Before Covid-19, air transportation in Europe: an already fragile sector

Updated versionGlossary of the main terms used

Introduction

A fragmented intra-european market before the crisis

Air transport, a low-margin sector

A European market less concentrated than in the United States

Numerous small actors

Covid-19 shock : historic companies in turmoil

Two giants in turmoil: Air France-KLM and Lufthansa

An unavoidable call for public assistance

Covid-19 shock : the resilience of the low-cost giants

The ultra low-cost will survive the crisis

Middle-costs in a more critical situation

It is not enough to be big and low-cost: the Norwegian counterexample

Conclusion of the first volume

Summary

Although European airlines were hit hard by the Covid-19 crisis, not all are in the same boat both in terms of their ability to withstand it and in terms of access to public aid. Specifically, certain “flag-carrier” companies, such as Air France-KLM or Lufthansa, in a critical financial situation, were saved thanks to government support. On the other hand, a few large low-cost airlines, such as Ryanair or Wizz Air have sufficient financial strength to enable them to overcome the crisis. The situation of middle cost companies such as easy Jet appears to be more uncertain.

Our thesis is that the European market, in a situation that was already fragile before the health crisis, is probably going to experience a strong restructuring movement that will benefit low-cost actors following the bankruptcy of small operators and the attrition of the large incumbent airlines, which will be forced to reduce their wings, unless they resolutely adopt a low-cost medium-haul model.

| This study was published in May 2020 and updated in December 2020. |

Didier Bréchemier,

Senior Partner, in charge of the transportation and travel sector at Roland Berger.

Emmanuel Combe,

University Professor, Professor at the Skema Business School, Vice-President of the Competition Authority.

After Covid-19, air transportation in Europe: time for decision-making

Europe in the face of American and Chinese economic nationalisms (1)

Europe in the face of American and Chinese economic nationalisms (2)

Europe in the face of American and Chinese economic nationalisms (3)

Towards personalised pricing in the digital era ?

Glossary of the main terms used

Point-to-point activity: activity consisting of transporting passengers from point A to point B without any connections.

Base: airport where a company operates and where aircrafts and crews are stationed, allowing, among other things, a flight schedule with early morning departures and late evening returns.

CSKO (unit cost per available seat-kilometre): an indicator that measures the unit cost of a seat for one kilometre by air. This cost decreases with the distance travelled.

Connection: a system that simply allows a passenger to switch from one flight to another at the same airport, without any guarantee of continuity, which is not the case with correspondence.

Corresponding: system that allows a passenger at the same airport to transfer from one flight to another by transferring his or her luggage and guaranteeing continuity of service between the two flights (e.g. in the event of a delay).

Hub: central airport that acts as a hub, connecting flights to each other through connections. A passenger travelling from point A to point C will stop at hub B, which connects flight AB with flight BC.

Long-haul: flights lasting more than 4 hours.

Middle-cost: airline whose CSKO is between 3 and 6 cents per kilometre (excluding fuel).

Medium-haul: flights lasting between 1 and 4 hours.

RASK (unit revenue per available seat-kilometre): indicator that measures the revenue generated by a seat over one kilometre on an aircraft.

Slot: the right to use a take-off slot at an airport for a given schedule.

Ultra low-cost: airline whose CSKO is less than 3 cents per kilometre (excluding fuel).

The authors of this two-volume study would like to thank Alexandre Charpentier, manager at Roland Berger, for his work as editor. The authors remain solely responsible for its content, which is not binding on the institutions and organisations for which they work.

The data used in this study come from Roland Berger and are derived from a variety of raw sources, including companies, private databases and IATA’s public reports.

Beyond air transport, the entire value chain of the aeronautics industry is severely impacted, from manufacturers (Airbus, Boeing, etc.) to all subcontractors (Daher, Safran, etc.). As the French newspaper Les Echos announced on the front page of its 28 April 2020 edition, we can speak about this industry as the “crisis of the century”. Also see: Guy Dutheil, “Coronavirus: Airbus et l’aéronautique s’enfoncent dans la crise”, Le Monde, 29 April 2020, as well as Véronique Guillermard, “Comment Airbus et Boeing tentent d’amortir le choc de la crise du Covid-19”, Le Figaro, 30 April 2020.

According to the IATA, the amount of airline tickets for flights to be operated over the next three months (which will not be used due to the cancellation of almost all airline activity) is $35 billion. To preserve their cash, airlines are offering the option of postponing flights and giving out credits instead of refunds.

According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the amount of airline tickets for flights to be operated over the next three months (and which will not be used due to the cancellation of almost all airline activity) amounts to $35 billion. To preserve their cash, the airlines are offering flight postponements or “credit notes” instead of refunds.

The Covid-19 crisis is an unprecedented shock for global air transportation1. According to the current head of the Air Transport Association (IATA), it is even “the worst crisis in the history of aviation”, far ahead of the events of 9/11 or the economic crisis of 2009.

It is true that estimates of the drop-in passenger air transport activity are staggering: despite a temporary rebound in June and July (due to the policies put in place after the lockdown ended), air traffic for the whole of 2020 is expected to be 66% lower than in 2019, according to the latest IATA forecast. Beyond the health crisis, the strong economic recession in the world in 2020, in the order of 5%, will undoubtedly impact air transport, whose activity is strongly correlated to economic growth 2. This fall in traffic must be compared with the structure of costs, partly composed of fixed costs, and airline revenues: whereas since the beginning of the health crisis, costs have fallen by 55%, revenues have fallen by 80%, leading to massive losses.

What’s more, the recovery in air traffic will be very gradual, with a return to pre-crisis levels only expected in 2024. The recovery will initially be seen on medium-haul routes and will primarily concern leisure and affinity customers.

In this unique context, most airlines, both in Europe and worldwide, have grounded a few of their planes, which means they have to bear high-fixed costs. The challenge is then for airlines to have access to enough liquidity in order to hold on to in order to survive for several months. In this race for cash, all instruments are now being mobilised by companies, whether it be the non-reimbursement of tickets (and their transformation into credit notes3), massive recourse to part-time working, the appeal for mass layoffs (like at British Airways), reduction of fixed structural costs, use of cash reserves or borrowing, renegotiation with aircraft rental companies, manufacturers and fleet financing bodies. For example, Lufthansa has made the decision to significantly reduce the size of its fleet from 150 aircrafts (out of a total of 760,

i.e. a decrease of 20%) and cut 22,000 jobs (i.e. 16% of its total workforce).

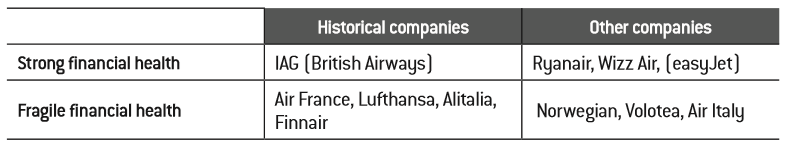

In this respect, not all airlines are in the same situation, both in terms of resilience and in access to public support.

European airline rankings by financial strength

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger.

The case of easyJet is atypical: the sharp fall in the share price is partly explained by a governance battle led for several weeks by one of the company’s founders calling into question certain strategic choices made by the management team, particularly regarding orders for new Airbus aircrafts.

Firstly, the so-called “flag-carrier” companies in a critical financial situation owe their survival to government support, in the form of guaranteed loans or equity investments. The Dutch, French, German, Italian and Norwegian governments supported the legacy carrier at all costs, even including a temporary nationalisation scenario (in Italy, from March for Alitalia, the country’s leading airline). It should be noted, however, that a legacy airline such as British Airways (IAG Group) has not yet applied for public support but carried out a capital increase of 2.75 billion pounds.

Secondly, we find many small companies that are in great financial difficulty, such as Air Italy, which did not receive public aid and were quickly forced into bankruptcy. This bankruptcy scenario is even more likely as the model of many airlines is based on the financing periods of lower activity (such as winter) by bookings made during the high season. In this respect, the Covid-19 crisis could not have come at a worse time, in the middle of the summer 2020 booking period.

Lastly, we find some European companies that have sufficient financial strength to face the crisis. This is particularly the case in Europe of large low- cost airlines such as Ryanair, Wizz Air and to a lesser extent, easyJet, who will be able to survive on their cash flow, obtain bank loans and/or “sale and lease back” their aircrafts. Similarly, in this category we find smaller airlines such as Air Caraïbes, that have enough liquidity and may carry out a capital increase, and will probably survive the Covid-19 crisis.

Our main thesis is that the European market, in a situation that was already fragile before the health crisis and with overcapacities on many routes, will undoubtedly undergo a strong restructuring movement, following the bankruptcy of small operators and the attrition of large incumbent companies, forced to downsize. This movement seems to be inevitable, regardless of the recovery scenario of traffic in Europe. We can even consider the probable scenario of the slow recovery of air traffic in Europe, only going back to normal in 2024, which will accelerate this restructuring movement.

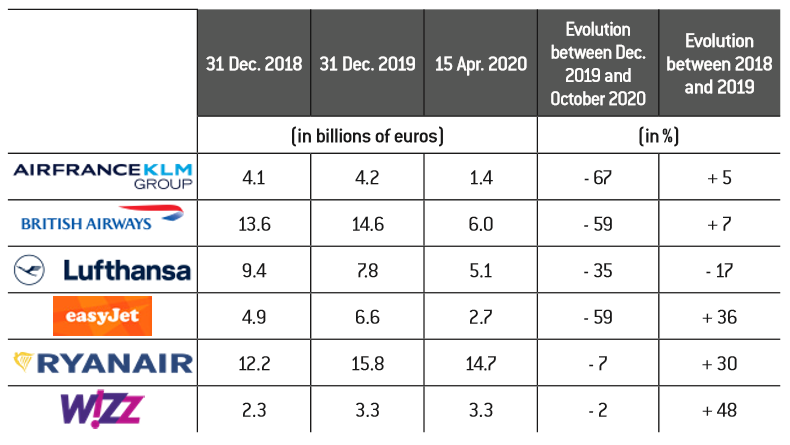

In this respect, the financial markets have naturally integrated these structural differences in the financial health of airlines long before the Covid-19 crisis. Indeed, throughout the year 2019, the market value of low-cost players has risen sharply (+ 33% if the three market capitalisations – EasyJet, Ryanair, Wizz Air – are compiled, compared with -2% if the capitalisations of International Airlines Group, Air France-KLM and Lufthansa are compiled). To measure performance gaps, we can remember that an airline like Ryanair was worth on average 3 to 4 times the market value of a group like Air France-KLM in 2019. Similarly, since the beginning of 2020, under the effect of the Covid-19 crisis, stock market sanctions appear to be fairly differentiated, between legacy carriers who have lost between 35 and 67% of their market value and ultra low-cost leaders whose whose market capitalisation has only fallen slightly4. In November 2020, Ryanair’s market capitalisation was equivalent to… 10 times that of Air France-KLM’s.

Evolution of market capitalisation during the Covid-19 crisis

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger.

The Covid-19 crisis occurred in Europe in a context marked by an already limited airline profitability. This is particularly true if we take as a scope the only intra-European medium-haul market, which does not perform as well as the long-haul market (often 10 points less in the operating margin). Recent years have also seen several medium-haul airlines go bankrupt: Aigle Azur, WoW Air, Small Planet Airlines and Germania, to name but a few.

While there are structural reasons for this low profitability, it is also due to the greater fragmentation of the European market compared to the U.S. market, which has been undergoing strong consolidation over the last 15 years.

However, in terms of profitability and ability to withstand the crisis, not all European airlines are in the same situation: while several legacy carriers such as Air France-KLM or Lufthansa will survive thanks to massive public aid, some low-cost operators such as Ryanair or Wizz Air will be able to get through the crisis by drawing on their reserves.

A fragmented intra-european market before the crisis

Air transport, a low-margin sector

The violence of the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on airlines can be explained by a structural reason specific to the sector: air transport is a high-volume but low-margin industry. Indeed, if we reason over a long period – since 2002 – and in aggregate – all regions combined -, the industry’s operating margin is around 3%. For the year 2019, this worldwide operating margin was 5.8%, even though we were at the top of the cycle (IATA 2020), which corresponds to a profit per passenger of only $6.85.

This structural weakness in margins stems from the fact that natural barriers to entry are fairly low, unlike in other sectors such as pharmaceuticals or automobiles. Indeed, excluding the availability of time slots at large congested airports and, for certain international flights, the granting of traffic rights by States, there are no major barriers to entry: a new airline can be launched with a few million euros of investment by leasing aircrafts. To use an economic terminology, air transport is like a “contestable market”: the possibility for a new player to enter the market quickly leads to a permanent pressure on prices and margins. To regain some market power, established companies have no choice but to lower their costs or to control a hub and network of alliances in order to limit the development of new entrants.

Another factor is that air transport is an industry of fixed and semi-fixed costs. The fixed or semi-fixed costs come from the payment of salaries (especially of aircrew), aircraft rentals (when not in full ownership), aircraft maintenance, and debts. These fixed costs represent about 50% of the operating costs of a conventional airline.

A small drop in activity – and especially a drop in the load factor – quickly leads to losses. As a result, the rate of entry and disappearance in air transport is high: every year, many new companies are created, while others, often small ones, leave the market. In 2019, which was a good year in terms of profitability, no fewer than 23 airlines worldwide have ceased operations.

A European market less concentrated than in the United States

However, although the profitability of air transport is structurally low, the profitability of European airlines, which was in line with the world average in 2019, contrasts with that of their American counterparts, which was more than double at 9.6%.

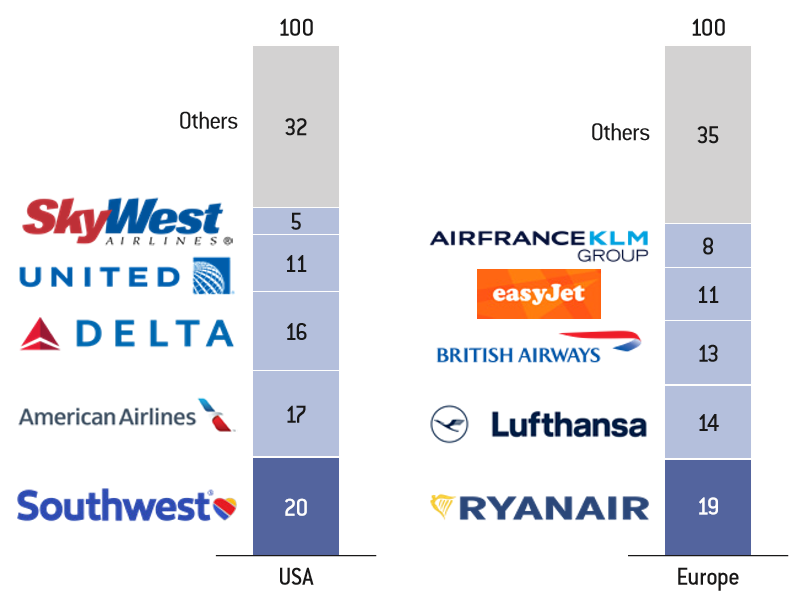

This differentiated situation can be explained by the evolution of the American market over the last 20 years: during the decade 2000 – and especially after the September 11th attacks and the recession of 2009 – American companies experienced a decade of losses, which led to numerous bankruptcies. The result has been a process of market concentration around four main players (American, Delta, Southwest, United). In 2019, the top four operators on the U.S. domestic market represented, in terms of the number of passengers, a market share of 64%. Moreover, among these four players, only one is a “middle cost” operator (Southwest) able to drive price competition. The other low-cost operators, namely Jetblue, Frontier and Spirit Airlines, are much smaller. This high concentration of the American market has also caused concern among many economists as it results in an increase in the average ticket price.

Share of intra-Europe/intra-US traffic by actors in 2019 (in %)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, Innovata.

In contrast, the European market remains for the moment a little less concentrated than the American domestic market: the top four operators (Ryanair, Lufthansa group, IAG and easyJet) account for 57% of the intra- European market. It should be added that, among the four leaders in the sector in Europe, two are “low-cost”, including one “ultra low-cost” (Ryanair), which contributes strongly to stimulating price competition. By comparison, the leading ultra-low-cost carrier in the United States, Spirit Airlines, has a market share of 3% and is only in 8th place in terms of capacity (seats offered).

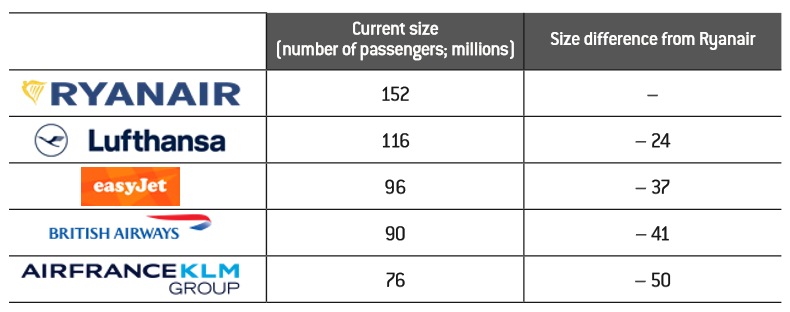

If one considers the number of passengers carried on medium-haul flights, it is striking to note that Ryanair was until 2019 the leading European carrier, ahead of Lufthansa. The difference in size was even more pronounced with the other companies: for example, the size of IAG on medium-haul represented only 59% of that of Ryanair.

Number of passengers carried by the European leaders in the medium-haul market

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger, based on airline company data.

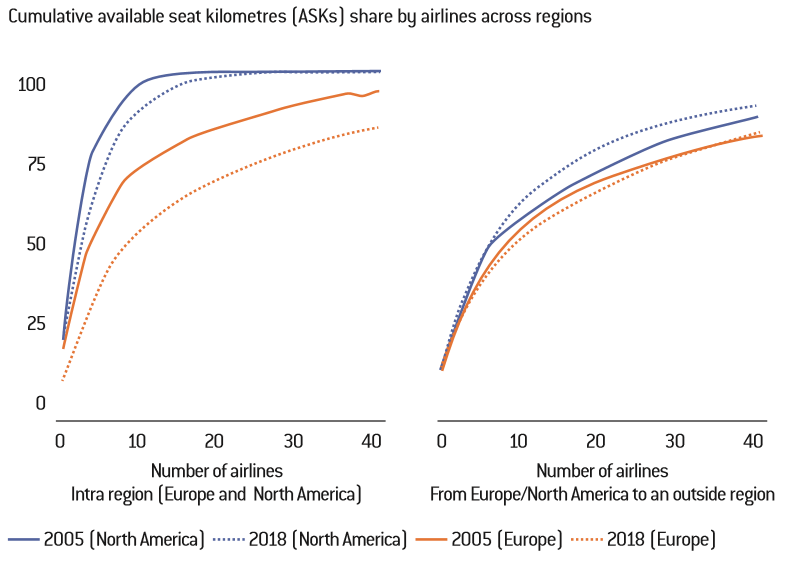

Numerous small actors

In addition to the least market concentration among the top 5 of these airlines, Europe is characterised by a very large number of small players: the tail end of the size distribution is very long, once you get past the top five companies. This lower concentration appears to be particularly marked on medium-haul compared with long-haul. Indeed, on long-haul, a movement of consolidation has already taken place, in the form of alliances, joint ventures (especially on transatlantic flights), bilateral agreements, while traffic rights limit the penetration of new players.

Conversely, on medium-haul routes, there will be more than a hundred airlines (scheduled flights) in Europe in 2020, with market shares of 1% or less; this is mainly due to the fact that each European country has at least one flag carrier, often inherited from the past, and has seen the creation of at least one low-cost operator on its territory. For example, Romania has a national airline, Tarom, which operates a fleet of 26 aircrafts and carried 2.7 million passengers in 2018; it also has a low-cost airline, Blue Air, which carried 3.9 million passengers.

Airline consolidation compared between Europe and the U.S.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

PlaneStats.com; Airline schedule data, IATA industry statistics.

Except for a few cases (such as Air Caraïbes in France), small players, whether low-cost or not, perform below average, confirming the key role that critical size plays. Indeed, achieving a critical size is a necessary (though not enough) condition for profitability in air transport, for at least three reasons.

The first is economic: air transport has high fixed costs, which are not limited to aircraft rent and maintenance, but also include marketing expenses or structural costs (real estate, reservation system, etc.). An increase in size therefore makes it possible to spread a portion of the fixed costs on a wider basis.

The second reason is the commercial attractiveness of a dense network, particularly for business customers and city breaks: a large size enables a presence in all major European airports, with local bases that generate traffic in both directions (both import and export), offers good frequencies and schedules (especially in the morning and at the end of the day), and also is supported by an attractive loyalty programme.

The third reason is more specific to the legacy airlines, which also offer a long-haul service and a system of connections from a hub. The density of the domestic and intra-European network is strategic to give credibility to the hub, by offering reduced waiting times between two flights, and to fill long-haul flights, especially by adding “small flows”.

Given the lack of critical size of many operators, it is hardly surprising that, even in periods of good global profitability, Europe regularly experiences bankruptcies of small players: for example, in 2019 (i.e. before the Covid-19 crisis), 23 airlines went bankrupt worldwide, 9 of which were European. We can notably mention Aigle Azur (France), XL Airways (France), FlyBMI and Thomas Cook (United Kingdom), Germania (Germany) or Wow Air (Iceland). By 2018, Monarch, Condor and Air Berlin had also gone out of business.

However, large size is not a sufficient condition for profitability, especially in the short-medium-haul segment. Among the major players on the market, it is necessary to distinguish between the situation of legacy carriers such as Air France or Lufthansa, which are in a delicate situation, and that of large low- cost operators, which are very profitable. The impact of the Covid-19 crisis on these different companies is likely to be quite differentiated.

1. Air transport appears to be less concentrated in Europe than in the United States and is less profitable. This situation is due both to the lower market share of the four leaders in the sector, but also to the existence of a very large number of small players. In such a market context, the Covid-19 crisis will set off a restructuring movement in Europe, whether by the attrition of certain players, bankruptcy or takeover.

Covid-19 shock : historic companies in turmoil

Two giants in turmoil: Air France-KLM and Lufthansa

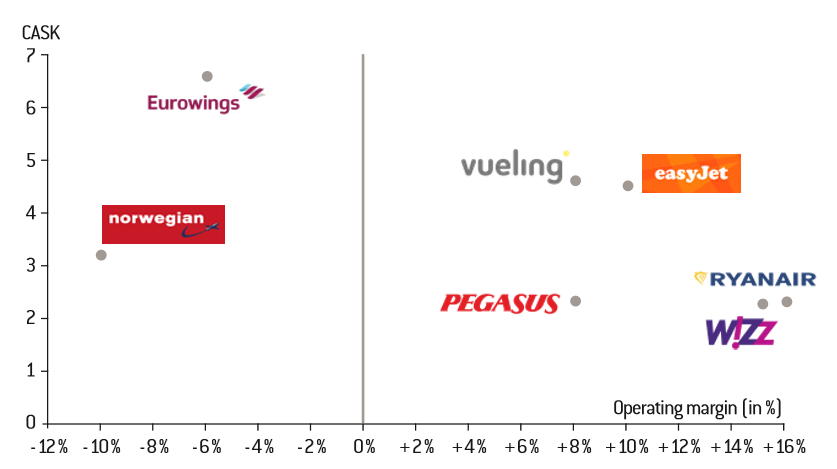

Seat Cost Per Kilometre (SCM) is the standard measure in the airline industry indicating the unit cost of transporting one passenger per kilometre. This cost decreases with the distance travelled, taking into account the existence of the fixed cost of the aircraft. In order to compare CASK levels between airlines, it is therefore necessary to reason over an equivalent distance. For medium-haul, we have taken an average distance of 1,200 km.

The three major historical leaders in Europe – Air France-KLM, Lufthansa and IAG (British Airways) – are present in two different passenger transport markets: the short /medium-haul segment (flights lasting less than 4 hours) and the long-haul segment, mainly from their hubs. In the short/medium-haul segment, they are also present on point-to-point flights, which link an origin destination to a final destination, and on their long-haul hubs, which provide connecting flights.

For the past 20 years, legacy carriers have been challenged in the point-to-point market by a new model, which conquered 40% of market share and which is spreading across the entire European continent: low-cost. Faced with this disruption, legacy carriers have reacted in different ways.

Some, like Alitalia, have not changed their model and are now facing attrition and near bankruptcy. Indeed, after several successive recapitalisations in recent years (2005, 2009, 2013), the Italian company was placed under trusteeship in mid-2017 following the rejection by employees of a restructuring plan in an internal referendum.

Conversely, others have chosen to entrust their entire point-to-point medium-haul network to a dedicated and resolutely low-cost subsidiary: this is the case of the IAG group with its Vueling subsidiary. IAG uses medium-haul only to supply its hubs, under its British Airways, Iberia and Aer Lingus brands.

Between these two polar cases, we find Air France-KLM and Lufthansa, which have taken a step towards transferring their medium-haul business to low-cost. Thus, Lufthansa has entrusted its subsidiary Eurowings with all point-to-point flights, while the hubs are still operated with the Lufthansa brand. As for Air France-KLM a small portion of its point-to-point flights has been entrusted to a low-cost subsidiary, Transavia. However, the scope of this activity remains limited – positioned at Orly, which is not the Group’s hub – and is complementary to that carried out by Air France KLM itself; the latter supplies the hub at Roissy Charles de Gaulle (CDG) but also most of the point-to-point routes (such as the major radial flights in France, with the Air France shuttle bus).

In terms of profitability, the IAG Group appears to be more profitable than Air France-KLM and Lufthansa. Its net income was 6.7% in 2019 compared with 3.3% for Lufthansa and 1% for AF KLM.

Moreover, this overall situation of incumbent companies masks a sharp disparity between the long-haul business, which is fairly profitable, and the short/medium-haul business, which has structurally loss-making for several years, mainly because of competition from low-cost carriers. Admittedly, some of the short/medium-haul flights are not primarily intended to be profitable insofar as they feed the hub with connecting flights: it is therefore normal that feeder flights may be structurally loss-making. However, this specificity does not call into question the overall finding of recurrent losses on the medium- haul point-to-point network.

While it is difficult to obtain an exhaustive view of the profitability of short/medium-haul business, several indices converge to conclude that this business is highly financially fragile.

Lufthansa’s point-to-point subsidiary, Eurowings, was loss-making until 2018, especially due to the integration of Air Berlin. Eurowings has a cost structure that is not consistent with its revenue structure. Eurowings had a cost per seat kilometre5 (CASK) of 6.6 cents in 2018 in the medium-haul segment, which is higher than the level of easyJet. On the other hand, revenue per seat kilometre (RASK) does not cover the CASK, which explains Eurowings’ losses in 2018.

As far as Air France is concerned, the domestic point-to-point network activity has been loss-making for several years: over the 2013/2018 period, cumulative losses amounted to more than €700 million. Three-quarters of the losses are concentrated on 20% of available seat kilometres, which led Air France in 2019 to cut 15% of its domestic network. Although the Transavia subsidiary has been generating a positive operating result since 2019, its limited size does not offset the losses on Air France-KLM’s entire short and medium-haul network. However, in 2019, Air France negotiated an agreement with the powerful SNPL (“Syndicat National des Pilotes de Lignes”, National Airline Pilots Union) to lift the number of Transavia France aircraft above 40.

An unavoidable call for public assistance

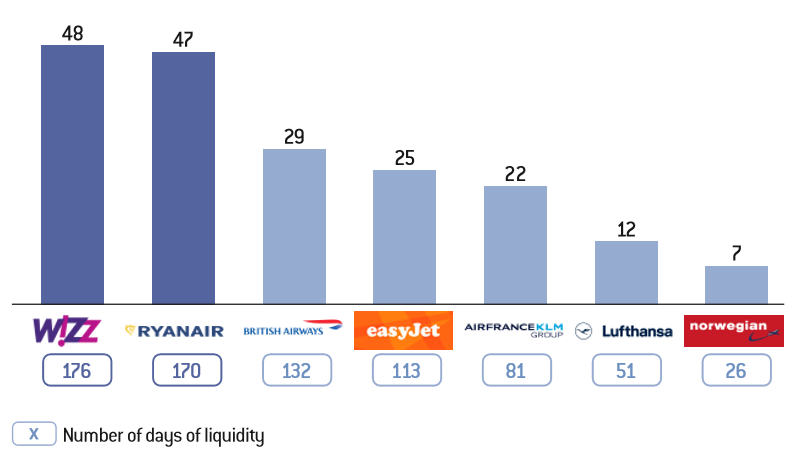

Given the violence of the Covid-19 crisis and the financial fragility of certain major legacy carriers in Europe, public support appeared unavoidable for Air France-KLM and Lufthansa groups. To assess the need for such support, it is interesting to estimate the capability of operators to overcome the crisis over time, without having any activity and without using external resources – i.e. by drawing only on their cash reserves and credit lines already subscribed.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, Ryanair was in possession of liquid assets representing 47% of its annual revenue, i.e. the equivalent of 170 days of “resilience”; this figure only lasted for 81 days for Air France-KLM, i.e. less than 3 months, and only 51 days for Lufthansa. With a different methodology, Crédit Suisse arrives at a different result but which nevertheless confirms the fragility of the legacy carriers: in the absence of any measures, Lufthansa had 25 days of cash flow and Air France-KLM 69 days at the beginning of the crisis.

Share of cash to revenue and number of days equivalent in 2019 at the beginning of the crisis (in %)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger, CAPA, Company data.

On 4 May 2020, the European Commission approved this state aid. See the European Commission press release: “State aid: Commission approves French plans to provide €7 billion in urgent liquidity support to Air France“, 4 May 2020.

Norwegian and EasyJet also received government support of €490 million and €600 million respectively.

Article 107 (ex Article 87 TEC), Chapter 1: Competition rules – Section 2: Aids granted by States, Official Journal 115, 09/05/2008 p. 0091 – 0092.

“Statement by Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager on a draft proposal for a State aid Temporary Framework to support the economy in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak”, European Commission, 17 March 2020.

Speech by Elisabeth Borne, Minister of Transport, Conclusion of the “Assises nationales du transport aérien” – Presentation of the national air transport strategy, 8 March 2019.

This low resilience stems from the fact that the cash position of a group like Air France-KLM was limited to 5.5 billion euros of immediately mobilisable cash at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, for an annual turnover of 27 billion euros: cash therefore represented only 20% of its 2019 revenues. Furthermore, Air France had to repay a debt of 1.2 billion in 2020 and its debt ratio exceeded 400% of shareholders’ equity. The call for public support was therefore inescapable and justified from an economic standpoint.

Firstly, it is difficult for large legacies to reduce their fixed costs, which on average account for half of their total costs. They can, of course, lay off employees, cancel aircraft orders (subject to penalties) or resell aircrafts. They can also decide not to pay dividends, not to refund customers to avoid cash outflows, by offering them a credit note on a future ticket, but this choice violates the European directive on passenger rights; which provides that in the event of cancellation, passengers have the choice between a refund and a credit note. However, even by mobilising these various levers, the sources of fixed cost reductions remain limited, given the large share of personnel costs: 40% for Air France, 30% for Lufthansa and IAG, compared with only 24% for Ryanair.

Secondly, the social cost of the bankruptcy of a large operator is probably higher than its private cost. Indeed, from a theoretical point of view, one could consider that bankruptcy simply leads to the replacement of the existing player by a new operator, which is the “natural” mechanism for resolving crises in a market economy. However, the costs of transition and market reorganisation are high: putting tens of thousands of employees out of work, even temporarily, is a cost to the community; moreover, the disorganisation and destabilisation of a network of lines, particularly a hub such as Roissy, would be costly and militates in favor of keeping the legacy carrier on the market. To put it bluntly, the larger the operator, the higher the social cost of bankruptcy: here we find the same mechanism for large banks, namely the “too big to fail” principle. Similarly, for a country like France, the demise of Air France could have an impact – beyond simply serving its Parisian base – on destinations that support regional economies and on the tourist attractiveness of this country.

Finally, this call for public aid is justified by the fact that other major historic companies in the world will also receive support from their States. This is the case of American companies, which have asked the Federal State for support up to 50 billion dollars, even though they are now the most profitable in the world. Here we are typically in an uncooperative game: if other countries support their legacy carriers, Europe’s best response is to do the same with its own operators.

Public aid has taken on many forms, ranging from general measures to defer social security contributions or to cover part-time working to measures more specific to air transport: deferral of the payment of certain taxes, guarantees for bank loans, or even the acquisition of shareholdings in the capital, the ultimate case being the nationalisation of the company.

As of October 2020, European governments have already taken several measures, including the following:

– The French government’s decision to grant Air France €7 billion in aid6. This aid consists of two loans: firstly, a €4 billion French State Guaranteed Loan (PGE). This 90% guaranteed loan is granted by a union of 9 banks with an initial maturity of 12 months, with an extension option of 1 or 2 years exercisable by Air France-KLM. Mandatory total prepayment conditions have been added in certain cases, such as a change of control of Air France-KLM or Air France. Secondly, the aid consists of a second shareholder loan of €3 billion, granted by the French State with a maturity of 4 years with 2 consecutive 1-year extension options exercisable by Air France-KLM. As with the PGE, mandatory early repayment conditions have been added to this loan. The company has also undertaken not to pay dividends until these loans have been fully repaid. In addition to Air France, the State is also in discussions with Corsair for a PGE aid that should exceed €100 million. An initial aid was refused in the spring by management because of conditions considered to be too restrictive;

– Similarly, the Dutch government decided to grant two loans of respectively

€2.4 billion (a loan guaranteed by the Dutch State up to 90% and granted by 11 banks) and €1 billion (a direct loan from the Dutch State) in June 2020. In total, the Air France-KLM group thus benefited from €10.4 billion in state aid between April and June 2020;

– The German government has also granted €9 billion in aid to Lufthansa. This is being channelled through the Federal Economic Stabilisation Fund (WSF) in the form of “silent participations” of up to €5.7 billion (€4.7 billion of which is in equity). The remainder of the aid granted to the company takes the form of a capital increase of up to 20% of the share capital of Deutsche Lufthansa AG, with WSF undertaking to sell its entire stake at the market price by 31 December 2023. The remaining aid is supplemented by a credit facility of up to €3 billion with the participation of KfW and private banks for a period of 3 years;

– Concerning the IAG group (British Airways, Iberia, Vueling and Air Europa), State aid came from the Spanish government which lent 750 million euros to Iberia and 260 million euros to Vueling. These loans are 70% guaranteed by Spain. The first repayments of this loan are not expected before 30 April 2023;

– the Belgian government has come to support Brussels Airline with a loan of

€387 million and a capital injection of €3 million;

– By a decree published in mid-March 2020, the Italian government plans to take control of Alitalia, injecting €600 million to keep it afloat. Alitalia was almost out of money, although it had already received 400 million euros from the Italian government at the beginning of 2020. In the beginning of September 2020, new public aid of 200 million euros was provided to compensate for the losses linked to the pandemic.

It should be noted that such public aid7, targeted at a specific company, infringe upon the rules on state aid in Europe. Indeed, Article 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) states that: “save as otherwise provided in the Treaties, any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods shall, insofar as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the internal market”8. However, in view of the exceptional circumstances, the European Commission has adopted a temporary framework, allowing Member States to ensure that sufficient liquidity is available to all undertakings in order to preserve the continuity of economic activity during the epidemic. Margrethe Vestager, Vice-President of the Commission responsible for competition policy, said: “Managing the economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak requires decisive action. We need to act fast. We need to act in a coordinated manner. With this in mind, the Commission will enable Member States to use the full flexibility foreseen under State aid rules to tackle this unprecedented situation.”9. This temporary framework provides for several types of aid, including state guarantees for bank loans taken out by companies. It is in place until 30 June 2020.

This policy of massive public aid to major historical companies also raises several questions:

– Insofar as it is differentiated according to players, public aid can lead to an imbalance in competition, to the detriment of small players who will have to survive without public aid. Support for the historical giants must not lead to implement exclusionary strategies, particularly against small players. Competition authorities should be very vigilant, notably with regard to the abuse of a dominant position. In the case of France, after the bankruptcies of Aigle Azur and XL Airways – positioned on international markets – there are still some major operators facing Air France, such as SNCF and easyJet on domestic radial and transversal routes. However, the competitive situation could be weakened for certain destinations, especially in the French overseas departments and territories, if niche players such as Corsair, Air Austral, Air Caraïbes or Air Tahiti Nui were less able to drive competition on the market, as they have done up to now. For example, on the market to the West Indies, competition is mainly between Air France and Air Caraïbes, which each have a market share of more than 35%, the third operator being Corsair (21%). On the island Reunion, the entry of French Bee in 2017, a low-cost subsidiary of Air Caraïbes, has led to increased competition: French Bee has gained a market share of 20% in two years, thanks to market growth (volume induction), itself the result of strong price competition. Competition on these markets is played out here between a large player (Air France) and smaller players such as Air Austral, Corsair and French Bee. On Cayenne, the situation is also that of a duopoly, between Air France (60% market share) and Air Caraïbes (40%). Beyond the French case, maintaining a certain degree of competition in air transport is first and foremost crucial for customers, whether in terms of price, quality or accessibility of territories. A competitive market is also a vector of economic efficiency, by imposing productivity gains on each operator. Competition is a “spur” to long-term economic performance;

– public aid is certainly accompanied by compensatory measures but it does not specifically address the issue of the structural competitiveness deficit of the incumbent operators. Thus, in the case of France, the government stated that the aid to Air France-KLM would be accompanied by compliance with “social and environmental” commitments. In particular, the restructuring of the domestic network is one of the counterparts demanded by the State, as the Minister of the Economy specified: “As soon as there is a rail alternative to domestic flights with a duration of less than 2 hours and 30 minutes, these flights will have to be drastically reduced, and in fact be limited for a transfer to a hub”. Air France will also have to meet commitments in terms of profitability and environmental impact, including “a 50% reduction in its CO2 emissions per passenger and per km between 2005 and 2030”. The objective of 2% sustainable alternative fuels by 2025 and the earmarking of investments in the renewal of the long and medium-haul fleet are also among the negotiated counterparts.

In addition to the direct aid granted to airlines, other structural reforms on air transport taxation could be envisaged, notably in the case of France, to restore the competitiveness of the French flag. In March 2019, at the conclusion of the Assises du Transport, Minister of Transport Elisabeth Borne acknowledged that: “I know that air transport bears a significant level of taxes and charges (the equivalent of almost 50% of the price of a ticket). It weighs on the competitiveness of our airlines and our hubs”10. This announcement has led to a 220 million euro reduction in charges between 2018 and 2019, mainly through a reduction in airport taxes and route charge rates. However, these measures do not completely reduce the tax-related competitiveness deficit that exists in France, compared to other European countries (estimated at 700 million euros by the, the National Federation of Merchant Aviation – FNAM). Elisabeth Borne also pointed out in the same speech that “some will consider that this is not enough”. Other levers such as the reduction of taxes (the solidarity tax known as the “Chirac” tax or VAT) have not been activated and have even been accentuated with the inclusion in the 2020 budget of an eco-tax that will be added to the price of a plane ticket for a flight departing from France.

Futhermore, the recent work of the Citizen’s Convention on Climate Change has generated the idea of an eco-tax on air transport. According to the Directorate General for Civil Aviation, the cost of this tax would be €4.2 billion for the sector.

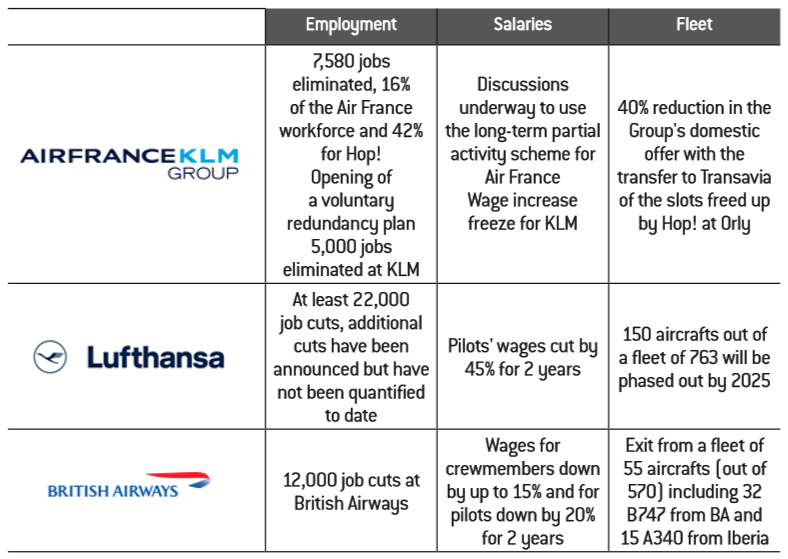

On top of this public aid, companies have made more or less marked adjustments in size and remuneration, with the aim of reducing their fixed and variable cost base (see table). As we have seen, these adjustments are taking place against a backdrop of a sustained fall in air traffic in Europe, which has resulted in significant losses for the incumbent companies in the first half of 2020: €1.55 billion for Air France-KLM, €3.6 billion for Lufthansa and €3.8 billion for IAG.

Number of passengers carried by the European leaders in the medium-haul market

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger.

The main adjustments include staff reductions with a decrease of almost 30% (12,000 out of 42,000 employees) at British Airways and 16% at Lufthansa (22,000 out of 135,000) with discussions underway to increase the target to 30,000 employees, i.e. 22%. At the same time, Air France is planning the departure of 17% of its staff (including 42% of the Hop! staff) but has a voluntary departure plan to reduce the number of departures (3,460 positions open to voluntary departure for ground staff, 403 positions for pilots and discussions are in progress for flight personnel).

Additionally, the three airlines have also sought to lower personnel costs with salary cuts, particularly for pilots: a 20% cut for IAG and a proposal by Lufthansa pilots to cut their salaries by 45% to avoid layoffs, a freeze on salary increases at KLM and via the long-term partial activity scheme for Air France.

These measures also involve a reduction in the companies’ offer. For example, Air France has put a plan in place (the Vesta plan) to decrease its domestic flights by 40% by the end of 2021. Lufthansa has also decided to part with 150 aircrafts between now and 2025, i.e. nearly 20% of its fleet, compared with 55 aircrafts for IAG.

2.Some historic European airlines, namely Air France-KLM and Lufthansa, will not be able to get through the Covid-19 crisis without massive public aid. While this public intervention is justified by the urgency and the liquidity crisis that these companies are experiencing, it may also distort competition, in particular for players that do not benefit from public aid. This public aid should be conditional on the pursuit of structural reforms, even though these historic companies suffer from a lack of competitiveness on short and medium-haul routes. A review of public policies on air taxation is also part of the solution, especially in order to reduce the differences in competition between European countries.

Covid-19 shock : the resilience of the low-cost giants

11. Let us briefly recall that low-cost is based on four main levers, which are more or less the same for all players: extreme simplification-standardisation of the product and the production process, which makes it possible to reduce unit costs (rapid turnaround, densification of seats, single fleet, etc.); outsourcing of all services that are not part of the core business (handling, etc.); and the development of new services, such as the development of new products and services, which are not part of the core business), which makes it possible to make part of the costs more flexible and to limit structural costs; the predominant role of paid options (seats and luggage, catering, etc.) as a source of revenue and profits; great operational agility, whether in the opening and closing of lines, staff employment contracts, etc.; and a high level of flexibility in the management of the company’s operations, whether in the opening and closing of lines or in the employment of staff. See on this subject, Le Low Cost, une révolution économique et démocratique, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, February 2014 and, by the same author, Le Low Cost, La Découverte, 2019.

While some legacies such as Air France-KLM and Lufthansa are in a delicate situation and only stayed afloat with the help of the States, only a few airlines will manage to survive the total stoppage of their activity for several months and the gradual recovery of the market. In addition to small players such as Air Caraïbes in France or the legacy carrier British Airways in the United Kingdom, we find a number of low-cost airlines11, which have in common that they are large and specialised in medium-haul flights (“pure players”). In terms of model and performance, however, it is necessary to distinguish between two quite different types of low-cost carriers: ultra-low-cost and middle-cost.

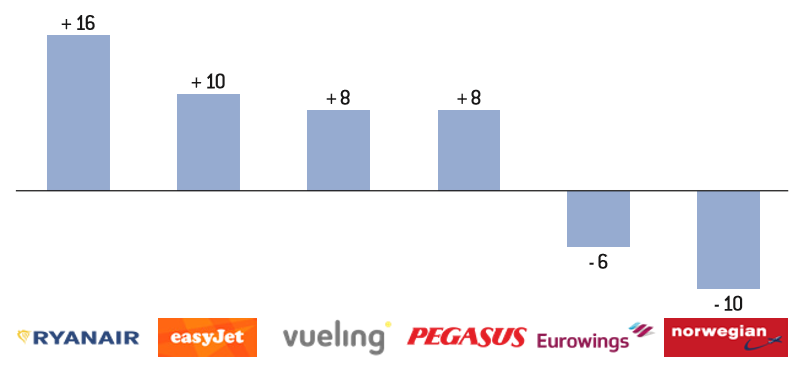

Operating margin for a sample of low-cost companies in 2018 (in %)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger, company data.

The ultra low-cost will survive the crisis

A first model, also found in the United States with Spirit Airlines, can be described as “ultra low-cost”: it brings together companies such as Ryanair, Wizz Air or Pegasus. These airlines operate with a very low unit cost base (measured in CASK) of around 2.5 to 3 cents, which does not drift over time. This cost base is more than half that of an incumbent on medium-haul routes, whose unit cost excluding fuel is between 6 and 8 cents.

Unit cost per seat kilometre cents in euros in 2018

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique – 2020

Source :

Roland Berger, company data.

Their network connects many regional cities in Europe, such as Ryanair, which, as of 2020, has more than 70 bases throughout the continent, or Wizz Air, which has more than 20 bases, most of which are in Eastern Europe. Setting up at regional airports allows tax limitation, or even benefitting from public subsidies for the opening of routes, and having great operational agility. In terms of customers, ultra-low-cost primarily attracts leisure and foreign customers who are very price-sensitive but are less concerned about frequencies, schedules and the choice of destinations. In terms of revenue, ultra low-cost fares are very low: for Ryanair, the average ticket reached 37 euros in 2019, plus 17 euros in paid options, making a total of 54 euros. In organisational terms, ultra low-cost has a very agile and opportunistic model, which quickly adjusts capacity and destinations according to changes in demand.

The great strength of the ultra low-cost model lies in the consistency between the structure of its offer, in terms of costs and lines, and that of the demand in terms of customers and revenues.

Like all airlines, ultra low-cost airlines are strongly impacted by the Covid-19 crisis. For example, Ryanair is expecting a 60% drop in its traffic in 2020, with only 50 million passengers flying, compared to 152 million in 2019. In October 2020, Ryanair only operated 40% of its capacity compared to the same period a year earlier.

However, ultra low-cost aircrafts have several advantages that will enable them to overcome the Covid-19 crisis and even come out of it stronger.

First of all, they have been generating double-digit profit margins for several years – between 12 and 20% depending on the year – which has allowed them to accumulate significant cash flow over time. The case of Ryanair is edifying in this respect: the Irish company had, at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, one of the most solid balance sheets in the sector, with €3.8 billion in cash equivalents and low debt, estimated at 69% of equity. 3.8 billion represented half of its annual turnover12 (7.6 billion in 2019). This means, as CAPA points out, that Ryanair could hold, without recourse to borrowing or asset sales, for 170 days, i.e. until the end of August 2020, not counting fixed cost reductions and the fact that Ryanair is making margins. The same applies to Wizz Air, which had a cash position equal to 48% of its turnover in 2019 at the beginning of the crisis.

In addition, Ryanair has its own fleet of more than 400 aircraft; on the basis of an average aircraft value of USD 25-30 million, the value of the unencumbered fleet is between EUR 5-7 billion (deducting a gross debt of EUR 3,9 billion excluding operating leases in December 2019), which illustrates Ryanair’s wide capability to find other sources of cash if necessary.

Second, ultra low-cost has an organisational structure characterised by low- fixed costs compared to variable costs. The stay of aircrafts on the ground therefore reduces a significant proportion of variable costs, like kerosene: the first cost item, fuel, represented 29% of variable costs at Wizz Air in 2018 and even reached 35% at Ryanair. Similarly, staff costs, which are almost a fixed cost, accounted for only 10% of the total cost for Wizz Air and 13% for Ryanair.

Thirdly, as we will see in the second volume of this study, ultra low cost companies have strongly adjusted their size to the crisis context by reducing their salaries and networks in order to reduce their fixed costs. Thus, during the first quarter of 2020, Ryanair’s loss amounted to “only” 185 million euros, while Wizz Air should make a positive net profit for the year 2020.

Under these conditions, although it will take some time for air traffic to return to normal, it is likely that Ryanair and Wizz Air will emerge from the Covid-19 crisis without too much damage and will even have enough financial resources, especially through indebtedness and the purchase of bankrupt companies, to take part in the probable restructuring of air transport in Europe, as we shall see in the second volume of this study13.

Middle-costs in a more critical situation

All things considered, the middle cost would be represented in the United States by a company such as Southwest, whose unit cost has, however, come very close to that of the major American majors. The unit cost difference with the majors is around 20%.

Alongside the ultra low-cost is the “middle cost” model, represented in Europe by airlines such as easyJet or Vueling, a subsidiary of IAG group14. These airlines have a unit cost excluding fuel (CASK) of around 5 cents, 60% higher than that of Ryanair. However, it is still 20 to 30% lower than the unit cost of a historic airline.

One reason for the higher unit cost of middle cost airlines is that they take off from major airports, where taxes are significantly higher.

These higher unit costs logically lead to an average price of ticket with options of 77 euros (61 + 16 paying options) in 2019, i.e. 25% more than Ryanair. The customer profile of easyJet and Vueling is more diversified than that of ultra-low-cost airlines: there are tourists, but also a business clientele, less price-sensitive but very dependent on the destination. This more “business” profile means that large middle cost airlines must take off from main airports and offer a consistent frequency of flights and adequate flight times. It also calls for the development of frequent flyer programs and travel facilitation, with massive investment in digital, value-added services (waiting rooms, speedy boarding) and ticket flexibility. Like the ultra-low-cost, the middle cost model is consistent between the structure of its offer, in terms of costs and lines, and the structure of demand, in terms of customers and revenues: unit costs are higher but offset by more significant unit revenues.

Middle costs have also been strongly impacted by the crisis: for example, easyJet reduced its capacity by an average of 60% in 2020. Given their positioning in the business customer segment, middle cost customers are in a less comfortable situation than ultra low cost customers. For example, EasyJet has gone negative for the first time in its history, with a loss of more than £1 billion in its 2019/2020 financial year. In early November 2020, Easyjet announced the sale of 11 aircrafts for £130 million to boost its liquidity. In total, the group says it has raised more than £2.4 billion in cash over the full financial year, with the sole aim of “getting through the crisis”. Vueling has also obtained a loan of 250 million euros from the Spanish government. For example, in April 2020, easyJet had a cash position of 1.4 billion pounds, to which must be added recent loans of 1.9 billion pounds, contracted with the sole aim of “getting through the crisis”. It should be noted that part of this loan – an amount of £600 million – was obtained from the Treasury and the Bank of England.

It is probable that middle cost airlines will benefit less from the crisis, as their main competitors are historic airlines such as Air France or Lufthansa, which were bailed out by their governments and will have the means to hold a “war of attrition” for many months. Middle cost airlines, which are already limited in their expansion by congestion at major airports, will only regain market share if legacies experience strong attrition, which will lead them to release slots.

It is not enough to be big and low-cost: the Norwegian counterexample

See “Norwegian Air Shuttle tirée d’affaire, pour le moment“, La Croix, 4 May 2020.

Being low-cost, even of large size, is not a sufficient condition to be profitable and to survive the Covid-19 crisis. In this respect, the case of Norwegian, Europe’s third lowest-cost airline in terms of passenger numbers, is interesting. This airline has been accumulating losses for several years and is heavily indebted: its debt reached 3 billion euros (at the end of 2018), for a turnover of 4.3 billion euros in 2019.

To explain this structural underperformance, it may be noted that, unlike other low-cost carriers, Norwegian operates in two markets of a very different nature: medium-haul and long-haul. Bringing together in the same entity two activities with very different cost and revenue levers contributes to the complexity of the operating model.

Furthermore, Norwegian has a cost structure that is not consistent with its revenue structure: its unit costs, when calculated over a distance equivalent to that of easyJet, are quite similar to those of a middle cost. On the other hand, on the revenue side, Norwegian has a unit revenue close to that of … Ryanair. The equation is therefore economically unsustainable.

Due to the Covid-19 crisis, Norwegian had to cancel 85% of its flights and even all of its flights to North America. Despite the measures taken, such as the temporary dismissal of 90% of the staff, refocusing on the medium-haul network, and reducing the size of the fleet (sale of aircraft, cancellation of an order for 87 Boeing 737 and 787), it will be difficult for the Norwegian low- cost airline to get through the crisis. According to Roland Berger’s estimates, Norwegian had a cash position at the beginning of 2020 that would enable it to go less than a month without any activity. The Norwegian State announced at the end of March that it was providing a guarantee for a loan of €275 million from Norwegian. Yet it is unlikely that this contribution will be sufficient to get through several months of crisis. Norwegian’s subsidiaries in Sweden and Denmark went bankrupt in April 2020 because they did not have the support of both countries. Although the Norwegian parent company experienced some relief in May 2020 thanks to a rescue package, which provided it with a contribution of €880 million (in exchange for the conversion of part of its debt into shares), its financial situation remains very precarious15. Norwegian posted a record loss of €455 million in the first half of 2020 (four times the previous year’s loss) and has enough to last until the end of 2020. In the absence of a new oxygen tank, Norwegian’s bankruptcy is likely: it will allow for growth opportunities for the players who will remain on the market in the future.

3.Some large low-cost airlines have strong profitability that will enable them to overcome the liquidity crisis. This is particularly true for the “ultra low-cost” model, embodied by Ryanair and Wizz Air, which have a large cash position and a great organisational flexibility.To a lesser extent, a “middle cost” operator like easyJet will manage to survive the crisis. It is likely that these low-cost airlines will play a role in the consolidation of the post-Covid European market.

Conclusion of the first volume

We have shown that, faced with the Covid-19 crisis, not all European airlines are in the same boat: while several historic operators such as Air France-KLM or Lufthansa will survive thanks to massive public aid, some major low-cost operators such as Ryanair, Wizz Air or easyJet should be able to get through the crisis by drawing on their reserves.

Given this heterogeneity in the financial situations of airlines, the fundamental question is who will be best equipped to take part in the probable restructuring movement after the Covid-19 crisis. This movement will take many forms: takeover of assets (and particularly the slots) of bankrupt companies, mergers and acquisitions, backing the most fragile players with solid companies in the form of capital contributions, attrition of the size of companies in difficulty which will free up airport capacity, etc.

We show in the second volume of this study that, in this future battle of the European skies, the large low-cost airlines such as Ryanair and Wizz Air could take advantage of the situation to go on the offensive and will try to consolidate their lead and positions; conversely, the large incumbent operators risk being marginalised and in attrition (reduction of wingspan) unless they take advantage of this crisis to accelerate their structural change in terms of medium-haul.