European Union : the grip of environmental bureaucracy

Introduction

EU Green Taxonomy: a prime example of administrative complexity

The four trials of sustainability

A surprising composition, to say the least

A text whose application is proving incredibly complex

An inconclusive result

What lies ahead

The corporate sustainable reporting directive (CSRD)

A directive born from failure

CSRD: thinking big

A painful birth

A particularly complex application

How did we get here?

And tomorrow?

The sustainable finance disclosure regulation

A chaotic application

A surprising result, to say the least

And tomorrow?

From green finance to sustainability… a complex journey

Initially, a very self-interested agreement

Standards war: in the end, European companies lose out

What can we do now?

Summary

On 11 December 2019, the new President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, presented the “European Green Deal”. At the heart of this ambitious project, which aims to make the European continent carbon-neutral by 2050, the financial world was given a key role: to direct investment towards the most “virtuous” companies in order to help them in this green transition.

To achieve this objective, three key pieces of legislation have been implemented: firstly, the “green taxonomy” defines the conditions under which an activity is “green”; secondly, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) constrains companies to produce a range of standardised environmental and social data; thirdly, based on this information, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) obliges financial institutions to communicate the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) objectives of their funds to investors, according to a precise categorisation.

Five years on, the results of this legislative construction of “green finance”, intended to be exemplary, are mixed to say the least. Companies are drowning under a “regulatory tsunami”, accusations of greenwashing are multiplying and, in 2024, for the first time, investors withdrew 30 billion euros from “green” funds.

At a time when the global economy is becoming increasingly competitive, this scaffolding of complex, sometimes incoherent and often costly legislation is not only proving lethal for many European businesses, but is also generating a “push-back” effect among citizens against environmental issues, fuelling votes for radical parties.

There is now an urgent need to move away from ideology and return finance to its original role: above all, to help build sustainable economic growth, i.e. growth that generates wealth, respects the environment and is socially viable.

This is the price that will have to be paid if Europe is to achieve its ambitious environmental objectives without risking political disintegration.

Emmanuel Bloch,

Doctor of Information and Communication Sciences, Associate Professor at the Université Panthéon-Assas in communication and CSR, and lectures at the IHEDN and INHESJ.

The acronym “ESG” stands for environmental, social and governance criteria, which are generally used as a basis for the extra-financial evaluation of companies.

Aswath Damodaran, “Sounding good or Doing good? A Skeptical Look at ESG”, Musings on Markets, 21 September 2020 [online].

European Commission, “The European Green Deal sets out how to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, boosting the economy, improving people’s health and quality of life, caring for nature, and leaving no one behind”, Press Release, 11 December 2019 [online].

“By the autumn we will put forward concrete proposals to simplify reporting requirements and in fact to reduce them by 25%”, Ursula von der Leyen, “Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament Plenary on the preparation of the European Council meeting of 23-24 March 2023”, European Commission, 15 March 2023 [online].

Ursula von der Leyen, “Statement at the European Parliament Plenary by President Ursula von der Leyen, candidate for a second mandate 2024-2029”, European Commission, 18 July 2024 [online].

Mario Draghi, “The future of European competitiveness”, European Commission, September 2024 [online].

“Council and Parliament agree to delay sustainability reporting for certain sectors and third-country companies by two years”, European Council, 7 February 2024 [online].

Clément Fournier, « CSRD : le chancelier allemand demande à l’Europe de revenir sur la directive », Novethic, 7 January 2025 [online].

Fabienne Schmitt, « Produits chimiques, bien-être animal : l’UE confirme le report de plusieurs lois du Pacte vert », Les Echos, 5 October 2023 [online].

Claire Avignon, « Face au souhait de simplification, ONG et syndicats défendent les textes européens sur la responsabilité des entreprises », AEF, 14 January 2025 [online].

“Sustainable finance: Commission’s Action Plan for a greener and cleaner economy”, Press Release, European Commission, 8 March 2018 [online].

According to Morningstar, in the second quartile of 2024, there was a slow recovery for Article 8 funds and further outflows for Article 9 funds. However, in the third quartile of 2024 this decline in investment towards the most virtuous funds seemed to be slowing down. (See “SFDR Article 8 and Article 9 Funds: Q2 2024 in Review”, Morningstar, 25 July 2024 [online]).

“The ESG1 bandwagon may be gathering speed and getting

companies and investors on board, but when all is said and

done, a lot of money will have been spent, a few people

(consultants, ESG experts, ESG measurers) will have

benefitted, but companies will not be any more socially

responsible than they were before ESG entered the business lexicon”.

Bradford Cornell (UCLA) and Aswath Damodaran (NYU)2.

On 11 December 2019, the new President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, presented the “European Green Deal3” as a “a roadmap for making the EU’s economy sustainable by turning climate and environmental challenges into opportunities across all policy areas and making the transition just and inclusive for all”.

This ecological ambition was translated into a list of “55 key actions4”, as well as a flurry of European regulations aimed at implementing the Green Deal throughout the European economy.

Aware of this, President Ursula von der Leyen announced in March 2023 that the Commission would simplify the regulatory burden on businesses by a minimum of 25%5, a commitment reiterated on 18 July 2024 in her speech to the members of the European Parliament (MEP6): “[…] I will put forward a new Clean Industrial Deal in the first 100 days […] We must be faster and simpler”. These commitments were echoed a few months later in Mario Dragui’s report “The future of European competitiveness7”, which he concluded with a reminder of the crucial need for simplification, even going so far as to suggest simplifying reporting requirements for SMEs by 50%.

In practical terms, this means postponing or suspending a number of regulations initially provided for in the Green Deal8.

But not everyone was enthusiastic about the announcement. EU countries, in the likes of France and more recently Germany, consider that it is urgent to take this regulatory break9 or even to review certain texts already in force10. They have gone so far as to threaten the use of veto power against recent delegated acts or new regulatory constraints11. Other players, including a number of environmental associations, are concerned about this pause and the consequences it could entail for the EU’s environmental objectives.

At a time when the President of the European Commission—who has spent the past five years steadfastly driving these laws forward—is now just as fervently advocating for their swift revision, citing the detrimental impact their implementation would have on the economy. An “omnibus” regulation designed to simplify taxonomy, the CSRD and the SFRD, is expected on 25 February. This has, unsurprisingly, sparked fierce opposition from numerous NGOs and trade unions12, as well as businesses frustrated by the constant instability of the regulatory landscape.

How did we get here?

In 2018, the Commission launched a roadmap “to boost the role of finance in achieving a well-performing economy that delivers on environmental and social goals as well13”, to encourage investments in sustainability. The aim is to encourage private investors to invest in sustainability. Indeed, if Europe wants to achieve the targets it set itself in 2015, which it revised upwards in 2020 (reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2050), it will need to invest no less than an additional €180 billion a year, funds that neither the Member States nor Europe are currently able to raise.

In order to achieve this objective, three key pieces of legislation were enacted:

– The EU Green Taxonomy, which aims to define the “green” activities that can be financed with sustainable finance (voted in June 2020);

– The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which aims to require companies to provide standardised information on their non-financial performance (voted in December 2022);

– The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), which aims to define the characteristics of a green fund. It also requires financial institutions to publish a range of environmental data on their customer investments (voted in March 2021).

These three texts are supposed to work together: companies publish environmental data according to the Taxonomy’s criteria, and banks use the data to ensure their investments go towards sustainable practices. In practice however, there are many inconsistencies between them. As a result, companies and financiers alike find themselves lost in a maze of sometimes incompatible texts, while environmental organisations are equally disappointed by the often-illegible results. Worse still, investments in the most “virtuous” funds have stagnated or even fallen since the beginning of 202414 and the major initiatives in favour of sustainable finance have seen their members leave one after the other15.

EU Green Taxonomy: a prime example of administrative complexity

“How does [the taxonomy] work?

Very simply”.

Interview with Pascal Canfin, Novethic, December 2019.

Considered to be the “founding” text of sustainable finance, Regulation 2020/852 of 18 June 202016 on the establishment of a framework to promote sustainable investment has the function of establishing “the criteria to be applied by the EU and EU Member States to decide whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable”.

Known as the “EU Green Taxonomy”, the main purpose of the text is to define the economic activities that can be considered “green”, i.e. those that meet at least one of the six following environmental objectives:

– Climate change

– Climate change adaptation

– Sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

– Transition to a circular economy

– Pollution prevention

– Protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

The four trials of sustainability

For an activity to be sustainable, “nothing could be simpler”, in the words of MEP Pascal Canfin, Ex-Chairman of the European Parliament’s Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety and a staunch supporter of this text. All that is required is for the activity to meet four distinct criteria:

– First, the activity must be “eligible”. In other words, it must be considered likely to meet at least one of the six environmental objectives listed above. For example, car manufacturing is considered an eligible activity because it potentially contributes to mitigating climate change.

– Second, the activity must meet precise technical criteria defined by the Commission. For example, the cars produced must emit less than 50g of CO2/km.

– Third, the activity must not have a negative impact on one of the other environmental criteria (the DNSH principle – Do No Significant Harm). For example, the cars produced must be recyclable by weight (circular economy) and have tyres that meet certain noise criteria (prevention of noise pollution).

– Fourth, the activity must meet certain minimum standards (respecting human rights, respecting the law), the so-called “minimum safeguards” of the EU taxonomy. For example, the cars produced must not be made by children or by workers who are kept in a form of “modern slavery”.

This scrutiny of activities must be applied to three financial indicators:

– Turnover: this involves determining the percentage of turnover that is “eligible” and then “aligned”, i.e. relating to sustainable activities according to the taxonomy.

– Capital expenses (CAPEX): the taxonomy requires companies to publish the proportion of their investments that relate to sustainable activities.

– Operating expenses (OPEX), i.e. the percentage of the company’s expenses that also relate to sustainable activities.

– Once the mechanism was defined, the Commission entrusted, in October 2020, a group of 50 multi-stakeholder experts – the Sustainable Finance Platform – with the mission of defining these so-called eligible activities, as well as the technical criteria that determine their potential alignment.

A surprising composition, to say the least

A few years later, the Commission attempted a similar approach by recruiting Fionna Scott Morton, an American, for the position of Chief Competition Economist in the European Commission. Faced with an outcry from many Member States, particularly France, over this appointment, she finally resigned in 2023.

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, an organisation founded in 2011 to develop sector sustainability standards in order to help investors compare the performance of companies in the same sector.

The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) aims to improve companies’ climate-related financial transparency.

See Part IV.

Frédéric Simon, « Des ONG quittent le comité du financement vert de l’UE invoquant des interferences politiques », Euractiv, 15 September 2022 [online].

For environmental NGOs, nuclear power cannot be considered “sustainable” as it is too polluting given the lifespan of nuclear waste . As for gas, it is a fossil fuel that emits CO2, so it has no place in the Taxonomy.

This organisation, supposed to represent all stakeholders, includes academics, NGOs, representatives from the worlds of finance and business, as well as representatives of European administrations.

The first surprise is that, from the outset, this platform was placed under the direction of an Anglo-Australian economist who, after starting his career as a financier in Australia, became a member of the steering committee of the PRI (Principles for Responsible Investment) – an organisation founded by investors at the initiative the initiative of Kofi Annan, then Secretary General of the UN, to define criteria for responsible investment. Europe entrusts responsibility for this platform to a member of an identical UN working group, which itself is not born from a European country17. Lastly, the platform’s members include Bloomberg, whose founder also funds two competing initiatives, the SASB18 and TCFD19 standards, which were “absorbed” in June 2022 by the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB)20, also a competitor of the European approach.

The internal tensions within the Sustainable Finance Platform, and between the Platform and the Commission, were revealed in September 2022 when the NGOs left the Platform21 following the inclusion of electricity production by nuclear energy and gas in the Green Taxonomy22, energy sources which the Commission considers to be sustainable.

In 2023, the latter renewed all Platfom members. While the President is indeed European, there are no longer any non-financial companies among its members. The 28 members of the Platform include insurers, bankers, NGOs, trade associations experts, but no preparers (i.e. data-producing companies). While Bloomberg is no longer a member – but still an “observer” – Americans are still present through the extra- financial rating agency Sustainalytics, a subsidiary of the Chicago-based asset management company Morningstar. As for one of the members of the European platform, he says that he also participates in the Australian equivalent (which does not seem to raise any ethical questions).

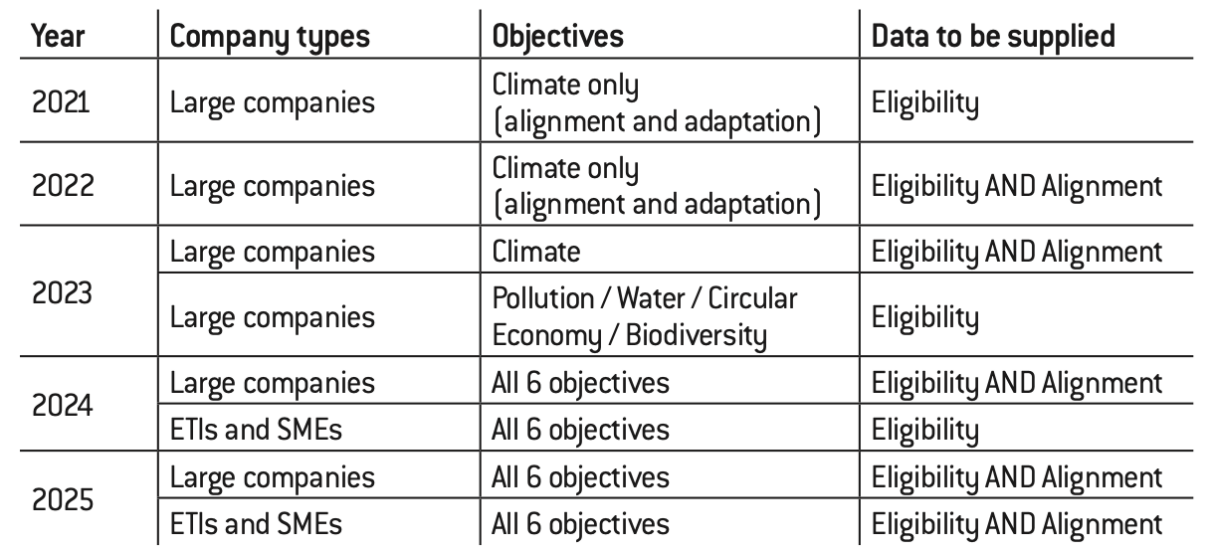

A deployment planned over several years

Given the complexity of the exercise, and the difficulty for the Sustainable Finance Platform to agree on green criteria, the application and roll-out of the Taxonomy has been spread over several years:

This timeline for gradual application masks the emergency situation in which many companies found themselves when they had to apply – and thus include in their 2023 annual report ––the texts published in the Official Journal of the EU on 21 November 2023.

A text whose application is proving incredibly complex

In the case of building renovations, the Taxonomy specifies that to be eligible “urinals must use a maximum of 2 litres per bowl per hour. The volume per flush of urinals fitted with flushes does not exceed 1 litre”.

According to criterion 7.6 “Installation, maintenance and repair of renewable energy technologies” of the climate change mitigation objective.

According to criteria 3.5 “Manufacture of energy efficiency equipment for buildings” of the transition to a circular economy objective.

As the Taxonomy data is published in the sustainability report defined by the CSRD (see chapter 3), it is audited either by the auditors, an independent third-party body or a sustainability i auditor (Order n°. 2023-1142 of 6 December 2023).

The Taxonomy has therefore been applied gradually. In 2021, large companies had to publish the proportion of their sales, CAPEX and OPEX eligible for the first two climate objectives (climate change mitigation and adaptation).

Then, in 2023, the exercise became more complex, since it became necessary to publish not only the eligible share of sales, CAPEX and OPEX, but also the share aligned (i.e. sustainable according to the criteria of the Taxonomy) with the two aforementioned climate objectives. This is where the text revealed it’s the extent of its inconsistencies and complexity.

Without going into too much detail, here are a few concrete cases to illustrate the consequences of a text that may seem “out of touch”:

– In 2022, with the first “eligibility” publication, financiers were surprised to find on the one hand Peugeot was declaring that 46% of its sales were aligned (i.e. sustainable), while on the other hand, Renault was announcing 0%. Although the companies’ vehicles differ, the significant gap between these two closely related manufacturers was surprising. It was simply the result of two diverging interpretations of the DNSH principle. Indeed, Annex C of the Taxonomy is so complex that its literal application means that no industrial company – even if it manufactures wind turbines or solar panels – can be aligned.

– The OPEX taken into account by the Taxonomy do not correspond to the “accounting” definition usually used by companies to calculate these same expenses. As a result, a complex restatement is required. For instance, the salary of an electrician who performs maintenance tasks can be aligned if these tasks are linked to a sustainable activity. Concretely, if during the day the worker maintains a combustion engine for three hours, this activity is not considered sustainable. On the other hand, if he then works for five hours on a solar panel, his work will be considered sustainable. And this calculation will have to be made for all maintenance workers and the entirety of their daily activities, which represents a considerable amount of reporting work;

– CAPEX must be taken into account to the nearest euro. In other words, if one replaces a halogen bulb with a highly energy-efficient LED bulb, the Taxonomy states this must be declared as a sustainable investment. In theory, then, every purchase of equipment (light bulbs, windows, doors, heating, washbasins, toilets23, etc.) should be systematically studied to determine whether it can be included in the sustainable investments category. To date, virtually no company has the information systems or human resources to make this type of calculation.

– Finally, since 2023, a company may have “green” activities according to one objective, and “non-green” activities according to another. For example, the manufacture of electronic boxes for the installation of photovoltaic panels may be considered “green” according to the climate change adaptation objective24. But it can also be considered “non-green” according to the circular economy objective25 to the extent that the chemical products these boxes contain present a risk. It is therefore up to the company to decide what objective it will pursue to establish the “green” proportion of its sales. This à la carte approach creates even more confusion and is in complete contradiction with the Taxonomy’s initial objective to definitely determine whether a company’s activities were green or not.

These examples might have been amusing would they not have real financial consequences for companies. Since 2025, the European legislator has provided for the information published by companies to be verified by “sustainability information auditors26”. The first consequence will be an immediate financial impact, as this audit—set to be particularly complex— will come at a cost. Secondly, the Taxonomy’s complex implementation means most companies will have to turn to experts (often audit firms) who will charge for this consultancy service. Companies must comply with the legislation; otherwise, auditors will publicly report their non-compliance. This can be a delicate situation, especially for investors or bankers who may not appreciate the warning. Especially as they themselves will have to indicate the sustainability of their investments or loans (i.e. include the declarations of the companies in which they invest or to which they lend money in their calculations).

An inconclusive result

In 2023, EY surveyed 277 listed non-financial companies27 to study the eligibility and alignment indicators published for the two climate objectives.

The survey found that, on average, companies in the sample reported 25% of their sales as eligible and only 8% as aligned, or “green”. Clearly, this figure masks significant disparities between sectors. For example, companies in the energy sector declare on average that 30% of their turnover is “green”, while this number is down to 2% for those in the high-tech and telecommunications sectors, or even 0% for those in the consumer goods sector.

While these variations can be attributed to the nature of the activities— bolstered by the boom in solar and wind power generation—they also pose challenges for the financial sector, the ultimate user of this data. Indeed, one of the fundamental rules for bankers and investors is to mitigate risk by diversifying investments. However, with results like these, the Taxonomy leads the financier to do quite the opposite.

As a result, investors tend to concentrate their financial risk on a few “green” companies, at the risk of creating a “green financial bubble”. Green companies are then overvalued, creating an increased risk of a crash when investors realise the disconnect between these values and the reality of the companies’ economic performance28.

What lies ahead

“IIGCC publishes open letter calling for gas to be excluded from EU taxonomy”, IIGCC , 12 January 2022 [online].

In the June 2021 version of the delegated act, the DNSH (“Do No Significant Harm”) on “pollution” prohibited certain products “unless it has been proven that their use is essential for society”. This notion of “essentiality” led to very varied interpretations and prompted the Commission to rewrite this paragraph in June 2023. The new version prohibits the use of these same products “unless it is estimated and documented by the operators that no other suitable substance or technology is available on the market to replace them and that they are used under controlled conditions”. New questions now arise regarding the estimation and meaning of the notion of “controlled conditions”.

Ana Lutzky, « Dix recours contre la taxonomie verte devant la Cour européenne: qui les porte, et sur quel fondement juridique? », AEF Info, 17 December 2024 [online].

“Commission welcomes agreement on postponing adoption deadlines for certain European Sustainability Reporting Standards”, European Commission, 8 February 2023 [online].

In the document “Platform on Sustainable Finance Draft Report on Activities and Technical Screening Criteria to be Updated or Included in the EU Taxonomy” published on 8 January 2025, the Sustainable Finance Platform admits that it “was not able to conduct a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of usability issues across the DNSH criteria of all Delegated Acts” (page 10).

The European Commission quickly realised the many problems caused by this text. First, the inclusion of the nuclear sector—advocated by France and several other European countries29—and gas-fired power stations in the list of green activities triggered strong reactions from the financial sector, particularly regarding the inclusion of gas30, with especially vocal opposition from Northern European countries. The fiercely anti-nuclear Austrian government has even taken the matter to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in an attempt to have the decision overturned. As a result, financial institutions have clearly announced that they do not plan to use this data for their green investments. A study published in May 2024 revealed that, on average, only 3% of the assets held by banks in the EU met the green taxonomy31.

Second the Commission was questioned about the complexity of this regulation and the financial cost of its application for companies. On this point, the discrepancy in the publication of Renault and Peugeot’s aligned sales figures revealed the consequences of the imprecision of the text. In June 2023, even though the regulation had not yet been fully implemented, corrective measures in the form of delegated acts had already been published. These did nothing to simplify the regulation, quite the contrary32.

Discontent with this Green Taxonomy has also manifested itself in a number of appeals to the ECJ challenging application criteria. According to the agency AEF Info, which studied these appeals, seven were lodged by NGOs (some of them anti-nuclear and others anti-wind turbine) and three others were lodged by Austria and an MEP on the question of the inclusion of energy from nuclear and gas sources in the Taxonomy, and by Dassault Aviation in association with the European Business Aviation Association on the exclusion of business aviation33.

In response to this regulatory setback, the Commission has officially tasked the Sustainable Finance Platform with turning this text into a reality.

The aim is to ensure that regulations are applicable and to update them in line with technical and technological developments34. A consultation, open to all stakeholders, was launched in October 2023 to gather ideas for amendments that could be implemented. By the end of December 2024, this consultation resulted in a 350-page document proposing a whole series of amendments, ranging from inclusion of new sectors to the simplification of DNHS criteria (but only for new activities35).

Therefore, the EU Green Taxonomy fails to meet most of its initial objectives. It was intended to be simple, but has turned out to be extremely complex; it was supposed to be an indisputable designation of “green” economic activities, but its application is imprecise and accused of greenwashing by environmental NGOs; it was intended to help financial institutions make informed investments, but is seen by these same players as encouraging the creation of “green financial bubbles”.

The corporate sustainable reporting directive (CSRD)

“The CSRD comes from a very good intention, but its execution is

dreadful. We’re going to mobilize dozens of people just to fill in boxes…

It’s an enormous constraint that won’t make us progress much. Why?

Because it assumes from the outset that companies have bad intentions.

It started from the idea that businesses act in bad faith and therefore

need to be overregulated”.

Florent Menegaux, Chairman of Michelin and Chairman of the UN

Global Compact – France Network36.

Drafted a few months after the taxonomy, the CSRD also raises questions.

Directive 2022/2464 of 14 December 2022 requires large European companies and SMEs to include “information necessary to understand the undertaking’s impacts on sustainability matters, and information necessary to understand how sustainability matters affect the undertaking’s development, performance and position” in their annual management reports. In essence, the vast majority of European companies are now required to provide a whole range of non-financial information.

A directive born from failure

The CSRD replaces a well-known directive for large companies: Directive 2014/95 on the “disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups”. Promulgated in 2014 and belatedly applied in France (January 2017), this directive required large companies to publish a description of their business model, the policies implemented, the results of these policies, the main risks identified and the key performance indicators linked to these risks and policies.

While the approach was traditional and aligned with consulting standards, its concrete application proved to be of little relevance.

Admittedly, all major companies published this information in their management reports, but the imprecision of the information requested meant that two companies in the same sector of activity presented different policies and indicators that were completely unrelated. What’s more, while in France the information published by companies was audited by an independent third party, this was not the case in the vast majority of other European countries, making the data published somewhat unreliable.

This directive was initially designed to ensure that large companies would work together on corporate social responsibility (CSR) issues.

In fact, this exercise, intended to provide “a sufficient level of comparability to meet the needs of investors and other stakeholders37”, missed its objective. And quickly, it became a burdensome exercise for companies, producing a result that was unusable for the intended beneficiaries.

Aware of this failure, the Commission decided to review its plans for 2019 and embarked on the CSRD project.

CSRD: thinking big

The new 2022 directive brings a number of structural changes. Firstly, it applies to all European companies (large, medium-sized and small), including subsidiaries of foreign groups. Only “micro-enterprises” are excluded. This represents approximately 300,000 companies in Europe. Secondly, it is based on the principle of “double materiality”. This highly conceptual approach to CSR considers that it is important to take into account both the risks and opportunities posed by environmental and social/societal constraints on the company, as well as the environmental and social/societal impacts of the company’s activities on its stakeholders.

“Double materiality” is in direct opposition to the notion of “simple materiality”, which only takes into account the risks and opportunities that environmental and social/societal constraints pose for the company (in other words, only CSR constraints that generate a significant financial cost or benefit for the company are taken into account).

Finally, to ensure that companies’ CSR performance is genuinely comparable, the CSRD is based on specific standards that define precise information – that is now audited by an independent third party – which companies must publish. In 2020, while the final text of the CSRD had yet to be finalised, the European Commission entrusted the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), a European association created in 2001 specialising in the production of financial standards, with the task of designing these future CSR standards.

A painful birth

The list of members, of which the author was a part, can be consulted here: “Europe’s voice in corporate reporting”, EFRAG [online].

Among the members selected were a representative of the London Stock Exchange and a representative of American extra-financial rating agency MSCI.

On this subject, see the document “Draft EFRAG Implementation Guidance 3 – List of ESRS datapoints” published by EFRAG at the end of December 2023.

A company whose activities cover several sectors will therefore have to comply with the corresponding sectoral standards.

EFRAG, “Exposure Draft ESRS Oil and Gas As approved by EFRAG SR TEG on 6 June 2024”, 26 June 2024, [online].

Finalizing the directive’s text took months, as stakeholders engaged in power struggles, each striving to include requirements for companies to disclose information on their own priority issues. However, the most complex part of the CSRD to design was not the legislative text itself, but the standards to which it refers (the European Sustainability Reporting Standards, ESRS), the drafting of which was entrusted to EFRAG. To this purpose, a group of 35 members38 representing all the stakeholders (mainly representatives of the world of finance, companies, audit firms, NGOs and some professional organisations) was set up under the leadership a former director of the audit firm Mazars and Chairman of the French Accounting Standards Authority (Autorité des normes comptables, ANC)39.

In May 2022, after two years of work, this group submitted a first version of the project to the European Commission, containing no fewer than 12 standards: 5 for the environment, 4 for social issues, 1 for governance and 2 cross-cutting standards defining the main principles (how to present the business model, how to analyse dual materiality, etc.). A preliminary analysis of these standards revealed that they required companies to provide more than 2,000 different data points. What’s more, the adopted approach required companies to respond to each of these points, unless they could demonstrate that it was not “material” (i.e., not relevant to the company given its activities).

The public consultation following the presentation of these standards generated a great deal of criticism from a number of European states that were particularly up in arms about the bureaucratic nightmare produced by the Commission. In the face of these negative comments, the Commission asked EFRAG to quickly review its copy and simplify the project. On 22 November 2022, EFRAG submitted a second, somewhat simplified version of these standards, with “only” 1,060 data points to be provided. However, this so-called “simplification” did not appease the opposition of some Member States, and the Commission had to rework the whole package. Since there wasn’t enough time to start over, the decision was made to simplify the implementation. Companies would then only have to comply with standards or data considered to be “material”, the Commission having reversed its approach (companies do not adhere to any standard – the two “cross-cutting” ones that are mandatory – unless they indicate that a subject is material, in which case they must fulfil the corresponding standard). Ultimately, there would be only 160 mandatory data items to provide, regardless of the circumstances, and 625 that would only need to be provided depending on their “materiality”, with the remaining 275 being “voluntary40”.

Once again, as with the Taxonomy, companies were given little time to integrate this new standard. The CSRD’s delegated act officially detailing these standards was published on 22 December 2023 in the Official Journal of the EU for implementation from January 1 2024, leaving companies just a few days to implement the new standard. And even though a first practically finalised version of these standards has been circulating since 31 July, companies have been left with less than six months to identify all the data they need to publish. For most of them, this has implied mobilising large teams and urgently turning to consultancy firms for help in rolling out this new reporting process. This represents A significant cost in human and financial resources, poorly estimated by both the legislator and the companies.

Finally, it should be kept in mind that the standardisation steamroller is far from at a standstill, since the CSRD also provides for the establishment of so-called “sectoral standards” and standards for SMEs.

Sectoral standards, defined on a sector-by-sector basis, will complement the 12 “generic” standards, which will be mandatory for all companies operating in the concerned sector41. A means of bypassing the materiality approach defined by the so-called “generic” standards. While these sector standards should –at last – make it easier to facilitate comparisons between similar companies, they risk turning the reporting exercise into a purely formal “checkbox” operation.

This is a far cry from the original approach, which aimed to highlight companies’ performance. Already, the 65-page draft oil & gas standard42 is proving so complex to implement that the Commission has decided to postpone its application for 2 years, attracting strong criticism from academics involved in the project43.

As for the draft standard for SMEs, EFRAG published a proposal open for public consultation from 22 January 2024 to 21 May 2024, which contained no fewer than 400 potential data points to be provided. Once again, EFRAG faced particularly critical feedback, both from SMEs themselves and from the administrations of European States. Ultimately, in response to opposition from the business world, which perceived the standard as incredibly complex for SMEs, EFRAG had to revise its proposal and present a new, simpler draft. The latest version, which has still not been validated, “only” contains 250 data points. EFRAG is due to publish a final version in 2025, which will then have to be validated by the Commission. This will give rise to a delegated act formalising the standard, which will apply to SMEs from 2026 onwards.

A particularly complex application

At an AFEP meeting, one of its members announced that he had had to recruit more than 10 people just for extra-financial reporting.

“Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards”, European Commission, 22 December 2023 [online].

Ibid.

Ibid.

Since the publication of EFRAG’s initial work, companies and European governments have voiced their concerns on the complexity of these standards and their implementation costs. While very large companies may be able to afford creating additional jobs44 to deal with the hundreds of data points required, the reporting burden instantly becomes much heavier for medium-sized companies and SMEs. Moreover, conceptual approaches such as the “business model” or the famous “double materiality” are far from trivial and require knowledge and skills that few companies possess in-house. These are essential since all these elements are mandatory and must be validated by an external third party.

In concrete terms, after defining its business model (a description of the main elements of the company’s general strategy that relate to sustainability issues45), its value chain, and the “interests and views of […] stakeholders” and how they are taken into account in the business model, the company must publish information on its “material impacts, risks and opportunities and how they inform its strategy and business mode46”. The two “transversal” standards that list the mandatory information alone represent no less than 68 pages of text. The 12 standards together make up a 284-page document47.

How did we get here?

This over-representation of audit firms in the PMO is simply due to the fact that most of these firms offered to provide staff pro-bono which the other stakeholders did not do. A golden opportunity for EFRAG, which then had free access to expert teams, including specialists in “standardization”.

From the outset of the project, by entrusting the task of developing sustainability standards to EFRAG and by appointing a former Mazars employee as Chair, the European Commission de facto gave responsibility of the project to “financiers” and audit specialists. This trend was subsequently reinforced by the organisation of the working group itself. In addition to the 35 stakeholders group, a Project Management Office (PMO) was set up. Composed mainly of experts from audit firms48, the PMO was intended to carry out all the administrative and drafting work. A rather interesting role for these audit firms, which were, in a way, creating the standards they would audit a few months later and advising companies on their implementation.

And tomorrow?

Given the complexity of the standards developed by EFRAG, the Commission has largely made them optional, requiring companies to report only on “material” topics. However, there are a number of pitfalls with this approach that can well threaten their relevance.

First of all, the question of materiality is likely to disappear under the impetus of the financial sector. If the optional nature of materiality is implemented too widely, comparability – the initial objective of the CSRD – will quickly become impossible. Moreover, due to pressure from investors and civil society, companies will need to disclose information on nearly all topics covered by these standards, regardless of their materiality.

Not to mention the growing role of non-financial rating agencies, which are hungry for ever more data to produce their assessments.

| Towards a “two-speed” CSR?

The CSRD principle implies that a company must provide the data required by the standards as soon as the subject is considered to be “material”. Until now, however, many companies have communicated on environmental issues – their recycling or water policies, for example – even though these issues were not “material” in the sense of the CSRD, given their activity. Now they are faced with a dilemma. If they address these points in their “sustainability report”, then the auditors consider that it is “material” and they must therefore follow the standard in detail. The other option is not to mention them – because they are not “material” – but in this case they risk being penalised by stakeholders (extra-financial rating agencies, partners, NGOs, etc.) who consider this information to be important. The solution? Produce two reports: a sustainability report that meets the CSRD criteria but is limited to “material” issues, and another report that lists issues that are requested but are not “material” in the sense of the CSRD. |

The French Association of Private Companies.

Esther Attias, « Critères ESG : casse-tête pour les entreprises, jackpot pour les cabinets de conseil et d’audit », Challenges, 29 February 2024 [online].

Laurence Boisseau, « CAC40 : les Big Four et Mazars raflent la mise pour les audits de durabilité », Les Echos, 9 April 2024 [online].

Dr. Volker Wissing, Dr. Jörg Kukies, Dr. Robert Habeck and Hubertus Heil, “Letter to Commissioners Albuquerque and Dombrovskis”, 17 December 2024.

The main consequence of this situation, apart from doubling reporting, is to transform the CSRD into a minimum compliance exercise.

Another key point of the CSRD that is largely overlooked is its cost. Even though the text specifies several times that “sustainability reporting standards should be proportionate and should not impose an unnecessary administrative burden on companies that are required to apply them”, it must be said that this is not the case. Initial estimates given by large companies at AFEP meetings49 suggest that the cost of a CSR audit has increased by a factor of 10 or 15 compared with the previous version (the extra-financial performance declaration, or, EPR). And that is without taking into account the cost of consultancy services to support the urgent implementation of the CSRD50 (see above).

Similarly, the SMEs issue has not really been resolved. Originally, the Commission had simply decided that SMEs would have a specific, “lighter” standard, and commissioned EFRAG to produce it (see above). In reality, however, this proved to be much more complex than expected. In fact, beyond the inherent complexity of the project, of the information requested from large companies also concerns their value chain, in particular their suppliers. There is a real risk that the obligations will “trickle down”, and SMEs rightly fear that they will find themselves inundated with requests for CSR information from their customers, even though the standards initially designed for them did not require them to produce this data.

In conclusion, today, the application of the CSRD remains to a great extent unknown. Medium-sized companies and SMEs are realising the complexity of what will be required of them and the associated cost of applying these standards, at a time when many of them are facing a complicated economic situation. Audit firms are posting numerous job offers across all the social media platforms, realising that while they have indeed created a phenomenal market51, they currently lack the necessary workforce to meet its demands. And finally, law firms that have succeeded in gaining recognition as “sustainability auditors” are eagerly preparing to tap into this new market.

As for the initial idea of a major European regulation, it is proving increasingly illusory. Although the directive of 6 July 2024, requires EU countries to incorporate it into their national laws, only 15 have done so to date, 9 are in the process, and 5 have yet to take any action. Germany, which has not yet transposed the directive, has even caused a stir by sending two successive letters – one on 17 December signed by 4 ministers52 and the other on 2 January signed by the Chancellor – calling for a review and a two-year moratorium on the application of the CSRD53.

The sustainable finance disclosure regulation

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR54) initially went relatively unnoticed, being aimed primarily at European financial institutions.

This text (2019) is based on the observation that the definition of “sustainability” varies, not only from one EU country to another, but between financial institutions. As a result, investors struggle to compare so-called “sustainable financial products,” which could lead to distorted investment decisions.

The SFDR aims to first harmonize the definition of “sustainable investments” and then, in an effort toward transparency, require financial institutions to publish their policy on integrating sustainability considerations in writing. The regulation also requires them to publish a series of 16 mandatory criteria (listed in a technical standards document) for each of their investment products, plus at least two criteria (one environmental and one social) from a list of 33 additional criteria.

Lastly, this regulation has given rise to the creation of three types of investments defined by three articles of the text – Article 6, Article 8 and Article 9 – which specify the principles, ranging from the non-sustainable to the so-called “impact fund”.

The investments identified in Article 6 do not display specific sustainability characteristics. The financial actor behind the investment is simply required to publish information on the likely sustainability risks, based on the expected return.

Investments that comply with Article 8 are those that promote environmental or social characteristics. In this case, financial actors must provide more detailed information, such as how they ensure compliance with these characteristics or the index used as a reference.

Finally, Article 9 investments, known as “impact investments”, are those whose objective is sustainable investment. In addition to the information provided in Article 8, the financial actor must indicate how the index selected is aligned with the sustainability objective selected and how this objective is to be achieved.

While the principle may seem straightforward, the technical features involved in applying the SFDR will soon prove to be simultaneously complex and irrelevant.

A chaotic application

Although the SFDR was adopted in 2019, it did not take effect until March 2021, and its implementation has raised many questions from the start.

Indeed, the 16 implemented indicators are based on data supplied by the companies that make up the financial product (for example, the proportion of hazardous waste in relation to total waste). It is therefore essential that the financial institution has access to this data. However, these technical data were developed in offices without taking into account the relevance of these criteria to business activities. Depending on their sector, some companies did not publish this data, considering it less relevant.

The second major question concerns the two additional criteria that must be chosen by the financial player from a list of 33. Once a criterion has been selected – take the case of “energy consumption by type of non- renewable energy – it is necessary to ensure that the data is available from all the companies involved in the financial product, in order to produce the required data, which can prove complex for financial products that aggregate investments in several dozen listed companies. Conversely, it requires companies wishing to attract financial investors to meet all 33 additional criteria.

This might be relevant had the SFDR’s technical criteria corresponded to data that companies were required to provide on an almost universal basis, for example key CSRD data. However, this is not the case. Although the CSRD has attempted to integrate most of these criteria into its own standards, the “material” aspect of the application of the CSRD means that companies are not obliged to produce this data. As a result, financial players find themselves at a disadvantage they are legally obliged to produce information they do not have access to for their clients.

Not to mention the fact that many of these criteria, drawn up without consulting companies, are of little relevance from a CSR point of view, as they are completely disconnected from the activity of the company to which they apply. For example, companies are asked to indicate the volume of hazardous or radioactive waste produced, regardless of activity, or “the presence of mechanisms to monitor compliance with the principles of the United Nations Global Compact55”, though only a limited number of companies in Europe have signed up to this UN initiative, which is voluntary and subject to a fee.

A surprising result, to say the least

The application of the SFDR has not failed to surprise both the financial community and CSR specialists. Indeed, as Le Monde pointed out in November 2022, a significant proportion of so-called “Article 9” funds were invested in activities linked to the fossil fuel industries56. A few months later, a third of these funds were downgraded by their creators to “Article 8”57. This classification is the result of a broader interpretation of a regulation that is so technically complex that it loses its purpose. What’s more, from 2023 onwards, the obligation for management companies to provide extra-financial indicators – which are still difficult to obtain for some – has accentuated this wave of downgrading funds from article 9 to article 8, creating even more confusion among investors.

Another factor overlooked by European legislators is perception. Indeed, “Article 9” impact investments aim to promote the financing of activities with a sustainability objective, regardless of other factors. To exaggerate: for example, if a plastic chemical manufacturer commits to biodiversity conservation on its sites, it could still be included in a biodiversity impact fund, despite its potential negative impact on climate or the environment.

And tomorrow?

From the moment it was introduced, the SFDR faced strong opposition from all sides. While the financial players complain about its complexity and the constraints it imposes, the defenders of the environment and major social issues are astonished at the results obtained from its application.

Today, the SFDR, which was intended to be primarily an investor information regulation, has become, in spite of itself, a system for the “labelling” of financial markets.

This is to the great displeasure of the European Commission and Member States, which are seeing their own CSR labels (such as the French SRI label) become inaudible.

More embarrassingly, financiers themselves now seem to be losing interest in CSR investments. An analysis of investment typologies by Morningstar58 reveals that over the third quarter of 2024, “Article 6” funds (i.e. those with no CSR objective) continue to attract the largest investment flows (96 billion euros in the third quarter), far ahead of “Article 8” funds (38 billion euros). As for “Article 9” funds category, they have been subject to continuous disinvestment over the last few months, losing 6.5 billion euros in the second quarter and 2.2 billion euros in the third quarter. This results in an outcome that is the opposite of what the SFDR intended.

Quickly made aware of the SFDR’s imperfections, the European Commission launched a large stakeholder consultation59 in 2023 to see how it could be improved. The objective was to assess the compatibility issues encountered by economic players between the SFDR and other major regulations (EU Green Taxonomy and CSRD).

From green finance to sustainability… a complex journey

“We need to achieve the most unified regulation possible in Europe,

instead of a proliferation of standards, including, to name just a few,

the SFDR regulation, the CSRD directives, and the CSDDD […]. Each

of these texts, often coming from different bodies, was a very legitimate

progress in its time; but today, their accumulation clearly lacks

coherence”.

François Villeroy de Galhau, Governor of the Banque de France,

ACPR conference, 26 November 2024.

Initially, a very self-interested agreement

According to La Lettre de l’Expansion on 15 January 2024, in 2023 the world’s largest banks generated 3 billion euros in fees by granting 583 billion euros in greenbonds and loans. BNP came out on top with 130 million euros in fees, followed by Crédit Agricole with 96 million euros.

Why has green finance become such an important part of the economy? Although there was initially a political will to direct investments toward more environmentally friendly activities to finance the energy transition, its success has primarily been driven by the enormous commercial opportunity for two key players: the finance industry and the auditing sector.

The 2008 financial crisis weakened the financial sector, not only economically (many banks posted huge losses), but also in terms of reputation. So much so, in fact, that one presidential candidate in 2012 had no hesitation in publicly stating: “My real adversary is the world of finance60”. Against this backdrop, political pressure, particularly at the European level, for the development of sustainable finance appeared to be an unhoped-for opportunity. By taking an active stance in this new area, financial institutions were able to clear their consciences – the money was no longer “dirty”, but serving a good cause – and, above all, they were able to “make up for it” by charging higher fees. Indeed, although it is rarely pointed out, the fees charged to investors who buy green funds are generally much higher than those charged for traditional funds61, on the pretext that the production of these funds requires specific know-how and expertise.

As for the audit sector, aware of the opportunity offered by this new concept, it mobilised all its forces and skills to work towards the construction of the standards and regulations that would structure this sustainable finance. As we have seen, the results of this investment were well worth the effort. A new market has suddenly opened up, with – as mentioned above – fees in the CSR field increasing by a factor of 10 or 15.

Standards war: in the end, European companies lose out

In particular, the structure of EFRAG’s ESRS “E1 Climate Change” standard has been remodelled to correspond to that of its ISSB counterpart (IFRS S2 Climate related disclosure).

Emmanuel Faber, « Exiger que la matérialité s’étende au-delà du domaine économique est en réalité simpliste », Le Monde, 10 October 2023 [online].

Faced with the regulatory cathedral being built by the European Union, the rest of the world has not been idle, and the counter-attack has been swift. It was led by the International Sustainability Standard Board (ISSB) – the CSR offshoot of the all-powerful International Financial Reporting Standards Board (IFRS), the international designer of financial rules.

Under the leadership of Emmanuel Faber, former Chairman and CEO of Danone, the ISSB has produced its own standard with a clear objective: to become the benchmark CSR standard for investors worldwide (especially in the Anglo-Saxon world). To achieve this goal, the ISSB’s approach has been simple and the opposite of that of EFRAG. While Europeans struggled to design a Kafkaesque regulatory environment, the Anglo-Saxons produced a simpler standard that would be implemented progressively, with the first part dealing solely with climate issues.

Recognizing the risk of being reduced to mandatory standards that lacked interest for companies, EFRAG made several attempts to engage with the ISSB to find common ground or, at the very least, ensure that most of the data requested from companies by the ESRS and the ISSB would align on climate-related issues. It must be acknowledged that these efforts were in vain. Admittedly, the ISSB listened to the EFRAG’s proposals, but ultimately did what it wanted, often forcing Europe to adapt its standard to limit divergences62.

The most recent manifestation of this standards war was a fairly virulent exchange of views between the ISSB and EFRAG in a series of articles published in the media. While Mr. Faber criticized the principle of double materiality63, which underpins the CSRD, as “simplistic” and inapplicable in Le Monde, Mr. Jancovici, the media-savvy CEO of Carbone4, sharply responded on LinkedIn. He emphasized that the ISSB’s approach would ultimately imply that “the company is not accountable to society as a whole, but only to its shareholders.”

This exchange between “experts” might make you smile if it didn’t have so much impact on European companies. On the one hand, they will be legally obliged to meet the CSRD obligations, and on the other, under pressure from their Anglo-Saxon investors, who have a strong presence in Europe and who, let us not forget, own around 40% of the CAC4064, they will also be obliged to meet the ISSB standards.

What can we do now?

“The confusion is exacerbated by the lack of a link between the SFDR regulation and the taxonomy. The definition of sustainability differs between the two texts, with the result that a financial product can be considered sustainable under the SFDR regulation without making any investment in activities aligned with the taxonomy”, “Le rapport public annuel 2024. L’action publique en faveur de l’adaptation au changement climatique. Volume 1”, Cour des Comptes, 13 February 2024, p 186 [online].

Enantiodromia or “running in the opposite direction”, imagined by Heraclitus and taken up by Jung, is the evil of a utopia that achieves the opposite of its stated objective through a lack of realism.

« Nous, Européens, ont besoin du nucléaire », Le Figaro, op. cit.

We urgently need to get back to the basics of sustainable finance. It is not a question of producing a profusion of data to enrich audit and consultancy firms, or to please extra-financial rating agencies, NGOs and financial analysts who are always looking for “innovative” models to justify the advice they give. We need to make our companies stronger and more virtuous in order to ensure the sustainable development of our European economies.

As a first step, it is vital that the Commission gets the authors of the legislative texts to work together. It is incomprehensible that the texts on which European green finance is based define “green” in different ways. For example, the SFDR makes it possible to promote a “green” fund (i.e. Article 8 or Article 9) even if it does not contain any activities that are “aligned” according to the Taxonomy65.

Secondly, it is necessary to break free from the enantiodromia66 phenomenon which, through excessive ideology and administrative complexity, is leading the European Union to the opposite of what is expected. It is essential to simplify legislation as fast as possible, and to introduce a gradual approach to its application. While the Anglo-Saxon approach is pragmatic—starting with a strong focus on combating global warming and gradually expanding into a broader environmental framework—Europeans initially envisioned an intricate “cathedral,” only to later realize its impracticality. So they rushed to simplify it, aware of the risks it posed to the economy. The result has been widespread dissatisfaction—companies feel they have wasted time navigating overly complex regulations, while stakeholders, rightly feeling betrayed by unfulfilled promises of transparency, are now protesting against rampant greenwashing.

Finally, and crucially, we must have confidence in economic players, as Florent Menegaux, Chairman of Michelin67 pointed out. The current approach, characterised by a great deal of bureaucracy and a constant call for transparency as a guarantee of corporate integrity, reflects the growing mistrust of European decision-makers towards the economic world. According to this perspective, additional regulations are necessary to provide a framework for companies perceived as primarily profit-driven. This outdated view remains prevalent in European institutions. Not only is it largely flawed in practice (if transparency were a guarantee of honesty, we would already know it), but it also leads to an endless and costly pursuit of ever-increasing transparency, which quickly becomes counterproductive and ultimately erodes trust among all stakeholders. A recent German study68 even shows that companies with higher ratings from non-financial rating agencies are more likely to be accused of greenwashing.

In conclusion, it’s uncertain whether these regulations will make Europe more sustainable or more sovereign. However, the constraints they impose on the economy and citizens are turning environmental issues into sources of frustration, driving extreme political support. The recent European elections are a clear example of this.

Beyond the political consequences of an environmental policy that often seems disconnected from reality, there’s a deeper question raised by the failure of key sustainable finance texts, such as the CSRD and SFDR: should sustainability issues really be entrusted to financiers? This is far from certain, given that the worlds of finance and sustainability have very different objectives.

No comments.