Are Europeans abandoned to populism?

A survey by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique across the 27 European Union countries and the United KingdomMethodology

Introduction

In 2024, support for the European Union is massive (87%)

Europeans approve of their country’s EU membership1

Rather than fuelling nationalism, the emergence of threats serves to reinforce the European idea

Europeans in search of public leadership

What can States do for their people?

Security stands out as the foremost demand

Europeans Seek Protection for Common Borders (86%)

Taking back democratic control of the public sphere

Reasonable voters left vulnerable to demagogues

What does it mean to be European?

Democracy embodies freedom

What else distinguishes populist voters?

Conclusion

Summary

Despite having been shaken by the rise of a protest vote that mainly benefited right-wing populist parties, and destabilized by institutional crises, in particular the failure of the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005, the European Union has stood firm. It has even demonstrated its ability to withstand, if not always overcome, unprecedented and particularly violent crises which, perhaps, would have destroyed it a quarter of a century earlier: financial, budgetary, institutional, migratory, political, health and geopolitical crises… The European elections of 2024 are marked by a threatening context, heightened by the prospect of a new surge in populist parties, mainly those on the right, parties that have historically been formed to express radical hostility to the European Union.

The data presented here does not contradict, but rather clarifies the hypothesis of a “populist” surge. By “populist” surge, we refer to an increase in electoral groups aiming to dismantle the European Union or even challenge the democratic structure defining the internal politics of each member state.

However, the latest study from the Fondation pour l’innovation politique suggests that during the European elections, the majority of the 360 million voters are unequivocally dedicated to both democratic principles and the European idea, possibly more so than ever before. This dual popular conviction is especially noteworthy given that it spans across a geographically extensive Europe that has achieved the highest level of state integration to date.

In 2024, the European idea, the principles it is founded upon, and the institutions that emanate from it enjoy strong support from most Europeans. Therefore, the question arises as to what the meaning of populist votes might be. It appears that many populist leaders and their adversaries lack a clear grasp of political realities, as they are ensnared in the same misinterpretation of populist voting. They mistake expressions of protest or grievances for a commitment to a radical split and conflate the voters with the leaders and representatives of populist parties.

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

Fondation pour l'innovation politique,

A French think tank for European integration and the free economy.

Victory for populism in the Netherlands: a national phenomenon or a European pattern?

The FPÖ and the challenge of Europe: Ideological radicalism and electoral constraints in Austria

Fratelli d'Italia : neo-fascist heritage, populism and conservatism

The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW)

Europe and our sovereignty

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

Dominique REYNIÉ,

Executive Director of the Fondation pour l'innovation politique

Nicola GADDONI

Diane de CHARRY, Clément DE CARO, Anne FLAMBERT, Éric GARCIA, Alice LE FAUCHEUR, Jean MICHEL, Claire-Marie MORINIÈRE, Enzo MUS, Claude SADAJ

Julien RÉMY

Julien RÉMY

GALAXY Imprimeurs

2024

Brice TEINTURIER,

Deputy Managing Director France

Federico VACAS, Deputy Director

Xavier BALEYTE, Data Processing Manager

Pierre LATRILLE, Senior Researcher

Alexandre LERAY, Senior Research Officer

Felix TENTILLIER, Research Officer

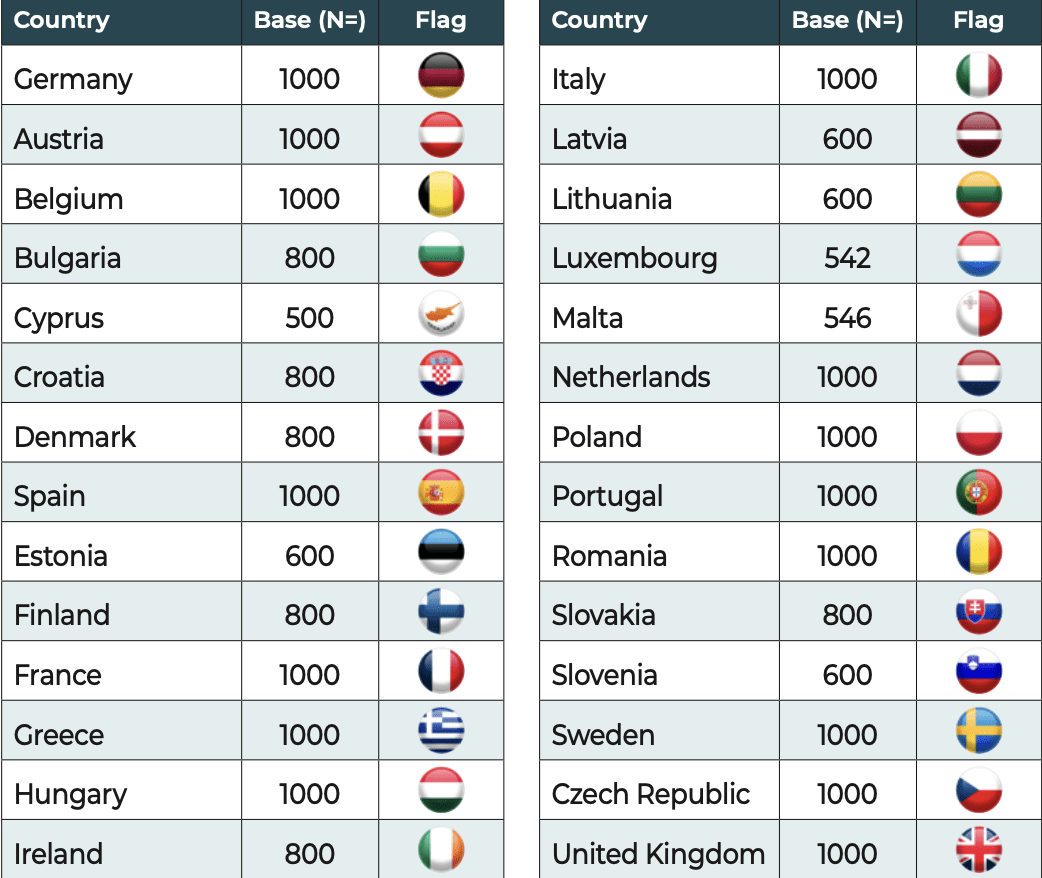

This survey is based on a questionnaire drawn up by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. It was carried out by Ipsos in all 27 EU member states and the UK, between March 22 and April 26 2024, among representative samples of the population aged 18 and over in each country. A total of 23,788 people were questioned. The survey was administered in 24 languages.

The survey was conducted online through the Ipsos Access Panel, with telephone interviews (in Cyprus and Malta). To ensure overall representativeness, the sample was selected using the quota method based on gender, age, profession, urban area, and region of residence. The final results were weighted according to the demographic proportion of each country.

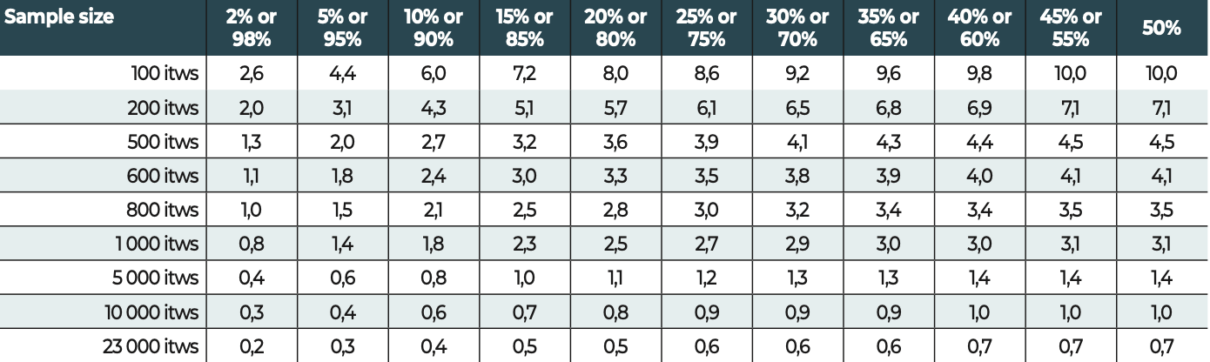

What is a confidence interval?

The confidence interval (also known as the margin of error) is the interval within which the desired value lies with a fixed probability (the confidence level). The amplitude of this interval depends on the confidence level, the observed value and the sample size. The calculation is only justified for random surveys. It cannot be determined in the case of quota surveys, but is considered to be close to that of random surveys.

Confidence interval (95% confidence level)

Observed results

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: In a sample of 1,000 respondents, if the measured proportion is 25%, there is a 95% probability that the actual proportion in the total population falls within the range of 22.3% to 27.7% (plus or minus 2.7 percentage points).

In this study, we compare the results from each of the 28 surveyed countries with the European average, the average of the six founding countries of the European Union, the average of the former Eastern bloc countries, and the average of the European countries that are NATO members.

The six founding countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) signed the Treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951 and the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, considered the foundational acts of the European Union. These countries have the most advanced integration processes within the EU. Analyzing public opinion in these nations provides valuable insights into the strength and durability of the European integration project. Additionally, these countries elect 43% of the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) in the 2024 European elections, giving them significant political weight in the European Parliament. Last but not least, as the largest economies in the European Union, they have a substantial influence on the Union’s economic policies.

The countries that formerly belonged to the Eastern bloc (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia) joined the European Union in 2004 and 2007. These countries, having experienced communist rule, may view European integration as a way to strengthen democracy, the rule of law, and human rights. Additionally, their recent history under Moscow’s control could influence their opinions on European security and foreign policy, especially in light of high tensions with Russia following the invasion of Ukraine.

Croatia and Slovenia have not been included in this subset. Although they were Yugoslav socialist republics, these two countries are not traditionally included in what is known as the former Eastern bloc, due to Yugoslavia’s non-alignment. This nuance is particularly important, as the history of their relationship with Russia differs from that of the countries mentioned above.

Despite having been shaken by the rise of a protest vote that mainly benefited right-wing populist parties, and destabilized by institutional crises, in particular the failure of the European Constitutional Treaty in 2005, the European Union has stood firm. It has even demonstrated its ability to withstand, if not always overcome, unprecedented and particularly violent crises which, perhaps, would have destroyed it a quarter of a century earlier: financial, budgetary, institutional, migratory, political, health and geopolitical crises… The European elections of 2024 are marked by a threatening context, heightened by the prospect of a new surge in populist parties, mainly those on the right, parties that have historically been formed to express radical hostility to the European Union.

The data presented here does not contradict, but rather clarifies the hypothesis of a “populist” surge. By “populist” surge, we refer to an increase in electoral groups aiming to dismantle the European Union or even challenge the democratic structure defining the internal politics of each member state.

However, the latest study from the Foundation for Political Innovation suggests that during the European elections, the majority of the 360 million voters are unequivocally dedicated to both democratic principles and the European idea, possibly more so than ever before. This dual popular conviction is especially noteworthy given that it spans across a geographically extensive Europe that has achieved the highest level of state integration to date.

In 2024, the European idea, the principles it is founded upon, and the institutions that emanate from it enjoy strong support from most Europeans. Therefore, the question arises as to what the meaning of populist votes might be. It appears that many populist leaders and their adversaries lack a clear grasp of political realities, as they are ensnared in the same misinterpretation of populist voting. They mistake expressions of protest or grievances for a commitment to a radical split and conflate the voters with the leaders and representatives of populist parties.In 2024, the European idea, the principles it is founded upon, and the institutions that emanate from it enjoy strong support from most Europeans. Therefore, the question arises as to what the meaning of populist votes might be. It appears that many populist leaders and their adversaries lack a clear grasp of political realities, as they are ensnared in the same misinterpretation of populist voting. They mistake expressions of protest or grievances for a commitment to a radical split and conflate the voters with the leaders and representatives of populist parties.

In 2024, support for the European Union is massive (87%)

Almost all voters feel part of the European Union. They clearly approve and support it. The first obvious paradox is the expansion of the populist vote among Europeans who are increasingly convinced by the European Union.

Europeans approve of their country’s EU membership1

In the remainder of the paper, we’ll use ″European Union″, ″Union″ and ″Europe″ as equivalents to reduce repetition and make the text more readable.

Cf. Dominique Reynié (ed.), Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

Despite recurrent challenges in recent years and the rise of a populist vote and rhetoric that is often more “anti-european” than eurosceptic, the European Union and, even more so, the euro, are widely supported by Europeans.

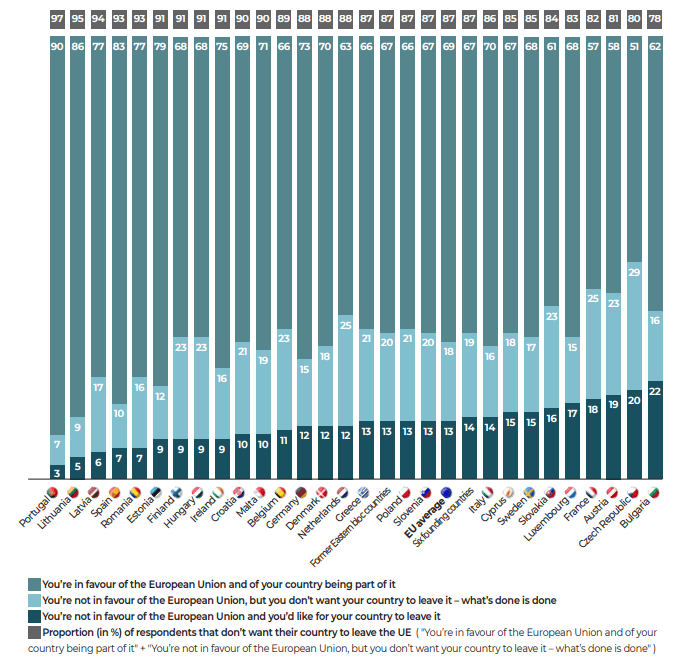

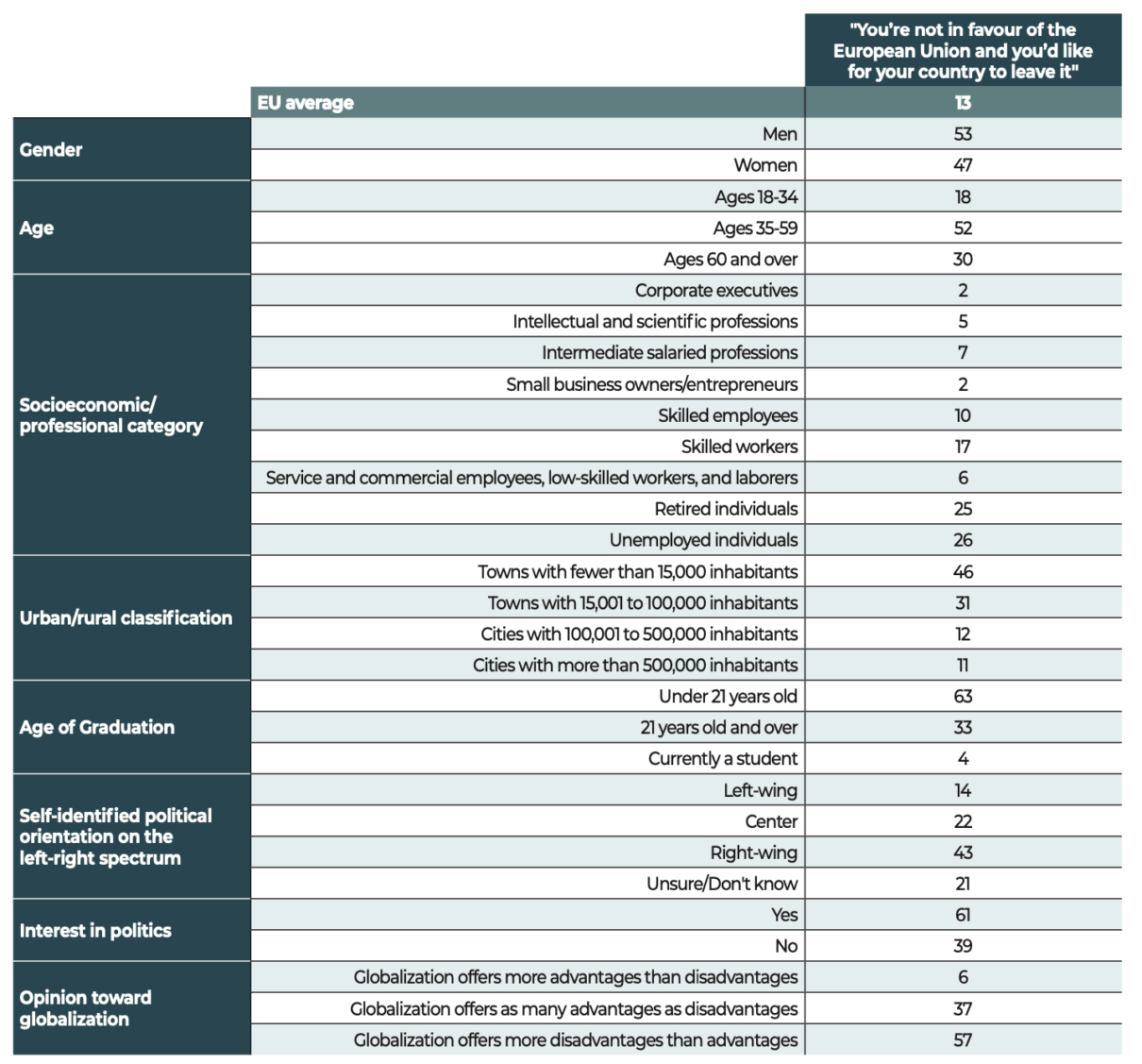

a. The desire to leave the European Union has become marginal (13%)

In 2024, more than two-thirds of Europeans (69%) support their country’s membership of the European Union; a fifth (18%), however, are not in favor but do not want to leave, on the grounds that “what’s done is done”. Ultimately, only 13% of Europeans would like to see their country leave the European Union. Support for the Union in principle is accompanied by strong backing for the institutions that represent it and act on its behalf: the euro, the Commission and the Parliament. This data highlights the weak influence of what we’ll call the “Exiters”, those voters who want to see their country leave the European Union, and who represent only a minority, if not marginal, group. The countries with the highest number of Exiters are Bulgaria (22%), the Czech Republic (20%), Austria (19%), France (18%), Luxembourg (17%), Slovakia (16%), Sweden (15%) and Cyprus (15%).

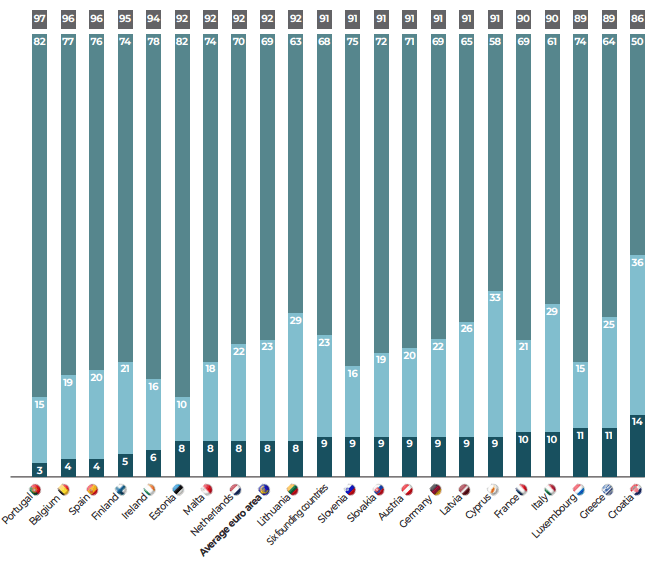

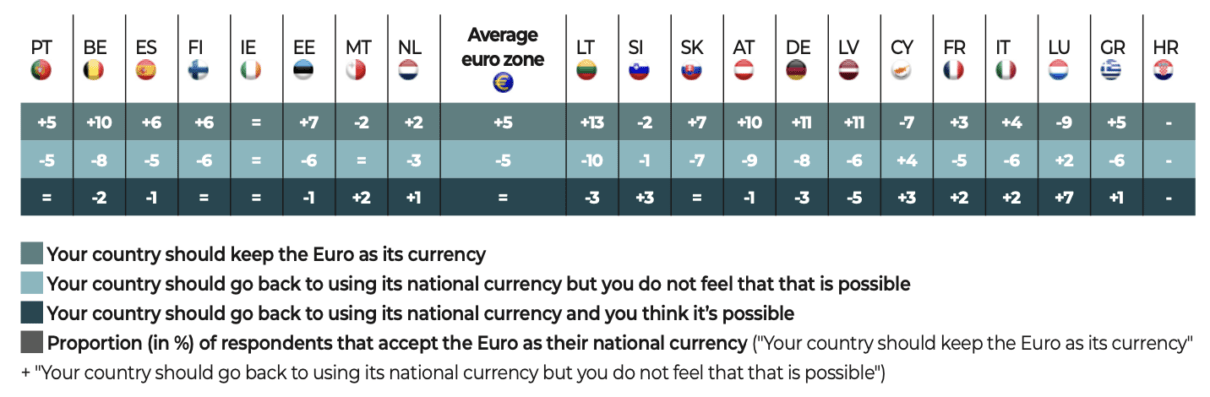

b. Support for the Euro: 92% of respondents say they accept the European currency

Within the euro zone, support for the currency is largely dominant, with more than two-thirds (69%) of respondents wishing to keep the euro; a further 23% say they would like their country to return to the national currency, but think this is not possible; thus, in total, 92% of respondents in the euro zone say they accept the European currency. Compared to the results of the survey Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century2, carried out in the summer of 2021, support for the euro is up by 5 points on average, although by 13 points in Lithuania (63%), 11 points in Latvia (65%) and 11 points in Germany (69%). The lowest level of support is found in Croatia (50% of respondents want to keep the euro). This is the last country to join the euro zone in January 2023, and it’s safe to assume that people are still adjusting to the single currency.

However, support for the euro is affected by the respondents’ financial situation: 54% of those experiencing financial difficulties support the euro, while among those who say they can get by easily on their income, the figure stands at 81%. A second significant divide concerns globalization. Almost all (98%) of those with a positive perception of globalization, those who believe it offers more advantages than disadvantages, want to keep the euro as their currency; but this support remains overwhelming (85%) among respondents with a negative perception of globalization, those who believe it offers more disadvantages than advantages. Clearly, these figures mean that those who have a negative opinion of globalization and at the same time want to return to the national currency represent only 15%.

European support for the Union

Question: ″Concerning the European Union, which of the following opinions do you most agree with?″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Unanimous support for the euro

Question: ″Regarding the Euro, which of the following opinions do you agree with most?″

Base: Euro zone

2021/2024 evolution

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: The figures in the table indicate the change in percentage points compared with the results of the survey .) Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century, Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

Cf. Freedoms at Risk, the Challenge of the Century, op.cit. pp. 49-50 [fondapol.org]; Katherine Hamilton and Dominique Reynié: “Support for the Euro Protects Europe”, Democracies under Tension, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, 2019, pp. 114 ff [fondapol.org]; Dominique Reynié (dir.), Où va la démocratie? An international survey by the Foundation for Political Innovation, Plon, 2017, pp. 265-267.

This emphasizes the significance of the heritage issue. Populist parties are unique in addressing both dimensions of heritage: tangible heritage, which pertains to overall living standards, and intangible heritage, which encompasses lifestyle. This gives rise to a form of heritage populism, with Fratelli d’Italia currently presenting the most organized manifestation of this phenomenon. For further insights, see Dominique Reynié’s works “Populismes, la pente fatale” (2011) and “Les nouveaux populismes”(2013), particularly.

Cf. Patrick Moreau, L’AfD, l’extrême droite allemande dans l’impasse, Paris, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, June 2024 [fondapol.org].

Cf. Christophe de Voogd, Victory for populism in the Netherlands: a national phenomenon or a European pattern?, Paris, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, April 2024 [fondapol.org].

In the past, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique has conducted a number of opinion polls in all EU member states. Each survey has shown more forcefully that hostility to the euro is perceived by voters as a threat to their personal and material interests3. Although anti-European rhetoric may have resonated positively due to its broad, anti-establishment nature, presenting as a rhetorical form of protest without consequences, anti-euro rhetoric is perceived as a direct threat to voters’ economic well-being4. Populists who staunchly oppose the euro, or express doubts about it, face the possibility of stagnation or even a decline in their electoral influence. This is the predicament faced by the AfD in Germany amid renewed discussions of “Dexit” – Germany’s potential withdrawal from the European Union and a return to the Deutsche Mark in 2023-2024.5. We saw a similar scenario unfold in the Netherlands during the parliamentary elections on November 22, 2023. Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV) emerged as the clear victor, securing a historic 25% of the votes cast. However, despite this success, the PVV was excluded from forming a government coalition, largely due to the party’s proposal for a “Netxit” – the Netherlands’ withdrawal from the euro6. For the PVV populists, compromise was essential on these issues to facilitate the agreement reached on May 15, 2024, forming a majority coalition. This coalition included the PVV, which is part of Marine Le Pen’s Identity and Democracy group, along with the neo-populist pro-farmers party (BBB), the Liberal Party (VVD) belonging to the Renew Europe group, and the anti- corruption party NSC.

On the other hand, however, this potent mechanism of public opinion constraining populist leaders is contingent upon the strength of the euro. It serves as a reminder that support for Europe and the euro is susceptible to shifts in the economic climate, a fact underscored by people’s attitudes towards globalization.

This is also true in eurozone countries. In Portugal (82%), Belgium (77%), Spain (76%), Slovenia (75%), Finland (74%), Slovakia (72%), Austria (71%), the Netherlands (70%), France (69%), Germany (69%), and Italy (61%), where the populist vote wields significant influence, public opinion remains in favor of retaining the European currency.

Thus, we observe two concurrent movements: a deepening of support for Europe and the euro, which now encompasses nearly all Europeans, alongside the expansion of the populist vote. These simultaneous trends necessitate that populist voters overwhelmingly endorse the euro, compelling populist leaders to embrace the idea of a European currency or risk alienating their base.

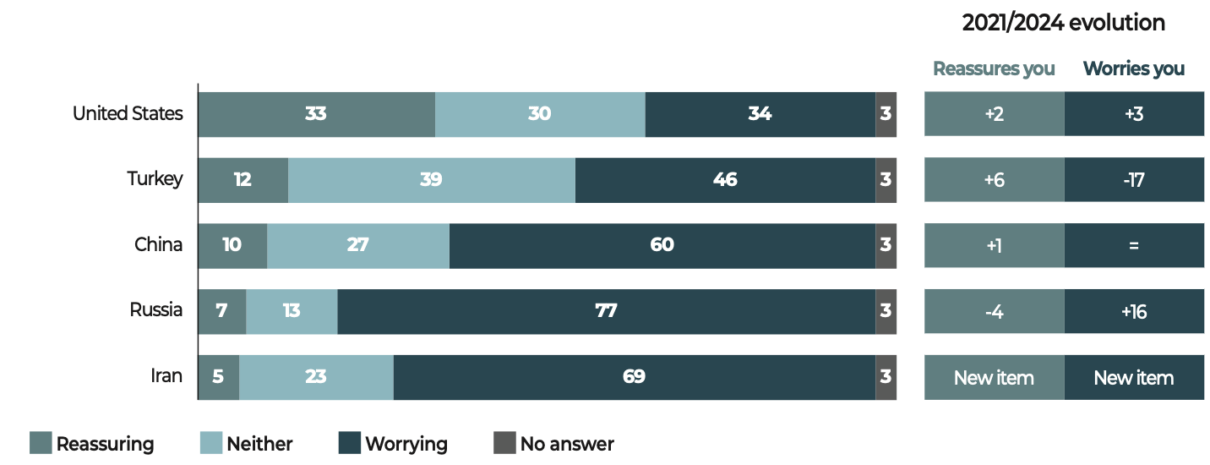

Who are the ″Exiters″?

Question: ″Concerning the European Union, which of the following opinions do you most agree with?″

Response: ″You’re not in favour of the European Union and you’d like for your country to leave it″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: Among those who responded ″You are not in favor of the European Union and would like your country to leave it″

(13% of respondents in the European Union), 52% are aged 35 to 59, 30% are over 60, and 18% are aged 18 to 34..

This can be seen precisely over the past quarter-century, as shown in Corinne Deloy’s book, Le vote des Européens. Vingt-trois ans d’élections nationales en Europe, Paris, Les Éditions du Cerf/ Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2024.

Examples include the Syriza party in Greece, Podemos in Spain and Die Linke in Germany. For more on Podemos, see Joan Marcet: “Podemos, entre populisme et radicalisme”, in L’opinion européenne en 2015, Paris, Éditions Lignes de repères/ Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Paris, 2015, pp. 23-31.

Cf. Stellina Galitopoulou: “La première victoire des populistes en Europe depuis la naissance de l’Union: analyse du scrutin grec de janvier 2015”, in L’opinion européenne en 2015, Paris, Éditions Lignes de repères/ Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Paris, 2015, pp. 13-21.

c. Support for Europe isn’t just a majority opinion; it’s also a tangible electoral reality

An analysis of electoral results in the member states reveals that support for the European idea is not primarily or mainly reflected through opinion polls, but rather through electoral choices. The endorsement of the European idea has primarily been demonstrated in national parliamentary elections. Since the inception of European integration, the majority of national elections in each member state – which has increased from six to twenty-seven – have resulted in a governing majority for parties or coalitions that favor the preservation or advancement of the European project7.

Political analysis often overlooks or underestimates one of the major lessons from the history of European integration: despite occasional dramatic events, a few votes against the European idea cannot overshadow the consistent democratic support for the Union’s construction. In nearly all member states, voters have consistently favored pro-European parliamentary majorities since their accession. Dozens of national legislative elections serve as evidence of this democratic backing for the European idea and its advancement. From the late 1990s to the present, anti-European parties have largely remained on the fringes of political life and power. Since the early 2000s, often right-wing and occasionally left-wing8 populist parties, have gradually participated in majority coalitions in countries such as Austria, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, and have even led majority coalitions. This occurred for the first time in Greece with Syriza in 2015, followed by Italy in June 2018 with Giuseppe Conte’s government involving the Lega and the M5S, and more recently since September 2022 with Giorgia Meloni. However, they have typically adhered to the fundamental electoral condition of maintaining ties with the European Union, except for the short-lived Syriza experiment in Greece9. Although they may make loud declarations and mobilize supporters, populist parties have yet to assemble a governing majority.

Rather than fuelling nationalism, the emergence of threats serves to reinforce the European idea

Since globalization began to take effect following the collapse of the Eastern empire, Europeans have been witnessing the gradual emergence of a world under American and Chinese domination. These two great powers are imposing an aggressive planetary duopoly that looks set to suffocate the nations of Europe. The advent of an undeniably more hostile world is now causing voters to converge on a European retreat, instead of a national one.

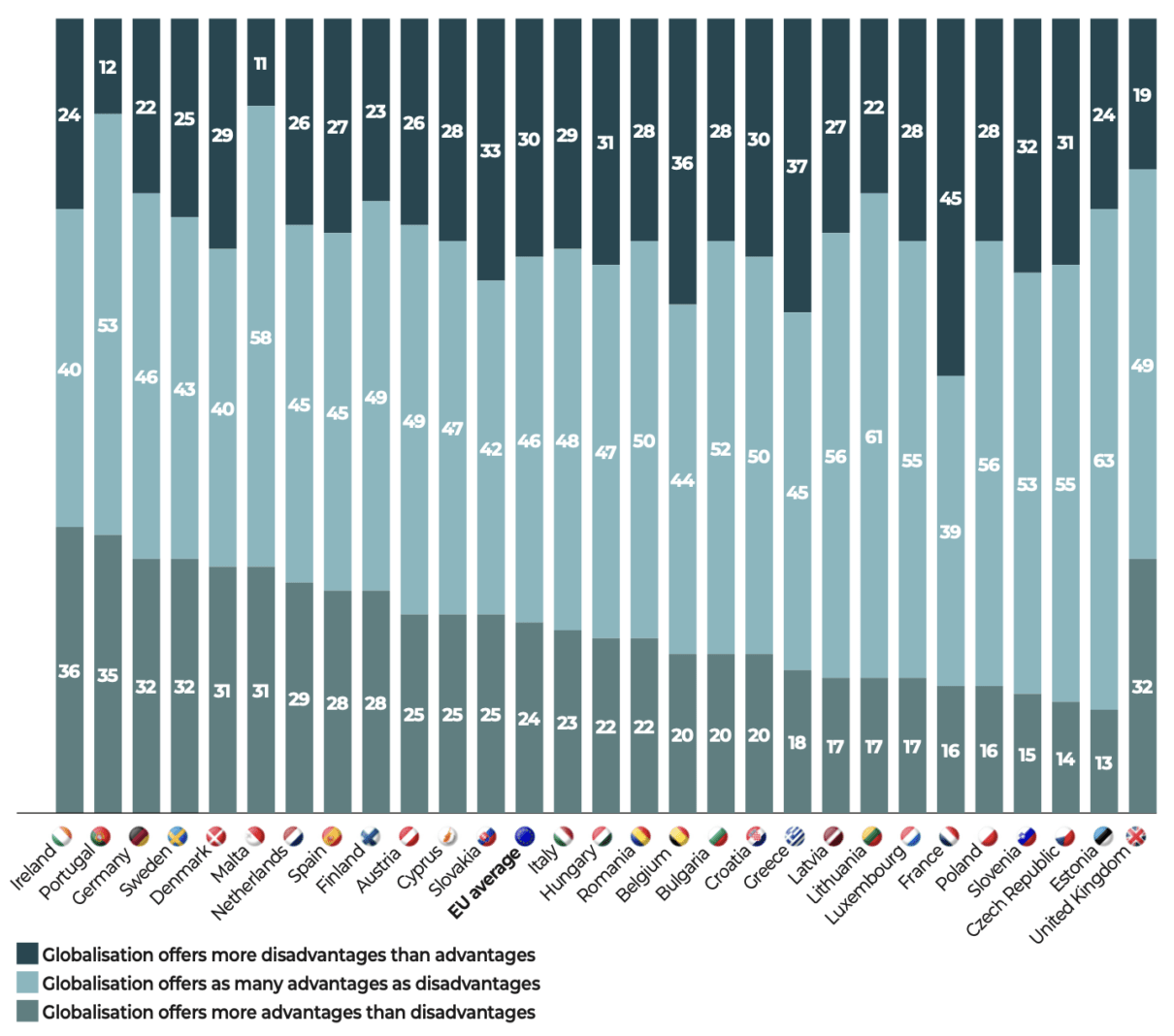

a. Globalization worries Europeans more than ever

On average, 24% of Europeans see more advantages than disadvantages to globalization; 46% view globalization negatively, seeing “as many advantages as disadvantages”, and 30% see more disadvantages than advantages. This negative assessment is much more widespread in some countries, notably France, which holds the European record: almost half (45%) of French people surveyed consider globalization to bring more disadvantages than advantages. On the whole, the level of opinion favoring globalization is never very high, and rarely exceeds one-third of respondents. Europeans are no longer enthusiastic about globalization. Today, it is a source of concern and, at the very least, mistrust. One of the primary reasons for support for Europe is the widespread desire to seek refuge from, if not shield oneself from, the adverse effects of globalization.

Globalization: the party is over

Question: ″Which of the following opinions do you most agree with?″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Globalization Perception in Relation to Municipality Size

Question : ″Which of the following opinions do you most agree with?″

Response: ″Globalisation offers more advantages than disadvantages″

Base : respondents from EU countries according to the size of the city in which they reside

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

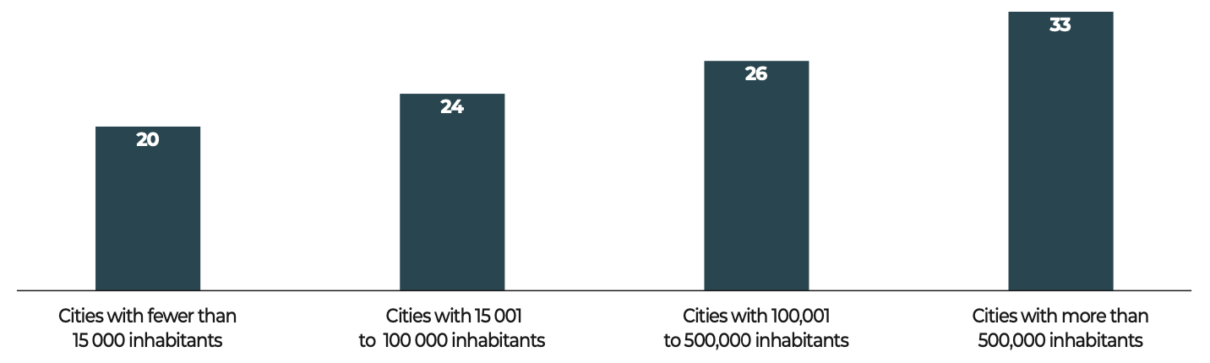

b. The aggressiveness of hostile powers (Russia, China, Iran, Turkey) favors the European idea

For many Europeans, globalization manifests as a series of increasingly diverse and violent

crises, exacerbated by the actions of states intent on strengthening their domestic despotism and expanding their influence abroad.

Russia and China, along with Iran and Turkey, are perceived as the nations that have ended the optimistic early phase of globalization. During this period, the rapid expansion of trade promised universal prosperity, enduring peace, and the spread of the democratic model. These countries now concern Europeans to varying extents, revealing a world for which Europeans no longer seem adequately prepared.

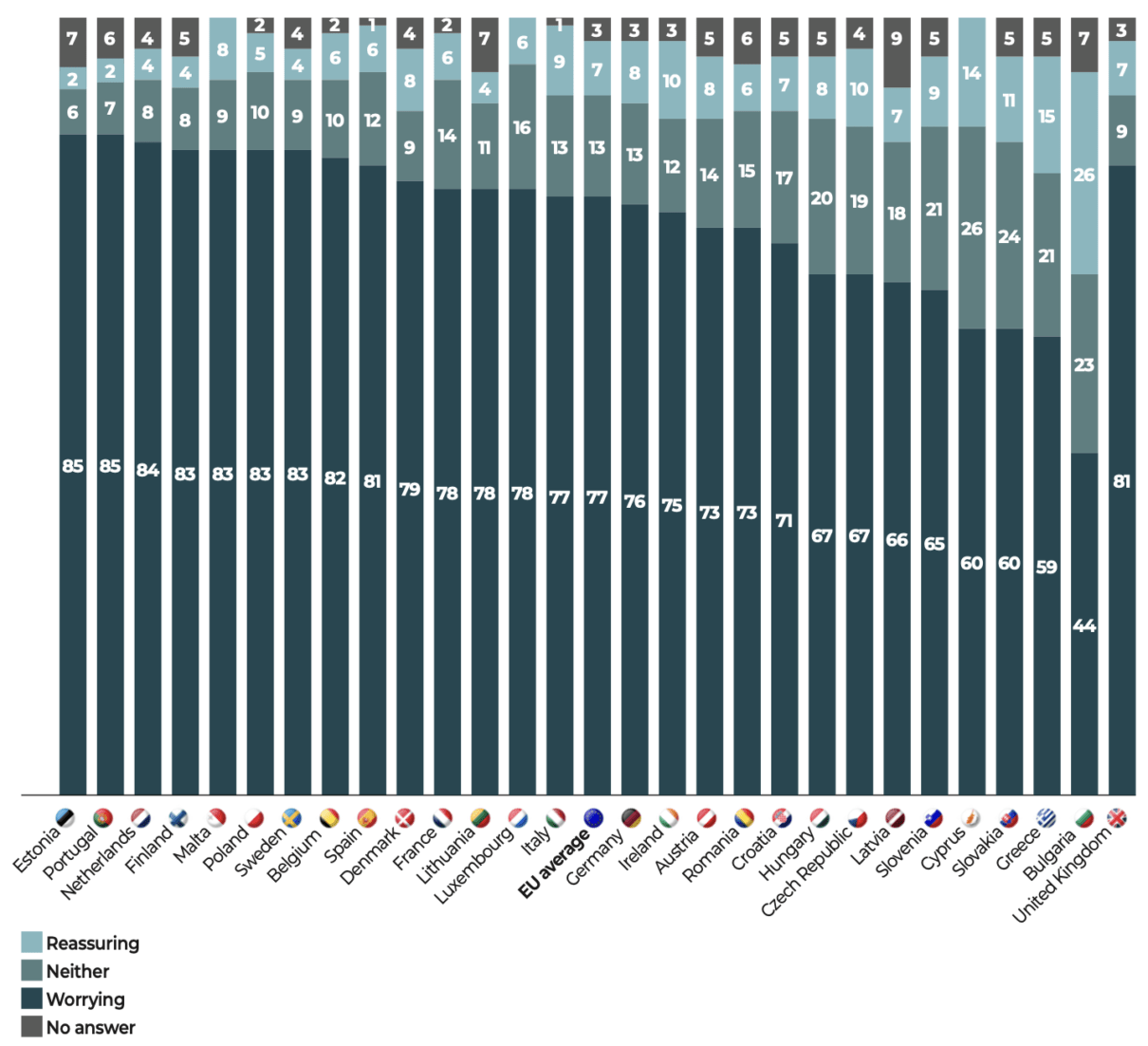

A hostile world

Question: ″For each of the following powers, please tell me if you think their posture on the international stage is worrying, reassuring or neither.″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: The figures in the table on the right indicate the change in percentage points compared with the results of the survey Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century, Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

• Turkey’s case warrants special attention due to its multifaceted geopolitical implications. Externally, Turkey’s assertive actions in the Mediterranean, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa pose a significant threat to European stability. Like Russia, Turkey is trying to regain some of its former influence. Turkey’s aggressive stance is rekindling concerns among its European neighbors. Three quarters of Greeks (72%) and almost all Cypriots (91%) express fears about Turkey’s behavior. The effects of Turkey’s activism are not confined to the international stage or to Turkey’s neighbors; they are also felt within European states, particularly in countries with a large Turkish diaspora.

In these countries, the level of concern about Turkey is higher than the European average (46%), as it is in France (50%) and Germany (52%). Concern is also widespread in Italy (47%) and Portugal (49%), even though these countries are not particularly home to a Turkish diaspora. In the case of Italy, this may be due to its perilous geographical proximity in the event of a regional conflict between Ankara and Athens, for example. But the deterioration of Turkey’s public image can also be explained by the ongoing tension with the European Union, particularly since the migratory crisis of 2015, in the distressing context of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s staging of a bellicose, willingly anti-Christian Islamism.

• Russia’s offensive against Ukraine has validated the concerns of those who viewed it as a significant threat. More than three-quarters of Europeans (77%) share this view, which has risen sharply since 2021 (+16 points). This shift in perception is particularly notable. The invasion of Ukraine, which began on February 24, 2022, heightened public awareness of Russia’s imperialist ambitions and forced Europeans to confront historical and geopolitical realities anew, reconsidering the enduring dangers inherent in international relations. Following the financial, migratory, and health crises, this latest collective shock has catalyzed a retreat within Europe and bolstered support for the European Union.

The Backlash against Russia

Question: ″For each of the following powers, please tell me if you think their posture on the international stage is worrying, reassuring or neither.: Russia″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

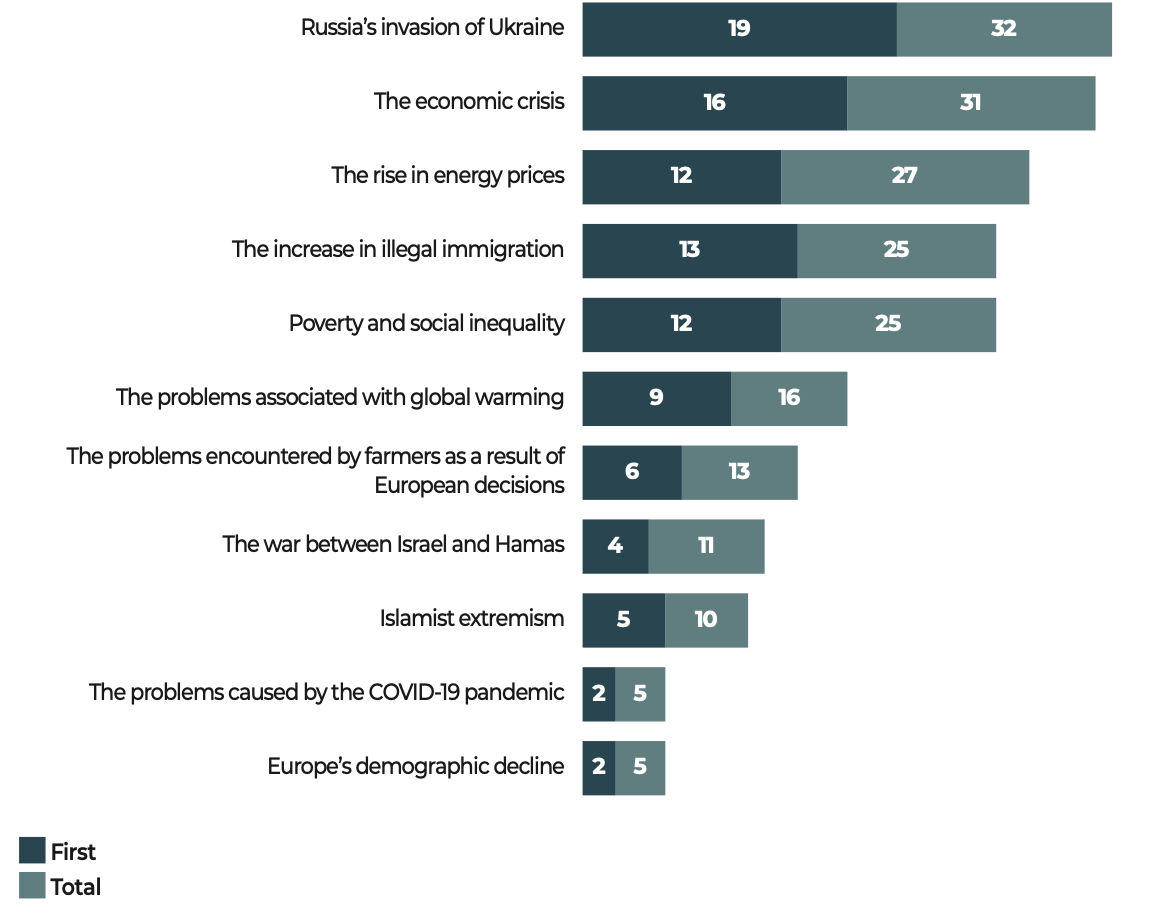

A European vote against Russian aggression

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

• Along with Russia and China, Iran is the third most worrying country for the majority of Europeans (69%). As our opinion poll was conducted between March 22 and April 26, 2024, well after the terrorist attack perpetrated by Hamas on October 7, 2023, Europeans have discovered new reasons to fear the external and internal geopolitical consequences of a religious dictatorship capable of provoking wars, attacks and major unrest within European societies. This is due to the mobilization of hatred based on religious sentiment, and the stirring up of anti-Semitism and its related manifestations on European soil.

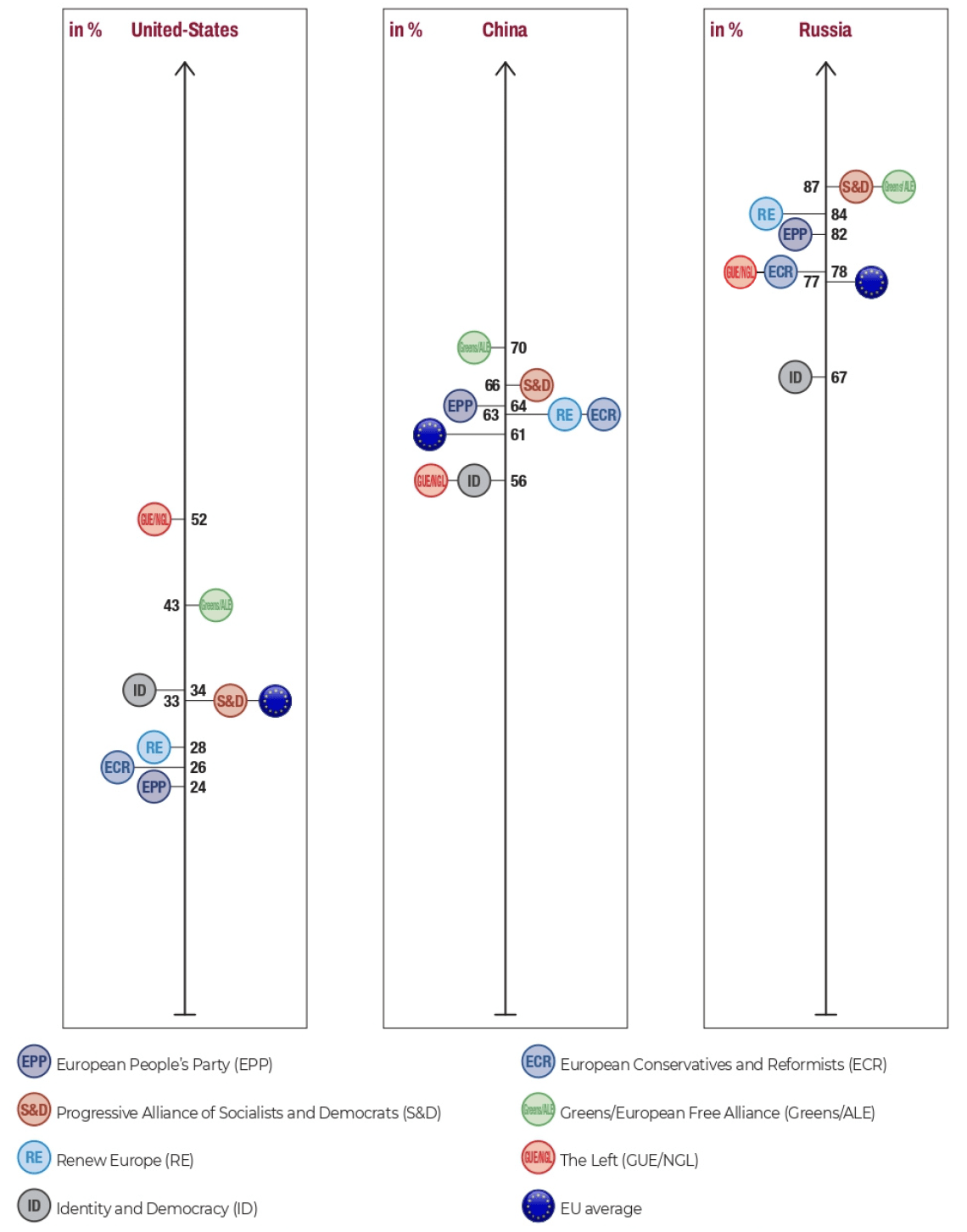

The United States, China and Russia judged by European electorates

Question: ″For each of the following powers, please tell me if you think their posture on the international stage is worrying, reassuring or neither.″

Response: ″Worrying″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: Among respondents who say they vote for a party that is a member of the EPP group in the European Parliament, 24% say they are worried about the international attitude of the United States.

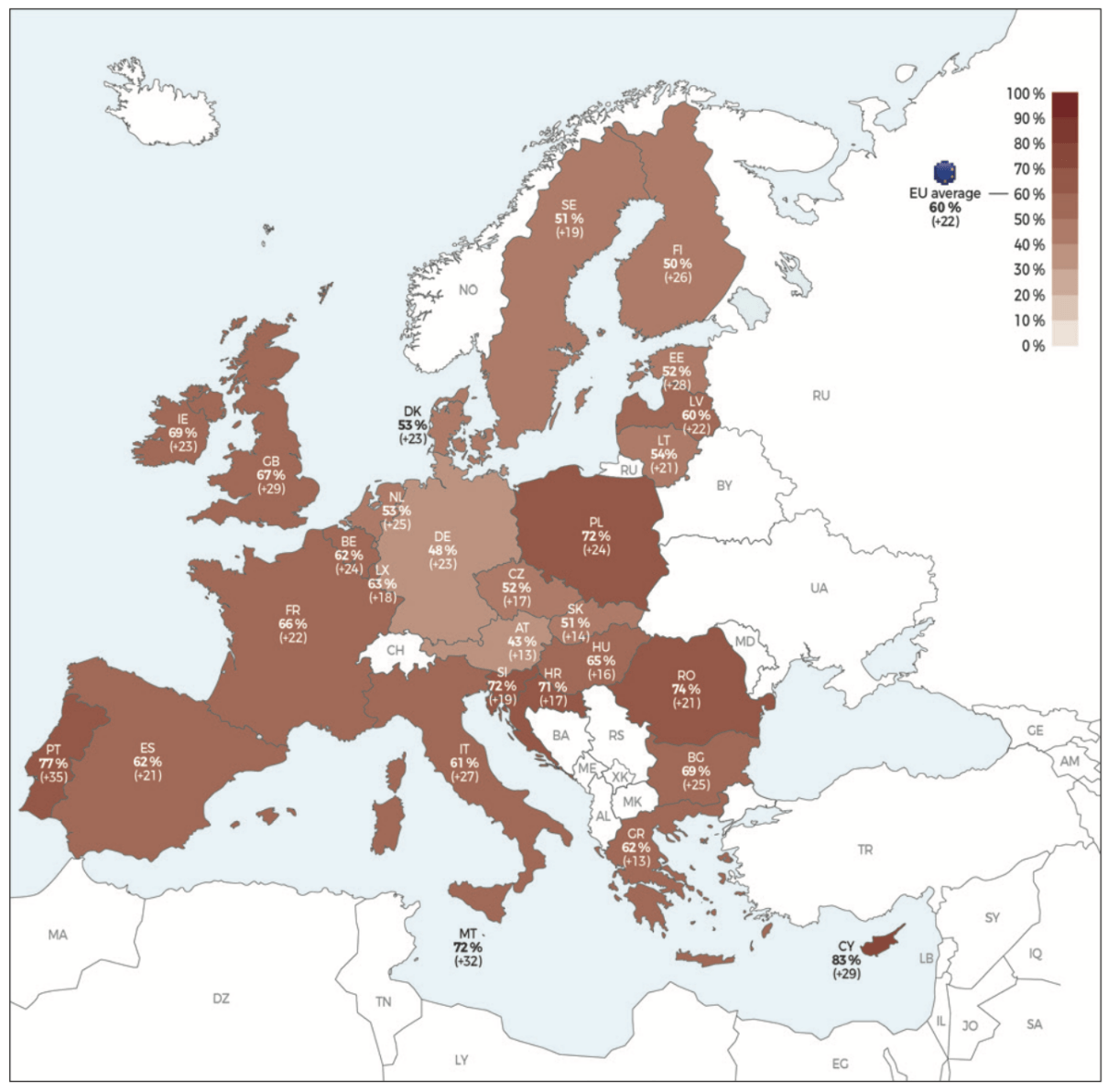

c. Fear of a new world war (60%)

Russia’s offensive in Ukraine has made Europeans aware of war once again, on a continent where peace, albeit partial and relative, has nonetheless been reassuring for over 80 years. In the spring of 2024, 60% of Europeans consider the outbreak of a new world war likely. The most worried are Cypriots (83%), Croats (71%), Maltese (72%), Poles (72%), Portuguese (77%) and Romanians (74%).

This figure is significantly higher than the results of our 2021 survey (Freedoms at Risk: The Challenge of the Century). The average increase is +22 points for the European Union as a whole. The strongest increase is recorded in Portugal (+35 points), Cyprus (+29 points) and Estonia (+28 points). Fear of a third world war is on the rise in every country surveyed. The increase is never less than 13 points.

War, once again on the European Union’s doorstep

Question: ″Do you think it is very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, or very unlikely that another World War breaks out in the coming years?″

Responses: ″Very likely″ and ″Somewhat likely″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: The figures in brackets indicate the change in percentage points compared with the results of the survey Freedoms at Risk, the Challenge of the Century, Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

d. From mere opinion to actual votes: Russian aggression serves as a catalyst for pro-European sentiment

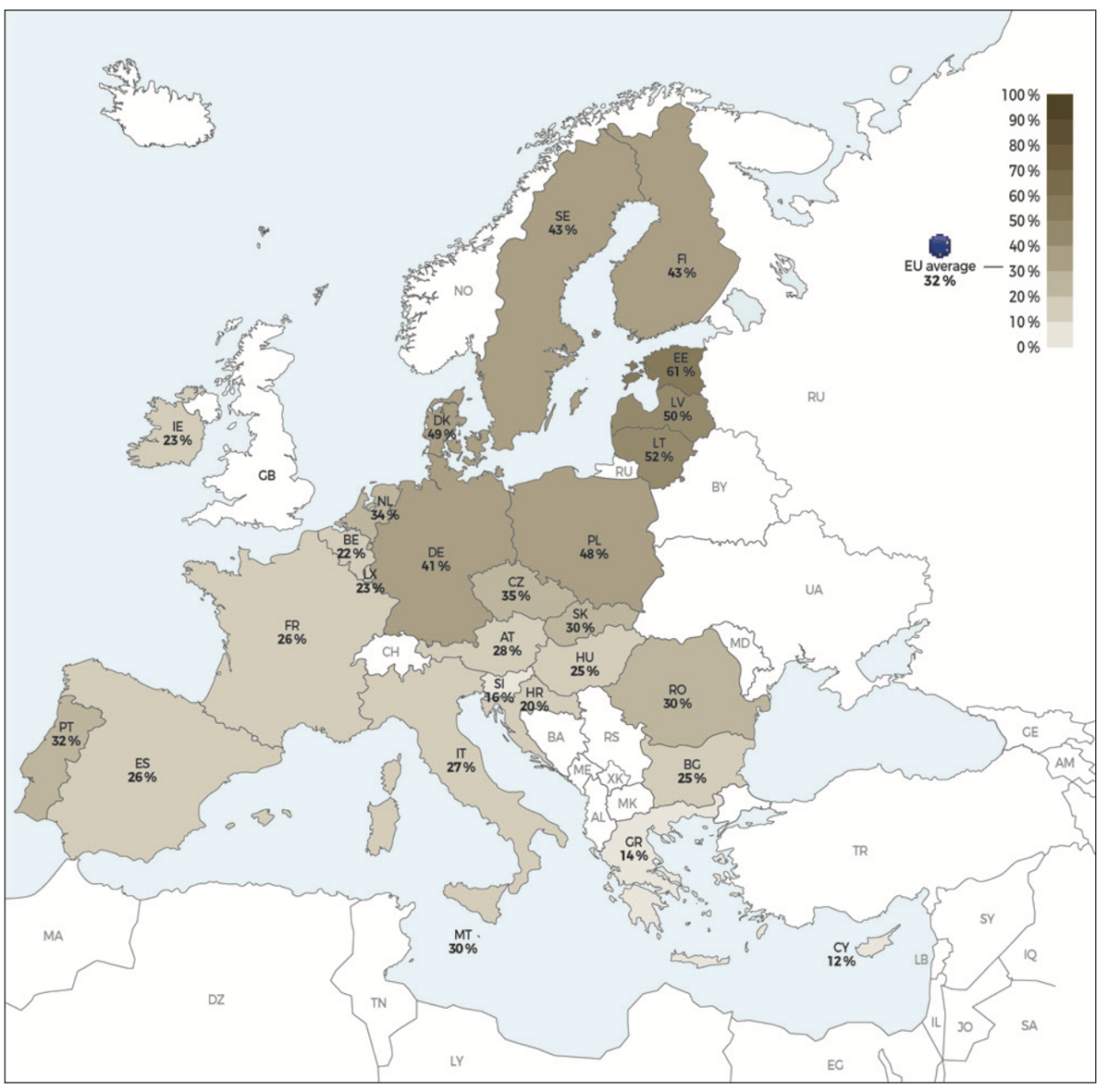

The survey highlights the consequences in terms of opinion of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Yet the issue is so severe, and so deeply worrying, that opinions translate into votes. The 22,788 voters questioned in our survey cite Russia’s aggression against Ukraine as their first or second reason for voting. The Russian attack was certainly the event that counted most in determining the vote in the June 2024 European elections. In total, a third of respondents (32%) cited Russian aggression as their first or second reason, and a fifth (19%) gave it as their primary reason. The role of this war in the electoral choice is even more important in countries bordering Russia, as can be seen by the place this aggression took in the voting choice of Lithuanians (52%), Estonians (61%) and Latvians (50%). In all the countries of the former Eastern bloc, the war in Ukraine was cited as the first reason for voting by 25% of respondents.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine influences June 2024 electoral ruling

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Response: ″Russia’s invasion of Ukraine″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

History and geography explain part of the electoral impact of this conflict, whether in the Baltic States, Poland or the Nordic countries. Yet other countries have made the war in Ukraine an important reason for their choice, without having the same history or geography, which attests to the general impact this aggression has had on electoral choice. There are, of course, other motivations, and they relate to other historical and geographical configurations, and other political situations. For example, the economic crisis is mentioned as the first or second reason for voting by 47% of Greeks, 37% of Spaniards and 39% of Italians.

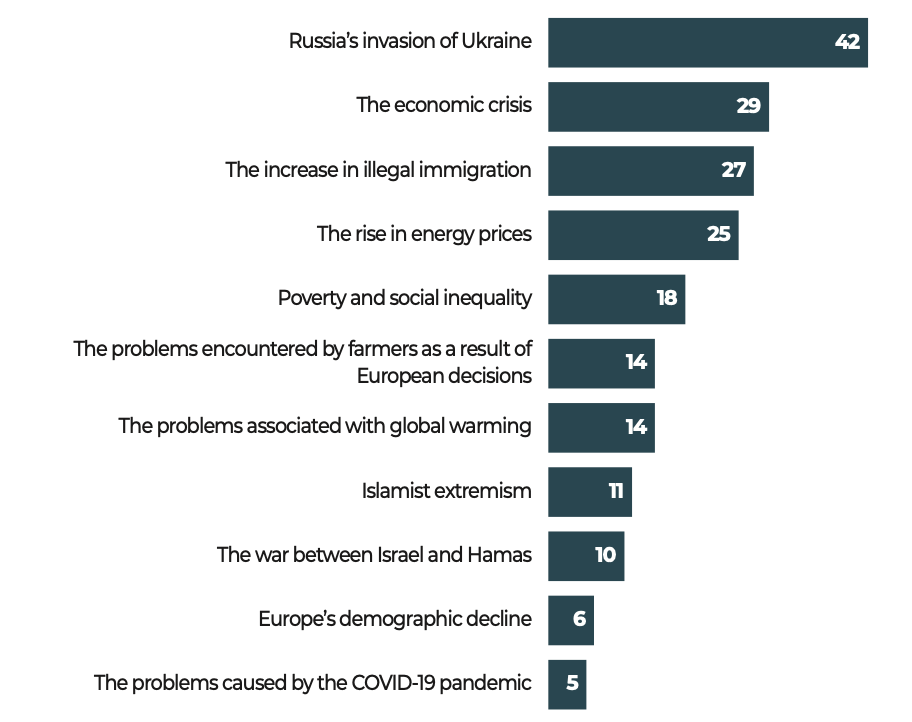

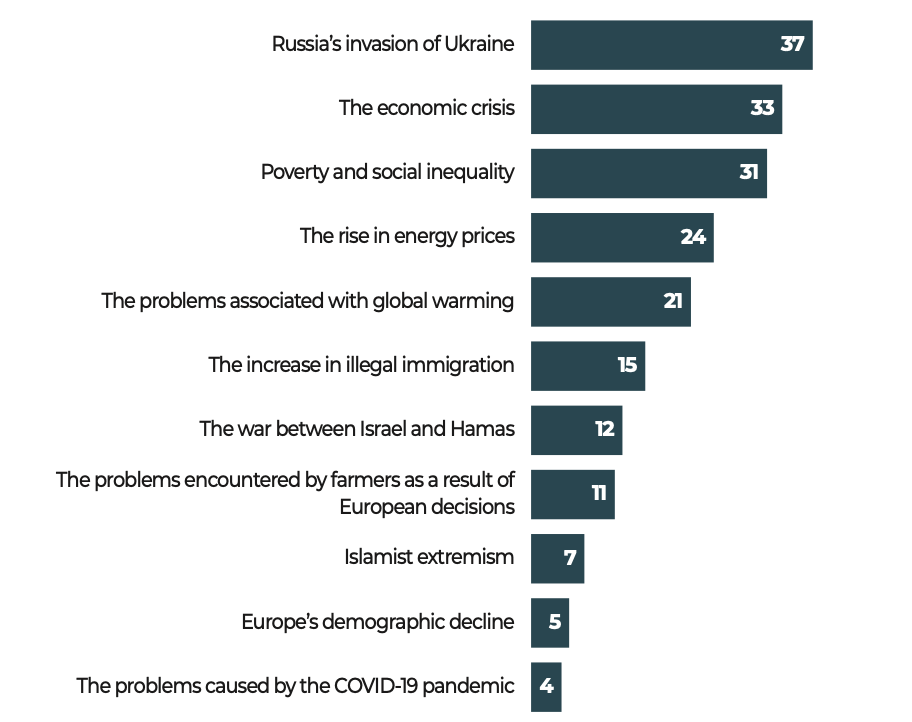

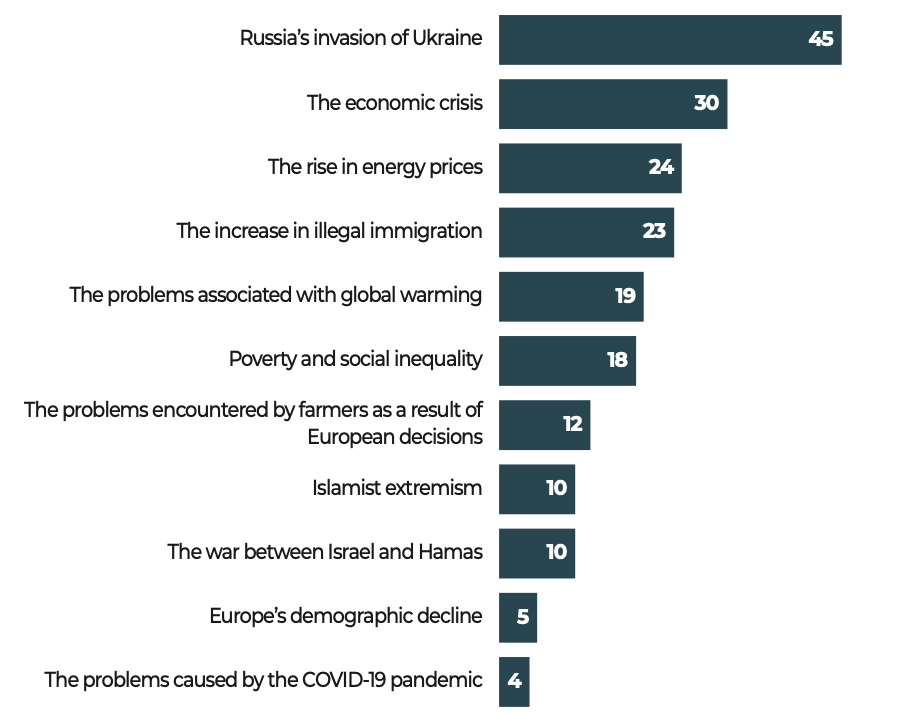

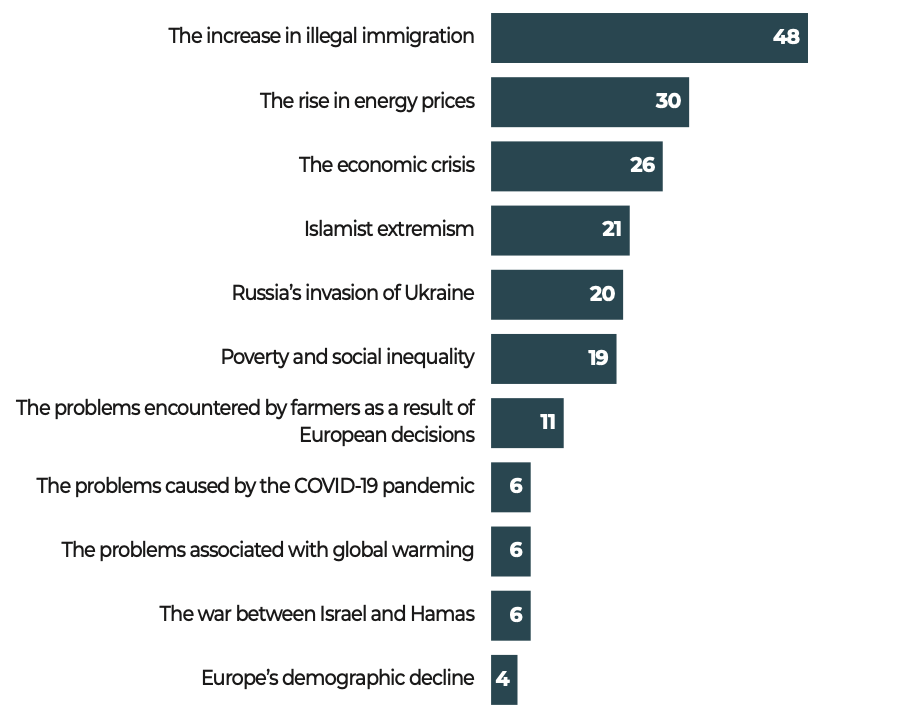

Finally, it is interesting to note that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine tops the list of reasons for voting among right-wing voters of parties associated with the European People’s Party (42% overall), left-wing voters of parties associated with the Social Democrats (37%), and center-leaning voters of Renew Europe member parties (45%); the war is ranked second as a reason for electoral choice among voters in parties belonging to the Green group (37%), and among those in the group associating populist parties in the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR, 29%), led by Giorgia Meloni. The attack on Ukraine came third in the reasons for voting for voters in parties belonging to the The Left group (26%), and fifth for voters in parties belonging to the Identity and Democracy group (ID, 20%), the group of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN).

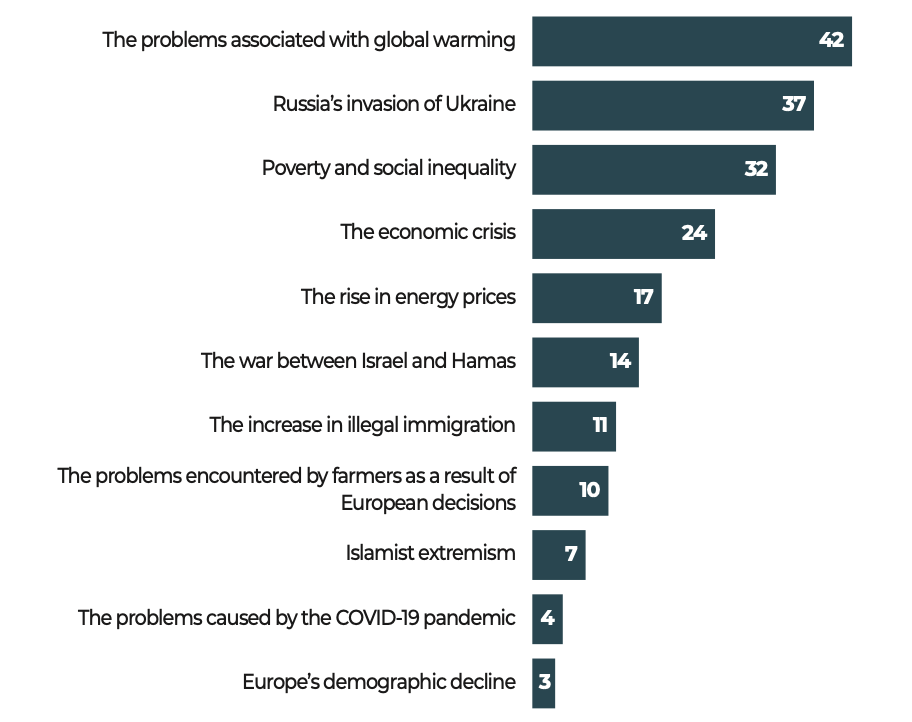

Top Issues Influencing EPP Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of European People’s Party (EPP) members parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

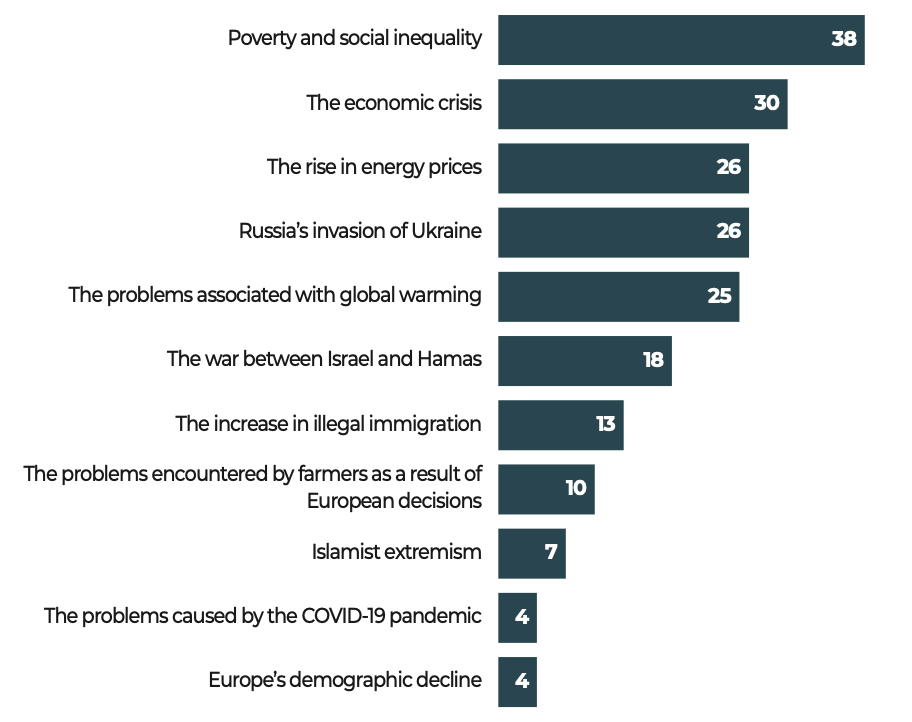

Top Issues Influencing S&D Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

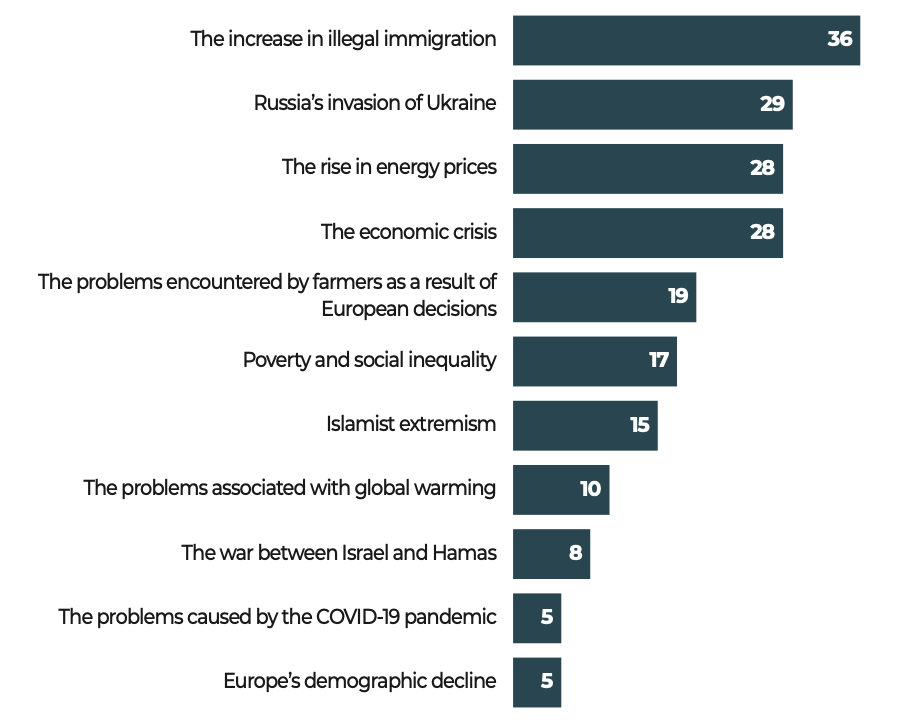

Top Issues Influencing Renew Europe Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of Renew Europe (RE) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Top Issues Influencing Green/EFA Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Top Issues Influencing GUE/NGL Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of The Left (GUE/NGL) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Top Issues Influencing ECR Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Top Issues Influencing ID Voters

Question: ″Which of the following recent problems in Europe will have the greatest influence on the way you vote/ your decision to vote in the European elections on 6-9 June 2024?″

First and second

Base: Voters of Identity and Democracy (ID) member parties

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Europeans in search of public leadership

What can States do for their people?

Cf. Dominique Reynié, “L’avènement d’un stato-scepticisme européen”, L’opinion européenne en 2008, 2008, Lignes de repères/ Robert Schuman Foundation, p. 11-36.

Cf. Libertés, l’épreuve du siècle, op.cit. p.55 ff [fondapol.org].

Europeans are deeply concerned about the current times, with a pervasive fear of societal decline. Foremost among their worries is the evident inability of States to meet the historic challenges facing Europeans. Confidence in the capacity of the State is waning, leading to a growing sense of what I call “stato-skepticism.” This skepticism towards national governance has been less frequently discussed compared to “euroskepticism,”which is often highlighted in media and political discourse. However, stato-skepticism is a significantly present and pervasive sentiment10. The survey results show that, for Europeans, this doubt with regards to the capabilities of national public power cannot continue without political risk. The demand for a European retreat implies the search for a European public authority.

a. Those forsaken by populists: the aftermath of ″Brexit″

In 2016, Brexit won with 51.9% of the vote (17,410,742 votes for; 16,141,241 votes against), and a 72.2% turnout.

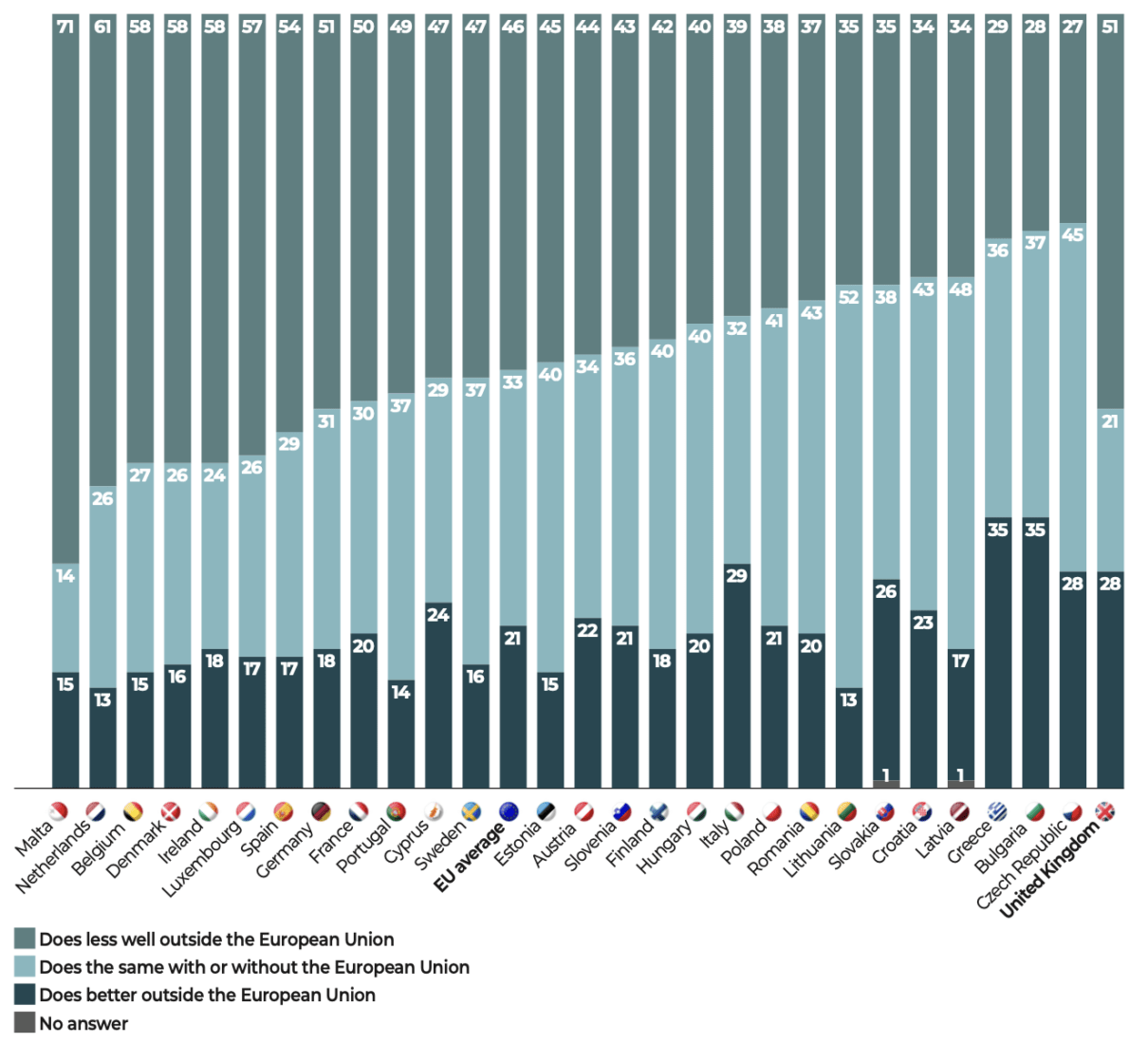

Since this historic referendum, which saw a country decide to leave the European Union, and following the implementation of this decision on January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom has become a third country to the European Union11. Now that the bitter divorce has been consummated, the British and Europeans find themselves looking back at the referendum that changed the face of the United Kingdom and the European Union. In 2021, 48% of British people believed that their country would fare worse outside the European Union; in 2024, 51% expressed this judgment. Similarly, in 2021, a third (33%) thought they would be better off without Europe; today, the figure is just 28%. In 2024, across the European Union as a whole, half (46%) think the UK will be worse off, and only a fifth (21%) of Europeans think the UK is “better off outside the EU.”

The other surprise of the British referendum was the political demise of the victors within days of their victory. The “brexiters” were unable to organize a united political force. Their victory was the result of a demagogic electoral mishmash. In the United Kingdom, as in France and the Netherlands, the forces thus united for a short time dispersed as soon as victory was achieved. A majority for nothing

Europeans Struggle to Understand Britain’s Departure from the EU

Question: ″The United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union in January 2020, following a referendum held in 2016. In your opinion, the United Kingdom:″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

In the founding countries of the European Union, which welcomed the UK on January 22, 1972, more respondents than the European average (49%) think the British will fare worse outside the EU. This critical opinion is shared by 50% of French people, 51% of Germans, 57% of Luxembourgers, 58% of Belgians and 61% of Dutch people. Fewer Italians (39%) share this opinion..

The British were wrong to leave the European Union

Question: ″The United Kingdom withdrew from the European Union in January 2020, following a referendum held in 2016. In your opinion, the United Kingdom:″

Base: UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: The figures in the 2021 columns present the results of the survey Freedoms at Risk: The Challenge of the Century, Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

Reading grid: 30% of men in 2024 answered ″Doing better outside the European Union″, 21% answered ″Doing the same with or without the European Union″, 49% answered ″Doing worse outside the European Union″.

Dear Brits, come back home!

Questions:

– EU countries: ″If the British wanted to return to the European Union, would you be in favour of or against this?″ ;

– UK: ″Would you be in favour of or against the United Kingdom returning to the European Union?″

Responses: ″Completely in favour″ and ″Somewhat in favour″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Freedoms at Risk: The Challenge of the Century, op.cit. p.51 [fondapol.org].

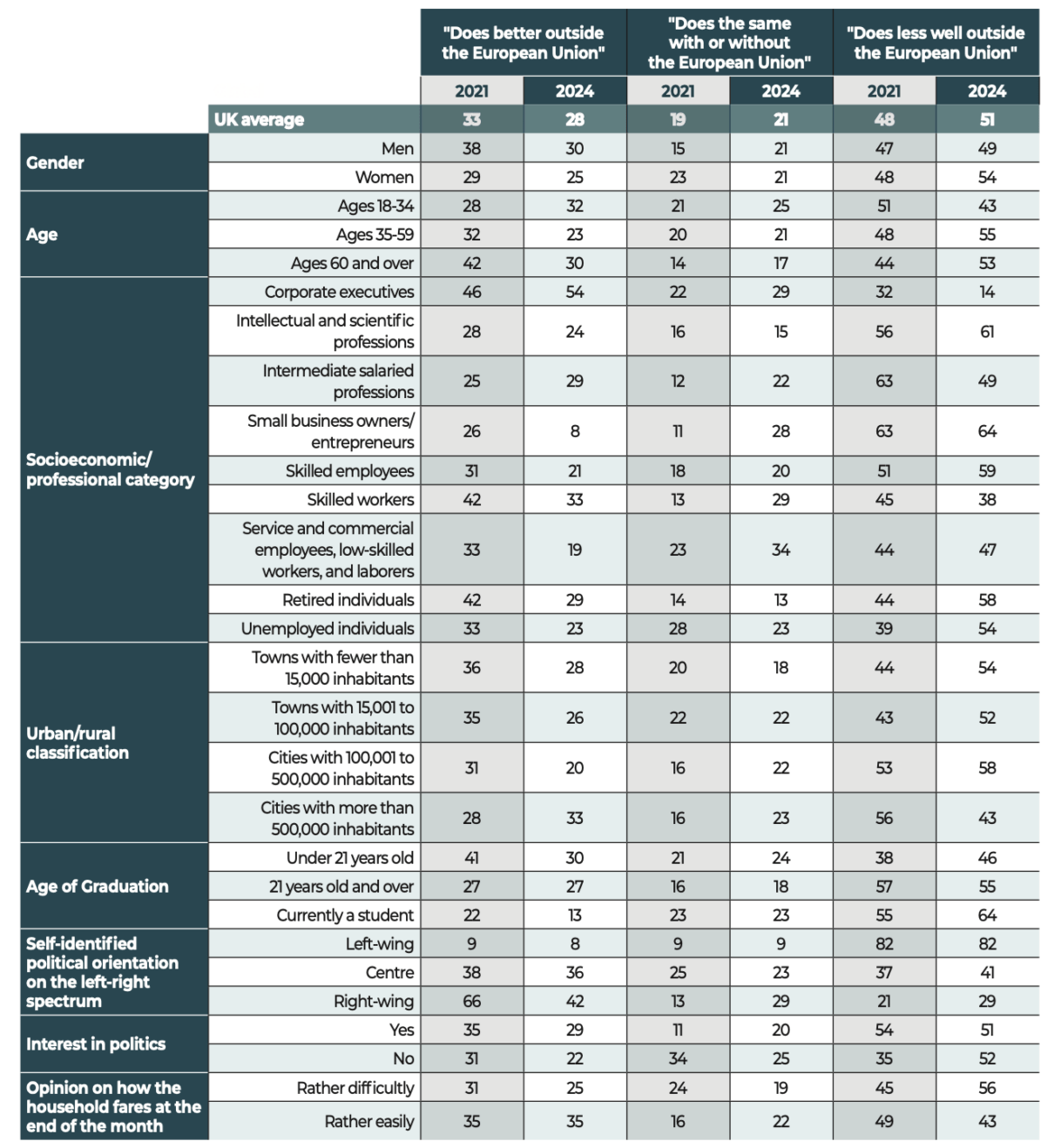

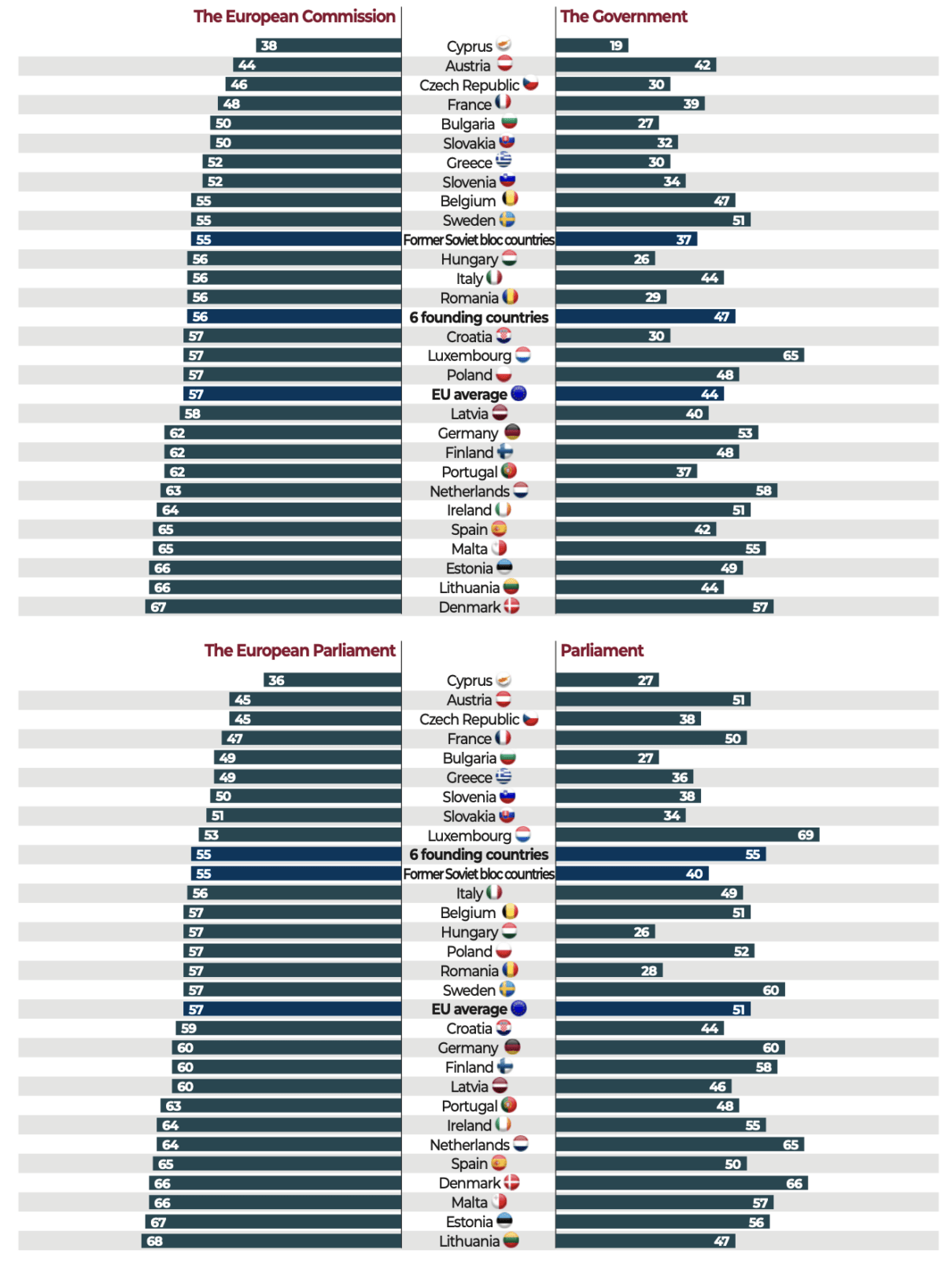

b. Shifting from Euroscepticism to “stato- skepticism”: European institutions garner greater trust than national counterparts.

Citizens’ support for the European Union is also reflected in their confidence in the European Commission (57%) and the European Parliament (57%). At a time of great political mistrust, it is worth noting that confidence in European institutions has risen sharply compared to our 2021 survey. Confidence in the European Commission has risen by 10 points, and confidence in the European Parliament by 10 points. By comparison, this level of trust is significantly higher than the confidence citizens have in their national political institutions, be it their national government (44%) or their national parliament (51%).

With the exception of Luxembourg, where trust in the European Commission (57%) is lower than trust in the national government (65%), in all other countries the Commission enjoys a higher level of trust than national governments. The European Parliament is also more trusted than national parliaments, with the exception of five countries: Luxembourg (53% vs. 69%), the Netherlands (64% vs. 65%), Sweden (57% vs. 60%), Austria (45% vs. 51%) and France (47% vs. 50%).

In the countries of the former Eastern bloc, which joined the democratization process about thirty years ago, there is an average gap of 18 points between confidence in the European Commission (55%) and confidence in the national government (37%), and a gap of 15 points between confidence in the European Parliament (55%) and confidence in the national parliaments (40%). This greater confidence in European institutions also reflects the perception of the European Union as a guarantor of the rule of law, democracy and freedoms, in countries where, in 2021, national governments were still perceived as a potential threat to democracy by 44% of their citizens12.

An illustration of European stato-skepticism

Question: ″I will now show you a list of institutions and ask you how much you trust them. For each institution, please tell me if you entirely trust them, trust them, distrust them or entirely distrust them.″

Responses: ″Entirely trust″ and ″Trust″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

c. Europeans’ Populist Vote: A Demand for Increased Government Authority?

Danger looms worldwide Europeans feel increasingly unstable, unwilling to navigate between two inconsistent powers: the compromised State, grappling with historical shifts, globalization, demographic changes, debt, energy and security issues, technological dependence, health concerns, and military unpreparedness; and the European Union, hindered by member states from flexing its strength. Understanding European sentiment today necessitates acknowledging a call for bolstering public authority.

The unanswered demand for this has fueled populist movements over the past twenty-five years. Conversely, a new grassroots desire for Europe is emerging in European opinion, encouraged by the expectation of enhanced public power. Faced with globalization and its threats, alongside adversaries of the Old Continent, most Europeans doubt their states’ self-reliance. Pragmatism, not idealism, is driving this sentiment, exemplified by the euro’s success.With deeper historical perspective that most of their leaders and representatives, they aspire to an additional European public authority, better equipped to face the changing times. Without the Europeanization of public powers, citizens will resign themselves to nationalist retreat.

Security stands out as the foremost demand

a. Support for NATO (65%)

Europeans find themselves with no alternative. Confronted with escalating threats and the widespread unpreparedness of their individual states, coupled with a recent lack of a unified military resolve, NATO has emerged as the sole viable security mechanism. This reliance on NATO highlights an opportunistic embrace of Atlanticism, dictated by the harsh realities at hand. While support for NATO signifies the enduring popularity of the American ally and the Europeans’ confidence that the United States will assist them in times of conflict, it also stems from a growing awareness of the perilous nature of the current era. This sense of danger is most acutely felt by the Baltic states, Poland, Finland, and Sweden, whose fears have been exacerbated by Vladimir Putin’s aggressive actions, effectively driving them into the protective fold of the Atlanticist military alliance.

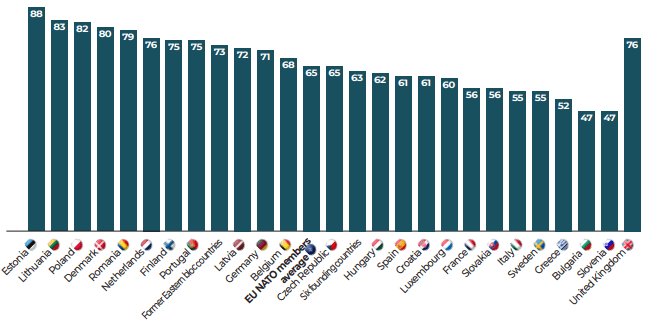

The war in Ukraine has reignited NATO’s sense of purpose. Originally established during the Cold War to secure Europe against the Soviet threat, NATO’s relevance has surged once again. Two-thirds (65%) of Europeans consider it “a good thing“ that their country is a member of NATO. Satisfaction reached record levels in countries bordering Russia: Estonia (88%), Lithuania (83%) and Poland (82%). Against this backdrop of high international tension, NATO is widely perceived as a dependable security framework for Europe. Indeed, it stands as the sole comprehensive security structure for the continent.

NATO membership is popular in most member countries

Question: ″NATO is a military alliance of European countries, including your own, Turkey, the United States and Canada. Do you think that your country’s membership of NATO is…?″

Response: ″A good thing″

Base: EU countries who are members of NATO and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Cf. our 2019 European survey, Démocraties sous tension, Fondation pour l’innovation/International Republican Institute, volume I, Victor Delage’s contribution: “Face aux nouveaux périls, renaissance de l’idée d’une armée européenne”, pp. 124-126 [fondapol.org].

Freedoms at risk: the Challenge of the Century, op.cit, 2022 [fondapol.org].

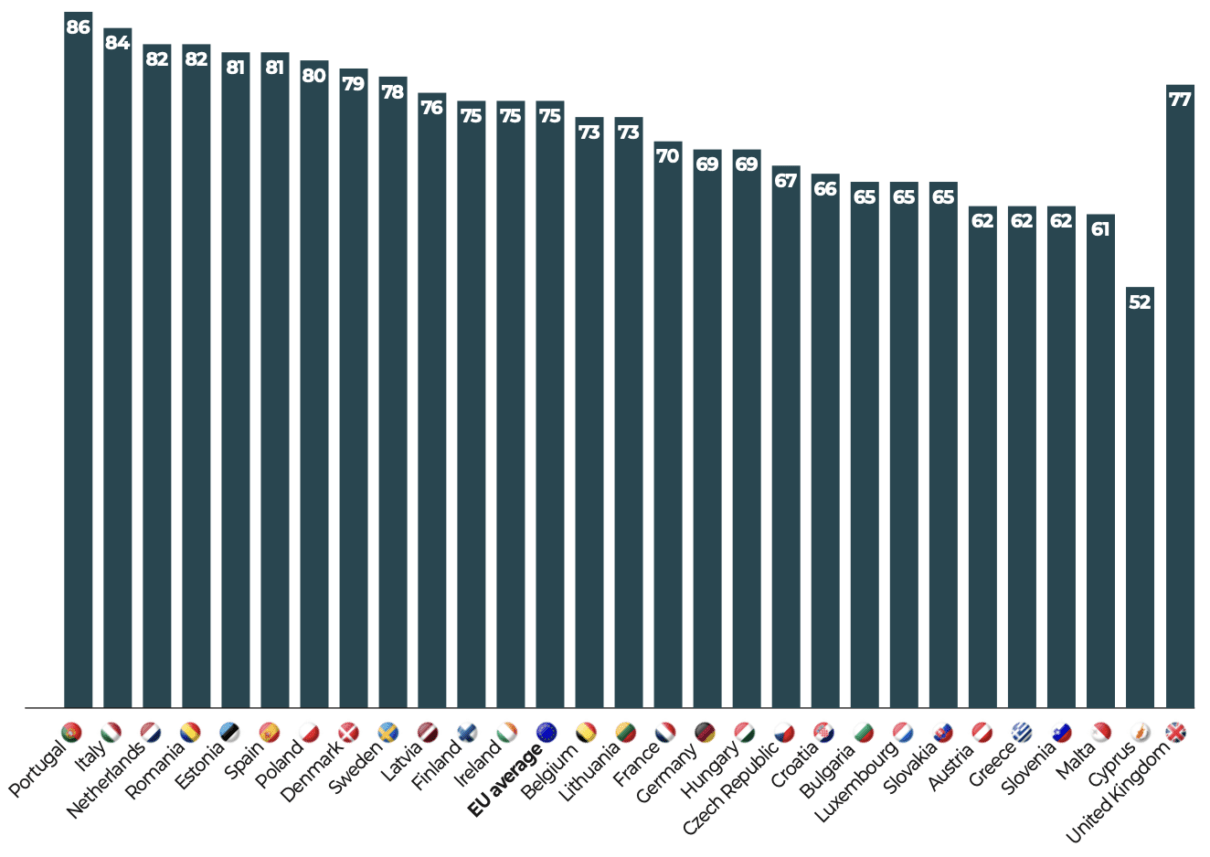

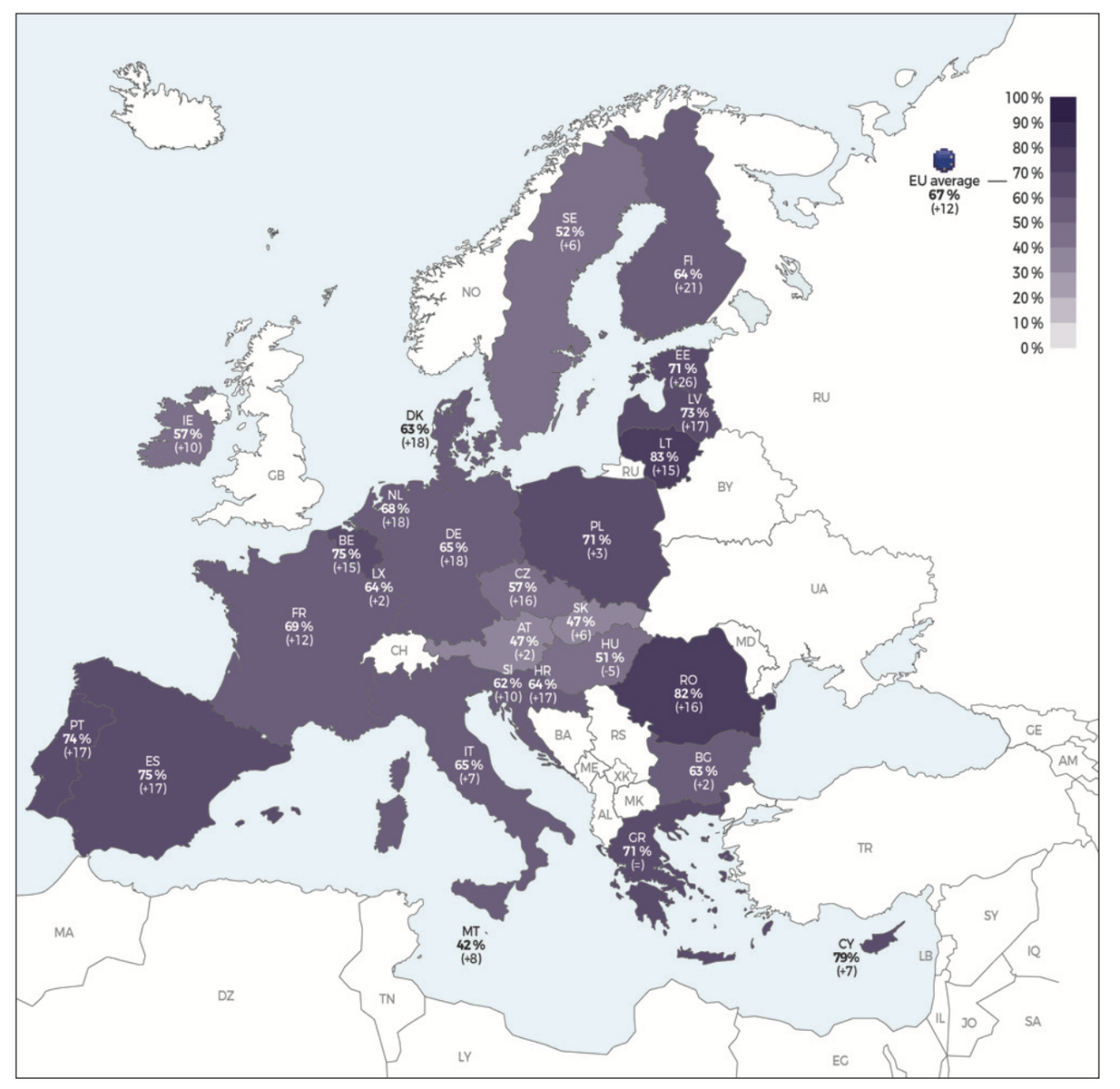

b. Europeans seek a unified army to compliment national armies (67%)

Two-thirds (67%) of Europeans are in favor of a common European defense. This preference is not new but has remained unfulfilled13 since the failure of the European Defense Community (EDC) in 1954, seventy years ago. The figures recorded in 2024 show a 12-point increase compared to our previous survey in 202114. The wish “that the European Union should have an army common to all member states, in addition to each country’s own army” is shared by a majority of voters, and in most states, with the relative exceptions of Austria (47%), Slovakia (47%) and Malta (42%).

The United States from a European perspective

Question:

– EU countries: ″In your opinion, if an outside military power attacked EU countries, could Europeans count on military assistance from the United States?″ ;

– UK: ″In your opinion, if an outside military power attacked the UK, would the British be able to count on military assistance from the United States?″

Responses: ″Yes, definitely″ and ″Yes, probably″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

That said, the desire for a common army reaches exceptionally high levels in Romania (82%) and Lithuania (83%). Support has significantlyincreased in Finland (+21 points), which recently joined NATO, and in Estonia (+26 points). Hungary is the only country where support hasdeclined (-5 points). The desire for a European army is not disconnected from reality. It is especially high (70%) among Europeans who fear the possibility of a new world war. Likewise, the idea of a common army is strongly supported (80%) by those who view their country’s NATO membershipfavorably.

The European Army: An Expression of Withdrawal Without Nationalism

Question: ″Would you like the European Union to form a joint army for all member states, in addition to national armies?″

Responses: ″Yes, absolutely″ and ″Yes, somewhat″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: The figures in brackets indicate the change in percentage points compared with the results of the survey Freedoms at Risk: the Challenge of the Century, ed. Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

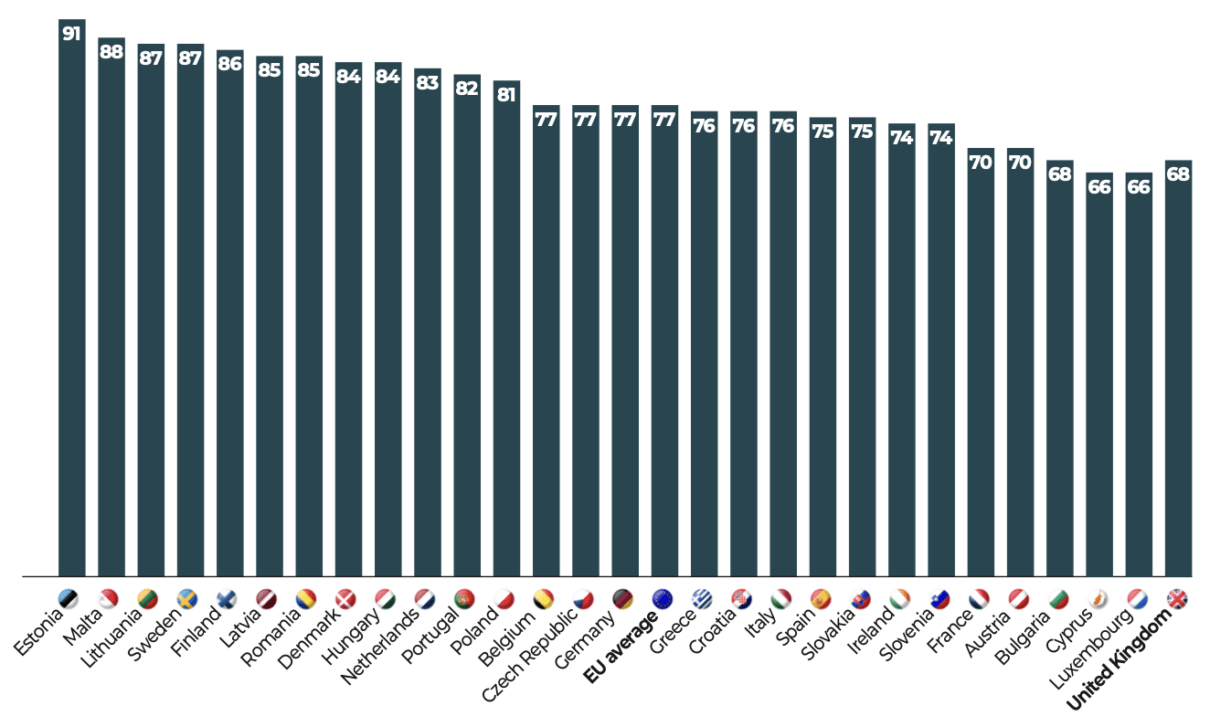

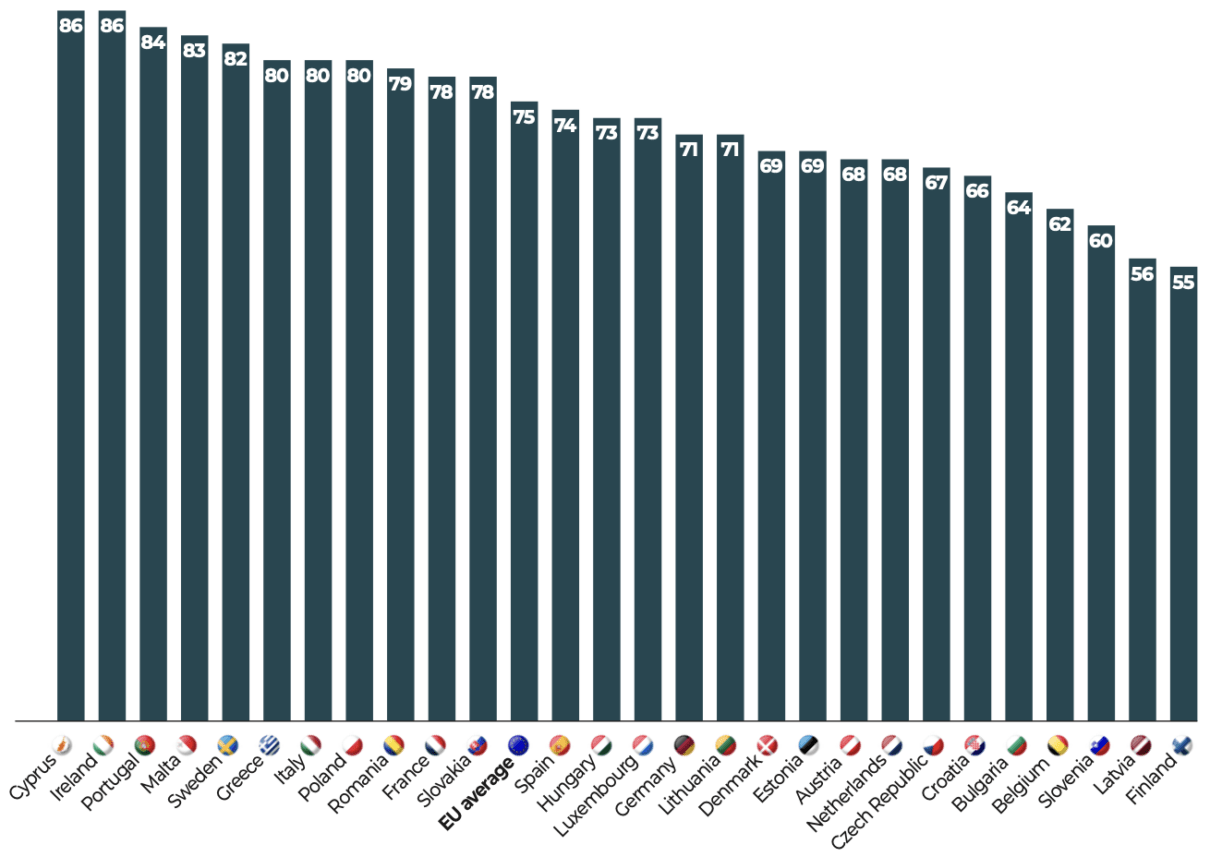

Europeans Seek Protection for Common Borders (86%)

Nearly all Europeans (86%) express a desire for the protection of the Union’s borders, a concern that is both fundamental and inherently political. When such a significant portion of respondents advocate for the strengthening of control and protection at external borders, they are asserting the existence of a distinct constituency, not only on a global level but also on a European one. They are demanding recognition of a political territory that is not that of a particular nation, but common to all European nations, and therefore to all Europeans.

In the same way, to claim recognition of a European territory is to distinguish a population living within its borders, which does not designate a particular European nation, but encompasses the populations of all European nations in a singular political community. The demand for common, controlled and protected external borders helps to affirm the existence of a European people.

However, if national borders are rendered ineffective and deemed undesirable, the absence of European borders equates to a denial of European identity. This is precisely what Europeans are protesting against because the absence of common, protected borders means that individuals from anywhere in the world can enter the European Union, even in violation of the law.

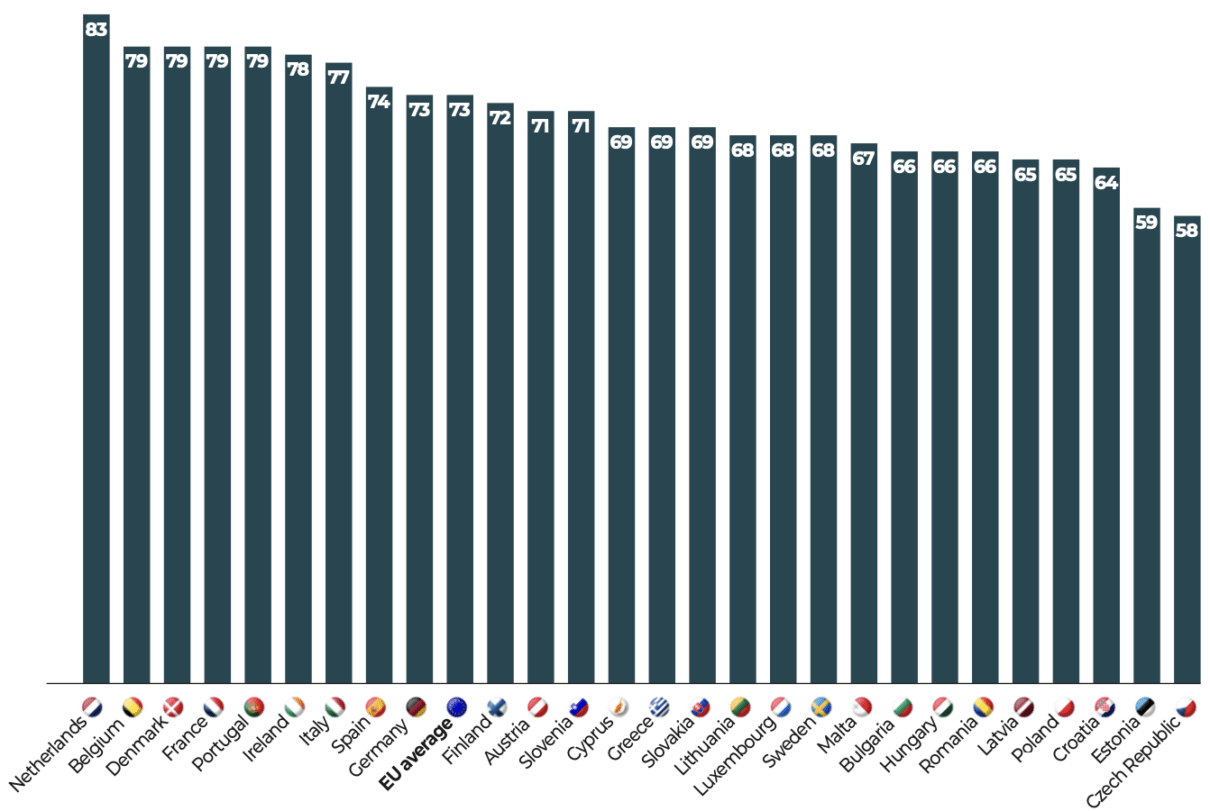

Europe Without Borders?

Question: ″Some people say that the European Union should strengthen the control and protection of its external borders. Do you personally…?″

Responses: ″Strongly agree″ and ″Agree″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Hence, the extreme sensitivity of public opinion to migration issues. The item ‘increasing illegal immigration’ ranks fourth in the list of ‘problems recently encountered in Europe’ and is bound to weigh heavily in elections such as those to be held on June 6-9, 2024. Notably, this item ranks after ‘the economic crisis’ and ‘rising energy prices’, two economic issues that partly overlap. This makes illegal immigration the second political factor, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, that motivated voters’ choice.

Illegal immigration was cited, in first or second place, on average by 25% of those questioned about the issues that determined their electoral choice in June 2024. In four member countries, this item was ranked at very high levels: Cyprus (58%), Austria (35%), Malta (34%), and Slovenia (33%), which are among the countries most affected by ‘improvised migration routes’, particularly since 2015. Studies show that Europeans are not opposed to immigration, but to illegal immigration and immigration without integration.

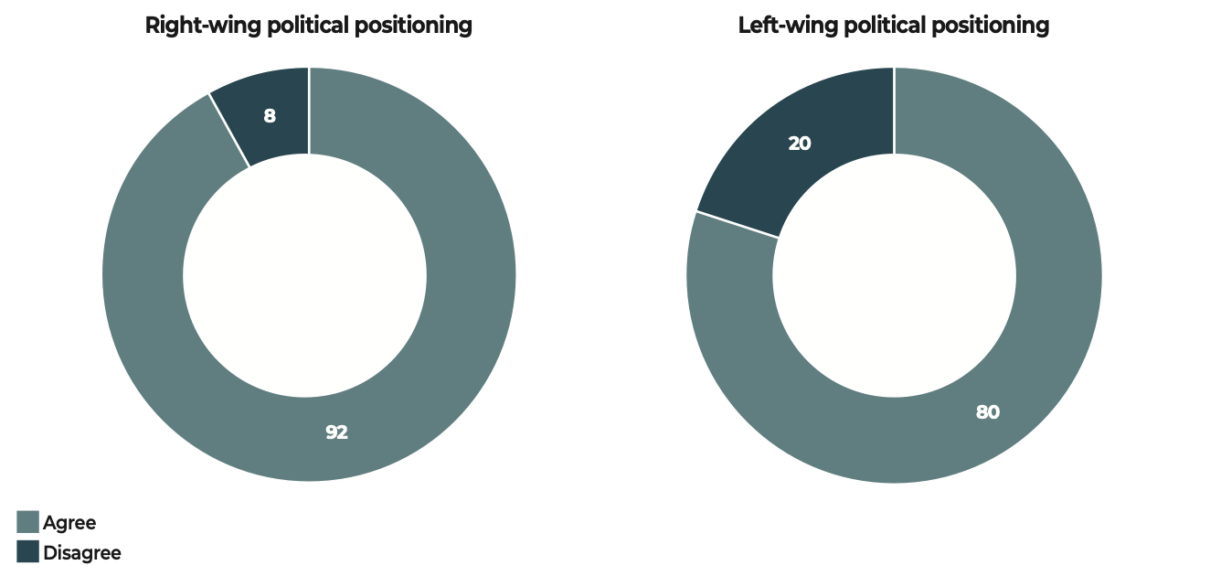

Whether left-wing or right-wing, Europeans want stronger common borders

Question: ″Some people say that the European Union should strengthen the control and protection of its external borders. Do you personally…?″

Responses: ″Strongly agree″ and ″Agree″ ; ″Disagree″ and ″Strongly disagree″

Base: respondents from EU countries on the left and right scales of the political spectrum

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Taking back democratic control of the public sphere

In the digital world, the demand for control over social networks mirrors the same need for borders, circumscription, and regulation seen in geographical, political, or regulatory contexts. Digital platforms, none of which are European but which govern and influence our lives, form the foundation of contemporary public space. They shape our social interactions and public and private exchanges, replacing the democratic stage once enabled by the printing press, the post office, the wired telephone, radio, television, and cinema since the 16th century.

The dematerialization of public space has led to a double loss of regulatory power.

Our public space, which was once governed by laws discussed and adopted by elected legislators and overseen by national authorities, has now been transferred to transnational platforms, effectively falling under the regulations of private companies. This is a phenomenon that European states are now keen to address due to its harmful and potentially irreversible effects, including the risk of losing our individual and collective freedoms and undermining the foundations of European culture and democratic life. But does Europe have the capability to counteract this trend? In essence, the preservation of our freedoms, border control, the fight against illegal immigration, and the aspiration for a European army all reflect the same demand for public authority.

The European Union must control the use of social networks

Question: ″Do you agree?: Social media platforms (Meta/Facebook, Instagram, X, WhatsApp, TikTok, Telegram, LinkedIn, etc.) have too much power over information and public debate and the European Union should be able to control them more″

Responses: ″Strongly agree″ and ″Agree″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reasonable voters left vulnerable to demagogues

Cf. Maria Elena Cavallaro, Gaetano Quagliariello, Dominique Reynié (dir.), L’Europe et la Souveraineté. Approches franco-Italynnes (1897-2023), éditions Plein Jour/Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2024; in Italian, the same authors: L’Europa et la Sovranità. Riflessioni italo-francesi (1897-2023), published by Rubbettino/Fondation Magna Carta, 2024.

All states claim sovereignty, regardless of their political systems. Popular sovereignty implies the freedom of the people, with the state serving as the instrument to execute collective decisions. However, will alone is meaningless without the power to act on it. There can be no popular sovereignty without public power. Today, many states—including European ones—lack the strength to maintain their independence in the event of armed conflict and cannot fulfill the will of their people. Does this mean they will no longer consider it?

For a long time, a nation’s political freedom has extended beyond mere sovereignty, defined as independence from neighboring countries. The current question is what power a so-called sovereign state can mobilize in service of the collective will, unless we accept the end of both state and popular sovereignty.15.

The idea of creating an additional European public power, which complements each nation’s authority, is highly justified to generate a new power that serves the associated peoples. Therefore, European integration only seems to threaten national sovereignty. In reality, building a European sovereignty offers the states of the Old Continent their only chance of survival in the emerging historical context. Although it might appear to conflict with national sovereignty, establishing a European public power is the only way for Europeans to regain the strength needed to both defend themselves and achieve their collective goals. Popular sovereignty without public power is futile; state sovereignty without popular sovereignty is tyranny.

What does it mean to be European?

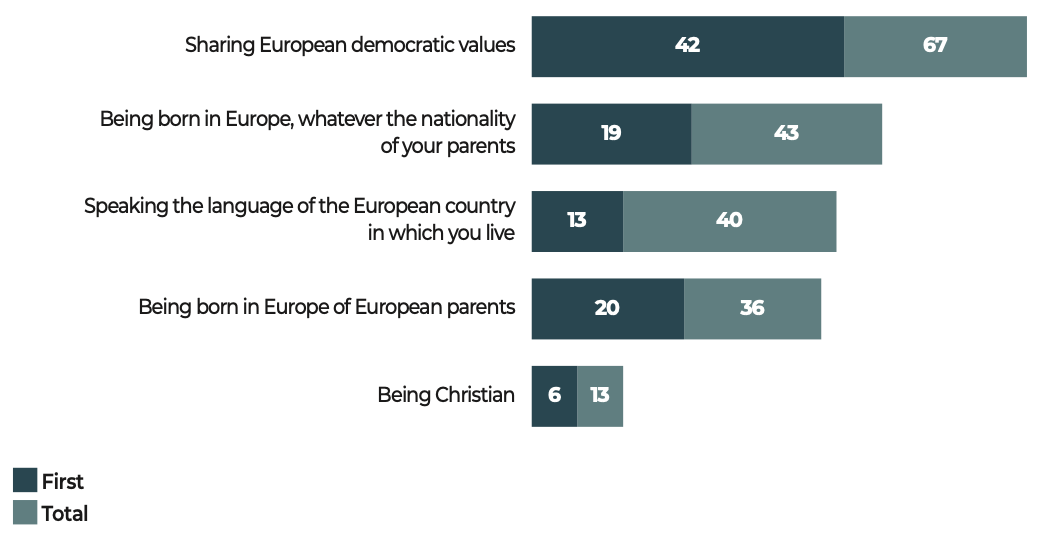

a. Sharing European commun values (67%)

When asked what “it means to be European,” the top response, either as the first (42%) or second (25%) answer, is “sharing European democratic values,” with a total of 67% of Europeans agreeing. Following this, 43% chose “being born in Europe, regardless of the nationality of one’s parents,” and 40% selected “speaking the language of the European country in which one lives.” The close ranking of a principle based on birthright and one focused on democratic values indicates confidence in the integration of immigrants. Thus, given respondents’ hostility toward illegal immigration, integration emerges as the major issue, rather than immigration itself.

Europeans share a definition of identity that is both political and inclusive. However, the preference for an open understanding of common identity implies, in return, the defense and promotion of European values. This explains why Europeans are less hostile to legal immigration than to illegal immigration and immigration without integration.

Integration is demonstrated by embracing European democratic values. It is a major political requirement, as it allows these values to be upheld by welcoming newcomers and ensures their continuity by passing them on. This moral imperative stems from the fear of eroding common values. “Sharing European democratic values” is cited as a definition of European identity by 73% of those over 60, compared to only 60% of those aged 18-34. The younger category is also more likely (48%) to consider being European as being born in Europe, “regardless of the nationality of one’s parents,” compared to 44% of those aged 35-59 and 36% of those over 60. These figures suggest that younger generations may be diverging in their views, or that demographic changes are leading to a shift towards alternative political or religious values.

A political definition of identity

Question: ″In your opinion, does being European mean…?″

First and Total

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

The religious criterion is only marginally used by respondents to define European identity. This reflects a continent that is partially de-Christianized and, more significantly, secularized. Religion is mentioned more frequently in countries of the former Eastern bloc: 18% of respondents there say that being European means being Christian, compared to an average of 13% in the European Union overall. There is a stronger attachment to a religious dimension of European identity in Bulgaria, where 24% of citizens affirm that being European means being Christian, as well as in Poland (20%), Slovakia (20%), and Hungary (18%). The highest response is in Greece, at 32%.

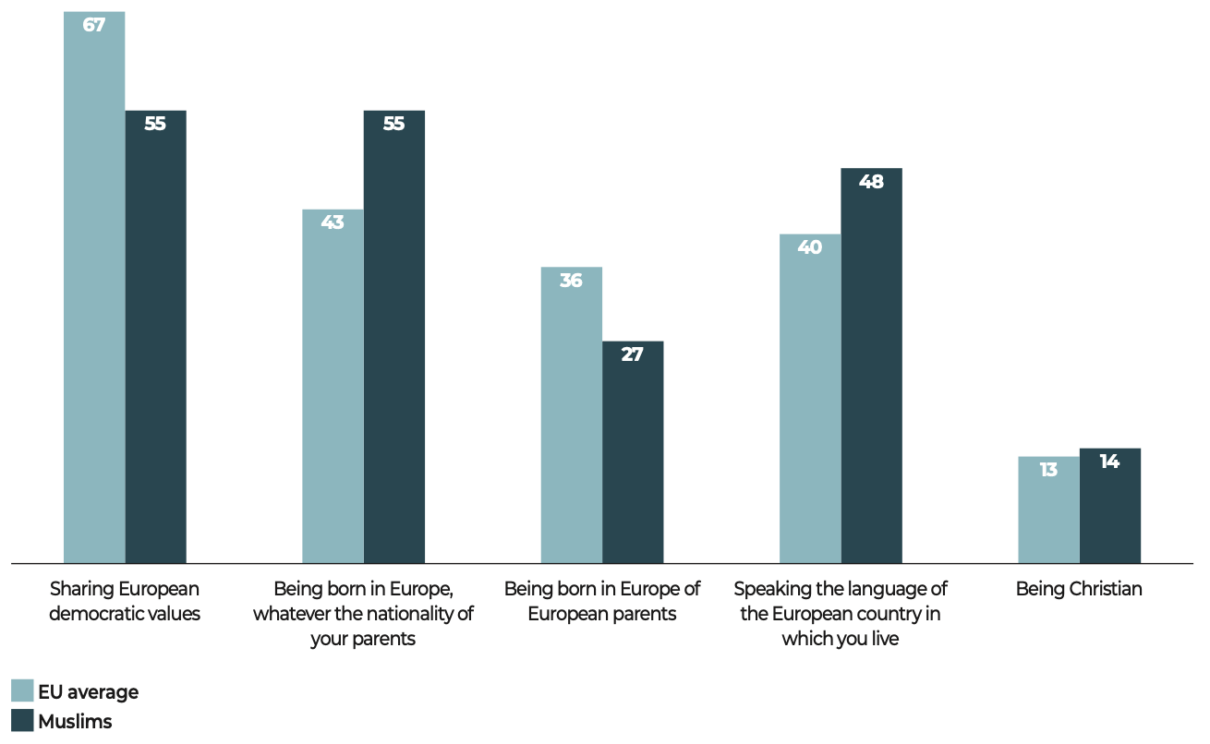

European Identity According to People of Muslim Faith

Overall, respondents of Muslim faith seem to share the same opinions as the average European. However, the survey revealed some notable differences. More than half of Muslim respondents (50%) are concerned about the actions of the United States on the international stage, compared to an average of 34% for all Europeans surveyed. Additionally, 32% of Muslims surveyed said that the war between Israel and Hamas would influence their vote in the European elections of June 2024, compared with an average of 11%.

In equal measure, half of Muslims (49%) say they find Russia’s international policy worrying. However, a significant minority find reassurance in Russia’s actions (22% compared to 7% on average). Iran’s international actions worry 39% of Muslims, while a fifth (18%) feel reassured by them. The perception of China’s international policy is even more varied: 36% of Muslims find Beijing’s actions worrying, while 28% find them reassuring. Notably, Turkey stands out for its popularity among Muslim respondents. Forty-five percent of them express reassurance regarding Turkey’s international policy, while 18% express worry.

The survey results indicate that the vast majority of Muslim respondents support strengthening control and protection of the European Union’s borders, with 78% in favor of this policy. External security and managing migratory flows are concerns shared by all EU citizens.

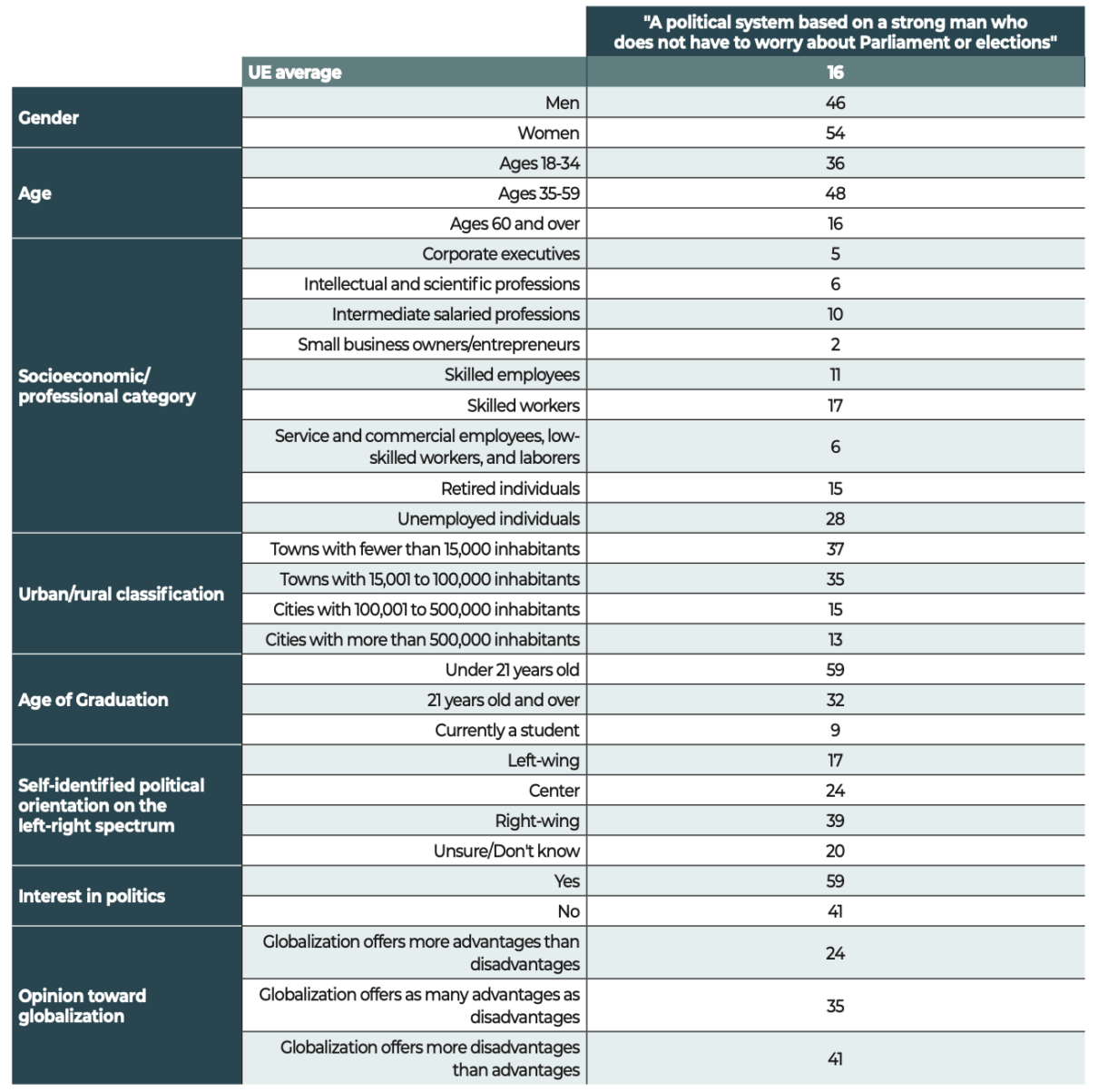

Lastly, the preference for an authoritarian regime is more prevalent among European Muslims. Support for a political system centered on “a strong leader who is not bound by parliament or elections” stands at 33%, well above the average of respondents (16%).

Muslim Europeans mostly identify with sharing European democratic values and being born in Europe as the defining factors of their European identity

Question: ″In your opinion, does being European mean…?″

First and second

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

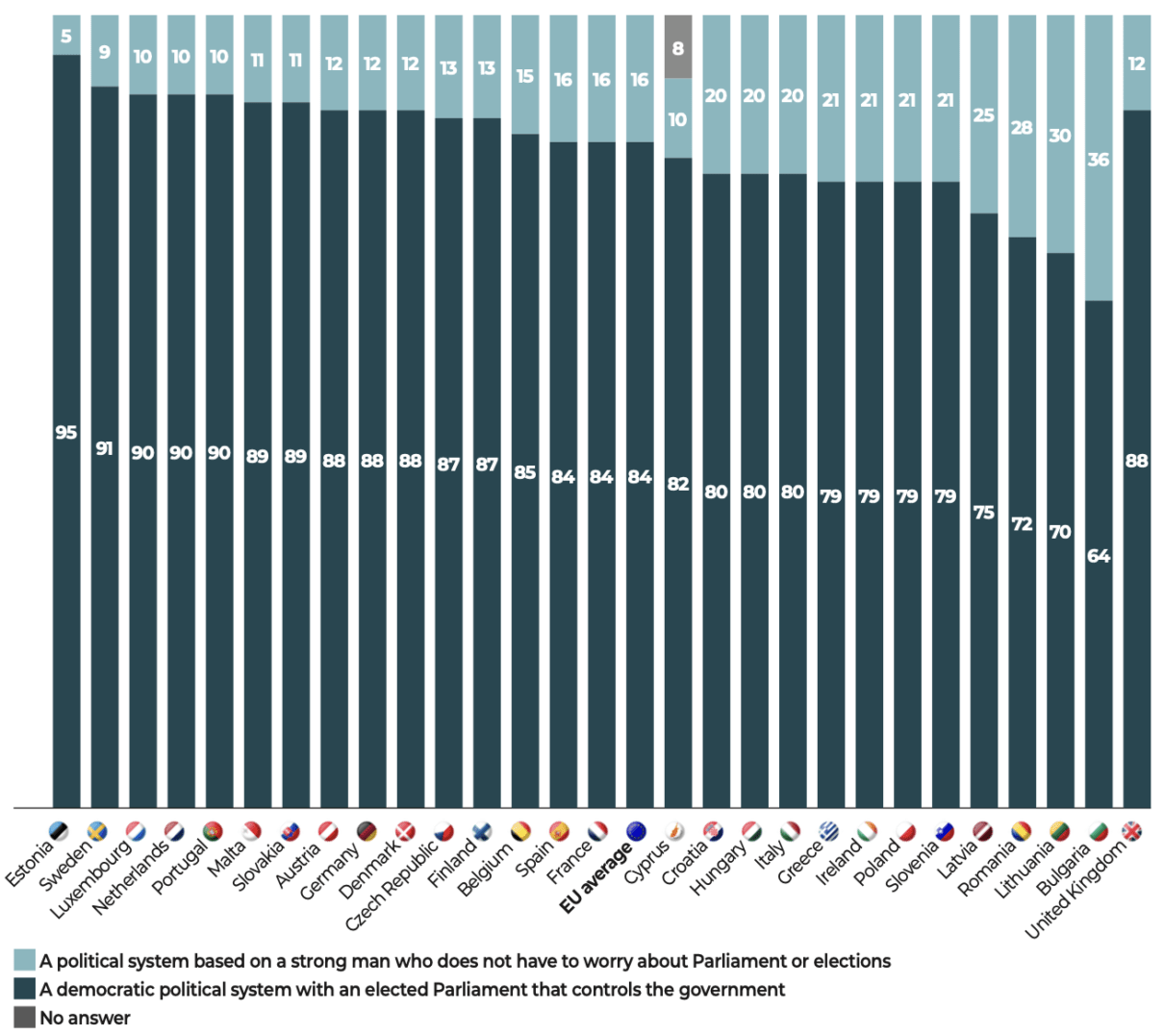

b. Europeans choose democracy (84%)

84 % of European citizens prefer a democratic political system, characterized by “an elected Parliament that controls the government,” over an authoritarian system, characterized by “a strong leader who is not bound to Parliament or elections.” The widespread preference for democracy and support for the European Union are so intertwined within the EU that they inevitably converge.

However, attachment to democratic institutions varies significantly based on respondents’ age. Indeed, 22% of 18-34 year-olds prefer an authoritarian political system over a democratic one, which is 6 points higher than the average, while only 9% of those over 60 hold this preference. These significant disparities highlight the risk of erosion in democratic culture. This risk is evident in the generational shift and the increasing influence of citizens more inclined towards authority rather than freedom.

Europeans desire a democratic political system featuring an elected Parliament that oversees the government

Question: ″Which of these two political systems would you prefer to govern your country?″

Base: EU countries and UK

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Profile of Europeans who approve of an authoritarian political regime

Question: ″Which of these two political systems would you prefer to govern your country?″

Response: ″A political system based on a strong man who does not have to worry about Parliament or elections″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: 46% of those who answered ″Have a political system based on a strong leader who is not bound to parliament or elections″ (16% of respondents in the European Union) are men, 54% are women.

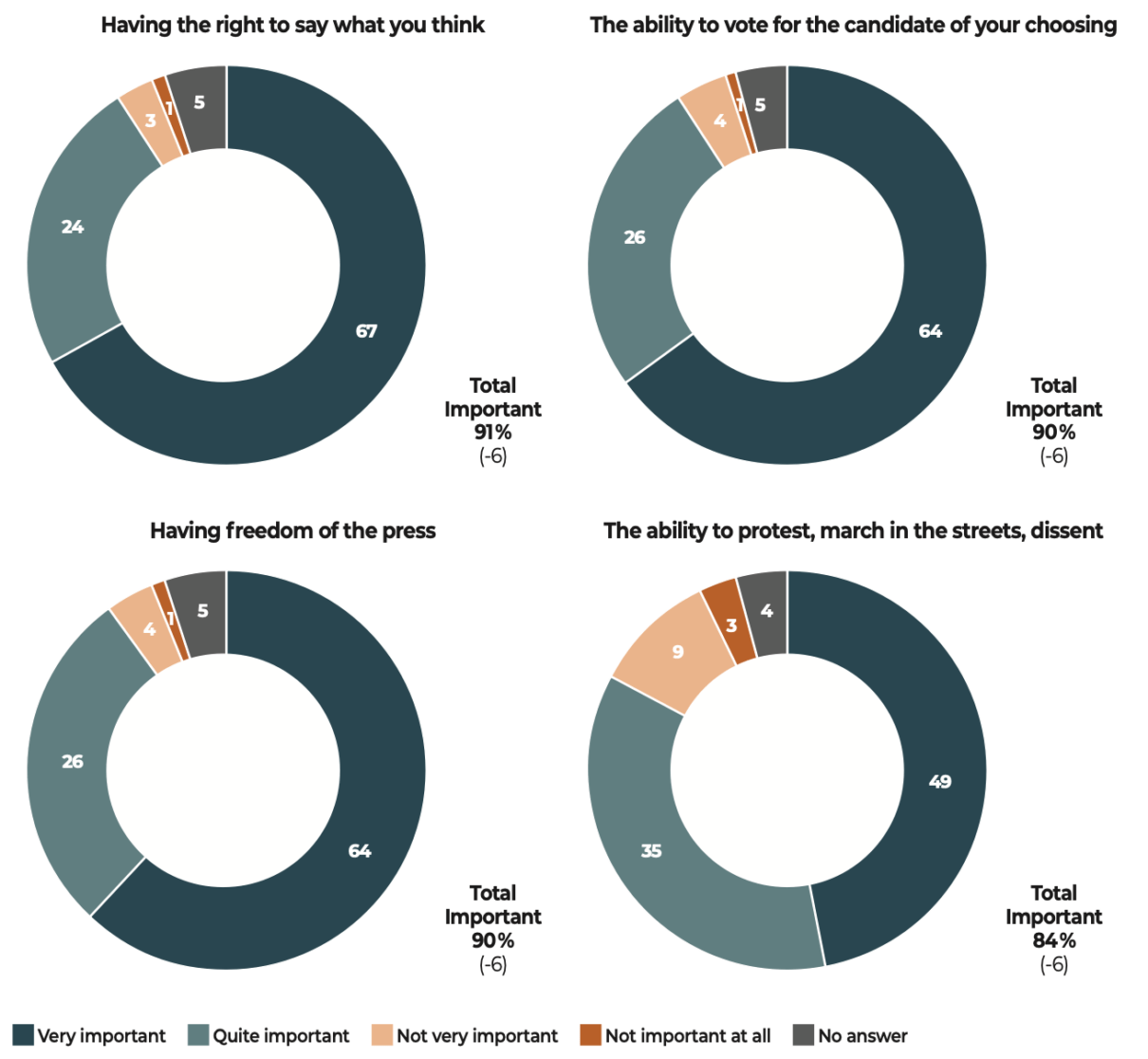

Democracy embodies freedom

European integration and democratization: a strong commitment to freedoms in former communist bloc states

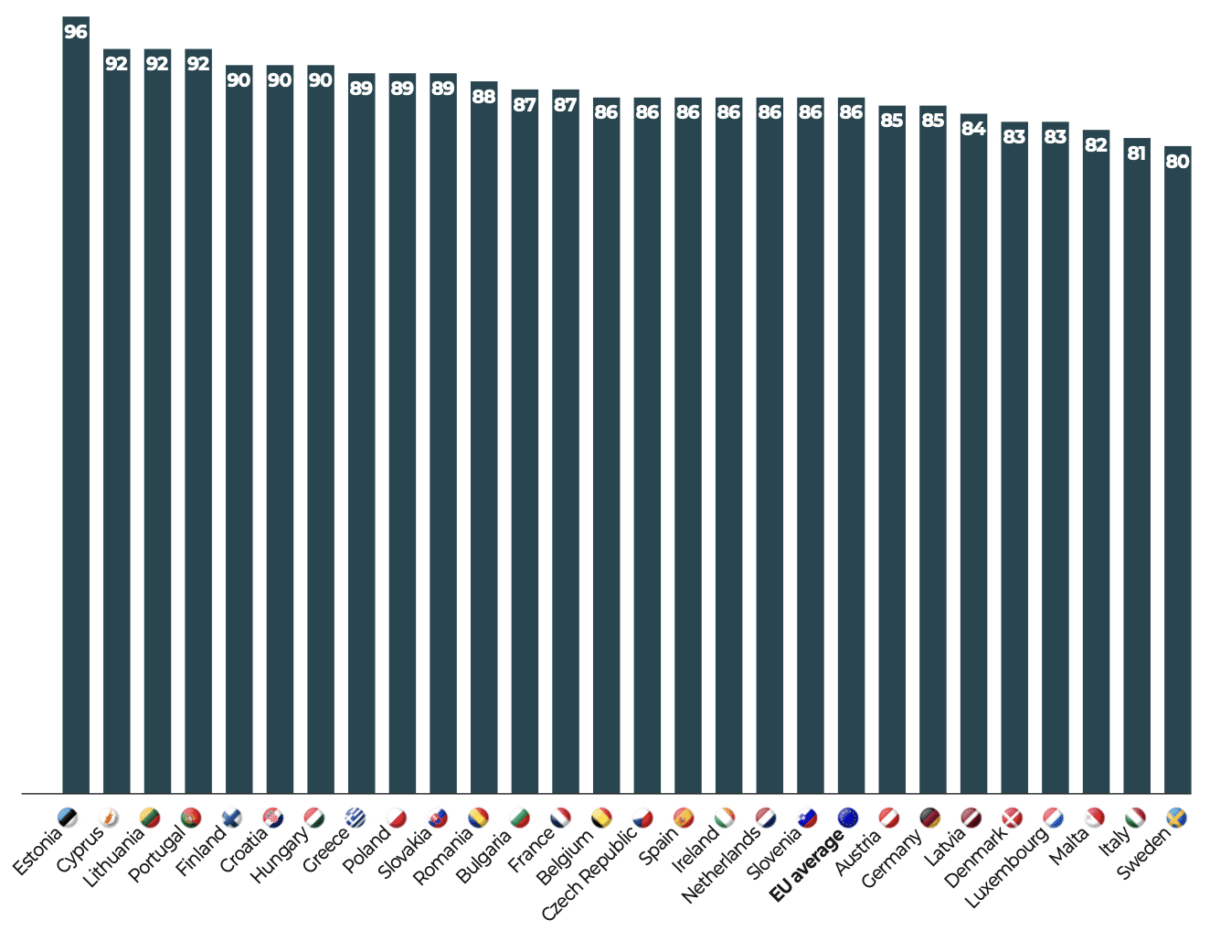

Twenty years after their integration into the European Union, the countries of the former Eastern bloc express a strong attachment to fundamental freedoms. Most respondents (82%) consider “the freedom to protest, to demonstrate in the streets, to challenge” to be important for the proper functioning of democratic regimes; the same goes for freedom of the press (88%) and “being able to vote for the candidates of one’s choice” (88%).

Comparable levels of support for fundamental freedoms can be observed in Croatia and Slovenia, two former communist countries that were not dependent on the Moscow regime. The majority of respondents recognize the importance of the freedom to protest, whether in Croatia (86%) or Slovenia (75%), freedom of the press (Croatia 86%, Slovenia 85%) and the ability to vote freely for the candidates of one’s choice (Croatia 89%, Slovenia 85%).

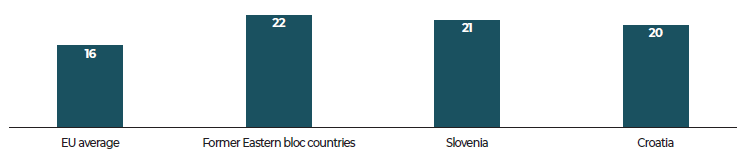

The continuing threat from Russia is reflected in support for their country’s membership of NATO, considered “a good thing” by 73% of respondents, compared with 67% for the average NATO country. Similarly, 38% of respondents in former Eastern bloc countries cite the invasion of Ukraine as a problem influencing their choice of vote in the June 2024 European elections, compared with a European average of 32%. Finally, it is important to note that in former communist countries, the preference for an authoritarian political system is shared by a fifth of those questioned.

In former communist countries, one-fifth of respondents express a preference for an authoritarian system

Question: ″ Which of these two political systems would you prefer to govern your country?″

Response: ″A political system based on a strong man who does not have to worry about Parliament or elections″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Europeans Define Themselves Through Freedom

Question: ″For each of the following items, please indicate whether it is important for a properly functioning democracy?″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Comment: Figures in brackets indicate percentage point changes in relation to the results of the survey Freedoms at Risk: the Challenge of the Century, Dominique Reynié (dir.), Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, Fundación Nuevas Generaciones, República do Amanhã, 2022 [fondapol.org].

What else distinguishes populist voters?

Members of the European Parliament: breakdown by country and political group, touteleurope.fr [fondapol.org].

a. Political groups in the European Parliament

This survey allows us to interpret respondents’ answers based on their stated intention to vote for one of the parties running in the election. Each party is affiliated with a group in the European Parliament.

By associating responses with a party’s voting intention and considering party affiliations to parliamentary groups, we can ascertain the average opinion of each parliamentary group’s electorate and compare these diverse electorates. For a political group to be established, it must consist of a minimum of 23 members from at least a quarter of the member states. During the 2019-2024 legislative period, the European Parliament comprised seven political groups:

• The European People’s Party (EPP): with 25% of MEPs, the EPP was the leading group by number of MEPs in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature. The EPP group brings together Christian Democrat and liberal-right parties. Its positions are generally pro-European. The main national parties belonging to this group are the CDU-CSU in Germany, the Peasants’ Party (PSL) and Civic Platform (PO) in Poland, the People’s Party in Spain, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), Les Républicains in France and Forza Italia in Italy. Fidesz, the political party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, was suspended from the EPP in 2019 due to its sovereignist stance. Fidesz left the EPP group in March 2023 to join the Non-affiliated members (Non-Inscrits Group – NI).

• Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament (S&D): the second largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (20% of MEPs), S&D is a center-left grouping of European socialist, social democratic and labor parties. Its positions favor European integration. National parties belonging to this group include the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), the Democratic Party (PD) in Italy, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Social Democratic Party of Romania (PSD), the Portuguese Socialist Party (PS), the Alliance of the Democratic Left (SLD) in Poland, and the Socialist Party (PS) in France.

• Renew Europe (RE) : The third-largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (14% of MEPs), Renew Europe is positioned at the center of the political spectrum, bringing together liberal and democratic parties promoting progressive ideas. The group defends a federalist vision of the European Union. At national level, the group is represented, among others, by the main parties in the French presidential majority (Renaissance, Horizons, MoDem), by Ciudadanos (CS) in Spain, by the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) in the Netherlands, and by the German Liberal Democratic Party (FDP).

• The Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA): the fourth largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (11% of MEPs), this group brings together environmentalist and regionalist parties that support minority self-determination. The Greens/EFA group is generally left-leaning, with a pro-European stance on European integration. The main national parties belonging to this group are Bündnis 90/Die Grünen in Germany, Europe Écologie Les Verts (EELV) in France, Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative in Austria and GroenLinks (GL) in the Netherlands.

• European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR): the fifth largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (10% of MEPs), the ECR is to the right of the European People’s Party, promoting socially conservative and economically liberal positions. As far as European integration is concerned, the European Conservatives and Reformists defend the concept of a “Europe of nations”. They therefore oppose further European integration of member states. National parties belonging to this group include Fratelli d’Italia (FDI) in Italy, Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, Vox in Spain and the Sweden Democrats. Reconquête!, the French political party of Éric Zemmour and Marion Maréchal, announced that it would join the ECR group in February 2024.

• Identity and Democracy (ID): the sixth-largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (8% of MEPs), ID is the most right-wing group on the political spectrum. It brings together several political formations classified as right-wing populists or extreme right-wingers. ID advocates Eurosceptic, even anti-European, identitarian and nationalist positions. Among the main national parties belonging to this group are France’s Rassemblent National (RN), Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom (PVV), Italy’s Lega, Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) and Portugal’s Chega.

• The Left in the European Parliament – GUE/NGL: the seventh largest group in the European Parliament during the 2019-2024 legislature (5% of MEPs), bringing together left-wing and far-left parties, including some left-wing populists, the group called “The Left” is the most left-wing in the European Parliament. In terms of European integration, it challenges the idea of a Europe of markets, and develops a radical critique of the current organization of the European Union. The main national parties belonging to this group are La France insoumise (LFI) in France, Podemos in Spain, Die Linke in Germany and Syriza in Greece.

• 7% of MEPs do not belong to any political group, but are considered “non-affiliated” and join a group with that name. Most non-affiliated MEPs belong to the Hungarian Fidesz party and the Italian 5-Star Movement (M5S)16.

| At the time of completion of this study the RN and the Lega announce their decision to no longer belong to the same group as the AfD. |

b. Voters of populist parties are in favor of the European Union and the euro

The question is: how do voters for populist parties in Europe differ from those who support parties that are part of a group in the European Parliament? Specifically, we aim to establish whether supporters of populist parties show unique patterns compared to voters of other political groups and the overall European average.

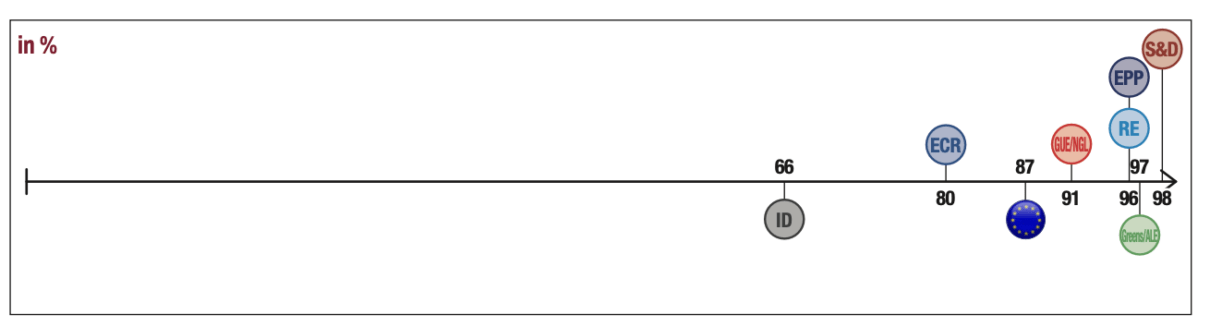

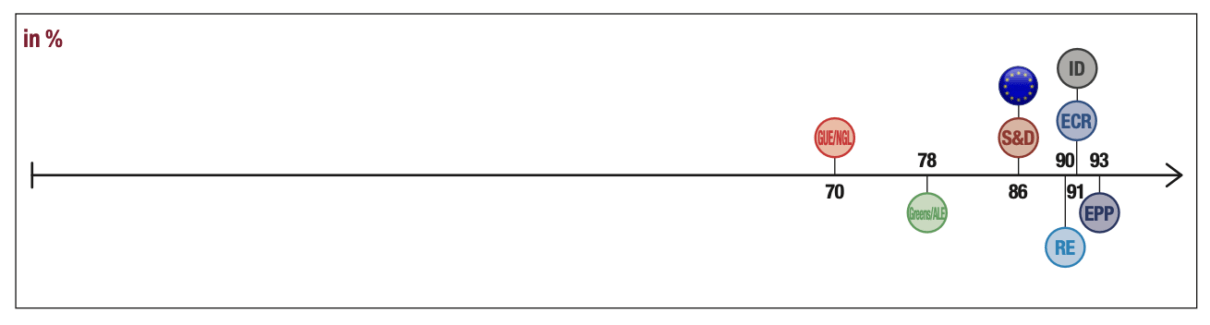

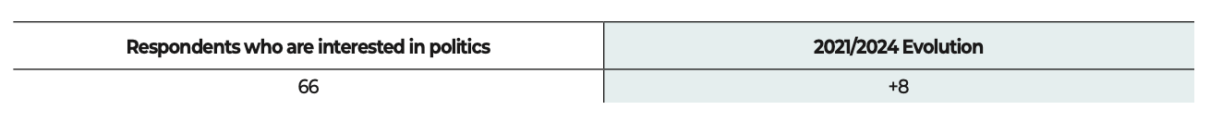

We found that 87% of Europeans support the European Union and their countries membership. On average, 66% of voters who intend to vote for a party belonging to the Identity and Democracy (ID) group, to which Marine Le Pen’s RN belongs, are also in favor of the European Union. The figure is even higher (80%) for voters intending to vote for a party belonging to the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, Giorgia Meloni’s group. The same applies to the euro, favored by 78% of ID voters and 90% of ECR voters.

Most voters in the two populist groups ID and ECR are in favor of the European Union

Question: Concerning the European Union, which of the following opinions do you most agree with?

Responses: ″You’re in favour of the European Union and of your country being part of it″ and ″You’re not in favour of the European Union, but you don’t want your country to leave it – what’s done is done″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: 96% of voters who say they vote for a party belonging to the EPP group in the European Parliament do not want their country to leave the European Union.

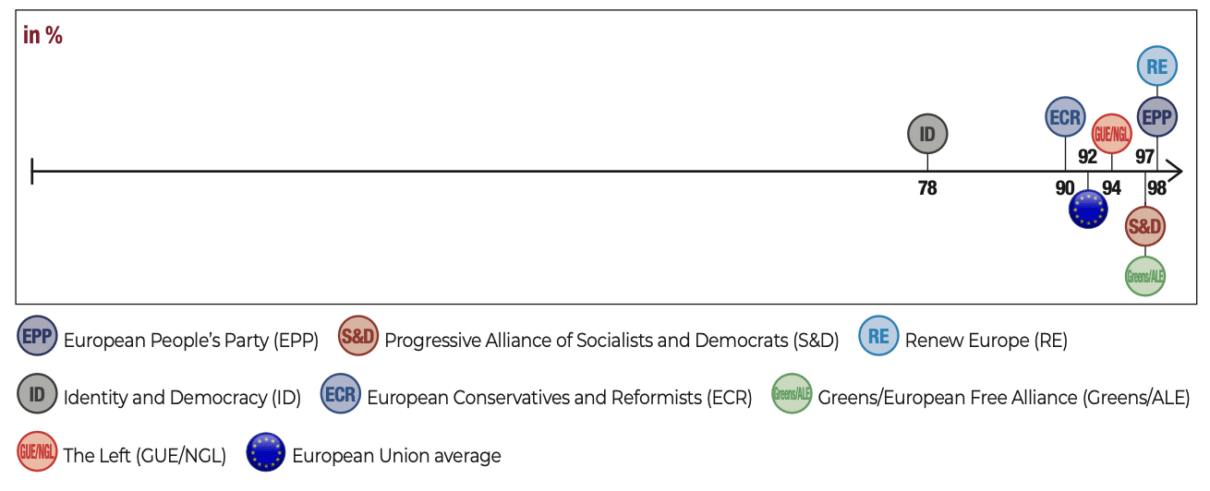

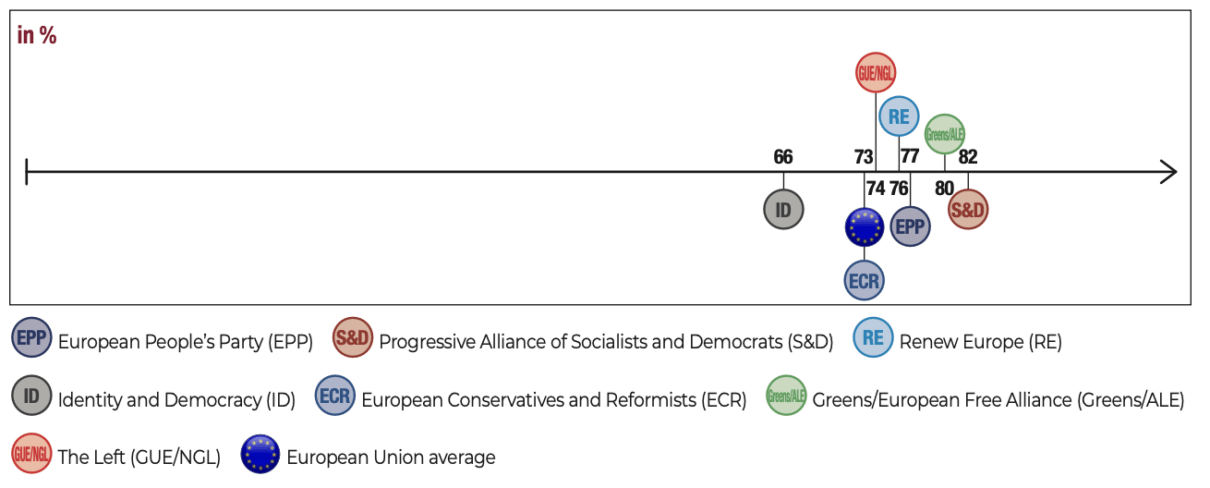

Almost all voters of the two populist groups ID and ECR are in favor of the euro

Question: Regarding the Euro, which of the following opinions do you agree with most?

Responses: ″Your country should keep the Euro as its currency″ and ″Your country should go back to using its national currency but you do not feel that that is possible″

Base: Euro zone

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: 97% of voters who say they vote for a party belonging to the S&D group in the European Parliament have accepted the euro as their currency.

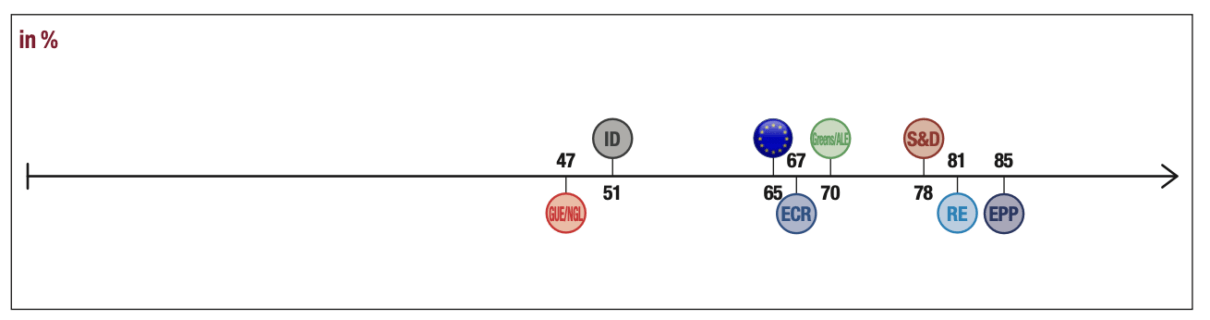

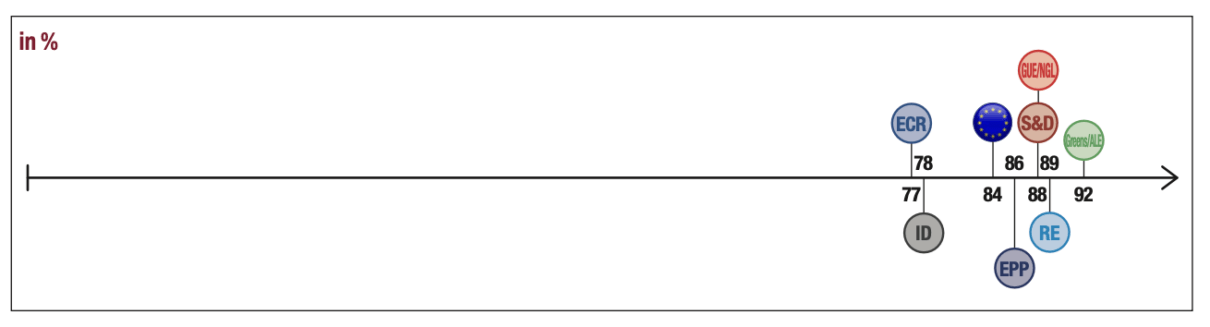

c. Voters of populist parties support NATO and a European army

Regarding their country’s NATO membership, ECR voters align closely with the European average. While ID voters show less enthusiasm, it’s worth noting that half of them support their country’s accession to the Atlantic alliance.

Among voters in the Left in the European Parliament group, support for NATO is only held by a minority

Question: NATO is a military alliance of European countries, including your own, Turkey, the United States and Canada. Do you think that your country’s membership of NATO is…?

Response: ″A good thing″

Base: Countries of the EU that are part of NATO

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: Among voters who say they vote for a party that is a member of the RE group in the European Parliament, 81% think their country’s membership of Nato is a good thing.

Majority support for a common European army in every electorate

Question: Would you like the European Union to form a joint army for all member states, in addition to national armies?

Responses: ″Yes, absolutely″ and ″Yes, somewhat″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: Among voters who say they vote for a party that is a member of the Greens/EFA group in the European Parliament, 73% are in favor of creating a common army for all member states.

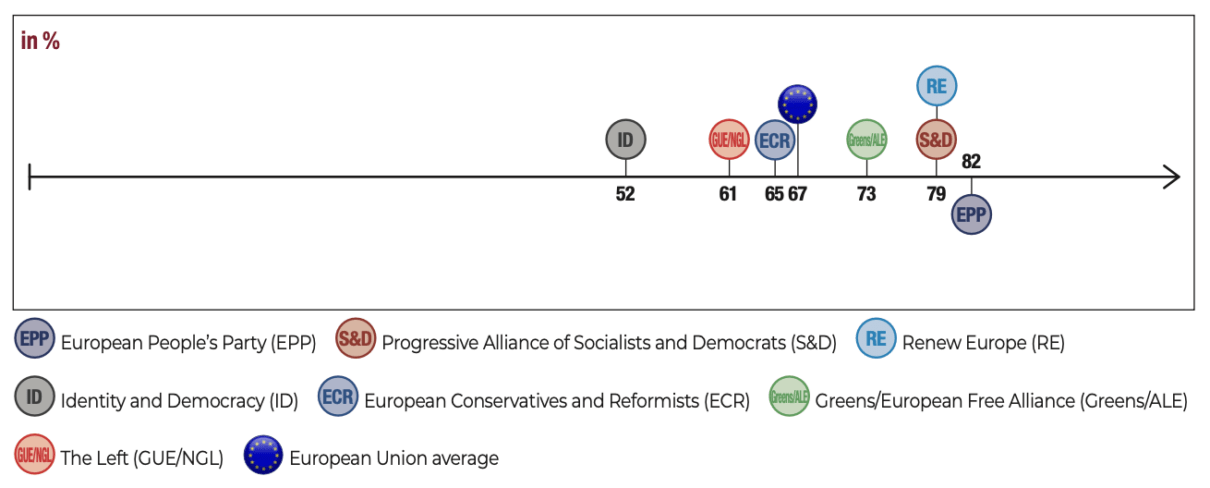

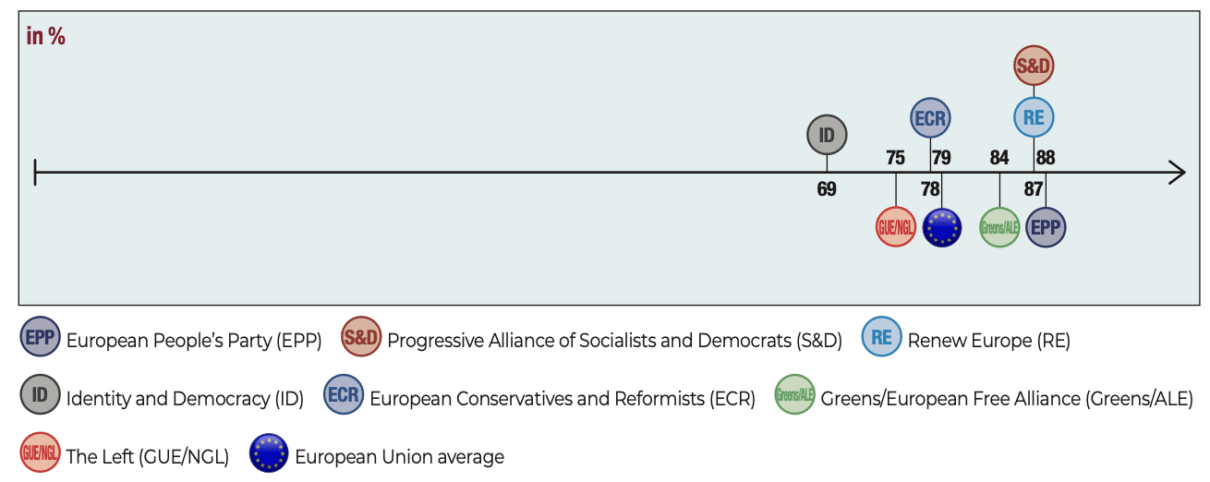

d. Voters of populist parties are almost universally in favor of strengthening common borders

While support among ID and ECR voters for enhancing, regulating, and protecting the European Union’s external borders may be very high, it’s worth noting that this sentiment is also prevalent among all electorates, including those of the far-left group (GUE/NGL) and the environmentalist group (Greens/EFA).

The emphasis on border protection highlights the alignment of populist voters with the broader electorate

Question: Some people say that the European Union should strengthen the control and protection of its external borders. Do you personally…?

Responses: ″Strongly agree″ and ″Agree″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: 91% of voters who say they vote for a party that is a member of the ECR group in the European Parliament agree that the European Union should strengthen the control and protection of its external borders.

The Control of Social Networks by Europe Unites Most Voters, Including Populist

Question: Do you agree? ″Social media platforms (Meta/Facebook, Instagram, X, WhatsApp, TikTok, Telegram, LinkedIn, etc.) have too much power over information and public debate and the European Union should be able to control them more″

Responses: ″Strongly agree″ and ″Agree″

Base: EU countries

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – June 2024

Reading grid: among voters who say they vote for a party that is a member of the ID group in the European Parliament, 66% agree that the European Union should be able to control social networks more.

e. Voters of populist parties are in favor of parliamentary government and freedoms

Even on a fundamental issue like the nature of the political regime, it’s challenging to clearly distinguish the voters of populist parties in the ECR and ID groups. Although there is a 6 to 7-point difference from the European average, the significance of this gap is hard to determine, as responses overwhelmingly converge towards a high level of approval for the democratic model.