The state of the right: Bulgaria

Introduction

The Bulgarian Right’s historical roots

The post-Communism Bulgarian Right

Founding of the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF)

The first split: UDF becomes a Centre-Right party

The coalition evolves into a unified party

The Three Rights: Democratic, Populist, and Extremist

The “Blues”: An authentic Right

The Populist Right

The Far Right

Conclusion

Abstract

The roots of Bulgaria’s Right date back to the Ottoman Empire. At that time, the national political class was divided between the Right of the “Ancients” (who advocated a peaceful progression towards independence, and that of the Left, the “Moderns” (youth groups), who were more radical. After independence was declared in 1878, Bulgaria’s liberals joined the conservative Right in its opposition to the left-wing socialist and agrarian parties. The Communist takeover in 1947 completely disrupted this scenario.

Today’s Bulgarian Right emerged from the struggle against the Communist regime which controlled the country for more than forty decades. In 1989, when the Communist power collapsed, dissidents and members of parties banned by the authorities were legalised and joined the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF). This composite coalition opposed the government led by the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), the successor party to the Communists. They joined forces because of their common desire to create a genuinely liberal democracy and a market economy in Bulgaria.

Originally of anti-Communist origins, today’s UDF is just one of several right-wing parties. In reality, the Bulgarian Right is split between the Centre Right, the Populist Right and the Far Right. The Centre Right is comprised of the UDF and Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (DSB). Populist groups, organised around a charismatic leader, have dominated the Right for ten years. For example, the National Movement Simeon II (NMS) led by the last King of Bulgaria, obtained close to 43% of votes in the 2001 election and dominated the country’s politics for four years. In 2005, the Populist Right because the leading opposition party. It was formed within the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) movement. In the 2009 legislative elections, the GERB received the majority of votes and its leader, Boyko Borisov, became Prime Minister. On the Far Right, “Ataka,” the National Union Attack Party led by former TV talk show host Volen Siderov, won less than 10% of the votes. On the other hand, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, which defends the interests of the Turkish minority, plays a pivotal role, alternately supporting the Right and the Left.

Antony Todorov,

How can the Right be analysed within the context of a post-Communist country’s politics? To begin with, it is difficult to define: today’s Right, twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Communist regimes, is the product of a somewhat heterogeneous anti-Communist opposition which united diverse political movements with opposing visions of the country’s future. While abandoning Soviet-type Communism ultimately proved to be a unifyin g programme, twenty years later that is no longer the case, now that Bulgaria has joined the European Union and NATO.

Today, several parties claim allegiance to the Right. In a post-Communist country such as Bulgaria, asserting one’s affiliation with the Right appears more prestigious and less questionable than a left-wing affiliation. These parties emerged only recently, even though some affirm that they are successors to traditional right-wing parties of the pre-Communist regime. Indeed, on the level of both the elites and the organisations and ideologies, any continuity between the pre-World War II political arena and that of today seems to be an abstraction and a pure product of political imagination.

Nonetheless, twenty years of political development did not leave the country’s reality unchanged: today, it has a post-Communist Right similar to the Right in most European countries and which seems to be rooted in contemporary Bulgarian society. Because today’s Bulgarian Right stems from the Post-Communist transition – strongly influenced by the impact of accession to the European Union – it is not just one Right which can be identified in Bulgaria, but at least three separate movements: a liberal Right, a populist Right and a radical, or nationalist Right.

Another methodological question consists of how to define the Right. The concepts of Right, Left or Centre, ¬often used in an effort to distinguish and classify political projects, ideologies and parties, have evolved from the French Revolution, but their content changed considerably from one era to the next. Their meaning also differs from one European country to another: the Right in Bulgaria and Romania is not the same as the Right in France or in the United Kingdom. The same holds true for the Left.

It is thus impossible to associate the Left and the Right with ideological movements on a quasi-permanent basis. Culturally, the conservative Right may oppose the liberal and socialist Left, just as in terms of economics, the socialist Left may oppose the liberal Right.

The Bulgarian Right’s historical roots

S.M. Lipset and S.T. Rokkan, Party Systems and Voter Alignment: Cross-National Perspectives (New York: freepress, 1967).

Bois, Paysans de l’Ouest (Paris: flammarion, 1960).

Doyno and I. Stoyanov, La restauration de l’Etat bulgare, 1762-1878 (Varna: ideas, University Presses, Varna free University, 2002).

Miliukov, La Constitution bulgare (sofia: sofia University Press, 2009), a facsimile of the 1905 original.

A. Todorov, Citoyens, élections et partis. La Bulgarie de 1879 à 2009 (Paris: est-ouest, 2010).

one of the era’s official

The initial emergence of the Bulgarian Right was the product of a long modernisation and political development process which followed the country’s independence (1878). A better understanding of the nature of this Right can be acquired by examining Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan’s social cleavages theory1. Social cleavages, which are structural conflicts that accompany the modernisation of European societies, ultimately form and change political structures and partisan families.

The rise and structuring of the public and private sector, secularisation, urbanisation and industrialisation are all key factors in the emergence of Western modern societies. Bulgaria did not escape such processes, which have been spreading throughout Eastern Europe since the last third of the 19th century. Yet a few unique characteristics should be highlighted to enable us to better grasp how a country such as Bulgaria experienced modernisation. First, there is the special role of the Orthodox Church, which has remained attached to the principle of ethnic emancipation of the Bulgarians who, in the early years of the modern era, were part of the Ottoman Empire. Second, urbanisation began somewhat belatedly, inasmuch as Bulgarian cities remained primarily Turkish until the end of the 19th century. Lastly, industrialisation and the emergence of a modern industrial society in the country occurred only after World War II and under a Communist modernisation plan during the 1950s and 1960s.

These particular conditions of Bulgaria’s modernisation impacted the potential characteristics of the profiles of the traditional Right: the absence of a traditional landed aristocracy, a weak national Orthodox Church, a society comprised mainly of a peasantry both middle-class and poor, and limited urban layers – conditions propitious for the advent of a populist and clientelist Right and for a weak urban and elitist Right.

Bulgaria did not elude the cleavage mechanism as defined by Lipset and Rokkan, and was also impacted by another political arena differentiation factor associated with the effects of the so-called “historic traumatism.”2 National emancipation as the Bulgarian community’s initial project since the end of the 18th century became a staple theme on the political landscape due to the dramatic events which shook the national consciousness and left a lasting impression on people’s minds. Historic traumas of this sort have followed in rapid succession in the history of Bulgarian society starting in 1876, when the national revolution failed: the wars of 1912-1918, the civil wars of 1923-1925 and 1941-1944, Stalinian Communism of 1948-1956, not to mention the Bulgarisation of the Turkish minority in 1984-1985 and, lastly, the fall of Communism in 1989-1990.

In the early 19th century, the national emancipation of the Serbs, Romanians and Greeks – Christian peoples and the Bulgarians’ neighbors – with the direct support of European powers, expedited the adoption by the Bulgarian intellectual elites of the national independence concept as the focal point of their political programme. Yet, although the identity strategy aimed at fostering national patriotism did not trigger conflict among members of the budding Bulgarian political class, the paths to national independence did become a major and long-lasting divisive issue.

The terms “Ancients” and “Moderns” (youth groups) first arose in Romania during the 1860s and 1870s within the context of the Bulgarian political emigration to Romania. They were used to distinguish between the two groups opposed to the Ottoman Empire: the “Ancients” were moderate businessmen who wanted Bulgaria to be independent, but were still reluctant to pay the price. They preferred to involve the major European powers in finding a solution to the Bulgarian issue and to achieve independence gradually and without any serious conflicts. The “Moderns” were revolutionaries influenced by late 19th-century radical, liberating and socialistic ideas. They wanted to enlighten the people so that they would rise up against the tyrant3.

This initial gap between the Ancients and Moderns reflected two radically opposed visions of society and politics, and marked the development of a decisive cleavage based upon a difference in political tactics under historically traumatic circumstances stemming from the 1870s’ uprisings against Ottoman domination. This cleavage had significant consequences: it became the decisive factor in shaping Bulgaria’s political landscape. The two opposition platforms were passed on to successive political generations and were adopted by various parties. The Ancients were interested in preserving the social status quo, natural hierarchies and promoting the elites’ prestige, while the Moderns, who were against all of this, kept on trying to enlighten the people and involve them in politics.

As soon as Bulgaria won its independence in 1878, two political movements emerged in the Constituent Assembly: the Conservatives and the Liberals– European labels which respectively correspond to the Ancients and the Moderns. However, as Russian historian Piotr Miliukov remarked at the time, “All of the people were liberals4, whereas the Conservatives represented only a small elite of rich shopkeepers and intellectuals whose destiny the people were scarcely capable of leading by themselves. The debate shaping the political sphere at the time focused on the Constitution and democracy, yet it was only the logical outcome of the preceding debate within the national elite between the Ancients and the Moderns. In this newer configuration, the Ancients played the role of pioneers in the formation of Bulgaria’s historic Right.

After 1894, a whole palette of modern political parties emerged from the liberal movement. This process had already begun in 1887, with the first split of the Liberal Party into the “moderates” and the “nationals.” The point of contention was once again an international issue: the major powers’ policy concerning the unification between the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia in 1885-1886. Russia’s opposition to this event sparked a lively debate among Liberals. Their political leader, Stefan Stambolov, decided to organise a new political movement, “Bulgaria for itself.” The latter led to the creation of a new political party, the National Liberals, who became increasingly russophobic. For their part, liberal opponents of the dictatorship, deeply involved in the 1885 coup d’état in Eastern Rumelia, chose to join the conservative russophiles, which in turn gave rise to the Popular Party, founded in 1894.

Although several political labels surfaced as a result of the split among the liberals (Democratic Party, Liberal Party, Progressive Liberal Party, Popular Party, National Liberal Party, Radical Democrat Party), two political groups remain: the conservative and the liberal. Yet each was still playing the role of the “Ancients” (elitism) while maintaining different political orientations in terms of foreign policy. Having formed their own political elite after serving in government, and distancing themselves from their revolutionary and popular origins, Bulgarian liberals “aged” and have become the defenders of traditional social hierarchies, while also remaining deeply devoted to “national ideals.”

Moreover, the role of the Moderns was gradually taken over by two new political forces which appeared at the end of the 19th century: the Socialists (1891) and the Agrarians (1899)5. The latter quickly adopted the legacy of the Moderns and the latter’s propensity for involving the public in politics. As Republicans, they asserted their radical rejection of the existing political system. Two left-wing parties existed then, but they were very dissimilar. The Bulgarian People’s Agrarian Union (BPAU) developed a national ideology predicated upon the specificities of a primarily agrarian country. The Socialists, to the contrary, emphasised the fact that Bulgaria’s capitalist development had positioned the country in a global process and that its distinctive national characteristics were thus bound to disappear.

In the early 20th century, there was a sort of “bipolar quadrille,” to borrow the expression which Maurice Duverger used concerning France, with four distinct political parties (Conservatives, Liberals, Agrarians and Socialists) assuming the Ancients’ and Moderns’ two traditional political roles; i.e., that of the Right and of the Left.

The Ancients’ elitism, deprived of any leverage in a country whose aristocracy had no longer existed since the 14th century, and in which egalitarian social psychology prevailed, was transformed within the next few decades into a nationalist populism aimed at promoting a strong identification of the people with the country’s leaders. Yet the perpetrators of the successive coups d’état of 1923, 1934 and 1944 obviously belonged to the same political milieu – that of an enlightened elitist Right. The main thrust of their political agenda was to establish the government of this enlightened elite comprised of political management professionals thought to uphold the truth.

Communism, whose leaders assumed power in Bulgaria in 1948-1949, seemed at first to mark an absolute victory for the Moderns, putting an end to the Ancients as a political organisation. Yet this was not really the case. The Communist Party, which governed without sharing political leadership, generated a paradoxical synthesis by assuming both roles at the same time, at least initially. Two objectives always present in the Communist regime’s politics have been implementing revolutionary change and maintaining the established order – two objectives which have always been the two key components of Communist regime politics. After a Stalinian period of sudden and radical changes in all areas (1947-1956), “real socialism”6 prevailed as a model for Communist modernisation and construction of a consumer society with a relatively advanced social State. Under such circumstances, the idea of a transformation which would broadly mobilise citizens was not eliminated from political discourse, but was gradually replaced by a focus on safeguarding the established social order, with all of its hierarchies and leadership mechanisms In a way the CP “aged” to become the “Order Party,” thereby assuming the conservative role.

After the Communist regime collapsed in 1989, the early days of transition were marked by resumed conflict between the Ancients and the Moderns, evidenced by the opposition between the anti-Communists and the ex-Communists. The ex-CP, or Order Party, took on the conservative role. In this new setting, the new Moderns’ discourse was paradoxically conservative, liberal and right-wing, whereas the Order Party remained left-wing. From this vantage point, the transition was a political and ideological profile change which impacted the two leading protagonists: the ex-Communists and anti-Communists. In order to become Social Democrats, as most of their counterparts had done in other Central and East European countries, the ex-Communists had to move towards progressivism, a departure from their initial post-1989 role as a conservative faction . The anti-Communists on the other hand, in order to promote the transformation of State Communism into a society based upon competition and inequalities, had to become more right-wing and abandon their revolutionary and mobilising discourse. This paradoxical role shift was evidenced by several transition-specific phenomena which often seemed inconsistent, contradictory and incomprehensible.

The post-Communism Bulgarian Right

Todor Zhivkov, a Bulgarian Communist leader (1911-1998), was in power from 1954 to

The formation of today’s political pluralism closely followed the dis- mantling of the Bulgarian Communist regime after November 1989. Communist leader Todor Zhivkov’s7 resignation marked the beginning of efforts to establish the country’s political forces on new grounds. The swiftness with which new political parties were formed typified this era.

Founding of the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF)

Notably Tchavdar Kuranov, a renowned sociologist critical of the former regime.

S. Malinov, Rise, Fall and Disintegration: The Bulgarian Center-Right in Power and in Opposition in Peter Ucen and Jan surotchak (eds.) Why We Lost. Explaining the Rise and Fall of Center-Right Parties in Eastern Europe (1996-2002) (Bratislava: international republican institute, 2005), pp. 5-27.

see the compendium of documents, “Yosifov, les origines – aperçu politique et chronologique” (Zhelyu Zhelev foundation, 2008).

see the website: http://www.omda.bg/bulg/news/parties_orgs.html.

This political differentiation process reunited the old and the new. Certain political forces which had already existed prior to 1989 re-emerged whose members primarily consisted of Bulgarian dissidents of the 1980s: Ecoglasnost, the Club for the Support of Glasnost and Perestroika, the Human Rights Committee, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF), the independent trade union Podkrepa, and the Committee for Freedom of Conscience.

Most of these groups had actually appeared five years earlier, after the government’s attempt to forcibly change the Bulgarian Turks’ proper names (the MRF), or following the anti-pollution demonstrations (Ecoglasnost). Some of these organisations’ most active actors were members of the CP and proposed a social change programme inspired by Gorbatchev’s perestroika (notably within the influential Club for the Support of Glasnost and Perestroika, which included prominent intellectuals). Another part had ties with the human rights movement, deeply focused on the call for compliance with the 1975 Helsinki Accords’ “third basket.” Despite their dissimilarities, these organisations had at least one point in common: dissidence and a keen concern for any issue pertaining to human rights.

Shortly after the Communist leader’s resignation, new political actors came on the scene, most of which were successor factions to traditional political parties banned in 1947-1948; namely, the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party (BSDP), Nikola Petkov’s Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union (BAPU), the Democratic Party, and the Radical Democratic Party in Bulgaria (RDPB). Historically, these restored parties have their roots in the 1940s’ anti-Fascist movement: during World War II, they were either allied with the Communists or collaborating with the latter to overthrow the pro-German government. Some of those parties’ historical leaders (notably the agrarians’ leader, Nikola Petkov), were symbolic figures of the anti-Fascist Resistance, yet they opposed the post-1945 single-party system. The process of rebuilding these organisations brought back onto the political scene their former leaders – older by then but still energetic and ambitious – along with new members who were younger and less sensitive to long-standing conflicts and debates.

In December 1989, a dozen non-Communist organisations formed a political coalition, the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), which quickly became a magnet for all organisations opposed to the Communist regime. Although the new coalition’s leaders included some members of the CP8, anti-Communism and its radical opposition to the CP soon became the basis for its political identity. Shortly thereafter, the new coalition expanded with the adhesion of other parties which, unlike the founding parties, were more responsive to the interests of the pre-Communism era’s political and social elites.

Apart from the new coalition, several anti-Communist political parties remained, either retaining their traditional Bulgarian names (National Liberal Party, Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization – IMRO), or European names (Conservative Party, Republican Party, etc.). Sometimes the founders of a new political party would try to appropriate a known political label and imitate the programme traditionally associated with it in order to gain material and organisational support from their European or North American counterparts. Initially, the Social-Democrat parties prevailed because of the general impression that international social democracy was more responsive to the changes in Eastern Europe and more likely to contribute its aid to the new democratic parties. Somewhat later, the conservative and Christian-democratic parties were more popular for the same reasons. Indeed, there has never been a religious tradition in Bulgarian political life and Bulgarian conservatism has always been a minority movement.

The UDF thus became the key organisation of what political analysts and political leaders would call from that point on the “Centre-Right,” or simply “the Right.”9 Under Bulgaria’s Soviet-type Communist regime, there was no organised and sustainable dissidence movement. Dissidence was manifested in individual acts or through rumours generated by public opinion, but rarely through real organisations. When such actions did occur, they were quickly dispersed by government secret services. Most of the dissident organisations were thus founded in 1989, just before the fall of the regime. In 1989, no group could claim to enjoy the prestige of Poland’s Solidarnosc, for example. That is why the best-known of the anti-regime organisations formed a meta-organisation, an “umbrella” alliance, to globally represent opposition to Communism.

When the UDF was founded in 198910, it was comprised of ten organisations:

-

- The Club for the Support of Glasnost and Perestroika, whose members were influential intellectuals who also included CP members, some of whom were excluded in 1989. As of 1991, it adopted the name Federation of Clubs for Democracy;

- The independent association Ecoglasnost, consisting of activists from the first Eco-Defence Movement for the City of Ruse, which for years was subjected to pollution from a chemical factory on the other side of the Danube;

- The Independent Human Rights Association, founded in January 1988;

- The independent trade union Podkrepa, which was originally a political organisation comprised of intellectuals, but whose aim was to develop a syndicalism opposed to the Communist regime;

- The Committee for the Defence of Religious Rights, Freedom of Conscience and Spiritual Values, which advocated for the Orthodox Church to be independent of the State, and for the restoration of its assets and status in Bulgarian society;

- The Club of Those Prosecuted after 1945, which demanded that their members’ criminal records be cleared and that compensation be made to them and to their families;

- The Federation of Independent Student Societies;

- The Civic Initiative founded in 1988 to promote public debate;

- The Bulgarian Social Democratic Party (BSDP), successor to the party dissolved by the Communist government in 1947;

- The Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Union (BAPU), successor to the Agrarian Party, which was dissolved by the Communist government in 1947.

This new coalition elected as its president Zhelyu Zhelev, an intellectual known for his criticisms of Lenin’s theories and for a book on Fascism published prior to 1989 in which he alluded to the similarities between Stalinism and Nazism. From the start, the UDF assembled highly diverse organisations and political visions ranging from left-wing moderates to anti-Communist liberals, or more right-wing groups. All were united by the idea of putting an end to the Soviet-type Communist regime and of opening up the field for a representative liberal democracy within the framework of a market economy founded upon individual private initiative and less State intervention.

In the months after the UDF was founded, a few new members joined it: the Radical Democratic Party and the Democratic Party (both successors to their historic counterparts) as well as new parties such as the Green Party of Bulgaria, the Unified Democratic Party (later known as the “United Christian Democratic Centre” – UCDC) and the New Social- Democratic Party (NSDP). These new memberships helped the coalition maintain its political diversity11.

This coalition was “Right” in name only, yet the 1990-1994 political scene opposing the UDF and the Bulgarian Socialist Party or BSP (the Communist Party’s new name since April 1990) made this new coalition the official representative of the fledgling Right. Anti-Communism was its core platform, which was shared by all participants and ensured its cohesion. The UDF took part in the “Round Table,” a post-Communist transition institution whose purpose was to negotiate a peaceful change. The coalition had common candidates run in the June 1990 Constituent Assembly elections, but contrary to its expectations, it failed to win a majority. The UDF held internal debates about the election results but continued to maintain representation in the newly elected Parliament and to constitute the major political force for citizen mobilisation. In August 1990, after a compromise was reached with the BSP, the Assembly elected Zhelyu Zhelev as President of the Republic. Numerous UDF-organised demonstrations had forced his Communist predecessor to resign. A government comprised of experts was formed which included some prominent UDF economists who worked jointly with BSP ministers.

The first split: UDF becomes a Centre-Right party

in eastern european countries, lustration refers to the exclusion from public office of certain former Communist party functionaries and those who collaborated with secret police forces.

The tension between the “moderates” and “intransigents” within the UDF continued to rise throughout this period: the former wanted to preserve political peace and negotiate key points with the ex-Communists, whereas the latter wanted to rid themselves of the ex-Communists and eliminate them from the political landscape. The intransigents supported the 39 UDF MPs who left the Parliament to avoid having to endorse the new Constitution, because they believed that it was influenced by the Communists. Already in May 1991, during the debates on the new Constitution, the UDF had been divided: two major organisations, the Social Democrats and the Agrarians, left the coalition, as did a majority of Ecoglasnost members. In fact, the coalition lost its left-wing and swerved more to the Right in its composition and political vision. Those groups were followed by the Green Party and part of the Federation of Clubs for Democracy (the liberals).

After it won, by a small margin, the October 1991 legislative elections which followed the adoption of the new Constitution, the UDF formed the first non-Communist government, headed by Philip Dimitrov. It obtained only 110 out of the 240 National Assembly seats, but the government it formed was supported by the Movement for Rights and Freedoms. This pivotal party, which then represented Bulgaria’s Turkish minority, supported the UDF because of its anti-Communist stand. The other groups resulting from the UDF split scored below the 4% threshold and therefore won no seat.

The UDF government then undertook vast reforms to privatise industries, restitution of property and farmland, enforcement of lustration in the civil service12 and reorientation of Bulgaria’s foreign policy towards the United States and Europe. One year later, the reforms seemed to slow down, raising some concern, and even discontent, notably among the working classes. Apparently the Turks, a rural population, were particularly affected by the agricultural reforms; land restitution was of little benefit to them. The MRF therefore decided to withdraw its support of the government, which resigned after a one-year term. The UDF found itself in the opposition, confronting a new government supported by the MRF, the BSP, and some of the UDF’s liberal MPs who had left the coalition.

A new wave of scissions ensued within the UDF, provoked this time by a conflict which opposed the party and President Zhelyu Zhelev. The party criticised the government for not having made an effort to reduce the economic reforms’ social cost. Between 1992 and 1994, two other fractions left the coalition: first, the liberals surrounding Zhelev and, shortly thereafter, the Democratic Party, along with an important faction of the Agrarians. Just before the early 1994 elections, the coalition signed a new agreement, this time between sixteen organisations: those which remained in the alliance, as well as a few new parties – notably the Bulgarian Democratic Forum (which claimed to be the successor party to the 1930s and 1940s’ Union of Bulgarian National Legions, a Fascist-inspired paramilitary group) – and the Republican Party. The new agreement provided for the merger of member parties into a single organisation, which was supposed to have a Christian-Democrat profile. The most influential party within the UDF seemed to be the United Christian Democrat Centre.

The early December 1994 elections were a relative failure for the UDF: the coalition lost close to 700,000 vote as compared to the preceding 1991 elections – nearly one-third of its electoral base. This failure brought about a change in direction (Ivan Kostov, the former Minister of Finance, became the Union’s Chairman) and expedited the coalition’s transformation into a single party with a Centre-Right profile. This evolution resulted from a conflict between the small UDF parties and parties which claimed to represent a long-standing political tradition, such as the Democratic Party and the Radical Democratic Party. They left the coalition in 1995, along with some agrarians, to form the People’s Union (PU) coalition, a new split which accelerated the UDF’s transformation into a unified party. In 1996, the Union was recognised as a permanent member of the European People’s Party (EPP).

The coalition evolves into a unified party

The year 1996 was decisive for the UDF’s transformation into a Centre- Right unified party. When the outgoing president, Zhelyu Zhelev, announced at the end of 1995 that he wanted to run for a second term, the UDF decided to select its own candidate. The PU, MRF and a few liberal parties supported the outgoing president’s candidacy. Faced with the risk of having two competing right-wing candidates oppose a single left- wing one, the right-wing parties decided to nominate a single candidate by means of primary elections. On 1 June 1996, these unprecedented primary elections were held and – to the surprise of most – the right-wing voter participation rate was quite high: some 860,000 citizens went to the polls, representing more than 12% of the electorate. The UDF candidate, Petar Stoyanov, designated as the common candidate, won the presidential elections in November with a very high score – an outcome that can also be explained by the BSP’s disappointment with the government, which had been in power since 1994 yet had failed to avoid the deep financial crisis and grave ensuing inflation of early 1997. The crisis led to demonstrations and multi-sectoral strikes, inducing the Socialist government to step down. The UDF was in the opposition camp at the time, and despite internal conflicts, it managed through much effort to be acknowledged by demonstrators as their political advocate. The interim government appointed by President Petar Stoyanov managed to calm the situation and to control inflation by introducing the “currency board” system just before the early elections, in which the UDF won by an absolute majority.

For the first time in Bulgaria since 1989, the new government, with Ivan Kostov as Prime Minister, succeeded in carrying out a full term. Those four years were a critical period for the country: financial stabilisation, reduced government spending, promotion of foreign investment, completion of privatisation, and, in 1999, the start of negotiations for accession to the European Union. They were highlighted by decisive steps take to become a member of NATO. The government thus fully supported the military operation against Serbia despite a public opinion that was rather reserved – if not hostile – to NATO’s air strikes. These were large-scale and simultaneous land, fiscal, budgetary and judicial reforms.

It was in 1998-1999 that the UDF finally became a unified party. Although the new statutes recognised the party members’ affiliations, its organisational structure was that of a unified party. In 1998, the UDF was acknowledged once again as a member of the EPP.

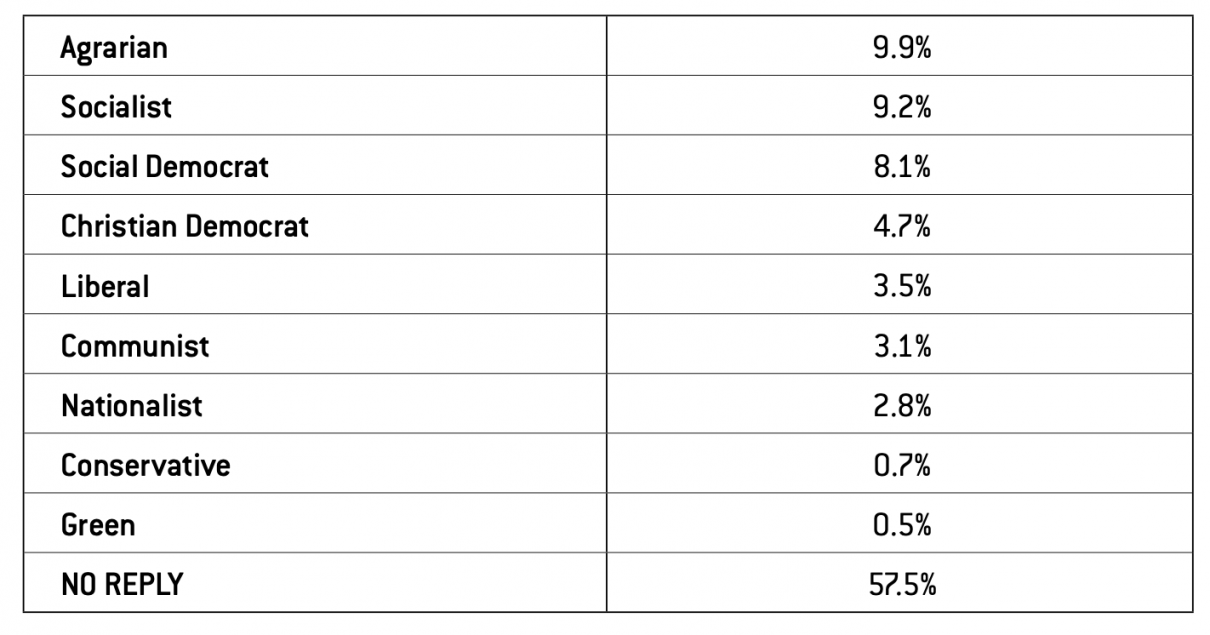

A study from that era (1999) shows that most Bulgarian citizens were still indifferent to ideological labels, but that nearly half of them had chosen one.

The Three Rights: Democratic, Populist, and Extremist

A. Todorov, Citoyens, élections et La Bulgarie de 1879 à 2009 (Paris: est-ouest, 2010), p. 134.

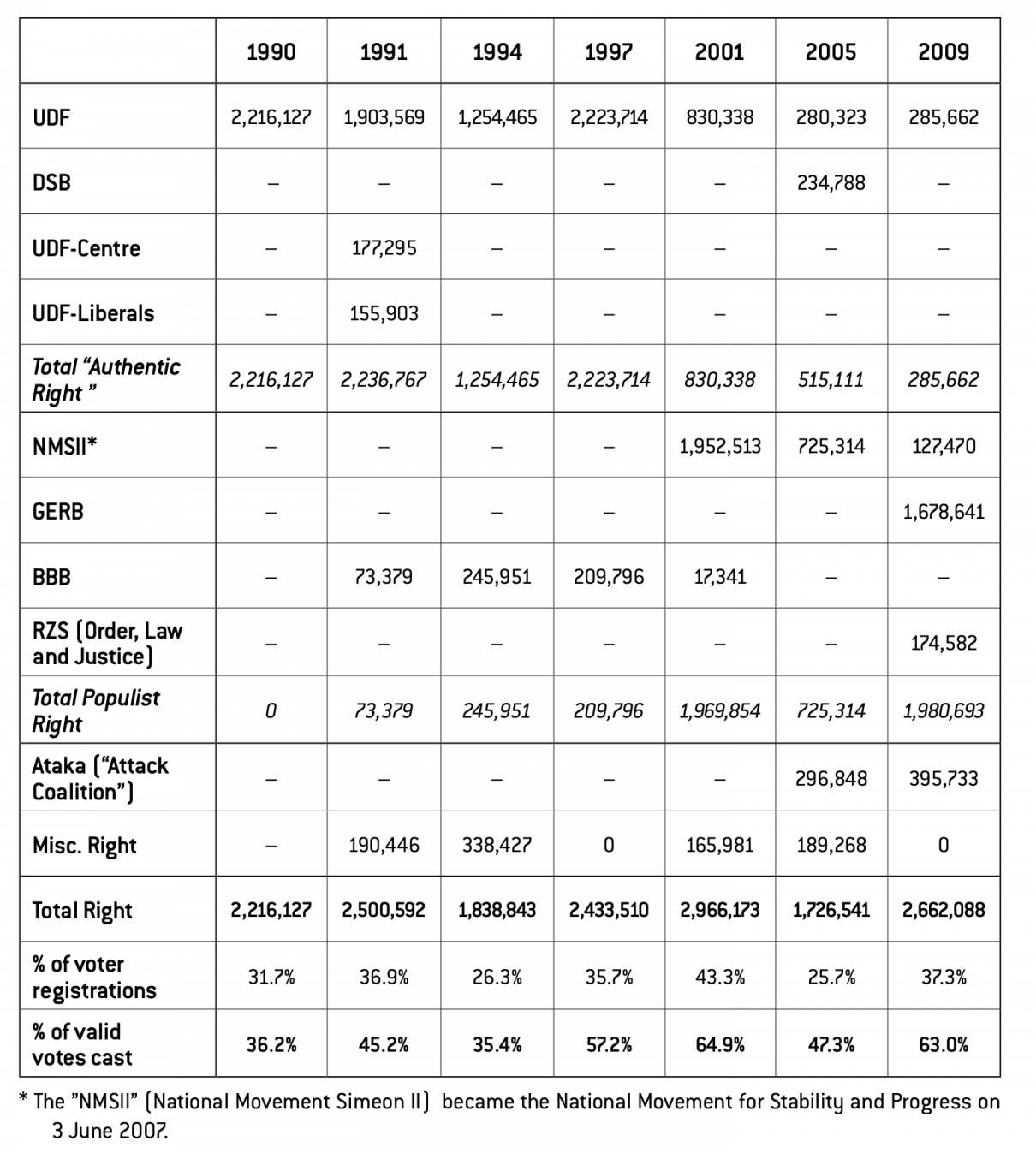

It was difficult for right-wing voters to choose between several parties which changed names during the transition. However, the total number of those who voted for the main right-wing parties (we do not include here all the names, which exceed forty in some elections) amounts to between one-quarter and two-thirds of the entire electorate. The vari- ances depend upon the mobilization or demobilisation according to the right-wing parties’ position and their chances of coming in first.13

Table 1: Responses to the open-ended question: “how do you define yourself politically?” (BBss gallup international, 1999)

The “Blues”: An authentic Right

A. Todorov, “Bulgaria” in Dieter Nohlen and Philip stover (eds.), Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook (Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft Mbh & Co), pp. 351-398.

Despite the internal changes and successes acknowledged by the UDF government, the party unexpectedly lost the June 2001 legislative elections. A new political party headed by ex-King Simeon of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (the National Movement Simeon II – NMSII) won the majority. The UDF leaders’ surprise and disappointment were unprecedented and scarcely tempered by the defeat of the BSP, their long-standing rival. The NMSII seemed to present an alternative to the endless clash between anti-Communists and ex-Communists throughout the democratic tran- sition. Politically, however, it was a right-wing alternative.14

Table 2: election results for the main right-wing parties (in number of votes)

A.. Todorov, “Les élections législatives bulgares de 2005,” La Nouvelle Alternative (2006), Vol.21, No. 68.

The UDF still did not want to recognise the NMSII as a right-wing party and refused to accept the adherence of the new movement to the EPP. The NMSII therefore became a member of the Liberal Alliance with the MRF which, from 2001 to 2005, was its partner in the government. The anger of UDF’s leaders was rekindled in 2001 when BSP leader Georgi Parvanov was elected President of the Republic because the UDF had failed to reach an agreement with the NMSII on a possible common candidate. However, it should be pointed out that the public rejected the UDF because it had shown little interest in the purchasing power issue due to the clientelism and corruption that reigned in this fast-growing party which governed without sharing its power.

Although the UDF refused to recognise the NMSII as belonging to the “authentic Right” (what the Union leaders called it), ex-king Simeon’s movement was indisputably a Centre-Right group. His liberal government pursued his predecessor’s reforms and successfully completed Bulgaria’s membership in NATO, as well as the negotiations for its accession to the European Union. In order to differentiate itself from this new political actor, the UDF used specific and caricatural names: in contrast to an “authentic Right,” there would be a “Populist Right” which, by implication, would not be authentic.

The 2001 defeat brought the resignation of Ivan Kostov, the head of the party, and led to a new split. In 2003, the defeat of the new UDF President and former Minister of Foreign Affairs Nadejda Mihailova – a candidate for Sofia’s Town Hall – triggered a separation process: members close to former Prime Minister Ivan Kostov left the party to form Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (DSB) on the eve of the 2005 legislative elections. The grounds for this split were personal, because there were no programmatic differences between these two “authentic Right” parties.

The 2005 legislative elections dealt the Right a hard blow. First, because it was then divided into three major parties: the UDF, the new party of Ivan Kostov (DSB) who had served as the UDF’s Prime Minister from 1997 to 2001, and the Bulgarian People’s Union, a Centre-Right coalition with the participation of the former Mayor of Sofia, Stefan Sofianski, who had left the UDF in 2004 to form his own party. The UDF’s scission stemmed primarily from conflicting opinion over what position should be taken towards the NMSII, inasmuch as the UDF was divided over whether or not to negotiate with the latter concerning the formation of a post-election governmental coalition, and Ivan Kostov was opposed to any contact with the “Tsarists” (a critical name for the NMSII)15.

Thus, divided into two opposition parties facing a government supported by the triple SP, MRF and NMSII coalition (social-liberal coalition), the UDF “heirs” lost much of their electoral base. This split puzzled voters, who massively withdrew their support. The “authentic Right” crisis led by the UDF and the DSB continued up to the 2006 presidential elections, when its candidate, jurist Nedeltcho Beronov, came in third, beaten by Attack (a nationalist and populist coalition – see below) candidate Volen Siderov. For the first time since 1992, the traditional Right was unable to qualify its candidate for the Republic’s presidency in the second round.

These defeats convinced the UDF and the DSB to join forces; the first time to propose common candidates for the 2007 local and European elections, and later to form the “Blue Coalition” on the occasion of the 2009 European and legislative elections. This coalition allowed them to surpass the 4% electoral threshold and to retain seats in Parliament. Having to compete with the GERB (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria created in 2007 and led by Boyko Borisov) placed the Blues in a difficult position. They supported Boyko Borisov’s government, particularly with regard to his anti-corruption policy, and saw in him a means of revenge against the BSP, “the sworn enemy.” This time, they supported the GERB’s membership in the EPP – support which they had refused to grant to the NMSII in 2001. They did, however, object to the GERB’s populism and lack of long-term vision.

The Populist Right

A. Todorov “Les élections européennes de juin 2009 en Bulgarie: la confirmation de l’éclatement du système partisan,” Revue internationale de politique comparée (2009).

While right-wing populist parties have always existed in Bulgarian politics, and have even momentarily had an impact on political debate, these organisations have never had a significant electoral influence: scarcely more than 1 to 2% of valid votes cast in post-1989 elections. The populist candidates’ presidential election scores have reflected a certain social dissatisfaction. Although these candidates cannot be deemed to belong to the Far Right, many elements of their political discourse may imply that they do.

For example, in the first round of the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections, George Gantchev, a former emigrant to the United States who had returned to Bulgaria – a comedian and writer as well as a master of moderate national discourse with conservative populist leanings– came in third with nearly 18% of the votes, while his party (the Bulgarian Business Bloc) did not exceed 4%. In 2001, Bogomil Bonev, the former Minister of the Interior under Ivan Kostov (UDF) – who resigned and left his party after earning a reputation as a strong candidate capable of restoring order to a chaotic society – came in third, winning more than 19% of the votes.

After making considerable effort to create structured centrism on the political scene, with the 2001 return home of ex-King Simeon of Saxe- Coburg and Gotha and the founding of his National Movement Simeon II (NMSII), this was the first time that a candidate belonging neither to an ex-Communist, nor an anti-Communist, group assumed power. This marked the first step in constructing a liberal Centre. The NMSII’s political partner, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF) – Bulgaria’s Turkish minority party – used this turn of events to complete its transformation from an ethnic party into a centrist liberal party. The NMSII, by virtue of its political profile, represented a liberal right-wing platform with a moderate populist bent. The UDF’s refusal to approve the latter’s membership in the EPP pushed the NMSII towards the Liberal Alliance, whose political profile was somewhat similar to its own.

The NMSII, hastily organised a few weeks prior to the June 2001 elections, became a political party while exercising its term of office. This led the NMSII to be organised first and foremost as a civil servants’ party, whose audience was linked to its chances of remaining in power. It was prone to clientelism, but its main problem was that it could not manage to venture beyond a pragmatic-oriented discourse and the rejection of any ideological identification. The party remained very personalised in its structure, in that its ultimate authority remained its leader – Simeon of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, despite the existence of independent political groupings affiliated with the party.

The NMSII came in second in the 2005 elections, losing one-third of its electorate. Many observers suspected it of having extensively resorted to “buying votes.” The NMSII managed to get two European MPs elected in 2009, thanks to the presence on its lists of a former Minister of European Affairs and a former European Commissioner Meglena Kuneva, but it failed to exceed the 4% threshold in the legislative elections which followed one month later. At that point it split, and some of its former ministers formed the Bulgarian New Democracy. Those who remained changed the party’s name to the “National Movement for Stability and Progress,” while retaining the NMSII acronym.

In 2007, a new right-wing party emerged: the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), headed by Boyko Borisov, a senior official of the Ministry of the Interior in the early days of the Simeon of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha government, and Mayor of Sofia since 2003. After a brief political career as the NMSII candidate in the legislative elections (he declined the MP mandate) and as an independent candidate for the office of Mayor of Sofia in 2005, he distanced himself from Simeon of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to form his own party. In the 2007 European and local elections, the GERB made spectacular strides and won more votes than the BSP, the government’s leading party. In 2009, the GERB obtained a relative majority and formed its government16.

According to its political profile, the GERB is a new product of the same process which brought the NMSII into Bulgarian politics and represented the second phase of a populist wave. The new party struggled for a time with its political profile, initially hoping to compete with the BSP on its left wing faction. The political climate, however, given the backdrop of a right-wing crisis, positioned it on the Centre-Right side. The GERB thus joined the EPP.

The new party was built from regional groups consisting for the most part of former police officers with close ties to Boyko Borisov and supported by local businessmen. That has had some impact on the way the GERB operates: it has a “personalist” structure which greatly relies upon its leader, as was the case with the NMSII, except for the fact that Boyko Borisov cannot bear the legacy of an aristocratic origin, despite what might be inferred from his haughty and paternalistic attitude towards the people. The new political leader has working class roots and makes a point of letting it be known. His style seems to be as reminiscent of Italy’s Berlusconi as of Russia’s Putin. It is no accident that his government has enjoyed unfailing support from the Attack parliamentary group (see below), without which he would not have a majority in Parliament.

A more conservative sign of this type of right-wing populism emerged with the formation of a party bearing the evocative name of “Order, Law and Justice” (RZS), headed by a former agrarian official, Yane Yanev. This new organisation succeeded in surpassing the 4% threshold and formed a parliamentary group in 2009. This party has an anti-corruption and moralistic platform. Initially, it supported the GERB, but quickly began to staunchly oppose the government. In seeking foreign support, it has grown closer to British conservatives and is attempting to present itself as the party representing a modern and conservative Right in Bulgaria.

The Far Right

A. Todorov, “Critique and humanism” in National populism versus democracy (2007), Vol. 23, No.1, pp. 85- 100 and http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2008-06-19-todorovantony-en.html.

The radical change in the 2005 elections was the arrival of a new party, the Attack coalition. At first, this coalition consisted of four small and rather diverse and heterogeneous autonomous organisations. Their common bond is their very negative opinion of external influences on Bulgaria. Some of the key figures belonging to this coalition originated from organisations whose members were former intelligence service agents. Others came from nationalist groups which were part of the former Communist Party. A third faction of this new coalition, which accounts for its current political profile, came from xenophobic and racist circles whose activity was fuelled by several incidents between Romanians and Bulgarians.

The party very soon became a centralised and unified structure. Its leader, former journalist Volen Siderov, had briefly belonged to an anti-Communist dissident group in 1989. As Chief Editor of the UDF newspaper Demokratzia for two years, he unsuccessfully ran as an independent candidate for the office of Mayor of Sofia in 2003, but was not very successful. He had become widely known in preceding years mainly through his role as host of the Skat TV talk show “Attack.” He had quickly drawn viewers’ attention with his ultra-nationalist, anti-gypsy, anti-Turk and anti-Semitic discourse. In 2002, he published a book, The Boomerang of Evil, whose tone was so anti-Semitic that it aroused the indignation of human rights organisations17.

Attack coalition leaders do not all share Siderov’s opinions, particularly his obvious anti-Semitism. Petar Beron, a biology professor and former UDF Chairman, is also a former intelligence service official. Although he objects to being labelled as anti-Semitic, he has been forthrightly nationalistic throughout his political career, particularly after leaving the UDF in 1992. He was also a candidate for the office of Vice-President along with populist George Gantchev in 1996. Although pro-Attack voters come from different social backgrounds, most originate from wealthy and educated families comprised of senior executives, shop keepers and middle- and upper-class entrepreneurs, and not from modest beginnings, as might otherwise be surmised.

The Attack Coalition, is a fragmented and heterogeneous party, and its electorate will probably evolve and gravitate towards populist candidates with a moderate nationalist discourse who will not dare – in word or actions – run the risk of being isolated and stigmatised by Bulgaria’s European partners. The emergence of the GERB is, indeed, a source of competition on the electoral scene.

The most effective way for an extremist organisation to attract attention is through its public activities: the leader of the Bulgarian National Union (BNU), the founder of Ataka, is a young man named Boyan Rassate. This group’s activists stand out with their shaved heads, ultra- nationalist and anti-gypsy graffiti, and their demonstration reminiscent of the Nazi parades of the 1920s. Yet organisations of this sort remain somewhat marginal in Bulgaria.

At the end of a long process marked by differentiations, separations and restructurings, today’s Bulgarian Right is no longer unified by the anti-Communism which was its ideological engine during the post- Communist transition years. It lacks common political reference points and remains divided into several movements stemming from the former UDF, as well as from other political camps

Despite its fragmentation into several political parties and groups, today’s Right is structured around three major movements: the moderate conservatives (the party of former Prime Minister Ivan Kostov, DSB), the Christian Democrats (although this label has not had much success in Bulgaria, today’s UDF seems to be closer to this group), and the traditional popular and populist Right, essentially gathered within the GERB.

Thus ends the long European partisan diversity assimilation process experienced in Bulgaria’s political milieu during the post-Communist transition. Nonetheless, Bulgaria’s partisan groups have maintained quite a few distinctive national characteristics derived from a national history disrupted by the modernisation challenges it faced after gain- ing its independence in 1878 and while under Communist rule from 1944 to 1989. Specifically, the persistence of certain values revolving around paternalist power perpetuates the existence of political parties strongly influenced by the personalisation of power. From this perspective, Bulgaria is not very different from other Central and East European countries.

No comments.