Payments, money and finance in the digital era (2)

Longer-term issuesIn technological matters

The real questions asked. The issues of blockchain governance and the “Buterin trilemma”, security, carbon footprint and interoperability are addressed

The real questions most-often avoided. Three questions are raised here: Should the issuance of retail CBDCs use blockchain or only take the form of central bank e-money (CBEM)? How should the validation of MNBC transactions be carried out? Can CBDC help facilitate cross-border transactions?

Poorly asked questions. These questions, which are closely related, concern the methods of issue, the traceability of transactions and the possibility of offline transactions, i.e. without access to the Internet.

In economic matters: cryptoassets, monetary policy and financial stability

The real questions asked. They relate to some of the monetary policy implications of issuing cryptoassets, in particular global stablecoins on the one hand, retail MNBCs on the other.

The questions most-often avoided or answered unsatisfactorily.

These questions can be grouped around five themes, which essentially concern CBDC: How can the different forms of CBDC co-exist? Is the risk of disintermediation by retail CBDC real and if so, are the measures envisaged by central banks to counter these risks likely to be credible and effective? Does the issuance of CBDC make monetary policy more effective? Should governments be in favour of issuing CBDCs? What role can international cooperation play in the design and management of cryptoassets and CBDCs?

The wrong questions asked: do cryptoassets threaten legal tender or would the issuance of CBDC threaten cryptoassets? Does CBDC need to be legal tender? Can the issuance of a CBDC play a major role in the internationalisation of a currency?

In societal matters

The real questions asked. A real issue with regard to retail CBDC is the relationship between identification, prevention of misuse of money and protection of privacy

The real questions most-often avoided. A seldom asked question, which has an economic but also and perhaps above all a societal dimension, is the role of competition and, in a related way, the respective roles of the public and private sectors in the production of money

The false question. A false question is the conception of money as an instrument of power

Recommandations

Summary

Beyond the immediate future, it seems useful to ask ourselves how we wish our society to evolve in areas that affect our daily lives and also potentially our privacy, notably if a CBDC is to be issued. To achieve that, a distinction is drawn between three approaches, without pretending to be exhaustive: technological, economic and societal. Within each area, the author distinguishes between issues he considers as fundamental and issues he deems less important, if not false, on the one hand, and between issues which are debated in public bodies or the media, often rightly so but also excessively in some cases, issues which are evaded on the other hand. Given that, so far, there are very few CBDCs and mostly experiments, most longer- term issues relate to possible CBDC issuance.

This questioning leads to the formulation of recommendations directed to public authorities and central banks. In particular, if a CBDC were to be issued, it should be aimed to stimulate innovation and not lead, even inadvertently, to the marginalisation of the private sector. The latter is best placed to anticipate and answer customers’ expectations, be it in the areas of payment services, savings or financing.

Christian Pfister,

Sciences Po and University of Paris-I-Panthéon-Sorbonne

The author is expressing his own views, unrelated to his capacity at Sciences Po or the University of Paris-I-Panthéon-Sorbonne. He thanks Thomas Argente, Françoise Drumetz, Jean-Michel Godeffroy, Andrès Lopez-Vernaza, Pierre-Dominique Renard and Nicolas de Sèze for their remarks and remains solely responsible for any errors.

I will distinguish three approaches here: technological, economic and societal. In each area, what is considered fundamental is distinguished from what is seen as less important or even false, and what is discussed in public bodies and the media, often rightly but sometimes also excessively, is distinguished from what is avoided. Given that, so far, there are very few CBDCs and mostly experimentations, most longer-term issues relate to possible CBDC issuance.

In technological matters

The real questions asked. The issues of blockchain governance and the “Buterin trilemma”, security, carbon footprint and interoperability are addressed

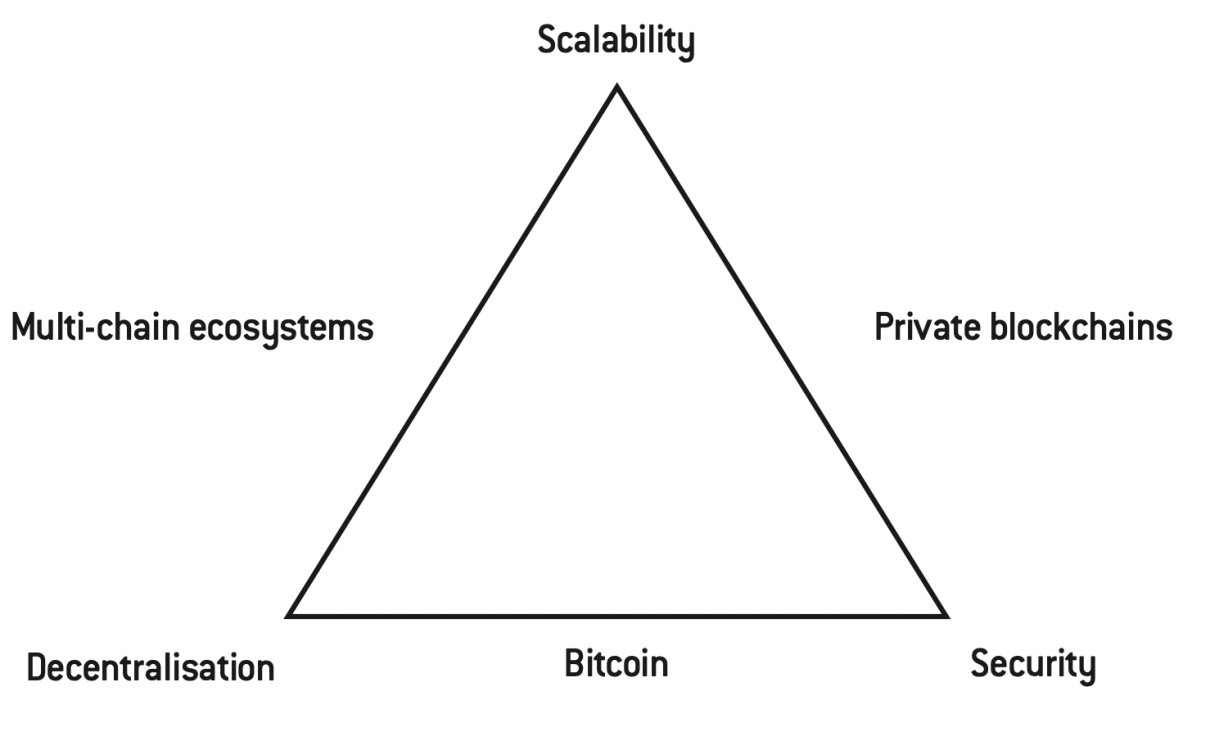

Vitalik Buterin, the creator of Ethereum, outlined the trilemma that bears his name, where a tension exists between security, scalability and decentralisation of the blockchain (see chart 1).

Chart 1: The “Buterin trilemma”

See Vitalik Buterin, “Why sharding is great: demystifying the technical properties”, vitalik.ca, 7 April 2021, where the author presents the trilemma his name is associated with.

Security is the expected feature of the e-euro mentioned in second place, by 18% of respondents to the ECB’s consultation following the publication of its report on a digital euro, but far behind privacy, mentioned by 43% of respondents, see European Central Bank, Eurosystem report on the public consultation on a digital euro, April 2021.

Ibid., p. 19.

Ibid., p. 3.

See Kantar Public, Study on New Digital Payment Methods, March 2022, p. 6.

See Raphael Auer, Codruta Boar, Giulio Cornelli, Jon Frost, Henry Holden et Andreas Wehrli, “CBDCs beyond borders: results from a survey of central banks”, BIS Paper, n° 116, June 2021.

For example, in the case of Bitcoin, scalability is sacrificed to ensure maximum security and decentralisation, while the use of private blockchains, proof-of-stake or sidechains improve scalability but introduce elements of centralisation and/or less security. Ethereum 2.0 (a term abandoned in favour of “execution layer”, Ethereum 1.0 being called “consensus layer” and the two layers forming Ethereum since 22 June 2022) aims to overcome the trilemma through data partitioning (sharding), with the work of validating transactions being assigned to a limited number of nodes drawn at random from a larger set1. However, this solution has yet to be fully deployed and tested in practice, particularly in terms of resilience to cyber risks.

Indeed, security is another real issue, which often appears if not in the mainstream media, then at least in specialist publications2. In principle, DLT should be more resilient than traditional forms of organising financial infrastructures which, based on centralisation, have a “single point of failure”. Indeed, in a DLT framework, all the nodes participating in the consensus must be neutralised to paralyse the system. It is well known that Bitcoin has never been the subject of a successful attack, as thefts of bitcoins occur on the exchange platforms and within wallets, the latter are often offered and managed by the former, which are all factors of centralisation. Within private blockchains, the issue of cybersecurity could be particularly acute for financial institutions, including central banks, whose reputation is largely based on the security they offer to the public. Similarly, maintaining the integrity of transactions would be crucial for a CBDC, as its use for illicit purposes could severely damage the reputation of the issuing central bank, even if the distribution of the CBDC – in this case retail – is carried out by intermediaries.

The question of the carbon footprint of mining is also a real issue, often mentioned in the media and in public debates about Bitcoin. Indeed, the use of proof-of-work is very energy intensive. One estimate is that Bitcoin mining could account for more than 0.5% of global electricity production. Although this figure is disputed and blockchain companies point out that the electricity used would otherwise be lost, without proposing alternative uses that are potentially more useful to society, the climate emergency means that the issue cannot be ignored. In that regard, the draft MiCA regulation provides for the inclusion of mining in the taxonomy of activities involving high energy consumption that must be highlighted by companies in their non-financial communication. In the same vein, the ECB has mentioned the issue of carbon footprint as a factor to be taken into account in the design of a possible digital euro3. This seems to exclude from the outset the use of proof of work as a means of consensus building if DLT is used by the digital euro. Nevertheless, the question of climate transition is posed at a much broader level than that of bitcoin mining or CBDC issuance. It is therefore at this level that the fight against climate change must be conducted, rather than by pointing out emblematic culprits at the risk of losing sight of the global objective.

The issue of interoperability is also very important and is part of the more general network effects of any use of an asset for monetary purposes. Indeed, since the construction of new infrastructures is risky, time-consuming and costly, a new payment instrument must be able to use existing infrastructures if it is to be adopted by a large public. For example, the Mondex card project launched by the National Westminster Bank in 1995 failed mainly because users (merchants but also, in the case of transactions between individuals, cardholders) had to use dedicated equipment. Furthermore, the requirement for interoperability must be built into the design of the instrument, as adapting existing infrastructures is generally even more costly than creating new ones. Interoperability is also a major requirement in the eyes of users: more than two-thirds of the respondents to the ECB’s consultation on a digital euro indicate that the euro should be integrated into existing banking and payment systems4. The issue of interoperability is not only relevant for the CBDC but also for private cryptoassets. For example, according to the Kantar study for the ECB mentioned above, the top three factors that could determine the adoption of a new payment method in the euro area are, in descending order, universal acceptance, instant and contactless payment, and the possibility of combining multiple payment methods into one solution5. The first and third factors obviously require a high degree of interoperability with existing infrastructures. The development of settlement services backed by cryptoassets has been touched upon (see volume 1), but the interoperability of stablecoins with existing payment infrastructures, and even with CBDCs, is probably much more important for these instruments whose monetary purpose is much clearer than for Bitcoin. However, there is one area where stablecoins may have a natural advantage over CBDCs: the issue of interoperability for cross-border transactions does not arise for them in the same terms as for CBDCs, since they circulate on a globally open infrastructure, the blockchain. On the other hand, according to a BIS staff study, central banks are not without reluctance to consider that CBDCs should be accessible to non-residents or, more precisely, that non-residents could use the CBDC of their home economy in their own issuing area6. This places limits, if not necessarily on the interoperability of MNBCs, at least on the use that holders might make of it.

The real questions most-often avoided. Three questions are raised here: Should the issuance of retail CBDCs use blockchain or only take the form of central bank e-money (CBEM)? How should the validation of MNBC transactions be carried out? Can CBDC help facilitate cross-border transactions?

In the opposite direction, see Christian Pfister, “Central bank digital currency”, Banque de France, 2020, and “Central Bank Digital Currency: One, Two or None?”, Working Paper 732, Banque de France, October 2019.

Raphael Auer, Codruta Boar, Giulio Cornelli, Jon Frost, Henry Holden and Andreas Wehrli, op. cit.

See Lael Brainard, “Private Money and Central Bank Money as Payments Go Digital: an Update on CBDC”s, federalreserve.gov, 24 May 2021.

• Should the issuance of retail MNBCs use blockchain or only take the form of central bank e-money (CBEM)? While central banks claim to be in favour of technological progress, they emphasise their “technological neutrality” (i.e. they do not intend to promote one specific technology over another). Nevertheless, it is difficult to see what a CBEM would bring to the user, given the current situation of domestic payments, if not in some economies that are lagging behind in terms of instant payments. Since this is the case in the euro area, the e-euro could thus take the form of a CBEM, just by opening the TIPS system directly to the public. However, a simpler and more direct way of strengthening competition, without risking crowding out a private supply but, on the contrary, stimulating it, would be to facilitate the establishment in the euro area of instant payment service providers that have proven their efficiency, whether they are pure providers, such as Swish in Sweden, or banks;

• How should the validation of CBDC transactions be carried out? If Po W is not used in the case of retail CBDC, because of a very unfavourable carbon footprint, can it be used for the much smaller number of transactions that would be carried out in wholesale CBDC, or should PoW be preferred? More specifically, in the case of retail CBDC, would it not be simpler and more efficient for transactions to be validated by the service providers distributing CBDC to the public, in a “two-tier” system similar to that used for a long time for the distribution of currency? The central bank would then only have to monitor the issuance of CBDC at the aggregate level, as it does today for fiduciary money. In the case of wholesale CBDC, it seems difficult to conceive that the validation of transactions on the blockchain should systematically involve the central bank, since this would amount to centralising the governance of the CBDC issuance blockchain, thereby largely losing the advantage of using DLT. It would therefore be necessary to accept that transactions be validated by the banks themselves. However, this issue has not been addressed in the public debates7.

• Can MNBC help facilitate cross-border transactions? The BIS study mentioned above8 notes that at the beginning of 2021 just over a quarter of the fifty central banks responding to the survey used in the study were considering incorporating interoperability features in cross-border or cross- currency payments into the design of their potential MNBC, despite the difficulty noted above of making infrastructures interoperable when they are not interoperable from the outset. Given that the interoperability of CBDCs requires the definition of standards, Lael Brainard, Vice President of the Federal Reserve, rightly mentions the question of the participation of her country’s authorities in the definition of such standards. It is true that, in doing so, she is placing herself in the perspective of maintaining the dominant role of the dollar as a reserve currency9, but other potential issuers than the Fed, such as the ECB, could place their approach in the same perspective.

Poorly asked questions. These questions, which are closely related, concern the methods of issue, the traceability of transactions and the possibility of offline transactions, i.e. without access to the Internet.

See Bank of England, Central Bank Digital Currency Opportunities, challenges and design, Discussion Paper, March 2020.

These questions concern the CBDC, but potentially also a programmable currency that could, for example, be issued by banks. On the first point, the question of issuing CBDCs in the form of tokens or accounts is often asked. Tokens would be the equivalent of cash in the digital sphere: they would be in bearer form and untraceable. As such, they would allow anonymous transactions to be carried out, including offline (in the latter case, by debiting one electronic wallet and crediting another, using, for example, near-field communication (NFC), a wireless communication technology that allows information to be exchanged between peripherals – smartphones, for example – up to a distance of ten metres). Accounts would be the equivalent of current bank accounts. They would be managed in all the organisations envisaged so far for CBDC at the level of payment service providers, as central banks prefer to rely on the latter’s experience in terms of “know your customer” (KYC), as well as on their infrastructure and staff, rather than opening accounts directly to users. At any level, accounts would not be anonymous and transactions could be traced. Furthermore, the need to access the account to conduct transactions would prevent offline use.

However, the opposition between tokens and accounts should rather be seen as simply reflecting two different ways of organising the issuing register10. For example, DLT makes it possible, provided it is used, to trace a token and, on that basis, to trace user identities. Similarly, transactions traced within accounts can be arranged so that certain information, such as the nature of the transactions, is not accessible to the account holder. Finally, it is possible to carry out transactions between accounts offline, subject to two conditions. First, the institution must agree not to apply certain AML/CFT controls, which is possible below certain amounts; second, the institution holding the account being debited must agree to assume a credit risk until the connection is re-established, and this risk can be curbed by placing a limit on the individual and cumulative amounts of offline transactions.

In economic matters: cryptoassets, monetary policy and financial stability

The real questions asked. They relate to some of the monetary policy implications of issuing cryptoassets, in particular global stablecoins on the one hand, retail MNBCs on the other.

See for example the speech by John Cunliffe, “Is ‘crypto’ a financial stability risk?”, bankofengland.co.uk, 3 October 2021.

See Anastasia Melachrinos and Christian Pfister, “Stablecoins: A Brave New World?”, 2021, Stanford Journal of Blockchain Law and Policy, 4(2), 113-138.

See Mark Carney, “Enabling the FinTech Transformation: Revolution, Restoration, or Reformation?”, bankofengland.co.uk, 17 June 2016.

See for example Ulrich Bindseil, Fabio Panetta and Ignacio Terol, “Central Bank Digital Currency: functional scope, pricing and controls”, European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series, n° 286, December 2021.

The implications for monetary policy and financial stability of the issuance of cryptoassets that have been discussed in the academic literature and central bank publications focus on three aspects, the first two of which relate only to financial stability:

– The beginning of the formation of a systemic risk in connection with the growing stock of cryptoassets, their high volatility, the establishment of links between traditional finance and cryptoassets, whether through the provision of services (custody, derivatives trading) or because of their financial links with DeFi players (see volume 1). Above all, regulators and central banks are concerned about the absence in many cases of regulation of firms in the sector11;

– Particular attention has been paid to stable coins, which are closely linked to the traditional financial sector via the management of the reserve to which they are almost all backed, and which provide the settlement instrument within DeFi (see volume 1). The risk is twofold. On the one hand, there may be disintermediation of the banking system through the issuance of stablecoins, such as MNBC, although the arbitrage of depositors in favour of stablecoins may be offset by investments of stablecoins with banks (deposits or securities purchases). On the other hand, if the creditworthiness of the issuer is in doubt, runs on stablecoins may occur, causing them to suddenly liquidate illiquid assets acquired in search of higher yields and thus causing potential stress in the financial markets;

– The increased risk of substitution for legal currency (“dollarisation”) that stable coins may also pose to emerging and developing economies. Indeed, access to stablecoins referenced to foreign currencies can be easier than access to bank deposits in these currencies. The realisation of this risk would have the consequences for financial stability noted above (disintermediation of banking systems), but also that of a loss of effectiveness of monetary policy through the “evaporation” of the base to which it applies12.

However, this risk should not be exaggerated. Firstly, the risk of dollarisation already exists in emerging and developing economies where the currency is not very credible, and/or banks are weak and/or payments are inefficient. Secondly, it can be managed by these economies, notably by applying exchange control measures preventing transfers from banks to cryptoasset exchanges or abroad. Thirdly, increased substitutability between legal tender and stablecoins – or more generally cryptoassets – contributes to disciplining economic policies. Fourthly, this risk potentially exists also with foreign CBDCs.

With regard to the consequences for financial stability and monetary policy of the issuance of retail CBDCs, the risk of disintermediation mentioned above has been repeatedly emphasised early on by central bankers, whether this risk occurs in normal circumstances or more acutely during financial crises, when access to the risk-free asset of central bank money with a few clicks could facilitate runs13. Disintermediation could then create a double problem of financial stability but also of monetary policy since the transmission mechanism of monetary policy relies largely on the predictable impact of changes in the monetary policy rate on banking conditions. Various proposals have been made to manage this dual risk14:

– Introduce individual holding limits (an overall limit would result in an appreciation of the CBDC when the issuance ceiling is reached and the CBDC is sought) which could only be effective if sufficiently rigorous control was put in place, as is the case in France with the so-called Livret A, the remuneration of which is tax-free and set by the Government, usually at above market interest rates;

– Set a penalty interest rate for the CBDC, either from the first euro or above a threshold;

– As a possible complement to the latter measure, vary the remuneration of the CBDC in a discretionary manner, i.e. without keeping a constant spread with the monetary policy rate but rather with the aim of influencing the holding, with interest rate cuts when the overall holding is deemed excessive.

However, questions remain about the credibility and effectiveness of these measures.

The questions most-often avoided or answered unsatisfactorily.

These questions can be grouped around five themes, which essentially concern CBDC: How can the different forms of CBDC co-exist? Is the risk of disintermediation by retail CBDC real and if so, are the measures envisaged by central banks to counter these risks likely to be credible and effective? Does the issuance of CBDC make monetary policy more effective? Should governments be in favour of issuing CBDCs? What role can international cooperation play in the design and management of cryptoassets and CBDCs?

In the opposite direction, see Christian Pfister, “Central bank digital currency” and “Central Bank Digital Currency: One, Two or None?”, op. cit.

On the remuneration of retail CBDCs in relation to other forms of central bank money and the objectives pursued by the central bank (monetary policy and financial stability), see Christian Pfister, “Retail CBDC Remuneration: The Sign Matters“, SUERF Policy Note, No. 205, November 2020.

It should be noted that the central bank’s balance sheet is a closed system: the central bank can only collect deposits that it has created itself, as it is the only one that can create or destroy central bank money (in the latter case, for example, by selling assets or letting them be redeemed).

On the management of central liquidity and the control of short-term interest rates by the central bank, see Françoise Drumetz, Christian Pfister and Jean-Guillaume Sahuc, Politique monétaire, second edition, de Boeck, 2015, chapter 6. Moreover, some institutions might prefer to finance themselves, albeit at, a priori, a higher cost but with a potentially longer maturity, in the financial markets rather than with the central bank. However, this would not change the amount of additional refinancing to be granted by the central bank, equal to the increase in the size of its balance sheet, for the reason given in the previous footnote (the central bank’s balance sheet is a closed system).

See for example Fabio Panetta, “A digital euro that serves the needs of the public: striking the right balance”, ecb.europa.eu, 30 March 2022.

See Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2020.

See for example Michael D. Bordo and Andrew T. Levin, “Central Bank Digital Currency and the Future of Monetary Policy”, NBER Working Papers, n° 23711, August 2017.

In this direction, see Christian Pfister and Natacha Valla, “‘New Normal’ or ‘New Orthodoxy’? Elements of a Central Banking Framework for the After-Crisis”, Working Paper 680, Banque de France, May 2018.

See for example Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et de la Relance, “Common Statement of the Ministries of Germany and France to the digital euro”, 14 July 2021.

For more on monetary sovereignty in the digital era and the differences between emerging and developing economies on the one hand, and developed economies on the other, see Christian Pfister, “Monetary Sovereignty in the Digital Era”, 2022, in Digital Assets and the Law: Fiat Money in the Era of Digital Currency, edited by Professor Filippo Zatti and Rosa Giovanna Barresi, Routledge-Giappichelli, forthcoming.

See for example Agustín Carstens, “Central bank digital currencies: putting a big idea into practice”, bis.org, 31 March 2021, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), The Rise of Digital Money: A Strategic Plan to Continue Delivering on the IMF’s Mandate, IMF Publication, 2021.

How can the different forms of CBDCs co-exist? Central banks most often only consider issuing a retail CBDC15. In fact, different configurations are possible. There may be two forms of CBDC, one wholesale and one retail, and the question of their coexistence, with parity maintained between them and with the other components of the monetary base (banknotes and reserves), arises. There may also only be one. It could be the wholesale CBDC, with the central bank letting stablecoin issuers meet public demand for programmable payment instruments. It can also be retail CBDC, with the central bank requiring institutions to make final settlement of transactions within systemic cryptoasset market infrastructures on its books, thus using reserves, as is already the case for other systemic payment infrastructures. Finally, it can be the same form of CBDC that is used for both wholesale and retail payments. To conclude the inventory of CBDC forms, there may be none, if for example a 100% reserve stablecoin model is preferred, for both wholesale and retail payment purposes (to simplify the discussion, the latter case is not examined in what follows immediately). At this point, however, it should be noted that central banks are most often opposed to 100% reserves, whether it is mandatory and therefore general, or the choice of the public. The main reason for this opposition is that 100% reserves, where the public’s assets are entirely covered by central bank deposits or treasury bills, just as stablecoins and CBDCs, leads to disintermediation.

The question of how to integrate the various forms of CBDC into the monetary base, maintaining its unity and, beyond that, the uniqueness of the payments system, and thus parity between central bank money and bank money, is closely linked to the question of the remuneration of CBDC and the existence or not of holding limits. Indeed, in order to maintain parity between reserves and wholesale MNBC, these two components of the monetary base must be remunerated in the same way and no limit can be placed on the holding of either. In other words, any friction in the arbitrage between the reserve and wholesale CBDC markets must be eliminated, even if it means that one of these two forms of monetary base (e.g. wholesale CBDC in a universe where all financial securities would have been “tokenised”) would eliminate the other. As a result, having only one form of CBDC for wholesale and retail payments implies that CBDC is remunerated like reserves and that no limit is placed on its holding16. However, this is likely to conflict with two central bank concerns: limiting disintermediation and protecting the public against negative monetary policy rates, i.e. interest rates on reserves and wholesale CBDC. The latter concern is implicit but evident, as all central banks with negative interest rate policies have either ended them (Sweden) or introduced a “two-tier” reserve remuneration system (Japan, Switzerland, Eurozone) to discourage banks from remunerating retail deposits at negative rates, when the interest rates on these deposits have approached zero. Such behaviour raises the question of the effectiveness of monetary policy, as central banks have deliberately obstructed a transmission channel for monetary policy. It also makes it extremely difficult to remunerate retail MNBC at negative rates, as the central bank cannot, without losing credibility, pursue a policy that it discourages banks from pursuing.

The sum of these constraints implies that limits should be placed on individual holdings of retail CBDC to limit disintermediation, assuming that this objective is credible, and that its remuneration cannot be negative, unless the central bank forever abandons a policy of negative or even very low positive interest rates. Finally, under these constraints, holding limits would also be necessary to avoid that, in case of the adoption of negative monetary policy rates, banks convert their reserves and possibly also their wholesale CBDC into retail CBDC, preventing the transmission of monetary policy to the financial markets, whether only the retail form or both forms of CBDC are issued. Furthermore, in order to make the remuneration of the retail CBDC punitive, at least when monetary policy rates are strictly positive, it is sufficient for the retail MNBC to carry a zero-interest rate. In this way, we arrive at the model that, without making it explicit as has just been done, central banks favour for the issuance of retail CBDC, whether this is effective, as is the case in very few countries (The Bahamas, in the Eastern Caribbean, Nigeria), or envisaged. Like banknotes, retail CBDCs would be remunerated at zero interest; unlike banknotes, they would be traceable and their holding limited at the individual level.

Is the risk of disintermediation by retail MNBC real and if so, are the measures envisaged by central banks to counter these risks likely to be credible and effective? To assess the reality of the risk, it is useful to consider the initial conditions. These may differ depending on the liquidity position of the banking system vis-à-vis the central bank. More precisely, the banking system’s position vis-à-vis the central bank is negative in the normal situation, which prevailed before the GFC: the banking system has a “structural liquidity deficit” and the central bank refinances it. Conversely, the banking system’s liquidity position has been creditor since then in most developed economies, and also even in many emerging economies since the Covid-19 crisis, because of the asset purchases made by central banks: the banking system currently has a “structural liquidity surplus”. In other words, the central bank is collecting the deposits it has created by purchasing assets17. In this regard, by mid-spring 2022, euro area banks held around €4.5 trillion in excess reserves with the Eurosystem, while the sight deposits they collected with the public amounted to almost €10 trillion. Therefore, around 45% of these sight deposits could be converted into a retail e-euro, resulting in a conversion between the reserves and the e-euro components within the monetary base and the central bank’s balance sheet, without increasing the latter or creating a need for bank refinancing. The banks would only get rid of an asset that yields very low remuneration, if any, while their balance sheet would shrink, on the assets side by reducing their holdings of reserves and on the liabilities side by reducing deposits collected with the public.

But it is possible to go further: even the formation of a refinancing need would only lead to a return to the situation that prevailed before the GFC, with banks becoming deposit collectors with the central bank rather than with the public. Indeed, in order to keep short-term interest rates under control, central banks would have no choice but to accommodate the demand for monetary base resulting from the new “autonomous factor” that CBDC would be18. While it is true that the central bank’s balance sheet would remain at high levels in these scenarios, or even expand, two observations should be taken into account.

Firstly, by issuing a retail CBDC, the central bank accepts in advance that it will be in this situation, even if it does not want to be; indeed, central banks have always accommodated the demand for banknotes in the past. Secondly, what matters is that central banks do not seek to influence the behaviour of banks through refinancing (de facto, the existence of a refinancing need did not prevent this neutrality before the GFC and, on the contrary, it was the asset purchases that aimed to interfere with market allocations).

Another factor to be taken into account in assessing the risk of disintermediation would be the “business strategy” of central banks, i.e. the characteristics of the retail CBDC and their charging by the central bank. In this respect, central banks often point to a double risk: that of not being “successful enough”, with the public shunning retail CBDC, and that of being “too successful”, with the public converting their deposits en masse into CBDC19. However, given the strong allergy of central banks to failure, the first risk is likely to be weighed less heavily than the second. Finally, if retail CBDC is to be remunerated at zero, a higher monetary policy rate should limit demand for it, as well as for banknotes and coins, which are in greater demand the lower the rate. This would limit disintermediation, in contrast with the previous factor.

With regard to the measures envisaged by central banks, beyond the characteristics of the product offered, to limit the risk of disintermediation by retail CBDC, the following remarks can be made:

– Introducing individual holding limits would have an administrative side but would probably be effective and credible as a transitional measure. If a financial crisis were to occur, as it inevitably will at some point, and the central bank were then to act as lender of last resort, as it routinely does, rationing the public’s access to monetary base at a time when the banking sector would be flush with it would be implausible and heavily criticised by the media, political staff and the public. The central bank could then find itself in the uncomfortable position of raising the holding limit or even removing it, reneging on an earlier commitment in the midst of a crisis. This signal could lead to confusion and loss of credibility. Finally, as mentioned above, limiting the individual holding of CBDCs in order to limit disintermediation could be an illusion as the public could turn to stablecoins referenced on the legal tender;

– Setting a punitive remuneration for the CBDC, e.g. a zero-interest rate when the rate of return on reserves would be positive, could also be criticised in terms of both the technical ease of remunerating the CBDC and the remuneration paid to the banks;

– Varying the remuneration of the CBDC in a discretionary way, so as to influence its holding, would probably be the worst measure because of its lack of transparency. Indeed, it would be tantamount to creating a new monetary policy rate that would be difficult to interpret. If, for example, the spread between the monetary policy rate and the MNBC remuneration rate were to increase, the latter being assumed to be lower than the former in order to structurally limit disintermediation, the public would be entitled to wonder whether the central bank had information indicating that the health of the banking system was deteriorating. Ultimately, this decision could cause a run, precipitating a liquidity crisis in the banking system that it was seeking to prevent. Moreover, the public debate would inevitably seize on the subject, as is the case in France for the Livret A rate, with the risk in the case of the digital euro of pressure on the ECB to pursue redistributive objectives that are not part of its mission.

All in all, if a retail CBDC is to be issued, a policy of gradually raising the ceiling and then removing it, and of indexing the remuneration to that of the monetary policy rate, should instead be adopted.

Could the issuance of a CBDC make monetary policy more effective? The answer to the question is mostly positive, although certain excessive expectations may be disappointed, especially as central banks, in the name of a do no harm principle, say they would rather forego greater monetary policy efficiency than do any harm to financial stability20.

If a wholesale MNBC were created, as it would have to be accessible at all times, it is likely that an intraday CBDC market would be appear, especially for reserve currencies outside central bank hours. It would then be difficult for the central bank not to adopt a real-time monetary policy. Both developments would contribute to increasing the range of investments, extending the control by the central bank of very short-term interest rates and encouraging intensive use of the possibilities offered by RTGS systems.

A retail CBDC, if remunerated according to a rule indexing it to the monetary policy rate (e.g. monetary policy rate minus 50 basis points), would allow the monetary policy rate to pass through to bank conditions more quickly than is currently the case. In effect, the CBDC interest rate would put a floor on bank rates: since the CBDC has no credit risk, it should not be possible to remunerate deposits less than it does. However, for this mechanism to be fully effective, two conditions would have to be met: retail CBDC would have to be held without limit and central banks would have to agree to put more pressure on bank margins.

Moreover, contrary to a widespread idea21, the issuance of retail MNBC does not allow interest rates to be set in the economy below the effective lower bound (ELB). Indeed, the ELB, which is slightly below zero due to the costs associated with holding cash, results from the existence of the latter, which is remunerated at zero. It is therefore on the currency that action should be taken, for example by remunerating it at possibly very negative rates, whether or not a CBDC is issued22.

Should the governments support the issuance of a retail CBDC? In developed economies, there are very few statements by members of the executive branch in that direction, except for a few ones from a monetary sovereignty perspective23. This is doubly surprising. On the one hand, the link between CBDC issuance and monetary sovereignty is hardly obvious, especially in the case of retail MNBC and in those economies where currencies are credible, banking systems resilient and payment systems perfectible but essentially satisfactory24. On the other hand, there are much closer links between the issuance of retail CBDCs and a subject at the heart of governments’ preoccupations, namely public finance, with arguments implying they can only support, at least to a certain extent, the issuance of retail CBDCs. The first link, which is easy to see and which is explicitly mentioned by the authorities of some countries, such as China, is to encourage the substitution of retail CBDC for fiduciary money, in order to reduce tax evasion. The second link, which is less direct and therefore more difficult to perceive, is that if the central bank’s balance sheet is to grow or remain at a high level achieved through purchases of government securities, it will have to invest in corresponding assets. It would then be natural for the central bank to choose to invest in government securities, as it usually does, both because they are in principle risk-free assets and because this behaviour is in line with the central bank’s issuing privilege to issue banknotes (in some countries, such as England and the United States, the central bank is even statutorily obliged to invest the counterpart of the banknote issue in government securities). Moreover, if the issuance of CBDCs is permanent, as is the case for banknotes, beyond seasonal fluctuations or those linked to specific events, the credit thus granted to the State would be permanent. The possible substitution of retail CBDC for cash, which is a priori much more expensive to issue and manage, would also increase seigniorage revenues. In total, the State would benefit from increased seigniorage, for the part corresponding to an increase in the central bank’s balance sheet, from the difference between the cost of issuing and managing the corresponding retail CBDC and the rate of a perpetual annuity, and for the part of the retail CBDC issuance replacing the issuance of fiduciary money, from a reduction in cost. It is true that the gain in tax revenue from the substitution of retail MNBC for fiat money and the gain in seigniorage from the substitution of retail CBDC for deposits should be limited by the economic costs of disintermediation. Indeed, disintermediation would cause banks to lose an inexpensive part of their resources (mainly sight deposits) and could hamper their liquidity management. The result should be more expensive and more cautious intermediation, with less credit distribution, which could marginally penalise growth, and therefore also public revenues.

Between the direct budgetary benefit of issuing an MNBC and its indirect cost through reduced intermediation, there should be an optimal level of CBDC issuance from a government perspective. Finally, it should be noted that more prudent banking intermediation should reduce the frequency and/or severity of financial crises, and thus in the long-term the resulting losses of economic activity and tax revenues.

What role can international cooperation play in the design and management of cryptoassets and CBDCs? As mentioned above, one of the main areas where CBDCs could bring about progress compared to the current situation, provided they are interoperable, is cross-border payments. This is therefore an area where, for example through the definition of international standards, there would be a collective interest in cooperating, which is most often only mentioned by international organisations25. However, in this field too, initial conditions matter: not all countries are at the same level in terms of mastering technologies, particularly DLT, and the most advanced countries in that field are naturally those that should have the greatest chance of seeing the standards they practice adopted at the global level. Moreover, there is competition between currencies which makes international cooperation difficult, with on the one hand the advantages of reserve currency status (increased seigniorage, more favourable interest rate conditions, better protection of the economy against exchange rate shocks), and on the other hand the risks of dollarisation for economies whose currencies and/or financial systems are the most fragile.

As previously mentioned in the case of global stablecoins, the risk of dollarisation of emerging and developing economies could be even higher in the case of CBDCs, which could more easily act as safe havens due to their lack of credit risk. However, it should be relatively easy to implement exchange control measures at the level of multi-MNBC schemes, at the cost of a possible shift in demand towards stablecoins, access to which would remain more difficult to control due to their global and less centralised nature. For this reason, which is essentially defensive in nature, a form of international cooperation could develop, mainly at the request of emerging and developing economies. These economies could find support from some of the more developed ones, concerned that the use of an e-dollar or that of global stablecoins referenced to the U.S. currency, might reinforce its status as the dominant reserve currency. On the side of developed economies, a concern could also be to avoid regulatory arbitrage by cryptoasset issuers whose teams might migrate.

The wrong questions asked: do cryptoassets threaten legal tender or would the issuance of CBDC threaten cryptoassets? Does CBDC need to be legal tender? Can the issuance of a CBDC play a major role in the internationalisation of a currency?

On the different multi-MNBC models, see Raphael Auer, Philipp Haene and Henry Holden, “Multi-CBDC arrangements and the future of cross-border payments“, BIS Papers, No. 115, March 2021.

See Kantar Public, op. cit.

See European Commission, “Consultation document – Targeted consultation on a digital euro“, 2022.

For a more detailed discussion, see Christian Pfister, “Monetary Sovereignty in the Digital Era”, op. cit.

• Are cryptoassets threatening legal tender or would the issuance of CBDCs threaten cryptoassets? In the media, the proposed issuance of CBDCs is often presented as a reaction of central banks fearing the marginalisation of their currency by cryptoassets. A distinction must be made here between first-generation cryptoassets and stablecoins. Given the poor monetary capabilities of first generation cryptoassets, there is little risk, except in economies with intense financial repression and where all confidence in legal tender is lost, that they will replace legal tender, unless and only to a certain extent if they are imposed as legal tender, as is the case in El Salvador. Similarly, the current uses of these cryptoassets for speculative purposes or in illicit transactions do not seem to be challenged by the issuance of CBDCs. With regard to stablecoins, noted beforehand, they could facilitate the dollarisation of emerging or developing economies, but the issuance of a CBDC in these countries would not be a “silver bullet”: it could not provide a substitute for the lack of credibility of the legal tender or the fragility of the banking system, which are the two main factors of dollarisation. A CBDC could therefore only be an effective barrier against dollarisation in economies where the main factor in dollarisation is the inefficiency of the payment systems, provided of course that the infrastructure supporting the issuance of the CBDC itself meets public expectations. Apart from the case of dollarisation, there are only two areas where cryptoassets, firstly stablecoins, could face competition from CBDCs:

– Cross-border payments, provided that the cross-border use of CBDC is allowed from both a regulatory (non-resident access to MNBC) and operational (interoperability) perspective. In this case, the competitor to stablecoins could be wholesale CBDC, for example in a multi-CBDC organisation where central banks would serve as correspondent banks and share a blockchain where different CBDCs would be exchanged26. It could also be retail CBDC, if non-residents were allowed to hold it outside their tourist or business stays in the CBDC issuing area, making it more difficult to control;

– DeFi where, due to its superior characteristics (absence of credit or liquidity risks), wholesale CBDC could substitute stablecoins for the settlement of transactions between institutions with access to the blockchain where it would circulate.

• Does CBDC need to be legal tender? It seems that very few people know what legal tender is, i.e. the obligation to accept a means of payment (fiduciary money in France, as in many other countries) in discharge of a debt. In fact, it is likely that most of the public confuses legal tender with the legal currency (the euro in France and in the euro area, the U.S. dollar in the United States…). This confusion is encouraged by the prohibition in most countries on paying amounts above a certain threshold (€1,000 in France) in cash, as well as by a set of public mechanisms which make banking activity appear to be largely a public service. These mechanisms include deposit insurance, with a ceiling of EUR 100,000 per institution in the eurozone, which covers the vast majority of depositors. It also includes supervision and regulation, carried out by public authorities with the objective of protecting depositors, which makes it very difficult for them to declare a default without implicitly acknowledging that they have made a mistake. Finally, when there is a risk of default, public aid in the form of liquidity and capital is often provided to institutions, particularly the largest ones, which benefit de facto from the adage of “Too Big to Fail” because of the disruption to the economy that would result from the closure of their activities. More generally, it is known that the use of constraints to promote the use of a payment instrument can only fail or even be counterproductive, as the obligation under the French “Terreur” (Terror) of 1793 to accept assignats or incur the death penalty, which led to a collapse of transactions, showed in a caricatural way. Similarly, financial repression measures are typically very ineffective in preventing the dollarisation of an economy. Indeed, it is because of their own characteristics (preservation of value for money, security, convenience, accessibility, preservation of privacy, etc.) that payment instruments are accepted. It is true that some sources, such as the ECB-commissioned survey previously cited, suggest that merchants themselves may, in countries such as France, wish that the digital euro become legal tender27. However, this apparently paradoxical result, which was obtained in this survey on a statistically very fragile basis (138 traders and retailers participating in the survey for the whole euro area), may reflect the perception of a moral hazard. Indeed, merchants may anticipate that, in return for the obligation imposed on them, all or part of the investment in the payment infrastructure necessary for the acceptance of the digital euro would be taken over by society. On the whole, therefore, there is a lack of convincing arguments for imposing legal tender for the CBDC. However, it is of course up to democratic bodies to decide. On 5 April 2022, the European Commission launched a public consultation on the digital euro, in which several of the 51 questions relate to legal tender28.

• Can the issuance of a CBDC play a major role in the internationalisation of a currency? To try to answer this question, it is necessary to distinguish once again between wholesale and retail uses. It should also be recalled that the main factors for the internationalisation of a currency are known (size and openness of the economy; development and depth of its financial markets; credibility of its economic and financial system) and that the availability of efficient payment infrastructures is not mentioned in the academic literature as one of these factors, even though it may indirectly contribute to them. It is therefore likely that these factors need to be observed before efficient payment infrastructures, for example through the provision of a CBDC, are offered. This is especially the case in international payments where inertia effects dominate, of which the current role of the dollar is the clearest manifestation, with a U.S. share of about 14% in global GDP, but over 40% in international bond issuance, over half in international transaction invoicing, and about 60% in global foreign exchange reserves. In contrast, while China is the world’s largest exporter, the share of the yuan in world foreign exchange reserves is slightly above 2%, reflecting the absence of some of the factors mentioned above but also the weight of the past. As regards the role that the issuance of a CBDC could play, the Chinese initiative to issue an e-yuan has led to questions about the existence of a “prime mover advantage” in this area. In fact, this advantage seems to be less relevant in technological matters and in periods of rapid change, as is the case for CBDCs, than in other contexts29.

Nevertheless, being the first major economy to issue a digital version of its currency – at this stage of the project, only for retail and mainly for domestic use – could give China an important role in the definition of international standards.

In addition, the availability of a wholesale version of CBDC could prove crucial for the liquidity of financial markets and their accessibility to international investors if the “tokenisation” of financial assets develops sufficiently.

In societal matters

The real questions asked. A real issue with regard to retail CBDC is the relationship between identification, prevention of misuse of money and protection of privacy

See Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Updated Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach. Virtual Assets and Virtual Asset Service Providers, October 2021.

See Fabio Panetta, “EDPB letter to the European institutions on the privacy and data protection aspects of a possible digital euro“, 18 June 2021, and Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (Cnil), “Euro numérique : quels enjeux pour la vie privée et la protection des données personnelles ?“, cnil.fr, 14 February 2022.

There is a potential tension between the expectation of anonymity of retail CBDC users, fostered by its assimilation to banknotes as an already known form of central bank money, on the one hand, and the need to enforce AML/CFT regulations and more generally to prevent the illicit use of money on the other. Indeed, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has nevertheless indicated that its standards apply to CBDC in the same way they do to cash30. The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) and the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL) in France concur that the rules of the AML/CFT framework for cash provide a good framework for the digital euro31. These bodies recalled that the principles of privacy and personal data protection, enshrined in Articles 7 and 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, must be balanced against the other rights and freedoms concerned while respecting the principles of necessity and proportionality as defined by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In the context of the Digital Euro project, this implies two principles:

– The principle of data minimisation, according to which the collection of personal information must be limited to what is necessary for the fulfilment of their regulatory obligations by the entities subject to the law (the CNIL thus recalls that there is no obligation to identify oneself to a merchant);

– The purpose limitation principle, according to which personal data may only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes, without being further processed in a way that would be incompatible with these purposes. In this respect, users of retail CBDC should be confident that the central bank, unlike possibly a Fintech or a Big Tech, will not seek to make any direct or indirect commercial use of their transaction data.

In any event, according to the same bodies, the architecture of the digital euro should be designed in such a way as to allow a confidentiality attribute ranging from anonymisation, at least on the transaction side, to a high level of data pseudonymity. In the same spirit, when connecting to an intermediary distributing the digital euro, in order to reload its wallet, the transaction data would be communicated to the intermediary only for transactions above a certain threshold.

In China, there are plans to offer four types of wallets capable of holding the digital yuan, with the service provider’s obligations being to know the customer increasing with the volume of transactions authorised, according to a system referred to as “managed anonymity”, allowing anonymity for small-value transactions and tracing for large-value transactions. In the case of the fourth category of portfolios, the least demanding one, it would be sufficient to provide a telephone number that the central bank would not know, the amount held would be limited to 10,000 yuan (i.e. about 1,400 euros) and the amount of unit transactions to 2,000 yuan (i.e. 280 euros).

More generally, whether it is CBDC or any other intermediated financial asset, an identification problem arises in developing economies where part of the population does not have identity documents. In these economies, the implementation of digital identification systems at the national level appears to be an essential complement to the objective of financial inclusion in compliance with KYC procedures.

The real questions most-often avoided. A seldom asked question, which has an economic but also and perhaps above all a societal dimension, is the role of competition and, in a related way, the respective roles of the public and private sectors in the production of money

See Bank of England, op. cit.

The production of money is now a private matter: fiduciary money, a large part of which circulates abroad, represents only about 13% of the narrow monetary aggregate M1, the rest being made up of residents’ sight deposits. The corresponding percentage was almost 50% for currency in France in 1947. If the retail CBDC is to regain a larger “market share” than it currently has, how can this be done under conditions of equal competition where the central bank, as holder of seigniorage income, would not prevent the emergence of private alternatives? In this perspective, the idea sometimes evoked of “shared seigniorage”, where the central bank would subsidise the banking system, would not be a solution for two reasons. The first is that banks are initially in a position where they benefit from a rent resulting from two factors: fiat money carries a zero-interest rate, allowing banks not to remunerate – or to remunerate only symbolically in times of high inflation and monetary policy rates – on sight deposits. The second reason is that such a subsidy would only benefit the insiders (the existing companies in the sector) and not those whose creation could not take place.

A priori, a cost-recovery approach by the central bank, combined with the government using the extra seigniorage provided by the issuance of the CBDC to reduce the most distorting taxes, thus benefiting the economy as a whole, would be more appropriate. However, because of the importance of fixed costs (setting up the infrastructure), a cost recovery strategy would only be compatible with an initial “creaming” of the market, similar to that practised by bank card issuers who, in the 1950s-1960s, initially targeted a market segment that was more sensitive to the demonstration effect than to the level of costs. However, this strategy would not be compatible in the short term with the accessibility objective set by central banks, unless the diffusion of CBDC ownership is rapid, which would risk destabilising the banking system. Moreover, a very rapid diffusion would probably have a chance of success only if it was based on a very aggressive commercial strategy (extensive offer of services, “free” for the user or undercharged), eliminating potential competitors from the start. An alternative could be a retail CBDC providing only a minimum level of services, which the Bank of England refers to as a “platform model”32, from which service providers would offer value-added services.

The false question. A false question is the conception of money as an instrument of power

See Kivanç Karaman, Sevket Pamuk and Yildirim-Karaman Seçil, “Money and monetary stability in Europe, 1300-1914”, Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 115, November 2020, p. 279-300 (restricted access).

Money is only an instrument to facilitate exchange in space and time. It is not an instrument of power by destination. This does not, of course, prevent money, like any other instrument, from being used by power, particularly in international relations, as shown by the American administration’s use of the dollar or, in a manner much more suited to the dramatic nature of the situation, the war in Ukraine. Moreover, there is no shortage of examples in history of the use of money by the authorities for budgetary purposes, with catastrophic consequences for the currency and therefore for the holders who had expected monetary stability33. Recently, with the Venezuelan petro, the attempt to launch a monetary instrument whose only real basis was the support that the government was supposed to give to it failed calamitously, however “crypto” the instrument was intended to be. Similarly, attempts to oppose power through the promotion of monetary instruments have not been successful: local currencies are stagnating and first generation cryptoassets, as we have seen, cannot establish themselves as currencies. We must therefore accept the idea that money and power coexist, without the former being the expression of the latter or the latter having to manipulate the former.

Recommandations

The analysis carried out in the two volumes of this study allows for the following recommendations to be made.

1. Continue to issue currency. However, in order to discourage the illicit use of the banknote, gradually withdraw high-denomination banknotes (over EUR 100 in the case of the single currency) from circulation, as has already begun to be done with the EUR 500 banknote (in the United States, the highest denomination is USD 100).

2. When cash is used less in consumer transactions (e.g. when less than one third of payments at the point of sale or between individuals are made with cash, instead of 73% in 2019 in the euro area) or if a retail CBDC is issued and bears interest (see recommendation 13), indexing banknotes and coins to an interest rate linked by a fixed spread to a monetary policy rate, allowing them to be remunerated. In order to be transparent, predictable and free of monetary policy messages, the indexation would follow a formula (e.g. deposit facility rate minus 50 basis points in the case of a digital euro). Moreover, to avoid the measure appearing punitive, it would have to be introduced when the rate of remuneration would be positive, without of course any guarantee that it would remain so, because of its indexation. The unit of value would then be completely dematerialised, represented by reserves and the CBDC if issued, and no longer by fiat money. This would be in line both with the process of dematerialisation of money over the centuries and in line with the nature of money itself as an abstract concept. The use of cash would certainly be made more difficult, but this is a modest price to pay compared to the abolition of the ELB which would thus be allowed and is justified in view of the services rendered by cash in terms of anonymity. After the convertibility of banknotes into metal and the abolition of fixed exchange rates, the abolition of the ELB would be a further step in freeing money from material constraints.

3. In view of the slow spread of instant payments in the euro area, facilitate the establishment and creation of national or foreign companies offering instant payment services at competitive prices.

4. Regulate the issuance of cryptoassets (an ongoing development in Europe with MiCA), drawing on the regulations for banks, e-money and money market funds, but not necessarily copying them, as for example a carefully managed stablecoin issuer is in principle less risky than a bank.

5. Regulate DeFi by analogy with traditional finance and using “entry points”.

6. For environmental reasons, subject capital gains from the sale of cryptoassets using proof-of-work consensus building to punitive taxation, or alternatively prohibit the regular sale of surplus electricity production to proof-of-work mining activities, unless it is shown by the promoters of the cryptoasset project that no other, socially more useful uses are possible.

7. Impose interoperability of stablecoins, above an issue threshold, with the CBDCs of the reference currencies when issued, the legal tender currencies in any case. Unless they are allowed to choose and actually choose bank status, stablecoin issuers would not be able to benefit from or contribute to deposit insurance, limiting the moral hazard created by the latter.

8. Cooperate in setting up common standards for wholesale CBDCs, so that they are interoperable from the outset.

9. Issue a wholesale CBDC on a DLT, permitted but allowing users to validate transactions themselves, otherwise the benefits of using the blockchain would be significantly reduced.

10. Implement a real-time monetary policy when a wholesale CBDC is issued, since users, if they have the possibility, will themselves carry out transactions within the day and because the functioning of real-time payment infrastructures would then be improved.

11. In developed economies, do not favour the issuance of a retail CBDC over regulated market solutions, such as stablecoins or bankcoins.

12. Allow, but not force, payment service providers, including regulated issuers of retail stablecoins, to back their issuance with wholesale CBDC. This authorization would be given under certain conditions imposed on the issuers concerned and, beyond that, on systemic issuers of stablecoins, such as the possibility for users to convert without limit and immediately, similar to the obligation imposed today on issuers of electronic money. The deposits of these financial intermediaries would be remunerated in the same way as those of banks (deposit facility rate in the euro area), but the institutions would not have access to central bank refinancing, so as to limit moral hazard and because they would not need it since their issuance would in principle be fully backed by central bank money.

13. If a retail CBDC is to be issued,

– Do not necessarily seek to make it legal tender;

– Make it compatible with the maximum number of existing means of payment, including foreign CBDCs issued in economies sharing the same technological and societal standards, and environment-friendly;

– Distribute it through a network of approved service providers, as is most commonly envisaged;

– Provide it with the minimum of services, so that it is simple, robust, cost- effective, fully accessible to the greatest number of people and so that the private sector can adapt its capabilities to the specific use cases expected by the various customer segments;

– From the outset, allow offline transactions and, to the extent that it uses the blockchain, as is most desirable, allow smart contracts;

– Back it entirely with public securities and pay the corresponding seigniorage to the State, so that it is the latter and not the central bank that decides whether or not to compensate the banks for the loss of rent caused by the competition between the CBDC and bank money;

– Do not limit individual holdings, except for a transitional period, as a holding limit would not be credible in times of crisis and raising it in such a situation could lead to a loss of credibility for the central bank;

– Remunerate it at a rate of zero as long as individual holdings are limited, then according to the same rule as fiduciary money, with a rate of remuneration that is preferably positive at the outset but with no guarantee that it will remain so and without waiting for fiduciary money to bear interest. Indeed, since fiduciary money allows for anonymity, it has an advantage over retail CBDC;

– Introduce a threshold of anonymity to facilitate its substitution for cash, which is more costly for the economy, in very small-value transactions, without facilitating illicit transactions. Above this threshold, allow transactions under pseudonyms, with the possibility for the judicial authorities to request the lifting of pseudonymity;

– When making payments in CBDC, whether anonymous or not, limit the collection of personal information to what is necessary for reporting entities to fulfil their regulatory obligations;

– Charge for access so that the central bank fully recovers the costs incurred, as established in the near future, such as the current calendar year, under accounting and parliamentary control.

14.Implement a digital identification system, at the highest possible (European or even global) level, in order to reduce the costs of identification, which is essential in centralised payment systems in order to implement KYC procedures, and to reduce cybersecurity risks, in particular that of identity theft.

No comments.