Achieving a new common agricultural policy

Introduction

The CAP has fulfilled its purpose

Agricultural policy must also guarantee the parity between agriculture and other economic sectors

Missions entrusted to the CAP justify public funding

From 1960 to 2010: the CAP moves from guaranteed prices to direct aid

From 1984 on, production regulation was achieved through milk quotas and the agriculture set-aside scheme

Decoupling breaks the link between aid and production

Decoupling is not a perfect solution, but it is long-term measure

The key challenge is to continue to adapt agricultural structures in an open market

Agriculture’s environmental conversion is a reality which calls for long-term policy and support

The new Member States’ agricultural potential will need to be increasingly relied upon

The post-2013 CAP budget will be the focus of debate

The agricultural sector is seeking a new pact with society

Conclusion: the future CAP will be a liberal, subsidised and green policy…

… But it must also promote solidarity

Bernard Bachelier,

Director of the Foundation for World Agriculture and Rural Life (FARM).

Discussions aimed at defining the post-2013 Common Agricultural Policy will be opening this November. The CAP – the leading, oldest and most integrated of existing Community agricultural policies – is a symbol of European construction. The issue of market regulation in a liberalised world is one of the topics on the agenda. Yet the CAP is also facing a turning point in which the sustainability and adaptation of its practices will need to meet the environmental and health-related expectations of society.

For the Common Agricultural Policy, the 2013 deadline will trigger a return to balances of power. Indeed, the European Union, whose CAP is the leading Community policy, needs to formulate its policy for the 2014- 2020 period. This does not mean a mere adjustment, but rather a redefinition of its economic, social, environmental and international vision, the positioning of the agricultural sector in society, management tools and the budget, namely the resources which taxpayers agree to devote to it. The negotiation process will actually begin with the November 2010 publication of a European Union communication, which is really a proposal outlining the discussion framework.

The CAP is in the line of fire of several potential challenges: in France, these are businesses, budgetary issues, ecologists and the development sector, and internationally they are exporting countries and poor countries, from the liberals’ viewpoint and – for different reasons – part of the Left and the Greens. This said, none of these groups are unanimously hostile to the CAP. “Friends of the CAP” are everywhere.

The biggest criticism comes from citizens voicing new expectations with regard to farmers and agriculture. These health-related and environmental expectations counter certain production practices for which the CAP is said to be, rightfully or wrongfully, responsible. The challenge for the agricultural sector is to regain, along with society at large, a contract which the farmers are in a position to fulfil to their fellow citizens’ satisfaction, yet with a sense of having done their duty.

Following are a few reference points which should help to shed light on the debates to take place over the next few months and what will be at stake in the future.

The CAP has fulfilled its purpose

The CAP was created by the Treaty of Rome signed on 25 March 1957 by the founding countries of the European Economic Community (EEC). Under the Treaty of Rome, the purpose of the Common Agricultural Policy is:

- to increase agricultural productivity by promoting technical progress (…);

- to ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural community;

- to stabilise markets;

- to assure the availability of supplies;

- to ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices. (Article 39 of the Treaty of Rome).

The French still have a vivid memory of the shortages which they endured during the last war. Technical progress must ensure food security. Moreover, the CAP was created to meet a cohesion objective for what remained a substantially agricultural Europe. In 1955, France had 2.3 million farms. The active agricultural population totalled 6.2 million people, or one-third of the total active population. Agriculture’s added value accounted for 10% of the gross domestic product. Food expenditures represented 20% of household consumption, most of which were in the form of unprocessed products (Source: Agreste, the bureau for statistics of the French Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries).

Agricultural policy must also guarantee the parity between agriculture and other economic sectors

The Agricultural Orientation Act enacted in 1960 and 1962 by the French Parliament at the initiative of Michel Debré and Edgar Pisani sets out in its Article 1: “The French Agriculture Orientation Act aims, within the economic and social policy framework, to create parity between agriculture and the other economic sectors.” Paragraph 7 of Article 2 stipulates that the agricultural policy’s objective is “to promote and favour a family-type farming structure likely to make optimal use of modern production techniques and to permit optimal use of labour and working capital.”

The entire French sector was restructured in the 1960s to include:

- priority given to family farms;

- technical progress and modernisation goals;

- co-management with professional agricultural organisations.

One outcome desired by the government and by all decision-makers at the time was to realise an increase of the average farm size and a reduction of their number, thereby freeing up labour forces to benefit other agricultural sectors.

Missions entrusted to the CAP justify public funding

The CAP fulfilled its purpose. It attained and exceeded its objectives: French people have an abundant, diversified, healthy and inexpensive food supply – so much so that the issue of national food security is no longer of concern to consumers. We will examine the criticisms regarding quality, but it should be pointed out that, in all of human history, food has never been healthier.

France has become one of the planet’s leading agricultural export countries. A first-class food industry sector has developed. French agriculture’s demographic transition evolved successfully without any major social upheavals. Any opinion on the CAP should always take into account these two significant achievements: a healthy and inexpensive food supply and the participation of farmers in the country’s economic and social growth.

Nonetheless, the economic equation of the consumers-producers-tax-payers triangle is clear: food prices continuously accessible to all and preserved farm income. It is up to the taxpayer to complete the “business model.

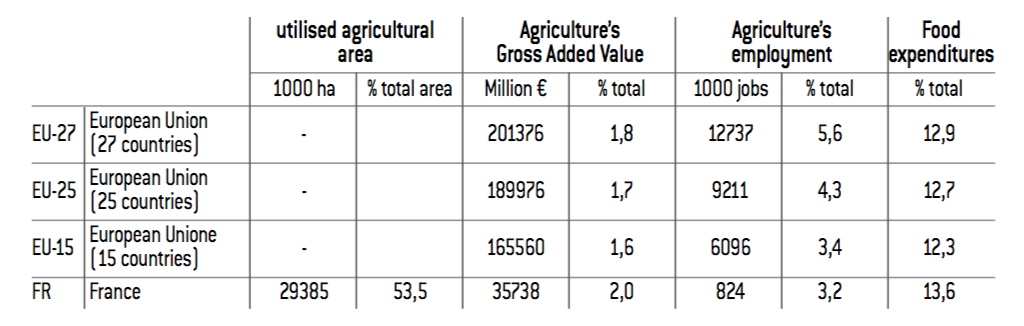

Tableau 1 : Key figures of the European union’s agricultural sector

Source :

European Commission – Eurostat, 2010.

From 1960 to 2010: the CAP moves from guaranteed prices to direct aid

The Common Agricultural Policy has been evolving in several stages since 1960 in terms of instruments as well as its goals. The reforms were dictated by three major requirements:

- to eliminate surpluses;

- to make European systems compatible with World Trade Organization rules;

- to introduce environmental requirements.

The original CAP provided mainly for price regulation. The primary instruments were the common market organisations created per product and structured by a regulation which stipulated its action mechanisms. Preventive measures allowed surpluses to be purchased and physical stocks to be constituted when prices dropped and to be stored when prices rose.

Community preference tends to favour the taxation of imports, thereby ensuring stable internal prices. Moreover, when export sales prices are lower than European prices, producers receive compensatory subsidies. These restitutions have been known to be the focus of CAP critics for their impact on developing countries’ agriculture. Every year during marathon negotiations, the Council defines reference prices for the internal market (target price), the import tax rates (threshold price) and stock purchases (intervention price).

To eliminate surpluses, the CAP can resort to two options: it can directly control production by setting quotas and setting aside land, or reduce reference prices.

From 1984 on, production regulation was achieved through milk quotas and the agriculture set-aside scheme

Henri Nallet “L’Europe gardera-t-elle ses paysans ? Une mise en perspective de la réforme de la CAP” – Paris – Fondation Jean Jaurès – Fondation européenne d’Études Prospectives – 2010.

In 1983, the European Union was collapsing under the weight of 600,000 tonnes of milk powder and 1.1 million tonnes of butter. Starting in 1984, the European Council decided to set milk production quotas. After some fifteen years, milk product stocks were reduced to an acceptable level. Yet quotas do not just control overall production volumes, they also distribute them among countries. They thus serve a territorial policy and limit intra-Community competition. Nonetheless, the decision was made to eliminate them by 2015 in annual increments of 1%.

In the early 1990s, grain stocks exceeded 30 million tonnes. In 1992, the Council decided to fallow from 5 to 15% of cultivated land by introducing a mandatory fallow system. The elimination in 2009 of the fallow land obligation, decided in the aftermath of the food crisis and development of biofuels, raised protests from ecological organisations because fallow land had become biodiversity refuges. Lastly, in 1999, several provisions were adopted to control beef production by setting caps on the number of animals raised per hectare.

The 1992 reform did not merely set aside land. As underscored by Henri Nallet1, it caused a major shift in the CAP by requiring that direct subsidies be attributed on a per-hectare basis. These were compensatory payments justified by the decline in institutional prices. It was the beginning of direct aid payments which concerned grain, oilseed crops and bovine cattle and which rapidly became a significant part of farmers’ income. In 1999, the Berlin Agreement strengthened the role of direct aid, especially for bovine cattle.. Direct aid payments soon represented 50% of farm revenue, an amount equivalent to the results obtained by production activities.

Decoupling breaks the link between aid and production

This change also met trade rule requirements. The Uruguay Round, in the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), was completed in 1994. On 1 January 1995, the World Trade Organization was created, making the GATT Treaty a permanent organisation. In the agricultural sector, the two major concerns were access to markets and subsidies. The Agriculture Agreement signatory countries agreed to open their markets by reducing customs tariffs and by lowering, or even eliminating, subsidies which distorted trade. The targeted forms of aid deemed to have a distorting effect on the markets were those associated with production and export subsidies.

In November 2001, the WTO Ministerial Conference which met in Doha, Qatar, decided to launch new negotiations called the “Doha Round” or “Doha Development Agenda.” What caused this Round’s negotiations to constantly stall was mainly a lack of consensus on agriculture.

In the early 2000s, however, the prevailing trend was to liberalise economies and markets. The European Union found itself in the crossfire of major exporting countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and Brazil, which had formed the Cairns Group, and poor countries which believed that the CAP was ruining their agriculture.

It was in this context that the Union decided to anticipate the WTO’s requirements. The Luxembourg Agreement of June 2003 established the principle of “decoupling” direct aid which consisted of eliminating the link between subsidies paid to farmers and production, whether this involved the choice of production or the quantities produced.

France set up the Single Payment Scheme (SPS) in 2006, calculated on the basis of surfaces held during the 2000-2002 reference period. The Member States had some flexibility in applying the decoupling according to type of production. They could resort to a partial decoupling and retain the link with production for a portion of the subsidies. France used this option with regard to certain crop sectors and livestock production.

Decoupling was implemented over the last decade. It is the focus of the most recent CAP reform adopted on 20 November 2008 under the European Union’s French presidency. This reform is referred to as a “Health Check,” because it corresponds to a rendez-vous clause decided in June 2003. As for decoupling, the 2008 decisions provide for a mandatory total decoupling by 2012, except for premiums for maintaining suckler cow herds and the ewe and goat premium.

Decoupling is not a perfect solution, but it is long-term measure

In view of the European Union’s inertia force, it would be surprising if the move towards total decoupling were to be challenged. It now seems to be one of the ways CAP is modernising its instruments. It is, however, worth examining systemic risks.

The disconnection between direct aid and production breaks the link between taxpayer support and agricultural activity. It ultimately raises the question of how legitimate the public considers such aid. It induces farmers to wonder about their function in society. Why are taxpayers paying “pensions” to farmers and what is society expecting in return?

There is no guarantee that decoupling aid will have no distorting effect on international markets. Direct aid generates security as well as equity capital which facilitate risk-taking and investments. From an international vantage point, the system symbolises the injustice afflicting farmers in poor countries. The latter cannot count on any safety net, yet they are exposed to the greatest environmental constraints and their markets are open to imports.

Furthermore, the uniformisation called for by the 2009 Health Check – even if it is left to State initiative – will weaken the scope of direct aid as a public policy instrument. Obviously, it will be very difficult to challenge the Single Payment Scheme, which has become an “acquired benefit.” Reactions to decisions announced on 23 February 2009 by Michel Barnier, then-French Minister of Agriculture, confirmed it. Michel Barnier decided to redeploy 1.4 billion euros of direct aid earmarked for crop production to animal productions and to create a hedging mechanism. These measures stemmed from a demand for justice and was aimed at preventing criticisms of the French mechanism’s excessive disparity. This fair and rational decision met with opposition from grain producers and nearly caused the collapse of the French National Federation of Farmers’ Unions (FNSEA).

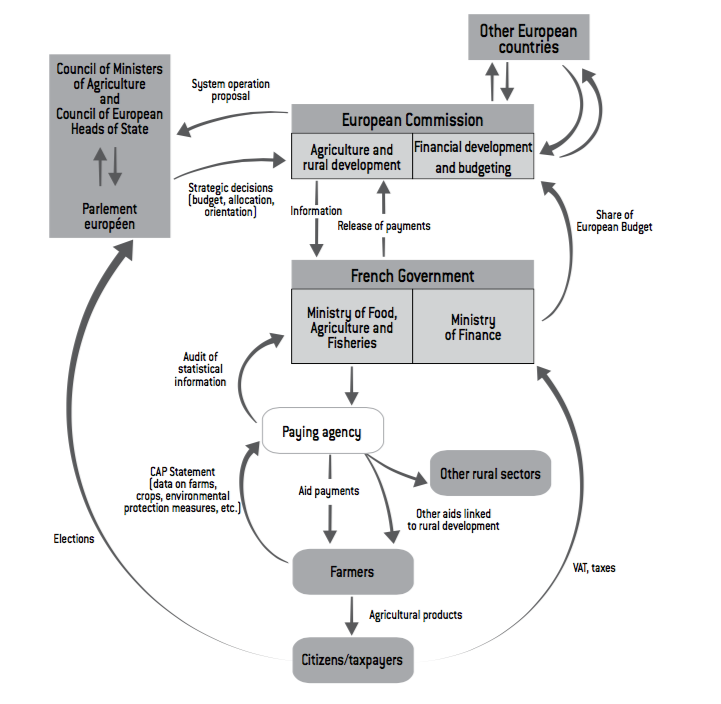

Graph 1 : organisation of the CAP

The key challenge is to continue to adapt agricultural structures in an open market

BIMAGRI « Les chiffres de l’agriculture et de la pêche » Ministère de l’agriculture et de la pêche – 2009.

Since 1992, reforms have been inevitably reducing market mechanisms. Intervention prices were pegged to world prices. In doing so, reforms liberalised the European market and exposed farmers to world prices. This opening of the markets will not be questioned within the framework of future CAP negotiations.

All prospective scenarios on the world food balance show that trade is likely to increase because consumers are not necessarily located near major agricultural production regions. Trade will increase because it balances structural or conjunctural deficits. Lastly, in a predominantly agricultural economy, agricultural exports constitute an essential share of the revenue of the States and farmers.

Managing the impact of the market opening does not mean returning to protectionist measures or juxtaposing regional groupings. While some regions such as West Africa would benefit from improved economic integration, global agricultural trade cannot be controlled by carving the planet into homogenous economic zones that do not exist.

However, the adaptation of European policy and agricultural structures to the market must be pursued and completed by focusing on market organisation mechanisms and the modernisation of structures and agricultural holdings.

- Community rules and tools aimed at ensuring transparency and promoting an equitable operation should be strengthened. These tools should give rise to two primary mechanisms: a market information system and the regulation of commodities futures markets.

- Professional organisations need to be modernised in order to secure their edge in trading activities and to help them manage risks. This involves:

- Insurance policies which are necessary to cover risks inherent in agricultural activities, crop insurance covering vagaries of production, and income insurance protecting against economic shortfalls. These forms of insurance call for private management capabilities and public support. They are decided upon by economic actors, individuals or mutualists.

- Structuring sectors by constituting powerful economic actors with cooperative or private statutes who assume risk management and contractualisation functions.

Public authorities may contribute to these changes by providing a legislative and regulatory incentive financing support framework, notably for insurances.

- Modernisation of agricultural holdings

French farms will need to enter a new modernisation stage because of increased land surfaces, the need to adapt their equipment, and access to technological innovations. This is required not only because of the opening of the European market, but it was made indispensable by the European Union’s enlargement and ensuing intra-Community competition.

The increase in land surfaces stems from generational changes. However, it is the public authorities’ responsibility to support transitions involving the loss of agricultural holdings which are not economically viable. The French model is predicated on a fabric of average-sized farms spread throughout the country. Yet the number of farm holdings has been constantly declining. In 2007, France had 326,000 commercial farms, as opposed to 2.3 million in 1955. Including coop farmers, there are 436,000 farm managers, of whom 18% are older than 552. The notion of “average size” and the concept of family have changed a great deal in the last 50 years. They will continue to adapt to the agricultural context while upholding France’s primacy of this principle. However, broaching this issue effectively would require ridding it of all taboos.

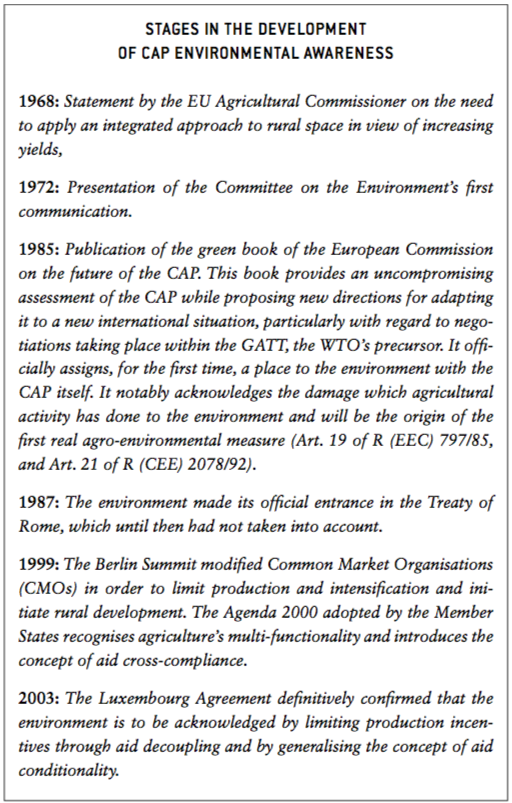

Agriculture’s environmental conversion is a reality which calls for long-term policy and support

The Common Agricultural Policy has incorporated society’s expectations in matters concerning environmental protection and healthy food quality. This concerns landscapes, water quality, soil pollution, biodiversity, greenhouse gas emissions, animal welfare, food risks, food quality and nutrition.

It is evident that these issues are all the more numerous and complex given that the relationship between citizens’ concerns and agricultural practices follow multiple paths. The first difficulty is thus that of legibility.

The CAP meets these challenges via two principal methods

- Conditions under which direct aid may be paid: Direct aid forms the CAP’s first pillar, however, such payments are conditional upon respecting three categories of requirements:

- Regulatory requirements as set out in 19 directives or European regulations.

- Good agricultural and environmental conditions, the definition of which is a matter determined by each Member State through application of the subsidiarity principle.

- The maintaining of surfaces as permanent pasture.

- The agro-environmental measures covered by the second pillar which resulted from the 1992 reform. The second pillar deals with measures which do not concern agricultural production, notably activity diversification, environmental protection, standard compliance by farm holdings and training. The second pillar is co-funded by the Community budget and the Member States. If the greatest difficulty is that of legibility, the second is the assessment of these policies’ outcomes, a question which calls for a review of five key points.

First, the reorientation of European subsidies from farmers to environmental and health-related aims is a reality. Instrument complexity is a technocratic jungle whose mechanism lacks transparency. There are no indicators with a long-term monitoring indicators. These flaws are real, and the conditions can and must be improved. Yet the tone has been set, as the Common Agricultural Policy has begun advancing towards a sustainable management of natural resources.

Second, farmers have read the signals set off by the European policy and they are sensitive to the citizen pressure exerted by both associations and consumer behaviours as relayed by industrial and distribution channels. The use of chemical products has lessened considerably. Sustainable agro-ecology and sustainable agricultural practices are multiplying. Farmers are giving the impression that they are being forced to adopt these changes, but the great majority of them are now practicing sustainable farming.

Third, the outcomes do not fully conform to citizens’ aspirations. Several reasons may explain their impatience. The target may not be exactly the same. France will become neither a biological garden nor a bocage. Clean agriculture will be a precision agriculture. Next, today’s available technologies will not make it possible to attain all of the objectives assigned to agriculture: inexpensive products in sufficient quantity, which is the reason why the issue of funding and ecological conversion is essential. If the consumer is not able to pay the additional costs, it is up to taxpayers to finance what must be considered to be a long-term investment.

Fourth, the importance of the landscape issue is underestimated. Landscapes are common assets by which citizens understand their relationship to the natural environment. There are growing local conflicts between farmers and rural non-agricultural residents. Farmers are not solely responsible for the repeated damage caused to landscapes as a result of expanding urban and industrial areas and the dispersion of the habitat and eolian installations. Yet as legitimate space managers, they ought to take better care of the agricultural landscape for which they are primarily responsible.

Fifth, research and innovation are impacting the market’s move towards new sustainable and economically viable agricultural practices. Innovations will come from private as well as public research acknowledged as fundamental. All programmes are being reoriented towards the development of resource-conserving solutions, but research is a long-term project.

Nonetheless, research in France is suffering from obsessive public reject of GEOs. The French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) claims to devote less than 2% of its budget to GEOs (source: an interview of INRA’s President profiled in Échos no. 272 of October 2010). Seed companies are no longer conducting trials in France and their research findings are primarily intended for American farmers. However, GEO rejection has a negative impact on all research on plant breeding. Future discoveries will initially come from the assessment of genetic resources and from the identification of genes contributing useful characteristics, thanks to cutting-edge laboratory equipment.

A global restriction-free approach will make it possible to offer farmers new varieties derived from traditional selection or transgenesis. Administrative officers or political leaders seem to be trapped by, or a party to, the French stalemate. European agriculture may suffer serious consequences which would affect its African country partners who are entitled to expect French research to be future-oriented. Inasmuch as the biological potential of plants contributes as much as ecological systems to an ecologically intensive agriculture, the latter cannot do without chemical inputs and biotechnologies. In addition, the initial concept of the “doubly green revolution” relied as much on ecological, as it does on biological, advances.

The new Member States’ agricultural potential will need to be increasingly relied upon

Alain Pouliguen « Pays de l’est intégration dans l’union européenne : de la reprise agricole à la crise » – Économie et stratégie agricoles – Déméter 2011.

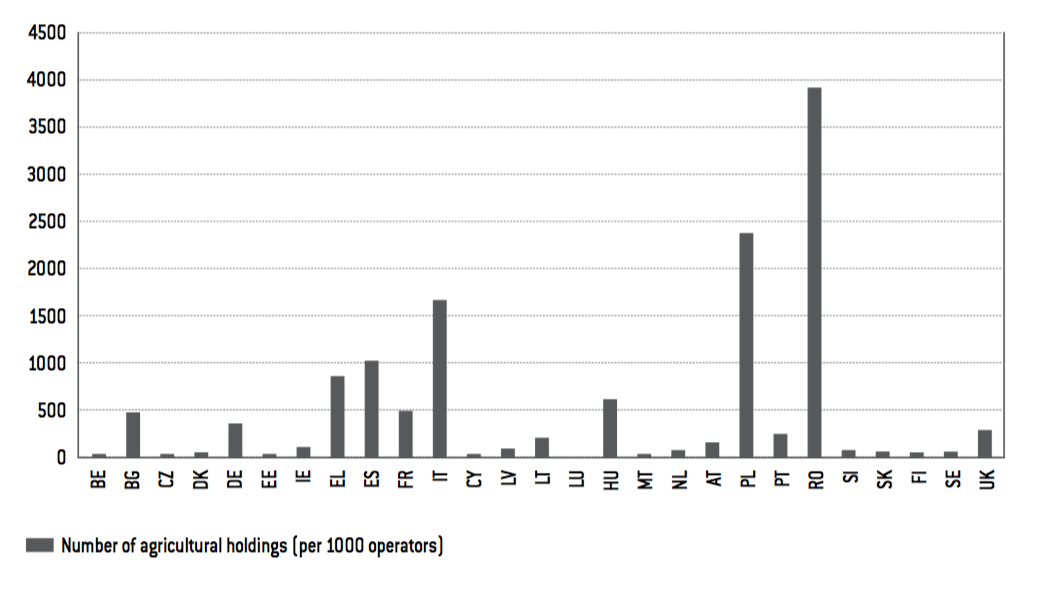

Ten new Member States from Central and Eastern Europe have joined the European Union: Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, and the three Baltic States, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in 2004, followed by Romania and Bulgaria in 2007. By adding Cyprus and Malta, which both joined in 2004, the number of EU Member States rose from 15 to 27.

The Union’s agricultural structure was extensively changed by due to a 64% increase in the number of farms, which soared from 5,600,000 in the EU-15 to 9,300,000 in the EU-25. Romania joined the Union with 3,900,000 holdings and Poland with 2,400,000. This situation exacerbated the Union’s agricultural disparity at a time when a new balance had been established in the wake of the preceding enlargements, notably when Spain and Portugal joined the Union in 1986.

The agricultural area increased by 26%, from 127 million hectares to 160 million hectares, whereas production only rose by 19%. The average holding size decreased from 22 hectares to 17 hectares, ranging from 3.5 hectares in Romania to 89 hectares in the Czech Republic (Source: European Commission statistics).

The fact that two new Member States occupy the range’s extremities speaks to the duality of their agriculture and of the legacy of popular democracies’ agriculture policies. This duality3 is based on the existence of two types of holdings: pure or partial subsistence familial farms, which prevail in Romania and Poland, and very large commercial farms which result from the privatisation of State farms.

These countries are confronting several forces whose convergence will take time. The modernisation and enlargement of small family holdings point to an employment issue. The impetus towards the commercialisation and intensification of large holdings gives them a solid export potential. New Member States have thus produced grain and sugar surpluses.

Joining the European Union has allowed these countries to benefit from agricultural subsidies and from structural funds accompanying modernisation. The impact of this funding was all the more important for the farmers’ income because the national currency exchange rates outside the euro zone were favourable for them.

To date, these new Member States have managed their membership and their domestic economic reforms. The EC agricultural economy has not yet experienced the full effects of their entry into the European Union. Intra-Community competition is expected to increase, thereby placing additional pressure on structure modernisation. These countries are also bound to become more vocal within the Community’s decision-making processes. It will be in their interest to maintain a strong Common Agricultural Policy as long as its application is favourable to them.

Graph 2 : Agricultural holdings (2007)

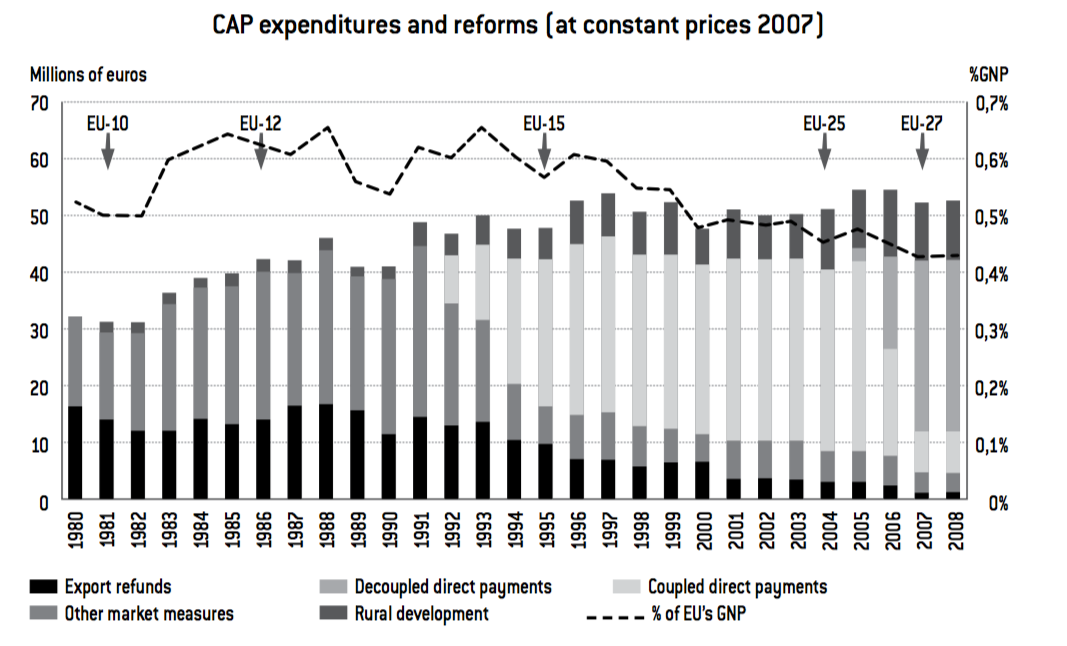

The post-2013 CAP budget will be the focus of debate

The CAP’s total budget is 57 billion euros, or slightly more than 40% of the 141.4 billion euro EU Budget 2010. The European Union’s financial prospects were determined in 2005 by the Heads of State and of Government for the budgetary period 2007-2013. The CAP is a single integrated policy. It represents 0.4% of the European gross domestic product. Moreover, until 2009, France was a net beneficiary of agricultural financing. France funds 18% of the EU budget. The return rates were 19.4% for the first pillar and 7.2% for the second pillar. Jacques Chirac and Gerhard Schröder reached an agreement in 2002 to uphold the CAP budget until 2013.

Graph 3 : CAP Budget

Source :

European Commission.

For the post-2013 CAP, all options are open. The European Commission is expected to announce its proposals for the Union’s multi-annual financial framework at the end of the first semester of 2011. Discussions will probably range from a reduction of 15%, as contemplated by the President of the European Commission, to a renewal at a level equivalent to the existing one. However, the progress realised by the new Member States will automatically bring about a redistribution which will reduce the share payable to French farmers.

Furthermore, the Lisbon Treaty strengthened the European Parliament’s powers and extended the scope of co-decision. The CAP is subject to co-decision, which provides that it be approved by the Parliament. The multi-annual financial framework will need to obtain the Parliament’s approval and the European Council’s unanimous vote. Nicolas Sarkozy also broached the issue of the European Council’s adoption of the CAP in order to ensure unanimity.

It is difficult to anticipate what the power relationship will be in Parliament as a whole. On the other hand, the Agricultural and Rural Development Commission expressed its preference for a “fairer, greener and more sustainable” CAP. In all probability, Parliament will lean in favour of environmental objectives and redistribution of aid. The allocation between the first and second pillars, as well as the Member States’ use of co-financing, may have an impact on subsidies received by the various farmer categories. French agriculture will likely need to enter a new stage of adaptation with reduced budgetary support. Although financial discussions may prove difficult, the reduction should not be significant, but could involve a redistribution

The agricultural sector is seeking a new pact with society

A new Pact for Europe – CAP 2014-2020 – Société des Agriculteurs de France.

Farmers are striving to make a new pact which would reconcile the agri- cultural sector and society. This idea of a pact – mentioned often in CAP reform proposals4 – stems from several of the farmers’ expectations, which are to renew their fellow citizens’ trust in them, clarify the missions entrusted to them, to reinstate the legitimacy of their role in society and to secure public financial support. It is also their wish to restore the coherence between the various functions, notably the two main ones: agricultural production and environmental services.

This coherence can be achieved by acknowledging the nature of food security’s public goods as natural resources. Coherence also comes from the conviction that acts of production themselves contribute to the management of natural resources, that there is not, on one side, production which would only concern the economy and market and, on the other, environmental activities needing to be remunerated by public authorities. Consequently, public transfers are not merely justified by paying for environmental services, but also by the specific nature of food productions..

Moreover, it is likely that a debate with French society would reveal a much greater consensus than the farmers anticipate, provided that all parties integrate the notion of time and long-term commitments. It is in this spirit that the pact would range from multi-annual individual, to collective, contracts.

These concepts may well be included in the next European agricultural policy because they are realistic and reflect everyone’s interests, even if they are the outcome of a long and tense negotiation process. These debates will constitute a new stage in European construction because overcoming the disparities between the 27 Member States is more crucial than the lack of consensus in France. That is why what is at stake is the Union’s ability to define an ambitious political vision. Pact and contract notions are good reference points, especially in a French context, but they cannot take the place of a political framework. Trust is not the out-come of the contract, but its prerequisite, the creation of a shared vision.

Conclusion: the future CAP will be a liberal, subsidised and green policy…

Two major challenges lie ahead. The first is to adapt Europe’s agriculture to an open market economy. Market operations will need to be improved and support provided for modernising agricultural structures so that they can take advantage of the markets. French agriculture must have support to achieve this, inasmuch as it will have to confront new intra-Community competition, and professional agricultural organisations will need to play a decisive role.

The second challenge concerns sustainability. Environmental rules will be toughened in response to pressure exerted by public opinion and many Member States. Care must be taken to ensure that the rules’ pace of implementation remains compatible with innovation.

… But it must also promote solidarity

In concluding, we will make a few suggestions for strengthening agricultural solidarity between Europe and developing countries. All farmers on the planet have to meet common challenges such as food security, sustainable production and the management of natural resources. These challenges are humanity’s public goods. Their value surpasses individual interests and must promote international solidarity with developing countries. Europe has the legitimacy, know-how, competence and means to play a key role in the agricultural area. It can regain the spearheading power that it lost. A few suggestions follow:

- to assert solidarity with poor countries’ agricultural policies in the new Common Agricultural Policy. The CAP should assert its determination not to decide upon any measure which could have a negative impact on poor countries and to consider its instruments’ potential validity in other contexts. It would be worthwhile to share market regulation, sector contractualisation or sector-structuring concepts. The point is not to transfer or impose, but to build together.

- to commit to finalising Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) which include protective and investment rules which allow the development of food sectors. The EU should be committed to promote a successful conclusion to Doha Round negotiations within the framework of the World Trade Organization in order to establish more equitable market rules for poor countries. From this vantage point, the European Union must confirm that refunds will be eliminated, namely export subsidies. That principle is included among the European Union’s proposals in negotiations with the WTO and is accepted by agricultural professions. Moreover, the decline in institutional prices has made such refunds moot. Their definitive elimination would spare Europe from confusion involving cut-price imports entering Africa from Asia or Latin America.

- to reconcile agricultural policies and EC development policies. The pursuit of these two policies by separate directorates-general has long spared Southern countries from being impacted by an overly restrictive defence of European agricultural interests. Today, that separation is having a crippling effect. European development policy has dismissed agriculture. It merely has a social perception of it and does not deal with it as an economic activity which requires public investments. Yet opening markets creates common interests. The moment has come to endow the European Union with a genuine agricultural development strategy which will ensure food security.

- to define and fund an ambitious programme promoting the economic structuring of sectors which would mobilise European competences in all areas contributing to agriculture’s economic environment: credit, insurance, professional organisations, supply, processing and marketing, training and technical support and access to technologies. European agricultural professions have nothing to fear from the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), nor from those which have partnership agreements with the European Union. They share a common conception of agriculture with these agricultural communities. The provision “Everything But Arms” opens the European market to duty and quota-free imports originating from the Least Developed Countries. Similarly, the priority is not to maintain a few export volumes for Europe, but to facilitate the emergence of a high-performance agricultural sector and thereby promote local economic growth.

- to promote European participation in the formulation and financing of new agricultural policies and corresponding funds, such as the Global Agriculture and Food Security Programme (GAFSP).

- to acknowledge the diversity of agricultural development situations, which implies the priority which African countries need to give to intensification. Europe must make certain that it does not prevent their having access to development aid by imposing environmental conditions which are not priorities for them.

This study highlighted what is necessary in order to move towards open and modernised agricultural economies and sustainable resource production and management practices. The gap separating the baselines is immense and must be conducive to maintaining the focus on diversity. We must never forget the contexts in which the 2.6 billion farmers inhabiting the planet are living. At any rate, the challenge is to invent new public policies – liberal ones which ensure public investment and promote the empowerment of professional and private actors.

No comments.