Victory for populism in the Netherlands: a national phenomenon or a European pattern?

Did the PVV’s triumph come as a surprise?

The Government in Crisis

A shift to the Right and the historic decline of the Left

The immediate causes

A campaign full of twists and turns

The fallout from October 7

The deep causes

Immigration and integration

Green policies perceived as « punitive ecology »

Shortages in the healthcare system

A Crisis of governance

Wokism and cultural insecurity

The European challenge

The PVV’s gambling strategy

The major divides in dutch society revealed

« Gevestigden » and « buitenstaanders » : established parties and “anti-system” formations

Political Compromise and the Dilemma of Progressivism

The « Somewhere » VS « Anywhere » divide

The 10 top concerns of the « Somewhere » and « Anywhere » people24

Anywhere (in brackets, item rank in Somewhere responses)

The PVV : extreme right or populism?

The evolutions of the PVV overtime

An overview of the radical right in the Netherlands

The dutch political outlook in spring 2024

Difficult Negotiations

An “unobtainable Chamber” or an impossible assembly ?

The Populist dilemmaThe Populist dilemma

From The Hague to Brussels, what lessons for Europe?

Summary

Commentary following the recent Dutch elections on 22nd November 2023 generally expressed surprise at the landslide victory of Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV (Partij voor de Vrijheid – Party for Freedom). With 23.5% of the vote and 37 seats out of 150, it was the most successful result in its history.

This outcome can be explained in part by the withdrawal from politics of the three major leaders of the outgoing coalition, starting with Mark Rutte, who had been in power for thirteen years, as well as by the ups and downs of an eventful campaign and the national and international context, marked by the Middle East crisis.

But it also reflects trends that have been perceptible since the populist venture of Pim Fortuyn. It confirms the electorate’s shift to the right and its growing lack of affinity with established parties. It reflects major socio- political developments: the fear of mass immigration in an overpopulated country; the failings of an accelerated ecological transition perceived as punitive; the crisis of governance and public representation; and the divide between the Somewhere and the Anywhere people, highlighted by David Goodhart.

Despite the considerable difficulties involved in forming a new coalition, the centre of gravity of Dutch politics has shifted. Given the economic and diplomatic weight of this relatively small country of 18 million inhabitants – which is a founding member of the EU and its fifth largest economy – this will have major consequences in Brussels.

What’s more, the Dutch example could well illustrate the two major dilemmas present throughout Europe: that of the progressives caught between mass immigration and ecological transition, on the one hand, and maintaining the welfare state and the purchasing power of low-income groups, on the other. Yet there is also the dilemma of populists, who are challenged in their sovereignist agenda by Europeans’ attachment to the Union’s major achievements and by the consequences of Moscow’s aggressive policy.

Christophe de Voogd,

Affiliated professor and associate researcher at the Centre d'Histoire at Sciences Po, Chairman of the Scientific and Evaluation Council of the Foundation for Political Innovation.

The Netherlands: The Populist Temptation

The FPÖ and the challenge of Europe: Ideological radicalism and electoral constraints in Austria

Fratelli d'Italia : neo-fascist heritage, populism and conservatism

The emergence of a conservative left in Germany: the Sahra Wagenknecht alliance – reason and justice (BSW)

The conversion of Europeans to right-wing values

“Sweden Democrats" : an anti-immigration vote

Political shifts and government majority in right-leaning France

2022, French presidential election impacted by crises

2022 The populist risk in France

2022, the Populist Risk in France - waves 2 and 3

2022, the Populist Risk in France - Wave 4

2022 the Populist Risk in France - Wave 5

Freedoms at risk: the challenge of the century

Democracies Under Pressure - A Global Survey - Volume I. The issues

Democracies under pressure - a global survey - volume II. the countries

The Knights’ Hall, at the heart of the Dutch parliament

Did the PVV’s triumph come as a surprise?

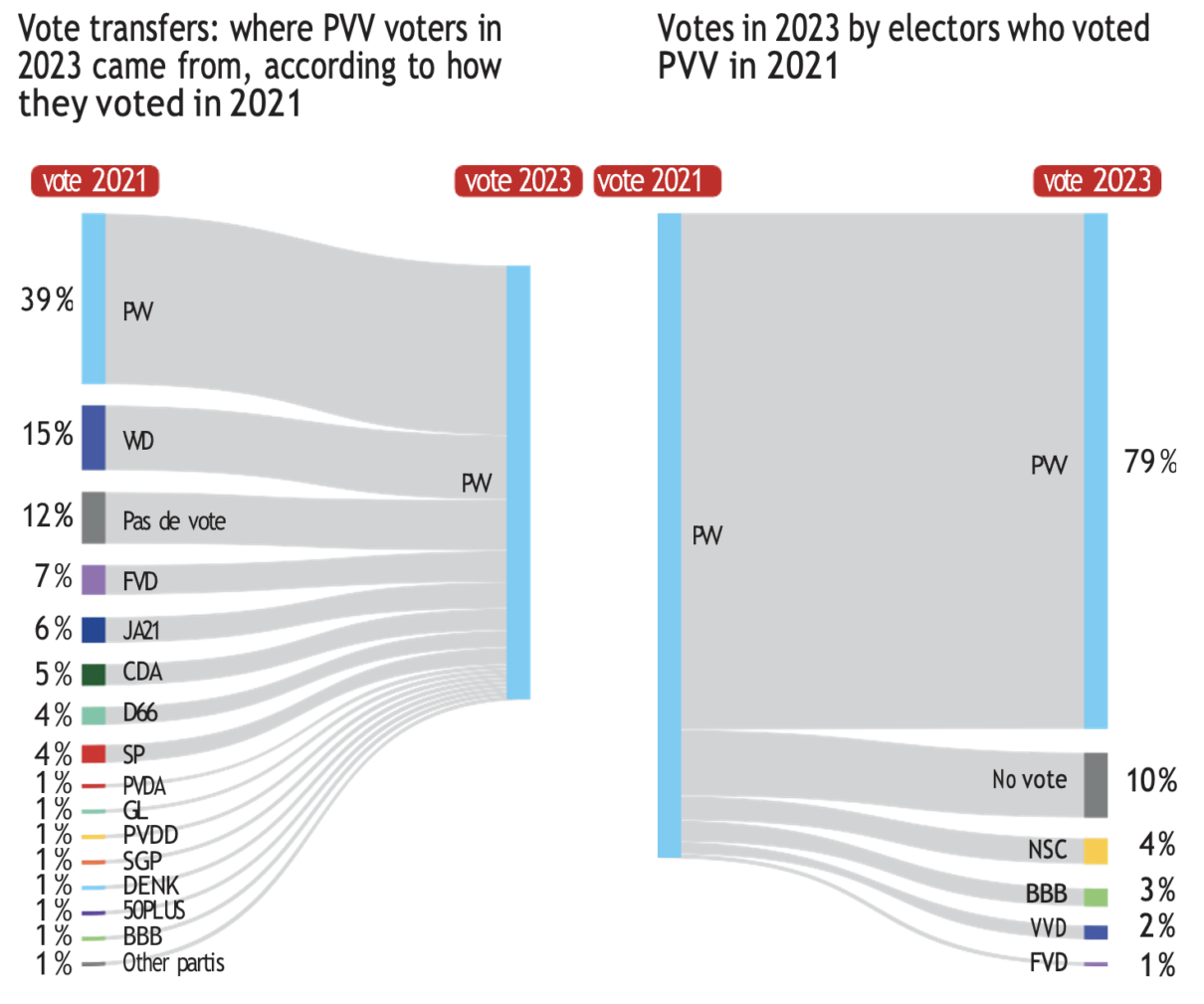

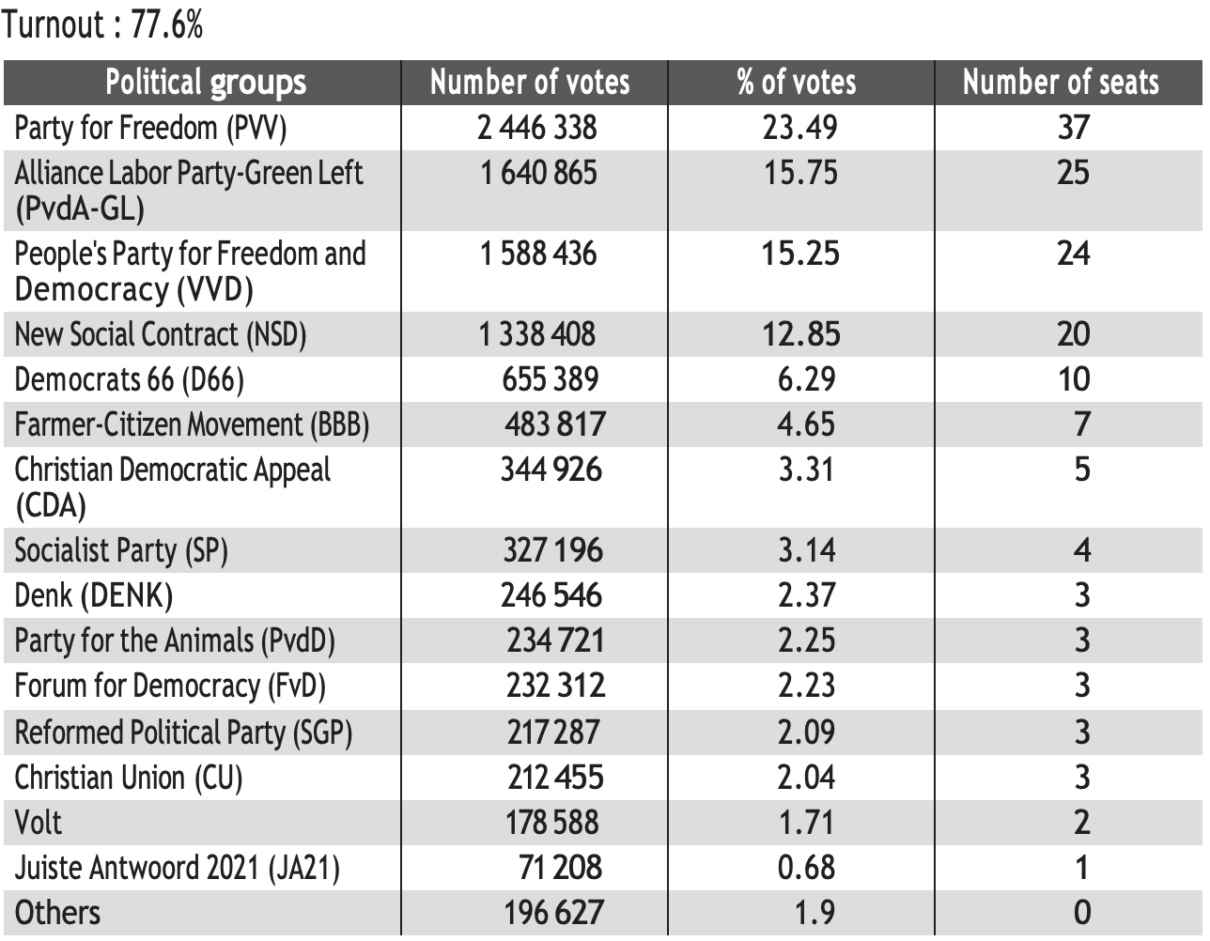

The general tone of the commentary that followed the latest Dutch elections on 22nd November 2023, both in the Netherlands and abroad, was one of ‘surprise’ at the landslide victory of Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV party. With 23.5% of the vote and 37 seats in a fully proportional electoral system, this party, founded in 2006, enjoyed an unprecedented success and more than doubled its result compared to the previous elections in 2021.

The Government in Crisis

Sur la gestion de la pandémie aux Pays-Bas, voir Christophe de Voogd, « Pays-Bas : le pari du confinement intelligent » dans Les États face au coronavirus, Institut Montaigne, mai 2020.

These early general elections are a direct consequence of the government crisis that arose in the summer of 2023, but which had already been brewing for many months over a government plan to reduce family reunification linked to the right of asylum. Faced with persistent opposition from the smallest party in the coalition that had been in power since 2017 (the CHU, the historic Christian Union) and had been reappointed after the 2021 elections – not without lengthy negotiations and a rebalancing – Liberal Prime Minister Mark Rutte offered the resignation of his government, prompting an early election. Shortly afterwards, he announced his decision not to head his party’s list, the VVD (People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy), and to leave national politics. Several months later, speculation is still rife as to his motives, given the apparently minor planned reform: limiting family reunification for asylum seekers. Wasn’t his withdrawal a symptom of the fundamental impossibility of reaching agreement between coalition partners on the highly sensitive subject of immigration? Or did it reflect political realism in the face of the growing unpopularity of the cabinet, which was rejected by nearly 60% of Dutch voters in the spring of 2023? The general wear and tear of power after thirteen years as Minister-President (this is the official title of the Prime Minister in the Netherlands) – a record for this position in the country’s history – and this, despite all odds: the migratory crisis of 2015, the pandemic of 2020-20211, war in Ukraine since February 2022 and a rebellious agricultural uprising since 2019? His ability to build eclectic coalitions has been a testament to his pragmatism and manoeuvring skills, from his first cabinet with the Christian Democrats (2010-2012), which was right-wing and supported by the PVV, to his fourth and final cabinet (“Rutte IV”), which fell in the summer of 2023 and was dominated by the progressive agenda of D66 (“Democrats of 1966”) ; but by that time, Mark Rutte had clearly exhausted all possible combinations. Unless his decision was influenced by a competing personal agenda: his wish to replace Jens Stoltenberg as Secretary General of NATO at the next summit in July 2024, which required an early resignation given the usual slowness with which coalitions are formed in the Netherlands, a period during which the outgoing government has to deal with current affairs.

Be that as it may, this withdrawal coincided with those of his main government partners: the leader of the Christian Democrats in the CDA (Christen Democratisch Appèl), Wopke Hoekstra, and above all Sigrid Kaag, leader of D66, a former senior UN official and wife of a former adviser to Yasser Arafat, who is very committed to international and social issues. These three departures were bad omens for their respective parties, in which they were the undisputed leaders, even if Rutte was less and less popular, while Hoekstra and Kaag were clearly rejected by the majority of the Dutch electorate.

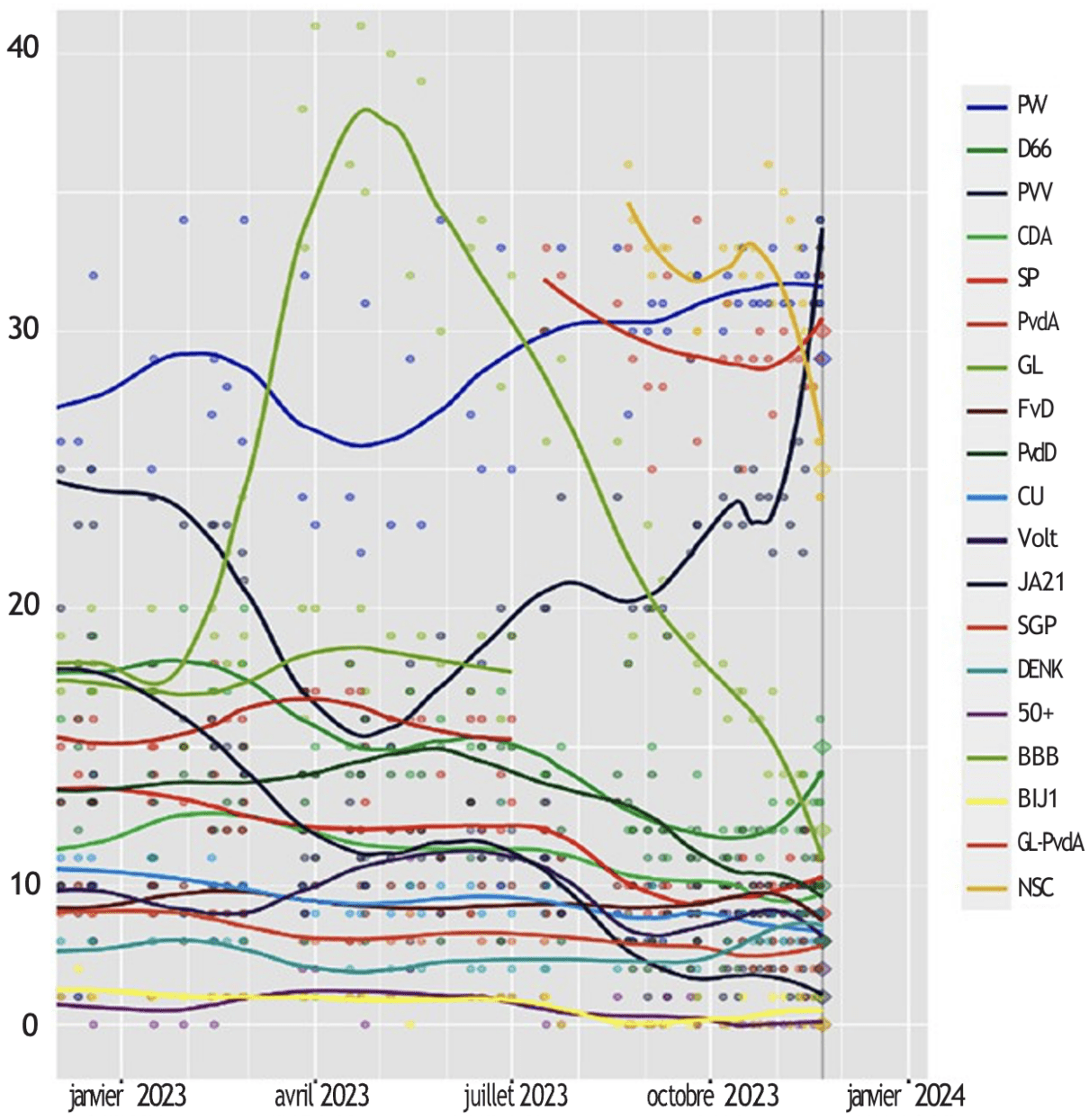

The VVD, D66 and the CDA were therefore likely to lose ground in the forthcoming elections. Likewise, the cause of the government crisis signalled the importance of migration issues on the electoral agenda. Last but not least, although the final order of the major parties remained uncertain for a long time, two trends were perceptible even before the election: firstly, the rapid rise in power of the PVV, which by the end of the campaign was competing with the Liberals as well as with the left-wing union list between the environmentalists of Groenlinks (the Green Left) and the social democrats of the PvdA (Labour Party). A trio closely followed by the new centre-right party, the NSC (New Social Contract) led by Pieter Omtzigt, the man who has been rising in public opinion over the last few years, a highly experienced parliamentarian and former member of the CDA. Moreover, all the polls showed that the electorate was clearly moving to the right, with at least 60% of voting intentions going to right- wing parties of all persuasions. In these conditions, the hope of a victory for the GL/PvdA list was nothing more than wishful thinking, because even if – considering the voting system and the extreme fragmentation of the electoral offer (20 parties were competing) – this party could come out on top on the evening of 22 November, it was in no position to form a left-wing coalition, predicted to receive around 35% of the vote, centre- left included.

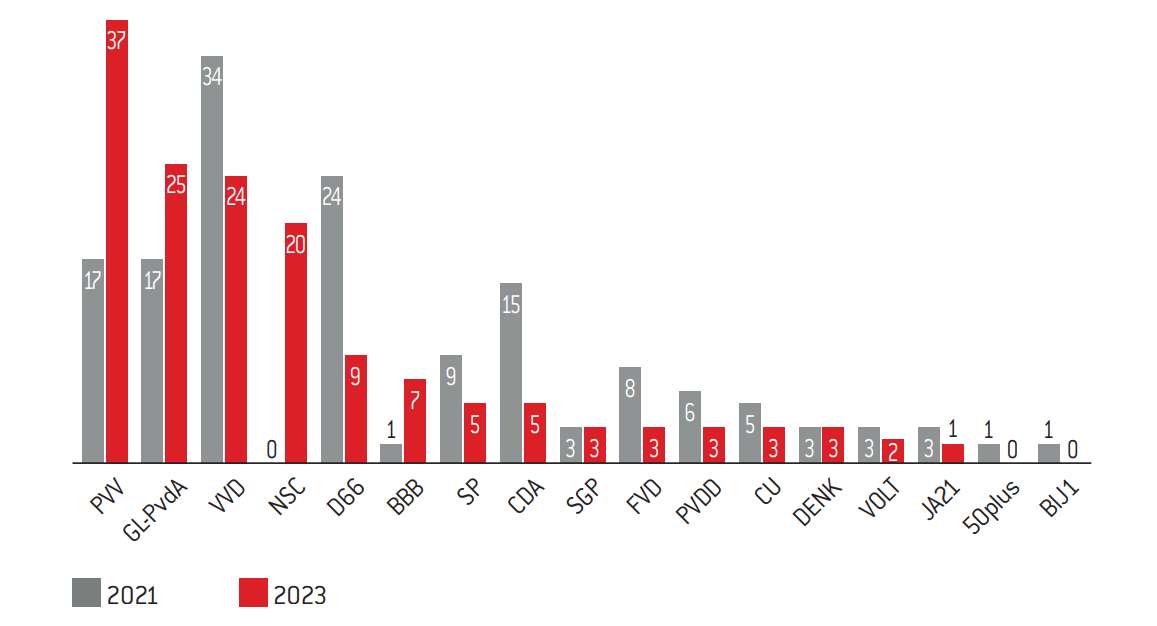

A shift to the Right and the historic decline of the Left

If there was any element of surprise, it lay more in the scale of the PVV’s success, which saw it far outstrip all its rivals. The GL-PvdA list came second with 25 seats, followed by the VVD with 24 seats and the NSC with 20. The PVV’s surge in the previous few weeks was thus accentuated at the polls, in an electoral phenomenon well known to political scientists: a late, but all the more powerful, crystallisation of the vote. The Right as a whole confirmed the success predicted in the polls, with 2/3 of the votes and seats (100 out of 150), but at the cost of a profound rebalancing in favour of non-traditional parties and to the detriment of the major government parties. The rest of the right-wing electorate was dispersed among smaller parties: the BBB (The Farmer–Citizen Movement), also a newcomer to national politics, born out of the farmers anger of recent years and the big winner of the spring 2023 provincial elections; the orthodox Protestant party SGP; the remnants of the long-standing flagship party of Dutch politics, the CDA ; and those of Thierry Baudet’s FvD (Forum for Democracy), which has been trying to outflank the PVV on its right since it was founded in 2016; and finally a split from the FvD, JA21. As for the Left, it suffered an even sharper defeat than predicted in the polls, despite a “strategic voting” effect explaining the decent score of the GL-PvdA alliance list; but as a result, this vote drained the pool of other formations, such as the very pro-European Volt, and above all D66, which lost almost two-thirds of its votes and its MPs. In total, the Dutch Left represents less than 30% of the votes and seats (45), continuing a decline that began some twenty years ago: its central party, the PvdA, has not led the country since 2002, playing second fiddle in coalitions dominated by the centre-right. The rest of the votes have gone to small parties that have emerged over the last twenty years to exploit an electoral niche: the Turkish and Moroccan communities for DENK and the animal cause for the PvdD (Party for the Animals).

Distribution of seats in the House of Representatives

Result: number of seats

Source :

Nederlandse Omroep Stichting – NOS Uitslagen Tweede Kamer 2023 [online]

Christophe de Voogd, Pays-Bas : la tentation populiste, Foundation for Political Innovation, 2010. And for a long-term perspective, Christophe de Voogd, Histoire des Pays-Bas des origines à nos jours, Fayard, 2003.

These results, which of course have to be considered in the specific context of the election, reflect the profound structural shifts that have affected Dutch politics since the beginning of the century, and in particular the “populist temptation” that began with Pim Fortuyn’s political venture in 2000-2002. The first lesson to be learnt from the 22 November elections is already clear: the idea of a return to “business as usual” after a populist interlude is clearly unsustainable given the country’s political development over the medium term2.

The immediate causes

A campaign full of twists and turns

The ups and downs of the campaign undoubtedly contributed to Geert Wilders’ sweeping victory. However, we must rule out from the outset the fallacy of the VVD’s “complacency” towards him, a common theme in commentary following the overture made in August by the new head of the Liberal list, Dilan Yesilgöz, who at the time had envisaged a collaboration with the PVV. However, the PVV only began to gain momentum in mid- September, before accelerating suddenly in mid-November: 20 seats on the 14th and 28 on the 21st. This calls for a closer look at the final weeks of the campaign. At the beginning of November, the Liberal leader went back on her August declaration and ruled out governing with Wilders as Prime Minister, a position she repeated on the 21st. The following day, the PVV won 37 seats at the polls. In other words, and given the chronology, Wilders’ sudden increase in support can be attributed to the VVD’s latest negative position. This is evident from the large number of votes that shifted from the VVD to the PVV during the election. It shows that most of the VVD’s voters preferred a clearly right-leaning coalition after the Rutte IV cabinet faced setbacks.

Other campaign factors were also decisive. Geert Wilders showed great skill in leaving aside the very radical anti-Islamic proposals of his program and concentrating on the fight against immigration and generous social promises: abolition of VAT on basic necessities, lower fuel taxes, increased housing subsidies, abolition of the deductible for medical treatment. He was also able to draw on his long experience in politics: first as a parliamentary assistant, then as a member of parliament since 2003, he is perfectly familiar with the workings of power, and in particular its true core, the Second Chamber, as well as the internal contradictions of the dominant party – the VVD – where he began his career under the aegis of Frits Bolkenstein. What’s more, he had numerous campaigns under his belt that showed him the limitations of maximalist positions, and he knew how to exploit the irresolution of his rivals. We saw this with Dilan Yesilgöz’s waltz-hesitation on the question of participation in a possible Wilders cabinet; the same goes for Pieter Omtzigt, whom the polls had long predicted as the future winner: the NSC leader has never been clear about his willingness to take on the leadership of the country, having long hesitated to create his own formation. Similarly, BBB leader Caroline van der Plas, after her triumph in the spring 2023 provincial elections, scuttled her own chances by declining any ambition for the post of Prime Minister, thus paving the way for a massive transfer of her electorate to the ideologically and sociologically close NSC, but also to the PVV, which has taken the lead in the fight against “punitive ecology”; lastly, Wilders, an excellent debater, prevailed in his duel with Frans Timmermans, the head of the GL-PvdA list, by challenging him on his social program and his “disconnection” with the people. Left-wing unity was also shaken by public disagreements between the traditionally pro-Israeli socialists and the more pro-Palestinian ecologists over support for Israel following the October 7 massacre.

The fallout from October 7

Clingendael Instituut, Tussen hoop en vrees. Van Ruslandschok naar Hamasschok (« Entre espoir et peur. Du choc de la Russie au choc du Hamas ») – De verzuchting naar eigentijdse gemeenschapsafbakening [online].

The repercussions of the crisis in the Middle East on Dutch public opinion deserve more detailed study, particularly as regards the exact impact on public opinion of the protests in favor of Palestine which began to multiply in major cities in November. Pro-Hamas and sometimes outright anti- Semitic slogans were voiced, incidents that could only shock the silent majority in the country of Anne Frank and Etty Hillesum, where almost the entire Jewish community was wiped out during the war. Similarly, even among young activists, the confusion between the Palestinian cause and the environmentalist struggle has been poorly perceived, notably with the appearance of Greta Thunberg wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh at a climate mobilization in Amsterdam on November 12. Could there be a correlation between these events and the concurrent acceleration in the rise of the PVV? In any case, the Clingendael Institute, which specializes in international relations, points to the escalation of the Middle East conflict and the rise of religious radicalism and anti-Semitism among public fears. The latest edition of its annual survey of Dutch opinion on the impact of international issues, carried out just after the elections, is significantly entitled: “From the shock of Russia to the shock of Hamas”3.

A final coincidence: the elections took place at a time when an important and highly controversial bill was being debated in Parliament: the spreidingswet, which provides for the distribution of asylum-seekers throughout the country – imposed if necessary upon municipalities – and which had already been adopted by the Second Chamber, was on the agenda of the First Chamber. Yet another reason for immigration to be at the heart of the electoral debate, further boosting the PVV vote beyond the party’s traditional electorate.

Pre-election polls: overlaping curves and PVV surge at the end of the campaign

Source :

Average of Ipsos and I&O Research surveys from January to the end of November 2023.

The deep causes

Immigration and integration

These individuals are the so-called nareizigers, who have come to join asylum seekers on a family basis, and whose growing numbers the Rutte government wanted to limit.

These figures must be multiplied by 3.5 for a comparison with France and by 4 for a comparison with Germany. Net migration fell to 141,895 in 2023, but remains the second highest in history after 2022, while asylum applications remain virtually constant (CBS figures: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek) [online].

Tussen hoop en vrees, op. cit., pp. 20-21.

Indeed, despite some observers’ tendency to downplay the issue, immigration and integration are the Dutch people’s third biggest concern, just behind governance and purchasing power. Moreover, the overwhelming majority (64%) are in favor of “strict borders” (strikte grenzen)4 to cope with migratory flows that have risen sharply in recent years, particularly as a result of the influx of Ukrainian refugees and the resurgence of non-European arrivals following the Covid crisis.

The context of the last elections was therefore very different from that of 2021, during which, the PVV party didn’t do as well as in 2017, after the migrant crisis in 2015-2016, which boosted their success at the time (obtaining 24 seats). Logically, the most burning issue is that of asylum. The country has witnessed a wave of unprecedented new applications since 2015: more than 49,000 new applicants (on an individual or family basis)5. Beyond this, it seems that immigration as a whole is spiralling out of control, with over 400,000 new arrivals in 2022, up 61% on the previous year. This is a record high and unparalleled in Europe, especially in proportion to the country’s population size, with a migratory surplus of over 223,000 people6. Migratory surplus has become a regular occurrence since the 2010s. In the decade before, the country had managed to keep flows under control, even experiencing a negative migratory balance in some years. However, the Dutch population is particularly sensitive to this issue due to the country’s extreme density, one of the highest in the world (450 inhabitants/km²), which makes the idea that “the Netherlands is full” (Nederland is vol) very consensual.

Faced with the current migration crisis, the political offer presented in the last elections was clearly divided: the old and new right-wing parties opted for a more restrictive policy, with the VVD itself abandoning its previous line, and going for the wishes of the majority of its electorate and the position of Dilan Yesilgöz, whose personal history (she was born in Turkey) and position as Minister of Justice make her very sensitive to the issue of integration. As for the PVV, this has been its very DNA – in particular the battle against Muslim immigration – ever since its creation following Wilders’ split with the Liberals on precisely this issue in 2003. Unsurprisingly, immigration appears to be the primary motivation (80%) for the PVV vote, and the second for the VVD.

It would therefore be difficult not to associate the clear overall victory of the right, and first and foremost that of Wilders, with their positions on immigration. Just as it seems likely that the left’s positions on immigration cost it dearly: no left-wing party – except to a certain extent the small SP (Socialist Party) belonging to the sovereignist left – proposed restricting migratory flows and the right to asylum, even pledging to provide illegal migrants with “safe routes” (veilige routes) and enhanced legal assistance. The GL-PvdA coalition has even gone so far as to ” proactively invite ” certain minorities persecuted elsewhere, such as LGBT communities, to the Netherlands. As we have seen, D66 and the CHU, who opposed the VVD on the issue of asylum, paid a high price at the ballot box. If another indicator were needed of the importance of this issue in public opinion, if not in the media, the priorities assigned to a new cabinet by the electorate as a whole show immigration and asylum in 3rd place (34%), just behind housing (39%) and inflation (36%) and ahead of health (31%). It should be noted that the No. 1 priority of the eco-socialist list, ecology, came a long way behind (20%), showing that the left has missed the point of the election.

The previously mentioned study by the Clingendael Institute confirms the findings of the election polls. It shows that immigration-related issues are clearly predominant in people’s perception of the impact of the international context on the Netherlands: 4 of the 5 main fears of the Dutch are linked to this issue; conversely, the threat of climate change is not only very far down the list, dropping from 3rd to 40th position in 4 years, but is now perceived by public opinion in a very different light to how it is worded by the political ecology movement: no longer “the fight” against global warming, but the “adaptation” to it7.

Green policies perceived as « punitive ecology »

This reversal of the national flag’s colors foreshadows the French agricultural crisis of 2023-2024 during which road signs in local communities where turns on their heads. The message from farmers was the same.

This evolution, both quantitative and qualitative in terms of perceptions of the ecological issue, is undoubtedly linked to the fact that it played an overall negative role in the elections. The policies pursued in its name are deeply divisive, with many blaming it for the country’s two major crises: the agricultural crisis and the housing crisis. These two sectors are bearing the full brunt of the strong measures of the last two Rutte cabinets, and in particular the ambitious “Climate Agreement” (Klimaatakkoord) signed by the coalition in 2019, from which several sectoral policies have flowed, including the law against nitrogen pollution (Stikstofwet) in 2021.

The long-lasting and strong anger expressed in the agricultural world, which began in 2019, is a direct consequence of this. Faced with the government’s plans, hardened over the years by the jurisprudence of the State Council and the outbidding of D66, the impact on agriculture and livestock farming in particular has been considerable: halving emissions (and by 70% near Natura 2000 protected areas) by 2030 and the forced disappearance of almost 3,000 farms. The response has been periodic blockages of the country’s major freeways, punctuated by numerous incidents. Ultimately, this anger reflects the radical change in the agricultural model imposed from above (Brussels and The Hague), with the accelerated shift from agro-industry to agro-ecology. It’s worth remembering that, despite its modest size (41,850 km²), this tiny country is the world’s second-largest agricultural exporter. It owes this success to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), from which it has historically benefited greatly, and to the long-standing support for agricultural modernization by the government, the banks – including the powerful Rabobank – and public opinion: all wanted abundant, cheap food to feed the ever-increasing numbers of city- dwellers in Europe’s most densely populated country.

This is why farmers feel “betrayed” and “abandoned”, words that have become commonplace in their protest vocabulary. A telling symbol of their revolt, the red-white-and-blue national flag has seen its colors reversed in rural areas to deplore a “country walking on its head” and to sound the alarm with this “flag of distress”8.

The concept of “punitive ecology” is closely tied to the severe housing crisis resulting from the drastic measures implemented by the Rutte government. These measures have had a twofold impact on the housing sector. Firstly, efforts to address nitrogen emissions have led to the halting of numerous construction projects, particularly near Natura 2000 protected areas close to urban centers. Additionally, the Netherlands, historically reliant on gas production from the Groningen region, has swiftly moved to ban new gas-powered construction, prohibit the sale of gas boilers from 2026, replace gas heating in 1.5 million homes by 2030, and ultimately phase out gas entirely by 2050. These actions have disrupted the housing sector, causing construction costs to soar. In some poorer communities and rural areas, these costs have surpassed real estate market prices, discouraging the development of new homes. Similar challenges are evident in the rental market, including social housing, where new ecological standards are driving up prices amidst inflation and high demand, particularly from low-income households.

Simultaneously, these policies are straining the electricity grid, with many regions on the brink of overload. This situation underscores the dilemma of transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources: how to meet rising electricity demand while most of it is still generated from fossil fuels, and renewable sources remain relatively inefficient and always intermittent. Despite efforts to shift towards renewables, 40% of Dutch electricity is still generated from gas-fired power stations, contributing to the country’s high greenhouse gas emissions. Confusion in public discourse between electricity (a secondary energy form) and the sources used to produce it (primary energy) further complicates matters, leading to misunderstandings both in the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Shortages in the healthcare system

Another significant concern for the Dutch is healthcare, which has been a consistent focus of public policy in the country for decades. Over the past 20 years, center-right coalitions have implemented strong budgetary savings to restore financial stability to the healthcare system. However, these savings have come at a cost to the population, including the transfer of a significant portion of health coverage to private insurance and the introduction of a high, uniform medical deductible (known as “eigen risico,” currently set at 385 euros for everyone). Furthermore, while there has been an effort to empower demand for healthcare services, there hasn’t been a corresponding increase in the availability of hospital services. Hospital administration remains highly bureaucratic in the name of efficiency, and access to care in communities is tightly regulated. As a result, there has been a resurgence of long waiting times for specialist consultations and examinations.

A Crisis of governance

However varied these issues may be, they are all linked in the minds of many Dutch people with the concept of poor governance, indicating a growing gap between the people and their leaders. This might come as a surprise to some, given the country’s traditional confidence in its institutions. However, this disconnection has been recurring amidst several political crises, revealing a history that is less harmonious than one may think. This very issue propelled Pieter Omtzigt to political success, following in the footsteps of Pim Fortuyn twenty years ago. Omtzigt emerged as a leading critic of mismanagement, particularly highlighted by his exposure of the family allowance scandal (kindertoeslagenaffaire), which involved the administration wrongly accusing numerous beneficiaries, many of whom were immigrant families, of receiving undue payments and then harshly demanding substantial reimbursements with penalties. The fallout from this scandal led to the downfall of the Rutte III cabinet in 2021. Beyond this scandal, the theme of governance being out of touch and excessively bureaucratized has gained traction in the country, resonating in issues such as immigration, ecology, and healthcare. This sentiment has fueled widespread distrust of the political establishment in The Hague : «politiek Den Haag» is a phrase now frequently used in public discourse and championed by populists.

Wokism and cultural insecurity

Although precise surveys are lacking again here, the PVV has tapped into Dutch people’s identity anxieties regarding the spread of Wokism. This ideology is widespread in cultural and academic circles and holds significant influence in ruling circles, extending beyond left-wing parties. The debate has centered on prominent Dutch historical periods, such as the Golden Age (“Gouden Eeuw“), long associated with figures like Spinoza and Rembrandt. This era, once celebrated, is now portrayed primarily in terms of slavery and colonialism. Consequently, its name has been removed from several museums, and its masterpieces now come with “contextualization” warnings9. The Prime Minister and the King himself have apologized on behalf of the nation and the royal family for what is now perceived as a dark past. Similarly, St. Nicholas Day, a popular holiday central to national folklore, has come under attack for racism and blackface, due to the figure of the “Black Pierrot” (Zwarte Piet), the valet (or slave?) of this legendary bishop. Here again, Geert Wilders has put forth the defense of traditions and the rejection of memorial repentance in the name of “the preservation of our culture”, a key theme of his program, finding a definite echo in the population: if opinion has evolved on the appropriateness of “apologies” for slavery and colonization, their supporters (above all the younger generation and the communities concerned) remain a minority, and even more so for the introduction of a public holiday or compensation for the descendants of slaves. As for St. Nicholas Day, it must remain as it is in the eyes of 89% of those surveyed10.

The European challenge

The slogan is deliberately ambiguous, meaning “the Dutch first” as well as “the Dutch in the front rank”.

As a result, the Eurobarometer consistently gives far more positive responses than national political surveys on membership of Economic and Monetary Union. This discrepancy, which extends to many other topics, had already been noted in the 2011 note on The Populist Temptation. It is striking, for example, that 50% of Dutch people say they are in favor of asylum, but at the same time 62% call for a stricter asylum policy (Ipsos, July 2023); and while they are in favor of a common European immigration policy, they want it to be very restrictive. Likewise, as pollsters are well aware, responses to simple questions are very different from those subjected to arbitration: massive approval of Europe’s energy independence (Eurobarometer, autumn 2023) falls sharply if coupled with the induced rise in energy prices (Eupinions, Bertelsmannstiftung, 2023).

Eupinons, Bertelsmannstiftung, 2023 and Tussen Hoop en vrees, Institut Clingendael, 2024.

This national priority, reflected in the PVV’s campaign slogan “The Dutch come first once again” (Nederlanders weer op 1!)11, naturally plays against Europe. Its program is unambiguous in its intention not only to reject any further deepening or enlargement, but also to leave the Union through a Nexit referendum. It has to be said that the responses of the Dutch population, always very europhile on the major principles at the heart of Eurobarometer surveys, are less forthcoming on specific issues and in purely national surveys:12 this explains the votes against the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe in 2004 and the Association Agreement with Ukraine in 2016. Similarly, as elsewhere in the West, support for Ukraine, which was among the strongest at the outset, eroded as the war progressed: while the Rutte government’s strong commitment to Kyiv (embodied in the forthcoming delivery of F16s and the signing of a 10-year security agreement) is still overwhelmingly approved by public opinion, Ukraine’s cause has lost ground: 57% of Dutch people believe that a Russian victory is likely, 30% see sanctions as ineffective and 60% see the reconstruction of Ukraine as a burden rather than an opportunity, even if a slight majority feel that a contribution should be made. As a sign of the times, the fear of a Russian victory in Ukraine is now only 17th in the list of international concerns13.

This major issue – in which Europe plays a decisive role – put the question of the relationship with Brussels at the heart of the electoral agenda. All the more so as, on other issues of concern to the Dutch, the Union is also perceived as highly pro-active and, for many, intrusive: this is the case for asylum and immigration, which are increasingly managed at EU level; for agricultural policy, with the Farm to Fork plan; and for ecological policy, with the Green Deal. This European dimension found a direct embodiment in Frans Timmermans during the election campaign: he had left the vice-presidency of the European Commission to head the eco- socialist list, and he had been the driving force behind the Green Deal in Brussels. In these circumstances, it is easy to understand how the elections were also a referendum on Europe, with Timmermans attracting the votes of convinced europhiles but also acting as a repellent for eurosceptics, including those on the left. Presented by his opponents as a symbol of “punitive ecology”, “migration laxity” and “bureaucratic governance”, he failed to generate the support he had hoped for from his international reputation: in fact, of all the heads of list, he achieved the worst individual score in terms of preferential votes (voorkeurstemmen).

The PVV’s gambling strategy

Dutch statistics now distinguish between people “with a background of immigration” (having at least one parent born abroad) and others “without a background of immigration” (parents born in the Netherlands). Immigration is therefore assessed over two generations.

Conversely, the PVV has been able to set – or reclaim – the major themes on the electoral agenda. It beat the NSC to the punch on the cross-cutting issue of governance, just as it did the BBB on punitive ecology. Similarly, he was able to link a number of concerns around the migration issue: hadn’t he explicitly articulated in his program the issues of health, housing, security and the country’s cultural identity with his main electoral hobbyhorse? The program thus reads:

“Non-Western immigrants are on average three times more likely to be involved in crime than native Dutch. Moroccans are 5 times more likely, and Somalis 6 times more likely. Figures that don’t lie. Our welfare state is under heavy pressure from non-Western immigrants, who are taking advantage of our social benefits and other facilities en masse. More than half of all welfare recipients in our country are now non-Western immigrants. But our education and healthcare systems can no longer cope with the continuous influx of additional foreigners. The influx of asylum seekers is also unbearable. Every year, this costs the Dutch taxpayer 24 billion euros.

It is absurd that Dutch policy increasingly regards asylum seekers and other immigrants as more important than the well-being and prosperity of the Dutch people.

Asylum seekers enjoy delicious free buffets on luxury cruise ships, while Dutch families have to restrict themselves whilst grocery shopping. Health care, which has become unaffordable for many Dutch people, is provided free of charge to asylum seekers. And by pampering illegal immigrants, the Dutch even have to pay for people who aren’t even allowed to come here. It’s absurd that holders of residence permits should benefit – often in priority – from our rental properties, while many Dutch people have to stay longer on the waiting list. The PVV chooses the Netherlands and puts an end to discrimination against the Dutch”14.

There’s no question that the issue of security is less appealing than it was twenty years ago. The country is now well below the average crime rate in Europe, which it had long cheerfully surpassed. Nonetheless, the populist rhetoric is reinforced by the statistics on origin available in the Netherlands, which confirm that non-European immigrants are 3 to 6 times more likely to be involved in crime than people with no migratory background15. Furthermore, the country suffers from serious drug trafficking, making it one of the main international hubs, much to the dismay of its neighbouring countries. The recent trial of Ridouan Taghi – one of the renown drug trafficking leaders – revealed murderous practices, including assassinations ordered from inside prison. In addition, the mafia has issued death threats against judges, politicians (including the Minister of Justice) and even the royal family. The Moroccan origin of the members of this network has earned it the name of Mokromafia and facilitated populist amalgamation with the issue of immigration in a country where Moroccans are the second largest foreign community. Last but not least, the issue is intertwined with the issue of Islam. The Dutch have indeed not forgotten the murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004, and Geert Wilders’ radical stance on Islam has earned him several assassination attempts and constant, constraining police protection over the past twenty years: a situation that lends credence to his narrative on the “threat of Islam” and contributes to his own personal reputation. The fact that two of the four negotiators for the next coalition – Dilan Yesilgöz and Geert Wilders – have received death threats raises questions about the smooth functioning of a democracy that has long been very peaceful, and where extreme political polarization is now discouraging vocations. Another illustration of this is the withdrawal from political life of Sigrid Kaag – the populists’ bête noire – who has been threatened even in front of her home.

The major divides in dutch society revealed

« Gevestigden » and « buitenstaanders » : established parties and “anti-system” formations

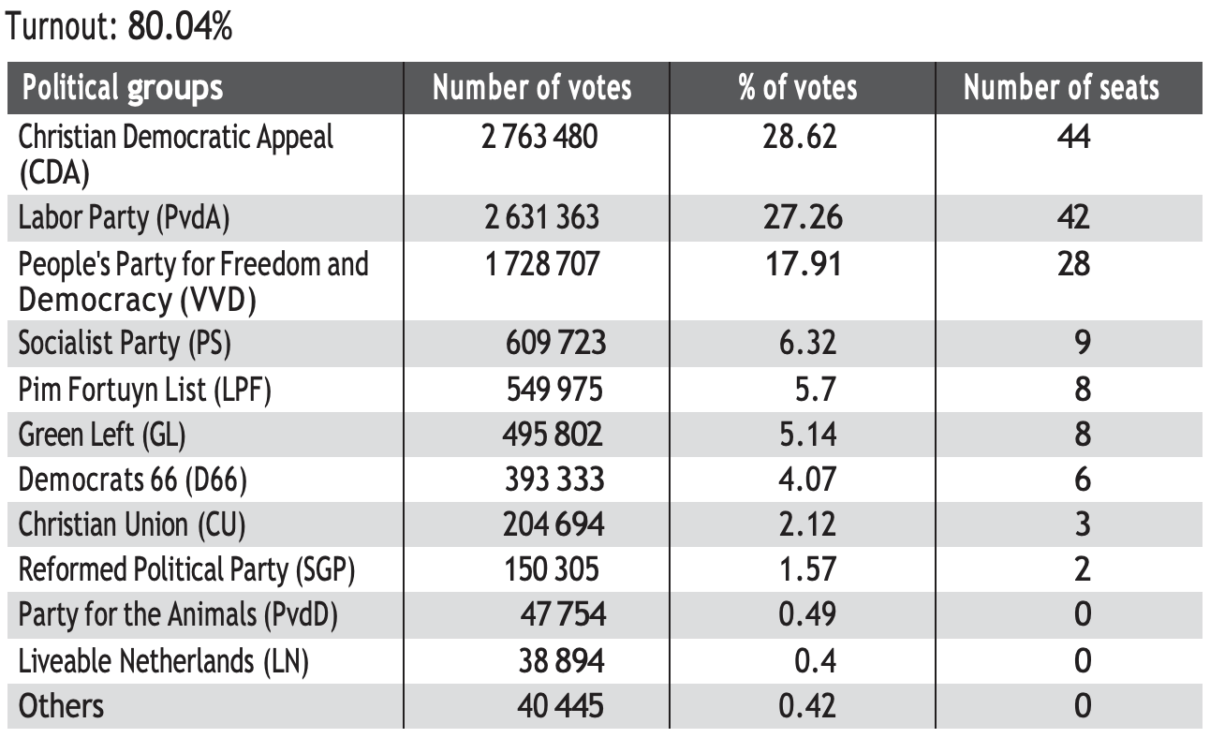

What Wilders’ victory means is that political disaffiliation with the major traditional parties is continuing in the Netherlands. While the country’s right-wing movement seems to be a lasting trend, it is above all the fragmentation of the political spectrum (15 parties are now represented in the House, compared to 17 in the previous legislature) and the steady shift in the electorate from “established” parties (gevestigden) to “anti-system” formations (buitenstaanders) that characterize the long-term trend. In 2003, the three traditional mainstream parties – Christian Democrats, Socialists and Liberals – accounted for three quarters of seats; by 2023, this figure will have dropped to just over a third (including environmentalists).

Results of the 2003 and 2023 elections

Source :

Corinne Deloy, Le vote des Européens. Vingt-trois ans d’élections nationales en Europe, éditions du Cerf, April 2024, p. 45.

Legislative elections on November 22, 2023

Source :

Corinne Deloy, Le vote des Européens. Vingt-trois ans d’élections nationales en Europe, éditions du Cerf, April 2024, p. 452.

Ronald Plasterk was commissioned to explore coalition possibilities following last winter’s election.

It seems that these parties no longer meet the expectations of their respective electorates. A leading Dutch editorialist, former socialist minister Ronald Plasterk, sums up this divorce as follows: “the PvdA has let down the workers, the CDA the farmers, the inhabitants of rural areas and the fishermen, and the VVD the entrepreneurs and the middle class”16.

Political Compromise and the Dilemma of Progressivism

For the relationship between immigration and social housing in France, see Michel Auboin’s note for the Foundation for Political Innovation, Les étrangers extra-européens et le logement social en France, April 2024.

Despite the shock of the 2020-2021 pandemic, unemployment in 2023 stood at 3.5% of the working population, the budget deficit at 1.5% and debt at 49.8% of GDP. Inflation, after peaking in 2022, fell back to 4.7%. GDP grew by just 0.6% in 2023 (sources: OECD and Statista).

It is impossible to discuss this progressive dilemma in depth at this point, as it is a highly debated concept in the field of social sciences. For a detailed analysis and bibliography, see Michel Forcé and Maxime Parodi, “Redistribution et immigration en Europe : y-a-t-il un dilemme ?”, OFCE Review, 169 (2020/5). This study is rather cautious about the relevance of the notion, but is itself open to methodological objections and reservations of interpretation. In any case, it provides rather favorable evidence for the validity of this dilemma in the Dutch context (see following note).

Ibid. p. 143. These figures come from the 2016 European Social Survey, and all recent surveys on the subject of migration suggest that they would be even more clear-cut today.

Willem de Koster, Peter Achterberg, and Jeroen van der Waal, “The new right and the welfare state. On the electoral relevance of welfare chauvinism and welfare populism in the Netherlands”, International Political Science Review, 34/1, pp. 3-20.

The explanation may lie in the fact that the “Rutte system” was based on a compromise between the right and left of government in favor of economic liberalism on the one hand, and societal progressivism on the other: on the one hand, a very proactive policy to maintain public accounts threatened by the major crises of 2008-2010 and 2020-2021, restore growth and strengthen European integration; and on the other, the promotion of an ambitious ecological agenda and the project of a multicultural society very open to immigration, which have become the new catchwords of the left, replacing its traditional social program. Hence the breakdown with the working classes, drawn into a distribution conflict with newcomers over the dwindling resources of the welfare state (benefits, public services, housing)17; as well as a breakdown with rural and semi-urban communities, now affected by immigration due to the forced distribution of asylum-seekers and who are now affected by the new environmental constraints. It’s understandable that the Left and the Christian Democrats, who historically represented these constituencies, have suffered particularly from this disconnect, to the advantage of anti-system parties. We are struck by the extent to which the NSC and BBB vote represents the former geographical and sociological base of the Christian Democrats of the CDA, from which its voters, executives and leaders originate. The VVD, for its part, is credited with the country’s very strong financial situation, but suffered from the high inflation of 2022 and weak growth of 202318 ; hence, both its preservation as a major party and its setback at the last elections. As for the Dutch left, it is clearly faced with the “progressive dilemma” formulated by David Goodhart, based on Milton Friedman’s analysis of the incompatibility between mass immigration and the welfare state19. The Dutch are undoubtably very open-minded people in principle, however, as for the issue of European integration, responses to specific questions are much more cautious: 48% make access to social rights for immigrants conditional on prior acquisition of Dutch nationality, as opposed to only 8% on arrival20. As a result, the rise of the populist vote has been described as “social chauvinism”21.

In any case, an analysis of this “progressive dilemma” should not be confined to general considerations on the relation between immigration and the welfare state: the Dutch example confirms that there is indeed a tension between the two, when rapidly increasing numbers of poor, unqualified immigrants place heavy demands on the welfare state, whose resources are simultaneously restricted by austerity policies and sectoral bottlenecks (health, housing).

The « Somewhere » VS « Anywhere » divide

Behind this political compromise and progressive dilemma lies, from a socio-political point of view, the divide analyzed by David Goodhart between, on the one hand, the “Anywhere”, who feel at home anywhere in the world and are sensitive to global issues, and, on the other, the “Somewhere”, with a more local outlook and more traditional ties, both regional and national22. The phenomenon is even more striking in the Netherlands, where the Dutch elites have been cosmopolitan for centuries, as a result of the country’s commercial and colonial history: and it is precisely these elites who have long forged and spread the cliché of a country open to the vast world. Goodhart’s model has been refined by Josse de Voogd and René Cuperus, who have carried out a systematic study of all Dutch municipalities and shown that, alongside objective variables (location, income, housing and, above all, level of education, which has become essential in a “diploma democracy”), personal perceptions play a key role in today’s socio-political cleavages: feelings of isolation and of poor health appear to be decisive factors that distinguish two different societies and two types of electoral behavior: the “integrated” (aangehaakt), who remain loyal to traditional parties (right- wing or left-wing), and the “disengaged” (afgehaakt), who more often abstain from voting or support “anti-system” parties23. Hence the need to address the current challenges with a multi-faceted approach, considering the complexity of the electoral landscape, which is influenced not only by major trends but also by voting practices in different areas, such as communities and neighborhoods. The Clingendael Institute’s survey with 50 questions shows how distinct these two worlds within one country are: their concerns and hopes about the global situation vary significantly, even though anxiety is widespread.

The 10 top concerns of the « Somewhere » and « Anywhere » people24

Tables and cross-referenced data taken from Tussen Hoop en vrees, op.cit., pp. 22 and 25.

“Somewhere” (in brackets, item rank in Anywhere responses)

1. Large-scale illegal immigration (34)

2. Foreign interference in migrant communities (26)

3. Influx of refugees due to conflict near the EU (43)

4. An Islamist attack in the Netherlands (15)

5. Emergence of extremist religious movements in various countries (12)

6. Cybersabotage of vital infrastructures (1)

7. Use of migration as a threat by neighboring EU leaders (25)

8. A “Great Replacement” (omvolking) in the Netherlands (49)

9. Unwanted heavy dependence on foreign countries for vital products (21)

10. Insufficient EU military capacity to defend its territory (17)

Anywhere (in brackets, item rank in Somewhere responses)

1. Cybersabotage of vital infrastructure in the Netherlands (6)

2. Russian victory in Ukraine (32)

3. Emergence of political parties advocating religious or racial discrimination (47)

4. Overpopulation worldwide (16)

5. Involvement in nuclear war (22)

6. Involvement in a war following an attack on an EU or NATO member state (14)

7. Threats to living standards following an international crisis (20)

8. Threats to the rule of law in Europe (21)

9. Increasing polarization and radicalization due to foreign disinformation campaigns (31)

10. Physical sabotage of vital infrastructure in the Netherlands (15)

There are shared fears of conflict on Europe’s borders (notably an extension of the Ukrainian conflict), but the assessment of major socio-political threats is clearly different between the two groups: immigration for the “Somewhere” group, discrimination for the “Anywhere” group.

The PVV : extreme right or populism?

The evolutions of the PVV overtime

Incidentally, the Clingendael Institute’s study distinguishes an “intermediate group” (tussengroep) between Somewhere and Anywhere.

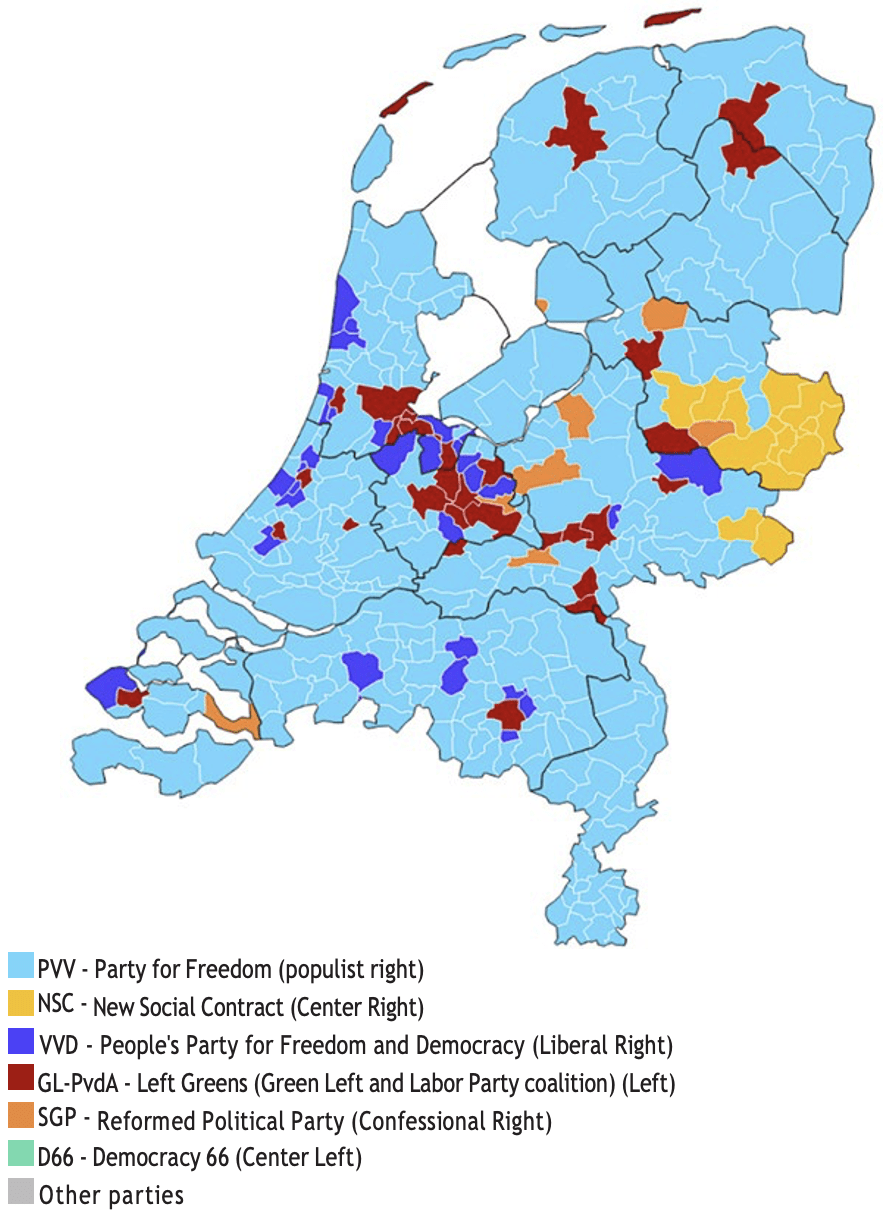

However, we must also take into account a twofold evolution which prevents us from seeing the “Somewhere”/”Anywhere” divide as a rigid and constant opposition25. Firstly, there’s been a shift in the geographical and sociological patterns of the PVV vote in the 2023 elections. The typical PVV voter, once mainly suburban, male, and middle-aged, now reflects the broader electorate. The party has gained popularity among young people and draws support from both urban and rural areas across the country. The traditional geographic divide, as described by Josse de Voogd and René Cuperus, from southwest to northeast, no longer holds true after the 2023 elections. Opposition to the PVV’s dominance is now concentrated in a curved “dike” stretching from the central-west to central-east regions of the country: from the liberal coastal areas to Overijssel (where the NSC has replaced the CDA), through the Amsterdam region and Utrecht province, which are shared between liberals and the left. Additionally, there are pockets of resistance in left-leaning university towns like Groningen and Nijmegen, wealthy VVD strongholds, and historic bastions of Protestant orthodoxy (SGP).

2023 Leading party in the 2023 elections

Source :

Nederlandse Omroep Stichting – NOS Uitslagen Tweede Kamer 2023 [online].

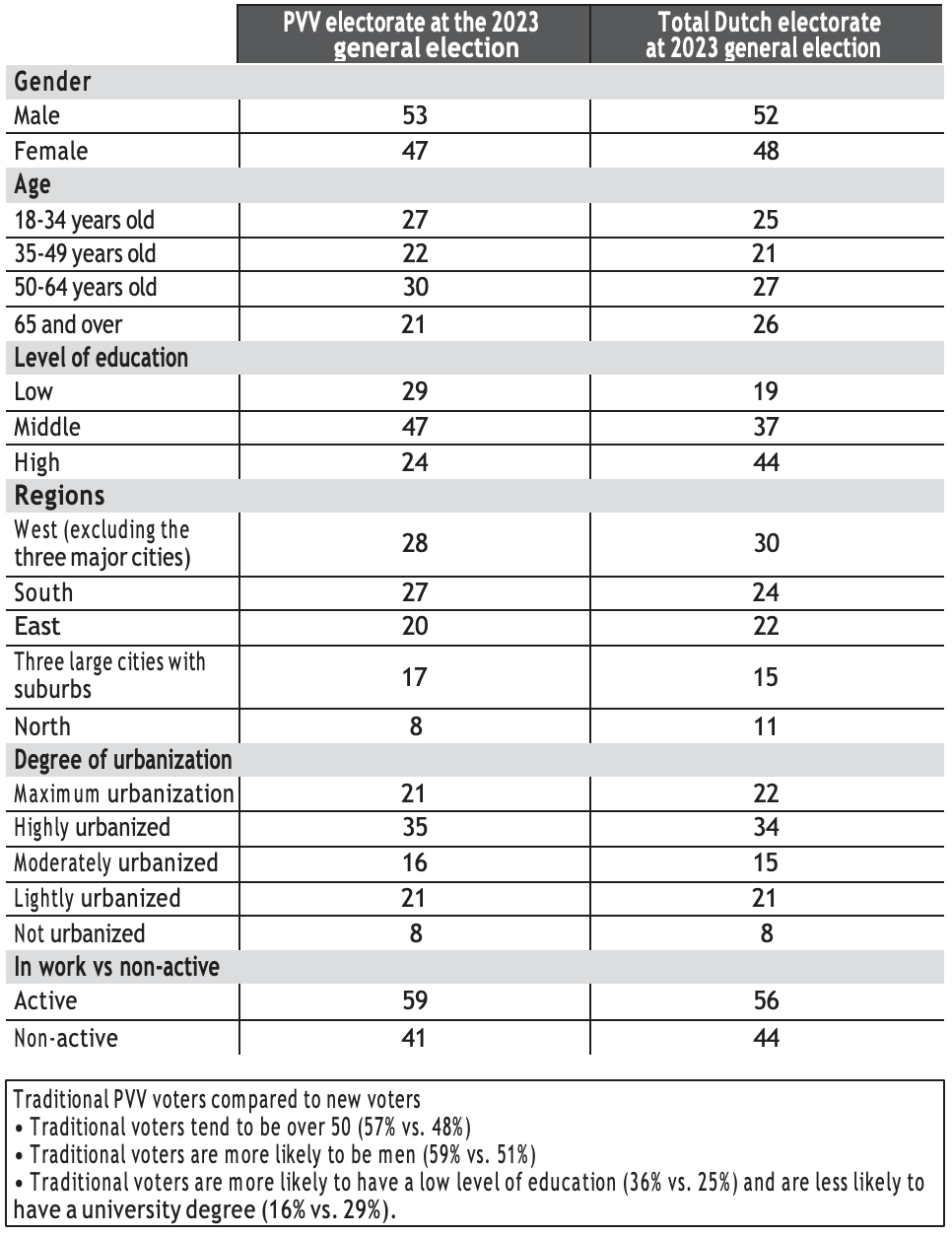

The PVV’s electorate is over-represented among those with a low level of education (short vocational training courses) and, as a result, a lower average income in a “knowledge economy” (kenniseconomie), which still sets it apart from traditional parties. However, the overall trend is for the PVV to become a catch-all party, with a wide range of motives for discontent and a wide range of dissatisfied profiles.

Geographical and sociological nationalization of the PVV vote

The profile of PVV voters differs only in level of education

Source :

Tweede Kamerverkiezingen 2023 – Ipsos Kiezersonderzoek, December 4, 2023 [online]

This increased appeal has been fueled by the party’s second significant evolution: its ideological and programmatic stance. This positioning challenges the characterization of the party as “extreme right,” a label that may be questionable as well for other similar parties across Europe. Unless one considers as extreme the four typical traits of the right of the right: prioritizing national sovereignty (which includes euroscepticism, potentially even advocating leaving the Union), emphasizing law and order, opposing mass immigration, and defending national identity.

The PVV itself has been classified in this category for a number of reasons: an initially, its ethnocultural nationalism, which once advocated for the integration of Dutch-speaking Flanders into the Netherlands; and its strong opposition to Islam, (and not only to radical Islam) extending to schools, mosques, and even the Koran, which raises constitutional concerns under Article 1 (anti-discrimination) of the Basic Law. Additionally, Wilders’ liberal background deviates from the typical profile of far-right leaders and aligns him more closely with Victor Orban, a personal friend (Wilders is married to a Hungarian woman). While both are staunch opponents of “gender theory,” they differ on their stance toward sexual minorities. The PVV, in line with the tradition of Pim Fortuyn, champions individual freedoms and the Western and Dutch way of life against the perceived threats of Islamism, power, and a justice system accused of serving “political correctness” at the expense of freedom of expression. Wilders himself has faced legal challenges over his anti-Moroccan remarks. This explains his “security hedonist” approach, which differs from the “identity conservatism” of an Orban or a Meloni, according to the distinction made by political scientist Gaël Brustier26. There remains one characteristic that is incompatible with the sought-after normalization, and which partly justifies the label “extreme right”: the solitary, authoritarian leadership of Geert Wilders, who is in fact the only declared member of this strange party with no members, no elections and very opaque funding.

Yet, Wilders still stands out in the panorama of the European radical right for his constant and unconditional support for Israel, where he spent two years in his youth in a moshav27 and even considered emigrating: the PVV thus declares itself “a great friend of the only true democracy in the Middle East: Israel”, going so far as to announce that “relations with Israel will be strengthened, including moving our embassy to Jerusalem”. This crucial point pits the PVV against the Dutch left, which has moved towards an increasingly pro-Palestinian stance, becoming hegemonic in its midst with the current Middle East crisis; but also against the new far-right of Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy.

An overview of the radical right in the Netherlands

The PVV’s sole representative in the European Parliament, Marcel de Graaf, now sits as a non-attached member following his falling out with Wilders.

On the evolution and characteristics of Fratelli d’Italia, see Marco Tarchi, Fratelli d’Italia : neo-fascist heritage, populism and conservatism, Foundation for Political Innovation, March 2024.

Laurent Bouvet, L’insécurité culturelle. Sortir du malaise identitaire française, Fayard, 2015.

Initially inspired by Roger Scruton, Thierry Baudet adopted a liberal- conservative position, defending Western culture and the sovereignty of its nations. However, since 2020, he has shifted towards xenophobic nationalism and shown affinity for authoritarian regimes. The party’s use of aggressive language and promotion of conspiracy theories, along with instances of anti-Semitic and homophobic remarks, now justify labeling it as extreme right-wing. However, this ideological and rhetorical escalation has led to the departure of prominent members of the Forum who wanted to remain faithful to its original vision, and who have created the new formation JA21. Above all, it has enabled the PVV to refocus on the social and identity aspirations of its more working-class and less educated electorate, using simple, direct language: a process reminiscent of the dialectic between Reconquête! and the Rassemblement National in France.

The war in Ukraine and the Middle East crisis have accentuated these cleavages. For the former, Wilders is taking an ambiguous stance, denouncing “the Russian aggressor”, but objectively serving him by opposing all military aid to Kyiv; Baudet, for his part, is increasingly siding with Putin, “a great hero, a fighter for Western civilization”, and played a key role in the “no” vote in the referendum on the Ukraine association agreement in 2016. As for the Gaza conflict, while Wilders remains unwavering in his support for Israel in general and Netanyahu in particular, Baudet rejects any “binary choice” and advocates “restraint”.

We can therefore put forward the idea of a reclassification of the Dutch sovereignist right around three poles that are well identified elsewhere in Europe, but whose precise themes vary according to personalities, cultures and political contexts: Thierry Baudet’s extreme right reminds us of Éric Zemmour’s positions (except on the Middle East); Wilders’ populist right is very close to the Rassemblement National28 ; finally, JA21 (1 deputy in The Hague and 1 in Brussels) represents the conservative-liberal tendency like Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia, and sits with them in the ECR group29.

All in all, in spite of its national specificities and the distinctive personality of its leader, the PVV fits well within the model of “heritage populism” conceptualized by political scientist Dominique Reynié: it draws on a concern for the future of both the social model and standard of living (tangible heritage) and the markers of national identity (intangible heritage). This concern is particularly strong among the low-skilled native population, who see mass immigration as competition for social benefits, jobs and housing, as well as a source of “cultural insecurity” in their immediate environment30.

The dutch political outlook in spring 2024

Difficult Negotiations

The slow pace of negotiations since the elections bears witness to the Dutch tradition of forming coalitions, which is always complex and often lacking in transparency. Hence the often lengthy time taken to finalize a new cabinet, which follows a highly formalized procedure: appointment of a “scout” (verkenner) to sound out possibilities, then an “informateur” to lay the foundations of the coalition agreement, before the ” formateur ” finalizes it. This slow process even reached a historic record (almost a year) with the formation of the last Rutte cabinet, even though the final decision was to renew the outgoing coalition. However, in the present case, given the right-wing’s widespread dominance and the evidence of a PVV/VVD/ NSC/BBB coalition with a clear majority on paper (88 seats out of 150), it is rather the unease felt throughout the political class at the populists’ sweeping victory that seems to be delaying the outcome.

It’s as if the other parties were reluctant to breach the cordon sanitaire surrounding the PVV – preferring to let another make the first move – given the stigma associated with forming an alliance with the “far right” is still powerful, at least in mainstream media if not in public opinion.

Consequently, the period since the elections has been characterized by a series of manoeuvres and theatrical coups from the VVD, the NSC and the PVV itself, making the outcome of negotiations highly uncertain.

An “unobtainable Chamber” or an impossible assembly ?

This game of cat and mouse prompts the question: is the PVV facing an “unobtainable Chamber” or on impossible assembly ? The question arises given the traditional parties still dominate the First Chamber. Conversely, there are many obstacles in the way of an alternative solution. The fragmentation of the Assembly and, above all, the profound disagreements between right and left on key issues (immigration, ecology and Europe) make the formation of an old-style center-right or center-left coalition unlikely. Those who would like to see such a coalition, and who are counting on public fatigue to bring about the long-awaited “return to normal” after twenty years of populist upheaval, are clearly banking on the NSC, which many people view as a new CDA, and not without reason, as we have seen. But Omtzigt, a man known for his intransigence on principles, would still have to drop key points from his program, notably the sharp reduction in immigration or the radical reform of governance. And the hypothesis of a final eviction of the PVV after the failure of negotiations clashes with the party’s steady rise in public opinion: in the spring of 2024, it is reaching a third of the votes and seats in the polls in the event of dissolution, while the VVD retreats and the NSC collapses. What’s more, recourse to new elections before the formation of a new coalition is unprecedented in national history.

However, Wilders’ ambitions are also constrained by three fundamental considerations. The first is his real electoral weight: in terms of the history of the populist movement, his success is certainly considerable, and has legitimately attracted the attention of commentators. Nevertheless, the PVV is not yet on a par with the historic results of the CDA and PvdA, which almost systematically exceeded 40 MPs in the House until the major changes of the 2000s. A precedent is often cited today: the PvdA triumphed in 1977 (53 seats) but was ultimately ousted from the new coalition. On the other hand, the high volatility of the electorate and the very delayed crystallization of the PVV vote (28% of PVV voters made their decision in the last week before the ballot) show that we are still dealing with a protest vote rather than a vote of conviction. In other words, electoral victory in no way means full agreement, let alone hegemony. This is reflected in the Dutch people’s preference for the next government: they would prefer a cabinet with a center-right focus (39% for a right-wing or center-right solution; 27% for a center cabinet, 22% left-wing or center-left).

The Populist dilemmaThe Populist dilemma

Dominique Reynié, Populismes : la pente fatale, Plon, 2011 and, edited by the same author, 2022. The Populist risk in France, Foundation for Political Innovation, 2022.

Last but not least, the PVV is faced with a dilemma which mirrors that of the left, and which, in the words of Dominique Reynié, could be called the “populist dilemma”: the impossible reconciliation between sovereignty, its fundamental political inspiration, and the electorate’s attachment to the major achievements of European integration, and above all to the euro31.

Given these circumstances, it’s not surprising that Wilders abandoned the planned referendum on Nexit, instead choosing Danish-style opting-out clauses, particularly in the area of migration. A vote in principle on this measure by the new chamber (chaired by someone close to Wilders) may well pave the way for a compromise, especially as the case for restricting migratory flows has received the unexpected support of the Commission’s report on the country’s demographic prospects: in its view, migratory flows must be limited if the Netherlands are to remain below the 20 million inhabitant mark, a maximum given the country’s density and the challenges of integration32. As a result, the formation of the new coalition depends, in line with the agenda of the last elections, on resolving a crucial question: will the partners be able to find common ground on the issue of immigration and, above all, asylum ? This is a point where Wilders, though willing to compromise on other issues, remains steadfast.

The European elections in June could well play the role of ultimate arbiter of peace. The polls confirm the leading position of the PVV. Could this be an incentive for its potential partners to come to an agreement as soon as possible?

From The Hague to Brussels, what lessons for Europe?

The PVV’s victory in the Netherlands has confirmed and strengthened the rise of the protest right – a trend evident in many EU countries, from Fratelli d’Italia and the German AfD to France’s RN and Portugal’s Chega.

The arrival of several of these parties to power has or will have a direct impact on the functioning of the European Council and the Union’s Council of Ministers. In this respect, whatever the exact formula of the next coalition in The Hague, its more eurosceptic orientation will be felt in Brussels, due to the economic weight of the Netherlands (5th largest GDP in the EU) and its special role as a founding country. Mark Rutte’s departure adds an important personal factor: since the Brexit and the multiplication of Franco-German disputes, he had become Emmanuel Macron’s main ally in strengthening European integration, to the point where the Dutch press spoke of a “bromance” between the two leaders. Whoever replaces Rutte will no doubt no longer play this role.

The second issue is, of course, the direction of the next European Parliament. Current projections for the June ballot give the far right between 20 and 25% of seats, clearly shifting the Assembly’s focus. The current broad coalition (EPP, Renew and Socialists) is likely to retain a narrow majority, especially as the radical right is divided into two competing groups (ID and ECR) and is at odds over major issues such as support for Ukraine. For many commentators, these reasons rule out the risk of a radical shift in Brussels. However, this is less certain when considered in terms of political dynamics, given the steady rise of the populists in the polls and shift to the right within the EPP itself: a process that will undoubtedly be reinforced by the closer ties initiated by Giorgia Meloni with this group, which will replace Renew at the heart of the new Parliament.

If we look closely, this configuration and dynamic at European level are very similar to those that characterize the Netherlands at this very moment, and make its domestic politics a subject of interest to all Europeans.

In conclusion, the Dutch example highlights two dilemmas: the progressive dilemma between mass immigration and the welfare state, which the left has been unable or unwilling to resolve, refusing to make a Danish-style aggiornamento on the subject of migration and thereby losing its historic clientele of the working and lower-middle classes. This “progressive dilemma” also concerns ecological policy, which is perceived as punitive by the same groups, whose housing, transport and purchasing power are particularly exposed to the bottlenecks and additional costs caused by a forced energy transition.

On the other hand, populists themselves are faced with the dilemma of having to confront their sovereignist agenda with the attachment of Europeans – including their own voters – to the material achievements of the Union, starting with the euro. Here again, this dilemma is doubled by the fact that sovereignism is not compatible with a sometimes marked complacency towards Vladimir Putin’s Russia, whose aggressive policies clearly pose a challenge to the security of all.

No comments.