Introduction

Hypotheses

The data

social situation and national origins

socio-demographic characteristics

national origins, citizenship and discrimination

Relationship with religion

A very prominent religion

Religion by age and sex

Understanding the importance of religion

The impact of supply, the impact of context

The effects of demand

“Existential security”

Political and social values

Politicisation and political participation

Right-left orientation

The issue of trust

Traditionalist values

Conclusion

Annexes

This study is taken from a communication presented to the 6th congress of the Associations Francophones De Science Politique (held in Lausanne from 5-7 February 2015). I extend my thanks to the organisers, Bernard Fournier and Damien Boone, for having given me the occasion to discuss a first draft of this work. I also thank Eric Geoffroy for his recommendations for corrections, although all views and opinions expressed here are the author’s own.

Summary

This paper* aims to use the data provided by the European Social Survey (ESS) to analyse the characteristics and values of Muslims in Europe. Do these Muslims constitute one homogeneous population united by their social and political values? Can any apparent differences be observed between Muslims and non-Muslims? The data shows that the Muslim population display certain unique characteristics in comparison with the rest of the population, but the Muslims’ own profile also varies in accordance with their country of residence. With regard to religion, the level of faith and frequency of practice appear to be relatively high among Muslims, which can be explained by a combination of factors relating to supply and demand. The data also backs up Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart’s theory regarding the link between “existential security” and secularisation.

Muslims are less politicised, and participate less in politics, than other groups. They are rarely sympathetic to right-wing politics, particularly in France where the left enjoys considerable support from the county’s Muslim population. In contrast to what we may have thought, Muslims display high levels of trust in public institutions, including the police. With respect to morals, the opinions of Muslims are more traditionalist than those held by the rest of the population. In a more general sense, it seems that the attitudes of Muslims to a certain extent resemble the attitudes displayed by the population of the country of residence, suggesting that the Muslim religion is not entirely immune to change. Nevertheless, it remains difficult to anticipate future developments due to the unpredictable dynamics of religiosity.

Vincent Tournier,

Professor of political science at the Grenoble Institute of Political Studies PACTE/CNRS.

A diverse community: a portrait of France's Muslims

Islam and democracy - Facing modernity

Islam and democracy - The foundations

Islam and the social contract

Islam and the values of the Republic

Education and Islam

Humanism and humanity in Islam

Religious pluralism in Islam, or the awareness of otherness

Valérie Amiraux, “Les musulmans dans l’espace politique européen. La délicate expérience du pluralisme confessionnel”, Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, n° 82, April-June 2004, p. 119-130.

Bernard Godard, La Question musulmane en France, Fayard, 2015.

Christopher Caldwell, Une révolution sous nos yeux. Comment l’islam va transformer la France et l’Europe, Paris, Éditions du Toucan, In his book Situation de la France (Desclée de Brouwer, 2015), Pierre Manent paints a negative picture of France’s current state and does not rule out a “default islamisation” of Europe (p.124).

One exception is the European Values See, for example, Pierre Bréchon, “Religion et valeurs en Europe”, Futuribles, n° 393, March-April 2013, pp. 75-87, as well as Pierre Bréchon and Frédéric Gonthier, Les Valeurs des Européens, Armand Colin, 2014.

We understand “country of residence” to signify the country that the Muslims were in when they completed the survey, whether these respondents hold the nationality of the country in question or not.

Outside the Balkans, a region that was left with large Muslim communities following the Ottoman conquests of the medieval period, it is only relatively recently that Islam has become established in Europe. This unprecedented situation is stimulating debate and provoking tensions,1 quite aside from specific problems linked to radicalisation and terrorism. The “Muslim question” is now very much a fixture on the European agenda.2

For some, these tensions are both secondary and temporary: ultimately, they can be put down to the prejudices of the native populations and should fade away in good time.3 For others, the cultural conflict with Islam is symptomatic of problems that run much deeper, and that risk generating unprecedented difficulties.4

In the face of this uncertainty, the role of social science is to provide information that is as factual as possible. The problem is that the data available is both sparse in volume and limited in nature. Paradoxically Islam remains the “blind spot for social science”, as sociologist Olivier Galland bemoaned in the aftermath of the January 2015 attacks in France.5 The lack of data can be felt particularly keenly when it comes to attempting an international comparison,6 which is all the more regrettable when we consider that a comparison between several countries can help to compensate for a lack of longitudinal data. Studying different countries puts us in a position to ask questions such as: do Muslims constitute a diverse or homogeneous population? Do they hold different values to the rest of the population? Do they feel an attachment to the values of their country of residence and, if so, can it therefore be deduced that there is a more efficient process of integration taking place than the news reports would have us believe?7 It questions such as these that we wish to address in this paper, through analysing the data provided by the European Social Survey (ESS). However, before presenting this data, let us first outline the hypotheses that will guide our analysis.

Hypotheses

Henry Laurens, Conversations avec Rita Bassil El Ramy, CNRS Éditions, 2009, p. 155.

Philippe d’Iribarne, L’Islam devant la démocratie, Gallimard, “Le Débat”, 2013, p. 35.

Bernard Lewis, Le Retour de l’islam, Gallimard, “Folio histoire”, 1985 ; Hamit Bozarslan, Une histoire de la violence au Moyen-Orient. De la fin de l’Empire ottoman à Al-Qaida, La Découverte, 2008.

Hugues Lagrange, “Le renouveau religieux des immigrés et de leurs descendants en France”, Revue française de sociologie, 2014, 55, n° 2, pp. 201-244 ; Vincent Tournier, “Les musulmans en France : religiosité, politisation et capital social. Enseignements de l’enquête ‘Trajectoires et origine’”, Politique et Sociétés, vol. 32, n° 2, 2013, pp. 89-120.

Two competing, and equally acceptable, hypotheses regarding Islam have become widespread. The first is inspired by the sort of critical analysis that has been a feature of scholarly thought since the days of Ernest Renan or Max Weber. It regards the religion of Islam as having a structuring effect on its followers, its intrinsic features producing a determined set of values and behaviours. According to this hypothesis, which emphasises the importance of the role played by religion, all Muslims must therefore display common traits, regardless of their country of residence.

A competing hypothesis sees religion as a more flexible variable. This hypothesis, which thus puts the importance of religion into perspective, considers that the latter, far from having a structuring effect, is in fact malleable and fluctuating, capable of adapting to its surroundings. As such, the same doctrinal body may be the subject of different appropriations

- olivier Galland, “Les jeunes musulmans et la République : l’angle mort des sciences sociales”, 11 February 2015, eu.com (available for consultation on www.telos-eu.com).

- one exception is the European Values See, for example, Pierre Bréchon, “Religion et valeurs en Europe”, Futuribles, n° 393, March-April 2013, pp. 75-87, as well as Pierre Bréchon and Frédéric Gonthier, Les Valeurs des Européens, Armand Colin, 2014.

- We understand “country of residence” to signify the country that the Muslims were in when they completed the survey, whether these respondents hold the nationality of the country in question or

and interpretations, in accordance with changing eras and locations. This hypothesis can point towards the precedent of Christianity, since this religion led to different realities: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Eastern Othodox, not to mention the numerous national and regional variations. Observers tend to favour this second hypothesis because it fits in better with the theory of the secularisation of our world, according to which religion no longer plays a decisive role in individual identity building. We must also acknowledge that this hypothesis also has the advantage of avoiding a sensitive debate on the nature of Islam, which is often perceived as being the “religion of the poor”.8 Both approaches have their limitations. The first is guilty of excessive essentialism, the second of excessive sociologism. It is quite obvious that a single religion can give rise to different realities: as with Christianity, Islam has experienced schisms and has evolved differently in different parts of the world. Must we therefore deduce that “Islam does not exist”?9 That would perhaps be jumping to conclusions. The diversity of a religion does not mean that it has no impact on values, but nor does it mean that this religion accepts an unlimited amount of values. “The fact that one thought accepts diverse interpretations does not mean that it is compatible with any interpretation whatsoever,” writes Philippe d’Iribarne.10 Furthermore, the socio-historic argument regarding diversity can be reversed: if history creates diversity, it can also create unity, above all in today’s climate where we are clearly witnessing the “revival of Islam” around the world.11

This is why a middle ground between the two appears to be the best solution.

We will therefore start from the assumption that Muslims in Europe do not constitute one homogeneous block, not just because they come from diverse backgrounds linked to historic migrations (the Turks who travelled to Germany, North Africans who ended up in France, Asians in England, and so on) but also because, as with other minorities, Muslims are influenced by the cultural context in their country of residence. However, neither can we discount the impact of religion, above all in these modern times characterised by a resurgence of religiosity among Muslim populations, as evidenced by surveys carried out in France that are confirmed by the ESS data, as we will see later on.12

The data

The list comprises eight options: Roman Catholic, Protestant, Eastern orthodox, other Christian denomination, Jewish, Islamic, Eastern Religions, other Non-Christian religions.

The ESS surveys constitute a precious source of information on European public opinion.13 They have been carried out every two years since 2002. Seven sets of data have been collected up until now, although the 2014 data is still not available in its entirety. We will therefore make do with the first six editions, carried out between 2002 and 2012.

In each of these surveys, only one question is asked about religion. To be more exact, respondents must indicate whether they consider themselves as belonging to any particular religion and, if so, which one.14 It is therefore a personal declaration.

The number of Muslim respondents in each of the editions of the ESS is too low (just a few dozen people) to enable a full statistical analysis. There is, however, a way of overcoming this obstacle: we will group together all the data released in the various editions from 2002 to 2012. By doing so, we will have access to an overall sample in which the number of Muslims reaches several hundred people, enough to reveal the broad trends.

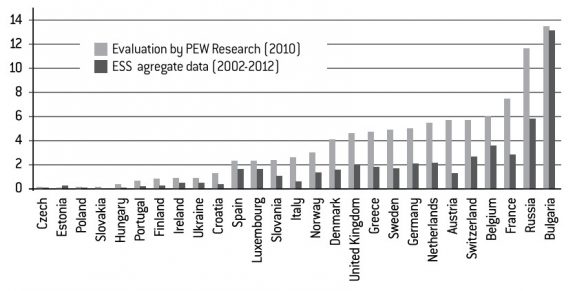

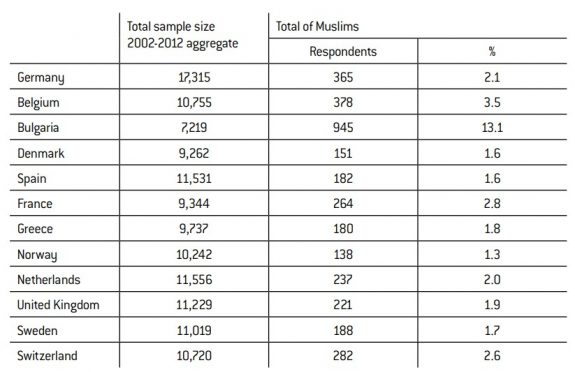

This method is obviously not without its drawbacks. By studying data that has been gathered over a period of ten years, any potential impact of the contemporary climate at the time of the individual surveys is negated. This is nevertheless only a minor issue, because the information collected concerns subjects that are not sensitive to cyclical fluctuation. Another drawback is that this solution does not entirely resolve the problem of under-representation. As Graph 1 shows, the proportion of Muslim respondents remains clearly inferior to the evaluations of the Pew Research Center.15

Graph 1: Muslims in Europe (as a %)

Claude Dargent, “La population musulmane de France : de l’ombre à la lumière ?”, Revue française de sociologie, 51, n° 2, 2010, pp. 219-246.

This under-evaluation of the number of Muslims compared with the Pew Research Center figures is not surprising. Surveys are known to chronically under-represent Muslims, something that can be explained for a number of reasons (difficulty of access, lower social integration, under-declaration, etc.), as has been shown in France.16 We also need to bear in mind that Muslim populations have only recently settled in Europe, which means that there will always be a natural difference between an estimation made at a certain given time (2010 for the Pew Research Center) and data gathered over a period of ten years (2002-2012). Indeed, the only correct estimation has been made in Bulgaria, where the Muslim presence has been established for longer.

Does this under-evaluation affect the quality of the data sample? Effectively, it is possible that the data over-represents the most integrated, highly qualified and politicised Muslims. Nevertheless, nothing indicates that a broader sample would mitigate this distortion, even if the greater number of respondents would be more satisfactory from the point of view of statistical analysis.

table 1: European countries where the aggregate sample totals at least 100 Muslims

source : ESS, aggregate data 2002-2012. unweighted figures.

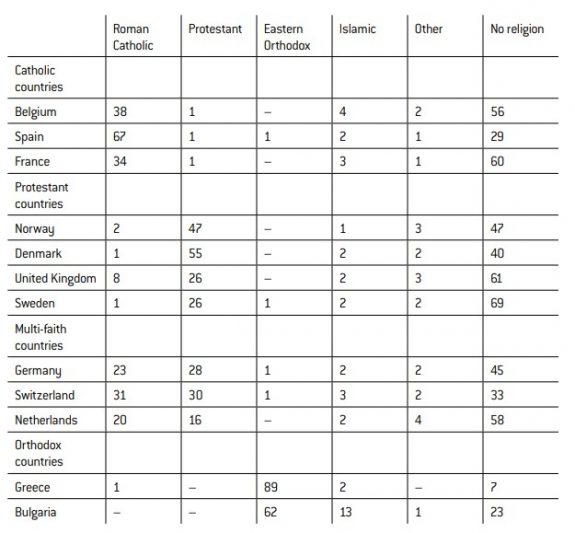

The analysis that follows will be limited to the twelve countries that provided a sample of at least 100 Muslim respondents (Table 1). The overall religious compositions of these countries vary considerably (Table 2). They can be classified into four main groups: traditionally Roman Catholic countries (Belgium, France, Spain), traditionally Protestant countries (Norway, Denmark, United Kingdom, Sweden), traditionally Eastern Orthodox countries (Bulgaria, Greece), and multi-faith countries (Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands). In the majority of these countries, secularisation is already at a very advanced stage, as demonstrated by the percentage of people who declare themselves to have no religion, which is very high in all apart from the Eastern Orthodox countries.

While not enough data is available to enable sophisticated analysis, there is nevertheless enough to construct a general overview. The ESS questionnaire addresses numerous different themes: politicisation, political participation, trust (in others and in institutions), and political orientation (on the left- right spectrum). The survey also provides information on the respondents’ relationship with religion, as well as perceived discriminations and cultural liberalism (respect for traditions, attitudes towards homosexuality, the role of women). It is nevertheless a shame that the questionnaire does not cover certain other themes, including significant issues such as national sentiment, levels of commitment to democratic values, freedom of expression, the relationship between the State and religion, and relationships with violence. Some questions on terrorism are included, but these are too general to be analysed here, dealing as they do exclusively with the risk of terrorist attacks. Furthermore, it is somewhat surprising that, in the context of surveys carried out in the post-9/11 period, not one question has been asked about the big geopolitical issues of this era, and above all the conflicts currently taking place in the Middle East.

table 2: Religious composition of the countries studied, 2002-2012 aggregate data (as a %)

source: ESS, aggregate data 2002-2012. Totals may not equate to 100 due to rounding.

We will present the results in four stages. Having given an overview of the sociodemocratic characteristics of European Muslims, we will study their relationship with religion in more detail by applying various hypotheses relating to “supply” and “demand”, before finally addressing their social and political values.

social situation and national origins

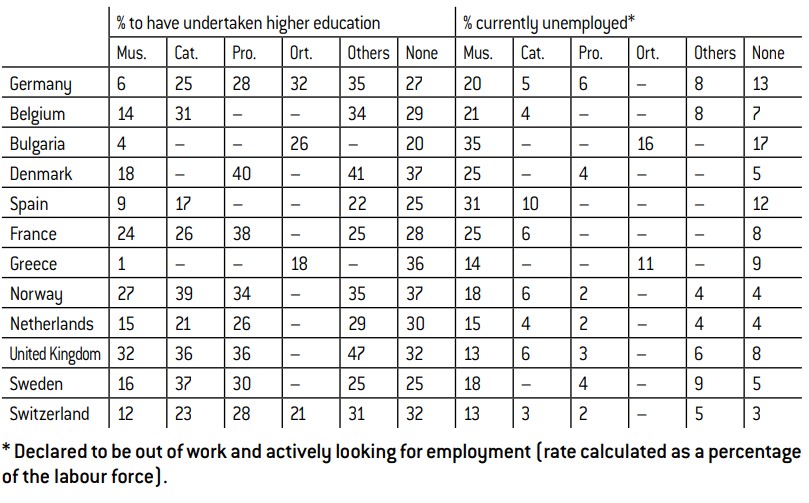

socio-demographic characteristics

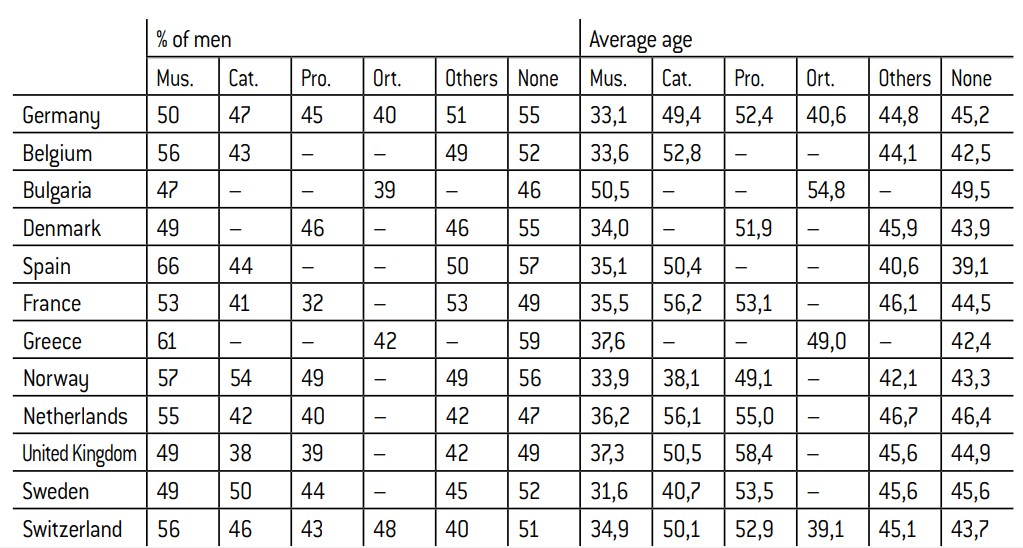

The socio-demographic characteristics of Muslims vary depending on their country of residence, but they do demonstrate certain common features. Muslim populations tend to be younger and more predominantly male than the rest of the country, which can be explained by their recent migrant background and a higher fertility rate (Annex 1). It is difficult to gauge the implications of this over-representation of men and young people, but it can be assumed to have some level of impact, particularly on the place occupied by this group in processes of education and socialisation.

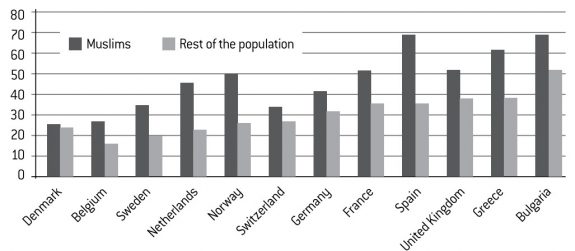

Graph 2: Proportion of people from a modest background (the lowest three deciles of income), as a %

Muslims often come from modest backgrounds (Graph 2). This can be seen from the responses regarding their level of income, although this information is somewhat fragile since the relevant question has only been included in the survey since 2008, reducing the size of the sample by half. However, these income inequalities are not entirely inflexible. In certain countries, the income of Muslims is not markedly different from the rest of the population’s: this is the case in Denmark, Belgium and Switzerland. On the other hand, the divide is at its widest in the Netherlands, Norway and Spain.

Muslims also hold less qualifications than the native population, although this also varies significantly from country to country. The proportion of Muslims who have undertaken higher education varies from 1% in Greece to 32% in the United Kingdom. In France, nearly a quarter of Muslims undertake higher education, which is more than in Germany (6%) or Sweden (16%).

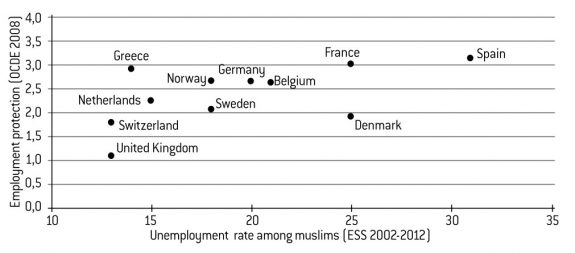

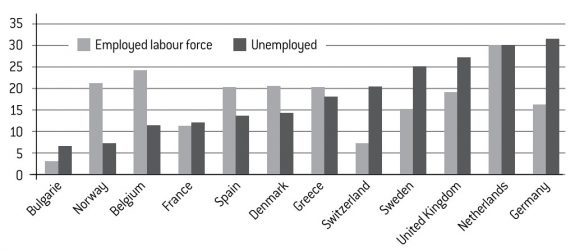

Graphic 3: Rate of unemployment of Muslims as a function of labour market flexibility

The unemployment rate indicated by the ESS 2002-2012 aggregate data differs slightly from the unemployment rate indicated by Eurostat in January 2008, apart from in Bulgaria, where the difference is However, the hierarchy of the countries remains the same in both lists. Without Bulgaria, the correlation between the two sources reaches 0.92 (0.62 when Bulgaria is included).

This is the “Protection of permanent workers against individual and collective dismissal” index (2008 data). This index runs from 0 (the least restrictive regime) to 6 (the most restrictive regime). This data is missing for Bulgaria.

Muslims find it hard to access the job market.17 Their unemployment rates vary from 13% (in the United Kingdom and Sweden) to over 30% (Spain and Bulgaria). Everywhere, the unemployment rate among Muslims is much higher than among the rest of the population.

We have tried to confirm whether there is a link between unemployment and the flexibility of the job market (Graph 3). To do so, we cross-referenced the unemployment rate with the OECD employment protection index.18 There is an underlying trend: the more flexible the job market, the lower the unemployment rate. As far as France is concerned, the level of protection afforded to employees does not seem to aid the employment prospects among an often under-qualified Muslim workforce. It can nevertheless be observed that, even for those countries with a similar level of employment regulation, unemployment rates vary greatly (for example, between Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark, or between Greece, France and Spain). It is therefore unclear whether deregulating the labour market is an adequate solution to the problem of professional insertion.

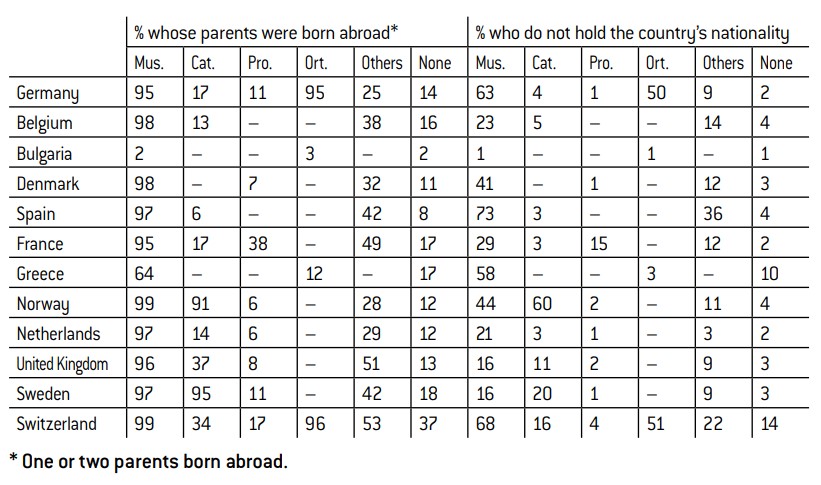

national origins, citizenship and discrimination

The survey does not provide any information on respondents with dual nationality, which is a shame because this would have constituted an additional indicator on the process of integration.

The overwhelming majority of European Muslims are from a Migrant background . Indeed, over 90% of them have a parent who was born abroad (Annex 2). Bulgaria and Greece are the only exceptions to this rule.

Consequently, on average, a high proportion of Muslims do not hold the nationality of their country of residence.19 This proportion nevertheless varies from country to country, since the legislation in effect across Europe is not uniform. In countries where the jus soli (or “right of the soil”) principle is enshrined in law, such as Sweden or the United Kingdom, a higher proportion of Muslims hold the nationality of their host country (in these two countries, only 16% of Muslims do not hold the nationality of their host country). On the other hand, the rates of access to nationality are lower in countries that enforce the jus sanguinis (“right of blood”) principle, like Germany and Switzerland, where around two-thirds of Muslims (63% and 68%) do not hold the nationality of their country of residence. In France, where a combination of jus sanguinis and jus soli is in effect, 29% of Muslims do not hold French nationality, a considerable amount. In every case, these figures underline that European Muslims maintain a close bond with their countries of origin, which further complicates the issue of immigration. They constitute a diaspora that is, to a certain extent, affected by the same anxieties that can be found throughout the modern Muslim world.

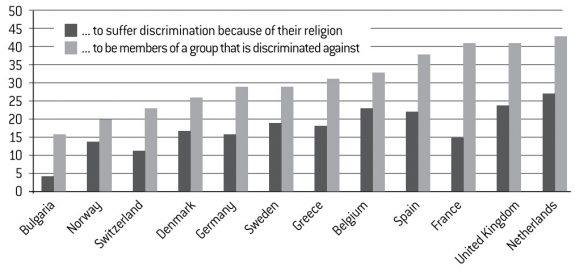

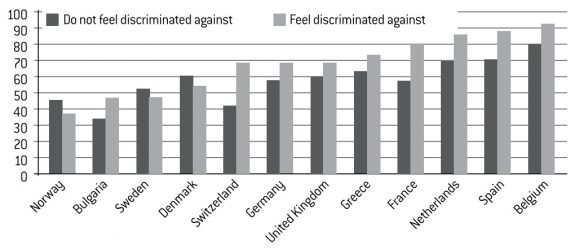

Graph 4: Proportion of Muslims who claim… (as a %)

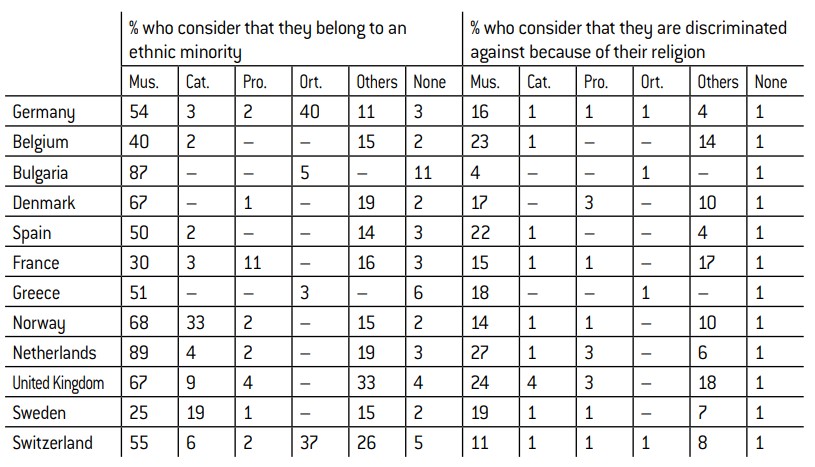

The sense of belonging to an ethnic minority is quite pronounced among European Muslims. This feeling is particularly commonplace in Bulgaria (87%) and in the Netherlands (89%); it is significantly less prominent in Belgium (40%), France (30%) or Sweden (25%).

At the same time, a significant proportion of Muslims (Bulgaria aside) experience the feeling of being discriminated against due to their religion. In France, 15% of Muslims declare that this is the case (a figure that rises to 25% among 15-24 year-olds). This is not exclusively a Muslim problem: other religious minorities often experience, albeit to a lesser extent, the feeling of being discriminated against. In France, perceived discriminations affect Muslims and the country’s other religious minorities to the same degree.

The sense of belonging to an ethnic minority is quite pronounced among European Muslims. This feeling is particularly commonplace in Bulgaria (87%) and in the Netherlands (89%); it is significantly less prominent in Belgium (40%), France (30%) or Sweden (25%).

At the same time, a significant proportion of Muslims (Bulgaria aside) experience the feeling of being discriminated against due to their religion. In France, 15% of Muslims declare that this is the case (a figure that rises to 25% among 15-24 year-olds). This is not exclusively a Muslim problem: other religious minorities often experience, albeit to a lesser extent, the feeling of being discriminated against. In France, perceived discriminations affect Muslims and the country’s other religious minorities to the same degree.

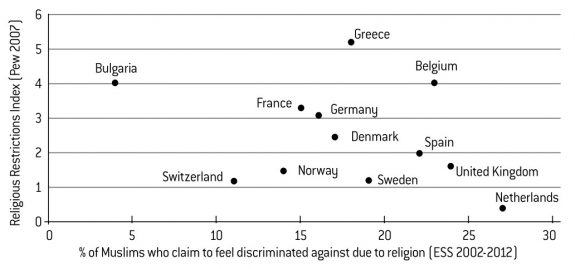

Contrary to what we might assume, there is no link between perceived discrimination and a country’s political approach to religion. To confirm this, we have used the Pew Research Center’s Religious Restrictions Index.20 As we can see, there is no obvious correlation (Graph 5). If we focus on the five countries that score lowest on this index, and that therefore have the least restrictive policies regarding religion (Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands), we see that the frequency of perceived discriminations varies significantly. A tolerant approach towards religion does not therefore necessarily prevent these feelings of discrimination from developing; inversely, restrictive policies do not always result in widespread feelings of perceived discrimination. The case of France is a good example: although it scores over 3 on the index, instances of perceived discrimination occur less frequently than in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands or in Sweden, states that – according to the Religious Restrictions Index – have a less restrictive political approach to religion.

Graph 5: Proportion of Muslims who claim to be discriminated against as a function of the religious restrictions in their country of residence

Therefore, multicultural policies do not necessarily eradicate the notion of perceived discrimination. This surprising result can be explained by the fact that the feeling of being discriminated against does not only result from public policy: we must also assume that it depends on the personal, everyday experiences of the individual. Having said that, neither did we find any correlation between the levels of perceived discrimination and levels of hostility in public opinion, as measured by the Pew Research Center in its Hostility Index. Perhaps another explanation is therefore more appropriate, one that sees multicultural policies to blame for fostering a sentiment of discrimination by placing too much emphasis on ethno-religious identities. Such an explanation is consistent with the data gathered, since we can observe that a sense of belonging to a minority group is often accompanied by a sense of being the victim of discrimination. In the Netherlands, for example, where perceptions of discrimination are widespread, 29% of the Muslims who believe that they belong to a minority group feel that they are also victims of discrimination, as opposed to only 12% among those who do not feel like they members of a minority. In short, pro-minority policies can make individuals more sensitive to the issue of discrimination, fostering among them a certain image of life in their society.

Another unexpected result is the weak correlation between unemployment and perceived discrimination. Indeed, we may have expected unemployed Muslims to be more likely to declare feelings of discrimination, but this is not the case. In several countries (Switzerland, Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany) unemployed Muslims are more likely to claim to be the victims of discrimination than those in work, but the situation is the absolute opposite in Norway, Belgium, Spain and Denmark, where employed respondents more frequently feel discriminated against. In France, there is no difference between the unemployed and those in work. In summary, the employment status of Muslims in Europe does not necessarily have an automatic bearing on the notion of perceived discrimination.

Graph 6: Proportion of Muslims who claim to be discriminated against as a function of employment status

Relationship with religion

The exact question is worded as follows: “Regardless of whether you belong to a particular religion, how religious would you say you are?” A scale of 0 to 10 followed, 0 signifying “not at all religious” and 10 “very religious”. We have grouped all responses from 7 to 10 in order to represent those who display a strong religiosity.

The exact question is worded as follows: “Apart from special occasions such as weddings and funerals, about how often do you attend religious services nowadays?” The possible answers were: “every day”, “more than once a week”, “once a week”, “at least once a month”, “only on special holy days” and “less often”. We have grouped all examples of the first three answers in order to represent a frequent religious practice.

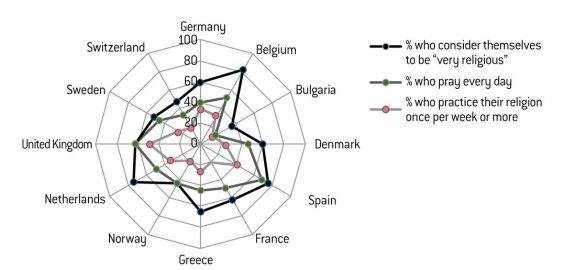

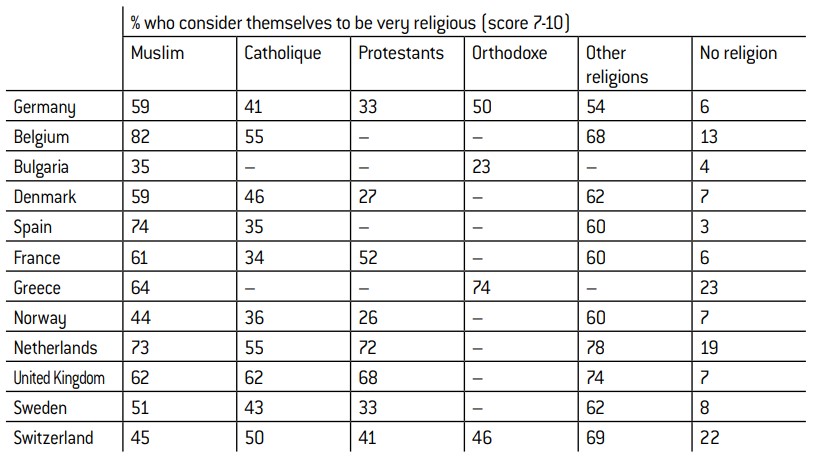

What does it mean to claim to be Muslim? Does the act of declaring oneself a Muslim automatically imply possession of a very distinctive religious identity, and a very strong dedication to that religion? Or on the contrary, do Muslims not keep their religion at arm’s length, as per the assumptions made by secularisation theories? The ESS survey provides various indicators that allow us to build a better overview of the profile of religious identities (Annex 3). We will focus on two of them: whether the respondents consider themselves to be religious21 and how frequently they practice their religion.22

A very prominent religion

Muslims display high levels of faith and religious practice in all European countries. There is nevertheless a certain degree of divergence from country to country (Graph 7). The level of religiosity is at its lowest in Norway and Switzerland, where 44-45% of Muslims consider themselves to be “very religious” (a score of 7-10 on the scale); this level is at its highest in Belgium (82%). Similarly, religious practice is less common in countries like Norway, Switzerland and France, where 20% of Muslims claim to attend weekly services, whereas it is at its highest in Spain (42%) and the United Kingdom (48%).

In general, levels of religiosity (the proportion of those who declare themselves to be a “religious person”) are noticeably higher among Muslims than among the majority populations. For example, the religiosity of Muslims in Spain is double that of the country’s Catholic majority (74% versus 35%). Similarly in France, the difference between Muslims and Catholics approaches double (61% versus 34%). Such gaps are not, however, uniform throughout Europe. In the Netherlands or the United Kingdom, the religiosity of Muslims is at a very similar level to that of Protestants. Concerning religious practice, the figures confirm that daily prayers and the attendance of religious services are very widespread features of Muslim life in Europe.

It should nevertheless also be noted that religious minorities (classified as “other religions”) also display high levels of religiosity and frequency of practice, at times even superior to those observed among the Muslim populations. It would therefore be false to assume that the phenomenon of a growing, or at least stable, religion is one that is unique to Islam. Secularisation seems to affect first and foremost Europe’s big traditional religions; in general, it is having less of an effect on minor religions.

Graph 7: Religiosity and frequency of practice of Muslims in Europe

Religion by age and sex

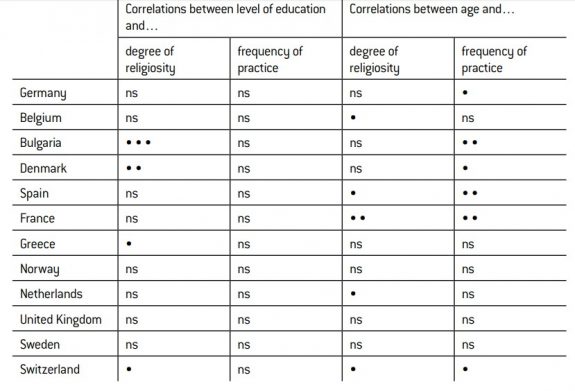

For Muslims, neither frequency of religious practice nor levels of faith appear to correlate with age, apart from Bulgaria where the youngest members of the Muslim population are considerably less religious than their elders (Table 3). This lack of correlation with age would seem to suggest that there is no intergenerational evolution to speak of; in other words, levels of religiosity and frequency of practice both generally remain stable, regardless of age. It is therefore not appropriate to speak of religious revival or decline, although it is again worth underlining that it is difficult to analyse the data from a diachronic perspective.

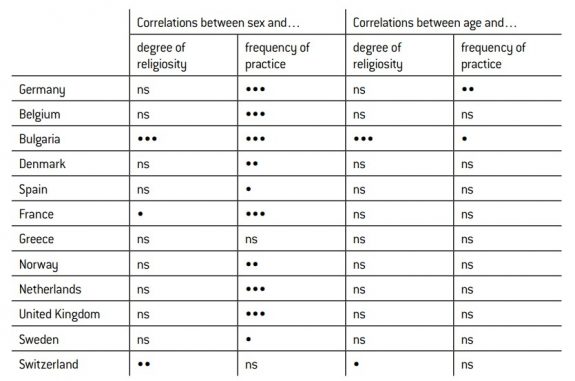

values: correlation coefficients. reading: the number of circles indicates the degree of correlation. 1 circle over the threshold of 0.01; 2 circles over the threshold of 0.05; 3 circles over the threshold of 0.1; ns: not significant. White circles indicate negative correlation, black circles indicate positive correlation (regarding sex, white circles mean that women are over-represented, black circles means that men are over-represented).

table 3: Effects of sex and age on Muslims’ relationship with religion

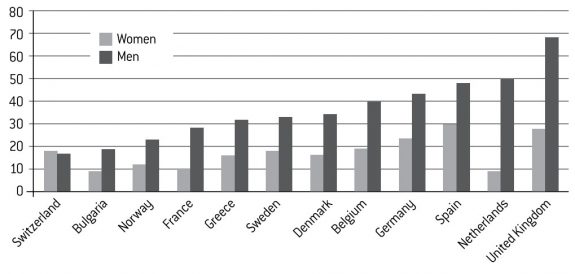

There is a gender divide between Muslim men and women that does not exist for other religions (Table 3). We note, for example, that Muslim men attend religious services up to twice as frequently, if not more, than Muslim women. This is the case in France, where 10% of women regularly attend a place of worship in comparison with 28% of men, and the same pattern is true of the United Kingdom (28% versus 68%) and the Netherlands (9% versus 50%) (Graph 8). We find no equivalent to this gender divide in other religions, with the possible exception of Eastern Orthodoxy in Greece. Men and women of other religions largely share the same practices, with women often practicing more frequently than men.

Graph 8: Proportion of Muslims that attend religious services once per week

IFoP study carried out between 25 February and 5 March 2011, surveying 547 Muslims aged 18 years and above.

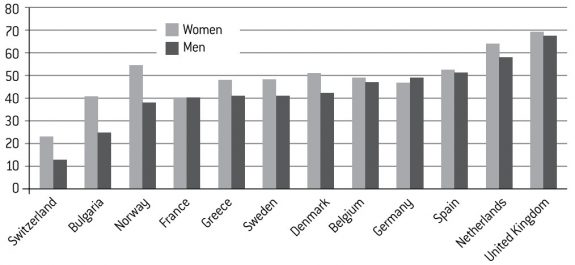

This difference between the sexes is all the more striking when we consider that, among Muslims, men and women display comparable levels of religiosity. Furthermore, they exercise very similar habits with regard to the daily prayer. Indeed, women tend to pray more than men (Graph 9). The European data confirms what had already been shown to be the case in France, by an IFOP survey in 2011, insofar as the ritual of the daily prayer was as common place among women (37% of whom claimed to pray every day) as among men (40%). On the contrary, only 16% of women regularly attended the Friday service at the mosque, as opposed to 35% of men.23

This particular characteristic of Muslim life does not really come as a surprise: according to the Quran, only the daily prayer is compulsory, while the communal prayer on Friday is only recommended for men, with women generally separated into their own dedicated area in the mosque. A rigid system of standards is therefore at work, structuring religious rituals along sexual lines. This organised segregation of men and women is even more important because it is a very visible aspect of Islam in European countries, meaning that this perceived sexual inequality has come to be seen as a central feature of Islam.

Graph 9: Proportion of Muslims who pray every day

Understanding the importance of religion

Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Sacré versus sécularisation. Religion et politique dans le monde, Éditions de l’université de Bruxelles, 2014 [2004].

Why is a high level of religiosity such a prominent feature among Muslims? Two types of hypothesis can be put forward: those relating to supply and those relating to demand. As the data is not suitable for in-depth analysis of the effects of supply, we will broaden the debate to consider the impact of the surrounding environment. We will then look at the issue raised by Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, who proposed the notion of “existential security” as a means of explaining the process of secularisation.24

The impact of supply, the impact of context

See Samir Amghar, L’Islam militant en Europe, Infolio, 2013.

Explanations relating to supply focus on the role of religious diversity, which creates an atmosphere of competition, and therefore of emulation, between different religions. One such explanation has been provided to make sense of the power that religion wields in the United States, where the coexistence of numerous religions has empowered each one to find its own identity, and continues to spark those religions into action in order to attract and retain followers. If we follow this approach through, religion can be seen as a market in which several different providers of spiritual goods compete against each other. As such, supply is creating demand.

This supply-based approach seems well-suited to Islam. The Muslim world has been in turmoil for many centuries, provoking an intense environment of internal competition. In Europe, many associations have formed in order to represent and supervise the Muslim population.25 These associations cover a wide spectre, from very militant organisations like the Muslim Brotherhood or other preaching movements borne out of Salafism or the Tabligh, to less mediatised associations that include the Sufi fellowships. This competitive nature of this environment is amplified by the intervention of foreign countries that like to exercise a certain level of control over their emigrants, whether it be the North African countries or Turkey, not to forget the countries in the Middle East – such as Saudi Arabia – that wish to act in a capacity of spiritual leadership. This has all led to a climate of active proselytism, with each group putting itself forward as the worthy custodian of true Islam.

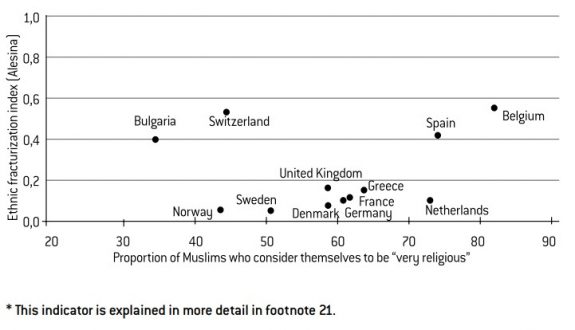

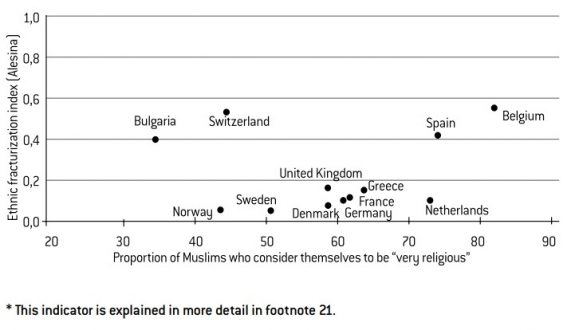

This militant dimension of Islam is obviously very important in the current climate, but the ESS data does not allow us to explore it in any depth. All we can do is to confirm whether there is a connection between religiosity and religious diversity. To do so, we will use the religious “fractionalization” index developed by Alberto Alesina.26 The analysis is not conclusive and agrees with Norris and Inglehart’s observations, which found that secularisation does not correlate to the absence of religious diversity. In other words, secularisation is not necessarily stronger in countries where one religion enjoys a monopoly. It must nevertheless be emphasised that the religious fractionalization index tells us nothing about proselytism or the competition between the different movements within the Muslim faith, and we are therefore unable to pass comment on this point. At the present time, an explanation relating to militant activism can be neither confirmed nor disproved, and such a notion must therefore be the subject of further investigation.

If we broaden our analysis to take the issue of context into consideration, combining levels of religiosity with the ethnic fracturization index offered by Alesina and his colleagues (Graph 10), another neat correlation becomes apparent. This index evaluates the ethnic diversity of a population by giving each country a score from 0 to 1. The correlation between this index and the level of religiosity is by no means negligible since, if we disregard Bulgaria and Sweden, the coefficient reaches 0.79. This result implies that religion can emerge as a means to assert one’s identity in an ethnically diverse climate, which corresponds well to the current situation that European societies find themselves in, with ethno-religious diversity on the rise. This sort of notion could also be suggested as an explanation for the strong religious vigour in the United States, a country that has experienced extremely high levels of immigration, and where religion can therefore serve as a point of reference for its residents’ personal identities.

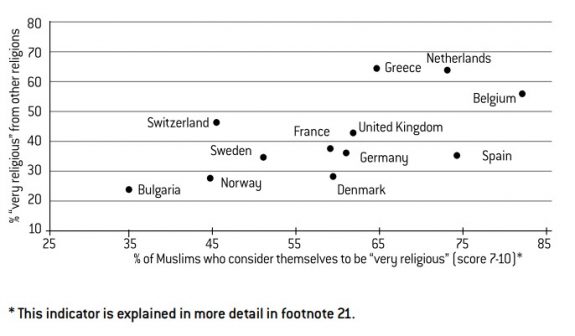

Graph 10: Religiosity and ethnic diversity

There is another interesting result related to the impact of social context that is worthy of our attention. A positive correlation exists between the level of religiosity of Muslims and the level of religiosity of the rest of the population (Graph 11). The existence of such a correlation (that also rings true with regard to the frequency of religious practice) leads us to conclude that the development of beliefs and practices is not disconnected from the place that religion occupies in society, which may serve either to impede or facilitate these processes. The religiosity of Muslims develops more easily in countries where the population itself is more religious. It is easy to understand why: a population that displays higher levels of faith or more frequent levels of religious practice helps to generate an atmosphere that is more conducive to religious expression, and arouses a certain air of competitiveness between different faiths.

Graph 11: Religiosity of Muslims and religiosity of other religions

The effects of demand

Now let’s turn our attention to the issue of demand, starting with issues arising from socioeconomic difficulties. There is a notion that religion, in line with Marx’s evaluation of the “opium of the people” – “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a world without heart” – serves as a refuge that compensates for various frustrating social or economic disadvantages.

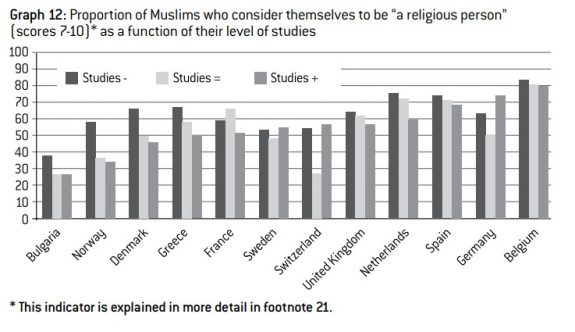

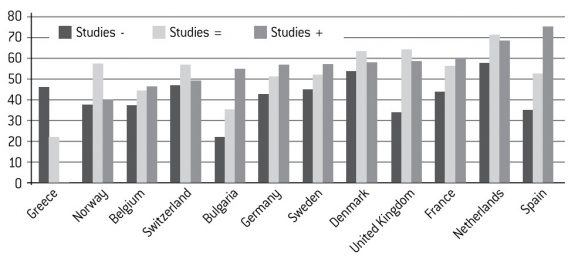

This explanation certainly contains an element of truth, since Muslims often come from modest backgrounds. However, the data still advises caution on this regard. The proportion of Muslims who declare themselves to be “very religious” varies slightly – and unevenly – depending on their social situation. This is the case if we look at levels of education (Graphic 12) but also levels of income. In at least half of the countries (Belgium, Sweden, France, United Kingdom, Spain, Germany), religiosity has practically no correlation with the level of studies. In particular, undertaking higher education does not automatically lead to a lower level of religiosity – far from it.

Graph 12: Proportion of Muslims who consider themselves to be “a religious person” (scores 7-10)* as a function of their level of studies

Another oft-heard explanation sees religiosity as a reaction against a perceived hostility or aggression coming from the social environment. On one level at least, this explanation is backed up by the data: at an aggregate level, there is indeed a strong correlation (r = 0.85) between the religiosity of Muslims and the discrimination they sense against their religion (Graph 13).

Graph 13: Perceived discrimination because of religion, by level of religiosity

The difficulty, however, is in establishing the dynamics behind this correlation. Can a phenomenon affecting only the minority (perceived discrimination) be the cause of a more widespread trend (religiosity)? The opposite hypothesis – the idea that a high level of religiosity results in increased sensitivity, exacerbating feelings of discrimination – should not be ruled out either: the more religious people become, the more receptive they are to the idea that their faith is looked down upon or unfairly Finally, let’s add one more conflicting element: we have not observed a correlation, at an aggregate level, between the degree of religiosity and the restrictions imposed upon religions by states. We cannot therefore conclude that showing dedication to Islam is a response to public policies concerning religion.

Furthermore, the “hostile reaction” explanation is at odds with the fact that the correlation between perceived discrimination and religiosity works much less well on an individual level (Table 4). In the majority of countries, individual correlations are weak at best, and at times non-existent. Therefore feeling discriminated against does not go hand in hand with an increased level of religiosity. In certain countries – such as Norway, Sweden and Denmark- religiosity is actually higher among those Muslims who claim not to feel discriminated against. The results also show that the correlation coefficients concerning frequency of practice are often stronger than those concerning religiosity. This is notably the case in France (Table 4).

values: correlation coefficients. reading: the number of circles indicates the degree of correlation. 1 circle over the threshold of 0.01; 2 circles over the threshold of 0.05; 3 circles over the threshold of 0.1; ns: not significant. White circles indicate negative correlation, black circles indicate positive correlation.

table 4: Effects of the level of education and perceived discriminations on the Muslims’ relationship with their religion

The fact that those who practice Islam are more likely to feel discriminated against than those simply of a Muslim faith suggests that we should re-frame the debate, in order to examine the difficulties directly related to certain aspects of Muslim practice. Rituals such as Ramadan, the prescribed diet and the daily prayer are sometimes an awkward fit in host societies, which can generate a sense of discrimination, even where no harm is intended. This underlines the total ambiguity of the current situation facing Muslims, above all in a secular and egalitarian country such as France, where their claims to be treated with equality sometimes appear to be at odds with their desire to partake in religious practices that require very specific arrangements.

“Existential security”

The thesis written by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart has now become essential reading for anyone looking to understand our relationship with religion. These authors propose a worthy interpretation of the situation, which resolves a number of difficulties. According to them, analysis of secularisation has been abandoned far too often on the pretext that it appears to contradict the preservation, or even revival, of religion that we are witnessing in certain regions of the world.

For Norris and Inglehart, these contradictory phenomena are easily explained if we consider that secularisation principally depends on what they term “existential security”, in other words the feeling of living in a safe and predictable environment. Their chain of thought has shades of Marxist analysis: when individuals feel safe, they turn away from religion; on the contrary, when they feel unsafe, they see religion as a source of comfort. Norris and Inglehart’s work nevertheless stands out due to its strictly sociological definition of security, as a concept that is reduced neither to the social position of individuals nor to social inequalities, but one that is also influenced by the manner in which institutions create a safe environment.

This theory resolves an apparent paradox: why does religion evolve so differently around the world, declining in certain areas at the same time as it prospers elsewhere? The explanation of the authors can be summed up in just a few short words: in countries that have been able to establish existential security, individuals no longer fear the future, which results in the process of secularisation. This is the case in Western Europe, where security exists in both a physical and social sense, mainly thanks to the strength of the welfare state. On the contrary, in the absence of this security, the presence of religion is preserved or even reinforced. This is the case in the United States, where a lack of security allows religion to remain an enduring presence in spite of economic prosperity; this is also the case in Eastern Europe, where the fall of the Berlin Wall may well have eliminated a widespread citizen surveillance system, but it also generated much uncertainty during the transition to a market economy.

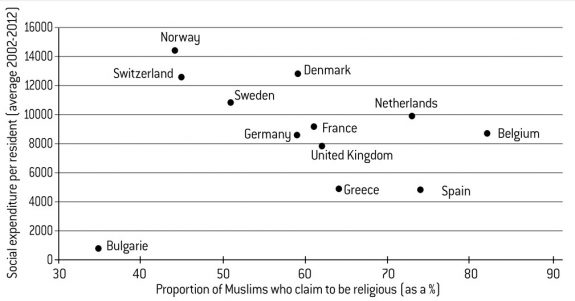

Graph 15: Religiosity of Muslims and level of social security

The case of Islam serves as a persuasive example for this theoretical framework. Muslim countries suffer from weak levels of economic development and a lack of democratisation, not to mention civil wars such as the one that afflicted Algeria in the 1990s. These are all factors that create conditions of insecurity that are conducive to the development of religion. This is an important point because, as we have seen, a large share of European Muslims are of migrant background; in this sense, they carry with them the anxieties that afflict their countries of origin.

But above all, where the notion of existential security is particularly pertinent in explaining why Muslims in Europe are such a diverse group. When we cross-reference degree of religiosity with development of the welfare state, represented here by social security spending, there is a strong correlation (-0.65 if we disregard Bulgaria). In other words, the higher the level of social security, the less prominent religion becomes. As such, the data confirms the hypothesis that those who feel safe about their own existence are less likely to seek refuge in religion.

Obviously, this correlation does not serve as 100% proof. It surely masks numerous intertwined effects that are hard to unravel. For example, countries that boast a strong level of social security also tend to be those where Muslims enjoy a higher level of income. However, no correlation exists between degrees of religiosity and levels of income, which implies that social security is indeed the more decisive variable at play here, above that of household income.

Political and social values

The ESS study offers an insight into a number of political and social values. We will look at four separate dimensions: relationship with politics (including both politicisation and political participation); position on the right-left political spectrum; trust in others and in institutions; and values relating to morals.

Politicisation and political participation

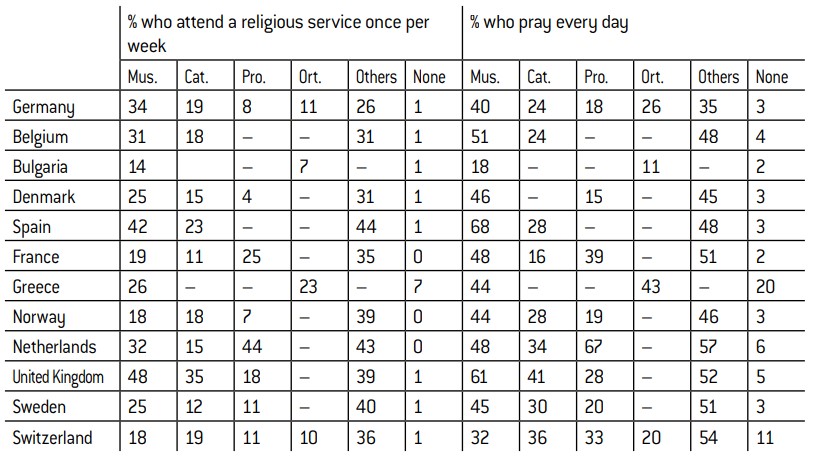

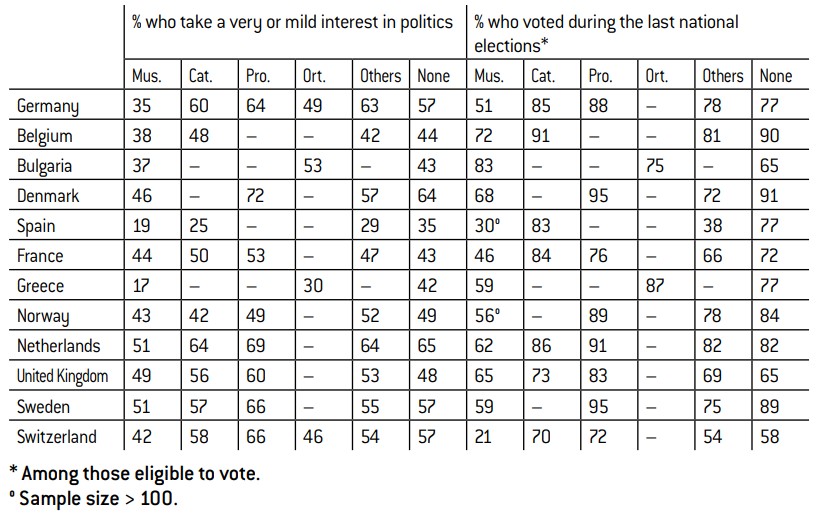

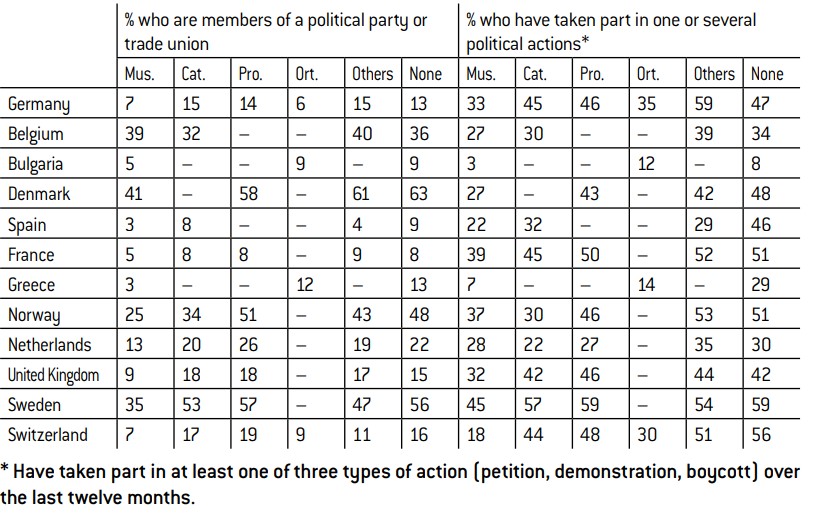

The relationship of the respondents with politics can be defined by studying four indicators: interest in politics, electoral participation, membership of a political movement or trade union, and participation in protests (such as a demonstration or a boycott) (Annex 4).

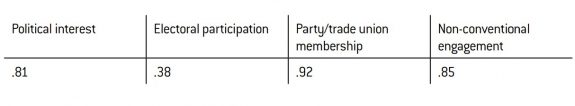

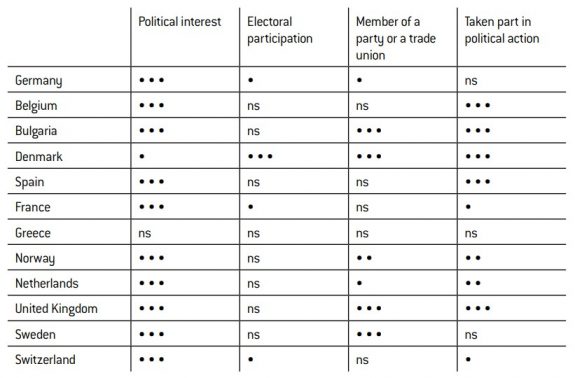

Two key trends emerge from these four indicators. The first is that there are

strong variations between Muslims of different countries. The level of interest in politics is, for example, very low in Greece (17% of Muslims claim to be interested in politics), whereas it is a lot stronger in the Netherlands and Sweden (51%). There are also significant differences regarding the membership of associations: in Spain and Greece, only 3% of Muslims are members of a party or trade union, while a much higher proportion are registered with such organisations in Sweden (35 %), Belgium (39 %) and Denmark (41 %). Participation in protests (having been involved in various forms of political action) varies from 3% in Bulgaria to 39% in France, and as high as 45% in Sweden.

These variations do not occur by chance. The levels of politicisation and participation demonstrated by Muslims are very sensitive to the political context of a country. This is shown by calculating the coefficients of the aggregate results between Muslims and the rest of the population (Table 5). As such, the higher a country’s general levels of political interest or participation, the higher the levels displayed by that country’s Muslims. This result rings true for all the indicators, with the exception of electoral participation, which is a particular case. Results from the other categories seem to suggest that Muslims are capable of adjusting to the local context, even if this does not concern the act of voting.

values: Pearson’s r (N = 12 countries). reading: for political interest, the correlation between Muslims and the rest of the population is 0.81, which means that the higher the general level of political interest in a country, the higher the Muslims’ political interest.

table 5: Aggregate correlations between Muslims and the rest of the population

Secondly, the levels of politicisation or participation demonstrated by Muslims are generally inferior to those displayed by the rest of the population. Often, the differences between these two groups are quite considerable, but this is not to say that there are no exceptions. For example, the level of political interest shown by Muslims is relatively high in countries like France, Spain and the United Kingdom, where it is around the national average.

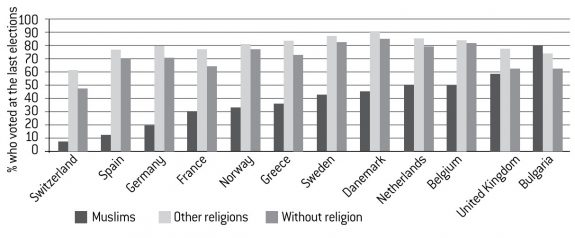

The low levels of political participation displayed by Muslims are particularly visible when they are offered the chance to vote (Annex 4). At election time, the Muslim turnout is considerably lower than for the rest of the population. In Switzerland, 21% of eligible Muslims turned out to vote at the last elections, compared with 66% of the rest of the population. In France, 46% voted, as opposed to 76% of non-Muslims. The participation rate is higher in Belgium (72%), where voting is compulsory, and in Bulgaria (83%).

These figures do however mask part of the truth. We must remember that a large share of Muslims do not hold the nationality of their country of residence. If we adjust the figures to take into account all Muslims who are old enough to vote (whether they possess the nationality of their country of residence or not), in reality only very few of them voted during the last elections (Graph 16). In Germany, only 1 Muslim in 5 (21%) participated at the last elections, as opposed to 78% of non-Muslims. In Spain, it is 1 Muslim in 6 (13%) versus 76% of non-Muslims; in Switzerland, it is 1 Muslim in 10 (9%, versus 58%). In France, 30% of Muslims voted, versus 71% of non-Muslims. The United Kingdom is the only country displaying a less considerable gap between Muslim and non-Muslim election turnout. It remains the case that, in the Muslim section of the population, only very few people are involved in voting and take a participatory role in democracy. There are multiple reasons for this, both social and legal, but this does not make it any less concerning from the perspective of civic and political integration, since it means that a large share of the Muslim population remains closed off from political life in European countries. In effect, the majority of Muslims are unable to relate directly to the issues and differences of opinion that are shaping the central national debates.

Graph 16: Electoral participation for the entirety of the voting-age population (with or without the nationality of the country)

There is another aspect that singles electoral participation out. In comparison with the other indicators concerning politicisation and participation, the Muslim vote is relatively less sensitive to social situation, and above all to the level of education (Table 6). The results do not show the same patterns for voting habits as they do for the other indicators since, as a general rule, a higher level of studies drives politicisation and participation up among Muslims, a trend that is also true of the wider population. In this way, the Muslim vote appears to be resistant to education: even those who have completed their studies tend not to participate in elections.

- 05 significant / • • 0.01 significant / • • • 0.001 significant / ns: not significant.

reading: in Germany, the level of education is strongly correlated with political interest; it is not correlated with involvement in protests

table 6: Individual correlations among Muslims between level of education and the indicators of politicisation and participation

source: ESS 2002-2012 aggregate data (Muslims only).

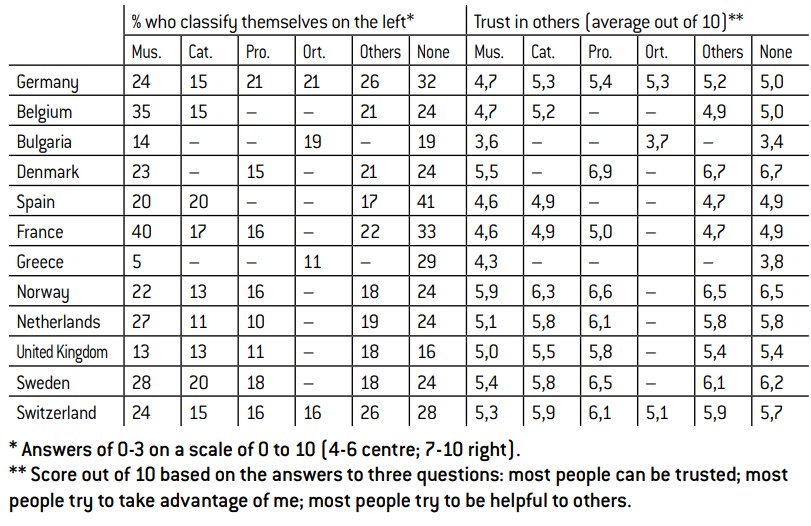

Right-left orientation

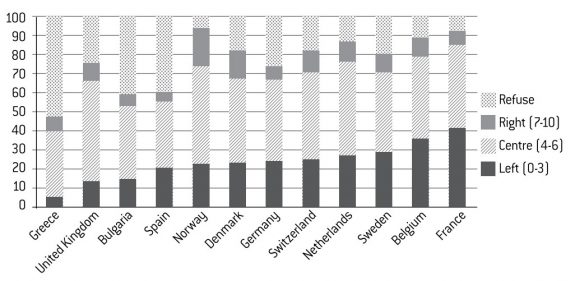

The figures available on political orientation are somewhat surprising (Annex 5). Muslims flatly reject right-wing politics, apart from in Norway, where they are just as likely to be positioned on the right as on the left (20% versus 22%). Everywhere else, the left-right ratio tends to go against the right, above all in Belgium and France where the left boasts the support of 35% and 40% of Muslims respectively (Graph 17).

Graph 17: Left-right classification of Muslims

France and Belgium are nevertheless extreme cases. In other countries, the left’s presence is not as strong and Muslims tend to position themselves towards the centre or, even more likely, as apolitical (or not give a response). As a result, the percentage of Muslims who position themselves neither to the left, nor to the centre, nor to the right is a lot higher than that of the non-Muslim population. In the United Kingdom, 25% of Muslims refuse to classify themselves, in comparison with 12% of non-Muslims; in Sweden, it is 20% versus 4%, and in Germany, 27% versus 7%. France, the only country where this difference can be considered negligible (8% versus 6%), once more constitutes a special case, influenced by a general reluctance in the country to reveal one’s political orientation. However, France apart, Muslims seem to find it relatively difficult to personally relate to the left-right scale of politics. This result provides one possible explanation as to the low turnout of Muslims at elections: if many Muslims tend not to vote, it is perhaps because they have been less successful in integrating the codes of national politics into their own lives. This is understandable, as these are codes that demand a certain familiarity with the history and culture of the country of residence.

The tendency among young Muslims to classify themselves to the left of the political spectrum has also been observed elsewhere (see Vincent Tournier, “Modalités et spécificités de la socialisation des jeunes musulmans en Résultats d’une enquête grenobloise”, Revue française de sociologie, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011, pp. 311-352).

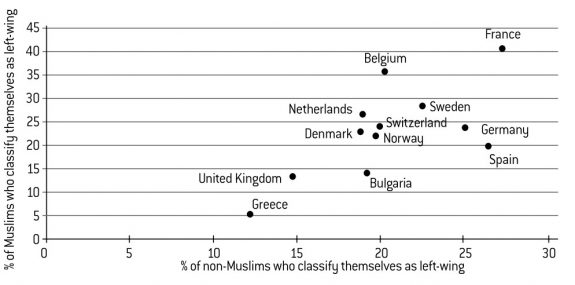

The French exception here is worthy of further investigation: why do so many of the Muslims who reside in France position themselves on the left of the political spectrum?27 Several hypotheses can be put forward: an inheritance from anti-colonial struggles; the strong ties between the right and Catholicism; left-wing sympathies to the plight of the minorities; the impact of militant associations; and the concentration of immigrants living in the so-called banlieues rouges (left-leaning suburban communes). These explanations are all perfectly plausible, but difficult to verify. A comparative analysis reveals another explanation: social context. The proportion of Muslims who classify themselves as left-wing is strongly correlated (0.76) with the proportion of the country’s population that claim to be left-wing (Graph 18). Just as for politicisation or religiosity, the political orientations of Muslims are therefore partially dependent on the overall characteristics of the country. In summary, each country has its own particular political environment that influences the political orientation of that country’s Muslims.

Graph 18: The left in Europe

The issue of trust

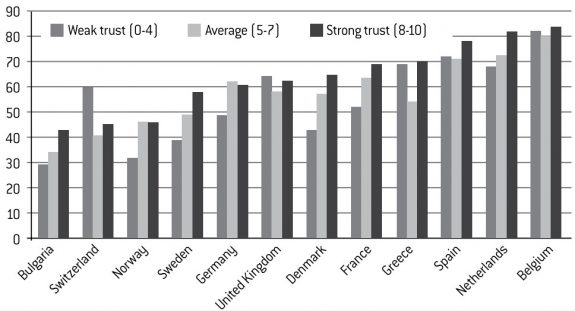

The indicators available to hand do not reveal a particular sense of distrust on the part of Muslims. Indeed, the reality is quite the opposite – and this is one of the most surprising results of the survey. The data available here is more varied, and two main themes can be identified: trust in others and trust in institutions. These two dimensions are evaluated in the form of three scales composed of a score from 0 to 10. We will study the issue of trust in the police, also attributed a score from 0 to 10, separately.

With regard to trust in others, Muslims differ only slightly from the rest of the population. They do generally appear to be a little more wary, but the main divergences on this regard are found in those countries where interpersonal trust is particularly high, such as in Denmark and Norway.

The most surprising result concerns the degree of faith that Muslims show in political institutions, assessed here in the form of three questions about levels of trust in parliament, politicians and political parties. In the majority of countries, the trust of the Muslim population in political institutions is equal to (and often even higher than) that observed among the rest of the population.

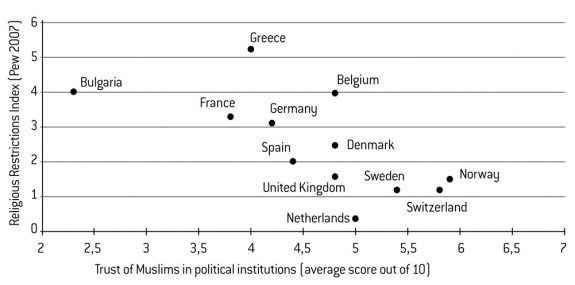

Economic and social difficulties do not, therefore, inspire an attitude of distrust. Furthermore, the trust of Muslims – in others and in institutions – seems to exist independently from their social situation: whatever the country, trust appears to be only slightly influenced by the respondents’ level of studies or income. Trust cannot be said, therefore, to be conditioned by social situation. On the other hand, the level of trust expressed by Muslims is closely linked to the level of trust displayed by the rest of the population. The degree of correlation reaches 0.94 for trust in others and 0.86 for trust in public institutions. The overall context of the country therefore has a major influence in this regard. Furthermore, trust is influenced by the actions of the countries themselves: the level of trust in political institutions is negatively correlated (–0.67) to the indicator concerning religious restrictions. In other words, the more restrictive the state’s policy with regard to religion, the stronger the Muslims’ distrust in political institutions becomes (Graph 19).

Muslims show a similarly high level of trust in another institution: the police. In almost all the countries, as much trust is shown in the police from Muslims as from the rest of the population (Annex 5). France is once more unique in this regard. With the exception of Bulgaria, it is France’s Muslims who show the least faith in the police. This is an indirect consequence of the over- representation of the left among France’s Muslims, since trust in the police is always weaker on the left than on the right. Nevertheless, this explanation is not sufficient because the distrust is generalised, and not determined by ideological preference. Other factors must therefore be taken into account, starting with the country’s overall social context, given that the results once more show that Muslim trust in the police is strongly correlated with the attitude of the rest of the population (0.81). Along with Bulgaria and the Netherlands, France is part of the group of countries that display least trust in the police. And, as a consequence, French Muslims have inherited this tradition of distrust from the other inhabitants of their country of residence. We will add one final remark: it has sometimes been suggested that distrust of the police can influence levels of religiosity. According to the data, this theory is not relevant since, on an individual level, there is almost no correlation between trust in politics and religiosity (Graph 19).

Graph 19: Trust of Muslims in political institutions and religious restrictions

Indeed, the opposite appears to be true: it is the more religious Muslims who tend to have more confidence in the police. This correlation is rarely strong, but it is nevertheless present in three countries: Bulgaria, Sweden and France. In France, 53% of those Muslims that do not trust the police claim to be very religious, a proportion that rises to 63% among those who have a regular level of trust, and 69% among those who strongly trust the institution of the police. The highest level of religiosity is therefore to be found among the most trusting Muslims.

Graph 20: Proportion of Muslims who claim to be “very religious” as a function of levels of trust in the police

Traditionalist values

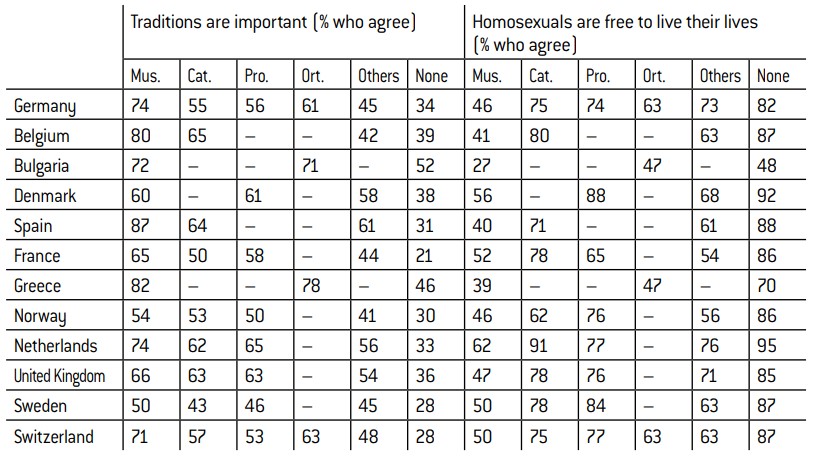

With regard to morals, Muslims display a relatively uniform set of values (Annex 6), revealed by four indicators: these include a general question on respecting traditions, a question on attitudes towards homosexuality, and two questions on the status of women. We will focus less on the latter, as these two questions were only included in three of the six editions of the survey (2004, 2008 and 2010), limiting the size of the data sample available.

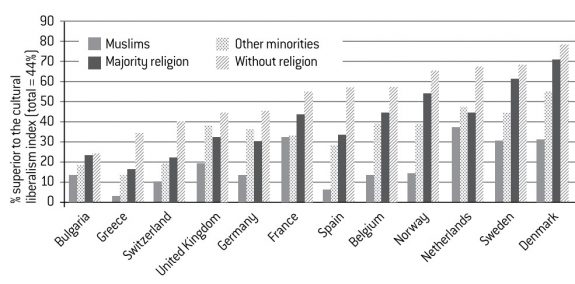

These four indicators display convergent trends. Muslims are found to hold more conservative values than the rest of the population. They place more importance on traditions, they are less likely to approve the notion that gay and lesbian people should be free to live their lives as they wish, and they find it harder to advocate for sexual equality in society. Nevertheless, we must be careful to emphasise that Muslims are not intrinsically resistant to the idea of moral liberalism, since a significant portion of them expressed favourable opinions concerning homosexuals and sexual equality.

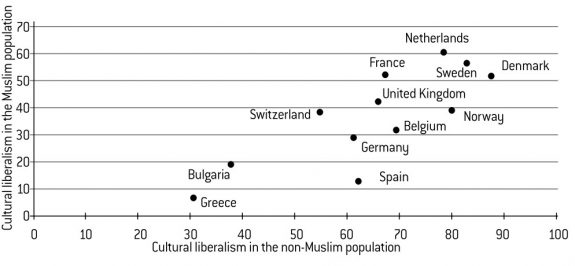

Their views on this regard are nevertheless noticeably different to those held by the rest of the population. This can be verified by devising a synthetic index on cultural liberalism. The index has been created by combining all the responses to the three questions relating to morals (Graph 21). The singularity of the Muslims is even more apparent since, in many countries, the attitudes shown by other religions towards cultural liberalism tend to more closely resemble those shown by non-believers. In this sense, Muslims are relatively isolated in their defence of traditional values. It is worth noting as an aside that France’s Muslims are among Europe’s most morally liberal.

Graph 21: Cultural liberalism as a function of religion

Of course, the Muslims’ distrust of cultural liberalism can partly be explained by their social origins. The proof is in their attitude to homosexuality, the only item for which the data sample is sufficiently large (Graph 22). In countries such as Bulgaria or Spain, the opinions of Muslims vary greatly in accordance with their level of studies. However, these variations are less apparent in other countries, which puts the impact of education into perspective.

Graph 22: Percentage of Muslims with a favourable view of homosexuality as a function of their level of studies

The opinions of Muslims are not static, and they depend to a certain extent on the surrounding social climate, since the correlation between the cultural liberalism of Muslims and that of the general population is very strong, as high as 0.80 (Graph 23).

Graph 23: Cultural liberalism in Europe

See Ruud Koopmans, “Religious Fundamentalism and Hostility against outgroups: A Comparison of Muslims and Christians in Western Europe”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41, n° 1, 2015, pp. 33-57. The three indicators of fundamentalism are as follows: “Christians [Muslims] should return to the roots of Christianity [Islam]”, “There is only one interpretation of the Bible [the Koran] and every Christian [Muslim] must stick to that” and “The rules of the Bible [the Koran] are more important to me than the laws of [survey country]”. Complementary information is available at the Berlin Social Center website (www.wzb.eu/en/press- release/islamic-fundamentalism-is-widely-spread).

Alberto Alesina and Edward L. Glaeser, Combattre les inégalités et la pauvreté. Les Etats-Unis face à l’Europe, Flammarion, 2006 [2004].

Gilles Kepel, Quatre-vingt-treize, Gallimard, 2012 ; Banlieue de la République. Société, politique et religion à Clichy-sous-Bois et Montfermeil, Gallimard, 2012.

The Muslim populations of Europe are not homogeneous. They each display variable characteristics depending on their country of residence, giving lie to the assertion that Muslims constitute one single block. Not only do they not display the same character traits but, furthermore, they are influenced by certain specific characteristics of their countries of residence, on matters such as the place of religion in society, relationships with politics or the issue of values in general. In other words, the opinions of Muslims are partially informed by their socio-cultural environment and the preferences of the wider population, which serves as confirmation of the important role played by contextual factors when it comes to forming political and religious identities. However, while the data available puts any notions of a stagnant or immobilised Islam into perspective, it also refuses to let us believe that religion holds no influence at all. Certainly, the Muslim religion allows for a margin of flexibility depending on the context in which it is practiced, but it still serves as a framework for the values and practices of its followers. Indeed, there are a series of constants that are displayed by Muslim people in the majority of countries. These Muslims, taken as a whole, possess a certain number of specific and unifying characteristics, manifested in both their religious and socio-political attitudes.

We will therefore be careful about drawing overly optimistic conclusions from these results, and even more so given the data does not allow us to make forecasts about the future. The idea of religious characteristics progressively fading away, due to the effects of integration, cannot be ruled out. But another factor may go against this, and even drive the process in the opposite direction: the strengthening of the religion. As we have seen, the religion of Islam would appear to be alive and well in Europe, and the indicators analysed here only tell a part of the story. By asking more specific questions, the Berlin Social Science Center has shown, with the help of a study carried out in 2008 in six European countries (France, Belgium, Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Sweden) that religious fundamentalism is more prominent among Muslims than it is among Christians. According to the data, 44% of Muslim respondents in these six countries answered in the affirmative to the three questions that served to gauge fundamentalist tendencies, as opposed to only 4% among the Christian respondents.28 The individual results stand at 30% in Germany and Sweden, 45% in Holland, 52% in Belgium and France, and 55% in Austria.

Contrary to perceived wisdom, religion appears to occupy a very prominent place in the lives of the Muslim population. The causes of this religious vigour are difficult to grasp. At the present time, there is nothing to say that they will be found exclusively, or even principally, within the internal mechanisms of European societies, whether in relation to perceived discrimination or distrust of institutions. Certainly, the feeling of being discriminated against is relatively commonplace among Muslims, but it only concerns a minority of people. Furthermore, we have observed no particular distrust towards public institutions, and any notion of distrust in the police is unsustainable. Finally, the level of religiosity does not seem to be affected by restrictive state policies towards religion.

Conversely, factors outside of Europe must not be overlooked, starting with the fact that a large section of the Muslim population comes from countries that have been unable to create the conditions of existential security outlined by Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart. From this point of view, European countries appear less like a source of religiosity than a source of secularisation. The ESS data shows that the degree of religious vigour displayed by the Muslims, far from being a random phenomenon, is partially dependent on the degree of existential security offered by the social security systems in the country of residence. This particular result is worthy of our attention at a time when the welfare state is being challenged by the effects of globalisation and “europeanisation”, and maybe also by the effects of increasing levels of immigration, one effect of which is to weaken feelings of social solidarity.29 To underline the impact of the welfare state on secularisation is not to advocate any particular political approach, but simply serves to underline that it will be difficult to engage in a process of secularisation for Muslims without retaining the mechanisms that have contributed to secularising Europe itself. The paradox is that it may become more and more difficult to maintain a high level of social protection in increasingly diverse societies, in terms of their ethnic and religious makeup. Can the legitimacy of the welfare state survive the progressive disappearance of the “making society” concept, if it is not compensated by an ambitious policy to foster integration? This issue will certainly be at the heart of the future European “social model” in a climate of mass migration. It is of particular relevance in France, where an increasing public demand for strengthened laïcité appears to coincide with the increasing volume of demands coming from the country’s minority groups.

For the moment, it is clearly impossible to know how the parallel dynamics of secularisation and integration are going to evolve, and even more so given the additional unknown of the international climate. Another unknown quantity concerns the evolution of moral values. This is a delicate issue, because there is a danger that the differences in attitudes between Muslims and non-Muslims on this subject will become irreconcilable, above all in Europe, the scene of triumph for cultural liberalism.

In short, a key question has yet to be resolved: are Muslims going to buy into the processes of secularisation and individualisation that are currently sweeping through modern European societies? Or are they instead going to lean towards reaffirming their rigid moral and religious values, as can already be observed in certain areas with a strong Muslim presence?30 These two evolutions are not necessarily mutually exclusive. On the contrary, they may in fact feed off one another, the re-islamisation of one group responding to the secularisation of the other, and vice versa. As we have seen, developing a better understanding of the ongoing dynamics at work is a crucial challenge concerning the future of European societies.

Abreviations used: Mus. (Muslim), Cat. (Roman Catholic), Pro. (Protestant), Ort. (Eastern Orthodox), None (without religion). A dash (–) in a box indicates that the sample size is insufficient (under 100 respondents).

Annex 1 : Sex, age, level of studies and unemployment

annex 2 : National origins and discrimination

annex 3 : Relationships with religion: religiosity and practice

annex 4 : Politicisation and political participation

annex 5 : Political orientation and level of trust

annex 6 : Moral liberalism

No comments.