Whoever pays off their debt gets rich

Glossary

Introduction

Debt in 2019 : a french exception ?

The authorities’ response to the health shock

Supply policies

Demand management policies

Output and inflation : what is the scenario for a way out of the crisis ?

The evolution of production: V, W or U-shaped?

Inflation trends: a hitch in 2020?

New challenges for the liquidity constraint ?

What will be the extent of the deterioration in public finances?

What role for financial innovation schemes?

Managing the sustainability constraint : do we have to respect our commitments ?

Fulfilment of commitments

Questioning of commitments

A difficult short-term for companies, a medium-term favourable to banks ?

Impact of the health crisis in the short to medium-term

Medium to long-term impact on fiscal and monetary policies

Conclusion

Summary

Questions about the usefulness of repaying one’s debts have recently multiplied in public debates. This study shows that paying off one’s debts actually allows us to avoid significant costs down the road. It opens with an observation: in France, between 2009 and 2019, both the private and public sectors have become more indebted. Although the situation has not become serious, our country is nevertheless an exception among the major developed economies. The study then explores the outlook. An increase in debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratios is occurring in 2020, particularly for public administrations. With the exception of some emerging economies, however, the likelihood that governments will not be able to access markets remains generally low.

Nevertheless, there have been calls to alleviate the debt burden through various subterfuges, often involving the central bank.

This is a dangerous illusion. Rather than engaging in a game of sorcerer’s apprentice, it would seem more reasonable, where public debt has reached very high levels, to control it through traditional adjustment mechanisms.

Private agents will have to adapt their asset management to the changing context. In the wake of the health crisis, access to bank credit can be expected to become more difficult for businesses and households. Beyond this, two contrasting scenarios are envisaged. The first, which is based on the implementation of adjustment policies in the most indebted countries coupled with structural reforms, leads to a preference for shares. In the second scenario, with inflation at the level of the 1950s and 1970s, recourse to debt benefits the wealthy.

Christian Pfister,

University of Paris-I- Panthéon-Sorbonne and Sciences Po.

Natacha Valla,

School of Management and Innovation, Sciences Po.

Animal spirits. Expression used notably by Keynes in his The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money to designate the appetite for enrichment.

Auction of public securities. Procedure by which Treasuries finance themselves by auctioning the securities they issue through financial intermediaries.

Basel III. Third set of agreements established in 2010 by the Basel Committee, which brings together the central banks and prudential authorities of the main developed and emerging economies. This agreement has notably resulted in a strengthening of banks’ capital requirements.

Budgetary dominance. Situation where monetary policy aims at stabilising the public debt, making the price level undetermined.

Cash flows. Net change in the amount of cash held by a business resulting from its resulting from its operation

Contingent liabilities. Financial obligations that are likely to arise in the future, depending on events that are difficult to predict, such as regulations, the valuation of which is therefore uncertain.

Counter-cyclical cushion. Additional capital requirement imposed on banks in the event of credit growth deemed excessive. It is the macro-prudential policy tool par excellence, whose objective is therefore to protect the economy as a whole, beyond the lenders and borrowers of the institutions to which it applies.

Credit or inflation risk premiums. A supplement of remuneration charged by an investor in fixed-income securities, such as fixed-rate bonds, to compensate the risk of loss of capital value, either because the borrower defaults (credit risk) or because prices rise (inflation risk).

Crypto-assets. Financial assets intended either to serve as monetary units or to finance projects through contributions of other crypto-assets (case of Initial Coin Offerings-ICO).

Currency debasement. Loss of the purchasing power of money due to a decrease in its metal content and/or an increase in prices.

Dividends. Remuneration paid to shareholders.

Effective limit on downward interest rates. The possibility of investing savings in cash seems to prohibit the setting of negative interest rates by central banks. However, there are costs associated with holding cash (transport, storage, insurance, etc.). These costs make it possible to set interest rates at a slightly negative level. For example, in the Eurozone, the rate for the deposit facility is -0.50%. The level beyond which agents store cash, which is difficult to estimate, is called the effective lower bound.

Exposure. In finance, holding of assets issued by an agent (“long” position) or sale of non-owned assets issued by it (“short” position).

Equity premium. Additional remuneration compared to that of a safe asset required by an investor in order to expose themselves to the risk of holding shares.

Financial intermediaries. Firms acting as intermediaries between savers and agents with financing needs, i.e. mainly banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

Financial repression. Policy limiting the financial choices of agents or even, when it applies to regulated agents, setting them strictly.

Fisher equation. An equation that decomposes a nominal interest rate into a real component, often assumed to be equal to economic growth in the case of long-term securities, and a component equal to expected inflation over the period corresponding to the maturity of the security.

Guarantors. Agents who, by providing a surety to a debtor, agree to take their place if they default.

Hedge funds. Lightly regulated funds aimed at institutional investors and high net worth individuals.

Key interest rates. Rates set by central banks to control money market rates.

Laffer curve. Curve linking the rate of tax pressure to the level of production: above a certain level of tax pressure, its increase becomes counterproductive, as the increase in the tax rate reduces tax revenues by discouraging productive effort. The Laffer curve joins the old adage that “too many taxes kills taxes”.

Modigliani–Miller Theorem. The authors show that, under certain assumptions, the cost of a company’s liabilities does not depend on its structure. For example, a company that finances itself by issuing shares, which is more expensive than debt because shareholders rank after creditors in the event of default, should be able to borrow more cheaply.

Moral hazard. Term derived from contract theory, applied in particular to the field of insurance (before motor insurance became compulsory, it had been noted that insured drivers drove faster than others). More generally used to refer to the fact that, by seeking to protect agents from the consequences of their actions, the public authorities reduce their incentive to be prudent.

Non-financial agents. In national accounts, private and public administrations, households (individuals and self-employed) and non- financial corporations.

Non-performing loans. Loans for which recovery is uncertain due to the borrower’s poor financial health.

Over-subscription. Demand exceeding supply at a securities auction.

Swap. Financial contract built on the basis of existing products; it is therefore a derivative contract. For example, an interest rate swap enables a fixed rate to be exchanged for a variable rate.

Solow growth model. Growth model inspired by neoclassical theory where the marginal productivity of capital is, in perfect competition, equal to the interest rate. Growth is balanced, therefore prices and interest rates are stable, when the interest rate is equal to the growth rate.

Spreads. Yield differentials corresponding to differences in the currency of denomination, signature or maturity.

This study mainly comments on gross debt.

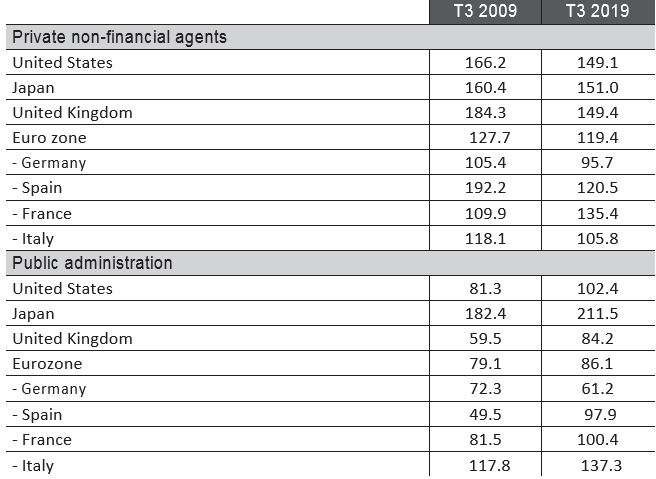

The idea that one could get rich by paying off one’s debts is paradoxical: by paying back, a debtor only reduces the size of their balance sheet, the reduction in their liabilities being offset by the reduction in their cash on the assets side. However, in financial theory as well as in day-to-day management, it is accepted that creditors monitor their debtors and seek compensation for the risks they incur. The basis of market discipline is thus that a debtor, when exposed to increased risk, is charged higher risk premiums. If their situation continues to deteriorate, they may even find themselves in the position where no one wishes to lend them anymore; they are then deprived of access to credit. While the Covid-19 crisis has resulted in a significant increase in the indebtedness of public administrations and companies, questions about the usefulness of repaying these debts have multiplied in public debates. This study shows that paying off one’s debts actually avoids significant costs. It begins with the observation that by 2019, in most major economies, the private sector had reduced its debt 1 compared to the situation that prevailed ten years earlier, when the global financial crisis was at its peak; conversely, over the same period, public debt has mostly increased. In France, both the private and public sectors became more indebted, although the situation did not become serious on either front.

Our study then explores the prospects. As a result of the public policy measures taken during the health crisis, the decline in economic activity and the fiscal support for it will lead to an increase in debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratios, particularly for public agents. With the exception of some emerging economies, however, the likelihood that governments will be unable to access markets remains generally low. In this context, it is not in the perspective of better access to credit that financial innovation schemes could prove particularly useful, whether it be the issuance of perpetual debt or even Eurobonds.

In recent months, however, there have been calls to alleviate the debt burden through various subterfuges, often involving the central bank. This is a dangerous illusion. The mechanisms that involve the balance sheet of the authority in charge of issuing money and guaranteeing its value and viability are complex. A sovereign default on the securities held by the central bank that would be imposed on it or a deliberate waiver of debt by the latter, where possible, would have mechanical consequences on the transfers from the central bank to the State, and thus on the taxpayer. In addition, these schemes would have monetary consequences, potentially very serious ones, on inflation. However, just as it is not possible to say at what point public debt becomes unsustainable, it is not possible to guarantee at what point the deterioration of the central bank’s balance sheet would make inflation accelerate. Rather than engaging in a game of sorcerer’s apprentice, it would seem more reasonable, where public debt has reached very high levels, to control it through traditional adjustment mechanisms, while minimising the cost of these policies through the adoption of structural measures.

Private agents will have to adapt their asset management to the context of high indebtedness and its valuation strongly affected by public action. In the wake of the health crisis, access to bank credit can be expected to become more difficult for companies and households. Beyond this, two contrasted scenarios are envisaged. The first is based on the implementation of adjustment policies in the most indebted countries, coupled with structural reforms. The investments of private agents should then favour equities and own funds. In the second scenario, with inflation levels comparable to those of the 1950-1970’s, private agents able to access credit would be particularly well placed to benefit from the appreciation of real assets. On the other hand, the actors with the greatest liquidity constraints and whose financial assets are essentially monetary, and therefore the most vulnerable, would largely lose out.

In order to take a reasoned look at the proposals for debt write-off, particularly public debt, this paper begins by making an observation on the debt in 2019, in light of the trends observed in the major economies over the previous ten years (Part I). The authorities’ response to the health crisis in economic terms is then presented (Part II), in order to assess how the recovery could unfold (Part III). At the centre of the questions, public debt management is analysed from a short-term perspective, that of the liquidity constraint, hence access to credit (Part IV), then from a medium to long-term perspective, that of the sustainability constraint, hence access to savings (Part V). Finally, the consequences for private agents, for their investment decisions as well as for their daily life, of the economic policy choices made to satisfy these two constraints are discussed (Part VI).

Debt in 2019 : a french exception ?

As shown in the table on the next page, between what has been called the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 crisis, French developments stand out among those of other major developed economies in two respects:

- When it comes to private non-financial agents (households and non- financial companies), debt ratios have generally followed a downward trend, while France’s debt rates have been increasing, becoming higher than those of Spain, for example, since 2018. Among our partners, these developments mainly reflect a decrease in household debt, notably due to net repayments of mortgages. In terms of level, the UK and U.S. debt rates are certainly higher than in France, but both are economies where households also have much more financial assets than in continental Europe, with the exception of the Netherlands, due in particular to the existence of pension Net debt ratios (differences between financial assets and liabilities) are therefore much lower there. In Japan, the debt ratio of private non-financial agents is also high, due to the fact that corporate debt is structurally even higher than that of their French counterparts, but it has fallen;

- With regard to the public sector, grouped here according to the national accounts classification of general government (State, local authorities and social security), the debt ratio in most countries rose sharply in the wake of the GFC, before becoming stable.

In the case of France, it has been declining since 2016, whereas it has been declining in the Eurozone since 2013, driven in particular by Germany, the latter showing that it is possible to make a fiscal adjustment without clear negative implications for economic growth (see Part V). Within the Eurozone, France’s public debt ratio only reached a plateau in 2016. In terms of level, two large countries stand out with a particularly high debt ratio: Italy and, above all, Japan.

Debt ratio (% of GDP)

Source :

Banque de France, Quarterly National Accounts and Eurostat.

From the GFC until the end of last year, the table therefore shows a deleveraging of the private sector and a moderation of public debt. France stands out to a certain extent, mainly because of households’ recourse to housing debt. However, the levels of debt reached in our country do not seem spectacular, whether it is private or public debt.

The authorities’ response to the health shock

The focus here is on economic aspects only, leaving aside the public health aspects, which are certainly essential in a broader perspective. Indeed, it should be possible to define a policy to fight pandemics with unchanged health and public spending (respectively nearly 12% and 60% of GDP in France), by reallocating resources. Until now, health spending does not seem to play a significant role in the worsening of public deficits. On the contrary, the latter is the result of related policies, in particular the use of a lockdown, a common-sense decision at the health level. From this point of view, and insofar as the diagnosis can influence the remedies to be prescribed, a distinction must be made between the health crisis and previous crises. This distinction is particularly relevant to the financial crises of the twentieth century, to which the Covid-19 crisis has been compared:

- The origins of the Great Depression, like those of the GFC, are generally attributed to causes internal to economies, particularly financial factors in the case of the GFC. The Covid-19 crisis has an external cause. In particular, this crisis cannot, any more than the Black Death of the fourteenth century, be attributed to “globalisation”, unless it involves any international trade or migratory flows;

- The current crisis is a supply shock, as lockdown implies a very sharp fall in production in many sectors (see Part III) and causes company failures. However, this shock also leads to a demand shock, which is currently smaller as a result of State intervention, but which could grow in magnitude, especially if unemployment rises sharply after lockdown.

As a result, the health crisis justifies the implementation of both supply and demand management policies, which are themselves closely linked to the debt process.

Supply policies

See Emmanuel Combe and Didier Bréchemier, Before Covid-19 air transportation in Europe: an already fragile and After Covid-19 air transportation in Europe: time for decision-making, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, May 2020.

The supply-side provisions aimed to limit the immediate impact of the crisis and its consequences on the exit from lockdown, by protecting the firms from the supply shock. However, they can have a significant deferred cost. There are two main types of measures:

- Public aid to businesses, which can itself take two forms. Public authorities can intervene by granting deferrals on taxes or social security contributions and by guaranteeing bank loans, especially loans to SMEs.They can also provide loans directly to companies in the sectors hardest hit by the crisis: many governments have lent to national airlines 2;

- Prudential measures ranging from the deactivation of the counter-cyclical cushion, as in France where it was contributing to moderate real estate lending, to the relaxation of capital or liquidity requirements, the delayed implementation of Basel III and accounting standards, and moral suasion to encourage financial intermediaries not to distribute dividends in 2020.

The first measures cited have implications for the level of indebtedness of the parties concerned: deferred payments constitute claims of the public sphere on the private sphere, in the same way as more direct credit arrangements. As for public guarantees on private loans, they are contingent liabilities which, as such, may result in payment obligations.

Demand management policies

On the effective limit of falling interest rates and ways of circumventing it, see Christian Pfister and Natacha Valla, “’Nouvelle normale’ ou ‘nouvelle orthodoxie’ ? Éléments d’un nouveau cadre d’action pour les banques centrales”, Revue économique, 68, special issue “Aspects de la crise“, September 2017, pp. 41-62.

See Virginie Robert, “Coronavirus : quand les États multiplient les chèques directs aux citoyens“, lesechos.fr, 19 April 2020.

In the context of the coronavirus pandemic, the two levers of monetary and fiscal policies have been activated.

Central banks first played their role of lender of last resort at a twofold level:

- At the national level, by refinancing the banking system, which was subject to high liquidity demands. For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) has launched a series of so-called “targeted longer-term refinancing operations” enabling banks to refinance themselves at four- year maturity at particularly advantageous interest rates and has relaxed its collateral requirements;

- At the international level, by bringing into play the swap agreements concluded between the most important of Because of the important role played by the dollar in international trade, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has also entered into swap arrangements with fourteen central banks of emerging countries, including Brazil, South Korea and Mexico.

In a more traditional way, in the face of an economic slowdown, central banks have also eased their monetary policies by lowering their key rates where they did not run up against the constraint of the effective downward bound 3.

In addition, they purchased assets in order to influence medium and long- term interest rates (maturities of two years or more).

Governments have intervened through fiscal policies to support individual demand in two ways:

- By supporting income through direct subsidies (e.g. in the United States 4), by increasing replacement income (longer unemployment benefits, increased short-time working compensation) and sometimes by lowering taxes;

- Easing liquidity constraints by authorising the suspension of property loan repayments (which has been implemented in the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom). However, this measure has the disadvantage of shifting the constraint onto the banks, and thus potentially causing the rest of the economy to suffer: a bank subject to an exogenous liquidity constraint may choose to ration its loan supply to agents it would otherwise have served.

Output and inflation : what is the scenario for a way out of the crisis ?

The evolution of production: V, W or U-shaped?

See Ministry of the Economy and Finance-Directorate General of the Treasury, “Flash conjoncture France – L’Insee estime l’impact d’un mois de confinement à -3 pts de PIB annue“, study written by the Bureau de l’analyse conjoncturelle, 30 March 2020.

See Robert Barro, José F. Ursúa and Joanna Wen, “The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the ‘Spanish Flu’ for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity”, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper n°6866,March 2020.

See OFCE’s Analysis and Forecasting Department, “Évaluation au 20 avril 2020 de l’impact économique de la pandémie de Covid-19 et des mesures de confinement en Comptes d’agents et de branches“, OFCE Policy Brief, n°66, 20 April 2020.

- See Scott R. Baker, A. Farrokhnia, Steffen Meyer, Michaela Pagel and Constantine Yannelis, “Income, Liquidity, and the Consumption Response to the 2020 Economic Stimulus Payments” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper n°27097, May 2020.

European Central Bank(ECB),”Résultatsdel’enquêtemenéeparla BCEauprèsdesprévisionnistes professionnels pour le deuxième trimestre 2020“, Press release, 4 May 2020.

European Commission, “Spring 2020 Economic Forecast: A deep and uneven recession, an uncertain recovery“, Press release, 6 May 2020.

According to converging estimates by INSEE, the Banque de France and the Observatoire français des conjunctures économiques (OFCE), each month of lockdown in France results in a loss of approximately 3 points of annual GDP 5. The sectors most affected are expected to be building and public works, industry (excluding the agricultural and food industries), energy, transport and certain services (hotels and restaurants, personal services, etc.). This impressive figure must be put into perspective: the cost of the Spanish flu (1918-1920) has recently been estimated at about 6 to 8 GDP points per country on average 6.

However, given a pandemic-related mortality rate of 2.1% (or 150 million people in relation to the current world population), the effects of the Spanish flu have also been felt over a long period of time, and the costs in terms of lost production have therefore been much greater in total than can be anticipated for Covid-19. What characterises the cost of the current pandemic in comparison with previous ones, including AIDS – which is estimated to have made around 40 million victims worldwide – is that it is highly concentrated over time.

More specifically, three scenarios for post-lockdown economic recovery can be considered:

- That of a rapid, V-shaped recovery seems Indeed, the opening up after lockdown has been gradual across sectors, regions and countries. The last point implies a gradual resumption of international trade. As in the 2008-2010 crisis and its aftermath, this trade, by coming to an abrupt halt, initially played a role in amplifying the crisis. It is expected to resume only gradually, thus not fulfilling its usual accelerating role inr the long run, where it grows faster than production. In addition, companies must put in place measures to ensure the safety of employees and customers, preventing an immediate resumption of production at pre-crisis levels;

- That of a W-shaped evolution would correspond to a resumption of the pandemic, following, for example, premature reopening post-lockdown or migratory flows from countries where it would not have been eradicated to The hypothesis of coordination between countries, so as to avoid the realisation of the latter possibility, is generally made by forecasters;

- The third scenario, the one that is very generally retained, is that of a U-shaped recovery, where the collapse of production linked to containment would be followed by a However, there are questions about the strength of the latter. On the one hand, if the crisis does indeed have the character of a temporary shock, not calling into question the long-term growth prospects, it is to be expected that demand will return fairly quickly to its pre-crisis level. In particular, the intervention of public authorities to considerably cushion the impact of the crisis on employment and income should support household consumption all the better as households, lacking access to certain goods and services, will have accumulated an overhang of savings during the containment.

In the case of France, the OFCE evaluates this overhang at 55 billion euros 7. This surplus of savings should notably enable purchases deferred by the crisis to be made, particularly those in durable goods, also stimulated by the probable destocking by retailers. It should also bring household consumption to a temporarily higher level than before the crisis, with the savings rate falling from a high level to return to the medium to long-term level. On the other hand, in countries where wage employment has adjusted sharply downwards, as in the United States, it may only start to recover gradually, with employers’ associations even expressing concern that government-distributed replacement income may act as a disincentive to return to the labour market. In the United States, however, a study shows a fairly strong consumer response to government support, with an increase from $0.25 to $0.35 in consumption per dollar of support in the ten days following its payment, mainly in food products and from the households most subject to liquidity constraints, i.e. a priori those on low incomes 8.

More generally, companies could go bankrupt and lay people off. In addition, companies, which are affected by the fall in their turnover during the lockdown period, could subsequently postpone their investments and give priority to the repayment of cash loans taken out when activity was at its lowest point.

It is the last scenario that the forecasters, surveyed by the ECB in the course of April 2020, favour on the whole, with a fall in the GDP of the euro zone of 5.5% in 2020 followed by a rebound of 4.3% in 2021 9, against the background of an upturn in activity at a “normal” rate from the third quarter of 2020. The profile of activity would therefore describe a U whose right-hand branch would be less steep than the left-hand branch. In its economic forecasts for the spring of 2020, the European Commission adopts a similar but more pronounced profile: a fall in GDP of 7.75% in 2020, followed by a rise of 6.25% in 2021 10. The expectations of the financial markets also appear to be consistent with a scenario in which economic growth would not be permanently slowed down.

After a correction in share prices of around 30% from mid-February to mid-March, partly as a result of the search for liquidity, most stock exchanges regained one third of the ground lost over the following two months, and even two thirds in the case of the S&P 500 index, which is highly concentrated in technology stocks.

Similarly, the price of gold, a safe haven par excellence during global crises, rose only moderately in dollar terms, gaining around 16% between the end of January 2020, when the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a state of public health emergency of international scope, and mid-July 2020. By comparison, gold prices had risen by more than 40% between mid-2007 and mid-2008, at the height of the subprime crisis.

Inflation trends: a hitch in 2020?

The evolution of inflation in the short, medium and long-term will be a decisive variable as regards the sustainability of debts and their future. In a period of containment, a greater fall in production than in consumption should in principle lead to a rise in prices. Nevertheless, the consumer price index reacts very quickly to changes in oil prices. The price of oil fell sharply at the beginning of the health crisis, due to the drop in demand in the most consuming sectors (transport, industry). In addition, the prices of products not consumed during this period (personal services or most of leisure services) were carried over, the composition of the index being reviewed only annually. This price carry-over, combined with lower energy prices, which are expected to have become less important in the consumer basket during the lockdown, could lead to a temporary underestimate of inflation.

This measurement problem should dissipate as businesses reopen. Inflationary pressure could then be felt as a result of the above-mentioned catching-up behaviour of consumption, while supply capacity will not be immediately restored (due in particular to supply disruptions or the delay resulting from the refurbishment of premises). Conversely, cash- strapped companies could make commercial offers. It is therefore difficult to anticipate how inflation will develop between now and the end of the year. Nevertheless, forecasters expect inflation in the euro zone to slow significantly to 0.4% in 2020 from 1.3% in 2019, followed by a rebound in 2021 (between 1.2% and 1.4%). By 2024, their inflation forecast (at 1.7%) does not vary more than in previous quarterly surveys conducted by the ECB: at this stage, therefore, no inflation slippage is expected (see Part V).

New challenges for the liquidity constraint ?

In a market economy, it is the role of banks and financial markets to provide access to credit for non-financial agents. However, the question arises in the short-term of how to manage the liquidity constraint. Economic activity is contracting (see Part III) and governments act as guarantors of credit to businesses, providing liquidity – for a total amount estimated by the European Commission at 24% of the Eurozone GDP – and providing alternative income and burden relief (see Part II). Against a background of heavy recourse to financial intermediaries and markets, will there be a demand for government securities? In order to have elements of an answer to this question, it is first necessary to assess the extent to which public finances are expected to deteriorate. In a second step, we will examine various financial innovations proposed to ease the liquidity constraint.

What will be the extent of the deterioration in public finances?

According to European Commission forecasts, the public deficit in the euro zone would increase from 0.6 to 8.5 points of GDP between 2019 and 2020, to fall back to 3.5 points of GDP in 2021. Taking into account variations in GDP estimated at -7.7% in 2020 and +6.3% in 2021, this would imply an increase in the public debt/GDP ratio of 17 points in 2020, reaching 103%, and a decrease of 3 points in 2021, in the absence of adjustments different from those forecast by the European Commission, for example due to the assumption of private debt by the public authorities. Moreover, according to these forecasts, the differences in situation would widen between Eurozone countries. Thus, Germany would see its public debt ratio rise from 60% in 2019 to 76% in 2020, compared with 96% to 116% for Spain, 98% to 117% for France and, above all, 135% to 159% for Italy. In the United States, again according to European Commission forecasts, the public deficit will reach 18% of GDP in 2020.

Towards a public finance crisis?

Should we then fear a crisis in public finances, which would occur if an auction of public securities did not find takers? In fact, this has not been the case. Since the start of the health crisis, auctions of public securities have been very largely oversubscribed in all developed economies, albeit initially at slightly less favourable terms for borrowers than before the health crisis, where, as in the euro zone, a cut in key rates had not been possible. Thus, for Olivier Blanchard, former IMF chief economist, the level of public debt in the industrialised countries was not worrying before the crisis, and is still not after its occurrence.

This is due to high savings in the face of low investment and interest rates close to zero. In the short-term, a public debt crisis is therefore, in his view, unlikely 11. Moreover, the liquidity of public securities markets is supported by central bank purchases and bank refinancing (see Part II) in industrialised countries.

The debt of emerging countries

The situation may be different in emerging and developing countries. These countries have faced significant capital outflows since the start of the health crisis, exposing them to a dual crisis in terms of exchange rates and public finances. More than a hundred of them have thus had to call on International Monetary Fund (IMF) loans, particularly those granted to deal with natural disasters. In addition, the aforementioned swap arrangements set up by the Fed with 14 central banks of emerging countries have eased the pressure on interest and exchange rates of the currencies of these countries. In total, examining the situation of 66 emerging or developing economies and taking four criteria into account (public debt, public and private foreign debt, borrowing costs and the rate of coverage of foreign payments – current account deficit and foreign debt service – by foreign exchange reserves), The Economist magazine notes that some 30 of them are in a fragile situation 12. However, they account for only 11% of the total GDP of these 66 countries and less than a quarter of their total public or foreign debt, and some of the countries in the most difficult situation, such as Lebanon or Venezuela, were there before the health crisis. Moreover, in mid-April 2020, the G20 suspended debt service on public loans to the 77 poorest countries and the G7 subsequently called on private creditors to do the same. To prevent these countries from defaulting (see Part V), however, debt forgiveness may be necessary.

What role for financial innovation schemes?

See “George Soros: “This crisis is truly endangering the survival of our civilisation“, remarks collected by Gregor Peter Schmitz, be, 17 May 2020.

See, forexample, Robin Wigglesworth,”Asolutiontotheloomingdebtcrisisinemergingmarkets“, ft.com, 4 May 2020.

Two types of financial innovation have been put forward as instruments for financing public deficits resulting from the health crisis, with a view to alleviating the liquidity constraint weighing on States.

The first, advocated by George Soros for Europe (he does not specify which European institution, but it could be the European Commission) in an interview with a Belgian newspaper in May 2020 13, would also be usable at the national level and would consist in issuing perpetual debt, a practice abandoned for several centuries in the economies that have resorted to it (essentially Britain and France). The second type of financial innovation, the use of which has been advocated at the European or international level, would aim to mutualise loans.

What about the use of perpetual debt?

George Soros points out that one of the advantages of perpetual debt is that it does not have to be repaid, from which he believes that it would impose only a very small budgetary burden. He cites a surprisingly low interest rate of 0.5%, whereas under the Ancien Régime (former political and social system), perpetual debt commonly bore interest at 4%. More generally, it is very difficult to anticipate at what rate perpetual debt can be issued. In fact, knowing that the term premium in principle increases with maturity in order to remunerate the investor for the price risk to which he is exposed, the term premium at the infinite horizon could, in theory, also reach an infinite – or in any case very high-level. The use of perpetual debt would therefore be costly. Consequently, if public spending related to the crisis is to be financed by an instrument earmarked for it, with the aim of easing the liquidity constraint on States, it would probably be better to issue very long-term securities (thirty years or more).

What about debt pooling?

Proposals for the mutualisation of public debt were first formulated in Europe by the European Commission as early as 2011, in the context of the sovereign debt crisis, and taken up by academics, under the term “Eurobonds”. They reappeared during the health crisis under the name of “Coronabonds”. The idea is to entrust a European agency, with the joint and several guarantee of all Eurozone member countries, with the task of issuing sovereign debt on behalf of States that would otherwise be subject to the risk of no longer being able to access the financial markets, or else at penalising conditions, a risk deemed unjustified. Furthermore, the guarantee provided by the highest rated issuers would enable the agency, and hence its debtors, to benefit from interest rate conditions close to those available to the original guarantors. However, it is questionable whether a liquidity constraint is necessarily harmful, justifying the implementation of a permanent mechanism and denying the capacity of financial markets to send warning signals to governments. Moreover, it is unlikely that this mechanism would offer a “free lunch”. On the one hand, it is clear that the best rated countries, by making a conditional commitment represented by their guarantee, will have to face deteriorated borrowing conditions. This is why they are often opposed to the introduction of Eurobonds. On the other hand, the debtor countries will not necessarily see a decrease in the average interest rates to which they have access to.

Indeed, in order for the scheme to be credible and the investors to accept a lower remuneration than they would receive by lending directly to the agency’s debtors, the securities issued by the agency must have some form of de facto or de jure “seniority”, just as it is accepted that a country does not in principle default on loans granted by the IMF. Holders of standard securities issued by the countries receiving loans from the agency would thus be “juniorised” and therefore enticed into charging higher risk premiums, reducing the advantage obtained by borrowers from the European agency. Ultimately, in accordance with the Modigliani–Miller theorem, according to which a change in the composition of liabilities in a balance sheet cannot change its average cost, this advantage would be cancelled out. All other things being equal, the average government bond rate of the countries in the zone would remain unchanged, only its dispersion among borrowers would be reduced. The average rate could even be increased if the issuance of Eurobonds was perceived as increasing the moral hazard on public finances.

This does not mean that Eurobonds are a bad idea, only that they are not a panacea. On a more positive note, the issuance of Eurobonds can be an opportunity to transfer competences to the European level, thus contributing to the implementation of structural reforms that would better homogenise the Eurozone and support the public finances of all member countries (see Part V). In addition, it should be recalled that within the framework of the monetary union, there are automatic pooling mechanisms with the ECB’s liquidity supplies and the Target balances (i.e. the balances of accounts between the central banks of the Eurosystem reflecting payments of all kinds between EU member countries made through the Target system). The very existence of the area thus guarantees a common liquidity base and constitutes a solidarity mechanism that prevents any payments crisis between member countries.

In addition, in response to the health crisis, the European Commission has borrowed €100 billion to cover Part of the costs of creating or extending short-time working schemes and the European Investment Bank (EIB) has set up a pan-European guarantee fund for loans to businesses to the tune of €200 billion. Furthermore, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) has undertaken to provide loans to European States of up to 2% of each beneficiary’s GDP. Finally, following an approach reminiscent of Coronabonds, since it is a temporary response to a specific crisis, France and Germany proposed on 18 May 2020 that the European Commission borrow €500 billion to provide budgetary allocations to the EU countries most affected by the health crisis. This loan can of course only be repaid through higher contributions from the Member States to the European Commission’s budget but, like any loan from a European or international organisation, it has the accounting advantage of not being included in the debts of the Member States. In response, the so-called “frugal” countries (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden) suggested that Community aid should take the form of loans and be accompanied by reform commitments on the Part of the recipient countries. On 20 July 2020, the 27 European states reached an agreement on a €750 billion recovery plan. Of the total amount, €672.5 billion is divided into two main categories: loans (€360 billion) and grants (€312.5 billion). In addition, there are various lines of the Commission’s multiannual budget for an amount of €77.5 billion, giving a total of €390 billion in grants.

Proposals similar to Eurobonds, involving the World Bank or the IMF to supplement investors’ payments, have been made at the international level for emerging and developing economies 14. They have the same limitations and should be interpreted as proposals for a more distributive role for international organisations.

Managing the sustainability constraint : do we have to respect our commitments ?

Access to credit, nowadays synonymous with access to financial markets, is based on a liquidity constraint, to which both public and private agents are subject. The analogy for public agents of the solvency constraint of private agents is the sustainability of public finances. This refers to the capacity of a State to meet its borrowing requirements in the future. However, today there is no way of forcing a State to respect its commitments. A distinction is therefore made between two ways of managing the sustainability constraint, depending on whether the commitments made are respected or not.

Fulfilment of commitments

See, for example, Alberto Alesina, Omar Barbiero, Carlo Favero, Francesco Giavazzi and Matteo Paradisi, “The Effects of Fiscal Consolidations: Theory and Evidence“, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper n°23385, May 2017.

The notion of “public debt sustainability” is unclear, reflecting the uncertainties surrounding any forecast. These uncertainties are particularly high in the case of a management that is a matter of not only economic but also political decisions. As a result, it is not possible to indicate ex ante at what threshold a public debt becomes unsustainable.

Two observations can be made, however, in order to keep to considerations of an economic nature:

– Assuming that a public debt/GDP ratio adequately reflects sustainability and that, if it has been reached, it means that the debt was sustainable, and by making a set of forecasts on economic growth, inflation and market interest rates, it is possible to calculate a primary public balance (i.e. excluding interest payments) stabilising the debt, which is then assumed to be sustainable. This balance makes it possible to avoid the “snowball effect” where a real interest rate on the debt higher than the growth rate of the economy (or a nominal interest rate higher than the nominal GDP growth rate, taking inflation as an exogenous variable) would lead to an uncontrolled increase in the public debt/GDP ratio. The so-called “Maastricht criteria” for public finances (debt ratio limited to 60% and deficit ratio limited to 3%) implicitly rely on such a calculation. On the basis of an inflation rate of 2%, very close to the inflation target of the ECB, a, a potential economic growth rate of 3% in the long-term – an assumption that is nowadays unrealistic – and a real interest rate at the same level, in accordance with Solow growth model, it is possible in the Fisher equation (nominal interest rate equal to the sum of the growth rate and the inflation rate) to stabilise the public debt ratio at the 60% level, once this has been reached, with a public deficit ratio of 3%. In the current context, satisfying the sustainability constraint does not pose a problem for States which, like France, have been able to take on debt for several years at negative rates, provided of course that the recession linked to the Covid-19 health crisis, which makes the real interest rate temporarily higher than the growth rate, does not last. However, this may be a difficulty for issuers who, like Italy, have to pay high spreads and whose potential growth is low.

Unlike private agents, States have, together with taxes, recourse to coercion to repay their debts. This is why the interest rate at which the Treasury can borrow is called the “risk-free rate” and provides a floor to the interest rates available to private agents. However, the tax levels already reached must not be “on the right” side of the Laffer curve where the tax burden has become such that “too many taxes kill taxes”. A government that believes it cannot raise taxes should therefore rely entirely on public spending cuts to release the necessary resources (the primary surplus) needed to stabilise its debt. It should also escape the “snowball” effect by reassuring savers by displaying a credible trajectory of primary surpluses, allowing it to finance itself at low interest rates, incorporating only low risk premiums. Finally, it should do so without lowering its growth prospects (the denominator of the debt/GDP ratio)

For some authors, these objectives are compatible provided that governments make sometimes difficult political choices, such as calling into question certain social benefits 15. The gain in credibility and the expectations of high potential growth generated by structural reforms thus make it possible to compensate, even in the short-term, for the recessive impact of budget cuts. This is therefore the path that countries such as Italy, where public debt and the tax burden have reached high levels while potential growth remains low, resulting in wide spreads, could take.

Questioning of commitments

See Francesco Bianchi, Renato Faccini and Leonardo Melosi, “Monetary and Fiscal Policies in Times of Large Debt: Unity is Strength“, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper n°27112, May 2020.

On this subject, see Françoise Drumetz, Christian Pfister and Jean-Guillaume Sahuc, Politique monétaire, De Boeck, 2nd ed. 2015.

See Natacha Valla and Christian Pfister, “Helicopter money: Panacea, shell game or Faustian pact?” The Eurofi Magazine, April 2020, p. 46.

See Council of the European Communities-Commission of the European Communities, “Traité sur l’Union européenne“, May 1992, eu, p. 26.

In order to challenge their commitments and relax the constraint on the sustainability of their public finances, governments can use three levers: fiscal and tax policy, cooperation from the central bank or pressure on it where it is independent, as is the case today in all developed countries and in a growing number of emerging countries, and a policy of financial repression.

Debt and fiscal policy

In terms of budgetary and fiscal policies, a first possibility is to default; a second is to use taxation to generate inflation. The latter case is a questioning of commitments to the extent that borrowing has been carried out at low levels of nominal interest rates, thus incorporating the promise of low inflation (the same argument applies when monetary policy is inflected to induce inflation).

Defaulting is obviously a hypothesis rejected by issuers on the grounds that it would be an outdated way to restore the sustainability of public finances, which is unthinkable in developed economies with large financial markets. More prosaically, to mention it would be self-fulfilling: savers would not want to lend to a State that would show no interest in repaying them. However, with the exception of central banks that could not accept it for statutory reasons, holders of securities issued by the Greek government have indeed been reduced by 70% in their rights in 2012. This is therefore a path that cannot be ruled out, even in developed economies.

A general default on government borrowing does, however, have drawbacks, notably that the defaulting government is cut off from access to financial markets. Admittedly, experience shows that this cut-off lasts only a few years: three or four years in most cases, more in the case of countries that refuse to implement fiscal and structural adjustment policies.

It thus took seven years for Greece to return to the financial markets. In fact, if default has the mechanical merit of temporarily restoring the sustainability of public finances, the policies implemented and anticipated must support this commitment in a credible manner. Three or four years is generally the time needed by lenders to make sure of this. In the meantime, in the absence of pressure on monetary policy or financial repression, the defaulting state must therefore either immediately cut spending to balance its budget or raise taxes, with the risk in both cases of triggering a recessive spiral if it is unable to restore growth prospects.

Another disadvantage of general default is that it can be very unpopular when a large proportion of public debt is held by residents, either directly or through pension funds or, as is the case in France, insurance companies. Consequentely, a country like Japan, where public debt reaches very high levels (see Part I), may be indebted at very low interest rates. This is partly due to the fact that, as public debt is held mainly by residents, the possibility of default is considered by savers to be very low. In the case of emerging countries in a position of great economic weakness even before the start of the pandemic and where a large Part of the debt is held by foreign investors, such as Argentina or Lebanon, a general default may nevertheless be a tempting option. In the case of highly indebted euro zone member countries, default is often represented as an alternative to an exit from monetary union followed by a devaluation of the restored national currency, in order to limit the risk of recession. However, this alternative is not credible because if the exiting country were given the politically costly opportunity to change the currency of denomination of the loans held by its residents, it would not be allowed to do so in relation to non-residents. Exemption from this duty would entail a high risk of retaliation by its former partners (for example, the imposition of customs duties that would cancel the transitory advantage of devaluation). Respecting this duty would annihilate the benefit expected from the dual operation of exit from the monetary union and devaluation by increasing the level of foreign debt, including that of intra-zone balances, in proportion to the latter. The only credible path for a member country of a monetary union that is reluctant to repay its debt is therefore that of default, as the example of Greece has shown. Besides, default may be selective vis-à-vis the central bank, including through a policy of fait accompli if the latter’s statutes oppose it.

If it does not default, a government may seek to act on its internal prices to devalue its debt, for example by substituting consumption taxes for production or income taxes and by imposing indexation .

In addition to the costs of inflation, this policy carries the risk of being ineffective if firms do not pass on tax increases to consumption, for example because of strong public aversion to inflation, or even of having a recessive impact, by burdening consumption, if they pass on the increase but not the tax cut on production, assuming that demand allows them to do so. The risk of a recessive impact is greater in the context of a monetary union, where this policy would undermine competitiveness.

Faced with debt, new objectives for monetary policy?

For its part, monetary policy can contribute to inflationary pressures to restore the sustainability of public finances. Thus, the central bank can “play into the hands” of the public authorities by agreeing to place itself in a situation of “fiscal dominance”, where the objective of monetary policy is no longer price stability but rather the sustainability of public debt. This is more likely to happen if the central bank is not independent. However, even if independent, the central bank can take on board the state’s financing difficulties and its negative economic consequences to place itself under “fiscal dominance” 16. In fact, even if the central bank is statutorily independent, it may be very difficult for it to refuse its support for state financing. For example, the latter may conduct a policy of public deficits that significantly increases the financing costs of private agents, which the central bank will then seek to protect against an increase in spreads that could place the economy in a lasting situation of underemployment. This kind of capture of the central bank by the public authorities is possible both in a given country and in a monetary union, insofar as the central bank aims to ensure a homogeneous transmission of monetary policy between private agents in the different countries. Indeed, this homogeneity presupposes in turn that the financing conditions of the States, which largely condition those of private agents, are themselves homogeneous, which may lead to support for securities issued by the country or countries in a delicate budgetary situation. Moreover, “hostage-taking” is more likely to achieve its goal if these securities are widely held by partner countries, as a default could cause them significant losses, in turn calling into question the transmission mechanism in the countries holding them, notably via the losses inflicted on financial institutions (banks, insurance companies and pension funds). Hence the need to ensure the sustainability of public finances in the member countries of a monetary union, as provided for in the Treaty on European Union.

Faced with the Covid-19 crisis, the question arises of concrete means by which the central bank could revive inflation while keeping it under control, so as to avoid hyperinflation whose economic and social consequences could be dramatic. In this respect, a parallel is often drawn with the periods following the two world wars.

However, the economic context was very different, with massive destruction of capital and the need to rebuild, human losses in the tens of millions, the virtual absence of competition from emerging economies and very promising growth prospects in connection with the reconstruction and catching-up of the United States. There is therefore no reason to believe that it would be sufficient to have the same monetary policy instruments as then to achieve comparable results.

What about the monetisation of public debt by central banks?

One way sometimes advocated to ensure the sustainability of public debt by creating inflation is to monetise this debt, i.e. having central banks create reserves by buying government securities. However, this requires a “monetary multiplier” mechanism, similar to the standard Keynesian- inspired diagram or the monetarist approach. An increase in the monetary base should lead to a multiple increase in credit, money supply (monetarist approach) and/or demand (Keynesian approach) and, ultimately, prices. While this relationship may have existed in the post-World War II period, in a period of financial repression when household investment opportunities were very limited, it is no longer verified. This is demonstrated in particular by the experience of massive purchases of public assets by central banks, which led to a very strong increase in the monetary base without a corresponding increase in inflation.

Nowadays, it is the credibility of central banks, i.e. their commitment to maintain price stability that anchors inflation expectations 17. In order to raise inflation beyond their target, central bankers would therefore have to change their rhetoric and, for this change to be credible in itself, adopt a very significant change in behaviour. Central banks are thus invited to show that they are coming to the rescue of fiscal policy by taking on redistributive tasks in place of elected bodies, by a policy of “currency-helicopter” 18 or by making debt forgiveness to states, or by lending to them on terms that are clearly off-market (free perpetual loans, for example).

More generally, the idea would be to damage the credibility of the issuer and the quality of the currency issued by making the central bank assume tasks that are not its own and which lead to a deterioration of its balance sheet. In particular, if the central bank were to make losses putting it in a negative net position, thus in technical default, it would end up being dependent on budgetary subsidies to ensure its operation.

However, if financial independence is not a sufficient condition for central bank independence, it is a necessary condition. Creditors of a private bank withdraw their money when the bank makes losses. Similarly, holders of currency, unable to demand repayment of legal tender because of the forced course, would seek to get rid of it if the central bank’s balance sheet deteriorated sufficiently. A substitution in favour of foreign currencies would result in currency depreciation, imported inflation and currency war if the same policies were simultaneously pursued abroad, an arbitrage in favour of real assets through their appreciation (see Part VI) and an arbitrage in favour of consumption through inflation.

The merits of statutory constraints against monetary financing

Such policies of debt write-offs by central banks would come up against statutory constraints, such as, in Europe, Article 123 of the Treaty on Economic and Monetary Union. Of course, the statutes can be changed, but it is a long and complex process that exposes the public authorities and the central bank to open conflict and to political debate with uncertain outcomes, particularly in a monetary union if member countries do not share the same objectives. Moreover, here again, the means would not guarantee that the desired goal, i.e. inflation well above the current central bank targets (usually close to 2%), would be achieved without the risk of slipping into hyperinflation. Indeed, for more than ten years now in the euro zone, much more so in Japan and again since the health crisis in the United States, the trend in inflation as well as inflation expectations extracted from financial markets rather reflect the difficulty for central banks in achieving a level of inflation sufficiently high to meet their target, despite efforts to do so.

In the event that the more radical means discussed earlier in this study were implemented, a strong public commitment to price stability, which seems to be reflected in the fact that perceived inflation is systematically higher than observed inflation, could stand in the way of a resumption of inflation. In the first instance, the public might pay less attention to what would appear to be a panel discussion because there is a cost to changing payment habits. Second, and no more than for the unsustainability of the public debt is it possible to know at what precise point in time this would intervene, the public could completely change their expectations, creating a “flight from money” effect. The latter, comparable to a run on deposits (bank run), would be likely to provoke an episode of hyperinflation similar to that of Germany in 1923 or more recent episodes in the emerging world (Venezuela, Zimbabwe).

Financial repression policy

By aiming to limit the formation of credit or inflation risk premiums, a policy of financial repression would complement the previous policies. The means used to this end would consist of constraining private agents in their portfolio choices, for example by imposing floors on the holdings of public securities by financial intermediaries and ceilings on interest rates, or by exchange controls. These practices were common in France until the 1980s. Nowadays, within the framework of the euro zone, Article 104 A of the Treaty on European Union nevertheless prohibits privileged access by Community bodies and public administrations to financial institutions 19.

An attenuated form of these policies is “yield curve control”, which prevents, through the administration of the financial market by the central bank, the incorporation of inflation or term premiums into the level of long-term interest rates. This practice was implemented by the Fed from 1937 to 1951 and is carried out by the Bank of Japan since 2016. In fact, after the Second World War, the Fed felt that its role in administering the government bond market had deprived it of some of its operational independence. It was only after a long period of opposition with the Treasury that the Treasury-Fed Accord released it from this role.

A difficult short-term for companies, a medium-term favourable to banks ?

The financial impact of the health crisis, in the short to medium-term, and then of the fiscal and monetary policies that could be pursued in the medium to long-term, deserves to be highlighted. We focus here on the case of developed economies (on the case of emerging and developing economies, see Part IV).

Impact of the health crisis in the short to medium-term

See Ryan Banerjee, Anamaria Illes, Enisse Kharroubi and José-Maria Serena, “Covid-19 and corporate sector liquidity“, BIS Bulletin, n°10, 28 April 2020.

See Banque de France, “L’impact de la crise du Covid-19 sur la situation financière des ménages et des entreprises: une première photographie à partir des données monétaires et financières à fin mars 2020“, Press release, 29 April 2020.

See European Central Bank (ECB), “Résultats de l’enquête d’avril 2020 sur la distribution du crédit bancaire dans la zone euro“, Press release, 28 April 2020.

See Stephen Frenay and Christophe Bonnet, “Comportement des investisseurs particuliers pendant la crise Covid-19“, Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF)-Direction des marchés, April 2020, p.6.

What is the impact of the health crisis on the financial situation of companies and households?

As far as companies are concerned, they must both generate cash flows to service their debt and sufficient profitability to satisfy their shareholders.

Based on a sample of 40,000 companies from 26 developed and emerging economies representing about 60% of GDP in the median country, a Bank for International Settlements (BIS) study estimates that 50% of companies would not have sufficient cash flow to service their debt in the year 2020 20. Moreover, if their sales were to fall by 25%, meeting their need for debt financing would increase their leverage by about 10 percentage points. From the start of the health crisis, companies have sought to strengthen their liquidity situation: in France, their bank deposits rose sharply in March 2020 (+40.6 billion euros), probably due to the liquidation of other assets, while at the same time there was a sharp increase in loans (+34.2 billion euros) 21. In the short-term, the ECB survey on bank credit distribution in the euro zone published at the end of April 2020 showed a forecast of a sharp increase in demand for treasury credit from companies in the second quarter of 2020 22. However, banks anticipated an easing of credit conditions, in conjunction with the improvement in their refinancing conditions thanks to the ECB’s targeted longer-term refinancing operations and the intervention of state guarantees (see Part II).

Beyond that, due to the effect of the health crisis on their results and debt, the financing conditions of companies should spontaneously deteriorate (more expensive and more difficult access to loans, higher equity premiums making access to the stock market more expensive). However, public policies could hinder these developments by encouraging banks to consolidate their lending to SMEs, which they do not have easy access to financial markets, for example by extending the guarantee of loans granted during the health crisis.

From forced savings to tighter conditions for access to credit?

As far as individuals are concerned, the fall in their consumption greater than that of their income has enabled them to provide the banks with liquidity to facilitate the financing of companies and governments. Households’ bank deposits have thus risen sharply – by nearly €20 billion in France in March 2020 – at the same time as the growth in their borrowing has halted, suggesting a significant increase in their financial savings. In addition, a study published by the Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) revealed that retail investors’ purchases of French equities quadrupled in March 2020: more than 150,000 new investors, aged ten to fifteen years less than regular investors in French equities, bought SBF 120 shares between 24 February and 3 April 2020 23. The question certainly arises as to whether these purchases respond to the search for “hits” in the equity market, without any prospect of sustainable investment, or to a more profound change in the direction of increased risk-taking by investors. However, it is clear that they have cushioned the fall in prices as households have acted as a counterpart to companies liquidating their financial investments.

Finally, a fall in their income that was lower than their consumption enabled households, particularly those facing the strongest liquidity constraints, to continue to repay their bank loans, thus eliminating a channel of transmission of the health crisis to the banking sector. Beyond short-term developments, banks could restrict their supply of housing loans to households in order to limit their total risks, while their exposure to companies and governments would be increased. In fact, as early as April 2020, according to the ECB’s survey on bank credit distribution, banks anticipated a sharp tightening of access conditions for individuals in the second quarter of 2020.

Medium to long-term impact on fiscal and monetary policies

See Émilie Candus, Christian Pfister and Franck Sedillot, “Où s’investit l’épargne des Français?” Bulletin de la Banque de France, n°214, November-December 2017, pp.5-21.

See Tanguy Aubert and Christian Pfister, “De l’or monétaire à l’or financier“, Réalités industrielles- Annales des Mines, November 2018, pp. 76-79.

Let us now focus on two contrasting scenarios, echoing those of compliance with or challenge to the commitments discussed in Part V. In the first scenario, the fiscal policy followed is that of adjustment; in the second, described as “flight forward”, “fiscal dominance” over monetary policy is implemented either by the central bank or following a selective default by the government vis-à-vis it, after the purchase of government securities in the framework of asset purchase programmes. It is assumed that inflation then resumes to levels comparable to those observed in France in the 1950s and 1970s: “fiscal dominance” produces the expected effects. The second scenario is implemented at the same time as financial repression measures to prevent the debt relief resulting from unanticipated inflation from being partly offset by an increase in inflation and/or default risk premiums on current and future issues.

Adjustment

The adjustment scenario corresponds to fiscal consolidation in the most indebted countries, which are most exposed to liquidity risk (see Part IV). Given its a priori recessive impact, it is likely to succeed only if accompanied by supply-side policies.

These should include the recapitalisation of banks, which in turn will allow credit to resume and capital to be reallocated to the most productive jobs. Indeed, the extreme slowness of bank balance sheet consolidation severely limits any economic recovery in a country like Italy, contributing to the “doom loop” between the deterioration of public finances and the situation of banks that the country has entered since the GFC. Thus, the ratio of non-performing loans to gross loans outstanding still reached 8.4% in Italy in 2018, instead of 6.2% – an already high level – in 2008 (comparable ratios are 2.8 and 2.7% for France, 2.9 and 1.2% for Germany). This recapitalisation could be partly carried out through bank mergers and alliances with foreign partners. Another structural reform with a potentially significant impact on the sustainability of public finances but also on the allocation of assets could concern contingent liabilities, i.e. principally pensions in countries with pay-as-you-go systems (mainly Spain, France and Italy, while Germany and, above all, the Netherlands have a certain degree of capitalisation). This reform could address both the rights in existing systems that are threatened by demographic change and the role that capitalisation could play in the future.

In this scenario, long-term interest rates would not adjust immediately as financial markets would wait until the government has shown its determination to effectively implement these reforms. Bonds from indebted countries would be an attractive investment. Despite bank recapitalisation, real estate could be relatively penalised if supply-side policies were pursued aggressively enough to restore “animal spirits” and subsequently demand for equity investments. Reversing the trend observed during the health crisis and in its wake, corporate debt would replace government debt, with investment loans taking over from treasury loans.

Flight forward

In a context of negative real yields, interest-rate investments (bank deposits, bonds, life insurance contracts in euros) would be penalised. In addition, in the event of a selective default vis-à-vis the central bank of a monetary union, there could be contagion of the risk of default to other members of the union, particularly the most indebted, for fear that they would do the same. There would also be a risk of the monetary union breaking up if the default was considered by some Member States to be in breach of the implicit rules of the union, in particular with regard to the losses inflicted on their residents, non-financial agents and financial intermediaries. Indeed, not only would the prices of the defaulting issuer’s securities collapse, but those of other sovereigns could do the same if investors anticipated that issuers could follow the defaulting country’s lead. Investors holding all of these securities, either directly or, more often than not, indirectly through financial intermediaries, could thus make heavy losses.

Conversely, beyond short-term turbulence in the event of default, which is particularly damaging in a monetary union where cross-holdings of financial assets are significant, indebtedness – and, with it, banking intermediation – would be encouraged by negative real interest rates. Real assets should thus play their traditional role as safe havens and grow faster than inflation.

By major asset classes, the comparison with the precedent of the 1950s-1970s does not, however, make it possible to make a clear guess as to what the evolution of prices might be:

- Although companies were favoured by a high level of indebtedness and prospects for rapid growth, equity investments did not pay particularly well during this period, perhaps due to the context of financial repression resulting, in particular, in unfavourable tax treatment. 24

- Gold, an investment suggested nowadays by a number of hedge funds with a view to monetary degradation, alongside crypto-assets, has only served to protect purchasing 25

- On the whole, real estate has been a very good investment, but, in addition to the level of inflation, it has benefited from specific factors that would not a priori be present in the future (demographic pressure, urbanisation of the population, strong growth in purchasing power, etc.).

In any case, in a “flight forward” scenario, the beneficiaries should be the households most able to access credit and diversify their assets beyond monetary investments, i.e. in principle the wealthiest households. Thus, according to the 2015 INSEE wealth survey, less than a quarter of households in the first quartile of disposable income are indebted, compared with two-thirds in the last quartile.

A type of currency used during the French Revolution.

A reduction of public debt by two-thirds by legal act in France in September 1797.

See Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, This Time is Different. Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press, 2009.

Professed and practised for centuries, through the experience of Law, assignats 26, the two-thirds bankruptcy 27 and post-war inflation, the non-repayment of debt or its repayment at a vile price thanks to monetary debasement is an old moon 28. Yet it led to dramatic episodes, such as the German hyperinflation of the inter-war period and the political and social dislocation which followed.

Even if such a disastrous scenario were not to materialise, choosing today not to assume the consequences of past spending would inevitably have important consequences for the distribution of income and wealth, and thus for future growth and for equity.

No comments.