2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

An electoral protest indicator designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politiqueThe key findings from Wave 5 of the electoral protest indicator

Introduction

Fifth wave of the electoral protest indicator 2022, the Populist Risk in France, designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

Voters are getting into motion while willingness to cast protest votes remains high

The potential for electoral protest: Wave 5

Willingness to engage in electoral protest behaviour is still a phenomenon of the majority (72%)

The reasons for abstention from voting and blank voting: protest behaviour rather than disappointed withdrawal

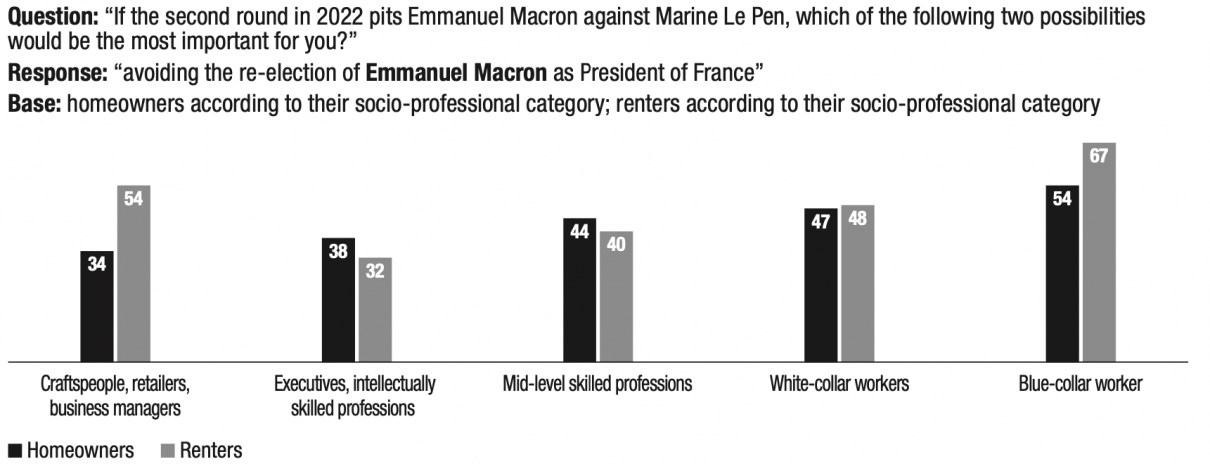

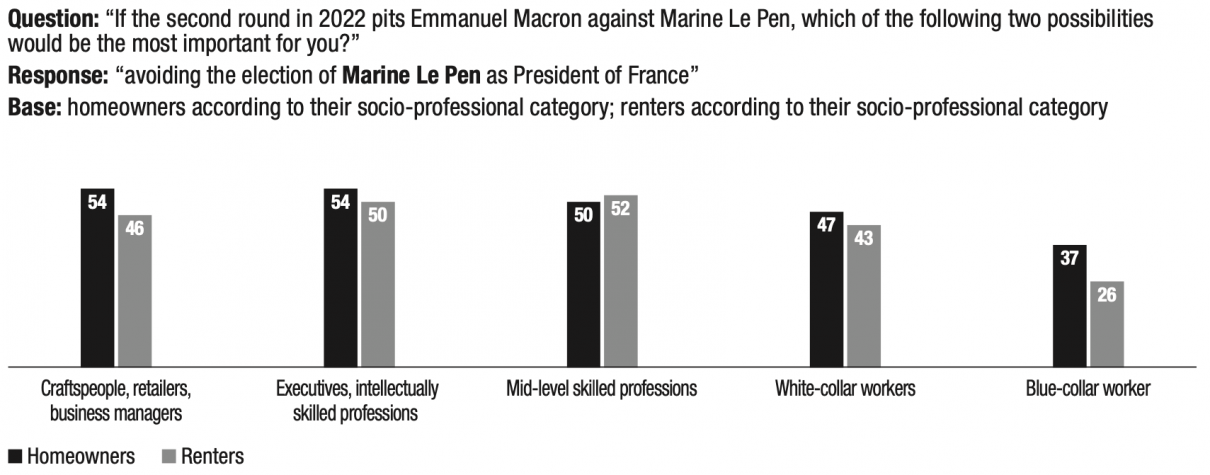

Willingness to vote for the right-wing is stable but the willingness to vote for the left is at its lowest since September 2019

In the event of a Macron-Le Pen duel, transfers of votes are uncertain

Interest in a candidate who does not hail from any political party

The idea of a non-party candidacy remains the preferred scenario for voters

Information on the profile of a candidate who does not come from any party

Rejection of parties conditions the expectation of a civil society candidacy

The populist risk is part of a troubled society

The presidential election could divide the French rather than unite them

Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and opponents of the health pass: an entanglement of anger feeds the protest vote

French people see their society as “increasingly violent”

Users of messaging applications, social media, video channels and “the right to have a firearm at home to ensure your safety”

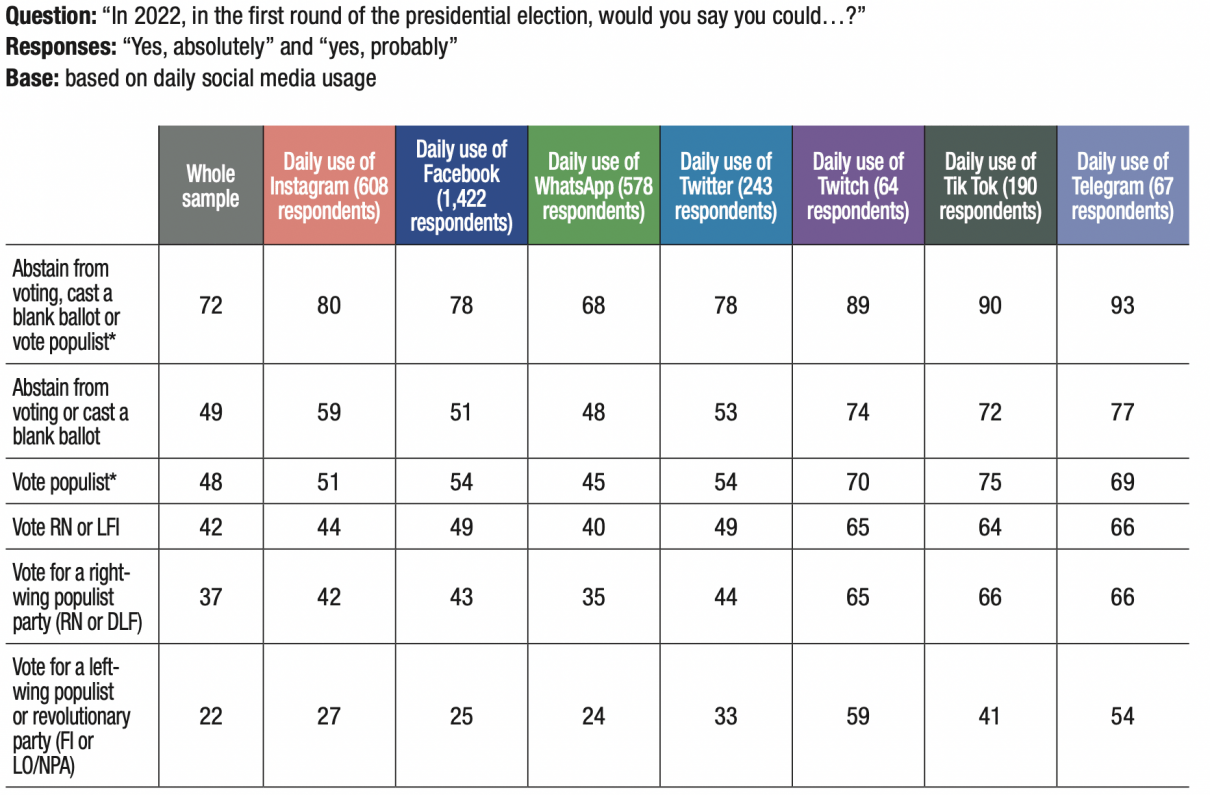

Regular use of social media is linked to protest behaviour

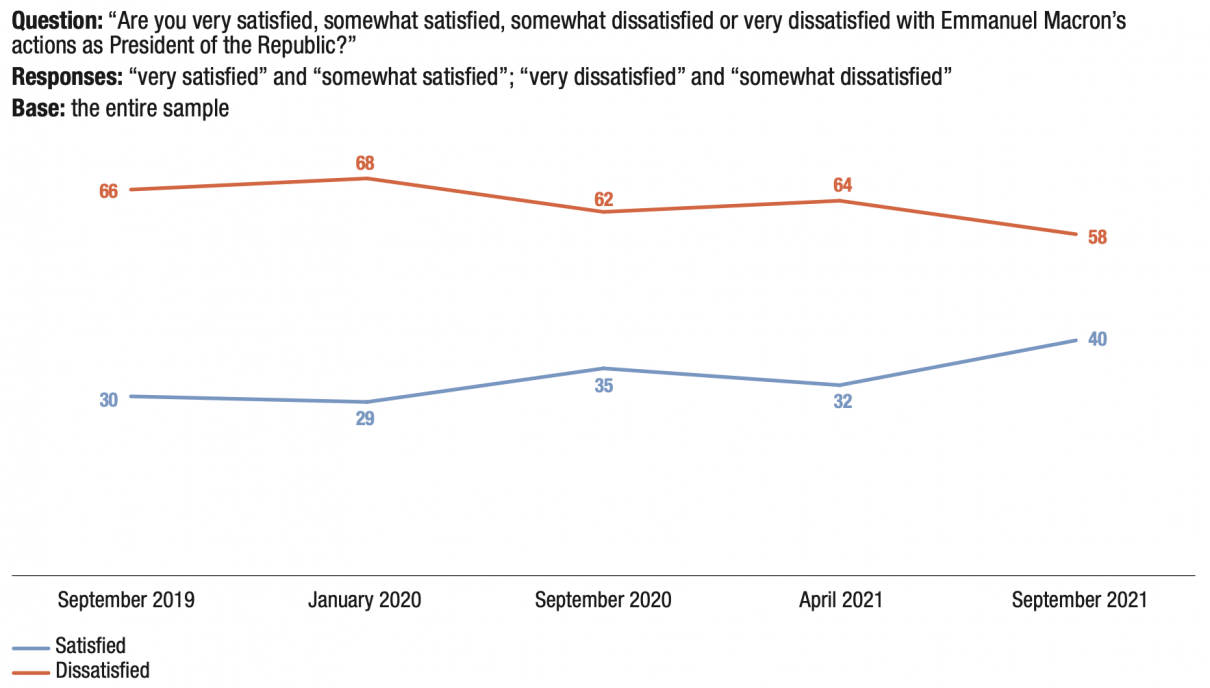

Support for managing the health crisis and for Europe is containing the populist vote

Increasing numbers of French people believe that the health crisis has been managed well

For populists, attachment to the European Union and the euro remains a major obstacle

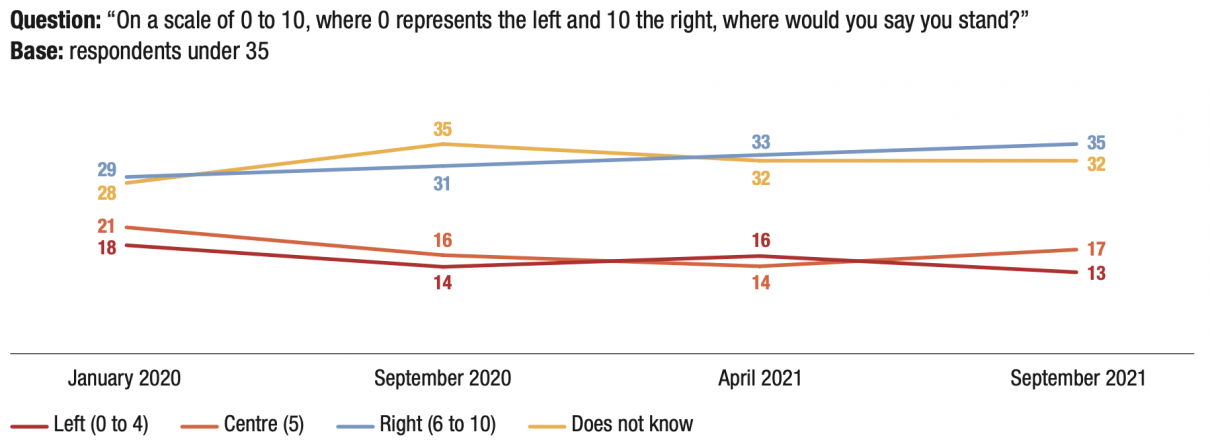

French society is predominantly right-wing

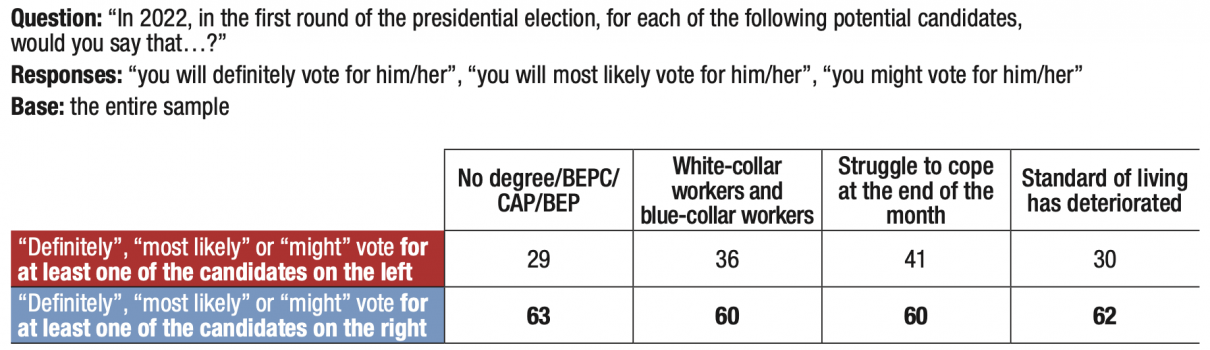

The predominance of the right observed by self-positioning on the left-right political scale

The preponderance of the right observed by the assessment of electoral potential

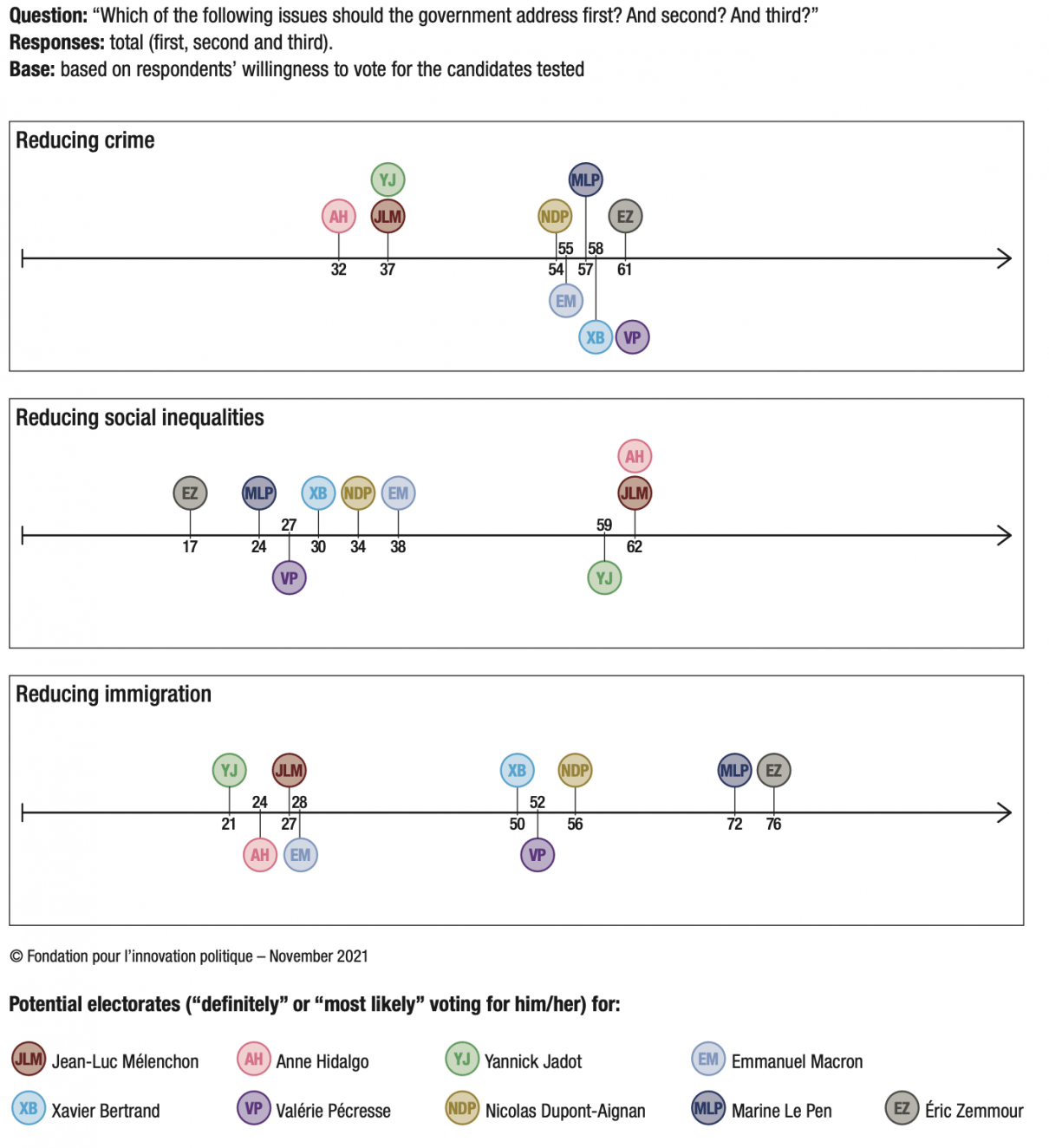

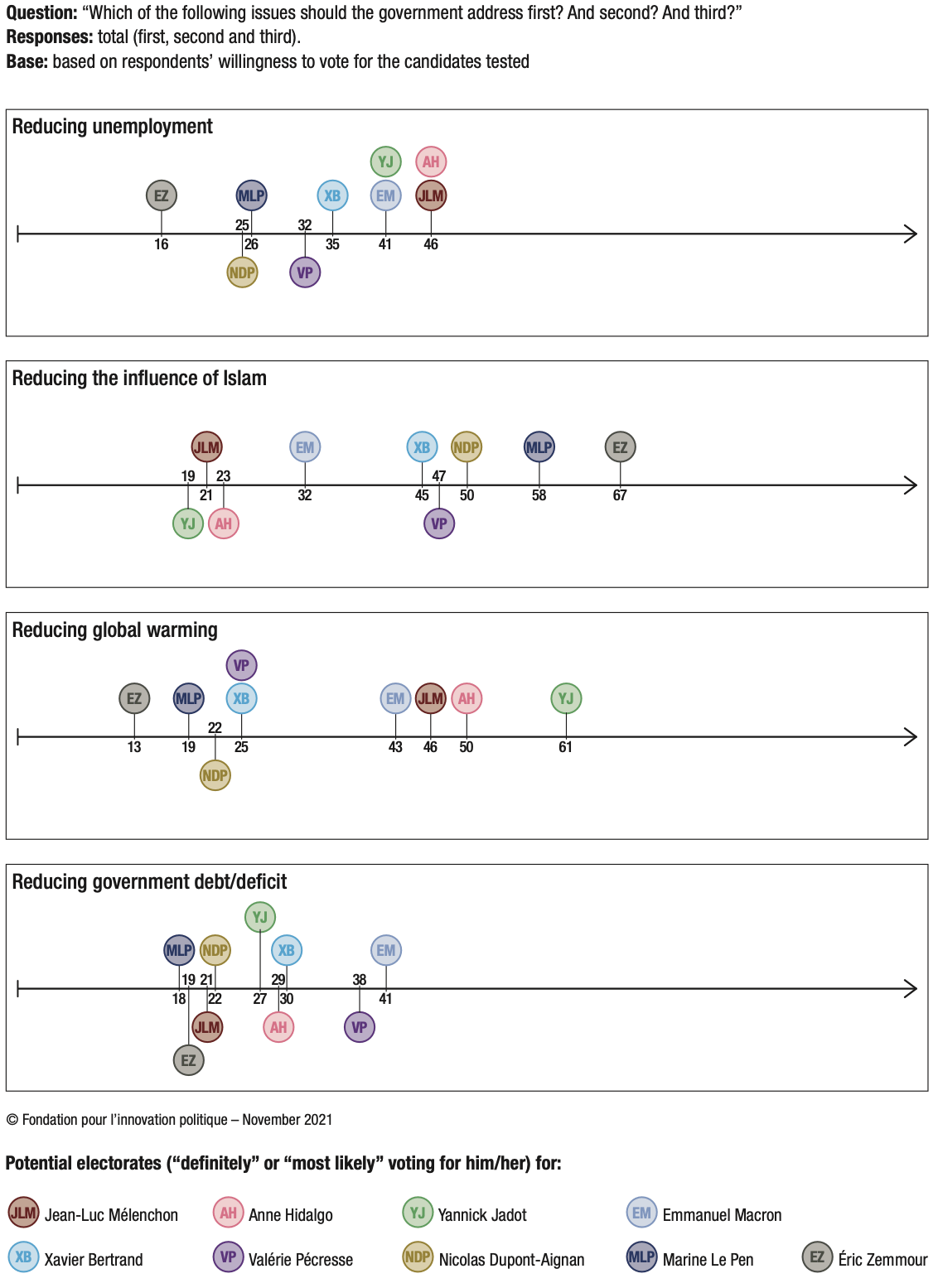

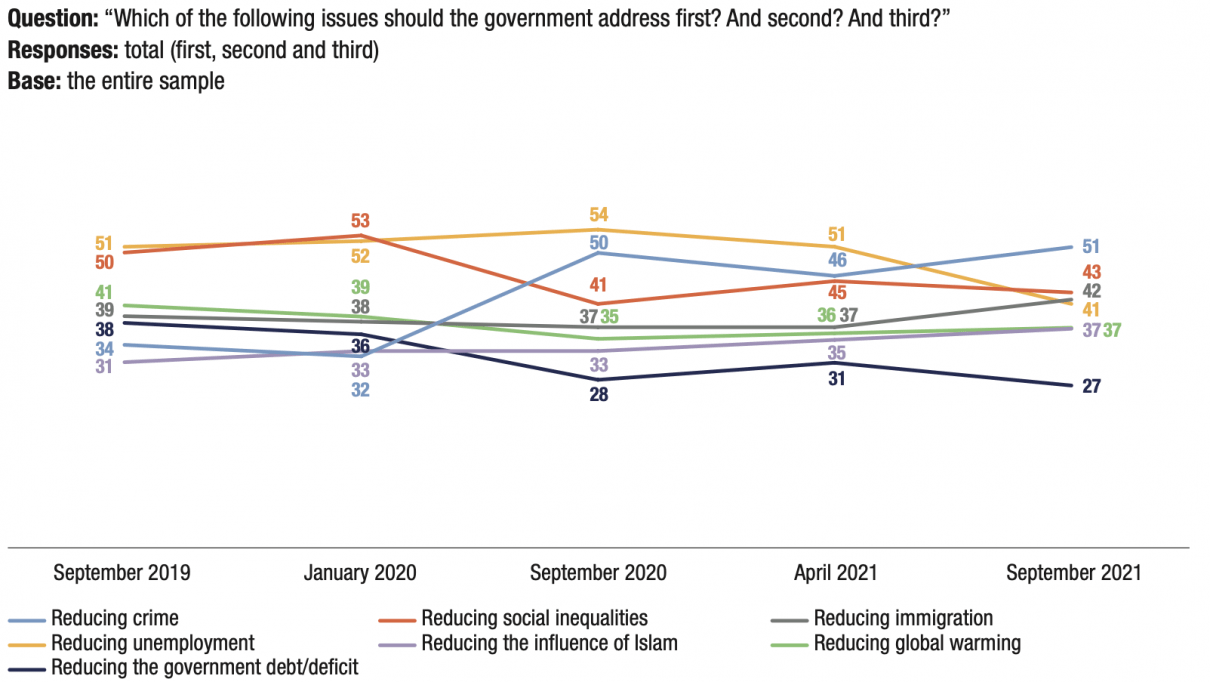

Concerns about crime, immigration and Islam are another way of verifying the predominance of the right in public opinion

Homeowner status is associated with a much more favourable electoral orientation towards right-wing candidates and Macron

Appendices

Definitions

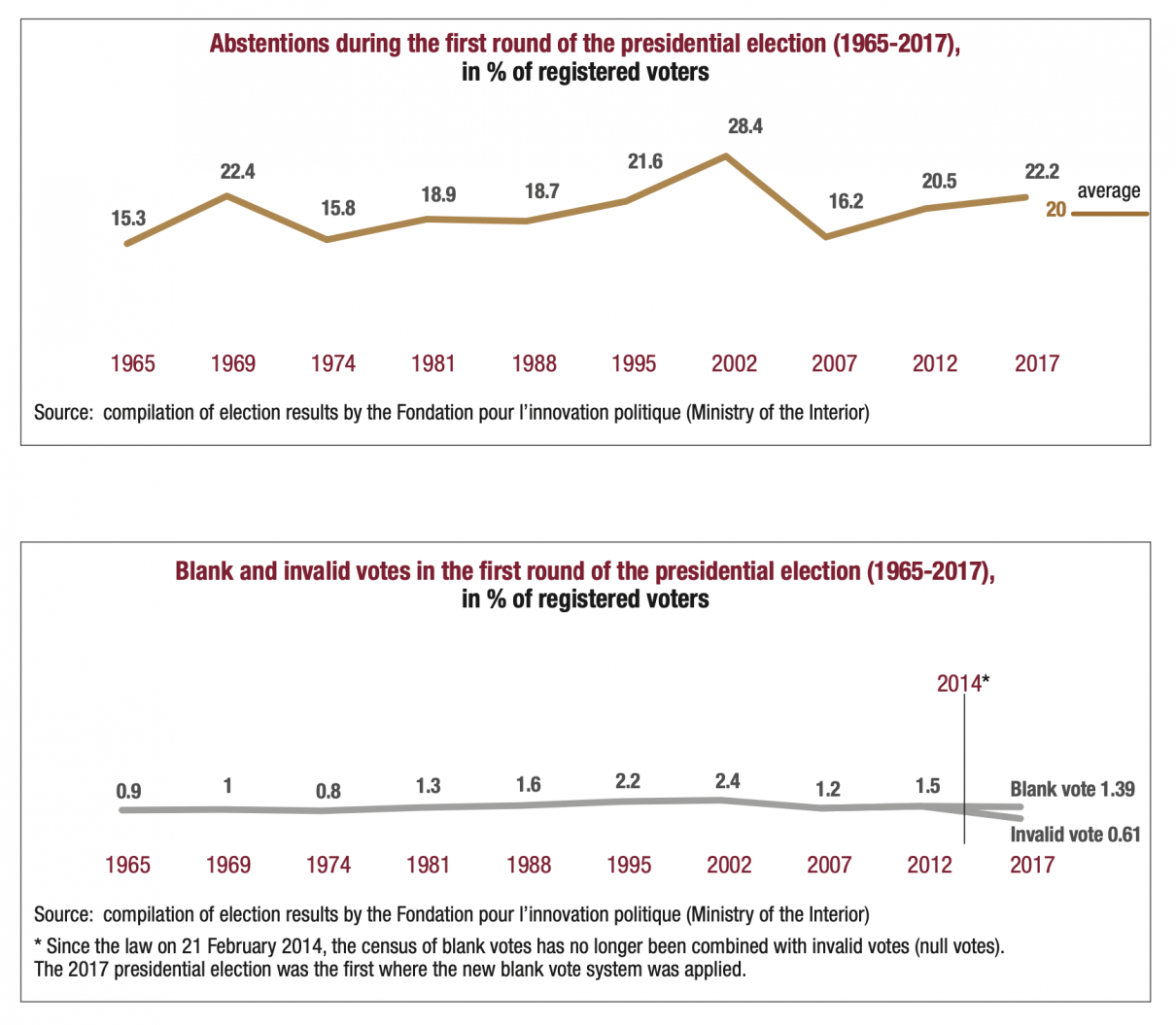

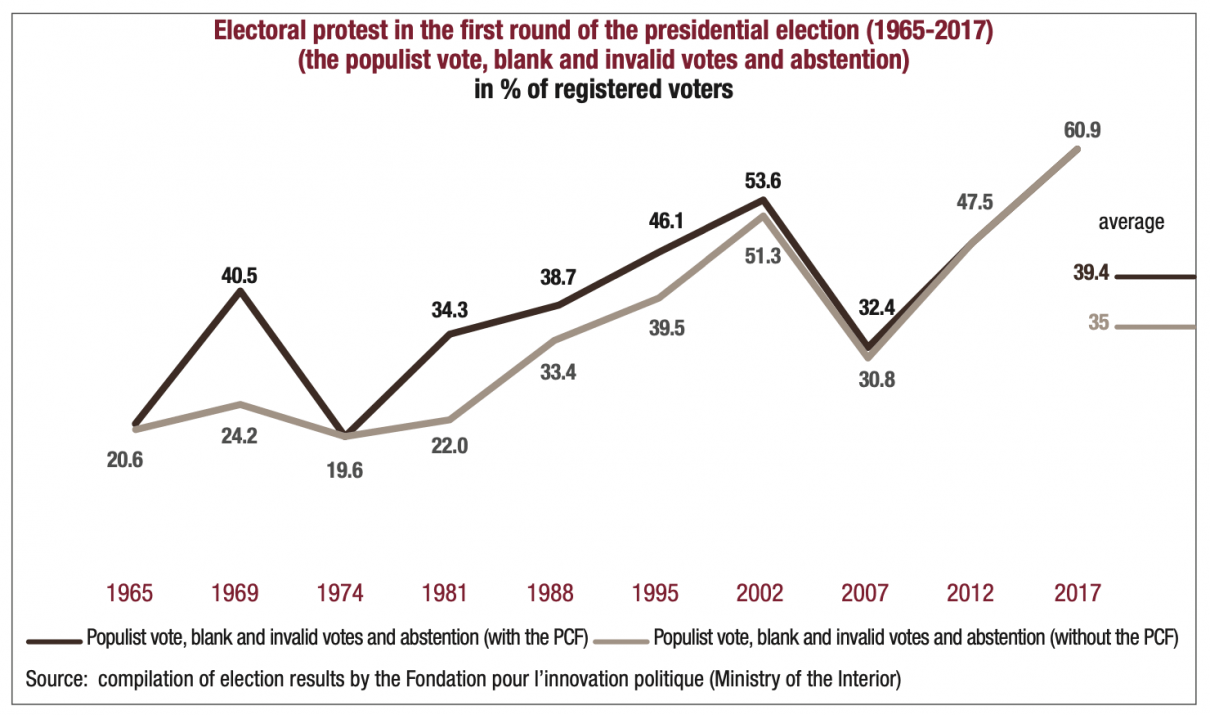

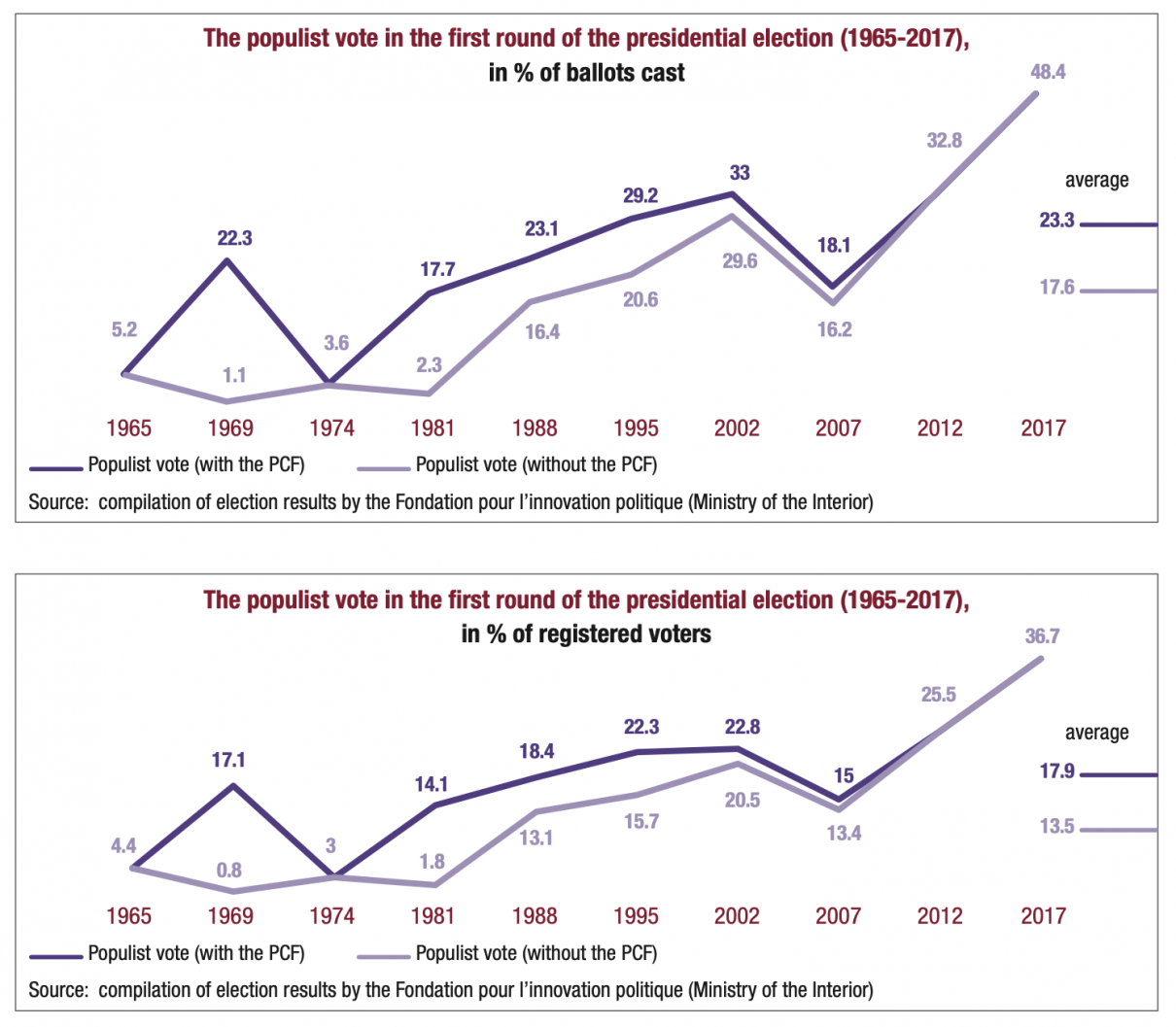

Electoral protest has come a long way. A look back at presidential elections since 1965

Summary

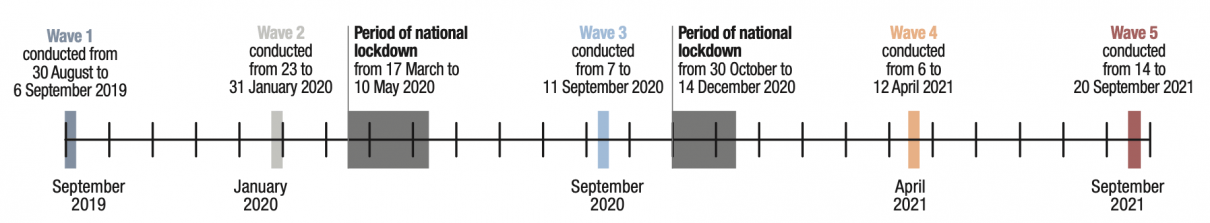

A few months before the first round of the presidential election, here are the results of wave 5 of our electoral protest indicator, launched in September 2019 in anticipation of the 2022 presidential election. Wave 4 was conducted from from 14 to 20 September 2021.

This Electoral Protest Indicator was developed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The survey was conducted by the polling institute OpinionWay. For each wave, the questionnaire is administered to a sample of more than 3,000 registered voters.

The results of wave 1 were published in October 2019, those of waves 2 and 3 were combined in a joint publication due to lockdown restrictions (October 2020) and those of wave 4 were published in June 2021.

All survey results are available in open-access on our website fondapol.org, as are the data, on data.fondapol.org.

Fondation pour l'innovation politique,

A French think tank for European integration and the free economy.

Dominique Reynié (dir.),

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

What next for democracy?

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

2019 European Elections. The weight of the political electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups

The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values

The key findings from Wave 5 of the electoral protest indicator

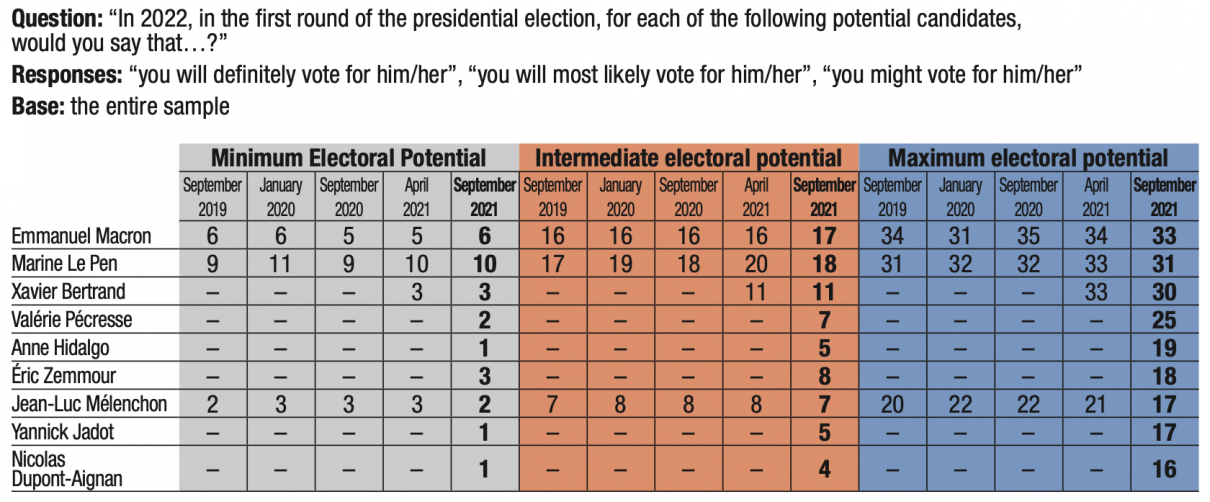

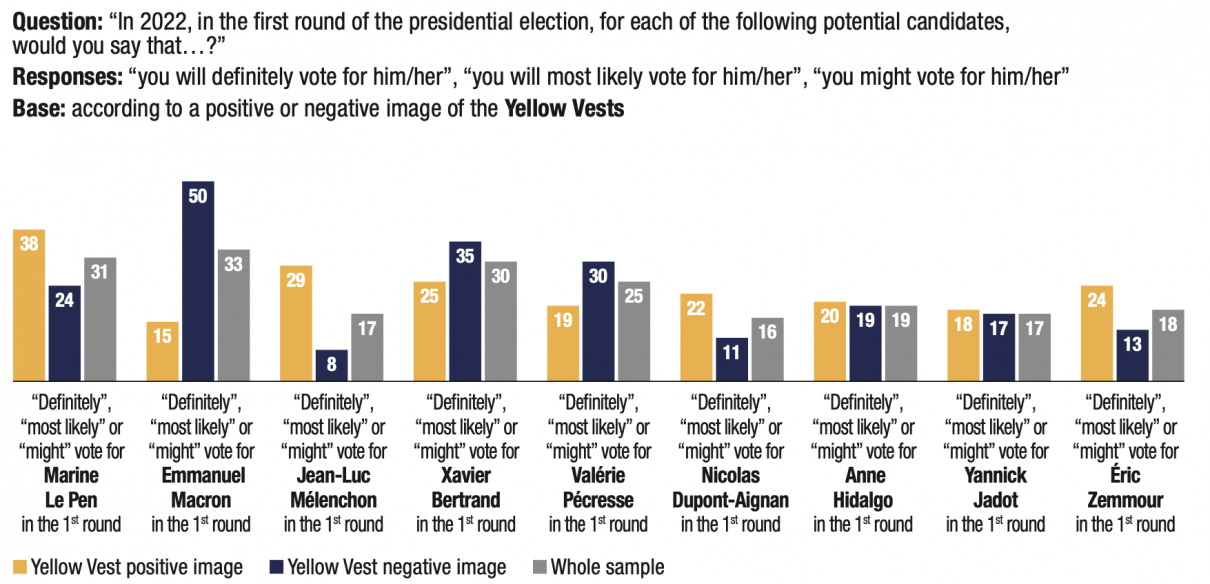

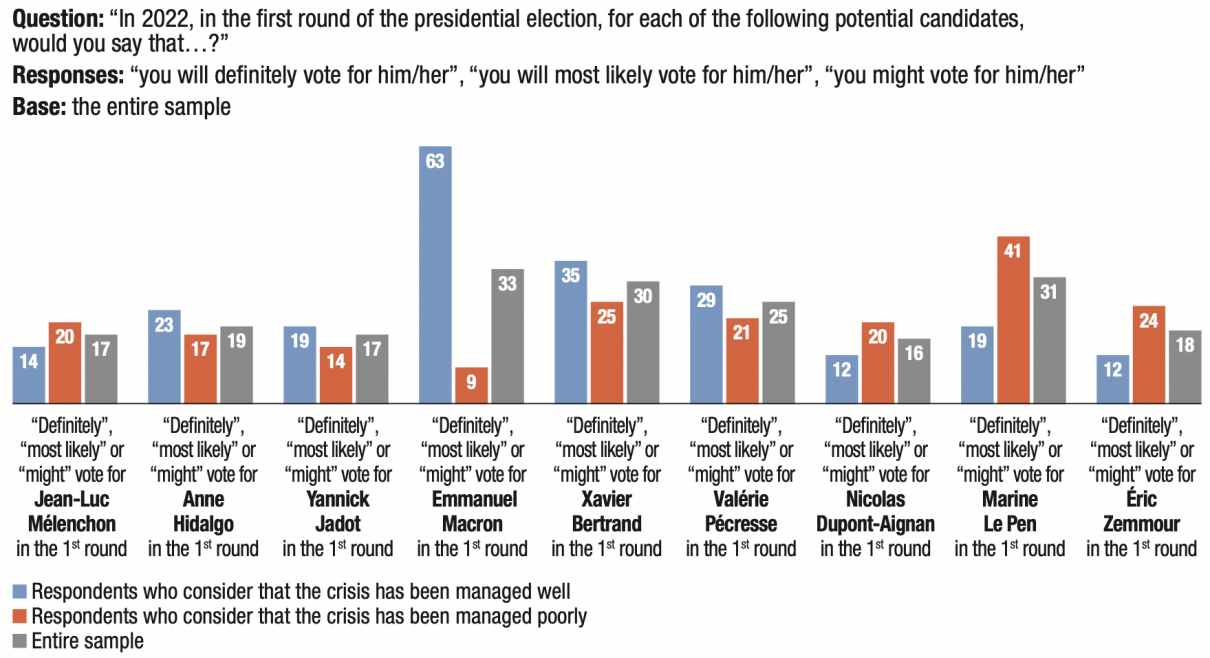

1. With six months to go until the first round of the presidential election, Emmanuel Macron is in a strong position. Marine Le Pen’s minimum electoral potential (10%) and, to a lesser extent, that of Emmanuel Macron (6%) are still the highest relative to the other candidates. The same applies to intermediate electoral potential, with 18% for the RN candidate and 17% for the incumbent president, compared to 11% for Xavier Bertrand, 8% for Éric Zemmour, and 7% for Valérie Pécresse and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. On the other hand, maximum electoral potential suggests a rebalancing of the balance of power between Emmanuel Macron (33%), Marine Le Pen (31%), Xavier Bertrand (30%) and Valérie Pécresse (25%), far ahead of Anne Hidalgo (19%), Éric Zemmour (18%), Jean-Luc Mélenchon (17%), Yannick Jadot (17%) and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (16%). But this “maximum” electoral potential is by nature more uncertain.

2. Only 12% of respondents believe that the presidential election will “bring the French closer together”, compared to 41% who believe that it will “divide the French more” and nearly half (46%) who answered “neither”.

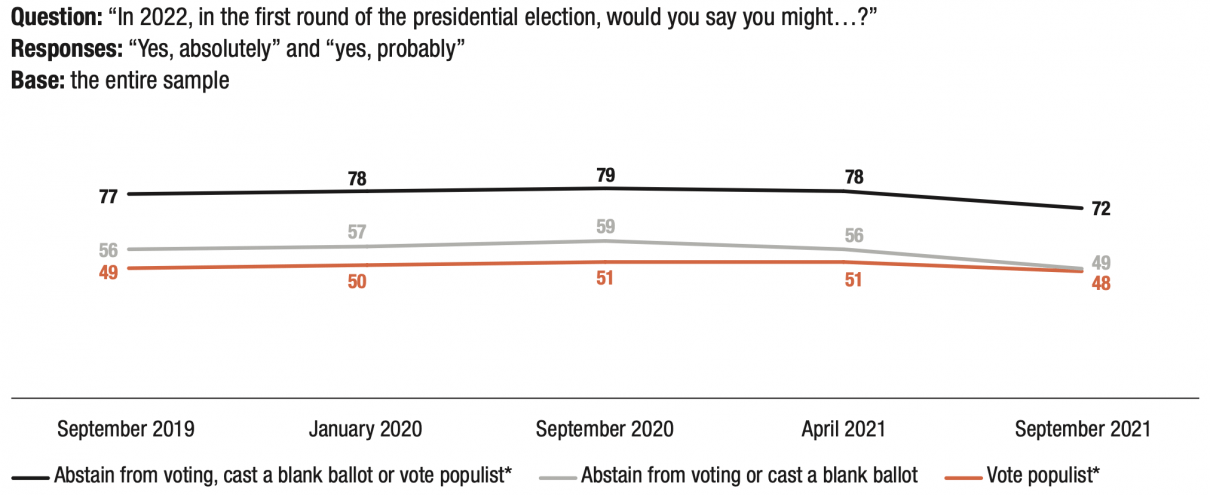

3. Preparedness to engage in electoral protest behaviour during the first round of the presidential election remains massive: 72% of respondents still plan to either vote for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/ NPA, abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. However, this figure is down by 6 points compared to the previous wave (April 2021).

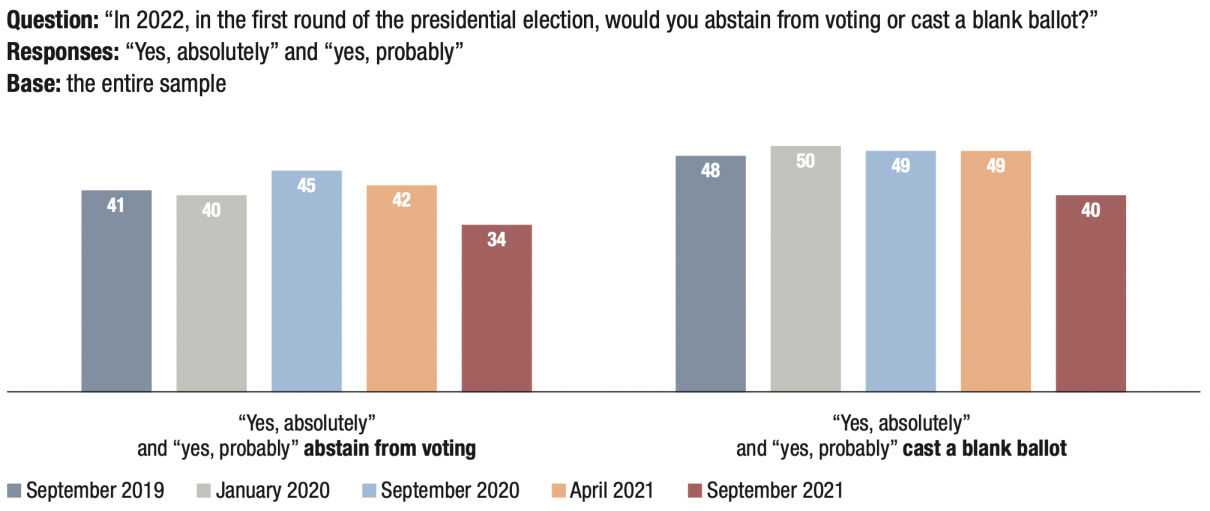

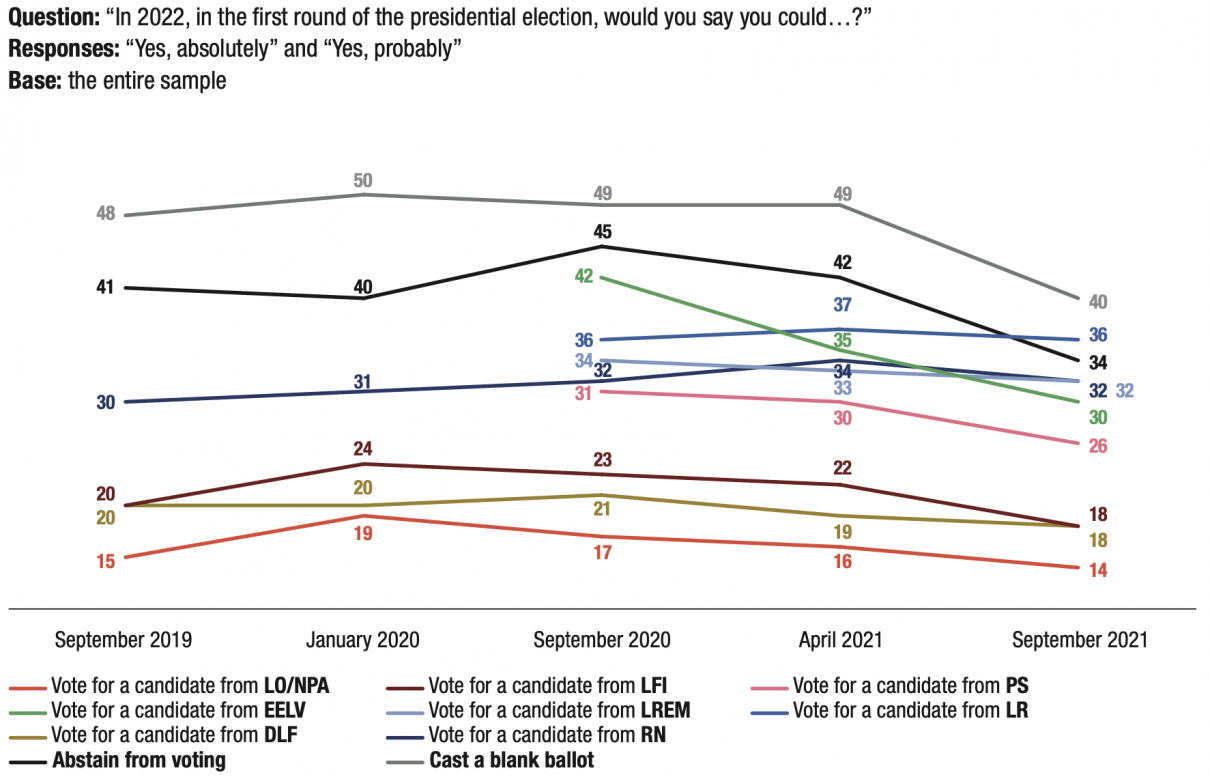

4. This development arises from the decline in abstention from voting and blank voting. For the first round of the presidential election, a third of the French (34%) say they might abstain from voting, compared with 42% in April 2021, and 40% that they might issue a blank vote, compared with 49% in April 2021. The results of wave 5 indicate that this contribution of participation is distributed between the different parties and does not currently benefit any one in particular.

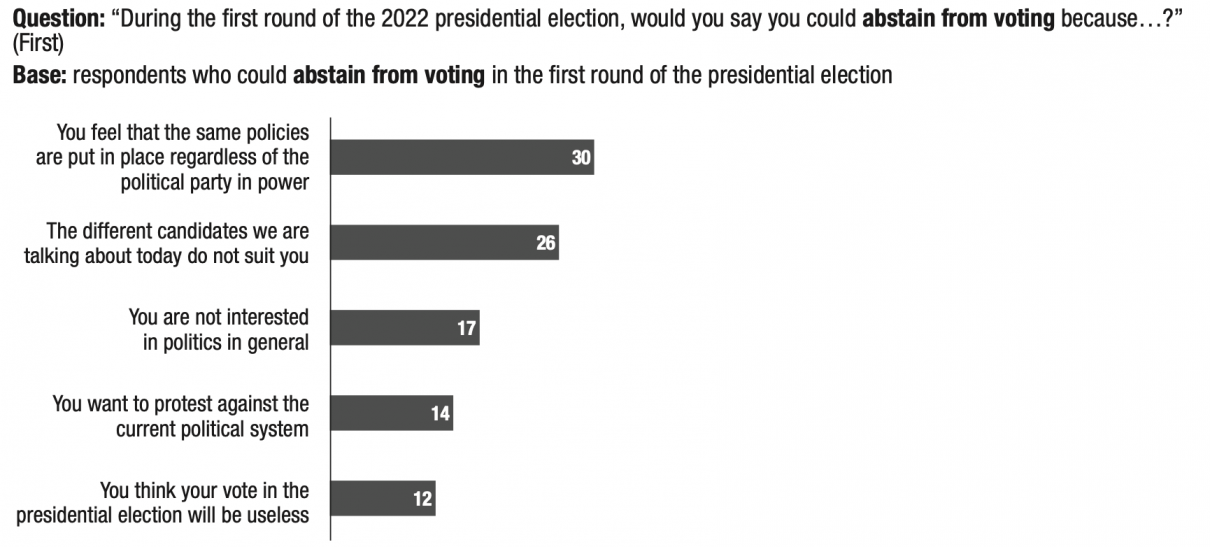

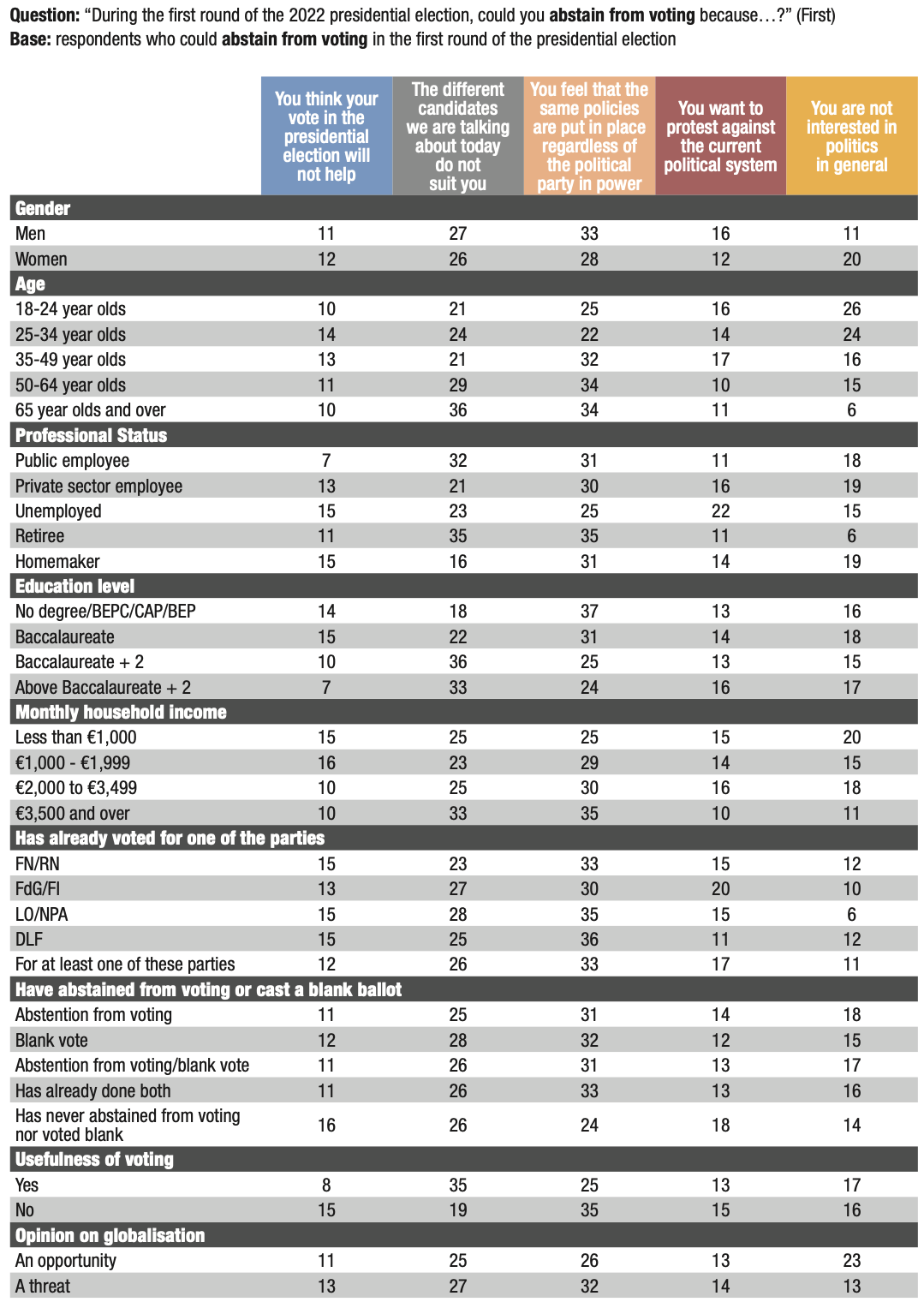

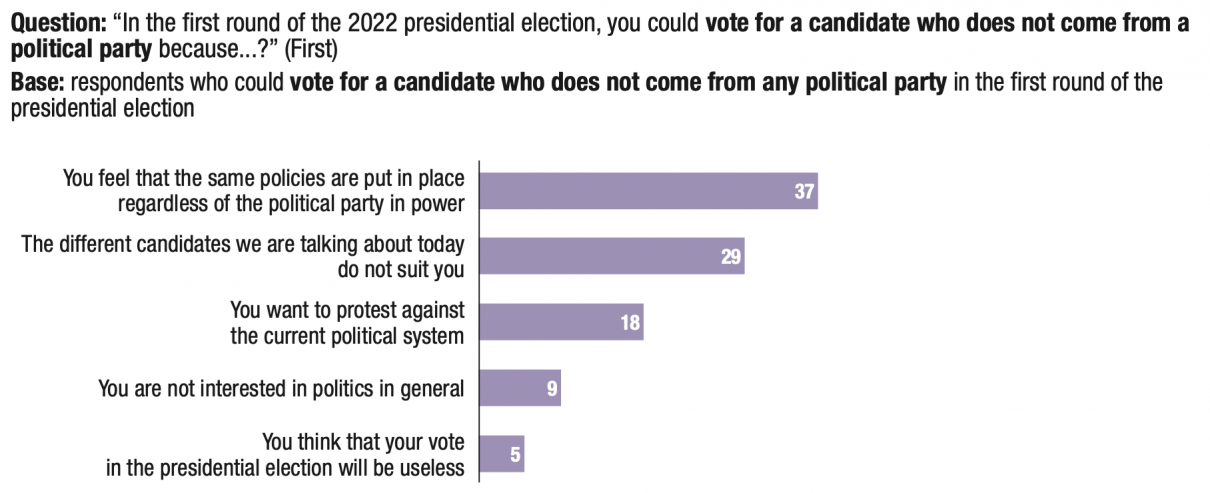

5. The willingness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot comes from various causes. In this wave 5, we assess the motivations of the individuals likely to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the presidential election. The main reasons chosen by the interviewees show that abstention from voting and blank voting result less from disinterest than from a form of protest: 30% say they want to abstain from voting because they “feel that the same policies are put in place regardless of the political party in power”, 26% because “the different candidates we are talking about today do not suit [them]”, 17% because “politics in general do not interest them”, 14% because they want to “protest against the current political system” and 12% because they think that their “voting in the presidential election will be useless”.

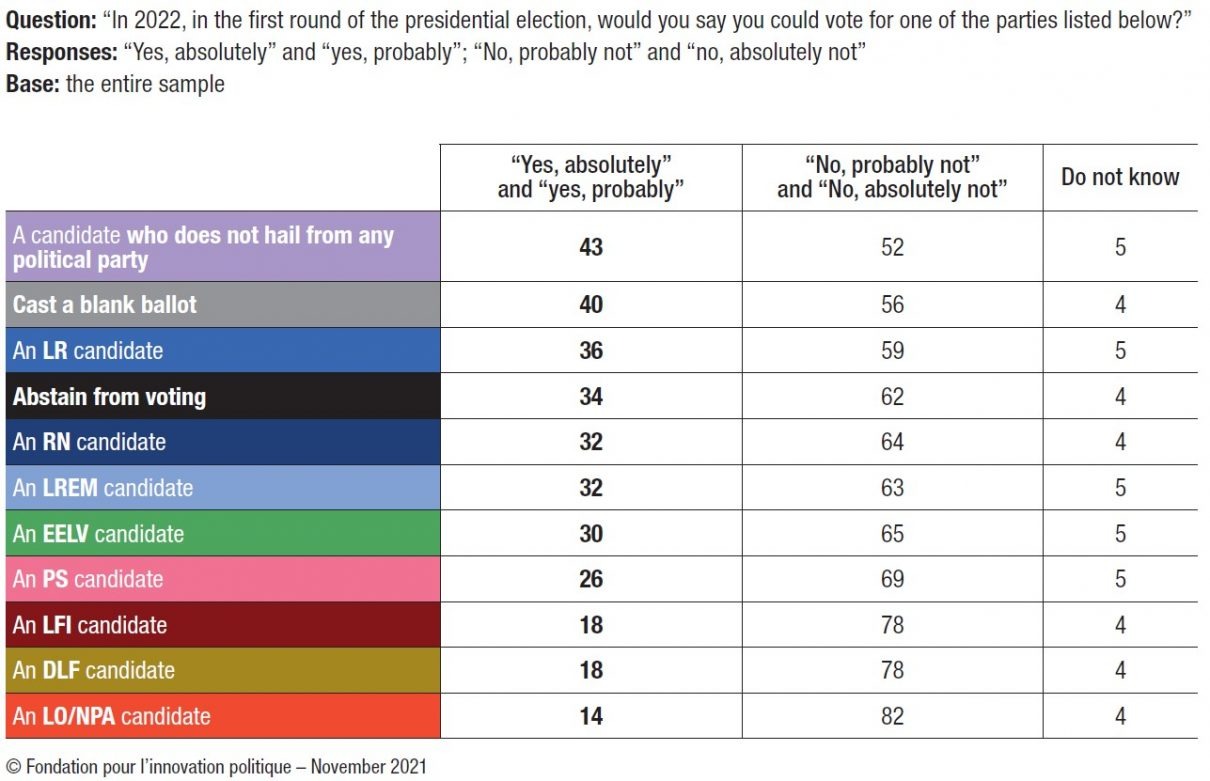

6. Among the parties sampled, willingness to vote LR is the highest (36%), while LREM (32%) fell by 2 points in one year (34% in September 2020). From a high level, however, preparedness to vote for the RN in the first round of the presidential election is eroding for the first time, from 34% in April 2021 to 32% in September 2021. On the left, the results are particularly poor. Support for LFI fell from 24% in January 2020 to 18% in September 2021, the lowest level since 2019. The same is true for LO/NPA, falling from 19% to 14% over the same period. The PS achieved its lowest result (26%), and EELV lost 12 points in one year, from 42% in September 2020 to 30% in September 2021.

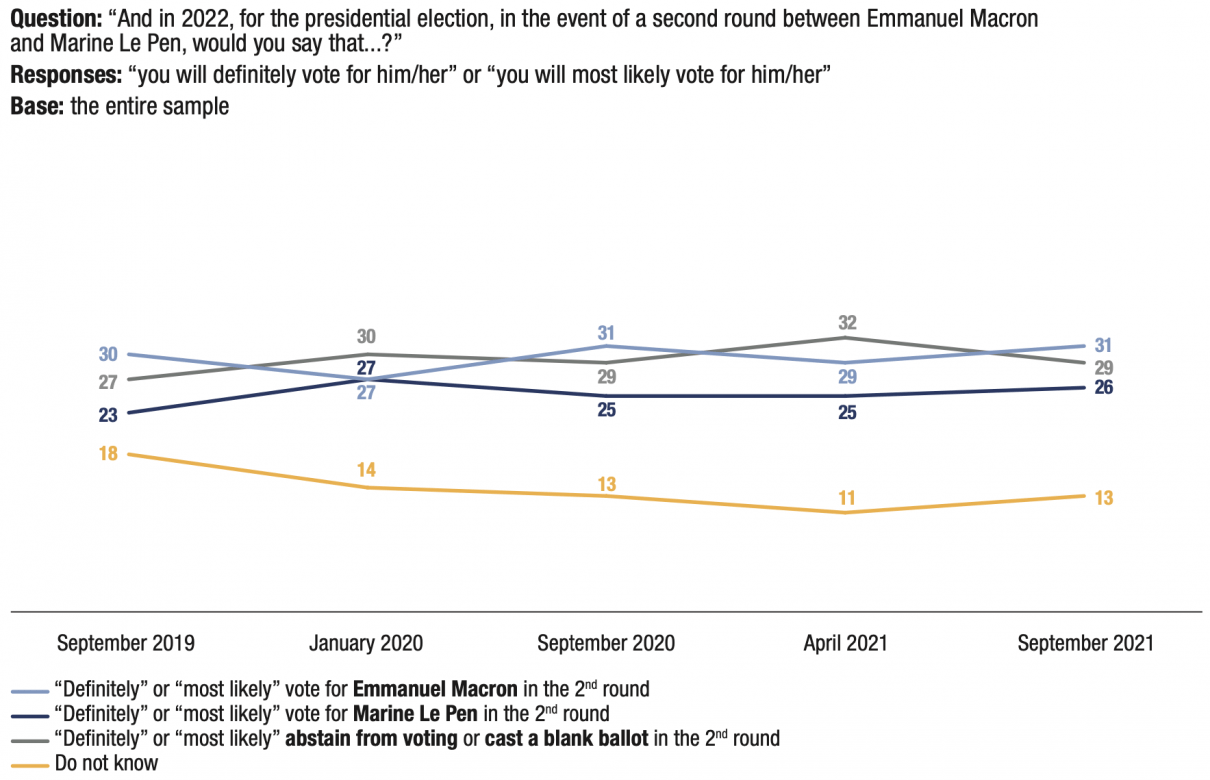

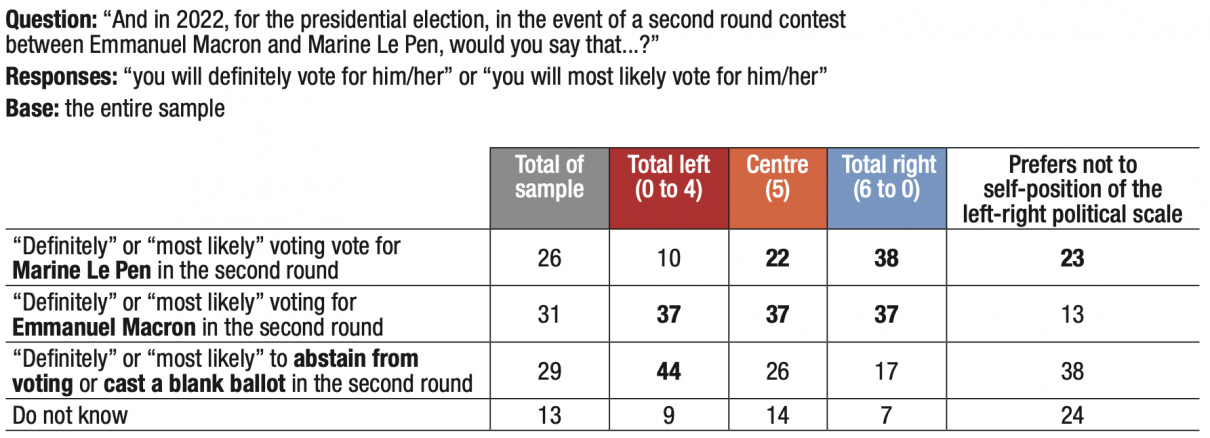

7. In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the share of people indicating that they will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for the RN candidate amounts to 26%, the second highest result after that of wave 2 (27% in January 2020). At the same time, the share of respondents who are “definitely” or “most likely” to vote for the incumbent president is at 31%, its highest result, on par with that of wave 3 in September 2020 (31%). The proportion of those who could abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot fell by three points, from 32% in April 2021 to 29% in September 2021.

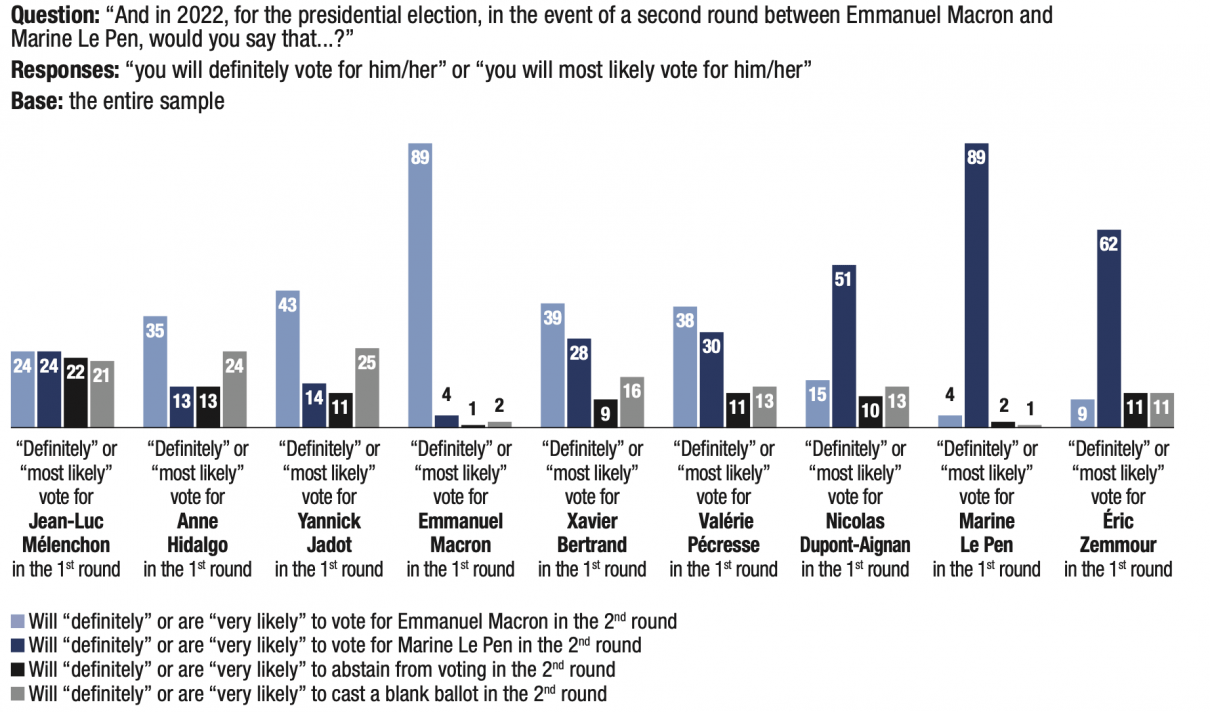

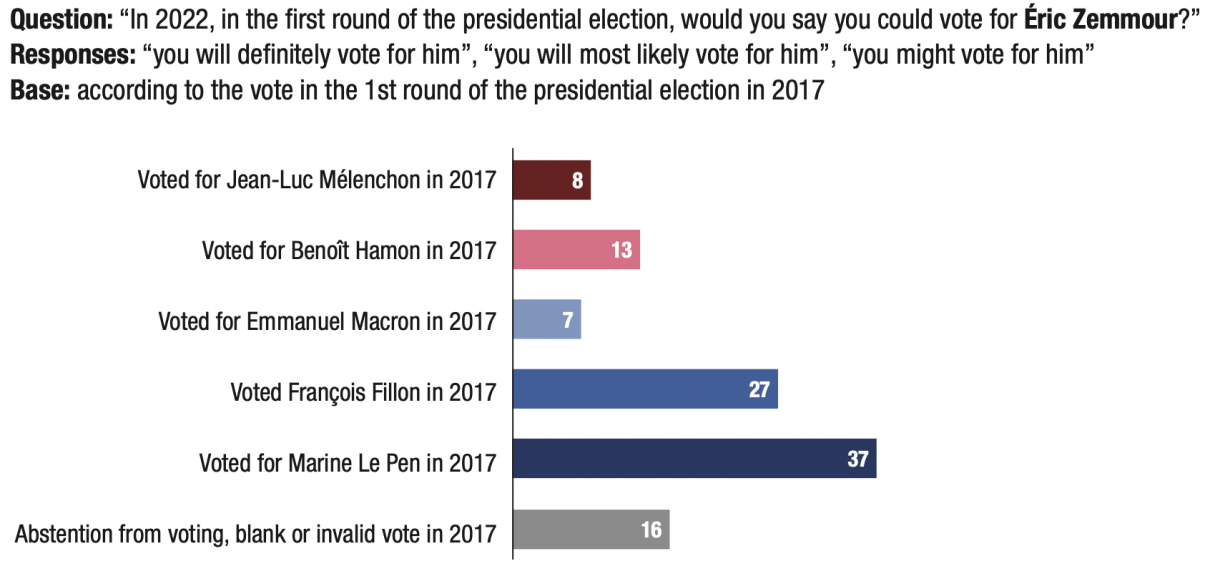

8. In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, 62% of voters who might vote for Éric Zemmour in the first round and 51% of those who might vote for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan express a preference for Marine Le Pen, while nearly a quarter of the voters of Éric Zemmour (22%) and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (23%) would abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. 9% of Éric Zemmour’s voters in the first round and 15% of Nicolas Dupont- Aignan’s voters would vote for Emmanuel Macron in the second round.

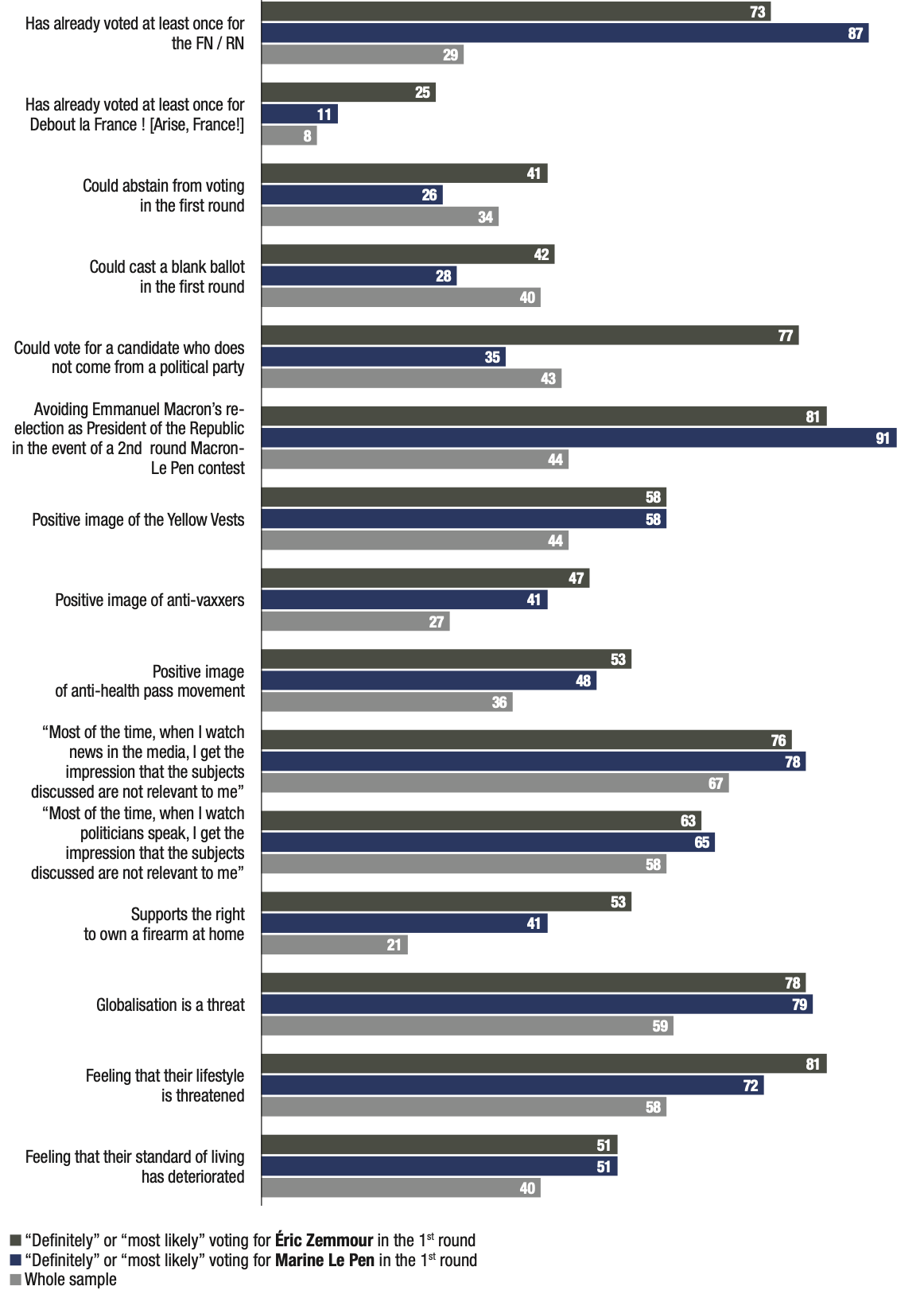

9. In the event of a Macron-Le Pen second round, the proportion of respondents who say they want to “avoid the election of Marine Le Pen” went from 53% in September 2020, then to 51% in April 2021, reaching 48% in September 2021. A large proportion (44%) said they wanted to “avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re-election”, i.e. 3 points more than in April 2021 and 4 points more than in September 2020.

10. 43% of respondents said they might “vote for a candidate who does not hail from any political party”.

11. Those who say they are “certain” or “very likely” to vote for Éric Zemmour in the first round of the presidential election are the highest proportion (77%) of voters expressing a preference for a candidate who does not come from a political party. A smaller but still significant proportion of respondents said they might vote for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (65%), Yannick Jadot (58%), Valérie Pécresse (51%), Xavier Bertrand (48%) and Anne Hidalgo (48%). This expectation is less widespread among the voters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon (43%), Emmanuel Macron (39%), who nevertheless embodies this profile, and Marine Le Pen (35%).

12. Preparedness to vote for a candidate who comes from civil society is one of the expressions of electoral protest. Voters who say they might vote for a candidate outside of any party explain this in terms of “feeling that the same policies are put in place regardless of the political party in power” (37%), by the fact that “the different candidates we are talking about today do not [suit them]” (29%), because they want to “protest against the current political system” (18%), because “politics in general do not interest [them]” (9%) and because they believe that their “voting in the presidential election will be useless” (5%).

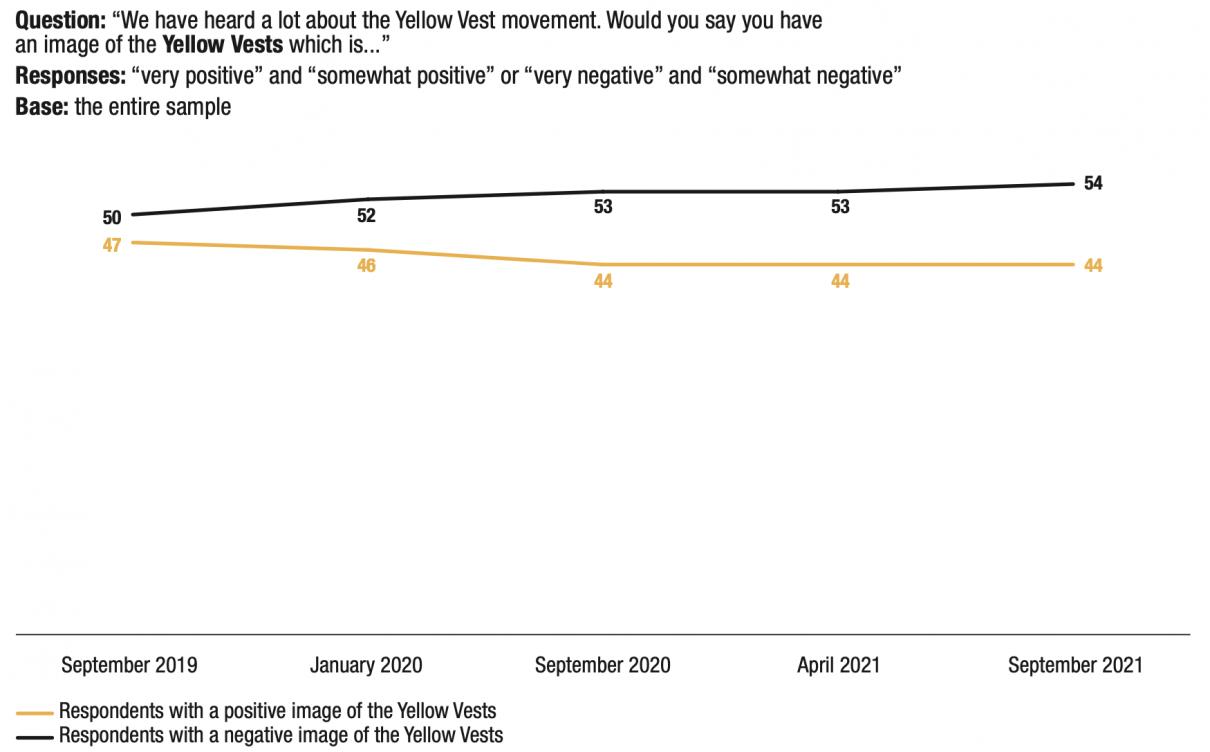

13. Sympathy for the Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and the anti-health pass movement is associated with a higher than average potential for electoral protest behaviour. In the first round, 84% of respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests said that they might opt for at least one of the protest behaviours (vote for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot), compared with an average of 72%. This figure rises to 89% for people who have a positive image of anti-vaxxers or the anti-health pass movement.

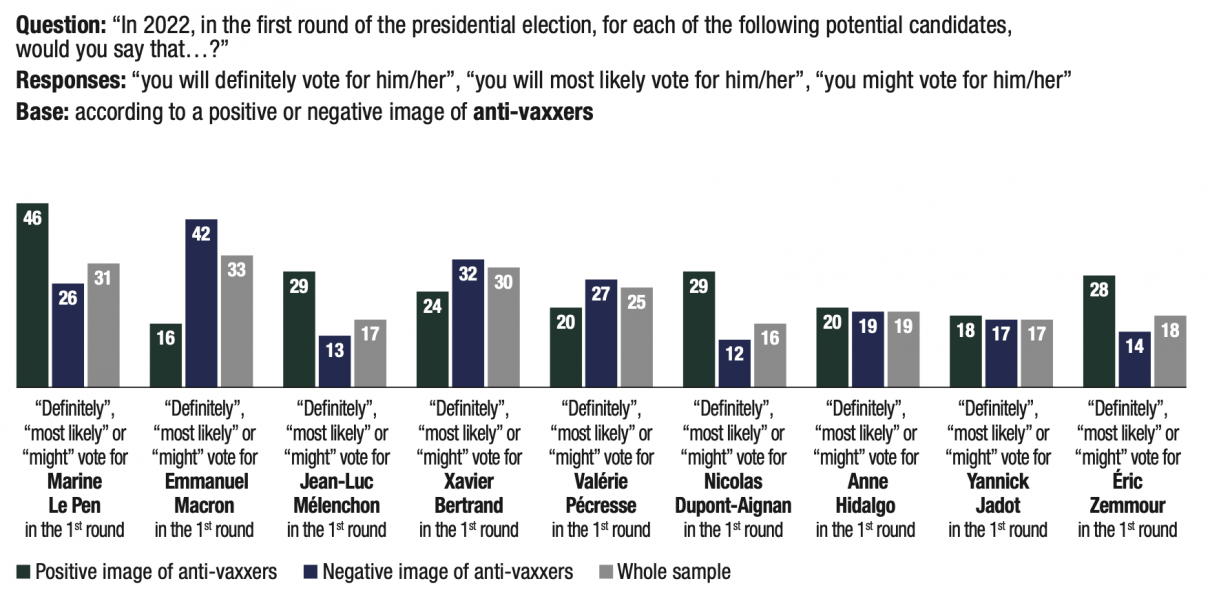

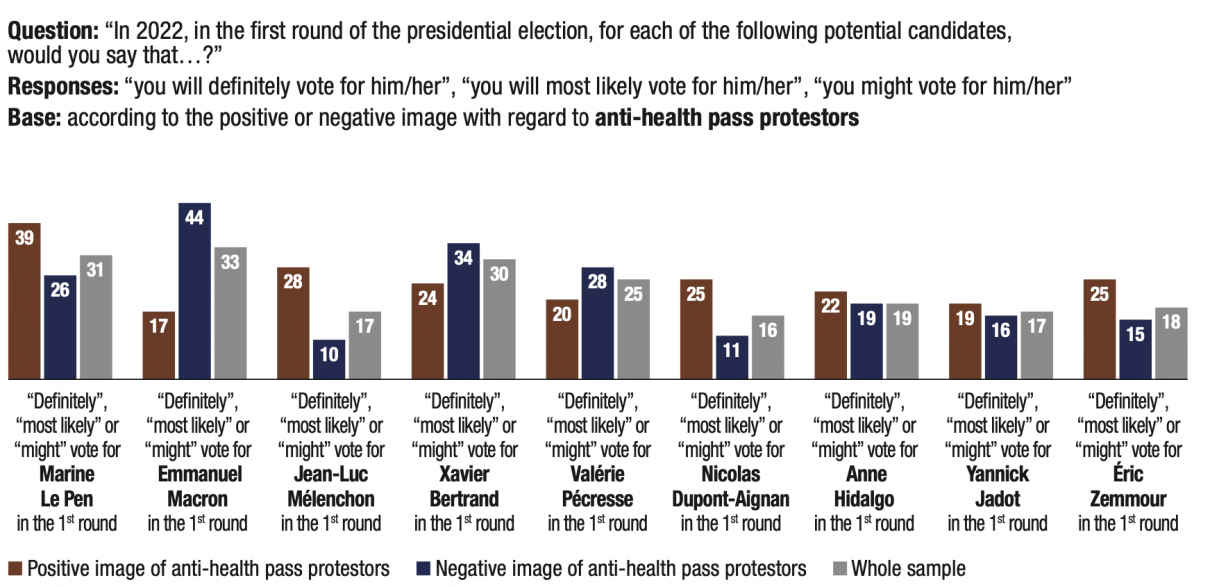

14. Respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers or the anti-health pass movement indicate a preference for protest candidates: 23% of those who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests, 28% of those who have a positive image of anti-vaxxers and 24% of those who have a positive image of the anti-health pass movement indicate that they are “definitely” or “most likely” going to vote for Marine Le Pen (compared with 18% on average). 13%, 12% and 12% respectively for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (versus 7%); 11%, 13% and 12% respectively for Éric Zemmour (versus 8%); and 7%, 10% and 9% respectively for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (versus 4%). In contrast, only 6% of those with a positive image of the Yellow Vests, 7% of those with a positive image of anti-vaxxers and 8% of those with a positive image of the anti-health pass movement say they are “certain” or “very likely” to vote for Emmanuel Macron, compared to 17% on average.

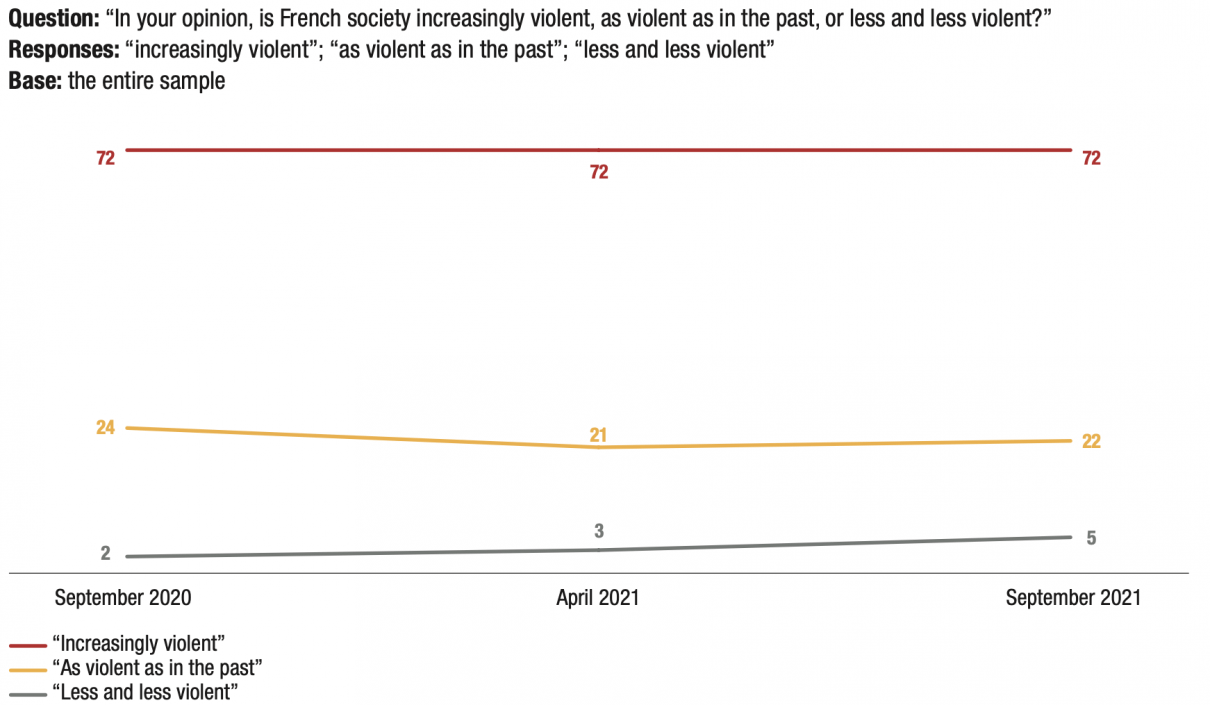

15. Three-quarters of respondents (72%) believe that “society is increasingly violent”, i.e. a figure identical to that of our previous waves (September 2020 and April 2021). Within political families, while this opinion is more widespread the further to the right one is, it is still in the majority on the left: 87% for RN supporters, 78% for LR, 68% for LREM, 64% for PS and EELV, 59% for PCF/LFI.

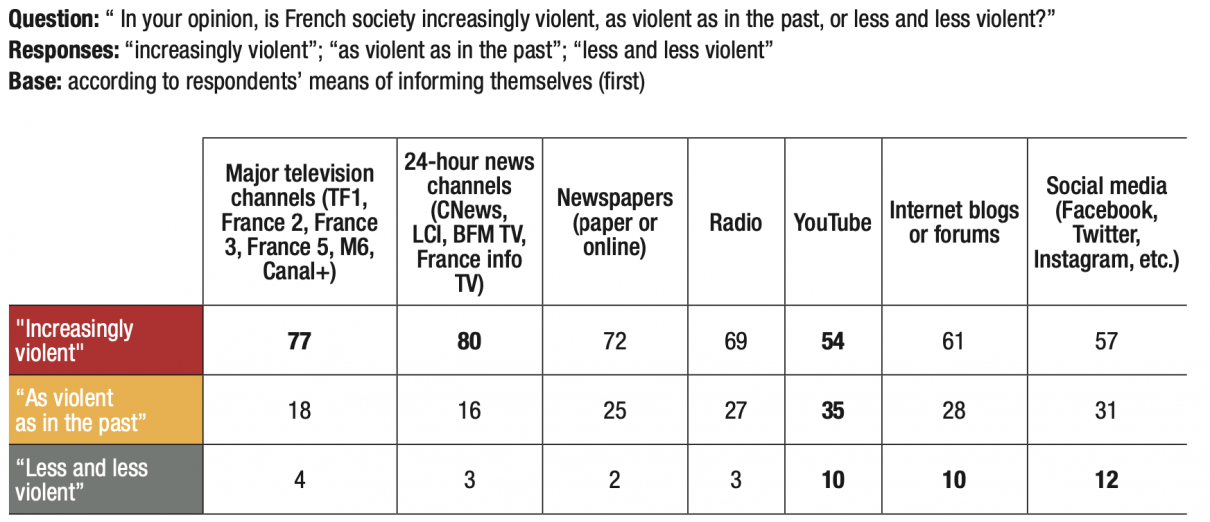

16. The idea of the right to own a firearm is much more widespread among 18-24 year olds (34%), including high school and university students (32%), than in the sample average (21%).

17. There is a link between spending time on social media and wanting the right to own a weapon at home. Of those surveyed who use Telegram daily, more than half (57%) support the right to own a gun at home. The same applies to those who use TikTok daily (42% wish to have the right to own a weapon), Twitch (44%), Twitter (29%) and Instagram (26%), and for those who inform themselves via blogs/forums (47%) and YouTube (41%). In contrast, for daily users of Facebook (22%) and WhatsApp (21%), the figures are similar to the sample average (21%).

18. Nearly three-quarters of French people (72%) do not trust the media. Similarly, the majority of respondents (58%) believe that “most of the time, when they watch news in the media, they get the impression that the subjects discussed are not relevant to them.”, i.e. an improvement of 3 points (61%) compared to wave 4 (April 2021).

19. Of the people who use Telegram daily, 50% use these “new sources of media” as their primary source of information (YouTube, blogs, forums or social media), compared with an average of 14%. Results are also very high for respondents who log into TikTok (46%) or Twitch (38%) daily and, to a lesser extent, Twitter (31%) or Instagram (28%). Daily users of WhatsApp (15%) and Facebook (18%) are the least likely to use new forms of media as their primary source of information.

20. The potential for electoral protest is affected by the regular use of social media. Stated willingness either to vote RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, or to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the presidential election is greater among those who use these new forms of media daily, especially Twitch, TikTok and Telegram. WhatsApp is the exception, with results below the average of the whole sample. Most daily social media users say they want to block the re-election of the incumbent president in the event of a Macron-Le Pen second round, while this response is chosen by 44% of the respondents of the entire sample. The figures are significantly higher among users of Twitch (69%) and Telegram (69%); this is still the case among users of TikTok (62%), Twitter (49%) and Facebook (48%). This is followed by average levels among Instagram users (45%) and a below average result among daily WhatsApp users (38%).

21. In September 2021, 45% of respondents believe that the government has managed the health crisis well, compared with 53% who believe otherwise. This discontent has nevertheless sharply decreased compared to April 2021, when only 29% of respondents believed that the crisis was managed well, compared to 68% who thought the opposite. The evolution of satisfaction with the management of the health crisis will undoubtedly weigh on the electoral decision. Using the Macron-Le Pen duel hypothesis, we can see that 70% of those who believe that the government has managed the crisis well want “to avoid the election of Marine Le Pen as President of France” (compared to the average of 48%). Conversely, 61% of those who believe that the government has mismanaged the health crisis say that above all they want to avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re- election.

22. However, while perceptions of the management of the health crisis and of Emmanuel Macron’s actions as President of the Republic have improved, 44% of French people continue to want to avoid the latter’s re-election in the event of a second round with Marine LePen.

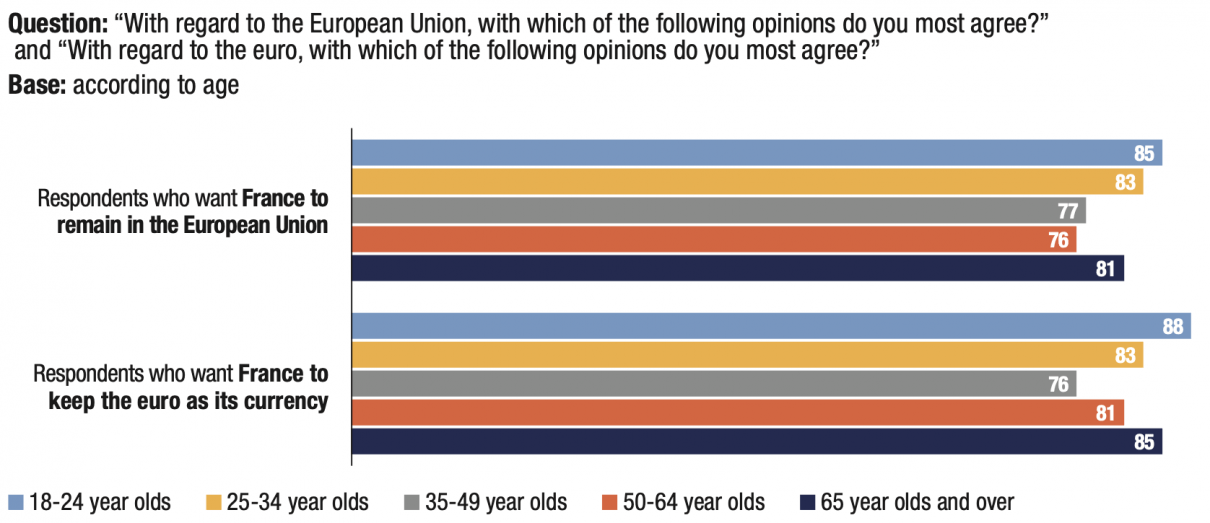

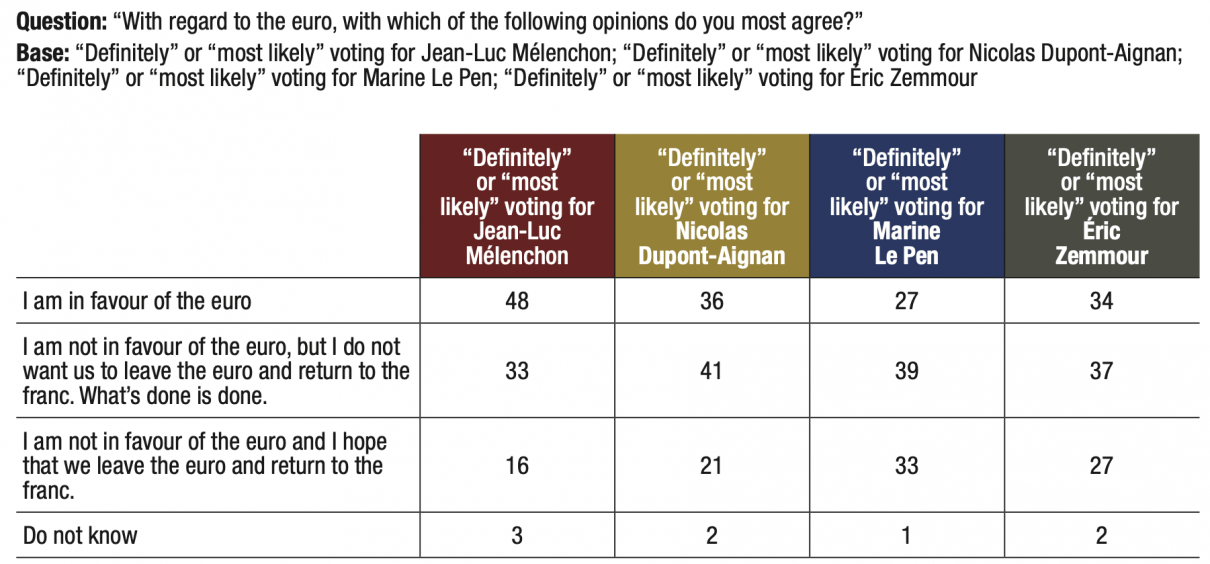

23. Since the first issue of our indicator, the French’s attachment to Europe and the euro has been constant. Wave 5 is no exception: more than three-quarters (79%) of respondents want France to remain in the European Union. A minority, stable at 18%, compared with 17% in April 2021, says they want France to leave the European Union. Similarly, most (82%) want to keep the euro, while only 16% of respondents want a return to the franc. Despite the controversies over the European Union caused by the initial management of the health crisis, European sentiment has not been altered. It remains the major obstacle for populists: 58% of respondents who might vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round in 2022 want France to remain in the European Union. The same applies to 55% of voters who might vote for Éric Zemmour and 85% of those who could vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

24. French society is clearly right-wing. The preponderance of the right can be observed by looking at their positioning on the left-right political scale. More than a third of voters are on the right (37%), a fifth (20%) on the left and 18% in the centre, while a quarter (23%) of respondents say they do not want to identify themselves on this scale.

25. The predominance of the right can be seen in the assessment of electoral potential. Based on data from the fifth wave of our indicator, 56% of voters surveyed might vote for at least one of the right-wing candidates tested (Xavier Bertrand, Nicolas Dupont- Aignan, Marine Le Pen or Éric Zemmour), while 34% of voters surveyed might vote for at least one of the left-wing candidates mentioned in the survey (Anne Hidalgo, Yannick Jadot or Jean-Luc Mélenchon). The electoral potential on the right is even higher if we include some of Emmanuel Macron’s potential voters. Another part of the Macronist electorate is rooted on the left, but its weight is not enough to challenge the dominance of the right.

26. The right has gained such momentum because it dominates the popular strata. After the quantitative defeat of the left comes the sociological defeat. The declared willingness to vote right-wing is major among respondents without a degree or with low qualifications (63%), those belonging to lower socio-professional categories (60%), or those who believe they are struggling to make ends meet at the end of the month (60%) or that their standard of living has deteriorated in recent years (60%).

27. The level of concern about crime, immigration and Islam is another way to measure the dominance of right-wing opinion. The three main concerns have changed markedly compared to our previous measurement (April 2021): “reducing crime” has moved from second to first concern (51%, up 5 points), “reducing social inequalities” has gone from third to second concern (43%, down 2 points), and “reducing immigration” goes from fourth to third concern (42%, up 5 points). The item “reducing unemployment”, the main concern in April 2021 (51%), was downgraded to fourth position (41%, down 10 points). It should be noted that while the concerns “reducing the influence of Islam” and “reducing global warming” are at the same level in September 2021 (37%), the concern for “reducing the influence of Islam” has increased by 6 points since September 2019 (31%), while “reducing global warming” fell by 4 points over the same period (41% in September 2019). Finally, “Reducing government debt/deficit” has increased from 38% to 27% in two years.

28. Two-thirds of respondents (66%) believe that “most immigrants do not share our country’s values and this poses problems for cohabitation”. This opinion is found among respondents both on the left and the right. Indeed, with regards to the 2017 electorates, negative opinions about immigration are shared by the majority of voters for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (51%), Emmanuel Macron (54%), François Fillon (76%) and Marine Le Pen (87%).

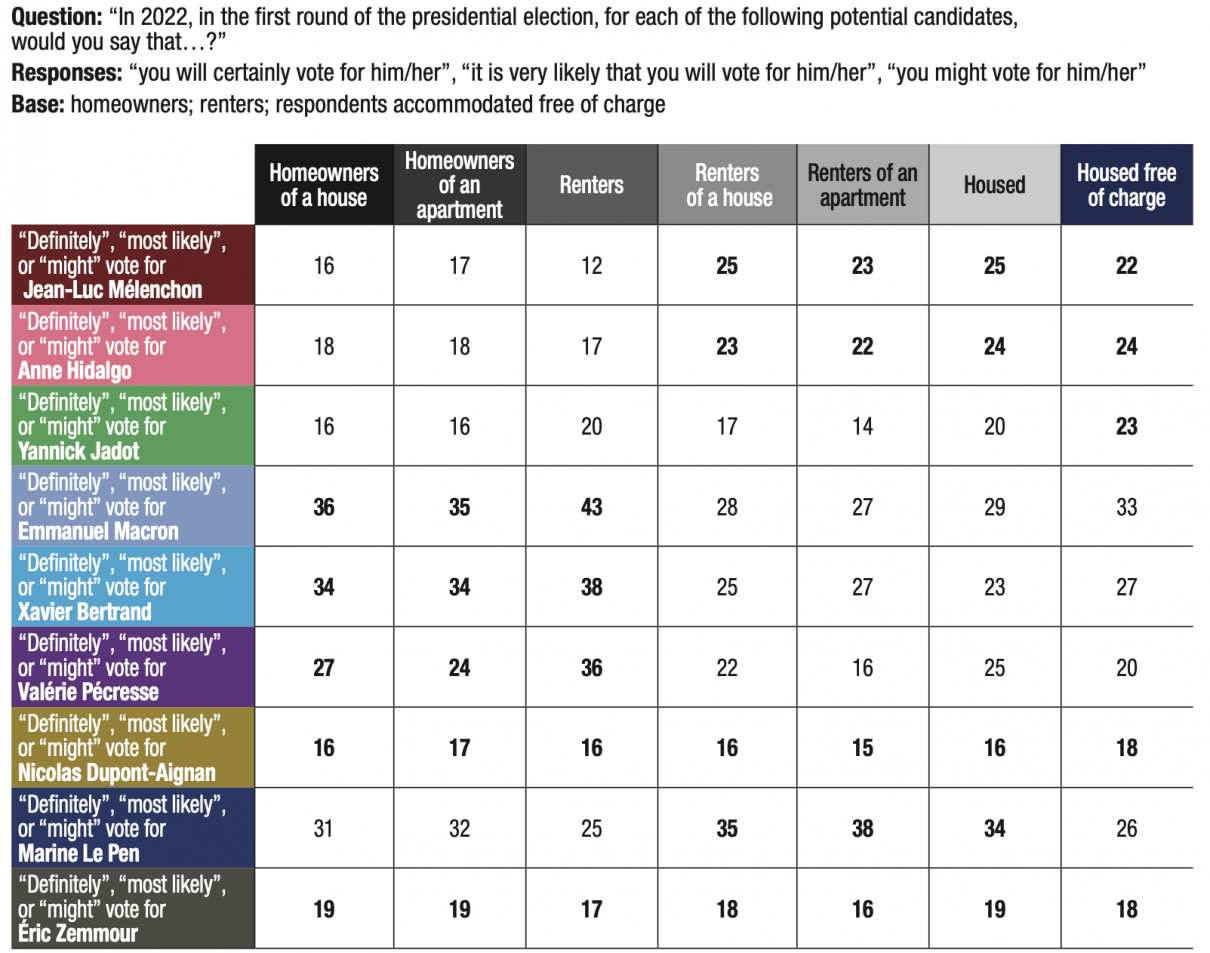

29. Homeowning France is right-wing. This is an additional way of measuring the weight of the right in society. On the other hand, renters are much more favourable to Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

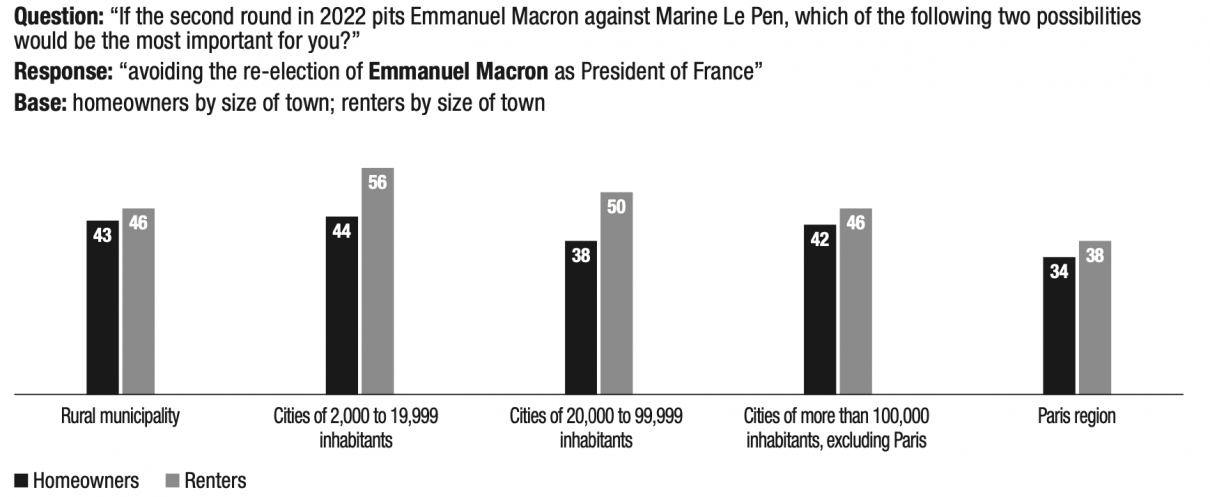

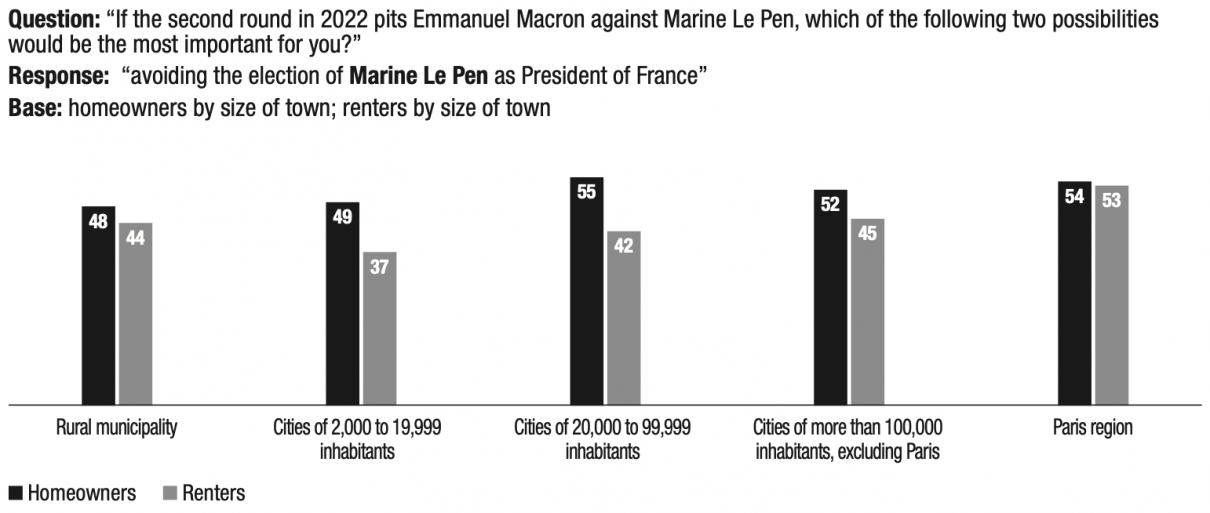

30. Renters living in small and medium-sized towns in France represent a potential electorate which may prove hostile to the incumbent president. One can discern here a return of the Yellow Vest crisis: 53% of renters in cities with 2,000 to 19,999 inhabitants and 57% of renters in cities with 20,000 to 99,999 inhabitants have a positive attitude towards the Yellow Vests (compared to 44% on average). This memory of the Yellow Vests may be rekindled by tensions in the property market linked to new residential strategies following the health crisis and the difficulties of lockdown in urban areas in general and in metropolitan areas in particular.

Fifth wave of the electoral protest indicator 2022, the Populist Risk in France, designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

2022, the Populist Risk in France is an indicator of electoral protest, designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The questionnaires are written by the Foundation’s team and the surveys conducted by the polling institute OpinionWay.

To ensure the soundness and interest of the data collected, the questionnaire is each time administered to a sample of 3,000 people registered on the electoral rolls and drawn from a sample of 3,423 people representative of the French population aged 18 and over. The representativeness of the sample is ensured by the quota method, with regard to criteria of gender, age, socio- professional category, category of urban area and region of residence. We carry out one measurement every six months.

| The fifth wave of our survey was administered from 14 to 20 September 2021, with a sample of 3,156 people. On 14 September 2021, 47 million French people were vaccinated*. France is now one of the most vaccinated countries in the world. In parallel with its vaccine strategy, the government has introduced a health pass, mandatory as of 9 August 2021, which consists of presentation of proof of vaccination. This situation has been accompanied by anti-vaxxers and anti-pass health protests in the country. As the presidential election draws closer, candidates are becoming clearer, despite the lack of strong candidates for the traditional parties. The emergence of Éric Zemmour on the political scene, although he was not yet officially a candidate when this survey was conducted, changes the balance of power from the right to the extreme right. On 13 September 2021, CNews announced the end of its collaboration with Éric Zemmour. |

Wave 1 of our survey was administered from 30 August to 6 September 2019, with a sample of 3,006 people. The presentation and analysis of the results resulted in a publication entitled 2022, the Populist Risk in France. Wave 1, is available in French and English on the fondapol.org website.

Wave 2 of our survey was conducted from 23 to 31 January 2020, with a sample of 3,055 people. The social and political context was tense at the time, particularly because of the retirement reform. We had therefore added certain contextual questions about the understanding and acceptance of this reform. The coronavirus pandemic and the first lockdown prompted us to postpone publication of the second volume.

Wave 3 of our survey was conducted from 7 to 11 September 2020, with a sample of 3,037 people. At that time, we were just emerging from the national lockdown (17 March-11 May 2020) and from a summer during which some restrictions had been lifted. The cycle of opinion in this third wave includes a rise in the number of coronavirus cases in France as well as fears of a second wave of the epidemic. The results of Waves 2 and 3 were combined into a single publication entitled 2022, the Populist Risk in France. Waves 2 and 3.

The fourth wave of our survey was conducted from 6 to 12 April 2021, with a sample of 3,012 people. The context was marked by a resurgence of the pandemic, a curfew and a new lockdown from 3 April. The vaccine strategy began to be deployed during this period.

This publication presents the results of the fifth wave. The text and questionnaire are available in French and English at fondapol.org, and the entirety of the data at data.fondapol.org.

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

By its unprecedented nature and intensity, the public health crisis appeared to sideline the Yellow Vests crisis and protests against the retirement reform. It is not clear that it extinguished the fire, however. The question arises as to how these overlapping crises will be expressed through the mechanisms of the 2022 presidential election. Our indicator aims to help understand and anticipate the contours of this future presidential election, with potentially European and therefore global consequences.

The electoral protest indicator estimates the potential of different possible electoral protest behaviours: abstention from voting, casting a blank vote, or voting for populist parties or candidates. In our indicator, the idea of a protest electorate covers three types of electoral behaviour:

– the stated willingness to vote for populist parties and candidates (Marine Le Pen, RN, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, LFI and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, DLF);

– stated willingness to vote for parties and candidates on the revolutionary left (LO/NPA).

– stated willingness to abstain from voting;

– stated willingness to cast a blank vote.

The definitions of populist voting, abstention from voting and blank voting, as well as the history of electoral protest in the presidential elections since 1965 can be found in the appendices to this study (see pages 47-50).

Voters are getting into motion while willingness to cast protest votes remains high

The potential for electoral protest: Wave 5

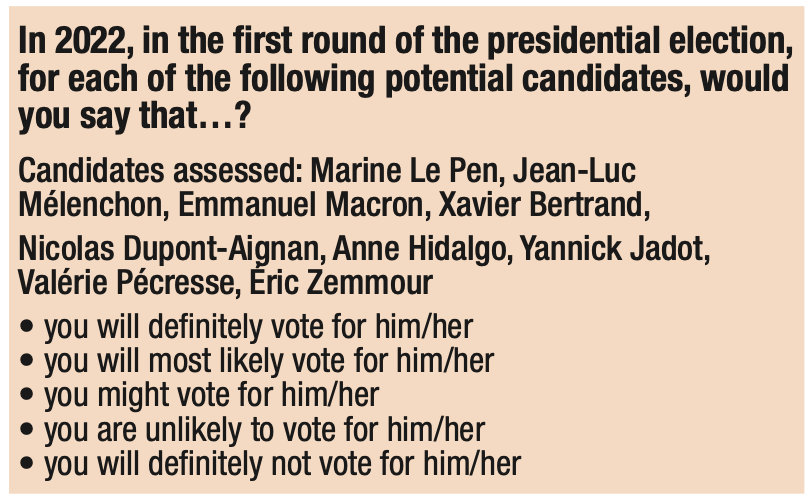

Looking ahead to the first round of the 2022 presidential election, the electoral potential is estimated thanks to the question shown below. This is the willingness declared by respondents to vote for a candidate. For wave 5, we added the electoral potential of the following political figures to the list of candidates tested: Nicolas Dupont- Aignan, Anne Hidalgo, Yannick Jadot, Valérie Pécresse and Éric Zemmour.

Using the answers provided, we were able to define electoral potential on a three-level scale:

– minimum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed who answered “you will definitely vote for him/her”;

– intermediate electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her” or “you will most likely vote for him/her”;

– maximum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents surveyed having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her”, “you will most likely vote for him/her” or “you might vote for him/ her”.

In September 2021, for the first round of the presidential election, the minimum electoral potential of Marine Le Pen (10%) and, to a lesser extent, that of Emmanuel Macron (6%), are still the highest. The same applies to intermediate electoral potential, with 18% for the RN candidate and 17% for the incumbent president, compared to 11% for Xavier Bertrand, 8% for Éric Zemmour, 7% for Valérie Pécresse and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. On the other hand, the maximum electoral potential suggests a rebalancing of the balance of power between Emmanuel Macron (33%), Marine Le Pen (31%), Xavier Bertrand (30%) and Valérie Pécresse (25%), far ahead of Anne Hidalgo (19%), Éric Zemmour (18%), Jean-Luc Mélenchon (17%), Yannick Jadot (17%) and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (16%). But this “maximum” electoral potential is by nature more uncertain and likely tovary.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: In September 2021, when asked about Marine Le Pen’s candidacy, 10% of respondents said they will “definitely” vote for her; 18% said they will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for her; 31% replied that they will “definitely” or “most likely” or “might” vote for her.

Willingness to engage in electoral protest behaviour is still a phenomenon of the majority (72%)

In this indicator, electoral protest behaviour refers to the willingness of a voter to vote for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/ NPA, abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the presidential election.

Our indicator of the potential for electoral protest is based on the combined total of respondents reporting an intention to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. While the level of electoral protest behaviour remains very high in September 2021 (72%), it is also the first time it has fallen since the first wave of this barometer (September 2019).

September 2019 – September 2021: trend in protest electoral potential in the first round of the 2022 presidential election

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

* The “populist vote” option here groups together respondents who answered that they could vote for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (RN, LFI, DLF, LO/NPA).

In wave 5, we can see that electoral protest potential in the strict sense – voting for at least one of the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA candidates in the first round of the presidential election – remains stable but at a high level: it concerns 48% of voters, i.e. a level comparable to the result of wave 1 (49%, in September 2019). On the other hand, we see a significant drop in the proportion of respondents who say they can “abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot” (49%) compared to wave 3 (59%) and wave 4 (56%). However, this figure of 49% remains high since it concerns half of the respondents. It can be considered that, with the election approaching, the interest of French people in the presidential election will grow. In this case, we could see a continued decline in the intention to abstain from voting or to cast a blank ballot; it would then remain to be known in favour of which candidate the fall in abstention from voting or blank voting in the voting intentions could be achieved. Indeed, it is not the lack of interest in this election that explains this high level of intention to abstain from voting that we are recording for the fifth time in a row. Most respondents (84%) believe that the 2022 presidential election is important for the country. The new element lies in the progressive transformation of the political offer, with, on the one hand, new official or potential candidates and, on the other hand, the appointment of strong candidates by political parties. However, this appointment was delayed for the PS and the LR and was made gradually, inevitably changing the movement of voting intentions. Moreover, the emergence of Éric Zemmour on the political scene probably contributes to the mobilisation of a fraction of those previously likely to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot.

The reasons for abstention from voting and blank voting: protest behaviour rather than disappointed withdrawal

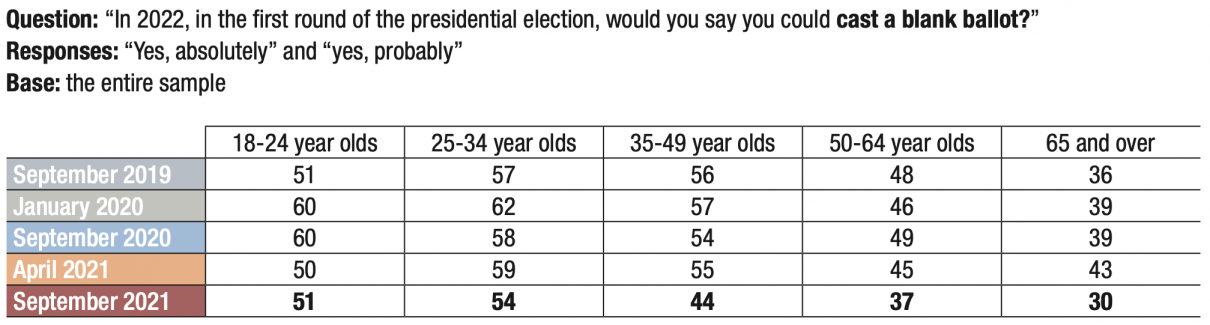

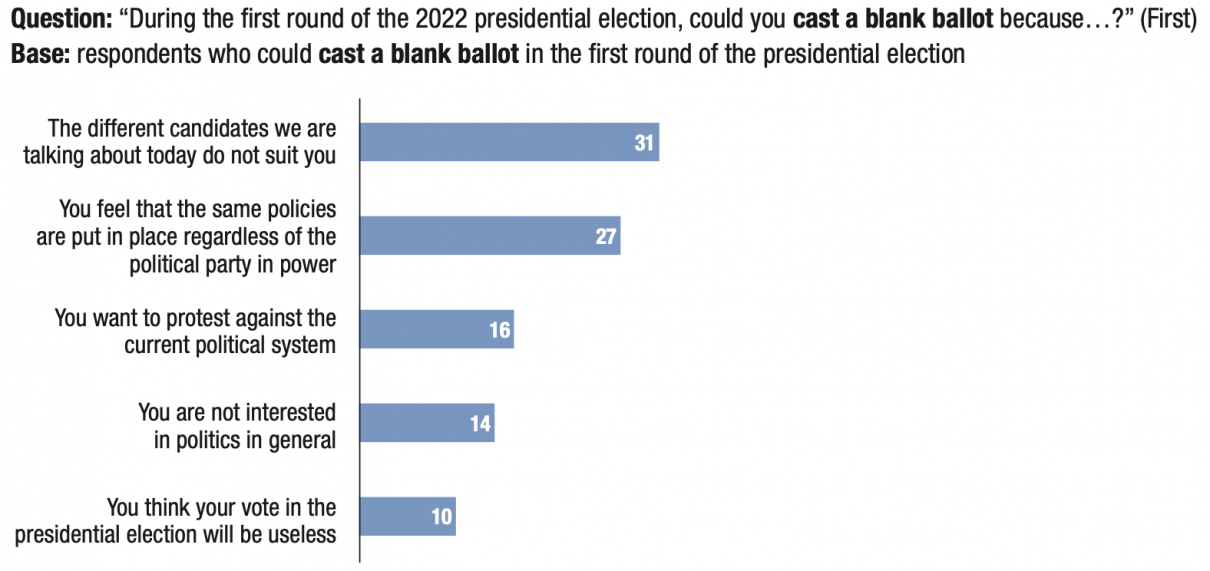

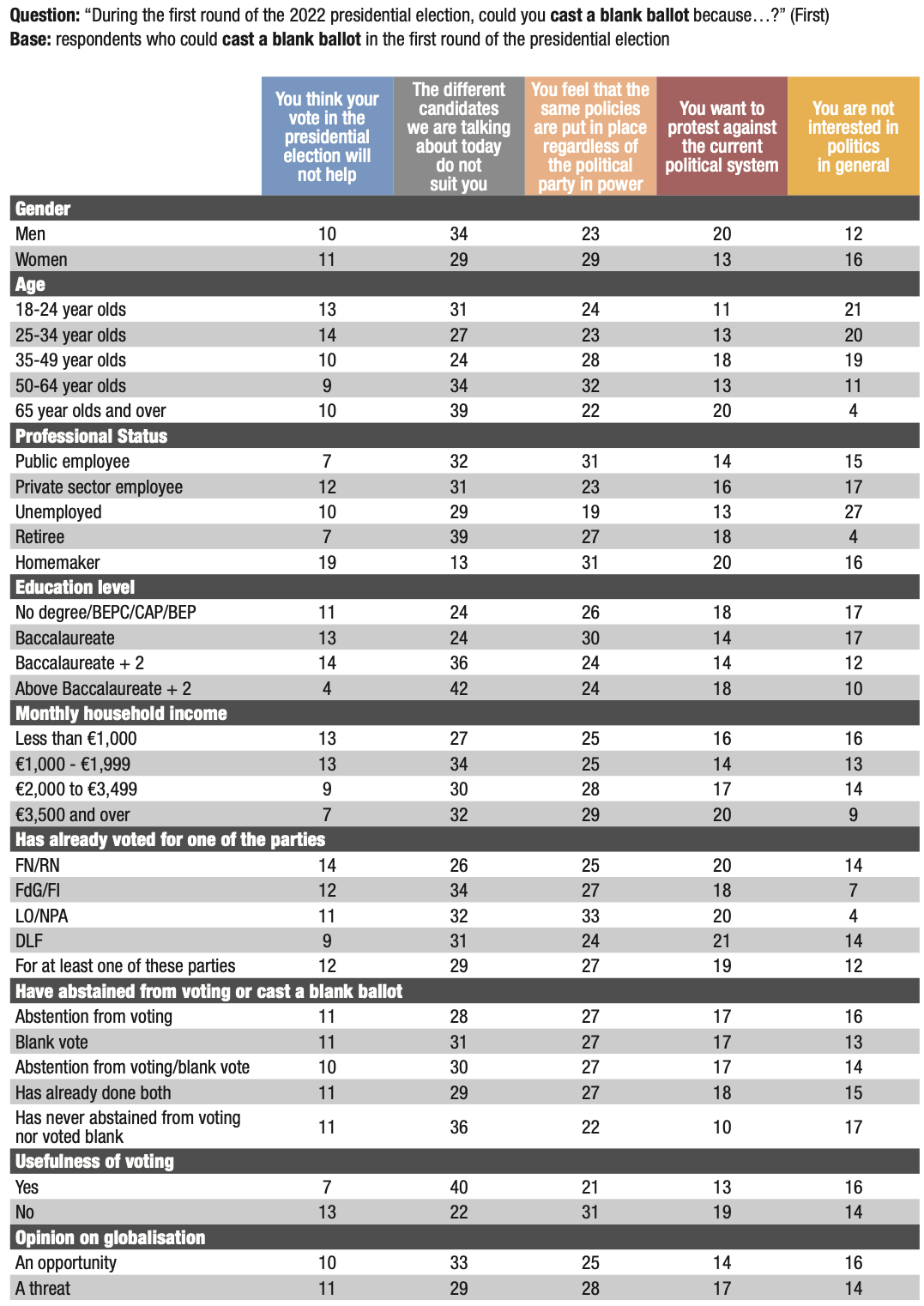

The indicator is not limited to estimating the willingness to vote populist. It also aims to assess willingness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot. In wave 5 (September 2021), willingness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the presidential election is the lowest among those we have recorded since the creation of our indicator. In the first round of the presidential election, a third of French people (34%) said they could abstain from voting and 40% said they could cast a blank ballot.

In September 2021, there was a decrease in willingness to abstain from voting and cast a blank ballot

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

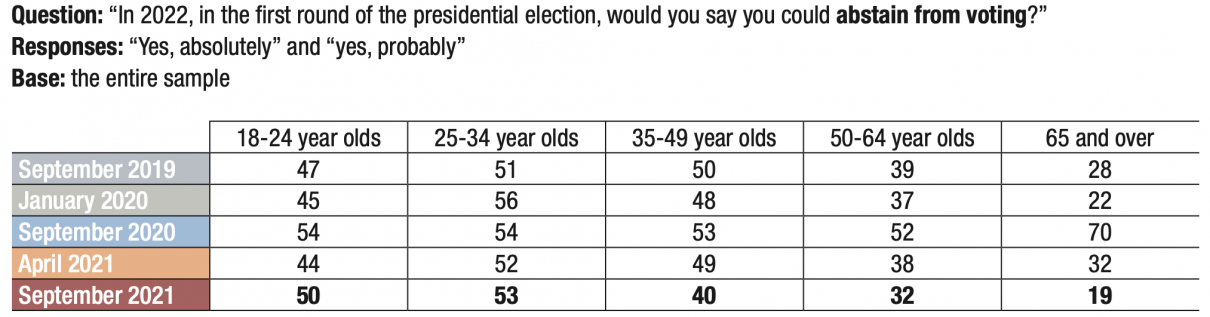

However, between April and September 2021, the willingness of 18-24 year olds to abstain from voting increased by 6 points, from 44% to 50%. The proportion of young people casting a blank vote remains stable (from 50% to 51%).

The first challenge in the battle for participation will be to mobilise the female electorate. Indeed, women are spectacularly more likely (41%) than men (28%) to say that they could abstain from voting; they are also more likely (45%) than men (35%) to say that they could cast a blank ballot.

The same applies to the mobilisation of the working classes, given their greater propensity to abstain from voting: 46% of respondents whose household income is less than €1,000 per month could abstain from voting, compared with a quarter (24%) of those whose household income is greater than or equal to €3,500. Similarly, 54% of individuals who report having an income of less than €1,000 could cast a blank ballot, i.e. 22 points more than those whose income is greater than or equal to €3,500 (32%).

Willingness to abstain from voting by age between September 2019 and September 2021

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Availability to cast a blank ballot by age between September 2019 and September 2021

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

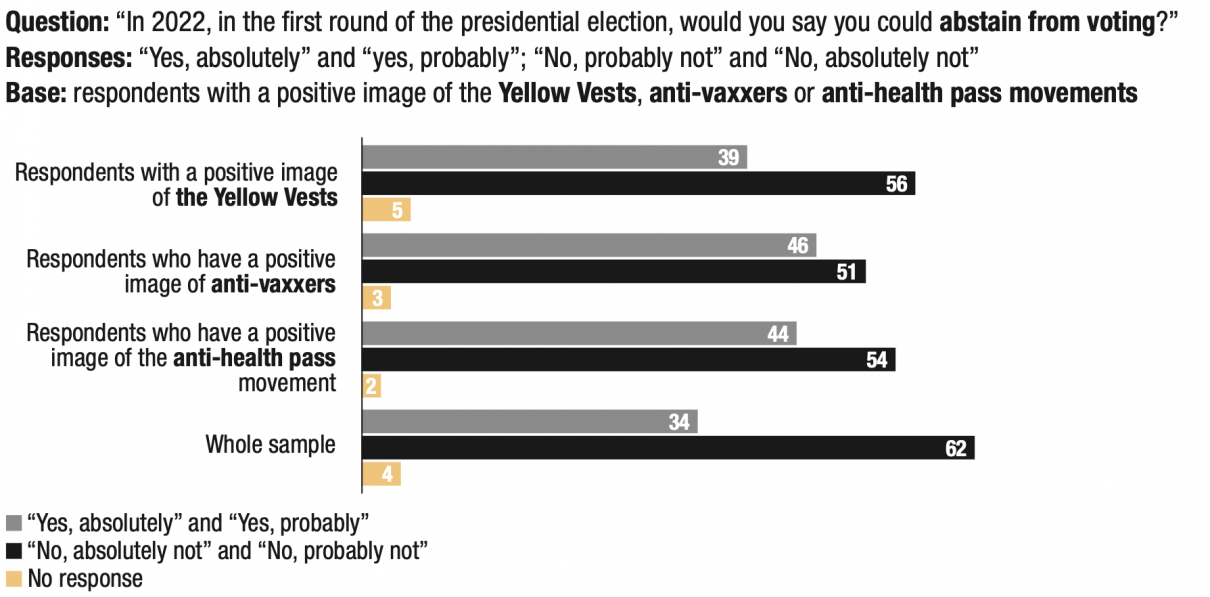

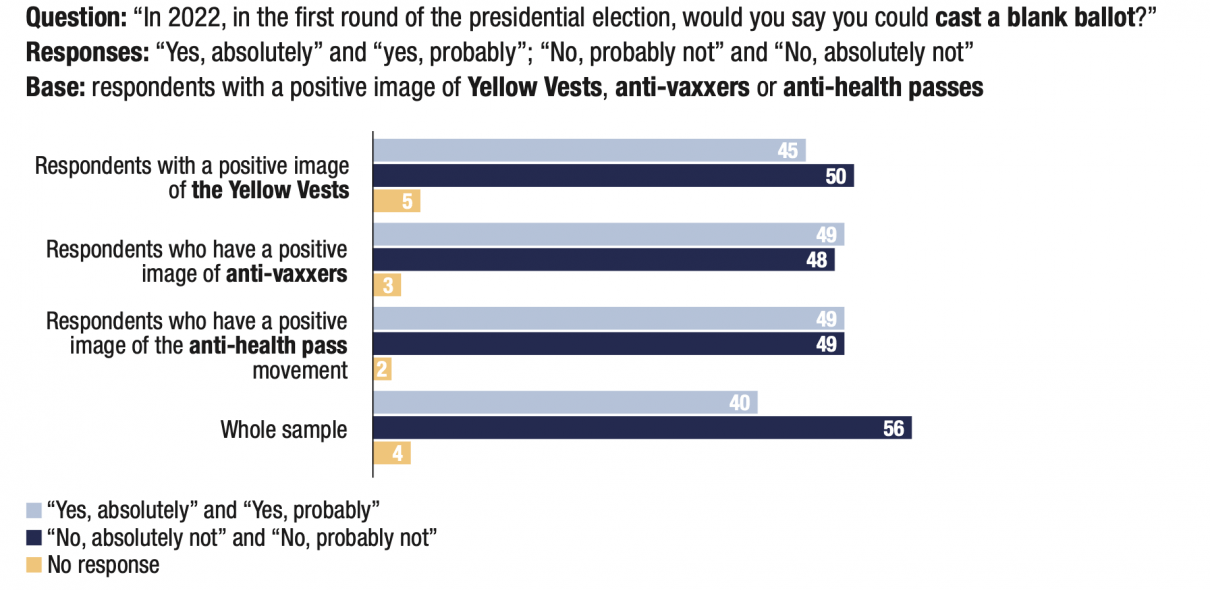

The willingness to abstain from voting in respondents with a positive image of the Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers or anti-health pass movements are greater than average…

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

… as well as their willingness to cast a blank ballot

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

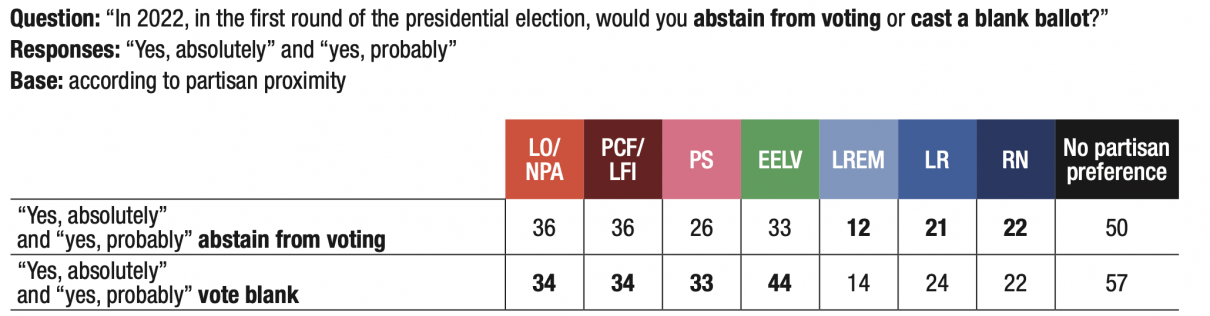

LREM, LR and RN supporters are the most determined to participate

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: 44% of EELV supporters could cast a blank ballot in the first round of the 2022 presidential election.

The willingness to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot comes from various causes. In wave 5, we assess the motivations of individuals likely to abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the presidential election.

The main reasons given by the interviewees show that abstention from voting and blank voting are less a form of disinterest than a form of protest.

The reasons for abstention from voting and blank voting:

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: 30% of respondents who could abstain from voting in the first round say they want to abstain from voting because they “feel that the same policies are put in place regardless of the political party in power”, 26% because “the different candidates we are talking about today do not [suit them]”, 17% because “politics in general do not interest them”, 14% because they want to “protest against the current political system” and 12% because they think that their “vote in the presidential election will be useless”.

The reasons for casting a blank ballot

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: 31% of respondents who could cast a blank ballot in the first round say they want to cast a blank ballot because “the different candidates we are talking about today do not [suit them]”, 27% because they “feel that the same policies are put in place regardless of the political party in power”, 16% because they want to “protest against the current political system”, 14% because “politics in general does not interest them” and 10% because they think their “vote in the presidential election will be useless”.

The reasons for abstention from voting and the profile of potential abstain from voting in the first round in 2022

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The motivations for casting a blank ballot and the profile of voters likely to cast a blank ballot in the first round in 2022

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Willingness to vote for the right-wing is stable but the willingness to vote for the left is at its lowest since September 2019

Among the parties sampled, willingness to vote LR is the highest (36%), while LREM (32%) fell by 2 points in one year (34% in September 2020). From high level, however, the willingness to vote for the RN in the first round of the presidential election is eroding for the first time, from 34% in April 2021 to 32% in September 2021.

On the left, LFI also fell, from 24% in January 2020 – the highest level recorded, linked to the opposition to retirement reform – to 18% in September 2021 – the lowest level. The same applies to LO/NPA (19% to 14% over the same period). Similar trends can be seen for the PS which is achieving its lowest result (26%), while EELV is down 12 points in one year, from 42% in September 2020 to 30% in September 2021.

September 2019-September 2021: evolution of willingness to vote for the different parties tested in the first round of the 2022 presidential election

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

In the event of a Macron-Le Pen duel, transfers of votes are uncertain

According to data from wave 5, in the context of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the share of people indicating that they will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for the RN candidate is 26%, the second highest result after wave 2 (27% in January 2020). At the same time, the share of respondents who will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for the incumbent president is at 31%, its highest ever result, on par with that of wave 3 in September 2020 (31%). The proportion of those who could abstain from voting or vote blank fell by three points, from 32% in April 2021 to 29% in September 2021.

Trend in declared voter intentions in the second round of the 2022 presidential election (September 2019-April 2021)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the transfers of votes in favour of the incumbent president will be observed closely. First, because of the high porosity between right-wing populists: 62% of voters who could vote for Éric Zemmour in the first round and 51% of those who could vote for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan express a preference for Marine Le Pen in a duel with Emmanuel Macron, while nearly a quarter of voters for Éric Zemmour (22%) and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (23%) would abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot and a minority would vote for Emmanuel Macron (9% and 15% respectively). Then, as we have already noted in previous editions of this survey, there is no barrier separating the voters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon from those of Marine Le Pen. Those who could vote for the LFI candidate in the first round are as likely to vote for Marine Le Pen (24%) as for Emmanuel Macron (24%), and 43% could abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot.

Furthermore, the behaviour of PS and LR voters seems unpredictable, as they oscillate between abstention from voting, indecision, populist temptation and support for the current majority. More than a third of those who could vote Hidalgo (37%) or Jadot (36%) in the first round said they could abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the event of a Macron-Le Pen second round, as well as a quarter of those who could vote for Bertrand (25%) or Pécresse (24%) in the first round. More and more voters say they would vote for Macron than Le Pen in the second round (39% of Bertrand’s voters express a preference for the incumbent president, 38% of those for Pécresse, 43% of those for Jadot and 35% of those for Hidalgo). However, a significant proportion seems open to the right-wing populist vote: 13% of potential voters for Anne Hidalgo, 14% for Yannick Jadot, 28% for Xavier Bertrand and 30% for Valérie Pécresse could vote for the RN leader. Unsurprisingly, most voters (89%) of Emmanuel Macron or Marine Le Pen in the first round would vote for their chosen candidate in the second round.

What electoral behaviour in the event of a Le Pen-Macron second round?

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Of those who say they will “definitely” or “most likely” voting for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round, 24% say they will “definitely” or “most likely” voting for Marine Le Pen in the second round in the event of a Macron-Le Pen duel.

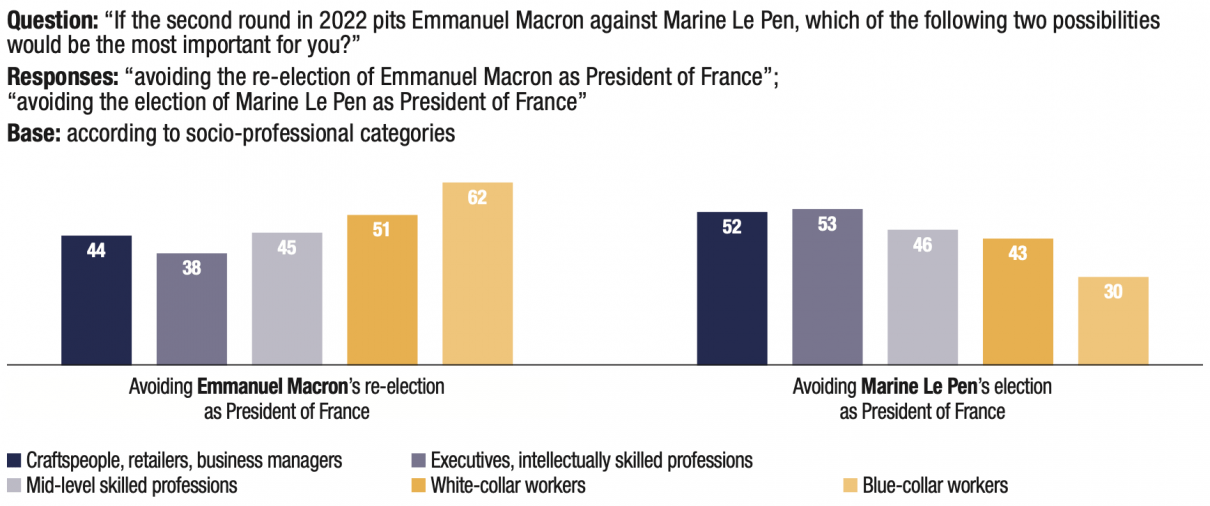

At the same time, it should be noted that the proportion of respondents who say they want to “avoid the election of Marine Le Pen” has fallen in one year, from 53% in September 2020 to 51% in April 2021, to become a minority position in September 2021 (48%). In contrast, a proportion of similar size (44%) said they wanted to “avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re-election”, i.e. 3 points more than in April 2021 and 4 points more than in September 2020.

Most white-collar workers and blue-collar workers say they want to avoid re-election of the incumbent president

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Interest in a candidate who does not hail from any political party

The idea of a non-party candidacy remains the preferred scenario for voters

“In 2022, in the first round of the presidential election, would you say you could vote for a candidate who does not come from a political party?”, 43% of respondents answered yes.

Willingness to vote for a candidate who is not from any party is higher than the willingness to abstain from voting, cast a blank ballot or vote for each of the tested parties.

The idea of a candidate who does not hail from any political party

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

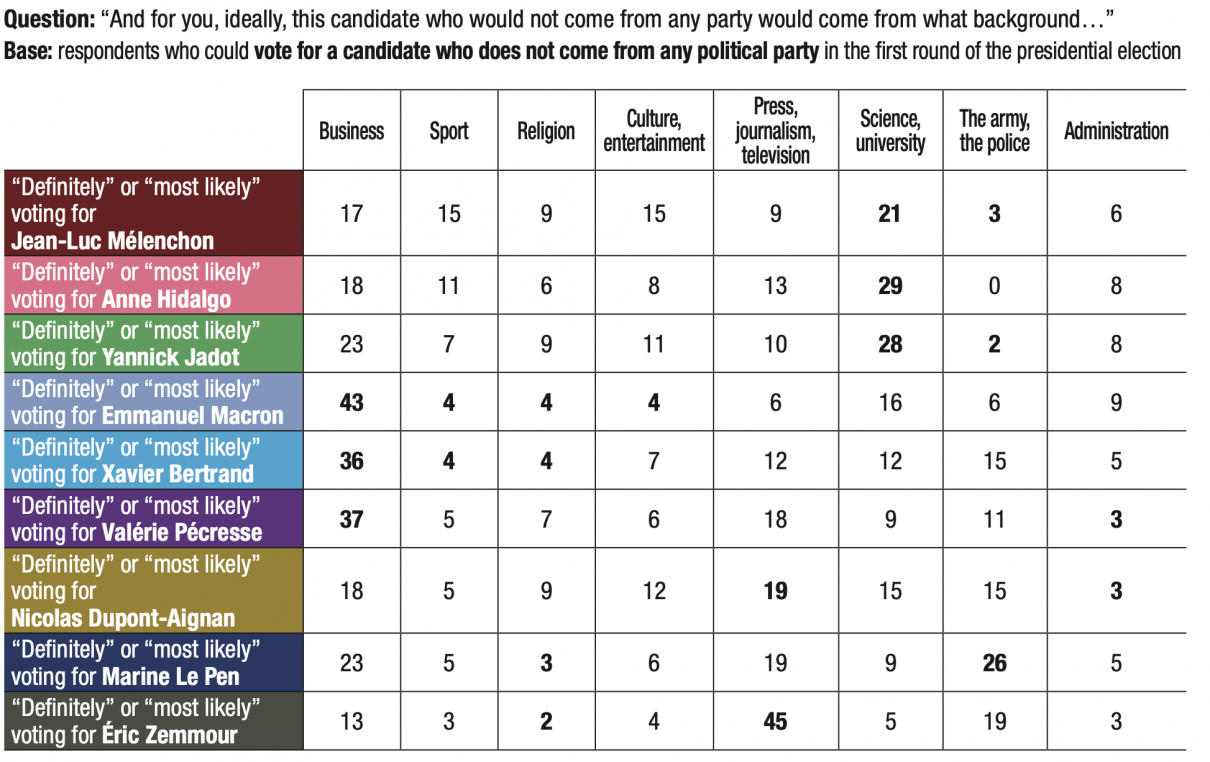

Among those who say they will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for Éric Zemmour in the first round of the presidential election, which has the highest proportion (77%) of voters expressing a preference for a candidate who does not come from a political party. There is a smaller but still very significant proportion of respondents who say they could vote for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (65%), Yannick Jadot (58%), Valérie Pécresse (51%), Xavier Bertrand (48%) and Anne Hidalgo (48%). This expectation is less widespread among the voters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon (43%), Emmanuel Macron (39%), who nevertheless meets this criterion, and Marine Le Pen (35%).

Information on the profile of a candidate who does not come from any party

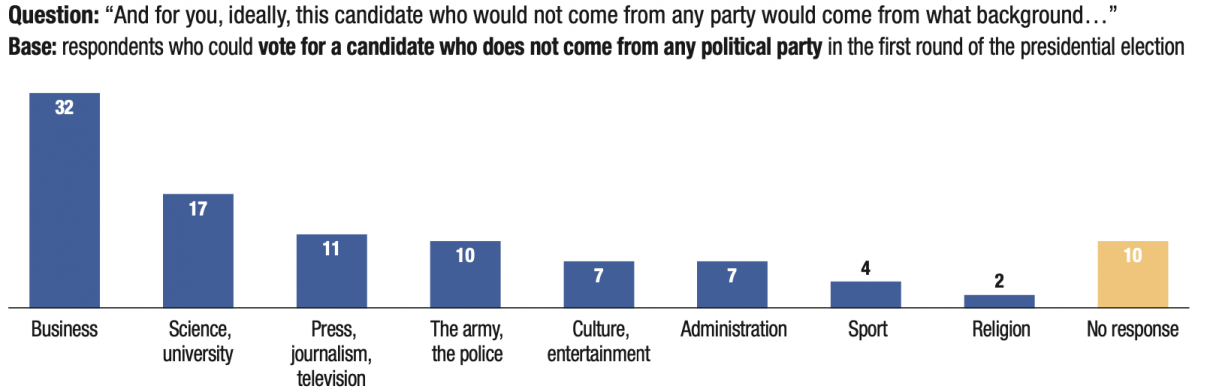

A third of voters (32%) who could vote for a candidate unaffiliated with any party would like to see someone from the corporate world

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Left-wing voters, who say they could vote PS or LFI in the first round, express a preference for a candidate from the scientific or academic world. Voters who support a candidate from the corporate world are among the respondents who will “definitely” or “most likely” vote for Emmanuel Macron, Xavier Bertrand or Valérie Pécresse. For the protest right, citizens who could vote for Marine Le Pen prefer the military and the police, while those who could vote for Éric Zemmour prefer the profile of the journalist.

The profile of the non-party candidate differs depending on electoral preferences

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Of respondents who say they are “definitely” or “most likely” voting for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, 21% want this candidate who does not come from any party to ideally come from a scientific or university background.

Rejection of parties conditions the expectation of a civil society candidacy

We assume that willingness to vote for a candidate from civil society is one of the expressions of electoral protest, alongside voting for anti-system candidates, abstention from voting and casting blank ballots. This is indicated by the motivations of respondents who say they could vote for a candidate from outside a political party.

The reasons for voting for a candidate who is not from any party

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Most respondents (82%) do not trust parties. Spectacularly high, this mistrust is even slightly higher than in wave 4 (80% in April 2021). The rejection of parties contributes to an increase in abstention from voting and casting blank ballots; it also encourages the emergence of other types of candidates. This is demonstrated by the unprecedented opposition of the second round of the 2017 presidential election between, on the one hand, an out-of-system candidacy, that of Emmanuel Macron, without an electoral past or a constituted party and, on the other, the anti-system candidacy of Marine Le Pen. Since their elimination in the first round of 2017, LR and PS have failed to regain public support. Their unpopularity undermines the chances of success for the candidates they choose. For LR and PS candidates, the benefits of party support have become uncertain. The party may have become the obstacle to a presidential victory, though it remains an important lever given funding needs and the sponsorship rule. Should it become official, Éric Zemmour’s entry into political competition would be likely to disrupt the political landscape.

Éric Zemmour’s potential pools of votes

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Portrait of the electorates of Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen: between convergences and differences

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The populist risk is part of a troubled society

The presidential election could divide the French rather than unite them

41% of citizens believe that the presidential election will “divide the French”. Only 12% responded that it will “bring the French together”. Almost half of respondents (46%) said “neither”. The idea that the presidential election will “divide the French” is more widespread among the wealthy (44%) and the middle classes (42%) than among the working classes (38%). Men (45%) are significantly more likely than women (37%) to make this judgement. Similarly, 45% of people with a monthly household income greater than or equal to €3,500 share this opinion, compared with 39% of those with a monthly household income of less than €1,000. The proportion of craftspeople, retailers, business managers (51%) and

executives, intellectually skilled professions (46%) believe that the presidential election will divide the French people more than the rest (compared with 43% among white- collar workers and 41% among blue-collar workers).

Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and opponents of the health pass: an entanglement of anger feeds the protest vote

France has seen a series of crises of different intensities, from the opposition to reforms or the Yellow Vest movement to the most recent, the Covid-19 pandemic and the formation of the movements that followed, the anti-vaxxers and then the anti-health pass movement.

The Yellow Vests still enjoy a positive image in public opinion

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

While anti-vaxxers and anti-health pass protestors are not an identical reproduction of the Yellow Vests, elements are common to these three movements, all of which are at odds with the institutional representative bodies and traditional intermediary powers. These movements embody the rise of rejection of institutions.

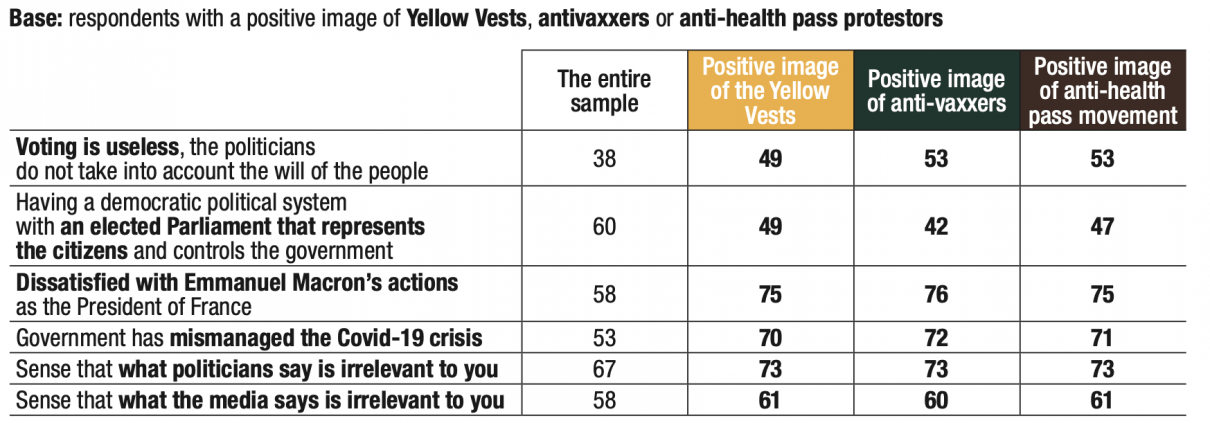

The profiles of respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and anti-health pass protestors reveal anti-system groups that seem to be breaking away from the democratic model and expressing strong criticism of the government.

Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and anti-health pass protestors: three anti-system movements

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Among those who have a positive image of anti-health pass protestors, 53% believe that “voting is useless, politicians do not take into account the will of the people”

In the run-up to 2022, sympathy for the Yellow Vests, anti-vaxxers and anti-health pass protestors is associated with a significantly higher than average potential for electoral protest. In the first round, 84% of respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests could opt for at least one of the protest behaviours given (voting for the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, abstain from voting or casting a blank ballot), compared with an average of 72%. This figure rises to 89% for people who have a positive image of anti-vaxxers or the anti-health pass movement.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

French people see their society as “increasingly violent”

Cited by Salomé Vincendon, “Selon Emmanuel Macron, ‘nous sommes dans une société de plus en plus violente’”, bfmtv.com, 3 June 2021.

Clashes during protests, increase in crime, racist attacks, anti-Semitic attacks, homophobic attacks, terrorist attacks, increase in anti-social behaviour, countless hateful comments on social media…

On 3 June 2021, Emmanuel Macron himself declared: “We are in an increasingly violent society1. This opinion is shared by three-quarters of respondents (72%), i.e. a figure identical to that of our two previous waves, September 2020 and April 2021.

Over the past year, 72% of respondents have deemed society increasingly violent

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Given its overall level, the assessment is present in all social categories, and in comparable proportions, whether among the wealthy (77%), the middle classes (70%) or the working classes (71%). However, opinion is significantly more widespread among people who believe that their standard of living has deteriorated (83%) than among those who believe that it has improved (52%).

This gloomy assessment concerns women (75%) more than men (68%), and the over 65 year olds (78%) more than the 18-24 year olds (46%), though their opinion remains close a majority.

Within political families, this opinion is more widespread the further to the right the party is, but it is still in the majority on the left: 87% for RN supporters, 78% for LR, 68% for LREM, 64% for PS and EELV, 59% for PCF/LFI.

French people who inform themselves through 24-hour news channels are the most likely to think that society is increasingly violent

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Among respondents who inform themselves via 24-hour news channels (CNews, LCI, BFM TV, etc.), 80% believe that French society is increasingly violent.

Users of messaging applications, social media, video channels and “the right to have a firearm at home to ensure your safety”

The high level of concern about security issues, the feeling that society is becoming increasingly violent and the opinion that the police do not have enough resources leads us, for the second time, to question whether, as a result, there is a demand among public opinion for the right to keep a weapon at home. The item “In France, to ensure their safety, the French should have the right to keep a firearm at home” was approved by 21% of respondents but rejected by 78%. However, one factor should be highlighted: though a minority, albeit a significant one given the question, the idea of the right to own a firearm is much more widespread among 18-24 year olds (34%), particularly high school and university students (32%).

More than a third (34%) of 18-24 year olds support the right to own a firearm at home

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The depiction of rising and unsettled conflict is fuelled by social media that depict acts of violence on an almost daily basis, with young people being the main users, including TikTok, Twitch and Instagram. There is a clear link between spending time on social media and wanting a gun at home. Of the respondents who use Telegram every day, more than half (57%) are in favour of the right

to keep a weapon at home. The same applies to those who use TikTok daily (42% want the right to own a weapon), Twitch (44%), Twitter (29%) and Instagram (26%) and those who are informed via blogs/forums (47%) and YouTube (41%). In contrast, for daily users of Facebook (22%) and WhatsApp (21%), the figures are similar to the sample average (21%).

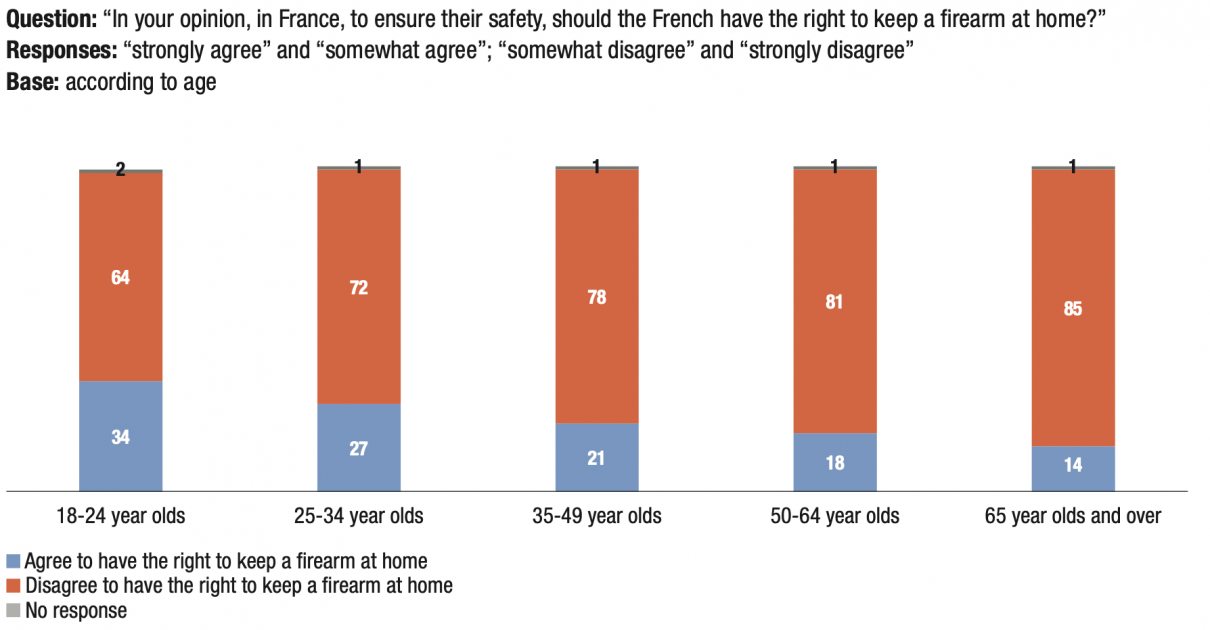

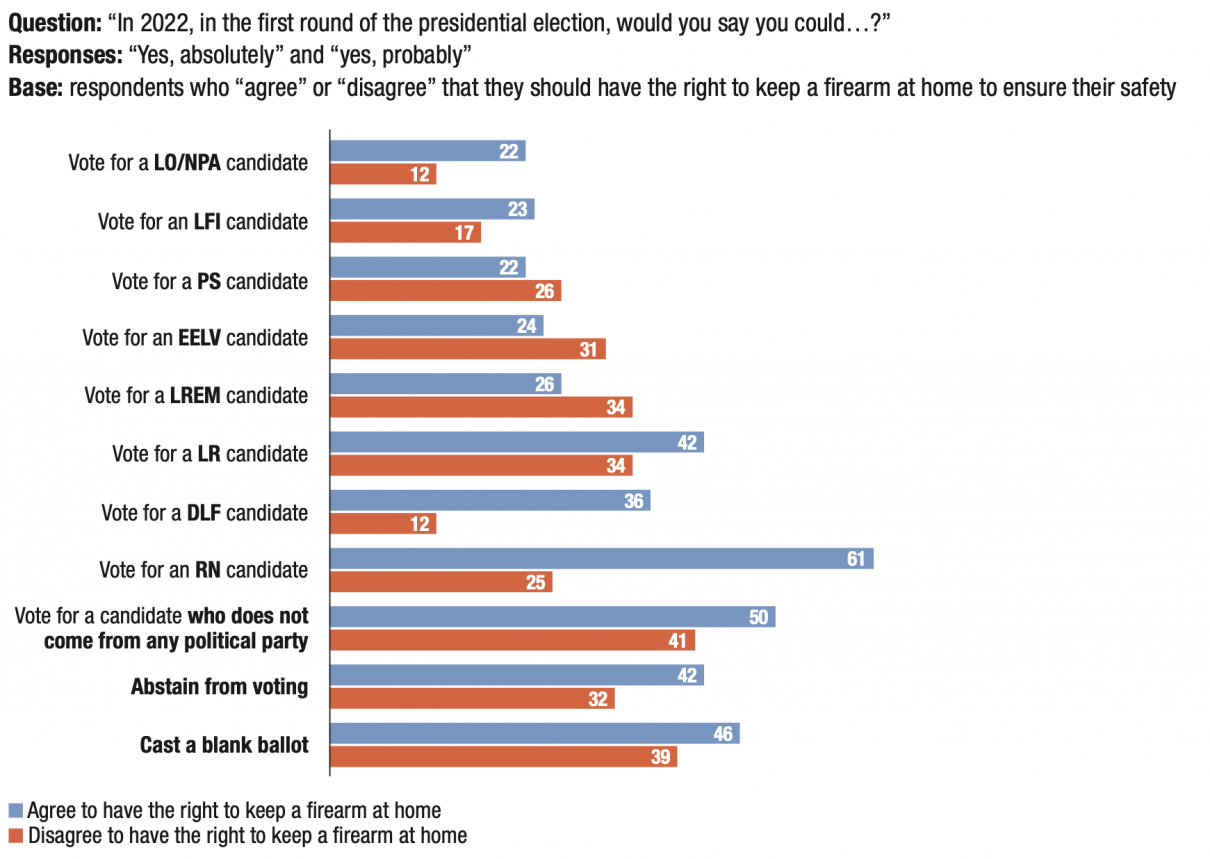

Respondents who want the right to keep a firearm at home express a strong willingness to vote right-wing, especially for an RN candidate

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Among those who agree that they should “have the right to keep a firearm at home”, 61% say they could vote for an RN candidate in the first round in 2022� Among those who do not agree that they should “have the right to keep a firearm at home”, 34% say they could vote for an LREM candidate in the first round in 2022.

Regular use of social media is linked to protest behaviour

The democratic public space is subject to structural changes, in particular due to the decline of traditional media. Thus, the results of wave 4 (April 2021) of our indicator, which reported a crisis in media representation, are confirmed: in September 2021: nearly three quarters of the French (72%) do not trust the media. By the same token, a large majority of respondents (58%) feel that “most of the time, when they watch news in the media, they get the impression that the subjects discussed are not relevant to them.” This is 20 points higher (38%) than those who feel that the media deals with issues that are relevant to them (4% of respondents did not respond).

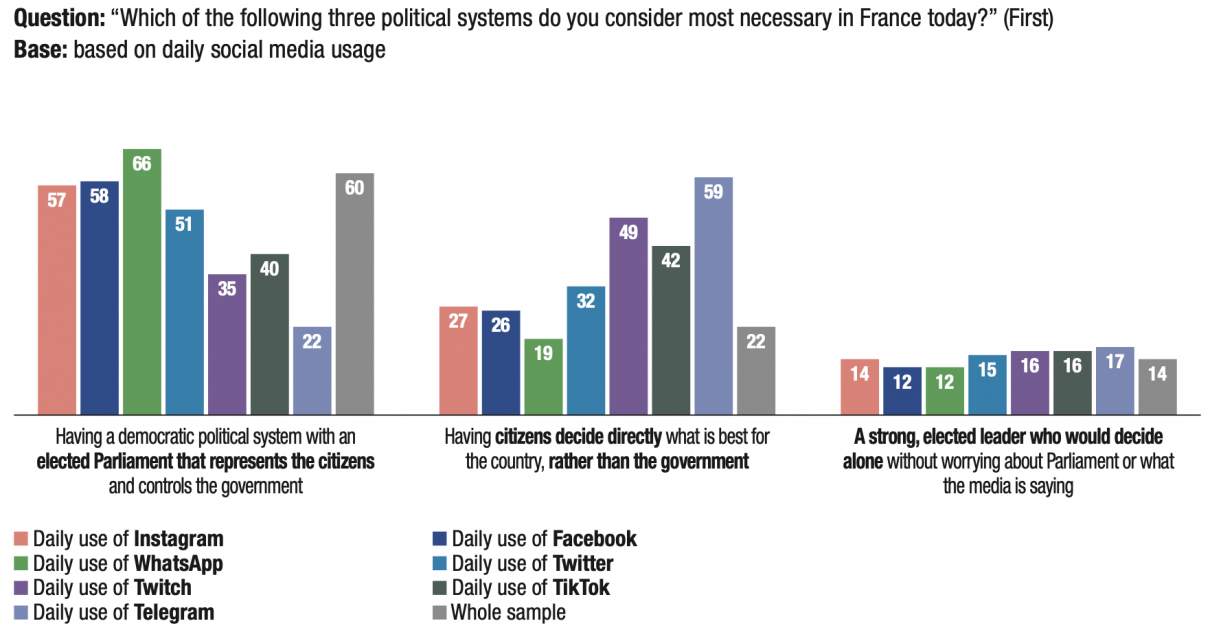

This crisis of representation is accompanied by the advent of a digital space through social media and telephone messaging applications. Our relationship to information has been upset. Thus, among people who use Telegram daily, 50% use “new forms of media” – YouTube, blogs, forums or social media – as their primary source of information (compared to an average of 14%). The results are also very high for respondents who log onto TikTok daily (46% get information via these “new forms of media”) or Twitch (38%) and, to a lesser extent, Twitter (31%) or Instagram (28%). Daily users of WhatsApp (15%) and Facebook (18%) are the least likely to use new forms of media as their primary source of information.

While providing access to information, social media and phone apps also work to circulate protest opinions. This first involves grouping users whose viewpoints are convergent, i.e. an aggregation effect; it then involves isolating this group from dissenting opinions with which they gradually lose all contact, or the “filter bubble” effect, whose mechanism therefore involves the radicalisation of the group’s viewpoints. Thus, wave 5 of our indicator confirms what we had identified in previous editions, namely that the potential for electoral protest is sensitive to the regular use of social media.

The stated willingness to vote populist, abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot in the first round of the 2022 presidential election is greater among those who use these new forms of media daily, particularly Twitch, TikTok and Telegram. The messaging app WhatsApp is the exception, with results below the sample average. At first glance the socioeconomic characteristics of the groups that consume these social media on a daily basis: the under-35 year olds, women, the unemployed, stay-at-home men and women as well as those whose monthly household income is less than €1,000 are the most likely to consume social media on a regular basis.

Daily use of social media and willingness to engage in protest behaviour

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

* The “populist vote” option here groups together respondents who answered that they could vote for at least one of the four proposed populist or revolutionary left-wing parties (RN, LFI, DLF, LO/NPA).

Memo for the reader: Among respondents who go on Facebook daily, 78% could abstain from voting, cast a blank ballot or vote populist in the

first round of the presidential election.

Regarding the second round of the presidential election, imagining the possibility of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, we asked respondents whether, above all, they would seek to “avoid the election of Marine Le Pen” or “avoid the re-election of Emmanuel Macron”. Most daily social media users say they want to block the re-election of the incumbent president, while this answer is chosen by 44% of the total sample. The figures are significantly higher among users of Twitch or Telegram (69%); this is still the case among TikTok (62%), Twitter (49%) and Facebook (48%) users. There are then levels corresponding to the average among Instagram users (45%); finally, we note a lower than average result among daily WhatsApp users (38%).

It should be noted that the Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram trio brings together users with trends that are relatively closer to the average and less minded to protest than Twitch, Telegram and TikTok.

Opinion on representative democracy and direct democracy among social media users

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

| “Voting is useless, the politicians do not take into account the will of the people”… The weakening of representative democracy bolsters protest opinion 38% of our sample believe that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people”. The consensus on the effectiveness of elections has been changed. These respondents who doubt the utility of voting have strong protest potential. Over three-quarters (77%) of them are dissatisfied with Emmanuel Macron’s action as President of the Republic, 19 points higher than the average (58%). Most (81%) do not feel concerned by the subjects that politicians talk about (compared to 67% on average) and more than two-thirds (69%) do not feel concerned by the subjects that the media talks about (compared to 58% on average). Less than half (47%) are in favour of “a democratic political system with an elected parliament that represents the citizens and controls the government” (compared to 60% on average). On the other hand, more than a third (34%) want “citizens to decide directly, instead of the government, what they think is best for the country” (compared to 22% on average). 15% approve of the figure of “a strong, elected leader who would decide alone without worrying about Parliament or what the media say”, a result similar to the whole sample (14%). A majority (57%) of respondents for whom “voting is useless” have a positive image of the Yellow Vests (compared to 44% on average), more than a third (38%) have a positive image of anti-vaxxers (compared to 27%) and 50% have a positive image of the anti-health pass protests (compared to 36%). Electoral protest is therefore more present within this share of the electorate: 38% could vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round (against 31% on average), 23% for Éric Zemmour (against 18%), 20% for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (against 16%) as well as Jean-Luc Mélenchon (against 17%) and only 16% for Emmanuel Macron (against 33%), 23% for Xavier Bertrand (against 30%), 19% for Valérie Pécresse (against 25%), 16% for Anne Hidalgo (against 19%), 14% for Yannick Jadot (against 17%). In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, 31% say they will “definitely” or are “very likely” to vote for Marine Le Pen (26% on average), 12% for the current president (versus 31%) and 41% would abstain from voting or cast a blank ballot (versus 29%). Regarding the second round of the 2022 election, if respondents are asked to choose between the option “avoid the election of Marine Le Pen” or the option “avoid the re-election of Emmanuel Macron”, a large majority say they want to block Emmanuel Macron (58%, compared with 44% overall). |

Support for managing the health crisis and for Europe is containing the populist vote

Increasing numbers of French people believe that the health crisis has been managed well

In September 2021, 45% of respondents believe that the government has managed the crisis well, while 53% believe the opposite. While those who believe it was mismanaged are the majority according to our indicator, this discontent has nevertheless sharply decreased compared to previous measures. This relatively tolerant opinion towards the government, observed in September 2020 (39% of respondents said that the government was managing the crisis well, compared to 59% that it was managing it poorly), quickly gave way to a widespread discontent in April 2021 when only 29% of respondents believed that the crisis was being managed well, compared to 68%.

Suddenly faced with an unprecedented and major crisis, those in charge gave, for a time, an impression of impotence and disorganisation. But lockdown, while painful and costly, eventually lost its utility thanks to a vaccination policy which was vigorously put into effect, even though it was regrettable that no French vaccine was developed. The French population is now one of the most-vaccinated in the world. The evolution of satisfaction with the management of the health crisis will obviously weigh on the electoral decision. Using the Macron-Le Pen duel hypothesis, 70% of those who believe that the government has managed the crisis well want to “avoid the election of Marine Le Pen as President of the Republic” (compared to 48% on average). Conversely, 61% of those who believe that the government has mismanaged the health crisis say that they want above all to avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re- election.

Assessing the management of the health crisis and the willingness to protest in the first round of the presidential election

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

September 2019-September 2021: change in satisfaction with Emmanuel Macron’s actions as President of the Republic

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The forecast for economic growth has changed to a predicted increase; the vaccination campaign is running at full capacity; bars, restaurants and cultural venues are all open; sports activities have resumed, etc. A new cycle has opened in the management of the pandemic. This naturally benefits Emmanuel Macron.

However, although the perception of the management of the health crisis and of Emmanuel Macron’s actions as President of the Republic have improved, 44% of the French continue to want above all to avoid his re- election in the event of a second round against Marine Le Pen. Of course, one can think that satisfaction will continue to increase as it becomes clearer that we have left the health crisis behind. On the other hand, it is not possible to rule out the pessimistic hypothesis of a relapse. If this were to happen, we can assume the consequences. But the assessment of government performance in the management of the health crisis may also play an increasingly important role in voter choices in April 2022, particularly if the return to normality were to be confirmed, which would mitigate the memory of difficulties, which is to say also the memory of the government’s performance.

For populists, attachment to the European Union and the euro remains a major obstacle

Since the first issue of our indicator, the attachment of French people to Europe and the euro has remained consistent. Wave 5 is no exception: more than three- quarters (79%) of respondents want France to remain in the European Union. A minority, stable at 18%, compared with 17% in April 2021, says they want France to leave the European Union. Similarly, most (82%) want to keep the euro, with only 16% of respondents wanting a return to the franc. Despite the controversies over the European Union created by its initial management of the health crisis, European sentiment has not been altered. It is a major obstacle for populists. Indeed, faced with the pragmatic embrace of Europe and the euro by part of their electorate, populists are forced to drastically limit their expression of Euroscepticism: 58% of respondents who may vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round in 2022 want France to remain in the European Union. The same applies to 55% of voters who may vote for Éric Zemmour and 85% of those who may vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

Younger generations are most attached to the European Union and the euro

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The euro is fragmenting populist electorates

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Among respondents who said they were “definitely” or “most likely” voting for Éric Zemmour in the first round, 27% said “I am not in favour of the euro and I want us to leave the euro to return to the franc”.

French society is predominantly right-wing

The predominance of the right observed by self-positioning on the left-right political scale

An initial way of assessing the weight of the right is based on what is called political self-positioning. Those surveyed were asked to self-position themselves on a left-right political scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is the most left-wing and 10 is the most right-wing: those choosing 0 to 4 are considered on the left, 5 in the centre, and 6 to 10 on the right. The respondents surveyed also had the option not to self-position themselves on this scale. The data shows that more than a third of voters self- position themselves on the right (37%), a fifth (20%) on the left and 18% in the centre. Finally, a quarter (23%) of respondents said they did not want to self-position themselves on the left-right political scale.

January 2020-September 2021: a shift to the right of new generations

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Note: the difference between totals and 100% represents non-responses.

Among those on the right, 28% say they are “definitely” or “most likely” voting for Marine Le Pen in the first round of the presidential election, 24% for Emmanuel Macron, 19% for Xavier Bertrand, 15% for Éric Zemmour or Valérie Pécresse, and 8% for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan.

Among the respondents in the centre, 20% state that they are “definitely” or “most likely” voting for the incumbent president, ahead of Marine Le Pen (13%), Xavier Bertrand (9%), Éric Zemmour (4%), Valérie Pécresse (3%) or Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (3%).

Willingness to vote for Marine Le Pen in the second round remains high among respondents in the centre

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

The preponderance of the right observed by the assessment of electoral potential

Our measurement of electoral potential confirms the position of French people as right-wing. Since its creation in 2019, our indicator assesses willingness to vote for a party or candidate in the 2022 presidential election. To do this, we have chosen a method asking the entire sample to decide on each of the candidates tested and to choose more than just one. We decided to do this in the hopes of better understanding the logic of transfer votes. According to data from the fifth wave of our indicator, 56% of voters surveyed could vote for at least one of the right-wing candidates tested (Xavier Bertrand, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Marine Le Pen or Éric Zemmour). Measured in this way, willingness to vote right-wing is 22 points higher than the willingness to vote left-wing (34%), i.e. for at least one of the left- wing candidates tested (Anne Hidalgo, Yannick Jadot or Jean-Luc Mélenchon). Finally, it should be noted that the electoral potential of the right is even higher if we include some of the voters who say they are prepared to vote for Emmanuel Macron. In this case, another part of the Macronist electorate should logically go to the left, but without being able to challenge the predominance of the right-wing in France.

The right can only gain such weight by dominating the working classes. After the quantitative defeat, this is the sociological defeat of the left. The declared willingness to vote right-wing is widespread among respondents without an educational degree (63%), belonging to lower socio-professional categories (60%), or those who believe they are struggling to make ends meet at the end of the month (60%) or that their standard of living has deteriorated in recent years (60%).

The willingness to vote right is also dominant among the working classes

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Memo for the reader: Among respondents without an educational degree, 29% say that they “definitely”, “most likely” or “might” vote for Anne Hidalgo, Yannick Jadot or Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Among respondents who belong to the group CSP- (white-collar workers and blue-collar workers), 60% say that they will “definitely”, “most likely” or “might” vote for Xavier Bertrand, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Marine Le Pen or Éric Zemmour.

We can also see that a significant proportion of left-wing voters in the first round of 2017 say they could vote for a right-wing candidate in 2022: 37% of voters for Jean- Luc Mélenchon and Benoît Hamon could vote for Xavier Bertrand, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Marine Le Pen or Éric Zemmour. Carried out in the other direction, the exercise shows that only 10% of François Fillon’s voters and 16% of those who voted for Marine Le Pen in 2017 could vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Anne Hidalgo or Yannick Jadot.

Moreover, within the group of voters who position themselves in the centre, the electoral potential

of the right is much higher: 57% of these voters say they could vote for at least one of the right-wing candidates and 35% for at least one of the left-wing candidates. The same applies to those who chose not to self-position themselves on the left-right political scale: 48% could vote for Xavier Bertrand, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, Marine Le Pen or Éric Zemmour, compared with 29% who could vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Anne Hidalgo or Yannick Jadot. A few months before the presidential election, the question is whether this realignment to the right will benefit a reformist right or a pro-rupture right.

Concerns about crime, immigration and Islam are another way of verifying the predominance of the right in public opinion

Concerns about crime, immigration or Islam are usually highlighted as right-wing markers. But it is not hard to imagine that they could come from a left-wing sensibility. Demand for safety is probably higher in working-class neighbourhoods; similarly, the desire to preserve employment or the standard of salaries contains a demand for regulation of immigration; finally, the defence of secularism is a left-wing idea, more obviously than it is a right-wing one. However, lines have been drawn in public debate and these three items have long contributed to the delineation of a right-wing opinion.

Hierarchy of concerns and willingness to vote

Hierarchy of concerns and willingness to vote (continued)

The three main concerns have changed markedly compared to our previous measurement (April 2021): “reducing crime” has gone from the second to the primary concern (51%, up 5 points), “reducing social inequalities” has gone from the third to the second concern (43%, down 2 points), and “reducing immigration” has gone from the fourth to the third concern (42%, up 5 points). The item “reducing unemployment”, the main concern in April 2021 (51%), has been downgraded to fourth position (41%, down 10 points). We note that if concerns about “reducing the influence of Islam” and “reducing global warming” are at the same level in September 2021 (37%), the concern about “reducing the influence of Islam” has increased by 6 points since September 2019 (31%), while “reducing global warming” fell by 4 points over the same period (41% in September 2019). Finally, “reducing government debt/deficit” has increased from 38% to 27% in two years.

Crime is at the forefront of concerns

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Source :

Note: the difference between totals and 100% represents non-responses.

| Public opinion on immigration is dominated by a negative sentiment.

Two-thirds of respondents (66%) believe that “most immigrants do not share our country’s values and this creates problems for cohabitation”; conversely, 30% chose “most immigrants share our country’s values and this represents cultural enrichment”. |

Homeowner status is associated with a much more favourable electoral orientation towards right-wing candidates and Macron

Since wave 4, we have included the ownership status of one’s dwelling as identification information in our questionnaire. The aggregation of waves 4 and 5 allows us to analyse a sample of 6,167 respondents: 3,855 declare themselves to be homeowners, 1,925 are renters and 387 are housed free of charge. In total, 750 respondents are owners of a secondary residence. According to INSEE, this homeownership status applies to owning, co-owning and having access to the property; the status of a renter or subletter applies to those who pay rent regardless of the type of housing they occupy; and the status of those housed free of charge applies to those who are not owners of their housing and do not pay rent.

Aggregating waves 4 and 5 of our indicator (April and September 2021) enables us to analyse results taking into account the ownership status of one’s dwelling2. A first reading looks at the electoral orientation of homeowners (of a house or apartment), renters (of a house or apartment) and those accommodated free of charge.

Electoral orientation according to the status of the occupant of the dwelling

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

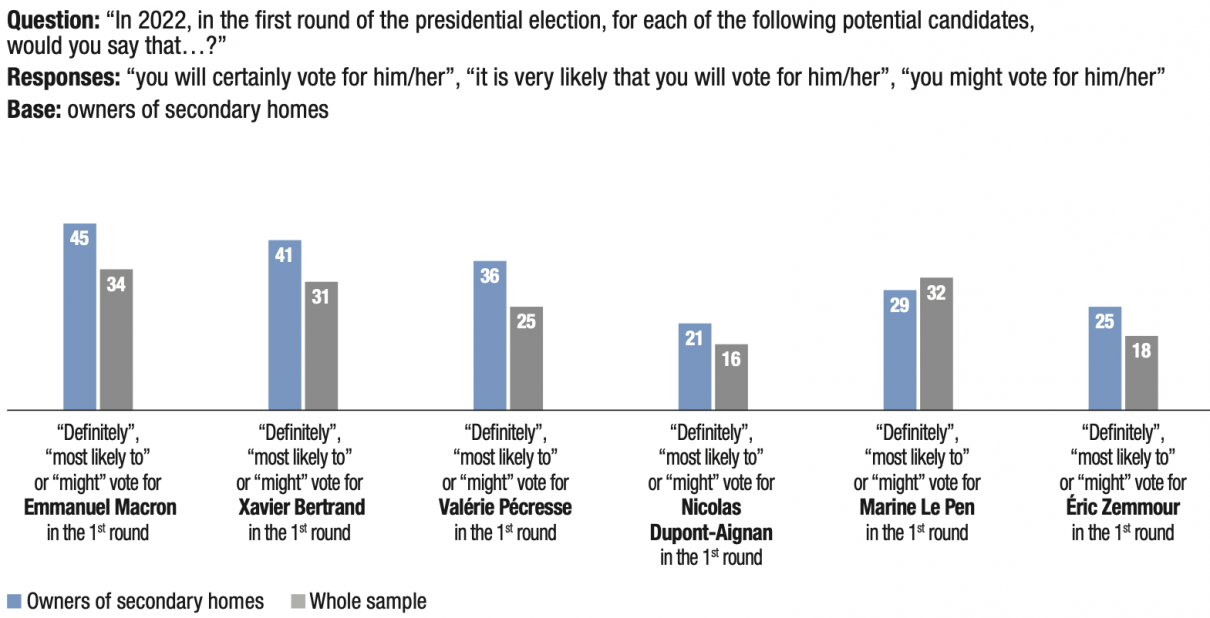

The end of the controversy sparked by the accusation that Housing Minister Emmanuelle Wargon was trying to attack owners of secondary homes is the best possible outcome for Emmanuel Macron: homeowners are overrepresented among his voters. They are also overrepresented in the LR electorate. Home-owning in France is associated with the right-wing. This is an additional way of measuring the weight of the right in French society. On the other hand, renters are much more favourable to Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Éric Zemmour and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan are the only ones to achieve similar results among homeowners, renters and respondents being housed for free. Among those who own secondary homes, the willingness to vote for the incumbent president or for LR candidates is much higher than the average. This can be seen in the case of Emmanuel Macron (45% of owners of a secondary home compared with 34% on average), Xavier Bertrand (41% compared with 31%), Valérie Pécresse (36% compared with 25%), Éric Zemmour (25% compared with 18%) and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan (21% compared with 16%). The only exception is Marine Le Pen, whose score among owners of secondary homes who say they could vote for her (29%) is lower than her average potential (32%). The president of the RN is still the representative of a populism that draws part of its strength from a section of the French population that was once socially destined for the left.

France’s property owners are both right-wing and Macronist

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

In the second round, more renters would vote for Marine Le Pen (27%) than Emmanuel Macron (24%). Homeowners would choose Macron (34%) instead of Le Pen (25%). Similarly, respondents living for free would support the incumbent president more strongly (32%) than his competitor (20%).

See Céline Arnold, “37 millions de logements en France au 1er janvier 2020”, insee.fr, 8 December 2020.

| According to INSEE, in 2020, 58% of households owned their main residence. This share has been stable since 2010, having increased steadily since 1982, partly due to the ageing population. The share of households renting out their main residence has remained at around 40% since 1990, a slightly lower level than in 1982. Finally, the proportion of those who are housed free of charge has fallen steadily since 1982 (2% in 2020)*. |

Term used by Dominique Reynié in an interview with Mériadec Raffray, “Cette crise confirme la cassure entre Paris et les territoires”, lopinion.fr, 19 November 2021 (reserved access).

Taking into account the place of residence reveals a potential electorate hostile to the incumbent president among renters living in small and medium-sized towns. It shows an afterglow of the Yellow Vests crisis. In this France of renters, 53% of renters living in towns of 2,000 to 19,999 inhabitants and 57% of renters in towns with 20,000 to 99,999 inhabitants have a positive attitude towards the Yellow Vests (compared to 44% on average). This memory of the Yellow Vests can be revived by the tensions introduced onto the market by new real estate strategies following the health crisis and the difficulties of lockdown in urban areas in general and metropolitan areas in particular.

More families want to leave metropolises for smaller cities than before. This process of “demetropolisation3” was notable previously, but it seems to be amplified by the Covid-19 crisis. The other notable strategy is the purchasing of a secondary home, but the effects on the real estate market are similar in nature. Consequently, households already living in small and medium-sized towns are experiencing a significant price increase for a product that generally represents an already high or very high cost, while incomes in small and medium-sized towns are lower than those in metropolitan France and the Paris region.

In cities with 2,000 to 99,999 residents, renters want to avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re-election

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.

Homeowners oppose the election of Marine Le Pen

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – November 2021.