The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values

France, Germany, Italy and the United KingdomKey findings

Introduction

Political self-positioning on a left-right scale reveals a shift to the right in European electorates

Immigration worries public opinion, on the right and left alike

A majority of respondents (60%) feel there is too much immigration

Voters reject the idea of open policies when it comes to migration

Concern about Islam goes beyond political affiliations

In France, 62% of citizens believe that Islam is a threat to the nation

A concern shared by our European neighbours

Preference for economic liberalism

A call for more freedom for companies

The size of companies shapes collective representations

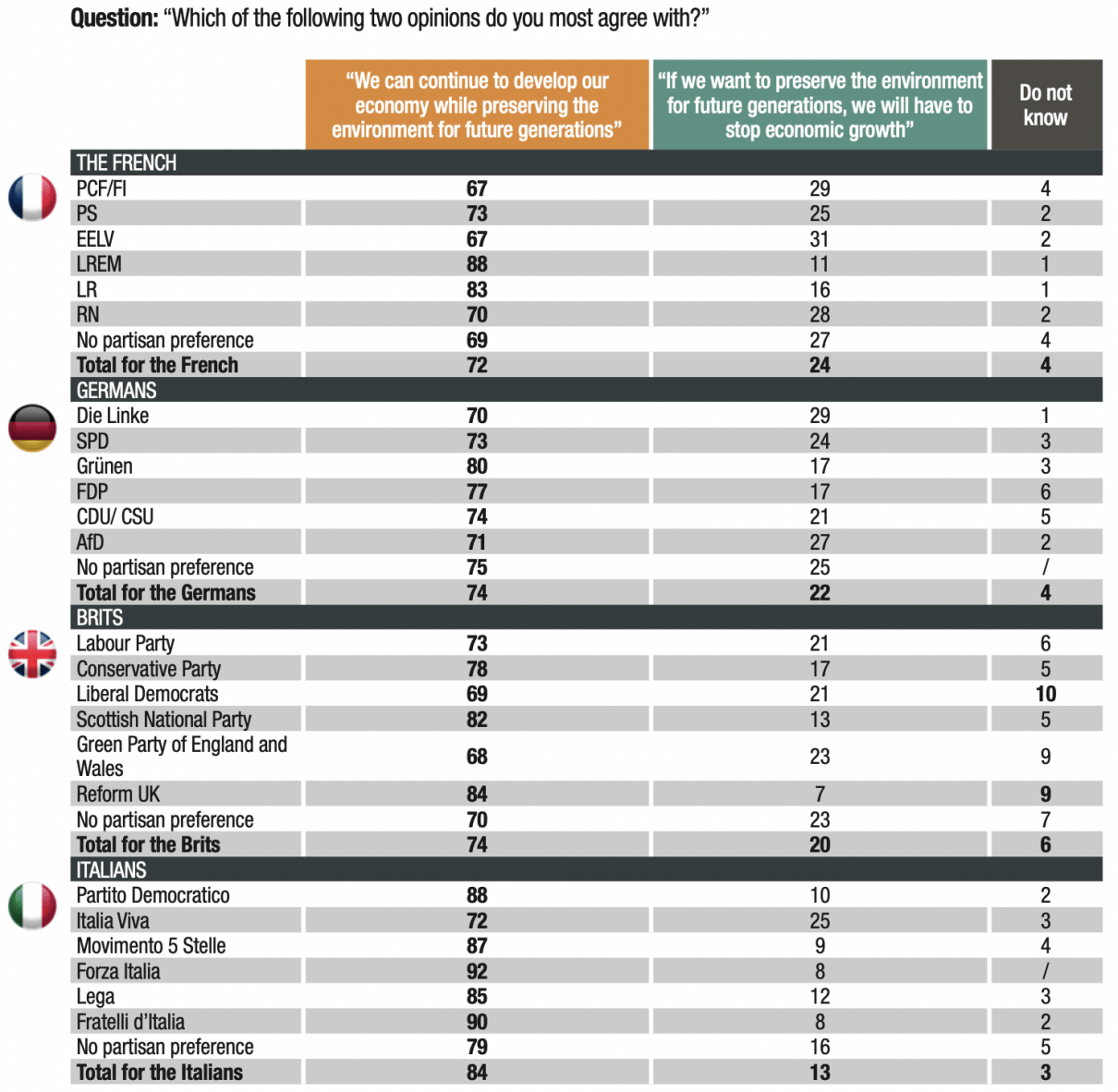

Economic growth is compatible with protecting the environment for 76% of respondents

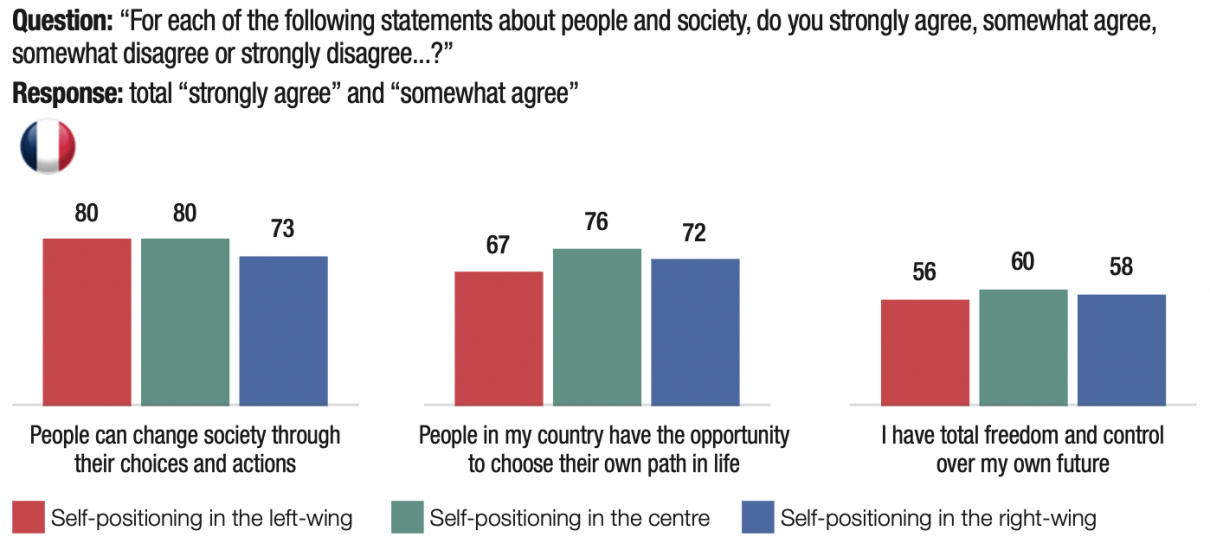

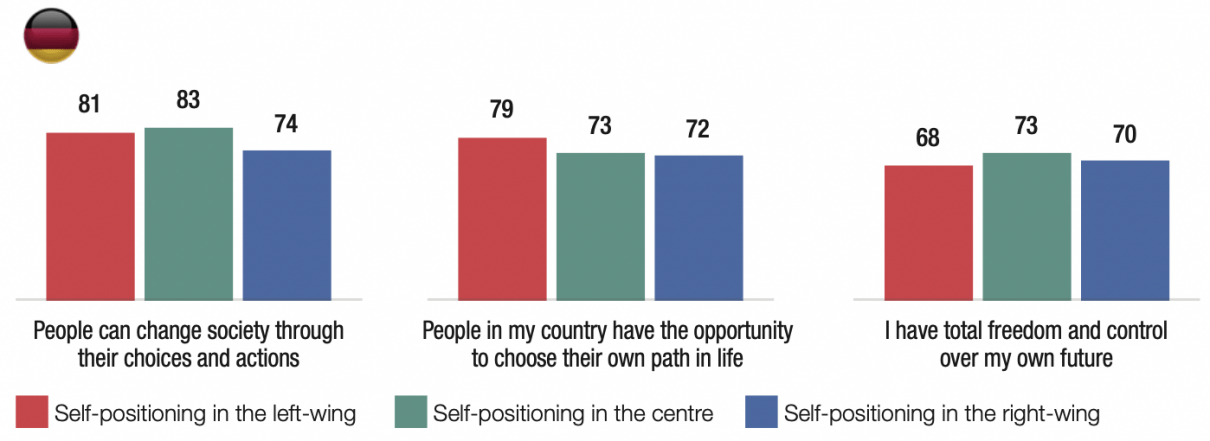

Individualism: a cross-party value

The autonomy of success elevated to a social norm

Individual responsibility trumps handouts

Conclusion

Summary

Rght-wing majorities are at the helm of most national governments in the European Union. Behind these electoral victories lies the question of the deeper-set conversion of Europeans to right-wing values. Voting results inform only partially about political preferences, as the factors that come into consideration during a vote are manifold – inability to choose, protest vote, desire for alternation, etc. Yet the disorders of contemporary society are profoundly changing our individual beliefs and value systems: the multiplication and intertwining of global crises, the deployment of globalisation, the ageing of our populations, the rise in immigration, the increase in the sense of insecurity caused by the rise in criminal behaviour and Islamist terrorism, the recomposition of the media realm, etc. Such a situation, revealing a historical shift on the European continent, invites us to pause and observe.

The data analysed in this study, taken from the Twelfth Wave of the Political Trust Barometer run by the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof), of which the Fondation pour l’innovation politique is a partner, are intended to contribute to a better understanding of the reasons for the rightward leaning that seems to be playing out in public opinion in four major European democracies: France, Germany, Italy and the UK. The diagnosis identifying a shift to the right in society is based here on the assimilation of values with right-wing culture, including nationalism via the identitarian question, economic liberalism and political liberalism indexed to individualism.

Victor Delage,

Director of Studies and Communications at the Fondation pour l'innovation politique.

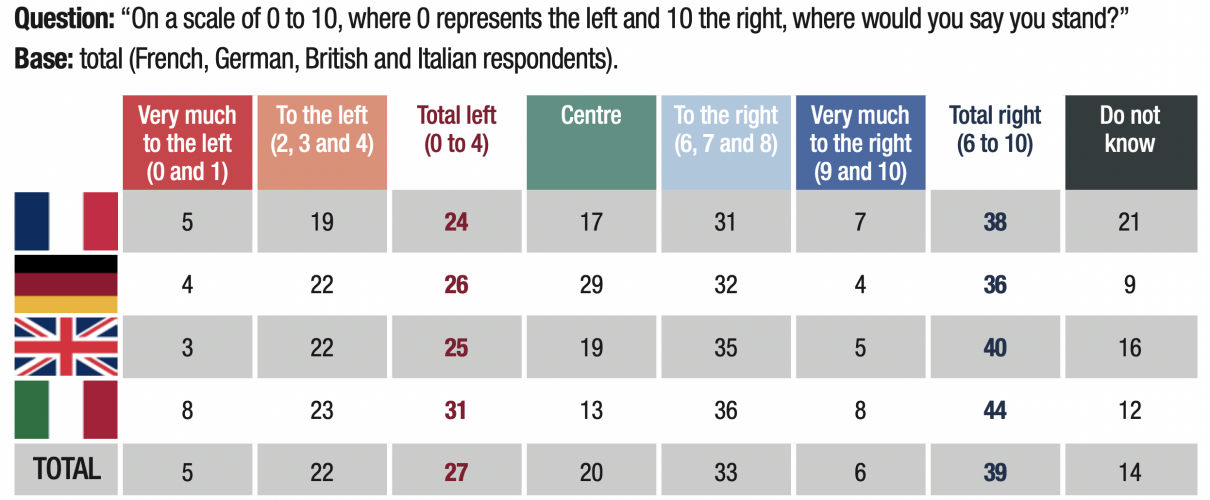

1. On average, in the four democracies studied, 39% of respondents self-position themselves as right-wing (between 6 and 10 on the scale), 27% as left-wing (between 0 and 4) and 20% as centrist (5).

2. Right-wing self-positioning leads in all four of the countries studied: 44% of Italians describe themselves as right-wing (31% as left-wing), compared to 40% of Britons (25% as left-wing), 38% of the French (24% as left-wing) and 36% of Germans (26% as left-wing).

3. While seniors are traditionally known for voting more conservatively than younger people, our data shows that it is the younger generations that most frequently self-position themselves as right-wing. Across all the countries, 41% of 18-24 year-olds and 41% of 25-34 year-olds rated themselves between 6 and 10 on the scale, a level comparable to that of the 65+ age group (40%) but 5 points higher than the 50-64 age group (36%).

4. In the past five years, the proportion of French people on the right end of the political spectrum has risen steadily, from 33% in 2017 to 38% in 2021. Over the same period, the proportion of citizens describing themselves as left-wing has remained stable (25% in 2017 and 24% in 2021), despite a slight drop in 2020 (22%).

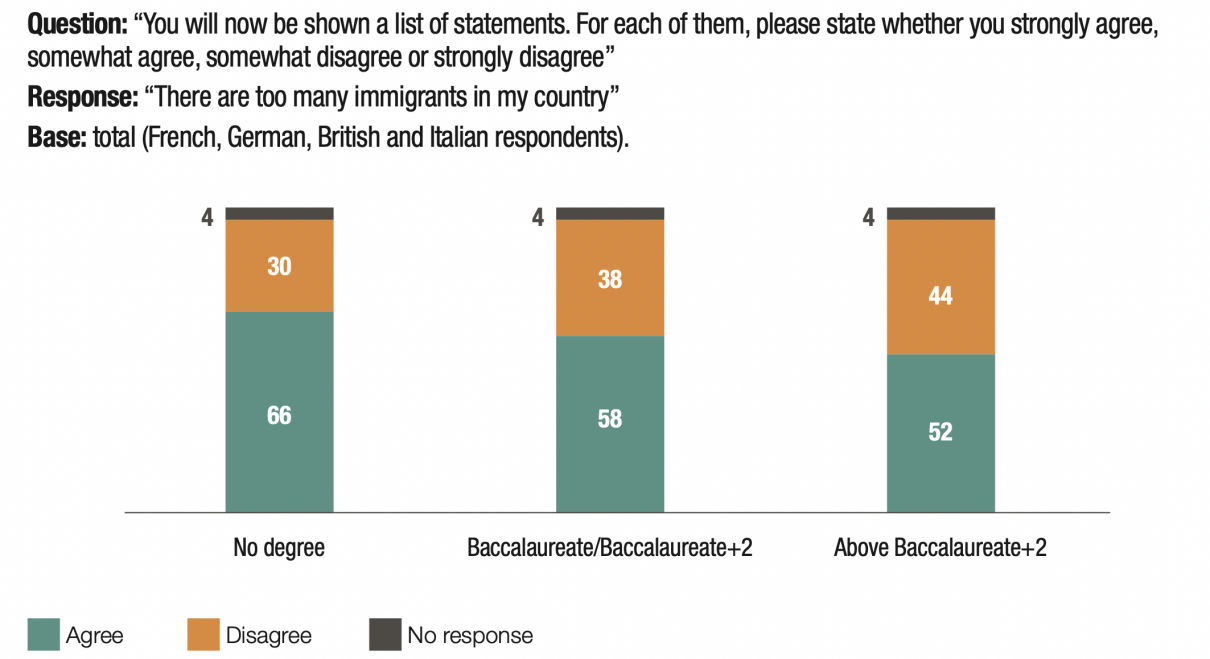

5. The view on immigration is dominated by a negative judgement. On average, six out of ten citizens (60%) agree with the statement that “there are too many immigrants in our country” (compared to 36% who disagree and 4% who did not respond).

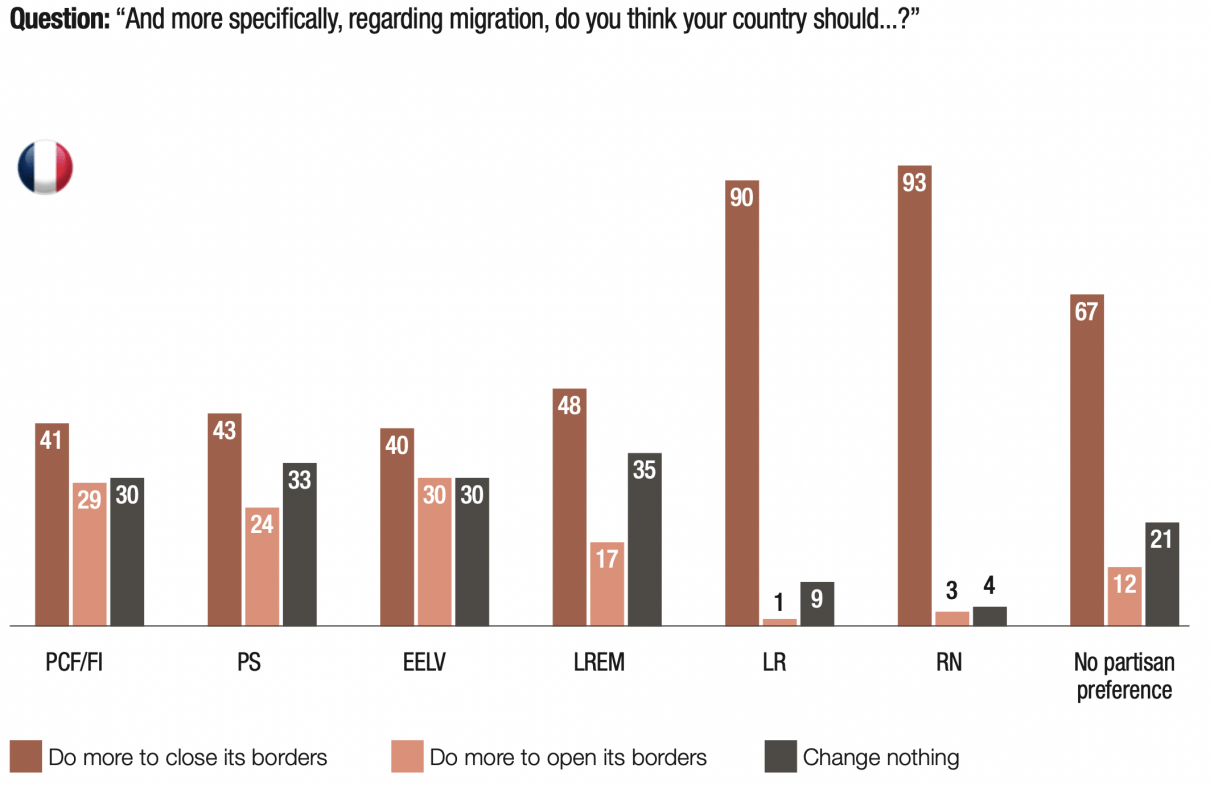

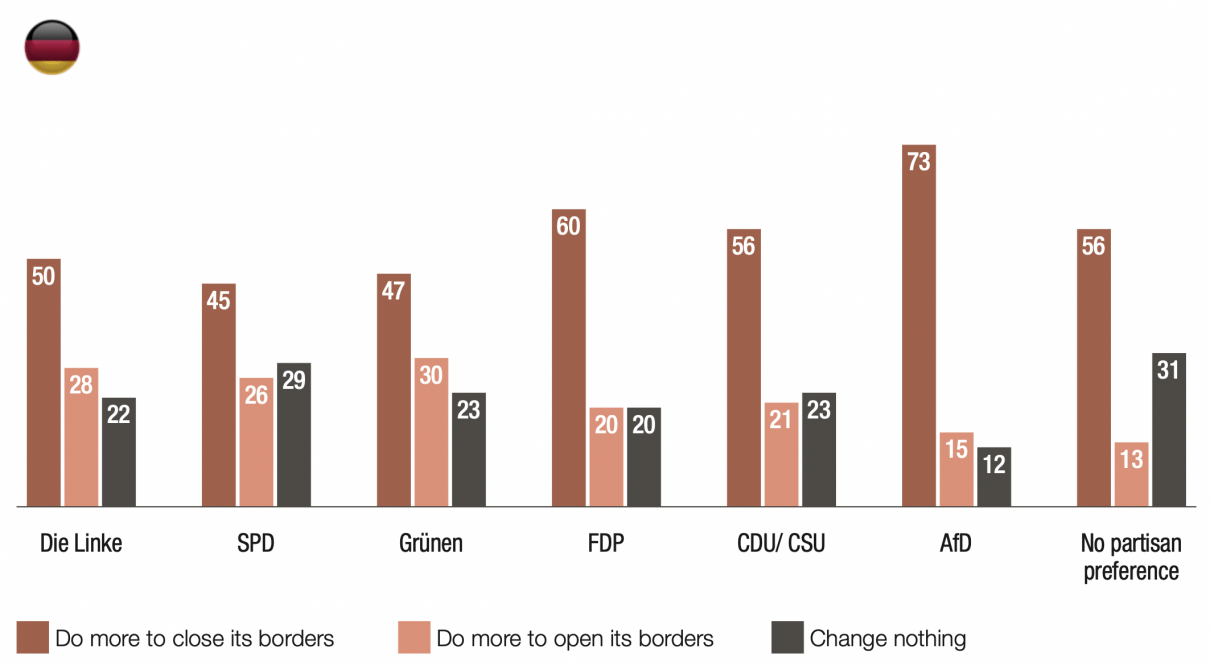

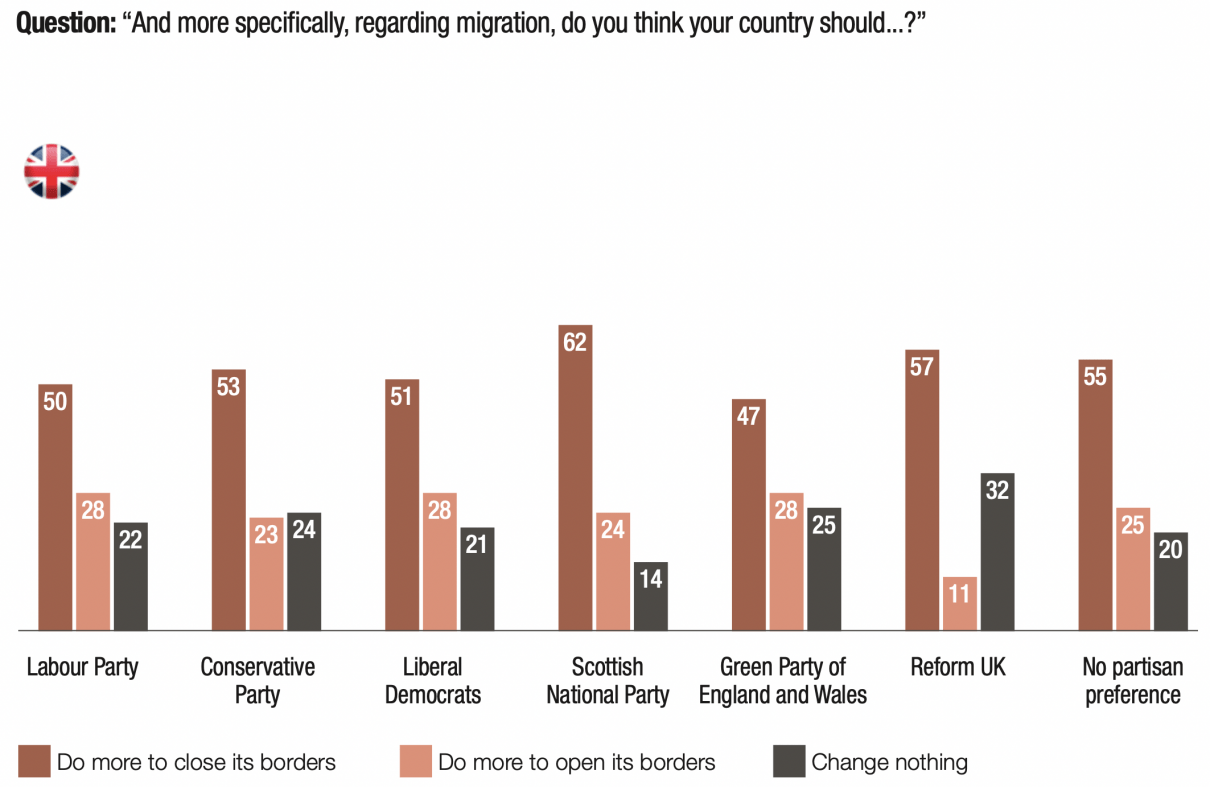

6. More than half of respondents (56%) feel that their country should do more to close itself off from migration, less than a quarter (23%) call for opening their country up more and 21% advocate for maintaining the status quo. The French (63%) appear to be the most averse to opening up, ahead of the Germans (54%), the Italians (54%) and the British (53%).

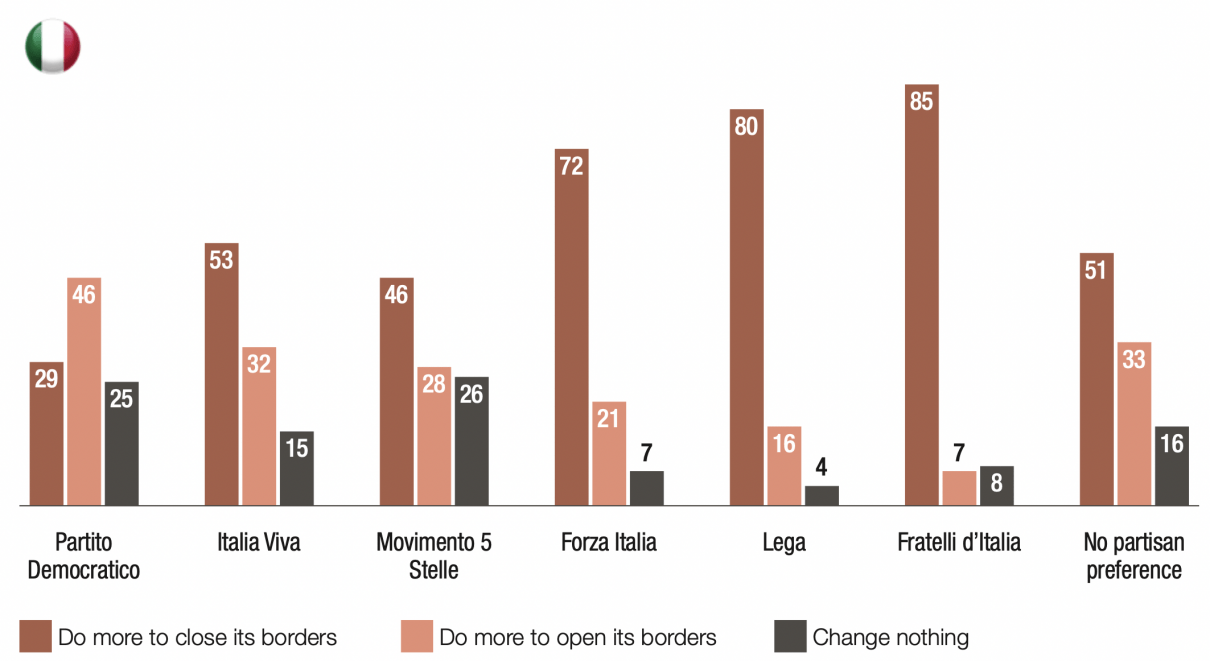

7. Out of the four democracies studied here, supporters of left-wing parties are more likely to be “pro-closure” than “pro-opening up” the country in terms of migration, or in favour of keeping the status quo – with the exception of supporters of the Italian Democratic Party (Partito Democratico).

8. In France, 62% of citizens believe that Islam is a threat to the nation.

9. In France, the fear of Islam is widespread among those who place themselves in the right- wing bloc (81%). The question appears to be very divisive to those in the left-wing bloc: almost half of left-wing supporters (45%) agree with the item “Islam poses a threat to the nation”, while the other half (52%) disagree and 3% of respondents did not answer.

10. A majority of respondents (54%) deemed that “in order to contend with economic difficulties”, “the State should place its trust in companies and give them more freedom”. 41% of those surveyed were in favour of the item “that the State control and regulate businesses more closely” (5% responded that they did not know).

11. Trust in companies is inversely proportional to their size. Trust in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is very high (74%) and they even rank among the institutions that invoke the greatest trust, while trust in large companies, whether public (45%) or private (44%), remains a minority phenomenon.

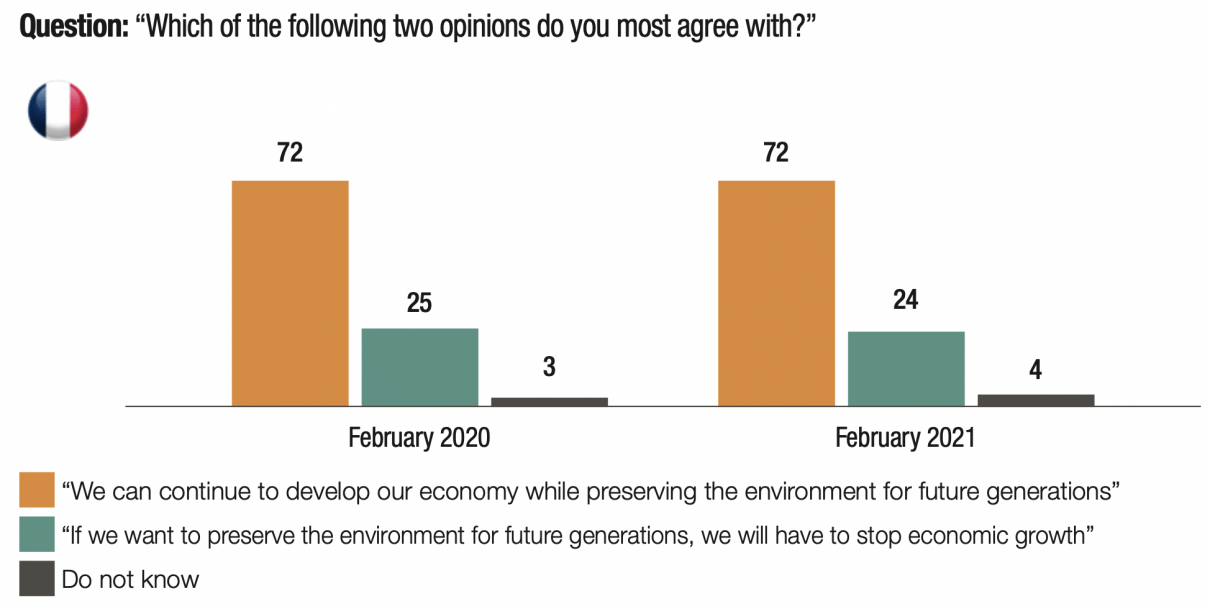

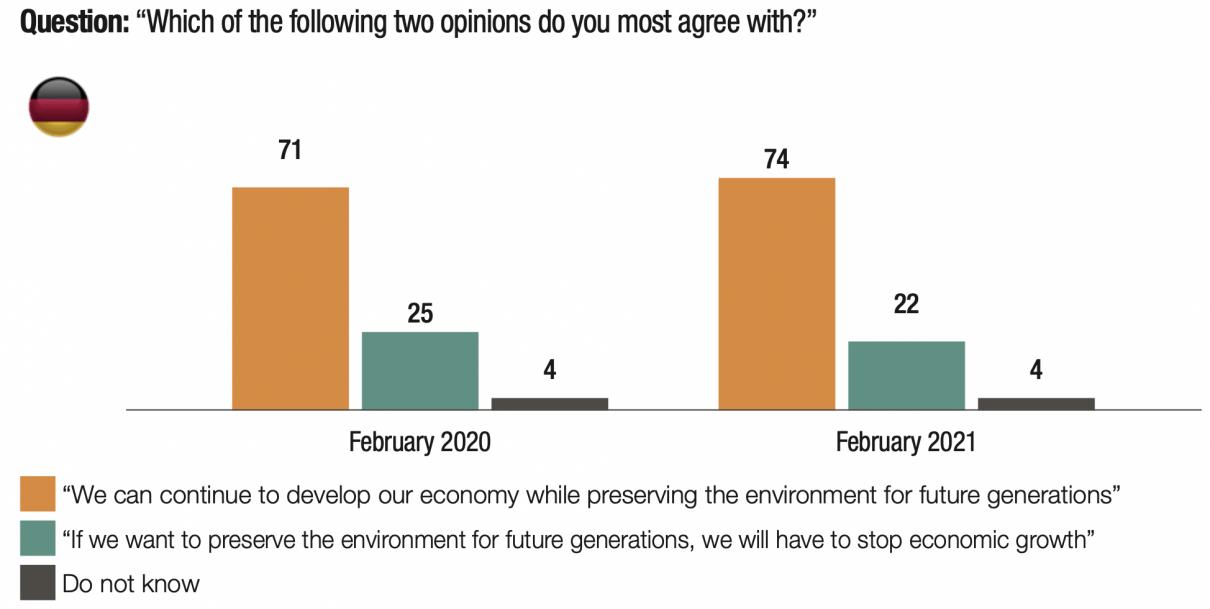

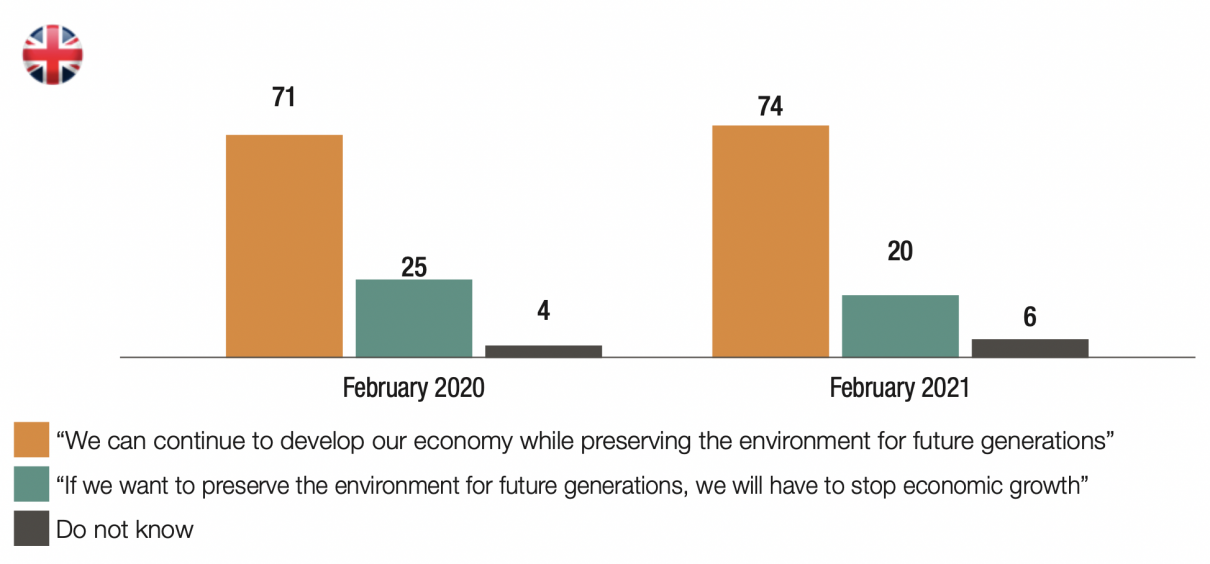

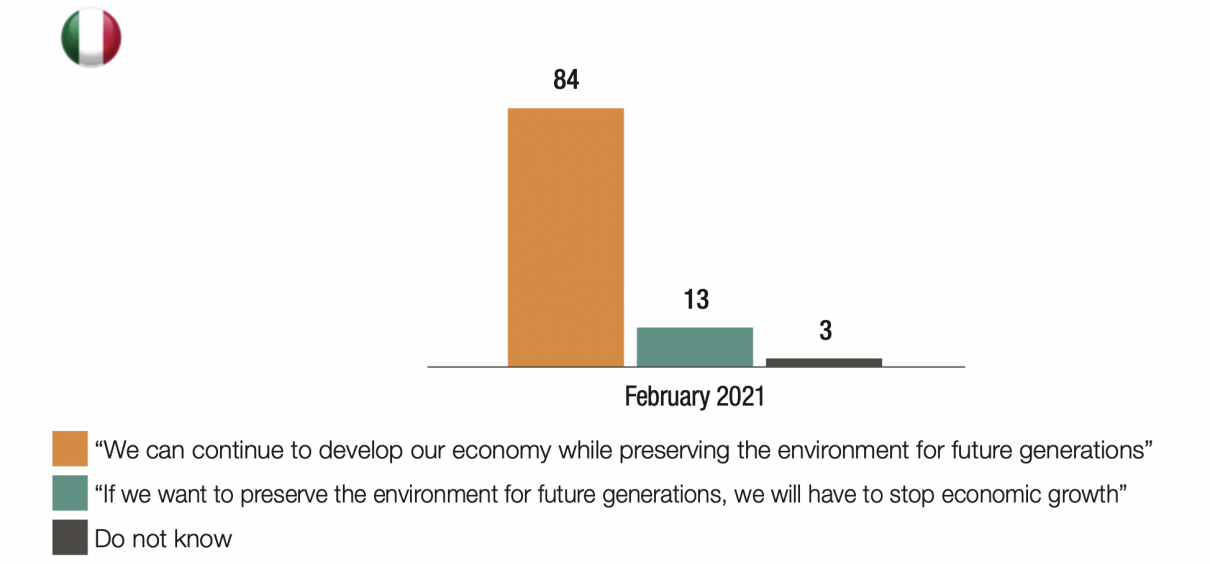

12. The impact of the media-borne discourse around punitive environmentalism and degrowth is spreading only to a limited extent in public opinion. According to 76% of respondents, “we can continue to develop our economy while preserving the environment for future generations”. The Italians are the most numerous (84%) to believe that growth and environmental protection are compatible. They are followed by the Germans (74%), the British (74%) and the French (72%).

13. A majority of supporters of the various parties in the four democracies replied that “we can continue to develop our economy while preserving the environment for future generations”. This is particularly true of supporters of the Socialist Party (73%), Europe Écologie-Les Verts (67%) and the PCF/FI (67%) in France; the Grünen (80%) and SPD (73%) in Germany; the Labour Party (73%) and the Green Party of England and Wales (69%) in the UK; and the Partito Democratico (88%) in Italy.

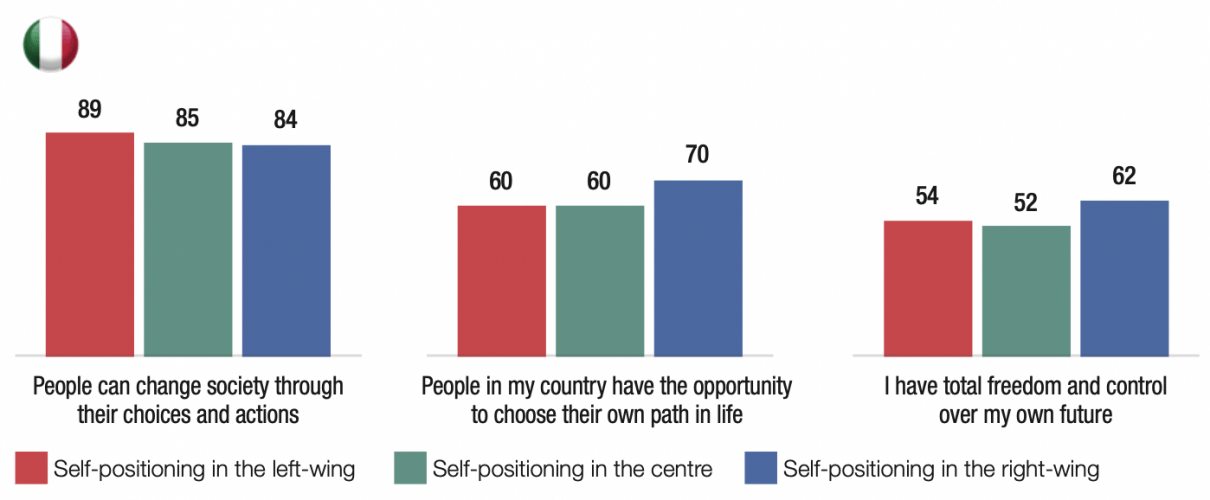

14. Our data show that individualism, on both the right and the left, is elevated to the rank of a social norm. A large majority of respondents believe that “people can change society through their choices and actions” (80%), that “people in their country have the opportunity to choose their own path in life” (69%), and, to a lesser extent, that they should have “complete freedom and control over their own future” (63%).

15. Almost three-quarters of all citizens (71%) believe that “many people manage to receive social benefits to which they did not contribute”. This is 46 points higher than the proportion of respondents who disagreed with this item (25%). A country-by-country analysis shows that France, where 57% of households do not pay income tax, is the country where the most citizens (73%) agree that many people are paid social benefits to which they have not contributed. They are followed by the British (72%), the Italians (72%) and the Germans (68%).

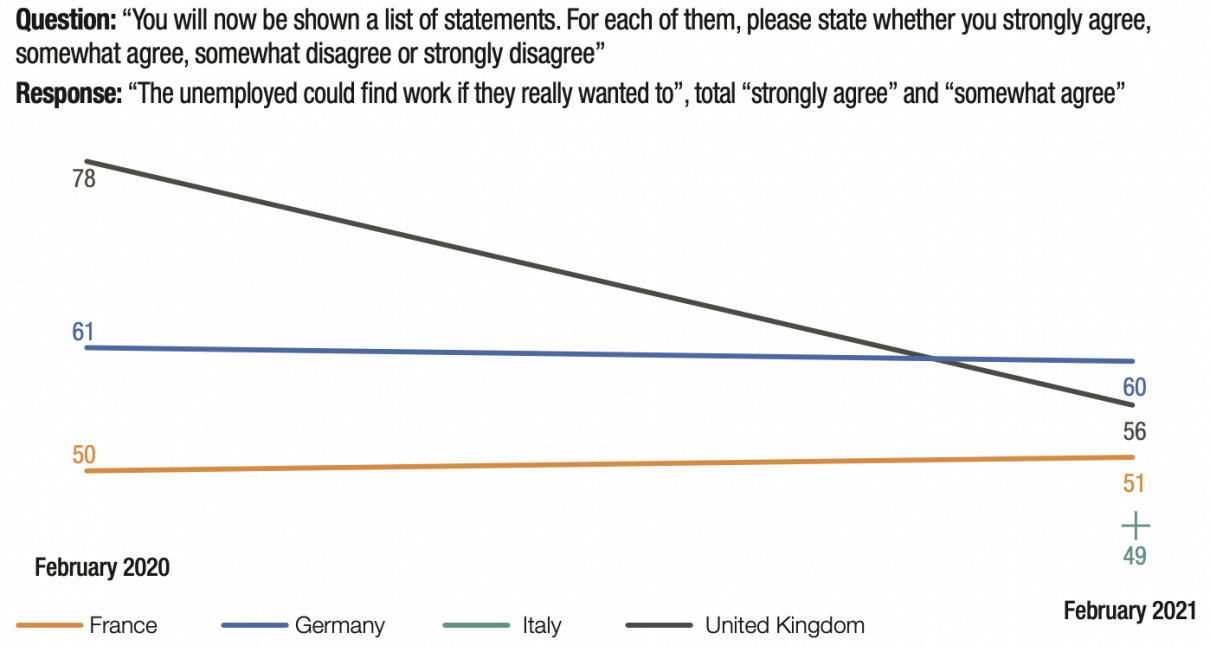

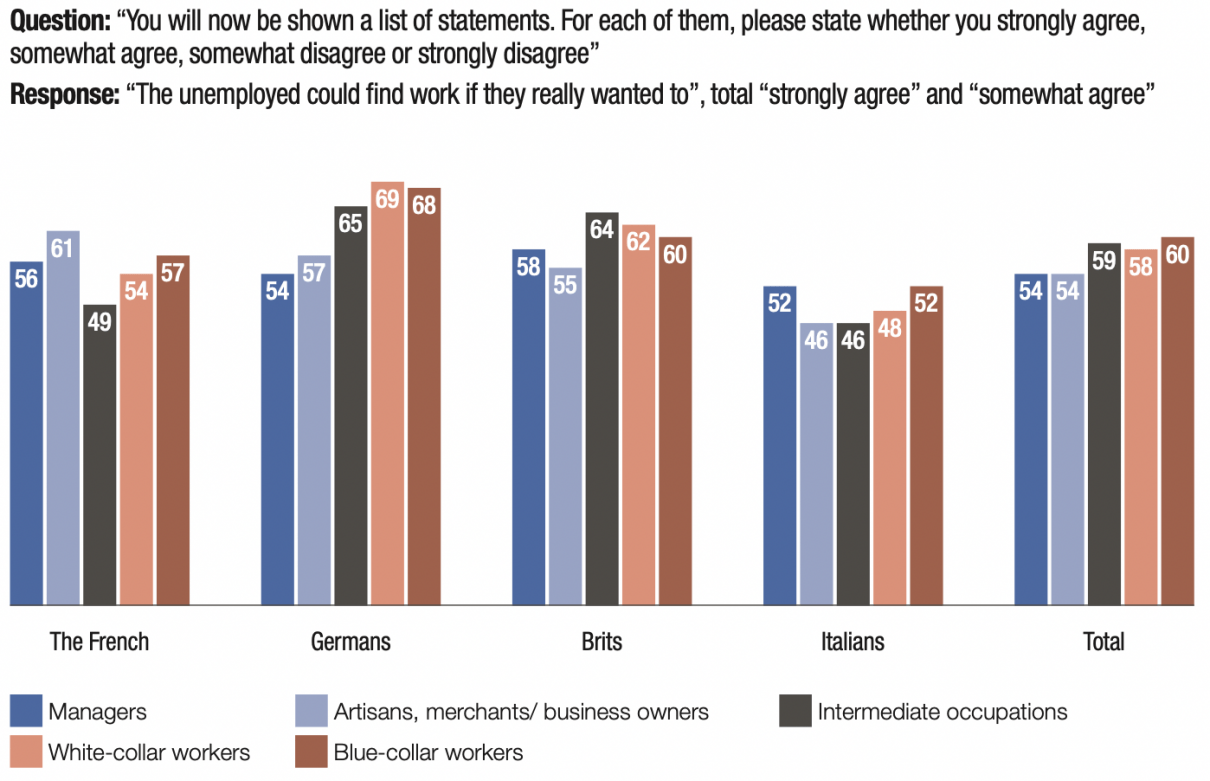

16. More than half of respondents (55%) believe that “unemployed people could find work if they really wanted to” (compared to 42% who “disagree” with this statement). In one year’s time, the proportion of people who believe that the unemployed take advantage of the system remained stable in France (from 50% in February 2020 to 51% in February 2021) and in Germany (from 61% to 60%), while it fell by 22 points in the UK (from 78% to 56%).

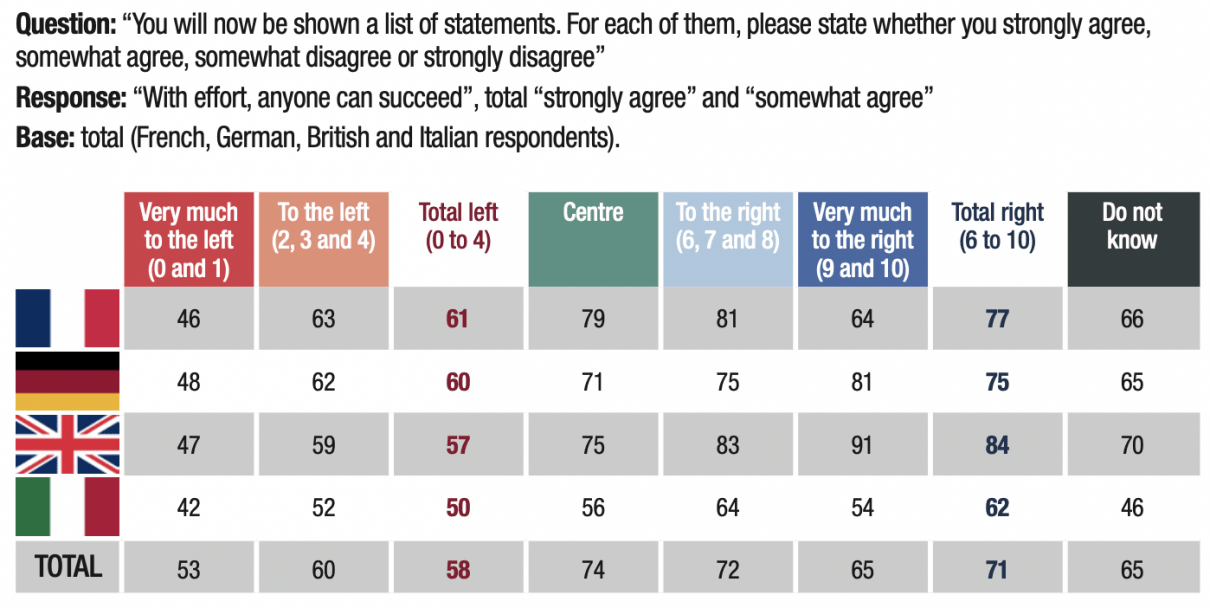

17. The respondents emphasise the notion of individual effort. More than two-thirds (68%) believe that “with effort, anyone can succeed”. A significant majority of respondents on the left end (58%) of the political spectrum agree with this view, although even more do so on the right end (71%). It can be noted that the differences between States are significant: 74% of the British, 69% of the Germans, 68% of the French and 55% of the Italians.

The data analysed comes from the twelfth wave of the Political Trust Barometer, a benchmark survey carried out by the Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po (Cevipof), in partnership with the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, the Conseil économique, social et environnemental (Cese), the Fondation Jean-Jaurès, the Institut Montaigne, the mutual insurance company Intériale and the Luiss University in Rome. For the past twelve years, this barometer has been enabling a longitudinal study of citizens’ trust in politics and institutions, as well as their relationship to democracy and its functioning.

The interviews were carried out in France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom between 20 January and 10 February 2021 using a self-administered online questionnaire by the OpinionWay polling company. In total, 7,603 people were surveyed. The full survey data is available to the public in open data at data.fondapol.org.

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), Les Droites en Europe, PUF, 2012.

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Estonia, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. For France, we consider that the government is tilted to the right because, despite LREM’s claim to be “neither right nor left”, the two recent successive Prime Ministers (Édouard Philippe and Jean Castex) are from the party Les Républicains. Similarly, in Italy, Mario Draghi, President of the Italian Council since 12 February 2021, comes from the liberal right, even though he has formed a government of national unity bringing together parties from the left and right, including populists.

See Guillemette Lano and Raphaël Grelon, with assistance from Victor Delage and Dominique Reynié, 2019 European Elections. The weight of the electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, July 2019, p. 3.

See Jérôme Fourquet, Fabienne Gomant, Ernst Hillebrand and Vincent Tiberj, Droitisation en Europe. Enquête sur une tendance controversée, Fondation Jean-Jaurès/Fondation européenne d’études progressistes, 2014.

Pierre Bréchon, “Valeurs de gauche, valeurs de droite et identités religieuses en Europe”, Revue française de sociologie, vol. 47, n° 4, October-December 2006, p. 728.

Pascal Ory, “À droite toute ?”, Le Débat, n° 191, September-October 2016, p. 147-154.

In 2012, a publication on “the right-wing in Europe” reported on their manifest success on the European continent, driven by the combined effect of the exhaustion of social democracy and the collapse of communism1. Nearly ten years later, right- wing majorities are at the helm of most national governments in the European Union. In April 2021, twenty-one out of2 the twenty-seven countries are led by economically liberal/conservative parties or by coalitions where the right-wing heads the government, not to mention Boris Johnson’s conservative government in the United Kingdom.

It can also be noted that since 1999, it is the European People’s Party (EPP) that has held the most seats in the European Parliament, the only European Union institution elected by direct universal suffrage. This is the classic conservative right. It includes in particular the French party Les Républicains and the imposing Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU). In the 2019 European elections, a look at the weight of the electorates at the European constituency level shows that the right-wing electorate (pro-European centre, pro-European right and populist right/far-right) garnered 110,955,811 votes and accounted for 55.9% of the votes cast and 27.9% of the total number of registered voters, far more than the left-wing electorate (pro-European left, ecologists and the populist left/far-left), which received 67,941,204 votes, 34.2% of the votes cast and 17.1% of the total number of registered voters3.

Behind these electoral victories lies the question of the deeper-set conversion of Europeans to right-wing values4. Voting results inform only partially about political preferences, as the factors that come into consideration during a vote are manifold – inability to choose, protest vote, desire for alternation, etc. – that we can only guess at the number of votes cast. According to Pierre Bréchon, coordinator for France of the large-scale European Values Study5, “identifying with the left or the right seems to be a choice stemming from a whole universe of values and not only to an electoral preference6”. Yet the disorders of contemporary society are profoundly changing our individual beliefs and value systems: the multiplication and intertwining of global crises, the deployment of globalisation, the ageing of our populations, the rise in immigration, the increase in the sense of insecurity caused by the rise in criminal behaviour and Islamist terrorism, the recomposition of the media realm, etc. Such a situation, revealing a historical shift on the European continent, invites us to pause and observe. This study is thus aimed at building a better understanding of the forces behind the rightward leaning in public opinion in four major European democracies: France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom. The diagnosis identifying a shift to the right in society is based here on the spread of right-wing values7, including nationalism via the identitarian question, economic liberalism and political liberalism indexed to individualism.

Political self-positioning on a left-right scale reveals a shift to the right in European electorates

On average, in the four democracies studied, when asked “on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represents the left and 10 the right, where would you say you stand?”, 39% of respondents self-position themselves as right-wing (between 6 and 10 on the scale), 27% as left-wing (between 0 and 4) and 20% as centrist (5). Right-wing self-positioning leads in each country: 44% of Italians describe themselves as right-wing (31% as left-wing), compared to 40% of Britons (25% as left-wing), 38% of French (24% as left-wing) and 36% of Germans (26% as left-wing).

It can be observed that 14% of all respondents do not position themselves on the left-right axis. These are generally people who feel removed from political life and consider that democracy is not working well. Note also that the right-wing bloc is made up of individuals from the centre-right to the far-right, while the left-wing bloc is made up of individuals from the centre-left to the far-left.

The French, Germans, Italians and British are more right-wing than left-wing

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

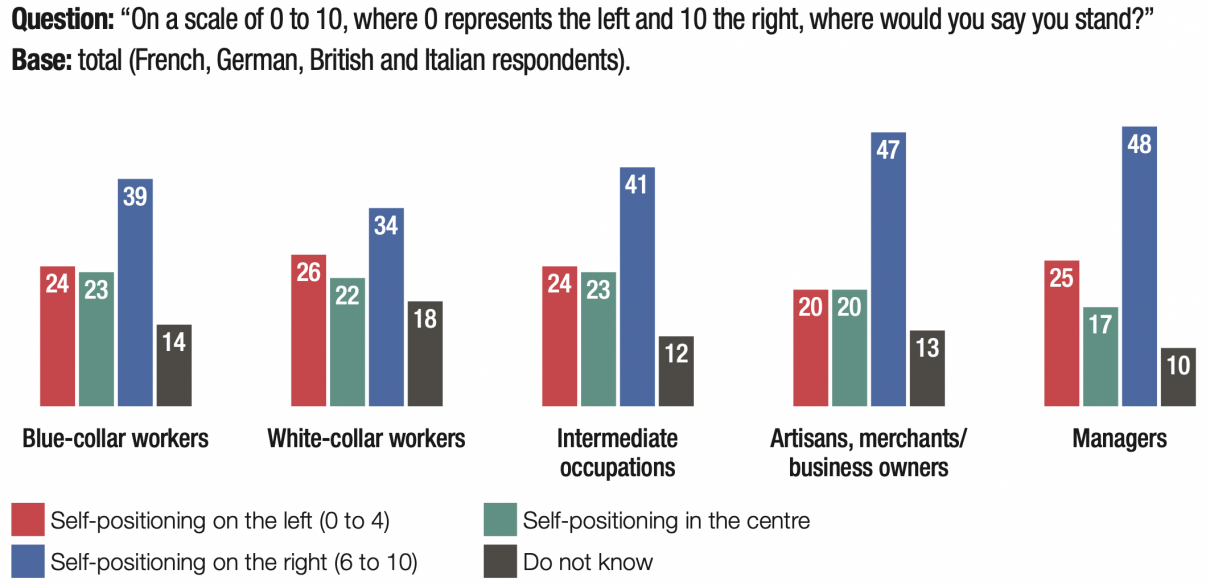

A crucial point stands out: while seniors are traditionally known for voting more conservatively than younger people, our data shows that it is the younger generations that most frequently self-position themselves as right-wing. Across all the countries, 41% of 18-24 year-olds and 41% of 25-34 year-olds rated themselves between 6 and 10 on the scale, a level comparable to that of the 65+ age group (40%) but 5 points higher than the 50-64 age group (36%).

In contrast, only 26% of 18-24 year-olds and 22% of 25-34 year-olds rated themselves as left-wing (between 0 and 4 on the scale), compared to 31% of those ages 65 and over and 29% of those ages 55-64. In the long run, this rightward move of young voters could structurally consolidate the anchoring of right-wing parties in Europe.

Regardless of socio-professional category, respondents always self-position themselves more to the right than to the left.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

The Political Trust Barometer’s inclusion of measures in Germany and the United Kingdom began in Wave 11 in February 2020. Italy, on the other hand, appears for the first time in this wave 12. Unlike France, no data is available for these three countries for previous years.

Bruno Cautrès, “La fausse mort du clivage gauche-droite”, Baromètre de la confiance politique-Vague 9, Sciences Po/Cevipof, 29 January 2018.

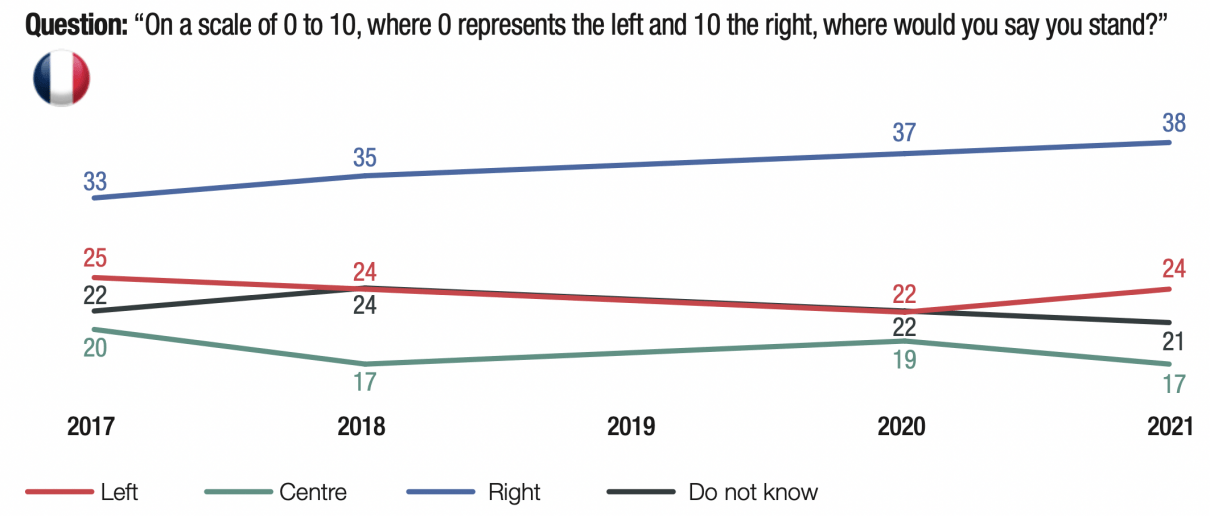

Where France is concerned, the Political Trust Barometer helps capture the evolution of political self-positioning since 20178. Over the past five years, the proportion of French people on the right end of the political spectrum has risen steadily, growing from 33% in 2017 to 38% in 2021.

In the same period, the proportion of citizens describing themselves as left-wing has remained stable (25% in 2017 and 24% in 2021), despite a slight drop in 2020 (22%). While the left-right divide holds steady in the collective imagination9, a shift has been in progress towards the right-wing for several years.

The rightward shift for the French

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Immigration worries public opinion, on the right and left alike

A majority of respondents (60%) feel there is too much immigration

For France, see Didier Leschi, Migrations : la France singulière, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, October 2018.

Dominique Reynié, Les Nouveaux Populismes, Pluriel, 2013, p. 299.

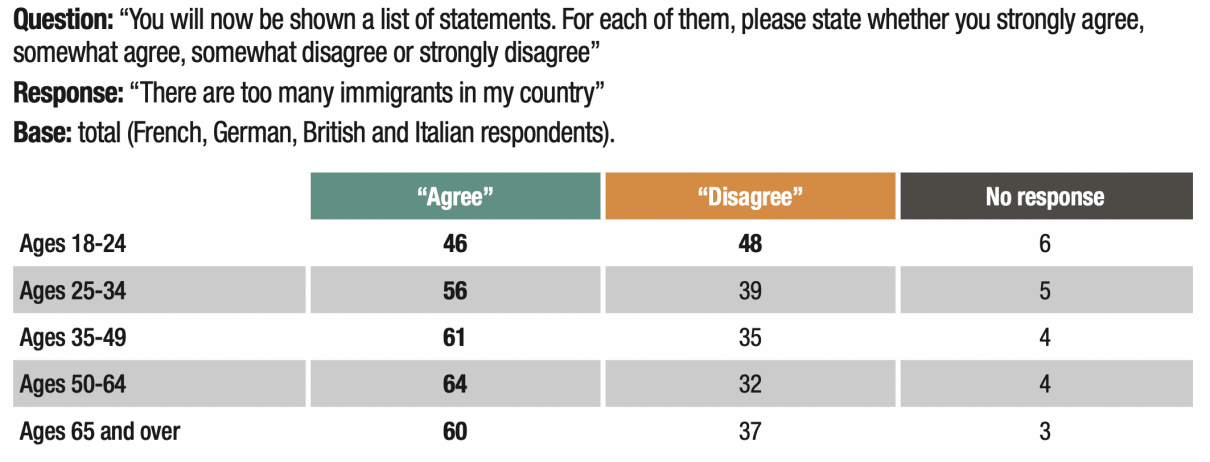

The migration crisis of 2015 revived the political issue of immigration in Europe. In the countries studied, heavily impacted by migratory movements10, the perception of immigration is dominated by a negative judgement. Thus, on average, six out of ten citizens (60%) agree with the statement that “there are too many immigrants in our country” (compared to 36% who disagree and 4% who did not respond). The item “there are too many immigrants in our country” received majority support, no matter the respondent’s nationality (60% of the French, Germans and Italians, 57% among the British).

Immigration stirs strong resistance in all segments of the population. As Dominique Reynié emphasises, “for the working classes, immigration generates competition on the labour market and puts pressure on wage levels; for the middle classes, it consumes an excessive share of the solidarity which [these middle classes] believe they are financing11”. The idea that there are too many immigrants is shared by two-thirds of those in the lower socio- professional categories (63%) and those who have not completed higher education (66%). However, this adverse sentiment remains in the majority in the higher socio-professional categories (58%) and those with the highest educational degrees (52%). In France, two-thirds (65%) of citizens belonging to the lower socio-professional categories believe there is too much immigration in their country. This is 10 points more (55%) than in the higher ones. Similar trends can be seen among our European neighbours, despite smaller differences between socio-professional categories: 64% of the lower socio-professional categories in Germany feel there are too many immigrants in their country (compared to 59% in the higher categories), 62% of the lower socio-professional categories in Italy (compared to 60%) and 59% of those in the UK (compared to 55%).

While 18-24 year-olds appear to be the age group least hostile to immigration, 46% of them nonetheless consider that there are too many immigrants in their country

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Regardless of the level of degree earned, the feeling that “there are too many immigrants” is shared by the majority

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Voters reject the idea of open policies when it comes to migration

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), 2022, the populist risk in France. An electoral protest indicator designed by the Fondation pour l’innovation politique. Waves 2 and 3, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, October 2020.

Three possible answers were offered to the question “And more specifically, regarding migration, do you think your country should…?”: open up more, close itself off more, or not change. More than half of respondents (56%) feel that their country should do more to close itself off from migration, less than a quarter (23%) call for opening up more and 21% advocate for maintaining the status quo. The French (63%) appear to be the most averse to opening up, ahead of the Germans (54%), the Italians (54%) and the British (53%).

Overall, the more right-wing people are, the more in favour they are of closed borders. Nevertheless, the proportion of left-wing party supporters who want their country to close itself off more when it comes to migration is significant. Out of the four democracies studied here, supporters of left- wing parties are more likely to be “pro-closure” than “pro-opening up” or in favour of keeping the status quo – with the exception of supporters of the Italian Democratic Party (Partito Democratico).

Immigration has become a central issue for all citizens, no matter their political affinities. According to the electoral protest indicator developed by Fondation pour l’innovation politique, 37% of the French feel that reducing immigration is one of the priorities which the government must address, ahead of reducing global warming (35%), the influence of Islam (33%) or the debt and public deficit (28%)12.

Left-wing supporters are more numerous to want their country to close their borders to migration than to want their country to open more or maintain the status quo

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Concern about Islam goes beyond political affiliations

In France, 62% of citizens believe that Islam is a threat to the nation

Wave 12 of the Political Trust Barometer asked citizens, solely in France, about their concerns with regard to Islam. More than six out of every ten respondents (62%) agree with the item “Islam poses a threat to the nation”. One-third (33%) disagreed and 5% did not answer. While socio- demographic variations exist, this fear is pervasive throughout the population. More men (65%) than women (60%) perceive Islam as a threat to the nation. Similarly, two-thirds of French people living in rural areas (65%) see Islam as a threat to the nation, i.e. 6 points more than for city dwellers in towns of 100,000 inhabitants or more where the level is already high (59%). The age effect stands out most prominently. It is the youngest generations that voice the least fear of Islam in their responses: 41% of 18-24 year-olds and 48% of 25-34 year-olds say that “Islam poses a threat to the nation”, compared to 59% of 35-49 year-olds, 74% of 50-64 year-olds and 70% of those ages 65 and over.

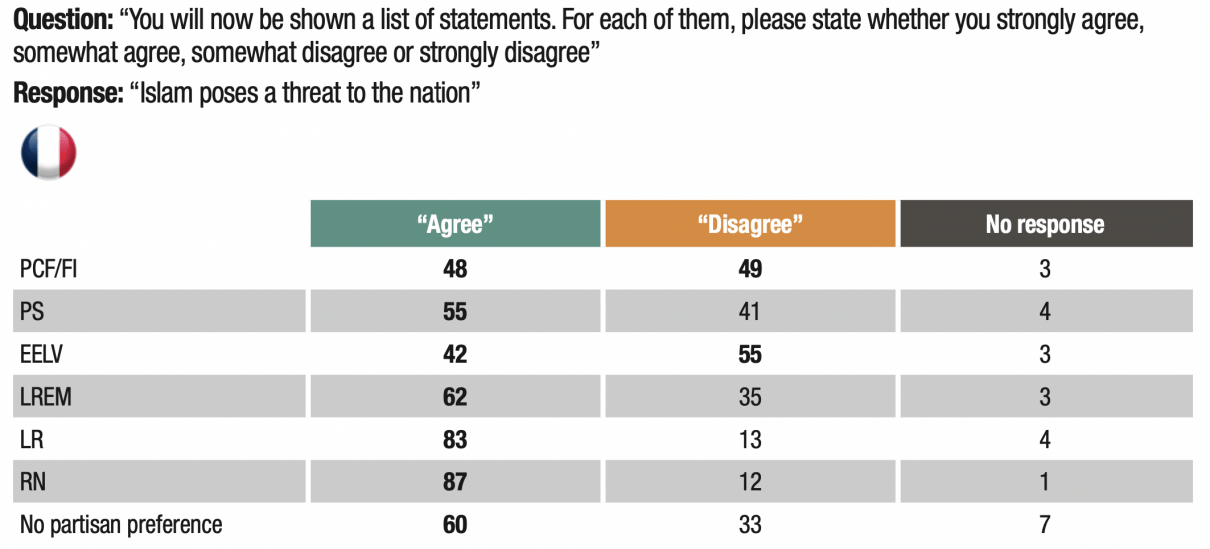

The fear of Islam is largely shared by those who place themselves in the right-wing bloc (81%). Meanwhile, the question appears to be very divisive for the left-wing bloc: almost half of left-wing supporters (45%) agree with the item “Islam poses a threat to the nation”, while the other half (52%) disagree and 3% of respondents did not answer. In detail, 55% of Socialist Party supporters, 48% of PCF/FI supporters and 42% of EELV supporters consider Islam to be dangerous to the nation.

The fear of Islam extends to all electorates

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

A concern shared by our European neighbours

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), What next for democracy? An international survey from the Fondation pour l’innovation politique, Paris, 2017.

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), Democracies Under Pressure, vol. 2, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, International Republican Institute, May 2019.

François Miquet-Marty and Rafael Guillermo Lopez Juarez, “Une droitisation identitaire”, Le Débat, n° 191, September-October 2016.

See Dominique Reynié (dir.), Islamist terrorist attacks in the world 1979-2019, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, November 2019.

These results can be put into perspective with those observed in the publication What next for democracy?, a survey conducted by Fondation pour l’innovation politique in 26 countries in 201713. According to these data, 62% of Germans, 57% of Italians and 50% of Britons then perceived Islam as a threat to their country. An update of these data will enable us to measure the changes, but there is no doubt that Islam remains a source of concern for European public opinion14.

Such results support the hypothesis that Europeans’ wariness with respect to Islam is multifaceted. The difficulties that arise, for example with regard to gender equality or freedom of opinion, can give rise to intercultural conflicts. For François Miquet-Marty and Rafael Guillermo Lopez Juarez, a large proportion of citizens feel that their country is “threatened (actually or potentially) in its identity, its landscapes, its way of life, and its values. This idea thrives on the evocation of an Islam visible in the public arena (veils and headscarves, halal butcheries, etc.)15”. On top of this comes16 the spectre of Islamist terrorism and the entrenchment of jihadism, which inevitably fuel this rejection. The disconnect between the fears that immigration and Islam stir in voters, and the difficulties experienced by some political parties – in particular, part of the left – in taking a clear position on these issues is fostering this shift to the right in Europeans’ values.

Preference for economic liberalism

A call for more freedom for companies

Pascal Perrineau, Le Grand Écart. Chronique d’une démocratie fragmentée, Plon, 2019, p. 42.

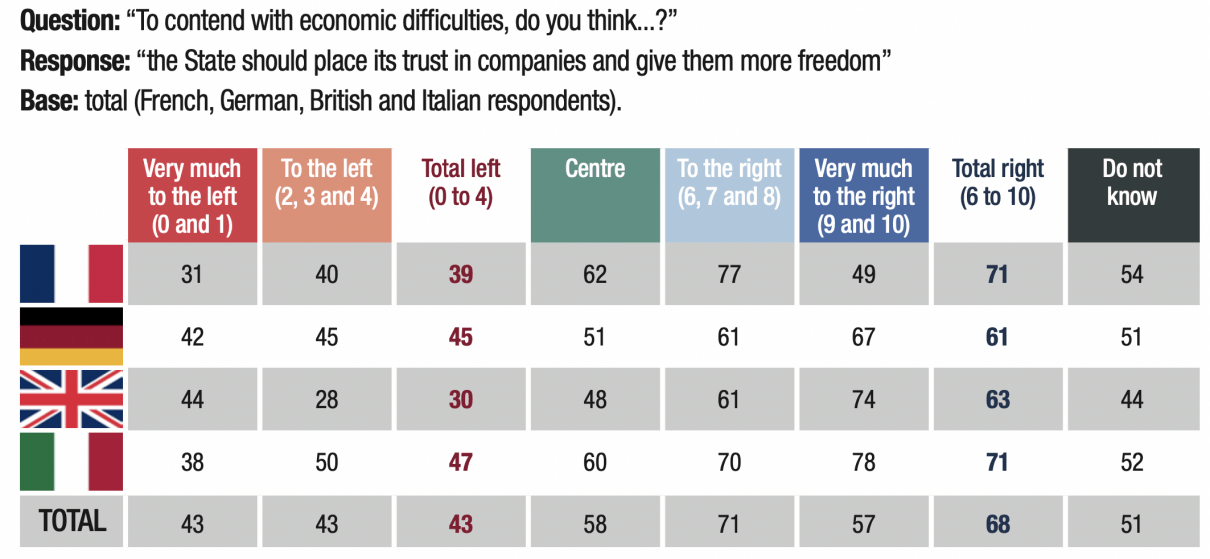

Protecting economic liberalism, defined here as limiting the role of the State in the economy and enhancing the freedoms of companies, receives majority support. Consequently, “to contend with economic difficulties”, more than half of the respondents (54%) deem that “the State should trust companies and give them more freedom”.

The metric reflecting citizens’ aspiration for economic liberalism must be tracked, as it delineates another major potential register of the shift rightward. Wave 12 of the Political Trust Barometer was run against the backdrop of the Covid-19 public health and economic crisis, which saw many European economies under State intervention. In such a singular period as this one, it is interesting to measure the degree to which citizens support or reject the values of the market economy: corporate freedom, trust in businesses, the growth economy or support for capitalism, for instance. 41% of those surveyed were in favour of the option “that the State control and regulate businesses more closely” (5% responded that they did not know).

It is notable to observe that some of the sociological characteristics of respondents have only a very slight influence on their support for the withdrawal of the State from the economy. The age criterion has no effect: overall, more than half of 18-24 year-olds (55%) as well as those ages 65 and over (55%) consider that the State should place more trust in businesses. Similarly, the “no diploma” group (53%) is just as much in favour of a freer economy as those with degrees requiring more than two years of post-secondary studies (53%). As pertains to social categories, the proportion of those from upper socio-professional categories (57%) who defend corporate freedoms is slightly higher than that of those from the lower ones (53%).

Political self-positioning uncovers more marked differences depending on individuals’ profiles. Trust in economic players and their freedoms is high among citizens on the right (68%) and in the centre (58%). At the other end of the political spectrum, more than four out of ten people (43%) self-positioning to the left defend corporate freedoms. Two interpretations are possible: this figure is 25 points lower than that of respondents on the right (68%), but also shows one in two left-wing citizens who feel that “in order to contend with economic difficulties”, the State should step aside and allow companies to make their own decisions. According to political scientist Pascal Perrineau, “we are moving away from a world in which a working class left-wing championing the values of economic anti-liberalism and universalism would be pitted against a well-off right-wing that associates economic liberalism with the rejection of universalist values”17.

Support for corporate freedoms is a function of left-right political self-positioning

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

As the data in the table illustrate, the formation of right-wing and left-wing blocs should not eclipse the heterogeneity of profiles within these two groups, particularly on economic issues. For example, it can be observed that in France, more than three-quarters (77%) of those who self-position between 6 and 8 on the right-left scale deem that “the State should place its trust in companies and give them more freedom”, as compared to less than half (49%) of those who self-position as very right-wing (between 9 and 10 on the scale). Several researchers have, in recent years, posited that the disparities on economic liberalism actually no longer align with the left-right divide, and claim that it has been replaced by a new divide between the winners and losers of globalisation. Nonetheless, here too caution is called for, as our data indicate minor variations by age, level of education or socio-professional category, for example on the issue of corporate freedom.

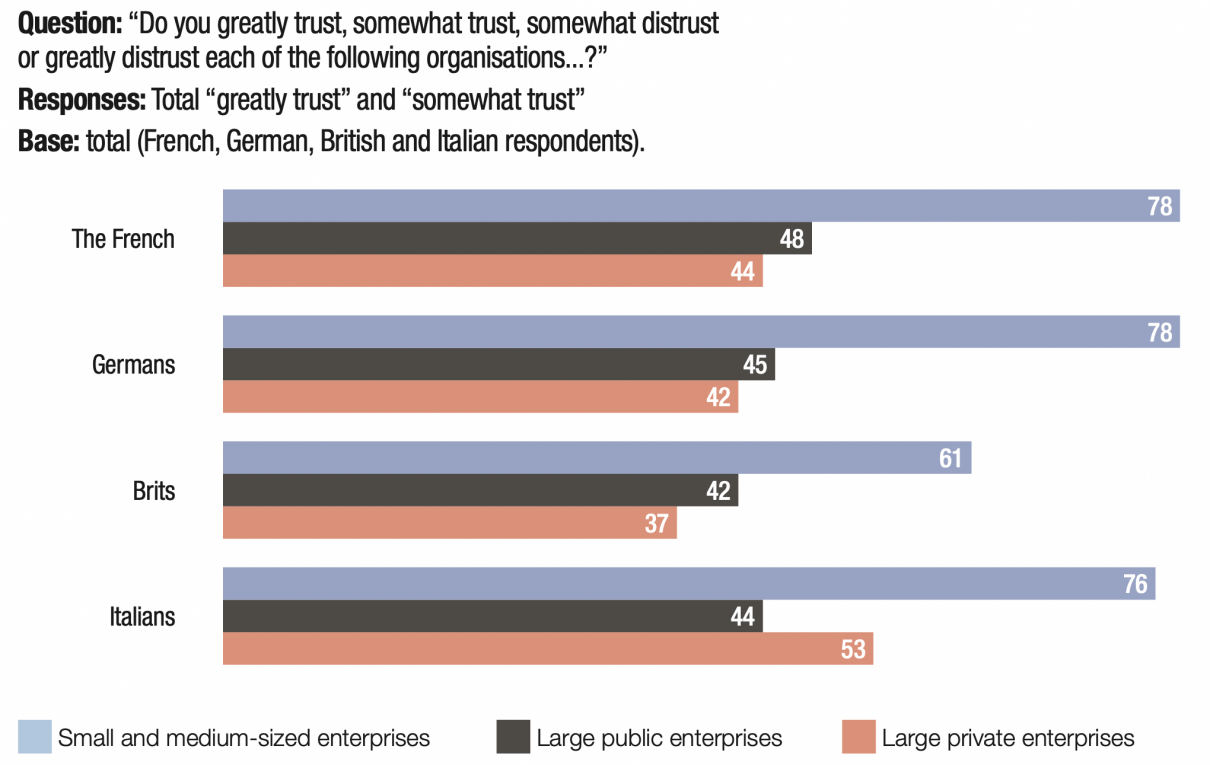

The size of companies shapes collective representations

Trust in companies is inversely proportional to their size. Trust in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is very high (74%) and they are even among the institutions that inspire the greatest trust, while trust in large companies, whether public (45%) or private (44%), remains in the minority.

Let us note nevertheless that the coronavirus crisis seems to be bringing about increased awareness of the importance of large companies in countries’ economic and social fabric, particularly in Germany and France. To wit, in February 2021, 45% of Germans trusted large public companies (compared to 40% in February 2020) and 42% trusted large private companies (compared to 38%). Similarly, the trust of the French is increasing: by 4 points when it comes to large public companies (from 44% in February 2020 to 48% in February 2021) and by 1 point for large private companies (from 43% to 44%). For SMEs, the level of trust has remained stable, as much in Germany as in France (in both countries, 77% in February 2020 and 78% in February 2021). Conversely, Brexit appears to be having an effect on these perceptions, visible by the 7-point drop in the trust voiced by the British in SMEs (from 68% in February 2020 to 61% in February 2021), a 4-point drop in trust for large public companies (from 46% to 42%) and a 5-point drop for trust in large private companies (from 42% to 37%). No comparison can be made for Italy, the country having been incorporated into the Political Trust Barometer for the first time in February 2021.

Trust in companies is inversely proportional to their size

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Economic growth is compatible with protecting the environment for 76% of respondents

Guillaume Bazot, Les coûts de la transition écologique, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

See an article from a collective for degrowth, “Confinement : en demi-résonance avec notre décroissance”, partipourladecroissance.net, 11 April 2020.

The impact of the media-borne discourse around punitive environmentalism and degrowth18 is spreading only to a limited extent in public opinion: more than three-fourths of respondents (76%) agree that “we can continue to develop our economy while preserving the environment for future generations”. Twenty percent of respondents say that “if we want to preserve the environment for future generations, we will have to stop economic growth” (4% say they have no opinion on the matter).

Looking more closely, Italians are the most likely (84%) to believe that growth and environmental protection are compatible. They are followed by the Germans (74%), the British (74%) and the French (72%).

During the public health crisis, some media put forward the idea that degrowth was gaining popularity during lockdown19. Our survey reveals the opposite: in one year’s time, the item “If we want to preserve the environment for future generations, we will have to stop economic growth” dropped by 5 points in the UK (from 25% in February 2020 to 20% in February 2021), by 3 points in Germany (from 25% to 22%) and by 1 point in France (from 25% to 24%). In Italy, included for the first time in the Political Trust Barometer, only 13% of citizens state they are in favour of degrowth.

The degrowth model is unappealing

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

In the four democracies surveyed, a large majority of supporters across the various parties still believes that “we can continue to develop our economy while preserving the environment for future generations”. This is particularly true of supporters of the Socialist Party (73%), Europe Écologie-Les Verts (67%) and the PCF/FI (67%) in France; the Grünen (80%) and SPD (73%) in Germany; the Labour Party (73%) and the Green Party of England and Wales (68 %) in the UK; and the Partito Democratico (88%) in Italy.

These results can be put into perspective with the perception that citizens have of the capitalist system, considered perfectible but not fundamentally rejected by citizens. In all four countries, more than half of the respondents (56%) want “the capitalist system to be reformed on certain points” and 14% “do not want the capitalist system to be reformed”. Only one-fourth (26%) stated that “the capitalist system needs to be reformed in depth”.

Whether on the right or on the left, respondents still believe that economic development and environmental protection can be reconciled

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Individualism: a cross-party value

The autonomy of success elevated to a social norm

See Madani Cheurfa, “Un peu plus d’avenir’: une inflexion du pessimisme ?”, Baromètre de la confiance politique-Vague 9, Sciences Po/Cevipof, 29 January 2018.

Our data show that, on the right as well as on the left, individualism – considered here as the recognised ability of each person to change society or to choose his or her’s own path in life – is elevated to the rank of social norm20. As such, a large majority of respondents believe that “people can change society through their choices and actions” (80%), that “people in [their] country have the opportunity to choose their own path in life” (69%), and, to a lesser extent, that they have “total freedom and control over their own future” (63%).

Individualism transcends the left-right divide

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

This phenomenon of individual empowerment can partly be associated with the distrust they express towards the political system as a whole21. Citizens’ scepticism about the effectiveness of democratic political procedures and institutions prompts them to rely solely on themselves in order to change society. As Madani Cheurfa points out, “we are thus witnessing a confirmation […] of the affirmation of this imposed individualism, both on the self (in response to the deficiency of political action) and on others (by making each person responsible for his or her own situation)22”.

Individual responsibility trumps handouts

See Julien Marion, “Près de 6 ménages sur 10 échappent à l’impôt sur le revenu”, bfmtv.com, 18 July 2017.

Just under three-quarters of all citizens (71%) believe that “many people manage to receive social benefits to which they did not contribute”. This is 46 points higher than the proportion of respondents who disagreed with this item (25%). A country-by-country analysis shows that France, where 57% of households do not pay income tax23, is the country where the most citizens (73%) agree that many people are paid social benefits to which they have not contributed. They are followed by the British (72%), the Italians (72%) and the Germans (68%).

Likewise, more than half of respondents (55%) deem that “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to” (compared to 42% who “disagree” with this statement). This result is all the more interesting to analyse as it came against the backdrop of Covid-19. To sustain employment and limit the effects of the economic and social crisis, a number of European countries have turned to part-time work. This is the case in France, but also in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom. That being said, the perception of the effects of these protection mechanisms varies greatly in terms of opinion: in one year, the proportion of individuals who find that the unemployed benefit from the system remained stable in France (from 50% in February 2020 to 51% in February 2021) and in Germany (from 61% to 60%), while it dropped by 22 points in the United Kingdom (from 78% to 56%). The latter’s exit from the customs union and the single market on 31 December 2020 may be another explanation. Again, no comparison with Italy is possible over the period in question.

Covid-19: Changes in respondents’ perception of the claim that the unemployed take advantage of the system

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Note: Measurements on Italy are being included in the Political Trust Barometer for the first time in this Wave 12. Consequently, no comparison can be made with previous years where this country is concerned.

Overall, a majority of all age groups state that they agree with the item “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to”. However, the proportion of the younger generations who agree with this statement (56% of 18-24 year- olds and 58% of 25-34 year-olds) is higher than the proportion of the older ones (52% of 50-64 year-olds and 55% of those ages 65 and over). It is as if, at a time in life when constraints – and disillusionment – have not yet been too great, gaining employment were, in the eyes of young people, a question of will. It should also be noted that the more educated individuals are, the less likely they are to believe that “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to”. Thus, 51% of graduates with “more than two years of higher education” agree with this statement, i.e. 6 points less than those with “no degree” (57%). When it comes to social categories, 56% of those in higher socio-professional categories believe that the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to, compared to 59% of those in the lower ones. This proves that, in public opinion, degrees and qualifications are no longer a guarantee of labour market entry.

Despite differences between countries, overall, the majority of people in the lower socio-professional categories believe that the unemployed could find work if they wanted to

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Lastly, the respondents emphasise the notion of individual effort. More than two-thirds (67%) believe that “with effort, anyone can succeed”. A significant majority of respondents on the left end (58%) of the political spectrum agree with this view, although even more do so on the right (71%). There are, however, significant differences between States: 74% of the British, 69% of the Germans, 68% of the French and 55% of the Italians believe that “the unemployed could find work if they really wanted to”.

Individual effort widely supported

Copyright :

Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2021.

Gaël Brustier, “La présidentielle 2022 marquera l’avènement de l’oligopole droitier”, slate.fr, 13 April 2021.

Raffaele Simone, Le Monstre doux. L’Occident vire-t-il à droite ?, Gallimard, 2010, p. 160.

As the data from our survey show, strong currents of rightward shifting are at work in France and, more generally, in Europe, particularly in Germany, Italy and the UK. In France, with one year to go until the presidential election, the electoral battle is taking place on the right. The question is whether this realignment to the right will work to the benefit of a governing right-wing party or the far-right.

This study also points to a failure on the part of the left. The fact that the left is in a slump or in difficulty almost everywhere in Europe is undoubtedly due to its failure to impose a collective vision for several years now.

As Gaël Brustier writes, the left sees “in the rightward shift (assuming it sees it at all) only the manifestation of guilty thoughts, when it is a more or less skilful interlinking of elements that offer an answer to the key issues in the present day. From this misperception arises an ardent passion for condemnation and finger-pointing, possibly causing even those in its ranks and, obviously, in its electorate to feel fed up24”. The left “has lost – to all appearances – the ability to shape the world25”.

No comments.