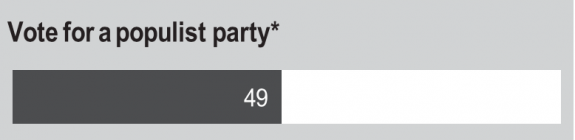

Considering the willingness to participate in electoral protest in terms of populist or anti-establishment voting, i.e. counting the people who responded “yes” to at least one of the four proposed parties, it appears that the protest vote potentially involves almost half of the electorate as of September 2019.

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

* The “populist vote” option includes respondents who have already voted at least once for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (FN/RN, FdG/FI, DLF, LO/NPA).

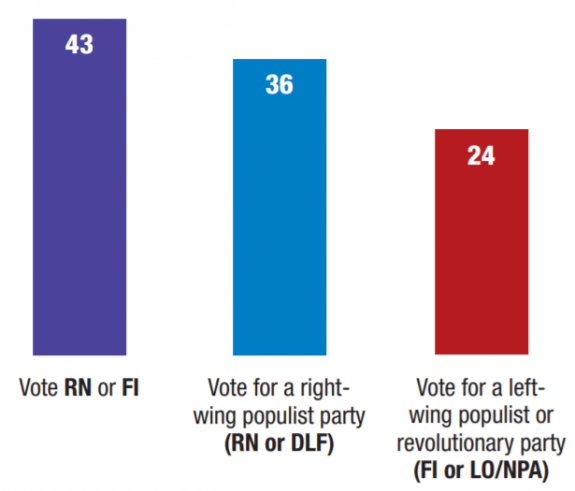

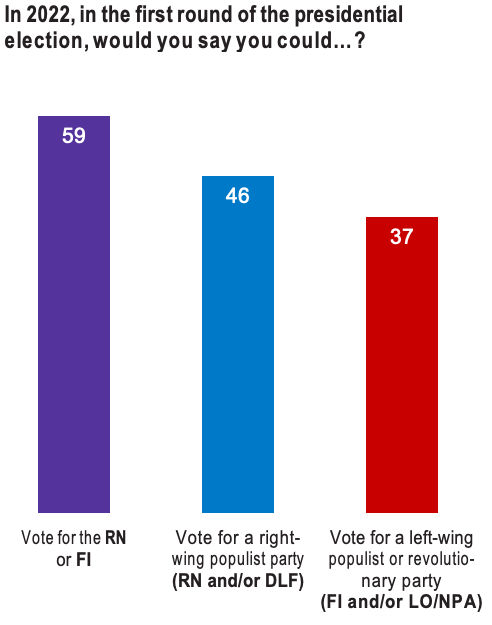

The protest nature of votes for the two main popu- list parties is confirmed by the fact that 43% of voters surveyed responded that they could, in 2022, vote either for the Rassemblement National or for France insoumise. Everything here indicates that the asser- tion of such an electoral will reveals a disregard for the ideological orientation of a candidate or political party, as long as said candidate or party has the ability to break with the political status quo.

However, right-wing populism retains a superior attractive force: more than a third (36%) of voters plan to vote for at least one of the two right-wing parties mentioned in the survey (RN or DLF), while nearly a quarter (24%) say they could vote for at least one of the two left-wing parties (FI or LO/NPA).

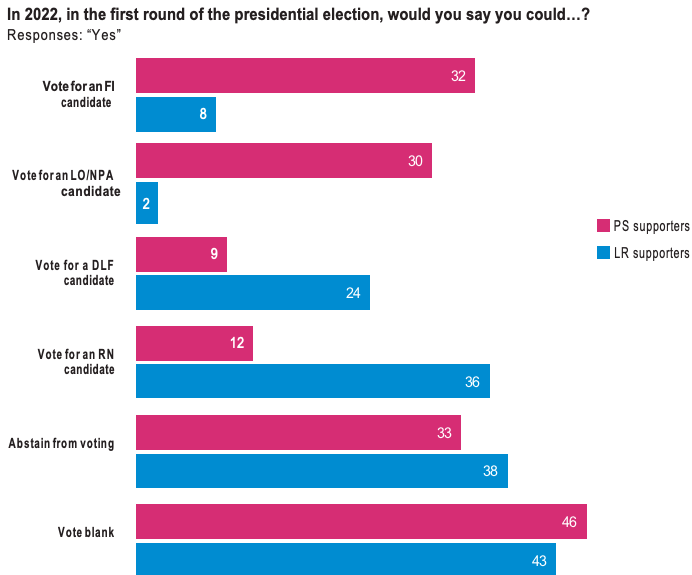

In 2022, in the first round of the presidential election, would you say you could…?

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

2022 Presidential Elections: The potential populist electorate

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

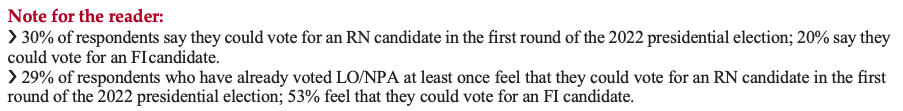

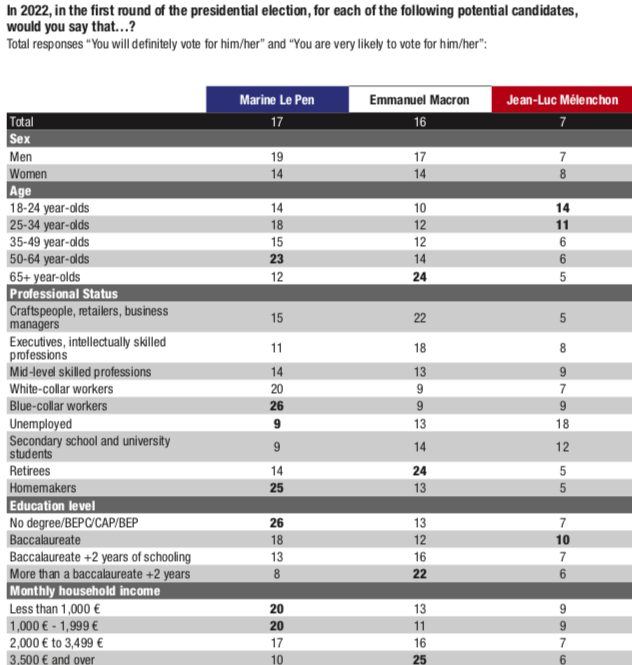

The duel of populisms is being dominated by the RN

Marine Le Pen’s “intermediate” electoral potential reaches 17%. This is the result of the total voter responses saying they will “definitely” (9%) or are “very likely” (8%) to vote for her in the first round of the 2022 presidential election. Readers are reminded these percentages are of the registered voters. As such, by way of comparison, Marine Le Pen’s score in the first round of the 2017 presidential election (21.3% of votes cast) amounted to 16.1% of registered voters.

According to our study, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s intermediate electoral potential amounts to 7% of voters, taking into account the responses of those who say they will “definitely” (2%) or are “very likely” (5%) to vote for him in the first round in 2022. In September 2019, the proportion of voters already declaring that they are “definitely” voting for Marine Le Pen (9%) in the first round in 2022 is four times higher than the proportion of voters declaring that they are “definitely” voting for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (2%) in the same first round. Marine Le Pen’s electoral potential (17%) is still far higher than that of Jean-Luc Mélenchon (7%).

The populist duel had already been won by Marine Le Pen in 2012 (17.9%) at Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s ex- pense (11.1%). In 2017 the race was much tighter, as the FN candidate (21.3%) was nearly caught up to by the FI candidate (19.6%). However, according to our study, in the run-up to 2022 the RN will solidify its leadership among the protesting electorate.

According to our survey, Emmanuel Macron’s inter- mediate electoral potential amounts to 16% of voters: 6% say they will “definitely” vote for him and 10% believe they are “very likely” to vote for him in the first round in 2022. By way of comparison, Emmanuel Macron’s score in the first round of the 2017 presidential election (24% of votes cast) represented 18.2% of registered voters.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

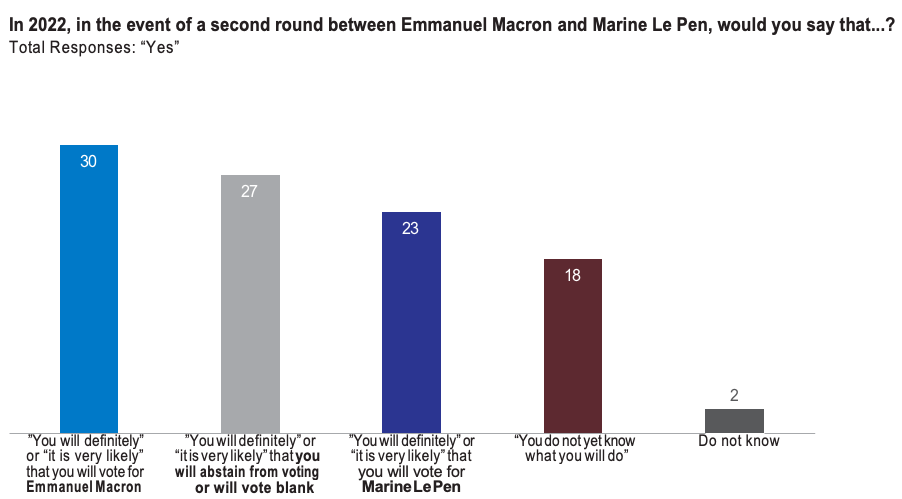

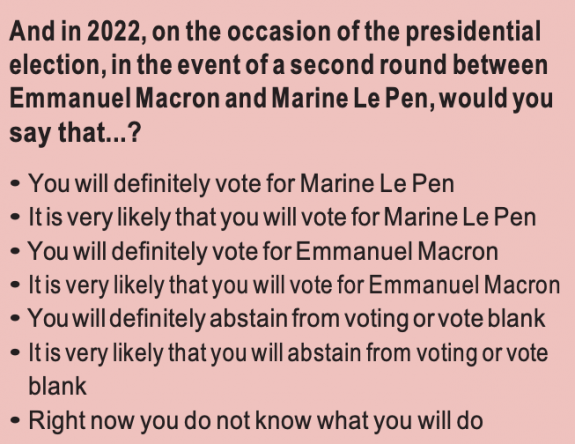

The case for a second Macron-Le Pen race and electoral protest votes

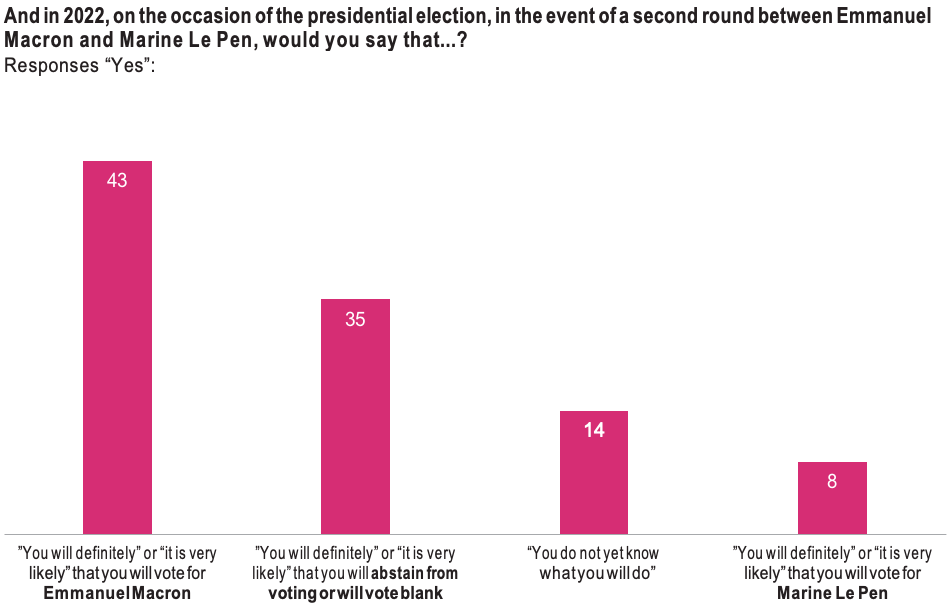

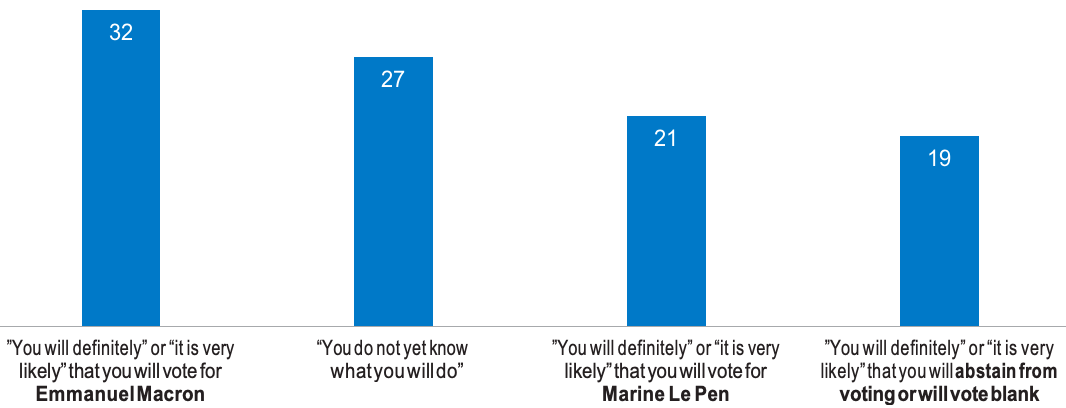

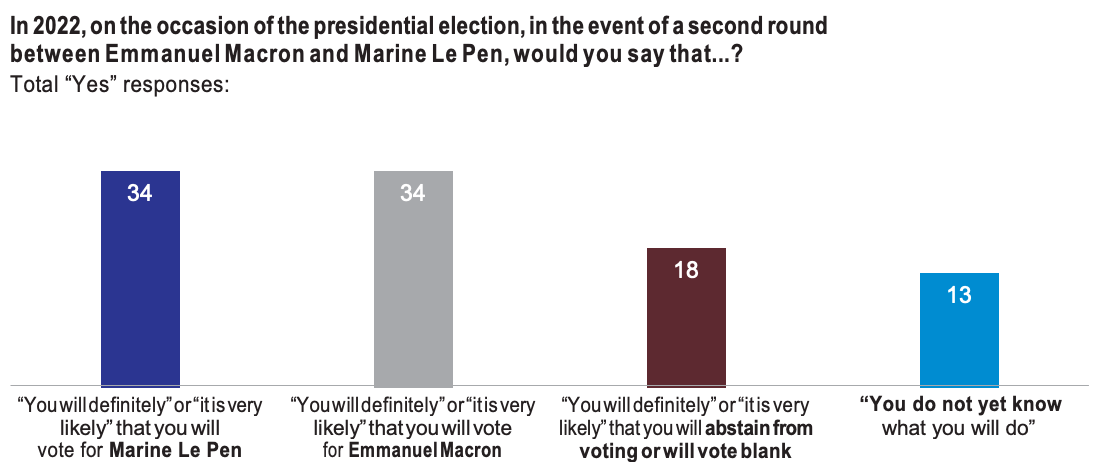

We asked our sample electorate about a hypothetical second round. The question was formulated as fol- lows:

By adopting this scale which now includes two levels rather than three, we are seeking a tighter assessment of the potential for electoral protest in 2022.

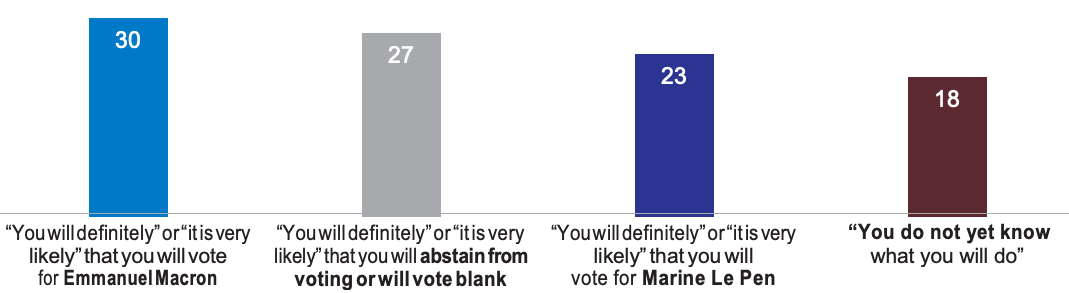

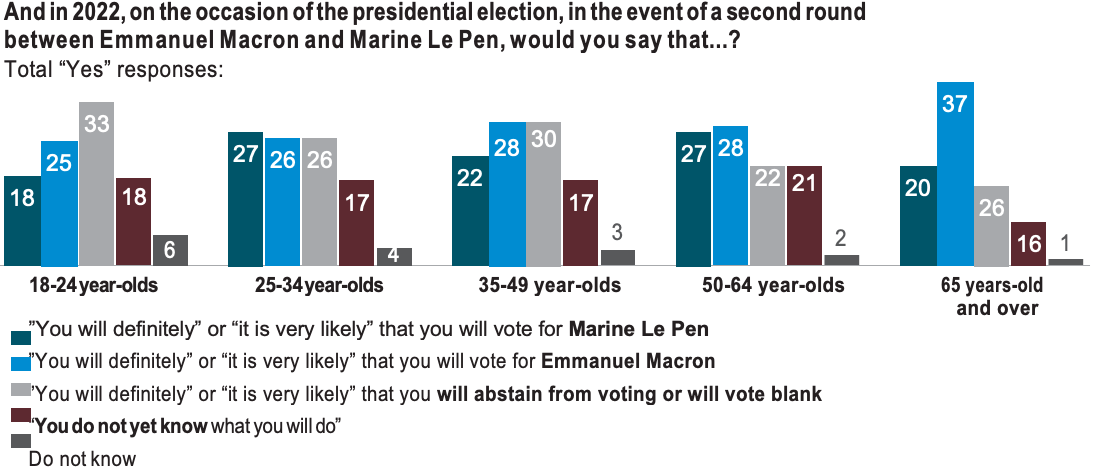

As such, when asked more specifically about a potential second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the electoral body is fragmented into three comparable blocs. Emmanuel Macron’s electoral potential (30%) is significantly higher than that of Marine Le Pen (23%). However, in the context of this competition, the proportion of voters who say that they will either definitely or are very likely to abstain from voting or vote blank is 27%. Yet, considering that the willingness to abstain from voting or voting blank has a protest aspect, the effects on the electoral decision could change. Indeed, a fraction of voters will move from partisan voting to blank voting or absten- tion, while others will do the opposite. The climate during the 2022 election year will largely determine the nature and meaning of these shifts. Furthermore, almost one-fifth (18%) of voters surveyed said they do not currently know what they will do in 2022.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The unknowns around the potential for electoral protest

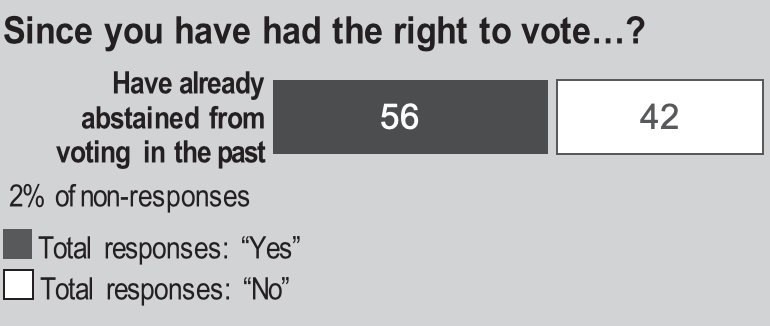

Electoral protest votes are multifaceted

a) One form of political protest is electoral protest, but this itself is multifaceted.

It can be expressed through the populist vote, but also manifests itself, in whole or in part, in withdrawal behaviours such as abstention and blank voting. More than half of voters (56%) have abstained from voting in the past. Abstention is thus a massive phenomenon. It seems to be gaining momentum. The 2017 presidential election saw abstention rates that are some of the highest in the history of electing the president by universal suffrage: in 2017, abstention (21.7%) reached the third-highest level since 1965, below 2002 (28.4%) and 1969 (22.4%). In the second round, in 2017, the level of reported abstention would be the second highest (25.4%), after that of 1969 (31.1%). In reality, we can consider the abstention record as having been achieved in 2017, insofar as the 1969 abstention was a reaction to a competition between two candidates who were moderate and very similar, if not identical (“six of one, half-dozen of the other”), the exact opposite of the situation in the 2017 second round. The 2017 abstention was thus incomparably higher compared to that of 1969.

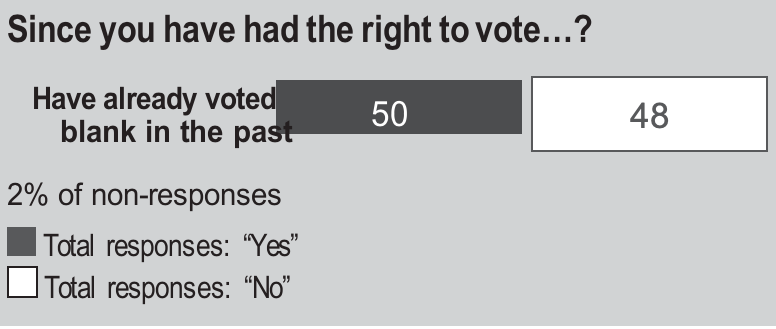

b) Furthermore, half (50%) of voters say they have cast a blank vote in the

The fact that in September 2019 half of those surveyed replied that they had voted blank in the past, although this category has only been recognised since 2014, provides retrospective insight into the content of the former “blank and invalid” category: the ballots in this category reflected more disapproval or discontent than misunderstandings of the electoral procedure.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The willingness declared to abstain from voting or vote blank creates a great uncertainty around the electoral decision. The outcome of the 21 April 2002 election was partly the result of demobilisation among left-wing voters who were, in retrospect, caught by surprise by Lionel Jospin’s elimination, which most did not want. Abstention and blank voting encourage errors of anticipation by the voters themselves and increase the risk of an electoral accident, that is to say an undesired outcome.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The PS and the LR, two electorates struggling in protest landscape

Recent political developments raise the question of what remains of the electorates of the former major government parties. What happens to the PS and LR votes in the current protest environment?

It is at least partly because of the lack of a figure representing their experiences that both electorates, on the left and the right alike, demonstrate such willingness to vote populist: 36% of voters who support the LR say they could vote for an RN candidate in the first round in 2022 and 24% for a DLF candidate; a third (32%) of voters who support the PS say they could vote for an FI candidate and 30% for an LO-NPA candidate.

a) Between populist temptation and electoral disarray

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

b) Two “orphan” electorates in the face of 2022

In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, more socialist supporters (43%) said they could vote for Macron than LR supporters (32%). But socialist voters are also more likely to consider abstaining from voting or voting blank (35%) than voters who say they support the LR (19%). The right-wing LR voters are clearly waiting to see more: over one-quarter (27%) say they do not yet know what they will do if such a situation arises.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Crossing partisan borders and the resources of the populist vote

Our figures show that a seemingly huge difference between two populist parties does not necessarily mean that the borders between them will not be crossed, if the two groups are both working from a populist perspective. 19% of individuals who have voted FN/RN in the past could vote for an FI candidate in 2022 and 22% of those who have already voted FI would be ready to vote for an RN candidate.

Similarly, 15% of those who said they had voted Mélenchon in 2017 also said they had voted FN/RN at least once and 7% of those who voted Marine Le Pen said they had voted FI at least once. The porosity of populist electorates seems stronger in one direction than in the other.

The current political and social context may favour a split vote, whether towards the left or the right. The Yellow Vests movement, bringing together people of all stripes who unanimously reject the current system, is a strong, unique expression of this new context. For example, 16% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters in 2017 said they would vote for an RN candidate in 2022. The same percentage (16%) of Marine Le Pen voters in 2017 say they could vote for an FI candidate.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The Yellow Vests, a new resource for the populist vote

Marine Le Pen’s intermediate electoral potential (17%) in the 2022 first round has a profile with well- known characteristics that can be found in our study. Manual worker and blue-collar voters are more likely to vote for Marine Le Pen (22%). The same applies to voters with little or no education (26%) and those whose monthly income is less than 2.000 € (20%). Lastly, they express a marked willingness to vote populist. When looking at the characteristics of this electorate, standard of living appears to be the most decisive factor: 68% of respondents who said they had a “very hard time making ends meet” plan to vote for at least one of the populist parties cited in our study. In contrast, Emmanuel Macron’s potential voters (16%) are more represented among the non-workers (20%), people over 65 (24%), graduates of higher education (22%) and people whose monthly income exceeds 3.500€ (25%).

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

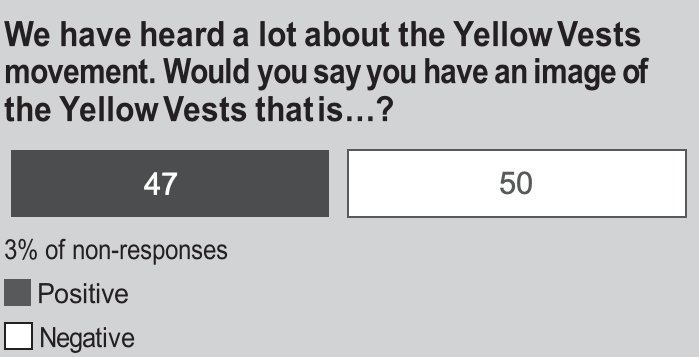

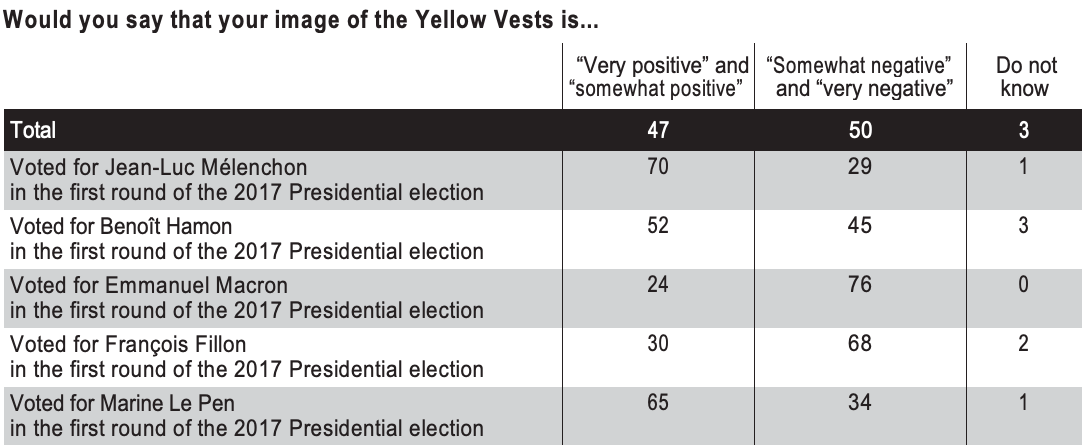

If it happens, the Macron-Le Pen duel in 2022 will not look like that of 2017. Of course a repetition will produce effects that are difficult to anticipate, above all because such a confrontation would involve the extension of a mandate that will then have been completed and thus be subject to public judgement. Moreover, the 2022 election decision will be affected, in one way or another, by the Yellow Vests movement. Our survey shows that after one year of existence, this unprecedented movement is still seen positively by 47% of French people. The most enthusiastic of these are found among supporters of the PCF or the FI (77%) and the RN (70%) as well as those who voted for Marine Le Pen (65%) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon (70%) in 2017. Populists have recognised themselves, their cause, and their anger in the Yellow Vests movement.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

The opposite is also true. Among the French who say they have a positive image of the Yellow Vests, almost all (90%) plan to use one of the six forms of electoral protest proposed by our survey in 2022: abstention, blank ballot or a vote for one of the populist and anti-establishment parties (RN, FI, DLF, LO, NPA). More than that, 71% of voters with a “very positive” image of the Yellow Vests said they could vote for RN or FI in 2022, though 17% believed they could vote for both, double the overall average recorded (8%).

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Source :

* The “populist vote” option here groups the respondents who answered that they could vote for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (RN, FI, DLF, LO/NPA).

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Among the respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests, 34% say they will “very likely” or “definitely” vote for Marine Le Pen in 2022 in the event of a second round pitting her against the incumbent president, which is 10 points above the overall average (23%). Similarly, 13% of those who report having a positive image of the Yellow Vests say they will “very likely” or “definitely” vote for Emmanuel Macron, 17 points below the overall average (30%). Furthermore, 34% of these voters who have a posi- tive image of the Yellow Vests believe they will “very likely” or “definitely” abstain from voting or vote blank, compared with an average of 27%. Half (50%) of voters with a “very positive” image of the Yellow Vests said they would “definitely” (34%) or “very li- kely” (16%) vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second-round duel against Emmanuel Macron.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

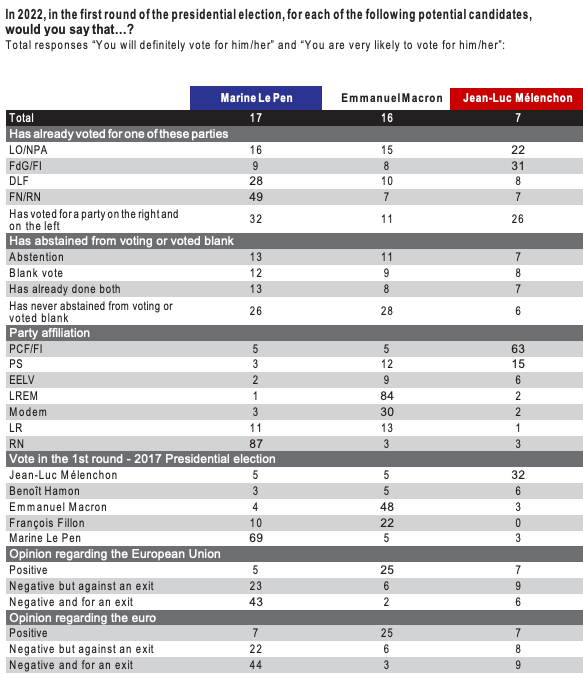

Women and young people are more resistant to populist temptations, but this may mean that they form an electoral reservoir

Overall, women’s protest voting behaviour is characterised by a larger contribution than men to abstention and blank votes, and a smaller contribution to the populist vote. For example, 59% of women surveyed said they had already abstained from voting at least once in their lives, compared with 52% of men; similarly, 54% of women said they had cast a blank ballot at least once, compared with 47% of men. Looking ahead to 2022, the majority of respondents said they could cast a blank vote (53%, compared with 44% of men); they were also more likely to say they could abstain from voting (44%) than men (39%).

While they are slightly more likely to vote for the FI (22%) than men are (18%), they are less likely (28%) than men to vote for the RN (34%). Similar- ly, a third of men (34%) said they had voted FN/RN at least once in their lives, compared with a quarter of women (26%). This difference also emerges in the hypothetical scenario in which Marine Le Pen would once again be a candidate in the first round of the pre- sidential election: 19% of men would “definitely” or “very likely” vote for her, compared to 14% of women.

However, this gap does not spare the Macron vote: 14% of women believe that they will “definitely” or “very likely” vote for the incumbent president in 2022, which is 3 points less than among the men (17%). In a hypothetical run-off between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron, more women (21%) than men (15%) said they did not know what their decision would be. The women’s vote could be one of the keys to the next presidential election.

The same applies to the youngest voters (18-24 year-olds). Their vote is somewhat favourable to Jean-Luc Mélenchon, whose intermediate electoral potential in these age groups is twice as high (14%) as his average score (7%). In a second round between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron, these voters’ choices will be a key element of electoral mobilisation: one-third (33%) of 18-24 year-olds say they will “definitely” or “very likely” abstain from voting or vote blank; 18% say they do not know what they would right now. Only one-quarter (25%) would do vote for Macron and 18% for Le Pen.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

Populist leaders suffer opposition attrition

Through their style, their rhetoric and their omnipre- sence in an election as important as the presidential election, Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon have become particularly prominent figures in the political world. Without a doubt, their personalities have strongly fostered the populist vote. However, this could now put a damper on its expansion.

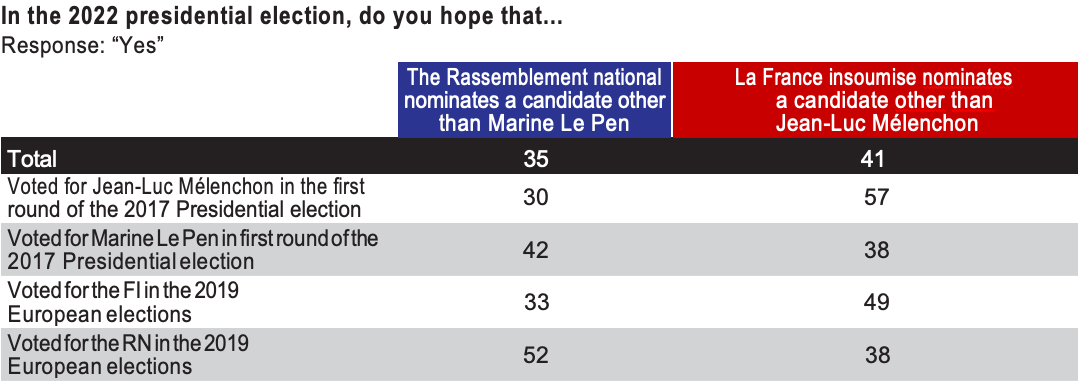

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s political longevity also came at a time when media exposure was much more limited than today. While populist leaders have been pleased to see social media and news channels continue to create a new public space from which they have benefited immensely, the intensity of the media regime now in place is no longer sustainable, whether for the populists or their competitors. Our study shows that attrition is occurring: 41% of respondents want another leader to replace Jean-Luc Mélenchon, which is already significant; that number rises to 57%, howe- ver, among his own voters from 2017. Similarly, 35% of respondents want Marine Le Pen replaced (this figure is lower, but it climbs to 42% among her own voters from 2017).

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

From the Republican Front to the Monetary Front: the euro resists populism

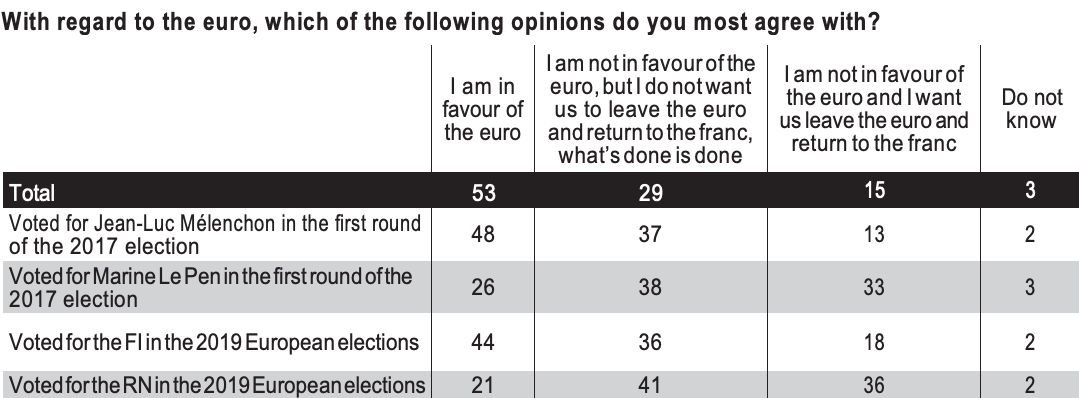

This is a key element of European opinion that has long been identified in the work of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. More than half of respondents (53%) are in favour of the European currency; more than a quarter (29%) say they are not in favour of the euro but at the same time feel that the European currency should not be phased out in favour of returning to the franc. Only a minority (15%) actually want a return to the franc.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2019.

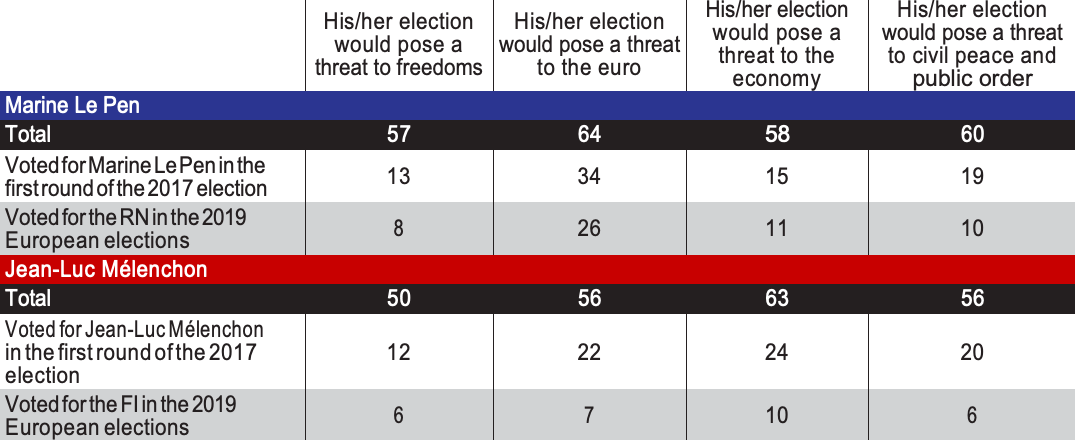

In the eurozone, and perhaps even beyond the European Union, this is the obstacle that populists in general and Marine Le Pen in particular face. Our indicator shows that her electorate is split on this issue: nearly two-thirds (64%) of voters who chose the FN candidate in 2017 want to keep the euro, compared with one-third (33%) who want to return to the franc. Moreover, while 64% of those polled believe that Marine Le Pen’s election would pose a threat to the euro, this fear was found among 38% of those who said that they had voted for the FN/RN at least once in the past, and 34% of those who had voted for Marine Le Pen before.

As for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the situation is even more striking, since almost all of his voters (85%) want to keep the euro and only 13% are in favour of a return to the franc.

A large part of the population seems to be looking for some kind of electoral insurrection, but the French are even more convinced of the need to preserve both Europe and the euro. Political leaders who threaten the European currency are seen as posing a risk to their own voters’ personal material wealth. Populist discourse which is hostile to the euro would seem like nothing more than an absurd paradox were it not explained by their need to not get caught in the trap of political normalisation. One cannot defend the euro without defending the European Union. The European Union cannot be defended without step- ping off the comfortable path of protest politics. The “republican front”, weakened by its reiteration and its assimilation into a dubious truce between opposed parties clinging to power, follows a sort of “monetary front.” This front is more powerful because it is based on voters’ material interests. By contrast, a major euro or European crisis would significantly increase the potential for electoral protest, to the point where it could win the presidential election.

The survey’s questionnaire

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

- Sex

- Age

- Region of residency

- Size of the municipality of residence

- Education level

- Occupation

- Status (working or not working)

- Monthly household income

- Party affiliation

- Vote in 2012 Presidential election (first and second round)

- Vote in 2017 Presidential election (first and second round)

- Vote in the 26 May 2019 European elections

- Self-positioning on a left/right political scale

- Are you very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with Emmanuel Macron’s actions as President of the Republic?

- Very satisfied

- Somewhat satisfied

- Somewhat dissatisfied

- Very dissatisfied

- In general, do you have the impression that science brings humanity…?

- More good than bad

- More bad than good

- About as much bad as good

- With regards to how you define yourself right now, would you say that your political choices ..?

- Very important

- Somewhat important

- Somewhat unimportant

- Very unimportant

- How easily do you live on your household income?

- With great difficulty

- With some difficulty

- Somewhat easily

- Very easily

- How often do you check social media such as Twitter or Facebook?

- Several times a day

- Once a day

- Several times a week

- Once a week or less

- Never

- Can you tell me what your religion is, if you have one?

- Catholic

- Protestant

- Muslim

- Jewish

- Other religion

- No religion

- Do not wish to respond

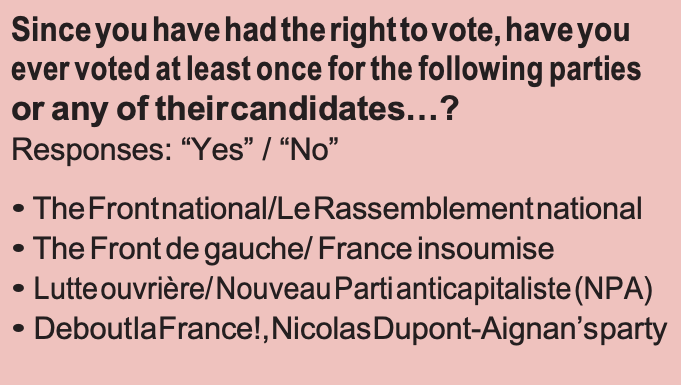

- Since you have had the right to vote, have you ever voted at least once for the following parties or any of their candidates…?

Responses:

- “Yes”

- “No”

- The Front national/ Rassemblement national

- The Front de gauche/ France insoumise

- Lutte ouvrière/ Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste (NPA)

- Debout la France!, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan’s party

- And since you have had the right to vote…?

Responses:

- “Yes”

- “No”

- You have abstained from voting

- You have voted blank

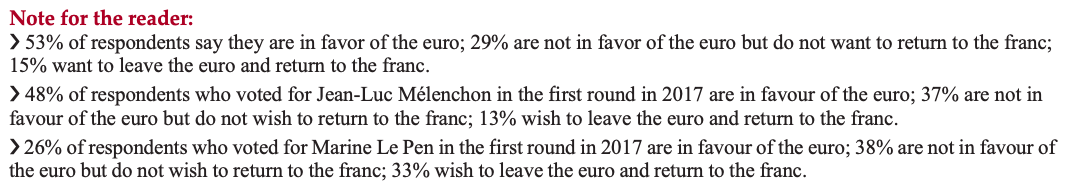

- With regard to the European Union, which of the following opinions do you most agree with?

- I am in favour of the European Union and of France being a

- I am not in favour of the European Union, but I do not want France to exit it, what’s done is

- I am not in favour of the European Union and I want France to exit it.

4. With regard to the euro, which of the following opinions do you most agree with?

- I am in favour of the

- I am not in favour of the euro, but I do not want us to leave the euro and return to the franc, what’s done is

- I am not in favour of the euro and I want us to leave the euro and return to the franc.

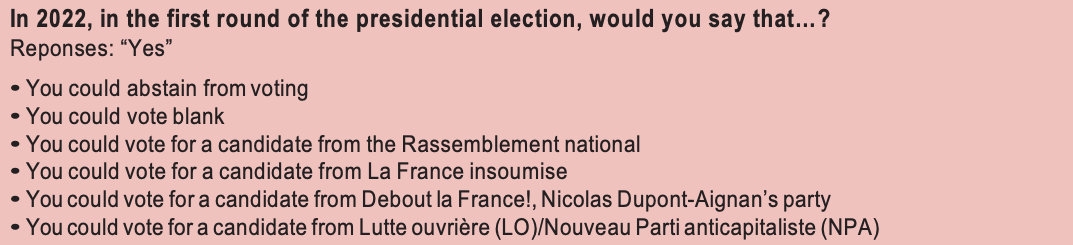

5. In 2022, in the first round of the presidential election, would you say ..?

Responses:

- Yes, absolutely

- Yes, somewhat

- Not really

- Not at all

- You could vote for a candidate from the Rassemblement national

- You could vote for a candidate from Debout la France!, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan’s party

- You could vote for a candidate from La France insoumise

- You could vote for a Lutte ouvrière (LO)/Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste (NPA) candidate

- You could abstain from voting

- You could vote blank

6. In 2022, in the first round of the presidential election, for each of the following potential candidates, would you say that…?

Assessed candidates: Marine Le Pen / Jean-Luc Mélenchon / Emmanuel Macron

- you will definitely vote for him/her

- you will most likely vote for him/her

- you might vote for him/her

- you are unlikely to vote for him/her

- you will definitely not vote for him/her

7. And in 2022’s presidential election, in the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, would you say that…?

- You will definitely vote for Marine Le Pen

- It is very likely that you will vote for Marine Le

- You will definitely vote for Emmanuel Macron

- It is very likely that you will vote for Emmanuel Macron

- You will definitely abstain from voting or vote blank

- It is very likely that you will abstain from voting or vote blank

- Right now you do not know what you will do

8. In the 2022 presidential election, do you hope that…

Responses:

- “Yes”

- “No”

- La France insoumise presents a candidate other than Jean-Luc Mélenchon

- The Rassemblement national presents a candidate other than Marine Le Pen

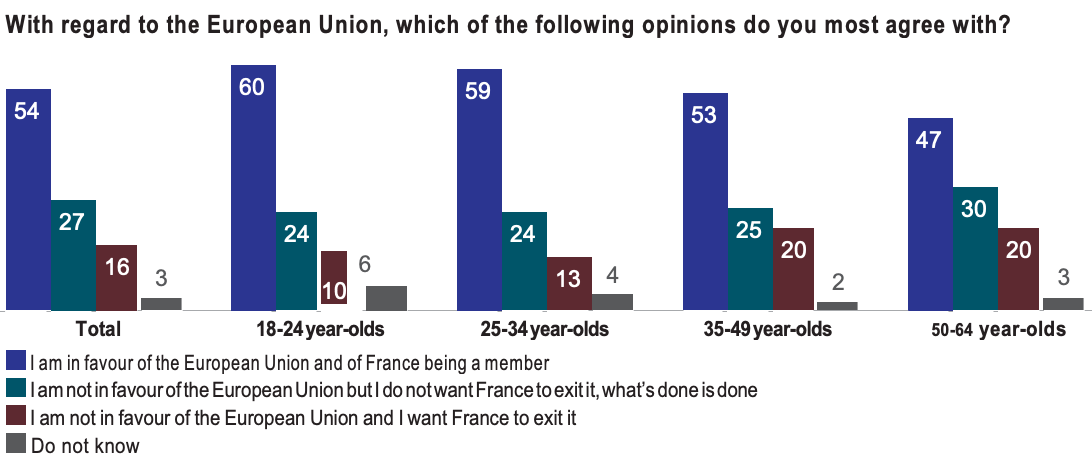

9. Do you agree with each of the following statements?:

“With regard to the 2022 presidential election and the candidacy of Marine Le Pen, some people say that…”

Responses:

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Strongly disagree

- Her election would pose a threat to freedoms

- Her election would pose a threat to the euro

- Her election would pose a threat to the economy

- Her election would pose a threat to civil peace and public order

10. Do you agree with each of the following statements?:

“With regard to the 2022 presidential election and the candidacy of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, some people say that…”

Responses:

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Strongly disagree

- His election would pose a threat to freedoms

- His election would pose a threat to the euro

- His election would pose a threat to the economy

- His election would pose a threat to civil peace and public order

11. We have heard a lot about the Yellow Vest Would you say you have an image of the Yellow Vests that is…?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

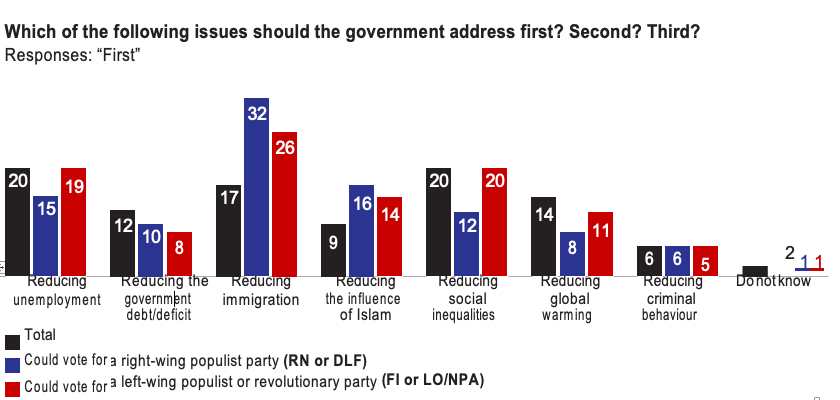

12. Which of the following issues should the government address first? Second? Third?

- Reducing unemployment

- Reducing the government debt/deficit

- Reducing immigration

- Reducing the influence of Islam

- Reducing social inequalities

- Reducing global warming

- Reducing criminal behaviour

No comments.