Swedes and Immigration : End of the consensus ? (2)

Introduction*

French-inspired suburbs on fire

Neo-poverty and social exclusion

Immigration and crime

New forms of suburban crime

Antisocial behavior

Concluding Remarks

Summary

Considered the great reference of the European social democratic model, Sweden has long enjoyed a solid reputation as a country with political consensus. However, the country now seems to be facing new challenges. Of particular note is the emergence of new forms of crime that have been fostered by the development of social exclusion zones resulting from problems related to immigration and the integration of immigrants. However, the debate on these issues is particularly difficult in this country as the Swedish public debate is reluctant to recognize the realities that could threaten the image of a peaceful society.

The French translation of this study is available on the Foundation for Political Innovation’s website.

The first section of this paper is entitled Swedes and Immigration: End of homogeneity? (1). The history of immigration in Sweden is unique. This country has long remained a homogenous society until recent yet massive immigration significantly altered its demographic composition. Over the past 20 years, Sweden’s share of its non-western population has increased from 2% to 15% of the total population, an unprecedented increase in Sweden’s history. The French translation of this study is available on the Foundation for Political Innovation’s website.

Tino Sanandaji,

Researcher at the Institute for Economic and Business History Research at the Stockholm School of Economics, author of four books and several state reports on Swedish tax and entrepreneurship policy, regular contributor to the National Review.

Introduction*

This text was written for the Foundation for Political Innovation. It was translated to French by Christophe de Voogd, former student of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, Doctor of History and Associate Professor at Sciences Po. Christophe de Voogd is the president of the Scientific and Evaluation Committee of the Foundation for Political Innovation. The French translation is available on our website.

The first part of this series of two papers, Swedes and Immigration: End of Homogeneity? (1), looks back at the history of immigration in Sweden and its acceleration in recent years. While Sweden long remained a homogenous country, it has been hit by a strong migratory wave. Despite its moral ambition to welcome the neediest of our world, the Swedish social model cannot economically support such a high immigration rate. Yet, even beyond the economic question exists the problem of integrating newcomers into the Swedish social fabric.

Sweden observed the riots that hit France in 2005 that highlighted the differences between the failed French integration model and the championed Swedish model as a symbol of success. It is worth noting that the situation in the French suburbs was then perceived as completely different from the Swedish context. However, by that time, some were already worried that Sweden’s immigration landscape was headed in the same direction.

In fact, between 2006 and 2012, Sweden experienced an increase in social exclusion. In 2006, 156 residential areas were faced with socioeconomic problems so acute that they were defined as “social exclusion”. In 2012, that number had risen to 186. Only a quarter of inhabitants from these areas were of Swedish origin – that is, born in Sweden to two parents born in Sweden (26% in 2006 and 25% in 2012).

This social segregation is directly related to the consistent overrepresentation of immigrants in both crime and regarding socioeconomic issues. Overrepresentation has even increased in recent decades. Thus, three-quarters (76%) of the seven most important street gang members in Sweden are immigrants or children of immigrants.

In addition, new forms of crime have developed in these areas, increasing Swedes’ concern about immigration. While Sweden is considered to be a liberal and tolerant country, its inhabitants adhere to many rules of etiquette that are harshly sanctioned by society if not respected. Indeed, the difficulties associated with the social exclusion of immigrants are reinforced by a façade of tolerance that does not translate into a mixed society but, on the contrary, reinforces a singular society. These phenomena question the idea of a successful integration model in Sweden.

French-inspired suburbs on fire

In 2005, France was shaken by violent riots. The triggering factor was tragic deaths in connection with a police pursuit in the suburbs of Paris. Clashes and car fires spread to other French suburbs and continued for several weeks. The Paris riots received major attention worldwide, including in Sweden. Suburban riots have since lost their news value, but when we look back to as late as 2005, the events were depicted as something foreign. In Sweden, the large-scale arson of cars was seen as something strange and scary, but distant. Swedish tabloid Aftonbladet (2005) depicted the events in the article “Worst Riots in France Since 1968”:

Burning cars and buildings lit up the night sky around Paris on Saturday when thousands of police officers unsuccessfully tried to curb the worst rioting France has experienced since the student revolt of 1968. About a hundred people were evacuated from two buildings when at least 20 cars burned in an underground garage in a suburb north of Paris. Similar scenes were reported from the towns of Lille in northern France, Rennes in the west and Toulouse in the southwest. At least 200 persons were arrested during the night, among them a group of minors with fire bombs. According to police, a total of over 750 vehicles were set on fire during the night, a quarter of which outside the Paris region.

The media analysis was not focused on the risk that the problems could reach Sweden, but to highlight Swedish integration as a positive role model for France. Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet wrote, for instance, about how the French media had described Swedish suburbs as a desirable example; the article “Rinkeby a Model for France” (2005) proudly declares:

“Rinkeby, a Swedish model for the suburbs.” That’s what French right-wing newspaper Le Figaro wrote yesterday. In the shadow of the French suburban riots, the paper’s correspondent went to see the Swedish integration model in order to report on neighborhoods where buildings are never more than five stories tall, where books in forty languages are available at the library and where kind-hearted, female police officers take their time to understand the old, African men who lack in Swedish-speaking skills. Rinkeby is described as “a neighborhood populated by immigrants, where order prevails and where life is pleasant to live.”

When we look back, it is interesting to note that the situation in the French suburbs as late as 2005 still was seen as something completely different from Swedish conditions. But already then, there were a few who warned that Sweden was moving in the same direction – often those who themselves were familiar with the developments in Swedish suburbs. They were, however, met with furious criticism. Today, it is easy to forget that at the time, immigration was not considered to have anything to do with integration. To create a link between immigration policy and poor integration was considered taboo and aiding and abetting xenophobic forces.

Sweden would soon suffer from car fires on a scale comparable with the French suburbs, including in Malmö’s Rosengård 2009 and in Stockholm’s Husby 2013. By this time, the image of Sweden as a safe utopia had been frayed at the edges. When French media reported on the Stockholm suburbs, it was no longer as role models but as something comparable with the events in Paris. For example, Swedish daily Metro (2013) published the article “French Media: It’s Like the Paris Riots:”

This week, the riots in Husby and many other suburbs of Stockholm have dominated Swedish media. But the events have also created great attention in foreign media. In France, parallels are drawn to the suburban riots in Paris in 2005. France 24 has spoken with Jenny Andersson, a researcher at the Center for International Studies in Paris, who says that the image of the perfect and equal Swedish welfare state has become “severely eroded.”

French social exclusion areas are known as banlieues. The word simply means suburb of a major city, but has, in the same way in Sweden, over time come to be associated with poor, segregated suburbs. Large-scale immigration from outside the West began much earlier in France than in Sweden, and those social conditions also emerged some decades earlier. Swedish school textbooks in the 1990s highlighted social problems and ethnic conflicts in the French banlieues as a remote problem that Sweden was spared, but that students could study in geography or social science classes.

In depth and scope, the social problems in Swedish areas of social exclusion have not yet reached the level of the French banlieues. However, today, the comparison is a matter of degree, not substance. Many phenomena that first were observed in France have now reached Sweden. In some cases, there has even been a direct cultural import from French as well as from American ghettoes. In the reporting, there have been speculations that the increase in car fires in Sweden was influenced by reports on car fires in Paris in 2005.

The arson of vehicles is not just a spontaneous form of vandalism, but a learned ritual action with profound symbolism. In both France and Sweden, it is common for car fires to become “contagious” in the sense that arson in one suburb inspires arson in other parts of the country. Already in the late 1970s, the arson of vehicles started to become a symbolic act of protest in France’s suburbs. These, in turn, may have been inspired by car fires in the context of political protest, such as the protests in 1968 in connection with the Vietnam War and political discontent among students.

Although the first car fires in the suburbs were spontaneous acts of vandalism against easy targets, the concept of car-torching has over time developed ceremonial characteristics. Car arson is now a default action when protests erupt against police as well as a New Year’s Eve feature in France. Chaos and disorder by the mass arson of cars have paradoxically become a carefully orchestrated tradition. Normally, about a thousand cars are torched every New Year’s Eve. Around the New Year, Time Magazine (2009) published the article “France’s New Year’s Tradition: Car-Burning:”

For much of the world, they became iconic of France’s worst social ills: the burned-out carcasses of thousands of cars set ablaze during nearly three weeks of nationwide rioting in 2005. But as yet another orgy of automobile arson on Wednesday demonstrated, the torching of cars in France has not only become an everyday event; it’s also now a regular form of expression for disenfranchised suburban youths wanting to make sure the rest of the country doesn’t forget they exist. And their fiery presence is never felt so strongly as it is each New Year’s Eve – the day of France’s unofficial festival of car-burning.

The fire department has kept complete data on vehicle arson since 1998, compiled by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency. Fire and rescue statistics specify the number of times the fire brigade has responded to fires. One call may involve several scorched vehicles. In connection with riots, it is common that many vehicles are set on fire in the same area. Since each call may involve multiple vehicles, the number of scorched cars is far greater than the number of calls.

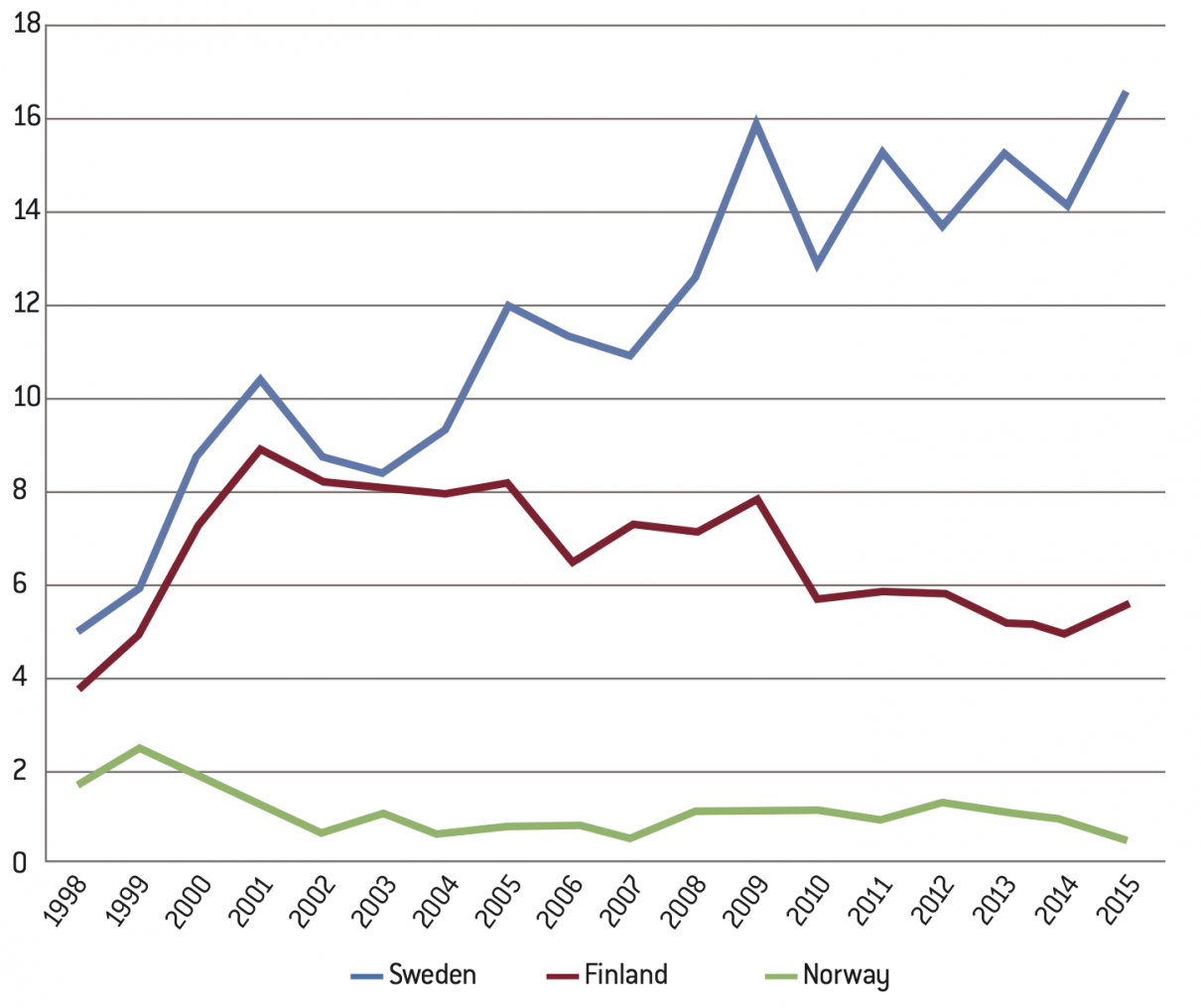

Between 1998 and 2015, the number of emergency calls in connection with vehicle arson increased from 434 to 1,609; that is, nearly quadrupled. For automobiles, the corresponding figure went from 380 to 1,428. During this period, the population increased by about ten percent. Preliminary figures for 2016 indicate that the previous year’s record will be beat with a good margin. Figure 5 compares the situation in Sweden with Finland and Norway from 1998. The graph shows vehicle arson from each country’s fire and rescue service per 100,000 inhabitants. To date, Norway has been relatively spared from mass torching. In the early 2000s, Sweden and Finland were close, but since then the arson of vehicles has dropped slightly in Finland while the phenomenon has increased sharply in Sweden. Data for Denmark is only available for later years and does not enable a comparison over time, but Denmark also has significant problems with car arson in immigrant-heavy areas in connection with social unrest. In 2014, vehicle arson was at 9.1 per 100,000 inhabitants, that is to say below Sweden but significantly above the levels in Norway and Finland.

Figure 5: Vehicle arson per 100,000 inhabitants in Sweden, Finland, and Norway

One of the more major events of unrest in recent years, which can be used as an example, are the weeklong riots which erupted just over three years ago in the suburbs of Stockholm. On May 13, 2013, Stockholm police received calls from the immigrant-heavy suburb of Husby. The residents were frightened by a 69-year-old man who was waving a machete around. After a deadlock, the older Portuguese immigrant was shot and killed by police. A week later, police was once again called to Husby. This time, residents reported about masked men burning cars with gasoline and Molotov cocktails. When police and firefighters arrived, they were met by a barrage of rocks.

Every morning the following week, Sweden woke up to new images of arson and riots. The rumors of racism and police brutality became the spark that ignited riots, even in other immigrant suburbs with previously rampant resentment against Swedish society. Police managed to quell the riots only after having called up reinforcements from other Swedish cities. The extent of material damage was approximately 200 burned cars, in addition to a number of burnt-out schools and cultural centers. Unemployment among immigrants has long been high, but the unrest during spring 2013 can hardly be explained by public cuts. Husby is a district that for many years has been a recipient of public investments, regeneration programs, integration projects, youth recreation centers and job market projects. The year before the riots, all junior high school students in Husby’s municipal schools received a new iPad. The reason for the riots is probably based on feelings of bitterness and alienation. That this is not about radical Islamist social disorder or a well thought out political rebellion but a spontaneous and juvenile reaction can be illustrated by how the Husby riots came to an end. A local community initiative arranged in the center of Husby square, large-scale hot dog grilling according to the principle a rock for a sausage. Swedish tabloid Aftonbladet (2013b) reported:

Yesterday, the rocks stopped falling over Husby. And the only thing that burned was the fire from hot dog barbecues.

“We’re doing this to spread love,” said Husby resident Zakaria. At midnight, the embers have died out in the barbecue by the Tempo store in central Husby. There was no organization behind the hot dog grilling, just the people in Husby, says Zakaria.

“First we bought the hot dogs and the buns, but then the stores gave us what we needed for free,” he says. Next to the barbecues was a sign: “Leave a rock, take a hot dog.”

Neo-poverty and social exclusion

Historically, in Sweden, the word poverty would usually be used for what today is called social exclusion. This is probably no coincidence. Poverty primarily refers to the lack of material resources. It can either be about absolute destitution or relative poverty, where you have low incomes compared to others in the same society. However, in today’s Sweden, what we fundamentally associate with social exclusion is neither material destitution nor relative poverty. Most people who today are considered and consider themselves to be socially excluded would be counted among high-income earners if they had lived in Sweden a hundred years ago, or in countries outside the Western world today. Sweden has, through a combination of high prosperity and low inequality, the lowest material poverty in Europe.

Economists with a material view of poverty predicted earlier in the last century that poverty would disappear as incomes increased. This, however, did not happen despite a multiplication of material standards. An alternative perspective on poverty has been presented by Nobel laureate Robert Fogel, who was of the opinion that poverty has a dimension beyond the material. “Mental” poverty can be seen as lacking human capital such as knowledge and skills, or lack of social capital such as standards of behavior, character development, trust and social networks. Lack of human capital and social capital leads to lower incomes while increasing the risk of unfavorable behavior such as substance abuse, crime, chaotic living conditions and broken families. This would explain why the social nature of poverty does not disappear despite rising incomes.

In Sweden too, poverty has a material component. For example, there are many retirees with low incomes and households who live off of social assistance and have a relatively low standard of living. Statistics Sweden reports disposable income for households of working age. In 1991, working households had about 25 percent higher income than non-working households, a difference that was expanded to close to 80 percent by 2013. At the same time as income from work and capital grows among those gainfully employed, many government assistance programs have become significantly less generous.

Phenomena such as crime and substance abuse have a much stronger connection to mental or social poverty. One way to illustrate this is to look at students who live off of student loans and grants. Students often have low incomes and live in cramped housing conditions but have low incidence of crime, antisocial behavior, substance abuse and other unfavorable behaviors common among the poor. The reason is that students have intangible assets in the form of high human and social capital, which is further strengthened by studies. Those who have low incomes due to social poverty are often also overrepresented in unfavorable behavior – not because the behavior is caused by low incomes but because social poverty causes low incomes and unfavorable behavior.

Accordingly, what exactly is meant by social exclusion is rarely clearly articulated. The fact that the term has nevertheless been widely used might be because it is semantically flexible and can be interpreted differently by different people. In addition, material poverty has been replaced by social inequality as the primary social problem in countries such as Sweden.

The lack of an exact theoretical definition has also led to the use of several different ways of measuring social exclusion. The empirical definition developed by Mauricio Rojas, former spokesperson on refugee and integration policy for the Liberal Party, was the most scientifically well-founded; it focused on residential areas rather than individuals. The measurement included, in addition to proportion of people working, also school results and electoral participation as a proxy of social capital, and was thereby more sociologically sophisticated.

The study of residential areas has some advantages. One is that the proportion of people working on an individual level does not necessarily reflect involuntary social exclusion, in that it also encompasses parental leave, regular sick leave and education. Hence, there is a normal level on the proportion of unemployed which has nothing to do with social exclusion. One way to measure involuntary social exclusion is to study residential areas below this level. Another advantage with studying residential areas as a whole in addition to individuals is that social exclusion is linked to residential segregation.

The Liberal Party continued along the path they embarked on in the run-up to the 2002 election success and in 2004, it published a much-noticed and in many ways innovative report entitled The Map of Social Exclusion. The report used Statistics Sweden’s geographical measurements to split the country into about five thousand residential areas and examined how many of those were affected by deep social problems. The two criteria for being defined as an area of social exclusion were the following: that 60 percent or fewer of the residents of working age were working; and that fewer than 70 percent completed primary school with complete grades, or that fewer than 70 percent voted in the most recent municipal election.

The Liberal Party’s report showed that the number of areas of social exclusion increased from three in 1990 to 128 in 2002. The series of reports was subsequently updated several times. The Liberal Party’s last report showed that the number of areas of social exclusion had continued to increase to reach 156 in 2006. The report received large media coverage, perhaps partly due to the report’s unusually high methodological ambitions.

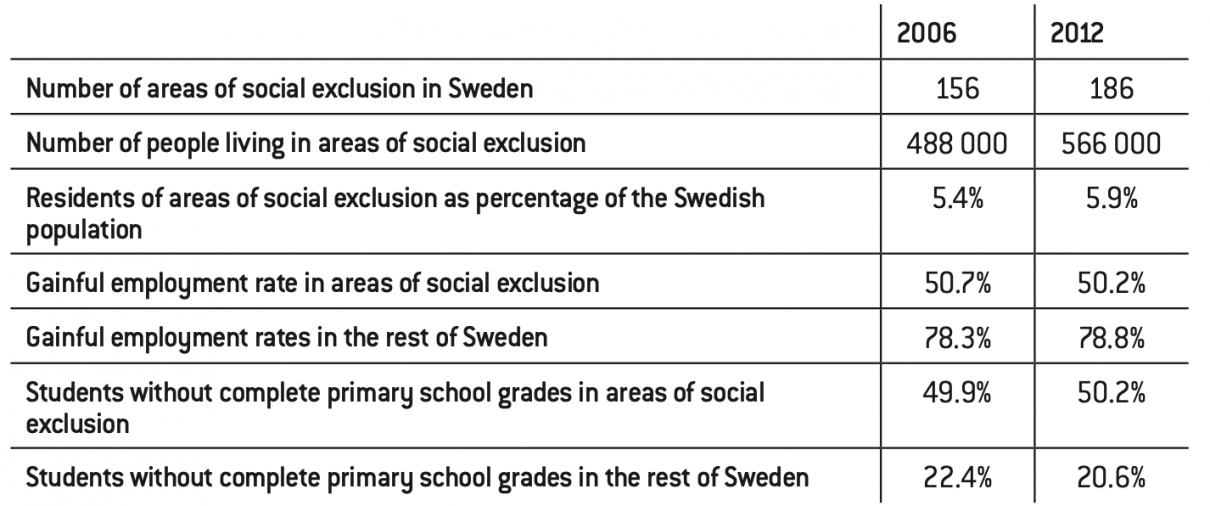

This is the background to which I in 2014 updated the Map of Social Exclusion up to the year 2012 – the last year for which statistics were available (Sanandaji 2014). The number of areas of social exclusion continued to increase between 2006 and 2012. In 2006, 156 residential areas had such major socioeconomic problems that they were defined as areas of social exclusion. In 2012, the number had increased to 186 residential areas. A significant proportion of the residents are second-generation immigrants, i.e., the native-born children of foreign-born parents. Only 26 percent of the residents of the areas of social exclusion in 2006 and 25 percent of the residents in 2012 had Swedish background, defined as native-born with two native-born parents. Table 4 summarizes the results, based on calculations by Statistics Sweden, which in addition to the number of areas of social exclusion show average outcomes for all areas compared to the rest of the country.

Table 4: Comparison of social exclusion between 2006 and 2012 (Statistics Sweden)

Immigration and crime

One of the most important effects of social exclusion on society occurs through crime – a sensitive and complex topic that will be discussed in the remainder of this chapter. Crime is not just a crass economic issue, but also associated with the moral dimensions around guilt, justice and revenge. Fear of the crimes of the Other has often been used to collectively blame groups and create hatred. Throughout history, there are several examples of factual or alleged crimes committed by immigrants that have provoked reprisals in the form of xenophobic violence – not seldom against innocent people. A rhetoric of threat and violence facing the own group may risk stirring up primal instincts. The issue of immigrant crime has been widely debated in recent years. The phenomenon raises strong opinions and emotions, and many contradictory statements have been voiced in the debate. This has caused the issue to seem intricate and shrouded in secrets. In fact, there is extensive research and public surveys on immigrants’ overrepresentation in crime. Since immigration to Sweden was small for a long time, there are few historical studies on immigration and crime. The source material is also limited. A few studies have, given the data that exist, reviewed immigrants’ historical share in specific crime types, such as homicide in Stockholm (Wikström 1992; Kaspersson 2000). In the 1970s, more extensive studies were conducted.

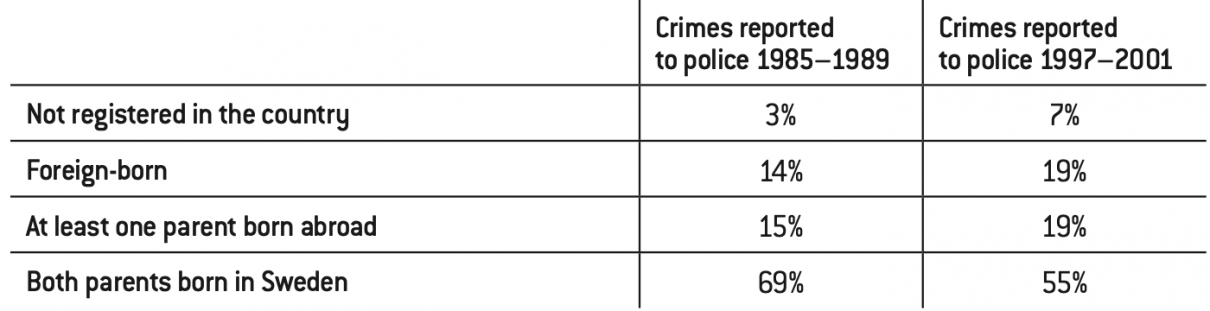

The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention has authored two much-noticed reports on immigrant crime in Sweden (1996, 2005). The reports compare registered crime based on country of birth and the parents’ background for the years 1985–1989 and 1997–2001. The reports find that foreigners have higher registered crime than people with Swedish backgrounds, which are summarized in Table 5 (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention 2005).

Table 5: Different groups’ share of crimes reported to police (Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention)

Note that people who were not registered in the country at the time of the crime were estimated to account for 3 percent of crimes in 1985–1989 and 7 percent of all crimes in 1997–2001. This group consists, among others, of “individuals waiting for a decision on a residence permit; individuals temporarily staying in Sweden during the five-year period as tourists or students; and individuals who have deliberately come to Sweden for criminal purposes.” Foreign-born generally have a significantly higher crime risk, something which applies even after controlling for a number of socioeconomic factors. The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2005) writes:

From previous research, we know that certain background factors, such as age and sex, vary in correlation with the risk of crime. Against this background, the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention has made a so-called standardization of the material in terms of sex, age, education and earned income. The standardization means that the different groups, by means of a statistical calculation, are “equated” regarding these factors. With this calculation, all groups receive an equal number of men, the same proportion of young people, and so on. It then turns out that the increased risk of foreign- born drops from 2.5 to 2.1. The elevated risk in the group that was born in Sweden of two foreign-born parents also decreases significantly, from 2.0 to 1.5. One reason for this is that these groups have a larger proportion of young men with low education and income compared to those born in Sweden by two Swedish-born parents.

The proportion of people registered for crimes vary between different countries of origin. The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2005) notes that “Those from North Africa and the Middle East have the highest recorded crime rates.” The proportion is, however, lower among immigrants from Southeast Asia. Foreign-born have a particularly high elevated risk when it comes to more serious violent crime. The elevated risk was 3.0 for assault, 4.1 for robbery and 5.0 for rape.

The Swedish Prison and Probation Service’s (2010) report gives detailed background facts on inmates serving long prison sentences, defined as four years or longer for men and two years or more for women. The report notes that “A majority (52.9%) of those serving long-term sentences originated from other countries than Sweden.” This includes foreign-born with Swedish citizenship, asylum seekers, those with residence permits, and temporary visitors. It is not clear what proportion of the approximately 47 percent of long-term prisoners born in Sweden who were second-generation immigrants. The most common crimes for both native and foreign-born long-term inmates were felony narcotics offenses or drug smuggling. Many of the foreign- born were from Eastern Europe and the Middle East: “The most common nationality of origin after Sweden was Poland, closely followed by Iran and Finland.” These figures underestimate the proportion of crimes committed by those from abroad as they exclude those who have been transferred to their home country in order to serve their sentence.

Rostami et al. (2012) studied street gang structures in Sweden using police records. 239 gang members in the seven gangs categorized by the police as the most prominent were examined in the study. All gang members are men and 76 percent of the gang members are first or second-generation immigrants. Despite immigrants’ significant overrepresentation in crime, many have denied that immigration causes increased crime – often by referring to so-called socioeconomic factors. Controlling for socioeconomic factors does contribute to increased understanding, but does not somehow magically erase the overrepresentation in crime. To try to control for socioeconomic factors in an analysis of immigration’s impact on crime is a textbook example of the statistical mistake commonly referred to as overcontrol. The conclusions regarding immigration’s impact on crime are not affected by the degree to which crime is explained by socioeconomic factors. This only changes the analysis from immigration increasing crime to immigration increasing the number with socioeconomic problems, which in turn increases crime.

The argument of socioeconomic factors had been more meaningful if Sweden had the tools with which we could easily solve “socioeconomic problems.” However, such is not the case. With effort, it is possible to reduce socioeconomic problems, but until the day someone actually fixes them, they are a part of reality and not something that can be excluded from the analysis. Neither are they temporary, transient phenomena that will resolve on their own. Both immigrants’ overrepresentation in crime and immigrants’ overrepresentation in socioeconomic problems have been constant or even increased slightly during recent decades.

Assume for argument’s sake that patriarchal culture increases both the risk of violence against women and the likelihood that women do not work. Controlling for upbringing in a family where the mother does not work would in that case reduce overrepresentation in crime, as family relationships are an indirect measurement of cultural differences.

To control for explanatory factors can often be interesting, but the correct interpretation of the results requires an understanding of what the analysis actually says. Socioeconomic problems, such as low education, can in themselves be caused by deeper underlying factors such as cultural differences or social capital, and cannot, in that case, be interpreted as an independent explanation variable. No matter how socioeconomic problems have arisen, they cannot be eliminated as long as they actually exist in reality. Despite intensive efforts, Sweden has not solved the socio-economic problems, and as long as socioeconomic problems exist, they must inevitably be taken into account. The socioeconomic problems of immigrants cannot be separated from analyses of immigration. In general, there is a widespread misconception that one, by referring to controlling for background factors, can conjure away unwanted effects of immigration. This is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of basic statistical methods, as well as what control means. Controlled for the amount of fat and sugar, ginger snaps contain the same amount of calories as crispbread. That hardly means that you can change your snack from crispbread to ginger snaps without gaining weight. A higher content of fat and sugar are properties which cause ginger snaps to contain more calories than crispbread. A statistical analysis that controls for nutritional content can be used to break down how these foods differ in terms of calorie content, but not for eliminating the relatively higher amount of calories in ginger snaps. Similarly, a statistical analysis that breaks down immigrants’ overrepresentation in crime into various constituents through controlling for background factors cannot be used to deny the causal effect of immigration on crime.

New forms of suburban crime

Over time, criminal structures have emerged in the suburban areas of Swedish cities. The dynamic effects of multicultural society were not, like so many predicted, an innovative Silicon Valley, but a parallel society with widespread tax fraud and illegal work. The dynamic element is that honest companies are corrupted or driven out of business by extensive shady activities. Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2012) concludes:

If a business dumps prices because it does not pay taxes or because it uses black money, then those businesses that try to be legitimate must keep up in order to compete. Then maybe they will end up registering every other transaction instead all of them.

In addition to tax evasion, the Swedish job market model has been eroded by irregular work for wages far below agreed rates. This is often done in combination with tax evasion and sometimes also public benefits fraud.

It was only during the latter part of the 1990s that the police began to see the emergence of a new phenomenon in some suburbs. According to the National Criminal Investigation Division (2014), the following was happening:

Local criminals joined forces and grew stronger in their criminal practice. With the threat and violence of power, these individuals created fear and unsafety in the local community, which led to criminal organizations increasing their power. Since the turn of the millennium, local criminal networks tied to geographic areas have become a growing problem in Sweden.

In 2014 and 2015, the Swedish Police Authority released two nationwide reports on the new phenomenon of 53 Swedish areas vulnerable to crime, of which 15 are considered to be particularly vulnerable. These 53 areas are characterized by that “local criminal networks are considered to have a negative impact on the local community.” The crimes that regularly occur and have become normalized include violence, riots, rock-throwing, drug trafficking, and so on.

Drug trafficking is perhaps the most important component of criminal activity, which more or less takes place in the open. The most common substance is cannabis, although heavier drugs occur, such as cocaine, methamphetamine and spice. The National Criminal Investigations Division (2014) states that “Younger criminals in these types of areas finance their addiction mainly in two ways: by selling, or by committing larceny. In this way, drug use is a natural gateway to crime.” Drug trafficking often leads to internal as well as external conflicts arising. The report further explains:

The high monetary value of drugs means that there is always a big financial risk factor, both for sellers and buyers throughout the distribution chain. This easily gives rise to debt situations. Disagreements in debt situations have in several areas led to some form of punishment or escalated to conflict.

In order to protect the commercial criminal enterprise, various methods, including the monitoring of passing vehicles in the areas, shakedowns, joint weapons caches, and internal moped transports. A shakedown is a form of extortion or robbery, where a debt is constructed and a sum is to be paid to compensate for a perceived or imaginary injustice. Weapons are hidden from the police by giving individuals in the younger group the task of storing and transporting them to individuals in the older group. Mopeds are important tools in the business in order to move both weapons and drugs, but also to engage in surveillance to see which vehicles pass by the territory.

In some cases, the impact of crime on the local community is so profound that it becomes an issue of so-called parallel societies. This includes components such as racketeering and a separate justice system where conflicts are solved directly in the criminal environment beyond the regular legal system. The mechanism is that over time, a normalization of the exceptional occurs in that burning cars in Rinkeby lose their news value, while the same event would generate major headlines if it had occurred in the Stockholm city center.

Parallel societies result in the emergence of new norms and institutions. Examples include “criminal networks that allocate money to a so-called security fund, from which relatives of sentenced criminals may turn to receive financial support during the time the sentence is served.” Through institutions like this security fund, crime risks increasing further, since the criminal career becomes like any profession, with its own social insurance system.

Independent law enforcement is a key component of a functioning society. A clear sign of the emergence of a parallel society is when it becomes difficult to enforce laws in an area. The residents are becoming less likely to testify or choose to withdraw their testimonies, something that has occurred in several cases in the areas vulnerable to crime. The unwillingness to cooperate with the legal system is not just a matter of local residents’ attitudes, but often a direct result of threats or violence. When a parallel society is established, it will not only be difficult for the police to work in the area; the National Criminal Investigations Division (2014) gives the following depiction of the situation:

However, a perception found during the study visits at the police authorities is that the officials dealing with applications for money, such as the Social Insurance Agency and Social Services, are subjected to the most pressure from the criminal environment. There are cases where it has been about direct unlawful influence and cases where it has rather been about self-censorship; that is, people are affected in the carrying out of their duties without being directly threatened. Fear of being subjected to crime can entail that the individual official modifies his or her behavior. It does not have to mean that the employee has been subjected to unlawful influence. Rather, it may be that this individual is passive or acts differently to avoid an unwanted event such as harassment, threats or violence in the future. Parking enforcement officers form another occupational group that has difficulty performing its work in several of the areas because of feeling threatened. There are also cases in which journalists have been subjected to threats and pressure.

Consequently, the police have been forced to develop specific methods and measures to be able to work in these areas. For example, they always work in double units in those areas that are designated as particularly vulnerable. The task of the extra unit is to ensure that the police vehicle is not vandalized while the regular unit carries out its mission. The vehicles also have reinforced windows to protect against rocks and other objects thrown at them. For the same purpose, the individual police officers routinely wear body armor, helmets and shields. Protective goggles are also an increasingly important tool for protecting against the green lasers with which the police is increasingly being attacked.

Antisocial behavior

Sweden may on the surface be a liberal society, but in practice all situations of human interaction is controlled by minute social rules. Only the slightest deviations from these rules are punished by silent social exclusion – pertaining to native- and foreign-born alike.

The media has portrayed a number of examples of antisocial behavior around Sweden, some of which are reproduced below. The disorder ranges from smaller transgressions, such as littering in libraries, via threats and sexual abuse to hand grenade attacks which have killed innocent children. Antisocial behavior includes violations of the formal and informal norms that govern social interaction, where there are elements of aggression and hostility. Here, behaviors which violate rules or disrupt the surroundings, but which occur without intent, should not be defined as antisocial behavior; this could for example include misuse of the laundry room due to lack of habit or language skills.

Antisocial behavior, such as egg-pelting and verbal epithets, however, constitutes conscious acts that express antagonism. Another category of antisocial behavior, such as littering or speaking loudly in public environments, can occur both as a demonstration of dominance or sheer comfort combined with an indifference to the well-being of the community. Not showing consideration for one’s surroundings by deliberately breaking the rules of order that others follow may also be regarded as a milder form of antisocial behavior.

Antisocial behavior often occurs locally and therefore mainly affects neighbors, classmates and those living in the same area. Antisocial behavior is present to varying degrees among native and foreign-born. To the extent it is more common in areas of social exclusion, it should be kept in mind that the antisocial behavior mainly affects others with foreign background.

Many of these problems are most common in places where many young people gather. This can apply to schools, recreation centers, entertainment venues and shopping centers. Disorder and brawls also spill over into areas that are intended for orderliness – including hospitals, public baths and libraries. Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet (2015) wrote about incident reports from libraries in the Stockholm area in 2013–2015:

In the reports, nearly 500 cases of violence, thefts and brawls in libraries in the Stockholm area during the past two and a half years are described, and the sheer amount of incidents testifies to serious problems. The libraries are open and unprotected spaces, they are centrally located and the children’s sections are often nicely furnished with sofas and cozy corners. They are popular places to go to, not just to read, but to hang out, dominate, and provoke.

The library staff describe youth gangs that disrupt by yelling, arguing, harassing staff and visitors, watching Internet porn and using libraries as substitutes for recreation centers:

“I see young people throw sunflower seeds inside the children’s section and on my next round I see several sitting around a pipe. The smoke smells strange!” “Security guards are called, they are unable to bring order to the premises and thus call for backup. The youth gang ignores both staff and guards and eventually they start an incident with one of our patrons. They physically attack the patron.”

– – –

“The four form a menacing ring around the part-time librarian and the boys say offensive and inappropriate things, including ‘I’m gonna kill you,’ ‘I’m gonna show you my cock,’ and so on.”

Likewise, there are many reported cases of disruptions in public baths, for example, the Karlslundsbadet in Landskrona. Local newspaper Helsingborgs Dagblad (2016) writes:

On Thursday evening, a large youth gang suddenly started throwing tables, chairs and other things into the pool and mess with the staff. It was early in the evening when about 15 young people around twelve years old and up, some of whom were adults, suddenly began to behave badly.

“They were rude and aggressive and threw tables around,” said one of the staff who was present at the time. The young people had been at the bath for a while and, among other things, had food there when some of them got the idea to smoke by the outdoor pool, where smoking is not allowed. But they didn’t accept being told. Then they started arguing instead.

Threats and unprovoked assaults also occur in other areas of healthcare. Local newspaper Sydsvenskan (2016) writes in an article on violence against healthcare professionals in Malmö:

Sydsvenskan has read hundreds of security guard reports from the hospital area in Malmö between 2014 and 2016 and gained insight into a world where threats and violence are almost part of everyday life. Another report describes how a nurse was threatened by a man who says he is going to “stick a knife” in her. Some incident reports are less dramatic: one describes how a relative of a patient told a nurse that he was going to “fuck your mother” when he was told to calm down after being enraged over a vending machine being out of order.

Vulnerable occupations also include park workers. Weeding in the suburban areas of Västerås is not without its challenges. Swedish Radio (2016) reports about these incidents, and about how the police repeatedly have been summoned to the aid of park workers:

“It’s been threatening situations with rock-throwing, and they’ve been jumping on cars. The atmosphere hasn’t really been pleasant, simple as that,” says Tony Gahm, director of the Department for Support, Leisure and Construction in Västerås.

What reactions have you received from the staff?

“They’re super worried and feel unsafe. Once surrounded, they’ve heard things like ‘We’re gonna kill you’ or ‘Fucking whore’.”

Yet another uniformed occupational group that has been affected is parking guards. Norwegian NRK (2016) was among the first to report that, for reasons of personal safety, parking companies do not send parking guards to Rinkeby and Tensta in the afternoons and evenings.

An article in Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter (2016) compiled the number of cases of rock-peltings of police during the first four months of 2016 to 30 incidents in Rinkeby alone. The strain that it means for first responders to work under these conditions is a significant work environment issue that may also affect their free time. The stress is a contributing factor to so many police officers resigning recently. The article also expresses Swedish Police Union president Lena Nitz’s concerns over the development. She believes that it is only a matter of time before someone is seriously injured. Moreover, the issue is bigger than that:

“Trying to obstruct the duties of the police using aggravated violence is a democracy issue.” She thinks that it’s serious if rock-throwing is normalized by the employer as well as the politicians and the Work Environment Authority. would probably had been some form of riots. We chose instead to wait them out.”

A brutal form of antisocial behavior is to use highly destructive weapons such as hand grenades. Daily Svenska Dagbladet (2016b) writes:

The influx of hand grenades into Sweden has increased over the last two years and does not seem to be slowing down. Sweden is one of the countries in Europe where the use of hand grenades has increased the most. The 8-year-old boy who died when a hand grenade exploded in an apartment in Biskopsgården in Gothenburg is the first death to be caused by a hand grenade in the last 20 years, according to researchers at the National Council for Crime Prevention. According to police, the blast could be an act of revenge for the brutal murders at a restaurant last year. The death is also seen as a consequence of the fact that criminals use explosives to a greater extent than before, where hand grenades are part of the increase.

“It’s really pure luck that we haven’t seen more deaths after those explosions that have happened,” says Linda Staaf, head of the intelligence unit at NOA, the police’s national operations division. She says that the number of seized hand grenades has increased, but also the number of detonated hand grenades – a new trend, she believes. Sweden stands out as a country in Europe where the increase is the highest.

Local daily Sydsvenskan (2015) describes a wave of hand grenade attacks in various locations in central Malmö, interviewing the head of the national bomb squad in Malmö:

“Hand grenades are now used in half of the explosions that take place. This was not the case previously. It’s scary and extremely serious,” he says and points out the risks to the public.

“A hand grenade is uncontrollable once it has been thrown,” he says and compares the risk when someone uses a gun.

“The gun is more targeted, and then the risk is lower that people in the surroundings are injured.” According to the NBS, a code of honor has previously existed among those who use explosives to only do so in isolated areas. But those days are over, they say. The risks to the public have also become more evident now that the explosions increasingly take place in residential areas and public places.

Swedish Public Television News (2015) reported the mind-blowing story that a hand grenade in Malmö can be cheaper than ice cream or falafel:

Illegal hand grenades are cheaper than ice cream on the market. This according to detective chief inspector Gunnar Appelgren, who handles felony weapons crimes, and who has been involved in raids seizing hand grenades in Sweden and in the Balkans in recent years. In co-operation with the Balkans police, he participated in stopping over one hundred grenades and about ten automatic weapons which were to be sent to Stockholm this year.

“Last year, we saw a load of 64 grenades and 16 automatic weapons that cost around 1,000 euros to buy from the Balkans,” says Appelgren to Swedish Public Television News. But it’s only the weapons that cost money. The 64 hand grenades are thrown in for free, or they cost one or two euros each – between ten and twenty Swedish crowns.

Concluding Remarks

Many immigrants do not perceive themselves as part of the Swedish community, including those with weak ties to their or their parents’ countries of origin. Instead, a common identity has developed among those of non-Western origin in the Middle East, Latin America, Africa, Central Asia, and, in some cases, the Balkans, as permanent “immigrants.” Economic and cultural exclusion are often linked, and they also amplify each other. In addition to political reforms, the solution to social exclusion would be facilitated by greater cultural integration of those with immigrant backgrounds, so that immigrants and those with Swedish background feel like parts of the same community with stronger reciprocity towards each other. This, unlike economic policy, is not something that is controlled by the state or can be forced to happen. Achieving a stronger cultural integration is a matter of discourse, norm formation and a voluntarily developed spontaneous order towards a national community. In Sweden, multiculturalism is an ideal, although there have rarely been clear ideas about what this actually entails in practice. Many have gone further and denied that Swedish culture and Swedish values exist at all. At the same time, integration is working less than most people wish. As mentioned previously, a survey by Sifo in 2016 showed that three quarters of the population do not think integration in Sweden is working well. There is also a paradox where many profess to multiculturalism as an ideal but do not act from it in their personal lives. Mella (2011) describes the results of a comprehensive annual survey on attitudes towards diversity:

Our study shows that the proportion of Swedes who interact with immigrants other than in work-related situations is not large, but rather a minority. The image that emerges from the Diversity Barometer entails that the majority have very few interactions with immigrants except for the necessary ones that occur at school or at work. As a rule, Swedes do not socialize with non-European immigrants. 40.9 percent never interact with non-European immigrants and 42.1 percent do so rarely.

Sweden is often ranked highest in the world when it comes to inhabitants’ self-reported tolerance towards neighbors from other ethnic backgrounds in inter-national attitude surveys. There is again an irony in the fact that Sweden is one of the countries where those from abroad find it most difficult to find new friends. Integration is a social process, but Sweden is not perceived as a particularly social country.

The Expat Insider report ranks the attractiveness of countries through surveys among foreign-born (immigrants and people working temporarily in the country). Sweden is doing well in many respects, but is ranked among the lowest in terms of how difficult it is for those from abroad to meet friends. In the 2016 survey, Sweden ranked fourth from the bottom among 67 surveyed nations, only before Denmark, Norway and Kuwait. About 60 percent of those surveyed indicated that they had difficulty finding friends in Sweden.

Together with other Nordic countries, Sweden also ranked lowest in terms of how welcome those from abroad felt. The Local newspaper (2016) interviews the founder of Expat Insider:

The famously reserved Swedes make Sweden among the most difficult countries for foreigners to feel at home in, according to a survey ranking the quality of life for expats around the world.

– – –

“Expats have a hard time feeling welcome in this country; they perceive the local population as unfriendly and distant, and they have trouble finding new friends, especially Swedish ones.”

In a similar survey conducted by the bank HSBC, Sweden ranked 45 out of 45 in terms of how easy expats experienced it was to find friends. This doesn’t mean that Swedes are deliberately dishonest in surveys on tolerance. If nothing else, the generosity of Swedish taxpayers shows that an overwhelming majority actually has great goodwill towards immigrants. The explanation to the paradox is probably located on a deeper level. Sweden’s exceptionally high social capital in terms of standards and rules of behavior makes the country well-functioning and tolerant. It also means that becoming an inside group member at the private level, such as at workplaces and in friendships, requires compliance with the norms. Many immigrants are not accepted into the group when they do not meet these implicit requirements. Simultaneously, the ideology of multiculturalism entails that Swedes are uncomfortable with demanding the same behavioral conformity from immigrants required by the other group. There is a high cost for Swedes to try to enforce these rules for immigrants. It is easier to quietly isolate oneself from those immigrants who do not comply with the often unconscious behavioral rules that Swedes have been raised with since birth.

Similar results can be seen from the latest 2017 Eurobarometer (EU 2018), with focus on immigration of immigrants in Europe. Sweden stands out as overall the country with the most tolerant attitudes toward immigrants. At the same time, Sweden is the European country with the highest share who believes that the integration of immigrants was unsuccessful. Fully 73 percent of Swedes respond that integration has been unsuccessful. At 64 percent, France is the country with the second-highest share who believes that integration has been unsuccessful. By comparison, countries such as Ireland and Portugal have fewer than 20 percent who believe that integration has been unsuccessful. Sweden is also the country whose inhabitants are most likely to state that fostering integration of immigrants is a necessary investment in the long run – a statement with which fully 91 percent agree.

Not surprisingly, then, the issues of immigration and integration are currently prominent in the Swedish public discourse, and are likely to remain so for many years to come.

No comments.