2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

The key findings from Wave 4

Introduction

2022, the Populist Risk in France: an indicator of electoral protest designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

Electoral protest has come a long way. A look back at presidential elections since 1965

With one year to go before the presidential election, the willingness for electoral protest is soundly established

The potential for electoral protest: Wave 4

The idea of a candidate unaffiliated with a political party appeals to a majority (55%)

Marine Le Pen elected in 2022: somewhere between an electoral accident and a breakaway vote

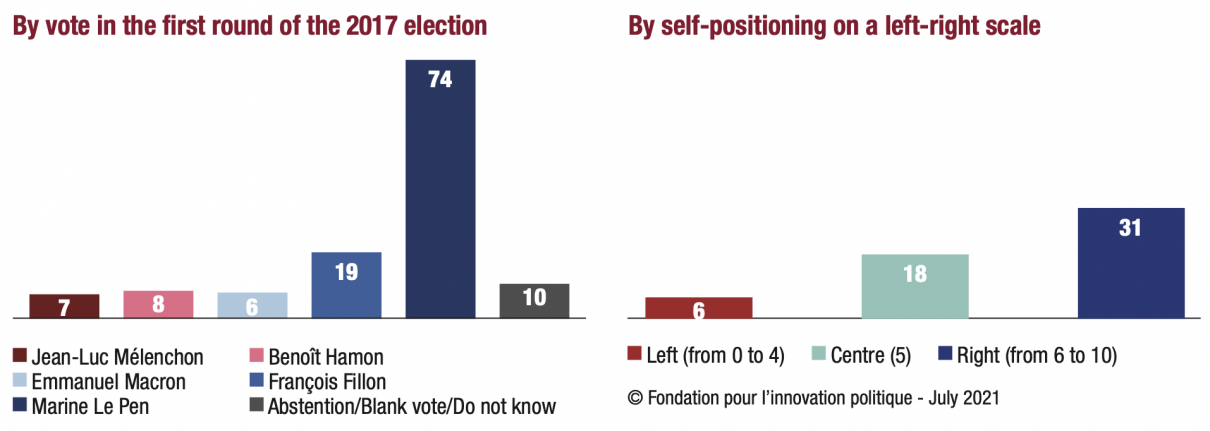

The electorate’s shift to the right could favour Marine Le Pen…

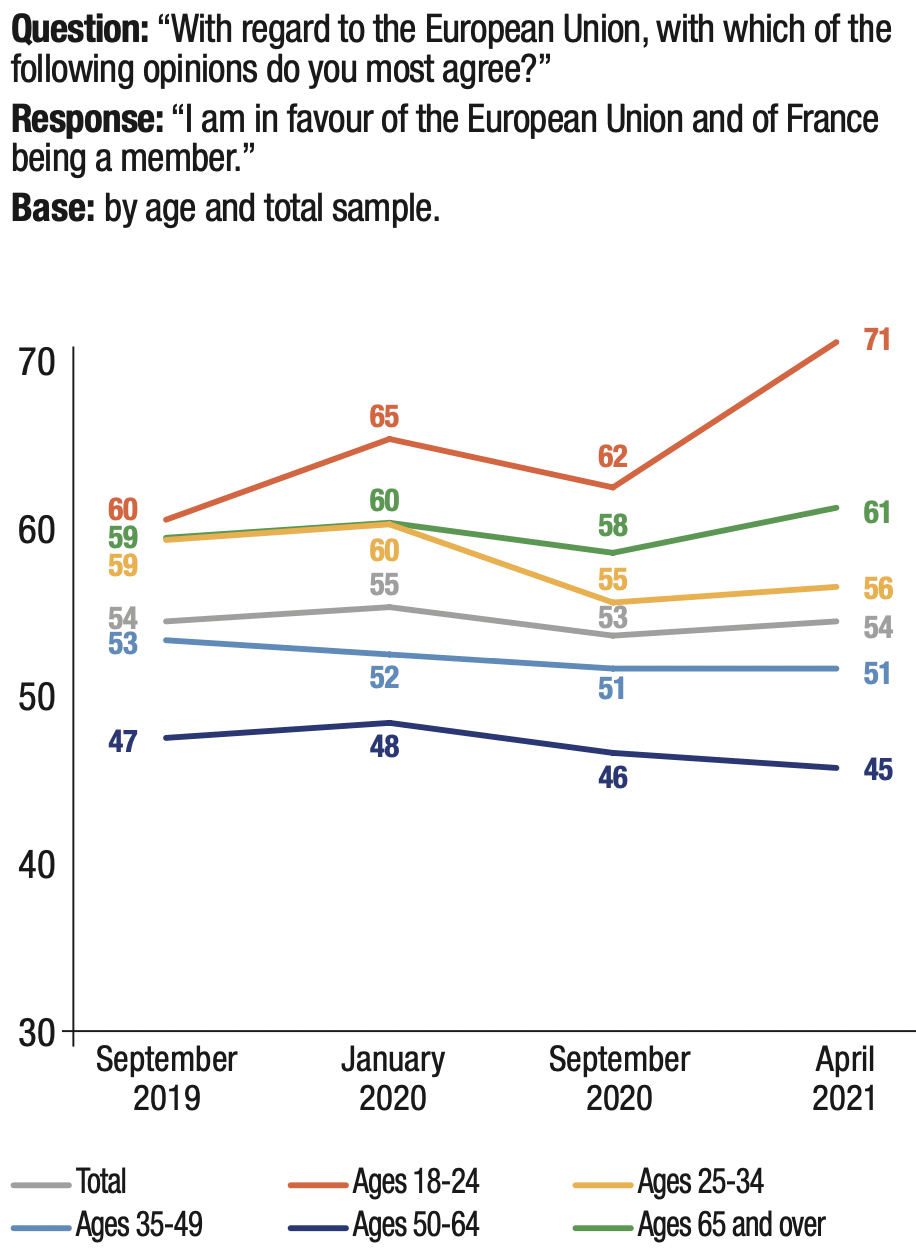

…but the health crisis has not altered attachment to Europe

The dual crisis of representation

The erosion of the privilege of competence granted to governing parties reduces the handicap of populist parties

The media depiction is questioned

Territorial divides and a rejection of centralism feed electoral protest

The willingness to cast a protest vote is growing significantly in rural municipalities, as well as in small and medium-sized cities

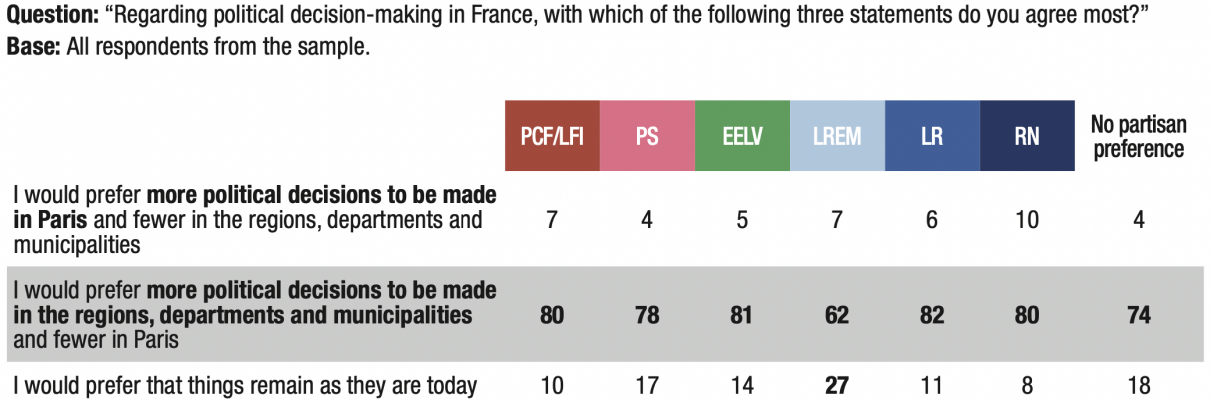

The majority wish (74%) is “for more political decisions to be made by the regions, departments and municipalities, and fewer in Paris”

The middle and working classes appear to converge in protest

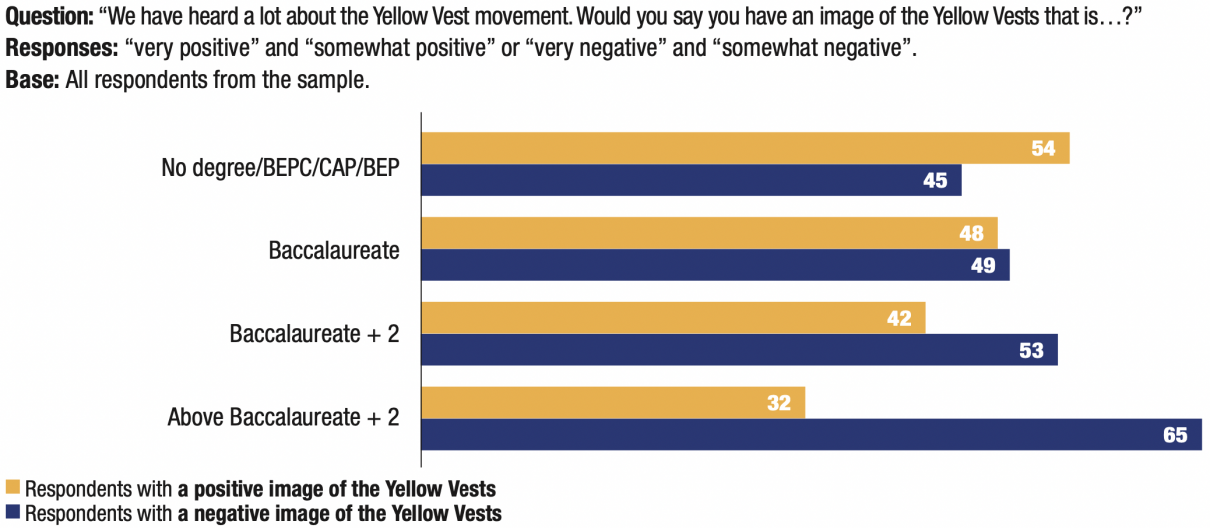

Support for the Yellow Vests is an element of electoral protest

The survey’s questionnaire

Summary

Since 2017, France has experienced a series of crises of differing intensities, from opposition to the retirement reform or the Yellow Vest movement to the most recent, the Covid-19 pandemic. The Fondation pour l’innovation politique aims to contribute to understanding how these different crises may affect the 2022 presidential election, a major political event for the French but also a vote with European consequences.

Here, we present the results of Wave 4 of our electoral protest indicator, launched in September 2019 looking ahead to the upcoming next presidential election. Wave 4 was conducted from 6 to 12 April 2021. The context of the survey remains marked by a resumption of the pandemic, a curfew (implemented on 3 March 2021) and a new lockdown instituted as of 3 April. However, the vaccine camapign launched during this period is a major new development, appearing to open up the prospect of an end to the crisis.

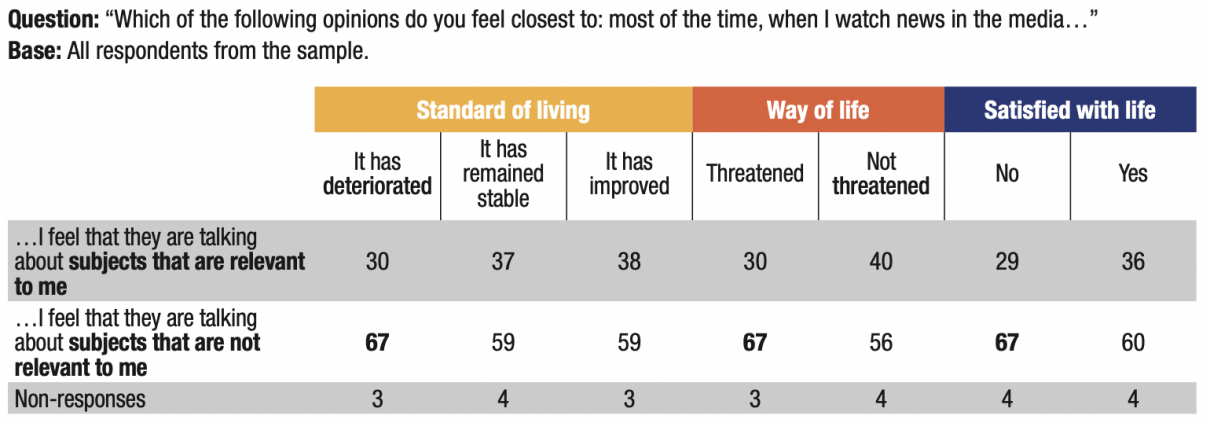

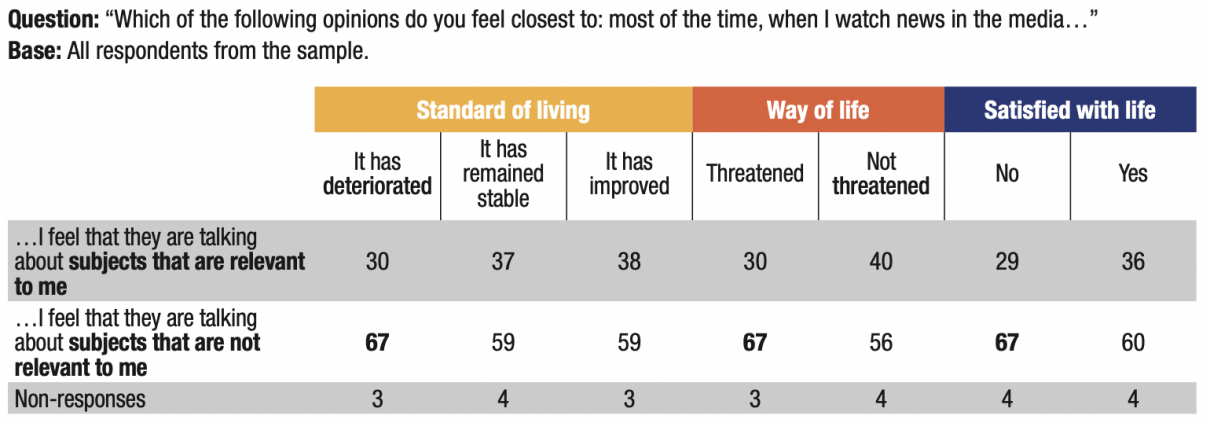

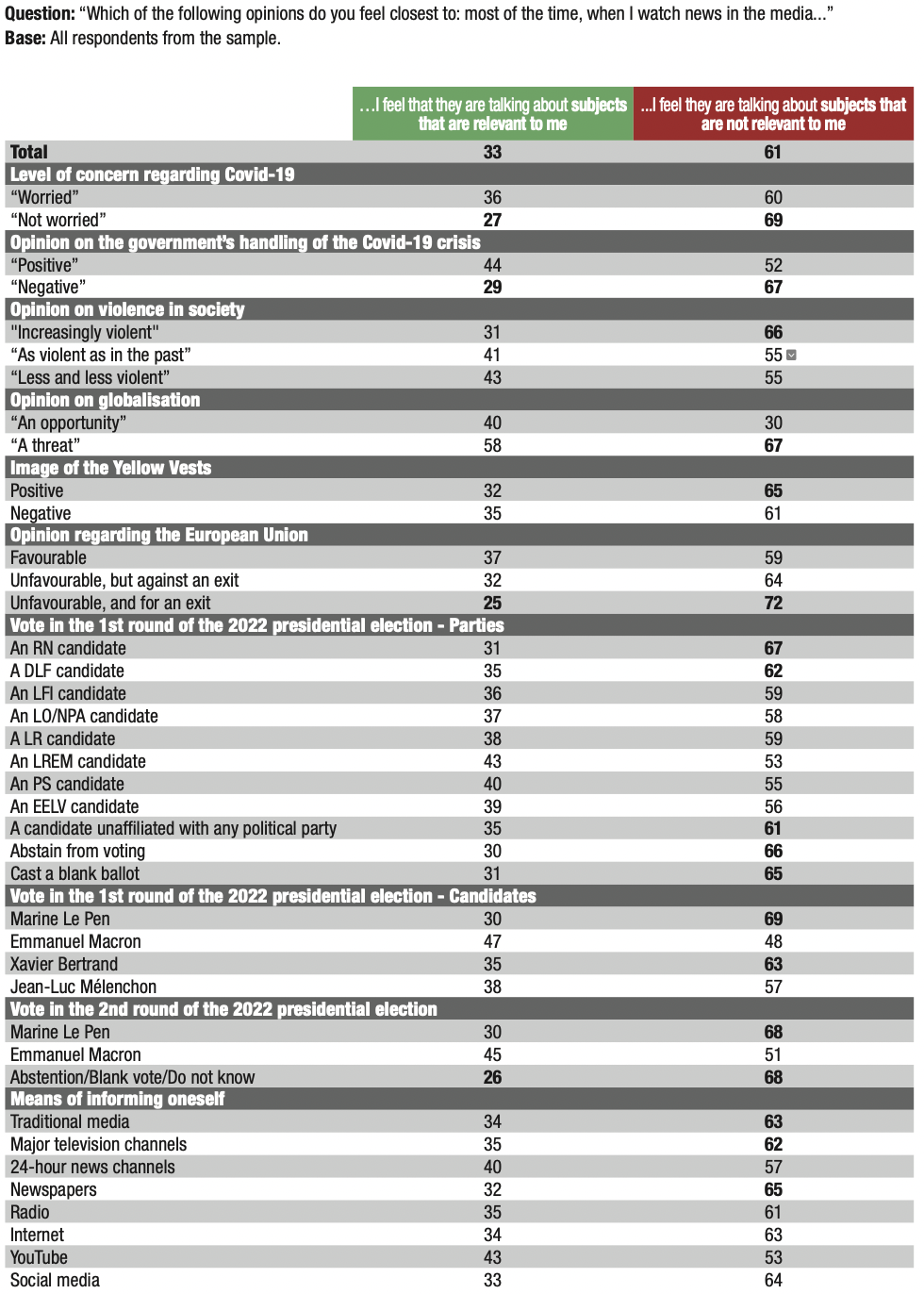

Out of the many lessons learned from the results of this Wave 4, of particular note are: the readiness for electoral protest in the middle and working classes; the continuation and affirmation of the right-wing shift in public opinion, particularly among the youngest populations; a challenge to media depictions (61% of respondents feel that the media talk about subjects that are not relevant to them) which complements the crisis of political representation already known;

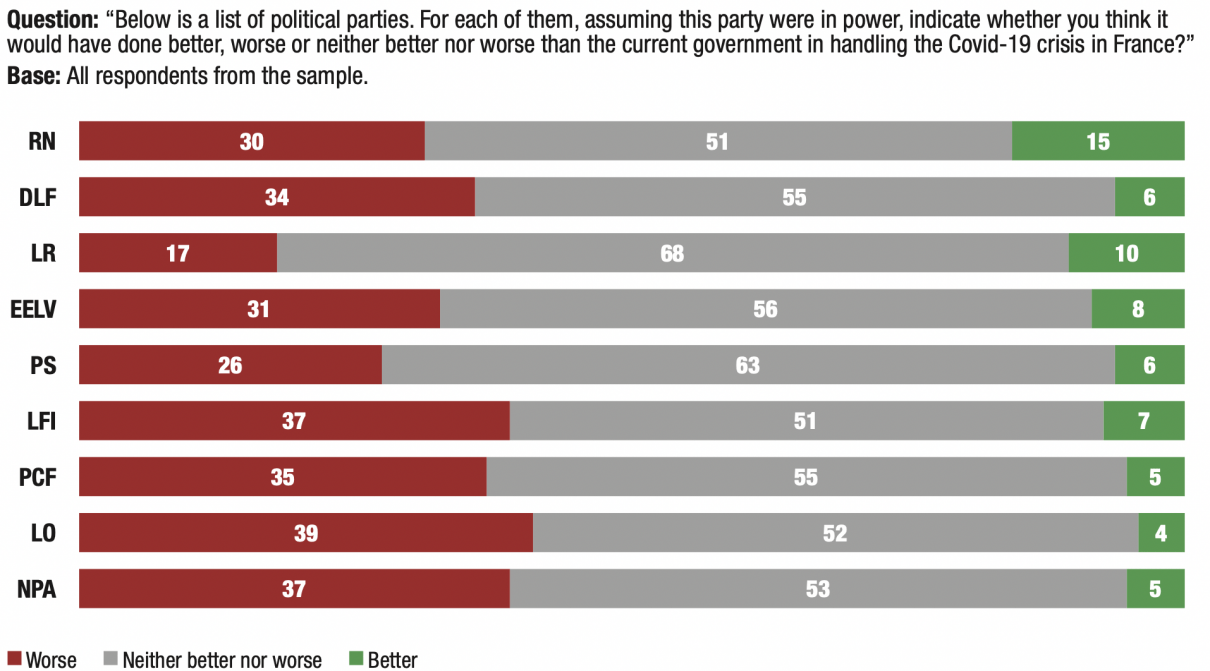

the uncovering of a link between the readiness for electoral protest and reliance on 24-hour news channels for information, with voters close to the RN or LR being more likely to find their information via these channels, though it would be inaccurate to reduce their audience to a right-wing world; the observation that, for a majority of respondents, opposition parties, whether on the right or on the left, would not have fared better had they been in charge of managing the pandemic; an attachment to Europe unaltered by the public health crisis; or the widely favourable opinion of the French to a move towards decentralisation.

This electoral protest indicator was developed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The survey was conducted by the polling institute OpinionWay. For each wave, the questionnaire is administered to a sample of more than 3,000 registered voters.

The results of Wave 1 were first published in October 2019. The results of Waves 2 and 3 were released in a single publication due to restrictions caused by the lockdown (October 2020). In this publication, we present the results of Wave 4. All survey results are available for free on our website fondapol.org as are the data, on data.fondapol.org.

Fondation pour l'innovation politique,

A French think tank for European integration and the free economy.

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

What next for democracy?

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

2019 European Elections. The weight of the political electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups

The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values

Dominique Reynié, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Abdellah BOUHEND, Victor DELAGE, Élisa GRANDJEAN, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Dominique REYNIÉ

Abdellah BOUHEND, Victor DELAGE, Anne FLAMBERT, Élisa GRANDJEAN, Katherine HAMILTON, Léo MAJOR

Julien RÉMY

the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

the polling institute OpinionWay

Guillaume Inigo (Project Director),

Bruno JEANBART (Vice President),

Clément ROYAUX (Project Manager)

July 2021

Abbreviations of the different political parties used in this study

DLF: Debout la France ! [Arise, France!] • EELV: Europe Écologie-Les Verts [Europe Ecology-Greens]

FdG: Front de gauche [Left Front] • LFI: La France insoumise [France Unbowed] • FN: Front national [National Front)] LO: Lutte ouvrière [Workers’ Struggle] • LR: Les Républicains [The Republicans]

LREM: La République en marche [The Republic Onward] • NPA: Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste [New Anti-Capitalist Party] • PCF: Parti communiste français [French Communist Party] • PS: Parti socialiste [Socialist Party]

RN: Rassemblement national [National Rally]

The key findings from Wave 4

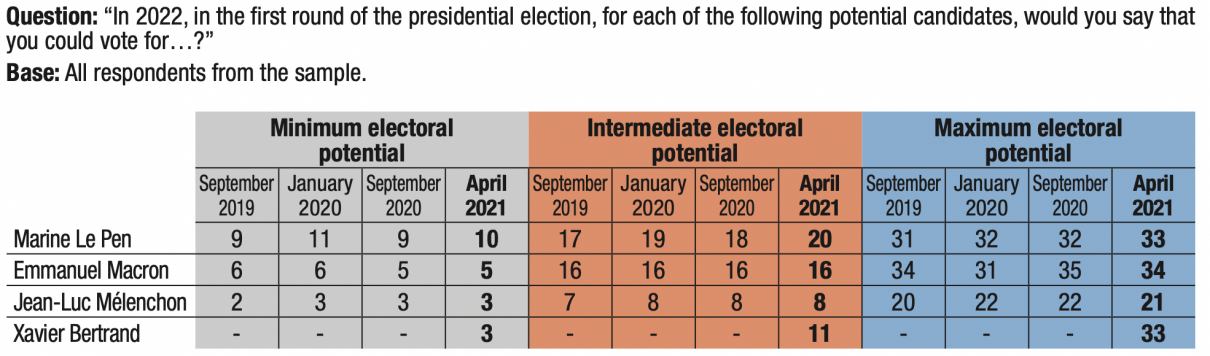

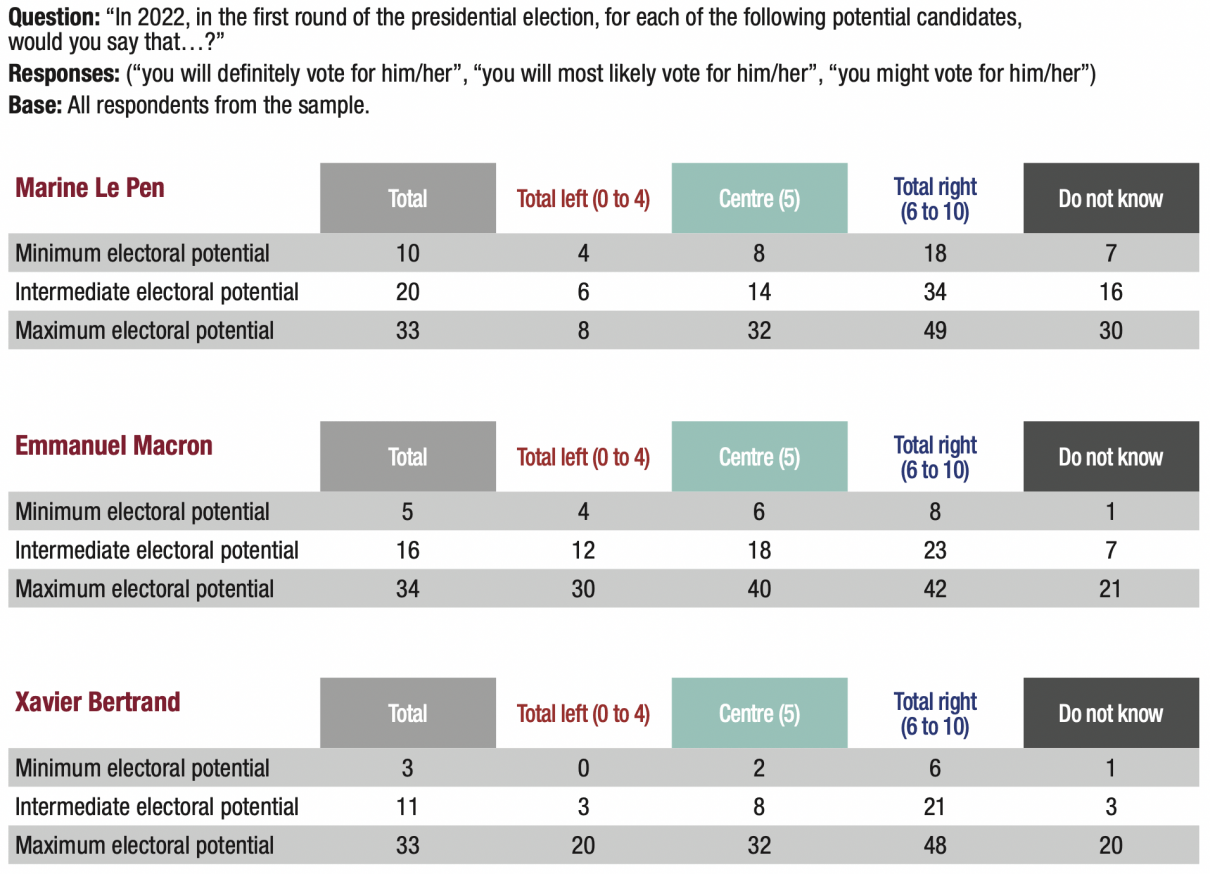

1. The data from Wave 4 (April 2021) confirm the solidity of the support for Marine Le Pen in a part of public opinion. For the first round of the 2022 presidential election, her electoral potential is the highest, with a minimum electoral potential of 10% (those “definitely” voting for the RN candidate) and an intermediate electoral potential of 20% (those who “might” or are “most likely” to vote for the RN candidate).

Emmanuel Macron’s minimum electoral potential is 5%, while his intermediate electoral potential amounts to 16%. A newcomer among likely presidential candidates, Xavier Bertrand obtained 3% of minimum electoral potential and 11% of intermediate electoral potential.

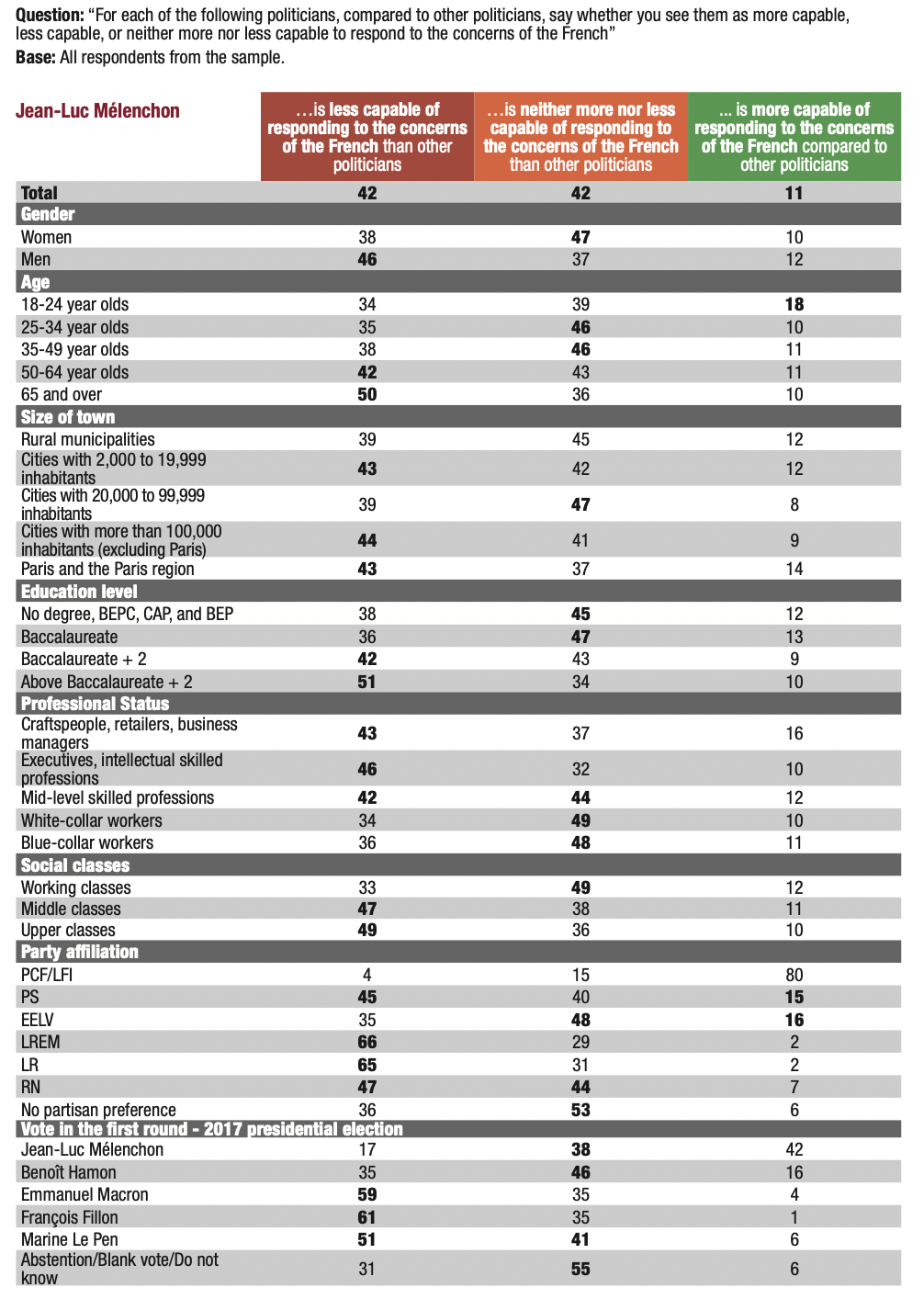

Lastly, Jean-Luc Mélenchon has minimum electoral potential of 3%, while his intermediate electoral potential is 8%.

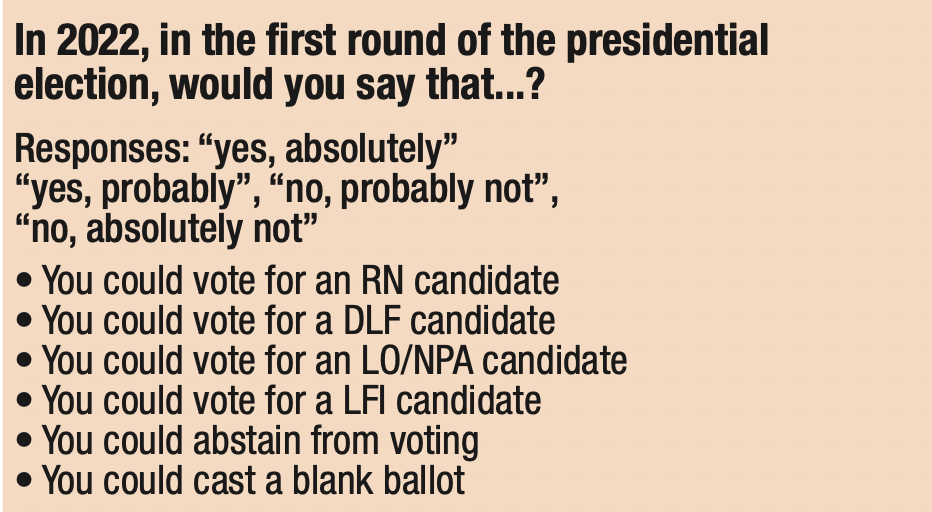

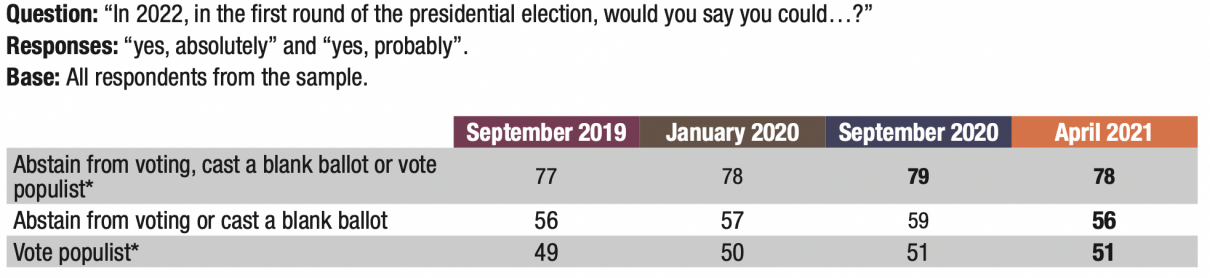

2. The potential for electoral protest remains massive: 78% of respondents are still contemplating voting for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, abstain from voting, or casting a blank ballot in the first round of the 2022 presidential election.

3. The proportion of respondents who said they might abstain from voting or leave their ballot blank in the first round of the 2022 presidential election remains very high (56%), but is nevertheless down 3 points compared to the previous wave in September 2020 (59%).

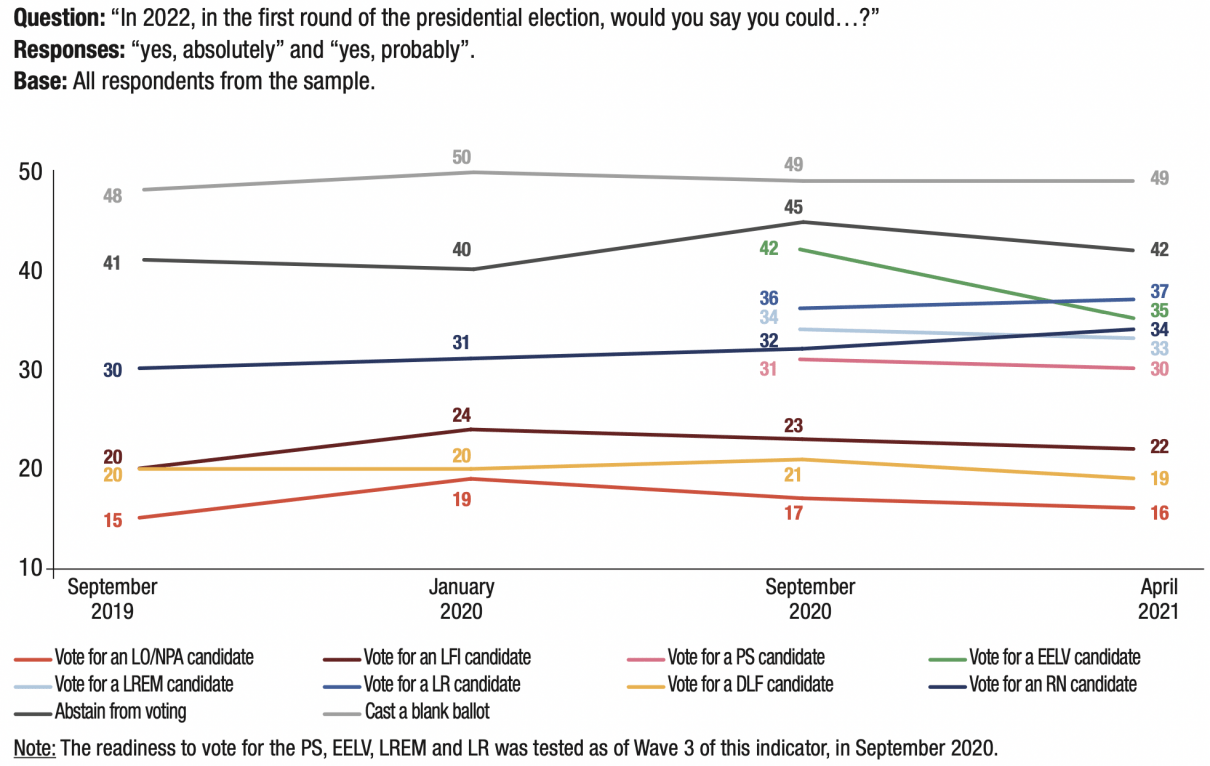

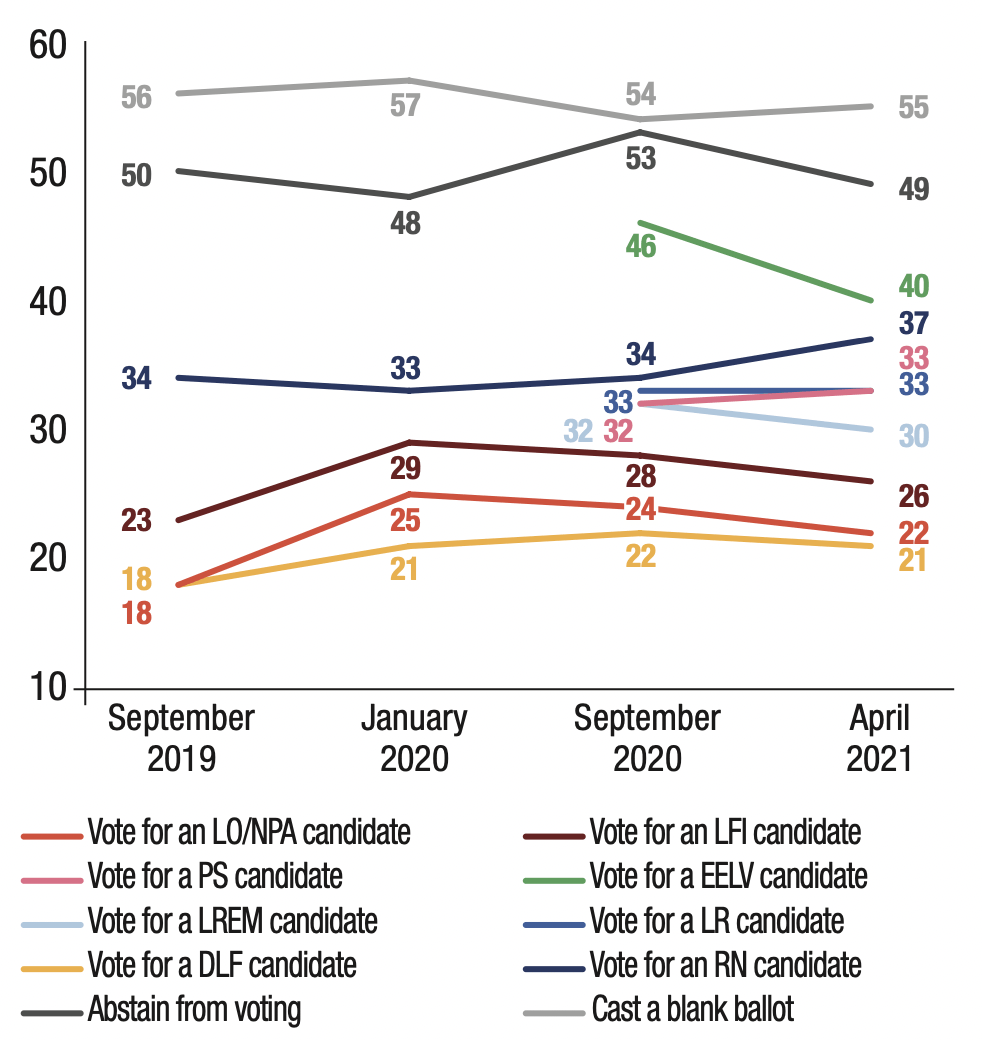

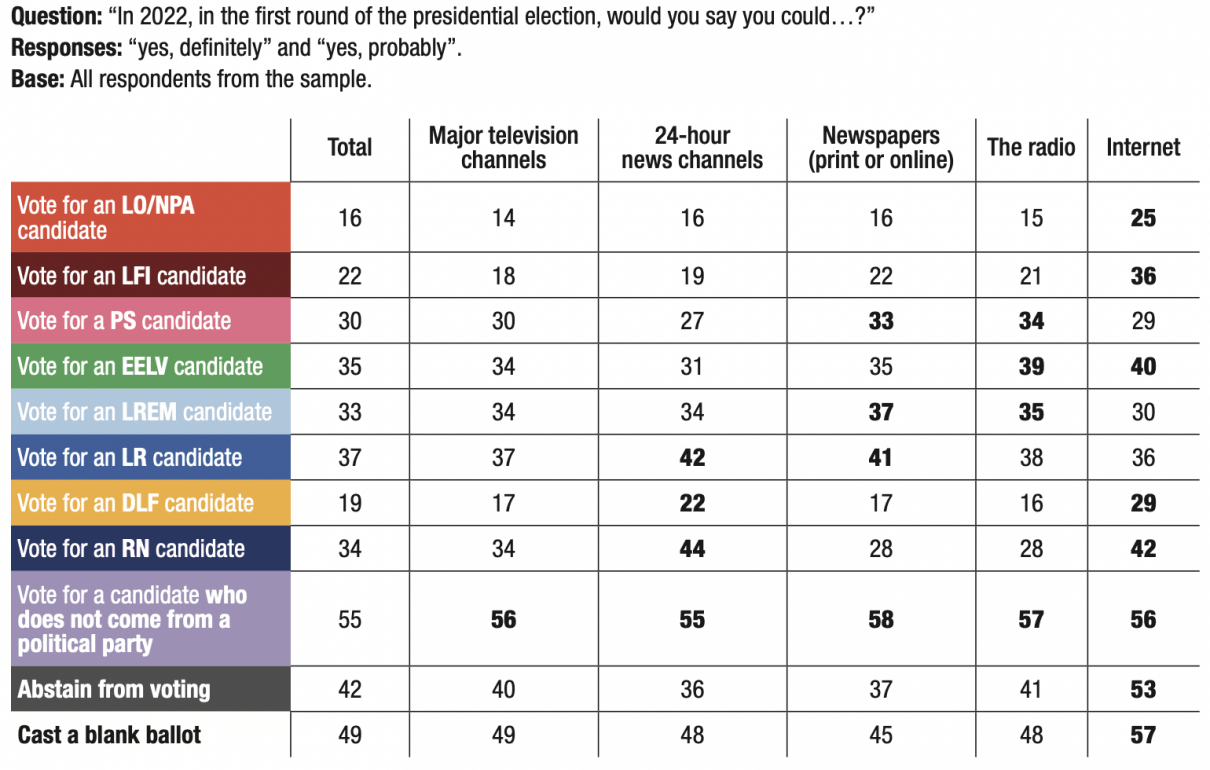

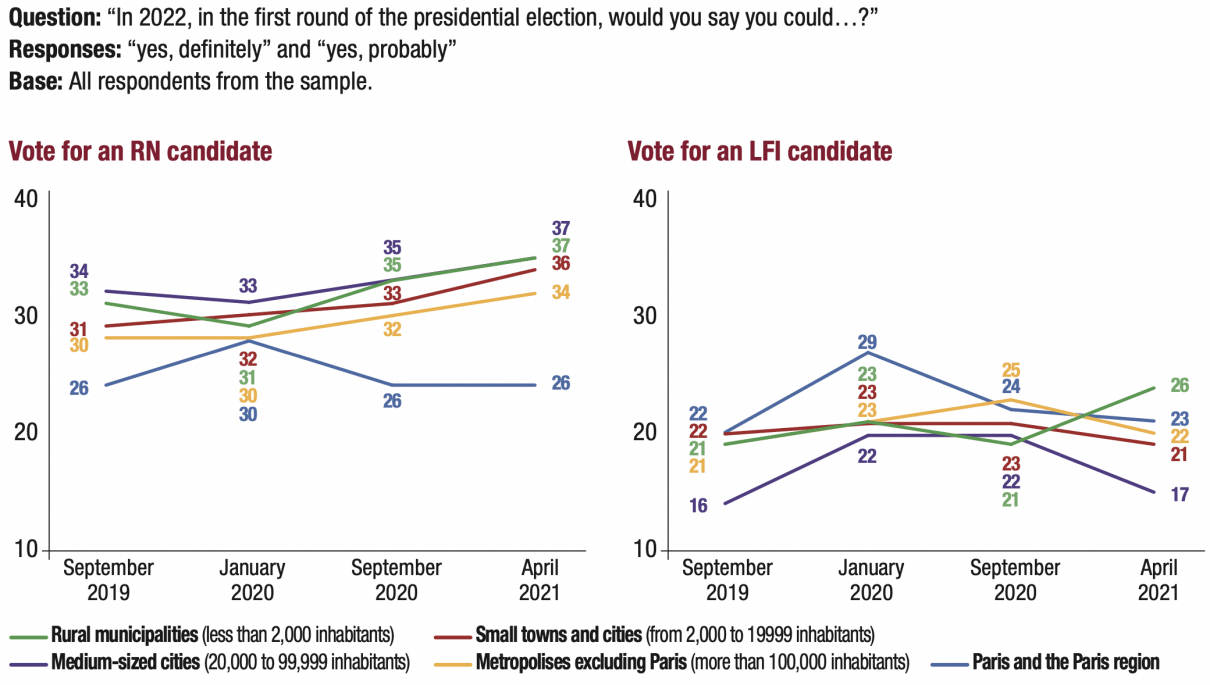

4. As pertains to voters’ readiness to vote for a party, and no longer for a declared candidate, we note an increase in the readiness to vote for the RN in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, i.e. an increase of 4 points, from 30% in September 2019 to 34% in April 2021. On the other end of the political spectrum, LFI remains at a level close to that of September 2019: 22% in April 2021, compared to 20% in September 2019.

The readiness to vote LR remains stable and high (37%, compared to 36% in September 2020).

The readiness to vote PS (30%, compared to 31% in September 2020) and the readiness to vote LREM (33%, compared to 34% in September 2020) are also stable, though at a lower level.

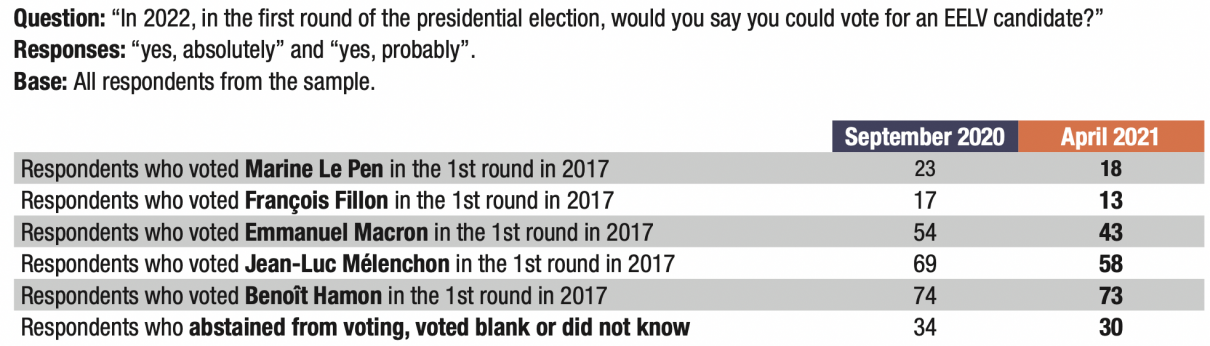

The readiness to vote EELV remains high but has fallen sharply, by 7 points, from 42% in September 2020 to 35% in April 2021.

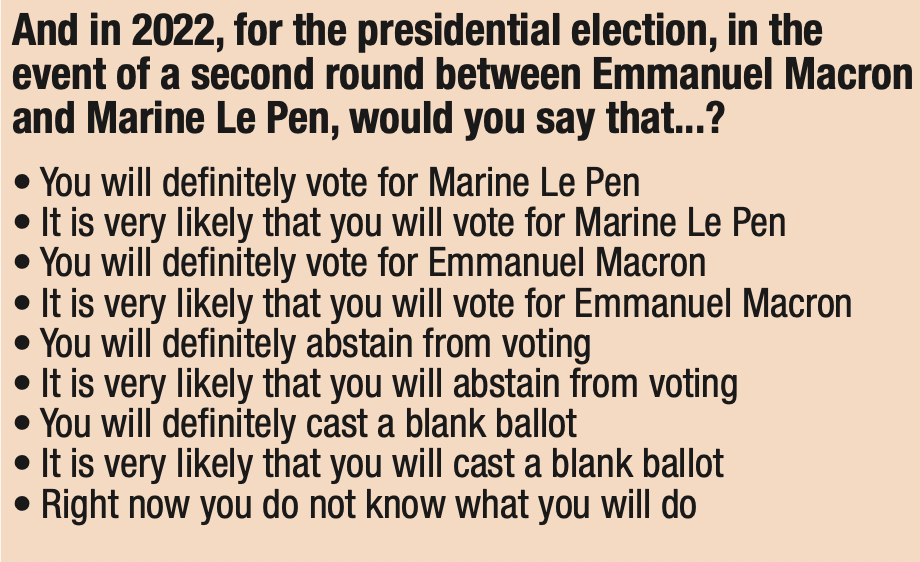

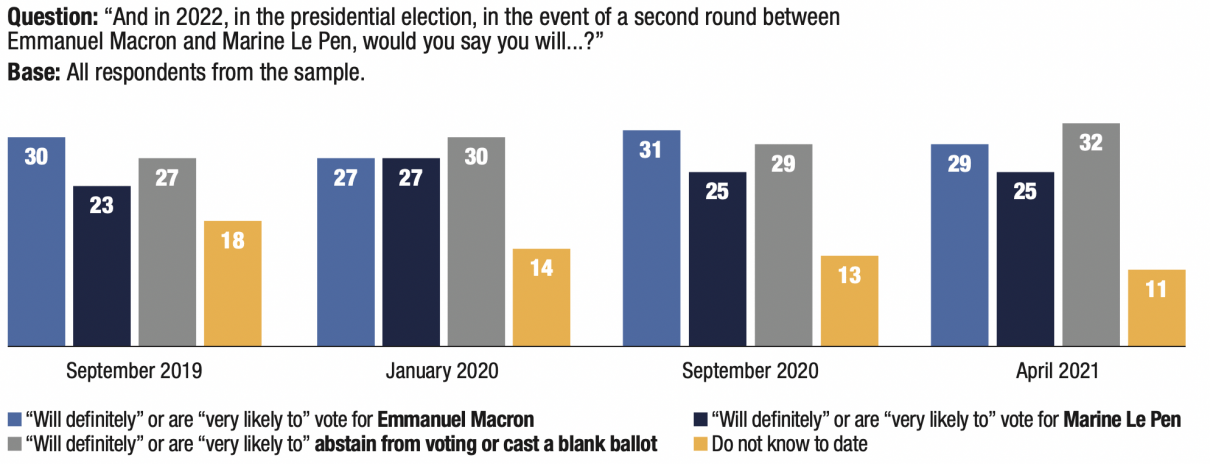

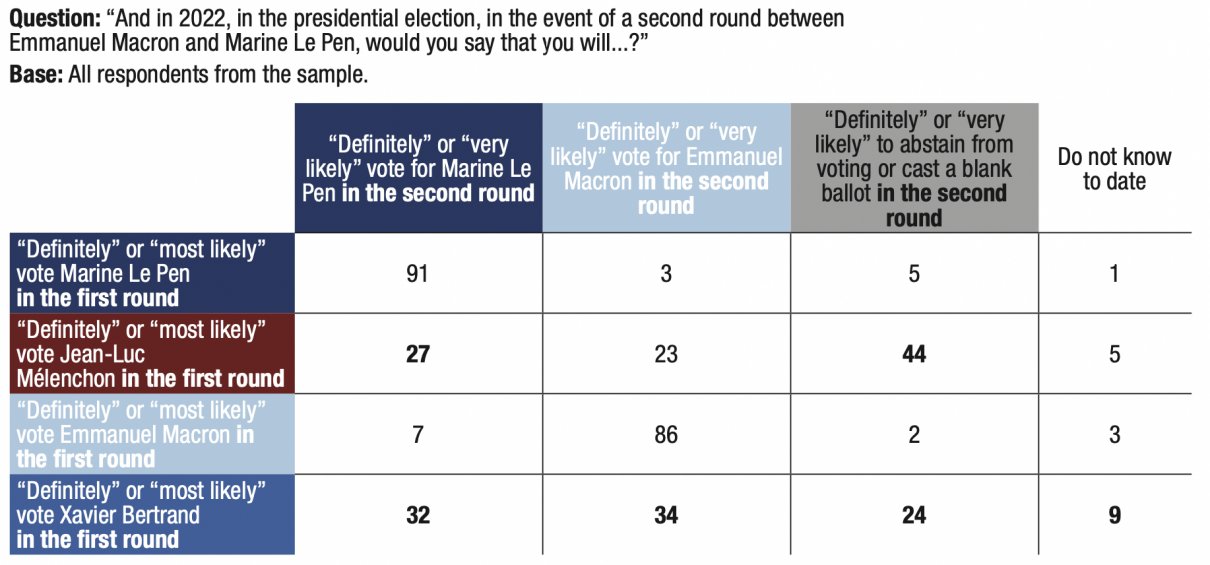

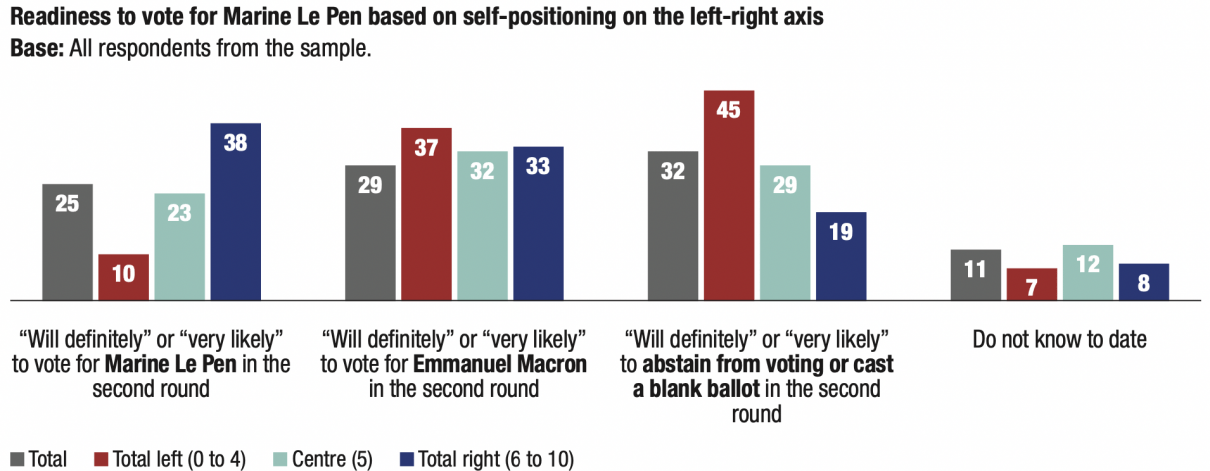

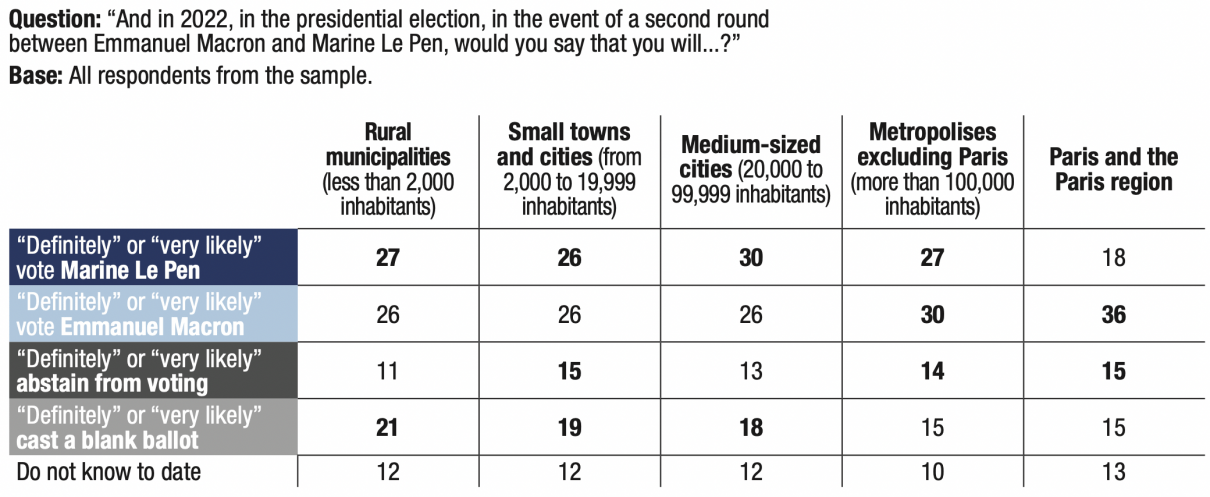

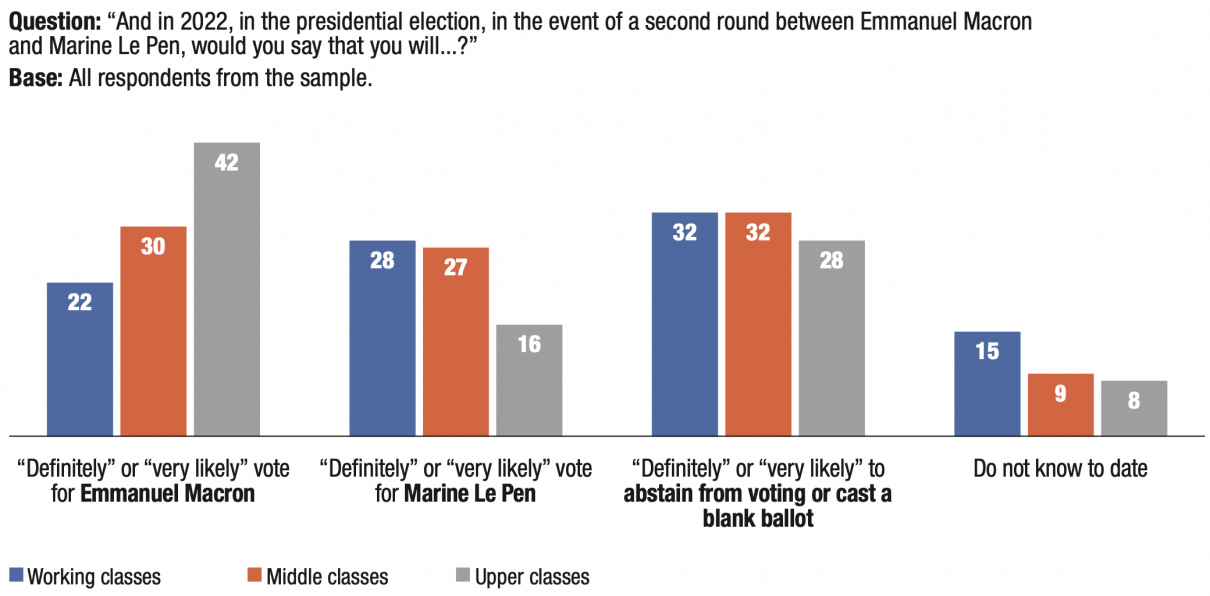

5. In a potential second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the gap narrowed in April 2021, with 29% of respondents saying they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Emmanuel Macron and 25% saying they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen.

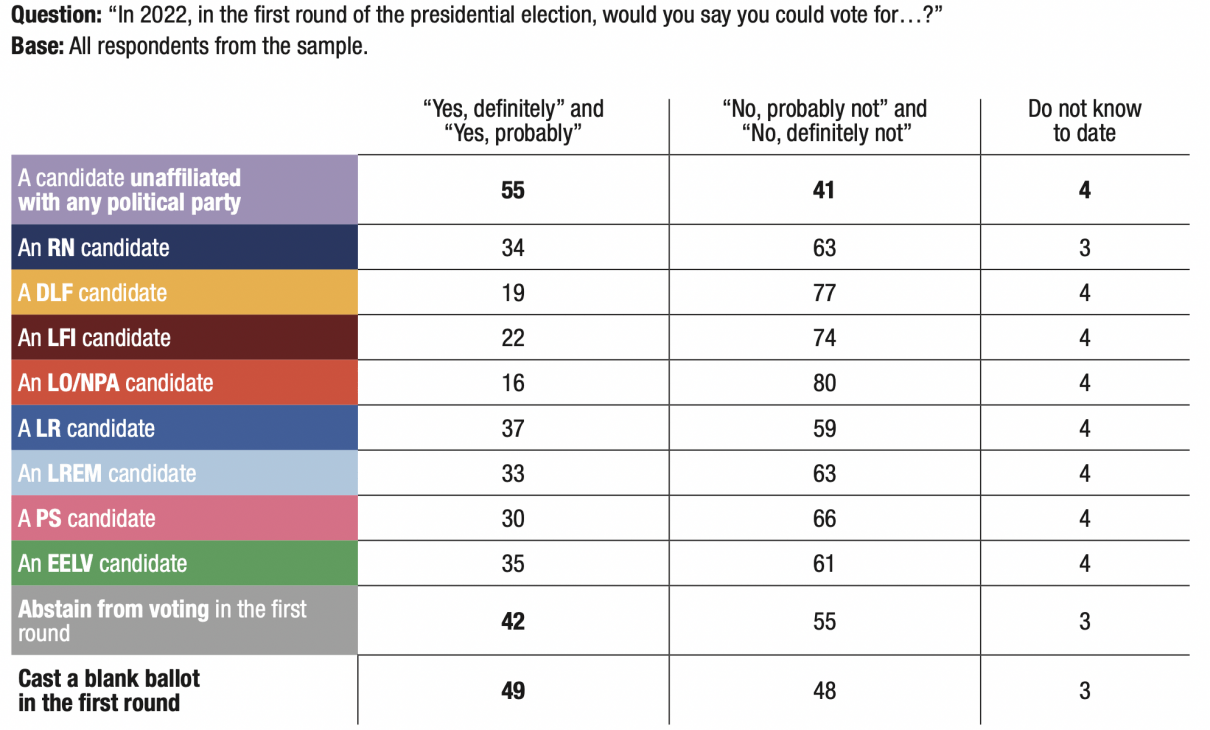

6. More than half (55%) of respondents said that in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, they could vote for a candidate unaffiliated with any party political party.

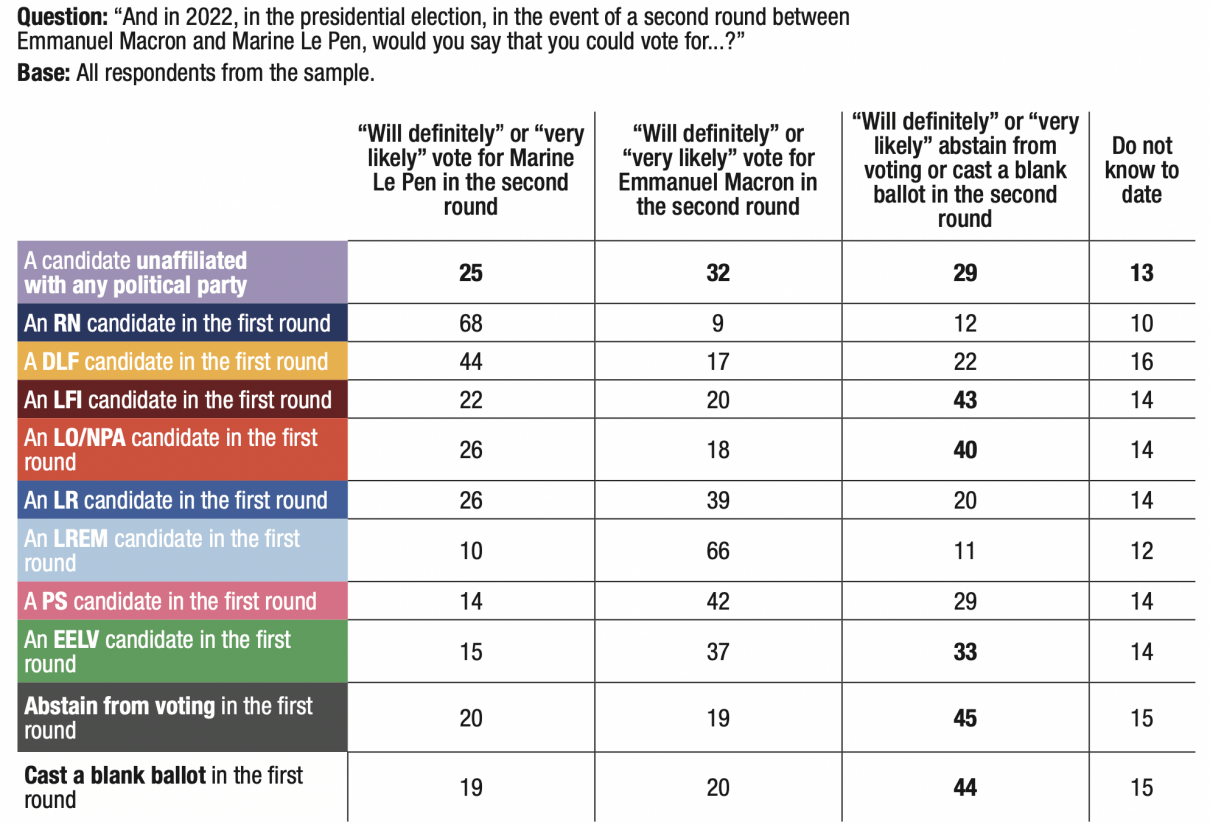

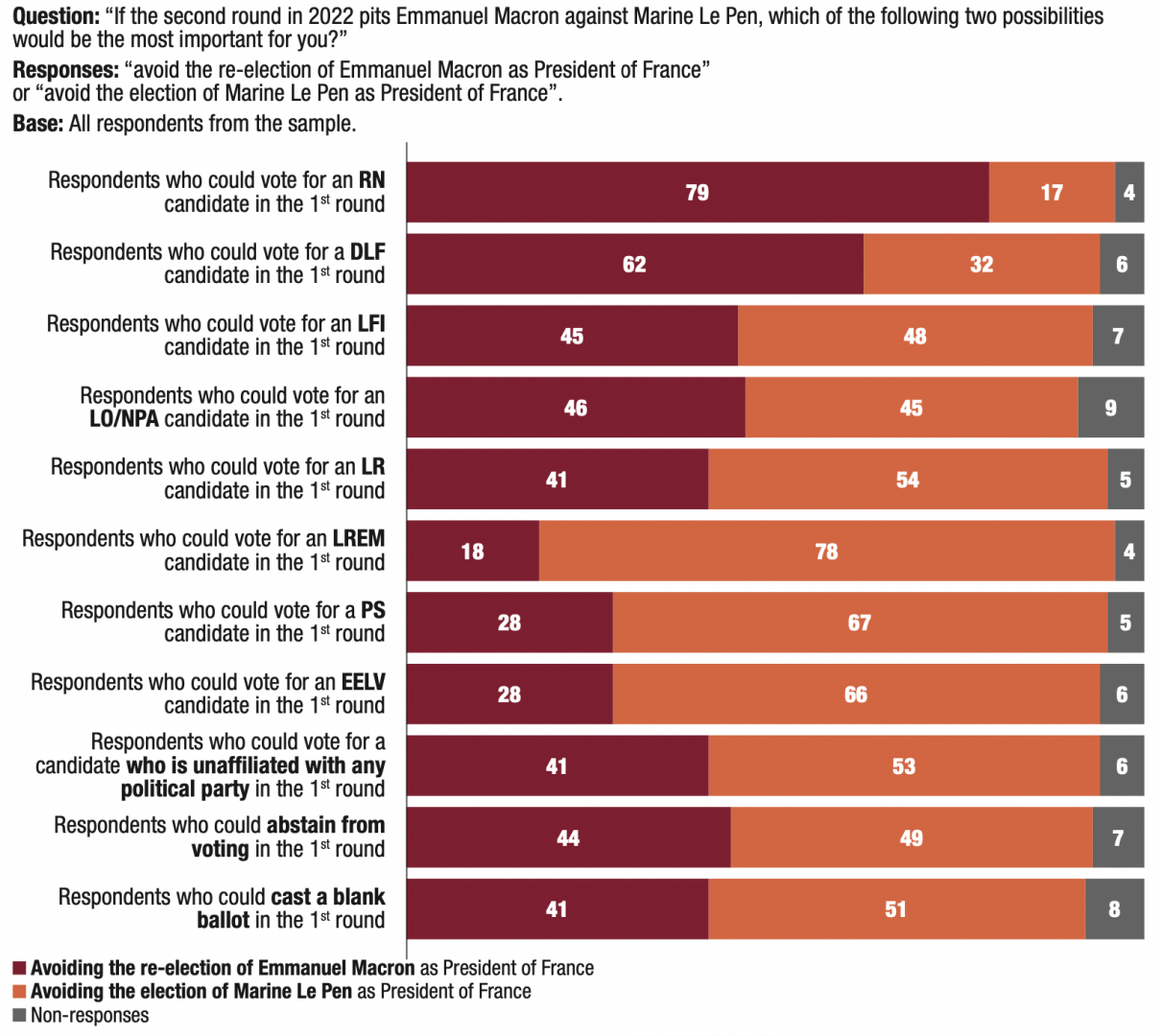

7. Marine Le Pen could benefit from a transfer of votes from the left in the event of a second round between her and the incumbent president. One-quarter of those who state they could vote LO/NPA (26%) or LFI (22%) in the first round of the 2022 presidential election say they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron.

8. Transfers from the right to Le Pen between the first and second rounds in 2022: one-quarter of those who state they could vote LR (26%) and 44% of those who state they could vote DLF in the first round of the 2022 presidential election say they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron. Out of those respondents declaring their readiness to vote for Xavier Bertrand in the first round, 32% said they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron, while one-quarter (24%) would abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot.

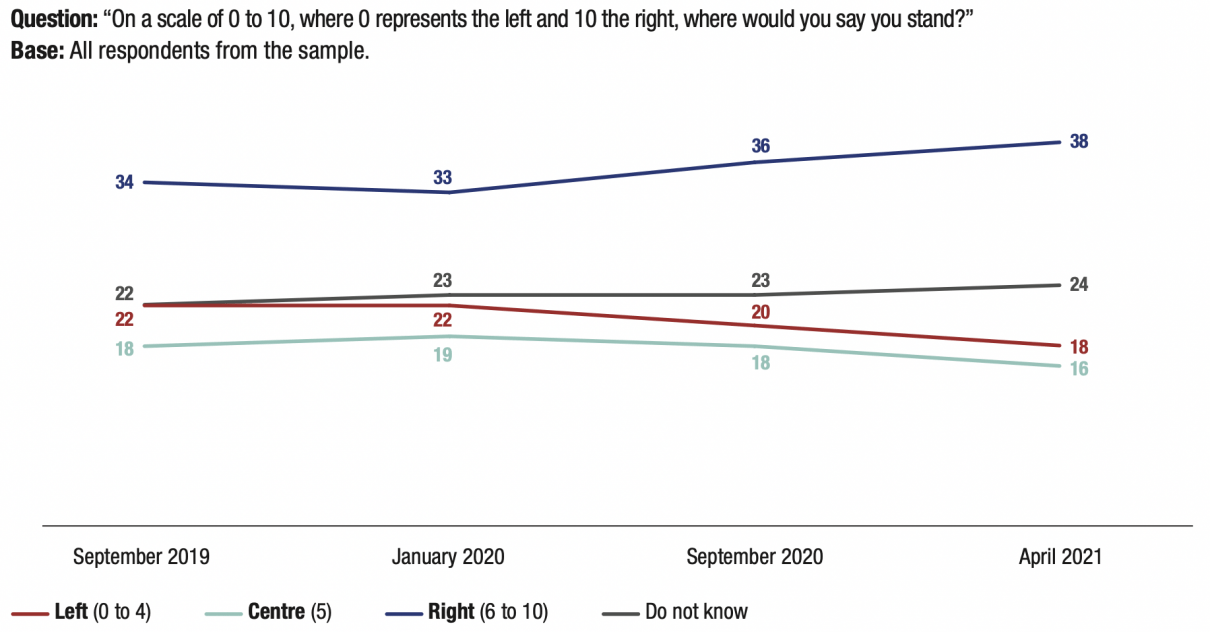

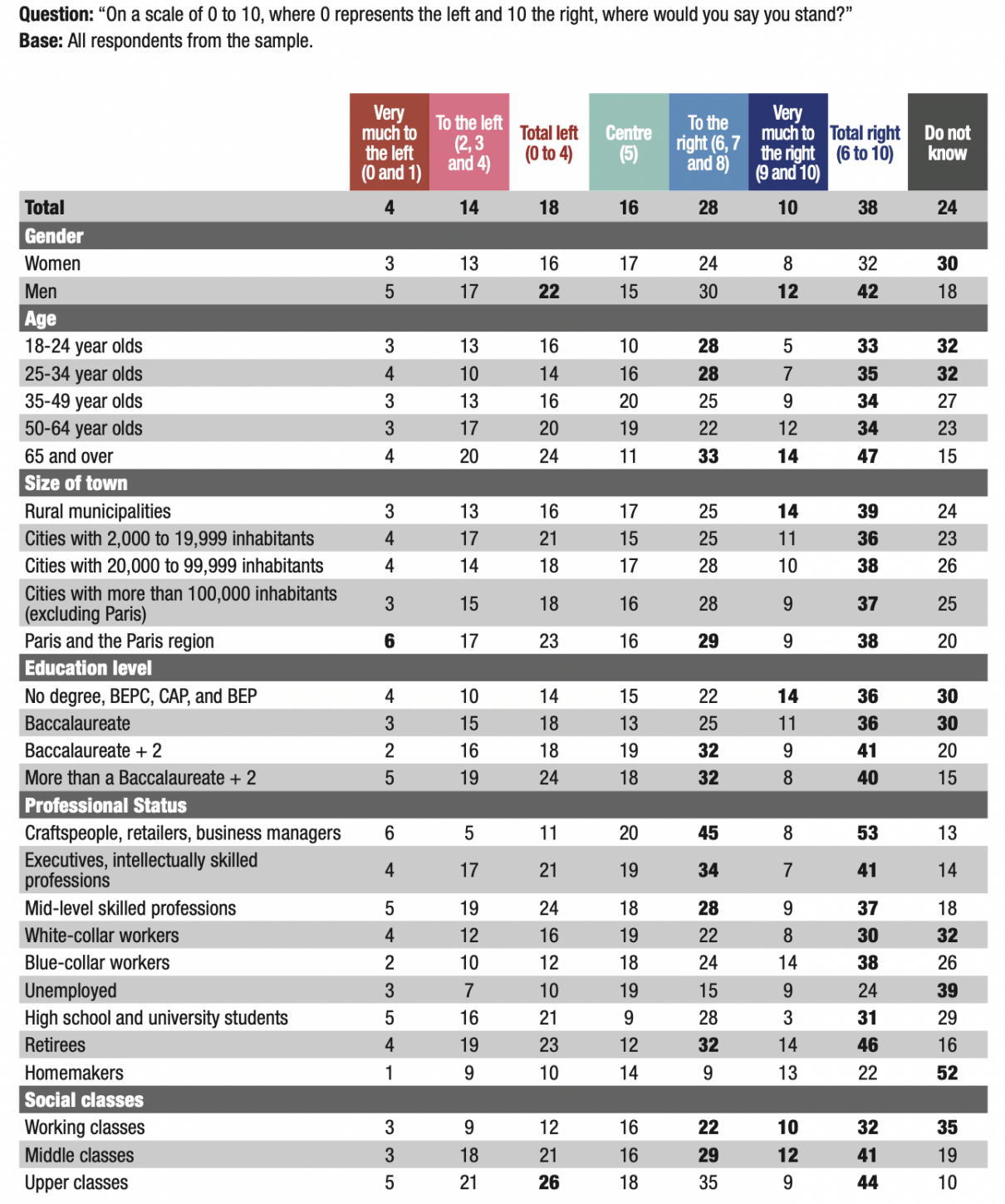

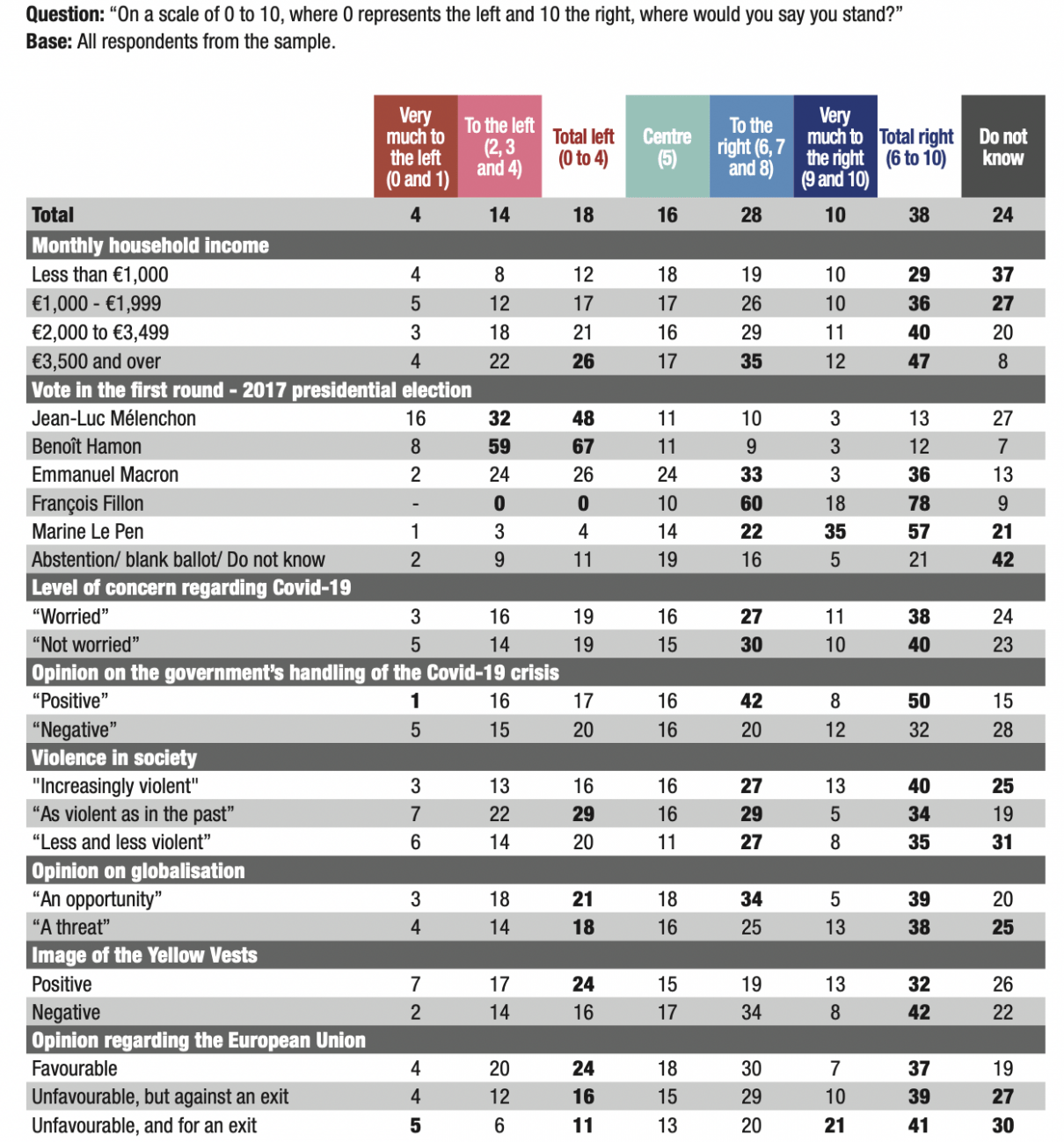

9. Almost four out of ten French people (38%) self- position themselves as right-wing (levels 6 to 10 on the left-right scale). Only 18% self-position themselves as left-wing (levels 0 to 4), while 16% position themselves in the centre (level 5). One-quarter (24%) of respondents did not self-position themselves on the left-right axis. Since September 2019, the proportion of respondents self-positioning as right-wing has increased by 4 points, from 34% to 38%. Over the same period, the proportion of respondents describing themselves as left- wing experienced a shift of the same magnitude, but in the opposite direction, as the proportion of those self- positioning as left-wing decreased from 22% to 18%. The right-wing’s lead over the left-wing, which amounted to 12 points in September 2019, increased to 20 points in April 2021.

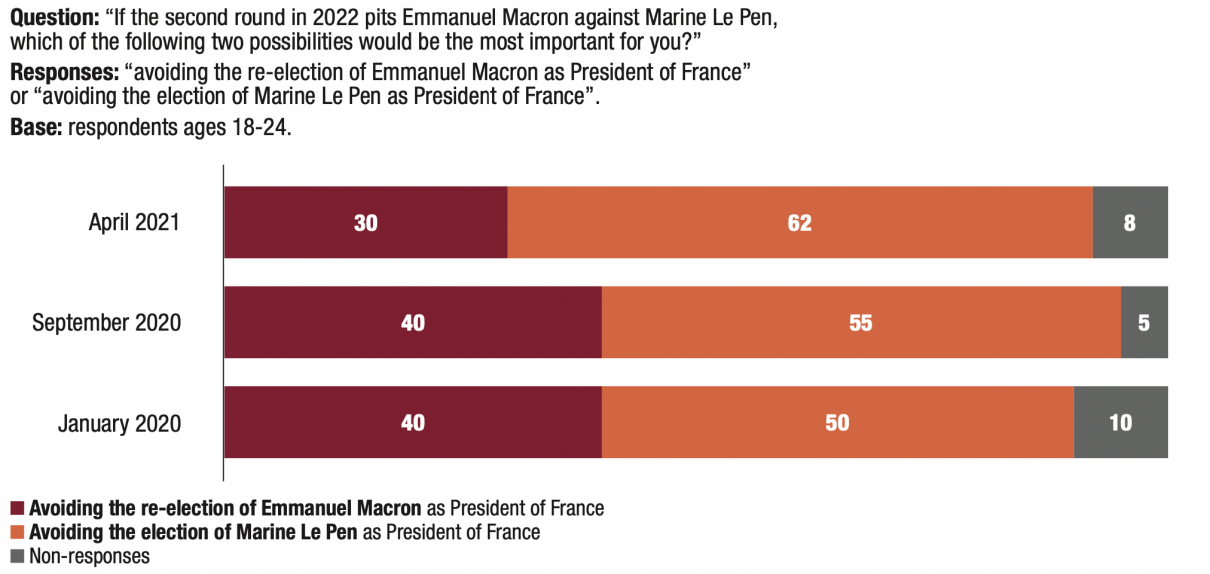

10. The shift to the right amongst young people is consolidating: while 23% of 18-24 year olds self- positioned themselves as right-wing (levels 6 to 10 on the left-right scale) in January 2020, 27% of them did so in September 2020 and 33% in April 2021, i.e. an increase of 10 points in fourteen months. Conversely, fewer young people self-positioned in the centre (19% in January 2020, 10% in April 2021) and the left-wing (18% in January 2020, 16% in April 2021).

11. Faced with the possibility of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, voters self-positioning as right-wing are significantly more likely to “definitely” or “very likely” vote for the RN candidate (38%) than to vote for the incumbent president (33%).

12. The majority (59%) of those who “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round in 2022 do not want France to leave the European Union; an even larger majority (68%) want to keep the euro as France’s currency. Almost all of those who “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon do not want their country to leave Europe (85%) or the euro (84%).

13. Despite the controversies that marked the management of the public health crisis, attachment to the European Union has not been dented. To wit, as noted in the previous waves of this survey, 79% of voters want to stay in the European Union.

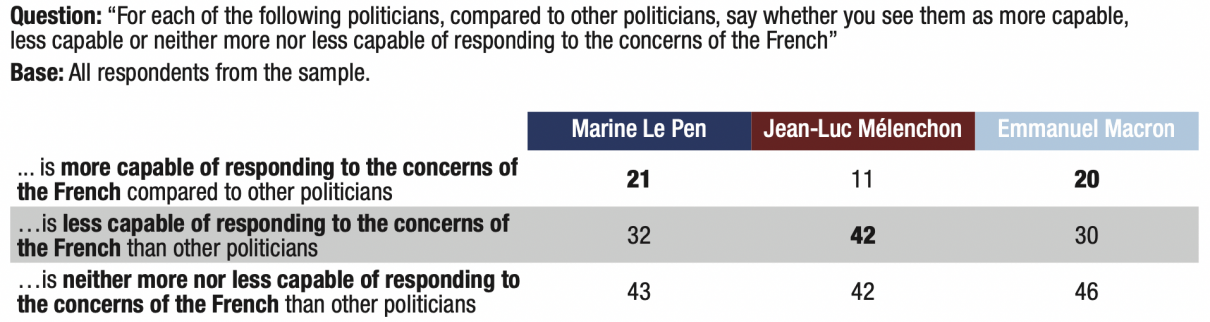

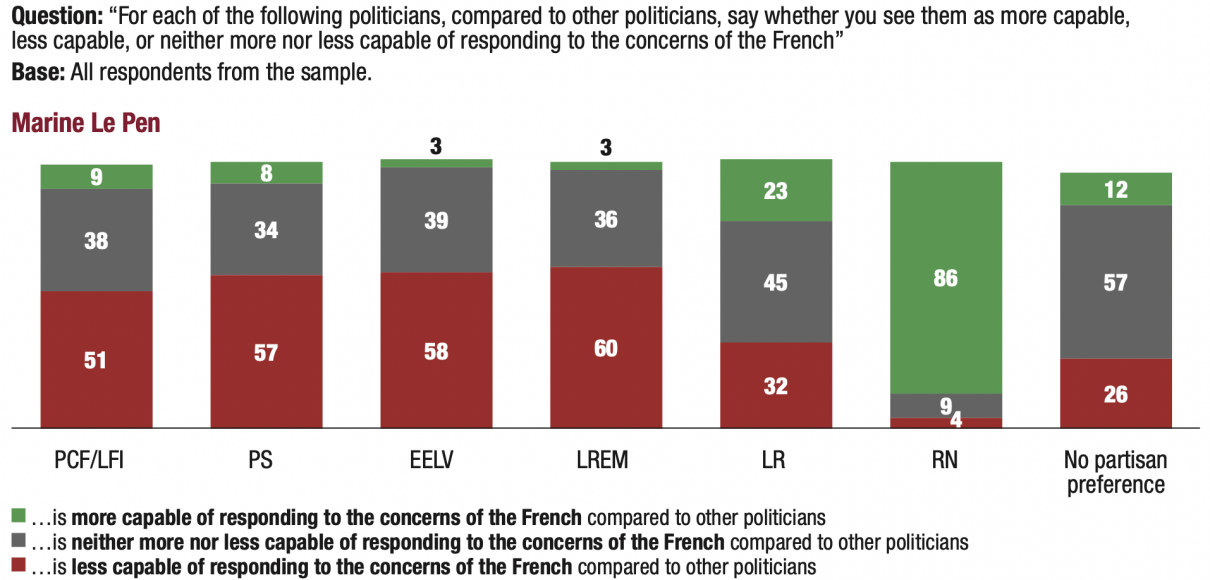

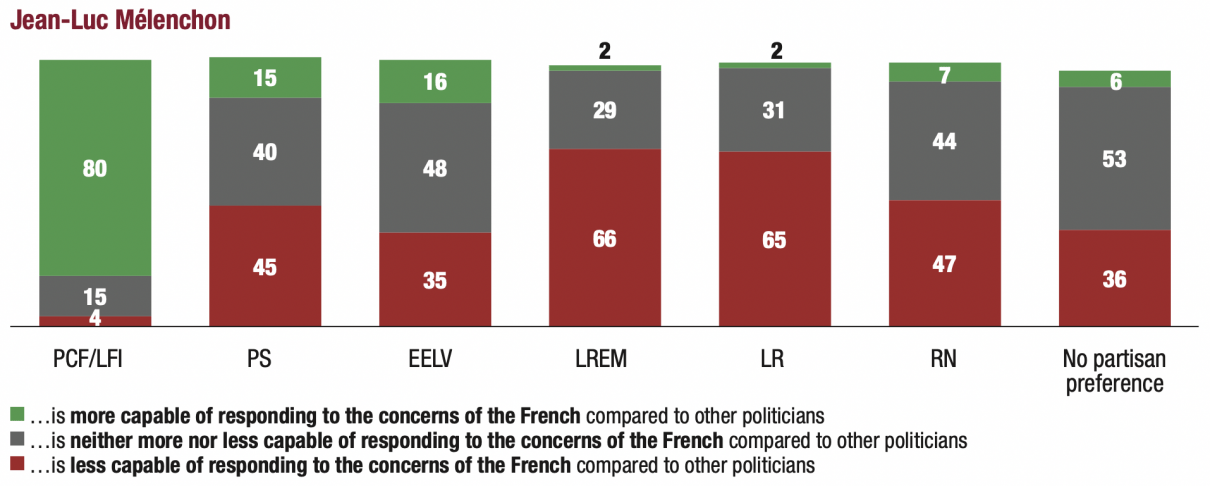

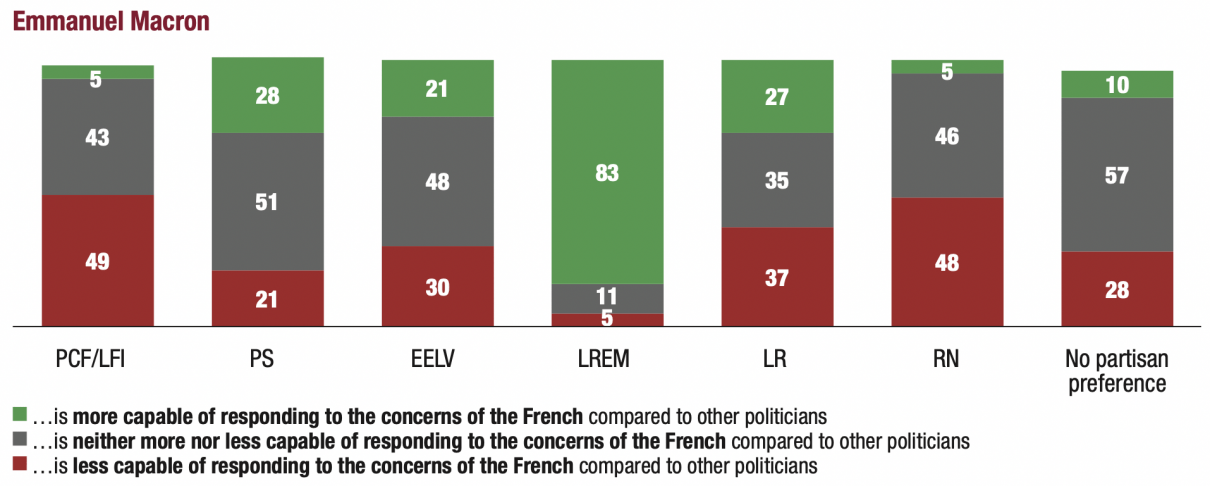

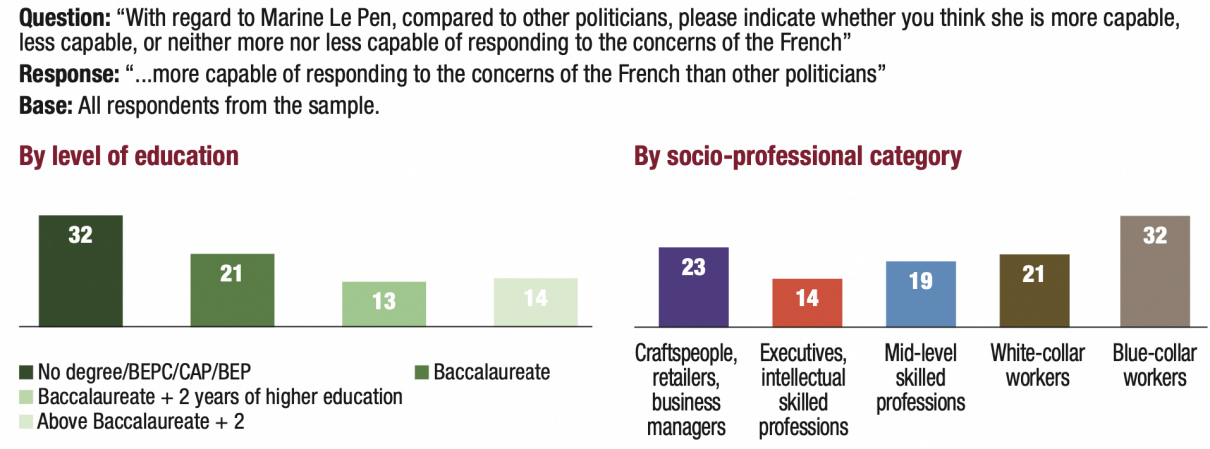

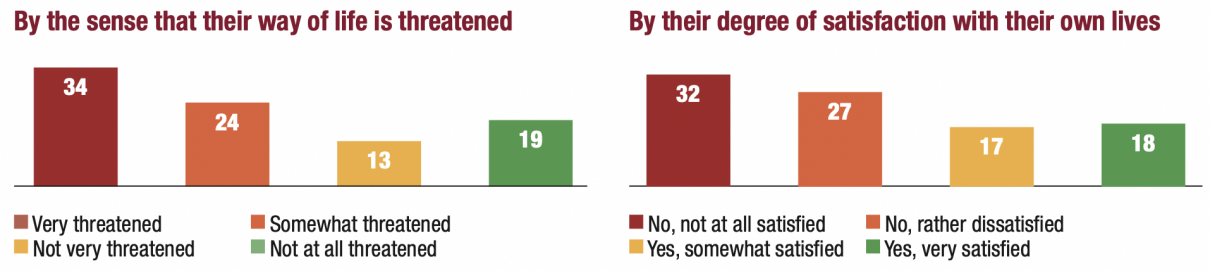

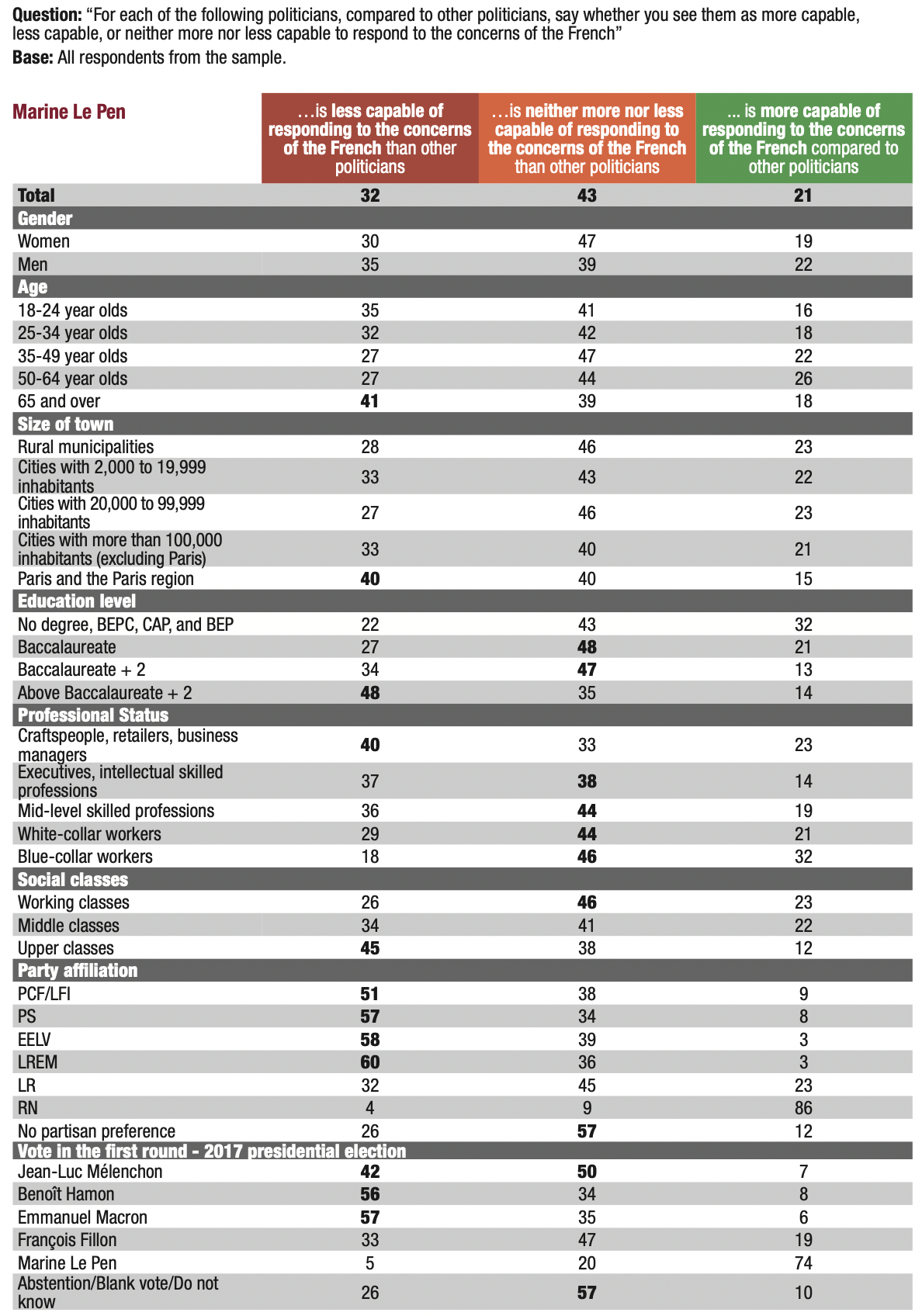

14. The erosion of the privilege of competence granted to governing parties reduces the handicap of populist parties. This trend is particularly favourable to Marine Le Pen: 21% of those surveyed considered her “more capable of responding to the concerns of the French” than “other politicians”. This proportion is the same (20%) with regard to Emmanuel Macron. In contrast, only 11% of respondents deemed Jean-Luc Mélenchon “more capable of responding to the concerns of the French” than “other politicians”.

15. For a majority of respondents, the opposition parties, whether right-wing or left-wing, would not have done better had they been responsible for managing the pandemic.

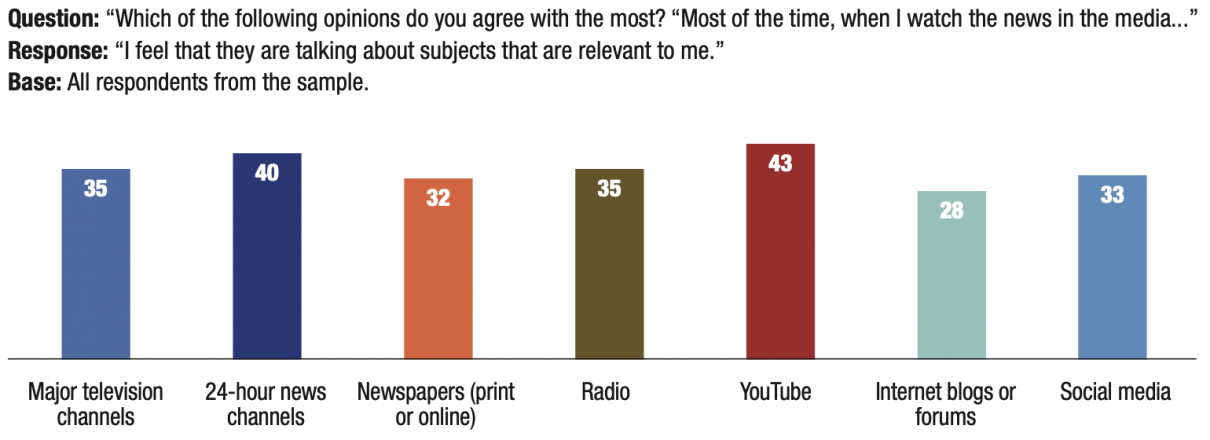

16. Voters close to the RN or LR are more likely to use 24-hour news channels as a source of information: 40% of respondents close to the RN and 33% of those close to the LR, compared with 30% of those close to the LREM, 27% of those close to the PS, 25% to the EELV and 25% to the PCF or LFI, and 28% of people declaring no partisan preference.

17. Within this group of news-channel viewers, the readiness to vote for Marine Le Pen is the greatest: 44% of respondents who rely on these channels for their news could vote for an RN candidate in the first round in 2022, a result 10 points higher than the sample average (34%), and 42% for those who could vote for an LR candidate. In the second round, 33% of those who rely on 24-hour news channels for their information “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen, 5 points higher than those who would for Emmanuel Macron (28%).

18. While a significant part of the right-wing audience, and even more so of the populist right, relies on these 24-hour news channels, we cannot, however, reduce the audience of these channels to a right-wing world. To this end, out of the respondents who rely on these news channels for their information, 34% state that they could vote for an LREM candidate, 31% for an EELV candidate and 27% for a PS candidate.

19. Part of the public experienced an unmet demand for information until the advent of 24-hour news channels. An indication of this can be found in the even stronger connection between the inclination toward protest behaviour, whether on the left or the right, and reliance on the Internet for news. Among those who use the Internet one of their their news sources, 42% could vote for an RN candidate in the first round, 36% could vote for an LFI candidate, 40% could vote for an EELV candidate, 53% could abstain from voting and 57% could cast a blank vote.

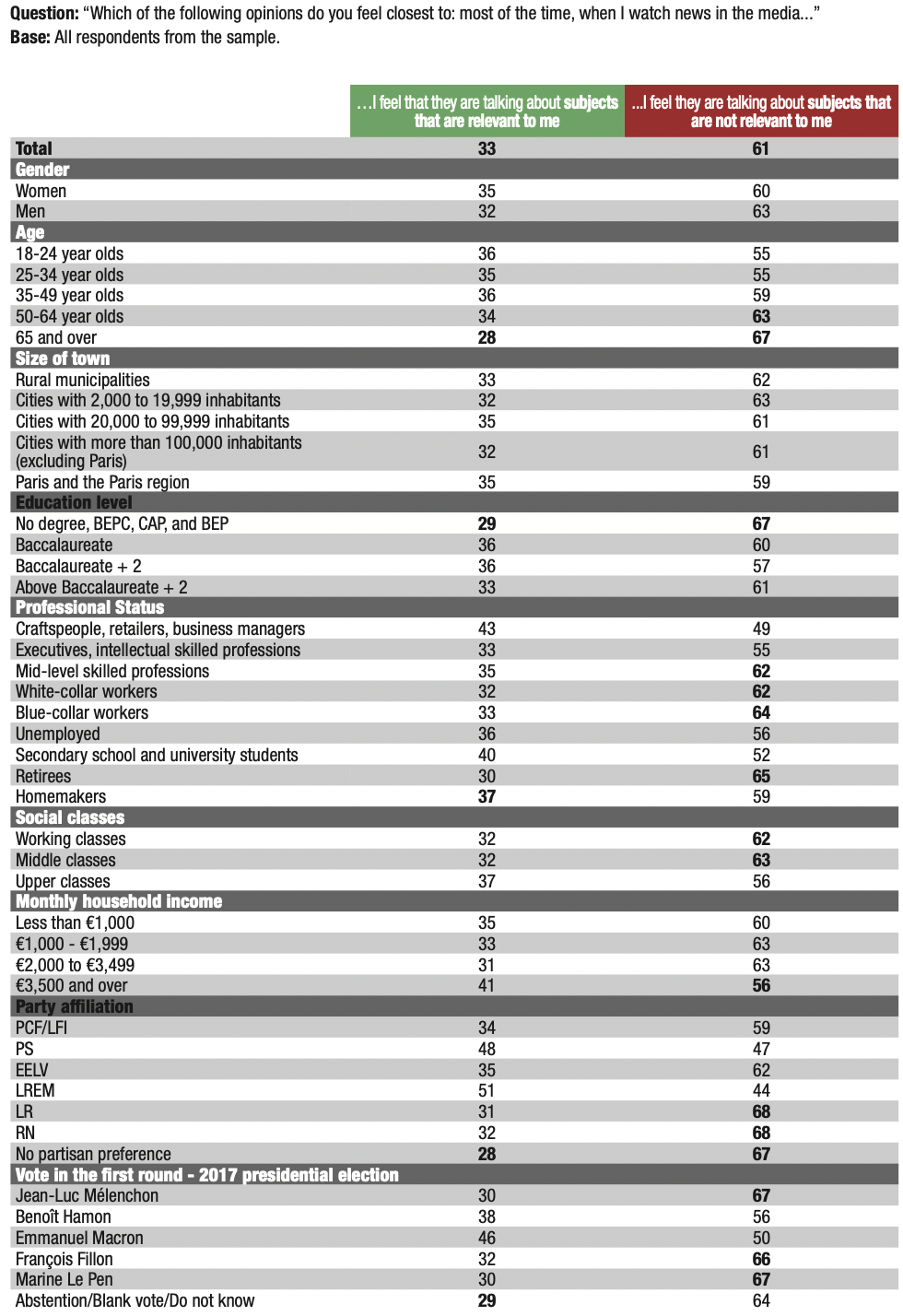

20. The media’s depiction is challenged: 61% of those surveyed feel that the media “talk about subjects that are not relevant to them”. One-third of respondents (33%) feel that the media deal with subjects that are relevant to them (and 6% did not respond).

21. The readiness for protest voting is much higher among those who do not find themselves reflected in the media’s coverage of the news: 83% of respondents who respond that the subjects covered by the media are not relevant to them could adopt one of the protest behaviours included in our indicator for the first round of the 2022 presidential election (vote for a populist or anti-establishment party, RN, LFI, DLF, LO, NPA; abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot).

22. We are experiencing a double crisis of representation, as the relevance of political messages is also being challenged: most voters (70%) deem that politicians “talk about subjects that are not relevant to them”, compared to one-quarter (25%) who feel that they “talk about subjects that are relevant to them” (5% did not respond).

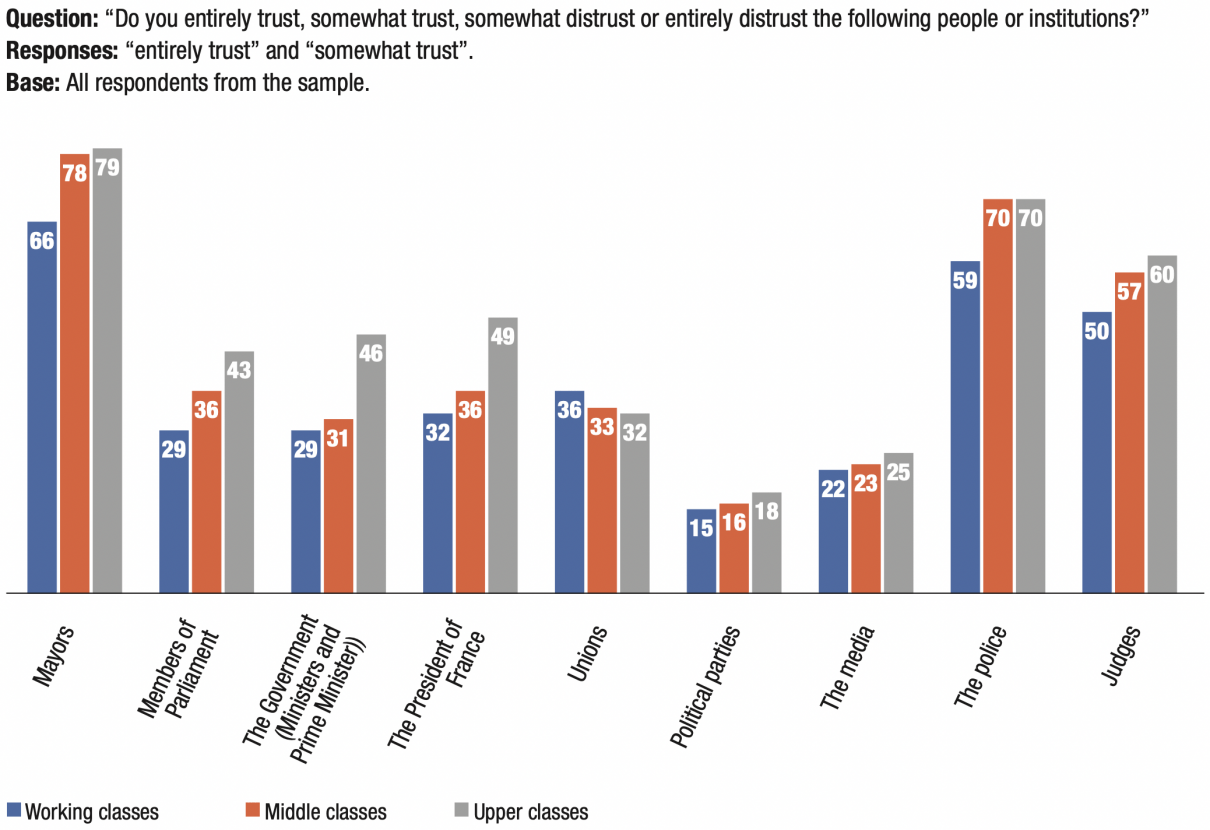

23. The distrust in institutions and the political system persists: 80% do not trust the political parties, 64% the government, 62% unions, 61% members of Parliament and 60% the President of France. Mayors (23%), police officers (30%) and judges (42%) manage to keep their heads above water with a minority of people distrusting them.

24. The French are largely in favour of a move towards decentralisation. Three-quarters of them (74%) would prefer “that more political decisions be made in the regions, departments and municipalities, and less in Paris”.

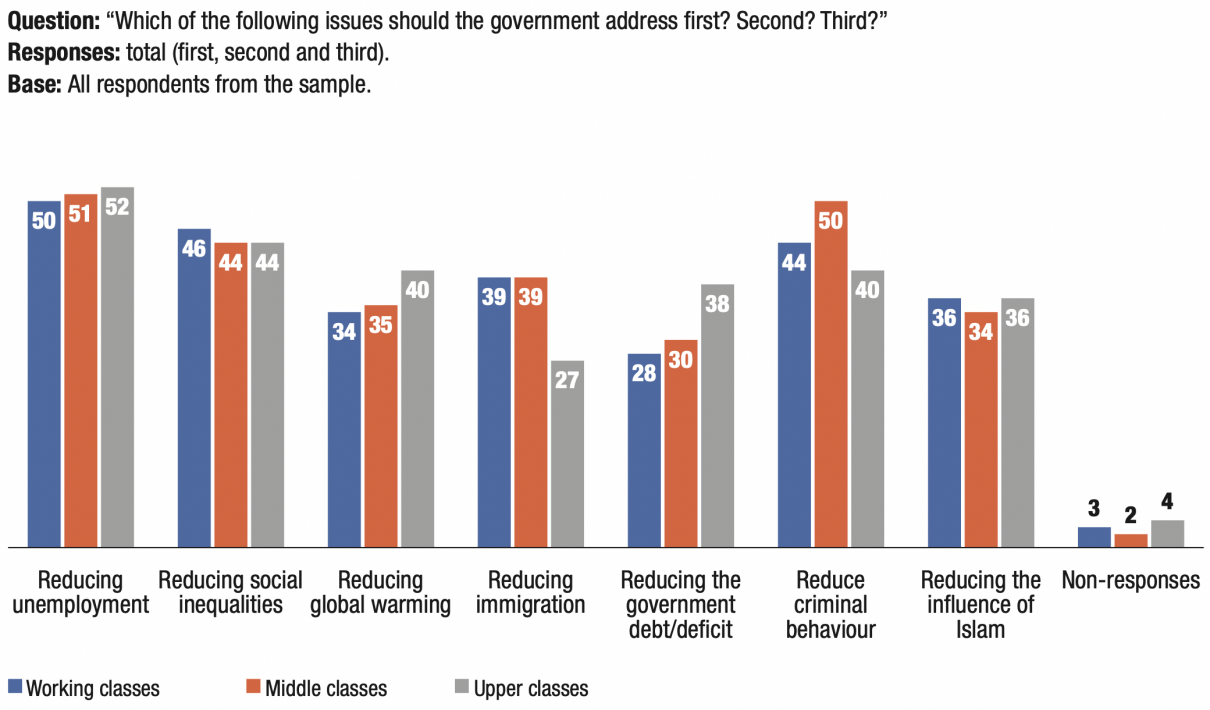

25. The middle classes and the working classes seem to converge in their protest behaviours. It should also be noted that the demand to fight crime is particularly high among the middle classes (50%), specifically 6 points higher than the working classes (44%) and 10 points higher than the upper classes (40%).

26. One-fifth of working-class (22%) and middle- class (21%) respondents said they “will definitely”or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round of the presidential election, compared to 12% of upper class respondents.

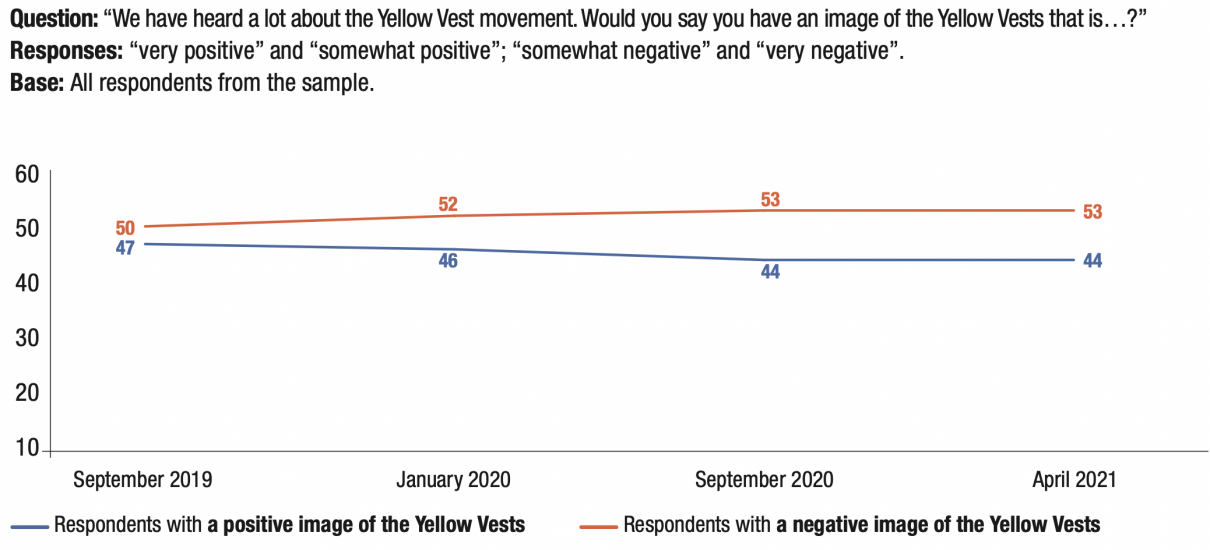

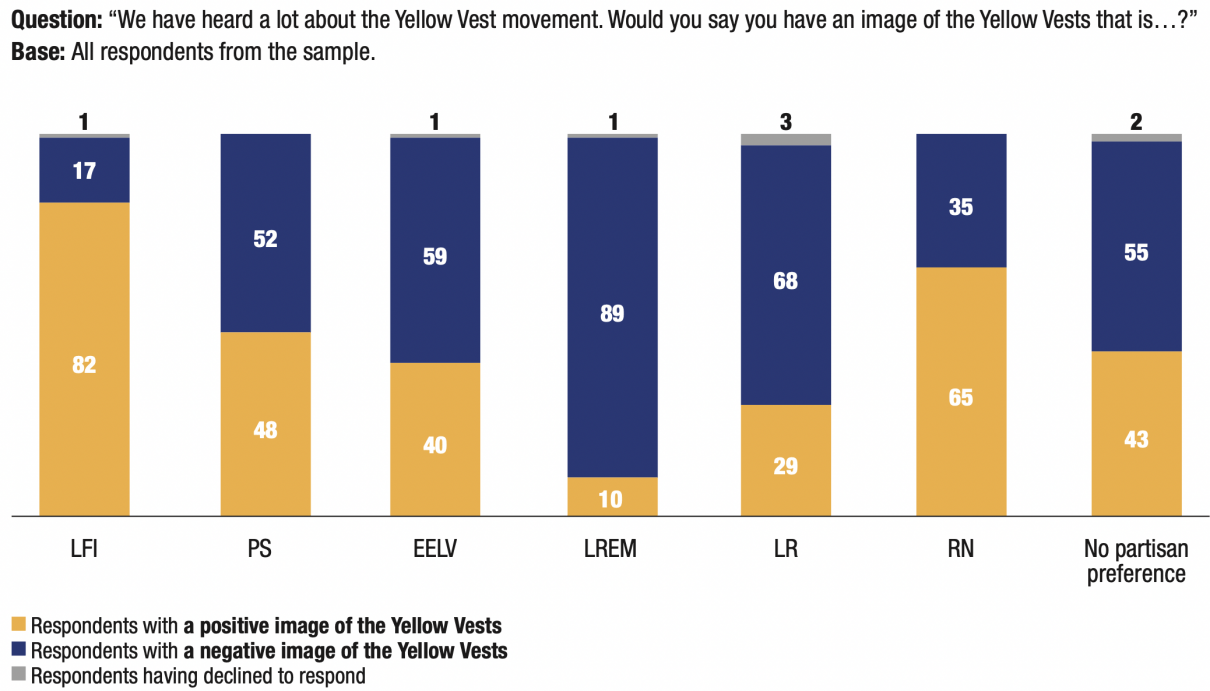

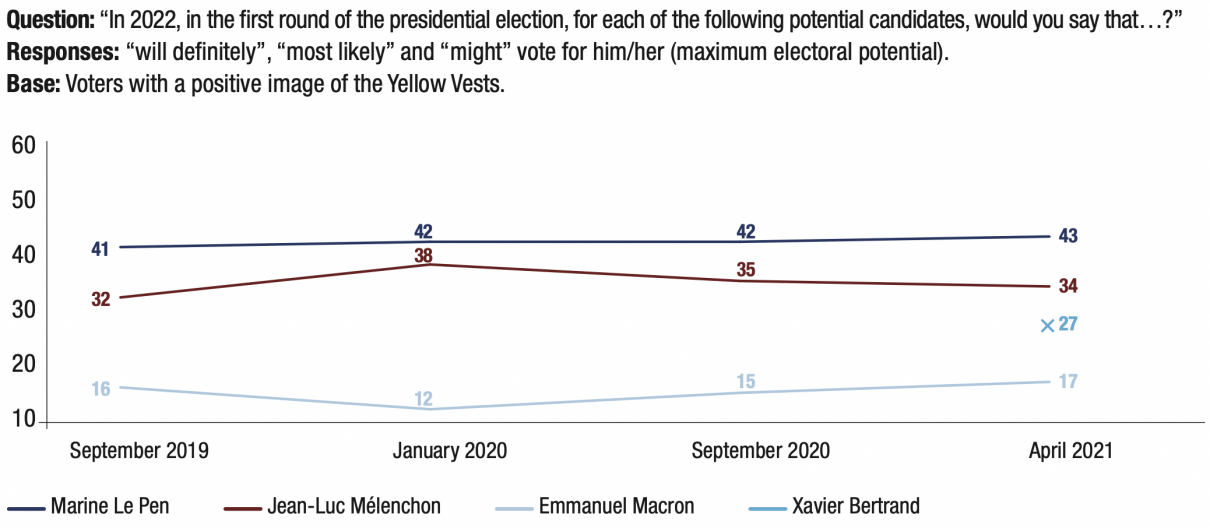

27. A significant proportion of the French (44%) continue to have a positive image of the Yellow Vests.

2022, the Populist Risk in France: an indicator of electoral protest designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

2022, the Populist Risk in France is an indicator of electoral protest, designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The questionnaires are written by the Foundation’s team and the surveys conducted by the polling institute OpinionWay. To ensure the soundness and interest of the data collected, the questionnaire is each time administered to a sample of 3,000 people registered on the electoral rolls and drawn from a sample of 3,423 people representative of the French population aged 18 and over. The representativeness of the sample is ensured by the quota method, with regard to criteria of gender, age, socio- professional category, category of urban area and region of residence. We carry out one measurement every six months.

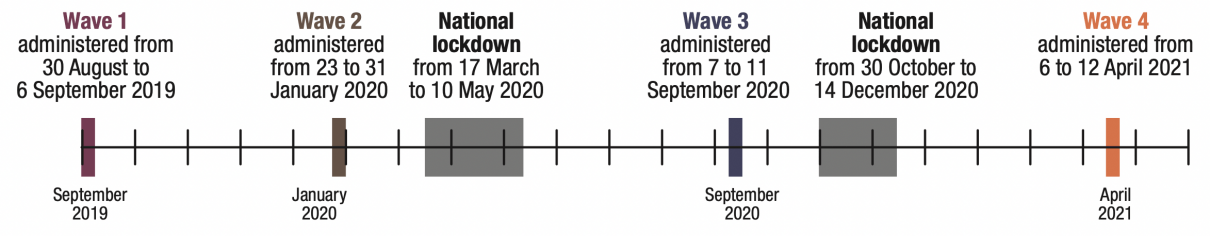

Wave 1 was administered from 30 August to 6 September 2019 to 3,006 people. The presentation and analysis of the results resulted in a publication entitled 2022, le risque populiste en France (2022, the Populist Risk in France), available in French and English on the fondapol.org website.

Wave 2 was administered from 23 to 31 January 2020 to 3,055 people. The social and political context was tense at the time, particularly because of the retirement reform. We had therefore added certain contextual questions about the understanding and acceptance of this reform. However, in the weeks that followed, the coronavirus epidemic led us to postpone the publication of the second volume. We have chosen to integrate the main results from the second wave in this edition, together with the results of wave 3.

Wave 3 was administered from 7 to 11 September 2020 to 3,037 people, i.e. after the period of lockdown (17 March-11 May 2020) and at the end of a summer when certain restrictions were lifted. The cycle of opinion in this third wave includes a rise in the number of coronavirus cases in France as well as fears of a second wave of the epidemic.

Wave 4 of our survey was administered from 6 to 12 April 2021, to a sample of 3,012 people. The context was shaped by a spike in the pandemic, a curfew (implemented on 3 March 2021) and a new lockdown implemented on 3 April. The vaccine rollout started to be deployed during this time, despite certain stops and starts, such as the decision on 15 March, following those in Germany, Italy and Spain, to “suspend as a precaution” and for a few days the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine, pending an opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

This volume therefore presents the results of the second and third waves. The text and the questionnaire are available in French and English on the fondapol.org website and the complete data are shared on data.fondapol.org.

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

See Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, Pluriel, 2013.

See “Loi du 21 février 2014 visant à reconnaître le vote blanc aux élections” [Law of 21 February 2014 on the recognition of blank voting in elections], vie-publique.fr, 24 February 2014 (www.vie-publique.fr/loi/20890-elections-vote-blanc).

By its unprecedented nature and intensity, the public health crisis appeared to sideline the Yellow Vests crisis and protests against the retirement reform. It is not clear that it extinguished the fire, however. The question arises as to how these overlapping crises will be expressed through the mechanisms of the 2022 presidential election. Our indicator aims to help understand and anticipate the contours of this future presidential election, with potentially European and therefore global consequences.

The electoral protest indicator estimates the potential of different possible electoral protest behaviours: abstention from voting, casting a blank vote, or voting for populist parties or candidates. In our indicator, the idea of a protest electorate covers three types of electoral behaviour:

– the stated willingness to vote for populist parties and candidates (Marine Le Pen, RN, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, LFI and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, DLF);

– stated willingness to vote for parties and candidates on the revolutionary left (LO/NPA).

– stated willingness to abstain from voting; – stated willingness to cast a blank vote.

a) The populist vote

The populist vote includes either votes cast in favour of a populist party or candidate, or the willingness to vote for a populist party. We characterise populist parties using the following elements:

– an appeal to the people, which is at the heart of the populist discourse. It is reflected in a rejection of representative democracy and in an exaltation of direct democracy. The populists’ appeal to the people is characterised by demands for the absolute sovereignty of electoral decisions, which are supposed to prevail over everyone and everything, including the principles and rules that form the bases of order and the rule of law;

– an anti-elite discourse, based on a summary social differentiation between a “people”, unified and mythologised, and political, economic, intellectual, and media “elites”, disqualified as forming an oligarchy (“the caste”, etc.).

–a narrative and an organisation marked by an authoritarian culture, found in the form of party built around an omnipresent leader;

– a nationalist programme;

– a xenophobic vision;

–a rhetorical style characterised in particular by exaggeration, simplification, disqualification of the adversary, a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories, etc.

Starting from the fourth criterion, we see a separation between two expressions of populism: the largely dominant expression that has met with major electoral successes deploys nationalism through xenophobia, denouncing not only the ruination of the people by the elites, but also by foreigners and immigrants. Xenophobic populism is most often right-wing, but also exists on the left in Europe. In France, left-wing populism is represented by Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his party, LFI. The latter, despite certain swerves onto xenophobic terrain, cannot compete with Marine Le Pen. This is why left-wing populism is outpaced by the right-wing populism of Marine Le Pen and the RN looking ahead to the election.

Since the first wave of our indicator, we have chosen to count Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and his party, DLF – a political offering that sits between the separatist right and the populist right – in calculating populist electoral potential. In 2017, during the interval between the two rounds of the presidential election, the DLF president signed a governing agreement with Marine Le Pen, agreeing to become her prime minister had the FN candidate been elected. Since then, Nicolas Dupont- Aignan’s stances, particularly in the context of the health crisis, have strengthened our initial choice to classify this party and its candidate in the populist category.

Lastly, it is important to distinguish between populist parties and parties from the revolutionary left. Indeed, some parties that share an anti-establishment vision take up neither the social simplicity nor the codes of popu- lism usually associated with it. They establish themselves differently within an internationalist outlook, based on a vision of society, history and revolution rooted in an ana- lysis defined by social classes. They claim to speak for a particular class, the manual labourers, possibly extended to “labour force” but not to “the people”, a sociologically indeterminate and politically inconsequential notion. Fundamentally, the parties of the revolutionary left do not identify with the principles and mechanisms of elec- toral democracy which populists, on the contrary, claim they wish to implement.

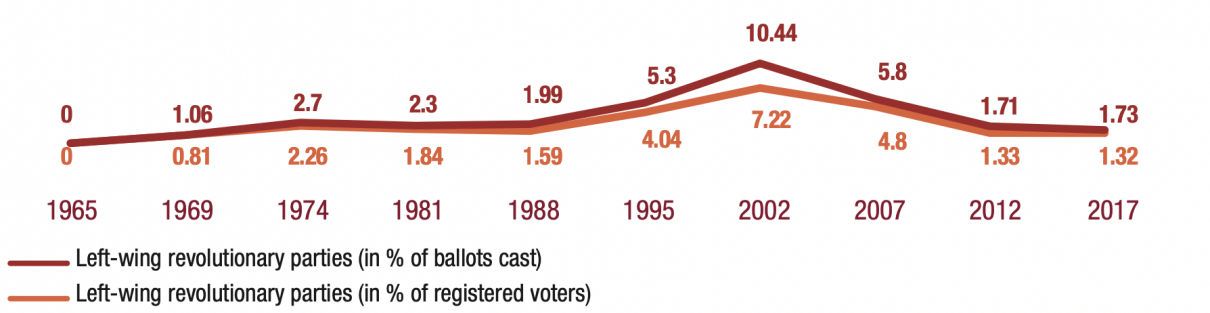

In France, the revolutionary left parties running in the presidential election, which they use as a convenient stage, belong to the Trotskyist movement. Here, however, while not overlooking these differences, we chose to include the far-left vote in calculating populist electoral potential so as to not unnecessarily increase the indicator’s complexity. Moreover, the electoral bearing of this revolutionary left is marginal, barring two exceptions: in 2002 (10.4% of votes cast and 7.2% of registered voters) and in 2007 (5.8% of votes cast and 4.8% of registered voters). Lastly, our study shows that the respondents who identify with this revolutionary left attest a strong willingness to vote populist, and at least in a proportion of this population, as part of an anti-system strategy.

b) Abstention from voting

Abstention from voting can come in different forms. Abstention from voting can be systematic or intermittent. The reasons for abstention are diverse: expression of disinterest, inability to choose, rejection of the political options available, or expression of a more general discontent. Insofar as only some abstentions are a form of electoral protest, it is difficult to assess this from electoral results.

However, here, we chose to include abstention when calculating the potential for electoral protest, as we ask people about their readiness to abstain from voting in 2022, a framing which pushes aside the logistical reasons for abstaining from voting (illness, absence, etc.). Also to be noted is the similarity between the abstention curve and that of the protest vote.

c) The blank vote

Until 2014, the census of blank votes was combined with invalid votes (null votes). The category was called “blanks and invalid”. Blank votes have been counted separately since the law of 21 February 20142. They were listed separately for the first time in the European elections in June 2014. The 2017 presidential election thus took place with the new blank vote system in effect. Here, as with abstention, we chose to include blank voting when calculating the potential for electoral protest, as we asked people about their readiness to cast a blank ballot in 2022.

Vote for revolutionary left-wing parties (excluding the PCF) in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

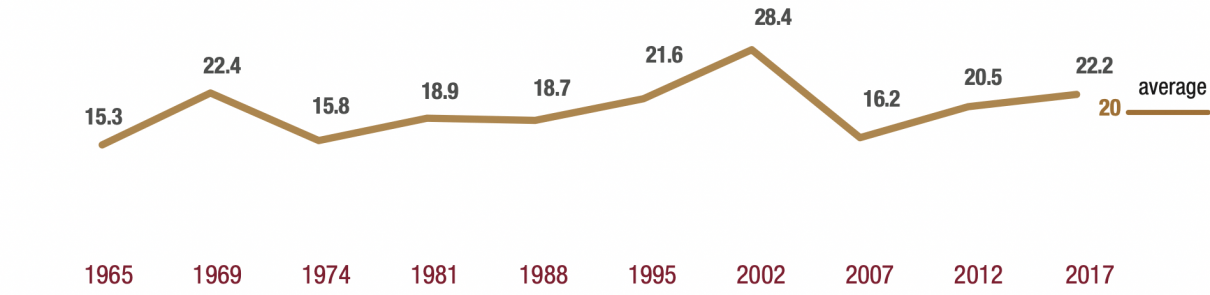

Abstentions during the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

in % of registered voters

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

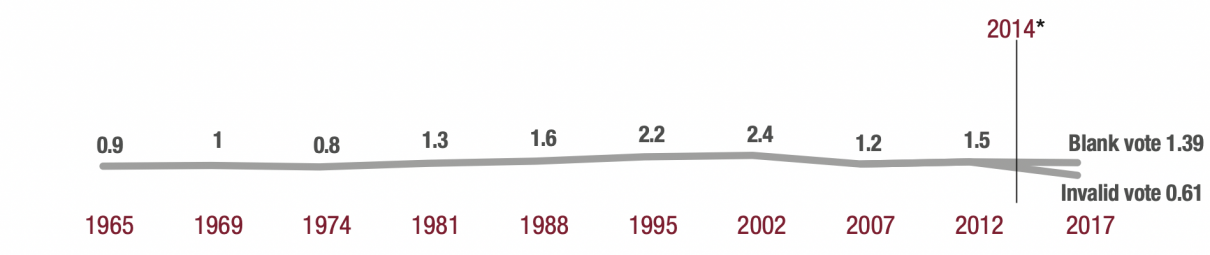

Blank and invalid votes in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

in % of registered voters

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

* Since the law on 21 February 2014, the census of blank votes has no longer been combined with invalid votes (null votes). The 2017 presidential election was the first where the new blank vote system was applied.

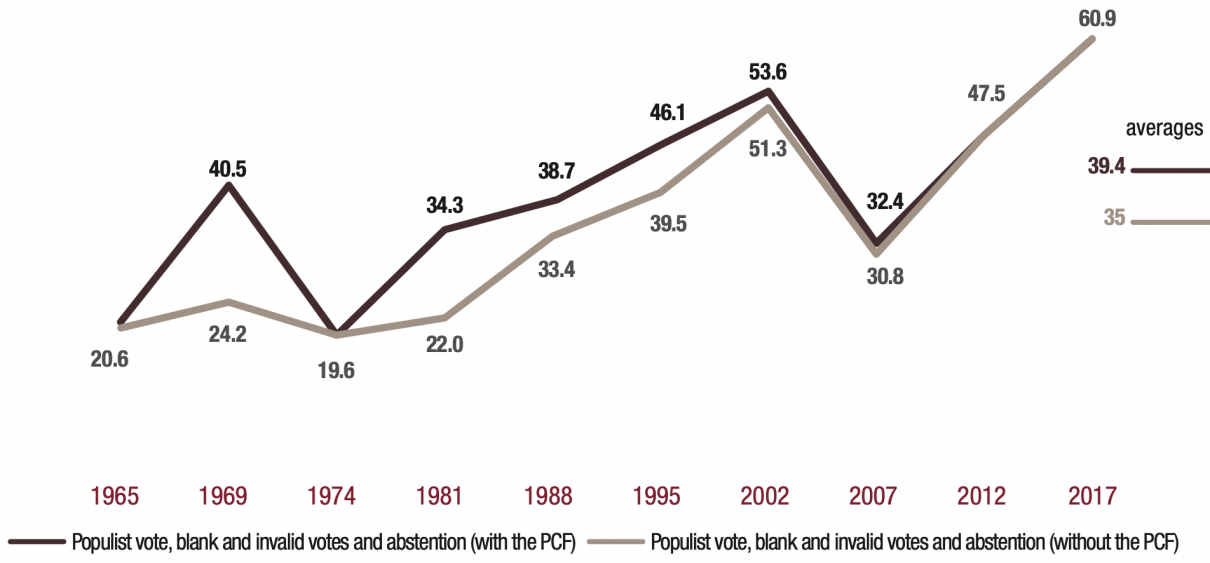

Electoral protest in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

(the populist vote, blank and invalid votes and abstention)

in % of registered voters

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

Selected Candidates: 1965: J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour); 1969: J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC); 1974: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR); 1981: A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF); 1988: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF); 1995: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Cheminade (SP); 2002: B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT); 2007: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT); 2012: M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP); 2017: M. Le Pen(FN), N.Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F. Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade(SP).

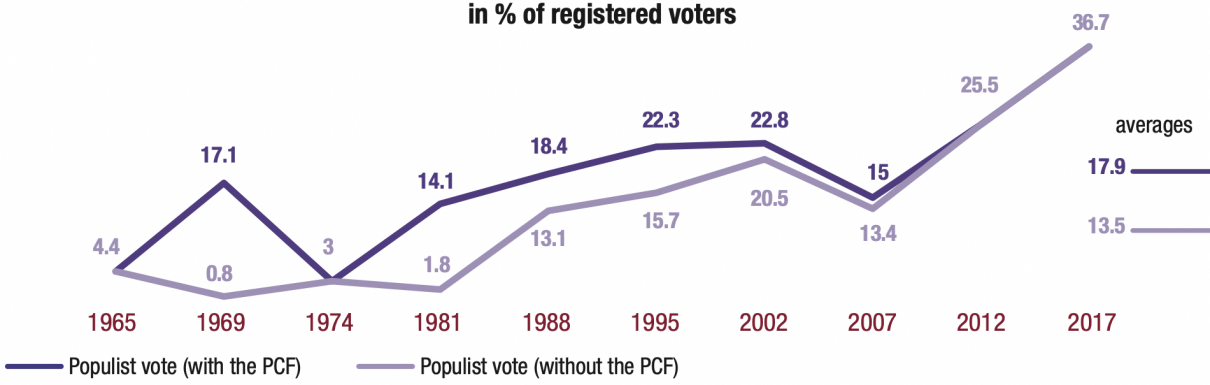

Electoral protest has come a long way. A look back at presidential elections since 1965

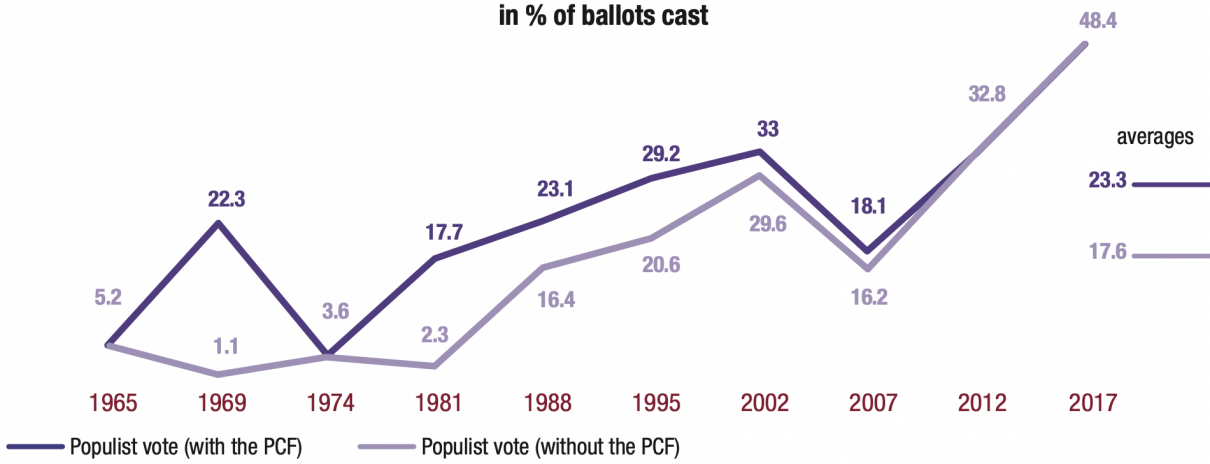

The populist vote has been steadily increasing since 1965. Following our definition of the populist vote, the curves below represent its evolution in the first round of presidential elections from 1965 to 2017. Over this period, the level of the populist vote varies according to whether or not we include the vote for communist candidates. During the heyday of the communist vote, between 1945 and 1981, the PCF was not generally considered a populist party. In fact, in many respects, this party met the criteria of populism that we propose here. In other respects, it was far from it, in particular considering its strong integration into the French system of political, union, academic and media elites. Given the purpose of our indicator, it would be inappropriate to open such a debate here. Nonetheless, in our reconstruction of the populist vote in the first round of presidential elections from 1965 to 2017, we have chosen to present two sets of data: one does not include the communist vote, and the other that does. We have not taken into account the vote for Pierre Juquin (2.10% of the votes cast in 1988), a dissident communist candidate. Finally, it is important to note that, in any case, from 1988 onwards, the PCF vote declined rapidly, to the benefit of the FN vote, which largely and systematically overtook it until 2017. The FN vote has also benefited from significant transfers from the communist electorate.

Finally, it should be noted that the results were calculated in relation to the votes cast and then in relation to registered voters, which makes it possible to integrate abstentions and the blank vote on the same level, offering the “electoral protest”, which we will define later.

The populist vote in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

The populist vote in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

Source :

compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

Selected Candidates: 1965: J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour); 1969: J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC); 1974: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR); 1981: A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF); 1988: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF); 1995: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Cheminade (SP); 2002: B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT); 2007: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT); 2012: M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP); 2017: M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F. Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP).

With one year to go before the presidential election, the willingness for electoral protest is soundly established

The potential for electoral protest: Wave 4

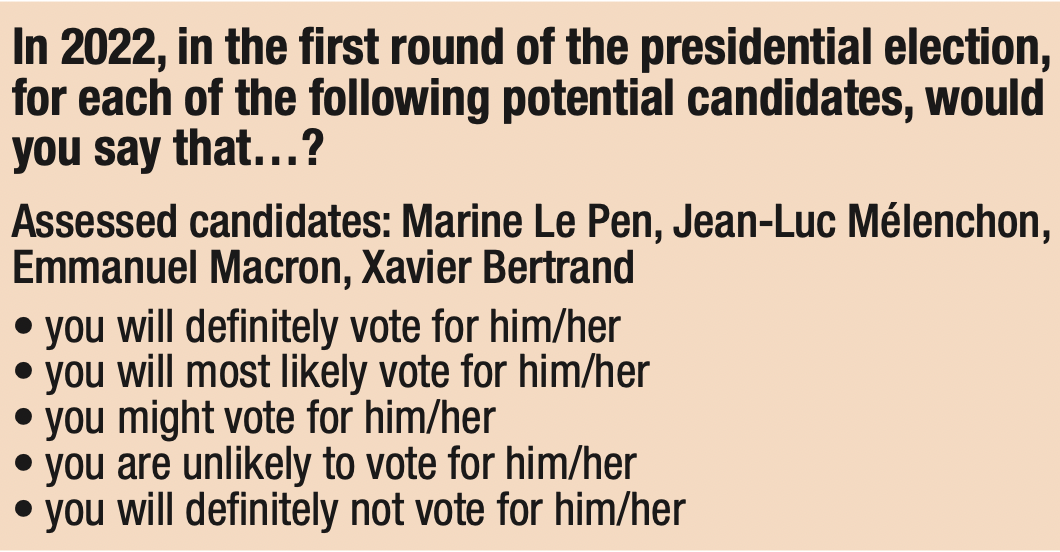

Looking ahead to the first round of the 2022 presidential election, the electoral potential is estimated thanks to the question shown below (for Wave 4, we added Xavier Bertrand to the list of assessed candidates, as he has formally stated his intention to run for election).

Using the answers provided, we were able to define electoral potential on a three-level scale:

– minimum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed who answered “you will definitely vote for him/her”;

– intermediate electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her” or “you will most likely vote for him/her”;

– maximum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her”, “you will most likely vote for him/her” or “you might vote for him/ her”.

The Wave 4 data confirm the strength of support for Marine Le Pen in a portion of public opinion. Her electoral potential is highest in the first round of the presidential election, with a minimum electoral potential of 10% (those “definitely” voting for the RN candidate) and intermediate electoral potential of 20% (“definitely” or “most likely” voting for the RN candidate). Emmanuel Macron’s minimum electoral potential amounts to 5%, while his intermediate electoral potential 16%. A newcomer to our list of proposed candidates, Xavier Bertrand sees his minimum electoral potential reach 3%, while his intermediate electoral potential is at 11%. Lastly, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s minimum electoral potential amounts to 3%, while his intermediate electoral potential is 8%.

The maximum electoral potential makes it possible to take into account all three categories of responses: respondents who feel they “might vote for him/her”, plus those who respond that they “will definitely” vote for him/her” and those who respond that they will “most likely” vote for him/her. When the maximum electoral potential is considered, the three candidates Emmanuel Macron (34%), Marine Le Pen (33%) and Xavier Bertrand (33%) balance out. Jean-Luc Mélenchon still appears to be lagging (21%). However, the very principle of our indicator, based on this three-answer scale of electoral potential, implies that the maximum potential is more uncertain than the intermediate potential, which is less certain than the minimum potential. The rebalancing of the forces at play revealed by the maximum electoral potential indicator is therefore more uncertain by nature.

While the maximum electoral potential of Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron and Xavier Bertrand are almost equivalent, Marine Le Pen’s minimum electoral potential remains much higher than that of her opponents

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Memo for the reader: In April 2021, when surveyed about Marine Le Pen’s candidacy, 10% of respondents said that they “will definitely” vote for her; 20% said they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for her; 33% said they “will definitely”, “most likely” or “might” vote for her.

Protest behaviour still in the majority for 2022

Since our first wave in September 2019, protest electoral potential has remained very high. In April 2021, most of those surveyed (78%) continue to consider voting for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, abstain from voting or casting a blank vote in the first round of the presidential election. Respondents’ tendency to vote for the candidate of one of these parties is unchanged (51%) compared to Wave 3 in September 2020. The proportion of respondents who stated that they could abstain from voting or cast a blank vote in the first round of the presidential election remains high (56%) but is nevertheless down by 3 points compared to September 2020 (59%).

September 2019-April 2021: trend in protest electoral potential in the first round of the 2022 presidential election

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

* The “populist vote” option here groups together respondents who answered that they could vote for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (RN, LFI, DLF, LO/NPA).

Trends in electoral potential in the first round of the 2022 presidential election (LFI, PS, EELV, LREM, LR, RN)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The readiness to vote for the PS, EELV, LREM and LR was tested as of Wave 3 of this indicator, in September 2020.

It should be noted that Wave 4 was carried out from 6 to 12 April 2021, thus before Marine Le Pen voiced her support for the open letter signed by retired generals and published in the weekly Valeurs actuelles on 21 April, and before the terrorist attack in Rambouillet on 23 April, which killed a police officer.

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), Tsunami dans un verre d’eau. Regard sur le vote Europe Écologie-Les Verts aux élections municipales de 2014 et de 2020 dans 41 villes de plus de 100.000 habitants, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, juillet 2020.

The willingness to vote for the RN has incessantly increased. In Waves 1 to 4, we noted an increase in the willingness to vote for the RN, i.e. an increase of 4 points, from 30% in September 2019 to 34% in April 20213. On the other end of the political spectrum, left-wing populist parties or revolutionary parties experienced a surge in Wave 2 of our indicator, in January 2020 (19% for LO/NPA, 24% for LFI, i.e. +4 points in both cases compared to September 2019), probably stemming from the protests against the retirement reform. However, by April 2021, they had returned to a level close to that in September 2019: 16% for LO/NPA (as opposed to 15% in September 2019) and 22% for LFI (versus 20% in September 2019).

The willingness to vote for LR remains stable and at a high level (37% versus 36% in September 2020). The willingness to vote for the PS (30% versus 31%) and for LREM (33% versus 34%) are also stable, though at a lower level.

The willingness to vote for EELV remains high, but has fallen sharply, by 7 points, from 42% to 35%. Some disengagement can be noted in those aged under 35, a group in which the readiness to vote for EELV decreased from 52% to 46% between Waves 3 and 4. This can be interpreted as a self-correction after the media buzz around a supposed “green wave” in the 2020 municipal elections, which analysis of the results shows did not materialise4. The willingness to vote for EELV fell by 6 points in the Paris region (from 42% to 36%) and by 8 points across the nation (from 42% to 34%). Lastly, EELV’s electoral potential dropped off considerably between Waves 3 and 4 among those who voted for Marine Le Pen, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, François Fillon or Emmanuel Macron in the first round of the 2017 presidential election.

EELV is increasingly seen as a credible alternative to those who chose Marine Le Pen, François Fillon, Emmanuel Macron, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Benoît Hamon in the first round in 2017

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

A tighter second round in the event of a Macron-Le Pen face-off

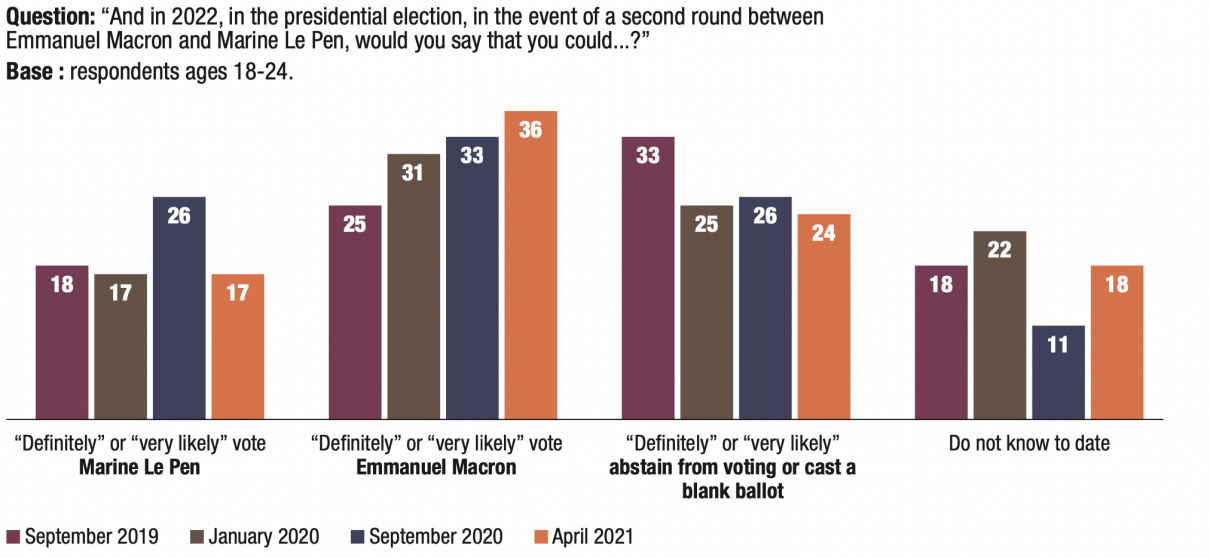

In a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the proportion of people who said they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for the incumbent president increased by 4 points between January 2020 (27%) and September 2020 (31%), widening the gap with Marine Le Pen (27% in January 2020, 25% in September 2020). In April 2021, the gap narrowed, with 29% for Emmanuel Macron and 25% for Marine Le Pen. Concurrently, the percentage of those who stated they “will definitely” or “very likely” abstain from voting or cast a blank vote increased by 3 points, from 29% in September 2020 to 32% in April 2021. Over the whole period, the readiness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot has increased by 5 points since September 2019, from 27% to 32%.

Trends in electoral availability declared for the second round of the 2022 presidential election (September 2019-April 2021)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.

The idea of a candidate unaffiliated with a political party appeals to a majority (55%)

Populist vote or support for a civil society candidate: figures of electoral protest

As 2022 approaches, not only has the idea of a non-party candidate not been dispelled by Emmanuel Macron’s five- year experience, but it remains the preferred scenario of voters to date. To the question: “In 2022, in the first round of the presidential election, would you say you could vote for a candidate unaffiliated with a political party?” 55% of those surveyed respond in the affirmative. We shall assume here that the readiness to vote for a candidate not hailing from any party is one of the ways in which protest is expressed, alongside the vote in favour of an anti- establishment candidate (the populist vote), abstention from voting and the blank vote.

However, while the readiness to vote for a populist candidacy and, to a large extent, the readiness to abstain from voting is found mainly in working-class categories, the readiness to vote for a candidate who unaffiliated with any a party is more characteristic of the higher-income categories. The profile is quite different. The latter type of voter is more likely to hold a higher- education degree (60%), belong to a higher income group (60%) or the middle classes (57%) rather than the working classes (50%); is a craftsperson, retailer, or business manager (65%), an employee of the public sector (60%) rather than the private sector (52%); posts a monthly household income greater than €3,500 (63%) and is aged 35 or above (56%).

This idea of a civil society candidate appeals to nearly half of respondents without a degree or with lower educational degrees (49%), compared to 60% of those with two years’ post-Baccalaureate education or a higher educational degree. Given the low proportion of Baccalaureate + 2 graduates amongst the older generations, one might interpret this as an age effect. Yet such a candidate is approved by 50% of those aged under 35, and in particular by only 40% of high school and university students, compared with 55% of those ages 50-64 and 56% of those ages 65 and over.

Parties that have governed in turn under the Fifth Republic, in particular the PS and LR, are rejected by the working and upper categories of society. Working- class groups opt for an anti-system vote, by supporting a populist party, or for a withdrawal from the political game, by abstaining from voting. The upper categories opt for an out-of-system vote by expressing their preference for a candidate not from a given party. The traditional parties are losing control of the presidential election, which has been the key to their control of political life since 1965.

The parties’ disrepute is encouraging multi- faceted protest

According to our Wave 4, 80% of respondents say they do not trust political parties. Distrust is spectacularly high, even though it has fallen slightly, for the second time in succession, compared to Wave 2 (84%) and Wave 3 (82%). This does not come as a surprise to anyone. For many years now, surveys have confirmed this state of affairs in public opinion, in particular the data from Cevipof ’s Political Trust Barometer. This long-lasting distrust ultimately eventually results in significant consequences for political life. To this extent, the growing disrepute of government parties has relatively worked out to the benefit of populist parties which, having not governed, derive from it the advantage of not having disappointed. The governing parties have seen the public turn away from them. The decline in the number of activists has long been underway. It heralded the electoral decline, which became perceptible in the volatility or dispersion of the vote as much as in the rise in abstention from voting. The presentation of and commentary on election results with respect to votes cast cannot long hide the reality of this decline, which in some cases borders on a collapse.

The governing parties have not looked on idly. They have tried to revive their legitimacy, in particular by organising primary elections – a remedy which have sometimes given the impression of hastening the progress of the disease. The PS, LR and EELV splintered in their primaries before being defeated in the first round of the 2017 election, while the second round pitted a candidate outside the system, Emmanuel Macron, against an anti-system candidate, Marine Le Pen, neither of whom had had to come through the primary stage.

Outside the system versus anti-system: the 2017 configuration remains

The second round of the 2017 presidential election stood out for an unprecedented face-off for a presidential election: on the one hand, a candidate outside the system, Emmanuel Macron, without an electoral past or constituted party; on the other hand, an anti-system candidate, Marine Le Pen, at the helm of a populist party. It is the disrepute of the traditional parties that establishes at the heart of the presidential election the clash between non-system and anti-system candidates. However, since the elimination in the first round of 2017 of the candidates presented by the traditional right and left the traditional right and left, distrust of the parties remains massive. The defeated parties, since 2012 where the right-wing is concerned and since 2017 where the left-wing is concerned, have failed to regain public support. The unpopularity of these parties hampers the chances of success of the candidates they choose.

In 2017, Emmanuel Macron was the unusual candidate and unexpected winner of a campaign that had been disastrous for the governing parties. When presented with the prospect of an election involving one candidate from each of the parties, voters’ readiness to choose a candidate who is unaffiliated with any political party is by far the highest. Of course, this result is high because voters who find their aspirations reflected in the idea of an out-of-party candidacy come from different political positionings, left-wing (54%), centre (56%) or right- wing (57%). Yet the advent of a non-party candidacy cannot be politically neutral. It would eventually be seen as more left-wing or more right-wing. However, the fact remains that by 2022, for traditional opposition candidates, the benefits connected with party support have become uncertain. A necessity when governing, has the party not become an obstacle to an LR or PS victory in 2022?

A candidate who is unaffiliated with any political party

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

The uncertainties of a new second round between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

Marine Le Pen elected in 2022: somewhere between an electoral accident and a breakaway vote

The electoral accident hypothesis

Any election results from a combination of participation and disengagement (abstention from voting or blank ballot). However, to be feasible, the possibility of electing a populist candidate as President of France (the most likely at this point is Marine Le Pen) must combine very strong mobilisation of the protest electorate in her favour and a historic disengagement, in the form of abstention from voting or blank voting of voters assumed to support a candidate from a government party in the second round (the most likely to date is Emmanuel Macron). In deciding to abstain from voting or casting a blank ballot, many voters do not realise that they are contributing to the outcome of the vote. To become reality, the election of Marine Le Pen must rely on a substantial share of abstention from voting or blank voting by voters who refrain from voting for her, but refuse to vote for the incumbent president. In using the expression “electoral accident” here, we refer to an election proceeding from a sum of behaviours that are not all driven by the intention to give rise to such an outcome. This is why, from the outset, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique’s electoral protest indicator is not limited to estimating readiness to vote populist: it also tries to evaluate the willingness to abstain from voting or casting a blank ballot.

The electoral accident scenario has already occurred. The most notable case was surely the first round of the 2002 presidential election. It is obvious that most of the left-wing voters who contributed to the record- high abstention rate recorded in the first round on 21 April 2002 (28% of registered voters) did not want a second round between Jacques Chirac and Jean-Marie Le Pen.

The possibility of a breakaway vote

In a different scenario, the term “breakaway vote” refers to the willingness to vote for Marine Le Pen in the second round of the presidential election expressed by voters who abstain from voting, cast a blank ballot or voted for Marine Le Pen or for candidates eliminated in the first round. The vote here is said to be “breakaway”, as it stems from a clear intention to promote the RN candidate’s victory in the event of another run-off against the incumbent president.

Readiness to abstain from voting remains very high, but is falling, particularly among 18-24 year olds

While readiness to abstain from voting in the first round of 2022 increased between January and September 2020 (from 40% to 45%), it dipped in April 2021 (to 42%), returning to the already-high level observed in September 2019 (41%). Half of voters (49%) remain ready to cast a blank ballot, the same level as in September 2020.

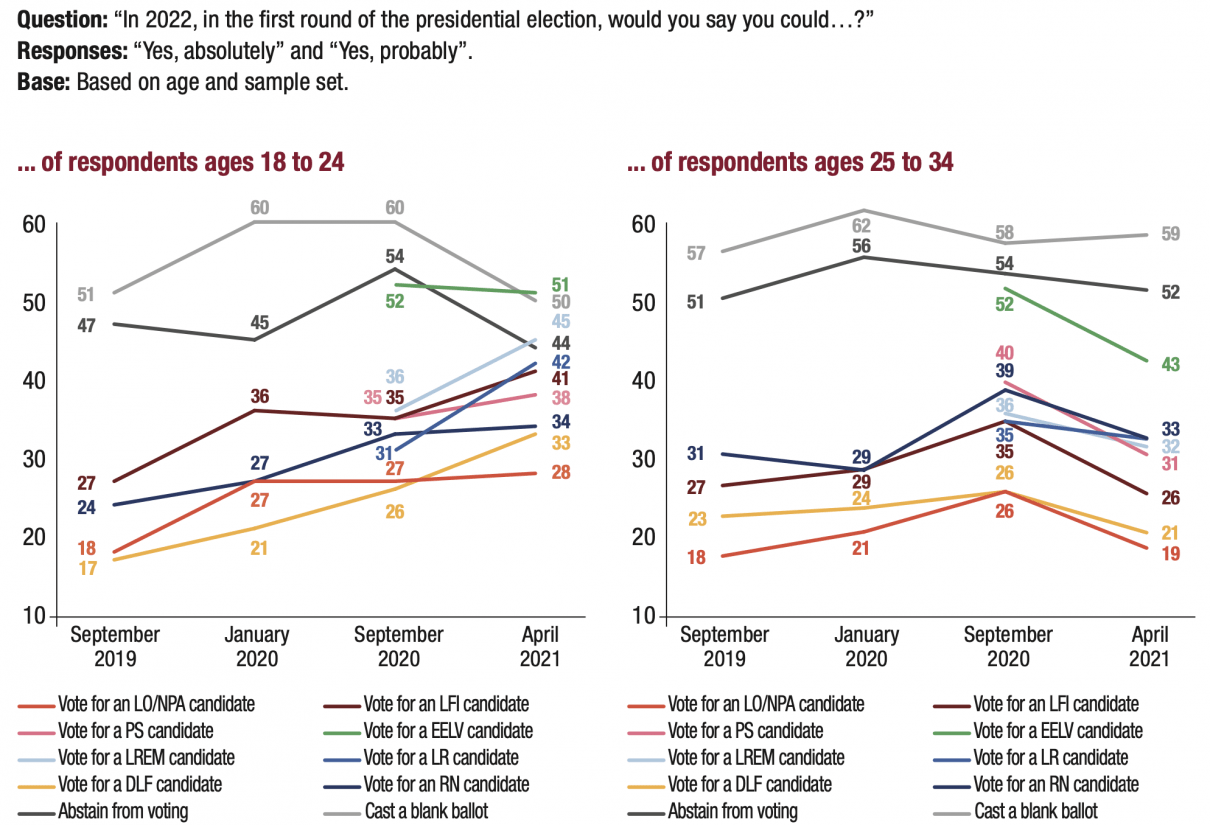

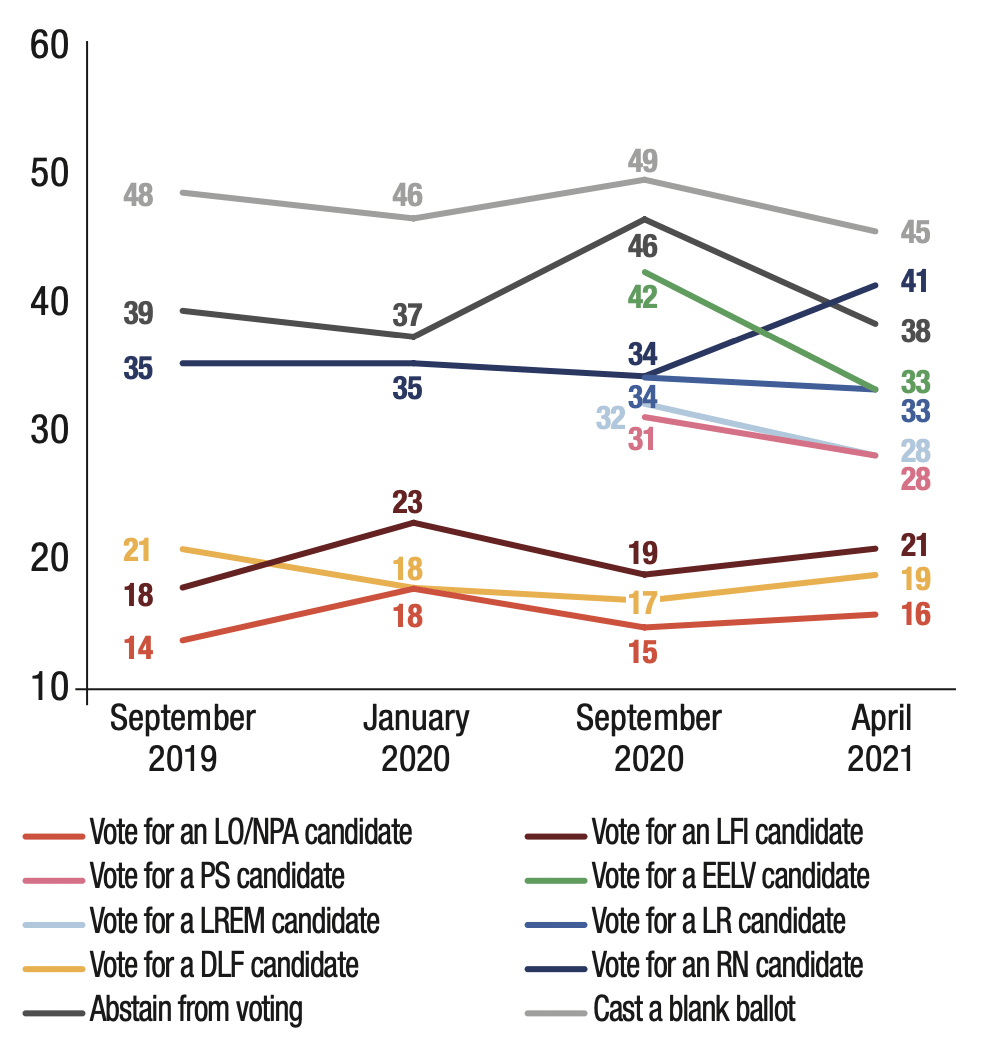

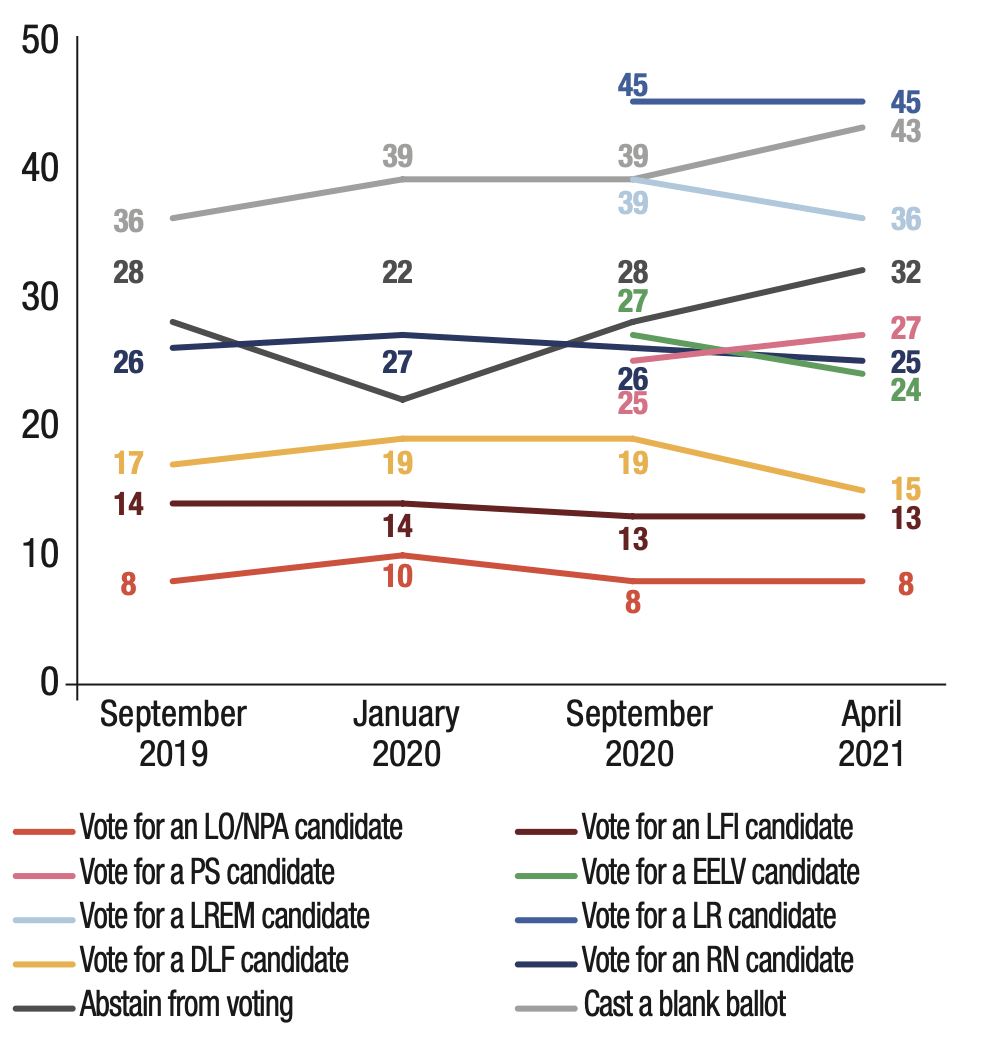

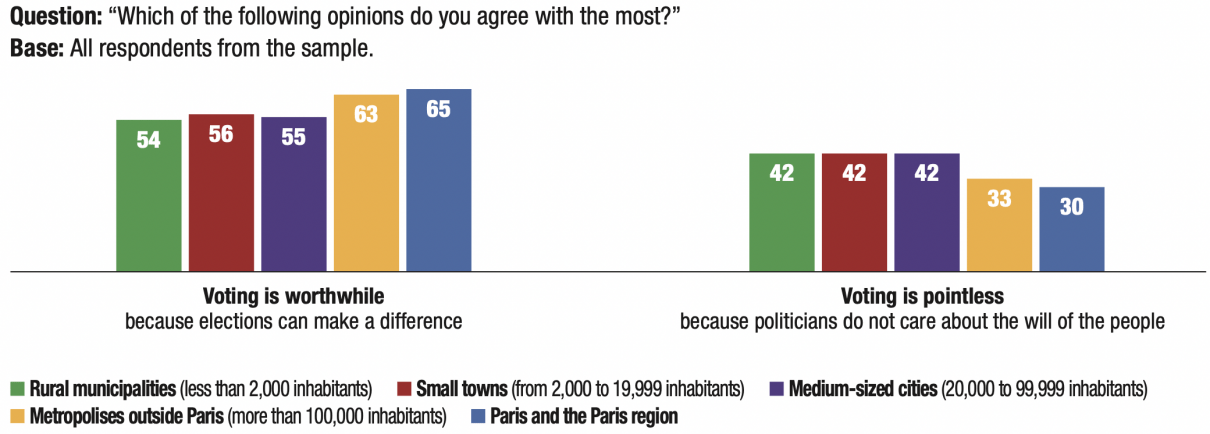

The increase in readiness to abstain from voting observed between January 2020 and September 2020 was driven in particular by two age groups, the 18-24 age group (for which in increase had been recorded, from 45% to 54%, i.e. +9 points) and the 50-64 age group (from 37% to 46%, again +9 points). The proportion of respondents reporting they could abstain from voting therefore fell in April 2021, particularly among 18-24 year olds (44%) and 50-64 year olds (38%). Note that 18-24 year olds are the most likely (68%) to deem that “Voting is worthwhile because elections can make a difference” (58% for 25-34 year olds, 53% for 35-49 year olds, 57% for 50-64 year olds and 66% for 65 and over). While the readiness to abstain from voting among 18-24 year olds has never been lower (44%) since the creation of our indicator, this movement comes along with an increase in readiness to vote for DLF (+7 points, from 26% in September 2020 to 33% in April 2021) and LFI (+6 points, from 35% to 41%). Data from April 2021 also shows a resurgence in interest among 18-24-year olds in the centre and right-wing parties, with a sharp increase for LREM (+9 points, from 36% to 45%) and LR (+11 points, from 31% to 42%). Lastly, it should be noted that the readiness of new generations to vote for the RN remains stable and at a high level (from 33% to 34%), as well as for the LO/ NPA (27% to 28%) and PS (35% to 38%). The readiness to vote for EELV remains the highest in this age group (51% versus 52%).

Compared to the previous wave, it remains important to note that those ages 65 and over say they are more likely to abstain from voting (from 28% to 32%) and cast a blank ballot (from 39% to 43%). This intention to disengage amongst older voters is likely to be seen as a consequence of the coronavirus crisis, or even a fear of contamination when going to vote in the presidential election. In this specific instance, the fear could diminish significantly depending on the deployment of the vaccine campaign. The readiness of these voters should be kept under watch, as we know the decisive role of these age groups in the overall level of participation and in the vote against populist parties. If this trend were to continue, the disengagement of a part of this electorate would be an additional challenge for moderate candidates.

A resurgence in interest from 18-24 year olds in LR, LREM, DLF and LFI

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

… of respondents ages 35 to 49

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

… of respondents ages 50 to 64

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

… respondents ages 65 and over

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

In the event of a second round between Emmanuel One of the consequences of this growing support for Macron and Marine Le Pen, the 18-24 age group shows President Macron is the decline in the propensity of 18- an increase in their willingness to vote for the incumbent 24 year olds to abstain from voting (-9 points, from 33% president since the first wave of our indicator (+11 points to 24%).

between September 2019 and April 2021, from 25% to 36%).

The dramatic increase in the willingness of 18-24 year olds to vote for Marine Le Pen recorded in September 2020 (Wave 3) was annihilated in April 2021 (Wave 4)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

In April 2021, more young people said they wanted to “block” Marine Le Pen

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

“No party preference”: abstention from voting or blank ballots

Our electoral protest indicator asks voters how close they feel to the following parties: LFI, PS, EELV, LREM, LR and RN. In April 2021, 42% of respondents said they had no partisan preference. While, considered as a whole, this group is socially heterogeneous, all those in it describe themselves as removed from politics. Their distrust in political parties is higher (88%) than the average (80%). Amongst those with “no partisan preference”, a majority (51% vs. 37% on average) feel that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people”. Their interest in politics is low: 70% have little or no interest in it (compared to 53% on average). More than three-quarters of them (77%) feel that political leaders talk about issues that do not concern them as voters (compared to 70% on average). 67% of them also feel that the media show news that is not relevant to them (compared to 61% on average).

The potential electoral behaviour of those with “no partisan preference” is characterised by a greater than average willingness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. For example, 69% of those surveyed said they had abstained from voting at least once in their lives before, compared with 55% on average; similarly, 65% of them said they had cast a blank ballot at least once, compared with 52% on average.

With a view to the first round in 2022, most of those “no partisan preference” believe it is possible they will abstain from voting (58% versus 42% on average); more people also say they could cast a blank ballot (67% versus 49%). Their willingness to vote for a populist candidate is lower than average: 28% for an RN candidate (compared to 34% on average), 19% for an LFI candidate (compared to 22% on average); the same applies in the event of a candidate from a governing party: 29% for an LR candidate (vs. 37% on average), 25% for an LREM candidate (as compared to 33% on average), 27% for a PS candidate (vs. 30% on average), 31% for an EELV candidate (as compared to 35% on average). It should be noted that the non-party candidate achieves an identical result (55%) to the average (55%) amongst those with “no partisan preference”.

Lastly, in view of a second round between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron, 16% of those with “no partisan preference” could vote for Marine Le Pen (compared to 25% for the sample as a whole) and 19% could vote for Emmanuel Macron (compared to 29%). Here again, the willingness to abstain from voting among those with “no partisan preference” (21% vs. 14% on average) and to cast a blank ballot (23% vs. 18%) is very high.

Facing Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen will also benefit from a portion of the left-wing votes

The Wave 4 data show that Marine Le Pen could benefit from ballots transferring from the left, were a second round to pit her against the incumbent president. One- quarter of those who state they could vote LO/NPA (26%) or LFI (22%) in the first round say they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron.

The proportion of PS voters in the first round willing to vote for Marine Le Pen in the second (14%) is significant, as is that of EELV voters (15%). The willingness to vote for Marine Le Pen in the second round is found in 20% of voters who say they intend to abstain from voting in the first round and 19% of those who say they intend to cast a blank ballot.

The risk of an electoral accident will be all the greater as the desire to block Marine Le Pen will be weaker

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Among those who could vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round, 27% said they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the second round and 44% said they “will definitely” or “very likely” to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. The voters of Jean- Luc Mélenchon – assumed to have been eliminated here in the first round – could thus play a decisive part in the second round, some opting for a breakaway vote by voting for Marine Le Pen, others by increasing the risk of an electoral accident, by abstention from voting or blank voting.

The course of the campaign on the right will not be without consequence on these scenarios, whether an electoral accident or a breakaway vote. One-quarter of those who could vote LR (26%) and 44% who could vote DLF in the first round say they “will definitely” or “very likely” to vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron.

Out of those respondents declaring their willingness to vote for Xavier Bertrand in the first round, one-third (32%) said they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in a second round pitting her against Emmanuel Macron, while one-quarter (24%) would abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot.

In the event of a second round between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron, the RN leader

would win back one-third of Xavier Bertrand’s electorate and one-quarter of that of Jean-Luc Mélenchon

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

The electorate’s shift to the right could favour Marine Le Pen…

In detail, those who self-positioned at 0 to 1 on the scale are considered “very much to the left”, 2 to 4 as “moderate left-wing”, 5 as “centre”, 6 to 8 as “moderate right-wing” and 9 to 10 as “very much to the right”.

See Victor Delage, The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021. The data analysed in this study comes from the twelfth wave of the Political Trust Barometer, a benchmark survey conducted by the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof), of which the Fondation pour l’innovation politique is a partner.

French opinion leaning rightward

Respondents were asked to self-position politically on a left-right scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is the most left- wing and 10 is the most right-wing. Those that placed themselves at 0 to 4 on the scale were considered on the left, 5 in the centre, and 6 to 10 on the right5. The persons surveyed also had the option not to self-position on this scale.

The data shows that more voters self-position on the right. Nearly four out of ten French people (38%) describe themselves as being right-wing (from 6 to 10 on the scale). Only 18% self-position on the left (0 and 4). 16% of respondents self-positioned in the centre (5 on the scale). Lastly, one-quarter (24%) of respondents did not place themselves on the left-right axis.

A comparison between these results and those observed in another study6 confirms the decline in the left-ward leaning of opinion (24% self-position on the left in the said study, based on data from February 2021 versus only 18% in our Wave 4, conducted in April 2021). The level of self-positioning on the right is the same (38%), as is that in the centre (17% in the aforementioned study and 16% in our indicator), while the proportion of respondents who do not know where to self-position on the left-right scale is 3 points higher here (21% in the cited study versus 24% in our Wave 4).

From September 2019 to April 2021, the proportion of respondents self-positioning as right-wing increased by 4 points, from 34% to 38%. Over the same period, the proportion of respondents describing themselves as left-wing experienced a shift of the same magnitude, but in the opposite direction, as the proportion of those self-positioning as left-wing increased from 22% to 18%. Consequently, the right-wing’s lead over the left- wing, which amounted to 12 points in September 2019, increased to 20 points in April 2021.

The rightward shift is gaining magnitude

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.

Younger generations increasingly self-identify on the right

Our data show an accelerated shift to the right amongst our youth: while 23% of 18-24 year olds self-positioned as right-wing (from 6 to 10 on the left-right scale) in January 2020, 27% of them did so in September 2020 and 33% in April 2021, an increase of 10 points in fourteen months. Conversely, younger generations are less and less likely to self-position in the centre (19% in January 2020, 10% in April 2021) and, to an even lesser extent, as left-wing (18% in January 2020, 16% in April 2021). It should be noted that while the proportion of 18-24 year olds who did not self-position on the left- right scale fluctuates depending on the wave (35% in January 2020, 41% in September 2020 and 32% in April 2021), it remains very high.

This data, combined with the fact that fewer and fewer young people identify with the left, could lead to the assumption that new generations identify less and less in a left-right divide. In reality, the idea that these shifts might be the result of younger people’s disinterest in politics should be dismissed: 18-24 year olds report an increasing interest in politics (33% in September 2020 versus 38% in April 2021), though the results remain below the average (46% in April 2021).

Without a candidate to support, respondents on the right tend to express a preference for Marine Le Pen

In the first round of the presidential election, among those self-positioning as right-wing (from 6 to 10 on the left-right scale), a third (34%) say they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for the RN candidate, 23% for Emmanuel Macron and 21% for Xavier Bertrand. Out of the respondents in the centre, i.e. in position 5 on the scale, 18% said they could vote for the incumbent president, ahead of Marine Le Pen (14%) and Xavier Bertrand (8%).

Not including the respondents self-positioning as “very much to the left” (0 and 1) and those who are “very much to the right” (9 and 10), the gap between the electoral bearing of a left-wing government (2, 3 and 4) and that of a right-wing government (6, 7 and 8) becomes clear. Not only does this gap still work to the right-wing’s advantage, but it increased from 7 points to 14 points between September 2019 and April 2021. When the two polarised segments (“very much to the left” and “very right wing”) are excluded, the comparison shows that the shift in public opinion is more towards the right- wing than it is towards Marine Le Pen herself. It is in the absence of a candidate supported by the governing right that Marine Le Pen could be elected president of the Republic.

The rightward shift is spreading throughout French society

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

The rightward shift is spreading throughout French society (cont.)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

The intermediate electoral potential of Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron, Jean-Luc Mélenchon

and Xavier Bertrand in the first round of 2022 as a function of respondents’ left-right self-positioning

Copyright :

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

Memo for the reader: Among those on the right (from 6 to 10 on the scale), 6% of respondents said they “will definitely” vote for Xavier Bertrand; 21% said they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for him; 48% said they “will definitely” or “most likely” or “might” vote for him.

Faced with the possibility of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, voters self- positioning as right-wing “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for the RN candidate (38%), 5 more points more than for the incumbent president (33%). Out of the voters self-positioning in the centre, one-third (32%) say they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for Emmanuel Macron, compared with one-quarter (23%) for Marine Le Pen. It is important to remember that voters self-positioning as right-wing (38%) are twice as numerous as those self-positioning in the centre (16%). It should also be noted that 37% of those self-positioning as left-wing say they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for Emmanuel Macron, 27 points more than for Marine Le Pen (10%). However, nearly half (45%) of these respondents self-positioning on the left say they could abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. While the number of respondents self-positioning as left-wing (18%) has fallen sharply, their mobilisation will count greatly for the incumbent president in the event of a second round between himself and Marine Le Pen.

Lastly, the electoral mobilisation of respondents not self-positioning themselves on the left-right scale – i.e. one-quarter of respondents (24%) – could also play a decisive role: 22% say they “will definitely” or “very likely” vote for Marine Le Pen, compared with 17% for Emmanuel Macron. Above all, four out of ten respondents (42%) who do not self-position on the left-right scale say they “will definitely” or “very likely” abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot (compared to 32% on average) and 20% say they do not know what they will do to date (compared to 11% on average).

A significant proportion of the French self-positioning as right-wing say in the first round they exclude voting for Emmanuel Macron (41%), Marine Le Pen (40%) and Xavier Bertrand (27%). Although no figure has yet emerged within the LR, a consensus candidate on the right would require a second look at both Marine Le Pen’s and Emmanuel Macron’s current positions.

The willingness to vote for Marine Le Pen is high among respondents self-positioning as right-wing, but also among those self-positioning in the centre

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

The concerns of the French

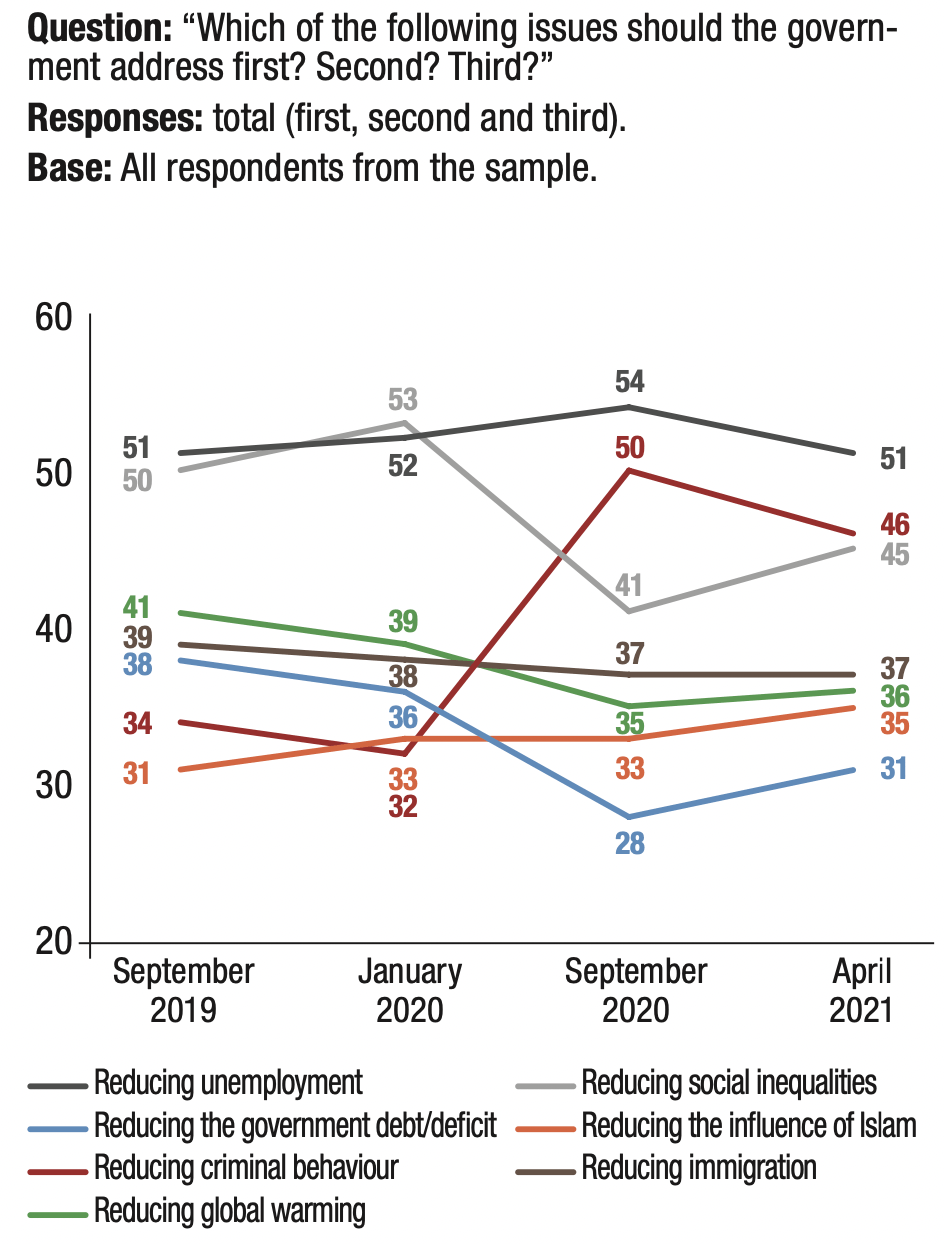

The French’s three concerns remain unchanged from our previous measure, namely: “Reducing unemployment” (51%, down by 3 points), “reducing criminal behaviour” (46%, down by 4 points) and “reducing social inequalities” (45%, up by 4 points). However, the ranking of priority concerns reveals two groups with very different political implications: on the one hand, criminal behaviour, immigration, Islam and debt; on the other, unemployment, inequality and global warming. Two systems of concern, one more right- wing, the other more left-wing, can be distinguished, though not necessarily in opposition to one another. The way these concerns develop will certainly weigh on the outcome of the presidential election. The more right-wing themes, notably Islam and immigration, will not disappear from centre stage by May 2022. Similarly, concern about crime will play a decisive part, especially as almost three-quarters (72%) of those surveyed deem that society is “increasingly violent”.

However, there has been an increase in concern about social inequalities, while unemployment maintains its position as the number one concern. A theme clearly anchored on the left, the concern for global warming, had experienced a first decline between Wave 1 (41%) and Wave 2 (39%), then a second, more marked decline during Wave 3 (35%). Wave 4 confirms this issue’s demotion (36%), which the EELV’s rhetoric connects with degrowth, when a preponderant portion of society aspires to consumer activity, purchasing power and material progress.

In public opinion, unemployment, criminal behaviour and social inequalities remain the priority issues

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

While the return of social concerns, the question of inequalities, should be more favourable to the left, it is important to keep in mind that the FN/RN has long been able to connect the social dimension with the national dimension.

…but the health crisis has not altered attachment to Europe

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), What next for democracy?, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2017, and Democracies Under Pressure. Volume 1. The issues, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2019.

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), 2022, the Populist Risk in France. Wave 1, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, October 2019.

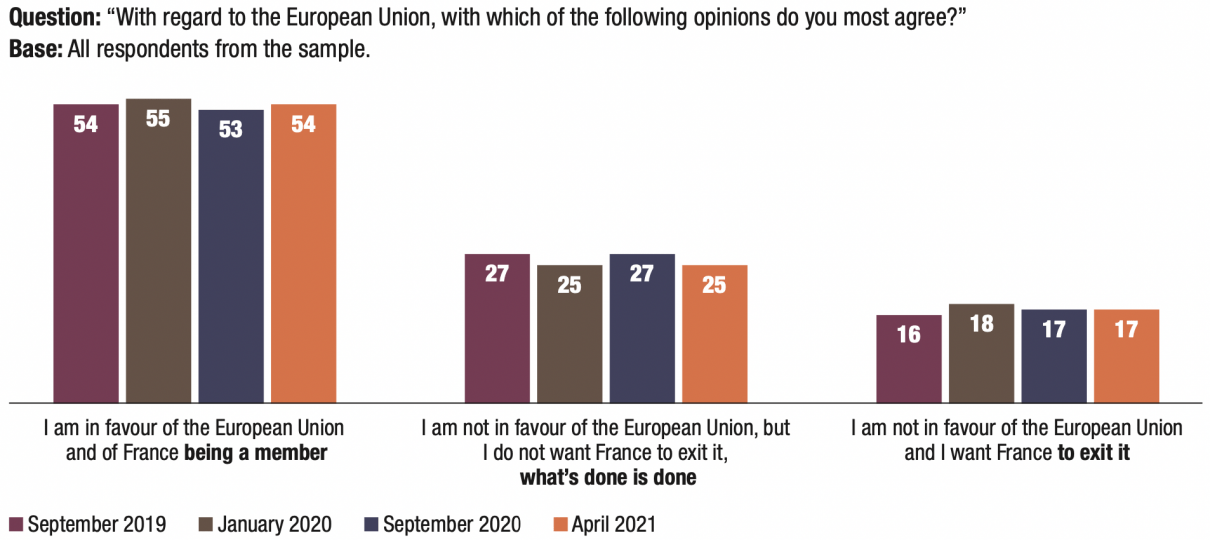

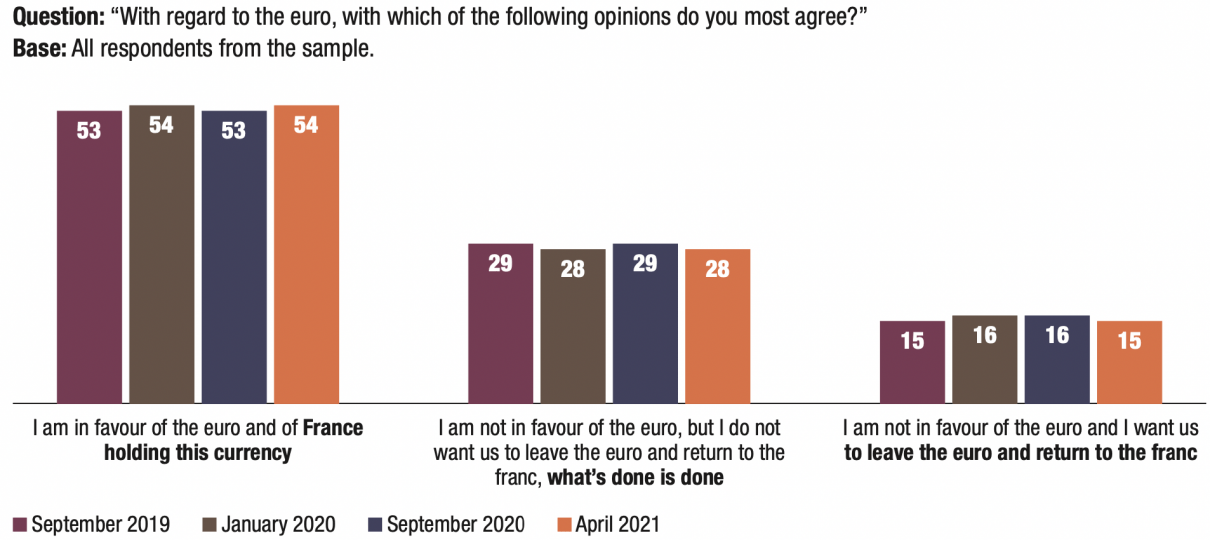

In 2017, Europe and the euro formed the great divide between Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron. Both in the previous studies of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and in the previous waves of our indicator , we had highlighted the obstacle which the French’s attachment to the European Union and the euro represents for Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. The health crisis has not weakened this attachment, despite the controversies over Europe that have been attempted. Thus, as in the previous waves, more than three-quarters (79%) of respondents wish to remain in the European Union.

The Covid-19 crisis and the French’s support for Europe

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.

The Covid-19 crisis and the French’s support for the euro

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not reach 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.

The majority of those (59%) who state they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round in 2022 do not want France to leave Europe; an even larger majority (68%) want to keep the euro. As pertains to Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the situation is even more striking since almost all those who state that they “will definitely” or “most likely” vote for the LFI leader do not want their country to leave Europe (85%) nor the euro (84%).

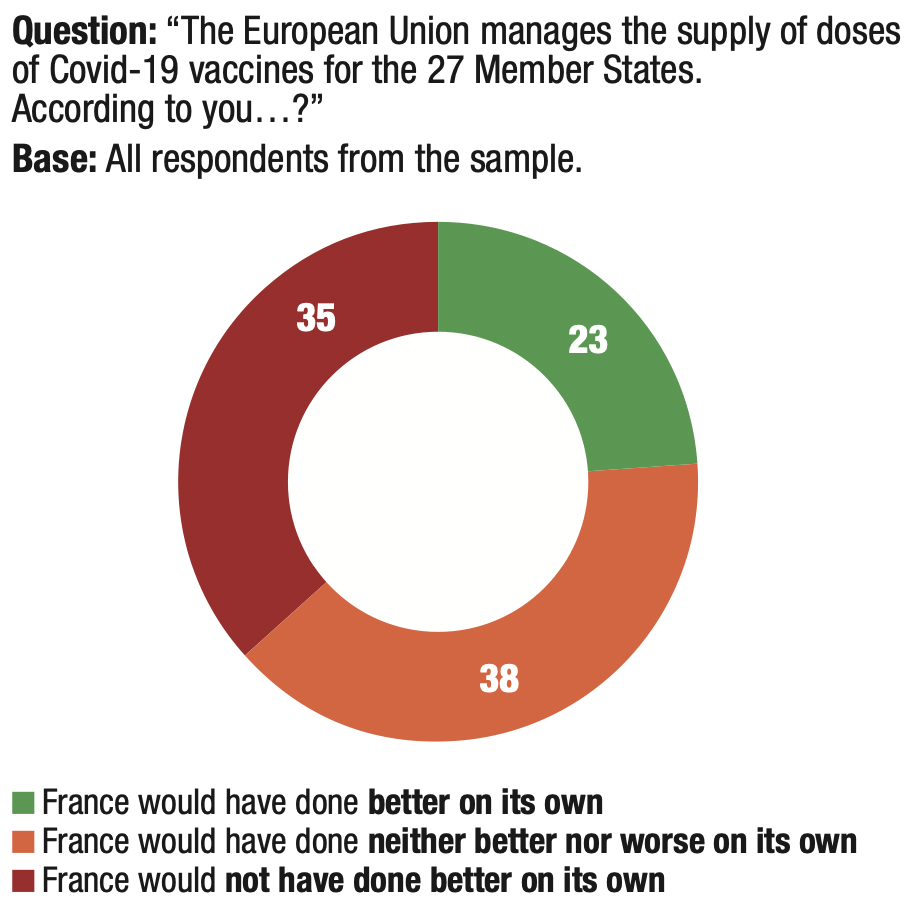

Europe’s management of vaccine dose supplies has not changed the lay of the land: admittedly, one-quarter (23%) of respondents feel that France would have “done better on its own”, but one-third (35%) feel that France would not have “done better on its own” and 38% feel that France would have done “neither better nor worse on its own”. Even among the group of respondents who say they are “against the European Union and want France to exit it”, only half (49%) feel that France would have done better on its own, compared with 15% who feel that it would not have done better on its own and 32% who claimed that it would have done neither better nor worse.

A particularly high proportion of younger people (18- 24 year olds) (45%) consider that the country would not have fared better without Europe (10 points higher than the average, 35%). While the proportions of those close to LREM (49%) and EELV (52%) who consider that France would not have fared better without the European Union are the highest, this opinion is strongly represented among those close to the PS (50%) and LR (42%), but also the PCF-LFI (42%).

Those close to the RN remain the most numerous (44%) to deem that France “would have done better on its own”. This opinion is also more widespread than the sample average (23%) among 50-64 year olds (28%), those with the lowest educational qualifications (27%), blue-collar workers (27%), respondents with a positive image of the Yellow Vest movement (29%), as well as among those who say they are dissatisfied with Emmanuel Macron’s action as President of France (27%).

One-third of respondents feel that France would not have fared better without Europe in terms of vaccine dose supplies

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The total does not reach 100% due to non-responses, which are not shown in this graph.

A sharp increase in 18-24 year olds supporting Europe

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

The dual crisis of representation

For a long time, populist parties and candidates were considered incapable of governing in public opinion: the demagogy and outrageousness of anti-system parties fuelled the idea that they were incapable of governing. In contrast, the “governing parties” and their candidates, from the left or the right, enjoyed a kind of privilege of competence, which more or less explicitly conferred on the populist vote a venturesome and dangerous character. Accepted by public opinion, a privilege of competence reserved for governing parties is a major obstacle for populist parties. Yet this privilege of competence seems to be eroding. This shift cannot be unrelated to the Covid-19 crisis. The unprecedented nature of this crisis inevitably placed the governing figures in situations of uncertainty, improvisation and backtracking that could not be concealed..

By its duration, the health crisis forced the government to acknowledge a certain powerlessness.

The erosion of the privilege of competence granted to governing parties reduces the handicap of populist parties

This phenomenon particularly benefits Marine Le Pen. Our indicator’s latest wave shows that 21% of those surveyed considered her “more capable of responding to the concerns of the French” than “other politicians”. This proportion is the same (20%) with regard to Emmanuel Macron. In contrast, only 11% of respondents deemed that Jean-Luc Mélenchon is “more capable of responding to the concerns of the French” than “other politicians”.

Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron are credited with the same capacity to address the concerns of the French

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this table.

There is no doubt that the timing and character of the exit from the health crisis will significantly contribute to the outcome of the next presidential election. While, up to now, there has been relative tolerance for the government’s handling of the crisis, dissatisfaction seems to be growing. Since our last survey, satisfaction with the government’s management of the health crisis has declined sharply. From 39% of the sample deeming that the government has managed the crisis “very well” or “somewhat well” in September 2020 to 29% in April 2021. The success of the vaccination campaign will therefore be decisive in the way public opinion develops.

For a majority of respondents, the opposition parties, on the right or on the left, would have done as well (or as poorly) had they been responsible for managing the pandemic. To the question: “Below is a list of political parties. For each of them, if they were in power, indicate whether you think they would have done better, worse or neither better nor worse”, the majority supports the response “neither better nor worse”, including when it comes to evaluating revolutionary left parties (LO and NPA) or populist parties (LFI, DLF or RN).

The opposition parties PS and LR are not credited with any higher capacity: only 6% of those surveyed feel that the PS would have done better, while 26% feel that it would have done worse; 8% feel that EELV in power would have done better and 31% worse; 10% feel that LR would have done better and 17% worse. The idea that any given political power is hardly more capable than another of solving problems has taken hold, at least in the present moment of this crisis.

One of the consequences of this shift in opinion, perhaps temporary, is its contribution to eroding the argument of an RN-specific incompetence.

Although this positive assessment is very much in the minority, it is the party most widely credited by the public with an ability to better manage the health crisis than the government in office (15%), an increase of 3 points (12%) compared to September 2020. While 30% of those surveyed feel, to the contrary, that it would have done worse, this figure places RN at the level of EELV, barely above the PS (26%), below DLF (34%) and PCF (35%), and well below LFI (37%), NPA (37%) and LO (39%).

Overall, the French feel that few parties would have done better than the current government in managing the Covid-19 crisis if they were in power.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – July 2021

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.