Digital Regulation: China, United States, France

Introduction

Three ways of regulating online content

In China: regulation focused on security

In France: regulation focused on citizens’ rights

In the United States: regulation focused on freedom

Convergence of content regulation methods

Digital platforms: the risks of poor regulation

Intervention by democratic countries in the regulation of online content

Antitrust regulation

Personal data protection

Conclusion

Summary

Aifang Ma analyzes how China, France and the United States have set up their regulatory frameworks for online content. The advent of the digital giants has created a latent but constant pressure to bring technological standards and business practices closer together, giving them unprecedented power and generating similar challenges for the three countries compared. They have set up regulatory frameworks to regulate content according to their own specific objectives. In China, for example, regulation is focused on national security and safeguarding the interests of the party-state. In France, the country of human rights, it is the citizen who must be lawfully protected. Finally, in the United States, freedom of expression takes priority.

Over time and through experience, it has become clear that China, France and the United States need to refine their regulatory methods without deviating from their fundamental objectives.

However, we have seen a convergence in their means of regulation, as digital platforms have acquired extortionate power. The censorship imposed by Facebook and Twitter on Donald Trump in 2021, or the monopolistic position of Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce platform, bear witness to this. France has long institutionalized its regulation with its National Commission for Information Technology and Civil Liberties (CNIL) and has been able to apply heavy sanctions through its more recent tool, the General Data Protection Regulation (RGPD), a reference text drawn up at European level.

In short, while authoritarian and democratic countries differed on the aims of regulating online content, it has to be said that digital giants, which in many cases have become more powerful than public authorities, have led national governments to mobilize similar means to control them.

Aifang Ma,

Doctoral student and lecturer at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics at Sciences Po, with a degree in French Language and Literature. Having simultaneously completed two Masters Degrees at Beijing Foreign Studies University and Sciences Po Paris in European Affairs, she worked successively at UNESCO in Paris and at the French Embassy in China in Beijing. She is the author of L’intelligence artificielle en Chine : un état des lieux, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2018.

Payments, money and finance in the digital era (1)

Payments, money and finance in the digital era (2)

Big tech dominance (1): the new financial tycoons

Big tech dominance (2) : a barrier to technological innovation ?

Digital sovereignty - steps towards a new system of internet governance

The blockchain, or distributed trust

Biotechnologies in China: a state of play

Tuer les lettrés et brûler les livres (Killing scholars and burning books), Chinese painting from the 18th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Jean-Pierre Cabestan and Laurence Daziano, Hong Kong: the second handover, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2020.

Min Jiang, “Internet companies in China: dancing between the party line and the bottom line”, Asie Vision, 47, Centre for Asian Studies at Institut français des relations internationales, 2012, pp. 1-50.

I’d like to start this note by sharing a personal experience with readers. Throughout my nine-day journey during a trip to China in October 2022, I witnessed a number of ways in which online content is regulated. Departing from Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris, I had access to Google, and was able to check my e-mails and watch an episode of a Korean soap opera on YouTube before boarding. When I arrived in Doha for a connecting flight, I checked my e-mails, using Google again. Then, when I arrived in Hong Kong, I was able to continue accessing Google, YouTube, WhatsApp and other applications I’d been using in France. In terms of access to information, there’s not much difference between Hong Kong and the Western world, even after the National Security Act1 came into force. In the evening, when I turned on the TV in a Hong Kong hotel, I was able to watch foreign channels such as BBC, TV 5 Monde and Arirang TV. However, the Cantonese and Mandarin channels, such as Phoenix TV and Shenzhen TV, only broadcast “positive” news about China.

After seven days of quarantine in Hong Kong, I left for Beijing. That evening, as I sat in my hotel, access to Google had become impossible: the page said “this site is inaccessible, www.google.com has taken too long to respond. Here’s some advice: check your connection; check your proxy and firewall. ERR_CONNECTION_TIMED_OUT”.

When I tried to access the official Cambridge University page, my screen displayed “404 Not Found”. The Financial Times application would not open, “unable to load”. Nevertheless, WhatsApp continued to work, although the response was not instantaneous. I drew two conclusions:

– the same country can regulate the Internet in different ways, as in mainland China and Hong Kong;

– not all authoritarian countries practice drastic censorship, as Qatar’s moderate censorship demonstrates.

It’s common knowledge that China has a more restrictive regulatory framework than Western countries, for both political and economic reasons. Politically speaking, a restrictive regulatory framework reflects the government’s need to maintain national security and prevent Internet users from making unfavorable socio-economic comparisons. Economically speaking, the fact that China has blocked access to the Chinese market for Silicon Valley giants contributes to the rapid expansion of Chinese companies, and indirectly, to the country’s international prestige2.

Nevertheless, to claim that China is more stringent than Western countries in terms of content regulation would be too simple, and would be based on two erroneous assumptions. Firstly, it assumes that content regulation methods in China and the West are necessarily different, and that there is no need to investigate further, for example, to find out to what extent the two worlds are similar. Identifying what they have in common is crucial, as it provides the basis for multilateral cooperation to tackle common challenges in regulating online content. Secondly, this comparison is based on the assumption that Western countries’ regulatory methods are homogeneous, whilst they do not necessarily use the same methods.

This note attempts to take a fresh look at content regulation in China and democratic countries in two ways. On the one hand, instead of considering China and the Western world as practicing diametrically opposed regulations, we will try to identify how these two universes converge in their priorities and their ways of regulating systemic digital firms. On the other hand, we will not consider democratic countries as a monolithic bloc when it comes to their content regulation strategies. On the contrary, we will try to establish a more nuanced picture and identify how democracies can differ from one another.

This note takes China, France and the United States as its objects of study, and conceptualizes their respective regulatory approaches in terms of security, citizens’ rights and freedom.

Three ways of regulating online content

When it comes to categorizing methods of regulating online content, it is first useful to look at the nature of a state’s political regime. For example, authoritarian countries such as China, Iran and Russia have created intranets within their borders. No democratic state has adopted this method. However, categorization based exclusively on a country’s political regime is not enough. Not only do countries with the same political regime not practice the same regulation, but it is quite possible to find countries with different political regimes but which practice similar regulation. For example, South Korea, despite its democracy, practices Internet censorship as extensively as Thailand. In 1995, it created the Information and Communication Ethics Commission. This is the first institution in the world to be responsible for Internet censorship. In addition, South Korea was the first country to require citizens to register on websites with their real personal information.

To better distinguish between the different forms of regulation, we propose adding a second criterion to that of political regime: the objectives behind regulation. Admittedly, states often have multiple regulatory targets, and it’s not always easy to distinguish which goals take priority over others. However, a closer look at the regulatory framework for online content, and a perspective on the institutionalization of regulation, can help identify what governments are particularly keen to achieve. Three methods of Internet content regulation, centered respectively on security, citizens’ rights and freedom, are analyzed in detail in this note. The conceptualization of these three models is based on the experiences of three representative countries: China, France and the United States.

In China: regulation focused on security

CAC, the Regulation of Internet Information Services, effective June 1, 2017, and the Regulation of Internet Information Services, effective June 1, 2020. These two regulations have the same name but differ in content.

Conseil d’État, Notice du Conseil d’État sur la délégation de la régulation de l’information et des contenus en ligne au CAC, August 26, 2014.

In China, ensuring regime security is the top priority for Internet content regulators. The importance of this priority is reflected in the subordination of economic and cultural objectives to that of regime security. For example, since March 2018, the Central Propaganda Department (CPD) has replaced the State Administration for Press, Publications, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT). The CPD oversees the Chinese film industry. Compared to its predecessor, the CPD places much greater emphasis on the ideological orientation of films. The fact that the regulators’ supreme objective is the regime’s survival comes as no surprise in an authoritarian context. A quick look at China’s regulatory framework shows the continuity of the priority given to national security.

China’s evolving content regulatory framework

The regulation of online content in China dates back to 1996, when the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) and the Ministry of Electronic Industry (MIE) issued ministerial regulations to clarify the conditions for connection to their Internet networks, ChinaNet and ChinaGBN. Politically sensitive content, and certain content that is not sensitive but morally offensive, is prohibited from circulating online. The Administrative Measures on International Internet Connection via ChinaGBN, issued on November 7, 1997 by the MIE, stipulate that it is forbidden for any organization or individual to use a computer to participate in criminal activities, including attacks against national interests and the disclosure of state secrets. It is forbidden to consult, duplicate and distribute pornographic content or content harmful to national security and social order. This passage is identical to the Article 10 of the Administrative Measures for International Internet Connection via ChinaNet, issued by the MPT on April 9, 1996.

Incessant disputes between MPT and MIE over their right to build and operate Internet networks in the 1990s finally exhausted the State Council. The latter decided to merge the two in 1998, creating the Ministry of Computer Industry (MII) and entrusting it with the portfolio of the Internet networks that the two ministries had been managing.

This institutional readjustment, coupled with the emergence of China’s first generation of Internet companies (most of them portal sites), shifted the regulatory framework for online content. The State Council Information Office (SCIO), set up in 1991 to direct overseas propaganda, has become the chief content regulator. This status was formalized by the ministerial regulation entitled Provisional Regulation of Internet Sites that Publish and Retweet News, issued by SCIO and MII on November 7, 2000.

On September 25, 2000, the State Council published the first text in China entirely devoted to the regulation of online content, the Regulation of Internet Information Services. This text contains a list of nine categories of content prohibited on the Internet. Despite the adjustments made to this list in subsequent years, it remains the main reference for regulators, who are constantly refining the regulatory framework. According to these regulations, content must not appear in cyberspace if it :

– opposes the fundamental principles of the Constitution;

– harms national security, divulges state secrets, endangers the government, disrupts national unity;

– harms national honor and interests;

– incites hatred and ethnic discrimination;

– disrupts national religious policy and promotes evil worship and feudal superstitions;

– spreads rumors, disrupts social order and stability;

– disseminates obscenity, indecency, gambling, violence, images of homicide and terror, or encourages crime;

– slanders or insults people, infringes people’s legal rights or interests;

– is prohibited by other laws and regulations.

On September 25, 2005, SCIO and MII published a new document expanding the list of 9 categories to 11, thereby broadening the list of undesirable content to include those inciting illegal gatherings, associations or demonstrations, and activities organized on behalf of illegal civil entities.

In addition to expanding this list to include a wider variety of content, Chinese regulators have refined the regulatory framework by factoring in other criteria. In 2013, following the detention of singer Wu Hongfei who had threatened on Chinese social network Weibo to bomb municipal authorities of housing and urban and rural development, the State Internet Information Office (SIIO) organized a forum on the social responsibility of celebrities on the Internet. Lu Wei, then Director of the SIIO and long known for his intransigence in regulating content, declared that celebrities should respect “seven basic guidelines”:

1) laws and regulations;

2) the socialist system;

3) national interests;

4) the legal rights and interests of citizens;

5) social order;

6) moral conduct;

7) the veracity of information.

Despite this clarification, the criteria for judging the legality of online content still remain unclear in China: the content regulations adopted to date have not clearly defined what they mean by “the fundamental principles of the Constitution”, “national interests”, or “national unity”.

This ambiguity continues in the Cybersecurity Act that came into force on June 1, 2017. Instead of listing unwanted content, Article 12(2) describes in very general terms the activities that individuals and organizations are prohibited from engaging in online. Its ambiguity may be justified by the fact that it covers more diverse areas than those covered by content regulation. Nevertheless, the fact that the regulations issued by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) in 2017 and 20203 have hardly clarified what is meant by unwanted content aptly illustrates a rather unclear situation on this subject in China. The last two regulations of 2017 and 2020 did not list which types of information are prohibited, but specified the qualifications and conditions that companies must meet in order to be able to disseminate content.

Online content regulatory agencies

We also need to put online content regulatory agencies into perspective. In 2000, SCIO was formalized as the regulatory agency for online content. Nevertheless, the creation of the Central Cybersecurity and Information Small Leading Group (CCI-SLG) on February 27, 2014, an inter-ministerial coordinating institution chaired by Xi Jinping, put an end to SCIO’s leadership. The CAC became the permanent office of the CCI-SLG and reported directly to the party leadership. In August 2014, the State Council proclaimed that the CAC would be the new chief regulator of online content4. Institutionally, the CAC has an advantage over the SCIO: as an agency under the direct responsibility of Xi Jinping, the CAC exercises its authority over both state and Party institutions, whereas the SCIO is placed under the responsibility of the State Council, and struggles to secure the cooperation of Party institutions. As a result, it is easier for the CAC to coordinate different ministries and enforce its decisions. From 2014 to 2022, the CAC operates as a sui generis regulator, evidencing that the Party has returned to the forefront of online content regulation.

Differential treatment of news providers

In China, news providers are treated differently according to multiple criteria, including their ownership structure and whether or not they are profit-making. In September 2000, the State Council introduced two systems: a licensing system for commercial content providers and a filing system (bei an zhi du) for non-profit providers. This framework evolved in November 2000. The two regulators, SCIO and MII, stipulated that non-news establishments are prohibited from broadcasting information they have gathered themselves. They must obtain authorization to broadcast news previously reported by the state media. In 2005, SCIO and MII refined this regulatory framework by specifying what they meant by “online news information units”, thus clarifying the conditions under which private media can cooperate with their state-run counterparts. For example, if state-owned media plan to cooperate with private media in activities other than offering news, SCIO must be informed 10 days before the cooperation begins. Media co-created by private and state media are considered private if the state holds less than 51% of the shares.

The most recent licensing rules were published by the CAC on May 2, 2017, and clarified several points by creating two categories of licenses – one for online news services and one for online newsgathering and reporting – and designating the institutions responsible for distributing licenses and the conditions for obtaining them. For example, private capital is not allowed to get involved in activities relating to political, economic or diplomatic newsgathering and reporting. Foreign investors are prohibited from setting up any online news organization, either alone or in collaboration with Chinese capital. The licensing system de facto deprives private companies of the possibility of broadcasting self-collected news.

These examples of regulation highlight the Chinese government’s priority: to safeguard the security of the regime against any risk of destabilization. State-owned media, under the direct supervision of public authorities, are generally trusted by the government. In the event of conflict, the security of the regime takes precedence over the individual freedom of Internet users and the commercial interests of companies, which is the case in the vast majority of authoritarian regimes.

In France: regulation focused on citizens’ rights

Antonio Gonzalez and Emmanuelle Jouve, “Minitel: histoire du réseau télématique français”, Flux, n° 47, 2002, pp. 84-89.

Content regulation in France is characterized by the central role played by the notion of law. Not only does the law protect freedom of expression on the Internet, it also protects citizens against online harassment, hate speech, pornography, gambling and so on. In other words, the French law represents both an assertive and a protective dimension. The dual dimension of the law greatly differentiates France from the United States, with the American framework clearly emphasizing the assertive dimension of the law.

The Internet appeared in France earlier than in China. As early as 1972, the National Center for Telecommunications Studies (CNET) developed the Cyclades network, the equivalent of the Arpanet network in the United States. It was abandoned by the French administration in favor of the Transpac network, which enabled the Minitel network in 19825.

Prior to the mid-1990s, the Internet was reserved almost exclusively for researchers and academics, with little access for the general public. In 1994, small ISPs such as Francenet, Calvanet and Worldnet began offering affordable subscriptions to households. In the mid-2000s, France experienced a real surge in terms of Internet expansion.

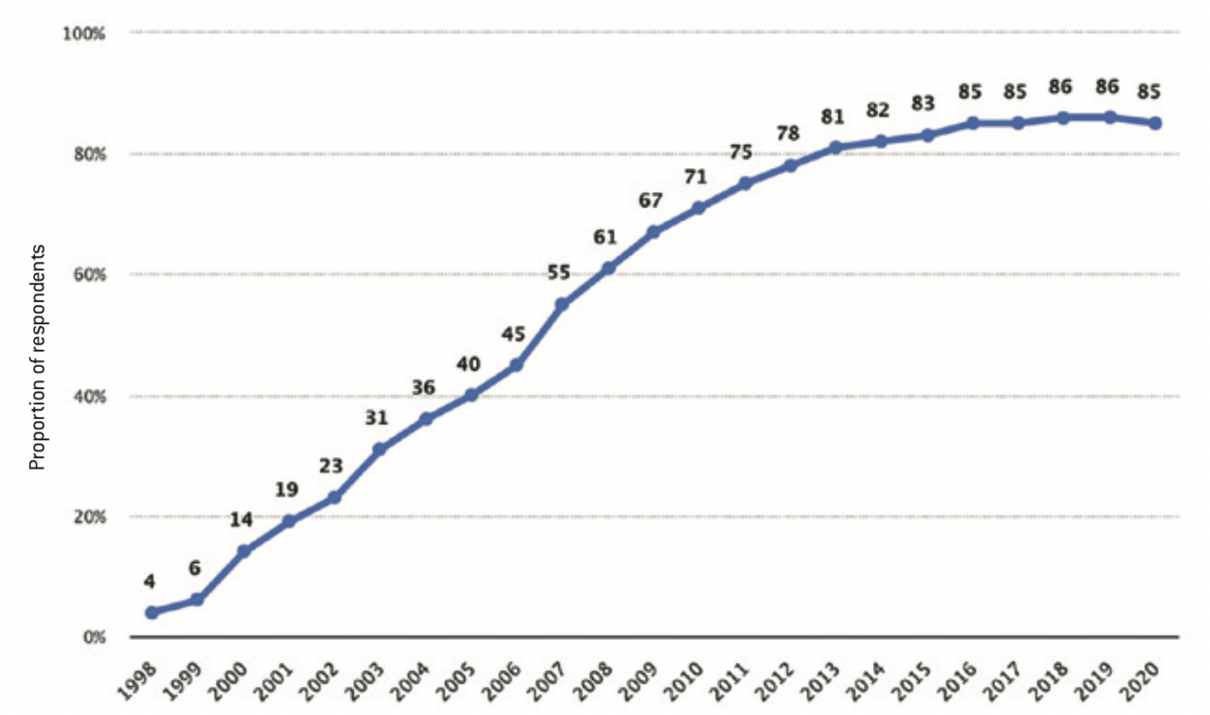

Internet access in France from 1998 to 2020

Source :

Statista.com

Jean-Christophe Féraud, “L’expansion d’Internet ou l’avènement du village global”, Les Échos, January 9, 1998.

Martine Esquirou, “Jospin dope son programme d’action gouvernemental en faveur d’Internet”, Les Échos, January 20, 1999.

“Données personnelles : Google condamné à 50 millions d’euros d’amende par la CNIL”, 20minutes.fr, January 21, 2019.

See legifrance.gouv.fr.

Raphaël Balenieri, “Haine en ligne : l’Assemblée nationale adopte la loi Avia, critiquée jusqu’à la fin”, Les Échos, May 13, 2020.

See Law no. 2004-575 of June 21, 2004 on confidence in the digital economy, art. 6-1: “Natural or legal persons who provide, even free of charge, for public access via online public communication services, the storage of signals, writings, images, or messages of any kind supplied by recipients of these services may not be held civilly liable for activities or information stored at the request of a recipient of these services if they were not actually aware of their manifestly illicit nature or of facts and circumstances revealing this nature, or if, as soon as they became aware of this, they acted promptly to remove the data or make access to it impossible”, and art. 6-2: “The preceding paragraph does not apply when the recipient of the service is acting under the authority or control of the person referred to in the said paragraph”.

See wikipedia.org: “Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal”.

As in China and the U.S., the rapid expansion of the Web in France was inextricably linked to the support of the French government. Confronted with the timid emergence of the Internet in France, Lionel Jospin, having just taken office at Matignon (French Prime Minister’s office), made the Internet one of his government’s top priorities. He proclaimed an ambitious action program in January 1998, entitled Programme d’action gouvernementale pour la société de l’information (PAGSI, Government Action Program for the Information Society), with the aim of “bridging the gap between France and the rest of the world in terms of information technologies”6. In January 1999, based on a highly satisfactory assessment of the PAGSI (70% of the 218 PAGSI measures had been implemented), Lionel Jospin adopted new measures to boost the Internet service in France, including the liberalization of 40-bit to 128-bit encryption to secure e-commerce, and the authorization for local authorities to build their own telecommunication infrastructures7.

The expansion of the Internet in France since the 2000s has been accompanied by the development of a legislative framework for the regulation of online content. It has to be said that France is deeply influenced by the regulatory approach of the European Union (EU), given the division of competencies between the national and European levels. The laws France has adopted, and the EU directives it has transposed, illustrate the central role of citizens’ rights. Their protection is achieved first and foremost by subjecting content providers – mainly embodied by digital companies – to a highly restrictive regulatory framework. This encourages companies to avoid harming the legitimate interests of citizens, notably by increasing the cost of transgression. This explains why, in France as in other EU member states, the regulatory regime is characterized by multiple constraints for companies and a high level of freedom for Internet users.

Deterrence is primarily financial. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force on May 25, 2018 in all EU member states, is a fundamental text on the protection of personal data. Complementing the French law of January 6, 1978 on information technology, files and freedoms, the GDPR has perfected the legal framework for protecting personal data. To ensure that digital businesses comply with the new rules, the GDPR has introduced exorbitant fines for transgressions: between 2% and 4% of the previous year’s worldwide annual sales, depending on the severity of the breach.

The high cost of violations is also reflected in the Digital Services Act and the Digital Market Act, two draft regulations that the European Commission adopted on December 15, 2020. Most (90%) EU platforms are small or medium-sized. These projects set up a system of asymmetrical obligations according to the size of the platforms: the highest cost of violation applies to “gatekeeper” platforms. “Gatekeepers” are defined as companies with sales of at least €7.5 billion over the previous three years, or with a market capitalization of at least €75 billion. They must also have 45 million monthly active users, 10,000 business users within the EU, and a central platform service in at least three member states. Failure to comply with the GDPR regulation will subject gatekeepers to a fine equivalent to 10% of their worldwide sales. Repeat offenders will face a 20% penalty. The European Commission can also impose merger bans or divestment requests on gatekeepers who fail to comply with the rules three or more times.

The centrality of Internet users’ rights in French regulations is also reflected in a number of measures enabling Internet users to hold platforms and regulators accountable in an effective way. In the event of conflict between Internet users, digital companies and the government, the French regulatory framework ensures that the government cannot afford to sacrifice the interests of Internet users by systematically invoking national security.

As a result, citizens have strong cards in hand to protect themselves against abuses inflicted by companies and regulators. In January 2019, for example, when civil organizations including None of Your Business (NOYB) and La Quadrature du Net appealed to the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL), it imposed a record fine of €50 million on Google. It criticized the company for failing to inform its users clearly enough about the use of their personal data. The CNIL thus became the first European regulator to sanction a digital giant by invoking the GDPR8.

The Avia Law9 adopted on May 13, 2020 by the National Assembly deepens citizen protection by introducing radical measures to combat hate speech. It requires major platforms, search engines, blogs and forums to remove any “manifestly illegal” hate content within twenty-four hours. Failure to comply with this provision exposes offenders to a fine of 4% of their worldwide sales. Platforms and search engines are also obliged to remove terrorist or child pornography content within one hour if notified by public authorities. The aim of these provisions is clearly to curb hate speech. However, the heavy financial penalties, the short deadline for taking corrective measures, and above all the absence of judicial intervention, are likely to force platforms and forums to remove any content reported, whether illicit or not, which therefore entails a risk of conflicting with freedom of expression. The controversy provoked by the Avia law did not die down after its adoption10.

In view of the risks that this legislation would pose to civil liberties, opposition senators referred the matter to the French Constitutional Council, which ruled against the core of the Avia law on June 18, 2020. Judging that this legislation takes measures that are disproportionate and unsuited to the aim pursued, the Council of Wise Men retested this text, emphasizing the need to protect citizens’ freedom of expression. Nevertheless, the new instrument of protection instituted by this legislation is the creation of an online hate observatory. Working in conjunction with platforms, search engines and civil associations, it will monitor and analyze trends in hateful content.

To improve legal certainty, French legislation and regulations on online content are often drafted in precise terms, to reduce regulators’ freedom of interpretation. Article 4 of the 1978 Data Protection Act, for example, thoroughly defined what personal data is. This definition takes into account multiple criteria such as transparency in data collection, the purpose of data collection, the preservation period, the possibility of rectification and consultation by the data subject, as well as cases of exception. This meticulousness is also reflected in the definition of platforms’ responsibilities. Paragraphs 2 and 3 of article 6 of the June 21, 2004 law on confidence in the digital economy stipulate in great detail the circumstances under which platforms are not responsible for the content they distribute11. This meticulous approach to content regulation in France helps to minimize abuses by digital companies and public bodies alike.

The central role played by rights protection in content regulation in France is inextricably linked to the country’s philosophical traditions. Home to the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, France is shaped by the role of a highly protective state. Accustomed to being protected by the State, the French people are inclined to constantly remind the State of this role, particularly during frequent demonstrations.

The contrast between citizens’ rights and the multiplication of restrictions on businesses and public institutions illustrates the centrality of citizen protection. This is what distinguishes France from China and the United States. In China, as we have seen, State interests are more important than those of citizens and companies. The U.S. government, for its part, is highly exposed to public scrutiny, and has limited leeway to assert objectives that diverge from those of citizens and companies. Nevertheless, it has to be said that American digital companies face fewer restrictions than in France. As the keyword for Internet regulation in the United States, “freedom” applies to both citizens and businesses. As a result, the American state intervenes little in the activities of digital giants, at least before the Cambridge Analytica12 scandal.

In the United States: regulation focused on freedom

See section 230 on wikipedia.org.

See The Bill of Rights, 1791: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, of the press, or of the citizens to peaceably assemble, or to petition the Government for redress for wrongs suffered”.

Kevin Breuninger and Dan Mangan, “Supreme Court rules for Pennsylvania cheerleader in school free speech case”, cnbc.com, June 23, 2021.

Kate Klonick, “The New Governors: the people, rules and processes governing online speech”, Harvard Law Review, vol. 131, 2017, p. 1598-1670.

Nancy Kim and D.A. Jeremy Telman, “Internet Giants as Quasi-Governmental Actors and the Limits of Contractual Consent “, Missouri Law Review, vol. 80, n°3, 2015, p. 723-770.

Companies and Internet users in the United States all benefit from a regulatory framework based on the principle of freedom. The Communications Decency Act (CDA), also known as Title V of the Telecommunications Act, was passed by the US Congress in 1996. Its initial aim was to restrict minors’ access to online pornography. Following strong protests from civil society, the U.S. Supreme Court abolished many of the CDA’s provisions. Nevertheless, section 23013 remained, and has subsequently become one of the most useful instruments for protecting online platforms. This section stipulates that neither providers nor users of computer-based interactive services should be treated as publishers of information. This principle is consolidated by two court decisions: Zeran v. American Online, Inc. in 1997 and Barnes v. Yahoo!, Inc. in 2009. Intermediaries are exempted from the responsibilities traditionally borne by publishers, even in circumstances where they publish, withdraw, delay or modify content. Internet users’ publications on YouTube, Amazon, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram as well as blogs or forums, for example, do not fall under the responsibility of the platforms. The CDA is probably the law that has contributed most to protecting freedom of expression in the United States. This high level of freedom has also facilitated the rapid expansion of Silicon Valley’s digital giants.

Freedom of expression is an integral part of the American national identity. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is the fundamental piece of legislation protecting this freedom. Incorporated into the Bill of Rights in 1791, this amendment was designed to protect individuals’ freedom of religion and free speech from government and congressional interference. The amendment prohibits Congress from establishing a national religion, and from interfering with freedom of speech and of the press14. Within this framework, it is up to the government to provide considerable justification if it interferes with citizens’ speech. However, some speech is not covered by the First Amendment, such as incitement to unlawful conduct (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969), belligerent language (Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 1942), commercial communications (Central Hudson v. Public Service Commission, 1980), and obscenity (United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses, 1933). The scope of unprotected content has been clarified by American jurisprudence, which contrasts with the ambiguity of content regulation in authoritarian countries. As mentioned earlier, the more precise the definition, the less latitude regulators have to interpret the legality of what citizens say.

In the 1990s-2000s, before the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed in 2015, lobbying by companies and civil associations for freedom of expression online was so strong that content was barely regulated. The Declaration of Independence for Cyberspace of February 8, 1996, made public by John Perry Barlow, Internet pioneer and co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), reflects American society’s disapproval of government regulation. In this liberal-minded text, Barlow expresses a rare hostility to the Telecom Reform Act, passed by the U.S. Senate in 1996, believing that those who passed the law were mistaken, failing to understand the difference between cyberspace and the real world: “this law was implemented against us by people who haven’t the slightest idea who we are, or where our conversation is being conducted. It’s […] as if illiterate people could tell you what to read”. In his view, the virtual world could very well regulate itself without government intervention.

The efforts of civil society to create a free cyberspace are encouraged by American jurisprudence. In several major rulings on the regulation of online content, American courts have ruled in favor of Internet users’ freedom of expression. Brandi Levy was a cheerleader at Mahanoy Area High School in Pennsylvania. After being kicked off her school’s team, she posted on Snapchat “Fuck school, fuck cheerleading, fuck softball, fuck everything!”. These words, along with the middle finger displayed in her post, earned her a one-year suspension from participating on any other team. Brandi’s case was taken up by the powerful American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), an influential association created after the First World War, which aims to defend Americans’ freedoms conferred by the Constitution. On June 23, 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brandi’s favor, holding that the high school was not authorized to regulate high school students’ off-campus speech. The Court made clear that, as nurseries of democracy, schools have an interest in protecting unpopular speech15.

In another colorful case, Elonis v. United States in 2015, the Supreme Court reversed the judgment handed down by the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. After being fired by his employer and leaving his ex-wife and children, Anthony Elonis published posts on Facebook against his ex-wife, former colleagues, an FBI agent, and a kindergarten. Although Elonis insisted that the content in question was a form of artistic expression and had a therapeutic function, for the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, it was sufficient that the people targeted by these messages considered them a threat for Elonis to be convicted. This reasoning was challenged by the Supreme Court, which held that the victims’ opinion was not sufficient: it was necessary to judge whether the author intended to threaten people, or whether he was conscious that his words would be taken as a threat.

Nevertheless, there are restrictions on freedom of expression. Nevertheless, these restrictions are meticulously detailed, scrupulously reviewed, and continually redefined through bitter negotiations between public authorities and civil society. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District in 1969, the Supreme Court ruled that schools could regulate students’ speech. School officials wishing to do so must demonstrate that the students’ remarks could cause real and substantial disruption to the school’s functioning or harm the interests of others. If facts on the ground support this hypothesis of disruption, schools are authorized to restrict freedom of expression. However, this case law was re-examined in the aforementioned Brandi Levy case, and the Supreme Court ruled that educational institutions must be cautious in censoring students’ off-campus speech.

While the US content regulation framework provides a high level of freedom, it nevertheless generates an unbalanced situation between companies and Internet users, often resulting in the latter’s failure to assert their rights. Because of their immunity, companies frequently expose Internet users to illegal content. In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff confirms the abusive practices of capitalists embodied by Google and Facebook. In her opinion, the platforms deliberately leave illicit content online (e.g. hate speech or pornography) in order to increase Internet traffic, collect more data on consumers, and train their algorithms with a larger amount of data.

The immunity of digital giants is reflected in their power to decide what content can or cannot remain visible online. A telling example is the censorship of Donald Trump by US platforms in January 2021, following the attack on Capitol Hill organized online by supporters of the former US president. His account was suspended by Facebook and Twitter. While it’s true that Trump incites violence and hatred through his online publications, the fact that companies decided to censor such an important public figure without seeking a judge’s opinion has generated significant controversy.

As private companies, they behave like “new governors”16 or “quasi-governmental actors” without being democratically appointed17.

An analysis of the content regulation frameworks in China, France and the United States therefore calls into question the prevailing view that the nature of a political regime is an almost exclusive criterion for explaining differences in content regulation. A closer look at the regulatory priorities in these three countries illustrates just how inadequate this criterion is.

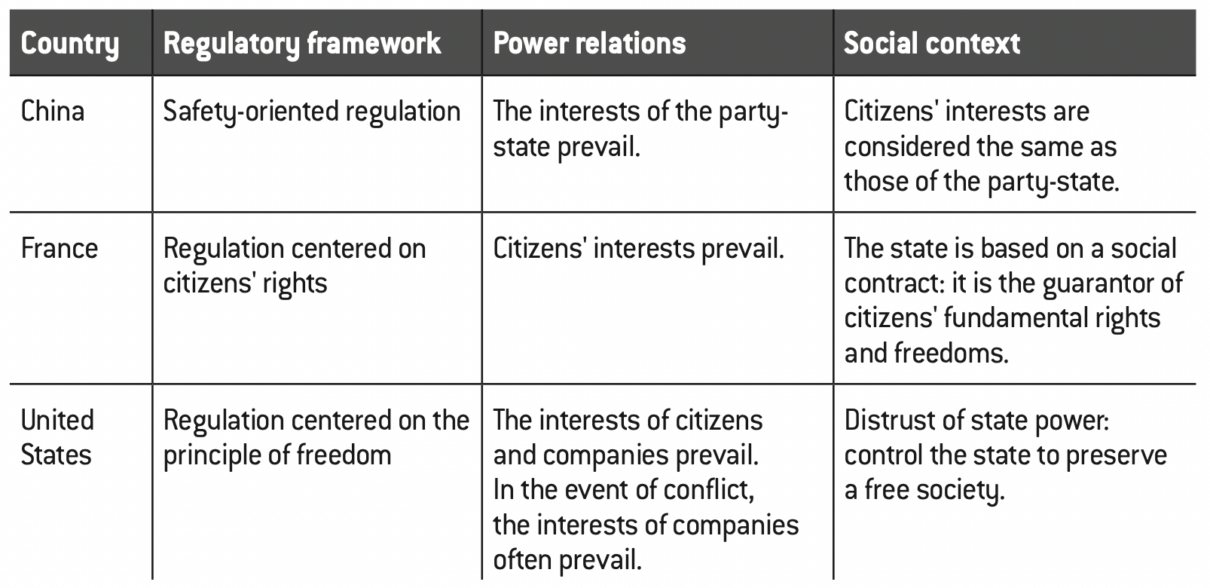

Summary of three modes of online content regulation

Convergence of content regulation methods

Qian Liang, “欧盟数据保护标准在全球的扩散” (The global dissemination of EU data protection criteria), “安全内参” (Internal references on security), secrss.com, February 24, 2022.

While authoritarian and democratic countries used to differ in terms of the aims of online content regulation, the situation changed with the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections via social networking manipulations attracted intense public attention in the U.S. and elsewhere. The fact that private interests – from Facebook and Cambridge Analytica in this case – were able to influence election results illustrates how the freedom and immunity granted to platforms can backfire on democracy itself. The scandal has given rise to an excess of regulation in Western countries, legislating, one after the other, to determine more clearly the limits of corporate activities. In this sense, Cambridge Analytica has brought content regulation in democratic countries closer to that of authoritarian ones, in that this event has put the United States and other countries under unprecedented pressure to impose constraints on platforms. It reveals that, contrary to what they proclaim in public, platforms undermine citizens’ freedom by surreptitiously guiding their electoral choices. The immunity of platforms in democracies is more than ever called into question by citizens.

In return, democratic countries’ attachment to data protection has influenced the agenda of regulators in authoritarian countries. Since the proclamation of the GDPR by the European Union on April 27, 2016, fourteen other non-EU countries have already adopted a similar level of protection before 202218. In China, the Personal Information Protection Law, adopted on August 20, 2021, is inspired by the structure and provisions of the GDPR. For example, the definition of personal data in the GDPR and its Chinese equivalent are very similar: it refers to data that can identify a person directly (surname, first name, age, etc.) or indirectly (cookies, IP address, etc.). Similarly, they do not cover information concerning legal entities or anonymous data.

Economic globalization goes hand in hand with the globalization of ideas and practices. The globalized operations of digital companies convey a latent but constant pressure to bring technological standards and business practices closer together. The converging trends in content regulation between China, France and the United States have four dimensions:

– national governments’ growing awareness of the exorbitant power of platforms;

– the growing importance of online content regulation;

– antitrust regulation of digital tycoons;

– the increasing attention paid by regulators to the protection of personal data.

Digital platforms: the risks of poor regulation

David Curry, “Apple Statistics (2022)”, businessofapps.com, October 28, 2022.

When it comes to the dangers posed by platforms, grievances of democratic countries are not so different from those of authoritarian ones. Internet companies are driven by commercial, not social logic. The imperative of making profits for shareholders and investors forces every company to set aside any consideration other than the commercial value of its activities. Nevertheless, the capitalist logic of profit-seeking is not a problem in itself. Rather, it is the absence of appropriate regulation that makes this frantic pursuit of profit problematic. An unregulated or ill-regulated company may well relocate its production sites (offshoring of content moderation by Twitter, Facebook, etc. ), exploit its employees (scandal with the “996” schedule – working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week – proposed by Jack Ma, the former boss of Alibaba), lower environmental protection standards (the delivery of meals ordered online increases pollution), collect user data with complete impunity (something platforms have been doing since the 2000s), spread fake or sensational news to boost online traffic (some Chinese portal sites are adopting this practice to attract a wider audience).

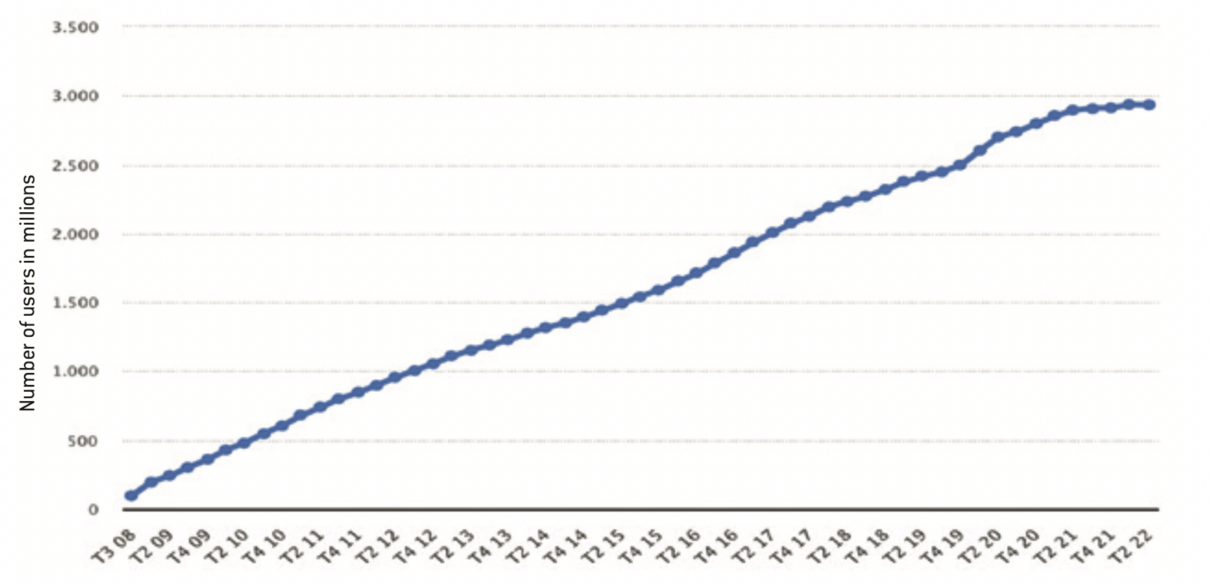

The power struggle between national governments and digital companies is far from reassuring at present, as the latter are in many cases proving to be more powerful than public authorities. At the end of 2021, Apple had 1.23 billion active users19. In February 2022, Facebook hosted 2.929 billion monthly active users.

Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide from Q3 2008 to Q2 2022

Source :

Statista.com

Pepper D. Culpepper and Kathleen Thelen, “Are we all Amazon primed? Consumers and the politics of platform power”, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 53, n° 2, 2020, p. 288-318.

Janet Burns, “Facebook and Google are under fire for shady data. Why not Uber?”, Forbes.com, April 18, 2018.

Kathleen Thelen, ” Regulating Uber : the politics of the platform economy in Europe and the United States “, Perspectives politiques, n° 16, 2018, p. 938-953.

Ivana Kottasova, “Now Europe loves Uber and Airbnb”, CNN, June 2, 2016.

Pepper D. Culpepper and Kathleen Thelen, “Are we all Amazon primed? Consumers and the politics of platform power”, Comparative Political Studies, vol. 53, no. 2, 2020, pp. 288-318.

Ibid.

Aifang Ma, Double Bind Regulation of the Internet and Social Media in Contemporary China, PhD thesis defended at Sciences Po Paris in June 2022.

Ivana Kottasova, “Now Europe loves Uber and Airbnb”, CNN, June 2, 2016.

Aifang Ma, L’intelligence artificielle en Chine : un état des lieux, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2018.

Aifang Ma, Biotechnologies in China : a state of play, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2020.

In e-commerce, the acronym B2B refers to all commercial relations between companies (“business to business”).

In e-commerce, C2C refers to commercial relations between private individuals (“consumer to consumer”).

Facebook could thus be the world’s most populated “country” by far, overtaking India and China, with Apple in 4th place. With their extensive user bases, digital companies are well placed to stand up to national governments. Knowing they have consumers on their side, they can successfully thwart legislation sought by public authorities.

Culpepper and Thelen have demonstrated how the alliance between platforms and Internet users has become a new form of power20. The example of Uber is revealing. In the United States, Uber was able to mobilize the support of its users by launching campaigns on social media platforms. In 2017, the company included the following sentence in its terms of use “Uber may use information collected to inform you about elections, referendums and other political processes related to our services”21. At a time when unfavorable regulations are likely to be introduced, Uber has often responded by adding a new service to its app through which users can submit their disapproval which is then addressed to mayors, and is much easier than writing a petition letter or organizing a street demonstration22. While recognizing that digital businesses can fail if Internet users focus more on their identity as citizens than as consumers, both researchers confirm how powerless national governments are when faced with this alliance between businesses and Internet users. This union puts public institutions at a disadvantage, because by regulating digital companies, they render themselves unpopular with voters.

The power of American platforms is also being felt in Europe. In 2016, having failed to convince the municipal governments of Barcelona and Berlin to authorize their accommodation rental services, Airbnb shifted its power struggle to the European level. With Europe as a whole having a far greater number of users than Barcelona or Berlin, Airbnb’s lobbying of the European Commission proved more successful. In June 2016, the European Commission published new rules, asking not to ban companies like Airbnb, which contributed €28 billion to the European economy in 201523. Platforms were given permission not to share their data with local governments, and it was now up to the European Commission to approve limits decided by local governments on the amount of accommodation rented under the sharing economy24. The reason why Airbnb’s demands were perceived as legitimate was that the company presented itself as the defender of consumer interests25.

The fact that digital companies are economically powerful is not a danger in itself. However, as Polanyi explained so well in The Great Transformation, economic factors must always be subordinate to the social ones, and not the other way round. Yet the acquisition of such influence by platforms means that they can prevent public authorities from protecting citizens against the potential dangers resulting from the frantic pursuit of private interests, and even discredit the “protector” role of public authorities. In the name of defending freedom of expression, platforms sometimes ignore hateful or violent comments online. In the name of entrepreneurial freedom, the richest platforms buy up small, innovative companies to create market over-concentration, reducing consumer choice. To be able to offer personalized services, companies are not shy about collecting massive amounts of data to draw up accurate user profiles. In short, today’s platforms operate on a model in which social welfare is sacrificed in favor of economic benefits.

The negative effects of the digital economy are not limited to democratic countries. The Chinese government is renowned for its strong state capacity to keep digital companies under control and resist their lobbying. However, it also faces numerous internal and external constraints, which limit its freedom of action26. The trajectory of China’s economic take-off roughly parallels that of the Internet’s development in China, and the digital economy has proven over time to be a key pillar in the upgrading of a country’s economic growth. Against this backdrop, the national digital champions grouped under the acronym BATHXJ27 have made themselves indispensable, both to public institutions and to Internet users. The dependence of national and local governments on certain digital companies is clear. At national level, they play a crucial role in driving innovation in cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence28 and biotechnology29. At the local level, they are an inescapable source of tax revenue. In 2018, the last year Alibaba made public its tax payments in Hangzhou, the company’s headquarters, the latter paid 51.6 billion yuan (around €7.37 billion), or 140 million yuan (around €20 million) a day. The Chinese government’s dependence on digital companies is very real.

Chinese citizens are also dependent on these national giants, and can sometimes support them, making Chinese digital companies a force to be reckoned with in the design of new regulations. For example, during the drafting of China’s e-commerce law in 2018, Alibaba – then China’s largest e-commerce platform – managed to insert a provision in its favor, much to the dismay of its B2B30 competitors like JD.com. Drafted in rather ambiguous terms, this provision consists of allowing merchants engaged in “sporadic low-value transactions” on C2C31 platforms to avoid having to register with market regulation agencies. This means that these merchants don’t have to pay taxes for sales made online, which helps Alibaba retain its merchants, gain popularity, and earn commission fees. B2B platforms are at a disadvantage in this process, as their merchants are obliged to register with market regulation agencies.

In both democratic and authoritarian countries, the economic power of online platforms is transformed into political influence. Citizens form a group whose trust companies and states compete for. In this competition for audiences, the party that succeeds in making itself the most indispensable will gain an advantage over its opponent, hence the need to regulate the activities of digital companies before it’s too late.

Intervention by democratic countries in the regulation of online content

Kate Klonick, “The New Governors: the people, rules and processes governing online speech”, Harvard Law Review, vol. 131, 2017, p. 1598-1670, and Shoshana Zuboff, “Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power”, Public Affairs, 2019.

Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act/Stop Enabling Sex Traffikers Act.

Pepper D. Culpepper and Kathleen Thelen, 2020, op cit.

“Hundreds across US protest Facebook allowing hate speech in India”, americanbazaaronline.com, November 15, 2021.

Rishi Iyengar, “What we know about the Facebook whistleblower”, CNN Business, 5 octobre 2021.

Content regulation in China began almost as soon as the Internet became available. On April 20, 1994, China joined the World Wide Web. With the installation of the first Internet server the following month, Internet connection between China and the rest of the world became a reality. Less than two years later, on February 1,1996, the State Council had already issued a provisional regulation on the international connection, prohibiting those connecting to the Internet from disseminating pornography or information that could disrupt to public order. In subsequent years, the Chinese government has continually refined the regulatory framework for online content, specifying, among other issues, the responsibilities of the relevant regulatory agencies, the categories of undesirable content, the obligations of platforms, as well as the qualifications that companies must obtain (such as the composition of editorial teams, licenses, etc.) in order to operate as content providers.

Unlike China, Western countries have been slow to regulate online content. These two opposing approaches stem from two different power relationships related to the Internet: while the Chinese government can comfortably assert its perception of the Internet as an extension of state power, the West tends to treat the Internet as an extension of the autonomous sphere of civil society. Since the fate of political parties in multi-party countries is largely determined by the electorate, the latter is able to assert their vision of things. Since public opinion on the Internet in France and the United States has long been characterized by its commitment to freedom of expression as an absolute right, this explains the many hesitations of Western regulators to intervene in online content. This situation has changed considerably, with the freedom and immunity of platforms increasingly being called into question. This change is linked to the change in public perception of the Internet. Public debates in vogue in the West emphasize the fact that platforms play the role of content publishers, and not mere “carriers”32 (“transporters” of content). Scandals such as Cambridge Analytica and Donald Trump’s censorship have shifted the position of voters: initially fervent supporters of online freedom of expression, they have become increasingly aware of how poorly or unregulated online content can impact the quality of public debate and democracy.

So it’s no surprise that content regulation has become increasingly important in the West in recent years. After China, France and the United States have begun to regulate the publication and accessibility of online content. Similarly, the immunity of digital platforms with regard to the content they distribute has been gradually reduced.

The increase in restrictions on both Internet users and companies in the West represents a kind of convergence in content regulation methods between democratic and authoritarian countries. This trend is evident in France, with the increased regulation of online speech and the accountability of platforms. The preceding analysis of French and European legislation embodied by the GDPR and the Avia law clearly illustrates the desire of French regulators to delimit the parameters of companies’ zone of freedom. What’s more, they are being asked to cooperate with the authorities by providing the information of guilty users, another point in common between China and France.

Even in the United States, where freedom is placed high on the altar of republican values, lawmakers have legislated to regulate the activities of digital giants. In 2018, the US Congress passed FOSTA33, which institutes a new federal crime related to sex trafficking. It represents an important amendment to Section 230 as it strips digital platforms of their immunity if they have knowledge or should have had knowledge of sex trafficking being organized through their services. Digital companies find themselves in a much less comfortable situation than in the 1990-2000s, as it is now easier for US legislators and regulators to gain the support of civil society. The natural association between government intervention in the activities of Internet companies and infringement of freedom has ceased to exist. To use Culpepper and Thelen’s terms, in the post-Cambridge Analytica era, Americans value their identity as citizens more than as consumers34.

Today, digital companies are being challenged on all sides by American civil society, making it easier for regulators to channel corporate activity into less offensive forms. Instead of seeing platforms as the embodiment of freedom of expression, as in the days of John Perry Barlow, Americans tend to treat them as a threat to their privacy. This shift in attitude provides eloquent confirmation of Shoshana Zuboff’s thesis that platforms undermine democracy in the name of free speech. From November 13 to 14, 2021, street protests took place in eight major U.S. cities, including Menlo Park in San Francisco, Facebook’s headquarters. Organized by India Genocide Watch (IGW), participants protested against Facebook who had allowed hate speech against the Indian Muslim community online. Signs displaying “Mark Zuckerberg Blood on Your Hands” or “Facebook Ending Genocide of Muslim in India”35 sum up the public perception of this company particularly well. Digital giants also face criticism from their own employees. Also at Facebook, Frances Haugen revealed many of the company’s problematic practices during the “60 Minutes” program on October 3, 2021. Among other things, this former employee mentioned how Facebook nurtured division, extremism and social polarization. According to her, the company was fully aware of the negative effects of its applications, but systematically chose solutions that maximized commercial profits, not the safety of users36.

In a nutshell, platforms and regulators in democratic countries are developing relationships that resemble those that exist in China. More concretely, the two parties are entering into a conflictual and competitive relationship. Their competition revolves around a number of contemporary issues: who has a better understanding of citizens’ interests? Whom are they most dependent on? Whom do they trust? The competition between these two parties is basically a competition for audiences and influence. In democracies, the emergence of the darker sides of online platforms, such as massive data collection and the dissemination of sensational content, is causing disenchantment among Internet users. The development of similar grievances in the East and West, in particular concerning the violation of privacy and the dissemination of false information, is becoming the foundation on which the convergence of content regulation methods is based. Given the current controversy surrounding hate speech in the West, epitomized by dramatic incidents such as the murder of Samuel Paty in 2020 and the storming of the Capitol by Trump supporters in 2021, it is likely that in the near future, democracies and autocracies will continue to develop common ground when it comes to their methods and objectives of online content regulation. Nevertheless, the convergence of regulatory methods currently in use has nothing to do with changes in the political regimes of the countries concerned. Above all, it demonstrates the similarity of the current challenges faced by governments with regard to online content.

Antitrust regulation

MyriamLavoie-MooreandJoëlleGélinas,”Desfusions-acquisitionsaufondementdel’économienumérique”, ledevoir.com, December 9, 2020.

Ibid.

Meiting Guo and Wanyi Huang, “全球反垄断利剑下,脸书多项收购交易受阻,谷歌等科技巨 头扩张步伐放缓” (with the zeal of antitrust regulation worldwide, acquisitions are becoming increasingly difficult, and the expansion of tech giants like Google is slowing), “21世纪经济报道”, (Economic report of the 21st century), September 12, 2021.

Ending Platform Monopolies Act, American Innovation and Choice Online Act, Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021, Enabling Services Switching Act and Merger Filter Fee Modernization Act.

Julien Baldacchino, “Numérique : Emmanuel Macron envisage “le démantèlement” des GAFAM”, France Inter, April 13, 2022.

Ibid.

The impressive growth of online platforms such as Big Tech (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft…) and BATHXJ is punctuated by the acquisition of small, innovative digital companies, regardless of the country in which these companies are located. However, they are profoundly impacted by factors threatening the survival of digital businesses in a hyper-competitive, fast-moving market. Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are the golden rule when it comes to the expansion of the digital economy, and serve several purposes. They help large companies “secure their strategic positioning and expansion in a market driven by innovation”37. The imperative to acquire “start-ups” also stems from the fact that – for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists alike – a digital company needs to grow very quickly to guarantee a return on investment38. Shoshana Zuboff points to another factor to explain the M&A zeal of platforms: a company established in a wide variety of activities is better disposed to tap into large quantities of data to train its algorithms. The quantity of data collected is positively correlated with the accuracy of algorithms in predicting user preferences, and therefore the ability of platforms to make profits from advertising.

Mergers and acquisitions of innovative start-ups are an important factor in sustaining platform expansion. In this respect, the growth models of the digital giants are all very similar. A long list of acquired digital companies hides behind the advent of each of these giants. From their creation to 2021, the number of companies acquired by Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft is 58839.

China’s digital giants are following the same path in their expansion, which means that today their business sector is characterized by great diversity. It’s commonplace to see a Chinese digital platform providing not only instant messaging and online payment services, but also artificial intelligence products, autonomous cars, drones, medical services, games and more. The diversity of activities is indissociable from corporate mergers and acquisitions. The example of Alibaba is revealing in this respect. As an e-commerce platform, Alibaba has acquired companies whose activities diverge significantly from its own, such as the Gaode Map application, which enables users to identify geographical locations with precision. This acquisition helped Alibaba gain a privileged position in the mobile Internet era, before expanding into entertainment and culture with the purchase of video-sharing platform Youku Tudou and the South China Morning Post, a daily newspaper rather critical of the Chinese government.

Nevertheless, the side-effects of mergers and acquisitions are not negligible. For the small start-ups targeted by this practice, being bought out is often the only way to guarantee the survival of their business, as they are unable to compete with the big companies that have already built up a large user base. Large platforms function like siphons, absorbing in their wake emerging innovators who are likely to become competitors later on. As a result, large systemic platforms are the heart of technological innovation that small start-ups cannot match. For consumers, the concentration of the digital market around a small handful of companies significantly reduces their possibilities and the ability to switch from one platform to another. The fact that platforms have succeeded in occuping monopoly positions gives them an advantage over consumers, who have to endure various disadvantages if they decide to boycott a particular product. For example, WeChat’s indispensability to Chinese Internet users makes its boycott unimaginable, as Internet users cannot easily find substitutes. These considerations have driven national governments’ to introduce antitrust regulation.

Today, antitrust regulation is a common concern in France, China and the United States. Despite its rapid intervention in the regulation of online content, the Chinese government has allowed companies considerable freedom to expand their business over a long period of time. Its intervention in mergers and acquisitions was very rare. Nevertheless, with the growth of these giants in increasingly sensitive areas such as finance and currency, the Chinese government started a wave of antitrust regulations from November 2020. On November 3, 2020, as Ant Group – Alibaba’s financial arm – prepared to list on the Shanghai and Hong Kong stock exchanges, the initial public offering valued at $37 billion was promptly halted by Chinese financial regulators. Following this event, an avalanche of legislative and administrative measures were put in place. On June 24, 2021, Chinese legislators approved the amendment of the Antitrust Law. The new version, which came into force on August 1, 2021, perfected the rules on monopoly agreements and market concentration.

In addition, Chinese regulators have imposed heavy penalties on violators of these rules. In February 2021, after six months of investigations into Alibaba’s monopolistic practices of forcing its merchants to sign exclusive contracts, the firm was fined a record 18.2 billion yuan, or 4% of the company’s 2019 sales.

US and European regulators have turned their attention to platform abuses of dominance almost at the same time as China. In 2019, the House Judiciary Committee in Washington launched an investigation into the monopolistic practices of Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple. In their report made public on October 9, 2020, lawmakers concluded that these four companies are all engaged in illicit practices, including eliminating competitors via acquisitions, charging high fees, or signing unequal contracts with small businesses. Lawmakers have suggested dismantling some of the platforms’ activities to reduce conflicts of interest or prevent acquisitions with anti-competitive objectives. Today, US regulators are showing more circumspection towards the M&A plans of major platforms, in stark contrast to their past insouciance, for example during Facebook’s takeover of Instagram. In May 2020, Facebook announced its takeover of Giphy, a gif image search engine. This takeover plan gave rise to antitrust investigations by the Federal Trade Commission, which has still not given the go-ahead.

The US antitrust legal framework has been perfected. On June 23, 2021, the House of Representatives passed five laws relating to antitrust in the digital economy40. These laws will help increase the budgets of market regulators, improve data portability, reduce the cost of interoperability, and contain mergers and acquisitions harmful to technological innovation.

European legislators concern for antitrust regulation is well known, and the misadventures of several American companies in Europe testify to this. Given the direct influence of the European regulatory framework on the French one, it is important to consider the measures taken at European level. Of all the American platforms based in Europe, Google has been subject to the most spectacular sanctions. From 2017 to 2019, the total amount of fines imposed on Google by the European Union was close to 8.2 billion euros: 2.4 billion euros in 2017 in the “Google Shopping” case, 4.3 billion euros in 2018 for abuses linked to the Android operating system, and 1.49 billion euros in 2019 for abuse of a dominant position via its AdSense advertising network. Facebook’s fortunes aren’t much better. The announcement of its acquisition of Kustomer in late 2020, a start-up specializing in customer relationship management, has aroused the suspicions of European regulators. At Austria’s request, the EU launched antitrust investigations from May 2021. In a press release dated May 12, 2021, the European Commission explained that without its authorization, Facebook would not be able to implement its plan to acquire Kustomer.

The adverse effects of digital market concentration do not significantly differ according to a country’s political regime. The similarity of these effects can explain the similarity of the regulatory approaches mobilized to date by national authorities. Despite chronological differences, Chinese, French and American regulators have all legislated on the antitrust issue by providing greater clarity of the rules, raising the financial cost of monopolistic practices, and conducting stricter reviews of company merger and acquisition plans. We can also see a convergence of public debated in these countries, particularly with new voices calling for the dismantling of platforms, thereby influencing the agenda of antitrust regulators. In China, at a meeting with thirteen platforms providing financial services in April 2021, the People’s Bank of China, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission and the China Securities Regulatory Commission asked them to separate their payment activities from other financial activities. In France and the USA, civil associations and political figures such as US Senator Elisabeth Warren and French President Emmanuel Macron have called for the dismantling of Big Tech41. In 2021, Bruno Le Maire, then French Minister of the Economy and Finance, expressed the same view: “In the same way that we dismantled the big oil companies at the beginning of the 20th century, we will have to dismantle the digital giants, restore competition, regulate the way they control data because they have acquired excessive power”42.

Personal data protection

“民众对个人信息保护意识增强 约三成愿意为隐私保护付费” (Public awareness of privacy of protecting personal information is growing, with around 30% of respondents agreeing to pay fees to protect privacy), news.youth.cn, December 6, 2019.

iiMedia Research, “艾媒报告2020年中国手机app隐私权限测评报告” (iiMedia Research’s iiMedia Research in 2020 on access to privacy via smartphone applications), February 25, 2020.

Léa Vermersch, “La protection des données personnelles aux États-Unis, une approche différente de Europe”, Blog Economie Numérique, February 18, 2019.

Yuebo Huang, “Personal Data Security in the US”, phcppsu.com.cn, June 21, 2022.

Léa Vermersch, op. cit.

Ibid.

The final point of convergence between China, France and the United States is the priority given to the protection of personal data. Regulators’ interest in this area stems from public awareness of the major platforms’ impunity when it comes to data collection. Whereas in the past, citizens attached little importance to this subject, more and more of them are realizing that the free services they enjoy come at with a price: that of surrendering their personal information. Citizens are also discovering that the personalization of online services is impossible without digital companies first having perfect knowledge of their consumption habits and preferences. Awareness of this trade-off between free and personalized services and the publicization of privacy has led to waves of protests in both democratic and authoritarian countries, which explains why personal data protection is rising to the top of the content regulation agenda.

In the three countries studied, the interest of regulators varies according to the concerns of Internet users. China is no exception. While the Chinese government is able to promote its own agenda by resisting public pressure, it cannot afford to go too far in the face of public opinion, as making itself unpopular is not good for the regime’s long-term security. On December 6, 2019, a research center at Nanfang Metropolis Daily, a relatively liberal daily newspaper, released the Annual Report on Personal Information Security in 2019. Drawn up on the basis of 10,702 questionnaires, the report shows that around 80% of respondents set their smartphones in order to raise the level of protection for their personal lives. Around 30% of respondents agree to pay a fee in order not to give up their personal data to applications43. The percentage of Chinese Internet users who say they read app terms of use has increased from 32.4% in 2018 to 36.4% in 202044.

In response to Internet users’ concerns, the CAC has issued several regulations to oversee data collection by apps. On December 30, 2019, the CAC and three other regulators released “Methods for Identifying Illegal Collection of Personal Data by Apps”. This document indicates six categories of illegal collection of personal data. An app is considered to be illegally collecting data if it:

– does not outline the principles of collection;

– fails to explain why and how data is collected; or

– collects data from users without obtaining their consent;

– collects data that has nothing to do with the services provided;

– transfers data to other parties without obtaining users’ consent;

– does not allow users to delete or correct collected data, or does not provide information enabling users to denounce the illegal practices of applications.

Under the aegis of the CAC, a public account has been created on WeChat, where Internet users can flag applications that do not comply with regulations related to the collection of personal information. The CAC said it had received more than 9,000 denunciations from January to September 2019. Inspired by the GDPR, Chinese legislators passed the PRC Personal Information Protection Law on August 20, 2021. Coming into force on November 1 of the same year, this law provides a new layer of protection for users, notably by prohibiting platforms from charging different prices based on algorithmic profiling. What’s more, like the GDPR, it includes extraterritorial effects: companies based abroad that collect data on Chinese consumers in order to provide them with services or products fall within the scope of this law.

In Europe in general, and in France in particular, the protection of personal data has always been on the agenda of legislators and regulators. The priority given to this issue in France is consistent with its regulatory approach, which focuses on citizens’ rights. Even before the Internet, the French legal framework was characterized by its “protective privacy” dimension. In 1978, France passed a pioneering law on the protection of personal data: the Act of January 6 on Data Processing, Data Files and Individual Liberties. Before being amended by the 2004 law on confidence in the digital economy, the 1978 law stipulated that no judicial, administrative or private decision involving an assessment of human behavior could be based solely on the automated processing of information giving a definition of the profile or personality of the person concerned. With the advent of digital technology, the scope of citizen protection has broadened. For example, the 2004 law mentioned above broadened the scope of the original Act to cover both automated and non-automated data processing.

French and European regulators have long been renowned for their ruthlessness towards companies daring to defy established rules. On October 20, 2022, the French National Commission for Information Technology and Civil Liberties (CNIL) issued a statement in which it imposed a 20 million euro fine on a facial recognition company Clearview AI. The latter violated the GDPR by collecting and using individuals’ photographs – without a legal basis – in order to build them into a “biometric template”. The individuals concerned were unaware that their photos had been collected. In another press release issued on September 13, 2022, the CNIL announced a fine of 250,000 euros imposed on Infogreffe, a company that provides legal information on companies and sells documents certified by clerks of the commercial courts. Charges against the company include preserving data beyond the authorized time limit, insufficient anonymization of information, and weak password protection for its users. France is unlikely to change course, as its citizen protection policy easily wins voter support.

The evolution of personal data protection in the USA has followed a similar trajectory to that of China, i.e. legislative activity in this area started relatively late. It’s true that privacy protection dates back to the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, which was intended to protect citizens against intrusions by public authorities, not private actors45. The Financial Privacy Act of 1978, the Privacy Protection Act of 1980, and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 all aimed to protect citizens from abuse by public authorities, for example, by protecting journalists and newspaper reading rooms from searches by government agents. It wasn’t until the 1970s, with the Griswold v. Connecticut and Roe v. Wade, that the Federal Supreme Court confirmed the right to privacy as a fundamental right46. Nevertheless, in the US hierarchy of norms, freedom of expression is superior to the protection of privacy. In March 2017, for example, Congress rejected a regulation aimed at preventing Internet service providers from selling the personal data they collect47.