Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Freedoms at risk : the challenge of the century

Globalization, the fruit of all-conquering democracy, is strengthening authoritarian regimes

Freedom: a new and historical crisis

Defending and expanding freedoms in the twenty-first century

Survey methodology

55 countries, 45 languages, 47,408 respondents

39 questions

Who are democracies afraid of

China worries the democratic world

A less influential Russia remains feared by its neighbors

Turkey is disorienting for Europeans

The United States is still considered the dominant global power

Public opinion dreads a return to war

What are democracies afraid of

Cultural diversity seen as a source of insecurity

Will we soon “no longer be able to resolve our disagreements peacefully”?

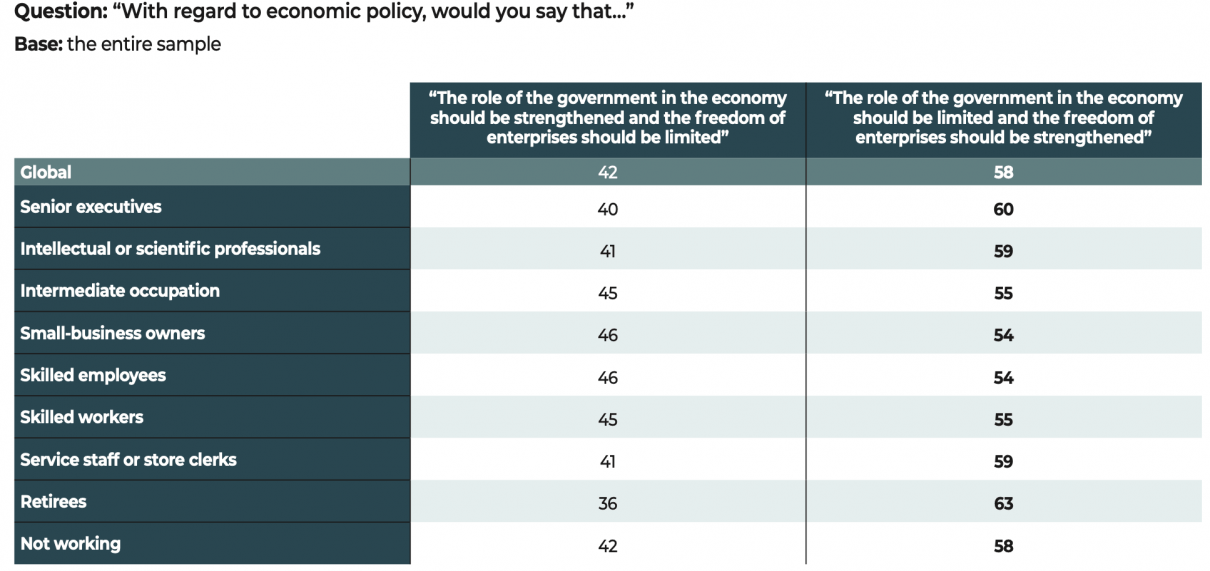

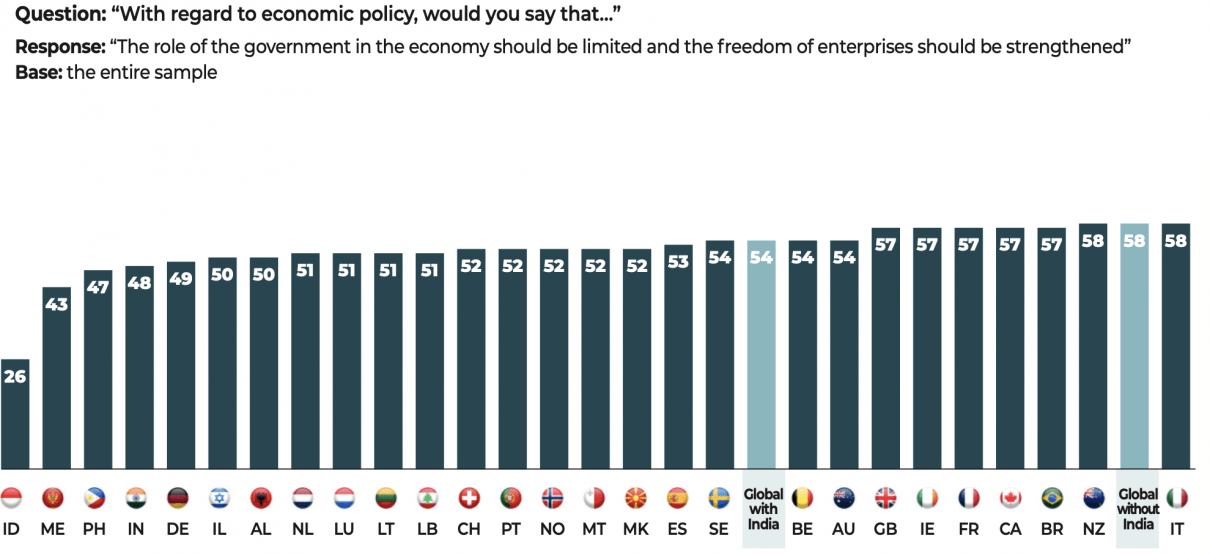

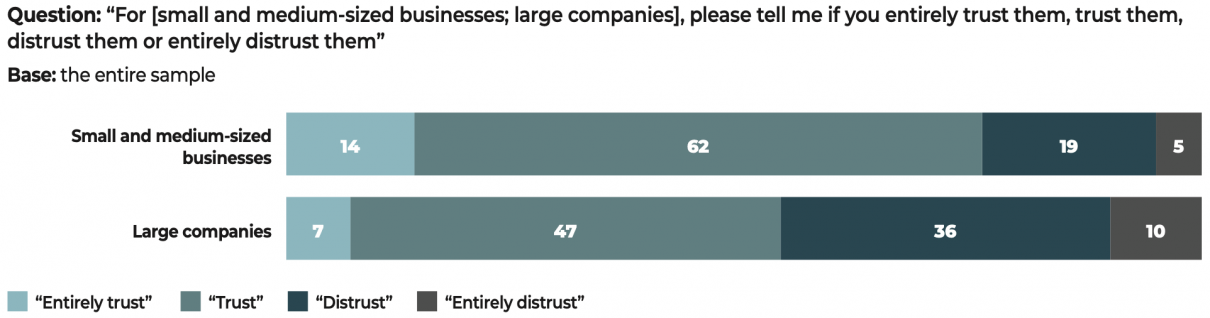

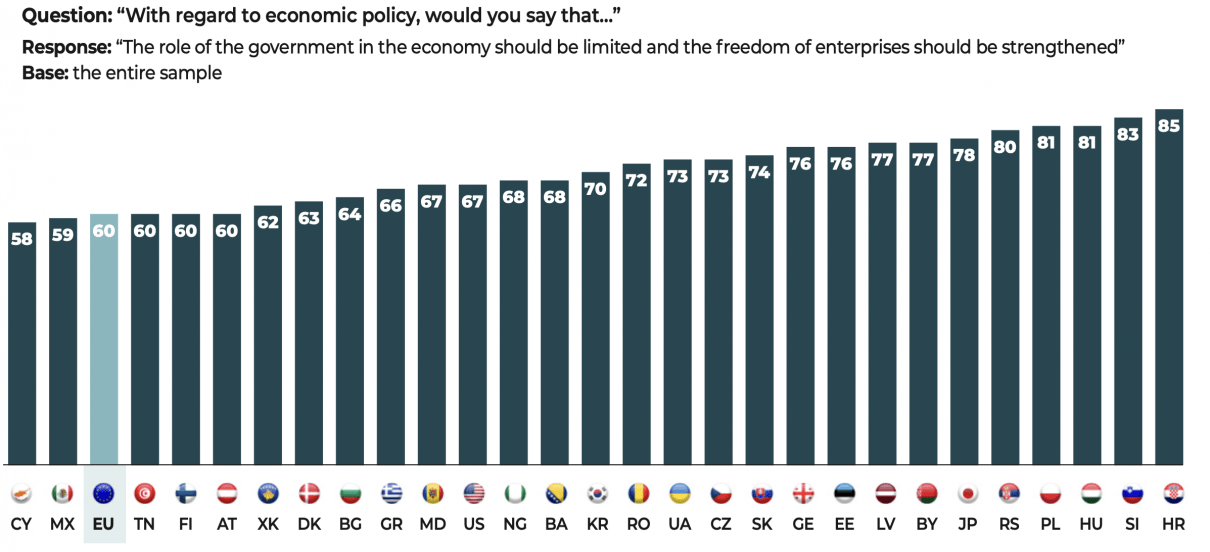

Concern about the risk of economic downgrading

Manipulation of information and foreign interference

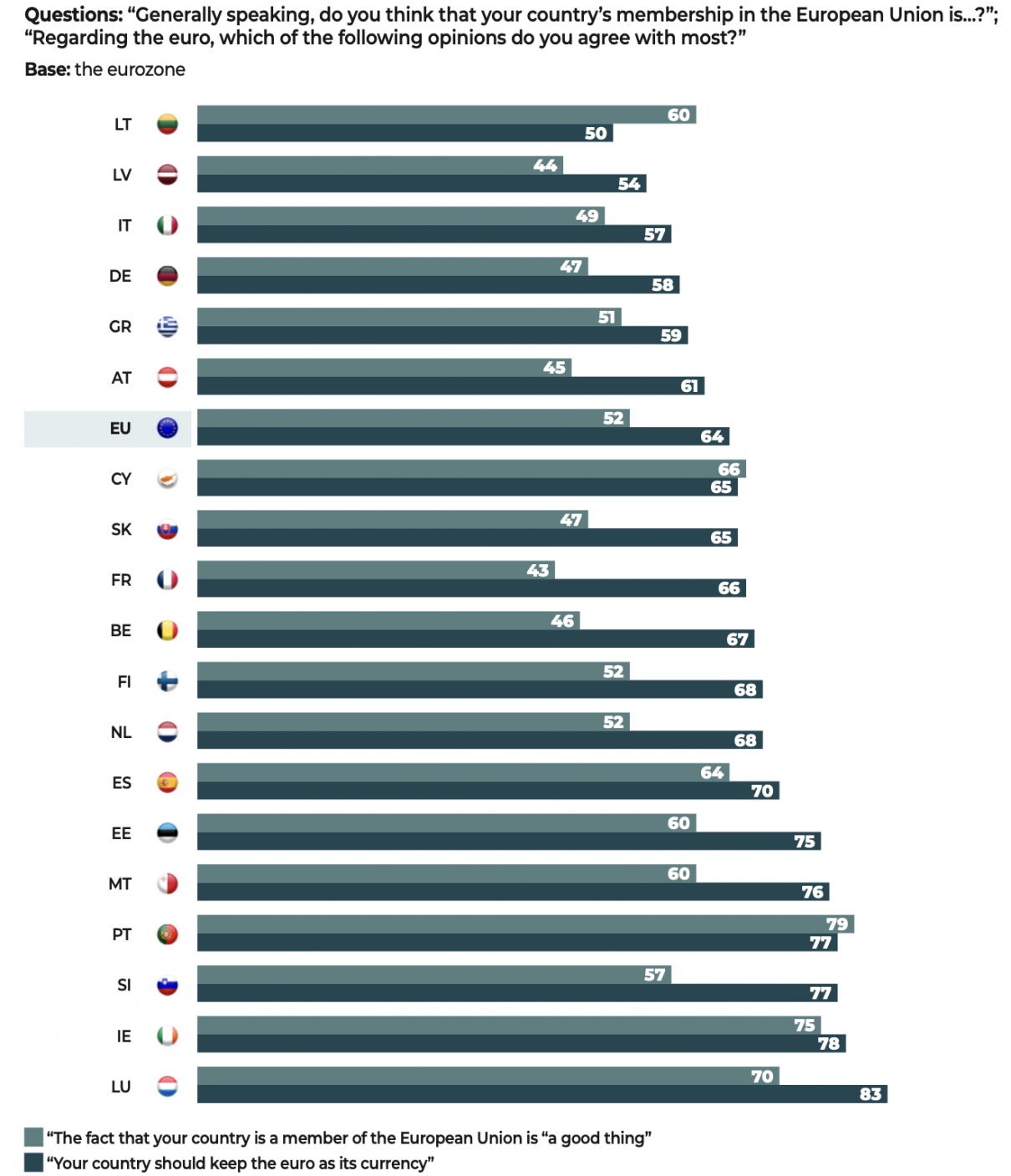

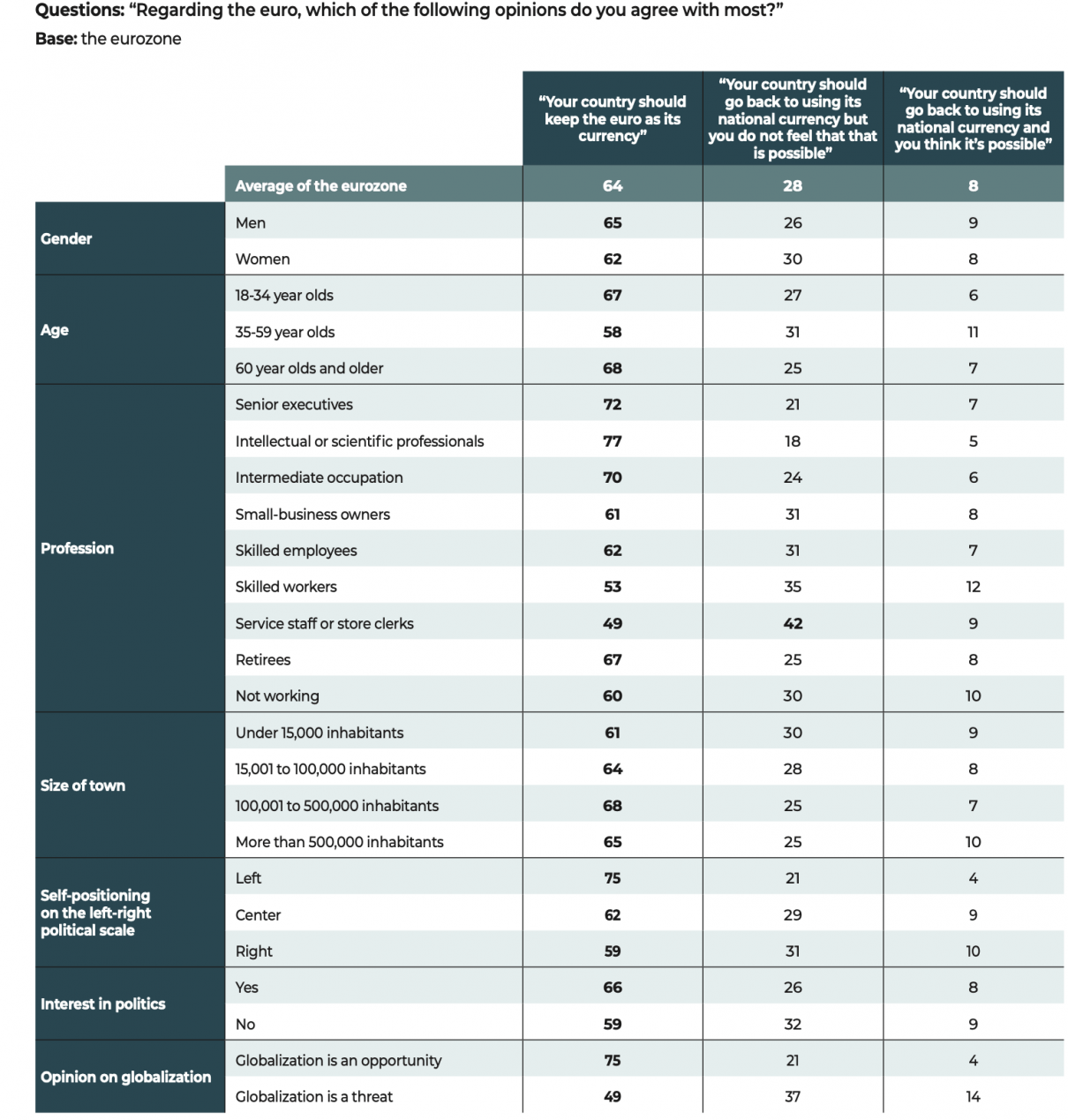

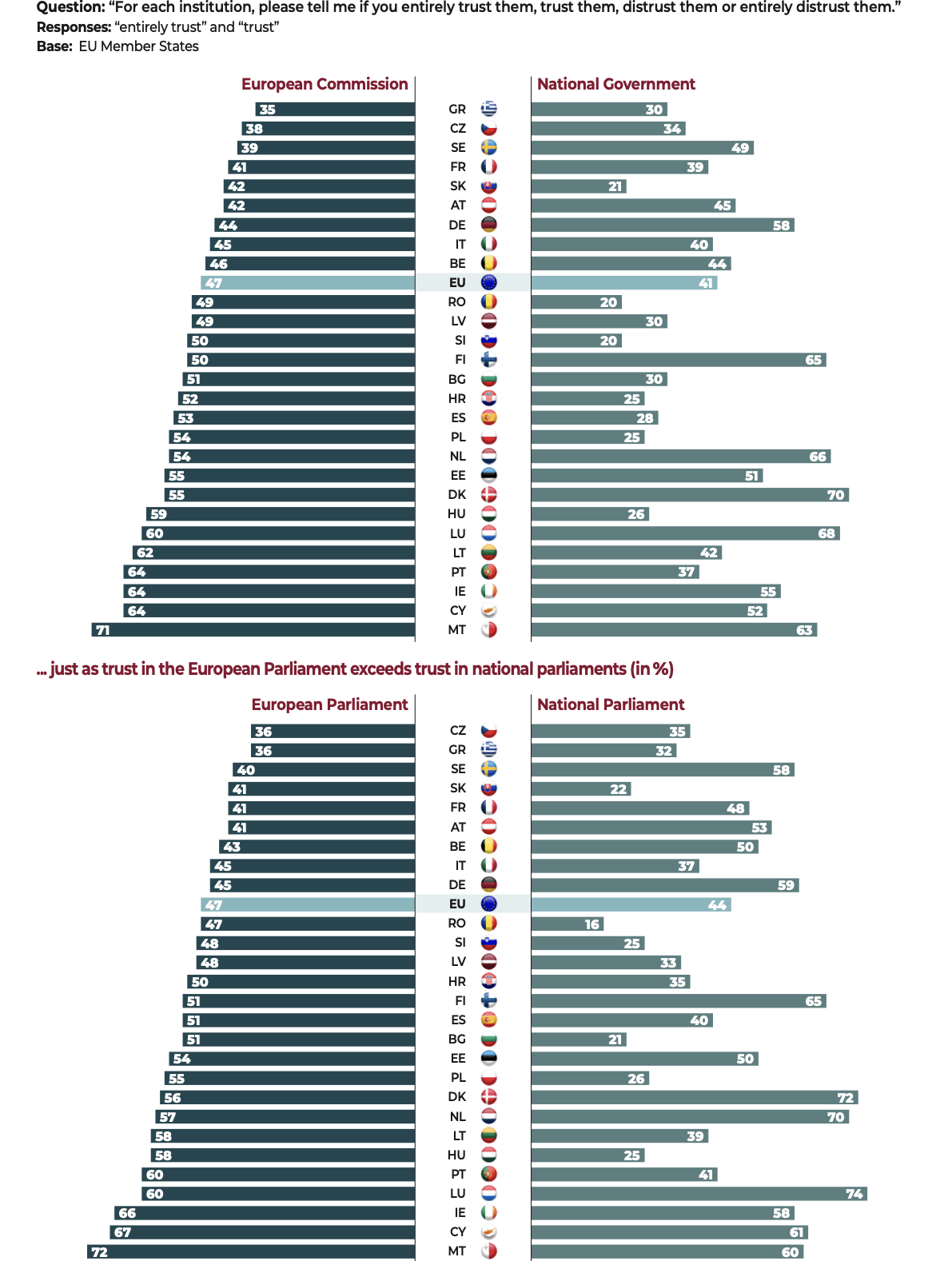

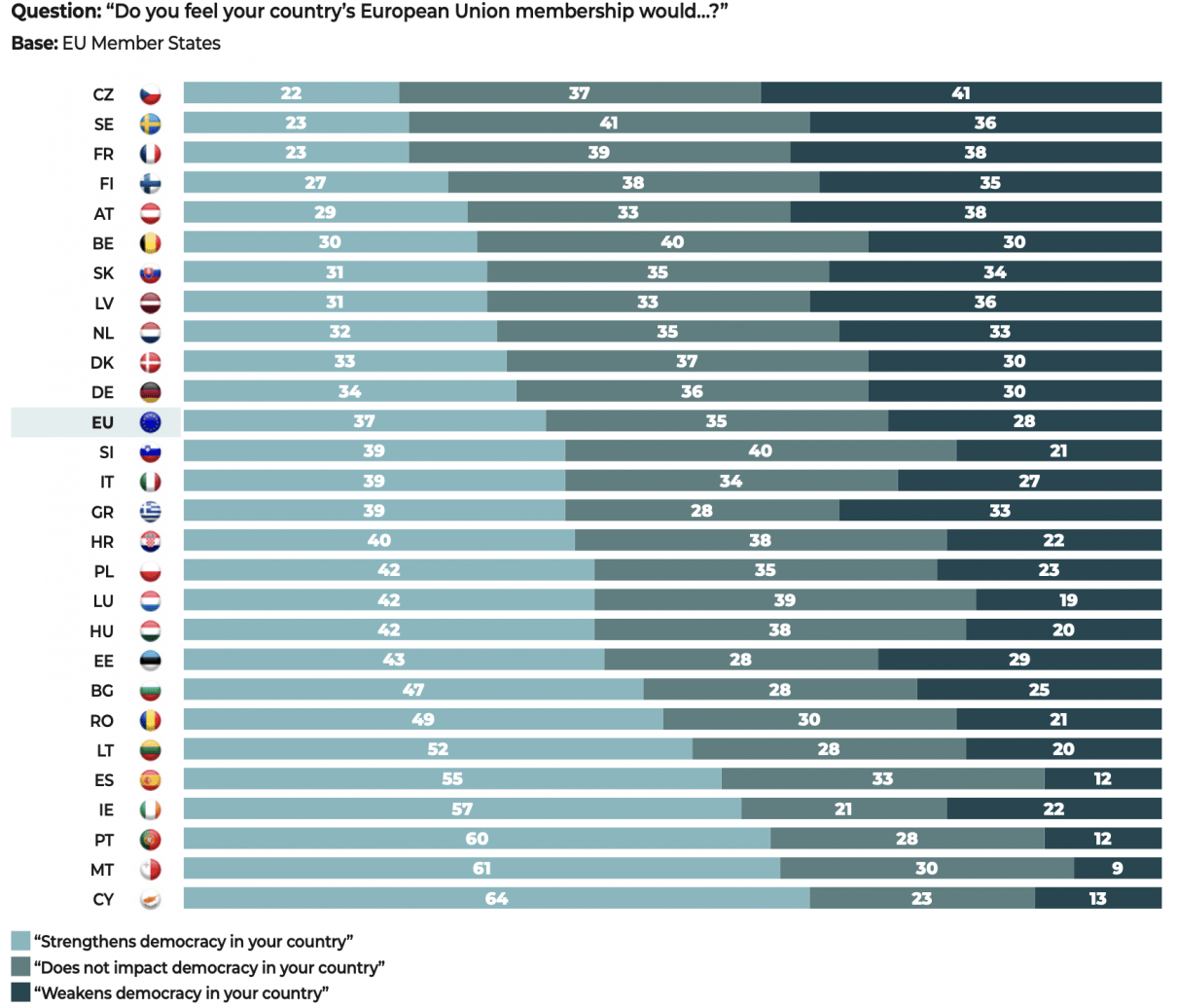

In a fragile democratic world, attachement to the European Union is growing stronger

Public opinion and the European idea

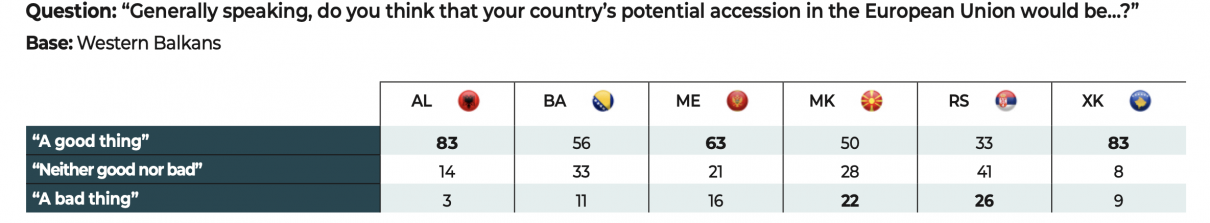

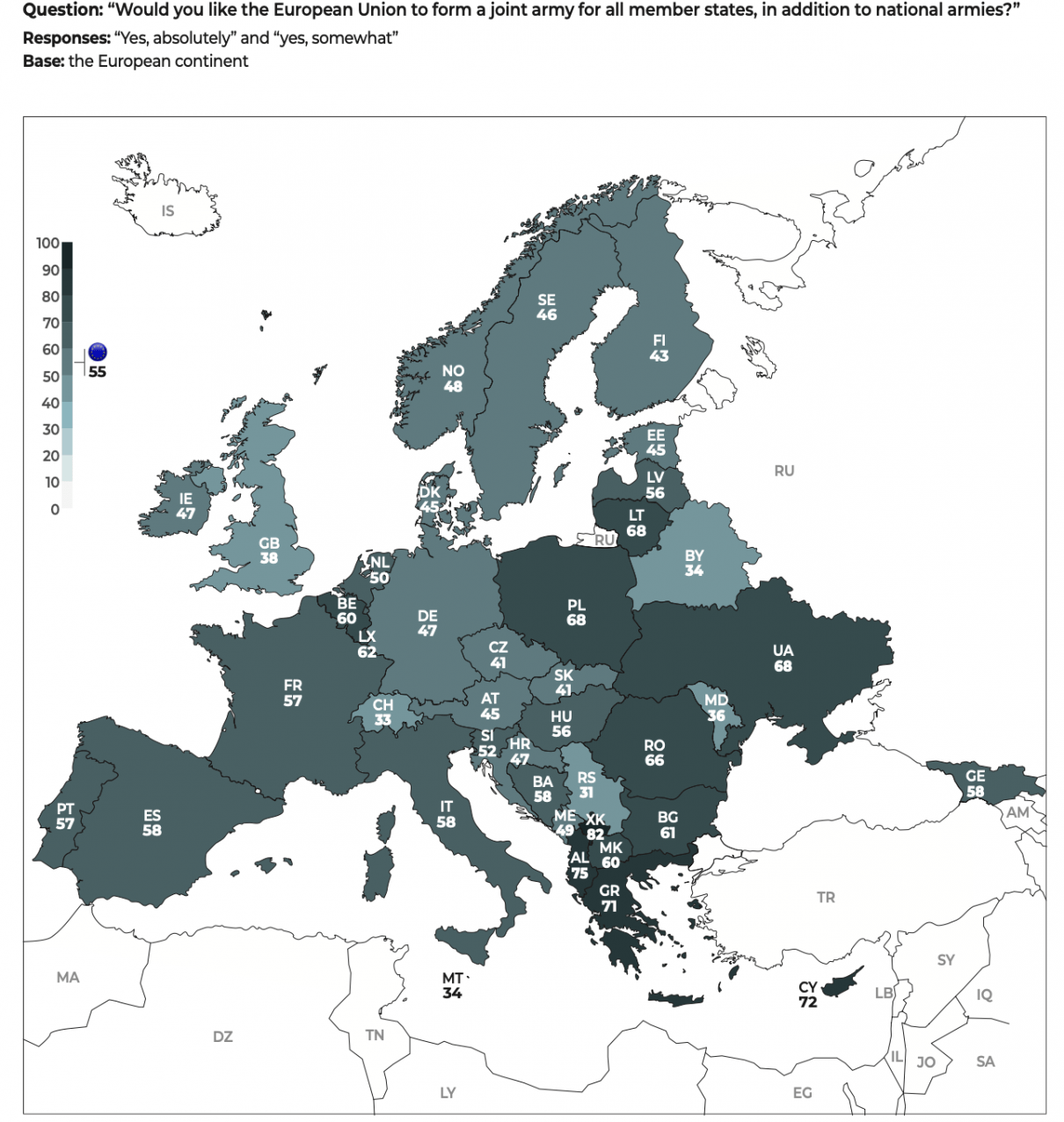

The Western Balkans: between European aspirations and weariness

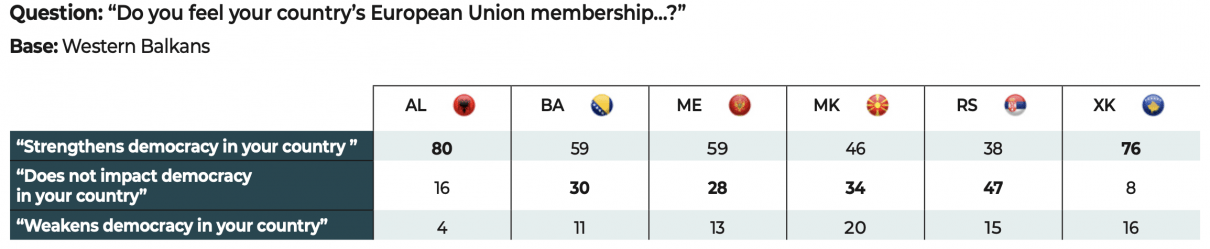

Support for European armed forces is reinforced

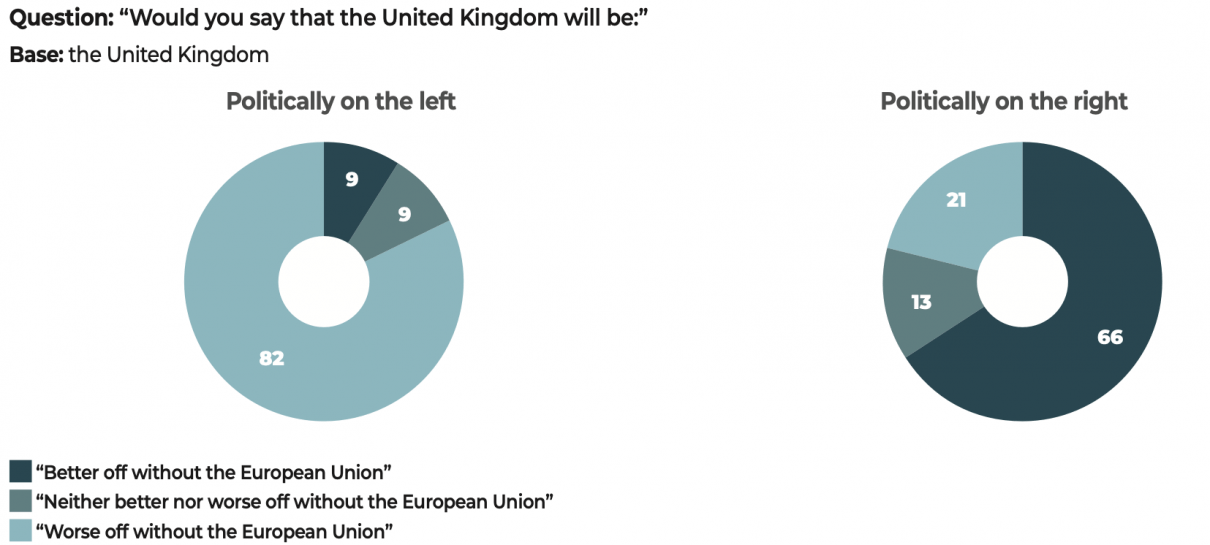

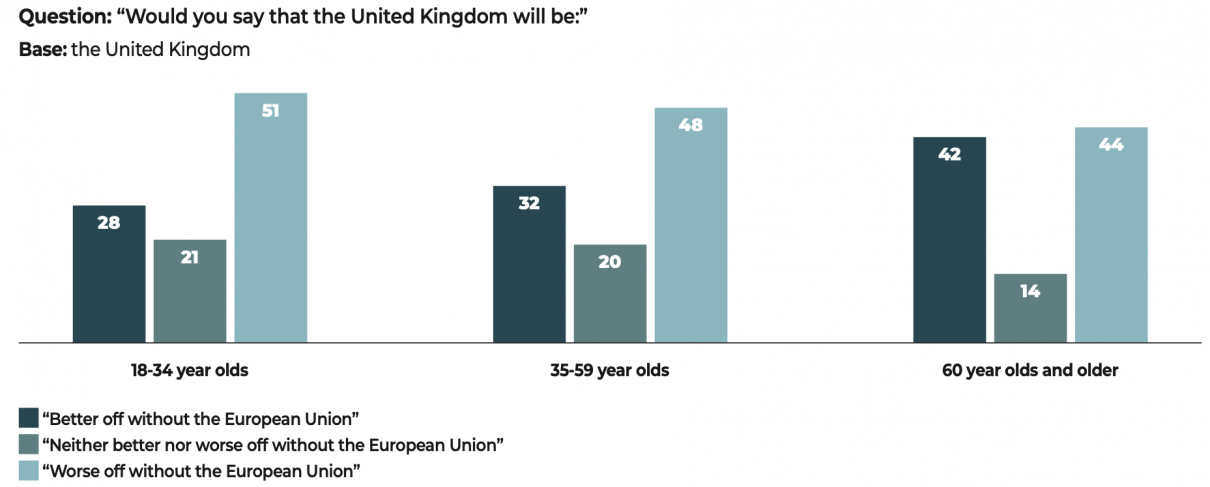

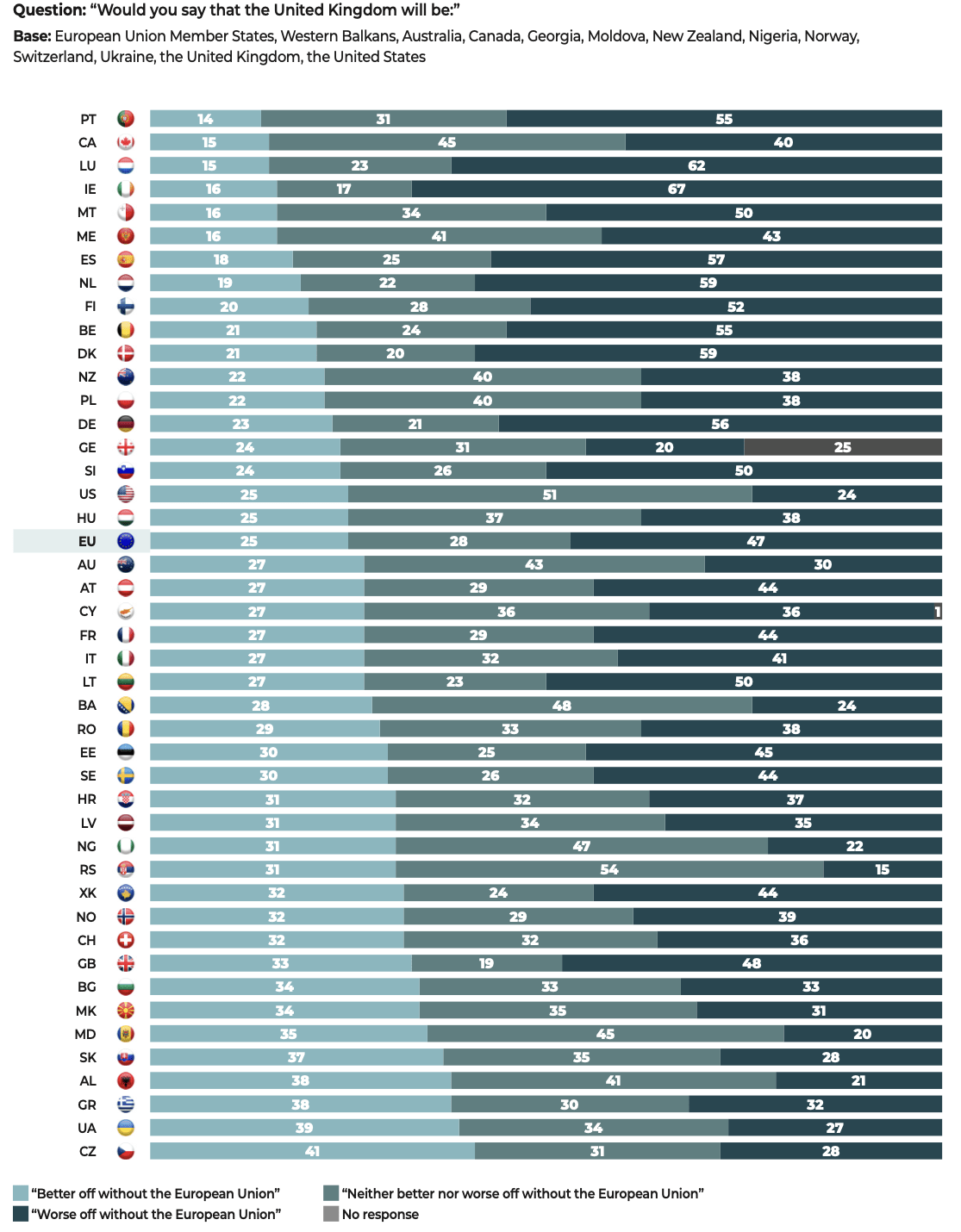

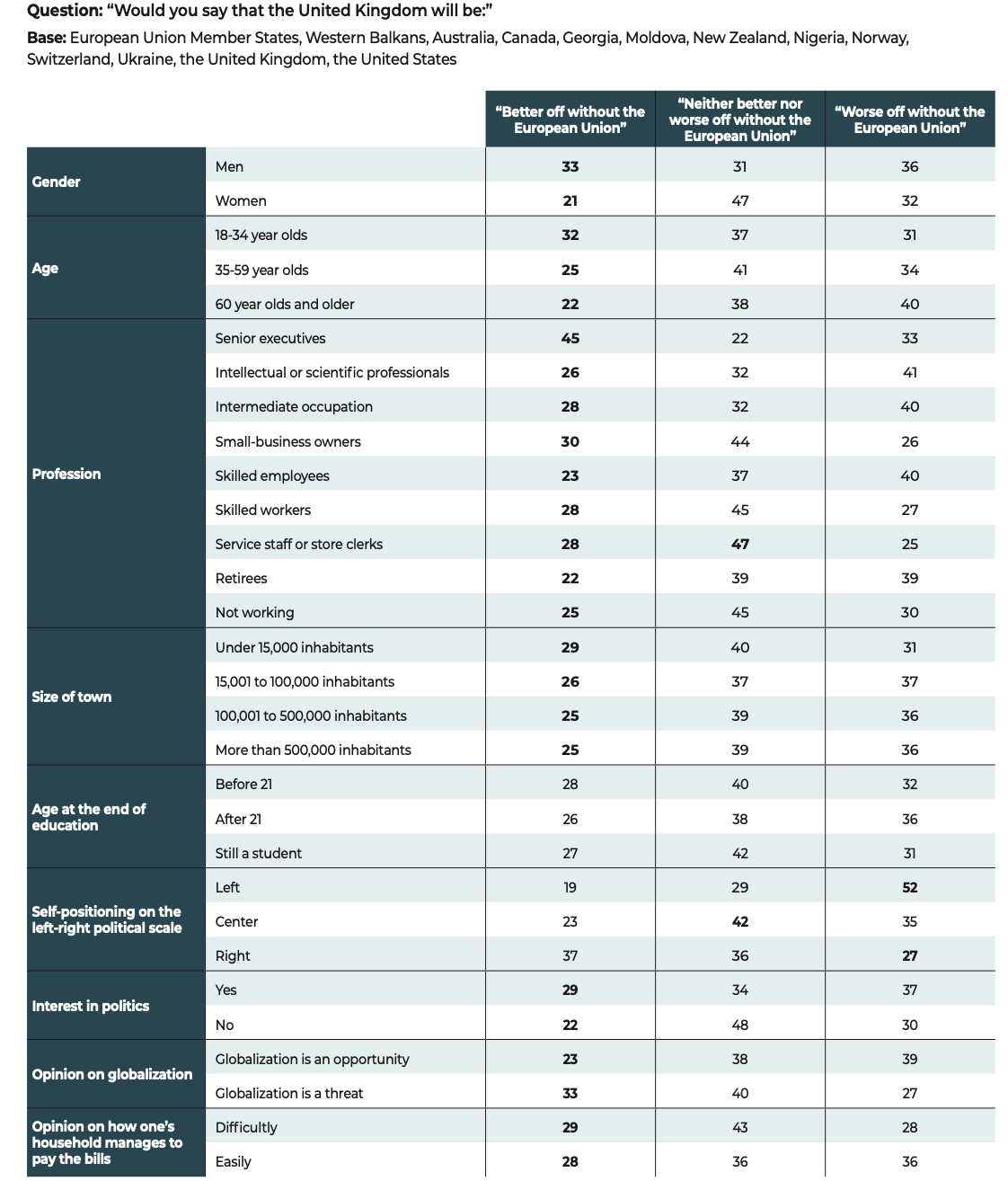

Brexit: a contrasting judgment on a historic decision

The democratic ideal resists

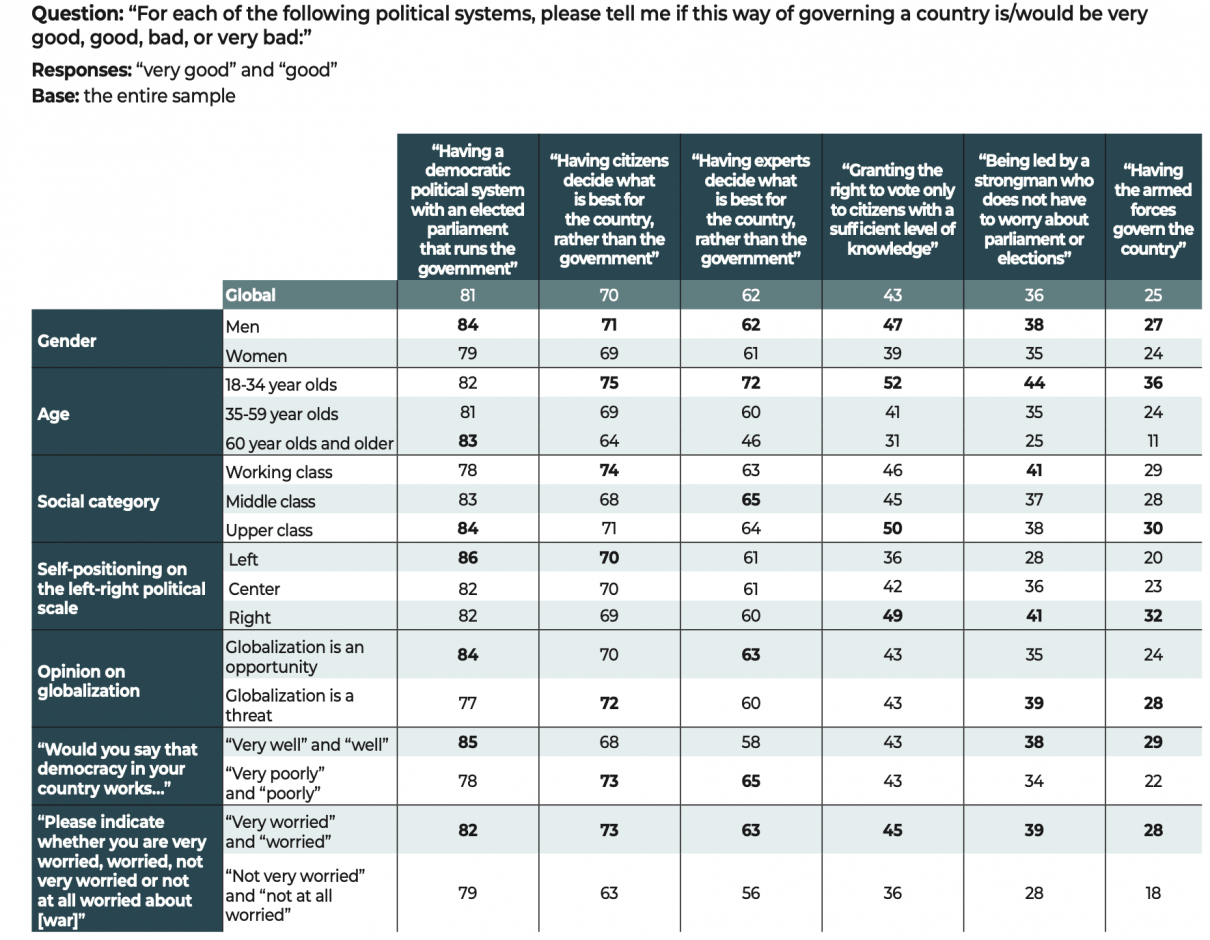

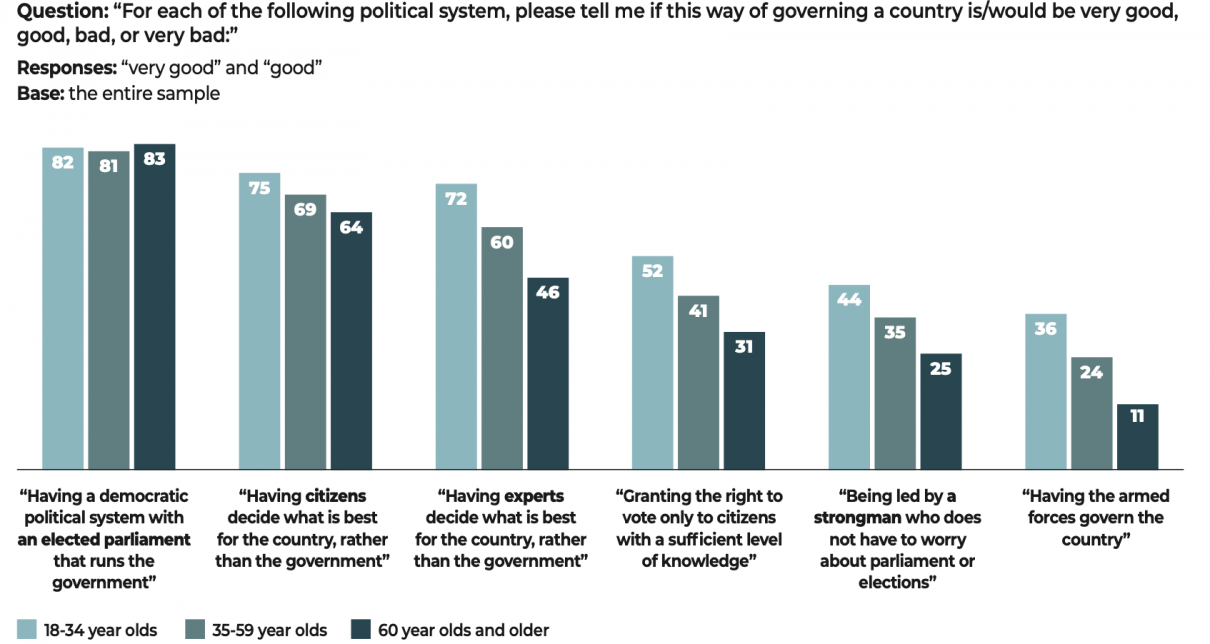

Widespread approval for representative democracy

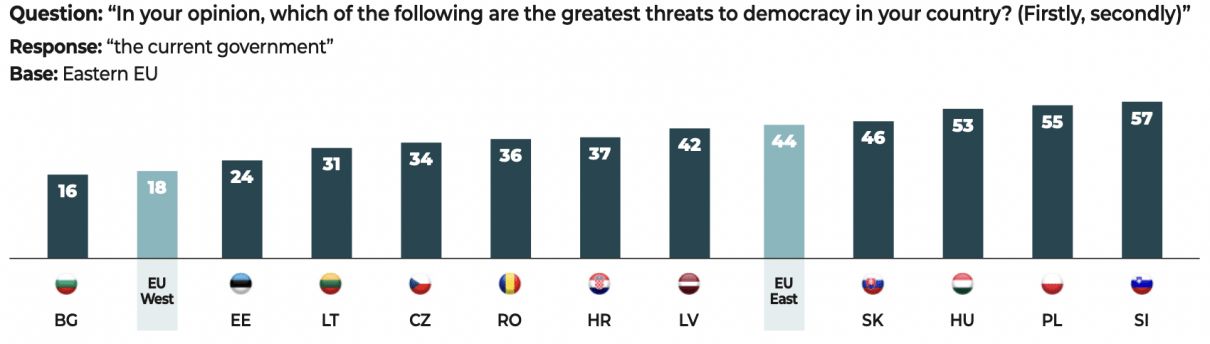

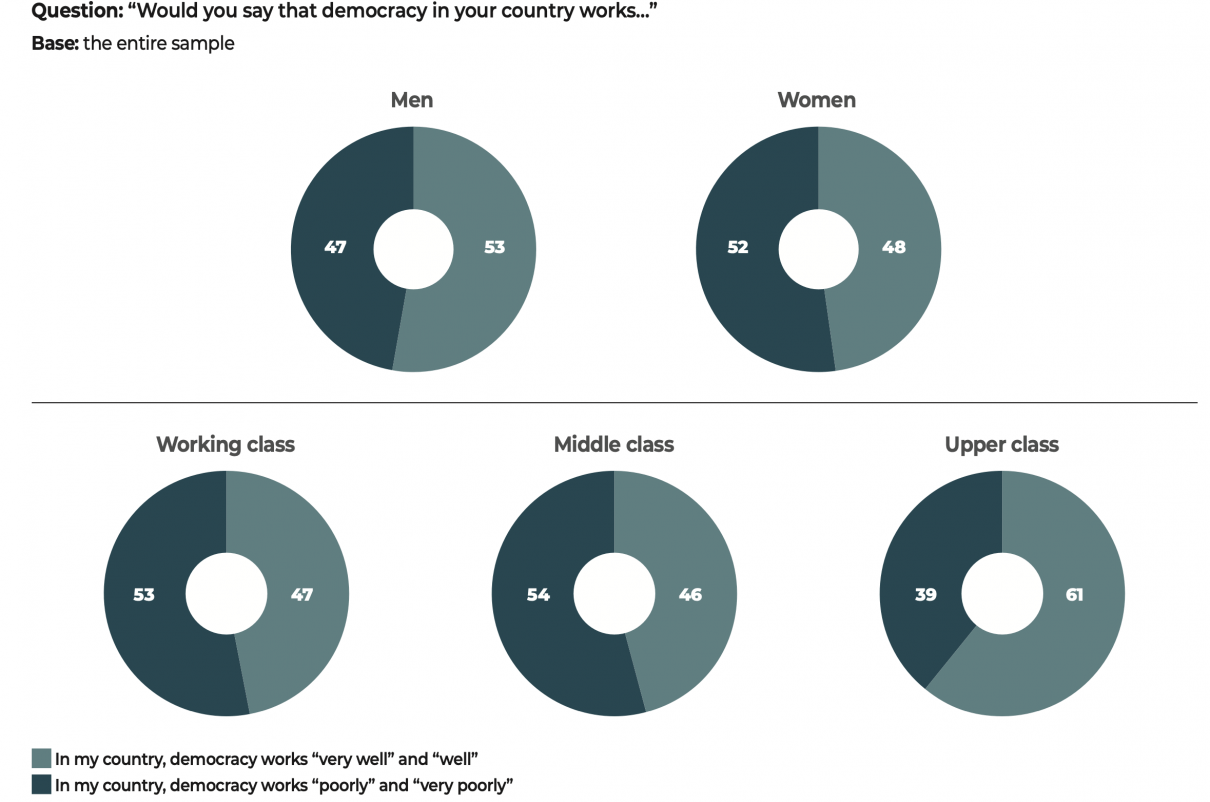

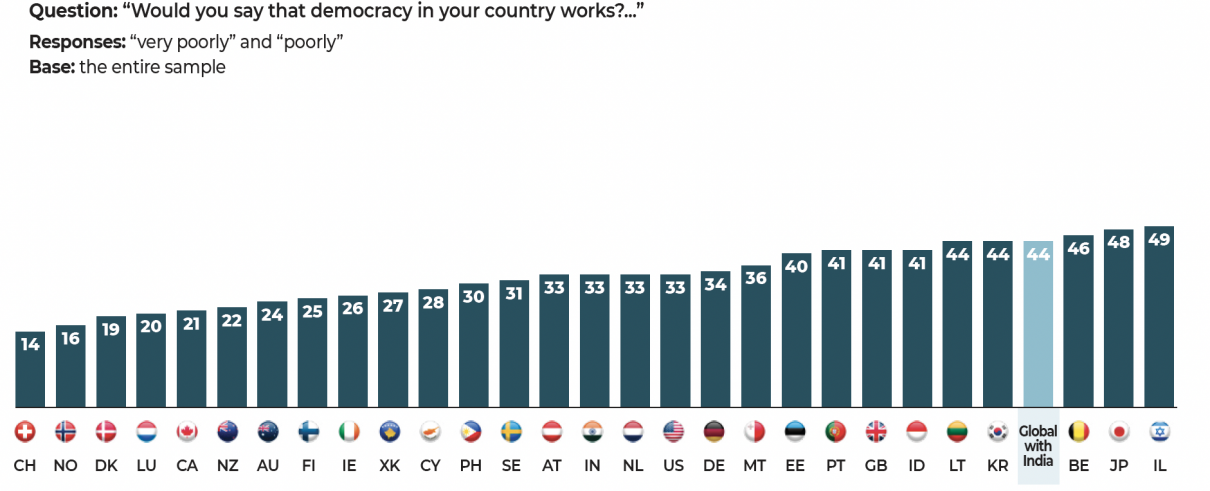

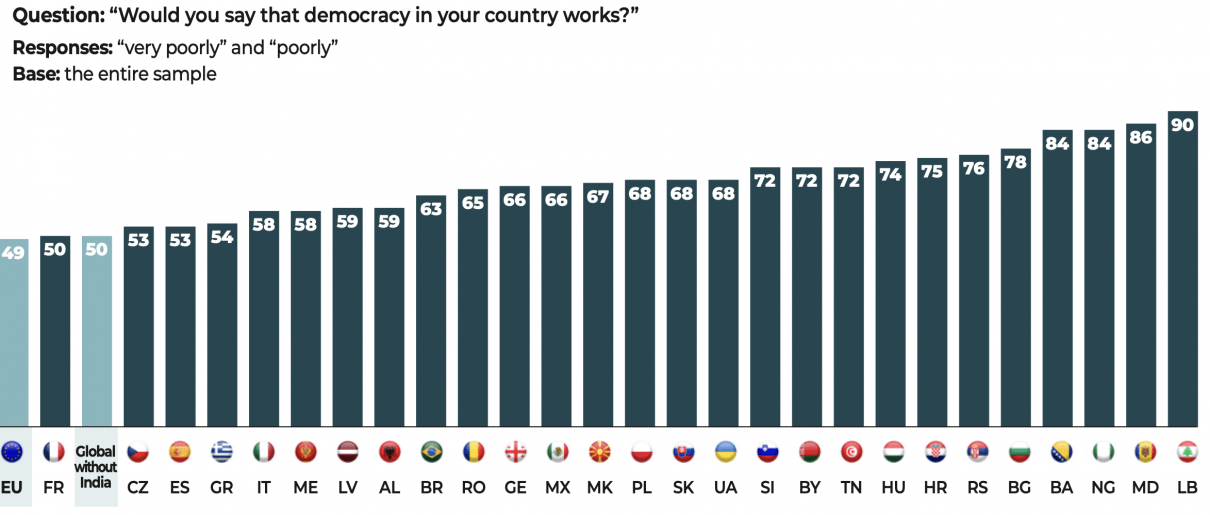

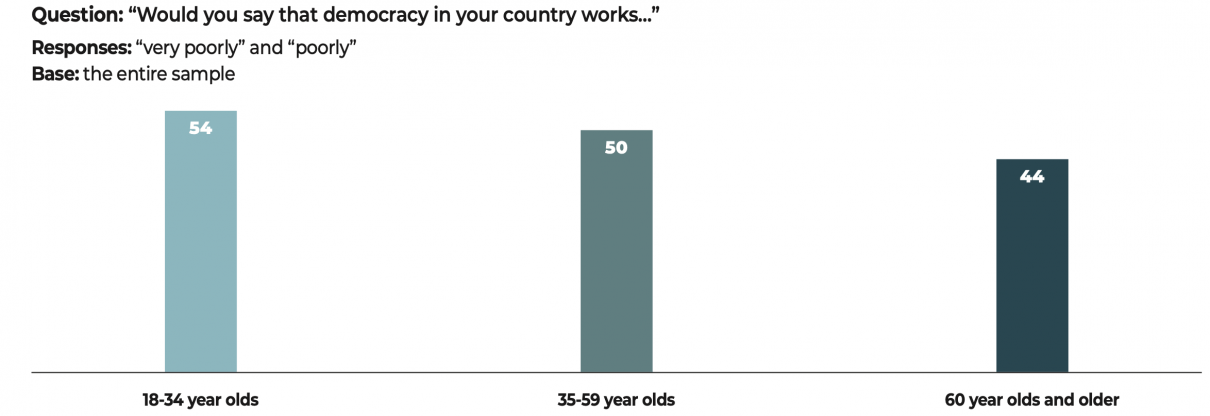

Criticism of the functioning of democracy in the name of democracy

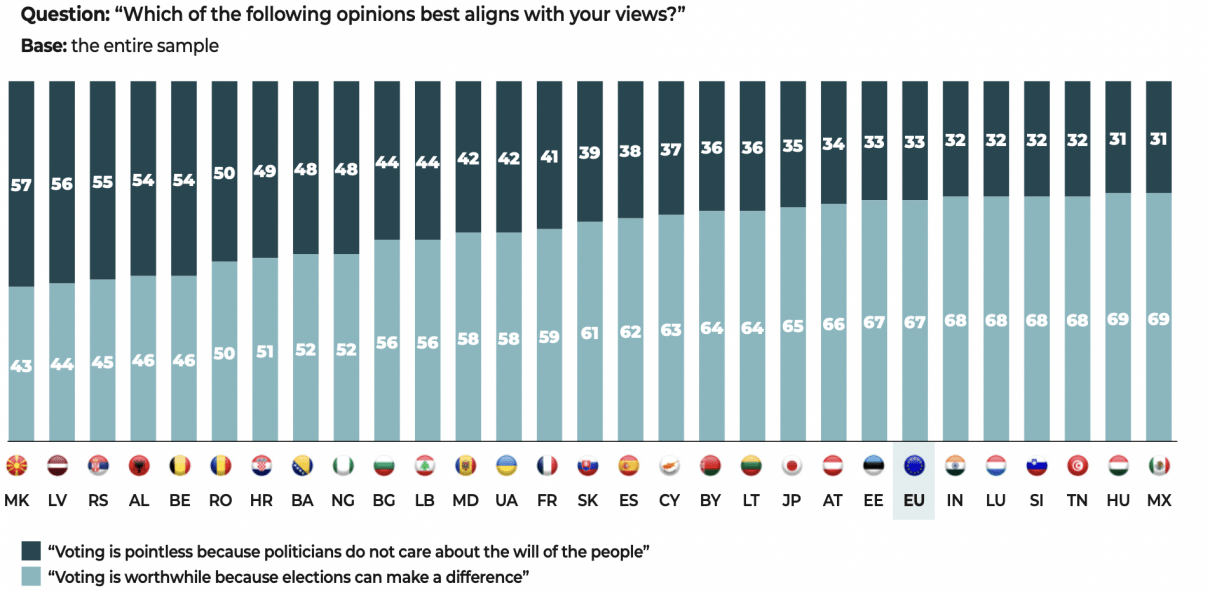

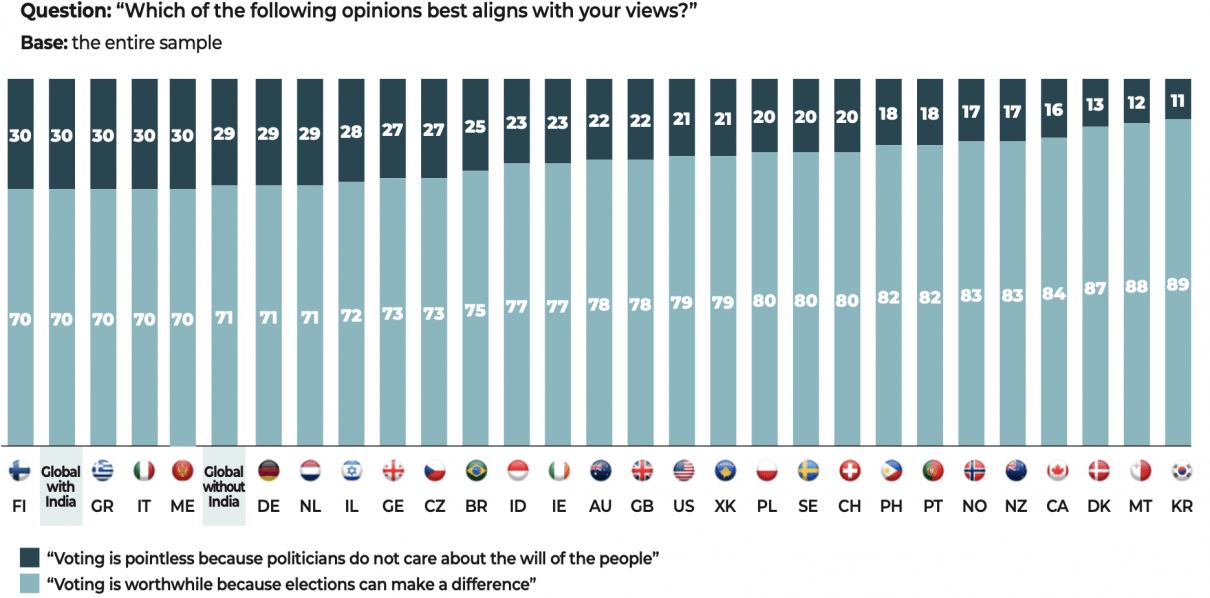

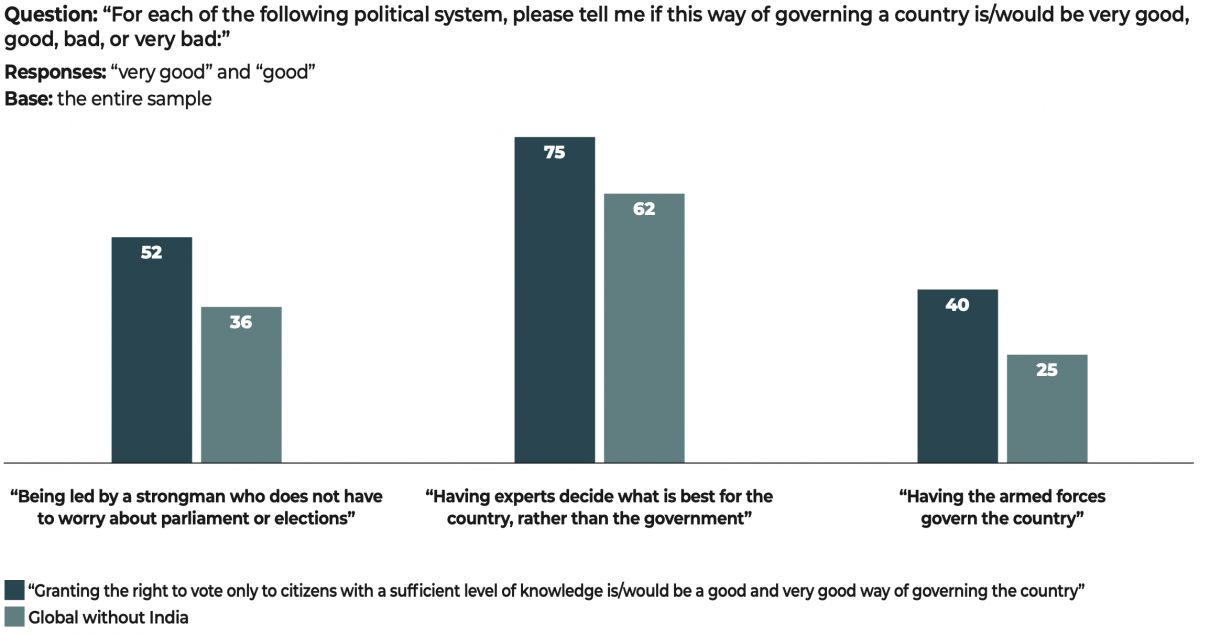

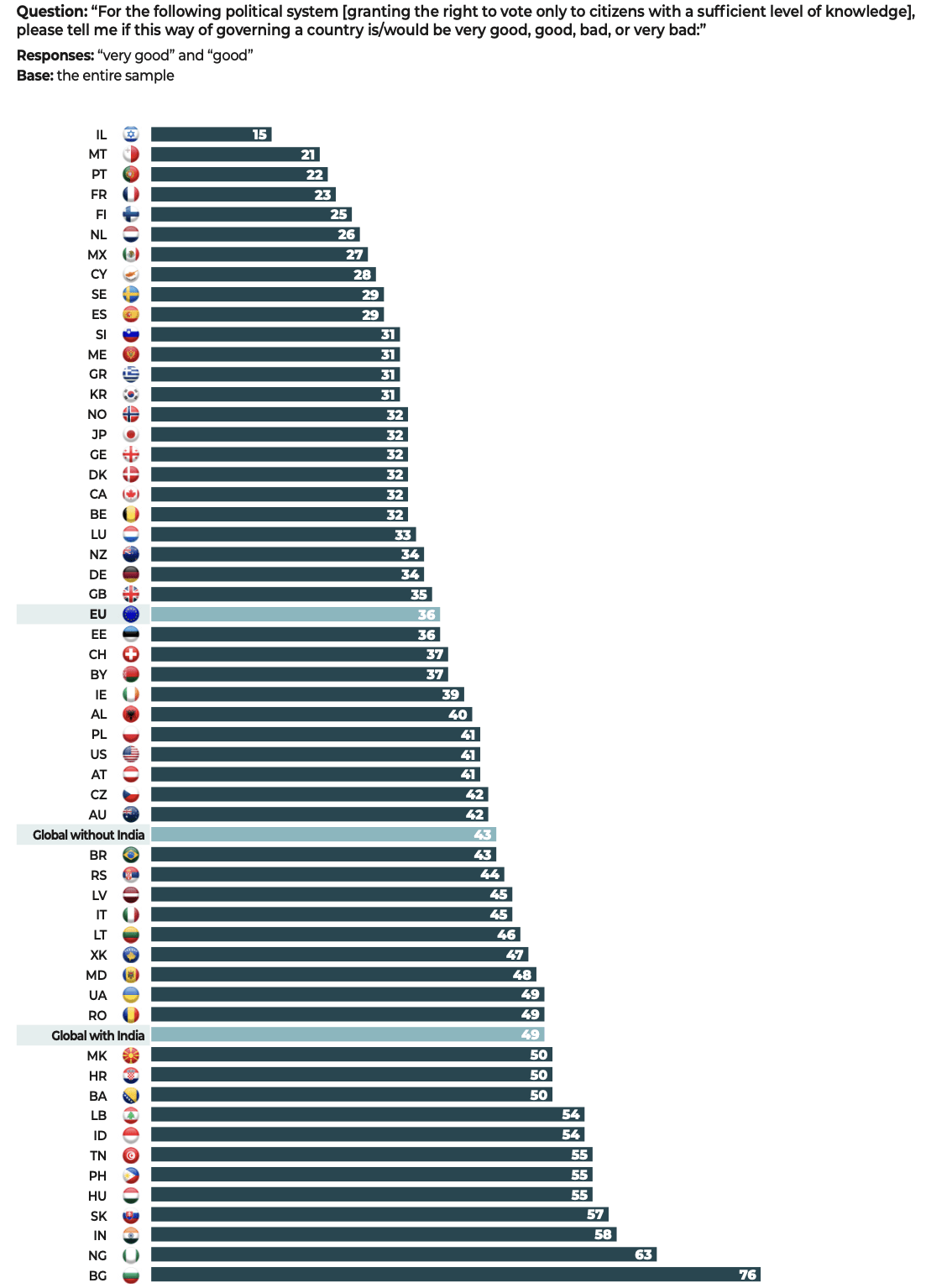

The efficiency of voting is questioned

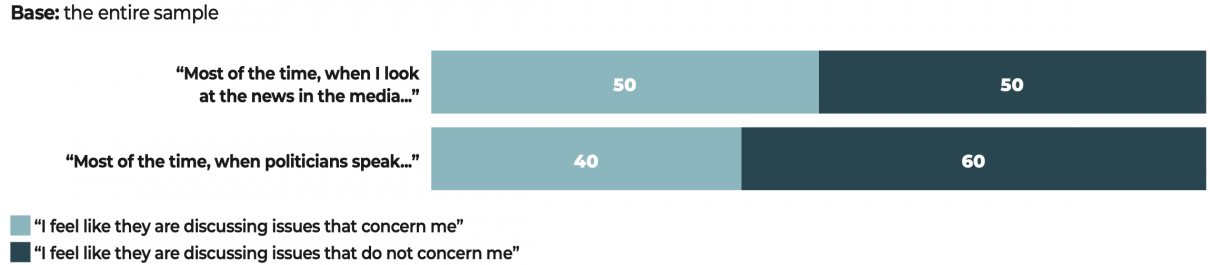

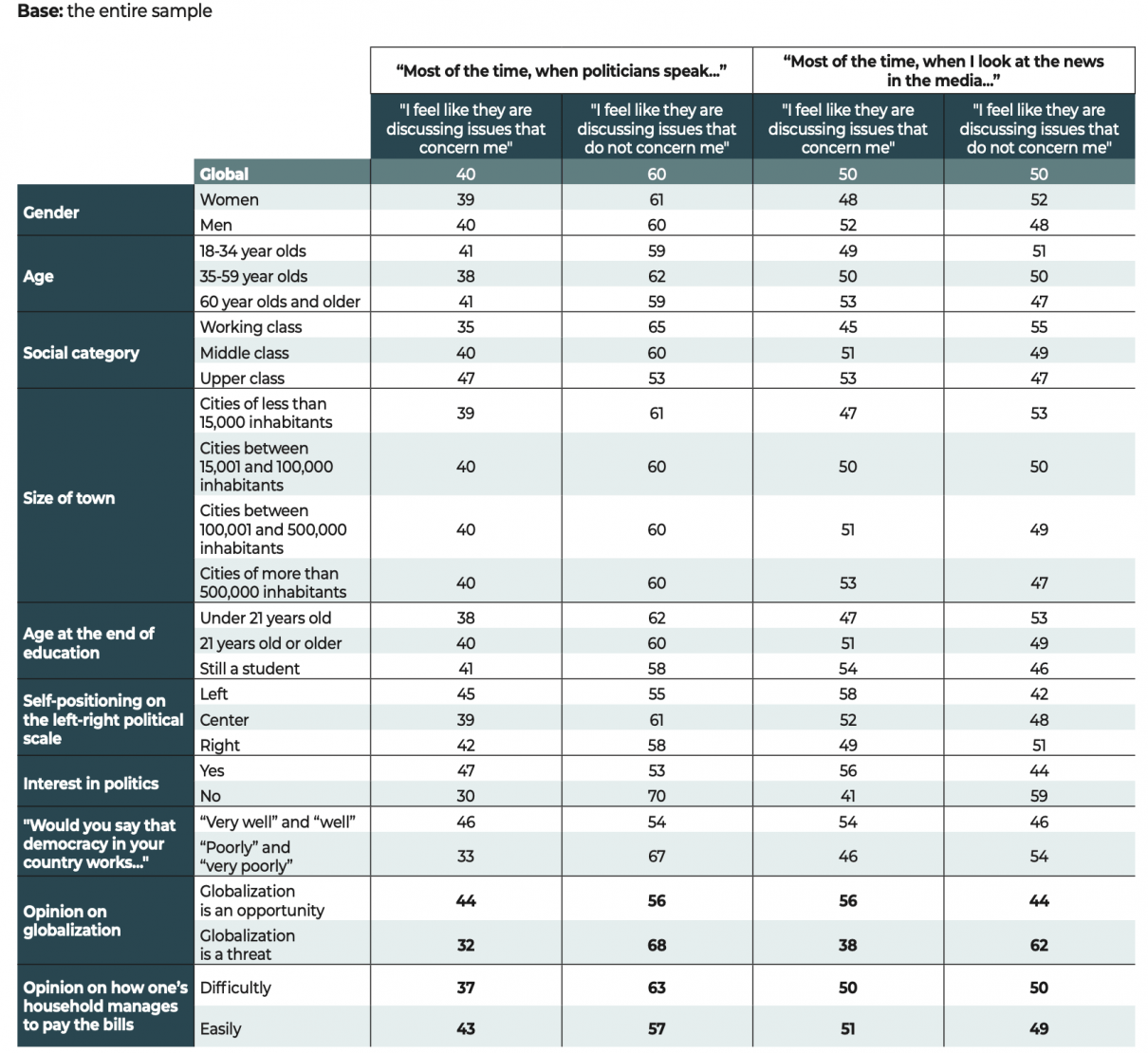

Politics and media: the double crisis of representation

Freedom of expression and pluralism are at the heart of democracy

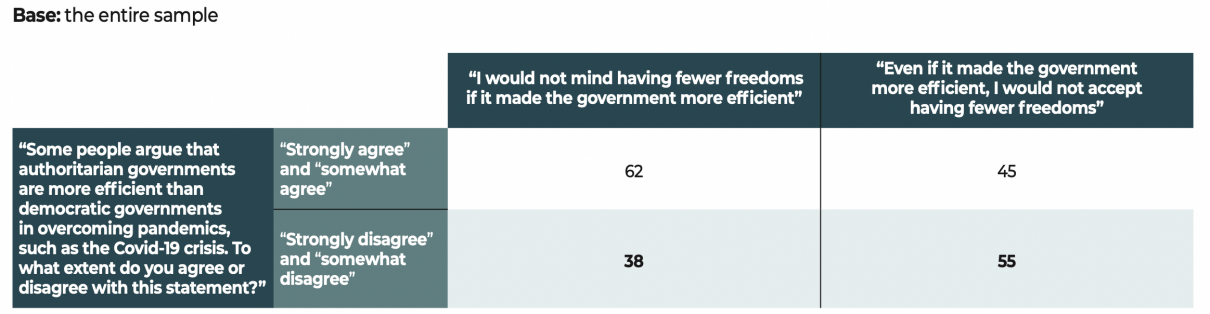

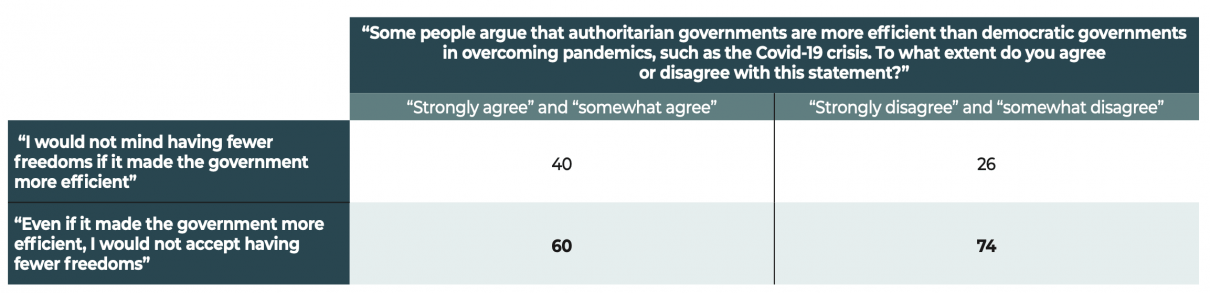

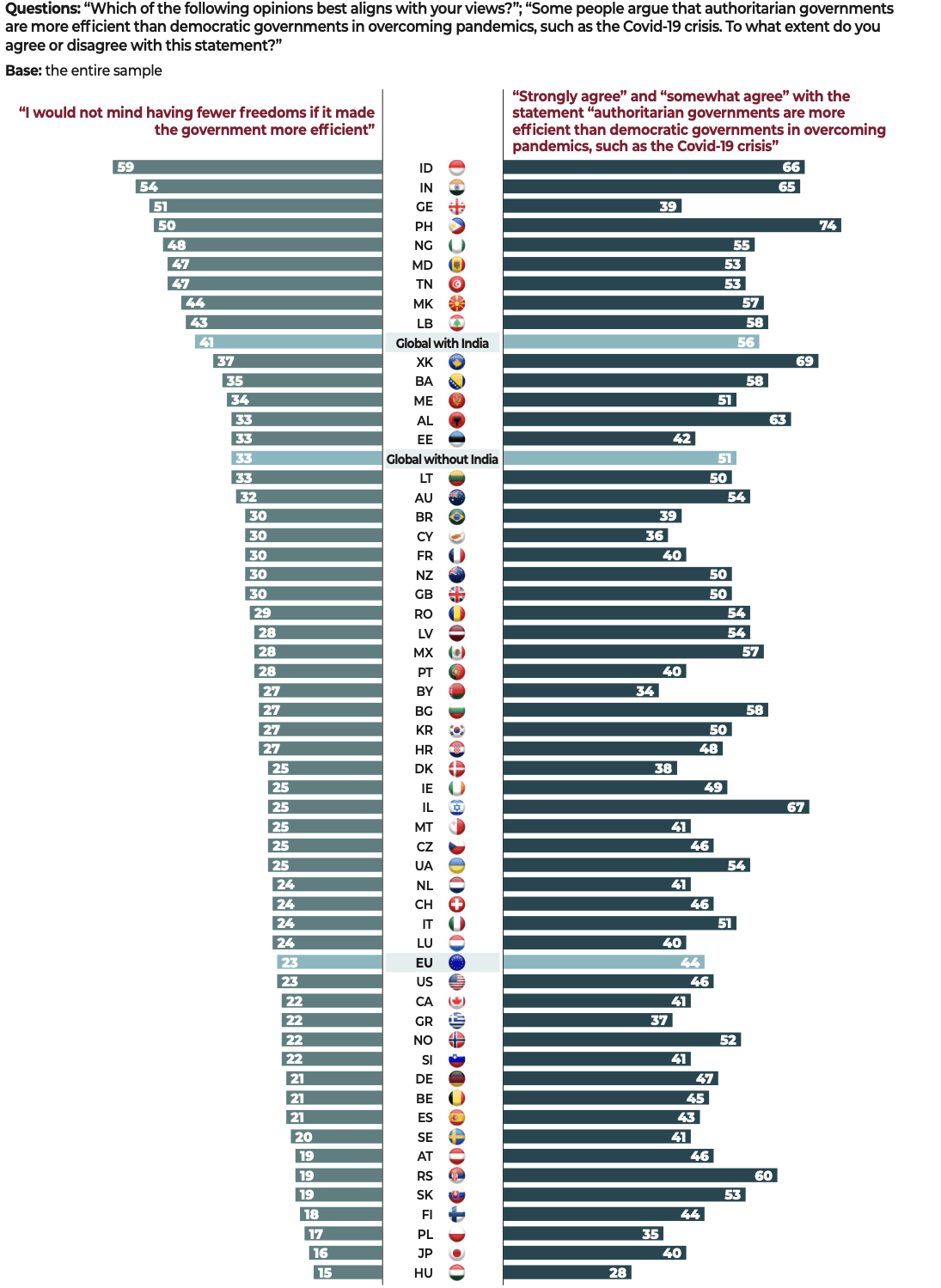

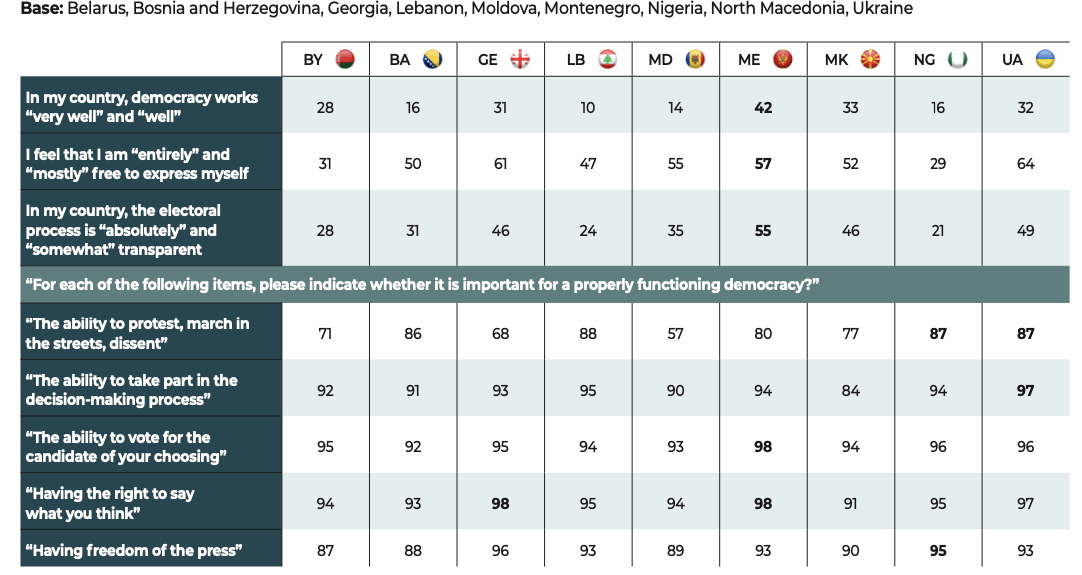

Faced with the challenge of Covid-19, citizens reclaim their attachment to the ideals of freedom

FONDATION POUR L’INNOVATION POLITIQUE

Governing bodies of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Supervisory Board

Executive Board

Auditing Committee

Ethics Committee

Scientific and Evaluation Council

INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE

Governing bodies of the International Republican Institute

Board of Directors

Executive Leadership

COMMUNITY OF DEMOCRACIES

Governing Council Member States for the Community of Democracies

KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG

Board of Directors Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung

THE GENRON NPO

Advisory Board the Genron NPO

Chair of the Board

Board of Directors

Auditor

FUNDACIÓN NUEVAS GENERACIONES

Board of Directors Fundación Nuevas Generaciones

The New Generations

Executive Director

REPÚBLICA DO AMANHÃ

República do Amanhã Supervisory Board

Executive Committee

Summary

Democracies today find themselves in a perilous situation, 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall signaled their moment of triumph. Externally, the current tensions between the democratic world and authoritarian regimes hark back to the Cold War. Internally, not since the 1930s have identity conflicts, populism, authoritarianism, racism and anti-Semitism undermined democratic societies to such an extent. For the democratic world, the combination of external and internal threats marks the obvious danger of the moment.

In the face of these major challenges, democratic societies still have one priceless asset that is illustrated in the results of our study. The citizens surveyed have confirmed their allegiance to freedoms and to democracy. Our data show that when they voice disapproval, more often than not, the object of their criticism is not the idea of democracy itself but rather the way in which democracy functions in their country.

This is the troubled context within which we have created the global survey Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century. This survey was born out of close cooperation between the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (France), the International Republican Institute (the U.S.), the Community of Democracies (intergovernmental organization), the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (Germany), the Genron NPO (Japan), the Fundación Nuevas Generaciones (Argentina) and República do Amanhã (Brazil).

The questionnaire was administered to 47,408 people, in each of the national languages, i.e. 45 languages for 55 countries: Albania, Australia, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kosovo, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Following our survey What next for democracy? conducted in 26 countries and published in 2017, and Democracies Under Pressure conducted in 42 countries and published in 2019, we now present Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century.

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Victor DELAGE

Abdellah BOUHEND, Margot COCQUET, Victor DELAGE, Léa GHILINI, Katherine HAMILTON, Camille JAFFIOL, Dominique REYNIÉ, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

Fondation pour l’innovation politique:

Abdellah BOUHEND, Margot COCQUET, Victor DELAGE, Anne FLAMBERT, Léa GHILINI, Élisa GRANDJEAN, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Camille JAFFIOL, Léo MAJOR, Dominique REYNIÉ, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

International Republican Institute:

Thibault MUZERGUES, Jan SUROTCHAK

Community of Democracies:

Patricia GALDAMEZ, Thomas GARRETT, Joanna ŁOZIŃSKA

Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung:

Hedwige HARDION, Caroline KANTER, Clara KUBLER, Dimitri MAUCHIEN, Nele WISSMANN

The Genron NPO:

Yasushi KUDO, Yuho NISHIMURA, Seiko WATANABE

Fundación Nuevas Generaciones:

Lorenzo AGÜERO, Julián OBIGLIO, María Anne QUIROGA

República do Amanhã:

Octavio de BARROS, Thomás de BARROS, Vasco CALDEIRA, Anthony TAÏEB, Renée ZICMAN

Robert HUNT

Alice CANDY, Katherine HAMILTON

Julien RÉMY

Brice TEINTURIER (Deputy Managing Director France)

Federico VACAS (Deputy Director), Alice TÉTAZ (Director of Studies), Salomé QUÉTIER-PARENT (Senior Research Officer)

GALAXY Imprimeurs

January 2022

Freedoms at risk : the challenge of the century

Dominique Reynié, University Professor at Sciences Po,

Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique.

“I believe that everything is always in question, that everything must always be saved,

that nothing is acquired definitively, and that there will never be rest on earth for men of goodwill.”

Raymond Aron, interviewed for television by Georges Suffert,

Un certain regard, ORTF, December 7th 1969

Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Why America Must Lead Again. Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump”, foreignaffairs.com, March-April 2020.

See Yves Bertoncini and Dominique Reynié, “The illiberal challenge in the European Union”, in András Sajó, Renáta Uitz and Stephen Holmes (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Illiberalism, Routledge, 2021, pp. 822-839.

Democracies today find themselves in a perilous situation, 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall signaled their moment of triumph. In an interview given in the spring of 2020, the man who would become president of the United States of America, Joe Biden, pointed out that not only has democracy stopped spreading but that it is actually in retreat: “Today, democracy is under more pressure than at any time since the 1930s. Freedom House has reported that of the 41 countries consistently ranked “free” from 1985 to 2005, 22 have registered net declines in freedom over the last five years.”1 Not even the most apparently robust democratic blocs have been invulnerable to this process of regression. Such is the case in the European Union, where elected governments are challenging the rule of law while claiming to be inspired by “illiberal democracy”.2

Significantly, the year 2021 ended with a “Summit for Democracy”, an event that President Joe Biden had first pledged in that same interview. In his keynote speech, delivered on December 9th, 2021, to representatives from 110 countries, Biden declared that “democracy is facing sustained and alarming challenges”. Seeming particularly worried, he spoke about trends “largely pointing in the wrong direction”, positing that “we stand at an inflection point”. “Will we allow the backward slide of rights and democracy to continue unchecked? Democracy doesn’t happen by accident. We have to renew it with each generation. […] In my view, this is the defining challenge of our time.” Also speaking at the summit, French President Emmanuel Macron echoed the American President’s concerns – “you have brought us together to talk about the only political model that allows us to defend these rights and freedoms: democracy” –, adding that the fight was “more necessary than ever”.

Globalization, the fruit of all-conquering democracy, is strengthening authoritarian regimes

Daniel Twining, “How Biden can beat the great-power authoritarians in China and Russia”, thehill.com, December 8th 2021.

The current tensions between the democratic world and authoritarian regimes hark back to the Cold War. China proclaims the superiority of its model, as the Soviet Union did in its time. Stalin’s Russia presented “people’s democracy” as the one true democracy, in opposition to representative democracy. China under Xi Jinping claims to have achieved authentic democracy by constructing a “socialist democracy with Chinese characteristics” that Beijing pits against “American democracy”. Moreover, by classifying its model as a “global democracy”, China proclaims it to be an appropriate solution for not just Chinese citizens but the whole world.

However, there is at least one major difference between our era and that of the Cold War, which lies in the fact that most authoritarian regimes do not reject the capitalist economy, or even globalization. Not only do the new economy and its accompanying innovations no longer destabilize regimes that are hostile to freedoms, they now enrich and strengthen them. No country illustrates this better than China, whose gradual rise to power accelerated after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 11th, 2001.

Globalization provides authoritarian regimes with important economic resources, but it also offers them new ways to influence the world and to destabilize liberal societies. For China, Russia and Turkey, today it is easier than ever to interfere in the domestic affairs of countries – above all those governed by democratic regimes, which are inherently more open since they are founded on the principle of disclosure, even transparency – to spy on them, to disrupt their public services through computer hacking and to disturb the public debate through the mass production of false information, by supporting protest movements, endorsing separatist claims, and interfering with electoral campaigns in order to influence the result but, moreover, to weaken democracy itself in the eyes of its own citizens. More broadly, they do so to discredit democracy in the eyes of the world; to indicate that a page is being turned, that the time has come for a world dominated by authoritarian powers, that the historical cycle of freedom has come to an end.

Therefore, even though globalization was born out of the collapse of communism, and while it may signal the triumph of democracy, its spread has not resulted in the continuous expansion of political liberalism. On the contrary, having initially blessed the democratic world, globalization now appears to be endangering it. Owing to many of its side effects in developed societies – deindustrialization, metropolitanization, dematerialization of professional activities, decline in social and economic status, the accumulation of vast wealth – globalization creates conditions that favor populist movements and authoritarian discourse.

For dictatorships, the challenge of the century is twofold: on the one hand, they must call into question the role played by democratic states and their principles in regulating the world order; on the other hand, they seek to lower the status of regimes that are founded on the rights and freedoms of the individual and that stir up emancipatory ideas in countries beyond their borders. As Daniel Twining, president of the International Republican Institute (IRI), points out: “Autocrats are attacking open systems in part to stymie their own people’s natural attraction to freedom. Great-power authoritarians in China and Russia view subverting democratic practice as central to their geopolitical ambitions; should not free nations see protecting and promoting democracy as part of ours?”3

Freedom: a new and historical crisis

See Dominique Reynié (ed.), Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2021, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, September 2021.

The twenty-first century, as it unfolds, appears to have become entangled in multiple power struggles that all seem to be curtailing the established freedoms of citizens. Thus, in the field of health, the outbreak of a pandemic that originated in Wuhan at the end of 2019 – caused by the Covid-19 virus – has resulted in a painful and costly ordeal for the whole world. It has forced our countries to impose restrictive measures, and even lockdowns, as well as to adopt health strategies based around the de jure or de facto obligation of vaccination, actions that fuel accusations of a “health dictatorship” voiced by a small but zealous section of society.

In the field of security, democratic societies have been transformed to combat terrorism, and in particular Islamist terrorism, which has been a global concern since the tragedy of 9/11.4 This terrorism gives rise to a culture of suspicion and surveillance. Out of fear of an attack, exceptional rules imposed in emergency situations are accepted and adopted as common law. Meanwhile, the fear of terrorism and Islamism keeps populists supplied with a steady stream of voters.

At the same time, freedom of speech is being challenged in increasingly multicultural democratic societies. Our sense of social cohesion is being corroded by mutual misunderstandings, distrust and hostility. Intercultural disputes escalate into conflicts over values when the core difference of opinion concerns fundamental freedoms such as freedom of speech or freedom of the press. For example, we need look no further than the tragedies caused by the violent responses to the publication of The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie in 1988 and of cartoons in Denmark in 2008, not to mention the attacks on Charlie Hebdo in 2015. This type of terrorism takes the form of an internal war against the values of a liberal society, as was the case for the attacks in Paris and its surrounding region on November 13th, 2015, or in Nice on July 14th, 2016. Not since the 1930s have identity conflicts, populism, authoritarianism, racism and anti-Semitism undermined democratic societies to such an extent.

Without the freedom to debate and publish, the democratic model amounts to nothing. Those freedoms make the model possible, legitimate and effective, since it is liberty that enables human ingenuity to reach its full potential. Yet our century has also seen the emergence of a new transnational and digital public space. The cause of this particular upheaval is not found beyond democratic borders, nor is it foreign or hostile to liberal values. It lies in the remarkable technological innovations developed by companies whose success is made possible by the freedoms they enjoy. However, although they have an extraordinary effect on the number of people participating in the public media space, the power of digital platforms – The Big Five (GAFAM) – is nonetheless problematic. What becomes of democracies if the laws enacted by elected assemblies no longer have the power to regulate our freedoms? What becomes of democracies if the power to guarantee those freedoms stealthily shifts from parliaments into the hands of monopolistic companies?

Lastly, we must consider the repercussions for liberal societies of the fact that freedom of speech is no longer secure in the very environment where it should be most closely safeguarded: at universities. Schools and universities are responsible for nurturing the generations that will shape tomorrow’s world. The decline of academic freedom therefore casts a shadow over the future of freedoms in general. Universities will lose their chief purpose if they fail to halt the destructive spiral of intolerance, censorship and violence. Just as inevitably, the decline of freedom within the university environment will also trigger the deterioration of the university itself, of its knowledge and its resources. Also at stake, in this regard, is our ability to produce competent, responsible, inventive and liberal elites, without which democratic states will lose the power advantage they have always held over authoritarian states.

Defending and expanding freedoms in the twenty-first century

Ibid.

In this difficult context, the world is also confronted with global warming, one of the greatest challenges of the century. We will assume here that the effectiveness of the response to global warming is dependent to a large extent on the democratic model, because of the pressure it allows citizens to exert on their rulers. Furthermore, as Daniel Twining underlines: “Responsive and accountable democratic institutions will be essential to solving the world’s toughest challenges – from climate change to social justice to inclusive prosperity. Authoritarians who usurp their people’s most basic rights to life and liberty are not going to be trustworthy partners in attending to the common good of humankind.”5 The ultimate success of the fight against global warming will therefore depend not only on the stability of the democratic model but also on the extent to which it spreads around the globe. The democratic world seems eager to be embodied, among other things, by its resolute commitment to combating global warming. Its determination is such that it may be necessary to advise caution and to ensure that this mission is pursued with discernment – in other words, by taking on board its psychological, political, economic and social effects. If poorly conducted, or dogmatic and authoritarian in nature, the fight against global warming will contribute to weakening the democratic system and the support of society, particularly for those with lower-incomes and the middle classes.

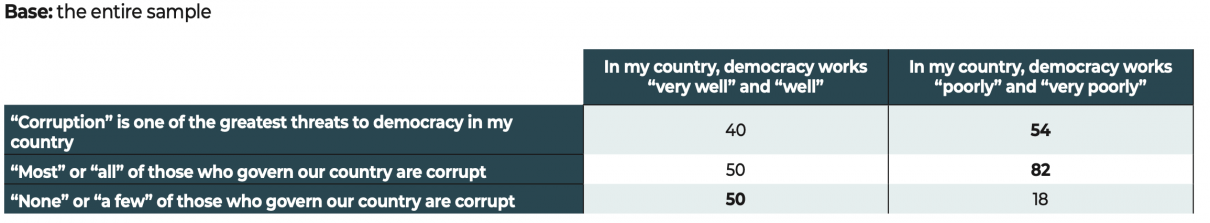

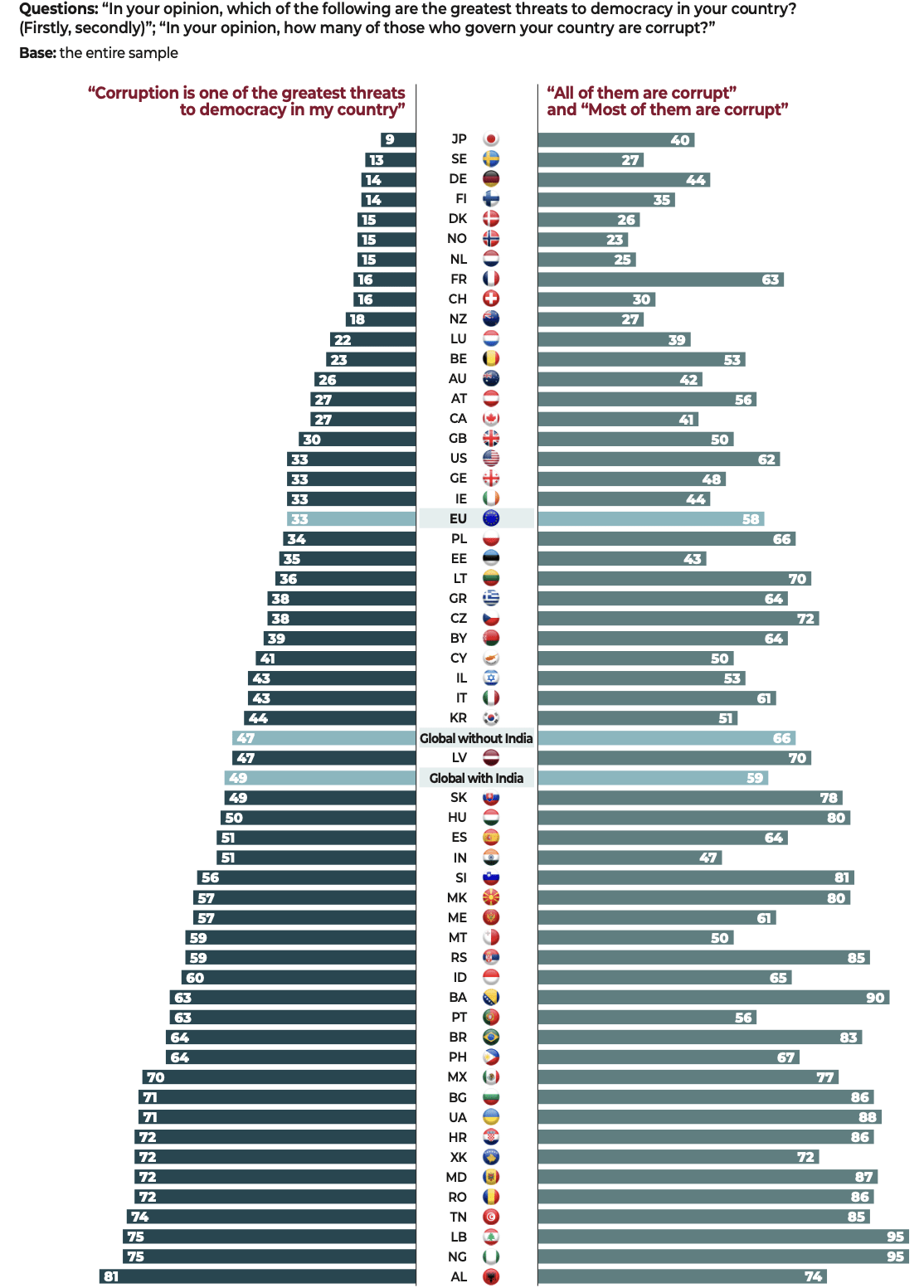

While we must defend the climate, we must also defend our freedoms. This means deploying necessary resources to fight against ignorance and disinformation. If we are no longer able to offer high-quality education and information to as many people as possible, there can be no democratic regime. Freedom will be lost if we fail to keep inequality in check and to fight the corruption that, as highlighted by the results of our study, is of the utmost concern to our citizens.

Lastly, freedom will vanish if we give up the notions of prosperity and power. Defending freedom also means defending conditions that are propitious to economic growth and to scientific and technical innovation. The democratic world must ensure that it has the resources required to sustain the social and human progress that both constitute its raison d’être and strengthen its legitimacy. But the democratic world must also continue to develop its power, including its military power. In the twenty-first century, it may seem troubling to compare the vast financial resources earmarked for the ecological transition with the weak level of investment into ensuring the prosperity of democratic societies and their capacity to guarantee their own security in an increasingly dangerous world: a world in which China is threatening Taiwan and Russia is threatening Ukraine; in which Turkey is pushing Azerbaijan to wage war against Armenia, threatening Cyprus and putting pressure on Greece; and in which the Iranian theocracy is on the verge of possessing atomic weapons.

In the face of these major challenges, democratic societies still have one priceless asset that is illustrated in the results of our study. The citizens surveyed have confirmed their allegiance to freedoms and to democracy. Our data show that when they voice disapproval, more often than not, the object of their criticism is not the idea of democracy itself but rather the way in which democracy functions in their country. Freedom is not cultural. It is a human aspiration. Within us lies the force most capable of guaranteeing the sustainability of democracy in the twenty-first century.

| This survey was born out of close cooperation between the Fondation pour l’innovation politique (Fondapol), the International Republican Institute (IRI), the Community of Democracies (CoD), the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS), the Genron NPO, Fundácion Nuevas Generaciones (NG) and the República do Amanhã.

Following our survey What next for democracy?, conducted in 26 countries in 2017, and Democracies Under Pressure (42 countries, 2018), we now present Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century, our new survey conducted in 55 countries. |

Survey methodology

fondapol.org, iri.org, community-democracies.org, kas.de, genron-npo.net, nuevasgeneraciones.com.ar/sitio/ and republicadoamanha.org.

The Fondation pour l’innovation politique (France), the International Republican Institute (the U.S.), the Community of Democracies (intergovernmental organization), the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (Germany), the Genron NPO ( Japan), the Fundación Nuevas Generaciones (Argentina) and República do Amanhã (Brazil) joined together to work on an extensive international survey conducted across 55 countries, the results of which are published below under the title “Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century”. The analysis of the results is available to the public, freely accessible on the respective websites of the seven partner think tanks.1 Six versions are available: in French, English, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese and Japanese.

This publication is a written analysis by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. The International Republican Institute, the Community of Democracies, the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, and the Genron NPO helped in creating the questionnaire, but the following is the result of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique’s work. All opinions expressed should be considered those of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique team and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and views of the partner institutions.

The study2 is based on a questionnaire designed by the teams working at the partner think tanks. It was administered by Ipsos, a leading polling company, across national samples selected from each of the 55 surveyed countries. This survey encompasses the 27 Member States of the European Union, the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia), other European countries that are not members of the European Union (Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Norway, Switzerland, Ukraine), or that have left it (the United Kingdom), as well as Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Lebanon, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Korea, Tunisia and the United States.

55 countries, 45 languages, 47,408 respondents

Albanian (Albania), Albanian (North Macedonia), Arabic (Lebanon), Arabic (Tunisia), Belarusian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Brazilian Portuguese, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Filipino, Finnish, French, Georgian, German, Greek (Cyprus), Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Luxembourgish, Macedonian, Maltese, Montenegrin, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian.

In the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, half of the interviews were conducted online and half were conducted in person.

In total, 47,408 people were surveyed. The study was conducted on the basis of representative national samples drawn from the population aged 18 years and above. Quotas for gender, age, profession, region and the size of respondents’ towns were used to ensure the representativeness of the samples and varied by country. The samples take into account the demographic weighting of each country. The approximate sizes of the samples were a thousand people in countries with more than 8 million inhabitants, six hundred people for those with 5 to 8 million inhabitants and five hundred people for countries with less than 5 million inhabitants. For some countries (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia), the sample size was increased to 800 people despite a population of less than 8 million in order to maximize the representativeness of the results.

The 39 questions to which those participating in our survey “Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century” were invited to respond is available on fondapol.org. It was administered in each of the national languages, amounting to 45 languages3 across the 55 countries. The data was collected over a five- week period (between July 9th and August 10th 2021, i.e. before the fall of Kabul) with the exception of Indonesia and the Philippines, where the questionnaire was administered between June 23rd and 30th of 2021. The survey was administered at a time when the countries were still, to varying degrees, going through the Covid-19 crisis. The interviews were all conducted via a self-administered online questionnaire with the exception of 10 countries, where in-person interviews were carried out: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina,4 Cyprus, Georgia, India, Kosovo, Malta, Moldova, Montenegro and North Macedonia. In all of these countries, these interviews were conducted according to the prevailing health regulations.

39 questions

The “Eastern European Union” sub-category is made up of Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The “Western European Union” sub-category comprises Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden.

This designation is without prejudice to positions on the status of Kosovo, and is in line with UN Security Council Resolution 1244 and the opinion of the International Court of Justice on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

For most of the questions, we asked respondents to answer by choosing a level on a four-point scale (e.g.“yes,absolutely”/“yes, somewhat”/“not really”/“not at all”) to assess, inter alia, levels of satisfaction, trust or optimism. In this document, for the sake of convenience and legibility, we usually present and comment on the results by adding up, on the one hand, the “yes, absolutely”/”yes, somewhat” answers and, on the other hand, the “not really”/”not at all” answers.

In some cases, respondents were asked to choose between two options. For instance, when asked for their view on globalization, the options offered to the respondents were “globalization is an opportunity” and “globalization is a threat”.

Some of the questions had three possible answers. When asked about the benefits to their country of NATO membership, for example, respondents could answer that the latter is “a good thing”, “a bad thing”, or “neither good nor bad”.

If they failed to respond to any of the questions, respondents received the following message: “Please try to answer the question. However, if you have no opinion on this question, you may move on to the next one by clicking ‘next question’” (the rate of non-responses was between 0% and 2% both online and in-person).

Lastly, the results are presented either by country or by sub- category. The overall results are presented in the “Global” category. The value of each country has been by weighted to take into account their demographic weight within the overall sample. Accordingly, the results from India make up 38.1% of the overall weighted sample. Because of this demographic weight, and unless otherwise specified in the document, the overall (“Global”) average does not include India.

For a given question, the “Global” average therefore corresponds to the results obtained from the 54 countries surveyed (excluding India). For a given question, the “EU” average corresponds to the results from across the Member States of the European Union, i.e. 27 countries, with values weighted according to demographic weight. We have also included separate “Eastern European Union”5 and “Western European Union”6 sub-categories. We use an average referred to as the “Western Balkans”, which corresponds to the Balkan countries that are not members of the European Union: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo,7 Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

The seven organizations made a collective choice to use, whenever possible the online method to administer this poll. In some countries, where freedom of expression can be limited, the online methodology was the only reliable solution to get to meaningful results.

The online methodology also allowed us to cover more countries, including some that usually do not appear in opinion surveys of public perception of democracies. We believed those countries deserve to be included in the final results, even though, for some, the individual samples may include some specific caveats that, for the sake of transparency, we would like to point to the attention of the reader here.

The samples conducted online in Belarus, Indonesia, Mexico, Montenegro Nigeria and the Philippines represent populations that are more urban, more educated, or more affluent than the general population. The survey results in these countries should therefore be viewed as more reflective of the opinions of the more “connected” segments of these populations, even if the weighting applied to the data makes it possible to correct for some of the sampling bias.

Furthermore, we would like to point out some specific situations in which the underrepresentation of certain groups and overrepresentation of others was difficult to avoid in the present state of online polling capacities:

– Nigeria: underrepresentation of Muslims (15% in the sample vs. 54% in the latest estimates).

– Belarus: underrepresentation of older respondents (the sample is 41% of 18–34-year-olds, 40% of 35–49-year-olds, and 7% of the 60+ age group – compared to numbers of 28%, 27%, and 28%, respectively, for these age groups). Bias partially corrected by data weighting.

– Indonesia: overrepresentation of Christians in the sample (17% Christian and 77% Muslim, vs. official estimates at 9% Christian and 87% Muslim).

– Lebanon: Overrepresentation of youth (53% of respondents fall within the 18–34 age group, compared to the expected 38%). Bias partially corrected by data weighting.

– Israel: the sample should be considered as for Hebrew speakers only.

– Tunisia: overrepresentation of the 18–34 age group (60% vs. an expected 35%), and underrepresentation of the older population (6% and 3% in the 50–59 and 60+ age cohort in the sample, vs. the 16% and 19% of the actual populations). Bias partially corrected by data weighting.

It is our hope that the experience of administering this survey in those countries will be used to correct the representativity issues we encountered in our samples, so that future surveys can set even higher standards for online and offline polling methodologies at the global level.

Finally, we hope that our investigation will contribute to helping those countries where freedom is restricted to progress on the road to democratization.

Who are democracies afraid of

The current tensions between the democratic world and authoritarian regimes hark back to the Cold War. China proclaims the superiority of its model, as the Soviet Union did in its time. Stalin’s Russia presented “people’s democracy” as the one true democracy, in opposition to representative democracy. China under Xi Jinping claims to have achieved authentic democracy by constructing a “socialist democracy with Chinese characteristics” that Beijing pits against “American democracy”. Moreover, by classifying its model as a “global democracy”, China proclaims it to be an appropriate solution for not just Chinese citizens but the whole world.

However, there is at least one major difference between our era and that of the Cold War, which lies in the fact that most authoritarian regimes do not reject the capitalist economy, or even globalization. Not only do the new economy and its accompanying innovations no longer destabilize regimes that are hostile to freedoms, they now enrich and strengthen them. No country illustrates this better than China, whose gradual rise to power accelerated after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on December 11th, 2001.

Globalization provides authoritarian regimes with important economic resources, but it also offers them new ways to influence the world and to destabilize liberal societies. For China, Russia and Turkey, today it is easier than ever to interfere in the domestic affairs of countries – above all those governed by democratic regimes, which are inherently more open since they are founded on the principle of disclosure, even transparency – to spy on them, to disrupt their public services through computer hacking and to disturb the public debate through the mass production of false information, by supporting protest movements, endorsing separatist claims, and interfering with electoral campaigns in order to influence the result but, moreover, to weaken democracy itself in the eyes of its own citizens. More broadly, they do so to discredit democracy in the eyes of the world; to indicate that a page is being turned, that the time has come for a world dominated by authoritarian powers, that the historical cycle of freedom has come to an end.

China worries the democratic world

In 2018, the 42 countries of the Democracies Under Pressure study were: Albania, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, North Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Although the European Union is the power that respondents consider least worrying, it is not an entity comparable to a traditional nation state.

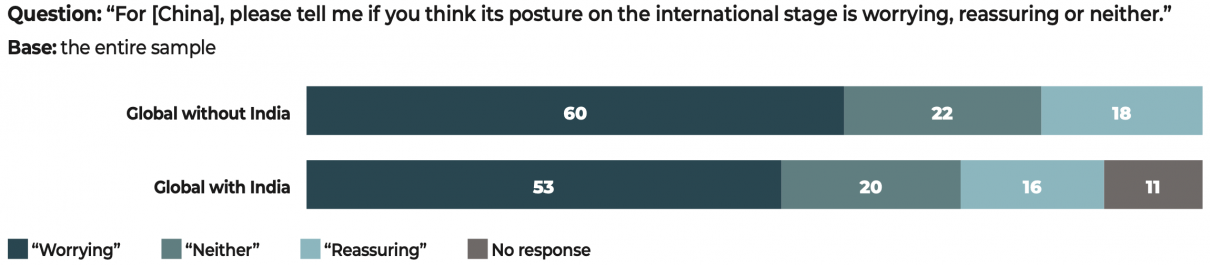

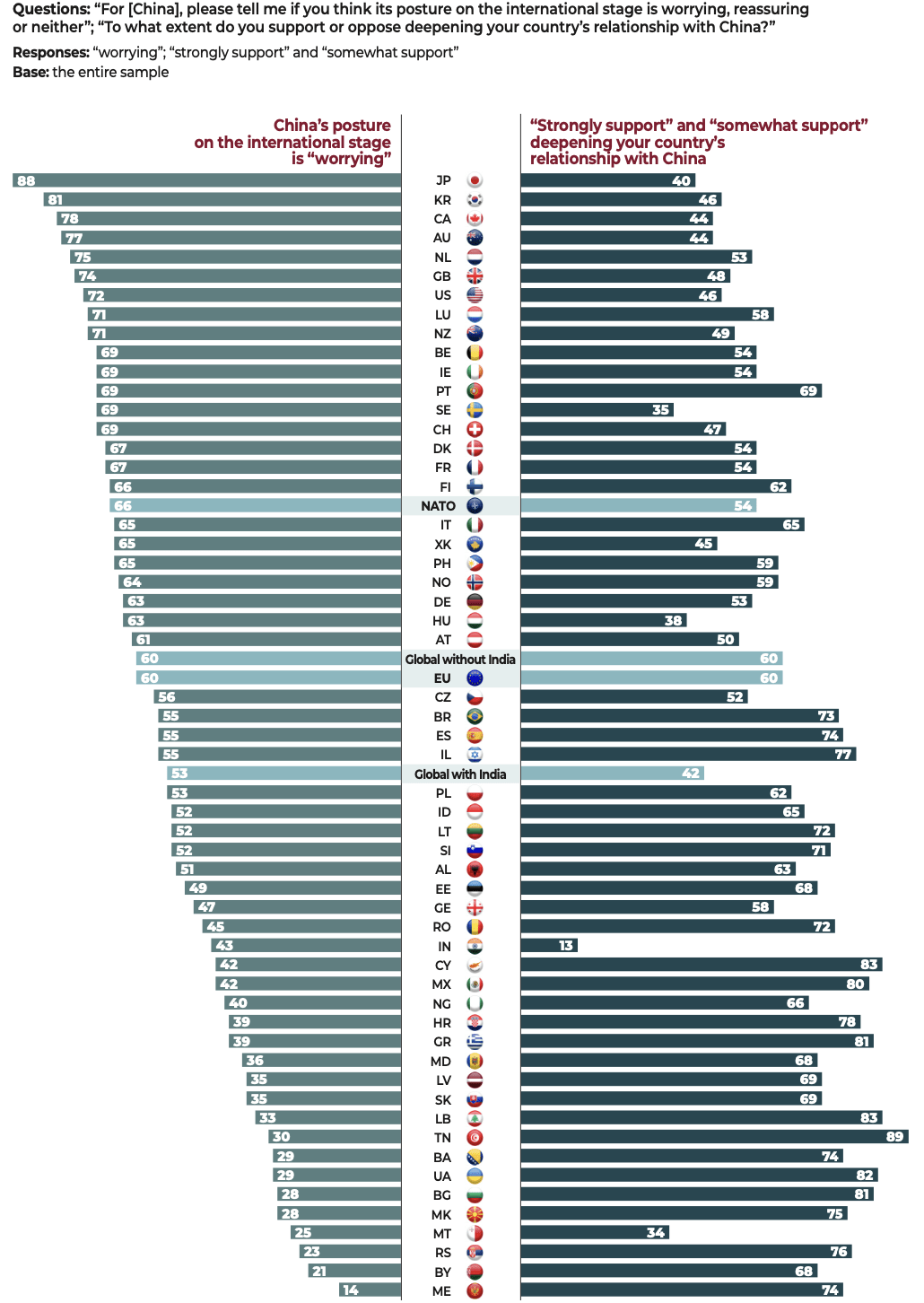

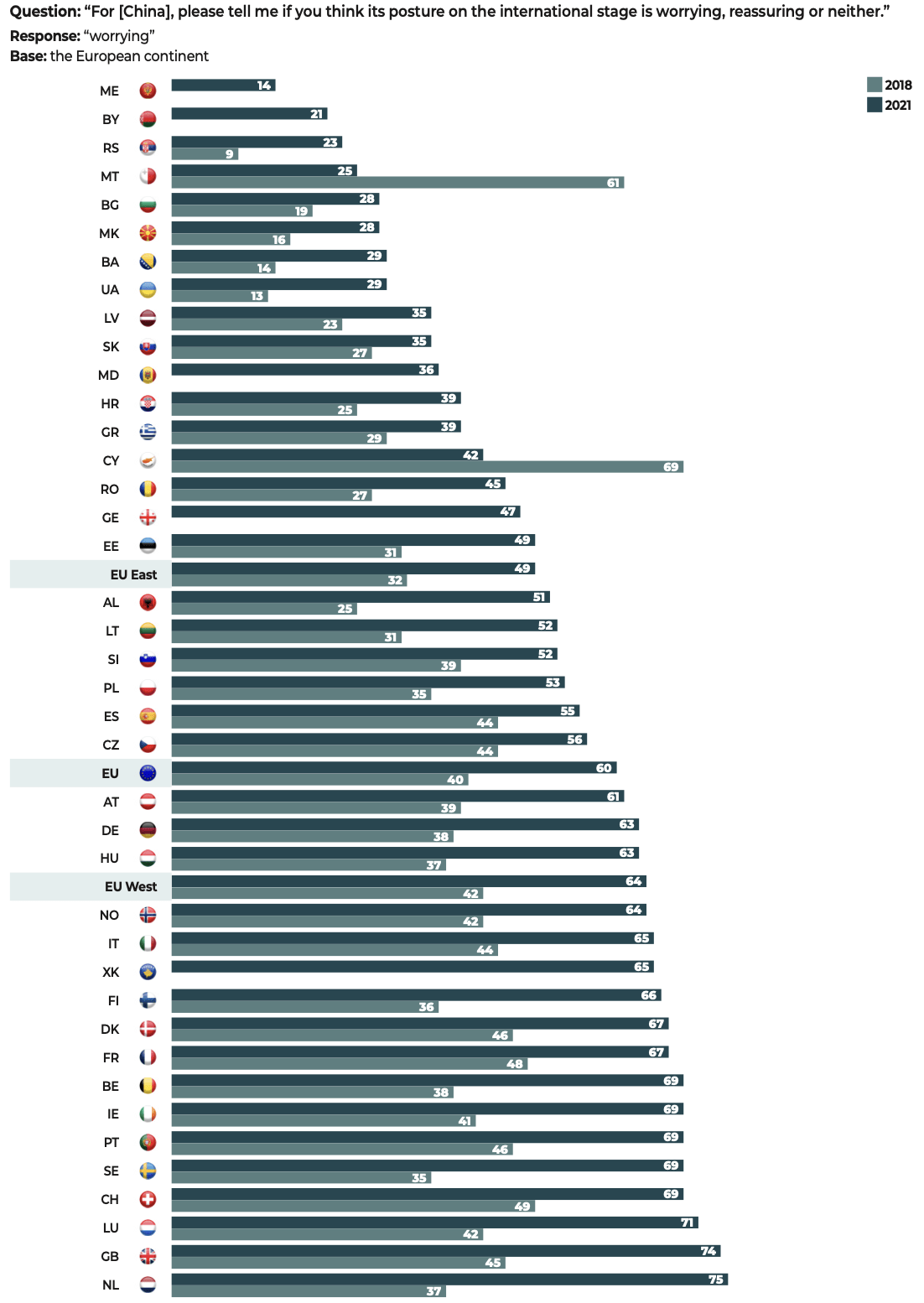

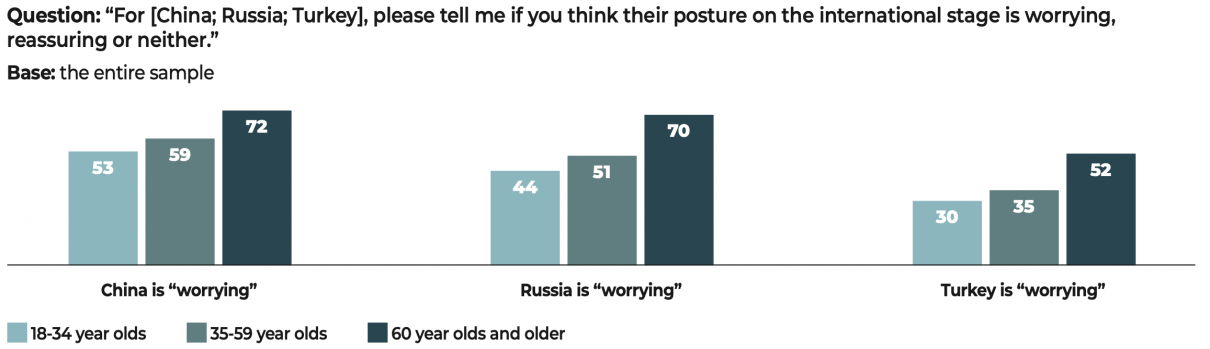

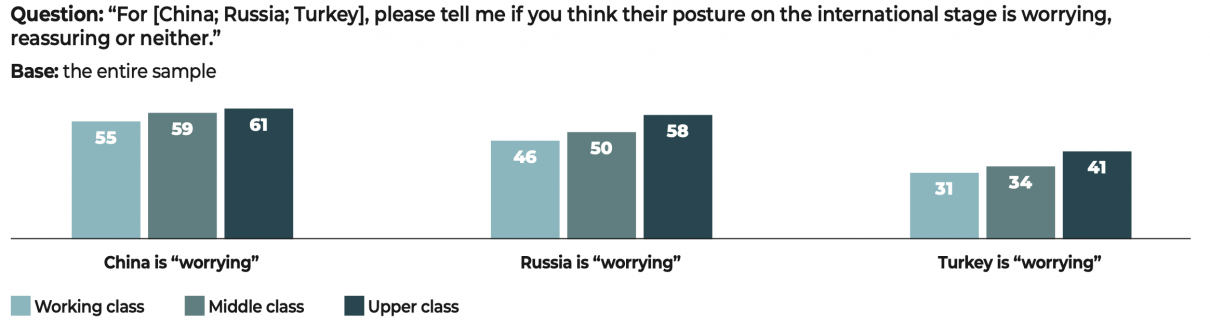

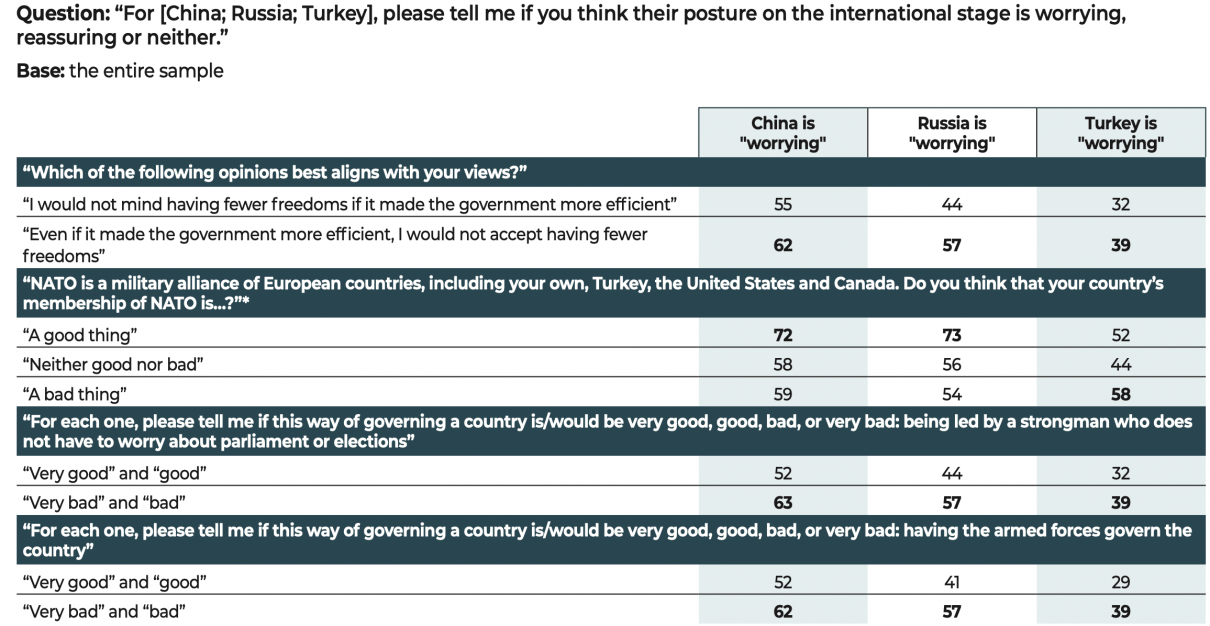

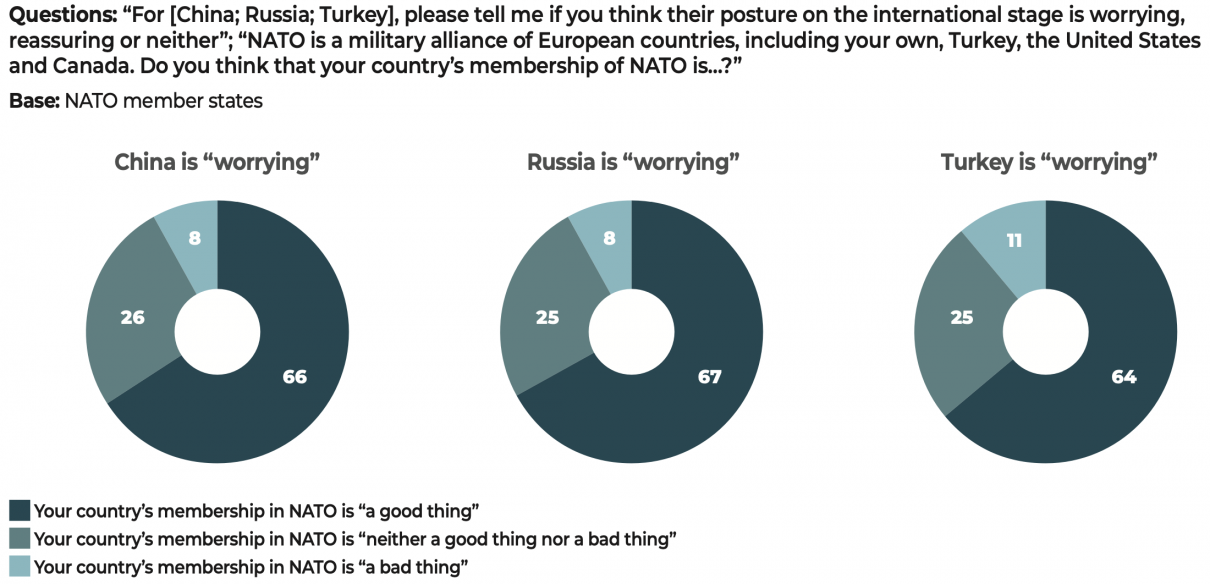

In our survey, we sought to establish how authoritarian countries are perceived. We asked the following question: “For [China, Russia, Turkey], please tell me if you think their posture on the international stage is worrying, reassuring or neither”. This shows that 60% of respondents consider China’s posture on the international stage to be “worrying”, 52% feel the same way about Russia and 37% about Turkey. Almost a quarter of respondents (22%) consider China’s attitude to be “neither worrying nor reassuring” while 18% consider it to be “reassuring”. In India, whose results are not included in the calculation of the global average owing to its demographic weight, concerns about China’s posture are shared by 43% of respondents (12% are reassured, 17% answered “neither” and 28% chose not to respond). In our 2018 survey of 42 countries,1 China’s reputation was less of a concern. In the eyes of the public, it was the least worrying, behind Russia and the United States.2

A strong majority of citizens are concerned about China (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

On this subject, see: Paul Charon and Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer, Les Opérations d’influence chinoises. Un moment machiavélien, Institut de recherche stratégique de l’École militaire (Irsem), 2nd edition, October 2021.

Jean-Pierre Cabestan, Laurence Daziano, Hong Kong: The Second Handover; Hongkong : la seconde rétrocession, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, juillet 2020; 香港: 二次回歸 ; 香港: 二次回归.

China is comfortable with, and at times even ostentatiously assertive about, its model, which combines the totalitarian organization of the state with a capitalist economy and high-tech control society. Externally, thanks to a soft power strategy presenting the image of a great civilization gloriously reclaiming its status as a global power, it has been able to increase its influence without immediately raising serious concerns. However, Beijing’s power play can no longer be hidden.3 The public now views the country’s desire to reshape the rules of globalization to its advantage and its geopolitical expansion projects – as evidenced by its brutal repression in Hong Kong4 and its increasingly frequent acts of aggression against Taiwan and, more generally, throughout the Asia-Pacific region – as a threat. Moreover, while the Covid-19 health crisis may have played in Beijing’s favor by destabilizing the Western world, and above all the United States, China is now suspected of having obstructed investigations into the origins of the virus. It is also accused of withholding information on both the severity of the pandemic on its territory and the speed with which it spread around the world.

| Fear of China rose drastically between 2018 and 2021

In 2018, among respondents from the 42 countries in the Democracies Under Pressure survey, half (49%) said they were worried about China’s posture on the international stage. In 2021, looking only at the same 42 countries from 2018, we see that this fear has increased sharply (65%). |

The desire to deepen relations with Beijing is counterbalanced by concerns about China (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

See Emilie Sweigart and Gabriel Cohen, “Brazil’s Evolving Relationship with China”, americasquaterly.org, October 19th 2021.

See Amb. Martha Bárcena Coqui, “Why Mexico’s Relationship with China Is So Complicated”, americasquaterly.org, September 28th 2021.

The Americas in the face of Chinese ambition

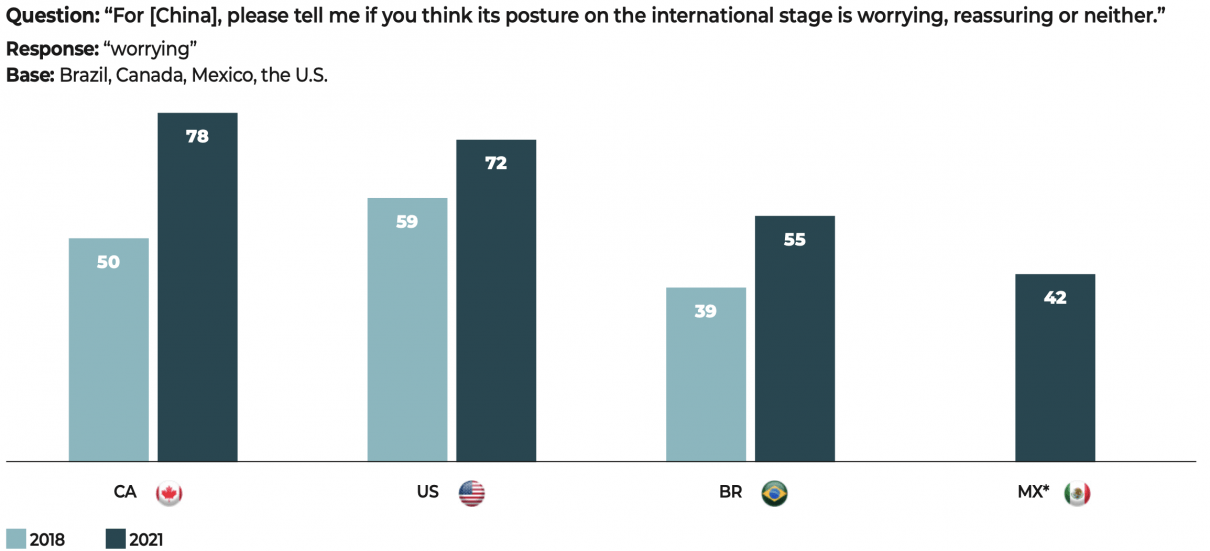

Concerns regarding China are unprecedentedly widespread among Canadians (78%), Americans (72%) and Brazilians (55%), though the prospect of a deepening of relations with China is causing discord among public opinion across the Americas. While the majority of Canadians (56%) and Americans (54%) are opposed to the deepening of relations, the same cannot be said of Brazilians. On the contrary, there is broad support for this proposal in Brazil (73%). In Mexico, concern about China is less widespread (42%) and most Mexicans (80%) want their country to deepen its relationship with China. It is worth bearing in mind that Beijing, under Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping, has multiplied the number of strategic partnership agreements and, in doing so, has become Brazil’s largest economic partner5 and Mexico’s second largest behind the United States; as time passes, Mexico is doing proportionally more trade business with China and less with the United States.6

In the Americas, China is a growing cause of concern (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

* Mexico was not on our panel in 2018.

See Anchal Vohra, “China Wants to Be Lebanon’s Savior”, foreignpolicy.com, July 9th 2020.

See David Sacks, “Countries in China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Who’s In and Who’s Out”, Council on Foreign Relations, March 24th 2021.

See Oluwatosin Adeshokan, “Why Is China Looking to Establish Banks in Nigeria?”, thediplomat.com, October 13th 2021.

| Lebanon, Tunisia, Nigeria: fragile states in favor of deepening their relations with China

One measure of Beijing’s growing influence can be seen in the number of governments willing to enter into economic partnerships with China. In Lebanon, Beijing is acting quickly to build infrastructure in the country and, above all, to unfurl the so-called Pan-Arab Highway linking Beirut and Damascus.1 Tunisia, in the midst of an economic and political crisis, joined the “Belt and Road Initiative” initiative in 2018, offering China opportunities for cooperation2 and prospects for greater influence in Africa. Lastly, Nigeria, the most populous country in Africa, has become a new El Dorado for Chinese business, whose increased investment there has coincided with diminishing levels of Western investment.3 |

See Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, “Indonesia and China inked a deal to promote the use of the Yuan and Rupiah. The political and economic implications are huge”, theconversation.com, October 14th 2020.

See “North Korean nuclear issue and US-China conflict greatest risks to peace in Northeast Asia in 2021”, The Genron NPO, March 2nd 2021.

China is viewed negatively in the Asia-Pacific region

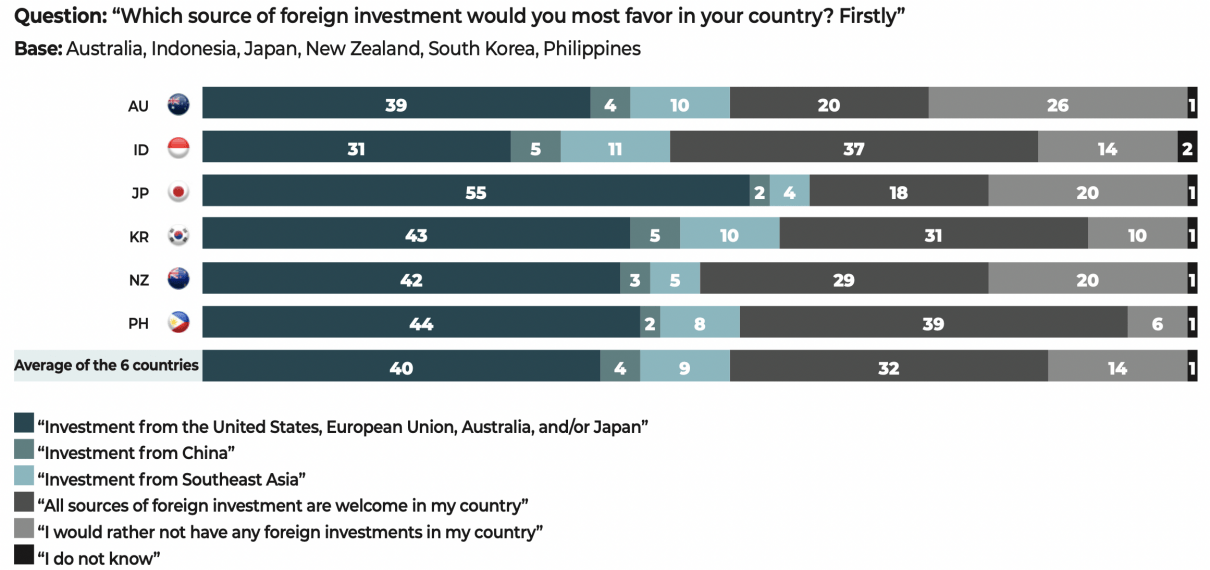

In the Asia-Pacific region, the level of concern is high among Filipinos (65%) and Indonesians (52%). However, both Filipinos (59%) and Indonesians (65%) want to see a deepening of their countries’ relationships with China. Indonesia and China signed an agreement in September 2020 to settle their trade transactions in their respective national currencies, thereby reducing their dependency on the dollar and other currencies.7

Concerns regarding China are even more widespread in New Zealand (71%), Australia (77%) and South Korea (81%). The same can be said of Japan, where in 2021 the fear is almost unanimous (88%) at a similar level to that registered in 2018 (91%). The impact of Beijing’s increasing military presence in the South China Sea is being felt across the entire region, leading to harsher public perceptions of China.8 New Zealanders (51%), South Koreans (54%), Australians (56%) and the Japanese (60%) are now opposed to the deepening of relations with China.

Finally, although the same fear is not as commonplace in India (43%), three-quarters of Indians (72%) are opposed to a deepening of relations with their neighbor, while territorial disputes between the two Asian giants remain unresolved.

Populations from the Asia-Pacific region favor investments by democratic powers over those from China (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

See A World Safe for the Party. China’s Authoritarian Influence and the Democratic Response. Country Case Studies from Nepal, Kenya, Montenegro, Panama, Georgia and Greece, International Republican Institute, 2021, pp. 54-60.

Quotation cited in Silvia Amaro, “China bought most of Greece’s main port and now it wants to make it the biggest in Europe”, cnbc.com, November 15th 2019.

China divides the European continent

Among Europeans (in EU Member States), concerns about China’s posture on the international stage have spread rapidly and are now shared by 60% of respondents, 20 points higher than in 2018 (40%). Greeks are among the least troubled by this potential threat (39%), although the level of concern there has also increased compared to 2018 (29%). The two countries have grown progressively closer since the 2008 financial crisis.

China intends to turn the Greek port of Piraeus into one of Europe’s biggest ports and a key logistical interface on the “Belt and Road Initiative”.9 Chinese President Xi Jinping said in 2019: “We want to strengthen Piraeus’ transshipment role and further boost the throughput capacity of China’s fast sea- land link with Europe.”10

Opinions are more divided in Eastern Europe. In that region, Bulgarians, Latvians, Slovaks and Croats are those least worried about China. On the other hand, a sense of concern is more prevalent in Lithuania, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland.

The Chinese posture is inciting anxieties in Europe (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

The “17+1”, or “16+1”, is a forum initiated by Beijing to extend its economic and political influence in Europe beyond the institutional and formal framework of the European Union and to pursue its flagship investment project, known as the “Belt and Road Initiative”. The “17+1” initiative includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia. Lithuania pulled out of the “17+1” initiative in March 2021.

In the Western Balkans, a third (33%) of respondents said that they were worried by China’s posture on the international stage, a similar amount to those who find it reassuring (34%). Kosovars are the exception (65% are worried by China’s behavior). Established in 2012, the “17+1” initiative11 is bearing fruit. Eastern Europe is a key region for the “Belt and Road Initiative” project launched in 2013. Chinese investments, such as the construction of a railway linking Belgrade and Budapest, seem to be winning people over: the data show that public opinion is more favorable to a deepening of relations with China in the Eastern European Union (64%) than in the Western European Union (59%). In the Western Balkans, support for stronger trade links with Beijing is greater still (70%).

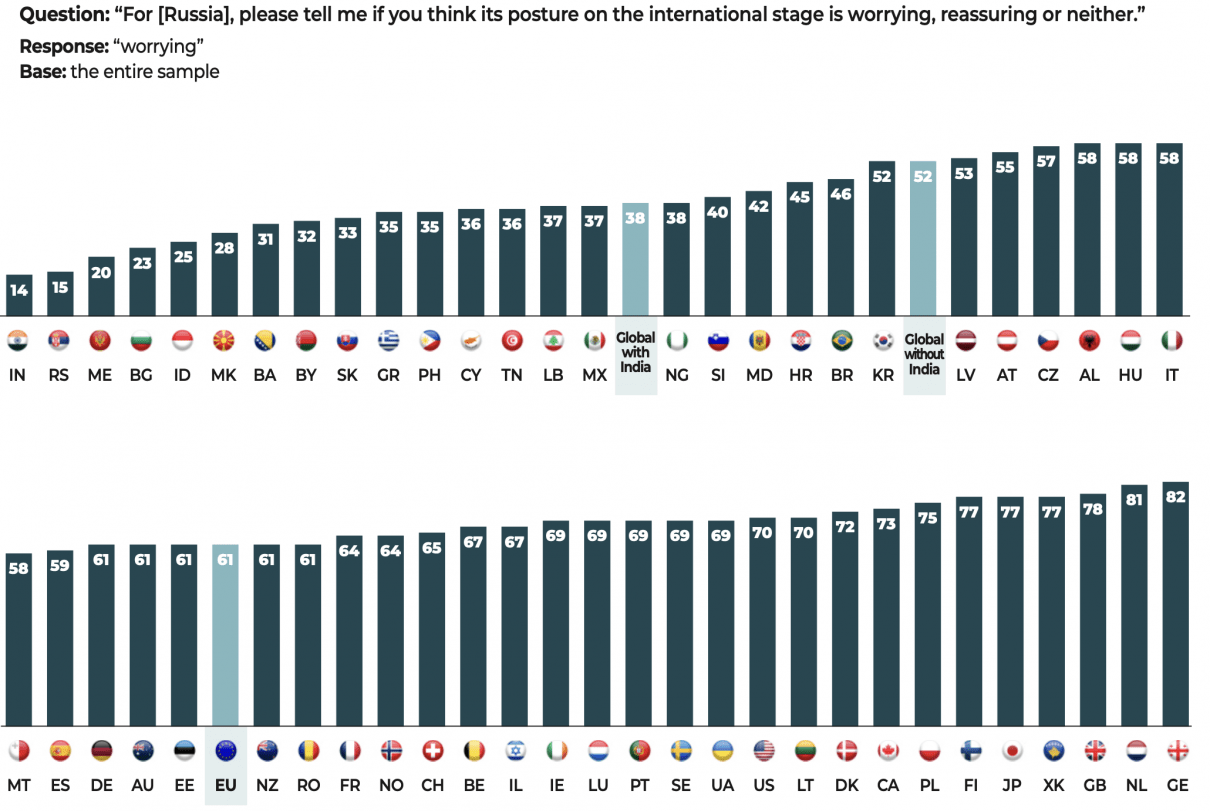

A less influential Russia remains feared by its neighbors

In the democratic world, Europe fears Russia the most (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

See “Russia cyber-plots: US, UK and Netherlands allege hacking”, bbc.com, October 4th 2018.

See Simone Tagliapietra and Georg Zachmann, “Will natural gas cooperation with Russia save the Greek economy?”, bruegel.org, April 20th 2015.

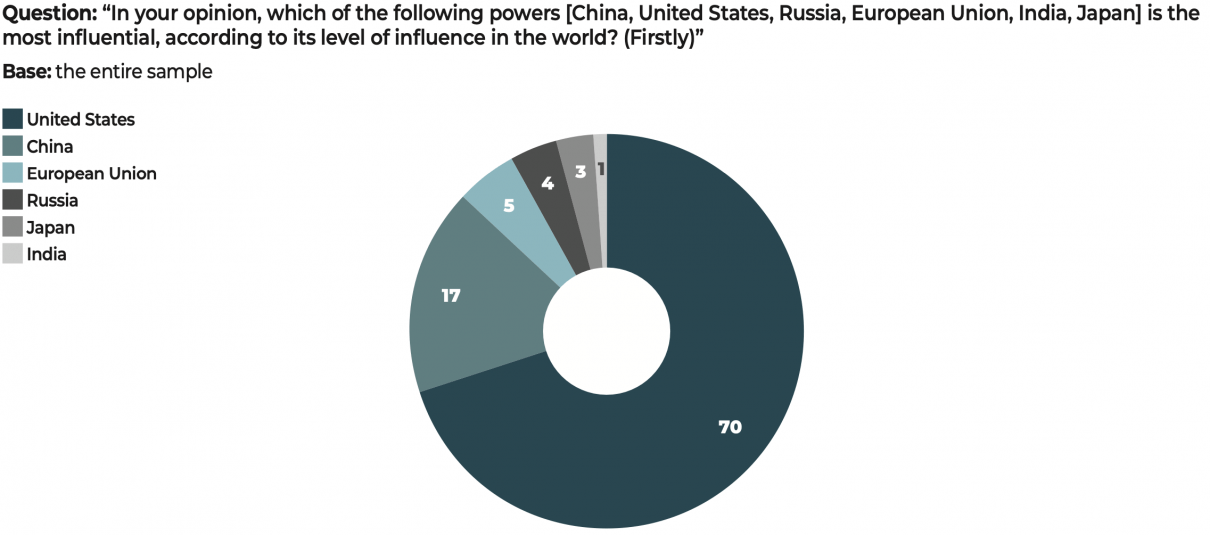

Russia has become a country with a fragile economy that is suffering from a rapidly ageing population. Only a small minority (4%) of those surveyed named Russia as the most influential global power. A majority (52%) of respondents nonetheless still indicate that they are worried by its posture on the international stage. This fear is particularly widespread among Georgians and Ukrainians, of course, but it is also prevalent among the Dutch, Brits, Finns, Danes and Swedes. In part, this can be owed to Russian interference in domestic affairs: the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have both been subject to cyberattacks by Moscow, particularly during election campaigns, which they have condemned.12

However, the level of concern has not risen between 2018 and 2021 in countries that are particularly sensitive to Russian pressure; indeed, although remaining high, it has actually gone down in some of these countries. For example, concerns about Russia are shared by 61% of Estonians (down 19 points from our 2018 survey), 53% of Latvians (down 13 points) and 70% of Lithuanians (down 4 points).

Greece is the exception in Europe, since only a third of respondents indicated that they were worried by Russia. In 2015, the two countries signed an agreement within the framework of the Turkish Stream, a major pipeline that passes through Greece and Turkey to connect Russia and Europe.13 Construction began in 2017 and the pipeline started operating in 2020.

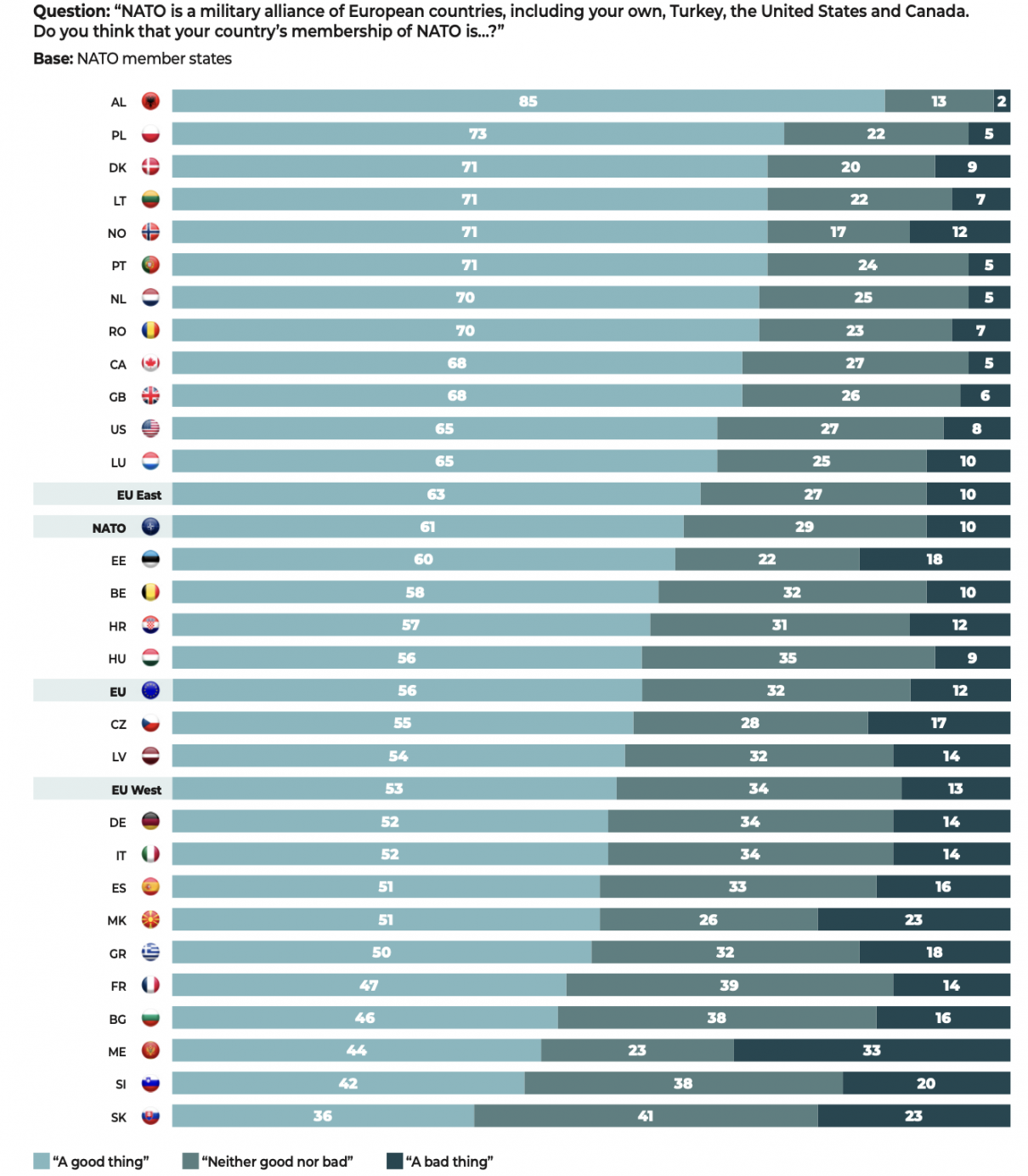

Russia’s posture is a cause of concern in NATO countries (66%), particularly in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States. Respondents who consider their country’s membership of NATO to be “a good thing” are more likely to express concern about Russia (73%) than those who see it as “a bad thing” (54%).

In the Asia-Pacific region, Russia is deemed worrisome by a majority of South Koreans, Australians, New Zealanders, and three quarters of the Japanese.

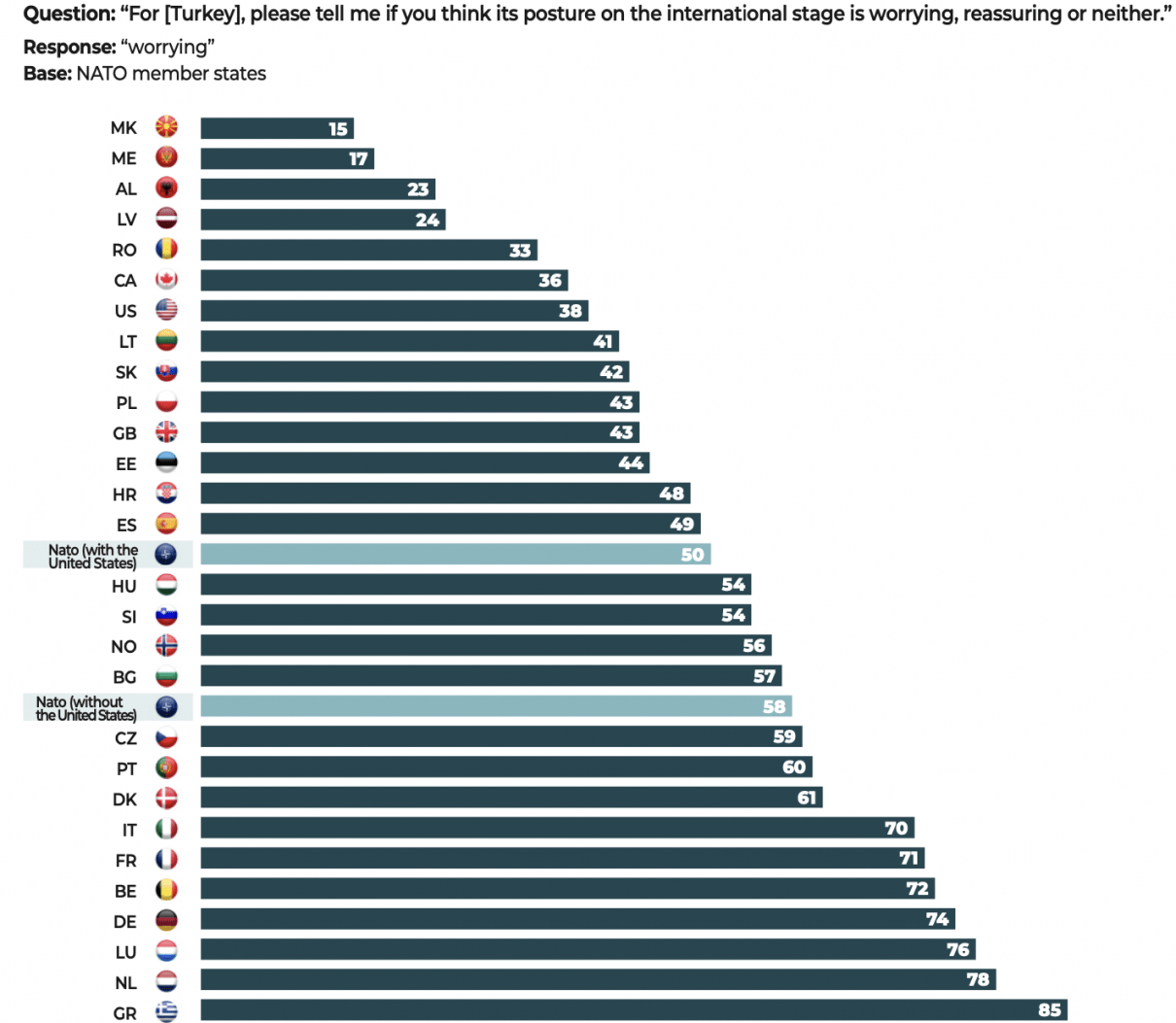

Turkey is disorienting for Europeans

See Tuvan Gumrukcu, “Turkey says sent Cypriot vessel away from its continental shelf”, reuters.com, October 4th 2021.

See Humeyra Pamuk, “Erdogan says Turkey plans to buy more Russian defense systems”, reuters.com, September 27th 2021.

See Steven Erlanger, “Turkish Aggression Is NATO’s ‘Elephant in the Room’”, nytimes.com, August 3rd 2020.

Turkey is the authoritarian power that the democratic world worries the least about: 37% of respondents say that they are worried about Turkey’s posture on the international stage, and only 19% find it reassuring. Public opinion seems to be on standby: almost half (44%) of respondents find it “neither worrying nor reassuring”.

However, in the European Union, Turkey (63%) is the main cause of concern ahead of Russia (61%) and China (60%). There are some Member States where people are particularly worried: the Netherlands (78%), Luxembourg (76%), Germany (74%), Austria (73%), Belgium (72%), France (71%) and Italy (70%). It is worth noting that these are Western European countries, most of which host sizeable Turkish communities. In the heart of Mediterranean Europe, Cypriots (95%) and Greeks (85%) are most troubled by Turkey’s posture, something that may be explained by the territorial disputes pitting Cyprus and Greece against Ankara, both over the island of Cyprus since 1974 and, more recently, over oil and gas exploration rights in the Mediterranean.14

Democracies outside the Euro-Mediterranean region seem less concerned with Turkey. Around a third of Americans (38%), Australians and Canadians (36%), the Japanese (34%), South Koreans and New Zealanders (32%) find Turkey’s posture on the international stage to be worrisome.

On average, half the population in NATO member countries (50%) are troubled by Turkey’s posture on the international stage. This figure rises to 58% if we remove the United States from the NATO average, which proves that it is principally Europeans who are worried about Turkey’s stance on the international stage. The country, which will celebrate the seventieth anniversary of its membership of the North Atlantic Alliance in 2022, has been stoking tensions for several years, particularly by purchasing a defense system from Russia that is incompatible with those of the North Atlantic Alliance15, by launching offensives in northern Syria, as well as by confronting Greek ships in the eastern Mediterranean and French vessels off the Libyan coast.16

Turkey, the NATO member country that worries Europeans and the Mediterranean region (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

The issue of immigration continues to shape public perceptions of Turkey, especially as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan puts pressure on the borders of the European Union: almost three-quarters (70%) of respondents in the European Union who believe that immigration is one of the greatest threats to their democracy are worried by Turkey’s posture on the international stage (compared with 50% overall).

See Richard Allen Greene and Oren Liebermann, “Tensions between Israel and Palestinians are sky-high. Here’s what you need to know”, cnn.com, May 16th 2021.

See “President Erdoğan, President Putin of Russia talk over phone”, Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, Directorate of Communications, iletisim.gov.tr, May 12th 2021.

See Omar Babakhouya, La Diplomatie turque au Moyen-Orient à l’ère AKP. Quel arbitrage entre idéologie et pragmatisme ?, L’Harmattan, 2020.

| The Israeli view on tensions with Turkey

Two-thirds (67%) of Israelis are worried by Turkey’s posture. President Erdoğan stepped up his aggressive rhetoric towards the Jewish state following the outbreak of tensions between Israel and Palestine in May 2021,1 shortly before our survey was administered. In a statement on May 12th 2021, Erdoğan announced that “the international community should give the State of Israel a strong and deterrent lesson”.2 Relations with the Jewish state have not always been so strained. In 1949, Turkey became the first Muslim-majority country to recognize the State of Israel. However, it broke off diplomatic ties in 2010 and the AKP party now endorses an Islamist-nationalist program that stands at odds with the Kemalist doctrine.3 |

Younger generations are less afraid of authoritarian powers (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

The higher the social category, the greater the fear of authoritarian regimes is (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Fears about authoritarian powers vary according to the respondents’ other concerns (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Meme for the reader: 72% of respondents who think their country’s membership of NATO is a good thing are worried about China’s attitude on the international stage.

* For this question, the sample is made up of populations from NATO member countries.

The United States is still considered the dominant global power

The United States remains by far the most influential power

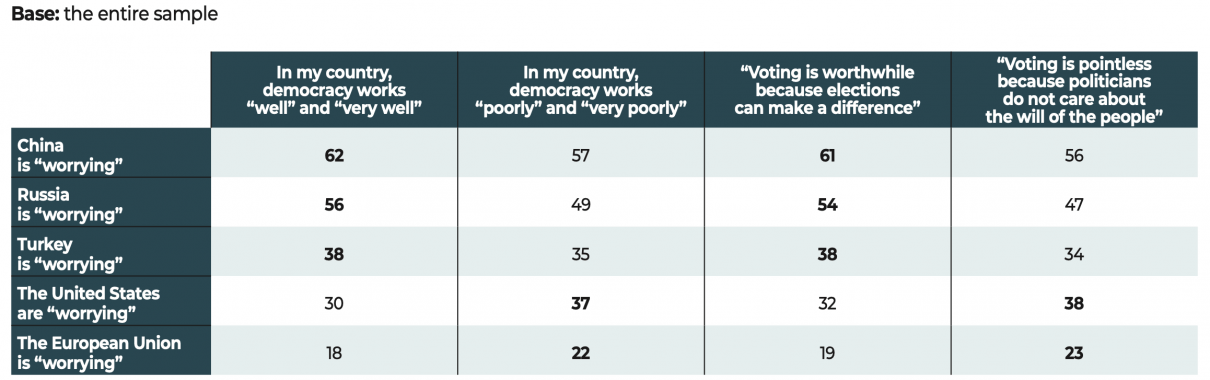

The views that respondents hold on American power tend to be influenced by how they judge the state of democracy in their own country. The latter is illustrated by how well they think democracy works and how worthwhile they think it is to vote. Thus, respondents of the opinion that democracy is not working well in their own country are more likely to think that the posture of the United States on the international stage is a cause for concern. On the other hand, those who think that their own democracy is working well are more worried about China, Russia or Turkey. The same correlation is found among the respondents who believe that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people”.

The public considers the United States to be the most influential power (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Respondents who are critical of how democracy works in their country are less fearful about authoritarian regimes (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Memo for the reader: Among the respondents who consider that “voting is pointless because politicians do not care about the will of the people”, 38% say they are worried about the attitude of the United States on the international scene.

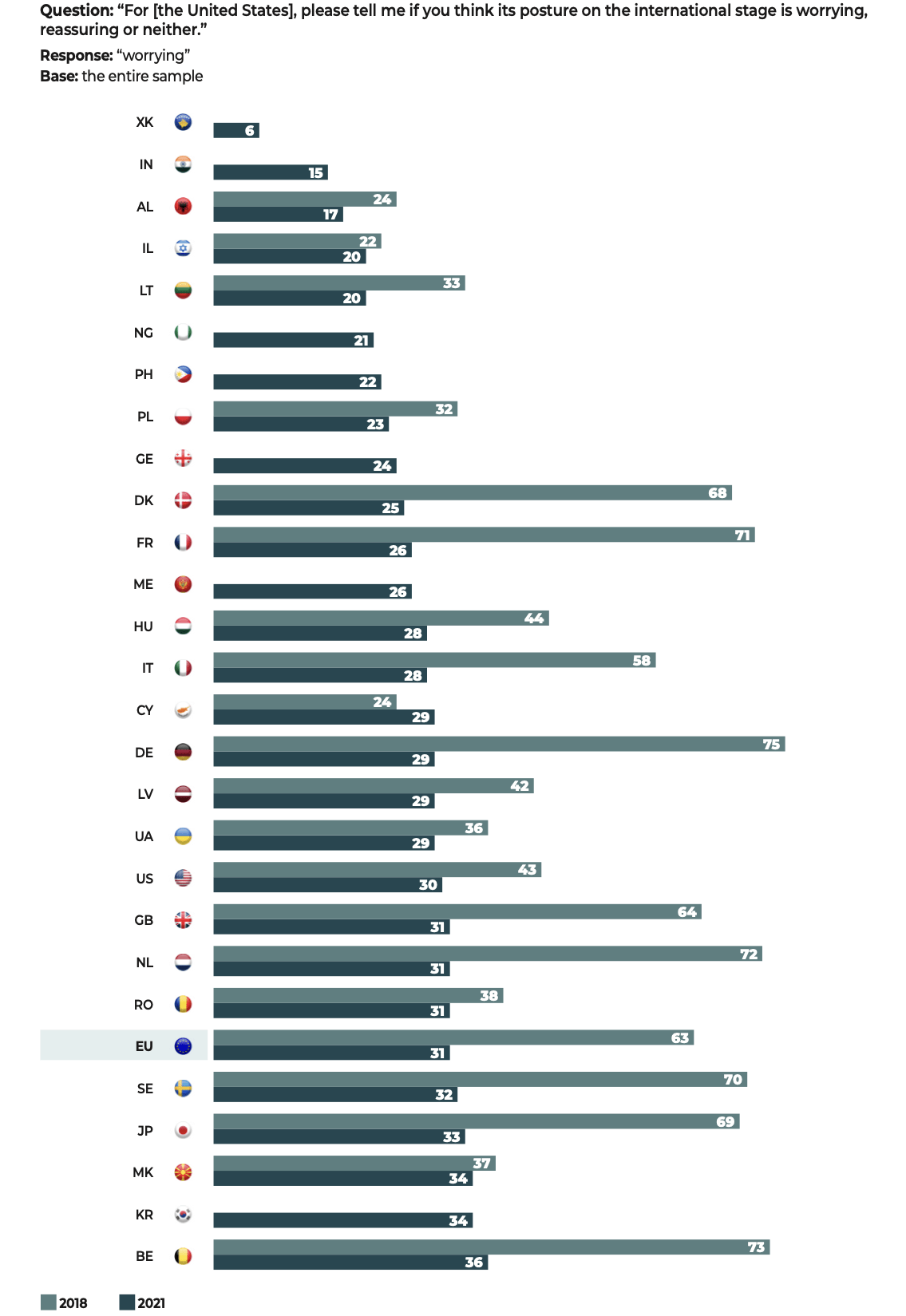

If we compare the 2018 and 2021 data for the 42 countries that took part in both surveys (i.e. excluding Belarus, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Kosovo, Lebanon, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Nigeria, Philippines, South Korea and Tunisia), the improvement in the image of the United States is even more pronounced: 56% of respondents expressed concern in 2018, compared to a third (33%) in 2021.

See John Glaser, Christopher A. Preble and A. Trevor Thrall, Fuel to Fire. How Trump Made America’s Broken Foreign Policy Even Worse (and How We Can Recover), Cato Institute, 2019.

Compared to our last international survey, the image of the United States has improved significantly: in 2018, over half of respondents (56%) were concerned by the power of the United States.17 Some of the Trump administration’s rhetoric and decisions concerning foreign policy and trade might have fueled the feeling that his presidency was an excessive additional disruption in an already uncertain world, something felt all the more keenly since it concerned the leader of the free world.18 This reaction can be seen within American society itself: although almost a third of Americans (30%) are still worried by their country’s posture on the world stage, this result is down by 13 points compared with 2018 (43%). Other countries in the Americas have followed the same trend: 41% of Canadians and 39% of Brazilians find the U.S.’ posture to be worrisome, compared to 76% and 53% respectively in 2018. Looking at the Americas as a whole, it is Mexicans who are most worried (46%) about the United States; however, since this is the first time the country has taken part in our survey, we are unable to draw a comparison with 2018.

Israel’s special relationship with the United States is also reflected in the results: in 2021, more than half of Israelis (56%) say that they find the United States to be a reassuring presence. The same is true of other friends of the United States, notably the Philippines, a historical ally with which it signed a mutual defense treaty in 1951. A majority of Filipinos (59%) also said that they were reassured by the American posture on the international scene, at a time when they are confronted with Chinese aggression in the South China Sea.

In the European Union, the deterioration of the image of the United States noted in 2018 has reversed in 2021. While 63% of Europeans found the American power to be worrisome in 2018, this number decreased to 31% in 2021.

NATO’s intervention in the Western Balkans at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries left a lasting impression. Attitudes towards the intervention in favor of Kosovo during the War in 1999 are still reflected in public opinion. Kosovars (87%) and Albanians (65%) are most likely to be reassured by the United States; on the other hand, Serbs (61%) and a significant number of Bosnians (37%) find the posture of the United States worrying. The American-led NATO bombing of Serbian targets during the Yugoslav Wars may explain the former country’s distrust of the United States, but also for Bosnians, who have a large Serbian population.

| The Special Relationship: the British are more reassured in 2021

In 2017 and 2018, only 16% of Britons said they thought the posture of the United States on the international stage was reassuring. In 2021, that figure has more than doubled (36%). The British sense of reassurance is likely to be felt even more keenly now that the two countries have entered into a military alliance with Australia and the United States to counter the influence of China (AUKUS). |

See Steve Scherer and Dave Graham, “Tensions over cars, protectionism loom at North American leaders summit”, reuters.com, November 18th 2021.

With the exception of Canada, the Anglosphere views the United States as a reassuring power

In the countries that make up AUKUS (Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States), a tripartite military alliance made public in September 2021 and formed to counter the influence of China, the posture of the United States is considered to be more reassuring in 2021 (36% among the British and 39% among Australians) than it was in 2018 (16% and 20%, respectively). This is also the case for New Zealand, which previously formed part of ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand and the United States), a forerunner of AUKUS: 15% in 2018, compared to 29% in 2021. These countries in the Anglosphere are increasingly preoccupied with Beijing. However, the United States’ neighbor to the north appears to be less effusive in its support; 41% of Canadians are worried by the posture of the United States on the international stage, a result that can be explained in part by trade tensions. The United States- Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in July 2020, has led to a trade tug-of-war. While NAFTA proposed a model for the integration and standardization of a common market in North America inspired by the European Union, USMCA is based to a greater extent on cooperation and is generating considerable tensions over the protection of certain strategic priorities (such as electric vehicles) that the signatory countries are prepared to fight tooth and nail to defend19.

See Andrew Moravcsik, “Why Europe Wins”, foreignpolicy.com, September 24th 2020.

| The European Union, a soft power influence

The European Union cannot be considered as a “power” in the same way that China, Russia and the United States are because it is not a state. As a system of close cooperation between 27 sovereign states, the European Union exerts an influence that is more akin to soft power through its internal market, its legal model and its normativism. The European Union cannot conceive of the use of hard power.1 This European Union, with its singular nature, is judged “reassuring” by almost half of respondents (44%), while 20% of respondents consider it “worrying” and more than a third (36%) think that it is “neither reassuring nor worrying”. |

American power is making people less anxious in 2021 than it did in 2018 (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

American power is making people less anxious in 2021 than it did in 2018 (in %) – continued

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

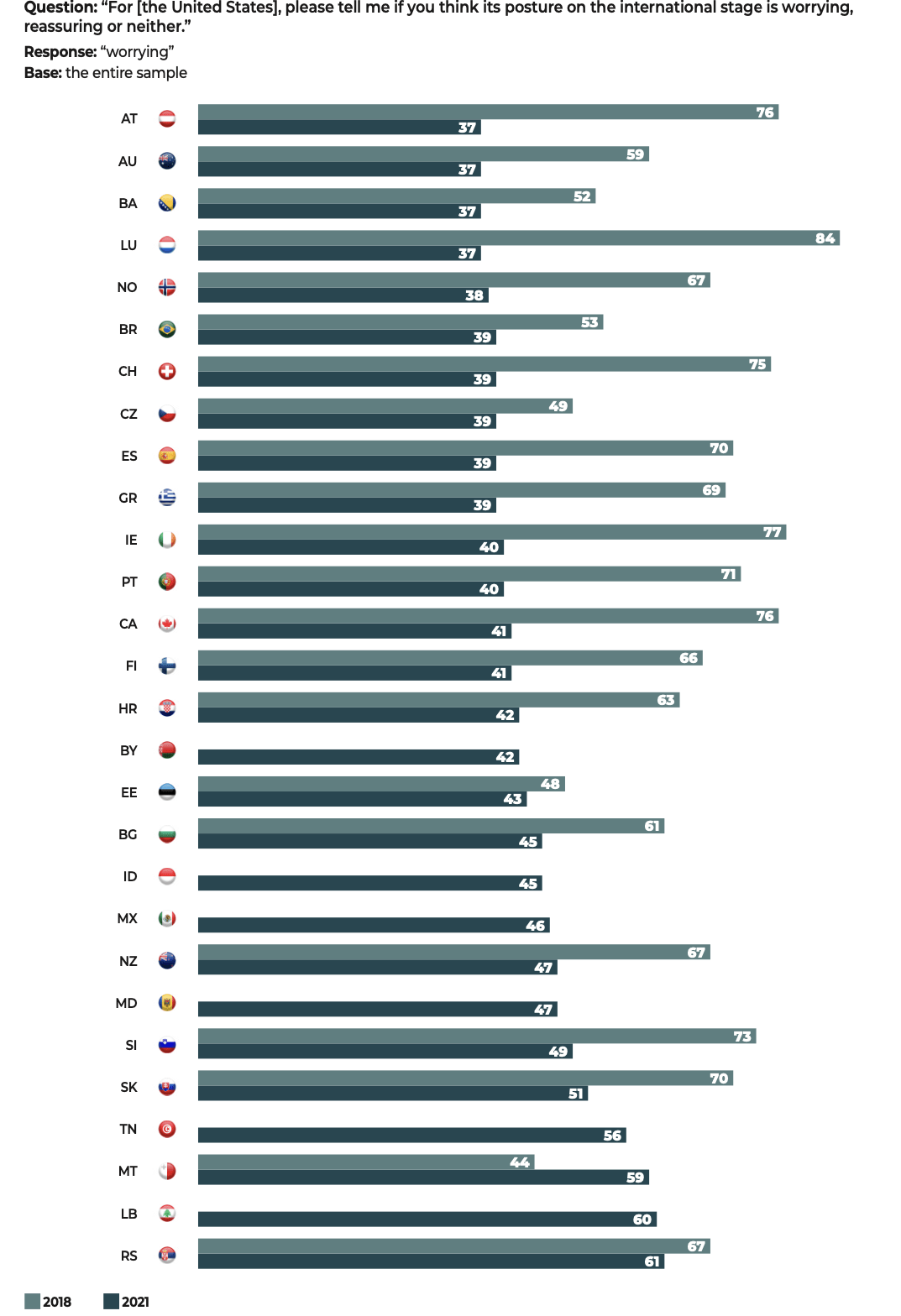

NATO membership does not ensure the perception of the United States as reassuring

Two-thirds of Americans (65%) consider their NATO membership to be “a good thing”. However, among the member countries of this alliance, not including the United States itself, only a third of those surveyed (32%) think that the posture of the United States is “reassuring”. This number is all the more underwhelming when we consider that the same proportion (32%) considers it to be “worrying”, while 36% find it “neither reassuring nor worrying”. In Eastern Europe, the attachment to NATO is stronger (63%) than in Western Europe (53%). Support for NATO in its member countries in the Western Balkans – Albania, North Macedonia and Montenegro – is higher still (67%).

In the European Union, Eastern countries are more attached to NATO membership than Western countries (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Fear of authoritarian powers and judgment on NATO membership (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Memo for the reader: Among those who say they are concerned about China’s attitude on the international stage, two-thirds (66%) think their country’s membership of NATO is “a good thing”.

Federal Election Commission, “Official 2020 Presidential General Election Results”, March 11th 2020, p. 8.

Federal Election Commission, Washington, “Federal Elections 2016. Election results for the U.S. President, the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives”, December 2017, p. 10.

| The United States, the world’s premier democracy, has suffered a setback

In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s presidency and Joe Biden’s ascension to the White House, two-thirds of Americans (67%) consider that democracy is working well in their country. This relatively high figure suggests that there are signs of recovery after the legitimacy of Biden’s election was strongly contested by some of the defeated president’s supporters, to the point that they stormed the Capitol on January 6th 2021. The record turnout for the election on November 3rd 2020, when more than 158 million votes were registered1 (compared to just over 136 million in 2016),2 may also be symptomatic of a healthy democracy. The results of our survey nonetheless show that great divisions, among the deepest of any of the countries surveyed, persist within American society. |

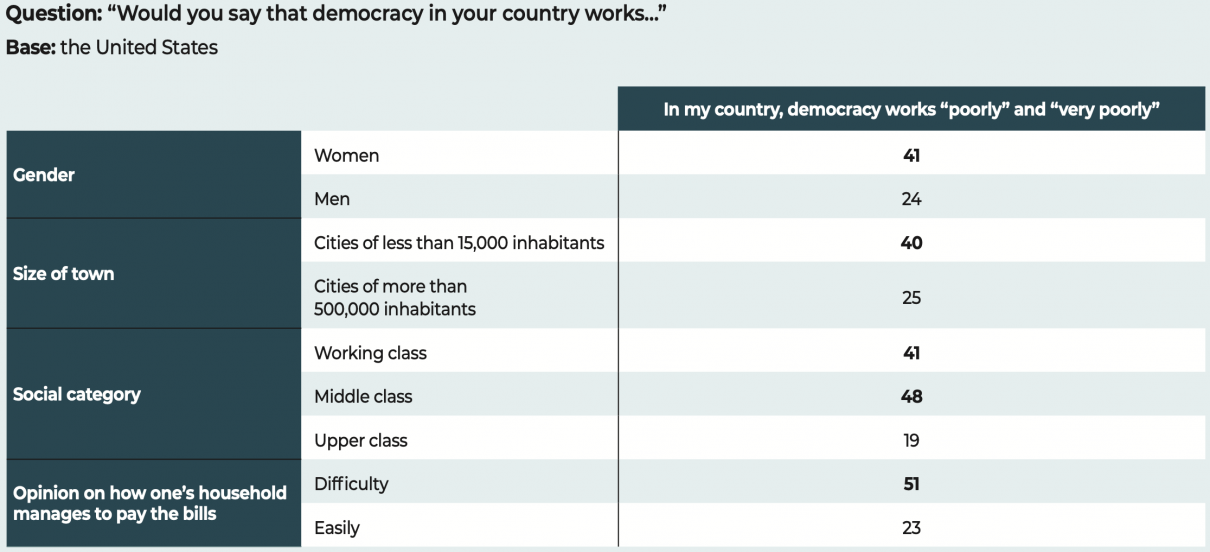

In the United States, women, small town dwellers and those with lower incomes are the most critical of the state of their country’s democracy (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Public opinion dreads a return to war

See Thibault Muzergues, War in Europe? From Impossible War to Improbable Peace, London: Routledge, 2022.

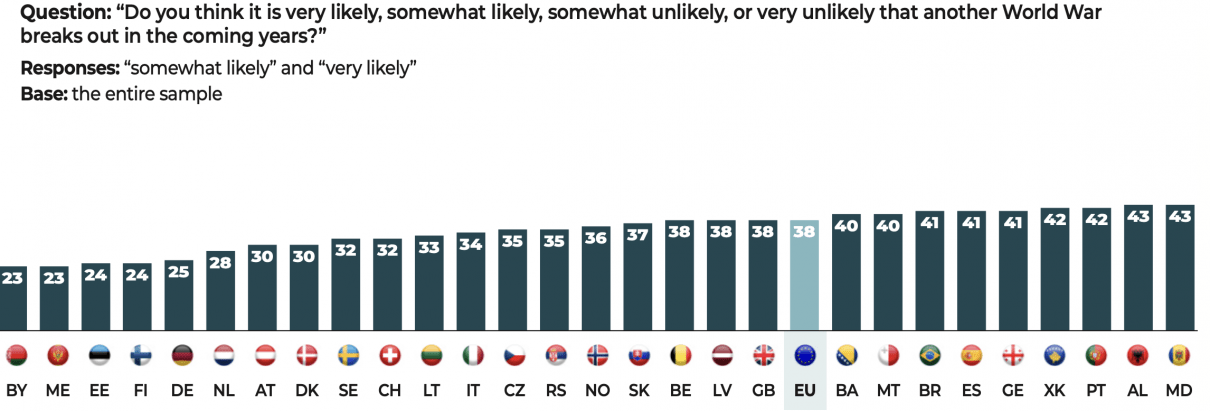

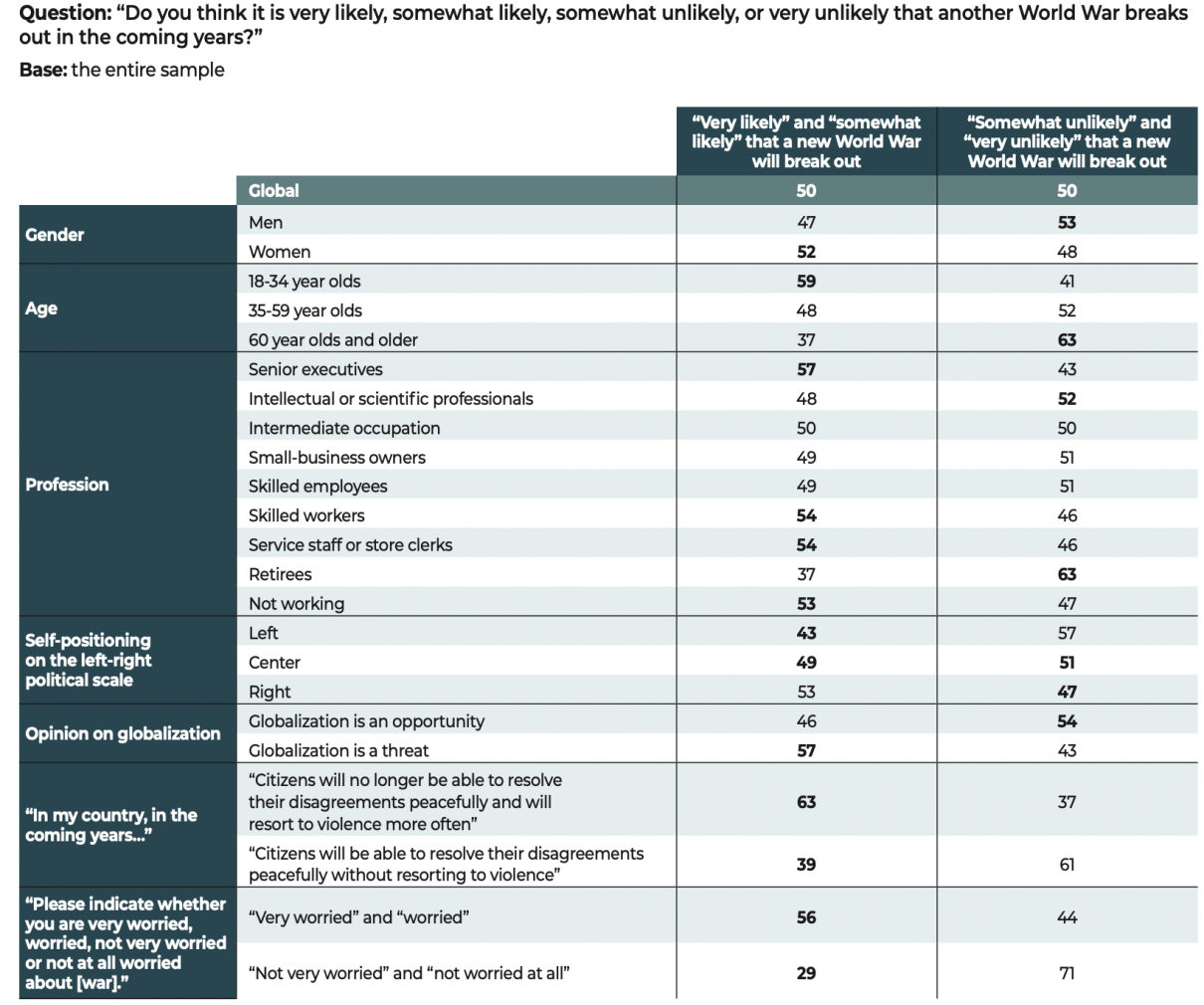

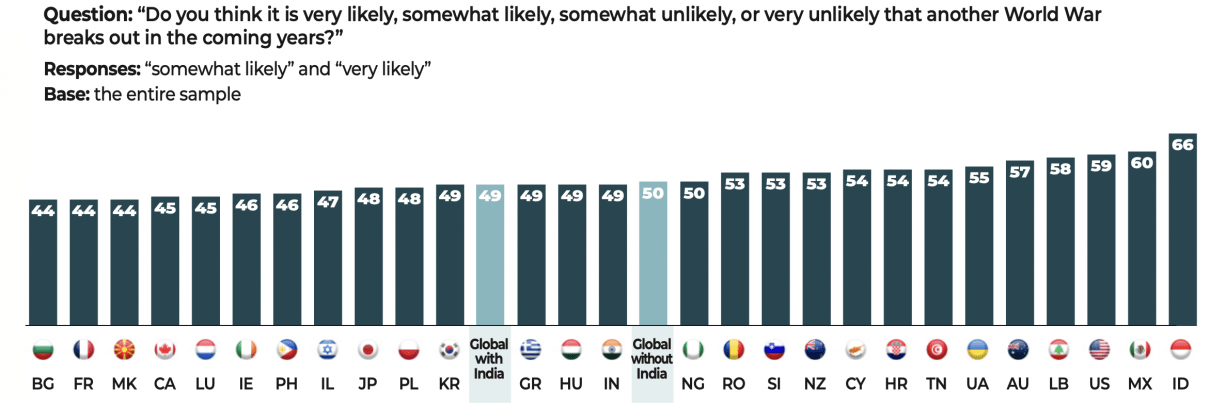

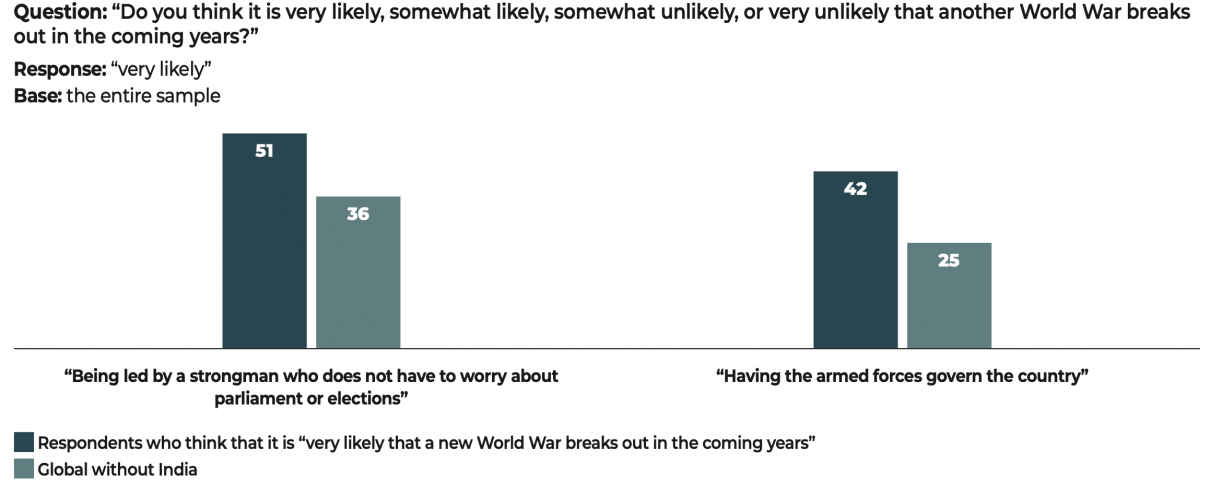

In the light of ongoing geopolitical upheaval, and in particular the rivalry between China and the United States, a significant number of people fear a return to war.20 Therefore, the prospect “that another World War will break out in the coming years” is considered “likely” by half the people surveyed (50%). Indonesians (66%), Mexicans (60%), Americans (59%), the Lebanese (58%), Australians (57%), Ukrainians (55%), Croats and Cypriots (54%) are the populations that most believe in the possibility of a new global conflict.

Despite the international turmoil, Europeans (EU) remain irenic in their outlook: only 38% of those surveyed believe that another World War is a likelihood in the coming years.

Some countries, despite being geographically exposed to a historically belligerent power, strangely seem to be even less worried. This is the case in Estonia and Finland, Germany, and the Netherlands. On the other hand, half of Greeks and Hungarians and a majority of Romanians and Slovenes fear the outbreak of another World War. The irenicism of Europeans is shared, broadly speaking, by the wider Western world. In NATO member countries, for example, if we include the results from the United States (59%), half of those surveyed (46%) think that the outbreak of another World War is likely in the coming years. However, that figure drops to 38% if we remove the United States from the calculation.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks had not yet happened.

| War in the 21st century

“The terrorist attack on the United States by Osama ben Laden,1 the gas attack on the Tokyo subway by the followers of the Aum sect, and the chaos created by Morris Jr. and his ilk on the Internet, where the degree of destruction is in no way less than that of a war, represent a half-war, a quasi-war, a sub-war, in short, the embryonic form of a new type of war. Whatever name one gives to these new forms of confrontation, they cannot make us more optimistic than in the past, because we have no reason to be optimistic. This is because the reduction of the functions of war in the strict sense does not mean that war no longer exists, because it will not be totally abolished, even in the so-called postmodern, post-industrial era. It will only have reinvested human society in a more complex, more extensive, more hidden and more subtle way. As Lord Byron said in the poem in which he mourns Shelley’s death, ‘Nothing has happened, once the water of the sea has changed and that is all.’ War, which has undergone the transformation of modern technology and the market system, will be made in even more atypical forms. In other words, while we are seeing a relative decrease in military violence, we are at the same time seeing an increase in political, economic and technical violence. Moreover, no matter what form violence takes, war is war, and even if its appearance has changed, it will always obey the same principles.” Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, written January 17th 1999, |

Are democratic societies deluded?

The prospect of a new World War (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Who thinks that a new World War is likely? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Are democratic societies deluded?

The prospect of a new World War (in %) – continued

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

What are democracies afraid of

At the same time, freedom of speech is being challenged in increasingly multicultural democratic societies. Our sense of social cohesion is being corroded by mutual misunderstandings, distrust and hostility. Intercultural disputes escalate into conflicts over values when the core difference of opinion concerns fundamental freedoms such as freedom of speech or freedom of the press. For example, we need look no further than the tragedies caused by the violent responses to the publication of The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie in 1988 and of cartoons in Denmark in 2008, not to mention the attacks on Charlie Hebdo in 2015. This type of terrorism takes the form of an internal war against the values of a liberal society, as was the case for the attacks in Paris and its surrounding region on November 13th, 2015, or in Nice on July 14th, 2016. Not since the 1930s have identity conflicts, populism, authoritarianism, racism and anti-Semitism undermined democratic societies to such an extent.

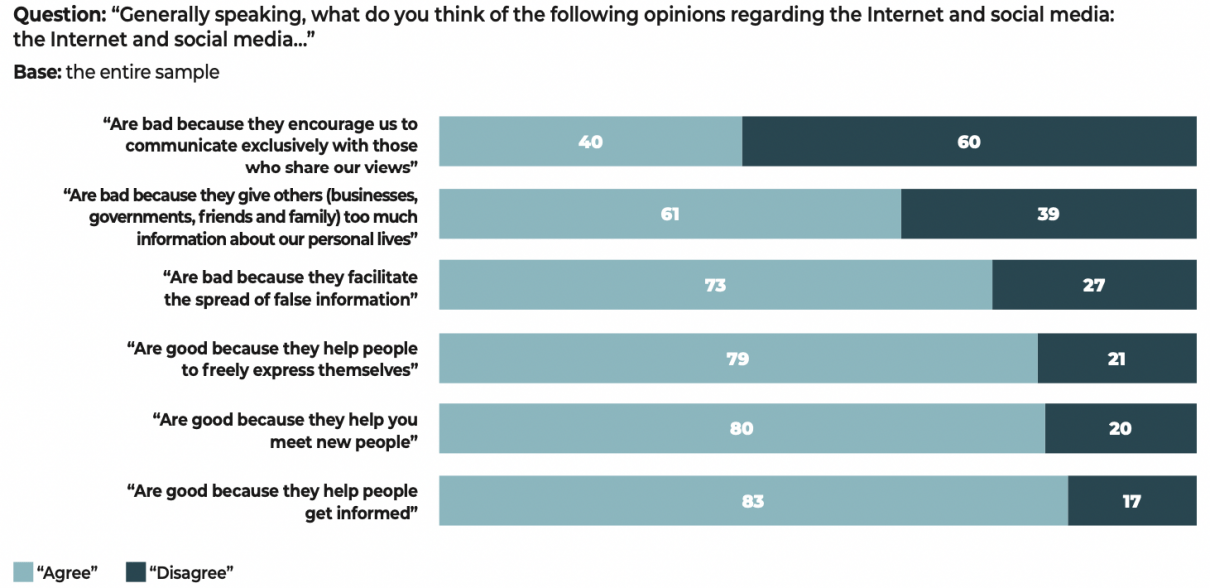

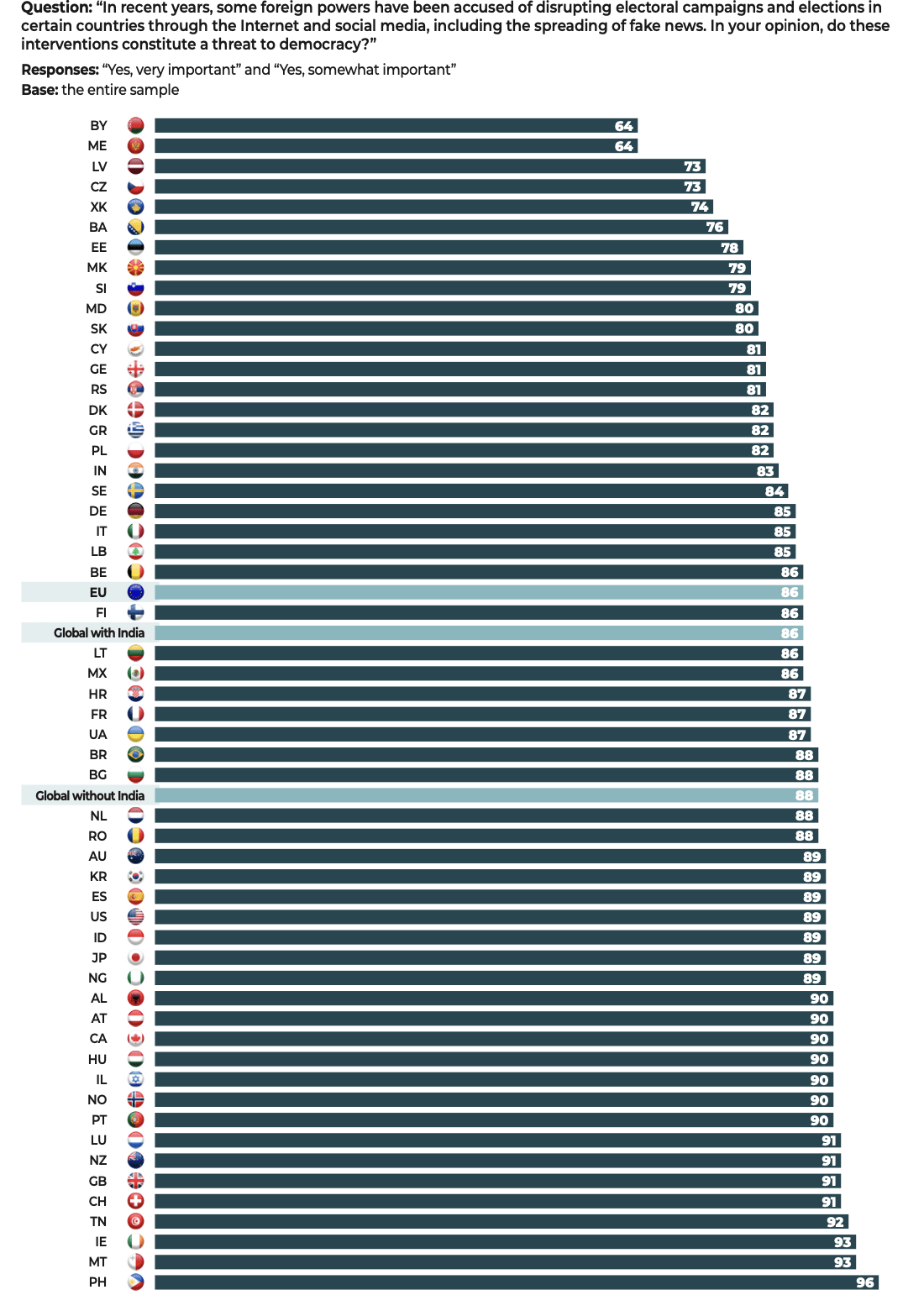

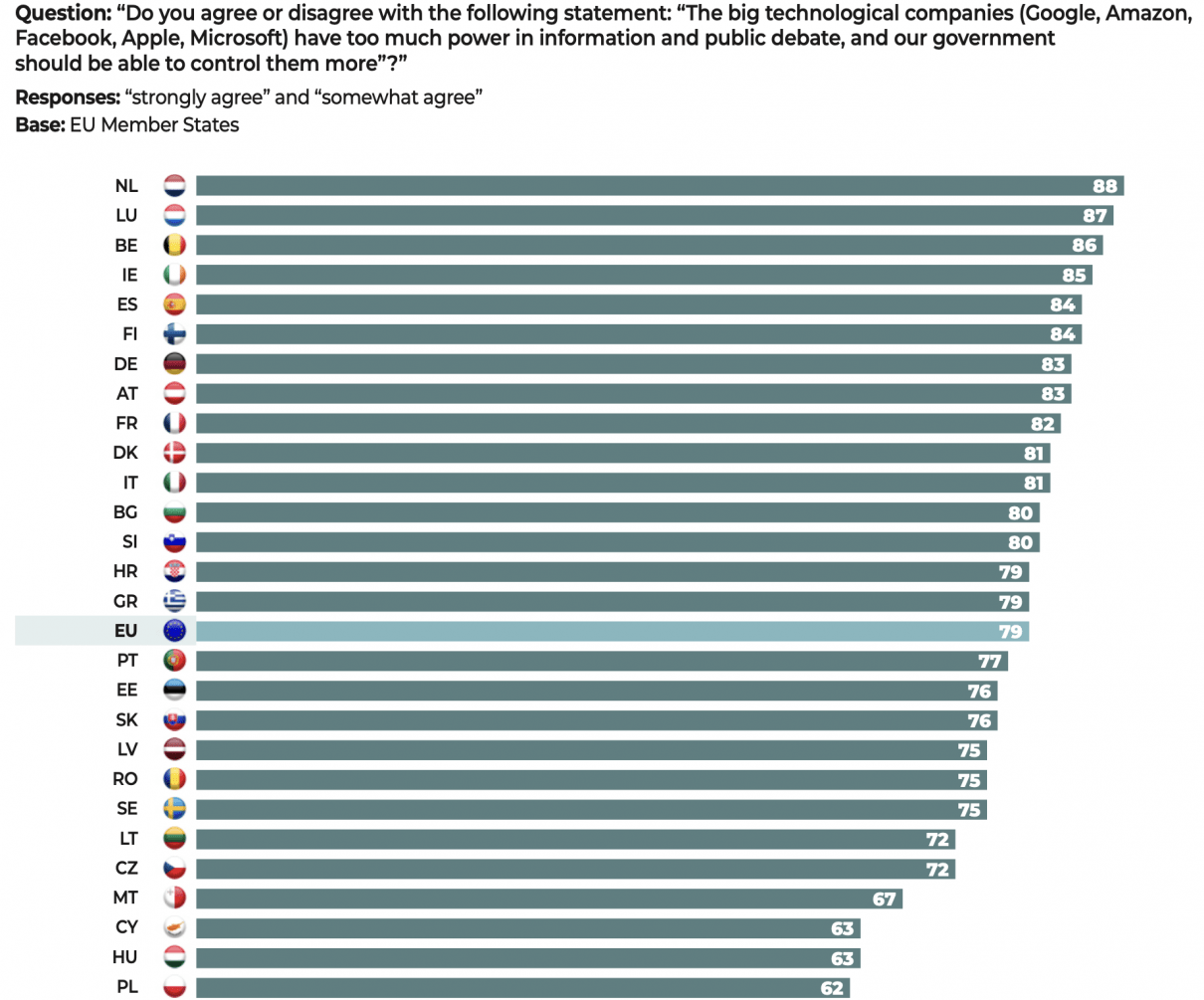

Without the freedom to debate and publish, the democratic model amounts to nothing. Those freedoms make the model possible, legitimate and effective, since it is liberty that enables human ingenuity to reach its full potential. Yet our century has also seen the emergence of a new transnational and digital public space. The cause of this particular upheaval is not found beyond democratic borders, nor is it foreign or hostile to liberal values. It lies in the remarkable technological innovations developed by companies whose success is made possible by the freedoms they enjoy. However, although they have an extraordinary effect on the number of people participating in the public media space, the power of digital platforms – The Big Five (GAFAM) – is nonetheless problematic. What becomes of democracies if the laws enacted by elected assemblies no longer have the power to regulate our freedoms? What becomes of democracies if the power to guarantee those freedoms stealthily shifts from parliaments into the hands of monopolistic companies?

Cultural diversity seen as a source of insecurity

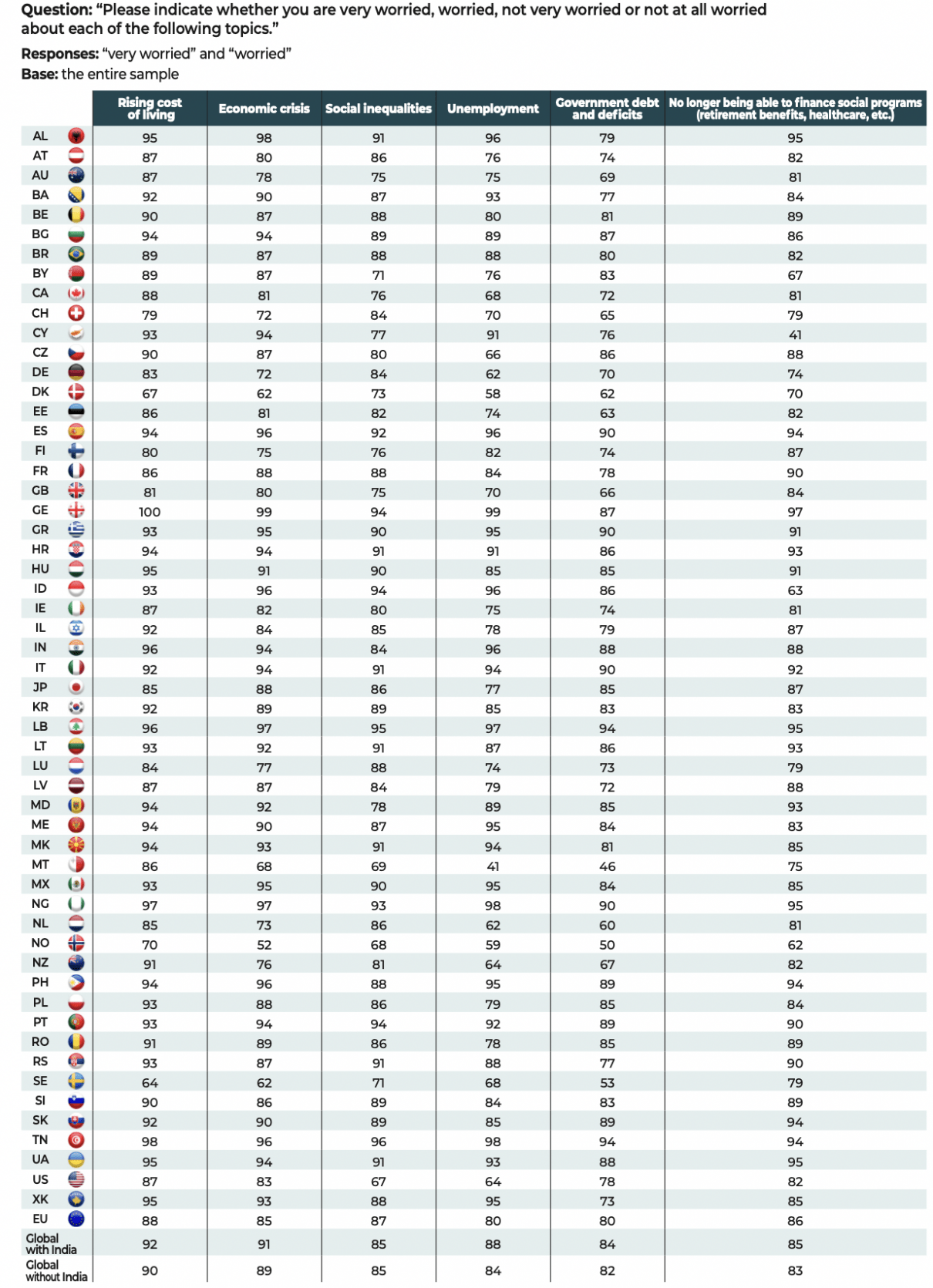

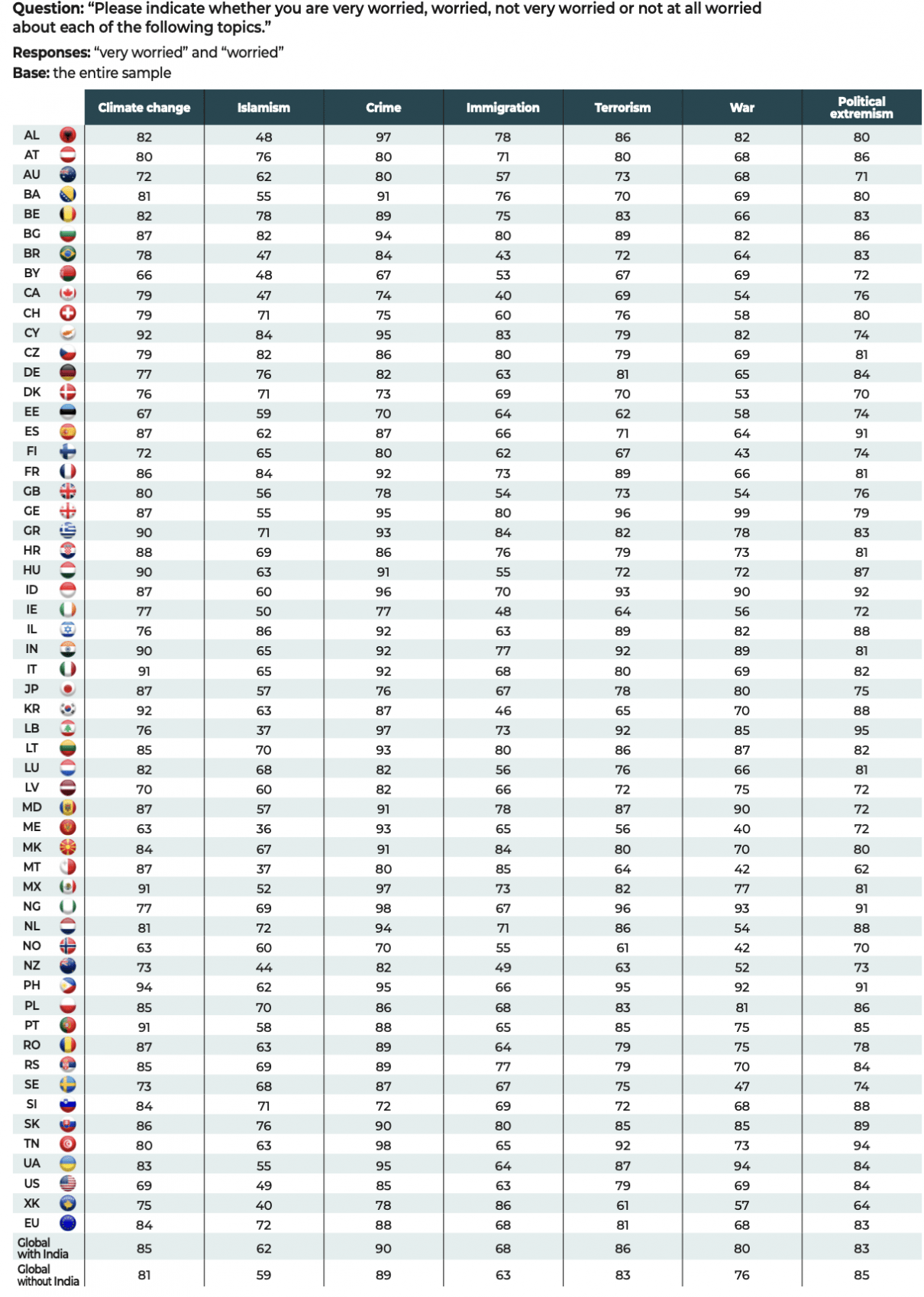

Climate change, crime, economic crisis, funding of social programs (retirement, health, etc.), government deficits and debt, immigration, Islamism, political extremism, rising cost of living, social inequalities, terrorism, unemployment and war.

See Dominique Reynié (ed.), Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2021, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, September 2021. To carry out this research, we used three types of sources: the information on attacks available via search engines, the cross-referencing of existing databases, particularly the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) and the Armed Conflict and Event Data Project (ACLED), and academic research.

Optimism and pessimism are found in equal measures. When asked “What do you think your country will be like tomorrow?”, more than a third of respondents (35%) replied that their country would be “not as good as it is now”. An average of 36% said their country would be “better than it is now” and 29% said it would be “as good as it is now”. The French are among the least optimistic in this regard, with only 9% believing that their country will be better tomorrow. The Lebanese (10%), Belgians (10%), Finns (12%) and the Japanese (12%) show similar levels of pessimism.

Crime and terrorism top the list of security fears

Among the main sources of fear named in the survey,1 concerns about security issues are very widely shared. A majority of respondents said that they were afraid of crime (89%), overwhelmingly so in Indonesia (96%), Albania, Lebanon and Mexico (97%), and Nigeria and Tunisia (98%).

Fear of terrorism is also globally widespread (83%) among Moldovans and Ukrainians (87%), Bulgarians, the French and Israelis (89%), Indians, the Lebanese and Tunisians (92%), Indonesians (93%), Filipinos (95%), Georgians and Nigerians (96%).

Intercultural conflicts

Large sections of the populations surveyed are afraid of immigration (63%). Immigration is undoubtedly one of the facets of globalization and, as such, it influences responses to several of the questions. For example, concerns about immigration are more widespread among those who consider globalization to be a threat (73%). Concerns about immigration are less common among those who, on the contrary, see globalization as an opportunity, though they remain substantial (58%). Similarly, while the fear of immigration remains most widespread in towns of under 15,000 inhabitants (67%), such concerns remain high in cities of over 500,000 inhabitants (60%) that are more closely associated with globalization.

Islamism and the terrorist threat

Islamism is another widely cited concern (59%). Islamism is associated with a threat to the fundamental values of democratic societies: freedom of the press, freedom of conscience, gender equality, freedom of sexual orientation, tolerance, etc. Of course, Islamism is also associated with the threat of terrorism. At least 48,035 Islamist attacks have been carried out over the last 40 years, resulting in the deaths of at least 210,138 people.2 Between 1979 and 2000, 2,194 attacks and 6,817 deaths were recorded (i.e. 4.6% of all Islamist attacks over the period 1979 to 2021). After the turning point of 9/11, 8,265 attacks were carried out between 2001 and 2012, causing 38,186 deaths (i.e. 17.2% of all Islamist attacks over the period 1979 to 2021). Finally, between 2013 and 2021, with the advent of the Islamic State and Boko Haram, there were 37,576 attacks and 165,135 deaths (i.e. 78.2% of all Islamist attacks over the period 1979 to 2021).

This rise in Islamist terrorism certainly fuels a fear of Islamism within democracies. This sense of fear is at its highest in Israel (86%), Cyprus and France (84%), Bulgaria and the Czech Republic (82%), Belgium (78%), Germany, Austria and Slovakia (76%). In predominantly Muslim countries, this fear of Islamism is prevalent in Nigeria (69%), Tunisia (63%), Indonesia (60%) and Bosnia-Herzegovina (55%). Lebanon (37%) stands as an exception.

| Democracies confronted with the violence of Islamist terrorism

“Terrorist violence mainly affects civilians. Death due to terrorism creates an unbearable sense of permanent vulnerability. People in the democratic world are more traumatized by terrorist violence because they have inherited an irenic culture, a logical consequence of the decline of interstate violence. But democracies are also more helpless because they represent a soft political order based on f reedom and human rights. Inevitably, democracies feel defenseless. A desire for repression, control, surveillance, expulsion and border closure is expressed in the open. It creates a culture of security, even paranoia, which is perpetuated by the inevitable measures designed to reassure much more than to prevent. Through the violence of jihadists, Islam and Muslims are raising irrepressible and growing fears. Fear of the other splits societies, and they end up opposing themselves: a propensity for violence, xenophobia, identity conflicts, and authoritarianism are the result.” “Islamism and populism: a relentless dialectic”, in Dominique Reynié (dir.), |

What are democracies afraid of? (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

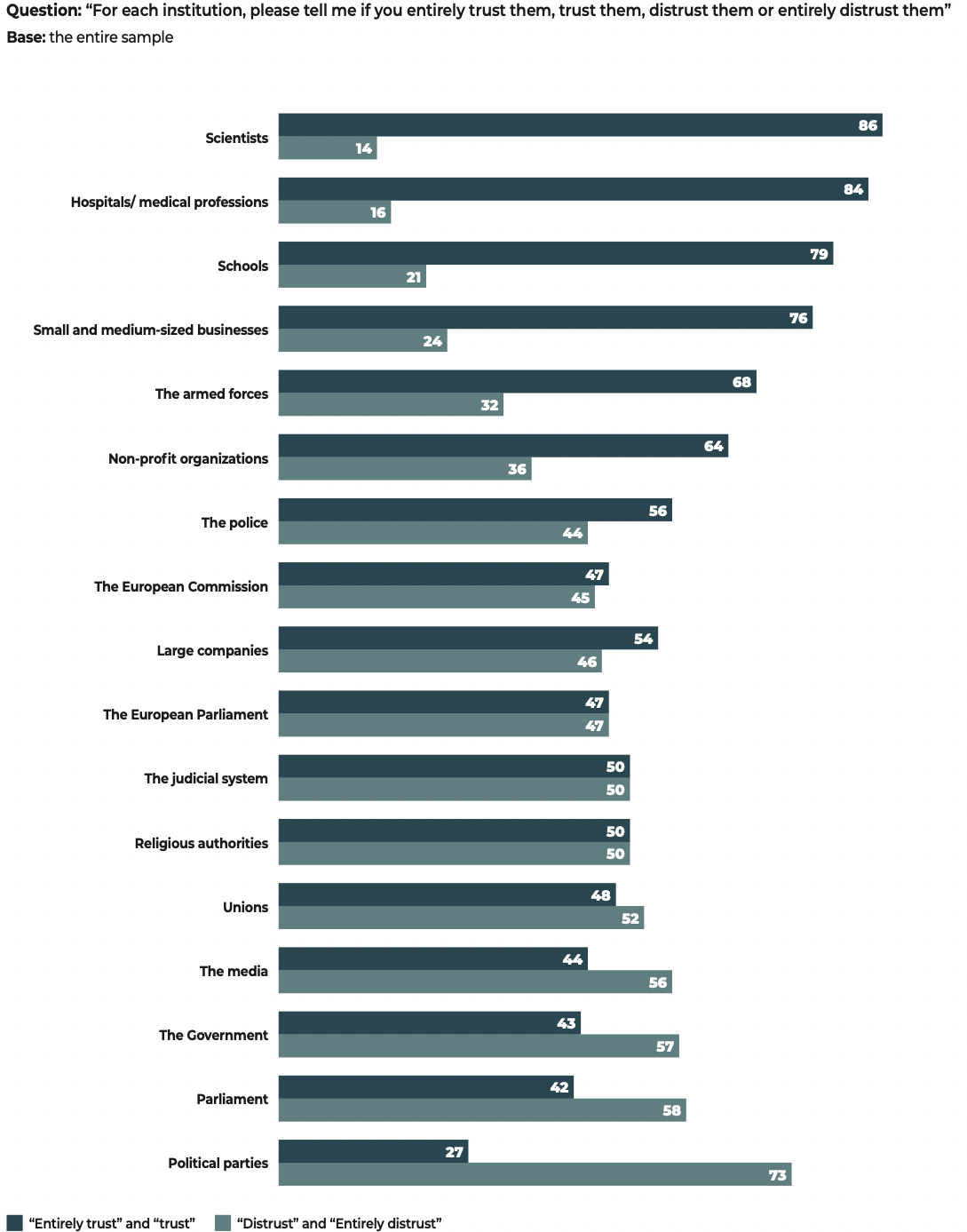

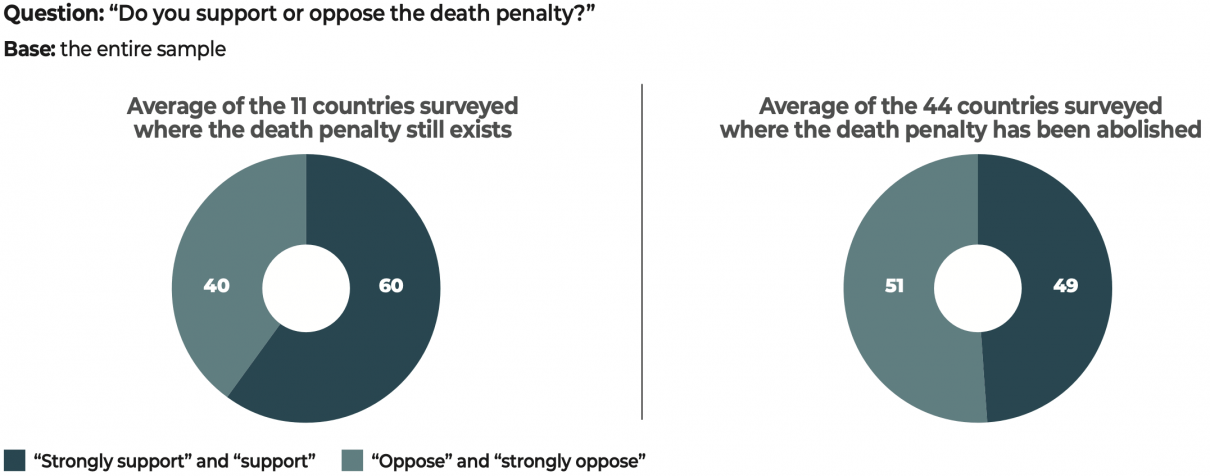

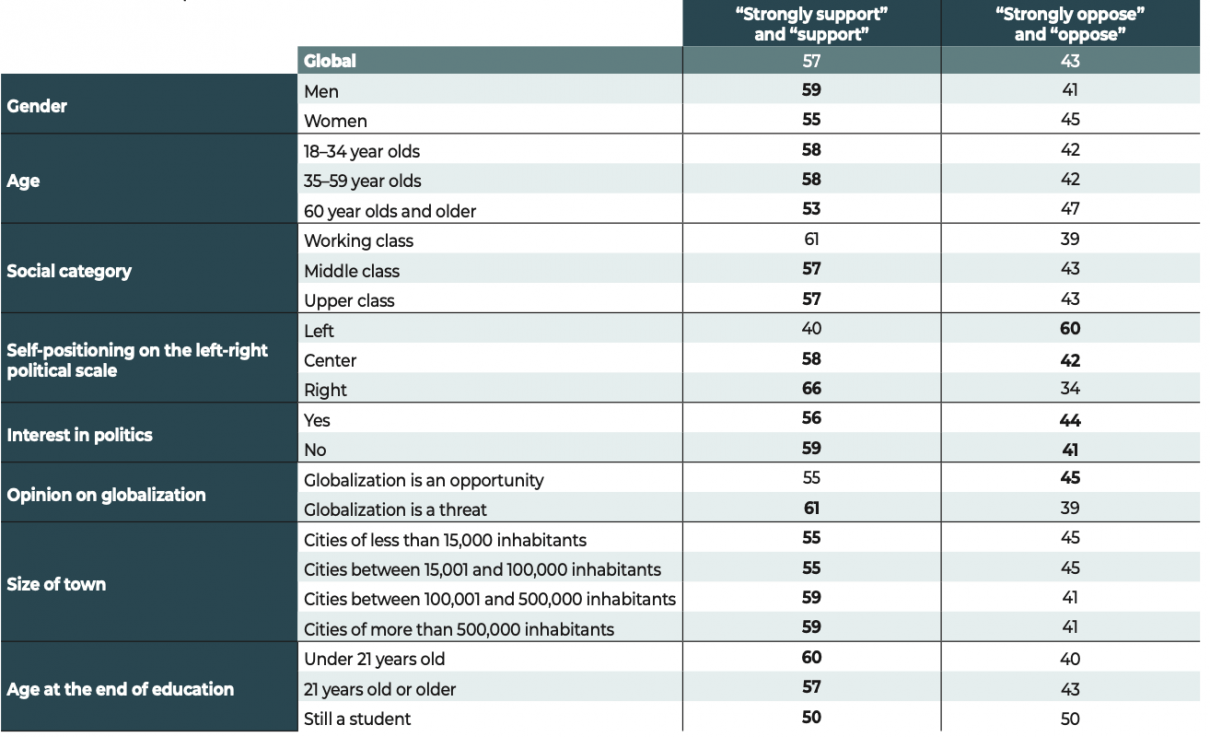

What are democracies afraid of? (in %) – continued

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Will we soon “no longer be able to resolve our disagreements peacefully”?

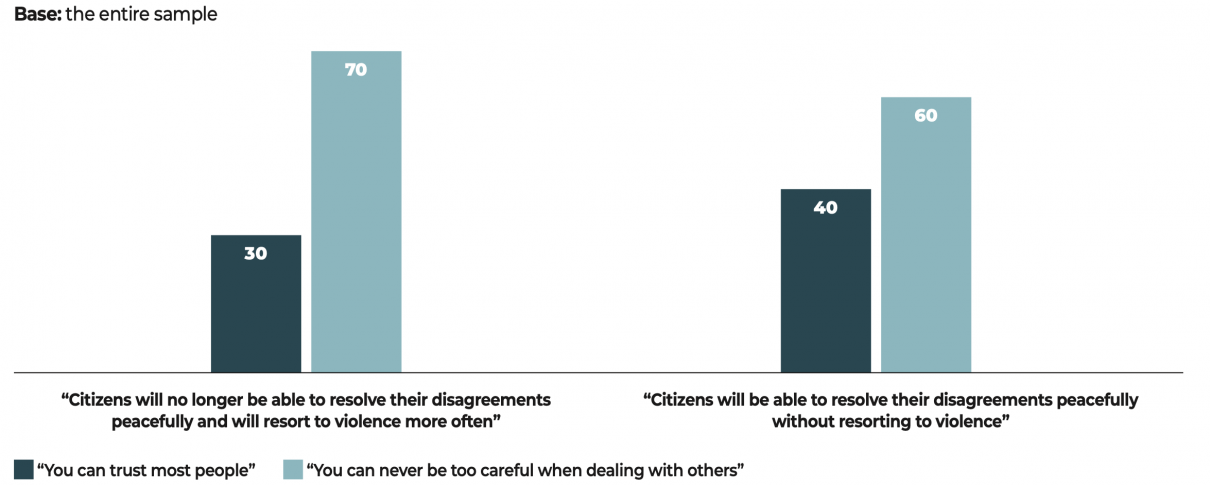

Democratic societies are undermined by mistrust…

On average, two-thirds (64%) of respondents say that “you can never be too careful when dealing with others”, while only 36% are of the opinion that “you can trust most people”. Distrust of others is more widespread among women (68%) than men (61%), more common among under 35s (67%) than respondents aged over 60 (59%), and also high among respondents with lower incomes (71% of service staff or store clerks) than those with higher ones (53% of senior executives).

Only in Indonesia (63%) and Northern Europe (57% of Finns, 56% of Danes, 55% of the Dutch and 52% of Norwegians) do a majority of respondents claim to trust others, with the exception of Swedes (45%).

… and the fear of “no longer being able to resolve disagreements peacefully”

Although a majority (56%) of respondents think that in the coming years citizens will “be able to resolve their disagreements peacefully without resorting to violence”, a significant minority (44%) chose the other option (“citizens will no longer be able to resolve their disagreements peacefully and will resort to violence more often”). It is worth noting that the Lebanese (76%), the French (71%) and Belgians (61%), who are among the most pessimistic with respect to the future of their own countries, are also the most likely to think that disagreements will lead to violence. On the other hand, in countries where a sense of interpersonal trust is more widespread, those who think that citizens will no longer be able to resolve their disagreements peacefully are in the minority: as is the case for 29% of Norwegians and Danes, and 33% of Finns and Indonesians.

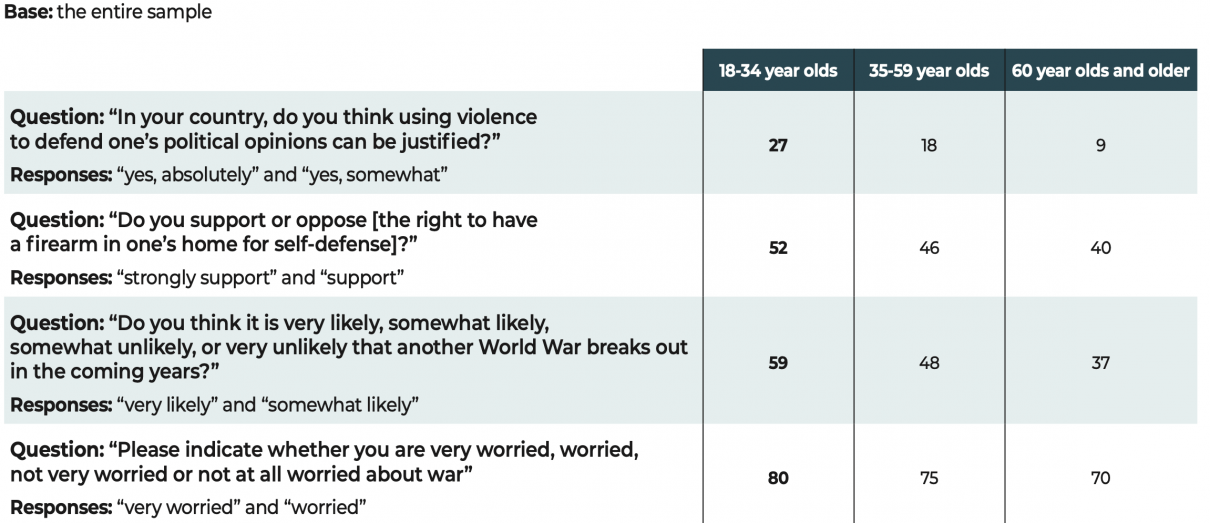

On January 6th 2021, the storming of the Capitol building by supporters of former President Donald Trump, which gravely disrupted the process to certify the results of the presidential election, demonstrated the fragility of the world’s premier democracy. The concept of using violence to promote one’s opinions is by no means absent from democratic societies: one in five respondents (19%) believe that “using violence to defend one’s political opinions can be justified”. In the European Union, 17% of respondents agree. Among the 55 countries surveyed, the highest percentages of people who support this statement were recorded in Kosovo (43%), Hungary (42%), India (33%), Lebanon (31%) and Moldova (30%).

Interpersonal distrust is more prevalent among those who believe that “citizens will no longer be able to resolve their disagreements peacefully and will resort to violence more often” (in %)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique – January 2022

Memo for the reader: 70% of respondents who think that “citizens will no longer be able to resolve their disagreements peacefully and will resort to violence more often” also indicate that “you can never be too careful when dealing with others”.

See “Banned weapons stoke deadly violence in Nigeria”, france24.com, June 9th 2018.

See Nemanja Rujevic, “Serbia: The land of guns”, Deutsche Welle, December 29th 2016.

See Ondřej Plevák, “Firearm ownership rights embedded into Czech constitution”, euractiv.com, July 23rd 2021.

U.S Government Accountability Office, “Firearms Trafficking. U.S. Efforts to Combat Firearms Trafficking to Mexico Have Improved, but Some Collaboration Challenges Remain”, January 2016.

Katy Watson, “Jair Bolsonaro and guns: A US culture war raging in Brazil”, bbc.com, November 15th 2021.

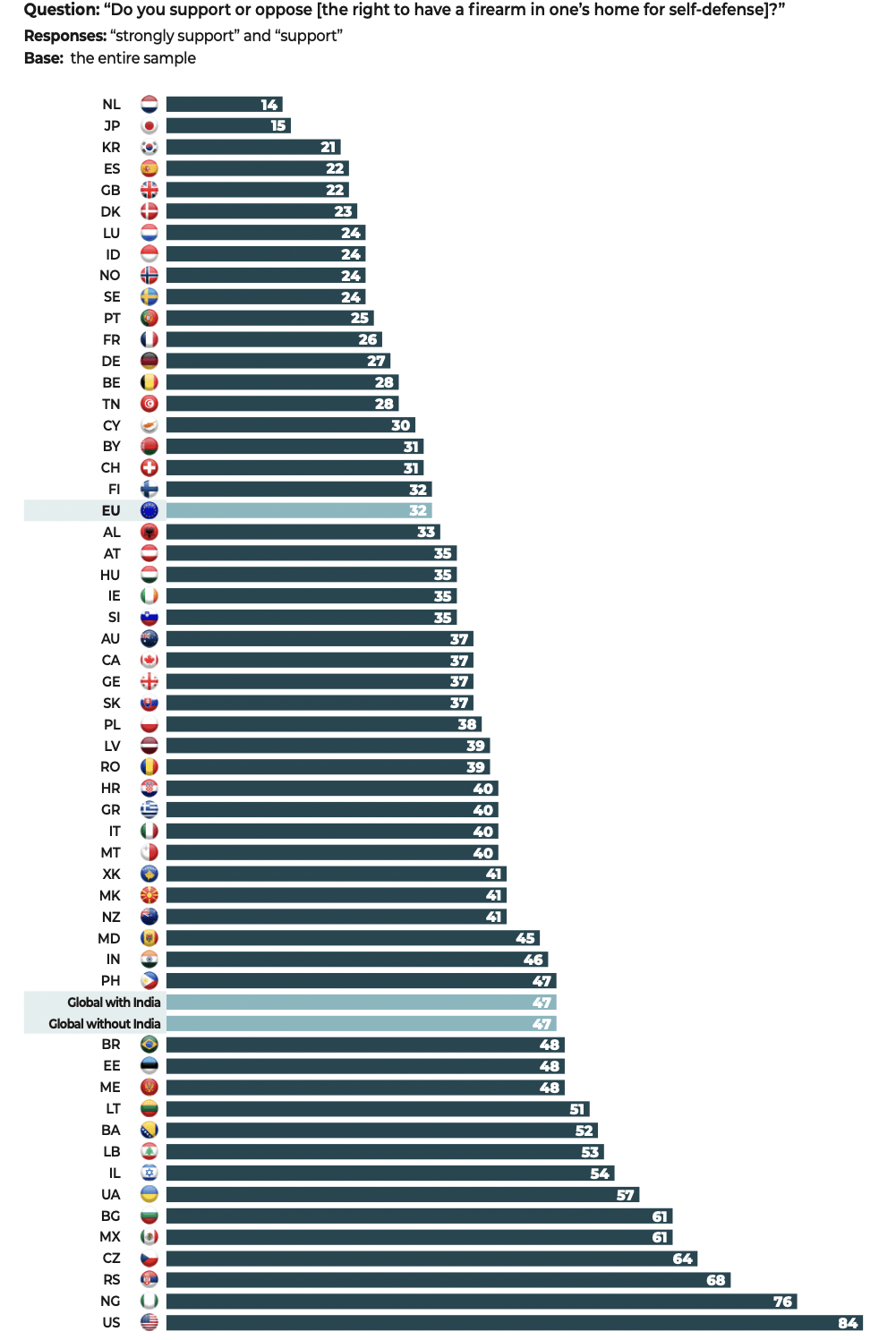

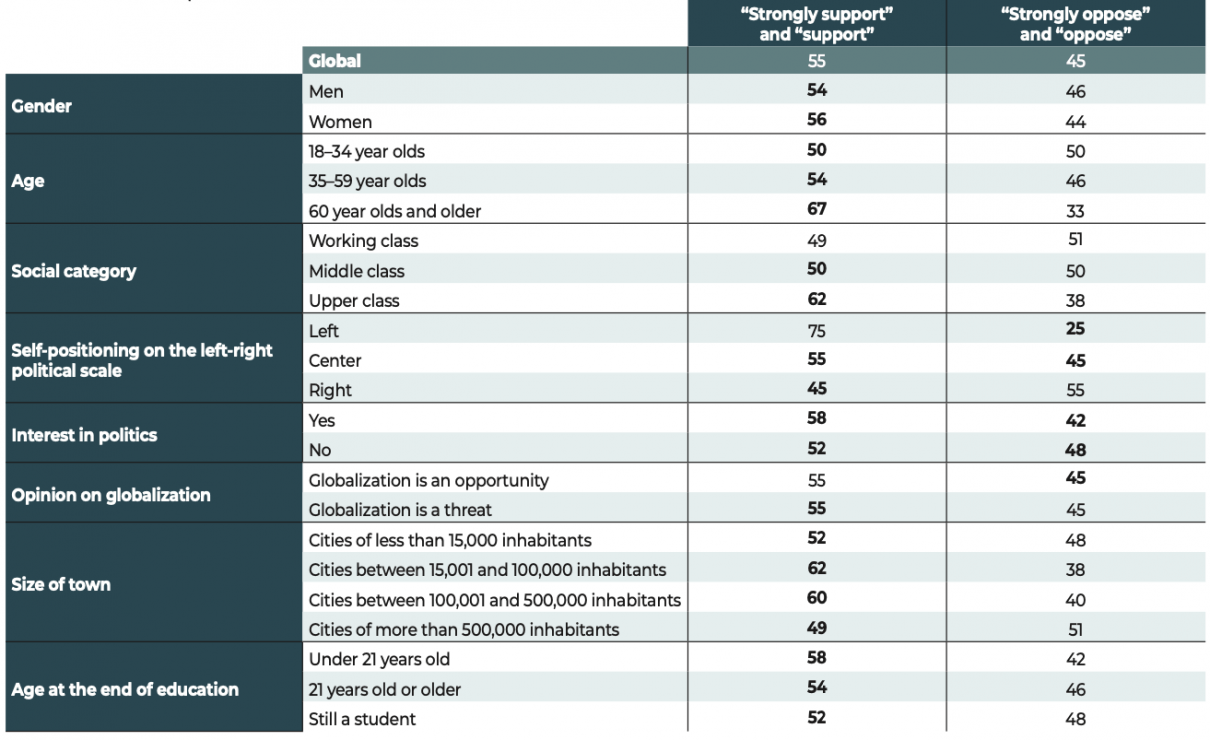

Half of respondents (47%) support the right to own a firearm for self-defense

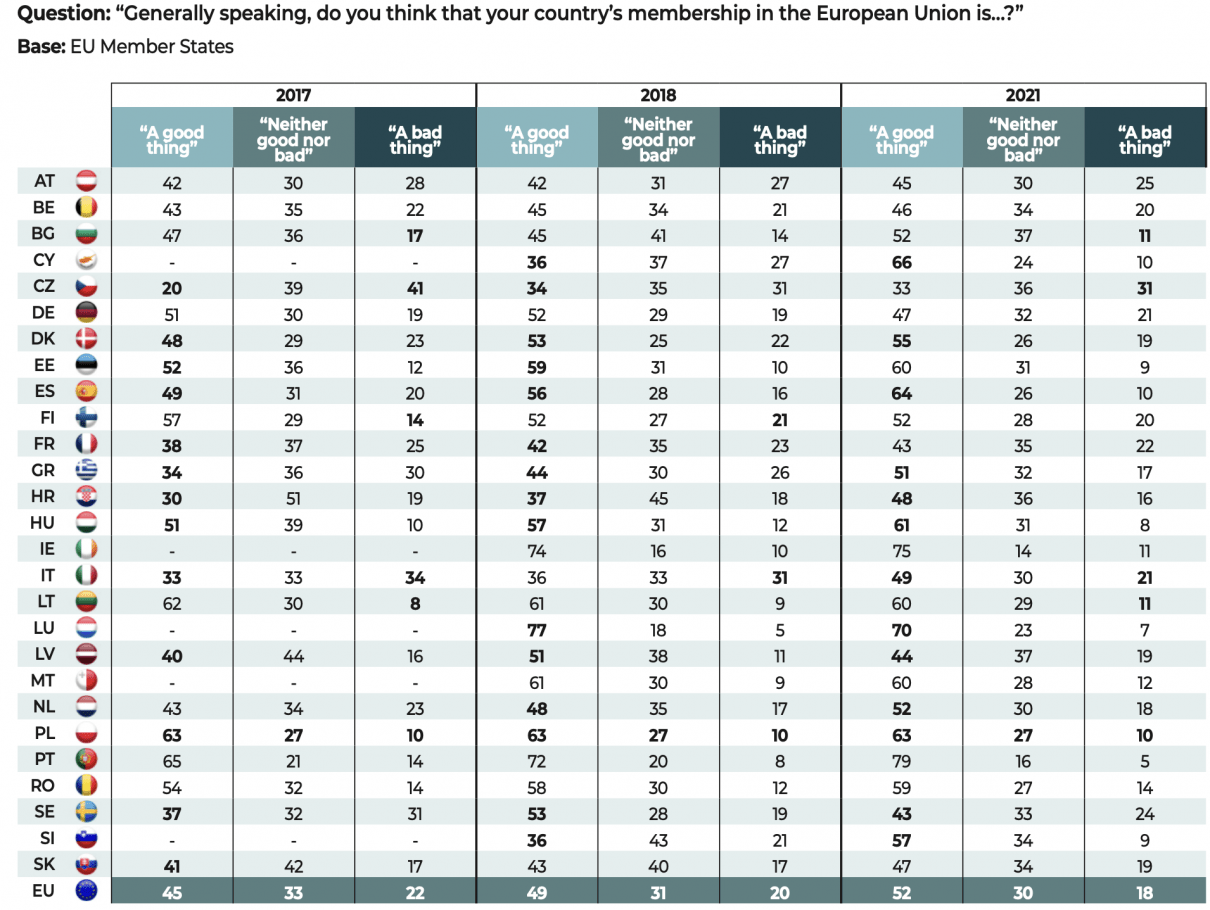

Half of respondents (47%) are in favor of the “right to have a firearm in one’s home for self-defense”. This opinion is more widely shared by men (52%) than women (43%) and is more commonplace among under 35s (52%) than over 60s (40%). Of course, the major differences in opinion registered on this subject between countries and groups of countries tend to reflect their different legal frameworks: for example, while a third (32%) of respondents in the European Union want the right to own a firearm, that proportion rises to 84% in the United States, where that right is guaranteed by the Second Amendment to the Constitution.