Fratelli d'Italia : neo-fascist heritage, populism and conservatism

Introduction

The debate over fratelli d’Italia’s political identity

The long march of the Italian “right” since 1945

The strategy of right-wing integration: the Movimento sociale italiano (MSI)

The refocusing strategy. Gianfranco Fini and Alleanza nazionale

Populist strategy: Matteo Salvini’s Lega

From the Popolo della Libertà split to power: the meteoric rise of Giorgia Meloni

Today, what is the ideological, organisational and European situation ?

On an ideological level

At organizational level

At European level

Appendix I

Summary

In Italy, on September 25, 2022, Fratelli d’Italia won the parliamentary elections as part of a coalition of the right (Italians call it coalizione di centro-destra, i.e. “center-right coalition”), comprising Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and Matteo Salvini’s Lega. This victory resulted in the investiture of the government led by Giorgia Meloni.

Fratelli d’Italia’s anticipated electoral success has sparked renewed interest in the party from the academic world, especially with regard to the identity of this political force.

Could this be the latest expression of a political family rooted in the fascist experiment that began a century earlier, or could it be a populist radical right that has been on the rise in Europe since the 1990s, or a novel, hybrid party combining elements of the old neo- fascist far right, right-wing populism and contemporary conservatism?

Marco Tarchi takes stock of the current debate, analyzing the origins and history of this party, as well as the factors of continuity and contrast with its political predecessors, the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) and the Alleanza Nazionale (AN). The author also highlights the factors behind Fratelli d’Italia’s rise to power, and the ideological, organizational and European challenges it now faces.

Marco Tarchi,

Professor of political theory and political communication at the Cesare Alfieri School of Political Science at the University of Florence.

The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW)

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

The Netherlands: The Populist Temptation

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

2022, French presidential election impacted by crises

Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

Source :

Statue of Dioscurus, Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, EUR, Rome, Italy, 1938-1943.

Francesco Boezi, Fenomeno Meloni. Viaggio nella « generazione Atreju », Gondolin, Verona 2020 ; Fabrizio Frullani, Da destra a destra. Storia, scena e retroscena del cammino di Fratelli d’Italia, Secop, Corato 2020; Francesco Giubilei, Giorgia Meloni. La rivoluzione dei conservatori, Giubilei-Regnani, Roma-Cesena 2020 ; Claudio Sabelli Fioretti, Giorgia on my mind. Le parole della leader della destra italiana, Aliberti, Reggio Emilia, 2022. Luigi Copertino’s view is more critical, Le colpe dei padri e le ambiguità dei figli. Il peccato originale della destra italiana, La Vela, Lucques, 2022, particularly pages 61-106. After the elections, this literary genre has been joined by a denigrating one with Andrea Palladino, Meloni segreta, Ponte alle Grazie, Milan, 2023.

Giorgia Meloni, Io sono Giorgia, Rizzoli, Milan, 2021, and for the French edition: Giorgia Meloni, Mon itinéraire. Autobiographie d’une leader politique conservatrice, Chora, 2022.

See Marco Tarchi, “Voters without a Party: the ‘Long Decade’ of the Italian Centre-Right and its Uncertain Future”, in South European Society and Politics, XXIII, 1, 2018, pp. 147-162; Elisabetta De Giorgi and Filippo Tronconi, “The Centre-right in a Search for Unity and the Re-emergence of the Neo-Fascist Right”, in Contemporary Italian Politics, X, 4, 2018, pp. 330-345; Pietro Castelli Gattinara and Caterina Froio, “Italy: the mainstream right and its allies”, 1994-2018, in Tim Bale and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (EDS.), Riding the Populist Wave. Europe’ Mainstream Right in Crisis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2021, pp. 170-192; Mattia Zulianello, “Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems” in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries”, in Government and Opposition, LV, 2, 2020, pp. 327-347.

See Leonardo Puleo and Gianluca Piccolino, “Back to the Post Fascist Past or Landing in the Populist Radical Right? The Brothers of Italy Between Continuity and Change”, in South European Society & Politics, 2022, pp. 1-25 [online]; Alessia Donà, “The Rise of the Radical Right in Italy: The Case of Fratelli d’Italia”, in Journal of Modern Italian Studies, XXVII, 5, 2022, pp. 775-794; Sofia Ventura, Giorgia Meloni e Fratelli d’Italia. Un partito personalizzato tra destra estrema e destra radicale, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Italia, s.l. 2022; Gianfranco Baldini, Filippo Tronconi and Davide Angelucci, “Yet Another Populist Party? Understanding the Rise of Brothers of Italy”, in South European Society & Politics, 2023, [online]; Joanna Sondel-Cedarmas, “Giorgia Meloni’s new Europe. Europe of sovereign nations in the Brothers of Italy party manifestos”, in Joanna Sondel-Cedarmas and Francesco Berti (eds.), The right-wing critique of Europe: nationalist, sovereignist and right-wing populist attitudes to the EU, Routledge, Abingdon, NY 2022, pp. 60-75; Marco Valbruzzi and Sofia Ventura, Fratelli d’Italia and Lega. Diversamente populisti di destra, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Italia, s.l. 2023; Davide Vampa, Brothers of Italy. A New Populist Wave in an Unstable Party System, Palgrave Macmillan, London 2023; Salvatore Vassallo and Rinaldo Vignati, Fratelli di Giorgia. Il partito della destra nazional-conservatrice, il Mulino, Bologna, 2023; Piero Ignazi, “Postfazione. L’altalenante percorso della Fiamma 1990-2022”, in Piero Ignazi, Il polo escluso. Profilo del Movimento Sociale Italiano, third edition, il Mulino, Bologna, 2023, esp. pp. 439-452.

Predictably, the success of the Italian parliamentary elections of September 25, 2022 (26% of the vote, 118 deputies and 66 senators elected) and the appointment of its leader Giorgia Meloni as Prime Minister, prompted academic interest in the Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) party, well after the media spotlight. Up until a year before the election, the production of books and articles on the subject had been limited to journalistic pieces, in some cases with apologetic or propagandistic intentions1, and to the autobiography of the main character2 in the rise of a party that – at least until 2019 – had been considered by observers as marginal and destined to play a secondary role not only within the Italian political system, but also within the center-right coalition, which was then led by Matteo Salvini’s Lega.

In the scientific sphere, citations had been few and far between, and more often than not limited to quick mentions in articles of a more general scope3. By contrast, the formation of the government led by Giorgia Meloni triggered a major flowering of contributions – books and articles published in international journals4 – which opened up an initial series of debates on the party’s still brief history, the reasons for its birth and the factors that enabled it to become Italy’s favorite party in less than ten years.

The debate over fratelli d’Italia’s political identity

There is now a vast scientific literature on this type of party. It was inaugurated by Hans-Georg Betz, Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe, Palgrave macmillan, London, 1994.

See Piero Ignazi, op. cit. p. 12. In the preface to the volume, Ignazi describes the founders of Fratelli d’Italia as those who did not accept the “concealment” of the original ideology and decided to “rekindle the flame”, reproducing the “mimesis” based on the “underestimation and euphemization of the Fascist regime”.

Ibid, pp. 441, 443-445, 449.

Salvatore Vassallo and Rinaldo Vignati, op. cit. p. 16-17. This term was also adopted by the author of this article in Marco Tarchi and Antonio Carioti, Le tre età della Fiamma. Da Giorgio Almirante a Giorgia Meloni, Solferino, Milan, 2024.

The discussion focused on FdI’s identity, the ideological foundations of its political discourse and the content of its programs. With an underlying question: are we dealing with a party that is at least partially new, or simply the most recent and most modern representative of a tradition that has its roots in a chapter of Italian history opened a century ago by the advent of fascism? Or, to put it another way, does Fratelli d’Italia still belong to the realm of neo-fascism, or should it be considered a representative of the populist radical right? Or should it be seen as the expression of a new, hybrid genre, combining certain aspects of the old extreme right, others of the national-populism that has flourished in almost all European countries since the 1990s5 and still others of conservatism?

Proponents of the first hypothesis point out that many of the party’s cadres – its president, over three-quarters of the members of the governing bodies, numerous representatives in Parliament and in regional and municipal councils – come from the Movimento sociale italiano (MSI) or Alleanza nazionale (AN), which succeeded it in 1995, and that, in the official speeches of its president, even since she became head of government, there are frequent references to the “long history” to which FdI is heir. What’s more, the party’s current headquarters have the same address as its predecessors, at 39 Via della Scrofa in Rome, and even in the rest of Italy, in many cases its federations and sections have remained, or returned, to the premises where Alleanza nazionale used to be. For some observers, these elements are enough to establish a relationship of substantial continuity between the present and the past. And even the first academic to approach the study of the MSI scientifically in 1989, Bologna University political scientist Piero Ignazi, by examining Fratelli d’Italia documents and programs, supports this interpretation.

In the afterword to the recent new edition of his best-known book, Il polo escluso, in which he attempts to summarize the developments of the Italian “national right” over the last thirty-three years (from 1990 to 2022), Ignazi asserts that Giorgia Meloni’s party is nothing more than the product of MSI nostalgists6 who, without openly declaring it, simply aim to resurrect Alleanza nazionale (AN). The stages of its journey from December 2012 to the present day are seen as so many steps on the “road of a more or less veiled nostalgism, sprinkled with abundant doses of eurosceptic sovereignism and xenophobic and security impulses”. According to Ignazi, the theses expressed in the motion of the party’s second congress in 2017 (to which we shall return) “denote an intimate sentimental and ideological harmony with neo-fascism, from which an ideal continuity is claimed”. And this “irresolute relationship with the past” is something the party would not rid itself of even in the following decade, continuing to display a “populist, conspiratorial vision” and an “illiberal substratum”, which the “seductive use of the figure of Giorgia Meloni, a devoted, convinced and passionate political representative, but overflowing with maternal and friendly feelings” would only serve to conceal.

Piero Ignazi acknowledges that the FdI has undergone a change in its transition from an oppositional role to that of governmental responsibilities, however he considers that this change could be “instrumental and conjunctural”. And, consequently, in his interpretation, he highlights what he sees as the “revanchist, even nostalgic tone, typical of a community that still feels loyal to the ‘Idea’, i.e. fascist ideology, more or less recalibrated in the post-war period”, speeches that would have characterized the convention with which Fratelli d’Italia, on December 14, 2022, celebrated its first ten years of existence and the “politico-ideal continuity with the MSI, idealized as a democratic party” whereas, writes the academic, it “had been rightly defined by the master of political science Giovanni Sartori as an ‘anti-system’ party7“.

Another argument often cited in the debate on Fratelli d’Italia’s ideological connotations is the presence, in its symbol, of the tricolor flame, which the MSI adopted from the outset and which, despite strong internal debate and external pressure, Alleanza nazionale maintained until its leader Gianfranco Fini decided to dissolve it to merge into Popolo della libertà, the short-lived center-right single party wanted and led by Silvio Berlusconi. Even those who acknowledge the party’s evolution over its ten years of existence can’t help but notice that, again because of this characteristic, the FdI doesn’t fail to be described as “the third party of the flame”8 and therefore linked, to some extent, to the events of Italian neo-fascism. The assertion is undoubtedly acceptable, but to understand whether Fratelli d’Italia has succeeded in emancipating itself from the history to which it belongs, and, if so, how and why, it is necessary to examine the complex trajectory of its “ancestors” in post-war Italy.

The long march of the Italian “right” since 1945

See Marco Tarchi, Esuli in patria. I fascisti nell’Italia repubblicana, Guanda, Parma, 1995.

For over fifty years, the term “neo-fascism” was used almost exclusively in Italy to characterize the political current which, in other countries, was called “extreme right”. This name was intended to circumscribe the dimension of the phenomenon to a desire for revenge, or at least vengeance, on the part of those who had been defeated in the civil war that had bloodied the country from September 1943 to April 1945 and who felt, in the new republican state, in the psychological condition of “exiles in their homeland”9.

The strategy of right-wing integration: the Movimento sociale italiano (MSI)

See Sandro Setta, L’Uomo Qualunque (1944-1948), Laterza, Bari, 1975; Marco Tarchi, Italia populista. Dal qualunquismo a Beppe Grillo, il Mulino, Bologna, 2015.

See Angelo Michele Imbriani, Vento del Sud. Moderati, reactionari, qualunquisti (1943-1948), il Mulino, Bologna, 1996.

In this study, when the type of election is not specified, it refers to the election of the Chamber of Deputies.

See Giuseppe Parlato, La fiamma dimezzata. Almirante e la scissione di Democrazia Nazionale, Luni, Milan, 2017.

See Marco Tarchi, Cinquant’anni di nostalgia. La destra italiana dopo il fascismo, Rizzoli, Milan, 1995.

With the definitive fall of fascism and the death of Mussolini, all that remained was to cultivate nostalgia for a bygone era, or to isolate themselves in resentment and a vain desire for revenge. On December 26, 1946, the birth of the Movimento sociale italiano offered a home to those tens of thousands of ex-servicemen who had been on the “wrong side”, the losing side, during the civil war, despite being unable, from the very first parliamentary elections on April 18, 1948, to win the votes of most of the many Italians who had shown their support for Mussolini right up to the fall of the regime – and who, at the first signs of the Cold War, had decided to support the Christian Democracy (CD) to create a “dam” against communism. The DC succeeded in giving this niche of irreducible posthumous followers of the Duce institutional representation by bringing a handful of deputies and senators into parliament.

The collapse of fascism, however, had another crucial political effect: it wiped out the “constitutional” right, heir to one of the many political traditions that had animated the Risorgimento, whose representatives, faced with the impetuous advance of the Fascists and the establishment of the authoritarian state, had withdrawn from public life or accepted a role as supporters of the regime. Accused of having compromised with the dictatorship, or of having favored its advent, moderate liberals and conservatives had all but disappeared from the scene. The republican political system was thus set up on a new basis, centered mainly around a centrist party with a relative majority, the Christian Democracy (DC), a clearly left-wing opposition party, the Italian Communist Party (PCI), the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), less radical and less strong, and a small number of minor formations, including the Republicans and the Social Democrats, destined to play the role of allies or rivals of the Christian Democracy according to circumstances and the convenience of the majority party. More or less ephemeral formations – from the Fronte dell’Uomo Qualunque (Front of the Ordinary Man), the first representative of the rich progeny of Italian populism10, to the various monarchist parties11 – gradually inserted themselves into the narrow space of the right, without ever being able to exert any real influence on the governmental dynamic. It was only at the cost of numerous internal discussions, rifts and splits, provoked by the refusal of many of its representatives to conclude agreements with the “traitors” who, in 1943, had preferred the King to Mussolini, or to soften hostility towards former overseas enemies in the name of the “defense of the West”, and to accept Italy’s membership of NATO, that the MSI succeeded, in the early 1950s, in integrating itself into this space.

For half a century, the MSI thus exercised a substantial monopoly on the political-electoral space of the right, without however succeeding in shedding the label of extremism that its opponents had attached to it. Efforts by its moderate leader Arturo Michelini (who remained at the head of the party from 1954 to 1969) to forge an alliance with the liberals and monarchists and give life to the so-called “Great Right” failed, as did attempts to include it, in an anti-communist function, in government coalitions dominated by the DC. On some occasions, the Christian Democrats accepted MSI votes in Parliament to counterbalance the temporary defection of some of their government allies and succeed in passing controversial legislation, but when the support of MSI deputies and senators proved indispensable for the launch of the one-color cabinet headed by Fernando Tambroni in the spring of 1960, the Christian Democrats preferred to force the head of government to resign and pave the way for the first center-left coalition with the Socialists. The fear of being accused of collusion with the fascists was too great.

These failures gave rise to fierce controversy within the MSI, sometimes leading to splits among its more radical components. However, none of the groups that attempted to challenge the MSI’s domination of its usual “hunting ground” over the decades ever managed to gain a firm foothold in the territory or a significant number of voters (moreover, few attempted to face up to the test of the ballot box), prompting most of them to turn to violent forms of action or to cultivate coup d’état projects. The 1970s, known as the “years of lead”, saw some of these small movements involved in what is known as the “strategy of tension”, between terrorist episodes and collusion with “deviant” sectors of the state security apparatus.

From the 1960s onwards, the MSI sought to accentuate its references to the right, to the point of changing its name and symbol in 1971 to become the Movimento Sociale Italiano-Destra nazionale (MSI-DN), in order to absorb what remained of the last monarchist party. Although it continued to win representatives in parliament and local councils at every election, and increasingly toned down its overt references to fascism, now limited to the rhetoric used in meetings with the militant base and at congresses, it failed to emerge from its marginality in the Italian political scenario. Even the militant renewal introduced by Giorgio Almirante’s secretariat (which lasted from 1969 to 1987) failed to break its isolation, which confined it to electoral support of around 5-6% – with the sole exception of the 8,7% in 197212 – at a time when, in other European countries, far-right political formations such as Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National in France and Jörg Haider’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs in Austria were beginning to renew their programs and broaden their electoral base. And this long period of stalemate gave rise to new internal clashes, this time with the more moderate current that wanted to transform the party into a “normal” right-wing liberal-conservative formation, resulting in the split, at the end of 1976, of half the members of the parliamentary groups in the Chamber and Senate and the birth of Democrazia Nazionale, destined to disappear after just three years, due to the derisory 0.6% obtained in the 1979 elections13. From then until the early 1990s, the MSI went through a long phase of political and electoral stagnation, despite two changes of national secretary (Gianfranco Fini from 1987 to 1990, Pino Rauti in 1990-1991, then Fini again)14.

The refocusing strategy. Gianfranco Fini and Alleanza nazionale

See Roberto Chiarini, “La destra italiana. Il paradosso di una identità illegittima”, in Italia contemporanea, 185, 1991, pp. 581-600.

See Marco Tarchi, Dal Msi ad An. Organizzazione e strategie, il Mulino, Bologna 1997.

Piero Ignazi, L’estrema destra in Europa, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2000 [1994], p. 56.

See Piero Ignazi, Postfascisti?, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1994.

See Herbert Kitschelt, The Radical Right in Western Europe, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1995; Jeffrey Kaplan and Leonard Weinberg, The Emergence of a Euro-American Radical Right, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick-London 1998. The term was originally reserved for studies of the American scenario: see Daniel Bell (ed.), The Radical Right, Doubleday Anchor Books, Garden City, N.Y. 1963.

Piero Ignazi, Il polo escluso. Profilo del Movimento Sociale Italiano, third edition, il Mulino, Bologna, 2023, p. 422.

At the Alleanza Nazionale program conference, held in Verona from February 27 to March 1st 1998, the day after Fini’s speech proclaiming the end of the era of confrontation between fascists and communists, Berlusconi distributed a copy of Libro nero del comunismo (The Black Book of Communism), just published by the Mondadori publishing house he controlled, and delivered a rousing speech against the crimes of his political enemies, claiming that their democratic evolution was only apparent.

It took the crisis of the traditional parties that followed the Tangentopoli scandal (the discovery by the Milanese judiciary of a vast network of administrative corruption and a system of illegal party financing) to change this state of affairs and inaugurate a new chapter in the history of the right in Italy. The discrediting of the parties that had governed the country for almost fifty years turned what had been the MSI’s weakness – its long distance from the places of power – into a point of strength, enabling it to claim its “clean hands” in the face of the dishonesty of the rest of the political class. Thanks to the first notable electoral successes in a series of municipal elections in 1993, the party, which had always suffered from the weight of its “illegitimate identity”15, finally succeeded a year later, after Berlusconi’s entry onto the scene as federator of a broad front of forces hostile to the left and the adoption of a new electoral law, to obtain a role in the government, subsequently changing its name to Alleanza nazionale and further accentuating its distancing from fascism16.

While this was happening in Italy, in other European countries, what Ignazi proposed to call the “post-industrial far right” was taking shape, unlike the “traditional” far right still linked to the memory and cult of fascism. While continuing to believe that certain anti-system traits and an ideology delegitimizing liberal democracy are present in the parties belonging to this family, Ignazi believes that they cannot be seen as “a revitalization of the ‘palingenic myth’ of fascism [as] they offer a response to the conflicts of contemporary society (this is the key to their success)”. For these groups, “the defense of the natural community against foreign presence (hence racism and xenophobia) is first and foremost an identity-based response to atomization and depersonalization ; the invocation of law and order, the direct appeal to the people and annoyance with representative mechanisms respond to the need for authority and guidance in a society where self- realization and individualism have torn the protective mesh of traditional social bonds; the recovery of traditional moral values is the response to post-materialist libertarianism17“.

A direct heir to the MSI, according to Ignazi, Alleanza nazionale had not adopted this innovative form, remaining in the limbo of a “post-fascism” whose contours were still uncertain18 and which would only later lead to a genuine evolution in relation to its original positions. Its emergence, however, put an end to the long period of neo-fascism’s monopoly on the far right, and revealed a scenario characterized by three distinct and competing paths of development of what academic literature has termed right-wing radicalism19: ideological fundamentalism combined with populism and national-conservatism.

Since the Fiuggi congress in January 1995, when it was decided to dissolve the MSI, the first of these paths has been taken by all those groups who have refused to abandon their identification with the fascist experience and who, despite the continuous and intense mobilization of their militant base, have been unable to break through the cordon sanitaire erected by the other political forces, or to emerge from marginality. The flagrant inconsistency of their electoral base (the lists linked to this political field, as a whole, did not exceed 1.3% in the 2018 legislative elections) marked the definitive defeat of this option. The other two had to wait for Alleanza Nazionale’s initial surge to fade before they could be more clearly delineated.

Between 1995 and 2009, the right-wing’s electoral space in the Italian system expanded to exceed the 15% threshold (15.7% in 1996, plus the 0.9% of competitors from Movimento Sociale-Fiamma Tricolore, a small nostalgic party led by former MSI secretary Pino Rauti), but at the same time its political influence, which at the start of Tangentopoli had appeared to be growing strongly (the MSI was able to exceed 30% in the municipal elections in Rome and Naples and win thirty-three municipal administrations in towns with more than 15,000 inhabitants between spring and autumn 1993), shrank. Although admitted in 1994 to the coalition that Berlusconi had created in order to defeat the union of left- wing forces, Alleanza Nazionale suffered from the outset from being a “junior partner” in this alliance, due to the greater electoral strength of Forza Italia and, above all, the preponderance of the Prime Minister’s media persona. While joining the government with five ministers and twelve under-secretaries of state was a major success, marking the end of the neo-fascists’ exclusion from the power game, managing relations with the allies proved no easy task. The greatest friction was with the Lega Nord, whose federalist program – the expression of a secessionist ideology – contrasted sharply with the nationalism and centralism of Alleanza Nazionale, but also with the ex-Christian Democrat component and with Forza Italia, where disagreements arose from time to time.

As early as 1996, certain strategic divergences between the members of the coalition became apparent. Fini, who was tending more and more to personalize his leadership and govern the party alone, making use of the extremely extensive powers conferred on him by the statute, without taking into account the – often divergent – demands of the internal currents, opposed Berlusconi’s choice to allow the birth of a technical government supported by almost all the groups present in Parliament, and preferred to provoke early legislative elections, in the hope of obtaining a result that would challenge the position of the founder of Forza Italia as absolute leader of the coalition. The manoeuvre failed, but AN achieved a historic score, with 15.7% of the votes cast, and its president then decided to make direct competition with Forza Italia even more obvious. To this end, writes Ignazi, he “emphasized a certain distance and separation from his own party in order to maximize politically the success of the image he enjoyed”20 and multiplied opportunities for contestation. In other words, to avoid suffering the consequences of his image as an extreme member of the alliance, he decided to bring his party closer to the center. Berlusconi’s response was to radicalize his criticism of the left, with whom Fini was seeking to establish a dialogue to achieve a shared reform of the institutions in the presidential sense, presenting himself as the real bulwark against the former Communists’ conquest of power21.

From then on, personal relations between the two men also began to sour, while within the party the gap widened between a liberal inspiration, favorable to privatizations and the laws of the market, and a “social” inspiration, in which distrust of capitalism persisted. Fini’s strategy suffered two defeats in 1999; firstly, in the referendum on the electoral law which, by definitively eliminating the proportional allocation of a proportion of parliamentary seats, would have made Alleanza nazionale indispensable – and therefore influential – in any future center-right coalition; and secondly, in the European elections, where Alleanza nazionale renounced its symbol to present a list including representatives of the People’s Party, heir to the DC, and the Radical Party, known for its progressive positions, thus losing a third of the voters it had won five years earlier.

Despite the centre-right’s success in the 2001 parliamentary elections (49.6% of votes cast) and the return to government, in which Fini was entrusted with the vice-presidency, the project cultivated by the president of Alleanza nazionale made no headway. His party fell to 12%, while the reintegration of Lega Nord into the coalition, after the harsh confrontation of previous years, further complicated agreements on the political and economic/social line to be followed. Confrontations between the two parties became frequent, forcing Berlusconi to change the composition of the executive in July 2004 and again ask Parliament for a vote of confidence. In the meantime, the leader of Alleanza Nazionale found new ways to accentuate his distancing from the ideas to which the majority of his party’s members had remained attached: for example, Gianfranco Fini proposed granting immigrants the right to vote in local elections, then, during a trip to Israel, describing the post-1938 period of the Fascist regime, in particular its racial laws, as “absolute evil”, and defending medically-assisted procreation while the Vatican was against it. These proposals sounded like a break with the ideological and cultural tradition from which AN had emerged, and were seen as such by many members of the party leadership, accentuating the internal rift. Without yielding to the appeals of dissidents, Fini continued along the path of rapprochement with European liberal-conservative circles, citing José María Aznar, Nicolas Sarkozy and David Cameron as models of a modern right-wing, even if this meant provoking a more significant split than the previous ones, that of La Destra, which obtained a score of 2.8% in the 2008 legislative elections.

Fini’s return to government following the center-right coalition’s success in the 2008 elections did not help matters. In November 2007, Fini publicly threatened to abandon the alliance, denouncing its inability to tackle the most pressing issues of the day. The same day, Berlusconi responded by announcing, without any prior consultation, the creation of a new party, the Popolo della libertà (PdL). Initially, Fini’s reaction was harsh, and included an attempt to create an alternative party, the Alliance for Italy, but the fall of the Prodi government prevented the operation from succeeding and, given the tight schedule of the forthcoming election campaign, forced him to join the cartel wanted by the Cavaliere. In the meantime, the Fare Futuro foundation, set up by the party’s liberal wing, continued to establish contacts with leading figures from the center and the moderate left, with the aim of finding interlocutors willing to legitimize Fini as Berlusconi’s successor at the head of the moderate camp. By choosing to be elected president of the Chamber of Deputies, the former president of Alleanza Nazionale wanted to assume a super partes profile, increasingly opposing him to the controversial figure of his ally-adversary far from the institutional “bon ton”. Clashes became so frequent that relations between the two men broke down for good: after a heated quarrel, Fini was expelled from the PdL and set up first his own parliamentary group, then a party, Futuro e Libertà per l’Italia (FLI), in an unsuccessful attempt to challenge the government in which he had participated. Many Alleanza Nazionale MPs and senators did not follow him, however, and FLI survived on the bangs of the system until the 2013 elections, when it suffered a resounding defeat, garnering just 0.47%, despite its participation in the centrist coalition led by outgoing Prime Minister Mario Monti.

Populist strategy: Matteo Salvini’s Lega

Cas Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007.

See Ilvo Diamanti, La Lega, Donzelli, Rome, 1993

See Giovanni Diamanti and Lorenzo Pregliasco, Fenomeno Salvini. Chi è, come comunica, perché votano per lui, Castelvecchi, Rome, 2019.

It was precisely the unfortunate conclusion of Monti’s experiment in technical government, supported by the center-right and center-left but highly unpopular due to the economic austerity measures implemented, that ushered in a new phase in the Italian right’s journey, the populist phase, embodied mainly by the Lega between 2013 and 2018.

Already considered a party of the populist radical right by Hans-Georg Betz in his 1994 study, and included in the same category by Cas Mudde thirteen years later22, the Lega has undergone a long series of ideological, tactical and strategic readjustments over the course of its history. Founded under the name Lega Nord in 1989 to unite into a single organization various autonomist movements that had developed in the country’s northern regions in polemics against the excessive centralization of state administration, cumbersome bureaucratic procedures, tax burdens, party corruption and the inefficiency of parliament23, it initially claimed a liberal identity, particularly in the economic sphere. The collapse of the First Republic, however, forced the Lega to abandon its role as a mere mouthpiece for the “voice of the North” and accept the logic of alliances, while always regarding them as precarious and provisional. The brief governmental experience of 1994-1995, however, demonstrated its inability to renounce attacks on the establishment, and the independence phase that followed showed even more clearly its populist mentality.

In addition to campaigns against immigration and partitocracy – themes that are always present in its programs – from this time onwards, the party has attacked the European Union and the “strong powers”, high finance and big industry, sometimes with conspiratorial arguments, as well as defending the family and traditions against progressive demands, rejecting homosexuality, calling for protectionist measures in the economy, hostility to the relocation of production processes and denouncing the negative consequences of globalization. Positions that enabled it to become the party favored by working-class voters in 1996. After September 11 2001, the denunciation of the Islamic threat in Europe and calls for the construction of a common Euro-American front to defend Western civilization against the pitfalls of Islamist terrorism became part of this framework. These are all characteristics that have enabled the Lega to join the family of radical right-wing populist parties.

However, in 2012, after a period of internal crisis triggered by the scandal of dishonest management of public funds, which led to the departure of historic leader Umberto Bossi – already diminished by a stroke in 2004 –, leading to the worst electoral results in the party’s history (4.1% of votes cast), the Lega managed to revive itself, electing Matteo Salvini as secretary and fully embracing the national-populist agenda.

Taking full advantage of the possibilities offered by social networks24, and displaying the aggressive and sometimes vulgar language of a “man of the people”, Salvini chose as his polemical targets the political class and the European Union, accused of not having responded effectively to the economic crisis of 2008-2011; intellectuals, accused of supporting all progressive proposals in the field of civil rights (marriages and adoptions for homosexuals, surrogate motherhood, etc.); and above all immigration, considered on the one hand as a source of unfair competition for native workers, and on the other as a threat to the country’s cultural cohesion and its people’s way of life). By emphasizing this danger and making it the focus of election campaigns, Salvini has taken the Lega from a regional to a national dimension, endorsing a nationalist, ultraconservative and xenophobic credo. His admiration for Putin’s Russia and Trump’s ideas led him to forge links with other parties on the European radical right, and to join Marine Le Pen’s Europe of Nations and Freedoms group in the European Parliament, later transformed into Identity and Democracy. Despite this radical ideological characterization, the new Lega, thanks to its electoral successes (17.4% in the 2018 parliamentary elections and 34.3% in the 2019 European elections), managed to gain primacy within the center-right coalition, to the detriment of Forza Italia, and thus be able to autonomize itself, to form a government with the other populist protest formation, the Movimento 5 stelle (M5S).

For just over a year, from June 2018 to August 2019, this coalition of anti-establishment forces was referred to as the most successful case of the strategy implemented by populist radical right parties on the European stage, and caused great concern within the European Commission and many foreign governments. However, in August 2019, Salvini made the serious mistake of wanting to end the agreement with the M5S, in the hope of being able to repeat or extend the success recorded in the European elections in early legislative elections, which the President of the Republic would not grant. This is how Salvini quickly turned a triumph into a disaster. Indeed, as soon as he left government, the Lega began to see voting intentions in his favor fall in the polls, and has been unable to reverse this trend ever since. At the same time, voters who had abandoned the Lega, finding Salvini unreliable, shifted their sympathies to Fratelli d’Italia. The Covid-19 pandemic, which saw Salvini uncertain for a long time about the position to adopt on containment and vaccines, then eager to enter the government led by Mario Draghi – a banker, thus one of the figures historically most hated by the Lega and in general by all populists – accentuated this process of rapid dissolution of the Lega’s electoral capital, which in just over three years fell from 34.3% in the 2019 European elections to 8.9% in the 2022 parliamentary elections.

This result marked the (at least temporary) defeat of a national-populism that seemed destined to inaugurate a cycle of hegemony in the right-wing space, and relaunched, with much greater force and on new foundations, the national-conservative project that had been embodied between 1995 and 2009 in Alleanza nazionale.

From the Popolo della Libertà split to power: the meteoric rise of Giorgia Meloni

See Alice Santaniello, “Il nuovo partito della destra. L’ascesa di Fratelli d’Italia dal 2012 al 2019”, in Trasgressioni, XXXVIII, 1, January-April 2023, p. 17.

The formulas reported are taken from ELEZIONI 2013/ Il programma di Fratelli d’Italia di Giorgia Meloni e Guido Crosetto, ilsussidiario.net, February 22, 2013 [online].

See In Europa a testa alta. Il programma di FdI-AN per le elezioni europee 2014 (FdI-AN program for the 2014 European elections), fratelli-italia.it [online].

See Alice Santaniello, op. cit. p. 79.

Ibid, p. 89, fig. 1.

“President’s governments” appear at times when the government has lost the support of its parliamentary majority, and the President of the Republic is trying to convince party leaders to form a new majority coalition capable of supporting an alternative government without having to go through new parliamentary elections.

The protagonist of this new phase in the history of the Italian right is undoubtedly Fratelli d’Italia (FdI). In the space of four years, Fratelli d’Italia has risen from 4.4% to 26% of the vote in parliamentary elections. After a year in the government led by its leader, Fratelli d’Italia now has 30% of the The sincerity of this distancing of FdI, its leaders and activists from the fascist sympathies and nostalgia cultivated by many of those who had been active in the two previous “flame parties”, has been the subject of much debate since the new acronym appeared on the Italian political scene. Aware of the doubts that existed in this respect, Giorgia Meloni decided to publish her autobiographical book to clarify her vision of the world and her objectives. As mentioned above, the statements made by the party’s representatives and its official documents have been the subject of numerous analyses. The authors have arrived at different interpretations: there are those who have observed an evolution in relation to its neo-fascist past, those who have placed it – along with the Lega – in the family of the populist radical right, and those who continue to consider it extreme right-wing. Each of these interpretations contains interesting elements and considerations that deserve close examination. In order to verify the solidity of the whole, however, it is necessary to reconstruct, in a synthetic way, the course of this political formation up to the present day: a course which has been less linear than its supporters claim, and which has passed through different stages, marked by rather diversified positions.

Almost all analyses converge on one point: when the party was created on December 16, 2012, the intention of its founders was not simply to bring together Alleanza nazionale veterans disappointed by the gradual wear and tear of Popolo della Libertà. The three main promoters – Giorgia Meloni, former president of Alleanza nazionale’s youth organization Azione giovani, who had previously been vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies and then Minister for Youth; Ignazio La Russa, an activist since the 1960s within the MSI, long a leader of that party and of Alleanza nazionale; Guido Crosetto, from Forza Italia and former undersecretary at the Ministry of Defense – had a more ambitious project in mind: to refound the entire center-right on a new basis. Centrodestra Nazionale was the name chosen by La Russa for the party he intended to found when he decided to split from Popolo della Libertà in reaction to Berlusconi’s decision to resurrect Forza Italia. What brought them together was their common aversion to the PdL leader’s decision to support the Monti government and revoke the primary elections organized to determine his successor at the head of the “single party”. To reaffirm the founders’ original intentions, almost a year after the birth of Fratelli d’Italia, Crosetto formulated a clear rhetorical question at the Atreju festival, a sort of party fair: “Who can represent the center-right, if not us?25“.

The program hastily drawn up for the February 2013 elections uses a hushed tone and limits itself to proposing a package of reforms in line with what former members of Alleanza nazionale merged into Popolo della Libertà have repeatedly advocated: direct election of the President of the Republic, abolition of perfect bicameralism, reduction in the number of members of parliament; reduction in debt and public spending; fight against waste and promotion of a new public ethic; reduction in the tax burden; separation of the careers of judges and prosecutors; support for the birth rate to combat demographic decline. Only a few proposals echoed national-populist theses: a nuanced critique of the euro, which “acts as an amplifier of the dysfunctions of nation-states”, and the assertion that “we believe in the Europe of the people, but not the Europe of finance and oligarchies”. On the subject of immigration, too, the formulas chosen are cautious: “Governing flows, controlling borders and enforcing respect for the law means guaranteeing reception, integration and solidarity”, while specifying that “in parallel with the uncompromising fight against illegal immigration, the path towards full integration of new citizens must be pursued at the same pace” and that “those who complete the full cycle of compulsory schooling and demonstrate full integration and a desire to obtain citizenship must be considered entitled to it”26.

The response at the ballot box was a modest 1.96%. This result, lower than expected, nevertheless enabled the party, as the “best loser” of the center- right coalition, to elect nine deputies, leading to a number of changes. Crosetto, who had been appointed party president at the time of the party’s creation, passed the baton to La Russa and, above all, an attempt was made to obtain the symbol of the tricolor flame from the Alleanza Nazionale Foundation, which held the rights to use it. Once this operation had been successful, the words “Centrodestra Nazionale” disappeared from the symbol, replaced by the flame and Meloni’s name. Another gesture clearly signifying the reintegration into MSI history was the decision to hold the second national congress (March 7-9, 2014) in Fiuggi, the place where Alleanza Nazionale’s founding ceremony had taken place more than nineteen years earlier, and to make Giorgio Almirante’s widow the guest of honor. However, the program drawn up for the following European elections, far from being in the post-fascist tradition, was resolutely oriented towards the themes dear to national-populist formations, which were gaining ground in many countries: exit from the euro and the EU’s fiscal and budgetary treaties, reduced interference by the Brussels institutions in national politics, “intelligent protectionism”, European cooperation against “uncontrolled immigration”, defense of the continent’s Christian roots and the sanctity of the family, European rules against speculative finance27. Rather than aligning itself with the positions of parties such as the Rassemblement National, the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) or the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), with which there is as yet no organic collaboration, the choice of these proposals reflects a desire to compete with the Lega Nord, at a time when it is coming under Salvini’s leadership, for a eurosceptic electorate that polls show is growing steadily.

However, the challenge launched by Giorgia Meloni, recently appointed FdI president, to her ally and rival, was not immediately successful. In the 2014 European elections, electoral results were on the rise, exceeding one million votes, but the 3.7% score failed to cross the threshold to elect members to the European Parliament. The new president’s first objective was therefore to restructure the organization so as to deploy effective proselytizing and propaganda throughout Italy, while the Officina per l’Italia, a workshop of ideas open to intellectuals from diverse backgrounds, had already been called upon for several months to define the political and cultural platform on which to build the new center-right. There was no shortage of obstacles, even internally, as the relative failure of the European elections had displeased some of the middle management, prompting a new split in November 2015 and the birth of the Azione Nazionale movement28, but the cohesion of the leading group, formed almost entirely in the same Roman youth milieu of Alleanza nazionale twenty years earlier, overcame the difficulties, and Giorgia Meloni’s candidacy for mayor of Rome in 2016, although not supported by Forza Italia, served as a moment of media and political revival : with the 12.3% she achieved, the young FdI leader boosted her credibility and popularity, at a time when Berlusconi – increasingly embroiled in lawsuits and scandals, was achieving the worst results in his party’s history.

Meloni’s approval ratings are now higher than those of the leaders of the allied parties29. However, they were not enough to win broader support. The party therefore relied on a more aggressive ideological line, radicalizing its earlier positions at the second national congress in December 2017.

The leitmotif of the program presented on this occasion – nationalism, referred to with some modesty as “patriotism” – was not new in contrast to the tone in which it was enunciated. Indeed, the slogan “Italians first” was accompanied by the expression of a “philosophy of identity”, from which stemmed the criticism of “radical universalism”, the accusation addressed to the UN of wishing an “ethnic substitution” in Europe inspired by an “abstract multiculturalist principle”, and the call for strict measures to stem migratory flows and counter the risk of Islamization of the continent30. It is these positions, contained in the motion approved by delegates (the Trieste theses), that have led some analysts to classify Fratelli d’Italia as part of the populist radical right. However, a reading of this motion-manifesto reveals that, alongside these positions, other ideas were rather inspired by a conservative philosophy destined, over time, to take precedence over the party’s political culture: the recovery of tradition and criticism of the cult of progress; reaffirmation of the central role of authority in society and in the state; praise for rurality; rejection of gender theory; valorization of Italy’s historical heritage: art, archaeology, landscape, nature. Even in foreign policy, there’s a search for balance between conservatism and radicalism: while, on the one hand, it is asserted that “Italy is part of the West, a natural ally of European nations, the United States and other peoples of European and Western culture” and that the Atlantic Alliance is its “natural sphere of military alliance”, on the other hand, it is claimed that Italy does not share “the logic of hostility towards the Russian Federation”, with which it is deemed “necessary and profitable to collaborate closely on the economic and strategic level”, including in the fight against terrorism.

In the immediate term, the benefits of this accentuation of the party’s anti-establishment ideological traits were limited. The competition from the M5S and the Lega was too strong. In fact, these two parties emerged as the winners of the March 2018 general election. The M5S, with 32.68%, not only confirmed its position as Italy’s leading party, but also succeeded in consolidating the supremacy it had acquired five years earlier. The Lega, with its spectacular leap to 17.35%, overtook Forza Italia for the first time, relegated to 14%. The result left Salvini’s hands free to find alternatives to the now classic center-right coalition (which lacked sufficient numbers in Parliament to form a government independently of support from other formations). The Lega leader took advantage of this opportunity to accept the idea of a “government contract” with the Movimento 5 stelle, based on a program in which some of the issues most dear to populists stand out, such as tougher policies against immigration or a drastic reduction in the number of MPs.

Faced with this new scenario, Fratelli d’Italia, which had once again made slight progress, obtaining 4.35% and tripling its number of seats in Parliament (19 deputies and 7 senators), seemed to have no option but to continue accepting a secondary role within the center-right. However, Salvini, who had long enjoyed good personal relations with Giorgia Meloni, tried to convince her to join the government led by Giuseppe Conte, a lawyer and university professor, a political outsider proposed by Beppe Grillo’s supporters. If Fratelli d’Italia had been part of the majority, the Lega would have had an ally to put the measures it felt particularly strongly about on the government’s agenda. The answer, however, was negative: Giorgia Meloni felt that the “yellow-green” executive (the symbolic colors of the M5S and the Lega) was too heterogeneous and too left-leaning. This rejection translated the Trieste theses into practice: populism could be an antidote to the degeneration of social ties in a context where “the bonds of belonging are scientifically broken to build a mass of citizen-consumers without history, roots, identity, homeland, community, religion or gender”, but only if the parties adopted an identity-based program. The “justicialist and demagogic populism that has spread in Italy”, i.e. that of the M5S, was instead destined to do nothing but damage. So it was better to stay out of government and focus his energies on developing the party’s local organizational structures.

This choice bore fruit in February 2019, at the regional elections in Abruzzo. Thanks also to the weakening of Forza Italia, Fratelli d’Italia succeeded in getting its allies to accept the candidacy of one of its representatives, Marco Marsilio, for the presidency of the region, who won with 48.3%. The novelty was considerable: for the first time, Fratelli d’Italia won the leadership of an institution, although it obtained far fewer votes than the Lega (6.5% vs. 27.5%), which had exploited the propelling effect of Salvini’s action as Interior Minister and his high media profile.

Three months later, the European elections confirmed the extraordinary effectiveness of the strategy combining “nationalization” and populist turn that the Secretary had imposed on the Lega: the 34.33% obtained at the ballot box (more than 9 million votes) was a result that no one imagined possible, neither among supporters nor opponents. However, the Lega cyclone did not sweep away Fratelli d’Italia, nor did Forza Italia, which fell to 8.79%, and the M5S, which saw its score almost halved (17.07%) compared to the previous year’s general election. With 6.46%, the list that continues to display Meloni’s name prominently in its symbol elected five MEPs, a result that will prove very useful later on.

Among the five elected is Raffaele Fitto, a young but already experienced politician – he was President of the Puglia Region and Minister from 2008 to 2011. A member of Forza Italia, he boasts an extensive network of personal contacts, built up during his two terms as an MEP in the EPP group. Thanks to him, in November 2018 Fratelli d’Italia was welcomed into the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) parliamentary group, dominated by the Polish PiS. Fitto was entrusted with the co-presidency of this group. Joining the Conservatives enabled FdI to dispel, at least in part, suspicions that it had remained, behind the facade, a post-fascist party, and to show that it did not suffer from the isolation to which the populist parties of the Identity and Democracy group had been condemned in the Strasbourg Parliament. A first step has thus been taken towards the more ambitious goal of achieving an influential position at international level. This translates into a gradual strengthening of relations with conservative circles outside Europe. With this in mind, in February 2020 Meloni got an invitation to the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, a major gathering of American conservatives. There she praised Donald Trump’s presidency. Two years later, she is invited to speak at CPAC, the most important political conference in the conservative world. In September 2020, she was entrusted with the post of president of the European Conservative and Reformist (CRE) political party, which she still holds, having been reappointed at the end of June 2023.

Meanwhile, in mid-summer 2019, Matteo Salvini had decided, as we mentioned, to end collaboration with the M5S and the first Conte government, betting that new elections would make him the arbiter of Italian politics, alone or in coalition with allies much weaker than the Lega, or perhaps in an alliance limited to just Fratelli d’Italia – with whom programmatic differences had by then narrowed sharply. The results of the European elections suggested that the Lega-FdI tandem could reach the 40% threshold, which would give them a majority of seats in Parliament. However, the President of the Republic rejected the request for early parliamentary elections, deciding to entrust the running of the country to a technical government. This government will never see the light of day due to the agreement between the M5S and the Democratic Party to form a second Conte government, this time “yellow-red”. Matteo Salvini’s plans thus ruined caused his sharp decline.

The extinction of Salvini’s star was followed almost immediately by the appearance of Meloni’s star, which the polls were beginning to indicate was on the rise. But it was the appearance of the Covid-19 pandemic that gave this turnaround far greater proportions.

From the outset of the crisis, Fratelli d’Italia expressed strong opposition to the confinement and imposition of the green pass, criticizing the choices made by the government and the European Union, siding with the defense of individual freedoms and calling for urgent economic support measures for productive categories hit hard by bans and restrictions. For its part, the Lega followed an erratic line, oscillating between demands for greater firmness in the fight against the epidemic and support for anti-vaccine protests. This enabled Giorgia Meloni to appear more coherent and credible, and to make up for lost time in the world of social media, where the number of her followers grew considerably. Her trump card, however, was her categorical refusal to join the executive led by former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi after the fall of the second Conte government. While Forza Italia and, after some hesitation and internal disagreements, the Lega, accepted the invitation to join the government of “national salvation” with their own ministers, Fratelli d’Italia denounced the imposition on the country of yet another executive that had not received electoral approval, and led an opposition that was flexible in its concrete choices (approving measures that seemed reasonable) but inflexible in its rhetoric and communication. Opinion polls, rising steadily in 2021-2022, showed that this choice was electorally profitable.

At the same time, the tendency to identify the party with its president was reinforced. Her success in the eyes of the public has helped to contain the emergence of internal currents. We find here a typical tendency of “flame parties” to surround the leader with an aura of incontestability, and all the more obviously in phases of success. Not having to hold a congress, due to the conditions imposed by the pandemic, nor to deal with internal affairs, entrusted to the vast group of trusted collaborators, and thus available to concentrate on her relationship with public opinion, Giorgia Meloni sought to consolidate in the collective imagination of Italians her figure as a still-young woman, strong and coherent, uncompromising in her principles and at the same time maternal and compassionate. Indeed, this is the image that emerges from her autobiography, a real publishing success. Almost two hundred thousand copies were sold. Her opponents have also unwittingly contributed to this effort at personalization: they have, for example, produced a video aimed at ironizing the emphatic tones of a Meloni rally (“I am Giorgia, I am a woman, I am Italian, I am Christian. They can’t take that away from me”), a popular meme on social networks which, instead of ridiculing the Fratelli d’Italia leader, boosted her popularity still further. So much so that, in the end, Fratelli d’Italia’s electoral success in September 2022 appeared to all as a personal success for the leader. No one disputed his appointment as Prime Minister, neither among his allies nor his opponents.

It was in the period of most direct competition with the Lega, from the moment Salvini scuttled the first Conte government and when his popularity began to plummet, that Giorgia Meloni made greater use of her populist stylistic repertoire, while selecting certain themes and toning down others. Denunciation of the elites, which had been the mainstay of her rhetoric in previous years, was limited to more general and less frequent accusations. The popular will was invoked only to encourage recourse to the ballot box and to close the chapter on “governments of the president” (of the Republic)31, without departing from that exaltation of the virtues of the common people which is one of the clearest indicators of the populist mentality. While recalling the close link between people and nation, it is on the latter that the emotional charge of the leader’s speeches is concentrated. And the same virulent criticism of immigration is often superimposed with calls for the return of cultural traditions tarnished by the progressive wave unleashed by the 1968 protest movement. The attack on the “LGBT lobby” and the “madness” of the theory of gender interchangeability – which, on certain occasions, such as the rallies organized in Spain to support the candidates of the Vox sister party, emerged with particular vigour – offered a striking example of this.

However, since June 2021, when Fratelli d’Italia overtook the Lega in the polls and began to glimpse the possibility of taking the reins of the coalition and thus leading the future government, these radical declarations have been accompanied with increasing frequency by more moderate attitudes more open to dialogue, particularly in institutional forums, in order to give the party a more responsible image.

The program presented for the 2022 elections reflected this process of “remodeling” by adopting a calmer tone, correcting certain earlier positions and moving from the usual accusations to more reasoned criticism, while broadening the scope of the themes addressed. Instead of denouncing the “techno-bureaucrats of Brussels”, for example, this program expresses the intention to “relaunch the system of European integration, for a Europe of the nations, based on the interests of the peoples and capable of facing up to the challenges of our time”. Even on the subject of immigration, the intentions are less bellicose. The proposals are limited to calling for “the defense of national and European borders as provided for in the Schengen Treaty and as demanded by the EU, with border controls and the blocking of landing stages to stop, in agreement with the North African authorities, the trafficking of human beings” and the stipulation of agreements between the EU and the states of origin of illegal migrants to manage repatriations. At the same time, the program calls for maximum intransigence against Islamic fundamentalism, but also against all forms of anti-Semitism and racism.

Other means of countering accusations of extremism on the part of opponents are mobilized, such as attention to the status of women and the dignity of the individual. This includes promoting the “fight against all forms of discrimination, promoting and supporting ways of emancipating women from cultural stereotypes that place them in a condition of subalternity”, as well as combating “all discrimination based on people’s sexual and sentimental choices”. Environmental issues are also taken into consideration. However, while on the one hand the need to update and operationalize the National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change and to implement the ecological transition envisaged by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan are supported, on the other, the need to preserve the productive system from the foreseeable negative effects of environmental policies is emphasized, “with particular attention to industrial sectors that are difficult to reconvert (e.g. the automotive industry)”. Considering these passages and the broadening of the programmatic horizons to include other issues neglected in the past, or dismissed in a few lines – starting with economic issues – it’s clear that this program sums up the task that awaits the party when it finds itself at the head of the country.

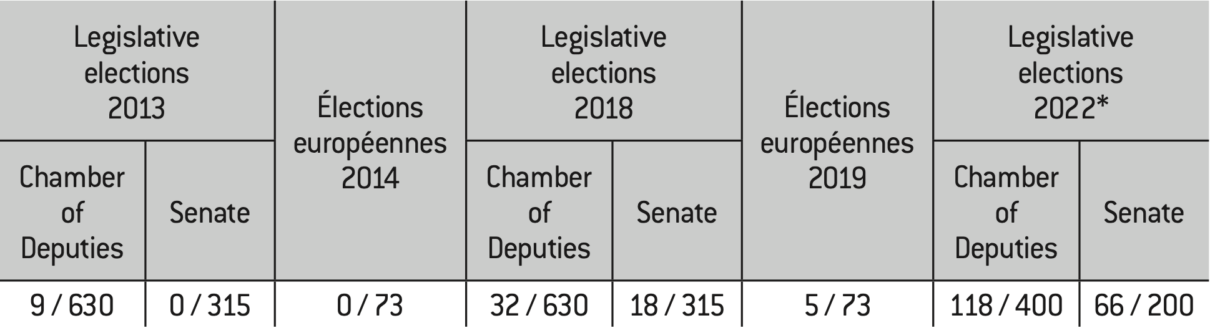

Number representatives elected from Fratelli d’Italia at legislative and European elections, from its foundation to the 2022 general elections

Source :

*The parliamentary elections of September 25, 2022 were the first to be held after the reform that reduced the number of deputies from 630 to 400 and the number of senators from 315 to 200.

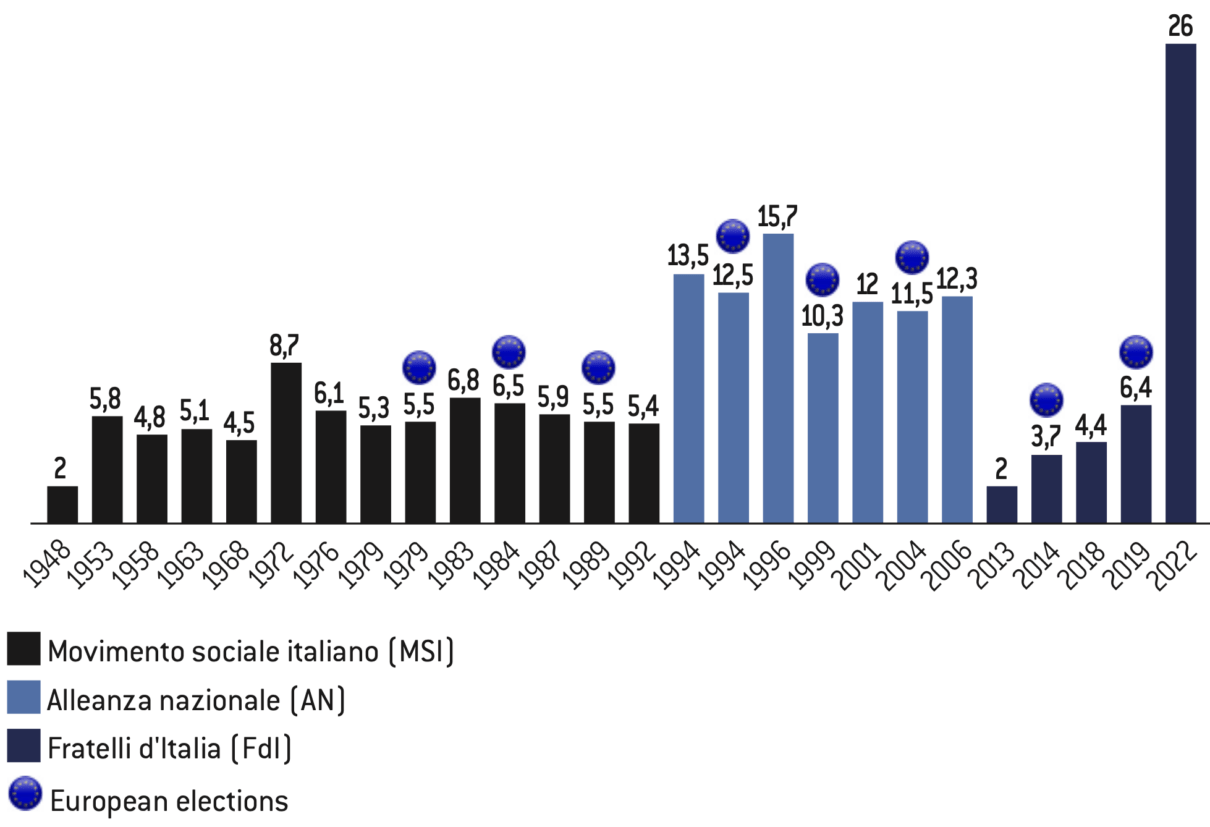

Chronology of the electoral results of the three “flame parties” (MSI, AN, FdI) in the Chamber of Deputies and the European Parliament elections (in %)

Source :

Salvatore Vassallo and Rinaldo Vignati, Fratelli di Giorgia. Il partito della destra nazional-conservatrice, Il Mulino, Bologne, 2023, p.222

Today, what is the ideological, organisational and European situation ?

On an ideological level

Giorgia Meloni, op. cit. p. 226

Ibid.

Ibid, p. 296: “Populism is the exact opposite [of the FdI vision]. It is the antivision, the idea that the role of politics is to bend to the mood of the people, to run after the impulses of the moment, to run after society instead of leading it”.

In a recent book-interview, La versione di Giorgia (Rizzoli, Milano 2024), the Italian Prime Minister asserted that “Fascism is not part of [her] camp, in the same way as any other authoritarian or totalitarian experience”.

As was easy to predict, by taking over the reins of government as the strongest party in the coalition, Fratelli d’Italia has entered a new phase in its history, forcing it to strike a balance between the salient image that won it so much support during the opposition years and the much more moderate and responsible image befitting all those who occupy the most prominent institutional roles. Observers who have described FdI as a radical right-wing populist party by simply analysing the content of its programs or the public statements of its representatives have recently had difficulty finding data to back up their thesis, even if they have tried to highlight the persistence of a certain verbal “slippage” among activists now assigned to government positions, As in the case of the risk of “ethnic substitution” due to excessive immigration rates evoked by the Minister of Agriculture Francesco Lollobrigida, who is also Giorgia Meloni’s brother- in-law, or of certain ambiguous statements on the Mussolini regime by La Russa, meanwhile elected to the post of President of the Senate.

Faced with unprecedented challenges, the party seems obliged to untie the residual knots that constrain its movements in today’s politico- ideological space, and not just in Italy. The harsh invectives against the European Union, ever-present in Meloni’s autobiography, which described it as “a playground for banker technocrats who feast on the backs of the people32” and as a “utopian and potentially tyrannical institution33“, have given way to generic proposals aimed at reforming the institutions of Brussels. Despite the persistence of a form of opposition to immigration and the demand for the EU to take effective measures to counter it, there is no longer any talk of the naval blockade to prevent migrant landings, which used to be a much-discussed issue. On the other hand, criticism of progressive arguments in the field of “ethical issues” is still frequent: although same-sex civil unions have been accepted in the 2022 election manifesto, surrogate motherhood, same-sex adoption and “gender” theories continue to be rejected.

The profile of Fratelli d’Italia in 2024 thus appears to be that of a political entity whose identity is still being defined, as it responds to the opportunities and challenges offered by the context in which it evolves. Firmly anchored on the right of the political spectrum and following a bipolar conception of systemic dynamics, the party uses a mix of conservative and nationalist ideas, presented as “sovereign patriotism”, as the basic ingredients of its message. Distrustful of populism – which contrasts with the cult of state authority of its leading representatives and is accused of being nothing more than the contemporary version of demagoguery34 – as much as of globalism and cosmopolitanism, its North Star is an idea of the nation which, while exhibiting certain nativist traits, no longer bears any trace of the expansionist and bellicose inclinations that had characterized fascism and neo-fascism. And, in its ideological references, anti-Semitism is totally absent. Indeed, the party’s leaders, led by Meloni, take every opportunity to affirm their attachment to democracy, to reaffirm their loyalty to the Atlantic Alliance in the name of the values of the liberal West, and to distance themselves from the Fascist experience35. The most appropriate formula to define FdI today therefore seems to be that chosen by Vassallo and Vignati: a national-conservative party, formed, above all at the top, by “Afascist democrats”, i.e. people who have now left behind the great divides of the xXth century and consider the conservatism/progressivism cultural divide to be the fundamental line of conflict of the present era.

Giorgia Meloni and Fratelli d’Italia are now forced to accept the challenge of de-radicalizing a party that has until recently made verbal radicalism its most effective weapon, and making its programs and image less and less extremist, so as not to experience in their turn the brutal decline that Salvini and the Lega suffered between 2019 and 2022. At the same time, it’s a question of mapping out a path to success for sister parties in other European countries. The aim is to rightitize the European People’s Party in order to bring about a change in the policies of the European Union.

At organizational level

With this in mind, Fratelli d’Italia faces a series of challenges: consolidating its organizational structure to complete the institutionalization process begun only a few years ago, increasing its capital of legitimacy at international level, stabilizing relations with coalition allies to avoid the risk of attrition from government action.

On the first two points, the road still seems long and full of pitfalls. The very rapid growth of its electoral score in unforeseen proportions has placed Fratelli d’Italia in a paradoxical situation, similar to that experienced by the Lega in 2018-2019: obtaining a large number of elected positions at local level – municipal and regional councillors, mayors, and deputies – without having the right personnel to fill them, and without having a network of organic connections with associations and interest groups capable of guaranteeing the collaboration of trusted experts and technicians.

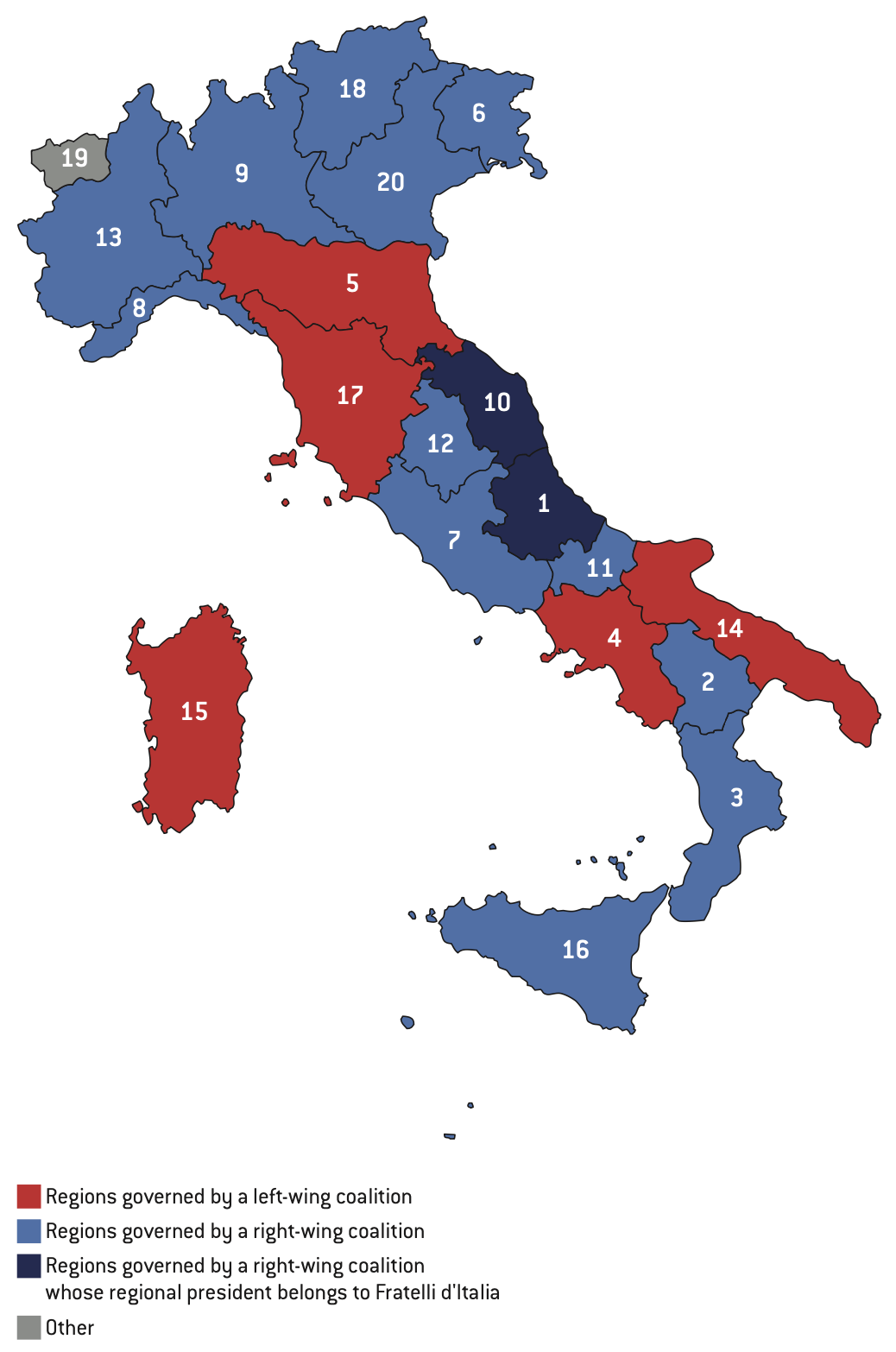

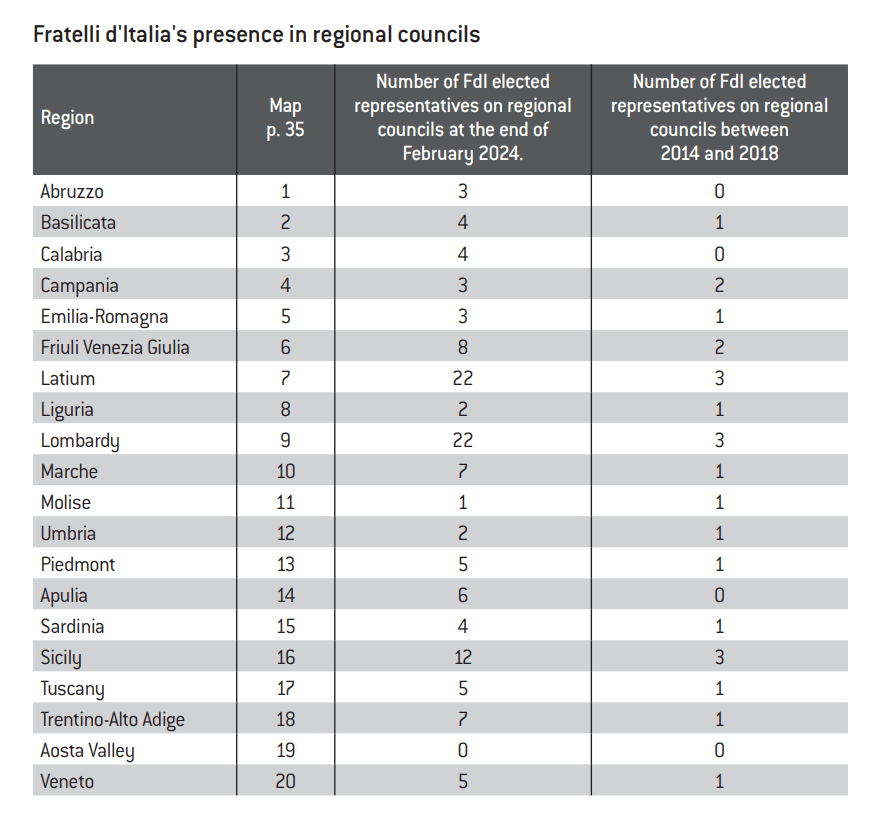

Political orientation of coalitions leading regional governments

Source :

Note: The figures shown on the map refer to the names of the regions in the table on the following page.

Fratelli d’Italia’s presence in regional councils

During its early years, in many small and medium-sized towns, the party did not even have premises where it could set up the offices of its municipal sections and provincial federations. Indeed, at the time of the merger with Popolo delle Libertà, the premises belonged to Alleanza Nazionale and had been entrusted to a foundation which held the exclusive right to use them. Only part of them were rented to Fratelli d’Italia. The second national congress in 2017 attempted to remedy these problems by initiating a new organizational phase. In 2019, the statutes were amended. More precise rules for the operation of the internal structure were established, including the obligation for all elected members, at all levels, to pay a financial contribution.

The organizational chart drawn up for this purpose is, on paper, highly complex; it reproduces the classic structure of mass bureaucratic parties. The president, elected by the congress, is surrounded at the highest level by a number of political bodies: the assembly, the management, the political coordination, the executive, the thematic departments. Additional bodies take on bureaucratic tasks: the guarantee commission, the administrative secretariat, the administration committee. In all these bodies, some members are directly appointed by the Chairman, while others are elected.

The same pattern is repeated, in simplified form, at local level, confirming the strongly hierarchical nature of the party, inherited from the tradition of the MSI and Alleanza Nazionale. As Vassallo and Vignati write, Fratelli d’Italia’s structure “is driven by the leader and the national executive”. The presidents and regional coordinations are structures dependent on this center: “they act in accordance with the movement’s national directives36“.

In theory, the party is characterized by strong internal democracy. The selection of candidates for institutional posts is based on the criterion of primary elections open to supporters. But in practice, things are different. After 2017, no national congress was held. Giorgia Meloni was chosen president by acclamation. Assembly and executive members were elected en bloc from a list presented by the presidency. The same was true of the regional and provincial leaders, almost all of whom were appointed by the national leadership, and some of those elected by the militant base were replaced on authority by the national bodies37.

In fact, FdI’s organizational model seems to reproduce the plebiscitary centralism38 that the MSI and AN had already experimented with: it’s a “party of the president”, whose personalization is further exacerbated by Giorgia Meloni’s intensive use of social media. This enables her to bypass the filter of internal bodies – rarely convened – and address members and supporters directly, as well as through her constant habit of using the pronoun “I” instead of “we” in her public speeches, thus assuming an exclusive representation of the party. While this pronounced leadership has so far borne fruit in terms of electoral results, it has certainly slowed down the institutionalization of the party and the empowerment of its middle managers, raising widespread doubts – repeatedly echoed by the press and observers – about the real degree of competence and capacity of the ruling class on which the President can rely.

At European level

As for the problem of international legitimacy, necessary for a party whose history is rooted in the neo-fascist heritage, the efforts made by Giorgia Meloni and her closest collaborators, in particular Guido Crosetto and Raffaele Fitto, were intense. They aimed above all to lend credence to Fratelli d’Italia’s Atlanticist and Western vocation, erasing all previous traces of sympathy for Putin’s Russia by asserting unconditional support for Ukraine, reiterated at every opportunity, and sharply toning down, but not abandoning, criticism of the European Union. To assert Fratelli d’Italia’s conservative credentials, Giorgia Meloni has mainly relied on her role as president of the European Conservatives and Reformists party, multiplying meetings over the years with representatives of allied parties, starting with Poland’s Morawiecki, Spain’s Abascal and Hungary’s Orbán. This strategic choice has led her to distance herself more and more from the national-populist formations in the Identity and Democracy group, which includes Salvini’s Lega, her partner in government, and the Rassemblement National. This distancing from Marine Le Pen has been particularly marked. Until 2017, Giorgia Meloni claimed to share the same ideals and political line with her, “for a Europe of peoples, homelands and sovereignties39“. The president of Fratelli d’Italia then gradually distanced herself from her, to the point of not hiding her preference for Éric Zemmour’s candidacy in the 2022 presidential election. Despite Marine Le Pen’s public congratulations and recognition of his electoral success in September of the same year, the rift continued to deepen, culminating in the announcement in February 2024 that Nicolas Bay, the only Reconquête! deputy in the Strasbourg Assembly, had joined the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group. A rallying behind which surely lies the action of MEP Vincenzo Sofo, who switched from the Lega to Fratelli d’Italia in 2021, the same year he became Marion Maréchal’s husband.

This affiliation caused much astonishment among Italian political commentators, as it was deemed to contradict Fratelli d’Italia’s ambition to be part of the new majority in the European Parliament after the June 6-9, 2024 elections and, consequently, to influence the choice of Commission President through an agreement with the EPP. The accession of Zemmour’s party could strengthen the conservative group numerically and perhaps ensure it a greater number of elected representatives than its competitors from Identity and Democracy, but the image of extremism that Reconquête! has forged abroad, notably due to the radicalism of its ideas on the fight against immigration and Islam, could constitute a serious obstacle to the project of an alliance with moderates and centrists. We know that this choice was not shared by some of FdI’s middle management. Clearly, Giorgia Meloni has decided to try a new gamble, after the many that have marked her political rise, convinced that she will win it. The European vote, which for Fratelli d’Italia promises to be a good one, entails serious risks for the head of the Italian government.

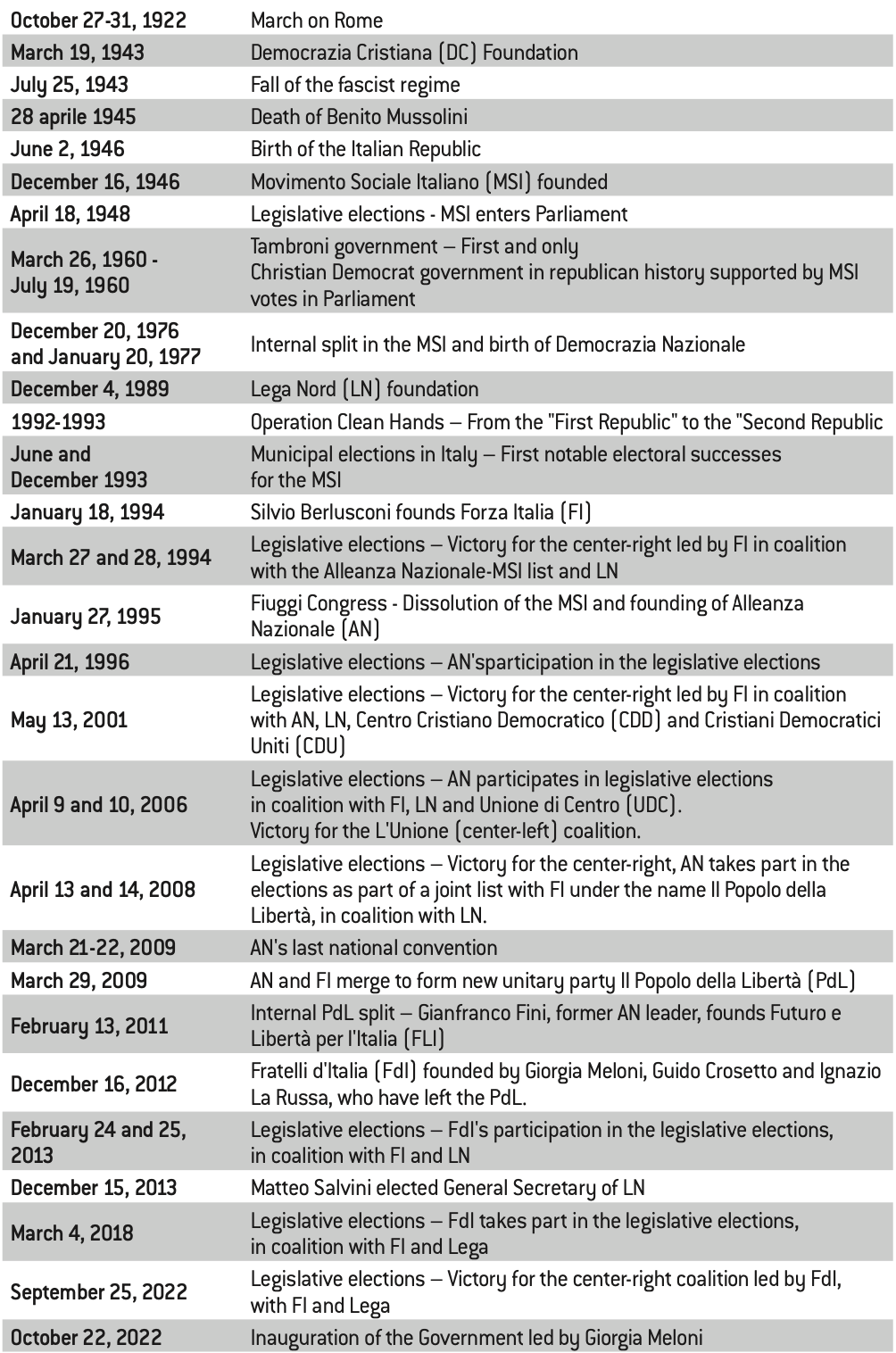

History of the Italian right Chronological overview since 1922

Appendix II

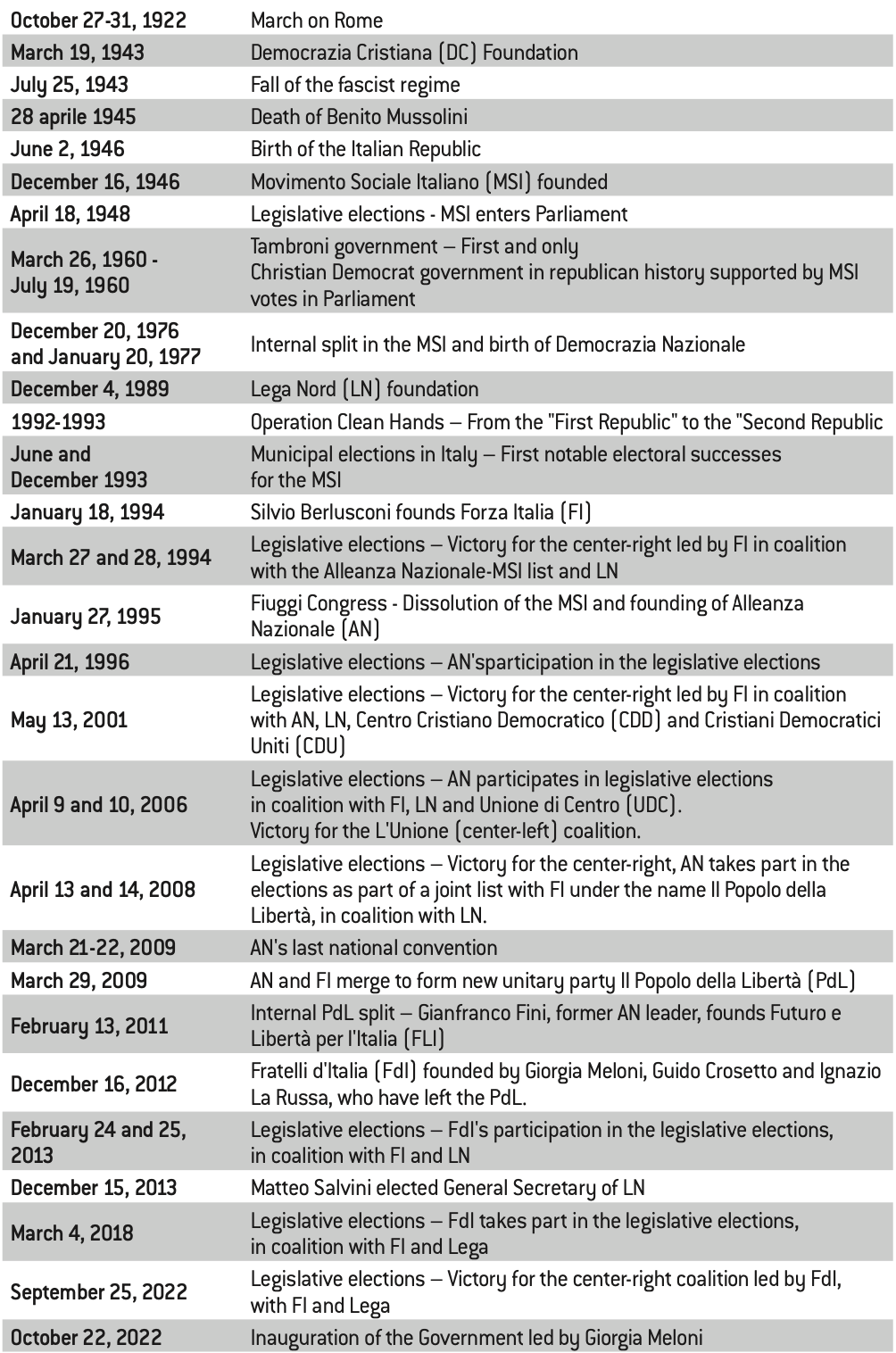

Chronology of Italian Governments since 1946

Source :

Note: the color coding indicates the political party affiliation of the head of government.

No comments.