“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

Introduction

The Sweden Democrats

History and development

Party platform and ideology

The Sweden Democrat’s electoral evolution

Regional differences in the Sweden Democrat vote

Public opinion in Sweden on immigration and refugees

The development of attitudes to refugees

The development of the public agenda

Who are the Sweden Democrats’ voters?

Previous studies on the characteristics of the Sweden Democrats

The situation in 2017

Explanations for the Sweden democrat vote

The Sweden Democrats’ position in the Swedish political system its possible future impact

The Sweden Democrat’s position in the national parliament

Consequences for Swedish Democracy and the Sweden Democrats’ future impact

Summary

The electoral behavior of Swedes in the parliamentary elections of September 9th, 2018 will provide new insights into the state of public opinion in a Europe facing the challenges of immigration and integration. This paper discusses the “Sweden Democrats”, a nationalist and anti-immigration party whose breakthrough in 2010 has been confirmed;

the author analyzes the evolution of this party, its sociology, the reasons for its success, its position within the Swedish political system and the consequences of its increasing influence on the future of Sweden. The French version of this study is available on the Fondation pour l’innovation politique’s website (fondapol.org).

Johan Martinsson,

Associate professor Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

The purpose of this report is to describe and analyze the electoral growth of the political party the “Sweden Democrats”. This includes describing their background, origin and their electoral development in Sweden. Further, the report will describe their political platform, their position within the Swedish political system and their current and potential future impact. Lastly, the report will describe the party’s electoral support in terms of demographic, social and political characteristics, as well as analyze and review the main explanations for their continued electoral success. The report will also apply a long term perspective on public opinion in Sweden concerning immigration and refugees.

The Sweden Democrats

The Sweden Democrats was formed during the winter and spring of 1988, and first participated in general elections in September of the same year. Still today, 30 years after their formation as a political party, after being represented in the national parliament during two consecutive periods, and after sustaining a standing in the polls as one of the three largest parties during several years, the Sweden Democrats suffer from their past reputation. Despite large and numerous efforts from the party leadership to normalize the party and broaden its appeal, they are often and repeatedly accused of having “brown roots” and a “nazi past” by political adversaries. Thus, the party is still regarded with great suspicion and as untrustworthy due to its history and origin, at least in the public debate and among the majority of other politicians and political adversaries. How important the party’s origin is for the general public today is less certain, since according to a recent poll by Novus from June 2018, the Sweden Democrats were by far the most favored political party among men (Novus, 2018).

Before summarizing the history of the party, though, we need to consider what type of party the Sweden Democrats is, and how they should be properly labelled. There is no widespread agreement on these considerations. The party is usually treated as belonging to a group, or “family”, of political parties in Europe that are sometimes labelled as the extreme right, radical right, far right, populist, anti-immigrant, xenophobic, nationalist or some combination of these (cf. Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2016, p. 237). Often, parties such as Dansk Folkeparti in Denmark, Fremskrittspartiet in Norway, Sannfinländarna in Finland, FPÖ in Austria, UKIP in the UK or Front National in France are mentioned as being part of that same family. Sometimes more radical parties such as Jobbik in Hungary or Golden Dawn in Greece are also regarded as belonging to the far end of this same ideological family. There are many and large differences between all these political parties, but they share some basic features such as having a nationalist outlook and being negative toward immigration and the reception of refugees. They are also often sceptic towards the European Union.

Therefore, how should the Sweden Democrats be labelled? For example, Anders Widfeldt uses the label “extreme right” in the title of his book (Widfeldt, 2014). Swedish sociologist Jens Rydgren on the other hand use the label “radical right” instead (Rydgren, 2008; Rydgren & van der Meiden, 2018), and Kokkonen (2015) uses the term “immigration critical”.

In this report I will use a descriptive label that is not negative in itself when labelling the party. First, it is doubtful that the Sweden Democrats can be said to belong to the right-end of the political spectrum unless one defines restrictive immigration policy as inherently right-wing. However, at times some parties clearly on the left have also advocated restrictive immigration policy, whether concerning labour immigration or asylum immigration. In addition, as argued by Widfeldt (2014, pp. 7-10) the term “right” can be said to have a slightly pejorative ring to it in the West or in Europe overall, at least in the Nordic countries. In addition, the Sweden Democrats have consistently emphasized in their programs and election manifestoes that they support the Swedish welfare state based on public funding, which is not typically regarded as a particularly right-wing stance. In sum, I therefore do not label the Sweden Democrats as “extreme right” neither as “radical right”. Additionally, while some of their rhetoric contains central elements of populism, this is a strategy that any party can use from time to time regardless of ideological content. The central elements of the Sweden Democrat platform is restrictive immigration and refugee policy and a nationalistic fundament where social cohesion is greatly valued and multiculturalism should be avoided. In essence, I find the most appropriate descriptive label for the Sweden Democrats is an anti-immigration and nationalist party.

History and development

The formation of the Sweden Democrats was initiated by people that had previously been members of former parties and earlier movements in Sweden. Partly, they came from the Sweden Party (Sverigepartiet) and the anti-immigration campaign group Keep Sweden Swedish (BSS, Bevara Sverige Svenskt), of which the former became fairly well-known and active during the 1980s (Widfeldt, 2014). In the first years, the party had links to various other groups in the racist, nazi or white power movement in Sweden. These links consisted either of people with a background in these other organizations, people with double memberships, or of those who had contacts and meetings with members of other organizations (Widfeldt, 2014, pp. 180-186). Early on, the party had among its (still quite few) members people who had been active in the Swedish nazi parties from the 1930s and 1940s, as well as volunteers from Waffen SS from the Second World War. Further, and perhaps most problematic for the Sweden Democrats, is that their first proper party leader, Anders Klarström, had previously been part of the Nordiska Rikspartiet, an openly neo-nazi party. During this period, the party was a marginal phenomenon and did not reach a wider audience, nor was it much covered by the media.

Thereafter, once Anders Klarström was replaced by Mikael Jansson as party leader in 1995, the party began its process of cleaning up its image and present itself like other political parties. For example, under Janson’s leadership, wearing uniforms at party meetings was banned and the consumption of alcohol was no longer allowed at party gatherings. Certainly, a substantial share of the Swedish public would not vote for a political party whose members wore uniforms. Furthermore, during this period, the second half of the 1990s, the party also explicitly distanced itself from nazi ideology and racism. The party also got rid of a number of people deemed too radical or behaving inappropriately, which led to the party spliting in two, and the more radical members instead formed the National Democrats (Nationaldemokraterna), which helped speed up the process of the Sweden Democrats presenting a clean image.

However, despite these efforts to normalize the party and cut ties with their origins, the party’s growth and electoral progress was fairly slow. Mikael Jansson was the first party leader with a clean record, meaning without any previous affiliations to compromising organizations. Instead, he had previously been part of an established party in Sweden, the Centre Party. Though he was sometimes seen as uncharismatic, uninspiring and as not being a particularly good public speaker, that was not necessary to reach a more widespread electorate (Widfeldt, 2014, p. 184).

Despite this normalizing of the party process that began under Mikael Jansson, some of the newer and younger party members were impatient and wished to push the party’s moderation further to broaden its appeal more quickly. In 2005, he was unseated and replaced by the current party leader, Jimmy Åkesson. A new leadership formed with four central figures who had all met when they were students at Lund University in the south of Sweden: Jimmie Åkesson, Mattias Karlsson, Björn Söder and Richard Jomshof. This new leadership was more suited for modern campaigns via mass media, and the new party leader was more skilled at gaining media attention, sometimes through controversial acts and statements. At the same time, this was also the period during which the party reinforced their zero-tolerance towards racist statements, and has repeatedly acted to exclude members who violated this policy. For example, between 2014 and 2018 approximately 40 members have been expelled from the party due to either racist statements, connections to racist organizations, or other inappropriate behavior. However, some of these 40 cases were also due to internal fights concerning how moderate or radical the party’s policies should be.

Another sign of the Sweden Democrats becoming normalized is the fact that from July 2018 they are members of the ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists) group in the European parliament, led by the Conservative party of the UK (Stone, 2018). Earlier, the Sweden Democrats were instead members of the EFFD group in the European parliament together with among others UKIP.

Party platform and ideology

It is now time to take a closer look at the Sweden Democrats’ main political platform. Since its founding in 1988 the party has issued several party and ideological programs, as well as election manifestoes. Their most recent principles program dates back to 2011, but they have also issued specific policy documents for certain areas and separate, shorter, election manifestoes.

In terms of ideology, the Sweden Democrats themselves define the party in their programs and manifestoes as a “nationalist” party, and have done so since their founding. They have also continuously emphasized their devotion to the social democratic concept of the “people’s home” (folkhemmet), although they point out that they view this concept as socially conservative idea (Sverigedemokraterna, 2011, p. 34). In essence, this concept has come to mean a comprehensive and publicly funded welfare state based on solidarity. The party combines ideas about social justice with traditional conservative values. In their 2011 principles program they advocate for “social conservatism on a nationalist foundation” (Sverigedemokraterna, 2011, p. 11).

In its most recent principles program from 2011, the shift towards a fully cultural nationalism has more or less been completed. In earlier programs there were still references to ethnicity, but not since 2011. The nation is now defined in terms of common identity, language and culture. The party now also explicitly states that those born in other parts of the world can become Swedish, or at least “assimilate to the Swedish nation” by later in life actively choosing to assimilate to it. In order for foreign born individuals to become members of the Swedish nation they should speak fluent Swedish, see themselves as Swedish, live in accordance with Swedish culture, and feel greater loyalty to Sweden than to any other nation (Sverigedemokraterna, 2011, p. 15). The Sweden Democrats state that they are not opposed to all immigration, but that it must “be kept at such a level and be of such a character that it does not constitute a threat to our national identity or to the welfare and safety of our country” (Sverigedemokraterna, 2011, p. 23). However, they are strongly opposed to multiculturalism and advocate an active assimilation policy.

In sum, the Sweden Democrats are strongly opposed to multiculturalism and prefer a very restrictive immigration and refugee policy. However, there is no evidence of classic racism, or any ideas about hierarchies of races or even of cultures, in their current principles program or election manifesto. Furthermore, their view of national belonging is purely cultural, combined with strong demands that those who immigrate to Sweden should assimilate and adopt Swedish culture and identity.

The Sweden Democrats are no longer a one-issue party. Their recent election manifesto for the 2018 election covers a wide variety of issues in addition to immigration such as healthcare, housing, social cohesion, crime, the labour market, research and education, culture and more (Sverigedemokraterna, 2018). I will here only briefly highlight some of the proposals and policies in the 2018 election manifesto that distinguish them from most other political parties in Sweden.

- Sweden should only receive asylum seekers from its neighboring countries, and only as long as the neighboring countries are considered safe, otherwise Sweden should accept no asylum seekers at all

- Higher demands for citizenship, such as language tests

- Economic incentives for immigrants to return to their home countries

- Generally longer prison sentences for crimes

- Make it possible to revoke citizenship for certain crimes such as terrorism

- Forbid child marriages and polygamy without exception

- Opposition to gender quotas

- Leave the EU / hold a new referendum about EU membership

The Sweden Democrat’s electoral evolution

In order to understand the electoral evolution of the Sweden Democrats we first need a short introduction to the Swedish election system. For a more comprehensive description of the election system and its history, see Hermansson (2016). In short, the Swedish election system is a party-based system where political parties present ranked lists of candidates. A fundamental principle of the Swedish election system is that of proportional representation (Hermansson, 2016). Further, the electorate is divided into 29 constituencies (which follow the counties, with a few exceptions) and voters cast their vote in the constituency where they are residents. The election system is designed to ensure both (national) proportional representation and the geographic anchoring of the candidates. Furthermore, there is a 4 percent threshold to the national parliament, meaning that the proportional representation relates to those parties who receive at least 4 percent of all votes nationwide. However, it is also possible gain representation in the national parliament by attaining at least 12 percent of the votes in a single constituency; this may result in a single representative being elected to the national parliament from that constituency.

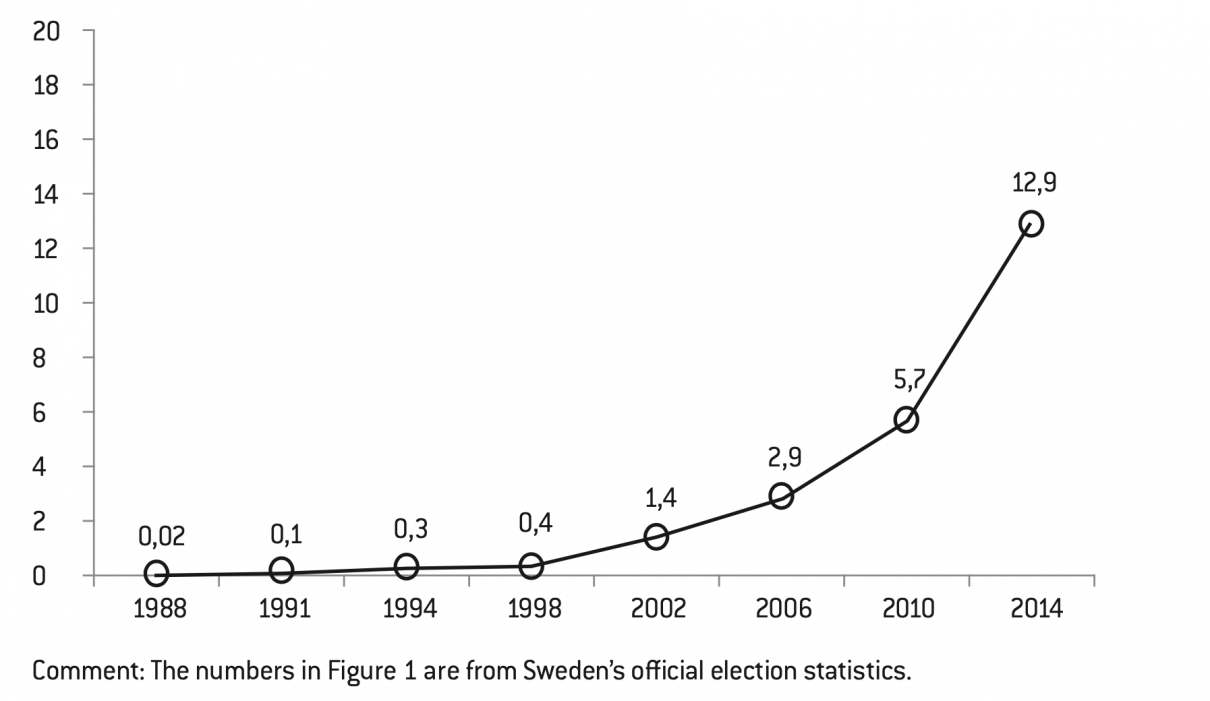

In the first election after the Sweden Democrats was founded, the very same year, they received a hardly noticeable share of the votes in the national parliament: 0.02 percent, only gathering about one thousand votes. In the beginning their growth was slow – ten years after their formation, in the 1998 election, they had only grown to 0.4 percent of the votes, or almost 20 thousand people. Thus, they were still a marginal party that was not often discussed in the public debate.

However, their growth steadily continued, and at a quicker pace. In the 2002 election they managed to more than triple their share of the vote, and more importantly increased their presence in local (municipal) assemblies dramatically. Although they received their first locally elected representatives already in 1991, these were just a few exceptions. But in 2002, the Sweden Democrats increased their number of locally elected representatives (Kommunfullmäktige) from 8 to 49. This resulted in a lot more attention for the party in the media. Another breakthrough in the 2002 election for the Sweden Democrats was that they now received clearly higher numbers in the south of Sweden. In no less than 5 of the 29 parliamentary constituencies they received at least 2.8 percent of the votes, and in one of them as much as 4.5 percent. This further increased attention to the party since it now became possible to imagine that they would actually one day gain representation in the national parliament – the Swedish Riksdag. If they could achieve similar numbers outside of the region of Skåne in the south of Sweden, they would pass the 4 percent threshold to the national parliament.

The next step in their electoral evolution came in 2006 when they once again markedly increased and more than doubled their national vote share to almost 3 percent. This also meant that they were now sufficiently large to be reported separately in the monthly polls that most large media outlets publish, rather than being hidden in the “other party” category, which further increased their continued visibility and improved their possibilities to convey their message to the larger public.

Figure 1: National parliamentary election results for the Sweden Democrats 1988-2014 (percent of votes)

Things then began to rapidly change. In the next election, they received 5.7 percent and representation in the Swedish Riksdag with 20 elected parliamentarians of the total 349 in the Swedish parliament. It also became clear that all of the larger well-known opinion polling institutes in Sweden had underestimated the Sweden Democrats’ support among voters. Most polls right before the election had them at approximately 4 percent rather than the almost 6 percent they received in the election. In 2014, the same story was more or less repeated. The Sweden Democrats doubled their vote share once again to almost 13 percent and increased their number of elected parliamentarians from 20 to 49. Before the election, the polls indicated a support of approximately 8 to 10 percent, but in the end they received almost 13 percent, to the surprise of most analysts and commentators.

At this time, we still do not know how many votes the Sweden Democrats will receive in the Swedish 2018 parliamentary election. However, they are certainly a center piece of the public debate and have been so for several years. Presently, most polls indicate that approximately 20 percent of Swedish voters intend to vote for the party. According to some polls, for example, Yougov, their supporters now amount to more than 25 percent of the electorate. If this is true, the Sweden Democrats would once again more or less double their vote share and could possibly become Sweden’s largest political party.

Regional differences in the Sweden Democrat vote

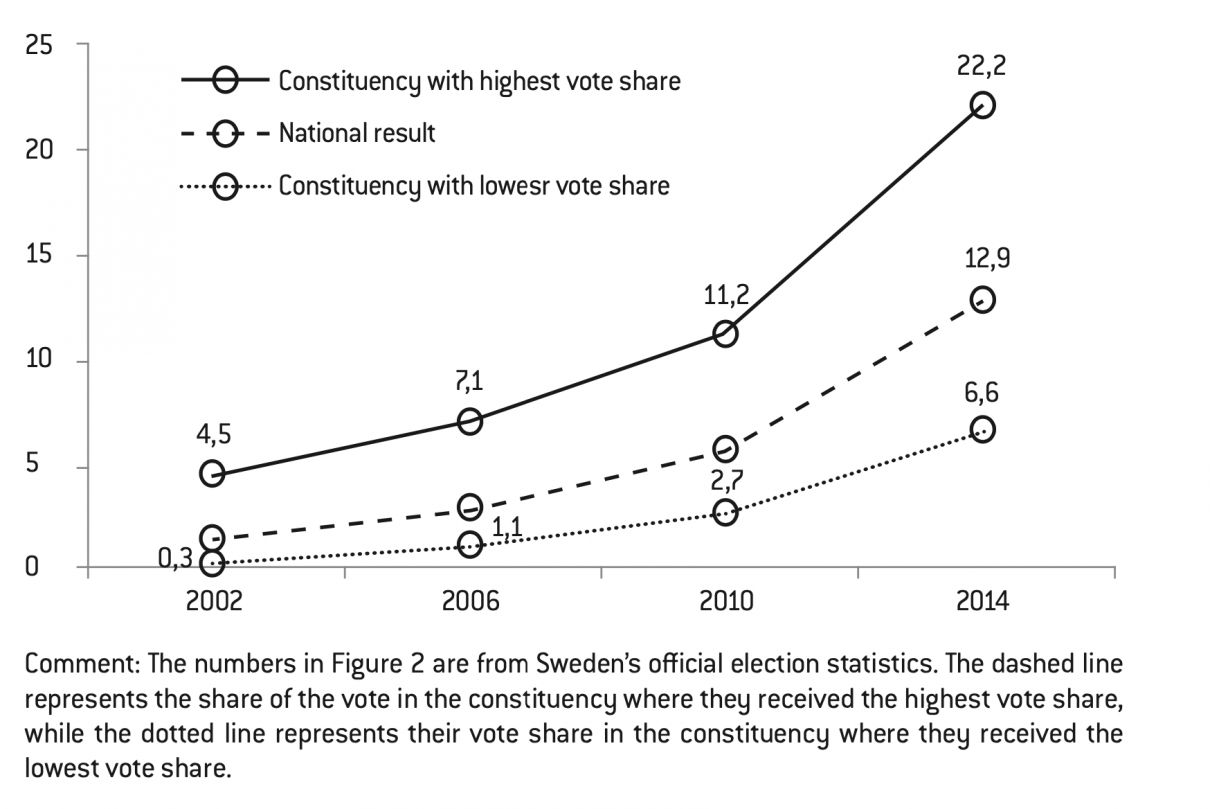

Since the vote share for the Sweden Democrats has always varied substantially between different parts of the country, they have already seen clearly higher (and lower) numbers in some of the 29 parliamentary constituencies of Sweden. Figure 2 shows the vote share in the constituency where they received the highest and the lowest vote share during the period 2002-2014, using the national result from the corresponding year as a point of reference.

Regional differences in the vote share of the Sweden Democrats from 2002-2014 (percentage of the vote)

As discussed above in connection to Figure 1, the 2002 election represented a regional breakthrough when they received 4.5 percent in one of the constituencies in the south of Sweden. In all four elections depicted in Figure 2, the highest vote share is from the region of Skåne in the south. In 2002 and 2006, the highest number is from the west Skåne constituency, and in 2010 and 2014 from the north-east Skåne constituency.

Conversely, the lowest vote shares for the Sweden Democrats are usually found in the northern part of Sweden and in the Stockholm region. In 2002, 2006 and 2010 their lowest results were found in Västerbotten (with also very low results in Jämtland and in Norrbotten). In 2014, the lowest vote share was instead found in Stockholm (Stockholms län).

The growth of the party’s vote shares has been quicker in their best constituencies than in their worst, which implies that the regional variation of their support has increased. In 2002, the difference between the constituency with the highest vote share and the constituency with the lowest vote share was 4.2 points, in 2006 it was 6 points, in 2010 it was 8.5 points and in 2014 it was no less than 15.6 points”

Public opinion in Sweden on immigration and refugees

In this section, aspects of public opinion that can be assumed to be closely related to the increasing support for the Sweden Democrats will be examined. In particular, I will focus first on the development of public attitudes towards the reception of refugees in Sweden, and secondly on the public agenda, particularly regarding which political issues or problems the Swedish public finds the most important.

For a long time, results showed that the share of the Swedish public who expressed negative attitudes towards receiving asylum seekers was slowly decreasing over time. However, this changed in 2016 during the aftermath of the European refugee crisis and the sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving in Sweden. This will be examined in more detail later. What seems to be particular about the upcoming election in September 2018 is that the issue of immigration and integration is now higher on the public agenda than it has ever been, and the issue of crime and law and order is one the issues that has risen the most quickly on the public agenda during recent years (Martinsson & Weissenbilder, 2018). These results have also been confirmed by numerous polls from private sector polling institutes.

The development of attitudes to refugees

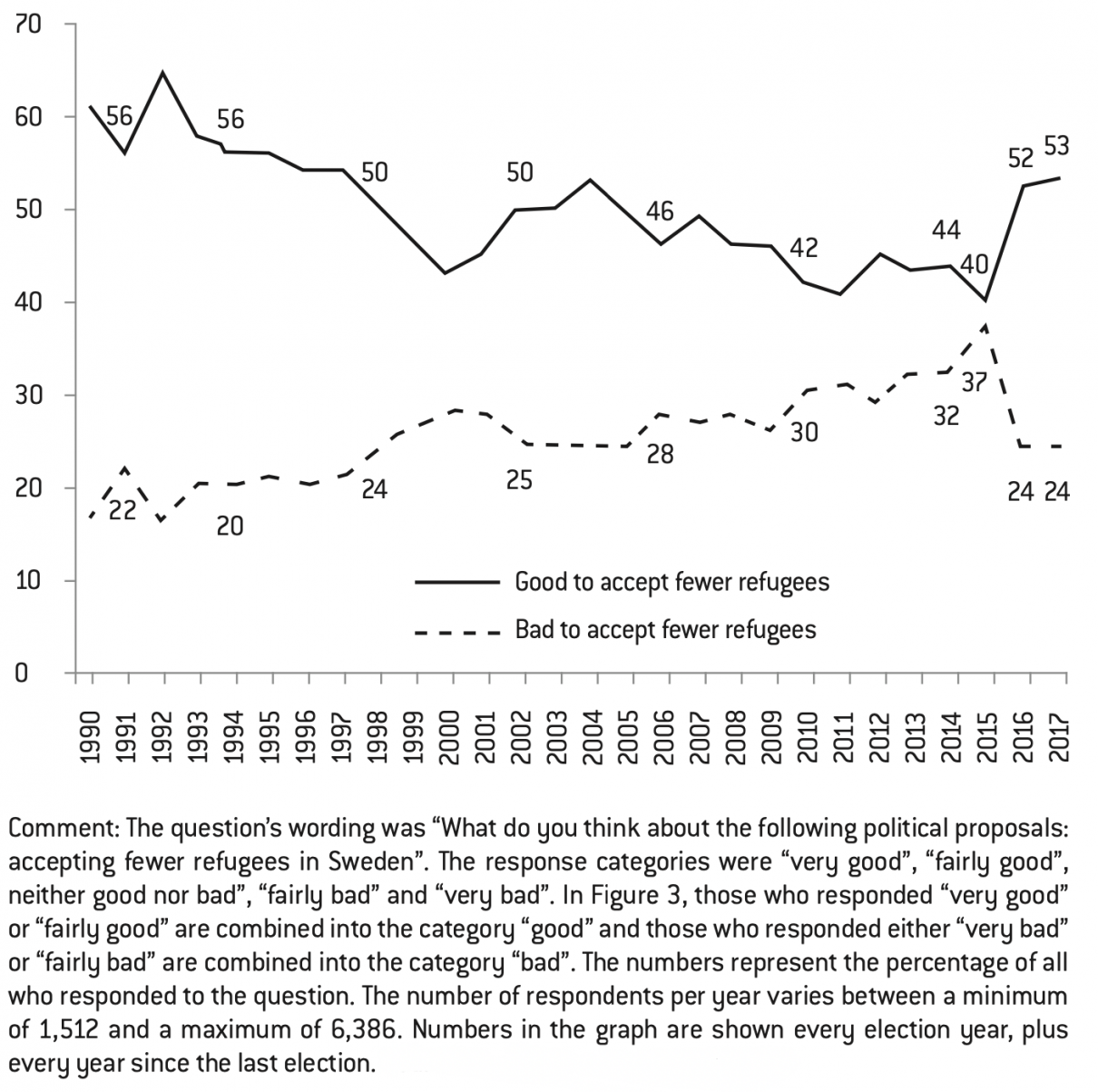

Now, let us start by taking a closer look at the development of public attitudes towards refugees in Sweden. Until recently, the long term trend that could be seen from the annual SOM surveys was that negative attitudes towards refugees were in decline. In the early 1990s, when Sweden received many asylum seekers from the former Yugoslavia, negative attitudes peaked with more than 60 percent saying that Sweden should accept fewer refugees (see Figure 3). From this point, however, negative attitudes gradually declined and in the 2010 election, when the Sweden Democrats first entered parliament, the share of those who wanted to see fewer refugees in Sweden was 42 percent compared to the peak at 65 percent in 1992.

Public attitudes towards refugees in 1990-2017 (percent)

Source :

The SOM surveys 1990-2017.

During the refugee crisis starting in 2015, the initial response was one of the more positive attitudes towards the reception of refugees and asylum seekers. During the fall 2015, the SOM surveys almost exhibited an even split between those who said it was a good idea to accept fewer refugees and those who said it was a bad idea (40 versus 37 percent). However, this was probably a brief effect of the intensified media reports of the number of people drowning in the Mediterranean that year. That same fall, public opinion changed in a more restrictive direction, and the next year the change was clearly visible in the SOM surveys with a large and quick increase of 12 percentage points of the share saying it would be good to accept fewer refugees and a similar rapid decrease in the share saying it would be bad of 13 percentage points.

While the most important factor that Figure 3 reveals about public opinion on immigration and refugees in Sweden is the long-term trend, it is at least equally important to acknowledge that public attitudes towards the reception of refugees in Sweden has always (with the exception of the early fall of 2015) been clearly more negative than positive.

The development of the public agenda

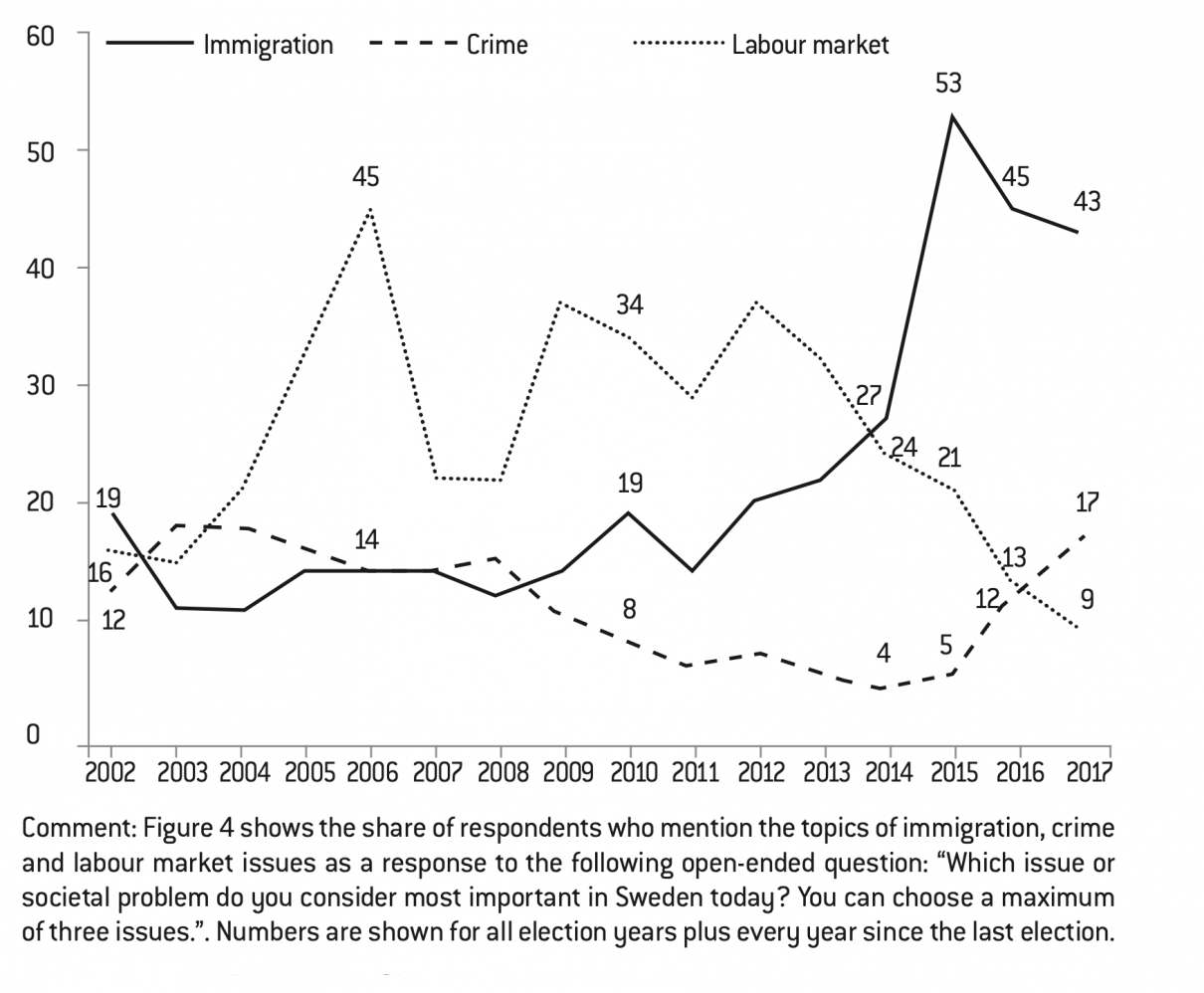

We will examine the development of the public agenda in Sweden on a few selected key issues: immigration, crime, and labour market issues such as unemployment. As previously shown by Martinsson and Weissenbilder (2018), the public agenda faced with the upcoming 2018 elections can be expected to differ substantially from the topics that usually dominate the public agenda during Swedish elections. Figure 4 shows this development since 2002 based on data from the annual SOM surveys at the University of Gothenburg.

Public saliency of immigration, crime and labour market issues in Sweden 1990- 2017

Source :

The SOM surveys 2002-2017.

The sharp rise of the immigration issue in the public agenda is a fairly recent phenomenon. Still, during the 2010 election when the Sweden Democrats first entered the national parliament, the issue was not among the top public issues, but considered one of the most important by 19 percent, which had more or less been the case for the last couple of elections. It was not until 2014 that the issue started rising noticeably and was mentioned by 27 percent of the public. However, one year later, in 2015, the situation was about to change completely at the start of the so-called European refugee crisis. Since then, the immigration issue has dominated the public agenda in Sweden. Immediately in 2015 as many as 53 percent said an immigration related issue was one of the most important issues. Despite a slowly decreasing share in 2016 and in 2017, the issue is still the one that is most often mentioned by Swedes (Martinsson & Weissenbilder, 2018).

Another issue that has increased quickly since 2015 is crime and law and order. In 2017, the issue was mentioned by 17 percent of the public. However, if we look further into the past, this is as unique of a situation as the immigration topic was. Between 2002 and 2008, the issue of crime was at about the same level of public salience.

Some other issues that have typically dominated Swedish election campaigns have seen a very different development. One such example is unemployment and labour market issues. As seen in Figure 4, unemployment has gradually lost its significance to large parts of the public starting in 2013. For a very long time, unemployment was a cornerstone of elections in Sweden, and one of the most important issues for voters. Still in 2006, unemployment was a prominent issue in the election campaign, and later on during the international financial crisis starting in the U.S. in the fall of 2008, and a few years thereafter, unemployment was an important topic to large parts of the public (e.g. 34 percent in 2010). However, in 2013 the issue started to lose in importance and has gradually been regarded as salient by fewer and fewer voters. In 2017, unemployment was mentioned by a mere 9 percent of the Swedish public. If unemployment is being discussed in the public debate today in Sweden, the discussion is most certainly about unemployment among newly arrived asylum immigrants. This development of the public agenda illustrates an important aspect of the shift in public opinion and in the conditions for different political parties to gain electoral success in a new attitudinal landscape.

Although the public agenda indicates that new issues are replacing old issues as the most salient to the public, older issues and conflict dimension can still be simultaneously important too. As Oscarsson (2017) has convincingly shown that the correlation between party choice and attitudes to immigrants and refugees has gradually increased during the last 15 years in Sweden. But Oscarsson (2017) also clearly shows that the polarization along the traditional left-right ideological continuum is still stronger at the voter level, and the cultural dimension, including in particular the issue of immigration, is mainly complementing the left-right dimension despite that it has clearly increased in strength recently.

We should also remember that not all those who say that immigration, integration and related issues are some of the most important problems in Sweden are negative to accepting refugees. There is a correlation, those who are negative towards accepting refugees are significantly more likely to also say it is one of the most important problems than those who are positive towards receiving refugees, but the difference is fairly small. Overall, 61 percent of those who think immigration is one of the most important problems think it is a good idea that Sweden should receive fewer refugees, while 26 percent think it is a bad idea and 13 percent take a neutral stance and say it is neither a good nor a bad idea. Among those who do not mention immigration as one of the most important problems, the share of those who think it is a good idea to receive fewer refugees in Sweden is instead 46 percent. In 2017, about two thirds (67 percent) of those who mention immigration as one of the most important problems prefer to receive fewer refugees.

The sharp rise in public salience on the immigration issue in 2015 is, naturally, connected to the equally sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers in Sweden in 2015 during the so-called “refugee crisis” in Europe. In his report on the history of migration to Sweden, Sanandaji illustrates that Sweden has had a high level of immigration compared to other West European countries for a long time. During the period of 1985 to 2015, Sweden had approximately four times as many asylum seekers per capita as other Western European countries (Sanandaji, Swedes and immigration: End of homogeneity? Fondation pour l’innovation politique, September 2018, p. 17). And in 2015, the difference became even greater. In fact, Sanandaji points out that according to the OECD, Sweden has had the largest per-capita inflow of asylum seekers ever recorded in an OECD country (Sanandaji, 2018, p. 9). This indicates that the issues of immigration, integration and national identity are not likely to disappear anytime soon in Sweden. In sum, both public attitudes towards refugees and the public agenda now provide fertile ground for the growth of the Sweden Democrats.

Who are the Sweden Democrats’ voters?

This section will describe the demographic, social and political make-up of the supporters of the Sweden Democrats. In their early history, such studies were not possible since they were too few to be included in any substantial numbers in regular social and political surveys. Even later on when they constituted a few percent of the electorate, such studies were fairly difficult and often burdened with scientific uncertainty. Most social science surveys usually include at most a few thousand respondents, so for a party with, say, 2-3 percent of the vote, a representative sample of 1,500 people would not even yield 50 supporters to study. This section will therefore rely on survey-based studies from the last ten to twelve years. First, earlier studies of the social and political composition of the party’s supporters will be reviewed. Second, they will be compared with international studies of similar parties. Lastly, previous analyses will be updated with the most recent available data from the annual SOM surveys at the University of Gothenburg and a general explanation for the Sweden Democrat vote will be reviewed.

Previous studies on the characteristics of the Sweden Democrats

One of the early accounts of the supporters of the Sweden Democrats Sören Holmberg (Holmberg, 2007) concludes that the Sweden Democrats supporters, more often than supporters of other parties, belong to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. However, they are most of all characterized by their low levels of trust in politicians – according to the survey “What next for democracy?” (page 30), published by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 77% of Swedes believe that most politicians are mainly interested in protecting their own interests. The supporters of the Sweden Democrats are also characterized by their negative attitudes towards immigration and refugees, and that they, unlike most voters, tend to see immigration and crime as the country’s most important problems.

More specifically, Holmberg (2007) found that the Sweden Democrats were overrepresented among men, younger people with low education levels, and the unemployed. When it comes to political attitudes, Holmberg (2007) also examined how the Sweden Democrats differ from other voters in approximately 30 political issues. He found that they could be characterized by other aspects such as being less positive to receiving refugees, more positive to cutting foreign aid, more positive to Sweden leaving the EU, lower trust in politicians, more positive to lowering taxes and by being less positive to a society with gender equality.

Eleven years later, many of these characteristics are still valid. In a series of book chapters based on survey data from the SOM Institute at the University of Gothenburg, Anders Sannerstedt has continued to analyze the Sweden Democrats (Sannerstedt, 2014, 2015, 2016) – by using data from the fall of 2015, he found that despite the Sweden Democrats rapid electoral growth, their social and political composition has mostly remained the same, with few exceptions (Sannerstedt, 2016).

Both Sannerstedt (2016), who relied on data from the SOM Institute, and Oscarsson and Holmberg (2016) who used data from the Swedish National Election Studies, have pointed out a noteworthy change from earlier years in the sociodemographic characteristic of the Sweden Democrat supporters. Since 2014, the Sweden Democrats are no longer a party that attracts young voters more than older voters. Previously it had been clear that younger people, and particularly younger men, were overrepresented among their supporters. According to Sannerstedt’s findings, this was still the case in 2013, but the difference disappeared in 2014, and in 2015, the structure became reversed with a higher share of Sweden Democrat supporters among people over 50 years of age than among people under 40 (Sannerstedt, 2016).

Summing up the results from both Sannerstedt (2016) and Oscarsson and Holmberg (2016), the supporters of the Sweden Democrats are characterized by being more popular among men, people living in the countryside, people with lower education levels, the unemployed or on long-term sick-leave, as well as those with subjectively reported bad personal health as well as among those with medium or low incomes. In terms of political attitudes, they are also overrepresented among people with no interest in politics, who have low levels of trust in politicians, and place themselves in the middle of the ideological left-right political scale (or slightly to the right of the center).

Overall, the results found for the Sweden Democrats follow an international pattern for nationalist and anti-immigration parties in Europe. For example, in a study by Rydgren (2008), low or medium education (as opposed to high education) was positively correlated with voting for a nationalist party in most of the six west European countries included in his study. In most of the countries, older voters were also more prone to vote for such parties. At the general level, socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals such as low income earners and the unemployed have mostly been found to be overrepresented among those voting for anti-immigration parties (van der Brug et al. , Fennema, van Heerden, & de Lange, 2014). Similar patterns have also been found for example for the FPÖ in Austria (Moreau, 2016). Also, men are usually more likely to support radical right parties than women, even when controlling for their political attitudes (Harteveld, van der Brug, Dahlberg, & Kokkonen, 2015).

The situation in 2017

The most recent data in the previous studies on the Sweden Democrats presented above are from 2015. This section will therefore update the analyses by Sannerstedt and others to examine whether the previous patterns still hold true or if the characteristic of the supporters of the Sweden Democrats has changed. The most recent comprehensive data set suitable for such an analysis is the SOM Institute annual national survey from 2017: a large scale representative social and political survey of the Swedish population collected slightly less than a year before the 2018 election. The SOM survey from 2017 consists of six different questionnaires that are fielded simultaneously and included a large set of various social, cultural, political and behavioral indicators. All six questionnaires included a core set of variables with, for example, party sympathy, while other indicators may sometimes be included in one or several questionnaires. For more information on the methodology and fieldwork of the SOM surveys, see Jansson et al (2018).

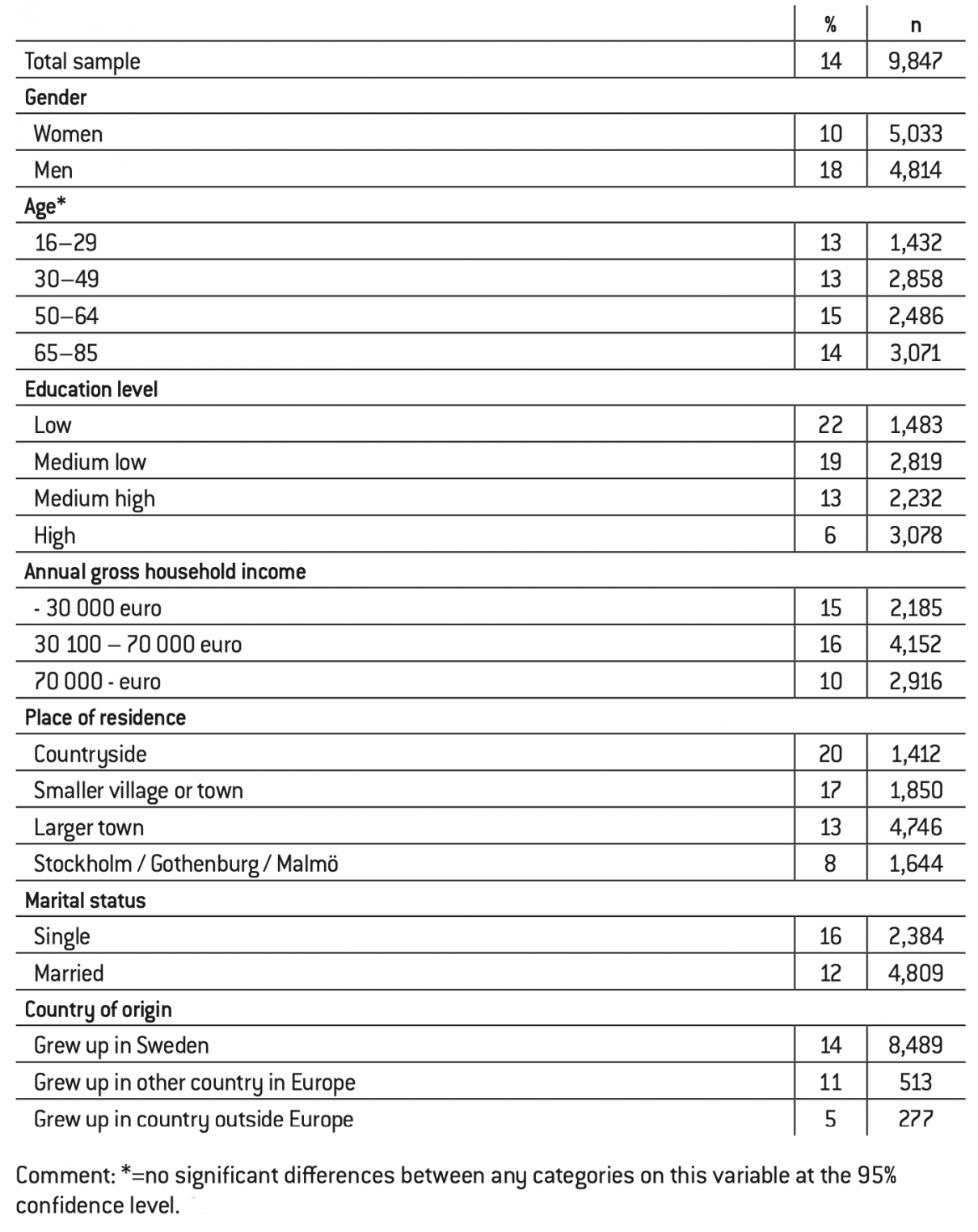

We will examine the characteristics of the Sweden Democrats’ support a bit less than one year before the 2018 election using a large number of demographic, socioeconomic and political characteristics, and compare these to previous studies on the Sweden Democrats. However, this data set does not ask which party people intend to vote for in the next election (or in a hypothetical election). Instead, it asks respondents which party they like best; their party preference. This is not quite the same thing, and sometimes there is a small discrepancy in how many votes for a party and how many actually like it best. Usually, these differences are fairly small, and the two concepts are very highly correlated. Other opinion polls from private polling institutes conducted during the same period show a similar level of support for the Sweden Democrats. In the SOM survey, the overall share of respondents saying that they like the Sweden Democrats best in the fall of 2017 is 14 percent. In a poll by TNS Sifo in October the same year the share saying they would vote for the Sweden Democrats if there were to be an election held today was 15 percent. A poll by Ipsos also estimated their electoral support in October of 2017 to be 15 percent.

First, we will take a look at the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. To a large extent, Table 1 reveals the same pattern as previous years in the studies by Sannerstedt (2016) and Oscarsson and Holmberg (2016). The Sweden Democrats in 2017 also have higher support among men than women with 18 compared to 10 percent. Also in 2017 we find that the old pattern where the Sweden Democrats had higher support among young generations is no longer present. In fact, there are no significant differences between any pairwise comparison among the four age groups presented in Table 1. Age is no longer a predictor of support for the Sweden Democrats. The differences between educational groups, however, is still strong. The support for the Sweden Democrats is highest among those with low education levels and lowest among those with high education levels (university level education). In fact, the support is more than three times as high among people with low education levels compared to those with higher education levels (22 versus 6 percent). The income pattern also persists with lower support among higher income groups. However, it is not the case that the Sweden Democrats’ main support comes from low income earners; their support among medium income groups is equally high. Likewise, the old pattern of lower support in the three largest cities is still valid.

Due to the large sample size, we can also compare groups with different origins and examine if there is a difference between those born in Sweden, in other countries in Europe, and outside of Europe. Although foreign-born now individuals now make up a large portion of the Swedish population, they is usually difficult to compare with nationals since they are often underrepresented in survey studies. The results in Table 1 reveal that there is no statistically significant difference between those born in Sweden and those born in other countries in Europe. But, if we examine those born outside of Europe, the support for the Sweden Democrats is clearly lower (5 percent compare to 14 percent for those born in Sweden). This difference is significant considering their 95 percent confidence level, despite the limited number of people born outside Europe in our data.

Support for the Sweden Democrats in different demographic and socio-economic groups in 2017

Source :

The national SOM survey 2017.

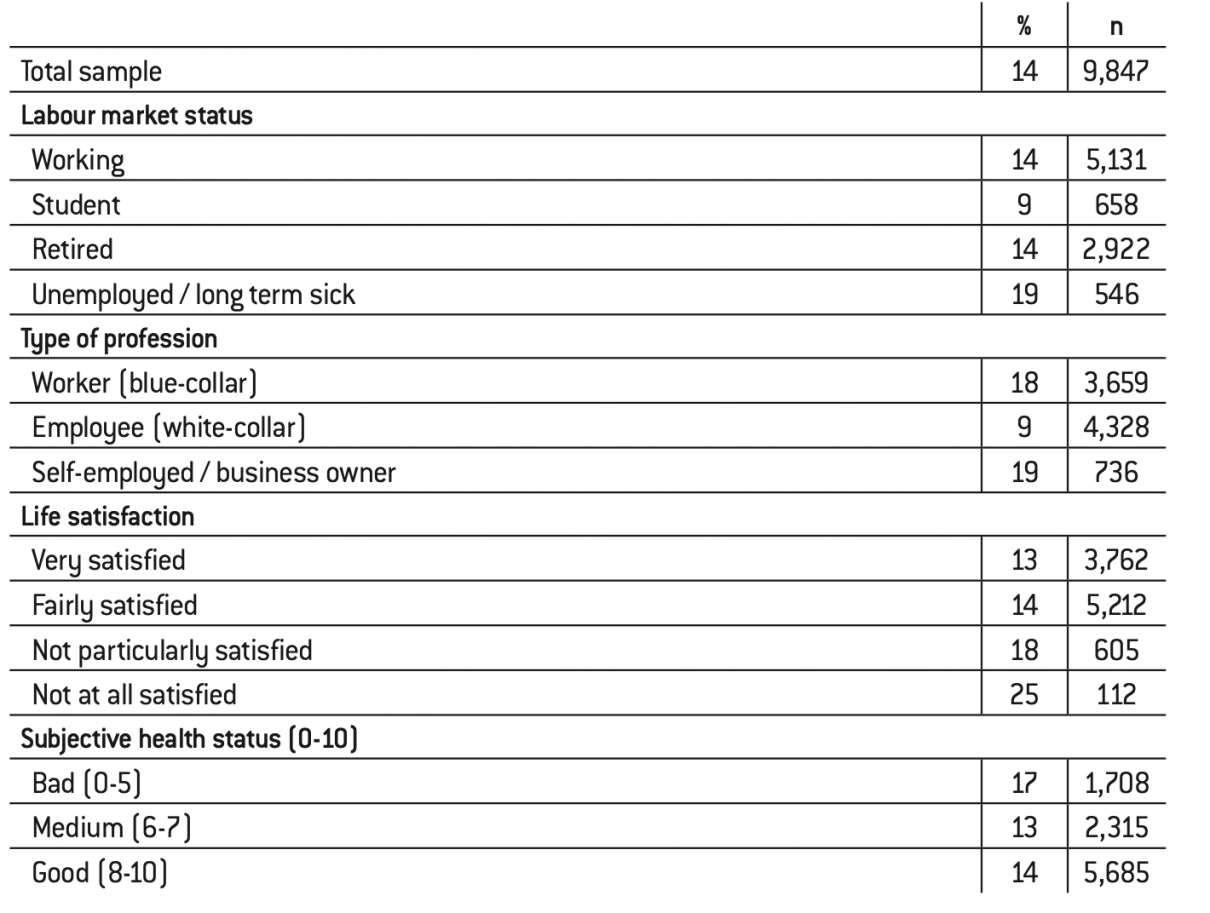

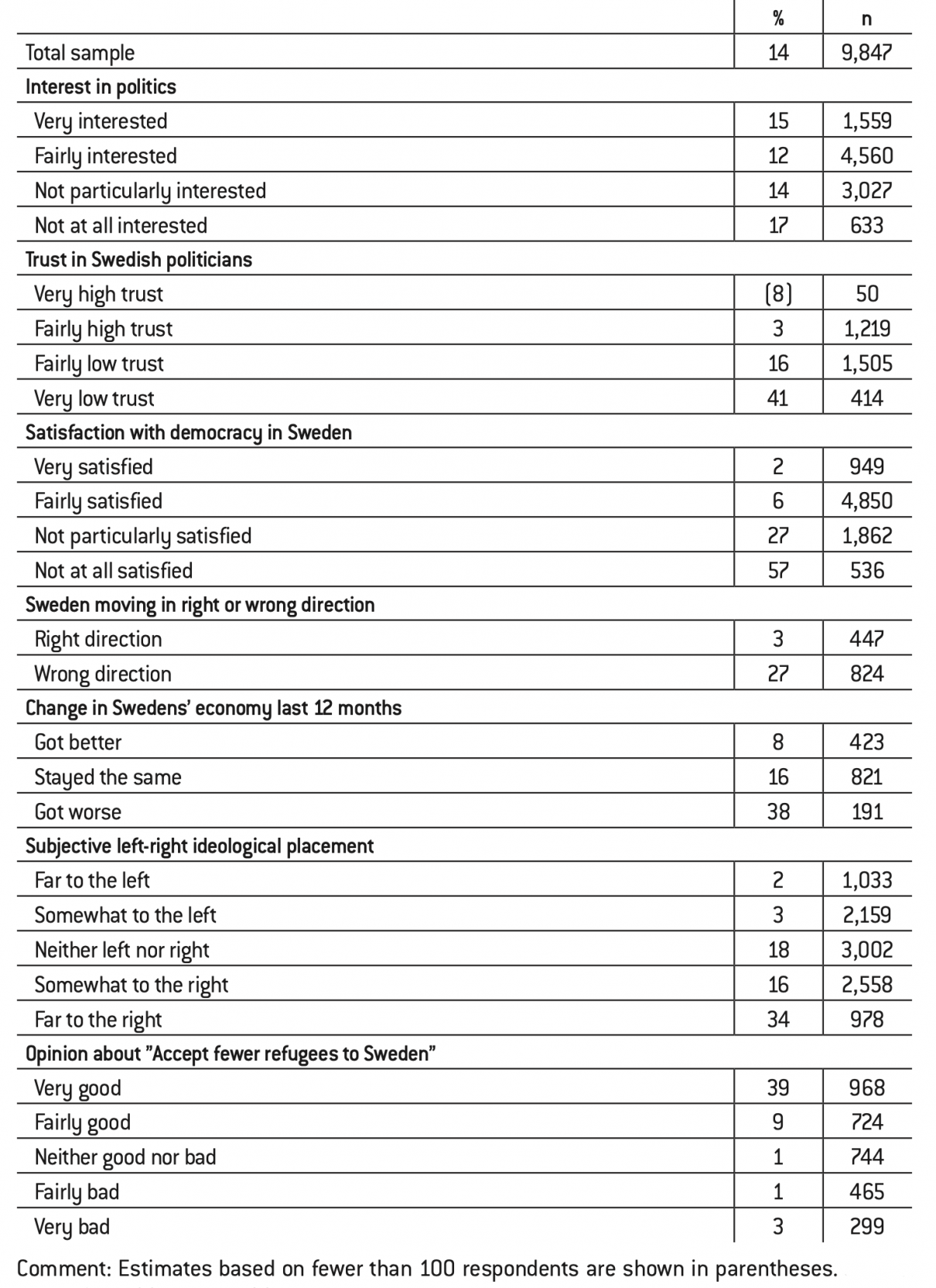

In Table 2, we also find a set of familiar patterns from previous studies, but many of these differences are now quite small, although still statistically significant in our unusually large sample of the Swedish population. The Sweden Democrats are still more popular among workers, and their support is still lower among students and higher among the unemployed and those with long-term illnesses. The familiar pattern of higher support among those with lower life satisfaction is still present, as well as the connection to subjective health status. However, the latter connection is quite weak, with 17 percent supporting the Sweden Democrats in the group with relatively poor subjective health and 14 percent in the group with relatively good subjective health.

Support for the Sweden Democrats by labour market situation, life satisfaction and health in 2017

Source :

The national SOM survey 2017.

In Table 3 we encounter another familiar pattern where the Sweden Democrats’ support exhibits a strong connection to trust in politicians. Their support is 41 percent among those with very low levels of trust in Swedish politicians and only 3 percent among those with fairly high trust. The same goes for satisfaction with the way democracy works in Sweden. The Sweden Democrats support is much higher among groups that are dissatisfied with democracy in Sweden, with as many as 57 percent of those not at all satisfied supporting the Sweden Democrats. However, it is important to remember now that the causal direction is far from clear cut. This pattern is not necessarily a result of a process where those who become less satisfied with democracy or lose their trust in politicians become more likely to support the Sweden Democrats. The other way around is equally possible, and according to some studies, it is even more likely (e.g. McLaren, 2011).

The level of interest in politics, though, does not seem to have any linear connection to the tendency to support the Sweden Democrats in 2017. Their support is lower among those with fairly high interest in politics (12 percent), but there is no significant difference between those with very high interest and those with low interest in politics.

Support for the Sweden Democrats by social and political attitudes and perceptions in 2017

Source :

The national SOM survey 2017.

The Sweden Democrats’ support is also very low among those who think that Sweden is currently moving in the right direction compared to those who say that Sweden is moving in the wrong direction. As expected, the Sweden Democrats’ support is also much higher among those who are strongly in favor of accepting fewer refugees to Sweden than among those who do not or who are more moderate in their opinion.

A clear finding that has not been covered as much in previous publications is that those who view the economic development in Sweden during the last year as more negative are far more likely to support the Sweden Democrats. Among those who say the economy has gotten worse, as many as 38 percent support the Sweden Democrats, compared to the 8 percent who say the economy has improved (Table 3). A logistic multivariate regression analysis of support for the Sweden Democrats including a large set of control variables, both socioeconomic and political, reveals that negative macroeconomic perceptions in fact has an independent effect and does significantly predict support for the Sweden Democrats.

Another striking finding is that, in 2017, the Sweden Democrats had a more pronounced ideological right wing profile among their supporters. In 2014, Oscarsson and Holmberg found that their support was largest among those who placed themselves neither to the left nor to the right (Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2016, p. 248). In 2017, on the other hand, this is clearly not the case. We can see in Table 3 that among those who place themselves to the ideological left, their support is almost nonexistent, and it is twice as high (34 percent) among those who say they are “far to the right” than among those who place themselves in the centre or “somewhat to the right” (16-18 percent). A closer examination of the annual SOM surveys reveals that this pattern had already started to change in 2015 and has been gradually reinforced over time. However, the cause of this change in connection to the left-right ideology and support for the Sweden Democrats is unclear.

Explanations for the Sweden democrat vote

There are several different types of explanations for voting for anti-immigration or radical right parties. Scientific studies have existed on this topic for several decades. Roughly speaking, most explanations are focused either on supply side factors or demand side factors. The supply side includes the anti-immigration or radical right parties themselves, their organization and policy programs and related factors, but also which other political parties are available options, and how they react to the appearance of these new parties. Among the demand side factors we find public opinion and the voters’ attitudes on relevant topics such as nationalism, immigration and refugees. In a general sense, macroeconomic developments, cultural shifts and changes in identities also belong to this group of explanations. I will not discuss the supply side factors here, but it is rather clear that the Sweden Democrats have skillfully, gradually and intentionally built and developed their party organization to make a broader electoral appeal possible since the mid-1990s.

At the individual level, several cross-sectional studies using micro-level data from voter surveys indicate that the most important explanation for the Sweden Democrat vote is – without any doubt – negative attitudes towards immigration. In the main publication from the Swedish Election studies program on the 2014 election, Oscarsson and Holmberg present a comprehensive analysis of what explains voting for the Sweden Democrats. In accordance with international scientific publications on voting for anti- immigration parties, they conclude that the Sweden Democrats’ vote is clearly primarily driven by issue voting, just like for most other political parties. Those who chose to vote for the Sweden Democrats primarily do so because their political opinions concerning immigration and refugees are in agreement with the views of the Sweden Democrats’ party (Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2016). In addition to anti-immigration attitudes, Oscarsson and Holmberg also find a separate, but weaker, effect of negative attitudes towards the EU. Most socioeconomic factors do not have any remaining direct effect on the propensity to vote for the Sweden Democrats in their multi-variate regression analyses. Socioeconomic factors mainly have an indirect effect channeled through anti-immigrant attitudes, although being working class, and being male, both have some remaining positive direct effect on the Sweden Democrat vote in their model.

In an early study of six west European countries, using data from the 2003 European Social Survey Rydgren (2008) has convincingly shown that xenophobic attitudes, or racism, are not necessarily important predictors of radical right voting. Rather, what he calls immigration skepticism, such as the view that their country should accept fewer immigrants, was found to be the most important driver of the vote. In addition to the increased saliency of the immigration issue and the negative attitudes to refugees, other long- term structural factors such as the decline in class voting and the perceived decreasing distance between mainstream parties in convergence with left- right issues are pertinent (Rydgren & van der Meiden 2018; Oscarsson & Holmberg 2016).

It is also well-known that voters of anti-immigration parties tend to be more discontent than the voters of other parties. For example, they have lower trust in politicians in general, in the political system, and are less satisfied with the way democracy works. However, it is far from clear that this should be an explanation, or a cause, of voting for anti-immigrant parties. Although it is difficult to study what actually causes different attitudes held by individuals, most research indicates that it is more likely to be anti-immigration attitudes that causes political discontent and low levels of trust rather than the other way around (Kokkonen, 2015; McLaren, 2011; van der Brug, 2003). A likely causal path is that negative attitudes towards immigration and refugees lead to an increased propensity to sympathize with anti-immigration parties, which in turn leads to lower general trust and generalized political discontent.

Taken together, what we know about explanations for voting for anti- immigration parties both from other countries and from studies on the Sweden Democrats probably indicate that given what we have seen concerning the development of public opinion in Sweden, the growth of the Sweden Democrats should not come as a surprise.

The Sweden Democrats’ position in the Swedish political system its possible future impact

In order to understand the position of the Sweden Democrats in the Swedish political system and their potential impact, we must first present an overview of the Swedish party system. For a more full account of the party system, its development and how it relates to those of other countries, see Aylott (2016). For a long time, Sweden used to be characterized as a five-party system with a Left party (former communist party), a large Social Democratic party, a Centre party (former agrarian-farmers), a Liberal party and a (liberal-conservative) Moderate party. These five parties used to collect 95 to 98 percent of all votes until the end of the 1980s (Aylott, 2016, p. 155).

The party system characteristics can be briefly summarized by the five-party model, a unidimensional conflict structure based on the left-right conflict, a two-bloc structure with the Left party and the Social Democrats to the left and the other three parties to the right, and a dominant Social Democratic party gathering at least 40 percent of the votes from the 1930s to the 1980s. The arrival of the Green party in 1988 and the Christian Democrats in 1991 changed this into a seven-party system, but essentially kept the two bloc- character, especially after 1994 when the Greens moved closer to the left bloc. However, during certain periods of time, the Social Democrats have cooperated with the Centre party rather than the Left party. This has possibly been due to both their size and the lack of unity among the centre-right parties. Since 2006, however, this clearly changed when the four centre-right parties under the lead of the new Moderate party leader Fredrik Reinfeldt formed the so called “Alliance for Sweden”, which reinforced the two bloc-structure of the party system. However, this model is now challenged by the arrival of a new party – the Sweden Democrats – which is quickly growing and can be said to make up a third “bloc” in the Swedish party system.

The Sweden Democrat’s position in the national parliament

After the entry of the Sweden Democrats into parliament in 2010, the party was kept away from all forms of cooperation or negotiations by all the other seven parties. As a response to their entry, they were isolated in the parliamentary work. The new situation that needed to be handled was that the governing coalition, the four centre-right Alliance parties, no longer had a majority of the votes in parliament. This meant that the Sweden Democrats could sometimes influence policies by voting against the government’s propositions together with the red-green opposition parties (Widfeldt, 2014). This led to some negotiations between the governmental parties and the Green party, which resulted in a deal concerning immigration and foreign policy, ensuring that the Sweden Democrats would not be able to influence their core issue: immigration.

A particularly interesting case during the beginning of the Sweden Democrats’ first mandate in the national parliament was when the centre-right government planned another income tax cut, which was a central part of their platform. The red-greens opposed this tax cut, as they had during their election campaign, but when the Sweden Democrats also declared that they would vote against such a tax cut, it became evident how fragile the parliamentary situation was and that the government could no longer count on their political program to pass through parliament. A few months later, the government instead announced that the income tax would be postponed. The next year, the Sweden Democrats declared that they were willing to support the income tax cut if the government was willing to negotiate with them (Widfeldt, 2014, p. 191). However, all such invitations were rejected and the Sweden Democrats remained a “pariah party”.

After the 2014 election and the reinforced electoral success of the Sweden Democrats, a set of events took place right after the election that clearly illustrates the other seven parties’ continued strong ambitions to keep the Sweden Democrats away from political influence. After the 2014 election, the centre-right “Alliance” government resigned and a new government led by Stefan Löfvén consisting of the Social Democrats and the Green party was installed. Like the preceding government, this one also lacked their own parliamentary majority, and even when the support of the Left party was taken into account, they did not command a majority of votes in the parliament. In the case of minority governments, it had been customary for some time that each party only voted for their own budget proposal. This time, however, things did not go as planned for the current government. When the budget proposals were reviewed in parliament on December 3rd, the Sweden Democrats decided to vote for the four centre-right Alliance parties’ common budget proposal instead of laying down their votes in the final round of voting. This led to the centre-right opposition budget receiving a majority of the votes and the government’s budget did not pass in parliament. The response from Prime Minister Löfvén was to announce that a new election should be held in order to clarify the parliamentary situation. However, after a few weeks, the new election was cancelled due to a deal between the two red-green government parties and the four centre-right Alliance parties presented on December 27th, known as the December Agreement (Decemberöverenskommelsen/DÖ). This agreement meant that the “largest party coalition” should be allowed to form a government and that they would be guaranteed to pass their budget. In practice, these party coalitions referred to the red-greens (including the Social Democratic Party, the Greens, and the Left party) and the Alliance (the Moderate party, the Centre party, the Liberals, and the Christian Democrats) (Bjereld, Eriksson, & Hinnfors, 2016). The intention was obviously to ensure that the Sweden Democrats would not be able to interfere with these two important parts of governing and to keep them away from direct political influence in parliament. In essence, the agreement would preserve the “two bloc” character of the Swedish multiparty system despite the fact that the Sweden Democrats had become so large that none of the two traditional left and right wing blocs were likely to attain a majority of the votes anymore.

Originally, the December Agreement was intended to last for eight years (two incumbency periods), until the 2022 election. However, it did not even last a full year. Already in October of 2015, it was declared no longer valid after a decision by the Christian Democrats to leave the deal (Bjereld et al., 2016). The analyses presented by Bjereld and colleagues (2016) also illustrate that within the Moderate party, it was those supporters who were closer to the Sweden Democrats’ policy views, concerning immigration and refugees, for example, that were most critical of the December Agreement.

Consequences for Swedish Democracy and the Sweden Democrats’ future impact

Altogether, it is probably fair to say that the strong position of the Sweden Democrats after the 2014 election has made the Swedish parliamentary democracy more unpredictable and unstable. Today, it is impossible to foresee how the next incumbency period would function if their standing in the polls remains and the Sweden Democrats attain about 20 percent of the seats in parliament, though it is very unlikely that they would be a formal part of a coalition government. Furthermore, continued and organized cooperation between a government and the Sweden Democrats in the form of bargaining and agreements in advance to ensure support for government bills is also fairly unlikely.

For the parliamentary system to function with a reasonable amount of predictability and without a government with a majority in parliament, this requires either a relatively passive opposition who refrains from actively trying to stop government proposals that they do not support, or a relatively passive government who refrains from presenting controversial bills to the parliament. One example of passivity from the opposition is for the four centre-right Alliance parties to not present a joint alternative budget proposal, which would allow the Sweden Democrats to support it and thus receive a majority of the votes, as what occurred in 2014. Instead, each of the parties could present separate budgets and then choose not to vote for the other parties’ budgets to avoid defeating the government. In fact, any kind of concerted action that would enable the uncalled-for votes from the Sweden Democrats to gain a majority in the parliament would have to be avoided.

Another option is that a new, broader government coalition that attains a majority by encompassing parties from both the left and the right bloc would be formed. If that were to happen, it is presently unlikely that it would include the largest parties from each bloc, meaning the Social Democrats and the Moderates. As suggested already in 2015 by Aylott and Bolin in their analysis of the Swedish 2014 election, it would be more likely that such a coalition would instead include the Social Democrats and some of the smaller centre- right parties such as the Centre party and the Liberals (Aylott & Bolin, 2015), and I personally believe that this proposition is still valid three years later.

In their analysis of the 2017 SOM survey, Falk and Oscarsson (2018) also find that support among the Swedish public for a government including parties from both the left bloc and the right bloc has never been higher – 39 percent favored such a government. Also, they find that around half of the Social Democrat supporters favored such a solution. Judging from recent opinion polls (e.g. Novus June 2018; Ipsos May 2018), however, this would be fairly challenging since a majority coalition based on the Social Democrats would currently require as many as five parties, including both the Left party and two parties from the centre-right bloc (for example, the Centre party and the Liberals).

Recent opinion polls concerning whether other parties should cooperate with the Sweden Democrats after the 2018 election presently give a somewhat unclear picture. Mainly, most voters still seem negative towards the idea of cooperating with the Sweden Democrats in parliament. According to a poll by Novus published by Swedish television on June 7th 2018, only 22 percent of those voting for other parties would like for their party to cooperate with the Sweden Democrats (SVT, 2018). Among those voting for the four centre-right Alliance parties, the share that favors cooperation is 34 percent, compared to 52 percent of those who oppose it.

Not much is known about how Sweden will be governed after the election in September 2018. Whether it will be by a weak government, by voluntarily passive opposition or some renewed version of the December Agreement, by a larger coalition of parties from both the left and the right bloc, or by a government cooperating with or at least passively supported by the Sweden Democrats remain unclear.

No comments.