Big tech dominance (1): the new financial tycoons

Introduction

The transformation of American tech champions into global asset managers

Huge reserves of cash sustained by enormous profits

Ultra-conservative cash management

A lasting and undesirable cash hoarding dynamics

Possible solutions to halt the “financialisation” of big tech firms

Speeding up cash distribution through greater shareholder involvement in decision-making ?

Discouraging cash retention through financial regulation?

Limiting future cash accumulation through taxation?

Conclusion

Appendices

Sample composition

The big tech companies

References

Résumé

American big tech companies are either idolised when they launch new products or vilified for their influence over our everyday lives, massive use of personal data, and low tax contributions. However, one issue remains largely concealed – their increasing influence over global finance.

Their unprecedented commercial success over the past twenty years has enabled them to accumulate huge reserves of cash. In contrast to their image as first-class innovators, they have chosen to manage this capital in an ultra- conservative manner. Their corporate treasurers now appear more like low- risk bond funds managers than working capital managers.

Several solutions exist to curtail this accumulation of cash: (i) increasing shareholders’ influence over the allocation of profits, thus encouraging distribution; (ii) imposing restrictions on big tech companies by means of financial regulation to discourage the retention of cash on their balance sheets; or (iii) increasing taxes on their profits, thus imposing a de facto limit on their potential for future hoarding.

However, all of these solutions are limited in that they attack the symptoms and not the cause of the problem – namely abnormally high profits, which are currently generated more by increasing monopolisation of key segments of the tech market than by the pursuit of a rigorous innovation process.

The second section of this paper is entitled Big Tech Dominance (2): A barrier to technological innovation? It proposes solutions to restore fair competition in the tech industry.

A French version of this study is also available on the website of the Foundation for Political Innovation.

Paul-Adrien Hyppolite,

Corps des Mines engineer and graduate of the École normale supérieure.

Antoine Michon,

Corps des Mines engineer and graduate of the École Polytechnique.

Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Facebook – hidden behind these familiar names are the top five global market caps at the time of writing. What do they have in common? They are all American tech companies that have achieved a degree of supremacy in their sector, which is without precedent in the modern history of capitalism. This dominance that we see today is partly the result of innovations, which have in many ways revolutionised our lifestyles and made a significant contribution to consumers’ and companies’ welfare.

From a consumer perspective, Microsoft and Apple have democratised access to cutting-edge information technology by speeding up computer development and precipitating the “smartphone revolution” with the launch of the iPhone in 2007. Google developed an extraordinary search engine providing quick and easy access to information and knowledge. The company from Mountain View also offers a variety of free services that many of us use every day: email (Gmail), navigation and orientation (Google Maps, Waze), data storage (Google Drive), collaborative work (Google Doc), etc. Amazon, on the other hand, offers an incredibly diverse range of goods on its e-commerce platform. Not satisfied with significantly cutting prices and delivery times by optimising its operations, the company is on the verge of revolutionising our approach to shopping. Through their rating and recommendation systems, Google and Amazon have furthermore considerably increased the quantity and quality of information available to consumers who, faced with a wider range of options, can now make more informed choices. Finally, through its social network and integrated messaging service, Facebook has simplified virtual communication and transformed our approach to social relationships.

From a business perspective, the big tech firms have prompted faster development and even encouraged the emergence of numerous activities. Google and Facebook enable businesses to easily gain a reputation and target potential consumers much more precisely and effectively than in the days when only traditional media (newspapers, radio, television) were available. Apple and Google have encouraged the development of mobile apps through their app stores and Amazon has provided outlets for numerous resellers through its “marketplace”. Cloud services offered by Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Oracle and IBM allow companies increasingly affordable access to premium quality back office services (hosting, computing capacity, storage, security, etc.). Finally, by freely sharing the source code of some of their machine learning tools such as TensorFlow (Google) or Open Neural Network Exchange (Facebook and Microsoft), the tech giants appear to foster innovation in artificial intelligence.

However, it does not take an expert to identify the negatives. Firstly, the tech giants cause a number of major social problems. For instance, an increasing number of studies point to the negative impact of smartphones and social media on health, especially among younger people (addiction, frustration, insecurity, depression, etc.)1. In schools, researchers have also observed that “connected” students are becoming increasingly distracted. These problems are becoming so serious that activist shareholders, who one would normally expect to be purely interested in profits, recently urged Apple to quickly introduce features enabling parents to more effectively control their children’s smartphone use2. In politics, the spread of fake news and, in a broader sense, the use of social media by foreign powers or ill-intentioned groups as part of interference strategies, threaten the health of our liberal democracies. Finally, the big tech firms’ lobbying power raises the issue of their influence over political and regulatory decisions.

Yet, in addition to these well-documented and widely debated social issues, we believe that the tech giants’ dominance also raises questions in terms of their impact on the economy. Facebook and Google clearly enable businesses to boost their visibility. However, the social benefits of the marketing expenses they generate are questionable. While experts are warning of a significant downturn in productivity growth in developed countries, we consumers are seeing fewer major innovations. For example, it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish iPhones from other smartphones. And while the tech giants, especially Google, are continually announcing ultra-ambitious and innovative projects in development (driverless cars, balloons, drones or satellites designed to bring high-speed Internet to the world), concrete results are undeniably rare and often disappointing (e.g. the Google Glass or Facebook Aquila drone). As such, it is reasonable to question whether the unregulated domination of the big tech firms is currently hampering innovation in the tech sector and, if so, what avenues the public authorities could explore to attempt to remedy this.

We will firstly demonstrate how the tech giants’ extraordinary profitability has resulted in an astounding accumulation of cash that barely finances the productive economy and does not benefit innovation. In contrast to their popular image as exceptionally dynamic companies, the big tech firms have in practice opted for an ultra-conservative capital management strategy. After exploring a number of potential solutions to counter this cash hoarding phenomenon, we will frankly address what we believe to be the root cause of the problem, namely an insufficiently intense competition in the tech market. This will lead naturally to our proposed solutions for restoring a fair degree of competition in the sector.

The transformation of American tech champions into global asset managers

Huge reserves of cash sustained by enormous profits

In order to identify the companies of interest for this study, we will begin by comparing the cash position of the main global tech companies at the end of 2017. In practice, a company’s cash position is a financial portfolio that typically includes pure cash and bank deposits, but also various types of liquid securities such as commercial papers, notes, bonds, etc.

Here and throughout the paper (unless specified otherwise) ‘Google’ refers to its parent company Alphabet.

a. Extreme concentration of cash

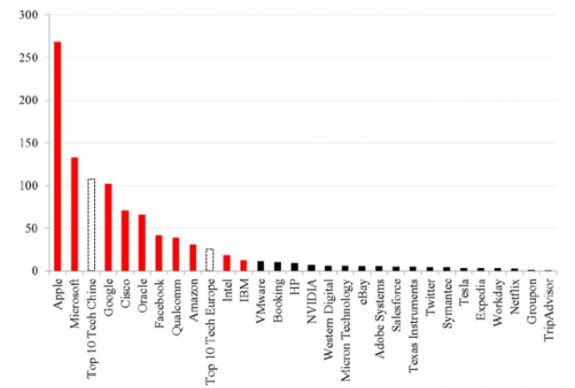

The exponential distribution shown in the graph below highlights an extreme concentration of cash among a small number of tech companies, which are mainly American (shown in red on the graph). In fact, the ten richest of these own seven times more cash than their Chinese counterparts and thirty times more than their European counterparts. Google3 alone possesses almost the same amount of cash as the ten richest Chinese tech giants put together ($102 billion versus $107 billion). Apple holds ten times more cash than the top ten wealthiest European tech companies ($269 billion versus $25 billion.

Graph 1: The world’s leading tech companies’ cash positions at the end of 2017 in billions of dollars (US)

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Those seeking details of the exact composition of Chinese and European company samples (“Top 10 Tech China” and “Top 10 Tech Europe”) should refer to Appendix 1(a).

It should be noted that we have chosen to exclude telecommunications companies such as AT&T and pure service providers or consulting firms such as Accenture.

The ten richest American tech companies are shown in red. This is a purely arbitrary limit insofar as we could just as easily have limited ourselves to the top five or extended the selection to the top fifteen. However, we believe that the top 10 includes the main American tech giants and provides a useful basis for comparison with their Chinese and European counterparts (cf. Top 10 Tech China and Top 10 Tech Europe).

At this stage, it is important to point out that we have chosen to limit our analysis to listed companies as they are subject to regulatory obligations enabling us to collect standardised, long-term data. Therefore, readers should not be surprised to find that familiar unlisted tech companies such as Uber or Airbnb in the United States or Huawei in China4 are not included. We will subsequently use the term “Top 10 Tech US” (or “big tech”) to describe the sample of the richest American tech companies, namely (in descending order): Apple, Microsoft, Google, Cisco, Oracle, Facebook, Qualcomm, Amazon, Intel and IBM.

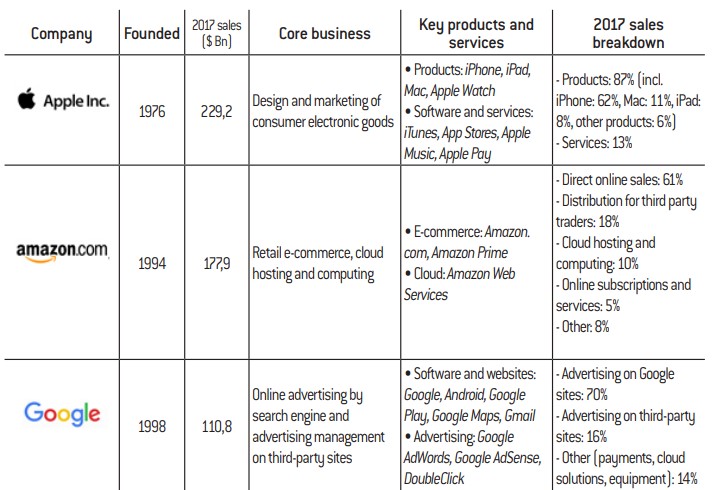

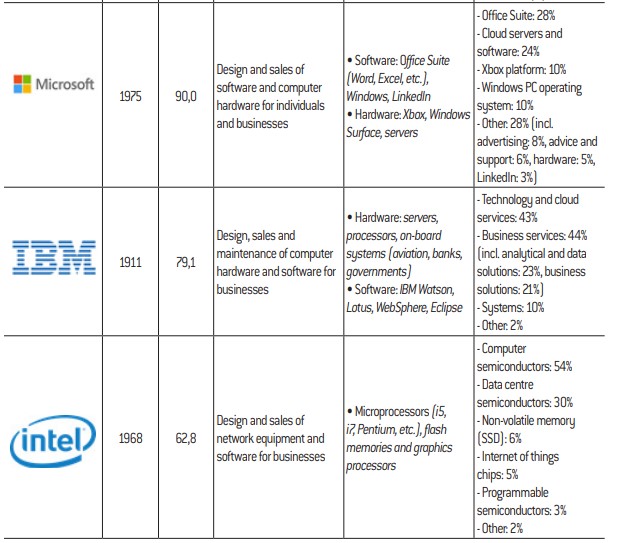

a. Companies with diverse business activities and income sources

It will be quickly apparent to readers familiar with the tech industry that our sample companies cover a wide range of business activities, namely

software, electronic equipment, web platforms and services (including cloud computing)5. A description of our ten selected tech giants’ activities can be found in Appendix 1(b).

However, the differences between companies in the sample should not obscure significant common features. All offer products or services related to information technology or the Internet and, as we will see later, hold at least one dominant position in one of their markets. Moreover, they all pursue business activities on several of the segments mentioned above. For example, Microsoft is a software developer (OfficeSuite), hosting and computing service provider (through Microsoft Azure), and electronic equipment producer (Surface computers and tablets, Xbox consoles, etc.). While Amazon is mainly known as an e-commerce platform, the company also provides hosting and cloud computing solutions (through Amazon Web Services) and develops and markets software integrated in electronic devices (Kindle tablets, Amazon Echo, etc.).

As such, several companies in the sample are in fact much less different than they may appear. Let us consider three familiar examples: Facebook-Google, Apple-Google and Amazon-Facebook.

- Facebook and Google offer their users different services, the former as a social network and the latter as a search engine. However, both rely on content providers to attract users and their value proposition for advertisers is similar – namely enhanced targeting of relevant Both companies’ main income source is therefore online advertising.

- Most of Apple’s profit is generated by designing and marketing cutting- edge consumer electronic devices, with iPhone sales representing no less than 62% of the company’s However, its main competitor, Google, has a very small share of this market. Its smartphones have never been a commercial success and their popularity is insignificant compared to the iPhone. The two companies are in fact locked in battle on a different front, namely the markets for mobile operating systems (iOS versus Android) and app stores (App Store vs. Google Play). While Google has secured itself a quasi-monopoly with other smartphone producers through its software, Apple is relying on the development of its own software to maintain its overwhelming margins in the high-end, cutting-edge consumer electronic device segment.

- Finally, like Facebook, Amazon’s business model is based on accumulating and processing its users’ data using sophisticated algorithms to create personalised experiences that encourage them to return to the platform.

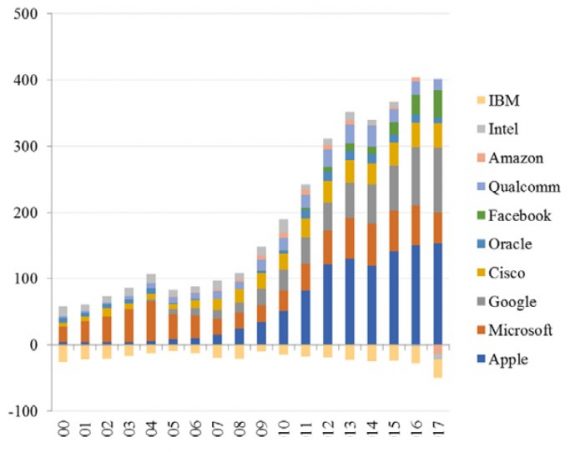

a. Comparing trends for cash and marketable securities over time

We will now examine historic trends in the American tech giants’ cash and marketable securities. Have these always been at their current record levels?

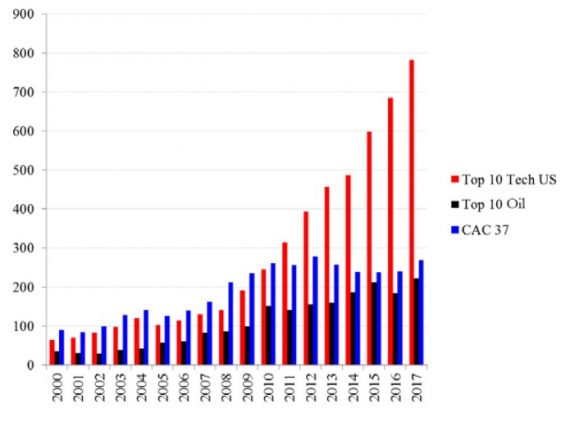

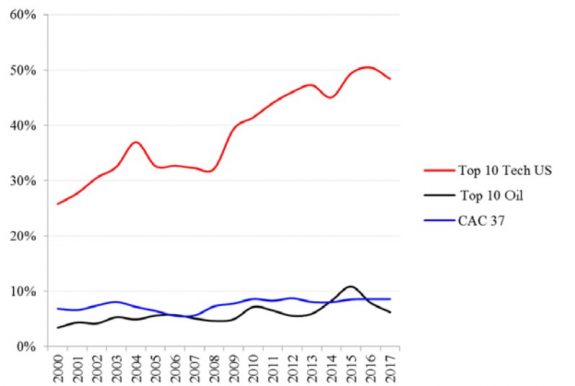

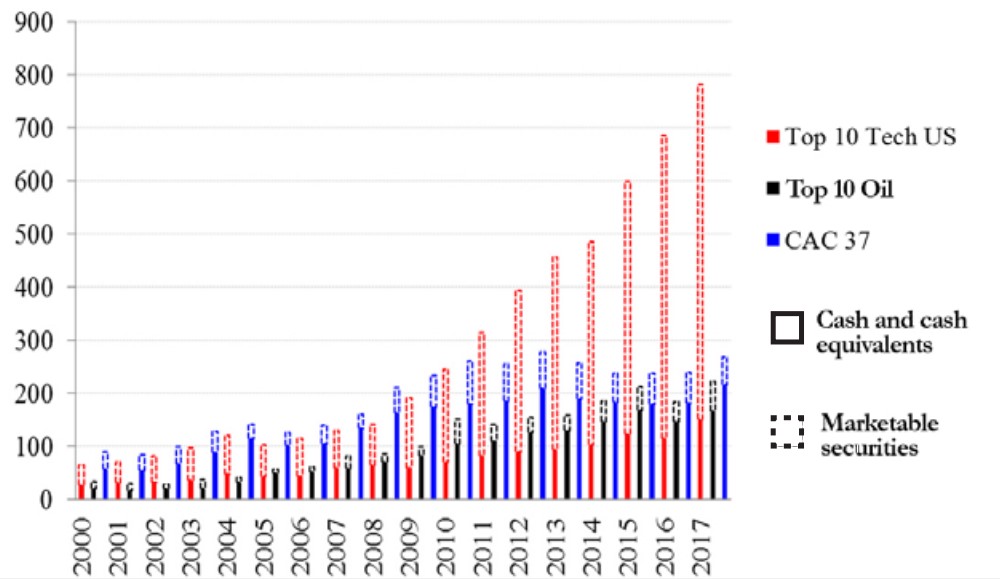

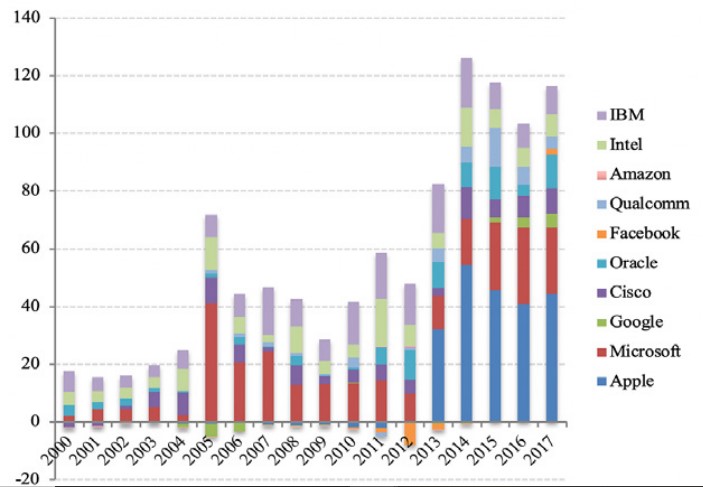

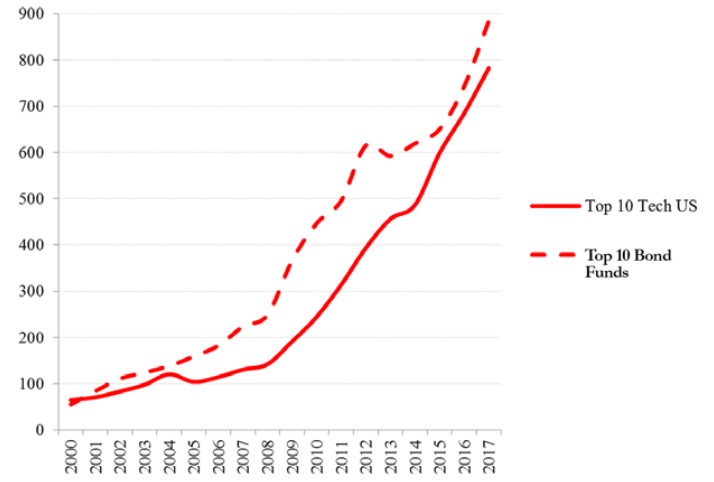

Between 2000 and 2017, the cash and marketable securities of the Top 10 Tech US shot up from €64 to €782 billion, representing 16% mean annual growth. This was particularly pronounced between 2008 and 2017, with 21% mean annual growth (compared to 10% between 2000 and 2008).

See Appendix 1(a) for details of sample composition.

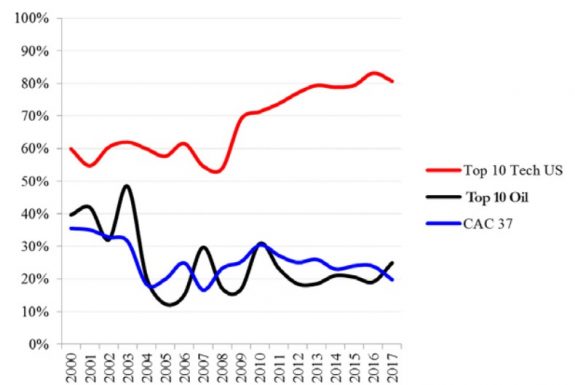

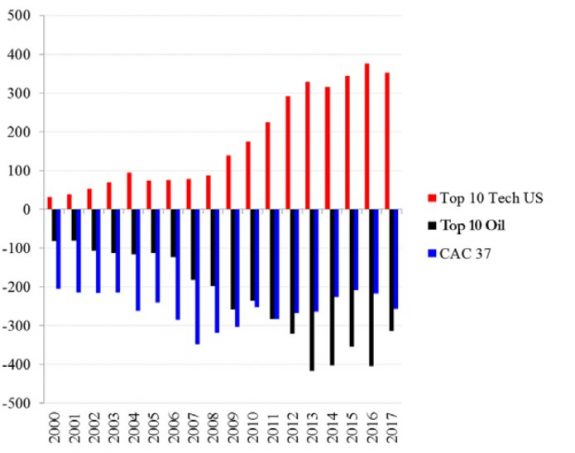

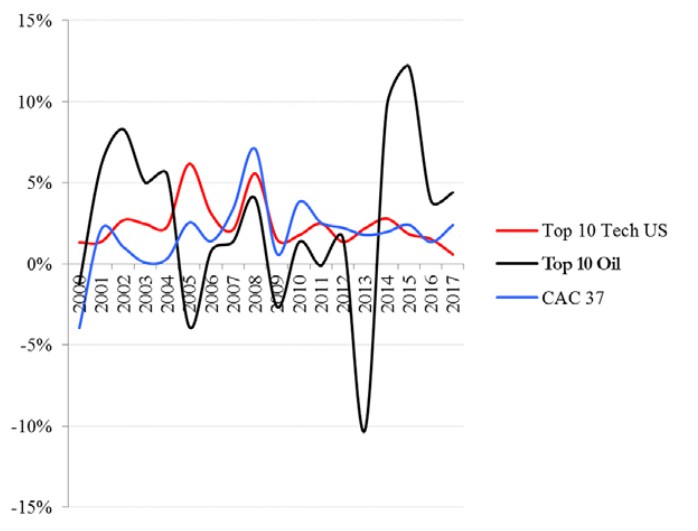

Considering the bigger picture, we decided it would be useful to compare these amounts with those seen in the oil industry, which includes companies that are considered to be particularly powerful and rich, and also with those of the “CAC 37”, which encompasses the main French companies included in the CAC 40 index (excluding its three banking institutions)6.

The results speak for themselves, with “Top 10 Tech US” currently holding 3.5 times more cash and marketable securities than “Top 10 Oil” (compared to 1.8 times at the end of 2000) and approximately 2.9 times more than “CAC 37” (compared to 0.7 times at the end of 2000). The growth of cash and marketable securities among the American tech giants was therefore on a completely different scale to that of the main traditional companies.

Graph 2: Comparison of cash positions in billions of dollars (US)

©Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

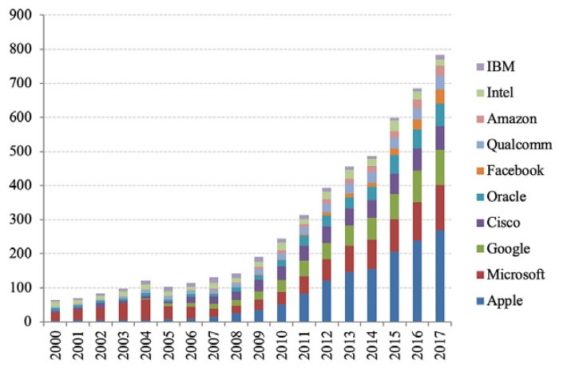

On closer examination of the dynamics of each company in the Top 10 Tech US sample, we note that the top 5 now account for 82% of the total cash and marketable securities (Apple 34%, Microsoft 17%, Google 13%, Cisco 9% and Oracle 8%) and that the rate of cash growth varies among companies. For instance, between 2008 and 2017, Facebook’s cash position grew at the frenetic annual rate of 73%. Apple (31%), Amazon (27%), Google (23%), Oracle (22%) and Microsoft (21%) are above the mean level, while Intel (5%) and IBM (0%) are below it.

Graph 3: Cash positions – Top 10 Tech US in billions of dollars (US)

©Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

a. Excess cash

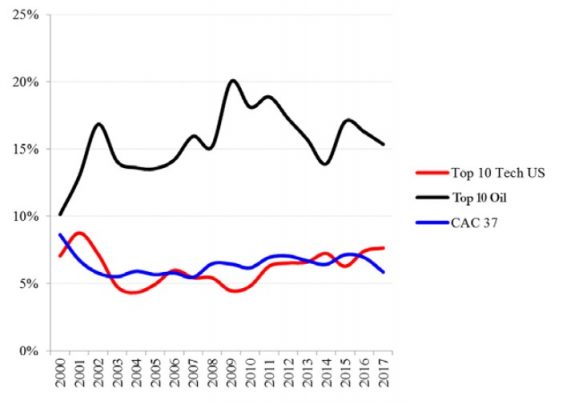

Having noted this meteoric growth in the American tech giants’ cash positions, we will now examine how this cash was accumulated in the first place. To that end, we must go back to the profits that fuel them, measuring them in economic rather than accounting terms in order to discard any non-monetary items included in income statements. Consequently, the relevant variable is free cash flow, or cash from operations less capital expenditures (capex). Compared to the revenues for each period, this indicates a company’s ability to convert its sales into available liquidity for acquisitions of other companies, shareholder remuneration, and finally, allocation to cash positions.

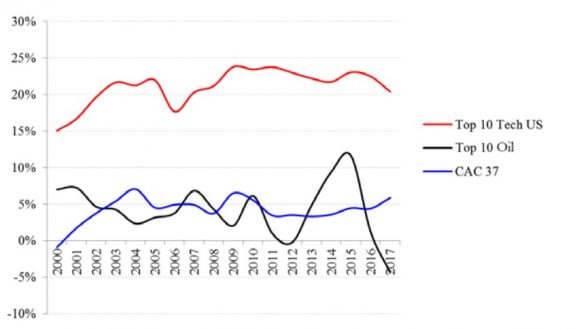

Graph 4: Comparison of free cash flow in percentage of revenues

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Therefore, caution is required when interpreting this profitability ratio since a resurgence of capital expenditure would automatically lower the ratio, even though this may reflect a company’s ability to invest in profitable projects and thus pave the way to accelerated future growth.

To that end, we will examine investment- and financing-related cash flows shown in the cash flow statements published by the companies in the sample.

Statistics show us that big tech companies converted 21% of sales into free cash flow between 2000 and 2017, which, in relative terms, makes them five times more profitable than the oil giants and the CAC 37 companies, whose mean proportion was just over 4%. To appreciate the full implications of this observation, it is worth noting that the 20% conversion of sales into free cash flow in 2017 generated no less than $185 billion. The tech giants’ ability to sustain this level of performance over the long term is truly remarkable.

However, we must also acknowledge the existence of significant disparities among the big tech companies. While Facebook, Oracle and Microsoft, for example, respectively converted 43%, 34% and 32% of their sales into free cash flow over the course of 2017, Amazon lagged behind at just 4%. This was due to its business being intrinsically less profitable but also to above-average capital expenditure levels7.

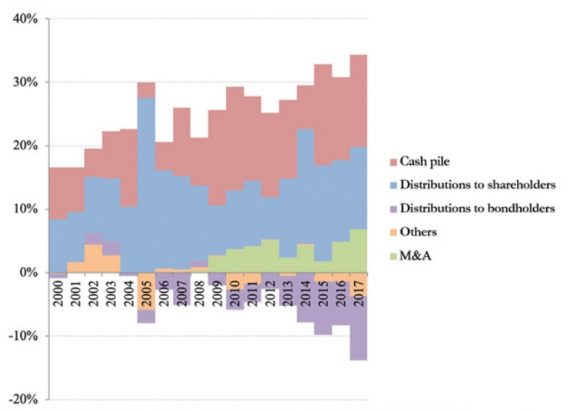

In order to understand how the tech giants allocate their profits, we will break down their free cash flow into its various uses8. It should generally be noted that some flows may be negative depending on companies’ divestiture activities and financing arrangements. Such may be the case, for example, if they issue more debt or capital than they eliminate by repaying the principal or repurchasing shares, or if they divest of more businesses than they acquire through mergers and acquisitions.

A breakdown of the big tech companies’ free cash flow reveals that despite their operations being remarkably profitable, the tech giants have issued debt securities in recent years. We will come back to the reasons for this situation later. In any event, if we calculate total free cash flow for the 2000-2017 period and add back negative flows corresponding to (net) resources, the capital allocation of big tech is as follows: 11% and 46% of “adjusted” free cash flow was used to finance the acquisition of companies (less divested businesses) and shareholder distributions (less capital raised) respectively, while 43% was used to increase the cash positions.

Graph 5: Allocation of free cash flow – Top 10 Tech US in percentage of revenues

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Hence, profits clearly outstrip any requirements in terms of financing new investments (capital expenditures and mergers and acquisitions) and shareholder remuneration. Every year, the resulting “residual” financial surplus, which has no real use in the productive process, augments the cash positions that we examined earlier.

a. Increasing share of financial assets in the balance sheets

Having analysed cash flows, we will now go back to stocks. We note that by allocating a significant share of the extraordinary profits generated by their business activities to their cash positions, the tech giants have prompted a gradual “financialisation” of assets on their balance sheets. Indeed, while the cash and marketable securities of the oil giants and the CAC 37 companies as a percentage of their total assets remained constant on average at approximately 6% and 8% respectively between 2000 and 2017, it rose almost uninterruptedly for the technology giants, from 26% at the turn of the 21st century to 48% seventeen years later.

As such, half of the big tech companies’ balance sheet assets now consist of liquid securities available for sale. Drawing on their operational success, the American tech giants have now become de facto financial portfolio managers and seem to edge closer every day to the tacit status of financial institutions.

Once again, this average trend masks differences between companies: the balance sheets of Apple (72%), Qualcomm (59%), Cisco (54%), Microsoft (53%) and Google (52%) exhibit the highest degree of “financialisation”, while those of IBM (10%), Intel (15%) and Amazon (24%) are at much more reasonable levels.

Graph 6: Comparison of cash positions as a percentage of total assets

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Ultra-conservative cash management

Having revealed the extraordinary sums accumulated by big tech companies in the form of cash and marketable securities, we will attempt to determine how these are managed. We will show that in contrast to their popular image as dynamic and innovative companies, the tech giants have in fact opted for an ultra-conservative capital management strategy.

a. Internal or external management?

Determining how these cash positions are managed is not an easy task, since most of the companies exhibit limited transparency in this area. However, some, including Cisco, Oracle and Facebook, state that they outsource cash management to specialist custodian financial institutions. Others such as Apple and Google appear to have opted for an internal management strategy. For instance, the Cupertino-based company set up its own management company, Braeburn Capital, in Nevada in 2005. Numerous sources concur that its rival from Mountain View also has its own team of traders. Several job vacancies posted on LinkedIn provide further evidence of this.

81% at the end of 2017 versus 25% for the oil giants and 20% for the CAC 37 While Apple and Oracle claim that the maturity of marketable securities in their portfolios does not exceed five years, the average maturity of their investments is impossible to estimate as they have disclosed insufficiently detailed financial information.

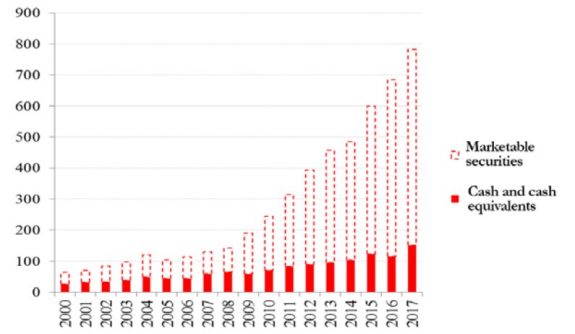

b. Increasing maturity of investments

Despite this lack of transparency with regard to management strategies, the companies’ annual reports combined with their regulatory declarations to the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) provide precious details on the maturity and nature of the assets that make up their cash positions. Firstly, the distinction between “cash and cash equivalents” and “marketable securities” gives an indication on their assets’ maturity. In accordance with the regulatory standards in force, “cash and cash equivalents” are any highly liquid investments with a maturity date that is up to three months from the purchase date, while “marketable securities” are any marketable assets available for sale with a maturity date that is over three months from the purchase date.

Unlike the oil giants and CAC 37 companies, it is apparent that the big tech invest most of their undistributed cash in financial assets with maturity dates of over three months9. Besides, the growth in big tech companies’ cash positions has been accompanied by a gradual increase in the share of relatively longer maturity investments (from 55% of total cash in 2007 to over 80% at the end of 2017).

Graph 7: Cash positions: cash versus marketable securities – Top 10 Tech US in billions of dollars (US)

©Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Graph 8: Comparison of cash positions – cash versus marketable securities in billions of dollars (US)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

These idiosyncrasies suggest that the tech giants currently have no intention of using these funds to finance investments or distributions, a sign that their cash positions have reached such high levels that they are no longer used for business operations.

Graph 9: Marketable securities as a percentage of cash positions

©Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

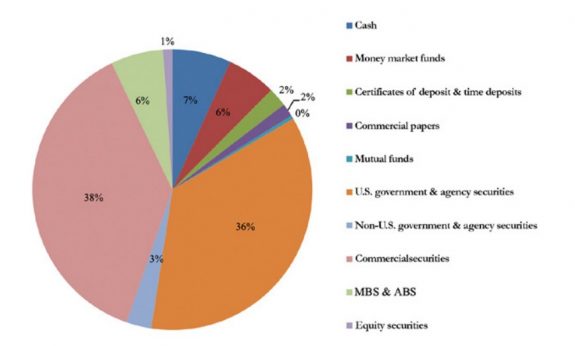

a. Ultra-conservative management and minimal return

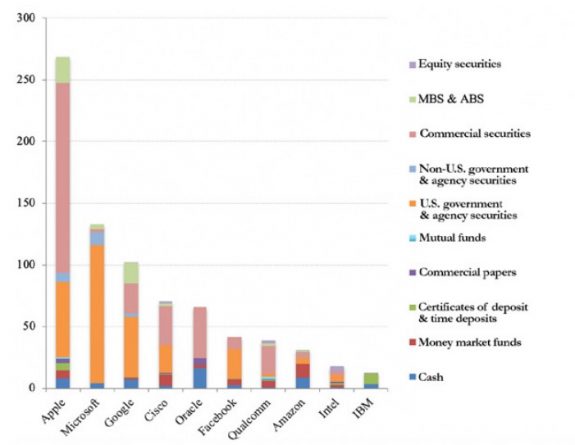

The regulatory declarations that we used to analyse the maturity of big tech companies’ investments also provide us with information on the various classes of assets in which they invest. An analysis of the data reveals that “pure” cash represents a low percentage of the total (7%). In fact, almost 80% of the aggregated cash position is invested in bonds, half of which are issued by governments or government-related agencies and half by companies (either financial or non-financial). This apparent diversification conceals a securities portfolio with a major emphasis on US sovereign debt. Several companies clearly appear to adopt an investment policy that excludes investment in foreign governments’ debt securities, including Facebook whose regulatory declarations explicitly state this.

However, there are interesting differences regarding investment profiles among big tech companies. For example, Apple, Oracle and Qualcomm stand out for allocating over 50% of their cash to corporate bonds, while Microsoft and Facebook use the vast majority of theirs to finance the US government. IBM, on the other hand, is extremely prudent in its allocation, since almost a third of its cash position is made of “pure” cash and two-thirds of safe bank debt. In contrast, Google allocates over 15% of its cash to mortgage-backed securities, while Intel allocates over 20% of its capital to shares in listed companies.

Graph 10: Breakdown of cash positions by asset class – Top 10 Tech US as at the end of 2017

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Even though some of these positions entail a relatively higher level of risk, the tech giants’ investment strategy is overall extremely conservative. They all state that their investment decisions are conditional on protecting their initial capital. This strategy clearly implies a strict focus on risk minimisation. For example, all the corporate bonds that they hold are “investment grade”, which means that they have been issued by well-established institutions with the best credit scores.

Graph 11: Breakdown of cash positions by asset class as at the end of 2017 in billions of dollars (US)

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

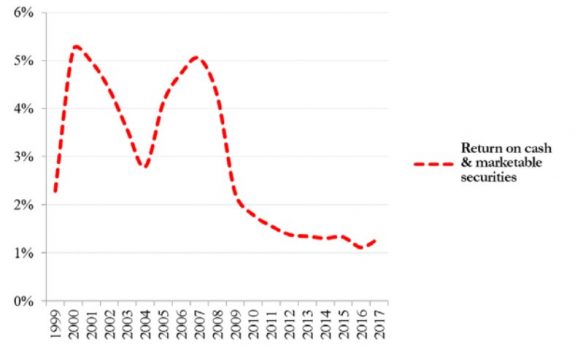

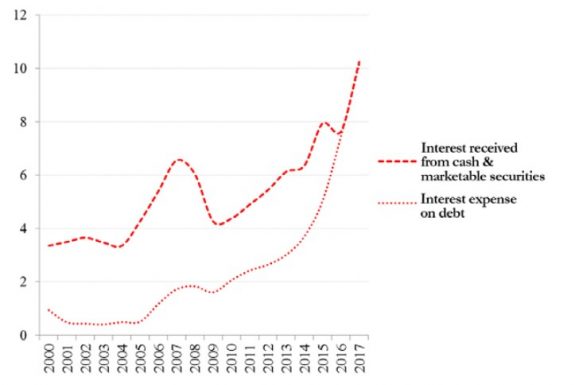

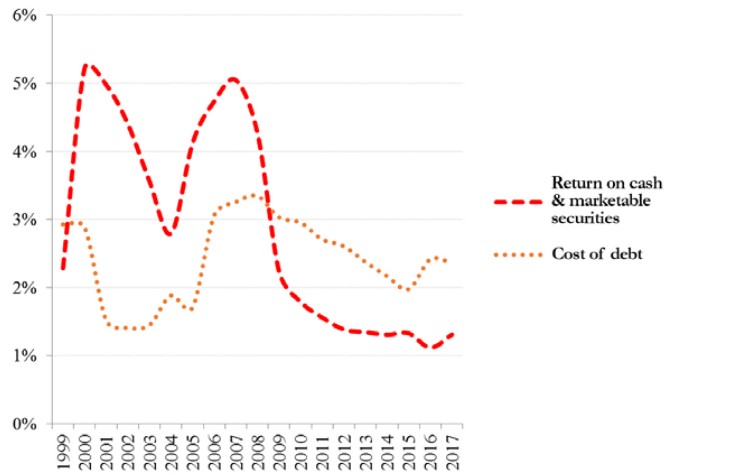

To avoid relying solely on the claims of the companies in question, we determined the average annual return on the big tech companies’ investments by taking into account the interest payments from the cash positions. As the graph below shows, this return is extremely low at approximately 1.3% per annum over the past five years, which is barely equivalent to the consumer price inflation in the United States.

Therefore, while the extraordinary rise in the tech giants’ cash positions seems to be coupled with an extension of the average maturity of the securities portfolio, this has not resulted in greater risk-taking. Far from their image as innovators investing massively in the development of future technologies, the tech giants actually allocate and manage their capital in an exceptionally conservative manner.

Graph 12: Average return on cash and marketable securities – Top 10 Tech US

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

A lasting and undesirable cash hoarding dynamics

More specifically, the law provides for taxation of undistributed profits that are reinvested in liquid securities, at a rate of 5%, and those reinvested in illiquid assets, at a rate of just 8%. We only mention the first rate in the body of the text as the second is not relevant to our analysis. It is worth noting that under the new tax code, American corporations will have eight years to pay this one-time tax.

Apple: 94%, Microsoft: 96%, Google: 62%, Cisco: 96%, Oracle 82%, Facebook: 38%, Qualcomm: 76%, Amazon: 31%, Intel: 60%.

It was indeed much less expensive to pay interest on debts equivalent to the distributed sums than to pay a flat tax of around 35% on the same repatriated Note that big tech companies make extensive use of tax avoidance techniques to register their profits made overseas in jurisdictions where tax rates are extremely low (Ireland, Luxembourg, etc.). We may therefore assume that although their effective tax rate in the event of repatriation would, strictly speaking, be lower than 35%, it would not be far off this figure.

To recap, the big tech companies have become key players in global finance by accumulating huge financial surpluses and their corporate treasurers appear more like managers of huge low-risk bond funds than working capital accounts. In terms of capital allocation, the scale and management of their cash positions leave no doubt as to the suboptimal nature of the current situation. However, can we expect this hoarding phenomenon to continue in the future? If so, what are the consequences for the economy?

a. Big tech cash hoarding: a temporary phenomenon or the new normal?

Tax arbitrage and the Trump reform

Many people claim that big tech hoarding is a temporary phenomenon as it was, for a long period, the result of a tax arbitrage, to which the Trump administration put an end last year by passing the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of

2017” (TCJA 2017). Before discussing the merits of this theory, we will take a moment to examine the idiosyncrasies of the American tax system and the recent changes made to it.

Until 2017, unlike most OECD countries, the United States levied a global corporate tax, whereby profits made by American companies overseas were taxable once they were repatriated in the United States at the federal corporate tax rate (35%) less taxes already paid overseas. The tax reform passed by President Donald Trump enshrined two major modifications: firstly, a cut in the federal corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%; secondly the replacement of the previous tax system by a territorial model under which only domestic profits are subject to tax, and the introduction of a 15.5% one-time tax on undistributed profits previously accumulated by American multinationals in their overseas affiliates, regardless of their intentions to repatriate10.

Given the cost of repatriating profits made overseas before TCJA 2017 was passed, the tech giants chose to accumulate their financial surpluses in their non-American affiliates – with the result of 82% of their current cash and marketable securities being domiciled overseas11 – and finance distributions to their shareholders (dividend payments and share repurchase programmes) by contracting debt on the US bond markets. With a general environment of low interest rates and high market confidence in the soundness of their business models, this arbitrage was a no-brainer12.

Consequently, the argument that distortions caused by the American tax system have influenced the tech giants’ capital allocation is absolutely relevant. However, it is unreasonable to suggest that these same distortions explain the entire hoarding phenomenon and hence the “financialisation” of the big tech companies outlined above.

For evidence of this, we need look no further than the trend of the big tech companies’ net cash positions, i.e. cash and marketable securities minus their debts. Although growth of the aggregated “net” position is, as one might expect, less sustained than the “gross” one, it is still very significant: an average of 15% per annum between 2000 and 2017 (versus 16% for the “gross” figure), 13% between 2000 and 2008 (versus 10%) and 17% between 2008 and 2017 (versus 21%). Thus, at the end of 2017, “net” cash and marketable securities reached $352 billion with debt equivalent to just 55% of “gross” cash and marketable securities (versus 242% for the oil giants and 195% for the CAC 37 companies).

Graph 13: Comparison of net cash positions (cash and marketable securities minus total debt) in billions of dollars (US)

©Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Finally, we should add that besides having access to other sources of finance such as domestic cash and marketable securities of $141 billion (as at the end of 2017), the tech giants faced no credit restrictions impeding bond issues if they had wished to distribute more cash to their shareholders or finance new investment projects. In other words, even if they had been able to repatriate all their cash domiciled overseas at no cost, it seems highly unlikely that they would have used them differently to the way we have observed.

Hence, the indisputable existence of a tax arbitrage that led big tech companies to issue debts rather than use their cash resources to pay for shareholder distributions only partly explains the hoarding phenomenon.

Graph 14: Net cash positions (cash and marketable securities minus total debt) in billions of dollars (US)

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

5% (tax rate) * 82% (percentage cash and marketable securities domiciled overseas) * 782 billion dollars (cash and marketable securities) = 99.39 billion dollars.

In other words: if appropriate investment opportunities existed, they would already have been financed.

Repatriation of cash: what scale, what impact?

We will now examine the present situation and try to anticipate the future. In contrast to the US administration’s previous attempts, including George W. Bush’s “repatriation tax holiday” in 2004, the Trump reform is unique in that it permanently eliminates the disincentive to repatriate profits while stopping short of any repatriation incentive. Whether or not they decide to repatriate their cash, the American tech giants will therefore pay a one-time tax of almost $100 billion over the next eight years13.

As of yet, only Apple and Cisco have publicly announced their intention to repatriate the majority of their cash domiciled overseas14. In their latest regulatory filings, Microsoft, Oracle and Qualcomm have made it clear that their overseas profits should be considered as being “permanently reinvested” there. Microsoft has even gone so far as stating explicitly that they currently do not intend nor foresee a need to repatriate these funds15. The “repatriation tax holiday” experience of 2004 moreover leaves us sceptical as to the interest of repatriation for tech giants. According to Moody’s rating agency, the five giants Apple, Microsoft, Google, Cisco and Oracle only decided to repatriate 9% of eligible sums at the time16.

While President Trump promised widespread repatriations followed by massive productive investment in the United States, it appears that the multinationals do not see things quite the same way. Furthermore, the reasons that lead us to believe that cost-free repatriation would not have radically changed the tech giant’s capital allocation in the past are still valid today and are likely to remain so, at least for a certain period of time. With abundant domestic financial resources and immediate access to the financial markets at significantly lower costs than their cost of capital, the big tech for sure do not have any “delayed” investments 17 and have so far been able to remunerate their shareholders generously.

The big tech companies’ capital expenditure as a percentage of revenues is currently higher than its long-term trend (8% and 7% in 2017 and 2016 compared to an average of 6% between 2000 and 2017). It is worth noting that at the time of the 2004 “repatriation tax holiday”- a similar situation in which companies had easy access to credit – the impact of repatriation on domestic investment proved negligible. Indeed, according to Wells Fargo (2018), less than 1% of repatriated sums were used to finance capital expenditure18.

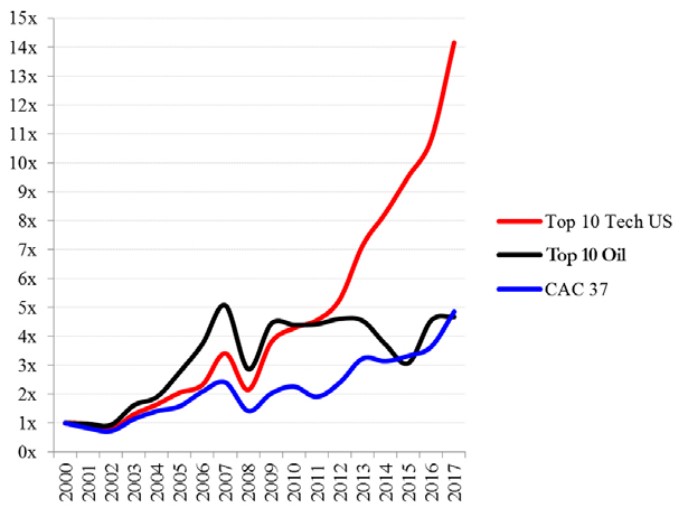

Moreover, in addition to the exceptional shareholder value creation generated by the spectacular rise in their share prices, the tech giants did not deviate from the average in terms of distributions. In the long term, their shareholders’ yield is indeed comparable to that of the CAC 37 companies.

Graph 15: Comparison of capital expenditures (as a percentage of revenues )

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Graph 16: Investment multiple of a diversified portfolio of shares for each sample

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Graph 17: Comparison of shareholder yield

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

For each period, the shareholder yield is calculated as a ratio of the sum of all forms of distribution (dividends, net share repurchases and net debt reduction) to market This measurement therefore does not include the other major component of shareholder return on investment, namely share price gain.

Graph 18: Dividends and net share repurchases in billions of dollars (US)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

However, could some giants take this opportunity to repatriate and return more money than usual to their shareholders? A number of recent announcements suggest that this might be the case. Apple and Qualcomm have revealed their plans to set up share buyback programmes of $100 and $30 billion respectively20. But on closer inspection, these two companies’ circumstances appear quite specific. With the lowest P/E ratio in the big tech sample, Apple’s share price seems under-valued given the company’s growth prospects. This announcement of a one-time distribution may therefore be interpreted as an attempt by the management to boost the share price and therefore avoid the return of activists to its general meeting of shareholders. As regards Qualcomm, the announcement was made following the abandonment of the acquisition of the Dutch semiconductor manufacturer NXP. Therefore, it was simply a matter of redistributing money that had been set aside specifically for this transaction. In any case, nothing would currently suggest that the other tech giants are likely to perform these one-time distributions.

Nevertheless, we think that big tech companies will gradually repatriate a large portion of their cash domiciled overseas in order to repay the face value of their debts when they reach maturity. We believe this is all the more plausible since the interest payable on these debts is currently roughly equal to the total interest generated by cash investments. In any event, it is unlikely that such repatriation will take place overnight for at least two reasons: on the assets side, there is no benefit in the tech giants selling off their bond securities before they mature as this could expose them to losses (especially in a context of rising interest rates); on the liabilities side, even if their debt agreements include early repurchase clauses, it would probably cost more to activate these than waiting until securities mature. This assumption is moreover confirmed by a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey with a representative sample of relevant companies. When asked “What will you do with your repatriated cash?”, most companies responded that they would “pay down debt”21.

Graph 19: Income from cash positions versus debt service – Top 10 Tech US in billions of dollars (US)

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Graph 20: Return on cash positions versus cost of borrowing – Top 10 Tech US

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Examples: 35% to 21% in the United States (a cut already implemented by Donald Trump in 2017), 3% to 25% in France by 2022 (in line with Emmanuel Macron’s electoral promise), 20% to 17% in the United Kingdom in 2020 (initial cut of 20% to 19% implemented in 2017).

In summary, the impact of Donald Trump’s tax reform on big tech capital allocation is likely to be moderate in the short term and more substantial in the medium term when the time comes to pay down the face value of debts issued in the past. Whatever the case, we do not expect this to affect the persistence of large sums of cash and marketable securities on the tech giants’ balance sheets.

Beyond repatriation – a multi-factor dynamic

Ultimately, a multitude of factors other than repatriation will impact the big tech’s cash position.

In purely fiscal terms, Donald Trump’s one-time tax on undistributed profits accumulated overseas is set to cut cash and marketable securities by €100 billion (i.e. 13% of current cash position) over the next eight years. However, given the trend for lower corporate tax in most developed countries22, the negative impact of this one-time tax is likely to be counterbalanced, all other things being equal, by lower tax on future profits. However, it should be noted that if the international community or at least Europe were to take firm action against tax havens and work towards harmonising tax rates, it is not inconceivable that tech giants may end up paying more tax on their profits than they currently do.

With regard to capital allocation, the question arises of whether the big tech companies’ future cash flows will keep on increasing their cash positions to the same extent as in the past, or whether there will be greater distribution to shareholders. With considerable projected profits reflected by the level of their valuation multiples (see the P/E ratio below), the balance of power between management and shareholders is set to remain largely in favour of the former. So it is highly likely that they will continue to retain a significant portion of future profits for the very same reasons that have hitherto driven them to accumulate such high levels of cash (risk aversion and maintaining financial independence from banks and financial markets).

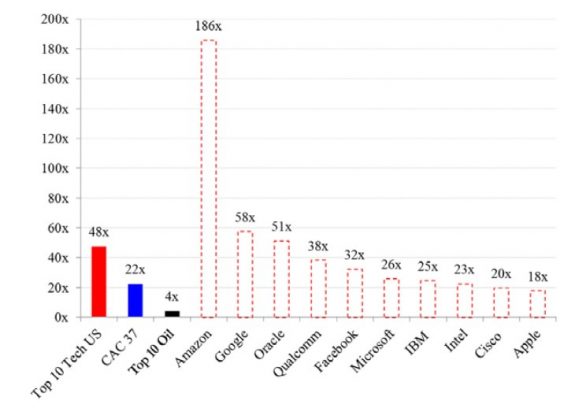

Graph 21: Comparison of P/E ratios at the end of 2017

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Estimated foreign exchange reserves as at the end of 2017 (in billions of dollars and percentage of big tech cash and marketable securities): Latin America: 858 (91%), Southeast Asia: 886 (88%), Middle East: 1119 (70%). Assets under management of the ten largest private global bond funds (in billions of dollars and percentage of big tech cash and marketable securities): 884 (89%). A list of the ten funds in question can be found in the appendix.

Of the $21 trillion in US sovereign debt, $5.6 trillion (30% of the total) is held by entities that are affiliated in one way or another to the US For example, creditors include the Social Security Trust Fund or the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund.

It should be noted that several companies in the sample have not yet developed the habit of regularly distributing cash to their shareholders. For instance, Amazon, Facebook and Google have never paid a single dividend. Amazon has not repurchased any shares since 2012. Google and Facebook began to do so in 2015 and 2017 respectively, although for derisory sums. However, their distribution policy may well change in the coming years, in line with the path taken by Apple since 2012. In this case, growth of the big tech companies’ cash positions would probably slow down naturally.

Finally, if the next wave of innovations (e.g. artificial intelligence, driverless cars, robotics, drones, etc.) were to prove relatively more capital intensive, the big tech companies may see their capital expenditure increase, which would de facto reduce their free cash flows and eventually limit their cash hoarding potential.

Although multiple factors with uncertain and potentially divergent effects are at play, it is likely that the tech giants will still retain high levels of cash in the future. We therefore consider big tech hoarding to be a more structural than temporary phenomenon. What are its consequences for the global economy? Can such microeconomic phenomenon have macroeconomic effects?

b. A sub-optimal capital allocation for the economy

Companies involved in cutting-edge industries such as information technology, electronics and biotechnology are generally expected to encounter investment opportunities whose financing requirements outstrip internally generated cash, prompting them to tap financial markets in order to speed up their growth. However, with capital allocation more akin to the patterns of old monopolistic industries than those of dynamic, innovative companies, the American tech giants have long since moved from being “net borrowers” with respect to the rest of the economy to the more comfortable position of “net lenders”. We believe this persistent trend is harmful from a macroeconomic perspective.

Orders of magnitude

First of all, we believe it is important to have some orders of magnitude in mind.

Cash and marketable securities accumulated by big tech companies between 2000 and 2017 ($718 billion) equates to almost one and a half times their total capital expenditure over the same period ($505 billion). To reach a figure approaching the $718 billion of capital held as cash and marketable securities, one would have to add the total value of mergers and acquisitions performed over the same period (i.e. acquisitions less divestitures). These hoarded sums are therefore truly colossal in proportion to the investments made. In absolute terms, they are comparable to the foreign exchange reserves held by central banks in the main emerging regions (Latin America, East Asia, the Middle East), or to the assets under management of the ten largest private global bond funds (see graph below)23.

Moreover, we estimate that approximately $281 billion of big tech companies’ cash is invested in US government securities, which represents just under 2% of total US sovereign debt excluding intragovernmental holdings24.

Finally, investments in corporate bonds amount to $294 billion, which is around 6% of the US investment grade market according to the estimates of Morgan Stanley25.

Graph 22: Cash positions of Top 10 Tech US vs. assets under management of top 10 bond funds in billions of dollars (US)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

Mean annual growth of total factor productivity: +1.9% between 1920 and 1970, +0.6% between 1970 and 1994, +1% between 1994 and 2004 (acceleration linked to the information revolution), and just +0.4% between 2004 and 2014. Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Princeton University Press, 2016.

With these orders of magnitude in mind, we will now examine the macroeconomic consequences of the tech giants’ approach to capital allocation and cash management.

b. Impact on productivity gains

We believe that their current capital allocation policy runs the risk of slowing down productivity gains and therefore hampering the economy’s potential output growth. As we have demonstrated, capital held as cash and marketable securities is allocated in an excessively conservative manner and therefore only contributes to a limited extent to financing the productive economy. Therefore, the big tech companies’ excessive cash hoarding could be a factor behind the marked slowdown in productivity gains observed in the US economy over the past decade by Robert J. Gordon26, and more specifically within the tech industry by John G. Fernald27.

In finance, assets that retain their value in the event of adverse macroeconomic shocks are described as “safe”. There are two complementary ways of interpreting this shortage of safe assets – either in terms of supply (the economy is not generating sufficient safe assets), or in terms of demand (economic operators have an excessive preference for safe assets). Our argument is based on the demand side.

This enables any given financial asset (e.g. a mortgage) to be split into ‘tranches’ to extract various risk levels from it. It should be noted that the topic of securitisation is currently back on the agenda of discussions in the EU, notably regarding the debate on European safe bonds.

In particular, the economists Ricardo Caballero (MIT) and Emmanuel Farhi (Harvard) documented the risk and consequences of the economy becoming caught in a ‘safety trap’ (a reference to the ‘liquidity trap’ from the Keynesian model).

Other macroeconomic impacts

Moreover, through their current cash management strategy, the tech giants are exacerbating the shortage of safe assets28, a key dynamics in the global economy causing a downward trend in the real risk-free interest rate and the associated rise in risk premia. While multiple factors, both temporary and structural, are regularly quoted to explain this shortage, the orders of magnitude mentioned above corroborate our intuition that big tech cash hoarding should also be considered.

In our opinion, this shortage of safe assets has three negative consequences. Firstly, the automatic increase in risk premia inevitably leads to rising inequalities in income and assets insofar as the proportion of high-risk assets in households’ financial portfolios tends to increase with wealth. Secondly, the scarcity of safe assets puts pressure on the financial industry to artificially “generate” more of them through techniques such as securitisation29. While there is nothing wrong with this as such, it nevertheless complicates the assessment of financial exposure on the market and may, if it becomes too systematic, jeopardise financial stability as seen in the subprime crisis of 2008. Thirdly, by maintaining the real risk-free interest rate at structurally low levels, the shortage of safe assets tends to reduce or even neutralise central banks’ ability to stimulate demand through a conventional interest rate policy in the event of economic slowdown30.

In short, the prospect of long-term big tech hoarding is a legitimate cause of concern. This leads us to the next question: what should be done from a policy perspective?

Possible solutions to halt the “financialisation” of big tech firms

However, it would not be an unreasonable proposition for the tech giants to entrust a significant portion of their cash to institutions specialising in productive capital allocation such as venture capital, growth capital and private equity funds.

By now, readers will have understood that we advocate a reallocation of the tech giants’ cash and marketable securities. However, the question of how to achieve this is far from straightforward. Indeed, it would be extremely regrettable if the big tech companies were to use their cash to become inefficient conglomerates as a result of mergers and acquisitions that offer no particular synergies with their own businesses, or were to take speculative positions on financial markets. Companies, especially those involved in the tech business, are fundamentally neither intended nor have the expertise to act as specialist financial institutions, as demonstrated by big tech firms’ poor performance with respect to financial investments. Their transformation into alternative investment funds is therefore inconceivable31.

Generally, we believe that the big tech firms’ dormant capital should be distributed to their shareholders in order for it to be reallocated within the rest of the economy. It would thus contribute to financing projects with the greatest potential for generating positive returns and contributing to growth. So, how do we encourage the distribution of cash that is already being hoarded and limit its future accumulation?

Speeding up cash distribution through greater shareholder involvement in decision-making ?

a. Passive shareholders

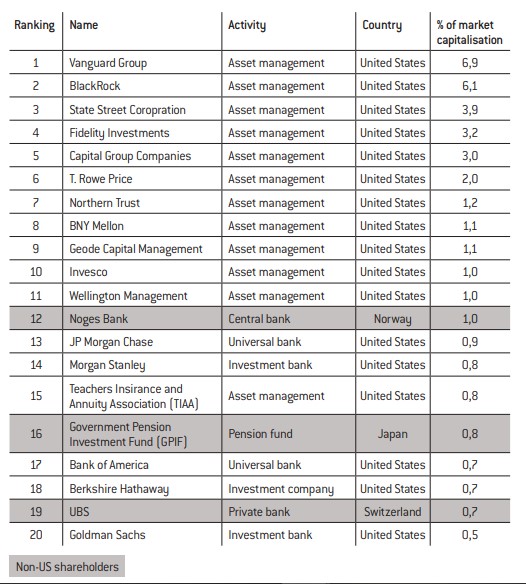

We will initially examine the influence of tech companies’ shareholders in decisions regarding capital allocation. At present, it is evident that the main shareholders in big tech companies are large American financial institutions (see table 1). While the three overseas entities included in the ranking of the top twenty institutional shareholders do not even hold 3% of the capital, the American asset management giants Vanguard, BlackRock, State Street and Fidelity alone hold over 20%.

Moreover, the various big tech companies tend to have the same shareholders. These “cross holdings” indicate that when investing in companies, American asset managers adopt an approach based more on diversifying their investments rather than on strategies resulting from a well-supported belief in the legitimacy of specific companies’ business models. Their approach to shareholding is therefore generally “passive” in that they have no intention of engaging in in-depth dialogue with management or other shareholders with a view to influencing the companies’ strategies. In fact, little pressure is exerted on the tech giants’ executives to distribute more of their excess cash.

Table 1: Top 20 institutional shareholders of the Top 10 Tech US (aggregated)

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018

The table shows the top twenty institutional shareholders in a fictitious company with a market cap equal to the sum of those of the ten tech companies in our “Top 10 Tech US”

Activists buy shares in a company that they consider to be under-valued with a view to initiating changes capable of harnessing its entire growth potential (strategic initiatives, financial restructuring, turnaround, improvement of operational performance, changes in corporate governance, ). Their proposals are either presented at general shareholder meetings or board meetings, or disclosed publicly if internal communication proves insufficient.

An action that involves picking up other shareholders proxies (voting rights) to gain a majority position and influence decision-making within the general shareholder meeting.

More precisely: $11 billion in dividends and $23 billion by stock buybacks in 2013; $11 billion in dividends and $45 billion by stock buybacks in 2014.

Apple and activist funds

However, this was not always the case. Between 2012 and 2013, two famous “activist”33 shareholders, David Einhorn (Greenlight Capital) and Carl Icahn (Icahn Capital Management) made a dramatic entry at the Apple general shareholder meeting via their respective investment funds. They demanded that the company’s huge cash reserves be used to finance distributions to its shareholders.

In March 2012, Apple believed it could silence persistent criticism of its capital allocation policy by announcing the introduction of a quarterly dividend (the first since 1995!) and launching a $45 billion share repurchasing programme over the subsequent three years. However, David Einhorn, who had been a shareholder since 2010 through his Greenlight Capital fund, then emerged as the most virulent critic of a plan that he considered woefully inadequate to substantially reduce the company’s obscenely high levels of cash and marketable securities. While condemning chronic problems in terms of cash accumulation, which he readily compared to a classic inventory problem, he claimed that anticipated suboptimal reinvestment of future cash flows was negatively impacting the company’s market cap. He believed the company should consequently distribute its cash overflow to generate value. In early 2013, just before the general shareholder meeting, David Einhorn publicly unveiled the plan he was proposing to the firm – namely to use its excess cash to distribute perpetual preferred stock (labelled “iPrefs”) to ordinary shares’ holders. This would be re-purchasable at any time by Apple at its face value and pay a perpetual quarterly dividend to holders. Following a simmering dispute with senior management, he filed a successful lawsuit against Apple claiming the illegitimacy of a proposed amendment to the company charter making any issue of preferred stock conditional on dual approval from the board and shareholders. In the end, Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook did not adopt David Einhorn’s plan. However, two months later, he announced that the upper limit of his share buyback programme would be doubled (from $45 to $100 billion by the end of 2015) and that the quarterly dividend would be increased by 15%. Apple’s management and board were given just a few months’ respite before Carl Icahn proclaimed via Twitter in August 2013 that he owned shares in what he described as “the most overcapitalised company in corporate history”. While David Einhorn caused a stir, Carl Icahn proved much more vocal and virulent using all means at his disposal (Twitter, interviews on CNBC and disclosure of letters sent to the CEO, Tim Cook) to condemn the company’s ultra-conservative approach to capital allocation. He demanded faster progress with the share repurchase programme, which he described as “the company making an investment in itself” given the disconnect between its fundamental value and market cap. In October 2013, he even announced on CNBC that he intended to start a proxy fight34 in order to secure a seat on the board, which he relinquished once the company announced the repurchase of a significant number of shares. The business news website Quartz summarised his strategy as: “come in second but with a bigger microphone”35.

In any event, these two examples clearly illustrate how minority shareholders have successfully influenced the capital allocation strategy of one of the world’s largest tech companies. Although it is of course always difficult to separate causality and correlation, many observers now agree that this twin campaign profoundly changed attitudes at the company’s top level. Within the space of just two years (2013-2014), $90 billion was distributed to shareholders as dividends (24% of the total) and stock buybacks (76% of the total)36. Since then, an additional $134 billion has been paid out, 27% as dividends and 73% via stock buyback.

b.Should shareholders be more involved in decision-making?

Since activist funds have demonstrated their ability to influence capital allocation, why not encourage their development by such means as altering the rules of corporate governance or earmarking a portion of savings for them? With a view to revitalising its economy, Japan, a country whose rules and culture were for many years skewed in favour of management at shareholders’ expense, recently initiated moves to relax the law concerning the governance of its companies and indicated that holdings by activist investors would no longer be unwelcome.37

However, such plans should be qualified for two reasons. Firstly, nothing currently suggests that activists have any difficulties raising capital. On the contrary, their increasingly frequent campaigns, which are amply covered in the specialist press, indicate that they are riding high. Secondly, their impact on the economy is open to debate (see the report “Shareholder activism research spotlight” from the Stanford Business School for a review of literature on the subject). While in many cases, such as that of Apple, their robust interventions enable breakthroughs in resolving aberrant situations, their surprising and aggressive claims can also, as much as anything, disrupt the smooth running of companies. Therefore, encouraging shareholder activism with the sole aim of resolving the specific problem of big tech cash accumulation could be like treating a patient suffering from digestive pain caused by a pancreatic disorder by prescribing a fast-acting treatment whose effects on the rest of the digestive tract are unknown, without first identifying the cause of the problem.

Discouraging cash retention through financial regulation?

GE Capital is GE group’s financial services unit; it manages its cash and marketable securities, derivatives portfolio, non-marketable securities investments, risk capital investments, project finance, etc.

If tipping the balance between management and shareholders through corporate governance reforms appears not to be the most appropriate solution for discouraging the big tech companies’ tendency of accumulating cash on their balance sheets, what leverage is available to regulators? Since the tech giants have, to some extent, become asset managers, it seems reasonable to regulate them as such.

a.L ow or non-existent financial risk

However, given the ultra-conservative approach to cash management revealed above, financial risk associated with big tech cash positions is unsurprisingly relatively insignificant:

- Market risk is Although interest rate rises are likely to reduce the market value of big tech companies’ bonds, they are sufficiently cushioned to ensure that they are unlikely to suddenly find themselves in a situation where they need to sell these off on the secondary market.

- Credit risk is low given their counterparties’ financial soundness (mainly the US government and very robust companies).

- Political risk (e.g. accelerated inflation, sudden currency devaluation) is negligible considering that their assets are mainly in dollars and issued by US

- Contagion risk or systemic risk is minimal as their positions are fully backed by equity

b.Monitoring their financial positions

Nevertheless, the tech giants’ cash positions remain extremely significant. Increasing scrutiny and closer monitoring of their development would be therefore beneficial. In this respect, the big tech companies’ current disclosure obligations associated with their status as listed companies may appear insufficient. To enable the financial sector supervisory authorities to conduct any necessary investigations, we suggest that the tech giants should be required to set up a financial institution to manage their cash holdings (exceeding their working capital requirements) based on the model of the General Electric

affiliate, GE Capital38. This obligation could be extended to any company with cash and marketable securities exceeding a limit defined by the regulator. General Electric and General Motors’ difficulties between 2008 and 2009, which resulted in costly bailouts for the taxpayer, remind us that the financial activities of non-financial companies can exacerbate their problems in difficult economic conditions.

c. Financial regulation and cash hoarding

But would this financial institution status really discourage big tech cash hoarding? Everything points to the contrary. For example, Apple has owned a dedicated management company (Braeburn Capital) since 2005, which has clearly not prevented the company from accumulating the highest levels of cash of all the big tech companies.

In more fundamental terms, it should be noted that the restrictions associated with such status are extremely limited. Financial regulation is typically focused on two key objectives: (i) informing and protecting savers, and (ii) maintaining financial stability. Institutions whose financing is not reliant on the former and which have no obvious impact on the latter are very loosely regulated. In this respect, big tech companies are typically comparable to family offices or American university endowment funds. Should tougher regulation be introduced for financial institutions that operate using equity capital without any leverage? This is an open question that we can only begin to answer by considering all the costs and benefits associated with implementing additional restrictions.

As previously mentioned, the main advantage of financial institution status is the ability to facilitate monitoring of the activities in question and provide the regulator with access to information where required. The recent history of GE Capital, although an extreme case, since the company’s financial activities were much more complex and sophisticated than those of the big tech firms have ever been, clearly illustrates the potential benefit of monitoring the financial positions of a non-financial group more closely. After it was designated a “systemically important financial institution” by the FSOC (US Financial Stability Oversight Council) in 2013, the General Electric affiliate moreover decided to divest half its assets39 to free itself from a status that had become too troublesome.

Limiting future cash accumulation through taxation?

- We observe that countries in which mean effective tax rates are particularly low report exceptionally high levels of profits before taxation.

In most countries, interest on debt is indeed deductible from taxable profits.

This is the amount of Apple’s unpaid tax in Ireland between 2003 and The company may actually have received preferential treatment since the 1990s. However, the European Commission cannot go back more than ten years prior to the initial request for information.

In the report on its investigation of Apple, the Commission moreover clearly specifies that “[this] is however outside the remit of EU state aid control”.

Under differential taxation, it was in fact in the administration’s interests to encourage tax avoidance to maximise its own tax revenue in the event of Some suggest that the US Treasury thus deliberately facilitated the transfer of US multinationals’ overseas profits to countries with low tax rates from 1996 (see Wright and Gabriel Zucman, op. cit., p. 10-11).

The proposal presented by the European Commission on 21 March 2018 notably provides for a 3% tax on revenues for digital services for groups whose annual revenues exceed (1) €750 million globally and (2) €50 million in The European Commission has presented this as a temporary measure pending a more extensive review of corporate tax rules at European level. It is not due to be implemented until 2020.

Which is close to the average global corporate tax rate (24%, source: KPMG).

Among the objectives agreed between France and Germany in Meseberg is the goal “to reach an EU agreement on a fair digital taxation by the end of ” (Declaration in Meseberg, 19 June 2018, p. 3), while in the conclusions adopted by the European Council on 28 June 2018 there is the following sentence: “The Council should consequently work on the Commission’s proposals regarding taxation of the digital economy”.

If financial regulation currently appears unlikely to limit big tech companies’ cash accumulation, could taxation be the solution? The basic principle is simple – higher taxation of tech giants’ profits would indeed reduce their capacity for hoarding. However, in order for such a solution to work, tax avoidance options that currently allow multinationals to transfer their profits to jurisdictions with more advantageous tax arrangements need to be drastically limited “upstream”.

a.Tax avoidance

To understand why tax avoidance is currently such a major issue, we will take a moment to consider the recent results of the empirical academic literature. Several studies reveal that multinationals are benefiting from low tax rates due to their ability to declare a significant portion of their profits in tax-efficient jurisdictions such as Ireland, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, to quote just a few examples in Europe40. In particular, Tørsløv et al. (2018) estimate that almost 40% of profits made by American multinationals overseas are declared in tax havens (or equivalents)41.

More specifically, the companies use a number of techniques to concentrate as much of their profits as possible in countries with the most beneficial tax arrangements. The first such technique simply entails internally manipulating so-called “transfer prices” or intra-group interest payments. In practical terms, an affiliate domiciled in a country with a high tax rate can reduce its taxable profits by importing goods or services (or borrowing money) at artificially high prices (or rates) from an affiliate in a country with a low tax rate42. A second strategy, which is particularly advantageous for tech companies, relates to the location of intangible assets (data, algorithms, patents, etc.). By registering such assets to an affiliate subject to a lower tax rate, companies can have royalties paid by an affiliate subject to a higher tax rate, thus reducing the latter’s taxable profits by the same amount. Although such avoidance techniques are well known, it is extremely difficult to tackle them in practice due to the asymmetry of information that inevitably exists between a company and its supervisory authority combined with a lack of cooperation between tax authorities whose interests are often divergent.

b. Tougher corporate transparency obligations and political pressure on “complicit governments”

In order to impede such forms of avoidance, it appears essential to address the issue in two ways: firstly, at company level by introducing tougher transparency obligations; and secondly at government level by significantly speeding up the process of cooperation and ultimately harmonisation at global or at least European level.

For instance, regulators could consider making corporate avoidance more difficult for companies by imposing more stringent disclosure obligations on them, particularly with regard to details of corporate structures, transfer prices, and intra-group royalty payments. However, this raises two issues. Firstly, avoidance strategies are mostly legal and therefore impossible to prohibit on a legal basis. Secondly, this is a two-speed race since the participants operate neither on the same line nor with the same resources. On one hand, large corporations do their utmost to constantly keep a step ahead of regulations and on the other, governments cannot and should not monitor everything.

In fact, the real issue with regard to taxation lies in cooperation and harmonising rules between states. In Europe, an effective mechanism already exists for tackling tax dumping within individual states (where a national tax authority shows preferential treatment to one specific company) but not between EU member states. For instance, the European Commission was able to use the “State aid” system to declare special tax arrangements granted by Ireland and Luxembourg to Apple and Amazon respectively as illegal. In August 2016, following a two-year investigation, the Commission ordered the Irish government to claim back the sum of €14.3 billion in illegal tax benefits plus interest from Apple43. The investigation notably revealed that the effective tax rate on Apple’s profits in Europe scarcely exceeded 1% in 2003 and subsequently even fell to a low of 0.005% in 201444. Ireland and Apple are currently challenging the Commission’s decision with the European Court of Justice. However, pending the outcome of the appeal, the Irish government has recently announced that it has recovered and escrowed the sum owed. Following a similar investigation, Luxembourg was ordered to recover €250 million from Amazon in October 2017. The investigation revealed that almost three-quarters of the profits made by Amazon in Europe were not taxed due to a tax-saving scheme backed by Luxembourg45. However, the only reason it has been possible to prohibit such avoidance strategies under European law is that they are akin to preferential treatment in view of national taxation rules.

Paradoxically, rather than tackling tax avoidance as such, the Commission has only been able to address inequalities between companies within a specific country in terms of optimisation opportunities. However, the main problem is in fact that multinationals are able to register virtually all their profits in countries with low tax rates in which the majority of their products are not sold46. Even if Apple had not received (alleged) preferential treatment from the Irish authorities, it would still have been in its interests to declare its profits in a country where the corporate tax rate is 12.5% rather than in France, Germany, Spain or Italy, where it is approaching 30%.

There are two options for resolving this problem – either tackle it head on by campaigning for harmonisation of the corporate tax base and rate within the scope of international or European cooperation, or bypass it by taxing companies’ revenues rather than profits. The first option is probably more likely to result in conflict since it would require coordination between states that have fallen “victim” to tax avoidance and the use of various means of exerting pressure on “complicit” states. It is worth noting in this respect that the Trump administration’s tax reform, which “territorialises” corporate tax, is rather good news in that it ends the US authorities’ contradictory incentives in terms of tackling tax avoidance47. However, any such anti-tax dumping campaign would inevitably be long, difficult and nevertheless uncertain in terms of its outcome. For the sake of pragmatism, would it therefore not be preferable to choose the second option, at least as a temporary solution?

Taxing revenues rather than profits? At France’s request, the Commission has in fact tabled a proposal aimed at taxing the biggest tech companies – or at least some of their digital services – based on their revenues rather than profits48. Besides constituting an initial step towards a form of European corporate tax harmonisation, such a measure would have the merit of considerably reducing companies’ potential for tax avoidance as they would have no choice but to pay the taxes in force in the countries in which they actually operate. It is worth noting that, based on results for 2017, a 3% tax on big tech companies’ revenues (the rate mentioned by the Commission) would be equivalent, in terms of tax revenue, to an (effective) 20% tax on their profits49.

Although the proposal was backed in June 2018 by France and Germany in the joint Meseberg declaration and subsequently by the European Council several days afterwards (although in a more cautious and qualified manner)50, it is still disputed by some behind the scenes. The Scandinavian countries have added their own dissent to the natural hostility shown by countries that benefit directly from the status quo, such as Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. This is seriously jeopardising the future of a reform which, like any decision on taxation in the EU, can only be adopted unanimously. Finally, firm opposition from the United States to a measure that, in their view, disproportionately penalises their tech champions, rules out any consensus at OECD level.

Besides these political issues and practical implementing difficulties (in terms of targeting digital services, setting rates and thresholds, etc.), the proposal also raises a major economic problem. It intrinsically runs the risk of penalising promising new companies that achieve large volumes of sales but have not yet reached the stage of profitability. Paradoxically, this is especially problematic in the tech industry where innovation and success often come at the cost of a long and difficult march towards profitability.

In summary, we have revealed the existence of an extraordinary process of cash accumulation by American tech giants, resulting from the ultra-conservative allocation of their free cash flow. Having observed that these tremendous “cash piles” are not funding the productive economy, we subsequently examined three solutions aimed at upstream limitation or downstream discouragement of this hoarding phenomenon.

It must be acknowledged that none of these is genuinely satisfactory. While more activist campaigns like those conducted by the investors David Einhorn and Carl Icahn at Apple between 2012 and 2015 would be welcome, it is difficult for the public authorities to encourage practices that are still relatively controversial and whose effects on other sectors of the economy remain relatively unknown.

Moreover, while using financial regulation to better understand big tech companies’ behaviour on financial markets and monitor developments in their cash positions seems relevant, we believe that, as things currently stand, introducing restrictions such as the mandatory establishment of dedicated financial entities (based on the model of GE Capital for General Electric) will not impede the cash hoarding dynamics.

Finally, although taxation may indeed help to slow down the process of cash accumulation, it will not fundamentally resolve a problem arising from the big tech companies’ extraordinary profitability.

We believe that this now results more from increasing monopolisation of key segments of the tech market than from the pursuit of an ambitious innovation process, however this may have been in the past. Previous solutions can therefore only be imperfect since they target the symptoms rather than the cause of the problem. The big tech companies’ financial hegemony, as reflected by their cash positions, should be interpreted both as a consequence and a factor in their attempts to consolidate a domination that is currently being imposed at the expense of new innovative companies.

Consequently, regulations should now focus on restoring the conditions for free and fair competition within the tech market.

Sample composition

Companies are ranked in descending order of their cash positions as at the end of 2017.

- Top 10 Tech US: Apple, Microsoft, Google, Cisco, Oracle, Facebook, Qualcomm, Amazon, Intel, IBM

- Top 10 Tech China: Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, Ctrip, NetEase, com, ZTE, Sina, Xiaomi, Sohu.com

- Top 10 Tech Europe: SAP, Rocket Internet, Dassault Systèmes, Infineon Technologies, Atos, Capgemini, STMicroelectronics, Spotify, Zalando, Delivery Hero

In addition to these samples of tech companies, we used samples of the main global oil companies, CAC 37 companies, and the largest global bond funds:

- Top 10 Oil: Total, BP, Petrobras, Sinopec, Shell, Rosneft, Gazprom, Eni, Statoil, PetroChina

- CAC 37: all companies included in the CAC 40 index except the three banking institutions (BNP Paribas, Société Générale and Crédit Agricole)

- Top 10 Bond Funds: Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund, Vanguard Total Bond Market II Index Fund, PIMCO Income Fund, Vanguard Total International Bond Index, Metropolitan West Total Return Bond Fund, PIMCO Total Return Fund, Vanguard Short-Term Investment Grade Fund, Dodge & Cox Income Fund, iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF, DoubleLine Total Return Bond Fund

The big tech companies

Table showing the top ten American tech companies by descending order of cash and marketable securities.

Copyright :

© Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018