Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2024

New edition - Data collected through 12 April 2024The main lessons of the study

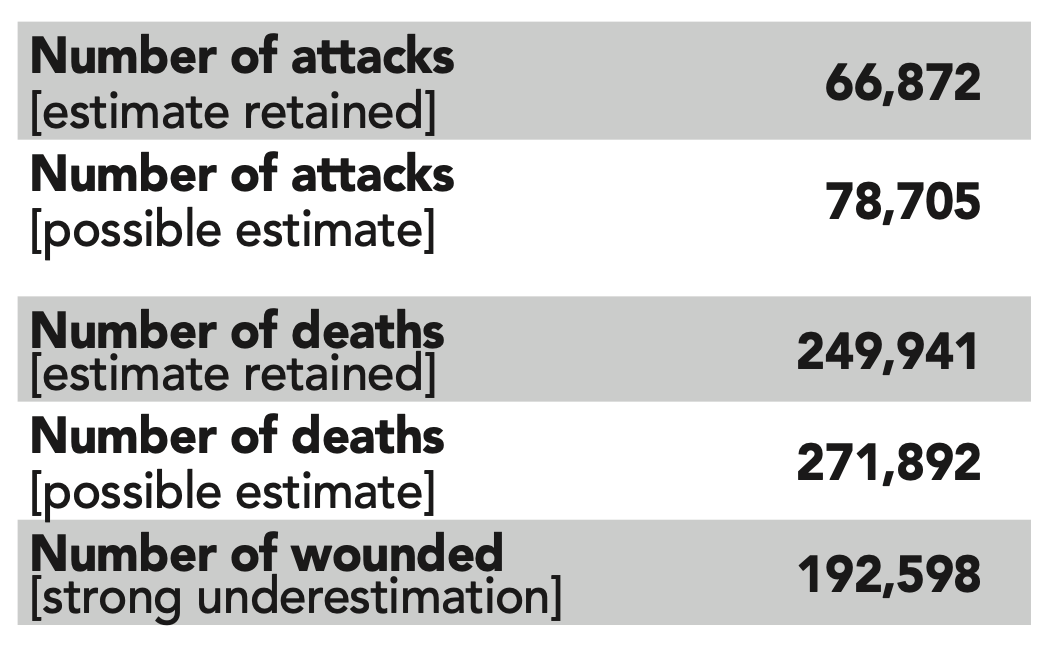

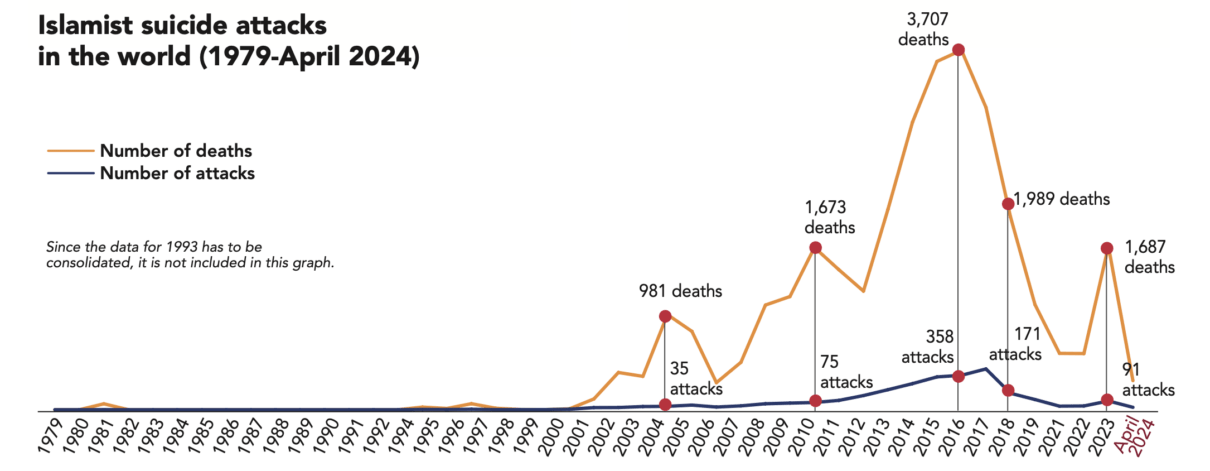

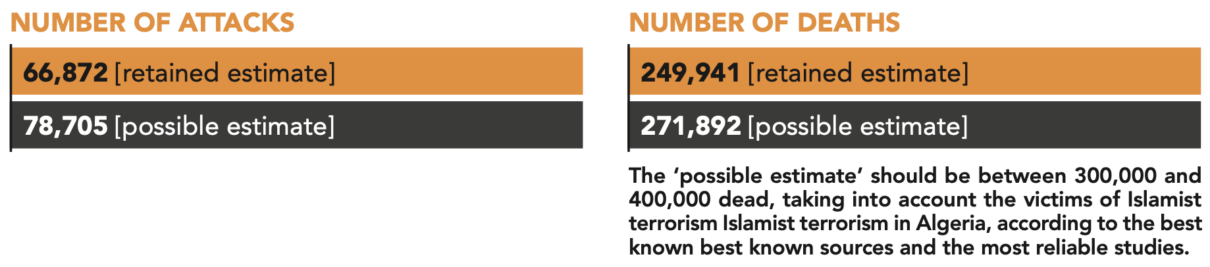

Between 1979 and April 2024, we recorded 66,872 Islamist attacks worldwide. These attacks caused the deaths of at least 249,941 people.

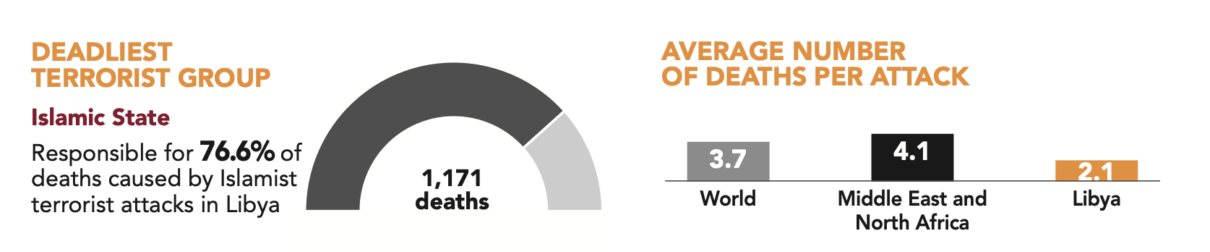

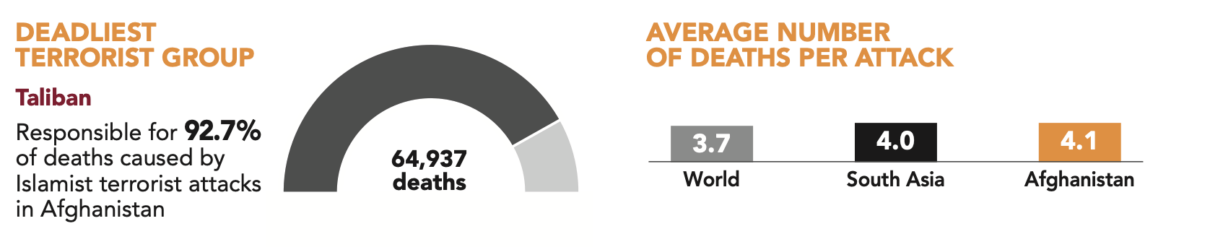

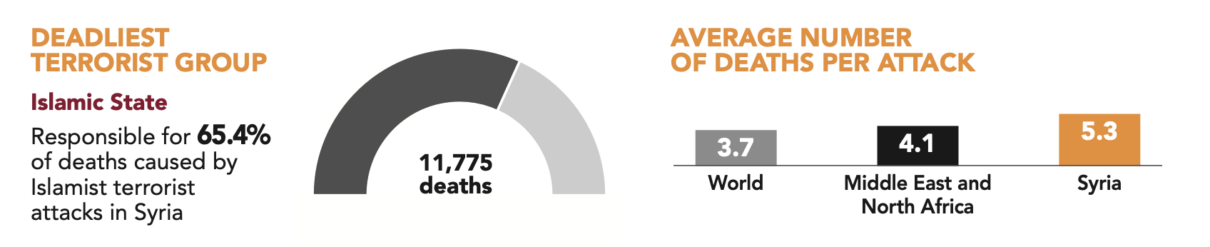

On average, an Islamist attack caused the deaths of 3.7 people.

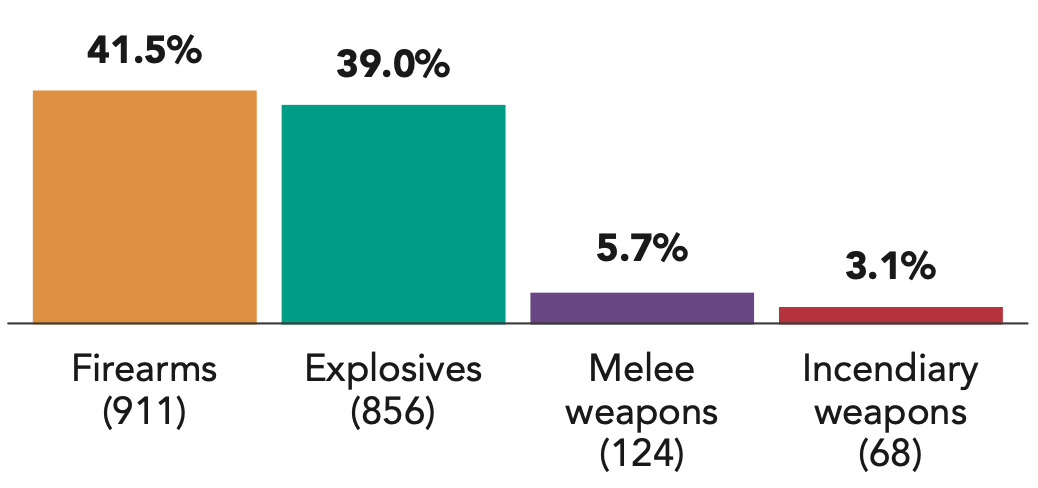

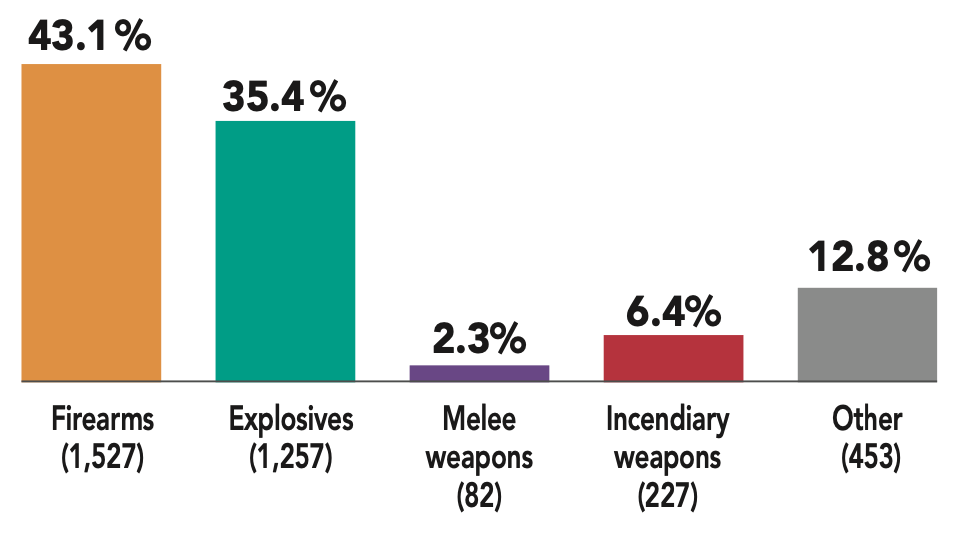

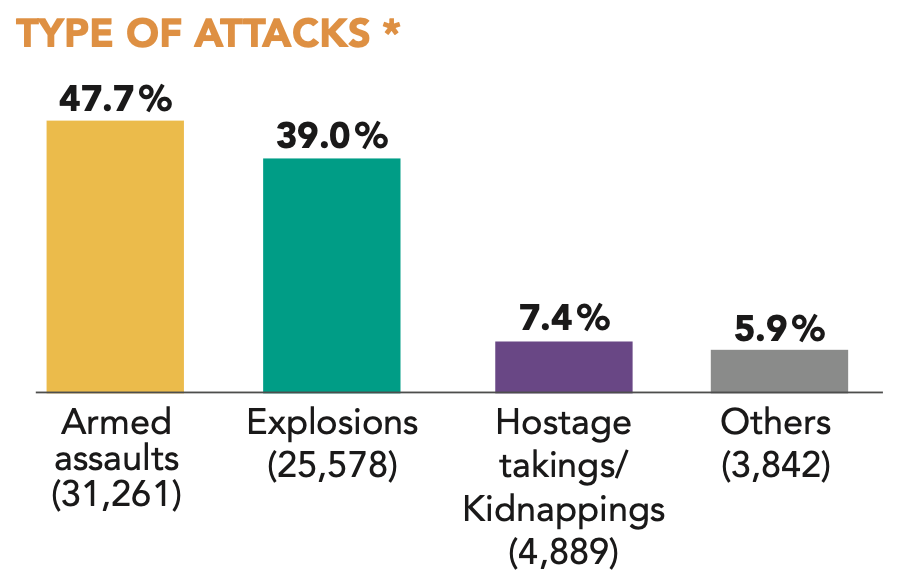

Firearms were the most used weapons (26,925), followed closely by explosives (25,832), melee weapons such as knives or machetes (2,479) and incendiary weapons (1,162)*.

The Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 96.7% of Islamist attacks between 1979 and April 2024.

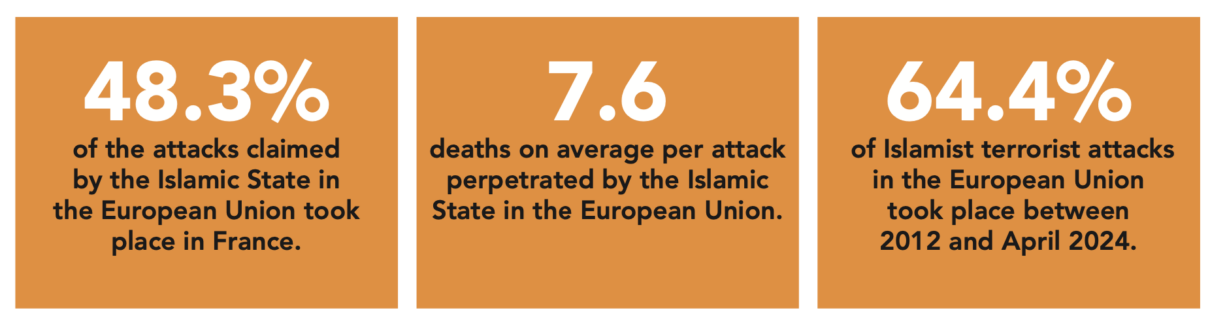

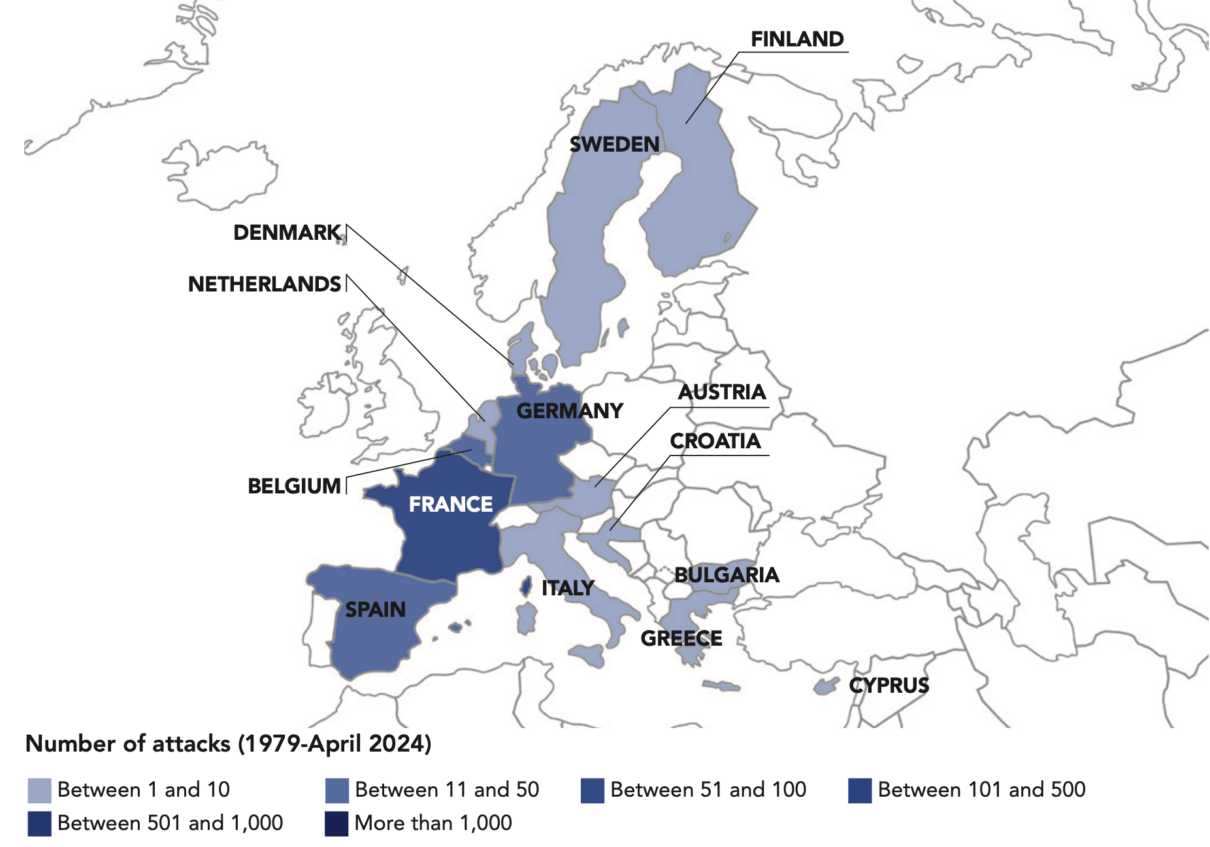

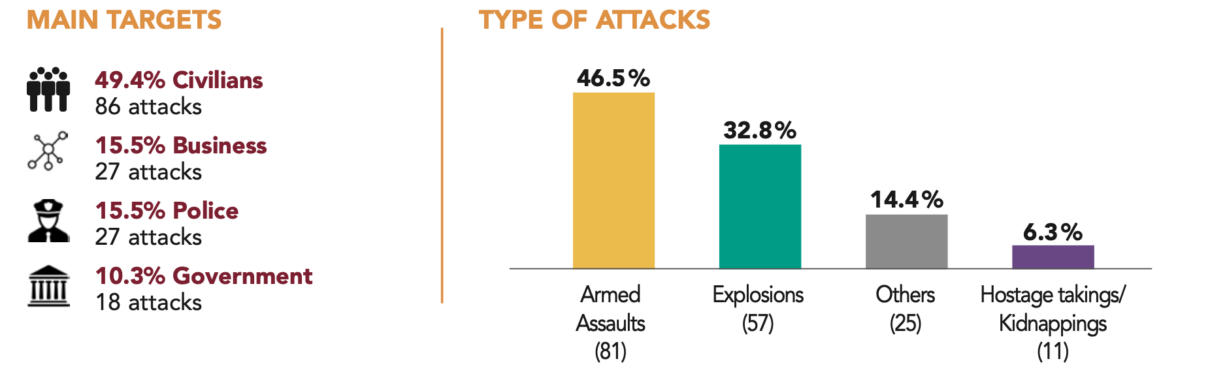

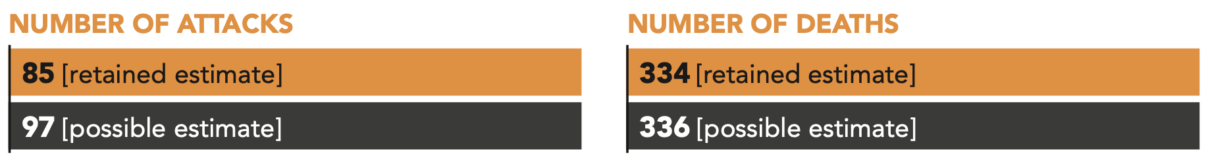

Within the European Union, France was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, with 85 attacks committed on its soil between 1979 and April 2024. At least 334 people were killed in these attacks.

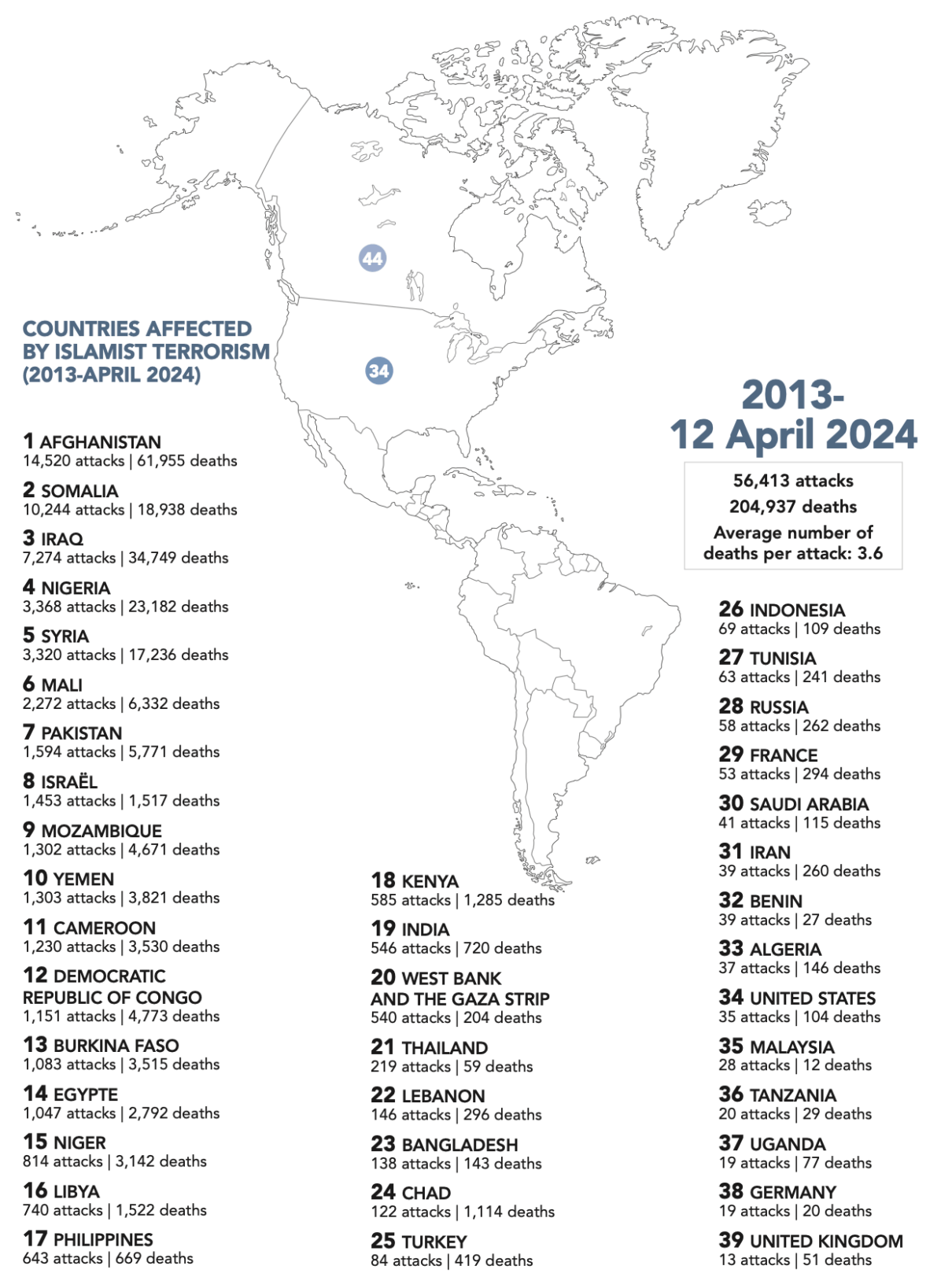

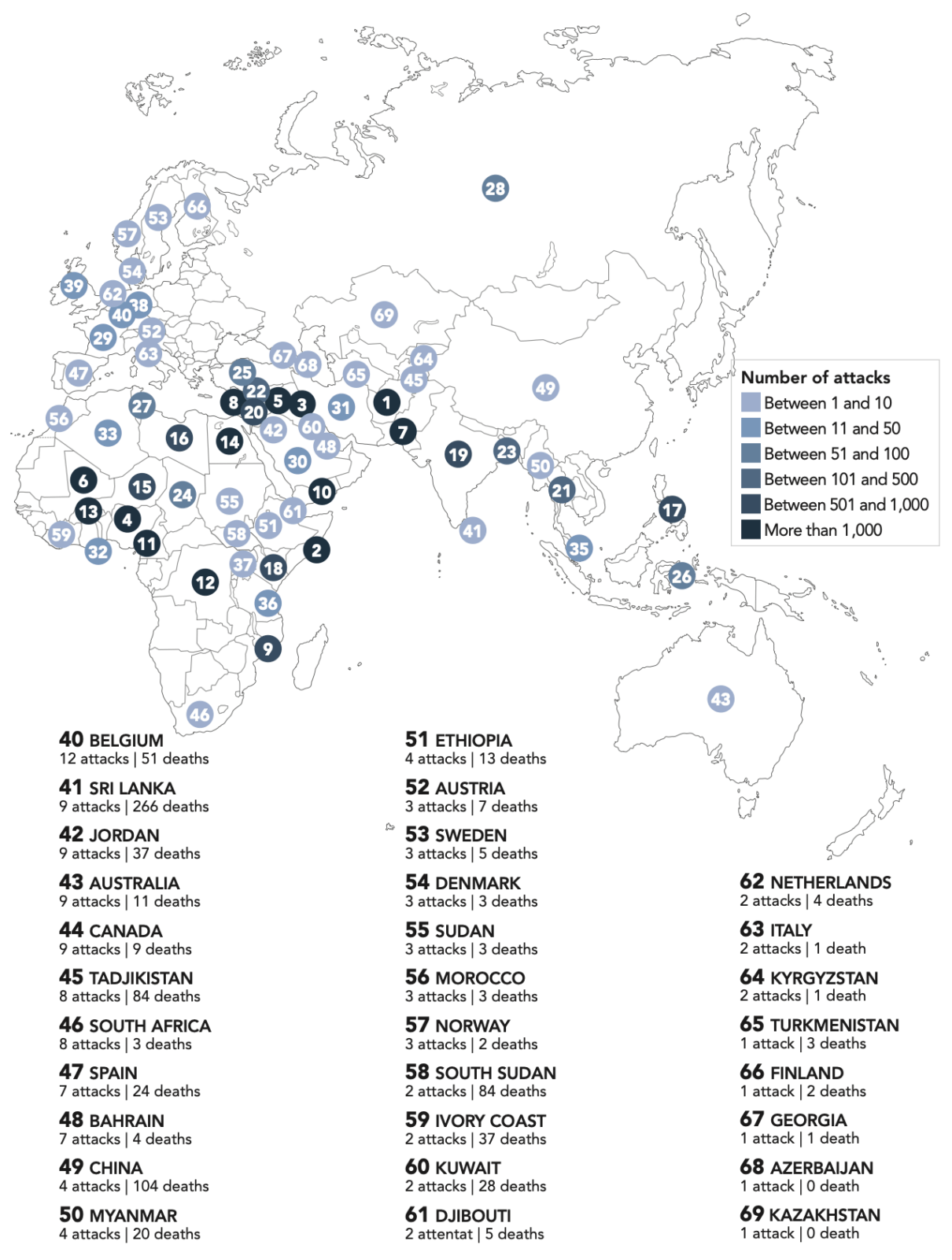

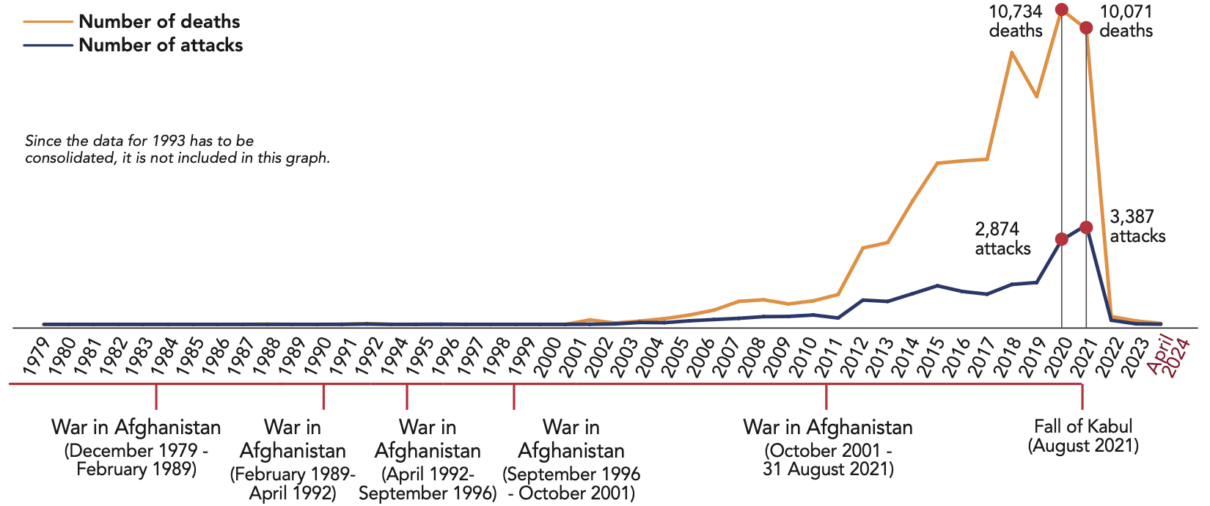

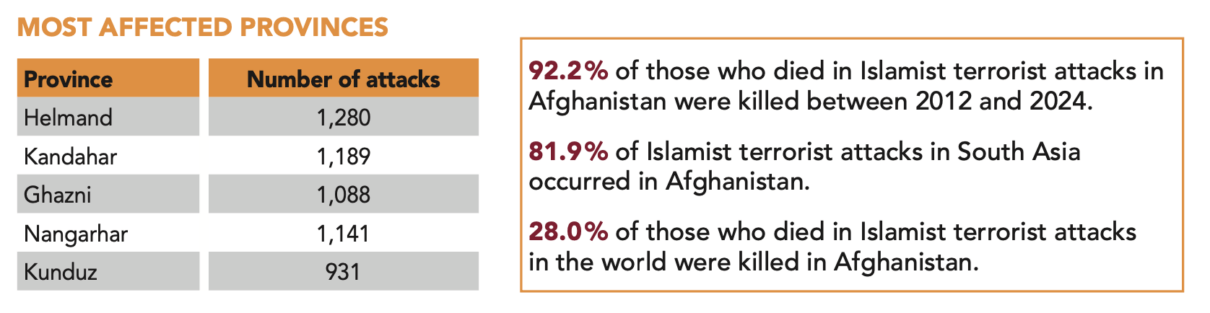

Afghanistan was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, ahead of Somalia and Iraq.

The indirect confrontation in Afghanistan between the American and Soviet powers is one of the major causes of Islamist violence of the 21st century.

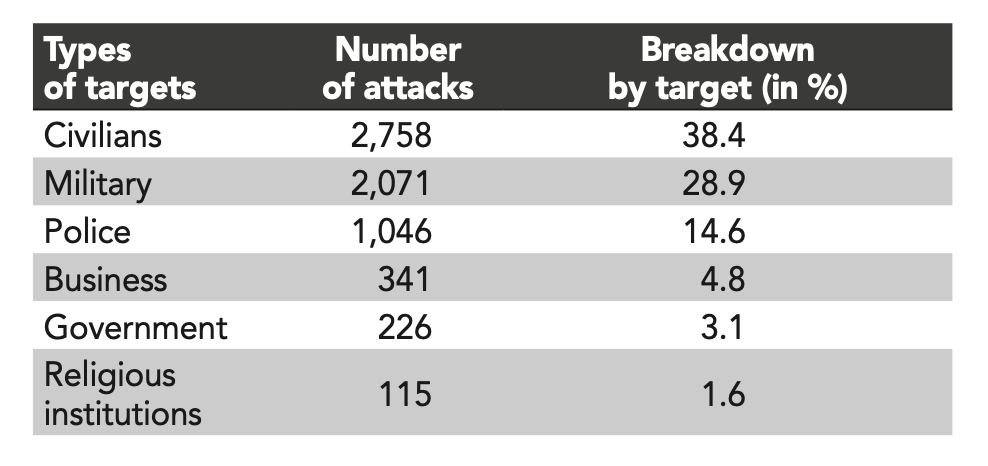

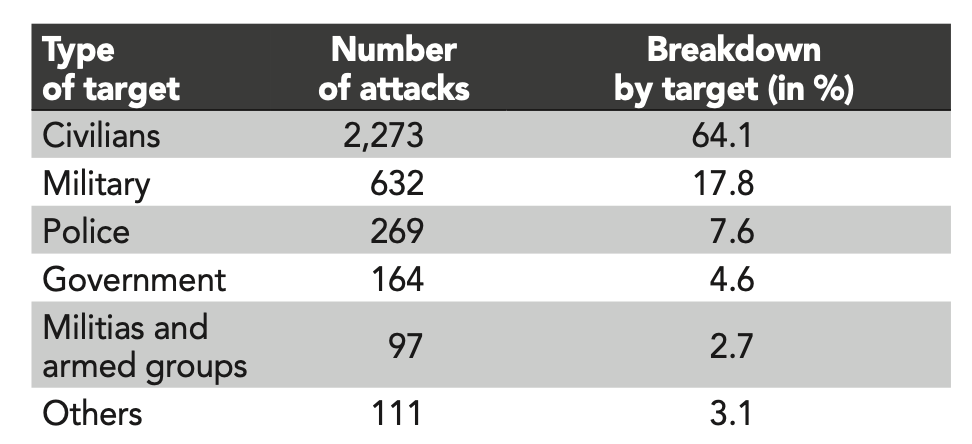

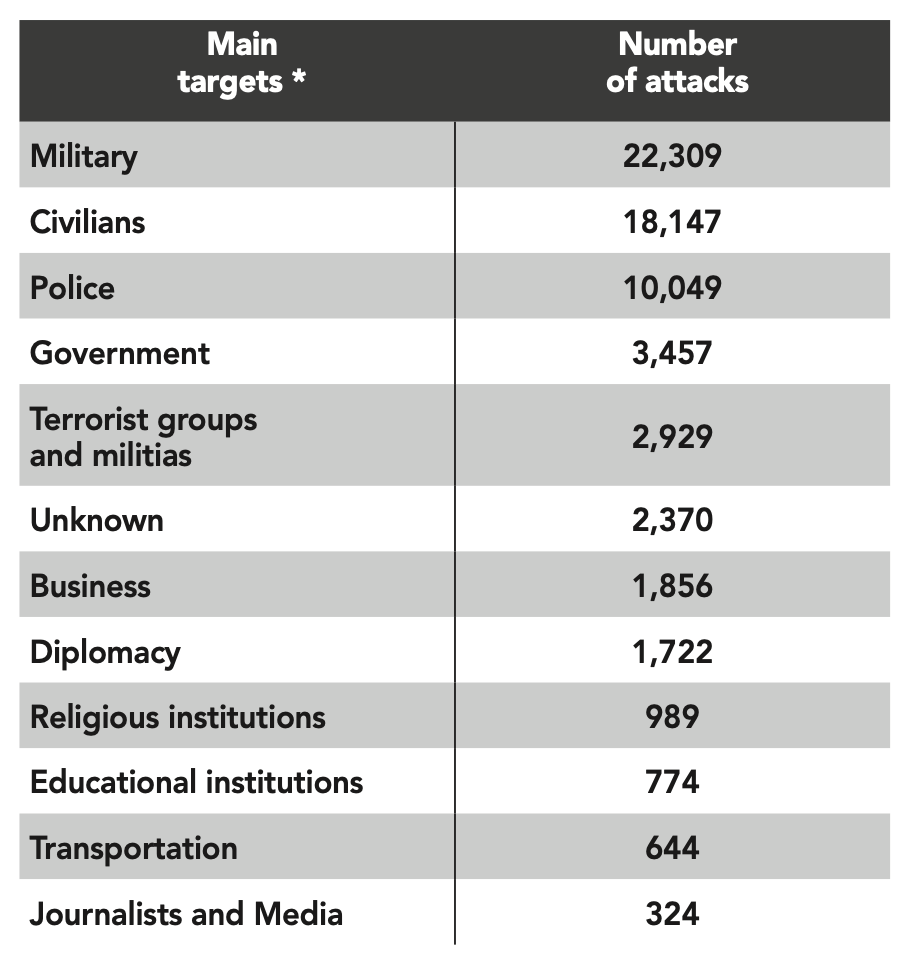

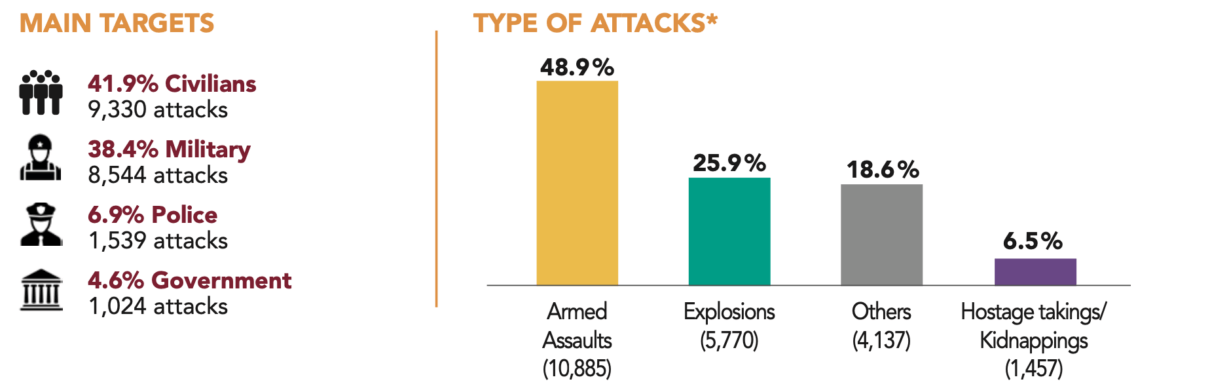

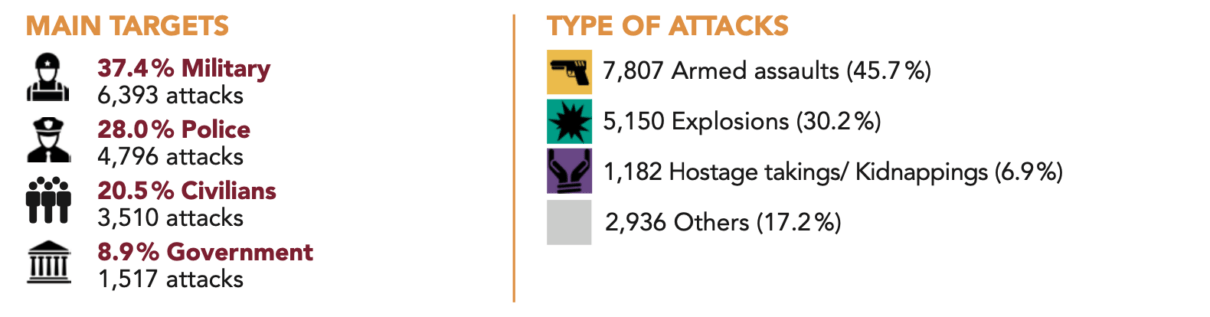

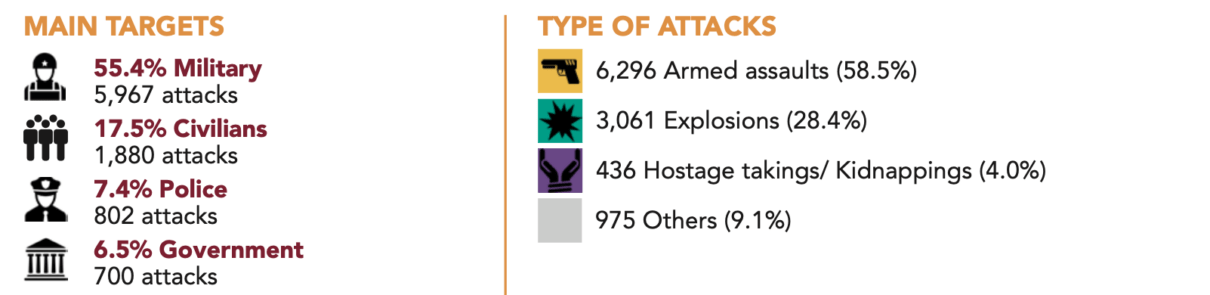

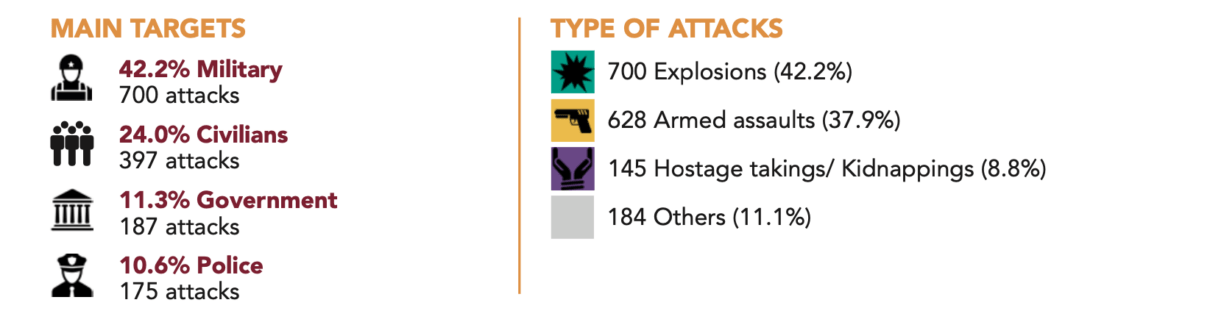

The military is the main target (34%) of Islamist terrorists, ahead of civilians (27.7%) and police forces (15.3%).

Most (86.3%) of Islamist terrorist attacks have occurred in Muslim countries1. Similarly, the vast majority of deaths from Islamist terrorist attacks (88.9%) occurred in Muslim countries.

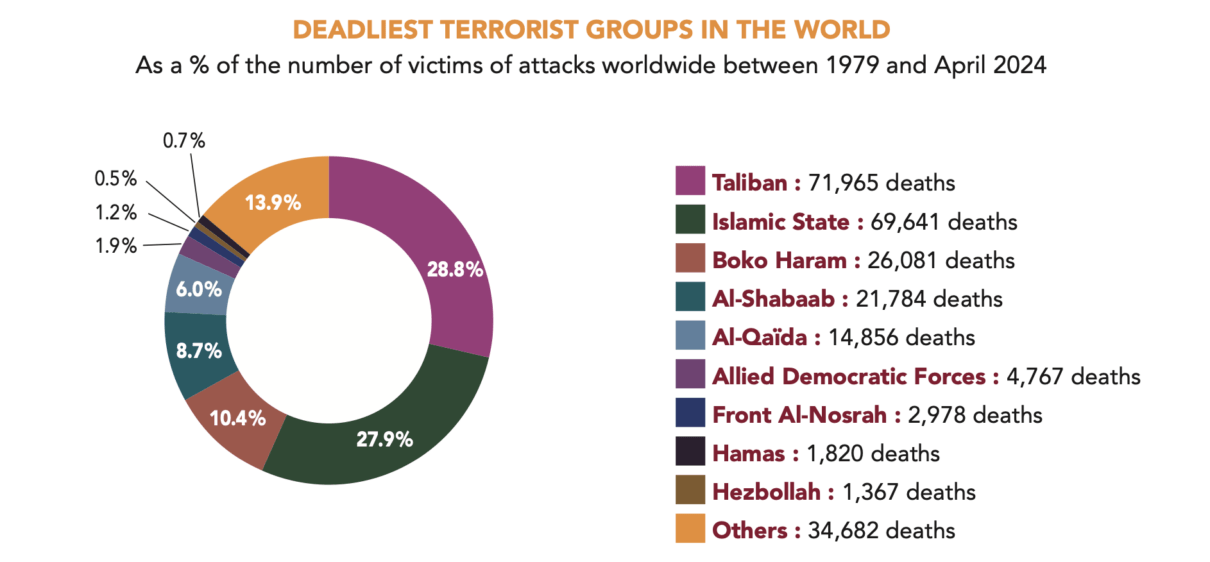

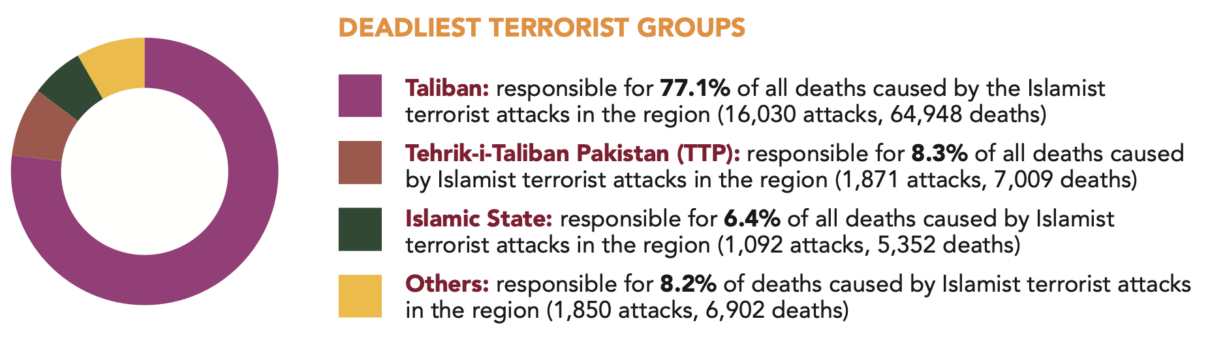

Over the entire period of time studied here, the Taliban was the deadliest group. Its terrorist actions resulted in the deaths of 71,965 people.

An assessment of Islamist violence in the world (1979-April 2024)

1979, the critical year

Definition of terrorism

Definition of Islamism

A global database of Islamist terrorist attacks from 1979 to April 2024

Why our study underestimates the reality of Islamist violence

The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000)

The Soviet-Afghan war, “matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism”

The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism

The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa

The export of jihad

The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012)

9/11 and the war on terror

Globalisation of Islamist terrorist attacks

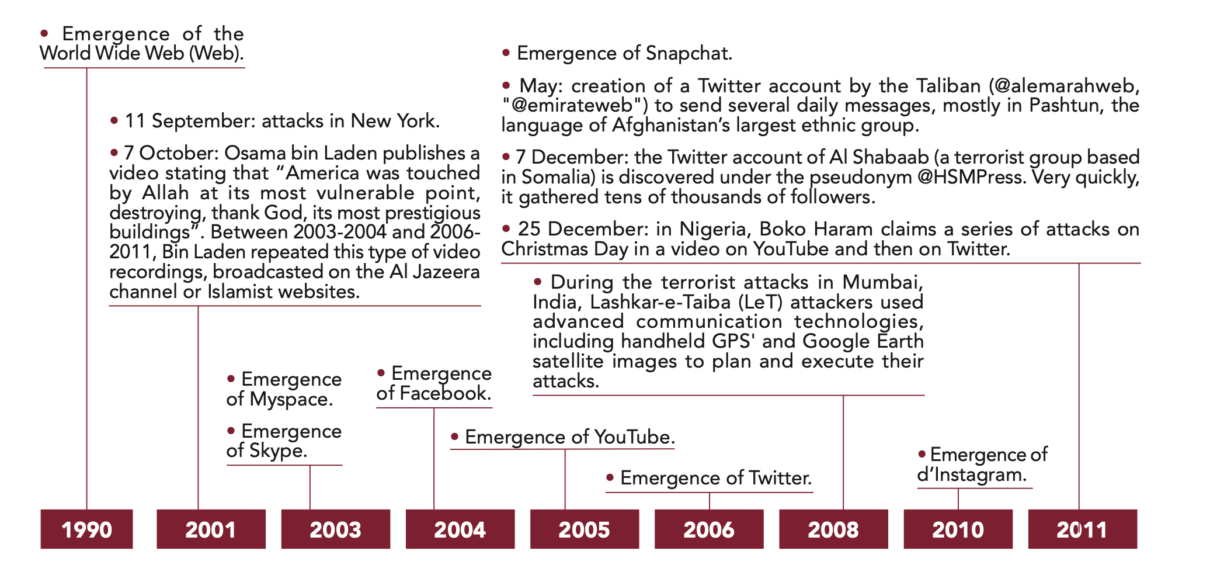

Terrorist migration to social media

The new faces of Islamist terrorism (2013-April 2024)

The Islamic State and the “management of savagery”

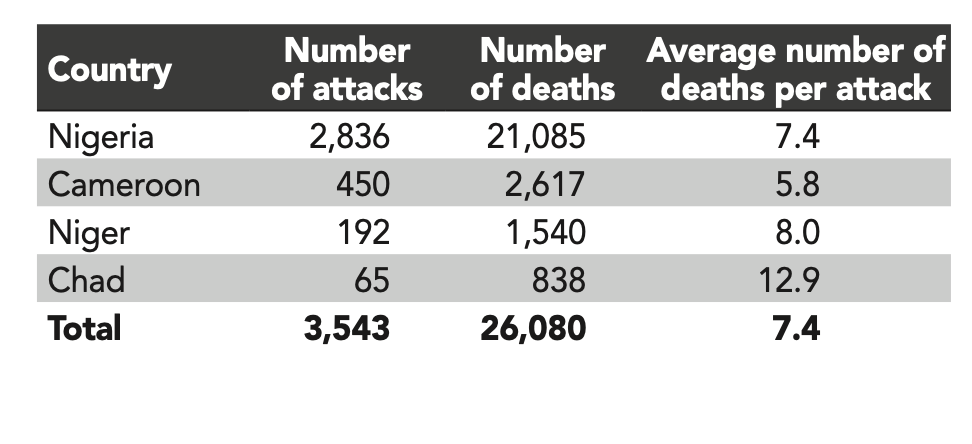

The Lake Chad region against Boko Haram’s mass terrorism

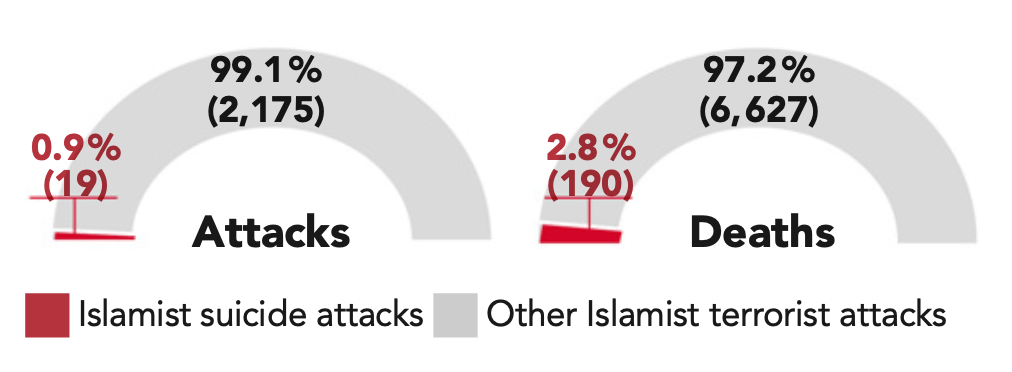

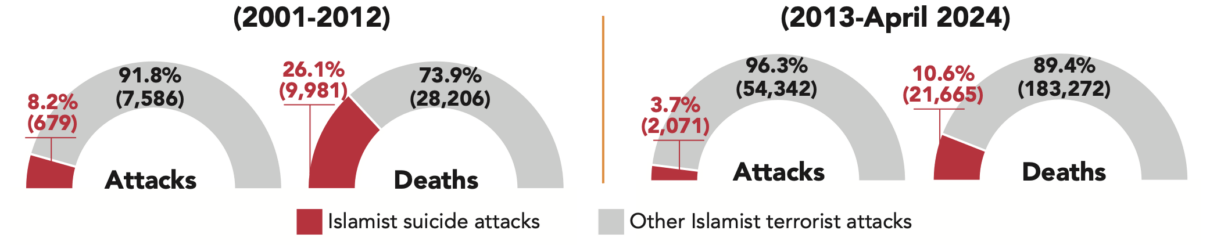

The suicide attack, the “martyr” and the terror

Afghanistan, the world’s hardest-hit country by Islamic terrorism

The resurgence of Islamist attacks in Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa, a hotbed of Islamist terrorism

The October 7, 2023 attacks in Israel: a historic turning point

The territories of Islamist terrorism (1979-April 2024)

The most affected countries (1979-April 2024)

Islamist Terrorist Attacks in the World 1979-2021

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019

Are Europeans abandoned to populism?

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

Dominique REYNIÉ, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

Joséphine STARON

Simon AMAT, Diane de CHARRY, Clément DE CARO, Anne FLAMBERT, Nicola GADDONI, Éric GARCIA, Mélodie JOURDAIN, Alice LE FAUCHEUR, Jean MICHEL, Claire-Marie MORINIÈRE, Enzo MUS, Dominique REYNIÉ

Julien RÉMY

October 2024

The main lessons of the study

Between 1979 and April 2024, we recorded 66,872 Islamist attacks worldwide. These attacks caused the deaths of at least 249,941 people.

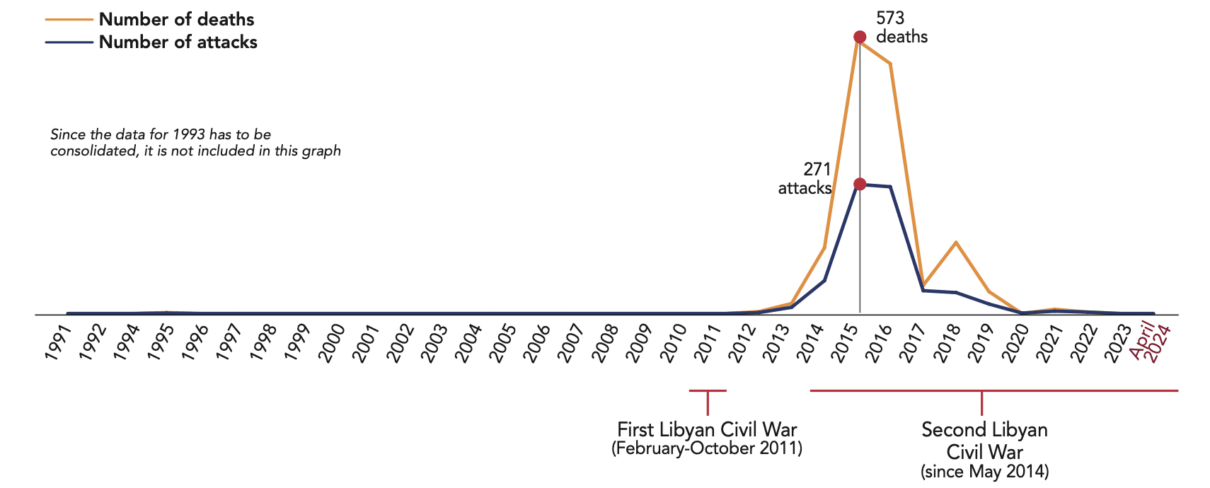

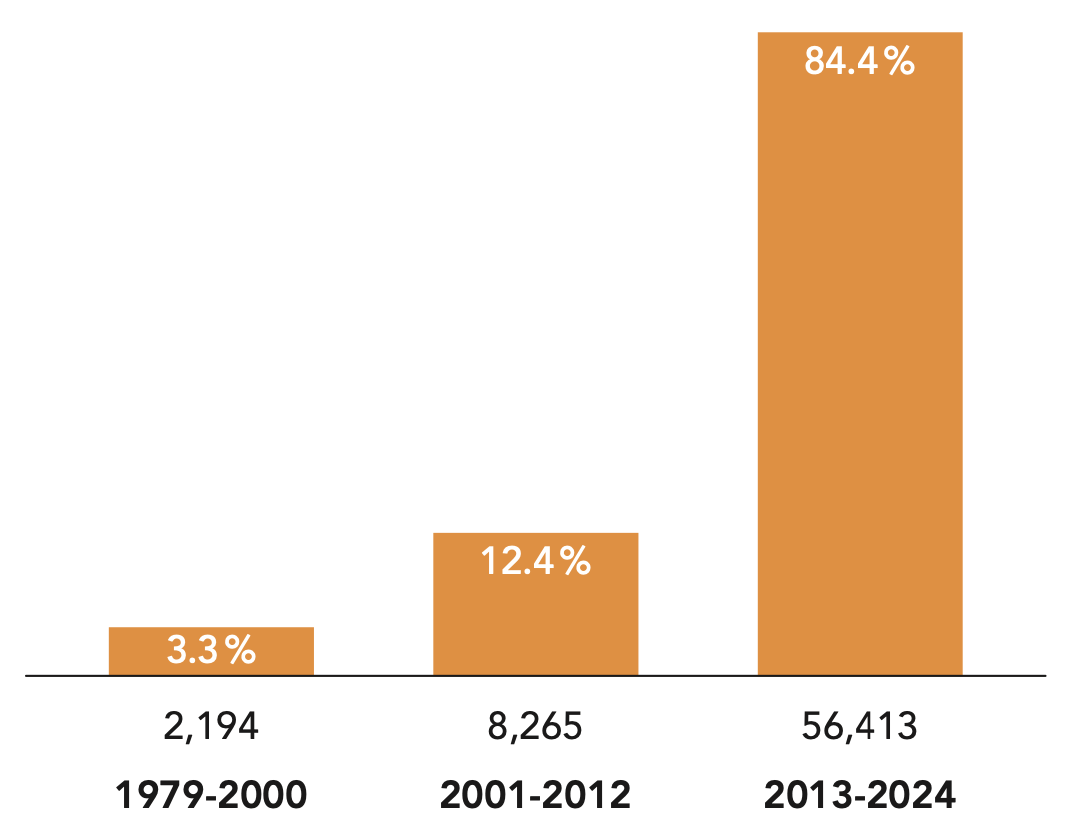

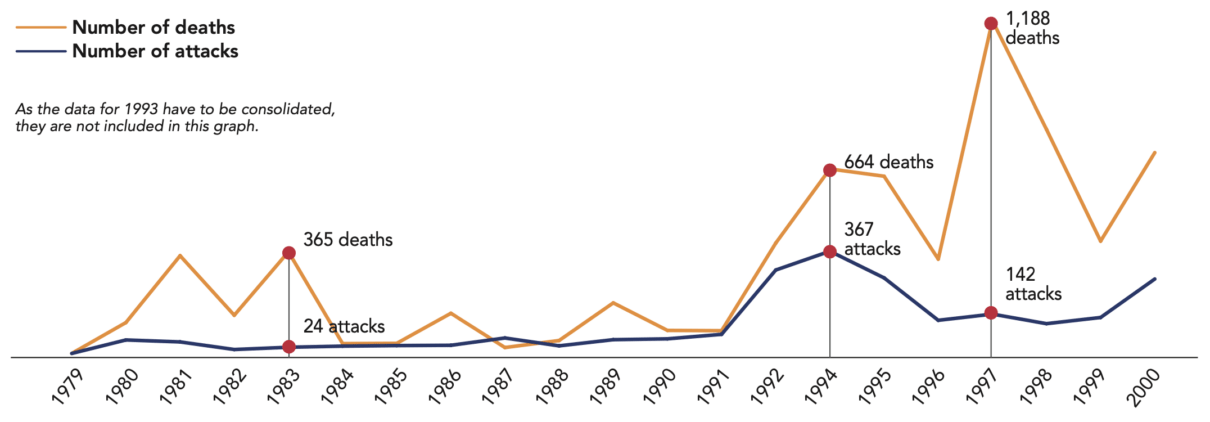

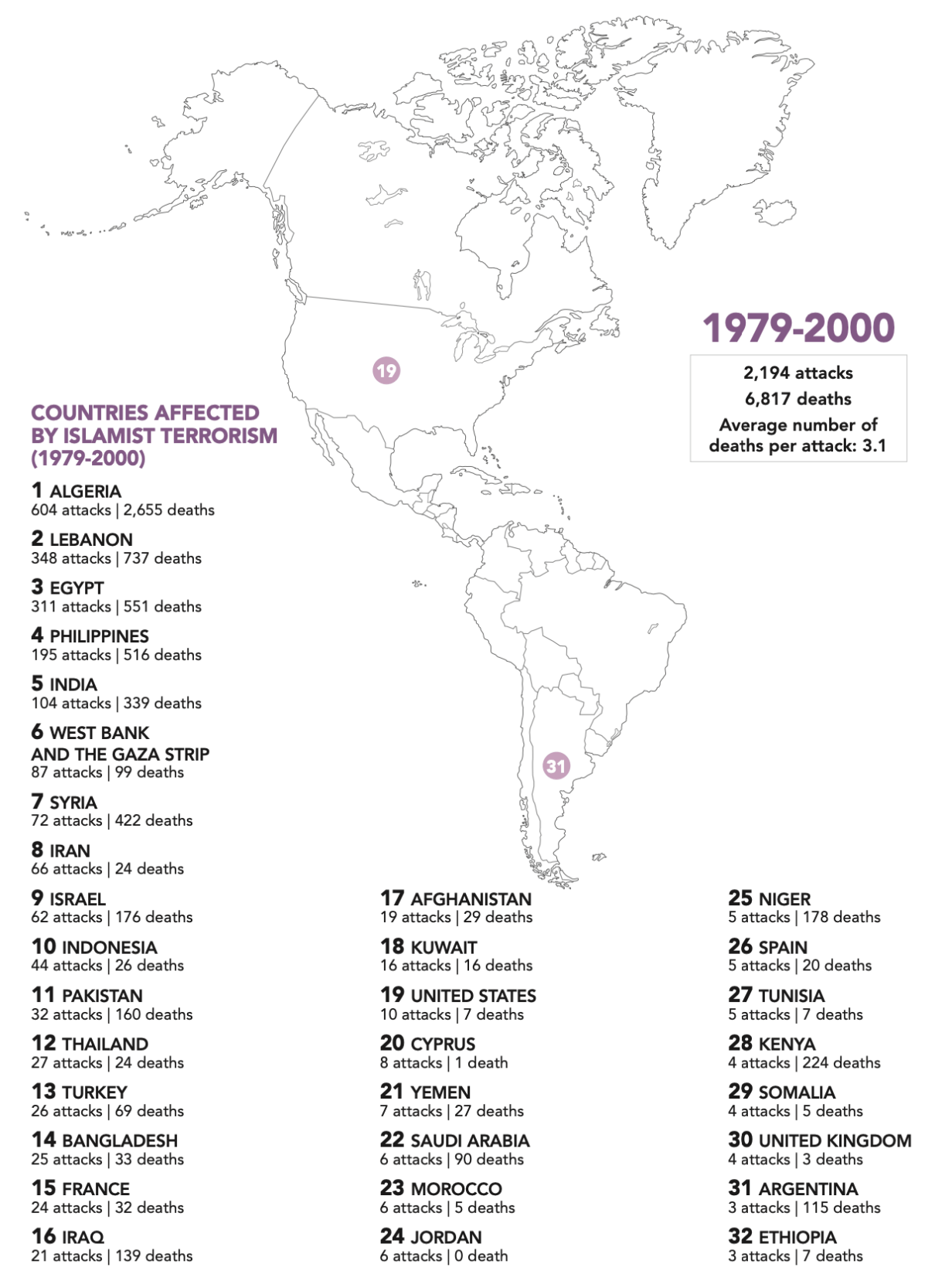

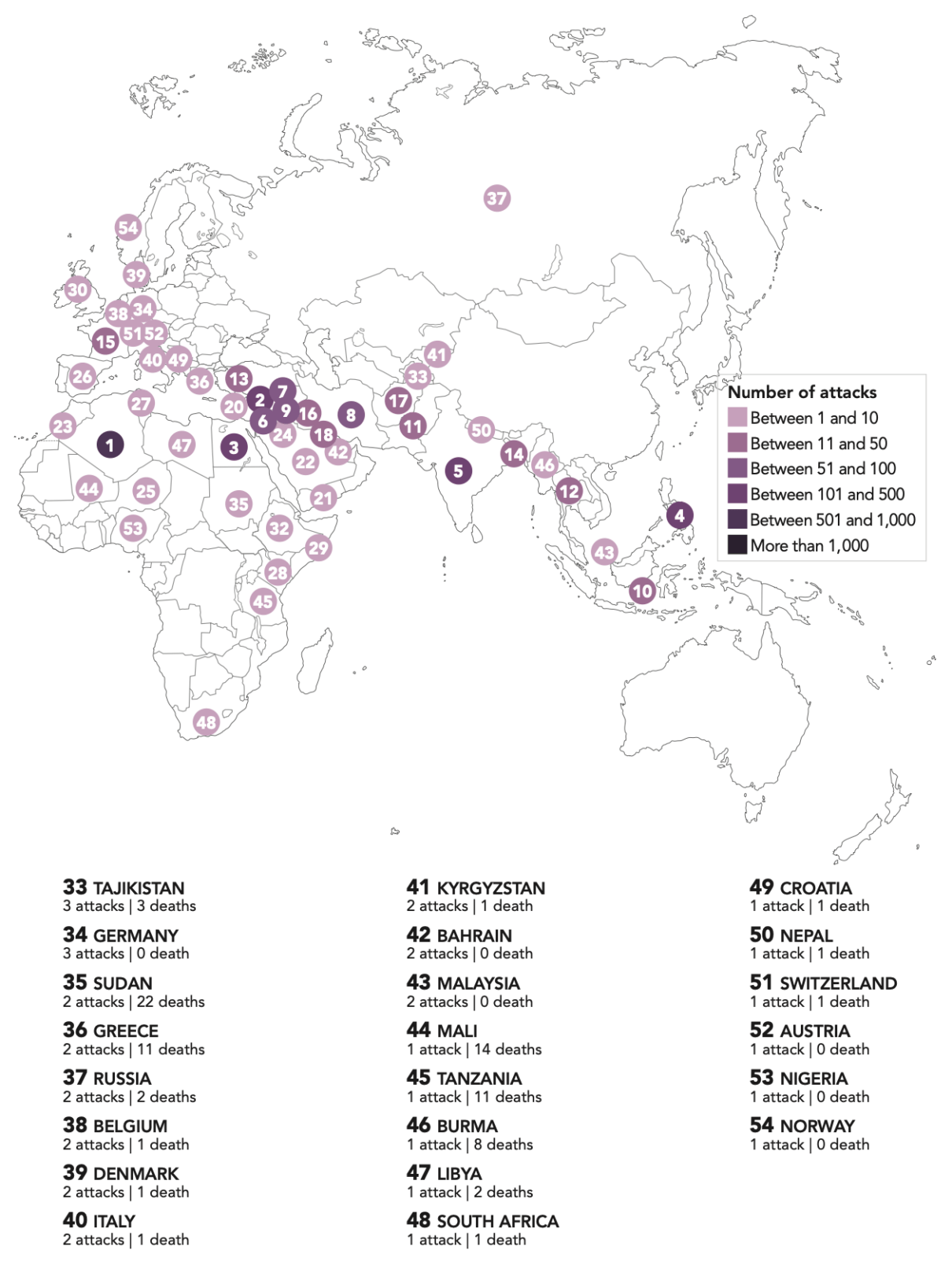

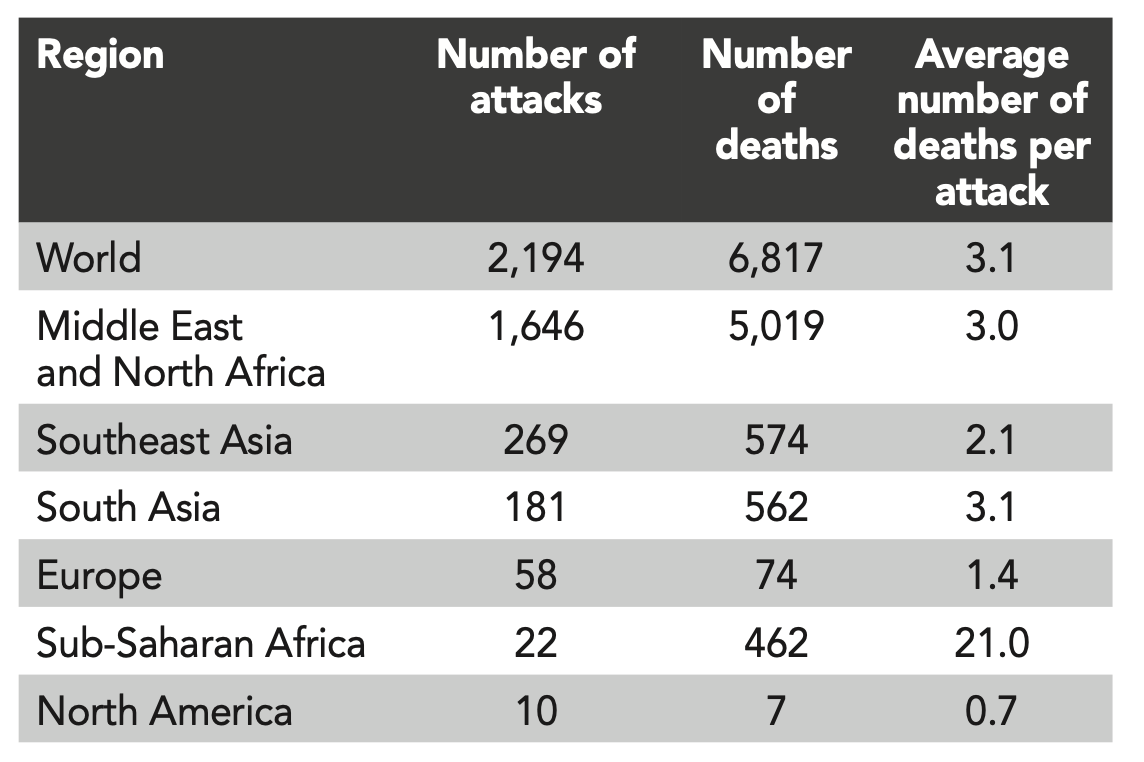

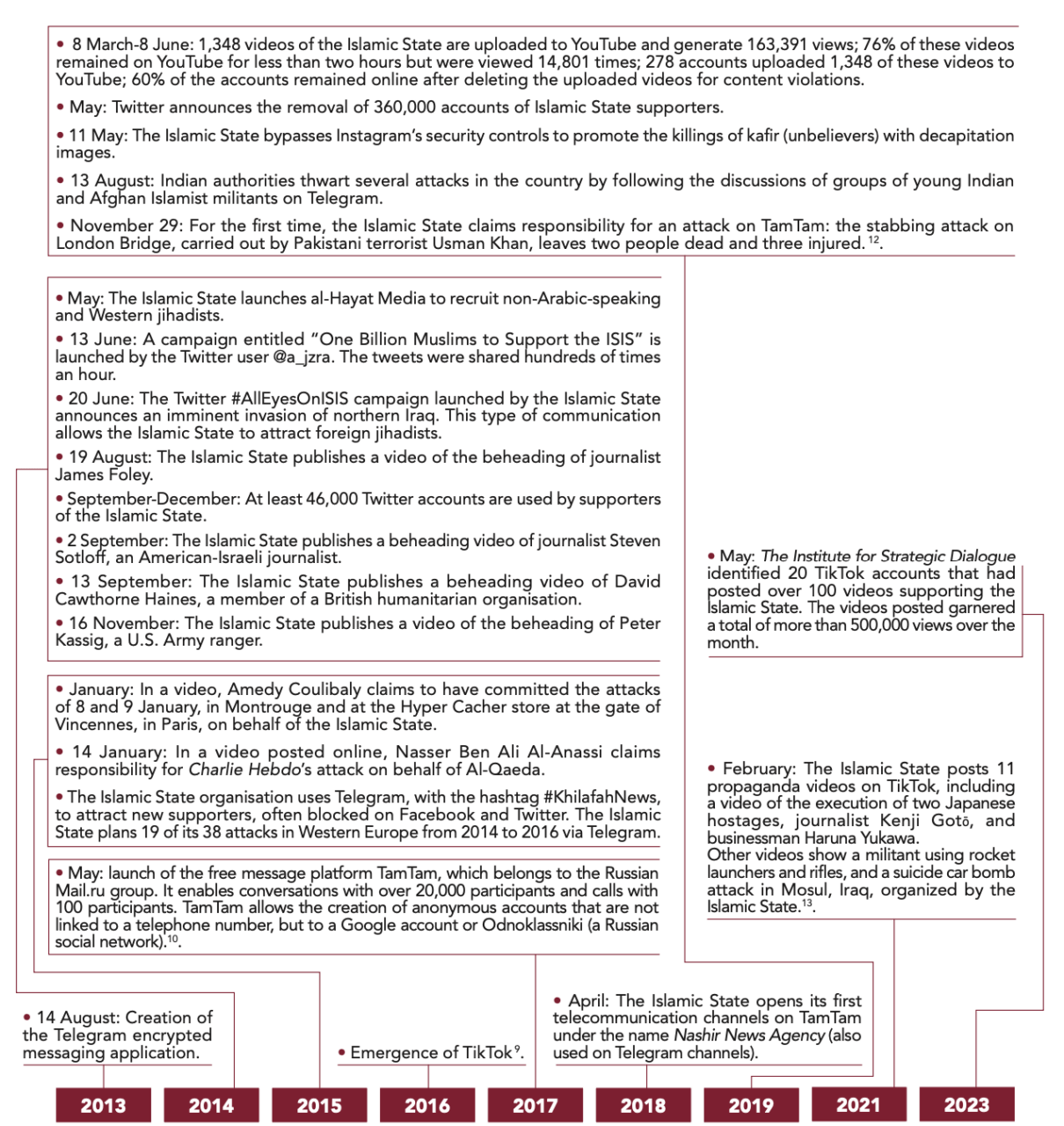

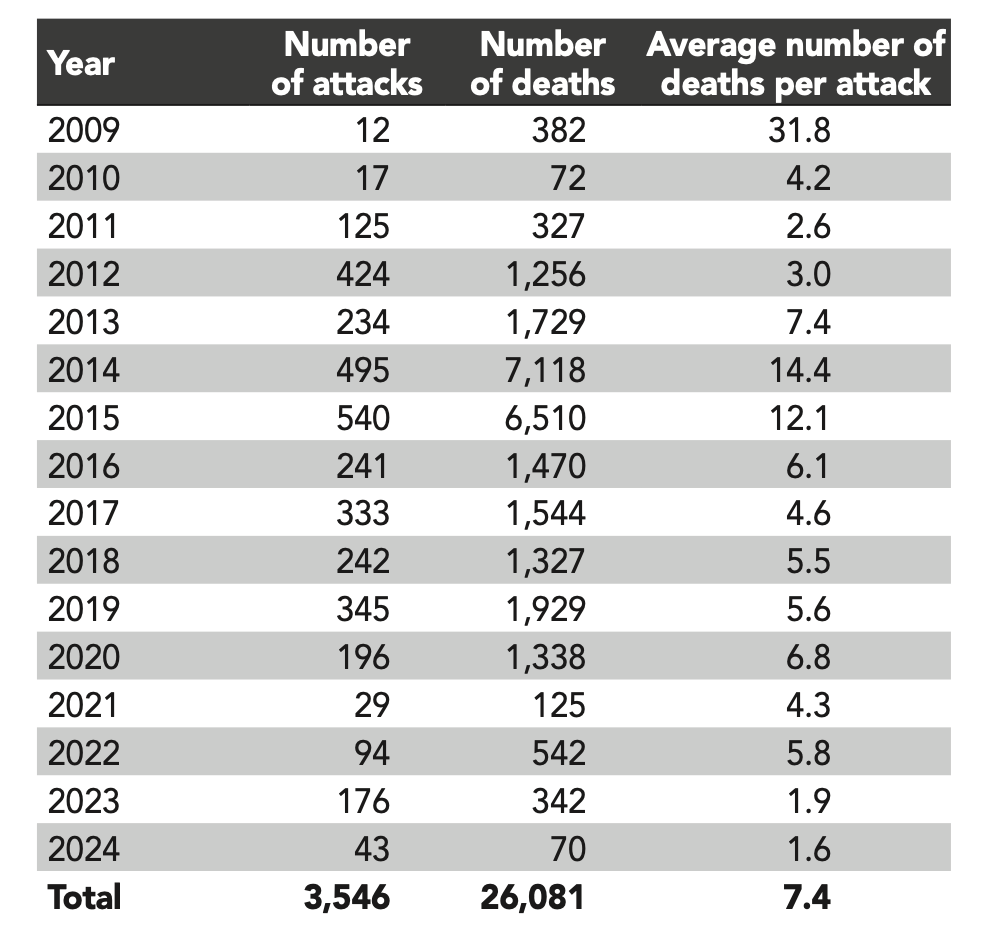

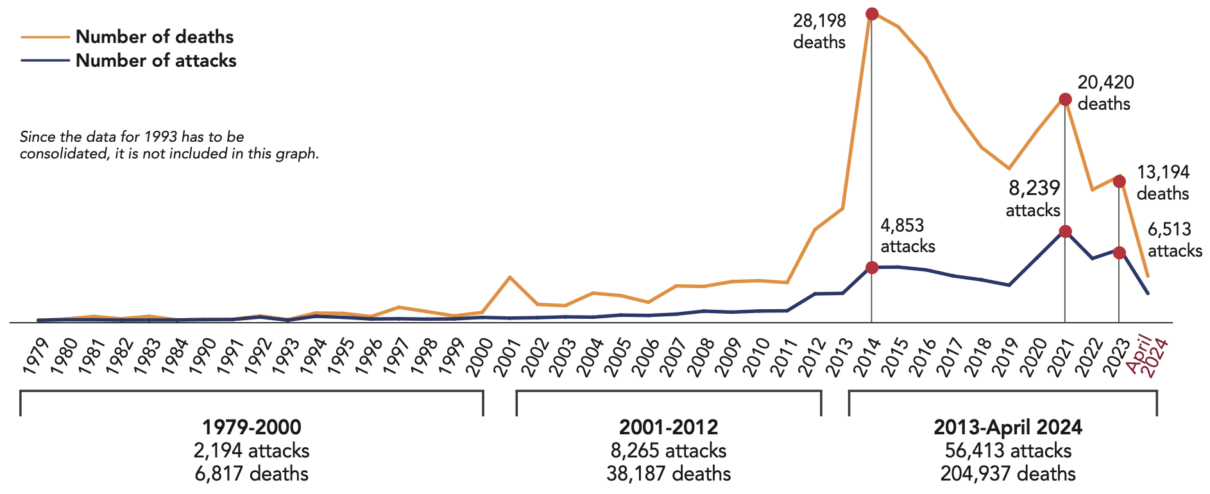

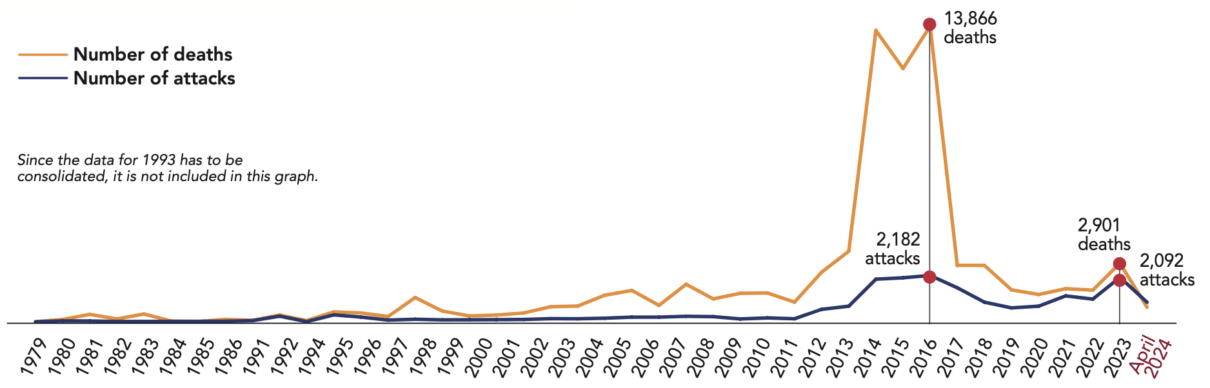

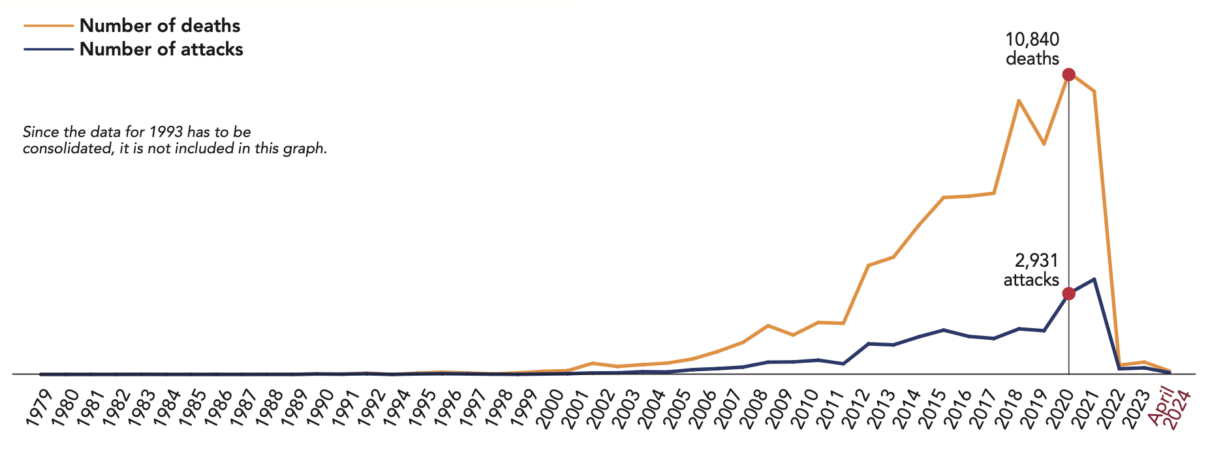

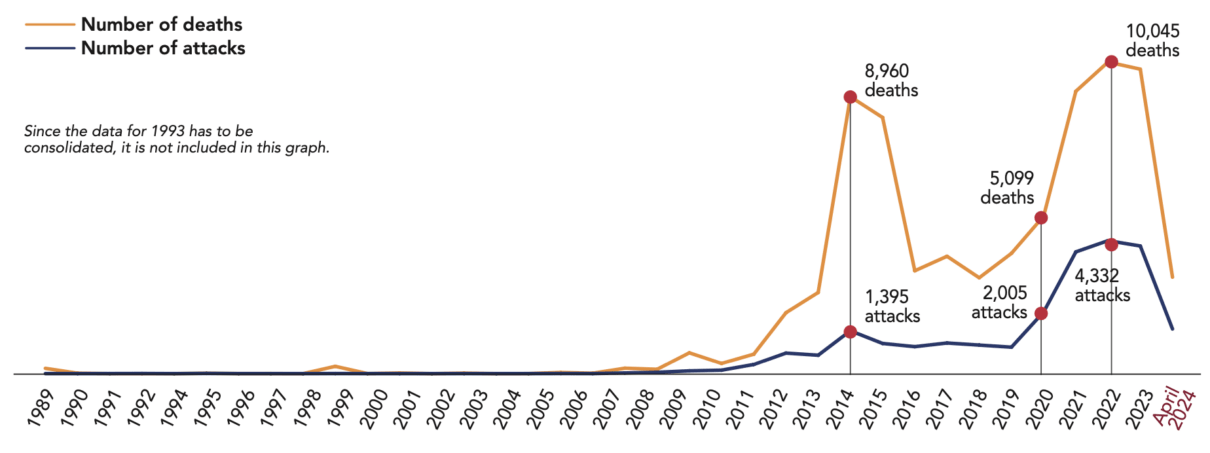

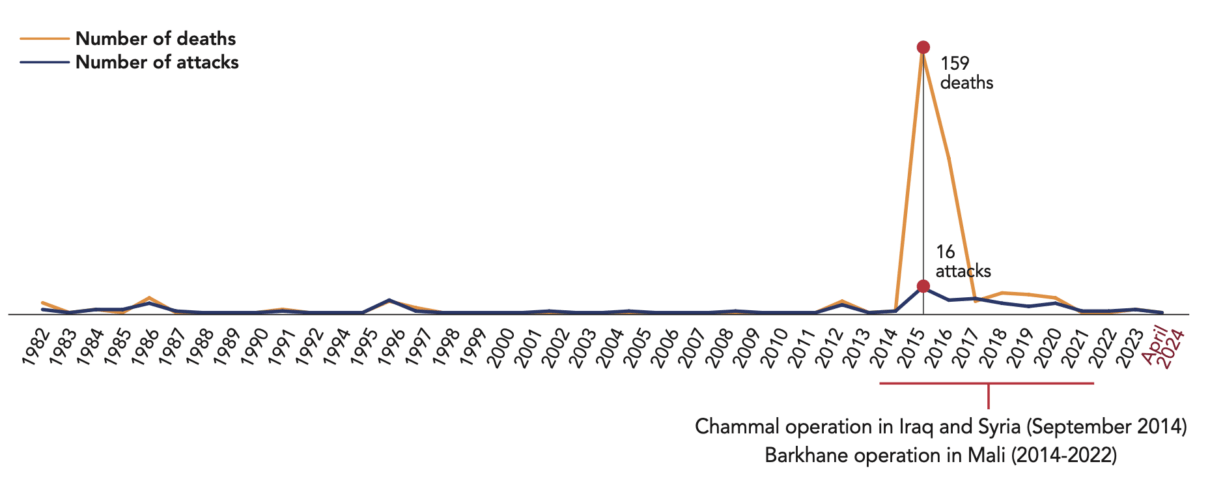

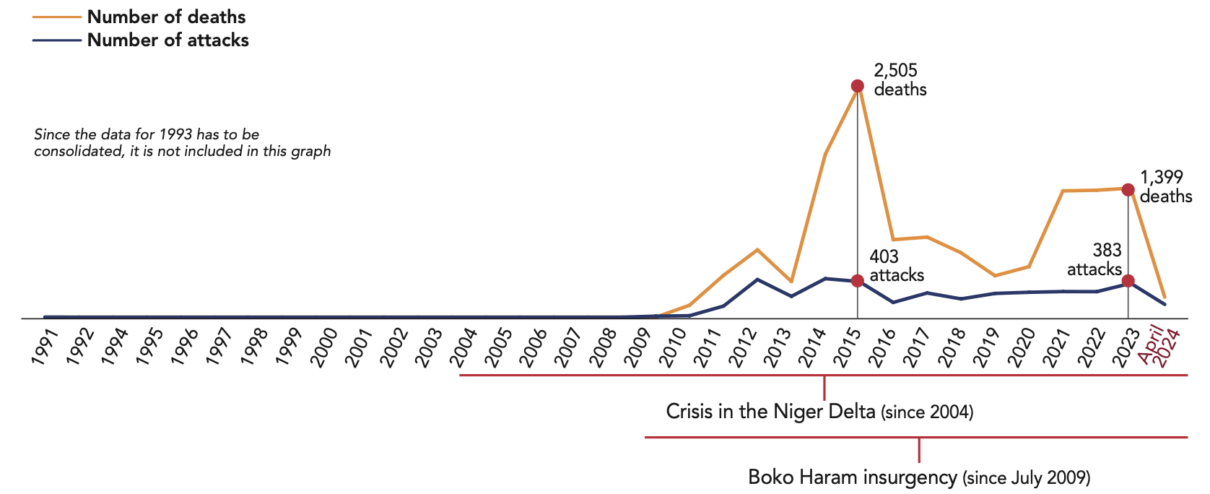

• 1979-2000: 2,194 attacks and 6,817 deaths.

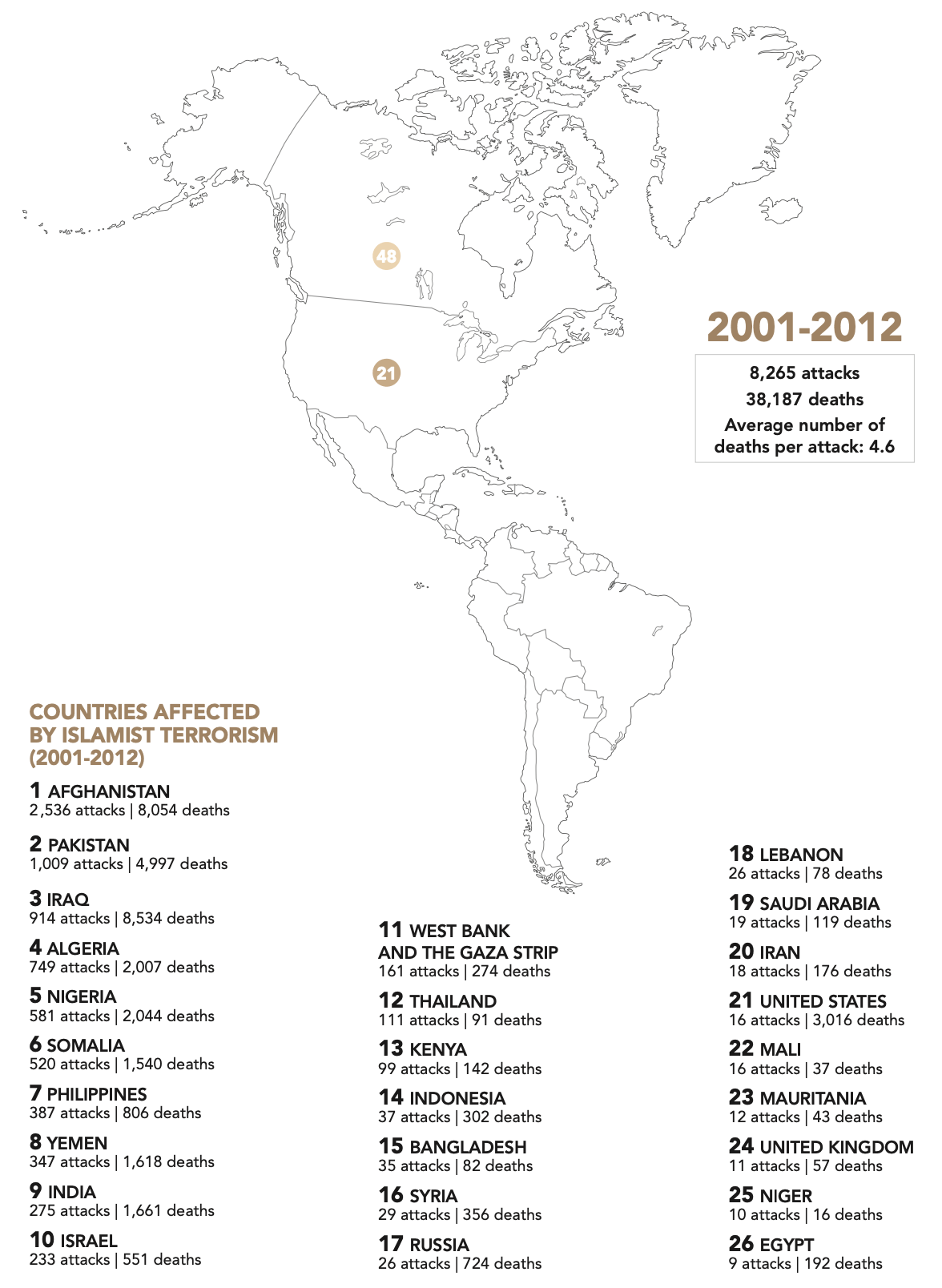

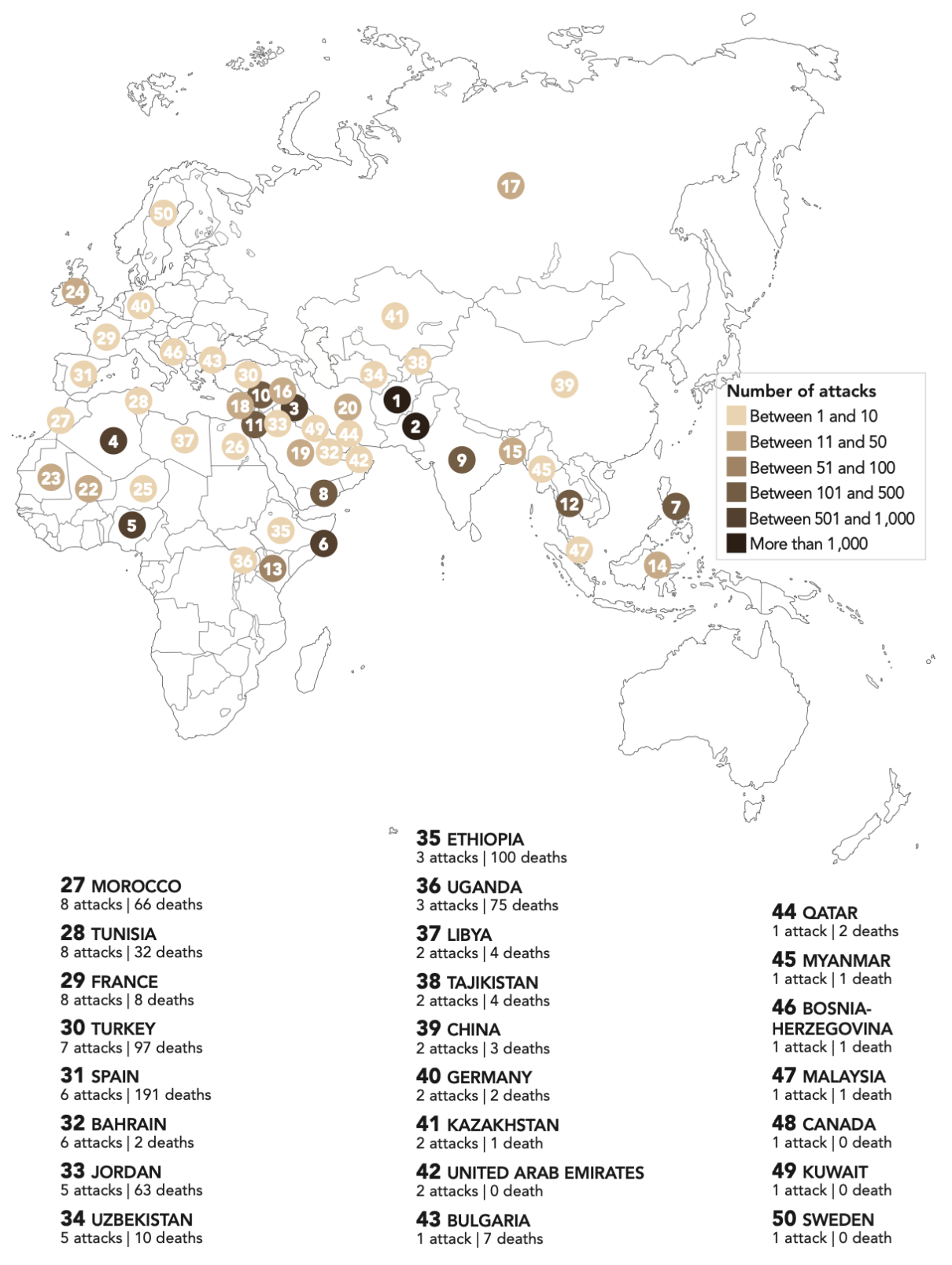

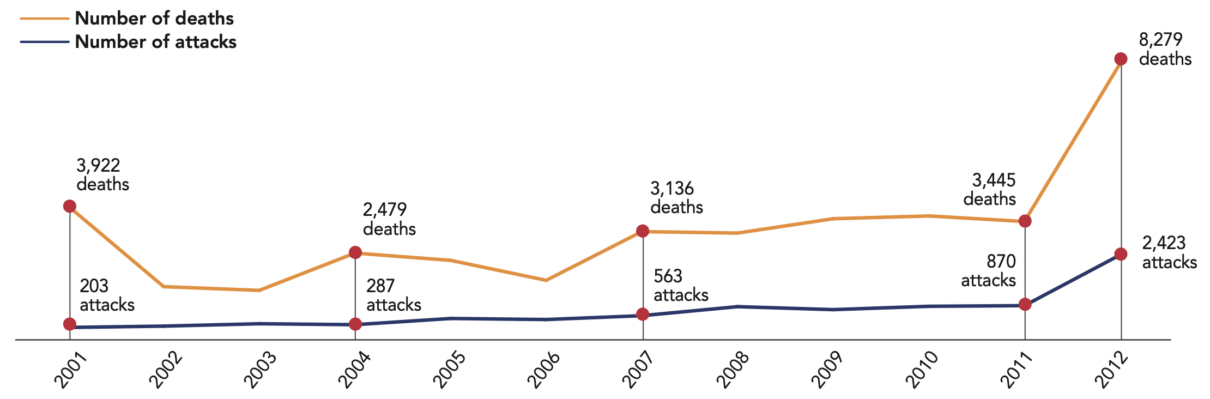

• 2001-2012: 8,265 attacks and 38,187 deaths.

• 2013-April 2024: 56,413 attacks and 204,937 deaths.

Islamist attacks around the world are more numerous today than ever before

Copyright :

Fondapol

Source :

Interpretive framework: Between 2013 and 2024, 56,413 Islamist attacks took place worldwide, representing 84.4% of all recorded attacks since 1979.

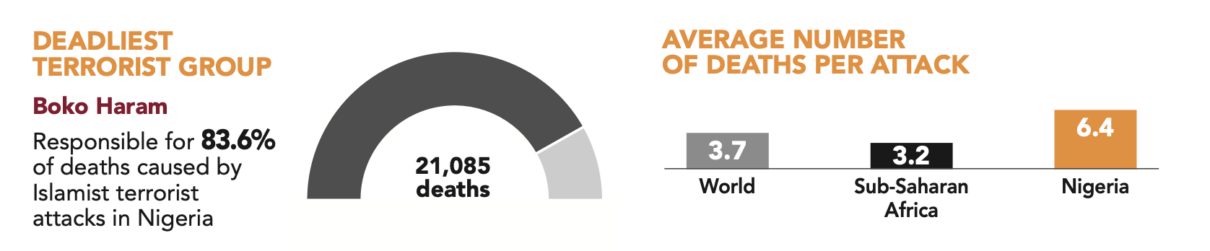

On average, an Islamist attack caused the deaths of 3.7 people.

• 1979-2000: an attack killed an average of 3.1 people.

• 2001-2012: an attack killed an average of 4.6 people.

• 2013-April 2024: an attack killed an average of 3.6 people.

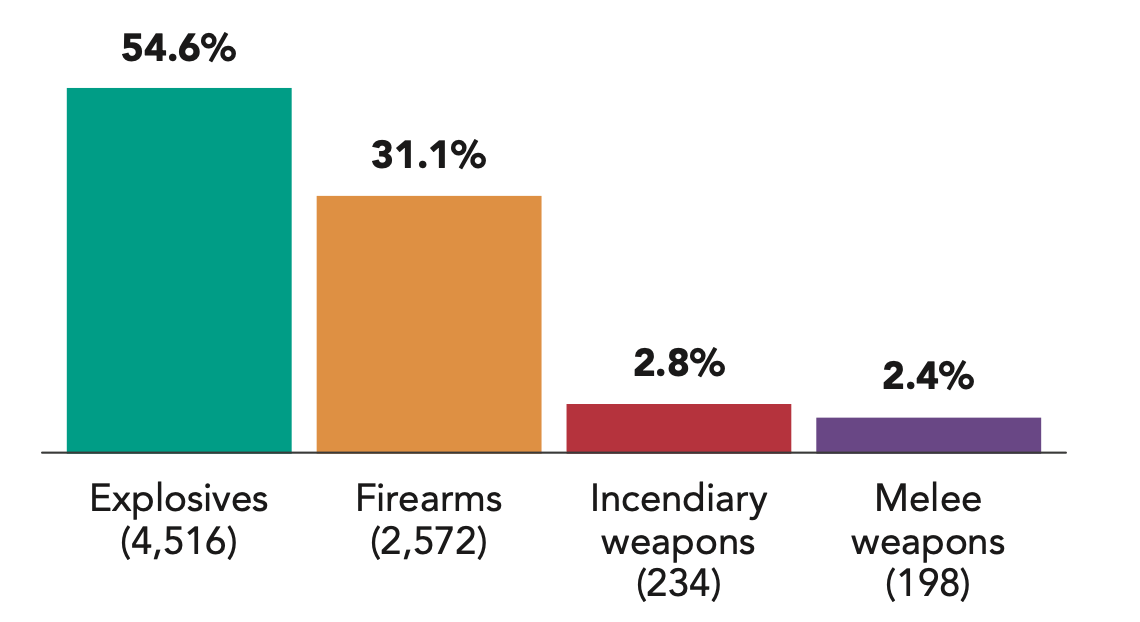

Firearms were the most used weapons (26,925), followed closely by explosives (25,832), melee weapons such as knives or machetes (2,479) and incendiary weapons (1,162)*.

*Data from Mozambique have not been included, as the databases used for this country do not allow us to identify the types of weapons used.

• 1979-2000: firearms (911), explosives (856), melee weapons (124), incendiary weapons (68).

• 2001-2012: firearms (2,572), explosives (4,516), melee weapons (198), incendiary weapons (234).

• 2013-April 2024: firearms (23,442), explosives (20,460), melee weapons (2,157), incendiary weapons (860).

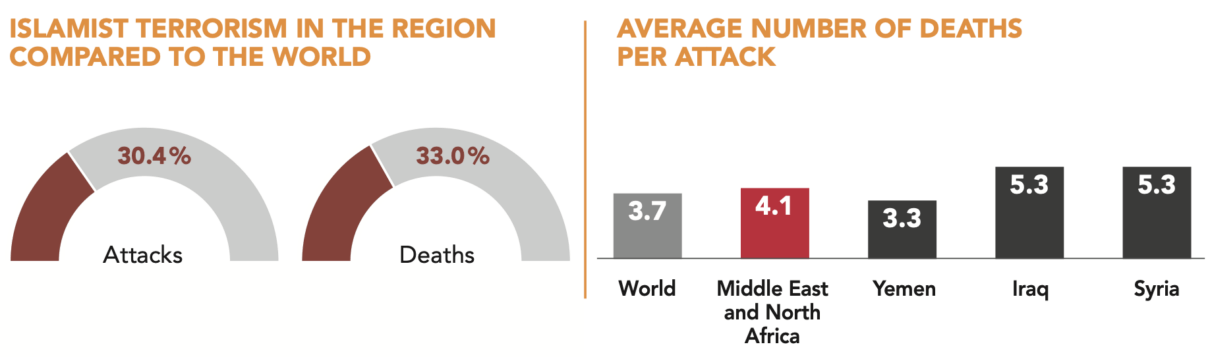

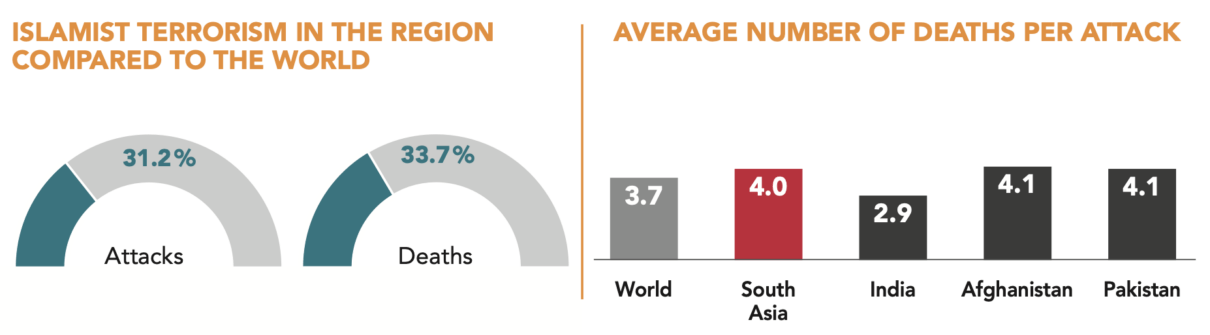

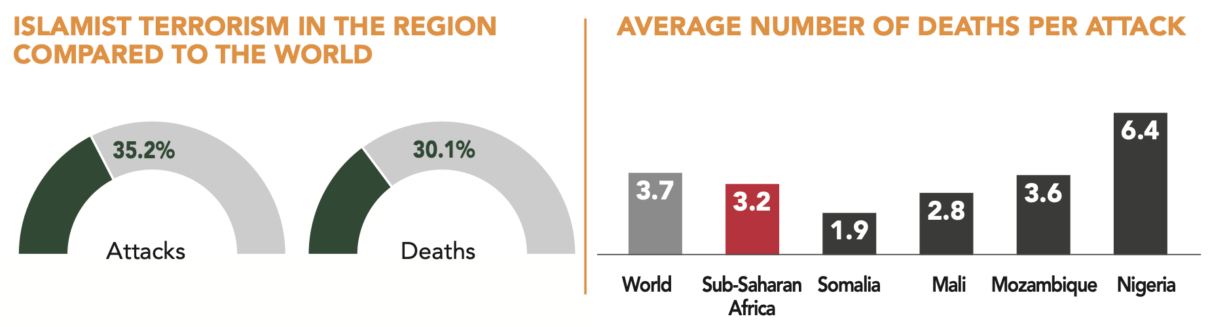

The Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 96.7% of Islamist attacks between 1979 and April 2024.

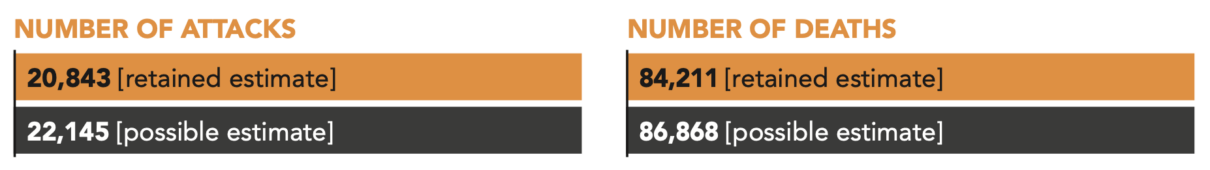

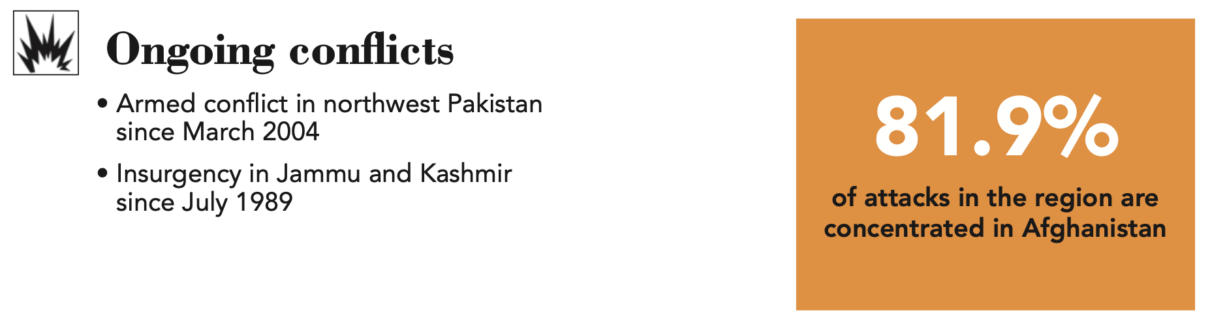

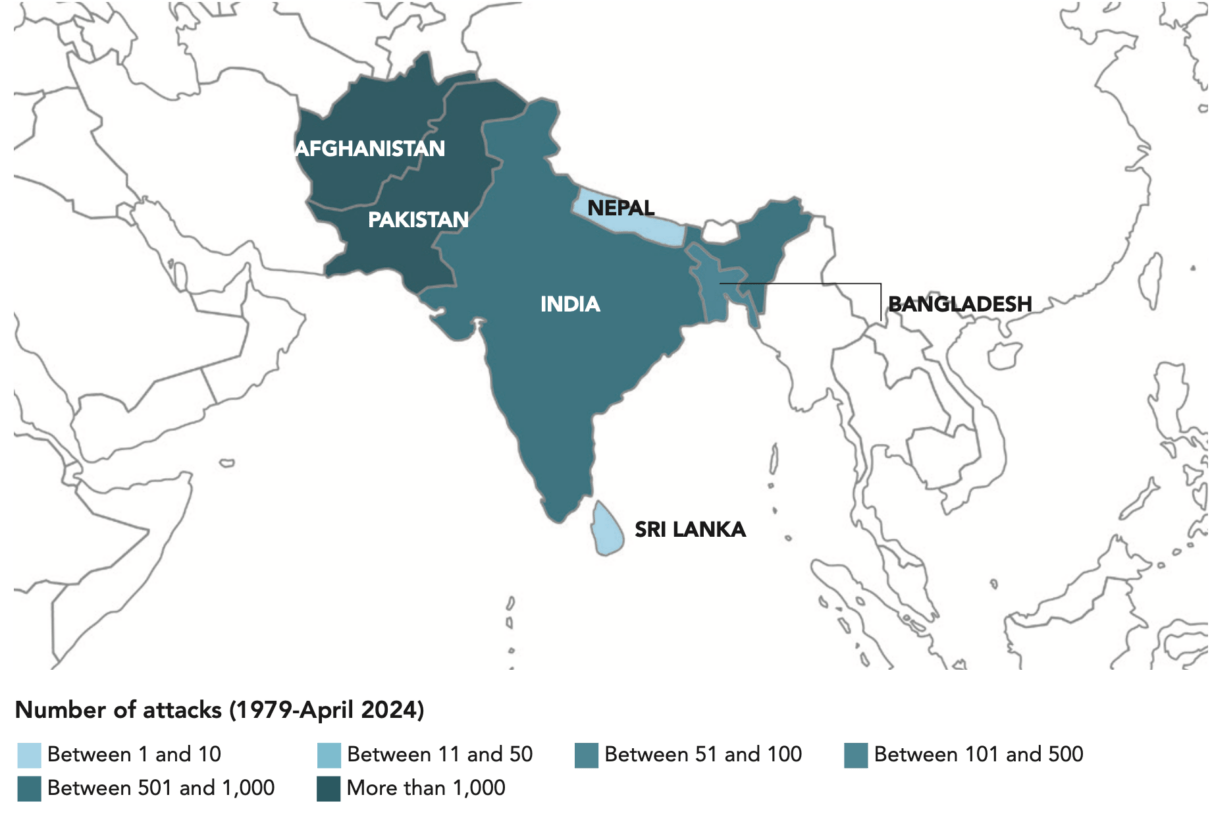

• South Asia: 31.2% of attacks, 33.7% of deaths.

• Middle East and North Africa: 30.4% of attacks, 33% of deaths.

• Sub-Saharan Africa : 35.2% of attacks, 30.1% of deaths.

• Southeast Asia: 2.6% of attacks, 1.1% of deaths.

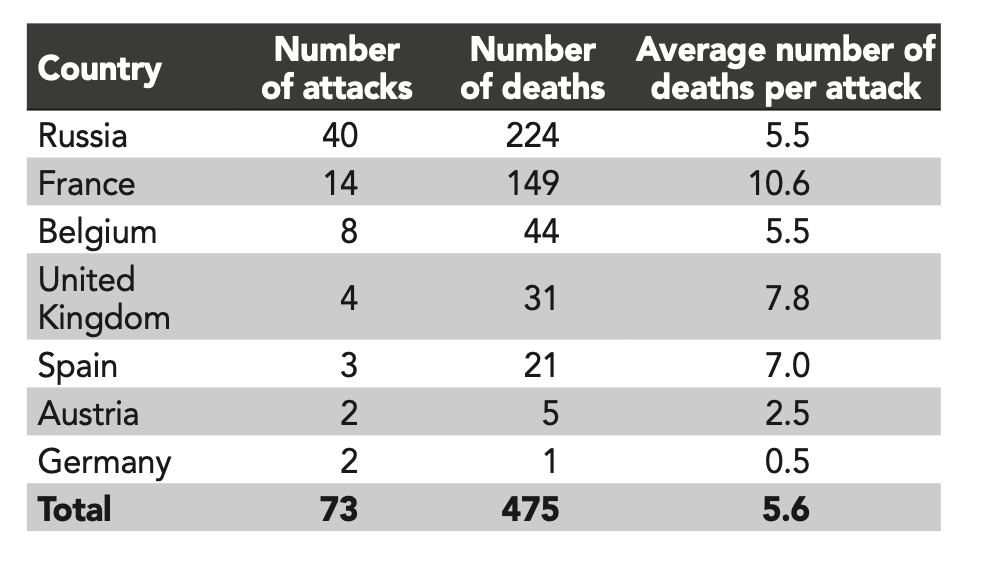

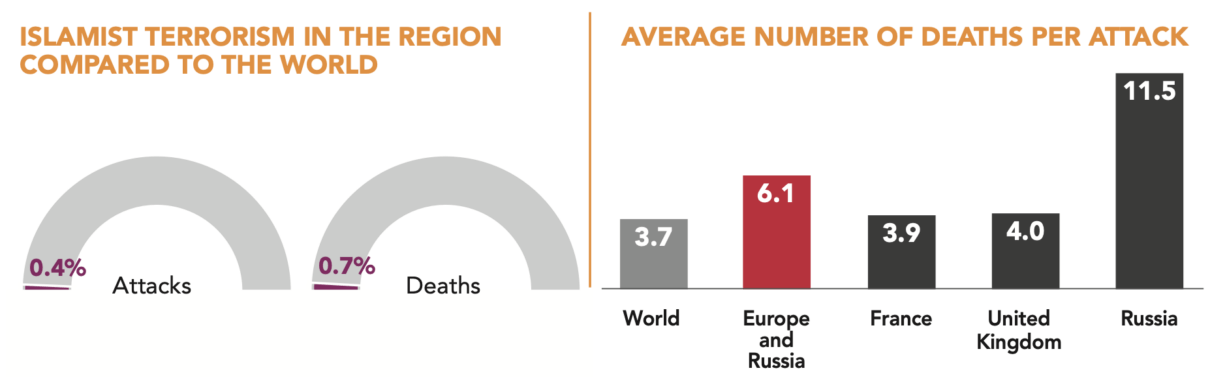

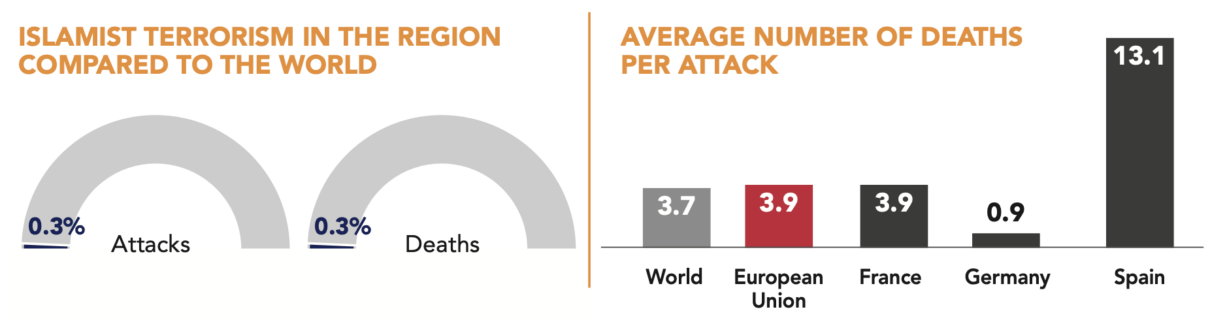

• Europe and Russia: 0.4% of attacks, 0.7% of deaths.

• North America: 0.1% of attacks, 1.3% of deaths.

• Oceania: 0.01% of attacks, 0.005% of deaths.

• South America: 0.004% of attacks, 0.05% of deaths.

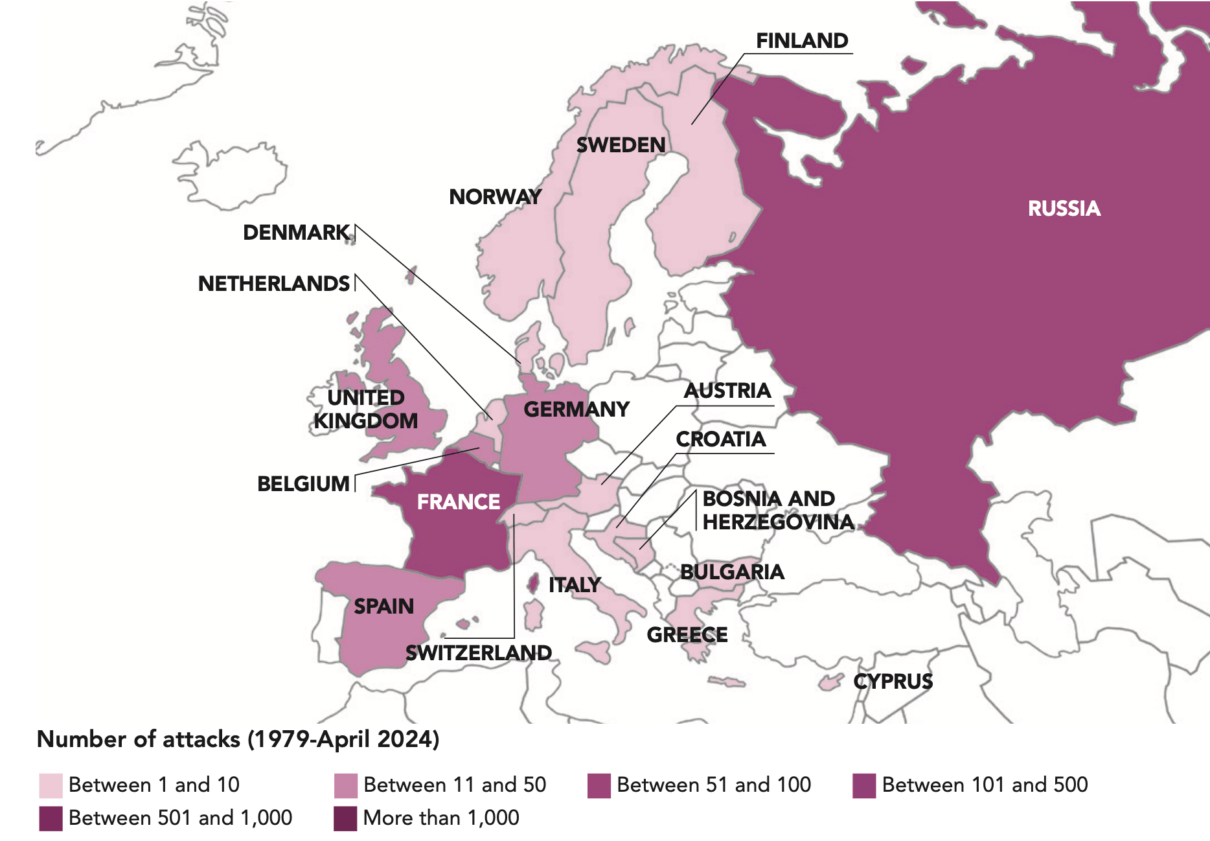

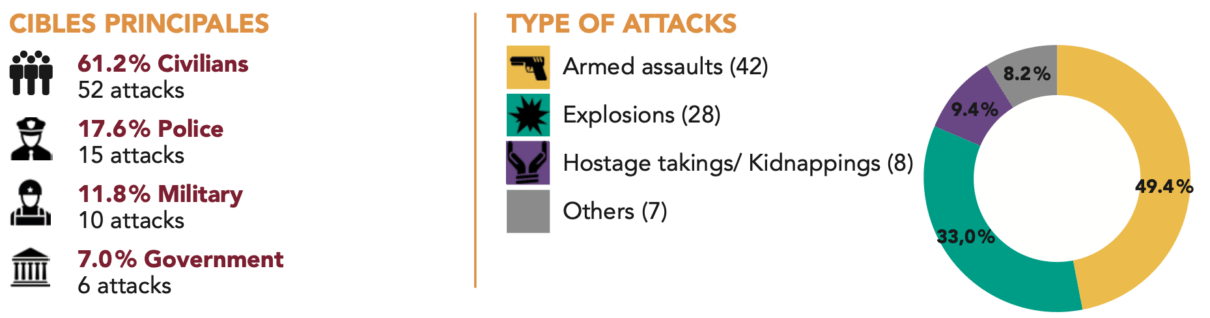

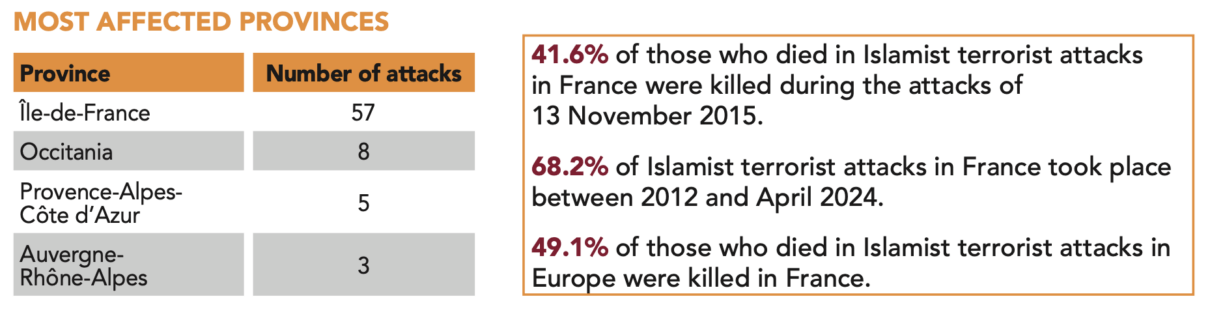

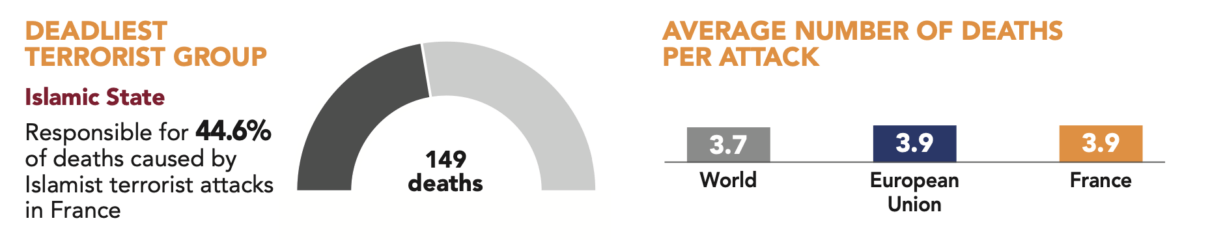

Within the European Union, France was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, with 85 attacks committed on its soil between 1979 and April 2024. At least 334 people were killed in these attacks.

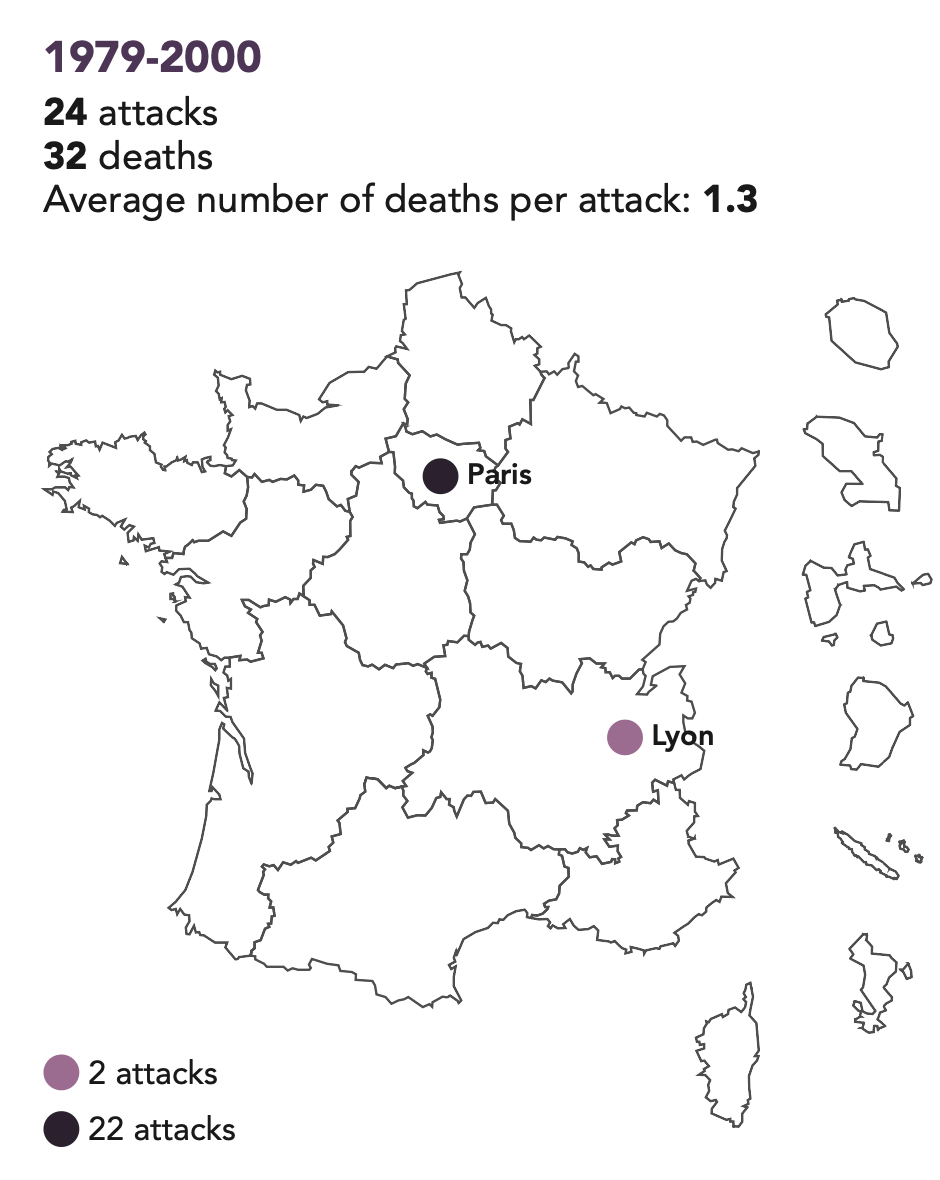

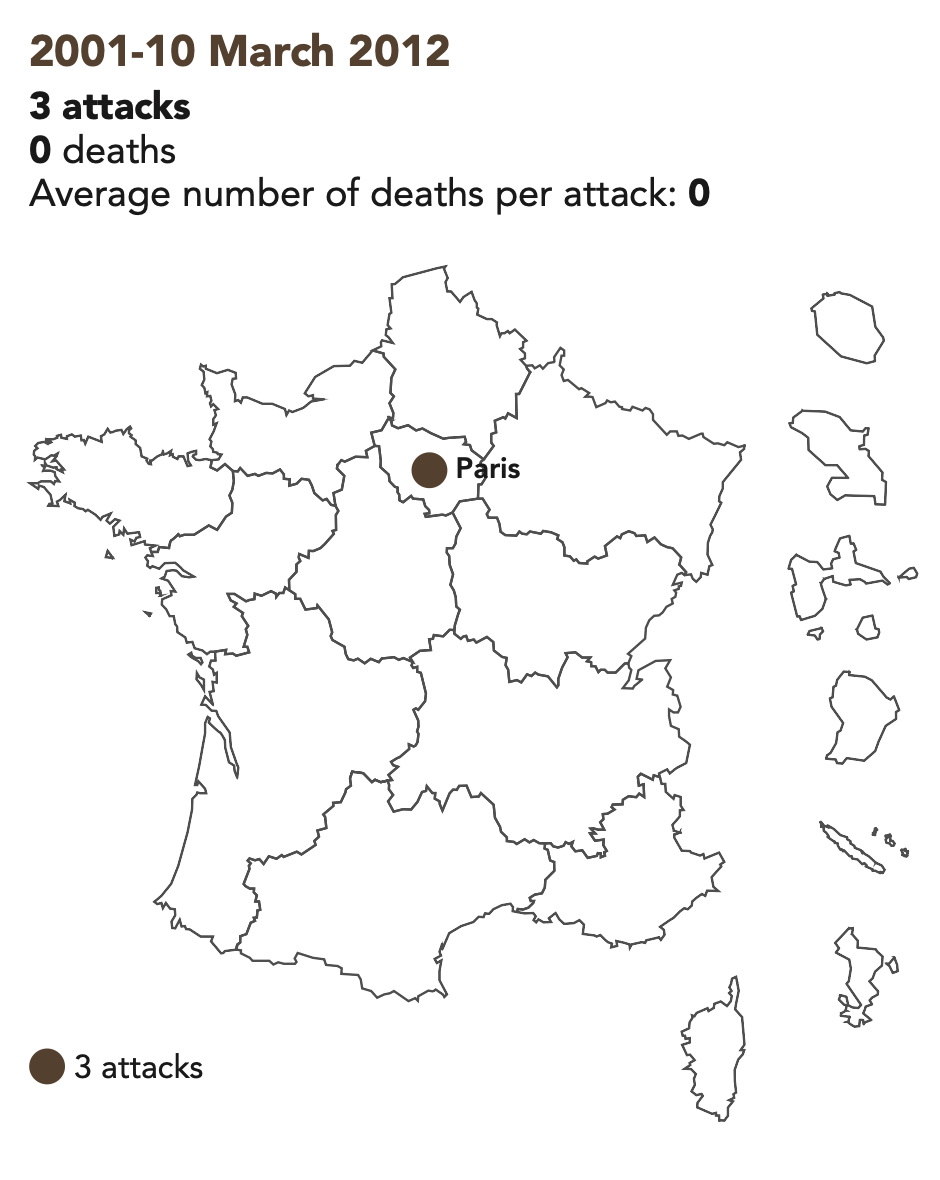

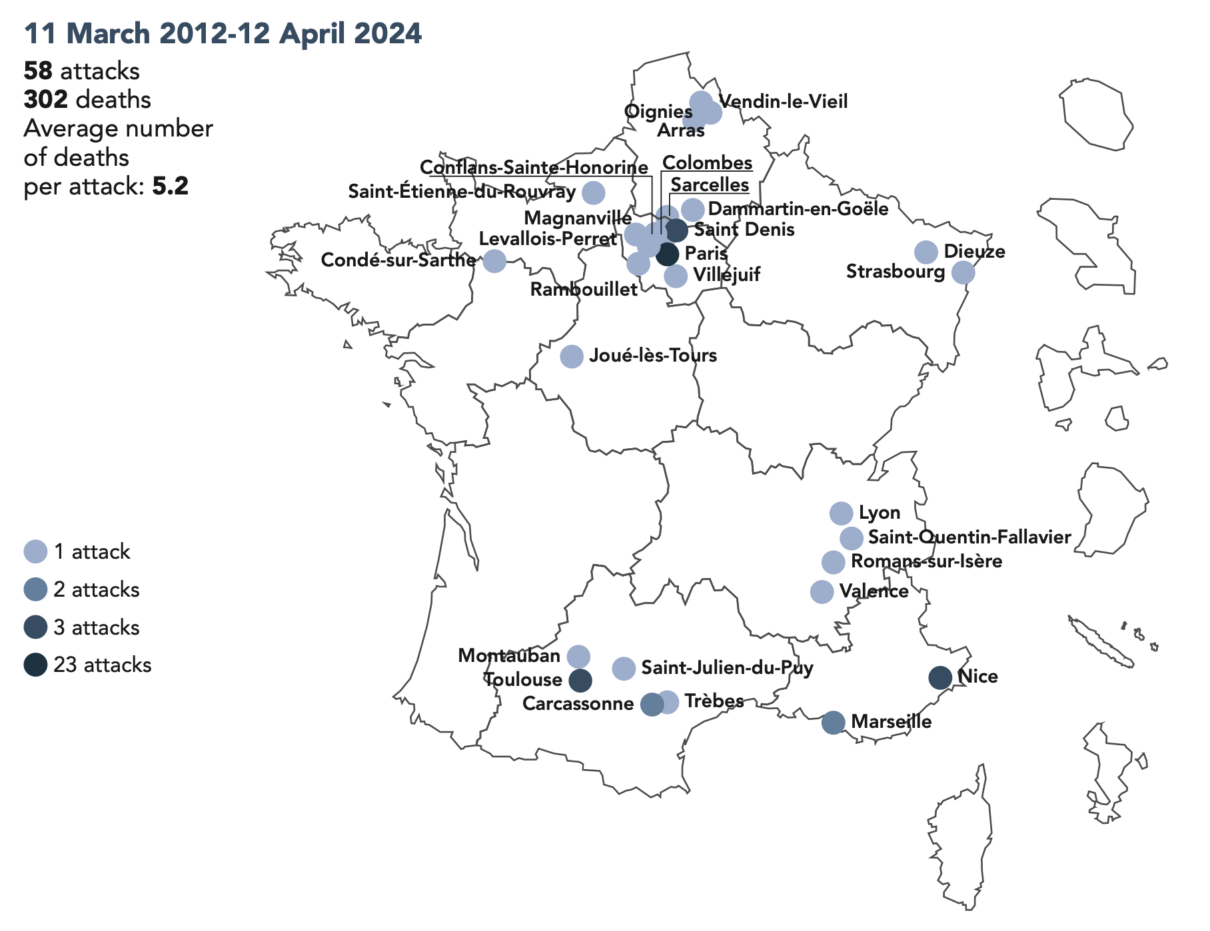

• 1979-2000: 24 attacks, 32 deaths.

• 2001-2012: 8 attacks, 8 deaths.

• 2013-April 2024: 53 attacks, 294 deaths.

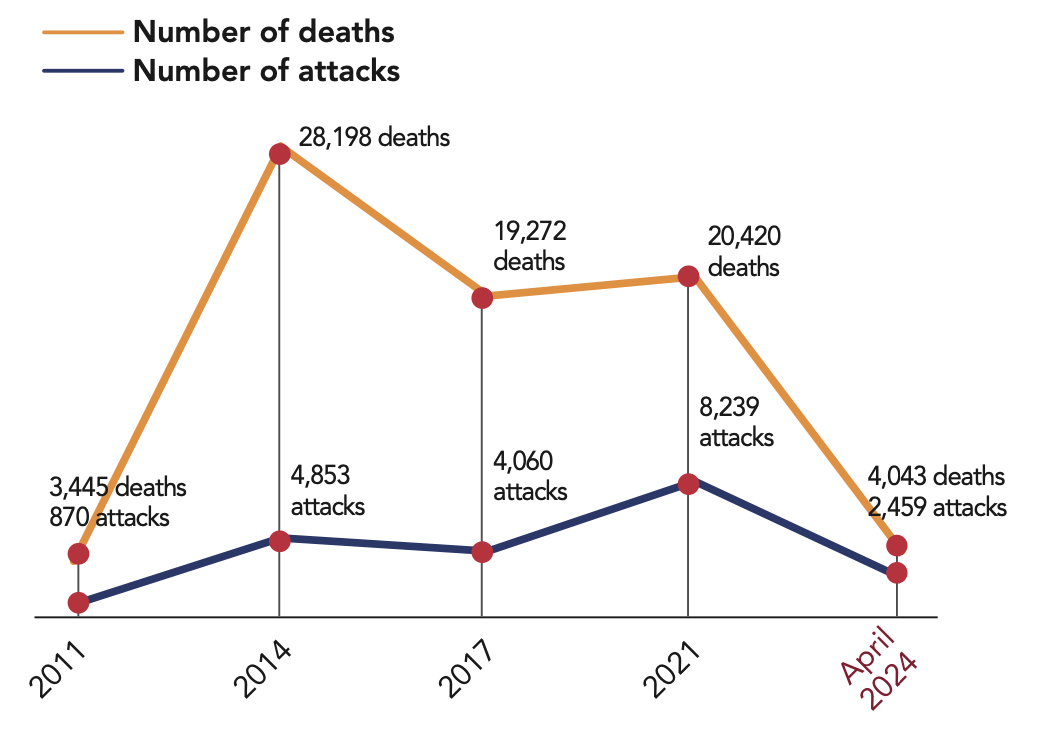

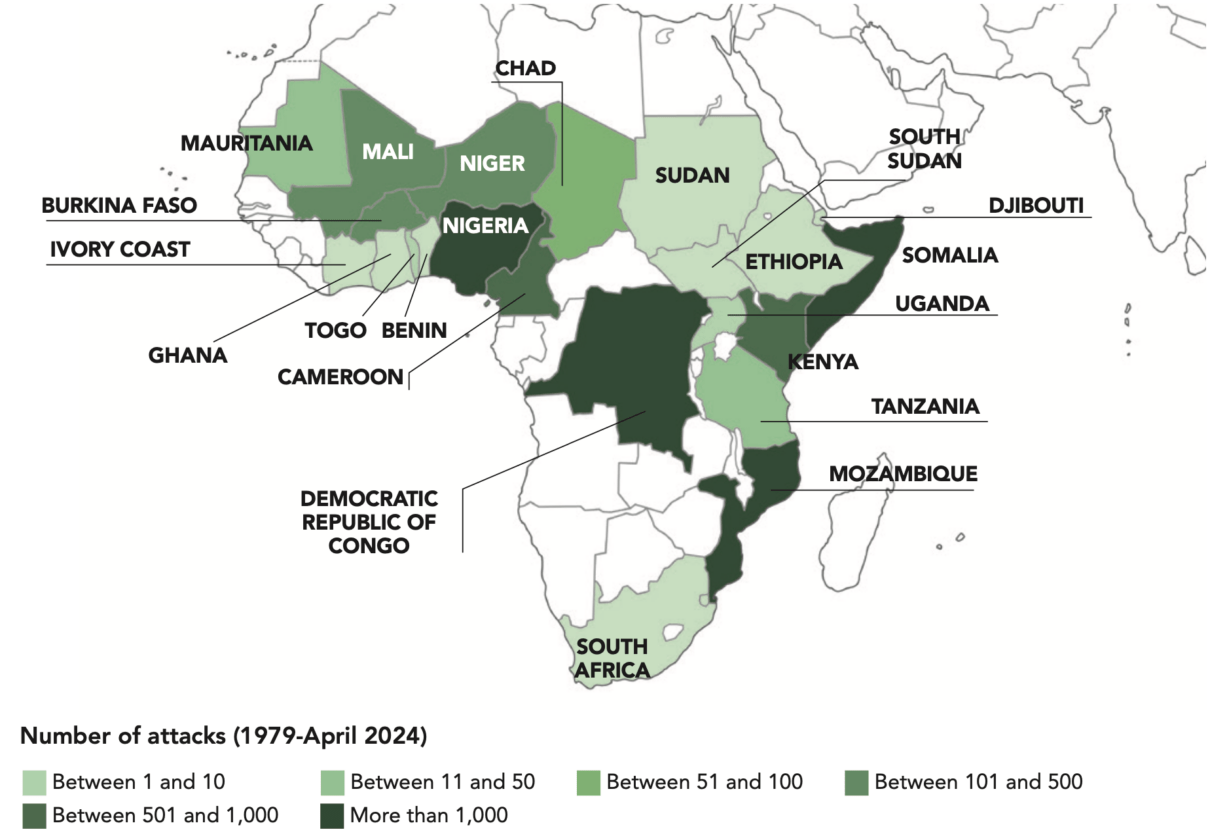

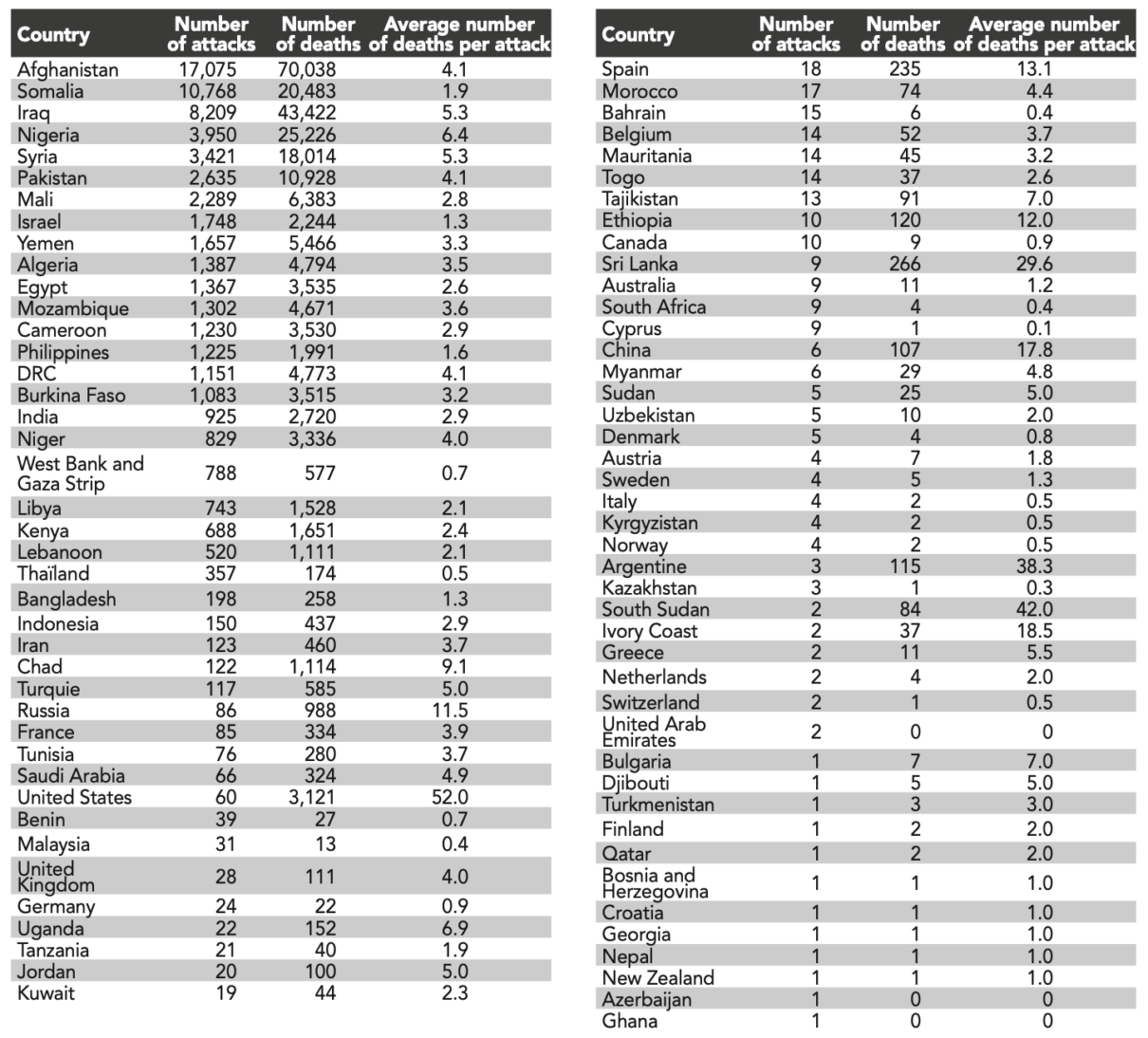

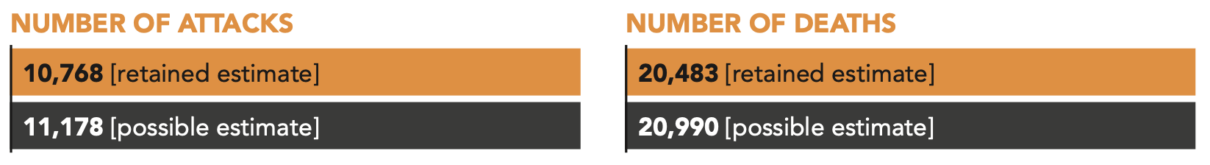

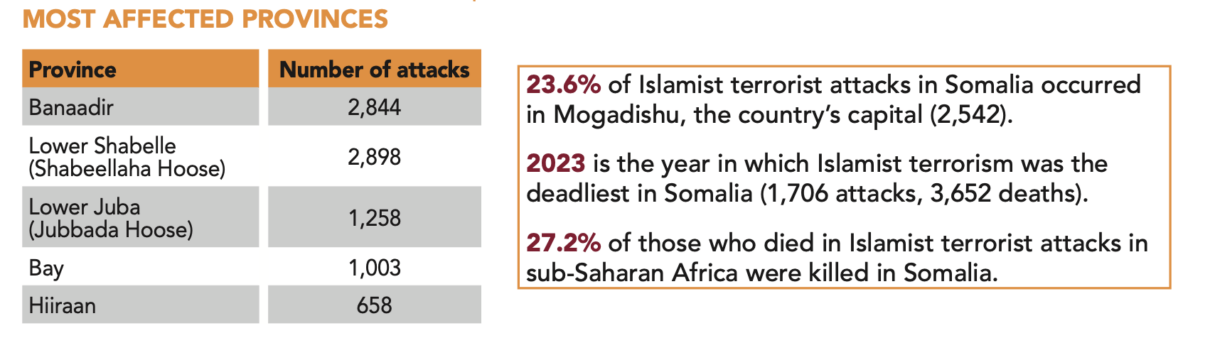

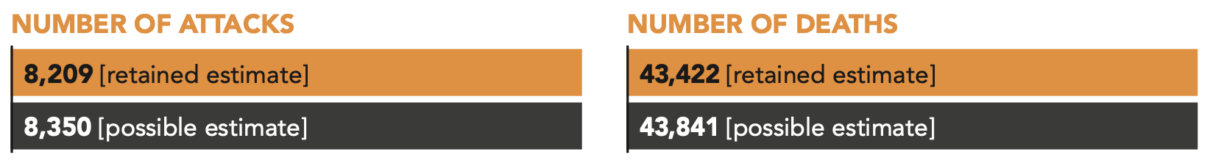

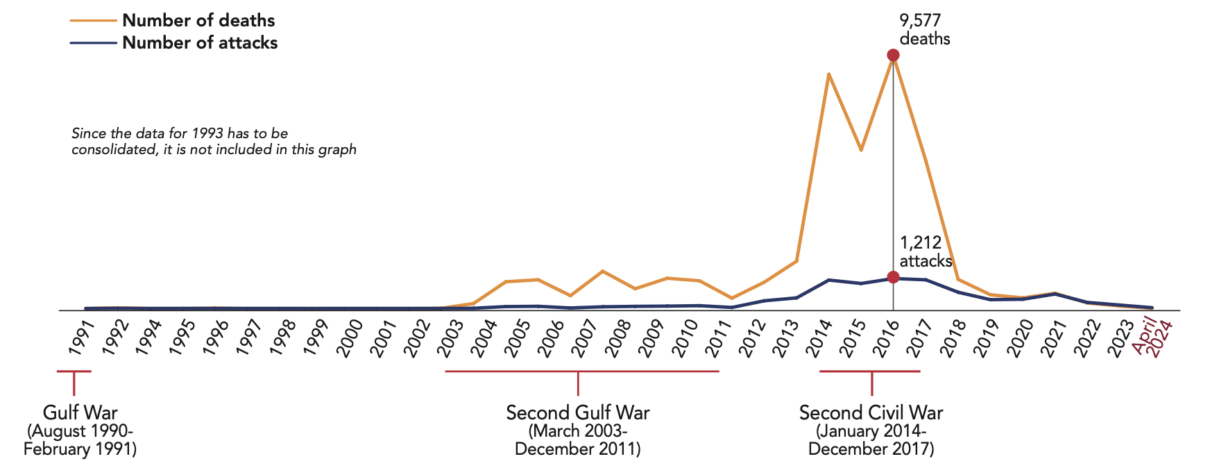

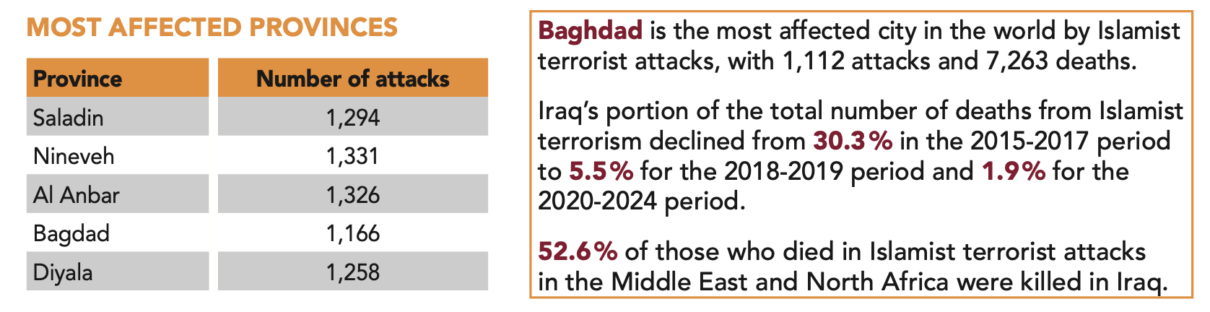

Afghanistan was the country most affected by Islamist terrorism, ahead of Somalia and Iraq.

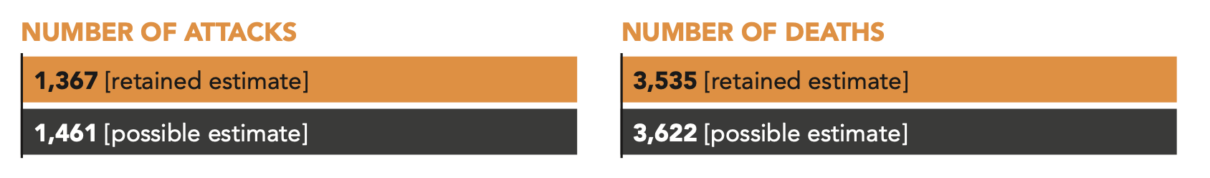

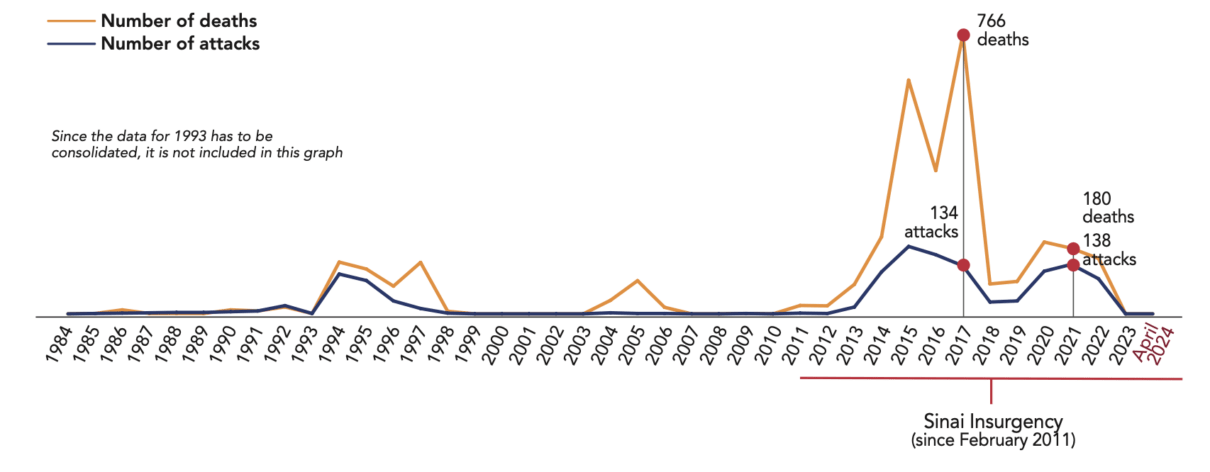

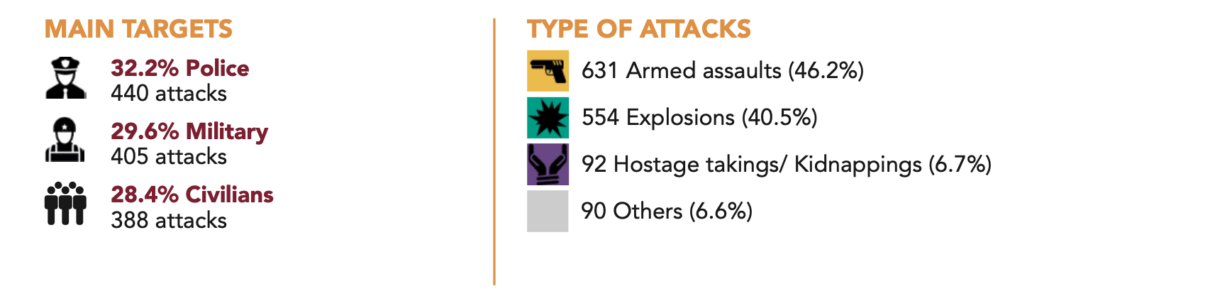

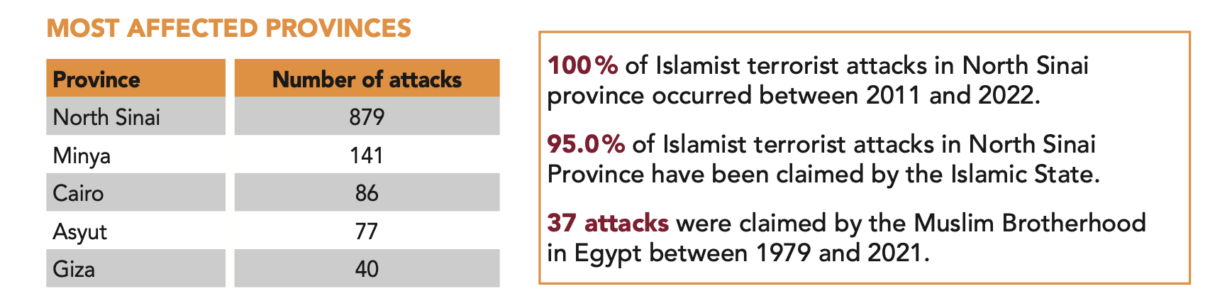

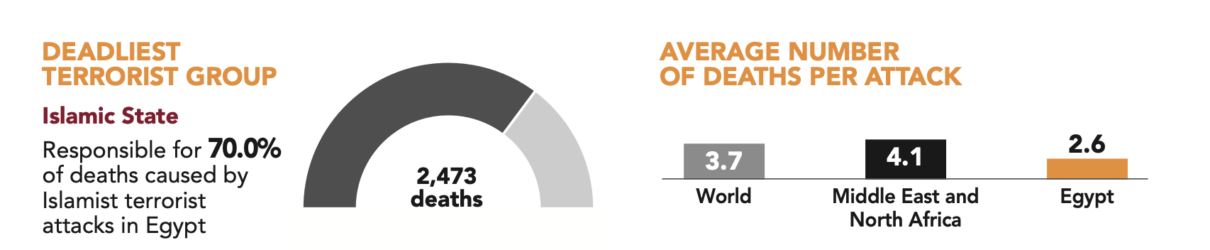

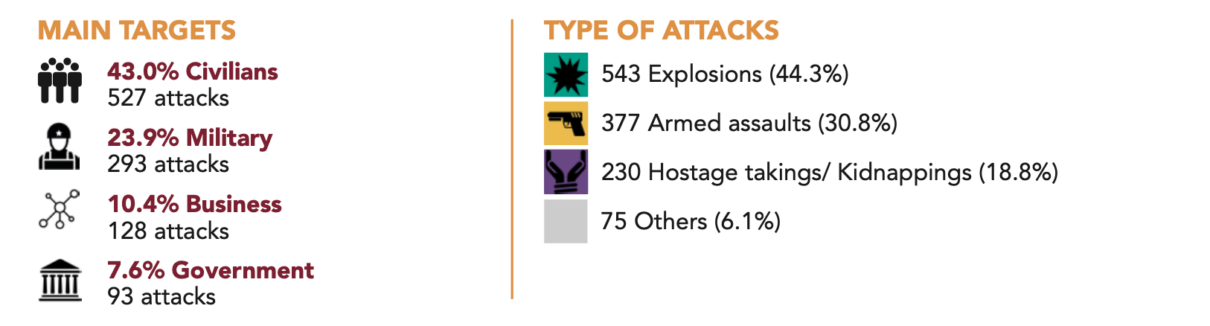

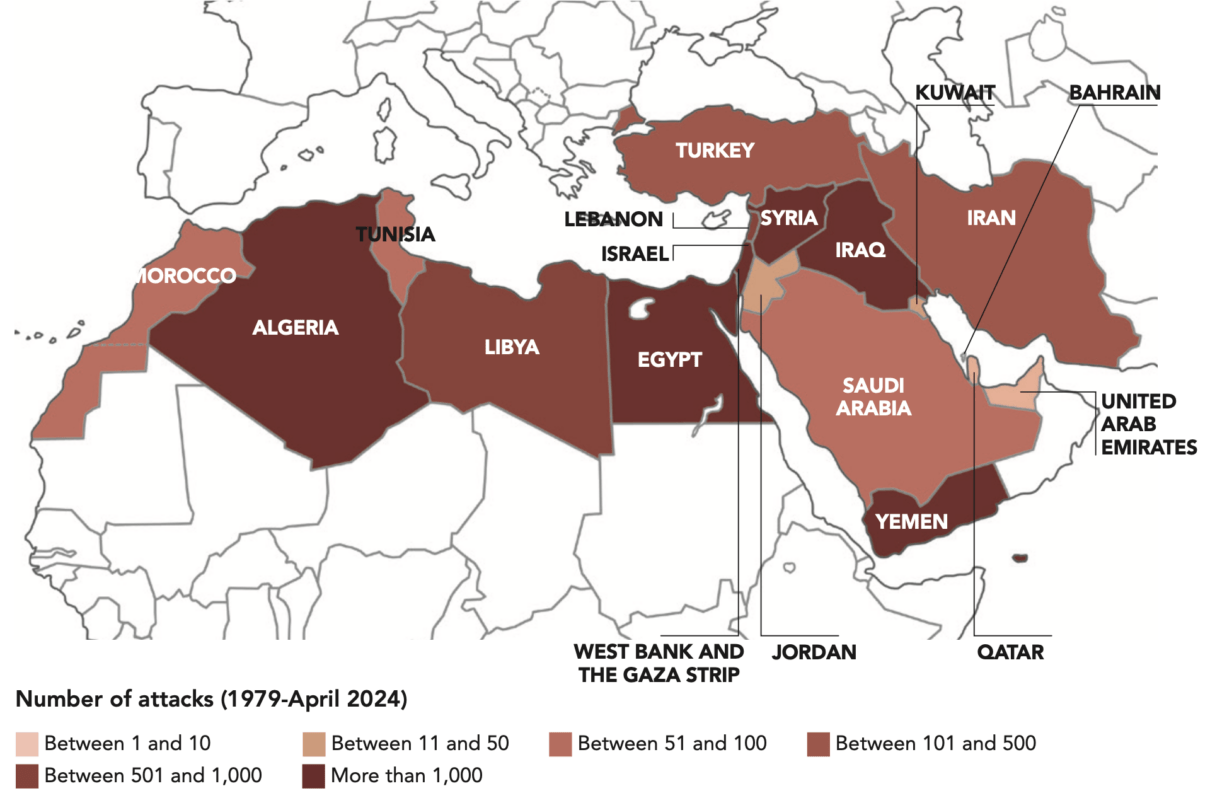

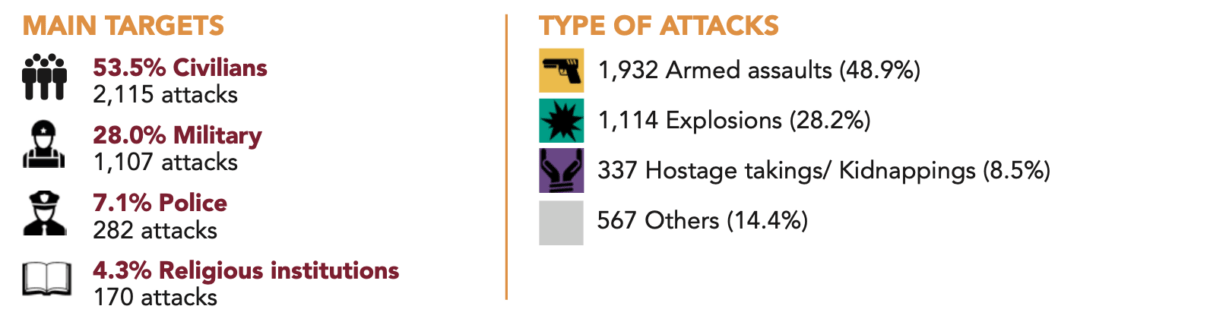

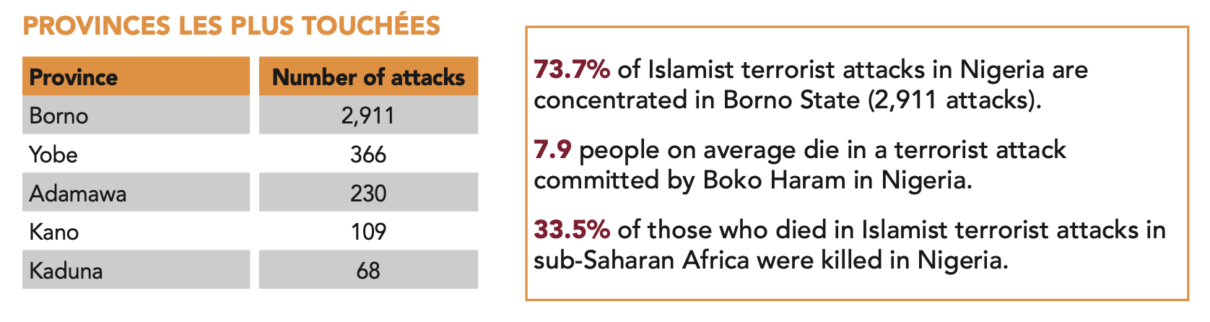

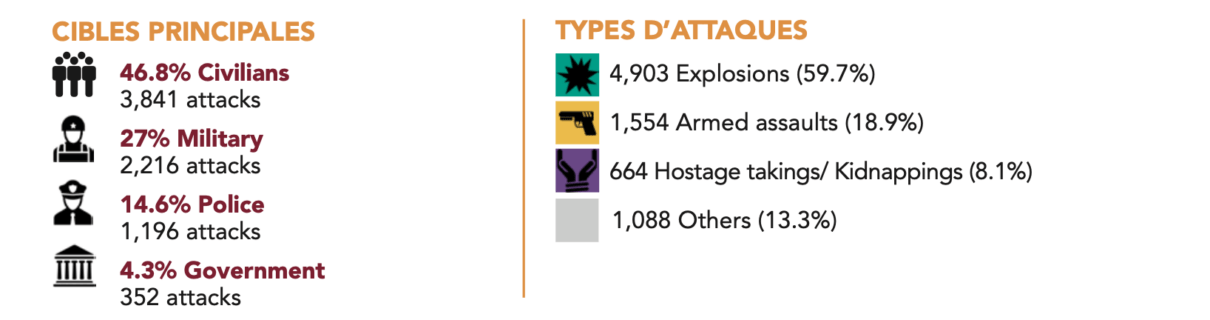

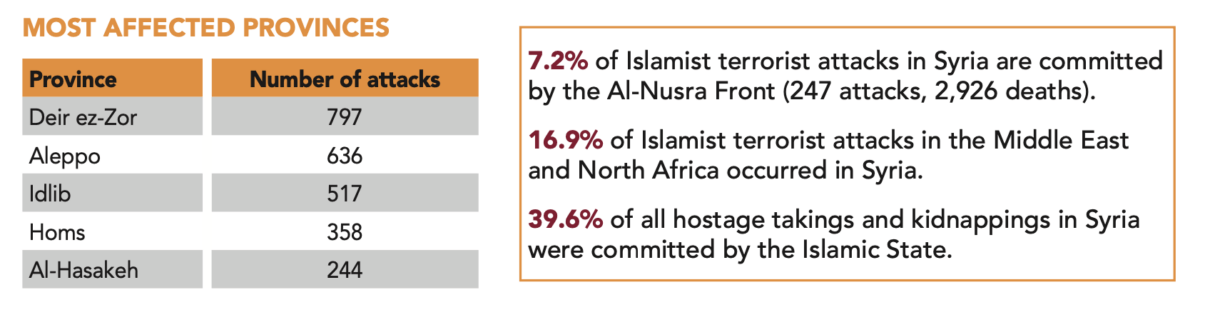

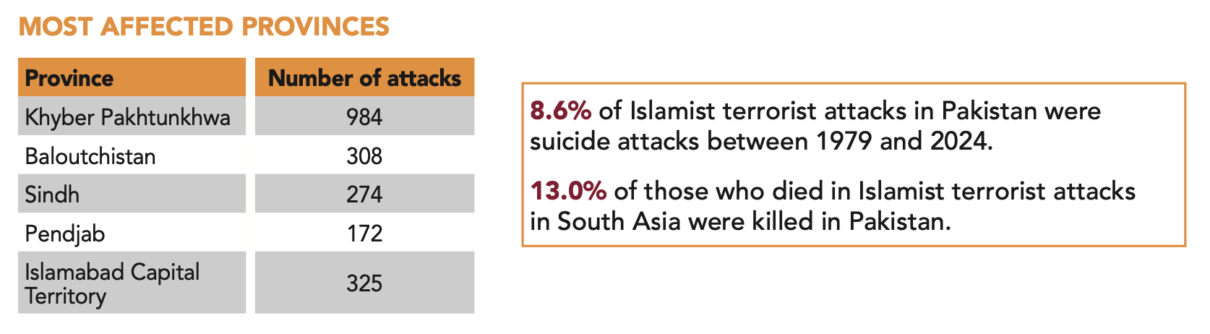

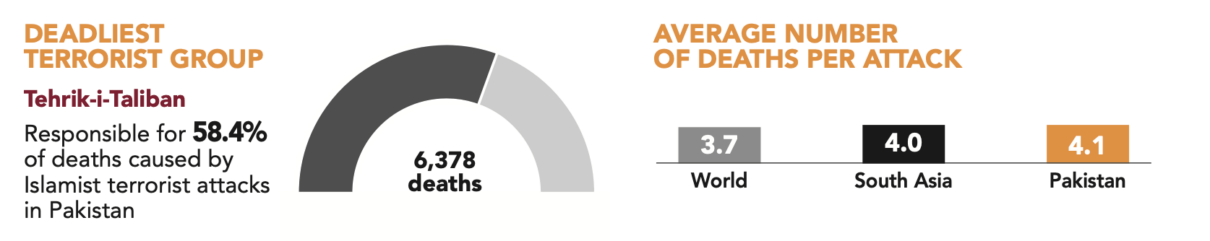

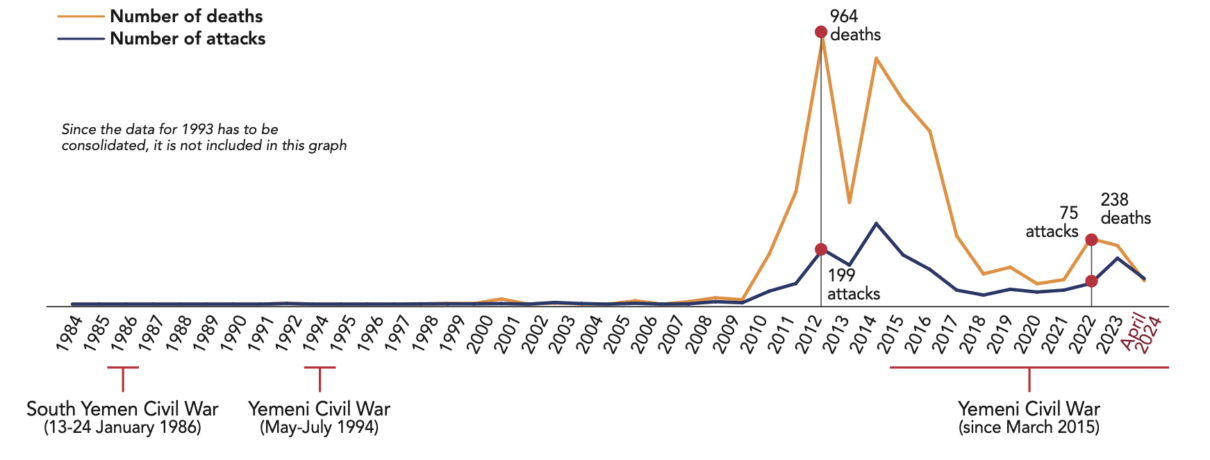

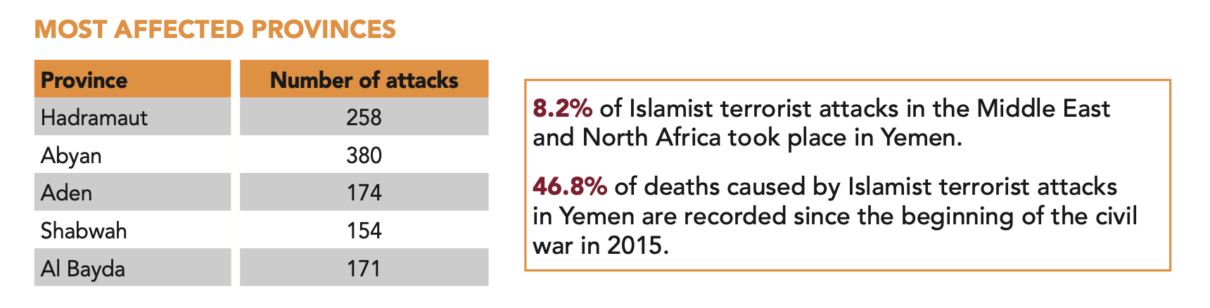

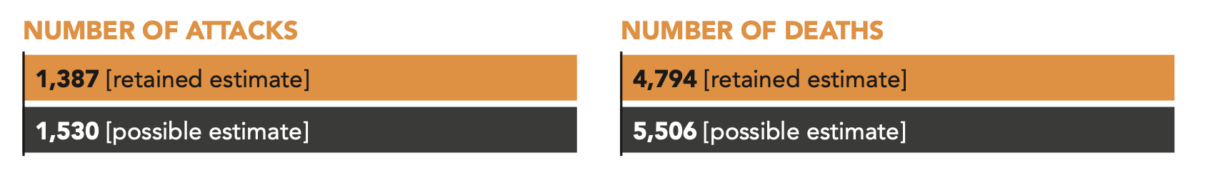

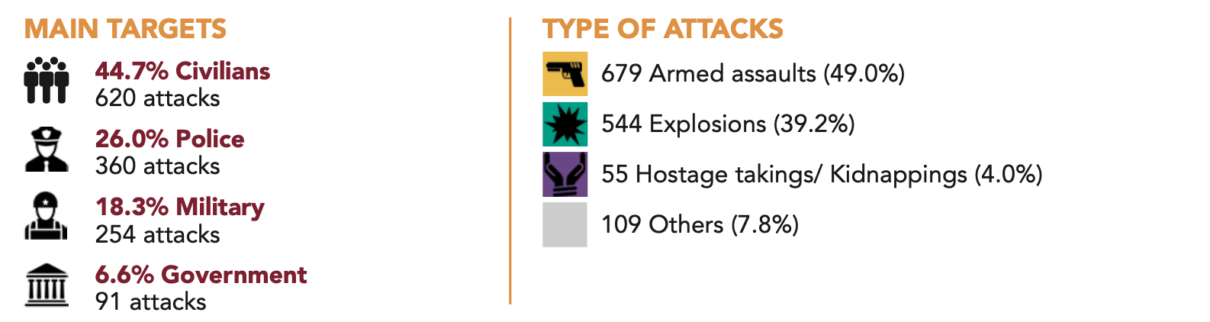

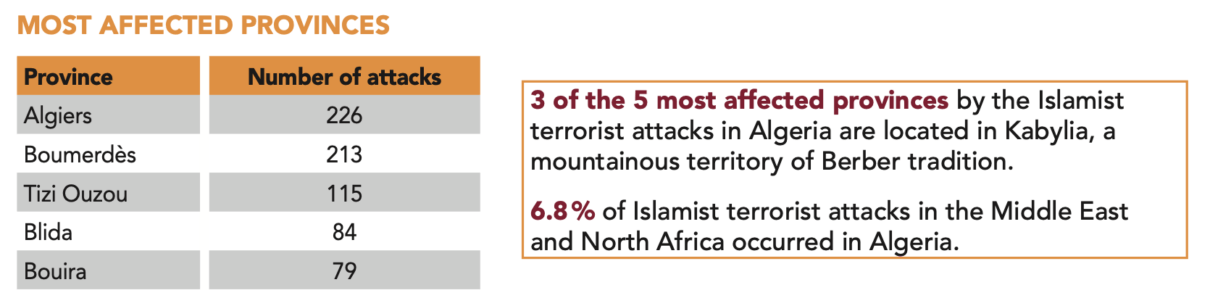

The countries most affected by Islamist terrorism are Afghanistan (17,075 attacks), Somalia (10,768 attacks), Iraq (8,209 attacks), Nigeria (3,950 attacks), Syria (3,421), Pakistan (2,635), Mali (2,289 attacks), Israel (1,748 attacks), Yemen (1,657 attacks), Algeria (1,387 attacks), Egypt (1,367 attacks), Mozambique (1,302 attacks) and Cameroon (1,230 attacks).

In these thirteen countries, 218,734 deaths were caused by Islamist terrorist attacks, representing 87.5% of the total number of deaths worldwide.

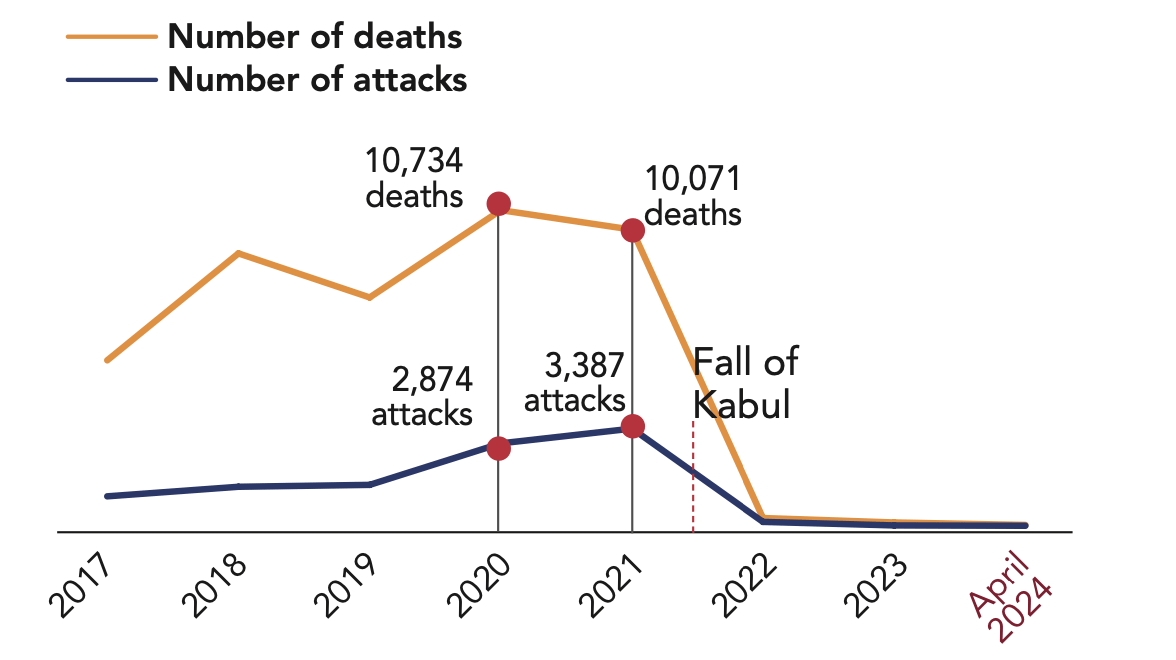

The indirect confrontation in Afghanistan between the American and Soviet powers is one of the major causes of Islamist violence of the 21st century.

The United States and Russia have also been hit by jihadist terrorism. During the period 1979-April 2024, there were 60 attacks in the United States and 3,121 deaths, and 86 attacks in Russia, resulting in 988 deaths.

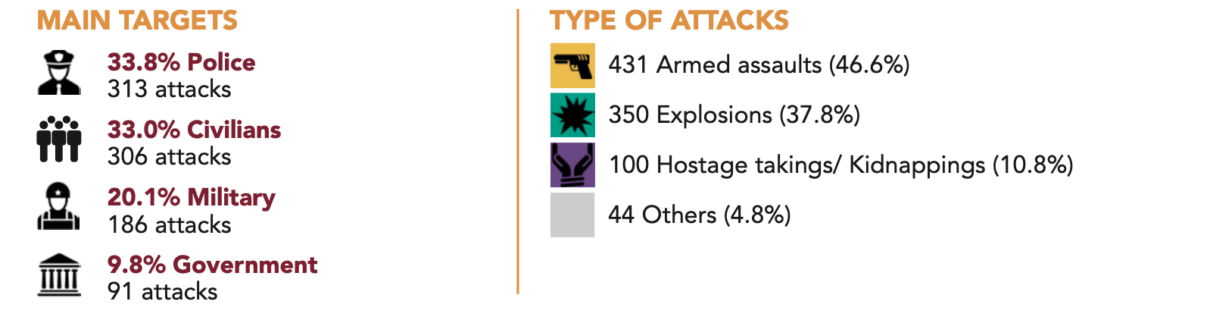

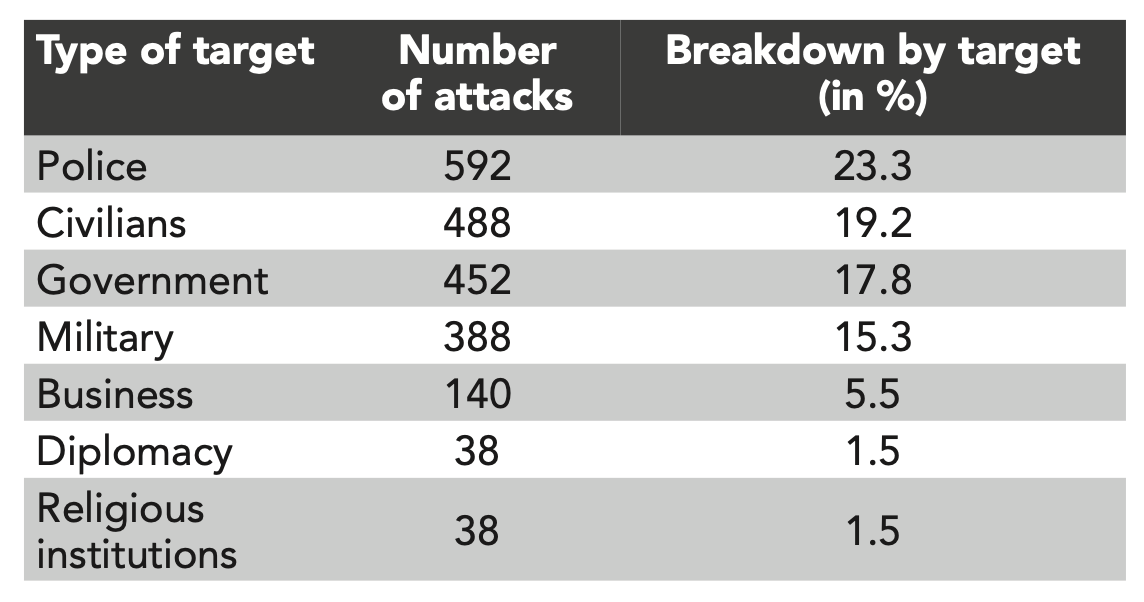

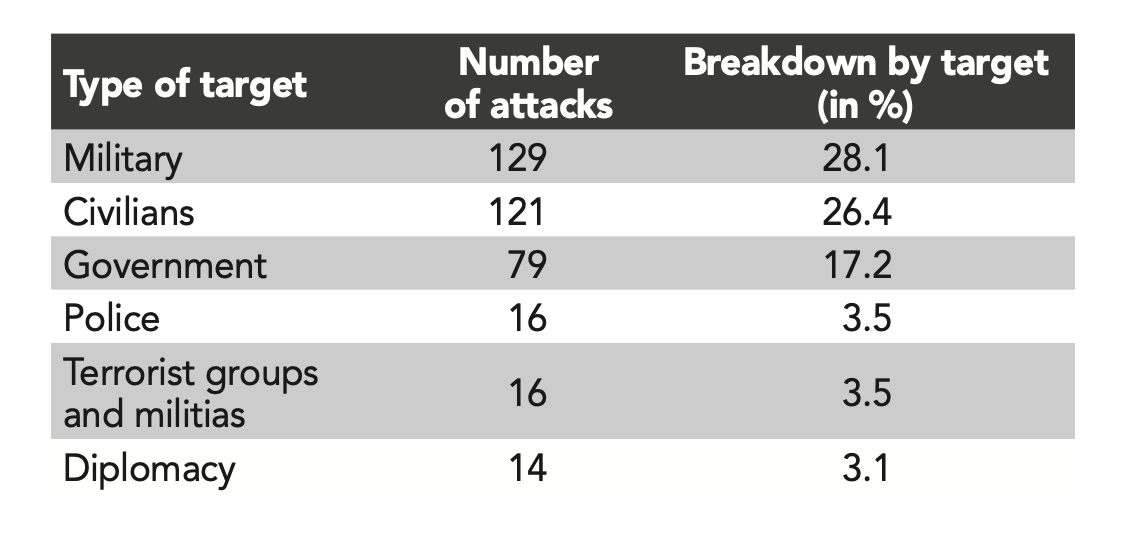

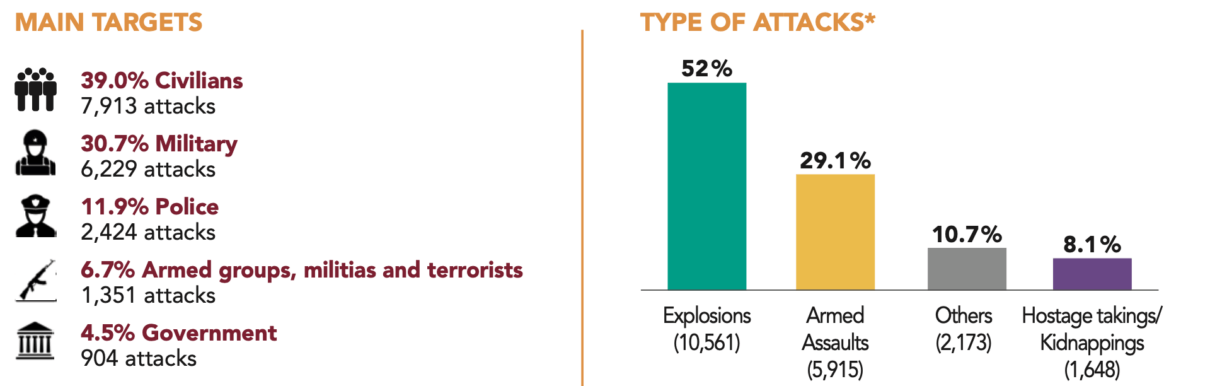

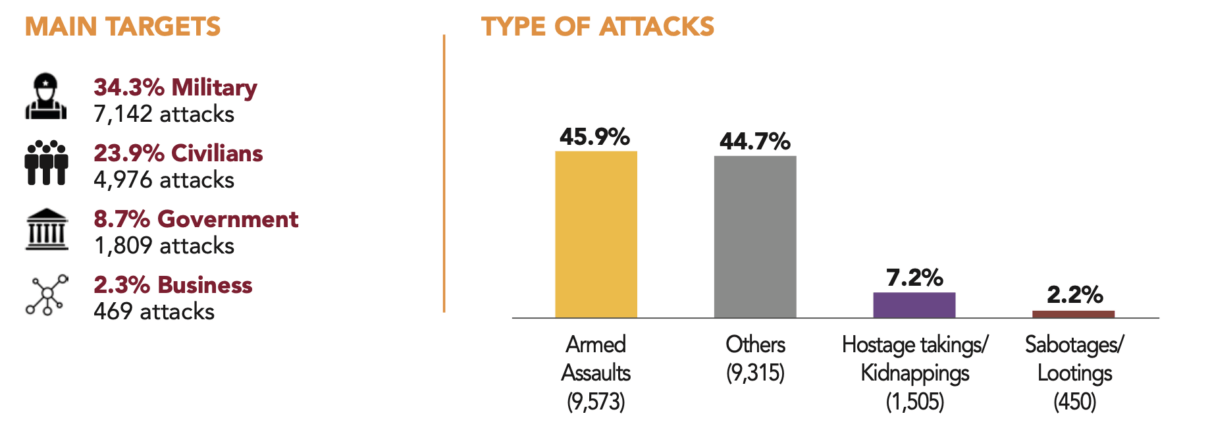

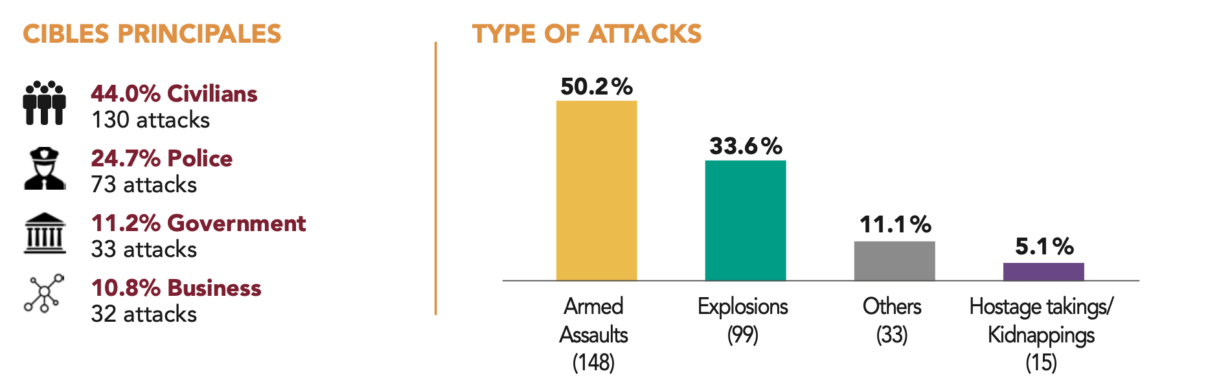

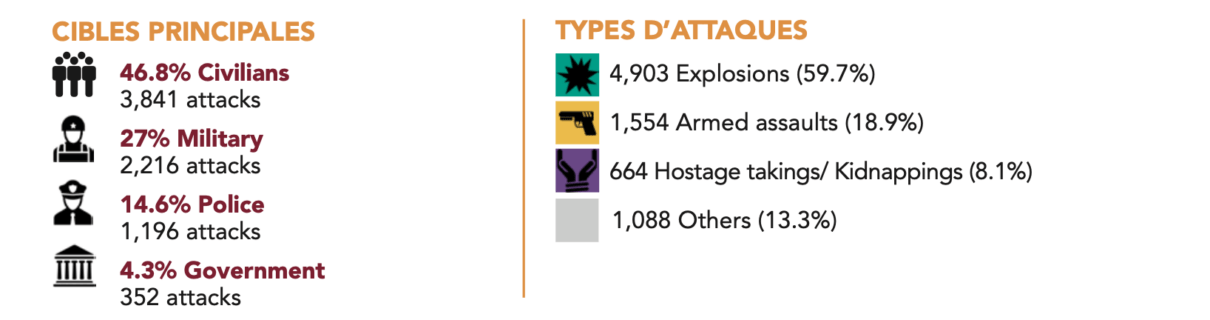

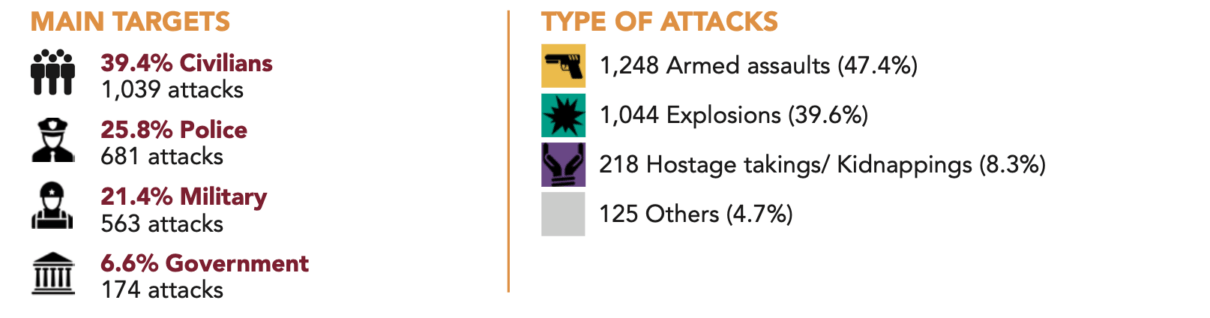

The military is the main target (34%) of Islamist terrorists, ahead of civilians (27.7%) and police forces (15.3%).

• 1979-2000: military (343 attacks, 15.6%), civilians (530 attacks, 24.1%), police forces (408 attacks, 18.6%).

• 2001-2012: military (1,410 attacks, 17.1%), civilians (2,506 attacks, 30.3%), police forces (1,424, 17.2%).

• 2013-April 2024 : military (20,556 attacks, 37.2%), civilians (15,111 attacks, 27.4%), police forces (8,217 attacks, 14.9%).

Most (86.3%) of Islamist terrorist attacks have occurred in Muslim countries1. Similarly, the vast majority of deaths from Islamist terrorist attacks (88.9%) occurred in Muslim countries.

Muslim countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, West Bank and Gaza Strip and Yemen.

• Number of Islamist terrorist attacks in Muslim countries: 57,726 attacks (86.3% of Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide).

• Number of deaths caused by Islamist terrorist attacks in Muslim countries: 222,236 deaths (88.9% of deaths caused by Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide).

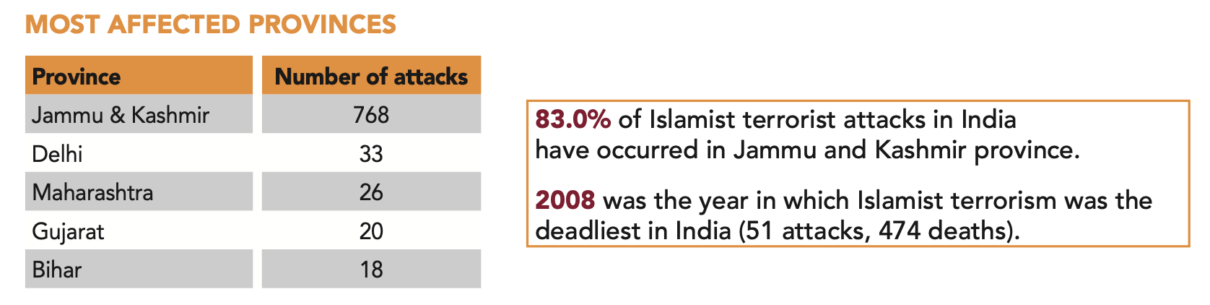

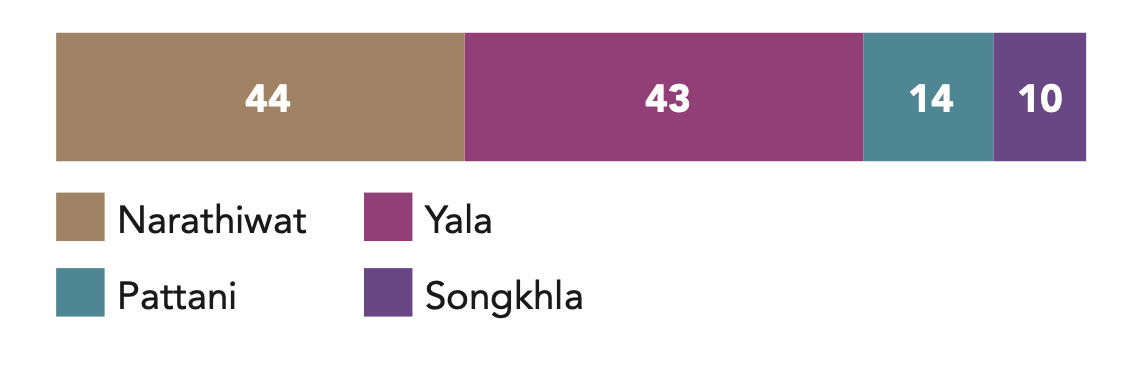

It should be noted that these figures underestimate the reality since they do not take into account the Islamist terrorist attacks perpetrated in countries with a non-Muslim majority where Muslim populations are concentrated in certain provinces. This is the case, for example, in southern Thailand, where Muslims are in the majority in the provinces of Satun, Yala, Pattani and Narathiwat, but also in the Philippines, in the region of Mindanao; in India, in the province of Jammu and Kashmir; and in China, in the Uyghur autonomous region of Xinjiang.

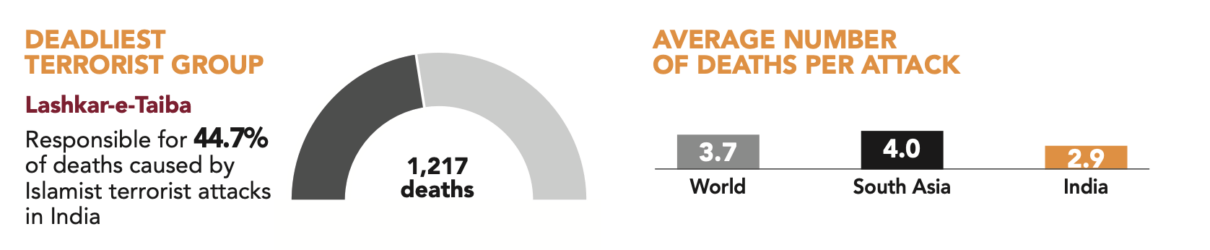

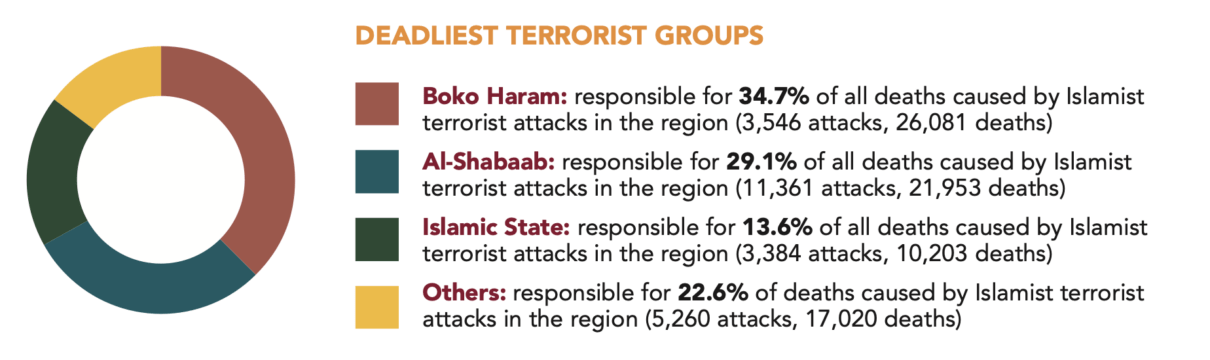

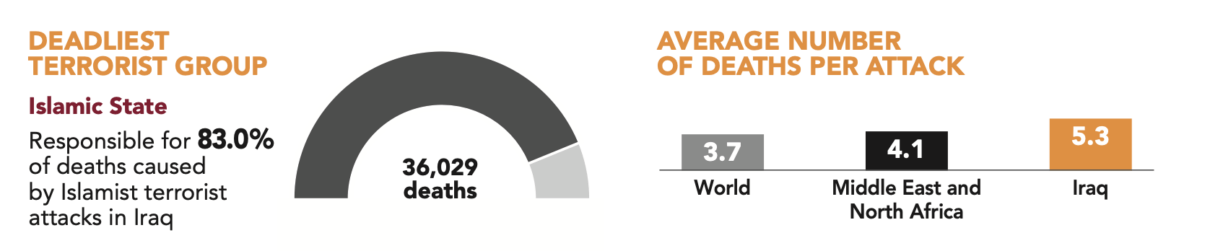

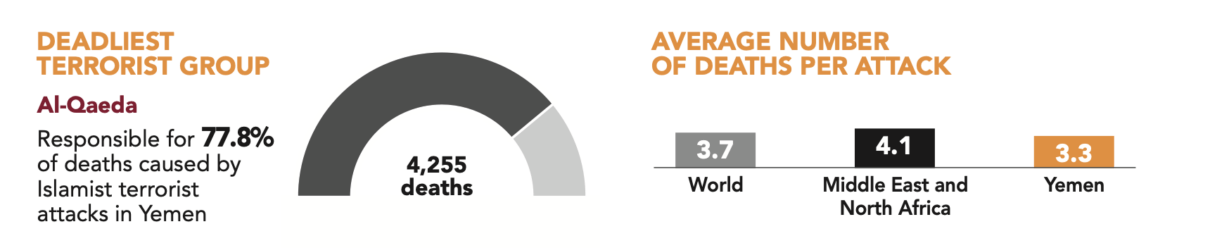

Over the entire period of time studied here, the Taliban was the deadliest group. Its terrorist actions resulted in the deaths of 71,965 people.

The data from Mozambique were not included as the databases used for this country do not allow us to identify the targets of the attacks.

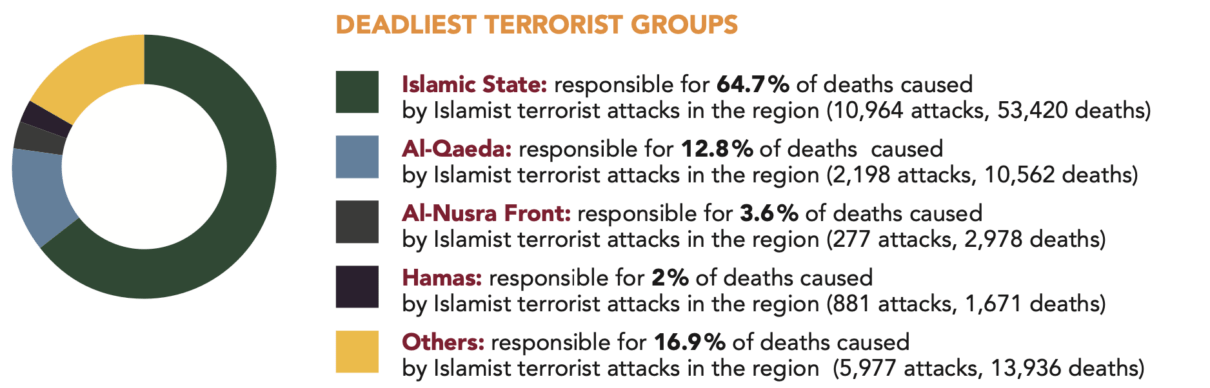

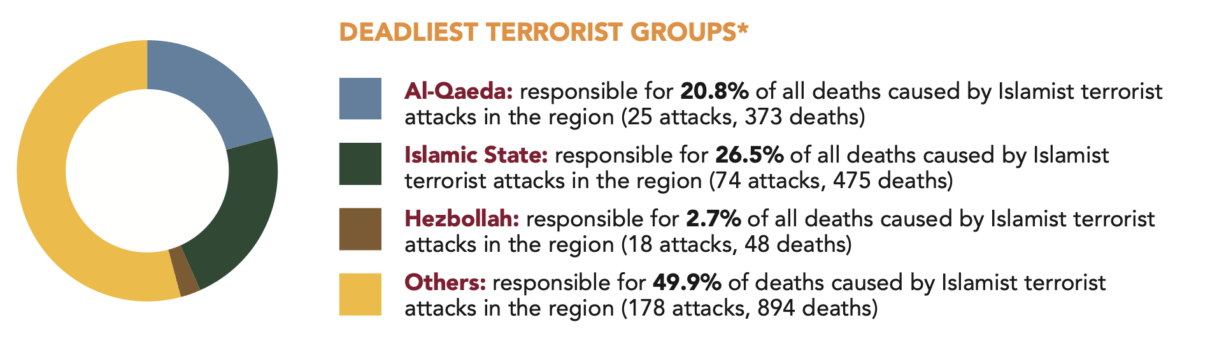

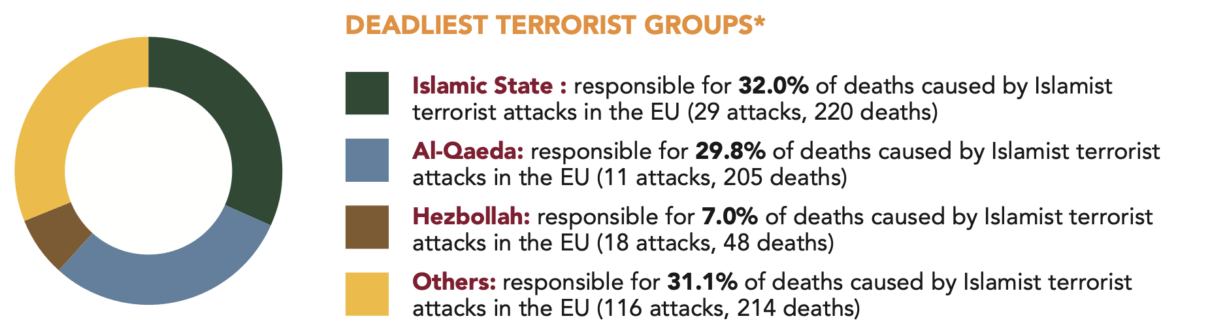

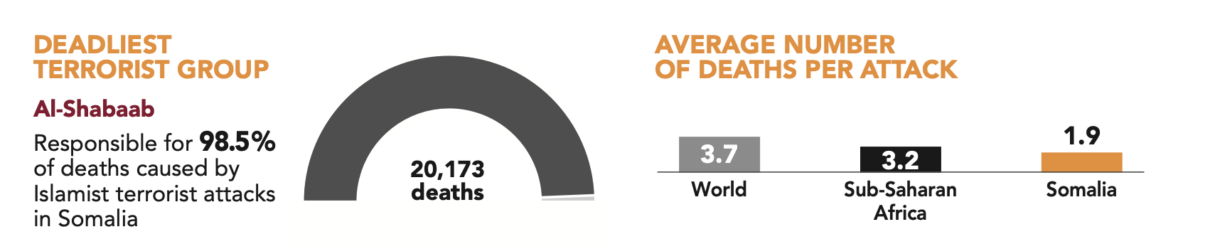

The deadliest terrorist organisations, taking into account their various offshoots, were the Taliban (71,965 deaths), the Islamic State group (69,641 deaths), Boko Haram (26,081 deaths), Al Shabaab (21,784 deaths), and al Qaeda (14,856 deaths). These five terrorist groups were responsible for more than three-quarters (81.8%) of the victims of Islamist terrorist attacks between 1979 and April 2024.

| The accuracy of the figures cannot imply such detailed knowledge of the observed reality; the degree of precision results from the calculation operations applied to the database. We could only reproduce exactly the result of these operations. |

An assessment of Islamist violence in the world (1979-April 2024)

Dominique Reynié, Executive Director of the Fondation pour l’innovation politique

“Transcript of Biden’s Speech on the U.S. Withdrawal From Afghanistan”, The New York Times, August 31, 2021 [online].

While 6,291 people were injured on the day of the attacks, thousands more suffered physical injuries, such as respiratory ailments or cancer, in the years following September 11, 2001, as documented by the World Trade Center Health Registry [online].

Figures from Humans Right Watch report, “I Can’t Erase All the Blood from My Mind”, Palestinian Armed Groups’ October 7 Assault on Israel”, 2024.

Fondapol has undertaken a significant effort to quantify and analyze Islamist terrorism worldwide, which resulted in a first report published in 2019, followed by another in 2021. This is the third edition. The striking surge in Islamist violence in recent years made this updated edition necessary. U.S. President Joe Biden emphasized this in August 2021, following the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and the Taliban’s takeover of Kabul: ‘The terrorist threat has metastasized around the globe, far beyond Afghanistan. We face threats from Al Shabaab in Somalia, al-Qaeda networks in Syria and the Arabian Peninsula, and ISIS attempting to create a caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and establishing networks in Africa and Asia.1. Three years later, our data confirms the relevance of these remarks. The expansion of Islamist terrorism since 2012-2013 is undeniable, particularly in West Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East, which was tragically illustrated by the Hamas attacks on Israeli territory on October 7, 2023.

The series of attacks on September 11, 2001 remains the deadliest in the history of terrorism, with 3,001 dead and 16,493 injured2. However, the attacks of October 7, 2023 represent the second most deadly Islamist terrorist event, causing the death of at least 1,195 people, injuring more than 3,400, and organizing the kidnapping of 2513. These attacks were the largest against Israel on its own soil since its creation in 1948. The October 7 pogrom was characterized by unprecedented violence: assassinations, torture, rape and hostage-taking of women, children and the elderly. To date (31 August 2024), 98 hostages are still being held by Hamas.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the deadliest attack to date was the takeover of the town of Palma in Mozambique by the Islamic State between 24 March 2021 and 5 April 2021: 1,193 people were killed during the 13-day occupation of the town, and 209 were abducted. They are currently presumed dead.

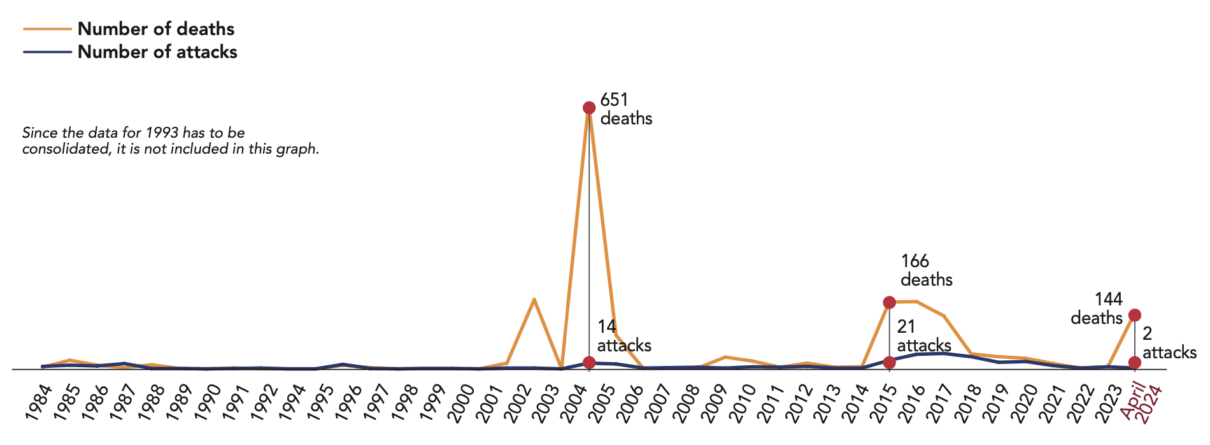

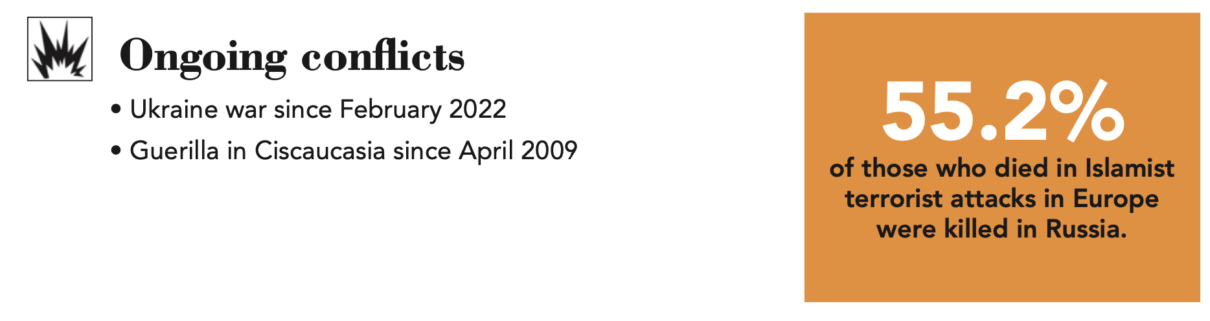

In Europe (excluding Russia), since 1979, there have been 209 attacks and 802 deaths. In France, the worst-hit European country over the same period, there have been 85 Islamist terrorist attacks, resulting in 334 deaths. In addition to France, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom were also impacted, sometimes more than once. Russia is also a target of Islamist terrorism, with 86 attacks and 988 deaths between 1998 and April 2024. In 2024, Russia was hard hit by two particularly deadly Islamist attacks: the first, on March 22 in Moscow, killed at least 144 people and injured almost 550; the second, on June 23 in the province of Dagestan, killed around 20 and injured around 40. Nevertheless, it is outside the Western world that countries have suffered more often and even more severely from Islamist violence.

1979, the critical year

See Gilles Kepel, Sortir du chaos. Les crises en Méditerranée et au Moyen-Orient, Gallimard, 2018, p. 23-69.

5. In his report for the Institut Montaigne, Hakim El Karaoui sets out the reasons why, in his view, it is possible to consider that the autonomisation of jihadism took shape in Afghanistan, namely ‘the arrival of several Islamist groups united by the Afghan conflict, the financial autonomy of the Afghan mujahideen thanks to American and Saudi funding, the actual practice of jihad for the first time since the end of the nineteenth century and its theorisation by the Muslim Brother Abdallah Azzam’ (La Fabrique de l’islamisme, Institut Montaigne, September 2018, p. 63 [online].

Gilles Kepel, Jihad. Expansion et déclin de l’islamisme, 2nd revised and updated ed., Gallimard, ‘Folio actuel’ series, 2003, p. 26.

Ibid.

We asked ourselves whether it was possible to truly know the extent of Islamist violence in the world, to make a database of it and to share the results with interested audiences in the form of a database accompanied by this study. To carry out such work, it was necessary first to determine the starting point of the database, to identify the most reliable sources, examine and validate them, then process the data collected, present the main lessons learned and, lastly, make the information collected available to the public.

We decided to start collecting data from 1979 onwards. This year was chosen by most specialists because it reflects the historical failure of Arab nationalism competing with the movements of Islamisation and the affirmation of jihadism4. That same year, a number of events precipitated this development: the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, the Iranian revolution, the signing of the Camp David agreements and the hostage-taking of the Great Mosque of Mecca by a group of Islamist fundamentalists in November-December 19795. For Gilles Kepel, what was happening that year was the result of “the fierce struggle between the Saudi monarchy and Khomeini’s Iran”6 but at the same time it was the time of a new indirect confrontation between the USSR and the United States: “The jihad financed in this country [Afghanistan] by the oil-monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula and the CIA is explicitly aimed at inflicting on the Soviet Union […] a ‘Vietnam’ that precipitates its fall. At the Islamic level, its function is also to divert radical militants around the world from the struggle against the American Great Satan – to which Khomeini incites them – and to channel them against the USSR. Afghan jihad has a cardinal importance in the evolution of the Islamist movement around the world. It became the ultimate cause, with which all militants, moderate or radical, identify themselves. It supersedes, in the Arab imagination, the Palestinian cause and symbolises the transition from nationalism to Islamism7”.

Definition of terrorism

« The threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation », Global Terrorism Database, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism (START), Université du Maryland, Codebook: Inclusion Criteria and Variables, juillet 2017, p. 10 [online].

According to this definition, acts of State terrorism are not included in our survey.

Like many concepts, terrorism is subject to controversial definitions. In this study, we define “terrorism” as political acts that meet the principle and criteria of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). In this context, a terrorist act is presented as “the threat of the effective use or use of unlawful force and violence by a non-state actor in order to achieve political, economic, religious or social objectives, through fear, coercion or intimidation”8. This definition is extended to the enumeration of a set of characteristics specifying the nature of the terrorist act:

– it must be intentional and result from a conscious calculation by the perpetrator;

– it must include some level of violence or threat of imminent violence, whether physical or material;

– the perpetrators of the incident must be non-state actors9.

To be included in the database, an event must also meet at least two of the following criteria:

– the violent act must have a political, economic, religious or social objective;

– the act must result from an intention of coercion, intimidation, or be motivated by the desire to spread an economic, political, religious or social message to a wider audience than that represented by the immediate victims; what matters is the intention of those who planned the attack or those who made the decision to carry it out;

– the action must be distinct from activities considered legitimate in time of war. The act must violate the framework defined by international humanitarian rules, in particular those concerning the prohibition of intentionally targeting civilians or non-combatants.

Our contribution focuses specifically on terrorist acts carried out by organisations or individuals claiming to be Islamists. The criterion defining a terrorist action and according to which “the violent act must pursue a political, economic, religious or social objective” must therefore be specified. This criterion is considered essential to our database and focuses on attacks that have been the subject of an Islamist claim or about which the available information indicates that it has been planned, decided and carried out in the name of Islamism.

Definition of Islamism

Janine Sourdel and Dominique Sourdel (eds.), Dictionnaire historique de l’islam, PUF, 1996, p. 411.

Ibid

Ibid

Ibid. See also Mehdi Mozaffari, “What is Islamism? History and Definition of a Concept”, Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, vol. 8, no. 1, March 2007, p. 21.

“By ‘Islamism’, I mean the normative political ideology that has as its core program the establishment of Islam as a state religion and the implementation of Islamic law (shari’a). Militant Islamism, then, is any form of Islamism that advocates the use of violence to achieve Islamist objectives. This same distinction is made by Islamists themselves, who refer to “Parties of the Islamic Call,” or al-da’wa al Islamiyya (i.e. Islamist groups that do not advocate violence) on the one hand, and “Parties of the Muslim Revolution,” or al-thawra al-Islamiyya (i.e. Islamist groups that do advocate violence)” (Edward W. Walker, ‘Islam, Islamism and Political Order in Central Asia’, Journal of International Affairs, vol. 56, no. 2, Spring 2003, p. 22, note 1).

For historians, “Islamism” is a term “used at the end of the nineteenth century to designate Islam as a religion and civilisation, but which has recently taken a new meaning of militant fundamentalist, traditionalist and proselyte Islam”10. Islamism now refers to “a trend demanding the strict application of the prescriptions of religious or shari’a law, some of which have been abandoned, as well as the principles of faith, by various modern governments in Muslim countries, particularly under the influence of European countries, Western ideologies and reformist movements”11. As a result of this evolution, the defenders of such a conception of Islam, the “Islamists”, advocate for a jihad that is “on the one hand, in their own country against ‘bad’ Muslims and corrupt rulers in order to establish, if necessary, a purely Islamic state, and on the other hand, more generally, against the secular values that dominate the non-Muslim world”12. The same authors consider that Islamism has many analogies with the Muslim Brotherhood movement13.

There are many other definitions of Islamism, often very detailed. To complete without unduly complicating matters, one can refer in particular to the definition proposed by Edward Walker, because of its relative clarity and conciseness: “By ‘Islamism’, I mean the normative political ideology that has as its core program the establishment of Islam as a state religion and the implementation of Islamic law (shari’a). Militant Islamism, then, is any form of Islamism that advocates the use of violence to achieve Islamist objectives. This same distinction is made by Islamists themselves, who refer to ‘Parties of the Islamic Call’, or al-da’wa al Islamiyya (i.e., Islamist groups that do not advocate violence) on the one hand, and ‘Parties of the Muslim Revolution’, or al-thawra al-Islamiyya (i.e., Islamist groups that do advocate violence) on the other hand14. Acknowledging that there are no universally accepted definitions of Islamism and terrorism, some researchers characterise it as an ideology whose key tenets include:

– Belief that Islam is not only a religion, but also a holistic sociopolitical system;

– Advocacy of shari’a (Islamic) law as divine state law;

– Belief that a transnational Muslim community, known as the Ummah, should unite as a political bloc;

– Advocacy of an ‘Islamic’ state, or Caliphate, within which sovereignty belongs to God15.

A global database of Islamist terrorist attacks from 1979 to April 2024

On April 28, 2019, the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag published a list of Islamist attacks. The list covers a shorter period, from September 11, 2001 to April 28, 2019. Up to 2017, the data is taken from the Global Terrorism Database. For the years 2018 and 2019, the journal has carried out its own census. Our data differs from that of Welt am Sonntag in at least three respects: firstly, we cover a period of forty years instead of eighteen, which enables us to track developments in Islamist terrorism, revealing in particular a phenomenon of globalization; secondly, Welt am Sonntag has chosen to count only attacks with at least twelve fatalities, whereas we ourselves have recorded all identifiable attacks; thirdly, Welt am Sonntag focused on attacks carried out by the main terrorist groups (Abdullah-Azzam Brigade, Asaib Ahl ab-Haqq, Abu Sayyaf, Ansar al-Din, Allied Democratic Forces, Algerian Jihadists, Ahrar al-Sham, Ansar al-Islam, Al-Ittihaad al-Islami, Al-Islah Party, Aisha-Brigade, Al-Aksa Martyrs Brigade, Al-Muaqioon-Biddam Brigade, Ansar-Al-Din-Front, al-Qaida, Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, Ansar al-Sunna, al-Shabaab, Ansar al-Sharia, Ansar al-Tawhid, Ansar ul-Islam, Boko Haram, Sunni Jihadist Movement of Iran, Deccan Mujahideen, Guardians of Religion, Armed Islamic Group, Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, Hezbollah, Hizb-i-Islami, Harkatul Jihad-e-Islami, Hakkani Network, Halqa-e-Mehsud, Hisbul Mujahideen, Hamas, Houthis, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Islamic Jihad, Islamic Front, Indian Mujahideen, Turkestan Islamic Party, Jaish al-Adl, Jaish-al-Islam, Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, Jaish-e-Mohammad, Jaish al-Fatah, Jaish-i-Islam, Jemaah Islamiya, Jund al-Khilafah, Jamiat ul-Mu- jahedin, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, Jundallah, Jundallah Pakistan, Jaljala Army, Kataib Hezbollah, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Lashkar-e-Omar, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Lashkar-e-Islam, Mujahideen Ansar, Mahaz-e-Inquilab, Moro Islamic Liberation Front, Moro National Liberation Front, Movement for Tawheed and Jihad in West Africa, Mujahedeen Shura Council, Armée Mukhtar, Front al Nosrah, Students Islamic Movement of India, Sipah-i-Mohammed, Salafia Jihadia, Shura des Moudjahidines de Derna, Special Purpose Islamic Regiment, Shura des révolutionnaires de Benghazi, Taliban, Tehrik-e-Taliban Islami, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, United Jihad Council); while our database lists, as accurately as possible, all Islamist attacks. So, in addition to attacks committed by the best-known groups, we also take into account attacks carried out by individuals or small groups claiming to be Islamists, without belonging to a particularly well-known organization. See “18 Jahre Terror”, Welt am Sonntag, no. 17, April 28, 2019, pp. 12-14.

We can quote, for example, the database made available by Le Monde on Islamic State group attacks from 2014 to 2016 [online], journalist Alexander Perry [online].

Global Terrorism Database, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism (START), University of Maryland [online].

The Global Terrorism Database did not provide information for 1993. The years 2018 and 2019 were not available from the GTD.

Extract from the Fondapol database 1979-2024.

Ibid.

As the ACLED database is regularly updated, we were able to modify some data from before 2021—these updates are minor.

It is within the framework of these definitions that we have conceived this work and that we propose here the result in the form of a database listing the Islamist terrorist attacks perpetrated in the world since 27 December 1979. The data included in our database does not extend beyond 12 April 2024, given the time required to validate and process the information collected. Indeed, while the attacks in Western countries have considerable visibility, due to the greater impact that violence can have in more peaceful societies, their ability to produce reliable data quickly and a particularly dense media presence, the same cannot be said for attacks that take place, much more often, in other parts of the world where all identification and intelligence processes become longer but cannot be as effective.

Therefore, the validation and classification of relevant events requires work that goes beyond the time we had to define in order to make this publication possible.

To conduct our research, we relied on three types of sources: gatherng information on attacks using search engines, cross-referencing existing databases, and consulting academic research. We used a range of databases that track both general attacks and specifically Islamist attacks16. All the databases we used were helpful in confirming and expanding our research17. However, most of these databases were incomplete or unevenly detailed. For some countries, regions, or time periods, there was a lot of information, but for others, the data was sparse or missing. For example, Wikipedia offers data organized by year or theme, but it is often fragmented and incomplete, making it unsuitable for statistical analysis. For our first edition, “Islamist Attacks in the World 1979-2019,” we primarily used the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) from the University of Maryland, USA18. This database covers terrorist attacks from 1970 to 2017. The value of this data set lies in its ability to record attacks, whatever their motivation.

This richness was also our main challenge, since we had to extract Islamist-type attacks from the 172,944 attacks recorded worldwide from 1979 to 2017. We therefore first had to select, verify and classify the data contained in the GTD. We then had to supplement it with our own information, in particular for the years 1993, 2018 and 201919.

Since the first edition of our study, in November 2019, the University of Maryland database has been updated to June 2020. Firstly, we were able to consolidate our data for the years 2018 and 2019.

For the period from July 2020 to April 2024, we used the Armed Conflict and Event Data Project (ACLED) database. This American non-profit organization specializes in data collection and mapping of all types of violent events worldwide, from 1997 to the present day. We have developed a filtering system, with three parameters, to retain only Islamist attacks:

1. The period: we have exported data for the period from 1 July, 2020 to 12 April, 2024;

2. Type of event: we then selected all terrorist attacks worldwide;

3. Islamist terrorist groups: finally, we have kept track of attacks perpetrated by an Islamist terrorist or by an Islamist terrorist group, with 656 Islamist terrorist groups recorded from 1979 to the present day.

We have excluded several types of events from our database:

– Operations initiated by state forces aimed at preemptively weakening a terrorist group (e.g., “On 12 March 2021, 3 Taliban were killed and 1 wounded in an Afghan military operation in Dih Yak district, Ghazni province. Additionally, 4 Taliban-planted IEDs were detected and defused in the district. Fatalities coded as 3”)20.

– Operations where the instigator is not clearly identifiable (e.g., “On 18 September 2021, clashes erupted between AQAP militants and unidentified tribesmen in Al Tariyah village, Hatib district (Shabwah), killing 1 and injuring others. The reason behind the clashes was not reported”)21.

For the Islamist attacks included in our database, we have provided the following information:

– the date ;

– the location of the attack: country, city, exact location when identifiable;

– the number of confirmed deaths and the number of wounded, including among the attackers; it is important to point out here that the number of wounded is obviously greatly underestimated by the information available;

– the perpetrator(s) of the attack ;

– target type(s) ;

– the type(s) of attack(s) involved;

– type(s) of weapon(s) used.

– description of the attack.

For the period June 2021-April 2024, we analyzed a total of 18,188 events, representing an average of 527 terrorist acts per month. We have worked with information provided by the Armed Conflict and Event Data Project (ACLED) to analyze it and create our own database22.

Why our study underestimates the reality of Islamist violence

It is obviously not possible to claim to offer an exhaustive database of Islamist attacks committed worldwide between 1979 and April 2024, for a number of reasons detailed below.

A certain number of attacks have not been listed. Despite our best efforts, it has not been possible to identify a certain number of Islamist attacks over the entire period in question.

a/ In some cases, the number of victims caused by Islamist attacks is insufficiently detailed. It is sometimes roughly estimated by the authorities of the country who, for political reasons, do not wish to collect and publish information on the subject. This is particularly the case with the Algerian state (see our box below).

b/ A number of attacks do not appear in our “retained estimate” when religious motivation is not clearly predominant in a combination involving another determination. Islamist terrorism takes place in singular and complex contexts that sometimes make it difficult to collect reliable data. This is particularly the case in situations of war, civil or international, independentist or separatist struggles and territorial conflicts that persist over long periods of time, where causalities are shifting or inextricable, as in the case of the Palestinian conflict, while in a completely different context, in Thailand for example, a separatist movement has led a Muslim minority to get involved with weapons in the name of objectives that can achieve, beyond political demands, a religious dimension.

c/ Islamist motivation is not always identified. Available data do not always allow news agencies to attribute the attack to the Islamist cause, especially if the country affected by the attack is characterised by weak administrative structures. The absence of claim of responsability can increase the likelihood that an attack will not even be recorded by agencies or that this information will not reach the press.

d/ The number of deferred deaths is practically unknown. However, it is certainly significant. Since victims who succumb to their injuries after an attack are almost never mentioned in the available information, it is impossible to know their exact number.

The death of Tahar Mejri, who died of grief on June 14, 2019, three years after losing his wife and son in the Nice attack on July 14, 2016, is another tragic illustration of what we refer to as ‘delayed deaths’. It is therefore also impossible to integrate these deaths into our database in a reliable way. Thus, according to our database, we record at least 249,941 deaths and 192,598 people wounded, which is less than the number of deaths. However, if we consider four cases of attacks, each carried out with different means, in three countries where the quality of information is excellent, we observe a completely opposite ratio between the number of deaths and the number of people wounded: in the United States, there were five times as many people wounded (16,493) than killed (3,001) in the 9/11 attacks; in France, there were three times as many people wounded (413) than killed (137) in the 13 November 2015 attacks; in Nice, in the 14 July 2016 attack, there were five times as many people wounded (458) than killed (87). In Israel, the attacks of October 7th, 2023, resulted in 3,400 injured and at least 1,195 dead, hence in three times more deaths than injuries. It should be noted here that both the Bataclan attack and the Nice attack led to survivors committing suicide several months or even years after the events. Our study goes back on this particular point. This information leads us to believe that the number of people wounded is much higher than that in our database. Certainly, developing countries, which are the countries where most attacks take place, do not have the same capacity to identify and care for people injured in an attack. Some of the injured are probably not even counted, while others die from their injuries after a certain period of time due to the inadequacy or fragility of relief systems and health institutions. If we applied the ratios of the four sample attacks to the number of casualties in our database (249,941), we would have to adjust this figure by multiplying it by three (hence 749,823 wounded) or five (hence 1,249,705). However, among all these injured people, it appears certain that several of them die from their injuries, and that the poorer and more lacking in rescue and medical resources the affected country is, the more numerous these deaths are.

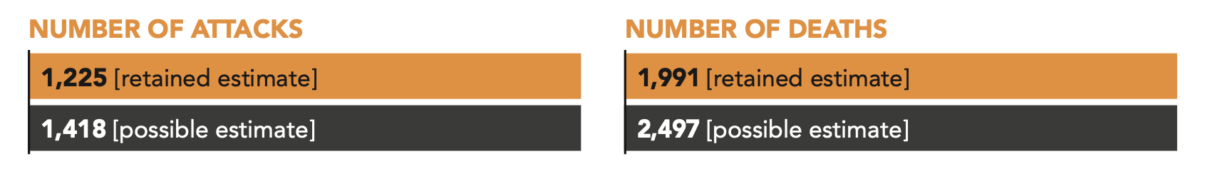

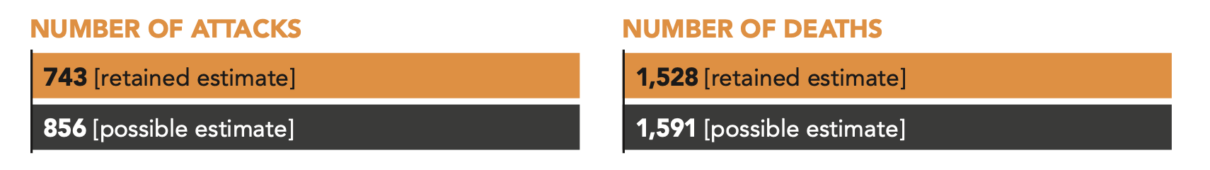

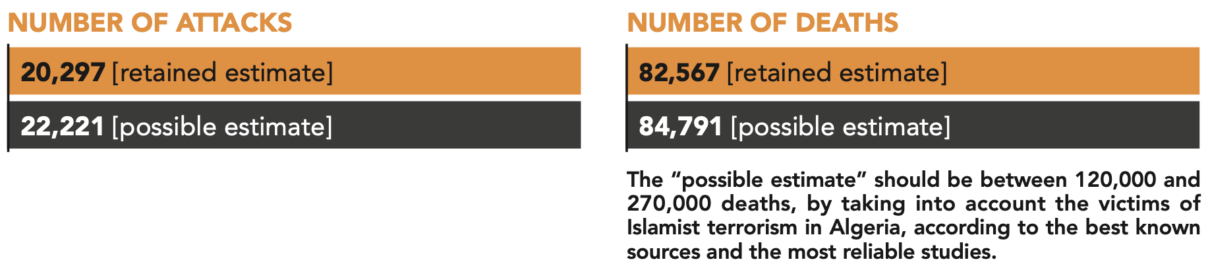

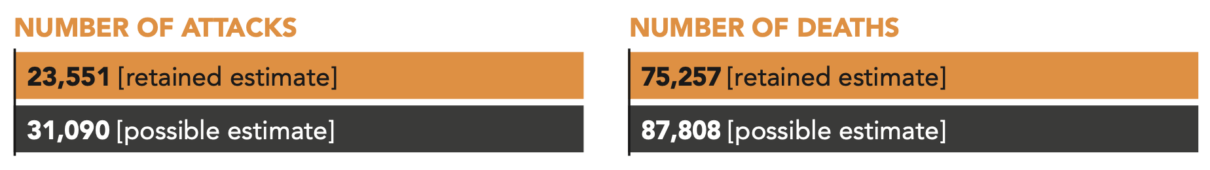

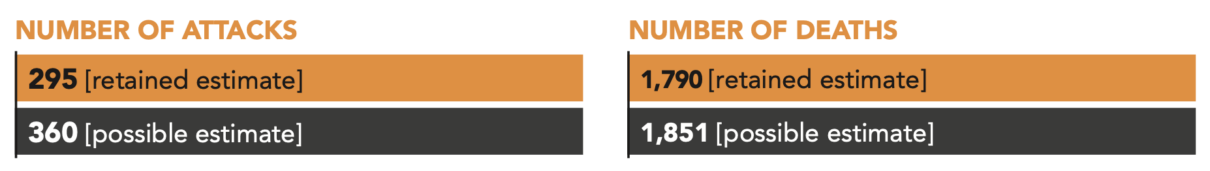

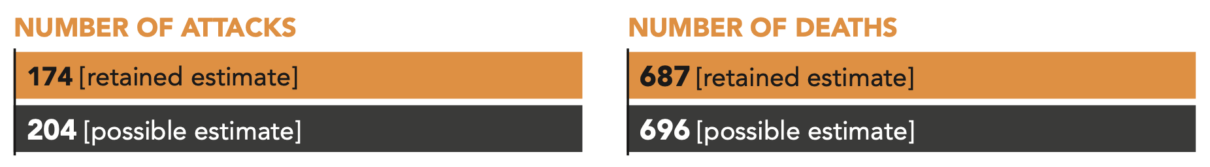

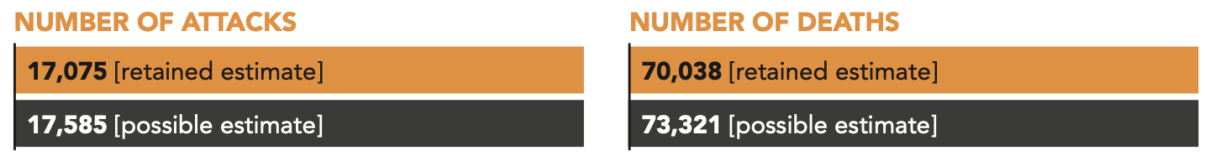

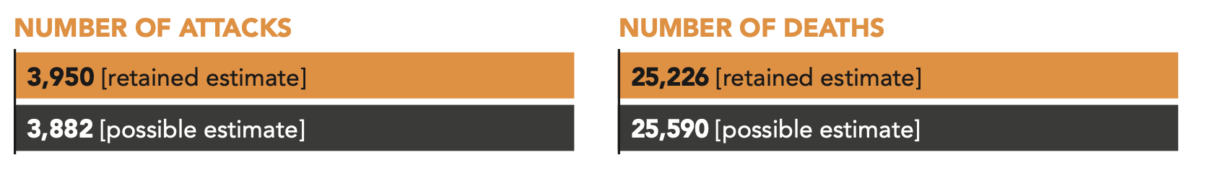

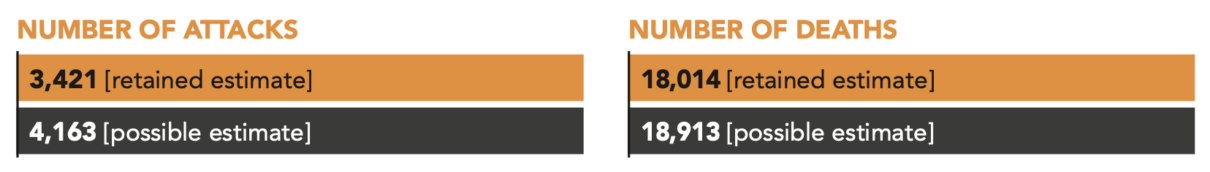

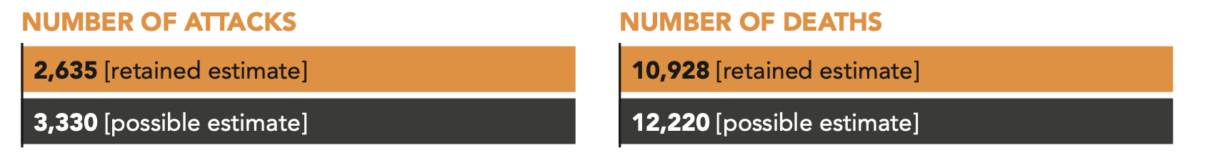

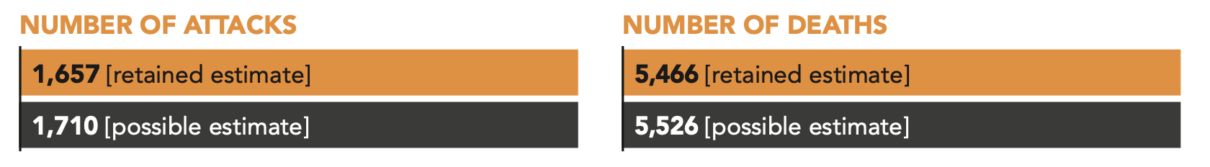

For these four reasons, we propose two types of quantification of Islamist violence, in the form of a “retained estimate” and a “possible estimate”. The “retained estimate” results from our database of attacks during the period 1979-April 2024, that were clearly motivated by an Islamist agenda. The “possible estimate” results from the identification of attacks that could be qualified as Islamist, including certain terrorist acts that are also based on separatist, political or social logic, which make it more difficult to attribute them to an exclusively or mainly Islamist motivation. In all cases, the number of victims, dead or injured, is significantly lower than a reality that cannot be more precisely known.

We have recorded 66,872 Islamist terrorist attacks that killed at least 249,941 people between 1979 and April 2024.

“The possible estimate” should be between 300,000 and 400,000 deaths considering the victims of Islamist terrorism in Algeria, according to the hypotheses based on the best-known sources and the most reliable studies.

Our research began in spring 2018. It gave rise to a first publication, in 201923, and a second in 202124. The study we publish here is based on the database we developed, within the limits previously indicated. The analyses that follow first present the evolution of Islamist terrorism from 1979 to the present day, before proposing a presentation and reading of the data according to the regions of the world and the countries affected by Islamist violence.

See Pierre Daum, “Mémoire interdite en Algérie”, Le Monde diplomatique, August 2017, p. 8-9 [online].

Fouad Ajami, art. cit.

See the pages “Algeria” on the website counterextremism.com; Audra Grant, “The Algerian 2005 Amnesty: The Path to Peace?”, Terrorism Monitor, vol. 3, n° 22, November 2017; “Algeria: Fundamentalist Conflict, 1980s-Present”, in James Ciment (dir.), World terrorism. An Encyclopedia of Political Violence. Ancient Times to the Post-9/11 era, Routledge, 2011, vol. I, p. 157.

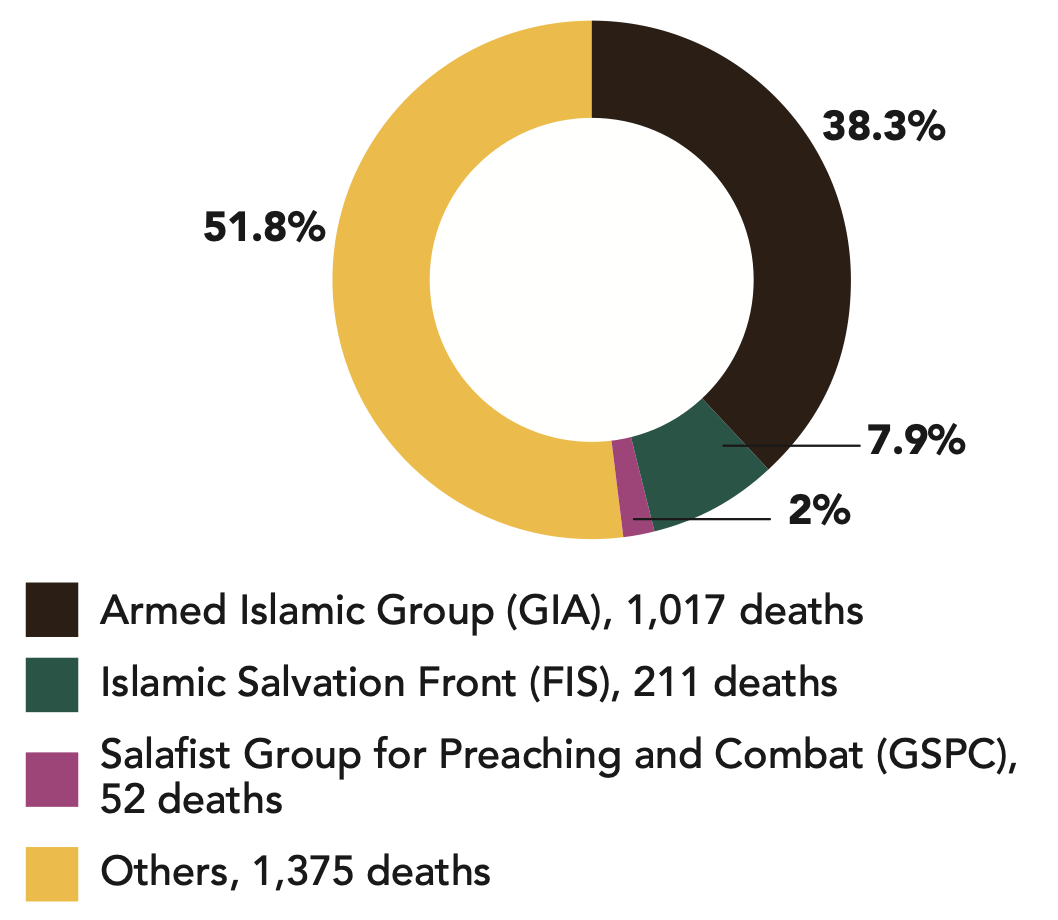

| The Algerian “black decade”: only an approximation is possible

The Algerian case illustrates particularly well the difficulty of providing an exhaustive database. Algerians refer to the period between 1991 and 2002 as the “black decade”, when various Islamist groups, in particular the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), opposed the Algerian state in a violent civil war whose outcome is difficult to document1. According to Fouad Ajami, “the precise number of Algerians who died in the civil war that broke out in 1992 will never be known. The Algerian leaders, who are not known for their loyalty to the truth and who have so much to hide, acknowledged in 1999 that 100,000 people were killed. More reliable estimates provided by Algerian civic organisations put the death toll at 200,000”2. Indeed, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika first estimated the number of victims at 100,000 in 1999. Then, in February 2005, the Algerian president gave a speech in which he put the figure at 150,000 deaths3. Fouad Ajami considers that the death toll could reach 200,000, arguing that it was in the interest of the Algerian government to minimise the losses4. This figure, which has been used in various works on terrorism in Algeria5, remains debated, particularly because it does not distinguish between victims who were members of the police or the army, terrorists and civilians. In a study published in 2008, Roman Hagelstein tried to distinguish between those killed in clashes between security forces and terrorists and those killed in massacres, bombings and assassinations. The study also distinguishes the number of missing persons, presumed to have been murdered in secret, with the author estimating the total number of victims at 44,0006. Regarding the victims of Algerian Islamist terrorism in the period 1991-2002, the available estimates that can be considered reliable because of the sources, authors and types of publication thus vary between 44,000 and 200,000. In any case, for this country and for this period, there is no data available to provide information on the number of attacks, their date, the modalities of action, the group responsible or the profile of the victims. For our database, these major uncertainties have several consequences: firstly, due to the lack of information, it is not possible to further specify the situation of Islamist terrorism in Algeria during this decade. In keeping with our method, we therefore only include in the “retained data” the cases that were reported. This choice leads to an undoubtedly significant underestimation of the number of attacks and victims in Algeria. On the other hand, we will include in the “possible estimate” category the indications concerning Algeria. Finally, as a consequence, this situation of great ignorance with regard to the Algerian case leads to an underestimation of the number of attacks and victims of Islamist terrorism in the world, both for the period after 1991 and for the period as a whole. |

The beginnings of transnational Islamist terrorism (1979-2000)

This work does not aim to shed light on the foundations of Islamism or to discuss the origins and justifications, in the context of Islam, of the use of violence and violence of a terrorist nature in particular. In a different way, we consider that our contribution lies in the information that can be obtained from the exploitation of a consolidated database and the analyses to which it can give rise. However, in order to understand the value of the data shared here, it is necessary to briefly recall the developments in Islamist terrorism since 1979.

See Mohamed Louizi, Liberér islam de l’islamisme, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, January 2018 [online] ;

Mohamed Sifaoui, Taqiyya! Comment les Frères musulmans veulent infiltrer la France, L’Observatoire, 2019; or Malik Bezouh, Crise de la conscience arabo-musulmane, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, September 2015 [online].

Until the mid-1970s, Islamism had little influence in the Middle East and North Africa. In the wake of decolonisation and the rejection of Western imperialism, the new States of the region affirm a nationalist and pan-Arab vision promoted by leaders such as Nasser or Boumediene and by movements such as Ba’ath, in Syria and Iraq, or the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) in Palestine. Islamist organisations are firmly contained or severely repressed, as Nasser did in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood. Founded in 1928 by Hassan el-Banna, the Muslim Brotherhood was established with the aim of restoring the political Islam that had disappeared with the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate proclaimed by Atatürk in 1924.

At the end of the 1970s, the Islamist claim was strengthened1. The increase in social inequalities and corruption of the elites were denounced. Islamist movements were trying to embody a political alternative to existing dictatorships or were engaging in violent actions, as in Syria, where the Muslim Brotherhood launched an armed struggle against the Baathist regime of Hafez el-Assad. These movements of Islamisation in Middle Eastern societies flourished all the more as Arab nationalism began to falter then collapsed. At the end of the decade, in 1979, a window of opportunity opened up for Islamists in the Middle East and North Africa.

The Soviet-Afghan war, “matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism”

The year 1979 was a pivotal year, the scene of several important events, including the Iranian revolution and the invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR. The Russian military operation precipitated the emergence of a new Islamism. At the same time, in Iran, the opposition led by the Shiite clergy, due to the context of intense social protest, forced the Shah to flee the country (16 January 1979). On 1 February 1979, Ruhollah Khomeyni came to power. He initiated the transformation of Iran’s imperial regime, accused of “Westernisation”, into an Islamic republic. In the wake of the Iranian revolution, Shia groups advocating armed struggle were formed. Among them is the Lebanese Hezbollah, created in 1982. Shia ideology is affirmed in the context of the process of Islamisation of the Middle East where it competes with Sunni legitimacy.

In Afghanistan, the Soviet invasion initiates the conflict which will be considered the matrix of contemporary Islamist terrorism2. Jihad is supported by Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Egypt. Jihadists who reach Afghanistan become “mujahideen”; they are seen as the liberators of a “land of Islam” (dar al-islam).

The 1980s and the emergence of Islamist terrorism

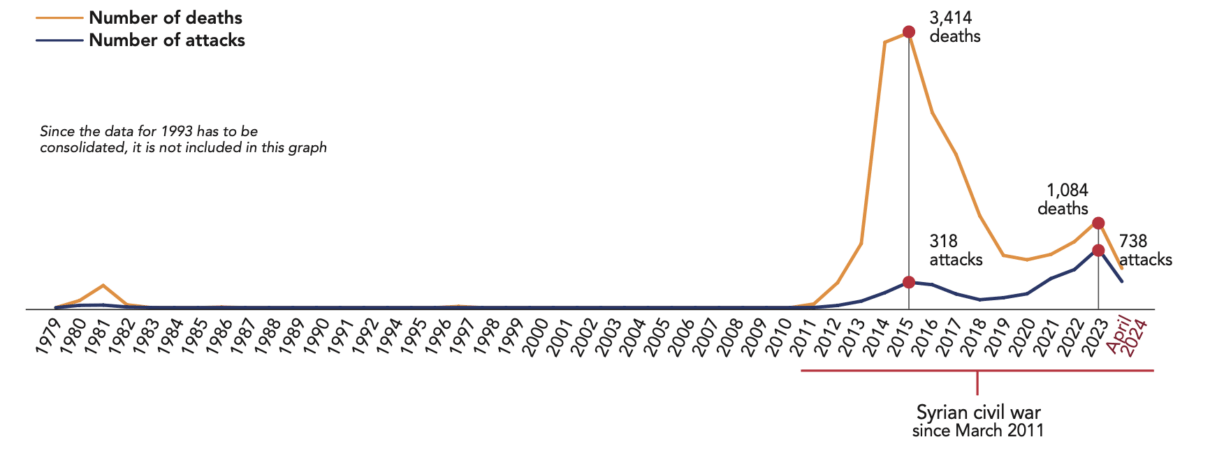

With 357 attacks, which cost the lives of 1,442 people, the 1980s are the least deadly years compared to the decades that followed. The emergence of Islamist terrorism is visible from the years 1980-1983 which correspond to the Muslim Brotherhood’s activism in Syria, in the midst of an uprising against the government of Hafez el-Assad.

From 1980 to 1982, there were 69 attacks on Syrian territory, representing nearly two-thirds (63.3%) of all Islamist terrorist attacks listed in the world during these three years. Attacks ceased after the repression of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, including during the Hama massacres by the Syrian army in 1982.

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world (1979-2000)

From 1980 to 1989, the country most affected by Islamist terrorism is Lebanon, with 133 attacks, which caused at least 515 deaths. In the grips of a civil war since 1975, the country has been experiencing the rise of small terrorist groups. This unstable national context and Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon in 1982 promote, the same year, the emergence of Hezbollah. A year later, the Shia organisation triggered a series of attacks on foreign institutions. An Italian patrol was hit on 15 March 1983, although no lives were lost, but on 18 April a new attack hit the United States Embassy in Beirut, resulting in the deaths of 63 people. At the end of the same year, on 23 October, an American base and a French patrol were terribly hit by an attack in which 299 people lost their lives. Hezbollah’s terrorist activism is particularly intense in Lebanon, where it committed 276 attacks from 1983 to 2000, but it is not limited to this. In all, by integrating the other affected countries, Hezbollah is responsible for 339 attacks from 1983 to 2000, killing 1,105 people. Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Cyprus, Denmark, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Kuwait and Tunisia are among the affected countries.

In September 1986, Paris suffered a series of six attacks, including the one on 17 September, rue de Rennes, in front of a store, which killed 7 people and injured 55.

These attacks were claimed by the Solidarity Committee with Arab political prisoners and the Near East, on behalf of the Lebanese Hezbollah.

The Lebanese organisation is also considered res- ponsible for the two attacks on the Israeli Embassy on 17 March 1992 in Buenos Aires (30 deaths, 220 wounded), as well as the attack of 18 July 1994 on a Jewish association, also in Buenos Aires (85 deaths, 236 injured). Over the whole 1979-April 2024 period, Argentina remains the only country in South America affected by Islamist terrorism, with three attacks.

Types of weapons used in Islamist attacks (1979-2000)

Source :

*As the available information on recorded attacks may be incomplete, the total number of attacks by weapon type does not equal 100%.

The 1990s and the spread of Islamist terrorism in the Middle East and North Africa

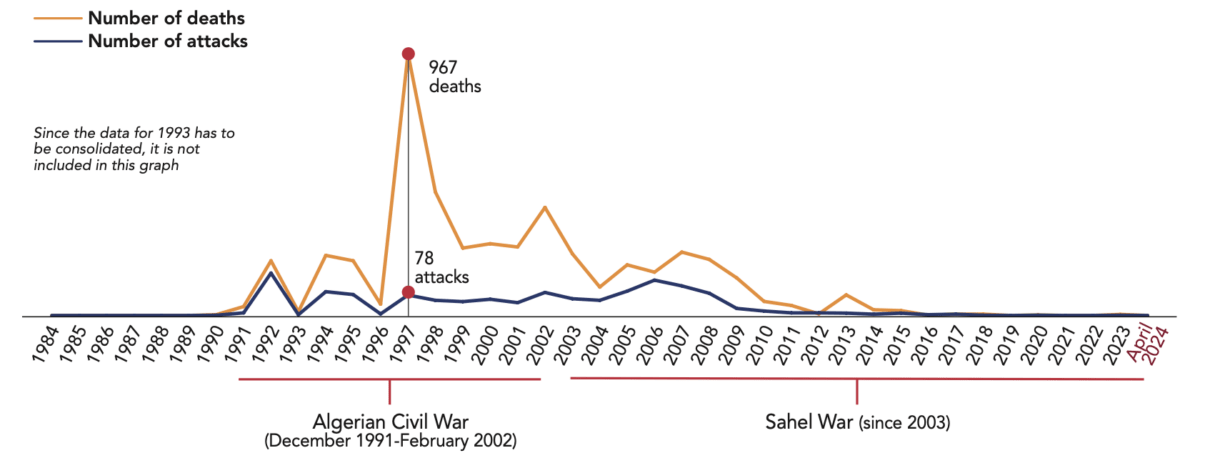

Due to a lack of information, it is not possible to specify the situation of Islamist terrorism in Algeria during this decade. In keeping with our method, we therefore only include in the “retained data” the cases that were reported. This choice leads to an undoubtedly significant underestimation of the number of attacks and victims in Algeria.

The withdrawal of the Red Army from Kabul on 5 February 1989 galvanised Islamist mobilisation, already stimulated in 1987 by the creation of Al-Qaeda, by Abdullah Azzam and Osama bin Laden. The globalisation of the jihadist struggle began then. The discourse is mainly based on the idea of a unified Muslim community (ummah) claiming autonomy from the ethnic, national and cultural specificities of each nationality. The objective is to establish the Caliphate and the exemplary prophetic city, which must also be extended to non-Muslim countries. The empowerment of the jihadist discourse in relation to classical, nationalist and political referents is not the hallmark of Al-Qaeda. It is taken up by all Muslims who came to Afghanistan to take part in the violent action. Following the Soviet withdrawal, these mujahideen returned to their countries of origin and spread the ideas of Jihadist Salafism there. Thus, in the 1990s, an increasing number of countries, particularly in the Middle East, were directly affected by Islamist violence.

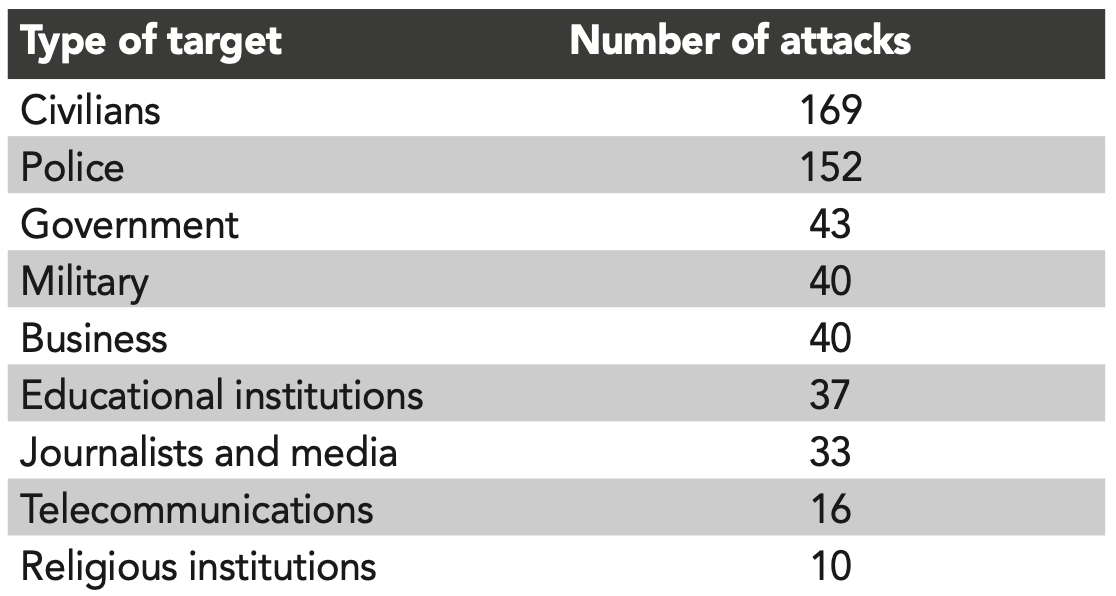

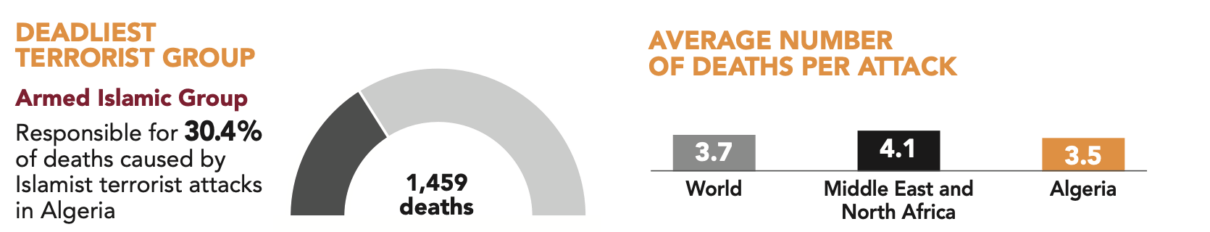

In Algeria, a number of jihadists gathered in militant groups since the beginning of the 1991-20023 civil war. The victory of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) in the 1990 municipal elections and the 1991 parliamentary elections, followed by the cancellation of these elections by the Algerian army and the resignation of President Chadli Bendjedid, triggered a “black decade”. Military and Islamist groups engaged in a terrifying struggle for power. The confrontation devastated the country. From 1990 to 1999, Algeria was the country that was hit the hardest by Islamist terrorism. There were 542 attacks, or more than a third (34.6%) of the attacks recorded worldwide during this decade by our database; there were at least 2,390 deaths, representing more than half (51.4%) of the victims of Islamist terrorism in the world between 1990 and 1999. The violence reached its peak in 1997: 967 people were killed following the parliamentary elections won by the Rassemblement national démocratique (RDN), supported by the army.

Deadliest terrorist groups in Algeria (1979-2000)

As a % of the number of victims of the attacks committed in Algeria during this period

During this “black decade”, religious figures and institutions were particularly affected, particularly Christians of foreign nationalities: twelve Croatian tourists were murdered on 14 December 1993, two Spanish nuns were killed on 23 October 1994 and seven French monks from Tibhirine were kidnapped and murdered in the spring of 1996.

Targets of Islamist terrorist attacks in Algeria (1979-2000)

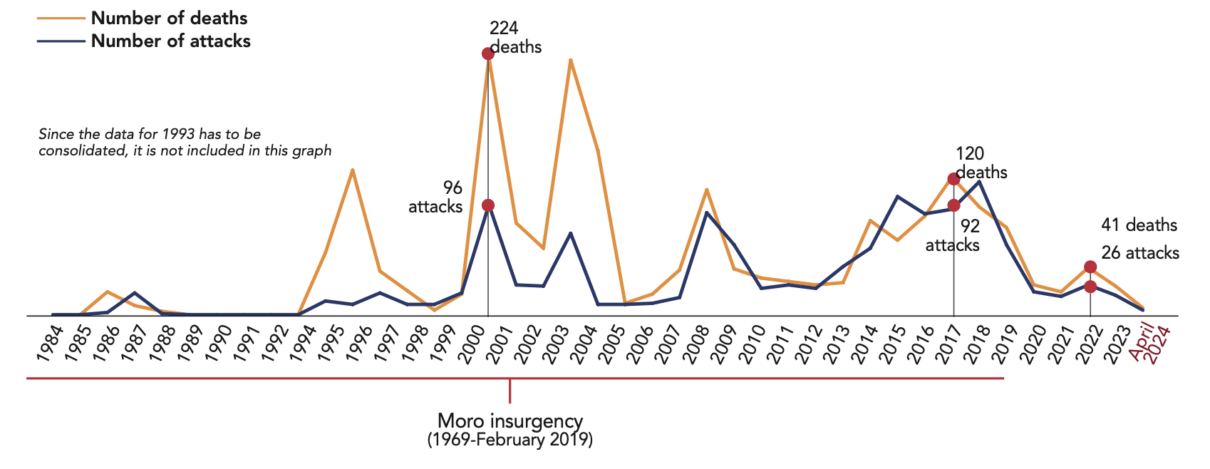

In Egypt, on the eve of the 2000s, the Islamist landscape was structured by two movements: al-Jihad and al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya. The objective of these two organisations was the establishment of an Islamic State, and the means to achieve this was terrorism4. In the 1990s, al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya launched 257 insurgent attacks against the government, killing 489 people.

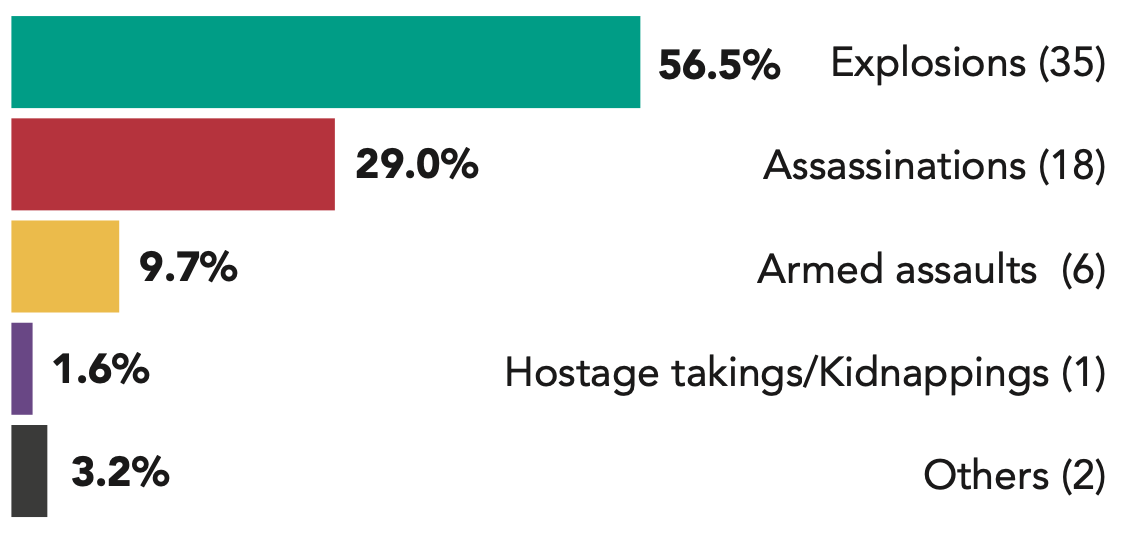

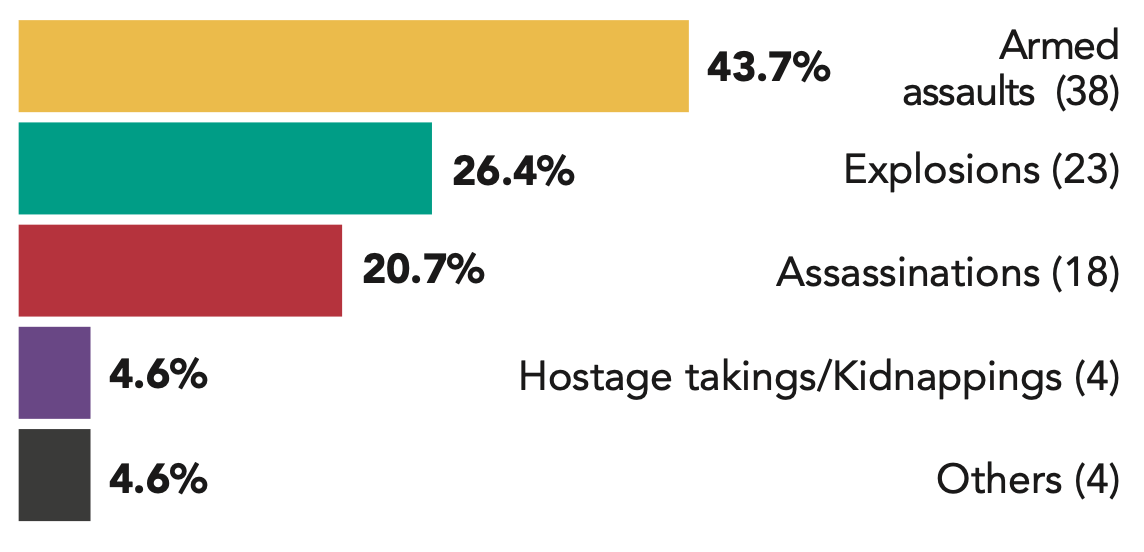

In the Middle East, the 1990s were marked by the Islamisation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. A transfer of power of sorts took place to the benefit of Hamas, a Palestinian Islamist movement born in 1987 at the beginning of the first Intifada, and to the detriment of the PLO, which came from the Arab nationalist movement. This evolution led to a change in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 1992, 417 leaders and activists of Hamas were arrested and taken to southern Lebanon, in the village of Marj al-Zuhur, after the assassination of an Israeli officer. A resolution of the Council of UN security necessitated their repatriation. This event is analysed by Gilles Kepel as “the transition which gave Hamas parity with the PLO, if not primacy, for the incarnation of the Palestinian cause, and consequently the Islamisation of its Arab and universal image5“. Beyond the political vicissitudes on Palestinian territory, “the increase in suicide attacks – in the face of the hardening of successive governments of Mr. Netanyahu and the intensification of colonisation – can be considered as the model for the mirror of which the international jihadism of Al-Qaeda would develop its preferred mode of action6“.

In our database, we clearly observe an increase in the number of attacks affecting the Israeli and Palestinian territories from the beginning of the 1990s. Terrorist attacks are largely incriminating to Hamas but also to the Palestinian Islamic Jihad Group (PIJ). Between 1979 and 2000, of the 62 attacks recorded on Israeli ground, 29 were claimed by Hamas and 13 by the PIJ. Out of 87 attacks in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, 65 were claimed by Hamas and 12 by the PIJ.

Types of attacks in Israel (1979-2000)

Types of attacks in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (1979-2000)

The export of jihad

Islamist violence has been on the rise in the Middle East and in North Africa from the 1980s onwards, and other regions of the world are also becoming hosts to this jihad, particularly Southeast Asia (Philippines), South Asia (India) and Europe.

Islamist violence in the world (1979-2000)

See Dominique Thomas, Le Londonistan. La voix du djihad, Michalon, 2003, p. 70.

Ibid., p. 62. On Salafo Jihadist activism in the United Kingdom, see also Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, Paris, Fayard/Pluriel, 2013, in particular the second part (“The conflict of identities”) and in particular its chapter 3, “Sharia law in Europe? “, p. 97.

Rapid empowerment and the increasing power of Islamism eventually raise fears of countries that have nevertheless worked for this movement or who used it for domestic political reasons or international relations. Thus, in the face of the Islamist threat, Saudi Arabia and Algeria have engaged in relentless repression. This is also the case for Egypt and Syria. In a decade, Salafists have changed categories: firstly admired as “freedom fighters”, they were then denounced as “fugitives”7.

This regional context forced many jihadists into exile: some, having returned from Afghanistan, became political refugees, often with the aim of exporting their Islamist struggle to new territories, including those that are not predominantly Muslim. They sought asylum in Europe. In the 1990s, these territories of settlement and conquest were first England and France. London thus became a hub for Salafo Jihadist activism in Europe8. Between July and October 1995, France was hit by a wave of Islamist terrorist attacks related to the Algerian context: on 25 July 1995 an attack in the Parisian metro resulted in the deaths of 7 people and 86 people wounded.

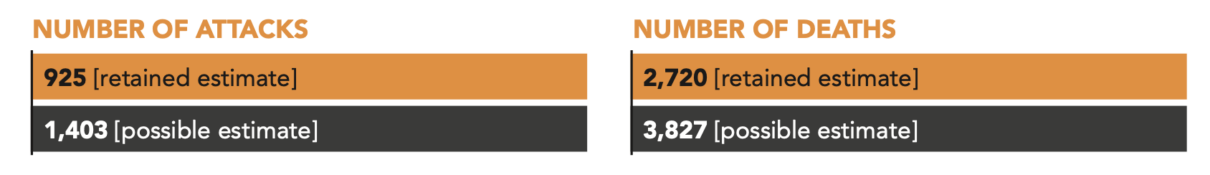

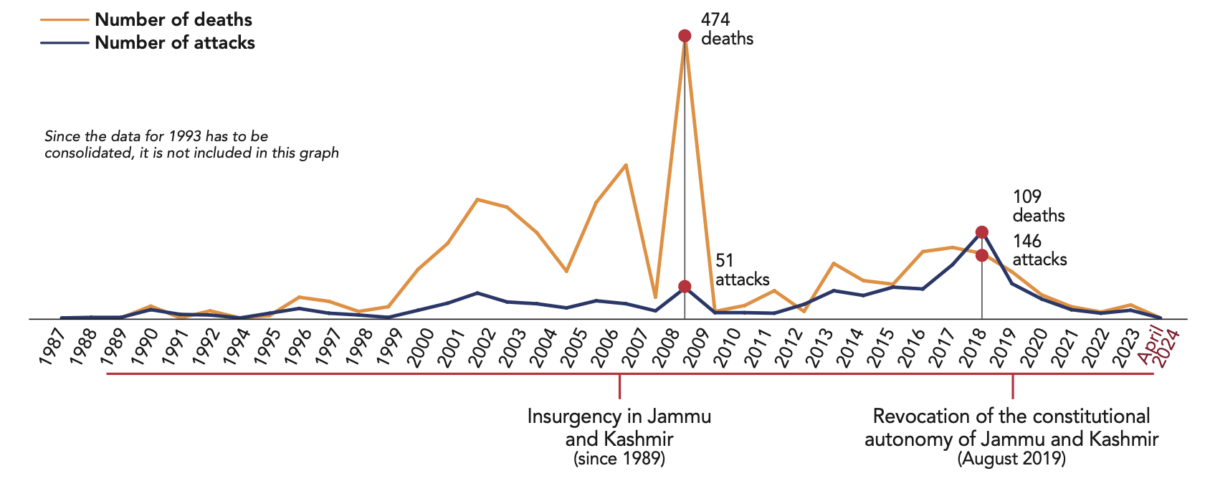

Asia was also hit hard between 1979 and 2000, particularly in the south and southeast. According to our database, we record the first Islamist terrorist attacks in India in 1986. The phenomenon remained sporadic until 1990. In that year, 12 attacks were carried out under the leadership of the Hizbul Mujahideen (HM) group and its supporters. The action of this Islamist group was rooted in the conflict between India and Pakistan over the border region of Jammu and Kashmir, but if the group wanted the region to be integrated into Pakistan, it was also campaigning for the establishment of a caliphate in the world.

The landscape of Islamist terrorism in India is fragmented: a number of groups revolve around the issue of independence, including Allah’s Tigers (“Tigers of Allah”), the Muslim Brotherhood, Harkat ul-Ansar and Jamaat-e-Islami. Between 1979 and 2000, most attacks (78.8%) were concentrated in Jammu and Kashmir. Since 2000 and the creation of the terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM), attacks have been both more numerous and more deadly (25 attacks and 126 deaths in 2000, 42 attacks and 200 deaths in 2001). These years also saw the Pakistani Taliban (Lashkar-e-Taiba) conducting terrorist campaigns in India.

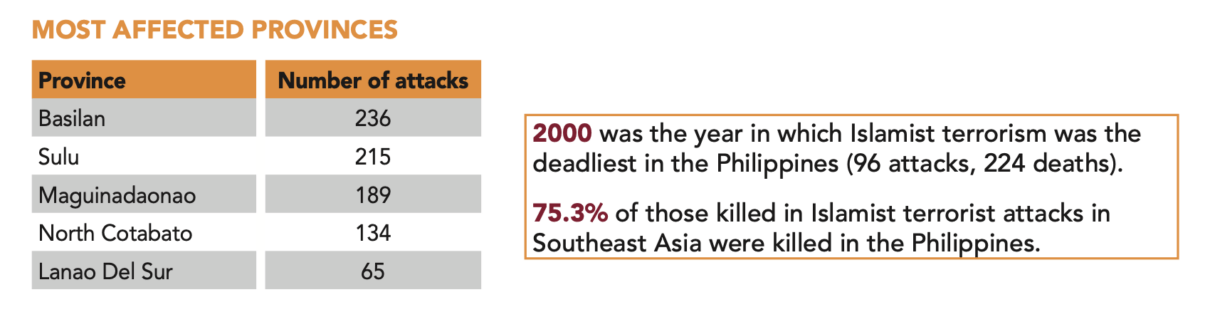

In the Philippines, Islamist terrorism is deployed as part of the separatist struggle of the Moro people, a Muslim minority in the south of the country. One of the main terrorist groups in the region, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), founded in 1991 by Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani, drew its inspiration from Islamist movements in the Middle East. The first demonstration of this terrorist movement occurred on 7 September 1986, when the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) attacked a Catholic church and a marriage ceremony in Salvador, on the island of Mindanao, killing 20 people and injuring 186. The group launched an attack on 15 January 1987 in the Manila metro, the capital, killing 8 people. In 1994, after an eclipse of sorts, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) carried out 7 attacks in the south of the country. It later became one of the main actors of Islamist terrorism in the Philippines in the following decades.

See Gérard Chaliand and Arnaud Blin (eds.), Histoire du terrorisme de l’Antiquité à Daech, Fayard, 2015; Franklin L. Ford, Le Meutre politique. Du tyrannicide au terrorisme [1985], PUF, 1990; Mario Turchetti, Tyrannie et tyrannicide de l’Antiquité à nos jours , PUF, 2001; Monique Cottret, Tuer le tyran ? Le tyrannicide dans l’Europe moderne, Fayard, 2009; Isabelle Sommier, Le Terrorisme, Flammarion, coll. “Dominos”, 2000; Henry Laurens and Mireille Delmas-Marty (dir), Terrorismes. Histoire et droit, CNRS Éditions, 2010.

On the Italian and French cases, see Isabelle Sommier, La Violence politique et son deuil. L’après-68 en France et en Italie, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 1998.

Data on all terrorist attacks worldwide is only available on the University of Maryland’s database, which has been updated through June 2020.

| The many faces of terrorism

Singular political violence that some authors trace back to Antiquity1, terrorism finds in the changes of the late nineteenth century new resources capable of multiplying power tenfold: ideology favours the recruitment of terrorists and their determination to act, technological developments provide increasingly powerful means of destruction, at the same time more manageable and easier to hide, and the advent of the newspaper and photography ensures visibility that gives terrorist actions a new impact. At the end of the 19th century, terrorism was dominated by secular causes: revolutionaries, anarchists and socialists, nationalists and separatists constituted the bulk of terrorist troops. Some attacks seem to be part of greater history, such as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo. For a century, until the end of the 1980s, tens of thousands of attacks overflowed the news, taking place in the context of conflicts that were part of nationalist or revolutionary logic, sometimes both. Examples include: the attacks in Algeria or France by the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the OAS; around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, those carried out by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) or the Black September Organisation, responsible in particular for the massacre of members of the Israeli sports delegation on 5 September 1972 during the Munich Olympic Games; those of Irish paramilitary organisations, in particular the Irish Republican Army (IRA); those of independentists, Catalans, Basques, Corsicans or Bretons; the actions of the Red Brigades in Italy, including the kidnapping and murder in 1978 of former Council President Aldo Moro, or, two years later, in 1980, the attack on Bologna railway station (85 deaths, 200 wounded) attributed to an extreme right-wing organisation, the Revolutionary Armed Nuclei (NAR); the murders in Germany of the Red Army Faction, found responsible for the deaths of 34 people between 1970 and 1998; the attacks and kidnappings in France of the Action Directe group, which claimed more than 80 attacks between 1979 and 1987, including the assassination of industrialist Georges Besse in 19862; the actions of the Japanese Red Army (JRA); the guerrilla actions of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia People’s Army (FARC-EP) or the Peruvian organisation Shining Path; the massacres of the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka between 1976 and 2009… Secular causes dominated terrorism until the late 1980s. After that date, there has been an increase in the power of Islamic-inspired terrorism. For several years now, Islamism has become the main motivation for terrorism3. According to our data, between January 2013 and June 2020, Islamist terrorist attacks (29,528) accounted for 32.1% of all attacks (91,994) worldwide but accounted for 145,225 deaths (65.3%) out of a total of 222,341 people killed. |

The turning point of 9/11 (2001-2012)

Louis Gautier (dir.), Mondes en guerre. Tome IV, Guerre sans frontières. 1945 à nos jours, Éditions Passé composés/ Humensis, Paris, 2021. See especially Louis Gautier, “Le temps des conflits”, Chapter III, pp. 143-204.

The attacks of 9/11 2001 perpetrated by Al-Qaeda on U.S. soil were the deadliest terrorist attacks in history, with a total of 3,001 deaths and 16,493 wounded. On that day, two hijacked airliners were launched against the towers of the World Trade Center in New York. A third aircraft had been directed at the Pentagon in Washington. On board the fourth hijacked aircraft, it was a passenger revolt that defeated the terrorists’ plan, as the aircraft crashed in the countryside in Pennsylvania.

The live and global broadcasting of this dramatic and spectacular event1 also marked the beginning of a new era in the media coverage of terrorism. In addition to the deferred information intended for specific audiences, immediate and comprehensive information is now available. This new public space profoundly affects the work of traditional media (television, press and radio). The advent of social media and smartphones is opening its doors of mass communication to countless new players, starting with terrorist organisations.

See Steven Pinker, La Part d’ange en nous. Histoire de la violence et de son déclin [2011], Les Arènes, 2017.

See the high level of trust that law enforcement institutions (Police, army and justice) enjoy in forty-two democracies, com pared to the crisis that affects most institutions. See Mathieu Zagrodzki, “The army, police, and justice: strong support for institutions of law and order”, in Dominique Reynié (dir.), Democracies Under Pressure, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 2019, vol. I, pp. 97-98 [online].

In the 28 countries of the European Union, a large majority (57%) of respondents answered that they could “not welcome more refugees because they increase the risk of terrorism in our country”. In the eleven countries of the former communist bloc that are now members of the European Union, this response concerns 72% of respondents (see Dominique Reynié, “The challenge of migration in the light of the refugee issue”, in Domnique Reynié (dir.), op. cit., vol. I, pp. 52-56.)

See Antoine Garapon and Michel Rosenfeld, Démocraties sous stress. Les défis du terrorisme global, PUF, 2016.

Opinion in favour of an authoritarian form of government is reaching levels that exceed the electoral scores of populist parties. The level is higher the younger respondents are (see Dominique Reynié, “The ghosts of authoritarianism”, in Domnique Reynié (dir.), op. cit., vol. I, pp. 39-40).

See Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, ed. revised and expanded, Fayard/Pluriel, 2013.

| Islamism and populism: a relentless dialectic

Terrorist violence mainly affects civilians. It reaches them at the heart of their ordinary lives, a world where no one has any reason to be on guard. Anytime, anywhere, anyone. Death due to terrorism creates an unbearable sense of permanent vulnerability. For a few days, a few weeks and sometimes longer, peace looks like war. People in the democratic world are more traumatised by terrorist violence because they have inherited an irenic culture, a logical consequence of the decline of interstate violence1. But democracies are also more helpless because they represent a soft political order based on freedom and human rights. Inevitably, in the face of terrorist violence and a war imposed on all, democracies feel defenseless. |

9/11 and the war on terror

According to a survey conducted by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, of the seventeen events proposed, half of the young people surveyed (47%) cite the attacks of 9/11 as one of the three most significant events (see Future Memories, Fondation pour l’innovation politique and the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, January 2015 [online].

The attacks of 9/11 have had a significant impact that changed the geopolitics of the Middle East2. Qualified by George W. Bush’s administration as the “war on terror”, the American response was brisk. On 7 October 2001, the United States launched a major offensive against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, accused of having supported Al-Qaeda. A year and a half later, on 20 March 2003, the American army invaded Iraq, in order to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s regime in the prospect of “democratising the Middle East”. Despite overwhelming military victories, the United States is failing to restore peace, or to eradicate Islamism. Confronted with the machine of American war in the long term, Islamists organised themselves, by acquiring an international dimension that keeps being reaffirmed. Between 2001 and 2012, the number of attacks and victims have increased in a spectular way, notably due to the attacks perpetrated by Taliban fundamentalists.

Their movement has been spreading in Afghanistan and in Pakistan since 1994. Two years later, they overthrew the government in place when Kabul was taken over. They established the regime of the Islamic Emirate from Afghanistan, headed by Mohammad Omar. In the years that followed, the Taliban persecuted minorities, established a well-founded regime on the strict application of shari’a law and welcomed numerous wanted jihadists, including the leader of Al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden.

In a few years, Afghanistan became a home for Islamic extremists from all over the world.

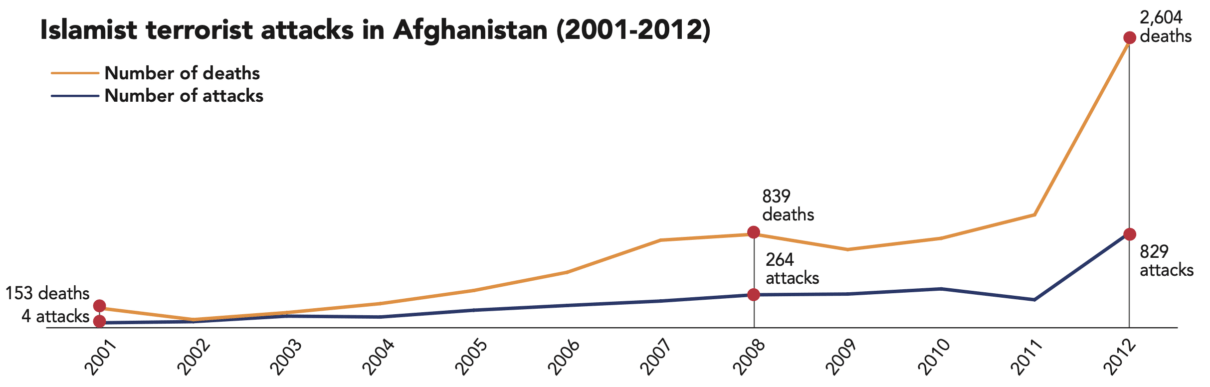

After the attacks of 9/11, the Taliban were driven out of power by an international coalition led by the Americans. From this moment on, there was an exponential increase in the number of attacks and the number of victims, in particular among international forces or members of the Afghan government. We went from 4 attacks and 153 deaths in the country in 2001 to 829 attacks and 2,604 deaths in 2012. In total, between 2001 and 2012, 2,536 attacks took place on Afghan soil, killing at least 8,054 people. This represents 30.7% of the total number of Islamist terrorist attacks worldwide between 2001 and 2012. The Taliban were responsible for most (95.2%) of these attacks.

The Talibans’ targets in Afghanistan (2001-2012)

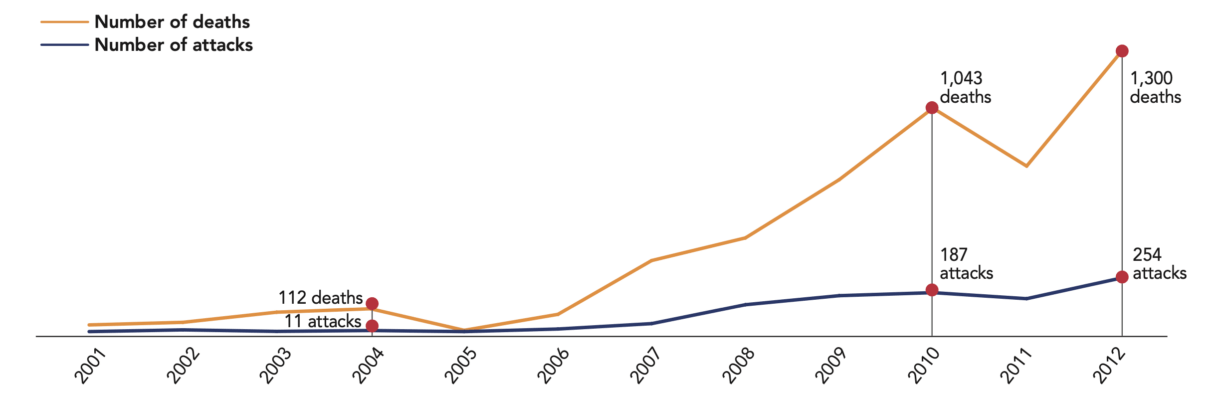

In Pakistan, we also witnessed the rise of groups multiplying terrorist acts between 2001 and 2012, with 1,010 attacks and 4,997 deaths. Very present in this country, the Taliban organised themselves from 2007 under the name Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP); they were responsible for nearly three-quarters (71.1%) of the terrorist violence over this period (2001-2012). Other Islamist groups are also active, such as Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (56 attacks, 386 deaths) or Lashkar-e-Islam (64 attacks, 115 deaths). In 2007, two terrorist attacks led by Al-Qaeda and its allies left their mark on the landscape of the country’s politics: on 18 October, an attack against a crowd gathered to welcome the former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, returning from exile, caused the death of 141 people and wounded 250. On 27 December, she was murdered in turn, victim of a suicide attack that killed 20 people and wounded more than a hundred.

Islamist terrorist attacks in Pakistan (2001-2012)

Between 2001 and 2012, Iraq was the third largest country most affected by Islamist terrorism, with 914 attacks. Particularly violent, these attacks caused the deaths of 8,534 people, with on average 9.3 people killed per terrorist action. By comparison, in the world during the same period, an attack killed an average of 4.6 people. The fight against foreign interference is a key reason for violence by Islamists. On 19 August 2003, the car bomb attack against the Canal Hotel, UN headquarters in Baghdad, killed 22 people. The year 2004 saw a series of terrorist attacks targeting coalition member countries in Iraq, with 5 attacks against personnel at military bases, checkpoints and patrols of the Multi-National Force-Iraq (MNF-I). At the same time, the development of hostage takings/kidnappings became more common to terrorist actions: while we do not record any hostage takings or kidnappings in 2001, 2002 and 2003, there were 27 in 2004, largely aimed at civilians from countries militarily deployed in Iraq (5 Americans, 4 Japanese, 3 South Koreans, 1 Bulgarian, 1 Canadian, and 1 Italian). Among the countries involved in the war, the United States was greatly affected: between 2001 and 2012, in Iraq, 34 attacks targeted Americans, including 15 during the year 2004.

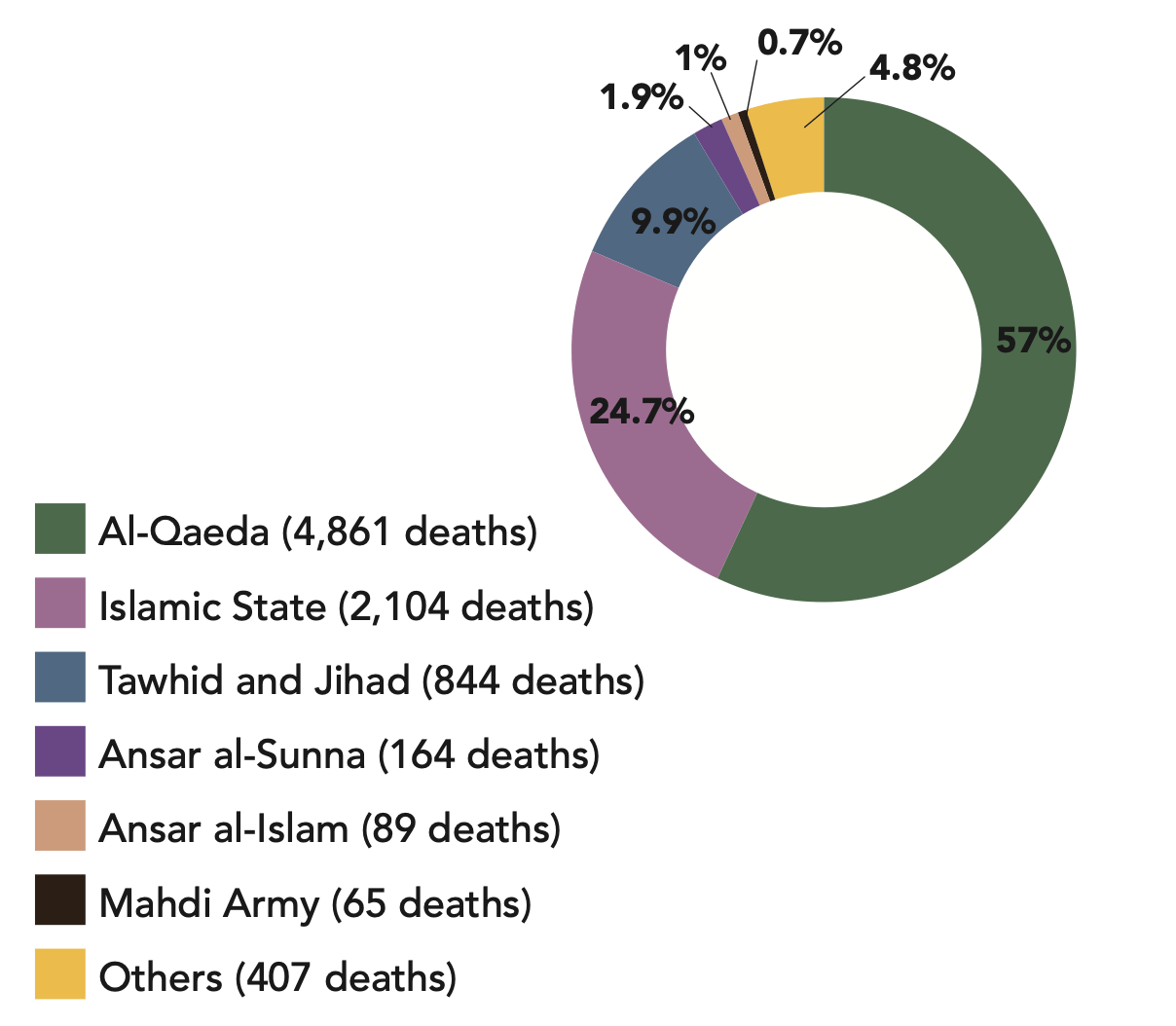

Deadliest terrorist groups in Iraq (2001-2012)

As a % of the number of victims of the attacks

Globalisation of Islamist terrorist attacks

Between 2001 and 2012, an increase in Islamist terrorist attacks is observable in several geographical areas in the world. Compared to the previous period (1979-2000), there was a sharp increase in the number of terrorist attacks, with 8,265 attacks (compared to a total of 2,194 between 1979 and 2000) and 38,187 deaths (compared to a total of 6,817 between 1979 and 2000). This dramatic increase is partly due to the globalisation of jihad, facilitated by the acceleration of the circulation of people and ideas.

Islamist terrorist attacks in the world (2001-2012)

Gilles Kepel, Sortir du chaos. Les crises en Méditerranée et au Moyen-Orient, Gallimard, 2018, p. 147.

See David Martin Jones, Michael Smith et Mark Weeding, “Looking for the Pattern: Al Qaeda in Southeast Asia- The Genealogy of a Terror Network”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 26, n° 6, November 2003, p. 443-457.

See Gabriel Facal, “Les groupes islamistes radicaux en Asie du Sud-Est–Panoramas institutionnels, réseaux d’affiliation et références”, Note d’actualité n° 10/16, Observatoire de l’Asie du Sud-Est, cycle 2018-2019, asiacentre.eu, July 2018 [online].

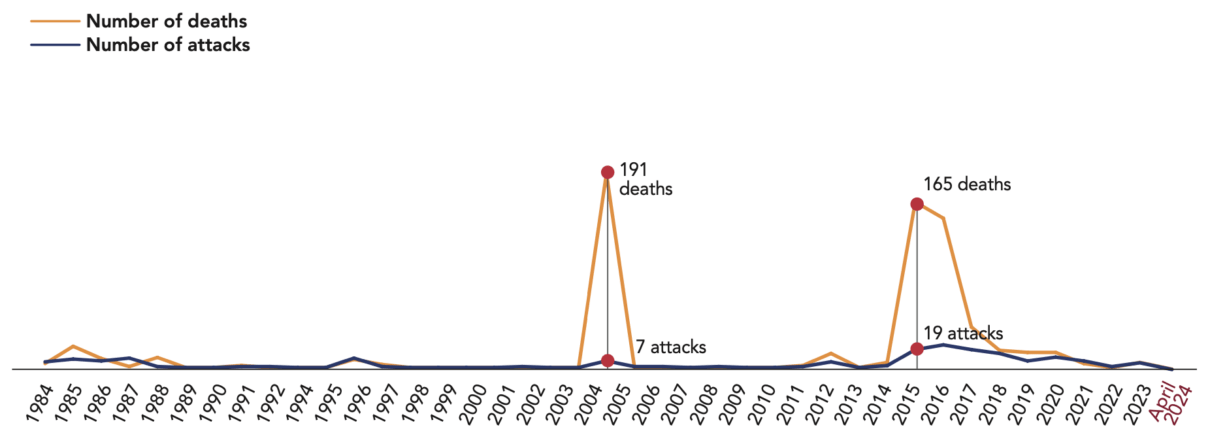

Since 2004, Europe has been confronted with a wave of attacks of a new magnitude. On 11 March, in Madrid, four trains exploded almost simultaneously. Claimed by Al-Qaeda, these attacks killed 191 people. On 7 July 2005, four explosions hit public transportation in London, killing 56 people and wounding 784. Though Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for these attacks, the terrorists, unlike those of 9/11, were natives of the United Kingdom. Gilles Kepel sees this as a change in the implementation of Islamist terrorist attacks, which now rely on “a human resource specific to the Western country targeted”3.

In addition, many Islamist movements are intensifying their inter-regional collaborations, such as in Asia. The 9/11 attacks on the ground claimed by Al-Qaeda and then the intervention in Afghanistan by American troops helped further the link between Osama bin Laden and various South Asian groups4, examples of which are Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) in Indonesia. The difficulty is to examine, in each context, the way in which people and violent groups combine local elements, regional and global within the referents, the objectives and the operating methods they mobilise and implement. Trends then appear to be oscillating between unrelated ethno-nationalism with global jihad and a transnational religious referent5. The situation in Thailand during this period takes part in this dynamic. From 2004 onwards, in the context of a separatist insurgency, the south of the country where a Muslim minority lives is crossed by violent activism. The two main groups Runda Kumpulan Kecil (RKK) and the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO), are then organised around a jihadist discourse. For a number of attacks occurring at this time, the Islamist character is sometimes found intertwined with ethno-nationalist claims.

According to our estimate between 2001 and 2012, we identify 111 attacks and 91 deaths in Thailand. According to the possible estimate, we count 146 attacks and 121 deaths over the same period. In the latter we also take into account the actions of terrorists accused of being Muslim separatist extremists.

Number of terrorist attacks by province in Thailand (2001-2012)

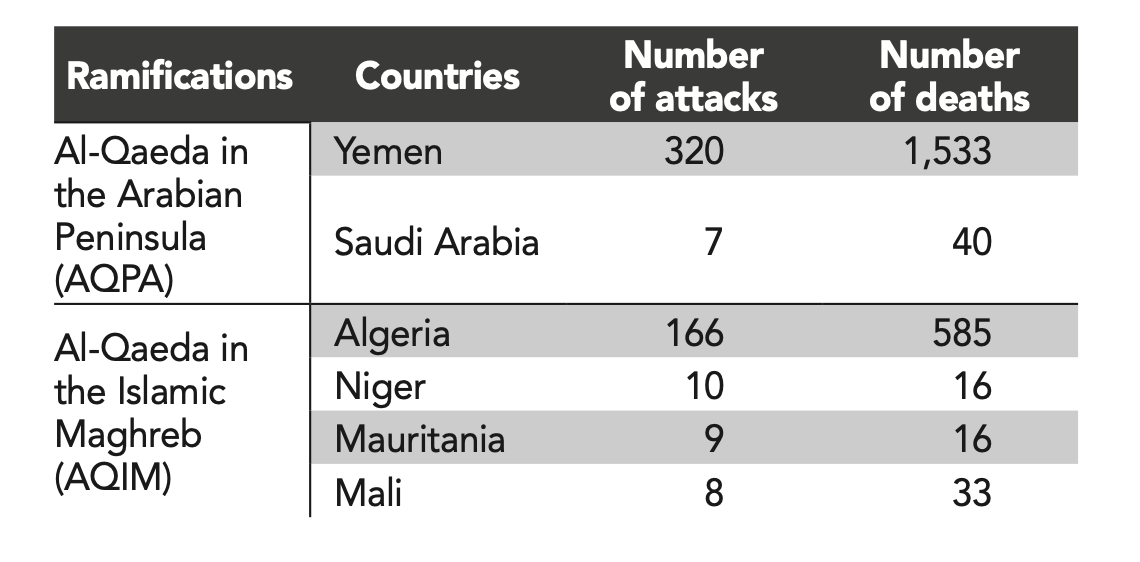

The rise of Islamist terrorism can also be explained by the development of Al-Qaeda’s ramifications, such as that of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQPA) or Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

The ramifications of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQPA) and of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (2001-2012)

These different branches develop a capacity to hit hard abroad, as shown by the three successive attacks of 9 November 2005 by Al-Qaeda in Jordan, at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Amman, which caused the deaths of at least 61 people, and the one on 28 November 2002 at the Paradise Hotel in Mombasa, Kenya, killing 16 people.

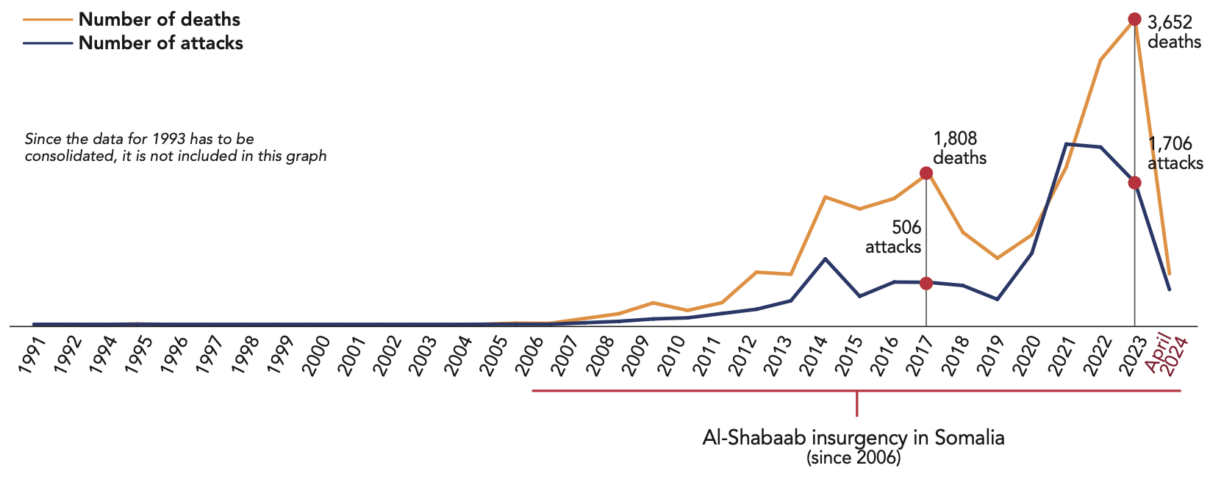

Relatively spared until then, sub-Saharan Africa became a target of Islamist terrorism in the second half of the 2000s. The creation and expansion of the Al Shabaab group, formerly the armed wing of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), in Somalia in 2006 was central. Pursuing the objective of overthrowing the Somali government in order to establish a regime founded on shari’a law, Al Shabaab has been cultivating close links with Al-Qaeda, thus forming part of the global jihadist movement6. The group’s activity goes beyond the borders of Somalia, where the group has committed 459 attacks and killed 1,396 people, to reach Kenya, where it attacked 97 times (126 deaths), and Ethiopia, where it struck twice, including the devastating attack (100 deaths) on 2 November 2007 against Ethiopian soldiers in a hotel in Dolo.

Al-Shabaab’s targets in Somalia (2001-2012)

Sub-Saharan Africa was also the first to suffer acts of violence by Boko Haram, which have been recorded in Nigeria since 2009. The considerable scale of its attacks between 2010 and 2012 (566 attacks, 1,655 deaths) foreshadowed its power of destruction over the next decade.

Types of weapons used in Islamist terrorist attacks (2001-2012)

Source :

*As the available information on recorded attacks may be incomplete, the total number of attacks by weapon type does not equal 100%.

Terrorist migration to social media

David Thomson, Les Français jihadistes, Paris, Les Arènes, 2014, “young people who discover hadiths on the Internet are completely deaf to all those who, at the mosque, can try to explain that the meaning of prophecies is part of a context: for them, who have come to sacred texts alone or with jihadist propaganda, the historical or figurative interpretation is an ‘innovation’, that is, the worst thing since it distorts and biases the meaning they think is original”.

Evan Kohlmann, cited in Gabriel Weimann, “Terrorist Migration to Social Media”, Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 16, n° 1, 2015, p. 181.

The Internet obviously plays a key role in the globalisation of Islamist terrorism. It turns out to be a powerful propaganda and recruitment tool7. The emergence of social media allows Islamist groups to interact effectively and often anonymously, to share documents and information, but also to establish a community of interconnected individuals. According to Evan Kohlmann, “90% of terrorist activity on the Internet takes place using social networking tools. These forums serve as a virtual firewall to help safeguard the identities of those who participate, and they offer subscribers a chance to make direct contact with terrorist representatives […]”8. Furthermore, cyber-terrorism is also a modality of attack for Islamist groups which thus multiplies their capacity for action.

Voir Dominique Reynié, « Le retour des foules », Commentaire, n° 182, 2023, pp. 273-284

| The impact of terrorist violence in a global public space within the reach of the individual media

From the mid-1990s onwards, access to visibility took on unprecedented proportions. The digital public space increased the impact of terrorist actions tenfold. The coupling of the Web with continuous news channels amplified the effects of Islamist violence. Al Jazeera, the Qatari channel launched in 1996, broadcasts in some 30 countries and develops information websites in the few languages that can be used to reach most residents of the planet. Social media and other secure messaging applications offer the most modest of these terrorist groups the tools of global action: communication, propaganda, organisation, recruitment… The smartphone extends to the end of the chain, i.e. the individual, the mastery of these powerful tools and access to all networks. Media coverage of the attacks always goes through the traditional media (agencies, television, radio and the press) but it no longer depends on them. In the universal public space, production information is absolutely disseminated. The Web and the smartphone give the human multitude the powers of a news agency with 2.8 billion correspondents and the influence capabilities of numerous media. Islamic terrorism thrives in the age of the individual media. The depth of the network, the strength of the images, and the play of algorithms mean that any attack can become a global event in a matter of minutes. |

See Georgia Wells, “Islamic State Turns to Teen-Friendly TikTok, Adorning Posts With Pink Hearts”, The Wall Street Journal, 21 October 2019.

See Gabriel Weimann and Alexander Pack, “TamTam: The Online Drums of Hate”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, p.1-16, June 28, 2023 [online].

Ibid

Ibid

See Ciaran O’Connor, “Hatescape: An In-Depth Analysis of Extremism and Hate Speech on TikTok”, Institute for Strategic Dialogue, August 24, 2021 [online].

The new faces of Islamist terrorism (2013-April 2024)

Hakim El Karoui, La Fabrique de l’islamisme, Institut Montaigne, September 2018, p. 85. Also see Hakim El Karoui, Benjamin Hodayé, Les militants du djihad, Fayard, 2021.

On 17 December 2010, the immolation of the young street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, in the Sidi Bouzid region ofTunisia, led to the flare-up of the Arab Spring. After some time raising hopes of democratisation, these events led, in the first half of the 2010’s, to electoral victories for parties close to the Muslim Brotherhood. While theyoccasionally failed to retain power, they are “sup- ported by increasingly conservative societies, also as a result ofthe spread of Salafism imported from Saudi Arabia”1.

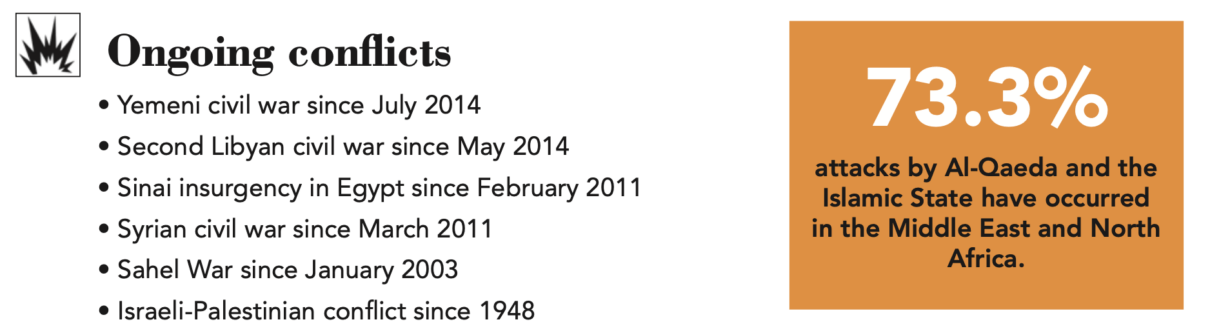

In this new context, jihadism is developing regionally, based in particular on the proclamation by the Islamic State (IS) of the Caliphate in Mosul in 2014. It is during this period that Islamist terrorism is the most deadly. There has been an unprecedented increase of the number of attacks worldwide. The rise of IS and Boko Haram is facilitated by chaotic geopolitical contexts that offer terrorists many opportunities for expansion.

The Islamic State and the “management of savagery”