The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW)

Introduction*

Who is Sarah Wagenknecht?

The new party

The Aufstehen Association (“Get up”)

Manifest für den Frieden (“Manifest for Peace”)

The creation of the Sahra Wagenknecht BSW – Reason and Justice Alliance (2023) and its first members

From stalinism to national-bolshevism? Sarah Wagenknecht and her political doctrine

Opinion data

The unfinished business of German reunification

The political system

Factors favoring the emergence of Wagenknecht’s party

Strong electoral potential in the new Bundesländer

Putting things into perspective

Summary

On 23 October 2023, Sahra Wagenknecht launched the “Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – Reason and Justice” (BSW), an association which will lead to the creation of a new political party under the same name on 8 January 2024, ahead of the European elections on 8 and 9 June 2024.

Sahra Wagenknecht defends left-wing positions on the economy, but her right-wing authoritarian cultural preferences (rejection of immigration, Woke culture, etc.) place her in a unique and unoccupied space in German politics. She could rally voters from the left as well as the right around her project, including activists that are anti-Vax, pro-Putin, anti-immigration, anti-Woke and prone to authoritarianism.

Patrick Moreau,

Ph.D. researcher in history and Doctor of State in political science (FNSP), and CNRS researcher in the Austro-French Centre (AFC) for Rapprochement in Europe

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

The Netherlands: The Populist Temptation

Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

2022, French presidential election impacted by crises

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

What next for democracy?

Mural Der Weg der Roten Fahne (1968-1969), the Dresden Palace of Culture, Saxony, Germany

The mural Der Weg der roten Fahne (“The path of the red flag”) was painted between 1968 and 1969 by a group of artists from Dresden, in the eastern German state of Saxony, then the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The mural depicts the march towards socialism in the style of Soviet realism. The Foundation chose this work to illustrate the publication of our study on the birth of Sahra Wagenknecht’s movement because of its contemporary relevance to German politics. Indeed, it was in this Land of Saxony, in 2014, that the PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West) movement was born based on the theme of rejecting immigration and Islamization. It is also in this Land that the right-wing populist AfD party (Alternative for Germany), founded in 2013, has achieved very high scores and is now capable of unprecedented electoral success. On December 17, 2023, an independent candidate officially supported by the AfD was elected mayor of Pirna, a town of 40,000 inhabitants near Dresden. This victory was the first for the AfD in a town of this size. The election was won in the second round despite a call from all the country’s political and social forces to block the far right. The new party founded by Sahra Wagenknecht, the “Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance”, is clearly trying to find its place between a revisited, or even revived, communist past and a growing protest from the working classes, who are worried about the economic situation and migration policies, a form of protest that is now mainly benefiting the far right (AfD).

Introduction*

Translations from the German are by the author of this note.

Patrick Moreau, “At the margins of the political system: Die Linke and the AfD in the 2021 Bundestag elections”, Revue d’Allemagne et des pays de langue allemande, pp. 217-235.

On 26 September 2023, the announcement by Bundestag member Sahra Wagenknecht that she would set up an association under the name Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) – Für Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit e. V. (“Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht BSW – Reason and Justice”) with the aim of creating a new party on 8 January 2024, was a major political event. The Wagenknecht split, which has badly hit the left-wing party Die Linke (“The Left”), comes as no surprise. It follows its electoral collapse at the Bundestag elections on 26 September 2021 (4.9%) and its defeat at the regional elections in Hesse in 2023 (3.5%) and in Bavaria (1.5%) 1. This split could lead to Die Linke’s disappearance from the Bundestag at the next general election in 2025, a hypothesis reinforced by a legislative reform of the representative status of candidate parties 2. Wagenknecht’s party could then fill the gap with a new program and a new organization bringing together members from across the political spectrum.

Who is Sarah Wagenknecht?

Christian Schneider, “Die brotlosen Jahre der Sahra Wagenknecht”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 12, 2019 [online].

Sahra Wagenknecht, Vom Kopf auf die Füße? Zur Hegelkritik des jungen Marx oder das Problem einer dialektisch-materialistischen Wissenschaftsmethode, Pahl-Rugenstein-Verlag, 1997.

On the history of the WASG, see Jürgen P. Lang, “Eine neue Linke? – Die Fusionsbestrebungen von PDS und WASG”. Jahrbuch Extremismus & Demokratie 18, 2006, pp. 171-188; Nils Schnelle, Die WASG – Von der Gründung bis zur geplanten Fusion mit der Linkspartei, GRIN Verlag 2, München edition 2007 and Andreas M. Vollmer, Arbeit & soziale Gerechtigkeit – Die Wahlalternative (WASG): Entstehung, Geschichte und Bilanz, Nomos, 2013.

Hubertus Knabe, Honeckers Erben. Die Wahrheit über Die Linke, Propyläen Verlag, 2009.

Maria Fiedler and Timo Lehmann, “Mit einem so unehrenhaften Diebstahl zu beginnen, finde ich völlig daneben”, Der Spiegel, October 25, 2023 [online].

Jürgen P. Lang, op. cit.

Matthias Meisner, “Linke: Wagenknecht verzichtet für Parteivize auf Wortführerrolle”, Der Tagesspiegel, February 11, 2010 [online].

On the positions of Antikapitalistischen Linken, see antikapitalistische-linke.de, 2013 [online].

Die Zeit, “Linke-Mitglieder beantragen Parteiausschluss von Sahra Wagenknecht”, June 10, 2021 [online].

Timo Lehmann, “Sahra Wagenknecht bleibt in der Linken”, Der Spiegel, September 4, 2021 [online]. Die Linke’s Federal Arbitration Commission rejected an appeal against this decision in May 2022.

See “Erfurter Parteitag 2022 – Die 1. Tagung des 8. Parteitages fand von Freitag, dem 24. Juni bis Sonntag, dem 26. Juni 2022 in Erfurt statt”, die-linke.de [online].

“Nach Wagenknecht-Äußerungen: Linke verliert so viele Mitglieder wie nie zuvor”, Der Tagesspiegel, October 13, 2022 [online].

See Peter Ahrens, “Franz Beckenbauer ist tot”, Der Spiegel, January 8, 2024 [online]; Augsburger Allgemeine, “Linke-Parteivorstand: Wagenknecht soll politisches Mandat zurückgeben”, Augsburger Allgemeine, June 10, 2023 [online] and “Unserer Verantwortung gerecht werden: DIE LINKE als plurale sozialistische Partei erhalten!”, die-linke.de, [online].

Sahra Wagenknecht was born in Jena on July 16, 1969, to an Iranian father and a German mother. During her school years, she was a member of the Freie Deutsche Jugend – FDJ (“Free German Youth”). In an interview, she explains that “the standard pre-military training for pupils in the GDR was extremely demanding: [that] she could no longer eat, which the authorities interpreted as a political hunger strike”3, subsequently forbidding her to carry out her studies. A job as a secretary was imposed on her, and she resigned after three months4. Wagenknecht supported herself financially by giving private Russian lessons5.

During this period, she read philosophical literature, notably by Hegel, and then discovered Marx: “I was given the complete edition of Marx for my 18th birthday, and I studied it in detail. At the same time, I had read Hegel, Kant and Aristotle. Of course, also Luxembourg, Hilferding and Georg Lukács as well as Goethe. My worldview and values came first and foremost from theory 6.”

The end of the GDR was, according to her biographer Christian Schneider, “the moment in time when the politician Wagenknecht was born”. She experienced it as “a unique horror”, as she believed that GDR socialism could still be saved. In the early summer of 1989, she joined the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED) to, in her own words, reform socialism and oppose the opportunists7. She considers and describes the fall of the Wall and the peaceful revolution leading to the end of the GDR as a counter-revolution8.

After reunification, from summer 1990 onwards, she studied philosophy and modern German literature at Friedrich-Schiller University in Jena and Humboldt University in Berlin. She then enrolled at the Dutch University of Groningen to study philosophy. She worked on the young Karl Marx’s response to Hegel9. It was Marxism that led her to study political economy. She wrote her doctoral thesis in political economy on “The limits of choice. Savings decisions and basic needs in developed countries”.

Her political career with the PDS (“Party of Democratic Socialism”) and Die Linke, from 1991 to 2023, took her on a roller-coaster ride of triumphs and defeats. From 1991 to 2010, Wagenknecht was a member of the leadership of the Communist Platform (KPF), classified as extreme left-wing by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. This is a grouping of orthodox communist members and sympathizers within the Party. It remained a member even after the merger of WASG (Arbeit & soziale Gerechtigkeit – Die Wahlalternative / Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative)10 and the PDS on June 16, 2007. The Party’s reformist-dominated steering committee considered the “positive vision of the Stalinist model” publicly defended by Wagenknecht as KPF spokeswoman11 to be incompatible with the PDS program.

From 1991 onwards, Wagenknecht was a member of the PDS12 steering committee, but from the outset was regarded as a “disruptive factor” by the party leader at the time, Gregor Gysi. According to him, Wagenknecht stood out in the mid-1990s because “despite her youth, she didn’t look modern, but rather conservative”. He points out that “there was now this young woman who desperately wanted to go back to the old days (GDR)”13.

In fact, Wagenknecht opposed a union with the WASG, which was to merge with the Linkspartei-PDS to create Die Linke, a project spearheaded by Gregor Gysi and Oskar Lafontaine, former Minister-President of Saarland and SPD and future husband of Sahra Wagenknecht.

Oskar Lafontaine, the first chairman of Die Linke (together with Lothar Bisky), made no secret of the fact that he was closer to Wagenknecht’s ideological positions than to those of the PDS reformers, who were oriented towards pragmatism and the march to power in the East. “Lafontaine and Wagenknecht were against privatization, in favor of expropriation and political strikes, had strong reservations about participating in government and defended a strict working-class orientation. This led to a shift in the balance of power within Die Linke.” The “categorical antagonism” between “capitalism” and “socialism” was regaining importance 14.

Wagenknecht’s list of positions in the PDS, Linkspartei-PDS and then Die Linke is long. From 1991 to 1995 and from 2000 to 2007, she was a member of the PDS or Linkspartei-PDS steering committee. Between 1995 and 2000, Wagenknecht left the steering committee, because Gregor Gysi considered her so “unacceptable” that he threatened to resign15. In 1998, she was a direct PDS candidate in the Bundestag elections in Dortmund. In March 2006, she was one of the initiators of the AKL (Antikapitalistischen Linken, [“Anti-Capitalist Left”]), a joint grouping of WASG and Left Party members16.

From 2004 to 2009, she was a Member of the European Parliament, sitting on the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs and as a substitute member of the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy. She has been a member of the Bundestag since 2009. Wagenknecht was elected party vice-president at Die Linke’s federal congress in May 2010 with 75% of the vote17, a position she held until May 2014. From 2007 to 2010, she was a member of Die Linke’s Program Commission, a sign of her influence. The draft program presented by this commission in March 2010 bears her signature. From November 2011 to October 2015, she was also the first vice-chairwoman of Die Linke’s parliamentary group. In 2019, Wagenknecht announced that she was stepping down from the movement’s governing bodies due to a burnout, and stepped down as chairwoman of the parliamentary group.

In June 2021, activists called for her expulsion for having caused “serious damage” to Die Linke with her book Die Selbstgerechten (“Well-meaning people”)18. This request was ultimately rejected19. Following the federal party congress in Erfurt in June 2022, the Wagenknecht movement is very weakened20. Janine Wissler and Martin Schirdewan, elected party leaders, Katina Schubert, Jana Seppelt, Ates Gürpinar and Lorenz Gösta Beutin, the new party vice-presidents, Harald Wolf, the federal treasurer, and Tobias Bank, the federal secretary, were all critical of Wagenknecht. Wagenknecht knows that a split with Die Linke is inevitable, and that the creation of a new party is a conceivable option21.

The acceleration of the crisis following the congress was due to the Ukrainian question and Wagenknecht’s unconditional support for Russia. Die Linke split, losing members22. Pro- and anti-Wagenknecht clashed at all levels of the Party’s administration and in the press. The resignation from the Party in March 2022 of Oskar Lafontaine, her husband since December 22, 2014, reinforced the hostility of the new Die Linke leadership, which saw the powerful Saarland federation collapsing like a pack of cards.

On June 10, 2023, Die Linke’s steering committee asked Wagenknecht to resign her Bundestag seat with immediate effect, on the grounds of anti- party activities23. This request is non-binding, since, in accordance with Article 38, paragraph 1, subparagraph 2 of the Basic Law, the mandate of a member of parliament belongs to him. On 9 October 2023, fifty party members filed a new request for Sahra Wagenknecht’s exclusion with the North Rhine-Westphalia Arbitration Commission, on the grounds that she wanted to set up her own party24. On October 23, 2023, she announced her departure from the Party and presented the association BSW – Für Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit to the press.

In conclusion, Sahra Wagenknecht is described as a remarkable figure in German politics. Her strength and style are backed up by well-documented analyses and brilliant rhetoric. Despite this, she has not managed to develop a strong political concept, or at least not yet. Her critique of capitalism carries weight, but it remains an analysis with no lasting organisational impact to date.

The new party

The Aufstehen Association (“Get up”)

See Albrecht von Lucke, “Bündeln oder spalten: Sammlungsbewegung statt Rot-Rot-Grün?” Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, Nr. 9/2018. p. 5-8 and Rainer Balcerowiak, Aufstehen und wohin gehts? Das Neue Berlin, 2018.

Constanze von Bullion, “Sozialismus, national gefärbt”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, January 16, 2018 [online].

See Michael Sauga, “Von Lafontaine lernen, heißt scheitern lernen”, Der Spiegel, May 15, 2022 [online]; Marcel Leubecher, “Mit Lafontaines Vision kann Gysi nichts anfangen”, Die Welt, January 14, 2018 [online] and Steffen Vogel, “Linke Sammlungsbewegung: Falsches Vorbild Mélenchon”, Blätter, March 2018 [online].

Gründungsaufruf. Aufstehen, die Sammlungsbewegung, September 4, 2018 (private archive).

“Wagenknecht will mit ”Aufstehen“ linke Kräfte bündeln”, Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger, September 4, 2018 [online].

Among the many examples: musical cabaret artist Florian Kirner, author Ingo Schulze, academic Wolfgang Streeck, historian Peter Brand, Die Linke economist Dieter Klein…

See “”Bunte Westen” wollen bundesweit mobil machen”, Die Zeit, February 16, 2019 [online] and Die Tageszeitung, “Rund 2.000 Menschen demonstrieren”, Die Tageszeitung, February 16, 2019 [online].

The Aufstehen Trägerverein Sammlungsbewegung e. V. (“Get up”) association, although unsuccessful, was the first step towards founding the Wagenknecht party.

In the aftermath of the 2017 Bundestag elections, Sahra Wagenknecht called for the creation of a left-wing rallying movement – but transpartisan25. The Aufstehen association, registered on 30 August 2018, was headquartered in Berlin. Playwright and cultural sociologist Bernd Stegemann was its director. Officially, Sahra Wagenknecht was not a member of the association. The aim of the movement was not to found an independent party, but to give the German Left represented in the Bundestag (Die Linke, the SPD and Bündnis 90/Die Grünen) a parliamentary majority and win back voters from Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)26.

In her search for an organisational model, Sahra Wagenknecht was inspired by the grassroots campaign “The People for Bernie Sanders” in support of the Democratic senator and 2016 US presidential candidate, as well as the “Momentum” campaign led by British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. The Wagenknecht-Lafontaine couple, who have always had close ties with Jean-Luc Mélenchon (which continue to this day)27, found a political and organisational reference model in La France insoumise movement created in France for the 2017 presidential elections.

Aufstehen made a programmatic offer that is only partially reflected in the party’s founding manifesto of 2023. Peace was the primary objective and Europe would have to become more independent of the United States. The state had to regulate the economy, be welfare-oriented, create jobs, ensure fair wages and innovate economically. The economy had to respect the environment. Privatisation had to be stopped and reversed. To save endangered democracy, lobbying and the influence of companies and banks should be limited, direct democracy should be strengthened, and donations from business to political parties should be banned. Public safety had to be restored by mass recruitment and better-equipped police forces. Security measures were also to be backed up by increased resources for the justice system and the extension of social work. Europe was to be reformed as a union of sovereign democracies. The right of asylum was to be guaranteed for persecuted people, and help was to be provided for refugees from war or climate-related causes. Arms exports to zones of tension were to be banned. The fight against poverty was imperative, but with priority given to those living in the countries of origin. Finally, a new world economic order was needed to raise living standards for all, in harmony with resources28.

Within a month, over 100,000 people had registered on the website 29. By the end of 2018, the association had 167,000 supporters, 80% of whom claimed not to belong to any party. Around 11,000 were said to be Die Linke members, over 5,000 SPD members and around 1,000 from the Greens. The list of those supporting the association was extensive, and also revealed the dissatisfaction of part of the left with the political situation30.

In her search for greater visibility, Sahra Wagenknecht discovered the French Gilets jaunes. In February 2019, Aufstehen called for a nationwide “Bunte Westen” (“Color Vests”) action. It was unsuccessful, with only 2,000 demonstrators across Germany31. At the beginning of March 2019, Sahra Wagenknecht announced her withdrawal from the Aufstehen leadership due to a burnout following health problems32. However, this is probably not unrelated to the fact that the movement failed to create a unitary dynamic, leaving the left more divided than ever and Sahra Wagenknecht largely isolated. This abandonment left it’s mark: Sahra Wagenknecht lost many of her key supporters, who had criticized her for being unprepared33. Although Aufstehen still exists, the organization is independent of BSW, but not hostile to it.

Manifest für den Frieden (“Manifest for Peace”)

Alexander Wallasch, “Friedensbewegt: Laut INSA steht die Mehrheit der Deutschen hinter dem Manifest von Wagenknecht und Schwarzer”, February 13, 2023 [online].

See Thomas Vorreyer, “Sie haben Angst vor uns”, Tagesschau, February 25, 2023 [online] and Berliner Zeitung, “’Aufstand für Frieden’: Fast 50.000 Menschen bei Schwarzer und Wagenknecht”, February 25, 2023 [online].

Among them were anti-vax executives such as Dresden-based publicist and Querdenken publisher Marcus Fuchs, physician Paul Brandenburg, pro-Putin propagandist Wjatscheslaw Seewald, Holocaust denier Nikolai Nerling, AfD politician Karsten Hilse, Saxony federation chairman Jörg Urban, Hans-Thomas Tillschneider from Saxony-Anhalt, elected representatives Gunnar Lindemann, Lars Hünich and Lars Günther ; and Compact magazine editor Jürgen Elsässer.

Manifest für den Frieden34 is an online petition launched on February 10, 2023 by Sahra Wagenknecht and feminist publicist Alice Schwarzer in her magazine Emma. The exact number of signatures is not known, but the figure of 899,998 is put forward35.

The pathos of the manifesto cleverly conceals what Sahra Wagenknecht had in mind: “Today is the 352nd day of war in Ukraine. More than 200,000 soldiers and 50,000 civilians have been killed so far […] an entire population has been traumatized. If the fighting continues this way, Ukraine will soon be a depopulated and destroyed country. Also, many people throughout Europe fear an extension of the war. They fear for their future and that of their children.” After this statement of solidarity with Ukraine, the tone changes: “And what is the aim of this war today, one year on?”. The answer is “a war against Russia”, a phrase coined by German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock36. President Zelensky is accused – due to the fact he is demanding weapons – of wanting to defeat Russia: “It is to be feared that Putin will launch a full-scale counter-attack at the latest when Crimea is attacked. Are we then inexorably heading down a slippery slope towards world war and nuclear war? It wouldn’t be the first major war to start like this. But it might be the last.”

Negotiations are the only way to avoid the worst: “Negotiating does not mean capitulating. Negotiating means making compromises, on both sides. That’s what half the German population believes too. This text shows de facto support for Russian aggression, the occupation of Crimea and the annexation of a large part of Ukraine. This did not prevent many intellectuals, theologians, artists and publicists from supporting the appeal.

The INSA polling institute, which carried out a survey on the reception of the manifesto, showed that 39% of those questioned answered that they “agreed” or “somewhat agreed” with the text, while the same proportion (38%) rejected the approach. More women (45%) than men (34%) approved of the text. The manifesto is more widely approved in the former East Germany (48%) than in the West (37%). Supporters of Die Linke and the AfD were more likely to have a favourable opinion of the manifesto (67%)37.

A call for a rally entitled “Aufstand für Frieden” (“Uprising for Peace”) was included with the manifesto. It was held on 25 February 2023 at the Brandenburg Gate38, and brought together 50,000 people according to the organisers – 13,000 according to the police39. While the vast majority of participants came from the German left and the pacifist movement, AfD leaders and activists, neo-Nazis and leading figures from the Querdenker movement (against measures to protect against the Covid-19 pandemic) were among the demonstrators40.

This manifesto is one of the pillars of Sahra Wagenknecht’s current partisan project, which involves exploiting the pacifism of Germans to attract new members to her party.

The creation of the Sahra Wagenknecht BSW – Reason and Justice Alliance (2023) and its first members

The association Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – BSW (“Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance – Reason and Justice”), founded and registered on 26 September 2023, is based in Karlsruhe. It is listed in the register of associations at the Mannheim District Court and is used as a functional tool designed to pave the way for the creation of the party “BSW – Reason and Justice”. The association is not intended to recruit members. It has a very active fundraising website (buendnis-sahra-wagenknecht.de/). The organizational core is made up of Aufstehen’s founders, who draw from the 2018 list of supporters and Die Linke’s membership database.

The association was presented at a press conference on 23 October 2023 by its president Amira Mohamed Ali, Bundestag members Sahra Wagenknecht (board member) and Christian Leye (vice-president), Lukas Schön (executive director) and IT entrepreneur and investor Ralph Suikat (treasurer). The latter – a millionaire – is portrayed in the press as Sahra Wagenknecht’s financier. Around this organizational core can be found a dozen current and former members of parliament. The “BSW – Reason and Justice” party was founded on 8 January 2024 in Berlin. The party is chaired by Sahra Wagenknecht and Amira Mohammed Ali, who, until recently, was chairwoman of Die Linke’s parliamentary group in the Bundestag. Amira Mohammed Ali, the first Muslim woman to chair a parliamentary group in the Bundestag, adopted Sahra Wagenknecht’s line on immigration after having been in favour of open borders and opposed to the expulsion of undocumented migrants. The association’s treasurer Ralph Suikat was also appointed party treasurer. The first step for the Party will be their entry in to the European Parliament. Thomas Geisel, former SPD mayor of Düsseldorf, and Fabio De Masi, former Die Linke member, are being considered as potential heads of the BSW party list for the European elections41.

The Association settled it’s scored in a statement entitled “Why we’re leaving Die Linke”42, proclaiming: “The conflicts of recent years have been focused on the political trajectory of the left. We have always argued that the wrong priorities and the lack of focus on social justice and peace were diluting the Party’s image. We have repeatedly pointed out that the focus on urban, young and activist communities is driving away our traditional voters. We have repeatedly tried to halt the decline of the Party by changing its political orientation. We haven’t been able to do that – and in the end, the party has become less and less popular with voters. The splittists no longer see a place for their views in the Party. They say they are motivated by the government’s inability to deal with the crises of our time and the “accepted narrowing of the corridor of opinion”, which has led to the rise of the AfD.

The issue of the party’s funding is at the heart of the media spotlight. The technique used consists of multiple donations of less than €1,000, which means that they do not need to be declared.

From a financial point of view, the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance seems to benefit from a Moscow practice that had benefited the German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei – DKP) until 1989, and still benefits a myriad of cultural or economic structures supporting Russia today. As of 10 December 2023, the association had received 1.1 million donations, mostly small amounts. Some donations, which are legally permitted under the law on associations, come from abroad, from European and non-European countries. The association has invested its donations at an interest rate of 1.75% in accounts held by Volksbank Pirna, which is known to be close to Die Linke. For many years, the chairman of the board, Hauke Haensel, has been organising “recognition trips” to Russia for the association’s members. Haensel recently accused the Federal Government of “culpable stupidity” for its involvement in Ukraine. According to information from the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales [BMAS]), the Marxist-Leninist Party of Germany (MLPD) also has an account at the Volksbank Pirna, as does the Russian state news agency Ruptly, which belongs to the Ria Novosti television network. According to the Bild newspaper, Wagenknecht’s treasurer, Ralph Suikat, is now in close contact with Haensel. This financial arrangement, by shifting from the founding of an association to that of a party, could prove dangerous for Wagenknecht, as the legislation on associations and political parties is different.

Die Linke’s party conference on 18-19 November 2023, held with the aim of appointing candidates for the European elections of June 2024, saw the nomination of Carola Rackete, a well-known refugee sea rescue activist who is not a member of Die Linke. This nomination demonstrates the party’s choice to continue its support for immigration and counter Wagenknecht’s anti-migration campaign.

From stalinism to national-bolshevism? Sarah Wagenknecht and her political doctrine

See “Marxismus und Opportunismus – Kämpfe in der Sozialistischen Bewegung gestern und heute”, [online].

See “Zur Diskussion: Prioritäten. Nachbetrachtungen zur Liebknecht-Luxemburg-Ehrung 2008 der Kommunistischen Plattform”, [online].

Andreas Bachmann, “Schweinereien machen wir nicht mit”, Der Standard, January 11, 2010 [online].

Anja Maier and Stefan Reinecke, “Ich war ein Kind, das gern allein war”, Die Tageszeitung, April 30, 2010 [online].

Die Berliner Zeitung, “Partei distanziert sich von SED-Unrecht: “Es gibt keine Rechtfertigung für die Toten an der Mauer” / Wagenknecht stimmt gegen Beschluss: PDS bedauert den Mauerbau, lehnt aber Entschuldigung ab”, July 3, 2001 [online].

Peter R. Neumann, “Rechts oder links?: Sahra Wagenknecht, die Nationalbolschewistin”, Der Tagesspiegel, September 11, 2023 [online].

Wagenknecht is, for example, hostile to proposals for European unemployment insurance, as they would offer a lower level of coverage than many states, including Germany.

See Finn Mayer-Kuckuk, “Das denkt Sahra Wagenknecht über China”, Table Media, October 24, 2023 [online]

and Uli Hauck, “Wie sich Wagenknecht präsentiert”, Tagesschau, October 23, 2023 [online].

Moritz Serif, “Wagenknecht stellt These auf: ‘Wärmepumpen klimapolitisch völliger Nonsens’”, Frankfurter Rundschau, March 26, 2023 [online].

“Wagenknecht plädiert für Verteidigungsbündnis mit Russland”, Die Zeit, January 17, 2017 [online].

Luisa Hofmeier, “Wagenknecht gesteht Irrtum ein – In Einschätzung von Putins Person leider geirrt”, Die Welt, February 25, 2022 [online].

Christine Dankbar, “Wagenknecht fordert Bedingungen für Ukraine: Geld nur bei Friedensverhandlungen?, Frankfurter Rundschau, September 25, 2023 [online].

Ibid.

See Sahra Wagenknecht’s statements on Palestine on TikTok [online].

Tagesspiegel, “’Gaza ist ein Freiluftgefängnis’: Wagenknecht gegen Bodenoffensive Israels”, October 23, 2023.

Sabine Kinkartz, “Deutschlandtrend: Antisemitismus breitet sich aus”, Deutsche Welle, November 2, 2023 [online].

Ruhrbarone, “Sahra Wagenknecht: ‘Antisemitismus wird bei uns nicht geduldet’”, June 19, 2021 [online].

Sahra Wagenknecht, Identitätspolitik und Cancel Culture – Wie selbstgerecht sind die Linken?, 2021 [online]

See N-TV, “Wagenknecht beklagt angeblichen Bürgergeld-Missbrauch durch Ukrainer”, November 10, 2023 [online] and Hase Post, “Sahra Wagenknecht berichtet von Sozialtourismus ukrainischer Flüchtlinge”, November 10, 2023 [online].

Marcel Leubecher, “Merkel verantwortet schlimmsten Rechtsruck nach 1945,” Welt, March 22, 2016 [online].

Dirk Muller, “So wird das Klima vergiftet und Ressentiments geschürt”, Deutschlandfunk, October 15, 2015 [online].

Ibid.

Rainer Woratschka, “Linke und Flüchtlinge: Ärger um Sahra Wagenknecht”, Tagesspiegel, January 14, 2016 [online].

Ipsos, “Nicht einmal jede:r dritte Deutsche plant diesen Winter eine Corona-Impfung”, October 16, 2023 [online].

The party’s founding manifesto seeks to dissociate Sahra Wagenknecht from her communist aura and to make people forget her past as spokesperson for the Communist Platform. However, it is important to recall her political position in the 90s. As several texts from that period show43, Wagenknecht was a thurifer of Stalin, “the man who modernised Russia and turned it into a leading power”. While the human costs are undeniable, these were marginal errors in a process that was positive overall. For these reasons, in 2008, Wagenknecht spoke out against the construction of a stele in the Friedrichsfelde central cemetery bearing the inscription “To the victims of Stalinism”44. In 2009, she adjusted her position slightly, explaining that historiography on both the right and the left had falsified the image of Stalin and that it needed to be clarified in order to make a real assessment45. This new approach subsequently resulted in a distancing from the 1992 theses: her former statements on the GDR have been relativised. Today, Wagenknecht is moving away from an apology of dictatorship towards reformist positions: “Socialism did not fail with the GDR, because it was not socialism. The GDR […] made democracy disappear”46. However, she refuses to characterize the GDR as a lawless state47. This position was confirmed in 2002, when she was the only member of Die Linke’s steering committee to vote against condemning the construction of the Berlin Wall 48.

Sahra Wagenknecht’s many publications reveal how her profile has evolved. Initially a naive Stalinist, she now strives to appear as a theoretician, in favour of a socialist economy based on vast redistribution programmes. On the other hand, her rejection of immigration and the Woke movement, her hostility to the European Union, her emphasis on national reference points and her pro-Russian orientation raise questions about the possibility of an authoritarian and populist direction. This is a complex transformation, the final phase of which needs to be analysed from 2021 to 2023, when the future programme of the Wagenknecht party was being drawn up.

For historians of the Weimar period, the Wagenknecht programme is reminiscent of National-Bolshevism in Germany in the 1930s, a thesis defended by the political scientist Peter R. Neumann49. The comparison is tempting: the fascination with Russia, the desire to break away from the capitalist system, the “anti-imperialist” nationalism, the redistribution of wealth and economic interventionist socialism, an ideological straddle between the nationalist right and communism… These are all common characteristics. However, we must remain cautious: Putin’s Russia is not Lenin’s or Stalin’s, the current economic crisis is not comparable to that of the Weimar Republic in the 1930s, the AfD is not the NSDAP and “orthodox” communism in Europe is in its death throes. The Wagenknecht project is a variant of post-communism, whose originality lies in the mixture of radical socialist theses and socio-cultural conservatism.

The opening lines of the text accompanying the creation of the association reflect an observation shared by a majority of Germans: “Our country is not in very good shape”: work is no longer considered a value, the political elites have emptied the public purse, and freedom and diversity of opinion have declined under the pressure of an authoritarian political culture. Many people have lost confidence in the state and no longer feel represented by any of the existing parties. “The Alliance Wagenknecht association was set up to prepare a new party that would give these people a voice once again”. The association advocates the recognition of common values and cultural traditions described as fundamental for social cohesion and the acceptance of a strong social state based on “economic reason”, one of the key words of the future programme. Wagenknecht draws on what makes people cringe: “no trains leave on time, you have to wait months to get an appointment with a specialist, there is a shortage of teachers and nursery places, and a shortage of housing”.

What are the causes of this situation? According to Wagenknecht, it is the transition from an industrial society to a service society due to the neo- liberal reforms of the 1970s and globalisation, which has led to a social regression towards lower-paid, basic service jobs. At the same time, the advent of a “knowledge societies” is benefiting graduates. They are not experiencing economic difficulties, and have lost touch with other social strata. Society is divided. Since then, the “market economy” has ceased to function, with financial groups imposing their laws and destroying democracy. Current inflation, which is a dominant theme in Germany, given the rising cost of consumer goods, is seen as a consequence of this uncontrolled capitalism”.

The aim is a fundamental correction of economic rules: the power of the market must be limited and the groups that dominate it broken. All of this must be done in a spirit of industrial nationalism: “German industry is the backbone of our prosperity and must be preserved. Once again, we need more forward-looking technologies made in Germany, more hidden champions, not less.” It should be pointed out that she does not mention a possible European path, a topic she has always been sceptical about, even going so far as to call for an exit from the euro50. Europe is seen as vulnerable to lobbying, undemocratic in terms of decision-making logic and economically unfair to the lower middle classes51. A broad investment policy and an international strategy are therefore required: “Germany needs a foreign economic policy that focuses on stable trade relations with as many partners as possible, rather than on the formation of new blocs and excessive sanctions, and that guarantees our supply of raw materials and cheap energy”. In other words, Russia and China52.

The ecological question came second, reflecting the decline in the polls of the importance of this issue. Sahra Wagenknecht attacked the Greens’ policy, arguing that “Germany’s energy supply cannot currently be ensured by renewable energies alone”. Although she does not mention nuclear power plants, she clearly supports this technology53.

Among the new party’s other programmatic priorities, social justice will be a central theme. Sahra Wagenknecht presents herself as the defender of low-income groups and advocates social measures to protect the most disadvantaged. In her view, politics should be reoriented “towards the common good”. The State would be responsible for implementing a fair wage policy, with a high level of social security. State interventionism will certainly be restrictive, but it will be the price to pay for achieving these objectives.

Internationally, the alliance is “in the tradition of German Chancellor Willy Brandt and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, who opposed Cold War thinking and action with a policy of détente, balance of interests and international cooperation”. Her main enemies are the United States, NATO and Biden. Wagenknecht dreams of a defensive alliance, a new security structure which, in the long term, should also include Russia54. While Wagenknecht’s pro-Russian stance is visible in the founding text of the alliance, nothing is said about the war in Ukraine. The question is whether Sahra Wagenknecht is an agent of Russian influence (Putin’s enthusiasm for her project is well known) or whether there is a well- founded political reasoning behind her pro-Russian position.

The answer is complex. On the one hand, Sahra Wagenknecht condemned the Russian aggression on 24 February 202255. On the other, she stated that the policy pursued by the United States in recent years was partly responsible for the crisis and defended the idea that Europe and Russia should maintain good relations in the interests of all, and that the security guarantees sought by Russia should be understood and accepted. On 8 September 2022, Wagenknecht indicted the German government and called for an end to sanctions against Russia, declaring: “Punishing Putin by plunging millions of families into poverty and destroying our industry while Gazprom makes record profits – yes, that’s stupid”56. In September 2023, she opposed European aid to Ukraine and demanded that the German contribution be made conditional on peace negotiations57.

On the Palestinian question, the differences of opinion already found in Die Linke are likely to be mirrored in Wagenknecht’s party. Sahra Wagenknecht has taken a cautious stance on the subject58: firstly, she believes that Israel has the right to defend itself against attacks by the terrorist militia Hamas; secondly, she is in favor of a two-state solution59; she adds that she considers “Gaza to have been an open-air prison for many years”; finally, faced with Israel’s military response, she says she hopes for a non-military solution. Sahra Wagenknecht had already been criticized for not standing up and applauding when Israeli President Shimon Peres visited the Bundestag in 2010. Indeed, during Shimon Peres’ speech on the Holocaust, Sahra Wagenknecht was one of three Die Linke MPs, along with Christine Buchholz and Sevim Dağdelen, who did not rise from their seats to applaud, prompting the press and Die Linke experts to point out the party’s anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. She would later try to justify her attitude: “I remained seated […] because Peres used this speech not only to commemorate, but also to talk about current Middle East affairs, and certain parts of this speech could be interpreted as preparations for war against Iran”60. Faced with a sharp rise in anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism in Germany in 202361, Wagenknecht took a stand in favor of protecting the Jewish community in Germany and rejecting all anti-Semitism62.

The Alliance’s text sets out its enemies: far-right, racist and violent ideologies, but also cancel culture, the pressure of conformity and the decline of freedom of opinion. The intensity of Wagenknecht’s attack on cancel culture needs to be further examined: she draws a distinction between, on the one hand, the traditional left she admires – as embodied by Jean-Luc Mélenchon – with its focus on the working class, workers in basic service professions, the unemployed, low wages and class politics, and, on the other, the “lifestyle left”, omnipresent in the media, universities and big cities, more present among young graduates and the middle and upper classes. Wagenknecht criticizes this left for ignoring the reality of life for “those down below”, for being profoundly intolerant and silencing any divergent opinions. Finally, Wagenknecht criticizes the multiculturalist vision, in which minorities, on the basis of their gender, origin or religion, refuse to recognize the superiority of common rules, threatening social cohesion63.

The text concludes on immigration: “Immigration and the coexistence of different cultures can be enriching […]. But this is only true if immigration remains limited to an order of magnitude that does not exceed the capacities of our country and its infrastructure, and if integration is actively encouraged and successful”. If non-European immigration is for Wagenknecht a major factor in social and cultural tensions, Ukrainian refugees are not treated any better, accused of social tourism and public welfare fraud64. The topic of migration in the Wagenknecht project was one of the most commented on by the press in 2023. However, this is nothing new: back in 2015, Wagenknecht opposed the proposal by Die Linke members to open up borders. Her argument was economic: this measure would only benefit industrialised countries that engage in wage dumping and play on competition between national and immigrant workers. Countries with high levels of emigration were considered to suffer considerable damage, because part of the well-educated local elite would emigrate65. Finally, an uncontrolled migration policy such as Angela Merkel’s favors the far right66, pits the poor against the poorest67 and creates security risks68. After the sexual assaults in Cologne in early 2016, Wagenknecht declared, much to the chagrin of Die Linke: “He who abuses his right to welcome loses the right to be welcomed”69, legitimizing forced returns.

Abgeordneten Watch, “Impfpflicht für bestimmte Berufsgruppen und weitere Änderungen im Infektionsschutzgesetz”, December 10, 2021 [online].

Patrick Moreau, “The Querdenker movement in Germany. Un nouveau mouvement social”, in Dominique Andolfatto, Citoyens dans la crise sanitaire, p. 165-177, Classiques Garnier, 2023.

However, the Alliance’s founding manifesto did not address two issues: Covid-19 and vaccination70. Sahra Wagenknecht has often been presented as a radical anti-vaxer71. In fact, she presents vaccination as an individual decision and asserts that at-risk groups must be vaccinated, even if the efficacy of vaccines remains to be proven. The government’s call in 2022 for mass vaccination to avert a hospital crisis led Wagenknecht to argue that an effective policy would first and foremost require reform of the German healthcare system, which has long been in crisis72. She therefore opposed a general obligation to vaccinate, and voted against a bill to make vaccination compulsory in the medical field73. The fact that she caught the virus did not change her position. In terms of electoral gain, her anti-vax stance will enable her to marginally reach the radical fringe of the movement74.

Opinion data

The Wagenknecht split is still too recent to allow us to accurately assess the prospects of this new party. To date, the polls available do not give any indication of possible electoral shifts. We therefore need to take a brief look at the German political system in order to identify the factors that are either paving the way for this new player or thwarting its rise.

The unfinished business of German reunification

German reunification is incomplete, and is often perceived as a failure, particularly in the new Bundesländer and in the eastern part of Berlin. In 2023, there are two profoundly different political systems in the former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). In the East, the national-populist AfD – Alternative für Deutschland (“Alternative for Germany”) party is the leading political force; Die Linke is weakened; and the struggling Greens and Liberals of the FDP risk failing to pass the 5% threshold.

In the West, the situation is very different. Admittedly, the AfD has made progress in recent months, but remains much weaker than in the East. Die Linke is declining, while the Greens are attracting most of their voters in the old Bundesländer.

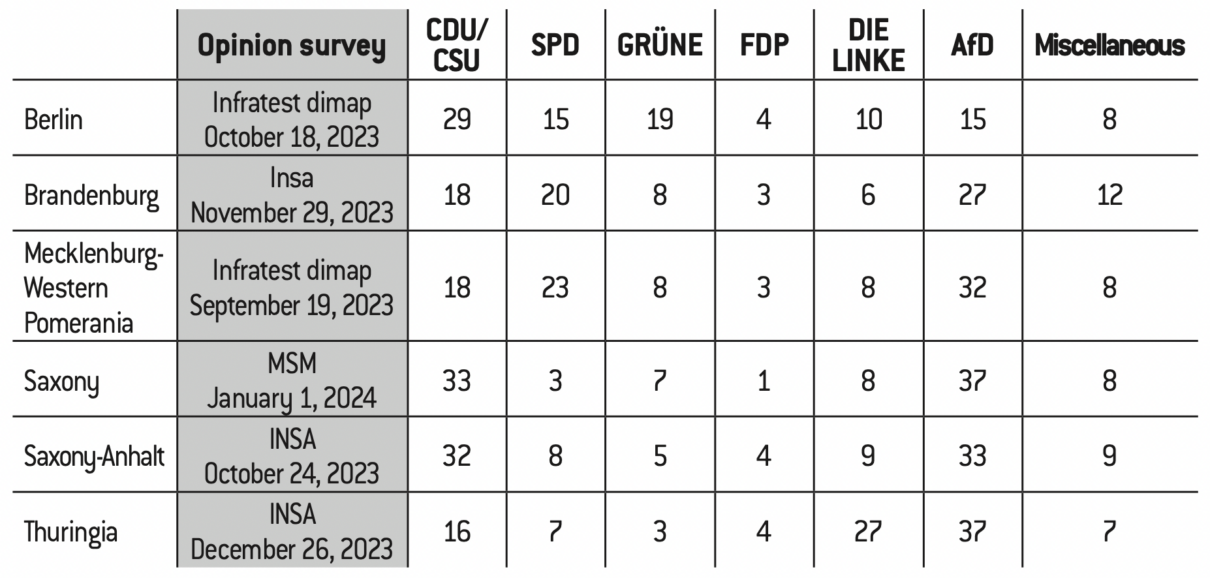

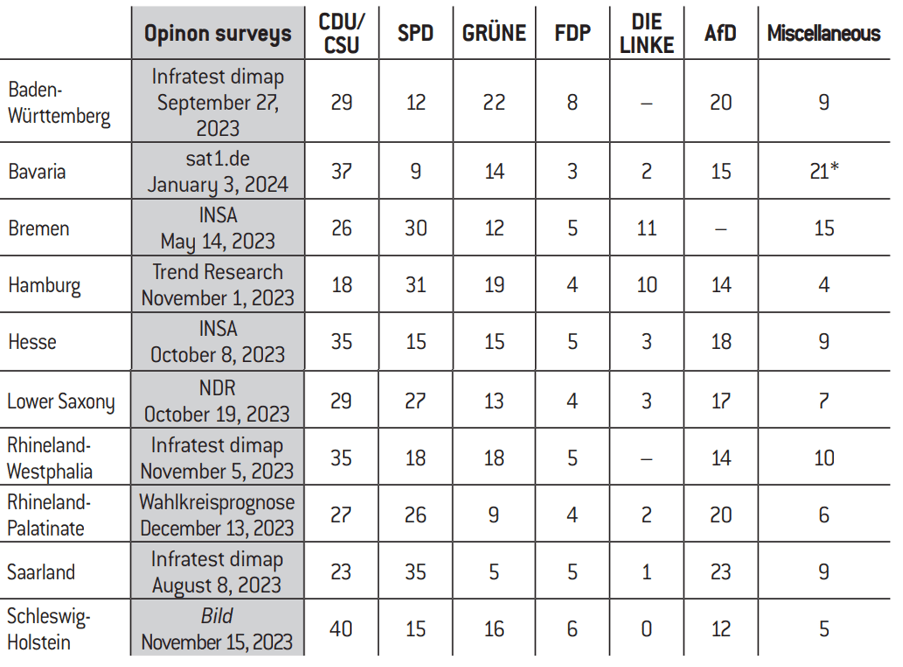

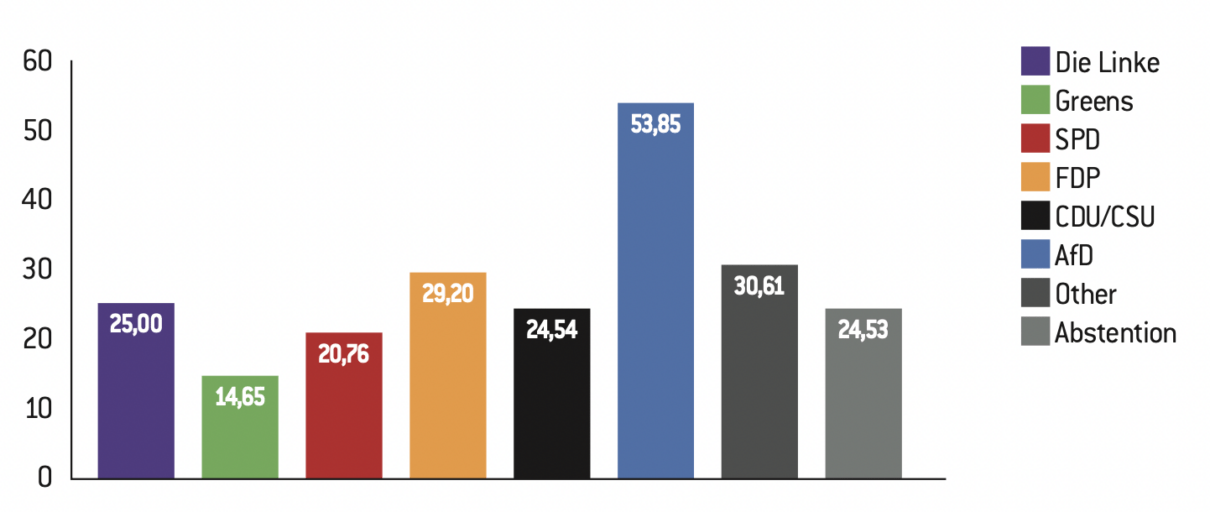

Voting intentions in the eastern Länder (in %)

Source :

Note: The next elections for these Länder will be held in September 2024 for Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, in summer 2026 for Saxony-Anhalt, and in autumn 2026 for Berlin and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

Voting intentions in the western Länder (in %)

Source :

Note: The next elections for these Länder will be held in winter 2025 for Hamburg, spring 2026 for Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, spring 2027 for Bremen, Rhineland-Westphalia, Saarland and Schleswig-Holstein, autumn 2027 for Lower Saxony, and autumn 2028 for Hesse and Bavaria.

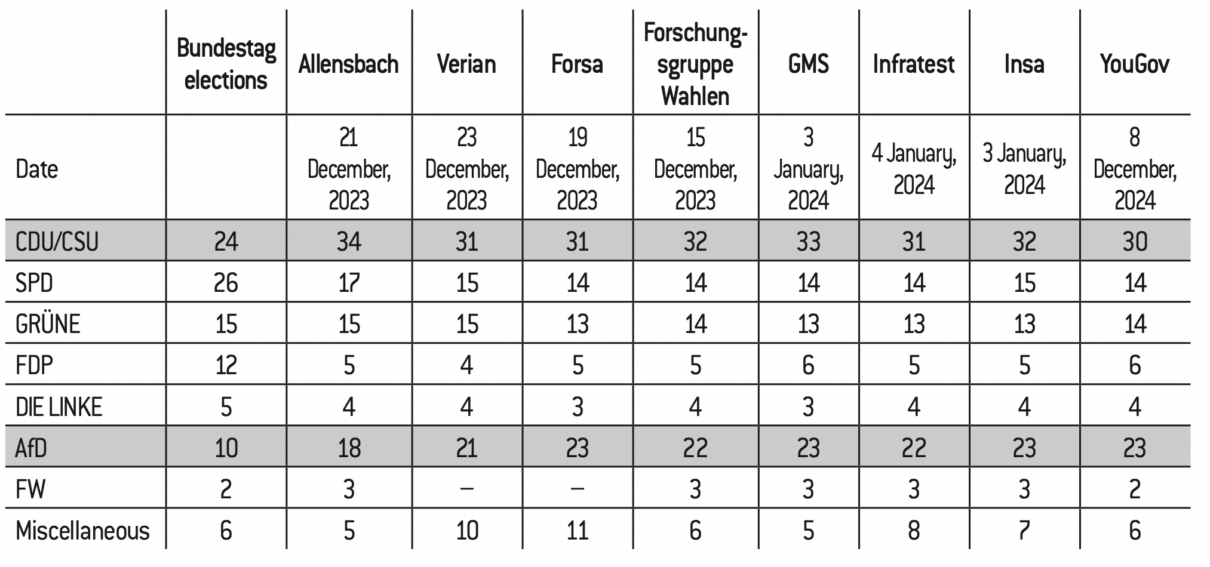

* The “Miscellaneous” category includes several parties, including Freie Wähler, a member of the Bavarian government coalition.

At national level, polls show that the Traffic light coalition (“Ampelkoalition”, linking the Social Democratic Party, the Liberal Democratic Party and the Greens) has lost its majority, that the FDP and Die Linke are in danger of failing to pass the 5% representativeness mark, and finally that the AfD has become the country’s second political force. What’s curious is that, despite the fact that Germans no longer want the Traffic light coalition, the CDU/CSU is making only marginal progress in the polls, and only the AfD seems to be benefiting from the current crisis.

National opinion surveys (in %)

If opinion polls remain at this stable level long term – despite the fact that we are still a considerable way from the next general election in 2025 – the future formation of a government will inevitably be very complex, both at national level and in the Bundesländer. In the East, four-party regional coalitions may become necessary to prevent the appointment of AfD minister-presidents. At national level, several options are possible: a grand CDU/CSU-SPD coalition; a CDU/CSU-Green alliance; a CDU/ CSU-Green-FDP alliance… All variants potentially just as unstable as the current coalition.

From these overall factors, we can draw an initial series of conclusions: a Wagenknecht party at 10% or more would upset the coalition mechanisms in the new Bundesländer and multiply the options at national level. This is certainly a difficult goal to achieve, but not an unrealistic one. There are a number of variables that could potentially pave the way for this new party.

The political system

Forsa market and opinion research institute on behalf of RTL Deutschland.

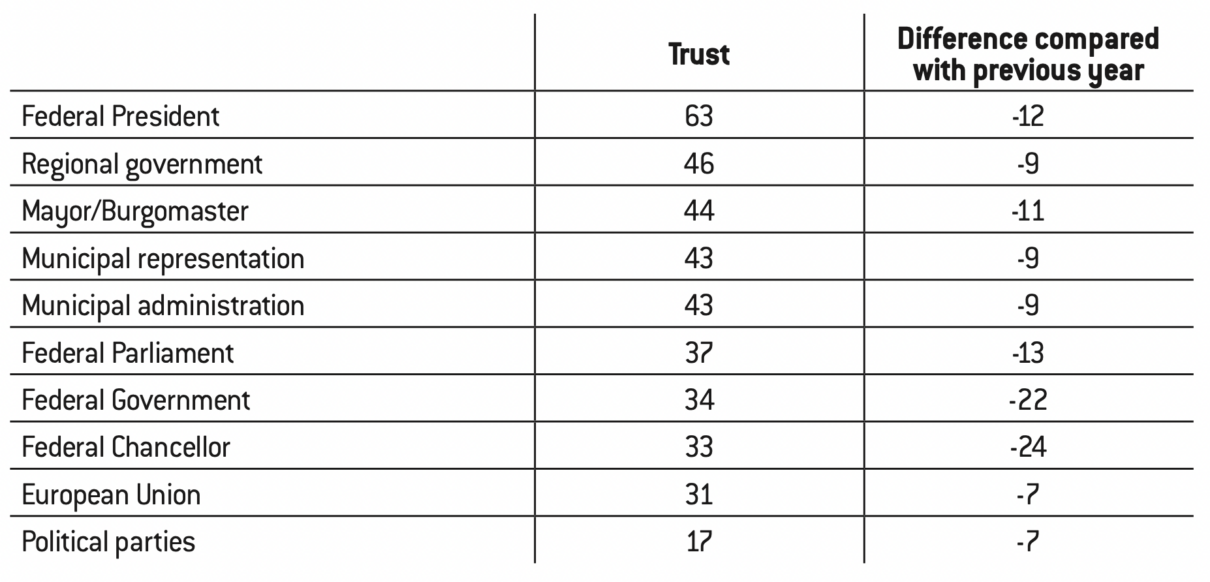

As highlighted by an RTL/NTV poll in 202275, the entire political system is widely distrusted.

Trust in political institutions at the start of 2023 (in %)

Politik & Kommunikation, “Welchen Institutionen die Deutschen vertrauen”, January 9, 2020 [online].

See Nadja Austel, “Umfrage-Klatsche für Merz: Mehrheit der CDU-Anhänger unzufrieden”, Merkur, June 18, 2023 [online] and Die Zeit, “Mehrheit der Unionswähler hält Merz nicht als Kanzler geeignet”, September 30, 2023 [online].

The RTL/NTV 2022-2023 barometer reveals clear differences between the new and old Länder. With the exception of institutions at local level, East Germans still have less confidence in political institutions than West Germans. The gap between East and West is particularly wide when it comes to confidence in the Federal President (53% vs. 65%) and in the European Union (20% vs. 33%) 76.

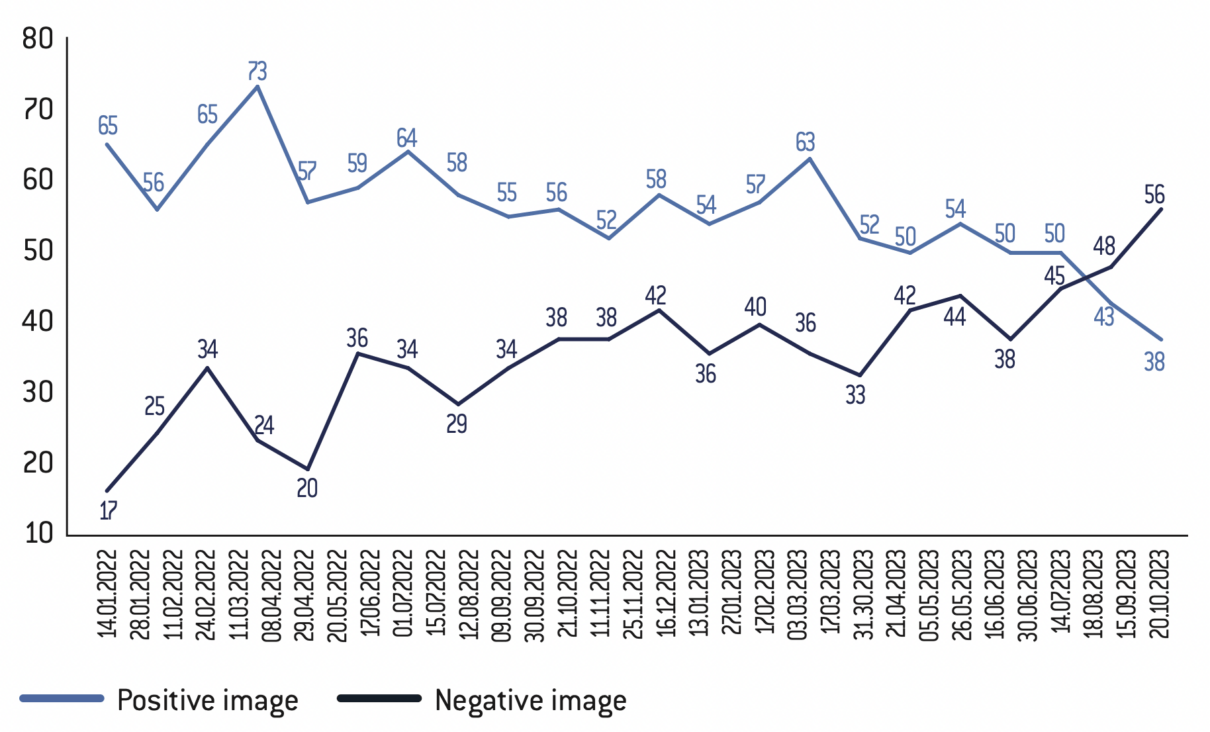

Analysis of the democratic parties’ image and programmes plays a key role in predicting a potential breakthrough for Wagenknecht’s party. The CDU still has no definitive modernised programme and its leader, Friedrich Merz, has disappointed a number of its voters77. The CDU, like the CSU, is unable to take advantage of the weakness of the Traffic light coalition. The SPD is paying the price of power and the country’s difficulties. The Chancellor’s image has deteriorated significantly. He was criticised for failing to reduce the cacophony within the coalition and for lacking authority. Several of his ministers are being challenged78. Lastly, his highly cautious policy of limited support for Ukraine combined with a financial scandal (the reallocation of €60 billion originally earmarked for the fight against Covid-19 to a fund for transformation and the climate) have weakened his political image. This budgetary manipulation was denounced by the Constitutional Court, triggering a major crisis for the Traffic Light coalition, which found itself having to “cobble together” a new 2024 budget as quickly as possible, characterised by massive savings on climate measures, energy prices, pensions, VAT, various forms of aid, etc. All these decisions further weakened the Traffic Light coalition’s voting position with the electorate.

Chancellor Scholz’s image (in %)

Source :

Statista

See Pressportal, “Stern-Umfrage: Nur ein Viertel der Deutschen hält Christian Lindner für vertrauenswürdig”, April 11, 2023 [online] and Focus, “Schlechtester Wert seit März! Nächste Umfrage-Schlappe für Lindner”, October 2, 2023 [online].

See Albrecht Von Lucke,“Zukunftspartei ohne Zukunft”, Taz, August 27, 2023 [online] and Samira El Ouassil, “Green New Waffendeal”, Der Spiegel, July 27, 2022 [online].

Hannah Köllen, “Umfrageschock für Habeck: Grünen-Minister gehört zu den unbeliebtesten Ministern”, Frankfurter Rundschau, May 24, 2023 [online].

See Patrick Bahners, Die Wiederkehr. Die AfD und der neue deutsche Nationalismus, Klett-Cotta Verlag, 2023 and Armin Pfahl-Traughber, Intellektuelle Rechtsextremisten. Das Gefahrenpotenzial der Neuen Rechten, Dietz Verlag, 2022.

The AfD is already classified as an extremist party in the Bundesländer of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt.

The FDP and its leader Christian Lindner, the current Finance Minister, are also increasingly contested79. The Liberals are getting dangerously close to the 5% mark, and their members are divided over whether the FDP should remain in the coalition. Finally, the ongoing war with the Greens is damaging both parties.

The Greens, elected to the Bundestag in 2021 and buoyed by a vast wave of public sympathy, are now perceived as a dogmatic party with no understanding of the economy80 and defending ideological choices at the antithesis of their past program (immigration, war in Ukraine…)81. The image of their leader, Robert Habeck, is deteriorating82.

The crisis affecting Die Linke is both organisational and ideological, and is likely to continue beyond its division. Janine Wissler’s party line, which focuses on urban populations, particularly young people, minorities, the promotion of the Woke discourse and support for immigration, is ill-suited to the new Bundesländer, which are characterised by an ageing population, deep-seated hostility to immigration and high levels of unemployment and poverty. The Party is also intellectually paralysed by the rise of the AfD in Die Linke’s historic strongholds.

The AfD seems to be going from strength to strength. Its popularity is growing in both East and West. The party’s division between conservatives and völkisch/New Right, which had been a crisis factor in the past, has now become a secondary issue. The moderates have left the AfD and de facto left the leadership of the party to ideologue Björn Höcke83. The only threat to the party would be its classification at national level by the Constitutional Protection Agency (Verfassungsschutzbehörde) as an extremist party84. The many civil servants, military personnel, police and state employees would then be forced to resign from the party or risk losing their jobs.

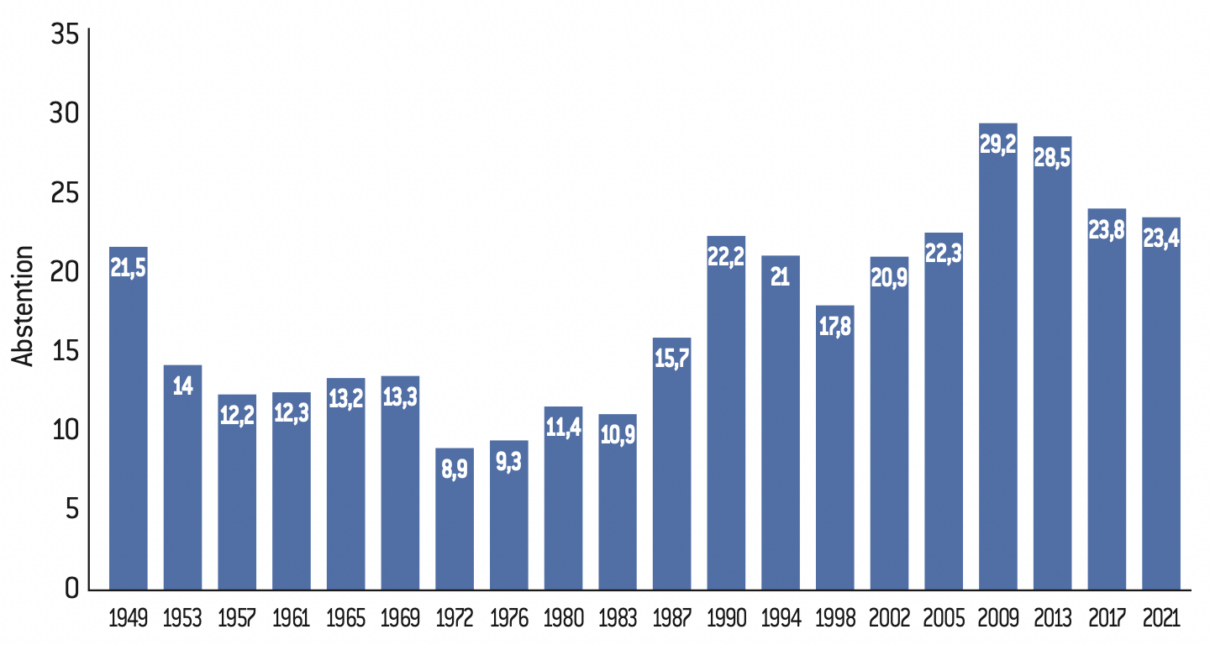

This brief review shows a political system that is out of breath and short of ideas. German democracy remains strong85, even if it is at risk of losing its stability. Many voters who are now abstainers are looking for a new political option. A good opportunity for a new party.

Abstainers in Bundestag elections (1949-1921) (in %)

Source :

Statista

Factors favoring the emergence of Wagenknecht’s party

Ibid.

Patrick Moreau, “Le courant Querdenker en Allemagne. A new social movement”, op. cit.

Karina Krawczyk, “’Anne Will’: Warum sich Sahra Wagenknecht nicht impfen lässt”, Waz, 1st of November 2021 [online].

Hannah Beitzer, “Russlanddeutsche mögen die Linkspartei lieber als die AfD”, Süddeutsche Zeitung, March 8, 2018, [online].

See Tomasz Kurianowicz, “Wagenknecht: Der Westen hat Putin aggressiv gemacht”, Berliner Zeitung, February 26, 2022 [online]; Christoph Link, “Putin ist kein durchgeknallter Nationalist”, Stuttgarter Zeitung, February 21, 2022 [online] and Gregor Mayntz and Eva Quadbeck, “Ich habe mehr Angst vor Trump als vor Putin”, Rheinische Post, May 17, 2016 [online].

Ralf Bosen and Marcel Fürstenau, “Ukraine-Krieg: Was denken Russischsprachige in Deutschland?, Deutsche Welle, April 28, 2023 [online].

See Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz, “Die wirtschaftliche Lage in Deutschland im Juni 2023”, June 14, 2023 and Deutschlandfunk, “Die Gründe für die Wirtschaftsflaute”, August 5, 2023 [online].

See Sahra Wagenknecht, Die Selbstgerechten. Mein Gegenprogramm – für Gemeinsinn und Zusammenhalt, op. cit.

The new Bundesländer were at the forefront of the fight against compulsory vaccination during the Covid-19 epidemic. The powerful Querdenker movement (“those who think differently”) stepped up street actions and sought confrontation with institutions and the police. The AfD and extreme right-wing identity and neo-Nazi movements joined in this protest, which has since died out, but which marked a step towards strengthening East German identity86. Sahra Wagenknecht, like a large part of Die Linke supporters, the far left and the esoteric movement, also opposed compulsory vaccination on the grounds of individual freedoms, and declared that she was not vaccinated87, a declaration that boosted her media popularity.

Germany is home to between 2.5 and 3.5 million Russian Germans (Russlanddeutsche) from the former Soviet Union (Russia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine). This highly heterogeneous community is for the most part socially integrated in Western, German-European society. Nevertheless, this population was, at least until the beginning of the war in Ukraine, pro-Putin and very attached culturally and linguistically to the Russian motherland. Russia has multiplied its communication channels and propaganda aimed at this minority88. Politically, after a long period of majority support and voting for the CDU/CSU, a small minority of Russlanddeutsche have found in the AfD a new party of representation89. Sahra Wagenknecht, who makes no secret of her sympathies for Russia90, can hope to attract many of these Russian Germans. Nevertheless, a poll conducted for Deutsche Welle in April 2023 indicates that this community is becoming increasingly critical of Putin and his policies91.

An issue that could greatly benefit Wagenknecht is that of the economic crisis and the onset of recession in Germany92. Sahra Wagenknecht has understood its importance perfectly. In her books, she analyzes the current problems in detail93 and sets out her solutions, which we have outlined above. Should the economic crisis intensify, the Wagenknecht party could win over many voters.

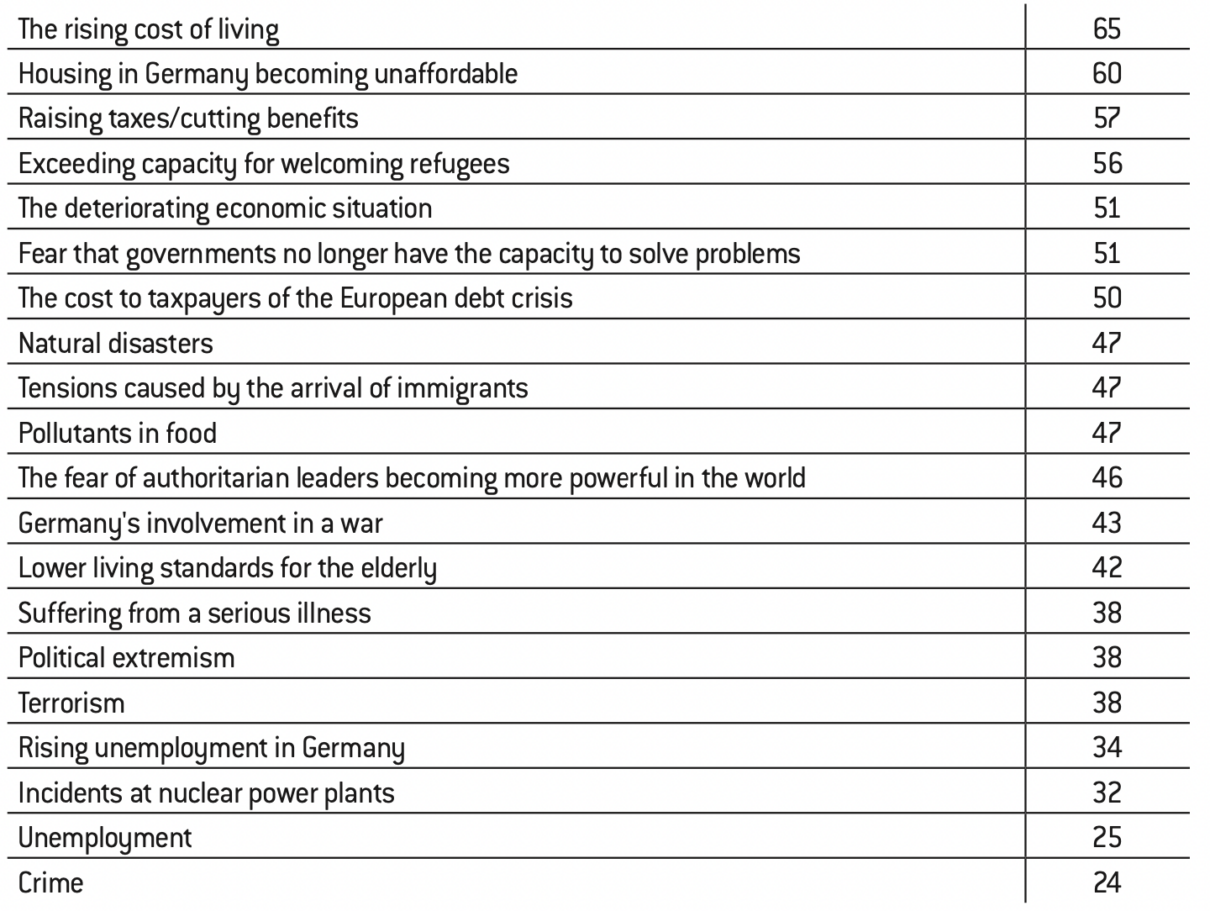

What are the current concerns? We have had an annual survey for 30 years, conducted by the insurance company R+V Versicherung. The 2023 edition highlights their evolution and shows how the state of opinion represents a window of opportunity for Wagenknecht’s party, even if its importance is still limited94.

The fear indicator – the average of all the fears tested – gives an idea of the state of mind in Germany. In 2023, the anxiety index increased for the second time in a row: it was 36% in 2021; 42% in 2022, and reaches 45% in 2023, its highest level for five years.

Germans’ main concerns in 2023 (in %)

Source :

R+V Versicherung

Der Spiegel, “Große Mehrheit der Deutschen befürwortet Scholz’ Aussage zu Abschiebungen”, October 26, 2023 [online].

Economy

In 2021, a majority of Germans feared tax increases and benefit cuts as a result of the Covid-19 crisis. In 2022, inflation set in and reached its highest level for almost 50 years. By 2023, the rising cost of living was at the top of the list of concerns. Despite an unfavourable economic climate and negative predictions, the fear of an economic crisis decreases in 2023 (-6 percentage points). Talk of an ultimate crisis of capitalism is therefore only partially effective.

In the face of Covid-19, fear of an increase in the number of unemployed has jumped to 40%. In 2023, the fear of losing one’s job and seeing the number of unemployed rise at national level is still of concern to a quarter of citizens.

The current problems of the eurozone remain an important issue for those surveyed: the high debts of some Member States are leading to fears that the debt crisis will cost the German taxpayer dearly. However, radical anti-Brussels rhetoric also appears to be relatively ineffective.

International

In 2021, 16% of those questioned feared that Germany would be drawn into war. By 2022, this figure had risen to 42%, an increase of 26 percentage points. In 2023, the percentage remains unchanged, with 43% concerned. Wagenknecht’s speech in favor of negotiations between Ukraine and Russia appears to be a promising topic for the party.

Politics

Germans traditionally have little confidence in their politicians. In 2023, 51% of those questioned fear that politicians will be overwhelmed by their responsibilities (+7 points). This figure reflects the poor image of the functioning of the Traffic light coalition and the ongoing migration crisis.

Immigration

Germans are increasingly concerned about immigration. The fear that the state and the authorities will be overwhelmed by asylum seekers is the one that has increased the most in 2023 (+11 points). The fear of tensions or violence arising from immigration policy has also risen sharply (46%, +10 points). The “welcoming culture” (Willkommenskultur) of the Merkel period has died, and Germans want to put a stop to immigration95. Of course, the AfD has made this issue its main battle-horse, but there is also a strong anti-migration movement on the left and in the Bundesländer. Wagenknecht’s social rhetoric (towards the fourth world and the German working class) is a limited but effective advantage because of its link with “competition” from immigration96.

Extremism

In 2023, 42% of those questioned feared Islamist extremism: 37% were concerned about right-wing extremism, while only 11% were worried about left-wing extremism. Finally, fear of terrorism is declining. In 2023, this fear is at the 19th place (38%). Wagenknecht’s communist past is therefore no longer an obstacle to her media popularity, and her discourse on the risks of the Islamisation of Germany resonates well97.

Her recent stance on Israel’s right to defend itself against Islamism reinforces her political compatibility with democratic parties, even if this does not necessarily mean electoral gains.

Cancel culture and Woke ideology

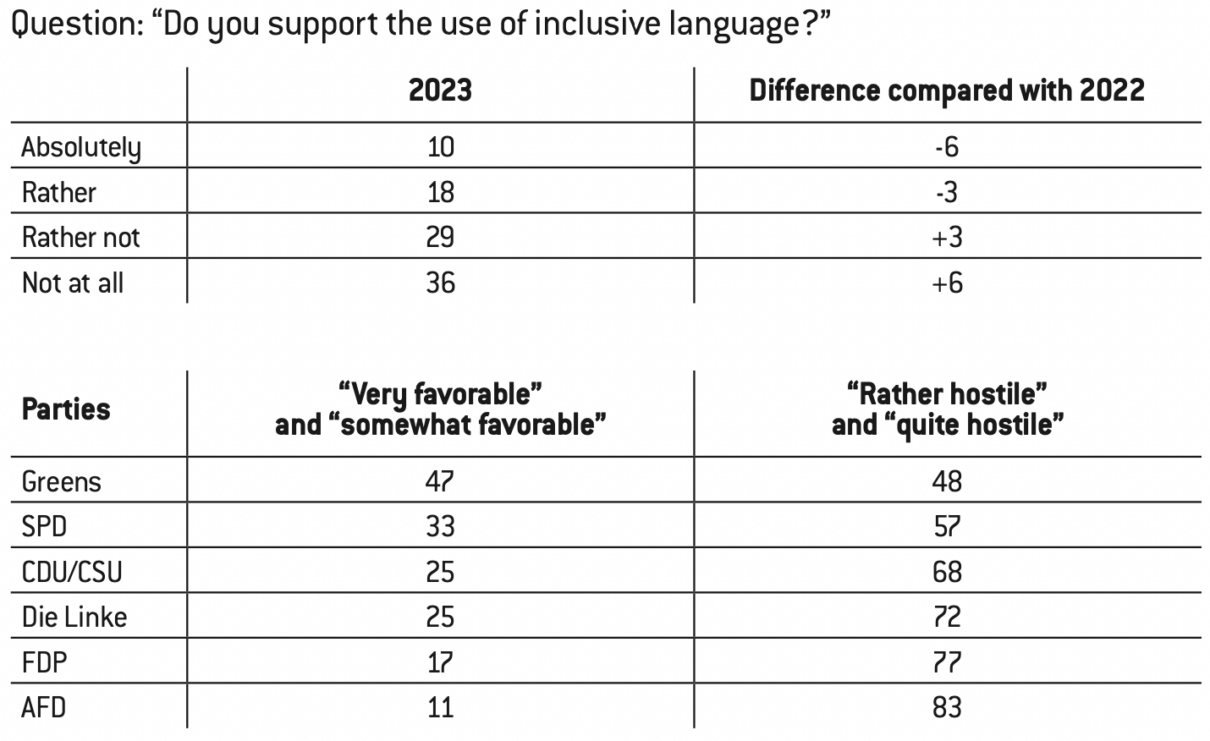

One of the central points of the Wagenknecht party programme is the rejection of Woke ideology, a view widely shared by respondents. In 2021, a quarter of those questioned (26%) were in favour of using a hyphen for non-gendered or inclusive writing. Two-thirds of people of voting age (65%) reject their use in the media and in the public space.

Opinion on the use of inclusive language (%)

Source :

Gendergerechte Sprache – KW 19/2021, Infratest Dimap, Welt am Sonntag

Peter Köpf, “Die Macht der Woken: Warum die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen wie Erziehungsanstalten wirken”, Berliner Zeitung, November 11, 2023 [online].

See Hans Monath, “Können wir noch frei reden? Zunehmende sprachlos”, Tagessepiegel, June 16, 2021 [online] and Stefan Niggermeier, “Worüber man in Deutschland auch nicht mehr frei reden darf: Juden. Und Hitler”, Übermedien, July 30, 2021 [online].

R+V study, op. cit.

See Frankfurter Rundschau, “Trotz Krieg in der Ukraine: Wagenknecht will mit Klimapolitik brechen und russisches Gas importieren”, October 31, 2023 [online] and “Wagenknecht stellt These auf: ‘Wärmepumpen klimapolitisch völliger Nonsens’”, March 26, 2023 [online]. See also Susanne Götze, “Zurück in die Fünfzigerjahre mit Sahra Wagenknecht”, Der Spiegel, October 27, 2023 [online].

Restricting freedom of opinion is another important issue for Sahra Wagenknecht, and a very popular one, including on the left98. An Allensbach poll from 2021 shows that freedom of expression has never been so threatened: only 45% of those questioned claim to be able to express their thoughts freely, a fact contested by a comparable proportion of respondents (44%)99.

Climate

Almost half of Germans remain concerned about climate change. Fear of climate change and natural disasters comes 10th and 11th (47% of respondents). In 2023, fear of global warming will reach its highest levels in western Germany (49%) and its lowest in eastern Germany (40%).

Since the tsunami in Japan, which hit Fukushima, the R+V survey has been asking people about their fear of nuclear accidents. At the time, more than half of those questioned said they feared such an accident. It has to be said that the debate on nuclear power, reignited by high energy prices, has not altered Germans’ concerns on this subject: just as in previous years, a third of the public still fear incidents in nuclear power plants100. Wagenknecht’s position on these issues (opposition to the Greens, support for a traditional energy policy using lignite coal and Russian gas) is in line with the views of the inhabitants of the new Bundesländer101.

Strong electoral potential in the new Bundesländer

MDRFRAGT, “Mehrheit dafür, dass Wagenknecht bei Landtagswahlen antritt”, October 24, 2023 [online].

“Mehrheit glaubt nicht, dass sich Wagenknecht etablieren kann”, N-TV, November 10, 2023 [online].

Sarah Wagner, L. Constantin Wurthmann, Jan Philipp Thomeczek, “Bridging Left and Right? How Sahra Wagenknecht Could Change the German Party Landscape”, Politische Vierteljahresschrift 64, 2023, pp. 621-636.

Zoe Lefkofridi, Markus Wagner and Johanna E. Willmann, “Left-authoritarians and policy representation in Western Europe: electoral choice across ideological dimensions”, West European Politics 2014, 37(1) pp. 65-90.

Sven Hillen and Nils D. Steiner, “The consequences of supply gaps in two-dimensional policy spaces for voter turnout and political support: the case of economically left-wing and culturally right-wing citizens in Western Europe”, European Journal of Political Research 2020, 59(2) p: 331-353.

A first wave of polls in the wake of the Wagenknecht split showed strong electoral potential in the new Bundesländer102 (in Thuringia, she could become the first or second party), but also in the West in Rhineland- Westphalia, Bremen… According to an Insa poll of 28 October 2023 for Bild am Sonntag, a Sahra Wagenknecht party could attract 14% of voters. In such a scenario, the AfD would drop to 17%, four points less than before. The SPD would get 15%, and the CDU/CSU 29%. The FDP and the Greens, with 5% and 12% respectively, would each lose one point with the creation of the Wagenknecht party. Die Linke, with between 3 and 4%, would fall below the representativeness mark103.

But it’s not all plain sailing. According to the RTL/N-TV barometer of 10 November 2023, a majority of those questioned (54%) do not believe that the new party can make a lasting impact on the German political landscape104. What’s more, 72% of those questioned said they did not trust Sahra Wagenknecht to solve Germany’s problems. Only a quarter of respondents (23%) consider her competent enough, and this positive judgement is most widespread among East Germans (39%), AfD supporters (49%) and Die Linke supporters (43%).

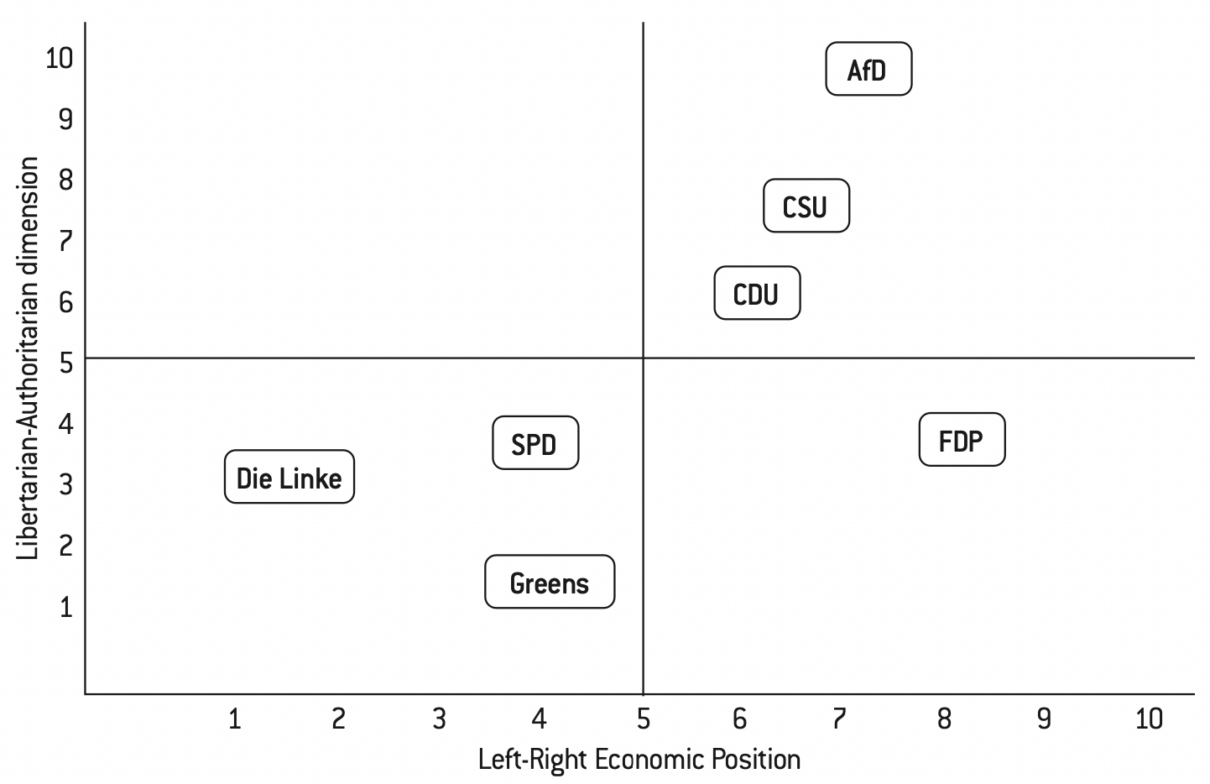

The uncertainties associated with this first poll call for caution. One research group has attempted a model105 using a presentation of the political space articulated around four systems of ideological preferences: economically liberal/socioculturally liberal; economically liberal/ socioculturally conservative; economically interventionist/socioculturally liberal; and economically interventionist/socioculturally conservative106.

Analysis of many European political systems, including Germany, shows that the left-authoritarian quadrant has a deficit of representative parties107.

German partisan space according to ideological preferences

Seymour Martin Lipset, “Democracy and working-class authoritarianism”, American Sociological Review, 1959.

Hanspeter Kriesi, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey, West European politics in the age of globalization, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Sarah Wagner, Bridging left and right?, op. cit.

Nils D.Steiner and Sven Hillen, “Vote choices of left-authoritarians: misperceived congruence and issue salience”, Electoral Studies, 2021.

Sarah Wagner, Bridging left and right?, op. cit.

Ibid.

The presence in political systems of voters with socio-culturally authoritarian and socio-economically left-wing views (“left-wing authoritarians”) is a phenomenon that has long been analysed108, and refers to the thesis of working-class authoritarianism. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the conceptualisation of globalisation’s “cosmopolitan winners” and “communitarian losers”109 has become a classic. The losers of globalization are individuals who suffer an objective or perceived decline in their standard of living due to the impacts of globalization. This group is most affected by austerity measures, and feels neglected by social- democratic parties due to a lack of socio-economic protectionism110. In Germany, the SPD and Die Linke have effectively neglected these voters. An overall positive context for the Wagenknecht project.

Possible electoral transfers to the Wagenknecht party from Die Linke and the AfD show that left-authoritarian voters are less likely to vote for the AfD when they prioritize economic issues111, but that “if they care more about immigration issues, the probability of the authoritarian left voting for the AfD rises from 15.7% to 24.7%”112. Furthermore,“if they consider immigration to be their main concern, the probability that they will vote for the AfD rises further to 34.3%”.

The following graph shows that 25% of Die Linke voters in the 2021 federal elections rate the Wagenknecht movement positively. This is also the case for 54% of AfD voters113.

In short, Sahra Wagenknecht finds her voters “among people dissatisfied […] with democracy, those who tend to position themselves as more socio-culturally right-wing and market-oriented, and those who support a more restrictive migration policy”.

Share of voters in the 2021 federal election who rate the Wagenknecht movement favorably (in %)

Ibid.

The authors of this research article conclude with this thesis: Wagenknecht has the ability to build a bridge to the right, but “she may not be able to convince Die Linke voters to vote for a new party”. The party most at risk would be the AfD, as Sahra Wagenknecht’s ability “to appeal to the far right is beyond doubt”. Her chances lie in her ability to offer left-wing authoritarian voters a welcome party114.

Putting things into perspective

The party was created on 8 January 2024 in Berlin. The official founding took place on 27 January in the same city. While the party’s foundation is assured, the creation of regional federations and the election of their leaders will take time. The party’s name will be decided after the next federal elections, and will not necessarily refer to Sahra Wagenknecht115. The regional elections in Saxony and Thuringia in 2024 will be the first major challenge for the party, should it decide to field candidates. The European elections in 2024 are surely the best opportunity for a new party to make itself known and convince voters who are looking for a party. They will also tell us whether the AfD will lose ground to the Wagenknecht party. Its results will depend in particular on the future of the Traffic light coalition. The possible establishment of a grand coalition would change the German national political landscape completely.

No comments.