Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2021

The main lessons of the study

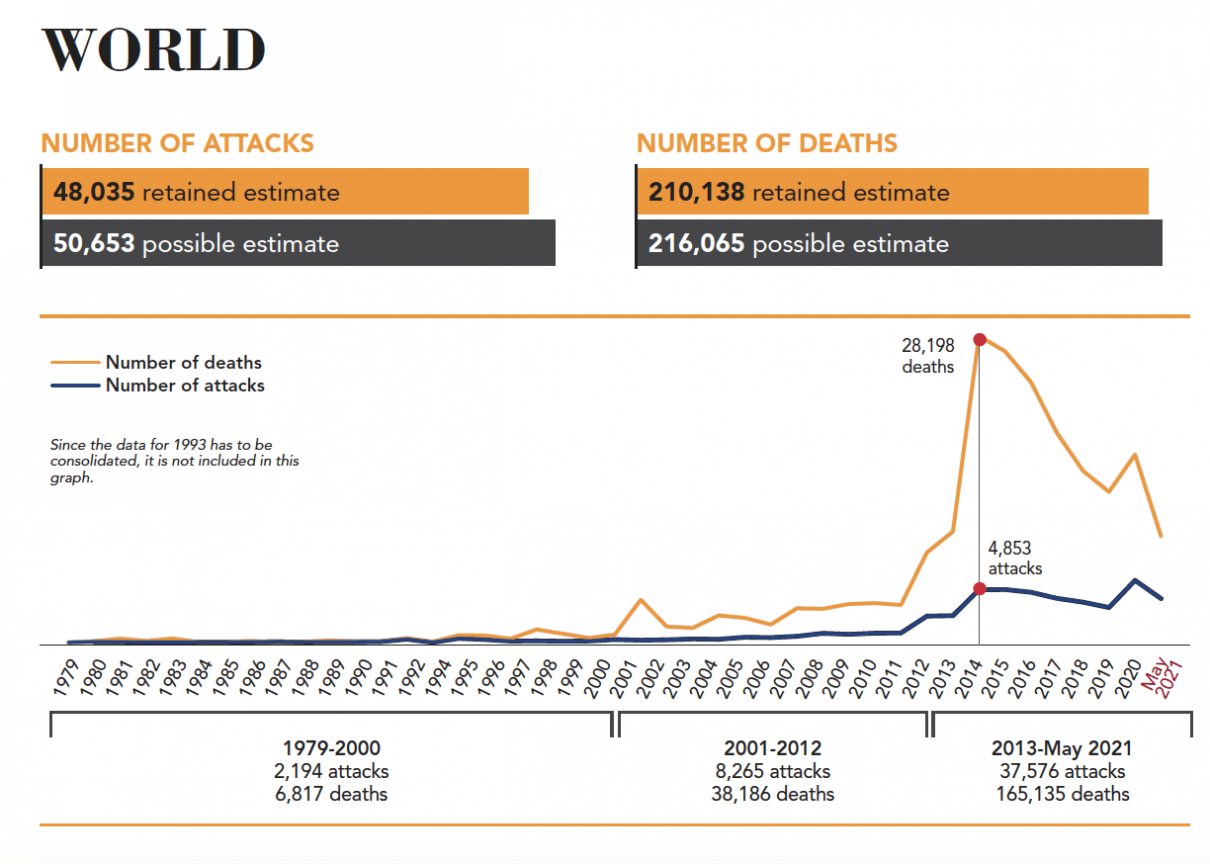

Between 1979 and May 2021, we counted 48,035 Islamist terrorist attacks around the world, which have resulted in the deaths of at least 210,138 people.

On average, an Islamist terrorist attack caused the deaths of 4.4 people.

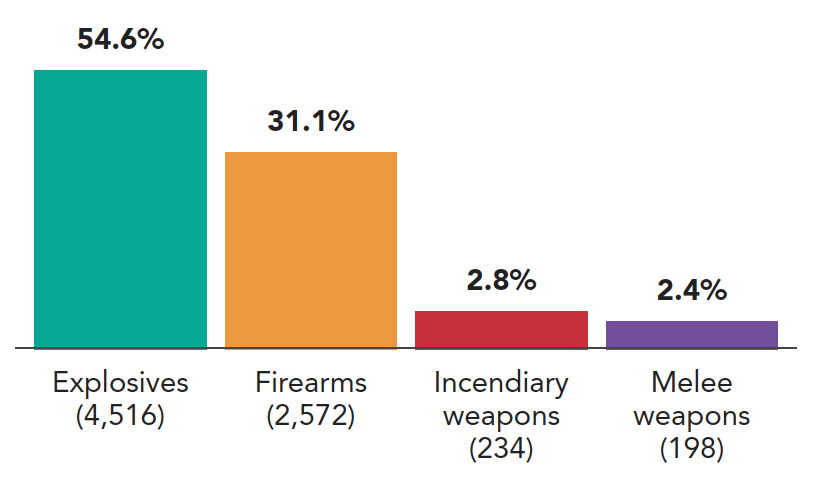

Explosives were the most used weapon (43.9% in 21,082 attacks), followed by firearms (16,649 attacks), melee weapons such as knives or machetes (2,120 attacks), and incendiary weapons (960 attacks).

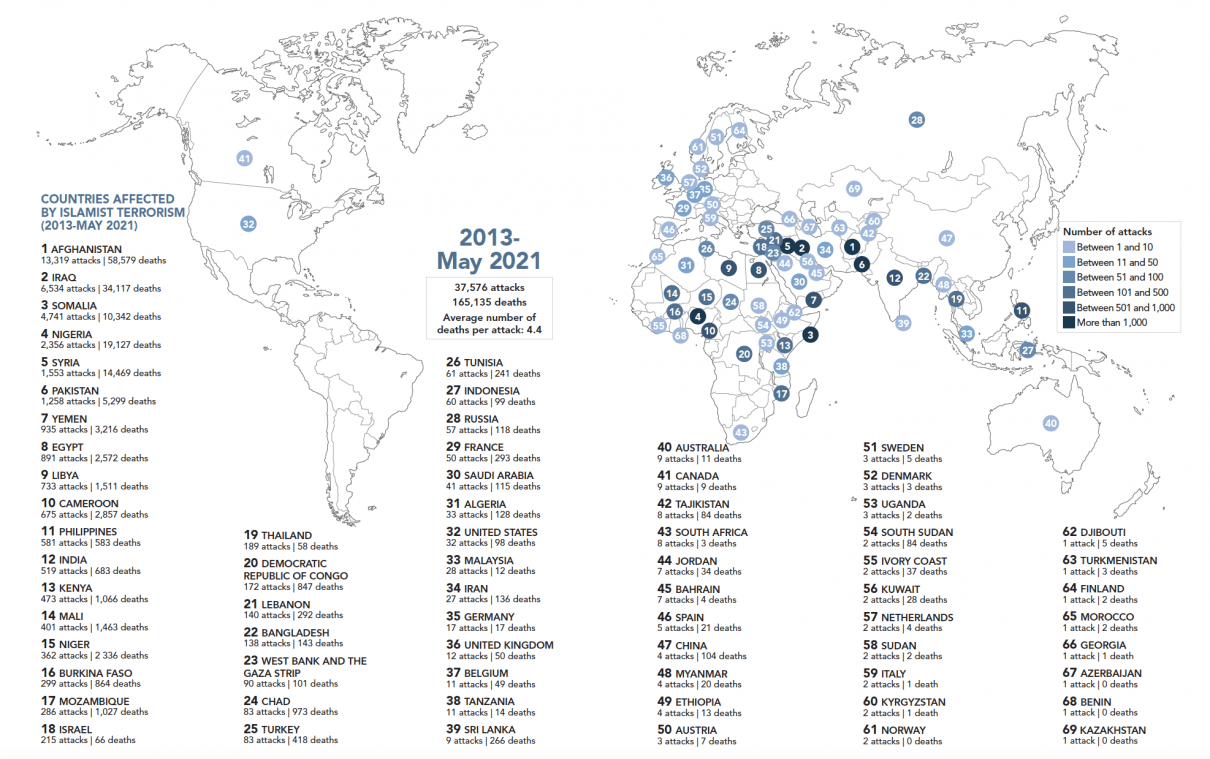

The Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 95.7% of Islamist terrorist attacks between 1979 and May 2021.

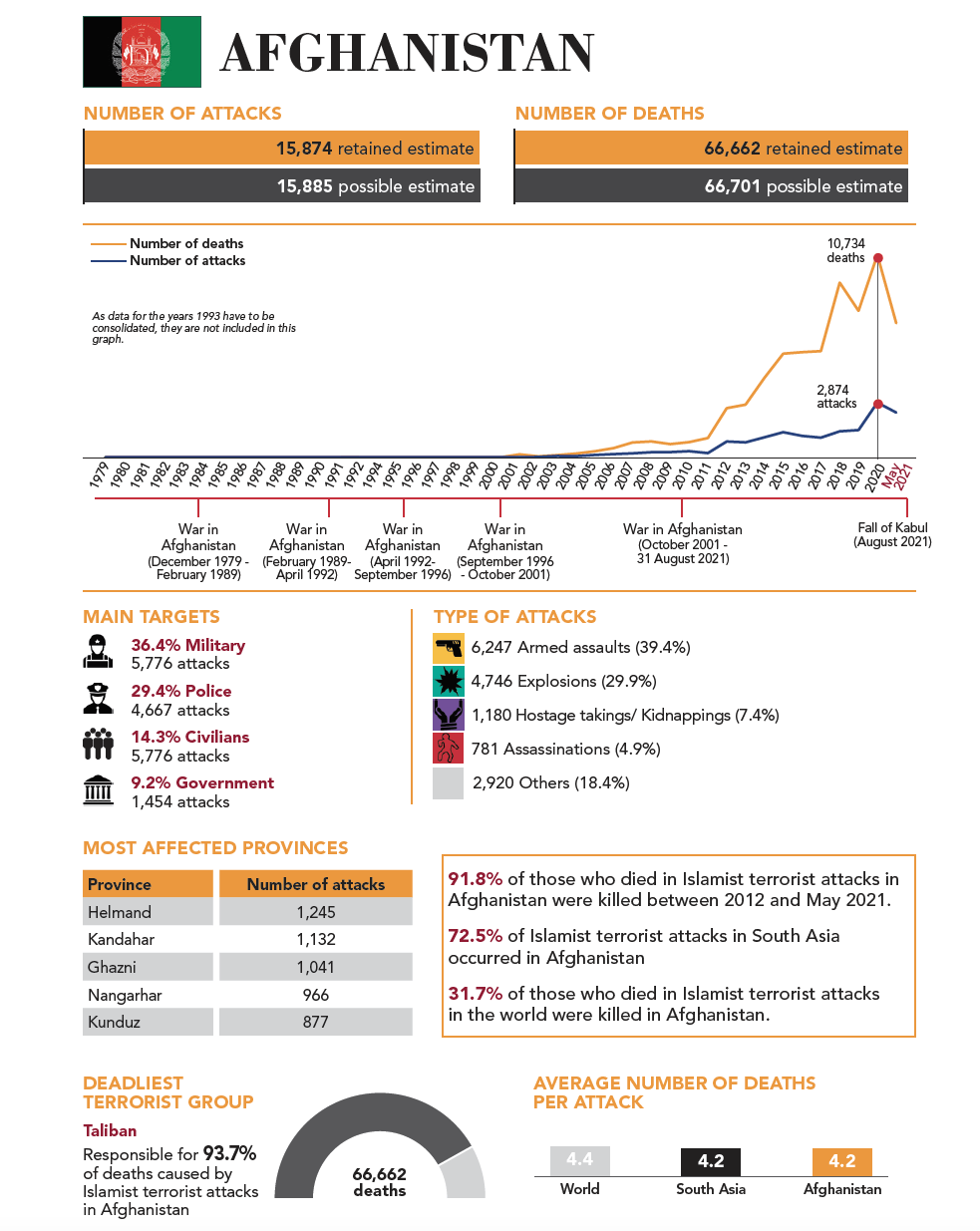

Afghanistan was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, ahead of Iraq and Somalia.

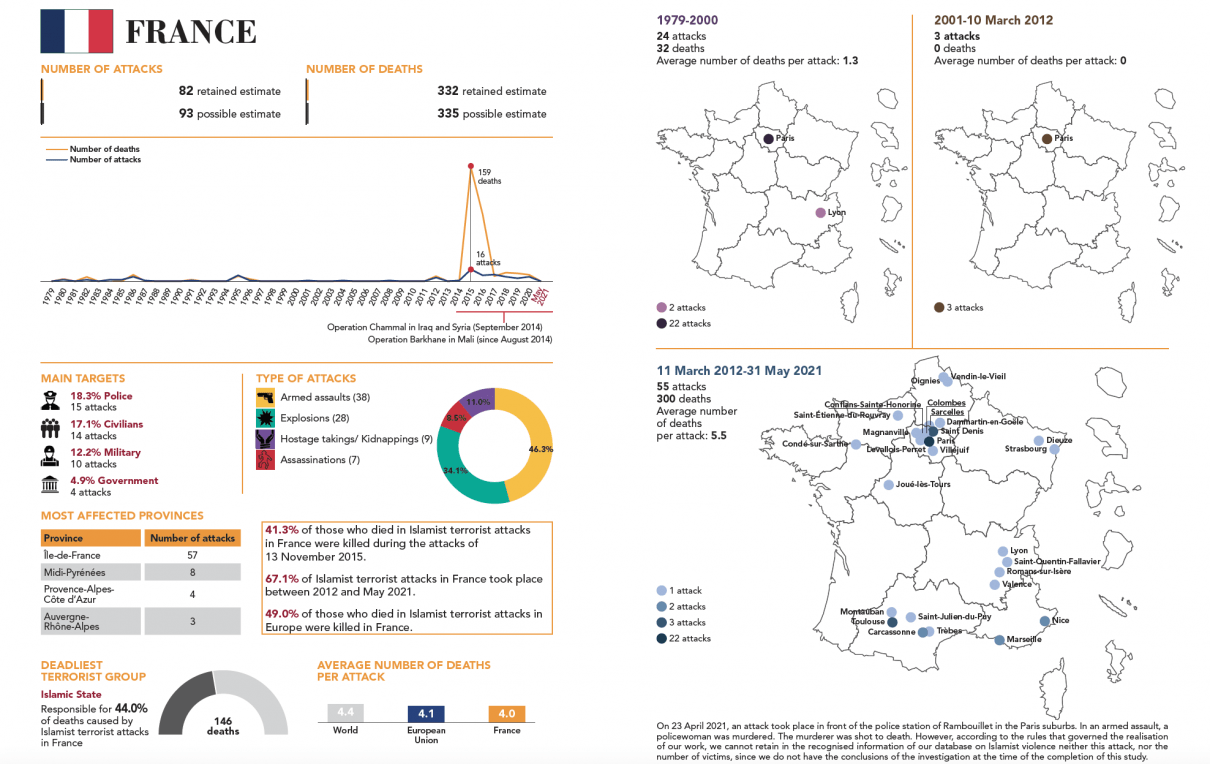

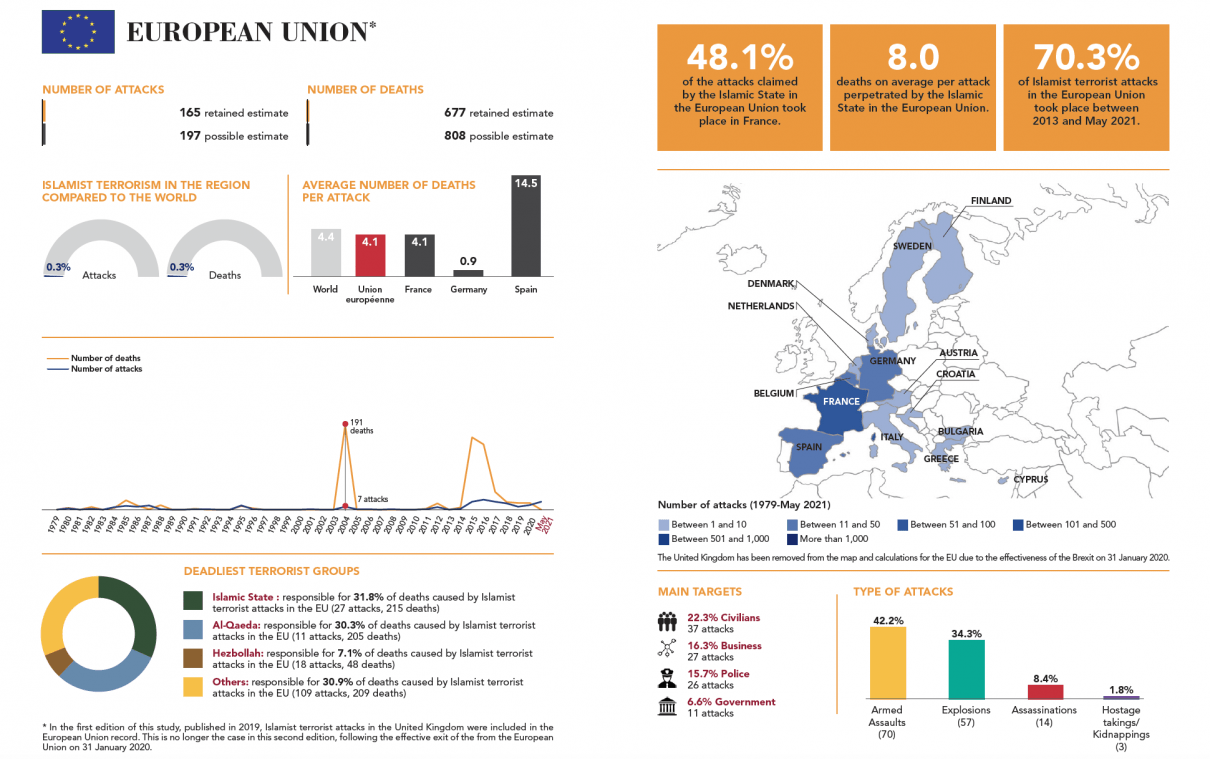

France was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism in the European Union, with 82 attacks committed on its soil between 1979 and May 2021. At least 332 people were killed in these attacks.

The indirect confrontation in Afghanistan between the American and Soviet powers is one of the major causes of Islamist violence of the 21st century.

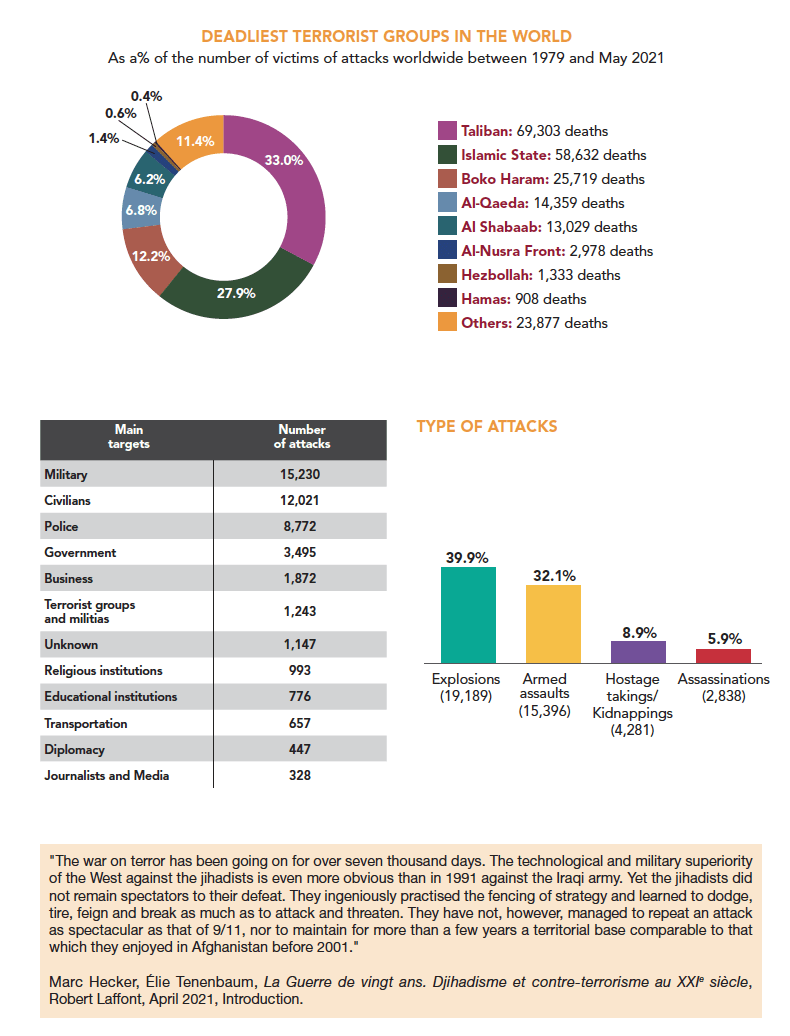

The military is the main target (31.7%) of Islamist terrorists, ahead of civilians (25.0%) and police forces (18.3%).

Most (89.5%) of Islamist terrorist attacks have occurred in Muslim countries1. Similarly, the vast majority of deaths from Islamist terrorist attacks (91.7%) occurred in Muslim countries.

Over the entire period of time studied here, the Taliban was the deadliest group. Its terrorist actions resulted in the deaths of 69,303 people.

An evaluation of Islamist violence in the world (1979-May 2021)

1979, the critical year

Definition of terrorism

Definition of Islamism

A global database of Islamist terrorist attacks from 1979 to May 2021

The reasons why, however, our study underestimates the reality of Islamist violence

The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000)

The Soviet-Afghan war, “matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism”

The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism

The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa

The export of jihad

The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012)

9/11 and the war on terror

Globalisation of Islamist terrorist attacks

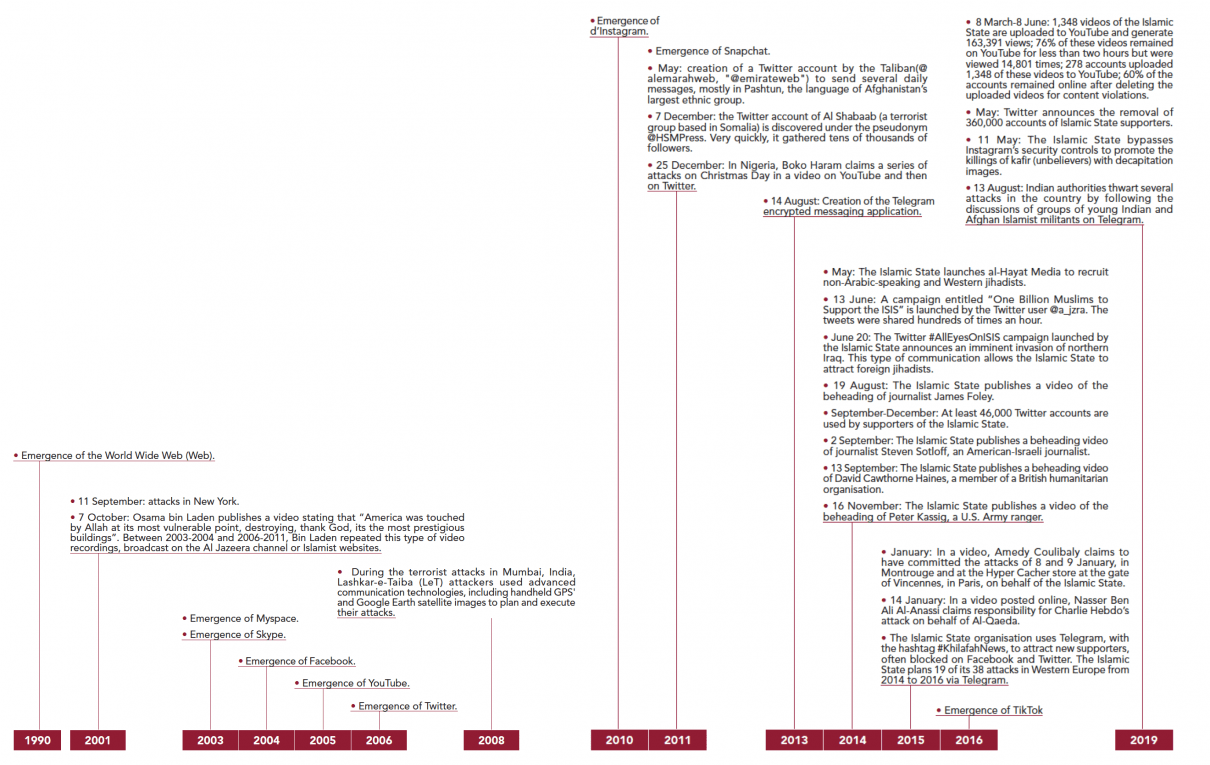

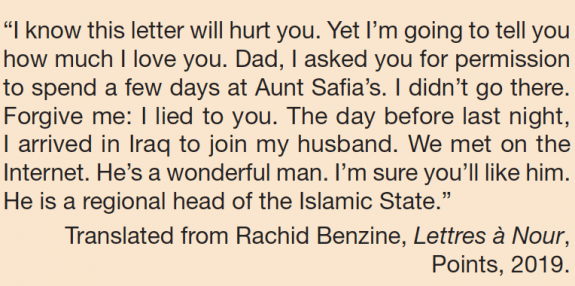

Terrorist migration to social media

The irruption of the Islamic State and Boko Haram (2013-May 2021)

The Islamic State and the “management of savagery”

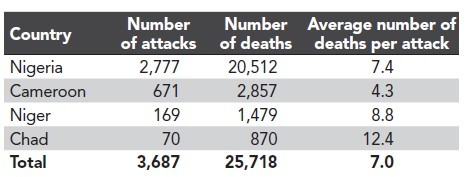

The Lake Chad region against Boko Haram’s mass terrorism

The suicide attack, the “martyr” and the terror

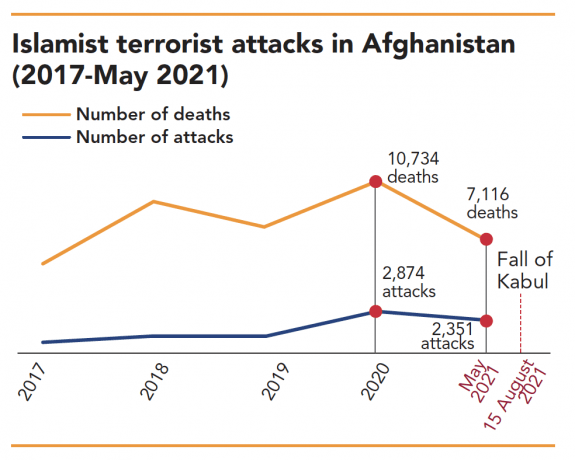

Afghanistan, the country most affected by Islamist terrorism in the world

In 2021, sub-Saharan Africa remains an epicenter of Islamist terrorism

The territories of Islamist terrorism (1979-May 2021)

The most affected countries (1979-May 2021)

Summary

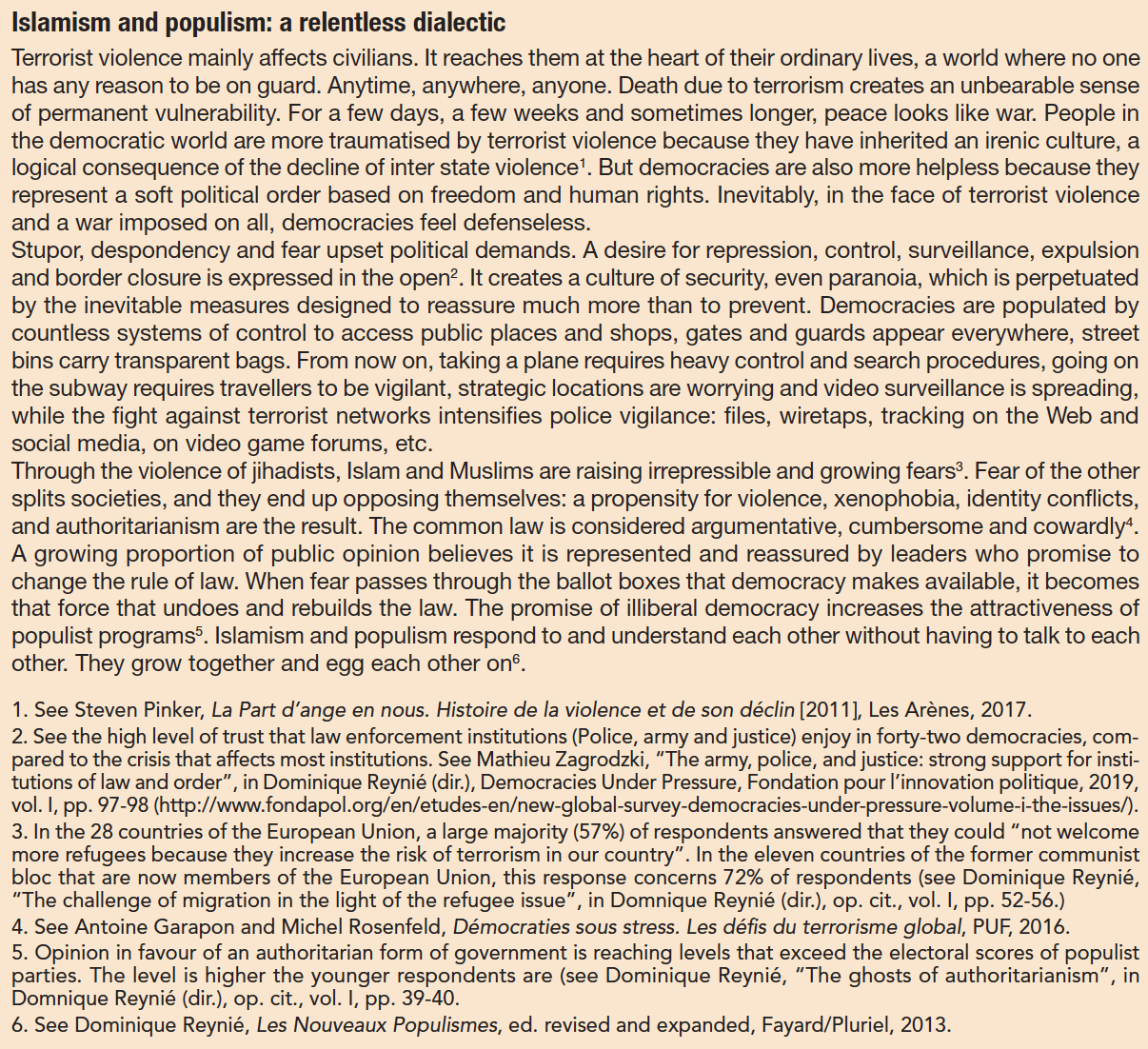

The period between the invasion of Afghanistan by the Red Army in 1979 and the capture of Kabul by the Taliban on 15 August 2021 corresponds to a rise in Islamist terrorism. As attacks have multiplied, they have struck all over the world, reaching into the heart of Western countries – New York, Madrid, London, Paris, Moscow… – exacerbating feelings of fear, mistrust and suspicion of Muslims, and even of anti-Muslim sentiment. In democracies, Islamist terrorism fosters both rejection of Islam and demands for authoritarianism.

Despite its importance, the reality of this violence has not been accurately measured. The Fondation pour l’innovation politique wanted to contribute to this assessment by quantifying Islamist terrorism, identifying the forms it has taken over the decades, listing the acts it may have inspired or initiated, estimating the number of its victims, and identifying the most deadly organisations and the countries most affected. This pioneering work was published in November 2019 in a report entitled Islamist terrorist attacks in the world. 1979-2019, available online at fondapol.org, in French, English and Arabic. To do this, we collected a huge amount of information, to the point of building a voluminous database available in open data on our website data.fondapol.org.

Two years later, we offer readers an update of our database, which has become indispensable for the description and understanding of a new and singularly problematic political reality. The update of the study proposed here extends through May 2021.

The revival of this important work echoes the commemoration of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. The twentieth anniversary of this tragedy coincides with President Biden’s announcement of the U.S.’ withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban takeover of Kabul on 15 August 2021, and the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops from Afghanistan on 31 August 2021.

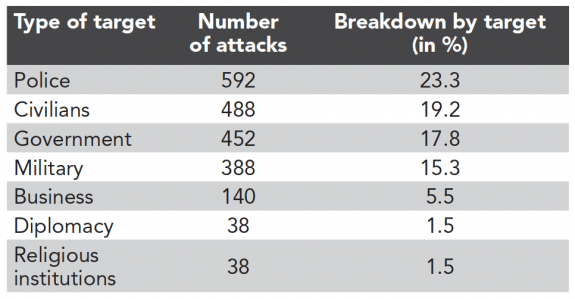

We believe that the mass of information gathered sheds new light on the phenomenon of Islamist violence. It makes it possible to better describe it, to better understand it, to document its severity. Thus, by way of illustration, we can establish that between 1979 and May 2021, at least 48,035 Islamist terrorist attacks took place worldwide. They caused the deaths of at least 210,138 people. On average, an Islamist attack has resulted in the death of around 4.4 people. We identify and quantify the modus operandi and targets. Explosives are the most common type of weapon used (43.9%), while the military is the main target (31.7%), ahead of civilians (25.0%) and police forces (18.3%). The picture of this phenomenon is becoming clearer. Afghanistan was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, ahead of Iraq and Somalia. Within the European Union, France was the country most affected, with at least 82 Islamist attacks and 332 deaths. We also show that the majority of Islamist attacks (89.5%) were in Muslim countries and that the victims were mainly Muslims, in the same proportions.

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022 The populist risk in France

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Abdellah BOUHEND, Victor DELAGE, Katherine HAMILTON, Léo MAJOR

Loraine AMIC, Abdellah BOUHEND, Victor DELAGE, Anne FLAMBERT, Léa GHILINI, Élisa GRANDJEAN, Madeleine HAMEL, Katherine HAMILTON, Camille JAFFIOL, Léo MAJOR, Sasha MORINIÈRE, Dominique REYNIÉ, Mathilde TCHOUNIKINE

Julien RÉMY

September 2021

The main lessons of the study

Between 1979 and May 2021, we counted 48,035 Islamist terrorist attacks around the world, which have resulted in the deaths of at least 210,138 people.

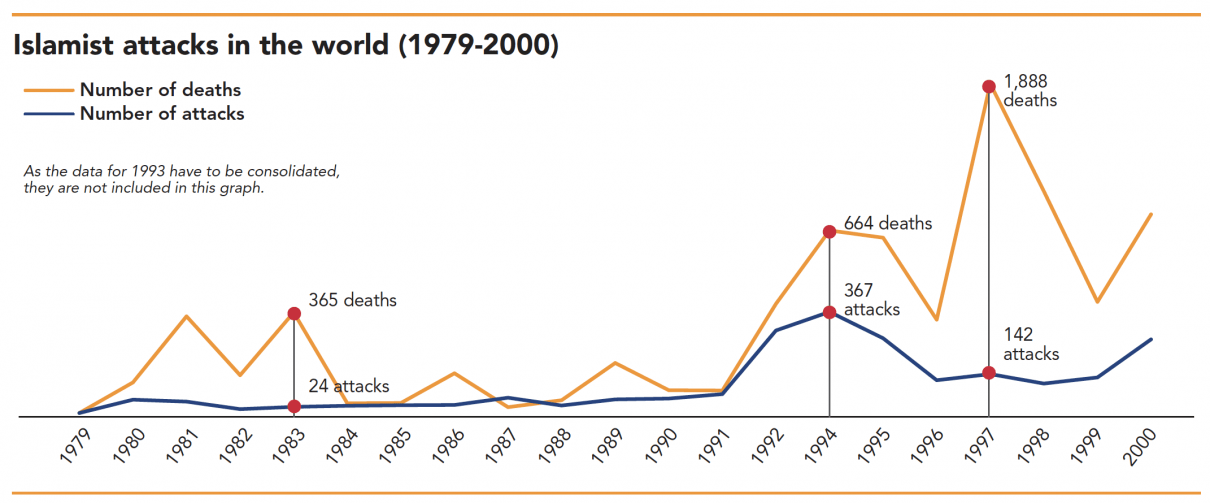

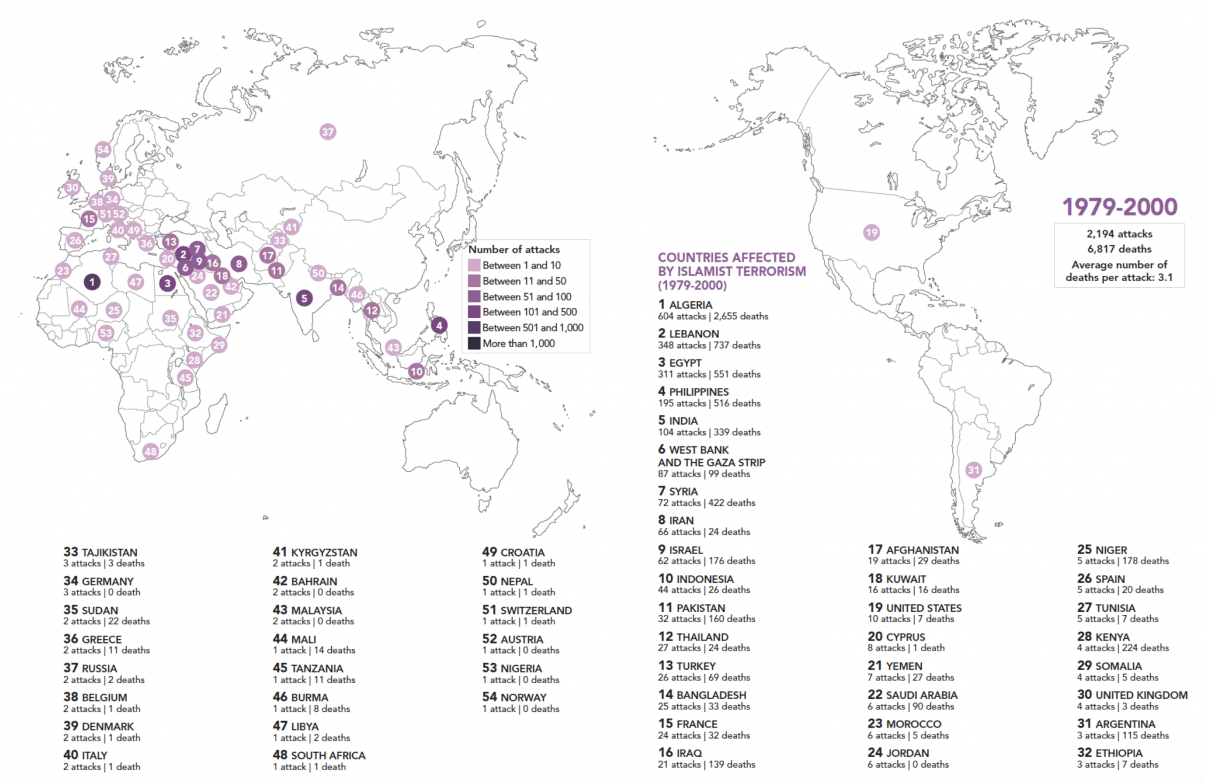

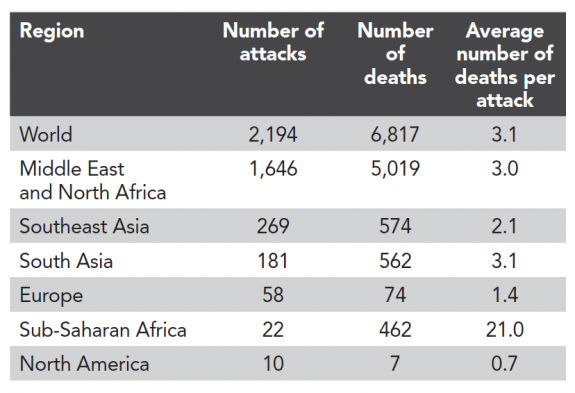

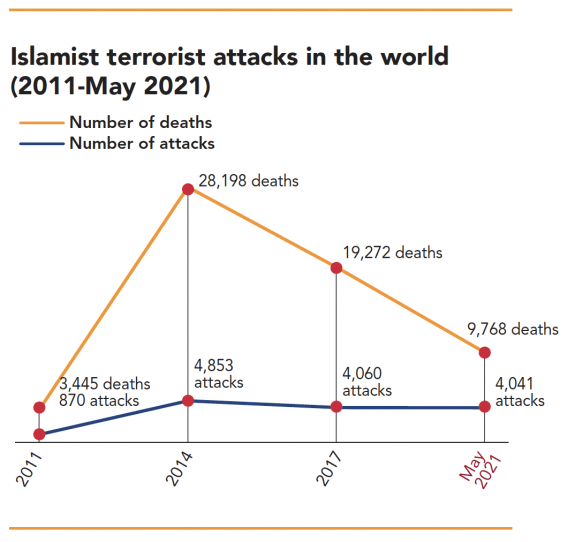

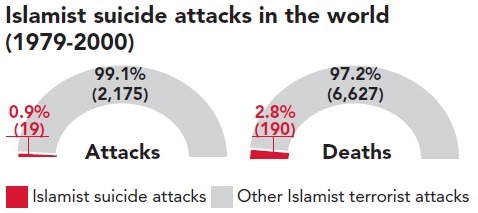

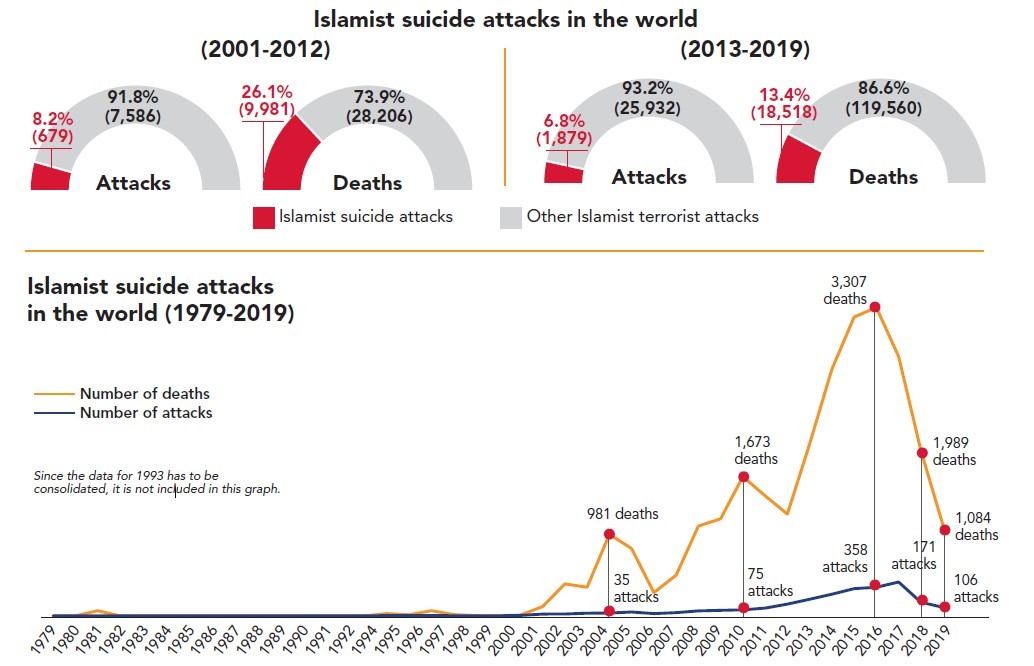

• 1979-2000: 2,194 attacks and 6,817 deaths.

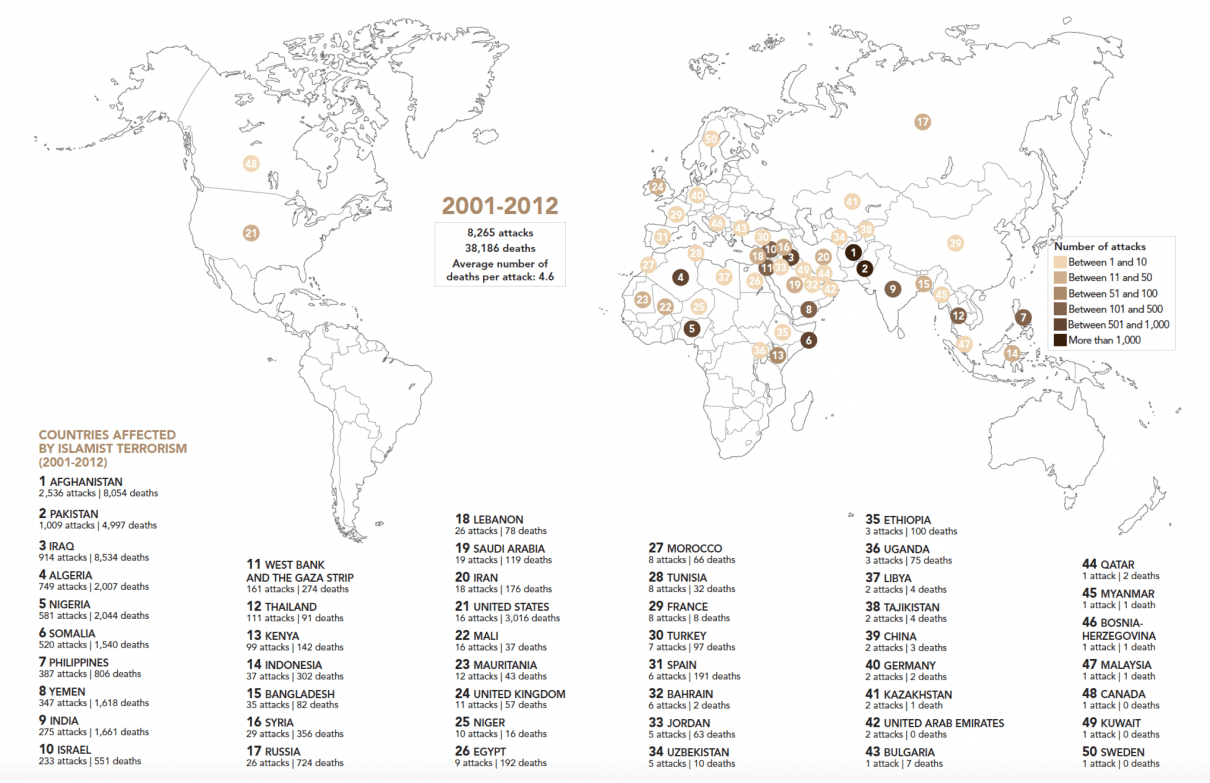

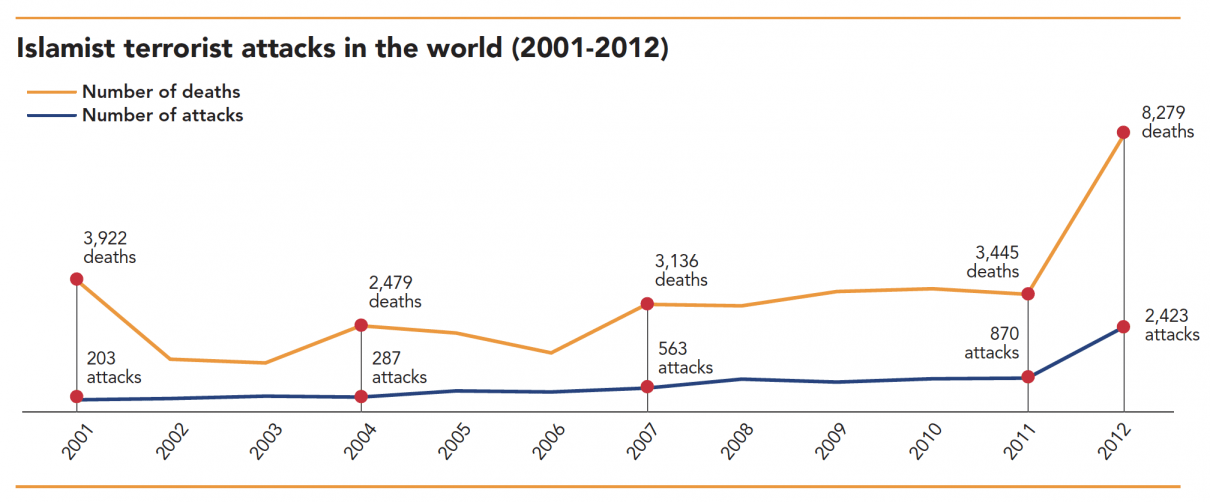

• 2001-2012: 8,265 attacks and 38,186 deaths.

• 2013-May 2021: 37,576 attacks and 165,135 deaths.

On average, an Islamist terrorist attack caused the deaths of 4.4 people.

• 1979-2000: an attack killed an average of 3.1 people.

• 2001-2012: an attack killed an average of 4.6 people.

• 2013-May 2021: an attack killed 4.4 people.

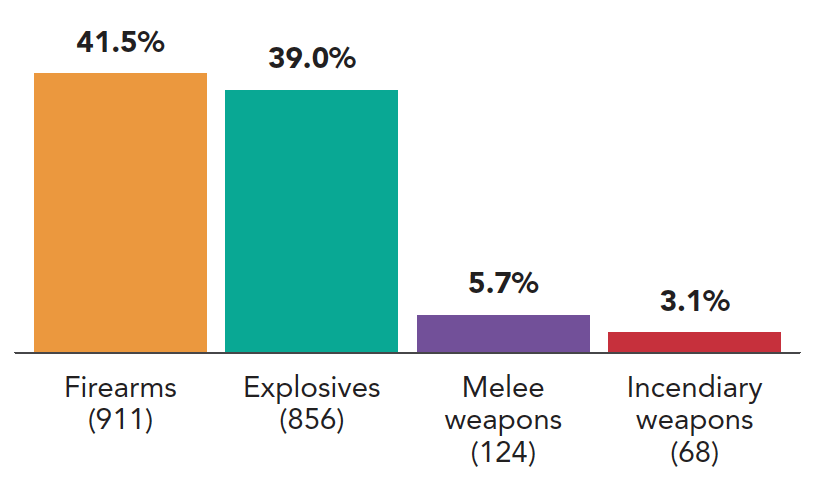

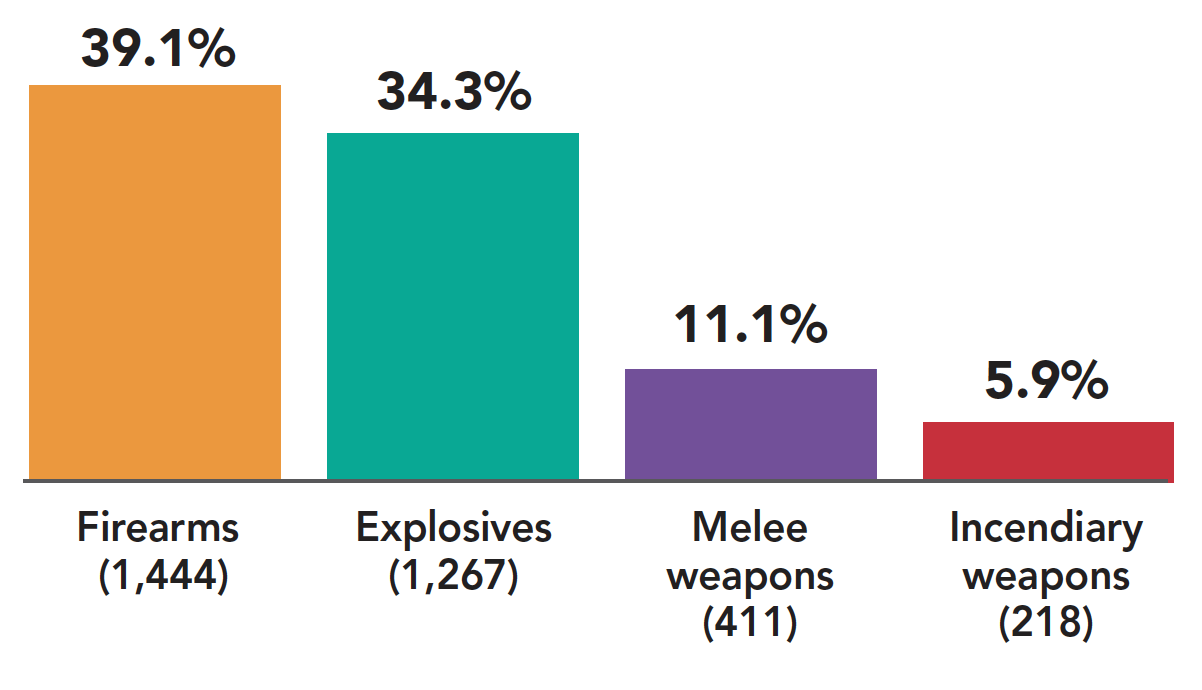

Explosives were the most used weapon (43.9% in 21,082 attacks), followed by firearms (16,649 attacks), melee weapons such as knives or machetes (2,120 attacks), and incendiary weapons (960 attacks).

• 1979-2000: firearms (911), explosives (856), melee weapons (124), incendiary weapons (68).

• 2001-2012: explosives (4,516), firearms (2,572), incendiary weapons (234), melee weapons (198).

• 2013-May 2021: explosives (15,710), firearms (13,166), melee weapons (1,798), incendiary weapons (658).

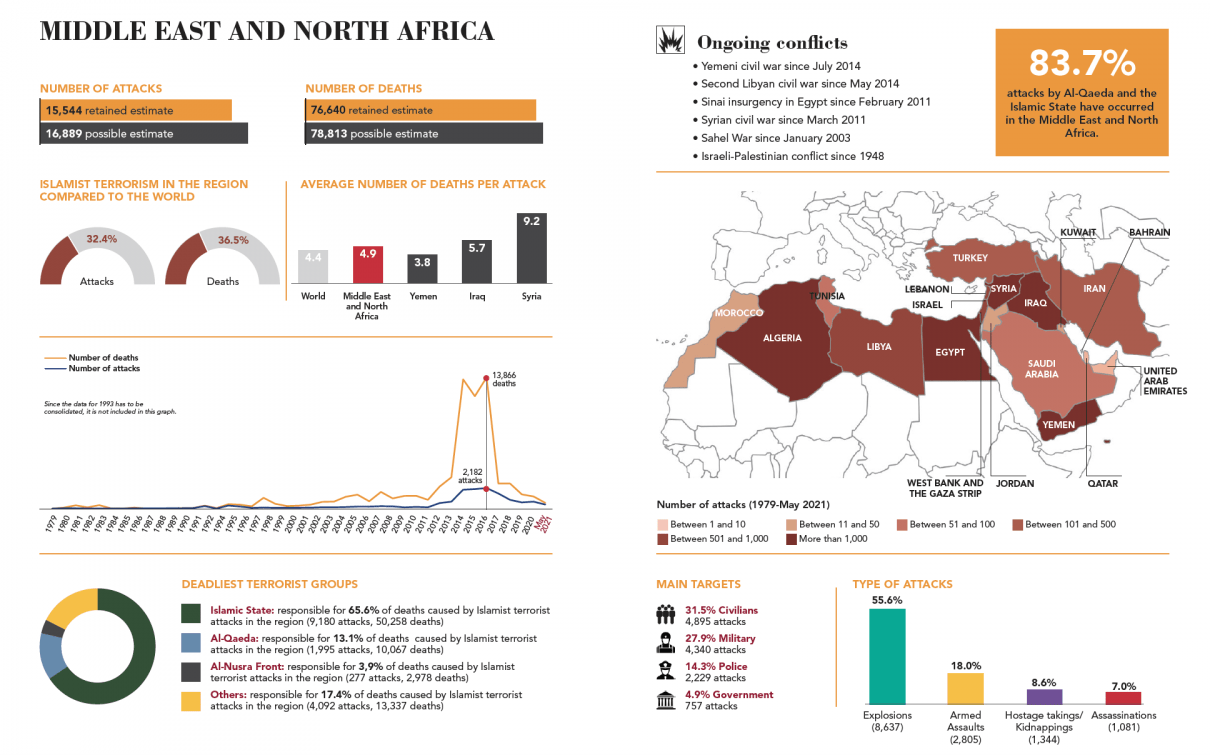

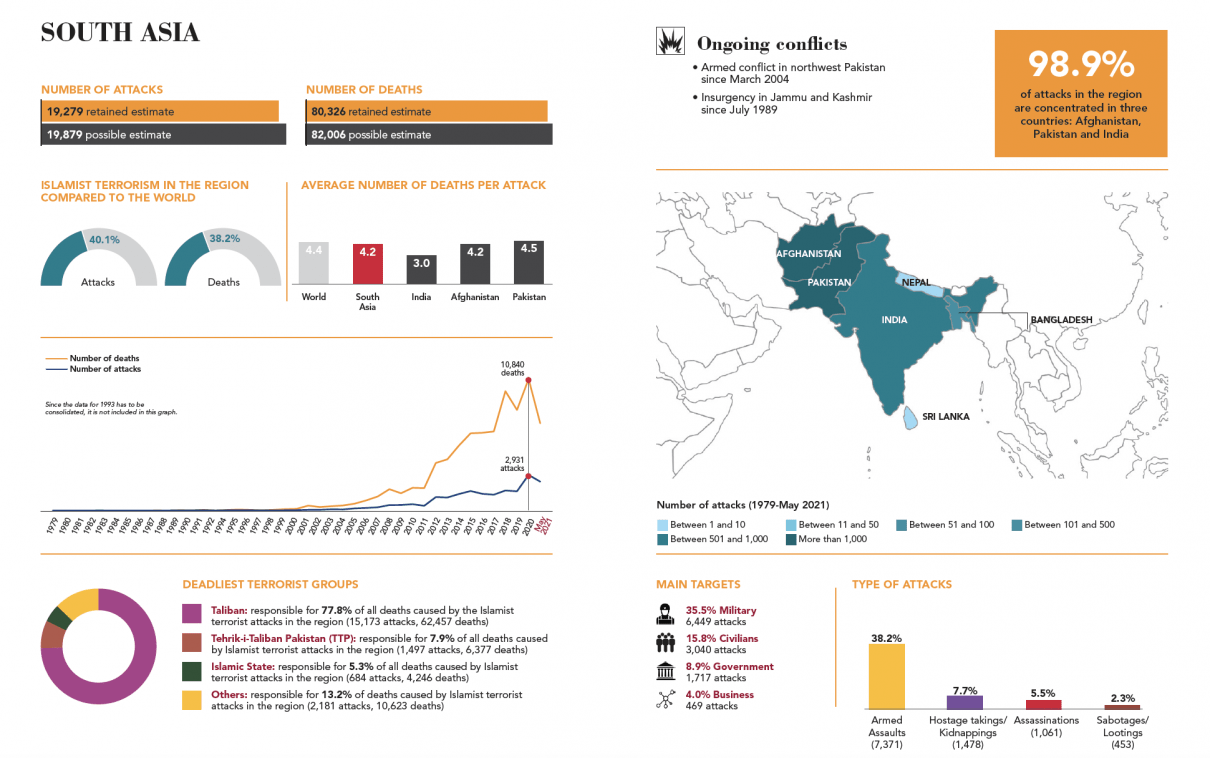

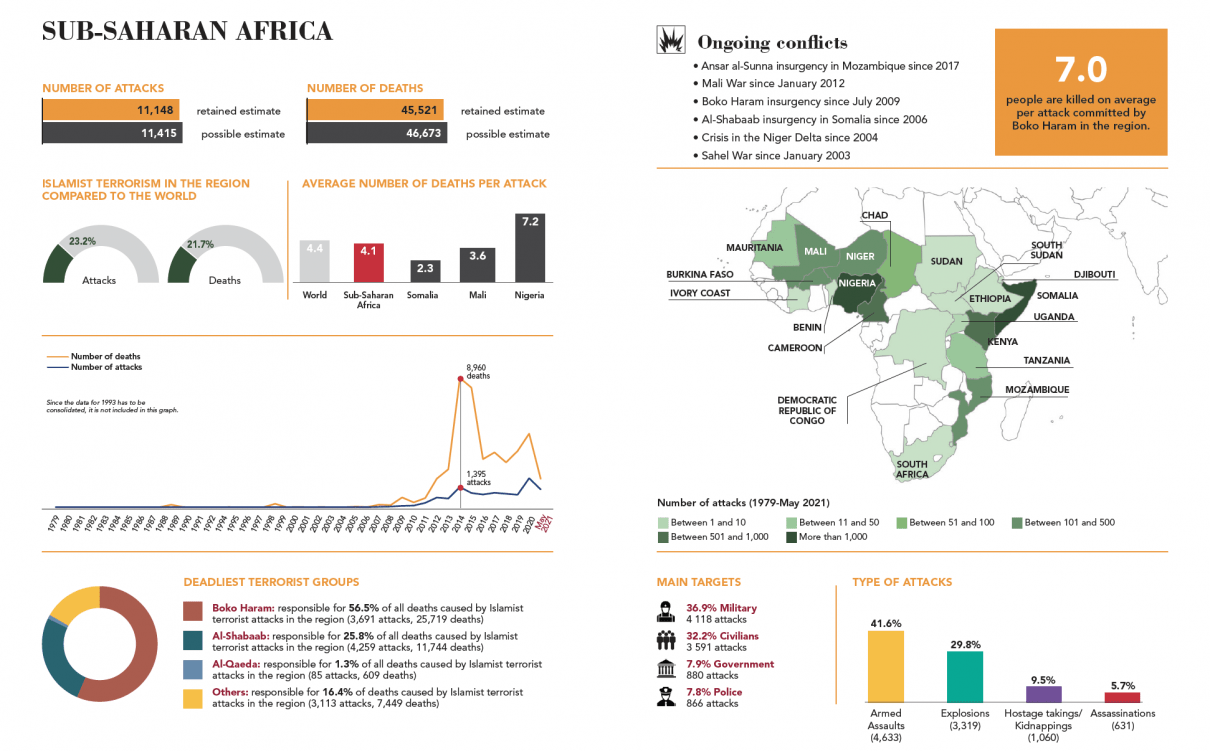

The Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 95.7% of Islamist terrorist attacks between 1979 and May 2021.

• South Asia: 40.1% of attacks, 38.2% of deaths.

• Middle East and North Africa: 32.4% of attacks, 36.5% of deaths.

• Sub-Saharan Africa: 23.2% of attacks, 21.7% of deaths.

• Southeast Asia: 3.5% of attacks, 1.2% of deaths.

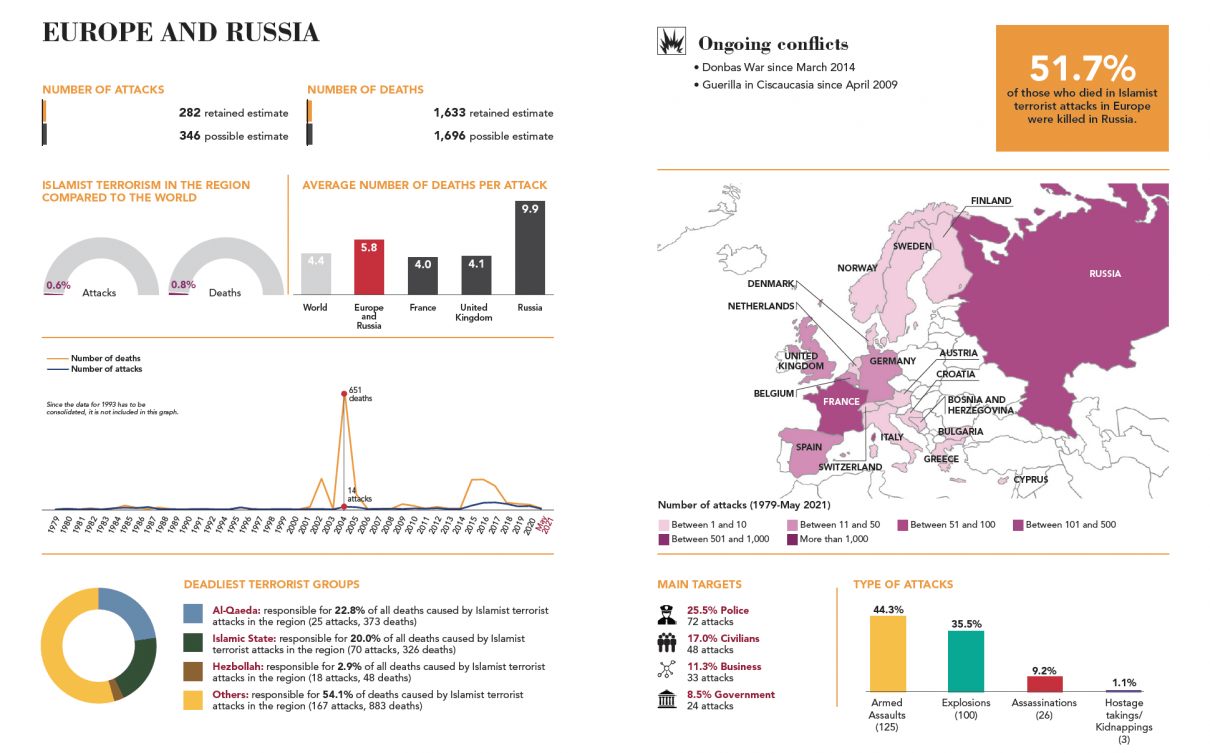

• Europe: 0.6% of attacks, 0.8% of deaths.

• North America: 0.1% of attacks, 1.5% of deaths.

• Oceania: 0.02% of attacks, 0.01% of deaths.

• South America: 0.01% of attacks, 0.1% of deaths.

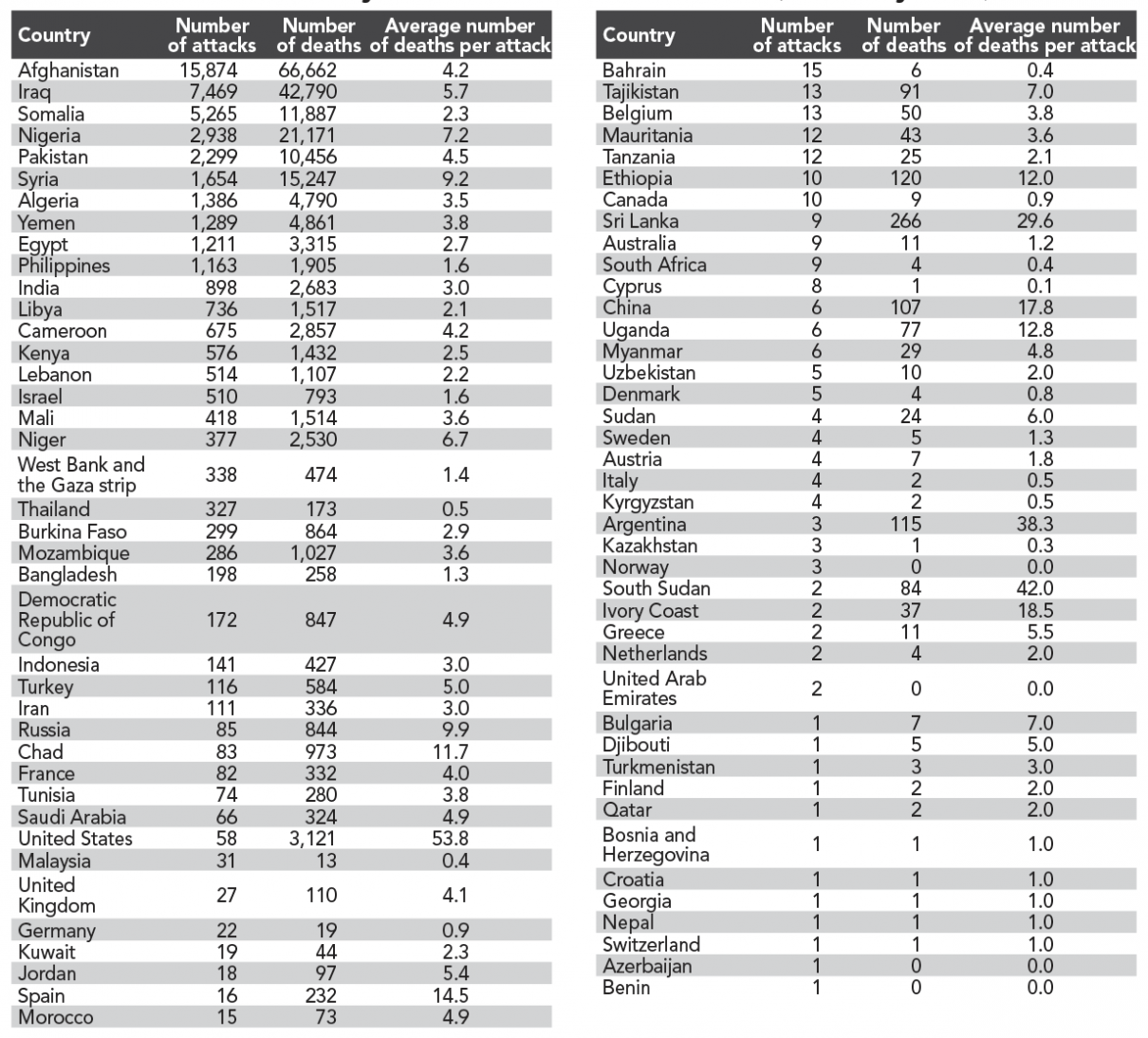

Afghanistan was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, ahead of Iraq and Somalia.

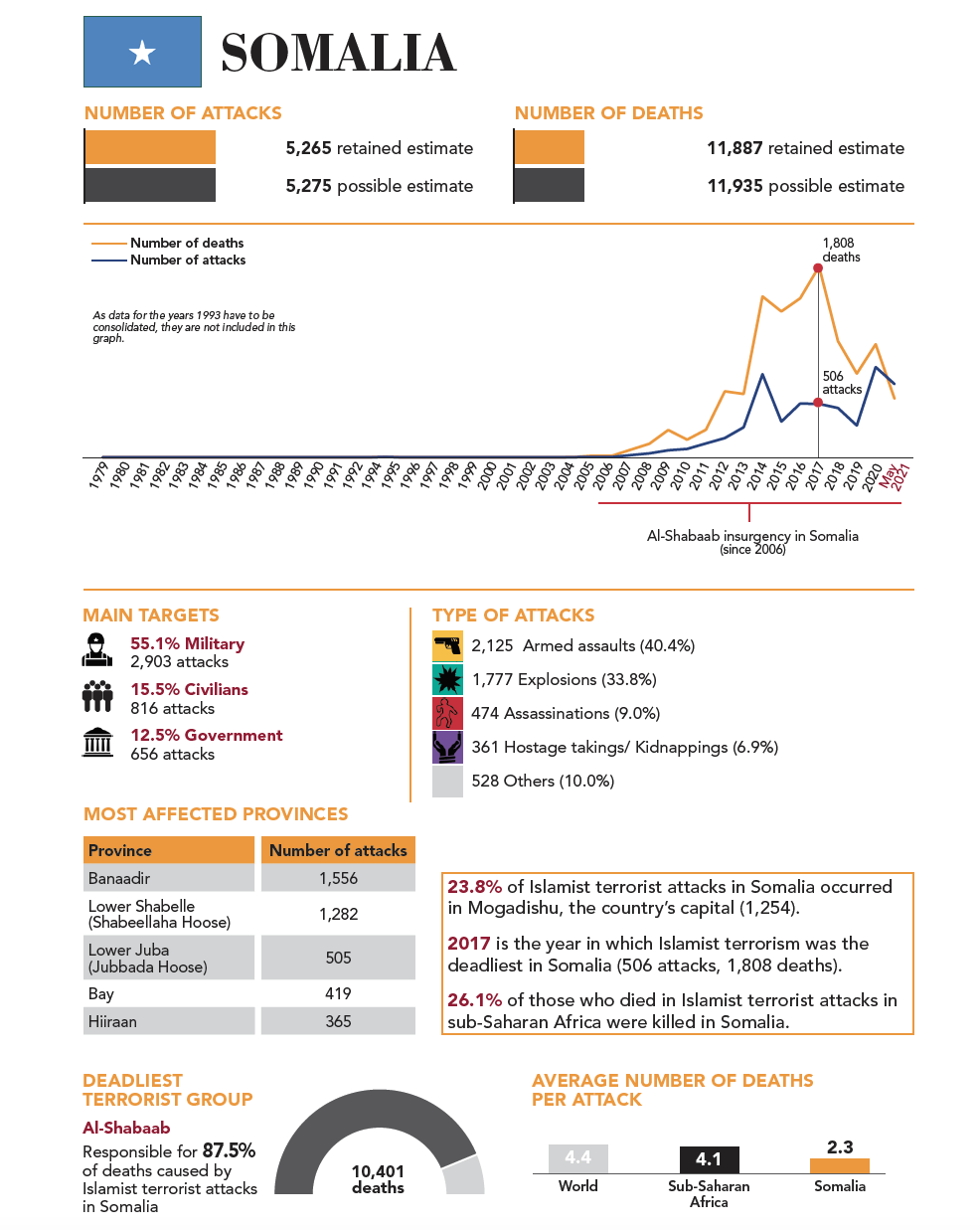

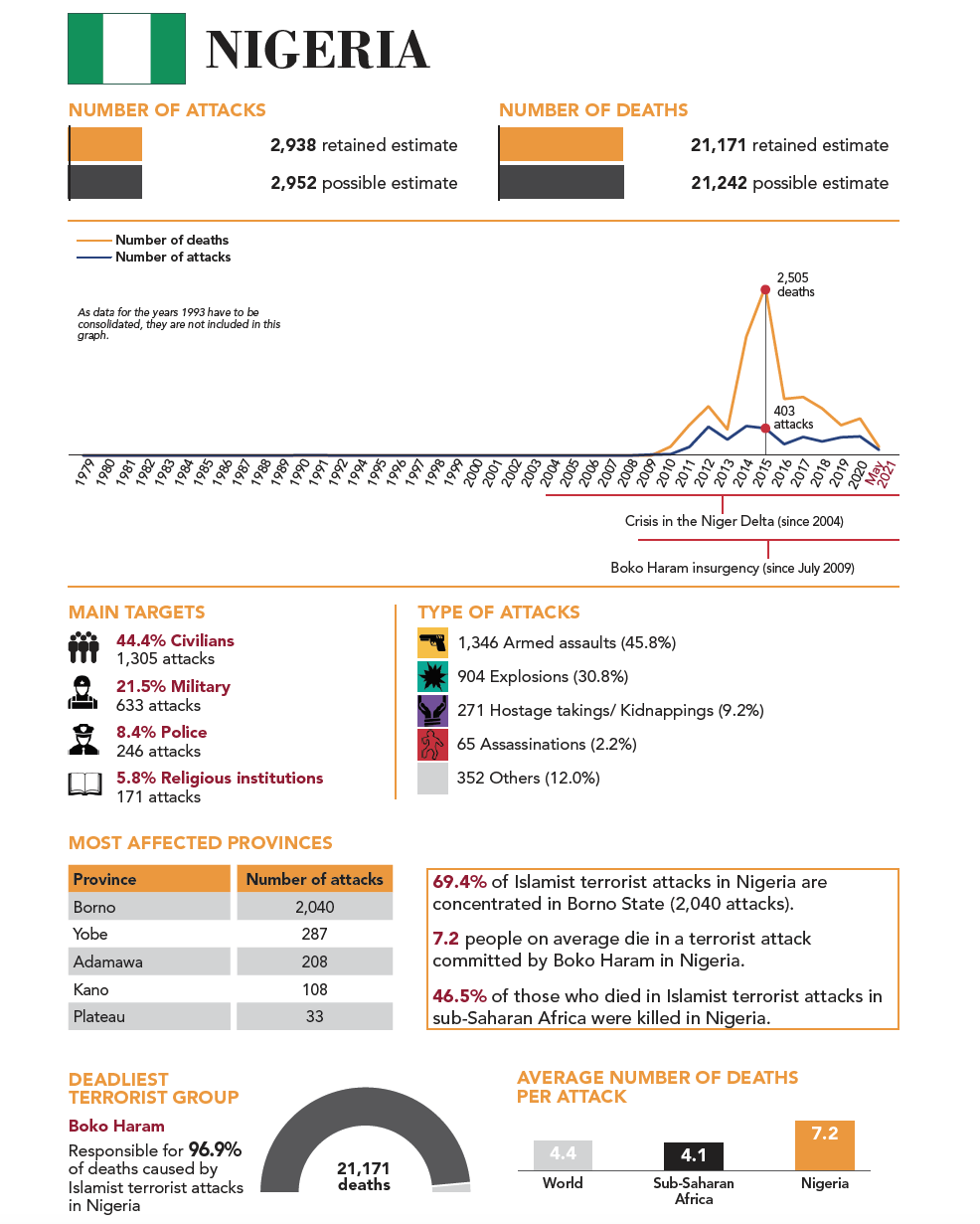

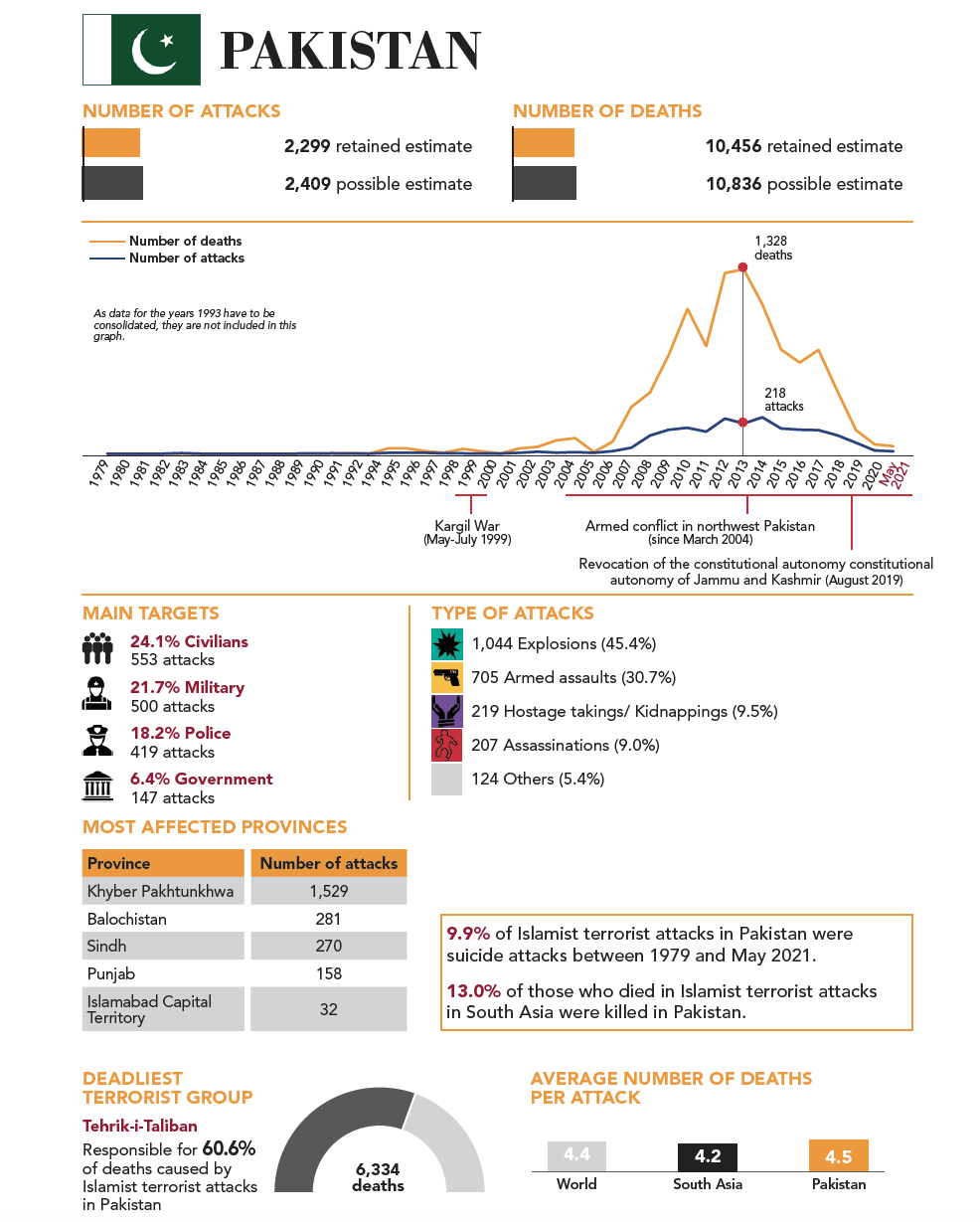

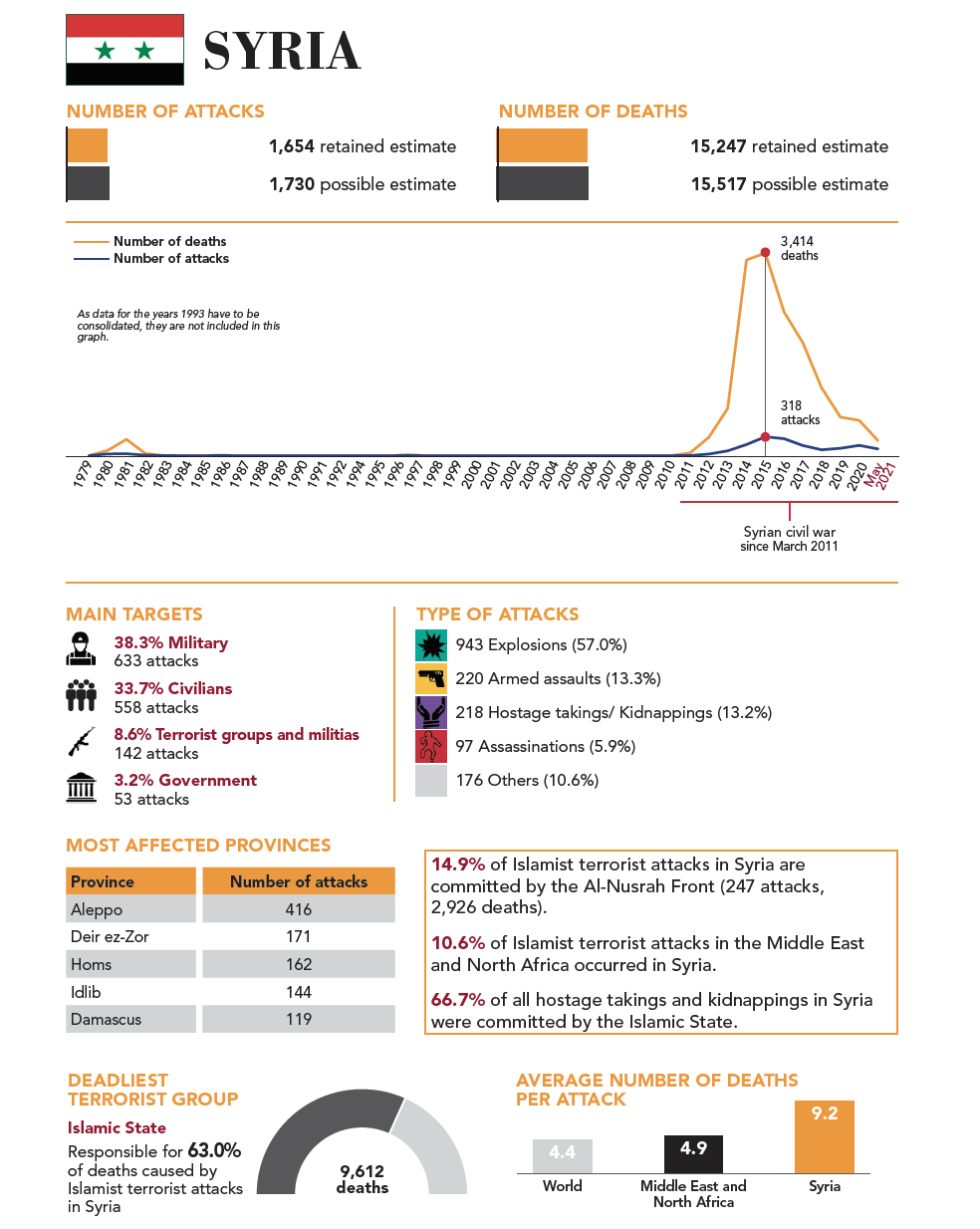

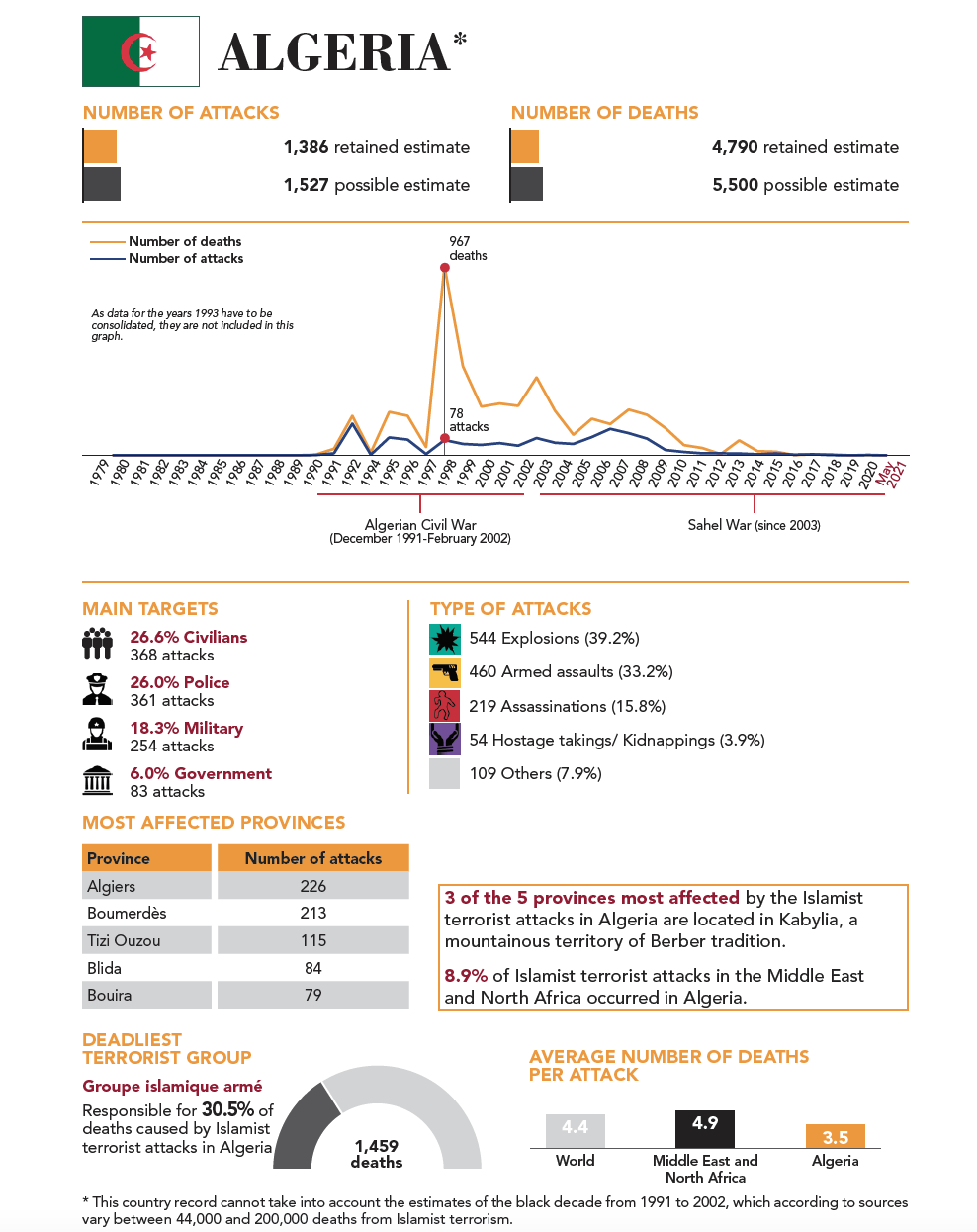

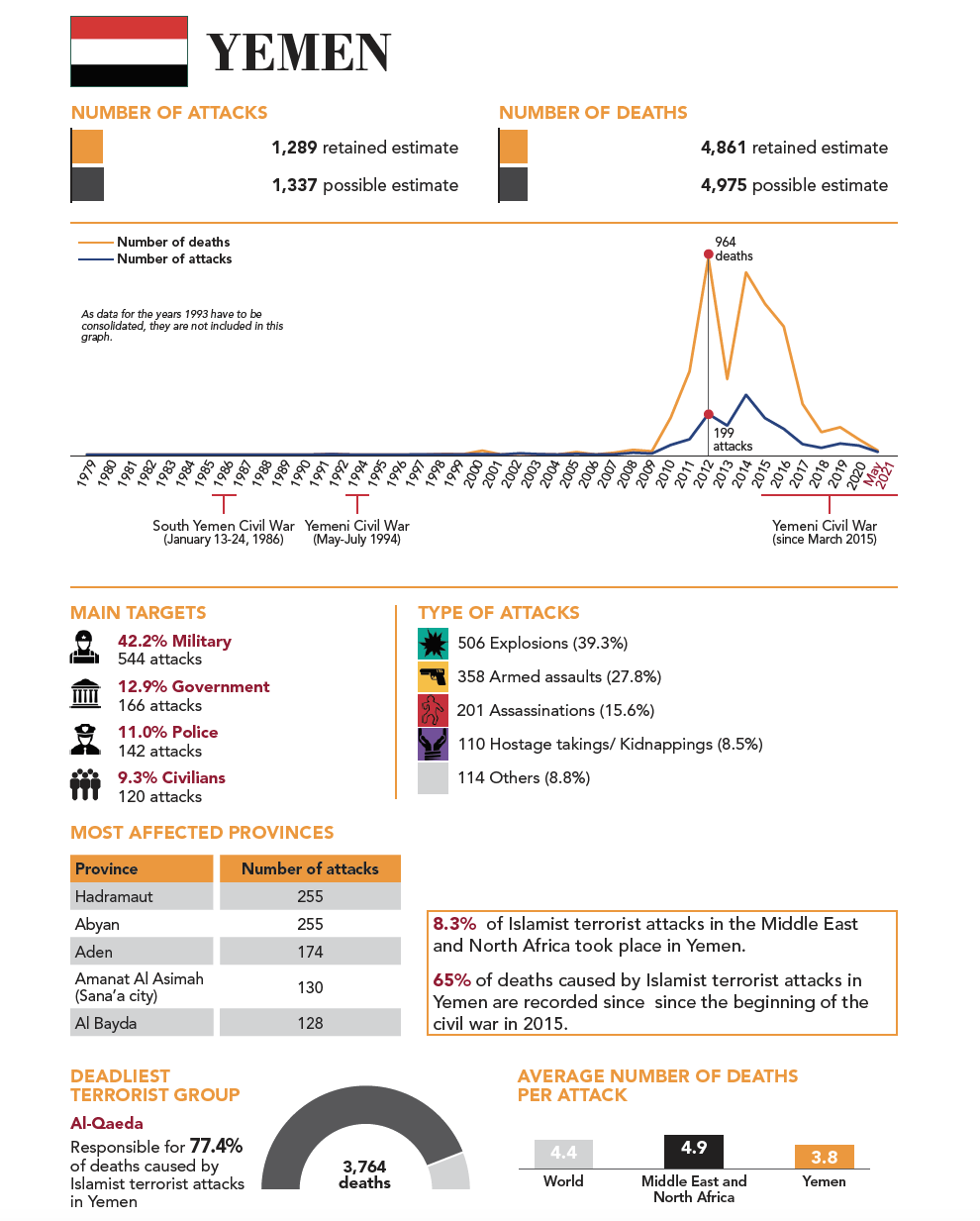

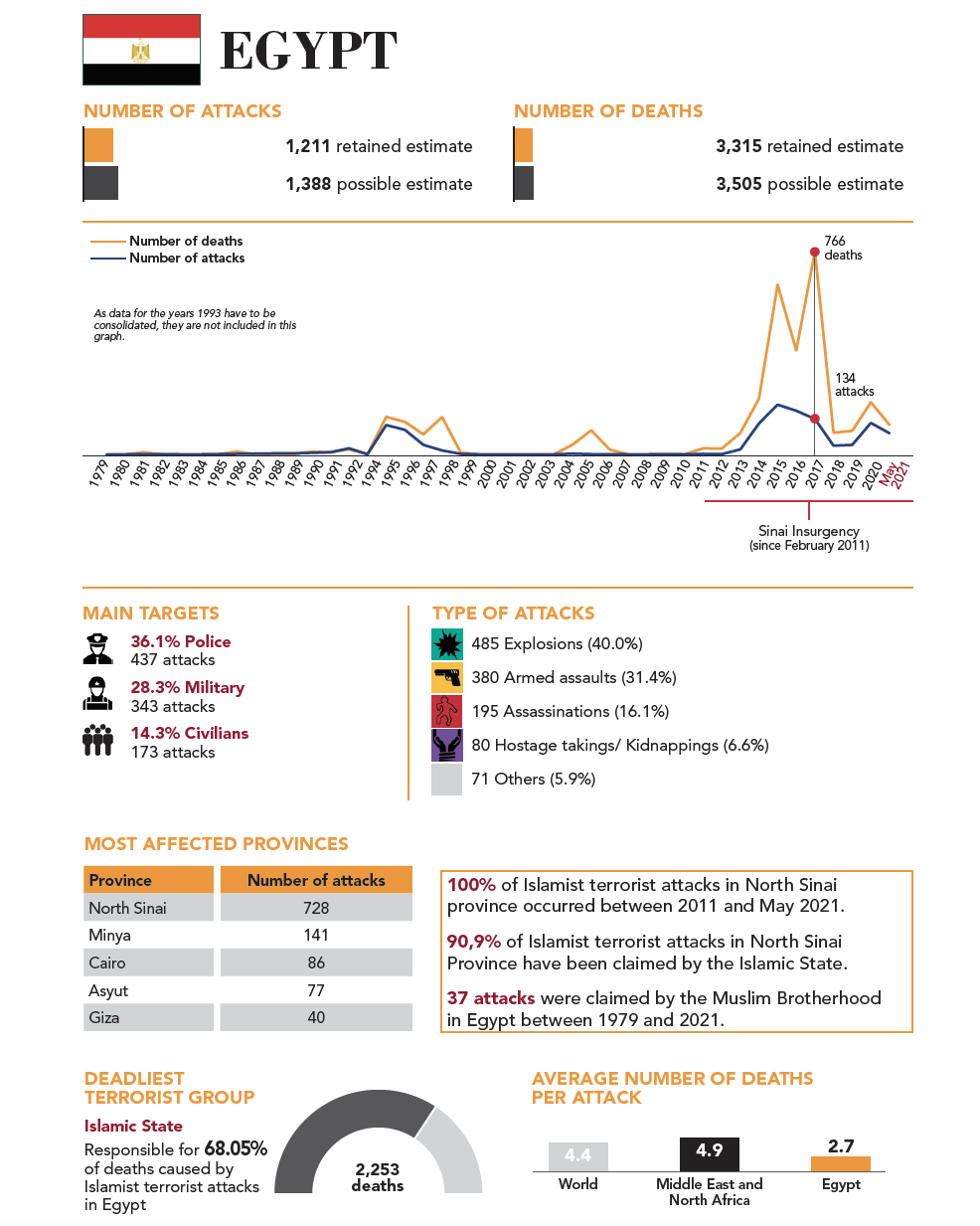

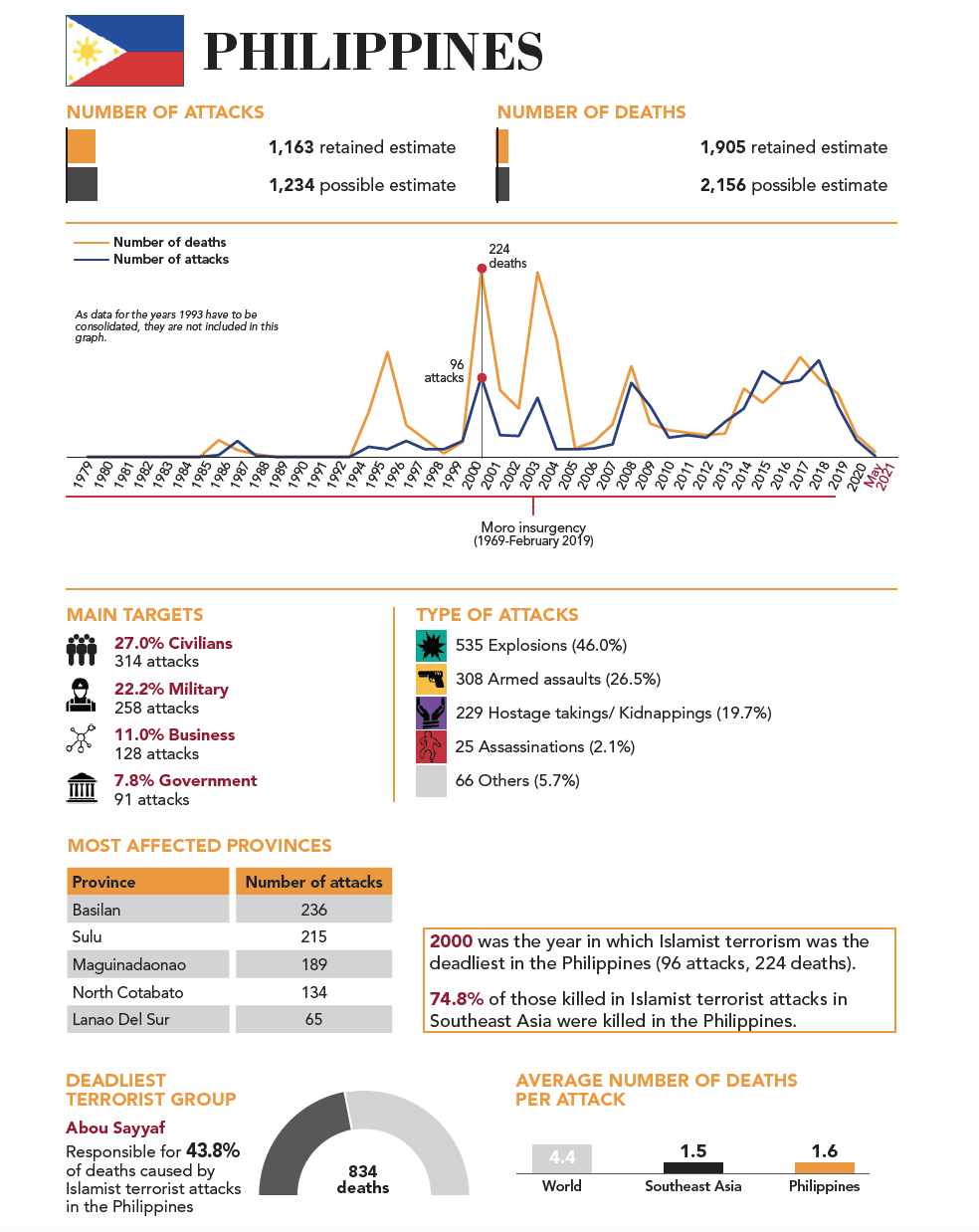

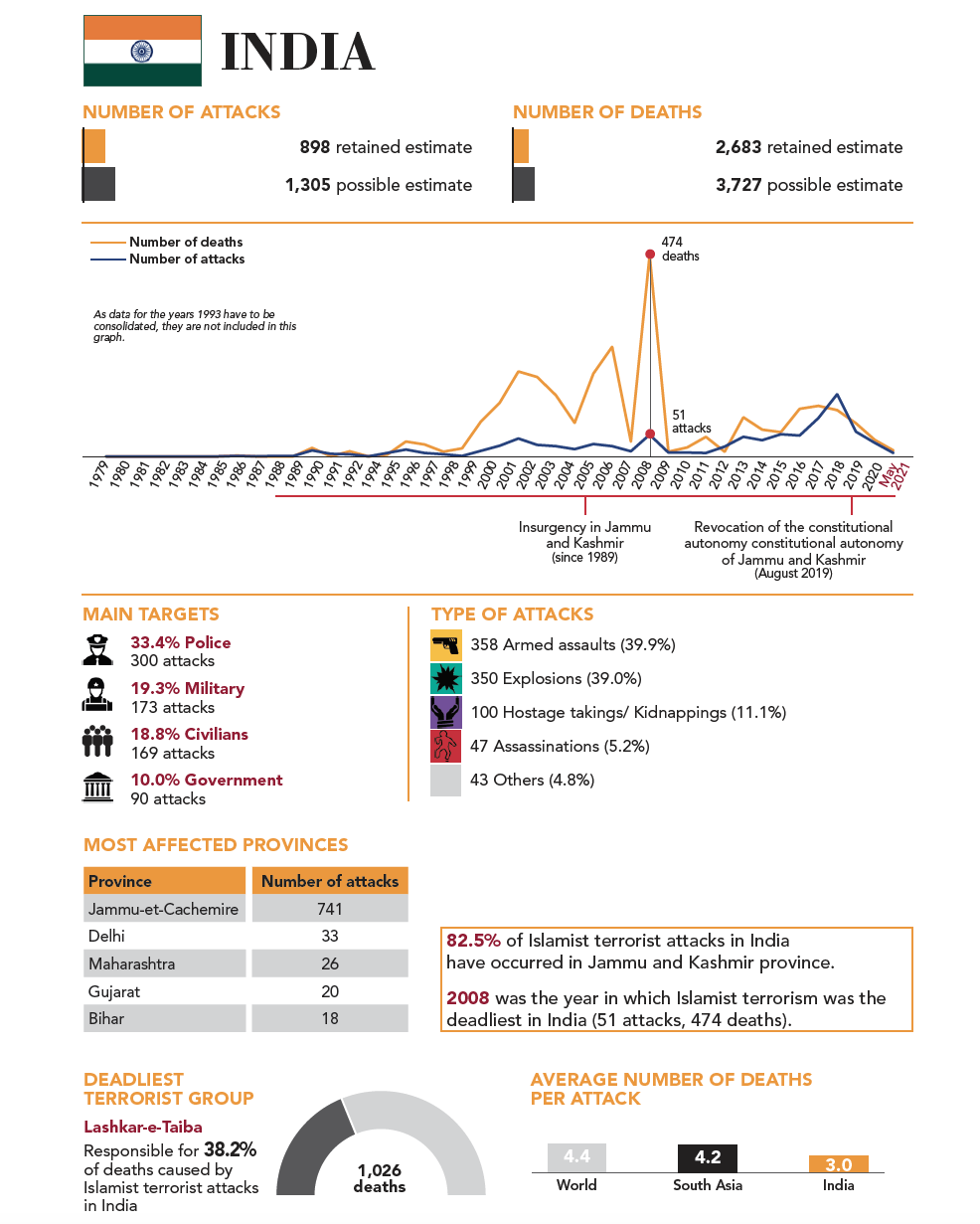

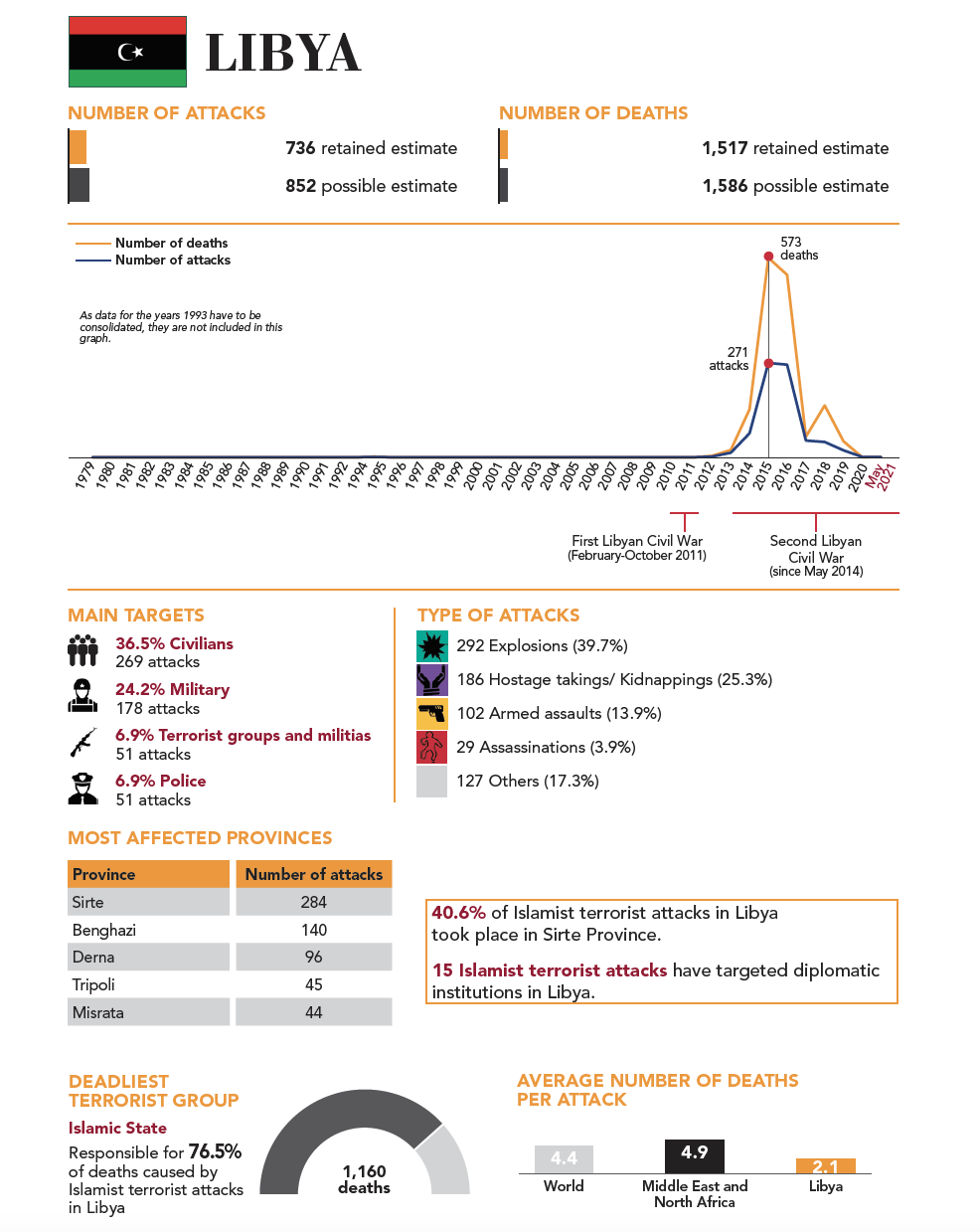

The countries most affected by Islamist terrorism are Afghanistan (15,874 attacks), Iraq (7,469 attacks), Somalia (5,265 attacks), Nigeria (2,938 attacks), Pakistan (2,299 attacks), Syria (1,654 attacks), Algeria (1,386 attacks), Yemen (1,289 attacks), Egypt (1,211 attacks), the Philippines (1,163 attacks), India (898 attacks), and Libya (736 attacks).

In these twelve countries, 187,284 deaths were caused by Islamist terrorist attacks, representing 89.1% of the total number of deaths worldwide.

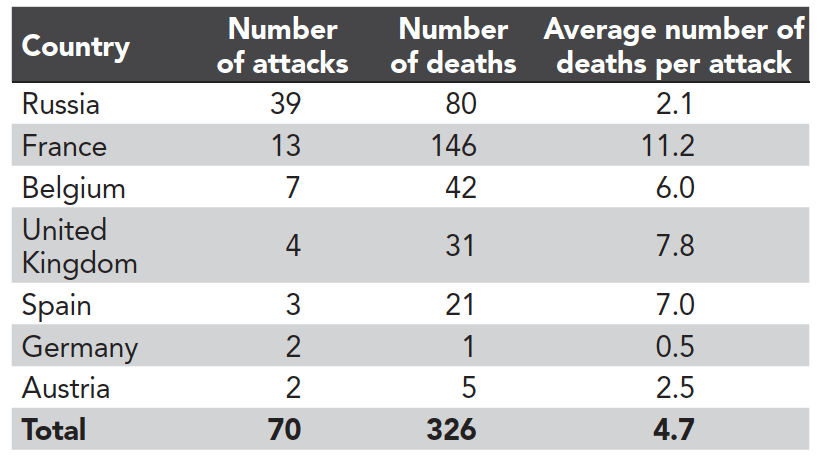

France was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism in the European Union, with 82 attacks committed on its soil between 1979 and May 2021. At least 332 people were killed in these attacks.

• 1979-2000: 24 attacks, 32 deaths.

• 2001-2012: 8 attacks, 7 deaths.

• 2013-May 2021: 50 attacks, 293 deaths.

The indirect confrontation in Afghanistan between the American and Soviet powers is one of the major causes of Islamist violence of the 21st century.

The United States and Russia have also been hit by jihadist terrorism. During the period 1979-2021, there were 58 attacks in the United States and 3,121 deaths, and 85 attacks in Russia, resulting in 844 deaths.

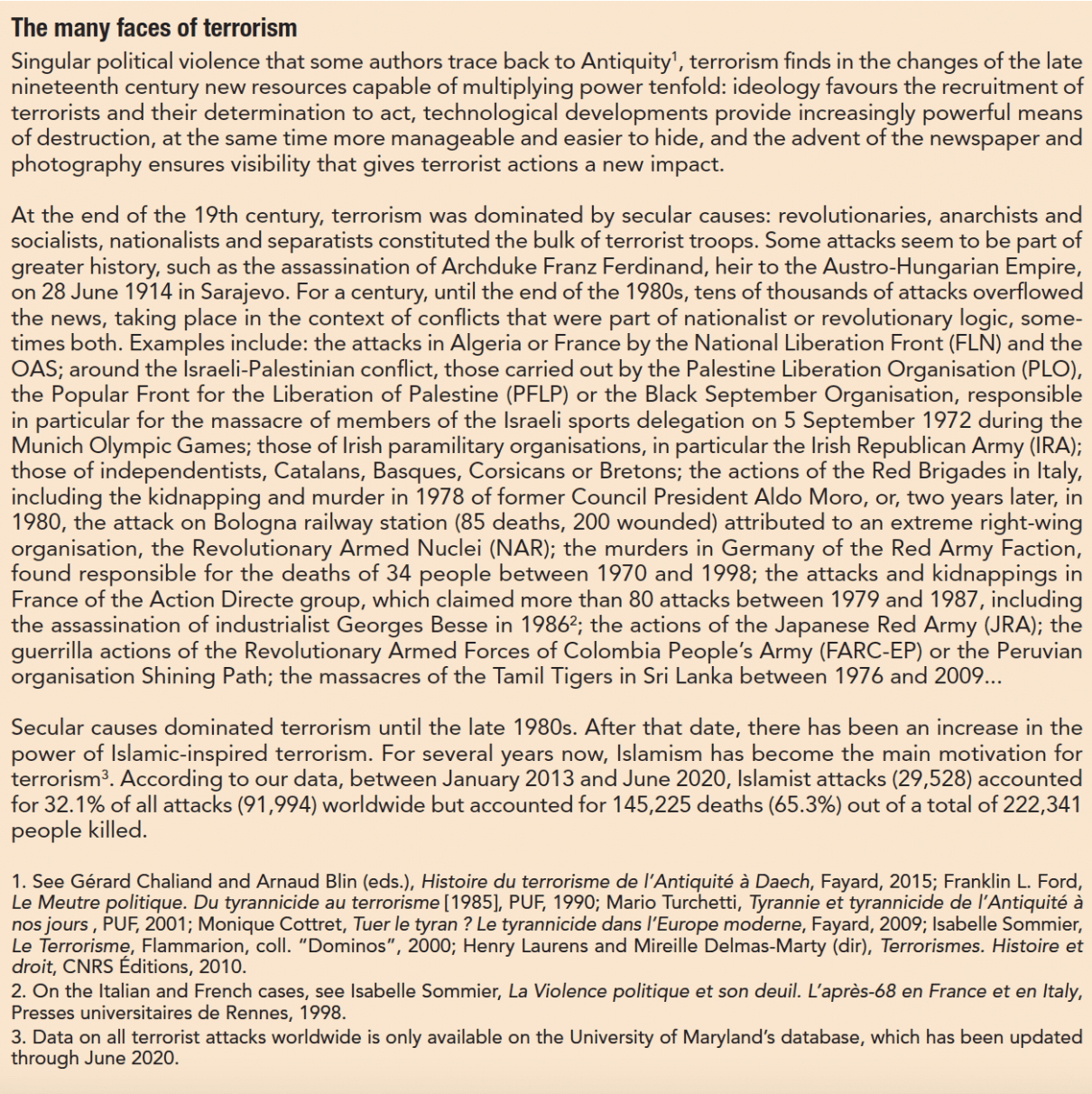

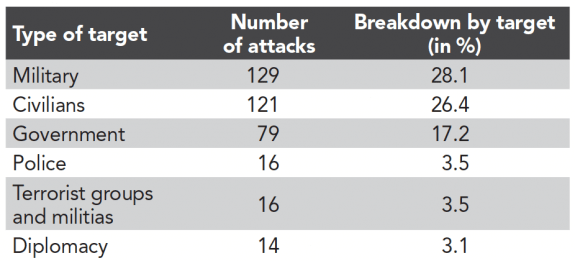

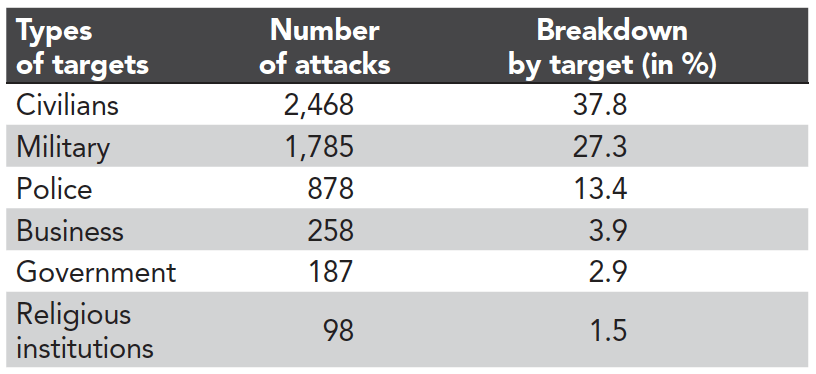

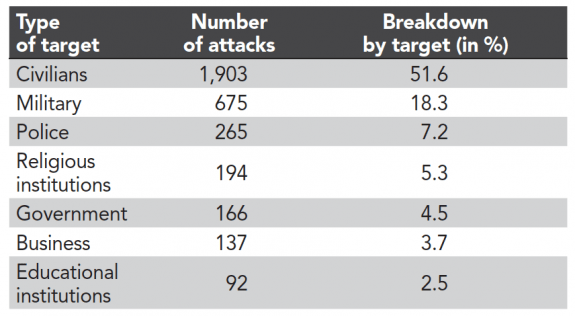

The military is the main target (31.7%) of Islamist terrorists, ahead of civilians (25.0%) and police forces (18.3%).

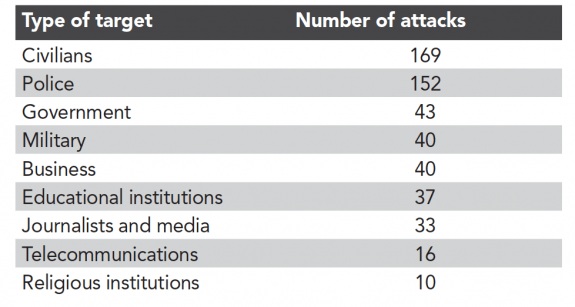

• 1979-2000: civilians (425 attacks, 19.4%), military (343 attacks, 15.6%), police (408 attacks, 18.6%).

• 2001-2012: civilians (2,169 attacks, 26.2%), military (1,411 attacks, 17.1%), police (1,427 attacks, 17.3%).

• 2013-May 2021: military (13,476 attacks, 35.9%), civilians (9,420 attacks, 25.1%), police (6,937 attacks, 18.5%).

Most (89.5%) of Islamist terrorist attacks have occurred in Muslim countries1. Similarly, the vast majority of deaths from Islamist terrorist attacks (91.7%) occurred in Muslim countries.

Muslim countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, West Bank and Gaza Strip and Yemen.

• Number of Islamist terrorist attacks in Muslim countries: 43,002 attacks (89.5% of Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide).

• Number of deaths caused by Islamist terrorist attacks in Muslim countries: 192,782 deaths (91.7% of deaths caused by Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide).

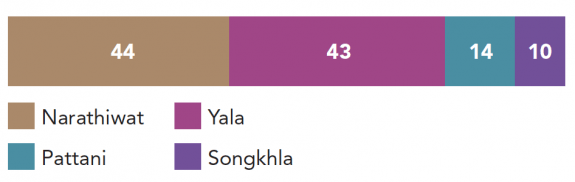

It should be noted that these figures underestimate the reality since they do not take into account the Islamist terrorist attacks perpetrated in countries with a non-Muslim majority where Muslim populations are concentrated in certain provinces. This is the case, for example, in southern Thailand, where Muslims are in the majority in the provinces of Satun, Yala, Pattani and Narathiwat, but also in the Philippines, in the region of Mindanao; in India, in the province of Jammu and Kashmir; and in China, in the Uyghur autonomous region of Xinjiang

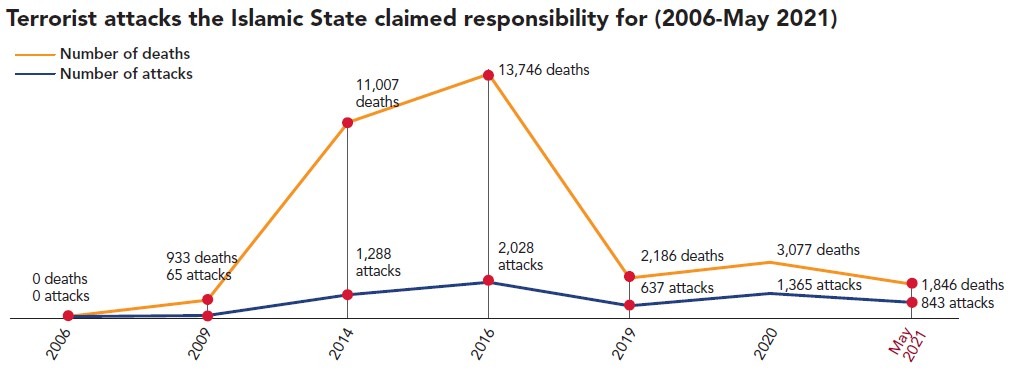

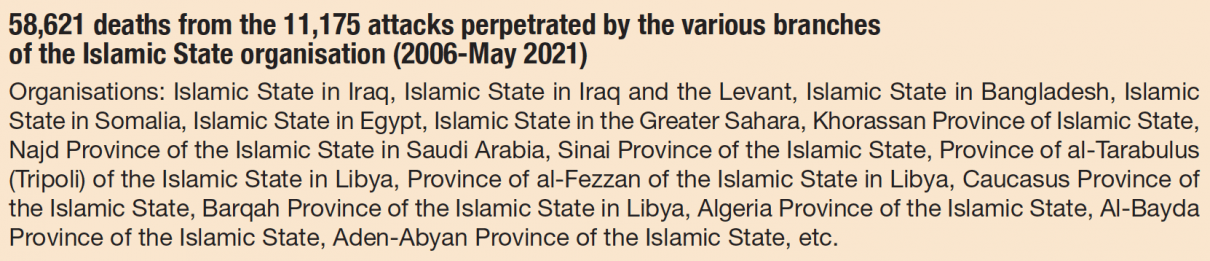

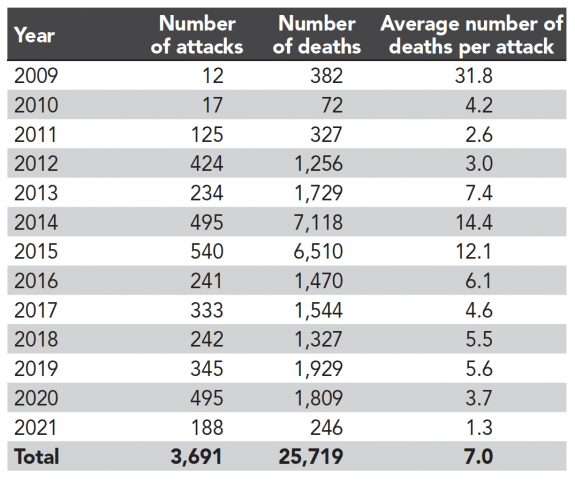

Over the entire period of time studied here, the Taliban was the deadliest group. Its terrorist actions resulted in the deaths of 69,303 people.

The deadliest terrorist organisations, taking into account their various offshoots, were the Taliban (69,303 deaths), the Islamic State group (58,632 deaths), Boko Haram (25,719 deaths), and al Qaeda (14,359 deaths). These four terrorist groups were responsible for more than three-quarters (80.0%) of the victims of Islamist terrorist attacks between 1979 and May 2021.

An evaluation of Islamist violence in the world (1979-May 2021)

Dominique Reynié,

Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Professor at Sciences Po, Paris.

“Transcript of Biden’s Speech on the U.S. Withdrawal From Afghanistan”, The New York Times, 31 August 2021.

While 6,291 people were injured on the day of the attacks, thousands more reported physical injuries related to the attacks of 9/11, such as respiratory diseases or cancers, in the years following these events, as evidenced by the World Trade Center Health Registry.

Following its first edition published in 2019, this is the updated version of our study on Islamist terrorist attacks around the world since 1979. The revival of this important work echoes the commemoration of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. The twentieth anniversary of that tragedy coincides with President Biden’s announcement of the U.S.’ withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban takeover of Kabul on 15 August 2021, and the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops on Afghan soil on 31 August 2021. According to the U.S. President, “The terror threat has metastasized across the world, well beyond Afghanistan. We face threats from Al Shabab in Somalia, Al Qaeda affiliates in Syria and the Arabian Peninsula, and ISIS attempting to create a caliphate in Syria and Iraq and establishing affiliates across Africa and Asia”1.

The series of attacks of on 9/11 was the deadliest in the history of terrorism, with 3,001 deaths and 16,493 injured2. In Europe (excluding Russia), since 1979, there have been 197 attacks and 789 deaths. In France, the European country most affected by Islamist terrorism over the same period, there have been 82 Islamist terrorist acts resulting in the deaths of 332 people. In addition to France, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have been hit, sometimes several times. It is, however, outside the Western world that countries have suffered from Islamist violence more often and more severely.

1979, the critical year

See Gilles Kepel, Sortir du chaos. Les crises en méditerranée et au Moyen-Orient, Gallimard, 2018, p. 23-69.

In his report for the Institut Montaigne, Hakim El Karaoui presents the reasons why, in his opinion, it is possible to consider that the empowerment of jihadism has taken shape in Afghanistan, namely “the emergence of several Islamist groups united by the Afghan conflict, the Afghan Mujahideen’s financial autonomy, thanks to American and Saudi funding, the effective implementation of jihad for the first time since the end of the 19th century and its theorisation by Muslim Brother Abdullah Azzam” (The Islamist Factory, Institut Montaigne, September 2018, p.19.

Gilles Kepel, Jihad. Expansion and decline of Islamism, 2nd ed., revised and updated, Gallimard, series “Folio actuel”, 2003, p. 26.

Ibid.

We asked ourselves whether it was possible to truly know the extent of Islamist violence in the world, to make a database of it and to share the results with interested audiences in the form of a database accompanied by this study. To carry out such work, it was necessary first to determine the starting point of the database, to identify the most reliable sources, examine and validate them, then process the data collected, present the main lessons learned and, lastly, make the information collected available to the public.

We decided to start collecting data from 1979 onwards. This year was chosen by most specialists because it reflects the historical failure of Arab nationalism competing with the movements of Islamisation and the affirmation of jihadism3. That same year, a number of events precipitated this development: the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, the Iranian revolution, the signing of the Camp David agreements and the hostage-taking of the Great Mosque of Mecca by a group of Islamist fundamentalists in November-December 19794. For Gilles Kepel, what was happening that year was the result of “the fierce struggle between the Saudi monarchy and Khomeini’s Iran”5 but at the same time it was the time of a new indirect confrontation between the USSR and the United States: “The jihad financed in this country [Afghanistan] by the oil-monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula and the CIA is explicitly aimed at inflicting on the Soviet Union […] a ‘Vietnam’ that precipitates its fall. At the Islamic level, its function is also to divert radical militants around the world from the struggle against the American Great Satan – to which Khomeini incites them – and to channel them against the USSR. Afghan jihad has a cardinal importance in the evolution of the Islamist movement around the world. It became the ultimate cause, with which all militants, moderate or radical, identify themselves. It supersedes, in the Arab imagination, the Palestinian cause and symbolises the transition from nationalism to Islamism”6.

Definition of terrorism

“The threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation” (Global Terrorism Database, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism (START), University of Maryland, Codebook: Inclusion Criteria and Variables, July 2017, p. 10, www.start.umd.edu/gtd/downloads/Codebook.pdf).

According to this definition, acts of State terrorism are not included in our database.

Like many concepts, terrorism is subject to controversial definitions. In this study, we define “terrorism” as political acts that meet the principle and criteria of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). In this context, a terrorist act is presented as “the threat of the effective use or use of unlawful force and violence by a non-state actor in order to achieve political, economic, religious or social objectives, through fear, coercion or intimidation”7. This definition is extended to the enumeration of a set of characteristics specifying the nature of the terrorist act:

– it must be intentional and result from a conscious calculation by the perpetrator;

– it must include some level of violence or threat of imminent violence, whether physical or material;

– the perpetrators of the incident must be non-state actors8.

To be included in the database, an event must also meet at least two of the following criteria:

– the violent act must have a political, economic, religious or social objective;

– the act must result from an intention of coercion, intimidation, or be motivated by the desire to spread an economic, political, religious or social message to a wider audience than that represented by the immediate victims; what matters is the intention of those who planned the attack or those who made the decision to carry it out;

– the action must be distinct from activities considered legitimate in time of war. The act must violate the framework defined by international humanitarian rules, in particular those concerning the prohibition of intentionally targeting civilians or non-combatants.

Our contribution focuses specifically on terrorist acts carried out by organisations or individuals claiming to be Islamists. The criterion defining a terrorist action and according to which “the violent act must pursue a political, economic, religious or social objective” must therefore be specified. It is considered essential to our database and focuses on attacks that have been the subject of an Islamist claim or about which the available information indicates that it has been planned, decided and carried out in the name of Islamism.

Definition of Islamism

Janine Sourdel et Dominique Sourdel (dir.), Dictionnaire historique de l’islam, PUF, 1996, p. 411.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. See Mehdi Mozaffari, “What is Islamism? History and Definition of a Concept”, Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, vol. 8, no 1, March 2007, p. 21.

“By ‘Islamism’, I mean the normative political ideology that has as its core program the establishment of Islam as a state religion and the implementation of Islamic law (shari’a). Militant Islamism, then, is any form of Islamism that advocates the use of violence to achieve Islamist objectives. This same distinction is made by Islamists themselves, who refer to ‘Parties of the Islamic Call’, or al-da’wa al Islamiyya (i.e. Islamist groups that do not advocate violence) on the one hand, and ‘Parties of the Muslim Revolution’, or al-thawra al-Islamiyya (i.e. Islamist groups that do advocate violence)”. Edward W. Walker, “Islam, Islamism and Political Order in Central Asia”, Journal of International Affairs, vol. 56, no 2, Spring 2003, p. 22, note 1.

Robin Simcox, Hannah Stuart, Houriya Ahmed and Douglas Murray, “Islamist Terrorism. The British Connection”, The Henry Jackson Society and The Centre for Social Cohesion, second edition, 2010, p. XVI (www.henryjacksonsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Islamist+Terrorism+2011+Preview-1.pdf).

For historians, “Islamism” is a term “used at the end of the nineteenth century to designate Islam as a religion and civilisation, but which has recently taken a new meaning of militant fundamentalist, traditionalist and proselyte Islam”9. Islamism now refers to “a trend demanding the strict application of the prescriptions of religious or Shari’a law, some of which have been abandoned, as well as the principles of faith, by various modern governments in Muslim countries, particularly under the influence of European countries, Western ideologies and reformist movements”10. As a result of this evolution, the defenders of such a conception of Islam, the “Islamists”, advocate for a jihad that is “on the one hand, in their own country against ‘bad’ Muslims and corrupt rulers in order to establish, if necessary, a purely Islamic state, and on the other hand, more generally, against the secular values that dominate the non-Muslim world”11. The same authors consider that Islamism has many analogies with the Muslim Brotherhood movement12.

There are many other definitions of Islamism, often very detailed. To complete without unduly complicating matters, one can refer in particular to the definition proposed by Edward Walker, because of its relative clarity and conciseness: “By ‘Islamism’, I mean the normative political ideology that has as its core program the establishment of Islam as a state religion and the implementation of Islamic law (shari’a). Militant Islamism, then, is any form of Islamism that advocates the use of violence to achieve Islamist objectives. This same distinction is made by Islamists themselves, who refer to ‘Parties of the Islamic Call’, or al-da’wa al Islamiyya (i.e., Islamist groups that do

not advocate violence) on the one hand, and ‘Parties of the Muslim Revolution’, or al-thawra al-Islamiyya (i.e., Islamist groups that do advocate violence) on the other hand13. Acknowledging that there are no universally accepted definitions of Islamism and terrorism, some researchers characterise it as an ideology whose key tenets include:

– Belief that Islam is not only a religion, but also a holistic sociopolitical system;

– Advocacy of Sharia (Islamic) law as divine state law;

– Belief that a transnational Muslim community, known as the Ummah, should unite as a political bloc;

– Advocacy of an ‘Islamic’ state, or Caliphate, within which sovereignty belongs to God14.

A global database of Islamist terrorist attacks from 1979 to May 2021

On 28 April 2019, the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag published a list of Islamist terrorist attacks. This list covers a shorter period, from 11 September 2001 to 28 April 2019. Until 2017, the data are extracted from the Global Terrorism Database. For the years 2018 and 2019, the newspaper constructed its own database. Our data differ from those of the Welt am Sonntag in at least three respects: first, we cover a period of forty years instead of eighteen years, which allows us to follow the evolution of Islamist terrorism, in particular by showcasing a phenomenon of globalisation; second, Welt am Sonntag has chosen to count only attacks that have killed at least twelve people, while we have recorded all identifiable attacks; thirdly, Welt am Sonntag focused on attacks by the main terrorist groups (Abdullah-Azzam Brigade, Asaib Ahl ab-Haqq, Abu Sayyaf, Ansar al-Din, Allied Democratic Forces, Algerian jihadists, Ahrar al-Sham, Ansar al-Islam, Al-Ittihaad al-Islami, Al-Islah Party, Aisha-Brigade, Al-Aksa Martyrs’ Brigade, Al-Muaqioon-Biddam Brigade, Ansar-Al-Din-Front, Al-Qaeda, Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, Ansar al-Sunna, al-Shabaab, Ansar al-Sharia, Ansar al-Tawhid, Ansar ul-Islam, Boko Haram, Sunni Jihadist Movement of Iran, Deccan Mujahideen, Religious Guardians, Armed Islamic Group, Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, Hezbollah, Hizb-i-Islami, Harkatul Jihad-e-Islami, Hakkani Network, Halqa-e-Mehsud, Hisbul Mujahideen, Hamas, Houthis, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Islamic Jihad of Uzbekistan, Islamic Front, Indian Mujahideen, Islamic Party of Turkestan, Jaish al-Adl, Jaish-al-Islam, Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, Jaish-e-Mohammad, Jaish al-Fatah, Jaish-i-Islam, Jemaah Islamiya, Jund al-Khilafah, Jamiat ul-Mujahedin, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, Jundallah, Jundallah Pakistan, Jaljala Army, Kataib Hezbollah, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Lashkar-e-Omar, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Lashkar-e-Islam, Mujahideen Ansar, Mahaz-e-e-Inquilab, Moro Islamic Liberation Front, Moro National Liberation Front, Movement for Tawheed and Jihad in West Africa, Mujahedeen Shura Council, Mukhtar Army, Front al Nosrah, Students Islamic Movement of India, Sipah-i-Mohammed, Salafia Jihadia, Shura of the Derna Mujahideen, Special Purpose Islamic Regiment, Shura of the Benghazi Revolutionaries, Taliban, Tehrik-e-Taliban Islami, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, United Jihad Council); while our database lists all Islamist terrorist attacks as accurately as possible. Thus, in addition to attacks by the best-known groups, we also take into account attacks by individuals or small groups claiming to be Islamists without belonging to a particularly well-known organisation. See “18 Jahre Terror”, Welt am Sonntag, nº. 17, 28 April 2019, pp. 12-14.

We can mention, for example, the database made available by the French newspaper Le Monde on the attacks committed by the Islamic State from 2014 to 2016 (www.leWorld.fr/les-decodeurs/visuel/2016/06/17/les-attacks-de-l-etat-islamique-ont-fait-plus-de-2-500-deaths-en-deux-ans_4952826_4355770.html) or the New York Times’ (www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/03/25/world/map-isis-attacks-around-the-world.html?mtrref=undefined&gwh=0EBB06650E2F0D8A452DEE9BDAA12379&gwt=pay&assetType=REGIWALL).

Global Terrorism Database, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism (START), University of Maryland (www.start.umd.edu/gtd/).

The Global Terrorism Database previously did not provide data for the years 1993, 2018 and 2019.

It is within the framework of these definitions that we have conceived this work and that we propose here the result in the form of a database listing the Islamist terrorist attacks perpetrated in the world since 27 December 1979. The data included in our database does not extend beyond 31 May 2021, given the time required to validate and process the information collected. Indeed, while the attacks in Western countries have considerable visibility, due to the greater impact that violence can have in more peaceful societies, their ability to produce reliable data quickly and a particularly dense media presence, the same cannot be said for attacks that take place, much more often, in other parts of the world where all identification and intelligence processes become longer but cannot be as effective. Therefore, the validation and classification of relevant events requires work that goes beyond the time we had to define in order to make this publication possible.

To carry out our research, we used three types of sources: the collection of information on attacks since 1979 via search engines, the cross-referencing of existing databases and academic research. There are indeed various databases on terrorist attacks in general and Islamist terrorist attacks in particular15.

All the databases in circulation were useful to us in confirming or enriching the work we were completing16. However, most of the databases available are very incomplete or unevenly documented. In some cases, information may be abundant about a country, region, year or period, usually very short, then very little or non-existent for another year or country. This can be seen on Wikipedia, where data by year or theme are available but very incomplete, fragmented and in a form that does not allow statistical processing.

For the first edition of Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2019, our initial source was the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) produced by the University of Maryland in the United States. This gigantic database compiles terrorist attacks between 1970 and 2017. The value of this set is to identify terrorist attacks regardless of their motivation. This abundance was also the main challenge for us, since we had to extract Islamist terrorist attacks from the 172,944 attacks recorded in the world from 1979 to 2017. We therefore carried out a selection, verification and classification of the data contained in the GTD. We then had to supplement it with our own information, particularly for the year 199317. We worked without the GTD for the years 2018 and 2019 since data for these years were not provided18.

Additional information about the 2nd edition of our study on Islamist terrorist attacks around the world. The years 2018 and 2019 have been consolidated and we have included new data for the period between January 2020 and May 2021.

Since the first edition of our study in November 2019, the University of Maryland database has been updated through June 2020. Firstly, we were able to consolidate our data for the years 2018 and 2019.

Secondly, by extracting Islamist-type attacks, we were able to identify relevant occurrences between 1 January 2020 and 30 June 2020.

For the period from July 2020 to May 2021, we used the database of the Armed Conflict and Event Data Project (ACLED). This American non-profit organisation specialises in collecting data and mapping all types of violent events around the world from 1997 to the present. We developed a filtering system, with three parameters, in order to retain only the Islamist terrorist attacks:

1. The time period: we exported the data for the period from 1 July 2020 to 31 May 2021;

2. The type of events: we then selected all terrorist attacks in the world;

3. Islamist terrorist groups: we have retained attacks perpetrated by an Islamist terrorist or by an Islamist terrorist group, 656 Islamist terrorist groups having been recorded from 1979 to the present.

We have excluded several types of events:

– Operations carried out at the initiative of a state force with the aim of preventatively weakening a terrorist group (ex: “On 12 March 2021, 3 Taliban were killed and 1 wounded in the Afghan military forces operation in the limits of Dih Yak district, Ghazni province. In addition, 4 Taliban planted IEDS were detected and defused in the district. Fatalities coded as 3”) ;

– Operations where the instigator is not clearly identifiable (ex: “On 14 October 2020, members of an Islamist militia from Mozambique clashed with the Tanzanian armed forces in Kitaya. At least 20 citizens were killed, and between 2 to 3 soldiers. The group of around 200 militiamen set several buildings on fire, including a cashew nut factory and a hospital; an armored personnel carrier was destroyed. The Islamic State claimed credit for the attack”).

For each Islamist terrorist attack in our database, we have provided the following information:

– the date;

– the location of the attack: country, city, and exact location when possible to identify it;

– the number of confirmed deaths and injuries, including attackers; it is important to note here that the number of people wounded is clearly very underestimated by the available information;

– the perpetrator(s) of the attack;

– the type(s) of target(s);

– the type(s) of attack(s) in question;

– the type(s) of weapon(s) used.

For the period July 2020-May 2021, we analysed a total of 10,978 events, which represents an average of almost 1,000 terrorist acts per month. We have harmonised the taxonomy between the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) and the Armed Conflict and Event Data Project (ACLED) to build our own database. It is available as open data on our website data.fondapol.org. However, as the University of Maryland has changed its privacy settings since our first publication in November 2019, our contract with GTD for post-2017 data no longer allows us to provide public access, which we regret. However, data from 1979 to 2017 and from 1 July 2020 to 31 May 2021 can be found on our datafondapol.org platform.

The reasons why, however, our study underestimates the reality of Islamist violence

It is clearly impossible to claim to propose an exhaustive database of Islamist terrorist attacks committed in the world between 1979 and May 2021, for a number of reasons detailed below.

a/ A number of attacks have not been recorded. No matter the efforts made, it is certain that a significant number of attacks falling under the Islamist category could not be recorded.

b/ A number of attacks do not appear in our “retained estimate” when religious motivation is not clearly predominant in a combination involving another determination. Islamist terrorism takes place in singular and complex contexts that sometimes make it difficult to collect reliable data. This is particularly the case in situations of war, civil or international, independentist or separatist struggles and territorial conflicts that persist over long periods of time, where causalities are shifting or inextricable, as in the case of the Palestinian conflict, while in a completely different context, in Thailand for example, a separatist movement has led a Muslim minority to get involved with weapons in the name of objectives that can achieve, beyond political demands, a religious dimension.

c/ Islamist motivation is not always identified. Available data do not always allow news agencies to attribute the attack to the Islamist cause, especially if the country affected by the attack is characterised by weak administrative structures. The absence of claim of responsability can increase the likelihood that an attack will not even be recorded by agencies or that this information will not reach the press.

d/ The number of deferred deaths is practically unknown. However, it is certainly significant. Since victims who succumb to their injuries after an attack are almost never mentioned in the available information, it is impossible to know their exact number. It is therefore also impossible to integrate these deaths into our database in a reliable way. Thus, according to our database, we record at least 210,138 deaths and 172,109 people wounded, which is less than the number of deaths. However, if we consider three cases of attacks, each carried out with different means, in two countries where the quality of information is excellent, we observe a completely opposite ratio between the number of deaths and the number of people wounded: in the United States, there were five times as many people wounded (16,493) than killed (3,001) in the 9/11 attacks; in France, there were three times as many people wounded (413) than killed (137) in the 13 November 2015 attacks; in Nice, in the 14 July 2016 attack, there were five times as many people wounded (458) than killed (87). This information leads us to believe that the number of people wounded is much higher than that in our database. Certainly, developing countries, which are the countries where most attacks take place, do not have the same capacity to identify and care for people injured in an attack. Some of the injured are probably not even counted, while others die from their injuries after a certain period of time due to the inadequacy or fragility of relief systems and health institutions. If we applied the ratios of the three sample attacks to the number of casualties in our database (172,109), we would have to adjust this figure by multiplying it by three (516,327) or five (860,545).

e/ For these four reasons, we propose two types of quantification of Islamist violence, in the form of a “retained estimate” and a “possible estimate”. The “retained estimate” results from our database of attacks during the period 1979-May 2021, that were clearly motivated by an Islamist agenda. The “possible estimate” results from the identification of attacks that could be qualified as Islamist, including certain terrorist acts that are also based on separatist, political or social logic, which make it more difficult to attribute them to an exclusively or mainly Islamist motivation. In all cases, the number of victims, dead or injured, is significantly lower than a reality that cannot be more precisely known.

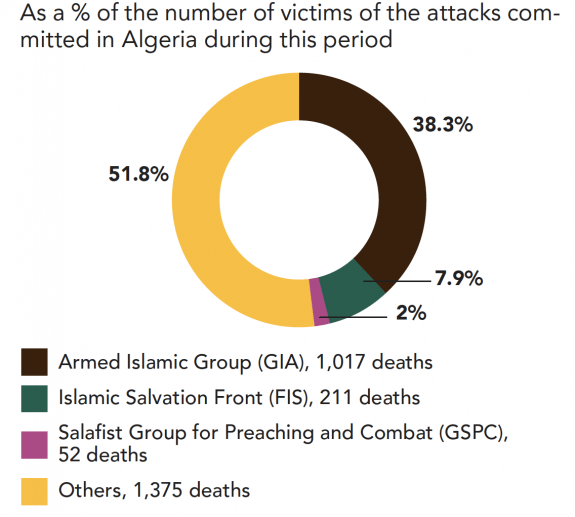

The Algerian “black decade”: only an estimate is possible

The Algerian case illustrates particularly well the difficulty of providing an exhaustive database. Algerians refer to the period between 1991 and 2002 as the “black decade”, when various Islamist groups, in particular the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), opposed the Algerian state in a violent civil war whose outcome is difficult to document1. According to Fouad Ajami, “the precise number of Algerians who died in the civil war that broke out in 1992 will never be known. The Algerian leaders, who are not known for their loyalty to the truth and who have so much to hide, acknowledged in 1999 that 100,000 people were killed. More reliable estimates provided by Algerian civic organisations put the death toll at 200,000” 2. Indeed, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika first estimated the number of victims at 100,000 in 1999. Then, in February 2005, the Algerian president gave a speech in which he put the figure at 150,000 deaths 3. Fouad Ajami considers that the death toll could reach 200,000, arguing that it was in the interest of the Algerian government to minimise the losses 4. This figure, which has been used in various works on terrorism in Algeria 5, remains debated, particularly because it does not distinguish between victims who were members of the police or the army, terrorists and civilians. In a study published in 2008, Roman Hagelstein tried to distinguish between those killed in clashes between security forces and terrorists and those killed in massacres, bombings and assassinations. The study also distinguishes the number of missing persons, presumed to have been murdered in secret, with the author estimating the total number of victims at 44,000 6. Regarding the victims of Algerian Islamist terrorism in the period 1991-2002, the available estimates that can be considered reliable because of the sources, authors and types of publication thus vary between 44,000 and 200,000. In any case, for this country and for this period, there is no data available to provide information on the number of attacks, their date, the modalities of action, the group responsible or the profile of the victims. For our database, these major uncertainties have several consequences: firstly, due to the lack of information, it is not possible to further specify the situation of Islamist terrorism in Algeria during this decade. In keeping with our method, we therefore only include in the “retained data” of the cases that were reported. This choice leads to an undoubtedly significant underestimation of the number of attacks and victims in Algeria. On the other hand, we will include in the “possible estimate” category the indications concerning Algeria. Finally, as a consequence, this situation of great ignorance with regard to the Algerian case leads to an underestimation of the number of attacks and victims of Islamist terrorism in the world, both for the period after 1991 and for the period as a whole.

We have recorded 48,035 Islamist terrorist attacks that killed at least 210,13819 people between 1979 and May 2021.

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Dominique Reynié (dir.), Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World. 1979-2019, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2019.

Our research started in spring 2018. It led to a first publication in 201920. The study we are publishing here is based on the database we have developed, which is available in open data on data.fondapol.org within the limits indicated above. The analyses that follow first present the evolution of Islamist terrorism from 1979 to the present day before proposing a presentation and reading of the data according to the regions of the world and the countries most affected by Islamist violence.

The accuracy of the figures does not imply such a detailed knowledge of the observed reality; the degree of accuracy results from the calculation operations applied to the database. We could only reproduce the exact result of these operations.

The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000)

See Mohamed Louizi, Liberér islam de l’islamisme, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, January 2018 (www.fondapol.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ISLAM-POLITIQUE-1.pdf); Mohamed Sifaoui, Taqiyya! Comment les Frères musulmans veulent infiltrer la France, L’Observatoire, 2019; or Malik Bezouh, Crise de la conscience arabo-musulmane, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, September 2015 (www.fondapol.org/etude/malik-bezouh-crise-de-la-conscience-arabo-musulmane/).

This work does not aim to shed light on the foundations of Islamism or to discuss the origins and justifications, in the context of Islam, of the use of violence and violence of a terrorist nature in particular. In a different way, we consider that our contribution lies in the information that can be obtained from the exploitation of a consolidated database and the analyses to which it can give rise. However, in order to understand the value of the data shared here, it is necessary to briefly recall the developments in Islamist terrorism since 1979.

Until the mid-1970s, Islamism had little influence in the Middle East and North Africa. In the wake of decolonisation and the rejection of Western imperialism, the new States of the region affirm a nationalist and pan-Arab vision promoted by leaders such as Nasser or Boumediene and by movements such as Ba’ath, in Syria and Iraq, or the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in Palestine. Islamist organisations are firmly contained or severely repressed, as Nasser did in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood. Founded in 1928 by Hassan el-Banna, the Muslim Brotherhood was established with the aim of restoring the political Islam that had disappeared with the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate proclaimed by Atatürk in 1924.

At the end of the 1970s, the Islamist claim was strengthened1. The increase in social inequalities and corruption of the elites were denounced. Islamist movements were trying to embody a political alternative to existing dictatorships or are engaging in violent actions, as in Syria, where the Muslim Brotherhood launched an armed struggle against the Baathist regime of Hafez el-Assad. These movements of Islamisation in Middle Eastern societies flourished all the more as Arab nationalism began to falter then collapsed. At the end of the decade, in 1979, a window of opportunity opened up for Islamists in the Middle East and North Africa.

The Soviet-Afghan war, “matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism”

See Gilles Kepel, “Le terrorisme islamiste est né en Afghanistan”, remarks collected by Héloïse Kolebka, L’Histoire, n° 293, December 2004, p. 18-19 (www.lhistoire.fr/%C2%AB-le-terrorisme-islamiste-est-n%C3%A9-en-afghanistan-%C2%BB).

The year 1979 was a pivotal year, the scene of several important events, including the Iranian revolution and the invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR. The Russian military operation precipitated the emergence of a new Islamism. At the same time, in Iran, the opposition led by the Shiite clergy, due to the context of intense social protest, forced the Shah to flee the country (16 January 1979). On 1 February 1979, Ruhollah Khomeyni came to power. He initiated the transformation of Iran’s imperial regime, accused of “Westernisation”, into an Islamic republic. In the wake of the Iranian revolution, Shia groups advocating armed struggle were formed. Among them is the Lebanese Hezbollah, created in 1982. Shia ideology is affirmed in the context of the process of Islamisation of the Middle East where it competes with Sunni legitimacy.

In Afghanistan, the Soviet invasion initiates the conflict which will be considered the matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism2. Jihad is supported by Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Egypt. Jihadists who reach Afghanistan become “mujahideen”; they are seen as the liberators of a “land of Islam” (dar al-islam).

The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism

With 357 attacks, which cost the lives of 1,442 people, the 1980s are the least deadly years compared to the decades that followed. The emergence of Islamist terrorism is visible from the years 1980-1983 which correspond to the Muslim Brotherhood’s activism in Syria, in the midst of an uprising against the government of Hafez el-Assad.

From 1980 to 1982, there were 69 attacks on Syrian territory, representing nearly two-thirds (63.3%) of all Islamist terrorist attacks listed in the world during these three years. Attacks ceased after the repression of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, including during the Hama massacres by the Syrian army in 1982.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

From 1980 to 1989, the country most affected by Islamist terrorism is Lebanon, with 133 attacks, which caused at least 515 deaths. In the grips of a civil war since 1975, the country has been experiencing the rise of small terrorist groups. This unstable national context and Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon in 1982 promote, the same year, the emergence of Hezbollah. A year later, the Shia organisation triggered a series of attacks on foreign institutions. An Italian patrol was hit on 15 March 1983, although no lives were lost, but on 18 April a new attack hit the United States Embassy in Beirut, resulting in the deaths of 63 people. At the end of the same year, on 23 October, an American base and a French patrol were terribly hit by an attack in which 299 people lost their lives. Hezbollah’s terrorist activism is particularly intense in Lebanon, where it committed 276 attacks from 1983 to 2000, but it is not limited to this. In all, by integrating the other affected countries, Hezbollah is responsible for 339 attacks from 1983 to 2000, killing 1,105 people. Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Cyprus, Denmark, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Kuwait and Tunisia are among the affected countries.

In September 1986, Paris suffered a series of six attacks, including the one on 17 September, rue de Rennes, in front of a store, which killed 7 people and injured 55.

These attacks were claimed by the Solidarity Committee with Arab political prisoners and the Near East, on behalf of the Lebanese Hezbollah.

The Lebanese organisation is also considered responsible for the two attacks on the Israeli Embassy on 17 March 1992 in Buenos Aires (30 deaths, 220 wounded), as well as the attack of 18 July 1994 on a Jewish association, also in Buenos Aires (85 deaths, 236 injured). Over the whole 1979-May 2021 period, Argentina remains the only country in South America affected by Islamist terrorism, with three attacks.

Types of weapons used in Islamist terrorist attacks (1979-2000)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa

The withdrawal of the Red Army from Kabul on 5 February 1989 galvanised Islamist mobilisation, already stimulated in 1987 by the creation of Al-Qaeda, by Abdullah Azzam and Osama bin Laden. The globalisation of the jihadist struggle began then. The discourse is mainly based on the idea of a unified Muslim community (ummah) claiming autonomy from the ethnic, national and cultural specificities of each nationality. The objective is to establish the Caliphate and the exemplary prophetic city, which must also be extended to non-Muslim countries. The empowerment of the jihadist discourse in relation to classical, nationalist and political referents is not the hallmark of Al-Qaeda. It is taken up by all Muslims who came to Afghanistan to take part in the violent action. Following the Soviet withdrawal, these mujahideen returned to their countries of origin and spread the ideas of Jihadist Salafism there. Thus, in the 1990s, an increasing number of countries, particularly in the Middle East, were directly affected by Islamist violence.

Due to a lack of information, it is not possible to specify the situation of Islamist terrorism in Algeria during this decade. In keeping with our method, we therefore only include in the “retained data” the cases that were reported. This choice leads to an undoubtedly significant underestimation of the number of attacks and victims in Algeria.

Targets of Islamist terrorist attacks in Algeria (1979-2000)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

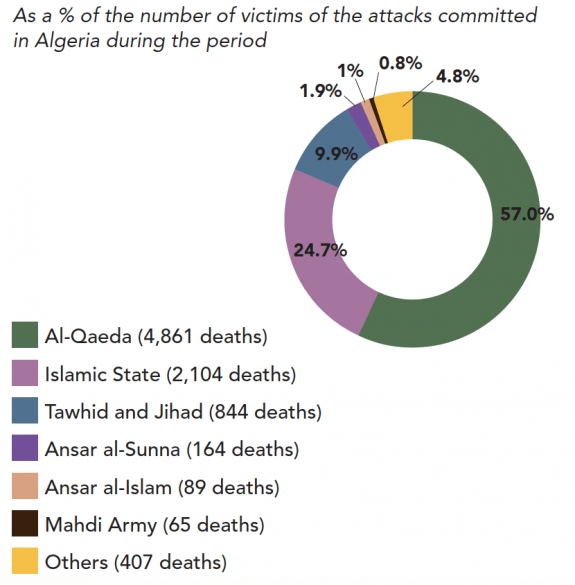

In Algeria, a number of jihadists gathered in militant groups since the beginning of the 1991-20023 civil war. The victory of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in the 1990 municipal elections and the 1991 parliamentary elections, followed by the cancellation of these elections by the Algerian army and the resignation of President Chadli Bendjedid, triggered a “black decade”. Military and Islamist groups engaged in a terrifying struggle for power. The confrontation devastated the country. From 1990 to 1999, Algeria was the country that was hit the hardest by Islamist terrorism. There were 542 attacks, or more than a third (34.6%) of the attacks recorded worldwide during this decade by our database; there were at least 2,390 deaths, representing more than half (51.4%) of the victims of Islamist terrorism in the world between 1990 and 1999. The violence reached its peak in 1997: 967 people were killed following the parliamentary elections won by the Rassemblement national démocratique (RDN), supported by the army.

During this “black decade”, religious figures and institutions were particularly affected, particularly Christians of foreign nationalities: twelve Croatian tourists were murdered on 14 December 1993, two Spanish nuns were killed on 23 October 1994 and seven French monks from Tibhirine were kidnapped and murdered in the spring of 1996.

Targets of Islamist terrorist attacksin Algeria (1979-2000)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

See Amr Hamzawy and Sarah Grebowski, “From Violence to Moderation. Al-Jama’a al-Islamiya and al-Jihad”, Carnegie Papers, n° 20, April 2010 (https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Hamzawy-Grebowski-EN.pdf).

Gilles Kepel, Sortir du chaos…, op. cit., p. 102.

Ibid., p. 99.

In Egypt, on the eve of the 2000s, the Islamist landscape was structured by two movements: al-Jihad and al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya. The objective of these two organisations was the establishment of an Islamic State, and the means to achieve this was terrorism4. In the 1990s, al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya launched 257 insurgent attacks against the government, killing 489 people.

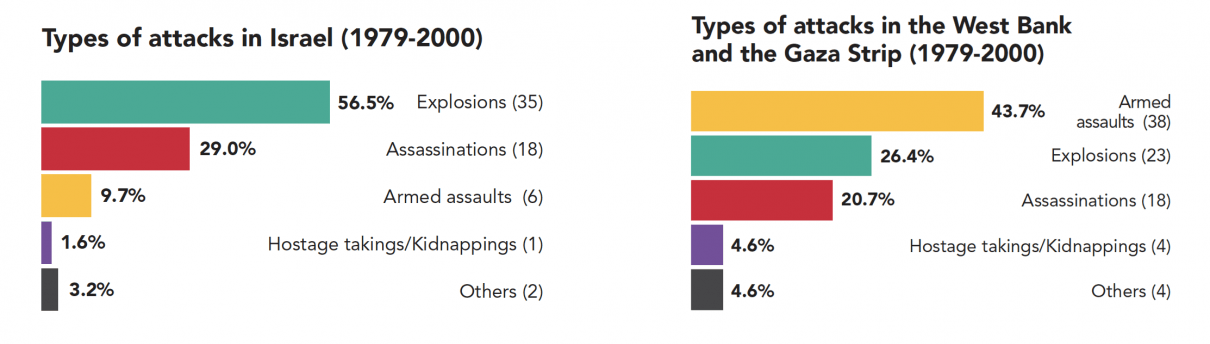

In the Middle East, the 1990s were marked by the Islamisation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. A transfer of power of sorts took place to the benefit of Hamas, a Palestinian Islamist movement born in 1987 at the beginning of the first Intifada, and to the detriment of the PLO, which came from the Arab nationalist movement. This evolution led to a change in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 1992, 417 leaders and activists of Hamas were arrested and taken to southern Lebanon, in the village of Marj al-Zuhur, after the assassination of an Israeli officer. A resolution of the Council of UN security necessitated their repatriation. This event is analysed by Gilles Kepel as “the transition which gave Hamas parity with the PLO, if not primacy, for the incarnation of the Palestinian cause, and consequently the Islamisation of its Arab and universal image5“. Beyond the political vicissitudes on Palestinian territory, “the increase in suicide attacks – in the face of the hardening of successive governments of Mr. Netanyahu and the intensification of colonisation – can be considered as the model for the mirror of which the international jihadism of Al-Qaeda would develop its preferred mode of action6“.

In our database, we clearly observe an increase in the number of attacks affecting the Israeli and Palestinian territories from the beginning of the 1990s. Terrorist attacks are largely incriminating to Hamas but also to the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Group (PIJ). Between 1979 and 2000, of the 62 attacks recorded on the ground, 29 were claimed by Hamas and 13 by the PIJ. Out of 86 attacks in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 65 were claimed by Hamas and 12 by the PIJ.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The export of jihad

See Dominique Thomas, Le Londonistan. La voix du djihad, Michalon, 2003, p. 70.

Islamist violence has been on the rise in the Middle East and in North Africa from the 1980s onwards, and other regions of the world are also becoming hosts to this jihad, particularly Southeast Asia (Philippines), South Asia (India) and Europe. Rapid empowerment and the increasing power of Islamism eventually raise fears of countries that have nevertheless worked for this movement or who used it for domestic political reasons or international relations. Thus, in the face of the Islamist threat, Saudi Arabia and Algeria have engaged in relentless repression. This is also the case for Egypt and Syria. In a decade, Salafists have changed categories: firstly admired as “freedom fighters”, they were then denounced as “fugitives”7.

Islamist violence in the world (1979-2000)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Ibid., p. 62. On Salafo Jihadist activism in the United Kingdom, see also Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, Paris, Fayard/Pluriel, 2013, in particular the second part (“The conflict of identities”) and in particular its chapter 3, “Sharia law in Europe? “, p. 97 sqq.

This regional context forced many jihadists into exile: some, having returned from Afghanistan, became political refugees, often with the aim of exporting their Islamist struggle to new territories, including those that are not predominantly Muslim. They sought asylum in Europe. In the 1990s, these territories of settlement and conquest were first England and France. London thus became a hub for Salafo Jihadist activism in Europe8. Between July and October 1995, France was hit by a wave of Islamist terrorist attacks related to the Algerian context: on 25 July 1995 an attack in the Parisian metro resulted in the deaths of 7 people and 86 people wounded.

Asia was also hit hard between 1979 and 2000, particularly in the south and southeast. According to our database, we record the first Islamist terrorist attack in India in 1986. The phenomenon remained sporadic until 1990. In that year, 12 attacks were carried out under the leadership of the Hizbul Mujahideen (HM) group and its supporters. The action of this Islamist group was rooted in the conflict between India and Pakistan over the border region of Jammu and Kashmir, but if the group wanted the region to be integrated into Pakistan, it was also campaigning for the establishment of a caliphate in the world.

The landscape of Islamist terrorism in India is fragmented: a number of groups revolve around the issue of independence, including Allah’s Tigers (“Tigers of Allah”), the Muslim Brotherhood, Harkat ul-Ansar and Jamaat-e-Islami. Between 1979 and 2000, most attacks (78.8%) were concentrated in Jammu and Kashmir. Since 2000 and the creation of the terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), attacks have been both more numerous and more deadly (25 attacks and 126 deaths in 2000, 42 attacks and 200 deaths in 2001). These years also saw the Pakistani Taliban (Lashkar-e-Taiba) conducting terrorist campaigns in India.

In the Philippines, Islamist terrorism is deployed as part of the separatist struggle of the Moro people, a Muslim minority in the south of the country. One of the main terrorist groups in the region, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), founded in 1991 by Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, drew its inspiration from Islamist movements in the Middle East. The first demonstration of this terrorist movement occurred on 7 September 1986, when the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) attacked a Catholic church and a marriage ceremony in Salvador, on the island of Mindanao, killing 20 people and injuring 186. The group launched an attack on 15 January 1987 in the Manila metro, the capital, killing 8 people. In 1994, after an eclipse of sorts, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) carried out 7 attacks in the south of the country. It later became one of the main actors of Islamist terrorism in the Philippines in the following decades.

The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012)

Louis Gautier (dir.), Mondes en guerre. Tome IV, Guerre sans frontières. 1945 à nos jours, Éditions Passé composés/Humensis, Paris, 2021. See especially Louis Gautier, “Le temps des conflits”, Chapter III, pp. 143-204.

The attacks of 9/11 2001 perpetrated by Al-Qaeda on U.S. soil were the deadliest terrorist attacks in history, with a total of 3,001 deaths and 16,493 wounded. On that day, two hijacked airliners were launched against the towers of the World Trade Center in New York. A third aircraft had been directed at the Pentagon in Washington. On board the fourth hijacked aircraft, it was a passenger revolt that defeated the terrorists’ plan, as the aircraft crashed in the countryside in Pennsylvania.

The live and global broadcasting of this dramatic and spectacular event1 also marked the beginning of a new era in the media coverage of terrorism. In addition to the deferred information intended for specific audiences, immediate and comprehensive information is now available. This new public space profoundly affects the work of traditional media (television, press and radio). The advent of social media and smartphones is opening its doors of mass communication to countless new players, starting with terrorist organisations.

9/11 and the war on terror

According to a survey conducted by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, of the seventeen events proposed, half of the young people surveyed (47%) cite the attacks of 9/11 as one of the three most significant events (see Future Memories, Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, January 2015, www.fondapol.org/en/polls-en/future-memories_a-survey-presented-by-dominique-reynie/).

The attacks of 9/11 have had a significant impact that changed the geopolitics of the Middle East2. Qualified by George W. Bush’s administration as the “war on terror”, the American response was brisk. On 7 October 2001, the United States launched a major offensive against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, accused of having supported Al-Qaeda. A year and a half later, on 20 March 2003, the American army invaded Iraq, in order to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime in the prospect of “democratising the Middle East”. Despite overwhelming military victories, the United States is failing to restore peace, or to eradicate Islamism. Confronted with the machine of American war in the long term, Islamists organised themselves, by acquiring an international dimension that keeps being reaffirmed. Between 2001 and 2012, the number of attacks and victims have increased in a spectular way, notably due to the attacks perpetrated by Taliban fundamentalists.

Their movement has been spreading in Afghanistan and in Pakistan since 1994. Two years later, they overthrew the government in place when Kabul was taken over. They established the regime of the Islamic Emirate from Afghanistan, headed by Mohammad Omar. In the years that followed, the Taliban persecuted minorities, established a well-founded regime on the strict application of Sharia law and welcomed numerous wanted jihadists, including the leader of Al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden. In a few years, Afghanistan became a home for Islamic extremists from all over the world.

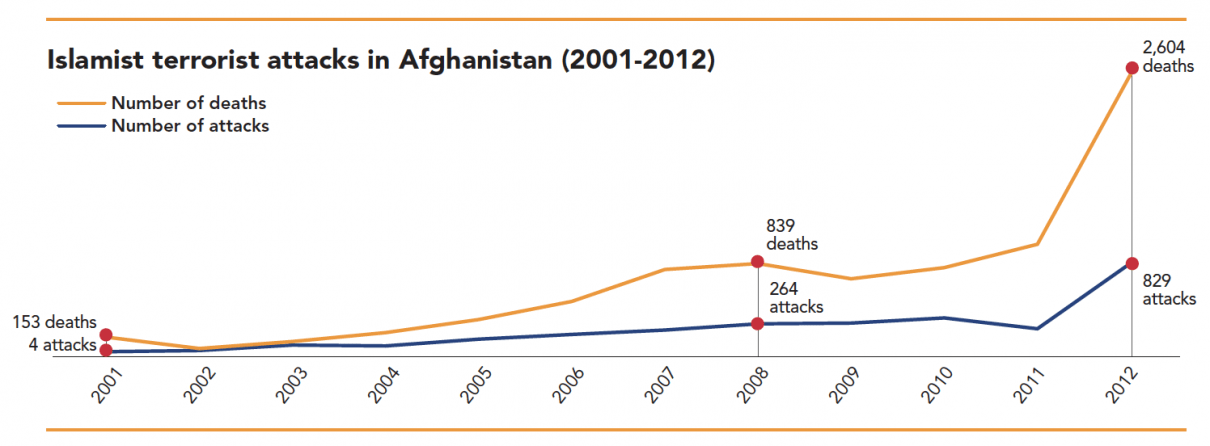

After the attacks of 9/11, the Taliban were driven out of power by an international coalition led by the Americans. From this moment on, there was an exponential increase the number of attacks and the number of victims, in particular among international forces or members of the Afghan government. We went from 4 attacks and 153 deaths in the country in 2001 to 829 attacks and 2,604 deaths in 2012. In total, between 2001 and 2012, 2,536 attacks took place on Afghan soil, killing at least 8,054 people. This represents 30.7% of the total number of Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide between 2001 and 2012. The Taliban were responsible for most (95.2%) of these attacks.

The Talibans’ targets in Afghanistan (2001-2012)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

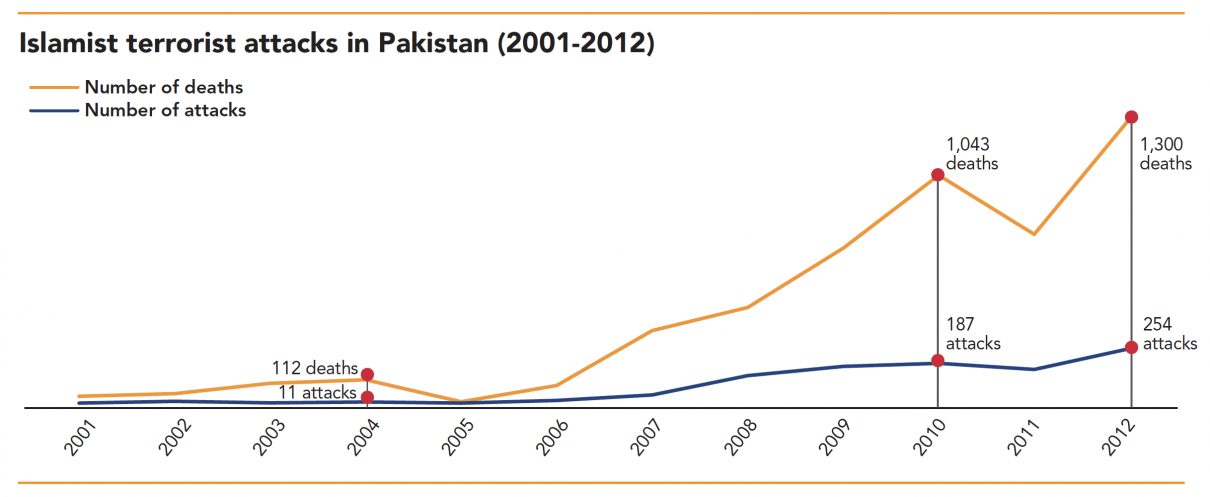

In Pakistan, we also witnessed the rise of groups multiplying terrorist acts between 2001 and 2012, with 1,010 attacks and 4,997 deaths. Very present in this country, the Taliban organised themselves from 2007 under the name Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP); they were responsible for nearly three-quarters of the (71.1%) of the terrorist violence over this period (2001-2012). Other Islamist groups are also active, such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (56 attacks, 386 deaths) or Lashkar-e-Islam (64 attacks, 115 deaths). In 2007, two terrorist attacks led by Al-Qaeda and its allies left their mark on the landscape of the country’s politics: on 18 October, an attack against a crowd gathered to welcome the former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, returning from exile, caused the death of 141 people and wounded 250. On 27 December, she was murdered in turn, victim of a suicide attack that killed 20 people and wounded more than a hundred.

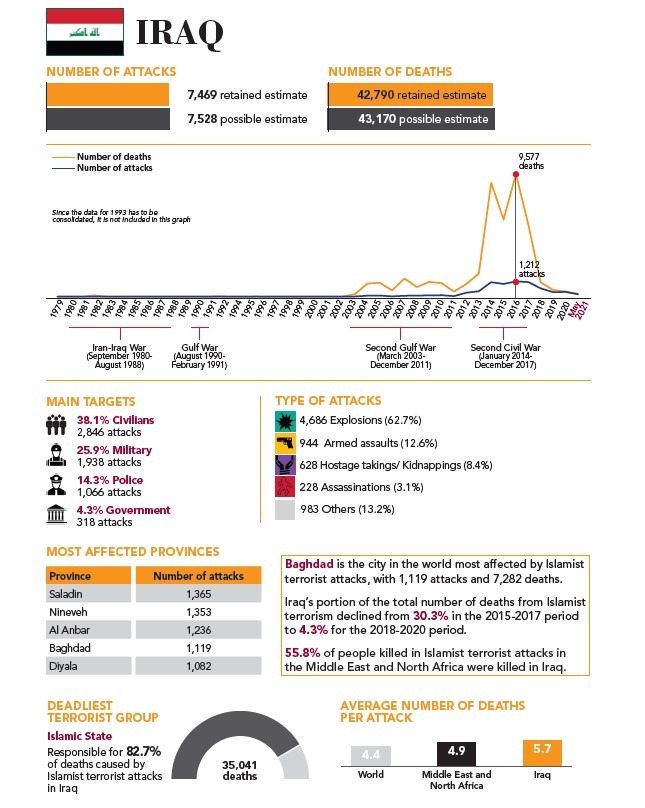

Between 2001 and 2012, Iraq was the third largest country most affected by Islamist terrorism, with 914 attacks. Particularly violent, these attacks caused the deaths of 8,534 people, with on average 9.3 people killed per terrorist action. By comparison, in the world during the same period, an attack killed an average of 4.6 people. The fight against foreign interference is a key reason for violence by Islamists. From the moment on 19 August 2003, the car bomb attack against the Canal Hotel, UN headquarters in Baghdad, killed 22 people. The year 2004 saw a series of terrorist attacks targeting coalition member countries in Iraq, with 9 attacks against personnel at military bases, checkpoints and patrols of the Multi-National Force-Iraq (MNF-I). At the same time, the development of hostage takings/kidnappings became more common to terrorist actions: while we do not record any hostage takings or kidnappings in 2001, 2002 and 2003, there were 27 in 2004, largely aimed at civilians from countries militarily deployed in Iraq (5 Americans, 4 Japanese, 3 South Koreans, 1 Bulgarian, 1 Canadian, and 1 Italian). Among the countries involved in the war, the United States was greatly affected: between 2001 and 2012, in Iraq, 34 attacks targeted Americans, including 15 during the year 2004.

Deadliest terrorist groups in Iraq (2001-2012)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Globalisation of Islamist terrorist attacks

Between 2001 and 2012, an increase in Islamist terrorist attacks is observable in several geographical areas in the world. Compared to the previous period (1979- 2000), there was a sharp increase in the number of terrorist attacks, with 8,265 attacks (compared to a total of 2,194 between 1979 and 2000) and 38,186 deaths (compared to a total of 6,817 between 1979 and 2000). This dramatic increase is partly due to the globalisation of jihad, facilitated by the acceleration of the circulation of people and ideas.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Gilles Kepel, Sortir du chaos. Les crises en Méditerranée et au Moyen-Orient, Gallimard, 2018, p. 147.

See David Martin Jones, Michael Smith et Mark Weeding, “Looking for the Pattern: Al Qaeda in Southeast Asia- The Genealogy of a Terror Network”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 26, n° 6, November 2003, p. 443-457.

See Gabriel Facal, “Les groupes islamistes radicaux en Asie du Sud-Est–Panoramas institutionnels, réseaux d’affiliation et références”, Note d’actualité n° 10/16, Observatoire de l’Asie du Sud-Est, cycle 2018-2019, asiacentre.eu, July 2018 (www.centreasia.eu/les-groupes-islamistes-radicaux-en-asie-du-sud-est-panoramas-institutionnels-reseaux-daffiliation-et-references-ideologiques-gabriel-facal/).

Since 2004, Europe has been confronted with a wave of attacks of a new magnitude. On 11 March, in Madrid, four trains exploded almost simultaneously. Claimed by Al-Qaeda, these attacks killed 191 people. On 7 July 2005, four explosions hit public transportation in London, killing 56 people and wounding 784. Though Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for these attacks, the terrorists, unlike those of 9/11, were natives of the United Kingdom. Gilles Kepel sees this as a change in the implementation of Islamist terrorist attacks, which now rely on “a human resource specific to the Western country targeted”3.

In addition, many Islamist movements are intensifying their inter-regional collaborations, such as in Asia. The 9/11 attacks on the ground claimed by Al-Qaeda and then the intervention in Afghanistan by American troops helped further the link between Osama bin Laden and various South Asian groups4, examples of which are Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) in Indonesia. The difficulty is to examine, in each context, the way in which people and violent groups combine local elements, regional and global within the referents, the objectives and the operating methods they mobilise and implement. Trends then appear to be oscillating between unrelated ethno-nationalism with global jihad and a transnational religious referent5. The situation in Thailand during this period takes part in this dynamic. From 2004 onwards, in the context of a separatist insurgency, the south of the country where a Muslim minority lives is crossed by violent activism. The two main groups Runda Kumpulan Kecil (RKK) and the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO), are then organised around a jihadist discourse. For a number of attacks occurring at this time, the Islamist character is sometimes found intertwined with ethno-nationalist claims.

Our database offers the reader the possibility to keep these events or not when counting the Islamist terrorist attacks. According to our estimate between 2001 and 2012, we identify 111 attacks and 91 deaths in Thailand. According to the possible estimate, we count 146 attacks and 121 deaths over the same period. In the latter we also take into account the actions of terrorists accused of being Muslim separatist extremists.

Number of terrorist attacks by province in Thailand (2001-2012)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The ramifications of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQPA) and of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

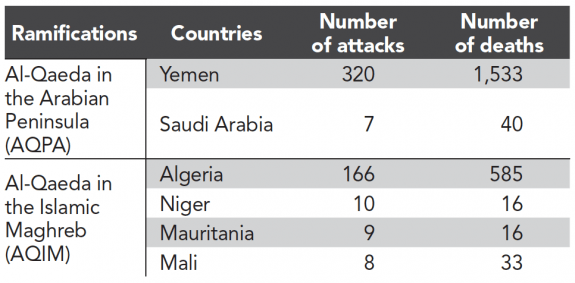

The rise of Islamist terrorism can also be explained by the development of Al-Qaeda’s ramifications, such as that of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQPA) or Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

These different branches develop a capacity to hit hard abroad, as shown by the three successive attacks of 9 November 2002 by Al-Qaeda in Iraq, at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Amman, which caused the deaths of at least 61 people, and the one on 28 November 2005 at the Paradise Hotel in Mombasa, Kenya, killing 16 people.

See Center for International Security and Cooperation (Cisac), “Al Shabaab”, cisac.fsi.stanford.edu (https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/al-shabaab).

Relatively spared until then, sub-Saharan Africa became a target of Islamist terrorism in the second half of the 2000s. The creation and expansion of the Al Shabaab group, formerly the armed wing of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), in Somalia in 2006 was central. Pursuing the objective of overthrowing the Somali government in order to establish a regime founded on Sharia law, Al Shabaab has been cultivating close links with Al-Qaeda, thus forming part of the global jihadist movement6.

Al-Shabaab’s targets in Somalia (2001-2012)

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The group’s activity goes beyond the borders of Somalia, where the group has committed 459 attacks and killed 1,396 people, to reach Kenya, where it attacked 97 times (126 deaths), and Ethiopia, where it struck twice, including the devastating attack (100 deaths) on 2 November 2007 against Ethiopian soldiers in a hotel in Dolo.

Sub-Saharan Africa was also the first to suffer acts of violence by Boko Haram, which have been recorded in Nigeria since 2009. The considerable scale of its attacks between 2010 and 2012 (566 attacks, 1,655 deaths) foreshadowed its power of destruction over the next decade.

Types of weapons used in Islamist terrorist attacks (2001-2012)

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Terrorist migration to social media

David Thomson, Les Français jihadistes, Paris, Les Arènes, 2014, “young people who discover hadiths on the Internet are completely deaf to all those who, at the mosque, can try to explain that the meaning of prophecies is part of a context: for them, who have come to sacred texts alone or with jihadist propaganda, the historical or figurative interpretation is an ‘innovation’, that is, the worst thing since it distorts and biases the meaning they think is original”.

Evan Kohlmann, cited in Gabriel Weimann, “Terrorist Migration to Social Media”, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 16, n° 1, 2015, p. 181.

The Internet obviously plays a key role in globalisation of Islamist terrorism. It turns out to be a powerful propaganda and recruitment tool7. The emergence of social media allows Islamist groups to interact effectively and often anonymously, to share documents and information, but also to establish a community of interconnected individuals. According to Evan Kohlmann, “90% of terrorist activity on the Internet takes place using social networking tools. These forums serve as a virtual firewall to help safeguard the identities of those who participate, and they offer subscribers a chance to make direct contact with terrorist representatives […]”8. Furthermore, cyber-terrorism is also a modality of attack for Islamist groups which thus multiplies their capacity for action.

The impact of terrorist violence in a global public space within the reach of the individual media

From the mid-1990s onwards, access to visibility took on unprecedented proportions. The digital public space increased the impact of terrorist actions tenfold. The coupling of the Web with continuous news channels amplified the effects of Islamist violence. Al Jazeera, the Qatari channel launched in 1996, broadcasts in some 30 countries and develops information websites in the few languages that can be used to reach most residents of the planet. Social media and other secure messaging applications offer the most modest of these terrorist groups the tools of global action: communication, propaganda, organisation, recruitment… The smartphone extends to the end of the chain, i.e. the individual, the mastery of these powerful tools and access to all networks. Media coverage of the attacks always goes through the traditional media (agencies, television, radio and the press) but it no longer depends on them. In the universal public space, production information is absolutely disseminated. The Web and the smartphone give the human multitude the powers of a news agency with 2.8 billion correspondents and the influence capabilities of numerous media. Islamic terrorism thrives in the age of the individual media. The depth of the network, the strength of the images, and the play of algorithms mean that any attack can become a global event in a matter of minutes.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

The irruption of the Islamic State and Boko Haram (2013-May 2021)

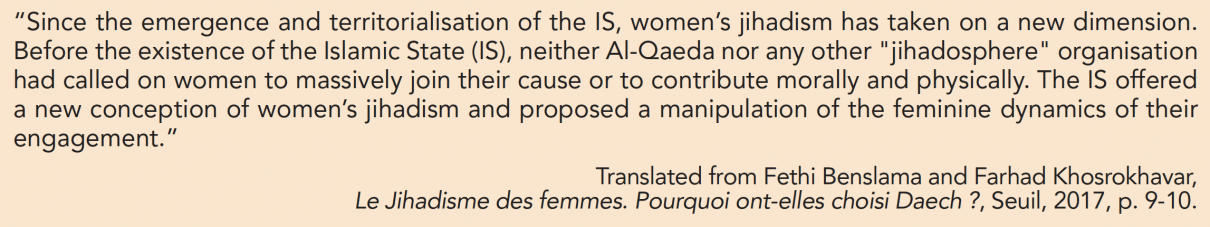

Hakim El Karoui, La Fabrique de l’islamisme, Institut Montaigne, September 2018, p. 85. Also see Hakim El Karoui, Benjamin Hodayé, Les militants du djihad, Fayard, 2021.

On 17 December 2010, the immolation of the young street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, in the Sidi Bouzid region of Tunisia, led to the flare-up of the Arab Spring. After some time raising hopes of democratisation, these events led, in the first half of the 2010’s, to electoral victories for parties close to the Muslim Brotherhood. While they occasionally failed to retain power, they are “supported by increasingly conservative societies, also as a result of the spread of Salafism imported from Saudi Arabia”1.

In this new context, jihadism is developing regionally, based in particular on the proclamation by the Islamic State (IS) of the Caliphate in Mosul in 2014. It is during this period that Islamist terrorism is the most deadly. There has been an unprecedented increase of the number of attacks worldwide. The rise of IS and Boko Haram is facilitated by chaotic geopolitical contexts that offer terrorists many opportunities for expansion.

The Islamic State and the “management of savagery”

Expression taken from “The Management of Savagery: the most critical stage the ummah will go through”, a text in Arabic published on the Internet in 2004 and written under the name of Abu Bakr Naji, a pseudonym of Mohamed Hassan Khalil al-Hakim, alias Abu Jihad al-Masri, an executive of Al-Qaeda. This text is intended to serve as a spiritual guide for many extremists. It explains the strategy to establish an Islamic caliphate. According to some commentators, the manifesto contains “103 pages of hate speech, against the Jews, against Christians, against the apostate, against democracy and its values. So much so that some have called it the Mein Kampf of the little jihadist. The interest of this book is that it puts us, right from the title, in front of the paradox of jihadism, which on the one hand advocates the unleashing of savagery, the installation of the law of the jungle, with the call for the destruction of the old order, and at the same time theorises the management of this savagery and its ‘administration'” (Abderrazak Sayadi and Alberto Fabio Ambrosio, “Terrorisme : anatomie du ‘Mein Kampf’ djihadiste”, contrepoints.org, 27 March 2018, www.contrepoints.org/2018/03/27/312678-terrorisme-anatomie-du-mein-kampf-djihadiste).

See Mathieu Guidère, Atlas du terrorisme islamiste. D’Al-Qaida à Daech, Autrement, 2017.

For example, the attempted attacks in Villejuif on 19 April 2015 and on the Thalys train on 21 August 2015.

See Anne-Aël Durand, William Audureau, Maxime Vaudano, Madjid Zerrouky and Gary Dagorn, “Les attaques de l’État islamique ont fait plus de 2 500 morts en deux ans”, lemonde.fr, 17 June 2016.

The group Islamic State emerged and then settled during the Iraqi civil war, between 2003 and 2011. The organisation was created in 2006 and, three times, its name change accompanied its expansion outside its Iraqi hub: first as an Islamic State in Iraq (ISI, 2006-2013), then as an Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, 2013-2014) and finally as an Islamic State (IS, from 2014).

Theorised in the 2000s, the strategy of the IS is to promote chaos, the “management of savagery”2, and to globalise jihad. Its objective is to cultivate religion in the minds of the masses, to make Islam the only political and social order, and to train young people in order to establish a militarised society. The IS operates in several ways. The terrorist group may incite individuals to act alone. These are the “lone wolves”. Popularised in the 1990s, this expression has been used by the IS through different publications. A lone wolf becomes radicalised, plans and executes an attack on their own, without being affiliated with a particular terrorist group, even if they can claim the attack on behalf of the IS3. It should be noted that failed attacks are generally not claimed by the Islamic State4. The Iraqi-Syrian “parent company” directly claims responsibility for the most deadly attacks5. For example, the attack on the Bardo Museum, Tunisia, on 18 March 2015, or the attacks of 13 November 2015 in France, were claimed the next day by the IS.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

As it gains momentum, the IS extends its battlefield. According to our database, it is from 2013 onwards that the organisation has multiplied the number of its terrorist attacks. For that year, we count nearly thirty-one times more attacks by the IS compared to the previous year (374 attacks in 2013, 12 in 2012).

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique

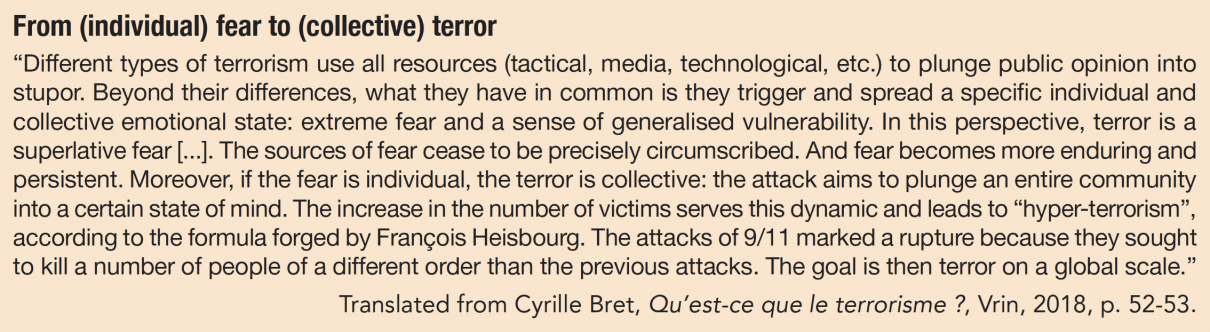

It should be noted that Boko Haram is not included here, although this group pledged allegiance to the IS in March 2015. We dedicated the following section to this terrorist group in order to highlight its uniqueness. Nevertheless, by adding the terrorist acts of Boko Haram committed since 2015 to the number of attacks perpetrated by the IS and its various branches since its creation in 2006, we obtain the figure of 13,559 attacks that caused the deaths of 73,456 people.