Covid-19: far right violent extremism and tech platforms' response

Presentation of tech against terrorism

Introduction

A rise in conspiracy theories and disinformation benefiting violent extremists

Behind the opportunism : the threat of accelerationism

From online chatter to offline action

Tech plateforms’ response and the future of content moderation

A lasting impact on human rights

A reflection on France’s ‘cyberhate’ law

Recommendations

Summary

Terrorists and violent extremists are manipulators seeking to exploit stress factors in our societies. The Covid-19 pandemic, its ensuing lockdown measures, as well as the spread of related mis- and disinformation online, thus represented an almost ideal opportunity for malevolent actors to exploit. Far-right violent extremists, in particular, quickly jumped on the opportunity offered by the Covid-19 crisis to anchor their hateful ideas into the mainstream and recruit new members. Whilst manifesting itself mostly online, this exploitation was not limited to the online sphere. It materialised in real world events as violent extremists blended themselves into anti-lockdown protests and as terrorists’ plans were eventually thwarted. Whilst the tech sector promptly responded to the wave of mis- and disinformation, the rapid changes in content moderation policy bear important consequences for the future of content moderation and freedom of expression online.

Indeed, the global tech sector, especially social media and content-hosting platforms, was particularly quick to respond to the spread of Covid-19 disinformation and conspiracy theories. In this insight piece, Tech Against Terrorism analyses how far-right violent extremists exploited the instability caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and what the tech sector’s response means for online freedom of expression and platforms’ accountability.

Maygane Janin,

Research Analyst at Tech Against Terrorism.

Her research interests focus on far-right terrorism and violent extremism, and on the use of internet for terrorist financing purposes.

Flora Deverell,

Research Analyst at Tech Against Terrorism. Her work focused on tech regulations and digital rights.

She has since left Tech Against Terrorism to pursue her training in law.

Big tech dominance (1): the new financial tycoons

Big tech dominance (2) : a barrier to technological innovation ?

Digital sovereignty - steps towards a new system of internet governance

The blockchain, or distributed trust

2022 The populist risk in France

Covid-19 - United States, China and Russia: Great Powers Worry Public Opinion

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019

Presentation of tech against terrorism

A pasting website is a website where you share content either by writing or most likely by pasting it into a textbox after which a shareable URL is created.

“Fintech is a term used to describe financial technology, an industry encompassing any kind of technology in financial services – from businesses to consumers. Fintech describes any company that provides financial services through software or other technology and includes anything from mobile payment apps to cryptocurrency […] Fintech has been used for many of the newest technological developments – from payment apps like PayPal or Venmo to even cryptocurrency.” (Anne Sraders, “What Is Fintech? Uses and Examples in 2020”, TheStreet, 11 February 2020).

Tech Against Terrorism is a public-private partnership supported by the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Executive Directorate (UN CTED). Tech Against Terrorism was launched in April 2017 at the United Nations Headquarters in New York and has since been implemented by Quantspark Foundation. As a public-private endeavour, Tech Against Terrorism is funded by both the tech industry via the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) and by governments. To date, the governments of Spain, the Republic of Korea, Switzerland, and Canada have provided financial support to Tech Against Terrorism.

Our core aim at Tech Against Terrorism is to support the tech industry in building its capacity to tackle the use of the internet for terrorist purposes whilst respecting human rights. We work with all types of tech companies, such as social media, pasting*, file-storage, messaging, fintech platforms**, and web infrastructure providers. Our core mission is providing the global tech industry with the tools needed to effectively tackle terrorist activity on their platforms. In doing so, we work across three streams:

1. Threat analysis and outreach

We carry out extensive open-source intelligence analysis to identify platforms at risk and build constructive working relationships with the tech sector, as well as facilitating public-private cooperation

2. Knowledge sharing and best practices

We facilitate intra-industry and cross-sector support mechanisms through online tools, guides, and practical datasets to support policy and content moderation decisions. Here we work closely with the GIFCT in organising global workshops and webinars. We also support companies through our membership and mentorship programmes

3. Tech development and operational support

We provide technical support and resources for tech companies to improve their counterterrorism mechanisms, for example through data science or development support. Examples of past work within this workstream includes our work with Jihadology.net*** and our current work on the Terrorist Content Analytics Platform****.

Tech Against Terrorism consists of an interdisciplinary team of counterterrorism policy experts, open-source intelligence analysts, and developers and data scientists. Our team composition allows us to comprehensively support the global tech industry in a manner that is effective, accurate, and human rights compliant.

See: “Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019”, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2019.

Formore information on Islamist terrorist groups’ exploitation of thepandemic, see: Julie Coleman, “The impact of coronavirus onterrorism in the Sahel”, International Center for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), 16 April 2020; Valerio Mazzoni, “Coronavirus: How Islamist Militants Are Reacting to the Outbreak”, European Eye on Radicalization, 30 March 2020.

For the World Health Organization, the infodemic designates the phenomenon of misinformation “spread[ing] faster and more easily than the virus”. See: United Nations Department of Global Communications (DGC), “UN tackles ‘infodemic’ of misinformation and cybercrime in COVID-19 crisis”, United Nations, 31 March 2020.

Ashton Kingdon, “The Gift of the Gab: The Utilisation of COVID-19 for Neo-Nazi Recruitment“, Global Network on Extremism and Terrorism (GNET), 7 May 2020.

Tech platforms and the Internet have, for a relatively long time now, been a crucial part of our social fabric, but have become an even more central element in the world’s response to the Covid-19 outbreak. As the world has confined itself, we have seen politicians and international organisations share updates with the public through social media and messaging platforms. We have seen separated friends and families further rely on online communications to stay connected. Coordinated via online platforms, we have also seen entire student and work forces being managed remotely. However, we have also seen the evolution and fragmentation of our information environment, including a surge in online content with clear overlaps with far-right violent extremist messages. Thus, the Internet, whilst connecting people at a time of social distancing, became a reflection of societies’ divisions and antagonisms as terrorists and violent extremists used it to propel their violent ideologies.

In a way, terrorists and violent extremists can be seen as manipulators, exploiting pre-existing grievances and stress factors in our societies and amongst individuals, such as gaps in governments’ capabilities or one’s search for answers in life. In light of this, it should come as no surprise that the Covid-19 pandemic, the ensuing lockdown measures and restrictions, as well as the subsequent economic instability and general anxiety were ideal stress factors for terrorists and violent extremists to exploit. The credibility gaps caused by some governments’ hesitant response to the virus and the flow of online misinformation and disinformation further provided a breach in conventional narratives and in government trust for malevolent actors to take advantage of. Islamist terrorist groups with an on-the-ground presence – such as the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, and al-Shabaab1– are thus attempting to benefit from fragile local governments being further destabilised by the crisis (especially in regard to health and security capacities) to present themselves as a viable solution and expand their control on the ground2. Meanwhile, far-right violent extremists in Western countries are exploiting the so-called Covid-19 ‘infodemic’3 to penetrate the mainstream and distil their ideologies to a larger audience.

Given that the exploitation of the Covid-19 crisis by far-right violent extremists has primarily been an online phenomenon, in contrast with Islamist terrorists, we decided to focus on far-right violent extremists’ online manipulation of the pandemic for this insight piece.

Indeed, there has been a prominent rise in far-right violent extremists’ online discussion and propaganda centred around the virus4 expanding into the mainstream as it was bolstered by a crossover between their ideologies and mainstream discussions of the crisis. Far-right violent extremists capitalising on the virus thus represent an interesting example of violent extremists’ distortion of the information landscape and of their use of online platforms. This paper will thus address the following issues:

- First, it will discuss far-right violent extremists’ manipulation of discourse about the pandemic;

- Second, it will assess the implications for future content moderation through the lens of current tech sector responses to the wave of disinformation and conspiracy theories;

- Finally, we included Tech Against Terrorism’s commentary on the recently dimissed French legislation to combat hate on the Internet, Lutte contre la haine sur internet (or Loi Avia), as this proposed law, and its rebuttal by the French Constitutional Council on the 18 June 2020, touched upon some of the most important debates with regards to online regulation globally.

Dr. John Richardson, Dr. Matthias Wasser, “The Symbols and Ideas of the Radical Right: Why Their Opponents Should be More Informed“, ConnectFutures, 26 May 2020.

Ben Makuch, “Neo-Nazi Terror Group Atomwaffen Division Re-Emerges Under New Name”, Vice News, 5 August 2020.

What is far-right violent extremism?

The label of far-right – or extreme right-wing; or ethnically and racially motivated – violent extremism and terrorism regroups a variety of different ideologies and networks; the main ones being divided between: neo-Nazism, white supremacism, white nationalism, and cultural nationalism. They gained the label of “far-right” as they share a number of ideological features including (but not limited to) racism, ultra-nationalism, ethnocentrism, anti-Semitism, opposition to equality and democratic principles, with mainstream far-right politics. However, important differences exist between the mainstream and the violent extremist far-right, with the major contrast being the use of violence.

“[A] key difference between the radical/populist right and the extreme-right is their willingness to use extra-state violence against political opponents and ‘racial’ enemies. The extreme-right embrace violence (whether fantasies of expanded state violence should they come to power, or terroristic, individual violence in the here and now) in order to promote an ideological agenda and this ideological agenda is, typically, a variation of fascism or neo-Nazism.”*

In contrast with Islamist terrorism, the far-right violent extremism landscape represents a relatively less structured, more decentralised and fragmented movement with a multitude of different groups and networks – some of them existing mostly online. Amongst the most influential groups and movements, we find:

- Ouest Casual (France based)

- The Nordic Resistance Movement (Sweden based)

- Feuerkrieg Division (mostly online, no physical central base)

- National Action and its armed branch Sonnenkrieg Division (UK based, both designated as terrorist organisations by the UK government)

- Atomwaffen Division (U.S. based, with European subgroups; now re-branded as the National Socialist Order)**

- Azov Battalion (Ukraine based, training a number of foreign fighters in the conflict in Ukraine)

- Blood & Honour and its armed branch Combat18 (Originally in the UK with a presence in Germany, Canada and the U.S.)

This timeline only includes attacks that have led to 10 deaths or more. Other far-right motivated attacks have taken place since 2011, including the Halle synagogue attack in Germany, which killed two people and the Poway synagogue shooting in the U.S., whereupon one person died, both in 2019.

For resources on Norway attacks, see: BBC News.

For resources on Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, see: BBC News.

For resources on Christchurch mosque shootings, see: BBC News.

“El Paso shooting: suspect “confessed to targeting Mexicans”, BBC News, 9 August 2019.

“Germany shooting: ‘Far-right extremists’ carried out shisha bars attacks”, BBC News, 20 February 2020.

Timeline of recent far-right terrorist and violent extremist attacks:*

- 2011 Oslo and Utøya attacks, Norway, 77 deaths**

- 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, United States, 11 deaths***

- 2019 Christchurch mosque shooting, New Zealand, 51 deaths****

- 2019 El Paso shooting, United States, 23 deaths*****

- 2020 Hanau shooting, Germany, 11 deaths******

A rise in conspiracy theories and disinformation benefiting violent extremists

According to the Ethical Journalism Network, both misinformation and disinformation designate information that are The key difference between the two being that disinformation is “deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country”, whereas misinformation is not. Both can be used – and are created in the case of disinformation – by terrorist and violent extremists to manipulate the information landscape to their own ends. We will focus here on the use of disinformation and the exploitation of conspiracy theories. See: “‘Fake News’ | Deep Fakes | Information Disorder | Disinformation | Misinformation | Mal- information”, Ethical Journalism Network.

For a more complete referencing of Covid-19 conspiracy theories see: Marc-André Argentino, Amarnath Amarasingam, “The COVID Conspiracy Files”, Global Network for Extremism and Technology (GNET), 8 April 2020.

5G, the successor to 4G, is the network that provides connectivity for cell phone use.

On the circulation of conspiracy narratives, including those revolving around the 5G technology, in French discussion groups on Twitter and Facebook, see: Iris Boyer, Théophile Lenoir, “Information Manipulations Around Covid-19: France Under Attack”, Institut Montaigne and Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), July 2020.

See: “Qui sont les ‘anti-5G’ qui se mobilisent sur le web ?“, fr, 29 September 2020.

“QAnon conspiracy theories about the coronavirus pandemic are a public health threat”, Marc-André Argentino, The Conversation, 8 April 2020.

“Covid-19 disinformation briefing N°.3 – Far-right exploitation of Covid-19”, ISD and BBC, 12 May 2020.

Marc-André Argentino, “QAnon conspiracy theories about the coronavirus pandemic are a public health threat”, art. cit.

Ibid.

See: “White Supremacists Embrace ‘Accelerationism’”, ADL, 16 April 2020.

As the Covid-19 outbreak forced the world into lockdown, the online space witnessed a surge in conspiracy theories and mis/disinformation5 about the origin and proliferation of the virus, and governments’ responses to it. While conspiracy theories exist most fervently and openly on the fringes of the Internet, Covid-19 related conspiracy theories quickly found their way onto mainstream tech platforms, particularly social media. Amongst the main conspiracy theories related to Covid-19, which are not exclusively found in far-right circles but also in other environments such as the far-left, we notably find the following ideological strains:6

- 5G and anti-government. Amongst the most popular, this theory is centred around the idea of China having caused the pandemic through 5G7, as well as governments’ lockdown measures and restrictions being aimed at restricting people’s freedom8. In France, researchers have observed an outburst of anti-5G discourse on social networks with the appearance of the coronavirus and have pointed out a significant porosity between various conspiracy theories 9.

- Social control. The driving idea behind this is the assumption that the “end goal [of the virus] is to impose social restrictions and force vaccinations”10 in order to be able to monitor and track the population.

- Bioweapon. A popular belief amongst the far-right is that the coronavirus is a human-made virus targeting people based on race, released intentionally or by accident.

- QAnon, the ‘deep state’ Emerging in 2017, QAnon and linked ‘deep state’ theories have been amongst the most prolific during the Covid-19 pandemic11, increasingly gaining ground on online platforms and attracting new audiences. QAnon-related theories on Covid-19 encompass different and shifting narratives on the virus – from a plot to damage President Trump’s standing, to a cover-up to arrest ‘deep state’ agents or a ‘spiritual warfare’ – whilst all relying on anti-government and xenophobic rhetoric12. Analysis of QAnon’s presence on social media underline the movement’s capacity to exploit the pandemic, in particular in using public social media accounts to reach broader and new audiences. QAnon supporters especially used public groups on Facebook discussing the pandemic to attract new followers to their own websites. In doing so, they managed to gather 80 million interactions on Facebook, between January and April 2020, an alarmingly high volume in comparison with the 6.2 million interactions for posts linked to the World Health Organization over the same time period13. In just three months, the number of QAnon hashtags on Twitter increased by 21%14.

- Chaos theories. These are theories comprising the idea that instabilities created by the pandemic should be furthered to bring about chaos and societal changes; these theories are similar to the idea of accelerationism, popular amongst far-right violent extremists. Accelerationism refers to the accelerated collapse of society as we know it through violent means – such as terrorism and guerrilla warfare – and non-violent means such as political and media manipulation to heighten the system’s existing tensions and further polarise society15.

Image boards, or chan boards, are online forum revolving mostly around the posting and sharing of images– an image is often required to post, for instance. They have become especially popular amongst violent extremists as they allowed to easily share images and memes (imagery being a key element of far- right violent extremism). For a definition of memes, see footnote 30 p. 25.

See: ADL, “QAnon”, art. cit.

In April 2019, a right-wing militia promoting QAnon conspiracy held 300 migrants at gunpoints at the U.S.-Mexico border. A year prior, on 16 June 2018 a QAnon supporter pleaded guilty on terrorist charges for having blocked the Hoover Dam in Nevada with an armoured vehicle in which a firearm and 900 rounds of ammunition were discoverd. See: ADL, “QAnon”.

Ben Collins, ‘Local FBI field office warns of ‘conspiracy theory-driven domestic extremists’, NBC News, 1st August 2019.

Recently, a QAnon linked conspiracy theory about the Wayfair online shop and child sexual trafficking made his way to French Twitter. See: William Audureau, “Comment le site de commerce Wayfair s’est retrouvé accusé d’organiser un réseau pédophile”, Le Monde, 16 July 2020.

Justin Ling “QAnon’s Madness Is Turning Canadians Into Potential Assassins”, Foreign Policy, 13 July 2020.

For more information on these platforms’ policies regarding QAnon related content, see: for Twitter, “QAnon: Twitter bans accounts linked to conspiracy theory”, BBC News, 22 July 2020; for YouTube, The YouTube team, “Managing harmful conspiracy theories on YouTube”, 15 October 2020 and “QAnon: YouTube moves to purge ‘harmful conspiracy theories’”, BBC News, 15 October 2020; for Etsy, Megan Farokhmanesh, “Etsy is banned QAnon merch”, The Verge, 7 October 2020; for TikTok, Kim Lyons, “TikTok removing accounts of users who share QAnon-related content”, The Verge, 19 Octobre 2020 and Alex Hern, “TikTok expands hate speech ban”, The Guardian, 21 October 2020; for Facebook, “An Update to How We Address Movements and Organizations Tied to Violence”, Facebook, 27 October 2020.

The QAnon movement

QAnon emerged in 2017 on 4chan, an image board* popular amongst far-right and violent extremists online networks, and is based on anti-government, anti-Semitic and xenophobic elements. The name QAnon is derived from the pseudonym of the 4chan user at the origin of the movement, “Q Clearance Patriot” (the letter Q standing for a secret defence clearance in the United States), warning of a conspiracy within the government to undermine Donald Trump’s presidency. QAnon supporters have an important mistrust of governments, and believe in a ‘deep state’, a global elite “of power brokers hell bent on enriching themselves and maintaining their Satanic child-murdering sex cult.”**

Whilst QAnon is not a violent extremist-led conspiracy movement, it is based on rhetorical elements commonly found in far-right violent extremist circles, and has led to violent acts in the US***. The surge of violence linked to QAnon even led the FBI to warn about the risks of domestic terrorism act motivated by conspiracy theories.**** QAnon is particularly compelling as a case study of how far-right rhetoric can infiltrate into the mainstream and motivate offline attacks. Namely, the conspiracy and its supporters increasingly made their ways from 4chan, a rather fringe platform, to mainstream social media (including Twitter, Facebook and YouTube), expending their audience reach every time. QAnon is also interesting in demonstrating how conspiracy theories can become influential across national borders. Whether through occasional linked conspiracy theories being spread internationally and in different languages,***** or with the broader QAnon movement gaining grounds outside the U.S., as has notably been the case in Canada recently.******

A number of major online platforms have recently taken action against the spread of QAnon related content on their platforms,******* most often on the ground of harmful disinformation, or threats of physical world violence. Twitter was amongst the first ones to do so, in mid-July, by banning thousands of accounts. In an attempt to respond to “shifting and evolving” challenges in moderating content, YouTube expanded its content policy to prohibit conspiracy theories “that have been used to justify real-world violence”. In doing so, it further expanded its policy on harmful misinformation and conspiracy theories. In accordance with its existing guidelines, the e-commerce platform Etsy has removed merchandise related to QAnon on the ground that such items “promote hate, incite violence, or promote or endorse harmful misinformation.” The platform also removed items related to the white supremacist group Proud Boys on the same ground. TikTok has also taken action against the conspiracy theory movement, removing accounts sharing related content on the ground that QAnon violates its disinformation policy. A few days after, the social media platform further expanded its hate speech policy to target “neighbouring ideologies” of neo-Nazism and white supremacy (including white nationalism and white genocide theory). In doing so, they also aimed at targeting “the spread of coded language and symbols that can normalise hateful speech and behaviour”. Finally, Facebook recently changed its community guidelines to limit the organisational capacity of groups that do not directly call for violence, but whose rhetoric demonstrates support for the use of violence. Beside removing QAnon content and networks that support the use of violence, Facebook has also started to implement a redirect counternarrative program, in partnership with the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET, the research arm of the GIFCT and a core TAT partner). Users searching for terms related to QAnon on Facebook and Instagram are now redirected to credible sources from GNET.

Overall, online platforms’ crackdown on QAnon demonstrates a shift in content moderation policy to cover online content and groups that do not necessarily make direct calls for violence, but whose rhetoric expresses support for the use of violence, or groups that present an important threat of offline violence. In doing so, they are indeed directly targeting groups based on assessment of harms and risk of real world violence.

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Blyth Crawford, “5G and the Far Right: How Extremists Capitalise on Coronavirus Conspiracies“, Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET), 21 April 2020.

Angie Gad, “The Coronavirus Isn’t Immune From the Far-Right“, Global Network for Extremism and Technology (GNET), 28 May 2020.

These conspiracy theories rapidly found their way into mainstream discourse on the virus, spreading virally on social media and messaging applications as individuals were searching for answers on the pandemic. Whilst not created by violent extremists, nor specific to one side or the other of the political spectrum, these conspiracy theories do, however, bear important similarities with far-right violent extremist discourses and share tenets usually endemic to these circles. Indeed, often based on the idea of a “global plot to subjugate humanity”16 and anti-government rhetoric, these conspiracy theories are for the most part racist, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic in nature. As “the foreign-created virus” became a recurrent topic of online discussion through conspiracy theories, violent extremists saw an opportunity to further exploit ideas that form the basis of their own rhetoric. Through such ideas present in Covid-19 related conspiracy theories, they found a way to sew their own messages into the mainstream. The convergence of such ideas is all the more compelling for some of the conspiracy theories that are directly linked to the far-right, notably the deep state (QAnon) theories, or those apocalyptic in nature and advocating for social chaos. A post by a far-right violent extremist supporter on Telegram (an instant-messaging application), reported by Angie Gad in an article for the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET), particularly exemplifies how the pandemic and the consequent instability benefits violent extremists: “We don’t need to convince the masses of our ideas. The pandemic has already done that… Whites panic bought guns, food, water, and prepare for social unrest all on their own […].”17

For violent extremists, it was then simply a matter of blending themselves into mainstream discussion and capitalising on the opportunity offered by the pandemic. Far-right violent extremists have thus taken to online platforms en masse to further spread disinformation and conspiracy theories, as well as their own hateful messages. They did so by not openly branding themselves as violent extremists, but rather by injecting themselves into public discussions with those whom they shared rhetoric elements and by posting links to more fringe websites they administered. A study by GNET found that some of the conspiracy groups on Telegram were ran by “known extremist Telegram users who dress [those groups] up as sources of information for those seeking answers”18.

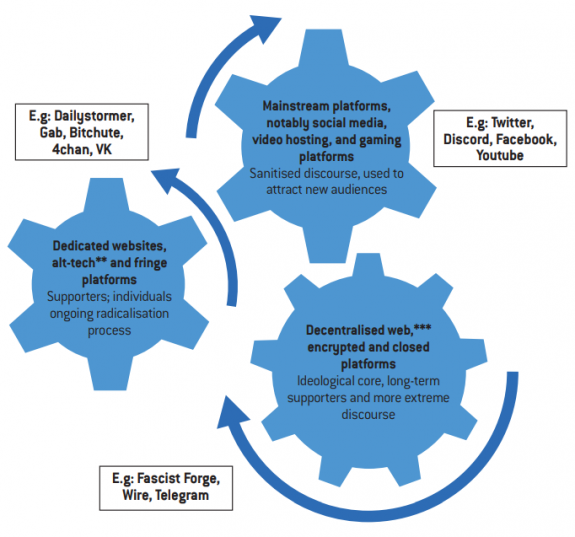

It should be noted that this summary is simplified in order to provide a broad overview of the violent extremist online environment in the Westernworld. Some of the platforms mentioned could be argued to exist in an overlap between the main categories proposed here. To learn more about how terrorists and violent extremists use the Internet, see www.techagainstterrorism.org, and listen to the Tech Against Terrorism Podcast at www. techagainstterrorism.fm.

The term “Alt-tech” refers to an alternative online ecosystem that has emerged in response from mainstream platforms deplatforming and banning certain violent extremist actors. This sort of clone online ecosystem is thus made of platforms that mimic mainstream ones in their purposes (social media, content sharing, video hosting) whilst presenting themselves as a “free speech” alternative to the moderation of mainstream platforms. The use of alt-tech platforms is not limited to far-right violent extremism, though certains platforms act as main hubs for them. On this, see: Megan Squire, “Can Alt-Tech Help the Far Right Build an Alternate Internet?“, Fair Observer, 23 July 2019.

On decentralised web, see: Zoe Corbyn, “Decentralisation: the next big step for the world wide web”, The Guardian, 8 September 2018; and “Analysis: ISIS use of smaller platforms and the DWeb to share terrorist content – April 2019“, Tech Against Terrorism, April 2019.

Terrorist and violent extremists use of the Internet is a broad and multifaceted phenomenon, exploiting the broader tech ecosystem for their propaganda, recruitment, financing and organisational objectives. However, the use of online platforms for propaganda and discussion purposes can be represented as follows*. By progressing through the different categories of platforms , from the lesser known to the major ones, terrorists and violent extremists exploit the online landscape to further gain publicity for themselves and their hateful ideologies.

Violent extremists’ online environment

Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “The risks of online radicalization in the COVID-19 era”, Center for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR), 26 April 2020.

Ibid.

As such, far-right violent extremists have tried to expand their reach to new audiences and anchor their ideas into the mainstream. Early on in the lockdowns, governments and experts alike voiced concerns about what an increase in social and economic grievances, paired with more time spent online, could do to contribute to radicalisation – not in the least among young people who are confined at home with outside recreational and cultural activities prohibited.19 The fact that online interactions can hold an important place in one’s radicalisation process has been acknowledged by the counter-terrorism community for quite some time now. However, the particularity of the Covid-19 pandemic, in this regard, is that it led to an unprecedented surge in online activities, especially amongst young people. A phenomenon summarised by Cynthia Miller-Idriss as:

“This dynamic creates a perfect storm for extremist recruitment and radicalization. Extreme isolation and increased online presence on gaming platforms, social media, and more creates growing possibilities for exposure to extremist content and expands the gateways that can lead to extremist radicalizations.”20

Terrorists and violent extremists thrive on insecurities and grievances, posing as the solution to the difficulties one might encounter in life, for example economic hardship, lack of a sense of belonging, feelings of anxiety or disillusion with society… With the pandemic creating an ideal ground for such anxiety and a need for explanations, combined with more time spent online, violent extremists are stepping up their propaganda efforts to appear as the simple solution to an unprecedented time of instability and insecurity.

The expression “zoom-bombing” is derived from “photo-bombing”, meaning “the act of appearing behind or in front of someone when their photograph is being taken, usually doing something silly as a joke”, Cambridge Dictionary.

“Trolling is defined as creating discord on the Internet by starting quarrels or upsetting people by posting inflammatory or off-topic messages in an online community.”, “Trolls and Their Impact on Social Media“, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Simon Purdue, “Zoom-bombing and the far-right latest assault on college communities”, Center for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR), 19 April 2020.

Kristen Setera, “FBI Warns of Teleconferencing and Online Classroom Hijacking During COVID-19 Pandemic”, FBI Boston, 30 March 2020.

Violent extremists’ online disruption efforts – the “zoom-bombing”* trend

College campuses in the U.S. have for a while been a favourite recruitment target for far-right violent extremists, plastering some with their propaganda flyers and disrupting on-campus activities. With colleges closing and the movement of classes from the physical world to the virtual world, violent extremists followed the online migration and began ‘Zoom-bombing’ online classes: breaking into classes held on video-conferencing online platforms to harass and ‘troll’** students and professors. Notably, “[u]sers have reported Zoom-bombers shouting racial slurs, drawing neo-Nazi insignia, sharing explicit or violent videos and ‘doxxing’ – sharing the confidential personal information of – faculty and participants.”*** The phenomenon has spread so widely and rapidly that the FBI issued a warning for the users of these platforms, alerting them of the possibility of these intrusions****.

Behind the opportunism : the threat of accelerationism

See: ADL, “White Supremacists Embrace ‘Accelerationism’”, 16 April 2019.

Telegram’s importance amongst far-right violent extremists has also been on the rise since the begining of the Covid-19 pandemic, with channels associated to violent extremist ideologies encountering an exponential growth of their audience since February-March According to a research by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, one channel linking white supremacism and Covid-19 even grew by 800%. See: Billy Perrigo, “White Supremacist Groups Are Recruiting With Help From Coronavirus – and a Popular Messaging App”, Time, 8 April 2020; and HOPE not hate, “Terrogram Network: A Spiral Towards Bloodshed“.

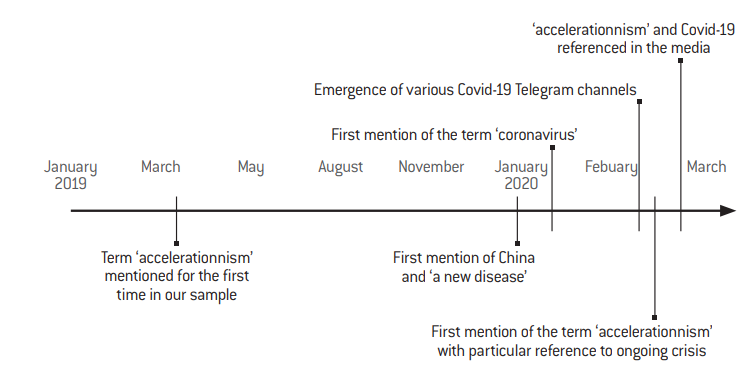

We assess the timeline of a particular topic of discussion, here accelerationism and Covid-19, by mapping the use of key terms on Telegram channels – g. when they first appeared on the channels analysed and if there has been an increase in their mention over time.

Violent extremists have long attempted to curate and exploit periods of instability and insecurity to spread their ideologies. One trend that has been increasingly present amongst far-right violent extremists over the last year, and that particularly reflects this attempt to feed on polarisation and instability, is accelerationism: the accelerated collapse of society as we know it through violent means – such as terrorism and guerrilla warfare – and non-violent means such as political and media manipulation to heighten the system’s existing tensions and further polarise society21. Based on a targeted monitoring and content analysis of 100 of far-right violent extremists, especially neo- Nazi, channels on Telegram, Tech Against Terrorism has studied how talks about accelerationism merged with discussions about the Covid-19 crisis.

The encrypted messenger app Telegram was chosen because of its ever- increasing importance amongst far-right violent extremist online circles, and especially amongst neo-Nazis22.

When reports emerged about violent extremists using Covid-19 as an impetus for accelerationist talks online, we decided to analyse how this was expressed on one of the most important messenger apps amongst far-right violent extremists circle: Telegram, a platform that Tech Against Terrorism has been monitoring for neo-Nazi content since 2019. In order to analyse how neo-Nazi accelerationist circles discussed the pandemic, we selected 100 channels based on a snowball sampling: starting with one neo-Nazi channel, we mapped out a network of neo-Nazi activity on the platform through the links shared on the original channel and included relevant public channels in our sample. The initial channel was located through a simple keyword search of neo-Nazi terms reflecting an adoration of Hitler, Nazi Germany, or a hatred of Jewish communities; neo-Nazi character of the identified channels was verified by Tech Against Terrorism’s research team. The analysis of the channels sampled and of the data retrieved allowed us to further confirm existing relations between the different neo-Nazi channels.

The first mentions of ‘accelerationism’ on violent extremist Telegram channels date back to 2019, and thus precede the Covid-19 pandemic. The first discussions around a new lung disease and mentions of China on violent extremist channels, for their parts, can be located to January and February 2020, approximately at the same time as when Covid-19 became a major news subject, and channels dedicated to the Covid-19 disease followed suit. Around March 2020, the association between accelerationism talks and the Covid-19 crises emerged on Telegram, shortly after the association of the two began to be referenced in a number of news articles23.

Timeline of mentions of key terms on 100 neo-Nazi public channels on Telegram

Source :

Tech Against Terrorism; Fondation pour l’innovation politique.

Since then, mentions of accelerationism on Telegram have been continuously increasing. As the pandemic was spreading around the world, accelerationism was becoming a central topic of discussion on violent extremist Telegram channels (see a visualisation of such a surge on one selected Telegram channel, next page). One reason for these more frequent uses of the term over time is most likely the intensifying media coverage around the pandemic and the measures it led to. This represented a favourable condition for accelerationists, as Covid-19 became a key subject of public discussion – and especially as the pandemic, the lockdown and other restrictions created more instability and contestation.

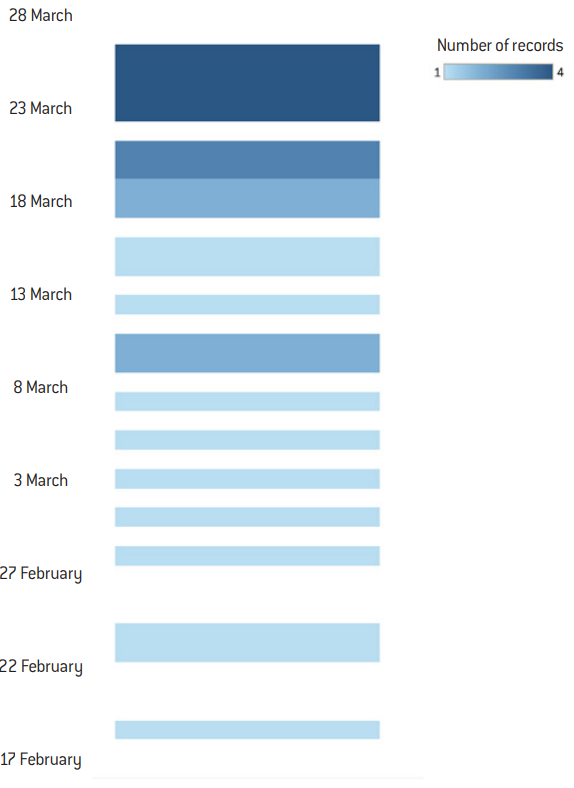

To better understand the language used by violent extremists discussing the Covid-19 pandemic on Telegram, we subjected a specific channel to further analysis. This channel was chosen for being mostly dedicated to accelerationist and Covid-19 talk, and thus heavily referencing the accelerationist ideology in light of the ongoing global pandemic. In this respect, we conducted a content analysis and mapped out the mention of the term ‘accel’ over time within this particular Telegram channel to better understand the use of language by far-right extremists. ‘Accel’ was deliberately chosen to account for variations, such as accelerate, accelerationism, accelerationist, or acceleration.

Mentioning of the term ‘accel’ from 17 February to 28 March 2020 on a Telegram channel

Source :

Tech Against Terrorism; Fondation pour l’innovation politique.

An apparently commonly discussed strategy to “weaponise” the virus was for infected violent extremists to purposely spread it, targeting minority communities and law enforcement.

Michael Colborne, “Asworld struggles tostopdeaths, far right celebrates COVID-19”, Al-Jazeera, 26 March 2020.

Hunter Walker, Jana Winter, “Federal law enforcement document reveals white supremacist discussed using coronavirus as a bioweapon”, Yahoo News, 21 March 2020.

It is important to state that any generalisation of this analysis should be treated carefully due to the small sample size. However, given the nature of this group and its quite large number of members, it does provide relevant insights into the change in language used by these circles over time.

Other researchers have also shown a rapid uptick of accelerationism in these channels, especially purposed towards talk of weaponising the virus24, stirring up social unrest, and accelerating the collapse of society25.

This threat has been recognised by federal law enforcements in the U.S., that have reported on far-right violent extremist groups considering weaponising the virus for terrorist purposes26, and has already manifested itself in real world events as we will see in the following section.

Ilham Maad, “Gardiens de la paix”, Arte Radio, 4 June 2020.

Sébastien Bourdon, “At Ukraine’s Asgardrei, a French connection”, Bellingcat, 1st May 2020.

Jean-Michel Décugis, Jérémie Pham-Lê, “Ultradroite : Aurélien C., un ‘suprémaciste’ soupçonné de projet terroriste”, Le Parisien, 26 May 2020.

France, far-right violent extremism & accelerationism

From a French perspective, it might be easy to conclude that concepts such as accelerationism are irrelevant in France and view the broader far-right violent extremist phenomenon as something alien and with limited influence in the country. However, one would be mistaken to believe in a French exception in this context. Far-right violent extremism is present in France, including talks about an upcoming civil or racial war and the collapse of our current society – both key elements of accelerationism. A podcast recently published by Arte Radio* is a striking example of the entrenchment of such hateful ideas amongst some members of law enforcement in France. Quite interestingly, audio messages captured in the podcast underline that French supporters of violent extremism evolve on the same online platforms (Bitchute, VK) as their international counterparts. An insightful inquiry by the online investigation platform Bellingcat also sheds light on the international connection of French far-right violent extremists by exposing the presence of French elements in an openly neo-Nazi music festival in Ukraine in December 2019.**

More research on French violent extremist networks is required to fully comprehend the extent of the threat in the country and how these networks interact with their international counterparts. In the meantime, the threat should not be overlooked, as highlighted by the recent arrest of a man plotting an attack on the Jewish community in France.***

From online chatter to offline action

A number of S. protests saw heavily armed protesters demonstrating in state capitals across the country.

Thomas Seymat, AP and AFP, “Coronavirus : aux États-Unis, extrême-droite et complotistes en embuscade”, Euronews, 26 May 2020.

See: “The Boogaloo: Extremists’ New Slang Term for A Coming Civil War”, Fighting Hate for Good (ADL), 26 November 2019.

A meme is “an image, video, piece of text, , typically humorous in nature, that is copied and spread rapidly by Internet users, often with slight variations”, Oxford Dictionary.

The Proud Boys had notably been banned from Facebook back in The social media platform has further taken action against the gang in light of its violent exploitation of the recent social unrest in the U.S. that followed the death of George Floyd. See: Taylor Hatmaker, “Facebook bans the Proud Boys, cutting the group off from its main recruitment platform”, Tedcrunch, 31 October 2018; David Klepper, “Facebook removes nearly 200 accounts tied to hate groups”, ABC News, 6 June 2020. Recently, the Proud Boys attracted media attention by promoting U.S. President Donald Trump’s mention of their group in a comment about white supremacism during the presidential debate on 29 September 2020: “Proud boys, stand back and stand by,” which they interpreted as a rallying cry. See: Shannon E. Reid and Matthew Valasik, “The Proud Boys are a far-right gang. Trump boosted them on national TV“, The Guardian, 3 October 2020.

See: Tess Owen,”The Anti-Lockdown Protests Are Getting Weird“, Vice News, 17 April 2020; and this tweet from Mark Pitcavage (@egavactip)

See: Mark Scott, Steven Overly, “‘Conspiracy bingo’: Transatlantic extremists seize on the pandemic“, Politico, 12 May 2020; Christina Gossner, “Anti-lockdown protests in Germany infiltrated by far-right extremists”, Euractiv, 14 May 2020; Jan Bielicki, Stefan Braun, Jan Heidtmann, “En Allemagne, une montée inquiétante de la contestation”, Courrier International, 21 May 2020, originally published in Süddeutsche Zeitung.

See: Alex Hern, “5G conspiracy theories fuel attacks on telecom workers”, The Guardian, 7 June 2020; Damien Leloup, “Les destructions d’antennes téléphoniques 5G augmentent en Europe”, Le Monde, 20 April 2020; Julien Lausson, “Pourquoi des antennes 5G sont-elles vandalisées en Europe ?”, Numerama, 13 April 2020.

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Blyth Crawford,”5 Gand the Far Right : How Extremists Capitalise on Coronavirus Conspiracies“, Global Network for Extremism and Technology (GNET), 21 April 2020.

On 15 March 2019, a 28-year-old white supremacist and follower of the “alt-right” movement (far-right, white nationalist movement based in the United States) carried out two mass shootings in two different mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 51 and injuring 49.

Coinciding with the time the first lockdown measures were enforced in France.

Jean-Michel Décugis, Jérémie Pham-Lê, “Ultradroite : Aurélien , un ‘suprémaciste’ soupçonné de projet terroriste”, art. cit.

See: Pete Williams, “Missouri man planned to bomb hospital during pandemic to get attention for white supremacist views”, NBC News, 30 March 2020; and Bridget Johnson,“White Supremacist in COVID-19 Hospital Bomb Plot Allegedly Wanted to Attack Power Grid”, Homeland Security Today.us, 31 March 2020.

All this disinformation and far-right violent extremist talk does not limit itself to online platforms but has found its way into real world activities and events through anti-lockdown protests around the world, 5G infrastructure attacks, telecom worker harassment, and folded violent extremist plots.

Anti-lockdown demonstrations criticising lockdown measures on the basis that they restrict freedom and calling for these measures to end have occurred throughout Europe (notably in Germany, Switzerland, Spain and Italy). However, protests in the U.S. have received greater media attention, most likely as a result of their scale and of the militarisation some of these protests have seen.27 Whilst the anti-lockdown protests represent a wide spectrum of political beliefs, with the majority of participants having no affiliation whatsoever with violent extremism, many violent extremist groups saw these protests as an ideal opportunity for publicity and for spreading their ideologies28. Thus, if some far-right violent extremist groups were amongst the first to organise protests in the U.S., they then started to blend themselves into the mainstream demonstrations.29 The Boogaloo (Bois)30, an American meme31 turned violent extremist movement calling for a second civil war, and the Proud Boys, a U.S. neo-fascist gang,32 were amongst the first far-right violent extremists to be spotted at anti-lockdown protests, openly displaying symbols associated with American far-right violent extremism33. In time, these demonstrations saw an ever-increasing violent extremist presence, as far-right violent extremists continued to capitalise on the pandemic and lockdown measures, and finding a great medium of communications and publicity in the aforementioned conspiracy theories and protests. If the link between violent extremists and anti-lockdown demonstrations has been the most striking in the U.S., the same combining of conspiracy theories, anti-government sentiments, and violent extremist motives can be observed in Europe. Protests in Germany, for instance, have been supported by the mainstream far-right whilst witnessing a mixture of conspiracy theory supporters. It is particularly important here to remember the role of violent extremists and neo-Nazi elements in spreading conspiracy theories.34 In a way, anti-lockdown protests represent the physical-world manifestation of the crossover between violent extremist ideologies and mainstream discussion on the pandemic.

Covid-19 related conspiracy theories also materialised themselves with acts of physical violence. Conspiracy theories linking the virus to 5G technologies, in particular, led to attacks on 5G infrastructure and telecom workers in the UK and in the Netherlands35. This phenomenon was encouraged by far-right accelerationists who saw this as a chance to create further social unrest36. Beyond these attacks and harassments on telecom workers, far-right violent extremists’ plots have also been thwarted in the U.S. and France since the start of the pandemic. On 26 May 2020, a man was arrested in France for planning an attack on the Jewish community. The man, whose online profile on social media showed his engagement with neo-Nazi material, including a French translation of the Christchurch shooter manifesto37, reportedly became increasingly violent over the weeks leading up to his arrest38 and demonstrated a particular interest for the reopening of places of worship in France once the lockdown was lifted39.

At this stage of the investigation, we can only assume that this man’s increased interest in far-right violent extremism over the recent weeks can be linked to the pandemic acting as a catalyst for action. However, other thwarted plans in the U.S. have, for their part, clearly been linked to Covid-19 and accelerationism. Early on in the pandemic, a white supremacist was notably killed during his arrest by the FBI as he planned an attack on a hospital hosting Covid-19 patients. Whilst the individual had been a supporter of white supremacist ideology and a proponent of “kick start[ing] a revolution” before the pandemic, details of a discussion he had with an undercover law enforcement agent reveal that the Covid-19 crisis accelerated his action. The individual viewed the increased media attention given to the health sector as an opportunity to promote and grab attention on violent extremist views40. These foiled attack plans show how violent extremists’ taking advantage of the virus, especially accelerationist talks, pose a real threat to security in Western democracies. This threat should in no case be underestimated as “lone-wolf” far-right attackers have demonstrated their capacity to act on their hateful beliefs in recent years – 2019 being a particularly tragic testimony year in this regard as the world witnessed four major far-right motivated terrorist attacks in New Zeland, the U.S., and Germany; including the tragic Christchurch mosques attack and the El Paso Shooting.

Tech plateforms’ response and the future of content moderation

Till Baaken, “YouTube’s Role as a Platform for Extremism”, GNET, 2 March 2020.

Casey Newton, “WhatsApp puts new limits on the forwarding of viral messages”, com, 7 April 2020.

As shown in this analysis, far-right violent extremists have capitalised on the pandemic to exploit and distort the media and information landscape, displaying once again their ability to use online platforms for their own agendas. However, tech companies – especially social media and messaging apps – were quick to react to the spread of Covid-19 disinformation and conspiracy theories shared on their platforms. While they did not necessarily target violent extremists in doing so, the content moderation policy changes introduced would also affect violent extremists’ capacity to benefit from the pandemic. In the following section, we will see what these changes mean for the future of online content moderation. In an attempt to ‘curb the spread’ of Covid-19 related online harms, a number of tech platforms have made changes to their content standards, often broadening their definition of harms to prohibit or disrupt the spread of conspiracy theories and mis/disinformation related to the virus. Prominent examples of this include YouTube’s decision to ban all conspiracy theory videos linking the coronavirus to 5G networks – a particularly welcomed move according to some experts given existing discussions about YouTube’s potential for extremist exploitation in reaching out to broad audiences41 – Twitter’s removal of any information that contradicts official health guidelines, and WhatsApp’s newest restrictions on the forwarding of messages (“messages that have been identified as “highly forwarded” – sent through a chain of five or more people – can only be forwarded to a single person [instead of five usually]”42). Such swift changes in platforms’ policies raise important questions around content moderation (COMO) strategies and the inherent challenges in tackling terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet and disinformation in a manner that respects human rights.

To know more about content standards and content moderation for tech platforms, see: “Protecting free expression in the era of online content moderation”, Access Now, May 2020; Tech Against Terrorism; and GIFCT.

What are content standards?

“Content standards” designate the broad set of guidelines available for a tech company to lay out what is accepted, or forbidden, on its platform, including: Terms of Service, Community Guidelines, and Acceptable Use Policies. By being the principal way for a platform to inform its users on what is prohibited or not, and thus on its content moderation policy and enforcement, content standards are essential for a platform’s transparency and accountability. Tech Against Terrorism advises tech companies to clearly lay out what they expect of their users, and how they intend to enforce their moderation policies in case of violation, as well as to explicitly prohibit terrorist use in their content standards. Such prohibition is also a requirement for membership to the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), an industry-led coalition formed by Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Microsoft which collaborates with a wide range of NGOs, academic experts, and governments.*

Due to the sensitivity of the work conducted by online content moderators, and especially to the potential mental health impact of this field of work, human content moderation is generally to be conducted in a professional work setting and can hardly be adapted to a working from home For this reason, tech platforms have increasingly been relying on automated moderation tools during the pandemic.

“Machine learning at its most basic is the practice of using algorithms to parse data, learn from it, and then make a determination or prediction about something in the So rather than hand-coding software routines with a specific set of instructions to accomplish a particular task, the machine is ‘trained’ using large amounts of data and algorithms that give it the ability to learn how to perform the task.”, Michael Copeland, “What’s the Difference Between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning?”, nvidia.com, 29 July 2016.

Emma Llansó, “COVID-19 Content Moderation Research Letter – in English, Spanish, & Arabic“, Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT), 22 April 2020.

Faced with a massive increase of content removed, due the the important relying on automated moderation tools between April and June 2020 in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, YouTube has decided to revert to its hybrid moderation system, combining artificial intelligence and human See: Rachel Kraus, “YouTube puts human content moderators back to work“, Mashable, 20 September 2020.

Human Rights Watch recently published a report on the issue of content moderation and deletion of war crime evidence, in which they also highlight how Tech Against Terrorism’s Terrorist Content Analytics Platform (TCAP) might help tackle this See: “Social Media Platforms Remove War Crimes Evidence“, Human Rights Watch, 10 September 2020.

The rapid response of tech companies to adapt their policies and service offerings to protect users and society as a whole has prompted people to question why such a response is not the norm. More than anything else, however, the question should be: what changes are being made to enable such an expedient response now, and how can we keep track of what ground is being covered by these measures for when this is all over?

Part of the answer is that in 2020 tech companies are able to fully rely on the systems, strategies, and partnerships that they have been carefully putting in place since 2017 and the establishement of the GIFCT. This means that in order to deal with the increased risk of misuse of their platforms, they have been able to capitalise on the investment they have put into needful policy work, effective content moderation solutions, and collaboration with researchers, civil society, and experts on the ground or fact-checkers. Over recent years, tech platforms have indeed increasingly been trying to efficiently respond to terrorist use of the Internet. They did so through increased content moderation efforts, including the development of machine-learning solutions, counter-narratives projects or through GIFCT whose hash-sharing consortium and crisis protocol system particularly demonstrate this commitment. Broadly speaking a “hash” is a unique fingerprint given to an online image or video. Through hash-sharing tech platforms have the possibility to quickly locate, take down, or prevent the uploading of, an image or video that has previously been identified as terrorist content. The Covid-19 crisis has also stressed the importance of well-functioning and robust public-private channels between governments and the tech sector.

However, the pandemic and its consequent rapid changes in policies also present the risks of encroachments on the policies that tech platforms had slowly and transparently built over recent years. This is exacerbated by the fact that human beings may be more out of the moderation loop than usual, notably because many employees have been sent home for social distancing purposes43. Whilst already widely used by major tech platforms to assist with their content moderation efforts, the use of artificial intelligence, specifically machine-learning44 to counter terrorist use of the Internet, is still in an initial phase. At the moment, such technology notably lacks the understanding of nuance and context (e.g. difficulties distinguishing between terrorist content and journalistic information). If the development of such technologies can be encouraged, human moderators remain essential, especially to avoid over-censoring and the taking down of legitimate content. Moreover, these technologies require important quantities of data to be perfected, which remains a barrier to entry with regard to using it to counter terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet – particularly when interested in predictive behaviour technologies.

In light of this, the Center for Democracy and Technology released a joint statement about concerns shared by industry actors and NGOs over tech companies’ increased reliance on automated moderation during this period – including the use of machine – learning based tools to detect and even adjudicate infringing content on their websites, rather than manual, human moderation45.

An increased reliance on automated moderation solutions raises the risk of false positives in taking down content that is legal, and raises questions about accountability in removal decisions 46. It becomes even more complicated when harmful content originates from users that are not affiliated with violent extremism, as is often the case at the moment, or when the content exists in a “grey area” (due to the lack of designation of far-right terrorists and violent extremists as terrorist entities by governments, these groups often exist in what is commonly called a legal “grey area”). Worse, however, is the risk that content denouncing human rights violations, including journalistic content that can serve as evidence of such violation, could be automatically removed 47, more so at a time where constitutional guarantees are weakened in certain countries.

A lasting impact on human rights

Reporters Without Borders, “Censorship and attacks, journalism in quarantine”, Reporters Without Borders.

Berhan Taye, Felicia Anthonio, “KeepItOn: Internet shutdowns during COVID-19 will help spread the virus!”, Access Now, 17 March 2020.

“Exigimos respeto a la libertad de expresión y al derecho a la protección de datos personales en Honduras”, Access Now, 20 March 2020.

David Kaye, Harlem Désir, Edison Lanza, “COVID-19: Governments must promote and protect access to and free flow of information during pandemic – International experts”, UN OHCHR, 19 March 2020.

About these processes, see: Tech Against Terrorism, “The Online Regulation The European Union“, 19 October 2020.

To learn about the issue posed by upload filters, see: Diego Naranjo, “Terrorist Content Online Regulation: Time to get things right“, EDRi, 16 March 2020.

There are multiple reports by human rights groups and advocates that the Covid-19 crisis is being used by some governments around the world to “establish or tighten control over the national media and to step up state censorship48.” Concerns around conspiracy theories, disinformation, and the threat of violent actors who wish to take advantage of such a situation can thus become easy pretexts for censorship. In the past, anti-democratic governments have used the security threat of terrorist and violent extremist exploitations of the Internet to try and arm-twist tech companies into silencing dissenting voices or restricting access to information. It is perhaps unsurprising that in the midst of this crisis, various governments have shut down the Internet in parts of their territories or restricted access to hundreds of sites49. Others have temporarily revoked constitutional guarantees, including around freedom of expression50. This is partly why clear content standards across the Internet are so important: they act as a defence against unlawful or ad hoc suppression. Attempts to criminalise information relating to the pandemic may create distrust in institutional information, delay access to reliable information, and have a chilling effect on freedom of expression51. That platforms are policed in a manner that follows rule of law precisely because it is a crisis and because the circumstances are exceptional is exactly the point.

In a joint announcement, David Kaye (United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression), Harlem Désir (Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Representative on Freedom of the Media, OSCE), and Edison Lanza (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, IACHR) all highlighted the importance of governments and tech companies working together to provide reliable information in the wake of false information about the pandemic that “could lead to health concerns, panic, and disorder.” However, they also emphasised that “resorting to other measures, such as content take-downs and censorship, may result in limiting access to important information for public health and should only be undertaken where they meet the standards of necessity and proportionality.”52

Such considerations are even more significant in light of recent developments in the world of online regulation: the EU is still drafting its new online regulation proposal 53, which could lead to the imposition of upload filters – automated programmes scanning data according to certain criteria, and allowing or preventing the upload of content depending on the result of the scan – and thus to increased reliance on automated tools54. In parallel, France recently attempted to pass a new “cyberhate law” obliging tech platforms to remove notified terrorist content within one hour, and the U.S. president signed an executive order that, whilst contested for constitutionality reasons, could remove tech platforms’ legal protection from liability for user generated content. As with other online regulation laws passed in Europe, notably the 2017 German Network Enforcement Act (NetzDG), human rights advocates and civil society groups have criticised these laws for potentially incentivising overzealous moderation and leading to the removal of lawful content. Nevertheless, many also regard such laws as necessary steps to ensure that tech companies have accountability and transparency due processes in place. What is clear, however, is that tech companies and governments alike must balance confronting new and evolving harms and threats to society in the online sphere whilst protecting human rights.

A reflection on France’s ‘cyberhate’ law

This bill was the first non-Covid-19 related law to be passed in the French parliament since March 2020 – only two daysafter the lockdown was lifted in the country, in May This has led to some commentaries regarding the French government using the wave of misinformation linked to the pandemic as “the perfect impetus” to have it passed despite its critics. See: Simon Chandler, “French Social Media Law Is Another Coronavirus Blow To Freedom Of Speech“, Forbes, 14 May 2020.

Unrelated to the law itself, it should be noted that a few days before the law was passed, civil society groups in France filed a lawsuit against Twitter for massive inaction against hateful messages on the platform, effectively calling on Twitter to take down content such as those covered by the “cyberhate” This lawsuit was prompted by a recent report by the same civil society groups indicating that there had been a rise in hateful messages shared on the platform during the lockdown. See: Martin Untersinger, “Twitter assigné en justice pour son ‘inaction massive’ face aux messages haineux”, Le Monde, 12 May 2020.

Since its first introduction in 2019, the law had been denounced by experts and civil society groups for the risks it poses to freedom of The law had notably been criticised by the French National Commission on Human Rights, as well as by David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression. He warned about the vagueness of the terms used to define terrorism (as well its incitement and glorification) in the French Penal code upon which the new bill relies that could lead to an “arbitrary and abusive interpretation of the law”. He also stressed that whilst tech platforms have a human rights responsibility, “censorship measures”, such as those implied by the duty to remove terrorist and hateful content, should not be delegated to private entities. It is indeed this risk for freedom of expression that was recognised in the French Constitutional Council’s decision to censor the core of the law, as it deemed such risk disproportionate with regard to the aim of the law. See: David Kaye, “Mandat du Rapporteur spécial sur la promotion et la protection du droit à la liberté d’opinion et d’expression”, UN OHCHR, 20 August 2019. These flaws in attempting to counter terrorist use of the Internet are not specific to the French bill. Critics have also raised similar concerns with regards to the German NetzDG and the draft EU online regulation to prevent the dissemination of terrorist content. See: Diego Naranjo, “Terrorist Content Online Regulation: Time to get things right”, art. cit.; Federico Guerrini, “The problem with Germany new social media hate speech bill”, Forbes, 3 March 2020.

See: Tech Against Terrorism’s commentary on the draft EU regulation and its impact on smaller platforms: Adam Hadley and Jacob Berntsson: “The EU’s terrorist content regulation: concerns about effectiveness and impact on smaller tech platforms”, VoxPol, 1st July 2020.

See: Tech Against Terrorism, “ISIS use of smaller platforms and the DWeb to share terrorist content”, Tech Against Terrorism, 29 April 2019.

On 24 June 2020, a new law was promulgated in France on regulating hateful online content55, aiming at countering the spread of hateful, discriminatory, and terrorist content online. All content usual to the playbook of the violent extremists discussed earlier.

A year after its first introduction to Parliament, the French national assembly adopted on 13 May 2020 this new, so-called “cyberhate” law or “Loi Avia”56. Bearing several similarities with the German NetzDG, this law would have required tech platforms to remove terrorist and child sexual abuse content within one hour once it had been reported to the platform by the French authorities, whereas other hateful and discriminatory content would have had to be removed within 24 hours once reported by the authorities or by users. Platforms failing to comply were to face a fine ranging from 250,000 to 20 million euros, or up to 4% of the platform’s global annual revenue. However, the core of the “cyberhate” law was censored by the French Constitutional Council on 18 June 202057. This effectively meant that the law was to be reduced to its prevention aspect, and that all requirements for tech platforms to take down notified content within one or 24 hours were deemed unconstitutional.

The fight to counter terrorist and violent extremist use of the Internet should not be ignored, especially at a time of intensified instability and disinformation. However, online regulation should not come at the price of accountability and freedom of expression58. We previously provided a commentary on tech companies’ slightly adapted content moderation processes to respond to Covid-19, and below we highlight what we consider to be the main problematic characteristics of the dismissed “cyberhate law”. We believe that despite the censoring from the French Constitutional Council, this commentary can still be relevant in underlining limitations common to a number of recent attempts to counter the spread of terrorist and violent extremist content online. This is especially the case given the important similarities between the dismissed “cyberhate law”, the German NetzDG and the draft EU regulation on online terrorist content59. Moreover, some of the criticisms we addressed to the law were also present in the Constitutional Council’s decision to censor it.

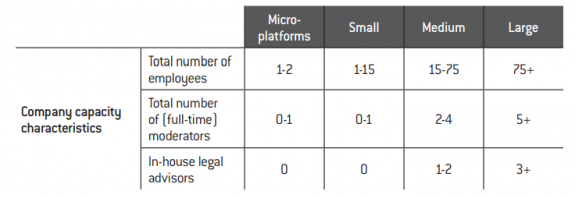

- A lack of consideration for smaller tech platforms’ The one-hour delay for removal of terrorist content is unrealistic for micro and small platforms. They have few employees (some are run by just one person) and lack the technical and human resources necessary to be able to respond to notifications of terrorist content within such a short deadline. A one-hour time period, and even a 24-hour one, would require constant monitoring from tech platforms to ensure compliance. It is a difficult, if not impossible, endeavour for most tech platforms. This strain bears the risk of reduced competition in the tech sector if smaller platforms are not able to catch up or are financially afflicted by the fines. Furthermore, research conducted by Tech Against Terrorism has shown that smaller platforms are heavily targeted by terrorist exploitation60. Yet, smaller platforms that are willing to tackle this exploitation but lack the scope to do so, and thus require the most assistance in tackling terrorist use of the Internet, may end up being left behind by this new legislation.

The short removal delay of the law was underlined by the French Constitutional Council as being particularly difficult for tech platforms to meet, and for being disproportionate with regard to the risk posed to freedom of expression. The Constitutional Council particularly underlined that the law included regulations that were “impossible to satisfy” for tech platforms, thus breaking the principle of equality with regard to public regulations.

Platform size classification used by Tech Against Terrorism *

* It should be noted that large platforms with more than 75 employees can still require substantial support when it comes to content moderation on a large scale, and balancing the need to counter terrorist use of the Internet with the safeguarding of human rights and freedom of expression. The size of the user base, its growth, and the volume of content posted daily on a platform, can also significantly impact a tech company’s capacity to moderate content.

- Risks for freedom of Due to the quick deadline and the broad scope of the law, tech platforms will not have the time to properly adjudicate on a content’s legality. Instead, there is the risk of an overzealous removal of content, with platforms indiscriminately taking down all content notified before properly assessing whether such content would in fact be considered illegal under existing French legislation. Even for the bigger tech platforms, the so-called GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft) in France, the short deadline to remove signalled content would require an important increase in resources dedicated to content moderation. One easy way to do so for the platforms that have technical resources will be an increased reliance on automated content moderation tools. Whilst automated content moderation has its benefits, current solutions are not fairly nuanced and require human overview to avoid the excessive takedown of content. It notably lacks the capacity to comprehend context; for example, whether a content is journalistic or shared in order to denounce a specific position. Thus, an increase in relying on such methods, instead of human moderation, presents important threats for freedom of expression as automated moderation risks excessively taking down lawful content.

The risks for freedom of expression were also underlined by the French Constitutional Council, which deemed that they were neither necessary nor appropriate or proportionate.

- Leaving tech platforms to adjudicate on The law itself does not create a new set of harms, nor does it create a new range of prohibited content. Everything, from hateful and discriminatory to terrorist and child sexual abuse content, is already illegal under French law (respectively as a limit to freedom of expression and under criminal code). However, the existing laws it relies on are themselves broad and can cover a wide range of content – it is the reason why current limitations to freedom of expression have to be decided upon by an independent judiciary body. The law thus shifts the responsibility of (rapidly) deciding what is hateful or discriminatory content to private tech companies, rather than offering tech platforms clear cut definitions and examples of what content is to be removed. Indeed, such a provision may in fact lead to a development where more influence over the online speech rulebook is given to tech companies.

In this regard, the Constitutional Council’s decision was a strong reminder that adjudicating on the legality of online content, in particular terrorist content, is “subject to the sole discretion of the [French] administration.” Yet, the required removal deadlines are deemed insufficient to obtain the necessary court’s decision to assess the illegality of a specific content. This decision is an important reminder of the significance of the rule of law in countering online terrorist content.

Even though the “cyberhate” law presented important risks for freedom of expression and did not consider the technical and human capacities of smaller tech platforms, the law also includes commendable points. Most of these commendable points touch upon the idea of preventing the spread of online hate and calling for greater cooperation, and have not been censored by the Constitutional Council. Hence, even though the law has been stripped of its core requirements for posing a too important risk to freedom of expression, the Avia law has been passed in France and will be implemented along its more “preventive” lines. Below, we provide a commentary on some of its positive requirements.

- Calls for increased cooperation in the tech The law, commendably, broadly promotes tools for cooperation and information sharing between platforms. However, it does so without specifying what these tools would be. More information in the future on how the French government plans to support said cooperation and how to properly account for smaller platforms in this regard would be beneficial.

- Increased transparency and The new legislation also calls for increased transparency and accountability from tech platforms, as well as from the French government, whose Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel – the French audiovisual authority – will oversee the enforcement of the law and will publish an annual report on it. However, this call for transparency does not take into account platforms’ sizes and individual capacities. Yet, these are important factors to be considered to avoid unrealistic expectations as to what metrics should be included in the transparency reports.

Recommendations

To know more about transparency reporting for smaller platforms, see: “Transparency reporting for smaller platforms”, Tech Against Terrorism. 2 March 2020.

Concerns around increased content moderation policy bearing the risk of online censorship should not be ignored now, nor forgotten once the Covid-19 public health crisis is declared to be over. Many of these problems will not be dispelled with the end of the pandemic and will have lasting implications for human rights and democratic functioning. In light of this, we recommend the following:

Tech companies should strive to:

- Improve accountability mechanisms, such as appeal and redress processes.

- Increase transparency on decision-making behind policy development and enforcement, especially with regard to content removal.

- Review changes in content moderation made in response to the Covid-19 crisis once the crisis is over.

- Produce special transparency reports detailing platform governance and content moderation activity during the Covid-19 pandemic. For small and micro-sized tech companies, taking record, even in a rudimentary manner, of at least some of these statistics will be invariably valuable as well61.

- Invest in improved understanding of the threat of far-right violent extremism on tech platforms

- particularly in giving further attention to how these groups can instrumentalise mainstream media and public discussion for their own purposes;

- in supporting efforts to promote improved understanding of how terrorist and violent extremists target youth online.

- Support the development of technical solutions to mitigate terrorist and violent use of the Internet whilst safeguarding fundamental rights and particularly freedom of expression.

- Continue providing support to small and micro-sized tech platforms who do not have the resources to tackle terrorist and violent extremist use of their services.

Governments should strive to: