Retirement: Lessons from the Swedish reforms

Introduction

The evolution of the Swedish retirement system

The appearance of the first occupational schemes at the end of the XVIIIth century

The break-off: the XIXth century

From 1900 to 1930, the establishment of universal pensions and the road to democracy

From 1930 to 1950, the birth of Swedish corporatism and the Saltsjöbaden agreements

The 1950s: The rise of the ATP system (Allmän Tilläggs Pension)

Reforms in the 1960-1970s

The 1990s crisis and the reformed pension system

How the reform was so successful

The role of Swedish political culture

Structuring the reform work

Conclusion

Annexes

Summary

No matter the country, the era, or the government, few things in politics are as contested as issues related to retirement and pensions reform. This paper aims to portray how pensions and pension reforms have evolved over time in Sweden.

Social policy and pension reforms are a result of their time. As such, this also represents the history of Sweden; how the country grew from being a tempestuous and poor war-torn country to the modern prosperous democratic welfare-state it is today.

Kristoffer Lundberg,

Kristoffer Lundberg, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, Sweden.

Swedish Political Parties

The translations used for the names of political parties in this study are as follows:

Centerpartiet: Centre Party

Kristdemokraterna: Christian Democrats

Liberaleerna: Liberals

Moderata samlingspartiete: Moderate Party

Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti: Social Democratic Party

See Gender Equality Index, 2017. At-risk of poverty is used as a proxy for social (“Income Mobility Statistics in Sweden”, 2018, ).

See Government Offices of Sweden, Ministry of Finance, “The Swedish Model”, 2017.

See Bo Könberg, Edward Palmer and Annika Sundén, “The NDC Reform in Sweden: the 1994 Legislation to thePresent”, in Robert Holzmann and Edward Palmer (eds.), Pension Issues and Prospects for Non-Financial Definede Contribution (NDC) Schemees, The World Bank, 2006, pp. 449-466.

By international comparisons, contemporary Sweden and the other Nordic countries are considered prosperous due to the even distribution of their resources. Furthermore, Sweden combines high levels of individual freedom and social mobility1, due, in large part, to the Swedish economic and social model which was designed for inclusive growth. The Swedish model consists of three fundamental pillars: a labour market that facilitates adjustment to change, a universal welfare policy, and economic policy that promotes openness towards the world and macroeconomic stability2.

The Swedish welfare policy is based on universal principles by which all citizens have access to social protection in the form of both publicly financed welfare services and social security. Welfare services can be offered by both private and/or public providers. These systems cover every individual throughout their lifetime. The public pension system is by far the largest system within the Swedish social security apparatus. It provided pension benefits for 1.036.311 men and 1.167.073 women, or roughly 22% of the total population in 2017, 2.917.171 men and 2.816.981 women of working age paid in pension contributions to the public pension system in 2017, or 60% of total population, according to the Swedish Pensions Agency. In total 82% of the entire population either paid contributions or received benefits from the national pension system.

In June of 1994 the Swedish Parliament approved a new pension system, introducing a pay-as-you-go Notional Defined Contribution (NDC) system combined with a minor Financial Defined Contribution (FDC) system3. The history of Swedish retirement reform can be understood in terms of the history of social welfare. Its development is far more complex and harder fought, politically, than what is often perceived of modern Sweden. It is easy to underestimate the uncertainties that riddled its historical past. Our historical bias underestimates the struggles in political and social battles, such as retirement reform.

This paper aims to describe how and in what environment the Swedish pension reform was devised. First, we will give a historical overview of the Swedish retirement scheme from the end ofthe XVIIIth century to its recent changes agreed upon in 2017. We will then discuss the lessons learnt from the reform process and its implications. The current retirement policy in Sweden is presented in detail in the annex.

The evolution of the Swedish retirement system

The appearance of the first occupational schemes at the end of the XVIIIth century

The development of income security within old-age and retirement reform in Sweden is tightly related to the history of modern Sweden, and how it unfolded. It is the story of how Sweden transitioned from a poor, war-torn, autocratic, agricultural country in the north of Europe, to the prosperous democratic country that it is today.

By the turn of the XVIIIth century Sweden was much less developed than other European countries. Although the country had flourished during the reign of freedom 1718-1772 (Frihetstiden), an era which had both provided peace and given rise to more freedom in society4, the country was shaken byseveral transformative and disruptive events: the assassination of Gustav III, the coup d’état against theKing Gustav IV Adolphe, the loss of Finland (one-third of the country and a fourth of the population) to the Russian Empire in 1809, and the lynching of the Marshal of the Realm Axel von Fersen on 20 June 1810. This period ended when one of Napoleon’s generals, Maréchal Jean Baptiste Bernadotte, ascended to the throne as King Karl XIV Johan of Sweden in 1818 and the country established a new Constitution, finally returning to stability.

In 1810, Sweden had 2.3 million inhabitants, the majority of whom worked in the agricultural sector. Aside from Stockholm, with around 75.000 inhabitants in 1800, most other cities were small. Althoughmost lived in poverty, Swedes enjoyed more individual rights than most of their European neighbours. Moreover, due to the universal catechetical requirements implemented by the clergy,literacy levels were also comparatively high, with at least one person in each family being able read.

The earliest pension schemes in Sweden were occupational (Allmänna Änke- and Pupillskassan 1788-1934). These pension schemes provided limited coverage for the upper levels of the clergy, thearmed forces and civil servants5.

The break-off: the XIXth century

Starting around 1860 thanks to the industrial revolution, the number of workers in manufacturing and services increased while the proportion of workers in agriculture began its one hundred and fifty year-old downward trend from well over half of the population to around 2% by the turn of the millennium. It also prompted urbanisation as people began moving from the countryside to their new jobs and workplaces in the rapidly growing cites. This dynamic is still at play today.

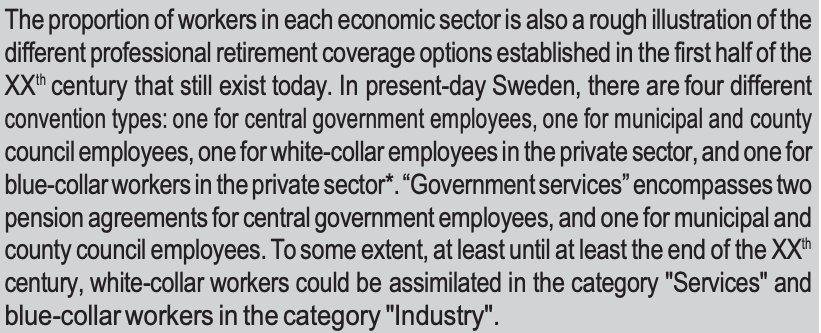

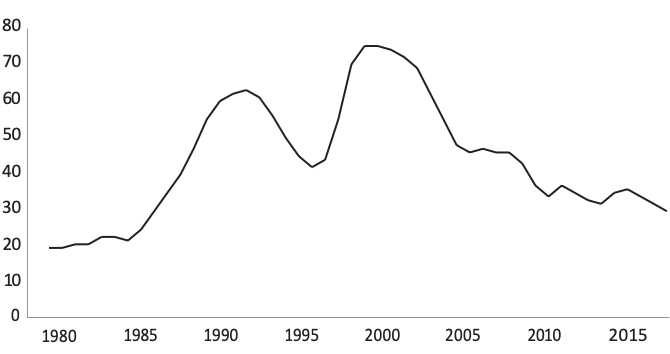

In the 1850s, Sweden was hit with poor harvests which triggered a crisis in the agriculture sector. This combined with rapid population growth and urbanisation created an unsustainable social and economic situation for many individuals and their families, and many chose to leave Sweden for the promise of a better life in North America, perhaps best described by the author Vilhelm Moberg in his book series The Emigrants6. In the mass migration that followed between 1850 and 1930, approximately 1.4 million people left the country. Some years as many as 1% of total population emigrated. In certain birth cohorts, one in five men and one in six women chose to emigrate7. The below figure also shows a marked shift from being a departure country to destination country during the 1950s.

Immigrants and emigrants as a share of population between 1850-2017

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique; data Statistics Sweden.

See Bengt Bergander , Försäkringsväsendet i Sverige 1814-1914, Berlingska Boktryckeriet, 1967.

See Mats Larsson, Mikael Lönnborg, and Sven-Erik Svärd, Den svenska försäkringsmodellens uppgång och fall, Erlanders Förlag AB, 2005.

Ibid.

Adolf Hedin (1934-1905) was a newspaper publisher, writer and politician.

See Mats Larsson, Mikael Lönnborg, Sven-Erik Svärd, cit.; The reforms included the law on occupational safety in 1889, support to sickness insurance funds in 1891 and accident insurance in 1901 (reformed in 1916).

Private life insurance and pension insurance emerged in Sweden starting around 1850. The principles for life insurance, based on mathematical probability theories developed by Frenchmathematicians Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal and the mortality tables developed the English mathematician Edmond Halley around the XVIIth century8, were of fundamental importance. The growing banking and insurance sectors were predominantly influenced by what happened in London,which is why the Swedish insurance industry was anglophone from the very beginning.

The Riksdag of the Estates (Ståndsriksdag) was dissolved in 1866. The parliament of the four estates – the Nobility, Clergy, Burghers, and Peasants – was replaced by a bicameral legislature. Votingrights were still limited to men only and was dependent on declared income. The bicameral legislature stood for over a century, until the unicameral assembly was introduced in 1970.

The first life insurance companies in Sweden operated in a limited market geared towards the upper echelons of society. In 1880, only 0.3% of the population had some form of pension insurance coverage9. Finding the market too limited both in scope and in size, private insurance companies tried to expand their business to other groups in society10.

With the further pauperisation of families working in the agricultural sector, the demand for other forms of insurance increased. Demand for insurance coverage, especially for those in their old age, increased in many groups in society, but primarily for workers and middle-class private sector groups (services and manufacturing sectors). The growth of the middle class in the cities also increased the demand for occupational pensions and private insurance. The first parliamentary resolution on compulsory pension insurance for workers was submitted to parliament by the liberal Member of Parliament Adolf Hedin11 in 1884. Although the Hedin motion did not pass through parliament, it set in motion several new initiatives, including an inquiry into occupational and pensions insurance for workers, and, more generally, a process of social change that would span the next 30 years. It also triggered a government commission on pensions (pension sutredningen) in 1895 and 1898. However, their findings were not implemented by the conservative government thatadvocated for more private insurance based systems. Despite their reservations, several reforms relatedto workers’ safety and insurance were gradually introduced over time12.

From 1900 to 1930, the establishment of universal pensions and the road to democracy

Arvid Lindman (1862-1936) was a naval admiral and conservative politician. He served as Prime Minister from 1906-1911 and 1928-1930.

Leif Lewin, Sveriges statsministrar under 100 år: Arvid Lindman, Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2010.

Karl Staaff (1860-1915) wasa liberal politician and lawyer. He served as Prime Minister 1905-1906, 1911-1914.

See Peter Esaiasson, Sveriges statsministrar under 100 år: Karl Staff, Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2010.

Nils Edén (1871-1945), Liberal politician and Prime Minister from 1917-1920.

Political tensions continued to increase in Sweden in the lead-up to the First World War and the country came close to war and rebellion after the dissolution of their union with Norway in 1905, inthe 1914 Courtyard crisis, and following the revolutions in Russia and Germany in 1917 and 1918.

Somehow, maybe thanks to a mixture of luck, bravery, and moderation, Sweden overcame these tribulations peacefully. The main issues were related to finding the fragile balance between passing democratic reforms all while preserving the existing social order and social cohesion. Around this time, the conservative government under Prime Minister Arvid Lindman13 introduced proportional elections, a system that remains to this day but with the right to vote, which was then exclusivelyreserved for men and determined through an income- dependent system14. In 1913 Karl Staaff’s15 Liberal government introduced a universal pension system calculated in two parts: one-part wascalculated as accumulation annuities and one-part as a pay-as-you-go supplement, subject to income. The pension age was set at 67 but the accumulated resources could be paid out earlier in cases ofdisability. The benefit level was low and it would remain as such until after the Second World War.The first universal pension benefits were paid out starting on 1 January 1914. The universal pensionbenefit was probably the first of its kind and was considered one of the government’s greatest achievements16.

In 1918 the Liberal-Social Democratic coalition government under Prime Minister Nils Edén17 introduced equal voting rights for men. Due to the political turmoil surrounding Europe towards the end of the war, the voting rights were quickly expanded to all elections at all levels, and moreimportantly, to all women, making Sweden a true democracy.

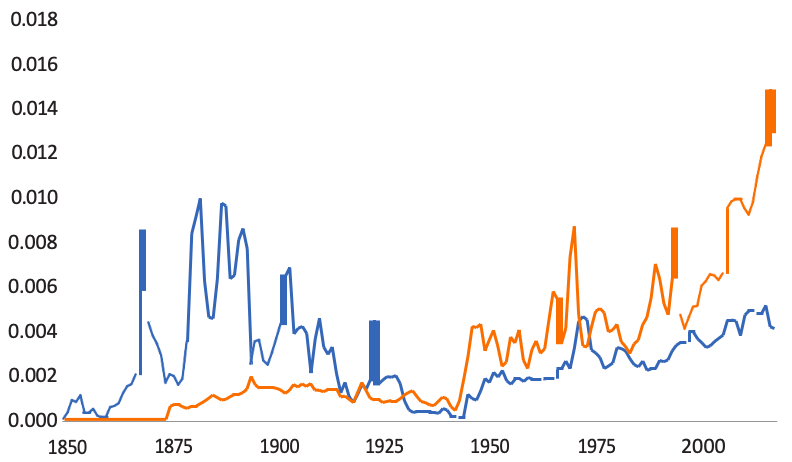

The 1920s was a period of great economic growth but also marked by great political instability andlabour market turmoil. During this decade, the country saw ten successive governments, often fromdifferent political parties. At the same time, there was a resurgence of social movements, as evidenced by the high number of disrupted workdays per 1.000 employees over this period.

Number of disrupted workdays per 1,000 employees in Sweden, 1905-2005

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique; Mikkelsen, F., 1992, Arbejdskonflikter i Skandinavien 1848-1980, Edvinsson, R., 2005, Growth, Accumulation, Crisis: With New Macroeconomic Data for Sweden 1800-2000.

On 14 May 1931 five people were shot dead by military troops called in as reinforcement by the police during a protest. TheÅdalen shootings was a series of events in and around the sawmill district of Ådalen, Kramfors Municipality, Ångermanland, Sweden. The events spawned raging national debate and deep division along political lines.

Ivar Kreuger (1880-1932) became one of the richest men of his His empire was built around the company Kreuger &Toll Ltd. which was highly exposed as a leader on international markets and severely hit in the financial crisis of 1929. IvarKreuger supposedly committed suicide in his Parisian apartment on Avenue Franklin-D.-Roosevelt on 12 March 1932.

Per Albin Hansson (1885-1946) was Social Democratic politician and Prime Minister from 1932-1936 and 1936-1946. He is credited for creating the concept of general social welfare (Folkhemmet).

Moreover, because the universal pension benefits were so low, demand for professional pensions increased. By the 1920s, the number of employees in manufacturing and services had almost doubled from 0.1 to 0.2 as a share of the population, while the share of employees in the working-age population declined from 0.5% to 0.3%. Furthermore, debates related to the coverage of blue and white-collar workers in the private sector continued and discussions on voluntary versus mandatory occupational pensions, public or private administration remained at the heart of political debates and negotiations with social partners for much of the post-war period. Eventually, in 1927, the law onvoluntary occupational pensions for white-collar workers was passed (1927 års lag om frivilligtjänstepensionering).

The economic boom of the 1920s ended abruptly with several disruptive events: the depression of 1931, the shootings in Ådalen 193118, and the collapse of Ivar Kreuger’s19 economic empire. Despite all this, Sweden matured as a democracy and, contrary to many other less fortunate countries in Europe, became an increasingly stable country throughout the 1930s.

In 1935, the universal annuity capitalisation was abolished and flat-rate universal pension benefits(folkpension) were introduced (Lag om folkpension) by Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson’s20 SocialDemocratic Government. This reform also meant that Sweden moved away from traditional privatelyfunded insurance to give way to more government-run pay-as-you-go pensions.

From 1930 to 1950, the birth of Swedish corporatism and the Saltsjöbaden agreements

See Lennart Schön, En modern svensk ekonomisk historia – tillväxt och omvandling under två sekel, Tredje upplagan, SNS Förlag, 2000.

Ibid.

See Assar Lindbeck, “The Swedish Experiment”, Journal of Economic Literature, 35, n°3, September 1997, pp. 1273-1319.

Committee regarding private sector employees (Kommittee angående privatanställda, 1931) and the Hartelius committee(1936). Also see Allmän pensionsförsäkring, Undersökningar av och förslag av pensionsutredningen, Principbetänkande, Statens offentligautredningar, SOU 1950:33, 1950.

Ibid.

Oskar Åkerström (1896-1964) was a Social Democratic politician and member of Parliament.

Tage Erlander (1901-1985) was a Social Democratic politician and the longest serving Prime Minister in modern Swedish history from 1946-1969.

See Betänkande av Pensionarbetsgruppen, Reformerat pensionssystem, Statens offentliga utredningar, SOU 1994:20, 1994.

Gustav Möller (1884-1970) was a Social Democratic politician and Member of Government in 1924-26, 1932-36 and1936-51 and credited as the father of Swedish social security and its welfare state.

See William Beveridge, “Social Insurance and Allied Services”, Parliamentary Archives, BBK/D/495, 1942.

Gunnar Sträng (1906-1992) was a Social Democratic politician and served as Minister for Finance in 1955-1976.

In the 1930s, the labour movement demanded to see improvement in workers’ conditions, specificallyasking for a raise in wages21. The unions became more focused on strengthening the long-term business environment within the industrial sector through high levels of investments and boosts ineconomic growth22. This new dynamic led to the resolution of conflicts of interest on the labourmarket and a transition towards corporatism and macroeconomic stability. In 1938, the centralist “Saltsjöbaden Agreement” between the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO) and the Swedish Employers’ Confederation (SAF) was agreed upon. This agreement aimed at the settlement oflabour market conflicts without government intervention23. According to the economist AssarLindbeck, a key driver of this change of pace and tone was the alliance between the Social Democratic Party and the unions.

With higher economic growth, increasing standards of living, and rapid changes in familystructures due to urbanisation, the demand for occupational pensions among workers increased once again in the interwar period. The issue of whether occupational pensions should be mandatory or optional for various categories of workers was addressed in parliamentary sessions in 1931, 1933,1934, 1935, 1936 and 1938, as well as in several committees and government inquiries24. In 1944, therewas Government inquiry on mandatory occupational pensions but its scope was limited to white-collarworkers25.

Another motion on mandatory pensions for all was raised by the parliamentarian Oskar Åkerström26 in 1944 (sv. Riksdagsmotion om obligatorisk tilläggspension). Pension related issues continued to be discussed in the parliamentary sessions of 1944, 1946, 1947, and 1950.

In 1946, the flat-rate universal pension benefit (folkpension), introduced in 1913 and reformed in1935, was amended to a unified universal pension across all municipalities (enhetlig folkpension). Indexation is then introduced in 1948. The pension and disability pension benefits were increased considerably on 1 January of the same year. In addition, the Social Democratic Government under Prime Minister Tage Erlander27 introduced survivors’ pensions, supplements for wives(hustrutilägg) as well as national and municipal housing supplements28.

The political debate on whether to opt for income replacement or minimum income security was quite contested, even within the Social Democratic party. Prominent figures of the labour movement, such the Minister for Social Affairs Gustav Möller29, opted for a universal minimum income policy in accordance with what Sir William Beveridge had proposed in the United Kingdom in 194230. Gustav Möller’s opinion had strong support within the party throughout the 1940s until the beginning of the 1950s when Gunnar Sträng become the Minister of Finance31.

The 1950s: The rise of the ATP system (Allmän Tilläggs Pension)

Allmän pensionsförsäkring…, op. cit.

In the 1950s the Government commission on pensions, established in 1947, concluded that “The way pension issues have been addressed in recent decades shows that they have always been a subject of interest from both societal and individual citizens’ groups. Optional retirement has now been significantly expanded for white-collar workers”32.

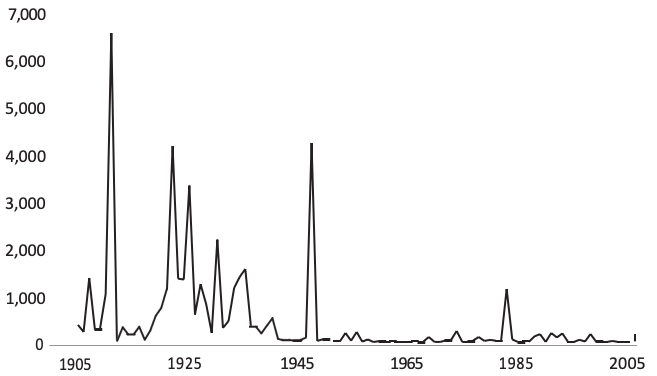

Government expenditure and taxes started to increase with the expansion of the “welfare state”. From 1950 to 1970, government expenditure increased from 18% of GDP to 31% while taxes share of theGDP increased from 18% to 36%, continuing until reaching its highest peak at 50% in 1990.

Tax Revenue and Government expenditure as a percentage of GDP, 1900-2010

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Ekonomifakta, IMF.

According to Bo Könberg, the basic ideas of the Income pension (NDC system) can be traced to the ideas in AÅkessons Commission (See Bo Könberg, “The Swedish Model for Pension – New Wine in New Bottles”, Scandinavian Insurance Quarterly, n°2/2008, February 2008, pp.99-109.

See Peter Ohlsson P, Svensk politik, Historiska media, 2014.

Ibid.

Bertil Ohlin (1899-1979) was a Liberal Party leader and economist, and was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in See Dick Harrisson, “Jag har ingen vilja till makt – Biografi över Tage Erlander”, Ordfront, 2017.

See Ohlsson, op. cit.

Göran Hägg, Välfärdsåren – svensk historia 1945-1986, Wallström & Widstrand, 2005.

See Ohlsson, op. cit.

See Lennart Schön, op. cit.

See Urban Lundberg, Juvelen i Socialdemokraterna och den allmänna pensionen, Hjalmarson & Högberg, 2003.

See Harrison, op. cit.

The commission led by O.A. Åkesson also suggested the introduction of a mandatory public income-related pension insurance for all33. The members of the commission opted for writing their own opinions (sv. särskilda yttranden) along party lines, where in the Social Democratic member and the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO) members were in favour of the Commission’s opinion while the white-collar workers and Conservative representatives were opposed. Despite these opinions, the Social Democratic and Centre Party Coalition Government demanded a new independentcommission instead of presenting the commission’s proposal to Parliament34.

The political debate further increased during the early 1950s, however, despite several improvements to the pertinence of the system. The indexation of the universal pension benefit was introduced and increased in 1948. However, with the rapid increases in economic growth and standards of living, it became obvious that the increases in benefits and coverage of workers were not enough to enable workers and low-income earners to live on their pensions35. The pension struggle then became apower struggle between Prime Minister Tage Erlander and main opposition leader of the Liberal Partyleader Bertil Ohlin36.

In 1955, the new pension commission produced its final report, recommending a mandatory and universal public pension for all. Furthermore, the Commission proposed pension benefits that would mirror past wages and depend on national living standards37. The Commission also proposedthat the pension age should remain at 67 years of age. Shortly after the 1956 election, the Pension Commission led by Per Eckerberg presented its final report. In this version, the LO and SocialDemocrats proposed a universal earnings-related public pension (Allmän tilläggs pension): ATP38. According to the proposal, the target replacement rate would be 65% of the average worker’s earnings.

In the fall of 1957, the Conservative party and the Liberals introduced the idea of holding areferendum on pension reforms39. A referendum was held on 13 October 1957. The referendum had three options: the first was the Social Democratic proposal to introduce a universal income-relatedpension. This option received 45.8% of the referendum vote. The second option was supported bythe Centre Party to introduce optional pensions, and it received 15%. The last option, supported by the Liberal party and Conservative party, preferred giving social partners the responsibility for pensions, and received 35.3%40. Although voter turnout was high, at 72.4%, and the Social Democratic option received more votes than the other options, no policy received an outright majority.

The struggle for the ATP also led to the dissolution of the Centre Party’s coalition with the Social Democrats on 25 October 195741. The entire government resigned, but Tage Erlander returned as Prime Minister with a Social Democratic Minority Government on 31 October 1957. The electionof 1958 led to a renewed Social Democratic Government under the leadership of Prime Minister TageErlander. With the smallest possible margin (one vote) in parliament, the government secured a majority. However, as the speaker of the House did not vote in parliament, the election resulted in aparliament without a majority.

When the decision on ATP was to be made in 1959, the reform was passed with the smallest marginof votes and the Government’s proposal to introduce income-related public pension for all workers waspassed through the lower House. The right-of-centre parties soon conceded on the issue42. It was after the ATP struggle in the 1950s that the Social Democrats became the majority party in Government43. Tage Erlander remained Prime Minister until 1969.

Reforms in the 1960-1970s

For twenty years, from 1950 until 1970, average growth in Sweden and in many other industrialised countries was around 4% annually44. In that time, often referred to as the “golden years”45, not only did living standards increase but many consumer goods such as cars, refrigerators, television, etc. became goods for the masses, and vacation travel also increased due to better infrastructure throughout Europe and aviation.

At the beginning of the 1970s, Sweden, like most other western countries, entered an era of reduced growth. There are many different explanations for this: external shocks from the global recession, the oil crisis, as well as structural changes in the economy with new technology and services taking over the industrial sector.

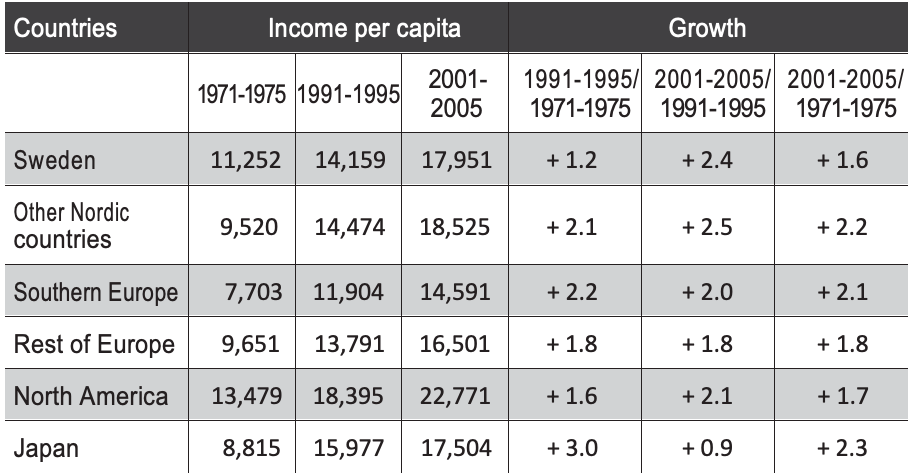

GDP per capita and economic growth in leading economies 1971-1975 and 2001-2005

Source :

Lennart Schön, En modern svensk ekonomisk historia. Tillväxt och omvandling under två sekel, SNS Förlag, 2000.

“Lag om pensionstillskott”, 1969:205, Socialdepartementet, 9 May 1969.

See Urban Lundberg, op. cit.

Lindbeck, op. cit.

In 1969, the pension supplement, a complementary benefit to the universal pension, was passed (sv.Pensionstillskott)46 and remained in place until 2003.

On 1 July 1976, the retirement age was lowered from 67 to 65 after an agreement made in 1974 between the Social Democratic Government and the Liberals. A flexible part-time pension was also introduced for those aged 60 to 65. The flexible part-time pension was calculated generously, which allowed for a benefit level of 65% including pension contributions. The flexible part-time pension became very popular and from 1976 until August 1980, about 89.000 Swedes opted for this benefit47. In the 1976 election the Social Democrats lost their majority for the first timein 40 years. The non-socialist parties lead by Torbjörn Fälldin from the Centre Party formed a coalition government. The non-socialist right-of centre parties would remain in power until 1982.

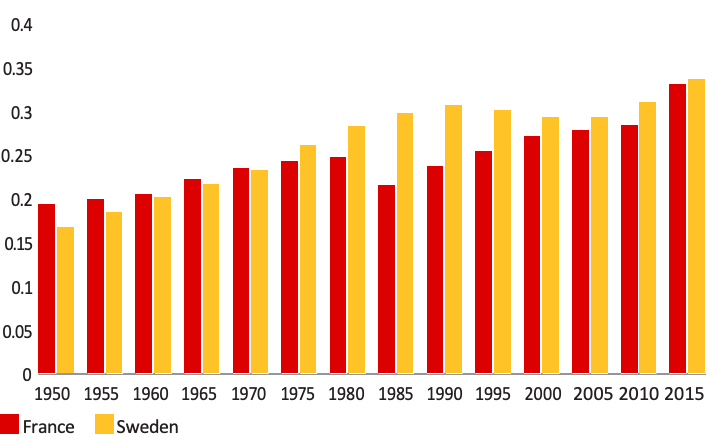

The premature ageing of the population from 1970-1990, compared to other OECD countries, together with sharp increases in the labour participation rates of women increased the political demand for more generous pension systems and child and elderly care48. From 1950 until the 1990s, Sweden experienced a rapid increase in the old-age dependency ratio.

Old-age dependency ratio* in Sweden and France from 1950 to 2015 (in %)

Source :

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

* The old-age dependency ratio is calculated as the number of individuals aged 65 and above divided by the number of individuals aged 20 to 64.

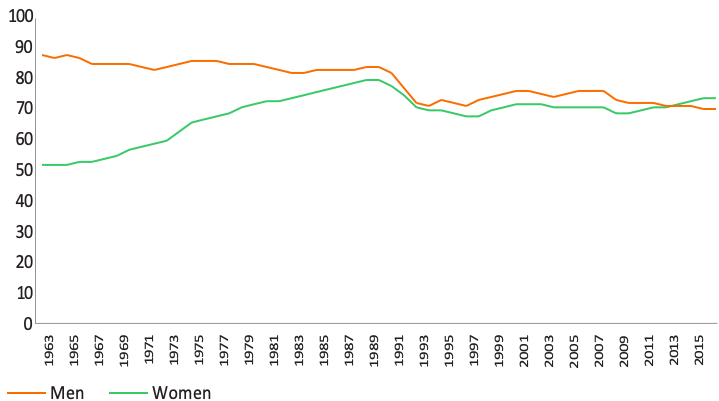

The figure below shows the employment ratio for men and women. From 1963 to 1990, female employment continuously increased from 53% to 81% while for male employment it suffered a small but steady decline from 89% to 85%. Employment rates, which had fallen due to the economic crisis of the early 1990s, then picked up again, with a slow yet steady increase.

Employment ratios for men and women 1963-2017

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, OECD.stat.

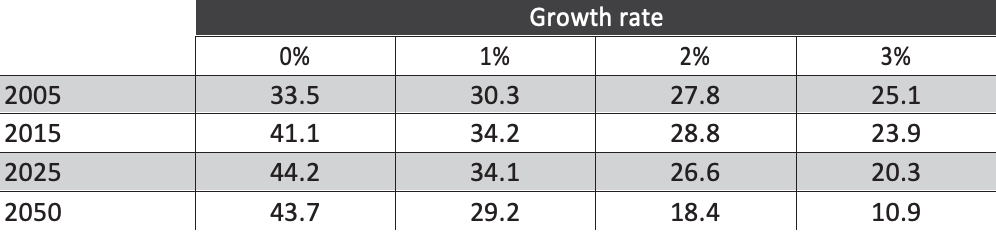

Despite the rhetorical differences between the political parties, there was a growing consensus across political lines that the pension system needed to be adjusted. The ATP system was perceived as financially unsustainable as there was a substantial risk of the pension contributions increasing fasterthan income levels would49. Given the high level of taxes as a percentage of GDP, at around 50% of GDP in 1990, further increases to finance pensions seemed limited.

Estimated pensions expenditure in the former pension system, wage share based on different assumptions for real income growth (from 1995) and maintained price indexation

Prop. 1993/94:250.

Source :

Prop. 1993/94:250.

Sture Korpi (1939-2017) was a Social Democratic politician and served as State Secretary in 1982-1991.

See Urban Lundberg, op. cit.

Anna Hedborg (b. 1944) is a Social Democratic politician and official and served as Minister for Social Insurance (1994-1996).

Ingela Thalen (b.1943) is a Social Democratic politician and served as Minster of Labour (1987-1991) and Minister forSocial Affairs (1990-1991, 1994-1996).

Bo Könberg (b.1945) is a Liberal Party politician and served as Minister for Health and Social Insurance in 1991-1994.

See Urban Lundberg, op. cit.

See Allmän Pension, op. cit.

In addition, the former system created few incentives to work. Thirty years of work would earn a pension, of which fifteen would impact the calculation: the pension benefit formula was based on the best fifteen years of work. The benefit calculation was therefore beneficial for individuals with a short but fast-growing career later in life. Hence, it was less beneficial for individuals with a slow growth in earning but a long career.

On 16 November 1984, the Social Democratic government lead by Olof Palme commissioned a Parliamentary Pension Commission (pensionsberedningen) lead by Sture Korpi50 State Secretary to Minister for Social Affairs Sten Andersson. The Commission united all the most relevant organisations in Swedish society: political parties, unions, the confederation of Swedish enterprises, pensioners’ organisations, organisations for the disabled, social insurance agencies, etc.51. The Parliamentary Commission also became a breeding ground for future prominent members ofthe Parliamentary Working Group on Pension such as Anna Hedborg52, Ingela Thalen53, and BoKönberg54.

Although the Commission had not been mandated to propose any changes, it was considered a huge success for its contributions to analysing how the pensions system worked and what challenges it faced55. The Pension Commission presented its final report in 199056.

The 1990s crisis and the reformed pension system

Ingvar Carlsson (b.1934) is a Social Democratic politician and served as Prime Minister in 1986-1991 and 1994-1996.

Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, The Swedish Pension Agreement and Pension Reform, Anglaise du rapport Detta är pensionsöverenskommelsen (Ds 2009:53), 2010, p.53.

Carl Bildt (born in 1949) is a Conservative Party politician and served as Prime Minister 1991-1994 and Minister for Foreign Affairs 2006-2014.

See Bo Könberg, Edward Palmer and Annika Sundén, art. cit.

Ibid.

The ECU was a basket of currencies used from 1979 to 1999 and before the euro.

The European Currency Unit was a basket of currencies used as a unit of account before being replaced by the euro 1 January 1999.

The first political step towards a new pension reform system was taken in the Government budget (finansplan) of 1991. The Social Democratic Government, led by Ingvar Carlsson57, opts for“opportunities for financing pension pledges within a framework of unchanged levels of taxation and contributions are highly dependent on economic growth58”.

In 1991, the Social Democrats were defeated by a four-party coalition led by the Moderate Partyleader Carl Bildt59. Shortly after the new Government took office, a Parliamentary Working Group on Pensions was formed. The Working Group began itswork in November 1991 when the Minister for Healthcare and Social Security, Bo Könberg, took its direction. In 1992, the Working Group published a “preliminary draft” containing almost all the elements of the reform60, the starting point of the reform being the need for a higher savings rate in the economy as well as the need to strengthen the incentives to work. Although the possibility of making changes within the framework of the existing ATP system had been thoroughly investigated by Pension Commission, the Parliamentary Working Group on Pensions settled that “the retirement system should be built up according to principles other than those underpinning public pension and ATP systems of today.” The Working Group presented a draft of a new system in August 1992 containing almost all principal elements61.

A brutal economic crisis hit Sweden in 1992. Government expenditure reached almost 76% of GDP in 1995 and the employment rate declined consistently throughout the 1990s. The many causes of the crisis are diverse and literature on this matter is vast. A combination of rapid credit expansion, both weak government finances and a weak current account, together with a fixed currency towards the European Currency Unit62 depleted the central bank’s power to defend its currency. In one last attempt to protect the Swedish currency, the Riksbank decided to raise its key interest rate to 500% on 16 September 1992. As a result, investments and the employment rate fell, and the country experienced its worst recession since the Great Depression. In November 1992, the fixed rate towards the ECU63 was abandoned and the Swedish krona quickly depreciated. These events led to an immediate crisis on the financial market and in the banking sector which had to be restructured and bailed out. Consequently, the Government debt as a percentage of GDP soared from around 40% in 1990 to 74% in 1994.

Government debt as a percentage of GDP, 1980-2017

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, data from the Swedish National Debt Office.

Source :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, data from the Swedish National Debt Office.

See Lennart Schön, op. cit.

See Reformering av det allmänna pensionssystemet, Prop. 1993/94:250, 1994.

Since 1994 several other countries such as Latvia, Italy, Poland, Norway and Kazakhstan have introduced systems very similar to the Swedish NDC system.

See Bo Könberg, Edward Palmer and Annika Sundén, art. cit.

See Urban Lundberg, op. cit.

See Inkomstgrundad ålderpensionssystemet, 1997/98:151, 1998, and Garantipension, Prop. 1997/98:152, 1998.

See Automatik balansering av ålderpensionssystemet, 200/01:70, 2001.

See Pensions at a Glance OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, 2013.

See Riksförsäkringsverket (RFV), The Swedish Pension Annual Report 2001, RFV, 2002.

Fredrik Reinfeldt (b. 1965) is a Moderate Party politician and served as Prime Minister from 2006-2014.

See Swedish Government Office-Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, The Pension Group’s agreement on long-term raised and secure pensions, 14 December 2017.

At the height of the economic crisis, the Government saw a substantial risk that the commitments made in the pension system could suffer and that there was a need for a new, modernised pensions system. In 1994, the Parliamentary Working Group on pensions (penisonsarbetsgruppen) presented its proposal64. On 8 June 1994, the Parliament adopted the guidelines and principles of the new pension system. It is worth pointing out that representatives of the Social Democratic opposition partyparticipated in the right-of-centre government’s work on the 1994 principle proposal. The pensionreform was passed by these five parties in June 1994, and its implementation began in 199565.Together, they constituted a large majority (around 85%) in parliament66.

The parliament decision also stated that it is “a major responsibility for the Contracting Parties to maintain support for the pension agreement”. The establishment of a group of guardians for the reform was also intended to “nurture and protect the agreement”. In this group, all agreements must be unanimous. The Parliamentary Pension Group consists of one parliamentarian from each political party supporting the agreement, except the Social Democrats who had two representatives because their Minister was also the chair of the Group.

The 1994 legislation meant that Sweden switched from a pay-as-you-go defined benefit system to one of defined contribution with both pay-as-you-go and capitalisation elements. The first being the Income Pension and the second is the Premium Pension (see Annexes). The new reform also included a separation of survivors and disability systems. These systems were now separated from the old-age system and moved over to the general budget.

Between 1994 and 1998, an implementation group was formed to solve practical and legislative issues with the reform67. In 1997, the reform was adopted by the Social Democratic party congress68. The reform resumed and parliament ruled on it in 199869. The new system came into effect in 1999,with transitional rules for cohorts born between 1938 and 1953. Contributions to the Premium Pensionbegan in 1995 and the first pension benefits for both the Income Pension and the Premium Pension were paid in 2001.

The automatic balancing of the Income Pension was legislated in 200170. The balance mechanism is triggered if assets (buffer funds plus the estimated value of assets in the form of contribution revenues) fall below the liabilities (accrued notional pension capital and capital value of outgoing pensions)71. Thebalance ratio is calculated for each year in the year after. The result is then used for the coming year. In 2002, the first annual report of the financial position of the public pension was produced72. All retirement benefits for pensioners in the former system were transformed according to the new rules in 2003.

Due to the financial crisis, the automatic balancing mechanism was triggered in 2010, 2011 and 2014, which led to a decrease in pension payouts. On account of these cuts, the right-of-centre government under Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt73 decided to lower the tax on pension income to compensate for the cuts in gross pensions. In the aftermath of the crisis, there was an adjustment to the automatic balancing mechanism where the buffer fund value was smoothed to a three-year average to lower the volatility.

Aside from these issues, the system worked smoothly throughout the 2000s and 2010s, and no otherchanges have been implemented. However, as individuals do not behave as expected by the originalsystem, there is a growing consensus on the need to adjust the system as a whole. The main issue has been that, despite the longer life expectancy, Swedes are not postponing their pension withdrawals and exiting from the labour market. Furthermore, individuals have been irrational in the Premiumpension system and consequently sub- optimised the use of this system overall.

On 14 December 2018, the Pension Group reached a new agreement on policy measures to strengthen the adequacy and sustainability of the pension system74. The new agreement stems from a desire to make several improvements in the system to make future pensions bigger and more secure. These measures include:

- Reformed and reinforced basic pensions (i.e. guaranteed pensions, housing supplements, )

- Reformed Premium Pension

- Strengthened financial sustainability of the pension system in the long-term by increasing the retirement age

- New measures for a better work environment and education for a sustainable working life

- A new delegation for older workers to combat ageism and discrimination

- A new advisory council with social partners

- A review of the tax deduction rules for occupational pensions

- Better measures for more gender-equal pensions

- Modernised investment rules for the pension buffer funds (the AP-Funds).

On 5 March 2020 the Pension Group agreed on an agreement to raise pensions in 2021 by introducing anew supplementary pension benefit (pensionstillägg) for workers with low wages and long working lives. The aim of the new benefit is to increase pensions while strengthening incentives to work.

How the reform was so successful

The role of Swedish political culture

Reforms in Sweden are stamped with a specific national political culture that calls for consensus, the staggering of change, and a particular organisation of assessment and work. Although Sweden is largely seen as a society founded on consensus today, this was not always the case. Changing the political mindset of an entire country is arduous, but not impossible. It is all about finding an acceptable compromise, called the “consensus process” in Swedish: förankringsprocessen. From an outsider’s perspective, this might seem odd, or even inefficient, but with consensus-driven agreements, the decision agreement is better accepted and tolerated by most people, and then quickly becomes the new norm. There is a word for this optimum in Swedish called “lagom”, which translates to an average that is just-right, an optimal average acceptable to everyone and something to aspirefor. The pension reform process in Sweden could be said to illustrate this notion well, considering the political debate it has generated.

The issue of pensions and its reform has always occupied an important place in this Scandinavian country’s public debate, as we have covered at length in recounting the history of the ATP system.These debates, so central to political history, have spanned generations. This is also why politicians have been able to master the art of disagreeing with each other. The reform, or rather the process of reforming, has benefitted from strong political support from both Government majority parties and their opposition. This institutional support is also what allowed for public support. In 1994, the decision between the five political parties behind the reform led to a solid agreement.

Structuring the reform work

When asked what kind of method should be used in any reform work, Bo Könberg, who participatedin the Pension Commission, stated that the creation of a small group was necessary to make progressquickly, and the number of participants should be limited75.

According to the Moderate Party politician and member of Parliamentary Working Group onPensions Margit Gennser76, these are some other lessons to be learnt:

- Keep the social partners at arm’s length;

- An inquiry on large structural changes should have some members who focus on policy and others that focus on The purpose of this strategy is to influence and create acceptance among political party members;

- A radical reform needs a good social working climate among inquiry members. Good group dynamics should not be underestimated;

- Strong political support from top-politicians is necessary.

While these elements may remain topics for debate, these views at least give some insight into take aways of the Parliamentary Working Group on Pensions. It is also important to note that although there was a consensus in the working methods of the Parliamentary Group on Pensions, some political parties are not part of this agreement. Furthermore, there is a long standing critique and debate on there form and the lack of transparency vis-à-vis the Parliamentary Working Group.

See Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, The Swedish Pension Agreement…, op. cit., p.53.

This paper aims to portray the reform process in Sweden in the long-term. Indeed, pension schemes are long-term commitments. In order to build confidence in such a system, the regulatory systems also need to be characterised by long-term stability77. The Swedish pension system is designed to be financially stable and hinges on a broad parliamentary majority in parliament.

The Swedish experience shows that it is imperative to use competent and efficient individuals capable of holding their heads high, with clear and solid instructions. Moreover, it is very important to build strong inclusive alliances from the outset with a common goal: on the one hand, to stand firm when the inevitable criticisms are voiced; on the other hand, to protect reforms and anchor the support of a political majority. Thus, it is not so much the reform as the reform process that matters.

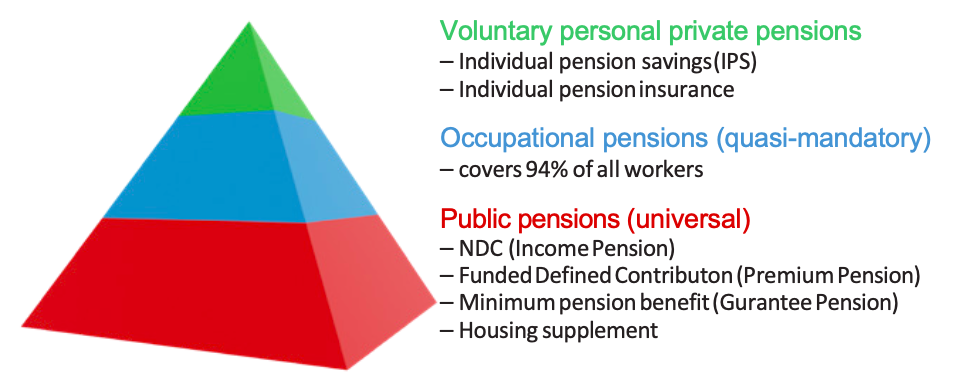

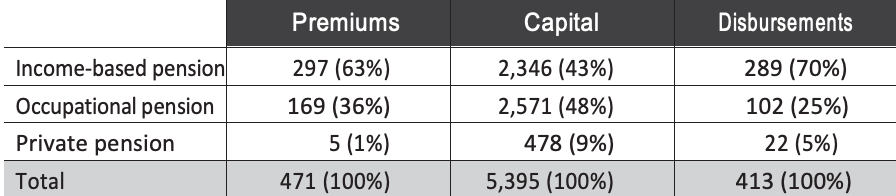

The Swedish pension system

The Swedish pension system is based on three pillars: the public pension scheme, which represents the largest pension income for most beneficiaries; occupational pensions, which are almost compulsory and cover about 94% of all workers 78; and lastly, optional individual private pensions that provide additional coverage and benefits.

Source :

Swedish Pensions Agency.

Swedish Pensions 2016* (in billions of SEK)

Source: Swedish Pensions Agency.

* Disbursements for occupational pension and private pension refer only to persons aged 65 and over.

Source :

Swedish Pensions Agency.

* Disbursements for occupational pension and private pension refer only to persons aged 65 and over.

The Premium Pension is classified as a private pension in terms of National Accounts.

In 2018, the BTP benefit was capped at 5,560 crowns per month (556€) for single individuals, and 2,780 (278€) for couples.

(0.07+0.1021)/(1-0.07) = 0.185.

The gender-neutral annuity divisors in the NDC system results in roughly 8% higher pension benefits for women (atage 65) compared to a system based on sex specific life expectancy. Given the current differences in life expectancy.

For additional information regarding the automatic balancing mechanism, please see the Annual Report of the Swedish Pension System 2017.

The activation of the balancing mechanism is based on the pension system annual reports that are published by the Swedish Pensions Agency.

See the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate (ISF), 2018, op. cit.

See Gabriella Sjögren Lindquist and Eskil Wadensjö, “National Social Insurance – not the whole Supplementary compensation in case of loss of income”, report for the ESS, n°5, 2006, Regeringskansliet, Ministry of Finance.

The occupational systems have been renegotiated towards more defined contribution schemes. However, long transitional periods apply.

The earnings-related old-age pensions consists of a notionally defined contribution pay-as-you-go component, the Income Pension (sv. inkomstpension), and a fully-funded, defined contributionpension system, the Premium Pension (sv. premiepension)79. In both systems, pension benefits are calculated on lifetime earnings and are set up as individual accounts. In addition, there is a residence based supplement, the Guarantee Pension (garantipension). The guaranteed pension is conditional anddepends on income-related public pension levels. Furthermore, there is a supplementary housingallowance for pensioners (Housing supplement for pensioners – bostadstilägg till pensionärer, BTP) that targets elderly individuals with low pensions and high housing costs80. Pensioners with low incomes and high housing costs may also benefit from a special supplementary housing allowance (Special housing supplement – sv. särkillt bostadstillägg till pensionärer, SBTP). Finally, there is a tax-free and income-tested programme for support for the elderly (Maintenance support for the elderly – äldre försörjningsstöd), which ensures that pensioners with very low incomes, often immigrants with few years of residence in Sweden, do not become dependent on social assistance. The amount of the benefitdepends on household income and housing costs, but is by design always higher than the socialassistance benefit and lower than the basic level for people receiving a guaranteed pension and housing supplement. The same rules apply to all men and women regardless of economic sector, as well as for employees and the self-employed alike.

The system covers all individuals born 1938 and later, with transitional rules for cohorts born between 1938 to 1953. Pension entitlements are calculated as 18.5% of the annual pensionable income up to a ceiling amounting to 496.305 krona (49.630 euros) in 2017. 16% is then paid to the Income pension and 2.5% to the Premium pension. The insured pay a pension contribution of 7% of gross pensionable income, and the employer pays 10.21%81. Pension contributions are also paid by the Government to cover pension entitlements credited for certain social insurance benefits in the case of unemployment, sickness, disability or parental leave. The retirement age is flexible and individuals can claim pension benefits from the age of 61 with no upper age limit. Furthermore, it ispossible to work and withdraw pension benefits. Under the Employment Protection Act, an employee isentitled to stay in employment until the individual turns 67 years-old. The government is planning for a proposal to raise the lower as well as the higher age (61 and 67) in 2020.

Income-related pension

The Income pension system works on an actuarial basis. At the time of pension benefit withdrawal, anannuity is calculated by dividing the individual’s total accrued contribution capital by a coefficientreflecting the life expectancy of both sexes at the exact date of retirement82. The individual can counteract the negative effect on the annuity caused by increasing life expectancy by postponing the date of pension benefit withdrawal. This system strengthens incentives to work and defers benefit withdrawals.

The earnings-related pension is aggregated at the beginning of the period by 1.6%, enabling the individual to receive in advance a share of the actual wage increase at the time the pension is paid. This allows for a more progressive distribution of pensions as life expectancy and mortality are distributed unevenly across income and levels of education. Individual earnings-related pension accounts are indexed, as a rule of thumb, by the growth in average earnings per contributor. If the economic equilibrium of the system deteriorates, the automatic balancing mechanism is activated and indexation is reduced until stability is restored83. This ensures that the system capable of financing its obligations with a fixed contribution rate and rules established independently of demographic or economic developments84.

Premium pension

The social insurance system also consists of a private mandatory fully funded defined-contribution system, the Premium pension. The system is administered by the state and financed by a contributionrate of 2.5% pensionable earnings, following the same transition rules as the pay-as-you-go system. Todate, there are about 800 funds available within the system with varying investment strategies and risks. When the individual enters retirement, he or she can choose a variable annuity or a unit-profit-annuity. With a variable annuity, the accumulated fund capital remains in the selected funds, whereas with a profit annuity, the money is withdrawn from the allocated funds and managed by the Swedish Pensions Agency. At retirement, from the age of 61, individuals can choose a fixed or variable annuity, either in part or in full. The Premium pension also allows for a survivors’ coverage, which can be subscribed for by a spouse or registered partner when applying for the pension benefit. The survivor’s coverage is actuarially neutral, and hence benefits are adjusted according to actuarial principles.

Income-independent minimum pensions and basic guarantees

The Guarantee pension benefits are funded by income tax. This benefit is proportionally reduced according to the number of years of residence, if the years of residence in Sweden are less than forty.The Guarantee pension and the earnings-related housing supplement for pensioners ensure an income level above the minimum income level in the social assistance system. All forms of basic securitybenefits for the elderly are available starting at the age of 65. The guaranteed pension is price-indexedand depends only on income from public pensions and survivors’ benefits. For those with the lowest income, the benefit is fully maintained, but for higher incomes, the benefit is reduced by 48% foreach additional krona of income related pension. This enables incentives to work for individuals with Guarantee pensions as well. The maximum Guarantee pension equal to 8.254 krona (825 euros per month 2018) for a single individual household and 7.363 krona per person (736 euros permonth 2018) for cohabitants. The Guarantee pension is fully phased out for incomes above 11.906 krona (1,191 euros) for singles and 10.553 krona (1.055 euros) for cohabitants/married couples.

Widow’s and survivors pension benefits are being phased out, since 1990. They have instead been replaced by a temporary and gender-neutral adjustment allowance. However, because of the long transition period, widow(er)s’ and survivors’ pension benefits will be paid out for several decades to come. A survivor will receive adjustment allowance for twelve months, but the payments continue if the survivor has children younger than 12 years-old. The size of the adjustment allowance and the widow(er)’s pension is based upon the deceased’s earnings.

Disability benefits, which are equivalent to disability pensions in most other OECD countries, are formally a part of the sickness insurance benefit scheme and are, since 2003, no longer a part of the pensions system. In addition, individuals with disability benefits accumulate pension entitlements in the national pension system. Contributions to the old-age pension system from these benefits are paid by the central government budget. Public old-age pension benefits for disabled persons, as foreveryone else, are based on lifetime earnings.

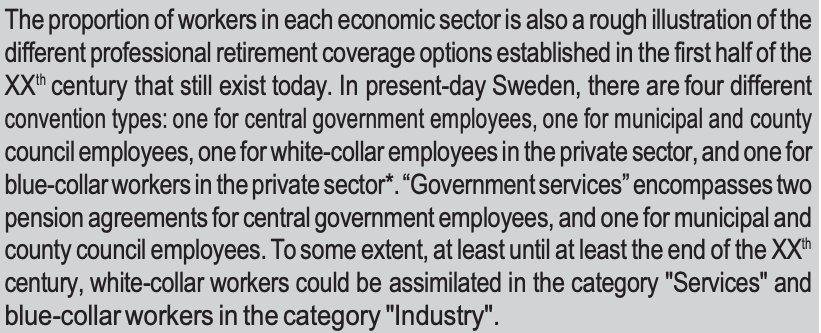

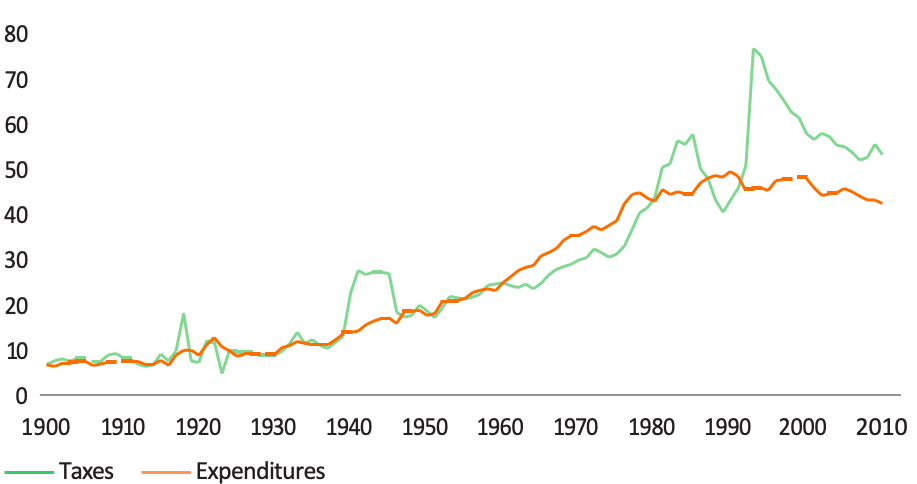

Occupational pensions

About 94% of all employees (in both the public and the private sector) are covered by occupational pension plans based on collective agreements between the unions and the employers’ confederations during the period 2001-201485. Scheme memberships are semi-mandatory for all employers andemployees working in an industry covered by such an agreement. There are four spheres of agreements: central government employees, municipal and county council employees, white-collar workers in the private sector and blue-collar workers in the private sector86. These collective agreements include occupational pension schemes financed through employers’ contributions, which provide pensions as a supplement to the public system, but also pension compensation for incomes above the public system pension ceiling. Thus, these schemes are most important for high-income earners. Four major occupational plans cover most workers and employees . It is possible to withdraw occupational pensions from the age of 55 and as a five-year lump sum or as a life time annuity.

Tax

All old-age pension benefits (including guarantee pension) and disability and survivors’ pensions are subject to income tax. Basic income-tested allowances (Housing supplement for pensioners, Special housing supplement and Maintenance support for the elderly) are tax exempt. Private tax-deductible pension savings have been abolished since 2016, except for individuals lacking occupational pension coverage. Funded occupational pensions and the mandatory Premium pension are taxed ETT (contributions Exempt, returns Taxed, benefits Taxed).

To strengthen the economy for the elderly, low-income pensioners receive a basic tax deduction for individuals 65 and over. This was introduced in 2009 and has been increased several times since. Inaddition, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that was introduced in 2007 taxes income from work ata lower rate than other sources of income.