Danish Immigration Policy: A Consensual Closing of Borders

Introduction

A policy driven by the challenge of national homogeneity

Denmark as a homogeneous society

The welfare state as a national principle

The influence of Danish populism on immigration policies

The danish immigration policy: firmness, closure and the welfare state

A vigorous integration policy

Restricting access to employment, family reunification and citizenship

A drastic asylum policy

Outsourcing asylum management to a third country

Danish immigration policy: popular ratification and democratic empowerment

The 2022 elections: Populists defeated and re-election of the Social Democrats

National cohesion and interpersonal trust

Danish immigration policy and the future of the European left

Summary

In the Danish parliamentary elections of 1 November 2022, the Social Democratic Party was returned to power. Although Denmark has changed its governing majority several times, it has had the same immigration policy for twenty years. This policy has been characterised by a drastic reduction in migratory flows, a strict integration programme, difficult access to citizenship and, from this point on, the willingness to use a non-European third country to process visa applications. Initiated by the right-wing government under pressure from the populist right, which in return gave its parliamentary support, Denmark’s immigration policy was taken up and extended by the Social Democrats when they returned to power in 2019. They were re-elected in 2022, with even more support than in 2019.

From the Danish perspective, migration policy is essential for the sustainability of the welfare state. The aim is to preserve the welfare state by limiting excessive or unjustified recourse to state aid on the grounds that they squander the country’s resources and undermine the political consensus by spreading suspicion. The welfare state depends as much on the level of trust in society as on the economic performance of the country.

In this sense, it can be said that the national homogeneity to which the Danes are committed is based less on ethnic than on political, cultural and moral grounds. Thus, Denmark has decided to restrict immigration and to impose a vigorous integration programme on newcomers. The effort to reduce the cultural gap between immigrants and the wider Danish society helps to cultivate and transmit interpersonal trust, trust in institutions and ultimately the entire Danish national model.

Danish immigration policy poses a fundamental question to Europeans: can the future of the welfare state be secured without a restrictive and inclusive migration policy?

Dominique Reynié (dir.),

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

Fondation pour l'innovation politique,

A French think tank for European integration and the free economy.

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

Swedes and Immigration : End of homogeneity? (1)

Swedes and Immigration : End of the consensus ? (2)

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

ABBREVIATIONS OF THE NAMES OF DIFFERENT DANISH POLITICAL PARTIES USED IN SOME OF THE TABLES AND CHARTS IN THIS PAPER

V: Venstre, Liberal Party (ALDE, Renew Europe)

A: Socialdemokratiet, Social Democrats (Party of European Socialists)

O: Dansk Folkeparti, Danish People’s Party (Identity and Democracy)

B: Radikale Venstre, Social Liberal Party (ALDE, Renew Europe)

F: Socialistisk Folkeparti, Socialist People’s Party (Nordic Green Left Alliance, European Green Party)

Ø: Enhedslisten, Red-Green Alliance (Left Group in the European Parliament)

Y/I: Liberal Alliance, Liberal Alliance (centre right)

C: Det Konservative Folkeparti, Conservative People’s Party (EPP)

D: Nye Borgerlige, The New Right (right – far right)

M: Moderaterne, The Moderates (centre/centre right)

AE: Danmarksdemokraterne, Danemark Democrats (Right-wing populist)

Q: De Frie Grønne, The Independant Greens (left-wing)

K: Kristendemokraterne, The Christian Democrats (center)

Å: Alternativet, The Alternative (Nordic Green Left Alliance, DiEM25, European Spring)

P: Stram Kurs, Hard Line (far right)

E: Partiet Klaus Riskær Pedersen, Party of Klaus Riskaer Pedersen/ The Citizen List (liberal)

On 3 December 2015, when the centre-right government of Lars Løkke Rasmussen proposed to end these derogations in a referendum, 53% of voters rejected the proposal. The terrorist attacks in France, especially those in January and November 2015, as well as the refugee crisis in the same year were among the factors behind this result.

See Silvia Adamo, ” The Danish welfare state: Balancing solidarity between Europe, immigration, and times of crisis“, Revue française des affaires sociales, Issue n°3, July-September 2015, pp. 159-180.

See “Ocean Vinking: “Il est impossible d’accueillir si l’on ne peut pas refuser l’entrée”, interview by Dominique Reynié with Eugénie Bastié, lefigaro.fr, 15 November 2022.

Svante Hansson, “Danemark”, in Pascal Perrineau and Dominique Reynié (eds.), Dictionnaire du vote, Paris, PUF, 2001, p. 281.

See Statistics Denmark, “VAN5: Asylum seekers by citizenship and type of asylum“, 2022.

OECD, “International Migration Database”, December 2022.

In the parliamentary elections of 1 November 2022, the Danes returned the Social Democratic Party to power. Although Denmark has changed its governing majority several times, it has nevertheless pursued an immigration policy inspired by the same principles for the past twenty years: a drastic reduction in migratory flows, a strict integration programme, difficult access to citizenship and, from this point on, the willingness to use a non-European third country to process visa applications.

As a member of the European Union, the Schengen area and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Denmark has been able to develop a unique policy after negotiating its room for manoeuvre as an EU Member State. Following the first referendum in which they rejected the Maastricht Treaty (by 50.7%) on 2 June 1992, the Danes obtained a series of derogations from European law. With these “op-outs”, a new Danish referendum was held on 18 May 1993, this time with the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty (56.7%). The country is exempted from most of the European Union’s criminal justice and home affairs system1. Denmark can opt out of the EU regulations and directives on justice and home affairs, to which migration and asylum policies are subject. Denmark may therefore legally treat third country nationals according to its own rules2.

The new Danish immigration policy was initiated by the right-wing government, under pressure from the populists of the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti), who gave their parliamentary support in return. This policy was adopted and pursued by the Social Democrats when they returned to power in 2019. They were re-elected in 2022, even more comfortably than in 2019.

From the Danish perspective, migration policy is essential for the sustainability of the welfare state. The aim is to preserve the welfare state by limiting excessive or unjustified recourse to state aid, which risks squandering the country’s resources and undermining the political consensus by spreading suspicion of abuse. The Danish experience reminds us that the welfare state depends as much on the level of trust in society as on the economic performance of the country.

In this sense, it can be said that the national homogeneity to which the Danes are committed is based less on ethnic than on political, cultural and moral grounds. Thus, Denmark has decided to restrict immigration and to impose a vigorous integration programme on newcomers. The effort to reduce the cultural gap between immigrants and the wider Danish society helps to cultivate and transmit interpersonal trust, trust in institutions and ultimately the entire Danish national model. Danish immigration policy poses a fundamental question to Europeans: Can the future of the welfare state be secured without a restrictive and inclusive migration policy?

Yet the left has become uncomfortable with the idea of a state that firmly controls its borders at a time when the question is particularly acute for the European mainstream left, which is largely defined by the welfare state. In European democratic societies, despite increasing migratory pressures, most national lefts seem unable to endorse a policy of reducing migration flows. In France, this idea has been the subject of a stigmatisation that still deeply permeates the world of politics, the media, intellectuals and non-profit organisations3. So much so that the French right itself, over the twenty-three years it has governed since 1974, has never been able to bring itself to tackle the migration issue head-on, despite a constant increase in public concern and its constantly asserted translation in the electoral success of anti-immigration parties, mainly the Front National/Rassemblement National, whose performance in the presidential election rose from 0.75% of the votes cast in the first round in 1974 to 23.2% in 2022, and from 17.8% in the second round in 2002 to 41.4% in 2022.

The Danish example is therefore particularly worth considering. It sheds light on the role that restrictive migration strategies might play in 21st century democratic politics. The case is all the more relevant because Denmark is economically and culturally open to the world. It may be recalled here that foreigners residing in Denmark and holding Scandinavian passports were able to vote in local elections as early as 1978, and that the measure was extended in 1981 to all foreign residents in the country4. However, governments have changed their perspective over the last twenty years, gradually moving towards an increasingly restrictive migration policy. Initiated by the right wing between 2001 and 2011, the policy of closure was not challenged by the Danish left when it returned to power from October 2011 to June 2015. The victory of the right-wing coalition in June 2015, coinciding with the onset of the refugee crisis, resulted in an accentuation of the restrictive policy, leading Denmark to become one of the least open European countries to immigration.

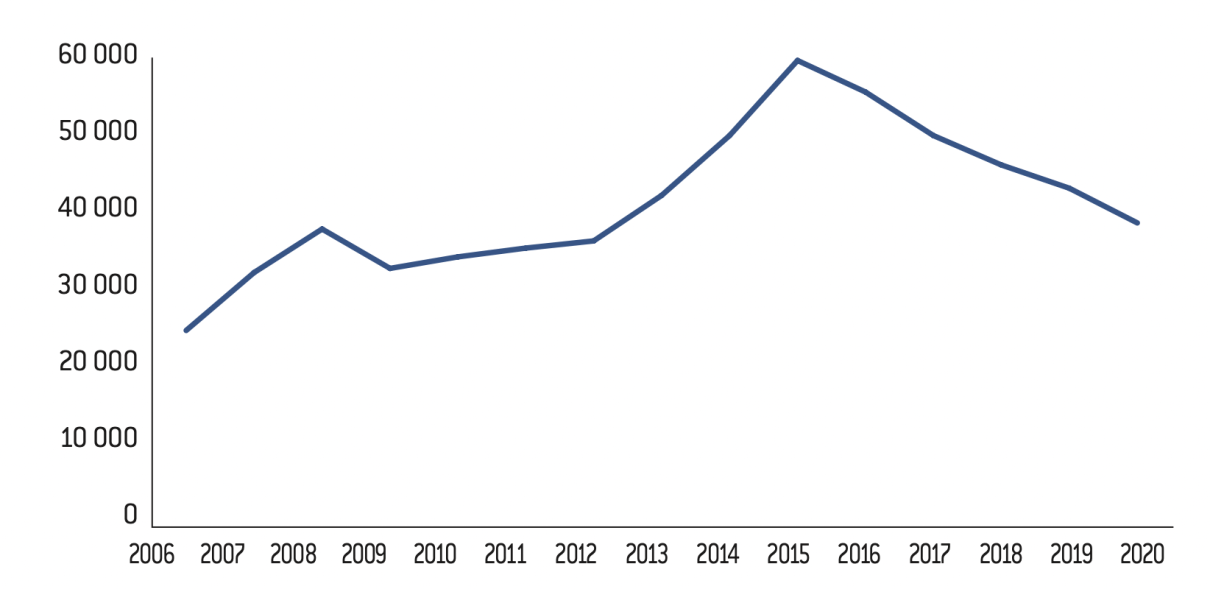

The Social Democrats have been in power since 2019 in a non-coalition government and were re-elected in the parliamentary elections on 1 November 2022. With 27.5% of the votes cast, they even improved their result compared to their victory in 2019 (25.9%). Danish migration policy has become consensual. Its particularly restrictive nature has a dissuasive effect on aspiring immigrants, as evidenced by the trend in the number of asylum seekers5: between 2014, the year before the refugee crisis, and 2019, the year before the COVID health crisis, the total number of asylum applications fell by 82%, from 14,792 to 2,716. The deterrent effect of this migration policy can also be seen in the number of foreigners (excluding asylum seekers) entering Denmark6: over the same period (2014-2019), the total number of migrants has fallen from 49,039 to 42,268 (-14%). The Social Democratic government is now working on the next step: the outsourcing of the management of visa applications to a third country, in this case Rwanda.

Annual immigration to Denmark, excluding asylum seekers (2006-2020)

Source :

Criteria for registration of non-Danish nationals in Denmark’s population register: to be in possession of a residency permit and to wish to stay in the country for more than 3 months. The data presented refers to migrants living legally in Denmark, registered in the population register and residing in the country for at least one year. Excluded are: asylum seekers and other non- nationals with temporary residence status.

Note: From 2006 onwards, Statistics Denmark has introduced a new method of calculation based on population data. Therefore, we have chosen to consider data from 2006 onwards.

Quoted by Nelly Didelot, “Au Danemark, la victoire idéologique de l’extrême droite“, liberation.fr, 4 June 2019.

On the subject of immigration, the Fondation pour l’innovation politique has already published several studies, including Didier Leschi, Migrations: la France singulière, October 2018; Tino Sanandaji, The Swedes and Immigration (1). The end of homogeneity?, September 2018, and The Swedes and immigration (2). The End of Consensus?, September 2018; Jean-Philippe Vincent, Éthiques de l’immigration, June 2018.

Via the following e-mail address: contact@fondapol.org.

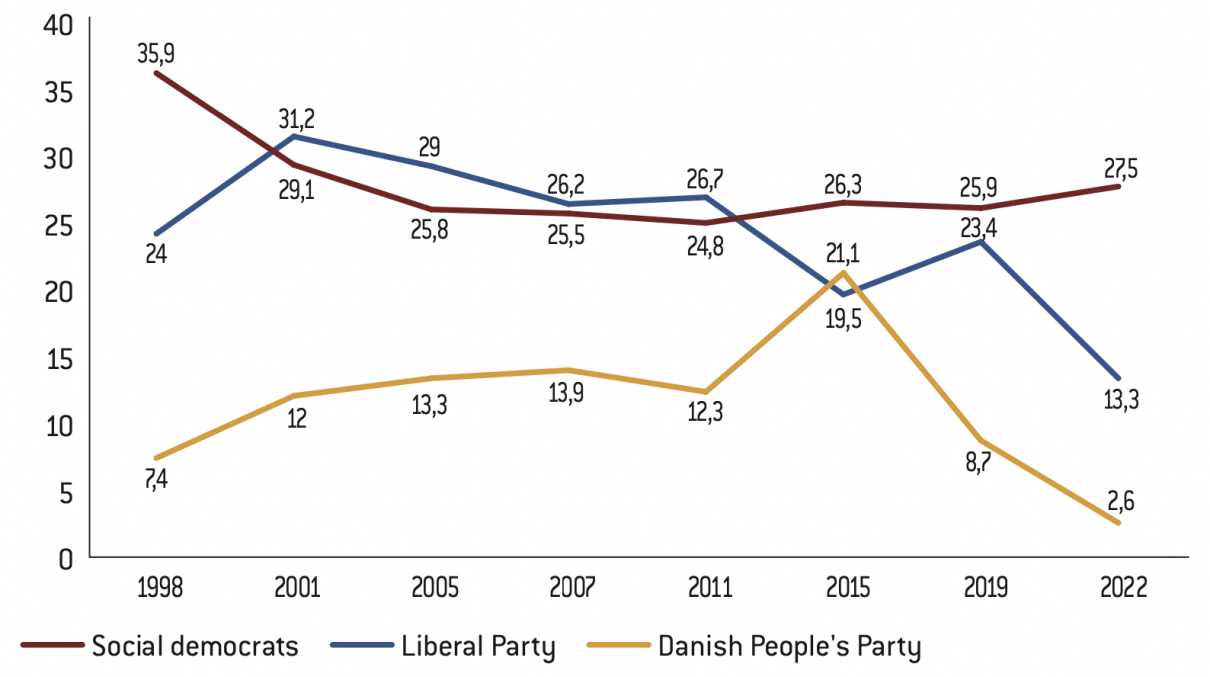

In addition to the reduction in migration flows, the second notable effect of this policy is the collapse of the main populist party, the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti). Having achieved its highest score (21.1%) in 2015, at the beginning of the European refugee crisis, it fell to 2.6% in the elections of 1 November 2022. However, the electoral collapse of the populists is the consequence of their ideological victory – which analysts had identified during the previous elections in June 2019, when the Danish People’s Party was already in sharp decline, with 8.7% of the votes cast: “Most of the anti-immigration, anti-asylum and anti-Islamic positions that essentially characterised the Danish People’s Party have gradually become normalized to the point of becoming ubiquitous, explained Susi Meret, an associate professor at Aalborg University. The ‘dominant’ parties have taken over its discourse”7. Thus, in 2022, the Social Democrats were re-elected (27.5%), with their best score since 2001. Such a score confirms the Social Democratic Party’s comeback among the working classes.

The purpose of this study is to present the formation of Danish migration policy and its main characteristics.8 This policy has been implemented through a succession of laws adopted over the last two decades.

| Danish immigration policy is the product of an abundant and complex legislative work. The summary that we are proposing here is designed to be enriched by additions and amendments that attentive and interested readers will want to share with us9. |

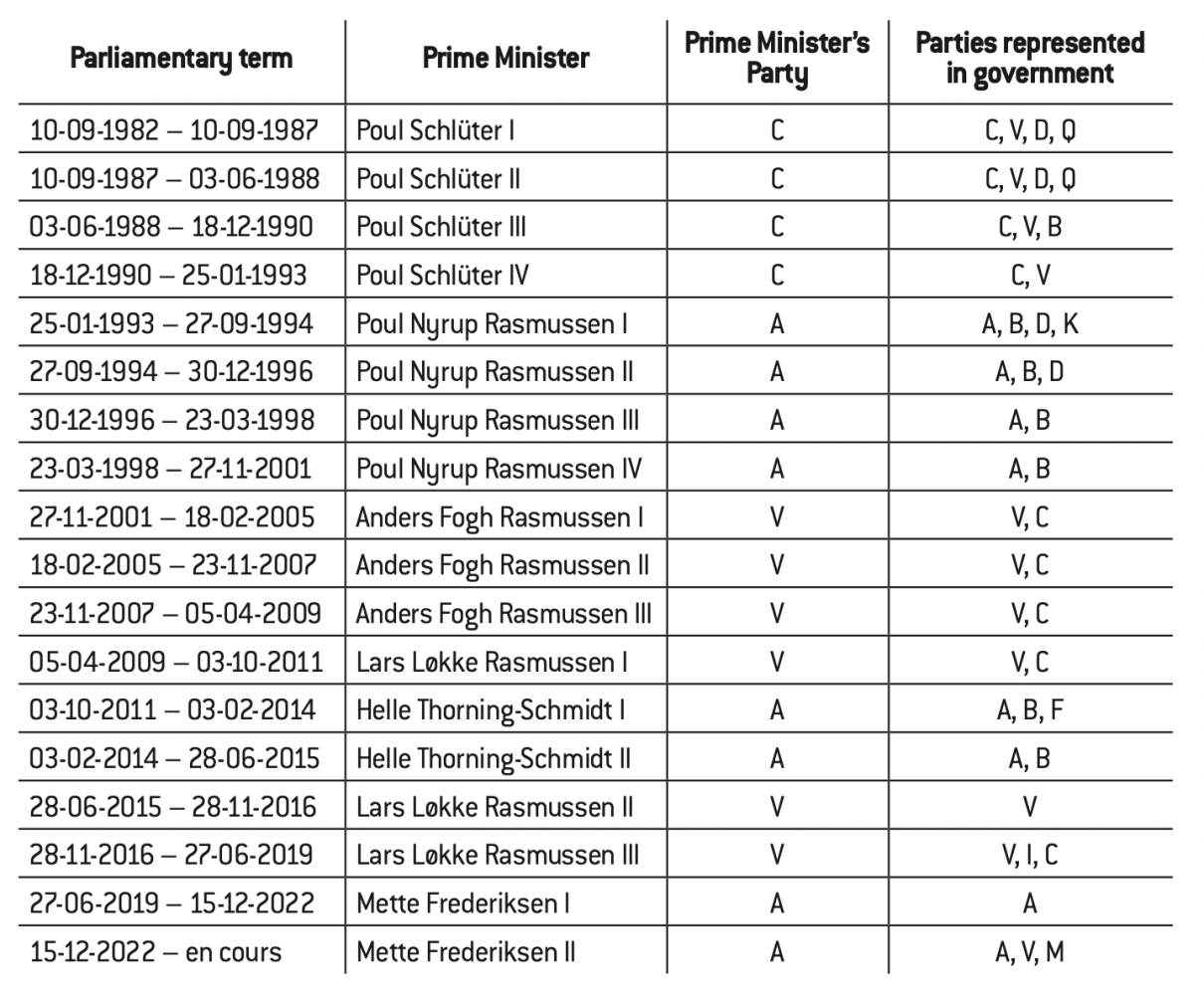

Political composition of Danish governments since 1982

Copyright :

Foundation for Political Innovation

Source :

Note: Since 1945, Denmark has had thirty-eight governments, twenty-four of which were formed on the basis of a coalition and fourteen without a coalition.

A policy driven by the challenge of national homogeneity

Denmark as a homogeneous society

See Garbi Schmidt, “Myths of ethnic homogeneity. The Danish case“, in Suvi Keskinen, Unnur Dís Skaptadóttir et Mari Toivanen (dir.), Undoing Homogeneity in the Nordic Region. Migration, Difference, and the Politics of Solidarity, Londres, Routledge, 2019, p. 35-48.

See Ulf Hedetoft, “Denmark: Integrating Immigrants into a Homogeneous Welfare State”, migrationpolicy.org, November 1, 2006.

Shahamak Rezaei and Marco Goli, “The ‘housebroken’ far-right parties and the showdown in Danish migration and integration policies”, in Maciej Duszczyk, Marta Pachocka and Dominika Pszczółkowsk (dir.), Relations between Immigration and Integration Policies in Europe. Challenges, Opportunities and Perspectives in Selected EU Member States, Routledge, 2020, p.106-124.

In Denmark, the idea that the nation stems not only from a common past but also from ethnic homogeneity is widespread among the population. N.F.S. Grundtvig (1784-1872), one of the historical figures of Danish nationalism and a member of the Constituent Assembly that gave birth to the first Danish constitution in 1849, placed his views within the Romantic family of nationalism, which was based on the idea of ethnically homogeneous ‘people’ sharing the same language and history10.

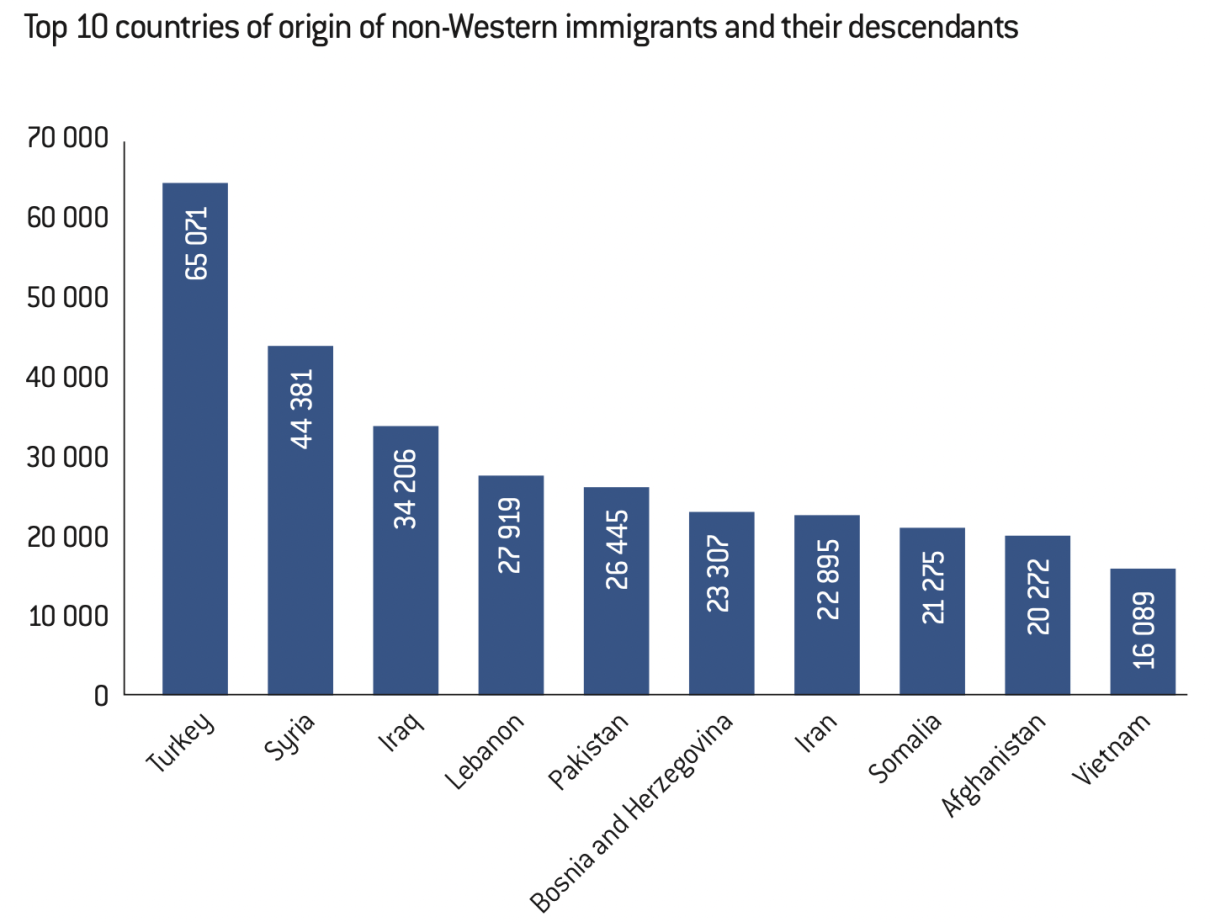

The idea of an ethnically homogeneous nation should certainly be put into perspective, as Denmark has experienced several waves of immigration in the course of its history. However, these waves were mainly from the Nordic countries and Western Europe. The concept of a welfare state formed from a culturally homogeneous population is therefore conceivable11. The first non-European migrants, especially from Turkey, Pakistan and the former Yugoslavia, arrived in the 1960s, often as foreign workers, to meet the needs of Danish industry. In 1973, with the first oil shock and its consequences for employment, it was decided to stop the influx of foreign workers. However, in the following decades, Denmark received many refugees from Vietnam, Chile, the Near and Middle East and Somalia, and their numbers increased rapidly with family reunification12. The first Immigration Act of 1983, considered one of the most liberal in the world, was then amended and tightened for the first time in the 1990s, and then on numerous occasions from the early 2000s.

Origin of non-Western immigrants and descendants in 2021

Source :

The welfare state as a national principle

See Silvia Adamo, “The Danish welfare state: Balancing solidarity between Europe, immigration, and times of crisis“, Revue française des affaires sociales, Issue 3, July-September 2015, pp. 159-180.

Ibid.

Ibid, p.163.

In Denmark, nation-building is deeply linked to the deployment of the welfare state, which is seen as dependent on a sense of solidarity between people who were born and have lived in the same country. Silvia Adamo points out that the principles that form the basis of the Danish welfare system are universality (the state provides a large number of services and benefits financed by general taxation), solidarity (the state is the main provider of social protection), the provision of a minimum standard of living (the state is responsible for ensuring a minimum standard of living for all) and territoriality (benefits are conditional on residence in Denmark, they are not exportable).13 However, migrants and those who have moved to other countries, by being able to access the benefits of the Danish welfare state, are changing the conditions of this solidarity14. This is all the more true since the oil shocks have weakened the Danish model of social protection. Therefore, in the 2000s, Denmark emphasised individual responsibility in order to reduce the tendency to expect handouts.15

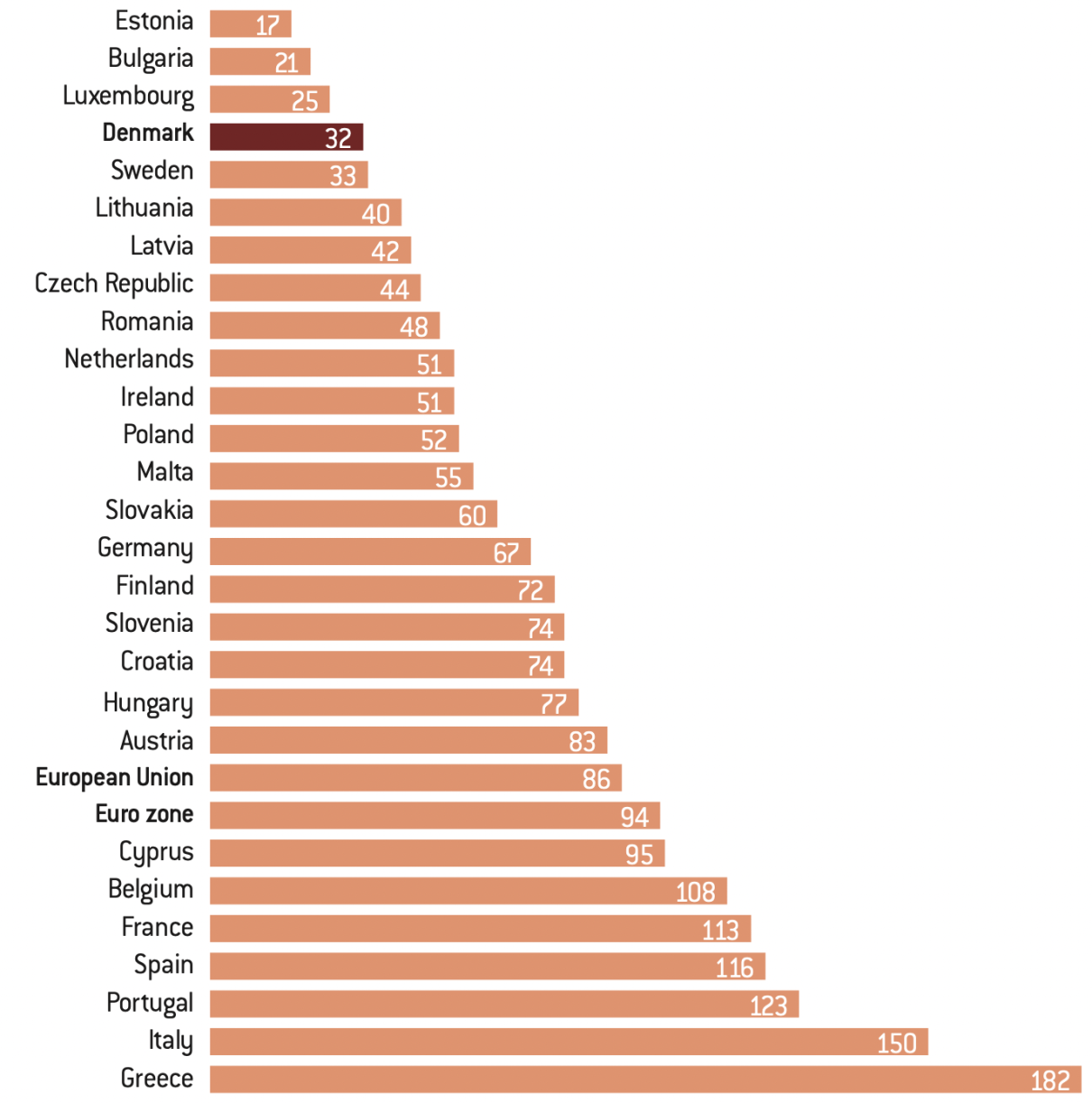

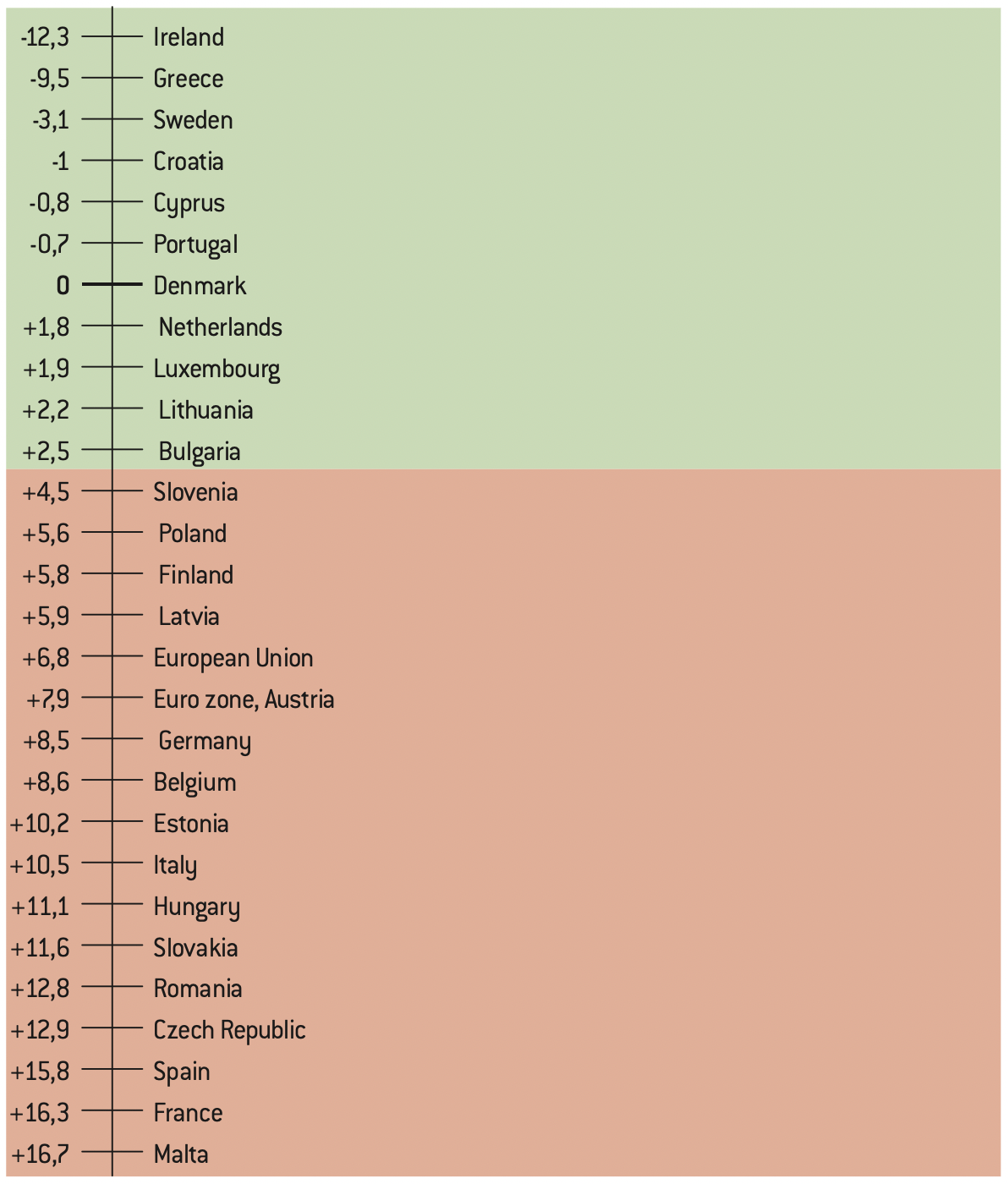

Public debt in Q2 of 2022 (% of GDP)

Source :

Eurostat

| Precise and tight budget negotiations at the heart of government coalitions

Most governments in Denmark have been based on minority coalitions. This situation makes stability dependent on close and precise negotiations between the coalition parties, but also requires that the views of parties outside the coalition be taken into account, particularly on the subject of fiscal policy. The phenomenon of minority coalitions can be seen as one of the explanations for the Danish budgetary rigour: “Most major budget policy initiatives during a government’s term of office will emanate from the coalition agreements […]. This medium-term economic and fiscal strategy enjoys broad political support in Denmark and has been followed by successive governments. The overall objective of the programme is to ensure that fiscal policy is sustainable in the long-term” [1]. [1]. Jón R. Blöndal and Michael Ruffner, “The Budgetary Process in Denmark“, OECD Journal of Budgetary Management, Vol. 4, n°. 1, April 2006, pp. 60-61. |

Evolution of public debt in percentage of GDP between 2019 and 2022

Source :

European Commission

| Fiscal rigour is as part of the Danish political culture

Along with Austria, the Netherlands and Sweden, Denmark is one of the European countries whose commitment to balancing its accounts and controlling its public debt is shared by both the right and the left, which has earned them the reputation of being ‘frugal’ by less rigorous states. It is certainly difficult to understand Danish immigration policy without bearing in mind this aspect of the national economic and political culture, which is deeply marked by the imperative of cautious management of public resources. |

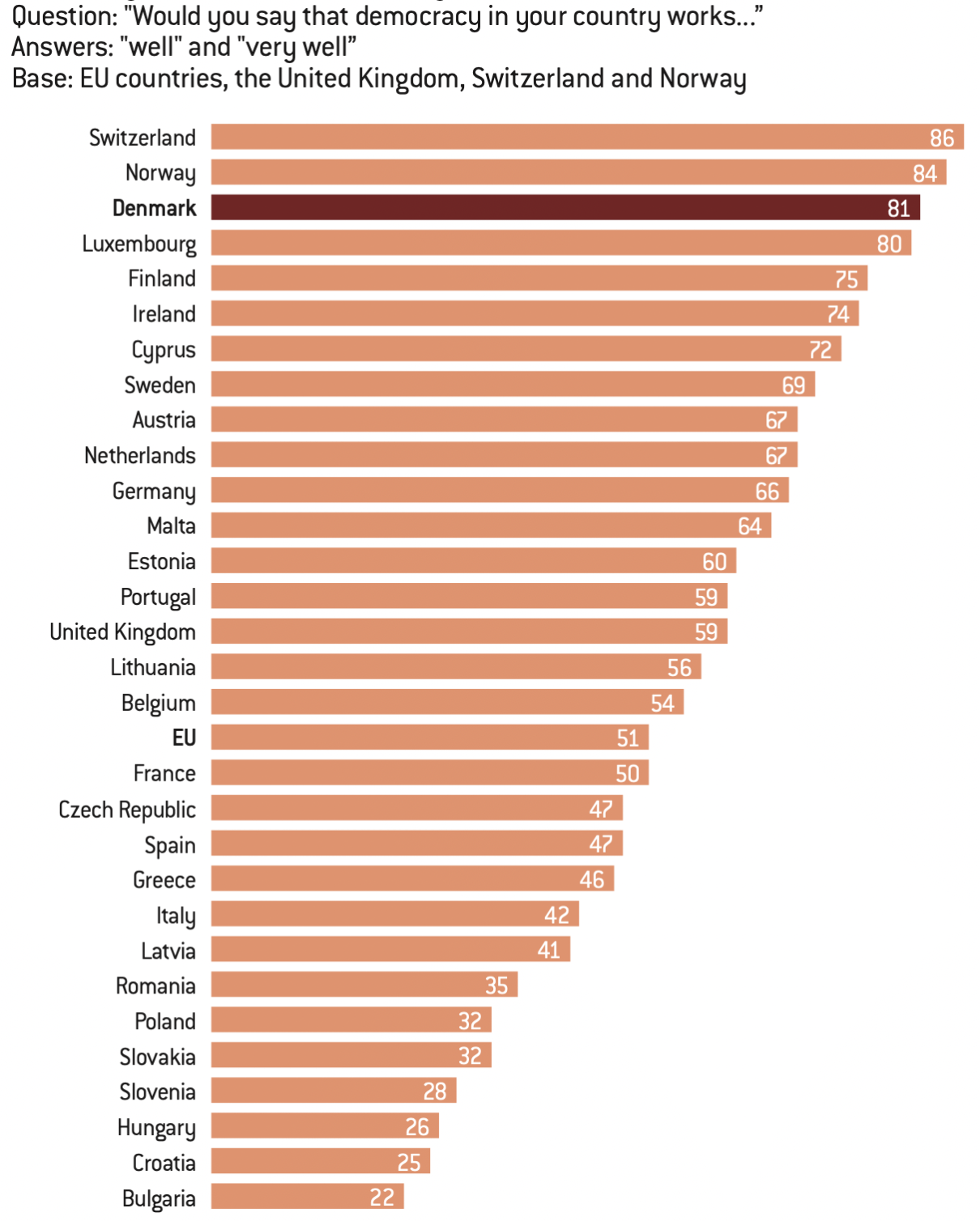

In the European Union, Danes are the most likely to consider that democracy works well in their country (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Source :

Dominique Reynié (ed.), “Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century”, survey carried out in partnership with the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, Community of Democracies, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Genron NPO, the Fundación Nuevas Generaciones and República do Amanhã, January 2022, 96 pages.

See Suvi Keskinen, Ov Cristian Norocel and Martin Bak Jørgensen, “The politics and policies of welfare chauvinism under the economic crisis”, Critical Social Policy, vol. 36, n° 3, August 2016, p. 321-329.

See Emily Cochran Bech, Karin Borevi et Per Mouritsen “A ‘civic turn’ in Scandinavian family migration policies? Comparing Denmark, Norway and Sweden“, Comparative Migration Studies, vol. 5, article 7, March 2017.

See Suvi Keskinen, Ov Cristian Norocel and Martin Bak Jørgensen, art. cit.

Many people have doubts about the sustainability of the Danish model, and some advocate greater liberalisation, recommending the cutting of state aid and protection for migrants who, as non-members of the national community, should not necessarily have access to national solidarity.

The economic and financial crisis of 2008 fuelled a growing interest in such approaches. This is particularly the case for the Danish People’s Party, which supports the exclusion of non-nationals from national solidarity. According to this logic, only ‘natives’, those who are part of the community deemed ethnically homogeneous, should be able to benefit from national solidarity.16 It then becomes a question of distinguishing between people, between those who belong to the national community and those who do not, between those who contribute to the production and redistribution of national wealth and those who are accused of taking advantage of the system. Economic integration is at the heart of the civic integration of migrants17, who are increasingly viewed as the part of society that weighs on the social system, at the expense of the historical members of the national community. A vision of ‘deserving’ migrants, those who contribute to the national effort, versus those who exploit the system, has gradually taken hold among the Danish ‘natives’, especially among the working class18. Thus, immigration and integration policies have been recast on the basis of a distinction between desired migrants and the others, between the ‘deserving’ and the ‘freeloaders’, particularly in the wake of the economic crisis, in view of their integration and their contribution to economic life and the welfare state, but also in terms of respect for the liberal values that characterise Danish society.

The influence of Danish populism on immigration policies

See Anders Widfeldt, The Growth of the Radical Right in Nordic Countries: Observations from the Past 20 Years, Migration Policy Institute, June 2018.

Ibid.

“Heritage populism” is a notion introduced by Dominique Reynié in Les Nouveaux Populismes (Paris, Pluriel, 2013) to qualify a type of populism responding to the fear or experience of a two-dimensional heritage crisis, i.e., the fear or experience of an erosion of tangible heritage – the standard of living, the material conditions of existence – and the fear or experience of a loss of intangible heritage – the lifestyle, the cultural and symbolic dimension of existence.

See Corinne Deloy, “Chronique européenne des élections”, by Bruno Cautrès and Dominique Reynié (eds.), L’Opinion européenne 2002, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po/Fondation Robert-Schuman, 2002, p. 360-363.

See Corinne Deloy, “Les élections en 2011”, in Dominique Reynié (ed.), L’Opinion européenne en 2012, Paris, Fondation pour l’innovation politique/ Fondation Robert-Schuman, 2012, pp. 145-147.

See Corinne Deloy, “Les élections en 2015”, in Dominique Reynié (ed.), L’Opinion européenne en 2016, Paris, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2016, pp. 115-118.

Ibid.

In Denmark, the demand for a restrictive migration policy was first voiced by the far-right parties, whose presence in the political landscape dates back to the 1970s. The Danish People’s Party, which was the strongest populist party for 30 years, was formed in 1995 as a result of a split with the Progress Party (Fremskridtspartiet), founded in 1972 by the tax lawyer Mogens Glistrup (this party now occupies a marginal position in Danish politics).

In economic terms, the Progress Party developed a typical right-wing populist, anti-tax, anti-elite discourse, particularly denouncing the intellectual elites and bureaucracy, but advocating ideas from the libertarian movement, such as the abolition of income tax and the rejection of the welfare state. The Progress Party also assumed a racist, at least xenophobic,and vigorously anti-Muslim culture19. The oil shocks and then the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988 brought waves of refugees, making immigration a matter of growing public concern. In the 1973 parliamentary elections, the Progress Party enjoyed immediate success and became the country’s second largest political force, with 16% of the votes cast and 28 of the 179 seats in the Folketing, the single chamber of the Danish Parliament. The 1980s, however, saw the party’s electoral decline and its founder faced difficulties within the party itself. In addition to his troubles with the law, he was mainly criticized for his strategy of questioning the welfare state. Within the Progress Party, those who defended the welfare state did so in the name of its ideological and electoral effectiveness. The welfare state became the axis of social chauvinism, offering the possibility of combining a right-wing principle, national preference, with a left-wing principle, solidarity. It was over the welfare state that a split in the party gave rise to the Danish People’s Party,20 which is a good example of this new type of heritage-related populism that emerged between the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first century21.

The name of the Danish People’s Party claims to appeal to the nation’s people, in a readily ethnic sense. Firmly opposed to immigration and multiculturalism, and promoting a restoration of “national identity,” the party is a right-wing populist nationalist party that defends the welfare state. This combination allowed it to soar in the polls until 2015. The party believes that immigrants are welcomed in too large numbers and too lavishly, at the expense of Danish taxpayers. Unlike the Progress Party, the Danish People’s Party does not question the generosity of the welfare state, but proposes that the benefits be reserved for the Danish population (i.e., the “native” population), the only net contributors to the nation’s resources. The interweaving of the issue of preserving the wealth of “the people” with the issue of their identity is reflected in the party’s criticism of the European Union, and in particular its opposition to the adoption of the single currency in 2000, in the name of national identity, a certain social model and a way of life threatened by European deregulation policies. The defence of the welfare state was combined with the defence of national identity and sovereignty to justify a programme aimed at closing the country and refusing to accept new inhabitants from abroad, in order to avoid destabilizing Denmark economically, financially, culturally or politically.

The 1998 parliamentary elections were the first national elections in which the Danish People’s Party took part. It won 7.4% of the vote and 13 seats in Parliament. In the next election in 2001, it became the third largest force in the country, with 12% of the vote and 22 seats. During the campaign, the party put immigration at the heart of the public debate. Voters elected a right-wing majority, allowing the formation of a coalition between the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, with parliamentary support from the Danish People’s Party22. In the parliamentary elections of 2005 and 2007, the Danish People’s Party remained the third largest political force in the country. The right wing maintained its majority and the parliamentary support of the Danish People’s Party. Although the Danish People’s Party does not participate in the government, it has a strong influence on public policies, especially those aimed at reducing migration flows.

A reversal of the majority occurred in 2011, when an alliance of left-wing parties narrowly won the elections. With 12.3% of the vote and 22 seats, the Danish People’s Party was in decline for the first time since 1998, but remained the country’s third largest force. These elections mark the end of austerity policies following the 2008 crisis. They also mark the wear and tear of the right-wing parties, which have been in power for ten years23. In 2015, the left was defeated in turn, as it continued its austerity policies. A right-wing coalition regained a majority, in particular thanks to the Danish People’s Party, which triumphed by becoming the largest right-wing party, with 21.1% of the vote and 37 seats24. Two main issues marked the 2015 election campaign: the welfare state and immigration. Kristian Thulesen Dahl, who succeeded Pia Kjærsgaard as leader of the Danish People’s Party, focused on defending the welfare state and rejecting immigrants deemed too numerous. In the eyes of part of the public, the party appeared to offer an alternative social-democratic proposal25 that would allow the welfare state to be maintained, or even strengthened, by reducing migration flows. To say the least, it was this political offer that caused the defeat of the left-wing coalition. The 2015-2016 migration crisis reconfigured the political landscape. The scale and brutality of the crisis precipitated the adoption by the Social Democrats of the Danish People’s Party’s proposals on migration policy. This shift paid off: the left regained its majority in 2019, notably by regaining part of its electorate at the expense of the Danish People’s Party, which suffered its first historic setback, with a score of 8.7% and the loss of 21 members of parliament.

The electoral results of the Social Democratic Party, the Liberal Party and the Danish People’s Party in the parliamentary elections (in % of votes cast)

Source :

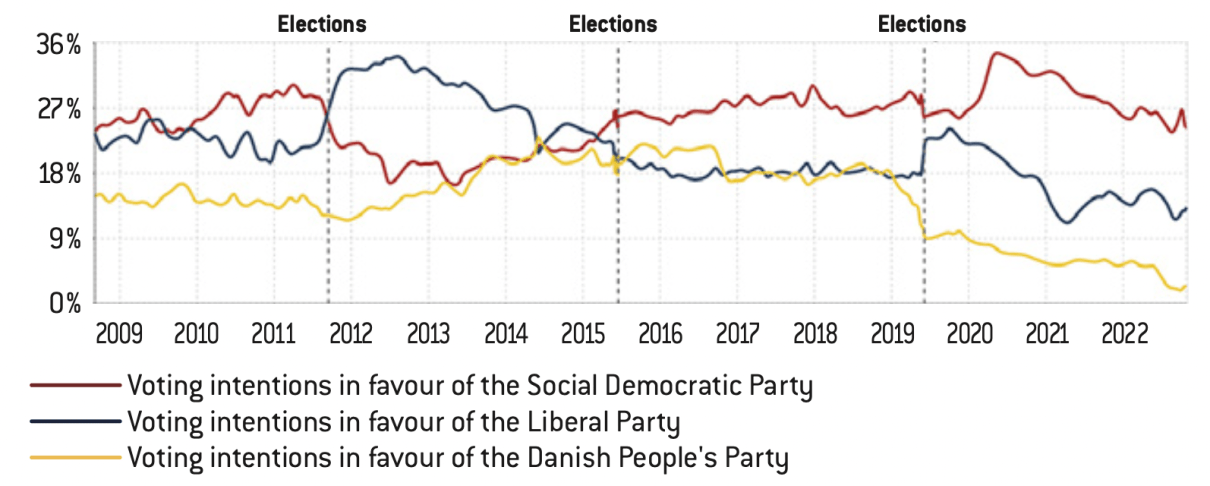

Opinion polls provide a more detailed picture of the shifting balance of power between the social democrats, the right and the populists. DR.DK has conducted 177 voting intention surveys since 2008. By looking at the results for the three main parties, the Social Democratic Party (left), the Liberal Party (right) and the Danish People’s Party (populist), we obtain information that the electoral results alone – which are by definition rarer – do not provide: between 2013 and 2015, the two main government parties, on the right and on the left, are dangerously challenged, to the point where they are almost surpassed by the populist party. The migrant crisis (2015-2016) seems to explain why the Danish People’s Party remains at its strongest peak, but then its decline began and continues to this day, precisely because of the migration policy in place since 2001.

Voting intentions in favour of the Social Democratic Party, the Liberal Party and the Danish People’s Party (September 2008 – October 2022, in %)

Source :

| The impact of the cartoon crisis

The Danish People’s Party has promoted the idea that immigration, especially Muslim immigration, exposes the country to anti-democratic and anti-liberal trends and risks undermining the national consensus. The fear of internal conflict generated by immigration was amplified by the intense global diplomatic crisis and the attacks that followed the publication of the Mohammed cartoons in the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten in 2008. * See also Dominique Reynié, “L’islam et le libéralisme européen”, in Les Nouveaux Populismes, Paris, Pluriel, 2013, pp. 115-127, and Lorenzo Vidino, La montée en puissance de l’islamisme woke dans le monde occidental, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2022, p. 16. |

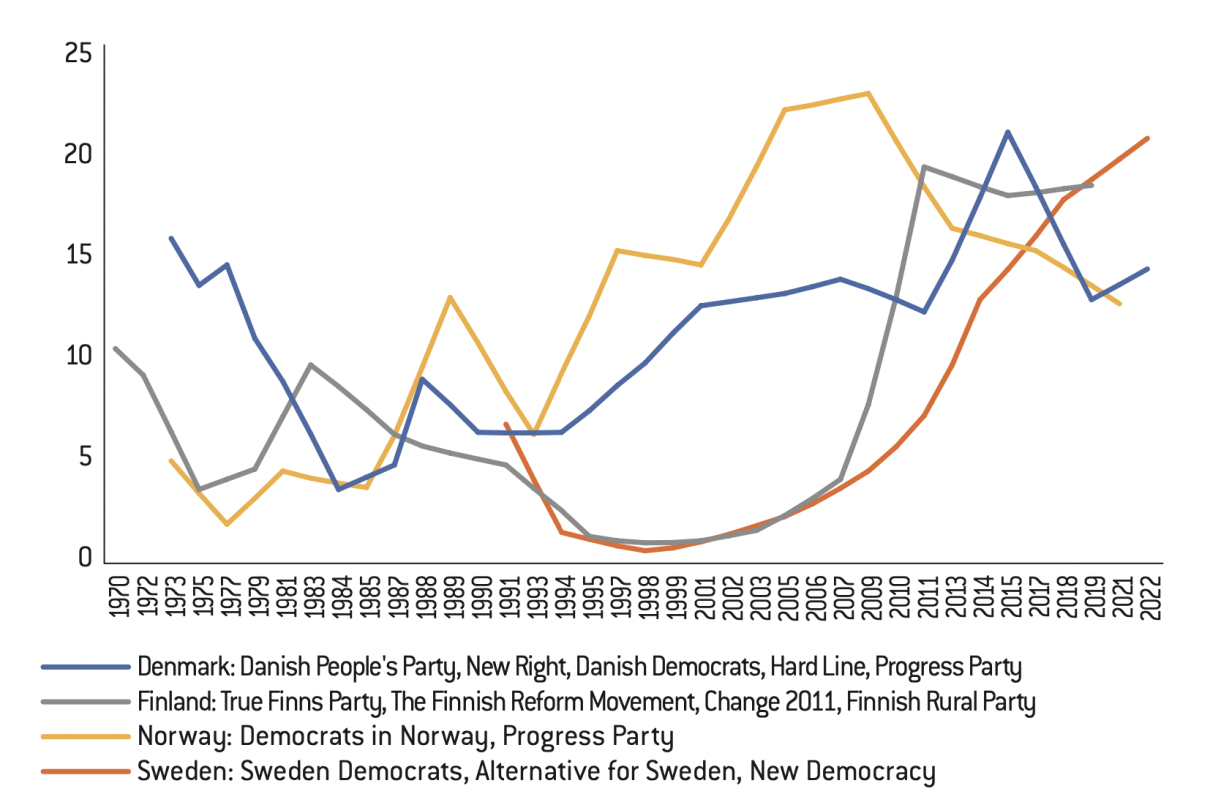

In the Nordic countries, the combined scores of the main right-wing populist parties show that their electoral influence remains very strong today (1970-2022, in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Reading grid: In 1991, the combined score of the main right-wing populist parties in the Swedish parliamentary elections was 6.8% of the votes cast. In the same year, it was 4.8% in the Norwegian parliamentary elections.

The danish immigration policy: firmness, closure and the welfare state

A vigorous integration policy

See Silvia Adamo, “‘Please Sign Here’: Integration Contracts Between Municipalities and Foreigners in Denmark”, Journal of International Migration and Integration, vol. 23, n° 1, March 2022, p. 321-342.

See Christèle Meilland, “Pénurie de main-d’œuvre et immigration ultra sélective“, Chronique internationale de l’IRES, n° 178, June 2022, p. 24-35.

See Silvia Adamo, “The Danish welfare state…”, art. cit.

See Silvia Adamo, “‘Please Sign Here’…”, art. cit.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Danish integration policy is governed by the Integrationsloven, which was passed in 1998 and has been amended several times since. This law sets out the rules for an immigrant seeking citizenship, integrating into the national model and adopting the fundamental values of Danish society. The rules differ according to the status of the residence permit26. Without going into detail about the evolution of the law, it is important to at least present the general legislative framework and the trend in integration policies.

The Danish system is decentralized. It is the responsibility of the ninety- eight municipal authorities to implement integration policies. These policies can therefore be interpreted and adapted to local circumstances. Integration of foreigners is primarily defined through their integration into the labor market27, while the residence permit is conditional on a capacity for self- sufficiency28. With regard to refugees and family reunification immigrants, two programs have been set up:

– a self-sufficiency and repatriation program for refugees and for unaccompanied minors, as well as for persons allowed to stay in Denmark on humanitarian grounds;

– an integration program for members of immigrant families. The aim is to enable immigrants to gain access to employment by improving their skills.

These programs must be offered by the municipalities within a maximum of one month after they take charge of the immigrants. The programs are for a period of 1 year, at the end of which the immigrant must be in employment. If the objective is not achieved, the duration of the program can be extended to a maximum of 5 years. These programs consist of Danish language courses, depending on the migrant’s level of education, and training offers to facilitate employment: skill improvement, internship, appointment of a mentor, partnerships between the city council and companies that take care of migrants, in exchange for subsidies. Municipalities receive financial compensation from the state for their contribution to the integration of newcomers29.

The content of the programs is specific to each refugee or immigrant who comes through family reunification. These programs are the subject of a contract co-signed with the municipality. If the parties to the contract, the immigrant and the municipality, do not agree on the content of the integration program, it is up to the municipality to ultimately determine it. The contract sets out the obligations, objectives and stages of the integration process in society. It should be noted that immigrants whose presence in the country is temporary (e.g. certain workers on fixed-term contracts or au pair students) are also covered by an integration program, but in a lighter form, with an introductory course and Danish language classes. This program is geared towards accessing the labor market and is not contracted. When entering an integration program, foreigners, including non-refugee and non- family immigrants, are required to sign a “declaration of residence and self- sufficiency” that affirms their willingness to adapt to the democratic and liberal values of Danish society.30

Refugees and immigrants under family reunification are required to sign the contract in order to receive social benefits. These benefits are also conditional on compliance with the contract: taking language courses and accepting job offers are mandatory. Failure to sign the contract or to comply with it will prevent the immigrant from obtaining a permanent residence permit and thus from being granted citizenship.31

| The government’s strategy to tackle ‘ghettos’

“The latest ghetto strategy was published in March 2018 in a white paper called Et Danmark uden parallelsamfund – Ingen ghettoer i 2030 (One Denmark without parallel societies – No ghettos in 2030) to combat ghettos for once and all in order to build a coherent Denmark. In the white paper, the government states that the strong population growth of citizens of non-Western origin has provided a breeding ground for parallel societies, where Danish values and norms are not the primary ones. Furthermore, it argues that 28,000 families with non-Western backgrounds live in isolation from the rest of the Danish society, both physically and mentally, in so-called parallel societies. The government’s ghetto strategy of 2018 consist of 22 initiatives and centers around four focus areas: – Physical demolition and reconstruction of vulnerable residential areas – More firm control of who can live in vulnerable residential areas – Strengthened police response and severer punishment must fight crime and create more security – A good start in life for all children and young people According to the Danish government, a ghetto is characterized as a physical cohesive public residential area constituting at least 1,000 residents who meet at least two of the following three criteria: – The amount of residents convicted for violations of the Criminal Code, the Firearms Act, or the Euphoriants Act exceeds 2.7 percent of the total amount of residents. – The proportion of residents aged between 18 and 64 years with no relation to the labor market or the education system exceeds 40 percent. – The proportion of immigrants and descendants from non-Western countries exceeds 50 percent. If the proportion of immigrants and descendants from non-Western countries exceeds 60 percent, the area is automatically considered a ghetto.” Seda Emine Agzigüzel, “A Matter of Security? A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Underlying Security Discourse in the Danish Ghetto Plan,” Malmö University, 2021, pp. 12-13. |

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, 2019, p. 244.

See “Les politiques d’asile du Danemark, entre fermeté et restrictions (2/2)“, interview with Romana Careja by Marie Robin, ThucyBlog N°166, afri-ct.org, October 28, 2021.

Over the past twenty years, successive governments have implemented numerous plans to improve and strengthen the integration of foreign populations. One of these plans in particular deserves some attention: it focuses on places of residence. Released in 2018, this plan aims to “dismantle parallel societies and immigrant ‘ghettos’ by 2030.” The term “ghetto” (ghettoer) was introduced into Danish law in 2010. For a given residential area, the “ghetto” is defined on the basis of a combination of employment rates, crime indicators, education and income levels, and the proportion of the population of non-Western origin. In order to dismantle these “ghettos”, the plan aims to more strictly regulate the possibilities of settling in them, as well as of renewing a lease. The objective is to fight against residential segregation and to avoid a concentration of immigrant populations. The plan imposes, for example, restrictions on the settlement of people receiving social assistance. In addition, the plan increases law enforcement resources in these neighborhoods, while at the same time creating areas with harsher penalties, i.e., areas where wrongdoing is more heavily punished than elsewhere.32 This aspect of the plan has been criticized in relation to the principle of equality before the law33, although equality remains in a sense, since everyone who commits an offence in the area concerned is exposed to the same risk of punishment. If, for the same offence, the punishment may be different, it is on the basis of the area, and not on the basis of the person.

Restricting access to employment, family reunification and citizenship

Christèle Meilland, art. cit, p. 31.

OECD, International Migration Trends 2003, Sopemi Edition, 2003, p. 198.

OECD, International Migration Trends 2007, Sopemi Edition, 2007, p. 260.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2014, OECD Publishing, 2014, p. 284.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, 2015, p. 208.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, 2019, p. 244.

See Danish Ministry of Finance/Agency for Digital Goverment, “Conditions for foreign citizens’ acquisition of Danish citizenship,” November 2022.

From 2002 to 2016, the law on foreigners was amended 93 times and 42 times between 2017 and 201934. These numerous changes have contributed to legal ambiguity, making it difficult for migrants to read and understand the texts. The large number of legislative changes testifies to the importance of the subject, both for the Danish right and left, since both have governed during this period. The basic logic is clearly to restrict immigration and tighten acceptance conditions. The following paragraphs review the main developments in terms of citizenship, access to work, obtaining a residence permit and family reunification. Overall, the texts adopted show, on the one hand, the convergence of views between the main political forces, including populists, on migration policy and, on the other hand, an affirmation of integration efforts.

Acquiring citizenship

In 2002, in order to be granted citizenship, it was necessary to have lived in Denmark for at least seven years, to have held a residence permit for two years (except for refugees, stateless persons and spouses of Danes) and to have passed a language test.35

From 2007, applicants for Danish citizenship must pass an enhanced language test, as well as a test of knowledge of Danish history and society36.

In 2013, new changes concerning citizenship were adopted: while there are three levels of language, applicants are required to pass an intermediate level 2 test or equivalent, as well as a test focused on civic participation and daily life37. Similarly, in 2014 access to citizenship was made easier for young people who were born and raised in Denmark38. Since 2019, a mandatory handshake is added to the naturalization procedure and precedes the delivery of the citizenship certificate39.

Being sanctioned for committing an offense impacts the possibility of applying for Danish citizenship. For example, receiving a fine of 3,000 kroner (about 400 euros) leads to ineligibility for a period of 4 years and 6 months. If the person is fined several times, the ineligibility is extended, since for each offence fined, a new waiting period is added to the previous40. Any prison sentence, even if suspended, permanently prevents access to Danish nationality. Finally, applicants for Danish citizenship must also have shown that they are able to support themselves for at least three and a half of the last four years, instead of four and a half of the five previously.

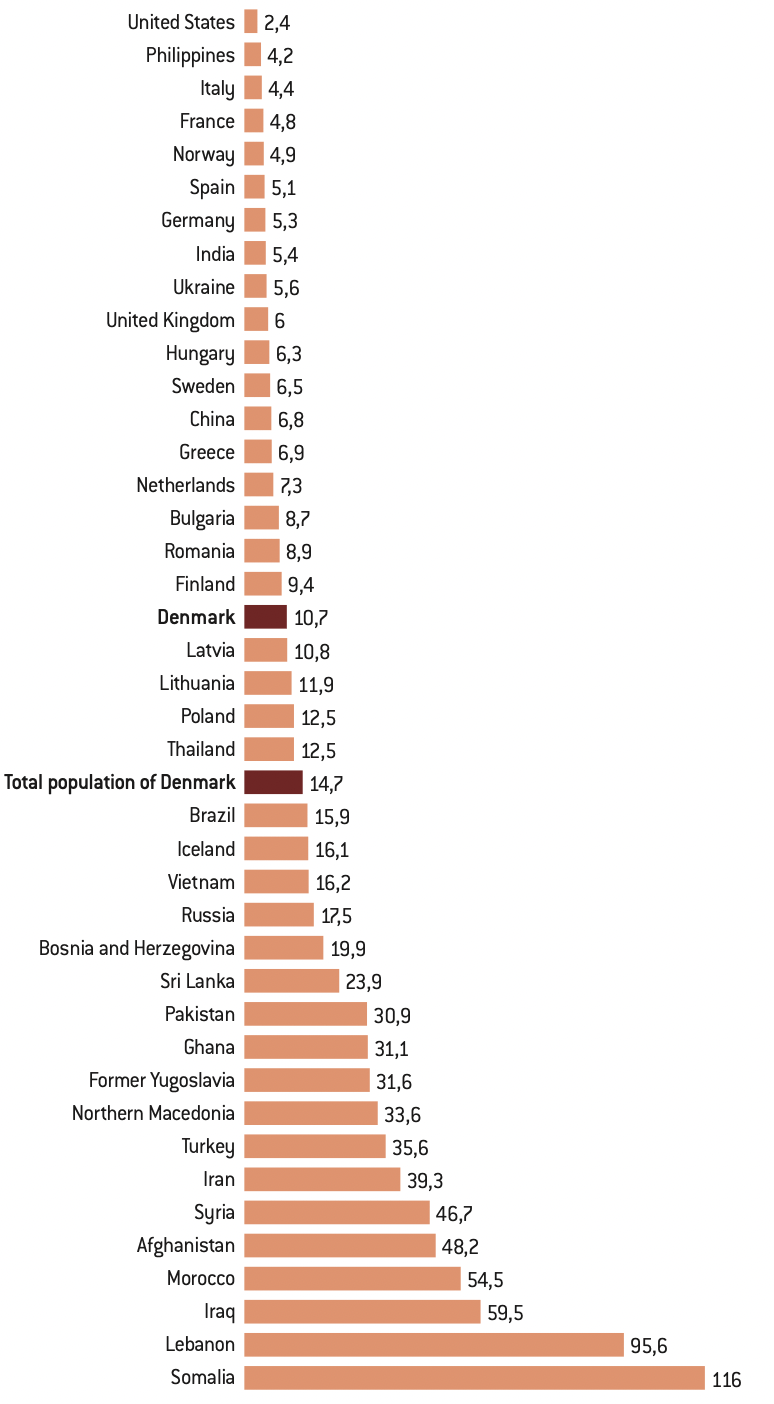

Violent incidents in Denmark per 10,000 inhabitants classified by country of origin of the perpetrators

Source :

Denmark Statistics.

Quoted in “Le Danemark durcit les règles de naturalisation“, rts.ch, 21 April 2021.

OECD, International Migration Trends 2004, Sopemi Edition, 2004, pp. 195-196.

OECD, 2007, op. cit, p. 260.

OECD, 2015, op. cit, p. 208.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, 2021, p. 278.

Christèle Meilland, art. cit. p. 29.

It is important to note that the text presented by the Social Democratic government, with the support of three opposition right-wing parties, gives a central place to “Danish values”. In the compulsory examination for applicants, five questions are on this theme, in addition to the oral and written language tests, which Mathias Tesfaye, the Danish Minister of Migration, commented, “We want to be absolutely sure that those who receive Danish citizenship, with all the rights that come with it, are well integrated into our society and have fully accepted it.”41 A circular from June 2021 states that the government will consider applications for citizenship based on the origin of the applicants, which is categorized geographically into five categories: the Nordic countries, other Western countries, Middle East, North Africa, and Pakistan (MENAP) countries, and other non-Western countries.

Foreign workforce

In 2002, professional permits were introduced to make it easier for foreign skilled workers in high demand sectors to obtain a residence permit, which can be extended to three years42.

In 2006, a government bill was passed with the support of the Danish People’s Party to allow foreign skilled workers to obtain a residence permit if they are qualified for a job with an annual salary of about 60,000 euros, including in sectors where there is no labour shortage. The law institutes the creation of a green card and the implementation of a points system, so that particularly qualified foreigners can access a residence permit of up to 6 months, allowing them to find a job corresponding to their skills. In addition, foreigners with higher education degrees are given 6 months to find a job43.

A reform adopted in 2014 grants companies facilities to bring in skilled workers from outside the European Union and the European Economic Area (EEA) via accelerated procedures. Similarly, students and researchers benefit from better arrival conditions and welcome facilities. In addition, foreigners studying for a master’s degree or doctorate can obtain a residence permit upon graduation44.

Foreign worker recruitment was relaxed slightly in 2019. In 2020, two new schemes were implemented:

– one allowing foreign nationals who have been working in Denmark for 2 years to obtain an extension of their residence permit for up to 2 years if the application is motivated by family or humanitarian reasons. Thus, foreign nationals who have been working in Denmark for at least 2 years can obtain this new residence permit for a period of 2 years, if the reason for which they had been accepted on Danish territory is no longer valid. For example, if a national of a given country who has a residence permit has it withdrawn because his or her country is no longer considered dangerous, or in the case of a separation that occurred shortly after family reunification;

– the second mechanism defines a list of skilled professions suffering from a labor shortage for which foreigners who have been offered a job can apply for a residence permit (provided that the employer respects certain conditions for training apprentices).

In addition, the “Settlement Card” which offers a change of status for professional purposes for certain graduates has been expanded. Now, students or graduates with a student migration status can change their status from student to worker.45

Denmark has a work visa policy that combines employment criteria, taking into account the tensions in the relevant sectors of activity, as well as a salary level criterion, with the aim of prioritising highly qualified workers coming into the country. Thus, since 2021, the immigration services can decide to grant a work visa by conditioning it on the type of job and an annual salary of more than 60,000 euros. Denmark’s work visa policy is therefore particularly selective in terms of immigration, despite the labour shortage that Denmark regularly faces. In 2022, companies and trade unions complained that these constraints were too restrictive, especially in the context of labour shortages following the post-Covid recovery. In January 2022, the government proposed lowering the minimum salary requirement for hiring an employee from outside the European Union to 375,000 kroner (about 50,400 euros) for a period of two years.46

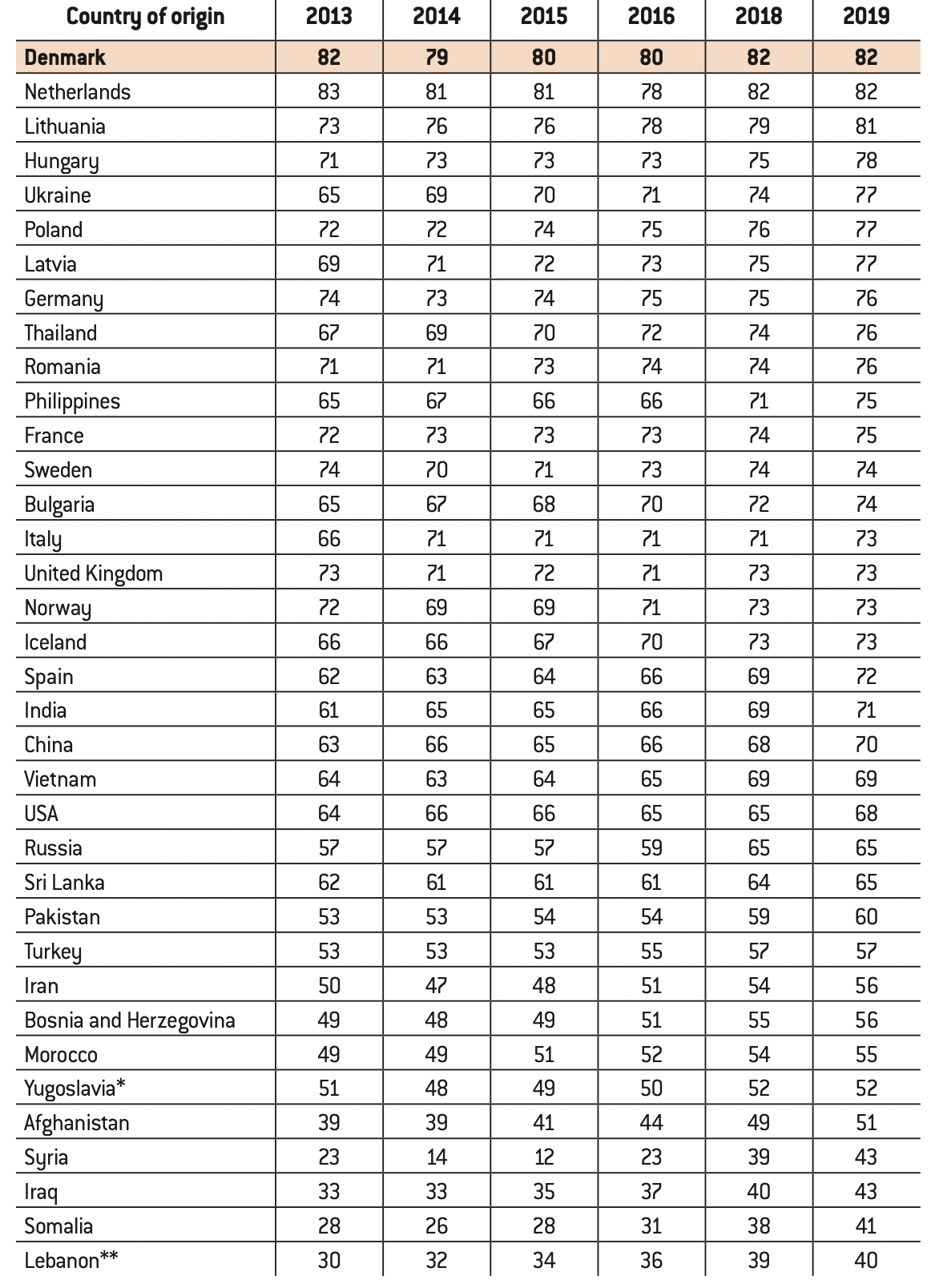

Employment rate of persons aged 30-64 in 2019 among the Danish population classified by country of origin (in %)

Source :

Denmark Statistics

Note: In 2013, the data provided do not refer to the 30-64 age group but to persons aged 30-59.

* Yugoslavia before its breakup.

** Some of the people from Lebanon are stateless Palestinians.

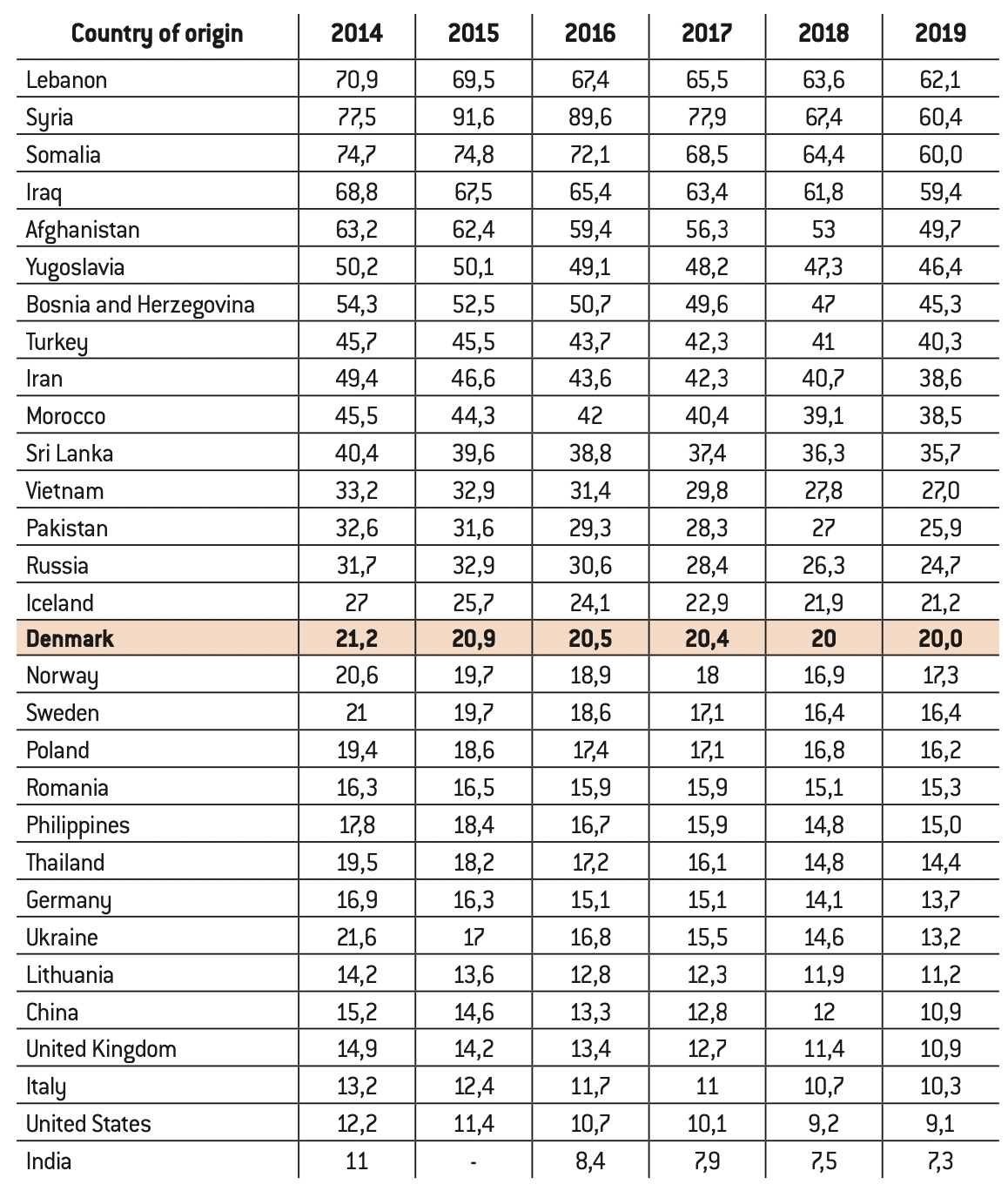

Share of the population aged 30-59 according to country of origin receiving full state social support among the Danish population (in %)

Source :

Denmark Statistics

See Silvia Adamo, ” The Legal Position of Migrants in Denmark: Assessing the Context around the “Cartoon Crisis”, European Journal of Migration and Law, vol. 9, n° 1, January 2007, p. 1-24.

OECD, 2007, op. cit. p. 260.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2011, Sopemi Edition, 2011, p. 300.

See Nils Holtug, “Danish Multiculturalism, Where Art Thou?”, in Raymond Taras (dir.), Challenging Multiculturalism. European models of diversity, Edimbourg, Edinburgh University Press, 2013, chap. 9, p. 190-215.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, 2018, p. 250.

See Silvia Adamo, “The Legal Position of Migrants…,” art. cit.

See Emily Cochran Bech, Karin Borevi, and Per Mouritsen, art. cit.

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid

Obtaining a permanent residence permit and expulsion policy

Since 2004, the management of visa rules has included an individual assessment to prevent an applicant from trying to stay in Denmark or to join a Schengen country after his or her visa has expired. If this criteria is not met, the visa is not granted. In addition, a waiting period (between 3 and 5 years) has been put in place to avoid abusive renewal of visas.47

The 2006 law also tightened access to the permanent residence permit by requiring applicants to pass an integration test and to prove 2.5 years of full-time employment.48 It should also be noted that in 2006 the requirements for obtaining a residence permit for religious representatives were tightened. The list of offenses committed by foreigners leading to their expulsion was also expanded.

The rules for obtaining a permanent residence permit were revised in 2010. A points system was created, which includes criteria such as language skills, integration into social life, employment and educational qualifications. These criteria can be modified to take into account the profile and status of the candidates (retired, youth…). It is required to have lived in the country for 4 years and not to have committed any serious offence on the national territory. However, a candidate who does not obtain the required number of points can request a temporary extension of his or her residence permit.49

When the left came back to power in 2011 (as part of a coalition involving the Social Democrats, the Social Liberal Party, the centre-left and the Socialist People’s Party), it abolished the Ministry of Refugees, Immigrants and Integration, which had been created ten years earlier in 2001 by the right. The competencies of this ministry were then divided between the Ministry of Social Affairs and Integration on the one hand, and the Ministry of Justice on the other. The change in the name of the ministry was intended to symbolize a political shift.

The permanent residence permit is issued on condition that four criteria are met:

– passing a language test;

– to be financially independent;

– to have resided in Denmark for five years (as opposed to four years previously);

– having worked in the same full-time job for 3 years.

The points system was abandoned in 2012, by the same left-wing coalition. But apart from a few discarded elements, the left has played on the continuity of previous policies, maintaining a so-called “pragmatic” approach, in order to mitigate the financial risk that immigration poses to the welfare state, the safeguarding of which ultimately appears to be the real priority.50

In 2015, the return of the right to power led to the re-establishment of the Ministry of Immigration and Integration. In 2016 and 2017, obtaining a permanent residence permit is made more difficult. A distinction is made between basic and additional conditions. If all conditions, basic and supplementary, are met, applicants can obtain a permanent residence permit after 4 years of residence in Denmark. If only the basic conditions are met, the residence permit is granted after 8 years.51

Family reunification

The conditions for family reunification change regularly. The main reforms are outlined here, in order to highlight the basic trend, marked by the desire to limit arranged or forced marriages, and to restrict the number of foreigners in Denmark in order to ensure proper integration of immigrants who are already here.52 The right-wing coalitions have gradually implemented numerous restrictions. Most of these restrictions have been maintained by the left-wing coalition from 2011-2015.53

In 2000, the Social Democratic government required that members of the couple applying for family reunification show at least as much connection to Denmark as to their country of origin. Spouses wishing to be joined by their partner are required to have a minimum size of accommodation.54 In 2004, the legislator also made it more difficult for children under the age of 15 with a parent living in another country to be reunited with their families, making admission conditional on integration potential. The left-wing coalition then extended this integration potential to children aged 8 or older.55 The condition of strong ties to Denmark was tightened in 2004. Thus, it became compulsory for both members of the couple to be at least 24 years old, unless one of the spouses has been a citizen for 28 years. In addition, the spouse receiving public assistance had to be able to provide a deposit of 50,000 kroner (about 6,700 euros) to be allowed to bring in his or her spouse in order to ensure that family reunification did not place an excessive burden on public expenditure.56 This amount increased to 100,000 kroner (about 12,400 euros) in 2010-11, at the end of the right-wing term, before the left-wing coalition reduced it back to 50,000 kroner (about 6,700 euros).

| The “24-års-reglen” (“24-year rule”)

The “24-års-reglen” (2004) is the name of a Danish law. It sets out a number of requirements for a married couple wishing to obtain a permanent residence permit in Denmark. Supported by all major political parties except Enhedslisten (Red-Green Alliance), the rule is intended to reduce both the number of forced marriages and family reunification immigration. The “24-års-reglen” requires compliance with four criteria: – age: spouses residing abroad can join their spouse in Denmark if both parties are at least 24 years old. Before the rule was introduced, one had to be at least 18 years old to apply for spousal reunification; – ties: the social ties between the couple in Denmark must be stronger than those with the country of origin; – means of support: the spouse residing in Denmark must prove that he or she is able to support the couple financially (the minimum income requirement is twice the social benefit rate). He/she must provide a deposit and must not have received any social benefits; – residence: the couple must prove that they own or rent a residence that can accommodate a maximum of two people per room and at least 20 m2 per person. The kitchen, lobby, laundry room and bathrooms are not included in this calculation. |

At the beginning of 2007, a simplified set of rules for family reunification was adopted: the precise definition of a level of income was abandoned in favour of a decisive criterion: only the ability to be self-sufficient is taken into account. In the same year, it was decided that the spouses of foreigners applying for family reunification would have to pass an immigration test, introduced in 2009, focusing on knowledge of Danish society and language.57

In January 2010, a further tightening of the policy was noteworthy: a spouse present in Denmark under family reunification cannot obtain a permanent residence permit if he or she has received government support during the three years preceding the application (previously one year). However, since March 2010, foreigners who come for family reunification do not need to have a permanent residence permit in order to receive support, but they do need to have had a residence permit for 5 years.58

With the return of a left-wing coalition to power in 2011, the admission criteria for family members were relaxed following a review of the requirement for spouses and partners to “demonstrate an attachment to Denmark. The legal residence time required to be exempted from this requirement is reduced from 28 to 26 years. Similarly, with regard to family reunification, the level of financial guarantees required for the arrival of a relative has been halved.59

In 2012, the point system for family reunification was also abolished. Now, foreigners applying for family reunification can obtain their residence permit if the spouse lives legally in Denmark, if the spouse and the applicant are at least 24 years old, and if the applicant passes a Danish language test no more than 6 months after obtaining the residence permit.

In 2018, a new political agreement was reached regarding family reunification, replacing the so-called attachment condition: sponsorship is required, the sponsor must speak Danish well, have 6 years of study in the country or have worked there for 5 years; the applicant must speak at least English or have some knowledge of Danish; he or she must also have completed one year of higher education (corresponding to Danish level) or have worked for 3 years during the last 5 years. At least four of these six conditions must be met.60

A drastic asylum policy

See Martin Bak Jørgensen, “Representations of the refugee crisis in Denmark: deterrence policies and refugee strategies“, in Dalia Abdelhady, Nina Gren et Martin Joormann (dir.), Refugees and the Violence of Welfare Bureaucracies in Northern Europe, Manchester University Press, 2020, p. 67-84.

Over the past 20 years, Denmark has sought to restrict asylum applications by increasing the conditions for obtaining a permanent residence permit, tightening the conditions for family reunification of refugees, and ultimately discouraging asylum seekers from coming to Denmark. The pace of restrictions has accelerated since the 2015 migration crisis in Europe. Since then, more than 100 restrictions have been introduced by the Ministry of Immigration and Integration. More than half of these restrictions concern refugees. The many changes in laws and procedures and the bureaucratization of the system can also discourage asylum seekers from applying.61 Here, we present the main reforms, including the process of outsourcing asylum applications.

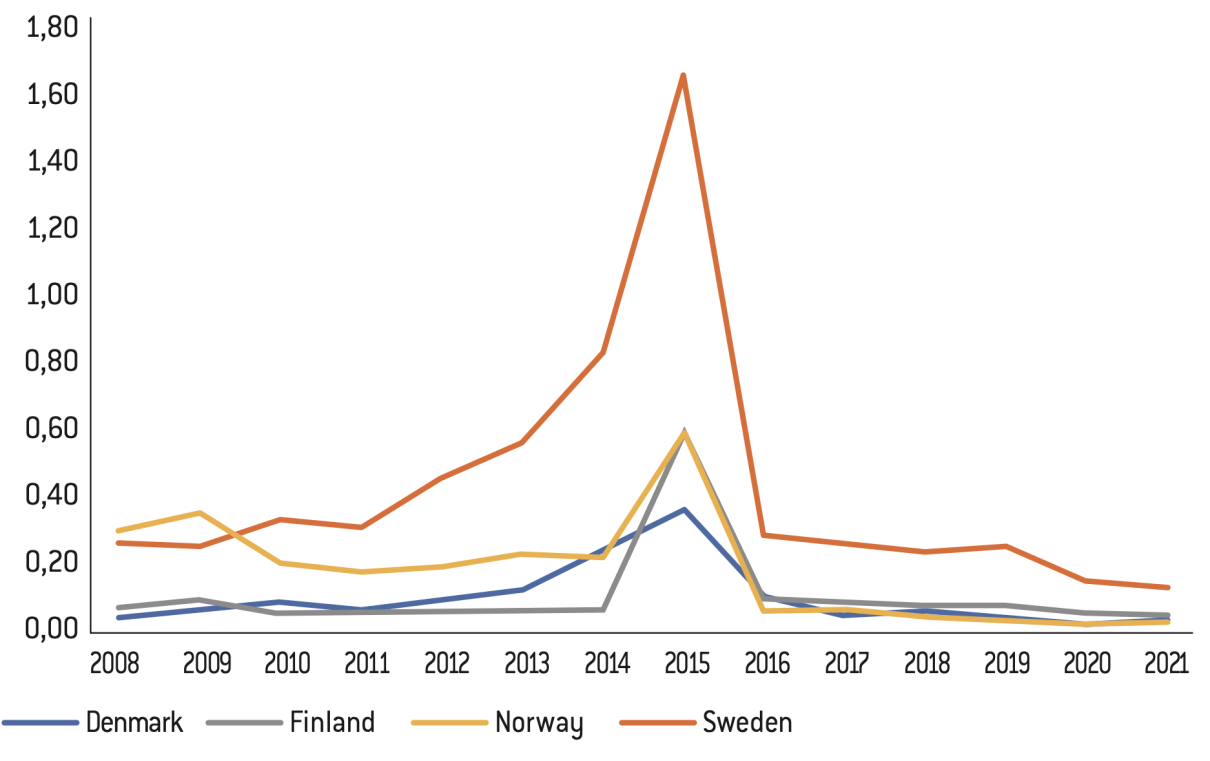

Number of asylum applications as a percentage of the total population (2008-2021, in %)

Source :

Eurostat

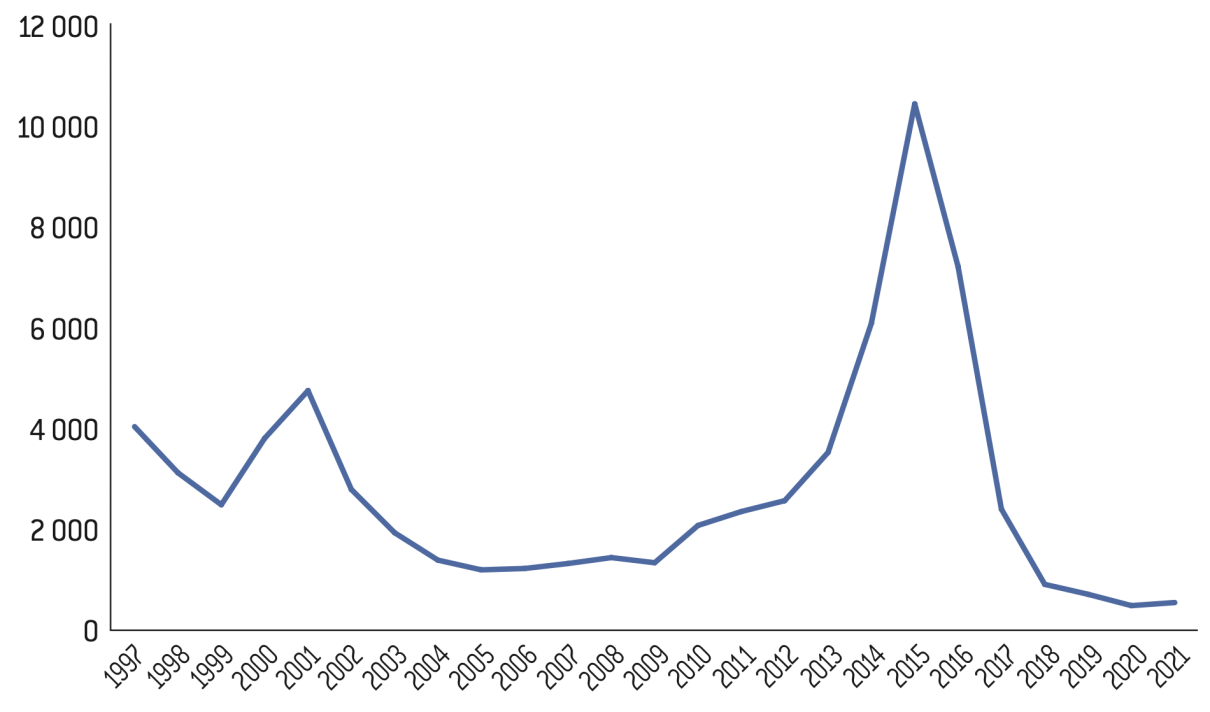

Denmark: residence permits granted under asylum (1997-2021)

OECD, 2003, op. cit. p. 198.

OECD, International Migration Trends 2004, Sopemi Edition, 2004, pp. 195-196

Ibid.

Refugees relocated to different countries under an agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2006, Sopemi Edition, 2006, p. 190.

See Constance Naud-Arcand, “The Divergence of Scandinavian National Policies on Irregular Migration: Comparisons and Explanatory Factors,” Dissertation in Political Science under the direction of Rex Brynen and Antonia Maioni, Montreal, McGill University, Department of Political Science, 2013.

OECD, 2011, op. cit, p. 300.

OECD, 2015, op. cit. p. 208.

OECD, International Migration Outlook 2016, OECD Publishing, 2016, p. 280.

Ibid.

See “Denmark’s asylum policies…,” art. cit.

Ibid.

See Martin Bak Jørgensen, art. cit.

Ibid.

Before 2002, it was possible to file asylum applications outside the Danish national territory. Since then, only applications filed within the national territory are examined.62 Similarly, since that date, persons whose asylum applications have been rejected must leave the country immediately, whereas they previously had 15 days to do so.63 The law states that to obtain permanent refugee status, it is now necessary to have resided in Denmark for seven years, as opposed to three years previously, and that only statutory refugees can obtain it, as opposed to those with “protection status”64.

As early as 2005, Denmark had introduced selection criteria for refugees with quotas65, based on their integration potential66. This approach reflects a desire to select prospective immigrants, including those who have been granted asylum.

In 2007, new measures concerning rejected asylum seekers who wish to return voluntarily were adopted: by committing to return to their country of origin, they can now benefit from six months of professional training in Denmark. Other incentives, in the form of constraints or threats, have also been introduced: the obligation to report daily to the police, transfer to a migrant detention center, the withdrawal of social benefits, the risk of imprisonment for one year67.

In 2010, the compensation for voluntary return of foreigners was increased from approximately 3,800 euros to 15,800 euros, in order to encourage foreigners present on Danish territory to return to their country of origin, especially those who represent a cost to the social system (pensioners and inactive people), or who are considered unsuitable for Danish society. The age for receiving the “reintegration allowance for the elderly” was lowered from 60 to 55, and the amount of the allowance was increased68.

Since 2012, refugees and asylum seekers have been able to reside outside refugee centers and have a job after 6 months in Denmark, and this is if they cooperate with the authorities in a satisfactory manner.

In 2014, the criteria for integration potential (based on skills and education) in the refugee screening process was removed by the left returning to power69. It was reintroduced in 2015 by the right70, accompanied by new restrictions:

– limiting the length of stay for refugees;

– easing the conditions for revoking their residence permits;

– reducing their economic benefits;

– deferring the right to family reunification for refugees with temporary protection71.

In 2015, at the height of the migrant crisis, the government purchased advertising space in Lebanese newspapers detailing new rules for refugees: a 50% reduction in social benefits for new refugees and a one-year delay in applying for family reunification.72 This policy was intended to discourage asylum seekers from applying to Denmark. It should be noted that the waiting time for a refugee to apply for family reunification increased from 1 year to 3 years in 2016. In 2021, this duration was considered a violation of human rights by the European Court of Human Rights. The duration was reduced to 2 years in 2022, but with the possibility of exceeding this period by one year in case of a “particularly high influx of refugees73.”

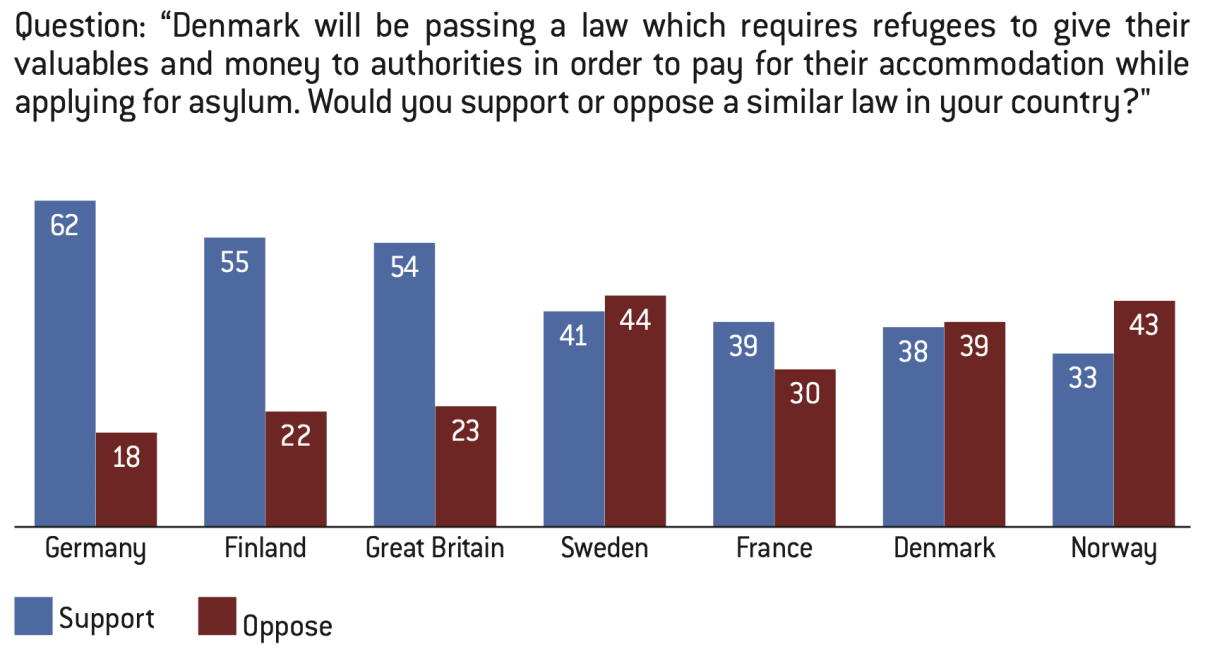

In 2016, the possibility of confiscating property belonging to asylum seekers was introduced to cover the costs of the procedure and accommodation. These new rules were highly publicized. This law, often referred to as the “Jewellery law”, transfers the financial responsibility for the arrival of their family under family reunification to the refugees, whereas the Danish state had previously been responsible for this. Although these measures sparked outrage in some parts of the public, they did not undermine Danish electoral support for a highly restrictive migration management policy.

In 2019, the right-wing has increased restrictions on access to permanent residency for refugees, as well as the possibility of family reunification.74 In addition, the integration benefit for refugees has been renamed the return benefit: the government is no longer focusing on the integration of refugees but on the preparation of their return, as the asylum should be temporary, until Denmark considers the country of origin safe again and the reason for asylum disappears. Refugees are seen as people who can be deported at any time and their integration possibilities are reduced accordingly. It should be noted that it is up to Denmark to define whether a country is safe or not and, ultimately, whether or not it is possible to return refugees to their country of origin.75

| The “Jewellery Law”: a brief review of a controversial law

The “Jewellery Act”, or “Jewellery Law”, was passed by the Danish Parliament on January 26, 2016. The bill had been introduced by the minority center-right government led by Lars Løkke Rasmussen. Among a set of measures actually intended to produce a deterrent effect, the text intends to drastically restrict the rights of asylum seekers. It includes the seizure of migrants’ valuables in order to contribute to the costs involved in the reception and processing of cases. The Danish authorities will have the power to search for and confiscate money, jewelry and other objects if their value exceeds 10,000 Danish kroner (about 1,340 euros) and if they have no sentimental significance (e.g. wedding rings). The bill was approved by 81 of the 109 MPs present out of the 179 members of the Folketing. Members of Social Democratic Party, whereas in the opposition voted to pass the measures. |

The Jewellery Law as perceived by the public

Source :

Outsourcing asylum management to a third country

See Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, Ahlam Chemlali, Zachary Whyte and Nikolas Feith Tan, Danish desires to export asylum responsibility to camps outside Europe. AMIS Seminar Report, University of Copenhagen- Saxo Institute-Centre for Advanced Migration Studies, Copenhagen, March 2021.

See “Les politiques d’asile du Danemark, entre fermeté et restrictions (2/2)“, interview with Romana Careja by Marie Robin, ThucyBlog n°. 166, afri-ct.org, October 28, 2021.

Ibid.

Ibid.

See “News comment by UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi on Denmark’s new law on the transfer of asylum-seekers to third countries“, unhcr.org, June 3, 2021.

The law on the outsourcing of visa processing was adopted on June 3, 2021, by a large majority of Danish MPs (70 votes against 24), under the social-democrat government of Mette Frederiksen. With this system, following a procedure to assess the transferability of applicants, Denmark seeks to direct them towards the third country where their application will be examined. Once their application has been registered, all asylum seekers in Denmark will be sent to a reception center in a host country outside the European Union76. If the migrant is not granted refugee status, he or she will have to leave the host country. Those who are granted asylum would still not be allowed to move to Denmark. On the contrary, they would be granted Danish refugee status on the condition that they remain in the host country, which would be responsible for managing visas77 and could transfer them to another host country. The plan is to have the host country handle all visa applications, with Danish funding. The choice of host country is under discussion with various countries, such as Egypt, Eritrea and Ethiopia, but the discussions with Rwanda seem to be the most advanced.

The Prime Minister’s stated objective is to deter asylum seekers from applying for refugee status in Denmark78. According to the government, this policy is based on humanitarian reasoning: it is about deterring people from coming to Denmark, by dissuading migrants from losing their money and risking their lives by using smugglers to try to reach the country via the Mediterranean.

This visa outsourcing policy has been criticized. It is accused of encouraging illegal immigration by discouraging those seeking to immigrate legally, at the risk of increasing the number of undocumented migrants and the dependence of migrants on smugglers. On another level, it is pointed out that outsourcing implies cooperation with military and security systems of third countries that may be authoritarian, or even responsible for repression and human rights violations, which could intensify violence, abuse and exactions against people in fragile situations such as refugees.79 Criticism is also voiced in terms of international law. The transfer of an asylum seeker from one state to another is not a violation of international law per se, as it is possible to share responsibility for the care of refugees between states. On the other hand, transferring an asylum seeker to a state that is not able to provide a full range of rights and protections to asylum seekers would be a serious problem.80 Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, expressed concern about the Danish policy of outsourcing visa management, to which he presented his objections.81 Beyond the humanitarian argument, there are risks of non-compliance with the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the European Convention on Human Rights. Denmark must thus guarantee respect for the principle of non-refoulement, and thus be able to prevent the transfer of persons with a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm. Denmark is called upon to ensure this, not only on its own soil but also within the center of the third country. Denmark is also asked to ensure that asylum seekers are provided with effective and reliable procedures, legal aid, and that they are properly informed about how the visa management system works, that asylum seekers can appeal the decision to an independent competent authority, and that they are not subject to arbitrary detention or other movement restriction measures.

It should be noted that in April 2022, the United Kingdom and Rwanda signed a memorandum of understanding providing for the establishment of an asylum partnership. Rwanda would undertake to receive asylum seekers from the UK, examine their applications, receive them and provide them with adequate protection if their applications are successful, or deport them if they are not.82

Danish immigration policy: popular ratification and democratic empowerment

The 2022 elections: Populists defeated and re-election of the Social Democrats

“Le Danemark veut transférer ses demandeurs d’asile dans d’autres pays“, Le Temps, June 3rd, 2021.

See Corinne Deloy, “Les élections en 2022”, in Dominique Reynié (ed.), L’Opinion européenne 2020-2022, Paris, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2022.

The group had given Mette Frederiksen an ultimatum to call a general election no later than the opening of the parliamentary session on October 4, 2022. The motion of no confidence was a consequence of the handling of the mink cull scandal. In November 2020, about 16 million minks were killed by government decision after the identification of a variant of the coronavirus in the country’s farms. However, it appears that in doing so, the government overstepped its authority in making the decision to cull mink as it had no legal basis to do so. On June 30, 2022, a commission of inquiry said that Mette Frederiksen had deliberately misled her fellow citizens but had been unaware that the mink cull was an illegal action. The Prime Minister emphasized the risk factor, arguing that she had a duty to protect the public.

Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has built her career on the left wing of the Social Democratic Party. She took over its leadership in June 2015. However, while she had fought against the proponents of a restrictive migration policy, she abruptly changed her position. According to her biographer Thomas Larsen, quoted by Le Temps, “her time at the Ministry of Labor, and then at Justice, opened her eyes to the flaws of Danish integration policy.” Thomas Larsen cites an internal strategy document of the Social Democrat Party. The paper, prepared in 2014 in the run-up to the arrival of Mette Frederiksen as party leader, argues that the Social Democrats’ hostility to restrictive immigration policies has driven concerned voters into the arms of the populist Danish People’s Party. The paper calls for winning back the electorate through a strong positioning on “politics based on values”.83 This is exactly what Mette Frederiksen did, both in 2019 and in 2022.

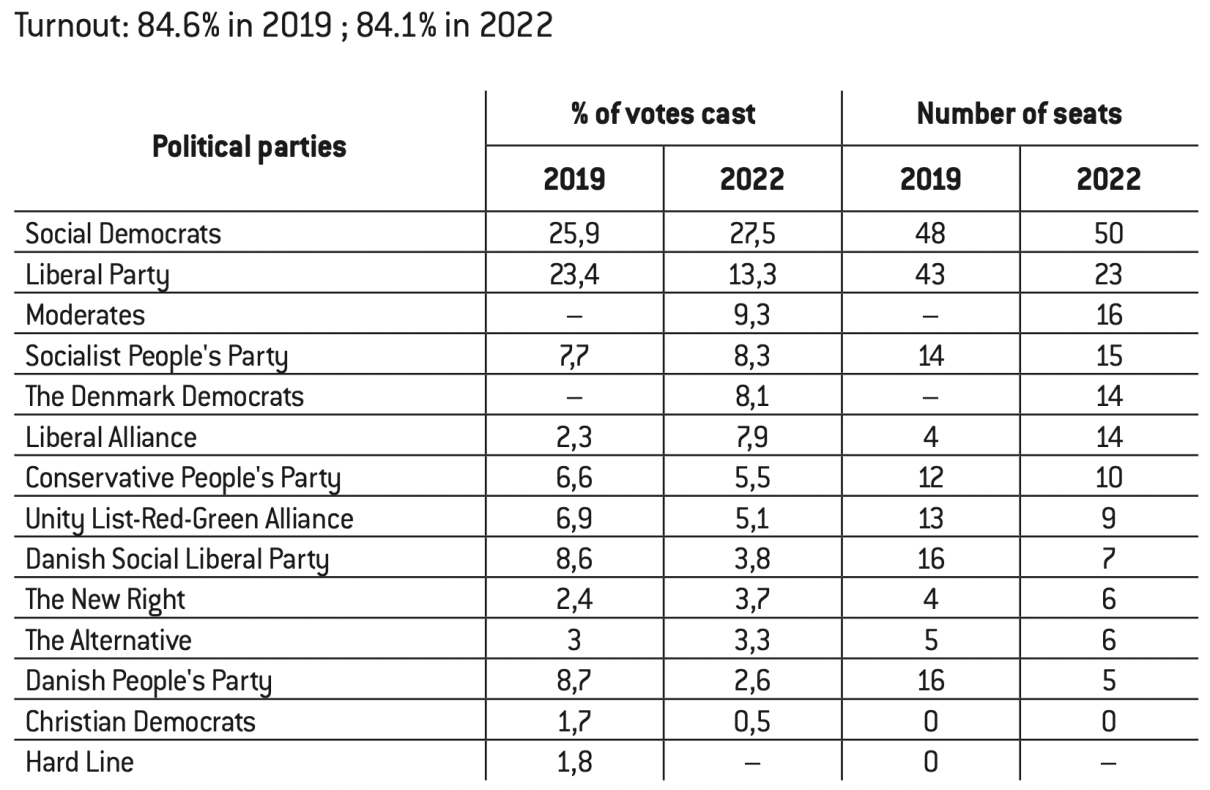

On November 1, 2022, the coalition of left-wing forces, called “Red Bloc”, came out on top in the Danish parliamentary elections84. The Social Democratic Party managed to stay in power, winning 27.5% of the vote and 50 of the 179 seats in the Folketing, two more than in 2019. The party remains by far the largest in the country.

Further to the left, the Socialist People’s Party won 8.2% of the vote and 15 seats (up 1). On the other hand, the Unity List – the Red–Greens Alliance won 5.1% of the vote and 9 seats, down 4 seats, while the green and pro- European Alternative won 3.3% of the vote and 6 seats. The centre-left Social Liberal Party was punished for being behind the collapse of the social democratic government, which led to early (seven-month) elections85. The Social Liberal Party won only 3.8% of the vote, dropping from 16 to 7 MPs, one of the lowest results in its history.

Together, these five left-wing parties won 48.1% of the vote and 87 seats. The left-wing forces also won the two seats in Greenland and one in the Faroe Islands, giving them a majority of 90 seats. The “Blue Bloc”, referring to the right-wing political forces, won 41.1% of the vote and 73 seats. The Liberal Party won 13.3% (23.4% in 2019), losing half of its MPs, from 43 to 23, its worst result since the 1988 parliamentary elections. The Liberal Alliance won 7.8% of the vote and 14 seats, an increase of 10 MPs from 2019; the conservative People’s Party won 5.5% of the vote and 10 seats (down from 12).

The Moderates, an independent formation that does not belong to either bloc, created by former Prime Minister (2015-2019) and Liberal Party leader Lars Løkke Rasmussen, entered parliament with 9.2% of the vote and 16 seats.

The most spectacular event was the further decline of the Danish People’s Party, led by Morten Messerschmidt. We should really call it a collapse as the Danish People’s Party obtained only 2.6% of the votes cast and 5 seats, compared with 16 in the previous parliamentary term, far from the 21.1% and 37 seats obtained in the 2015 elections. It recorded its worst result in twenty-four years since it entered the Folketing. However, it is worth noting the emergence of the Denmark Democrats, a new populist party reminiscent of the Sweden Democrats, founded by Inger Støjberg, the former minister of Immigration and Integration (2015-2019) and former member of the Liberal Party. With 8.1% of the vote and 14 MPs, the Danish Democrats are entering parliament. The New Right, the nationalist party, obtained 3.7% of the vote and 6 seats (compared to 2.4% cent and 4 seats in 2019).

Finally, it is worth noting that voter turnout in 2022 (84.1%) was close to that of 2019 (84.6%), thus remaining at a high level, even if it is the lowest since 1990.

During the campaign for the 2022 parliamentary elections, Mette Frederiksen expressed her desire for a broad coalition government. Its composition was announced on December 15, 2022. The new Frederiksen government includes ministers from the Social Democratic Party, the liberal Venstre party (center right/right) and the Moderates (centre/centre right). Together, these three parties have 89 MPs, one short of the Folketing’s majority of 179. However, four other parties, with a total of 10 MPs, have indicated that they will support the new government: the Union Party (centre-right), the Social Democratic Party of the Faroe Islands, Siumut (Greenland’s Social Democratic Party) and Inuit Ataqatigiit (Greenland’s Left Party).

The Danish parliamentary elections in 2019 and 2022

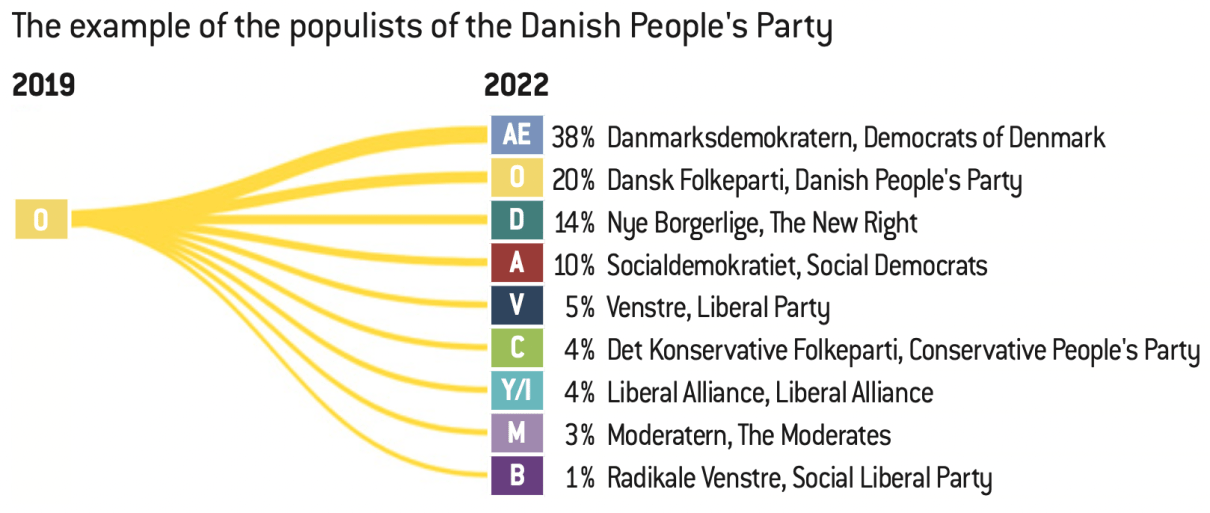

Electoral transfers between 2019 and 2022 (parliamentary elections)

Source :

Note: Opinion data for the 2022 parliamentary elections show that 10% of voters who voted for the Danish People’s Party in 2019 responded in the October 27, 2022 poll that they would vote for the Social Democrats on November 1, 2022. Here we see the value of Danish parties combining the defense of the welfare state with a restrictive and integrative migration policy.

In 2022, the Danish People’s Party retains only 20% of its 2019 voters. Its electorate has split between the Social Democratic Party and competing populist parties: 38% of the Danish People’s Party’s voters in 2019 say they will vote for the new Danish Democrats in 2022, and 14% for the New Right.

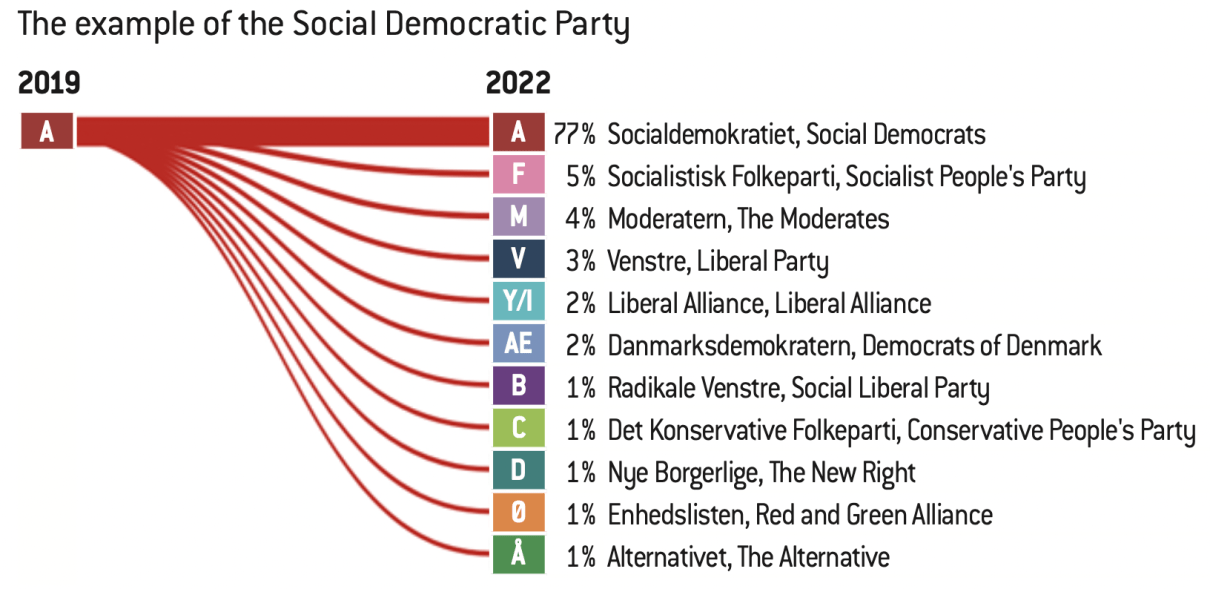

Electoral transfers between 2019 and 2022 (legislative elections)

Source :

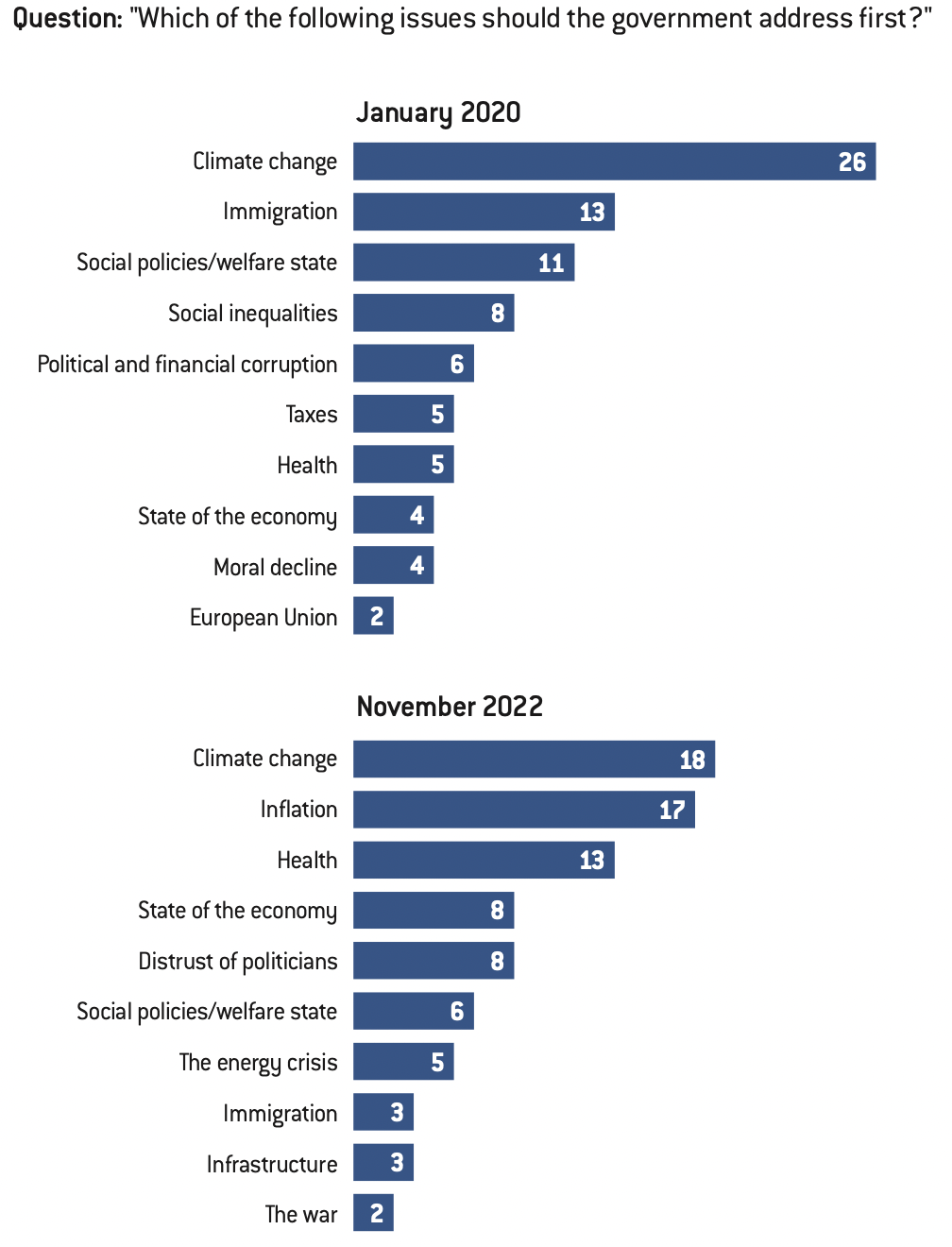

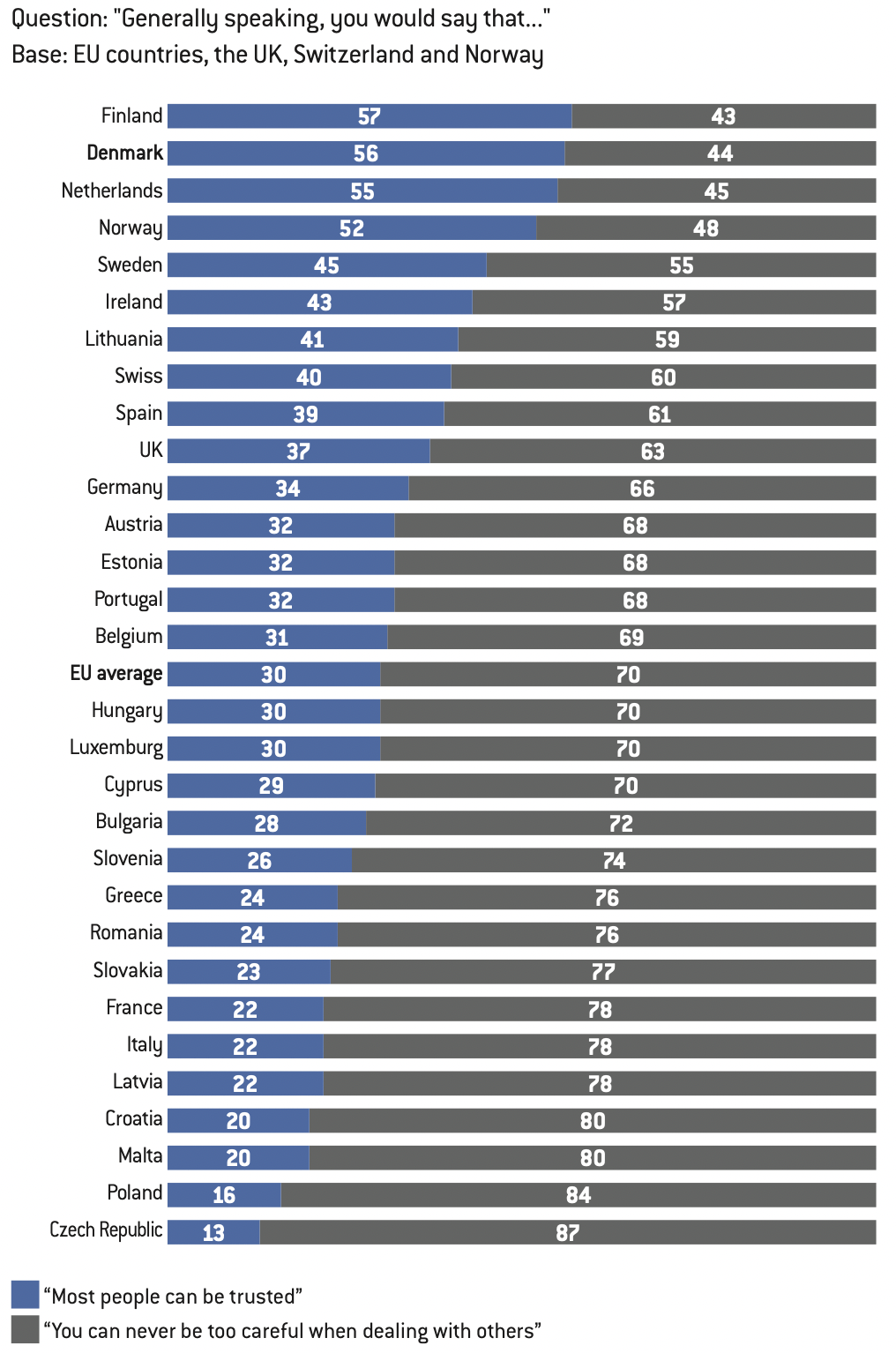

Note: Between the 2019 and 2022 elections, the Social Democrats retained most of their voters: 77% of Social Democratic voters in the 2019 election said in an October 27, 2022 poll that they intended to continue to vote for the Social Democratic Party in the November 1, 2022 election. Among voters who voted Social Democrat in 2019 but said they would vote for another party in 2022, 14% opted for a more right-wing party: 4% for the Moderates, 3% for the Liberal Party, 2% for the Denmark Democrats, 2% for the Liberal Alliance, 1% for the Social Liberal Party, 1% for the Conservative People’s Party and 1% for the New Right. These shifts to right-wing parties highlight the systemic electoral pressure on Danish politics in general and on the Social Democrats in particular. Clearly, the Social Democrats would run the risk of losing a significant proportion of their voters if their migration policy were deemed inadequate or ineffective. Only 7% of Social Democratic voters in 2019 said they would vote for more left-wing parties in 2022 (5% for the Socialist People’s Party, 1% for the Red-Green Alliance and 1% for the Alternative)*.