Anti-Semitic Attitudes in France: New Insights

In his report of October 2004 entitled Chantier sur la lutte contre le racisme et l’antisémitisme [Review on the fight against racism and antisemitism], Jean-Christophe Rufin noted that far-right involvement in antisemitic attacks was decreasing, while a minority of young people from immigrant backgrounds were increasingly responsible for this violence.

Is this still the case today? To find out, we embarked on an unprecedented project including two opinion polls conducted by Ifop, one of which was administered online with a representative sample of 1,005 individuals aged 16 and over. The other was conducted face-to-face with a sample of 575 individuals who stated that they had been born into French or non-French Muslim families, lived in France and were aged 16 and above.

With regard to this context and its political consequences, I take the liberty of refer- ring to the new supplemented edition of my book Les Nouveaux Populismes, Fayard/ Pluriel, 2013.

Ten years after the ‘Rufin report’, regular surveys commissioned by the French National Consultative Committee on Human Rights (CNCDH) reported a decline in antisemitic prejudice in public opinion. However, data collected by the Kantor Center show that the number of violent antisemitic incidents was three times higher between 2004 and 2013 than in the decade from 1994 to 2004. Even if we accept the theory that prejudice is declining, there has been a clear increase in violence towards Jews. Moreover, there has been a resurgence of racist language towards figures such as French Justice Minister Ms. Christiane Taubira and Ms. Cécile Kyenge, the Italian Minister for Integration.

The issue of antisemitism, xenophobia and racism is once again rearing its head in democracies, both in Europe and in France. It is sad to note that this is actually nothing new. However, we must focus our concerns and action on the resurgence observed since the early 1990s. This resurgence can probably be attributed primarily to globalisation and the way it has

affected democratic societies in tangible and cultural terms, which is described by some as an ‘identitarian’ phenomenon. It moreover reflects the overthrow of the old order by a new order of emerging countries and, in France, the vague feeling of a world that, if not hostile, is certainly less benign. Added to this are the consequences of migratory phenomena that were triggered decades ago but whose effects, it seems, are suddenly being felt in terms of the entrenchment of a de facto multicultural society contributing to the destabilisation of western countries in general and European countries in particular. Population ageing appears to be a further factor prompting fear and insularity. Moreover, in some countries including France, unease has increased as a result of the public authorities’ fiscal crisis, not only from an economic and social perspective, but also in political and cultural terms, with the notion of governments incapable of action and social and state paralysis gaining credence1.

Translator’s note: Dieudonné M’bala M’bala is a French comedian and activist whose antisemitic comments prompted the French government to ban his shows and political gatherings in early 2014.

Finally, in order to understand this new wave of hostile attitudes, we must look to the major influence exerted by a new player, the Web, which has rapidly taken on a key role both with regard to news and also political engagement, rallying of activists, and the expression of ideas in general and protest in particular. The Web’s strength is amplified by its apparent and partly genuine virtues including egalitarianism, spontaneity, authenticity, immediacy and universality. However, this new public space is substantially underpinned by the unique possibility of issuing, receiving and sharing messages and opinions without necessarily having to provide one’s identity and thus take responsibility for them. This is an unprecedented situation in the entire history of press freedom and freedom of opinion. These tools provide those expressing antisemitic or racist views with extraterritorial status, and ultimately de facto impunity, whereby states governed by the rule of law are no longer able to defend humanist values or punish those guilty of infringing them. In contrast

authoritarian regimes are still able to impose total censorship in their countries, while also enjoying an unprecedented ability to encourage the dissemination of devastating messages around the world.

The Dieudonné affair2 in France provided a condensed version of this new set-up, revealing activism among networks and groups that – let us not forget – constituted a very small minority, yet were capable of generating and spreading views of an undisputedly antisemitic nature on a large scale. This controversy revealed two sides of the public space. On one side was the formal, institutional and official public space represented by the traditional media. On the other was its mirror image, the Web, a sort of informal, anomic, unofficial, underground public space, made up of social media, discussion forums, and video sharing sites.

Gilles Finchelstein, Dominique Reynié and Simone Rodan-Benzaquen ‘Nos démo- craties sont menacées’; Camille Bedin ‘L’antisémitisme au quotidien’; and François Pupponi, ‘Sarcelles après l’émeute’, Le Figaro, 23 October 2014 (these articles can be accessed online.

Gilles Finchelstein, Dominique Reynié and Simone Rodan-Benzaquen, ‘La lutte contre l’antisémitisme est une lutte pour la République’ ; Annette Lévy-Willard ‘L’antisémitisme, une spécificité française ?’; and Nonna Mayer, ‘L’opinion française n’est pas antisémite’ Libération, 23 October 2014.

What was considered an emerging phenomenon by the Rufin report in 2004 took hold towards the end of the decade. Although there is more to the Web than this, it has nevertheless become a formidable means of spreading antisemitic, xenophobic and racist views. This was all condensed in the Dieudonné affair, whose outbreak was no accident, but rather the sign of more profound change. It manifested an attempt to redefine norms, conventions, and perhaps even values, customs, history and lessons learned from the past. An initially improvised media initiative, the controversy prompted such remarks and such a response, both positive and negative, that it is impossible not to view it as a reflection of our times.

There is a big difference between opinions and violence. In France, the number of antisemitic incidents has not fallen below the threshold of 400 per year since the early 2000s, with 2014 seeing a dramatic rise (+ 91%). Indeed, 527 antisemitic incidents were reported between January and July 2014 compared to 276 in the same period of 2013. Half of all racist incidents target Jews, who probably represent less than 1% of the population. Unfettered antisemitism has taken hold on the Web. In the summer of 2014, during demonstrations against Israeli intervention in the Gaza Strip, cries of ‘Death to the Jews!’ were heard in the Place de la République in Paris. In Sarcelles, this led to Jewish-owned shops being ransacked and an attack on a synagogue.

Recent atrocities are part of the same trend with the killing of Ilan Halimi by Youssouf Fofana’s gang in 2006, the murder of Jonathan Sandler and the children Gabriel Sandler, Arieh Sandler and Myriam Monsonego in 2012 by Mohammed Merah, who also killed the unfortunate Imad Ibn Ziaten, Mohamed Legouad and Abel Chennouf, and finally the Brussels massacre perpetrated by Mehdi Nemmouche in 2014. It would be a mistake to view these tragedies as causeless acts. They reflect our times and as such inevitably tell us something about their essence.

It is now important to determine how democratic governments can continue to teach, promote and defend the values upon which they are founded and thus survive. In these terms, the fight against racism and antisemitism responds not just to a need to protect individuals and groups who suffer as a result of these phenomena, but also the absolute necessity of ensuring the existence of the democratic order in the new century. The findings of this study substantiate or clarify certain initial assumptions while contradicting others. Overall, a picture emerges of a society in which antisemitic feeling is high in pockets that, although currently relatively small, may reasonably be expected to grow.

The study also reveals a society that believes that most of the groups that constitute it are the victims of prejudice and racism including Jews, Muslims, North Africans, black people and white people. Some findings are encouraging and even reassuring while others are concerning and even very worrying. On the whole though, the survey provides compelling arguments for immediate collective action both from the government, and to a greater extent from civil society, with a view to bringing all sides together and everyone making an effort to acknowledge and understand one another.

Finally, I would like to point out that these two studies are a contribution from the Fondation pour l’innovation politique to work building on the antisemitism seminar held on 16 October 2014. We organised this event jointly with the American Jewish Committee and Fondation Jean-Jaurès. It also involved a significant partnership between the right-leaning Figaro and left-leaning Libération daily newspapers. The seminar was moderated by Simone Rodan- Benzaquen for the American Jewish Committee, Gilles Finchelstein for the Fondation Jean-Jaurès and Dominique Reynié for the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. Of the thirty attendees, four parliamentary representatives were actively involved in this work – two members of the National Assembly, Claude Goasguen and François Pupponi, and two senators, David Assouline and Chantal Jouanno – as well as a local elected representative, Camille Bedin. Le Figaro was represented by Vincent Trémolet de Villers and Libération by Annette Lévy-Willard. Following this first seminar, three articles were published in Le Figaro3 on 23 October and significantly, three others were published in Libération4 on the same day. This seminar will be continued to examine forms, drivers, and means of tackling antisemitism in greater depth. We took a joint decision to extend the scope of this seminar to include hostility towards Islam and racism. The same approach, methods and resources will be adopted while also extending the circle of experts, politicians and stakeholders in government, state education, police and justice. Any heads of social, educational, cultural and religious organizations who may wish to join us will also be included.

The second survey was conducted with 575 individuals of Muslim origin, i.e. people stating that they were born into a Muslim family and were aged 16 and above. No statistics are available to create a genuine quota-based sample for this group. After stratification by region and geographical setting (municipality size), Ifop determined guideline quotas (gender, age, occupation) based on INSEE 1 statistics on immigration in France and empirical data on the Muslim-origin population from its national surveys. During fieldwork, individuals aged 16 to 17 were overrepresented to ensure sufficient numbers and subsequently reduced to their actual weighting for statistical analysis of the study. In this second survey, questionnaires were administered face- to-face on the street between 4 and 9 October 2014.

The purpose of the second survey is to test the hypothesis that a new form of antisemitism has emerged.

This was put forward almost fifteen years ago by Pierre André Taguieff and cited by Jean Christophe Rufin in his 2004 report. It seeks to determine whether Muslims living in France are more or less likely than the mean for the national population to exhibit prejudice towards Jews and even develop an antisemitic outlook. Generally, in a sample of 1.000 individuals, the proportion of Muslims is not sufficiently high to enable a significant analysis of the data collected. We therefore also decided to ask Ifop to interview a sample consisting solely of individuals of Muslim origin, i.e. people stating that they had been born into a Muslim family. These individuals could be either French or non-French nationals. We hope that this initial survey will pave the way for a series of new social science surveys. This will help us to better understand our society and ourselves, thus increasing our chances of taking appropriate action in everyone’s interests.

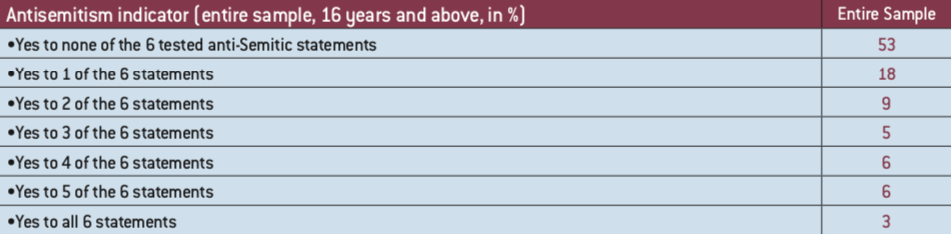

The formulation of an antisemitism indicator

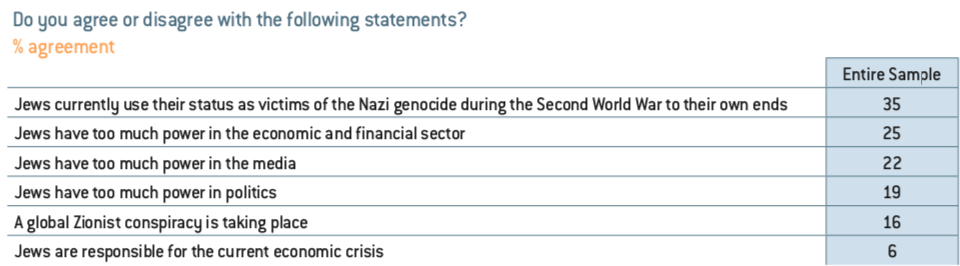

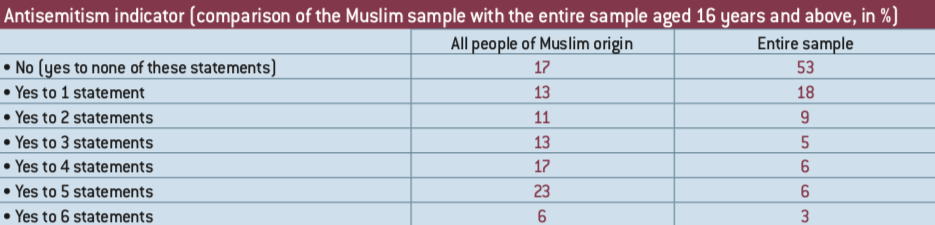

The aim of this survey is not only to ascertain the percentage of respondents exhibiting one anti-Jewish prejudice, but also the percentage exhibiting several such prejudices in order to shed light on the profile of respondents whose value system combines several prejudices towards Jews and who therefore demonstrate an antisemitic outlook whose level is considered by this study to increase as the number of prejudices rises on a scale of 1 for the group of respondents that exhibit one antisemitic prejudice to 6 for those who exhibit them all.

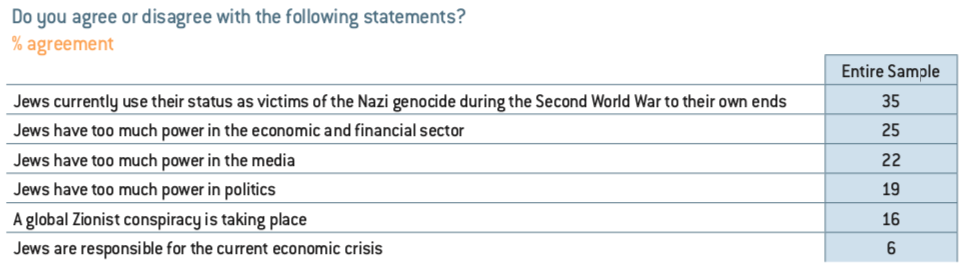

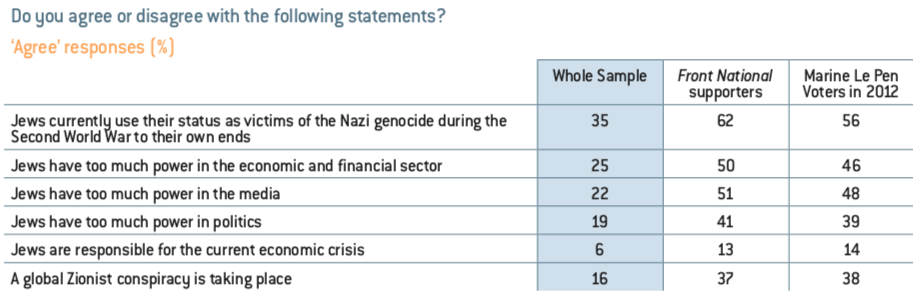

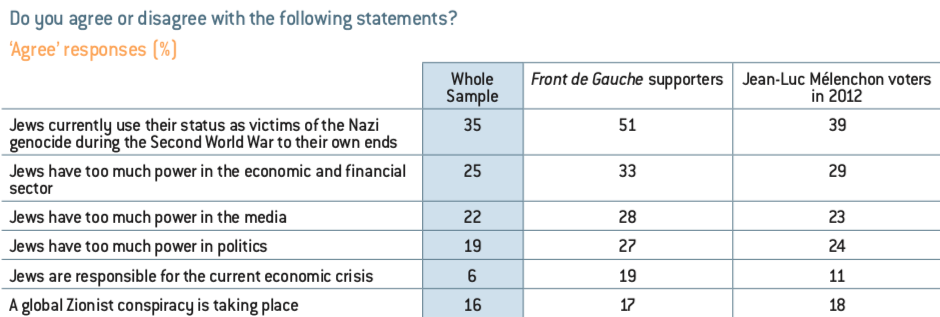

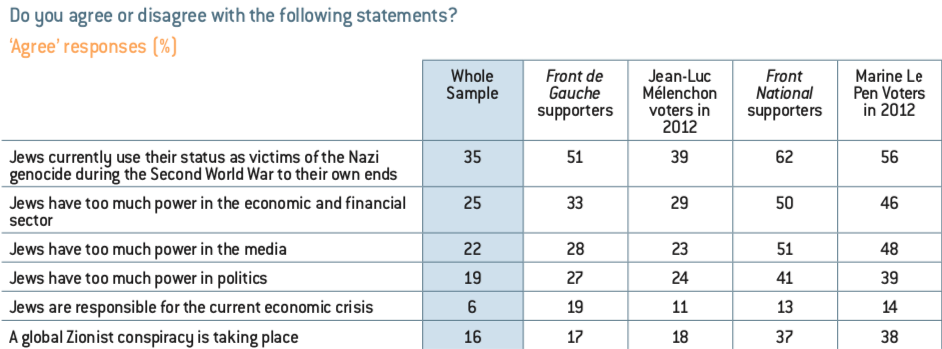

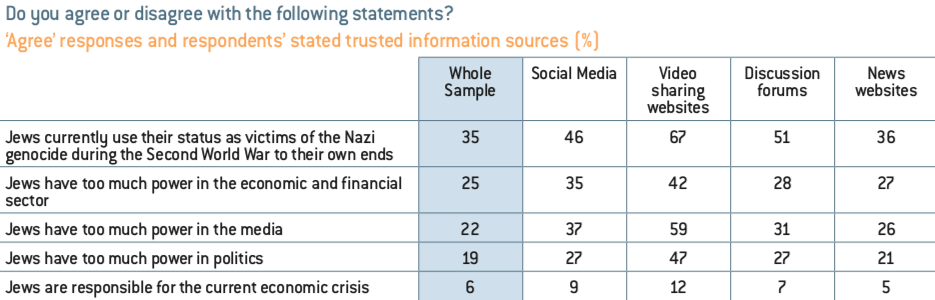

When the questionnaire was drafted, the following list of six opinions regarding Jews was used to create the indicator: ‘Jews currently use their status as victims of the Nazi genocide during the Second World War to their own ends’ (35%); ‘Jews have too much power in the economic and financial sector’ (25%); ‘Jews have too much power in the media’ (22%); ‘Jews have too much power in politics’ (19%); ‘A global Zionist conspiracy is taking place’ (16%); ‘Jews are responsible for the current economic crisis’ (6%). Just over half of the respondent sample (53%) stated that they did not share any of these six prejudices, while 3% shared all six prejudices.

The data presented in this analysis are taken from the results of the two surveys. Survey data relating to the 575 individuals stating that they were born into a Muslim family are accompanied by a note to that effect. Other data relate to the sample of 1,005 individuals who are representative of French people aged 16 and above.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

1. Antisemitic opinions in a society that is not antisemitic

Trends for antisemitic views run through French society as a whole. Their severity must be assessed based not only on the number of people who share them, but also by considering the degree of violence they embody. The most widespread prejudice against the Jews (35%) is that ‘Jews currently use their status as victims of the Nazi genocide during the Second World War to their own ends’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

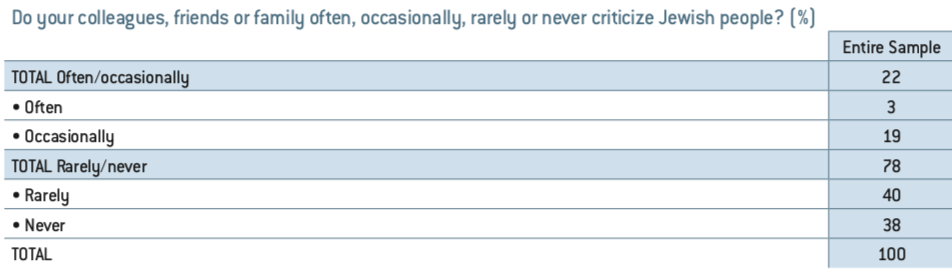

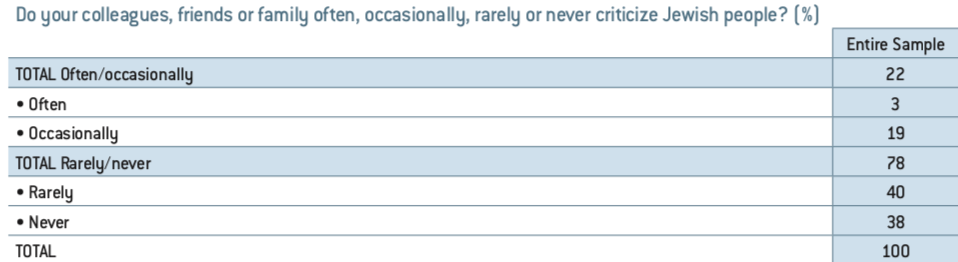

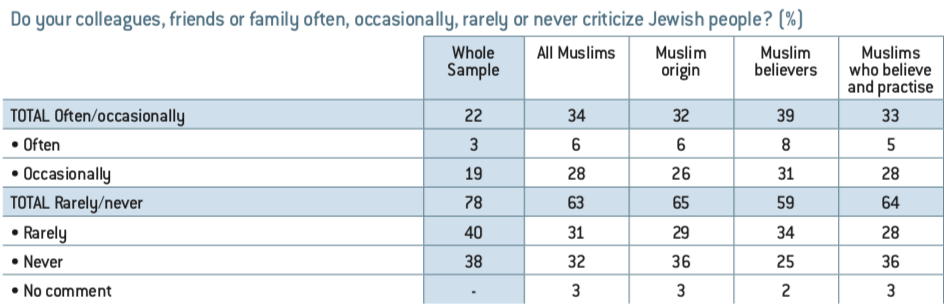

Over a fifth of respondents (22%) state that their colleagues, friends or family ‘often or occasionally’ ‘criticize Jewish people’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

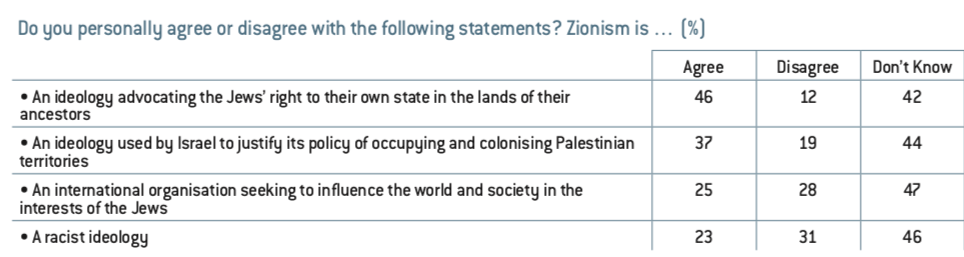

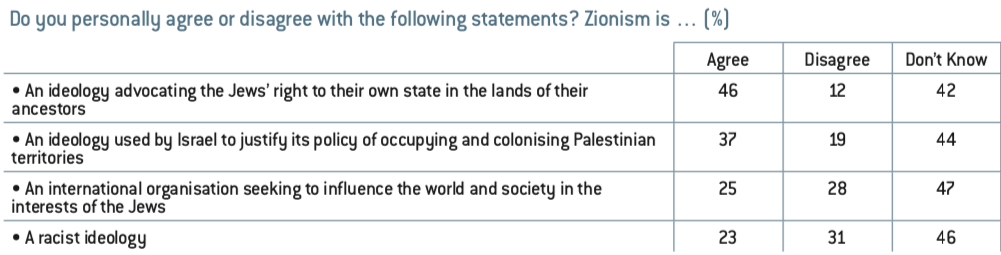

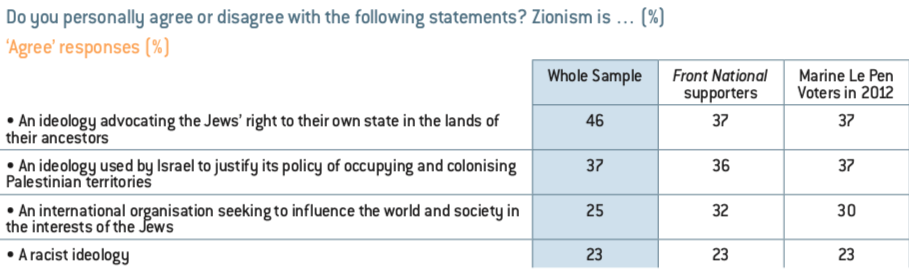

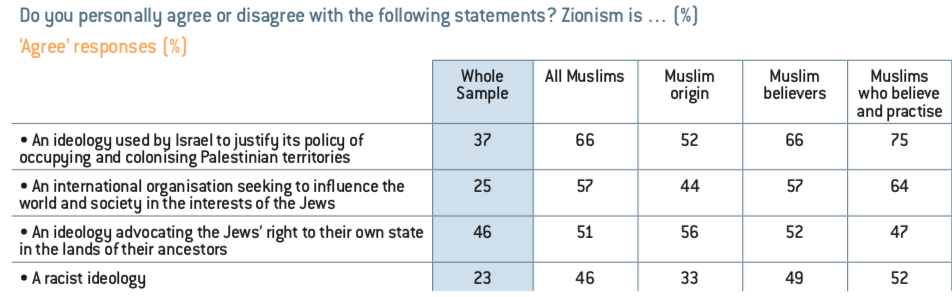

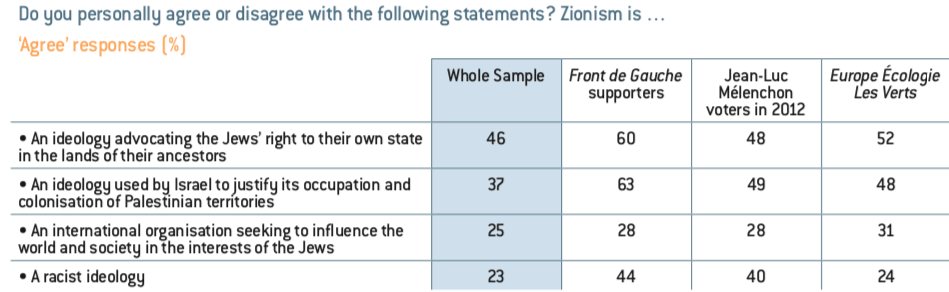

While the questions relating to Zionism meant nothing to a large proportion of respondents (between 42% and 46%), they revealed robust criticism from a section of society towards Israel’s policies and also the strength of one of the most widespread antisemitic opinions: 25% of respondents believe that Zionism is ‘an international organisation seeking to influence the world and society in the interests of the Jews.’

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

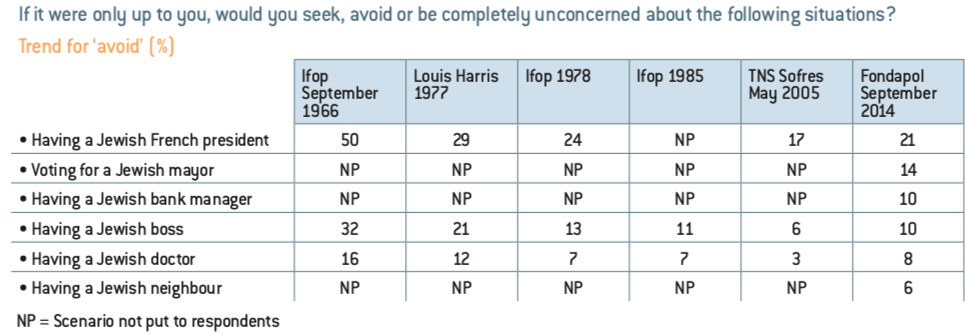

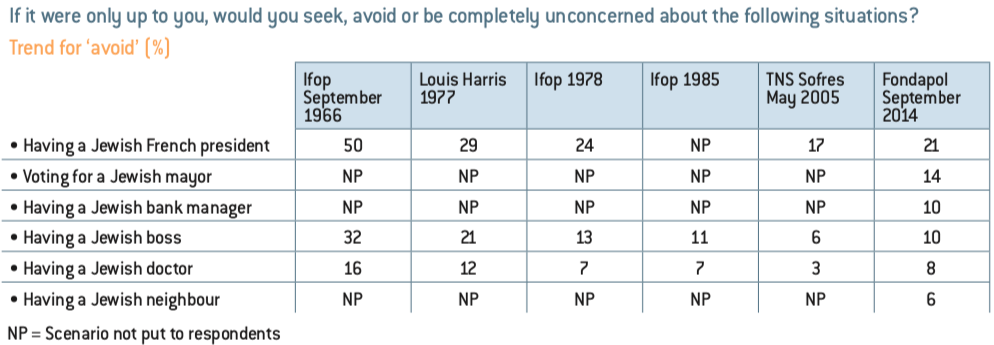

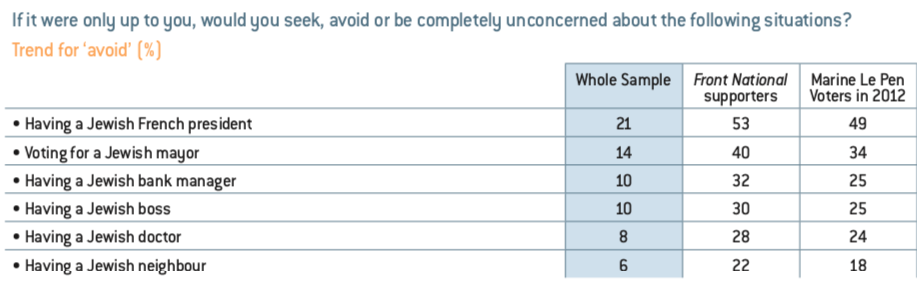

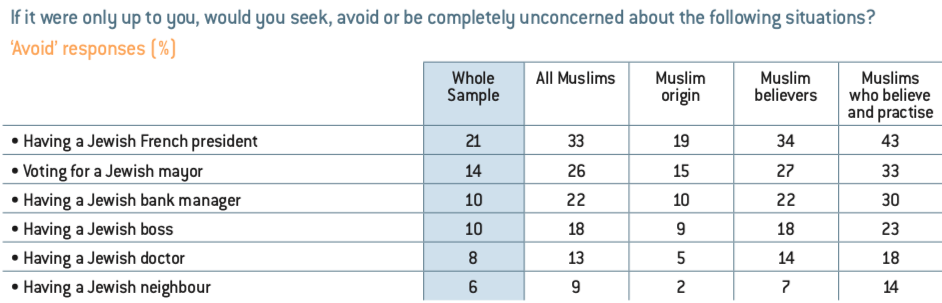

Moreover, the notion of electing a Jewish French president is rejected by a fifth (21%) of respondents. We note that ten years earlier, this proposition was rejected by fewer respondents (17%). We also note that 6% of respondents state that they would rather not have ‘a Jewish neighbour’. This demonstrates the difficulty of analysing the types of results we obtain from a survey on this issue – while in abstract terms, 6% is a low proportion of the population, in concrete terms, the desire to avoid having a ‘Jewish neighbour’ reflects a very high level of hostility. In this type of questionnaire, we must not only take account of percentages, but also the intensity of opinions.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

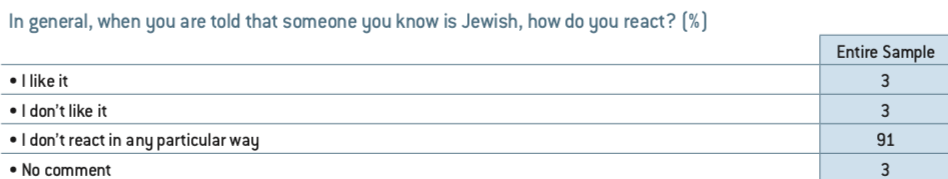

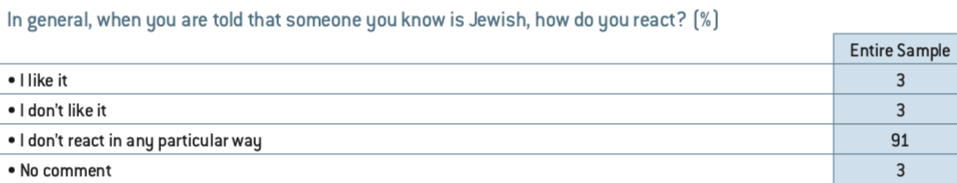

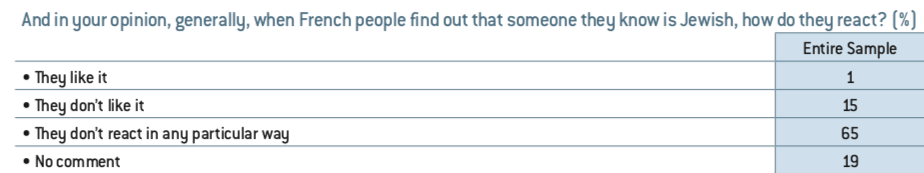

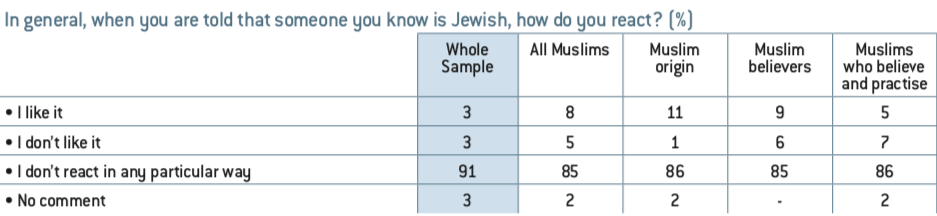

It is apparent that where the questions prompt respondents to talk about their perceptions not just of Jews in general but of Jews in reality, their responses show a reduction in antisemitic prejudice.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

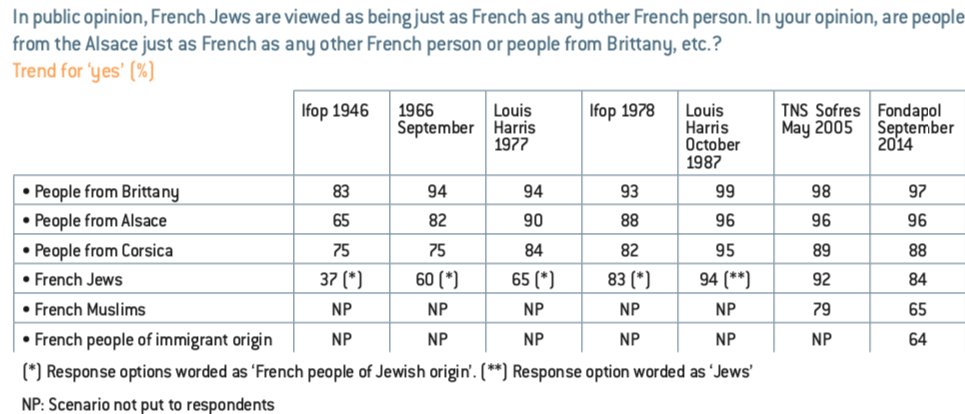

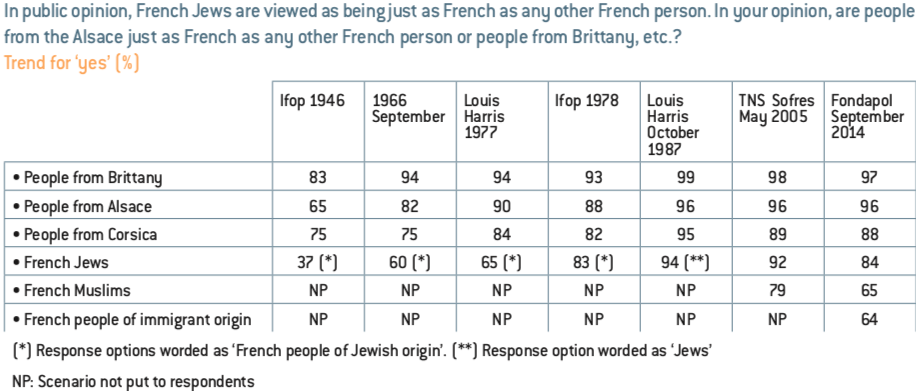

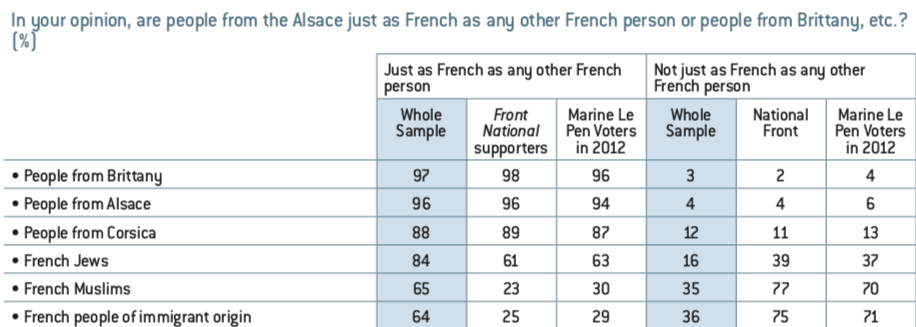

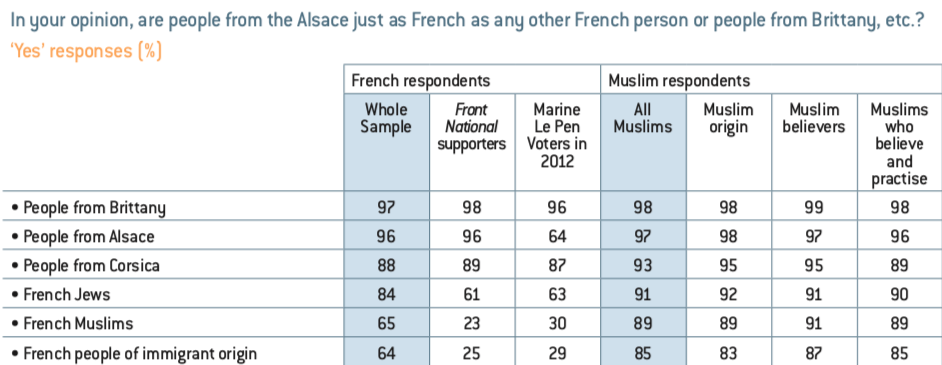

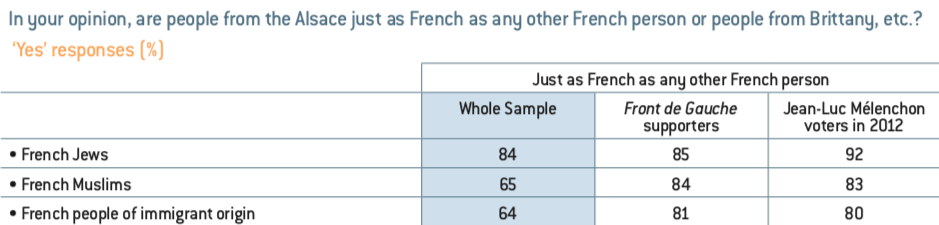

Moreover, most respondents (84%) believe that ‘French Jews’ are ‘just as French as any other French person’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

2. Tackling antisemitism and teaching about the holocaust are widely endorsed objectives

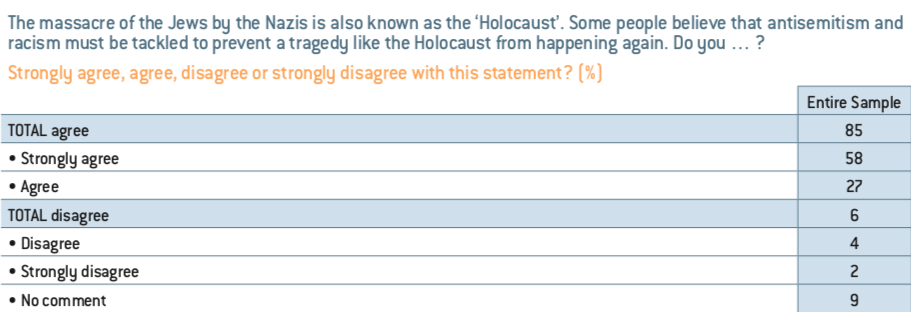

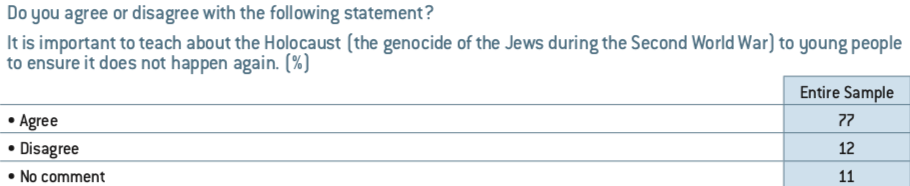

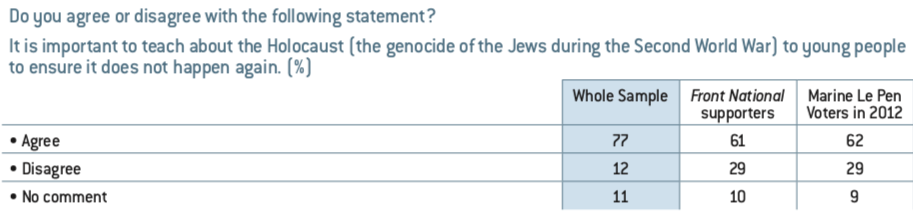

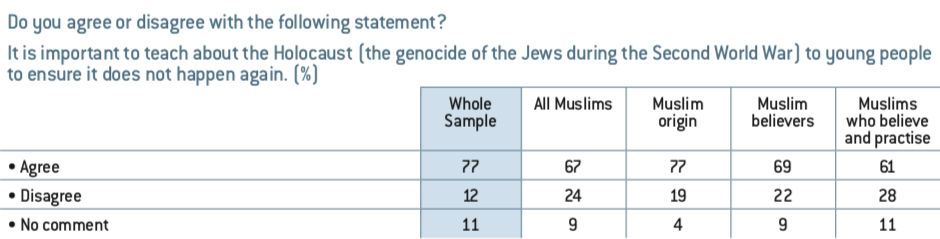

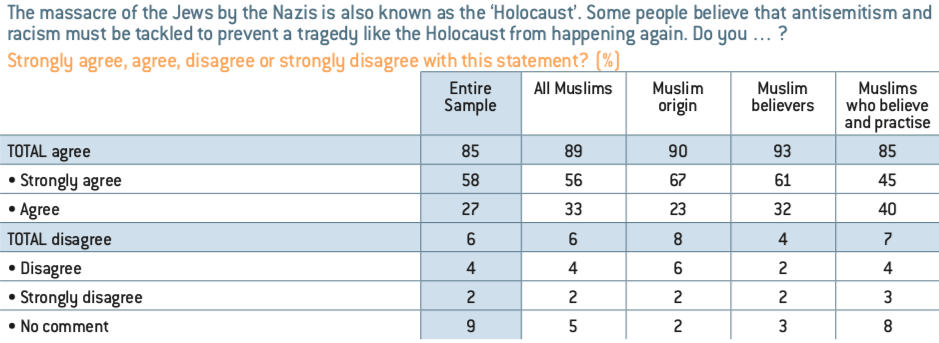

The study needs to be supplemented with questions relating to the fight against antisemitism and racism, portrayals of the past, and the role that history could play in citizenship education policies. However, it is nevertheless apparent that respondents overwhelming subscribe to the idea that teaching about the Holocaust should be incorporated into schemes aimed at tackling antisemitism and racism.

Source :

Source: Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Over a fifth of respondents (22%) state that their colleagues, friends or family ‘often or occasionally’ ‘criticize Jewish people’.

Source :

Over a fifth of respondents (22%) state that their colleagues, friends or family ‘often or occasionally’ ‘criticize Jewish people’.

While the questions relating to Zionism meant nothing to a large proportion of respondents (between 42% and 46%), they revealed robust criticism from a section of society towards Israel’s policies and also the strength of one of the most widespread antisemitic opinions: 25% of respondents believe that Zionism is ‘an international organisation seeking to influence the world and society in the interests of the Jews.’

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Moreover, the notion of electing a Jewish French president is rejected by a fifth (21%) of respondents. We note that ten years earlier, this proposition was rejected by fewer respondents (17%). We also note that 6% of respondents state that they would rather not have ‘a Jewish neighbour’. This demonstrates the difficulty of analysing the types of results we obtain from a survey on this issue – while in abstract terms, 6% is a low proportion of the population, in concrete terms, the desire to avoid having a ‘Jewish neighbour’ reflects a very high level of hostility. In this type of questionnaire, we must not only take account of percentages, but also the intensity of opinions.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

It is apparent that where the questions prompt respondents to talk about their perceptions not just of Jews in general but of Jews in reality, their responses show a reduction in antisemitic prejudice.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Moreover, most respondents (84%) believe that ‘French Jews’ are ‘just as French as any other French person’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The study needs to be supplemented with questions relating to the fight against antisemitism and racism, portrayals of the past, and the role that history could play in citizenship education policies. However, it is nevertheless apparent that respondents overwhelming subscribe to the idea that teaching about the Holocaust should be incorporated into schemes aimed at tackling antisemitism and racism.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The idea of teaching about the Holocaust to fight racism and antisemitism is very widely supported.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

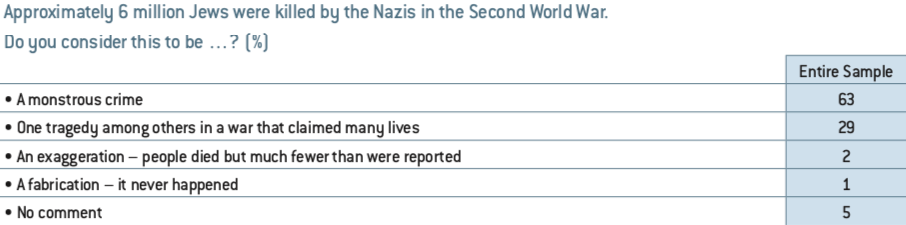

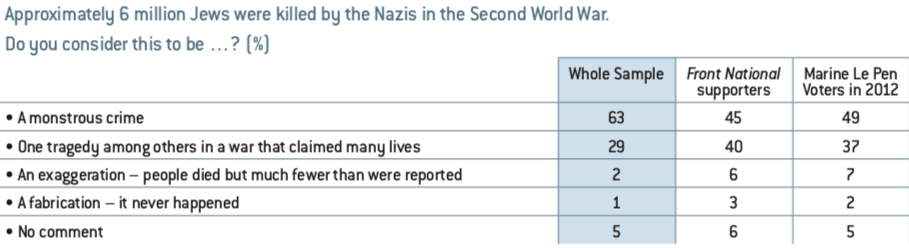

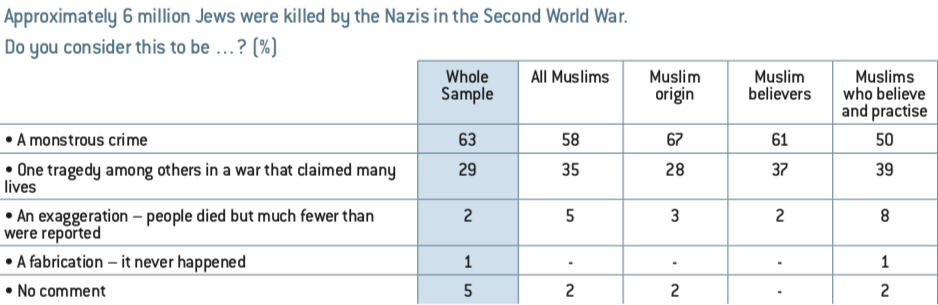

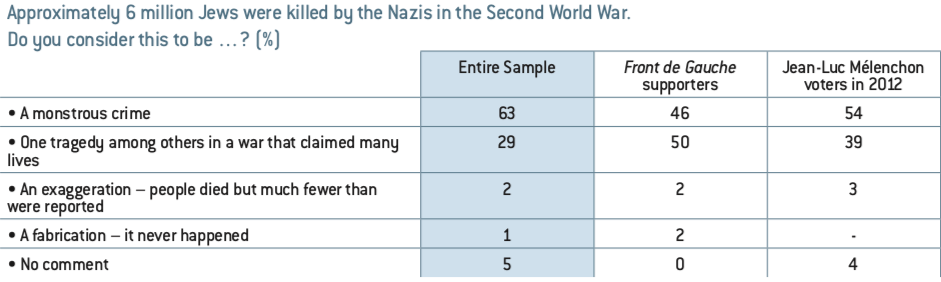

Moreover, the notion of Holocaust denial is non-existent in French public opinion.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

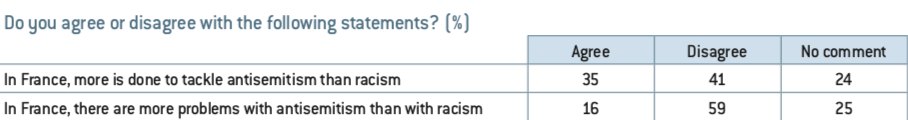

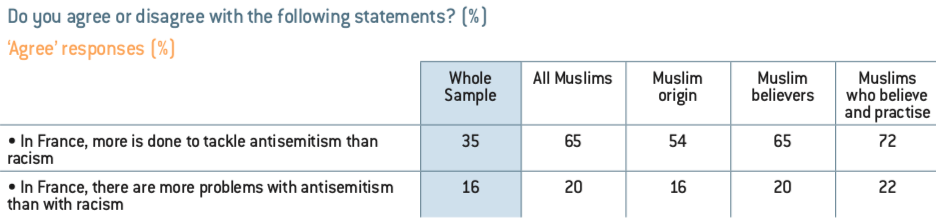

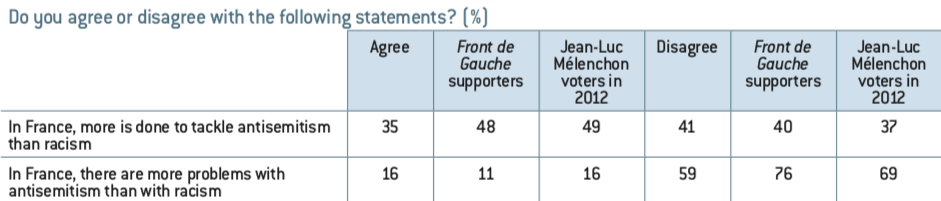

Of all the information provided by this survey, one of the most striking points is the fact that only 16% of respondents state that they agree with the statement that in France, ‘there are more problems with antisemitism than with racism’. In other words, 59% believe the contrary despite the unequivocal picture provided by data on antisemitic attacks. In France, antisemitic acts account for 50% of all racist acts although the Jewish community represents less than 1% of the national population. It should therefore be noted that from a public perspective, antisemitic attacks are not as resonant or memorable as we might expect given the nature and seriousness of these incidents.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Although the author should point out that he would have responded that he did not consider the pre-emptive ban of a show justified.

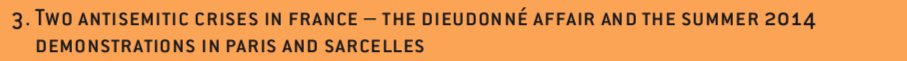

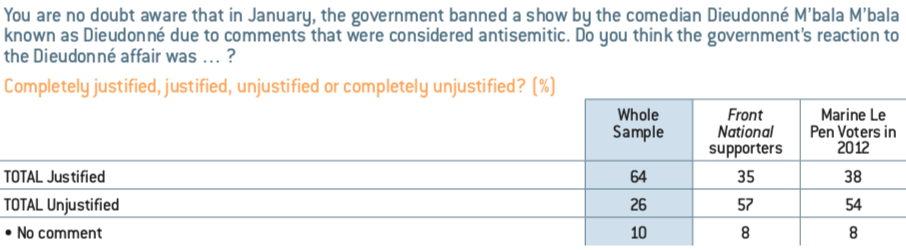

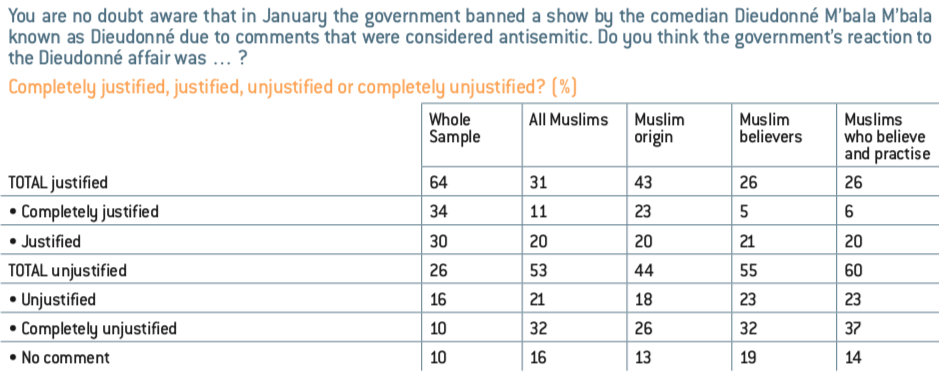

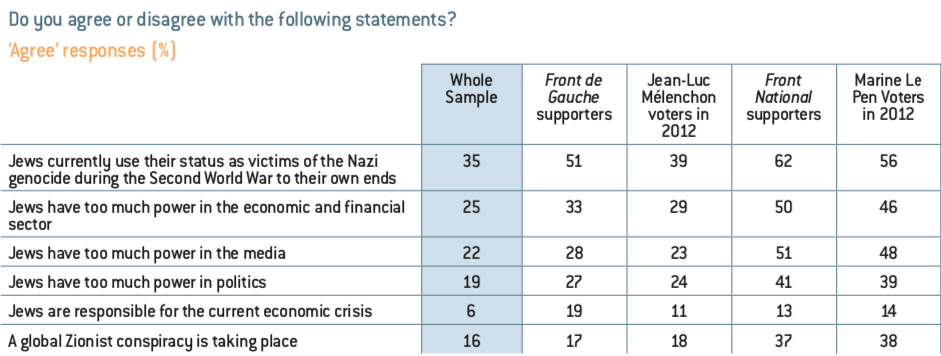

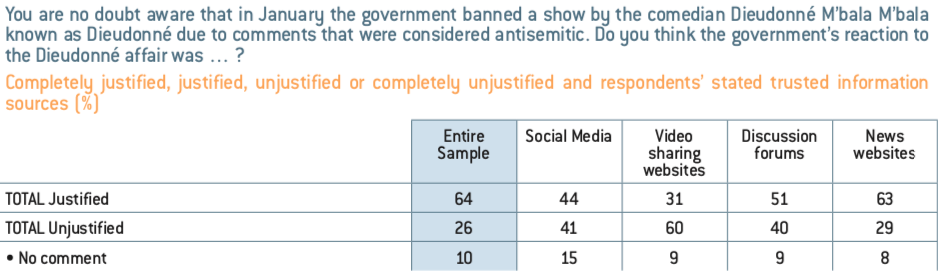

Between 2013 and 2014, two crises revealed that pockets of antisemitism exist in French public opinion. The decision to ban Dieudonné’s shows following the comedian’s repeated outrages and vile comments was considered ‘justified’ by 64% of respondents and ‘unjustified’ by a quarter of respondents (26%)1.

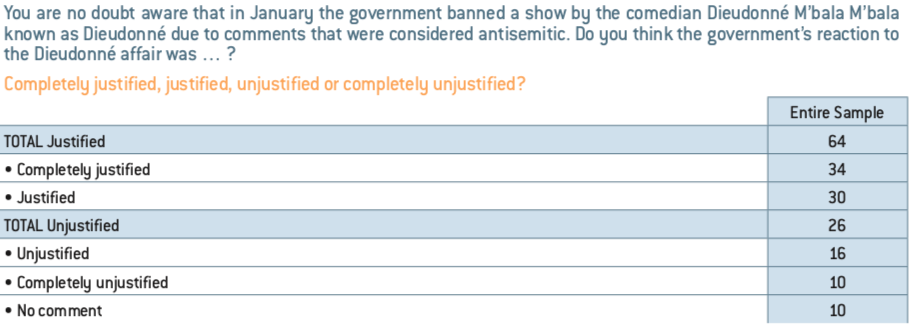

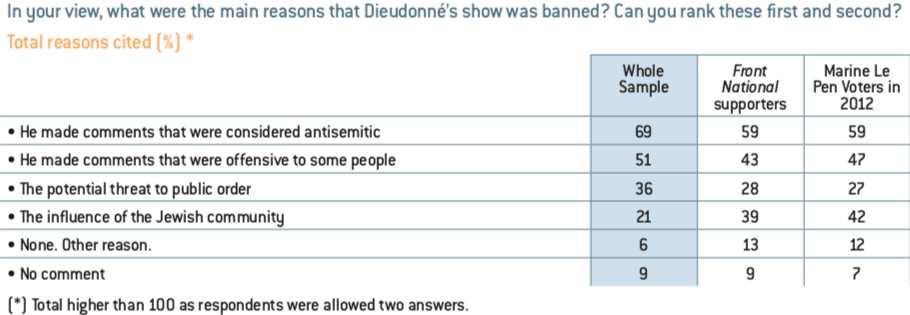

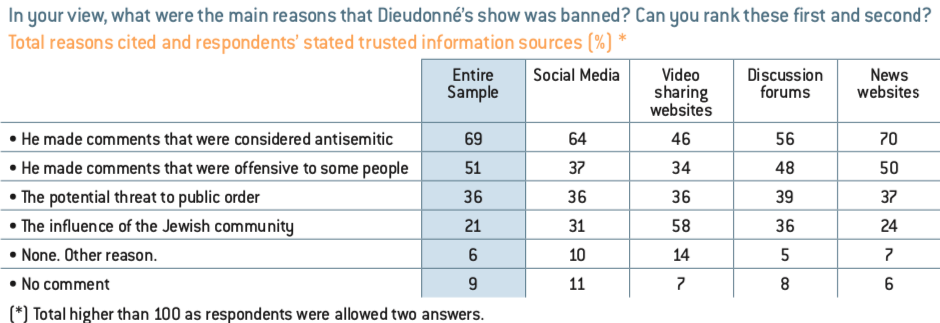

Although respondents were fully aware of the reasons why these shows were banned, a fifth (21%) still claim that they believe it was down to the ‘influence of the Jewish community’.

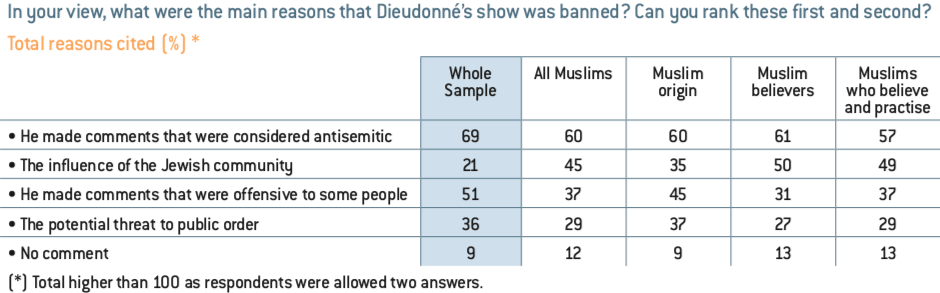

The table should be read as follows: 36% of respondents cited the potential threat to public order in first or second place as one of the main reasons Dieudonné’s show was banned.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

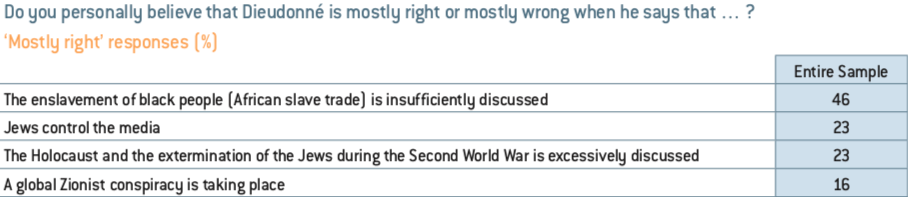

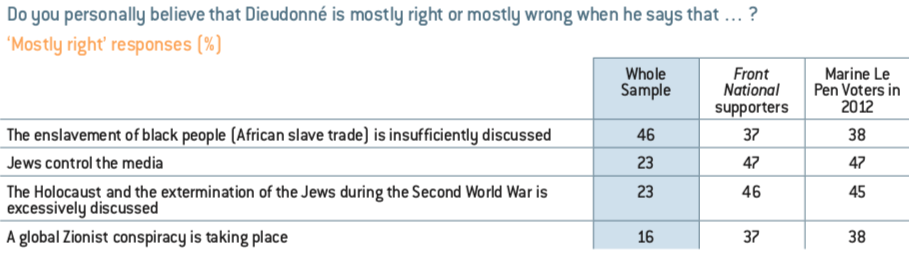

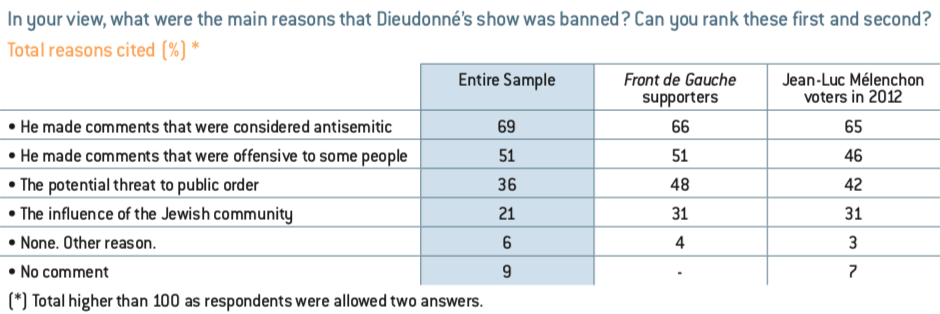

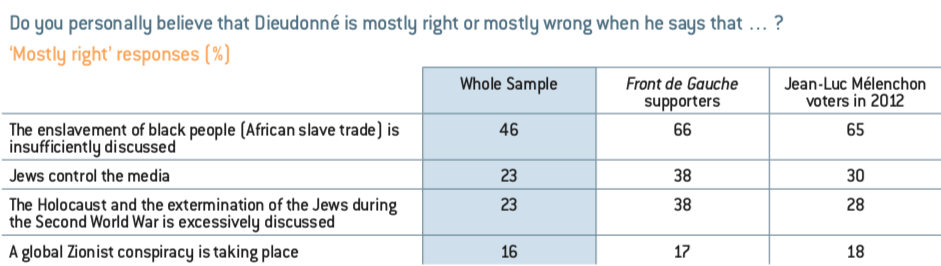

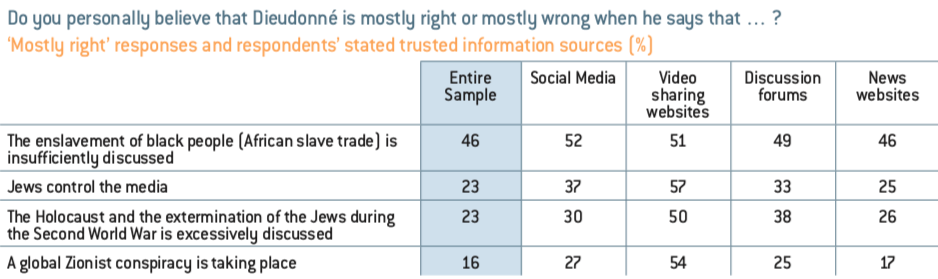

By asking the sample whether they approve or disapprove of the comments made by Dieudonné in his shows or online, we were able to ascertain the reality of antisemitic views, which, although in the minority, are shared by a significant proportion of respondents. For instance, 16% state that they share some of the opinions expressed by Dieudonné including: ‘A global Zionist conspiracy is taking place’ (16%).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

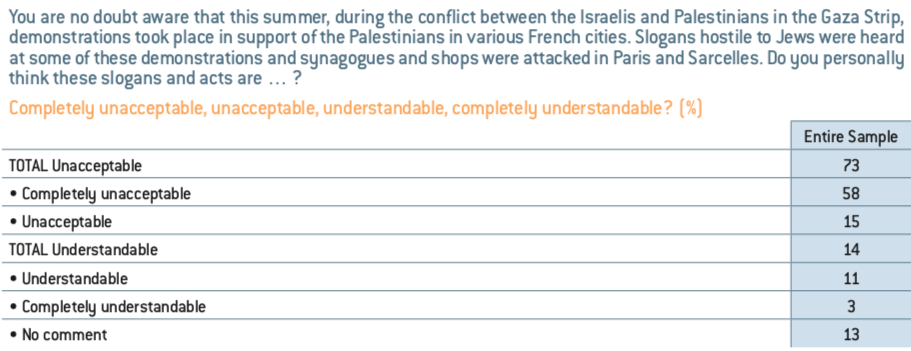

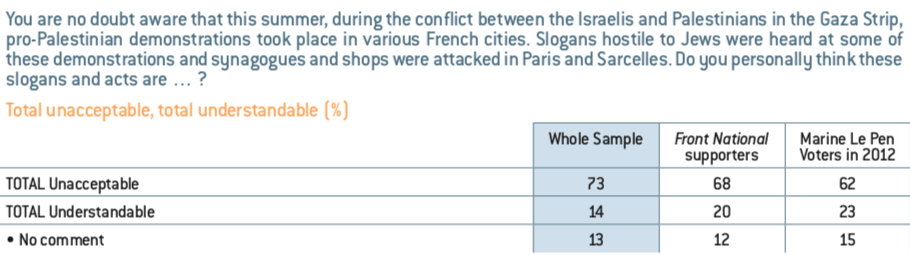

In the summer of 2014, during the military operation conducted by Israel in the Gaza Strip, over 400 demonstrations were organised in France as a sign of support for the Palestinians. In Paris and its suburbs, these gatherings gave rise to slogans hostile to Jews. This threatening language ultimately culminated in violence that was undisputedly antisemitic in nature. A very large proportion of respondents stated that such actions are ‘unacceptable’ (73%), a further sign of French society’s relatively sound principles.

It could be argued that the wording of the question, which offers a choice between ‘unacceptable’ and ‘understandable’ does not allow an accurate assessment to be made of public opinion on this issue. Indeed, it is possible to both ‘understand’, i.e. identify a system of causality, and consider ‘unacceptable’ the attack on a synagogue or the ransacking of shops on the grounds of them being owned by Jewish people, due to the policy pursued by Israel. However, if we look at responses given to the questionnaire by those who chose the ‘understandable’ option, there can be no further doubt that this option was favoured by respondents who are most inclined to express antisemitic views.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

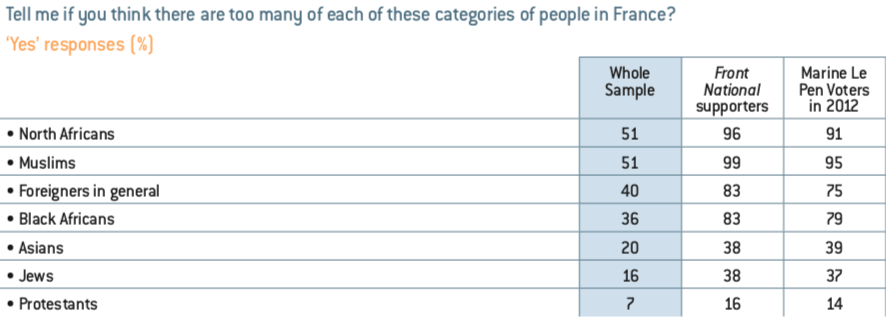

If the far-right Front National is not an antisemitic party, it is at very least a party of antisemites. According to our survey, of all the political parties and supporters who rally round these parties, supporters of the Front National and people who voted for Marine Le Pen in the 2012 French presidential election are the political and partisan group that express by far the most antisemitic and xenophobic views. FN supporters and voters reflect the views of the party’s founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen, more than the more controlled rhetoric that its new leader, Marine Le Pen, seeks to present.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

While a mean of 21% of respondents state that they would prefer not to have a Jewish French president, 53% of FN supporters and 49% of people who voted for Marine Le Pen in 2012 share this view. A very high proportion (22%) of FN supporters state that they would prefer not to have ‘a Jewish neighbour’, while the percentage of Marine Le Pen voters sharing this view is not much lower (18%).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

What is particularly striking is that FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters are even more divergent from other respondents on the issue of teaching about the Holocaust – twice as many of them than the mean state that they do not agree with ‘teaching about the Holocaust to young people to ensure it does not happen again’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters are by far the most likely to dispute the fact that the Holocaust is a special case. Once again, the comments made by its founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen, in 1988 left more than just memories, and have indeed provided the equivalent of a doctrine open to Holocaust denial.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

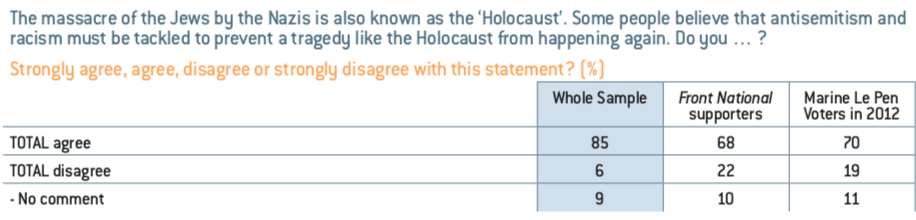

Three times more FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters than the mean disagreed with the idea that it is necessary to tackle racism and antisemitism to ‘prevent the Holocaust from happening again’.

Among them, more than the mean believe that the slogans and acts seen during the crisis of summer 2014 are ‘understandable’. In light of their responses to other questions, this ‘understanding’ can under no circumstances be viewed as ‘sociological understanding’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Of all the respondent categories, the Front National supporters (39%) and Marine Le Pen voters (37%) most frequently stated that ‘French Jews are not just as French as any other French person’ versus a mean of 16%. Three- quarters of Front National supporters (77%) and Marine Le Pen voters (70%) took the view that ‘French Muslims are not just as French as any other French person versus a mean of 35%. Moreover, 75% of Front National supporters and 71% of Marine Le Pen voters believe that ‘French people of immigrant origin are not just as French as any other French person’, versus a mean of 36%.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

While a mean of 26% of respondents believe that the ban on Dieudonné’s show was ‘unjustified’, this rises to 57% among FN supporters and 54% among Marine Le Pen voters. Here again, it is unlikely that this can be explained by their liberal attitudes.

39% of the FN supporters and 42% of respondents who stated that they voted for Marine Le Pen in 2012 ascribe the ban on Dieudonné shows to the ‘influence of the Jewish community’.

The table should be read as follows: 69% of respondents cited ‘he made comments that were considered antisemitic’ in first or second place as one of the main reasons Dieudonné’s show was banned. 59% of the Front National supporting respondents gave the same response.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

More FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters also believe Dieudonné was right to express antisemitic prejudice. However, their level of approval for the opinion that ‘the enslavement of black people (African slave trade) is insufficiently discussed’ is lower, this time, than the mean score.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters generally express a level of xenophobia towards North Africans, black Africans, Muslims and ‘foreigners in general’ that is impossible to overlook. It is apparent from these findings that the Front National in 2014 is still the same party founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen in 1972 and whose leadership passed to his daughter Marine Le Pen in 2011. Marine Le Pen is in fact not the leader of her own party but that of Jean-Marie Le Pen.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

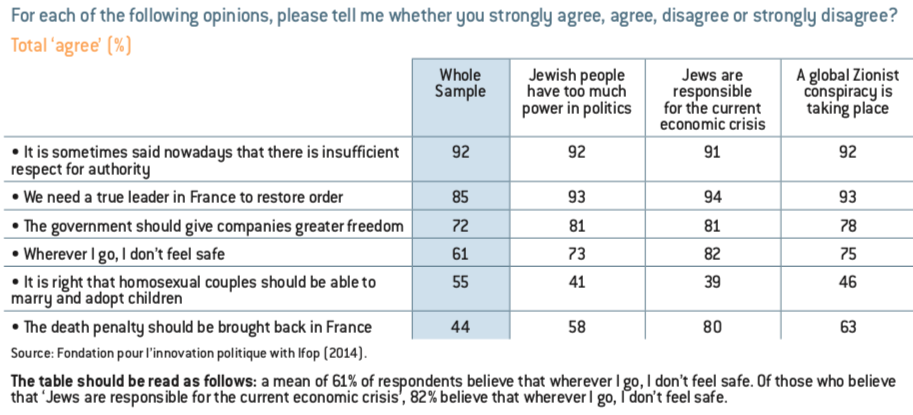

It should be noted that the list of FN priorities includes greater freedom from government for companies. This combination of political authoritarianism, xenophobia and economic liberalism fits perfectly with the Front National agenda and, once again, not that of the party currently led by Marine Le Pen, but the one founded and led by Jean- Marie Le Pen for such a long time that it has remained true to his vision.

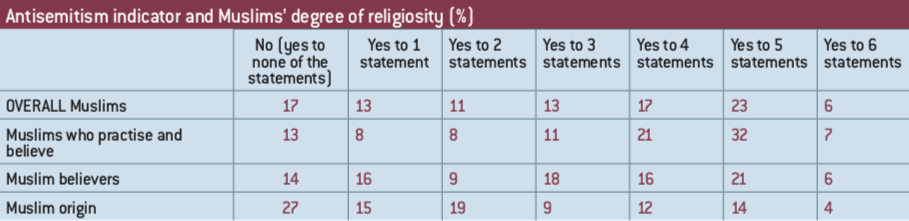

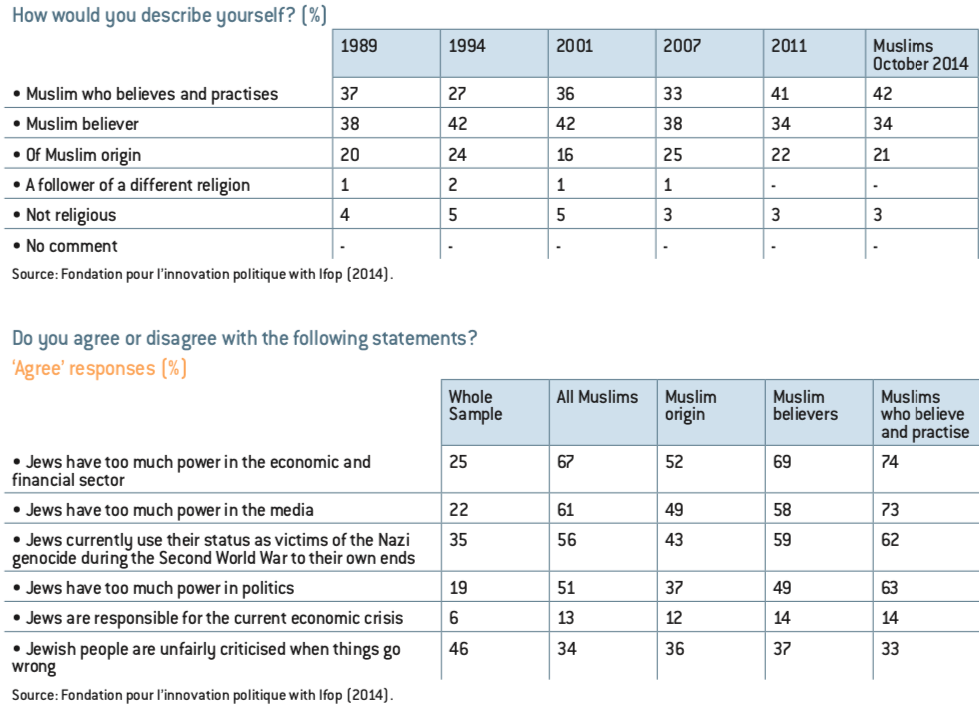

Two to three times more Muslim respondents than the mean exhibit prejudices towards Jews. This proportion rises as respondents’ stated commitment to their religion increases. Thus, while 19% of all respondents state that they endorse the idea that ‘Jews have too much power in politics’, this figure rises to 51% for the Muslim group as a whole. This question demonstrates the effects of respondents’ degree of religiosity on their support for antisemitic statements – indeed support for the above statement is 37% among people who state that they are of ‘Muslim origin’, 49% among ‘Muslim believers’, and 63% among ‘Muslims who believe and practise’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The Dieudonné affair highlights the genuine existence of a major division between Muslims and the rest of society. This is reflected among other things by the fact that the majority of Muslim respondents (53%) consider the ban on the show to be ‘unjustified’ compared to a quarter (26%) of the total sample aged 16 and above.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Moreover, almost half of Muslim respondents (45%) believe that ‘the influence of the Jewish community’ is the main cause of the ban, which is double the mean score (21%).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

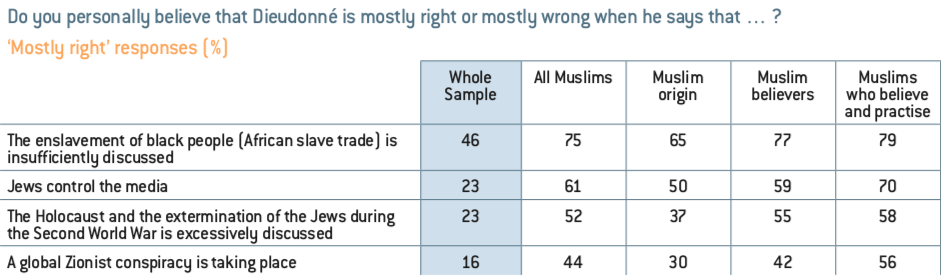

The proportion of Muslims who state that they share Dieudonné’s views is considerably higher than the mean. This declared support may lead some respondents to express the most characteristic forms of prejudice. For instance, the idea that Zionism ‘is an international organisation seeking to influence the world’, which is so typical of the antisemitic mindset, is endorsed by high numbers of Muslim respondents (44%) compared to a mean of 16% for the group aged 16 and above. Here again, the percentage rises in step with respondents’ level of religious involvement. The existence of a Zionist conspiracy is given credence by 30% of those who describe themselves as being ‘of Muslim origin’, 42% of ‘Muslim believers’ and 56% of ‘Muslims who believe and practise’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

By testing respondents’ approval or rejection of opinions attributed to Dieudonné, we discover that the hypothesis of support for the view that a conspiracy is taking place, one of the chief components of the antisemitic mindset, is corroborated. Over half of Muslim respondents (57%) believe that Dieudonné is ‘mostly right’ when he says that Zionism ‘is an international organisation seeking to influence the world and society in the interests of the Jews’. This proportion rises to 64% among Muslims who believe and practise.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

A third of Muslim respondents (33%) state that they would prefer not to have a ‘Jewish French president’. We have already seen that the level of rejection for this proposition is considerably higher among FN supporters (53%) and Marine Le Pen voters (49%).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

A certain degree of dissatisfaction is reflected in the fact that twice as many Muslim respondents than the mean believe that more is done in France to tackle antisemitism than racism.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Respondents’ attitudes to past tragedies (in this case the Holocaust) prompt very different responses to those provided thus far. It could even be said that these responses are unexpected given the findings reported above. Indeed, most Muslim respondents approve of the idea that it is important to teach young people about the Holocaust in order to prevent it from happening again.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The view of the Holocaust as an exaggeration or fabrication does not resonate among Muslim respondents. This study suggests that the notion of Holocaust denial is expressed to no greater extent in Muslim opinion than in national opinion in general.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Contrary to these findings, more Muslims (34%) than the mean (22%) respond that their colleagues, friends or family ‘often’ or ‘occasionally’ criticise Jewish people.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

85% also state that they do not react ‘in any particular way’ when they find out that someone they know is Jewish.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

In terms of respondent groups, considerably higher numbers of Muslims than FN supporters and Marine Le Pen voters view ‘French Jews’ as ‘just as French as any other French person’.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Based on all the data collected, it is nevertheless apparent that only 17% of Muslim respondents share none of the prejudices towards Jewish people versus 53% for all respondents.

The notion that it is necessary to tackle antisemitism and racism to prevent a tragedy like the Holocaust from happening again is however more widely endorsed among Muslim respondents (89%) than the entire sample (85%).

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

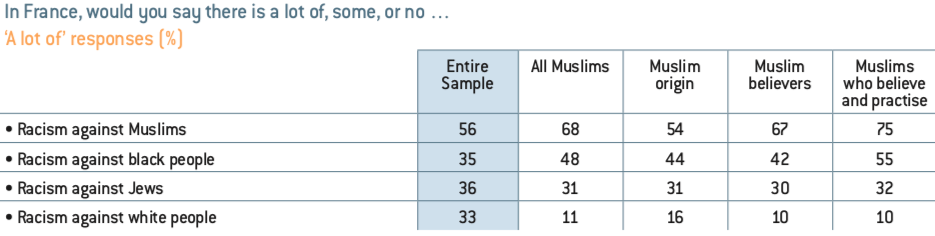

Muslims’ perceptions of racism are affected by their feeling that they are victims of it. Accordingly, two-thirds (68%) of Muslim respondents believe that ‘racism against Muslims’ exists in France and a third (31%) believe that ‘racism against Jews’ exists.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Translator’s Note: The Front de Gauche or ‘Left Front’ is a left-wing political movement formed in 2009. Jean-Luc Mélenchon was its candidate in the 2012 presidential election.

On the political right, respondents describing themselves as FN supporters give almost the same responses as respondents who stated that they voted for Marine Le Pen in the 2012 French presidential election. It could even be said that consistency between these two groups is striking. In contrast, on the political left, the opinions of respondents describing themselves as supporters of the Front de Gauche2 differ from those of respondents who stated that they voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in 2012. In both groups, negative views of Jewish people are more widespread than in society as a whole. However, these views are significantly more prevalent among Front de Gauche supporters than Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters, thus widening the gap with the national mean.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Anti-Jewish prejudice is more widespread within the Front de Gauche movement than in French society as a whole. It is nevertheless less prevalent than in the Front National party.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Anti-Jewish prejudice is more widespread within the Front de Gauche movement than in French society as a whole. It is nevertheless less prevalent than in the Front National party.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The Dieudonné affair reveals hostility towards Jews among Front de Gauche supporters and those who voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Higher numbers in this category of respondents (31%) than in the whole sample (21%) view the Jewish community as one of the main causes of the ban on the shows in question.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Generally speaking, it is evident that the proportions of Front de Gauche supporters and Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters who approve of the opinions expressed by Dieudonné that we tested are significantly higher than the overall mean.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Finally, it should be noted that almost half of Front de Gauche supporters (48%) and Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters (49%) believe that more is done in France to tackle antisemitism than racism.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Despite this, 87% of respondents describing themselves as Front de Gauche supporters and 84% of those who state that they voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in 2012 believe that it is important to teach about the Holocaust (versus an overall mean score of 77%).

Responses to questions regarding Zionism reflect the stance taken by the Front de Gauche on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. On this issue, Front de Gauche supporters diverge more from the national mean than Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters. This can probably be explained by the fact that the category of ‘Front de Gauche supporters’ also includes respondents who consider themselves to be supporters of the French Communist Party or small far-left parties (Lutte Ouvrière, Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste, etc.), which were not provided as options due to their limited influence in French society and among the electorate in particular, hence their very poor results in the 2012 presidential election.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

A second major difference between respondents who support the Front de Gauche or those who voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in 2012 on one hand, and respondents who support the Front National or those who voted for Marine Le Pen in 2012, is the fact that the former group do not consider individuals to be more or less French based on their origins or religion. This reflects the ideology espoused by the Front de Gauche and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, which is deeply rooted in republican ideology. It is also perhaps symptomatic of their pro-Third World legacy, which is further evidence that the Front National and Marine Le Pen voters constitute a special case.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Front de Gauche supporters and even Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters are more likely than the average respondent to dispute the fact that the Holocaust is a special case. Unlike Front National supporters, they do not doubt that the Holocaust genuinely occurred and therefore cannot be described as Holocaust deniers. However, more respondents in this category view it in the same terms as other World War II tragedies, thus detracting from its special status. Most Front de Gauche supporters and Jean-Luc Mélenchon voters do not endorse the view that the Holocaust is a special case.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Political organisations and elected officials are not alone in suffering the effects of a crisis of confidence in representative institutions. The traditional media is also met with distrust. At the same time, the emergence and subsequent establishment of universally accessible digital media have given rise to a sort of parallel media environment infused with an underground protestor culture easily given to conspiracy theories regarding past and current events.

The table should be read as follows: a mean of 22% respondents believe that Jews have too much power in the media. Of those who trust social media as a source of information, 37% believe that Jews have too much power in the media.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Our study suggests that views expressed by news website users are comparable to those of individuals who use traditional media (press, radio and television). As such, news websites are no more associated with the generation and dissemination of antisemitic messages and opinions than traditional media.

In contrast, the trio of social media, discussion forums and video sharing forums constitute a media environment that is particularly conducive to the emergence and spread of antisemitic opinions.

A comparative analysis of views on the Dieudonné affair shows that the sample as a whole is much less inclined to express antisemitic prejudice than individuals using social media, discussion forums and video sharing websites. Consequently, while a mean of 25% of respondents believe that the ban on Dieudonné shows was ‘unjustified’, this proportion exceeds 40% among social media and discussion forum users, and reaches 60% among video sharing website users.

The table should be read as follows: a mean of 64% of respondents believe that the government’s reaction to the Dieudonné affair was justified. Of those who trust news websites as a source of information, 63% believe that the government’s reaction to the Dieudonné affair was justified

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Moreover, while 21% of respondents aged 16 and above believe that ‘the influence of the Jewish community’ was behind the decision to ban these shows, this proportion rises to 58% among users of video sharing websites.

The table should be read as follows: a mean of 36% of respondents cited the potential threat to public order in first or second place as one of the main reasons Dieudonné’s show was banned. Of those who trust discussion forums as a source of information, 39% cite this potential threat in first or second place.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

Users of video sharing websites are more likely than any other category to personally endorse Dieudonné’s comments. A majority of these respondents believe that he is right to state that ‘Jews control the media’ (57%) or that ‘a global Zionist conspiracy is taking place’ (54%).

The table should be read as follows: a mean of 23% of respondents believe that Dieudonné is mostly right when he says that Jews control the media. Of those who trust video sharing websites as a source of information, 57% believe that Dieudonné is mostly right when he says that Jews control the media.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique with Ifop (2014).

The findings of our survey suggest that although age, qualifications and income are possible factors in individuals’ expression or approval of antisemitic views, these opinions are much more consistently linked to a set of interconnected perceptions and political views. Indeed, antisemitism is largely associated with a section of society in which distrust and rejection are widespread and which is dominated by an authoritarian culture hostile to immigrants and the world (except in the case of Muslim respondents) as well as to diversity in all its forms.