Swedes and Immigration : End of homogeneity? (1)

Introduction *

Historical migration to Sweden

Contemporary migration

Economic effects of migration

A moral superpower

Conclusion

Summary

The history of immigration in Sweden is unique. This country has long remained a homogenous society until recent yet massive immigration significantly altered its demographic composition. Over the past 20 years, Sweden’s share of its non-western population has increased from 2% to 15% of the total population, an unprecedented increase in Sweden’s history.

The French translation of this study is available on the Foundation for Political Innovation’s website.

The second section of this paper is entitled Swedes and Immigration: End of the consensus? (2).

Considered the great reference of the European social democratic model, Sweden has long enjoyed a solid reputation as a country with political consensus. However, the country now seems to be facing new challenges. Of particular note is the emergence of new forms of crime that have been fostered by the development of social exclusion zones resulting from problems related to immigration and the integration of immigrants. However, the debate on these issues is particularly difficult in this country as the Swedish public debate is reluctant to recognize the realities that could threaten the image of a peaceful society.

The French translation of this study is available on the Foundation for Political Innovation’s website.

Tino Sanandaji,

Researcher at the Institute for Economic and Business History Research at the Stockholm School of Economics, author of four books and several state reports on Swedish tax and entrepreneurship policy, regular contributor to the National Review.

Introduction *

This text was written for the Foundation for Political Innovation. It was translated to French by Christophe de Voogd, former student of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Doctor of History and Associate Professor at Sciences Po. Christophe de Voogd is the president of the Scientific and Evaluation Committee of the Foundation for Political Innovation. The French translation is available on our website.

This chapter will discuss the topic of Sweden and immigration, starting out with a historical perspective in order to arrive at the current state of affairs, described from a variety of perspectives. It is largely based on several chapters of the Swedish book, Massutmaning: Ekonomisk politik mot utanförskap och antisocialt beteende (Sanandaji 2017), which translates as “Mass Challenge: Economic Policy Against Social Exclusion and Antisocial Behavior.”

Sweden was until recently a homogeneous country, and only in recent decades began receiving large numbers of refugees from outside of Europe – in the past decade more per capita than any OECD country. This makes Sweden an interesting case study for analyzing the social and economic impact of sustained refugee migration to a European welfare state. Indeed, during the period of 1985–2015, asylum immigration to Sweden was roughly four times greater per capita compared to other Western European countries, so that the share with non-Western migrant background rose from 2 to almost 15 percent of the Swedish population. This transformation has garnered a great deal of international interest, as Sweden for long had been portrayed as the archetypical welfare state, with idealized social outcomes. Instead, it has now become the leading example of the recent attempts to combine a generous welfare state with multi-culturalism.

Today, one often hears claims that Sweden is a nation shaped by extensive immigration; historically, however, it has not been a country of immigrants. The geographically and culturally isolated Sweden was long one of the world’s most homogeneous countries. Naturally, there has always been a certain amount of immigration, but not on a vast scale until modern times. Still in 1940, only roughly one percent of Sweden’s population was born abroad, and not more than one in a thousand born outside of Europe.

It may always be argued that fundamentally, we are all immigrants, since we know that Sweden was empty of people after the last ice age. According to archaeologist Sven Rosborn, the first documented inhabitants of Sweden were nomads who lived in the Malmö area about 14,000 years ago. However, it is indeed questionable to define those who moved into uninhabited territories as immigrants. Immigration usually refers to the voluntary relocation from one country to another.

The Swedish-language encyclopedia Nationalencyklopedin defines immigrants as “people who move from one country to another to settle there for a long time, according to the population register in Sweden for at least one year.” Consequently, those who moved to Sweden when the ice retreated and to other uninhabited land areas are rather to be defined as colonizers. Similarly, moving into an area by means of violent war does not constitute immigration, but invasion. Neither were slaves, forcibly transported to for example America or the Arab world, immigrants. Since we do not know the details, it is difficult to determine whether migration during prehistoric times was voluntary immigration, but most things indicate that it was rather colonization of uninhabited spaces, or wars that sometimes ended with the annihilation of the existing culture.

Historical migration to Sweden

That Sweden was a homogeneous country with low immigration was, until recently, rarely questioned. Contrarily, it was a well-known fact. For example, Elina Haavio-Mannila (1983) writes:

Compared with other European countries, Sweden used to be a linguistically and culturally homogenous country. Only the small groups of Lapps and Tornedal Finns broke this unity. After the Second World War, however, Sweden became an immigration country.

Rewriting history and portraying Sweden as a country of immigration, like the United States, is a rather new phenomenon that seems to have arisen as part of the argument against xenophobia. Recently, there has been a tendency to exaggerate the extent of immigration with anecdotal examples, which are often vague when it comes to describing how many immigrants actually came. This has been in particular with regard to the Walloons.

Walloon immigrants who came in the 17th century from present-day Belgium irrefutably made a strong impression on Sweden. This was not a large group, neither in the 17th century nor during the Walloon immigration that occurred in the 19th century. Many Walloons left Sweden after a few years, which was common for historic labor immigration. The article “The Walloons – a Small Group” (Statistics Sweden 2006) states:

Of the roughly 2,500 who came, about 2,000 stayed. Although they only made up less than a quarter of one percent of the population of the time, 900,000 Swedes, they have made deep impressions. In Walloon research, about 100,000 of today’s Swedes are estimated to be descendants of Walloons. Walloon immigration of 1,000 or 2,000 individuals in the 17th century corresponded to about one-tenth or two-tenths of one percent of the country’s population at the time. Moreover, it was spread out across several decades. By comparison, in 2015 Sweden took in approximately 134,000 immigrants, according to Statistics Sweden. There were also many who left Sweden, and parts of both immigrants and emigrants are native-born Swedes returning to or leaving the country. Immigration minus emigration is called net immigration. In 2015, Sweden had a net immigration of foreign-born individuals of around 82,000 people – or 0.84 percent of the population of nearly ten million inhabitants.

Even after considering that Sweden has a much larger population now than in the 17th century, today’s immigration is nearly 200 times larger than the Walloon immigration per capita – in other words, not comparable in scale with modern immigration. Another reason why Walloon immigration cannot be used as a parallel to today’s immigration is that most of the net immigration to Sweden today is from the Third World. Walloon immigration was made up of highly skilled labor from a technologically more advanced region.

Evidently, Walloons from present-day Belgium and northern France are not the only example of historic immigration. A more important group that came over longer periods of time were German immigrants. Again, these were also immigrants who, thanks to unusual skill sets, made important contributions to Sweden although they were few in number.

In the Middle Ages, Germany was a comparatively more advanced country than Sweden. German immigrants were often what we today would call foreign experts in trade hubs and mining towns. German burghers periodically made up a significant proportion of the population in some of the larger towns of the time. They organized trade and financing, not least with Germany. That immigration was a small proportion of the population is simply because cities and mining towns accounted for an extremely small proportion of the population of medieval Sweden. The overwhelming majority of the population were peasants. In rural areas, where most lived, there was no German immigration to speak of.

There were no systematic population statistics recorded during these periods, but there is still enough data to make estimates possible. For instance, Sidén (2008) estimates the number of Germans in Swedish cities during the High Middle Ages and arrives at “a proportion of the population of normally 10–20%.”This should be seen in relation to the fact that only about five percent of Sweden’s population lived in cities. Taking this into account, the proportion of Germans in the total population was between one half and one percent.

A subsequent immigration of Germans, Scots, Dutch, and other groups during the era of the Swedish Empire was also concentrated to the higher echelons of society, including nobility and military officers. The influx of immigrants to the elite has contributed to overstating immigration due to anecdotal impressions. Many Swedish noble families, for example, have foreign backgrounds and foreign-sounding names, but the nobility accounted for only about half a percent of Sweden’s population at the time.

Consequently, the reason why immigration had a major impact on how history is told is because it was both exotic and concentrated to the elite strata of society; not because Sweden was a country of immigration like today – or like the United States in the 19th century. From 1871 and onwards, Statistics Sweden has reported systematic data on the number of immigrants per year. From this, the image emerges that immigration used to be a fraction of today’s figures, even after taking the smaller population into account.

Over the years, most immigrants to Sweden have arrived from Finland, which was long part of the same kingdom as Sweden. Migration from Finland made an imprint on the population. But not even here are the figures comparable to current levels. Perhaps the most famous example is the immigration of slash-and-burn so-called Forest Finns, who came to escape famine in Finland and break new ground in less populated parts of Sweden. This is mentioned in economic historian Eli Heckscher’s Sweden’s Economic History from Gustav Vasa (1935–49), estimating that between 12,000 and 13,000 immigrants came to these areas:

It is obvious that this immigration did not, even with the inclusion of immigrants’ descendants, represent a great migration wave in the modern sense of the concept. For all Finnish communities combined, there is a calculation intended to apply to the end of the 17th century but not presented in detail, which stipulates that 12,000 to 13,000 was the figure for the Finnish population in Sweden.

During the industrial revolution, and also prior to it, Sweden, like other countries, imported most of its technology from abroad. Naturally, a small country would not have been able to develop all these technologies on its own. We also know that immigration made a relatively small contribution to the flow of technology. Most of it came through information, not by migration. This is basically self-evident, even today. By far, the most important country from which Sweden imports technology and cultural impressions is the United States – in spite of negligible immigration from Silicon Valley, Hollywood, or New York. The explanation is that information flows through different channels; there was no need for successful entrepreneurs to physically move to Sweden in order for their innovations to reach the country.

Some industries were created in Sweden by immigrants, but most industries made use of foreign technology without immigration. Even the industries that were developed through important contributions by immigrants were created in other European countries without immigration. Long-term comparisons of various industrialized nations show that technology eventually trickles in regardless of the exact channel, indicating extremely strong underlying forces. In order to estimate the role of immigration, it does not suffice to point out what immigrants have built and conclude that it would not otherwise have happened. It is indeed true that immigration increased the flow of technology to Sweden, but the question is how much. The important question is what the alternative would have been, and how much it would have differed from what actually happened. In recent years, there has been a tendency – focusing on anecdotal and almost mythological arguments – to inordinately exaggerate the role of immigration for historical economic development; this is more often than not done without any figures or stringent analysis.

Contemporary migration

Since 1871, Statistics Sweden has compiled annual statistics on immigrants. Between 1871 and 1940, Sweden received an average of about 6,000 immigrants per year. This is a low level of immigration, even in relation to the population of the time – on average about five million. Further, a large proportion of those immigrants were Swedes returning from North America. Of the others, almost all came from Western European countries. Hallberg (2001) writes that “In the 1800s, during the time of the great emigration, immigration was relatively minor and mainly consisted of returning Swedish- Americans.”

It is interesting to note that the period when industrialization peaked and Sweden turned into one of the world’s wealthiest nations was characterized by very low immigration. Until the mid-19th century, Sweden’s GDP per capita was average in a European perspective – that is, below the Western European mean but higher than Eastern Europe, and far higher than Asia and Africa of the time. Before World War Two, Sweden was the world’s ninth wealthiest country, a higher ranking than today (Maddison 2010). Consequently, it is difficult to argue that Sweden became wealthy due to high rates of immigration. It was not until World War Two that Sweden experienced immigration comparable in scope with current levels. Refugees from neighboring countries were not registered, meaning that accurate statistics are unavailable. It appears as though some 150,000 to 170,000 immigrants came during the war. Most were from other Nordic countries and often returned when the war was over. The so-called Alien Inquiry (SOU 1967:18) reports figures of how many people from abroad were present in Sweden in February of 1939 and May of 1945. The number rose from about 24,000 to 195,000 – that is, an increase of 171,000, including many war children. While refugees from Western European countries that remained democratic returned home after the war, many refugees from the Baltic countries and Eastern Europe remained in the country. Thousands of refugees with Jewish background were rescued by Sweden during the Second World War, many of whom stayed.

Immigration to Sweden then takes off during the postwar period in the form of labor immigration from Europe. According to a Statistics Sweden’s (2004) report, the number of foreign-born tripled in the course of 20 years – from 198,000 in 1950 to 538,000 in 1970. The report further states:

[L]abor immigration [was] primarily a Nordic phenomenon, and secondly a European. The migration from outside Europe was negligible. Efforts in the former Eastern bloc to free themselves from the Soviet Union are reflected in the migration to Sweden. The Hungarian Revolution in the fall of 1956 resulted in Hungarians fleeing to Sweden. After the Prague Spring in 1968, Czechs fled to Sweden.

There were also many who came from Greece, Italy, Germany, and former Yugoslavia. Refugees and family-based immigrants normally stay in the country they have moved to, whereas labor migrants often return home. Since much industrial labor migration was temporary, postwar labor immigration is often overstated.

The most important group of immigrants were from Finland, which increased by nearly 200,000 between 1950 and 1970. Immigrants from European countries outside the Nordics grew by just under 100,000 – fewer than many imagine. Non-European migrants increased by nearly 20,000. Here, the main country was Turkey followed by the United States and Canada.

The latter is worth emphasizing. Today, immigration from outside of Europe is associated with developing countries, but further back, non- European immigrants mainly came from North America. Immigration is not a homogeneous phenomenon, and it is often useful to divide migrants into categories based on human capital, the reason for immigration as well as the development levels of the countries of origin and cultural proximity to Sweden.

A common division of countries of origin are European and non-European. Another and perhaps slightly more informative division is Western and non- Western, especially in historical comparison. The West is here defined as Western Europe, the rest of the EU, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The difference between the West and Europe is that the West does not include the less developed Eastern European countries, but includes the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. As late as 1980, the number of immigrants from non-Western countries in Sweden only made up just over one percent of the population, and those from developing countries only a tiny fraction of the population.

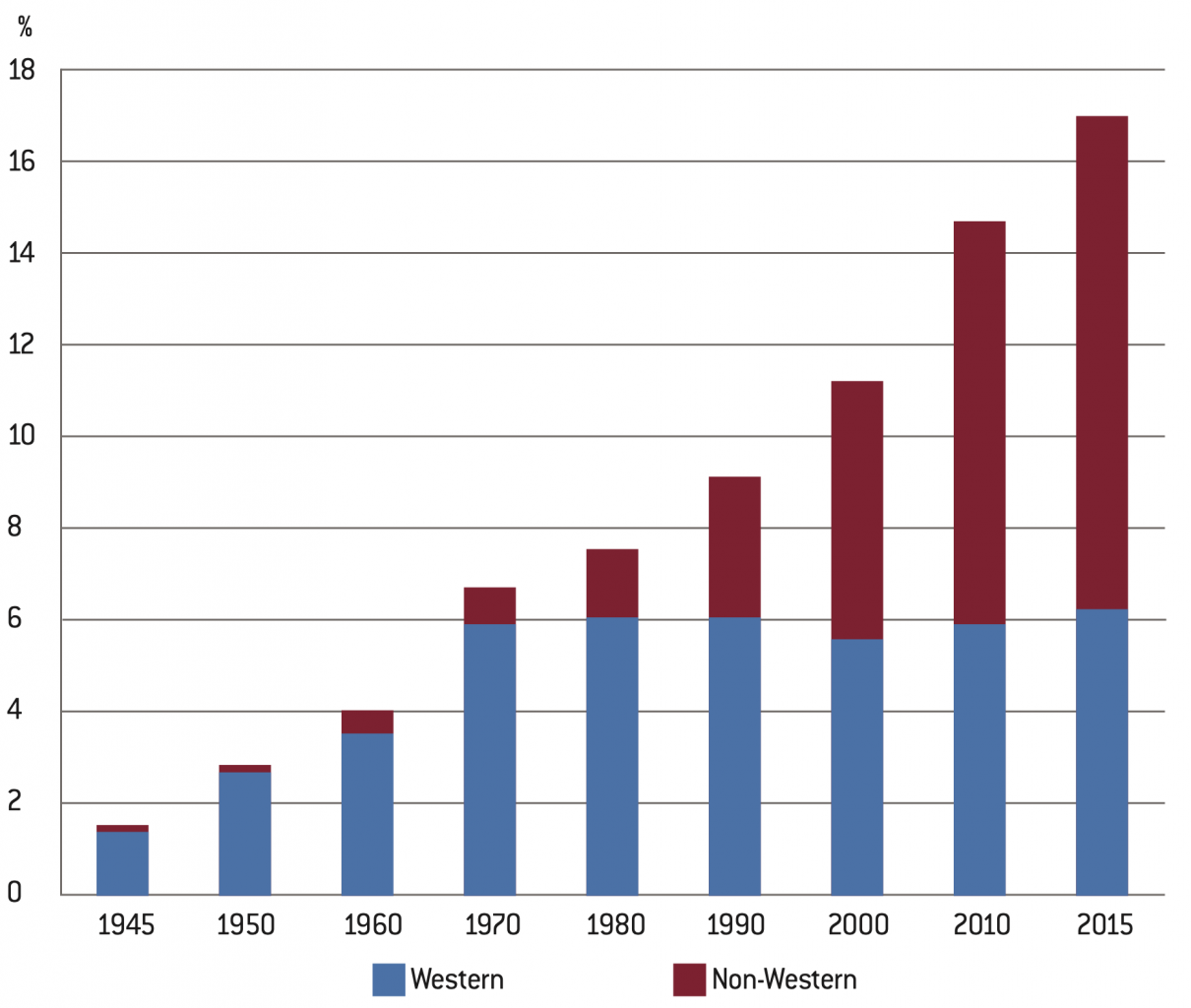

Figure 1 shows the proportion of immigrants in Sweden’s population in 1945 broken down by Western and non-Western origin. The chart illustrates that Sweden had relatively high immigration during the first postwar decades, a bit slower in the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s, and again an acceleration in recent years. It also shows the striking differences in countries of origin. The Western immigrant group as a proportion of the Swedish population has not increased since 1970, while the proportion of non-Western foreign-born has increased rapidly. Naturally, Sweden has continued immigration from the Nordic countries and the rest of the West, but the proportion has been stable since many also return and elderly immigrants pass away. The increase of non- Western immigrants is due to the fact that the labor migration of the 1980s was replaced by refugee and family-based immigration.

Figure 1: Immigrants’ proportion of the population, Western and non-Western origin (Statistics Sweden)

Western Europe is here defined as Germany, France, United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, Greece, Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland.

As for interpreting the figures, it is important to distinguish between the three concepts of asylum seekers, refugee immigrants and immigrants. Asylum seekers are not part of the official population, and all are not granted asylum. Many also return voluntarily or withdraw their applications for asylum. Immigrants are defined as those who have permanent or temporary residence permit, that have registered a residence with the population register, and who intend to remain for at least one year. Asylum seekers who are granted asylum and stay become refugee immigrants after a few years. In addition to refugee immigrants, there are many other immigrant categories, such as family-based immigrants and immigrant workers. Since it usually may take about a year to be granted asylum, and another year or more to be assigned a residence in a municipality, it usually takes a few years before an increase in the number of asylum seekers is visible in the increase of the number of immigrants.

Therefore, the description below does not include the 2015 record number of asylum seekers who have not yet had time to fully make an imprint on official population statistics.

The Migration Agency reports the number of asylum seekers from 1984 and onwards. A total of just over a million people applied for asylum between 1984 and 2015. A total of 515,000 were granted asylum as refugees or equivalent and approximately 800,000 were granted family-based residence permits. Relatives who arrive directly in connection with refugees, or within two years of their arrival, are defined as relatives of refugees; those who arrive later from the same countries only count as family-based immigrants. All who seek asylum are not granted a residence permit. Historically, a little over 40 percent were granted asylum in the first instance – a figure that has increased to about 55 percent in recent years.

The proportion who returns differs widely between different categories. Immigrant workers from Europe and students tend to return home, while the vast majority of refugees and their families tend to stay. A Statistics Sweden (2011b) report explains:

Among immigrant workers from outside the EU and the Nordic countries, the re-emigration is almost equal to that of Nordic citizens. Less than 40 percent of this group of immigrant workers remains in Sweden after ten years. This can be compared with those who arrive as refugees and are granted asylum in Sweden. Of those individuals, 96 percent remain in Sweden after ten years. Seniors and relatives who immigrate also re-emigrate at a relatively small extent.

The number of asylum seekers and immigration in general varies from year to year, but the trend increased until the end of 2015, when tighter border controls led to a sharp decline. Even after deducting emigration, Sweden’s net immigration relative to the population surpassed the U.S. record of transatlantic migration in the 1880s of around 0.67 percent per year. In Sweden, this figure was about 0.2 percent per year between 1940 and 1990, but increased slowly until the mid-2000s. Around the year 2006, there was an acceleration. Sweden surpassed the U.S. record mentioned above in 2009, reaching a net immigration rate of 0.8 percent of the population in 2014 and 2015. Since, as has been stated, a few years of lag exist between asylum application and immigration status, this record is likely to be surpassed in 2016, but then fall as the effects of stricter asylum policy and border controls start to be felt.

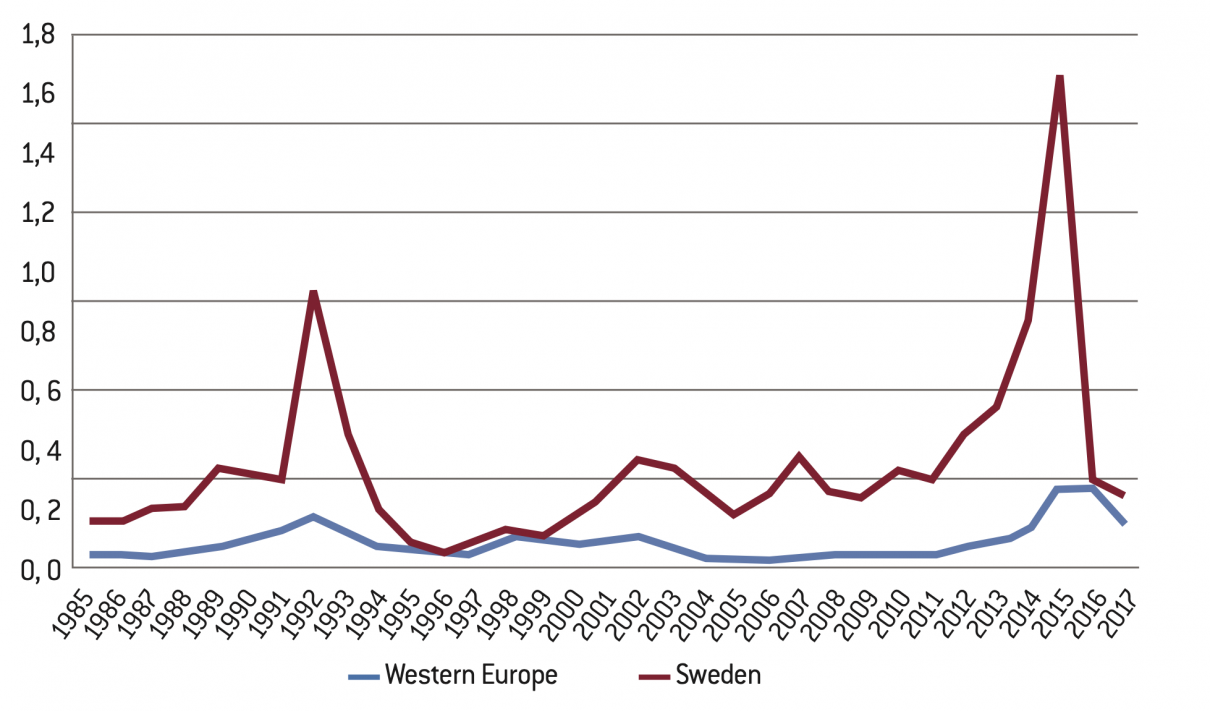

Eurostat reports the number of asylum seekers to various European countries since 1985. During the period of 1985–2015, Sweden is at the top per capita, with about four times as much asylum immigration in relation to the population compared to other Western European countries. Asylum immigration in relation to the population is significantly higher in Northern European countries as well as Switzerland and Austria than in southern and Eastern Europe. Even if Sweden often has been far above the average, the country began to diverge even more from the rest of Europe in recent years. The asylum immigration to Sweden of 2014 and 2015 in relation to the country’s population is not only a record for Sweden, but is unique among industrialized nations. OECD (2016a) concludes: “in 2014–2015, Sweden saw the largest per-capita inflow of asylum seekers ever recorded in an OECD country.” Naturally, and as noted above, not all asylum seekers are granted asylum, though data for asylum seekers is easier to obtain for past years. Figure A shows the number of asylum applicants per hundred inhabitants in Western Europe and Sweden from 1985 to 2017. Sweden has consistently had higher rates than the average of Western Europe, and also experienced greater tops in periods of high refugee migration, such as the war in Bosnia in the early 1990s and the 2015 refugee crisis. Figure 2 also shows the sharp reversal in policies following the 2015 peak, both in Sweden and Western Europe overall. After imposing most restrictive policies, the inflow has been sharply reduced in both cases. Sweden continues to be above the Western European average, but was in 2017 no longer the country that took most asylum seekers per capita – having been surpassed by Germany, Greece, Iceland, Luxembourg, and Austria.1

Figure 2: Asylum seekers per one hundred inhabitants in Sweden and Western Europe, 1985–2017 (Eurostat and UNHCR)

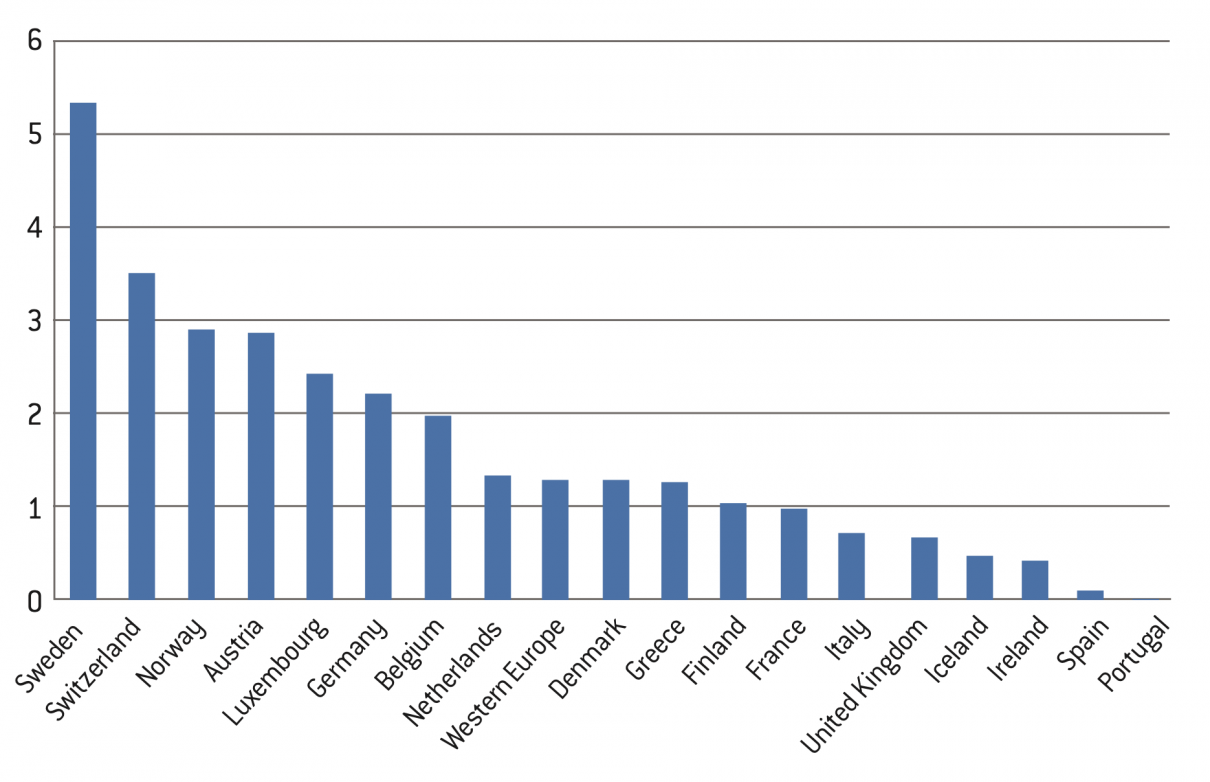

Figure 3 shows the number of refugees that have been granted asylum in Western European countries during the period of 2000–2017, based on Eurostat and UNHCR statistics. Again, Sweden stands out as the country with the most generous refugee policy. It should be noted that these numbers only include granted asylums and that many migrants bring their families and kin. Therefore, in the long run, the number of immigrants from refugees-source countries tends to be greater than the number of granted asylums. While some migrants return to their home countries, the long-run cumulative effect of generous asylum policies can be demographically substantial. The figure also shows the great variance in refugee policies in Europe. A small number of typically wealthy Northern European countries diverge by having had very substantial refugee migration, whereas the UK and Southern Europe, relative to their population, have accepted far fewer asylum seekers. The numbers in Eastern Europe are even lower.

Figure 3: Asylums granted per one hundred inhabitants in Western Europe, 2000–2017 (Eurostat and UNHCR)

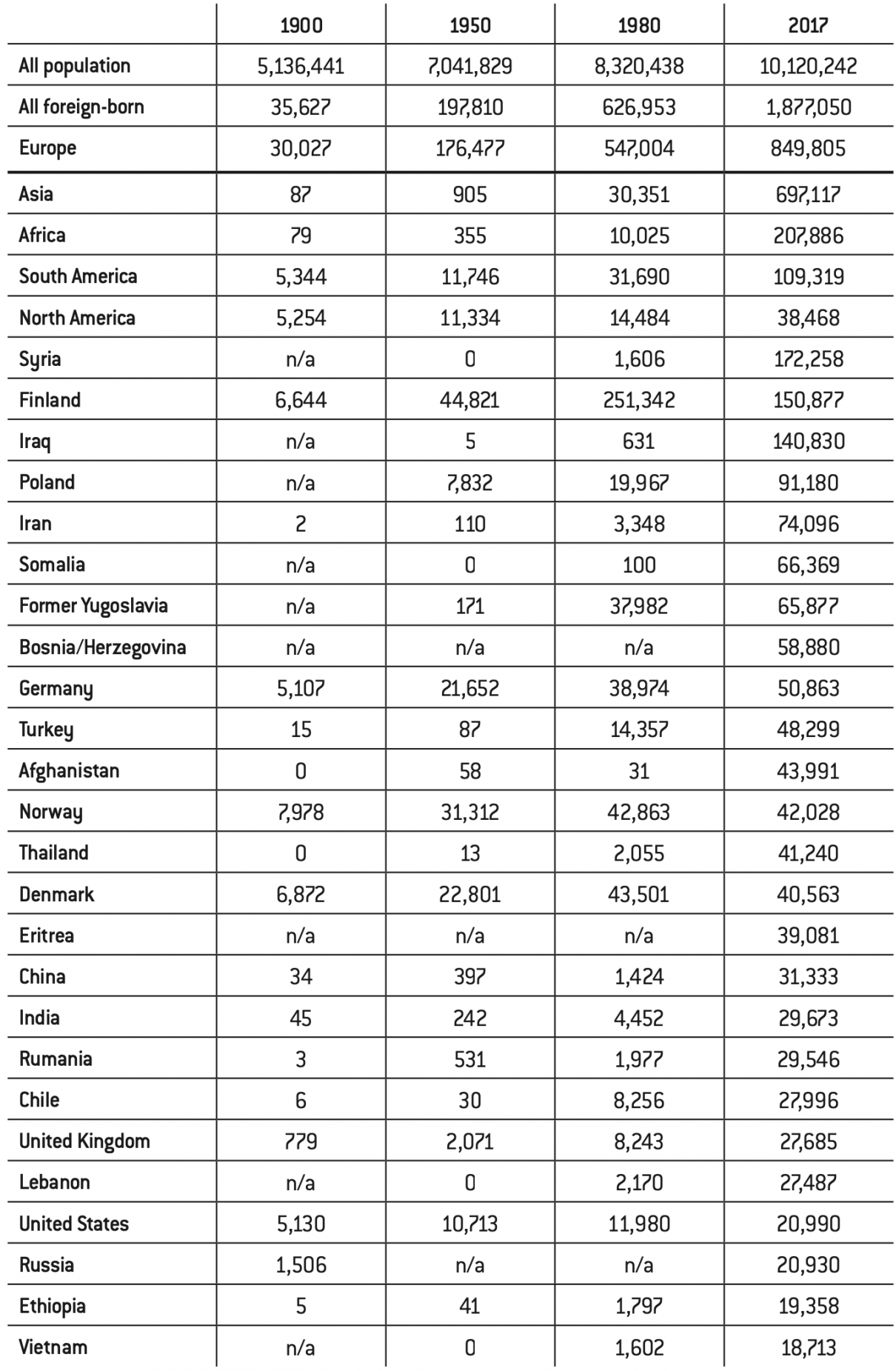

Table 1 shows the resident population of Sweden and the 25 currently largest migrant groups, from 1900 to 2017. The source for this data is Statistics Sweden that has for a long time collected comprehensive demographic data. The table shows how few non-European migrants Sweden had until recently, and also how quickly the foreign-born population has expanded since 1980. Sweden does not have a dominant migrant group, but rather a fairly large number of migrants from a wide variety of countries.

Table 1: Resident population in Sweden and the 25 largest migrant groups, 1900–2017 (Statistics Sweden)

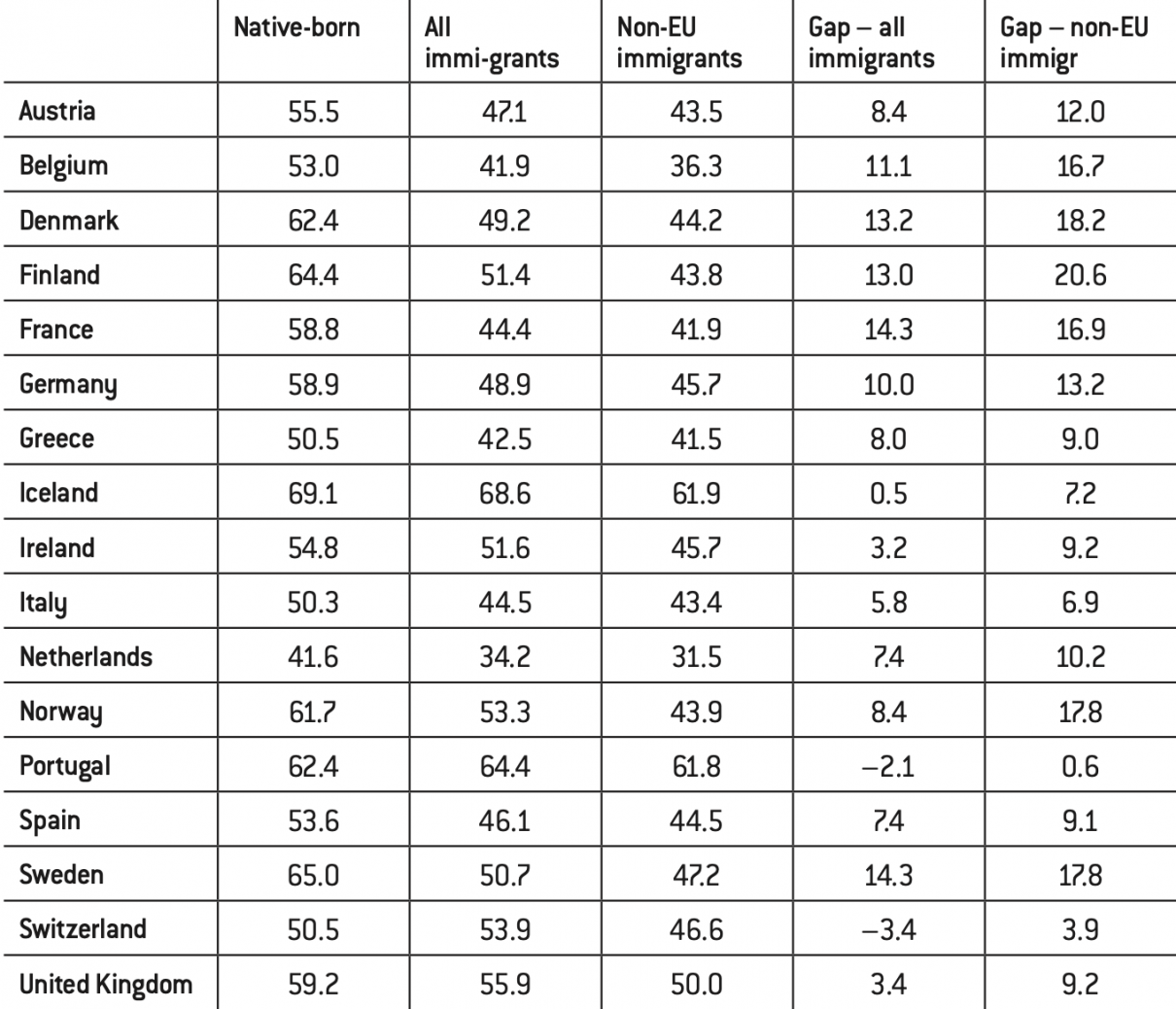

Table 2 shows the full-time employment rate in the year 2015 for individuals in various Western European countries, 20–64 years of age, obtained from Eurostat. The employment rate is shown separately for the native-born population, all migrants (both European and non-European), and migrants from outside of the European Union. Sweden has the highest total employment gap between natives and foreign-born, although not the highest employment gap between native-born and non-EU immigrants. Note that France also has an equivalently high gap in total employment.

Table 2: Full-time employment rate in Western European countries for individuals 20–64 years of age, in 2015 (Eurostat)

Due to this rapid immigration, Sweden today has a population increase that is in line with developing countries like Bangladesh. In the coming years, the population is growing at a rate of 1.5 percent per year, which is significantly above normal levels for mature industrialized countries; this rate of increase would entail more than doubling of the population in about 50 years. One reason is that Sweden, apart from immigration, has unusually high birth rates among wealthy nations – most likely due to generous parental leave, daycare and child subsidies. The number of people of Swedish origin – born in Sweden with one or two parents born in Sweden – has been stable at around 7.7 million, and is expected to remain stable going forward, with a slight increase through birth surplus (Statistics Sweden 2011a). This differs from the situation in most other European countries. Therefore, Sweden has had more births than deaths every year except for five of the past 200 years.

An aging population will lead to the few having to support the many, but immigration also means that the few have to support the many. The social exclusion of immigrants is too high for it to be offset by a more favorable demographic profile. Although foreign-born make up a higher proportion of working-age people, the dependency ratio is higher than among native-born, simply because many of them of working age do not work.

According to Statistics Sweden, 18.5 percent of the population was born abroad in 2017. When second-generation immigrants, who were born in Sweden with two foreign-born parents, are added, 24.1 percent of the population has foreign background – a total of nearly 2.4 million individuals.

Economic effects of migration

Historically, integration was not a problem. The immigrants of the 1950s and 1960s had the qualifications required to obtain employment in the Swedish job market of the time. These jobs were in many cases located in the Swedish manufacturing industry, which was running at high capacity and needed foreign labor. Major Swedish enterprises such as Volvo, SKF, and Asea were frequently and actively recruiting abroad. The language requirements in the job market were less stringent than today, and learning often took place quickly at work. A large proportion of the immigrants also originated from linguistically and culturally close countries. An important difference with today’s job market was that far more professions lacked formal educational requirements, both for native and foreign-born labor. Naturally, in addition to employment immigration, migrants who were not recruited as labor and who lacked qualifications upon arrival also came to Sweden. In these cases too, most people were able to procure the necessary knowledge to be able to get to work.

The fact is that immigrants, as late as the mid-1970s, unlike today, had a higher or equal employment rate as those born in-country (Ekberg and Hammarstedt 2002). Since then, native-born have on average had a stronger position on the job market than foreign-born, but the difference between the groups was small until the end of the 1970s. As the nature and composition of immigration changed during the 1980s, a sharp gap in employment and gains from employment arose around 1990. With the exception of the deep recession in the early 1990s, the job market gap has been relatively stable since then, while immigrants’ share of the workforce has increased. Jan Ekberg (2009) writes:

Over time, there have been very large changes in employment rate and employment-based income among foreign-born. During the 1950s and 1960s, as well as most of the 1970s, foreign-born had the same or periodically higher employment rate during working age than native-born. Towards the end of the 1970s, the image changes.

As labor migration transitioned into refugee and family-based migration, the job market integration progressively deteriorated. Today, there is a significant gap in which foreign-born on average are significantly less likely to work. During the same period, immigrants have fallen behind native-born in salary growth. Compared to native-born, foreign-born are more often found in low- wage jobs and more often work part-time. This means that the average income of immigrants is significantly lower than that of native-born; this is especially true for non-European immigrants. The combination of a lower employment rate and lower wages means that significant income gaps have opened up between native-born and foreign-born. New arrivals who do not enter the job market are not given an opportunity to contribute to the common welfare and risk ending up in a state of long-term social exclusion.

Job market definitions on what counts as employment are often wide. There is no perfect measurement which captures what is colloquially referred to as “a real job,” or which is more formally known as regular work – that is, jobs that are not created by government programs. In the latest available figures, foreign-born have approximately four times higher unemployment rate.

Two other commonly used measurements are employment rate and gainful employment rate, which in theory are based on the same definition and are basically intended to measure the same thing. Employment is a considerably broader term than actual jobs. People in job market programs, those on sick leave and those who only work a few hours per week can also be counted as employed. Hence, to be considered employed does not equate with being able to support oneself. Sweden has a large number of job market programs and publicly subsidized jobs that also count as employment. The employment rate is a measure of the proportion who perform any kind of work, internship or job-like tasks which is calculated using the Workforce Study (so-called AKU), where a representative sample of several thousand adults answer questions about their situation. Gainful employment rate has the same theoretical definition as employment rate but is calculated in a different way. Gainful employment rate is based on the job market statistics on file, which collects income data from the Swedish Tax Agency’s income statements register. Henceforth, the chief focus will be on the gainful employment rate.

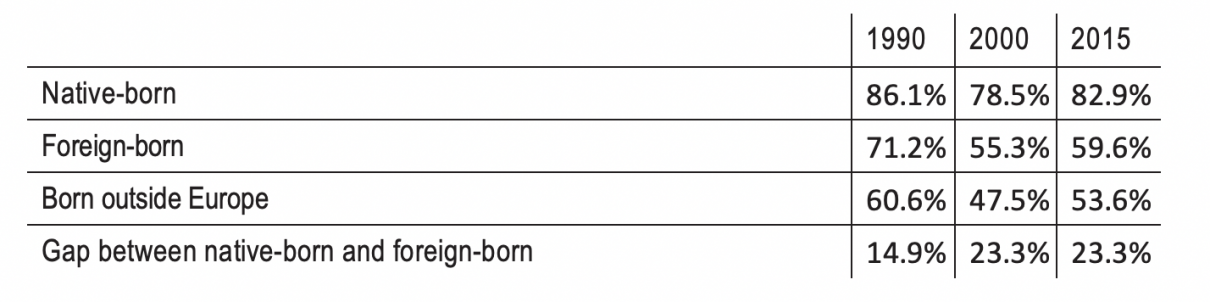

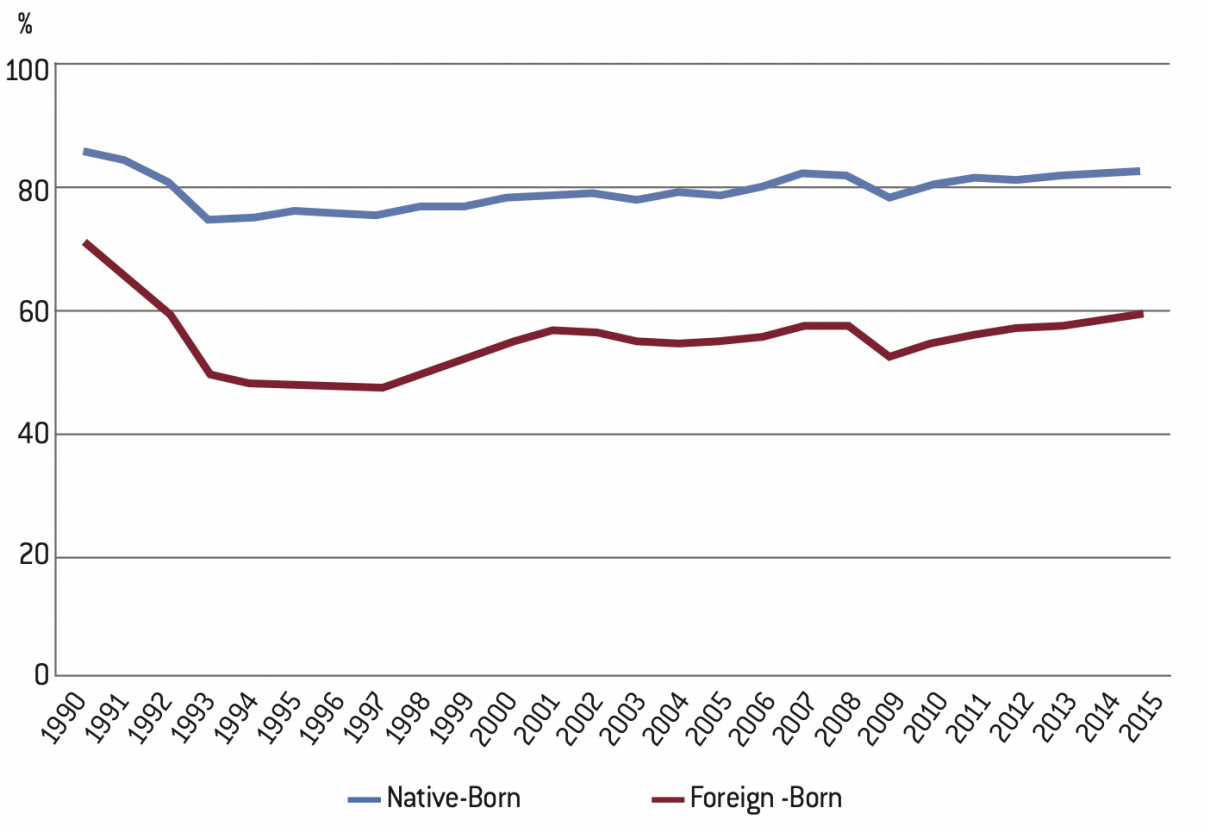

The most recent complete figures for gainful employment rates that are available from Statistics Sweden are for the year 2015. In that year, 82.9 percent of native-born and 59.6 percent of foreign-born people aged 20–64 were gainfully employed. The figure is particularly low among foreign-born immigrants from outside of Europe; only 53.6 percent of those of working age were gainfully employed. The gap in gainful employment rate has remained at this level for a long time, with some fluctuations. The crisis of the early 1990s hit immigrants harder and somewhat widened the gap. However, there was a recovery in the second half of the 1990s, after which the numbers have remained relatively stable. The proportion of those gainfully employed has increased both among foreign and native-born, but because the increase has been about the same in both groups, the gap between these groups has not shrunk during the past 15 years.

Table 3 compares the figures for 1990, 2000, and 2015 – whereas Figure 4 shows the development throughout the period between 1990 and 2015.

Table 3: Percentage of gainfully employed persons 20–64 years of age, in 1990, 2000, and 2015 (Statistics Sweden)

Today, the job market situation for immigrants compared to the rest of the population is somewhat worse than it was in 1990, and almost identical to what it was in 2000. It is interesting to note that the integration of immigrants into the job market has neither improved nor worsened significantly for 15 years. Apart from the turbulence associated with the 1990s crisis and other economic fluctuations, the gap between the groups has been stable for a long time. In other words, the integration of immigrants into the job market appears to have stabilized at a low level.

Figure 4: Percentage of gainfully employed persons aged 20–64, 1990–2015 (Statistics Sweden)

The proportion of people who work among those who arrive in Sweden gradually increases as the newcomers learn Swedish and enter the job market. However, the process is slow. By the time the earlier annual cohorts who arrived many years ago have become integrated, many new annual cohorts have arrived who start at a low level, and after a sufficiently long period of time those who have managed to get into work reach retirement age and leave the job market.

While the proportion of foreign-born people working has been stuck at low levels, the average job income of foreign-born workers has had a poorer development than for native-born. In 2015, the income per gainfully employed person of working age was approximately 12 percent lower among foreign- born than among native-born. The percentage of people of working age who were gainfully employed was, as discussed above, also considerably lower. The combination of the fact that a lower proportion is working and that those who do work have lower average incomes mean that foreign-born of working age have almost 40 percent lower job income than native-born. The gap is even greater among non-European immigrants of working age, who have almost 50 percent lower job income than native-born. The differences in the proportion who work and average income are so large that they outweigh immigrants’ demographic advantage in terms of a higher proportion at working age. This in turn means that foreign-born generate less income and pay less in taxes despite the group’s often-mentioned advantageous demographic profile.

The main reason for the deteriorated job market position is a compositional change in foreign-born; from European employment immigration to refugee and family-based immigration from low-income countries. Immigrants from the Nordic countries and the rest of the Western world still do well in the job market, but today make up an increasingly smaller percentage of the group foreign-born. The fact that refugee and family-based immigrants fare worse is primarily because, or perhaps exclusively because they possess a lower average human capital.

Such an analysis was made in the Long-Term Survey 2015 of PIAAC – a knowledge test in language, math, and computer skills of a representative sample in various OECD countries. PIAAC is the adult version of the school test PISA. A striking result of the OECD’s analyses was that immigrants and native Swedes who had the same human capital fared about equally well in the job market (Bussi and Pareliussen 2015). This was confirmed by Swedish government inquiry Long-Term Survey (SOU 2015:104), which is worth quoting at length:

Among foreign-born with good or high skills, the proportion of those who work is 87 percent compared to 51 percent for those with inadequate skills. A very important and positive result from the PIAAC survey is that there are no significant differences between foreign- and native-born when it comes to having a job, if taking into account the level of the individual’s skills. The equal opportunities to have a job if you have good skills neither seems to be explained by the fact that foreign-born to a higher degree would work in professions that do not correspond to their skill levels. The same picture emerges in an OECD study on Swedish PIAAC data controlling for a wide range of background variables. The survey makes the assessment that the Swedish job market mainly looks to individuals’ skills, and as a whole does not seem to be characterized by ethnic discrimination.

In addition to this, there are probably additional, amplifying explanations to why immigrants have lost ground on the Swedish job market. In recent decades the economy has undergone changes which may have hampered the job market integration for many groups of immigrants. Technological change and the structural changes that this has caused have increased the demands on the workforce. The fact that technology and globalization have eroded the demand for simpler jobs makes it difficult for foreign-born without higher education or specialist skills to gain a foothold in the job market.

Most of the simple and average jobs in the manufacturing sector which the labor migrants of the postwar era came to Sweden to perform have disappeared. Instead, the types of occupations which have been added are highly qualified specialist occupations that place higher demands on education, language skills and work experience. Technology in the form of computers, robots and automation has replaced routine jobs characterized by well-defined and repeated tasks; and this while globalization and trade with countries like China have helped reduce the amount of simpler manufacturing jobs. There is still a large number of low and middle-skilled jobs remaining in the service sector. Automation and trade have had less impact on routine service professions such as store employees, taxi drivers or security guards. But even for this category of occupations, the competition has become tougher. A much debated issue in Sweden is the cost of immigration for the public sector. In principle, immigration need not be a cost. Historically, immigration generated an economic surplus, which in the early 1970s was estimated to the equivalent of one percent of the gross domestic product of the time (Ekberg 2009). Later, immigration transitioned to become a net cost as the immigrants’ position in the job market weakened, which meant that the group paid less in taxes and generated significant costs in subsidies and transfers. Research shows that the effect of foreign-born on public finances after the 1980s became a fiscal net cost (Ekberg 1999; Gustafsson and Österberg 2002; Storesletten 2003; Ekberg 2009; Ekberg 2011; Flood and Ruist 2015; Ruist 2015; Aldén and Hammarstedt 2016).

Immigration always generates costs for welfare as well as revenue in the form of taxes and fees. The question is to determine whether revenue or costs are higher. In practice, this is done by estimating how much immigration increases public sector revenue in the form of taxes and fees, and then by deducting additional expenses for welfare and subsidies. It is therefore about a net profit or net cost for public finances. In addition to direct fiscal effects, there may also be a broader impact on the economy. Although immigration generates a deficit for public finances, it could in theory create socio-economic surpluses that outweigh these costs. It may involve direct gains through exchanges on the job market, or so-called dynamic effects through increased entrepreneurship or innovation pace. However, from a purely empirical point of view, no such socio-economic surplus has been detectable in Sweden (Ekberg 2009).

But there are major effects on public finances. Ekberg (2009) summarizes and discusses the interesting question regarding what gainful employment rates are required for immigration to turn to create a surplus for the public sector: In Sweden, there are a number of surveys on how the public sector during different periods has rebalanced revenues between immigrants and natives. In summary, the results show that the public sector until around 1980 re-allocated income from migrants to natives on an annual basis. During this period, immigrants had a good employment situation and from this perspective a favorable age structure. The annual net revenue appears to have peaked in the early 1970s, when it amounted to about 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). As the immigrants’ employment situation weakened, the annual revenue decreased to reach a zero level in the mid/late 1980s. In the 1990s, the net revenue turned into a net cost, i.e., an income redistribution from natives to immigrants. By the mid/late 1990s, the net annual cost for natives was 1.5 to 2 percent.

A moral superpower

Immigration is not a unitary phenomenon, and immigrants are not a homogeneous group. There is significant variation in how well immigration succeeds in different societies and at various times, depending on who immigrates and the host country. Even within the same country during the same period, there may be considerable variation in how well different groups of immigrants manage to integrate into the economy and society. Therefore, it is basically meaningless to talk about whether immigration carries positive or negative effects; the answer is simply: it depends. Harvard professor George Borjas (1999), perhaps the world’s leading expert on the economics of immigration, has summarized the state of research by writing: “The most important lesson of the research is that the economic impact of immigration will vary by time and place, and that immigration can be either beneficial or harmful.”

Historically, successful examples of migration include the transatlantic migration to the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sweden during the early postwar period, Jewish immigration to Israel from the Soviet Union after the fall of Communism, and the employment-based immigration to Australia and Canada. In these cases, immigrants melted into the fabrics of their new countries, caught up or surpassed native-born in terms of socio-economic success, and thus contributed to advancing the country. Swedish refugee immigration, in sharp contrast to these examples, is a less successful example of large-scale immigration.

The Swedish refugee policy was long justified by pointing to successes in other countries where immigrants elevated the host country both economically and socially, although the outcome in Sweden has been the opposite. In the Swedish debate, the less successful examples of immigration are rarely talked about, even when they, for the most part, are located considerably closer to current Swedish conditions. Thus, it is still more common to talk about America of the 1800s or the Walloons in the 17th century than, let’s say, refugee immigration to neighboring Nordic countries, immigration from former colonial countries to France, Belgium and Holland, or historical Roma immigration to Sweden. There is no guarantee that successful immigration to other countries says anything about immigration to Sweden – especially when successes often are based on highly skilled employment immigration, but rarely, if ever, on unskilled refugee immigration from the Third World to a welfare state.

No comparable country has taken in more refugees in relation to its population than Sweden. Eurostat reports the number of asylum seekers to various European countries since 1985. During the period of 1985–2015, Sweden is at the top per capita, with about four times as much asylum immigration in relation to the population compared to other Western European countries. Overall, asylum immigration in relation to the population is significantly higher among Northern European countries as well as Switzerland and Austria than for Southern and Eastern Europe. Although Sweden has long been above the average, the reception of refugees started to pull away from the rest of Europe relatively recently.

An obvious question to ask is why the number of asylum seekers has varied so much over time (as previously shown in Figure 2). A common misconception is that the explanation lies in mainly external factors beyond Sweden’s control. This is not the case. A country with Sweden’s geographical location has great control over the number of asylum seekers. The increase in asylum seekers to Sweden over time primarily depends on the political decision to loosen border protection and control, which made it easier to come to Sweden and apply for asylum, and secondly that it has become easier to be granted asylum for those who arrive here. The generous welfare programs and the progression of wars also affect the number of applications, but these are more secondary factors. The most important factors in refugee policy are border controls, and how many who can physically get to Sweden. The cause is the way in which asylum immigration is controlled in practice. International agreements that have been executed, in particular the UN Refugee Convention, provides major rights to refugees with protection needs once they have crossed the country’s borders. Sweden has admittedly no obligation to give refugees permanent residence, but often does so for humanitarian reasons. The right to asylum, however, only applies to those who have crossed the Swedish border. There are millions who have a right to asylum in Sweden and who would use it if they could, but who are outside Sweden and therefore have no right to seek asylum.

At a first glance, Western countries have rules that seem generous, but have nevertheless maintained a restrictive refugee policy. The trick that the countries have used in order to regulate immigration is not to give asylum seekers entry visas and to refuse to accept applications for asylum at embassies. Since Sweden is geographically isolated, refugees must often be smuggled across Europe or try to fly to Sweden on fake passports. These two options, however, have historically been difficult to implement, which has kept the number of asylum seekers down. Even those who manage to reach Sweden had no guarantee to remain during the periods when the rules have been strictly applied. These factors kept the application pressure low.

As Sweden dismantled its border protection and went towards a more generous asylum policy, the number of asylum seekers increased while the proportion that was allowed to stay also increased. This peaked in 2014 and 2015, when the EU’s external border collapsed and it became possible to reach Sweden from the Middle East via land. At the beginning of the 2015 refugee crisis, the government refused to regulate immigration for political reasons. It was claimed incorrectly that border checks and border protection would violate international law or still would not work. After a few months, the government gave in and introduced stronger border protection and controls. This resulted in the number of applications falling by about 95 percent in a very short time.

Sweden has since introduced less generous rules regarding permanent residence and family-based immigration. The number of asylum seekers in 2016 is just under 30,000 people. It is still a relatively high level, above the Swedish average from the 1980s to the early 2010s, which in itself was already a high level compared to other countries and Sweden’s refugee policy in the past. Whether Sweden wants to receive more or fewer asylum seekers in the future is mainly a political question. If the goal is to reduce the number of asylum seekers, it would be easy to further tighten the rules, strengthen border security, improve checks of fake or stolen passports, and change the procedures of the Swedish Migration Agency. The international conventions that Sweden and most other countries have signed allow them great freedom to design their own asylum policies. The application pressure is not something exogenous or deterministic beyond Sweden’s control, but is essentially driven by the country’s asylum policy.

Sweden is also a knowledge-based economy where the existing workforce has a high average level of education. This means that the productivity difference between the native and the foreign-born workforce will be even greater here than in less demanding job markets in Southern Europe, for example. The contrast with the lower skill levels of the Third World is even sharper in the knowledge-intensive Swedish economy, where low-productivity workers generate little or even zero benefit to the employer. However, in less knowledge- intensive sectors in average-developed economies, the contrast is not as great. Nor is there any country where the gap in measured human capital between native and foreign-born adults is larger in the knowledge test PIAAC. OECD (2016b) writes: “Data from the OECD survey of Adult Skills suggests that the disparity between Sweden’s foreign- and native-born adults with very basic literacy is the largest among surveyed countries.” Sweden has, not unexpectedly, a large gap in terms of the proportion of foreign-born with formal education, not least since a high proportion of immigrants arrive here from countries with low education levels. OECD (2016b) observes that Sweden receives an unusually high number of refugees and then points out: “As a result, the educational disparity in Sweden between foreign- and native- born individuals is among the largest in the OECD.”

Many expected that the same high level of trust and tolerance that explain Sweden’s comprehensive refugee immigration would also deliver successful integration. This was not the case, though. As will be discussed at the end of this chapter, high trust and social capital can, paradoxically, be exclusionary to the extent that closely knitted groups are more difficult to gain access to for outsiders. The success factors behind Swedish society may have led to excessive self-confidence regarding how well integration should work and justified an outsized refugee policy. The job market, school and the rest of society’s capacity to absorb new arrivals were overloaded. Sweden’s attempt to, during a period of time, adhere to an immigration policy that radically deviated from that of other countries failed and ended with a sharp tightening. The stricter border controls and rules that were introduced in late 2015 resulted in a 95 percent drop in the flow of refugees in a short time, and a 99 percent reduction in the number of unaccompanied minors. Here, too, Sweden differed and closed its borders quicker than most other countries.

Today, Sweden has fallen into a situation where the public joins conflicting values. Extremely high tolerance for immigration is combined with the fact that many do not socialize with non-European immigrants. In addition, there is widespread pessimism about the possibility to achieve integration. Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet (2016a) discusses this and Sweden’s often paradoxical culture in an interview with Associate Professor Bi Puranen at the Institute for Future Studies:

Three-quarters of the population believe that integration isn’t working well. Meanwhile, four out of ten Swedes don’t know any immigrants from a non- European country, according to new figures from SvD/Sifo. Yet Sweden is seen as a moral superpower. In a series of articles, Svenska Dagbladet investigates integration in Sweden, the world’s most different country. We see a new Sweden emerge, where “we” and “them” are becoming clearer. The resistance to accepting refugees continues to increase and integration is limping.

– – –

Sweden and the Swedes, who are we today and what do we represent? The current self-image, that we salute the Jante Law, bow down to Luther and are somewhat shy and introverted, is probably quite exaggerated. The Swede is rather a loner who celebrates privacy, with great trust in the state, and who continues to have relatively great respect for what’s different. This is shown by, among other things, Bi Puranen’s research.

She has also mapped out “culture and values collisions” – issues or opinions that stand out in comparison to other countries’ perceptions and which could be said to capture Swedishness in the year 2016: gender equality, religion, nationalism, views on premarital sex, abortion, parenting, divorce, LGBTQ issues, and domestic violence. Here, the Nordic countries – and mostly Sweden – differ from the international norm.

“This tolerance risks making us intolerant of other views and ideas and that we see ourselves as a moral superpower,” says Bi Puranen.

Professor Assar Lindbeck has often been described as the doyen of Swedish economics, and expressed some unequivocally illustrious thoughts a few years back on an economics seminar (Lindbeck 2013):

Now, one should realize that these problems cannot be solved through a more flexible job market and increased wage distribution. It is, therefore, naive to believe that the employment difficulties of immigration can be solved by, during unrestricted immigration, allowing wages to fall to the level where low- skilled workers who can’t speak Swedish also get jobs. A wealthy country like Sweden, with nine million inhabitants in a world of billions of poor people, could not possibly have unrestricted immigration. It must have a restrictive immigration. And it must be very restrictive if one is to protect the wages and welfare systems in wealthy nations. This is absolutely inevitable. Even Gunnar Myrdal realized this many years ago when he wrote that the welfare state is a national project. With that, he believes that the benefits a nation manages to gain by successful economic development over a century cannot be offered the rest of the world without our system failing.

No comments.