Glyphosate, separating "the wheat from the tares"

Glossary

Glyphosate, from admiration to disgrace

A reassuring scientific risk assessment

The IARC classification: glyphosate considered as “probably carcinogenic to humans”

Isolated, the IARC violently fights back

Conflicts of interest and lack of neutrality at the IARC

A key point in the IARC’s evaluation : non-hodgkin’s lymphoma

Other scientific allegations concerning glyphosate

The case of glyphosate in urine

Reflections on parallel “science”

Accusations against a German scientific agency on glyphosate

The European opinion on glyphosate

Journalists as protagonists in the controversy

Political actions

Conclusion

Words or expressions followed by an asterisk are explained in the glossary at the beginning of this study.

Summary

Glyphosate has long been considered as an herbicide* with no unacceptable health risk. In 2015, its classification as “probably carcinogenic” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) changed the situation, and in 2017 the European Unionrenewed its authorisation for only five years with France even wanting to “get out of glyphosate” in three years time. However, otherofficial risk assessment agencies have contradicted the IARC’s opinion and, as our study attempts to show, this discrepancy is notscientifically explainable. On the other hand, the IARC has a clear lack of ideological neutrality and some IARC experts have financial ties with lawyers exploiting the tort law in the United States based on the IARC’s opinion on glyphosate. In Europe, claims of a universal contamination of the population by this herbicide was propagated following urine analyses of volunteers.

However,the unreliability of the tests used in these activist campaigns has been established. The glyphosate case confirms the necessityof trustworthy scientific authorities to separate “the wheat from the tares”. In addition, the influence of activist structures having a pretence to science and the questioning of official risk assessment agencies present a problem in terms of risk management by thepolitical authorities and public perception. All the more so when journalists entered the debate, some involved in interpreting scientificevidence whilst others drew attention to the supposed influence of Monsanto on researchers or on scientific risk experts.

Marcel Kuntz,

Research Director at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Professor at Grenoble-Alpes University, 2017 gold medal recipient from the French Academy of Agriculture.

Group of experts for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) “State of the science of endocrine disrupting chemicals“, 2013, p.10.

In Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm), Endocrine A far-reaching challenge for research, Health information, inserm.fr, updated 2 October 2018. Also see the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (Anses), Endocrine disruptors, anses.fr, updated 24 July 2019.

Weeds. Plants that grow on cropland independently of any human seeding. They are commonly referred to as “noxious plants” or “weeds”. Among the most harmful for the cultivation of certain cereals is poppy which can also be a reservoir of viruses, datura (nightshade family) and ragweed, a highlyallergenic plant. These weeds are difficult to eliminate without herbicide*. There are also parasitic plants such as broomrape.

Conservation agriculture. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as an agriculture based on a continuous minimum mechanical soil disturbance, or even the elimination of plowing, permanent organic soil cover and diversified crop species grown in sequences orassociations. Its cultivation systems are diverse: simplified cultivation techniques, no-till, direct sowing under plant cover, etc. Conservationagriculture aims to maintain and improve the agronomic potential of soils while maintaining regular and efficient production.

LC/ MS-MS analysis. Liquid Chromatography (LC) with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS-MS) is an analytical technique that combines the power of compound separation of chromatography with the ability to analyse (ionised derivatives) the separated compounds. The mass spectrometer has an ionisation source in which the effluent from the LC column is transformed into charged particles. This allows compounds to be identified andpossibly quantified with a high degree of sensitivity and selectivity.

Acute reference dose. For any chemical substance to which a subject may be exposed, there are two thresholds of health risk. The acute reference dose (ARfD) defines the maximum amount of a substance that can be ingested by an individual over a short period without risk of harmful health effects. It is calculated from a ‘no observable effect level’ (NOEL*). The maximum residue limit (MRL) defines the maximum acceptable concentration without risk to health, even if this exposure is repeated every day throughout the life of the person.

Epidemiological studies. There are two main types of such studies: experimental ones where the researcher intervenes by choosing the subjects and on the exposure of subjects via the factors and times of exposure, and observational studies where the researcher does not intervene on the exposureconditions of the subjects. Among the latter are incidence studies, where observations take place over time (longitudinal studies) on a group or groups of subjects to measure changes in their health status. In this category, cohort studies involve two groups: subjects exposed to the studied risk factor and subjects not exposed to this risk factor (control group). The two groups are followed (prospective cohort) then compared with each other as to their state ofhealth. These are expensive studies. Case-control studies compare subjects with a condition/disease (“cases”) to subjects without (“controls”) at agiven time or retrospectively. The two groups should ideally be as similar as possible, the only difference being signs of the disease. The goal is to identify the origin of the disease and to define its causes (professional activity, diet, exposure to a chemical substance, etc.).

Exposure (acute, sub-chronic or chronic). Acute exposure is a single contact of less than 24 hours. Sub-acute or sub-chronic exposures consist ofrepeated contact for 1 to 3 months. Chronic exposure is a repeated exposure lasting more than 3 months. Modes of exposure may be oral, inhalation, dermal or through the placenta.

Genotoxicity/ Mutagenicity. A substance (synthetic or natural) or a radiation is said to be genotoxic when it is capable of compromising the physical or functional integrity of the genome (DNA). Mutagenicity is a special case of genotoxicity: an agent is said to be mutagenic if it changes the genome of an organism so that the number of genetic mutations is higher than that occurring naturally. Genotoxicity is an indication of thecarcinogenic potential of an agent, but is neither necessary (there are non-genotoxic carcinogens) nor sufficient (intervention of multiple factors). The study of genotoxic and/ or mutagenic effects is conducted on bacteria and mammalian cells or human lymphocytes.

Herbicide. Crops can face competition from weeds* which limit their potential. There are selective herbicides that can be used on cereals, corn, beets, etc.Less numerously authorised, non-selective, also called total herbicides, such as glyphosate, are effective on all weeds as well as on cultivatedspecies. Notable are contact herbicides, which act at the point where they come into contact with the plant, and systemic herbicides, which migrate throughthe plant, to the roots for example, which is the case for glyphosate.

Mutagenicity. See Genotoxicity/Mutagenicity*.

NOAEL (no observed adverse effect level)/ NOEL (no observed effect level). NOAEL refers to the highest dose of a substance for which no toxiceffect was observed in exposed animals compared to a group of control animals. NOEL is the highest dose or exposure level of a substance thatproduces no noticeable (observable) effect on tested animals.

Endocrine disruptors. There are many definitions of endocrine disruptors. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) an endocrine disruptor is “an exogenous substance or mixture that alters function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently causes adverse health effects in anintact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations”1. The endocrine system includes all organs that secrete hormones. Endocrine disruptors, therefore, potentially affect various body functions (metabolism, reproductive functions, the nervous system, etc.). Today, scientifically, but also under pressure from activists, the definition of endocrine disruptors tends to broaden. However, most substances labelled as endocrine disruptors are most often only suspected of having this type of activity. To date, there are in fact very few proven endocrine disruptors2.

Pesticides. The word comes from the Latin cida (“to kill”) and pestis (“contagious disease”). They are therefore substances used to fight against organisms harmful to crops such as pests, pathogens or weeds* (in this case the term plant protection products is used), to protect the environment andfight diseases and vectors of diseases (biocidal products) or for veterinary purposes (treatment of animals). One distinguishes between herbicides, insecticides, fungicides (against microscopic fungi), rodenticides (against rodents), parasiticides (against parasites), nematicides (againstroundworms), bactericides or even virucides. The marketed products (specialties) may contain one or more active ingredient and formulation productswhich improve the physical properties of the active principle (solubility, stability, power of penetration, etc.). Glyphosate is the active ingredient invarious formulations, including various types of Roundup, which is a trademark.

Teratogenic. The term refers to a substance or process that causes foetal malformations after exposure of the mother. These substances can bediverse (drugs, alcohol, tobacco, etc.). Some viruses can also be teratogenic.

Toxicology. A scientific discipline whose vocation was, at its origin, to study poisons, but today is more generally interested in all products likely to have effects on an organism (the toxicity of products, including natural ones), in exposure to these products, in the means of detecting them and intherapeutic methods to combat them, as well as in the establishment of preventive measures.

This study is the fifth in the Fondation pour l’innovation politique’s series on agritechnologies and biotechnologies, under the scientific direction of Ms. Catherine Regnault-Roger, professor emeritus at the University of Pau and the Pays de l’Adour, member of the French Academy of Agriculture and the National Academy of Pharmacy.

Already published:

Cited by E. Smith and D. M. Secoy (1976), “Early Chemical Control of Weeds in Europe“, Weed Science, vol. 24, n°. 6, pp. 594–597. JSTOR.

R P Singh, Introduction to Weed Management, Applied Zoology, Weed Management collection, 2008.

The author does not express the official position of his employer in this study. He has received no income related to the marketing of agricultural,biotechnological or agrochemical products.

Ludovic Henneron et , “Fourteen years of evidence for positive effects of conservation agriculture and organic farming on soil life”, Agronomy forSustainable Development, vol. 35, n° 1, January 2015, p. 169-181.

Atrazine was not reauthorised in the European Union in 2003 because of its above-limit concentrations in groundwater, but remains authorised inthe United States, for example.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

From Antiquity, texts have emphasised the problem posed by weeds*. At the Neronian time, Columella wrote in his De Re Rustica: “But to me it seems the mark of a very poor farmer to allow grass to grow among his crops, for it detracts greatly from the yield if weeding is neglected”1. In modern times, weed control remains essential since contamination can reduce the value of a crop either by competing with cultivated plants or by affecting its quality. Weeds can also increase the cost and farmer’s worktime 2.A variety ofagricultural weed control methods exist 3. Although perceived negatively by public opinion, herbicides*, also known as weedkillers, remain the most effective. They have been used to destroy weeds since the end of the 19th century, notably by the use of dilutedsulphuric acid, which is corrosive and not effective on all weeds. The first herbicides derived from organic chemistry appeared shortly before World War II. It was discovered that synthetic analogues of natural plant growth regulators (phytohormones), such as 2,4-D, marketed from 1946, could be used as a selective herbicide, acting specifically on dicotyledonous plants while not affectinggrasses.

However, weeds can sometimes be beneficial and herbicides can help weeds to become useful, such as in the context of conservation agriculture* (where the ground is permanently covered with vegetation and is no longer tilled, apart from the sowing line when seeds are sown). A long-term experiment by the National Institute for Agronomic Research (INRA) has confirmed that the manner by which the soil is tilled, or not, is the most determining factor for soil biodiversity. According to this criterion, conservation agriculture is more efficient than conventional and even organic agriculture4. Herbicides participate in conservation agriculture where the ground cover by plants between two successive crops is destroyed by a weedkiller, thus allowing for reseeding.

However, the drawbacks of herbicides include a possible loss of biodiversity in or around the field, possible contamination of runoffand groundwater5, as well as health risks for users if insufficiently protected.

For all these reasons, herbicides, like other pesticides*, are subject to scientific risk assessments6, which has led to many of them being banned. Stringent requirements make it difficult nowadays to introduce new herbicides onto the market7. Marketingauthorisation also has to be reassessed periodically, and it is in this context that glyphosate hit the headlines.

Glyphosate, from admiration to disgrace

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Chelate“, Encyclopædia Britannica, access date: 21 December 2020.

Various molecules of this family had been tested at the company but did not show herbicidal At first, Franz thought that this type ofmolecules was converted by plants into beneficial derivatives for them. See “John Franz“, web.mit.edu, September 2007.

Glyphosate diffuses throughout the plant and prevents the synthesis of certain amino acids that make up The plant continues to grow, untilit is fatally deficient in protein.

Glyphosate is biodegradable in the scientific sense of the term, but not in the regulatory sense because its disappearance is not fast enough under all conditions to meet the standards in the matter; this has forced Monsanto to alter its advertising of Roundup as biodegradable.

“The Stop glyphosate initiative“, European Citizens’ Initiative Forum – Success Story, April 2018.

N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine, more commonly known as glyphosate, an analogue of the natural amino acid glycine, was firstsynthesised in the 1950s by the Swiss chemist Henri Martin, employed by Cilag. With no identified use, the molecule was sold to othercompanies. It was first employed for its chelating properties8, in this case of metals, and was, therefore, used to clean boilers and pipes as of 1964. John Franz, a Monsanto chemist working in the company’s agricultural division in 1967, synthesised various molecules ofthe phosphonic acid family, including glyphosate, which he identified as an herbicide in 19709.

Monsanto patented the invention and marketed it from 1974 under the Roundup brand name. The product was first appreciated byfarmers to control hard-to-eliminate perennials. It then, in various formulations, became the most widely used weedkiller in the world. Itssuccess in agriculture, urban, industrial and garden sectors was due to various factors: its low cost and high efficiency, both against monocots and dicots10 (i.e. a “total herbicide”), and especially its short persistence allowing rapid reseeding after use11. Glyphosatehas also become an important element in conservation agriculture; to weed without having to till the soil.

John Franz received many awards and Roundup was named one of the “Top Ten Products that Changed the Face of Agriculture” by Farm Chemicals magazine in 1994. The patent came into the public domain in 2000 and the molecule is now synthesised by many companies, especially Chinese ones. How has glyphosate gone from the status of an almost miraculous product to that of French and European disgrace in such a short time12?

A reassuring scientific risk assessment

On this principle and exceptions, see: chemicalsafetyfacts.org/dose-makes-poison-gallery/, https://endocrinesciencematters.org/non-monotonic-dose-responses-2/non-monotonic-dose-responses-technical-overview/.

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, Hazard and Risk.

Gary Williams, Robert Kroes and Ian C. Munro, “Safety Evaluation and Risk Assessment of the Herbicide Roundup and Its ActiveIngredient, Glyphosate, for Humans “, Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, vol. 31, n° 2, April 2000, p. 117-165.

Glyphosate has been studied extensively, itself or as a formulation, as have its adjuvants – including tallow amines, also known as polyoxyethylene amines (POEA) – and its main metabolic derivative produced in plants, aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA). In order to understand what follows, it is necessary to first explain some general principles of health risk assessment. First, according to Paracelsus’ principle, “the dose makes the poison”13. In addition, the distinction between risk and hazard is essential: risk is the “probability that a person will suffer harm or a harmful effect to their health when exposed to a hazard”. This takes into account thehazard (“any potential source of damage, harm or harmful effect to something or a person”) and exposure to the hazard (i.e. thedose)14. To summarise: risk = hazard x exposure to hazard.

As a result, those in favour of banning a product have an interest in ignoring Paracelsus’ principle. Without this principle, the mere fact of detecting a product, even at an extremely low dose and even when a risk has not been proven, becomes publicly unacceptable. Even more so if it is a source of publicised concern that opposition organisations, which are now extremely well-organised, know too well how to trigger.

There are several types of toxicology* studies15, including in vitro or animal (in vivo) experiments, where the dose and exposure time may vary (acute, sub-chronic or chronic exposures*) or epidemiological* studies (experimental or observational) which focus onthe incidence of disease and their cause in a human population16.

The following lines and paragraphs summarise a review article published in 200017. Oral absorption of glyphosate and AMPA is low, and studies of Roundup formulations have demonstrated low skin penetration. When present in an organism, both molecules areexcreted in urine, in a largely unmetabolised form, and do not bioaccumulate in animal tissues. No significant toxicity was detected in toxicology studies with acute, sub-chronic or chronic exposure. However, irritation is a well-known symptom in the event of direct eyecontact with a Roundup formulation.

Data on genotoxicity* – the ability to cause damage to genetic material – has not provided any convincing evidence of direct DNA damage in vitro or in vivo. Roundup and its components do not appear to present a risk of inducing mutation in humans. In animals, lifetime feeding studies have not demonstrated any tumourigenic potential for glyphosate. As a result, it was concluded that glyphosate is non-carcinogenic.

Glyphosate, AMPA and POEA are not considered as teratogens* (i.e. do not cause foetal malformation) or to be toxic for humandevelopment. Two multi- generational animal studies did not reveal any effect of glyphosate on fertility or on reproductive parameters.Likewise, there was no effect on reproductive tissues of animals treated with glyphosate, AMPA or POEA in chronic and / or sub-chronic studies. Nor did standard endocrine disruption* studies demonstrate any effect. Therefore, it was concluded that the use of Roundup does not cause adverse effects on development, reproduction or endocrine systems in humans and other mammals under normal use.

“No Observable Adverse Effect Doses” (NOAEL*) have been identified in all sub-chronic, chronic, developmental and reproductionstudies for glyphosate, AMPA and POEA. By comparing these NOAELs to the highest exposure estimates, it was concluded that, under actual and expected conditions of use, Roundup herbicide does not present any risk to human health. However, in 2015, the evaluation by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) was to change everything.

The IARC classification: glyphosate considered as “probably carcinogenic to humans”

See International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), “IARC Monographs Volume 112: evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides“, iarc.fr, 20 March 2015.

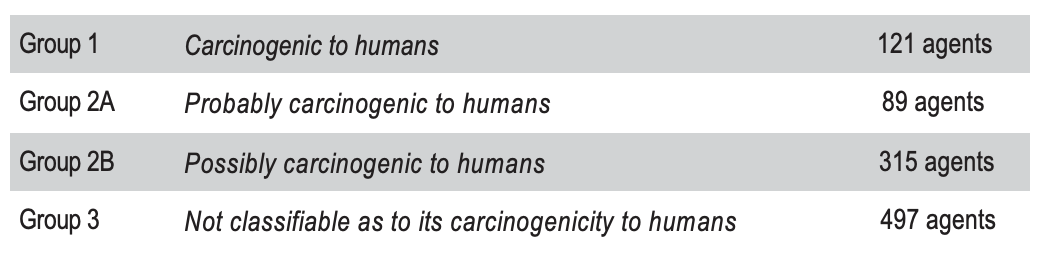

On 20 March 2015, the IARC published its evaluation of five organophosphate pesticides: four insecticides and one herbicide,glyphosate18. IARC evaluations are performed by a panel of experts and result in a “Monograph” which includes a classification of thelevel of carcinogenicity of the product concerned, in this case, glyphosate, in group 2A (“agent probably carcinogenic to humans”) (see table below).

Source :

International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC.

Such as the manufacture of art glass, glass containers and pressed ware, occupational exposure as a hairdresser or barber, or night shift work.

Such as indoor emissions from household combustion of biomass fuel (primarily wood).

On this subject, in Europe, it is ECHA and not the IARC which officially “gives an opinion on the proposed harmonised classification of substances as carcinogenic“.

In this group, glyphosate joins certain other chemicals; synthetic or which can form spontaneously (e.g. during cooking, such as acrylamide), in consumption habits (red meat, drinks hotter than 65°C) and professional19 or domestic20 activities. It should be noted that the agent “carcinogenic to humans” category includes the consumption of alcoholic beverages, processed meat or even indoor emissions from domestic combustion of coal.

These examples illustrate the rigid nature of these classifications. It is evidently the excessive consumption of meat (the famous toxicologists’ “dose”) that is causing the problem, rather than a moderate consumption. The informative value of this type ofclassification for the public authorities is also questionable, especially in relation to the multiple official risk assessment agenciesrecently created21. It is precisely via these agencies that the glyphosate file remerged.

Isolated, the IARC violently fights back

This document leaked and was made public by See “Renewal Assessment Report. Glyphosate Addendum 1 to RAR. Assessment of IARC Monographs Volume 112 (2015): Glyphosate“, gmwatch.org, 31 August 2015.

EFSA, “EFSA explains the carcinogenicity assessment of glyphosate“, europa.eu, 12 November 2015, p.4.

See Genetic Literacy Project, “What do global regulatory and research agencies conclude about the health impact of glyphosate?”, geneticliteracyproject.org, s.d.

See Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)-World Health Organization (WHO), “Joint FAO/WHO meeting on pesticide residues, Geneva, 9-13 May 2016“, 16 May 2016.

Reuteurs, “W.H.O. Report Links Ingredient in Roundup to Cancer“, The New York Times, 20 March 2015; “Roundup weedkiller ‘probably’ causes cancer,says WHO study“, The Guardian, 21 March 2015.

See Francisco R. Paumgartten, To be or not to be a carcinogen; delving into the glyphosate classification controversy, Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. vol. 55 São Paulo 2019; in French: Hervé Le Bars, “Le glyphosate est-il cancérogène ?“, Science & Pseudo-Sciences, n° 323, January-March 2018, p. 63-75.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), “IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Preamble“,January 2019, p. 2.

European Chemicals Agency (ECHA).

This document (in French) critically analyses the IARC findings, including the results of the animal studies retained by the IARC, which ECHA deemed to have been obtained by protocols not complying with the OECD guidelines: Philippe Stoop, forumphyto.fr, 20 November 2017.

See the letters exchanged between Christopher Portier and EFSA in 2015 and 2016 (Glyphosate: EFSA responds to critics).

Letter of Christopher Portier to Vytenis Andriukaitis, europa.eu, 27 November 2015.

At the authorities’ request, various official risk assessment agencies reexamined the glyphosate case and all contradict the IARC’s conclusion. In Germany, on 31 August 2015 the Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR), the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, drew up a document for the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)22. On 12 November 2015, the latter then stated that “glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans”23. In the world, a dozen other agencies concluded similarly24. The World Health Organization (WHO), the governing body of the IARC, distanced itself, especially in the context of a meeting with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) dedicated to pesticide residues*25. It is, therefore, incorrect to assert, as has been claimed, that the “World Health Organisation (WHO) has said that glyphosate can “probably” cause cancer”26. Various individuals have tried to understand, on a scientific basis, the difference between the IARC evaluation and that of the otheragencies27. Perhaps this could be explained by the different objectives of these agencies: the IARC evaluates hazards (i.e. the effect a substance may have), whereas the other agencies evaluate risk (i.e. the effect the substance actually has)? However, this explanation does not appear credible on reading the IARC’s “preamble” to its classifications: “Although the Monographs programme has focused on hazard identification, some epidemiological studies used to identify a cancer hazard are also used to estimate an exposure–responserelationship within the range of the available data”28.

In addition, European regulations also imposed a hazard assessment by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), and this agency additionally contradicted the IARC on glyphosate29.

In fact, the data reviewed by the IARC and the other agencies do in fact converge, but with differences, as detailed below. Divergences are rather evident in the interpretation of the data30. It would not be unusual for the IARC to give different weighting to certain data and then the controversy could have simply been ended by providing such an explanation. However, this was never the position of the IARC, which, on the contrary, attacked the other agencies head-on, in particular the EFSA. Kathryn Guyton, an IARC official and responsible officer for “Monographs”, denigrated the work of the European agencies: “In my understanding, theevaluation of the European health authorities was entirely written by the manufacturers of glyphosate”31. Christopher Portier, a scientific expert in the IARC glyphosate working group, also overstepped the scientific framework by being extremely hostile with regard tothe EFSA evaluation32. Portier even appeared to be entrusted with a mission of lobbying politicians who he met in various Europeancountries. For example, in 2015 he sent a letter to the European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, Vytenis Andriukaitis, in which he attacked the EFSA33.

Conflicts of interest and lack of neutrality at the IARC

See Kate Kelland, “Is your weed killer carcinogenic?“, reuters.com, 18 April 2016.

See email from 22 January 2016 exchanged for the preparation of this meeting. The names deleted in this document are those of Francesco Forastiere, Ivan Rusyn and Hans Kromhou.

The Risk-Monger, “The Portier Papers“, 13 October 2017.

United States District Court, Northern District of California, “Roundup Products Liability Litigation. Deposition of Christopher Jude Portier, D.“, New York, 5 September 2017.

Email by Christopher Portier, 9 November 2015.

CEO, “Setting the record straight on false accusations: Dr Portier’s work on glyphosate and IARC”, 19 October 2017.

See United States Disctrict Court, Northern District of California, “Roundup Products Liability Litigation. Expert Report of Charles W.Jameson, Ph.D., in Support of General Causation on Behalf of Plaintiffs”, 12 May 2017.

Complete file on this case compiled by Marcel Kuntz, “Glyphosate: Why did IARC produce such a questionable classification?”.

The investigation was led by David Zaruk and made public in a series of The names of Bernard Goldstein, Peter Infante and Martyn T.Smith are cited as litigation consultants in the context of benzene lawsuits and members of the IARC Benzene Working Group (see The Risk-Monger, “The Corruption of IARC 1/4: IARC Monographs Produced for US Tort Law Firms ”, risk-monger.com, 24 August 2019).

An email written by Kathryn Guyton, IARC Scientist and Acting Head of the IARC Monographs Group, stated the IARC “does not encourageparticipants to retain working drafts or documents after the monograph has been published”. See Kate Kelland, “Exclusive: WHO cancer agency asked experts to withhold weedkiller documents”, reuters.com, 25 October 2016.

Letter by Christopher Wild to the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology from the S. House of Representatives, 11 January 2018.

Kate Kelland, “In glyphosate review, WHO cancer agency edited out ‘non-carcinogenic’ findings”, com, 19 October 2017.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), “IARC rejects false claims in Reuters article (‘In glyphosate review, WHO cancer agency edited out ‘non-carcinogenic’ findings’)”, 24 October 2017.

See Marie-Monique Robin’s invitation email to Aaron Blair, 18 August 2016.

Christopher Portier’s aggressive conduct did not fail to draw attention. It subsequently became common knowledge that he was paid by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF)34, an American anti-pesticide organisation, which, in itself, is not reprehensible, but there should have been more transparency. For example, his letter to the European Commissioner, Vytenis Andriukaitis, makes no mention of this link. Portier’s relationship with anti- pesticide organisations is also highlighted in a talk he gave on behalf of the Health and Environmental Alliance (HEAL) as part of an ECHA consultancy in 201635. In addition, in January 2016, three other members of the IARC glyphosate working group assisted Portier in a private meeting with Vytenis Andriukaitis, where the EFSAattacks were reiterated36, suggesting widespread collusion within the working group rather than just the people mentioned above.

David Zaruk (under the alias “The Risk-Monger”) provided more shattering evidence37 based on a testimony made by Portier under oath in a United States court38: in the week following the publication of the IARC’s glyphosate evaluation, Portier signed a contractwith two law firms that were preparing to sue Monsanto on behalf of victims of cancer “caused” by glyphosate. Portier’s fee as a litigation consultant was more than $160,000 (until June 2017), plus travel expenses, for his work in providing his analyses of glyphosate for one law firm, and more than $144,000 for his work at another lawfirm. A confidentiality clause stipulated that Portier was to refrain from disclosing this employment to a third party. Emails provided during the hearing also reveal the key role that he attributed himself after the IARC evaluation. In an email addressed to this body, Portier pledged to protect the reputation of the IARC and its Monograph on glyphosate, and not to let the opinions of the BfR and the EFSA weaken thestrength of the IARC Monograph”39.

The phrase “I do not intend to let this happen” written in this email, as well as his lobbyist activities mentioned above, is especially evocative when his ties with lawyers exploiting the IARC classification are taken into account. Portier admitted during his hearing that he had actually worked for the law firm Lundy Lundy Soileau & South for two months prior to March 2015, i.e before the date of his involvement in the IARC glyphosate working group.

The Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), “a campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobby groups in EU policy making”40 which participates in various political ecologycampaigns (against biotechnologies, pesticides, and nuclear energy, for example) stepped in to defend Portier, explaining that “one reason we are writing this factsheet to defend Dr. Portier is because he helped us a lot in our work”41.

The hearing in the U.S. revealed an additional conflict of interest for Charles William Jameson, another member of the IARC glyphosate working group, who was also paid to write an expert report to support complaints based on the classification of glyphosateby this working group, at an hourly rate of $40042.

Numerous documents reveal other conflicts of interest, as well as an obvious lack of neutrality on behalf of several members of the IARC working group and exposing its questionable working methods43. Equally disturbing are the conflicts of interest for experts involved in previous IARC work and their ties to law firms, as seemed to be the case for the benzene working group in 200944.

The lack of transparency of the IARC regarding its opinion on glyphosate raises questions. The journalist Kate Kelland highlighted theIARC’s refusal to release the working group documents that led to the classification of glyphosate45. Former IARC Director, Christopher Wild, also refused to attend the United States House of Representatives Science Committee hearing on the IARC’s functioning (see below) and wrote a letter to this committee in which he stated the “IARC would be grateful if the House Science Committee would take all necessary measures to ensure that the immunity of the Organization, its officials and experts, as well as the inviolability of its archives and documents, are fully respected”46. Kate Kelland also published an investigation showing thatbetween the draft version and the published report of the IARC glyphosate Monograph, several passages were changed. This in itself is not unusual, but what is unusual is that all the changes converge, in order to strengthen the conclusion of the carcinogenic classification of this herbicide47. Even if the IARC replied48, the verification of its explanations is always confronted by the lack of transparency of its work.

Finally, it should be mentioned that Kathryn Guyton, an IARC official who had agreed to testify in 2016 before the travesty of justicecalled “The International Monsanto Tribunal” but did not receive WHO autorisation to appear, suggested the organiser, Marie-Monique Robin, notoriously anti-Monsanto, invite Aaron Blair (chairman of the glyphosate working group) instead, not bound by the duty of reserve49.

A key point in the IARC’s evaluation : non-hodgkin’s lymphoma

A variable (e.g. another substance) is a confounding factor if it is related to the exposure studied (here glyphosate) and if it is associated with the disease in unexposed subjects.

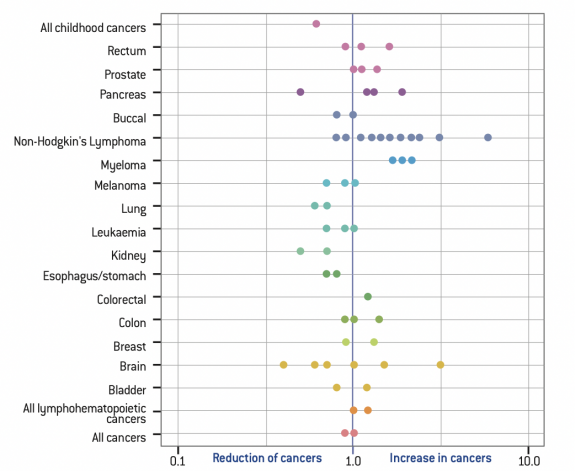

Observational epidemiological studies have investigated the possible links between glyphosate and an increased risk of cancer in itsusers. It is well known that these types of studies may be prone to bias and error, in particular because of the so-called confoundingfactors 50. It is therefore not surprising to obtain contradictory results, with some studies finding a link between glyphosate and cancer whilst others conclude a lower incidence of cancer in the users of this herbicide.

Explanation: Each point represents a study that assessed the relative risk of developing cancer between individuals exposed to glyphosatecompared to those who were not. The dots on the left side of the blue line (values <1) mean that, on average, individuals exposed to glyphosate wereless likely to get this type of cancer. Dots to the right of the blue line (values >1) mean that individuals exposed to glyphosate were more likely to get thistype of cancer. Confidence intervals (the uncertainty associated with the risk estimate) are not shown in this graph.

Examples of epidemiological studies linking the occurrence of various types of cancer and exposure to glyphosate

Source: Andrew Kniss, “Glyphosate and cancer – revisited”, 11 August 2018.

For example, memorisation bias: a subject with a pathology (“case”) can remember more from past exposures than a subject not affected bythe pathology (“control”).

See cited article by Philippe Stoop.

See cited article by Hervé le Bars

For critical comments, see Stoop, “Pesticides and cancer among farmers: the rush towards irrefutability”, europeanscientist.com, 12 September 2018.

John Acquavella, David Garabrant, Gary Marsh, Tom Sorahan and Douglas Weed, “Glyphosate epidemiology expert panel review: a weight ofevidence systematic review of the relationship between glyphosate exposure and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or multiple myeloma”, Critical Reviews inToxicology, vol. 46, suppl. 1, September 2016, p. 28-43.

Gabriella Andreotti et , “Glyphosate Use and Cancer Incidence in the Agricultural Health Study”, Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 110, n°5, May 2018, p. 509-516.

See The Risk-Monger, “Glyphosate: How to fix IARC”, 27 September 2017.This article shows that, at least in the case of Monograph 118 on welding fumes, the IARC took into account unpublished A document reports aconfidentiality commitment to allow the consultation of this data.

See Kate Kelland, “Cancer agency left in the dark over glyphosate evidence”, com, 14 June 2017).

See Occupational Cancer Research Center, “North American Pooled Project: pesticides, agricultural exposures, and cancer”, 2013.

Whilst it seems unlikely that these studies reflect the reality, it confirms the necessity for a critical analysis of all published data toidentify possible biases and limitations, which is, therefore, a matter for specialists.

A number of studies (see graph above) seem to indicate (overall, but with the above-mentioned reservations) a link betweenglyphosate and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which are cancers of the immune system, more precisely the lymphatic system. It is this indication that the IARC working group selected, speaking of “limited evidence of carcinogenicity in humans for non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma” which, nevertheless, had a non-negligible weighting in its classification decision.

Looking in detail, it appears that this “limited evidence” comes from four case-controlled, retrospective epidemiological studies.This type of research is known to be subject to bias51 and the level of proof of these four studies was very low52. In addition, 17 other studies indicated the absence of a carcinogenic risk for humans53. “Cohort” studies (i.e. the follow-up of subjects over time, termed longitudinal, prospective statistical studies), considered as less biased54, did not indicate a link between glyphosate and cancer.Researchers considered the prospective Agricultural Health Study (AHS) published in 2005 to be the only reliable assessment of the risk of NHL for users of glyphosate55. This independent, publicly-funded study included more than 50,000 farmers and did not identify any increased risk of cancer in glyphosate users. However, two limitations should be noted – the relatively low number of cases and a follow-up period of less than 10 years – but which do not preclude solid statistical power. The IARC thus based their evaluation on the most reliable results (the AHS study published in 2005) but also on the results of less reliable studies. The AHS later lifted the limits mentioned above and confirmed the absence of a link between glyphosate and NHL56. The IARC explained that they had not taken into account these latest results since they had not been published in a scientific journal at the time of their discussionson glyphosate.

However, this rule was not always respected by the IARC concerning unpublished data57 and they were in fact aware of thisunpublished AHS data at the time. In fact, Aaron Blair, retired from the National Cancer Institute in the United States and “Overall Chair”of the IARC glyphosate working group, had participated in at least the first phase of this AHS study. Court documents cited above revealedthat Blair knew that new AHS data had demonstrated no link between increased risk of cancer and exposure to glyphosate. In his testimony under oath, he also stated that this ignored data would have altered the IARC analysis, i.e. that it would have made it lesslikely that glyphosate would meet the criteria to be classified as “probably carcinogenic”58.

In addition, Aaron Blair was also involved in another unpublished study, the North American Pooled Project59, which came to the same conclusions as the AHS one did. Blair did not inform the IARC glyphosate working group of this study and let them vote, including himself, in favour of a link between glyphosate exposure and cancer, knowing it was wrong.

Other scientific allegations concerning glyphosate

For critical views on publications by Anthony Samsel and Stephanie Seneff, see Keith Kloor, Pacific Standard Staff, and Hank Campbell.

For a summary of Krüger’s claims, see her presentation as a “witness” at the mock justice of the “Monsanto International Tribunal”.

Lene Nørby Nielsen et al., “Glyphosate has limited short-term effects on commensal bacterial community composition in the gut environment due to sufficient aromatic amino acid levels “, Environmental Pollution, vol. 233, February 2018, p. 364-376.

EFSA, “Evaluation of the impact of glyphosate and its residues in feed on animal health”, European Food Safety Authority Journal, vol. 16, n° 5, May 2018.

EFSA (ibid.).

See Kuntz, The Séralini affair-The dead-end of an activist science, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 26 September 2019.

Biochemical ELISA tests are based on the binding of an antibody to the target that it is capable of This binding then gives rise to asignal that is visualised.

Examination of the figures in the publication casts doubt on the validity of this See Monika Krüger et al., “Detection of Glyphosate Residuesin Animals and Humans”, Journal of Environmental & Analytical Toxicology, vol. 4, n° 2, 2014.

Pesticides, in general, and glyphosate in particular, have extensively motivated scientific studies. Publications reporting harmful effectsvary in quality: certain are credible, while others are limited in scope, not to mention certain outlandish demonstrations. Hence, the importance of the work of official agencies and their neutrality, in order to separate the “wheat from the tares”.

The outlandish demonstrations category includes the series of publications “Pathways to Modern Diseases” by Anthony Samsel and Stephanie Seneff which suggest a link between exposure to glyphosate and intestinal disorders, obesity, diabetes, cardiac disease, depression, autism, infertility, cancers and Alzheimer’s disease, etc.

Stephanie Seneff’s affiliation with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has given her some credibility in the press, but she has no actual experience in this field. These two authors did not conduct any study, satisfying themselves with speculative correlations, without evidence60.

The work of the German veterinary Monika Krüger, a specialist in microbiology and infectious diseases in animals should also bementioned. Krüger believes that glyphosate is responsible for harm in farm animals61. She demonstrated an effect of glyphosate on potential pathogens and beneficial bacteria on the intestinal flora of chickens. This herbicide can, in fact, potentially affect the metabolism of certain bacteria, a subject of risk assessment. However, Krüger’s study was only performed in vitro. It should bementioned that such an effect was not found in the intestinal bacteria of rats exposed to high doses of glyphosate62. This question, therefore, remains open.

Krüger then published a study that investigated the presence of glyphosate in new-born piglets with malformations on a Danish farm. The weakness of this work lies in the lack of proof of cause and effect. The EFSA notes that “malformations in newborn piglets on a Danish farm have been attributed to glyphosate simply because residues of this active substance were found at extremely variable concentrations in different organs and tissues of these animals. In the absence of any control group and taking into account the rather low dietary exposure of the sows and the results of a multitude of developmental studies, this assumptionis not sufficiently substantiated to be relied upon”63. The question is, why has such an effect not been observed elsewhere, such as in the United States, for example?

Krüger also detected glyphosate in dairy cows in Denmark, at levels she claimed to be correlated with biochemical changes in these animals’ blood, which the researcher attributes to the chelating effect of glyphosate. The EFSA reports that “During the current assessment, it was concluded that the small amount of ingested glyphosate is not expected to bind trace elements to such an extent that clinical signs might occur. Furthermore, this study presented major methodological deficiencies (e.g. the absence of a control group), severely affecting its reliability”64.

All this did not prevent Krüger from gaining notoriety among anti-GMO and anti-glyphosate activists. She is herself considered anactivist opposed to this product, based on her studies which have, however, been refuted, reminiscent of the Séralini phenomenon inFrance65. Krüger’s influence surged following one of her publications claiming to validate an ELISA test (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)66 manufactured by Abraxis (USA) for the detection of glyphosate in urine. This publication claims to find more glyphosate in the urine of individuals consuming conventionally farmed products than in those consuming organic products, andsimilarly in chronically ill persons compared to healthy ones67. Following this publication, Krüger cofounded a laboratory for the detection of glyphosate in urine.

The case of glyphosate in urine

Nicole Sagener, Euractiv, 7 March 2016.

See Stéphane Foucart, “Les trois quarts des Allemands seraient exposés au glyphosate”, lemonde.fr, 8 March 2016.

See www.gmwatch.org/en/news/latest-news/16268-glyphosate-found-in-german-breast-milk which has been contradicted by Steinborn et al.

Bill Wirtz, “Urine testing for pesticides: new dodgy science straight out of France”, Comment Central, 20 December 2019.

See Niemann, et al. A critical review of glyphosate findings in human urine samples and comparison with the exposure of operators andconsumers. J. Verbr. Lebensm. 10, 3–12 (2015).

For a comparison of data from both techniques, see agriculture-environnement.fr/2019/02/21/ biocheck-un-laboratoire-aux-curieuses-analyses.

See Collectif Réso’them, “Controverses autour du glyphosate et de ses impacts”, May 2019, p.9.

A campaign launched in Germany in 2016 by the Heinrich-Böll Foundation (allied with the German Green Party) claimed that an”overwhelming majority of Germans were contaminated by glyphosate68“. The French press reported on this “Public mobilisation”69. MEPs themselves participated in the experiment, providing credibility to the idea of a universal contamination of the population bythis herbicide. Even more disturbing: breast milk was also contaminated70.

In France, a similar campaign, named “Volunteer Pissers”, in analogy to the “Volunteer Reapers” who destroy GMOs, was launched in April 201771. Thousands of volunteers participated, including celebrities. The analyses were performed by Krüger’s company andall results were positive. The authorities were demanded to ban all pesticides* (synthetic only, since pesticides used in organicfarming are never targeted by “anti-pesticide” campaigns) and complaints were filed.

However, the fact that these tests gave 100% positive results contradicts other scientific studies72. In addition, it is well known tospecialists that an antibody can also bind to other molecules, especially if they are abundant, leading to false positives in routine ELISA tests. Such tests have been validated for detection in a simple medium such as water, e.g. before capture, but not for a more complex medium such as urine (except by Monika Krüger). Detection based on chromatographic separation, associated with mass spectrometry, known as LC/MS-MS*, is considered as the most reliable.

The unreliability of the tests used in this activist campaign was established when farmers themselves took the initiative to be tested by both methods in parallel. The results of the LC/MS-MS analyses contradicted those of the ELISA tests73. Nevertheless, the campaign had paid off. Thus, a document destined for agricultural education and available via the official organisation Educagri affirms that “the surveys in France resulted in 100% presence in urine”74 and relates other misinformation, e.g. the citationon several occasions the works of Séralini or even Samsel and Seneff75.

Reflections on parallel “science”

B. The purpose of the author of this study is not to condemn activism in itself, which may be esteemed, but to analyse new approaches in thehistory of science.

See Marcel Kuntz, “Science and false sciences et fausses sciences”, marcel-kuntz-ogm.fr, 9 January 2011.

Alexandre Moatti, Postures, dogmes, idéologies, Odile Jacob, 2013.

For details on Criigen (in French), see ecolopedia.fr, 5 March 2019.

“About Mission”. The purpose here is not to denigrate all the work carried out by the CollegiumRamazzini, in particular after its creation in 1982, but to illustrate an increasingly frequent tendency of disseminating systematically alarmist messages in the media and to entice, by a group effect, other scientists in this worldview.

See https://citizens4pesticidereform.eu/ (note the plethora of associations) and https://risk-monger. com/2018/11/04/why-the-activist-manifesto-is-manifestly-wrong/.

For the refutation of a study on aspartame, see EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS), “Statement ontwo reports published after the closing date of the public consultation of the draft Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of aspartame (E 951) as afood additive”, European Food Safety Authority Journal, online journal, 11, No. 12, December 2013. For the rebuttal of another study on another sweetener, see Nicolas Guggenbühl, “Carcinogenic, sucralose?No, reaffirms EFSA“, foodinaction.com, N.D., and of a study on radiofrequencies, see International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation (ICNIRP) “ICNIRP note on recent animal carcinogenesis studies“, icnirp.org, 4 September 2018.

The concept of parallel “science” arose as a result of activist anti-GMO initiatives76, having pretence to science but which are truly at the planned service of a political project aiming to replace scientists by mediatised “experts”, sympathisers of the political project at hand, in particular for risk assessment77. These experts can be self-proclaimed or, on the other hand, even recognisedscientists. In the latter case, the concept joins that of “alterscience”, developed by Alexandre Moatti where people trained in sciencemobilise their knowledge in favour of alternative theories or the reconstruction of disciplines for ideological or personal gains78. This “alterscience” concept involves those who, alone against the entire scientific community, claim to be right. Today, however, this notion of the lone researcher is outdated since many activist organisations claiming scientific notoriety exist, such as the Committee for Independent Research and Information on Genetic Engineering (Criigen79) in France and its equivalents in other countries. The Collegium Ramazzini is such an organisation, described as “an independent, international academy founded in 1982 by Irving J. Selikoff, Cesare Maltoni and other eminent scientists. It is comprised of 180 internationally renowned experts in thefields of occupational and environmental health. The mission of the Collegium Ramazzini is to advance the study of occupational and environmental health issues”80.

Its list of members includes Aaron Blair and Christopher Portier, as well as three experts in the previously cited IARC benzene evaluation. In the Ramazzini conglomerate, we also find the Istituto Ramazzini which has a research laboratory in Italy and doesnot hesitate to affix its logo next to those of associations from the world of political ecology81. In addition, some of its work has been refuted82.

When their theories are contradicted by official risk assessment agencies, the “anti-” organisations readily appropriate the results of such scientific-pretending activist structures. Considering the importance that alarmist theories on health and the environment have acquired in society, it is not surprising that scientists also adhere to such a vision of the world and that someprovide their support for certain approaches that do not have respect for the facts as a priority. In such a context, it is conceivable that these scientists could find themselves numerously in the IARC working groups.

The proliferation of false allegations clearly presents a problem for the authorities in terms of risk management and public perception. In addition, the mediatisation of organisations of parallel “science” is often associated with campaigns aimed atdiscrediting official agencies.

Accusations against a German scientific agency on glyphosate

Pesticide Action Network, Press release, 2 March 2016;“Glyphosate: Environmental organisations press charges against Monsanto, BfR and EFSA for assessment of glyphosate”, eureporter.com.

Pierre Morel, Mauricio Rabuffetti…, op. cit.

Ibid., 27’39” to 28’00”. Poorly written by the BfR, this sentence is almost incomprehensible: “Due to the large number of submitted toxicological studies, the RMS was not able to report the original studies in detail and an alternative approach was taken instead. The study descriptions andassessments as provided by GTF were amended by the deletion of redundant section (such as the so-called ‘executive summaries’) and new enumeration of tables” (“Renewal Assessment Report. Glyphosate”, art. Cit., P. 1).

“The technical databases that have been used for the literature search include:…” (“Renewal Assessment Glyphosate…“, art. cit., p. 1).

“Additional publications cited in a recent document prepared by the NGO ‘Earth Open Source’…”, ibid.

Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR), “Frequently asked questions on the procedure for the re-assessment of glyphosate within theframework of the EU active substance review”, 12 November 2015.

See Claire Robinson, “Glyphosate: Expert finds BfR guilty of plagiarism from Monsanto”, gmwatch.org, 11 October 2017, and Dr.Stefan Weber, “Expert opinion on adherence to the rules of good scientific practice in the subsections, B.6.4.8 Published data (released since 2000)”,30 September 2017.

See“Criminal complaint filed against EU authorities after glyphosate approval”,gmwatch.org, 5 December 2017.

See Stéphane Foucart “Glyphosate : l’expertise européenne truffée de copiés-collés de documents de Monsanto”, fr, 16 September 2017, (limited access); Id., “Environnement : Les industriels auraient intérêt à avoir face à eux un contre-pouvoir scientifique plus fort”, lemonde.fr, 30 September 2017, (limited access); Stéphane Foucart and Stéphane Horel, “Glyphosate :révélations sur les failles de l’expertise européenne”, lemonde.fr, 26 November 2017, (limited access); Stéphane Horel, “Glyphosate : les ONG portent plainte contre les agences d’expertise européennes”, lemonde.fr, 4 December 2017; Id., “Au Parlement européen, les impasses de la commission pesticides”, lemonde.fr, 16 May 2018, (limited access); Stéphane Foucart, “Glyphosate : les autorités sanitaires ont plagié Monsanto”, lemonde. fr, 15 January 2019, (limited access).

Arthur Neslen,“EU report on weed killer safety copied text from Monsanto study”, theguardian.com, 15 September 2017 and “EU glyphosate approval was based on plagiarised Monsanto text, report finds”, theguardian.com, 15 January 2019.

BfR, “Glyphosate: BfR has reviewed and assessed the original studies of the applicants in depth”, BfR Communication no. 028/2017, 15 September 2017.

BfR, “Glyphosate assessment: BfR rejects plagiarism accusations”, bund.de, 20 September 2017.

The BfR is the responsible agency on behalf of the reporting member state (RMS) for glyphosate, in this case in Germany. A first campaign to discredit the agency claimed that it had only taken into account documents provided by manufacturers grouped together as the Glyphosate Task Force (GTF). This campaign was accompagnied by the announcement of the filing of complaints by six anti-pesticide organisations and was taken up by the media83. These allegations are based on an interpretation of a document from December 201384 reporting on the BfR’s evaluation, part of which is presented in the French TV documentary entitled “Pesticides: la malediction du soja” [Pesticides: the curse of soya] broadcast in the France 2 investigational programme, Envoyé Spécial85. Page 1 is shown on the screen with one of its sentences magnified and presented as proof of the exclusive use of data from the GTF86. On the other hand, other sentences on the same page explaining that the BfR also carried out an independent analysis from the scientific literature87 and examined the publications cited in a document published by an organisation close to political ecology88 are not magnified and are thus illegible on the screen. Its methodology was explained by the BfR in a press release from November 201589, which did not deter France 2 from broadcasting its documentary in February 2016, also containing other inaccuracies, including the repetition without criticism of Krüger’s mentioned previously theories.

A variation on this theme was launched at the end of 2017 in a report commissioned by Helmut Burtscher-Schaden, member of theAustrian ecology organisation, Global 2000, which accuses the BfR of having plagiarised, i.e. having simply copied and pasted GTFmanuscripts for its report. At first glance, these accusations may seem credible since they involve a certain Dr. Stefan Weber, an expert on plagiarism90. Again, this campaign was accompagnied by the announcement of the filing of a criminal complaint91 and the allegations of plagiarism were widely relayed by the international press. In France, the newspaper Le Monde even dedicated noless than six articles to the

The European opinion on glyphosate

See EFSA, “EFSA explains risk Glyphosate”.

EFSA, “Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the potential endocrine disrupting properties of glyphosate”, European Food SafetyAuthority Journal, 15, n° 9, September 2017, abtract.

See EFSA, “EFSA explains risk Glyphosate”.

EFSA, “EFSA explains the carcinogenicity assessment of glyphosate”, 12 November 2015.

The above shows that this difference does not explain the opinion of the IARC, which also diverges on the interpretation of the studies reviewed by all.

See Kuntz, The Séralini affair-The dead-end of an activist science, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 26 September 2019.

The main difference between the 2015 EFSA report and previous evaluations is a new “safety measure”: the introduction of a standard of “acute reference dose*” to be used to revise the maximum residue levels for glyphosate. It appears that the EFSA, by revising the acceptable level of user exposure and daily intake for consumers, had revised the toxicity of this herbicide somewhat upwards96.On the other hand, the EFSA upholds that “the weight of evidence indicates that glyphosate does not have endocrine disruptingproperties”97. The agency also concludes that “glyphosate is unlikely to be genotoxic (i.e. damages DNA) or to present a carcinogenic threat to humans” and that “neither the epidemiological data (i.e. on humans) nor the evidence from animalstudies have demonstrated causality between exposure to glyphosate and the development of cancer in humans”98.

In the above-mentioned document, the EFSA suggests that the “this distinction between active substance and pesticide formulation mainly explains the differences in how EFSA and IARC weighed the available data.”99. It should be reminded here that the IARC has never put forward any such explanation, which is actually contradicted by the fact that both agencies considered both studies taking into account commercial formulations (including epidemiological studies) and studies using the substances alone. Therefore,this “diplomatic” explanation from the EFSA (which did not prevent this agency from being attacked by members of the IARC working group, as mentioned above) does not hold, especially since a more scientific document from the agency identifies differences in the interpretation of data100.

It is true that, unlike the IARC, the EFSA also took into account studies conducted by manufacturers (according to regulations)101. This point clearly incites suspicion. However, it should be pointed out that these regulatory studies are typically conducted by specialised service providers following current recommendations and are consequently of good technical quality (when this is not the case, they are rejected by the EFSA). In addition, it should be reminded that, in the Séralini case, the repetition of experiments by independent laboratories confirmed those of manufacturers and not those of activists102.

Journalists as protagonists in the controversy

See for example, Daniel Cressey, “Widely used herbicide linked to cancer”, com, 24 March 2015.

However, in the S., the media generally did not follow up on the many agencies that contradicted the IARC, whose opinion is still largelypresented as the “definitive” analysis.

See Jennifer Martin, Cutting Through the Clutter on Glyphosate, Food Inside, 14 January 2016.

See Barbara Lewis, “European scientists say weedkiller glyphosate unlikely to cause cancer“, Reuters, 12 November 2015; Niamh Michail, “Glyphosate is unlikely to cause cancer, says EFSA”, 13 November 2015.

See Sarantis Michalopoulos, “WHO agency isolated in glyphosate fight”, com, 20 November 2017; Justin Worland, “European Safety Group Recommends Pesticide Glyphosate Despite Cancer Concerns”, Time, 12 November 2015.

See “Nouvelles accusations sur les résultats du Circ”, lafranceagricole.fr, 24 October 2017.

See Reuters, “Virginia lawyers get prison terms for $200M Roundup extortion scheme”, 18 September 2020; In France the leftist newspaper Libération mentioned it after being questioned by readers: Cyrine Ben Romdhane, “Procès Monsanto : pourquoideux avocats des parties civiles ont-ils été condamnés ?” Libération, 28 September 2020; Le Monde published a factual article: Arnaud Leparmentier, “Un des avocats anti-Monsanto condamné à deux ans de prison“, Le Monde, 24 September 2020.

See, for example, Arman Azad, “Dozens more breakfast foods test positive for trace amounts of weed killer, report says“, CNN, 24 October 2018; Oliver Milman, “Weedkiller found in wide rangeof breakfast foods aimed at children“, The Guardian, 7 August 2018. For a critical view, see: Michael Fumento, “Ignore the Ominous Headlines About Glyphosate In Food“,realclearmarkets.com, 12 March 2019.

See Gil Rivière-Wekstein, “Envoyé spécial : Élise Lucet face à une avalanche de critiques“, agriculture- fr, 29 January 2019.

The reader will be able to get an idea of the brutality of this clash between journalists by typing (in French) “attaques contre Ducros et Woessner” on a search provider.

For recent figures, see EFSA, “Pesticide residues in food: track trends with our browsable charts“, 2 April 2020.

See Marcel Kuntz, “Crash de Cache Investigation“, marcel-kuntz-ogm.fr, 18 February 2016.

Dominique Dupagne, “Le glyphosate, les écologistes et la science“, fr, 30 November 2017.

The term “agribashing” is used by French farmers.

Stéphane Foucart, “Ce que les “Monsanto Papersrévèlent du Roundup”, fr, 18 March 2017, (limited access). Anotherinterpretation has been proposed: Monsanto considered glyphosate to be safe, but anticipated that its safety would be questioned (see “Le thriller Glyphosate pour les nuls”, forumphyto.fr, 6 November 2017).

“Monsanto Papers : des dérives inadmissibles”, fr, 5 October 2017.

“Monsanto Papers : les leçons d’une enquête”, fr, 3 June 2017.

Stéphane Foucart and Stéphane Horel, “Monsanto papers, les agences sous l’influence de la firme”, fr, 5 October 2017, (limited access).

Note that Portier is not a toxicologist, but a statistician.

For some critical thought: “Stéphane Foucart et Stéphane Horel récompensés par le Prix européen du journalisme d’enquête…vraiment ?”, over-blog.com, 16 March 2018.

Stéphane Foucart, “Le désherbant Roundup classé cancérogène”, fr, 25 March 2015.

Ibid.

See Gil Rivière-Wekstein, “Nouvelle étape dans la guerre contre le glyphosate”, agriculture-environnement.fr, 4 May 2015.

See the available emails: “Les ‘Portier-papers’, Stéphane Foucart et le CIRC”, over-blog.com, 2 November 2017.

USRTK is an American anti-GMO association created to force product labelling for foods containing USRTK then engaged in the fightagainst glyphosate (often associated in the United States with GMO crops). For an investigation on USRTK, see “Les eaux troubles des Monsanto Papers”, agriculture-environnement.fr, 13 May 2019.

See “Celles qui ont révélé les ‘Monsanto papers’ racontent comment Monsanto triche”, interview with Carey Gillam and Kathryn Forgie,net, 24 October 2017. This site, idealogically close to political ecology, explains that Carey Gillam and Kathryn Forgie are at the origin of the Monsanto papers: “Carey Gillam started as a journalist, having worked for Reuters for more than 20 years. She has worked for two years for USRTK, particularly on the Monsanto case. Kathryn Forgie is a lawyer at Andrus Wastaff attorney firm and represents the class action of some of the plaintiffs against Monsanto”.

For example, the above-mentioned Blair’s court hearing revealled his and Portier’s interactions with USRTK lobbyist Carey Gillam: The Risk-Monger, “Carey Gillam: A Rachel Carson for our Time?“, 10 October 2017.

The reader can find the details on this Internet campaign by searching for “Henry Miller + Forbes + Monsanto” and can get an idea of theauthor’s other writings here.

EFSA, “EFSA Statement regarding the EU assessment of glyphosate and the so-called Monsanto papers”, 29 May 2017, p.5.

It is also intriguing to notice similarities between the glyphosate case and the Séralini case. First, some constrained doubts were also expressed by the scientific press after the publication of the IARC’s opinion103. Second, whereas the divergence between the IARC and other agencies is often mentioned by the mainstream media104, many of whom are puzzled105 or take at face value that the divergence can be explained by the “diplomatic” reason given by the EFSA (i.e. as mentioned above: the EFSA had considered only glyphosate, whereas the IARC had also assessed formulations)106 or even defend the IARC107. The press, as a whole, remained very quiet about Christopher Portier’s ties with litigation lawyers, a notable exception being La France Agricole108. Similarly, the fact that two lawyers received prison terms for a $200M Roundup extortion scheme received little media coverage109.

Another similarity with the Séralini case: anouncements by anti-pesticide organisations were, in both cases, widely reported on bythe press. The media coverage of traces of glyphosate in everyday consumer products and of the famous detection of glyphosate in urine are examples110 confirming that our mentality has not integrated the fact that simple detection is not synonymous with a health problem.

The Envoyé Spécial French TV programme in 2016 devoted entirely to glyphosate also deserves mention. After starting with a balanced coverage of a glyphosate supporter and opponent, the programme then became one-sided with a long interview with Séralini, a report on malformed animals in Denmark and the campaign to detect glyphosate in urine. The programme was criticisedon social media and by certain journalists111. The latter, notably Emmanuelle Ducros and Geraldine Woessner, were in turn attacked by other media112.

Other programmes, also hosted by the journalist Élise Lucet, in particular that of 2 February 2016, which had completely misinterpreted the EFSA’s figures concerning the presence of pesticides in food113, had already attracted numerous criticisms114. Toconclude in relation to the information provided by public service broadcasting, it should be noted that when the glyphosate AHS study was published, a journalist explained quite justly that “to date, there is no solid evidence allowing to affirm that glyphosate iscarcinogenic”, however, showed his bias by regretting that “the best arguments to fight this herbicide” had not been used115. Therefore, the incomprehension of the agricultural world in the face of what it considers a never-ending critique116 from France Television is not surprising.

In the case of glyphosate, a major event occurred in March 2017 concerning the Monsanto company. The newspaper Le Mondeannounced that “American justice has declassified the company’s internal correspondence. As early as 1999, the company worriedabout the mutagenic* potential of glyphosate”117.

These documents became known as “The Monsanto Papers”. Throughout 2017, these internal documents, made public as part of a collective action brought before a federal court in California resulted in a veritable journalistic carpet bombing, with no less than sixarticles in Le Monde, plus an online chat and two editorials. The message is always the same: Monsanto manipulates information to the detriment of public health (Volkswagen is also condemned in one of the editorials118).

The IARC is presented as the “United Nations agency against cancer”, undoubtedly to enhance its status, and as a “model for an in-depth overhaul of European expertise”119: “how can this spectacular divergence (between the IARC and other agencies) be explained? Most observers cite a major reason: to make their conclusions, the other agencies relied heavily on confidential data provided by … Monsanto, whereas the IARC did not have access to this data”120. In addition, “to save glyphosate, the company undertook by all means to prejudice the ‘United Nations Cancer Agency’”. However “a renowned toxicologist will soon expose the matter: Christopher Portier”121. In the end, the Varenne Award and the 2018 Investigative Reporting Award of the European Presswere awarded to two journalists from Le Monde, Stéphane Foucart and Stéphane Horel for their investigations into these Monsanto Papers122.

The clear-cut positioning of the two journalists from Le Monde in favour of the IARC became clear after the publication of theclassification of glyphosate as a probable carcinogen in March 2015: “the IARC evaluations have the highest level of recognitionin the scientific community, but are often attacked by displeased industrialists”123, such as those prejudicial to the BfR – “a third of the committee members are directly employed… by agrochemical or biotechnology giants!”124 (in fact, three out of twelve members and involving companies not selling glyphosate at the time125, otherwise they would not have been able to participate in delivering Bfr’s evaluation).

Yet the drama does not end there. Closer examination of declassified documents in the U.S., including those obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, revealed that the name of the journalist who was at the origin of the Monsanto Papers campaign also appears inthese documents, since it is read that Kathryn Guyton, the IARC official who piloted the classification of glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen”, recommended Christopher Portierto contact Stéphane Foucart, and the latter thanked him for his help afterwards126. There is nothing wrong with this in itself, but these emails, part of a clearly longer series which are not available, suggest that this journalism owes much to the contribution of Christopher Portier, who himself is evidently not neutral in the matter.

It is therefore legitimate to take an interest in the history of these famous Monsanto Papers and to reexamine their interpretation. It was actually the organisation US Right to Know (USRTK127) which made the documents resulting from the legal procedurepublic, in collaboration with a lawyer of one of the law firms involved in the class action against Monsanto128. It is difficult to come to a clear conclusion on the basis of only the released documents. However, there is certainly an anti-glyphosate triad between lawyers specialised in litigation against corporates, professional activists and some members of the IARC working group129, which merits a credible journalistic investigation.

Concerning Monsanto’s influence on scientific information, two aspects need to be distinguished: on one hand, the regulatorystudies provided to the agencies, and there is no evidence in these documents as to a desire to falsify these studies. On the other hand,publications in scientific journals or in blogs gave rise to wide media coverage condemning the ghostwriting practiced by Monsanto,notably concerning articles by the American biologist Henry Miller, published in a blog on the site of the economic magazine Forbes130 but which will not be developed here since blog articles are unlikely to have influenced the assessment agencies. Anotheraccusation concerns “five articles in several scientific fields (toxicology, epidemiology, animal studies, etc.) [published] in September 2016 in the journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology”131. These articles were commissioned and funded by Monsanto, via aconsultancy firm, which is clearly mentioned in the articles, but the authors’ declarations of interest were not complete.

The question rightfully asked by the European Commission to the EFSA is whether the articles mentioned in the Monsanto Papers could have unduly influenced the agency’s evaluation. It should be reminded that the EFSA evaluation dates from 2015 and that the five articles mentioned above were published at a later date, and, therefore, could not have influenced it. The EFSA provided a very detailed response, including two other scientific reviews which had been published earlier (in 2000 and 2013): “Following this investigation, EFSA can confirm that even if the allegations regarding ghostwriting proved to be true, there would be no impact on the overall assessment as presented in the EFSA conclusion on glyphosate”132. The reasons given in this answer are as follows: “the two review articles in question are an analysis of regulatory guide line studies already included in the applicant’sdossier” and “their provenance was evident from the Declarations of Interest and Acknowledgements in the articles themselves”. According to the EFSA, “the review articles simply served to summarise or substantiate the industry position on glyphosate that had been presented, as required by the regulatory framework in the applicant’s dossier”.

An analysis on how Monsanto’s image gradually deteriorated is not the purpose of this study. Nevertheless, these facts explain theeasy acceptance of a “good versus evil” narrative, that this company is a major influencer and whose products are by definition toxic. Whether in the media or on social media, the first concern is not usually the distinction between true and false. However, the ties between a reference scientific organisation and a private company is clearly considered as discrediting giving rise to unreservedmoral judgment. This suspicion is likewise maintained towards other official risk assessment agencies. For enlightened choices, individual or collective, these agencies do not deserve to be discredited or instrumentalised by polical authorities themselves.

Political actions

The EFSA opinion seems to point to gaps in the evaluation of the product rather than to make a definitive conclusion (see EFSA, “Request for theevaluation of the toxicological assessment of the co-formulant POE- tallowamine”, European Food Safety Authority Journal, 13, n° 11, November 2015).

Translated from a declaration by the Minister to the French press.

Jean-Michel Bos, “EU to extend use of glyphosate for up to 18 months“, Euranet Plus News Agency, 1st June 2016.

Translated from a quote in “La Commission proposera une ré-homologation pour 10 ans”, lafranceagricole.fr, 17 May 2017.

Translated from a quote in “Glyphosate : Hulot pour une agriculture intensive en emploi plutôt qu’en engrais”, ouest-france.fr, 22 September 2017.

This allegation comes from a publication by an activist scientist claiming that exposure to glyphosate or another herbicide cause changes in the antibiotic susceptibility of two bacteria, which has attracted media attention, but has not been confirmed and even contradicted using the samebacteria by Pöppe et al. “Selection for Resistance to a Glyphosate-Containing Herbicide in Salmonella enterica Does Not Result in a SustainedActivation of the Tolerance Response or Increased Cross-Tolerance and Cross-Resistance to Clinically Important Antibiotics”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Nov 2020, 86 (24) e01204-20.

See Reuters, “Macron says glyphosate to be banned in France within three years“, 27 November 2017.

See Sarah Elzas, “Macron backs down on pledge to ban glyphosate in France“, Radio France Internationale, 25 January 2019.

See Reuters, “France clamps down on use of weedkiller glyphosate in farming“, 9 October 2020.