Introduction

On power and knowledge

On realpolitik

On the grand chessboard, the grand game of go, and the grand game of noopolitics

On the ego of states and the cunning of the ego

On state stoicism : soul therapy for states

The noopolitics prince, or “where deep thoughts are a duty”

On noopolitical positivism

Summary

Geopolitics is the interaction between power and land. Noopolitics is the interaction between power and knowledge. This interaction is both reflexive and disruptive. It implies a profound change to geopolitics and the art of governance, because it is concerned with the art of allowing knowledge to reign over power. Above all, it aims to avoid the current situation whereby power reigns over knowledge, which has resulted in our most brilliant minds handing over their sciences to States, sciences that should be put at the service of humankind and peace. Noopolitics recognises the existence of a noosphere, which is an ocean of knowledge with which all States share a coastline and which they can use to make up for any deficiencies in their kinesphere, the sphere of their freedom of movement.

As such, it is restricted States that are forced to innovate; all States are cognitive but their cognitive immaturity nevertheless results in them waiting to be restricted before they innovate – as with the example of China today. States, like individuals, are also unaware of their best interests, acting in accordance with a very limited rationale. While traditional geopolitics asserts that States are motivated by the acquisition of power over others, for its part noopolitics asserts that the only source of power is power over the self. This is the basis for state stoicism. Ultimately, wars can only exist due to the coexistence of knowledge and ignorance: knowledge is needed to cause the enemy harm, and ignorance to harm the conflict itself. Faced with absolute knowledge, wars can no longer exist.

Dr. Idriss J. Aberkane,

Affiliated scholar of the Kozmetsky global collaboratory at stanford University, lecturer on the knowledge economy at the ecole centrale paris and research engineer in neuroergonomics and biomimetics at the edole polytechnique (paris-saclay University), former intern of the department of experimental psychology at the University of cambridge, ambassador for Unesco-Unitwin’s complex systems digital campus, professor on the knowledge economy at Mazars University in their “Next MbA” program. idriss.aberkane@polytechnique.edu

idriss.aberkane@polytechnique.edu

Article 12 of the Universal declaration of human rights: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.” the evidence provided by edward snowden clearly demonstrates that the Agency’s actions are routinely in contravention of this article.

Geopolitics is the interaction between power and land. Spatio-politics is the interaction between power, space and time: within space, distances are functions of time. Noopolitics is the interaction between power and knowledge, between power and wisdom. It is the politics and geopolitics of knowledge. It has profound implications. They explain the behaviour of yesterday’s princes, their errors and their inclinations, and enable tomorrows leaders to overcome these errors. Furthermore, in our globalised world, it does not matter who holds sovereignty, as everything must start with sovereignty over the self. Noopolitik asserts that it is this sovereignty that, at every level of human organisations, is the source of all good and the source of all power. In this sense, it transcends Realpolitik in ways that we will go on to explore. Power will be defined as external control, knowledge as external awareness, and wisdom as an awareness of and control over the self. Originally, the term “noopolitik” belonged to a more limited vocabulary, describing national politics in which power must control knowledge. The aim of this treatise is to extend, reverse and then transcend this principle: if noopolitics is the interaction between power and knowledge, we wish to codify the art of enabling knowledge to reign over power and not the other way round.

Initially popularised by John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt at the RAND Corporation – one of the research and development bodies of the American military industrial complex, along with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) – noopolitik was defined as the national politics of knowledge, the art of controlling knowledge and data in order to prevent and, inevitably, dominate. This is still illustrated today, although not particularly clearly, by the National Security Agency. However, this noopolitik was also already being defined as the art of being “in Athena’s camp”, which is to say belonging to the side that holds the knowledge and wisdom. There is therefore a common thread running through the first noopolitics, which was actually a close contemporary of the emergence of the first World Wide Web, and that which we are codifying in this treatise. This sense of continuity and change in perspective recalls the relationship between simple tactics and Antoine de Jomini’s “grand tactique”. For while Ronfeldt and Arquilla extensively explore the interaction between power and information, they entirely neglect the interaction between power and wisdom, despite their avowed desire to position their work “in Athena’s camp”. But we know today that the NSA – which, in contravention of human rights1, has set itself the objective of intercepting every form of communication in the world-lacks nothing in information, but demonstrates a cruel lack of “Grande noopolitique” explores precisely this interaction, and here we will refer to it simply as noopolitics. Henceforth, we will define noopolitik as the politics of knowledge, and noopolitics as the geopolitics of knowledge.

Noopolitics explores the interaction between the noosphere (the sphere of all knowledge), the geosphere, in which for convenience we will also include the demosphere (the sphere of peoples) and, finally and most importantly of all for traditional and realist geopolitics, the kinesphere (the sphere of all possible actions). A human being’s kinesphere is the sum total of his or her possible movements. We have simply extended this notion to States, and we will do the same with others (in particular, notions of wisdom and stoicism) because noopolitics is a humanism. We can also explain the kinesphere with the help of Xenophon: “Strategy is the art of preserving one’s liberty of action”. Furthermore, history tells us that States are constantly seeking to increase their capacity for action, and that science and technology serve as formidable levers for these capacities – what we might call game changers-without altering their level of Because States stand shoulder to shoulder, by increasing their freedom of action they also necessarily wish to reduce that of their neighbours.

There is a simple equation to explain the relationship between States and technology: an immature State with underdeveloped technology is less dangerous than an immature State with advanced technology. The immense danger that humankind is currently confronting stems from the fact that its States are immature but their technology is relatively advanced. Considered as a paradigm, noopolitics is simultaneously rich and simple, modern and classic. It is modern because the 21st century, the century of knowledge and of our new renaissance, will necessarily be noopolitical, but classic because it also recalls, develops and even transcends Sun Tzu, Marcus Aurelius, Ibn Khaldun, Machiavelli, Clausewitz, Talleyrand, Jomini, Mackinder, Paul Kennedy, Raymond Aron and Zbigniew Brzeziński. It shares its premises with neoclassic geopolitics, particularly that of Brzezinski, who was in some way our age’s Metternich. Its outlooks include conflict resolution through transcendence rather than concession, but also the politically magnificent notion of a “peace-industrial complex” that will be developed in another treatise.

Since noopolitics is a simple paradigm – and since Talleyrand wrote that “when one is right, one does not write forty pages” – this treatise seeks a simplicity akin to The Art of War or The Prince, in the form of a pamphlet whose sections can be consulted by the reader more or less independently from one another.

On power and knowledge

We owe this expression to sheik Abdoulaye dieye and his disciple sheik Aly N’daw, who developed it in his “initiatory journey of peace”, as well as to hervé trouillet, who was a true living incarnation.

1.1

For both humans and States, two forms of power exist: power over the self and power over others. Power over the self is infinitely greater than power over others, but fear and anxiety lead to a preference for the former over the latter.

1.2

The ego stems from the fear and anxiety of annihilation. The ego of States-not their interests – has been at the source of all geopolitical ills ever since war first

1.3

States, just like humans, are fascinated by power over others and disregard power over themselves. This is invariably the source of their self-destruction.

1.4

In much the same way as humans focus their attention on what they do not have rather than what they have, only realising that they have neglected the true use and value of a faculty or an asset once it has been lost, States tend to focus more attention on pursuing new territories and new interests rather than on consolidating what they already have. If only France had been fully aware of and grateful for its possession of Louisiana! If only Napoleon had been satisfied with the territories he held prior to his Russian campaign! In both cases, the ego spoiled everything.

1.5

The internal greatness of States nevertheless becomes evident in the event of a crisis. When unwittingly plunged into hardship, States realise the value of what they had and what they have been stripped of. What they have materially lost, they therefore gain immaterially in the form of wisdom and awareness, which nobody can take away from them but themselves. For a material asset can be removed from one’s possession by others, whereas only the holder can choose to part company with a philosophical asset.

1.6

In a more general sense, there is sometimes a balance between the material and immaterial wealth of States, or between the wisdom and possessions of a State.

1.7

A man who has power but no wisdom is a danger to himself and to others. There is no point in developing the functions of an organisation whose mind is sick, in the same way as it is useless and dangerous to give a weapon to a madman. A sick State that is developing and enhancing its means of action is a cause for concern. A State is better off being strong of mind and weak of body than vice versa: in its day, through stamina, Chinese civilisation ultimately prevailed over the Mongols because it was stronger mentally than they were physically. A wise man with no power over others at least has control over himself. Furthermore, such a man is a treasure for humankind, who will always find protectors. Just as with Diogenes being looked down upon by Alexander, despite his apparent hardship he enjoys far more independence in his time than his level of power would suggest. However, the perfect man and the perfect State – as with Alexander or Marcus Aurelius and their respective empires – are those which simultaneously possess both wisdom and power.

1.8

In effect, given the choice between power over the self and power over others, immature States are fascinated and enthused by power over others. But what is better? To have a formidable tool but no sense of judgement, or to have an excellent sense of judgement but no tools? Surely the primum non nocere principle confirms that it is better to be a wise man without power than a tyrant without wisdom, as the latter is a danger to both himself and others. But for the State incarnate, the real State, it is crucial to constantly maintain a healthy relationship between power and wisdom, between tools (both destructive and constructive) and a profound knowledge of how to employ those tools, the wisdom to make use of them. Along these lines, Sufis claim that all action is but a manifestation of one’s knowledge of the world. In this respect, they demonstrate a perfect understanding of noopolitics, of which they are precursors (as all wise men are).

1.tf

A Prince must beware of any organisations that seek absolute and total power over others – full-spectrum dominance – and the logos, like puerile signs o’ the times, that are associated with such control. Such organisations have no self-awareness. Despite believing that they are serving a greater good, they are in fact humankind’s worst enemies and the most certain of paths towards its self-destruction. All the while, thanks to Realpolitik, they sincerely believe themselves to be nobly serving a higher interest.

1.10

The two sorts of power exercised by States were recently named soft power and hard power, the combination of which is known as smart power. If we had to compare States to human beings, we would better see the limits both of hard and smart power. Smart power is the capacity to charm, to win over hearts and minds. Put bluntly, hard power is the capacity to rape, to seize the body regardless of heart and mind. Expecting a nation State or people to fall in love with their rapist is to assume a certain neurosis or mental confusion on their part. It is both fascinating and symptomatic to see that this is exactly what has been expected of many Arab States over the last sixty years, as Zbigniew Brzezinski perceptively notes. In reality, recent history shows that simply raping States has never led to their hearts and their minds being won over. It is nevertheless the latter two elements that govern the body. Today the United States of America controls the bodies of Afghanistan and Iraq, but has no control over their hearts and minds. For this situation, read also Napoleon in Spain at the start of the 19th century. It is of course less likely that a people will allow its heart to be won over after it has been raped. In terms of political success, soft power is far and away the best form of authority, while hard power is only sustainably effective as a means of dissuasion, to be therefore used in defence. We have committed an untold error by using hard power in attack and soft power as a form of defence, when it should manifestly be the other way round: hard power must be used to dissuade, and soft power to conquer.

1.11

Bricks and mortar did a lot more for the Roman Empire than gladius and pila. A term was coined for the method of war employed during the 2003 invasion of Iraq: shock and awe. It is nevertheless important to understand that when destruction is used to shock and to awe a population, it will arouse the strongest resistance: Sun Tzu recommended never cornering an army, for fear that this can dangerously strengthen its resolve to fight, in the same way as the psychological flight or fight mechanism produces a desperate reaction from a cornered animal. Shock and awe by destruction can, at best, only lead to despair and thus to suicide attacks by way of retaliation. Shock and awe by construction, on the other hand, knows no limits: it inspires a fascination in peoples that can be transcendent. States therefore have the capacity to shock and awe by behaving in a manner that is politically, philosophically and technologically exemplary, and while the capacity for destruction can only have limited political results, the capacity for construction, which is positive, knows no limits. Total destruction exists; total construction does not.

1.12

All empires must balance the art of consolidation with the art of conquest, and Paul Kennedy sets out a clear case for imperial overstretch being a classic trigger for the self-destruction of empires. Overstretching empires spend fortunes on hard power, in the form of human, material, financial and technological resources. They do so not just to provoke the hatred of others, but to occupy territories whose values end up looking ridiculous when compared to their final cost. Afghanistan may well belong to the new “geographical pivot of history” (Mackinder), but its occupation has guzzled up astronomical sums from NATO that would have been better spent on infrastructural, academic, political and economic consolidation. The result is a soft power disaster, as it only leads to hate, contempt and despair. In terms of hard power, it demonstrates the unexpected vulnerability of the forces deployed, and above all their ineffectiveness. In effect, these forces have displayed a lamentable poor objectives-to-means ratio, in direct contrast to the two great Georges of America’s military history (Washington and Patton) who, fighting for a just and noble cause, delivered victories that were seemingly beyond their means.

1.13

Since immature men and States prefer to focus their attention on what they do not have rather than what they already have, the fascination of peoples and history books – history being entirely subjective, its biases and automatisms imprinted on the collective conscience – is centred far more on the conquerors than the consolidators. Idriss Shah reminds us that “History is not usually what has happened; history is what some people have thought to be significant” and that “effort makes some great men famous; even greater effort enables other great men to remain unknown”. If Napoleon had chosen to consolidate France’s territories rather than attempt to conquer Europe, would he have been so admired in his day? Yet what remains of his empire today, aside from a few good ideas and the consequences of the series of subsequent ultranationalist wars whose global nature had repercussions for the whole world? For Mao Zedong is, without doubt, the geopolitical heir of a process that was initiated during the Seven Years War, and then taken to another level by Napoleon.

The United States had the opportunity to consolidate an Atlantic peace union by investing in awe-inspiring infrastructure such as a “hyperloop” train line from San Francisco to Kiev, whose cost would still be less than the thousands of billions of dollars spent supporting their presence in the Gulf since 1981. If it had done so, perhaps its empire would not be staring at its imminent decline, as it is today. Furthermore, when an empire invests in consolidation, and provided it has the means to ward off invaders, it gains so much in soft power that it is subsequently able to conquer significantly more than if that money had been spent on the military. If, in the 21st century, an army no longer serves as a means of conquest, then so much the better. Conquest is a much too serious business to remain a supreme military mission, unless such a conquest also results in the conquest of the self. Vinci qui se vincit.

1.14

The majority of humans aim to have, in order to do and to be. Our society, defined by the industrial revolution, tacitly considers the human to be a tool, a cog in the economic wheel. This is why society has no interest in poor people. As such, individuals define themselves by their function in society: I am a teacher, I am a doctor or I am a baker. It would seem strange to present oneself as follows: I am myself, I am what I am, I am human. In order to exist socially, individuals must have (degrees, credentials) in order to do (a job) and thus to be (present themselves as a teacher, baker, etc). A wise man is the one who is in order to do and to have, and who starts by defining himself regardless of the approval of others2. The wise State follows in the same vain: defined by itself, it is interested in what it is rather than what it has. It is only in these conditions that a State or an individual can be a treasure for humankind. Armed with this philosophy, is it really so surprising that the existing international system – with its rights based purely on the mutual recognition of States – results in so many conflicts?

On realpolitik

2.1

Geopolitics and diplomacy together constitute a material medicine3 for humanity. Geopoliticians are at least as important as doctors, since the health that they work to maintain is strictly superior than that which doctors look after. There are interesting parallels to make between geopolitics and medicine, and these parallels can be used to explain the particularities of Realpolitik; for when the doctor-realpolitician makes an incision, it is not cells that are killed but human beings.

2.2

Humanity is a human made out of humans. The majority of politicians believe that the unity of some humans is required to govern all the rest. However, in the human body, there is no one small group of cells that unify the identity and the action of all cells. The central nervous system of the human body is not governed by a few neurons.

2.3

The human made out of humans can prove worthy of adulation but also ridicule, in the same way as the crowd is often much less reasonable and wise than the individual. But when crowds are given the opportunity to share their knowledge – as is the case with the virtual crowds that contribute to Wikipedia – we can see the extent of their collective excellence. Excellence, as recognised by the State or society, reinforces the ego, meaning individually brilliant people can be collectively stupid while average individuals can form an excellent group.

2.4

The ego prevents both the individual and the State from working in groups. Under certain conditions, merely functional groups are worth more than truly excellent individuals, something that our education strategy should recognise. It is the ego of the State that gets in the way.

2.5

A State’s ego is believed to be that of its leaders. However, in reality there is a constant exchange going on between the individual and collective egos, to the extent that we no longer know which one feeds the other. Unhealthy nationalism makes unhealthy nationalists, and vice versa.

2.6

Humankind has a physiology that sees it naturally lose and gain cells on a daily basis. The fact that its population is constantly growing is not a good thing if its wisdom is not also growing, but neither is it necessary to reduce the population; it is necessary for the population to stabilise of its own accord, and only if it is not innovating and learning as quickly as it is growing. Such a stabilisation must not come about through the use of force or cunning, but rather via a mutual, conscious and exemplary consensus being reached.

2.7

The art of making a decision regarding the health of humankind is like the art of making a decision regarding the health of a human. It is this similarity that led to the emergence of Realpolitik, which is simply defined by the adage “the end justifies the means”. It is in the name of this principle that individuals found guilty of high treason in the Middle Ages were tortured in the most horrific manner. Which is to say in the name of the preservation of public order, the same reason for which Socrates, Jesus or Martin Luther King were killed, and the same reason given any time a State acts against its own best interests while mistakenly believing that it is preserving them. The fundamental moral difference between medicine practiced on humans and medicine practiced on humankind is that a human has individual rights that a cell does not.

2.8

The practice of Realpolitik works as follows: 1) identify the highest objective for the common good; 2) attain it by absolutely any means necessary, in principle by respecting only the laws of physics because they are the only ones to be non-negotiable. All the abuses of empires stem from this practice, from the Napoleonic massacres in Spain to those supported by the USA and justified by its Monroe Doctrine, in particular during Operation Condor. However, there is an underlying rational principle that can be understood at the heart of these actions: if I acquire power over a certain people, they will subsequently suffer less. I therefore choose to cause a little suffering today, so that they may enjoy life more tomorrow. Many empires have evolved in this way, claiming and considering – whether they believe it or not – that their power will be more beneficial to the people targeted than that which already reigns over them. Sometimes this principle is true, yet sometimes it must be transcended.

2.tf

Primum non nocere, “first do no harm”. But the methods of Realpolitik can be compared to the scalpel: they spill blood and leave scars, to the extent that patients and witnesses must be anaesthetised before any operation. This explains the maxim that “the first casualty of war is truth”. This anaesthesia is known to us as misinformation and propaganda. The scars include terror, hate, violence and desire for vengeance. Realpolitik, by its very methods, sews the seeds for tomorrow’s wars while purporting to build today’s peace.

2.10

The legitimacy of any Realpolitical intervention is defended on the following terms: inaction has its victims, so too action. The rights of an individual being necessarily worth no more than one life, it therefore becomes legitimate to violate them as soon as at least two lives are at stake. However, in the same way as the de jure abolition of mass torture constituted a conceptual leap forward, transcending medieval forms of governance without threatening the security of populations (and on the contrary, increasing it), there must be a transcendent paradigm change capable of surpassing Realpolitik and making its methods redundant. This paradigm change is held within Noopolitik.

2.11

Knowledge and wisdom interact in a profound and subtle way with Realpolitik. Technology, for example, can be used to modify the available means of political action. Armed with a new social technology – the concept of social engineering – we could overthrow a government without, in theory, spilling any blood, although in practice the transformation from peaceful protest to coup d’état will always claim innocent lives, as was the case in Ukraine in 2014 (but not in Bulgaria in 2013). Applied knowledge can alter how an operation is carried out, be it surgical or realpolitical. What is essential is that it can also alter why an operation is carried out, its raison d’être, and above all that it can transcend the latter, in such a way that an operation that would have been very costly in terms of human lives could be substituted for another with an entirely different raison d’être. The European Union is one such example of transcendence, which has rendered any military conflicts between European States futile, although it does not prevent them being transposed onto conflicts between NATO – its biggest founder, geopolitically speaking – and other organisations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

2.5

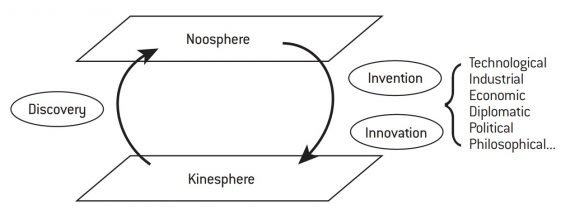

Interaction between the noosphere and the kinesphere can be illustrated in the following way:

CC3 – Dr. Idriss J. Aberkane, 2015

The noosphere – the sea of knowledge – is accessible to everyone, in the sense that everyone possesses a stretch of its coastline, and the biggest restriction to this access is not exogenous but endogenous. When applied, knowledge changes not only a State or organisation’s capacity for taking action, but also their reasons for doing so. Generally speaking, States only change their capacities for action when they are absolutely forced to: this is the reason why all-out wars have been such motors for technological innovation because, although all disruptive innovation is initially thought to be ridiculous, all-out war gives States the intellectual means to contemplate the ridiculous (as with the Nazi Wunderwaffen campaign, for example). We will see how this principle can be used to cast a critical eye over the economic-military confrontation between the OECD and the SCO.

On the grand chessboard, the grand game of go, and the grand game of noopolitics

3.1

Brzezinski described neo-realist geopolitics as “the Grand Chessboard”. There is a clear parallel to be drawn between international relations and the game of chess, in terms of the importance of controlling the centre of the chessboard in order to control the game. The heart of the African continent was the setting for an intense geopolitical combat between France and the United Kingdom that reached its climax at Fachoda, where the two nations came close to triggering a global-scale conflict (yet another since the Napoleonic wars and the Seven Years war). That France backed down, as the Foreign Office had correctly predicted she would, was largely due to the lingering after-effects of war in 1870. Today the hearts of many geopolitical chessboards are balkanised – in other words, divided into several States and/ or areas seeking independence – in order to ensure that no one power is able to take exclusive control of them. This is the case in the Great Lakes region of Africa, the Himalayas and around the perimeter of the Caspian Sea. Every region where empires have confronted each other over the course of history has been balkanised. If South America is less balkanised than Africa, it is because the Treaty of Tordesillas shared the continent out between only two empires. That North America was de-balkanised in such a decisive and unexpected (albeit shockingly genocidal) manner in the 19th century has led to a national American feeling of manifest destiny, something that they have paradoxically denied to Latin America and the rest of the world. Often on the Grand Chessboard, independentist peoples and leanings are also used as pawns to occupy strategic positions: examples include Kosovo, Transnistria, Crimea, Dagesta, Chechnya, Afghanistan and Xinjian, where more often than not any sense of moral legitimacy is pushed to one side.

3.2

As strategy is the art of preserving one’s means of taking action, it also has a dimension more akin to the game of Go. The art of restricting the opponent’s available moves is crucial. As such, today’s China is geographically restricted in almost every way possible, just as the Soviet Union during the Cold War and the Russian Federation following its conclusion. War is the last argument of kings: it is only when a power can no longer develop its capacity to take action in any other way that it decides to do so by war. The First World War, for example, was largely triggered by a situation simultaneously resembling a game of Go and a game of chess. From chess, there is the will of France and the United Kingdom to weaken the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires by balkanising the territories under their control, and by providing political and material support to separatist movements as embodied by

T.E. Lawrence’s role on the Arab peninsula. From the game of Go, there is the desire to restrict the moves available to the German Empire. The latter intended to build a railway track from Berlin to Bagdad, in order to secure a source of oil supplies. It was the perfect alliance: that of a resource-weak industrial power and an industrially underdeveloped country with rich resources. The Ishtar Gate, at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, bears witness to the era of this alliance. But France and England did absolutely everything in their power to prevent the construction of this railway (the pipeline of its day). The First World War then broke out when nationalist sentiment grew out of Germany’s control in Serbia, an essential point on the track’s route, for Germany, which was prepared to compromise on all other points, could not to do so when it came to oil supplies. In the same way, France and the United Kingdom had come close to initiating a first world conflict only sixteen years earlier when the French presence across the breadth of Africa impeded the possibility of a railway track from the Cape to Cairo. The two powers then found themselves as allies in the fight against Germany, in accordance with the British doctrine of the balance of power. History is written by the winners and, as the Triple Alliance won the First World War, today its books present the “Hun” as the baddies, even if Germany was well within its rights to push ahead with its plans for a Berlin-Bagdad railway line.

3.3

China is today’s equivalent of Germany, and Brzezinski has nicknamed Central Asia the “global Balkans” in recognition of this region’s potential to become the stage for a new worldwide conflict. Effectively, China is a new industrialised continental power that is seeking access to oil, just like Germany in its day, and NATO, like the Allies, have used every means in their power to encircle China. Were it not for the presence of nuclear weaponry, there is no doubt that a conflict would have already broken out between the SCO and the OECD countries, just as it did in 1914 between the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance. We can already see how one piece of technology – the nuclear weapon – has changed the geopolitical rulebook, and has reduced the potential third world war to nothing more than a “new cold war” that we have been secretly involved in since 1991, and openly year on year since China and Russia’s first double veto at the Security Council.

3.4

In this sprawling modern game of Go, China is largely encircled and almost all the States that provided or planned to provide her with oil have experienced troubles or been balkanised, such as Libya, Iraq, Iran, Venezuela, Syria and Sudan. That leaves Angola, a country that therefore may be about to experience troubles itself. As for the old Berlin-Bagdad railway line, it certainly has its own modern-day equivalents such as Russia’s Southstream project, due to which Bulgaria has undergone several changes in government, including that which took place in the spring of 2013.

3.5

However, these neoclassical geopolitical rules all fail to take one key fact into account: States are cognitive. In other words, States learn and become more intelligent under pressure. This is what Nassim Nicholas Taleb has called “antifragility” or, in the words of Alexander the Great, “what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger”. To take the case of China, the intense geopolitical pressure that this country is currently under actually makes her much more intelligent and much stronger. We know that it was a great error on the part of Germany to enter into an armed conflict in an attempt to see its Berlin-Bagdad railway track become a reality, and that this manoeuvre, a posteriori, was not in the country’s best interests. Similarly, even if nuclear weaponry did not exist today as a means to reasonably prevent her, it would still not be in China’s interests to try to increase her capacity for action by way of an armed conflict in Central Asia. In reality, it is those empires with the greatest capacity for action that prove to be the architects of their own downfall by acting in the wrong way, and it is only when they are more restricted that they become wiser and more circumspect: in this way, empires become enriched by constraint and adversity. This is the case with modern China, a country that should wake up every day thankful for its containment: all that it may be losing out on in the kinesphere, it is compensated for one hundred times over in the noosphere. An essential rule of noopolitics therefore centres around the existence of an escape route from the kinesphere to the noosphere, a vertical movement that is available for all States that are no longer able to move horizontally. Unfortunately States almost always wait until they are no longer able to move in the kinesphere before starting to explore the noosphere, whereas it is the latter that should always be explored first.

3.6

One of neorealism’s main limits is that it does not sufficiently recognise the existence of a noosphere, of this sea of technologies, ideas, concepts and wisdoms to which all States have access, even when they are entirely bound geopolitically. Here, they will always be able to rediscover their capacity for action. Better still, it is only the States themselves that can restrict their own access to the noosphere whereas, geopolitically, access to the sea can be blocked by another State.

Like humans, States are their own worst enemies. Furthermore, those they believe to be their enemies are in fact their best teachers. Israel should bless Palestine, just as China should bless the OECD, because the antagonist is the best teacher. The awareness of such a truth precedes the transformation of the antagonist into agonist and then into friend because, in fine, the antagonist prevents empires from acting against their own transcendent interests. Being restricted in the kinesphere obliges States to explore the noosphere, whose borders are always open to them but to which they too regularly close themselves off. Furthermore, the State that believes that it is causing damage to another by limiting its kinesphere (as with the OECD’s attitude towards the SCO, for example) does not understand that in reality it is going to make it stronger, because it will naturally push that State towards the noosphere. The second State will therefore be able to consolidate its presence in the noosphere, a process that the first State will never have the means to reverse.

3.7

The superior strategy is therefore not the art of increasing one’s movements, but that of increasing one’s wisdom, of improving not how and what actions are taken but why they are taken, developing actions until they become greater and more transcendent. Neorealism fails to understand that States are cognitive, but unaware of where their best interests lie. The difference between neorealism and noopolitics mirrors that which exists between classic economics and behavioural economics. In the same way that the perfectly rational Homo Economicus does not exist, neither does Homo Geopoliticus. States are not perfectly rational, they commit errors and they have blind spots. Furthermore, it is only the State itself that can ever restrict its own exploration of the noosphere. The same is true of individuals. Only your ego can stand between you and the path to wisdom. Only a State’s ego can prevent it from walking down that same path.

3.8

Therefore in the same way as psychology – through its understanding of how the ego works – has enriched economics, it can also enrich geopolitics. Because, just as behavioural economics exists, so too does behavioural geopolitics. The latter is enshrined within noopolitics, and is borne out of the fact that all States have an ego that is their eternal worst enemy, something that must be recognised, for example, by every wise man living in Jerusalem today.

On the ego of states and the cunning of the ego

Martin van creveld phrased it as follows: “we possess several hundred atomic warheads and rockets and can launch them at targets in all directions, perhaps even at Most european capitals are targets for our air force. let me quote general Moshe dayan: ‘israel must be like a mad dog, too dangerous to bother.’ […] we have the capability to take the world down with us. And i can assure you that that will happen before israel goes under.” (from the articles ‘we have the capability to take the world down with us’, the guardian, 21 september 2003, and ‘the war game’, the observer, 20 september 2003). israel is not to blame for such neurosis although, as any state or individual, it is solely responsible for its own recovery. All states, and in particular young states, have at some stage been slaves to the fear of death and suffering, exacerbated further in israel’s case by its people’s memories of the holocaust. can a state be entirely built around one mantra of “never again”? others, for example Aly N’daw, have responded better to this question than i.

death only exists down here on earth, not in the death is an exception to existence, not the rule: “And death once dead, there’s no more dying then” (william shakespeare) or “we do not die in the true life” (boualem Aberkane). Muslims, like Jews and christians and so many others, consider that the task of the believer is to “die before dying”, so as to achieve the state of the afterlife down here on earth. they too will not die in their true life, and they too have a great and beautiful collective soul, which is desecrated every day by their ego.

“human beings are members of a whole, in creation of one essence and if one member is afflicted with pain, other members uneasy will remain.”

4.1

Just like individuals, States have an ego. States have a true self and what the Sufis call a “self that commands”. The “self that commands” is by some distance their worst enemy, much worse than all their external enemies put together. It not only forces them down a path to self-destruction, but makes the latter seem irresistible to their unhealthy conscience. The “Samson option” or the “mad dog doctrine”4 are just two examples, among thousands, of such a symptom affecting a neurotic State.

4.2

The Sufis define the “self that commands” as that which cries “give me what I want!” and the true self as that which pleads “give me what I need!”. States, like individuals, suffer from sicknesses of the soul, which are the source of all political and geopolitical evils. And just as Jung understood that all neuroses stems from the fear of suffering, the same is true of all State neuroses and psychoses: it is in attempting to avert suffering, unrest, an invasion and so on that States justify their wrongdoings, inflicting much greater pain and suffering on themselves and others than that which they were originally attempting to avoid. It is in the name of the greater good, and often in seeking to avoid the worst, that evils are committed.

4.3

States are believed to be aware of their best interests and to act in accordance with them, but nothing could be further from the truth. States are almost always unaware of their own transcendent interests and, more often than not, it is only when they are plunged into what they consider to be a disaster that their condition improves. Sick States are incapable of differentiating between what is good for them and what is bad, of discerning a blessing in disguise from a poisoned chalice.

4.4

Let us take the case of Georges Clemenceau who, without reason, is still seen as a French national hero. Clemenceau thought sincerely – whether he was aware of his emotional inclination or not – that it was in France’s best interests to impose the Treaty of Versailles and to occupy the Ruhr. We now know that, were it not for these humiliations, Germany would not have willingly turned to the architects of the Second World War. Believing himself to be acting in France’s best interests, Clemenceau played a decisive role in the origins of her eventual submission. Now we know how heavily emotional and psychological dynamics, as a reflection of popular sentiment, weighed on this decision. In no way was it in France’s interests to demand the diktat of Versailles; French interests would have been far better served by a grand show of European clemency. We can nevertheless now see that it was due to France’s condition of state neurosis and psychosis that it was incapable of acting in an exemplary and merciful manner. Quite simply, the latter are values that still tend to be derided for being too feminine. Nowadays there is an immense array of neurotic and psychotic States, and all of them are involved in wars, above all in the Middle East, where peace will only be achieved by finding a remedy for these State psychoses, and in particular the most violent of all: the fear of abandonment and annihilation.

4.5

States pride themselves on the means that they have at their disposal: as soon as a State develops greater means, it becomes arrogant. They pride themselves on their armies and their secret services, on their technologies and their budgets. We regularly hear ministers base their importance on the billionaire budgets that they claim to have orchestrated. Yet despite all of these means, the States have no idea how to use them for their best interests. The assertion must be written down and repeated, and those who share it are doing their own bit for world peace: States do not know what is in their best interests!

4.6

Because often, in the same way as a child longs for candy, what States desire can cause them more harm than good. It is hard for the geopolitician to admit that States behave like children with weapons, but this is the reality of the world. In the same way, what States consider to be great calamities could in fact be of great benefit to them. The idea of granting the deserved title of “French by spilled blood” to all the indigenous people of the French Empire would have seemed like an absolute calamity to both the Fourth and Fifth Republic. However, there was surely a way to unify the identity and grandeur of the French Empire with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, by putting in place local governance based on principles that would have stabilised migratory flows. The solution was there the whole time, waiting in the noosphere. But the idea was never formulated because not enough time nor attention – which are to the noosphere what quantity of movement is to the kinesphere – were dedicated to finding it. However, the cost of finding it would have been absolutely negligible when compared to the cost of decolonisation, for colonisers and colonised alike.

4.7

Where does the State ego come from? Every ego systematically stems from the fear of dying. Thus young States have a particularly dangerous ego, principally for them but also for others. They flaunt vast, irrational nationalist myths that pander to base instincts and base emotions. These States are those most often found at war, teaching themselves by raising the fear of annihilation to the level of a national myth, and they often end up annihilating others: “There where the millions live their dreadful lives, killing millions more!” sung Richard Francis Burton.

4.8

If we study national existence throughout history, it appears to often serve primarily as a form of defence against another national existence. Nation States, armed with a leader and a flag, have often existed purely to guard against others: pity those which, like the Native Americans, find themselves confronted by a State without even having one themselves! Before the race for nuclear armament came the race for States, entities that ultimately serve to protect themselves from one other, or to eradicate those without a State.

4.tf

Since the ego stems from the fear of dying, and the ego of a State is nationalism, antinationalism is paradoxically the best way to reinforce nationalism, because this is what it feeds off. The external threat, the survival instinct, is effectively what both individual and State egos feed off. We must therefore not oppose nationalism, but rather transcend it. This is particularly true of the Middle East, where the nationalist sentiment only strengthens when we say to it: “be afraid of me!” It is only when we sincerely offer a message of “don’t be afraid” to nationalisms that they will be able to come together and transform into a treasure for humankind. Here’s hoping that Israel and Palestine take the time to ponder this life-saving lesson.

4.10

Being plunged into a hostile world, where death and suffering are a constant possibility, manifested in flesh and even more present in fear and in the mind, is part of the human condition and destiny. In a world without death or suffering, the ego would not exist. From a thermodynamic perspective, such a world – defined by the death of the ego – could be imagined as a world in harmony, an eternal world. This stands in stark contrast to the unbalanced world in which we currently find ourselves, which is defined by its temporal nature, the mobile image of an immobile eternity as Plato so accurately understood it. The ego-less paradise alone is worthy of being defined as the “end of history” – any other definition, not based on the individual and collective death of the ego, can never be anything more than presumptuous.

4.11

What prevents me from engaging in conversation with a stranger, whereas a baby is happy to smile at anyone? What dissuades me from sharing information, confidence, a social bond or an emotional attachment with others? Invariably, it is through fear of suffering and of being killed. This is the fear from which the ego is formed. If it didn’t exist, as is the case in the afterlife5, human society would live in total peace and harmony, and would above all be united together in a collective super-organism, united in its diversity, as emphasised by the sumptuous verses of Saadi Shirazi inscribed at the Hall of Nations6. For it is the ego that forms tribes and then States-which are modern hyper-tribes – out of an instinct for survival, but it is also the ego that prevents them from co-existing in As far as the deformation of truth goes, the ego is by nature pure dissonance.

4.12

In some ways, the Internet is the realisation of the aspiration for a world without the threat of death because, in spite of the presence of suffering and neurosis on the web, there is no immediate physical menace. Without doubt, there are a number of threats that do exist on the Internet, notably psychological and social in nature, one of the most abominable being the violation of privacy. Those who sew fear and distrust on the Internet are doing an immeasurable disservice to humankind. But we will see that a powerful method of pacifying the ego is to circulate knowledge about oneself and others.

4.13

Memories of atrocious events committed many millennia ago still reinforce the egos of the present and the future, but memories of acts of compassion can also pacify them. This omnia ad omnia interaction between the egos of the past and the future makes the collective and individual dynamics of human egos a complex system, in the scientific sense of the term. More precisely, the system is chaotic. It is an example of the “butterfly effect”: one standalone act of compassion in the depths of the Namibian desert can contribute to world peace. The Sufis call this interrelation of all things, whose form can only be discerned by the Magnanimous, the Naqsh (or Great Drawing/Design).

4.14

Among the ills of the ego can be found the desire for total control. The fear of abandonment makes the national ego want to control and subjugate its allies. The fear of dying makes the national ego want to arm itself with a Ministry of Defence, which actually serves as a Ministry of Attack. Sheik Aly N’Daw has successfully shown that the United Nations Security Council, made up of the planet’s most war-inclined countries and biggest arms dealers, is in effect the Insecurity Council. The ill ego will legitimise preventive war and intervention way beyond its borders, because preventive defence is attack and because it will believe that peace will only be achieved when it has finally taken control of all that exists out of its present reach. This neurosis is at times reflected by popular culture, which often bears witness to the spirit of an era. A fine contemporary example is provided by the superhero Captain America, who launches his shield as a weapon to slice up his enemies. The shield’s symbolic nature, its clear manifestation of neurosis and psychological immaturity, speaks for itself. The desire for total control, which sees defence perniciously transformed into attack, has seen every army deployed for the defence of a country’s integrity become an instrument of conquest: from those deployed by France’s revolutionary National Convention, which then passed into the hands of Napoleon; from those deployed in the fight against Carthage, which passed into the hands of Macedonian phalanxes; from those deployed by Washington and his successors, which passed into the hands of the military industrial complex. It is fortunate that, despite several Mongol invasions, China had hitherto remained isolationist, even if this situation is now well and truly over.

4.15

Yet the ego, avid for total control, will only find peace when it destroys itself and, in particular, when the State, instead of seeking to dominate everything apart from itself, manages to take control over itself. State stoicism is soul therapy for States, because the ego will not find peace in external dominance, but in internal control. This applies to both the individual and the State. As Idries Shah underlines, “Nothing can defile the Sufi, and he in fact purifies everything.” The same goes for the State, which reaches wisdom through the sacred application of what is within rather than through profane external actions. And the way for a State to conquer that sacred internal empire is via state stoicism.

On state stoicism : soul therapy for states

5.1

Stoicism is the art of self-control. The empires that practice it are treasures for humankind, and they enjoy unlimited soft power: they have the power to charm the entire world and, as with the philosopher’s stone, to create gold out of everything, thus rendering raw materials obsolete. Neorealism believes all international relations exist in the name of conquering others, but this is only true because the lion’s share of States have an unhealthy ego. But the sacred and true objective of international relations is not to conquer others but to conquer oneself.

5.2

A State’s ego can cause the deaths of entire peoples, sacrificed either for or against it. However, once this ego is pacified or transcended, the State becomes aware of the absolute futility of these ancient desires, for which so many collective lives have been sacrificed. Would the victims of Verdun not be turning in their grave to see how a German can now feel so at home in France, just like the Frenchman in Germany? Humankind’s most serious psychoses are state psychoses. State stoicism can be their cure. It is soul therapy for States.

5.3

However, it must be understood that soul therapy is a bitter medicine, as the soul of the individual – like the soul of the State – almost never takes the initiative to self-administer it. It takes the soul to suffer from severe pain for it to make the decision to care for itself. Furthermore, to care for the soul is to respond to the call to “give me what I need!”; for every demand of this nature, the soul will hear a thousand commands of “give me what I want!”

5.4

Thus the great danger of democracy, as successfully understood by Plato, is that a people will demand “give me what I want!” a thousand times more than they will plead “give me what I need!”. Contemporary pseudo-democracies (which are “pseudo” because their indirect nature is strictly speaking more oligarchic than democratic) have therefore become a theatre for promises that are over-inflated, impossible to keep and, above all, pernicious. However, leaders and States demonstrate exactly the same weaknesses as their peoples: they demand, like De Gaulle in Biafra or Napoleon in Russia, “give me what I want!” when they should be requesting “give me what I need!”. And the unhealthy desires of their egos result in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

5.5

Jimmy Carter learned the hard way that the soul never seeks its own therapy, and that a politician who aims to give his country what it wants will always be more popular than one who aims to give it what it needs. Perhaps America’s greatest president between Kennedy and Obama, Carter was never re-elected and nor was he even truly appreciated until the present day because, whereas Reagan gave the American people what they wanted, Carter tried to give them what they needed. He began his mandate by urging for wisdom and self-control, the perfect illustration of state stoicism: even if the era of cheap oil must come to an end, why would we not take advantage of this opportunity to transform our country technologically, why would we not turn this great transformation into a national effort during which everyone can show the same spirit of self-sacrifice as they do at times of war, uniting efforts to build rather than to destroy? This brilliant discourse of the “moral equivalent of war” shone a light on the fear outlined by William James: human egos are much more disposed to work in a team – as a tribe-when facing imminent death, than they are in times of peace. The “Carter Doctrine” was later to become a term coined for the exact opposite of this discourse: securing the Gulf oil reserves by force, something which is still in effect forty years The politician knows the gap that still exists between the ideal and the real, but he or she must under no circumstances abandon the ideal. As Sheik Aly N’Daw underlines, you can kill the dreamers but you cannot kill their dreams.

5.6

It is a lot easier to convince a people to carry out violent acts against others as opposed to violent acts against themselves. Reinforcing the collective ego-built out of fear, pride, vanity and vengeance – is an efficient electoral tool, but it can have extremely dark and dangerous long-term effects for all humankind. All European wars have constituted nothing more than an interminable ping-pong of the ego: A crosses the border of B, B crosses the border of A, and yesterday’s guilty become tomorrow’s It is both sad and amusing to consider that the political thinker can take a clearheaded look back over the hundreds of wars that the world has known, and can discern their obvious futility.

5.7

What must be willingly sought is neither an enlightened dictatorship nor a democracy of the ego (the awful “one ego, one vote”). Instead, we must seek ego-free democracy, driven by a people asking for what it needs, a mature people that can only have reached that maturity by trial and error, to which they have an inalienable right. And even if these trials or errors may cost human lives, it will never be to the same extent as the ego wars that have gone before or the trials and errors of politicians, and the futile attempts of oligarchs throughout history to control humanity via blindfolding (Brzezinsky’s “tittytainment” being one of umpteen examples).

5.8

The only way a truly mature people can exist is by making of wisdom a national culture, available to everyone, not just the reserve of the philosopher or the modern shaman, hierophant or medicine man. This people is aware of the ills of the soul and that there is no shame in treating them, whereas today nobody admits to – let alone treats –neuroses and psychoses that are nevertheless incredibly prevalent in society and are at the source of all violence.

The noopolitics prince, or “where deep thoughts are a duty”

6.1

In terms of quantity, rather than transcendent quality, the volume of world knowledge doubles every seven to nine years. Nowadays, we do not go wanting for data, information or low-level knowledge. What we cruelly lack are concepts, elegant and unifying paradigms, transcendent knowledge and, above all, wisdom. Modern-day research is no more than a factory that produces and processes data, and the researcher is merely a data zombie, a laying hen obliged to conceive articles and to beg for quotations and financing. It is a system that has abandoned all transcendence and, what’s more, the majority of transcendent publications have been rejected throughout history and continue to be today, since peer review equates to peer pressure which, brought to its logical conclusion, is one-track thinking. Today’s research is not disruptive and transcendent by aspiration, but only when it is forced to be, or even by accident.

6.2

If we must talk here about research (in both sciences and humanities; for example, information technology owes a lot to philosophers), it is because research is the infrastructure for the creation of knowledge. It does not seem possible to direct research, because to guide it would be to limit it. Yet it can be urged on and inspired: encouraging, or even obliging, researchers to work on what they really love, and not just on the best-of-a-bad-lot handed down to them by academia, could be a way to boost their creativity and productivity. However, research is fundamentally non-linear, and any attempt to linearise it is, although reassuring for the limited mind, limiting in itself.

6.3

A very strong correlation can be traced in China between the increase in the number of scientific publications and the growth of gross exports. Of course, correlation does not equate to causation, but this growth proceeds from Chinese noopolitics, which is a factor for peace. The country has decided to urge its researchers to produce as many papers as possible (from which the preposterous university rankings lists are essentially drawn, the most influential of which is unsurprisingly Chinese) which has led to numerous abuses, but which also clearly correlates to its progress in the knowledge economy. Research is an infrastructure developed for the production of knowledge. Knowledge is being extracted today as oil was yesterday, which at least suggests a realisation that knowledge is the new oil, even if this may not be the right way to extract it.

6.4

We know then that knowledge will be the oil of the future. But whereas matter is finite, knowledge is infinite. And any exploitation of the value of matter proceeds from knowledge, which is ultimately not only the most essential resource in the world but also one that encourages sharing, because knowledge exchanges are positive sum (Soudoplatoff’s law: to share knowledge is to multiply; to share matter is to divide). It is essential for States to better produce, but also to better distribute knowledge; to profoundly reform their education systems in order to structure them around love rather than a duty to knowledge. For love (appetite) is the only stimulus capable of maintaining a high flow of knowledge over the long term.

6.5

Yet maintaining a high flow of knowledge is absolutely a duty for all States, and in particular for a democracy. This duty saves more lives than any other, and remedies pain and ignorance in civilisations, which is why it is so sacred.

6.6

Furthermore, if the circulation of knowledge is an infrastructure, States must consider it as such and consequently make the necessary investments: this is Bruce Cahan’s law. After all, what is a superpower? A vast connected territory, and a population to match. The art of connecting one’s population is strictly noopolitical, and is the result of the construction of simultaneously solid and flexible infrastructures that are cultural and social, but also technological (tablets and the Internet today, neuroergonomics tomorrow).

6.7

Edgar Poe described paradise as that place “where deep thoughts are a duty”. Governance via the expression of this national duty is the true noopolitik. It is a strictly internal effort, focused on the self and not on anybody else. Its goal is not to acquire the knowledge to venerate power, but to have the power to venerate wisdom and transcendent knowledge. As the Sufis put it: the worst scholar is he who visits a prince, the best prince is he who visits a scholar. This phrase perfectly describes the noopolitical prince: knowledge reigns over power, and not the other way round! Did Socrates ever ask for an audience with a general? Did Diogenes ever visit Alexander? Such a proverb reminds us that a State becomes corrupted when its knowledge is placed at the service of power, and that it is only healthy when power is serving wisdom.

6.8

As noopolitik involves making changes to the self, it is generally unpopular. However, its applications are vast and any State that masters it is a treasure for humankind and will be the birthplace of marvels, like the Internet and the personal computer in their day. It is a duty for all States to be treasures for humankind, and they must start by being treasures for their own people, because it is the State’s responsibility to serve the people and not the other way round. It is also interesting to note that every time military technology is put at the service of civilians, it becomes a treasure for humankind. This observation is at the heart of the military industrial complex, which is the wilful transformation of weapons of mass destruction into means of mass construction. By this process, empires will be able to consolidate in the blink of an eye, rather than expand, and to cultivate their soft power through exemplariness, the shock and awe of hope rather than that of despair. For despair is finite, whereas hope knows no limits.

6.tf

It is vital that today’s States guarantee a high flow of confidence, knowledge and wisdom. The ruler who can master this art is the Prince of Noopolitics. In its preamble, Unesco declares that such an art is the only way to bring about world peace. However, the absolute danger would still be to lay the foundations for a high flow of knowledge, but without wisdom. This would only result in strengthening the ego by placing new and more powerful technologies at its disposal. A rich and powerful ego is something we should all fear.

On noopolitical positivism

7.1

Any war can only exist due to a combination of knowledge and ignorance. Knowledge is needed to cause harm, and ignorance to transcend the conflict; knowledge to harm the enemy – yet today’s enemy is in truth tomorrow’s friend, as any general who kills someone today deprives their grandchildren of a possible future friend – and ignorance to harm the conflict, which is the only eternal enemy. Any war therefore requires a certain mastery of the art of war but also the absolute ignorance of the art of peace. The latter is in fact the war against the ego, an inner struggle that Muslims who still have some memory on the subject refer to as the “greater jihad”. This mixture of ignorance and knowledge is the gunpowder of all wars, which fuels these parasites of humankind.

7.2

Clausewitz uses the term “fog of war” to refer to the unawareness of your enemy’s actions. Yet if we consider war itself to be the true enemy, the ignorance of how to destroy it is the “fog of the war on war”. As far as noopolitics is concerned, the fog of war is the unawareness of the means available to make peace, the ignorance of how to effectively wage war on war. It is the unawareness of how to make peace because, as Martin Luther King taught us, peace is so much more than the mere absence of war.

7.3

It is apparent that in the context of total and absolute knowledge, wars would no longer exist. This observation is the basis for noopolitical positivism. Burton described the afterlife and the dissolution of the ego (“I”) in a context of total knowledge: “This “I” may find a future Life, a nobler copy of our own, /Where every riddle shall be ree’d, where every knowledge shall be known; /Where ‘twill be man’s to see the whole of what on Earth he sees in part.”

7.4

“If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” The more States develop their capacity for destruction, the more they will see destruction as the only solution to their problems. Regretfully, the Middle East serves as a clear illustration of this. This is why feminine-minded leaders are needed there, like Ruth Dayan, for whom conciliation, compassion, patience, humility, self-sacrifice and harmony are the everyday tools of her trade. There is a profound link between women and peace, because socio-evolution has often entrusted women with the role of preserving the life that only they can bring to the world, and men with the role of taking it away. It thus follows that patriarchal values are built around competition, vengeance and war, while matriarchal values are built around compassion, patience and unconditional forgiveness.

7.5

The prisoner dilemma is a concise expression of noopolitical positivism. Two prisoners are separately interrogated, and given the choice either to betray the other or to say nothing. If the two stay quiet, they are freed; if one says nothing and the other betrays him, he is condemned to twenty years of prison and the other is free; if the two betray each other, they are each condemned to five years of prison. The strategy that makes most sense from an individual perspective is betrayal and, being so individually, it therefore becomes the most probable and stable strategy collectively, even though it is not the best strategy for the group. This situation corresponds to the Nash equilibrium, which is stable. The situation where the two prisoners trust each other is the Pareto optimum, which is unstable. It can be demonstrated that the Pareto optimum becomes even more unstable with the addition of more participants, whereas the Nash equilibrium becomes ever more stable.

7.6

Nuclear disarmament is a prisoner dilemma because, if only one power decides to keep its weapons, the others have too much to lose by themselves disarming. The signing of the Kyoto Protocol has a similar appearance, because States think that it will induce negative growth, or at least an economic slowdown (although nothing could be more false!), and that any country that does not respect it will have an advantage over all the others. In reality, as Gunter Pauli has demonstrated, in the same way as the sudden and total abolition of slavery forced the northern states of the USA to be the first to change their production paradigm and to thus become industrialised before the southern states, the abolition of pollution would force us to enter a new industrial and economic paradigm (the “blue economy”, as Pauli calls it) with a significantly higher rate of growth. However, it must be acknowledged that, in the case of nuclear disarmament, we are failing because the Pareto optimum and the Nash equilibrium are different. What’s to say that there is no one situation of world peace that is simultaneously stable (Nash equilibrium) and collectively optimal (Pareto optimum)? This thought experiment is an example of noopolitical positivism because, if such a situation does exist, it can only be found in the noosphere, just like any transcendent resolution of a conflict.

7.7

Ultimately, geopolitics is much more about controlling peoples than it is territories: controlling a territory is only of interest if it directly or indirectly leads to control over a people. When geopolitics is submerged in absolute knowledge, its great futility becomes evident: planet Earth is but a dot in the universe, and there are quite simply more stars in our galaxy than individual beings throughout the entire history of humankind. And there may well be the same number of galaxies in the universe as there are stars in the Milky Way. The disappearance of a star, or even an entire galaxy, will up until now have been more frequent than the loss of individual humans in the history of the universe. This illustrates quite how ridiculous wars over resources really are when placed into the context of the immensity of knowledge and of the universe, and that energy supplies – the source of all wars, ahead of capital, which is no more than a ration coupon in comparison – are perfectly plentiful for everyone in the universe. Noopolitics is the practice of submerging geopolitics in absolute knowledge; it can therefore clearly be seen that transcendence is a natural method of noopolitics.

7.8

There are, as Ghandi would say, easily enough resources on Earth to satisfy everyone, particularly when knowledge lends a disruptive helping hand in developing those resources. But, as Ghandi also used to say, there are not enough earthly resources to satisfy everyone’s ego, and certainly not every country’s ego. As for knowledge, it can – if we so desire – guarantee infinite growth.

7.tf

Geopolitics is therefore a science that will lead humanity to its own destruction, and just like any human who will only ever have been a hundred billion times rarer than a whole star in the universe, geopolitics retains its importance because it deals with errors and deaths, things that are rarer than entire stars.

7.10

In conclusion, to understand the extent to which knowledge can hold all the causes of a conflict in the palm of its hand, let’s analyse the very vertebral column of almost all the great conflicts over history: the Silk Route. It was the stage for the saga of Alexander the Great, then for the crusades, for all the wars over Jerusalem, and today the route has ended up becoming the Oil Route, as strategically significant and contested as it ever was. In the same way as illiterate peoples were mobilised during the Crusades by talk of kicking the infidels out of the holy city, today religions are used to control or unsettle the Oil Route. But where does this route come from? The answer is knowledge: the Chinese planted mulberry trees to regenerate their soils and, one day, decided to use what they had believed to be a waste material, the protein fibre of the silkworm of the mulberry tree. The reason behind hundreds of years of war was borne out of knowledge about a little moth. All the wars of the twentieth century were linked to oil, and they remain more so than ever at the start of the twenty-first century, with the OECD doing all in its diplomatic power to cut off China, just as the Allies had tried to with Germany in 1914. However, Paolo Lugari has demonstrated that it is possible to produce renewable hydrocarbons in locations far from the Silk Route. By planting Caribbean pines in the desertified lands of Las Gaviotas in Colombia, the Italian visionary created prosperity out of almost nothing, in particular by using the pines’ rosin, discovered to be the source of an excellent biodiesel. This is just one example of the infinite disruptive power of knowledge, and the infinite peaceful power of wisdom. For men and States are in reality able to create their own routes for silk, oil or gold wherever they so choose. In the great and ultimately happy story of humanity, the last 5,000 years – during which we have believed that these routes make humankind rather than it being humankind that reigns over these routes – will prove to have been nothing but a short diversion.

7.11

It is up to humankind to reign with wisdom over the land, and not up to the land to reign over humankind. When will we stop dying in the name of territories? When will we start to feed territories with our wisdom rather than with our blood?

7.12

Let us progress beyond routes for silk or oil. It is possible to create, in any location and at any time, routes for wisdom. That is the true meaning of being in Athena’s camp.

7.13

It is up to power to bow down to Truth, not Truth to bow down to power. Truth is the supreme form of power.

No comments.