The state of the right : Austria

Austrian People’s Party (OVP)

An overview of OVP’s history: 1945-2010

The OVP’s programmes and values

The OVP’s organisational structure

The Austrian Far Right

The Austrian political system vs. Proporz

History of the Austrian Far Right

Programmes of the Far Right

Organisation and financing of Far-Right parties

Balance of Electoral Power within the Austrian Right

Geographical distribution of Austrian parties

Socio-demographic distribution of Austria’s right-wing and Far Right parties

The reasons for voting for the Right and the Far Right

Conclusion

Summary

The Austrian Right is represented by the Austrian People’s Party (OVP), and the Far Right by the Freedom Party of Austria (FPO). Founded in Vienna in 1945 by conservative Christian-Socialists, the OVP formed a coalition in the post-World War II government with the Social-Democratic Party of Austria (SPO) and the Austrian Communist Party (KPO). The latter eventually left the coalition in 1947, leaving the Conservatives and Social Democrats to share the leadership. Austria then entered a period of economic prosperity, thanks primarily to the economic policy of the conservative political duo, Julius Raab-Reinhardt Kamitz. The OVP won the absolute majority in the 1966 elections and governed alone. Its leadership was short-lived, however, since Social Democrat Bruno Kreisky led his party to victory in 1970. The OVP, perceived as outdated by an Austrian youth longing for change and tending to favour the Left, remained in the opposition for 17 years. From 1987 to 2000, an SPO-OVP Grand Coalition ruled Austria, while Jörg Haider’s FPO gained stronger electoral support. In the 1999 elections, the FPO obtained more votes than the OVP, there by becoming the country’s second largest party. OVP leader Wolfgang Schüssel chose that moment to integrate the FPO into a small coalition government. Once in power, the Far Right used its credit and protestor base to help the OVP gain more popularity. Yet this strength was short-lived. The OVP-FPO coalition collapsed and the October 2006 early elections marked a failure for the OVP, as the SPO once again became Austria’s ruling party.

The Far Right, on the other hand, made exceptional progress. Since then, the Social Democrats and the People’s Party have been co-habiting within Grand Coalition governments, with FPO steadily gaining ground.

The OVP’s programmes have changed through the years. Although it defined itself in 1972 as a “progressive-centre party” rooted in the Christian-Social tradition, its 1995 “Vienna Programme” anchored the party more to the right and advocated tenets of economic liberalism. Since its founding in 1945, the OVP has been an organisational “umbrella,” endowing its federations and peripheral organisations with broad autonomy. The agenda of the FPO, founded in 1956, entailed putting an end to the sharing of power and posts between the OVP and SPO (the Proporz system), opposing European construction and “protecting the Austrian homeland” from immigration. During its term serving in the government, the party experienced an internal crisis which led to its scission and the creation, in April 2005, of the BZO – which Haider headed until his death in 2008. Austria’s Far Right is now governed by Hanz-Christian Strache’s FPO.

Patrick Moreau,

Docteur of History, Higher Doctor of Political science, Researcher at CNRS, UMR 7236 Université de Strasbourg.

The Austrian People’s Party (Österreichische Volkspartei – OVP) is currently the ruling party within the framework of the Grand Coalition formed with the Social Democratic Party of Austria (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs – SPO). This coalition has experienced considerable tensions since 2009 due to the economic situation (the euro crisis), differences of opinion on policy (the Europe issue) and, lastly, the historic legacy of competition from the Far Right. The common government programme fails to conceal the partners’ malaise in a political system which a majority of voters perceive as blocked.

Austrian People’s Party (OVP)

An overview of OVP’s history: 1945-2010

In the wake of Austria’s Anschluss by the Third Reich in 1938, the elites of the Austro-Fascist era were arrested and sent to concentration camps. In Dachau, a group of politicians, among them Leopold Figl and Alfons Gorbach, examined the reasons for the failure of the First Austrian Republic and the idea of reforming a Christian Social Party was born. The name chosen ¬– the Austrian People’s Party – underscores the determination to create a social and political integration party based on Christian, as well as liberal, values. On 17 April 1945, the OVP was founded in Vienna and endowed with internal associations (Bünde) whose purpose was to open up the new organisation to all levels of society (see below).

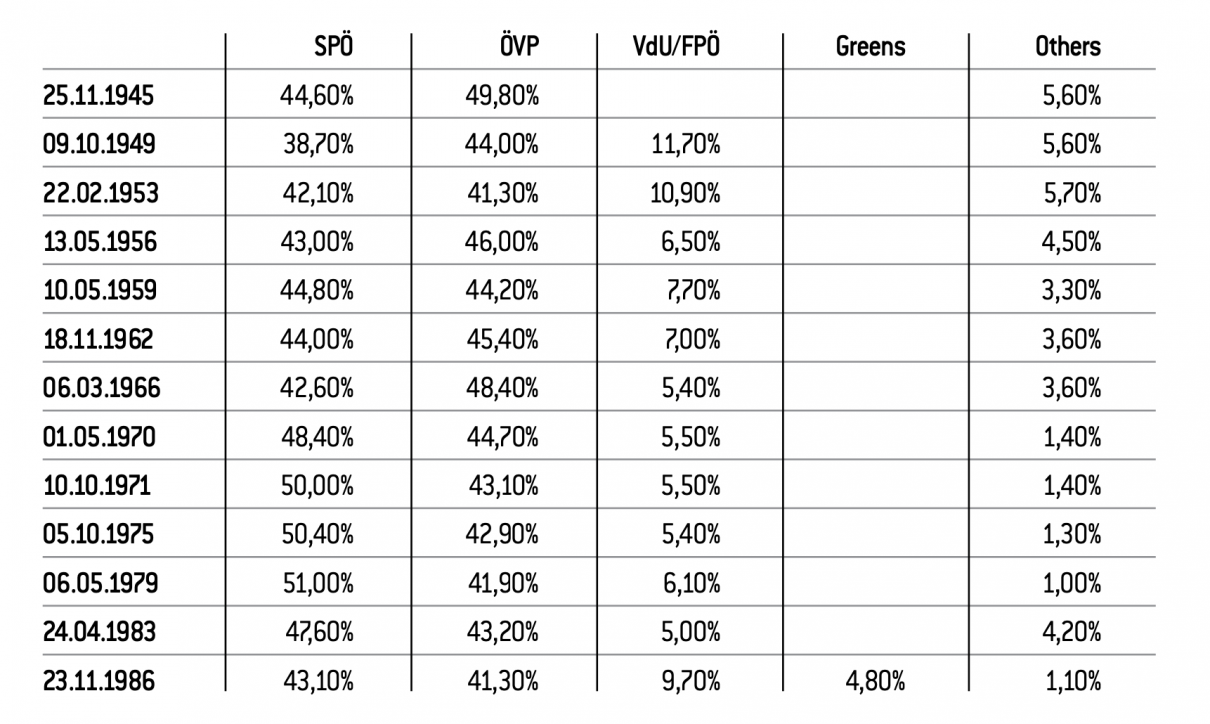

In agreement with Stalin, whose army occupied the city, the Austrian Republic was proclaimed on 27 April by an initial OVP/SPO/KPO (Communist Party of Austria) “concentration” government, which remained in office until December 1945. During the November 1945 elections to the National Council (Nationalrat), the OVP won 49.8% of the votes (SPO: 44.6% and KPO: 5.5%) and an absolute majority of mandates, thus forming a second concentration government.

In 1952, Julius Raab became the OVP’s leader (Obman) and began a process of reconciliation with the SPO along anti-Communist lines, causing the KPO to withdraw from the government in 1947. The 1949 National Council elections saw the emergence of a new Far Right political actor: the Federation of Independents (Verband der Unabhängigen – VdU). The OVP won the election, but lost the absolute mandate majority (44%, -5,8%), while the VdU obtained 11.7% of the votes. As of 1949, the Far Right became a quasi-mandatory partner for a small coalition. The VdU, with its German-National leanings, compelled the OVP to politically transform itself by accusing it of upholding anti-Austrian values. The Party became a conglomeration of Catholics, Liberals and Nationalists whose primary common value was anti-Marxism. From April 1953 to April 1961, Austria was governed by four successive Grand Coalition governments. The political system, reduced to two and one-half components – OVP/SPO/FPO (the latter being the Freedom Party of Austria, VdU’s successor party) – became ineffective inasmuch as the Grand Coalition’s partners had divided the office’s power and benefits between themselves.

Table 1 : 1945-1986 national Council elections

Source :

Austrian interior Ministry (simplified table)

see Ernst Trost: Österreich ist frei – Leopold Figl und der Weg zum Staatsvertrag (Vienna: 2005).

This period corresponds to Austria’s economic golden age, buoyed by the social market economy promoted by Finance Minister Reinhard Kamitz (1952-1960). Inflation, which was over 30% before 1950, dropped to 1.1% in 1958. The Grand Coalition lowered taxes, consolidated the budget and promoted business start-ups while enlarging the share of nationalised industries. The “Raab-Kamitz course” of Austria’s economic miracle remains today the OVP’s benchmark – a reminder that the State of that era did not create debt. Raab’s popularity reached its zenith in 1955. On 15 May, Austria and its allies signed a State Treaty which gave the Austrian Republic its current political configuration. In Article 4 of said Treaty, Austria agrees not to enter into any political or economic union with Germany. Article 9 obliges Austria to dissolve all National Socialist organisations and to prohibit the activities of any new Fascist or Nazi organisation. Lastly, the Austrian State agrees to pay USD 150 million to the Soviet Union, in exchange for evacuation by the allies of their occupied zones. The new independent State at last declared its permanent neutrality.1

The OVP’s defeat in the 1959 elections resulted in Raab’s withdrawal. Within the party, an increasing number of voices were calling for a reform and a debate on programmes. In 1960, Alfons Gorbach became the head of the OVP and replaced Raab as Federal Chancellor on 11 April. The next three years of government were marked by a slowdown in Austria’s economy and by growing tensions between the OVP and the SPO over how to modernise the economy and the role which nationalised industries should play in it.

Although the outcome of the 18 November 1962 general election was that the OVP became Austria’s leading party (OVP: 45.4%, SPO: 44% and FPO: 7%), the political climate within the party was poor. The Grand Coalition’s continuation was hotly debated within the OVP. Josef Klaus, leader of a group of reformers known as “Young Turks,” began calling for a coalition with the FPO in the early 1960s, but was unable to impose this strategy. The year 1963 was key for the OVP. Raab’s failure to win his candidacy in the Austrian Republic’s 1963 presidential elections precipitated his appointment as the head of the OVP in 1963.

Klaus became Chancellor on 2 April 1963, but abandoned the idea of forming a small coalition with the FPO.

Klaus described himself as a modernizer and a man open to young people’s concerns. Bolstered by this image, he contributed to the OVP’s greatest political triumph in April 1966. The party won 48.35% of the votes and 85 mandates, and the SPO joined the opposition. On 18 April 1966, the first OVP government emerged. It quickly lost favour with the public, however, after it adopted unpopular economic measures and raised taxes.

For its part, in 1966, the SPO appointed as its chairman the highly intelligent Bruno Kreisky, who forced his party to adopt a modernisation agenda. Public opinion –particularly young people – started to increasingly perceive the OVP as anti-liberal, reactionary and antiquated. Kreisky, like Willy Brandt in Germany or Olof Palme in Sweden, became the idol of youths who were leaning more and more to the Left and were anxious to transform the society. The SPO won the March 1970 general elections, with 48.4% of the votes and Kreisky decided, with the FPO’s support, to constitute a minority government – a choice which surprised many. Bruno Kreisky was, in fact, Jewish, albeit a non- practicing one and anti-Zionist, but anti-Semitism continued to be very widespread in the FPO’s German national wing. The OVP remained an opposition party for 17 years, unable to compete with Kreisky’s talent as a communicator and politician.

The Kreisky era, which spanned four governments from 1970 to 1983, was a period of transformation for Austrian society which the OVP, backed by the Catholic Church, attempted to resist. “Bruno” became the idol of a politically left-wing youth, while the OVP seemed to be increasingly reactionary. The latter’s problems were all the greater in that the SPO managed to reconcile with the Catholic Church. Nonetheless, as time went on, the OVP’s popularity grew. Kreisky was ageing and disadvantaged by over-exposure to the media. In the 1983 general elections, the SPO lost some ground (47.6%; OVP: 43.2%; FPO: 5.5%) and its absolute majority. Austria’s political system experienced a schism in 1983 as new actors came on the political scene. In 1979, Alois Mock, who had been appointed as the OVP chairman, created a new party management body, the “presidium,” imposed the Federation’s primacy over the internal associations (Bünde), and took charge of the party on every level, including its finances. In 1983, Mock effectively criticised the SPO’s economic policy, which allowed the OVP to gain votes (43.2%, +1.4%, +4 seats). Another promising actor emerged – the ecologists of the Alternative List of Austria (Alternative Liste Österreichs – ALO), who obtained 1.4% of the votes in 1983.

Kreisky decided to withdraw and left the post of Chancellor to Fred Sinowatz, who stayed in the position until 16 June 1986. Lacking a majority, Sinowatz negotiated with the FPO. The latter’s chairman, Norbert Steger, and then became Vice-Chancellor and Federal Minister of Commerce, Trade and Industry, with his party managing two other ministries (Defence and Justice). The Sinowatz government, confronted with economic problems brought about by the nationalised industries’ crisis, gave the OVP an opportunity to acquire both economic and ideological skills. The November 1986 general elections were somewhat of a defeat for the OVP: the party only won 41.3% of the votes (SPO: 43.1%). That election’s two winners were the FPO (9.7%), in which Haider’s personality and the Green Alternative Party (4.8%) gained more notice. The SPO and the OVP then faced the question of what to do with Haider. Franz Vranitzky, who had become Chancellor, openly disliked Haider and terminated the SPO-FPO coalition on 25 November 1986. Mock, who wanted a coalition with Haider, encountered resistance from a large fringe of the OVP. The only remaining option was an SPO-OVP Grand Coalition.

For the next two decades, the Austrian political system had four components. While the traditional Social Democrat and Conservative political circles were losing support, the FPO and the Greens (Grüne) were gaining ground.

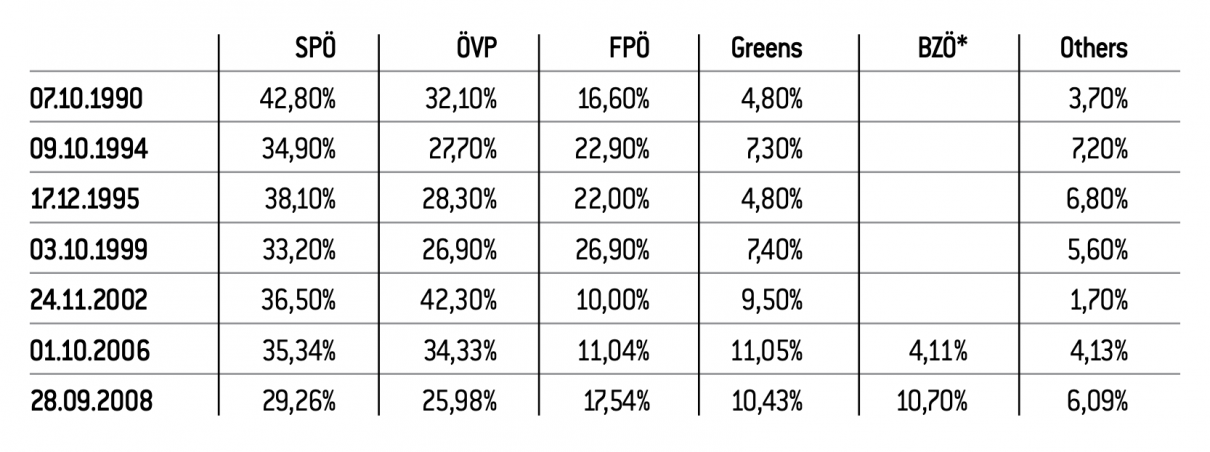

Table 2 : 1990- 2008 National Council Elections

Source :

Austrian interior Ministry

*Alliance for the Future of Austria (Bündnis Zukunft Österreich)

- The Proporz is the Austrian system under which the sPO and the OVP share political power and exert their influence on the country’s economic and civilian see below.

From 1987 to 2000, Austria was governed by an SPO-OVP Grand Coalition. During the Vranitzky third, fourth and fifth (1990-1997) and the Klima government (1997-2000), the OVP managed to stabilise its ranks and stand up against the FPO in the elections. The Far Right’s results at the polls, however, showed that the democratic parties’ efforts would remain futile until 2002 and that the SPO was also losing a fringe of its traditional constituents – particularly workers – to the FPO. There are many reasons behind this weakening of the OVP, yet they can be reduced to four main factors: the electorate’s rejection of the Proporz system,2 the population’s strong and persistent reservations about European construction, the vacuity of the OVP’s new programme and, lastly, the lack of a charismatic leader capable of competing with Haider. The question of the European Union and what role Austria should play in it was a key factor in the democratic parties’ weakness, including that of the OVP. In contrast to the SPO, the OVP, lacking a programme, hoped to regain its popularity by presenting itself as the European party par excellence. On the occasion of the 1994 referendum on European Community membership, three-fourths of the Austrian constituents voted in favour of this option. Yet scepticism about Europe remained high among all sectors of the population. Haider, who seized this topic for his anti-European crusade, took advantage of collective concerns about the end of neutrality, the opening of the markets and trans-European immigration.

In 1997, the electorate, incensed by a deadlocked system and European integration costs, challenged OVP Chancellor Klima’s decision to perpetuate the OVP-SPO Grand Coalition and its economic policy, determined in accordance with the Maastricht criteria. In the 1999 elections, the SPO won only 33.1% of the votes (-4.9%) and the OVP 26.9% (-1.3%) – its worst score since 1945. The FPO became the country’s second strongest party, defeating the OVP by 416 votes (26.9%, +5%).

Despite his electoral defeat, Schüssel enjoyed a strengthened position within the OVP. The party was grateful to him for having kept the OVP at the level of the FPO, which (based on the polls) had been expected to win by a greater margin. The question again arose as to whether or not to seek an alliance with the FPO, which was opposed by fourteen European Community countries. Schüssel weighed the risks carefully and banked on the fact that international pressure would cause the majority of Austrians to rally around the government, and that the FPO, despite being anti-European and xenophobic, would not again call into question the established democratic order. The future proved him right. He thus opted for a small coalition. In the first Schüssel government, Susanne Riess-Passer, Haider’s “right arm,” became Vice-Chancellor and Minister of Public Services and Sports, while the FPO was entrusted with five other ministries: Finance, Justice, Defence, Social Security and Transports.

The reasons why Haidler did not ask for the chancellor position and why Schüssel opted for an alliance with the FPO are still not known. Haider knew that he could not immediately become chancellor, since the OVP had brought up a possible return to a Grand Coalition in the event of a Haider ultimatum. He was certain, however, that he could force the OVP to adopt his anti-European, anti-migration and security party lines, and banked on the next elections to become the first FPO chancellor. Schüssel, who proved to be a better tactician, wagered on the government’s “corruption” of the FPO. He was bet on a consensual-type government practice that would enable the Austrian government to avoid political pitfalls and appease international ire. European Community sanctions were lifted in September 2000, after a committee proved there was nothing anti-democratic about the government’s policy. Schüssel emerged from this episode with higher ratings, to the detriment of the SPO-Green opposition.

Haider realised too late that he had been trapped and called for Vice- Chancellor Riess-Passer’s resignation, thereby initiating a crisis inside the FPO, which entered a phase of decline. Schüssel seized this opportunity to impose his party line and to call for early elections. The OVP became Austria’s leading party (42.3%, +15.4%). The SPO (36.5% +3.3%) and the Greens (9.4%, +2.5%) also gained ground, while the FPO experienced drastic losses (10.1%, -16,9%). Haider committed a second strategic error by agreeing to participate in the second Schüssel government, which lasted from 28 February 2003 to 11 January 2007. The weakened FPO appointed Hubert Gorbach as Vice-Chancellor and Federal Minister for Transport, Innovation and Technology and Ursula Haubner as Federal Minister of Social Affairs. However, the OVP completely dominated the government. In April, 2005, Haider left the FPO and founded the Alliance for the Future of Austria (Bündnis Zukunft Österreich – BZO). The difficulties confronting this new party, which remained in the Schüssel government, made the coalition increasingly unstable. Schüssel therefore decided to hold the 1 October 2006 early elections, which brought a resounding defeat to the OVP, which obtained only 34.3% of the votes (-7,9%), thereby allowing the SPO to once again become Austria’s leading party (35.3%, -1.1%). The Greens captured 11% (+1.5%), while the Far Right held its ground with 15% of the votes (FPO: 11.4%, +1.3%; and BZO: 4.1%). On 8 January 2007, after months of negotiations, the OVP and SPO reached an agreement on the Grand Coalition. On 9 January 2007, Wolfgang Schüssel resigned and was replaced by Wilhelm Molterer, one of his loyal supporters.

The Gusenbauer government lasted from 11 January 2007 to 2 December 2008. The OVP appointed Molterer Vice-Chancellor and Minister of Finance, and took charge of six other ministries. The coalition very soon lost momentum. The SPO caused it to break apart when it announced that it supported holding referendums on the ratification of European treaties. In response, on 7 July, Molterer issued a press release denouncing the SPO’s anti-Europeanism and Gusenbauer’s style of government. The two parties agreed to hold early elections.

The election campaign’s main theme was inflation (3.5%) and speculative price increases. The 28 September 2008 election was a political disaster which revealed how allergic the electorate had become to the SPO/OVP Grand Coalition. The SPO garnered only 29.2% (-6.8%), the OVP 25.9% (-8.3%), and the Greens 10.3% (-0.6%). The Far Right made exceptional gains: the FPO obtained 17.5% of the votes (+6.5%) and the BZO 10.7% (+6.6%). In the election’s aftermath, the OVP realised it was cornered and had no other option than to form an alliance with the Far Right in a new Grand Coalition. The party then tried to regain momentum by keeping Schüssel and his friends out of key positions. The Faymann government, which took office on 28 December 2008, included, other than OVP’s Vice-Chancellor Erwin Pröll – in charge of Finances – six OVP ministers.

The OVP’s programmes and values

All quotes are from the Salzburger Programm.

All quotes are from the Grundsatzprogramm. see: http://www.oevp.at/download/000298.pdf.

The OVP has always considered its programmes somewhat of a burden to the management of political power. Sustaining the “Grand Coalition” model has often compelled the OVP, in the name of governmental consensus, to pursue a policy in direct conflict with its programmes. The Party adopted a benchmark programme only in 1972, while it was in the opposition – the 1972 “Salzburg Programm” – which was recast in the 1990s within the 1995 “Vienna Programme.”

In 1972, the OVP defined itself as a “progressive-centre party”3 rooted in the Christian-Social tradition. Its slogan was “liberty, equality, service, partnership, division of tasks and participation,” and its goal was to create a “society of partnerships” in a “dynamic democracy” relying upon direct democracy. Nonetheless, this partnership’s limits were clear: “The OVP’s view of participation and democratisation remains restrictive in the sense that the limits of participation rights cannot extend beyond private ownership.”

As for the economy, the OVP defended “the social market economy” portrayed as a third alternative option between capitalism and socialism. Every citizen would be free to consume and work at will, but social partners must control the system to avoid excessive monopolistic or socialist tendencies. Immigrant workers, a “necessary evil,” would have no place in Austrian society until they have been socially and culturally integrated. In its efforts to win more voters, the party spoke of its “new responsibility” towards citizens. The OVP, aware of its limited appeal to young constituents, abandoned its traditional conservative approach, promoting the “right of youths” to experience “new social existence models.” Women were promised true equality in terms of opportunities and rights. The family remained the conservatives’ ideal, but the housewives concept was dropped from the programme, together with any notion privileged relations with the Catholic Church. Lastly, the OVP stressed the country’s neutral role with regard to, or in response to, European construction.

The 1995 “Vienna Programme,” which took up a few themes from 1972, may nonetheless be called “neo-conservative” because it combined conservative with neo-liberal values. It promoted five main principles and the OVP proclaimed itself to be the “party of the liberal Rule of Law and of open society” and of the “ecological and social market economy.” It was an “Austrian party in Europe, a socially integrating ”Volkspartei” (people’s party), and lastly, a “Christian-Democrat” group.4 The party’s 1972 progressist positioning “in the centre” was replaced by a conservative Weltanschauung (world view), indicative of the OVP’s determination to win back Catholic voters, the Austrian nationalist rhetoric being a response to the FPO’s German-Nationalist positions. The programme revolved around ten principles: liberty, service, partnership, subsidiarity, participation, accountability, sustainability, justice, security and tolerance.

There were noticeable ideological differences with the 1972 programme. To use but a few examples, equality is dropped and made a part of the “justice” component. According to the OVP, human beings are unequal in their talents, abilities, preferences and interests. As for direct democracy, OVP described referendums as “useful tools,” yet ones which should be used sparingly. It praised the Churches for their educational and moral endeavours.

Austrian society was still marching towards equality, as the OVP was pleading for gender equality and the introduction of a quota for women serving in public office, but the nuclear family (a couple and two children) remained the ideal. “Alternative” lifestyles were dropped from the text, but the previous rejection of abortions was, as in 1972, reaffirmed. At the same time, the OVP called for strengthening competition and privatisations in the economic sector. The FPO’s positions on immigration accounted for this party’s rise in popularity. The OVP, however, maintained its “efforts to promote the integration of foreigners living in Austria,” but also the “imperative of strictly limiting immigration.” The European Community continued to be seen in a positive light, but the OVP stressed the fact that Austrians should see themselves “as citizens of their region and their homeland.”

Overall, this programme, designed to distinguish the OVP from the SPO’s “socialism” and preempt the FPO’s xenophobic platform, has been sufficiently vague to survive until 2010 and it is currently being revamped. The bank and euro crises which made State intervention necessary have now compelled the OVP to reassess the role of neo-liberalism. The Far Right’s strong electoral breakthrough in 2008 required the party to deal with national and international migration and security issues (terrorism and the proper response to it). Lastly, despite the relatively good condition of Austria’s economy, the future of the health system, pensions and the role of globalisation in the Austrian economy need to be examined.

The OVP’s organisational structure

see the website derstandard.at, 10.2008.

see Ferdinand Kaarhofer, “Arbeitsnehmerorganisationen,“ in: Dachs–gerlich (eds.), Politik in Österreich, pp. 462 to 479.

see Josef Kramer and gerd hovorka, “interessenorganisation der Landwirtschaft,” in: Dachs – gerlich…, Politik in Österreich, pp. 480 à 498.

see Die ÖVP, 348.

The OVP is a Volkspartei (people’s party) represented in every Austrian social strata. Since its founding in 1945, it has served as an organisational umbrella endowing its regional federations, as well as its numerous internal and peripheral associations, with broad autonomy.

In 2008, the OVP had some 700,000 members (1945: 490,000, 1970: 720,000; 1986: 695,000 and 2002: 622,000) consisting of party members, six internal associations (Bünde), closely related organisations and trade and farmers unions. It is by far the country’s largest party, since the SPO had, in 2008, about 300,000 members, the FPO 40,000, the BZO 10,000 and the Greens only 4,600.5 The total membership attained by combining the few available figures concerning this complex organisational body is 1.2 million members, since the 700,000 figure takes into account members with double, triple or quadruple affiliations. A comparison of Austria (8 million inhabitants) to Germany (81 million inhabitants, with the conservative political parties CDU and CSU members totalling 523,000 and 168,000, respectively) shows that the OVP has a remarkably large constituency in the country.

The OVP is built like a pyramid with the party’s highest political body, the Presidium, at the top, a national supervisory body and a limited presidium. All powers are concentrated in this body, which decides the daily strategies and political positions which the party shall take. The OVP has a vast network of internal associations and groups enjoying close and friendly ties with each other at the national, as well as regional and local, levels. The party’s internal national associations cater to youths (Young People’s Party, with about 100,000 members) employers (Austrian Economic Alliance) farmers (League of Austrian Farmers, 270,000 members), women (OVP-Frauen), workers (League of Austrian Workers and Employees) and seniors (Austrian Seniors Alliance, with 305,000 members). All of these associations are legally independent from the OVP, which is largely self-financed. Many other organisations not directly affiliated to the party, but with close ties to it, could be added to this list. Another organisation which should be mentioned is the OVP’s Political Academy (Politische Akademie der OVP – www.polak.at), which provides public education, political analysis and executive training programmes.

The OVP’s loyal constituency in the country can be accounted for by its strong representation within the professional bodies: the League of Austrian Workers and Salaried Employees is a splinter group of the Austrian Trade Union Federation (Österreichische Gewerkschaftsbund – OGB – which has 1.3 million members). In the 2009 national round of elections of representatives to the Chamber of Labour (Arbeiterkammer), the OVP garnered 2.6 million votes (24.94% of the votes and 212 seats), while the Social Democrats won 55.8% of the votes.6 The League of Austrian Farmers (Österreichischer Bauerbund – OBB) has about 250,000 members. In the Agricultural Chamber national elections, the OVP captures an average of 80% of the votes.7

Despite a legally required annual accounting of party financing, the OVP’s financial status is not well-known. OVP’s receipts vary according to its obligatory reimbursements of campaign costs (2004: 14,338,891 euros; 2006: 23,605,049; 2008: 19,752,742). Donations, at least on paper, are very (too) low (2004: 1,001,453 euros; 2006: 3,353,321; 2008: 1,973,839). Yet, no doubt because of its financial relations with the above-mentioned associations, the party is able to conduct highly intensive campaigns and to maintain a sizeable staff (2004: 60 full-time staff members in the main headquarters, 25 in the Parliamentary Club, 50 in the regional offices, up to 80 people in each of the regional federations, not to mention the specialised sections with staffs of varying sizes responsible for propaganda and programmes).8

The Austrian Far Right

The Austrian political system vs. Proporz

The Austrian political system – consisting of a bicameral structure (Chamber of Deputies and Senate) and a federal organisation – is weakened by the parties’ exercise of power.

Since 1945, Austria has had 27 governments, 17 of which were SPO/ OVP dual coalitions. The SPO governed alone from 1970 to 1983, and the OVP governed once from 1966 to 1970. The Far Right (FPO) co-governed with the SPO from 1983 to 1987, and with the OVP from 2000 to 2006.

This ménage à trois situation is the key dilemma of Austrian politics. The long-term continuation of Grand Coalitions has led to a blocking of the political system particularly noticed by voters because of the Proporz system. This term masks an oppressive clientelism which often forces citizens to seek a career in politics, or to ask a favour in order to become a member of one party or the other.

Jörg Haider’s successes at the polls since 1986 are based for the most part on his proclaimed desire to end this system. Moreover, if the OVP and SPO are not in the majority, they have no other political alternative than to ally with the Far Right. The latter’s 2005 split into two camps (FPO and BZO) did nothing to solve the problem. In the future, the SPO needs to consider a three-pronged coalition (SPO-Greens-BZO), while the OVP will have to choose between an OVP-FPO or an OVP- FPO-BZO coalition. This electoral mechanism has had some psychological ramifications: the Far Right’s vote has become trivialised.

A review of the Austrian Far Right’s election results shows that their share increased steadily from 1983 to 1999. Today, more than one- quarter of the electorate votes for the FPO. An internal crisis which led to the split of the FPO – now headed by Heinz-Christian Strache – and the creation, in April 2005, of the BZO (headed by Haider until his death in 2008) brought the Far Right to its 1999 level: 28% in the 2008 general elections after including the votes garnered by the FP and the BZO. Understanding the reasons for the Far Right’s outstanding position in the Austrian political system calls for a brief overview of its history and its constituency base.

The FPO’s rise to power in 2000, which, in 2010, was still one of the most electorally powerful National-Populist parties in Western Europe, signalled the structural changes affecting the parties’ traditional system in many democracies. Obviously Austrian society, like many of its neighbours, was suffering from well-known problems: collective discontent, fear of unemployment and of economic change, tendency to withdraw into itself, xenophobia, etc. These factors condition and favour the emergency of FPO-style parties.

History of the Austrian Far Right

See : http://www.fpk.at/.

The FPO’s history can be divided into four major periods, each of which sheds light on the present.

In the first period, the FPO was, at the time of its founding in 1956, a party with liberal and National-German tendencies, with most of its constituency located in Carinthia and in Vienna. Yet it was extremely isolated as a result of its ideology. The FPO’s gradual integration into the political system was made possible by the OVP and SPO parties, which used it as a means to pressure their coalition partner. The small SPO-FPO coalition of 1983 completed the FPO’s integration into the political system.

The second period began when young Haider rose to power after being elected head of the party in 1986, and an impressive succession of electoral victories began. Haider, who denounced the system’s weaknesses, scandals, favouritism and inequalities, managed to acquire the reputation of a modern-day “Robin Hood” as an advocate for the best interests of the “people” and ordinary citizens. From 1993 on, he strengthened FPO’s anti-establishment image by taking on the European and xenophobia issue.

The third period is that of association with power, which constituted a trap for both the FPO and Haider. The FPO’s voter support plummeted on the occasion of the 2002 National Council election and the party entered a decline phase. It was also weakened by Jörg Haider who – at least temporarily – lost what had made him so successful since 1986: his ability to gauge the concerns of the masses. FPO’s political and organisational collapse was expedited by Haider’s excessive anti-Semitic and pro-Saddam slips.

The fourth period was marked by the founding of the BZO, which was initially an organisational failure. The end of the OVP-BZO coalition and establishment of the OVP-SPO Grand Coalition in 2006 showed that by that time the BZO was nothing but a marginal party. Heinz-Christian Strache, often referred to as a young Haider clone, took control of the FPO from 2006 to 2008. He consolidated the party and its finances, restructured its community-based auxiliary organisations and led a non-stop campaign to listen to the voters’ collective concerns about Europe and immigration. Haider then changed strategy and focused on restoring his reputation. He strove to be thought of as a paterfamilias who cared about his province’s constituency, but also – in his role as Minister President of Carinthia – as a rational politician governing his land in coalition with the SPO. Haider’s plan succeeded. In 2008, the BZO won more than 10% of the voters and the FPO 17.5%. Haider’s death in 2008 left the field open for Strache, who began his rise to power (see below). Lastly, the FKP party emerged from a BZO scission in 2009, headed by the charismatic Uwe Scheuch and by Minister President of Carinthia Gerhard Dörfler.

The Far Right is currently split ¬– but for how long? ¬– into three groups: the FPO, the BZO and the Freedom Party in Carinthia (Die Freitheitlichen in Kärnten – FKP).9

Programmes of the Far Right

see : fpoe.at\fileadmin\Contentpool\Portal\wahl08\FP_-Wahlprogramm_NRW08.pdf: ”Österreich im Wort.”

Nina horaczek and Claudia Reiterer, HC Sein Aufstieg. Seine Hintermänner. Seine Feinde (Vienna, 2009).

see: “Programm des Bündnis Zukunft Österreich,” in: http://www.bzoe.at/assets/files/Programm_BZOE_ pdf

Heimat means homeland

The FPO’s programme for the 2008 elections, “Our promise to Austria,” and the FPO campaign with its radical political profile clearly focused on societal, security and immigration issues. These themes were an ideological asset and are still omnipresent in 2011.10 As in previous programmes, the party’s flagship theme for the 2008 elections was immigration. The FPO advocated “a humane and consequential return” of foreigners to their homelands, particularly criminals and “parasites of the social system.” As for Muslims, the FPO announced that it wished to ban “politico-religious victory symbols” such as minarets, and to penalise such “constitutional norms” violations as “violence against women, abuses of freedoms of the press and of speech, as well as cruelty to animals,” a traditional European Far Right expression for ritual slaughter. Teachable children would have to take a language test which, if failed, would cause them to be excluded from the educational system. Foreigners would be subject to a reduced social security system which would not compensate them in case of serious health problems. In the event of long-term unemployment, they would have to leave Austria. The labour market would be protected by a national preference system. In short, an analysis of FPO’s programme shows that it is a model of protest populism, xenophobic, security-conscious, homophobic nationalist and anti-European, which deliberately targets the list of social strata or population groups most discontent with, or most threatened by, Austria’s economic and social situation.

Since 2005, Strache has managed to make the most of his “young leader” physique.11 In the press, while Haider is photographed in gay nightclubs, his magazine photos show him surrounded by young and beautiful groupies. For the 2008 election campaign, he decided to attack one of the Left’s mythical figures, Che Guevara. He published a song on the Web – “Adios, Che” which was heard over 200,000 times and later played all over the world. His (apparently) very natural style is pleasing and achieves its goal: he is popular, sexy and (thanks to his trendy clothes) attains a credibility and political aura which seems to be a welcome contrast to the “old politician” style. His young supporters obviously do not understand the extent to which Strache’s style is an intentional attempt to imitate the 1990s’ Haider style. Experts taught the man how to speak, smile and dress, although he deserves credit for his undisputable talents as a communicator and his obvious charisma.

In the 2008 elections, the BZO’s main goal was to prevent, at any cost, the continuation of the Grand Coalition. Its programme entitled “Because of you, Austria” encompassed several series of more or less populist measures, but it was still more liberal than the FPO’s, despite the greater importance given to security and immigration issues. This programme was nonetheless perfectly adapted to Haider’s strategy: to attract potential protesters hostile to both immigration and the continuance of the Grande Coalition, yet who did not want to vote for what they considered an overly extreme FPO party.

A new programme was adopted on the occasion of an Extraordinary Congress meeting in Vienna in May 2010.12 The party defined itself as “a force for reform and right-wing liberal control.” Its preamble still credited Jörg Haider’s intellectual legacy and set out the main points of the party’s policy in terms of continuity as well as change, emphasising traditional liberal themes. A priori, it seemed evident that it had broken away from the Far Right’s conventional themes.

This impression is confirmed in the programme’s introduction, which summarises, in ten points, the party’s ideas. The parties’ traditional system and the Proporz are rejected in the name of the need to modernise Austrian politics by calling for broader citizen involvement. In the proposal “Man’s freedom is intangible” (point 1), the BZO wishes to return power to the people, as citizens should “dominate the State.” Freedom, the first principle, conditions all others (point 2). This implies a strong and constant call to order which can only reach its full potential within a democracy. The social State must be reformed to curb the emergence of an “all-risk insurance” mentality and to compel citizens to significantly contribute to its universality and preservation (point 3). “With The Heimat13 , tradition and culture form the identity of the State and of the people” and such “roots” are the key to the future (point 4). They must be protected from globalisation and immigration. What the BZO first demands of migrants is that they integrate into Austrian society. They must respect dominant Western Christian culture’s norms, under penalty of repression. Point 5, “No freedom without ownership,” calls for the State to be reduced to a minimal management and service role. The notion of “family” is acknowledged (point 7) as the “core unit of society” (point 8), and it should be afforded “maximum autonomy.” The right to a “private sphere” is declared inalienable. Point 10,“Sustainable Development,” revolves around ecology and nature preservation. The BZO opposes nuclear energy and genetics, and advocates for an “energy autarchy” and the systematic use of environmentally friendly technologies. In the ten explanatory chapters, the BZO presents itself as pro-European and in favour of a “European house,” but is critical of the existing policy to integrate Turkey into the EU and of the latter’s rapid enlargement, and of the European Commission’s actions. The BZO defends the right to asylum for political reasons, yet wants to put an end to immigration, including immigrants of European origin, except for the immigration of elites useful to the country, provided that the latter agree to become integrated. In conclusion, the programme’s moderate tone, the absence of Strache-type racism liberal economic positioning can only point to a profound change in the BZO’s ideology. What the BZO’s members and voters may think of it in the spring of 2011 remains to be seen.

Organisation and financing of Far-Right parties

A complete rebuilding of the FPO organisation on the national and regional levels is only partially attainable based upon available data.

in 2002, the FPO had 1,248 local groups and 237 support points. Today’s FPO members are organised into local groups, but mainly into district groups comprised of members and supporters from several communes.

No internal data is available concerning the number of members constituting all of the party’s auxiliary The figures cited were gathered during interviews.

Martin strutz, Maximilian Linder and Josef Jury were elected to seats in the National Council and Peter Mitterer and Peter Zwanziger in the Upper Chamber.

Special aspects of the FPO’s organisation deserve special attention in that they make it easier to understand how this party currently functions: membership trends, auxiliary organisations, parliamentary splinter groups, inner workings and, lastly, funding.14

In October 2000, the FPO had 51,296 members, as compared to 44,959 members in 2004.15 Its electoral successes in the 2008-2010 period allowed it to recruit more members. Although the official number of current members is not known, it is estimated at about 50,000, which does not include sympathiser groups in the party’s auxiliary organisations.

The organisations with Haiderian party “ties” included those representing young people, women, students, liberal professions, employers, teachers, the self-employed, university graduates, seniors, etc. Until 2002, the FPO managed, through these groups, to represent citizens from all strata of Austrian society and to conduct targeted propaganda campaigns. The FPO’s 2002 crisis and the ensuing scission of the BZO greatly weakened these auxiliary structures. At present, they seem to be experiencing a modest revival in tandem with the FPO’s growing success at the polls.16 One noteworthy example is the increasingly influential Freedomite Employees (freiheitlichen Arbeitnehmer), which has been acknowledged since 1 July 1999 as a “union member organisation” of the Austrian Trade Union Federation (OGB). After winning 67 seats in 2009 in the Workers Chamber (12 for the BZO, 483 for the FSG – the Social-Democrat Group of Socialist Trade Unionists (Fraktion Sozialistischer Gewerkschaftler) – and 212 for the conservative party workers’ organisation, OAAB), the FPO is now the third-largest party of this Chamber.

The FPO is Austria’s third largest parliamentary force at the national and regional level. After an agreement was reached between the FKP and the FPO, the three FKP members elected to the National Council17 joined FPO’s Parliamentary Club, as did the two FKP members elected to the Upper House. In early 2011, the FPO thus had 37 seats in Parliament and nine in the Upper House.

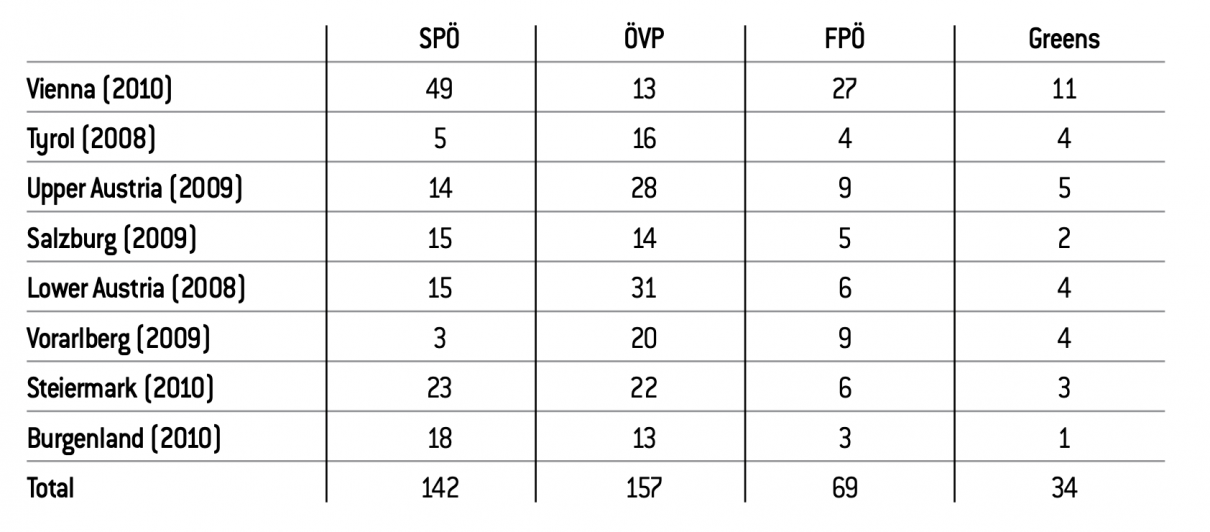

Table 3 : Members Elected to the Austrian Landtag (simplified table)

These parliamentary groups are essential to the party’s organisational life, since the deputies, parliamentary attachés and splinter group staffs double the regional federations’ modest permanent staff. Strache – who had learned a lesson from Haider’s communications strategy and the unwieldiness of the OVP and SPO parties – was committed to a modern (and costly) conception of politics: employing PR firms for election campaigns, making massive use of the media and the Web, maintaining a very lean central apparatus and a small circle of advisors, and buying political market information and analyses (from experts and polling companies). The FPO only rarely does street campaigning and most of its activities revolve around Strache’s meetings and party events.

This party has numerous contacts with Far-Right parties and groups in Europe (the National Front, Danish People’s Party, Ataka, etc.). Its closest current contacts are with the Vlaams Belang in Belgium and the Citizens Initiative for Cologne (Bürgerbewegung pro Köln) in Germany, which the FPO supports in its anti-Islam campaign. Strache models his campaigns on those of the Swiss People’s Party (Schweizerische Volkspartei), even if official contacts between the two organisations are few and discreet.

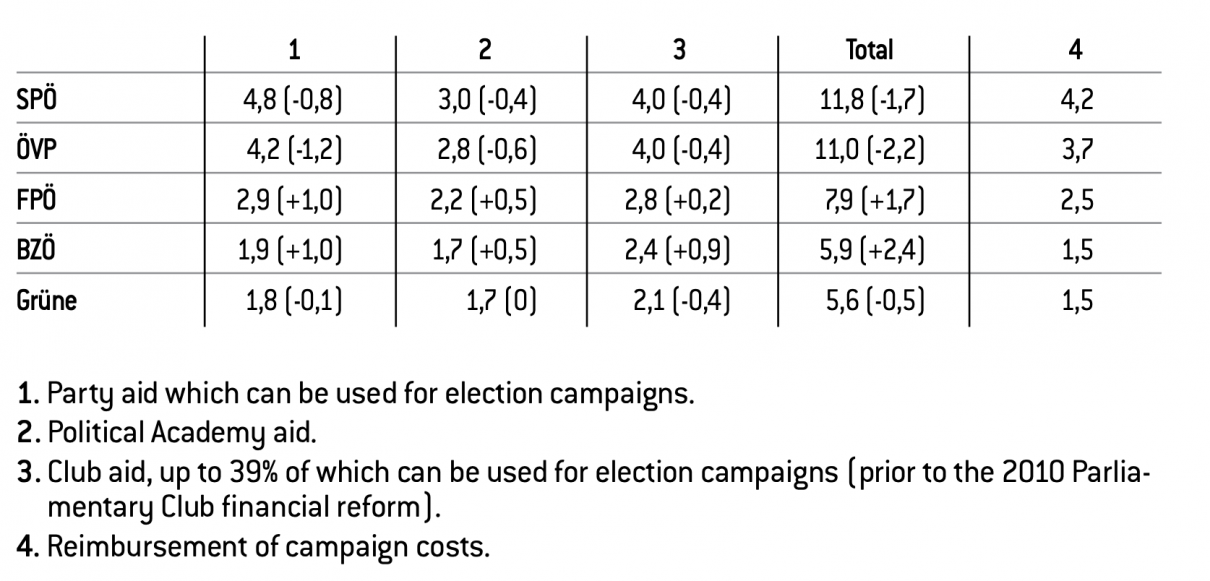

Table 4 : 2009 Party Funding (in millions of euros) and 2008-2009 Trends

The sPO will receive 9 million euros (13.2 in 2010, -1.3); OVP 4 million (5.2 in 2010, -1,2), the greens 3.7 million (4.1 in 2010, -0,4).

This ambition to open up to the liberal movement has facilitated the promotion of new senior officials in the Two examples: Walter sonnleitner, head of the BZO’s list in Vienna – but not a party member – was, until he retired, the ORF’s economic editor and is President of the Association for Austria’s Middle Classes founded in April 2010. As the author and co-author of many books and articles on economics, he is an undisputed expert in his field and a bona fide liberal. The BZO’s new general secretary, Christian Ebner (aged 40), who was appointed in May 2010, is a former OVP member who also defines himself as a liberal. he manages an economic advisory company (EbnerBiz Consulting gmbh) and wishes to profile the BZO’s expertise in economics. Although it is certain that the party’s three Vice-Chairpersons – gerald grosz, Ursula haubner and herbert schreibner – are long-term haiderians, there is nonetheless an increasing number of National-Liberals in the party.

see: Eugen Maria schulak, herbert Unterköfler: Die Wiener schule der Nationalökonomie. Eine geschichte ihrer ideen, Vertreter und institutionen, Bibliothek der Provinz, 2009.

To finance its political activities, the FPO had 7,192,471 euros in 2009. In 2011, it will receive 3 million euros of aid at the national level, supplemented by 2.3 million in support of Political Academy activities, and 3.5 million in aid to the National Council’s Parliamentary Club. Vienna’s election was a godsend for the party, since the FPO’s official aid increased by 70% (7 million euros in 2011 vs. 4.1 million n 2010, or +2.9 million).18 These funds are all the more significant for party activities in the state (land) since the party maintains only a very limited permanent staff and most of the FPO’s freiheitlich activities will be taken over by the FPO’s elected representatives in the commune and state legislature (Landtag). The funds saved will be reinvested into the media campaigns of the FPO, which has no more regional debt and now has the benefit of a substantial financial cushion.

In the aftermath of the FKP’s scission, the BZO’s shortcomings far outnumbered its assets. Besides its still-sound finances and its parliamentary splinter group in the National Council (17 seats), which remained practically intact, the party was decimated. In 2011, it was cautiously estimated that it has a maximum of 3,000 members. Regardless, the party is virtually absent from the communal and regional political scene (except in Upper Austria, Steiermark and Vienna). Its only hope of survival resides in its media coverage until such time as it recruits new members, even as the FPO is reabsorbing what was once the Haiderian BZO’s electoral base. The only solution is therefore to seek out new individuals to head the party19 and to cater to disenchanted voter groups. That is why the BZO is trying to reorient itself along liberal lines which correspond to a strong intellectual tradition20 – one that has yet to politically materialise.

In 2010, the FKP decided to seek a rapprochement with the FPO, on a model similar to that of the CDU-CSU. Although the FKP remains autonomous, it is represented in the FPO leadership. It is estimated that 90% of Carinthia’s Haiderian BZO members went over to the FKP. Since this party should not exist outside of this state, most of the FKP sympathisers from the other länder have joined the FPO. The FKP also has a mini-organisation for youths, the club Kärnten-Jugendorganisation, and four auxiliary organisations, only three of which have been set up in all of Carinthia (farmers, workers and trade unions). It has 19 elected representatives in the Landtag, two of whom are in the Bundesrat (Upper Chamber). Since December 2009, its three representatives in the National Council have been integrated into the FPO’s Parliamentary Club, while remaining FKP members. The party’s influence depends on its governmental action, since the FKP appoints the Minister-President of Carinthia (Gerhard Dörfler) and three out of six other ministers (Uwe Scheuch, Harald Dobernig and Christian Ragger). In this context, the party seems to be able to maintain its significant success at the polls despite early signs that Jörg Haider’s reputation image may be losing its lustre. Despite some internal resistance, reunification under the FPO banner may be a likely middle-term outcome.

In view of its lack of activists, the BZO decided to win liberal voters by intensifying its media campaigns, a costly strategy. The BZO’s 2008 official financial report confirms the latter’s relative prosperity, with a volume of over 4 million euros. The funding of the BZO’s Parliamentary Club was 1.5 million euros in 2008 and 2.55 million in 2009.

With this degree of financial security, the BZO appears to be in a position to pursue its propaganda activities in 2011 and 2012, but if it is unable to garner substantial votes in future regional and national elections, its modest war chest is bound to shrink, resulting in the party’s inevitable demise.

Balance of Electoral Power within the Austrian Right

Geographical distribution of Austrian parties

The OVP and SPO have almost always fought for the top spot in National Council general elections, except in the 1999 election, in which the FPO became the second-place Austrian party, beating the OVP by 400 votes. The OVP has been dominating politics in five Bundesländer, or federal states (Upper Austria, Styria, Upper Austria, Tyrol, and Vorarlberg), and has managed to appoint the Minister-Chairman continuously since 1945. This was also the case in Burgenland from 1945 to 1964, in Carinthia from 1991 to 1999, and in Salzburg from 1945 to 2004. In 2010, the OVP continued to dominate the four Bundesländers’ politics and govern in various political constellations.

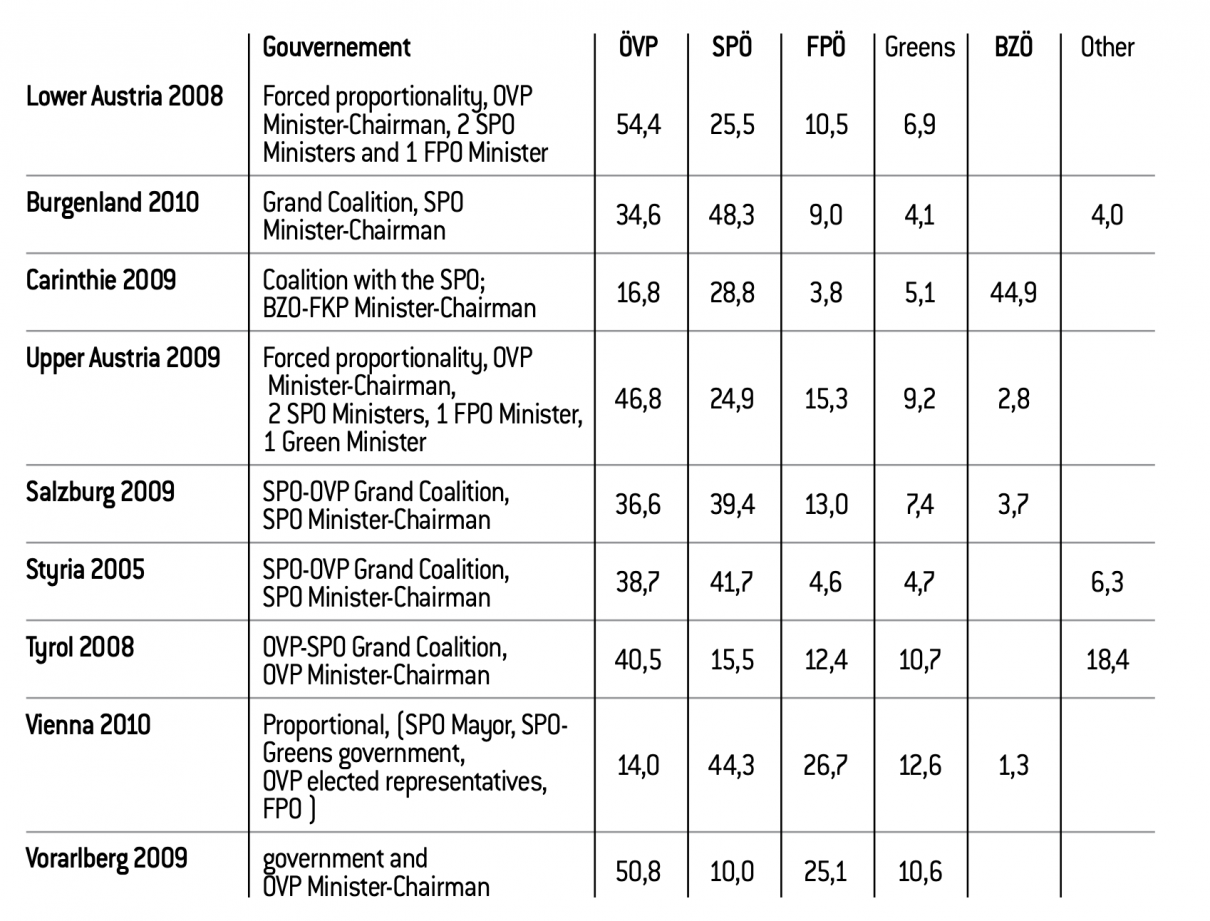

Table 5 : 2008-2010 Regional Elections

By computing the national mean for each party’s election results in the Bundesländer for the 2010-2011 winter period, we obtain the following results: OVP: 35%, SPO: 34%, FPO: 16%, Greens: 9% and BZO: 2%. Regional results translate into the same trend observed at the national level: an almost equal sharing of power between the SPO and the OVP. At the communal level, the OVP took advantage of the FPO’s and the Greens’ low representation and won in five federal states.

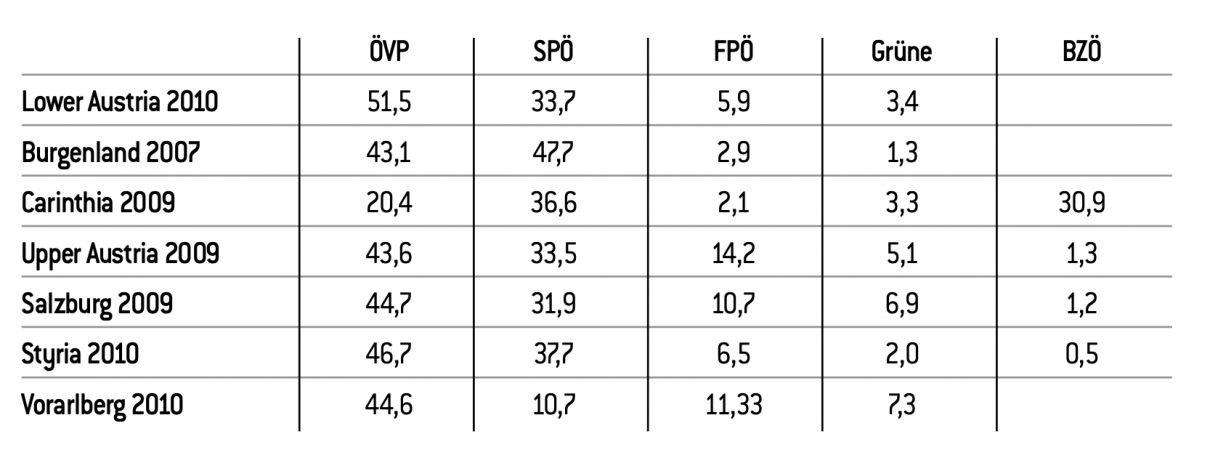

Table 6 : 2005-2010 Communal Election Results for the Parties

This table shows that the OVP’s results are strong in rural communes and small towns, while the SPO’s strength lies in large cities and communes with key manufacturing and service industry sectors.

Socio-demographic distribution of Austria’s right-wing and Far Right parties

see Thomas hofer and Barbara Toth (Ed.), Wahl 2008. Sieger. Sensationen (Vienna, 2008). On the 2006 general election, see Fritz Plasser, Peter A. Ulram (Ed.), Wechselwahlen. Analysen zur Nationalratswahl 2006 (Vienna, 2007).

see Fritz Plasser and Peter Ulram, “Die Wahlanalyse 2008. Wer hat wen warum gewählt?” (Vienna: Presseunterlage, 2008); and sORA, Nationalratswahl, in: http://www.sora.at/images/doku/sORA_isA_ Analyse_NRW_2008.pdf

In September 2008, all of the democratic parties experienced a somewhat humiliating defeat. The OVP obtained 26% of the votes (-8.3% as com- pared to 2006), the SPD 29.3% (-6%) and the Greens 10.4% (-0.1%). The FPO’s results rose eleven points and it garnered 17.5% of the votes, the BZO also gained ground with 10.7%, an increase of 6.6%.21

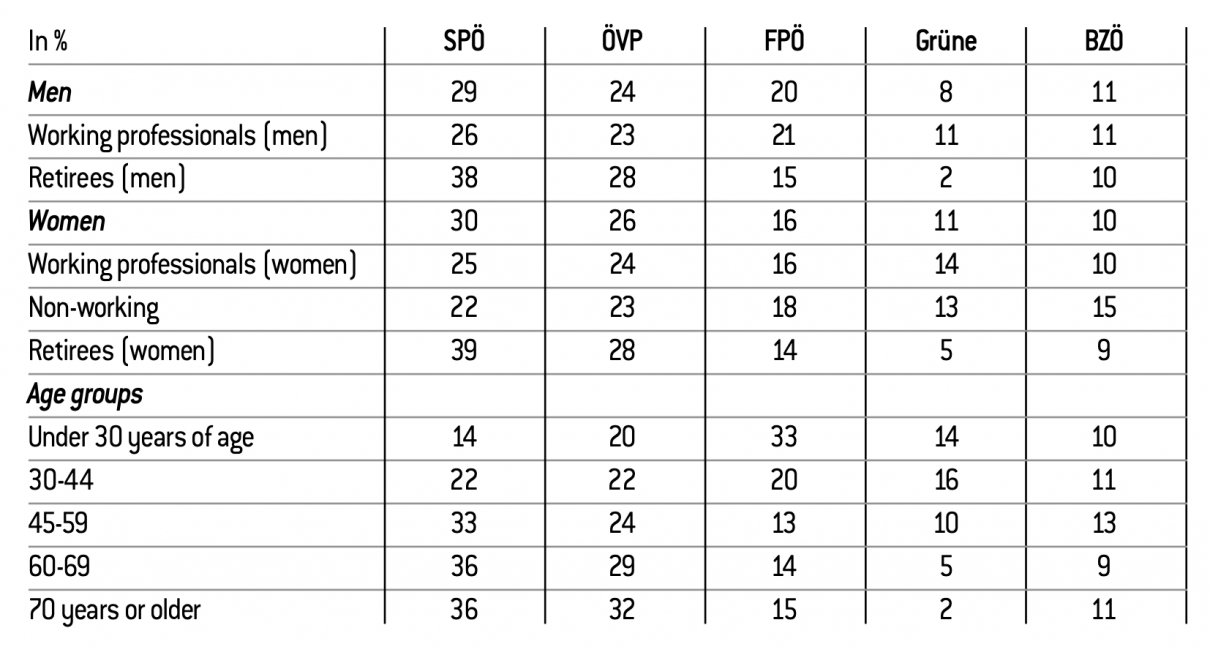

An analysis of voting trends between 2006 and 2008 shows that a fringe of electors belonging to the country’s leading parties rejected the Grand Coalition, which led to heavy losses for the OVP (116,000 votes) and the SPO (106,000 votes), with these transfers profiting the Far Right (the FPO and BZO).22 A gender breakdown of voters shows that the OVP remained, as in 2006, a party which women slightly preferred. If the parameter “Working Professional” is included, the OVP obtained its best election results in 2008 among retirees of both genders.

Table 7 : 2008 Electoral Choices: sociography (1)

Source :

gfK Austria, election exit poll

The possibility for 16 to 18 year-olds to vote for the first time in a national election – a measure desired by the OVP – benefited the FPO, since it was Austria’s most popular party among the “under 30” category. By adding the BZO’s scores (10%) to those garnered by the FPO, we find that 43% of young voters (one-third of whom were in the 30-44 age group) voted for the Far Right. The OVP obviously was finding it increasingly hard to recruit young members through its internal associations, while the “over 60” group was the category which cast the most votes for the OVP.

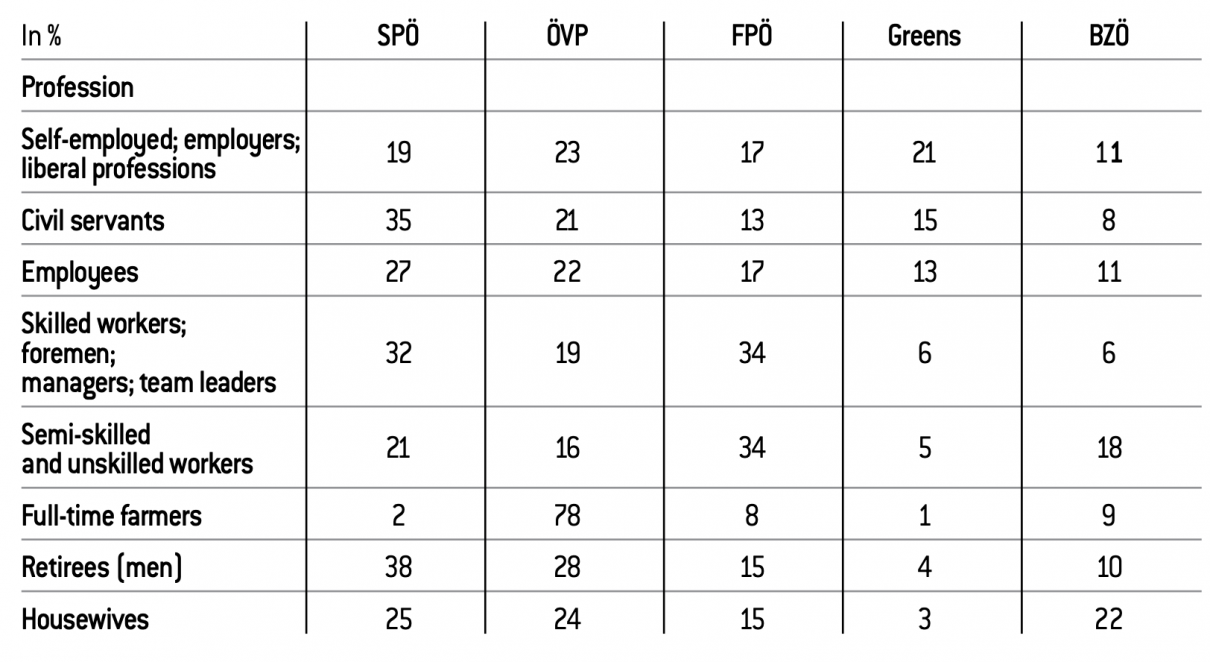

Table 7 : 2008 Electoral Choices: sociography (2)

Source :

gfK Austria, election exit poll

The breakdown by profession shows that in 2008, as in 2006, the OVP was the leading party among all self-employed categories, notably farmers. The SPO won the most votes among civil servants (35%) and employees (27%). In every worker category, the SPO was only the number two party, while the FPO scored exceptional results (34%).

It is clear in the post-election political landscape that the SPO was the preferred party of retirees and civil servants. Aside from farmers’ vote, the OVP did not win the support of any particular social category. The Greens (Grüne) were getting older and, for the most part, recruited members among the more highly educated. The FPO, and to a lesser degree the BZO, were the parties of workers, youths and individuals working in the private sector.

The reasons for voting for the Right and the Far Right

To explain the new power relations produced by the 2008 election, it is helpful to examine the voters’ motivations.

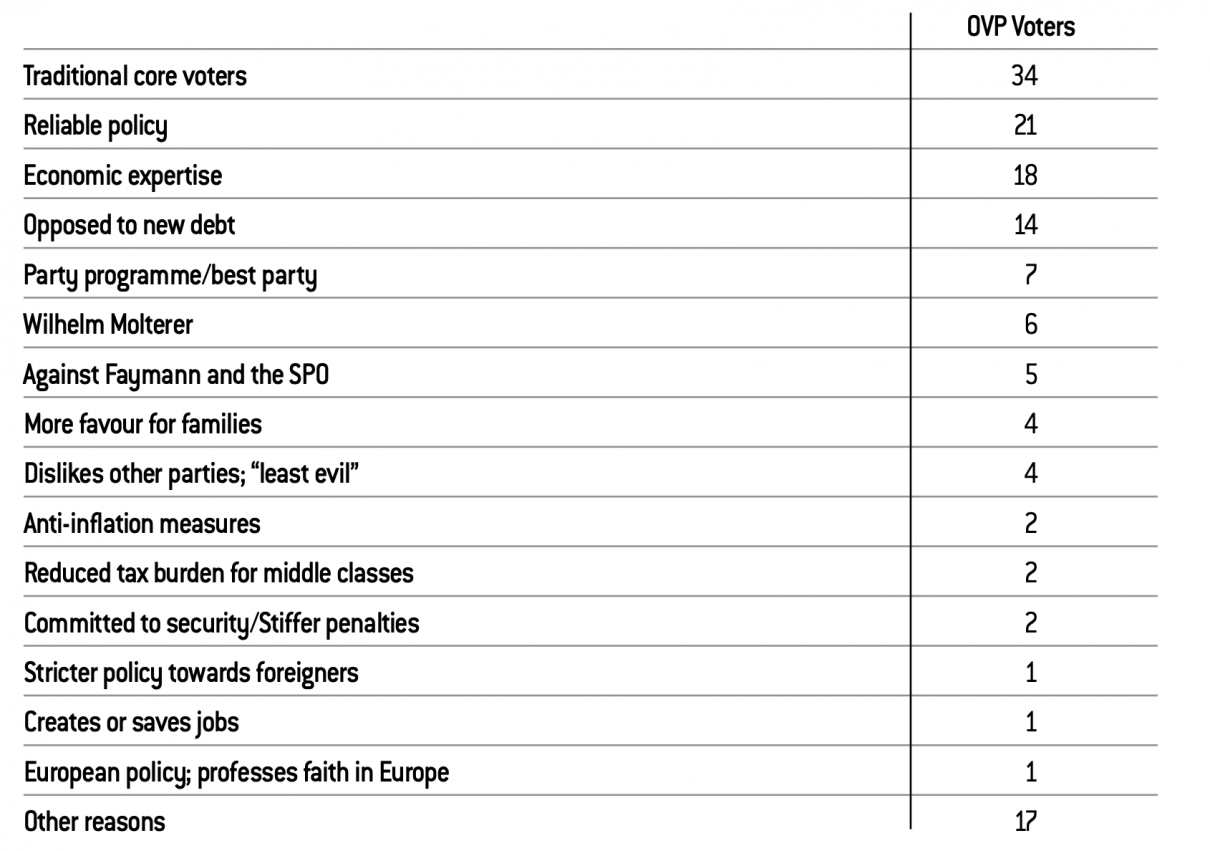

Table 8 : Reasons for Voting for the OVP – simplified Table (2008)

Source :

gfK Austria, 2008 election exit poll

Those who voted for the OVP in 2008 did so primarily out of loyalty to the party, its past policy, and its economic expertise. The scorecard was nonetheless poor for the OVP, whose candidate, Molterer, did not appeal much to voters who were not very enthusiastic about the party’s programme, either. The commitment to Europe and security, which constituted the core focus of the party’s propaganda, no longer motivated voters. It was clear that the party was, in terms of capabilities, limited to its economic platform. The SPO, on the other hand, scored points because of its commitment to ordinary folk (17%) and social justice (16%). Party loyalty (36% of the votes) was also a dominant factor. To conclude, the 2008 election showed that the OVP was incapable of meeting voters’ expectations, whereas the Far Right knew how to exploit voters’ fears.

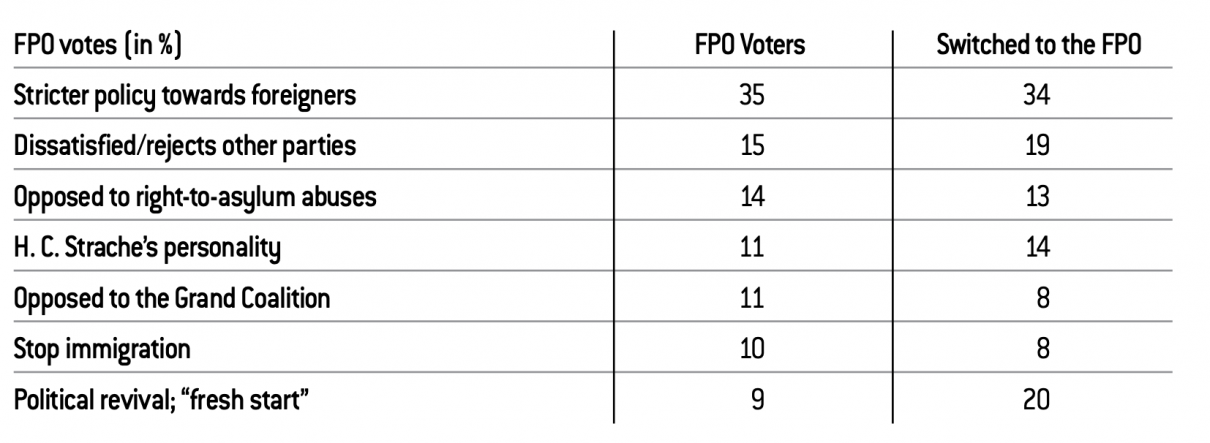

It may be helpful to analyse this breakthrough by the FPO and the BZO by examining the voters’ motivations.

Table 9 : Reasons for Voting for the FPO – simplified Table (2008)

Source :

gfK Austria, 2008 election exit poll

Those who chose to vote for the FPO in 2008 (60% of FPO voters and 53% of voters who switched to the FPO) did so, as in 2006, primarily because of the issue of immigration, as shown by the results from the combined categories “Stricter policy towards foreigners,” “Opposed to right-to-asylum abuses,” and “Stop immigration.” The two parameters “Strach’s personality” and “Opposed to the Grand Coalition” helped to mobilise the FPO’s electorate.

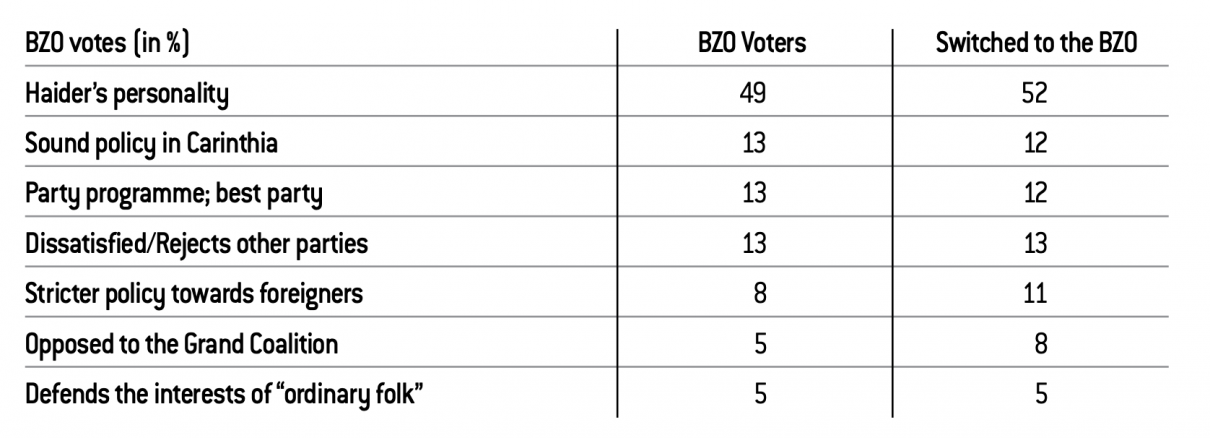

Table 10 : Reasons for Voting for the BZO – simplified Table (2008)

Source :

gFK Austria, 2008 election exit poll

The choice made by over 60% of voters in favour of the BZO was dictated – for every category of this party’s electorate – first by “Haider’s personality” and second by his “sound policy in Carinthia,” which can also be attributed to his personality. The “party programme” played a greater role than it did in the case of the FPO and matched the BZO voters resolve to prevent a new Grand Coalition. These FPO and BZO panels show that the two electorates had the same opinions on many issues (rejection of immigration, opposition to the Grand Coalition), but that, ultimate, FPO and BZO voters’ views were more different than similar. The FPO is first and foremost a xenophobic party, whereas the BZO is a “groupie” party.

The FPO and the BZO managed to unite numerous anti-establish- ment voters worried about the future, disoriented by economic ten- sions, critical of the political system and of European construction, and opposed to an OVP-SPO Grand Coalition and to immigration. Each of these issues is still timely today and explains, for example, the FPO’s September 2009 election triumph in Lower Austria and the October 2010 election in Vienna.

Demographic projections (source: sTATisTiK AUsTRiA, statistik des Bevölkerungsstandes, 10.2008) show 24.2% of the 60-or-older age group by 2015, vs. 22.6% by 2008, 32.4% by 2035 and 34.1% by 2050.

see August gächter, “Migrationspolitik in Österreich seit 1945, Arbeitspapiere Migration und soziale Mobilität,” in 12, October 2008; and Rainer Bauböck, “Nach Rasse und sprache verschieden – Migrationspolitik in Österreich von der Monarchie bis heute,” institut für höhere studien (ihs), Vienna, at: http://www.ihs.ac.at/ publications/pol/pw_31.pdf.

see Christian Fries, Regina Polak and Ursula hamachers-Zuba (Eds.), “Die Österreicherinnen. Wertewandel 1990-2008,” Bericht zur Europäischen Wertestudie 2008 – Österreichteil (Vienna, 2009).

Unemployment at the European level: EU 27: 5%; EU 16: 10%.

Austria today is confronted with social and economic hurdles which the OVP, working within the framework of the Grand Coalition, is striving to resolve.

The first challenge is demographic. As in nearly all of the EU’s industrialised countries, one serious problem is the ageing population. By 2050, the over-60 age group may represent over one-third of Austria’s total population.23 In confronting this demographic challenge, all of the country’s political parties claim to be pro-family. Most of these principle- based positions have been all but obliterated by the economic crisis, as the Grand Coalition has only modestly increased family allowances and has dropped – at least for now – a plan to reform the tax system. Slowing down the ageing of the population can be achieved – unless there is a radical change in familial strategies – only by massive recourse to immigration, an option which the majority of Austrians reject.

In 2009, however, Austria was a land that welcomed immigration. The latter began in the 1960s and sharply increased as of the 1980s. The immigrants were of three origins: first, the former Yugoslavia (297,606 people) and Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The Austrians have had mixed but not hostile reactions to this type of migrant, since many Austrians have ancestors (and often family names) reminiscent of their Czech or Hungarian roots. Such is not the case with the Turks (110,105 immigrants) – the Hapsburg monarchy’s hereditary enemy.

Ranked lowest on the acceptance scale are the Africans, who have been consistently – and persistently – denounced by the media as “crime- prone elements.”

Austria’s political parties, with the exception of the Greens, who are very attached to their multicultural profile, are striving to either limit the migratory flows (OVP and SPO) or to stop them (BZO and FPO). The Grand Coalition is opposed to Turkey’s integration into the European Community, in the name of migratory risk. As for new EU members, the Grand Coalition is calling for longer timeframes before removing the freedom to live and work in Austria. The key issue on which the parties disagree is that which concerns the migrants already residing in Austria. The Far Right wishes to send them back to their homelands when they are unable to find work. The OVP and SPO reject such measures, but have nonetheless made family reunification very difficult for non-Europeans.24 Hidden behind this extremely rigid immigration policy (which, moreover, is largely ineffective), and compounded by a strong collective xenophobia.25 are economic concerns. Until now, Austria has always been a very prosperous country, despite a temporary decline in its exports in 2009. This economic success relies in part on a very broad social consensus group, the powerful Austrian Trade Union Federation (OGB), which strives to prevent strikes and work disputes – a strategy naturally supported by the OVP and the SPO.

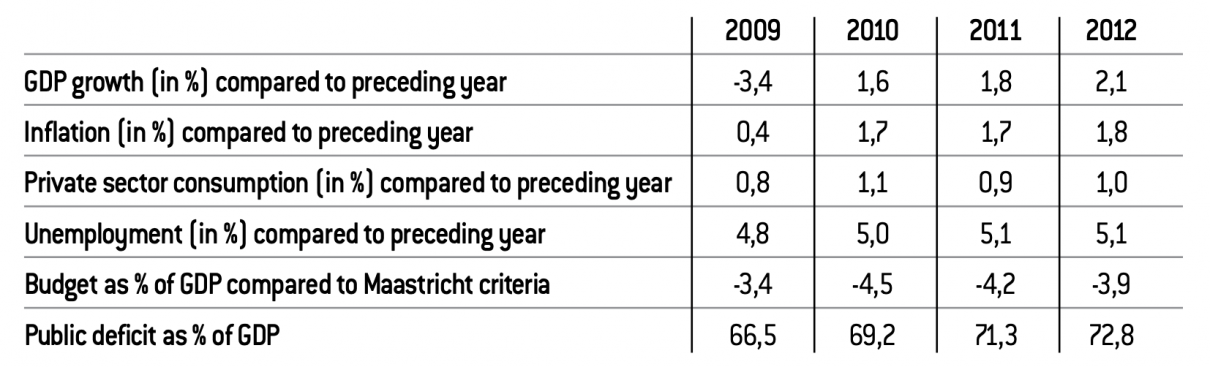

The OVP stresses the Coalition’s economic track record, for which it takes the credit. This record is actually rather good, compared to that of other European countries navigating these crises.

In September 2010, 5.9% of the population was unemployed, which was the same level as in 2004. Compared to what it was in September 2009, the unemployment rate had fallen by 8.7% (-12.6% for men and -3.9% for women, -8.6% for the 15-24 age group, and -17.3% for the long-term unemployed). At the European level, it is in second place, after Holland (3.9%).26

Austrian economists expect an additional decline in unemployment by 2012, provided that Austrian growth reaches 2.5% annually, a perfectly conceivable objective based on the country’s current economic performance.

Table 11 : Austria’s Economy: Austrian Central Bank Projections (15 June 2010)

One of the positive factors is domestic consumption, which rose again in 2010 (+0.25%, as compared to the last quarter of 2009), despite the strong increase in energy costs which interrupted the trend by boosting inflation (1.9% in July 2010). Exports also improved.

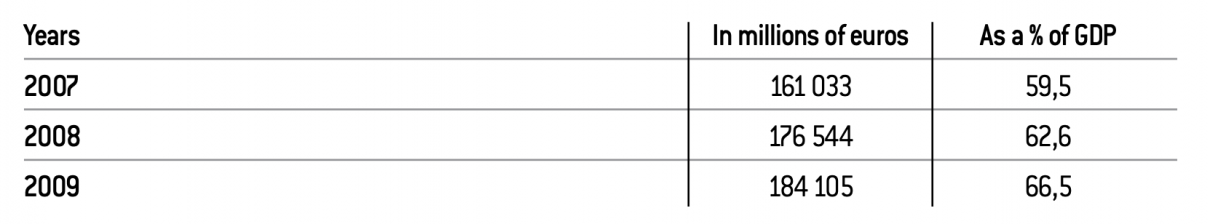

Although the financial crisis has affected Austria less than France and Germany, it still poses a challenge for the State budget, which must help stabilise the euro and the banking system, as well as reduce the public deficit. In 2009, when public debt reached 184 billion euros, the Court of Auditors stressed in its March 2010 structural analysis that, in 2013, 15.2% of the State budget (11.4 billion euros) would be allocated to service the debt. If no measure is taken, the future of public investments in priority sectors (research and training, for example) will be threatened.

Table 12 : Austrian state Deficit

Source :

statistik austria, 29.3.2010

In order to comply with the Maastricht criteria, Austria must reduce its deficit. For 2011, the government decided on a savings and tax pro- gramme totalling 2.8 billion euros in order to resume meeting the criteria by 2012. These savings’ measures, which will naturally be unpopular, are a risky step for the Grand Coalition, which knows that the Far Right is capable of preparing an ambush in the 2010-2013 period of regional elections and the year-end national elections of 2013.

No comments.