Pogroms in Palestine before the creation of the state of Israel (1830-1948)

The precarious situation of jews in muslim societies

Pogroms in the 19th century under the Ottoman Empire

Mehemet-Ali’s Progressivism and Arab Response: The Pogrom of 1834

The Pogroms of August 1838

The decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of islamic anti-zionism

The emergence of Western anti-Semitic tendencies

The Pogroms of 1920 and 1921

The Pogroms of 1929 and the role of the Grand Mufti

The British Commission of Inquiry and testimonies of the Pogroms of 1929

The Arab rejection of the British mandate and the pogroms of 1936-1948

1936: the beginning of the “Great Arab Revolt” against the British Mandate and the Zionist movement

Proposal of the Peel Commission Plan for Palestine’s Partition Met with Arab Rejection

1947: United Nations Partition Proposal Faces Fresh Arab Opposition and Increased Violence

The “Battle for the Roads” Pushes Zionist Forces to the Edge of Defeat

April 1948: Implementation of Plan Dalet to Break Encirclement and Secure Territorial Continuity for the Future Jewish State

***

Summary

On October 7, 2023, a pogrom took place in Israel for the first time since the creation of the Jewish state. According to the French Press Agency (AFP), the anti-Semitic massacre perpetrated by the terrorist organization Hamas claimed 1,160 victims, mostly civilians, men, women, old people and children all of whom died in atrocious conditions often after being raped and tortured. The terrorists took approximately 250 people hostage, some of whom were released in exchange for prisoners, while others died in captivity, although the number of deaths was unknown at the time of publication.

This act of unprecedented violence failed to generate the the expected expression of solidarity, particularly in view of the historical context, seventy-nine years after the first Nuremberg Trials. On the contrary, we quickly saw the emergence of a more or less accepted argument establishing a causal link between Israeli policy in the Palestinian territories and the violence of October 7, 2023. However, a historical review of relations between the Jewish and Arab communities of Palestine shows that in the century preceding the creation of the State of Israel, Palestine was already the scene of numerous pogroms of a violence comparable to that of October 7.

From 1830 to 1948, these repeated massacres aimed to expel the Jews from Palestine, dissuade European refugees from seeking sanctuary there, and thwart the establishment of a ” Homeland for the Jewish people” through extreme violence.

Georges Bensoussan’s research underscores that murderous anti-Semitism plagued the Jews of Palestine long before the formation of a Jewish state. Therefore, the events of October 7, 2023, cannot be comprehended without contextualizing them within this history of pervasive anti-Jewish violence in Palestine. Advocates of a “two-state solution” must acknowledge this reality.

Dominique Reynié

Jews praying in front of the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, illustration from the book

Those Holy Fields: Palestine, illustrated by pen and pencil

by Samuel Manning, published in 1873.

Georges Bensoussan est l’auteur des ouvrages Les Origines du conflit israélo-arabe (1870-1950), Paris, PUF, Collection Que sais-je?, 2023 ; Les Juifs du monde arabe : la question interdite, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2017 ; Juifs en pays arabes : le grand déracinement, 1850-1975, Paris, Tallandier, 2012 ; Une histoire intellectuelle et politique du sionisme : 1860-1940, Paris, Fayard, 2002.

Albert Memmi, Juifs et Arabes, Gallimard, 1974.

“The famous idyllic life of Jews in Arab countries is a myth! The truth, since I’m forced to come back to it, is that we were first and foremost a minority in a hostile environment. […] Never, I repeat never […], have Jews lived in Arab countries as anything other than diminished people. […] The Muslim masses, he continued, were among the poorest on the planet. And ours? Who could have visited one of our ghettos without being frightened? Why shouldn’t we, too, have a slate to present to the world? It’s true that the Arabs were colonized. But what about us? What have we been, for centuries, if not dominated, humiliated, threatened and periodically massacred? And by whom? Isn’t it time we were heard on this subject: by Muslim Arabs!1.”

Albert Memmi

The precarious situation of jews in muslim societies

The Jewish condition in Muslim societies is governed by the dhimma, which institutes the status of dhimmi for Christians and Jews. A dhimmi is a “protected person” (this is the meaning of the word in Arabic), and as such is an inferior and submissive subject, restrained by a host of discriminatory and fiscal measures. According to historians specialized in Islam, Janine and Dominique Sourdel, dhimma is based primarily on a verse of the Koran: “Fight those who do not believe in God or the Last Day, who do not declare unlawful what God and His Messenger have declared unlawful, who do not practice the religion of Truth, among the holders of Scripture, until they pay the jizya, in compensation for this benefit and because of their inferiority” (Koran, IX, 29). As a result, note the two authors of the A Glossary of Islam, a two-tier society was created: “on the one hand, the level of the masters, distinguished above all by their membership of Islam, and on the other, the level of non-Muslims, who did not enjoy the same rights2“. This society “carried within it the seeds of intolerance which were to characterize, in every era and in every region, the rigorist Muslim states confronted with the problem of religious minorities3“.

In the nineteenth century, a great many accounts of Jewish life in Arab-Muslim lands reveal a condition characterized primarily by contempt. In 1910, a Western traveler to Yemen4 wrote: “The Jew is the beast on whom one beats at any time, for no reason, to calm one’s nerves, to appease one’s anger”. Between Jews and Arab-Muslims, coexistence is fragile, and remains at the mercy of the slightest incident, especially when Jews forget what Muslim society calls “their sense of humility”. Codified violence keeps everyone in their place, at the risk of being accompanied by the spilling of blood.

Based on a study of the archives of Islamic courts in Palestine, Israeli historian Amnon Cohen reconstructs the reality of the condition of Jewish dhimmis before the beginnings of Zionism, based on legal and administrative sources spanning almost six hundred years, from the Prophet to Saladin in the XIIth century. These documents attest to the fact that the so-called “Pact of Umar”, i.e. the codification of the dhimma, “had retained for many generations an indisputable character”. However, contrary to its official name, the “Pact of Umar” is not a treaty signed between two parties. It was not the subject of negotiation, but a constraint exerted on subjugated populations.

The dhimma is inscribed first and foremost in space, through radical separation from the Muslim majority. For example, in public baths in Jerusalem, where all residents are allowed to go, Jews must continue to be distinguished from Muslims. In everyday life, the Jew must wear a yellow turban. Removing it or wearing any other color is interpreted as an attempt to pass oneself off as a Muslim. Jewish women must wear a yellow garment or piece of cloth to distinguish themselves from Muslim women. The nudity of public baths meant that another distinctive sign was required: any Jew entering the baths had to carry a bell to signal his arrival.

While every bathhouse guest receives a towel, it’s customary to reserve for Jews the most tattered and worn-out towels. The public baths are just one example of the radical system of segregation embodied by a dhimma that embraces all aspects of life.

Pogroms in the 19th century under the Ottoman Empire

Abraham Yaari, Massaot Eretz-Israel (James’ Journey to Jerusalem), in Hebrew, Ramat Gan, Massada Editions, 1976, quoted in Renée Neher-Bernheim, La Vie juive en Terre sainte 1517-1918, Calmann-Lévy, 2001, p. 118-119.

In the nineteenth century, under the Ottoman Empire, Palestinian Jews lived mainly in Jerusalem, Safed and Tiberias. Haifa and Saint-Jean-d’Acre had smaller communities. In Jerusalem, as is often the case in the Arab-Muslim area, the Jewish condition was marked by a climate of humiliation and widespread fear, as witnessed in the nineteenth century by the Jewish traveler Abraham Yaari in his book Voyages en Eretz-Israel5: “The Arabs are violently hostile to the Jews, and persecute the children of Israel in the streets of the city. If a notable or even lower-class citizen lays their hands on a Jew, we have no right to reciprocate, whether Arabs or Turks, for they are of the same religion. If a Jew is hit, he must adopt a supplicant attitude and not retaliate with unkind words, lest he receive even more blows, for, in their eyes, we are people of nothing. Sephardim behave like this because they’re already used to it. But Ashkenazim are not yet used to being struck by Arabs, and they respond with insults if they can speak their language. If not, they gesticulate in anger, and then they are beaten even more. […] It’s the same for the uncircumcised (i.e. Christians) who are in exile [sic] like the Jews, except that the uncircumcised have a lot of money, because they receive it from the kingdoms of Europe, and with this money they can bribe the Turks. The Jews don’t have enough money to do the same, therefore they’re even more “exiled””.

In 1831, “Southern Syria” (the Arabic name for the province known to Westerners as the “Holy Land” or Palestine), of which Safed was a part, was annexed by Mehemet-Ali, Viceroy of Egypt. Safed’s Jewish community, one of the largest in the country, had long been predominantly Jewish, as evidenced around 1625 by the Italian orientalist Franciscus Quaresmius, who wrote of Safed that it was “inhabited mainly by Hebrews, where they have their synagogues and schools”. The community was strengthened by the arrival of Russian Jews (1776-1781), followed by Jews from Lithuania (1809-1816).

Mehemet-Ali’s Progressivism and Arab Response: The Pogrom of 1834

The vilayet was a major administrative subdivision of the Ottoman Empire.

Abraham Yaari, Letters from the Land of Israel (Igrot Ereṣ Yiśra’el ), Ramat Gan, Massada, 1971, p. 358, and quoted in R. Neher Bernheim, Jewish Life in the Holy Land, Calmann-Lévy, 2001, p. 171.

The Druze are a religious movement stemming from Ismailism, itself a sub-branch of the Shiite obedience. See larousse.fr [online].

Safed is part of the vilayet6 (wilaya in Arabic) of Sidon, and the vilayet’s Jews live mainly in Safed and Tiberias. From 1831 onwards, Egyptian governance of “Palestine”, delegated by Méhémet-Ali to Ibrahim Pacha, led to a process of modernization that upset the traditional social balance between communities, and, ultimately, to an uprising by the rural Arab population that focused its violence on the Jews.

Indeed, one of Mehemet-Ali’s main decisions was to favor Jews and Christians, who had hitherto been overlooked, in the management and administration of his provinces, including the Nile Valley and “Palestine”. He also sought to surround himself with many Westerners to carry out major reforms and large-scale projects.

It was under his reign that Ashkenazi Jews obtained the annulment of the Ottoman decree prohibiting them from settling in Jerusalem. Hence the anger of the main notables, both Islamic religious dignitaries and local rural chiefs who, from Nablus to Hebron, and from Jerusalem to Jaffa, saw their power henceforth strictly controlled by the administration of Mehemet-Ali of Egypt and not by Istanbul. What’s more, Governor Ibrahim Pasha, sent by Mehemet-Ali, implemented a major tax reform that introduced equality before the law: this was bound to upset the privileged, who had been brought back under common law, and upset the social balance as soon as they could no longer live – as they once did – off the taxes paid by non-Muslims. Added to this were new taxes on harvests, particularly olives, which remained a major produce in the region.

Continuing with his reformist approach, Ibrahim Pacha implemented compulsory conscription through a lottery system that involved the entire population. This decision added to the dissatisfaction of the predominant peasantry. This policy of openness towards Christian and Jewish minorities provoked the wrath of both conservative and popular circles, suddenly forced to admit the disappearance of the discriminated condition of the Jews, which until then had been the only mark of their presumed superiority. They then fomented and led an insurrection to get rid of them, targeting non-Muslims and, in particular, Jews, who were to pay a high price. It was against this backdrop that, in May 1834, revolt broke out in the regions of Nablus, Hebron, Bethlehem and Safed. Furious farmers, probably incited by a local preacher named Muhammad Damoor who proclaimed himself an “Islamic prophet”, attacked the Jews, destroying their homes and committing all manner of violence. The pogrom officially began on June 15, 1834. It lasted thirty-three days. It was carnage. Armed Arab and Bedouin villagers, as well as the inhabitants of Safed (including Turks), massacred the Jews and raped their wives. The death toll probably exceeded five hundred. Synagogues were looted and then set on fire, and precious objects stolen or destroyed. In his book The Events of Time (Korot Ha Itim), Rabbi Menahem Mendel of Kamenitz bears witness to the violence: “On Sunday, Sivan 18, looters from neighboring villages (Safed) went on the rampage. They were joined by residents of other provinces. With swords and deadly weapons, they threw themselves on Jews, pushed them to the ground, tore off the clothes of both men and women, drove them naked from the town and ransacked their possessions. Nothing remained. They even tore up the Torah scrolls as well as the talettim and Tefillin7.”

From his hiding place, Rabbi Israel of Shklov sent several letters to the consuls of foreign states in Beirut. He informed them in detail of the hardships endured by several of their nationals, Jewish subjects “protected” by foreign powers. In response, the consuls encouraged Ibrahim Pacha to go to Safed to quell the rebellion. He entrusted this mission to the Druze emir8, Emir Bashir, who came down to Galilee from his home in Lebanon. By mid-July 1834, the riot had subsided and most of the rioters had fled. Several of their leaders were arrested and executed in the street. When the Jewish residents of Safed came back to their homes after the looting and destruction, despite the aid from consuls to the neediest among them, the majority found themselves devastated. They managed to salvage less than 10% of their belongings’ worth. Additionally, the sole Hebrew printing press in the entire Syria-Palestine region, established three years prior by an Ashkenazi Jew named Israel Bak (1797-1834), was demolished.

The violence quickly spilled over from Safed into Judea, further south. Ibrahim Pasha assembled several thousand Egyptian soldiers and marched towards Jerusalem. The journey was arduous, hindered by insurgents controlling the villages along the road. Upon reaching the Holy City, Ibrahim Pasha liberated six hundred Egyptian soldiers who had been barricaded in the citadel and ultimately quelled the rebellion. Meanwhile, the Ottoman authorities had allowed the rioters to go unchecked.

The Pogroms of August 1838

Renée Neher-Bernheim, op. cit., p. 173.

The 1834 pogrom was repeated in August 1838. Over three days, the Druze, supported by Arabs, rebelled against Egyptian rule and once again attacked the Jewish community in Safed. The devastation mirrored that of 1834, with Jews murdered, homes plundered, synagogues desecrated, and women assaulted. Many Jews sought refuge in Saint-Jean-d’Acre or Jerusalem, resulting in fewer than a thousand families remaining in Safed. Louis Loewe, who would later serve as the secretary to the renowned English Jewish philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore, was in Palestine at the time and can attest to these events: “In addition to everything they had looted, the Druze demanded from the Jews a sum equivalent to 2,500 English pounds, which, of course, the Jews were unable to pay. The Druze then seized the rabbi in charge of the Ashkenazi community, an elderly man, tied his hands and feet and placed the blade of a sword on his neck. They threatened to cut off his head if the money is not paid immediately. He did not ask to be spared his life, which he was willing to sacrifice it if it meant saving his community. All he asked for is that a little clean water be poured over his hands so that he can say a prayer and proclaim that God is just in all his ways. Then all present let out a heart- rending cry, and the Druze themselves seem to have been touched. They withdrew the sword and finally agreed to a settlement with the community, giving it time to find a way to borrow the sum demanded9.”

The pogroms of Safed in 1834 and 1838 were driven by religious animosity, a pattern similarly seen in the massacres of Christians by the Druze on Mount Lebanon in 1860. Between 9 July and 17, 1860, violence erupted from Lebanon and the Golan Heights, reaching Damascus. Nearly six thousand Christians fell victim to the bloodshed, with almost a third of the city’s Christian population left by the Ottoman governor Ahmed Pasha to face the attackers. This massacre prompted a mass exodus of Christians seeking refuge in Europe, Africa, the Americas, and even Egypt. Many Christian families of Syrian and Lebanese descent found sanctuary in Egypt towards the close of the nineteenth century.

The decline of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of islamic anti-zionism

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had allied itslef to the Central Powers during the Great War, its Arab territories fell under the control of the United Kingdom and France. This division, agreed upon in secret by the Franco-British Sykes-Picot agreements in 1916, was formalized at the San Remo Conference in April 1920. Subsequently, in July 1922, the League of Nations granted mandates to France (for Syria and Lebanon) and to the United Kingdom (for Palestine and Mesopotamia).

In Palestine, the Balfour Declaration of November 1917 pledged London’s commitment to establish a “national homeland for the Jewish people.” This vision, advocated by the Zionist movement emerging in the late nineteenth century, immediately encountered opposition from the Arab community. Initially political in nature before 1914, this opposition assumed an Islamic character from 1920 onward, tapping into and amplifying longstanding longstanding Muslim rejection of Jews. This rejection mirrored the historical treatment of dhimmis, who sought to shed their subordinate status and claim equality with Muslims.

The emergence of Western anti-Semitic tendencies

Nathan Weinstock, Terre promise, trop promise, Odile Jacob, 2011, p. 129.

A tributary of the Jordan which flows into Lake Tiberias.

Nathan Weinstock, op. cit. p.131.

Nadine Picaudou, Les Palestiniens. Un siècle d’histoire. Le drame inachevé, Brussels, Éditions Complexe, 2003.

In many languages, including Arabic, between 1919 and 1928, and distributed worldwide.

Prior to 1914, Arab opposition to Zionism, especially among the educated Christian Arab elite in Palestine, who were more literate than the Sunni Muslim majority, made a clear distinction between Jews and Zionists. However, after the Great War, with the rise of Islamization of anti-Zionism, this distinction faded away. This shift was evident during the first massacres in Jerusalem in 1920 and in Jaffa (Tel-Aviv) in 1921, where chants like “The Jews are our dogs” and “We will drink the blood of the Jews” replaced slogans targeting Zionists.In 1919, leaflets circulated in Jerusalem and Jaffa likened “Jews”, not specifically Zionists, to “poisonous snakes”10. That same year, explicitly anti-Jewish slogans called for violence: “The Yarmouk11 will be full of blood, but Palestine will not belong to the Jews”12.

This “outright rejection of Zionism”13 soon reproduced the oldest themes of Western anti-Semitism familiar to Christian Arabs. In the immediate aftermath of the Great War, a powerful wave of anti-Semitism swept across Europe, making the Protocols of the Elders of Zion14 a success. In Palestine, the rejection of Zionism made this anti-Semitic forgery of Russian origin a cornerstone of his discourse. Appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies in March 1921, Winston Churchill travelled to Cairo, where he received Palestinian delegates who, in the memorandum they handed over to him, took up the main anti-Semitic themes conveyed by this forged document. They would do so again on several occasions during the interwar period. In the same way, they reminded Westerners of the “killing of Christ by the Jews” and their “attempt to poison the prophet”. Henceforth, Arab anti- Zionism drew openly on the sources of European anti-Semitism.

The Pogroms of 1920 and 1921

In the spring of 1920, the Muslim pilgrimage of Nabi Mussa (the Prophet Moses), scheduled for April 4, happened to coincide with the Jewish Passover (Pesach) that year. Against the backdrop of the Balfour Declaration and the newly established British presence, this convergence of holidays took on a distinct political significance. The pilgrimage holds historical weight as it was established by Saladin, who facilitated Muslim reconquest of Jerusalem after the Battle of Hattin in 1187. This Friday, April 4, 1920, was a day of “great prayer”. In front of an ecstatic crowd (including six hundred pilgrims who had entered the city the day before), the mayor of Jerusalem called on everyone to “give their blood for Palestine”. The crowd chorused: “We will drink the blood of the Jews”. In his turn, the leader of the pilgrims raised his voice and shouted: “Slaughter the Jews” (Itbah al Yahoud!). This was the signal for a four-day outburst of violence (April 4-7, 1920), during which the mob ransacked, mutilated and killed Jews as they passed through the very heart of Jerusalem. The British-led Arab police contingent refused to intervene, and some Arab policemen even took part in the riot. More than two hundred Jews were injured, mostly by stabbing. Six were killed. Many women were raped.

The British appointed a commission of inquiry (known as the Pallin Commission), which presented its conclusions a few months later. It held Palestinian associations responsible for the violence. The first consequence of the pogrom was to uproot the Jews who had always lived in Jerusalem’s Old City, many of whom moved to the city’s western districts.

A year later, violence broke out in Jaffa, a mixed city where twenty-six thousand Arabs and sixteen thousand Jews live together. Following a demonstration organized on May 1er (Labor Day) by Jewish, Communist and Socialist demonstrators, who found themselves in conflict as they often did, some Arabs interfered. Strangers to the quarrel, they turned it into a pogrom, forcing open the doors of an immigrant home and massacring its inhabitants. As in Jerusalem the previous year, some of the Arab policemen refused to intervene, or even took part in the murders. Among the victims was the father of modern Hebrew literature, Yossef Haïm Brenner. On May 5, 1921, the French consulate’s translator, a witness to the events, reported: “The city of Jaffa was soon the scene of extreme savagery. Muslims and Christians were beating with sticks all the Jews they met on their way15.”

From May 4 onward, the riot expanded to neighboring towns, escalating to even more alarming levels. Ultimately, fifty Jews and fifty Arabs lost their lives, the latter at the hands of British police. Similar to the events in Jerusalem the previous year, the rioters showed no discrimination between Jews who had resided there for generations and recent Zionist immigrants. Their attacks were not aimed solely at Zionists but at Jews as a whole. Following these riots, Jewish society in Palestine grappled with a sense of vulnerability. It became acutely aware of the seemingly unyielding nature of Arab opposition. In 1922, a prominent Jewish journalist, Itamar Ben Avi, eldest son of the great renovator of the modern Hebrew language, Eliezer Ben Yehuda, wrote: “The waves and stormy seas of Islam will be unleashed in the end. If we fail to stem the tide by means of an agreement […], it will flood us with its wrath. […] Tel Aviv, in all its splendor, our coasts and all their beauties will be annihilated16.”

The Pogroms of 1929 and the role of the Grand Mufti

This is in contrast to the powerful Nashashibi family, who represent more of a commercial bourgeoisie centred around Palestine’s largest city, Jaffa.

Nadine Picaudou, op. cit. p. 82. The author even specifies that it was as early as 1922 that the Palestinian national movement wanted to make Palestine “a pan-Islamic cause”, p. 83.

Quoted in Benny Morris, Victimes. Histoire revisitée du conflit arabo-sioniste, Éditions Complexe, 2003, [first English edition, 1999], p. 130.

Report sent to the Quai d’Orsay, quoted in Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, tome 2, Fayard, 2002, p. 172.

At the time, the British police force in Palestine numbered a total of two hundred and ninety-two officers.

Benny Morris, op. cit. p. 131.

Appointed (rather than elected) by the British in the spring of 1921, Amin al Husseini assumed the role of Mufti of Jerusalem representing both a powerful clan and a rural, archaic Palestine17. He elevated the Jewish- Arab conflict to the religious sphere, exacerbating tensions with frequent provocations surrounding the issue of the “Wailing Wall” (Kotel Ha Maaravi).

In front of the Wall, Jews had only a small area for prayer, a passageway approximately four meters wide. At that time, there was no expansive plaza as we know today. This narrow piece of land belongs to a religious Muslim foundation; it is Waqf property and therefore theoretically inalienable. At least two Jewish attempts to acquire it, in 1840 and 1911, were unsuccessful. After the Turks, the British refused to accept any proposal to cede it.

At the head of the Muslim Supreme Council, where the British had placed him in 1922 (after having been enthroned as Mufti of Jerusalem by the same British), the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem used “Jewish provocations” as a pretext to set up a “committee for the defense of Muslim holy places in Jerusalem”, Al Buraq al Sharif (the Arabic name for the Western Wall), in November 1928. At the same time, he convened an Islamic conference to be held in the city three years later.

In the spring of 1929, following the Yom Kippur incident of the previous year, the Grand Mufti escalated his own provocations against the Jews. The calls of the muezzin echoed as loudly as possible during Jewish prayers, amplified by the booming public address system. At crucial junctures in the Jewish liturgy, he orchestrated traditionally boisterous Sufi ceremonies, complete with cymbals, conducted right beside the Wall. To further disrupt the prayers of the faithful, the Grand Mufti had an entrance carved into one of the walls adjacent to the Esplanade of the Mosques (Temple Mount), effectively transforming the holiest of Jewish prayer sites into a squalid, cacophonous corridor, littered with refuse and frequented by the mules of Muslim merchants.

In May 1929, Jewish worshippers gathered in front of the Wall and were insulted and pelted with stones. In June 1929, the British High Commissioner, John Chancellor, proposed restricting Jewish access to the Kotel (“Wailing Wall”), in the hope of satisfying Muslim fears of an outbreak of violence. It was all in vain, as many Arab leaders had realized that sectarian hatred was the only way to revive a divided and flagging national movement. If they manage to politicize the religious question, explains historian Nadine Picaudou, it could become “a powerful tool for mobilizing Muslims around the world18.”

At the same time, supporters of Zionist leader Zeev Jabotinsky (whose movement had left the Zionist organization four years earlier) were determined not to back down. They demanded that the British recognize the presence of Jews in front of the Wall as a right, not a tolerance, a demand officially reiterated on August 11, 1929 by the Zionist Congress meeting in Zurich. The tension increased as Tisha Be Av approached, the 9th day of the month of Av (August 15, 1929), a day of mourning in Jewish tradition commemorating the destruction of the two Temples. The previous day, August 14, three thousand Jewish worshippers had gathered in front of the Wall. In the Arab community, rumors spread that Jews were preparing to march on the Mosque Esplanade. Leaflets were distributed in the city and surrounding Arab villages, urging people to “attack the Jews” and march on Jerusalem to “save the holy places” [sic] from Jewish insult. “These barbaric acts have stirred the hearts,” reads one of the leaflets, “and the people have begun to clamor ‘War, Jihad, Rebellion’. […] O Arab nation, the eyes of your brothers in Palestine are upon you […] and they are awakening in you the religious feelings and national ardor to rise up against the enemy who has mocked the honor of Islam, raped women and killed widows and infants19.”

Jabotinsky’s movement responded by marching its Betar activists past the Wall on August 15 (Tisha be’Av). The movement’s younger members flew the Zionist flag (blue and white), chanting “The Wall is ours”. For the Muslims, this was a provocation which, the very next day, Friday August 16, led to a counter-demonstration with the same cry of “The Wall is ours”, but punctuated by calls to “slit the Jews’ throats”. Incidents remained limited, however, despite the murder on Saturday August 17 of a Jewish child who had been beaten to death by his Arab neighbor for trying to retrieve a ball he had accidentally dropped in his garden.

Yet, it was within the Arab community that tension reached its peak, fueled by rumors of an impending Jewish assault on the Mosque Esplanade. Meanwhile, across the divide, the Jewish community buzzed with fears of impending massacres. In the days leading up to Friday, August 23, emotions ran high, with apprehension mounting as armed Arab villagers began converging on Jerusalem from Thursday, August 22, brandishing sticks and knives.On Friday, August 23, the situation deteriorated rapidly. Amidst the large Arab crowd gathered for the Friday congregational prayer, the call to “attack the Jews” spread well before noon, even before the conclusion of the prayer. Following the imam’s impassioned speech, men poured out of the mosque to assail the Jewish quarters. A chaotic mob armed with an assortment of weapons including sticks, knives, sabres, clubs, and pitchforks surged through the Jewish quarter of the Old City, adjacent to the Esplanade of the Mosques, inflicting beatings, injuries, and fatalities upon Jews in their path. The violence then spilled over into the Mea Shearim quarter, exclusively inhabited by Orthodox Jews. On August 28, Georges Achard, head of the French Consulate in Jerusalem, reported: “It was a scene of carnage, with the Arabs slitting the throats of those in front of them or stoning them to death, and showing no mercy for the women and children20“.

The police were overwhelmed. The British forces21, reduced to less than a hundred soldiers, were outnumbered, despite reinforcements sent in over the following days. Arab policemen, even though they were mandatary government officials, refused to fire on the rioters. The violence spread to Hebron on the same day. There, the only British policeman present in the city, Raymond Cafferata, would testify to the collusion of many Arab policemen with the rioters (see below).

In Jerusalem, while no English policeman opened fire, the Haganah (Jewish self-defense militia formed in 1920; “Haganah” means defense in Hebrew) managed to protect several Jewish neighborhoods with the help of a few Christian Arabs who came to the aid of their Jewish neighbors. Historian Benny Morris writes: “The simultaneity of several armed attacks on outlying neighborhoods led the Jews at least to assume the existence of centralized coordination and preparation22“. Two significant Jewish libraries, belonging to Joseph Klausner and S.J. Agnon, were destroyed in Jerusalem, resulting in the loss of over three thousand rare documents on the history of Palestine in the flames. This tragedy occurred five years after Agnon had already lost his library in Berlin to a fire. On Friday, August 23, seventeen Jews lost their lives in and around Jerusalem.

The violence spread to Tel Aviv on August 25, where Arab demonstrators attempted to enter the city. British police responded by opening fire. Simultaneously, in Haifa, Arab rioters ransacked the Jewish district of Hadar ha Carmel, resulting in 23 deaths. As a consequence, 60% of Jewish villages in Palestine came under attack, with homes and equipment destroyed, crops set ablaze, and livestock slaughtered. Six Jewish settlements were completely obliterated.

The most horrific massacres occurred in Hebron, home to six hundred predominantly Orthodox Jews, on Saturday, August 24, 1929. Within two hours, sixty-seven Jews, including twelve women and three children from the ultra-Orthodox community, were brutally murdered. Raymond Cafferrata, the English police chief in Hebron, along with a lone Jewish policeman, courageously fired on the rioters, while Arab policemen refused to intervene. Amidst the chaos, hundreds of Jews were rescued by their Arab neighbors in Jerusalem, Hebron, Saint-Jean-d’Acre, and Lydda. Even near Tel Aviv, Arab police officers stepped in to protect Jews amidst the turmoil.

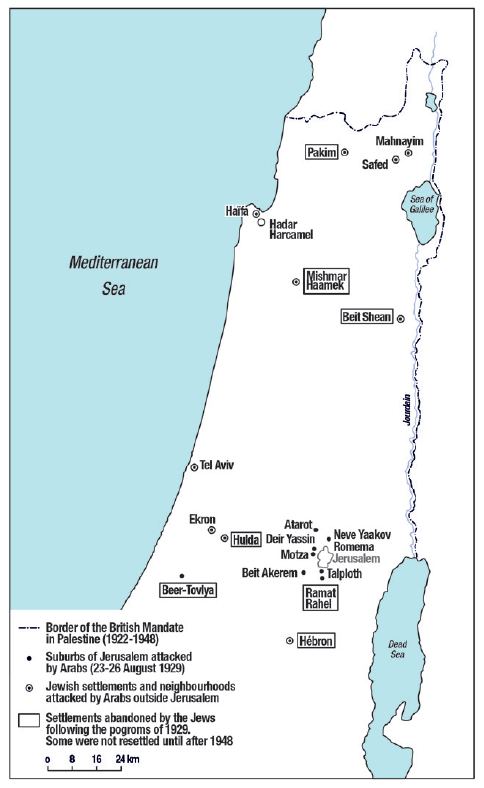

The Pogroms of 1929

The British Commission of Inquiry and testimonies of the Pogroms of 1929

Nathan Weinstock, op. cit. p. 202.

Albert Londres, Le Juif errant est arrivé (1929), éditions 10-18, 1975, p.198.

Nathan Weinstock, op. cit. p. 203.

Abdul Wahab Kayyali, Histoire de la Palestine, 1896-1940, translated from Arabic, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1985.

Nathan Weinstock, op. cit. p. 204.

Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, Tome 2, p. 175.

The Hebrew term Yishuv referred to the community of Jews living in Palestine before the creation of the State of Israel.

A Russian Jew who became a British citizen, Haïm Weizmann chaired the World Zionist Organization between the wars, and was one of the main architects of the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

Dominique Bourel, Martin Buber, p. 400.

Henry Laurens, op. cit. p. 176.

Georges Bensoussan, Une Histoire intellectuelle et politique du sionisme, Fayard, 2002, p. 839.

Ibid. p. 839.

Raymond Cafferrata, the English police officer on duty in Hebron, told the British commission of inquiry: “When I heard shouting in a room, I went up a sort of corridor or tunnel, and saw an Arab cutting the head off a child with a sword. He had already hit him and was about to strike again with the sword, but when he noticed my presence, he tried to land the blow on me. But he missed. He was almost at the end of my rifle barrel. I shot him in the groin. Behind me lay a Jewish woman covered in blood next to a man I recognized, despite his civilian clothes, as an Arab police officer from Jaffa, named Issa Shérif. He was bending over the woman, a dagger in his hand. He saw me and rushed into a nearby room, where he tried to lock himself in, shouting in Arabic: “Your honor, I am a policeman” […]. I entered the room and shot him dead23.”

The massacre in Hebron marked the end of the city’s Jewish community. Just two days later, what remained of the six hundred Jewish residents left the town under British escort. On August 29, another massacre stained the historic Jewish community of Safed, claiming the lives of eighteen Jews. Five days prior, on August 24, a preceding massacre had resulted in the deaths of twenty-six Jews, each murder accompanied by heinous acts of atrocity, sexual abuse, and torture. In Safed, Hebron, and Jerusalem, it was predominantly Orthodox Judaism that bore the brunt of the massacres. The overall toll of the riots amounted to one hundred and thirty-three Jews and one hundred and sixteen Arabs killed, the latter mostly at the hands of the British police. Three hundred and thirty-nine Jews and two hundred and thirty-two Arabs were also injured.

All the witnesses – Jewish, English, Western consular staff – seemed stunned by the barbarity of the riot. In Hebron, the brutality reached horrifying levels, with Jewish children subjected to torture before being mercilessly murdered. French senator Justin Godart, who had founded the France- Palestine association three years prior, documented these atrocities in his notebooks. “Among those killed, some had their throats slit by the neck or face, while others suffered unimaginable mutilations,” he wrote. “A rabbi’s testicles were removed, and two women had their left hands burned.” The accounts of the Hebron atrocities are chilling: a paralytic was killed and had his eyes gouged out, his daughter raped, and her breasts mutilated; a baker was bound, had his hands and feet tied, and his head placed on a stove; a lady identified as Mrs. Sokolov sat down and slit the throats of six yeshiva students; a schoolteacher from Tel-Aviv was murdered, his throat brutally slashed; a father-in-law, son of the rabbi, was praying when he was scalped and had his brains removed.

The extreme cruelty displayed in Godart’s narrative may spark fears of it being a propaganda story. At the same time, the French journalist Albert Londres, who had returned to the area, provided feedback of the Hebron massacres that supported the French senator’s version: “Around fifty Jewish men and women had taken refuge outside the ghetto, at the Anglo-Palestinian bank. [The Arabs […] were quick to sniff them out. It was Saturday 24th at nine o’clock in the morning. […] But here it is in two words: they cut off hands, they cut off fingers, they held heads over a stove, they enucleated eyes. […] Men are mutilated. Girls as young as 13, mothers and grandmothers, were jostled in blood and raped in chorus24.”

However, the rioters did not attack the English soldiers who embodied the colonial presence. Historian Nathan Weinstock notes that “what we see here is the crystallization of the age-old hatred for the dhimmi, which takes on fearsome forms as soon as the latter pretends to shake off the yoke that weighs him down…”.25 For Weinstock, this massacre was similar in nature to the one that struck Assyro-Chaldean Christians in Semile, Iraq, four years later. He sees this massacre as a continuation of the large-scale massacres (which caused around two hundred and fifty thousand victims) which, between 1914 and 1919, had decimated the Assyro-Chaldeans exterminated by the Turks and Kurds in the conflicts during the Ottoman Empire.

Although fiercely anti-Zionist, the Palestinian Communist Party, appalled by the violence, ordered its members to join the ranks of the Jewish defense. The atrocity of the crimes prompted several Muslim notables to issue a joint proclamation dissociating themselves from the “actions of the mob26“. Despite the fact that several Arab families came to the aid of Jews in distress, many also noted the “perfect equanimity with which these horrors were greeted by the Muslim population, even when they stayed away from the killings27“.

In Arab society, the account of events does not mention the massacres, but speaks of the “Al-Bouraq revolution”. Thus, “Arab memorialists,” comments historian Henry Laurens […], “consider the acts committed during the violence to be entirely legitimate and overlook the fact that the victims were mainly defenceless civilians – women and children – while they are indignant about the Jewish reprisals28“. The widespread ignorance of the inflicted suffering and, with a few exceptions, the absence of collective introspection, was verified throughout the Arab world. This is evident in fundraising efforts aimed at supporting the families of Arab rioters involved in the massacres.

For Jewish society, the shock was immense. The Haganah had shown itself to be largely incapable of protecting its own people. Jewish leaders were convinced of the need to transform this modest militia into a small army, and no longer rely solely on the British for defense. The trauma was all the more violent as the Yishuv29 was weakened by a a difficult immigration situation and an economic depression from which it had only recently begun to recover. Like others, Haïm Weizmann30, president of the World Zionist Organization, was overcome by pessimism: “The current Arab leaders, murderers and thieves, want only one thing – to throw us into the Mediterranean Sea”, he wrote to Albert Einstein on November 30, 192931.

On August 31, 1929, the Muslim Committee for the Defense of the Holy Sites published its version of events. The Jews, it explained, were trying to take over the Esplanade of the Mosques and were causing disturbances around the Western Wall (Al Buraq), prompting the Muslims, in self-defense, to react. In agreement with the Grand Mufti, the Committee demanded that the British disarm “the Jewish soldiers” (the Haganah). This version of events, explains Laurens, “has remained dominant in Muslim writings to this day32.”

London appointed a commission of inquiry. Headed by Sir Walter Shaw, it arrived in Jerusalem on October 25, 1929, and as the hearings progressed, in a very tense atmosphere (fifty-seven attacks were deplored between the beginning of September and mid-November 1929), the Commission became increasingly disillusioned, fearing that the situation was becoming insoluble. At a hearing on December 2, 1929, the Grand Mufti, after referring at length to the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion33“, compared himself to Jesus, who, he explained, had been confronted in the same place 1,900 years ago by a tribunal at the request of the Jews who had denounced him.

The fragile trust that had been established here and there in Palestine between Jews and Arabs was shattered. Ties of conviviality and friendship were called into question. Understanding, already precarious, regressed by several decades. The cooperation that sometimes prevailed frayed, if not disappeared altogether, at a time when Jewish demographics were at their worst. For the first time since 1914, fear gripped a large part of Jewish society in Palestine (one hundred and seventy thousand souls). “Are we sitting on a volcano?” read the headline on September 6, 1929, in the Hebrew daily Doar Ha Yom, the mouthpiece of Jabotinsky’s revisionist Zionism34. Many feared that an eruption of violence would lead to the complete annihilation of the Jewish National Homeland. “The idea of a general massacre of the Jews,” declared Ben Gurion in January 1930, “has gained ground35“.

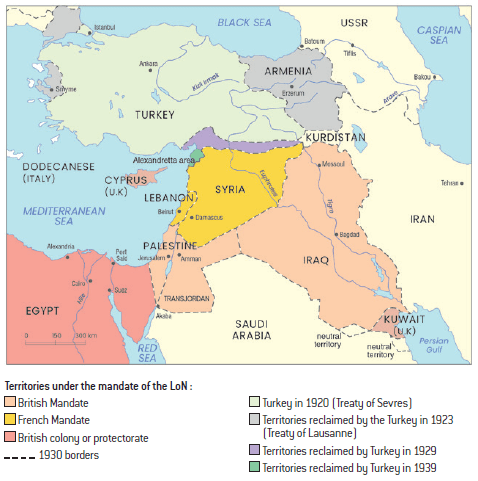

The borders of 1930

The Arab rejection of the British mandate and the pogroms of 1936-1948

1936: the beginning of the “Great Arab Revolt” against the British Mandate and the Zionist movement

Many of them of German origin and often professors (among them Gershom Scholem) at the fledgling Hebrew University of Jerusalem, inaugurated that same year in 1925, intended to renounce the nation-state of the Jewish people in favor of a binational Jewish-Arab state in Palestine. Lacking any interlocutors, the association eventually dissolved itself in 1933.

Quoted by Henry Laurens in Le Retour des exilés. La lutte pour la Palestine, Robert Laffont, 1998, p. 473. Archival source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nantes, Jerusalem file B. 110.

In The Price of Israel. Écrits politiques 1917-1974, Éditions de l’éclat, 2017, pp.14-15.

The “Great Arab Revolt” against the British Mandate and the Zionist movement began on April 15, 1936. Violence immediately broke out in the mixed cities, particularly in Jaffa, where nine Jews were killed in the space of a few hours on April 19, 1936 (causing Jewish residents to flee to Tel Aviv), undermining the credibility of the elders of Brit Shalom36, an association of Jewish intellectuals founded in 1925. Isolated Jews were murdered in the countryside, and Jewish vehicles were increasingly forced to travel in convoys, especially on the Tel Aviv/Jaffa-Jerusalem Road, the Yishuv’s main communication route. Ambushed convoys were destroyed, and their members, including children, were murdered to the last man. The rebels took no Jewish prisoners and left no wounded behind.

The first witnesses were struck by a display of cruelty that stunned and shook those who remained in favor of dialogue: “Stoned and clubbed, they were murdered, crushed to such an extent that two corpses could not be identified”, notes a French diplomatic report of the time37. The barbarity of some of the murders, in which the victims were found with their organs cut out and stuffed into their mouths, their bodies disemboweled and mutilated, their children tortured, as well as the destruction of crops and fruit trees, stunned the Jewish population and left everyone wondering about the future of the Jewish National Homeland. Many were repulsed by this accumulation of violence. Some, including those most sympathetic to Arab nationalism, saw it as casting a shadow over the legitimacy of the revolt.

On June 6, 1936, Gershom Scholem wrote to his friend Walter Benjamin, who had remained in Germany: “For several weeks now, the Arab side has been waging a veritable partisan war, with increasing violence, revealing a hitherto unsuspected strength that is nothing less than terrorism and barbarism. The general strike in Arab cities – and no doubt also to a large extent its financing – is certainly being imposed on the population by the internal terror exercised by the Arabs themselves…38“. The repetition of assassinations, whose sordid details cluttered the press, eventually triggered a reaction of hatred, particularly among Jewish youth.

In response to the Arab rebellion, the Mandatory Authority set up the Royal Commission for Palestine, headed by Lord Peel. It travelled to Palestine at the end of 1936 to interview a large number of protagonists, both Jews and Arabs. Including the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, who, after an initial refusal, agreed to appear before the commission and declare: “Give us independence, and we will deal with the Jews on our own!”

Proposal of the Peel Commission Plan for Palestine’s Partition Met with Arab Rejection

At first, the Zionist camp rejected the Peel Plan, but they changed their minds at the Zionist Congress held the following month in Switzerland: Ben Gourion and Weizmann, in particular, succeeded in reversing the initial trend, and the Congress ultimately voted in favor of the partition plan.

Alluding to the massacre of Assyrian-Chaldean Christians in 1932, when Iraq had just gained its independence.

Quoted in Nathan Weinstock, Promised Land, Too Promised, op. cit. p.249.

Ibid, p. 270.

In Georges Bensoussan, Juifs en pays arabes, op. cit. p. 609.

He perfected the “gas truck” technique that enabled the first systematic massacres of Jews using gas (carbon monoxide), at Chelmno, Poland, on December 7, 1941.

Fertile Crescent and Swastika. The Third Reich, the Arabs and Palestine, Éditions Verdier, 2009 (first German edition, 2006).

The Commission’s plan (or Peel Plan) was made public at the beginning of July 1937, a thick four-hundred-page document from which it emerged that the partition of Palestine was the only viable solution. On the Arab side, the refusal was immediate and unanimous39. The impasse was all the more difficult as the Grand Mufti refused to provide any assurances to the Jewish community within the framework of a future Palestinian Arab state : “We doubt neither the sincerity nor the humanity of the Mufti’s intentions and those of his colleagues,” wrote the Peel Commission’s rapporteurs, “but we cannot forget what has recently happened, despite the provisions of a treaty and explicit assurances, to the Assyrian minority in Iraq40; nor can we forget that the Arab politician has never concealed the hatred he feels for the National Home and that this now permeates the entire Arab population41. ”

The rebellion resumed on a larger scale in autumn 1937, reaching its peak in autumn 1938. This time, in contrast with the early months of the “troubles” as they were then known, London was determined to put down the uprising so as to have a free hand in a Europe where the spectre of war with Hitler’s Reich was looming large. At the same time, he distanced himself from the Zionist movement. Thus, with the promulgation of a new White Paper in May 1939, the Arab rebellion, while militarily broken, won the political battle by obtaining satisfaction on two of its main demands: Jewish immigration and the sale of land. At the same time, it reiterated its refusal to grant any national rights whatsoever to the Jewish population, as suggested by the slogan: “The English to the sea and the Jews to the grave42“.

In September 1939, the outbreak of war in Europe made Palestine a hub of British mobilization. The country had a front-row seat for both the war in the Mediterranean and the Balkan campaign in 1941. This was even more true in the spring of 1942, with the advance of the German army (Afrika Korps) commanded by Rommel, whose troops advanced towards Egypt, where they entered in the early days of summer 1942. Both British and German intelligence services acknowledged the Arab population’s sympathy for the Afrika Korps. On June 16, 1942, the former Grand Mufti, who had taken refuge with his followers in Berlin since November 1941, declared on German radio (Radio Zeesen), in Arabic, that there would be no compromise in Palestine because the Jews had no right to the land. On July 7, 1942, when the Afrika Korps was less than 100 km from Alexandria, Radio Zeesen again broadcast in Arabic: “Kill the Jews before they kill you (…) Arabs of Syria, Iraq and Palestine, what are you still waiting for? The Jews are planning to rape your women, kill your children and destroy you. According to Islam, defending your lives is a duty that can only be fulfilled by destroying the Jews (…) Kill the Jews, burn their property, destroy their stores, annihilate these minions of English imperialism. Your only hope of salvation lies in annihilating the Jews before they destroy you43.”

Meanwhile, on July 13, 1942, in the greatest secrecy, the Reich set up a commando named after its leader, the “Walther Rauff kommando44” that arrived in Athens on July 29 to await a transfer order to Africa. The mission of these twenty-four SS officers and NCOs was to organize the mass murder of Jewish communities in Libya, Egypt and, above all, Palestine. To this end, Berlin counted on the participation of the Arab population: “Countless Arabs, some of them already organized, voluntarily offered their support to the Germans”, according to German historians Mallmann and Cüppers45.

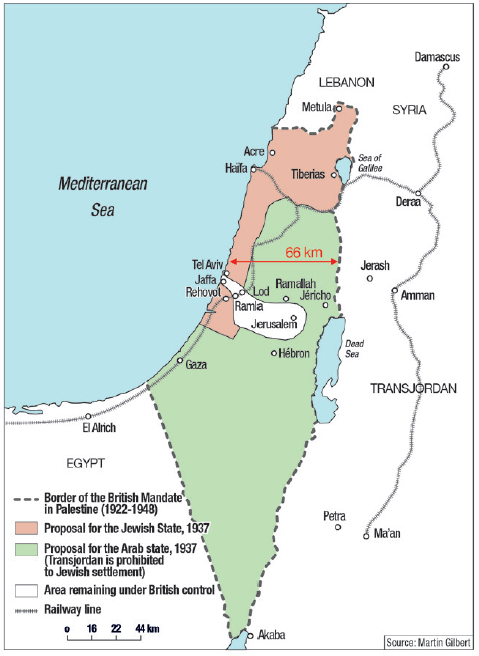

Peel Commission project, 1937

Distance between the sea and the Jordan River

1947: United Nations Partition Proposal Faces Fresh Arab Opposition and Increased Violence

By the spring of 1945, with the conclusion of the war in Europe and the Mediterranean, Palestine faced the same challenges as it did in 1939. While the years of conflict had seen relative calm, tensions flared up again in 1945 between the Zionist movement and the United Kingdom, which persisted in its White Paper policy.

However, crippled by the six-year war it had endured and preoccupied with the onset of the Cold War, the United Kingdom decided in February 1947 to hand over the Palestinian issue to the United Nations. The UN set up an ad hoc commission (UNSCOP46), which gradually worked towards a solution similar in every respect to that of the Peel Report of 1937. This led to a rise in tensions between Arabs and Jews, particularly in the autumn of 1947 when the United Nations was on the verge of coming to a decision. For its part, London announced the definitive departure of its troops by mid-May 1948.

From Morocco to Iraq, the Palestine issue is starting to ignite the “Arab streets”. Several Arab politicians warn that if a satisfactory solution in Palestine is not reached, “severe measures” will be taken against all Jews in Arab countries. On November 24, 1947, the head of the Egyptian delegation to the United Nations General Assembly, Mohammed Hussein Heykal, warned that “the lives of millions of Jews in Muslim countries would be threatened by the establishment of a Jewish state. The partition of Palestine could create in these countries an anti-Semitism even more difficult to uproot than the anti-Semitism the Allies tried to eradicate in Germany.”47

Following the United Nations vote on November 29, 1947, reactions in Arab countries were often violent. In many of them, the atmosphere resounded with calls for the massacre of “all Jews”, including children. This is no mere rhetoric, when we recall that on November 2, 1945, on the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, particularly barbaric pogroms took place in Benghazi and Tripoli in Libya, leaving dozens of Jews massacred in atrocious conditions. In November 1947, as soon as the UN decision was known, identical scenes of terror broke out in Bahrain and Syria, where Jewish schools, synagogues and private homes were attacked. In Aden, seventy-five Jews were killed during a riot. In Cairo, several bomb attacks on places frequented by the Jewish community led to the death of around one hundred Jews between June and November 1948.

Within the Arab forces, public discourse suggested an imminent large- scale massacre. “We will wipe you off the face of the earth”, declared the Secretary General of the Arab League in New York on May 15, 1948, the day after the proclamation of the State of Israel and the first day of the invasion. […] “It will be a war of extermination and a memorable massacre that will be remembered like the Mongol massacres and the Crusades .” He adds, with regard to the partition plan, that “The partition line will be nothing but a line of fire and blood. « These statements are no mere boasts. In fact, since December 1947, Arab operations in Palestine have been aimed at “emptying localities of any Jewish presence. Wherever Arab armies prevailed in 1948,” explains Belgian historian Nathan Weinstock, “the Jewish population was effectively massacred (…) or expelled. […] The final objective therefore seems to be, as far as possible, to liquidate all Jewish presence in Palestine.”

For on November 30, 1947, the day after the United Nations’ decision, the conflict between Jews and Arabs erupted in Palestine. While the Haganah was ordered to avoid any action against women and children, the dissident Jewish troops (Irgun and Lehi) did not adhere to such restrictions – nor did the Palestinian militias, who deliberately targeted civilians.

The “Battle for the Roads” Pushes Zionist Forces to the Edge of Defeat

Even before the Uinated Nations decision, Jewish civilians were targeted: on November 10, 1947, six Jewish passengers on a bus from Netanya to Jerusalem were shot dead, and on November 30 seven other Jewish passengers were killed in the same circumstances. On December 2, 1947, an Arab mob armed with knives and axes stormed the Jewish market in the center of Jerusalem, attacking the Jewish population without distinguishing between civilians and soldiers. They were repulsed by the Jewish defense force, despite the hostile attitude of the British forces. Ten days later, on December 12, 1947, twenty-eight civilians from the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem were murdered. The following day, in retaliation, the Irgun carried out several attacks in Jaffa, Jerusalem and Haifa, killing sixteen Arabs. During these first months of fighting, Jewish casualties, most of them civilians, amounted to more than fifty deaths a week (for a population of 600,000). Finally, seven thousand Jews fled the towns near Jaffa and became refugees in their own country.

But it was on the roads that the main battle took place, and it was also there, more often than not, that the systematic killing of Jewish civilians captured in ambushes took place. The Arab-led “battle for the roads”, aimed at isolating Jewish settlements, was about to be won at the end of March 1948. The Zionist forces were on the verge of defeat. To counter this strategy of suffocation, the Haganah equipped its vehicles with a flimsy “armoured” covering (simple sheet metal plates), which did not prevent its convoys from falling one after the other into ambushes, often with very heavy human casualties. The attackers took no prisoners; all members of the Jewish convoys were killed, including women and children, and their corpses often mutilated. Once the news broke, the effect on the Jewish population was intense.

The Jewish settlement of the archipelago made the Arab blockade more effective, eventually reducing the Jewish positions to the point of complete surrender, generally followed by the destruction of the village and the massacre of its population. Each ambush resulted in dozens of deaths. In February and March 1948, entire convoys were almost completely wiped out.

It was against this backdrop that in early April 1948 the combined Jewish forces (Lehi, Irgun and above all the Haganah) embarked on a policy of offensive and reprisal (Plan Dalet) aimed at regaining “control of the roads”, by concentrating their efforts on the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem axis, where Jewish convoys were totally prevented from moving.

The systematic massacre of civilians by Palestinians contributed to the radicalization of Jewish society. This led to a growing conviction among Jews that they were fighting for their survival, feeling cornered. For instance, on April 16, 1948, following the British departure from Galilee, Palestinian forces attacked the ultra-Orthodox Jewish quarter of Safed (which had already endured two pogroms in August 1929. The memory of these pogroms, along with those of the 19th century, lingered heavily in the minds of the Jewish inhabitants – see above): “Our morale is very high, the young people are enthusiastic, we’re going to massacre them48” cabled the Arab commander of the region to the regional commander of the Arab Liberation Army. The Arab desire for “ethnic cleansing” is an essential key to understanding Jewish violence in return. The declared refusal to “live with the Jews” [sic] provokes a similar reaction when Jewish weapons become victorious, resulting in the destruction of hostile Arab villages so as not to allow a “fifth column” [sic] to form behind Jewish lines.

April 1948: Implementation of Plan Dalet to Break Encirclement and Secure Territorial Continuity for the Future Jewish State

In Paix et guerre au Moyen-Orient, p. 85.

The “Dalet plan,” initiated at the start of April 1948, was designed to forestall the looming specter of complete annihilation. Historian Henry Laurens wrote: ” This plan has an essentially military purpose, it is not a political plan to expel the Arab populations49.” Its primary goals were to dismantle encirclement threats that posed existential risks to the Yishuv and to secure territorial continuity for the prospective Jewish state. The expulsion of Arabs, in this context, was a repercussion of all-out warfare, not the principal objective of the military operation.

The tragic events unfolding in central Palestine, particularly in the towns of Lydda (Lod) and Ramleh, following their seizure by the Israelis on July 12 and 13, 1948, brought into stark relief the brutal reality of massacre. It became evident that Palestinian forces, distinct from the regular Arab forces that entered Palestine on May 15, 1948, adhered to a grim norm: the massacre of captured Jews, irrespective of their civilian or military status, gender, or age. The war cry of the Palestinian militiamen, Itbah al Yahoud! (“Slaughter the Jews!”), taken literally, reflects the absence of prisoners.

It’s difficult to estimate the number of victims of atrocities committed on both sides, although it’s believed that the rapid advance of Jewish (and later Israeli) troops prevented several massacres. Between April and November 1948, the Israelis seized almost four hundred Arab villages, while the Palestinians took control of only half a dozen Jewish settlements. Hence the limited number of massacres perpetrated by Palestinian militias.

The conflict was also marked by massacres perpetrated by Jewish (and later Israeli) troops, primarily in the Arab village of Deir Yassin. On April 8, 1948, in the battle for the Arab village of Al Qastal, which blocked the road to Jerusalem, the main Palestinian military leader, Abdelkader al Husseini (nephew of the former Grand Mufti), was killed. In retaliation, Arab militiamen murdered their fifty Jewish prisoners of war. On April 9, near Jerusalem, one hundred and twenty fighters, nationalist militiamen from the Irgun and the Lehi, targeted this small village of six hundred and ten inhabitants. The ensuing battle lasted nearly twelve grueling hours, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. However, it was at the conclusion of this prolonged conflict that the massacre occurred, constituting a war crime that was swiftly condemned by the Jewish Agency and the Haganah. During this atrocity, entire families were mercilessly gunned down, and twenty-five prisoners were executed after surrendering. Both sides exploited the tragedy for propaganda purposes, intensifying panic and contributing to the exodus of the Arab population.

For weeks, the Arab media sensationalized the horrific toll of this war crime, inflating the death toll to four hundred. (However, current consensus on the Palestinian side acknowledges one hundred and seven victims, including combatants.) This exaggerated narrative served to demoralize Arab populations and hasten their exodus from the region. The magnitude of the massacre also cast a shadow over the battle of Deir Yassin. Unlike Deir Yassin, which involved a battle, this incident became a focal point, akin to a “Palestinian Oradour” (a reference to the French village massacred during World War II). Consequently, other tragedies, such as the massacre of almost two hundred Jewish prisoners from the Kfar Etzion kibbutz after their surrender, were marginalized and relegated to the background.

On April 13, 1948, four days after the tragedy of Deir Yassin, a Magen David Adom (the Jewish equivalent of the Red Cross in Palestine) medical convoy set out from Jerusalem in an attempt to reach Hadassah Hospital was killed. The ten-vehicle convoy included nurses, doctors, university professors, several wounded and an escort of a few armed soldiers. Ambushed on the outskirts of Jerusalem, the convoy was machine-gunned for six hours. The British, who were on the scene, refused to intervene and also prevented the Haganah from doing so. At the end of the siege, the buses were doused with petrol and set on fire. Seventy-seven people were burned alive. Intervening late in the day, the British recovered around twenty wounded.

Finally, on November 29 1947, the UN adopted the plan to divide Palestine into two states. On May 14, 1948, as the British Mandate came to an end, David Ben Gurion proclaimed the birth of the State of Israel. However, instead of proclaiming the birth of the State of Palestine on the same day, contingents from five Arab countries, with the backing of the Arab League, invaded the Jewish state.

For several centuries, Muslim theological polemics against Judaism did not give rise to any real Judeophobic passion. However, in the 19th century, the emancipation of the Jews, encouraged in particular by some European schools (and above all the network of Alliance israélite universelle schools50), resisted the submission inherent in the dhimma which, although abolished in law by the Ottoman Empire (1856), was still very much alive in people’s minds. As article 31 of the Charter of Hamas (acronym for “Islamic Resistance Movement”, 1988), the Palestinian Islamist movement, demonstrates : “In the shadow of Islam, followers of the three religions, Islamic, Christian and Jewish, can coexist in security and trust. It is only in the shadow of Islam that security and trust can be found, and recent and ancient history is a good witness to this.”

Indeed, the liberation of the Jewish dhimmi sounds like an offense in part of the Arab-Muslim world, where it remains impossible to consider “Jewish otherness on an equal footing”. To this day, this cultural blockage fuels the Arab-Israeli conflict, when “emancipated Jews” claim to be rebuilding a nation-state on the “land of their ancestors”.

Today, the Jewish dhimmis, those “children of fear” (or “of death”), are not forgiven for having succeeded in creating a state that ranks among the most developed countries in the world. And one that has held its own against several Arab armies in the course of numerous wars. For the Arab psyche, the State of Israel remains an unforgivable slap in the face, a mystery and a heartbreak. It is also a a humiliating blow to the prevailing sense of stagnation within the Arab world, providing fertile ground for the propagation of the myth of the “Jewish conspiracy.”

Over the past thirty years, this anti-Semitism has become more radical. It has also become more Islamized, inspired by the work of the Egyptian “Muslim Brother” Saïd Qutb, whose essay Our Fight Against the Jews, published in the early 1950s, remains the benchmark of contemporary fundamentalism to this day. For Saïd Qutb, the Jews are guilty of having emancipated themselves from Muslim domination and created a Jewish state in the heart of the Arab-Muslim world. They are responsible for the “modern doctrines of atheistic materialism” (in no particular order, communism, psychoanalysis and sociology) that have led to “the destruction of the family and the collapse of sacred relations in society”. The evil work of “three Jews” – Marx, Freud and Durkheim – illustrates the subversive role of the Jews in “contemporary immorality destined to destroy humanity”.

Saïd Qutb’s Islamic Judeophobia joins the politically-inspired racist anti- Semitism of the XXe western century, marked by the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”. The more the Arab world failed to destroy the State of Israel, the stronger the “Jewish conspiracy” theory became. In 1988, Article 32 of the Hamas Charter explicitly refers to “the endless intrigues of the Zionists who, after Palestine, want to extend from the Nile to the Euphrates”. In order to “promote the objectives of the Zionists”, Jews are now openly accused by Hamas of mastering the world’s wealth and controlling the media. And, in the past, of having been behind the French and Russian Revolutions, as well as the two world wars. This “genocidal” ideology (when it aims to destroy a sovereign state) is mirrored in the Lebanese Shiite militaro-religious movement Hezbollah (“Party of God”), which also advocates “all-out war” against Israel and the Jews.

The sovereignty of the State of Israel, where Muslims are for the first time in the history of Islam under Jewish domination,” writes Islamologist Méir Bar Asher, “is therefore an intolerable anomaly. Indeed, not only do Jews have no right to dominate Muslims, but the opposite must happen, as has been the case throughout history, for Islam must dominate all other religions51.” Bar Asher continues: “From a Muslim perspective […] Jews are supposed to lead a life of humiliation and poverty in the shadow of Islam; that this is no longer the case is an endless scandal.

When the murderous discourse imputes to the victim the design it harbors against them, the Jews and Israel are accused of a genocidal project against Muslims, indeed against humanity as a whole, as article 15 of the 1988 Hamas Charter (revised in 2017) shows: “the Zionist project is not aimed solely at the Palestinian people; it is the enemy of the Arab and Islamic Ummah, whose security and interests it gravely threatens. It is also hostile to the Ummah’s aspirations, unity, rebirth and liberation, and has been the main source of its problems. The Zionist project also represents a great danger to the security, international peace and stability of humanity as a whole”.

Focused on the Jewish state, this anti-Judaism, rooted in Muslim origins, is currently fueling a surge of imagery reminiscent of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer. Its goal isn’t just to morally discredit Israel as a Jewish state, but also to dehumanize the Jewish people themselves. It insinuates, like background music, that the vanishing of the Jewish state would secure the salvation of the Muslim world tomorrow.

Because only dhimmis are tolerated, the idea of a sovereign Jew is metaphysical nonsense. The problem is no longer the “surplus people” of pre- 1945, but the “surplus State” whose disappearance will guarantee the world’s happiness. This demonological anti-Zionism masks an anti-Semitism that advocates the extermination of the Israelis “as a principle”. Not because of what they do, but for who they are. Yet, despite this tide of calls for mass murder, the Western media pay little attention to contemporary Muslim anti-Semitism. This indifference calls into question their ability to listen to a reality that is far removed from their frames of thought, and, for some of them, to rid themselves of a latent or repressed anti-Semitic prism. Yet, the whole experience of the last century has taught us that great catastrophes are always preceded by warning signs that go unheeded by those whose first duty it was to take them seriously.

We would like to express our gratitude to Virginia Ricard for proofreading this study in English.

No comments.