AfD: the German far-right at a dead end

Introduction

The fragmentation of the political system

Emergence and strengthening of the AfD

Foundation and sociological development of the AfD electorate

AfD organization, financing and communication

Germans, Europe and the AfD

German opinion and the European Union

Perceptions of democracy and European institutions

Germans’ perception of Russia since the war in Ukraine

The AfD’s European program

Challenges and outlook for the AfD

Unfinished German reunification: a springboard for the AfD

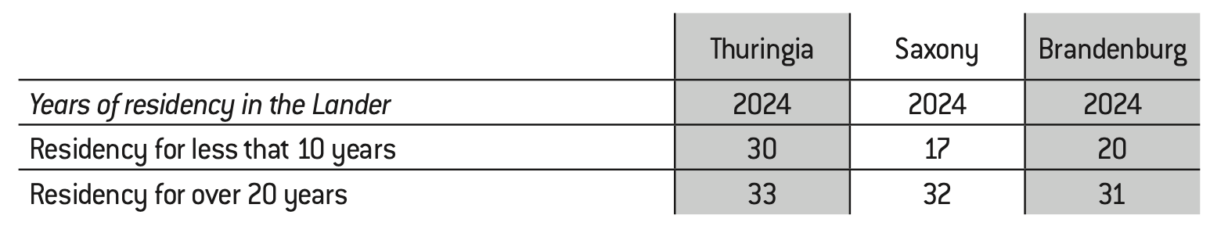

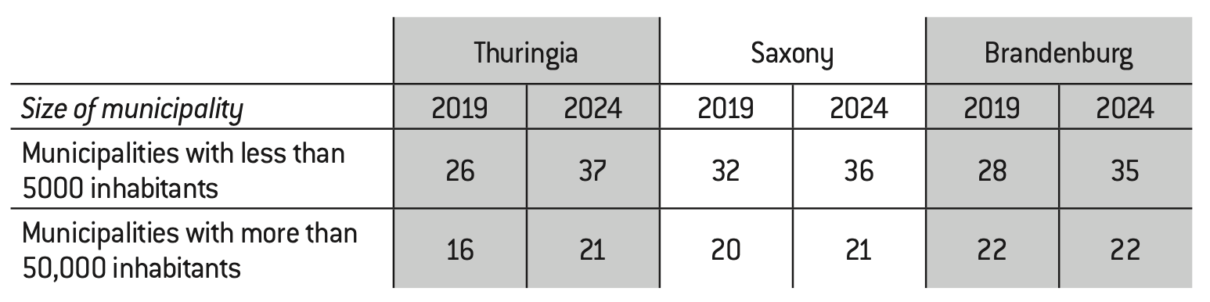

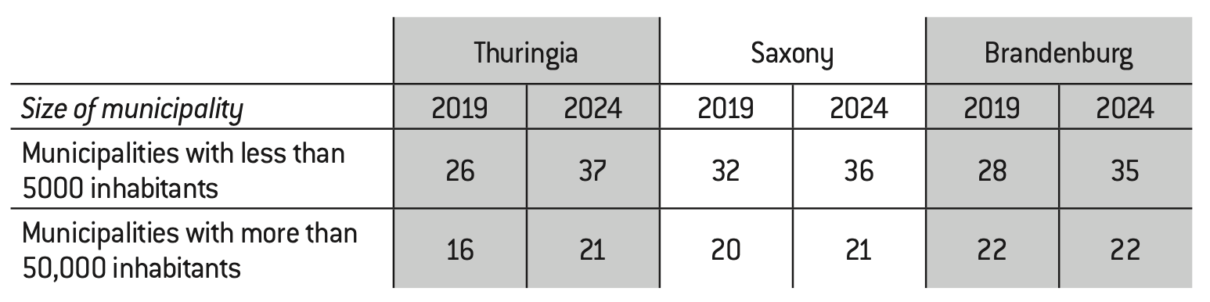

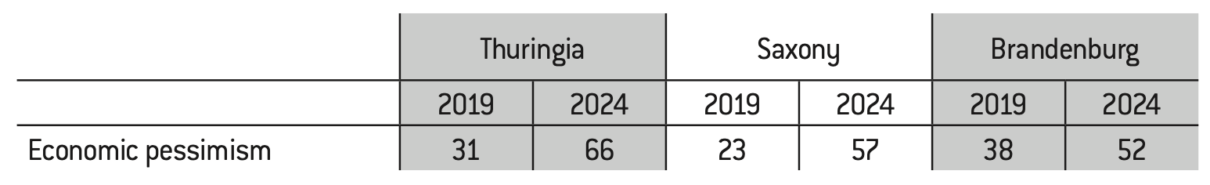

How Economic Difficulties Influence Support for the AfD

Internal radicalization, opposition and risks of banning

Religious and trade union institutions confront the AfD

AfD and Moscow: controversial links under fire

AfD marginalized by the far-right in European Parliament

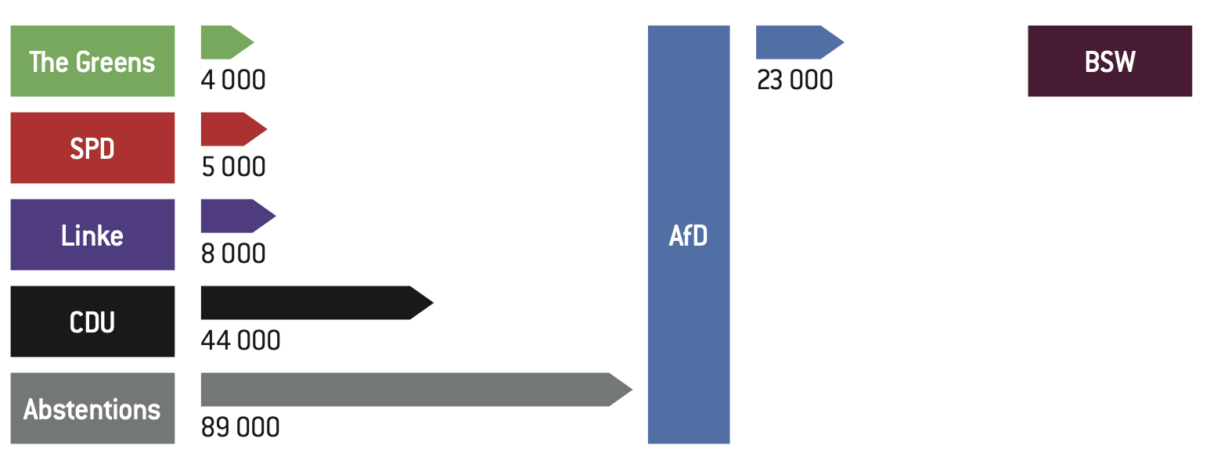

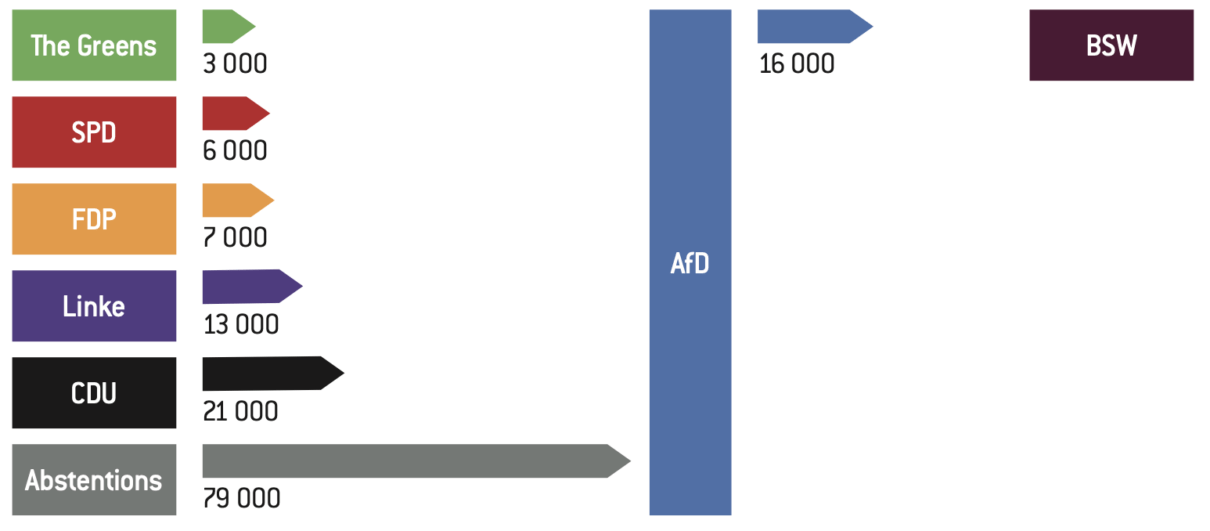

Elections in Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg

Conclusion

Summary

The June 2024 European elections in Germany highlighted the rise of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). With 15.9% of the vote, this far-right party, founded in 2013, came second and won 15 seats in the European Parliament, its best score to date. The AfD continues to grow, as demonstrated by the September 2024 regional elections in Saxony, Thuringia and Brandenburg, where it achieved around 30% of the vote.

The 2015 migration crisis marked a significant turning point, bringing the AfD’s key themes to the forefront of public debate: immigration, the rejection of Islam, security, family values, nationalism, and criticism of the “old parties” for their failures. The party has capitalized on this environment, which has become even more favorable since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the energy supply crisis. The AfD is now a major player in German politics. Over the past decade, it has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from a protest party into a membership-based party capable of shaping a distinct ideological corpus.

With elections to the Bundestag looming (in 2025), the Traffic Light coalition, led by Olaf Scholz and comprising the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Liberal Democratic Party (FDP) and the Greens, has been hit by a series of major electoral setbacks.

Like the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), the AfD has taken advantage of the crisis in the German political system and the mistrust of traditional parties.

Despite the offensive waged by the other parties, the churches, employers, civil society and the German secret services, the AfD continues to resist, rising in prominence to the point of raising concerns about the potential collapse of the Brandmauer (“firewall”) between democratic parties.

This momentum should not cloud our judgment, as the party still faces significant challenges. In the European Parliament, its radicalism has left it isolated, leading to its exclusion from the Identity and Democracy (ID) group led by the Rassemblement National (RN). Domestically, despite having strong regional support in the East, the AfD remains without a coalition partner, making its path to power far from certain.

Patrick Moreau,

Doctor of History, Doctor of State (FNSP) in political science, CNRS, specialist in extremist parties in Europe.

Are Europeans abandoned to populism?

The FPÖ and the challenge of Europe: Ideological radicalism and electoral constraints in Austria

Victory for populism in the Netherlands: a national phenomenon or a European pattern?

Fratelli d'Italia : neo-fascist heritage, populism and conservatism

The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW)

The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

The Netherlands: The Populist Temptation

Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Dessau’s former Schultheiss Brewery was built between 1896 and 1899 as an industrial building of impressive size. The historic brick architecture is listed as an industrial monument in the city. After bankruptcy, some of the buildings fell into disrepair, while others were used by cultural institutions.

Copyright :

Bildarchiv Monheim GmbH / Alamy Banque D’Images

The fragmentation of the political system

Patrick Moreau, The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW), Foundation for Political Innovation, January 2024 [online].

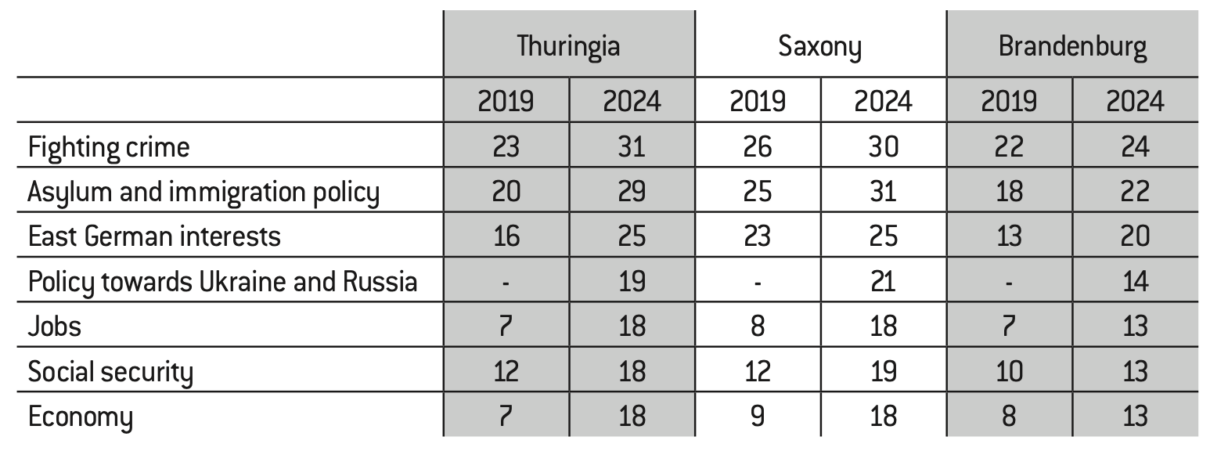

Germany is facing a political crisis due to the weakening of the Traffic Light coalition (Ampel-Koalition), which includes the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the Greens. The rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), particularly in the new federal states (Bundesländer), but also to a lesser extent in the West, is not the cause of this crisis, but rather one of its consequences. The ongoing polarization of German society is benefiting the AfD, which, despite its political radicalism and even extremism, is managing to attract a broad electorate. The diversity and motivations of these voters will need to be carefully analyzed after the elections in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg in September 2024.

For all the parties involved, the European elections were an essential step on the road to the 2025 Bundestag elections. The central question is the electoral survival of the Liberal Democratic Party (Freie Demokratische Partei – FDP) and The Left (Die Linke), which are threatened by the September 2024 regional elections with the prospect of failing to break the 5% representation barrier. Another key question is the place that smaller parties will take in the 2024 regional and 2025 national elections. Two new players will be present: the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – Reason and Justice (Bündnis Sarah Wagenknecht – BSW)1, which in the European elections largely absorbed votes from Die Linke and marginally from the AfD, and the Free Voters (Freie Wähler), targeting CDU-CSU and AfD supporters2. In 2025, the list could grow even longer with Hans-Georg Maasen’s Union of Values (Werteunion), which aims to bring together conservatives uncomfortable with CDU-CSU politics, and the Islamist party Democratic Alliance for Diversity and Renewal (Demokratische Allianz für Vielfalt und Aufbruch – Dava), which targets immigrants with German citizenship. The growing fragmentation of the political system raises the question of future government coalitions, both at Bund level and in the new Bundesländer. In any case, the AfD will not be a national or regional coalition partner, which is much less obvious at municipal level, as the “firewall” (Brandmauer) is clearly crumbling.

Emergence and strengthening of the AfD

Foundation and sociological development of the AfD electorate

Deutscher Bundestag, Bundestagswahlergebnisse seit 1949, bundestag.de [online].

Die Bundeswahlleiterin, “Elections to the 8th European Parliament on May 25, 2014” [online]; for elections in Saxony: “Wahlen”, wahlen.sachsen.de [online]; for elections in Thuringia: “Wahlen”, [online]; for elections in Brandenburg: “Wahlen”, [online].

Lewandowsky Marcel, ‘,Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)”, in Frank Decker and Viola Neu (Hg.), Handbuch der deutschen Parteien, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 2018, pp. 161-170; Patrick Moreau, L’autre Allemagne. Le réveil de l’extrême droite, Paris, Vendémiaire, 2017.

a. A brief history of the AfD

The origins of the AfD (Alternative for Germany) go back to March 25, 2010. Chancellor Angela Merkel declared before the Bundestag that, to save Greece from financial disaster, she saw no other option than massive financial aid from the European Union. The Chancellor justified this choice by referring to an “absence of alternatives”, which explains the name “Alternative für Deutschland” chosen by the new party.

Numerous economists from across the political spectrum voiced their disagreement with the Chancellor. In 2012, a Hamburg economics professor, Bernd Lucke, decided to create a rallying movement, Bündnis Bürgerwille – BBW (“Alliance of Citizen Will”). The aim of this movement, which claimed to be supra-partisan, was to impose the holding of popular consultations on issues related to sovereignty and monetary policy. At the time, this approach resonated strongly with middle-class and small- business associations, primarily those with conservative leanings, as well as political parties like the CDU-CSU and FDP. In this context, the future founders of the AfD were able to tap into a vast network of sympathizers and supporters who, by 2013, provided the financial resources needed to found a party.

On April 14, 2013, five months before the Bundestag elections, the AfD held its founding congress. Within a few weeks, the party had a foothold in all the federal states and was able to publish its list of candidates. The AfD benefited from tremendous media propaganda – negative, admittedly, but which helped to popularize its themes. In the Bundestag and regional elections in Hesse on September 22, 2013, the AfD failed to pass the 5% threshold (4.7% in the Bundestag, 4.1% in Hesse), but in May 2014 it made a decisive political breakthrough in the European elections (7.1% of the vote and 7 elected representatives). The three regional consultations that followed took place in the new Bundesländer (9.7% in Saxony, 10.6% in Thuringia and 12.2% in Brandenburg) and marked further steps in the AfD’s organizational and electoral consolidation3.

Thematically, the 2013 Bundestag election campaign focused primarily on European issues. Subsequent elections, however, the Afd introduce new themes – immigration policy, public safety, family protection, values and the nation. The arguments put forward by the AfD and the iconography of the anti-immigration campaign, dominant from 2015 onwards, show that this party was typologically close to other national-populist parties, such as the French Front National or the Austrian FPÖ. The criticism of the “old parties” present in the Bundestag, the call to save social protection systems threatened by the arrival of “foreigners”, the criticism of Islam, presented as a political religion antithetical to democratic constitutional principles, and the denunciation of uncontrolled immigration, reinforced the impression of a shift towards nativism.

The refugee crisis is the main factor behind the AfD’s breakthrough. On August 31, 2015, Angela Merkel’s phrase “Wir schaffen das!” (“We can do this !”) became the symbol of a society open to the world’s misery. The arrival of over 900,000 registered migrants and refugees in 2015 triggered a political crisis, particularly within the CDU-CSU, and provided the AfD with an opportunity to exploit public anxiety and rejection of Islam. The slogan “Mrs. Merkel must go” quickly became the AfD’s leitmotif . In the March 2016 elections, the party established itself nationwide as a political force to be reckoned with4.

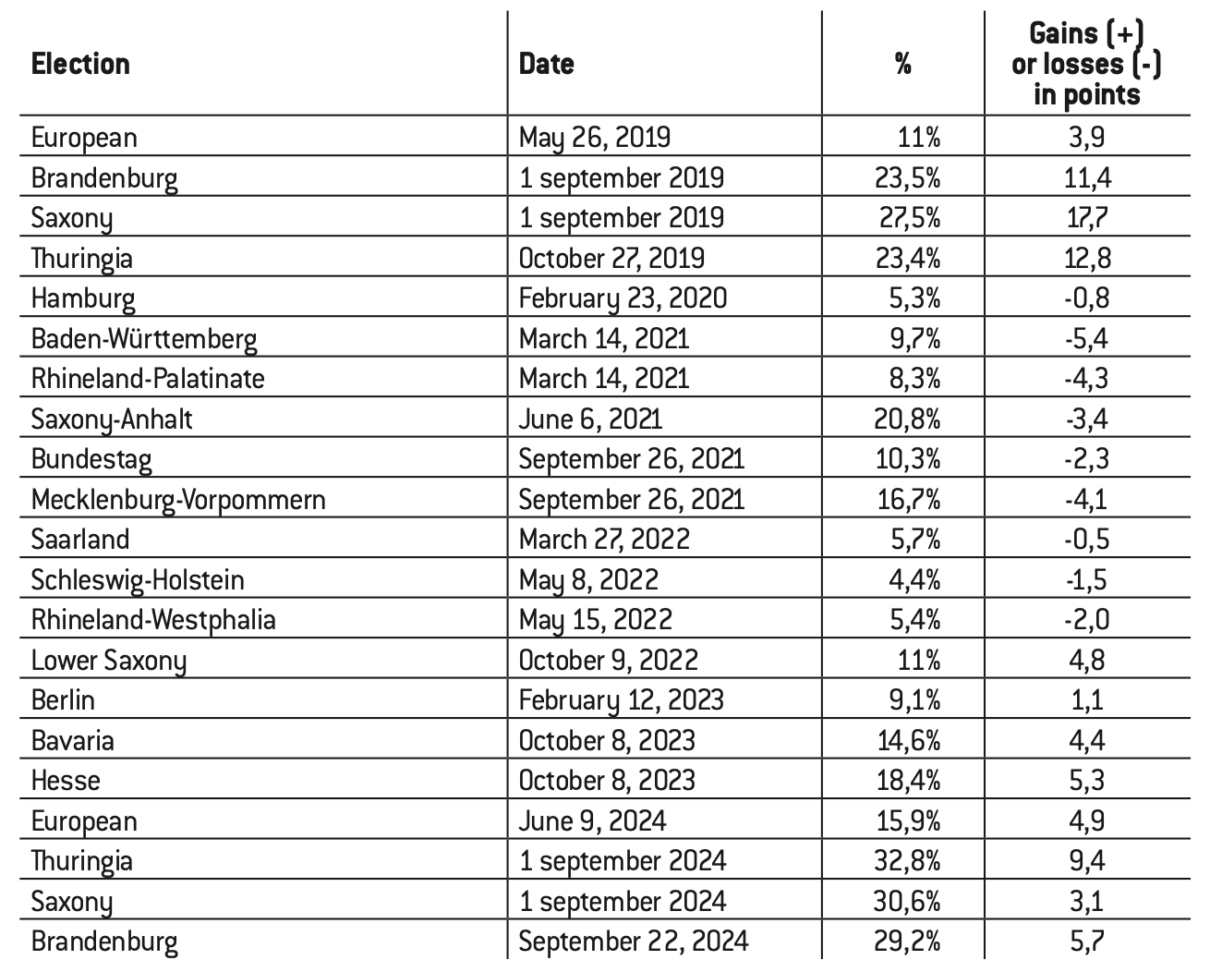

AfD results in national, regional and European elections (2019 – 2024)

Source :

Bundeswahlleiterin [online].

Fabian Virchow, ,,Landtagswahlen: AfD punktet dort, wo Wirtschaft vor Herausforderungen steht”, Ifri.org, March 2020 [online].

The percentages shown represent the share of new voters from each party in relation to all new AfD voters in 2017 (i.e. 3,820,000 new voters).

Ann-Katrin Müller et al ,,Warum so viele junge Leute die AfD gewählt haben”, October 10, 2023 [online].

In 2017, the AfD experienced an internal political crisis due to the clash of three political lines: the “conservative of values” from the CDU-CSU, the national liberals from the founding group, and the national völkisch wing, representing far-right movements (völkisch referring to a concept of ethnicity-based nationalism). After the national liberals were ousted from the leadership in 2022, the party came under the control of the völkisch faction, led by Björn Höcke5. This has radicalized the AfD’s discourse and accentuated the party’s anti-feminist, anti-immigration, anti-Islam and anti-Woke propaganda. In the elections in Lower Saxony, Bavaria, Hesse and Berlin in 2022 and 2023, the AfD made significant gains in these western Länder, as well as in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg in September 2024.

b. Bundestag elections 2017 and 2021: reasons behind the AfD vote

The AfD is a very young party compared to most of its competitors. To understand its strengths and weaknesses in 2024, we need to look back to the Bundestag elections of 2017 and 2021. During these elections, AfD circles became more stratified, establishing a presence in key regions and consolidating groups of voters who now form the party’s stable electoral base. A typical voter profile is emerging, which applies to both the 2024 European elections and the regional elections in the new eastern federal states.

In the summer of 2017, half of those surveyed were critical of the current CDU/CSU/SPD Grand Coalition, particularly due to perceived growing social inequalities and the existence of poverty-stricken areas in crisis regions. This disaffected electorate was primarily concentrated in the new federal states and included voters with lower levels of education, blue-collar workers, and supporters of Die Linke and the AfD. Polls indicated that many voters viewed the AfD as a protest party, valuable for “calling out what’s wrong.” As a result, the AfD leadership focused its messaging on immigration, the primary concern of Germans—a theme that remains relevant today.

In the 2017 Bundestag election, the CDU/CSU alliance had its worst result since 1949, securing just 32.9%, while the SPD suffered its worst showing post-war with 20.5%. The AfD’s breakthrough was particularly strong in the new federal states, where it garnered 21.9% of the vote (+16.1 points), compared to 10.7% (+6.3 points) in the West. Increased voter turnout in both East and West played a key role in the AfD’s success. The party drew voters from across the political spectrum, including nearly 980,000 from the CDU/CSU (25%6), 400,000 from Die Linke (10%), and 470,000 from the SPD (12%). However, the largest share of its support came from 1.2 million former non-voters from 2013 (31%).

15% of men and 9% of women name the AfD as their favorite party, according to 2017 data. Furthermore, the higher the level of education, the fewer voters the AfD attracts. A breakdown by age group shows that the AfD performs best among 25 to 59-year-olds, a demographic motivated by fears of unemployment and the deterioration of their personal circumstances. Additionally, this group exhibits strong hostility toward immigration, which is seen as posing both economic and sexual competition7. The youngest voters and those over 60 tend to resist supporting the AfD. A breakdown by professional category confirms the “proletarianization” of the AfD vote, which became evident in regional elections during the 2016-2017 period. Among blue-collar workers and the unemployed, 21% supported the AfD, while 12% of white-collar workers and the self-employed, and 11% of retirees, also cast their votes for the party8.

The AfD choice in 2017, as in 2024, is driven by a strong sense of loss of control. AfD voters feel at the bottom of society, and are convinced that they are facing a social “downfall”. On the political front, party elites and institutions are perceived as out of touch with reality and incapable of listening, especially on the issue of migration. AfD voters are by far the most dissatisfied with the way German democracy works (80%). At the heart of the AfD choice ( i.e responses to “The main reasons for my AfD choice”) are “curbing crime” (61%) and “controlling the arrival of refugees” (60%). These are the areas in which the party’s program is considered credible by its voters. All main themes of the AfD’s 2024 campaigns.

In the 2021 federal elections, the AfD recorded an electoral failure compared to 2017. The party lost 2.3 pts and finished in fifth place with 10.3% of the vote. The SPD won this election with 25.7% of the vote (+5.2 pts), ahead of the CDU/CSU (24.1%, -8.9 pts), Alliance 90/the Greens (14.8%, +5.9 pts) and the FDP (11.5%, +0.8 pts). The Left obtained just 4.9%, halving its result from the last federal election (-4.3 pts)9.

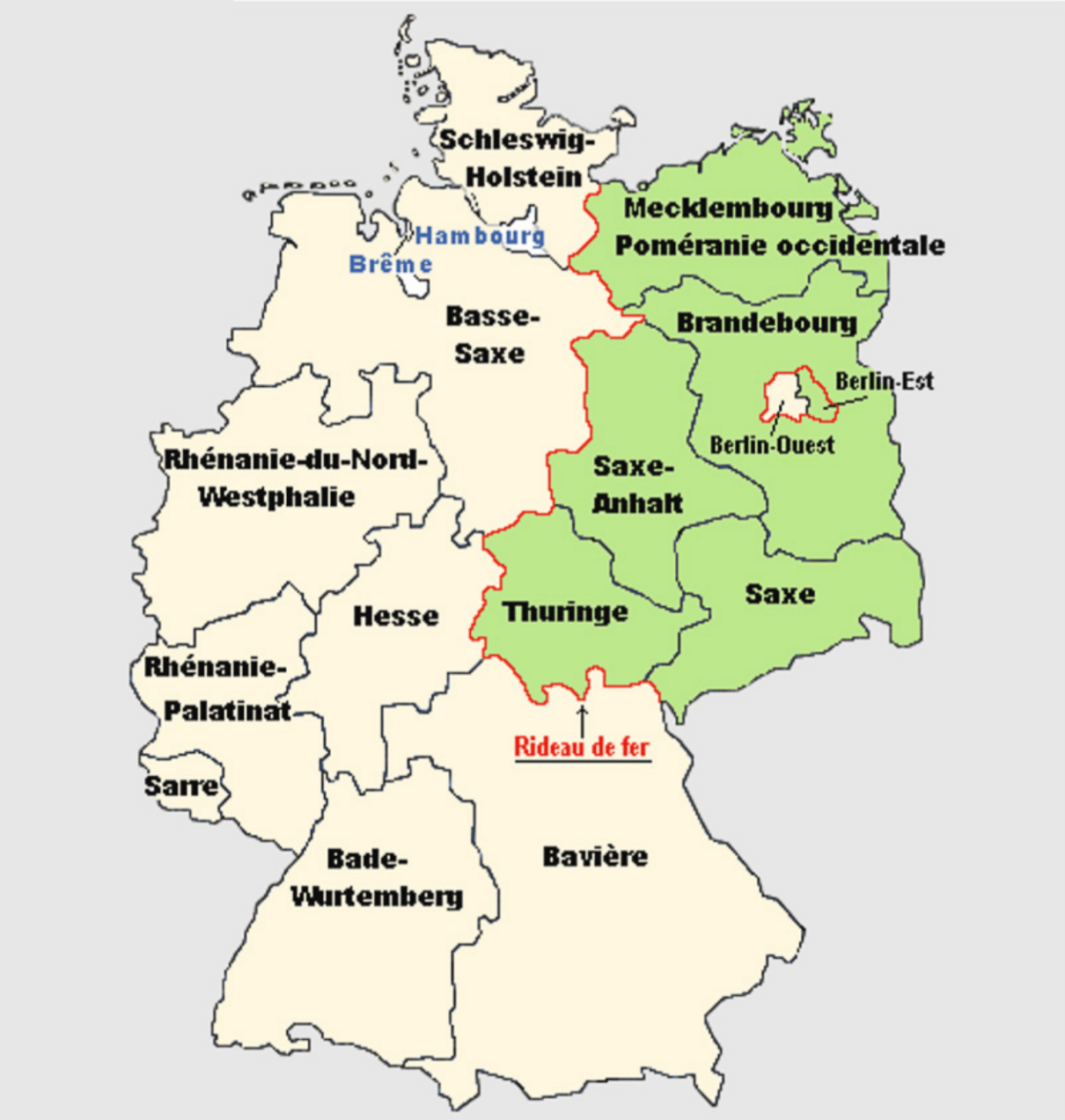

Germany divided into the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in the West, and the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the East.

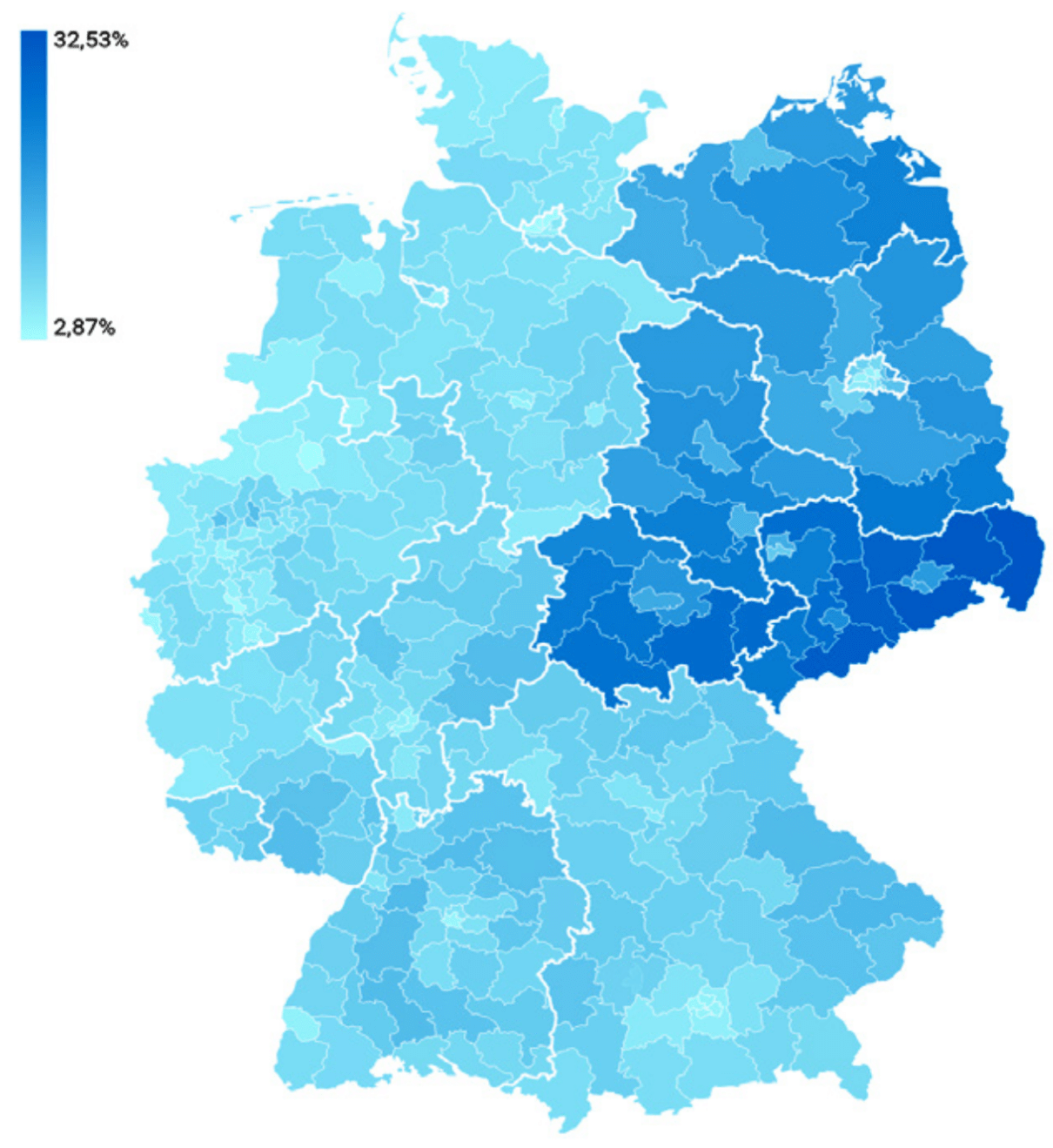

Second votes for the AfD in the 2021 Bundestag elections Zweitstimmenergebnis der AfD

Copyright :

Der Bundeswahlleiter 2020

Source :

Electoral Atlas – Federal Returning Officer, bundeswahlleiterin.de

Note: AfD’s second votes in the 2021 Bundestag elections. The voter has two votes. With his first vote, he elects a candidate in his constituency; there are 299 constituencies in all. With the second vote, he or she chooses a party’s Landesliste. The second vote is decisive in determining the balance of power between the parties in terms of the number of mandates.

Viola Neu and Sabine Pokorny, ,,Wahlanalyse der Bundestagswahl in Deutschland”, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, September 26, 2021 [online].

Among the other categories: 25-34 year-olds (12%, -2 pts), 45-59 year-olds (12%, -2 pts), 60-69 year-olds (12%, -2 pts).

Viola Neu and Sabine Pokorny, op.cit.

Knut Bergmann et al, ,,Landtagswahlen: AfD punktet dort, wo Wirtschaft vor Herausforderungen steht”, iwkoeln.de, October 11, 2023 [online].

The AfD lost 80,000 votes to the CDU/CSU, 260,000 to the SPD, 210,000 to the FDP, 60,000 to the Greens, 180,000 to abstainers and 180,000 to various smaller parties. The only gains came from Die Linke, which lost 90,000 votes to the AfD. As in 2019, the AfD achieved its best results in the new Bundesländer (18.9%), compared with just 8.2% in the West10.

Analysis by age group showed that the party remained strong among 35-44 year-olds (15%, -1 pt vs. 2017). It declined among 18-24 year-olds (7%, -3 pts) and was very weak among those aged 70 and over (5%, -2 pts)11. The 2017 gender gap persists (women 8%, men 13%). Broken down by level of education, the AfD attracted 13% of those with a lower level of education and only 6% of those with a baccalaureate or higher. In conclusion, the sociography of the AfD vote in 2021 was close to that of 2017: self-employed (9%, -3 pts), blue-collar workers (21%, +0 pt), unemployed (17%, -4 pts), white-collar workers (11%, -1 pt), pensioners (7%, -4 pts). The AfD’s neo-proletarian character was thus confirmed in 2021.

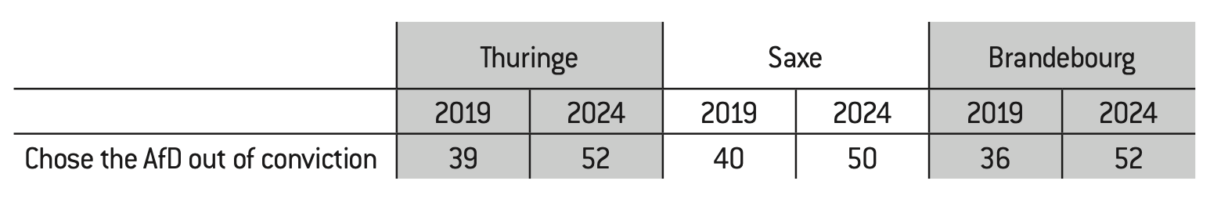

When asked about their reasons for choosing the AfD, respondents cited “immigration” (40%), “government policy during the COVID-19 pandemic” (18%), “social security and pensions” (17%), and “work and the economy” (11%). The party’s programme played a central role in voters’ decisions, with 71% selecting the AfD based on its program, 14% based on its candidates, and 7% due to long-term partisan loyalty. By 2021, the AfD had evolved from being merely a protest party to an ideological force, offering its electorate a relatively unified profile, as confirmed by the 2024 polls12.

The elections for the period 2022-2023 show that the AfD, over and above the migration issue, is gaining strength in transition regions13. These are municipalities or districts with a high employment rate in energy-intensive companies or the automotive industry, i.e. “industrial branches to which decarbonization is a challenge”. This is the case in Hesse and Bavaria. The study by the Institute for German Economics (IW) shows that, in Bavaria’s structurally-changing regions, the AfD gained an average of 3.1 percentage points more than its overall result (14.6%). In Hesse, it gained 2.6 pts on average. After immigration, the theme of transformation has become an effective mobilizing force for the AfD. In 2024, the party is attracting individuals experiencing the “stress of transformation.” These are not primarily the poor or unemployed, but rather “members of the middle class who feel threatened by the prospect of downward mobility in the face of structural changes”.

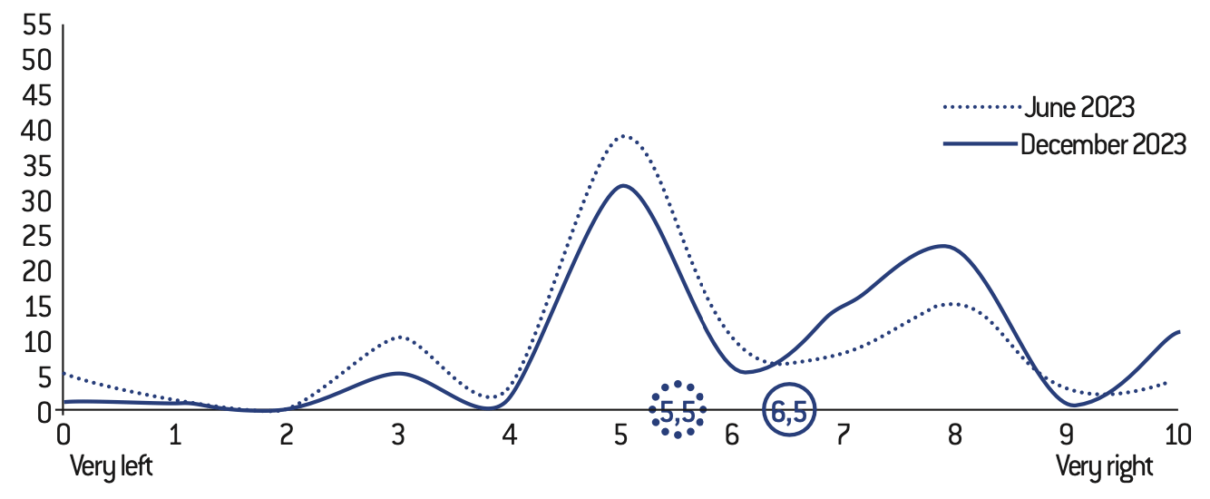

In its reports on the AfD, the Ministry of the Interior refers to a radicalization of the party, which can be read in the texts, but which is also measurable in the polls. An analysis by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung at the end of 2023 supports this thesis. It shows that, with an average of 6.5, the AfD electorate is by far the most right-wing on the left-right scale (SPD 4, CDU/CSU 4.7, Greens 3.3)14.

Self-assessment of AfD voters on the left-right scale

(scale from 0, very left-wing; to 10, very right-wing)

Source :

Sabine Pokorny, “Bäumchen wechsel dich? Politische Einstellungen im Wandel”, kas.de, February 18, 2024, p.41 [online].

32% of AfD voters rank in the middle of the scale with a value of 5, while 23% rate themselves at 8. Finally, 11% of the electorate score 10 on the left-right scale, well above the electorate average of 6.5. A comparison over time shows a “clear shift to the right of the AfD electorate” in just six months. The pollsters note that positioning at values 3 and 6 has become rarer. On the other hand, AfD voters are now positioning themselves more often at values 7 and 8. Very right-wing positioning, value 10, has “also risen sharply”, from 4% to 11%. A strong signal of the AfD’s ongoing radicalization15.

c. Regional elections in Hesse and Bavaria: Announcing the AfD’s electoral breakthrough at the European elections in June 2024

The regional elections in Hesse and Bavaria in October 2023 provide an insight into the reasons behind the AfD’s success at the European elections in 202416. On a national level, the party certainly gathers more voters in percentage terms in the new Bundesländer, but its current score is based on its rise in power in the old Bundesländer, which bring together 68 million inhabitants compared with 15 million in the East (an increase of a few points is therefore more significant in the West than in the East).

In October 2023, the AfD in Hesse won 18.4% of the vote, an increase of 5.3 pts on 2019. In Bavaria, the party won 14.6% of the vote (+4.4 pts).

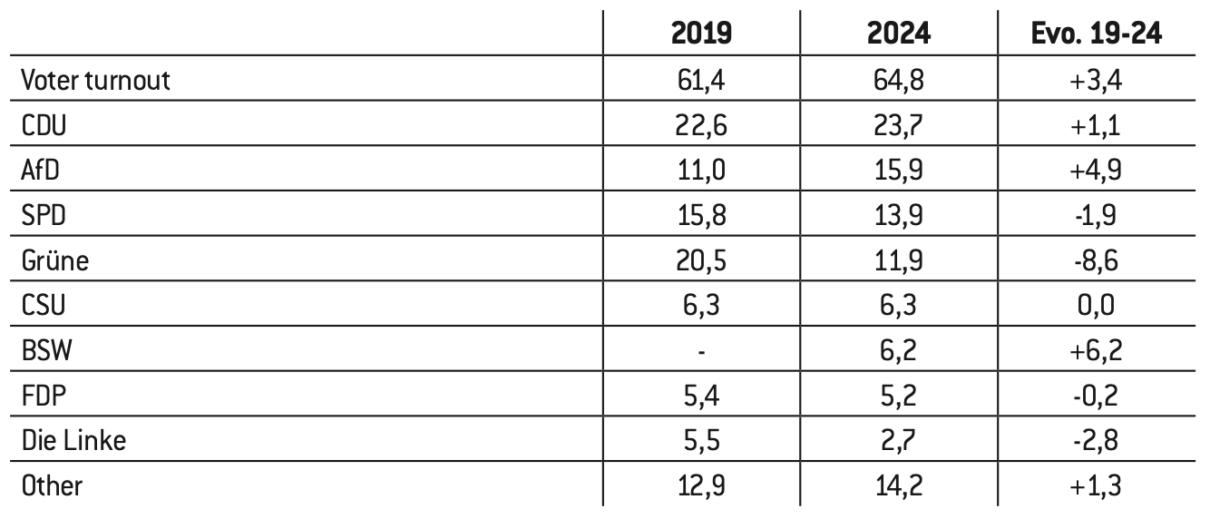

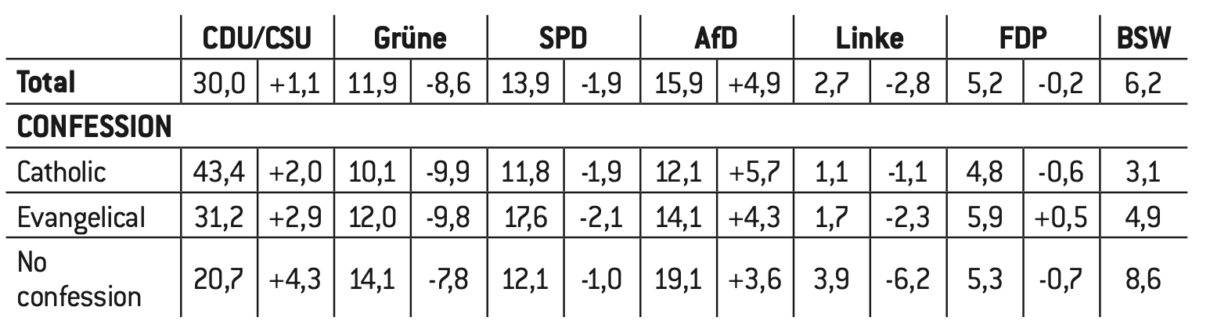

Results of the main parties at the 2024 European elections and 2019-2024 trends (in %)

Source :

Bundeswahlleiterin [online].

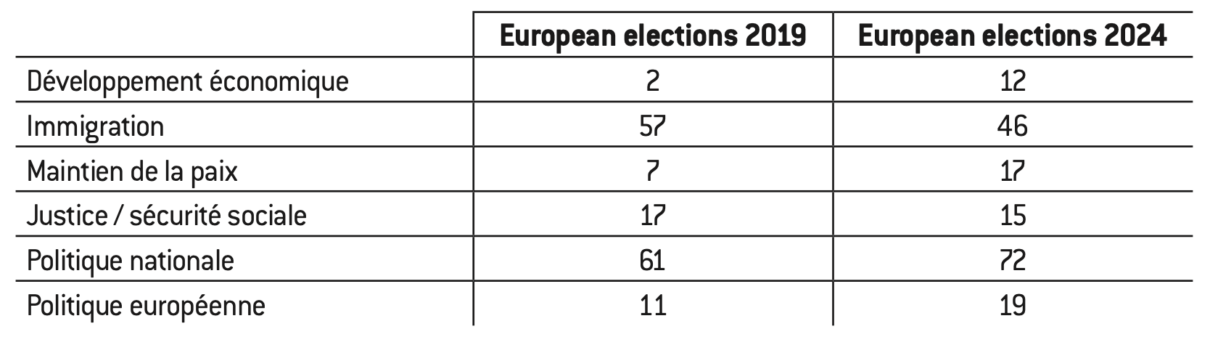

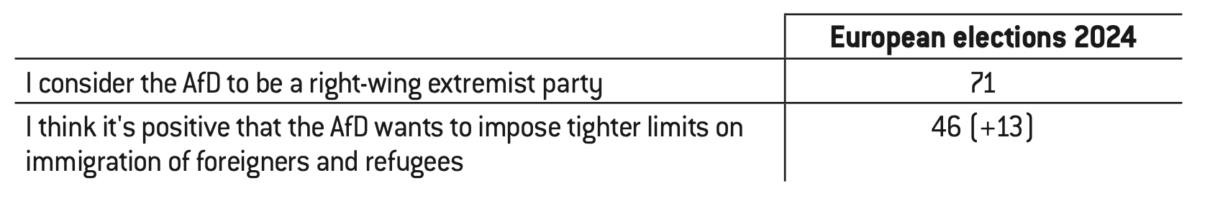

Party choice was driven by … – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 9, 2024 [online]

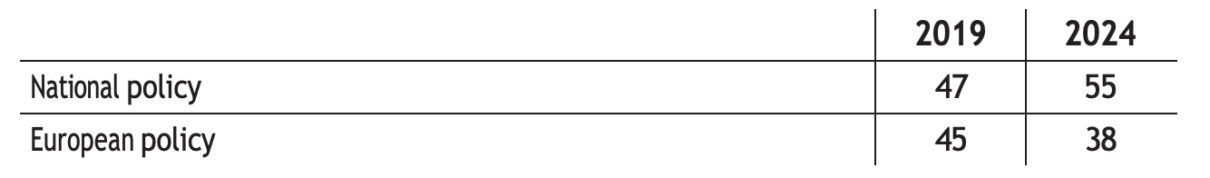

The CDU/CSU won the European elections with 30% of the vote, well ahead of all other parties. The Union parties sent 29 members to the European Parliament (23 CDU and 6 CSU). The Union’s result was significantly better in West Germany (32.4%) than in East Germany (20.7%).

After their record result in 2019, the Greens suffered heavy losses and now stand at just 11.9% (-8.6 pts), while the SPD fell to 13.9% (-1.9 pts), its historically lowest result in European elections. The AfD rose to 15.9% (+4.9 pts) and won 15 seats in the European Parliament (+4). In the new Bundesländer, the AfD obtained 28% of the vote, compared with just 13% in western Germany17.

If we compare the AfD’s results at the European elections with the Bundestag elections in 2021, the AfD’s progress is greater in East Germany than in West Germany. With the exception of Berlin (Saxony: 31.8%, Thuringia: 30.7%, Saxony-Anhalt: 30.5%), the AfD scored best in the East. Analysis of polls from 2023 shows that the AfD’s maximum voting intention was 22/23% at the end of the year. The AfD began to decline in January 2024, initially following Correctiv’s publication of the Potsdam meeting on remigration18. This was further compounded in the spring by corruption allegations involving MPs Bystron and Krah, suspected corruption profiting Moscow and ties with China. However, this phase of decline ended in the summer of 2024. The crisis within the ruling Traffic Light coalition, a sharp increase in uncontrolled immigration, and several terrorist attacks committed by immigrants fueled the AfD’s electoral resurgence.

The Left party (Die Linke) dropped to 2.7% (-2.8 points), largely due to the split led by Sahra Wagenknecht and the formation of her new party, the BSW. The BSW made a notable but limited breakthrough, securing 6.2% of the vote. The FDP remained relatively stable at 5.2% (-0.2 points), though it remains at risk of falling below the 5% threshold in future elections. Other parties accounted for 14.2% of the vote, including 2.7% for the Free Voters (Freie Wähler) and 2.6% for Volt.

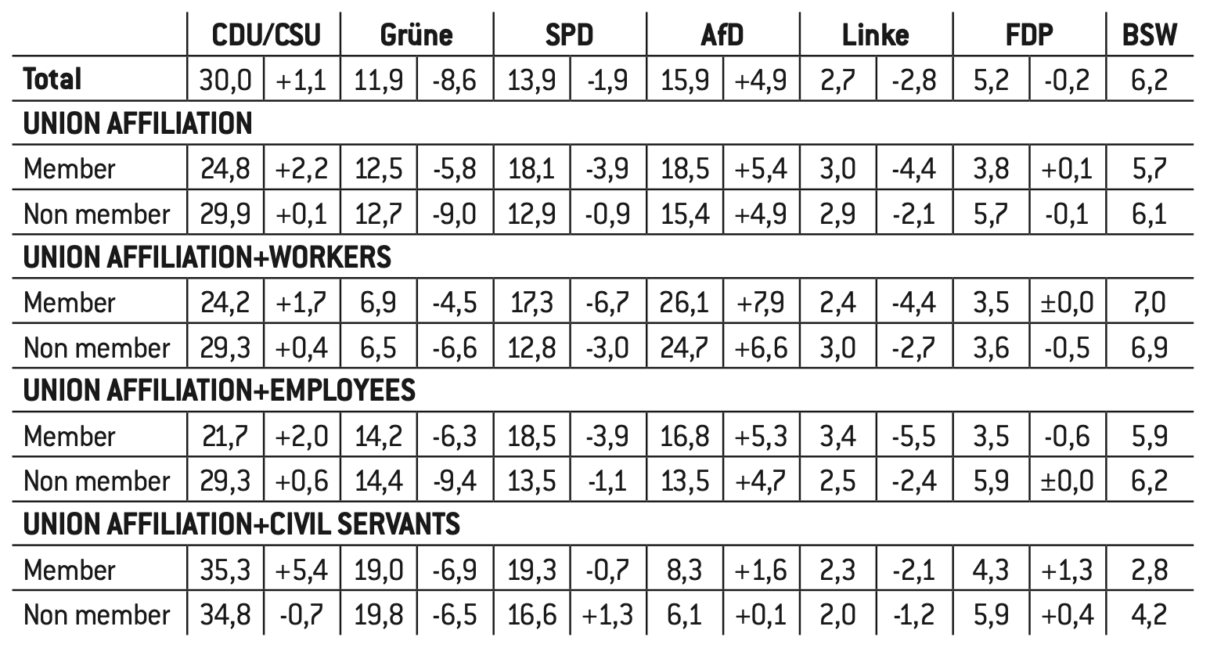

Results of the winning parties in the Länder

Source :

Bundeswahlleiterin, Europawahl 2024 [online].

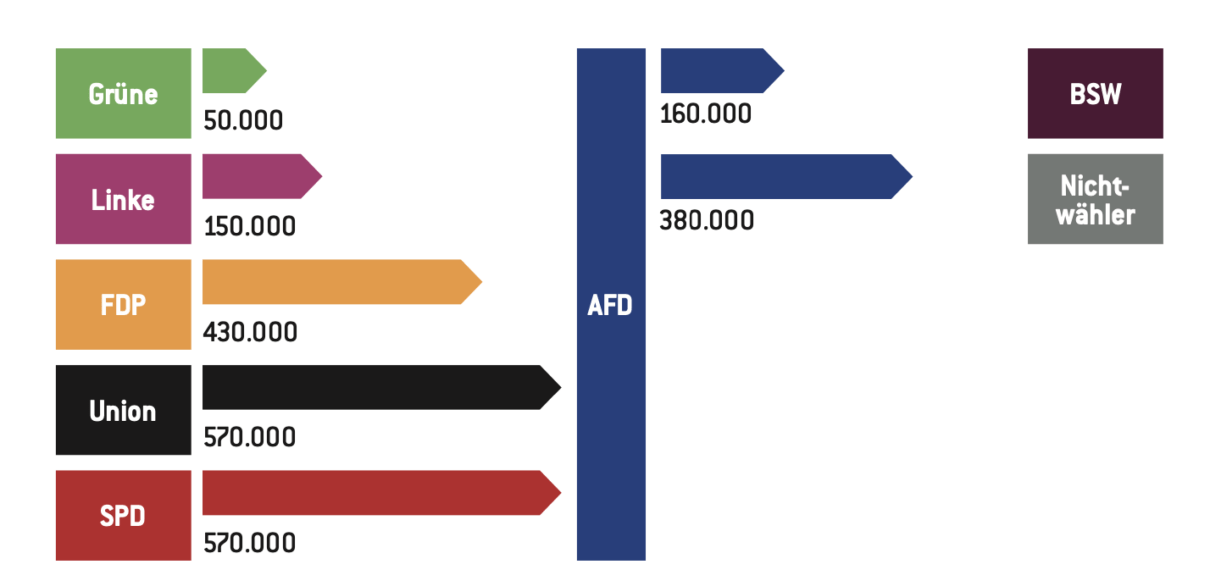

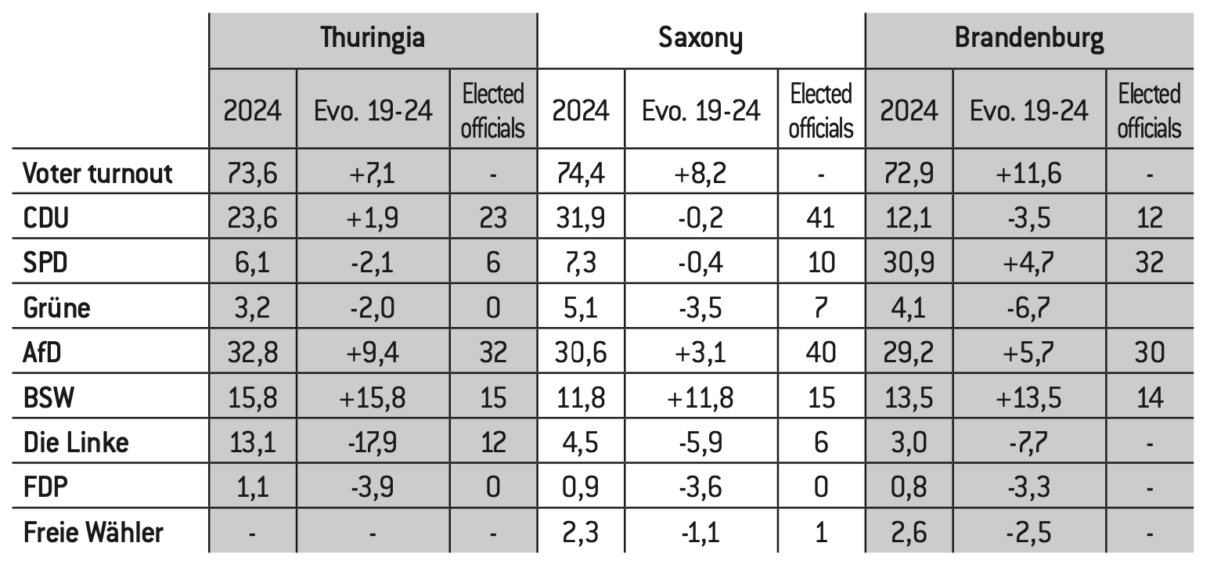

Compared to the 2021 federal elections, the CDU/CSU gained 1,450,000 voters from the SPD and 560,000 from the Greens. However, the Union suffered losses to the AfD (-570,000) and BSW (-260,000). The AfD gained voters from almost all parties (SPD and CDU/CSU: 570,000 each, Die Linke: 150,000). The only significant loss: 160,000 AfD voters in 2021 join the BSW. This transfer shows that the BSW is in a position to trim not only the AfD electorate, but also that of Die Linke, a trend confirmed by the regional elections in the new Länder in autumn 2024.

Electoral transfers 2021 – 2024 in thousands of votes

Source :

Viola Neu / Jochen Roose, Tabellenanhang zur Europawahl in Deutschland am 9. Juni 2024 [online].

In both the Bavarian and Hessian Länder, as well as in the 2024 European elections, the AfD’s breakthrough stemmed from similar causes. However, two events in the final days of the European election campaign, widely covered in the media, had a notable impact. The floods in Bavaria, presented as further evidence of the need for stronger climate policies, failed to improve the Greens’ poor standing among voters. In contrast, the murder of a police officer by an Islamist had a mobilizing effect for both the CDU/CSU and AfD, with the AfD successfully diverting attention away from its troubled campaign, which had been marred by the Krah and Bystron scandals (see below).

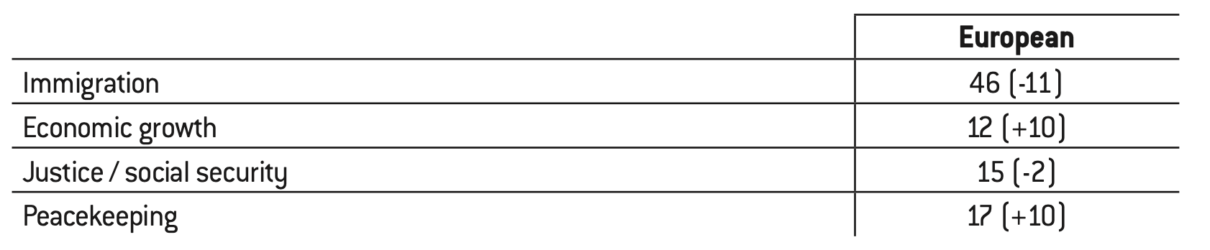

What themes influenced your decision to vote AfD?

Source :

Wer wählte die AfD – und warum? October 18, 2023, tagesschau.de. Survey results in Hesse and Bavaria [online]. Source: Viola Neu / Jochen Roose, Tabellenanhang zur Europawahl in Deutschland am 9. Juni 2024.

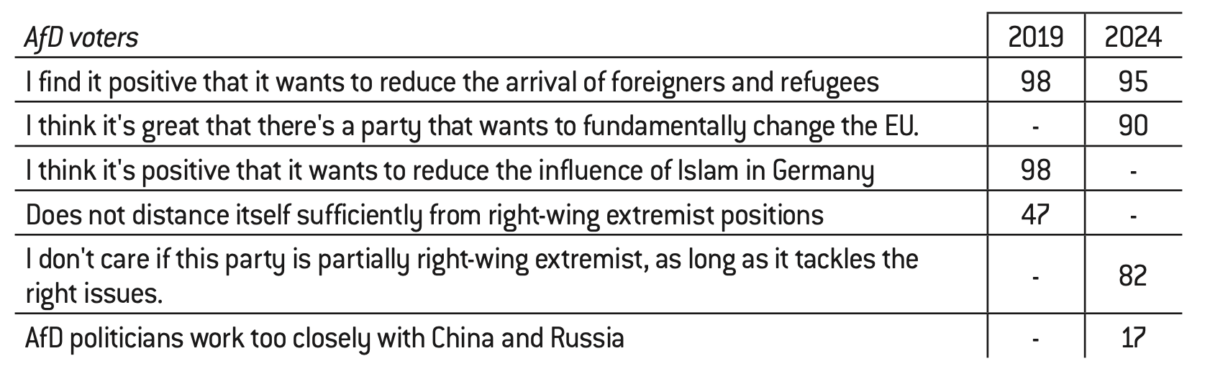

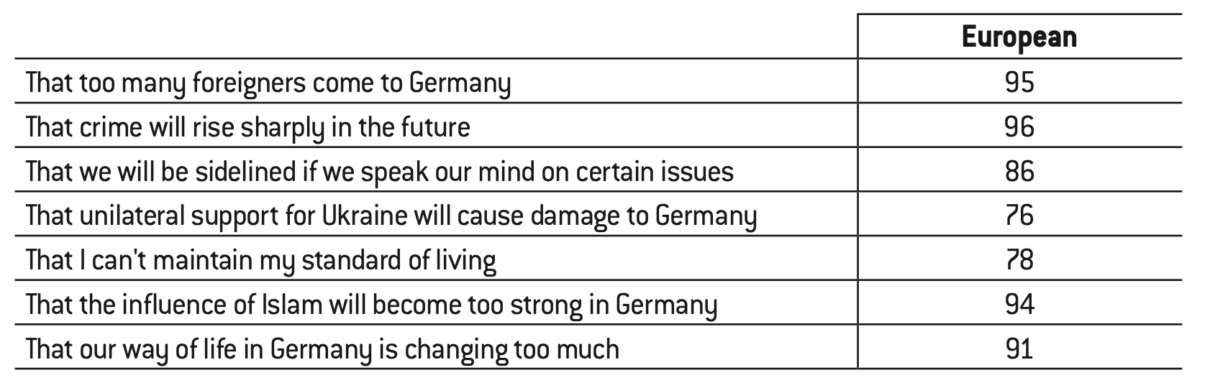

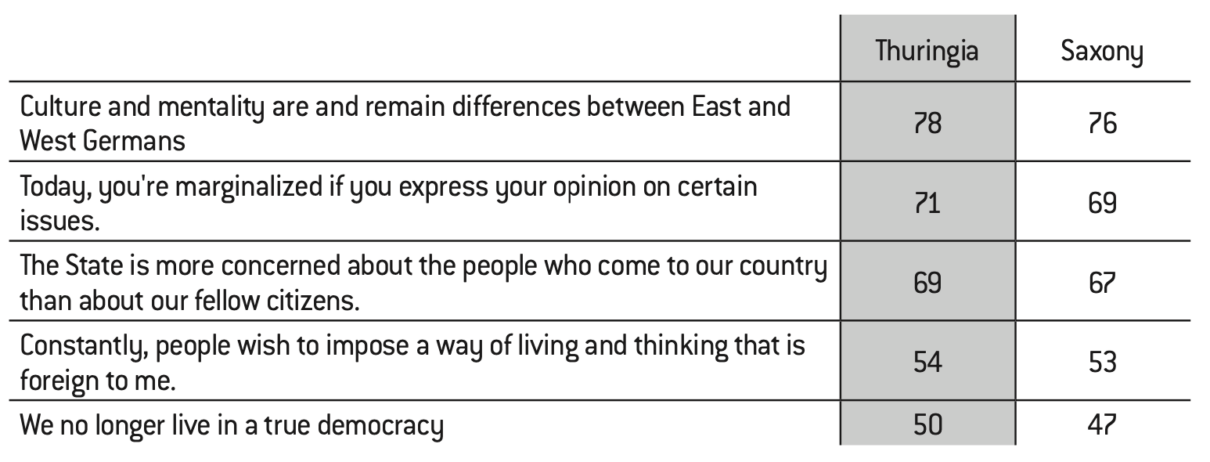

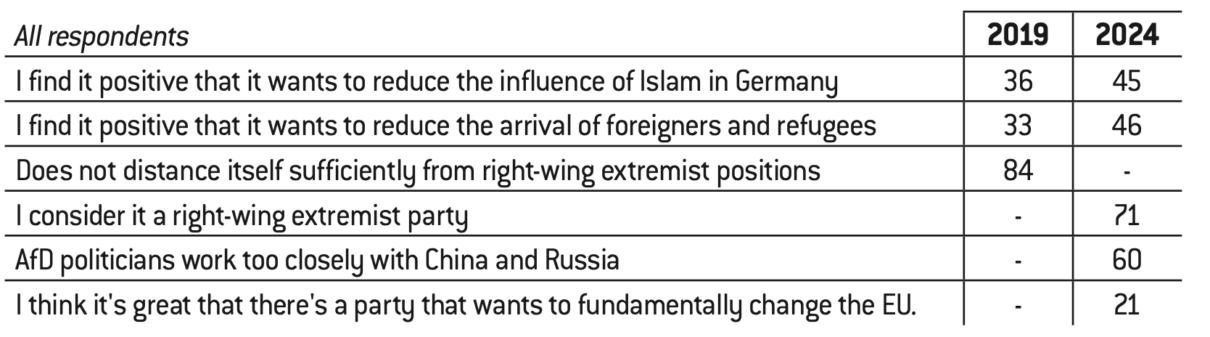

Apart from the issues of migration and Islam, the AfD has a rather bad press in 2024. It is perceived as a right-wing extremist party, pandering to Russian and Chinese interests and promoting a “different Europe”, which the vast majority of Germans do not want.

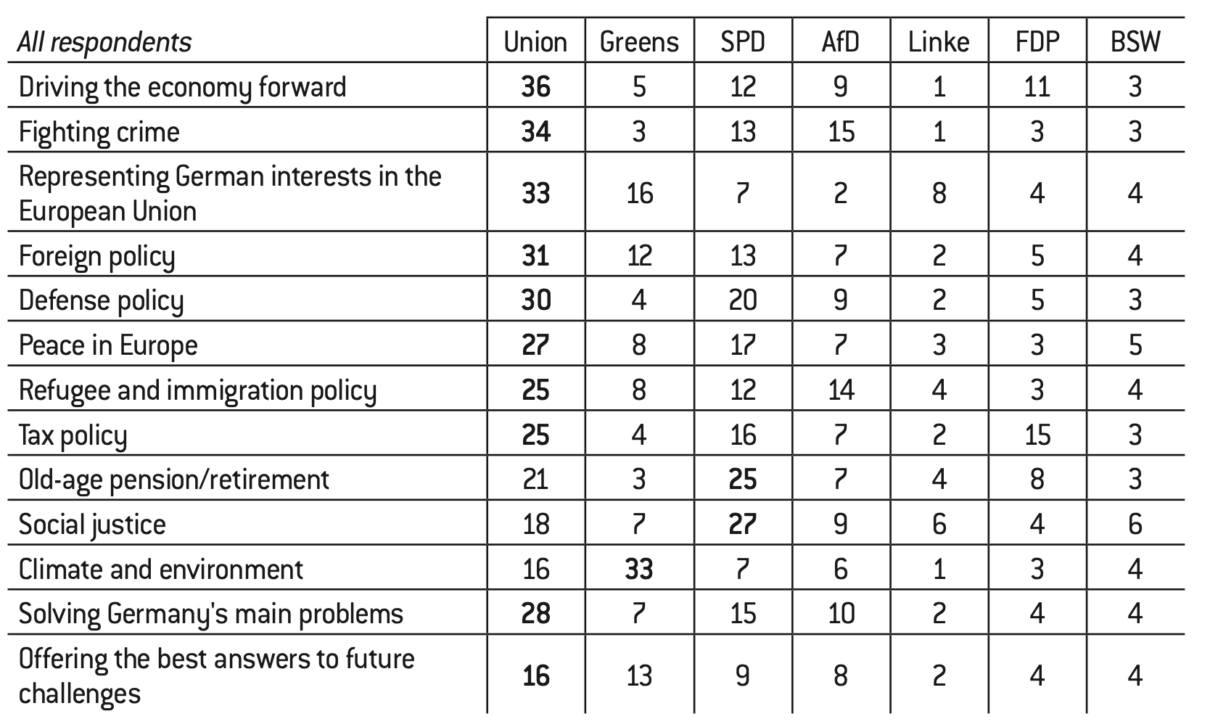

An analysis of the parties’ perceived areas of competence shows that the Union dominates nearly all issues, with the exception of the environment (where the Greens lead with 33%), pensions (SPD, 25%), and social justice (SPD, 27%). Despite voters’ negative view of the Chancellor, the SPD remains the second most credible party overall. The BSW, on the other hand, lacks a clear profile. Since 2019, the AfD has gained limited credibility in areas such as immigration and crime prevention. It also ranks on the issue of “answers to future challenges” with 8%, just one point behind the SPD (9%) and well ahead of the FDP (4%), BSW (4%), and Die Linke (2%).

Skills of the main candidate parties – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 9, 2024 [online].

AfD supporters can be described as “Teflon” voters. This electorate is virtually indifferent to the criticisms and arguments of competing parties. Their party is perceived as a victim of unjustified attacks. This explains why the Bystron and Krah scandals (see below) did not lead to a massive loss in support, particularly in the new Länder.

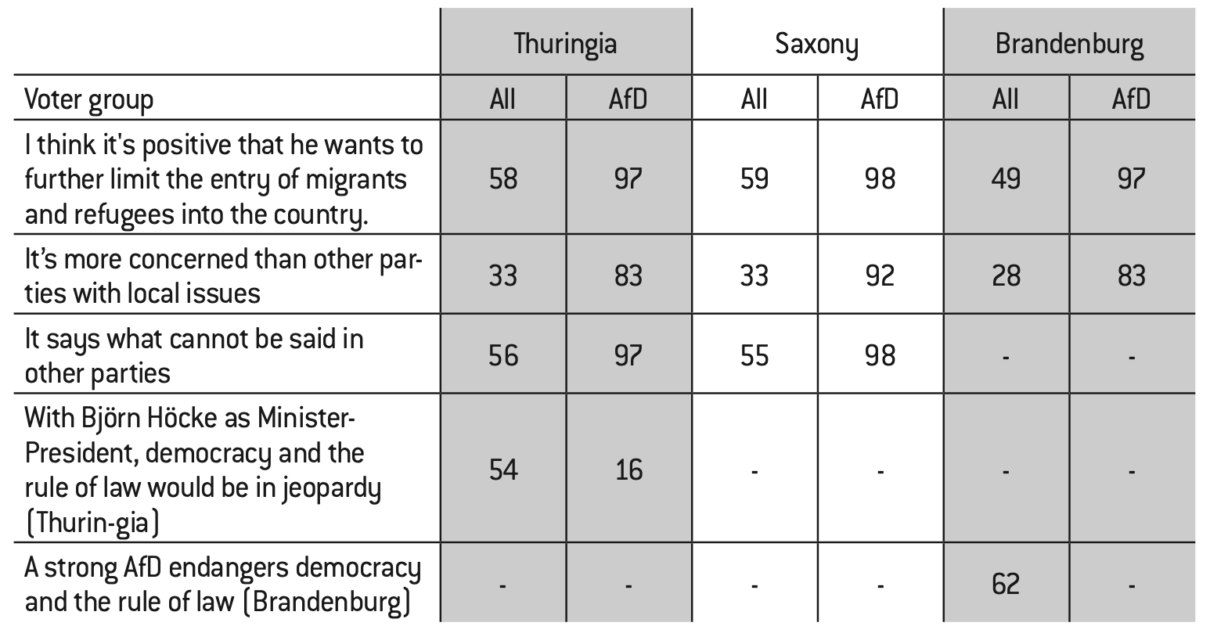

AfD voters: Perception of their party (in %)

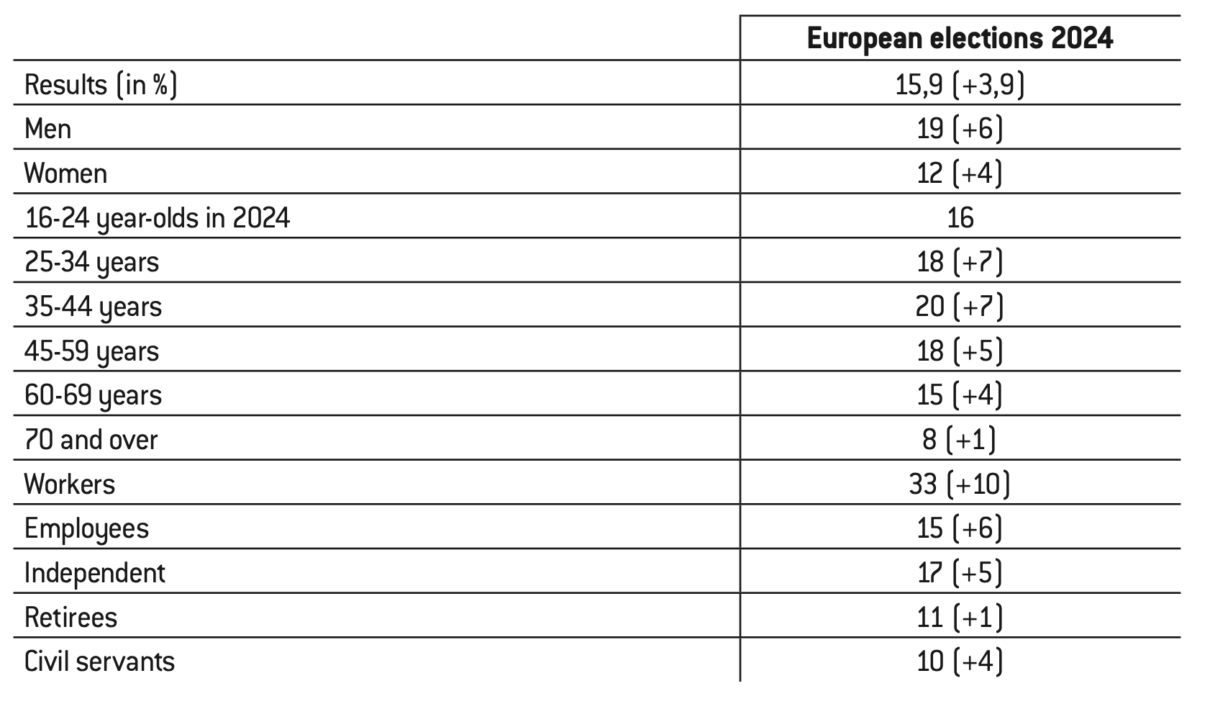

Sociology of the AfD vote at the European elections in 2024 (evolution from 2019)

Source :

Wer wählte die AfD – und warum? October 18, 2023, tagesschau.de. Survey results in Hesse and Bavaria [online].

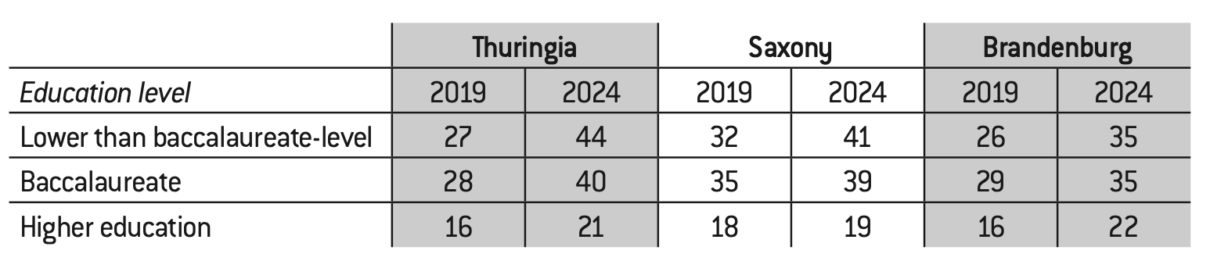

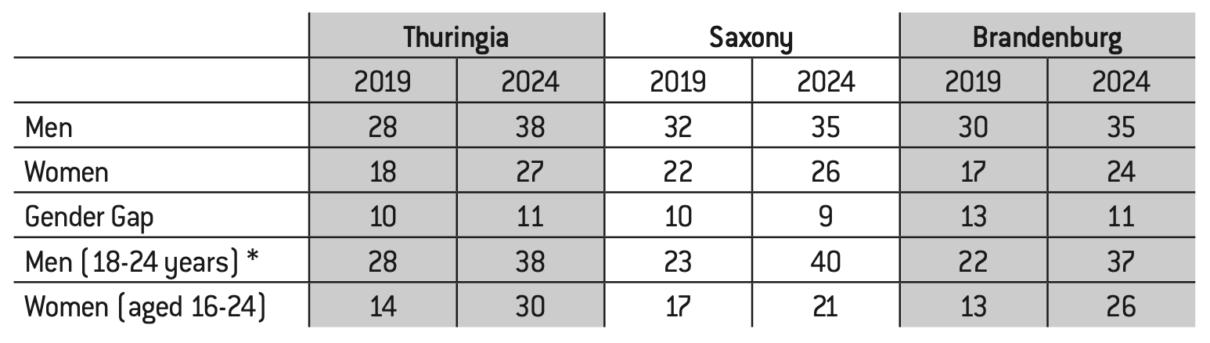

The AfD made gains across all age groups in 2023 and 2024, but its success was concentrated among those under 60. The age breakdown for voters under 25 in 2024 is not directly comparable to 2019, as 16- to 18-year-olds were eligible to vote for the first time. However, the trend is clear: in 2024, the AfD won 16% of the vote among 16- to 24-year- olds, particularly young men (21%). In this group, the AfD outpaced all other parties. Educational level continues to follow the pattern seen since 2015: the lower the educational level, the stronger the AfD’s performance. Its 2019-2024 gains were most pronounced among those with lower educational qualifications (high school diploma: 18.7%, +6.3 points; secondary school leaving certificate: 22.5%, +7.4 points).

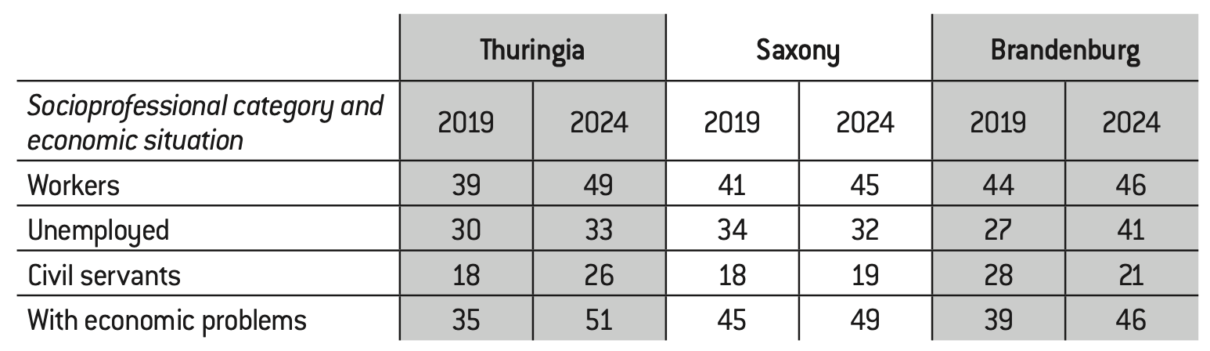

In 2024, the AfD saw increased support across all social strata, especially among blue-collar workers and the self-employed. The party was also over-represented among voters in poor economic conditions, with 32% support (+13 points). Geographically, only the major cities continue to resist the AfD’s rise.

The main reasons for voting AfD in the European elections in 2024

Source :

Wer wählte die AfD – und warum? October 18, 2023, tagesschau.de. Survey results in Hesse and Bavaria [online].

AfD voters’ fears: “I’m very worried…”.

Source :

Wer wählte die AfD – und warum? October 18, 2023, tagesschau.de. Bavarian survey results [online].

The AfD vote continues to be driven by voters’ disappointment with the policies of other parties. However, it is the party’s programmatic offering that is increasingly persuasive. In this sense, the AfD is no longer a one- dimensional protest party.

Perception of the AfD – All voters

Source :

Wer wählte die AfD – und warum? October 18, 2023, tagesschau.de. Survey results in Hesse and Bavaria [online].

These data show that the AfD has become a people’s party (“Volkspartei”) for all types of population. What unites the party’s voters is not so much their occupation, gender, level of education or age, but their ideological choice. Criticism of the established parties leads to a radical rejection of the political system and democracy. The most important theme is immigration, which in various ways serves to rally the party’s clientele. The issue of extremism plays only a very marginal role for AfD supporters, which casts doubt on the electoral effectiveness of current “anti-fascist” campaigns. The AfD’s successes in the new Bundesländer in September 2024 have given it renewed electoral momentum in both the West and the new Länder. If the Traffic Light coalition’s migration policy fails and the current economic crisis worsens, the AfD’s electoral future will look bright.

AfD organization, financing and communication

Bundeszentral für politische Bildung, ,,Mitgliederentwicklung der Parteien”, bpb.de, October 21, 2022 [online].

Deutscher Bundestag , “Fundstellenverzeichnis der Rechenschaftsberichte”, bundestag.de [online].

Deutscher Bundestag, “Rechenschaftsbericht der AfD veröffentlicht”, bundestag.de, April 16, 2024 [online].

Idem.

Frankfurter Allgemeine, “Kein Geld für AfD-nahe Desiderius-Erasmus-Stiftung”, faz.net, November 10, 2023 [online].

” Bundestag beschließt Finanzierungsregeln für parteinahe Stiftungen”, zeit.de, November 10, 2023 [online].

Pfahl-Traughber Armin, Intellektuelle Rechtsextremisten. Das Gefahrenpotenzial der Neuen Rechten, Dietz, Bonn, 2022.

a. Expanding membership

The AfD reported 40,131 members in January 202419, then 48,000 in June 2024. The party has experienced rapid growth in its membership, although still lagging behind its competitors: the CDU (371,976 members in 2022), the CSU (131,000 members in 2023), the SPD (365,190 members in 2023) and Alliance 90/Les Verts (126,451 members in 2023)20.

At the time of its foundation, the AfD had 10,000 members, rising to over 17,000 by the end of 2013. The party also has a youth organization, Young Alternative for Germany (Junge Alternative – JA), which currently has 2,100 members. One of the AfD’s main problems is its difficulty in recruiting women (17% in 2018)21. The party has a solid financial base: apart from donations (6,463,027 euros in 2021, 3,866,321 euros in 2022), the AfD receives statutory reimbursements (11,002,878 euros in 2021, 10,409,359 euros in 2022)22.

b. Profile of party executives

The AfD is co-led by Tino Chrupalla, a house painter23, and Alice Weidel, an economist specializing in China24. It has 78 elected representatives out of 733 in the Bundestag, 251 members in the Landtag out of a total of 1,894, and 15 elected members in the European Parliament. It is also affiliated with the Desiderius-Erasmus-Stiftung, a foundation “close to the party”25, which is currently involved in a heated legal battle over its funding26.

Although there is no official internal sociology of AfD executives and elected representatives, an analysis of their professions shows that they include police officers, lawyers, doctors and teachers, but hardly any blue-collar workers or craftsmen. The high level of education (university studies, master’s degrees and doctorates) of AfD members in the Länder and in the Bundestag enables them to be very active participants in parliamentary committees. In this context, despite attempting to present itself as a credible party capable of governing, the AfD often draws attention through deliberate provocations and positions that remain highly radical.

c. Media presence and influence on social networks

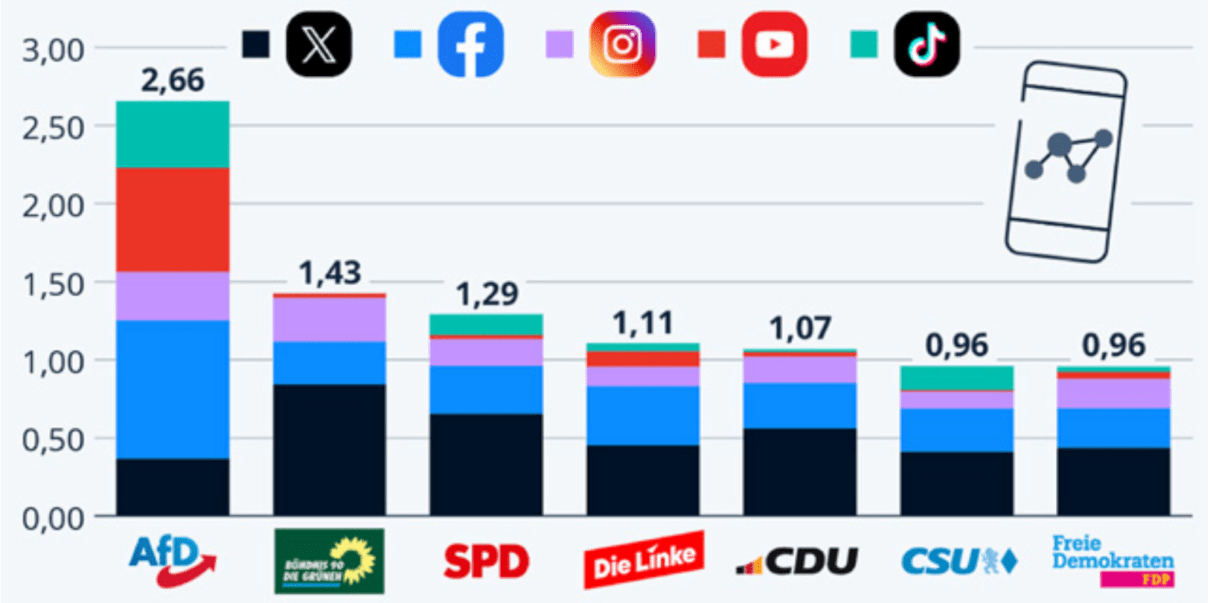

The AfD’s electoral strength is correlated with its media presence. The party was inspired by the experience of the FPÖ in Austria27. It operates its own television channel (AfDTV), a central publication (AfD Kompakt), and maintains a vast network of publications and affiliated structures aligned with New Right ideologies28. Out of all the parties represented in the Bundestag, the AfD has the strongest presence on social media.

The use of social networks by German political parties

Source :

AfD auf Social Media am breitesten aufgestellt, statista.com, February 27, 2024 [online].

According to a Statista study, the AfD has largest following (2.66 million) across social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, Instagram, Youtube and TikTok. The Greens are in second place with 1.43 million followers, but remain far behind the AfD29. In the European elections, TiKTok was to play a central role in the AfD’s breakthrough among the under -25s30.

La présence des partis sur TIKTOK en juin 2024

Source :

AfD siegt bei EU-Wahl dank TikTok – Kulturnachrichten – Kultur – WDR, wdr.de, June 10, 2024 [online].

Germans, Europe and the AfD

German opinion and the European Union

European Commission, “Standard Eurobarometer 100 – Autumn 2023”, europa.eu, December 2023 [online].

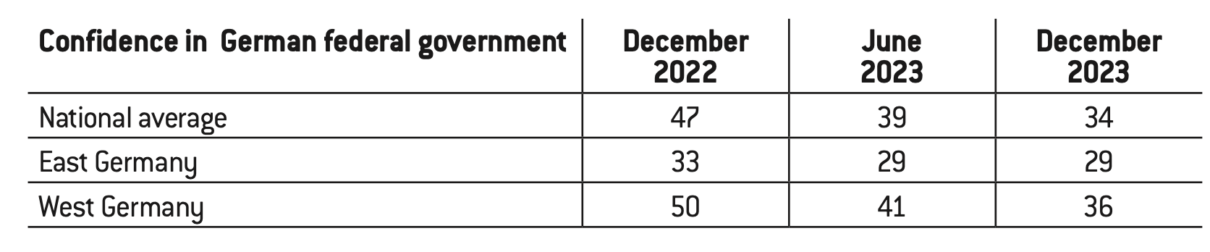

To measure German attitudes towards Europe, we have two complementary surveys from late 2023: the Eurobarometer survey carried out in autumn 202331, and a study published by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in February 202432.

According to the Eurobarometer survey, more than three-quarters (78%) of Germans consider themselves to be EU citizens. The proportion is stable compared to the previous survey in summer 2023 (+1 pt). However, the gap between West Germany (81%, +3 pts) and East Germany (65%, -6 pts) has risen sharply in just a few months, from 7 to 16 pts. While Europe enjoys a generally positive reputation, certain issues continue to cast a shadow.

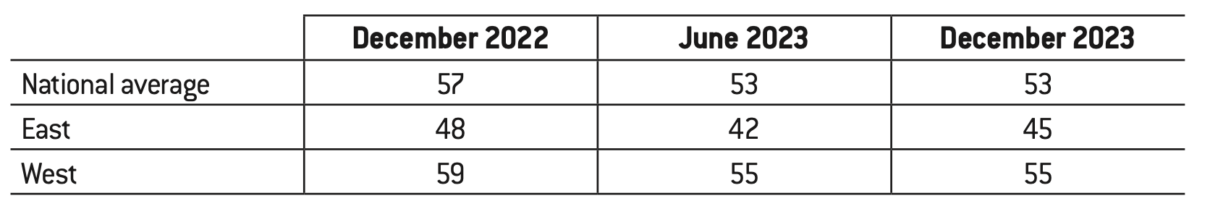

Confidence in the future underlines the disconnect between the two Germanies

Source :

Sabine Pokorny, “Bäumchen wechsel dich? Politische Einstellungen im Wandel”, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, February 18, 2024 [online].

As we can see, confidence in the future remains relatively stable in both western and eastern Germany, although at a rather low level. The Konrad Adenauer Stiftung study shows that among CDU/CSU voters, who were previously more optimistic than the average, confidence fell significantly between December 2022 (67%) and December 2023 (56%). Meanwhile, AfD voters recorded the lowest level of optimism (25%) in December 2023.

According to Eurobarometer data, 55% (+4 pts) of Germans believe that their voice matters in the European Union, and that Germany’s interests are well taken into account (65%, -2 pts). It is worth noting that almost half of those questioned (48%) believe that decisions should be taken at European Union level, which has been a demand of the AfD since its inception.

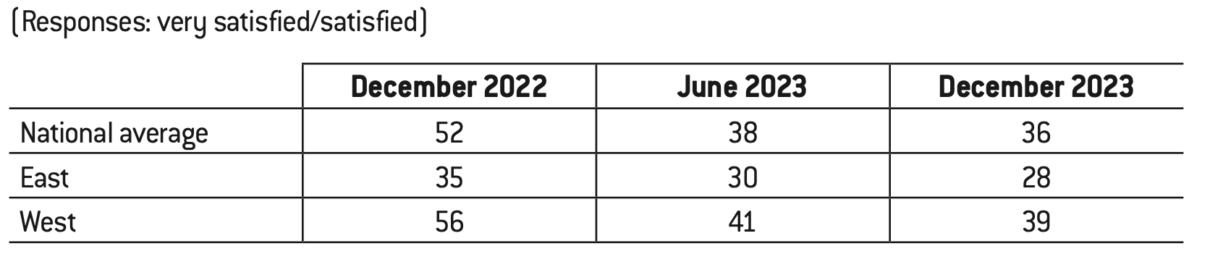

East Germans and West Germans assess the functioning of democracy in their country

Source :

Sabine Pokorny, “Bäumchen wechsel dich? Politische Einstellungen im Wandel”, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, February 18, 2024 [online].

Data from the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung reveal two key trends: first, the assessments of how democracy functions in Germany are converging between East and West Germans. Second, this convergence is occurring against a backdrop of declining satisfaction among West Germans. The data highlight a significant drop in satisfaction with the functioning of German democracy, particularly in West Germany, which had previously been a stronghold of public support for democracy. In the span of a year, satisfaction has fallen sharply, from 52% to 36%.

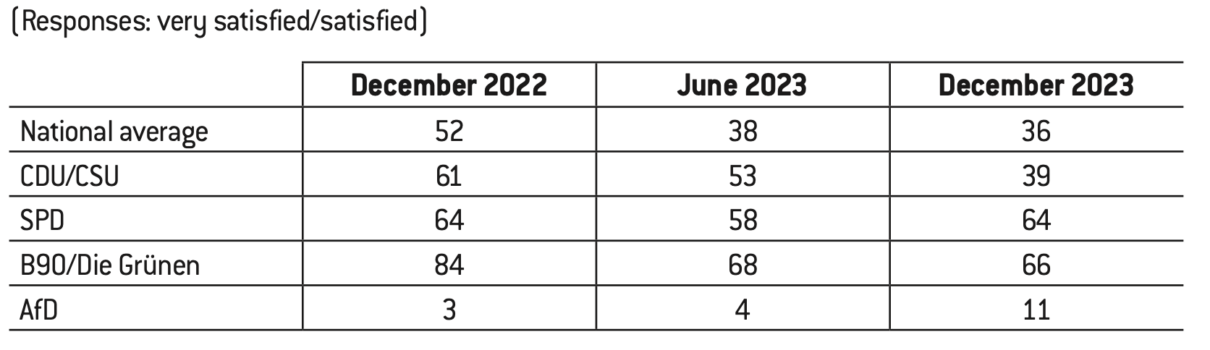

Satisfaction with democracy by partisan proximity

Source :

Sabine Pokorny,”,Bäumchen wechsel dich? Politische Einstellungen im Wandel”, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, February 18, 2024 [online].

As we can see above, the sharp decline in satisfaction with the functioning of democracy in Germany over the past year is largely driven by dissatisfaction among right-leaning Germans. This reflects a political convergence between the opinions of West Germans and East Germans, as mentioned previously. A majority of CDU/CSU supporters are now expressing dissatisfaction, aligning more closely with AfD supporters, who have consistently shown high levels of discontent. The overall 16-point drop in satisfaction with democracy highlights the growing rightward shift within the German electorate.

Perceptions of democracy and European institutions

Sabine Pokorny, ibid.

Satisfaction with democracy has declined sharply since 2022. According to the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, only 28% of East Germans and 39% of West Germans are now satisfied with democracy. The steepest negative trend is seen among CDU/CSU voters. Pollsters attribute this to “CDU/CSU voters low confidence in the federal government,” as well as the ongoing crises involving immigration, economic decline, inflation, and the environment. The drop in confidence is especially pronounced in the West, which helps explain the AfD’s electoral gains in the 2023 regional elections. Unsurprisingly, AfD voters remain among the most critical of how democracy functions. Satisfaction with democracy decreased more significantly between 2022 and 2023 among those with lower levels of education (-21 points) than those with medium or higher levels (-15 points)33.

According to the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the police had the highest level of public trust in December 2023, with 75%, followed by the courts at 63%. Trust in public service media was highest among those with a high level of education (59%), while among individuals with low or medium levels of formal education, only about half expressed trust in public media (49% and 46%, respectively). Trust in public service media was lowest among AfD voters, with just 10% by the end of 2023.

Confidence in the Bundestag also saw a decline, dropping from 51% in December 2022 to 42% by June 2023 across both West and East Germany. In West Germany, trust stood at 44%, while in East Germany, it was notably lower at 34%.

Source :

Sabine Pokorny, ibid.

Confidence in the federal government has also fallen by 13 pts compared to 2022 (34%, -13 pts). This decline can be seen in West Germany (-14 pts), but is less drastic in the East (-4 pts).

According to Eurobarometer data, at international level, the majority of Germans (58%) have confidence in NATO (+4 pts in one year), but here too there is a wide gap between East Germans (37%) and West Germans (63%)34.

When asked what the European Union means to them, 56% of Germans associate the EU primarily with the freedom to travel, study, and work across Europe. However, 36% see the EU as synonymous with excessive bureaucracy.

To strengthen Europe’s influence, 81% of Germans support a common foreign, security, and defense policy among member states. On the other hand, support for EU enlargement, including the potential addition of Ukraine and Turkey, declined in Germany between 2022 and 2023, dropping to 38% (-2 points).

Finally, with regard to membership to the European Union, Eurobarometer data show that 71% of Germans do not believe their country would be better off if they left the EU. However, while on average almost half (48%) of Germans have confidence in the European Union, there is a striking divide on this point between West Germans (53%) and East Germans (30%).

In 2023, half of Germans (50%) expressed confidence in the European Parliament, 46% in the European Commission, 48% in the European Central Bank, and 43% in the European Council. However, there are significant differences in trust levels between East and West Germany. For example, trust in the European Parliament is 23 points lower in East Germany (32%) compared to West Germany (55%), marking the lowest level of trust in the EU. Similarly, trust in the European Commission is 20 points lower in the East (30%) than in the West (50%), the lowest level among EU member states. Trust in the European Council also shows a gap, with only 25% of East Germans trusting it, compared to 47% of West Germans.

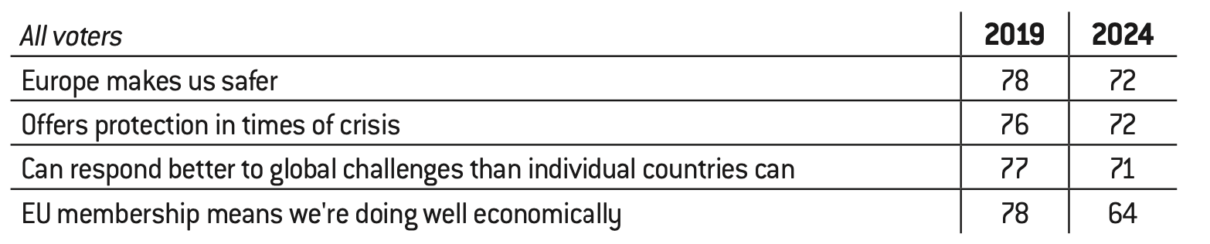

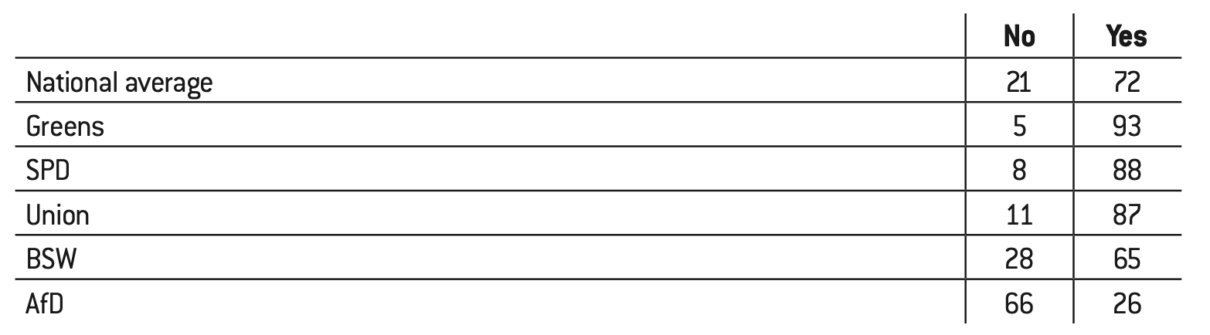

These trends were reaffirmed in the 2024 European elections. While Europe’s overall reputation remains positive, it weakened slightly between 2019 and 2024. The AfD remains the only party that does not believe Europe offers protection in times of crisis35.

Perception of the European Union – 2019 – 2024 (in %)

The EU offers protection in times of crisis – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

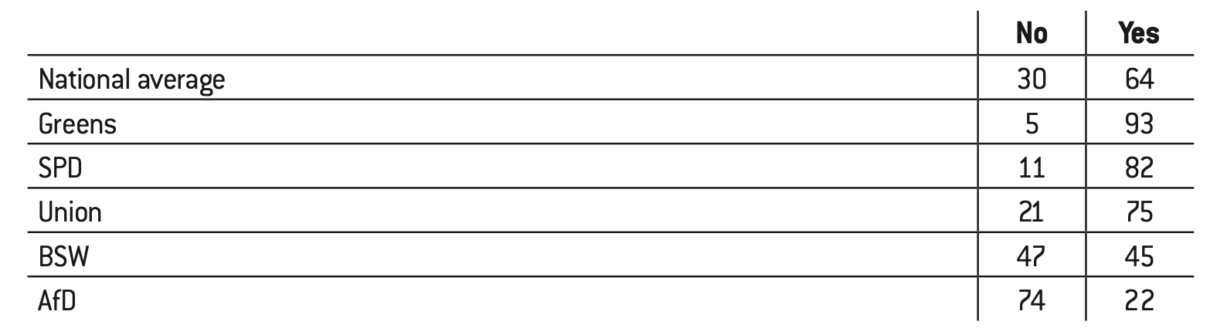

The AfD is also the only party convinced that Europe is in economic crisis.

EU membership means we’re doing well economically – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

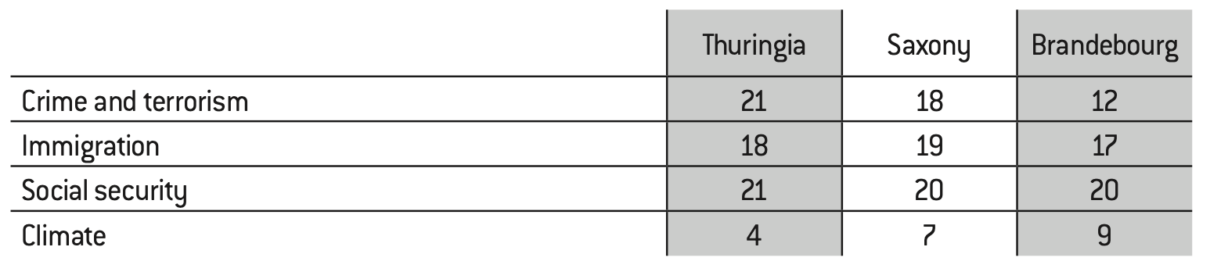

Germans’ overwhelming support for the euro (82%) continues to pose a significant challenge for the AfD, whose program includes advocating for a return to national currencies. In contrast, the issue of borders and immigration presents the far-right party with opportunities for electoral gains. By the end of 2023, more than three-quarters of Germans (78%) supported a common EU policy on migration and asylum. While the majority of Germans surveyed expressed no issues with immigration from other EU countries, attitudes were notably different towards migrants from non-European countries. In this case, 53% of Germans were opposed to such immigration, marking a 5-point increase compared to 2022.

This theme is expected to play a significant role in the 2024 European elections, as well as in the regional elections in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg in September 2024.

Germans’ perception of Russia since the war in Ukraine

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine plays an important role in shaping German opinion. Most Germans see Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as a threat to European security (79%) and a danger to Germany (76%). However, in December 2023, only half of those questioned (49%) said they were satisfied with the Federal Government’s reaction to the Russian attack on Ukraine. If we take a closer look, support for the government’s response to the attack on Ukraine came mainly from the western part of the country (53%), while in its eastern part, people were mostly unsatisfied (63%). The situation is similar when it comes to assessing the European Union’s reaction to the Russian attack: 55% of West Germans are satisfied with Europe’s reaction, compared to just 34% of East Germans36. The Germans most supportive of the AfD are also the ones who disapprove the most of their government’s and Europe’s responses to Putin’s war, likely due to the fear of being more directly and rapidly exposed to its consequences.

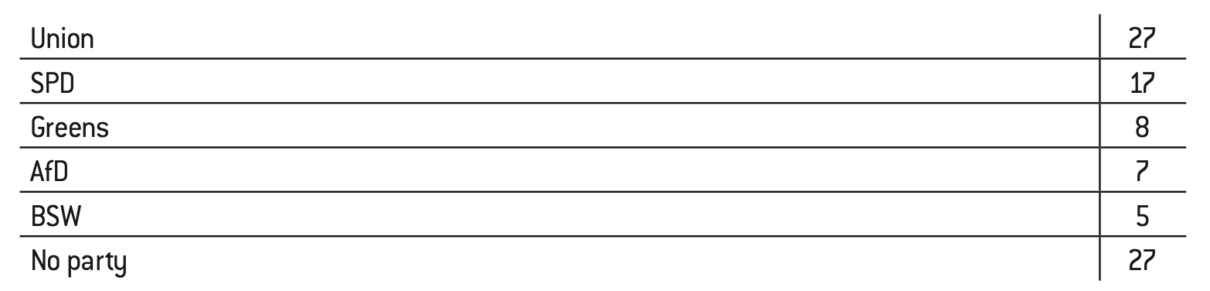

According to the Infratest Dimap poll, a significant portion of voters (27%) are skeptical about the current parties’ ability to restore and secure peace in Europe, reflecting the prevailing sense of pessimism in West Germany.

Which party do you trust most to restore and secure peace in Europe – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

Pia Lamberty, “Jahrestag des russischen Angriffskriegs auf die Ukraine : Glaube an Propaganda – und Verschwörungserzählungen”, cemas.io, February 22, 2024 [online].

European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, ”Digital Services Act – Application of the risk management framework to Russian disinformation campaigns”, Publications Office of the European Union, op.europa.eu, 2023 [online].

European Commission, ”Standard Eurobarometer 100 – Autumn 2023″, europa.eu, December 2023, [online].

European Commission, ”Standard Eurobarometer 100 – Autumn 2023″, europa.eu, December 2023, op.cit.

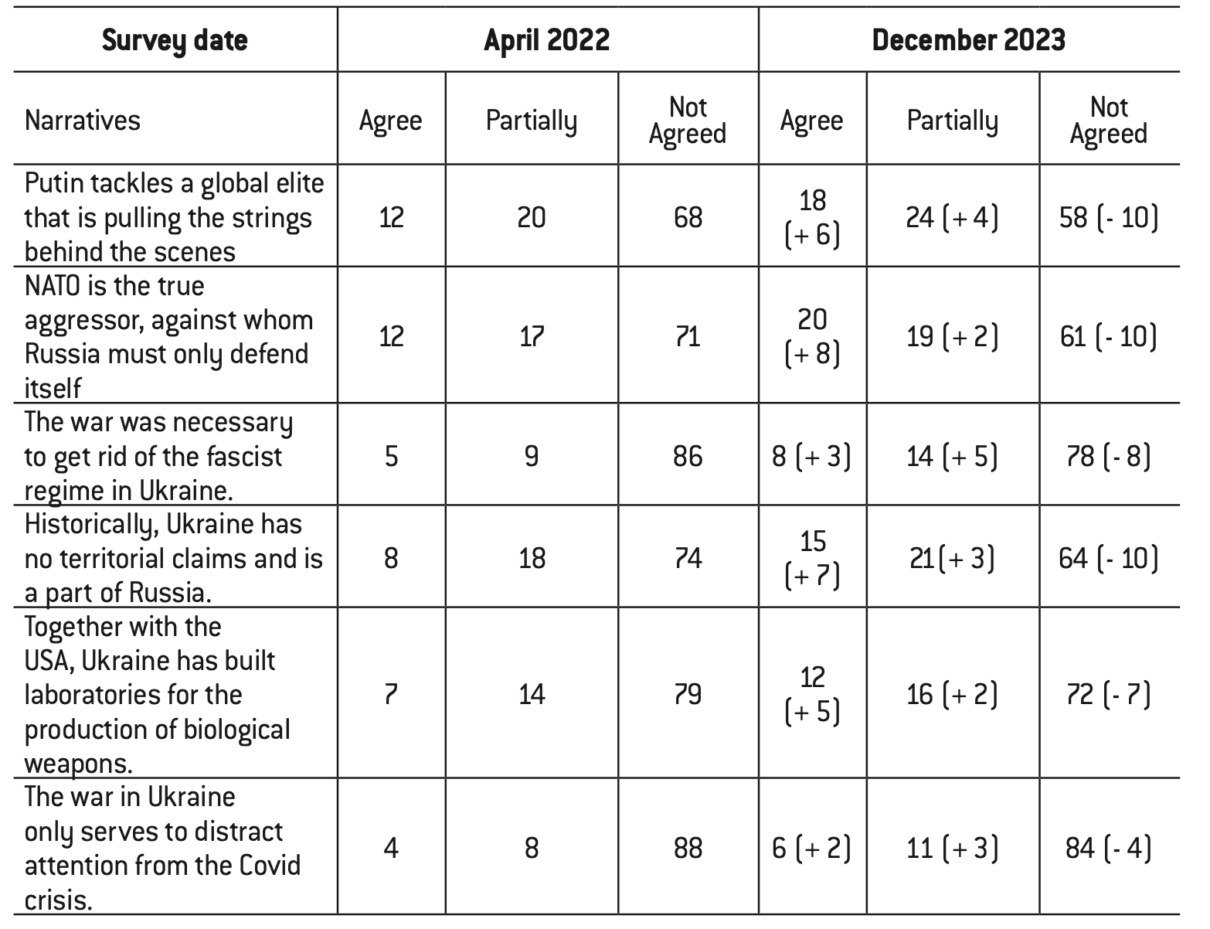

In a series of seven polls, CEMAS measured the growing approval of Russian narratives aimed at undermining Ukraine37. The European Union has shown significant interest in Russian propaganda, describing it as an integral part of Russia’s military strategy and a threat to public security and electoral processes within the EU38. Yet 77% of Germans and 81% of Europeans fear the negative effects of disinformation on democracy39. Indeed, the spread of fake news, especially from troll factories in Moscow and Beijing, and its amplification by AfD and right-wing extremist media, can be measured. As a result, there is strong public support for combating Russian propaganda, with 66% of Germans backing the ban on Russian outlets like Sputnik and Russia Today across the European Union. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 81% of Germans advocate for greater European cooperation on defense issues. In Germany, 71% support bolstering Europe’s military production capabilities. The Eurobarometer survey also looked at the energy policy consequences of Russian aggression. Most Germans (80%) are in favor of massive investment in renewable energies to ensure the EU’s energy security40.

Pro-Russian conspiracy and propaganda narratives and trends 2022-2023 (in %)

Source :

Pia Lamberty, “Jahrestag des russischen Angriffskriegs auf die Ukraine: Glaube an Propaganda – und Verschwörungserzählungen”, cemas.io, February 22, 2024 [online].

This table shows that, between 2022 and the end of 2023, while Russia failed to convince the majority of Germans, a growing minority became sensitive to Kremlin propaganda. The data from these surveys shows that Germans maintain a strong identification with the European Union, alongside robust support for Europe’s response to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, including economic sanctions against Russia. Most Germans also back an energy transition focused on renewable sources. The vast majority are satisfied with life overall, and don’t expect things to get any worse in the coming year. The primary personal concern for Germans is the rising cost of living, while at the European level, immigration and the war in Ukraine dominate concerns. Clearly, the AfD, and its program, was able to attract around 15-20% of voters, but lacked broader electoral reserves.

The AfD’s European program

a. The European Union as a community of sovereign states

The AfD’s 2024 program41, building on earlier versions from 2016 and 2017, aims to cover a wide range of political, economic, social, and cultural issues, demonstrating that it is not a monothematic party. The program reveals the party’s clear and structured ideological framework, positioning it not only as a party of protest but also as a force for rupture and ideological conflict.

Regarding Europe, the AfD proposes a radical transformation of the European Union, envisioning it as a community of free, self-determining sovereign states—a “federation of European nations,” rather than a “superstate” or “United States of Europe.” The AfD advocates for the EU to focus on a few key areas: protection of external borders, strategic autonomy to secure Europe, a strong common market, and the preservation of Europe’s diverse cultural identities. The party argues that the EU, as it currently exists, is unreformable and calls for its refoundation through national referendums on issues such as new treaties, sovereign rights, EU membership, or continued participation in the monetary union and other supranational projects.

However, this vision increasingly diverges from the preferences of many German voters, who tend to support a more integrated and cooperative European Union.

b. Transformations of European institutions and mechanisms

The AfD proposes abolishing the European Parliament, with legislative power transferred solely to the Council, which would be bound by the decisions of national parliaments. It also calls for enshrining the principle that all decisions require unanimous agreement from member states. The EU’s administrative structure should be reduced, and European parties eliminated. To prevent undue influence on the Commission, the AfD advocates for a mandatory register of lobbies active in Brussels. Additionally, the party calls for the creation of a “new Court of Justice,” with judges appointed by national constitutional courts.

The AfD aims to protect the “cultural sovereignty” of nations from the EU, rejecting a “culture of guilt and shame” over Europe’s colonial history. It insists that German be given equal status alongside English and French in European institutions. The party opposes the creation of a “European education area” and advocates for greater sovereignty for member states in educational matters. It promotes freedom of research and teaching, while rejecting EU-funded research programs.

For the AfD, the euro is a failure, and the party advocates for a “return to national currencies.” It calls for the elimination of shared financial responsibility and transfer payments between member states. Cash is presented as the preferred method of payment, while the digital euro is rejected. The EU budget should be reduced, and centralized investment management abolished, with a focus on national and regional labor markets. Large multinational companies should be “taxed according to their economic activity in the state that collects the taxes,” though the AfD opposes a Europe-wide financial transaction tax. German companies should benefit from low tax rates, and the party rejects any form of CO2 pricing.

In ecological matters, the AfD denies human responsibility for climate change and opposes a ban on combustion engines. It believes energy policy should remain within national control and advocates continued support for fossil fuel production and nuclear power.

c. AfD calls for an overhaul of German foreign policy

For the AfD, German foreign policy is in need of renewal. Its goal is “balanced cooperation between all European states”, a task for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). The party supports the idea of aligning pan-European foreign policy interests, “without limiting the sovereignty of national states”.

Although the AfD recognizes the importance of good relations with the United States for both Germany and Europe, it insists these relations should be within the framework of a “global partnership of equals.” The party argues that U.S. geopolitical and economic interests are increasingly divergent from Germany’s, citing “the massive U.S. effort to block the Nord Stream gas pipeline” as evidence. As a result, the AfD believes Germany must assert its foreign and security policy interests independently. The party calls for the normalization of relations with Russia, stating that Russia’s geostrategic position and the “historical and economic interdependencies” between the two nations require diplomatic solutions to the current conflict in order to ensure peaceful German-Russian relations.

The AfD’s demands include “restoring uninterrupted trade with Russia,” “immediately lifting economic sanctions,” and reopening the Nord Stream pipelines. It also advocates for strengthening Germany’s relations with the Eurasian Economic Union.

The party views the world as moving toward a “multipolar order,” which makes it crucial for Europe to develop a collective security system by “pooling their armed forces in a defense community.” However, it does not see NATO as capable of fulfilling this role. While rejecting the idea of a European army, the AfD supports the Bundeswehr as the “cornerstone of German sovereignty.” According to the party, the German military is currently ill-equipped to defend the country, both in terms of personnel and resources. Therefore, the defense budget must be adjusted to meet Germany’s strategic security needs, with a focus on procuring new equipment primarily from German and European manufacturers.

In conclusion, the AfD’s program has attracted support from Germans who are Eurosceptic, pro-Russian, anti-American, and concerned about immigration. However, the party’s extreme nationalism continues to alienate a significant portion of the electorate.

Challenges and outlook for the AfD

Unfinished German reunification: a springboard for the AfD

Patrick Moreau, The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance for Reason and Justice (BSW), Foundation for Political Innovation, January 2024.

Der Beauftragte der Bundersregierung für Ostdeutschland, “”Zum Stand der Deutschen Einheit” Bericht der Bundesregierung 2023″, bundesregierung.de, September 27, 2023; Hanz Omar Sayami et al. Was die Deutschen heute eint – und was sie noch immer trennt”, spiegel.de, September 13, 2020; Susanne Dähner et al. “Vielfalt der Einheit – Wo Deutschland nach 30 Jahren zusammengewachsen ist”, berlin-institut.org, 2020 [online].

Ibid.

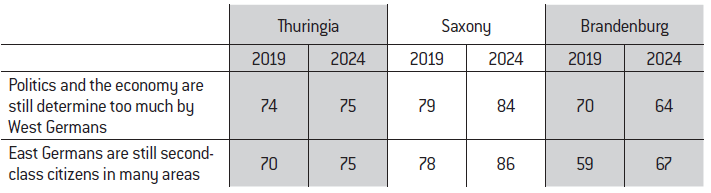

German reunification is unfinished business, and its deficits provide fertile ground for the AfD Sahra Wagenknecht’s42 BSW to grow. The annual publication on the state of this process certainly shows clear progress, but not enough to bridge the existing gap between East and West43.

In 2023, 33 years after reunification, an Infratest Dimap survey highlighted the persistent divide between East and West Germany. A significant portion of respondents from both regions noted ongoing challenges in East-West integration44. In the West, 56% of people felt there was “even less or no unity,” a sentiment echoed by 62% of respondents in the East. In East Germany, there remains a strong feeling of being treated as second-class citizens (43%), which has contributed to the solidification of a distinct East German regional identity.

This identity divide is clear in how people identify themselves. In the East, 40% of those surveyed said they primarily identified as East German, while 52% saw themselves as German and only 5% as West German. In contrast, in the old West German states, just 18% identified primarily as West Germans, 76% identified as German, and only 2% saw themselves as East German.

This regional split also affects perceptions of the AfD. At the end of 2023, 67% of West Germans viewed the AfD as a threat to federal democracy, compared to only 43% of East Germans who shared that opinion45.

How Economic Difficulties Influence Support for the AfD

Alternative für Deutschland, “,Leitantrag Der Bundesprogrammkommission Programm Der Alternative Für Deutschland”, afd.de, June 14, 2023 [online].

Deustcher Bundestag, “Alice Weidel: Den Bürgern droht die Verarmung und dem Mittelstand die Insolvenz”, bundestag.de, December 27, 2022 [online].

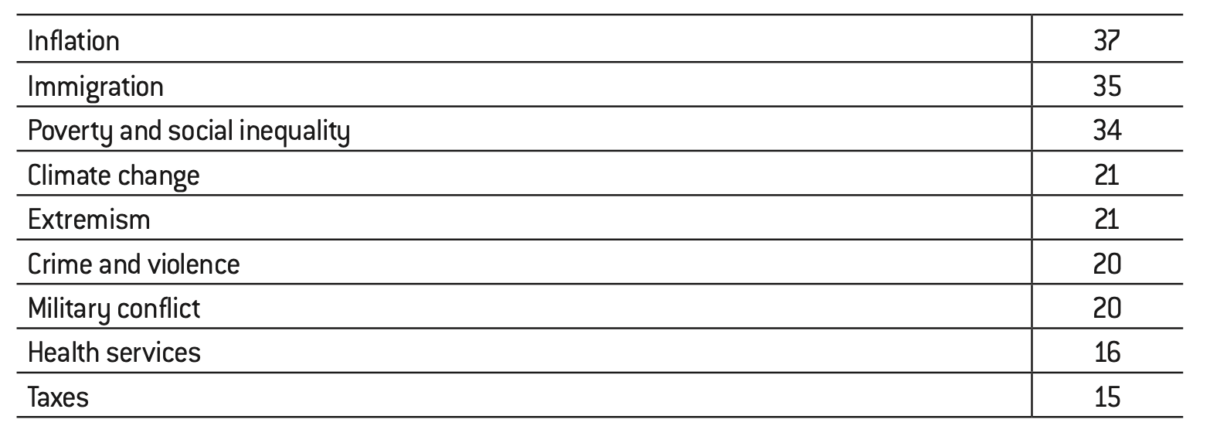

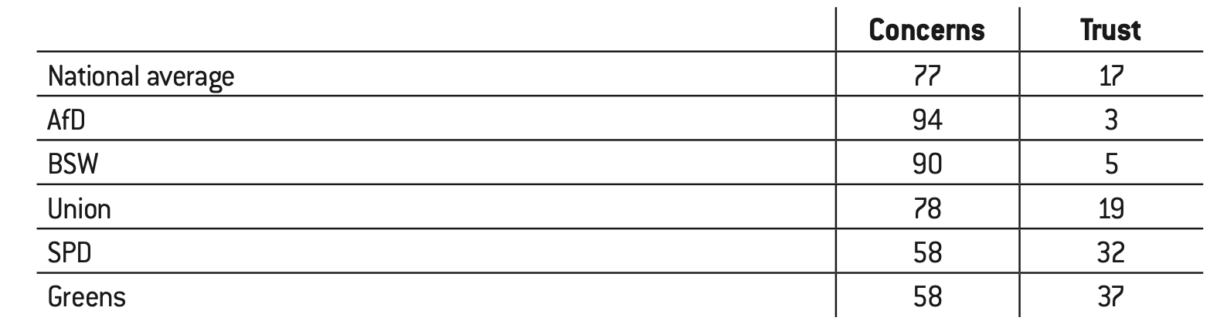

In addition to denouncing inflation, which mainly has an impact on low-income families, the AfD criticizes the weakening of the German economy46, ongoing relocations and the bankruptcy of small and medium- sized businesses47. In 2024, 77% of Germans are worried about the economic situation of their country, with fear of unemployment becoming a widespread issue among the population48. This anxiety is notably high among AfD and BSW supporters, but it also affects voters across the political spectrum.

Newsletter Statistik und Arbeitsmarktberichterstattung der BA – 6/2024 June 4, 2024,

On average, around 2.61 million people were registered as unemployed in 2023, i.e. 5.6% of the population. In January 2024, there were around 2.81 million unemployed people in Germany. This represents an increase of around 168,000 from the previous month (6.1%), a trend that continues into the summer of 202449. As a result, themes like deindustrialization, offshoring, corporate bankruptcies, and rising unemployment naturally became central to the AfD’s European election campaign.

Fears of the German population in February 2024

Source :

Welche drei der folgenden Themen bereiten Ihnen in Deutschland am meisten Sorgen?, statista, 2024 [online].

Indeed, the German economy has been in a near-constant state of crisis for almost four years. The most recent episode, Russia’s attack on Ukraine in February 2022, caused energy and food prices to rise sharply, affecting a country that is particularly sensitive to inflation (the inflation rate in 2023 was 5.9%)50.

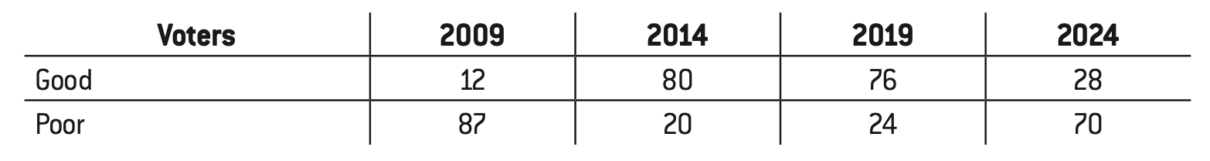

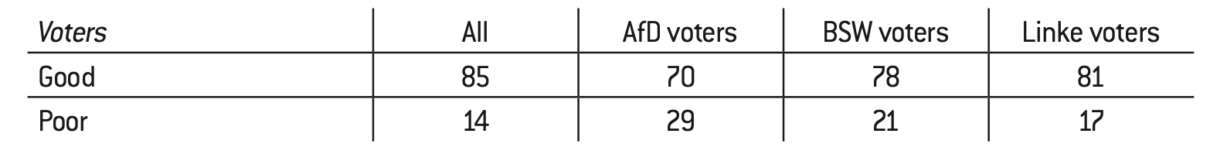

Polls reveal a remarkable shift in Germans’ economic outlook between 2014 and 2024. By 2024, 70% of respondents held a very negative view of the country’s economic situation, marking a dramatic reversal over the decade.

Economic situation in Germany – 2009 -2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

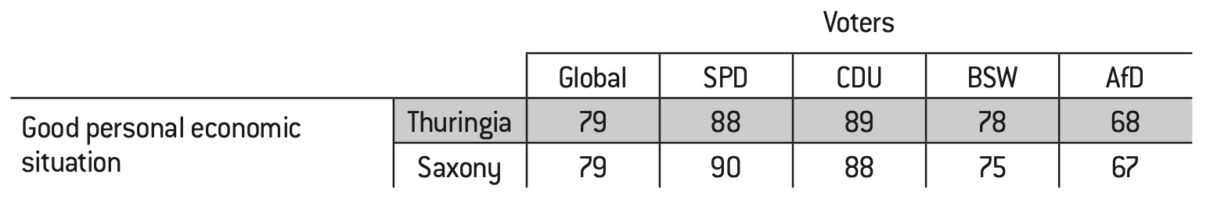

Personal economic situation in Germany – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

This pessimism is all the more surprising given that the individual situation of those surveyed is reported as “good” (85%). This negative perception is primarily found among AfD voters, and marginally among BSW voters.

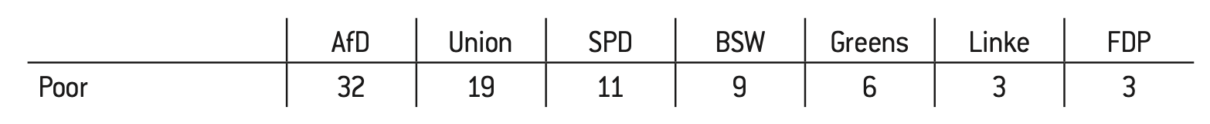

Electoral choice of respondents in poor economic circumstances in Germany -2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

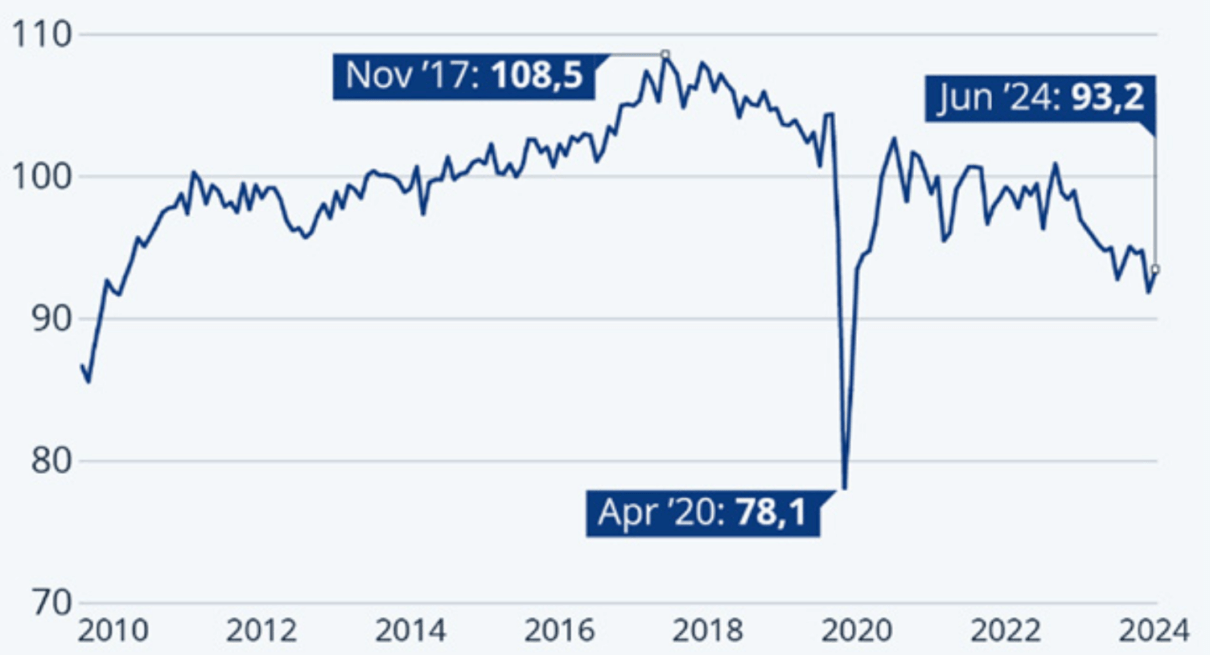

Today, Germany is often referred to as “the sick man of Europe.”51 According to experts, the primary cause is a “paralyzed global economy,” coupled with inflation that is curbing consumer spending. The main sector in crisis is industry, the backbone of the German economy, which accounts for just over a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product52.

German manufacturing index

Source :

Produktionsindex des produzierenden Gewerbes in Deutschland. [online].

Finally, rising interest rates continue to negatively impact the economy in 2024, as they hinder both the construction sector and overall investment.

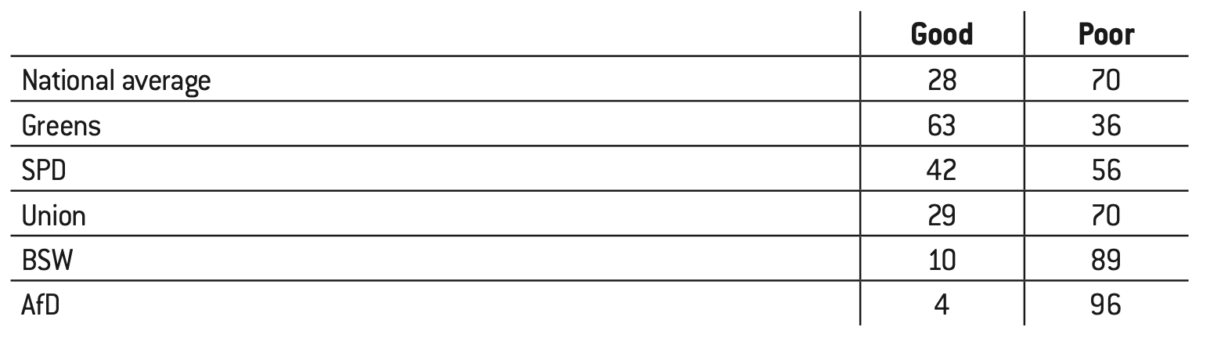

The economic situation in Germany: breakdown by party – 2024 (in %)

Source :

Tagesschau, June 24, 2024 [online].

The Traffic Light coalition’s fiscal policy is another factor contributing to the current recession. The Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling on November 15, 2023, forced the coalition to cut spending, which has led to recent farmer protests and a worsening economic climate53. For analysts, the state is becoming a “brake on the economy”. Analysts argue that the state is becoming a “brake on the economy.” The reduction in state support options, especially the resources now missing from the climate and transformation fund, will slow business investment in these areas and increase the risk of relocation — a key issue for the AfD.

Internal radicalization, opposition and risks of banning

Tagesspiegel, “”NPD light”: Die AfD pflegt enge Kontakte zu Rechtsextremen und Neonazis” tagesspiegel. de, 21 jullet 2023 [online].

Patricia Haensel, “Wo AfD und Junge Alternative gesichert rechtsextrem sind”, rnd.de, February 27, 2024. [online].

Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, “Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021″, bmi.bund.de, June 2021 [online]. Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, ,,Verfassungsschutzbericht 2022″, bmi. bund. de, August 2023 [online].

Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, “Rechtsextremismus entschlossen bekämpfen – Instrumente der wehrhaften Demokratie nutzen”, bmi.bund.de, February 13, 2024 [online].

Alexandra Tadey, “Demokratiefördergesetz:Wo sich die Ampel-Parteien uneinig sind”, zdf.de, February 8, 2024 [online].

Tagesschau, ,,Baumann sieht “infame Kampagne” gegen AfD”, tagesschau.de, January 21, 2024 [online]. WELT Netzreporter, “GESICHERT RECHTSEXTREM: “Diffamierung” Afd Sachsen sieht sich als Opfer eines politischen Schachzugs”, youtube.com, December 22, 2023 [online].

Süddeutsche Zeitung, ”AfD-Verbot? – Politiker und Juristen zeigen Risiken auf”, sueddeutsche.de, February 14, 2024 [online].

NZZ, “Der Geist ist aus der Flasche : Jetzt äussert sich auch Olaf Scholz zu einem möglichen Verbot der AfD”, nzz.ch, January 24, 2024 [online].

Rbb 24, “NPD-Nachfolgerin bekommt keine staatlichen Gelder mehr”, rbb24.de, January 23, 2024 [online].

Jörg von Heinemann and Pia Lorenz, “Keine Parteienfinanzierung für Verfassungsfeinde: Eine Blaupause für die AfD?”, rsw.beck.de, January 23, 2024 [online].

Ursula Knapp, “AfD im Aufwind: Petition fordert, Höcke die Grundrechte zu entziehen – und jetzt?”, fr.de, January 26, 2024 [online].

Tottmann Berit, Strategisches Framing bei Björn Höcke – wie ein rechtsextremer Politiker den Rahmen sprengt, in ZRex – Zeitschrift für Rechtsextremismusforschung, Jg. 2, Heft 1/2022, pp. 128-140.

In addition to frequent contacts with neo-Nazi groups54 and identity mouvements55, the AfD has been growing more radical internally. This has sparked debate over the possibility of banning the party under Article 21 II of the Basic Law, which states: “Parties which, through their objectives or the behavior of their members, tend to undermine or eliminate the liberal and democratic basic order, or which endanger the existence of the Federal Republic of Germany, are unconstitutional.” The Federal Constitutional Court is responsible for determining whether a party is unconstitutional.

Supporters of banning the AfD point to the fact that the party’s regional branches in Saxony, Thuringia, and Saxony-Anhalt have been classified by regional Offices for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungsschutz) as “confirmed right-wing extremists.” Additionally, the AfD’s youth organization, the “Junge Alternative,” has also been designated as extremist56. The AfD as a whole is currently classified as a “suspected case of right-wing extremism,” a designation the party is actively contesting in court57.

Meanwhile, Interior Minister Nancy Faeser’s proposal to step up the fight against right-wing extremism with 13 flagship measures58 has sparked debate about the risks to freedom of expression in Germany, particularly within the ranks of FDP and CDU/CSU59. The AfD has capitalized on this controversy, positioning itself as a victim of what it calls the “anti-democratic cartel” of parties60 – a popular argument in the new Bundesländer (former East Germany).

A ban of the AfD by the Constitutional Court is considered highly risky and unlikely by the majority of constitutional experts61, which explains the reluctance of Chancellor Scholz and the President of the Republic62. However, other efforts have been initiated to weaken the AfD on different fronts.

The Federal Constitutional Court’s decision to exclude “Die Heimat” from public funding of political parties for six years provides a possible framework63. A campaign has been launched to ban public funding of the AfD, which would effectively cause its political decline64.

A final aspect of the anti-AfD effort involves a petition submitted to the Bundestag, signed by over 1.6 million people, seeking to strip Björn Höcke, the leader of the AfD in Saxony, of his fundamental political rights (Grundrechte), which would render him ineligible65. The petition cites Article 18 of the Basic Law: “Whoever abuses the freedom of expression, in particular the freedom of the press, the freedom of education, the freedom of assembly […] to fight against the liberal and democratic basic order, loses these fundamental rights”. Unlike similar attempts in the 1960s and 1970s, all of which failed, this approach has a more realistic chance of succeeding66.

Regardless of the outcomes of these actions or the effectiveness of Faeser’s plan, the AfD remains relatively secure in the short term, as any dissolution procedure would take years. While street mobilization against the AfD appeared effective momentarily, it has now subsided. A notable “perverse effect” of these efforts is that increased pressure on the AfD strengthens the shared identity of its supporters, driving them to become more radical in response.

Religious and trade union institutions confront the AfD

Here, this term refers to individuals who declare to the court that they have abandoned their religious affiliation, and are therefore no longer subject to the compulsory tax paid to the various denominations.

Deutschlandfunk, “KathoNegativrekord 2022: Mehr als 500.000 Menschen ausgetreten”, deutschlandfunk. de, June 28, 2023 [online].

Anna Siebenhaar, “Für deutliche Mehrheit haben christliche Werte kaum Bedeutung”, mdr.de, November 20, 2023 [online].

Tagesspiegel, “Kirche gegen Rechtsextremismus: AfD wirft katholischen Bischöfen “Polithetze” vor”, tagesspiegel.de, February 23, 2024 [online].

Pressemitteilungen der deutschen bischofskonferenz, “Völkischer Nationalismus und Christentum sind unvereinbar”, dbk.de, February 22, 2024 [online].

Annette Zoch, ,”Deutsche Bischöfe warnen vor der AfD”, sueddeutsche.de, February 22, 2024 [online].

In 2022, 24% of Germany’s 84,669,000 inhabitants were Catholic, 21.9% Protestant, 3.8% Muslim and 46.2% had no religious affiliation67. Dechristianization is accelerating, affecting both Catholics and Protestants. In 2022, the German Catholic Bishops’ Conference (DBK) announced a record number of departures68 (522,821 Catholics69), while Protestants report 380,000 resignations70.

An MDR survey reveals that the trend of de-Christianization is most pronounced in the new Bundesländer71. The majority of the 23,000 respondents place little importance on Christian values, with 77% viewing the influence of churches in society as weak, compared to 18% who see it as strong. Nearly two-thirds of participants (64%) believe that leaving the Church is not an issue, while only 27% view it as a problem. Additionally, 70% of those surveyed think that the influence of churches will decline in the future, with just 20% predicting it will remain stable and only 3% believing it will increase.

The two major denominations have come out against the AfD, a move that the party leadership has condemned72. The Bishops’ Conference, in a four-page manifesto73, states: “We make it clear that völkisch nationalism is incompatible with the Christian image of God and man […] Extreme right-wing parties and those proliferating on the bangs of this ideology cannot therefore be a place of political activity for Christians and are not eligible. The dissemination of extreme right-wing slogans – which include racism and anti-Semitism – is also incompatible with full-time or voluntary service in the Church”74. Protestants take the same line, but are cautious as to not ostracize Protestant members of the AfD75.

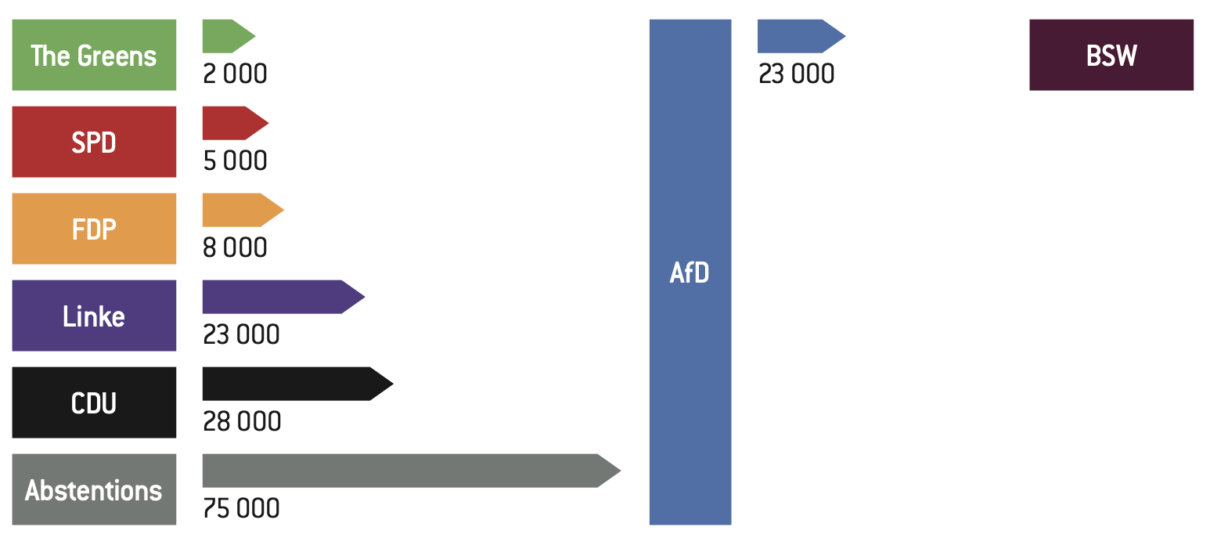

An analysis of denominational affiliations during the 2024 European elections reveals that the AfD has strong support among voters with “no confession,” highlighting the ongoing de-Christianization of the new Bundesländer.

European elections on May 9, 2024. Voting choices in social groups (difference from 2019 elections)

Source :

Viola Neu / Jochen Roose, Tabellenanhang zur Europawahl in Deutschland am 9. Juni 2024 [online].

Rüdiger Soldt, ,,Unternehmer und Gewerkschaften positionieren sich gegen die AfD”, Frankfurter Allgemeine (faz.net), February 26, 2024 [online].

Hans-Jürgen Urban, ,,Kampf um die Hegemonie: Gewerkschaften und die Neue Rechte”, blatter.de, March 2018 [online ]; Süddeutsche Zeitung, ,,Soziologe sieht wachsenden AfD-Einfluss auf Betriebsräte”, sueddeutsche.de, September 18, 2019 [online]; Till-Reimer Stoldt, ,,Wo ist sie hin, die Macht der Arbeiter?”, welt.de, April 26, 2022 [online]; Bose Sofie, ,,Gewerkschaften und Rechtspopulismus in Europa”, Länderstudie Deutschland, January 2023 [online].

In conclusion, it is difficult to gauge the impact of the churches’ positions on the AfD’s electoral potential. Clearly, this influence is minimal in the East. In the West, mass demonstrations—100 events with 3.5 million participants—were attended by many Christians who expressed their opposition to the AfD on the basis of their faith.

At the end of February 2024, trade unions and employers took a stance against the AfD, intensifying their opposition during the regional elections in September 202476. This alliance stems from the observation that, since the 2017 Bundestag election, trade union membership no longer acts as a barrier to supporting the AfD. Research shows the party’s growing penetration into trade unions, strengthening its ties to the working class77. Nevertheless, the campaign had no significant effect on the AfD’s connection with labor, as reflected in the party’s 2024 electoral results.

European elections on May 9, 2024. Voting choices in social groups (difference from 2019 elections)

Source :

Viola Neu / Jochen Roose, Tabellenanhang zur Europawahl in Deutschland am 9. Juni 2024 [online].

AfD and Moscow: controversial links under fire

Annika Leister, “AfD-Politiker: Habe nie Geld von “irgendeinem Russen” erhalten”, t-online.de. April 4, 2024 [online].

Pierre Emmanuel Ngendakumana, ,,Von der Leyen castigates far-right AfD over Russiagate scandal”, politico.eu. April 13, 2024 [online].

Lukáš Prchal, Zdislava Pokorná, “Důkazem mají být zvukové nahrávky. Cořekl Koudelka vládě o proruské síti a německém politiku Bystroňovi”, denikn.cz, April 2, 2024 [online].

Emanuele Bonini, “Czech Republic ‘shuts down’ Voice of Europe, spread pro-Russia news”, eunews.it, March 28, 2024 [online].

Maik Baumgärtner et al. “Das fragwürdige Netzwerk von AfD-Politiker Petr Bystron”, spiegel.de, April 13, 2024 [online].

Jean Peters and Marcus Bensmann, “Tschechischer Parlamentarier bestätigt: Bis zu einer Million Euro russisches Geld soll über Polen geflossen sein”, correctiv.org, April 5, 2024 [online].

Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Europas Moderner Rechtsextremismus: Ideologien, Akteure, Erfolgsbedingungen und Gefahrdungspotentiale, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2021.

Géoconfluences, “Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)”, géoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr, 2018 (updated December 2023) [online].

Armin Pfahl-Traughber, “Intellektuelle Rechtsextremisten: Das Gefahrenpotenzial der Neuen Rechten”, Dietz Verlag, 2022.

Alex Hock et al. “Mehr als 100 AfD-Reisen zum Gefallen Russlands”, welt.de, October 23, 2020 [online].

RadioFreeEurope, RadioLiberty , “German Nationalist Leader Petry Met With Putin Allies In Russia’s Duma”, rferl.org, February 21, 2024 [online].

Sven Becker and Melanie Amann, “Russische Stiftung bezahlte Krimreise von AfD-Politiker Pretzell”, spiegel. de, January 21, 2017 [online].

Silvia Stöber and Andrea Becker, “Wahlbeobachtung auf Bestellung”, tagesschau.de, September 19, 2021 [online].

Robert Kiesel, “Maschinengewehr, Hakenkreuze und Nachtwölfe: Die skurrilen Urlaubsbilder des AfD- Politikers Gunnar Lindemann”, tagesspiegel.de, November 14, 2019 [online].

Ibid.

RadioFreeEurope, RadioLiberty, “Lavrov To Meet Members Of Germany’s Far-Right AfD Party”, rferl.org, December 8, 2020 [online].

Zeit Online, ”Alice Weidel reist mit AfD-Kollegen nach Russland”, zeit.de, March 9, 2021 [online].

Giles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina, “To Russia with love? German populist actors’ positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin.” In: The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-wing Populism in Europe. Populismstudies. org, March 8, 2023 [online].

“Parteireise nach Russland mit Tantra-Masseurin – AfD prüft Sanktionen”, welt.de, March 3, 2023 [online].

”The war is an afterthought at the St. Petersburg forum, once a marquee event for Putin” [online].

Robert Wagner, “Nach Putins “Sicherheitskonferenz”: AfD-Politiker feiert Russland als Paradies auf Erden”, fr.de, 22 aout 2023 [online].

Catherine Belton et al. “Kremlin tries to build antiwar coalition in Germany, documents show”, Washingtonpost.com, April 21, 2023 [online].

On 11 April 2024, the AfD faced massive criticism during a current affairs session entitled ‘’Shedding light on the possible involvement and cooperation of AfD parliamentary group members with authoritarian regimes‘’, included on the agenda at the request of the SPD, Alliance 90/ The Greens and the FDP78. AfD member of parliament and second-place candidate in the European elections, Petr Bystron, was suspected of having received money from Russia, which he denied79. The AfD leadership supported Bystron, invoking the presumption of innocence. Their defense strategy involved demanding access to information from Czech secret services to establish the AfD MP’s innocence or guilt.

The Bystron affair poses extreme risks for the AfD, not only because of the ongoing judicial investigations in Germany and Belgium, but also because of its implications at European level80. At the beginning of April, “Denik N” published a detailed report on Bystron and his involvement in the “Voice of Europe” affair81. The Czech secret service, BIS, reportedly participated in a closed cabinet meeting with Czech politicians. During this meeting, BIS allegedly informed the participants about the existence of “documented evidence” (sound recordings) that could indicate a payment to Bystron, as well as to other politicians from France, Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Hungary. However, the recordings have remained partially classified.

The Czech government has placed “Voice of Europe” and its operators, pro-Russian Ukrainians Viktor Medvedchuk (a close associate of Putin) and Artem Martschewski, on a list of sanctions against Russia82. The Czech government justified its decision by stating that Moscow had financed, via “Voice of Europe”, the election campaigns of pro-Russian politicians83 who were running in the 2024 European elections. Indeed, Pavel Žáček, member of the liberal-conservative party (ODS) and chairman of the parliamentary security committee in the Czech Republic, confirms the following: ” The money paid to agents working in European politics – including the AfD – reached the Czech Republic via Poland. It was, in any case, several hundred thousand euros, up to one million”84. The AfD faces another challenge: Maximilian Krah, the head of the AfD candidate list for the European elections, has previously given interviews to Voice of Europe and met with Viktor Medvedchuk. This has raised concerns among observers about potential corruption involving the MEP, although these suspicions have not yet been confirmed. Additionally, one of Krah’s staff members of Chinese origin has been arrested for spying for China85.

The AfD’s relations with Russia extend back several years, originating in 2015 when Alexander Gauland, a prominent figure among the AfD’s neoconservatives, visited the Russian embassy in Berlin86 for “strategic analysis”. A move that was not well received by the “liberal” members of the party. Following their political marginalization, the AfD programmatically aligned itself with Moscow, becoming a conduit for Putin’s asymmetrical war against Germany and the EU87.

An analysis of the AfD’s programs from 2013 to 2024 illustrates this thesis. In 2013, the AfD led by its founder Bernd Lucke embraced Western values and supported NATO. This was made clear in their electoral programme for the 2014 European elections: “NATO is and remains (a) transatlantic security architecture whose decisive anchor is the alliance with the U.S. (…) The AfD approves (…) an EU common foreign and security policy”. In stark contrast, the AfD’s program for the 2024 European elections is dominated by anti-Western sentiments. The party seeks to go beyond the EU, calling for Germany to be granted observer status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which is dominated by China and Russia88. Additionally, the AfD advocates for cooperation with the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). In the preamble to the 2024 program, the “domination of non-European great powers” – primarily the USA – is blamed for the fact that “European states [are actors in] conflicts” that “diametrically oppose fruitful trade relations in the Eurasian space”. At the same time, the concept of a “multipolar world order” makes its appearance in the program (Chapter Europa neu denken)89.

To understand the reasons behind the AfD’s ideological shift, it’s important to distinguish between two distinct periods. The first spans the time before Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, while the second begins in February 2022 and continues to the present.

During the first period, an internal alliance within the AfD between neoconservatives and the völkisch movement – those associated with Björn Höcke – led to the increasing influence of Aleksandr Dugin’s theses on Eurasia. Dugin’s vision of an inevitable “Fourth Rome” led by Russia, dominating Europe, became a key ideological reference for the AfD’s leadership and its New Right circles, as well as for figures like Alain de Benoist in France90. The growing connection between the AfD and these ideas was evident in the frequent travels of AfD deputies to Russia. These trips played a crucial role in the party’s evolution, often serving as deliberate provocations—such as when AfD officials visited Crimea after its annexation by Russia, or the separatist regions of Luhansk and Donetsk, both backed by Moscow. In October 2021, Die Welt reported on over 100 such trips, highlighting their significance in shaping the party’s trajectory91.