2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France: An indicator of electoral protest in the run-up to the presidential election

The main lessons from waves 2 (January 2020) and 3 (September 2020)

Electoral protest is on the rise.

Introduction

2022, the Populist Risk in France: an indicator of electoral protest designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Wave 1, wave 2, wave 3: with each wave, a context of crisis (to be continued)

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

Presidential election: the populist temptation remains

Estimating the electoral potential of a protest climate

In September 2020, most voters (79%) still envisage protest behaviour for 2022

Clearly weakened in wave 2, Emmanuel Macron finds a more favourable position in wave 3 in the event of a second round against Marine Le Pen

Opposition to the retirement reform favoured a merging of both left and right-wing populist electorates

The willingness to abstain from voting and voting blank remains a basic trend

For 2022, voters do not reject PS, LREM, LR and, even less so, EELV candidacies

The populist risk falls into the process of democratic deconsolidation

More than a third of the French (37%) question representative democracy

Detachment from representative democracy serves right-wing populism

The idea of a government in which the people would decide for themselves aggregates protesting worlds

The new media, a public space conducive to populism

The resources of electoral protest

Society is perceived as increasingly violent

The choice of a protest vote is asserting itself among voters who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests

The health crisis reinforced a rejection of globalisation

Women and young people seem to offer new reservoirs for electoral protest

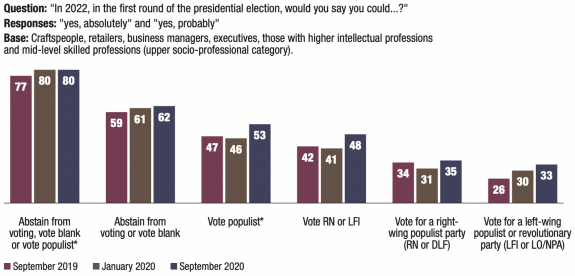

The progress of electoral protest does not spare the upper socio-professional category

Fragile resistance to the populist surge

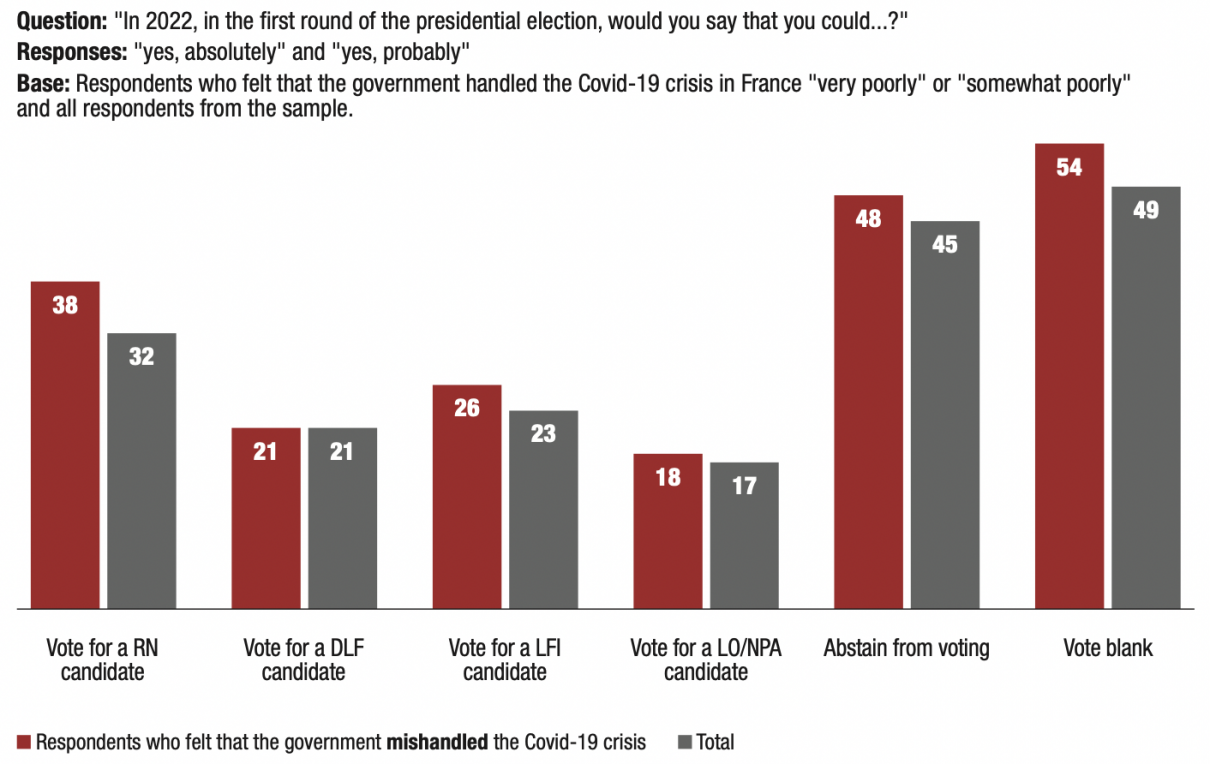

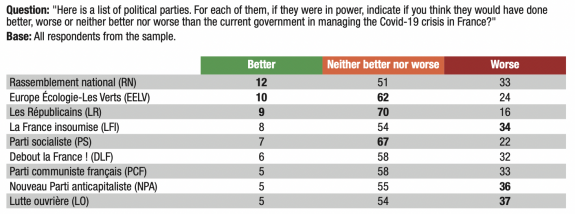

Coronavirus concerns will affect the presidential election

The survey’s questionnaire

DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

Summary

Here are the results of waves 2 and 3 of our electoral protest indicator, launched in September 2019 in view of the upcoming presidential election. Wave 2 of this survey (from 23 to 31 January 2020) took place in the context of a deep social and political crisis mixing the persistence of the Yellow Vests’ protests with demonstrative opposition to the retirement

reform.

The context of wave 3 (from 7 to 11 September 2020) is that of a suspended or postponed conflict, under the effect of the health crisis brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. This wave 3 is a continuation of the unprecedented collective experience of lockdown, between 17 March and 11 May 2020, followed by new spikes in contamination and the fear of a second wave of the pandemic.

As each crisis wave is added to the previous one, the question arises as to how this unrest, unprecedented in its anomic form and intensity, will express itself in the 2022 presidential election. Our indicator aims to help understand and anticipate the outline of this future presidential election, keeping in mind that the largest political event in France is not without European consequences.

The election protest indicator was developed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the survey was administered by the polling institute OpinionWay. For each wave, the questionnaire is administered to a sample of more than 3,000 people who are registered to vote.

The results of wave 1 led to an initial publication (October 2019) available here. Here are the results of wave 3, with which we are also presenting those of wave 2, as its publication was postponed due to the lockdown. All the results of the survey are freely available on our website data.fondapol.org.

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

2022 The populist risk in France

What next for democracy?

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

2019 European Elections. The weight of the political electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Agathe BAILLEUL, Victor DELAGE, Willy DELVALLE, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Dominique REYNIÉ

Agathe BAILLEUL, Victor DELAGE, Willy DELVALLE, Anne FLAMBERT, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Sasha MORINIÈRE, Mélanie ULLMO

Agathe BAILLEUL, Katherine HAMILTON

Julien RÉMY

the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

the polling institute opinionway

Guillaume INIGO (Project Director),

Bruno JEANBART (Deputy Managing Director),

Clément ROYAUX (Project Manager)

October 2020

Abbreviations of the different political parties used in this study

DLF: Debout la France! [Stand Up, France!] • EELV: Europe Écologie-Les Verts [Europe Ecology – The Greens] • FdG: Front de gauche [Leftist Front] •

LFI: La France insoumise [Unsubjugated France] • FN: Front national [National Front] • LO: Lutte ouvrière [Workers’ Struggle] •

LR: Les Républicains [The Republicans] • LREM: La République en marche • NPA: Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste [New Anti-Capitalist Party] •

PCF: Parti communiste français [French Communist Party] • PS: Parti socialiste [Socialist Party] • RN: Rassemblement national [National Rally]

2022, the Populist Risk in France: An indicator of electoral protest in the run-up to the presidential election

The main lessons from waves 2 (January 2020) and 3 (September 2020)

Electoral protest is on the rise.

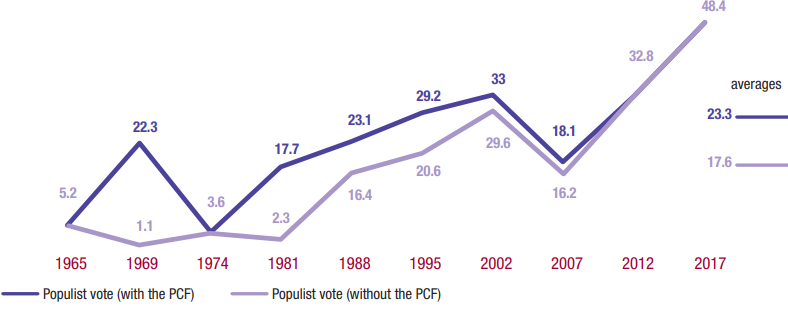

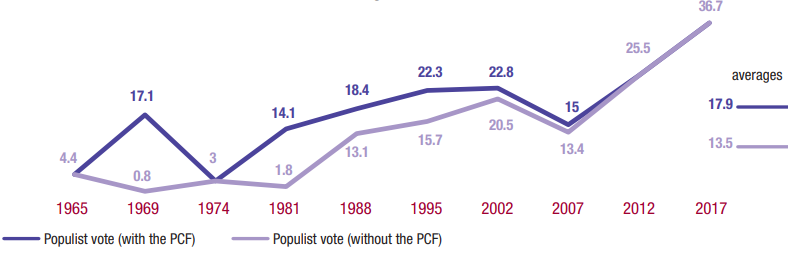

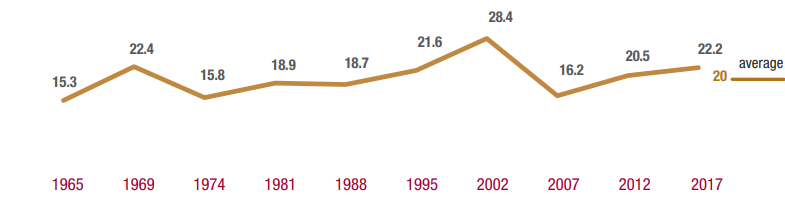

The first graph depicts populist and anti-establishment votes in the first round of the presidential election. The level varies depending on whether or not the PCF vote is included. We offer two datasets: one including the Communist vote, with the exception of Pierre Juquin’s candidacy in 1988, the other not including it. It should be noted that the results were calculated based on the ballots cast as well as the registered voters, which makes it possible to subsequently integrate abstention and blank (or invalid) votes into the same assessment, offering the possibility of an overall assessment of electoral protest from 1965 to 2017.

The populist vote in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017) in % of ballots cast

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

The populist vote in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017) in % of registered voters

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

Selected Candidates: 1965: J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour); 1969: J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC); 1974: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR); 1981: A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF); 1988: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF); 1995: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Cheminade (SP); 2002: B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT); 2007: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT); 2012: Mr Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP); 2017: Mr Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F. Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP).

2022, the Populist Risk in France: an indicator of electoral protest designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

2022, the Populist Risk in France is an indicator of electoral protest, designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The questionnaires are written by the Foundation’s team and the surveys conducted by the polling institute OpinionWay.

To ensure the soundness and interest of the data collected, the questionnaire is each time administered to a sample of 3,000 people registered on the electoral rolls and drawn from a sample of 3,423 people representative of the French population aged 18 and over. The representativeness of the sample is ensured by the quota method, with regard to criteria of gender, age, socio-professional category, category of urban area and region of residence. We carry out one measurement every six months.

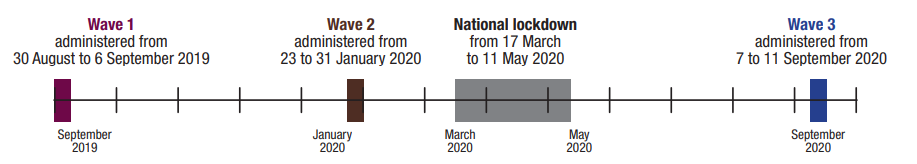

Wave 1 was administered from 30 August to 6 September 2019 to 3,006 people. The presentation and analysis of the results resulted in a publication entitled 2022, le risque populiste en France (2022, the Populist Risk in France), available in French and English on the fondapol.org website.

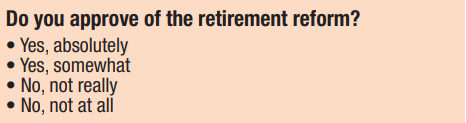

Wave 2 was administered from 23 to 31 January 2020 to 3,055 people. The social and political context was tense at the time, particularly because of the retirement reform. We had therefore added certain contextual questions about the understanding and acceptance of this reform. However, in the weeks that followed, the coronavirus epidemic led us to postpone the publication of the second volume. We have chosen to integrate the main results from the second wave in this edition, together with the results of wave 3.

Wave 3 was administered from 7 to 11 September 2020 to 3,037 people, i.e. after the period of lockdown (17 March-11 May 2020) and at the end of a summer when certain restrictions were lifted. The cycle of opinion in this third wave includes a rise in the number of coronavirus cases in France as well as fears of a second wave of the epidemic. This volume therefore presents the results of the second and third waves. The text and the questionnaire are available in French and English on the fondapol.org website and the complete data are shared on data.fondapol.org.

Wave 1, wave 2, wave 3: with each wave, a context of crisis (to be continued)

The first wave of our barometer (September 2019) was dominated by the Yellow Vests movement, both broad and deep, carrying an unprecedented radicalism. The second wave (January 2020) took place in a context that did not see the destabilising effect of the Yellow Vests dissipate, but in which an opposition to the retirement reform was mixed in and partly reinforced. The third wave then (September 2020) took place in a context where the conflict generated by the two previous crises seemed momentarily suspended or postponed because of the historic health crisis we are experiencing. In fact, during our first three waves, each crisis cycle was added to the previous one, rather than taking its place. Perhaps this is due to the strange nature of this year covered by our three studies, from September 2019 to September 2020.

What the notion of electoral protest covers here

See Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, Pluriel, 2013.

See “Loi du 21 février 2014 visant à reconnaître le vote blanc aux élections“, vie-publique.fr, 24 February 2014.

The question arises as to how these crises, which are superimposed one on top of the other, how this incessant agitation, so disruptive in its dispersed, anomic character, in the intensity of which it has proved capable, will be expressed through the mechanisms of the 2022 presidential election. Our indicator aims to help understand and anticipate the contours of this future presidential election, with potentially European and therefore global consequences.

The Electoral Protest Indicator estimates the potential of different possible electoral protest behaviours: abstention from voting, voting blank, voting for populist parties or candidates. In our indicator, the idea of a protest electorate covers three types of electoral behaviour:

- Voting, or a willingness to vote, for populist parties and candidates (Marine Le Pen, RN, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, LFI and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and the DLF);

- Voting, or a willingness to vote, for parties and candidates on the revolutionary left (LO and NPA).

- Abstention from voting and blank votes.

a) The populist vote

Populist voting includes votes, here meaning the willingness to vote for a populist party. We characterise populist parties using the following elements1:

- An appeal to the This is the heart of populist discourse, which is a fundamental feature of democratic politics. It is reflected in a rejection of representative democracy and an elevation of direct democracy. The populists’ appeal to the people is characterised by demands for the absolute sovereignty of electoral decisions, which are supposed to prevail over everyone and everything, including the principles and rules that form the bases of order and the rule of law. This is the fundamental difference between liberal democracy and populism, which sometimes calls itself “illiberal democracy.”

- An anti-elite discourse, based on a summary social differentiation between a “people”, unified and mythologised, and political, economic, intellectual, and media “elites”, disqualified as forming an oligarchy (“La Caste”, ).

- A narrative and an organisation marked by an authoritarian culture, found in a form of party built around an omnipresent leader.

- A nationalist programme.

- A xenophobic vision.

- A rhetorical style notably characterised by exaggeration, simplification, disqualification of the opponent, a tendency to conspiracy explanations, etc.

Starting with the 4th criterion, we see a separation between two expressions of populism: the largely dominant expression that has met with major electoral successes deploys nationalism through xenophobia, denouncing not only the ruination of the people by the elites, but also by foreign people, immigrants. Xenophobic populism is most often right-wing, even if it exists on the left in Europe. In France, left-wing populism is represented by Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his party La France insoumise. He does not want to or cannot make a lasting commitment to xenophobia, despite a few steps in that direction. He has paid the electoral price as he is outpaced by the right- wing populism of Marine Le Pen and the RN.

Lastly, wenotearhetorical style characterised in particular by exaggeration, simplification, disqualification of the adversary, a tendency to conspiracy theories, etc.

As the case of Nicolas Dupont-Aignan and his DLF party is uncertain, sitting as it does between the sovereigntist right and the populist right, we have made the choice to take it into account in the calculation of the populist electoral potential. In 2017, during the two-rounds of the presidential election, the president of Debout la France had made an agreement with Marine Le Pen’s government after which he would have become her prime minister in case of the election of the candidate of the Front national.

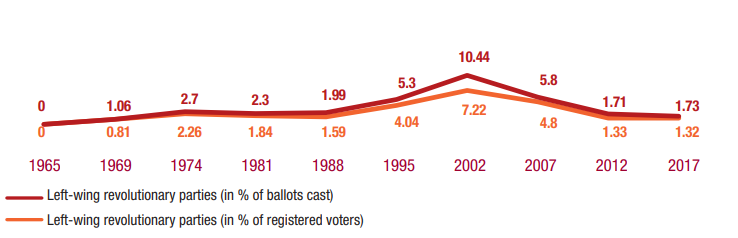

Fundamentally, it is important to distinguish between populist parties and parties from the revolutionary left. In fact, some parties put forth an anti-establishment vision without the codes of populism, instead speaking in terms of internationalism and social classes. They claim to speak for the working class, possibly extended to include all “working people,” but not “the people” writ large. Indeed, they do not recognise themselves in the principles and mechanisms of electoral democracy that populists, on the contrary, claim they wish to implement. In France, these are the far-left Trotskyite parties. However, here, without dismissing these differences, we chose to integrate the far-left vote into the calculation of the populist electoral potential so as not to unnecessarily increase the complexity of the indicator, bearing in mind, on the one hand, that the electoral weight of this anti-establishment left is marginal, with two exceptions in 2002 (10.4% of the votes cast and 7.2 percent of registered voters) and in 2007 (5.8 percent of the vote cast and 4.8 percent of registered voters), and, on the other hand, that the respondents who recognise themselves in the parties of this anti-establishment left and who vote for their candidates testify in our study to a great willingness to vote for populist parties, no doubt animated by their anti-systemic strategy.

b) Abstention

There are varied forms of abstention. Notably, abstention may be systematic or intermittent. The reasons for abstention are diverse: expression of disinterest, inability to choose, expression of a rejection of the political choices or even more general discontent. Since only some abstentions are a form of electoral protest, it is difficult to assess this from electoral results. However, here we choose to include abstention in the calculation of the potential for electoral protest because we are asking people about their willingness to abstain from voting in 2022. We will also note the similarity between the abstention curve and that of the protest vote.

c) The blank vote

Until 2014, the census of blank votes was combined with invalid votes (null votes). The category was called “blanks and invalid”. Blank votes have been counted separately since the law of 21 February 20142. They were listed separately for the first time in the European elections in June 2014. The 2017 presidential election was the first where the new blank vote system was applied. Here, we choose to include blank voting in the calculation of the potential for electoral protest because we are asking people about their willingness to vote blank in 2022.

Vote for revolutionary left-wing parties (excluding the PCF) in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017)

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

Abstentions during the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017) in % of registered voters

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

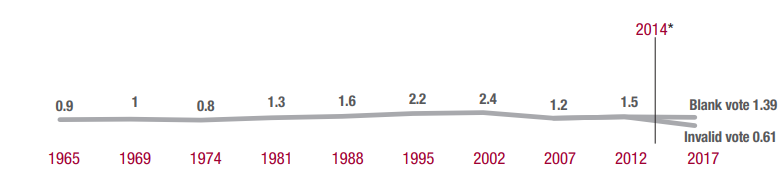

Blank and invalid votes in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017) in % of registered voters

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

* Since the law on 21 February 2014, the census of blank votes has no longer been combined with invalid votes (null votes). The 2017 presidential election was the first where the new blank vote system was applied.

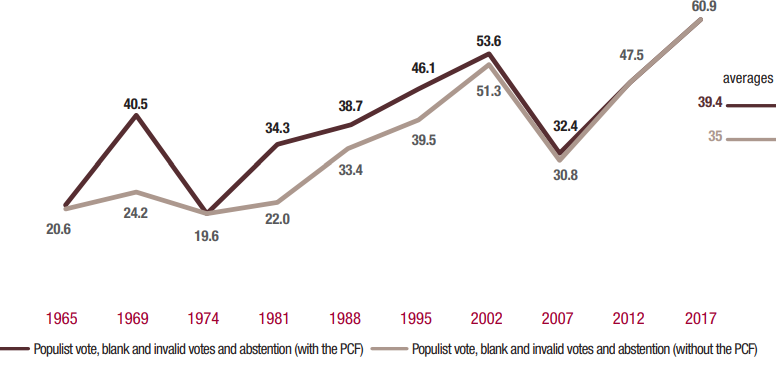

Electoral protest in the first round of the presidential election (1965-2017) (the populist vote, blank and invalid votes and abstention) in % of registered voters

Source :

Compilation of election results by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Ministry of the Interior).

Selected Candidates: 1965: J.-L. Tixier-Vignancour (Comités Tixier-Vignancour); 1969: J. Duclos (PCF), A. Krivine (LC); 1974: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), B. Renouvin (NAR), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Krivine (FCR); 1981: A. Laguiller (LO), G. Marchais (PCF); 1988: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), A. Lajoinie (PCF); 1995: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), R. Hue (PCF), J. Cheminade (SP); 2002: B. Mégret (MNR), J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), R. Hue (PCF), D. Gluckstein (PT); 2007: J.-M. Le Pen (FN), A. Laguiller (LO), O. Besancenot (LCR), M.-G. Buffet (Gauche populaire et antilibérale), G. Schivardi (PT); 2012: M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FdG), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP); 2017: M. Le Pen (FN), N. Dupont-Aignan (DLF), F. Asselineau (UPR), J.-L. Mélenchon (FI), P. Poutou (NPA), N. Arthaud (LO), J. Cheminade (SP).

Presidential election: the populist temptation remains

Estimating the electoral potential of a protest climate

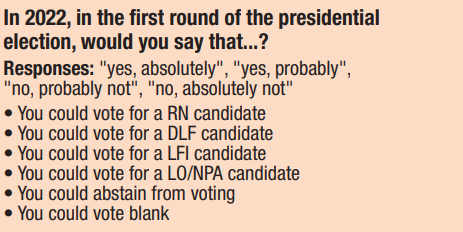

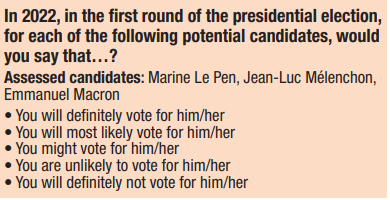

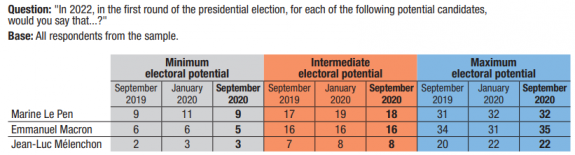

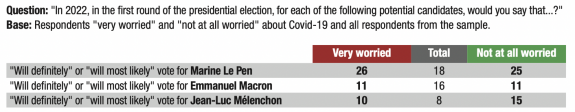

For the upcoming first round of the 2022 presidential election, the electoral potential of the parties and candidates is estimated based on the following question:

The responses provided allow us to define electoral potential on a three-point scale:

- minimum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having responded “you will definitely vote for him/her”;

- intermediate electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her” or “you will most likely vote for him/her”;

- maximum electoral potential, which reflects the proportion of respondents having chosen “you will definitely vote for him/her”, “you will most likely vote for him/her” or “you might vote for him/her”.

We must distinguish here between the electoral potential of a party or a candidate, which is the willingness declared by the interviewees to vote for this party or candidate, and the potential for electoral protest, which refers to the willingness declared by the interviewees to adopt electoral protest behaviour (abstention from voting, voting blank, or voting in favour of populist or anti-establishment parties or candidates).

As such, our indicator defines the electoral potential of populist candidates and compares them with the electoral potential of Emmanuel Macron.

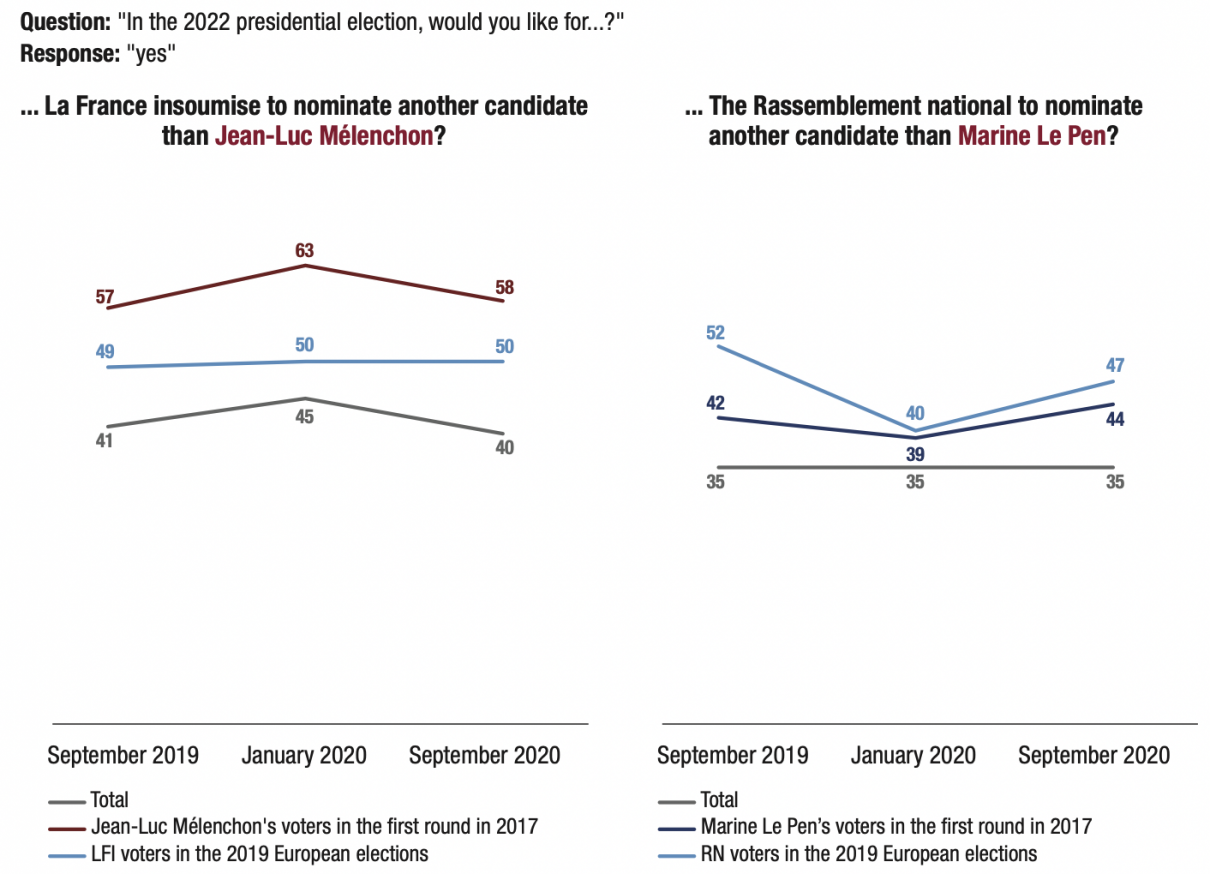

Wave 2 of our indicator (January 2020) recorded the effects of the crisis generated by opposition to the retirement reform. We notably observed variation in Emmanuel Macron’s electoral potential for the first round of the presidential election. Wave 3 (September 2020), conducted in the context of the health crisis, shows a significant recovery.

Memo for the reader: in September 2019, regarding Marine Le Pen’s candidacy, 9% of respondents replied that they “will definitely” vote for her; 17% replied that they “will definitely” or “will most likely” vote for her; 31% replied that they “will definitely”, “will most likely” or “might” vote for her.

The electoral potential of Emmanuel Macron is recovering. Those of Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon remain stable, at a higher level for Le Pen

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

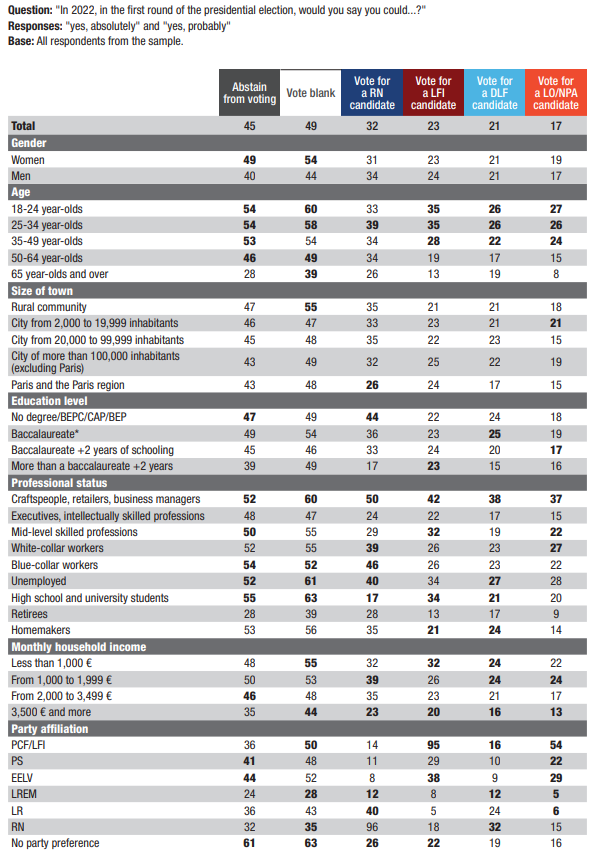

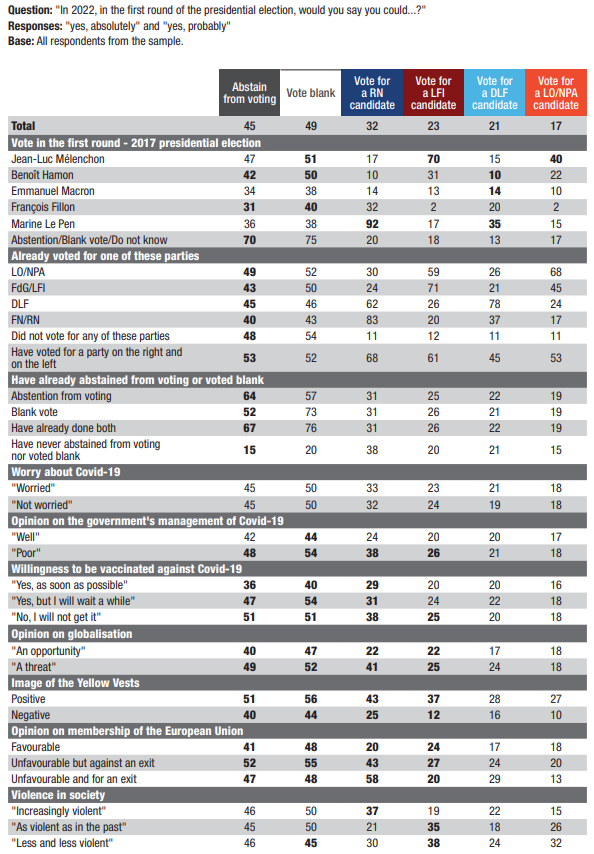

The hotbeds of electoral protest potential

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

The hotbeds of electoral protest potential (continued)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

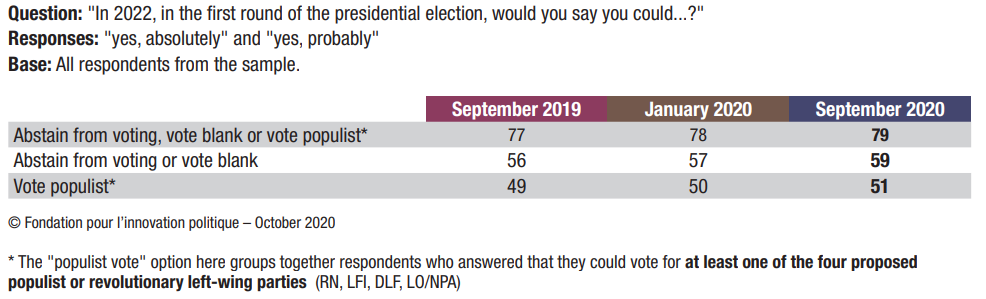

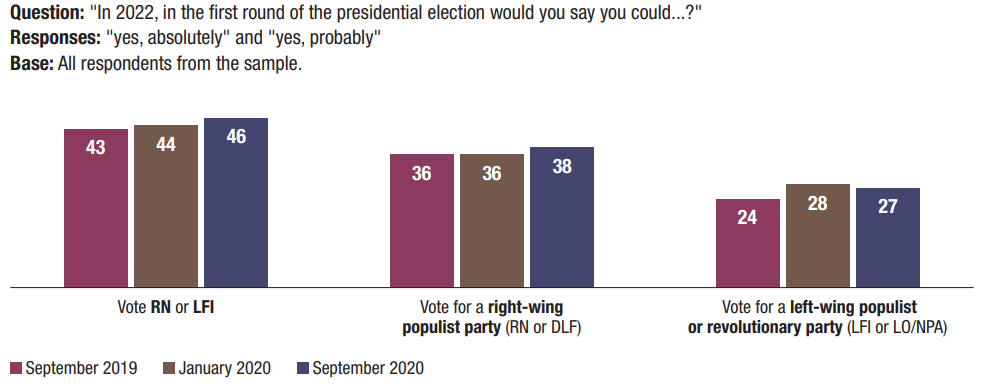

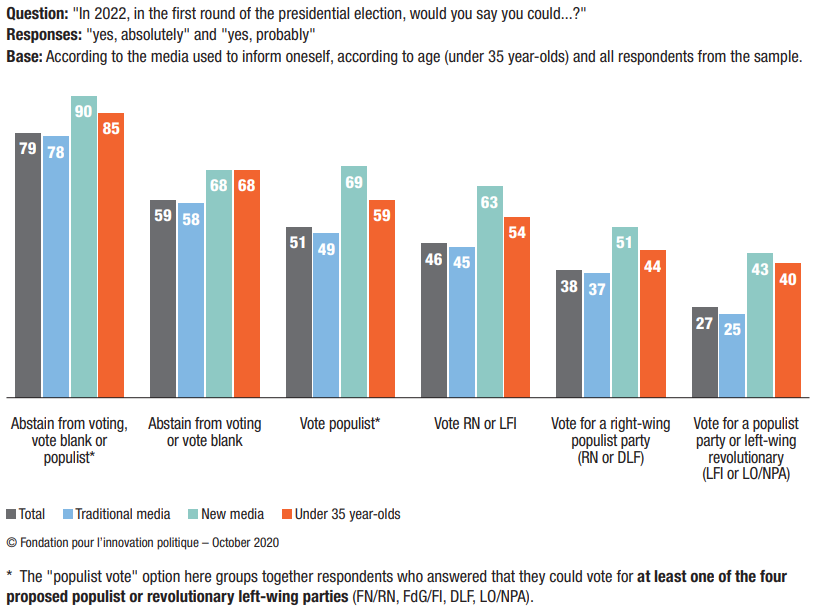

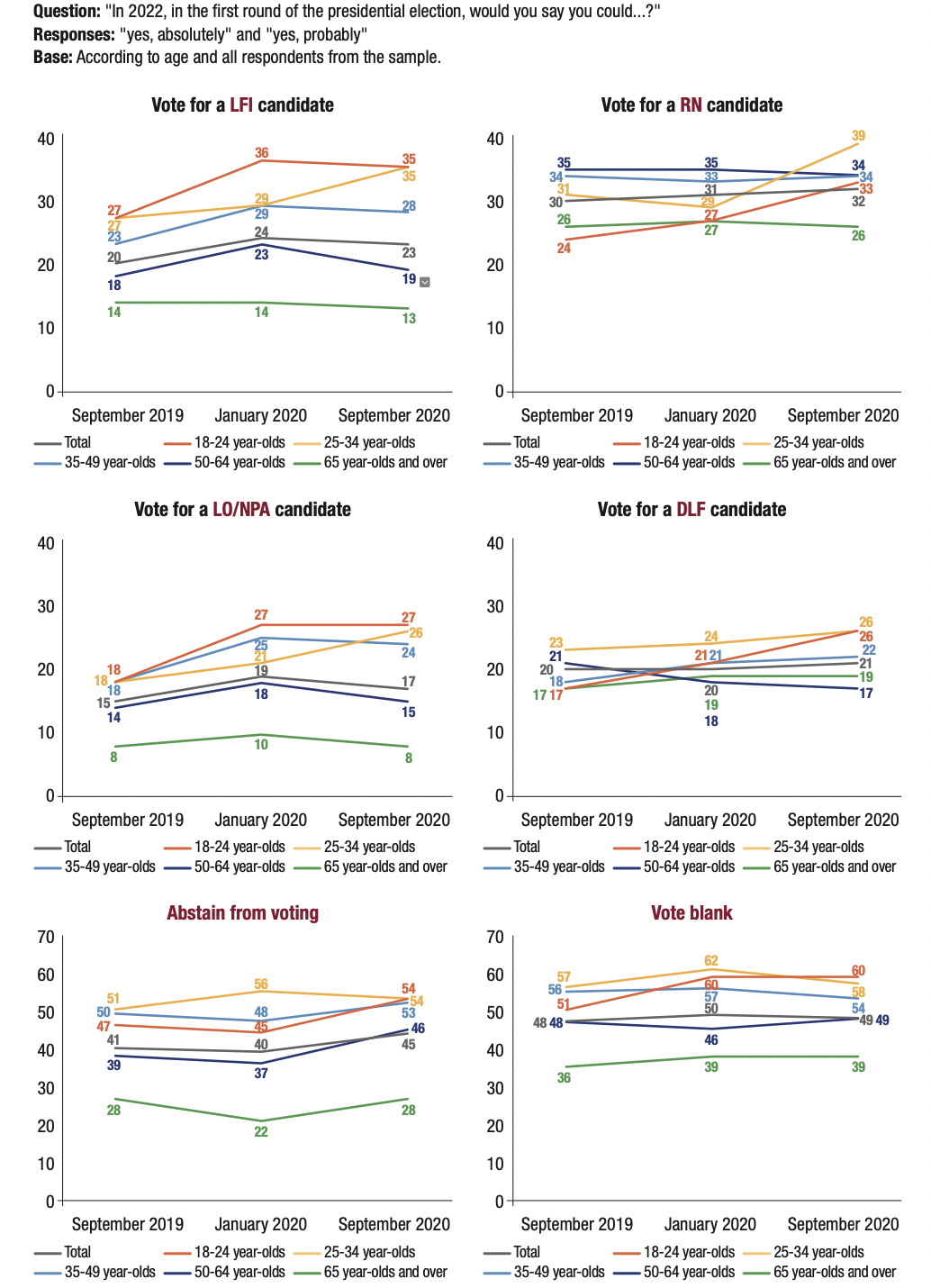

In September 2020, most voters (79%) still envisage protest behaviour for 2022

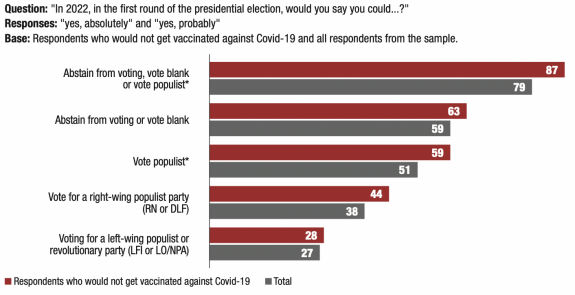

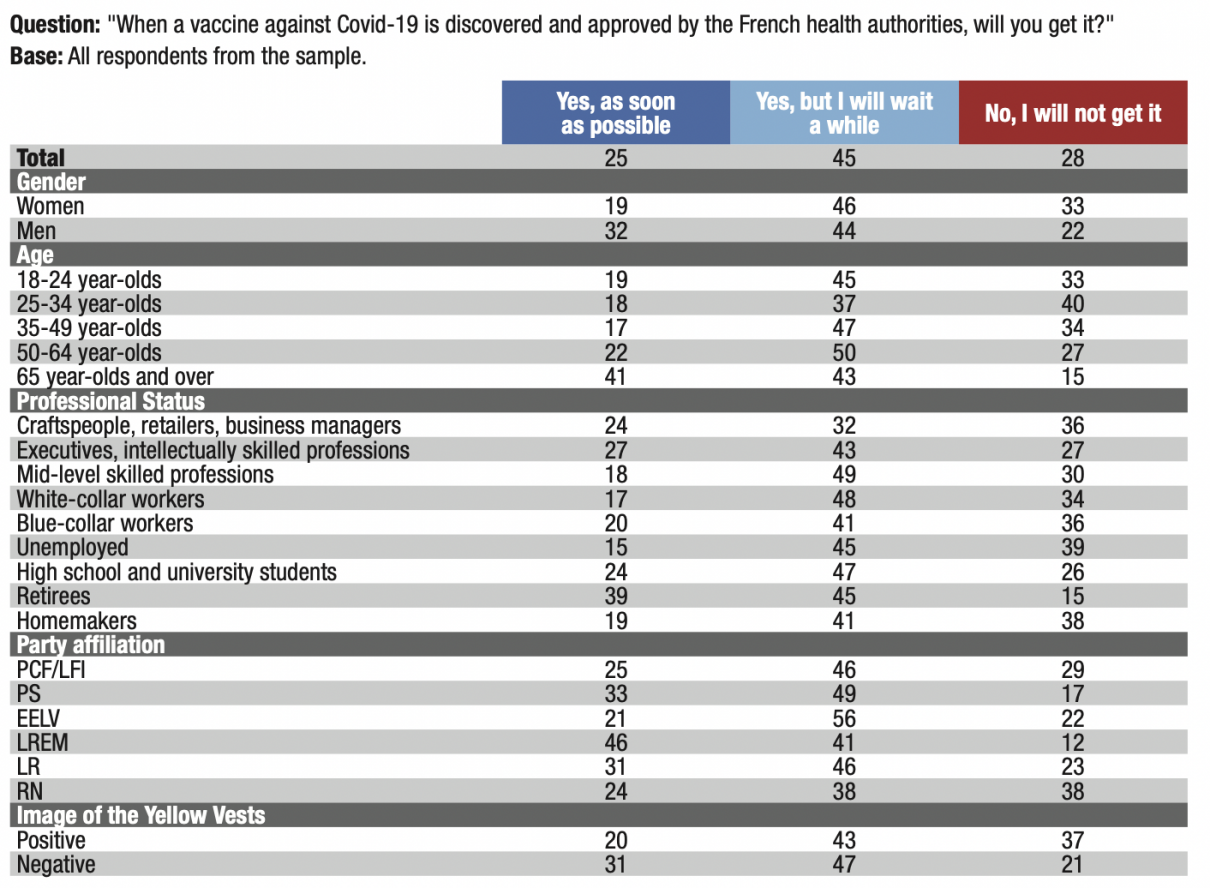

The third wave of our indicator shows that most respondents (79%) say they are willing to opt for one of the tested behaviours relevant to electoral protest, i.e. voting for RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA, abstaining from voting or voting blank. The electoral protest potential strictly speaking concerns 51% of voters who say they are willing to vote for at least one of the RN, LFI, DLF or LO/NPA candidates. Furthermore, a large majority of respondents (59%) said they could abstain from voting or vote blank in the first round of the 2022 presidential election.

September 2019-September 2020: evolution of the electoral protest potential for the first round of the 2022 presidential election

As we observed in September 2019, the attraction capacity of right-wing populism is much greater than that of left-wing populism. In September 2020, 38% of voters plan to vote for the RN or DLF, compared to 27% for LFI or LO/NPA.

The surge of the populist vote accompanies its right- wing nature. In addition, 46% of respondents could vote for at least one of the two major populist parties, the RN and LFI.

Since September 2019, the willingness to vote for populist parties has been on the rise

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

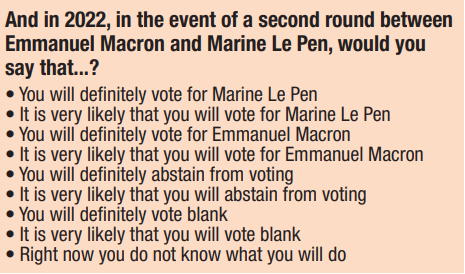

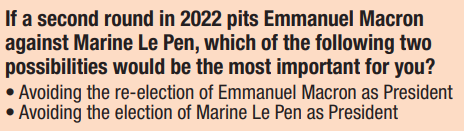

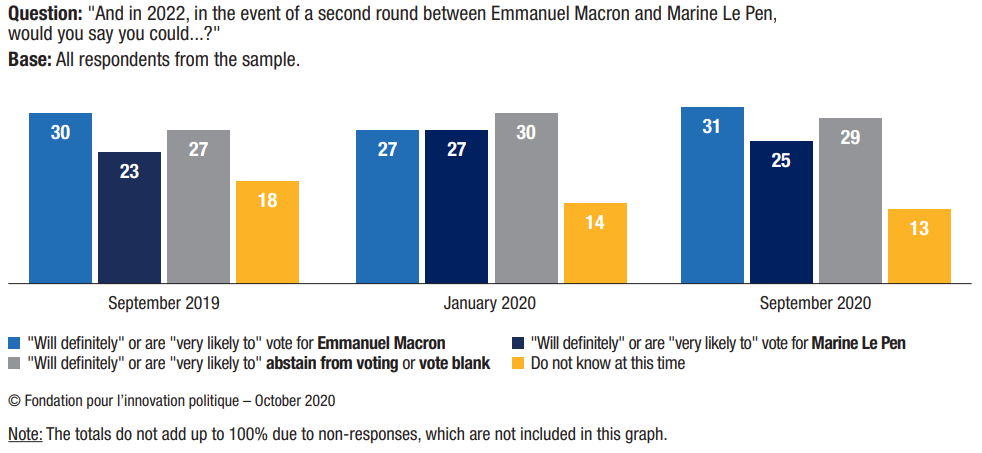

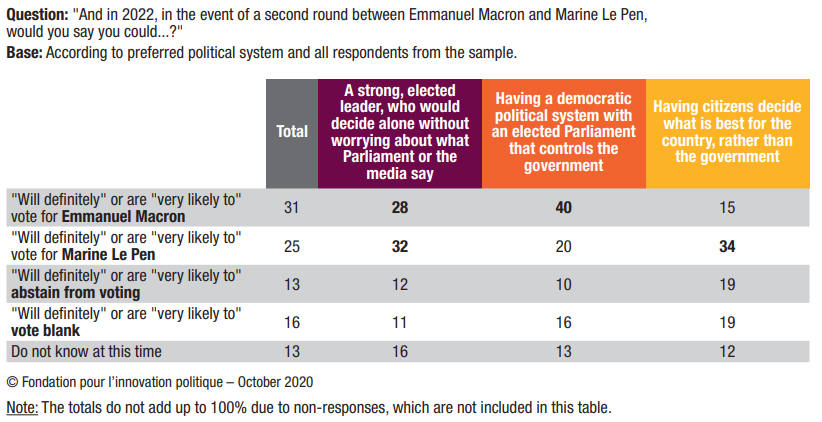

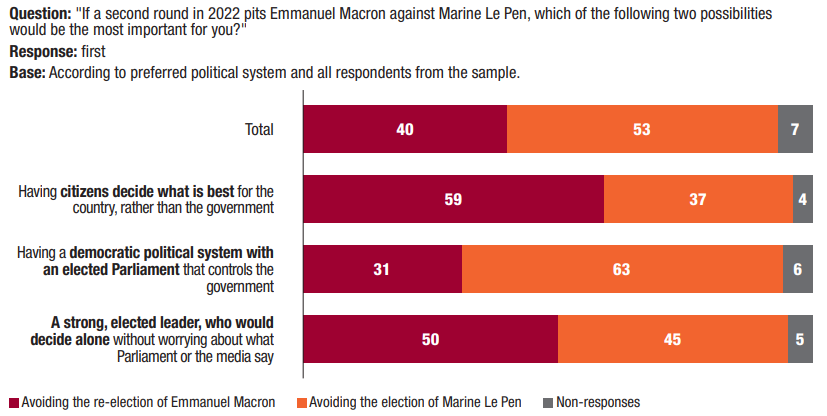

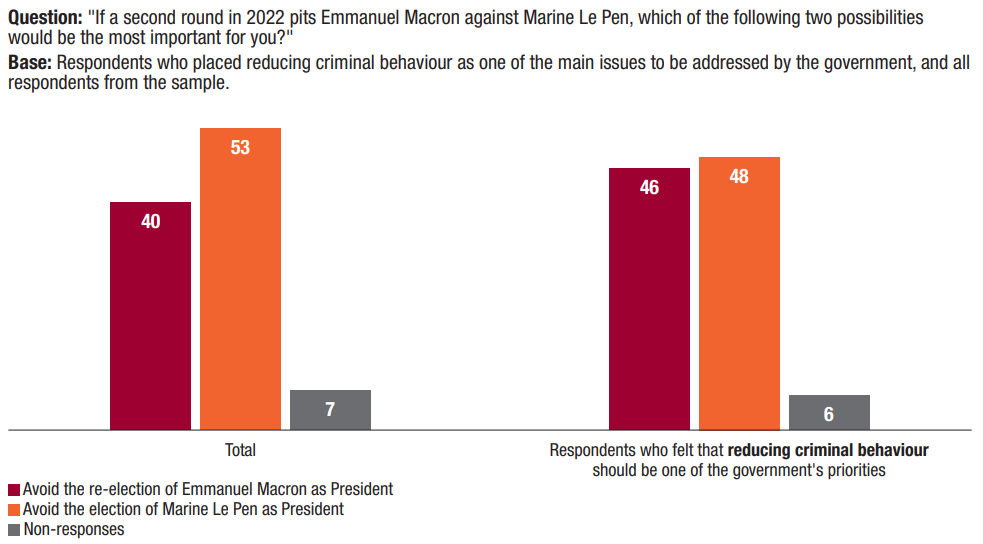

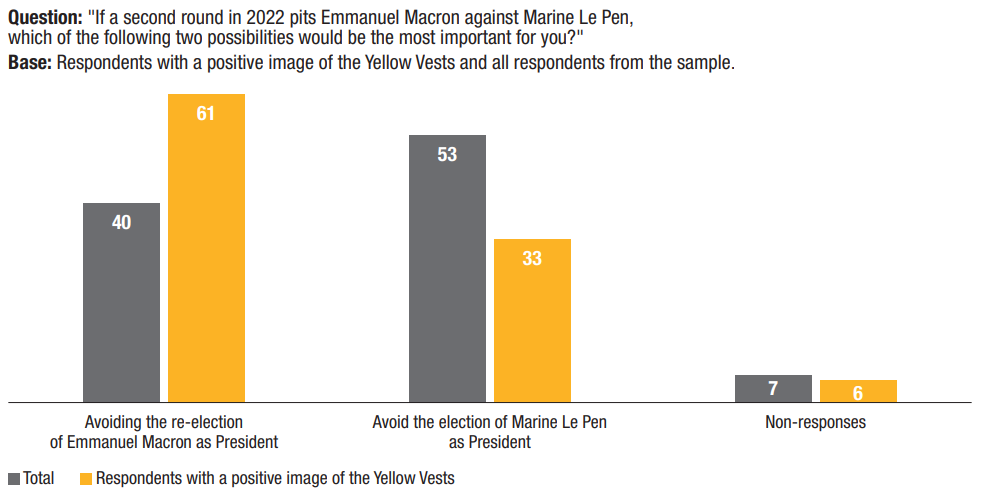

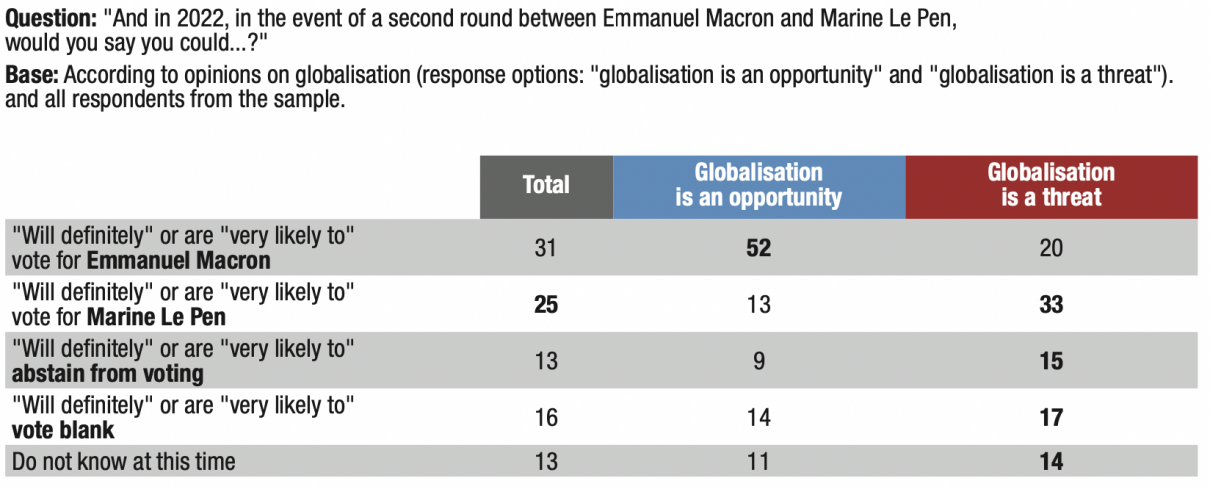

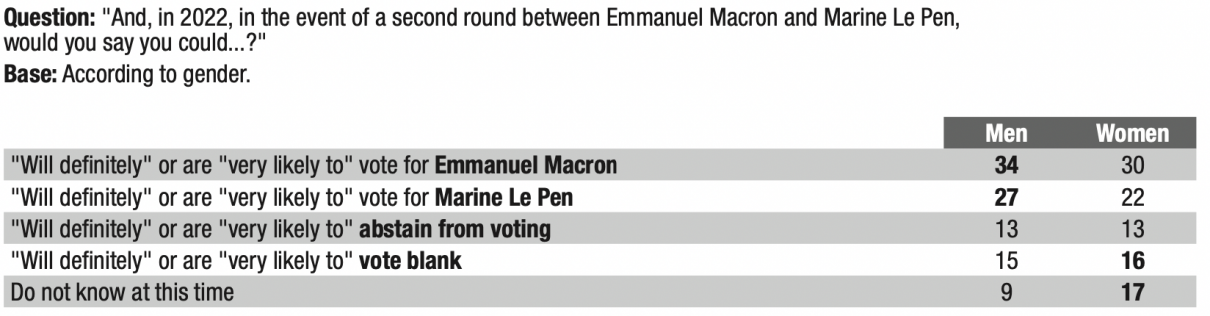

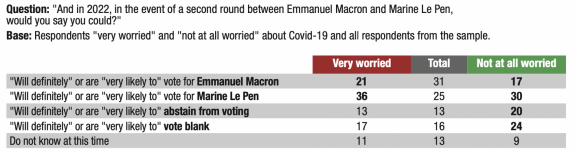

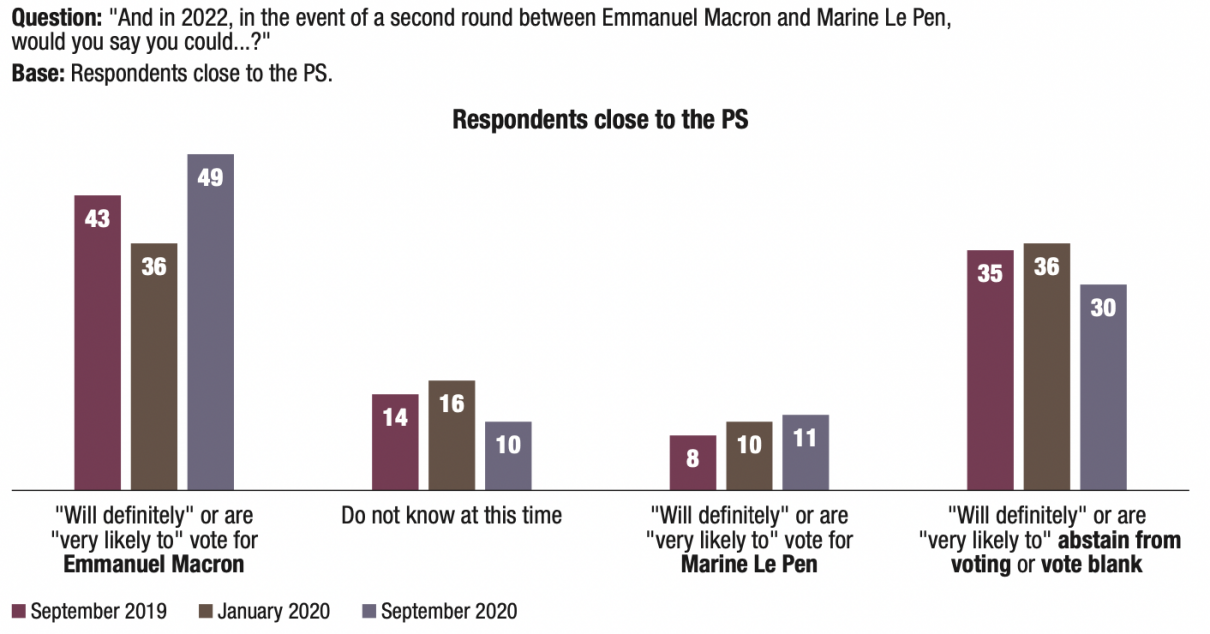

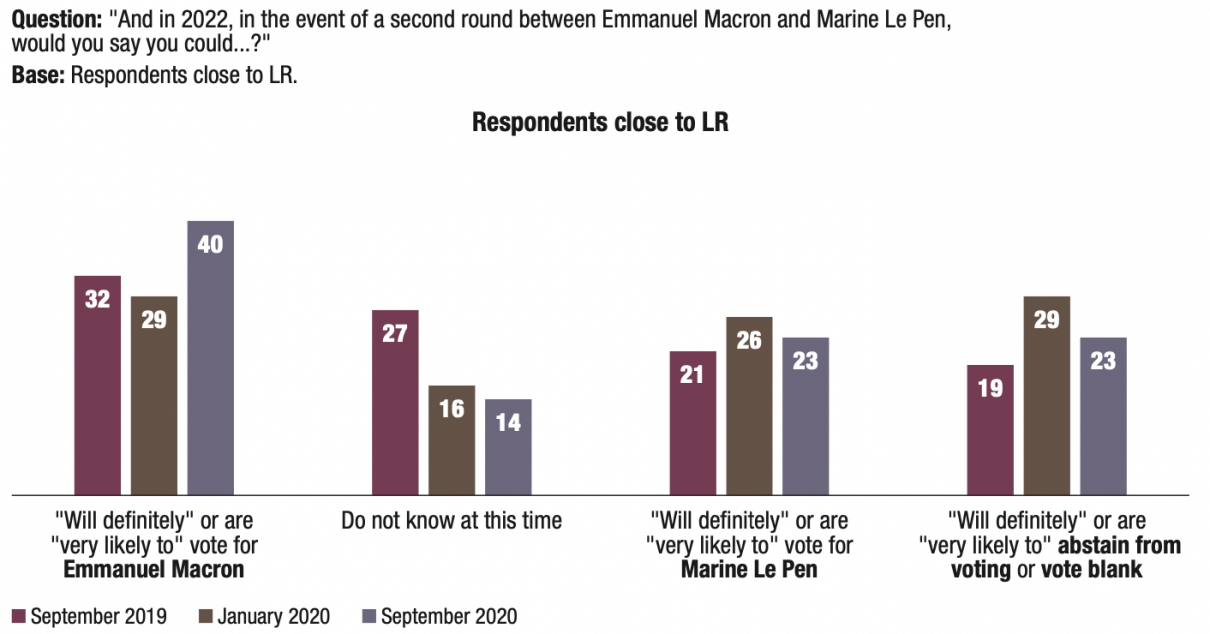

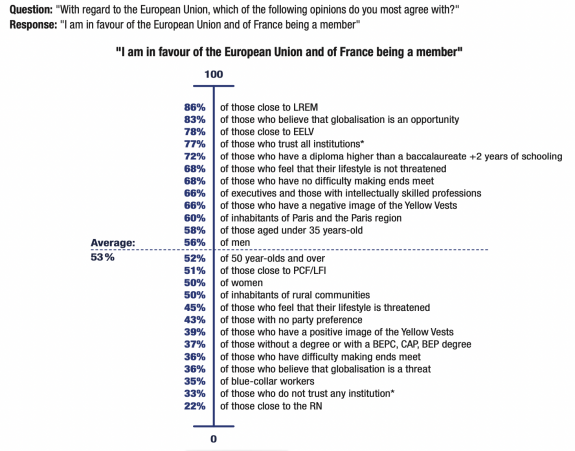

Clearly weakened in wave 2, Emmanuel Macron finds a more favourable position in wave 3 in the event of a second round against Marine Le Pen

Between wave 1 (September 2019) and wave 2 (January 2020), the willingness to vote for Marine Le Pen increased by 4 points (from 23 to 27%). Conversely, the willingness to vote for Emmanuel Macron decreased by 3 points (from 30 to 27%). The two candidates were therefore on a level playing field. Wave 3 (September 2020) is marked by a clear recovery in the readiness to vote for the current President in this configuration. The gap again becomes favourable to Emmanuel Macron since 6 points separate him from Marine Le Pen (31% versus 25%).

Anticipated changes in electoral behaviour during the second round of the 2022 presidential election (September 2019-September 2020)

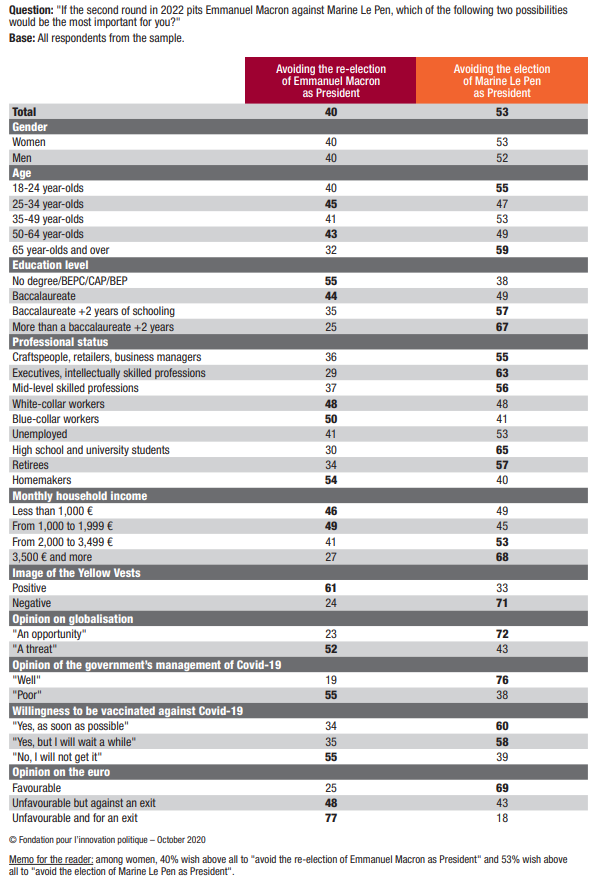

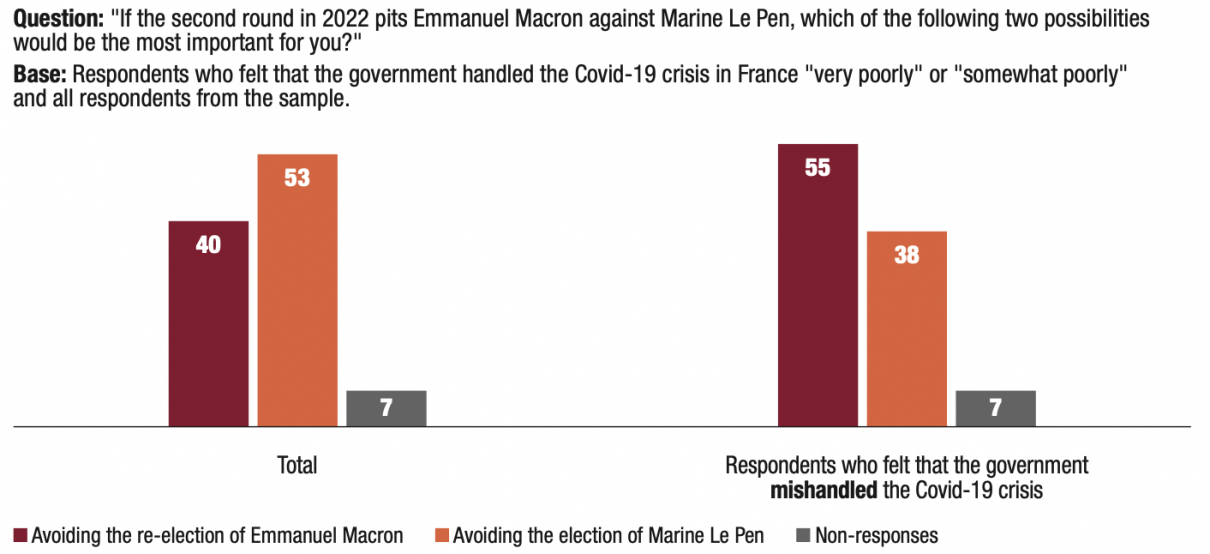

In addition to the gap between the electoral potential of Emmanuel Macron and that of Marine Le Pen, which widens between January and September 2020, at the same time, the desire to above all else avoid the election of Marine Le Pen to the presidency is progressing significantly.

This was one of the particularly striking facts of wave 2 (January 2020): the proportion of those questioned who said they wanted to avoid Marine Le Pen’s election as President became a minority (48%). On the other hand, an approaching proportion (45%) said they wanted to avoid the re-election of Emmanuel Macron. Wave 3 (September 2020) saw the desire to prevent the leader of the RN from acceding to the Elysée Palace increase by 5 points and become a majority (53%), while the proportion of respondents saying they wanted to avoid Emmanuel Macron’s re-election fell by the same amount, to 40%.

What would be more important: avoiding the re-election of Emmanuel Macron or the election of Marine Le Pen?

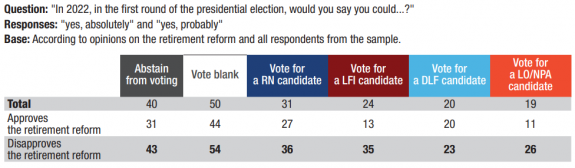

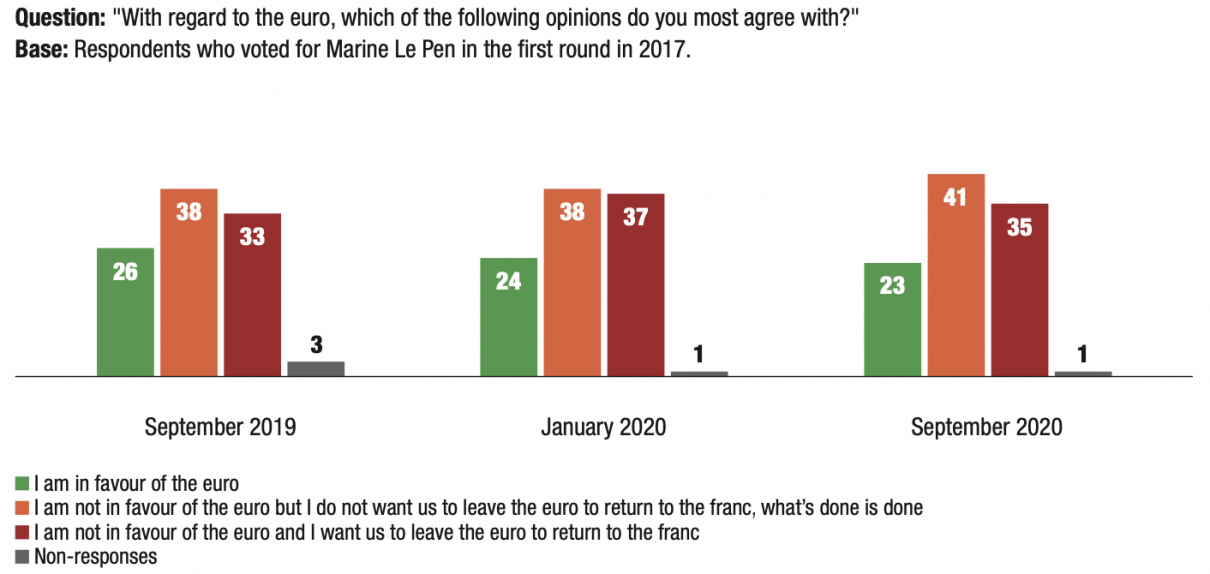

Opposition to the retirement reform favoured a merging of both left and right-wing populist electorates

The political and social climate at the beginning of 2020 remained marked by the Yellow Vests movement. However, the context was further aggravated by the contestation of the retirement reform. Wave 2 of our barometer (January 2020) reveals a high potential for electoral protest among respondents who do not approve of the reform: 89% of them said they could abstain from voting, vote blank, vote populist or vote for the extreme left in the first round of the 2022 presidential election. Opposition to the retirement reform thus pushes a further proportion of the electorate into protest, particularly on the left: 35% of those opposed to the reform said they could vote for a LFI candidate, compared with 24% on average, and 26% said they could vote for an LO/NPA candidate, compared with 19% on average.

Memo for the reader: among the respondents who said in January 2020 that they approved of the retirement reform, 31% said they could abstain from voting in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, 44% could vote blank, 27% could vote for a RN candidate, 13% could vote for LFI, 20% could vote for DLF and 11% could vote for LO/NPA.

There was a strong pull to a protest vote among opponents of the retirement reform (January 2020)

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

To the question “Which of the following political parties do you feel closest to, or least distant from?”, Le parti communiste français (PCF) and La France insoumise (LFI) have been combined into one response option (PCF/LFI). For the other questions, only LFI is concerned.

In this context of social contestation, our indicator highlights a process of merging populist left- and right-wing electorates. In January 2020, voters close to parties on the extremes of the political spectrum rejected this reform: 90% of PCF/LFI3 sympathisers and two-thirds (65%) of voters close to the RN said they were opposed to it. Most PCF/LFI (91%) and RN (82%) supporters said they understood the strikers’ discontent.

Support for the methods of opponents of the reform was broadest among PCF/LFI respondents (74%) but also concerned almost half of RN supporters (48%). These figures are well above average: almost three- quarters (74%) of French respondents understood the dissatisfaction, but only one-third (32%) approved of the methods they used.

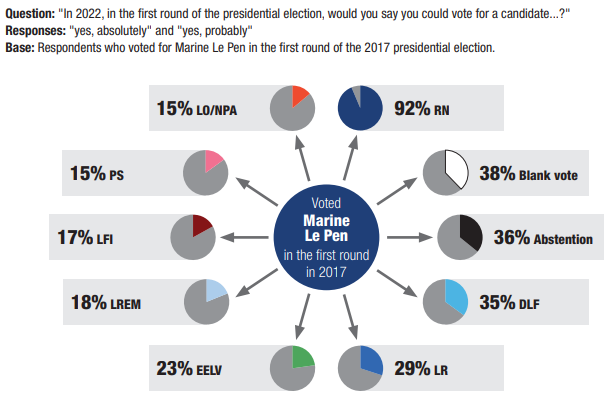

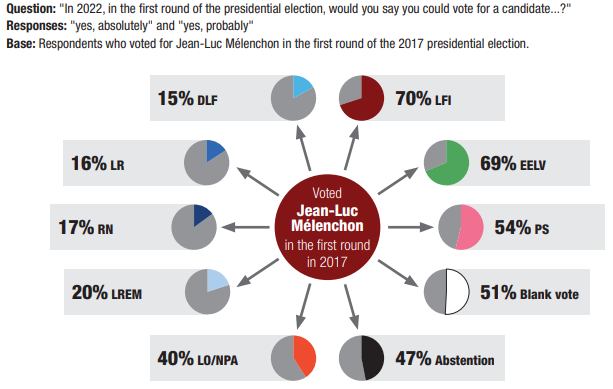

Opposition to the retirement reform has made the protesting electorates more porous. Thus, one in five voters close to the RN (21%) had a positive image of LFI’s attitude during the social movements prompted by the reform. A comparable proportion (22%) of those who said they were close to the PCF/LFI had a positive image of the RN’s action during these demonstrations. Wave 3 (September 2020) shows the persistence of a porosity between right-wing and left-wing populism, despite the suspension of the retirement reform. Thus, 17% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters in the 2017 presidential election say they are ready to vote for a RN candidate in the first round in 2022. The same is true (17%) for Marine Le Pen’s voters in 2017, who respond that they could vote for a LFI candidate. Lastly, 13% of those who voted for Jean- Luc Mélenchon in 2017 say they “will definitely” or are “very likely to” vote for Marine Le Pen in the event of a second round against Emmanuel Macron in 2022.

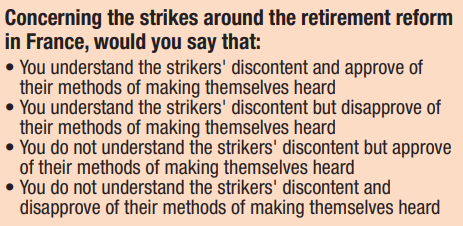

The willingness to abstain from voting and voting blank remains a basic trend

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), “Tsunami dans un verre d’eau, Regard sur le vote Europe Écologie-Les Verts aux élections municipales de 2014 et de 2020 dans 41 villes de plus de 100 000 habitants“, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, July 2020.

Abstention did not spare the presidential election, as we saw in 2017, where it reached historic levels in the first round (22.23%) and even more so in the second (25.44%), although it did oppose Emmanuel Macron to Marine Le Pen. The same was true for the blank vote, which reached a very high level in the second round (8.52% of voters).

The municipal elections of 2020 took place in unprecedented circumstances largely brought on by the epidemic crisis. A historic abstention rate was recorded in these elections, in both the first (55.34%) and second rounds (58.40%)4. Although these elections are reputed to be the type of ballot – along with the presidential election5 – for which the French are most mobilised, these municipal elections had an abstention rate in the second round that was 8.5 points higher than that of the 2019 European elections (49.88%), which are generally of less interest to the French.

While the exceptional conditions surrounding this election and the fear of contracting the coronavirus played a role in this massive abstention, our indicator shows a fundamental phenomenon: almost half (45%) of the voters questioned in our survey responded that they could abstain from voting in the first round in 2022, i.e. that they “will definitely” (15%) or are “very likely to” (30%). This is a significant increase if we consider the level recorded in January 2020 (40%) and September 2019 (41%). Half of the voters (49%) say they would be willing to cast a blank ballot, confirming the level recorded (48%) in September 2019.

From September 2019 to September 2020, the willingness to abstain from voting increased

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

The high readiness to abstain from voting declared in September 2020 for the 2022 presidential election partly reflects a difficulty in anticipating future electoral behaviour today, but it is also the expression of a lack of interest in politics. This disinterest can be temporary or lasting. In this case, it may announce a withdrawal from electoral life motivated by disappointment or discontent.

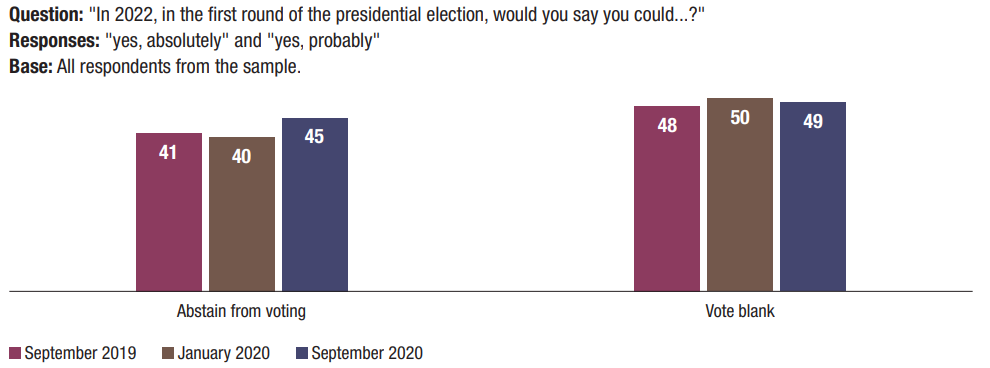

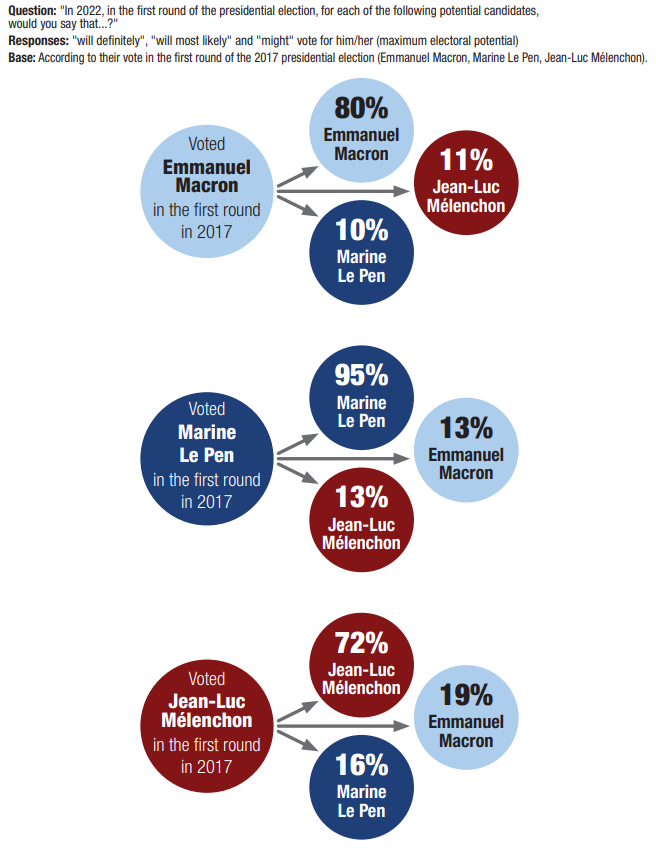

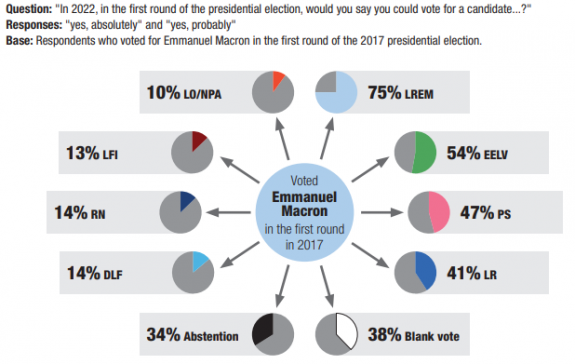

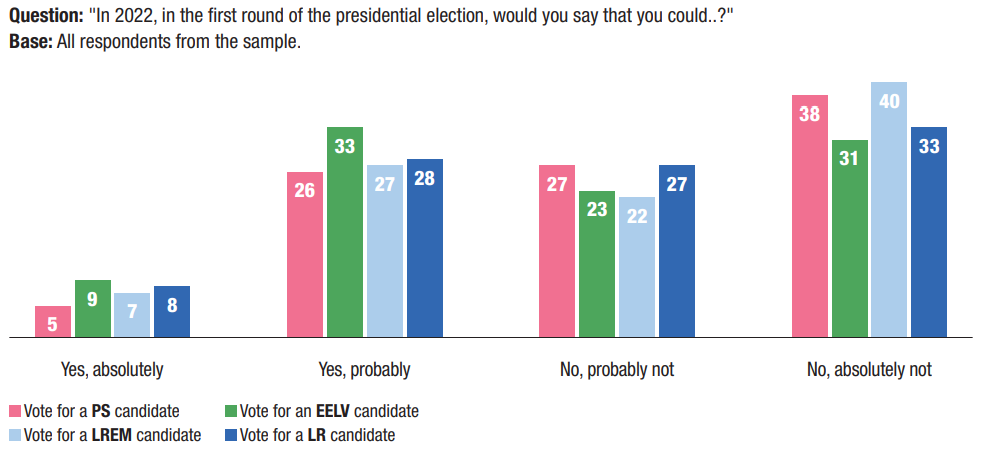

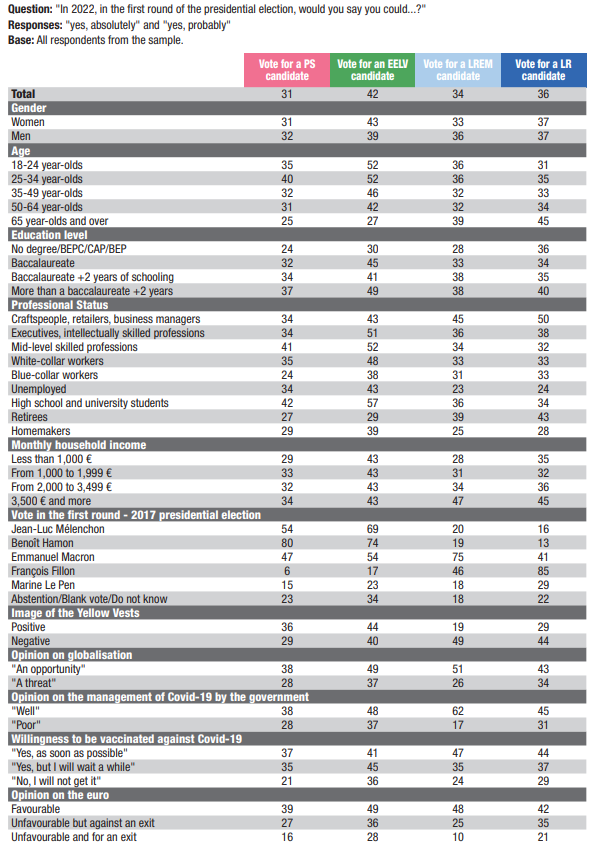

For 2022, voters do not reject PS, LREM, LR and, even less so, EELV candidacies

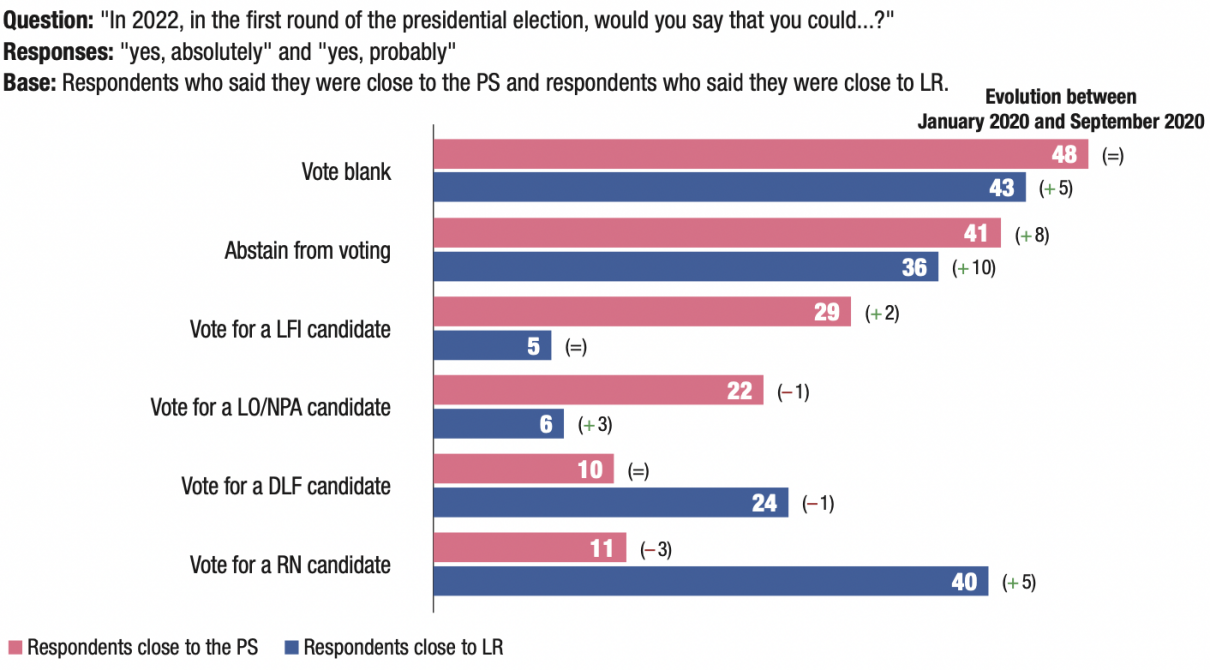

In wave 3 (September 2020), we tested the willingness of voters to vote in the first round of the next presidential election for the following parties: PS, EELV, LREM and LR. However, at this stage, we were unable to indicate the names of candidates due to the degree of uncertainty and the range of possibilities.

Almost three-quarters of respondents (72%) said they could vote for at least one of these four parties. In detail, more than one-third (34%) of citizens say they could vote for an LREM candidate. This is 3 points more than for a PS candidate (31%), 2 points less than for an LR candidate (36%), and 8 points less than for an EELV candidate (42%).

The potential behaviour of the 2017 electorate by Emmanuel Macron, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Memo for the reader: among the respondents who voted for Emmanuel Macron in first round of the 2017 presidential election, 80% said they “will definitely”, “will most likely” or “might” vote for him in the first round in 2022, 11% plan to vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon and 10% for Marine Le Pen.

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

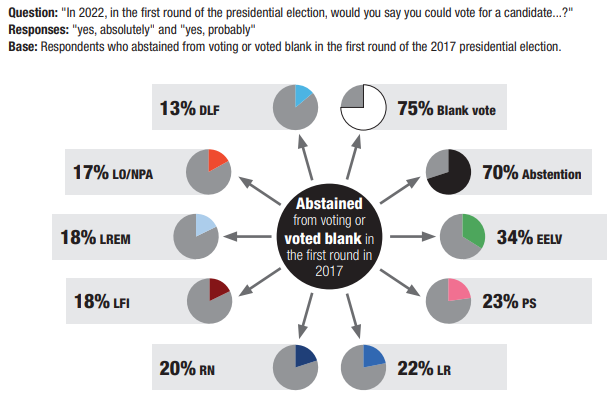

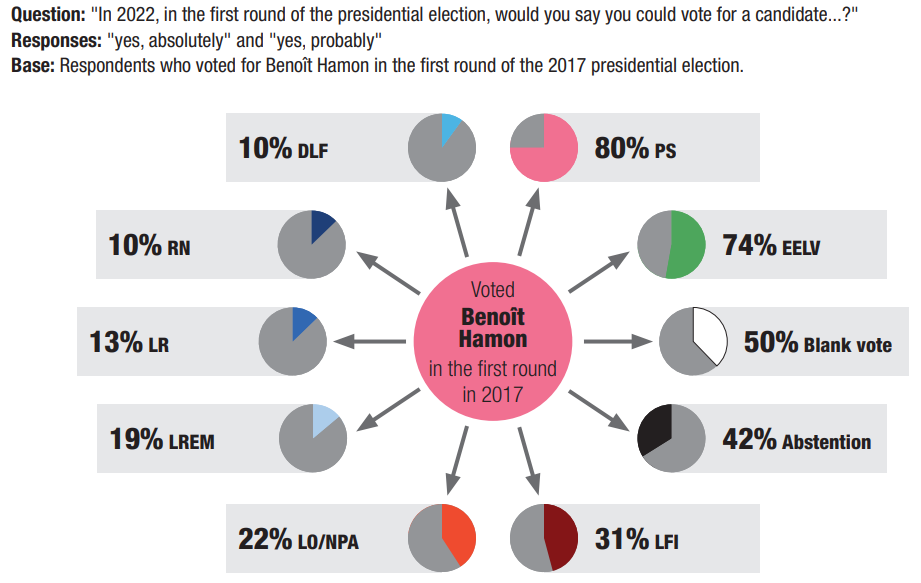

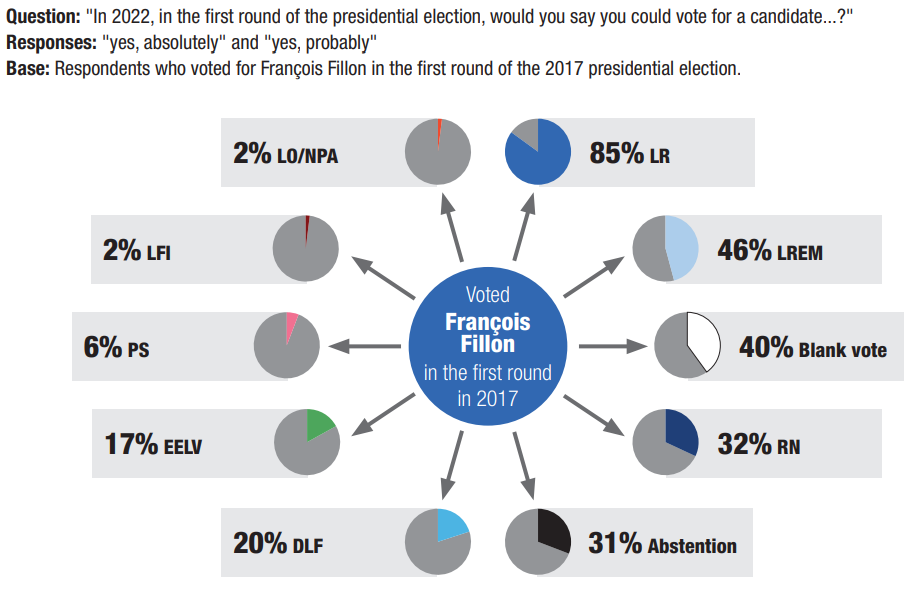

The potential behaviour of 2017 electorates in 2022

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Memo for the reader: among the respondents who voted for Emmanuel Macron in the first round of the 2017 presidential election, 75% said they could a LREM candidate, 54% could vote EELV, 47% could vote PS, 41% could vote LR, 38% could vote LR, 38% could vote blank, 34% could abstain from voting, 14% could vote DLF, 14% could vote RN, 13% could vote LFI and 10% could vote LO/NPA.

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

The potential behaviour of 2017 electorates in 2022 (continued)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

The potential behaviour of 2017 electorates in 2022 (continued)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% as respondents were asked to comment on each candidate and not to choose from them.

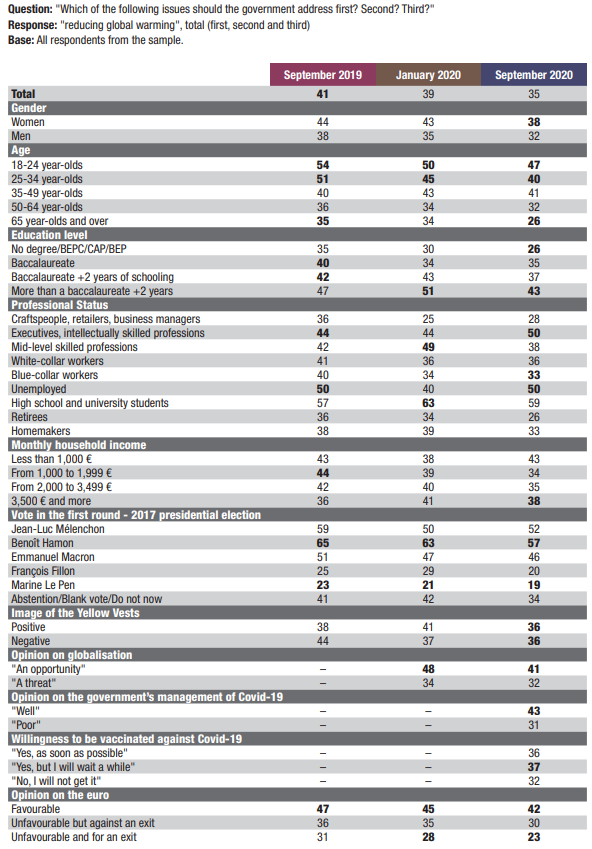

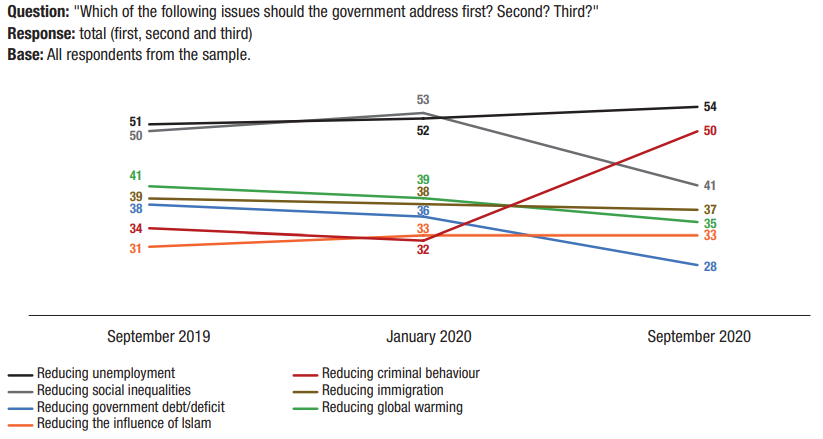

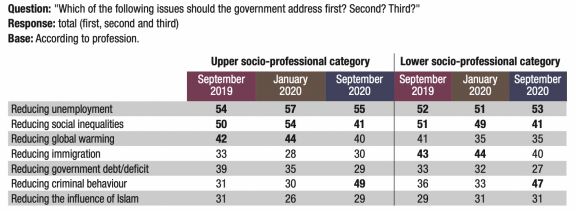

For the question “Which of the following issues should the government address first? Second? Third?”, respondents were asked to rank (first, second or third) three of the seven proposed options. In analysing the results, we have used the “total” here, which represents the percentage of respondents who mentioned one of these options, either first, second or third, within the list of seven options.

The availability to vote EELV is high compared to its competitors

As noted above, the appeal of an EELV candidacy stands out: 42% of voters would be willing to vote for a candidate of that party. This is more than for any other party tested in our indicator. The readiness to vote Green also stands out in terms of the diversity of profiles among its potential voters. More women (43%) than men (39%) say they could vote for an EELV candidate. Half (52%) of under 35 year-olds say they could vote for an EELV candidate, but this also concerns a large proportion of the 35-49 year-olds (46%) and the 50-64 year-olds (42%). Those aged 65 and over are the most reluctant to the Green vote (27%).

Variations also exist according to socio-professional categories, even if the results are still very high compared to the other assessed parties: blue-collar workers (38%), craftspeople, retailers, business managers (43%), white-collar workers (48%), executives or those with intellectually skilled professions (51%) and those with mid-level skilled professions (52%) are numerous in saying that they could vote Green in 2022. Interestingly, and reflecting the diversity of opinion within this electoral potential: 44% of respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests and 40% of those who have a negative image of the Yellow Vests said they might vote for a Green candidate.

Furthermore, our data show the existence of electoral reservoirs favourable to a Green vote in 2022. Three- quarters of Benoît Hamon’s voters (74%) in the 2017 presidential election say they are ready to vote for an EELV candidate in the first round in 2022. The same is true for 69% of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters and 54% of Emmanuel Macron’s voters in 2017. It should be noted that nearly a quarter of Marine Le Pen voters in 2017 (23%) also responded that they could vote for an EELV candidate.

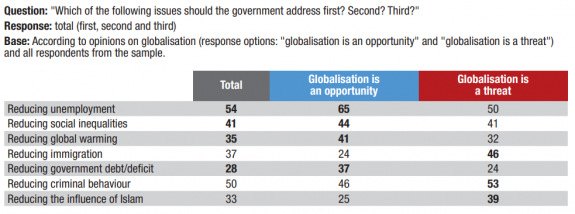

Nevertheless, the fight against climate change seems to have been relegated to the background. To the question “Which of the following issues should the government address first? Second? Third?”6, the answer “reducing global warming” shows a sharp drop in one year across the board (-6 points), from 41% in September 2019 to 35% in September 2020, finding itself in 5th position in the priorities that the government should address, behind unemployment (54%), criminal behaviour (50%), social inequalities (41%) and immigration (37%).

The certainty of voting for EELV in 2022 is more affirmed than for the PS, LR and LREM

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Note: The totals do not add up to 100% due to non-responses, which are not included in this graph.

EELV seems to attract a wide range of voters…

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

…At a time when concern about global warming appears to be sharply declining

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

The populist risk falls into the process of democratic deconsolidation

More than a third of the French (37%) question representative democracy

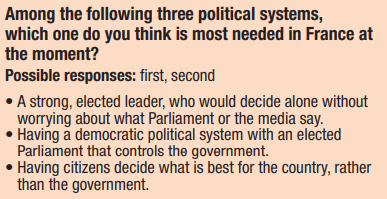

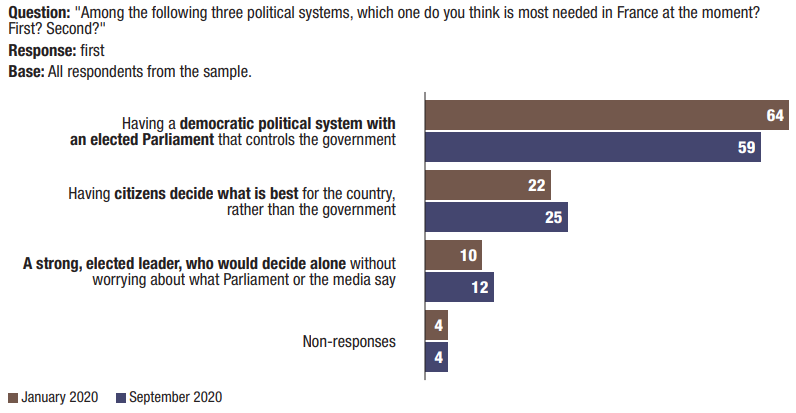

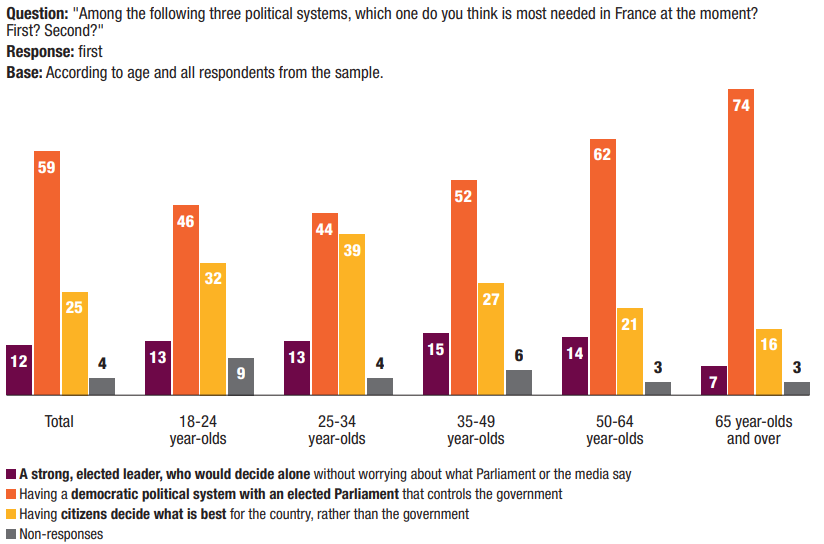

As part of our indicator of electoral protest, we asked respondents to rank three systems of government.

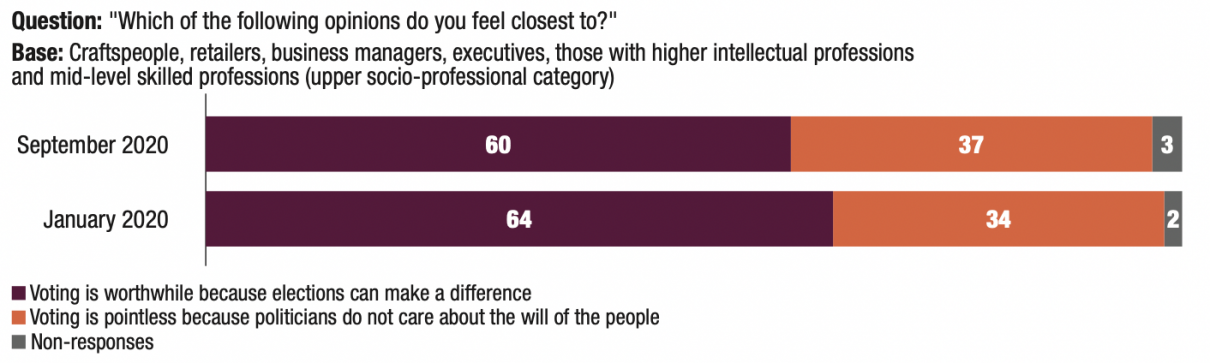

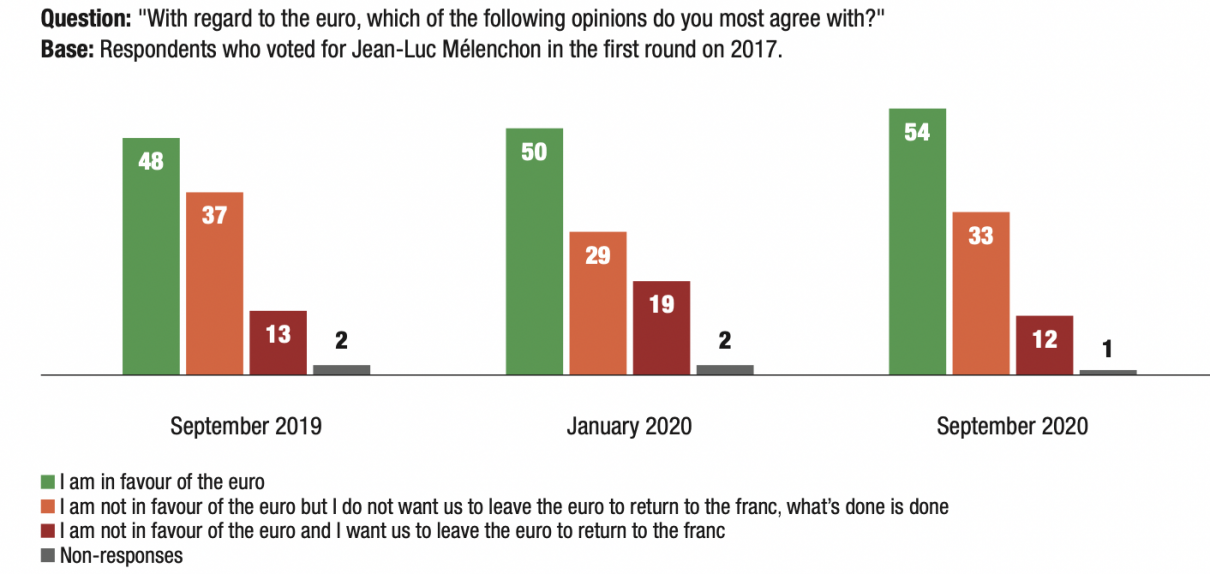

Such a level of scepticism about voting (38%) corresponds to the level we measured in France in September 2018 in our international survey Democracies Under Pressure. This proportion was 30% for the average of the 42 surveyed countries and 34% for the average of European Union member states.

The attachment to representative democracy is no longer self-evident. In wave 2 (January 2020), less than two- thirds (64%) of the surveyed population placed the regime of having “a democratic political system with an elected Parliament that controls the government” in first place. Wave 3 (September 2020) shows a decline of 5 points to 59%. This decline in support for the representative democracy model is coupled with scepticism about the usefulness of voting: more than a third of respondents (38%) believe that “voting is worthwhile because elections can make a difference”7. However, neither of the two alternative systems garnered broader support: 25% of respondents rank the system where “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” as their preferred system, up 3 points from January 2020 (22%). Lastly, a minority (12%) express a preference for “a strong, elected leader, who would decide alone without worrying about what Parliament or the media say,” up 2 points from wave 2 in January 2020 (10%).

Representative democracy is less convincing than in January 2020

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

The preference for representative democracy is only supported by a relative majority of blue-collar workers, craftspeople, retailers, business managers and the unemployed

Between waves 2 (January 2020) and 3 (September 2020) of our indicator, support for representative democracy declines in all social categories. However, this decline is stronger for those in the upper socio-professional category (i.e. craftspeople, retailers, business managers, executives, those with intellectually skilled professions and mid-level skilled professions), from 65 to 59%, than in the lower socio-professional category (white and blue- collar workers), from 54 to 49%.

Craftspeople, retailers and business managers are the least likely to support the representative regime (38%), ahead of blue-collar workers (44%) and white-collar workers (52%). Respondents belonging to the lower socio-professional category are more favourable (30%) than the average (25%) to a direct democracy type of regime where, according to our questionnaire, “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government”. However, it is also in these categories that the preference for an authoritarian model based on a “strong leader” has broader support (17%) than the average (12%).

Support for different types of political systems according to socio-professional category

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Preference for electoral democracy also varies according to professional status

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

In terms of professional status, more people without a professional activity rather than those with a working activity favour the regime of representative democracy (66 versus 54%). A minority of the unemployed (44%), homemakers (42%) and the self-employed (49%) choose representative democracy firstly among the three political systems.

The attachment to representative democracy grows with age

Age is another major fault line. The preference for representative democracy varies greatly from one generation to the next. While almost three-quarters (74%) of those 65 and over still consider our political model to be preferable to the other two, less than half of 18-24 year-olds (46%) and 25-34 year-olds (44%) share this view.

However, when it comes to the preference for a strong elected leader, the notable differences between age groups observed in wave 2 (January 2020) are diminishing. The reduction in the differences is due both to a fall in the proportion of young people declaring a preference for an authoritarian regime, which fell from 16 to 13% among 18-24 year-olds and from 15 to 13% among 25-34 year-olds, and increased in the proportion of those declaring a preference for a “strong leader” that is progressing among the 35-49 year-olds (from 10 to 15%) and the 50-64 year-olds (from 8 to 14%).

Among 35-49 year-olds, the preference for representative democracy dropped sharply (-11 points), from 63 to 52%. In addition to the progress in support for a “strong leader”, this movement of opinion is combined with an increase in preference for a system in which “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” (from 23 to 27%).

Among 25-34 year-olds, a similar dynamic is at work, with support for representative democracy declining from 51 to 44% in favour of the direct democracy model (from 30 to 39%). This is to be put into perspective with the particularly marked scepticism among 25-34 year-olds, who are the least numerous (54%) to consider that “voting is worthwhile because elections can make a difference”, compared with 60% on average. It is noteworthy that 18-24 year-olds, while few say they prefer representative democracy (46%), nonetheless express, on par with those aged 65 and older, the highest level of attachment to voting of any age group (66%).

The idea of direct democracy is very present among the under 35 year-olds, the over 35 year-olds are more loyal to the representative system

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

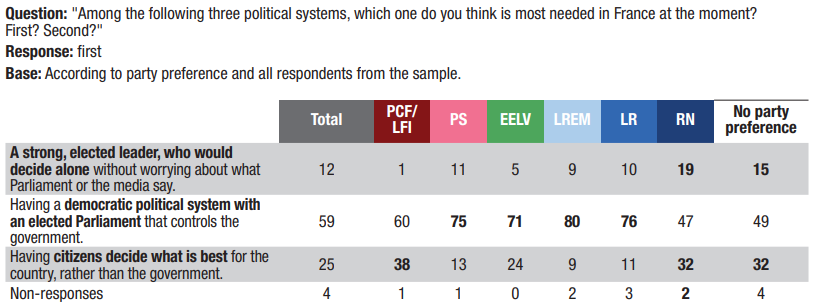

Detachment from representative democracy serves right-wing populism

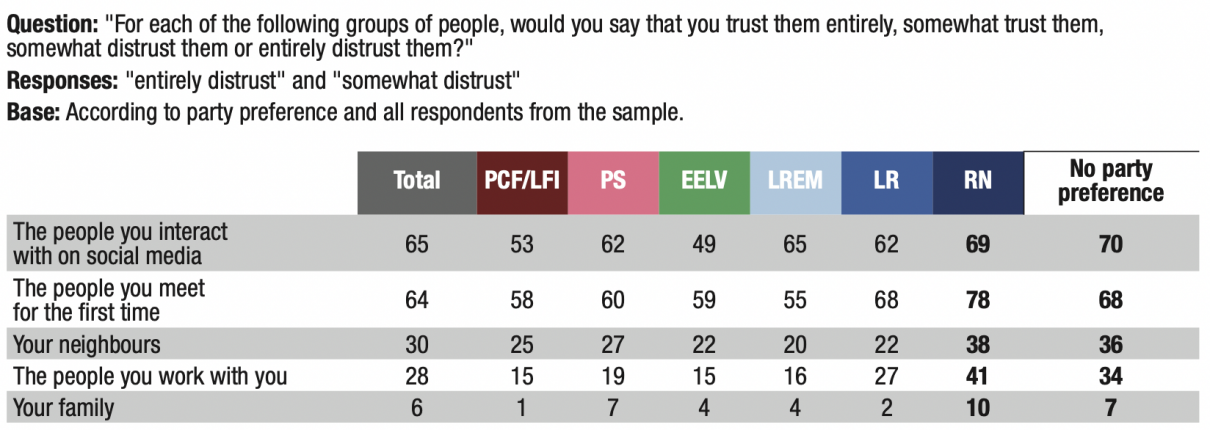

With regard to partisan lines, this detachment from our democratic model can be observed more particularly on both extremes of the political spectrum, especially on the extreme right. The preference for representative democracy concerns 60% of those close to the PCF/LFI and 47% of those close to the RN, well below those close to the PS (75%), LR (76%) and LREM (80%). However, it is important to note that support for representative democracy is also very low among those who declare having no party preference (49%).

This group of respondents who indicated that they did not feel close to any of the proposed parties should not be overlooked as it represents 1,163 respondents, or 38.3% of the sample (3,037 interviewees). They appear to be largely in favour of a regime where “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” (32%, compared to 25% on average) or, to a lesser extent, a regime with “a strong, elected leader, who would decide alone without worrying about what Parliament or the media say” (15% compared to 12% on average).

LREM supporters are most attached to the representative system, LFI supporters to direct democracy and RN supporters to a strong leader

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Preference for a strong leader appears to be non-existent among PCF/LFI supporters (1%), while it is widely expressed among respondents close to the RN (19%, 7 points above average). Both of these groups are more likely to support a system in which citizens decide what is best for the country rather than the government, whether PCF/LFI supporters (38%) or those close to the RN (32%), compared to 25% on average.

The appetite for a “strong leader” is not exclusively part of a protest dynamic. In fact, 14% of respondents expressing satisfaction with Emmanuel Macron’s action as President believe that a strong leader is necessary in France today, compared to 11% of those who say they are dissatisfied. This preference is not exclusive to the extreme right either, since it is shared, albeit to a lesser degree, by some supporters of the PS (11%), LR (10%), and LREM (9%).

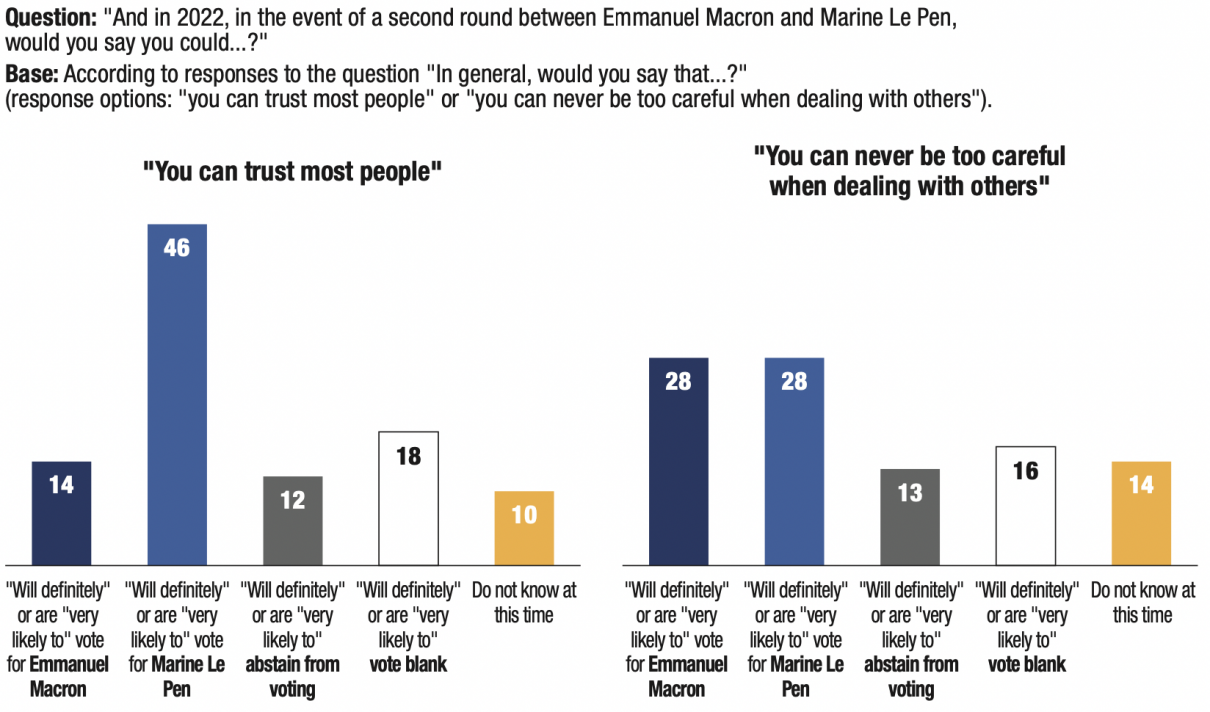

The idea of a government in which the people would decide for themselves aggregates protesting worlds

Respondents favouring a political system where “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” are characterised by a very negative assessment of their personal situation, a system of protest opinions and very high levels of distrust.

Among respondents who favour a government by citizens, 72% feel that their lifestyle or the way they live is threatened (compared to 60% on average) and 32% say they have difficulty living on their household incomes (compared to 22% on average). More than a third (36%) say they are dissatisfied with their lives (compared with 27% on average).

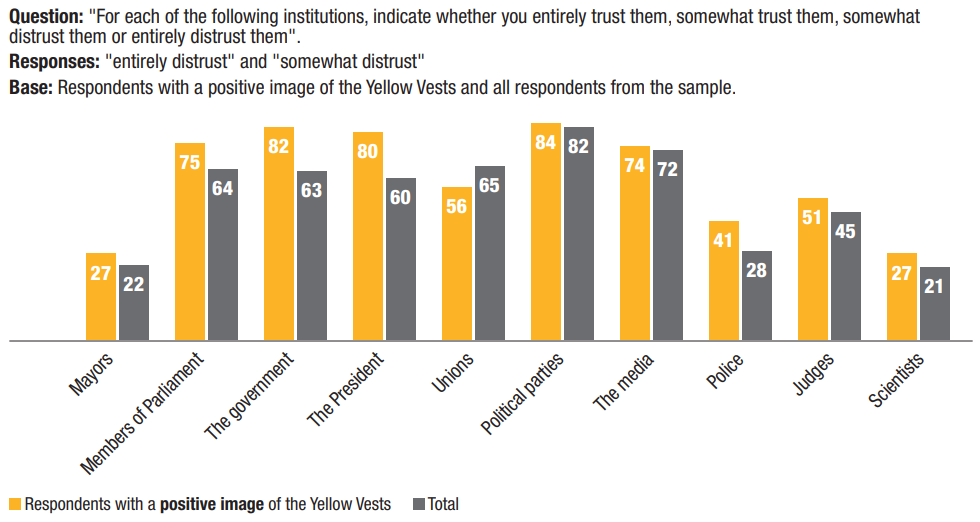

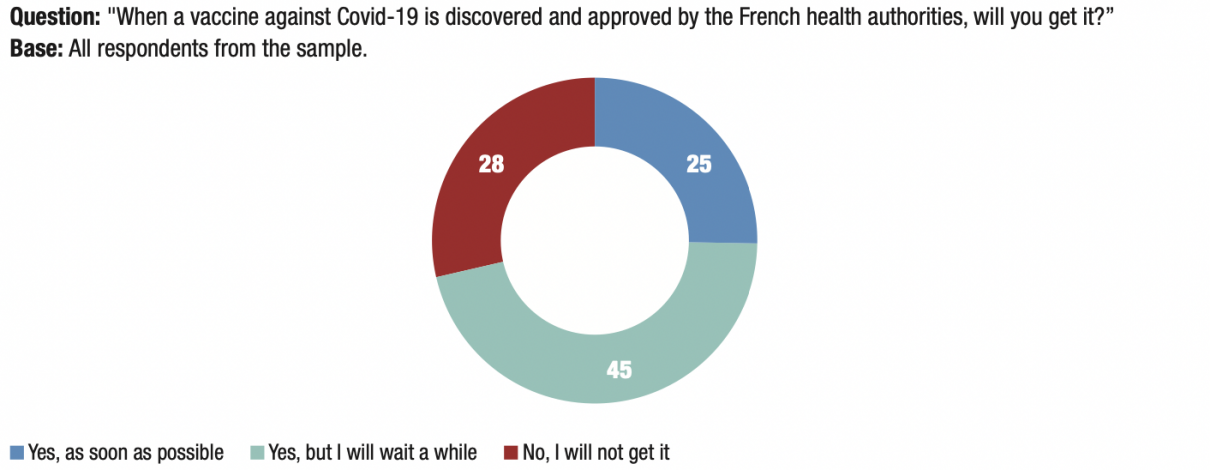

A large majority (66%) have a positive image of the Yellow Vests (compared with an average of 44%). They believe that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people” (56% compared to 38% on average), express a mistrustful attitude towards globalisation (71% consider globalisation to be a threat, compared to 60% on average) and their opinion on immigration is significantly more negative than average: 68% think that “for France, economically speaking, immigrants are a disadvantage because their integration is expensive” (compared to 60% on average) and 70% think that “most immigrants do not share France’s values and this causes problems of cohabitation” (compared to 63% on average). Within this “direct democracy” group, there is also a high proportion of “anti-vaxxers”: 39% of them say that they would not agree to receive a possible vaccine against Covid-19, even if it had been approved by the French health authorities (compared to 28% on average). Additionally, 30% of respondents preferring a regime where citizens decide what is best for the country rather than the government say they would be in favour of having the right to own a gun in their homes (compared with 23% on average).

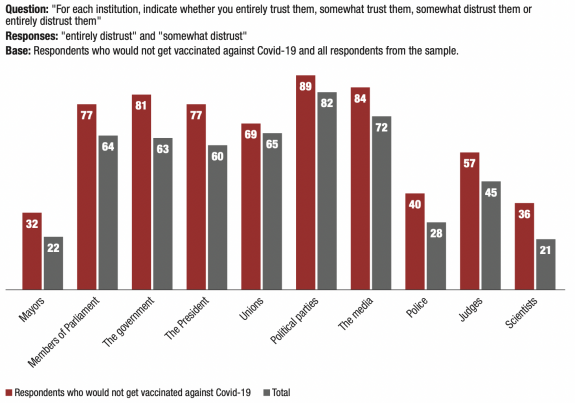

It is less surprising to find in this group the highest levels of mistrust of institutions. It should be noted that this marked mistrust goes beyond the government and representative institutions: 88% of these respondents do not trust political parties (compared to 82% on average), 84% do not trust the government (compared to 63% on average), 82% do not trust members of Parliament (compared with 64% on average), 79% do not trust the President (compared to 60% on average), 78% do not trust the media (compared with 72% on average), 67% do not trust unions (compared with 65% on average), 56% do not trust judges (compared with 45% on average), 45% do not trust the police (compared with 28% on average), 33% do not trust mayors (compared with 22% on average) and 31% do not trust scientists (compared with 21% on average).

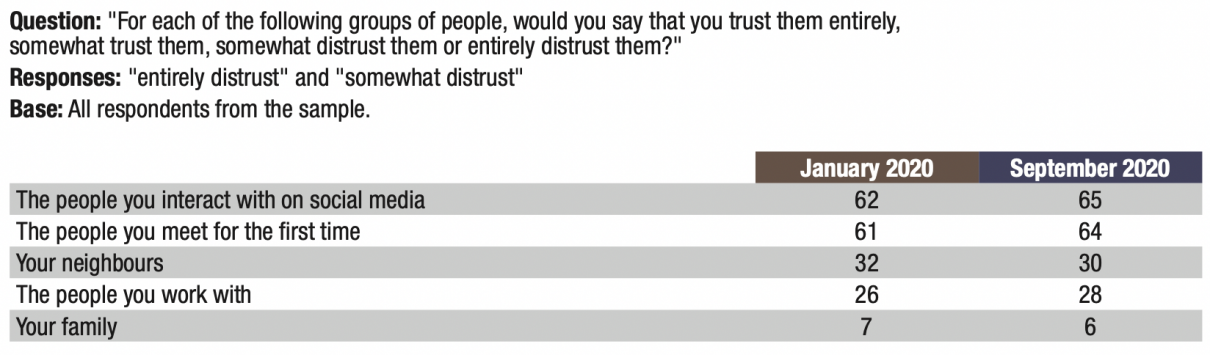

Above all, this mistrust extends to the interpersonal sphere, a characteristic feature of the populist disposition: 39% do not trust their neighbours (compared to 30% on average) and 36% do not trust the people they work with (compared to 28% on average). The differences between this group and the average are smaller with regard to family (8% do not trust them, compared to 6% on average) and people met on social media (66% do not trust them, compared to 65% on average). Thus, respondents who favour a political system in which citizens make decisions instead of the government are more likely to feel distrustful of others: most (79%) feel that one can never be too careful when dealing with others, compared to 73% on average.

A first look at their envisaged electoral behaviour in the first round of the 2022 presidential election suggests a high potential for electoral protest, directed towards the populist offer on both the right and the left. Indeed, 42% could vote for a RN candidate, 10 points above the average (32%); 26% could vote for a DLF candidate, 5 points above the average (21%); 35% could vote for a LFI candidate, 12 points above the average (23%); and 26% could vote for a LO/NPA candidate, 9 points above the average (17%). The willingness to abstain from voting (57% versus 45% on average) and to vote blank (59% versus 49%) is also very high.

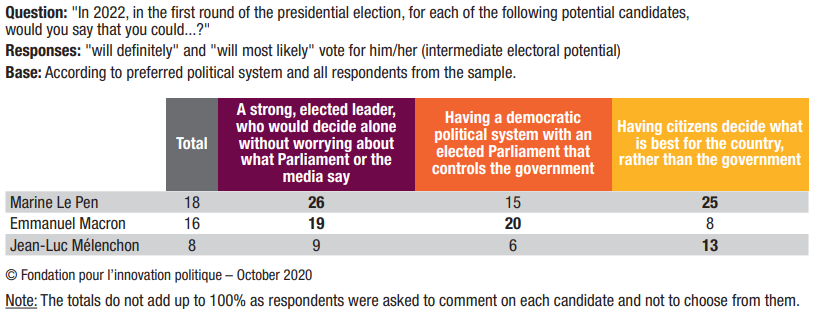

French politics is suffering from a process of democratic deconsolidation. As a result, the protest forces are given a bigger platform. The populist risk therefore seems greater. Our indicator tests six types of protest behaviour: abstaining from voting, voting blank, voting for the RN, LFI, DLF and LO/NPA. Out of all respondents, 4% answered “yes” to each of these options. Yet this proportion is higher among those who favour a regime where citizens decide directly (6%) and doubles (8%) among those who express a preference for the authoritarian model (having a strong leader in power). However, the demand for a strong leader is not exclusively in favour of populist candidates. Among voters expressing a preference for the authoritarian model, 26% say they “will definitely” or are “very likely to” vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round, but 19% say they are willing to vote for Emmanuel Macron. The same situation would be found in the case of a second round that would oppose these two candidates. Among voters expressing a preference for the authoritarian model, 32% said they would vote for Marine Le Pen, but 28% said they would vote for Emmanuel Macron.

Emmanuel Macron, who is therefore also identified as a figure of a “strong leader”, to whom some of those close to LREM seem receptive, as we have seen. On the other hand, among those who express their preference for this authoritarian model, only 9% say they are willing to vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round of the presidential election.

In the first round, the preference for “a strong leader” benefits Marine Le Pen first, then Emmanuel Macron, and the preference for a government by the citizens benefits first Marine Le Pen, then Jean-Luc Mélenchon

In the second round, voters who support a regime with a strong leader are split between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen

The preference for a regime where “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” represents a significant fraction of the electorate (25%). However, as we can see, a quarter of this electorate (25%) is inclined to vote for Marine Le Pen in the first round of the presidential election, more than for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (13%), the biggest proponent of a constitutional assembly (a group of representatives tasked with drafting a new constitution), or Emmanuel Macron (8%), who is nevertheless the first president to give responsibilities to a Citizens’ Convention (a panel of French citizens in charge of coming up with policy propositions) chosen at random. Moreover, it is among those who prefer that “citizens decide what is best for the country, rather than the government” that the wish to avoid the re-election of Emmanuel Macron (59%) prevails over the will to avoid the election of Marine Le Pen (37%).

Supporters of a government by the citizens are the most numerous to want above all to avoid the re-election of Emmanuel Macron

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Detachment from representative democracy works in favour of right-wing populism. Marine Le Pen’s candidacy appears to be in tune with both an electorate calling for a more authoritarian government as well as an electorate calling for a more direct democracy, probably understood here, at least in part, as integrating referendums into the political system. There remains the electorate expressing a preference for representative democracy, more favourable to Emmanuel Macron (40% “will definitely” or are “very likely to” vote for him in the second round) than to Marine Le Pen (20%). Anything that weakens electoral democracy favours the progress of populism.

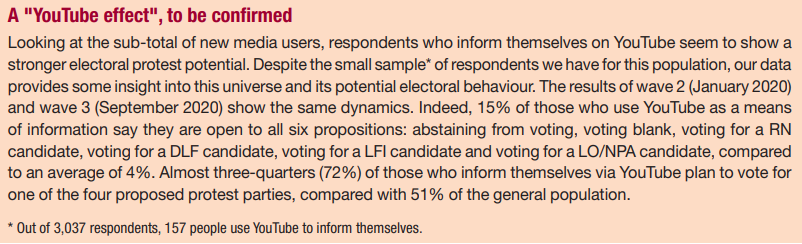

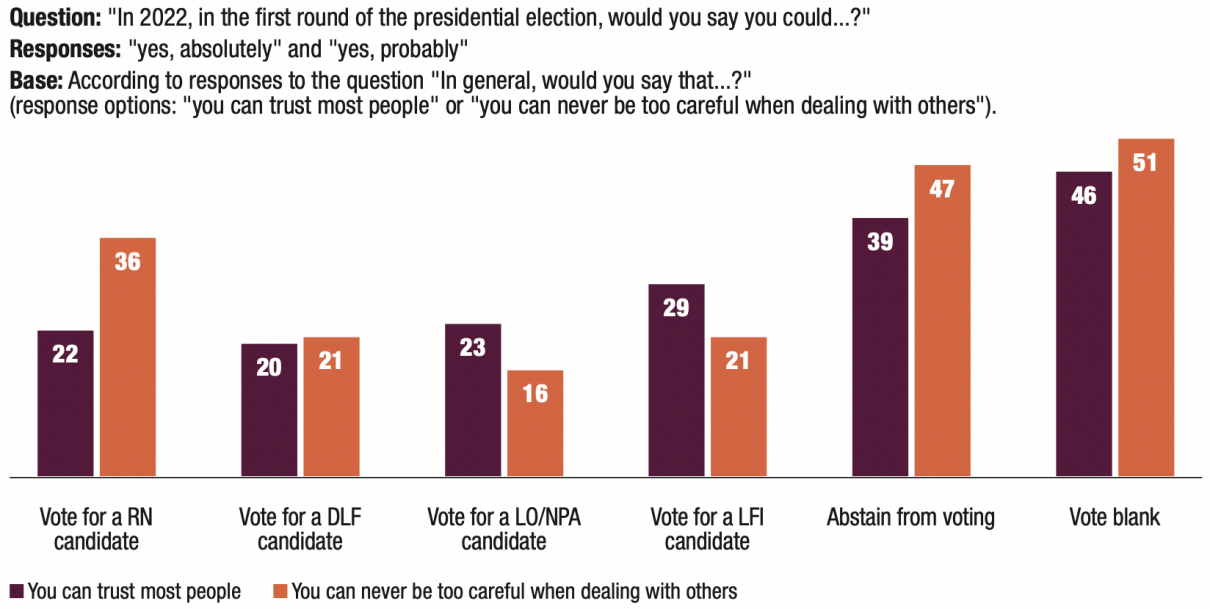

The new media, a public space conducive to populism

The democratic public space is subject to structural changes, particularly due to the decline of the traditional press and the advent of a digital space that is more favourable to populism. Our indicator shows that the potential for electoral protest is sensitive to the sources of information of the respondents.

We consider two aggregates: on the one hand, the “traditional media”, bringing together those who get their information from major television channels, 24-hour news channels, newspapers (print or online), or radio; on the other hand, the “new media”, bringing together those who get their information from YouTube, blogs, forums or social networks. It can be observed that the declared willingness to vote for a populist candidate in the first round of the 2022 presidential election is higher among those who inform themselves through these new forms of media. The control of this variable by taking into account the age of respondents confirms a specific effect of the platform of information, particularly in the case of populist voting. This could be a systemic explanatory factor for populist voting in particular and anti-politics in general.

Users of new forms of media are more prone to protest behaviour

From the very beginning of the lockdown (March-May 2020) in France, there has been a significant increase in the use of the Internet and social media. On this subject, see Valentin Cimino, “Avec le confinement l’utilisation des réseaux sociaux augmente de 61%“, siecledigital.fr, 27 March 2020.

The “new media” effect benefits all protest parties: in the perspective of the first round of the next presidential election, 42% of respondents informing themselves on new forms of media say they could vote for a RN candidate, 10 points higher than the average (32%); 37% could vote for LFI, 14 points higher than the average (23%); 30% could vote for DLF, 9 points higher than the average (21%); and 28% could vote for LO/NPA, 11 points higher than the average (17%). Between waves 2 (January 2020) and 3 (September 2020), the proportion of voters informing themselves on new forms of media who plan to vote for RN in the first round increased from 36 to 42%.

Again, between waves 2 and 3, this evolution accompanied a phenomenon of increased right-wing political activity on social media, which constituted a significant portion of the information consumed via new forms of media. Indeed, during wave 2 (January 2020), 25% of respondents on the left of the political spectrum and 23% of those on the right said they discussed the news “often” or “from time to time” with people they “met on social media”. In wave 3, in September 2020, a right-wing trend is visible, with 16% of left-wing respondents reporting discussing current events with other people on social media, compared to 27% of right- wing respondents.

In order to account for this evolution, one must at least hypothesise the contextual factor and political agenda. The beginning of the year 2020, at the time wave 2 was administered, was dominated by movements opposed to the retirement reform that favoured stronger left-wing activity online, while the fall of 2020 was dominated by the pandemic, to which was added a rise in themes related to security issues, criminal behaviour, Islam and immigration, mobilising a much more right-wing electorate online.

The risk of a “sounding board” effect on social media

An inquiry into the way the French inform themselves reveals two worlds, shared between traditional and new forms of media, notably social media, as a new public space. Beyond those who claim to use them as a means of getting informed, many citizens cross these spaces and interact in them, including to exchange about current events8: 21% of those who use social media discuss “often” or “from time to time” what’s going on in the country with the people they meet online.

It is therefore appropriate to look at the profiles of these populations and, in particular, at the dynamics of politicisation that animate social networks.

An initial look at socioeconomic characteristics confirms that young people are the most numerous to regularly discuss how things are going in France on social media: this concerns 30% of 18-24 year-olds and 29% of 25-34 year-olds, compared with 23% of 35-49 year-olds, 18% of 50-64 year-olds and 14% of those aged 65 and over. There is no difference between men and women (21% in both cases), nor between upper socio-professional and lower socio-professional categories (24 versus 22%).

Compared to the average, they are also populations that are closer to the extremes and that show an openness to populism. In fact, around a quarter of the respondents who voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (23%) and Marine Le Pen (25%) in the first round in 2017 discussed what’s going on in the country “often” or “from time to time” on social networks. By way of comparison, this concerns 20% of people who voted for Emmanuel Macron, 20% of people who abstained from voting, voted blank or did not wish to respond, 15% of those who voted for François Fillon and 11% for Benoît Hamon.

Given the algorithms governing social networking platforms and the suspected effects of the polarisation of opinions, it is worth asking to what extent respondents encounter opinions contradictory to their own when exchanging views on these networks.

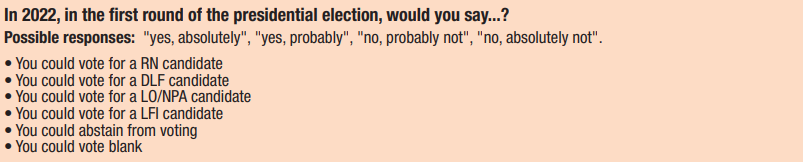

A distinction must be made between those who say they use social media for discussion and those who say they also use them for information. We discovered that 50% of people using social media simply to “discuss the way things are going in the country” say they feel that the people they meet online share their opinions. However, among those who say they use social media as a means to inform themselves, a very large majority (62%) believe that the people they meet share their opinions. This result is particularly worrisome in the sense that the social network is used here as a means of information and we now know that the posting of content is subject to rules that favour a “sounding board” effect that deteriorates the quality of the information circulating on a social network.

This phenomenon is found among the potential populist electorate: 55% of those who say they could vote for the RN in 2022 say that the people with whom they interact on social media share their opinions, compared to 50% on average; the same is true (57%) for respondents who say they could vote for a LFI candidate.

Memo for the reader: among all the respondents, 50% feel that the people they meet on social media share their opinions on the way things are going in France. Among the people who could vote for a RN candidate in the first round of 2022, 55% feel that the people they meet on social media share their opinions on the way things are going in France.

On social media, protesting worlds are more likely to find opinions convergent with their own

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Regarding a future first round wherein Marine Le Pen, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Emmanuel Macron would be candidates, 58% of those who believe they “will definitely” or “will most likely” vote for Marine Le Pen consider that the people they meet on social media share their opinions on current events. This impression is shared by 61% of those who would vote for Jean-Luc Mélenchon and 43% of those who would vote for Emmanuel Macron. Furthermore, among the voters who say they “will definitely” or are “very likely to” vote for Marine Le Pen in the second round in 2022, 57% feel that the people they meet on social media share their opinions on how things are going in France.

This concerns 38% of those who “will definitely” or are “very likely to” vote for Emmanuel Macron. The results of our barometer confirm that social media are a new public space particularly favourable to the circulation and sharing of protest and populist opinions, between users whose convergent views are radicalised by a process of mutual reinforcement, an effect often referred to as the “sounding board” or “filter bubble” effect.

The resources of electoral protest

Society is perceived as increasingly violent

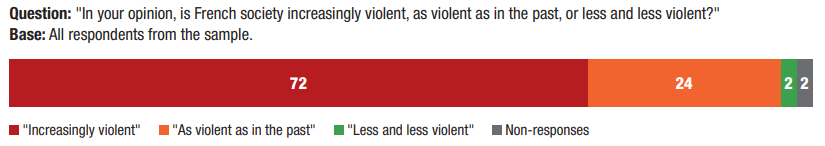

Three-quarters of respondents (72%) feel that society is “increasingly violent”

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

See “Insécurité et délinquance en 2019: une première photographie“, Interstats Analyse, no. 24, January 2020.

Inevitably, with such a high level (72%), this opinion is present in all social categories, but slightly more so among women (73%) than men (71%), more overwhelmingly present among those aged 65 and over (77%) than among 18-24 year-olds (59%), where it nevertheless continues to be in the majority. This opinion is shared by three-quarters of rural residents (75%), but is also very prevalent in cities with morethan 100,000 inhabitants (71%), notably Paris (69%). This dominant feeling is found across the political spectrum, although it is more pronounced on the right. It should be noted that the feeling of an increase in violence is part of a reality documented by the statistics of the Ministry of the Interior9. The crime rate increased sharply in 2019.

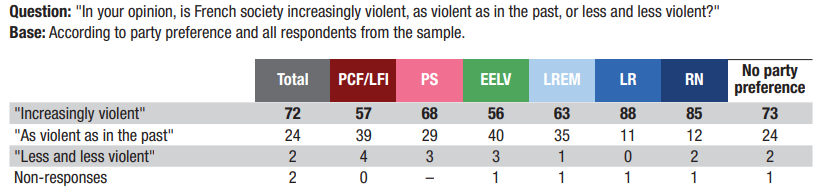

The idea that society is “increasingly violent” dominates, both on the left and on the right

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Memo for the reader: among those close to the PCF/LFI, 57% believe that society is “increasingly violent”, 39% believe that it is “as violent as in the past” and 4% believe that it is “less and less violent”.

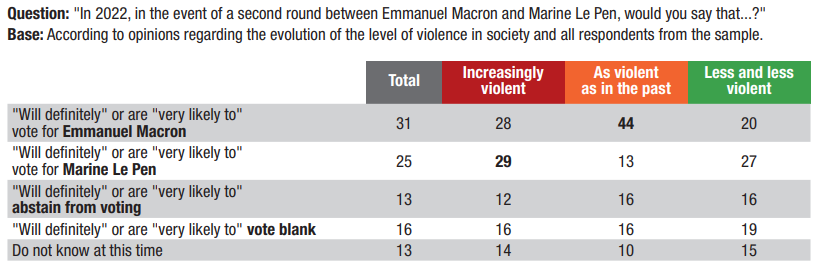

Voters who consider society to be increasingly violent tend to vote for Marine Le Pen

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

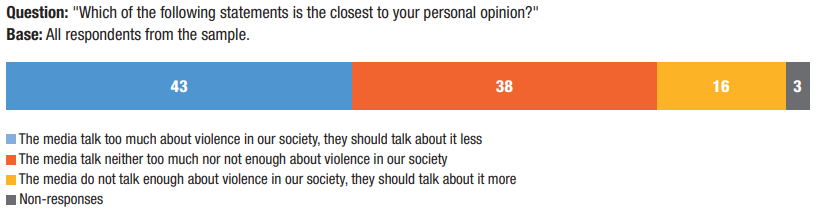

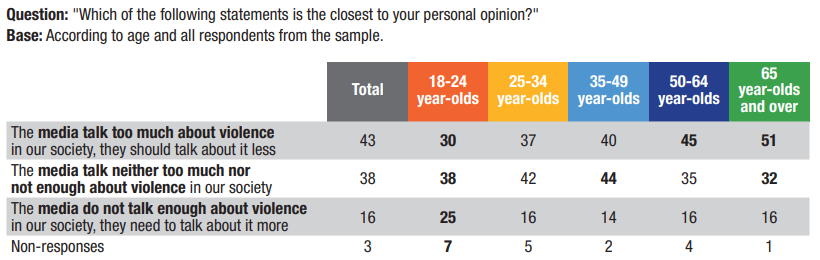

This representation of a rising and unsettled conflictual atmosphere can be fuelled by 24-hour news television channels or by social media, which stage acts of violence on an almost daily basis. This trivialisation of violence by the new media may lead part of the public to want to distance themselves from these images: 43% of people respondents believe that “the media talk too much about violence in our society, they should talk about it less”, compared to 16% who think that “the media do not talk enough about violence in our society, they should talk about it more”. Almost 4 in 10 French people (38%) think that “the media talk neither too much nor not enough about violence in our society”.

43% of the French consider that the media talk too much about violence

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

See Sandra Laffont, “Violence, réputation, blasphème… : au collège, l’éducation aux médias face au pouvoir des smartphones“, lemonde.fr, 4 September 2020.

According to a 2018 survey, the use of screens, social media and video games is spectacularly high among young people, with a quarter (26%) of 18-22 year-olds estimating that they spend more than 5 hours a day on social networks and 10% more than 8 hours each day. See Les Addictions chez les jeunes (14-24 ans). L’urgence d’une politique de santé et de sécurité publiques, Fondation pour l’innovation politique- Fondation Gabriel Péri-Fonds Actions Addictions, June 2018.

This number may seem contradictory. However, it leaves open the possibility of an interpretation that would not imply inconsistency of opinion or a flaw in the measure: society is increasingly violent and the media talk too much about it in a way that would be considered inappropriate. For example, the coverage would be reduced to an observation whose repetition would provide no way out, no vision on how to reverse such a trend, and end up disappointing or discouraging some, and exasperating others.

It should also be noted that a quarter of 18-24 year-olds (25%) consider that the media do not cover the topic of violence enough and that they should talk about it more, 9 points higher than the average (16%) of the sample. One of the explanations may be found in the abundant sharing of videos on cell phones of high school students via social media, such as Snapchat or Instagram, and which can be extremely violent, as a recent report10 pointed out. Scenes of torture, looting, burning cars and fights are thus spread among the youth, who may perceive a discrepancy between what they have access to11 and what they see in traditional media sources.

Younger people are the most likely to consider that the media do not talk enough about violence

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

For the question “Which of the following issues should the government address first? Second? Third?”, respondents were asked to respond by ranking (first, second or third) three of the seven proposed options. In analysing the results, we have used the “total” here, which represents the percentage of respondents who mentioned one of these options, either first, second or third, within the list of seven options.

Furthermore, we note that respondents close to the RN are twice as numerous (34%) as the average of the sample (16%) and five times as numerous as respondents close to the PCF/LFI (6%) to consider that “the media do not talk enough about violence in our society”.

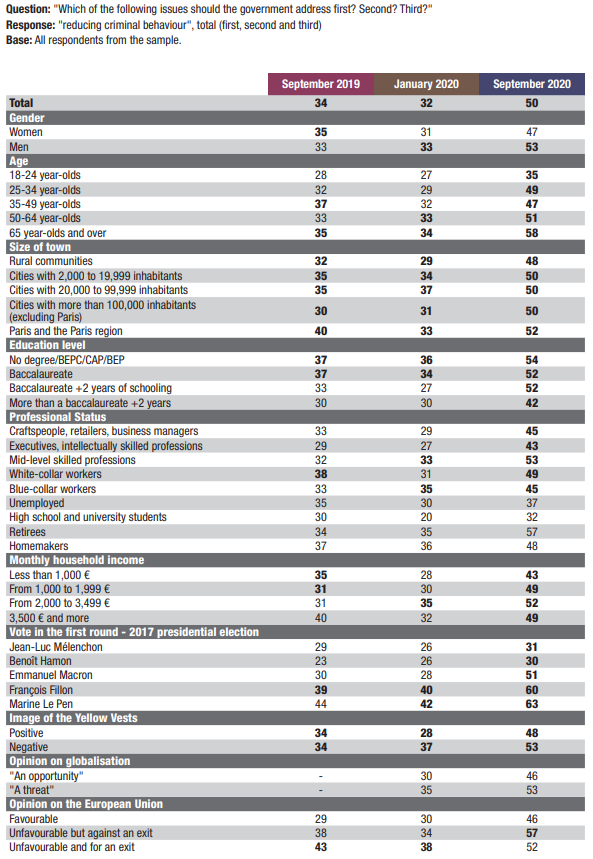

Security is already a key issue for 2022

Among the concerns tested, safety emerged as a central theme. Between waves 1 (September 2019) and 3 (September 2020), to the question “Which of the following issues should the government address first? Second? Third?12“, the answer “reducing criminal behaviour” shows the highest increase (up 16 points, from 34 to 50%). In September 2020, a majority of French people (50%) therefore consider the problem of criminal behaviour to be one of the priorities that the government must address, behind unemployment (54%) but ahead of the other problems: social inequalities (41%), immigration (37%), global warming (35%), the influence of Islam (33%) and government debt/deficit (28%).

List of priorities: unemployment and criminal behaviour at the top

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

In one year, a leap in concern over security

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Thus, in one year, from September 2019 to September 2020, our barometer recorded a 10 point drop in the need to reduce the government debt/deficit (from 38 to 28%), a 9 point drop for the need to reduce inequalities (from 50 to 41%), a 6 point drop for the need to reduce global warming (from 41 to 35%) and a 2 point drop for the need to reduce immigration (from 39 to 37%). On the other hand, there was a 2 point increase for the need to reduce the influence of Islam (from 31 to 33%), and a 3 point increase for the need to reduce unemployment (from 51 to 54%), all of which was dominated by the 16 point increase for the need to “reduce criminal behaviour” (from 34 to 50%).

Among those who believe that “reducing criminal behaviour” should be one of the government’s priorities, 38% say they might vote for a RN candidate in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, 6 points higher than the average (32%). By contrast, only 17% say they would vote for a LFI candidate, 6 points lower than the average (23%). The fight against criminal behaviour will be a decisive issue if there is a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen in 2022. Indeed, the rise in security concerns would likely erode the opposition to the election of Marine Le Pen and, symmetrically, encourage the mobilisation of voters hostile to Emmanuel Macron.

In 2022, the security question would play to the advantage of Marine Le Pen in a second round against Emmanuel Macron

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Everyone (or almost everyone) loves the police… and would like to see their resources increased

Police officers are favoured highly in public opinion (69% of respondents say they trust them), even if there are generational differences: 75% of French people aged 50 and over trust the police, compared with 56% of those under 35. Furthermore, respondents who are “very left-wing” on the political spectrum express the most critical opinion of the police (only 42% trust the police, compared with 76% of respondents who are “very right-wing” on the political spectrum).

Trust in the police is more widespread in rural municipalities and in cities with less than 100,000 inhabitants. In cities with less than 2,000 inhabitants, 74% of the respondents trust the police, 71% in cities with 2,000 to 19,999 inhabitants, 73% in cities with 20,000 to 99,999 inhabitants and 67% in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants (excluding Paris, where 63% of the inhabitants trust the police).

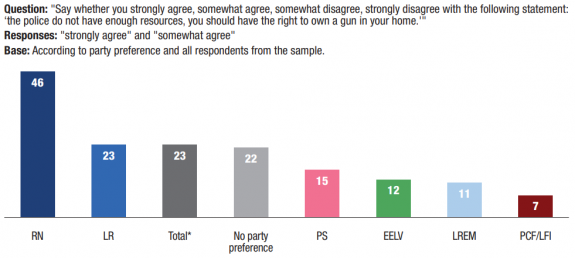

Among those who consider that the police do not have enough resources, 23% wish to have the right to own a gun in their homes

In connection with the expression of this confidence in the police, more than three-quarters of those surveyed (77%) believe that the police do not have enough resources to ensure security in France. Among those who consider that the police do not have enough means, almost a quarter (23%) would like to have the right to possess a gun in their homes. Those under 35 years of age are the most favourable (30%), i.e. 8 points more than those aged 50 and over (22%). This opinion is also more widespread among those with fewer qualifications (27% compared with 16% for those with a higher education diploma) and those living in the most modest households (28% for households with less than 2,000€ per month compared with 17% for households with 3,500€ or more per month). There are wide variations dependent on party affiliation, but the figure of 22% among those who declare having no party preference is particularly noteworthy.

* Proportion of the sample who consider the police to be under-resourced (77%).

Note: this question was asked to respondents who answered “does not have enough resources” to the question “In your opinion, in France, to ensure security, would you say that the police…?” (response options: “has too many resources”, “has enough resources” and “does not have enough resources”). This constitutes a sample of 2,331 individuals out of the 3,037 respondents.

RN supporters are the most favourable to “the right to own a gun in their homes”

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Among the respondents in favour of the right to own a gun in their homes, almost all (89%, compared with 79% on average) plan to adopt one of the six protest behaviours proposed in the first round of the next presidential election (abstention from voting, voting blank, voting for one of the populist or anti-system parties, i.e. RN, LFI, DLF, LO/NPA). The majority (57%) of respondents who wish to have the right to own a gun in their homes would vote for the RN in the first round in 2022, compared with 32% on average. Only 16% would vote for the LFI, compared to 23% on average. In the event of a second round in 2022 between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, 45% of respondents in favour of the right to own a gun would vote for the RN candidate (versus 25% on average), 18% would vote for the current President (versus 31% on average), 24% could abstain from voting or vote blank (versus 29% on average), and 12% do not yet know what they would do (versus 13% on average).

The choice of a protest vote is asserting itself among voters who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests

Since the first demonstrations in October 2018, the Yellow Vests movement has barely weakened in public opinion. It seems to have become a structural element of the French protest landscape. It is a radically atypical social and political movement, unprecedented under the Fifth Republic. In a complete break with the traditional representative bodies, with no organisation or programme, the Yellow Vests continue to embody a movement that rejects institutions.

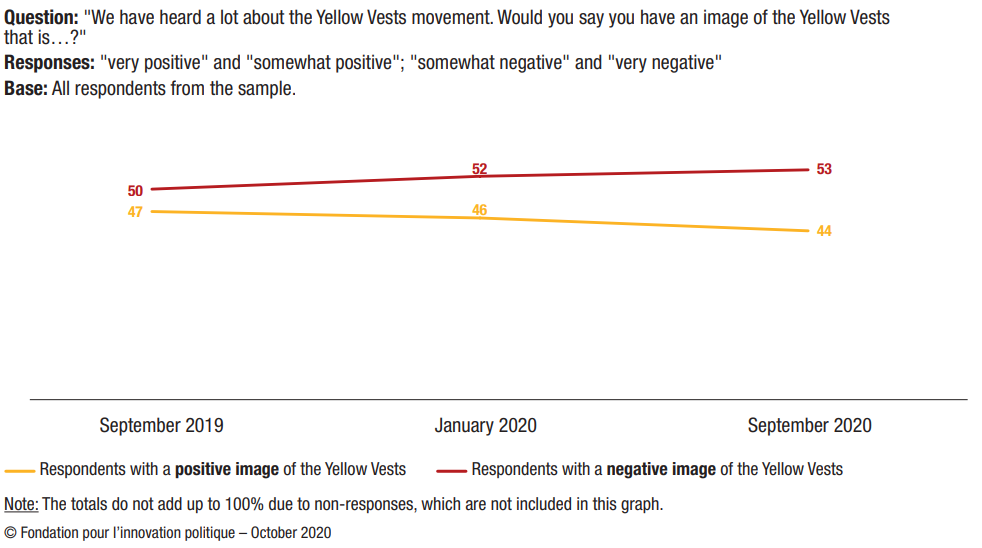

The Yellow Vests movement continues to be viewed positively

Our survey shows that after two years of existence, this unprecedented movement continues to be viewed positively among 44% of the French, even if there has been a moderate but consistent decline since the first wave of our electoral protest indicator (47% in September 2019, 46% in January 2020).

Support for the Yellow Vests remains particularly high among PCF/LFI supporters (80%), RN supporters (63%) and, to a lesser extent, PS supporters (50%), EELV supporters (49%) and respondents with no party preference (46%). Support is lowest among LR (27%) and LREM (10%) supporters.

French people who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests tend to be more distrustful of institutions than the average of the sample

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

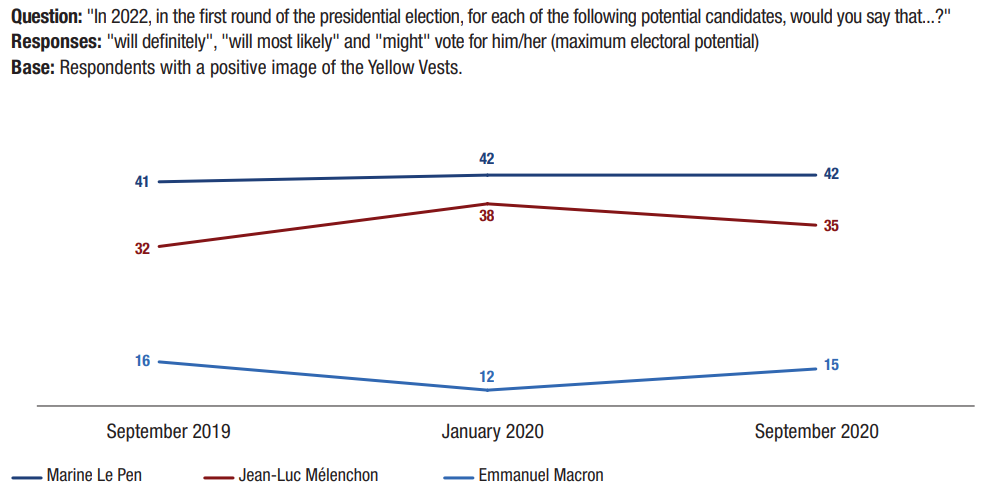

Wave after wave, the choice of a protest vote for 2022 is asserting itself among voters who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests. In September 2020, a strong majority (65%) declare they would vote RN or LFI in the first round of the next presidential election, 19 points above the average (46%), compared with 63% in wave 2 (January 2020) and 59% in wave 1 (September 2019). In the same vein, the results of wave 3 (September 2020) show that 66% of people with a positive image of the Yellow Vests say they could abstain from voting or vote blank, compared to 61% in January 2020 and 62% in September 2019. In the event of a second round between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, the majority (61%) of respondents who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests would primarily want to avoid the re- election of Emmanuel Macron, compared to one-third (33%) who say they want to avoid the election of Marine Le Pen.

French people who have a positive image of the Yellow Vests are more likely to vote Marine Le Pen than Jean-Luc Mélenchon in 2022

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Positive image of the Yellow Vests fuels voting against Emmanuel Macron

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

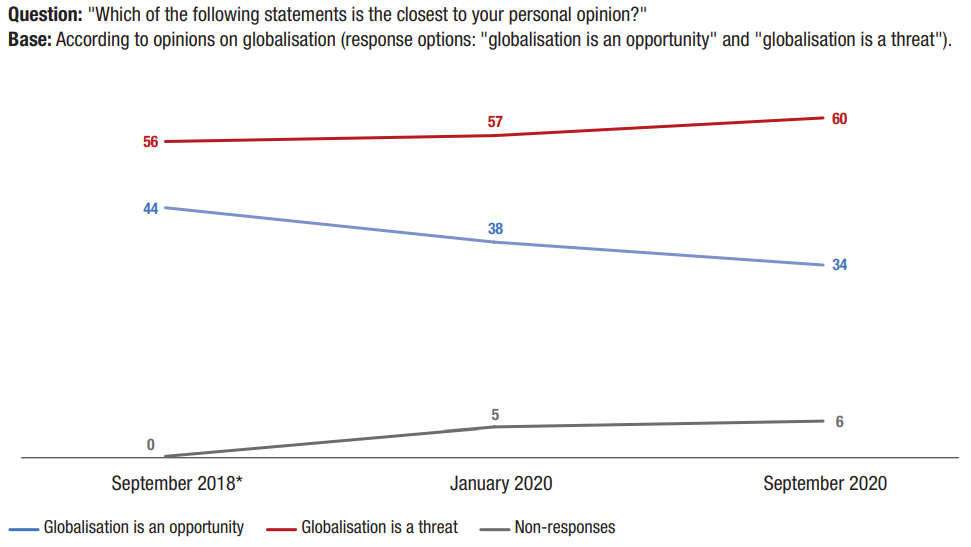

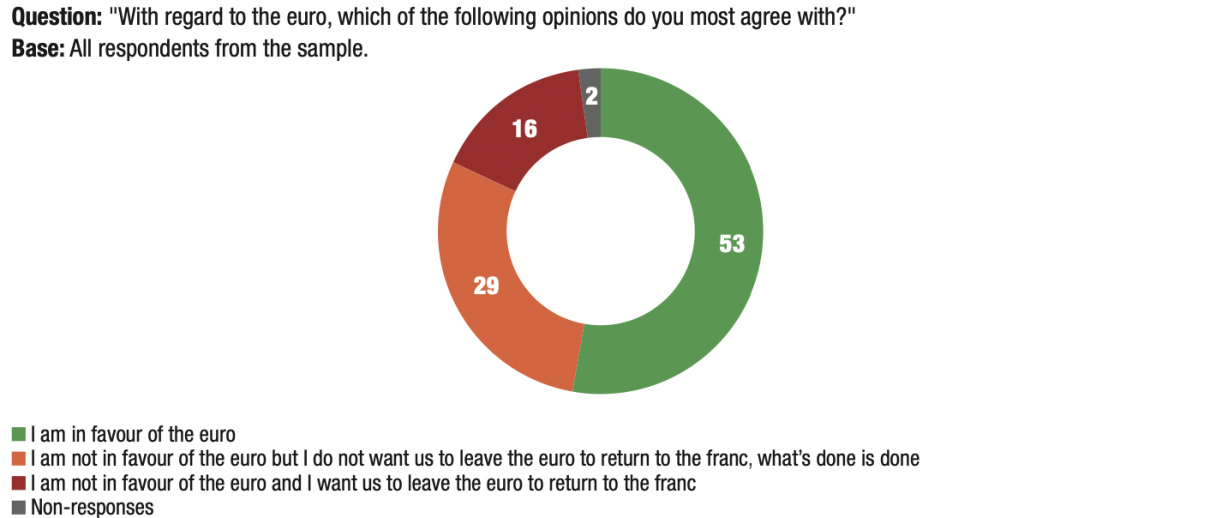

The health crisis reinforced a rejection of globalisation

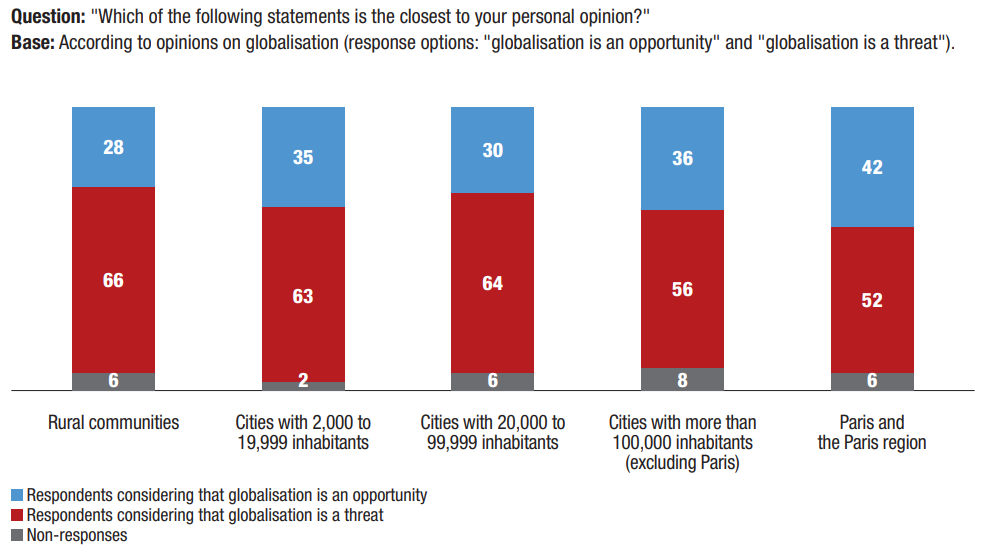

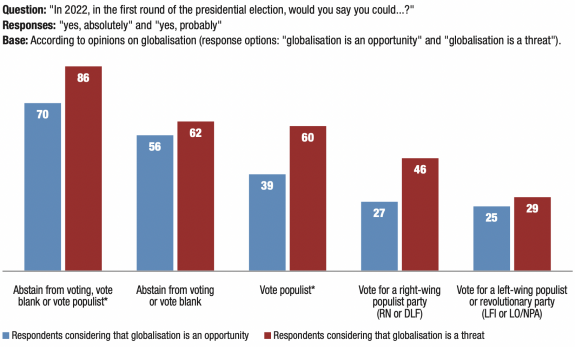

A clear majority of French respondents (60%) perceive globalisation as a threat. The coronavirus pandemic is both a paradigmatic example of the risk of being “without borders”, fostered by international flows of people and goods, and the embodiment of people’s dependence on globalisation. Our indicator shows that the coronavirus is having a definite, and still ongoing, impact on French public opinion’s assessment of globalisation.

In September 2020, when asked respondents to choose between the following two proposals, “globalisation is a threat” and “globalisation is an opportunity”, a majority of respondents (60%) chose “globalisation is a threat”, an increase of 3 points (57%) compared to wave 2 (January 2020). Only one-third (34%) of respondents see globalisation as “an opportunity”, while a high proportion chose not to answer the question (6%).

In September 2020, most (60%) of citizens perceive globalisation as a threat

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

With the exception of 18-24 year-olds, among whom it is a minority (43%), the perception of globalisation as a threat is a majority opinion among all other age groups: among 25-34 year-olds (56%), 35-49 year-olds (61%), 50-64 year-olds (65%) and those aged 65 and over (61%). The relationship to globalisation varies according to the level of education, but is never very favourable.

It is true that its perception as a threat concerns three- quarters (73%) of people without a degree or with a BEPC, CAP or BEP degree, with only 47% of those with a level above having a baccalaureate degree seeing globalisation as an opportunity, as opposed to 46% who see it as a threat.

Globalisation is of particular concern in rural France

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Hostility to globalisation is much more widespread among RN supporters (81%), PCF/LFI supporters (67%) and those with no party preference (64%), but it remains in the majority among those close to LR (54%), PS (53%) and EELV (52%).

Among LREM supporters, only 34% believe that “globalisation is a threat”. They are the only ones to consider globalisation as an opportunity (64%).

Memo for the reader: of those who believe that globalisation is an opportunity, 65% consider that reducing unemployment should be one of the government’s priorities; of those who believe that globalisation is a threat, 50% consider that reducing unemployment should be one of the government’s priorities.

The fear of globalisation is that of a France that is more afraid of criminal behaviour, immigration and Islam

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – October 2020

Fear of globalisation fosters electoral protest