Future memories

A survey on memories of the 20th century among 31,172 young people aged between 16 and 29, carried out in 24 languages, across 31 countries.Remembering together, today and tomorrow

Survey methodology

1914-1918 : the first World War

1939-1945 : The second World War

Germany

URSS

Japan

Italy

USA

France

United Kingdom

The most important event of the second World War

The extermination of the Jews by the nazis and the use of the atomic bomb

What do the new generations know about the nazi extermination camps ?

An unpunished crime ?

A century of massacres and genocides

Democracy and totalitarianism

Assessments of the nazi politics

Is the German-soviet pact remembered ?

Memories of communists regimes

Perceptions of democratic systems

1939-45 : Did my country act in the interest of human dignity and freedom ?

How we know about history : a triumph for schooling

Knowledge of the first World War

Knowledge of the second World War

Knowledge of the Holocaust

Question:

« In your opinion, what, in general, are the most effective ways of making young people aware of history? »

Places to strengthen and pass on memories

Why learn about history ?

Why visit the extermination camps ?

What memorable events have taken place since 1989 ?

2011, 2012, 2015 : Three surveys of young people around the world

What are the values of an ideal society ?

What are attitudes towards diversity ?

Political ideas

Religion

Nationality

Summary

The Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah wished to work together to identify the memories of the last century from which our present century – the 21st – will be formed.

What do the new generations remember of the events of the 20th century? How about the increasingly numerous members of those first generations to have spent only their childhood in the 20th century – what do they think?

Which memories of the 20th century will they carry forward? It is an important question, as it will fall to them to ensure not only that the story of the 20th century lives on, but that the lessons drawn from those events continue to be heeded.

We surveyed on memories of the 20th century among 31.172 young people aged between 16 and 29, carried out in 24 languages across 31 countries.

The 31 countries in the survey are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The present study offers an analysis of the survey’s results.

The full data is available for free, in 24 languages, on data.fondapol.org.

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

Dominique REYNIÉ

Corinne DELOY

Natasha CAILLOT

Marine CARON

Virginie DENISE

Anne FLAMBERT

Anne-Catherine FLEURY

Delphine GONEBERT

Tristan GUERRA

Rémi VELEZ

Julien RÉMY

Clarisse DEUBEL

Galaxy Imprimeurs

Robert HUNT

2015

Remembering together, today and tomorrow

The two-year period of 2014-2015 has emerged as a moment for reflection on the 20th century. In a short space of time, we are commemorating a series of events that helped to shape those hundred years, in order to remember the darker side of our recent history, yet also to acknowledge its passing: the centenary commemorations for the outbreak of the First World War (1914) and the Armenian genocide (1915); the 70th anniversary of the Normandy Landings (1944), the end of the Second World War and the liberation of Auschwitz (1945); and also the 20th anniversary of the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda (1994) and the 40th anniversary of the birth of the Khmer Rouge regime (1975).

To commemorate is to recall our memories of an event. This involves us acknowledging the circumstances from which an event may have arisen, from which genealogy it is the result. This is work carried out by

historians, with the help of archives and other sources. But to commemorate is also to recall memories at a ceremony, to remember together. The act of recalling memories of a certain event at a ceremony implies an intention to publicly retell its story, loud and clear, for everyone to hear. It therefore entails a desire to delve beyond the mere comprehension of historical facts, to look deeper by sharing what we have learnt from this event, whether it be positive or more traumatic. More explicitly, a commemoration aims to repeat the lessons that have been accorded and retained from an event. And herein lies the political aspect of commemoration, as to remember together is to act as a community: without commemoration, there is no community. To come together in order to express – and then repeat, since commemoration also implies repetition – the lessons that we have agreed to draw from a fact or event, is to reaffirm the values that underpin the community.

For us, commemorating the great events that shaped the 20th century, remembering them together, is to reiterate the political and moral value that we have accorded them. For example, by recalling these events – be they tragic, such as the outbreak of the Great War; or happy, like the Liberation – we convey not just our attachment to a national community but also a vision of peace, of progress and of liberty. Nevertheless, a commemoration does not necessarily stop at events that are exclusively relevant to national history. In this sense, the Nazi extermination of the Jews; the genocides of Armenians by the Turks, or of the Tutsis in Rwanda; the fall of the Berlin Wall; or the attacks on 11th September 2001, are all memorable events, commemorated because they belong to a universal history, pertaining in our eyes to our shared human condition.

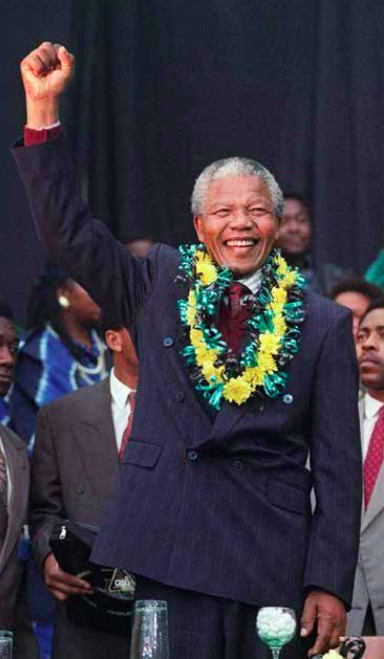

Commemoration can be thought of as a purely national, or even nationalistic, act. The establishment of a memorial orcommemoration is often at the centre of the construct of national history, of a nation’s invention. Yet the act of commemorating can also be considered beyond simply a national gesture, and as one with a universal reach. This perspective offers an alternative way, and provides different reasons, to commemorate events as momentous as the outbreak or end of war, and the act of genocide. Or, to give some happier examples, the landing of the Allied forces in Normandy; the creation of the European Union; the collapse of communism, or the end of Apartheid in South Africa.

By approaching commemoration in a way that blends events that have played a role in national history with those that form part of a more universal history – these can occasionally be one and the same, as is the case with the persecution of the Jews –, we affirm our sense of belonging to a community that is instinctively national, but that is also founded on more general human values. To put it another way, by doing so we affirm that we belong to a particular community and nation, our own, but that we simultaneously belong – in a different way – to the European community and to a broader human community.

What do the new generations remember of these events? How about the increasingly numerous members of those first generations to have spent only their childhood in the 20th century – what do they think? Which memories of the 20th century will they carry forward? It is an important question, as it will fall to them to ensure not only that the story of the 20th century lives on, but that the lessons drawn from those events continue to be heeded. The young people who participated in this survey did so not as historians, but as citizens. We looked to gauge how they classify, in a political and moral sense, the 20th century’s most significant events: the two World Wars, the Russian Revolution in 1917, Nazism, communism, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the genocides perpetrated against the Armenians, the Jews and the Tutsis, decolonisation…

We also surveyed them about the sources of their historical knowledge, about the role played by school, by books, by fiction or documentaries, but also by family members or the internet, and even about the value of memorials, the pertinence of commemorations.

Lastly we wanted to know which events, in their eyes, define their era, as history never stands still. We asked them to single out the events that they believe to have been of most importance since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and up until the election of Pope Francis in 2013, a period covering the Tiananmen protests in 1989; the end of Apartheid in South Africa in 1991; the 9/11 attacks in 2001; the creation of the Euro in 2002; the war in Iraq in 2003; the financial crisis or election of Barack Obama in 2008; and the Arab Spring in 2011. All of these events – and even more recent happenings, such as the fatal attacks against Charlie Hebdo‘s offices and the freedom of expression, against the police and French Jews, which cost the lives of 17 people between 7th and 9th January 2015 – are fresh in the collective memory. They have entered the collective conscience and will in time overlap older memories, inevitably altering our perception and interpretation of those earlier events.

We become attached to commemoration in itself, precisely because it allows us to act as a community and to create a shared experience, which may also satisfy our desire for sociality. Yet the true worth of commemoration still lies in the values themselves insofar as it shares them, firstly between members of a nation, then with other nations and, lastly, with the new generations who will make up tomorrow’s community and humanity. It is in this spirit that the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah wished to work together to identify the memories of the last century from which our present century – the 21st – will be formed. This is to say, to identify both the place reserved for the old values of freedom and justice by the new generations, and what the future holds for these values in an age of globalisation. It is a way of trying to guess the future of our humanity, while hoping in some way to contribute to that future.

The results presented in these pages make up only part of all the data collected. The reader can consult the results of our survey in full on the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah website or on the Fondation pour l’innovation politique website.

Survey methodology

The question is: «In your view, during the Second World War, did the government of your country act entirely in the interests of human dignity and freedom, somewhat in the interests of human dignity and freedom, somewhat counter to the interests of human dignity and freedom, or entirely counter to the interests of human dignity and freedom?».

The survey was designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah. It was carried out by the Ipsos institute, which surveyed 31.172 people in national samples of roughly 1.000 individuals, aged between 16 and 29 years. The questionnaire was taken to 31 countries, and in doing so was translated into each of the different national languages (24 in total). It consisted of 33 questions. The collection of the data was carried out over a four-week period (14th July to 11th August 2014) in order to neutralise the effects of changing present day circumstances. A quota system for the respondents’ age, sex and place of residency was used to ensure that the samples were representative of a cross-section of society. However, as the survey was distributed as an electronic questionnaire, the samples from emerging countries are more representative of middle-class and well-off sections of the population.

Young people were surveyed in the following countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdomand the United States of America.

Respondents were surveyed on both their opinions and their knowledge. The survey is complemented by socio-demographic data, enabling a group analysis based on social characteristics and gender, in addition to national trends. It is important at this stage to stress that certain questions judged as sensitive – those referring to the events at Tiananmen Square or opinions regarding the Maoist period – could not be asked in China. Elsewhere, a question referring to a specific historical context was not included in the questionnaire of certain countries for which it is not applicable (this is the case for the question found on page 74 of this document 1 in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, India, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Poland).1

Certain questions required the young people to classify their knowledge about a certain event on a scale comprising four levels: “very detailed”, “quite detailed”, “not very detailed”, “not detailed at all”. We then proceeded to total, on the one hand, the “very detailed” and “quite detailed” responses and, on the other, the “not very detailed” and “not detailed at all” responses. We indicate these overall totals on each occasion. The respondents were sometimes asked to select several options (as many as three) out of a list of possible answers, for example when we asked them for their opinion on the most important events to have taken place around the world since 1989.

European (EU) averages were calculated to provide combined data for the 19 member states of the European Union represented in the survey. This average takes into account the demographic weight of each country’s 16-29 year-olds across the continent.

It was not possible to replicate the same procedure on a global scale for the purpose of this study, due to the disparities in population sizes between the countries: weighting these 31 countries in this way would see all, or nearly all, of the countries disappear under the weight of just two of them: China and India. The results would therefore not be of interest.

We focused our analysis on the responses of young people (16-29 year-olds), limiting comparisons by age sub-groups (16-19 year-olds, 20-24 year- olds, 25-29 year-olds) to relevant cases that reveal notable discrepancies or that refer to issues that lend themselves to such age group comparisons. Finally, expressions such as “the youth of France”, “young Indians” or even “Australians” – that is to say, where there is no qualifying mention of age – always relate to the 16-29 year-old individuals surveyed.

1914-1918 : the first World War

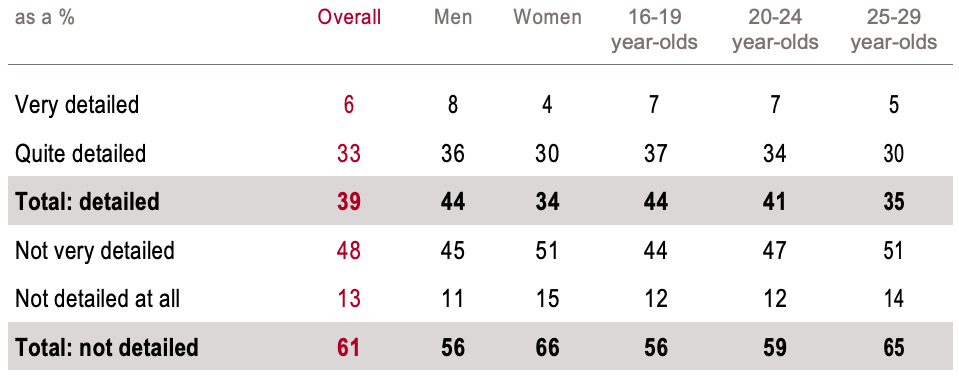

Question:

«Do you feel that your knowledge of the First World War is very detailed, quite detailed, not very detailed or not detailed at all?»

This question does not test the knowledge of those surveyed, but rather asks them to assess how informed they feel about, in this case, the two World Wars. The results reveal that a majority of the respondents (61%) consider that they do not have adetailed level of knowledge about the First World War (“not very detailed” and “not detailed at all”), against 39% who believe themselves to have a detailed level of knowledge (“very detailed” or “quite detailed”). The number of those who judge their knowledge to be “detailed” is a little higher within the European Union (42%), where the Italians come out on top (62%), followed by the Austrians (49%), the Germans, the Hungarians, the Lithuanians, the Romanians (48% in each case 2)

and the Danes (46%). Outside the European Union, the Swiss (46%) and the Turks (53%) are those who believe themselves to be the best informed about the Great War.

It will be noted that many more Chinese (59%) and Indians (58%) believe themselves to be well-informed than Americans (36%), but that the Japanese (79%), the Czechs (76%), the Estonians (75%), the Dutch (73%), the Latvians (73%), the Ukrainians (73%), the Russians (69%) and the Spanish (68%) are those who most frequently claim to be poorly informed on this matter.

Which courtines are judged to be responsible for the first World War ?

Question:

« In your opinion were the following countries responsible for the First World War? »

Answers to a question like this inevitably result from a mixture of personal knowledge and impressions, and political and cultural sensibilities, which are all in part influenced by national perceptions. For a majority of the respondents (80%), Germany is responsible for the First World War, along with Austria-Hungary (59%) and Russia (57%). Notably, a majority of Austrians (56%) judge Germany to have been responsible. Serbia is only cited by a third of the young people surveyed (36%) but by two-thirds of the Austrians (64%), a majority of the Italians (57%) and, of course, the Croats (56%), by nearly half of the Japanese (49%), the Turks (48%), the Swiss (47%), the Hungarians (45%) and the Czechs (43%), but by only 29% of the Serbs. As many Germans (75%) judge Germany to have been responsible as Austrians who point the finger at Austria-Hungary (74%), whereas significantly fewer Hungarians (58%) consider that responsibility lies with their country’s former empirical incarnation. The tendency to see responsibility lying with one’s own country is less commonplace among the French (49%), the British and the Russians (32%).

Even though France is judged to be responsible by a minority of all respondents (43%), it is held responsible by the majority of the Turks (79%), Chinese (60%), Greeks and Indians (58%), Japanese (57%) and Hungarians (54%) surveyed. The responsibility of the USA is cited by a third of all respondents (34%), including the Russians (34%), but more frequently by the Greeks (65%), the Japanese (62%), the Indians (53%), the Turks (50%), the Croats (48%), the Chinese (46%), the Spanish (45%), the Ukrainians (44%), the Hungarians and the Serbs (41%).

The Japanese stand out in the way they seem to consider every country to have been responsible for the Great War: Germany (70%), Russia and the UK (66% in both cases), the USA (62%), France (57%), Austria-Hungary (52%) and Serbia (49%).

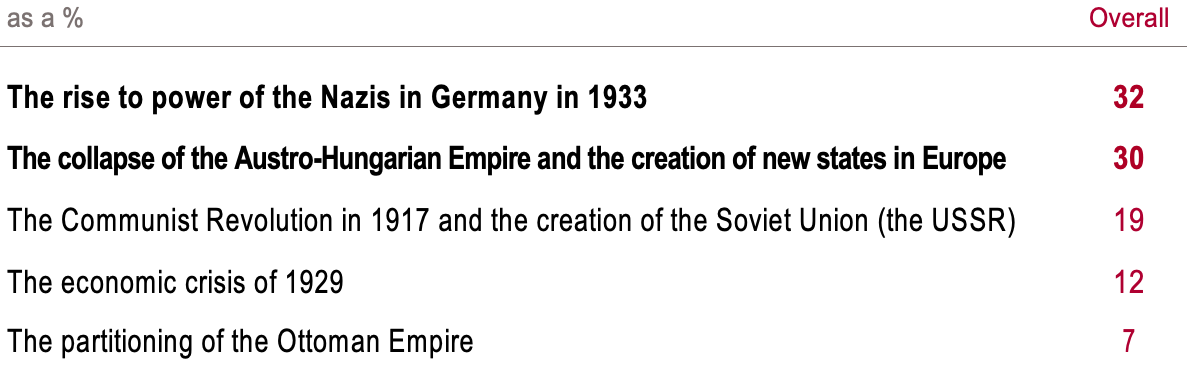

1914-1918 : Consequences of the war

Question:

« In your opinion, which of the following is the main consequence of the First World War? »

The results demonstrate that national traumas are reflected in the different perceptions as to the consequences of the GreatWar. The Germans (41%) largely point towards the Nazi rise to power; it is the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and thecreation of new states in Europe that is most strongly felt by young Austrians (56%) and Hungarians (47%), but also by young Czechs (49%), Serbs (45%), Italians (42%), Romanians, Lithuanians (38%) and Croats (35%). The Turks single out the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire above all else (52%).

For a third of the young people surveyed (32%), the Nazi ascent to power in Germany in 1933 is one of the main consequences of the First World War. More than a half of young Britons are of this opinion (54%), as are nearly half of the Americans (48%), 44% of Israelis, 41% of Australians, Canadians, French and Germans, and 40% of Belgians and Japanese.

On the other hand, only 19% of the respondents cite the 1917 communist revolution and the creation of the USSR as being one of the main consequences of the First World War. But this proportion increases notably among the Lithuanians (33%), Latvians (35%) and Estonians (38%), and among the Polish (30%), Ukrainians (28%) and Russians (39%) for evidently different, even opposite, reasons – even within one country, as is the case with Russia. For some Russians, the 1917 revolution remains a glorious event, for reasons that have less to do with communism and more to do with nationalism. For eastern European countries, those surveyed in the Baltic States or Ukraine, 1917 represents the birth of what will become the Soviet Empire. A higher than average proportion of Japanese (22%), as well as Greek (21%), respondents cite the 1929 crisis among the main consequences of the Great War, thus demonstrating a more personally relevant, economic reading of the war’s aftermath.

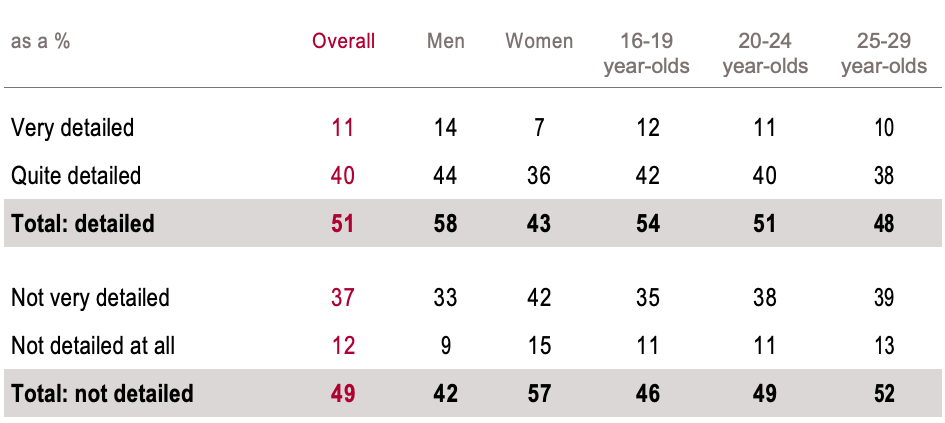

1939-1945 : The second World War

Question:

« Do you feel that your knowledge of the Second World War is very detailed, quite detailed, not very detailed or not detailed at all? »

The responses suggest that the new generations know the Second World War better than the First. Half of those surveyed (51%) feel that their knowledge on this matter is detailed. Israel and Denmark (75% in both cases) have the highest percentage ofrespondents with a detailed knowledge of the war of 1939-45. In Austria (71%), Germany (66%) and Italy (65%), the number of those who believe themselves to have a detailed knowledge of the conflict is significantly higher than the European average (53%). A below- average proportion of French (49%) and Belgians (46%) believe themselves to be well-informed on the matter,despite the significant impact that the conflict had on their countries. Outside Europe, less Australians (39%), Canadians (46%) and Americans (46%) claim to have a detailed knowledge than Russians (56%) and also Chinese (65%). But it is the Japanese (25%) who feel least knowledgeable, with three-quarters of them (75%) having answered that they felt under-informed about the Second World War (answers “not very detailed” or “not detailed at all”).

The male respondents believe themselves to be more familiar with events from the two World Wars than their female counterparts. A comparison shows that a higher proportion of men (44%) than women (34%) feel that they are knowledgeable about the 1914-18 conflict. The gap widens in relation to the Second World War: 58% of men, as opposed to 43% of women, believe themselves to have a detailed knowledge of this war.

A link to schooling is evidently decisive when it comes to evaluating one’s personal knowledge of the subject. However, what counts is not so much the level of education, but rather the status of still being in education when taking the survey. While two thirds (67%) of those who left education before 21 years of age do not feel that they have a detailed knowledge about the First World War, this figure is only 57% among those who are still students. The same difference can be seen regarding the Second World War: 56% of those who ended their studies before turning 21 judge their knowledge to be insufficient, as opposed to 46% of young people who are still in education. This data offers evidence of the intimate correlation between the memory and education. The academic memory progressively diminishes as the respondents enter the professional world, leaving their schooling behind. This suggests that other sources of historical knowledge are therefore necessary.

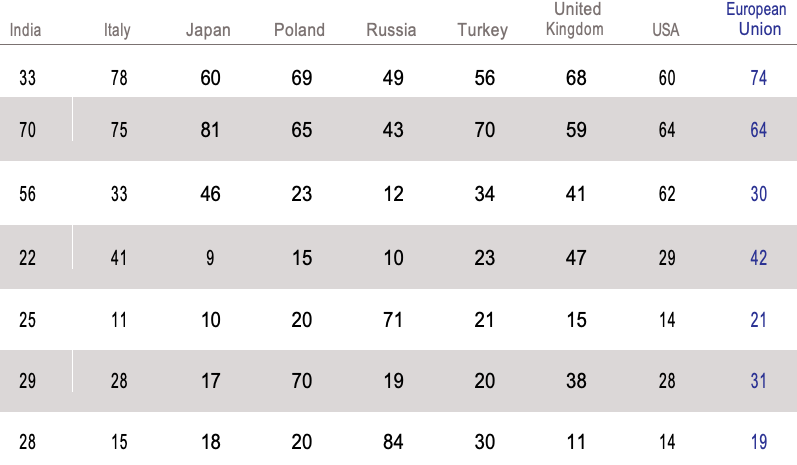

Which courtines are considered to be responsible for the second World War ?

Question:

« In your opinion, were the following countries responsible for the Second World War? »

In the eyes of almost all of the young people surveyed (92%), Germany is the country mainly responsible for the Second World War. This is an opinion shared by 94% of young Europeans, including notably 93% of Germans and Austrians, but also 98% of Israelis, 96% of French, 85% of Americans, and three- quarters of Indians (78%) and Japanese (77%).

Among the young people who feel well-informed about the Second World War, almost all (95%) judge Germanyto be responsible for the conflict, as opposed to 88% among those who deem their knowledge of the matter not to be detailed. In the same way, among those who claim to be knowledgeable about the extermination ofthe Jews, the same proportion (95%) is found to share the conviction that responsibility lay with the Germans, as opposed to 89% among those who deem themselves insufficiently informed about the Holocaust.

While only half of those surveyed (52%) single out the responsibility of Japan in the outbreak of the global conflict, this proportion rises to above three-quarters among the Japanese themselves (77%). Almost all of the Chinese respondents (92%) share this opinion, as well as two-thirds of Indians (69%) and Americans (67%).

Germany

URSS

Japan

Italy

USA

France

United Kingdom

The survey reveals the Europeans to be divided. 64% of Croats, 63% of Hungarians, 62% of Spanish, 61% of Czechs and 58% of Italians judge Japan to be responsible for the conflict, as opposed to a third of the Romanians (32%) and Germans (32%), 38% of the Latvians, Dutch, Austrians and Italians, 39% of Estonians and 42% of Lithuanians. The responsibility of Italy is less frequently singled out overall (43%) as it is by the Italians themselves (60%). The citizens who most frequently single out Italian responsibility for the outbreak of the war are the Greeks (67%), the Serbs (65%), the Croats (58%), the Turks (55%), the Ukrainians (55%), the French (54%), the Czechs (53%) and the Poles (50%), while not even a third of the Germans, Latvians or Danes (32%) share this view, along with only 30% of the Dutch, 29% of the Estonians and 17% of theRomanians surveyed.

Two-thirds of the young people surveyed (63%) hold the Soviet Union responsible for the Second World War. Of course, Russian responsibility is less heavily cited than that of Nazi Germany (92%), but it is cited more frequently than that of imperialist Japan (52%) or fascist Italy (43%).

Two times as many young Europeans (61%) as young Russians (33%) pointed towards the responsibility of the USSR. But the role of the USSR is much more frequently cited by young people from the eastern part of the Old Continent, which subsequently remained under Soviet influence for many years (87% in Poland, 82% in Finland and Hungary, and 72% in the Czech Republic), or in countries that were members of the Soviet Union, like Latvia (77%), Estonia (80%), Lithuania (80%) and Ukraine (77%). Three-quarters of the Croats surveyed (76%) share the same opinion.

Young people in Western Europe are slower to point the finger at the USSR, but a majority of them do so in Italy (69%), Switzerland (68%), Spain (67%), Greece (68%), Austria (61%), France (60%), Denmark and Belgium (53%), Germany and Israel (51%). The youth of Turkey (76%) are more inclined to point towards Russian responsibility than young Americans (52%), Canadians (53%) or Australians (48%); meanwhile, two-thirds of the Turks (65%) cite the responsibility of France and three-quarters (71%) cite that of theUnited Kingdom.

1939-1945 : Consequences of the war

Question:

« In your opinion, which of the following were the two main consequences of the Second World War? »

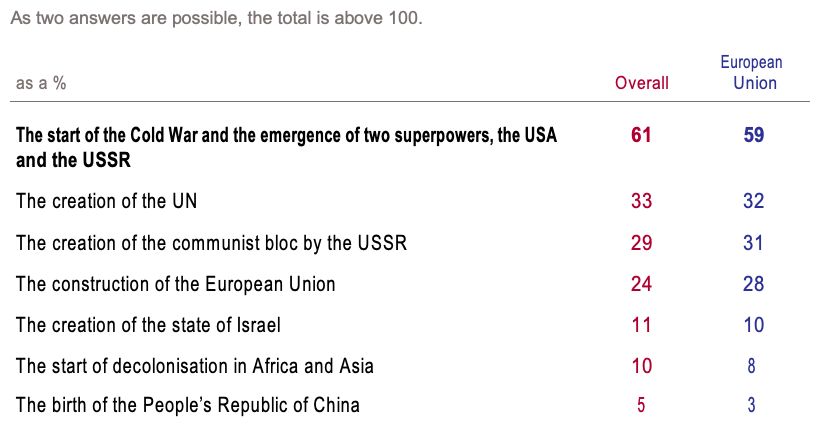

The perceptions of the new generations regarding the consequences of the Second World War are dominated by the outbreak of the Cold War between the two new superpowers (61%). This opinion is particularly widespread among the Americans (65%) and the Russians (77%), as well as among the Estonians (68%), the Chinese, Greeks and Ukrainians (69%), the Serbs (70%), the Lithuanians (73%) and the Croats (77%).

Among the young people surveyed, the creation of the UN (33%) is most frequently cited in those countries whose diplomacy is shaped by political neutrality, such as Switzerland (40%), Austria (42%) and Finland (52%).

The number of young Europeans is greater than the overall average in pointing towards the creation of the communist bloc by the Soviet Union (31%) and the construction of the European Union (28%).

Along the same lines, the creation of the People’s Republic of China (5%) is cited by 35% of Chinese, the creation of the state of Israel (11%) is cited by 78% of Israelis and by 23% of Turks, and the start of decolonisation in Africa and Asia (10%) is cited by 16% of Indians and 21% of Japanese.

Relatively few Spanish respondents (19%) point towards the birth of European unification, perhaps because their country did not actively participate in it. This would explain the fact that only 13% of Turks, 14% of Poles, and 24% of Romanians and Britons classify this event among the two main consequences of the Second World War. But this does not explain why only 21% of Italians gave this same answer, even though their country was one of the founder members of the European Union. Conversely, among the other founder states, a larger percentage of young people cite the birth of the Union: the French (31%), the Dutch (36%), the Belgians (40%) and the Germans (44%). But even here the link is not so simple, since certain EU states that were not founder members are also revealed to be above the average on this regard: the Greeks (30%), the Hungarians (31%), the Danish (34%), the Finnish (43%) and the Austrians (51%), the latter group of respondents also representing the highest proportion to cite the creation of the UN (52%), thereby appearing to attach a unique importance to cooperative transnational action.

There is however no automatic correlation between national or regional history and the answers of those surveyed. That is to say, if European unification is cited by a quarter of all respondents (24%) yet by only 28% of Europeans, it is because young Europeans do not believe it to be one of the two main consequences of the war. It is understandable that the young people surveyed see the creation of the European Union as less memorable than the start of the cold war, given that the creation of the Union was, by nature, a less spectacular event: it was a largely uneventful agreement between free nations that overcame previous disputes and conflicts. Perhaps the creation of the European Union is a less memorable event precisely because it was so efficient in fulfilling its essential mission of restoring peace, liberty and prosperity to Europe.

In the list of the main consequences of the Second World War, the creation of the communist bloc by the Soviet Union is cited by less than a third of the young people surveyed (29%). This same proportion was registered among the Europeans (31%), theAmericans (31%) and the Russians (31%).

The story is different with respect to the former members of the communist bloc, where the creation of that bloc by the USSR is more likely to be perceived as one of the two main consequences of the Second World War. This is the case whether in the countries that were a part of the former USSR – like Lithuania (52%), Latvia (49%) or Estonia (42%) – or in those states that were simply members of the communist bloc, like Poland (58%), the Czech Republic (54%), Romania (43%), Ukraine (36%) or Hungary (34%).

Western Europeans are among those who least frequently cite the creation of the communist bloc as one of the two main consequences of the global conflict from 1939-45: 15% of the Austrians, 17% of the Finns, 18% of the Dutch and the Swiss, and 20% of the Danes.

Less than one Israeli in ten (6%), 13% of the Japanese and 14% of the Turks mention the creation of the communist bloc as one of the main consequences of the war from 1939-45.

The most important event of the second World War

The extermination of the Jews by the nazis and the use of the atomic bomb

Question:

« In your opinion, which of the following were the 3 most importantevents of the Second World War? »

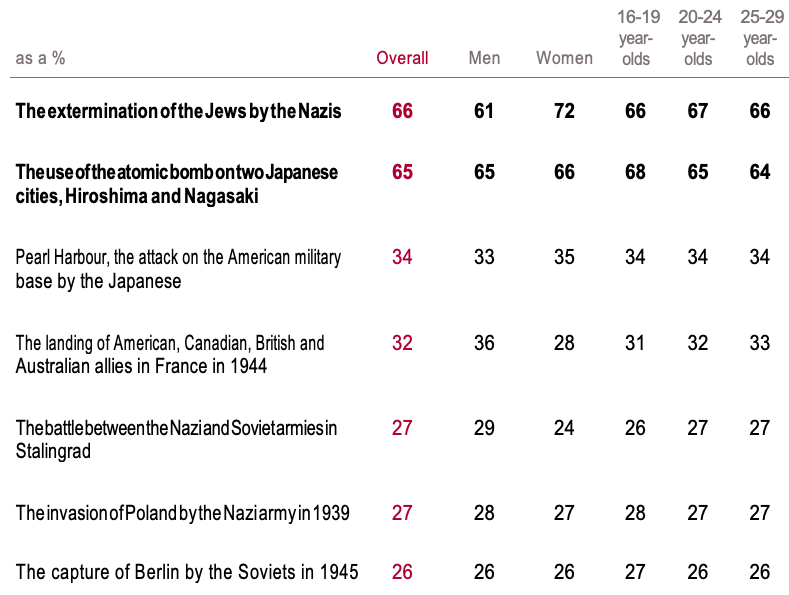

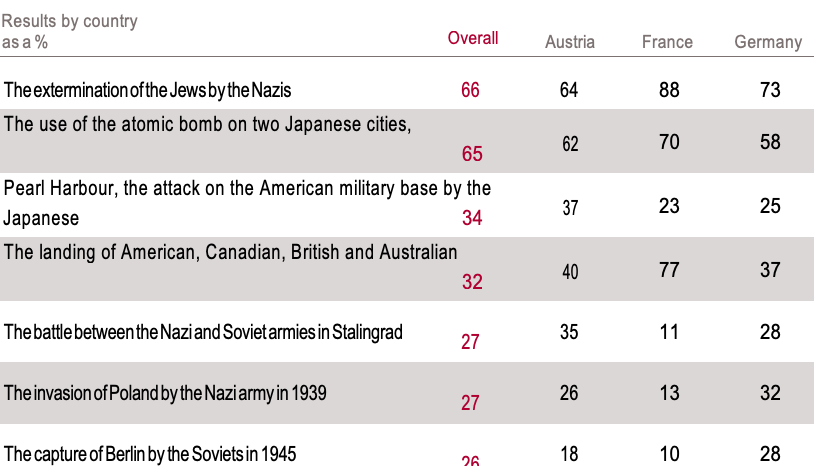

Two thirds of the young people surveyed consider the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis to be the most important event of the Second World War (66%). Europeans most frequently cite this event (74%), above all the Spanish and Lithuanians (71%), the Czechs and Swiss (72%), the Germans, Croats and Danes (73%), the Italians (78%), the Belgians (82%), the Dutch (86%) and the French (88%). For the Americans, the Holocaust comes third (60%) behind the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (64%) and the attack against the Pearl Harbour military base by the Japanese army (62%).

Young people in emerging countries seem to remember the Second World War differently. As such, the extermination of the Jews is much less frequently cited by the Indians (33%) and the Chinese (38%), the Ukrainians (46%), the Russians (49%) and the Turks (56%). But the Americans and the Japanese (60%), despite not being from emerging countries, can also be found among those who attach least importance to the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis during the Second World War.

The survey results place the extermination of the Jews in first position (66%) ahead of the six other events suggested. The use of the atomic bomb on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is placed almost at the same level (65%), most frequently cited by the Japanese (81%), but also by the Croats (83%), the Serbs (80%), the Hungarians (79%), the Italians (75%), the Estonians and the Greeks (73%), the Finnish (71%), the French, Indians and Turks (70%).

The attack on the Pearl Harbour military base by the Japanese in 1941 is cited by a third (34%) of all respondents. A closer inspection of the countries where young people most regularly named this event among the three most important reveals a lot about what was at stake there, and the background to this battle: the Americans (62%) and the Japanese (46%) but also the Chinese (65%), the Indians (56%), the Australians (53%), the Canadians (42%) and the British (41%) all regularly underlined the importance of this event.

The Normandy Landings (32%) are more frequently cited by the French (77%) than by the British (47%), the Canadians (42%), the Americans (29%) and the Australians (26%), whose troops nevertheless played a key role in the operation. These results are all the more surprising given the way cinema has raised the profile of this decisive battle.

The invasion of Poland by the Nazis in 1939 (27%) still holds the attention of the Germans (32%) and particularly the Ukrainians (37%), the British (38%), the Israelis (47%), and of course the Poles (70%), as well as a fifth of the Russians surveyed. The Battle of Stalingrad, during which the Nazis were confronted by the Red Army (27%), is most often cited by the Latvians (32%), the Lithuanians and Romanians (33%), the Austrians (35%), the Serbs (36%), the Greeks (43%) and the Ukrainians (59%). It will come as no surprise to read that the majority of the Russians (71%) cite the Battle of Stalingrad. It is the Americans who least frequently attach importance to this historic battle (14%).

The capture of Berlin by the Soviet forces, in 1945, is cited by 26% of the young people surveyed, including 34% of Romanians, 40% of Latvians and Serbs, 41% of Estonians, 66% of Ukrainians, but as many as 84% of Russians.

Three-quarters of young women (72%) cite the extermination of the Jews, as opposed to under two- thirds of men (61%), who are nevertheless more likely to cite the destruction of the two Japanese cities by the atomic bomb (65%). Those under 20 years of age tend to single out American use of the atomic bomb (68%), while the older respondents cite the Holocaust above all else (67% of those aged 20-29 years).

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

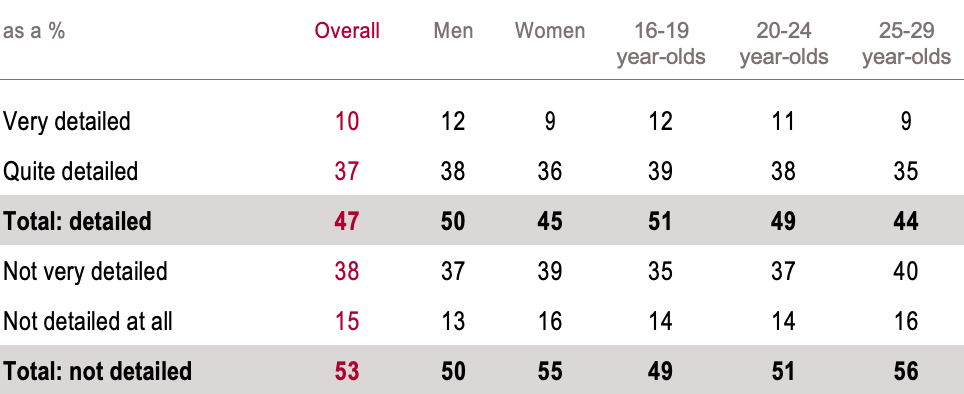

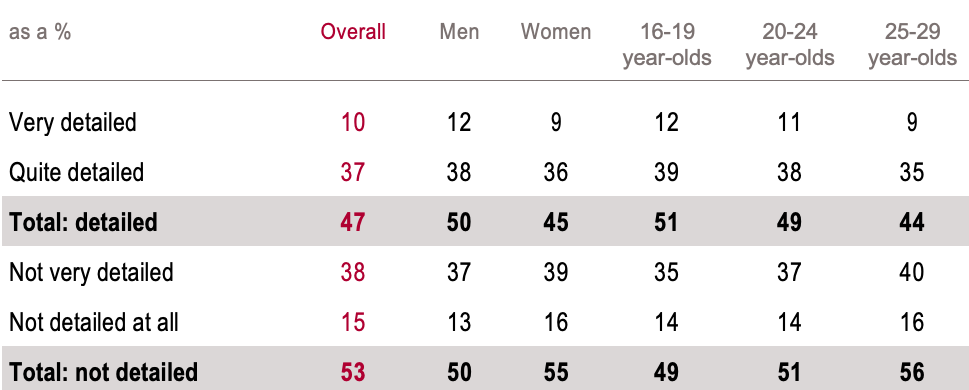

Question:

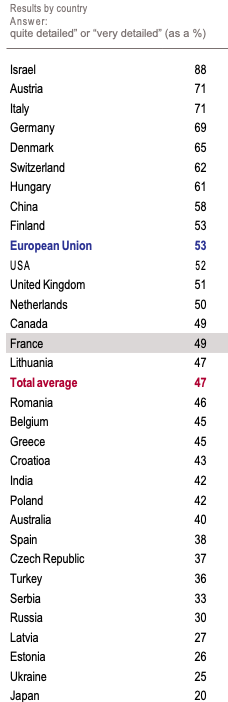

« Do you feel that your knowledge of the extermination of the Jews during the Second World War is very detailed, quite detailed, notvery detailed or not detailed at all? »

Out of all the countries surveyed, and leaving aside the young Israelis who proved to most frequently deem themselves (88%) to have a detailed knowledge of the extermination of the Jews, it is in Europe where most young people surveyed (53%) claim to have a detailed knowledge, notably in Austria and Italy (71%), in Germany (69%), in Denmark (65%), in Switzerland (62%) and in Hungary (61%).

As an overall average, 53% of respondents do not feel that they possess a detailed knowledge about the extermination of the Jews. The countries whose 16-29 year-olds indicated a lower-than-average knowledge on the subject are Ukraine (75%), Estonia (74%), Latvia (73%), Russia (70%), Serbia (67%), Turkey (64%), the

Czech Republic (63%), Spain (62%), Australia (60%) and even Poland (58%). The Japanese recorded the highest rate of respondents who do not believe that they have a detailed knowledge of this subject (80%).

Although 51% of those surveyed say that they have a detailed knowledge of the Second World War, the same can only be said for 47% specifically regarding the extermination of the Jews. It is worth noting that the Europeanaverage (53%) is higher than the average of all respondents. However, there are other significant discrepancies. On this question, age is a factor once more, and there is a notable difference between the 16-19 year-olds (51%) and the 25-29 year-olds (44%), offering more evidence of the increased sense of knowledge among respondents who are still exposed to a school environment: 51% of those who are still students feel well-informed, as opposed to 41% ofthose who finished their studies before 21, and 45% of those who finished studying after the age of 21. This clearly reveals that, although being in education evidently improves one’s perception of knowledge of this subject, this memory is fragile. It starts to become vague once schooling is complete, even among those surveyed who went on to further education.

Among the young people who feel well-informed on the extermination of the Jews, 71% consider this event to be one of the three most important during the Second World War, as opposed to only 62% of those who feel poorly-informed. The same line can be drawn connecting those who believe it necessary to preserve the concentration camps in order to keep this memory alive: 69% of the latter cite the extermination of the Jews, as opposed to 54% among those who do not consider the preservation of those camps to be a necessity.

What do the new generations know about the nazi extermination camps ?

Question:

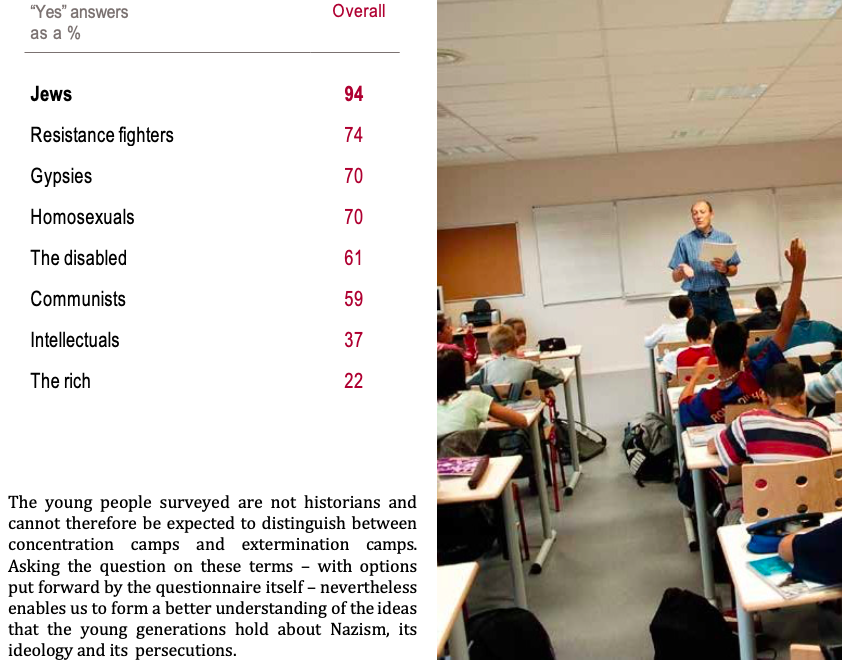

« In your opinion, were the following populations targeted by the Naziextermination camps during the Second World War? »

An unpunished crime ?

Question:

« In your view, have the main people responsible for the extermination of the Jews and the massacres of the Second World War been punished? »

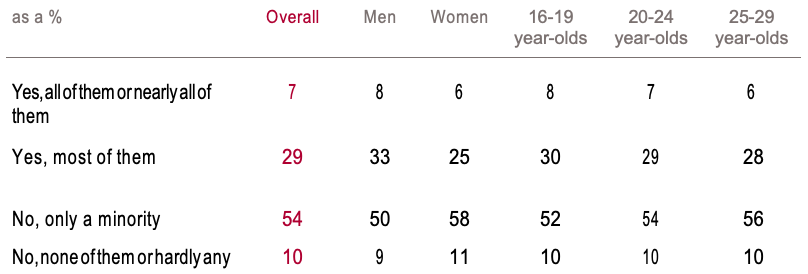

Two thirds of the young people surveyed (64%) believe that those mainly responsible for the extermination of the Jews and the massacres of the Second World War have not been punished. In this way, the opinions of the new generations paint the image of a century during which justice was not fully carried out. The data shows divergences between the different age groups: the idea that the majority of those responsible have not been punished is shared by 62% of 16-19 year-olds, and by 66% of 25-29 year-olds.There is an even clearer difference between the genders: only 59% of men are of the opinion that those responsible have not been punished, while this ratio reaches 69% among the women.

This judgement is more commonplace among young Europeans (69%) than it is among the sum total of those surveyed (64%).

By and large, those Israelis surveyed are found to be in accordance (70%) with the Europeans. The Serbs (85%) are the most critical, followed by the Croats, Spanish and Greeks (81%), the Czechs (77%), the Romanians (76%), the Lithuanians (75%), the Poles (74%), the Italians (73%), the Germans, Austrians, Latvians and Swiss (70%) and the French (69%).

Conversely, in 6 of the 31 countries, the feeling is found to be wider spread among young people that the majority of those responsible have been punished. This is the case in Australia and Finland (50%), the Finns being the only Europeans apart from the Danes (54%) to share this more optimistic viewpoint, alongside the Indians (59%), the Americans (61%) and the Chinese (63%).

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

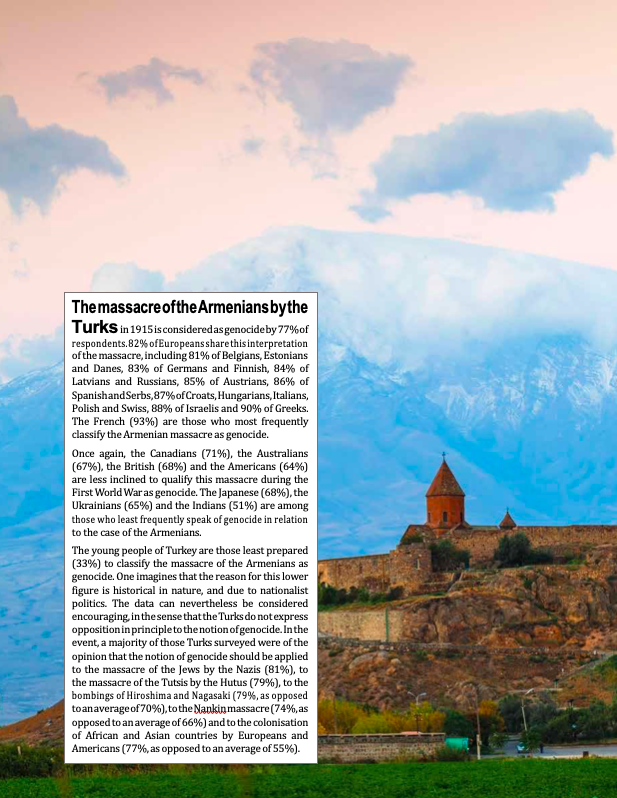

A century of massacres and genocides

Genocide is often defined as “the intentional, systematic and programmed physical extermination of a group or part of a group because of their ethnic, religious or social character”. Not all large-scale massacres are genocides. General consensus over the use of the term

applies only to the massacres of the Armenians, the Jews and the Tutsis. Are the new generations capable of immediately identifying the specific and unique character of genocide?

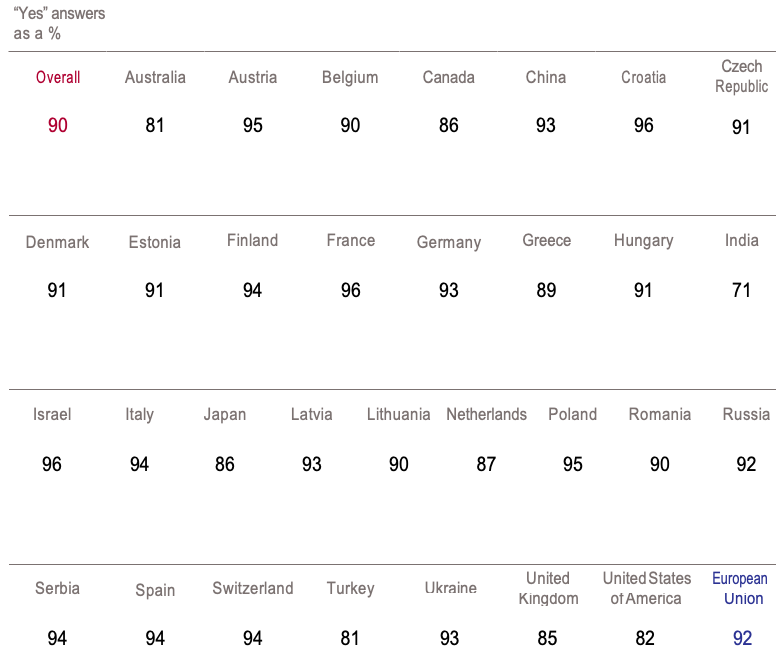

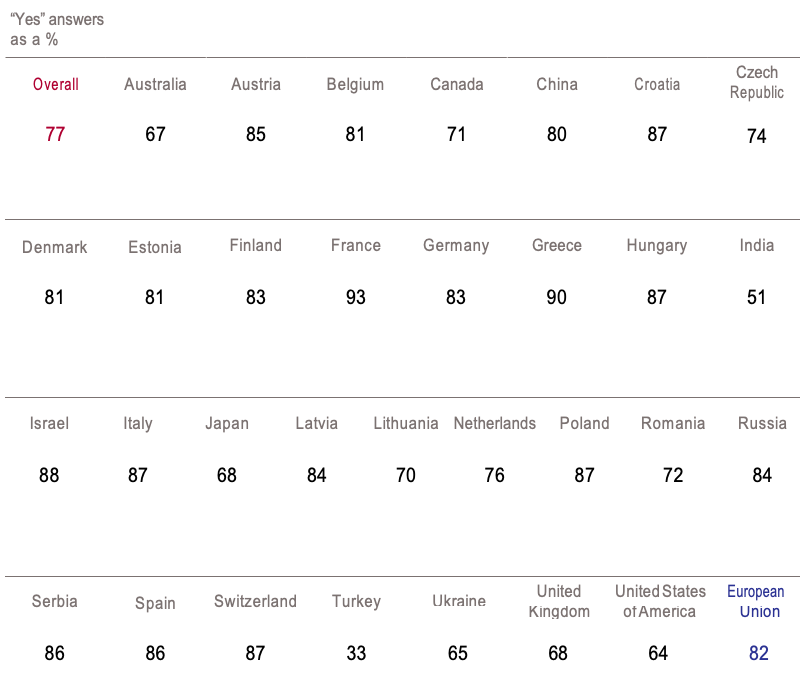

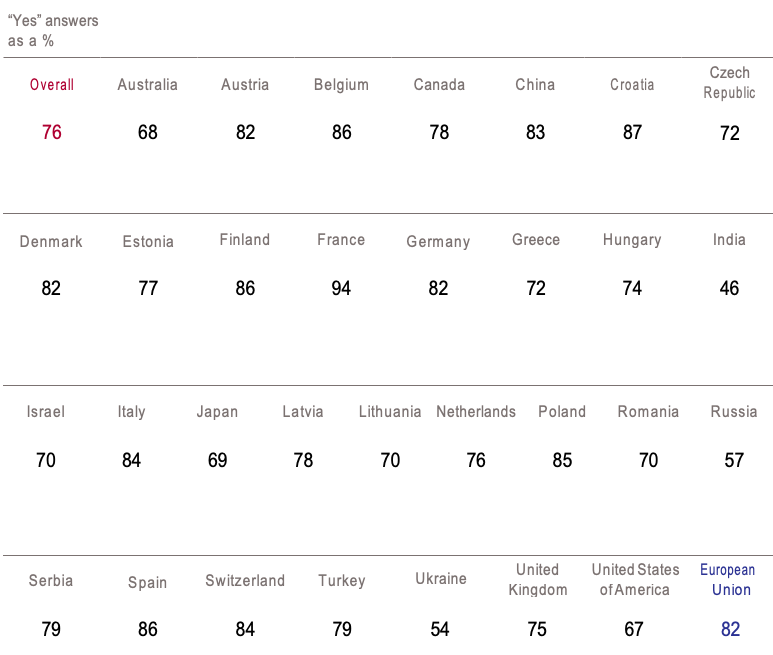

The results show that, out of the options available, the young people label the massacre of the Jews by the Nazis (90%), the massacre of the Armenians by the so-called “Young Turks” (77%) and the massacre of the Tutsis by Hutu Power (76%), as genocides.

Question :

« In your view, can we talk about genocide in each of the following conflicts…? »

Question:

« In your view, can we talk about genocide in relation to the massacre of the Jews by the Nazis during the Second World War? »

Question:

« In your view, can we talk about genocide in relation to the massacre of the Armenians, by the Turks, in 1915? »

Question:

« In your view, can we talk about genocide in relation to the massacre of the Tutsis, by the Hutus, in 1994? »

Democracy and totalitarianism

Assessments of the nazi politics

Question:

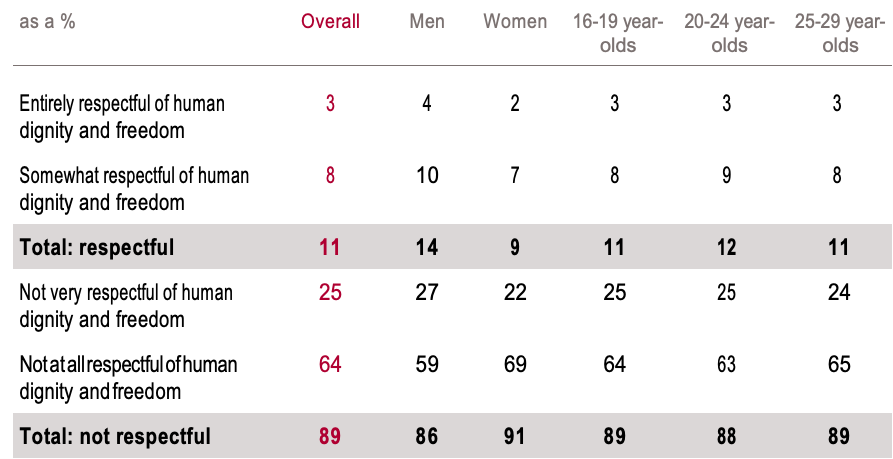

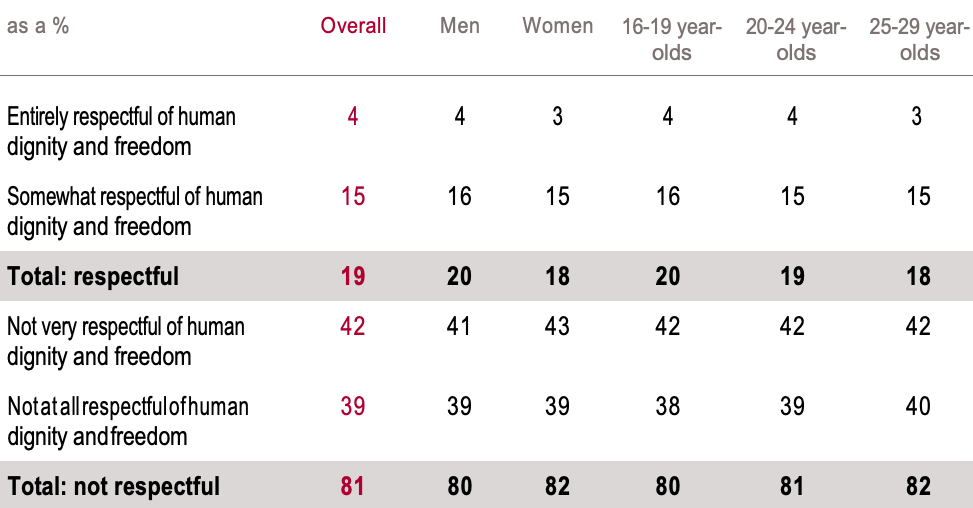

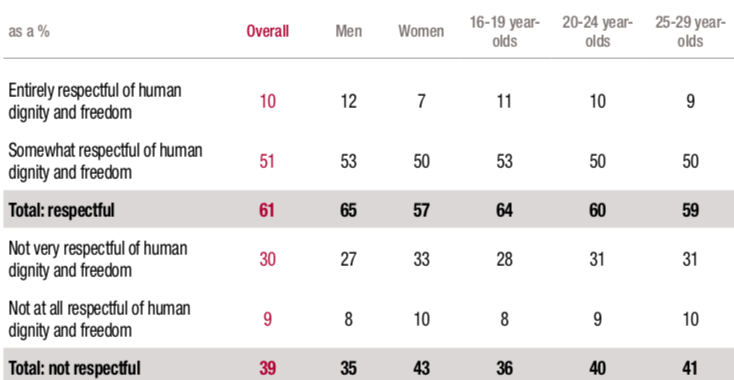

« In your view, was the political system of Nazi Germany entirely respectful of human dignity and freedom, somewhat respectful of humandignity and freedom, not very respectful of human dignity and freedom, ornot at all respectful of human dignity and freedom? »

Almost all of the young people surveyed think that the Nazis did not respect freedom and human dignity. This opinion is even more widespread among young women than young men.

The Israelis (97%), the French (97%), the Spanish (95%), the Germans, Austrians, Greeks and Serbs (94%) are all but unanimous in their negative perception of the Nazi regime. The same can be said of young Europeans as a whole.

While these figures are very high, it is nevertheless quite amazing to read that 11% of respondents could consider Nazi Germany’s politics to have been respectful of human dignity and freedom. The Indians (36%), the Russians (28%), the Turks (20%) and the Chinese (18%) most frequently registered such an opinion.

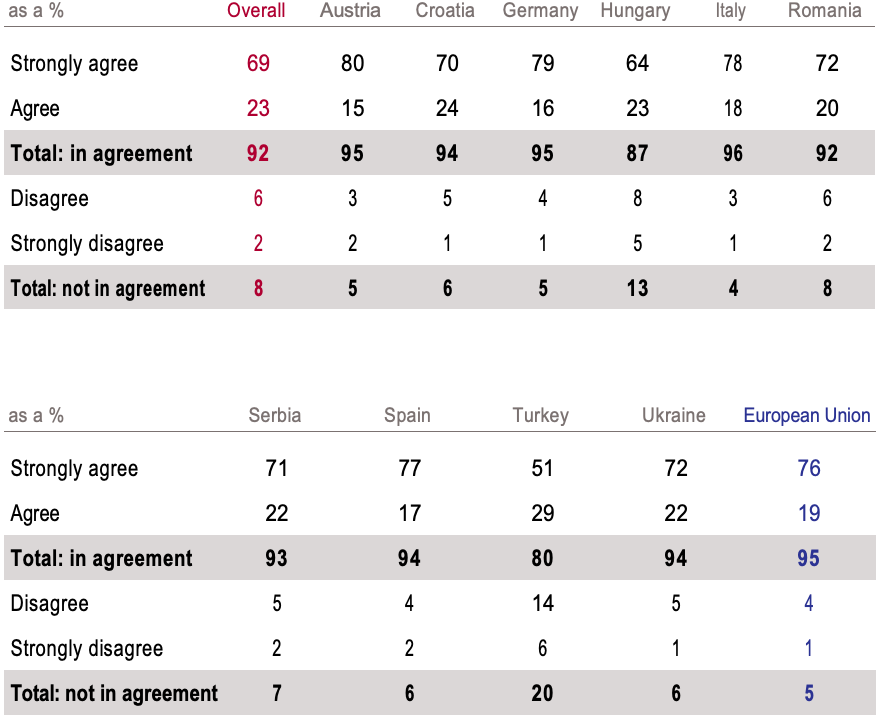

All the same, Nazism is considered by young people overall (92%) to have been a criminal regime, responsible “for the death of millions of people”.

Question:

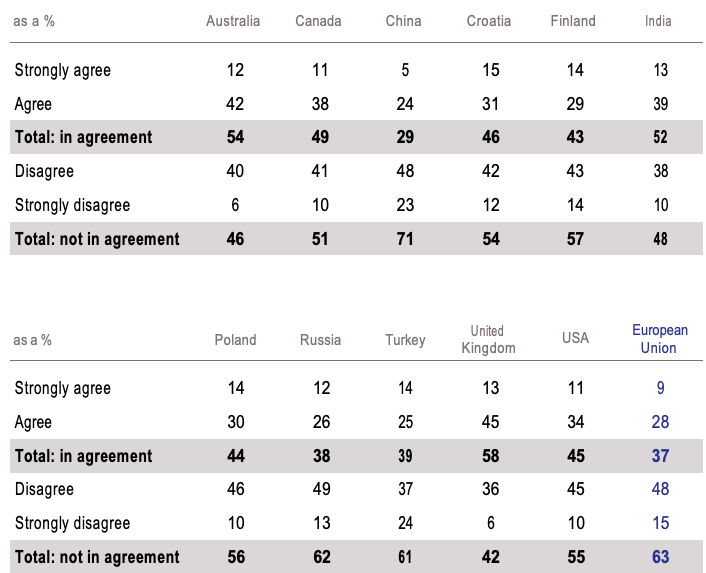

« Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree with the following statement: ‘The Nazi regime caused the deathof millions of people’? »

It makes sense that those young people who claim to be well-informed about the extermination of the Jews during the Second World War are more likely (95%) to judge the Nazi regime to have been responsible for

the death of millions of people than those respondents who do not feel well-informed on the extermination of the Jews (90%).But the difference is marginal.

Is the German-soviet pact remembered ?

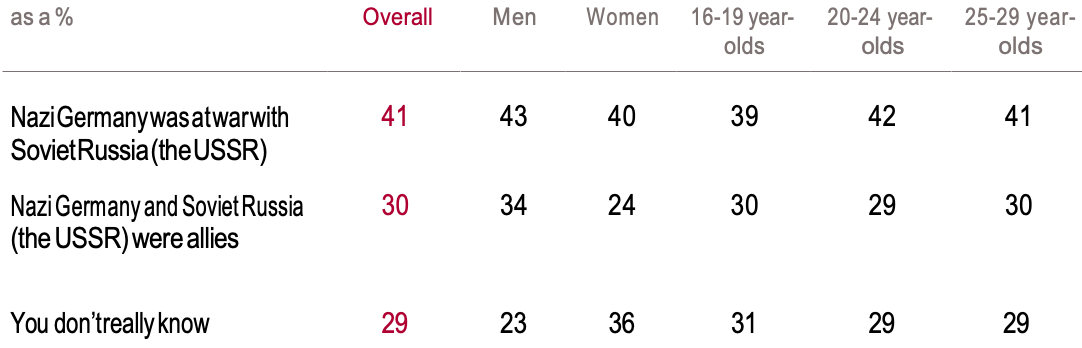

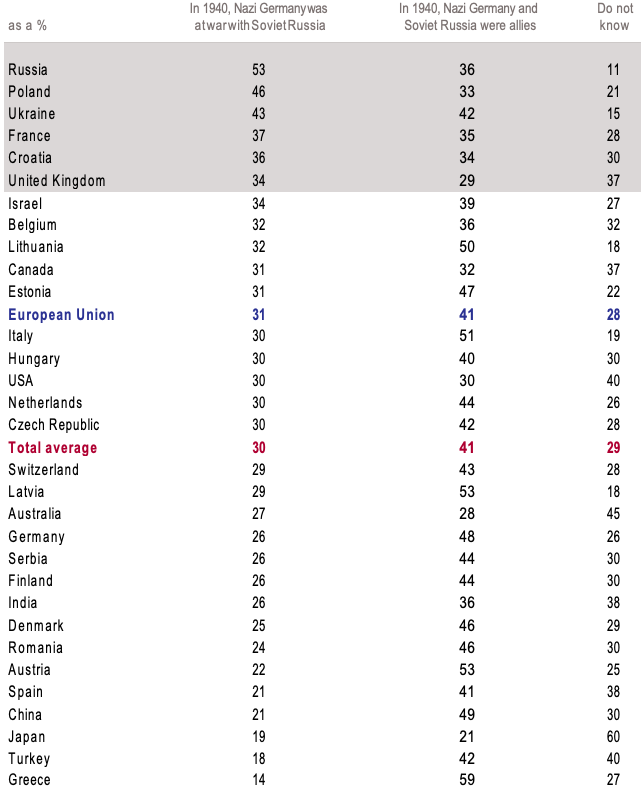

Question:

« In your opinion: in 1940, Nazi Germany was at war with Soviet Russia (the USSR), Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia (the USSR) were allies, or you don’t really know? »

Cf : Retour sur l’alliance soviéto-nazie, 70 ans après, Stéphane Courtois, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, July 2009 and the book Sortir du communisme, changer d’époque, Stéphane Courtois (dir.), October 2011, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, PUF, Paris, pp. 509-552.

On 23rd August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a so-called “non-aggression” treaty. In reality, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact established an alliance between the two countries, particularly since the agreement determined that Poland would be shared between the two.3 Knowledge of this alliance is important in understanding not only the Second World War but also totalitarianism, one of the principal and most devastating political phenomena of the 20th century. In June 1941, the invasion of the USSR by the Nazi armies would result in the German- Soviet pact being terminated, and subsequently in the USSR joining forces with the Allies.

However, according to 41% of the young people surveyed, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were already at war with one another in 1940. Only 30% of the respondents knew that the two countries were allies, while 29% claimed not to know the answer to the question. In only six countries did more 16-29 year-olds answer correctly than answer incorrectly. Out of all the countries surveyed, only the Russians registered a majority (53%) of correct responses regarding the Nazi Germany-USSR alliance in 1940.It is surprising to note that less than half of the Poles (46%) knew the right answer, even though their country was the main victim of this pact.

A majority of Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians incorrectly assert that Nazi Germany and the USSR were at war with one another in 1940, yet their countries were nevertheless in a similar situation to that of Poland. The Baltic states were invaded by the Nazis in 1940, before the latter were chased out and replaced by Soviet forces. It should be noted that the French understand the nature of the German-Soviet pact better than the majority of those surveyed, whereas the Japanese are those who most frequently admitted their ignorance on the subject (60% claimed not to know).

It will also be noted that the young people who feel well-informed about the Second World War were more frequent than the average in giving the correct answer (40%), yet a similar amount of these young people (41%) incorrectly indicated that Nazi Germany and the USSR were at war with one another in 1940. On the other hand, the young people claiming to be poorly-informed on the conflict were quick to admit their ignorance (45%). Finally, among all those surveyed, more men (34%) than women (24%) gave the correct answer.

Memories of communists regimes

Russia under Stalin

Question:

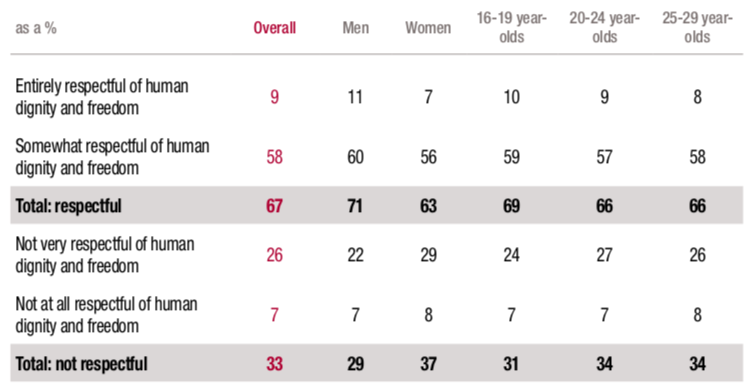

« In your view, was the political system of communist Russia entirely respectful of human dignity and freedom, somewhat respectful of humandignity and freedom, not very respectful of human dignity and freedom, ornot at all respectful of human dignity and freedom? »

The majority of the young people surveyed have a negative view of communism. Almost all young Europeans (89%) share this perception, even though this is less than for Nazism (93%). This critical standpoint unites the youth of both Eastern and Western Europe; the view is shared by 94% of Poles and Frenchmen, 93% of Lithuanians and Finns, 91% of Austrians and Croats, and 90% of Germans, Italians and Estonians. On the other hand, Russian opinions are more divided: only a small majority

53%) believe that the communist regime was not respectful of human dignity and freedom.

Considered by a very large majority to have been hostile towards freedom and dignity, the Soviet communist regime does nevertheless enjoy a positive image among the Chinese: for nearly three-quarters of them (72%), the political system of the USSR was respectful of human dignity and freedom. A majority of Indians (52%) also share this opinion.

China under Mao

Question:

« In your view, was the political system of China under Mao from 1949 to 1976 entirely respectful of human dignity and freedom, somewhat respectful of human dignity and freedom, not very respectful of human dignity and freedom, or not at all respectful of human dignity and freedom? »

The Chinese Communist regime (1949-76) is viewed negatively by a great majority of the young people surveyed (81%), who view it as a system that was not respectful of human dignity and freedom. This is broadly similar to the way in which young people view the regime of Soviet Russia. As with the Soviet regime, young Europeans (89%) and young North Americans (77%) have particularly negative sentiments regarding Mao’s China. The responses were almost unanimously negative from France (94%), Finland (92%), Germany and Austria (91%), as they were among the Belgians, Spanish and Swiss (90%).

However, 56% of Indians conversely do believe that the political system in China under Mao was respectful of human dignity and freedom, as do 43% of Russians, 39% of Ukrainians and 33% of Turks. It bears reiterating that this question was not put to Chinese respondents.

Communist deaths

Question:

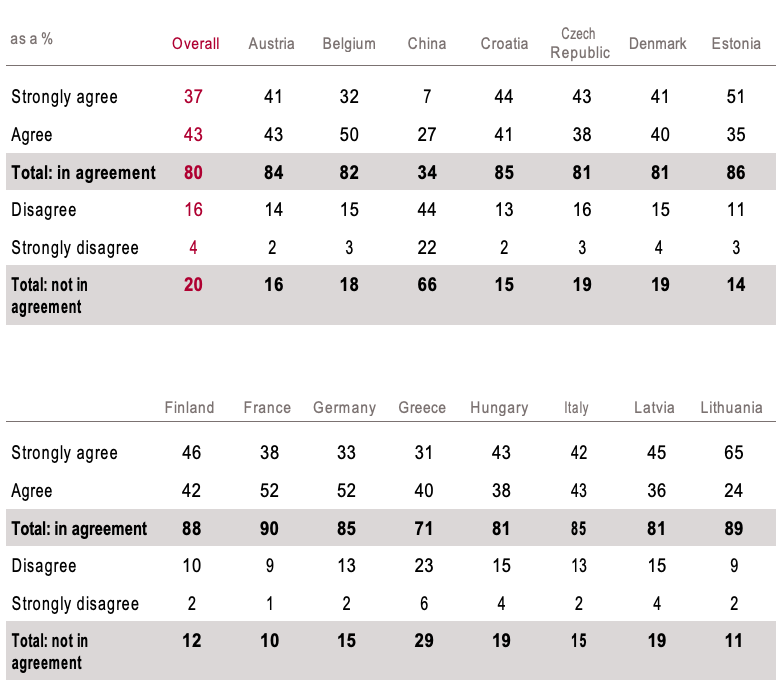

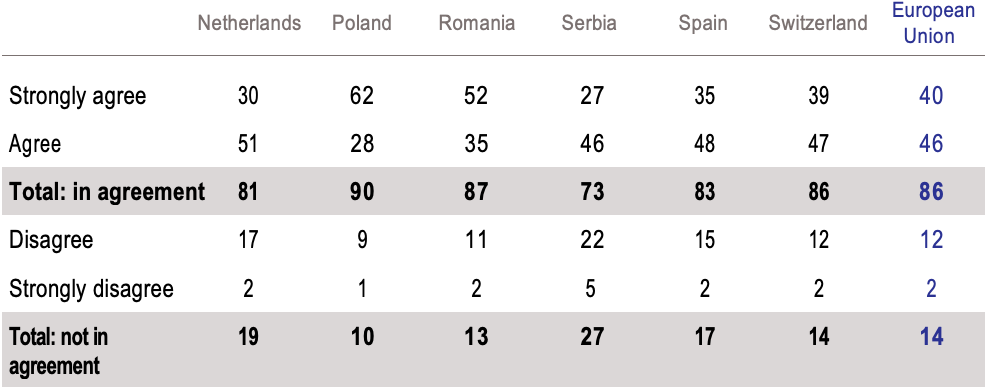

« Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree withthe following statement? ‘Communist regimes have caused thedeath of millions of people’ »

Those who least frequently agree with this statement are the Serbs (27%), Greeks (29%), Japanese (32%), Turks (33%), Russians (44%) and Chinese (66%). In keeping with previous responses, however, a majority of young people hold communist regimes responsible for “the death of millions of people” (80%). This conviction is as strong in Europe as it is in North America. The majority is weaker in Greece (71%), Japan (68%) and Turkey (67%), where it nevertheless remains above two thirds of those surveyed. In Russia, even though opinion is divided, a small majority (56%) declare themselves to be of the view that communism “has caused the death of millions of people”.

The Chinese were the only respondents to express a view to the contrary. Yet a third among them still indicated their agreement with this statement (34%). The fact that this question could be put to the Chinese, and the result obtained from it, are two of the most striking features of our survey.

It is notable that, while three Ukrainians in ten (30%) consider the Russian communist regime to have been respectful of human dignity and freedom (39% are of the same opinion regarding China under Mao), three-quarters of them nevertheless agree with this critical statement about communism.

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

Perceptions of democratic systems

Question:

« Do you strongly agree, agree, disagree or strongly disagree withthe following statement? ‘Democratic regimes have caused thedeath of millions of people’? »

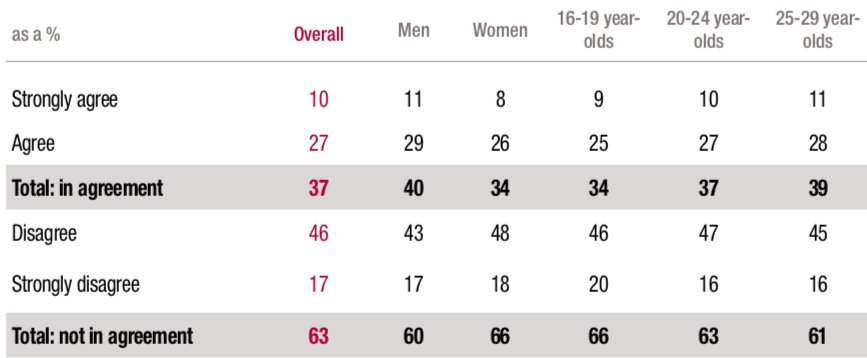

No surprises, therefore: Nazism and communism are considered as criminal regimes by the majority of the young people surveyed.As far as Nazism is concerned, not one country proves to be an exception to the rule. On the other hand, when it comes to communist regimes, a significant section – if not majority – of young people from China, India and Russia go against this general opinion. If the same type of judgement is now requested regarding democratic regimes, it can be noted that the overall assessment is much more favourable than for Nazi and communist regimes, but that the swing in opinion is not as pronounced as might have been expected. In fact, more than a third of respondents (37%) indicate their agreement

with the idea that “democratic regimes have caused the death of millions of people”. It may be noted that, in this case, young Europeans (37%) register the same rate of agreement as the overall average (37%). Maybe the respondents are bearing in mind the victims of the First World War, which involved several democracies, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War, or even the periods of colonisation and crises of decolonisation. Those who most regularly held democratic regimes responsible for “millions of deaths” were the British, Australians, Indians, Canadians, Croats, Americans, Poles and Finns.

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

Question:

« In your view, during the Second World War between 1939 and 1945,was the political system of the United States of America entirely respectful of human dignity and freedom, somewhat respectful ofhuman dignity and freedom, not very respectful of human dignity and freedom, or not at all respectful of human dignity and freedom? »

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

Out all the respondents, those who most frequently consider the political system of the USA not to have respected human dignity and freedom over the period 1939-45 were found in Serbia (64%) and Japan (63%). For the Serbs, one hypothesis could be that this negative judgement is the expression of a wider anti-American sentiment resulting from their country’s pro-Russian stance and the role played by the USA during the wars in the former Yugoslavia. For the Japanese, their negativity is surely the consequence of the bombings of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. Elsewhere, these two bombings, as well as other attacks on German cities, may go some way to explaining the negative opinion towards American politics expressed by the Turks (57%), Greeks (52%), Croats (49%), Spanish (46%), Austrians (46%), Latvians (44%), Germans, British, Indians and Swiss (43%). Other, more recent events, almost certainly play their part too. The negative perception of the military intervention in Iraq in 2003, for example, could partly explain the responses of the young people in Spain and Turkey.

Question:

« In your view, during the Second World War between 1939 and 1945, was the political system of the United Kingdom entirely respectful of human dignity and freedom, somewhat respectful of human dignity and freedom, not very respectful of human dignity and freedom, or not at all respectful of human dignity and freedom? »

By and large, the same reasons can be used to explain why the proportion of those surveyed who consider the British political system not to have respected freedom and human dignity between 1939 and 1945 can reach 62% in Japan, 61% in Turkey, 49% in Serbia, 45% in Greece and India, and 38% in Croatia and Spain. The tight sense of military collaboration

between American and British forces perhaps binds the two countries together in a negative sense, as far as public opinion is concerned. In the case of the Indians (45%), the high incidence of negativity towards the British political regime may well also have its roots in the crisis of decolonisation.

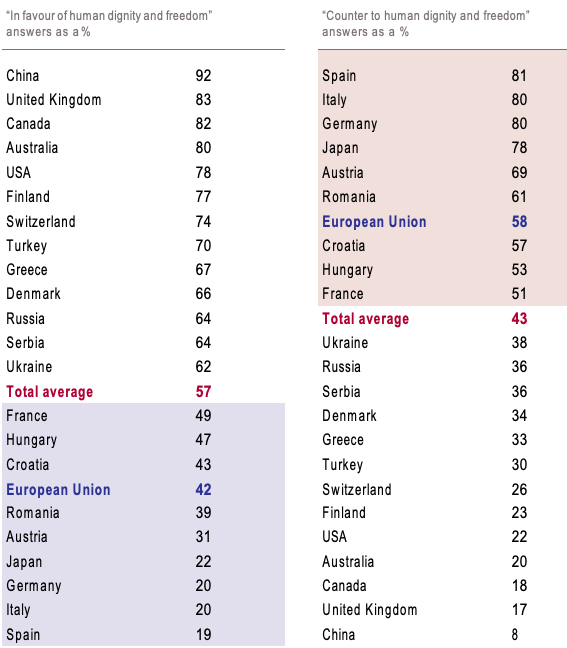

1939-45 : Did my country act in the interest of human dignity and freedom ?

Question:

« In your view, during the Second World War, did the government of your country act in favour of or counter to the interests of human dignity and freedom? »

This question is difficult since it asks the new generations to make a political and moral judgement on the role of their country and behaviour of their people during the Second World War.

Does it bear underlining that an overwhelming majority of Germans offer an appropriately negative evaluation on the role of their country’s government during the Second World War? Or, on the other hand, is it shocking to read that a fifth of young Germans feel that the Nazi government acted in the interests of human dignity and freedom? And what to say of the young Austrian respondents, fully one third of whom share the latter viewpoint? We may question how much the Hungarians and Croatians know about their national history, if we consider the amount of them who feel that their governments acted in the interests of human dignity and freedom during this period. If not, then it certainly needs to be asked what definitions of these values could have led to such a judgement.

The tables below show two different ways of illustrating the same results; nevertheless, it struck us as being of interest to present the data using this dualperspective.

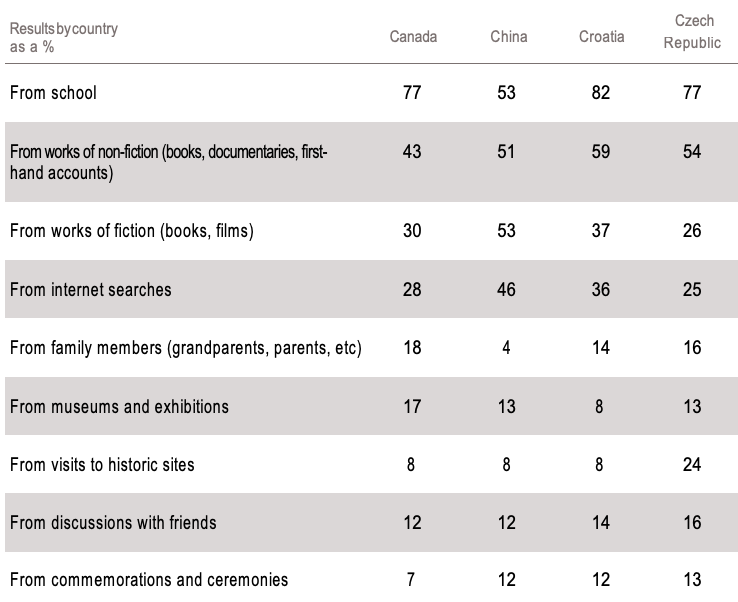

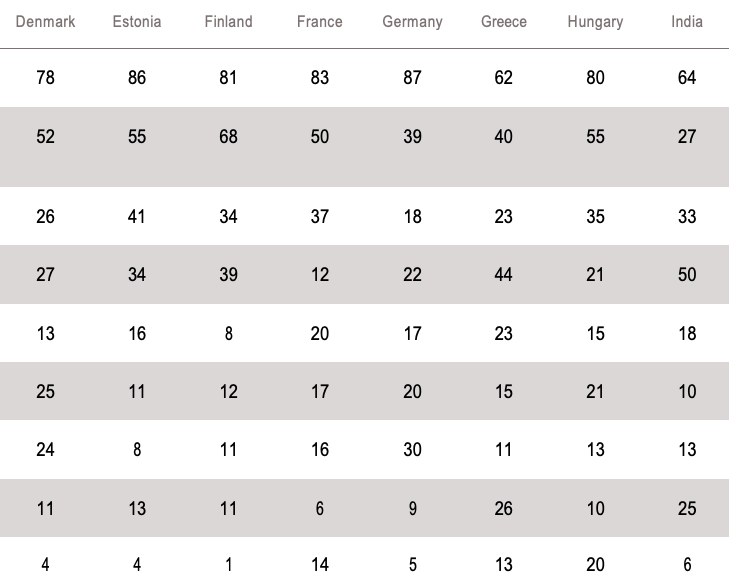

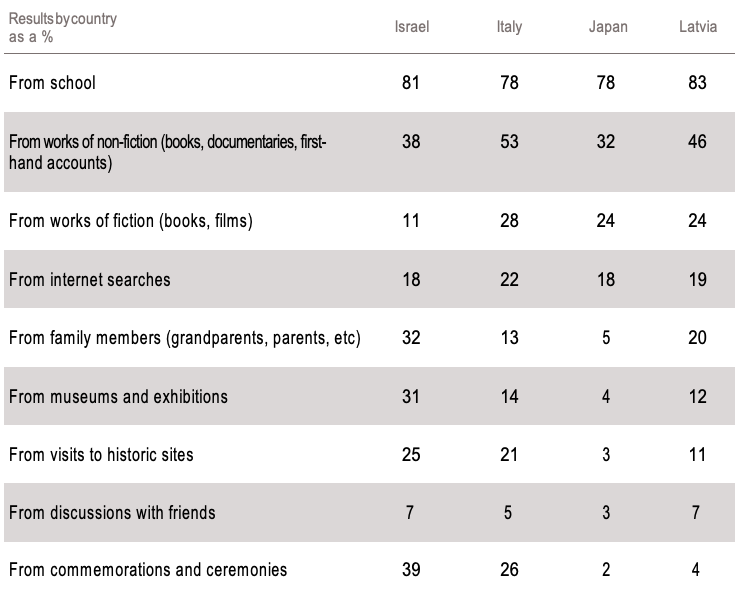

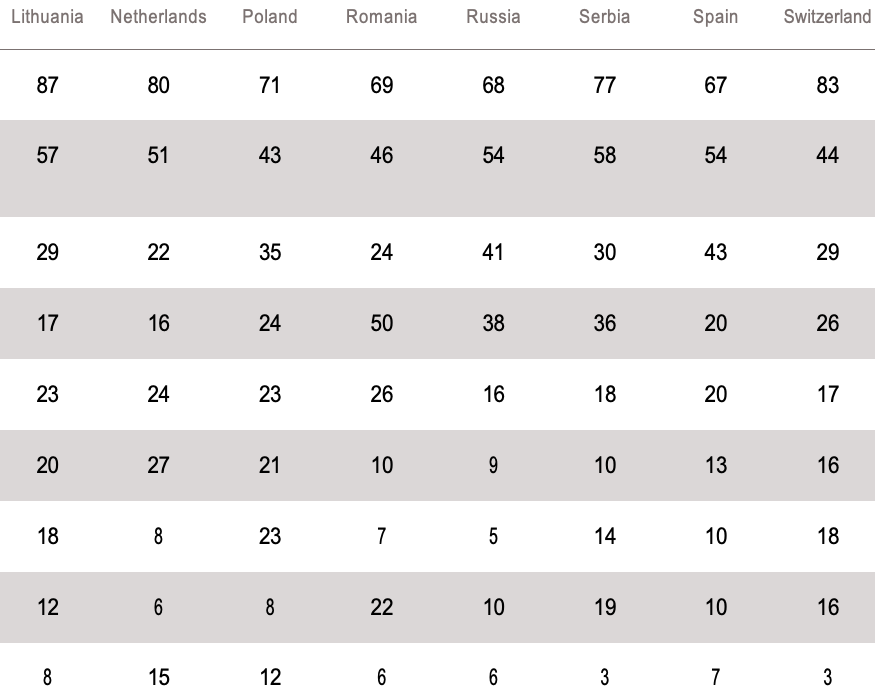

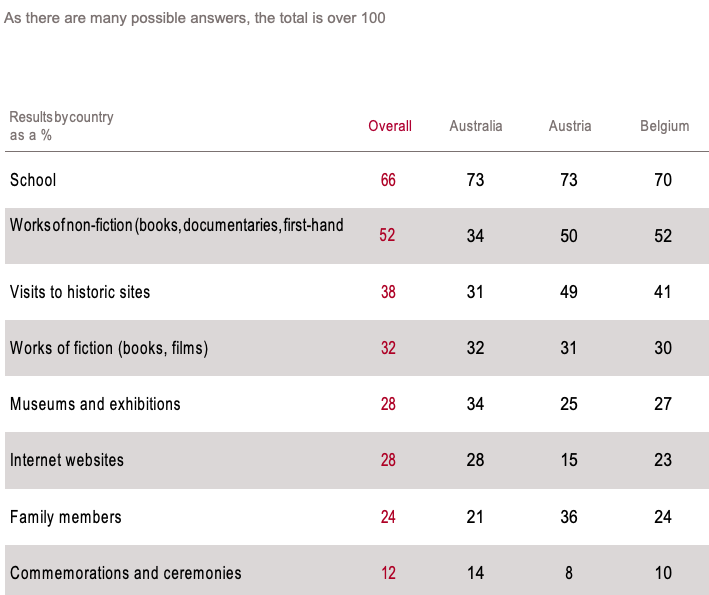

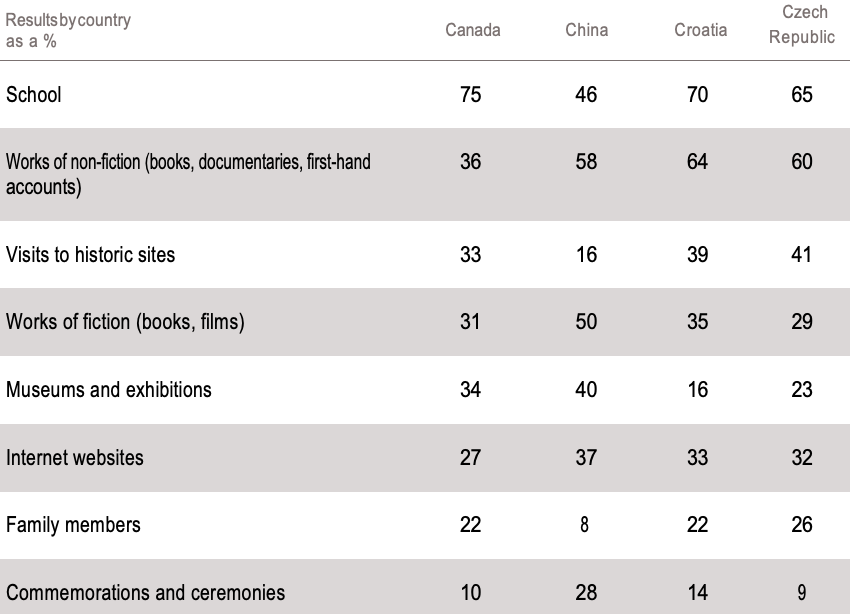

How we know about history : a triumph for schooling

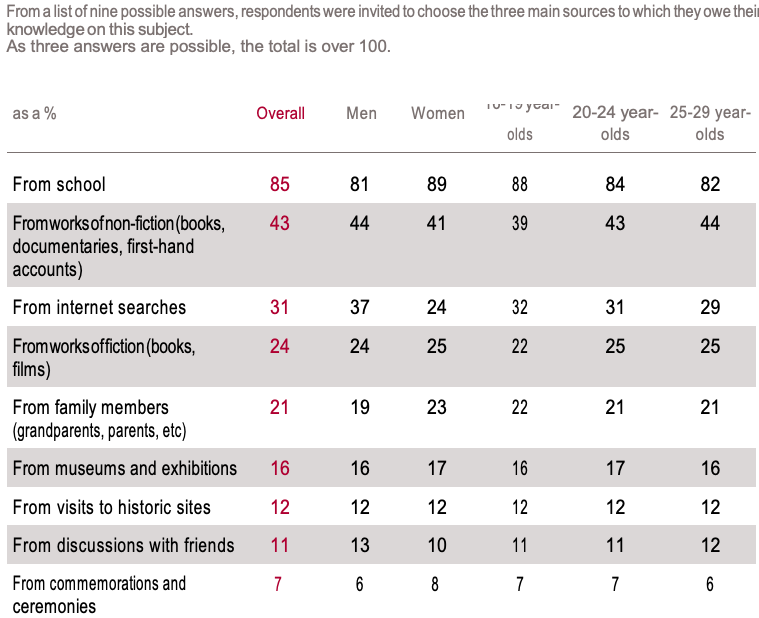

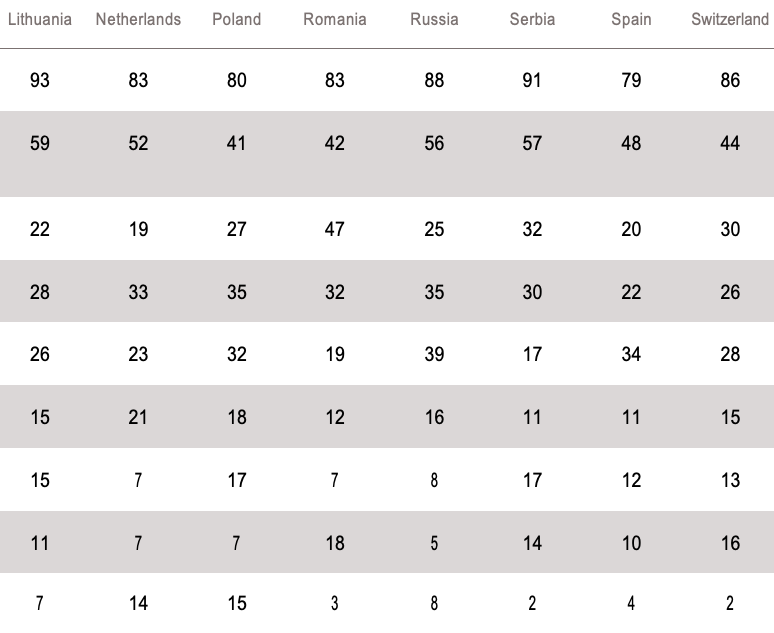

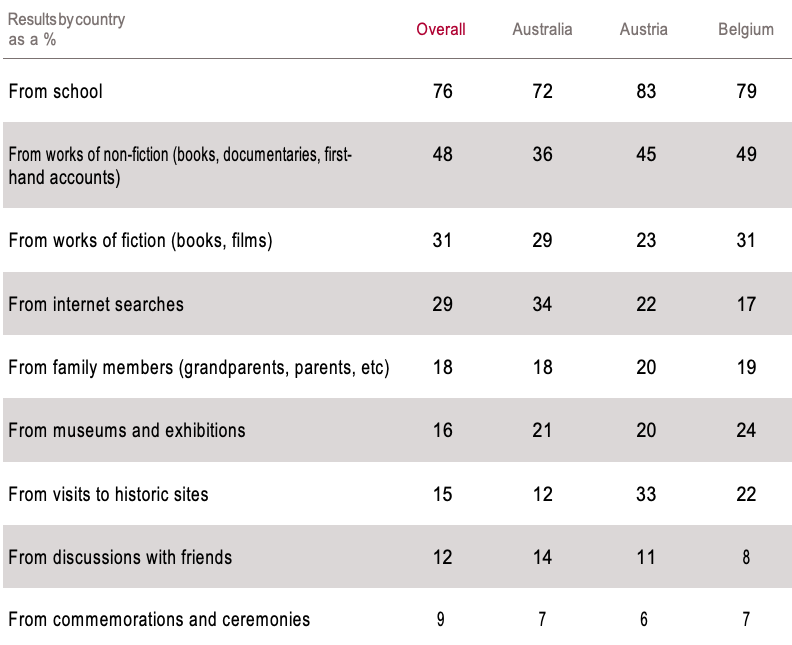

Knowledge of the first World War

Question:

« How did you acquire your knowledge of the First World War?

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

School (85%), works of non-fiction (43%) and the internet (31%) are the three main sources through which 16-29 year-olds claim to have acquired their knowledge on the First World War. The answers provide evidence of the central role played by schooling. This result is both obvious, yet at the same time challenging: obvious, because school thereby appears to fulfil the teaching role with which it is entrusted; challenging, because our dependence on schooling to feed our collective memories on this subject is therefore immense.

While 85% of those surveyed cite school as being one of the three main sources of their knowledge of the First World War, it can also be observed that the proportion is even higher among those who were most recently in contact with school. As such, 16-19 year-olds are those who most frequently single out the majorrole played by school (88%).

The internet, which features among the top three sources of knowledge overall, was chosen less often by the older respondents, which suggests that the internet is playing a growing role in the construction of the collective memory of the future. It is also notable that men (37%) more regularly consider the internet to be one of their three main sources of information than women (24%). On the other side of the coin, women (23%) more frequently cite the role of family members than men (19%). The central role of schooling is never challenged, and it is chosen as the main source of knowledge on the First World War in each of the 31 countries surveyed. The other results do vary from country to country, as shown in the data for the following countries.

Source :

The results for all the countries are available at www.fondationshoah.org or www.fondapol.org.

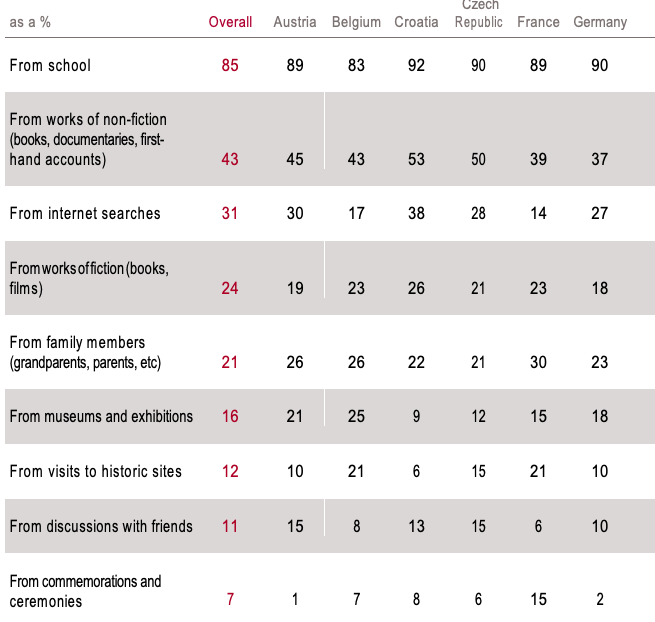

Knowledge of the second World War

Question:

« How did you acquire your knowledge of the Second World War? »

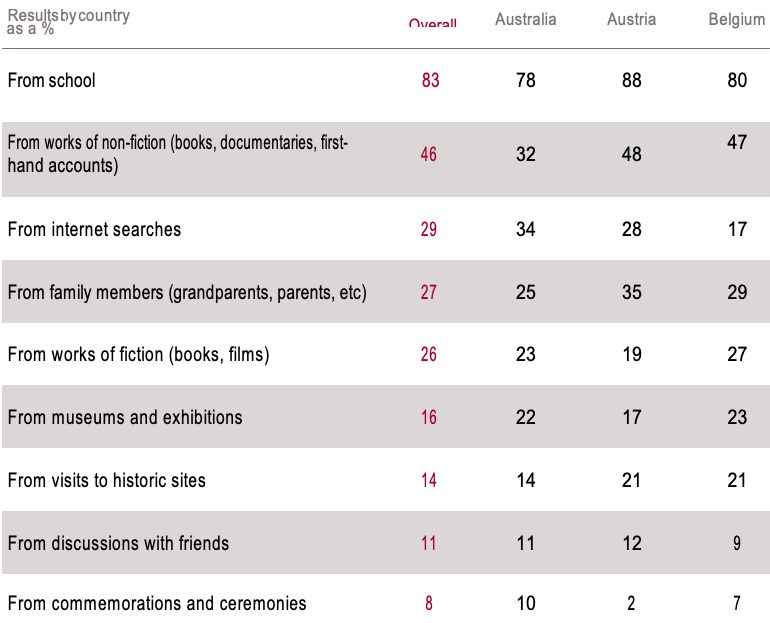

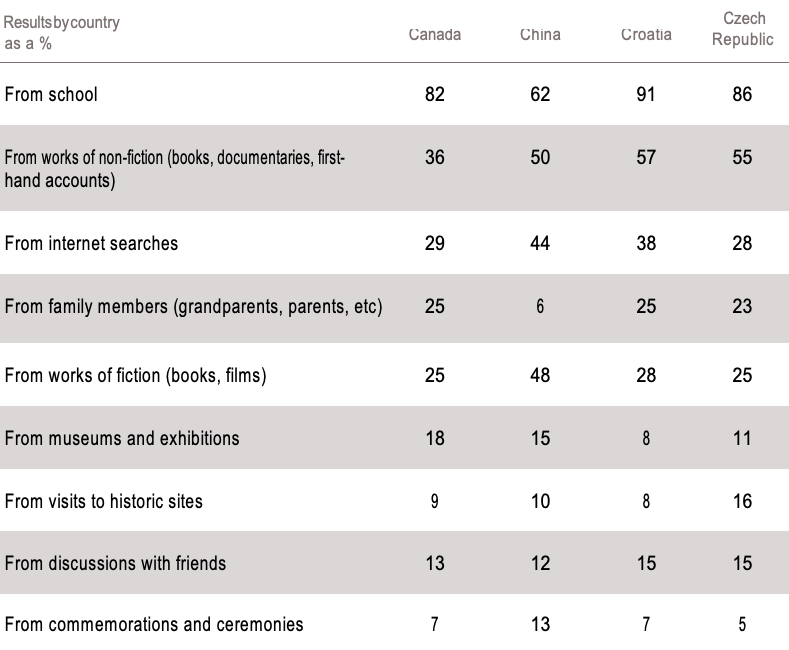

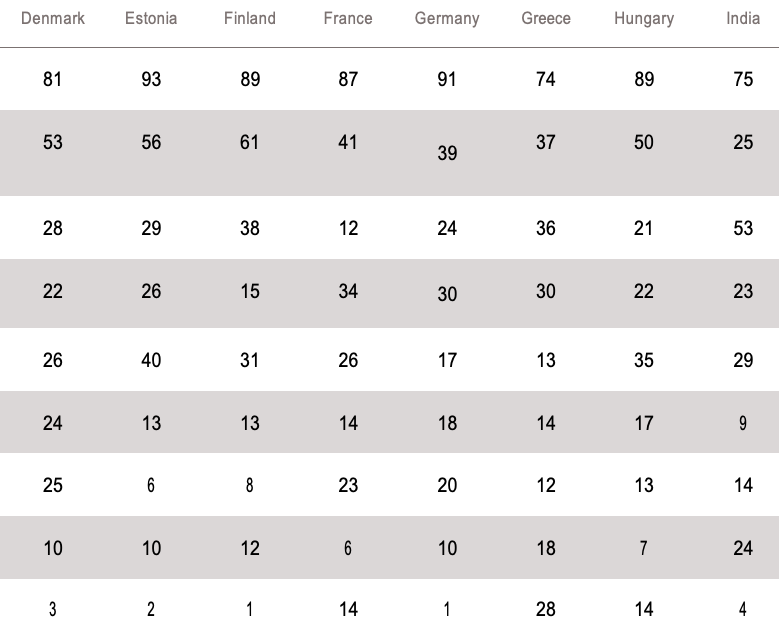

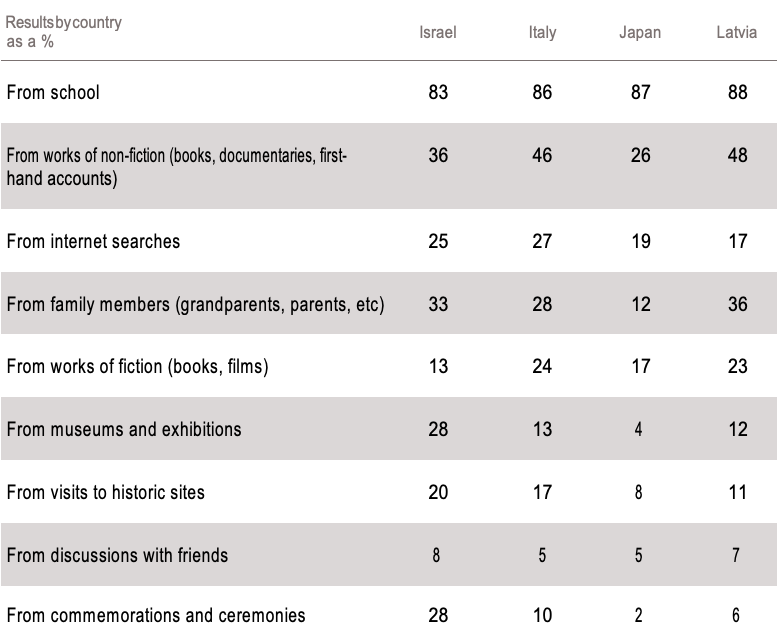

The choice of the top three sources through which the new generations feel they owe their knowledge of history does not vary between the First and Second World War. School (83%), fictional works (46%) and internet research (29%) once more come out on top. The exact proportions of all responses registered by each of them are also very close.

As far as the numbers of those who chose school is concerned, the gap between the male respondents (79%) and the female respondents (88%) is significant,

even if the established order is never shaken up. Another notable gap appears with respect to the use of non-fictional works, more often cited

by men (48%) than by women (43%). A gap of the same size also exists regarding the importance of family members, this time in favour of the young women (29%). The greatest difference is to be found in relation to the prominence of internet research, more often cited by male respondents (35%) than by female respondents (22%).

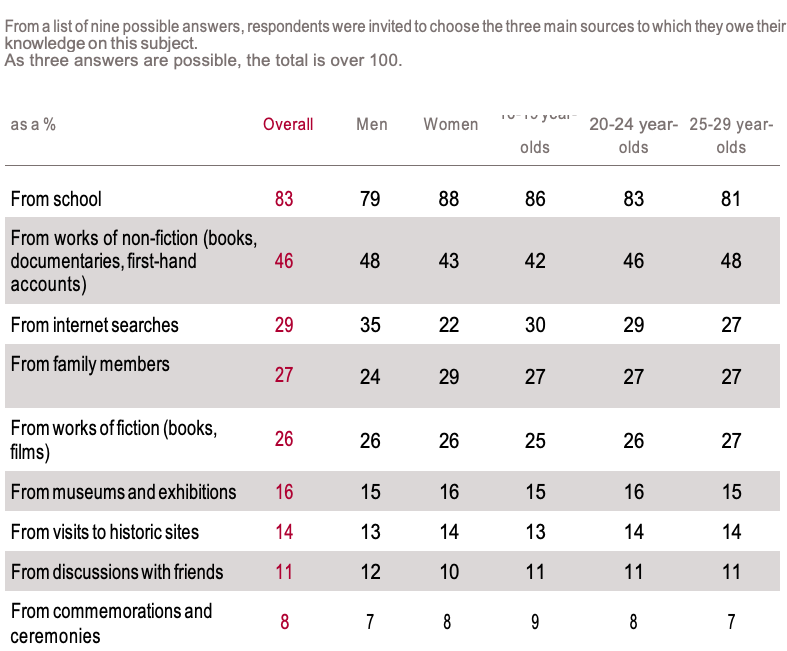

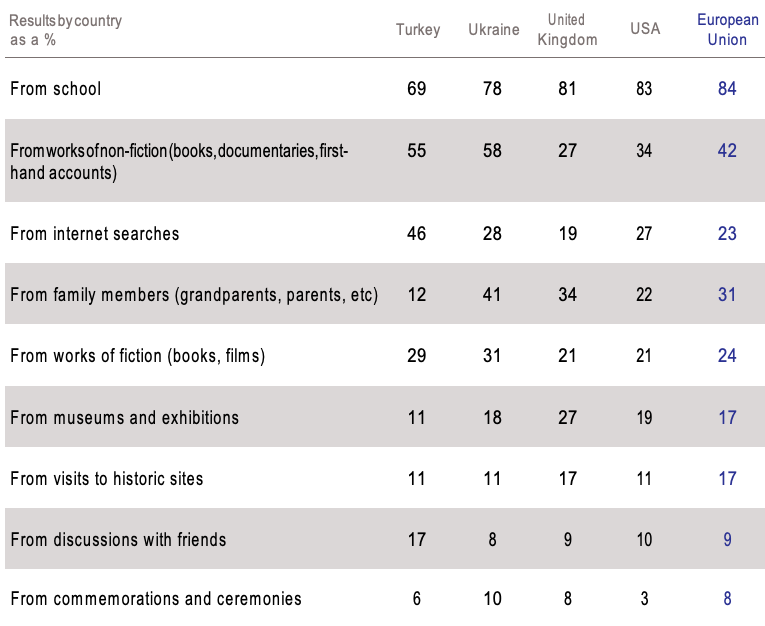

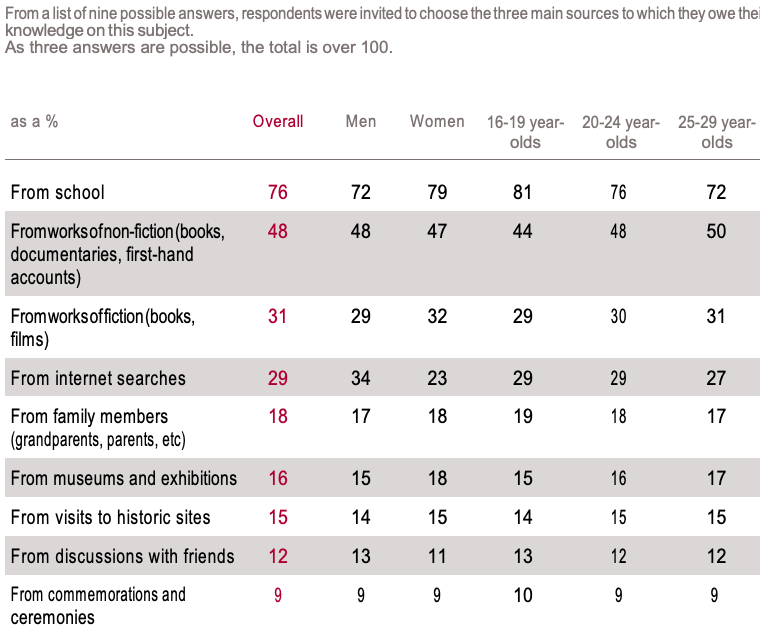

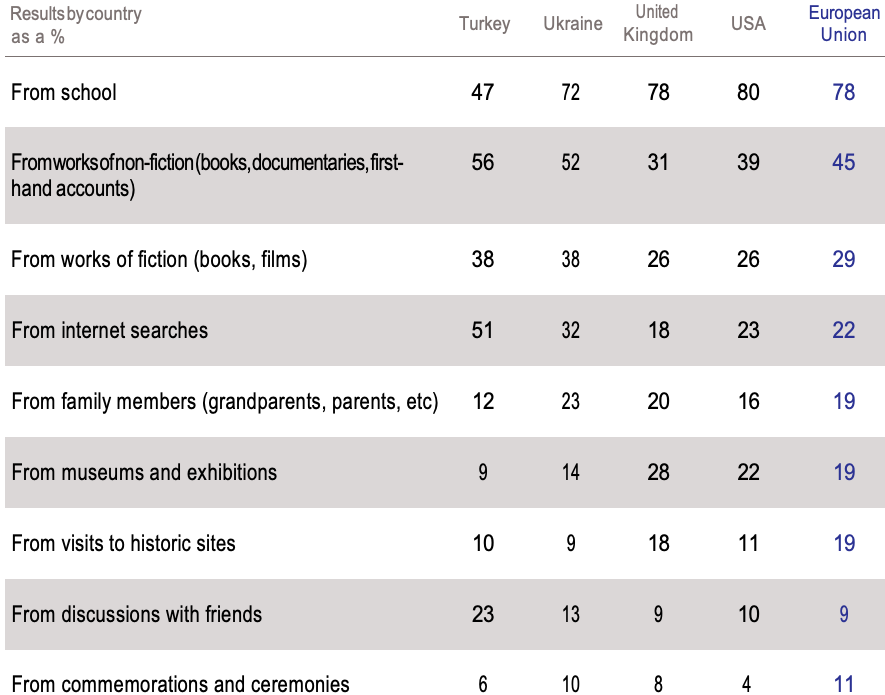

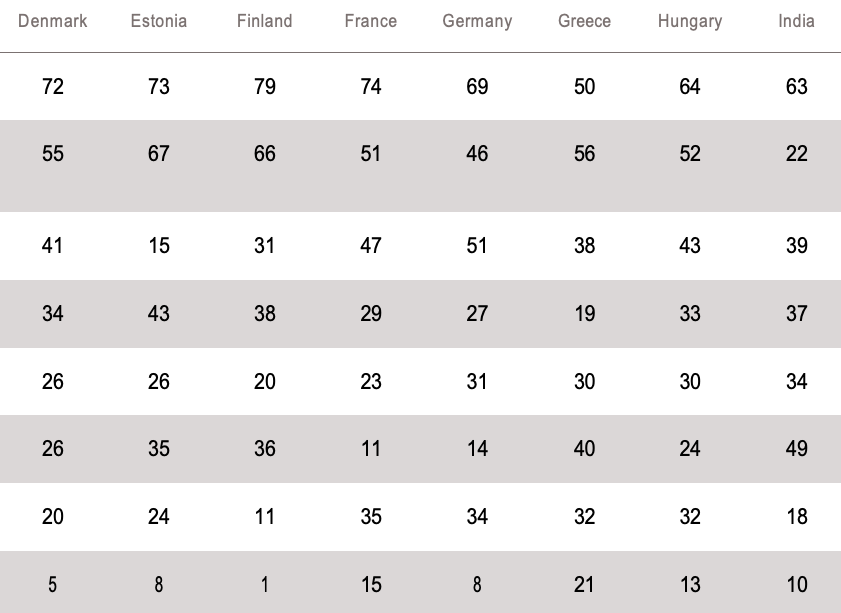

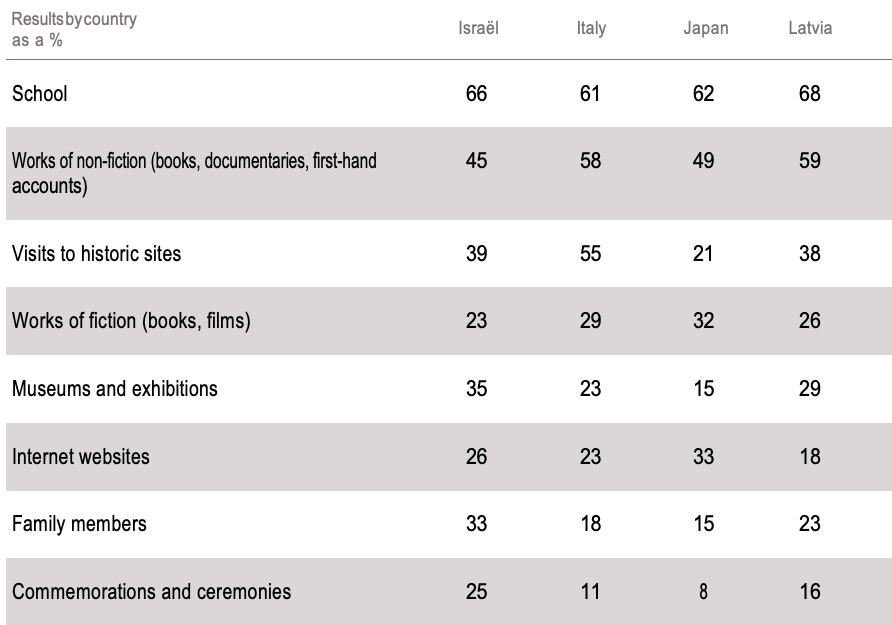

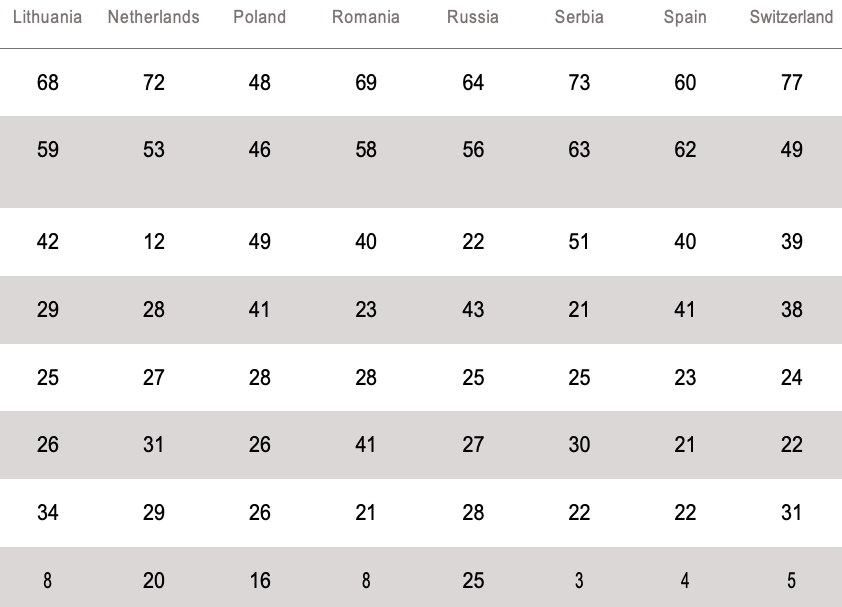

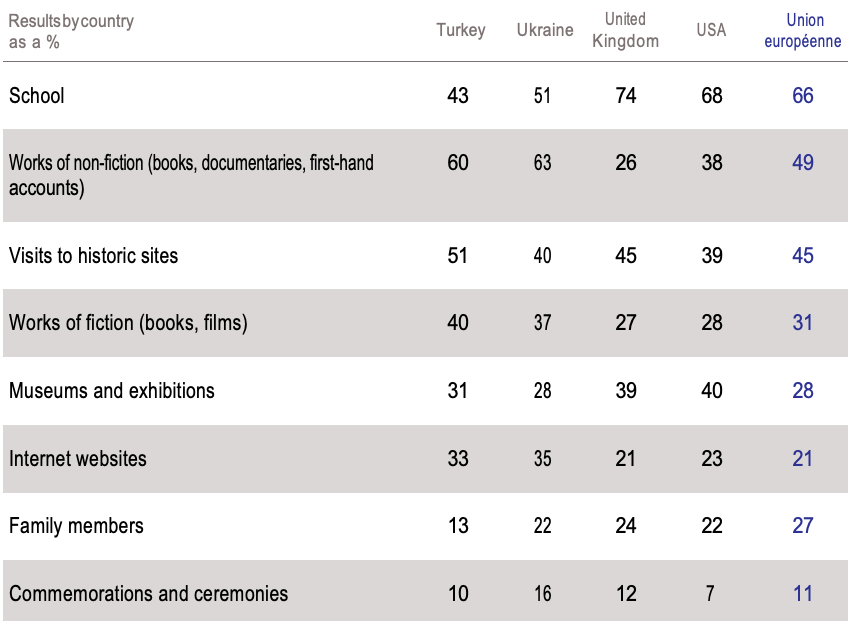

Knowledge of the Holocaust

Question:

« How did you acquire your knowledge of the Holocaust? »

Once again, taking those surveyed as a whole, the results show that knowledge about the extermination of the Jews during the Second World War comes principally from schooling (76%). While non-fiction works are again cited in second position by half of the young people surveyed (48%), third place this

time goes to works of fiction (31%) ahead of internet research (29%). The order at the top is therefore different than that of the World Wars. Internet research is again, and invariably, cited more often by the men (34%) than by the women (23%) surveyed.

The differences in the responses provide evidence of a unique culture and history in each country. As such, schooling is ranked as the single main source of knowledge about the extermination of the Jews during the Second World War by all but one of the countries, Turkey, where young people instead cite non-fiction works (56%) and internet research (51%), with school (47%) only arriving in third place.

The importance of family members, cited by 18% of the respondents, is most frequently underlined by the Greeks, Poles, Lithuanians and Ukrainians (23%), the Dutch (24%), the Romanians (26%) and the Israelis (32%).

Museums and exhibitions, cited by 16% overall, are cited most often as one of the main sources of knowledge about the extermination of the Jews by respondents in Australia, Hungary and Poland (21%), the USA (22%), Belgium (24%), Denmark (25%), the Netherlands (27%), the United Kingdom (28%) and Israel (31%).

Visits to historical sites (15% overall), receive a higher than average mention in Italy (21%), Belgium (22%), Poland (23%), the Czech Republic and Denmark (24%), Israel (25%), Germany (30%) and Austria (33%). Commemorations and ceremonies, which register an overall score of 9%, are most often cited by the Greeks and Czechs (13%), the French (14%), the Dutch (15%), the Hungarians (20%), the Italians (26%) and the Israelis (39%).

Question:

« In your opinion, what, in general, are the most effective ways of making young people aware of history? »

This question is very different: it is no longer about identifying the sources through which one has acquired historical knowledge, but instead singling out those whose use one supports for future generations. In this way, the answers given by the 16-29 year-olds also serve as a sort of feedback on their own experiences, which may either be ongoing or recent, depending on each individual case

By and large, school continues to dominate (66%), but its leading role is contested by works of non-fiction (52%). In some cases, school is relegated to second place (as in Greece, Spain, Turkey and Ukraine) or even third place (in China).

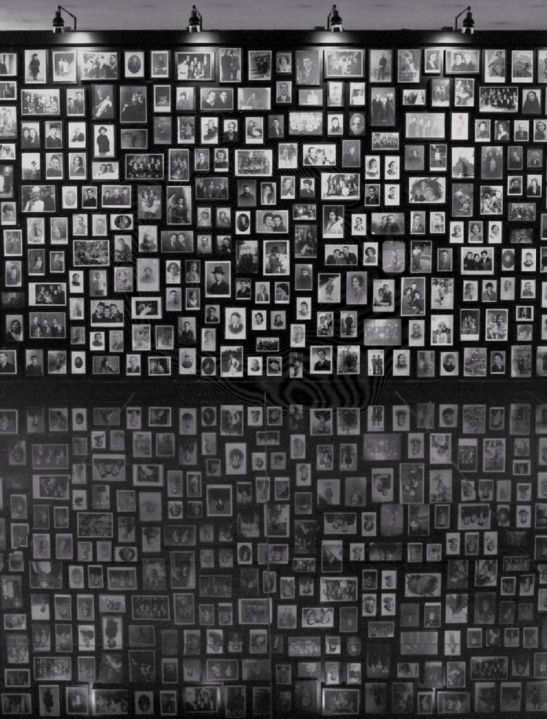

Places to strengthen and pass on memories

Question:

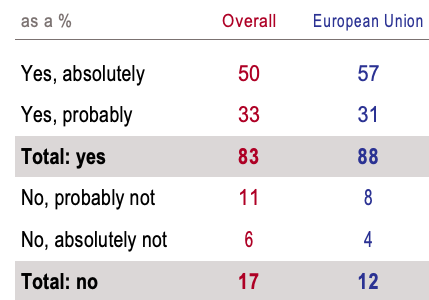

« In your opinion, should what remains of the concentration camps be preserved for the public to visit? »

A positive view towards the preservation of what remains of the extermination camps is expressed by a majority of the respondents (83%). This point of view is almost unanimously supported among the Italians (93%), the Germans, Polish and Czechs (92%), the Austrians (91%), the Belgians (89%), the Danes, French and Dutch (88%). It will be noted that the Chinese also very readily share this opinion (89%).

While the Israelis are almost all behind the idea that such memorials are necessary (98%), the Russians are among those who least understand or accept them (67%), along with the Ukrainians (68%).

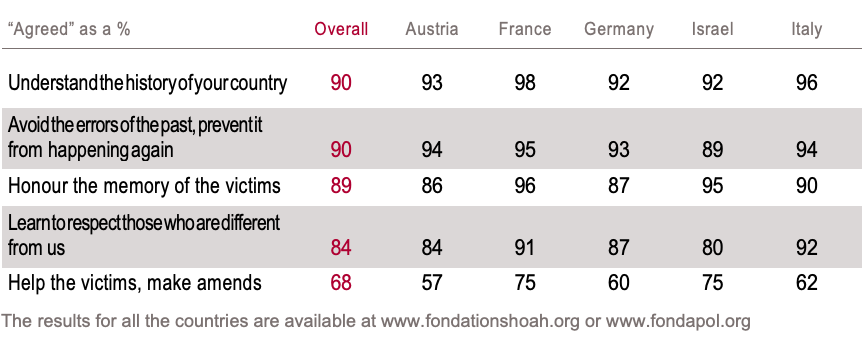

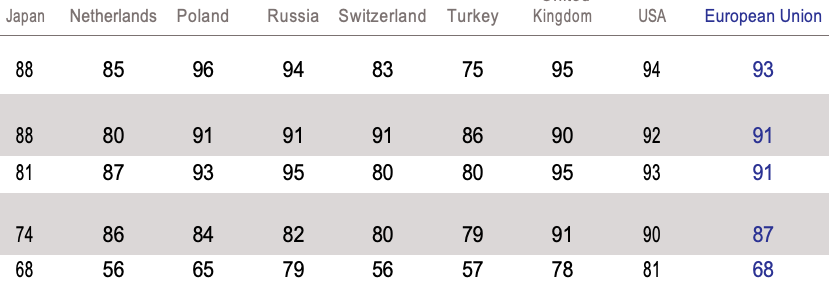

Why learn about history ?

Question:

« In your opinion, knowing the history of the Second World War makes it possible to … »

The results demonstrate a unanimous agreement among the new generations as to the reasons why we should learn about the historic crises of the 20th century.

It will be noted that history’s function in helping victims is, in comparison with the other options here, the one that receives the least attention from the respondents. The young people surveyed who are, proportionally, the least convinced by this facet of historical knowledge are the Italians (62%), the

Danes and Lithuanians (61%), the Germans and Hungarians (60%), the Belgians (58%), the Austrians, Ukrainians and Turks (57%), the Dutch and Swiss (56%), the Finnish and Latvians (55%).

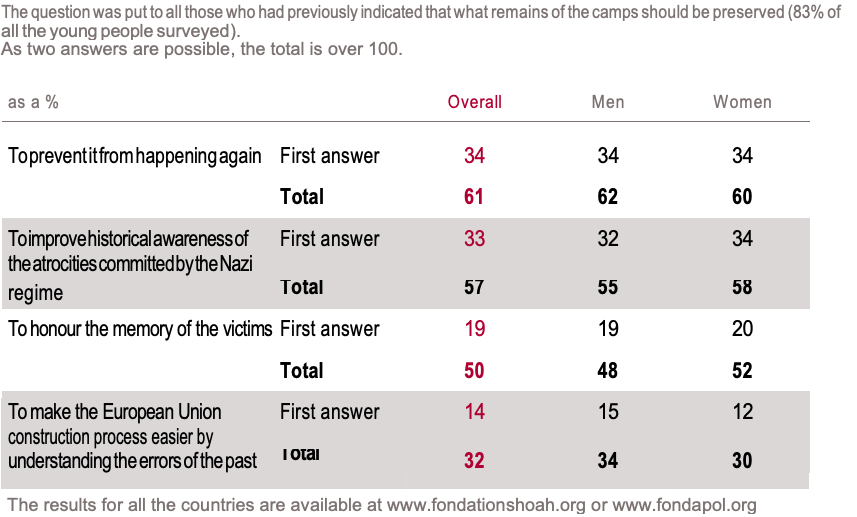

Why visit the extermination camps ?

Question:

« What is the main reason for the preservation of the concentration camps? »

|

The majority of those surveyed (61%) consider that what remains of the camps should be preserved “to prevent it from happening again”. The young people who most frequently offer this opinion are the Japanese (85%), the Ukrainians and Israelis (70%), the Italians (69%) the Germans (68%), the Austrians, Finnish, Serbs and Turks (67%).

The option “to improve historical awareness of the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime”, chosen overall by 57% of respondents, was most frequently cited by the Israelis (80%), the Greeks (72%), the Australians (70%), the Canadians and British (68%), the Americans and Russians (66%), the Danes and Lithuanians (62%).

Half of the respondents (50%) consider that the preservation of these places should aim “to honour

the memory of the victims”. Such reasoning is most frequently put forward by respondents in the Netherlands (70%), the United Kingdom (64%),

Australia (63%), the USA (62%), Canada (61%), Croatia and Serbia (59%), Belgium, France and Ukraine (58%), and Poland (57%).

Overall, 32% of the respondents chose the option “to make the European Union construction process easier by understanding the errors of the past”. This is almost exactly the same proportion as among the Europeans themselves (31%), and this response was most frequently cited by young people in Japan and Denmark (51%), Estonia and Romania (50%), Spain (48%), Finland (46%), Italy and the Netherlands (44%), the Czech Republic (39%), Turkey (38%) and Lithuania (37%). The Germans (29%) and the French (23%) showed less interest in this option.

A different follow-up question was put to those who had previously indicated that it was not necessary to preserve what remains of the camps (17% of the young people surveyed).

Question:

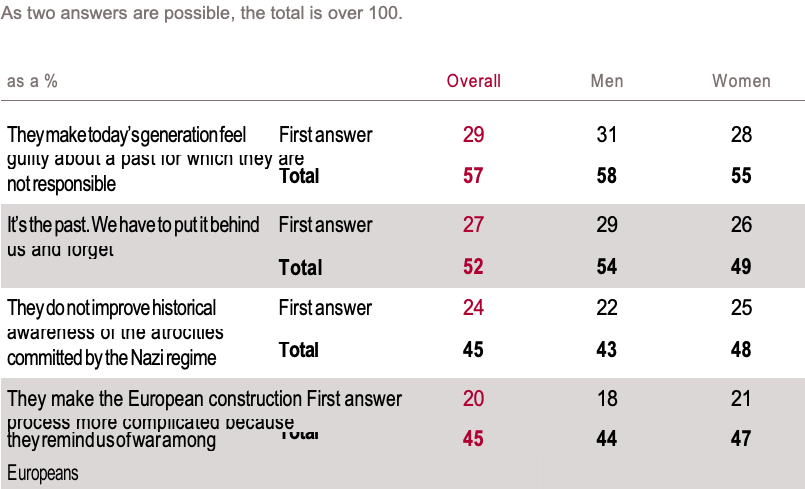

« What is the main reason why the concentration camps should not be preserved? ».

“They make today’s generation feel guilty about a past for which they are not responsibe” is the answer cited by fully 57% of those who do not believe that what remains of the camps should be preserved. This option was most frequently chosen by the Poles (74%), the Chinese (73%), the French (67%), the Austrians (65%), the Israelis (65%, but from a low number of respondents), the Germans, the Turks and also the Croats (63%).

Finally, it will be noted that the idea that preserving the camps may “make the European construction process more complicated because they remind us of war among Europeans” is no more widely cited in Europe (42%) than it is among the respondents overall (45%).

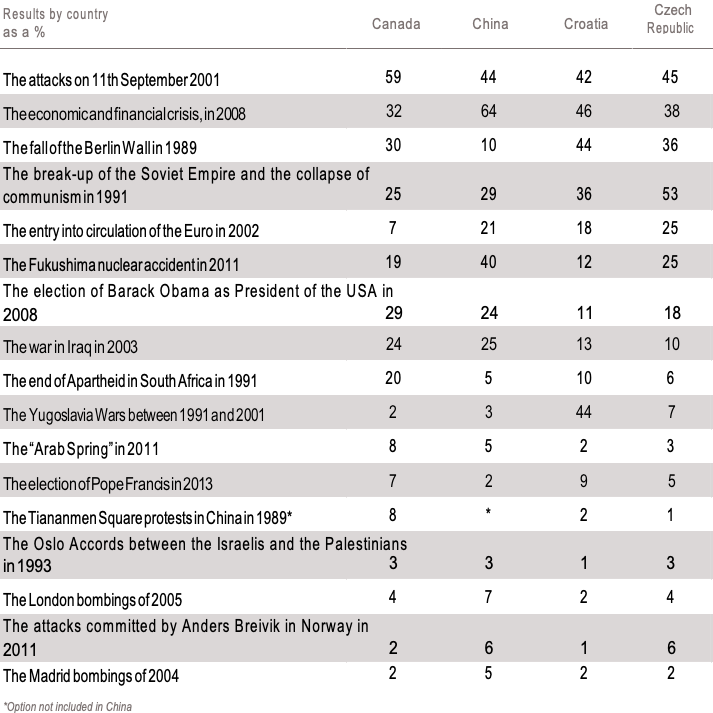

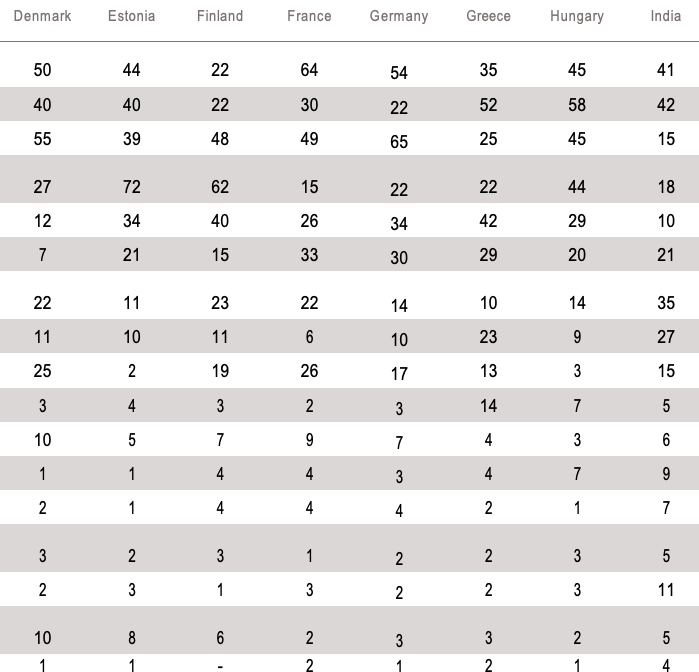

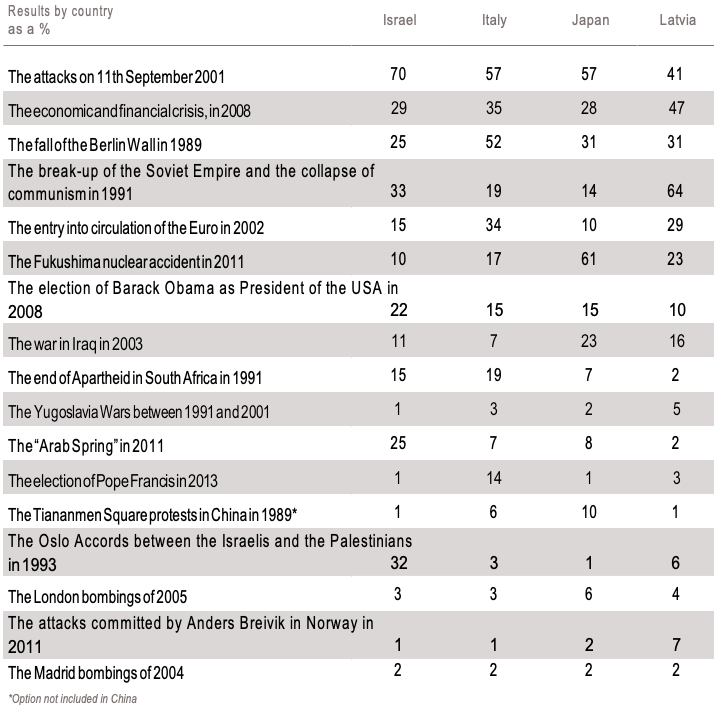

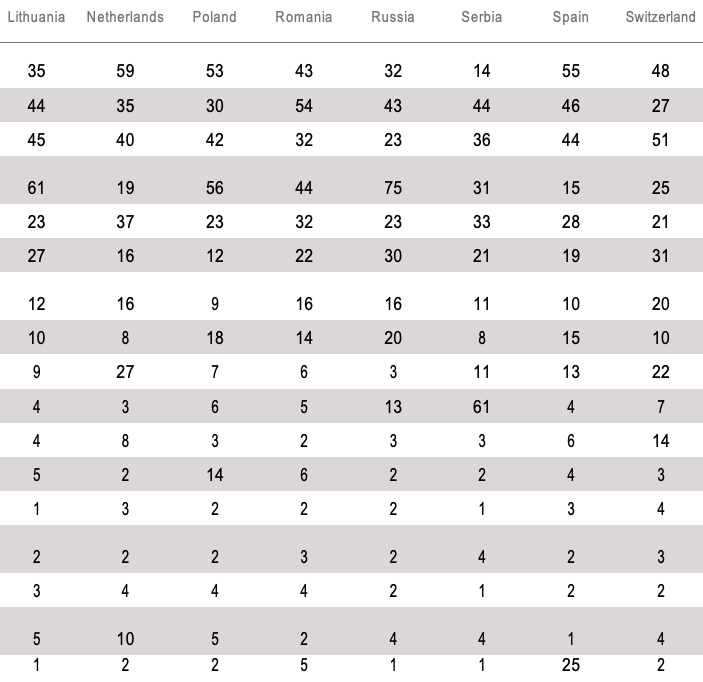

What memorable events have taken place since 1989 ?

Question:

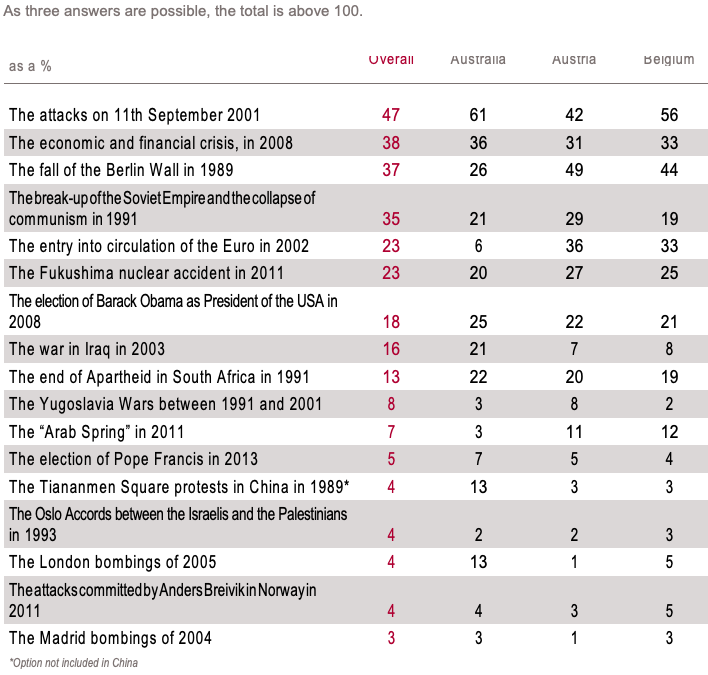

« Here is a series of events that have happened since 1989. Which are the three most important ones, in your opinion? »

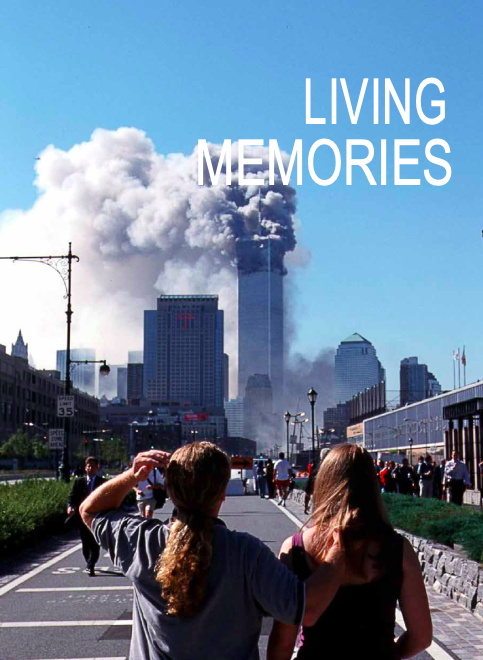

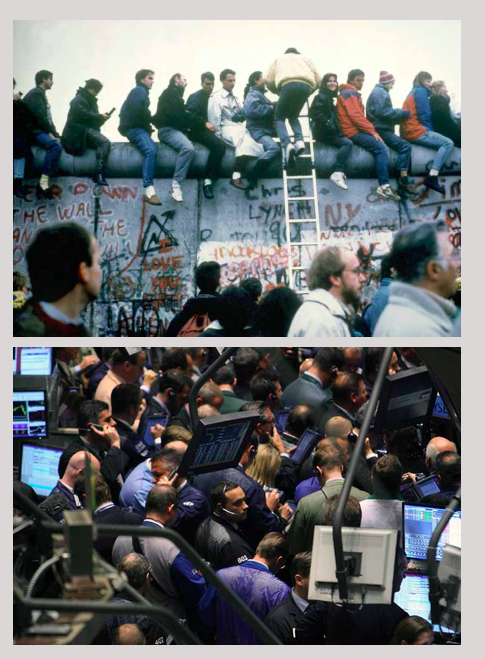

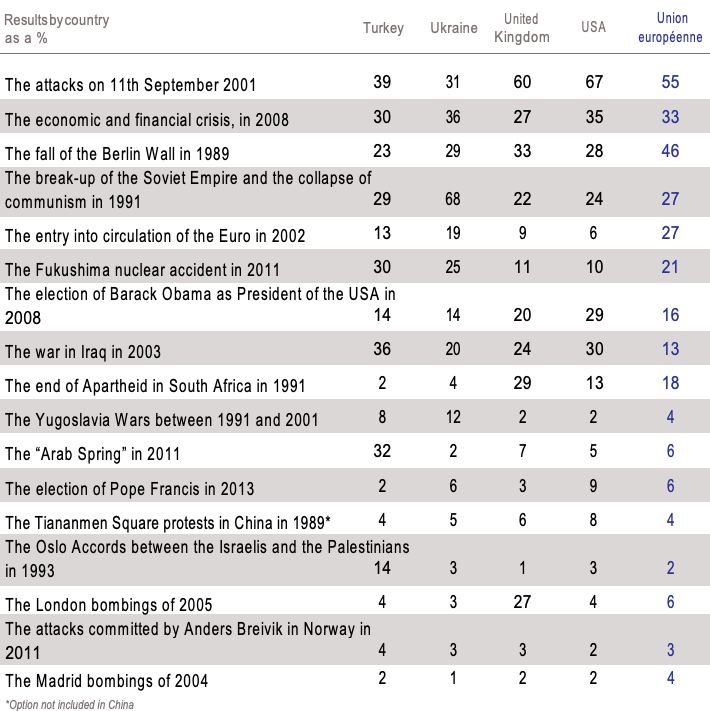

From the options put forward, half of the young people surveyed (47%) cite the 9/11 attacks in 2001 as one of the three most significant events to have taken place since 1989. The economic and financial crisis in 2008 (38%), the fall of the Berlin Wall (37%) and the collapse of the USSR (35%) come next, in a cluster of answers that were each chosen by around a third of all respondents. Nearly a quarter of young people cite the launch of the Euro (23%) and the Fukushima nuclear accident (23%).

The events of 11th September 2001 represent the option most frequently chosen in half of the 31 countries surveyed, an option featuring more often among the choices of North Americans (67%) than of Europeans (55%). This option was chosen by nearly three-quarters of the Israelis, two-thirds of the French, and by a large majority of the Australian, British, Canadian and Dutch respondents.

The second most cited event overall, the economic and financial crisis in 2008, came out on top among the Chinese (64%), the Hungarians (58%), the Romanians (54%), the Greeks (52%), the Croats (46%) and the Indians (42%). It was chosen less often by the youngest respondents, who have perhaps been less exposed to its effects as the majority are still to leave school: a third of 16-19 year-olds (33%) chose this option, as opposed to 40% of the 25-29 year-olds.

Nearly four out of ten young people identify the fall of the Berlin Wall as being one of the three most important events since 1989 (37%). For the Germans themselves (65%), the fall of the Berlin Wall has been the single most important event over these years, and the same goes for the young people in certain neighbouring countries, notably the Danes (55%), the Swiss (51%) and the Austrians (49%). Still in the western part of the Old Continent, half of the Italians (52%) and French (49%) cite this event.

The fall of the Berlin Wall is also cited in first place by the Lithuanians (45%) and in second place by the Finns (48%), both countries that border the former USSR and that lived under the influence of the Soviets for many years. By surveying those aged from 16 to 29 years, we are addressing members of the population who were born between 1985 and 1998. The first major historic event of relevance to these generations is, objectively speaking, the collapse of communism in 1989. Alive when the Berlin wall came down, but probably too young to take an interest at the time, the new generations do not now attach the same importance as their elders to a nevertheless major event that is considered as the starting point for a new era. When asked, they are more likely to cite the attacks of 11th September 2011, a tragic event and one that is fresher in their collective memory. The new generations are the first since 1917 not to live in the shadow of nearby communist regimes, which now barely exist if we concede that China has henceforth adopted a post-communist system that, although retaining a nationalist and authoritarian dimension, has now adopted capitalist production methods.

Further east, young people still largely point towards the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of communism in 1991 as being the most important events: this is the case in Russia, (75%), Estonia (72%), Ukraine (68%), Latvia (64%), Finland (62%), Lithuania (61%), Poland (56%) and theCzech Republic (53%).

More than a quarter of young Europeans (27%) underline the importance of the entry into circulation of the Euro. Logically enough, this proportion is even higher among those who are directly affected by the single currency: the Greeks (42%), the Finns (40%), the Dutch (37%), the Austrians (36%), the Germans and Italians (34%), the Belgians (33%), the Spanish (28%) and a quarter of French respondents (26%). This event is also chosen by a third of Romanians (32%), and roughly the same proportion of Serbs (33%), the latter being official applicants to the European Union. On the other hand, the Euro is only identified by 23% of Lithuanians, who have just adopted this currency, whereas the Estonians (34%) and Latvians (29%) – who were already members of the Eurozone – more regularly cite the creation of the single European currency. Meanwhile, this event is mentioned less by young Danes (12%) and Britons (9%) who, although living outside the Eurozone, are still likely to take, or to have taken, holidays in the Southern European countries where the currency is in use.

The Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011 is judged to be one of the three most important events since 1989 by a quarter of all respondents (23%). Obviously, it is the Japanese who most frequently cite this event (61%), more frequently in fact than the 9/11 attacks (57%). The accident is also cited more regularly by the Chinese (40%), the French (33%), the Swiss (31%), as well as by the Germans, Turks and Russians (30%).

Nearly a third of Americans (29%) and Canadians (29%) understandably chose Barack Obama’s election as President of the USA in 2008, but they were joined in doing so, more surprisingly, by the Indians (35%).

The war in Iraq in 2003 is considered to be one of the main global events to have taken place since 1989 by only a third of Americans (30%), compared with 27% of Indians and 36% of Turks, the latter being a country that, of course, shares a border with Iraq.

The wars in the former Yugoslavia (1991-2001) are considered most memorable among the Serbs (61%) and the Croats (44%). Meanwhile, the signing of the Oslo Accords is cited by a third of Israelis (32%) and 14% of Turks.

The end of Apartheid in South Africa in 1991 is highlighted by 13% of young people, including 18% of young Europeans. This event is more regularly mentioned by those whose political sympathies lie to the left (21%), than to the right (11%) or in the centre (12%).

Certain events, which received huge media coverage, are only very rarely cited. This is the case of the “Arab Spring”, only chosen by 7% of those surveyed. Only the youth of Turkey (32%) and Israel (25%) attach a high level of significance to this event.

Although there is a decisive geographical factor at play here, the answers also demonstrate that the new generations live in an increasingly globalised world. Their memories are attached to the place that they live and the part of the world that they know, but not exclusively so.

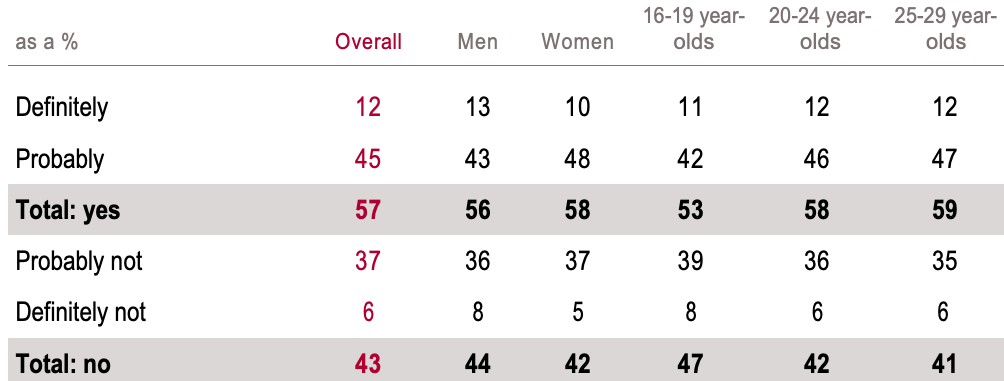

Question:

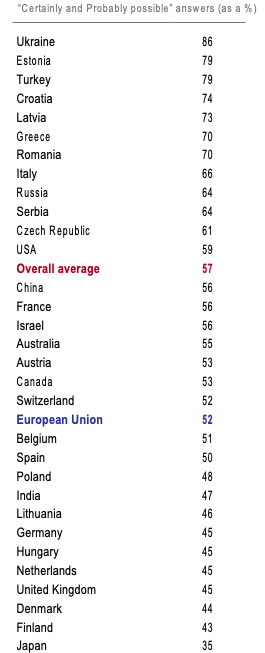

« Do you think a Third World War could happen in the next few years? »

Most of the young people surveyed (57%) believe that a third World War could take place: a majority of the respondents in 22 out the 31 countries surveyed consider it to be a real possibility. This opinion is expressed first and foremost in Ukraine, a country currently at war, and in Russia, a heavily militarised country presently involved in several conflicts, including one with Ukraine. The possibility of a new World War is also feared by the majority of young people in Estonia and Latvia, countries close to Ukraine and neighbours of Russia, whose populations include a significant minority of Russians. It will be noted that in Lithuania, a Baltic republic with only a slight Russian presence among its population, the percentage of people who share this fear is significantly lower.

The prospect of a new World War in the years to come is also widespread among the Romanians, the Czechs and the Italians; it is feared by three-quarters of Croats and by two-thirds of Serbs, who have only just emerged from a destructive conflict; this fear is also very prevalent among young Turks, from a country which borders Syria, and young Greeks.

It should lastly be noted that the idea that we risk experiencing a Third World War is more commonplace among those young people who feel threatened by globalisation (65%) than by those who consider it to be an opportunity (54%).

2011, 2012, 2015 : Three surveys of young people around the world

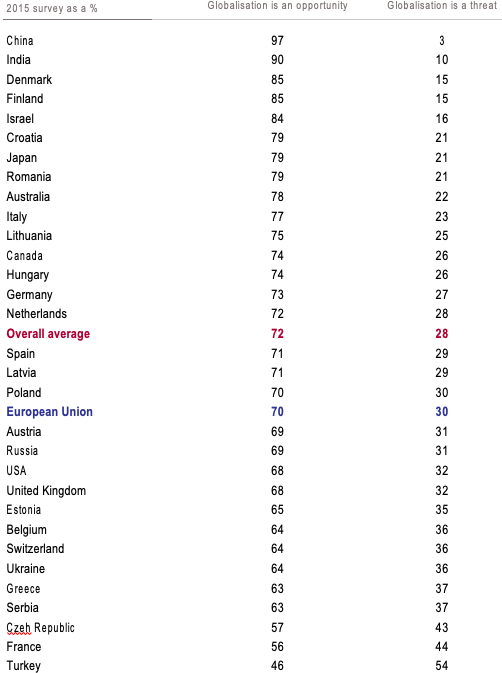

Question:

« Which of the following statements is the closest to your personal opinion: globalisation is an opportunity, or globalisation is a threat? »

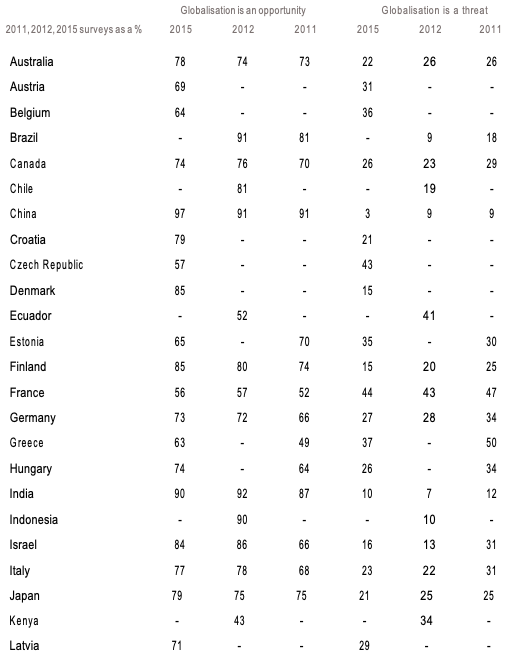

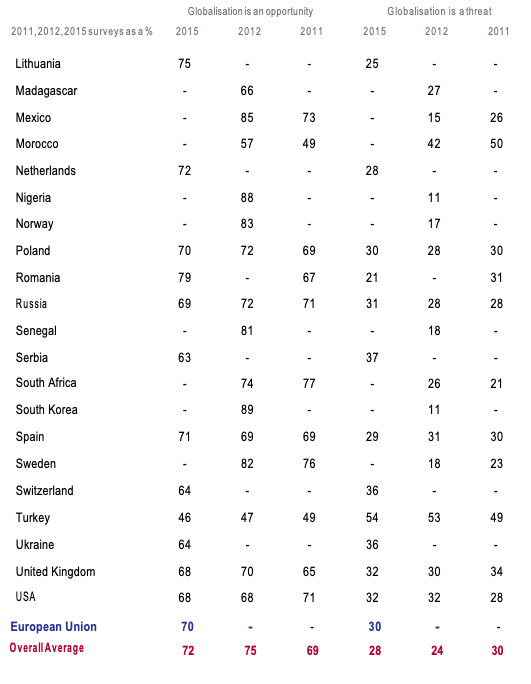

The first survey entitled 2011, The World’s Young People involved 32,714 young respondents in 25 countries and in 20 languages. The second survey, entitled Youth and Sustainable Development was carried out in 2012, in partnership with Nomadéis and the UN, involving 30.000 young respondents in 30 countries and in 21 languages.

Ever since the first international survey of young people carried out by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, in 2011, the same observation has been made: for the new generations, globalisation is overwhelmingly considered as an opportunity4. There are only very few countries where a majority of young people view it as a threat. In 2015, this is the case in only one country, Turkey, where a sense of fear seems to become stronger as the years go by. It is a result that clearly sets the young people of Turkey aside from the youth of other emerging countries, who embrace globalisation with enthusiasm. China and India are the most obvious examples, for the third time.

Having said this, since 2011, young people in developed countries have also started to globalisation in an increasingly favourable light. As such, between 2011 and 2015, the level of negativity towards it has diminished in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Japan and even in Germany. The clearest progression has been made in Israel, where globalisation is perceived as an opportunity by 84% of the young people, as opposed to 66% in 2011. This movement is neither general nor irreversible, as shown in the USA where levels of positivity towards globalisation among young people have dropped by 3 points between 2011 and 2015.

The overall results in Europe show that, in 2015, nearly three-quarters of young people (70%) have a positive perception of globalisation. With only a few exceptions, this sense of positivity is noticeably growing, impressively so in Greece, as it is in Hungary or Romania.

In Northern European countries, like Denmark and Finland, the positive view of globalisation shown by young people reaches comparable levels to those recorded in the emerging countries. However, in other cases, the young people of countries that are in many ways similar – such as the Baltic States – are capable of expressing diverging opinions regarding globalisation. In 2015, the gap between the level of positivity towards globalisation registered in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia is as high as 10 points.

Since our first survey in 2011, France has belonged to the group of countries whose young people most fear globalisation. Second-to-last in the overall standings for this question, the young people of France are dead last in the list of European countries surveyed. Yet we can nevertheless take heart from the fact that the majority of the French people surveyed do view globalisation as an opportunity.

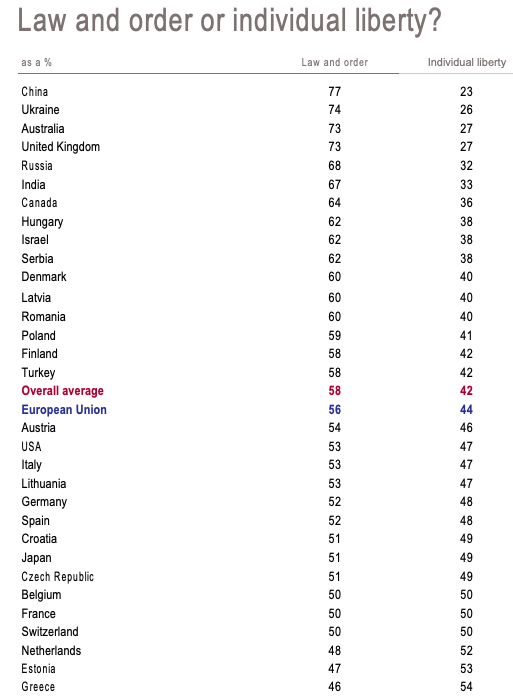

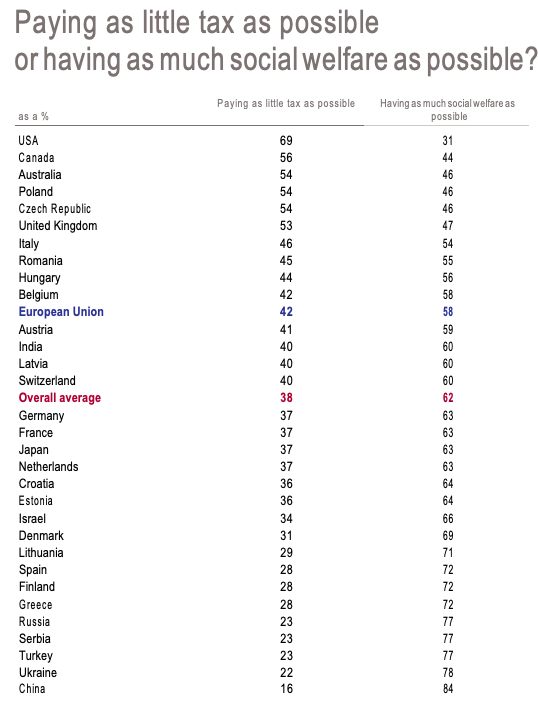

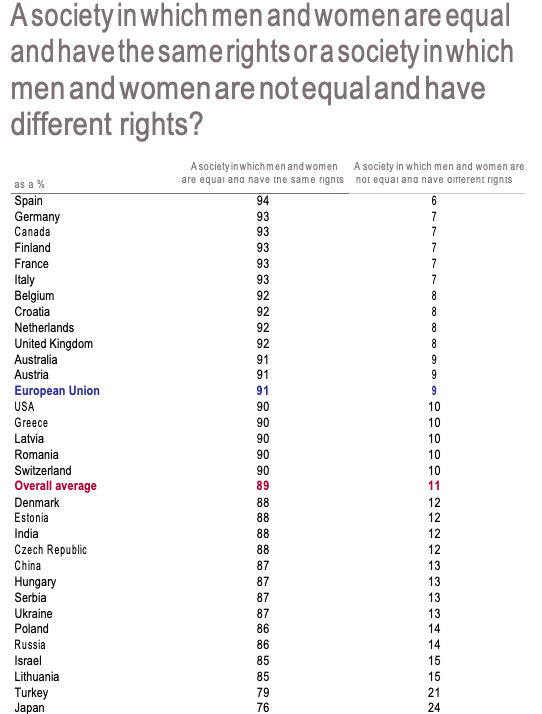

What are the values of an ideal society ?

The members of each group share a collection of experiences. And this particular generation seems to demonstrate a set of common values and behaviours, perhaps as a result of these experiences. The values and preferences that emerge from the answers to our questions are not, of course, necessarily backed up by everyday actions. For example, even if the respondents profess here their agreement with the opinion that men and women are equal, it does not automatically mean that their behaviour is never

misogynistic. Nevertheless, the existence of this ‘culture of recognition’ does already constitute a step in the right direction, in this case for sexual equality but also more generally in terms of a greater respect towards human diversity. There is a powerful link between a study such as this into the memories of genocides, world wars and the biggest, most dramatic events of the 20th century, and a culture of tolerance and respect.

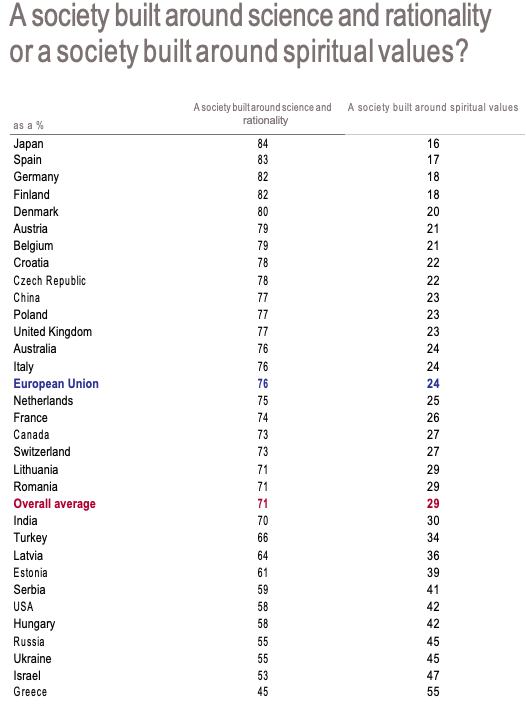

Question :

« What would characterise your ideal society? Please indicate your choice on the scale between the two opposites. »

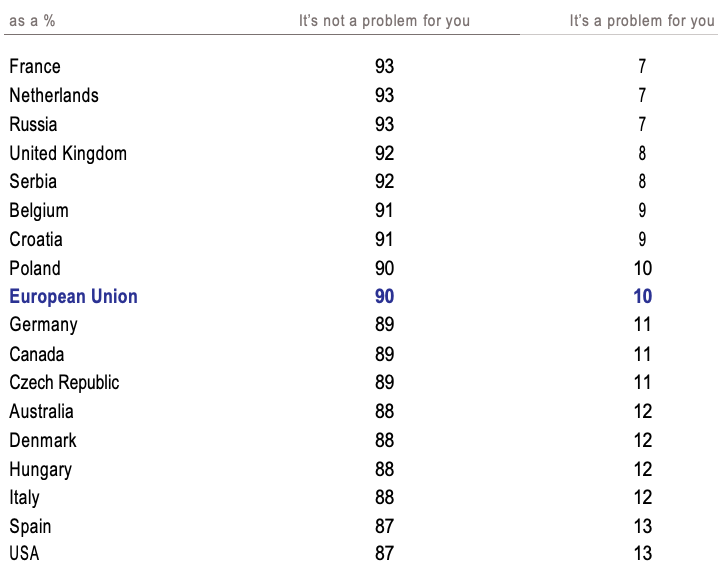

What are attitudes towards diversity ?

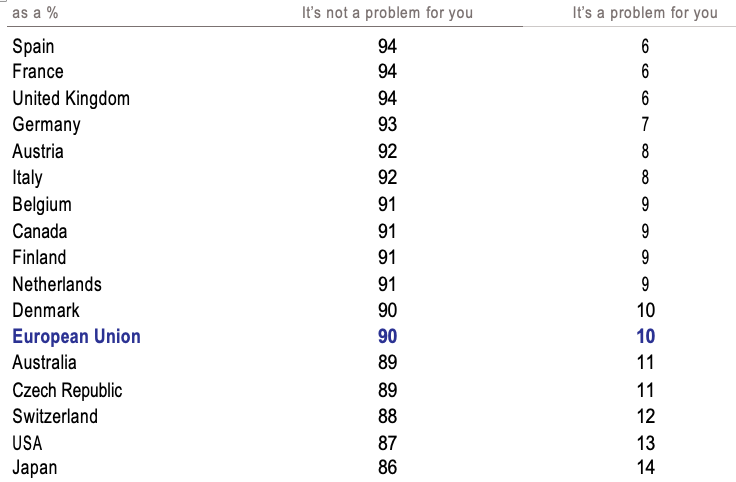

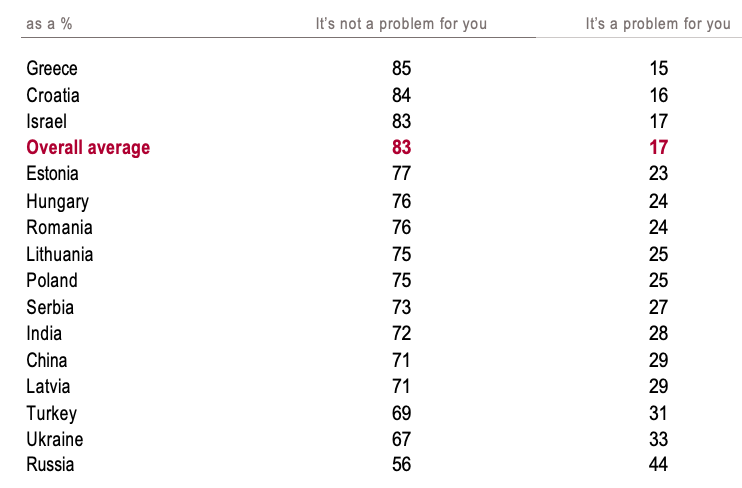

SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Question:

« What do you think of people with a different sexual orientation from you? »

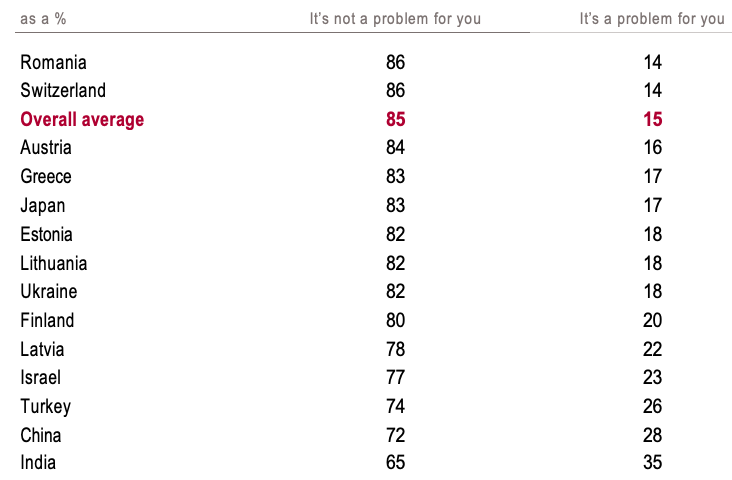

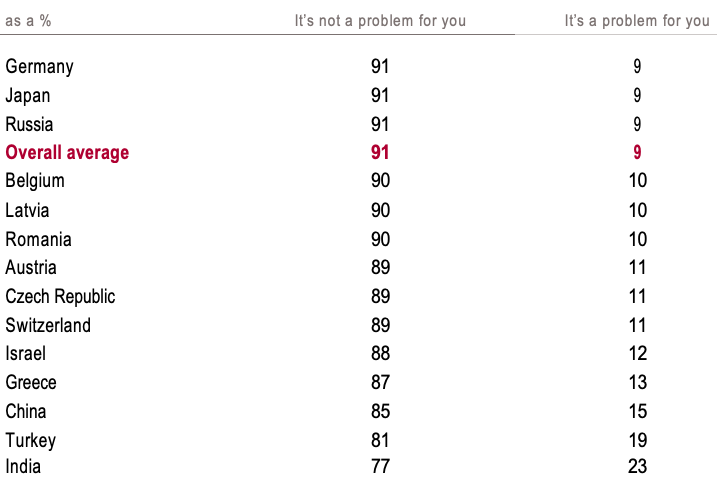

Of all the attitudes towards diversity, notions towards those of a different sexual orientation are the least tolerant. However, this is only relative in the sense that, overall, only 17% of those surveyed acknowledge that this is a problem for them.

On this regard, the level of tolerance among the men surveyed (77%) is significantly lower than that among the women (88%). In the same way, for those aged between 16 and 19 years, diversity of this nature is more readily accepted than among the 25-29 year- olds, which suggests that a cultural process is at work.